FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Unique International College [2017] FCA 727

Table of Corrections | |

In [762(c)], the word “Tre” has been replaced with the words “Unique did not inform Tre or Mrs Simpson that he”. |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION First Applicant COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to bring in short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons within 21 days.

2. Stand the matter over for a further case management hearing on Friday, 28 July 2017.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

[1] | |

[4] | |

[16] | |

[33] | |

[35] | |

[63] | |

[79] | |

[103] | |

[108] | |

[113] | |

Australian government form entitled ‘Request for VET FEE-HELP’ | [118] |

Consent form giving permission to Unique to apply for a ‘Unique Student Identifier’ | [123] |

Acknowledgment form acknowledging that online students had received an orientation program | [125] |

Consent form consenting to the use by Unique of still photographs or videos of the applicant in its promotional materials | [129] |

[130] | |

Acknowledgment form acknowledging that the cost of the course had been disclosed | [131] |

[133] | |

[136] | |

[148] | |

[170] | |

[191] | |

[215] | |

[225] | |

[248] | |

[250] | |

[284] | |

[307] | |

[358] | |

[366] | |

[370] | |

[374] | |

[375] | |

[398] | |

[435] | |

[448] | |

[464] | |

[480] | |

[485] | |

[505] | |

[530] | |

[538] | |

[595] | |

[607] | |

[641] | |

[641] | |

[655] | |

[673] | |

[690] | |

[692] | |

[710] | |

[723] | |

[723] | |

[724] | |

[727] | |

[730] | |

[757] | |

10. Application of Principles to Facts as Found – The Individual Consumers Case | [758] |

[758] | |

[762] | |

[766] | |

[769] | |

[771] | |

[772] | |

11. Application of Principles to Facts as Found – The System Case | [773] |

[779] |

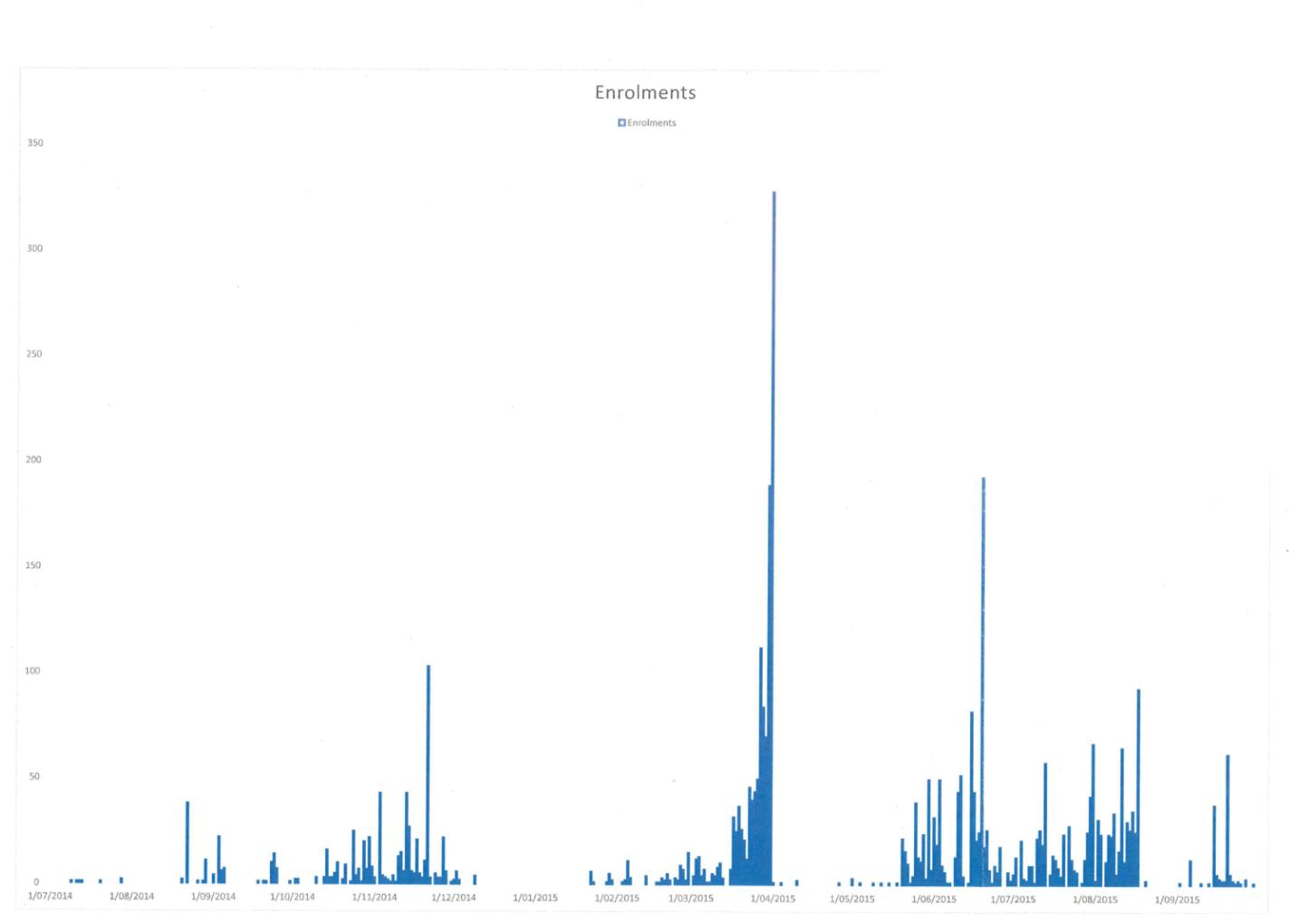

1 The Applicants are the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (‘Commission’) and the Commonwealth of Australia (‘Commonwealth’). The Respondent ('Unique') is a vocational education and training provider operating from Granville in Sydney's west. The Applicants accuse Unique of having breached various provisions of the Australian Consumer Law (‘ACL’): by behaving unconscionably towards six persons it sought to enrol in its courses; by having a system for enrolling its students which was itself unconscionable; and by engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct. They also allege that Unique sought to have people enter into unsolicited consumer agreements without complying with the additional requirements of Division 2 of the ACL.

2 I have concluded that the Applicants have succeeded in proving most of these allegations.

3 The parties are to bring in short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons within 21 days.

4 The Applicants’ case is confined to the period commencing on 1 July 2014 and concluding on 30 September 2015 (the ‘relevant period’). During the relevant period, Unique offered potential students courses in respect of which many students would be eligible for a kind of Commonwealth financial assistance known as ‘VET FEE-HELP’. The four courses relevant to this proceeding were: a Diploma of Management, an Advanced Diploma of Management, a Diploma of Salon Management and a Diploma of Marketing. Unique also offered other courses but these were not eligible for VET FEE-HELP.

5 VET FEE-HELP is a shorthand for Vocational Education and Training FEE Higher Education Loan Program. During the relevant period, which spanned some 15 months, the VET FEE-HELP scheme had these pertinent features:

it was available to Australian citizens or holders of a permanent humanitarian visa who were resident in Australia, provided that they were enrolled in a full fee paying course approved for VET FEE-HELP (as Unique’s four courses were);

the Commonwealth would pay in full whatever the tuition fee was for each unit of the approved course and would treat the combined amounts as a loan to the student;

the loan would be repayable through the tax system once the student began to earn more than the ‘minimum repayment income’ ($53,345 for the period 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015; $54,126 for the period 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2016) on the income above that amount at a sliding scale of between 4% to 8%. The highest rate became applicable at $99,070 during the relevant period;

each person had a maximum lifetime amount which could be borrowed through this and other related schemes (such as HECS). This amount was indexed and was $97,728 for the 2015 financial year. The amount which the student had at any time borrowed was specified in an account maintained by the Commonwealth called the FEE-HELP balance;

there was a 20% loan fee on top of the tuition fee which was also payable to the Commonwealth and which was debited to the student’s FEE-HELP balance; and

the amount of the student’s FEE-HELP balance was indexed to the Consumer Price Index (‘CPI’).

6 An important plank in the Applicants’ case is the suggestion that Unique told prospective students that its courses were free or were free if the student did not earn more than the minimum repayment income. Such a statement, if made, would have been incorrect. Although a student did not have to pay any money upfront on enrolment, the effect of the scheme was that he or she would be left with a CPI indexed debt equivalent to the relevant tuition fee along with an additional 20% fee charged. Whilst it was true that the debt only became repayable once the student earned more than the minimum repayment income and was, at least in that sense, contingent, this is by no means the same as having no debt. Further, the debiting of the FEE-HELP account by the amount of the fee combined with the lifetime cap on that account (here, around $98,000) meant that the student incurring a VET FEE-HELP debt diminished the amount of VET FEE-HELP assistance available to him or her in the future. Those two features guarantee that it is wrong to suggest that a course in respect of which a student would be eligible for VET FEE-HELP was a course which was free. I hasten to add that it was Unique’s position that it had never made such statements.

7 Another important aspect of the Applicants’ case was Unique’s incentive procedures. Of these, there were three.

Unique gave students who enrolled in any of its four courses approved for VET FEE-HELP a free laptop/iPad or, in some cases, a $1,000 cash gift with which to purchase such a device (or were promised an iPad and $200 cash as they progressed through their courses).

It also conducted a student referral programme under which a student who referred another student who enrolled in a VET FEE-HELP course would receive at least a $200 reward and sometimes more (provided, of course, that the student lasted until the census date for their course, which triggered the Commonwealth’s payment obligation to Unique).

Allied with that scheme, Unique also engaged third party contractors to carry out enrolments on its behalf on a commission basis. Following some government disquiet, these arrangements were terminated after 31 March 2015 (with the exception of some payments to Mr Christopher Bell, a Unique employee to whom Unique paid commissions up to 30 June 2015, allegedly because of an administrative oversight).

8 Unique commenced teaching operations some time shortly after October 2007 when it was granted registration under the relevant State and Federal regulatory regimes. For a number of years thereafter its operations were modest and consisted of training a mix of mostly overseas students, but also some who were local. Its enrolment numbers for the years 2008-2013 were as follows:

Year | Number of Students enrolled |

2008 | 177 |

2009 | 367 |

2010 | 394 |

2011 | 676 |

2012 | 789 |

2013 | 631 |

9 Until 2009, VET FEE-HELP had existed in a form which required that for courses to be eligible there had to exist credit transfer arrangements with another institution offering a higher education award. This was to encourage ‘pathways into higher education’. This required, in practice, VET providers to enter into course credit transfer arrangements with those other institutions. Unique actively sought out and secured such arrangements during the period 2011 to 2012. The institutions with which it entered into credit transfer arrangements during this period included the University of Ballarat, the Australian Catholic University and the University of New England. Even so, Unique did not obtain registration of any of its courses at that time for VET FEE-HELP. Because its courses were not approved under the VET FEE-HELP scheme, Unique was not able to offer VET FEE-HELP funding for its students.

10 Consequently, during this period the VET FEE-HELP scheme had no effect on Unique’s enrolments.

11 In 2012, however, there was a change in government policy following a review of the VET FEE-HELP scheme and it was decided by the Commonwealth that there would be a change in the laws under which VET FEE-HELP was provided. With effect from 1 January 2013, the requirement that a VET FEE-HELP eligible course count towards a course at another institution of higher education was removed. Having been apprised of these potential changes by the Department of Education and Training (‘the Department’) in June 2012, Unique commenced a process of obtaining registration of four of its courses for VET FEE-HELP under the revised scheme and it achieved that registration on 27 November 2013 (the cause of the one year delay in obtaining registration is of no present relevance). Its enrolment numbers now substantially increased as follows:

Year | Number of Students enrolled |

2013 | 631 |

2014 | 3,251 |

2015 | 4,677 |

12 A factor which may have contributed to this dramatic increase in enrolments was Unique’s practice from 1 January 2014 of making its courses available online. Before that time, it had been necessary for students to attend at its Granville premises. However, once the four courses which were offered under VET FEE-HELP were made available online, this removed the necessity for any geographical link to Unique’s premises.

13 The increase in Unique’s enrolments directly increased its revenues. Those revenues and net profits after tax for the financial years 2013-2015 were thus:

Year | Revenue | Net Profits after tax |

2013 | $1,702,612 | $40,301 |

2014 | $15,942,949 | $8,214,031 |

2015 | $56,183,632 | $33,779,726 |

14 The severing of the geographical nexus with Granville at the end of 2013 also allowed Unique to obtain enrolments from persons distributed widely across eastern Australia. It did so by sending staff members on road trips to various inland urban centres and conducting thereat ‘sign-up’ meetings at the homes of a chosen local resident. It is not disputed that these ‘sign-up’ trips were made across many regional areas of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland and that many students were signed up via them.

15 With that background set out, it is useful now to turn to the Applicants’ pleaded case.

3. The Applicants’ Pleaded Case

16 At the risk of stating the obvious, the Applicants’ case was not that Unique had behaved unconscionably towards the Commonwealth. It was not said that the Commonwealth itself had been misled or that Unique should compensate the Commonwealth for bad loans made. Its case instead was focussed on the proposition that it was Unique’s students who had been the victims of the allegedly unconscionable or misleading behaviour. From time to time, the Applicants pointed to the very significant sums which Unique had received from the Commonwealth to buttress their substantive submissions. For example, it was put, not without force, that the possibility of deriving such enormous revenues could easily be seen as providing a motive for Unique to strive to increase the number of its enrolments. At other times, it seemed to be advanced as a form of forensic panacea for whatever difficulty of proof might, at any particular point in the trial, have been encountered by the Applicants.

17 But the Applicants’ case is not a case about the misappropriation of Commonwealth funds, nor is it a case, despite the way it was sometimes depicted outside the courtroom, about rorting by Unique of a Commonwealth scheme. The Applicants’ case was, from beginning to end, a case alleging the unconscientious exploitation and misleading of students. Such a case is by no means the same as a case which directly alleges that the Commonwealth has been defrauded. It is quite possible for the rorting of a scheme to happen without exploitation of students. It is also equally possible for exploitation of students to occur in the absence of rorting. One needs to be careful to distinguish the two and to ensure that one’s instinctive sense of outrage at one matter, which was not alleged or proved, does not affect one’s assessment of the other.

18 The Applicants’ case had two distinct elements although, as will be seen, they were to an extent intertwined.

19 The first element was located in Part 2 of its Amended Statement of Claim dated 9 May 2016 (‘ASOC’) and was focussed on Unique’s enrolment processes. In a nutshell, the allegation was that Unique had an enrolment process and that this process was inherently unconscionable. Paragraph 21 of the ASOC pleaded the nature of the enrolment process. Paragraph 22 pleaded the alleged failures which inhered within that process. Paragraph 23 pleaded the kinds of consumers who might be ensnared by such a process. Paragraph 26 pleaded that Unique had done this to maximise its revenues. Paragraph 28 alleged correlatively that it was likely also to have caused loss to the consumers. Paragraph 29 brought it all together and alleged, for various reasons, that the conduct thus disclosed was unconscionable.

20 These allegations may be summarised as follows:

21 It was alleged that Unique had targeted particular locations for enrolment purposes. These towns and cities were said to be situated in areas where inhabitants were generally people of lower socio-economic means and/or were comprised of a higher percentage of indigenous persons than the average eastern Australian town or city. These locations were said to include: Bankstown, Boggabilla, Bourke, Brewarrina, Emerton, Moree, Taree, Toomelah, Walgett, Wagga Wagga and Granville. At these locations it is then said that Unique conducted marketing operations by, inter alia, calling on consumers at their homes for the purpose of conducting group marketing activities. At these group marketing events, it is alleged that Unique’s staff told the attendees that its courses were free or free until they reached a particular level of income following completion of their chosen course. At the same time, free laptops were allegedly handed out to those who signed up. It is also alleged that the staff were on remuneration arrangements which were based on the number of students whom they were able to convince to enrol.

22 Against the backdrop of what the Applicants alleged was involved in the enrolment process, they went on to then allege a number of matters which they said that process did not include. It was said that Unique did not:

ascertain whether the students had the capacity to pay the course fees;

explain to the students the nature of the VET FEE-HELP scheme; in particular, the nature of their obligations to the Commonwealth if they received a loan under it or that they would be left with a contingent debt;

ascertain whether the students intended to undertake the course;

ascertain whether the students understood they were enrolling in a course; or

ascertain whether the students had read and understood the forms they were asked to sign (and related allegations).

23 At the risk of oversimplification, the enrolment process alleged was therefore one involving group meetings at homes in particular areas at which consumers of educational services were given laptops if they signed up to courses and were told either that the courses were free or, at least, would be free until they achieved a certain level of income. This marketing was performed by Unique’s staff members who were paid by reference to the number of consumers they successfully enrolled. Forms were then filled out which were not explained and, at the same time, no effort was made to ascertain the suitability of any particular student for a course. No explanation of the VET FEE-HELP system was given.

24 The second part of the case was not concerned with Unique’s system. Instead, at paragraphs 31 to 143 of the ASOC, the Applicants set out their case that Unique had engaged in unconscionable behaviour towards six identified consumers. The allegations in each case related to the signing up of each of the six consumers to Unique’s courses at three separate signing up meetings conducted by its staff in outlying parts of New South Wales. The visits were to areas which the Applicants identified as being socio-economically disadvantaged and with a high proportion of indigenous members of the community. The three visits and the consumers involved were as follows:

Walgett (on Friday, 10 October 2014) in respect of Ms Natasha Paudel (referred to in the Applicants’ pleading as Consumer E);

Tolland, a suburb of Wagga Wagga (on Monday, 30 March 2015), in respect of Ms Kylie Simpson (Consumer A) and Mr Tre Simpson (Consumer F); and

Bourke (on Wednesday, 10 June 2015) in respect of Ms Jaycee Edwards (Consumer B), Ms Fiona Smith (Consumer C) and Ms June Smith (Consumer D).

25 The thrust of the case was, subject to minor variations between the various consumers, three-pronged.

26 First, it was said that Unique had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in relation to each of the consumers (apart from Ms Natasha Paudel) because it had not informed any of them that the courses were not free and that each would be left with a debt to the Commonwealth under the VET FEE-HELP scheme. These were alleged to be ‘representations by silence’ which were false or misleading (or likely to mislead or deceive). In relation to some of the consumers, it was further alleged that direct representations of a misleading nature were made; for example, that the laptop and course itself would be free (June and Fiona Smith).

27 Secondly, it was alleged that Unique had behaved unconscionably towards the consumers because of its failure to explain the nature of what they were signing up to in circumstances whereby, putting it shortly, this was combined with an aggressive enrolment process and where there were elements of disadvantage in the circumstances of each of the individual consumers. I will delay explaining these individual circumstances for now save to say that they largely related to issues of literacy and education.

28 The third prong was a narrow allegation that Unique had engaged in the practice of seeking to procure entry by the six consumers into unsolicited consumer agreements without complying with the additional requirements of Division 2 of the ACL. This was also put forward as an element of the Applicants’ case on unconscionability.

29 An interesting aspect of the case alleged in relation to the individual consumers is that it relied, in part, on the Applicants’ more general system case pleaded in relation to Unique’s enrolment processes. This can be seen, for example, at paragraph 48 of the ASOC (in relation to Ms Kylie Simpson) which explicitly picks up the system case pleaded at paragraphs 21 and 22. A related curiosity is that the system case at paragraph 27 of the ASOC alleges that the individual consumers’ cases are to be seen as manifestations of the system case. It is possible this results in some circularity. However, it is best not to be distracted by these pleading issues in the abstract. This is because the pleadings do sufficiently identify the four principal areas of evidentiary dispute between the parties. These are:

the nature of Unique’s enrolment system;

the events at Walgett on 10 October 2014;

the events at Tolland on 30 March 2015; and

the events at Bourke on 10 June 2015.

30 The Applicants also relied upon some events at Taree although not in relation to individual consumers. Each of these topics is hotly in dispute between the parties. Unique says that its enrolment processes were proper and called witnesses from amongst its staff and officers to make good this point. These witnesses were cross-examined extensively by Senior Counsel for the Applicants to suggest that their evidence was unreliable. The basic thrust of the cross-examination, to strip it of much of its undoubted subtlety, was that the evidence produced by Unique of its proper processes was concocted after the event for the purposes of this proceeding.

31 Some of the witnesses called by Unique in relation to its systems also gave evidence about the events at Walgett, Tolland and Bourke. Their evidence was to the effect that the presentations to would-be consumers which Unique, through its staff, had conducted had been adequate and appropriate. The Applicants called a number of witnesses who were present at these meetings to give evidence about the deficiencies of what had occurred. These witnesses were cross-examined by Senior Counsel for Unique with a view to establishing, inter alia, that their recollection was not clear or that they did not know precisely what was going on.

32 The case therefore presented the unusual spectacle of most of the witnesses being subject to serious credit attacks. Both sides achieved a measure of success in this regard. The resolution of the factual debate in this case is, therefore, a very complicated affair and, if I may say with respect, much more complicated than either side’s submissions assumed. Both sides argued that most of their own witnesses were reliable and most of the other side’s were not. This was an overly simplistic approach to a much more complex situation. Many of the witnesses on both sides were plainly unreliable in one way or the other. A dose of realism in the parties’ submissions would have been helpful. I will start with the evidence before moving to my ultimate findings.

4. The Applicants’ Lay Witnesses

33 There were eight lay witnesses for the Applicants. There were also some formal affidavits read relating to enrolment data which do not need to be assayed. The eight lay witnesses were:

Natasha Paudel;

Margaret Simpson;

Kylie Simpson;

Jaycee Edwards;

June Smith;

Fiona Smith;

Larissa Kidwell; and

Penny Martin.

34 I deal with these in turn.

35 Ms Paudel affirmed an affidavit in this proceeding of 29 March 2016. She gave oral evidence on the fourth day of the trial which was 9 June 2016.

36 The evidence of Ms Paudel relates to events which most likely occurred on 10 October 2014 (the date on her enrolment form) at Walgett. Ms Paudel is around 30 years old, Aboriginal and lives in Walgett with her family. At the time of the events which underlie this proceeding, she was living with her parents as she had been involved in a car accident and was in the process of recovering. This should be emphasised because her recovery from this car accident was a part of the Applicants’ case on unconscionability. I admitted evidence by Ms Paudel that at this time she thought she was in a ‘vulnerable headspace’ but only as evidence that that was her own opinion. There was no expert testimony that the sequalae of the car accident rendered Ms Paudel vulnerable or unable to understand what she was doing.

37 She completed year 12 at high school although not any further training. She has good computer skills and can use the internet. When she gave evidence in the proceeding she was employed as a school learning support officer at Walgett Primary School. She has also worked part time at a women’s refuge. She has had a number of other responsible positions such as the hostel manager for the Darungaling Hostel which assists Aboriginal people engaged in tertiary study in the Newcastle area. She has also worked at the Attorney-General’s Department assisting Aboriginal people involved in cases before the Local Court and the Victims Compensation Tribunal. As I relate below, she has previously earned more than $50,000 per annum.

38 Ms Paudel gave her evidence in a careful and considered fashion. Both sides submitted that she was a witness of credit whose evidence should, in general, be accepted. I agree with those submissions. She struck me as an impressive witness who was both intelligent and endeavouring to assist as much as she could by her evidence.

39 Mr Alan Tighe is a member of the extended family of Ms Paudel’s mother and is known to Ms Paudel. At some point in October 2014, Ms Paudel was driving with another person along Sutherland Street in Walgett when she saw a group of about four to five people standing outside a house she knew to be Alan Tighe’s. One of these persons was Mr Billy Jones, who was also known to Ms Paudel. She decided to pull over to the kerb and ask Billy Jones what was going on. He replied, in effect, that if she wanted to get a free iPad or laptop she should sign up for a Diploma of Management or Salon Management. Ms Paudel’s evidence did not include the suggestion that Billy Jones had said explicitly that the iPads and laptops would be free but I am satisfied that this was conveyed. Ms Paudel subsequently reported the conversation to her cousin, Trishy Anne Walford, and in that account of her initial conversation it is apparent that she attributed to Billy Jones the statement that the iPads and laptops would be free. As will become clear, iPads and laptops were being handed out at Alan Tighe’s house and it is altogether plausible, indeed likely, that Billy Jones would have said this.

40 Ms Paudel gave evidence that she also asked Billy Jones which course he was doing and he said that he was doing salon management. This made Ms Paudel laugh, I infer, because of the unlikelihood of Billy Jones being involved in salon management. It was probably at this point that Billy Jones told Ms Paudel that the courses being offered were also free. Ms Paudel did not mention this in her evidence in chief but she did mention it under cross-examination. She was challenged as to whether she was mistaken and that the reference to the courses being free was perhaps really a reference to the iPads and laptops being free but this she did not accept. Although, as I indicate below, she did not pretend to have a perfect recollection of the precise train of events, I am satisfied nevertheless that Billy Jones did say this to her.

41 The impression that this encounter between Ms Paudel and Billy Jones, which opens with a fragment of conversation about an unidentified course and free computer equipment, does not make terribly much sense is borne out, I think, by the fact that Ms Paudel was disinclined, at least initially, to take Billy Jones seriously.

42 In any event, by that evening it seems that Ms Paudel had understood that the deal being offered by whomever Billy Jones had himself been talking to was that she would receive a free iPad or laptop if she enrolled in a course and the course was free. She said as much to her cousin, Trishy, at least in relation to the iPad and laptop.

43 But the iPad and laptop were not her only motivations. Ms Paudel also gave evidence that she had some interest in doing a management course at this time. In fact, she claimed to have been in negotiations with another government provider possibly to ‘do a management role back in Newcastle’ at that time. I infer that her interest in returning to Alan Tighe’s house to explore the situation further was therefore twofold. On the one hand she was motivated by a significant interest in obtaining free computer equipment; on the other, she also had some interest in the subject matter of the courses being offered.

44 Ms Paudel and Trishy then decided to go back to Alan Tighe’s house the next day and to find out what it was all about. Ms Paudel did not explain in her evidence why she thought that the iPads and laptops would still be available the next day at Alan Tighe’s house but the most likely explanation is that something else to that effect may have been said to her by Billy Jones. Perhaps, alternatively, she did not know this but just thought it was worth a try. I do not need to resolve this issue, however, because there is no doubt that she did go back and that the iPads and laptops were still available when she did

45 It was Ms Paudel’s evidence that she and Trishy arrived at Alan Tighe’s house just after lunch on the next day. Upon entering the home, Ms Paudel saw two sales representatives sitting at a table, both of whom were Indian women. I interpolate at this point that I am satisfied that the two women involved were Ms Mandeep Kang and Ms Jasmeen Kaur (‘Jasmeen’), both employees of Unique. There was also a third male employee present who I am satisfied was most likely Guramrit Singh Jandu (‘Rubbal’). On the table were piles of forms with the words ‘Apply for VET’ written on them. There were also boxes filled with iPads and laptops.

46 The tableau was as follows: there were a number of people standing around the table some of whom were known to Ms Paudel; she saw people filling out the forms with the assistance of one of the sales representatives; and, upon completing the forms, being handed an iPad or laptop in a box. Ms Paudel described the room as one in which people were ‘coming and going’.

47 She very frankly agreed that her recollection of events was not perfect which was a reasonable concession to make and to her credit for so doing. Under cross-examination she agreed that the two women had said they were an ‘approved provider’. I suspect she really meant by this that they had said Unique was an approved provider. It would be natural for them to have said so and in her evidence Ms Paudel appeared to accept that someone had mentioned Unique at some stage during her time at Alan Tighe’s house. I accept that the following answer that she gave about this during cross-examination at T-331 was not as clear as it could have been:

‘Did they tell you – or someone tell you – I withdraw that. Did one of the Indian ladies tell you they were from Unique College?---I can’t remember if they said those words, but I just remember Sydney. So – yes.’

48 However, given the practical exigencies of the situation I think this would have been said and I take this answer to be some evidence, although perhaps not the best, that it was. In any event, I accept that Ms Paudel was informed by the two Indian women that the courses were being offered by Unique. It is very likely at around the same time that she was also told there were two courses on offer: the Diploma of Management and the Diploma of Salon Management. She had, of course, heard this the day before from Billy Jones in her initial encounter with him on Sutherland Street. The question of timing is an inference I have drawn but there is no doubt this was said and this seems to be the natural time at which it would have been said.

49 At some point, one of the sales representatives handed Ms Paudel one of the forms headed ‘Apply for VET’. She saw the words ‘Diploma of Management’ on the form together with a figure of around $20,000. The $20,000 was a reference to the tuition fees for the course in the Diploma of Management. Of course, she had been told by Billy Jones the day before that the courses were free. Ms Paudel herself was puzzled by why the course would cost $20,000 but did not think to ask about this at the time. In any event, as she accepted under cross-examination, whatever had been said about the courses being free, she knew by the time it came to considering the form that the course she was signing up to cost around $20,000.

50 It is necessary to pause here to observe that Ms Paudel did not give evidence that any of Unique’s representatives had told her that the courses were free. Her evidence about the courses being free was singularly derived from what Billy Jones had told her. And, contrary to her prior belief, she knew once she saw the forms that at least one of the courses actually cost $20,000. It is fair to say, therefore, that the only evidence about what Unique’s representatives said about the cost of the course was that which was contained in the forms she was handed. Ms Paudel’s evidence establishes that she knew that the forms said the course cost $20,000.

51 Some interim conclusions follow from this. First, no-one from Unique told Ms Paudel that the course would be free. Secondly, Unique – through its application form – told at least Ms Paudel, that the course would cost $20,000. Thirdly, Ms Paudel understood this.

52 Ms Paudel also accepted that she had been told that the $20,000 tuition fee would be paid by a loan from the government which would not be repayable until she earned more than $50,000 (although, as I have explained, the minimum repayment income was $53,345 at this time, I do not make anything of this discrepancy). During her cross-examination, Ms Paudel said that her understanding about VET FEE-HELP at this time was not complete (she understood it ‘a little bit’: T-323.11). In this, she is no doubt correct. I do not think, for example, that at the signing up session she understood that the loan would be paid back through the tax system. However, I am satisfied she understood that the tuition fees would be lent to her and that she would have to repay them when her income reached around $50,000.

53 Some other matters emerged during the cross-examination. It seems likely that she was told that the course was offered online which made it attractive to her and that it was possible to cancel enrolment prior to some date not made very clear in the evidence. I infer that the date in question was what is known as the census date. I explain this concept more fully below. For present purposes, I am prepared to infer that Ms Paudel was told she could withdraw up to the census date. It seems she was also told that a support person was offered by Unique who could be called in the case of query and that she would be sent further documentation by that person.

54 At some point during this process – most likely at its conclusion – Ms Paudel completed the paperwork encompassed in the forms she had been provided. It appears that the forms had asterisks next to sections which she was asked to complete but that employees of Unique filled out the balance of the form later on. In particular, there were several sections containing ticks which Ms Paudel said were not done by her (I accept Ms Paudel could recognise her own handwriting). Some of these ticks were next to statements acknowledging matters such as that particular information had been provided or that she had read and understood the obligations arising from the VET FEE-HELP scheme. I accept that Ms Paudel did not tick these boxes and had not been acquainted with these matters (although as I explain later, I am also satisfied that she understood what she was doing).

55 The forms also included a signed declaration in the following terms:

‘I acknowledge that I have been given the correct information on the total due fees for my chosen course which is ____________________ and understand that I have to start repaying the due fees plus the 20% loan fee back once I start earning above the minimum threshold __________________ as per VET FEEHELP Information for 2015.’

56 Ms Paudel did not recall the 20% fee being mentioned although she accepted that it was possible that it had been mentioned. I am not satisfied that the 20% fee was not brought to her attention.

57 Importantly, she did say, however, that one of the Indian ladies had said to her that if she started to earn more than $50,000 she would have to start repaying the government. For completeness, Ms Paudel had, at the time she signed the form, already previously earned more than $50,000, so I do not think that for her the possibility that repayment would become necessary was academic

58 All up the filling out of the forms appears to have taken about 15 minutes and she was otherwise present at Alan Tighe’s house for about half an hour. She described the form filling as ‘very quick’: T-320.14.

59 No evidence was led that Ms Paudel received a laptop. I infer, however, that she did. It was one of the reasons she had gone to Alan Tighe’s house and Unique’s representatives were in fact giving out laptops. I can see no reason why this would not have occurred.

60 Ms Paudel did not report seeing the representatives of Unique giving an introductory session during which they explained the details of the courses to the people present. I discuss this in more detail below but Unique’s witnesses gave evidence that such a detailed introduction did occur and that it was during that introduction that the nature of the courses and the VET FEE-HELP scheme were fully explained. Because Ms Paudel is a reliable witness I am confident that she did not see such an introduction being given whilst she was there. Had she done so it would have been mentioned in her evidence; but it was not. Counsel for Unique – correctly accepting with respect that she was a reliable witness – put to Ms Paudel that she may have arrived after the information session was given, with which she agreed

61 For present purposes, it is sufficient to accept that contention. There is no utility in asking, in relation to the case concerning Ms Paudel, whether the introductory session was in fact given if she was not there when it is said to have occurred.

62 After she left Alan Tighe’s house, Ms Paudel began to develop doubts over the legitimacy of the enrolment process and, in fact, that what was involved with the enrolment process was some form of ‘scam’. These doubts were inspired by a conversation she had with a relative of hers who warned her that enrolling in the course would merely leave her with a debt. She subsequently received an email from Unique and decided to call the college. During that telephone call she was told that Unique did not involve a ‘scam’. She subsequently received some emails from Unique about the courses but she has never taken any further step to pursue the course in which she had enrolled on that October day. As at the date of the hearing she was unaware whether she had a VET FEE-HELP debt or not.

63 Mrs Simpson swore two affidavits in this proceeding; one of 25 January 2016 and another of 17 May 2016. She gave oral evidence on the fourth and fifth days of the trial which were 9-10 June 2016. Her being called was chiefly to give evidence in relation to two of the six consumers in the Applicants’ individual consumers case which, as I have explained, also bears on the Applicants’ system case.

64 Primarily, Mrs Simpson gave evidence of the difficulties encountered by her grandson, Tre Simpson, referred to hereafter as ‘Tre’. Tre is now a 22 year old Aboriginal man. He requires full-time supervision (for reasons which I shall explain) which Mrs Simpson has provided to him his entire life. Unique accepted in its written submissions that Mrs Simpson’s evidence of Tre’s demeanour and nature was credible and was the product of many years of close range observation. Tre’s conditions are many. He has neurofibromatosis, also known as Von Recklinghausen’s Disease, Attention Deficit Disorder, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (Adolescent). Until just before the trial, he was taking Risperidone, an antipsychotic medicine, and at earlier times he has taken dexamphetamine, Ritalin and anti-depressants. A few months prior to the events which I am about to relate, he was diagnosed with depression as a result of which he did, on occasion, take Mirtazapine. I note in passing that he no longer does so, although he continues to be prescribed Risperidone.

65 According to Mrs Simpson, although Tre is 21 he acts like he is 15. He cannot manage money or handle change. He does not talk much and particularly not to strangers. When he does speak (usually to friends or family) Mrs Simpson said it is often very difficult to follow what he is saying. He speaks without thinking, has no patience and cannot concentrate. He becomes abusive without provocation. Because of his difficulties, Mrs Simpson is unable to leave Tre unsupervised and has to attend meetings with him as she said he cannot look after himself. The evidence suggests that Tre can read, at least to an extent. He left school after completing year 10 at high school and Mrs Simpson gave evidence that he had used a computer in the past. I accept this evidence.

66 Tre was not called to give evidence before me. Although no explanation for this was given, I am prepared to infer that Tre was unwilling to travel to Sydney for the hearing. Certainly Mrs Simpson gave evidence that he was too scared to do so. Unique made no criticism of the decision by the Applicants not to call Tre. I think it reasonably plain that his various difficulties would have made the eliciting of evidence from him very difficult.

67 Nevertheless, that leaves me in something of a quandary. Although I am aware from Mrs Simpson’s evidence of the various difficulties which Tre faces, I am not aware of the extent to which these problems may be obvious to others. I say that having particular regard to Mrs Simpson’s evidence that he is silent around strangers. She also gave evidence that he could answer simple questions.

68 It has not been shown to my satisfaction that Tre’s difficulties would have been obvious to Unique’s staff. Accepting Mrs Simpson’s evidence that he did not look healthy because he did not eat properly, he might merely have seemed at the sign-up meeting an unhealthy and silent youth; perhaps a not unrecognisable condition to those used to dealing with young adults in Tre’s situation. Although Mrs Simpson gave evidence that he could be abusive at times it was not her evidence that he was abusive during the meeting.

69 Turning then to what Mrs Simpson said happened at the meeting (which was not the only topic she addressed in her testimony), it was largely unhelpful to Unique. For that reason Unique submitted that this aspect of her evidence was unreliable whilst not going so far as to submit that Mrs Simpson was dishonest. I think it useful to begin with what Mrs Simpson’s account was, then to address these criticisms.

70 Lavina Merritt (whom Mrs Simpson calls Aunty Vennie) had driven over to Mrs Simpson’s house following a chance encounter in the street. This occurred as Mrs Simpson was en route home after visiting her daughter’s house. Aunty Vennie had pulled up in a car driven by a man with whom Mrs Simpson was not familiar. She said that that he ‘looked Indian in appearance’. A short discussion ensued which involved, in a similar fashion to the conversation between Ms Paudel and Billy Jones in Walgett, the topic of free laptops. Mrs Simpson gave evidence that she then walked home, soon after which she again met with Aunty Vennie and that same man whom she now believed to be ‘some kind of salesman because he was not from around my area’. This occurred out the front of Mrs Simpson’s house.

71 Mrs Simpson then invited the two of them into her home, which provided Aunty Vennie with an opportunity to remark to Tre that a free laptop was available to him. Mrs Simpson’s evidence was that Tre then ran through the house and said “Aunty Vennie’s got laptops’. He was to Mrs Simpson’s observation excited. This was not a novel situation for Mrs Simpson. On a prior occasion, Tre had obtained a free laptop from some other vocational entity. When Tre mentioned the free laptop on this occasion she remarked ‘Oh Tre, not again.’

72 At this point, Tre was running through the house looking for his tax file number and pension card (he receives the disability support pension). It seems likely that he was told that he would need these and it seems to me that it is most likely Aunty Vennie who told him this.

73 The three of them then drove from Mrs Simpson and Tre’s house in Wagga Wagga to Aunty Vennie’s house at Tolland. When they arrived, Mrs Simpson saw about 10 people there which she said caused her to remark to Aunty Vennie ‘What a line up, it’s like Centrelink’. The people who were there were all signing application forms. As will be seen, this is apt to suggest that Mrs Simpson and Tre had arrived at an event which had already commenced.

74 When she arrived, Mrs Simpson saw two women sitting at a long table who were of Indian appearance. It is clear from evidence led later in the trial that these must have been Mandy Kang and Jasmeen. They did not identify themselves or where they were from. According to Mrs Simpson, one of these women immediately handed her some papers and a test to complete. At the time this occurred, Mrs Simpson said that no explanation was provided for what this paperwork was. In any event, she and Tre went to the front of the house and sat on some tables and chairs on the front lawn.

75 Before turning to what Mrs Simpson and Tre did with this paperwork, it is useful to describe what it was. The paperwork was comprised of eleven separate forms:

1. A pre-enrolment questionnaire;

2. A pre-enrolment test;

3. An acknowledgment form headed ‘Information session’;

4. An enrolment application and agreement form;

5. An Australian government form entitled ‘Request for VET FEE-HELP’;

6. A consent form giving permission to Unique to apply for a ‘Unique Student Identifier’;

7. An acknowledgment form acknowledging that online students had received an orientation program;

8. A consent form consenting to the use by Unique of still photographs or videos of the applicant in its promotional materials;

9. An evaluation form assessing the student induction process;

10. An acknowledgment form acknowledging that the cost of the course had been disclosed; and

11. A student feedback form.

76 In her affidavit, Mrs Simpson said that she filled out these forms as best she could for Tre. This included his name, age and address. In relation to the second document mentioned above (a pre-enrolment test) she said that she obtained assistance from a friend of hers who was present at the meeting, called Mel Connors. I shall call her Mel. During her cross-examination, Mrs Simpson gave additional evidence that Mel might have assisted with filling out some of the other forms too.

77 During her cross-examination, Mrs Simpson was taken to a number of the documents referred to above. In a number of instances she denied the writing was hers although in others she accepted it was.

78 The forms are, nevertheless, interesting and by themselves throw light on what was taking place. I deal with each in turn:

79 The first form was that entitled ‘Pre-Enrolment Questionnaire’. Its front page said this:

‘(The purpose of this questionnaire is to determine the potential student’s suitability to the course.)

Unique International College (UIC) delegate will use this form to conduct an interview with each applicant to assess suitability into the qualification. The SMD179 Local Student enrolment application and agreement form will be completed and signed by all local students after an interview has been successfully completed. Students who wish to enrol under VET FEE-HELP program must complete additional documents e.g. Request for VET FEE-HELP assistance forms, VFHD 2 information session acknowledgement form etc.

A Student meets the entry requirements in line with SMP 133 Student entry requirements, enrolment and orientation policy if the student provides satisfactory answers to all the following questions asked by Unique International College (UIC) Delegate.’

80 Mrs Simpson’s affidavit evidence was that she filled the form out with Tre. According to her affidavit evidence, Mel did not help with this form but only with the maths questions which were in the second form, the pre-enrolment test. In cross-examination it appeared that Mel’s role might have touched upon other forms. In any event, the critical point is that Mrs Simpson gave no evidence of any person from Unique conducting the test as this form suggested should have happened.

81 The evidence led by Unique in relation to Mrs Simpson and Tre consisted of the testimony of Ms Kang, Jasmeen, Mr Christopher Bell and his partner, Thea Merritt (‘Thea’). As will be seen, these witnesses gave evidence of an allegedly invariable practice of Ms Kang’s of conducting a presentation at the start of each meeting. It was during this presentation that she imparted what was said to be an adequate explanation of the nature of the course and, more generally, the VET FEE-HELP scheme to the assembled potential students. Jasmeen and Mr Bell gave corroborating evidence of this practice. Ms Kang gave evidence of having given assistance to Tre in completing some of the paperwork by filling out his student feedback form (form 11 in my list above). As I discuss when dealing with Ms Kang’s evidence, I reject this. Ms Kang completed this aspect of the paperwork without consulting him when she discovered it was incomplete. Later in these reasons I conclude that the evidence of all four of these witnesses on the topic of Ms Kang’s presentation is unreliable.

82 Something additional should also be said of the evidence of Thea. She is Aunty Vennie’s granddaughter. She was present at the same meeting at Vennie’s house. She corroborates Ms Kang’s evidence that a presentation was given at the outset of that meeting. However, that may be irrelevant because Mrs Simpson’s evidence suggested that she and Tre arrived at a time when the 8 or 9 people present at the meeting had begun filling out the forms, that is to say, after the time at which Ms Kang would have allegedly given the presentation to which she testified.

83 If that be so, there arises no direct collision between Ms Kang’s evidence about her presentation and Mrs Simpson’s evidence about the meeting because they can be reconciled by the fact that Mrs Simpson and Tre arrived late.

84 Thea’s evidence complicates this, however. During her cross-examination at T-1241 Thea gave evidence that Mrs Simpson and Tre had arrived with Mrs Simpson’s daughter, Kylie Simpson (‘Kylie’) and that Kylie had been present during Ms Kang’s presentation. This carried with it the further implication that Mrs Simpson and Tre had been present for the presentation. Thea also contradicted Mrs Simpson’s evidence that she and Tre had filled out the forms outside the front of the house. She said, rather, that she had seen them filling the forms out inside the house with the others.

85 How may this conflict be resolved? It has not yet been necessary to deal with the evidence of Kylie who was also present at the meeting. Kylie, like Tre, is one of the persons in the Applicants’ individual consumers case and it will be necessary to deal with her evidence in relation to that aspect presently. However, she also gives evidence which has ancillary relevance to the case about Tre. This is because she too came to Aunty Vennie’s home.

86 Kylie’s affidavit evidence about this was that she had been at home with Mrs Simpson and Tre. One might have taken from this at least that Kylie lived in the same home as Mrs Simpson. However, Mrs Simpson’s evidence was that Kylie lived around the corner. I think that Kylie’s evidence simply means therefore that Kylie was at Mrs Simpson’s home. Kylie said that Aunty Vennie came around and took Mrs Simpson and Tre to Aunty Vennie’s home in Tolland. She then said that Aunty Vennie returned about 20 minutes later and took her and Regina, who is her sister, to Aunty Vennie’s home at Tolland.

87 Unique submitted that Kylie’s evidence contradicted Mrs Simpson’s as to whether both were present at the house at Tolland at the same time citing T-430.1 and T-464.21.

88 Mrs Simpson’s evidence was, at T-430, that Aunty Vennie took the two of them to her home. When they returned to Mrs Simpson’s home afterwards, Kylie was there and it was then that Aunty Vennie took Kylie to her home. Kylie’s evidence was that the three of them (Mrs Simpson, Tre and herself) were at Mrs Simpson’s house, Aunty Vennie picked up Mrs Simpson and Tre and took them to her house. It was at this point that Aunty Vennie returned and took Kylie and Regina to her house. On this view, Mrs Simpson and Tre were still at Aunty Vennie’s house along with the Unique employees when Kylie arrived. Consistent with that version of events, Kylie said she saw Mrs Simpson and Tre there.

89 Kylie was cross-examined by Senior Counsel for Unique. I will expand on this later when I deal with her direct evidence about her own dealings with Unique. However, I formed a strong view during her cross-examination that, with respect, she had very little grasp of what was going on around her. For example, she was asked during her examination in chief about the forms she had signed at the sign-up meeting. The exchange with counsel is reproduced below:

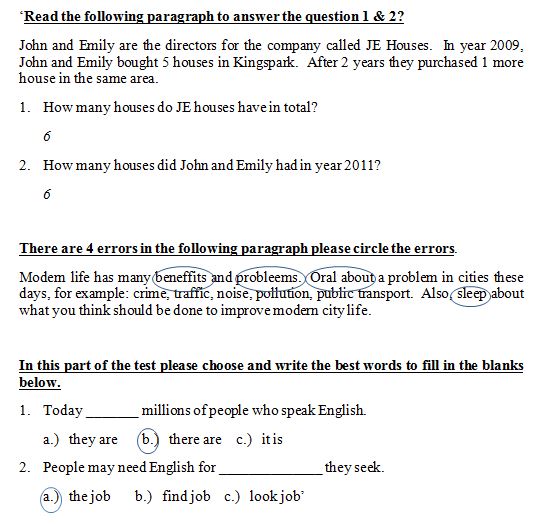

‘Did anyone read the following text to you:

“John and Emily are the directors for the company called JE Houses. In year 2009, John and Emily bought 5 houses in Kingspark. After two years they purchased one more house in the same area.”

1. How many houses do JE houses have in total?’

(errors in original)

90 At T-452, Kylie answered this question ‘Six’ (the question was whether anyone read her the question). This was not an isolated example of her comprehension difficulties. In her affidavit of 25 January 2016 at paragraph 35 she said that she thought that she might be signing up to a course but during her oral evidence at T-460 she said that no one said anything about a course to her and she did not think she was signing up to one. She then agreed at T-460 during oral evidence that her affidavit evidence in this regard was incorrect (i.e. she had not thought she was signing up to a course) but then moments later during oral evidence she indicated at T-461 that she may have been signing up for a course.

91 She was asked whether she understood the course was offered online. During her cross-examination at T-471 this exchange occurred:

‘See, well, did you understand the course that was being offered was online course? --- Online?

Yes, online? --- I’ve got no internet at home. I couldn’t do nothing at home because I’ve got no internet.

But did you understand the course being offered was online? --- No. This one here, all the ticks on here, I never ticked all these ones here.

What was that, I’m sorry? --- This one here.

Yes? --- 4 to 6.

Yes? --- I never seen this one, I never ticked all these ones here.’

92 She also gave evidence about her signature which I cannot accept. She was taken to the forms that were filled out in support of her application to enrol in a Unique course. During cross-examination at T-474 she acknowledged that the signature contained in one of the forms was hers but she denied earlier in her cross-examination at T-455 and T-457 that other signatures in related forms were hers. For privacy reasons, I will not set out a copy of the signatures on those pages. However, I will record that the signatures are all the same so that Kylie’s evidence makes no sense.

93 In addition to these matters, I should record that Kylie presented as a witness who seemed to have little grasp of what was being said to her. She appeared emotionally flat and unengaged. Like her brother, Tre, Kylie has Von Recklinghausen Disease and suffers from severe migraines. She cannot read or write very well. Although 44 years of age she has never worked because of her disabilities. It was my impression that Kylie is a person of very limited capacities. It is also clear that this would be obvious to anyone who spoke with her.

94 In making those remarks I have taken into account the fact that in many cases indigenous people find it difficult to give evidence in the context of a courtroom so that what sometimes appear to be demeanour related issues are in fact cultural artefacts.

95 Despite that, I do not think that I can rely upon Kylie’s evidence. This is not because I think she was seeking to deceive the Court. I do not think that to be the case. Rather, it is because I found it very difficult to extract any coherent narrative from it. Her affidavit evidence did present a clear narrative but the disjunct between it and her oral evidence is such that the obscurity of the latter causes me to doubt the apparent coherence of the former.

96 Consequently, Kylie’s evidence is of little use in resolving the conflict between Mrs Simpson and Thea. On balance I have come to the view that I should prefer Mrs Simpson’s evidence about this over Thea’s. The reason is that I think it more likely that Mrs Simpson would recall who she attended the meeting with, particularly when Tre and Kylie are close relatives. As I later explain about Thea, there is also reason to doubt her reliability as a witness.

97 I therefore conclude that Mrs Simpson and Tre did not arrive with Kylie. Further, I accept Mrs Simpson’s evidence that she and Tre did not see a presentation by Ms Kang.

98 Returning then, perhaps at length, to the pre-enrolment questionnaire handed to Mrs Simpson and Tre, it will follow, if it did not already appear clear, that the interview by Unique’s delegate referred to in it certainly did not happen in Tre and Mrs Simpson’s case. So far as the filling out of the questionnaire itself was concerned the evidence was a little unclear. It seems Tre wanted Mrs Simpson to fill it out for him in its entirety but she pointed out that parts of it called for his signature. In filling out the questionnaire and, so it seems, the other forms, Mrs Simpson derived no assistance from the Unique staff who were present.

99 There were six questions on the first page of the questionnaire accompanied by a series of ticks in fields alongside those questions. The questions seem to have been intended to gauge the suitability of the candidate for the chosen course. This is apparent from part of question 3 which, relevantly, was as follows.

‘If yes, does the student meet the minimum entry requirements? (Please answer this question in conjunction with the question in the questionnaire).”

100 Mrs Simpson’s evidence was that, apart from question 4, all of the ticks on this page had not been placed there by her. Question 4 asked what the intended mode of study was and there Mrs Simpson said she had ticked a box marked ‘online’. Why she decided to tick that box was not established in the evidence. At best one can surmise that she may have thought that this might justify the apparently free iPad or laptop.

101 But the other questions are instructive. Question 2 asks what course was to be studied and here there is a tick next to ‘Diploma of Management’. Question 5 poses a series of questions which may be summarised as questions asking whether the student has sufficient computer skills to use Word, email, Excel, PowerPoint and Skype. Next to all of these there are ticks in the column marked satisfactory. Because I accept Mrs Simpson’s evidence about the writing on this form, it follows that these marks were placed there by someone not being her or Tre. Under cross-examination, Mrs Simpson agreed that her friend Mel had joined her to help her with filling out the form at the time the questionnaire was being completed. Mrs Simpson accepted that the ticks on the questionnaire which were not in her own handwriting might have been done by Mel. At other parts of the evidence, Mrs Simpson suggested that Mel helped with the maths questions (which are not located in the questionnaire).

102 The second page of the form includes in the same unidentified hand an indication that Tre has ‘advance’ technical skill, a proposition for which there can be no foundation. Mrs Simpson accepted that she had indicated on this second page that Tre had access to a computer and the internet at home (which does not, in fact, appear to have been correct) and he did not require extra assistance or have medical conditions. Tre’s signature appears on this page and her evidence was that it was his signature.

103 The second form was entitled ‘pre-enrolment test’. It consisted of a series of questions. There are six questions on the first page.

104 They, and the hand written answers appearing under them, were as follows:

‘Student Name: TRE SIMPSON

Please indicate in 200 words or less why you want to undertake study in this course? NEED EDUCATION

Please indicate any issues in 200 words or less that you believe may affect your studies (e.g. illness, disability, family commitments, works commitments, etc).

NO

What career path would you like to enter into on the completion of this course? Explain briefly in 200 words or less.

MANAGER

Are you currently employed in industry of your chosen study? Explain briefly in 200 words or less.

NO

Why have you chosen to do complete your studies through online study mode?

NO

Why have you chosen to study at Unique International College?

EASY FOR ME’

(Italics indicate handwriting)

105 Mrs Simpson’s evidence was that she filled in Tre’s name and the words ‘need education’ but the other answers were not in her handwriting. It is clearer in the case of this second form that Mel assisted in its completion (because it is this form which contains the maths questions). I conclude that some of the other answers were written by Mel. I say ‘some’ because, in fact, it may be that there are three different handwriting styles evident on this page. The identity of the third person is unclear.

106 The following page of the test involves questions intended to show the student’s aptitude for the course. For example:

107 The answers to ‘1’ and ‘2’ are correct. The answers 1(b) and 2(a) have been circled correctly. Mrs Simpson said she did not see this page and I conclude that it was completed by Mel. Similar remarks may be made about the balance of this test, that is to say, parts of it were completed by Mrs Simpson, some by Mel, perhaps some by someone else. No-one suggested that Tre had much input into the process, apart from applying his signature.

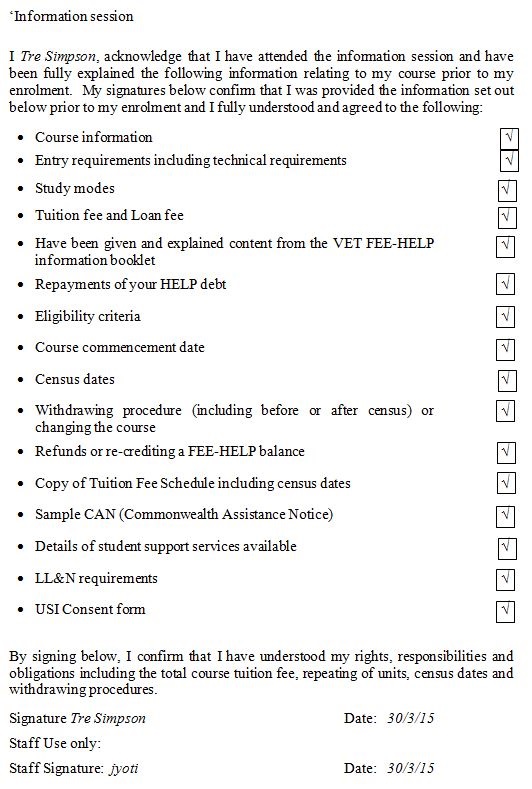

Acknowledgment form headed ‘Information session’

108 The next document was a pro forma certification in this form:

(italics indicate handwriting)

109 The ticks in the boxes were handwritten but Mrs Simpson’s evidence was that the handwriting was not hers. The signature is Tre’s and Mrs Simpson wrote his name at the top of the form. There are some other matters which should be observed about this form. First, for the reasons I have given, is the fact that none of the matters which Tre is taken to have certified were explained to him on this form, were explained either to him or Mrs Simpson. That, of course, includes this form itself. Secondly, as I explain later in these reasons at [483], the signature of ‘Jyoti’ which appears under Tre’s signature could not have been affixed on the date it bears. Jyoti Chaudhary was not in Tolland at this meeting. To the extent that this form suggests in some way that Ms Chaudhary was a witness to the matters Tre is apparently certifying, this impression is false. Thirdly, in relation to the ticks it was Mrs Simpson’s evidence that she thought it likely that they had been placed there by Mel but this was only because:

‘I would say she would have, because she’s the only one there doing the paperwork with us.’

110 This rather suggests that Mrs Simpson’s evidence about how much of the forms had been filled out by Mel was influenced by an assumption on her part that the ticks had been placed on the forms at the meeting and not subsequently.

111 This is consistent with a more general observation about Mrs Simpson’s evidence as to how she filled out the forms. It is this: in her efforts to assist the Court in her evidence about how the forms were filled out she was at times prone to give answers based not on what she recalled but, where she could not remember, on what she thought she had done; that is to say, her evidence about the forms was attended by a degree of ex post facto reconstruction. I do not mean this critically and it was an understandable position in the circumstances.

112 It is of some significance in the present context, however. Mrs Simpson’s testimony is some evidence that the only other person who helped fill out the forms was Mel. However, I do not think that her evidence can exclude the possibility that some other person filled them out later. It was part of the Applicants’ case that this, in fact, had occurred. I deal with the evidence relating to that later in these reasons at [126]-[127], [133]-[134], [278]-[281], [443]-[446], [483]-[484], [527]-[528] and [556], but these observations will mean that Mrs Simpson’s evidence is not to be seen as reliably contradicting such a case.

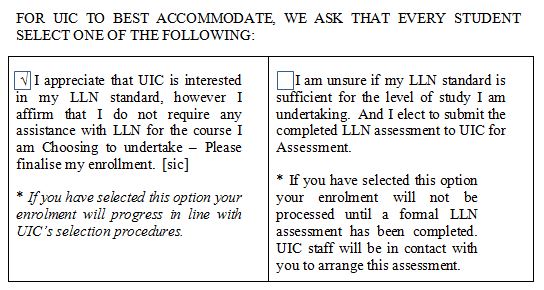

Enrolment application and agreement form

113 The next form was entitled ‘Enrolment Application and Agreement Form’. This form was six pages long. The way it was completed would suggest to the reader that the applicant was Tre Simpson, that he was born in Australia, that his highest level of education was year 10, that he spoke ‘excellent’ English, that he was unemployed and that he wished to do the Diploma of Management full-time in April 2015. The form indicated Tre’s desire to complete a Diploma of Management because a tick appeared in a box next to that course. Next to that box were the words ‘Tuition Fee $22,000’.

114 On page 4 of the form there was a section dealing with language, literacy and numeracy (‘LLN’). It explained that Unique provided LLN support to students who required it. This was followed by two boxes as follows, the left one of which was ticked:

115 There may be difficulties in understanding how a person with literacy problems might be expected to approach this question but that is not presently relevant. There was another section on the same page which appeared to indicate that Tre had ‘Advanced’ computer skills (by circling the appropriate answer in a box so marked).

116 Mrs Simpson’s oral evidence in chief was that neither she nor Tre had ticked the ‘Advanced’ box or the LLN box. Insofar as the rest of the form was concerned she confirmed, with a degree of uncertainty, that some parts were in her handwriting and others (principally signatures) were in Tre’s. Although this was explored in some detail, I do not think I need to set it out. But she did give evidence that parts of the form had not been filled out by her in addition to the two I have already mentioned. These were:

the ticks on p.2 (indicating completion of year 10);

the year ‘2012’ in the same section;

the section headed ‘Diploma of Management. VET FEE-HELP. Full time six months. Part time 12 months. Tuition $22,000’ (T 408); and

the course start date at p.3.

117 I pause here to note that the completion of the first two of these parts she attributed to Tre, whereas the second two she attributed to an unknown third party. Generally speaking, Unique submitted that Mrs Simpson seemed overly clear that the handwriting was not hers whenever the topic of VET FEE-HELP arose, although it did not say this was the result of deliberate deceit on her part. It was an unconscious bias, so it was said, arising from her understandable concern for her grandson. More specifically, Unique suggested that her testimony was influenced by her natural concern that Tre not be burdened by a debt for a course he did not complete. This suggestion seems somewhat at odds with the proposition that Mrs Simpson was not deliberately lying to the Court and I do not accept this criticism of her evidence. Although I do think that there was a degree of unconscious reconstruction in her evidence as to the filling out of the forms, I do not think that she displayed the unconscious bias for which Unique contended. Whilst it is true that her evidence about those parts of the form referring to VET FEE-HELP was that the writing was not hers, an alternative explanation is that these parts were filled out by Unique employees after the event. As will be seen later in these reasons at [126]-[127], [133]-[134], [279]-[281], [443]-[446], [483]-[484], [527]-[528] and [556] that is the interpretation I favour.

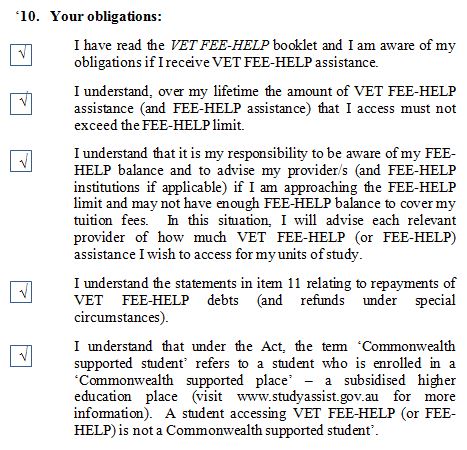

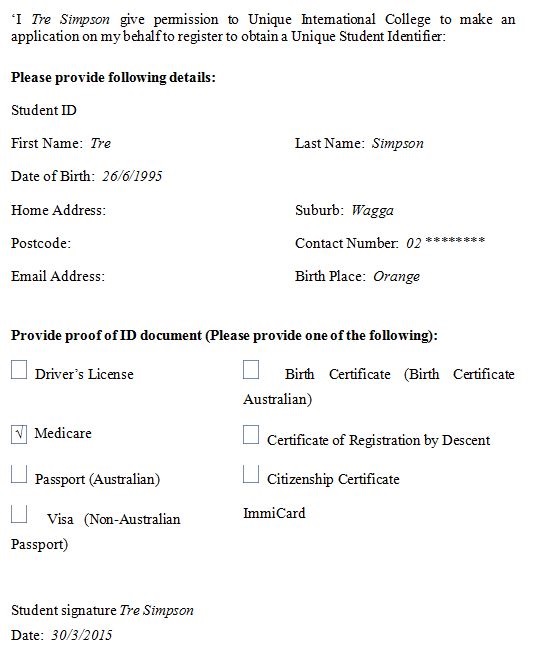

Australian government form entitled ‘Request for VET FEE-HELP’

118 The next form was a government form headed ‘Request for VET FEE-HELP assistance’. By this form a person could request VET FEE-HELP. This form contained expected fields for completion such as name and address, date of birth, course to be studied and Australian citizenship/residency. It also had fields for the applicant’s tax file number and, at item 10, a section headed ‘Your obligations’. This section was as follows (including ticks):

119 This was then followed by items 11 and 12 which were as follows:

‘11. By signing this form, you also:

● declare that:

- you have read the VET FEE-HELP information booklet and are aware of your obligations if you receive VET FEE-HELP assistance; and

- the information on this form is complete and correct and you can produce documents to verify this if required.

● request that:

- the Commonwealth lend you the amount of the VET tuition fees for the units in your course outstanding at the census date and to use the amount so lent to pay your provider on your behalf.

● understand that:

- if you are a full fee-paying student, a loan fee of 20% will be applied to the amount of VET FEE-HELP assistance provided (if you are a subsidised student in a state or territory that has implemented subsidised VET FEE-HELP arrangements, you will not incur a loan fee). The loan fee will be included in your VET FEE-HELP debt. You should contact your provider for more information;

- you will repay to the ATO the amount that the Commonwealth has loaned to you (plus the loan fee if applicable). These repayments will be made in accordance with Chapter 4 of the Act when your income reaches a certain level, even if you have not completed your studies;

- your debt with the Commonwealth will remain if you withdraw or cancel your enrolment after the census date but that your debt may be removed by your provider in special circumstances;

- your HELP debt will be indexed annually in line with the Act;

- you will not be able to obtain VET FEE-HELP assistance for VET unit(s) of study if you do not meet the TFN requirements;

- you will no longer be able to obtain VET FEE-HELP assistance when the total amount of VET FEE-HELP (and FEE-HELP assistance) you have obtained reaches the FEE-HELP limit as set out in the Act;

- you are able to cancel this request, in writing, at any time, with your provider, and that it will no longer apply from that time. However, this must be done by the census date, otherwise you will have a debt to the Australian Government that you are legally required to repay;

- if your eligibility for VET FEE-HELP changes you must notify your VET provider;

- the Department of Education collects your information in accordance with the Australian Privacy Principles for the purpose of administering Commonwealth assistance, including verifying eligibility for a HELP loan. It is also collected for the purpose of research, statistics and programme assurance. If you do not provide the information required on this form you may not be eligible for Commonwealth Assistance;

- the authority to collect and share this information with other government agencies including, but not limited to, the ATO and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection for the purpose of verifying your eligibility is contained in Part 5-4 Division 179-20 of the Act;

- the information may not otherwise be disclosed without your consent unless authorised or required by law;

- full details of how the department handles personal information for the purpose of the Higher Education Loan Programme can be found at www.studyassist.gov.au;

- the Department of Education’s Privacy Policy, including information on access and correction of personal information and how to make a complaint, can be found at www.education.gov.au/condensed-privacy-policy; and

- giving false or misleading information is a serious offence under the Criminal Code Act 1995.

Go to item 12

12. Declaration:

Signature Tre Simpson

Date: 30/3/15.’

120 Mrs Simpson’s evidence was that she wrote Tre’s name on the first page of the form but nothing else that appeared on that page. Under the section headed ‘Your obligations’, which I have set out above, she was clear that she had not filled out any of it nor had Tre. She was not able to assist the Court in relation to whether the ticks were already there when the form was signed by Tre or not.

121 It was Mrs Simpson’s account that the tax file number appearing on the first page of the form must have been put there by representatives of Unique after the forms were handed in. Mrs Simpson deposed that there was some perfunctory conversation with one of the Indian ladies (Ms Kang or Jasmeen) and also with Mr Bell. Nothing of substance passed during these conversations, although it seems that Mr Bell took a photo of Tre, most likely on his iPhone.

122 In short, I find that none of this form was explained to Mrs Simpson or Tre. They were quite unaware of what Tre was signing.

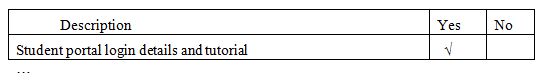

Consent form giving permission to Unique to apply for a ‘Unique Student Identifier’

123 The following form is headed ‘Unique Student Identifier Consent Form’:

(italics indicate handwriting)

124 Most of the handwriting on this form was Tre’s according to Mrs Simpson. Some of it was not. However, nothing important turns on this form and it is not necessary to consider it further.

Acknowledgment form acknowledging that online students had received an orientation program

125 The next form is entitled ‘Acknowledgement of Orientation for Online Students’. The form was filled out with Tre’s name and birthdate which Mrs Simpson confirmed was in Tre’s handwriting. This text then appeared at the top of the form:

‘I confirm that I have attended the Unique International College Pty Ltd orientation program on the date 30.3.15 by phone / face to face (Please circle). This orientation covered the following information regarding my enrolment at Unique International College:’

126 Mrs Simpson gave evidence that this handwriting was neither hers nor Tre’s. There was then set out a long list of matters which were said to have been explained with a field for ticks. Since it is repetitive, I will simply set out the first which is representative:

127 I have concluded that neither this tick nor the others appearing on the form were in Mrs Simpson’s or Tre’s handwriting. Although I find that Tre’s name and signature did appear at the end and these appear genuine.

128 As should now be apparent, I conclude that no such orientation program was administered to Tre. Further, in the time available to them on the evidence before me, neither Mrs Simpson nor Tre could have properly understood this form.

Consent form consenting to the use by Unique of still photographs or videos of the applicant in its promotional materials

129 The next form was a consent form by which the putative student consented to the use by Unique of photographs of them. It is signed by Tre. No part of the Applicants’ case turns upon this form and I can pass over it.

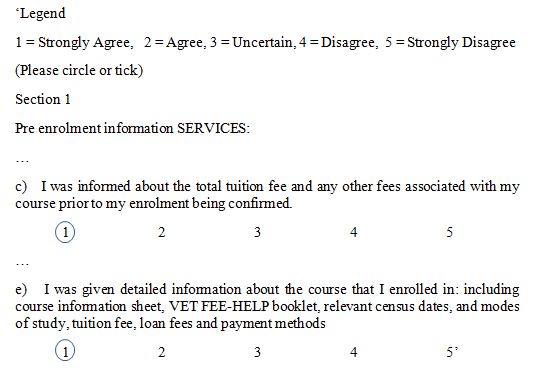

Evaluation form assessing the student induction process

130 The next form was entitled ‘Evaluation of the Student Induction Process’. This document appeared to be an assessment of the presentation which Mrs Simpson and Tre, on the findings I have made, did not see even if it actually took place. There was no direct evidence about the handwriting or the ticks on this form. I think it most likely, however, that Tre’s name was written on this form by Mrs Simpson (or possibly Tre) but the ticks are most likely by some other person.

Acknowledgment form acknowledging that the cost of the course had been disclosed

131 The next form was an acknowledgement in these terms:

‘I acknowledge that I have been given the correct information on the total due fees for my chosen course which is 22000 and I understand that I have to start repaying the due fees plus the 20% loan fee back once I start earning above the minimum threshold 53000 as per VET FEE-HELP information for 2015.

Student Signature: X Tre Simpson

Unique International College Staff would like to thank you for choosing our college & wish you a pleasant learning experience.

Thank you’

(italics indicate handwriting)

132 Mrs Simpson’s evidence about this was that the signature was Tre’s but that the numbers $22,000 and $53,000 were not on the form at the time that she saw it.

133 The last form was entitled ‘Student Feedback Form’. Mrs Simpson’s evidence was that the handwriting on the form was neither hers nor Tre’s and that she had not read it. Section 1(c) and 1(e) were in these terms:

134 The circling of ‘1’ signified ‘strongly agree’. Mrs Simpson did accept that the signature on the second page was Tre’s. These are it seems to me, therefore, further examples of form filling by some third party tending to suggest, incorrectly, that matters which had not been explained had in fact been explained.