FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Murray on behalf of the Yilka Native Title Claimants v State of Western Australia (No 6) [2017] FCA 703

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The First Respondent prepare a final minute of Determination to reflect these reasons and any updated tenure for agreement by the parties.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS | ||

WAD 498 of 2011 | ||

BETWEEN: | GS (DECEASED), PATRICK EDWARDS AND MERVYN SULLIVAN Applicants | |

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA First Respondent SHIRE OF LAVERTON Second Respondent CORINA BENNELL, LISA BENNELL, MATTHEW BENNELL, CENTRAL DESERT NATIVE TITLE SERVICES LTD, COSMO NEWBERRY (ABORIGINAL CORPORATION), BRETT DIMER, HILDA DIMER, JARED DIMER, SHAUN DIMER, SHONDELLE DIMER/GARLETT, RON HARRINGTON-SMITH, HARVEY MURRAY ON BEHALF OF THE YILKA NATIVE TITLE CLAIMANTS, ALISON TUCKER (NEE BARNES), DANIEL TUCKER, FABIAN TUCKER, KATHY TUCKER, MICHAEL TUCKER AND QUINTON TUCKER (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondents | |

JUDGE: | MCKERRACHER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 JUNE 2017 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The First Respondent prepare a final minute of Determination to reflect these reasons and any updated tenure for agreement by the parties.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS | |

WAD 303 of 2013 | |

BETWEEN: | HARVEY MURRAY ON BEHALF OF THE YILKA NATIVE TITLE CLAIMANTS Applicant |

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA First Respondent PATRICK EDWARDS AND MERVYN SULLIVAN Second Respondents |

JUDGE: | MCKERRACHER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 JUNE 2017 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The First Respondent prepare a final minute of Determination to reflect these reasons and any updated tenure for agreement by the parties.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MCKERRACHER J:

INTRODUCTION

1 Following a lengthy contested hearing, I held that both the Yilka claimants and the Sullivan claimants hold exclusive native title (subject to extinguishment) across the respective claim areas: Murray on behalf of the Yilka Native Title Claimants v State of Western Australia (No 5) [2016] FCA 752 (Yilka No 5) (at [1028]). (The claim area of the latter is only slightly smaller than the former). Both applicants had made out their respective claims. It follows that they would be entitled to hold native title (Yilka No 5 at [2478]). I concluded that, subject to confirming certain extinguishment matters as set out in Yilka No 5, there would be a determination that native title exists in relation to the determination area claimed by each applicant. (These reasons adopt the same definitions as those in Yilka No 5).

2 At [2479] of Yilka No 5, I deliberately indicated that rather than say more at that stage about the form of any “determination or determinations”, I would allow the parties a reasonable opportunity to consider and negotiate those matters in the light of the findings that I had made. Accordingly (at [2480]), I ordered, amongst other things, that:

With respect to settling the form of the Determination or Determinations, the parties consult in relation to all matters that may be pertinent to a proposed form of Determination or Determinations to give effect to these reasons.

3 For several months mediation has ensued between the Yilka applicant and Sullivan applicant (as well as other parties), primarily regarding the form of a determination and whether one or two Prescribed Bodies Corporates (PBCs) would be appropriate. There has subsequently been considerable mediation on costs issues which resolved a court dispute which had been listed for next month. It has now been resolved.

4 Pursuant to order 1 and order 2 of the orders made in Yilka No 5 and order 1 of the orders made by consent on 13 December 2016, the Sullivan applicant filed an alternative proposed form of determination (Sullivan Minute) because of disagreement with the form of the Minute of Proposed Orders and Determination of Native Title provided to the Court by the State (State Minute). The State Minute is agreed by the State, the Yilka applicant and Gold Road Resources Limited, a respondent which has been particularly active only in the issue of whether there is to be one PBC or two.

5 A minute was also provided by various other respondents, Mr Ron Harrington–Smith, Ms Alison Tucker (nee Barnes), Mr Daniel Tucker, Mr Fabian Tucker and Mr Michael Tucker, which seeks that any recognition should also include those parties. Those respondents have never participated in any meaningful way in the substantive issues in the years over which this hearing has ensued. This, despite ample opportunity to do so both prior to delivery of judgment in Yilka No 5 and prior to filing of the competing minutes by the participating parties. Accordingly, I do not propose to adopt the minute advanced by those respondents.

THE ISSUE

6 The remaining issue is whether there should be one determination or two and/or one PBC or two. Only the Sullivan applicant supports the dual outcome.

APPLICATION OF THE STATUTORY FRAMEWORK

7 Section 13(1)(a) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA) authorises the making of an application to this Court under Pt 3 of that Act “for a determination of native title”. “Determination of native title” is defined in s 225 NTA and must contain “who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights” (s 225(a)). Pt 3 NTA sets out the “rules” for making applications of that kind (s 60A(1)(a)). Section 61(1) NTA is one of a number of provisions containing rules that govern such applications. It is in the form of a table that identifies the applications that may be made and the persons who may make each of those applications.

8 As discussed by the Full Court in CG (deceased) on behalf of the Badimia People v Western Australia (2016) 240 FCR 466 (at [41]), the Court's jurisdiction to hear and determine applications that relate to native title is conferred by s 81 NTA. That jurisdiction is limited by s 213(1) NTA which provides that in making a determination of native title, “that determination must be made in accordance with the procedures in [the NTA]”. Section 94A requires any order in which this Court makes a determination of native title to set out details of the matters mentioned in s 225 NTA.

9 In Badimia (at [41]) the Full Court reinforced the Court’s findings in Commonwealth v Clifton (2007) 164 FCR 355 (at [58]), that where there is more than one native title claim group seeking a determination over a particular area, each claim group must have its own authorisation pursuant to s 62 NTA.

10 This approach was followed in Lake Torrens Overlap Proceedings (No 3) [2016] FCA 899 in which Mansfield J found (at [120]) that the proposed joint determination was not within the scope of either overlapping application. The Court found that there was no evidence before the Court that a combined claim group, as asserted, had authorised the making of such a claim. His Honour observed that:

they might have been expected to have brought first such a claim rather than the competing claims presented. The history of claims concerning Lake Torrens provides no basis for being confident that such a claim has been, or would be, authorised by such a combined claim group. Unlike the circumstances in Daniel, there was no joint application.

11 The Sullivan applicant submits that the reasoning of the Full Court in Badimia indicates that the procedures relating to making and authorising a combined claim must be followed by the relevant combined group in order for a combined claim description to be reflected in a determination of native title. Further, the Sullivan applicant submits that s 67 NTA provides support for this statutory construction, as claims must be heard together but remain separate claims.

12 In my view the point is different in this application. The Sullivan applicant in evidence has confirmed that it would include the Yilka applicant in its application. While the Yilka applicant has submitted a different position, that position (on my findings) had nothing to do with the criteria and merits under the NTA of the Sullivan applicant as such. Further, the Yilka applicant now firmly advances a joint position and in my assessment, may be taken to have done so on the basis of sound advice and requisite authority.

THE SULLIVAN APPLICANT’S ARGUMENTS

13 The Sullivan applicant says that the Sullivan Minute (attached as Annexure 1 to these reasons) is drafted in such a way that it is consistent with the language and purpose of all the provisions in the NTA and contemplates mechanisms that may specifically recognise the need for the interests of different parties to be respected and recognised. (A subsequent minute was forwarded to the Court. Nothing turns on the changes in that subsequent minute.)

14 As the Sullivan applicant notes, the main difference between the State Minute and the Sullivan Minute is that the Sullivan Minute proposes a determination that describes the native title holders in Sch 3 as, essentially, the respective claimants in both Harvey Murray v State of Western Australia (WAD 297 of 2008, WAD 303 of 2013) (Yilka Claim) and GS (deceased) v State of Western Australia (WAD 498 of 2011) (Sullivan Claim) and proposes that separate PBCs hold the respective native title in trust for each.

15 Under the Sullivan Minute the separate descriptions of the respective common law native title holders is similar, the Sullivan applicant says, to the three determinations in Budby on behalf of the Barada Barna People v State of Queensland (No 7) [2016] FCA 1271; Budby on behalf of the Barada Barna People v State of Queensland (No 6) [2016] FCA 1267 and Pegler on behalf of the Widi People of the Nebo Estate #2 v State of Queensland (No 3) [2016] FCA 1272 (together the Barada Barna Widi determinations) determined by Dowsett J. The Sullivan applicant notes that the Barada Barna Widi determinations were made in favour of the Barada Barna People in one area, the Widi People in connection with a number of parcels in another area and the third determination was in favour of the Barada Barna and Widi Peoples, concerning a shared area. The Court ordered that the native title was to be held in trust by two PBCs, one for the Barada Barna and the other for the Widi. The Sullivan applicant is of the view that unlike the Barada Barna Widi determination, these claims wholly overlap and therefore it is not necessary to have two separate determinations. They also note that although the Barada Barna Widi determination orders were made by consent under s 87 NTA, they could not have been made unless the Court was satisfied that the terms of the proposed determinations were within the power of the Court.

16 The Sullivan applicant contends the Court should order:

(a) one determination describing the two separately authorised claim groups as common law native title holders; and

(b) that each group of common law native title holders have their native title held in trust by the respective PBC.

Nature of claim group rights

17 The Sullivan applicant submits that the traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert Society do not necessitate that the Yilka and the Sullivan claim groups effectively merge for the purposes of the determination. The Sullivan applicant notes that native title rights and interests may be either communal, group or individual rights or interests, in relation to land or waters: Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 (at [33]), see also De Rose v South Australia (No 2) (2005) 145 FCR 290 (at [28]–[31] and Northern Territory v Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakaya Native Title Claim Group (2005) 145 FCR 422 (at [114]).

18 The Sullivan applicant points to the following matters:

(a) in Yilka No 5, I found that the rights and interests possessed by the Yilka claimants and the Sullivan claimants were not communal and are a coalition of at least two subsets of the Western Desert Society, and one such subset are:

those who assert connection by their own or an ancestor's birth or long association, is not a group with any basis in tradition, but is more appropriately characterised as an array of subsets each comprising individuals or small groups of related individuals claiming through a common ancestor.

The other subset is the wati who claim rights and interests in the claim areas. Moreover, the Sullivan claim had been “established independently of and in addition to the Yilka claim”;

(b) while there is a requirement to gain consent from native title holders in relation to certain native title decisions under the NTA, there is no express requirement to consider the interests of the broader native title group in managing and using native title benefits or consulting with them regarding land management in a post determination context. The Sullivan applicant contends that as the Yilka applicant would not agree to authorise a combined claim group, a single PBC of both the Sullivan and Yilka native title holders would be unworkable: See Yilka No 5 (at [1235]). As such, the Sullivan applicant voices could be ignored (for example see Yilka No 5 (at [1188]) regarding what HM and Mrs Murray said about the inclusion of elder and wati, Mr Harris, in the Yilka claim);

(c) there is no reason that if two PBCs are created, the two corporations cannot make arrangements to develop a single interface as was the case in Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara v State of Victoria (No 5) [2011] FCA 932. In the Barada Barna Widi determinations no single interface document was agreed on and yet the State of Queensland agreed to a consent determination in terms of two PBCs. Nevertheless, proponents and governments have been dealing with many landholders at once, when developing infrastructure projects for example, including more than one native title holding group in the case of adjoining or overlapping claims. Dealing with numbers of landholders has not been an insurmountable problem for governments and proponents and is already dealt with effectively by the future act regime in Pt 2, Div 3 NTA;

(d) the Sullivan applicant stresses the finding in Yilka No 5 (at [1235]) that the Sullivan application was established independently of the Yilka claim as follows:

while accepting the Yilka evidence and accepting the Sullivan evidence for almost the same area of land and in respect of the same customs, traditions, rights and practices, nonetheless, I consider that the Sullivan claim has been established independently of and in addition to the Yilka claim.

The Sullivan applicant notes that it had to be established independently because throughout the hearing the Yilka applicant strenuously maintained its position that it was not entitled to be within the Yilka claim and the "Yilka applicant's written submissions catalogue endless criticisms of and weaknesses in the Sullivan applicant's evidence." (Yilka No 5 at [10]);

(e) the claims were not brought together because the Yilka applicant did not invite the Sullivan to be claimants, nor did the Central Desert Native Title Service (CDNTS) conduct any research on their behalf;

(f) the Yilka applicant did not invite the Sullivan applicant to any potential claim group meeting when preparing the Yilka claim or invite them to any authorisation meeting; and

(g) at no time did the Yilka applicant entertain the inclusion of the Sullivan applicant. In fact, the Court observed in Yilka No 5 (at [760]) that:

the strong attack the Yilka applicant has made on the lay evidence in support of the Sullivan claim would not give the impression that there is much likelihood that the Sullivan claimants' claims would be recognised by the Yilka applicant in the reasonably near future.

19 The Yilka applicant has informed the Sullivan applicant that the Yilka Aboriginal Corporation ICN 8415 (YAC) will be the PBC for the purposes of s 56(2)(b) and s 56(3) NTA and will perform the functions mentioned in s 57(1). The Constitution of YAC is in evidence. The Sullivan applicant has also drafted rules for a Sullivan applicant PBC which have been lodged with the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporation. These reasons do not examine in any detail the respective content of such constitutions which should be a matter for settling once the determination is made.

20 There is no evidence, the Sullivan applicant says, that the Yilka applicant now accepts the Sullivan claimants as native title holders in the overlapping claim area. There is no evidence from the solicitor for the Yilka applicant, that he has approached the Sullivan applicant, as their proposed potential future lawyer, to plan a way forward regarding any conflict of interest. The Sullivan applicant also says that the solicitor for the Yilka applicant has not consulted with the Sullivan claimants about the YAC's Rule Book, despite the fact that this corporation was established for the purpose of being the PBC for the common law native title holders. In particular, the Sullivan applicant says that he has not consulted with them about cl 5.7:

The Directors may refuse to accept a person to be a Member even if the applicant has applied according to Rule 5.1(a) and meets all the eligibility requirements to be a Member.

And cl 5.12(a):

[all members may] attend, speak at and - depending on the Member 's level of rights under Traditional Law and Custom - participate in and be involved with decision-making at a General Meeting.

21 These clauses allow a wide discretion and have never been approved by the proposed combined Yilka and Sullivan claim group. The Sullivan applicant also submits that there are a number of other problematic clauses in the YAC constitution, about which there has been no consultation with the Sullivan applicant. Further, given its past conduct, the Sullivan applicant contends that it could not be expected that any procedural fairness will be afforded to the Sullivan claimants by CDNTS.

22 Next, the Sullivan applicant submits:

(a) that the issues between them are not intramural because the nature of the claim groupings are not communal and are separate groups of individuals;

(b) many places within the Western Desert, such as Warburton, Blackstone, Tjirrkarli, Wiluna and Tjuntjuntjara have the same Western Desert Cultural Bloc (WDCB) laws and customs as the Yilka claim area (and hence the Sullivan claim area) (Yilka No 5 at [324] and [336]). The concept of a large overarching society, as compared to a communal claim in other matters (see, for example, Moses v Western Australia (2007) 160 FCR 148, Banjima, Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 153 FCR 120, Graham on behalf of the Ngadju People v State of Western Australia [2014] FCA 516, Griffiths v Northern Territory (2006) 165 FCR 300, Gumana v Northern Territory (2005) 141 FCR 457), is complex yet it is demonstrated by the plethora of WDCB determinations over a large area of Australia across three States. All of the determined claims comprise individuals or small family groups as described in Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha v State of Western Australia (No 9) [2007] FCA 31 and Yilka No 5 as being part of the wider “society” of the WDCB;

(c) the meaning of "society" in the native title context has developed from the jurisprudence since Yorta Yorta. The term "society" is not one that appears in the NTA. It was used by the plurality, Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ, in Yorta Yorta rather than the term "community", to emphasise what their Honours described as the close relationship between the identification of the group and the identification of the laws and customs of the group. It is difficult to separate questions about the relevant society from questions of laws and customs. The two are inter-dependent and laws and customs do not exist in a vacuum;

(d) in Harrington-Smith the relevant “society” was also said to be the WDCB. Nevertheless, Lindgren J had some doubts as to whether a cultural bloc amounts to a “society”'. He did proceed on the basis that it did exist at both sovereignty and the time of the claim in order to determine whether the whole of the Wongatha people's claim was part of WDCB society;

(e) Lindgren J found that landholding of the WDCB is at the level of the individual, or, perhaps, small groups of individuals, each member of which was linked to the same area as each other member. In the judgment summary (at 6), Lindgren J stated that:

[i]t is conceivable that an individual or a small group of individuals may have native title in a smaller area representing a constellation of Dreaming sites or tracks, but there are not group rights and interests in the Claim areas as such.

It should be noted that the persons who comprise the Yilka claimants and the Sullivan claimants both were claimants respectively in Harrington-Smith being Cosmo Newberry and Wongatha claim groups; and

(f) The Cosmo Newberry and Wongatha claim groups were said to be similar but different. In Harrington-Smith (at [726]):

Dr Sackett said that there were similarities between the laws, customs, rights and interests that he reported on in relation to the Cosmo Newberry Claim, and those reported on by Pannell/Vachon in relation to the Wongatha Claim, although he said that there were differences.

In other words, and this can be borne out by the evidence of the Yilka claimants and their refusal to include the Sullivan claimants in their claim group, the groups are similar but different under the overarching WDCB.

23 The Sullivan applicant also refers to Narrier v State of Western Australia [2016] FCA 1519 where Mortimer J stated at [377]:

[o]ne of the key features of Western Desert society which differs from other Aboriginal societies is the way that individuals and groups gain association with, and rights and interests in, particular areas of land. It is not simply by descent, whether biological or adoptive. It is broader than that …

24 If the State and Gold Road are each correct that one common law native title holding description should appear in the determination and one PBC is appropriate because both the Yilka applicant and the Sullivan applicant hold their native title rights and interests under WDCB laws and customs, then this would mean, according to the Sullivan applicant, that other potential individuals and groups should also be included in the determination and PBC because they are simply part of the WDCB. (I would pause to put aside this hypothetical contention. Had such people given such evidence the position might be different).

25 The Sullivan applicant stresses that in Yilka No 5, I was satisfied that on a more detailed examination of the claim, the Sullivan applicant should never have been excluded from the Yilka claim (at [1157]). Yet, it was excluded. If there was to be a single PBC as proposed by the Yilka applicant, then it should be incumbent on CDNTS to facilitate and assist the Yilka applicant and Sullivan applicant, not just their lawyers, to work together now and into the future. The Sullivan applicant notes that no such arrangements have been implemented despite the proposal of a single PBC model being put forward. There is doubt in my view, that on a single PBC model, this is correct.

26 The Yilka applicant and the Sullivan applicant brought separate claims. The Court had to consider whether the Sullivan applicant, in particular, held rights and interests under WDCB laws and customs separate and distinct from the Yilka applicant because both applications were separately filed. The nature of the WDCB laws and customs can and does include a multitude of individuals and groups holding rights and interests distinct from each other in circumstances where people from one group are often not aware of the other's existence (and often do not know that Aboriginal people from thousands of kilometres away are part of the same society). The Sullivan applicant says that the Sullivan applicant and the Yilka applicant are not part of a “community” or separate communities in the sense of the definition in s 223(1) NTA regarding whether the native title rights and interests are "communal, group or individual"; they are individuals.

Two Prescribed Bodies Corporates

27 It follows, the Sullivan applicant argues, that if s 225(a) NTA provides that a determination of native title is a determination of "who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title" are, then each group should also have their rights and interests comprising the native title held in trust by each group's respective PBC.

28 It is common ground that there can be more than one PBC within a single determination area. In Daniel v Western Australia [2003] FCA 666, the Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi claimants made a claim seeking orders that the people holding the native title rights and interests were the Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi people collectively or, alternatively, the people holding the native title rights and interests in the Ngarluma country are the Ngarluma people and the people holding the rights and interests in the Yindjibarndi country are the Yindjibarndi people. At first instance the Court ordered the alternative proposition. On appeal from Daniel, the Full Court in Moses (Moore, North and Mansfield JJ) in effect made two determinations of native title within a single determination area. This is the approach the Sullivan applicant puts forward in these proceedings. The Full Court's Determination provided that:

Subject to [2] above, native title rights and interests exist in the following parts of the Determination Area:

(a) ‘Ngarluma Native Title Area’ (as defined in the First Schedule); and

(b) ‘Yindjibarndi Native Title Area’ (as defined in the First Schedule).

29 In the Determination the native title holders are described as follows (at [5]):

The non-exclusive native title rights and interests which exist in the Determination Area are held by:

(a) 'Ngarluma People’ (as defined in the Third Schedule) in relation to the Ngarluma Native Title Area: and

(b) 'Yindjibarndi People' (as defined in the Third Schedule) in relation to the Yindjibarndi Native Title Area.

30 In Lovett (at [32]–[41]) it was recognised that the area the subject of the consent determination was traditionally shared by the Gunditjmara people and Eastern Maar people. There was an area that was part of the determination where only the Gunditjmara people held native title in trust by the Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation (Gunditjmara PBC). As the Sullivan applicant notes, to comply with the respective requirements of s 56(2) and s 57(2) NTA, separate meetings were heard by the separate common law native title holders. The Gunditjmara people held a meeting and resolved that the Gunditjmara PBC be the PBC for the purposes of the NTA and that it hold the native title of the Gunditjmara people in relation to the overlap area in trust. The Eastern Maar people were also found to hold native title over the same area held by the Gunditjmara. The Eastern Maar People held a meeting where they resolved to incorporate the East Maar Corporation as their PBC. The Gunditjmara and the Eastern Maar peoples then met and resolved that the respective corporations would be the PBC in relation to each of their interests. This was the first time in Victoria that two PBCs had been appointed over one determination area. Citing Moses (at [376]-[386]), North J held that s 56(2)(a) and s 57(2)(a) NTA allows for two PBCs for one determination area where there are two groups that hold interests in the same area and each intends to nominate its own PBC. The State of Victoria, like the State of Western Australia, had an interest in developing a single interface to deal with native title matters in relation to overlapping determination areas and matters arising under heritage legislation. Yet the parties were able to make arrangements outside the terms of the determination to ensure efficient communication in relation to these matters.

CONSIDERATION

31 Importantly, it is common ground that the form of the determination be it one PBC or two, (amongst other matters) is, at this juncture, an issue within my discretion. That is, nothing in the pleadings or findings compels a position one way or the other pursuant to the provisions of the NTA or otherwise. It may be said that the contentions helpfully advanced by the Sullivan applicant, as well as the considerations below, are all relevant to the exercise of the discretion. Accordingly, the required ground is one of weighing all these matters.

32 There is another general point. The Sullivan applicant is correct to say that I raised criticisms of the Yilka applicant in its treatment of the Sullivan applicant. But what I have to deal with now is the most functional regulation of dealing in the future between these and external parties. There is, in my view, reason to believe the Yilka applicant will absorb and reflect on such criticism with a view to co-operating with the Sullivan applicant in a better future.

33 I reiterate that all parties other than the Sullivan applicant propose a single determination and a single PBC.

34 It is trite to note that usually the framework of the NTA suggests a single determination of native title in relation to a particular area (including an area that has been the subject of overlapping claims), the delineation of the relevant native title rights and interests and the nomination of a registered native title body corporate to perform specified functions in relation to that native title (including usually, in some cases, by acting as trustee of that native title). The NTA contemplates that the body corporate functions in respect of all native title in an area the subject of multiple claims will be performed by a single registered native title body corporate (whether as trustee of that native title or as agent of the common law holders): see Lake Torrens per Mansfield J (at [99]-[127]. In this way, the NTA provides third parties with a single point of interaction with the common law holders. Intra-indigenous issues are resolved between the common law holders in accordance with traditional law and custom, within the framework of the body corporate and the requirements of the Native Title (Prescribed Bodies Corporate) Regulations 1999 (Cth) and in accordance with agreed dispute resolution mechanisms. Failing such resolution, there is recourse to other forms of protection and relief.

35 There can be no doubt that the determination of multiple registered native title bodies corporate in respect of essentially the same area would defeat this objective and have the effect of:

(a) conferring upon those bodies corporate separate and distinct procedural rights under Div 3 of Pt 2 NTA in respect of future acts in the determination area; and

(b) enabling those bodies corporate to bring separate and distinct compensation applications under s 50(2) NTA in respect of compensable acts within the determination area.

36 In my view, these outcomes would not accord with the findings in Yilka No 5, including that the Yilka claim and the Sullivan claim were in the nature of representative proceedings brought by the members of the claim groups for their respective rights and interests in reliance on their common membership of the WDCB society (Yilka No 5 at [476], [494] -[495] (representative proceedings) and [329], [336], [759], [903] to [908] (membership of WDCB society and pathways)).

37 The Sullivan applicant has relied heavily on my finding (at [1235]) that “the Sullivan claim has been established independently of and in addition to the Yilka claim”. However, this finding does not necessarily support the Sullivan Form of Determination. I accept the submission of the non-Sullivan parties that the finding means no more (in this context) than that the evidence led by the Sullivan applicant was sufficient to establish the members of the Sullivan claim group hold individual rights in the Sullivan claim area pursuant to the traditional laws and customs of the WDCB society, in the same way that the evidence led by the Yilka applicant established the individual rights of the members of that claim group. That is, the bases upon which the members of the two claim groups hold native title in the determination area are indistinguishable and the evidence led by either applicant would have been sufficient to establish the existence of native title. This is apparent from the immediately preceding findings that “the Sullivan applicant has also made out its claim”, “the evidence in support of the [Sullivan] claim was just as persuasive” as that in support of the Yilka claim, “the Sullivan claimants should have been included in the Yilka claim”, and “[i]f that had occurred as it should have done, all the evidence would have been in the one claim”. There is no need, then, in my view, to refer to the separate claim groups (nor any other potential combinations or permutations of common law holders) in the determination.

38 As discussed above, the Sullivan applicant rely on decisions such as Daniel/Moses, Lovett and the Barada Barna Widi determinations to support their contention that there should be two separate PBCs. However, in my view, these decisions are distinguishable on the facts. On the present issue which is rather peculiar to this case, I have not found other decisions particularly pertinent.

39 In Daniel/Moses the Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi peoples were entirely distinct traditional groups determined to hold separate native title rights in relation to separate areas of country. There was only a small area that was determined to be traditionally shared country. In those quite different factual circumstances, Nicholson J considered that:

…that there is nothing in the statutory provisions to inhibit nomination of more than one PBC in respect of native title rights in the determination area where that is supported by and follows from the findings of fact made with respect to the holding of such rights in that area by different groups and accords with the intention of each of them.

40 In Lovett, as discussed above at [30], the Gunditjmara people and the Eastern Maar people were also considered to be separate and distinct traditional groups, with different apical ancestors with separate areas of traditional country, albeit also with a traditionally shared overlap area. In those circumstances, North J considered (at [39]) that:

It is convenient to the Gunditjmara people and the Eastern Maar people to have their native title rights and interests held by separate bodies corporate. The Gunditjmara people have rights and interests in the Part A area in which the Eastern Maar people do not have rights and interests. The Eastern Maar people assert interests, not yet determined, in relation to areas east of the determination area and their body corporate will be able to represent them in relation to this area.

41 The Barada Barna People and the Widi People were also separate traditional groups with their own traditional country and shared area of traditional country.

42 Mansfield J's observations in the Lake Torrens, also relied on by the Sullivan applicant, concerned competing applications brought on behalf of different traditional groups/societies who were asserting an individual claim for native title to the exclusion of the others. In the present circumstances, I accept the State’s submissions that there would be no improper amalgamation or merger of different traditional groups if a single PBC was established.

43 In Clifton, the issues were confined to whether a person or group could obtain a determination of native title in their favour without having brought an application under s 61 NTA. The issue that arose on appeal in Badimia, was whether or not the Court, having decided the only native title before it was not made out, should make a determination that native title does not exist.

44 The Sullivan claimants' separate status as litigants in this proceeding arose from a dispute, which did not reflect traditional law and custom. As such, it is not appropriate to be reflected in a separate determination of native title.

45 The Yilka and Sullivan applications were pursued on the basis of the same traditional laws and customs and have a wholly, or at least partly, overlapping membership.

46 While I am conscious of the matters to which the Sullivan applicant has pointed, I consider that the relevant key findings in Yilka No 5 which guide the outcome of the current debate include the following:

(a) both the Sullivan and Yilka applications were pursued on the basis of the traditional laws and customs of the WDCB (Yilka No 5 at [92], [322]–[323], [327], [337], [368], [746], [753], [773], and [774]) and the pleadings and points of claim for both the Yilka and Sullivan applications were virtually identical (Yilka No 4 at [774] and [783]);

(b) both the Sullivan and the Yilka applicants agreed that, under WDCB traditional laws and customs, rights and interests in the trial area were possessed by persons who met the same relevant criteria of birth, long association or ritual authority and in respect of whom that claim was recognised by other members of the WDCB (at [368], [746], Annexure 2, Sch 2, cl (c) and Annexure 5, Sch 2, cl (c));

(c) the Sullivan application was pursued on the basis that the members of the Sullivan claim group fulfilled the relevant WDCB criteria and, therefore, should have been included in the Yilka claim group (Yilka No 5 at, for example, [12], [461], [746] and [774]);

(d) importantly, the Sullivan claim group was defined by the Sullivan applicant itself at trial in terms which included those members of the Yilka claim group who also fulfilled the relevant WDCB criteria (Yilka No 5 at [12], [754] and [760]);

(e) the Yilka applicant accepted that certain members of the Sullivan claim group met the relevant WDCB criteria and held rights and interests in part of the claim area (Yilka No 5 at [777], [786] and [1152]); and

(f) other members of the Sullivan claim group also met the relevant WDBC criteria (including recognition) (Yilka No 5 at, for example, [1034], [1103], [1120] – [1123], [1137] – [1139], [1148], [1150], [1152] and [1185]) and should, therefore, have been included in the Yilka application (Yilka No 5 at [791] and [1235]).

47 These findings suggest any determination should identify the native title holders represented by the Sullivan applicant in the same manner as the native title holders represented by the Yilka applicant and should not draw a distinction between them which has not been drawn by the findings.

48 In my view, in the determination it would not be appropriate or necessary to state that the native title rights and interests of one applicant group are independent of, or additional to, the rights and interests of the other.

49 There is no evidence that if two PBCs are created in this instance that those PBCs will make arrangements outside the terms of the determination to develop a single interface to deal with native title matters and ensure efficient communication in relation to those matters.

50 To the contrary, in my view, it would undesirably entrench the existence of two camps which should always have been one.

51 I am also mindful that the creation of two PBCs in this instance would mean, for example, that a non-native title party seeking to do a future act would be required to negotiate twice with two different entities and such negotiations could result in two different outcomes. It is quite impractical to establish two competing native title holding bodies whose membership is wholly or substantially overlapping.

52 It must also follow, considering that approach, that in this instance two separate PBCs (as proposed by the Sullivan Minute) is not appropriate.

HABITATS

53 I also note, as a matter of minor detail, that the Sullivan Minute introduces the words “habitats and” to the non-exclusive right described in para 4(c), such that the right reads “the right to maintain and protect habitats and places and objects of significance…”. The rights contained in para 4 of the State Minute were those contained in the draft Yilka Determination annexed to the reasons in Yilka No 5 (at Annexure 2) (as amended by the Court in [743] of Yilka No 5). There was not any "particular difficulty about the terms of the Yilka Determination Sought" as I noted in the reasons and it is not clear what the reason is for the addition to para 4(c) in the Sullivan Minute. I do not support that change.

FINALISATION OF THE DETERMINATION

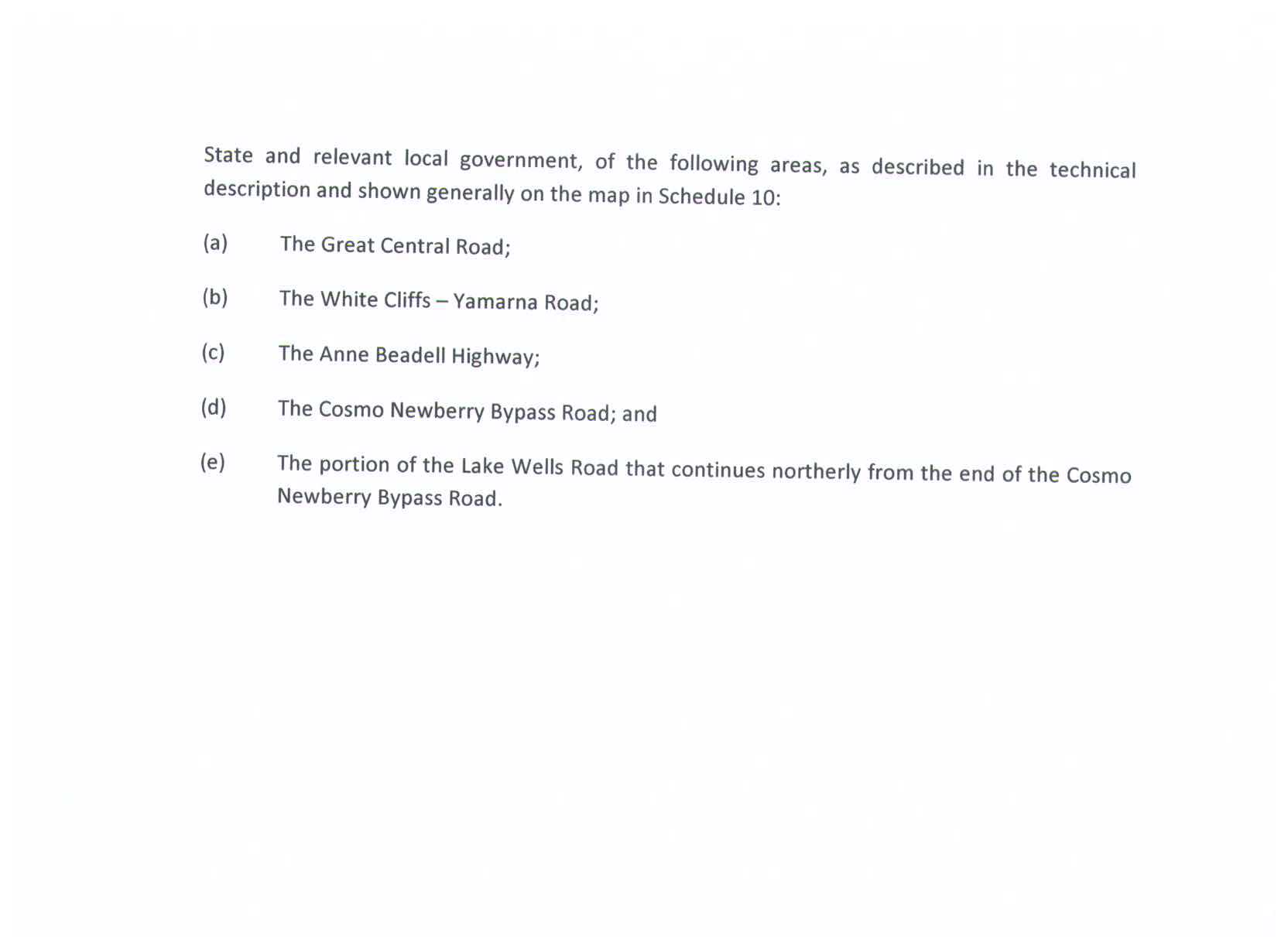

54 A number of maps are to be completed prior to any final determination. Further, given the length of time which has passed since the tenure was last updated in the parties’ draft minutes it will also be necessary to check the status and currency of the tenure prior to a determination. Now that the final form of determination has been determined I note that the State will work with the other parties to complete the necessary mapping and tenure updates prior to a final determination. I will ask the State to prepare the final form of determination to reflect these reasons and updated tenure.

CONCLUSION

55 Whilst this determination reflects the past, its main function relates to the future. It is not appropriate to perpetuate the errors of the past by isolating the two groups. It is time they worked together. It is time for the leaders to take responsibility to see that this occurs. I do not intend to penalise others within the groups and others external to them by requiring them to deal with an unwieldy and inappropriate set of multiple structures. This is not to say that all difficulties are in the past. It is to say that it is time to move on from them.

56 As one positive sign of prospective harmony, I am pleased to note that the dispute about costs was agreed between the parties.

I certify that the preceding fifty-six (56) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice McKerracher. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE 1

…

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Yilka Claims being WAD297 of 2008, WAD303 of 2013 and the Sullivan Edwards Claim being WAD498 of 2011 be determined together.

2. In relation to the Determination Area, there be a determination of native title in WAD297 of 2008, WAD303 of 2013 and WAD498 of 2011 in terms of the attached Minute of Determination of Native Title.

3. Upon the determination taking effect:

(a) The native title of the Yilka common law holders in the Determination Area is to be held in trust by the Yilka Aboriginal Corporation (ICN: 8415);

(b) The native title of the Sullivan Edwards common law holders in the Determination Area is to be held in trust by the Sullivan Edwards Aboriginal Corporation (ICN:????);

(c) Subject to paragraph 3(a) above, the Yilka Aboriginal Corporation (ICN: 8415), incorporated under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth) is to:

(i) be the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of ss 56(2)(b) and 56(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); and

(ii) perform the functions mentioned in s 57(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) after becoming a registered native title body corporate.

(d) Subject to paragraph 3(b) above, the Aboriginal Corporation (ICN: ????), incorporated under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth), is to:

(i) be the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of s 57(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); and

(ii) perform the functions mentioned in s 57(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) after becoming a registered native title body corporate.

4. The State’s interlocutory application in WAD 297 of 2008 dated 15 October 2012 be dismissed.

5. The Applicant in WAD 297 of 2008 and WAD 303 of 2013 pay the costs of the Applicant in WAD 498 of 2011 in all three proceedings.

MINUTE OF DETERMINATION OF NATIVE TITLE

THE COURT ORDERS AND DETERMINES THAT:

1. Native title rights and interests exist in relation to the whole of the Determination Area.

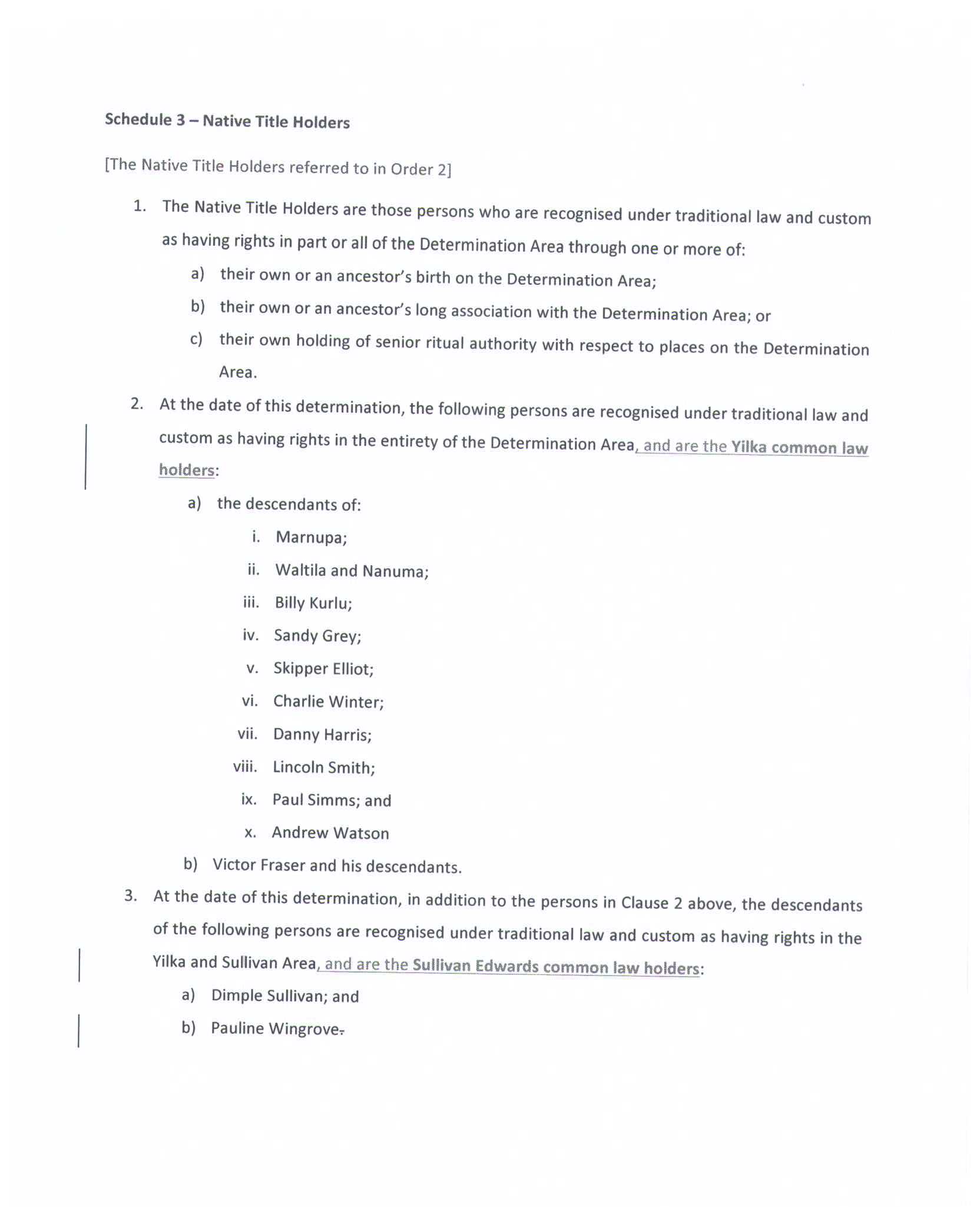

2. The native title is held by the persons described in Schedule 3 (native title holders) that includes the Yilka common law holders and the Sullivan Edwards common law holders whose separate claims were established independently of and in addition to each other.

3. Subject to Orders 6 and 7, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to each part of the Determination Area referred to in Schedule 4 [being land and waters where there has been no extinguishment of native title or areas where any extinguishment must be disregarded] is the right of possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that part as against the whole world.

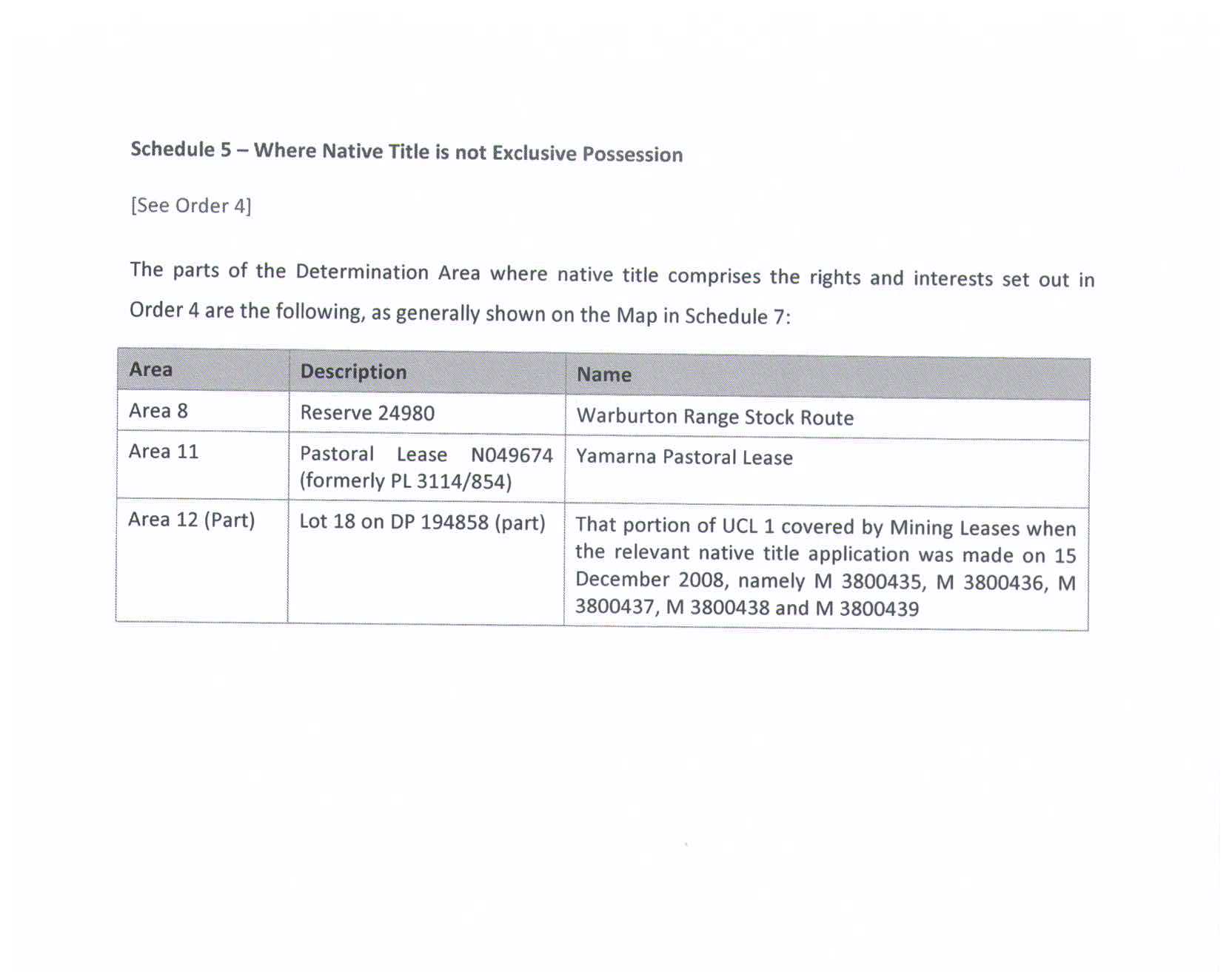

4. Subject to Orders 5, 6 and 7, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to each part of the Determination Area referred to in Schedule 5 [being land and waters where there has been partial extinguishment other than where such extinguishment must be disregarded] are the following rights or interests:

(a) the right to access, to remain in and to use that part for any purpose;

(b) the right to access and take for any purpose resources of that part;

(c) the right to maintain and protect habitats and places and objects of significance in or on that part.

5. The native title rights and interests referred to in Order 4 do not confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the native title areas or any parts thereof on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

6. The native title rights and interests are exercisable in accordance with and subject to the:

(a) traditional laws and customs of the native title holders; and

(b) laws of the State and the Commonwealth, including the common law.

7. Notwithstanding anything in this determination, there are no native title rights and interests in the native title areas in or in relation to:

(a) minerals as defined in the Mining Act 1904 (WA) (repealed) and in the Mining Act 1978 (WA) as in force at 31 October 1975; or

(b) petroleum as defined in the Petroleum Act 1936 (WA) (repealed) and in the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Resources Act 1967 (WA).

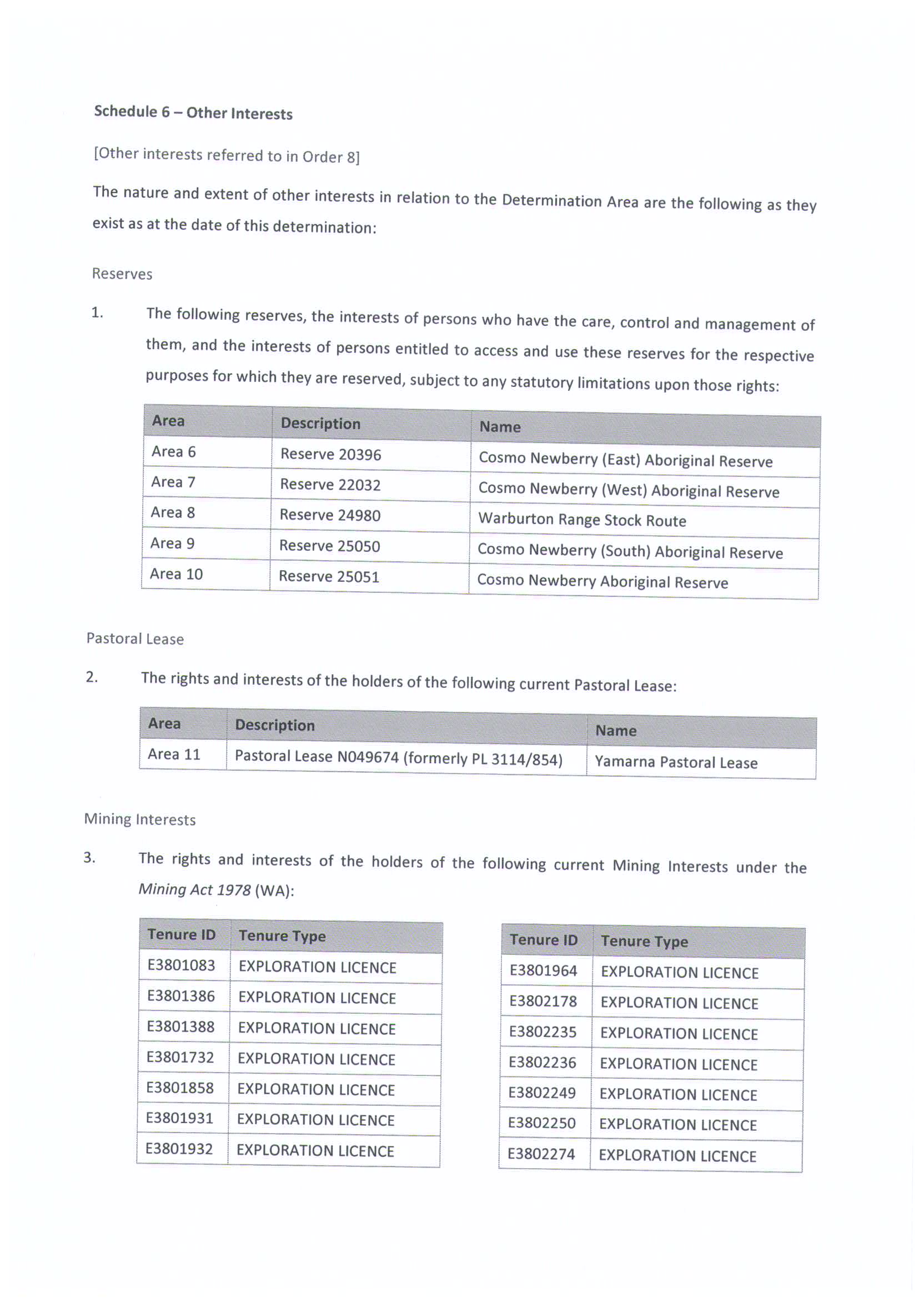

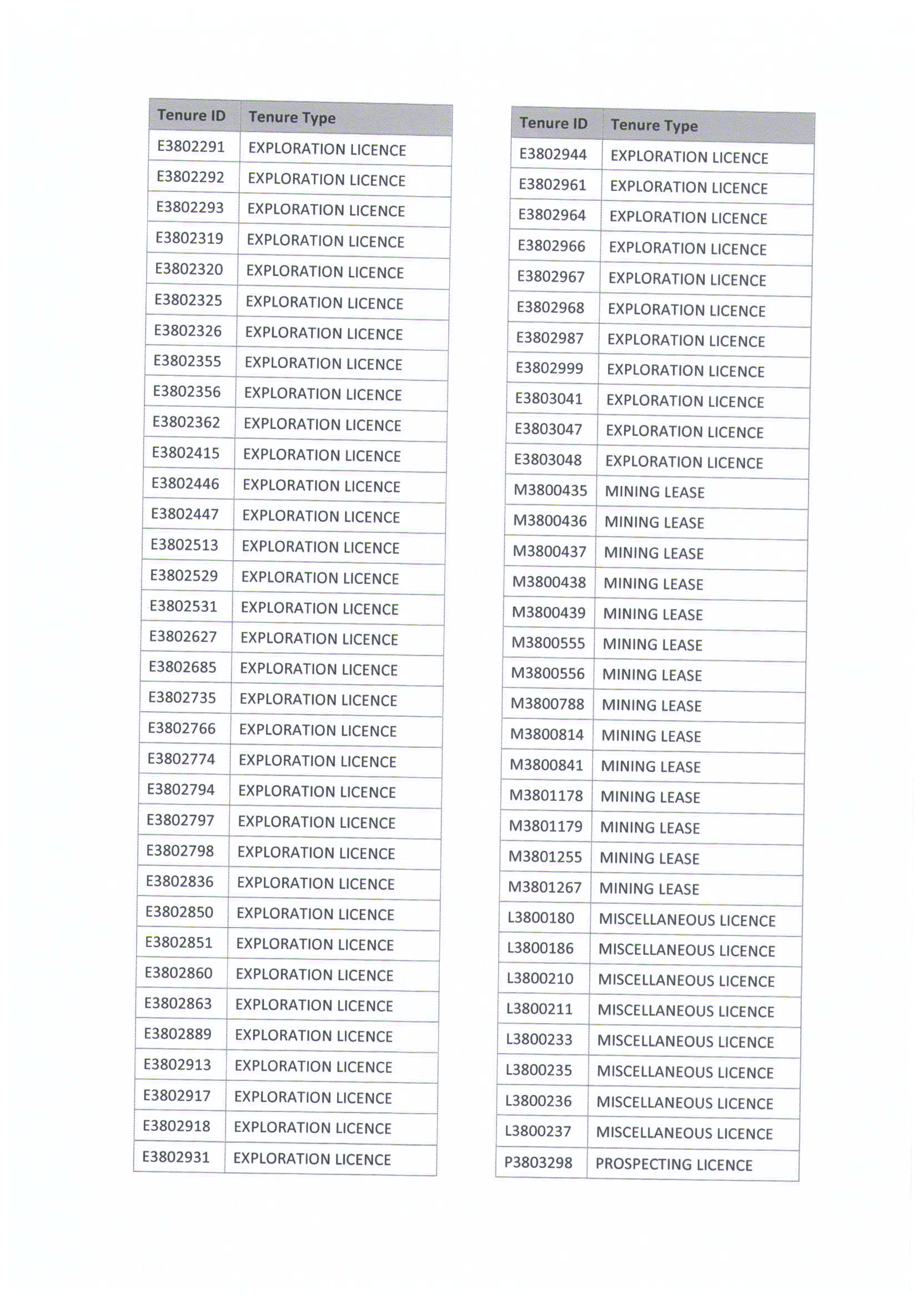

8. The nature and extent of other rights and/or interests in relation to the Determination Area are those set out in Schedule 6 (other interests).

9. The relationship between the native title rights and interests and the other interests is as follows:

(a) the other interests co-exist with the native title rights and interests;

(b) the determination does not affect the validity of those other interests; and

(c) to the extent of any inconsistency, the native title rights and interests yield to the other interests.

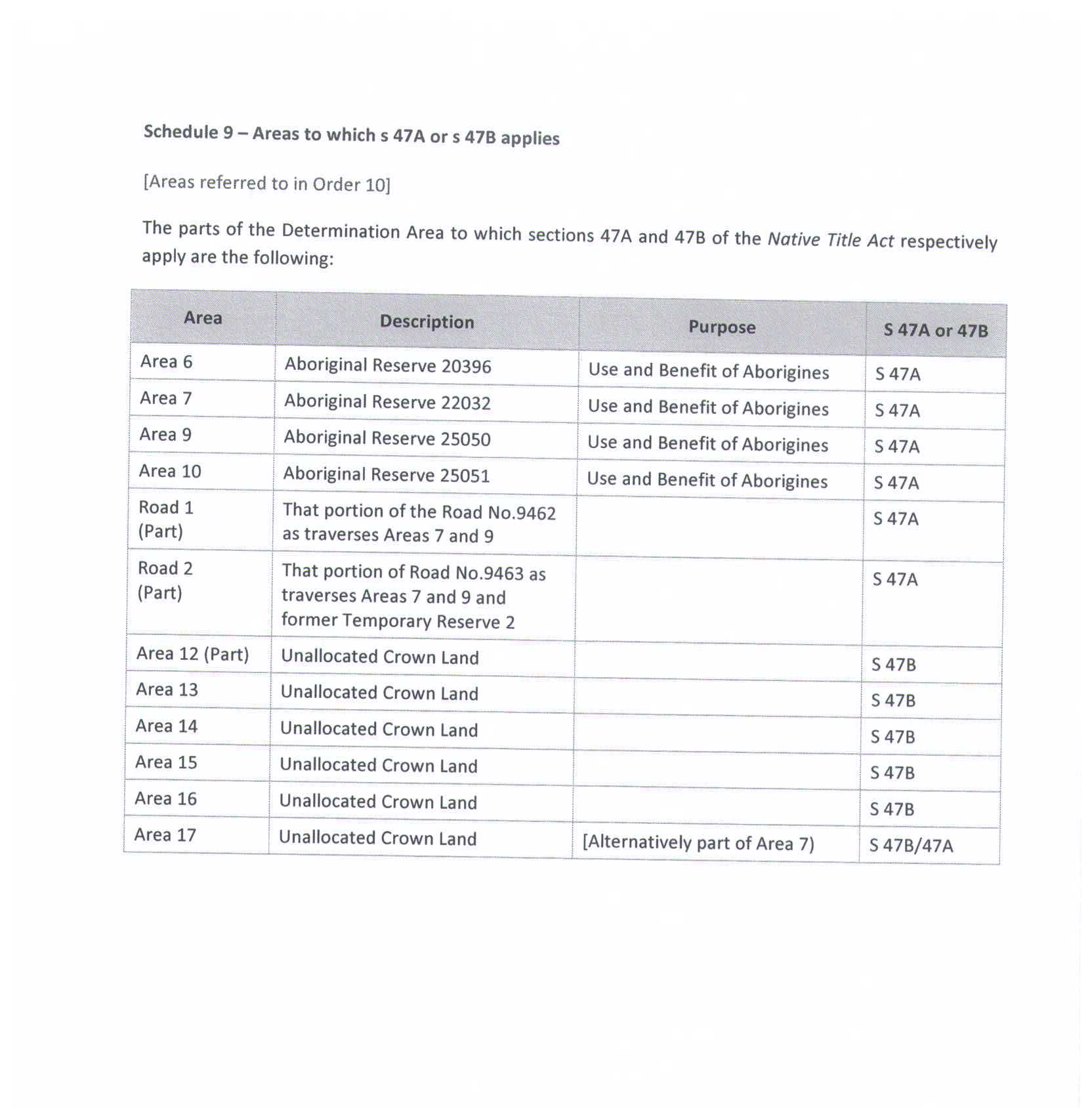

10. For the avoidance of doubt, sections 47A and 47B of the Native Title Act respectively apply to the areas described in Schedule 9.

11. In this determination, unless the contrary intention appears:

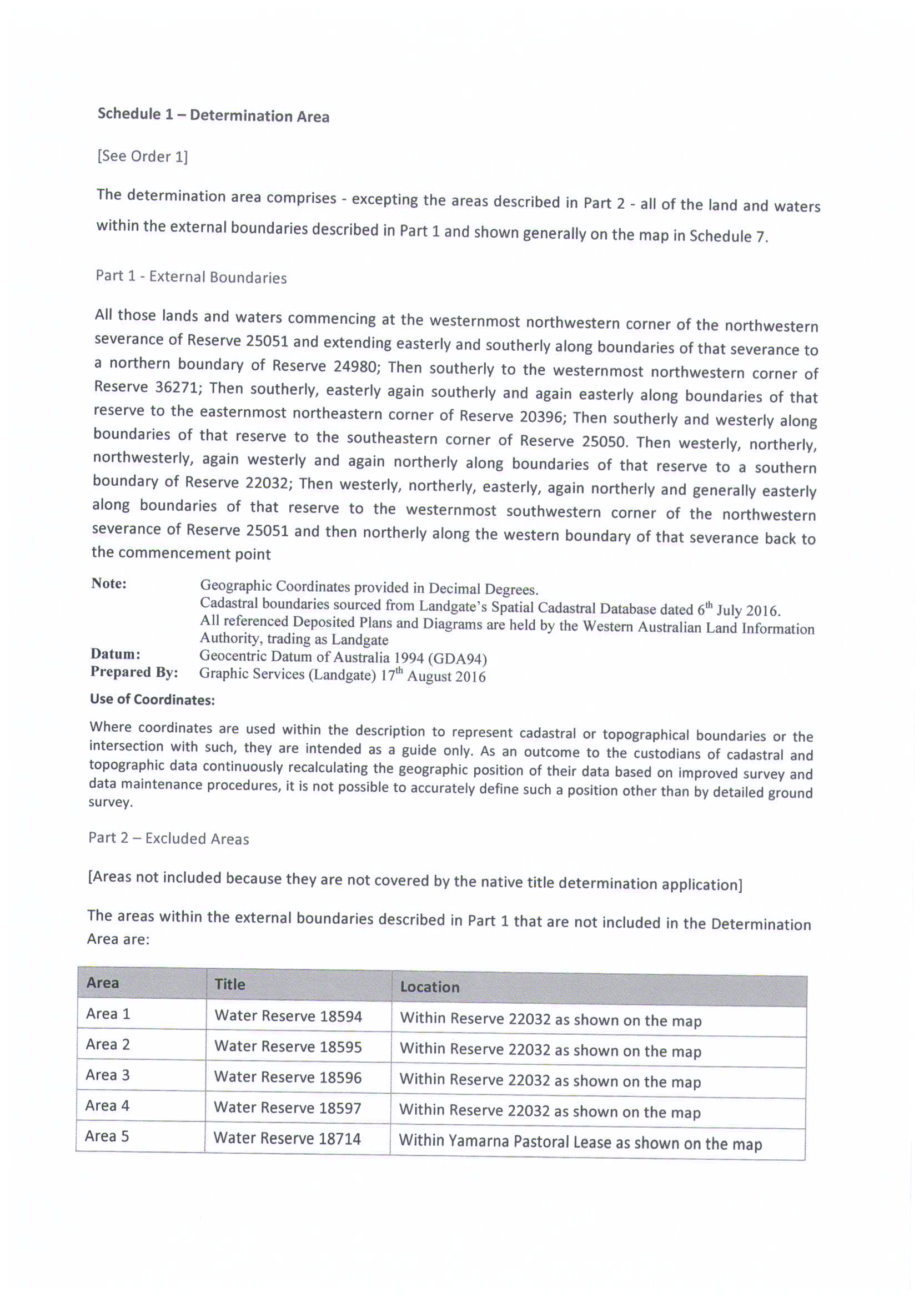

Determination Area means the land and waters described in Schedule 1 Part 1;

land and waters respectively have the same meanings as in the Native Title Act;

Native Title Act means the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth);

State means the State of Western Australia;

Sullivan Edwards Claim means the application for a determination of native title made in Federal Court proceeding No. WAD 498 of 2011.

Sullivan Edwards common law holders means the holders of native title rights and interests described in Schedule 3 at [3];

Yilka common law holders means the holders of native title rights and interests described in Schedule 3 at [2];

Yilka Claims means the application for a determination of native title made in Federal Court proceedings No. WAD 297 of 2008 and WAD 303 of 2013; and

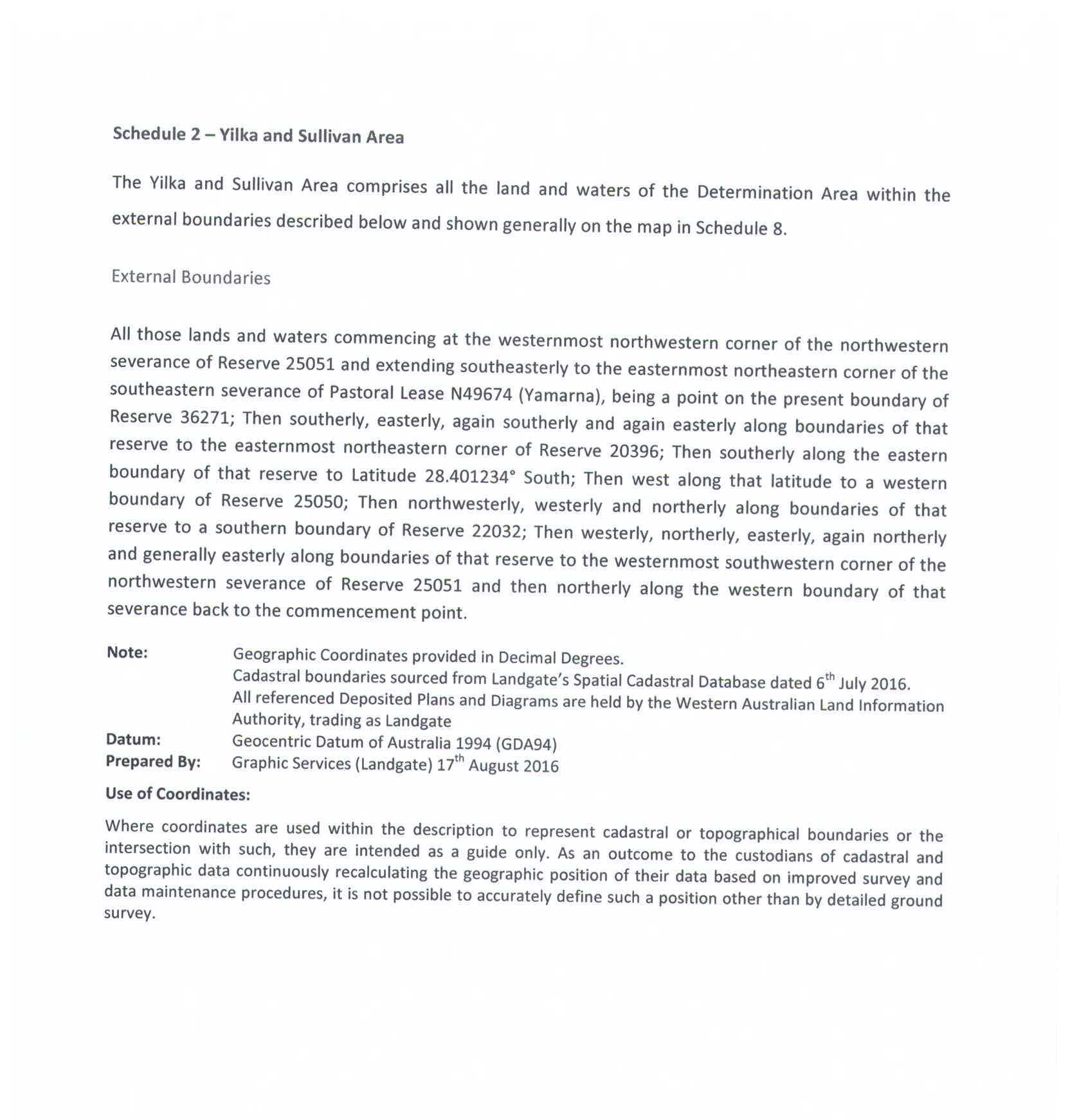

Yilka and Sullivan Area means the land and waters described in Schedule 2.

12. In the event of an inconsistency between the written description of area in the Schedules and the areas depicted on the Maps in Schedules 7 and 8, the written descriptions shall prevail.

WAD 297 of 2008 | |

ELECKRA MINES LTD AND URANEX NL | |

Fifth Respondent: | TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED |

WAD 498 of 2011

Respondents | |

Fourth Respondent: | ELECKRA MINES LTD AND SASAK RESOURCES AUSTRALIA PTY LTD AND URANEX NL |

Fifth Respondent: | TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED |

Sixth Respondent: | GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LIMITED |