FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Helicopter Tjungarrayi on behalf of the Ngurra Kayanta People v State of Western Australia (No 2) ]2017] FCA 587

ORDERS

WAD 410 of 2012 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | HELICOPTER TJUNGARRAYI , RICHARD YUGUMBARRI, FRANCES NANGURI, RITA MINGA, EUGENE LAUREL, DARREN FARMER, SANDRA BROOKING, JANE BIEUNDURRY, and BARTHOLOMEW BAADJO Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA, SHIRE OF HALLS CREEK and CENTRAL DESERT NATIVE TITLE SERVICES LTD Respondents | |

AND: | ATTORNEY-GENERAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Intervenor | |

WAD 326 of 2015 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | BOBBY WEST and JOSHUA BOOTH Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA and CENTRAL DESERT NATIVE TITLE SERVICES LTD Respondents | |

AND: | ATTORNEY-GENERAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Intervenor | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Following conferral with the parties and the intervenor file a minute final determination to be made in these proceedings.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BARKER J:

1 A question has arisen between the parties to this native title proceeding and the Commonwealth of Australia as intervener, in the course of negotiating a consent determination, whether the prior extinguishment of native title rights and interests in the Part B claim area is to be disregarded having regard to the terms of s 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA).

2 Relevantly – where s 47B applies – as provided by s 47B(2), for all purposes under the NTA in relation to the application, any extinguishment of the native title rights and interests in relation to the area that are claimed in the application by the creation of any prior interest in relation to the area must be disregarded.

3 Section 47B(1) specifies when the section applies:

(1) This section applies if:

(a) a claimant application is made in relation to an area; and

(b) when the application is made, the area is not:

(i) covered by a freehold estate or a lease; or

(ii) covered by a reservation, proclamation, dedication, condition, permission or authority, made or conferred by the Crown in any capacity, or by the making, amendment or repeal of legislation of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory, under which the whole or a part of the land or waters in the area is to be used for public purposes or for a particular purpose; or

(iii) subject to a resumption process (see paragraph (5)(b)); and

(c) when the application is made, one or more members of the native title claim group occupy the area.

4 The State of Western Australia contends that each of two petroleum exploration permits – EP 451 and EP 477 – granted on 28 September 2006 and 20 April 2011, under the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Resources Act 1967 (WA) (PGERA), constitutes a “lease” for the purposes of s 47B(1)(b)(i) of the NTA, and so s 47B does not apply to the application. That is one question for present determination.

5 The Commonwealth contends that, notwithstanding the decision of the Full Court in Banjima People v Western Australia (2015) 231 FCR 456; [2015] FCAFC 84 (Banjima FC), the exploration permits are not covered by s 47B(1)(b)(ii) because the area in question is “to be used for a particular purpose”, and so s 47B does not apply to the application. That is the second question arising for present determination.

6 Procedurally, these two issues were identified as separate questions for hearing.

7 On 18 October 2016 I made orders by consent requiring the filing of a statement of facts and issues, the relevant documents to be tendered in evidence at the hearing, and submissions.

8 The following materials went into evidence:

The applicants’ statement of facts and issues.

The State’s statement in response.

The Commonwealth’s statement in response.

The applicant’s bundle of documents.

The affidavit of Ms Maia Charlotte Williams, with annexures.

The statement of agreed facts by the Ngurra Kayanta and Ngurra Kayanta #2 applicants and the State.

9 The issues arising as separate questions are therefore to be stated as whether or not s 47B of the NTA applies in relation to the Part B claim area on the basis that when the Ngurra Kayanta #2 application was made on 30 June 2015, the area may have, because of either or both of EP 451 and EP 477, been covered by:

a lease within s 47B(1)(b)(i) of the NTA; or

a permission or authority under which the whole or a part of the land or waters in the area is to be used for public purposes or for a particular purpose within s 47B(1)(b)(ii) of the NTA.

10 To the extent finally relevant either to submissions made by the parties or to this judgment, the agreed facts and evidentiary material are referred to below.

Is each permit a “lease”?

11 The State develops its contention first by drawing attention to the definition of “lease” provided by s 242 of the NTA:

(1) The expression lease includes:

(a) a lease enforceable in equity; or

(b) a contract that contains a statement to the effect that it is a lease; or

(c) anything that, at or before the time of its creation, is, for any purpose, by a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory, declared to be or described as a lease.

References to mining lease

(2) In the case only of references to a mining lease, the expression lease also includes a licence issued, or an authority given, by or under a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory.

12 In short, the State argues that, when read with other provisions of the NTA, s 242(2) makes the exploration permits into leases for NTA purposes.

13 The State observes that s 242(2) was not included in the first draft of the Native Title Bill 1993 (Cth) but was introduced following further consultation, and refers to the terms of the Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum, Native Title Bill 1993 (Cth):

The addition of subclause (2) provides that for the purposes of mining leases only, licences or authorities to mine are to be treated in the same way as mining leases. This amendment is part of a package of amendments to treat licences and authorities to mine in the same way as mining leases. The related amendments are found in amendments 66 and 67.

14 It may be noted, in passing at this point, that the Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum refers to licences or authorities “to mine” being treated in the same way as mining leases.

15 The State points out that amendments 66 and 67 are consequential proposed amendments to the definition of “lessee” as a result of the expanded definition of “lease” that is now reflected in s 243(2) of the NTA which provides, in effect, that in the case of a lease that is a mining lease because of s 242(2), the expression “lessee” means a person to whom the licence or authority was given or any person who subsequently acquires the licence or authority.

16 The State also draws attention to what the Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum states in respect of amendments 66 and 67:

This clause defines what is meant by the term ‘lessee’ for the purposes of this Bill. The addition of subclause (2) makes it clear that for the purposes of a mining licence or authority that is a mining lease because of subclause 227(2) [now subsection 242(2)] a person holding such a licence or authority is to be regarded as a lessee for the purposes of the Bill. These amendments are also consequential upon the treatment of mining licences and authorities which give similar rights to mining leases in the same manner for the purposes of this Bill.

17 By reference to Wilson v Anderson (2002) 213 CLR 401; [2002] HCA 29 at [59], the State observes that s 242(2) postulates the existence of an interest which, although described as a “lease”, is not a lease at common law.

18 From that postulation the State draws the submission that anything described as a “lease” in the NTA is a “lease” by virtue of s 242(1)(c).

19 Thus, the State contends, the definition of “lease” in s 242 extends to include licences and authorities to mine. As to the definition of “mine”, the State relies on the definition of that verb provided in s 253, as follows:

mine includes:

(a) explore or prospect for things that may be mined (including things covered by that expression because of paragraphs (b) and (c)); or

(b) extract petroleum or gas from land or from the bed or subsoil under waters; or

(c) quarry;

but does not include extract, obtain or remove sand, gravel, rocks or soil from the natural surface of land, or of the bed beneath waters, for a purpose other than:

(d) extracting, producing or refining minerals from the sand, gravel, rocks or soil; or

(e) processing the sand, gravel, rocks or soil by non‑mechanical means.

20 The State submits each of the two exploration permits, by the terms of s 38 of the PGERA under which each was granted, “authorises the permittee, subject to this Act and in accordance with the conditions to which that permit is subject, to explore for petroleum”.

21 It follows, the State submits, that each permit, being an authority to explore, is an authority to “mine”; and so is a “lease” by virtue of s 242(2) of the NTA.

22 The State also notes that “mining lease” is defined in s 245 of the NTA in the following way:

(1) A mining lease is a lease (other than an agricultural lease, a pastoral lease or a residential lease) that permits the lessee to use the land or waters covered by the lease solely or primarily for mining.

23 The qualification, “solely or primarily for mining” is the subject of further submission by the State.

24 The State accepts it is only licences and authorities under the PGERA that are “solely or primarily for mining” (as “mine” is defined in s 253 of the NTA) that fall within this definition of “mining lease”, and contend that the permits satisfy that qualification.

25 By contrast, the applicant contends that the exploration permits do not come within the definition of a “lease”. It submits the extended definition of “lease” in s 242(2) applies in the case only of references to a mining lease, that is to say where a provision expressly refers to a “mining lease”. Thus, the applicant submits, because para (b)(i) does not refer to a “mining lease” but only to a “freehold estate or a lease”, it does not pick up the exploration permits in this case.

26 The applicant accepts that while the reference in para (b)(i) to a “lease” might include a mining lease under the Mining Act 1978 (WA) or a retention lease under the PGERA, by reason of s 242(1)(c) of the NTA, s 242(1) and (2) do not have a cumulative operation such that any reference in the NTA to a lease includes a “licence issued or an authority given, by or under a law of the … State”, in the extended definition. It submits that such an interpretation or construction would contradict the opening words of s 242(2) itself: “in the case only of references to a mining lease”.

27 Following the hearing on this question of construction, and the reserving of judgment on it by me, Mortimer J delivered a reserved judgment in Narrier v State of Western Australia [2016] FCA 1519. At [1194] to [1210], her Honour dealt with the issue whether an exploration licence granted under the Mining Act falls within the meaning of “lease” in s 47B(1)(b)(i) of the NTA. Because her Honour decided it did not, and her Honour’s analysis appeared directly relevant to the question before me, I invited the applicant and the State to make further submissions having regard to her Honour’s analysis.

28 Mortimer J’s analysis at [1194] to [1210] is as follows:

1194 In its reply submissions, given the findings of the Full Court in Banjima People v Western Australia (No 2) [2015] FCAFC 171; 328 ALR 637, the State did not press its alternative submission under s 47B(1)(b)(ii) about the exploration licences.

1195 That leaves its submissions that these licences fall within the meaning of ‘lease’ in s 47B(1)(b)(i). The State submits that the definition of ‘lease’ in s 242 of the NT Act includes licences and authorities to mine. Relying then on the definition of ‘mine’ in s 253 of the NT Act, the State submits that a mining exploration licence is a ‘lease’ for the purposes of the NT Act, and therefore within s 47B(1)(b)(i).

1196 Section 242 provides an inclusive but not exhaustive definition of the term ‘lease’:

Lease

(1) The expression lease includes:

(a) a lease enforceable in equity; or

(b) a contract that contains a statement to the effect that it is a lease; or

(c) anything that, at or before the time of its creation, is, for any purpose, by a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory, declared to be or described as a lease.

References to mining lease

(2) In the case only of references to a mining lease, the expression lease also includes a licence issued, or an authority given, by or under a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory.

1197 The State relied on the effect of s 242(2). Its submissions describe the addition of subs (2) to the original draft of the Native Title Bill 1993 (Cth) and refer to the Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum and to the explanatory material which related to the corresponding expansion of the definition of ‘lessee’ in s 243(2). There is nothing in this explanatory material which assists the State’s argument, as it simply repeats (as extrinsic material is wont to do) the terms of s 242(2).

1198 The real source of the State’s submission is the definition of ‘mine’ in s 253, which provides:

mine includes:

(a) explore or prospect for things that may be mined (including things covered by that expression because of paragraphs (b) and (c)); or

(b) extract petroleum or gas from land or from the bed or subsoil under waters; or

(c) quarry;

but does not include extract, obtain or remove sand, gravel, rocks or soil from the natural surface of land, or of the bed beneath waters, for a purpose other than:

(d) extracting, producing or refining minerals from the sand, gravel, rocks or soil; or

(e) processing the sand, gravel, rocks or soil by non-mechanical means.

1199 The terms of (a) indicate, the State submits, that if a ‘licence’ falls within the definition of ‘lease’ then a licence to ‘mine’, as defined in s 253, must include an exploration licence. By this route, the State reaches the exclusion in s 47B(1)(b)(i).

1200 I do not accept the State’s submission, as it distorts the exclusion in s 47B(1)(b)(i), and does not give effect to the text of s 242(2).

1201 Section 242(1) contains a general definition of ‘lease’ for the purpose of the NT Act. As I have noted, it is inclusive, not exhaustive. However, the remainder of Div 3 of Pt 15 then goes on to identify, and make specific provision about, a number of common lease types which might coexist on land over which native title is claimed. Unsurprisingly, one of the kinds of leases for which specific provision is made is a mining lease.

1202 Section 245(1) provides:

A mining lease is a lease (other than an agricultural lease, a pastoral lease or a residential lease) that permits the lessee to use the land or waters covered by the lease solely or primarily for mining.

1203 Agricultural, pastoral and residential leases all have their own definitions: see ss 247, 248 and 249.

1204 Division 3 of Pt 15 is, as s 241 states, a definitional division. The purpose of s 242(1) is to indicate what kinds of transactions are to be comprehended by the term ‘lease’, and this will inform the meaning of the word in the more specific definitions which follow. So that, for example, a residential lease under s 249 will include a lease that is enforceable in equity.

1205 The purpose of s 242(2) is to give an extended operation to the term ‘lease’ only in the case of mining leases. The effect is that wherever the NT Act uses the term ‘mining lease’, that is to be taken as including a ‘mining authority’ or a ‘mining licence’ issued or given under a law of the Commonwealth or a State or Territory.

1206 Whatever kind of authority or permission is given must still meet the definition of a ‘mining lease’ in s 245, and whether it meets that definition will be determined by the activities it authorises. To fall within the extended definition of a mining ‘lease’, there must be permission for the lessee to ‘use the land or waters … solely or primarily for mining’.

1207 Despite the definition given to the verb ‘mine’ in s 253, in my opinion the NT Act defines a mining lease more narrowly, even taking into account s 242(2). It looks to the use of the land, and requires that the land be used ‘solely’ or ‘primarily’ for mining. There is no evidence that the exploration licences in question permitted the licensee to use the land or waters they covered ‘solely’ or ‘primarily’ for mining.

1208 Accordingly, I reject the State’s submissions that the identified exploration licences which cover all or parts of the parcels said by the applicant to be subject to s 47B fall within s 47B(1)(b)(i). The existence of the exploration licences does not render s 47B(2) inapplicable.

1209 In Banjima (No 2) [2013] FCA 868; 305 ALR 1, the submissions put to Barker J by the State were that mining exploration licences fell within s 47B(1)(b)(ii) and for that reason s 47B(2) could not apply to areas covered by such exploration licences. After an examination of the authorities and, with respect, detailed consideration, Barker J rejected that argument: see [1208].

1210 I infer the State did not press the same argument in this case because of Barker J’s finding in Banjima (No 2), which was affirmed on appeal: see Banjima [2015] FCAFC 84; 231 FCR 456 at [115]-[118].

29 In its supplementary submissions, the State accepts that, as a matter of construction, the issues considered in Narrier, while not dealing with petroleum permits under the PGERA, are substantially the same as those here. I agree.

30 However, the State maintains the submissions it has previously made and submits that I should not follow the decision of Mortimer J on the basis that her Honour clearly erred in making her finding.

31 As to error, the State submits:

That her Honour erred in finding that, despite the definition given to the verb “mine” in s 253 (which includes “explore or prospect for things that may be mined”) and despite s 242(2), the NTA nevertheless defines a mining lease more narrowly.

In particular, her Honour made reference to the fact that s 245(1) refers to land being used “solely or primarily for mining” and considered there was an absence of evidence to establish that the relevant exploration licence before her permitted the licensee to use the land or waters covered by the licence “solely” or “primarily” for mining.

32 The State submits that her Honour’s reasons are apt to be understood in two ways:

(1) that “mining” has a distinct and narrower meaning than the term “mine”, so that where a mining authority permits (only) exploration it will never be an authority permitting “mining” (the construction issue); or

(2) that a mining authority which permits (only) exploration may be an authority permitting “mining”, but it will be a question of fact and evidence as to what the authority permits (the evidentiary issue).

33 The State says that in Narrier the question of whether there was a distinction between the meanings of “mining” and “mine” was not raised by any party before her Honour so that, in that regard, her Honour had no assistance from the parties in reaching the particular conclusion(s) that she did.

34 The State says the issue before her Honour was, similarly to these proceedings, whether or not s 47B(1)(b)(i) of the NTA applied to “mining leases” that were authorities granted for the purposes of exploration.

35 The State makes further submissions about how the expressions “mining” and “mine” affect the constructional issue in this case.

36 It also makes submissions about what it calls the evidentiary issue, namely, a finding, as a matter of fact, that there was no evidence that the exploration licences permitted the use of the licence area “solely” or “primarily” for mining.

37 The applicant, in its supplementary submission, makes two further points by reference to Narrier.

38 First, that the reasoning in Narrier at [1200]–[1207] holds that:

(1) despite the definition of the verb “mine” in s 253 of the NTA, including explore or prospect, a mining lease as defined in s 245 looks to use of the land for mining in a narrower sense, that is, the recovery of minerals: first two sentences of [1207];

(2) the exploration licence did not permit the licensee to use the land and waters covered by the licence “solely or primarily” for mining, whether or not, or assuming that, the word “mining” in mining lease is to be read in an extended sense to include exploration: second and third sentences of [1207].

39 The applicant submits that the reasoning has equal application to a petroleum exploration permit granted under the PGERA, with the result that the first proposition in Narrier applies because a petroleum exploration permit authorises the permittee only to explore for petroleum (s 29 and s 38 of the PGERA) and not to recover (mine) petroleum, which can be done only under a production licence (s 49 and s 62 of the PGERA).

40 The second proposition in Narrier applies, the applicant submits, because a permit does not permit the permittee to use the permit area solely or primarily for mining petroleum (assuming the word “mining” in “mining lease” is to be read in an extended sense to include “explore”). The permit conditions requiring further approval before exploration can be carried out, and/or the status of the land as unallocated Crown land available for other uses, means that a permittee is not permitted to use the permit area solely or primarily for mining (exploration).

41 The applicant further submits that, in Narrier, Mortimer J observed that the purpose of s 242(1) of the NTA is to indicate what kinds of transactions are to be comprehended by the term lease which will inform the meaning of the word in the more specific definitions of particular kinds of leases that follow (ss 245–249B), and that the purpose of s 242(2) is to give an extended operation of the term lease only in the case of a mining lease: Narrier at [1204]–[1205]. That is consistent, the applicant submits, with its submissions in this case that the text of s 242(2) is clear in that it is only in the case of a reference to a “mining lease” that s 242(2) is engaged. The definition in s 242(2) is not engaged in relation to s 47B(1)(b)(i) because s 47B(1)(b)(i) refers only to a lease; it does not refer to a mining lease.

42 The applicant submits this textual reading of s 242(2), that the extended definition of mining lease to include a licence or authority is not engaged in relation to s 47B(1)(b)(i) because (i) refers only to a lease, is consistent with the context in which para (b) of subs (1) operates in defining when land is not vacant Crown land. Conferral of a statutory right to mine might be described in the NTA as a lease, but is not a lease of land. And Crown land covered by a statutory right to mine is or remains vacant (or unallocated or unalienated) Crown land. The applicant submits this context confirms the textual reading of s 242(2) as being engaged only when there is a reference in the NTA to a mining lease, and not when there is a reference only to a lease. Thus Mortimer J was right to observe in Narrier, at [1200], that the State’s contention that a licence or permit to explore for minerals is a lease within s 47B(1)(b)(i) “distorts [that] exclusion, and does not give effect to the text of s 242(2)”. So, a statutory right to mine might be described in the empowering statute as a lease, and fall within the definition of lease in s 242(1)(c), but the context of s 47B reveals a contrary intention that such a thing is not a lease for the purposes of s 47B(1). Further, the instruments in issue are not even described as a lease.

43 The State contends there are several difficulties with the applicant’s supplementary submissions. It notes that the definition of “mining lease” in s 245(1) provides:

A mining lease is a lease (other than an agricultural lease, a pastoral lease or a residential lease) that permits the lessee to use the land or waters covered by the lease solely or primarily for mining.

44 Therefore, it submits, it is only licences and authorities under the PGERA that are “solely or primarily for mining” (as defined in s 253 of the NTA) that fall within the expanded definition of “mining lease” in s 242(2).

45 As to the applicant’s submissions that the definition of “lease” in s 242(2) applies only where a provision in the NTA makes specific reference to a “mining lease”, the State contends there are several difficulties with that submission too. First, if that was the intention, the expanded definition should have been included as a subsection to s 245 of the NTA (which defines “mining lease”), not as a subsection to s 242 (which defines “lease”). The applicant’s submission is to the effect that the Court is to construe s 242(2) as somehow detached from the remainder of s 242. In the State’s submission it is plain, when one reads s 242 as a whole, that s 242(2) flows on from, and is intended to deal with, the same subject matter as s 242(1), particularly given the terms of s 242(1)(c), which provides for “anything that ... is … declared to be or described as a lease” to be a “lease”.

46 Secondly, the State says such a construction would not accord with Div 3 of Pt 15 of the NTA. Relevant provisions in that Division can only logically be read as meaning that a reference to “lease” includes reference to a “mining lease”. Section 241 provides that Division 3 contains definitions “relating to leases”. Section 243, which defines “lessee”, includes s 243(2), which refers to “a lease that is a mining lease”. Section 245, which within Division 3 defines “mining lease”, commences “[a] mining lease is a lease ...”.

47 Thirdly, the State says, it is plain from the context of the NTA, as a whole, that it is intended that the term “lease” is to be read as including a mining lease. The State says there are only a very limited number of places in the NTA where the term “lease” is used without qualification. Section 47B(l)(b)(i) is one instance. Section 44H uses the term “lease” in a global way. It is not restricted to a particular type or classification of a “lease”. Another instance is s 24IC, which deals with “Future acts that are permissible lease etc. renewals”. It is apparent from s 24IC(l)(e) that “lease” in s 24IC includes leases which permit mining (that is, mining leases). This is confirmed by s 24IC(4)(c). Section 24IC has been found to apply to mining leases granted pursuant to the Mining Act. In contrast, in other sections of the NTA, mining leases are specifically excluded from those classes or kinds of lease which are affected by a particular provision. That is not to alter the definition of “lease”, but rather to identify which particular category or kind of lease is relevant in a particular instance. For example, s 21(3) (which deals with the validation of “intermediate period acts”) refers to “a grant of a freehold estate or a lease (other than a mining lease)”. This specific exclusion of mining lease from certain treatments of “leases” is replicated at ss: 23B(2)(c)(viii); 43A(2)(a)(i); 230(b) (which defines a “category B past act” as “a past act consisting of the grant of a lease where ... the lease is not a mining lease”); 232B(3)(g); and 232C(b). Each of these provisions only makes logical sense if the term “lease” otherwise includes a mining lease. That is, the specific exclusion of mining leases on these occasions where the term “lease” is used can only be necessary because “lease” otherwise includes mining leases.

48 The State submits that if mining leases were similarly meant to be excluded from the treatment of a “lease” under s 47B, then the same form of words would have been used as had been used in numerous other provisions. But to the contrary, the same wording as included at s 24IC and s 44H was adopted and enacted. Thus, as a matter of construction and interpretation, having regard to the explanatory memoranda, that drafting and its consequence was intentional.

49 The State also observes that in other sections of the NTA, specific categories of lease are referred to, for example in s 229(3)(a), which provides that:

A past act consisting of the grant of:

a) a commercial lease, an agricultural lease, a pastoral lease or a residential lease;

50 The State says such specific usage is replicated in s 23B(2)(c)(iii), (iv), (v) and (vi).

51 The difficulty with the applicant’s argument, the State says, is apt to be demonstrated in that the applicant does not contend that any mining lease is excluded from s 47B(l)(b)(i). Rather, it is any mining lease that is not described by relevant State Acts as a “lease”. Those “State leases” are included in s 47B(l)(b)(i) because, according to the applicant, s 242(1)(c) provides as much. Instruments of the kind as relevant here are not “leases” because, seemingly, they are not described as “leases” by State legislation.

52 What is not explained by the applicant, the State contends, is why s 242(1)(c) does not apply with equal force to all mining leases as they are defined and characterised by the NTA. It is entirely irreconcilable that s 242(2) of the NTA, being a Commonwealth law which defines a mining lease to include, relevantly, instruments of the kind considered here, is not apt to enliven the operation of s 242(1)(c). In order for the applicant’s argument to succeed, that is a necessary finding to be made. Such a construction disregards s 242(2) and, critically, s 242(1)(c).

53 Notwithstanding the carefully constructed submissions of the State, I consider that the analysis provided by Mortimer J in Narrier is not clearly wrong, that it is applicable to the present construction issue before me, and that I should apply it, with the result that neither of the petroleum exploration permits in issue before me constitutes a “lease” for the purposes of s 47B(1)(b)(i).

54 In the result, the question is one of construction having regard to text, context and purpose of the statutory provision and not one to be resolved by reference to broader conceptual or policy issues that may be thought to underlie it.

55 I agree with the analysis provided by her Honour in Narrier and the conclusion that her Honour arrived at, and expressed at [1200], that to accept the State’s submission would distort the exclusion in s 47B(1)(b)(i) and not give effect to the text of s 242(2).

56 In my view, it is plain from all the materials that the State relies upon, including the Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum, that it is only licenses or authorities under State and Territory legislation that give similar rights to mining leases that will be relevant. In that regard, the licences or authorities in question must, as provided for by s 245 of the NTA, license or authorise the use of land or waters “solely or primarily for mining”. It is not open, in that context, to conclude that mining means exploration.

57 To the extent that there is any ambiguity in the legislative text in that regard, it should be resolved in favour of the result that s 47B is to apply unless it is clear that the Parliament has excluded the operation of the provision.

58 In my view, for the reasons that Mortimer J has given in Narrier, the Parliament has, at the least, left the question of the exclusion of s 47B in the case of licences and authorities to explore, but not actually to mine minerals or produce petroleum, ambiguous.

59 I find, therefore, in relation to the first separate question arising, that the exploration permits in question in this case, being for exploration only, do not constitute mining leases in the manner described in the NTA and so, in each case, the permit is not a “lease” for the purposes of s 47B(1)(b)(i). As a result, s 47B applies to this application.

Is the area to be used for a particular purpose?

60 The Commonwealth contends that the two exploration permits are to be contrasted with those found by the Full Court in Banjima FC not to be covered by s 47B(1)(b)(ii) and that, having regard to the PGERA under which these petroleum permits were granted, and their terms, they should be considered to comprise a permission or authority whereby the Part B claim area “is to be used … for a particular purpose”.

61 The Commonwealth develops its argument in the following way.

62 The Commonwealth submits the reason why the exploration licences considered in Banjima FC were held by the Full Court to suffer the same fate as the proclamation in Northern Territory v Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakaya Native Title Claim Group (2005) 145 FCR 442; [2005] FCAFC 135, is because the licences did not define or specify the way in which exploration was to be carried out. They contend that was significant for at least two reasons. First, although the Full Court implicitly accepted that using ground-disturbing or mechanical exploration equipment on the land would amount to use of the land for the purpose of exploration, the terms of the licences, and the supporting provisions of the Mining Act, prohibited the use of such equipment without the approval of the Minister. As there was no evidence of any such approval having been given, the Full Court held that there was no permission or authority in existence at any relevant time for that category of use of land. Secondly, the terms of the licences permitted exploration to be carried out by way of an airborne geophysical survey without the licensee engaging in any physical activity on or under the surface of the land. Although that particular activity was permitted or authorised by the licences, the Full Court held that it was not an activity that amounted to “use” of the land. The nett result was that, just as the proclamation in Alyawarr encompassed “potential but unascertained uses”, the exploration licences considered in Banjima FC encompassed “potentially permitted” uses.

63 The Commonwealth contends that neither EP 451 nor EP 477 can be characterised in that way. Each permit is subject to minimum work requirements (imposed pursuant to s 43 of the PGERA) that define particular exploration activities that must be undertaken by the permit holder within a specified timeframe. Whilst the work requirements include activities (such as gravity surveys) which, by parity of reasoning with the airborne geophysical survey considered in Banjima FC, would not constitute use of the land for the purposes of s 47B(1)(b)(ii), the permits must be viewed as a whole. They prescribe a range of exploration activities, including extensive physical activity on the land that is properly categorised as using the land.

64 The Commonwealth submits that, in the circumstances, EP 451 and EP 477 provide for the subject land to be used for the purpose of petroleum exploration, and thus for a particular purpose within the meaning of s 47B(1)(b)(ii) of the NTA.

65 The Commonwealth submits that EP 451 and EP 477 will be permissions or authorities “under which” the relevant area “is to be used”, if the terms of the permits, when read with the associated statutory provisions, exhibit an intention to use the subject land for the requisite purpose. They contend that is an objective inquiry, the relevant intention being as to the future use of the subject land. Further, the relevant intention will be demonstrated if the permits either limit the use to which the subject land may be put, and so prevent any other use of the land, or positively require the use of the area to which they relate for the particular purpose of petroleum exploration. The Commonwealth contends that EP 451 and EP 477 are permissions or authorities of the latter kind.

66 The Commonwealth submits the obligatory nature of the minimum work requirements imposed by the permits is evident from the language of the condition itself (“shall carry out”), and reinforced by the statutory imperative in s 90(1) of the PGERA to commence the defined work within a prescribed period of time. The combined effect of s 15(1) and s 38(1) of the PGERA, it submits, is that the minimum work requirements are to be carried out on any land within the permit area, save to the extent that a condition under s 91B(2) has been imposed. When regard is had to the nature and scope of the activities prescribed by the minimum work requirements, in the Commonwealth’s submission, the imputed intention to be associated with the grant of EP 451 and EP 477 is that the whole of the land covered by the permits is to be used for the purpose of petroleum exploration.

67 The Commonwealth further submits the exception to the above is the extent to which EP 451 was subject to a condition under s 91B(2) of the PGERA, which prohibited the permit holder from entering part of the land in the permit area. The Commonwealth contends they would accept that a condition in those terms, coupled with the express carve out from s 15(1) of any land subject to such a condition, is inconsistent with an intention to use that land for the purpose of petroleum exploration. However, in its submission, the point is moot in this case because the affected land was no longer part of the permit area by the time the Ngurra Kayanta #2 application was made, and in any event, was not located within the Part B claim area.

68 The Commonwealth submits that, putting that issue to one side, when the terms of the permits are read with the relevant sections of the PGERA, EP 451 and EP 477 are properly characterised as permissions or authorities under which the whole of the land covered by the permits (and so the whole of the Part B claim area) is to be used for the particular purpose of petroleum exploration. EP 451 and EP 477 simply cannot be characterised as permits that amount to a “mere permission or authority” to explore for petroleum. They say that, if that is accepted, then s 47B(2) of the NTA does not apply to the Part B claim area.

69 They note the applicant seeks to avoid that result on three bases. First, the applicant contends that the exploration permits did not require that any part of the Part B claim area be explored or used for the purpose of exploration, in the sense that, even if there were a requirement for (or obligation on) the permit holder to use the land or waters the subject of the permit, and says there was no obligation to do any of the things in the table (that is, the minimum work requirements), or any other things, in the Part B claim area itself.

70 The Commonwealth contends that if the applicant’s contention is that the exclusionary paragraph in s 47B(1)(b)(ii) is only engaged if the permits stipulate that the specific metes and bounds of the land in the Part B claim must be used, or alternatively that every square metre of land in the permit area must be used, then it should be rejected as it appears to be based on a misreading of Banjima FC at [107]-[108]. It submits the point being made by the Full Court in those passages was that the exploration licences in question did not require any part of the UCL parcels in the claim area to be used because, for the reasons explained above, there was no requirement that any land to which the licences applied be used at all. The condition imposed by s 63 of the Mining Act that the holder of an exploration licence “will explore for minerals”, could, in that case, be met without the licence holder ever setting foot in the licence area.

71 In the Commonwealth’s submission, Banjima FC is not authority for the constructional limit contended for by the applicant. They submit that if the Full Court had been of the view that, as a matter of construction, the requirements of s 47B(1)(b)(ii) could not be met unless the terms of the licences specifically required the metes and bounds of the UCL parcels in the claim area (or part thereof) to be used, then it could have determined the issue on that basis alone without needing to consider any other aspect of the licences or statutory provisions, because clearly the licences did not contain such a term. Indeed, no permission or authority would contain such a term and the Full Court’s reasons should not be read in this way.

72 The Commonwealth further submits that secondly, the applicant’s contention that the condition in cl 1(2) of the exploration permits (that the permittee shall not commence any works or petroleum exploration operations in the permit area except with, and in accordance with, the approval in writing of the Minister), means that it cannot be said that land “is to be used” under the permits. It says that rather, any use would be “under” the “separate and prior” approval, if any, given by the Minister. In the Commonwealth’s submission, that contention is wholly inconsistent with the statutory scheme under the PGERA, and with the terms of the permits, read as a whole.

73 The Commonwealth notes that the structure of the scheme under the PGERA is such that all exploration for petroleum in the areas covered by EP 451 and EP 477 occurs “under and in accordance with” the permits themselves. That flows from the combined operation of s 29(1)(a) of the PGERA, and s 15(1) and s 38(1). There are no provisions in the Act that “otherwise permit” exploration for petroleum. Further, it notes that there is no provision for exploration to occur under a “separate” approval from the Minister. Indeed, there is no provision in the Act that even requires the approval of the Minister to be given in relation to the conduct of any exploration activity or operation under a petroleum permit (other than the need to obtain the consent of the Minister under s 15A to enter upon reserved land).

74 The Commonwealth further notes the Minister’s general power under s 43(1) of the PGERA to grant an exploration permit “subject to such conditions as the Minister thinks fit”, needs to be understood in that light. While the Minister can impose conditions that regulate the exercise of the rights conferred by a permit, including by imposing duties on the permit holder, absent express statutory provision (such as in s 91B), the Minister cannot impose conditions that derogate from the authority conferred by the permit by virtue of ss 29(1)(a), 15(1) and 38(1) of the PGERA. Consequently, the approval required by cl 1(2) of the conditions in EP 451 and EP 477 should be understood as operational in nature. They contend it is not the source of authority to carry out petroleum exploration and the same can be said of the approvals required by the “Schedule of Onshore Petroleum Exploration and Production Requirement”. They submit that that understanding of the statutory scheme is reflected in the terms of endorsed condition 1.

75 The Commonwealth submits that the applicant similarly (and wrongly) seeks to use cl 1(1) and (2) of the conditions in the exploration permits to oust the operation of s 90(1) of the PGERA, which inverts the process of construction. The Commonwealth contends the starting point must be the terms of s 90(1), which do not contain any qualification on the operation of the provision. If a permit is subject to a condition that meets the description in the section (which is clearly designed to pick up conditions imposed under s 43(2) of the PGERA), then the obligation in s 90(1) is enlivened. In any event, there is no tension between cl 1(2) and s 90(1). The permit holder simply needs to obtain the approval within the six month period prescribed by the section. Any delay or difficulty in obtaining the approval may provide the basis for an exercise of the Minister’s discretion under s 90(2).

76 The Commonwealth further submits that the applicant’s reliance on Banjima FC (at [108]) is misplaced for another reason. The absence of Ministerial approval was of significance to the Full Court because the terms of the exploration licence in question otherwise prohibited a particular use of the land. They submit that, in other words, the terms of the licence did not exhibit an intention that the land was to be used for the purpose of exploration (or at least not used in that way). Further, the reasoning of the Full Court cannot be transposed onto EP 451 and EP 477, which are in fundamentally different terms because they contain positive obligations to use the land.

77 Thirdly, the Commonwealth notes, the applicant contends that the exploration permits cannot satisfy the exclusionary paragraph of s 47B(1)(b)(ii) because they were not exclusive. The argument appears to be, the Commonwealth says, that as a matter of statutory construction, the words “is to be used” should be understood as conveying the “state of affairs” that exists when Crown land “is applied to a purpose or use and no other”. The Commonwealth notes the applicant does not cite any authority for that construction, and submits the Full Court in Banjima FC expressly disavowed any reliance upon a requirement that the use of land under a permission or authority must be exclusive.

78 The Commonwealth contends there is no textual support for the construction proposed by the applicant, and that if Parliament had intended that the exclusionary paragraph could only be satisfied if the land was to be used for “a particular purpose and no other purpose”, then it could easily have said so. Further, by invoking the line of authority discussed in Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 at [217]-[242]; [2002] HCA 28, the applicant’s position seems to be, in truth, that the exclusion should only operate if land has been reserved by the Crown (for a public purpose). Putting to one side the issue of purpose, the Commonwealth submits, the applicant’s approach would require the words “condition, permission or authority” to be read down so as to not extend the exclusion beyond land that is covered by “a reservation, proclamation, dedication”. But as the Full Court observed in Alyawarr, at [185], the collocation “reservation, proclamation, dedication, condition, permission or authority” is of wide import. In the Commonwealth’s submission, there is no reason of text, context or purpose to read down plain words deliberately adopted by the legislature.

79 The Commonwealth submits the applicant’s reference to the definition of “unallocated Crown land” in s 4(1) of the Land Administration Act 1997 (WA) (LAA) only serves to highlight the difficulty with the applicant’s approach. Under that definition, “unallocated Crown land” is not limited to Crown land that is not reserved, declared or otherwise dedicated under statute. Crown land will also not be “unallocated Crown land” if an “interest” is known to exist in the land, and the definition of “interest” includes, for example, a profit-a-prendre and an easement.

80 Finally, the Commonwealth contends that contrary to what is contended for by the applicant, the collocation of words used by the Parliament in s 47B(1)(b)(ii) more closely reflects the views expressed by Mansfield J in Coulthard and Others v South Australia and Others (2014) 218 FCR 148 at [112]; [2014] FCA 101:

…the general purpose of ss 47A and 47B is to enable Aboriginal people in occupation of an area where there are no longer competing third party interests to have the Court disregard the earlier tenure history of the area in determining whether native title rights and interests exist.

(Emphasis added)

81 The applicant, however, submits the exploration permits are indistinguishable from the exploration licences under the Mining Act that were considered in Banjima FC and Banjima People v State of Western Australia (No 2) (2015) 328 ALR 637; [2015] FCAFC 171 (Banjima FC2). In my view, the applicant is correct in so submitting, substantially for the reasons it submits.

82 Section 38(1) of the PGERA provides that a petroleum exploration permit, while it remains in force, authorises the permitee, “subject to this Act and in accordance with the conditions to which the permit is subject”, to explore for petroleum, and to carry out such operations and execute such works as are necessary for that purpose, in the permit area.

83 Section 43(1) of the PGERA provides that a permit may be granted subject to such conditions as the Minister thinks fit and specifies in the permit. Section 43(2) provides that the conditions may include conditions with respect to work to be carried out by the permittee or in relation to the permit area during the term of the permit, or amounts to be expended by the permittee in carrying out such work, or conditions with respect to both of those matters including conditions requiring the permittee to comply with directions given in accordance with the permit concerning those matters.

84 EP 451 is subject to endorsement 1, which provides that:

In addition to any specific conditions that are endorsed on this instrument, the holder in exercising the rights granted herein must first ensure that all necessary consents and permissions have been obtained and applicable compensation has been agreed or determined and that consultation has occurred where the lawful rights of other land users and occupiers are concerned so that the activities of those other land users are not interfered with to a greater extent than is necessary for the reasonable exercise of the rights and performance of the duties of the holder of this exploration permit.

85 EP 451 has three endorsed conditions (subcll 1, 2 and 3). Subclause 1 provides that “subject to sub-clause 2”, during a year of the term of the permit set out in the first column of the table set out in the conditions (reproduced below), the permittee “shall carry out” in or in relation to the permit area, to a standard acceptable to the Minister, the work specified in the minimum work requirements set out opposite that year in the fourth column of the table, and “may carry out” other works “in relation to the permit area”.

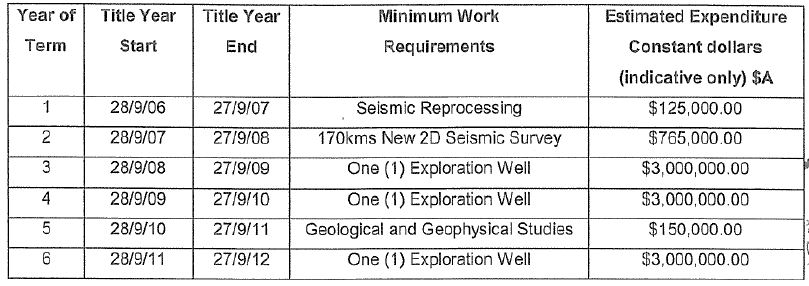

86 The table mentioned in subcl 1 is as follows:

87 Subclause 1(2) provides that the permittee “shall not commence any works or petroleum exploration operations in the permit area except with, and in accordance with the approval in writing of the Minister”.

88 Subclause 1(3) provides that pursuant to s 91B of the PGERA access to lands within listed block numbers is prohibited. The blocks are depicted on the attached map.

89 EP477 has the same endorsement 1, and the same conditions in subcl 1(1) and (2), with a similar table, but does not have subcl 1(3) dealing with s 91B access conditions.

90 In my view, the exploration permits do not either limit the use to which the Part B claim area might be put or positively require the use of the area for a particular purpose. First, the exploration permits did not require that any part of the Part B claim area be explored or used for the purposes of exploration when the claimant application was made, as discussed in Banjima FC at [107]-[108].

91 The permit areas also extend beyond the Part B claim area. Even if there was a requirement for the permit holder to use the land or waters the subject of the permit, there was no obligation to do any of the things referred to in the table above, or any other things, in the “area” with which s 47B is concerned, being the Part B claim area. The contention that the expression, “is to be used” in s 47B(1)(b)(i) means “is permitted or authorised to be used” was rejected by the Full Court in Banjima FC at [114]. See also Banjima FC2 at [18].

92 Secondly, the conditions referred to above expressly provide in subcl 2 that the permittee “shall not commence any works or operations” in the permit area except with, and in accordance with, the approval in writing of the Minister. See the significance of this in Banjima FC at [108].

93 This means, in my view, that it cannot be said that land “is to be used” under the exploration permits; any use would be “under” the approval, if any, given by the Minister. It also means that the endorsed conditions are not of the kind referred to in s 90(1) of the PGERA which provides, relevantly, that the permittee shall commence to carry out works or operations, where specified in any endorsed conditions, within a period of 6 months after the day on which the permit comes into force. Subclauses 1(1) and (1)(2) of the endorsed conditions provide otherwise.

94 This is consistent, in my view, with other features of the statutory scheme. The requirement in s 90(1) when applicable (but not in this case) is subject to s 90(2), which provides that the Minister may, for reasons that he or she thinks sufficient, exempt compliance with the requirements of s 90(1) and direct the works or operations be done within some other period specified in the instrument. Section 97 of the PGERA additionally allows a permittee to apply for a variation or suspension of, or for exemption from compliance with, conditions to which the permit is subject, of the kind referred to above (see s 97(1)(g)); and the discretion conferred upon the Minister by s 97(1)(i) and (j).

95 Furthermore, as the applicant says, under s 95 of the PGERA, directions have been issued requiring compliance with the “Schedule of Onshore Petroleum Exploration and Production Requirement – 1991”. Part V of the conditions relates to drilling, and para [501(1)(a)] of the conditions provides that a new exploration well shall not be commenced without prior approval. Part VII of the conditions relates to geophysical and geological surveying, and para [704(1)] of the conditions provides that a geophysical or geological survey cannot be carried out except with the approval of the Director.

96 Thirdly, I consider the exploration permits do not affect or preclude other uses of the Part B claim area. For example, the PGERA and the Mining Act are not mutually exclusive; tenements under each may be granted in relation to the same land: see s 117(c) of the PGERA, and s 159 of the Mining Act. The land here is unallocated Crown land and may be dealt with under the LAA notwithstanding the exploration permits: see ss 5(1)(b), 24, 91(5) and 164(1)(b) of the LAA, and s 15A of the PGERA.

97 I also consider there is force in the applicant’s submission, as to purpose, that the concept employed in s 47B(1)(b)(ii), in defining that Crown land under claim is not to be treated as “Vacant Crown land” (being the heading of s 47B) if the land “is to be used” under an instrument, conveys the state of affairs considered in the line of authority discussed in Ward at [217]-[242] as to when Crown land is applied to a purpose or use and no other. The grant of an exploration permit over Crown land under the PGERA, in circumstances where the land remains available for disposition and use under the LAA, may be seen not to be an act by which the Crown has bound itself to some particular purpose, to adapt what Higgins J said in the Williams v Attorney General (Government House Case (1913) 16 CLR 404 at 462; [1913] HCA 33, so as to produce that state of affairs. The land is, relevantly, vacant Crown land or, in the language of the LAA (s 4(1)), unallocated Crown land.

98 Finally, I accept the applicant’s submission that the purposes of EP 451 and EP 477 did not constitute a particular purpose within s 47B(1)(b)(ii)). In view of the statutory and endorsed conditions outlined above, exploration for petroleum is not a particular purpose within the meaning of s 47B(1)(b)(ii): see Banjima FC at [111]; Banjima FC2 at [25], [33] and [39]; Alyawarr at [187]; Griffiths v Northern Territory (2007) 165 FCR 391 at [160]; [2007] FCAFC 178.

99 For these reasons, I find, in relation to the second separate question that the exploration permits did not constitute permissions or authorities falling within para (b)(ii). As a result, s 47B applies to this application.

Orders

100 I will hear from the parties as to what formal orders should now be made.

I certify that the preceding one hundred (100) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Barker. |