FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Hart v Commissioner of Taxation (No 4) [2017] FCA 572

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed with costs.

2. The penalties imposed by the respondent be confirmed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

1 This is an appeal by the applicant, Michael James Patrick Hart, a solicitor, brought by an application under s 14ZZ of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) against an objection decision dated 10 December 2009. The objection decision was made on behalf of the Commissioner of Taxation. It is convenient to refer to all decisions simply as decisions of the Commissioner.

2 In 2002, Mr Hart was advised that his tax affairs for the 1997 to 2002 financial years would be audited. The Commissioner subsequently issued a notice of assessment and a notice of amended assessment to Mr Hart in respect of the 1997 income year ended 30 June 1997. These assessments addressed two sources of what the Commissioner assessed to be undeclared income. Mr Hart lodged an objection to each assessment, which gave rise to the objection decision. Only Mr Hart’s objections in respect of penalty were allowed in the objection decision for the 1997 income year, whereby the penalties imposed were reduced from 75% to 50%. By this appeal, Mr Hart sought to have his objections allowed in full, or in the alternative for the revised 50% penalties imposed to be reduced to zero, or otherwise to be reduced from the level imposed. The onus was on Mr Hart to show that the assessments were excessive, or that the penalties either should not have been imposed at all or should have been imposed for a lesser amount.

3 The Commissioner had also raised assessments against Mr Hart for the 1998 to 2002 income years. Mr Hart’s objections and the Commissioner’s 10 December 2009 objection decision also related to those years. Mr Hart’s objections were allowed in full in respect of the 2002 income year. The assessments raised by the Commissioner in respect of the remaining 1998 to 2001 income years are the subject of review proceedings commenced by Mr Hart in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. Those Tribunal proceedings are in abeyance pending the outcome of this appeal.

setting the scene – an Overview of the competing cases

4 The competing cases as finally arrived at in this Court can be stated in an overview sense with beguiling simplicity. The Commissioner contended that two amounts were correctly included in Mr Hart’s 1997 assessable income by way of the assessment and amended assessment. The two amounts were:

(1) a portion of the net income of a law firm practice unit trust (Practice Trust) with which Mr Hart was involved, or alternatively a portion of the net income of a beneficiary of the Practice Trust (Outlook Trust), being $220,398 (or alternatively some lesser amount) – referred to below as the Practice Amount; and

(2) a portion of the income earned by a group of trusts (Income Earning Trusts) from tax planning and tax scheme services with which Mr Hart was involved, being $275,481 (or alternatively some lesser amount) – referred to below as the IET Amount.

5 As noted above, the Commissioner also imposed 50% penalties upon Mr Hart under the former s 226 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (ITAA 1936) for failing to declare the Practice Amount and the IET Amount (and the equivalent amounts in subsequent years) as assessable income in his tax returns. The Commissioner contended that the penalties imposed were justified.

6 In respect of the Practice Amount of $220,398, the Commissioner relied on:

(1) s 97 (when read with ss 95A(1) and 101) – an argument that the Practice Amount was a trust distribution which was properly taxable under the ITAA 1936; and/or

(2) Part IVA of the ITAA 1936 – an argument that the series of transactions in question was a scheme entered into for the dominant purpose of obtaining a tax benefit which offended the tax anti-avoidance provisions in Part IVA.

7 In respect of the IET Amount, the Commissioner relied solely on Part IVA.

8 Thus the Commissioner made and defended the assessment on the basis of trust distributions and Part IVA, and the amended assessment on the basis of Part IVA, and in so doing, defended the penalties imposed. The Commissioner did not need to prevail on both approaches for the assessment in relation to the Practice Amount of up to $220,398 (although the final amount arrived at may differ according to the finding made), but he did need to prevail on his Part IVA case for the amended assessment in relation to the IET Amount of up to $275,481.

9 Mr Hart contended that because of his effective use of an arrangement involving a series of trusts and related transactions, including a loan in the case of the Practice Amount, known as the “New Venture Income Scheme” (NVI Scheme), neither s 97 nor Part IVA applied to permit the amounts referred to above to be included in his assessable income for the 1997 income year, necessarily removing the basis for any penalties for the Practice Amount. It was not clear whether it was asserted that there was a single loan agreement with multiple payments, or more than one loan agreement. For convenience, these reasons will refer to the asserted loan in the singular form, irrespective of whether it was asserted to be one loan or multiple loans.

10 In the alternative, Mr Hart contended that even if s 97 or Part IVA applied, the basis for excluding the additional amounts from his original 1997 tax return was sufficiently arguable such that in all the circumstances either no penalties should have been imposed or lesser penalties were warranted for either the Practice Amount or the IET Amount.

11 Part IVA has changed since the relevant periods in this appeal. In particular, substantial amendments that applied retroactively to post-15 November 2012 schemes have no application to this appeal.

The Commissioner’s first approach – trust distributions – Practice Amount only

12 The Commissioner’s first approach, pertaining only to the Practice Amount of up to $220,398, was to treat payments that were in fact made to Mr Hart or to his benefit as trust distributions, relying on the trust beneficiary provisions in s 97(1) of the ITAA 1936, together with the provisions in ss 95A(1) and 101 supporting the operation of s 97(1). This aspect of the Commissioner’s case, advanced in two alternative ways by reference to two different trusts, effectively sought to bypass altogether the NVI Scheme that Mr Hart relied upon because of what amounted to asserted defects in the implementation of that scheme. Essentially the Commissioner’s case was that whatever the intent and effectiveness of the NVI Scheme in the abstract, the scheme had not been made to apply in practice for the Practice Amount, or at least part of it. The shorthand description of “defects” in the way in which the scheme was implemented is one that I have attributed to this aspect of the case, rather than being the language used by the Commissioner, but it does capture in a pithy way the essence of what the first approach entails.

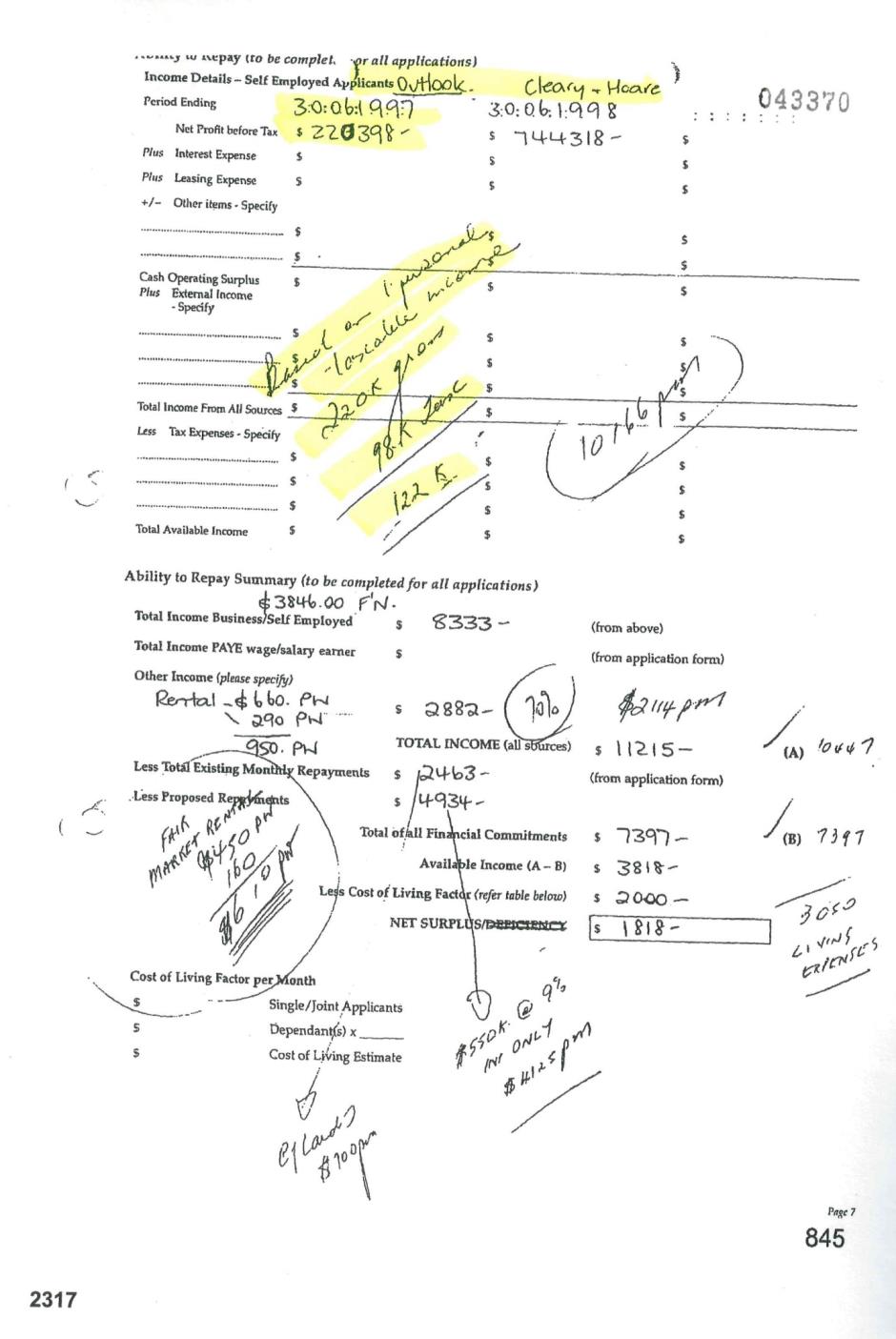

13 The Commissioner’s first approach was primarily referrable to the Practice Trust itself, but alternatively referable to one of its unitholders associated with Mr Hart, the Outlook Practice Trust, referred to in these reasons as the Outlook Trust. An important aspect of the Commissioner’s case on this argument was to look at business records by which payments were made or recorded as being made and collateral business records such as bank loan applications with bank officer notations referring to Mr Hart’s income. It is essentially an argument that, in all the circumstances, the actual receipt of money derived from legal practice earnings by Mr Hart or to his benefit was enough for that money to be taxable income at law as trust distributions. That was especially so having regard to the terms of the trust deeds for the Practice Trust and for the Outlook Trust, which the Commissioner contended had the effect of making actual payments to a beneficiary a trust distribution.

14 Mr Hart’s evidence was that he received payments from the Outlook Trust in the 1997 income year totalling $185,698, but denied receiving that money as assessable income, asserting that the money was advanced to him as a loan. He therefore denied that these payments constituted trust distributions either from the Practice Trust or from the Outlook Trust. As part of this argument, he asserted that the Commissioner’s reliance on the deeming provision in s 95A of the ITAA 1936 in aid of the application of the trust distribution provisions of that Act was not any part of the Commissioner’s pleadings or any part of his submissions prior to the closing submissions, amounting to a change of case that should not be permitted to be relied upon.

15 The Commissioner’s response was that the pleadings did sufficiently engage the deeming provision in s 95A (if needed). Senior counsel for the Commissioner further submitted that this Court could not be satisfied that the money flows to Mr Hart or to his benefit was the product of a loan arrangement because of the lack of direct documentation beyond abstract trust resolutions, the contrary indications in the payment records, the bank officer comments on the loan documentation and no interest and no repayments since the money was received by Mr Hart or to his benefit 19 years prior to the time of trial.

The Commissioner’s second approach – Part IVA, ITAA 1936 – Practice Amount and IET Amount

16 The Commissioner’s second approach relied upon the tax anti-avoidance provisions in Part IVA. This approach applied either alternatively or additionally to the first approach in relation to the Practice Amount of up to $220,398. Part IVA was the Commissioner’s sole case in respect of the Income Earning Trusts and the IET Amount involving up to $275,481.

17 Part IVA in certain circumstances operates to deny the effectiveness of schemes brought into existence for the dominant purpose of obtaining tax benefits. By the application of Part IVA, the Commissioner sought to deny Mr Hart the benefit of the NVI Scheme and thereby bring both the Practice Amount and the IET Amount to account as taxable income in his hands. An important aspect of the application of Part IVA is the need to predict, objectively, what would have been done had the scheme not existed. Mr Hart maintained that the NVI Scheme had been effectively implemented in respect of both the Practice Amount and the IET Amount and both amounts were therefore immune to the operation of Part IVA.

18 Because there are a number of individuals, companies and trusts involved in this case, it is convenient to have early in these reasons an alphabetical list summarising who the various entities are, together with some non-contentious facts such as the date of establishment of various trusts:

Terms | Definition |

Annesley No 3 Trust (Annesley No 3) | Established on 30 May 1997. Haven Sea Pty Ltd was trustee for the relevant income year. |

Annesley Trust | An Income Earning Trust for the relevant income year. Annesley Trust was established under Annesley Investments Pty Ltd by deed dated 1 May 1994. Haven Sea Pty Ltd was appointed trustee of Annesley Trust in 1995 and was trustee for the relevant income year. |

CHC Discretionary Trust (CHCDT) | An Income Earning Trust established in September 1996. The trustee in the relevant income year was Cleary Hoare Corporate Pty Ltd. Mr Hart was a beneficiary of the Trust in the relevant income year. |

Cleary & Hoare Practice Trust (Practice Trust) | A discretionary unit trust which was established in 1993 to carry on under the name “Cleary Hoare” the legal practice previously carried on by the law firm Cleary Hoare. |

Cleary Hoare | The law firm Cleary Hoare Solicitors of which Mr Hart is a Principal together with Ian Collie, John Hoare and Steven Grant. The name of the firm was previously ‘Cleary & Hoare’, however these reasons use the current name of the firm. |

Cleary Hoare Corporate Pty Ltd (CHC) | The entity that promoted the NVI Scheme. Trustee for the CHC Discretionary Trust in the relevant income year. Mr Hart was a director of the company in the relevant income year. |

Cleary Hoare Trust Account | The trust account of the legal practice held at the National Australia Bank in accordance with the requirements of the Queensland Law Society. |

Comlaw Consultants Pty Ltd | Original trustee of Comlaw Trust. |

Comlaw Trust | A unit trust established in 1993 of which Comlaw Consultants Pty Ltd was the original trustee. Haven Sea Pty Ltd was appointed trustee of Comlaw Trust in 1995 and was trustee in the relevant income year. Comlaw Trust’s intended role was to seek out income earning opportunities from property related ventures which were thought likely to emerge after the recession of the early 1990s. Before June 1993, the unit holdings in the Comlaw Trust were restructured with the result that one half was owned by interests associated with Mr Hart, John Hoare and Steven Grant, and the other half by the Canowindra Trust controlled by Ian Collie. |

Haven Sea Pty Ltd | Appointed as trustee of Annesley No 3 and Annesley Trust and was trustee of both trusts for the relevant income year. Haven Sea Pty Ltd was deregistered on 9 April 1999. Mr Hart was a director of Haven Sea Pty Ltd for the relevant income year. |

Ian Collie | Principal of Cleary Hoare and associate of Mr Hart. |

Income Earning Trusts | A generic name for the following trusts: LM Income Discretionary Trust, CHC Discretionary Trust and Annesley Trust, being the various trusts which resolved to distribute amounts through the NVI Scheme. |

John Hoare | Principal of Cleary Hoare and associate of Mr Hart. |

Lake Mylor Pty Ltd | Trustee for LM Income Discretionary Trust. |

LM Income Discretionary Trust (LM Income Trust) | An Income Earning Trust for the relevant income year. LM Income Trust was established on 9 May 1997 with Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee. |

Michael Hart (Mr Hart) | The applicant (taxpayer) and the Principal of Cleary Hoare. One of the trustees of the Practice Trust. |

Oak Arrow Pty Ltd | Trustee for Oak Arrow Trust and registered on 19 September 1989. An entity which owned the residential property in which Mr Hart resided until 1998. Mr Hart is a shareholder and at various times has been a director of Oak Arrow Pty Ltd. |

Outlook Crescent Pty Ltd (OCPL) | Trustee of the Outlook Trust and one of the unitholders in the Practice Trust. |

Outlook Practice Trust (Outlook Trust) | Mr Hart’s discretionary trust, and a unitholder of the Practice Trust. The original trustee of the Trust was Radgolf Pty Ltd but for the relevant income year was OCPL. Together with Mr Hart, the Trust was a beneficiary of the Income Earning Trusts. |

Patricia Hart (Mrs Hart) | Wife of Mr Hart. |

Steven Grant | Principal of Cleary Hoare and associate of Mr Hart. |

Notice of assessment and notice of amended assessment

19 On 23 November 2004, acting on the stance taken on both the trust distributions issue and on the Part IVA issue, the Commissioner made a determination under s 177F(1)(a) of the ITAA 1936 to include the Practice Amount of $220,398 in Mr Hart’s assessable income for the 1997 income year. On 3 December 2004, effect was given to that determination by the Commissioner issuing a notice of assessment which included the Practice Amount in Mr Hart’s assessable income for the 1997 income year and imposed additional tax for the late return and an understatement penalty and interest. On 7 February 2005, Mr Hart lodged a notice of objection to the assessment.

20 On 8 March 2006, acting on the stance taken on just the Part IVA issue, the Commissioner made a determination under s 177F(1)(a) of the ITAA 1936 to include the IET Amount of $275,481 in Mr Hart’s assessable income for the 1997 income year. On 26 April 2006, effect was given to that determination by the Commissioner issuing a notice of amended assessment which included the IET Amount in Mr Hart’s assessable income for the 1997 income year and imposed additional tax for the late return and an understatement penalty and interest. On 1 June 2006, Mr Hart lodged a notice of objection to the amended assessment.

21 As noted above, objections to these assessments were disallowed, giving rise to this appeal.

22 While the case for Mr Hart in bringing the appeal and the case for the Commissioner in meeting it involved a large volume of documentary material, both pleadings and evidence, presented in the form of some 18 court books, the underlying relevant facts, although complicated, were largely not in dispute and the contested evidence was quite limited. Indeed, such factual disputes as did exist were in a limited compass and mainly concerned questions of characterisation. Two interlocutory disputes about evidence are detailed below.

23 The Commissioner mostly relied on documents obtained from Mr Hart, associated entities and financial institutions, exercising statutory powers to obtain that material. The great bulk of the evidence was by way of affidavits for the Commissioner producing those documents, and statements or affidavits for Mr Hart commenting in some way upon that material (some of those comments being inadmissible and rejected). In light of the way that the case unfolded, including by way of pleadings, it is not necessary to detail even in précis form much of that evidence, although it has been examined in differing degrees of detail, guided by the submissions of the parties as to the live issues in the case. The key remaining evidence was expert evidence relied upon by the Commissioner.

24 Only two witnesses were cross-examined in a limited way, being:

(1) Mr Hart; and

(2) Mr David Van Homrigh, a forensic accountant expert witness called by the Commissioner for the purposes of cross-examination in relation to his report, as amended and supplemented, containing financial analysis of money flows between various bank accounts, related calculations and opinions.

25 The cross-examination of Mr Van Homrigh made a limited difference to the outcome of this case. The real dispute was what his evidence was capable (and not capable) of establishing. The cross-examination appeared largely to be directed to this aspect, but did not noticeably advance Mr Hart’s case on the asserted shortcomings in Mr Van Homrigh’s evidence.

26 Mr Hart relied upon some limitations arising from the approach that Mr Van Homrigh took, which was to “trace”, in the sense of tracking rather than in the equitable sense, flows of money from the Income Earning Trusts to the Outlook Trust and thence to accounts controlled by Mr Hart. Mr Van Homrigh did not attempt to give any opinion as to the derivation of income by the Income Earning Trusts nor show any link between specific deposits and withdrawals.

27 The cross-examination of Mr Hart was ultimately very important in a number of critical respects, discussed in some detail in these reasons. Of particular importance was cross-examination of Mr Hart on his assertion that money he received which was ultimately sourced from legal practice income was the product of a loan and on issues of compliance with the terms of the authorisation allowing a unit trust to operate Cleary Hoare, the law firm of which Mr Hart was a Principal.

28 The Commissioner, in the course of the cross-examination of Mr Hart, tendered Mr Hart’s 1991 and 1992 income tax returns, which were admitted as exhibits without objection. Those income tax returns showed Mr Hart had declared an income for taxation purposes from salary paid by Cleary Hoare, apparently meeting any suggestion that Mr Hart had never received income from that firm in taxable form.

29 The evidence also included a notice to admit facts served by the Commissioner on Mr Hart, some limited portions of which were disputed by him. Specific reliance was placed by the Commissioner on the facts that were not disputed as to payments made.

30 Most of the factual disputes between the parties turned on what should be made of the evidence and in particular the characterisation that should be given to various transactions or other events. Importantly, it was common ground between the parties that relevant income was derived by the Outlook Trust as a beneficiary of the Practice Trust and the Income Earning Trusts.

31 Necessarily many other facts derived from the pleadings and evidence not warranting specific reference have helped to inform the determination of this dispute.

Interlocutory disputes as to evidence

32 Two pre-trial interlocutory applications were heard in relation to evidence giving rise to separate judgments as follows. The first interlocutory application concerned the admissibility of Mr Van Homrigh’s expert evidence sought to be relied upon by the Commissioner. This evidence went to showing the receipt of money by Mr Hart or to his benefit in relation to the IET Amount (such receipt mostly not being disputed by Mr Hart in relation to the Practice Amount). The parties agreed that the conclusion reached should be reflected in orders made in Chambers, with reasons to follow later. The evidence was held admissible by orders made in Chambers, with reasons published on the eve of the trial: Hart v Commissioner of Taxation (No 2) [2016] FCA 897. Mr Van Homrigh’s expert report, as amended by two supplementary letters, was admitted into evidence at the trial as a single exhibit.

33 Immediately prior to the trial there was an interlocutory hearing on the question of whether or not legal professional privilege asserted by Mr Hart had been waived over advice given to him by way of two opinions provided to him by Mr David Russell QC in 1996, an issue as to whether privilege attached in the first place ultimately being conceded by the Commissioner. Privilege was found to have been waived. The parties were content for reasons to be provided at the time of final judgment, which took place immediately prior to delivery of this judgment: Hart v Commissioner of Taxation (No 3) [2017] FCA 571. At the trial Mr Hart tendered the two documents by Mr Russell QC without objection (the Commissioner would have tendered them if Mr Hart had not) and each was admitted into evidence.

Summary of the facts leading to the assessments

34 The following narrative is drawn from the pleadings, agreed facts and documents not apparently in dispute, aided by submissions for the parties in narrowing the scope of the material requiring more detailed consideration. More detailed consideration of key aspects of the evidence takes place below in the context of the legal analysis pertaining to the issues raised.

35 In 1969, Mr Hart became a solicitor. He initially practised in Rockhampton as a sole practitioner and later in partnership with others between 1971 and about 1980. In about 1980, the three-partner legal practice he was involved in was transferred to a unit trust in which the units were held by discretionary trusts for the three previous partners, with Queensland Law Society approval. The need for, and strict compliance with the terms of, such an approval, is of considerable importance to the Part IVA aspect of this appeal.

36 At various stages between the 1980 establishment of the Rockhampton law firm unit trust and 1989, Mr Hart alternated between practising as a solicitor, working in other unspecified business activities conducted directly or indirectly through discretionary trusts, and working for a company which went into receivership in late 1989.

37 In January 1990, Mr Hart joined a Brisbane firm of solicitors, Cleary Hoare, as a salaried partner. His main interest and expertise was in tax and revenue-related work.

38 Between December 1990 and February 1992, Mr Hart was a bankrupt by reason of guarantees he had given before he moved to Brisbane in January 1990. He relies in part upon that bankruptcy to assert an asset preservation motive for steps taken to isolate him from asset ownership and from the receipt of money as income, and thereby to inform the predictive exercise required in applying the terms of Part IVA.

39 After his discharge from bankruptcy, Mr Hart began discussions about becoming a partner of Cleary Hoare. However, by early 1992, Cleary Hoare was facing financial difficulties. The National Australia Bank (NAB) was owed more than $1.7 million. Mr Hart was not prepared to assume any personal liability to NAB in respect of that debt because it had been incurred prior to his arrival at the firm. By a partnership agreement contained in a partnership deed dated 1 July 1992, his company, later and at all relevant times known as Outlook Crescent Pty Ltd (also referred to as OCPL), through him as its nominee formally became a partner in Cleary Hoare.

40 Mr Hart then became involved in internal discussions at Cleary Hoare as part of negotiations with NAB to prevent the firm from failing. In November 1992, the partners of Cleary Hoare asked Mr Hart to assume management of the firm.

41 From November 1992 onwards, as manager of the business of Cleary Hoare, Mr Hart set about refocusing the firm’s client base away from property and mortgage work and towards providing services to the small business clients of accountants. Those services were in the areas of restructuring, taxation (including capital gains tax), stamp duty, superannuation and the sale and purchase of businesses. Mr Hart described these services as having an “emphasis upon asset protection”. This interest and focus upon asset protection was advanced as being the dominant explanation for the transactions which he relied upon to justify his declared assessable income of $100 in his original 1997 tax return.

42 Mr Hart was only prepared to remain with Cleary Hoare if the partners agreed to restructure the firm with the establishment of a unit trust to operate the practice. As part of the circumstances giving rise to imposing this requirement, Mr Hart referred to the fact that at least two of the partners of Cleary Hoare were subject to a claim for many tens of millions of dollars, later settled by a consent judgment of more than $80 million, but not enforced against those partners. Mr Hart considered the risk of bankruptcy of those partners was significant and hence did not want them to own individually any interest in the firm.

43 As requested by Mr Hart, the partners of the firm agreed to restructure Cleary Hoare. As a result, on 29 January 1993, the Cleary Hoare Practice Trust (Practice Trust) was established with the original trustees being Donald Cleary, John Hoare and Steven Grant. The Practice Trust was a unit trust designed and intended to continue the legal practice lawfully under the name “Cleary & Hoare”, in conformity with the Queensland Law Society Rules made under the Queensland Law Society Act 1952 (Qld).

44 On the establishment of the Practice Trust, its units were held by discretionary trusts for the families of Messrs Hart, Cleary, Hoare and Grant. The question of whether the Law Society Rules were strictly complied with in arriving at that position is of some importance to the question of whether the scheme that Mr Hart sought to rely upon could be undone by the operation of Part IVA.

45 The units in the Practice Trust associated with Mr Hart were held by the Outlook Practice Trust, referred to in these reasons as the Outlook Trust, the trustee of which was Outlook Crescent Pty Ltd (as noted, also referred to as OCPL). Mr Hart relied upon a number of documents by which the restructuring of the ownership of the legal practice to the Practice Trust, trading as Cleary Hoare, was carried out. From 29 January 1993, the business of the Practice Trust known as Cleary Hoare was conducted by Messrs Cleary, Hoare and Grant as trustees instead of as partners.

46 Mr Hart initially did not take a position as a trustee of the Practice Trust (trading as Cleary Hoare) because that would have required him to sign documentation with NAB exposing himself to the then liabilities of the prior partnership and may have led to assertions that he was liable for the rental obligations for leases of office space at the Colonial Mutual Building in Queen Street, Brisbane. The position of Mr Hart’s trust in holding an equal number of units in the Practice Trust afforded him the benefits of an equal equity holder but, by not being a trustee, avoided the risk of detriment by not being personally exposed to the indebtedness to the bank nor to the indebtedness to any other creditors of the Practice Trust.

47 The direct effect of the financial restructure of Cleary Hoare is detailed in Mr Hart’s statement. The details do not need to be referred to. What matters is that Mr Hart was apparently immunised from the previous debts of Cleary Hoare incurred during its time as a partnership prior to it being acquired and run by the Practice Trust. As noted above, that history and the fact of immunisation from trading debts incurred by the former legal partnership form part of the matrix of evidence by which Mr Hart sought to provide a dominant reason for the structure and transactions which were the subject of dispute in this appeal.

48 It should be noted that there is an important distinction to be drawn between asset protection able to be achieved by the legal and equitable ownership of tangible assets from the point of acquisition by someone other than Mr Hart, and the protection of more transient year-by-year cash or chose in action assets (such as money held on deposit in bank accounts pursuant to a creditor relationship with a bank), received by way of income, a loan or otherwise. For the latter category, taxation considerations may loom large and even dominate.

49 By way of explanation as to why the arrangements were entered into, Mr Hart’s statement described how, from at least 1993, he spoke at seminars attended by accountants about the asset protection advantages of conducting trading businesses through a discretionary trust with a corporate beneficiary which was owned by a discretionary trust rather than individuals. He said that working in the area of providing specialist tax advice carried a significant risk of later being judged to have been wrong and hence a significant risk of being sued for negligence. He said that his experience of bankruptcy in the early 1990s reinforced his desire to protect assets. He produced copies of some of the papers he had presented on these topics. As discussed below, a significant focus of those papers was on taxation advantages associated with these arrangements. Moreover, there was no suggestion Mr Hart’s prior bankruptcy had anything to do with any negligence suit or anything to do with Mr Hart’s professional activities, nor that any such issue had arisen other than as a theoretical risk. There was evidence that exposure to debts incurred by others was a risk to Mr Hart in the early 1990s, as noted above in relation to the debts owed to NAB. However that risk was addressed by asset ownership strategies, including as to the legal structure adopted by Cleary Hoare, rather than by income or cash flow strategies.

50 Mr Hart said that the income for the 1997 income year which was the subject of these proceedings was derived by the trustees of a number of trusts. The Practice Trust and the Outlook Trust had been long established by 1997. Mr Hart also detailed income earning activities in the 1994, 1995 and 1996 income years of entities with which he was associated.

51 During the 1997 income year, the Outlook Trust included the Practice Amount sum of $220,398 in its assessable income as a unitholder in the Practice Trust pursuant to s 97 of the ITAA 1936. Also during the 1997 income year, Haven Sea Pty Ltd, as trustee of the Annesley No. 3 Trust, became presently entitled to all the income of the Outlook Trust for that year as part of an NVI arrangement. It is that particular aspect of the arrangements for the 1997 income year, post the Practice Trust distribution to the Outlook Trust, that represents the operative part of the assessment raised by the Commissioner against Mr Hart so as to bring that sum of $220,398 to account as assessable income in his hands.

52 Also during the 1997 income year, the Annesley No. 3 Trust became presently entitled to part of the income of each of three trusts known as the Annesley Trust, the CHC Discretionary Trust and the LM Income Trust, each of which was controlled by Cleary Hoare Corporate Pty Ltd. Each of those three trusts promoted and implemented a separate NVI arrangement. Those arrangements were an operative part of the amended assessment raised by the Commissioner against Mr Hart so as to bring a portion of that money, namely the IET Amount of $275,481, to account as assessable income in his hands. The Commissioner sought to justify that amount by showing via Mr Van Homrigh’s evidence that an amount in excess of that sum could be shown to have been received by, or to the benefit of, Mr Hart.

53 The terms of the NVI Scheme were set out in the first schedule to Mr Hart’s statement. That schedule is relatively short and is convenient to reproduce because it helps in understanding, in a summary way, what was sought to be achieved by the scheme and how (per original):

NVI SCHEME

1. NVI had been developed in the 1996 income year following consideration by [Mr Hart] of the judgment in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Peabody (1994) 181 CLR 359. The opinion of senior counsel was obtained in February 1996 which both analysed and supported the efficacy of the NVI concept.

2. Whilst NVI came within the definition of a “scheme” (s177A(1)), it was considered that it was not adversely affected by the anti-avoidance provisions contained within Part IVA because it would not be a scheme to which Part IVA applied as set out in s177D since it would not be possible to identify a taxpayer who was intended to obtain a tax benefit. This was primarily because it was to be used by taxpayers who utilised trusts, without a pattern of previous income distributions, to commence new income earning ventures.

3. The principal features of the NVI scheme were set out in a written précis provided to the Commissioner by Ian Collie on 24 September 2001. The document stated:

1. Principal features:

1.1 Relevant to discretionary trusts and discretionary unit trusts (“the distributing trust”) which are either:

1.1.1 newly established without any trading history; or

1.1.2 established in a previous year but without a pattern of distributions.

1.2 At least two recipient trusts between the distributing trust and the ultimate beneficiary.

1.3 Gift by ultimate beneficiary to non-associated trust in order for first recipient trust to qualify as potential beneficiary.

1.4 Gift of capital to capital trust.

2. Principal Issues:

2.1 S. 100A.

2.2 Part IVA.

2.3 Deductibility of qualifying gift.

2.4 Gift on capital account.

4. In addition to its use being restricted to trusts, the implementation of NVI in the 1997 income year also relied on the involvement of an entity (Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd) with substantial tax losses. That company and its directors/shareholders/advisors were independent of any person associated with Cleary Hoare.

5. NVI was seen by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd and its directors/shareholders as providing an opportunity to recover some of its tax losses without any adverse impact of the continuity of ownership or business tests that might have applied otherwise.

54 As the above text of Schedule 1 to Mr Hart’s statement indicates, aided by the context of other evidence and in particular the written opinions of Mr Russell QC in 1996 (legal privilege having been found to be waived), the NVI Scheme was developed in the 1996 income year, following consideration by Mr Hart of the decision and reasons of the High Court in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Peabody (1994) 181 CLR 359. With the benefit of the generic internal opinion of Mr Russell QC, obtained in February 1996 and later substantially revised in the second external opinion, the NVI Scheme concept was thought by Mr Hart not to be adversely affected by Part IVA, primarily due to the scheme’s use of trusts with no pattern of previous income distributions. This meant that it was difficult to identify a single taxpayer who received or was intended to receive a tax benefit in the absence of the scheme, with the evident intention of thereby thwarting the application of Part IVA, including in particular the predictive element of what would have happened in the absence of the scheme. The Commissioner relied upon a number of passages from Mr Russell QC’s two opinions in support of his arguments as to the dominant purpose of the application of the NVI Scheme to the Practice Amount and the IET Amount.

55 As previously indicated, the particular events and transactions involved in the application of the NVI Scheme to the Practice Amount and to the IET Amount during the 1997 income year were mostly not in dispute. It was not disputed that there had been a series of distributions through a network of interposed trust entities associated with Cleary Hoare or its associates to a company carrying tax losses, and the making of gifts by way of promissory notes to and through entities that were associated with Cleary Hoare or its associates, including Mr Hart. The characterisation of the last stage whereby money was paid to Mr Hart or to his benefit was in dispute as to whether that reflected a loan as contended by Mr Hart, or whether that was at law a further distribution of the Practice Amount as contended by the Commissioner. Similarly, there was a dispute as to the Commissioner’s alternative case to the effect that, even if the payments were not at law trust distributions, the application of Part IVA meant that, in the absence of the scheme, the money would still have been paid to Mr Hart and instead been taxable, whereas Mr Hart contended that such payments would not have taken place in the absence of the scheme.

56 The area of common ground was not quite as clear in relation to the IET Amount and money flows. It seemed to be accepted by Mr Hart that there had been a series of distributions of income derived by the Income Earning Trusts through a network of interposed trust entities associated with Cleary Hoare or its associates to a company carrying tax losses, and the making of gifts by way of promissory notes to and through entities that were associated with Cleary Hoare or its associates, including Mr Hart. The lack of clarity emerges by reason of the dispute as to what the evidence establishes took place at the last stage. The Commissioner contended that Mr Van Homrigh’s evidence went at least some way in showing that again money flowed to Mr Hart or to his benefit, whereas Mr Hart disputed that this evidence was capable of establishing such a flow of funds. This disagreement necessitates discussing Mr Van Homrigh’s evidence in greater detail below.

57 Mr Hart said that at all times material to these proceedings he had been:

(1) a trustee of the Practice Trust;

(2) a special unitholder of the Practice Trust;

(3) a director of Outlook Crescent Pty Ltd, the trustee for the Outlook Trust and an ordinary unitholder in the Practice Trust; and

(4) a beneficiary of the Outlook Trust.

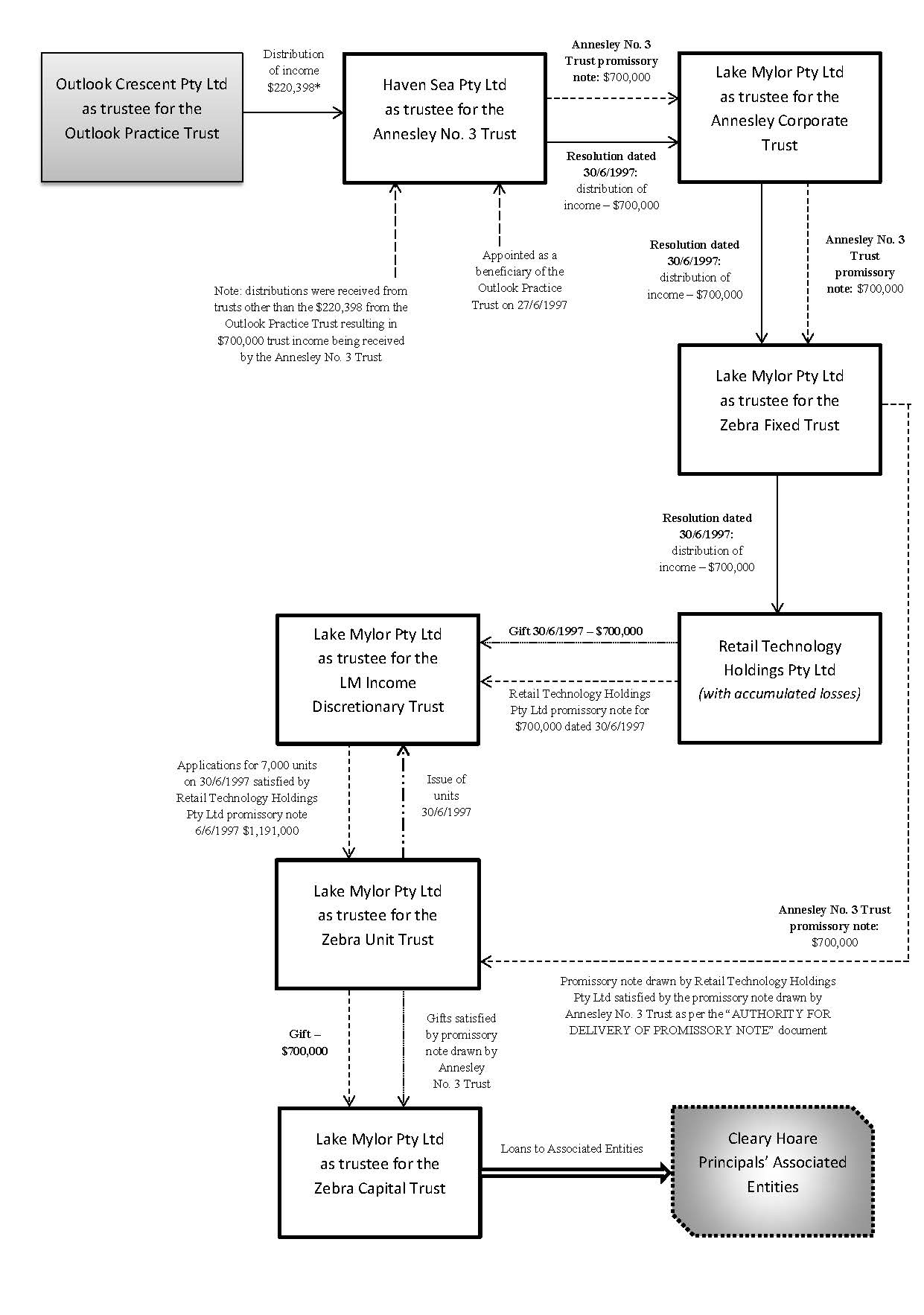

58 Before turning to the largely undisputed narrative of the transactions in question for each application of the NVI Scheme, it is convenient to reproduce below, for illustrative purposes and to make the narrative easier to follow, flowcharts furnished in support of the Commissioner’s arguments. These flowcharts were not an essential part of the Commissioner’s argument, but provided a convenient means of understanding essentially undisputed transactions, in the nature of a visual aide memoir to assist in reading a rather dense narrative. Apart from some inadvertently confusing duplication between the two flowcharts which was intended to be a helpful cross-reference, but which has been removed for clarity so as to refer to the two arrangements separately, the substantial dispute is neatly reflected in the last (disputed) step in each of those flowcharts concerning the stage at which, on the Commissioner’s case, money was ultimately received by or to the benefit of Mr Hart.

59 The narrative detailing those two series of transactions, and reflected in the flowcharts below, is contained in the Commissioner’s third further amended appeal statement:

(1) at [52] and [53] in respect of the Practice Amount and the scheme relied upon by Mr Hart referred to as the “Practice Trust NVI Scheme”; and

(2) at [102] in respect of the IET Amount and the scheme relied upon by Mr Hart referred to as the “Income Earning Trusts NVI Scheme”.

60 It was confirmed at the trial that Mr Hart’s earlier further amended appeal statement remained responsive to the Commissioner’s third further amended appeal statement. In particular, Mr Hart’s further amended appeal statement at [2] accepted that most of the transactions did occur as referred to, albeit that the sequence of several of the transactions was not accepted. Nothing ultimately turned on anything to do with the precise sequence of events as pleaded by the Commissioner. Those issues which remained either not accepted or actively disputed are identified below. Mr Hart at [3] of his further amended appeal statement also relied upon additional facts largely summarised above concerning his professional arrangements and those of Cleary Hoare, his bankruptcy, his concerns as to asset protection and the trust arrangements entered into.

61 As alluded to above, the last step in each flowchart below, based on those two series of transactions, reflects a live and important dispute between the parties:

(1) as to the characterisation of the largely undisputed fact of payments going to Mr Hart or for his benefit in the case of the Practice Amount – the question of whether or not Mr Hart established that such moneys were received by him or to his benefit as a loan is a fact in issue to be adjudicated upon and resolved; and

(2) as to the source and destination of the payments said by the Commissioner to have gone to Mr Hart or his benefit in the case of the IET Amount, and said by the Commissioner to have been sourced, directly or indirectly, from the Income Earning Trusts – the source and destination of that money requires adjudication and resolution, especially as to the effect of Mr Van Homrigh’s evidence.

The Practice Trust NVI Scheme flowchart and transactions narrative

62 The Commissioner’s flowchart in relation to the Practice Trust NVI Scheme, remembering the dispute noted above as to the last stage marked “Loans to Associated Entities”, depicted the following:

63 The narrative which the above flowchart depicts from [52] of the Commissioner’s third further amended appeal statement is as follows (per original):

(ii) The Practice Trust NVI Scheme

52. Based on the documents and information supplied by the Applicant and his advisers the respondent understands that the Practice Trust NVI scheme for the 1997 income year comprised the following steps, matters, transactions and events:

(a) On 9 May 1997, the LM Income Trust, the Zebra Fixed Trust and the Zebra Unit Trust were settled.

(b) On 30 May 1997, the Annesley No. 3 Trust and the Annesley Corporate Trust were settled.

(c) On 27 June 1997, the following events occurred:

i. The directors of OCPL as trustee of the Outlook Trust resolved to appoint Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley No. 3 Trust as a tertiary beneficiary of the Outlook Practice Trust.

ii. The directors of OCPL as trustee of the Outlook Trust resolved to distribute all the income for the year ended 30 June 1997 to the Annesley No. 3 Trust.

(d) On 30 June 1997, the following events occurred:

i. The directors of Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley No. 3 Trust resolved to distribute $700,000 to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust. The resolution stated that the distribution was to be by bearer promissory note drawn by ‘the Company’ for $700,000 with the balance by cheque payable as directed by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd.

ii. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust resolved to distribute $700,000 to the Zebra Fixed Trust. The resolution stated that the amount was to be paid forthwith by delivery of a bearer promissory note received by Annesley Corporate Trust from Annesley No. 3 Trust for $700,000 to the Trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust or as otherwise directed by it.

iii. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust resolved to distribute $700,000 to the fixed beneficiary (being Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd). The resolution stated that the distribution was to be paid forthwith by delivery of a bearer promissory note received by Annesley Corporate Trust to the fixed beneficiary or as otherwise directed by it.

iv. A bearer promissory note was issued by Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley No. 3 Trust for $700,000. Receipt of the bearer promissory note is acknowledged by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust and Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust.

v. By letter from Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd it advised that it has decided to make a gift of $700,000 to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd in its capacity as trustee of the LM Income Trust.

vi. A bearer promissory note was issued by Retail Technology Pty Ltd for $700,000. Receipt of the bearer promissory note is acknowledged by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust and Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust.

vii. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust resolved to accept the gift of $700,000 from Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd by way of delivery of a bearer promissory note drawn by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd. It was further resolved to subscribe for 7000 ‘B’ units at $100 each in the Zebra Unit Trust with the promissory note to be delivered in satisfaction of the application monies.

viii. Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust made application for 7,000 units in the Zebra Unit Trust with payment of the application monies by means of delivery of the bearer promissory note drawn by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd.

ix. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust noted that an application for units had been received from Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust for 7,000 units at $100 each together with the bearer promissory note referred to in the application in satisfaction of the application monies. It was resolved to accept the promissory note of $700,000 issued by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd as payment in satisfaction of the application monies and to issue units.

x. Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust issued a unit certificate for 7,000 ‘B’ units to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust.

xi. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust noted that it had as the trustee of the LM Income Trust received a gift of $700,000 from Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd. It was further noted that Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd was the fixed beneficiary of the Zebra Fixed Trust with the result that the Zebra Fixed Trust qualified as a beneficiary of the Annesley Corporate Trust. It was also noted that the Annesley Corporate Trust had received a final income distribution from the Annesley No. 3 of $700,000 by way of delivery of a bearer promissory note. It was further resolved to make a final income distribution of $700,000 to the Zebra Fixed Trust by delivery of the promissory note to the trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust or as otherwise directed by it.

xii. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust noted that the trust had received a final income distribution from the Annesley Corporate Trust of $700,000 by way of delivery of a bearer promissory note. It resolved to:-

make a final distribution of income in the amount of the above total to the fixed beneficiary to be paid forthwith as to the amount of the promissory note by delivery of the promissory note to the fixed beneficiary or as otherwise directed by it.

xiii. An undated document, titled ‘AUTHORITY FOR DELIVERY OF PROMISSORY NOTE’ addressed to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust and Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust from Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd and Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust in regard to the distributions of income from the Annesley Corporate Trust:-

• authorised the promissory notes issued by Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley No. 3 to be delivered to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust;

• in satisfaction of the obligations arising under the bearer promissory note for the same amount drawn by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd and delivered by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust in respect of the application for ‘B’ units in the Zebra Unit Trust;

• to be delivered by the [sic] Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee for the Zebra Unit Trust in respect of any gift it resolves to make to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust.

64 The sequence of events reproduced above from [52(d)] of the Commissioner’s third further amended appeal statement is not accepted by Mr Hart. However, the asserted correct sequence was not pleaded and no argument was advanced as to how or why the unstated correct sequence made any difference given that all the events described at [52(d)] took place on 30 June 1997. Moreover, the Commissioner did not ultimately rely upon any particular sequence of events on that day, and Mr Hart did not ultimately dispute any particular sequence of events on that day.

65 There was no specific pleading to [53] of the Commissioner’s third further amended appeal statement as follows, but it is apparent that [53(3)(ii)] in particular reflects the dispute between the parties as to the characterisation of the money received by Mr Hart or to his benefit, his case being that the money was received as a loan (per original):

53. Further steps in the NVI scheme included:

(1) On 1 July 1997, the Zebra Capital Trust was settled.

(2) On 2 July 1997, the following events occurred:

i. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust resolved to make a gift of $700,000 out of capital of the trust to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust. It was further resolved that the gift be satisfied by way of delivery of a bearer promissory note for $700,000 issued by Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley No. 3.

ii. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust resolved to accept the gift of capital for $700,000 from Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust. It was further resolved to accept delivery of the bearer promissory note in satisfaction of the gift.

(3) On a date or dates unknown

i. Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust lends $700,000 to Cleary Hoare Principals and associated entities including entities associated with the applicant

ii. who in turn lends a corresponding amount to the applicant.

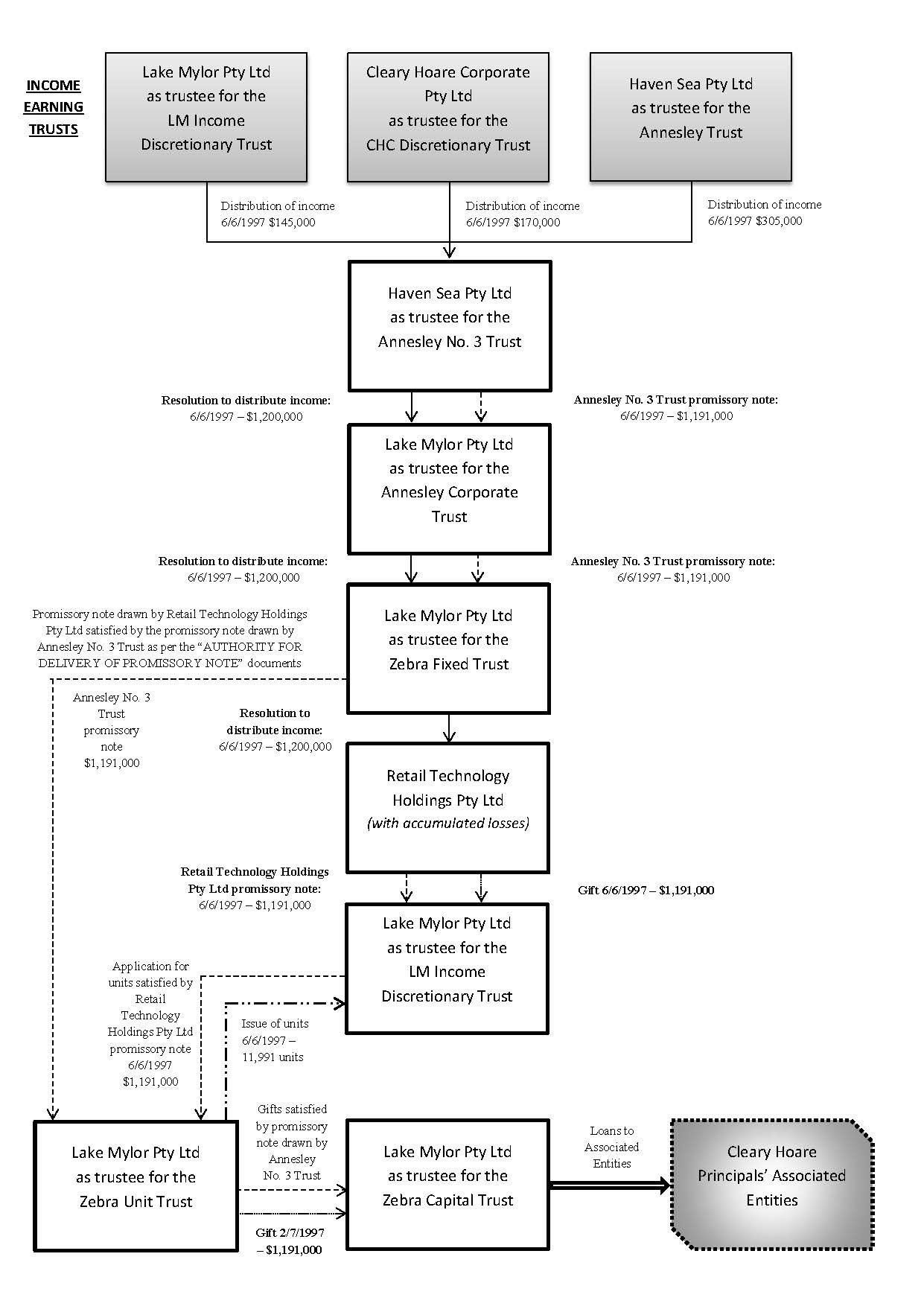

The Income Earning Trusts NVI Scheme flowchart and transactions narrative

66 The Commissioner’s flowchart in relation to the Income Earning Trusts NVI Scheme, remembering the dispute noted above as to the last stage marked “Loans to Associated Entities” whereby Mr Hart denied that the evidence demonstrated that he received this money at all, depicted the following:

67 The narrative which the above flowchart depicts from [102] of the Commissioner’s third further amended appeal statement is as follows:

(ii) The Income Earning Trusts NVI Scheme

102. Based on the documents and information supplied by the Applicant and his advisers the respondent understands that the Income Earning Trusts NVI scheme comprises the following steps, matters, transactions and events:

(a) On 9 May 1997, the LM Income Trust, the Zebra Fixed Trust and the Zebra Unit Trust were settled.

(b) On 30 May 1997, Annesley No. 3 and the Annesley Corporate Trust were settled.

(c) On 6 June 1997, the following events occurred:

i. The directors of Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Trust resolved to distribute $305,000 to Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of Annesley No. 3.

ii. The directors of Cleary Hoare Corporate Pty Ltd as trustee of the CHC Discretionary Trust resolved to distribute $170,000 to Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of Annesley No. 3.

iii. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust resolved to distribute $145,000 to Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of Annesley No. 3.

iv. The directors of Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of Annesley No. 3 resolved to distribute $1,200,000 to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust. The resolution stated that the distribution was to be by bearer promissory note drawn by ‘the Company’ for $1,191,000 with the balance by cheque payable as directed by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd.

v. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust resolved to distribute $1,200,000 to the Zebra Fixed Trust. The resolution stated that the distribution was to be paid forthwith and as to the amount of $1,191,000 by delivery of a bearer promissory note received by Annesley Corporate Trust from Annesley No. 3 to the Trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust or as otherwise directed by it.

vi. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust resolved to distribute $1,200,000 to the fixed beneficiary (being Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd). The resolution stated that the distribution was to be paid forthwith and as to the amount of $1,191,000 by delivery of a bearer promissory note received by Annesley Corporate Trust to the fixed beneficiary or as otherwise directed by it.

vii. A bearer promissory note was issued by Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley No. 3 Trust for $1,191,000. Receipt of the bearer promissory note is acknowledged by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust and Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust.

viii. An ‘AUTHORITY TO PAY’ was issued by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust authorising and directing Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley No. 3 Trust to pay $9,000 to the Cleary Hoare Trust Account.

ix. By letter from Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd it advised that it has decided to make a gift of $1,191,000 to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd in its capacity as trustee of the LM Income Trust.

x. A bearer promissory note was issued by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd for $1,191,000. Receipt of the bearer promissory note is acknowledged by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust and Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust.

xi. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust resolved to accept the gift of $1,191,000 from Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd by way of delivery of a bearer promissory note drawn by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd. It was further resolved to subscribe for 11,991 ‘B’ units at $100 each in the Zebra Unit Trust with the promissory note to be delivered in satisfaction of the application monies.

xii. Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust made application for 11,991 units in the Zebra Unit Trust with payment of the application monies by means of delivery of the bearer promissory note drawn by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd.

xiii. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust noted that an application for units had been received from Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust for 11,991 units at $100 each together with the bearer promissory note referred to in the application in satisfaction of the application monies. It was resolved to accept the promissory note of $1,991,000, issued by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd as payment in satisfaction of the application monies and to issue units.

xiv. Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust issued a unit certificate for 11,991 ‘B’ units to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust.

xv. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust noted that it had as the trustee of the LM Income Trust received a gift of $1,991,000 from Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd. It was further noted that Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd was the fixed beneficiary of the Zebra Fixed Trust with the result that the Zebra Fixed Trust qualified as a beneficiary of the Annesley Corporate Trust. It was also noted that the Annesley Corporate Trust had received a[n] interim income distribution from Annesley No. 3 of $1,200,000 of which $9,000 was by way of cheque payable as directed and the balance by delivery of a bearer promissory note. It was further resolved to make an interim income distribution of $1,200,000 to the Zebra Fixed Trust by delivery of the promissory note to the trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust or as otherwise directed by it.

xvi. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust noted that the trust had received an interim income distribution from the Annesley Corporate Trust of $1,200,000 of which $1,191,000 had been paid by delivery of a bearer promissory note. It resolved to:-

make a[n] interim distribution of income in the amount of the above total to the fixed beneficiary to be paid forthwith as to the amount of the promissory note by delivery of the promissory note to the fixed beneficiary or as otherwise directed by it.

xvii. An undated document, titled ‘AUTHORITY FOR DELIVERY OF PROMISSORY NOTE’ addressed to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust and Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Fixed Trust from Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd and Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust in regard to the distributions of income from the Annesley Corporate Trust:-

• authorised the promissory notes issued by Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley No. 3 to be delivered to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust;

• in satisfaction of the obligations arising under the bearer promissory note for the same amount drawn by Retail Technology Holdings Pty Ltd and delivered by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust in respect of the application for ‘B’ units in the Zebra Unit Trust;

• to be delivered by the [sic] Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee for the Zebra Unit Trust in respect of any gift it resolves to make to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust.

xviii. The sum of $9,000 was paid to the BDO Nelson Parkhill Trust Account.

(d) On 30 June 1997 the following events occurred:

i. The directors of Cleary Hoare Corporate Pty Ltd as trustee of the CHC Discretionary Trust resolved to distribute $550,375 to Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of Annesley No 3.

ii. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the LM Income Trust resolved to distribute $89,625 to Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of Annesley No 3.

iii. The directors of Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of Annesley No. 3 resolved to distribute $700,000 to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Annesley Corporate Trust. The resolution stated that the distribution was to be by bearer promissory note drawn by ‘the Company’ for $700,000 with the balance by cheque payable as directed by Lake Mylor Pty Ltd.

(e) The Zebra Capital Trust was settled on 1 July 1997.

(f) On 2 July 1997, the following events occurred:

i. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust resolved to make a gift of $1,191,000 out of capital of the trust to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust. It was further resolved that the gift be satisfied by way of delivery of a bearer promissory note for $1,191,000 issued by Haven Sea Pty Ltd as trustee of Annesley No. 3.

ii. The directors of Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust resolved to accept the gift of capital for $1,191,000 from Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust. It was further resolved to accept delivery of the bearer promissory note in satisfaction of the gift.

iii. Lake Mylor Pty Ltd, as trustee of the Zebra Unit Trust, resolved to make a gift of $700,000 to Lake Mylor Pty Ltd, as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust. It was further resolved that this gift be satisfied by delivery of a promissory note issued by Haven Sea Pty Ltd, as trustee of Annesley No. 3.

iv. Lake Mylor Pty Ltd, as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust, resolved to accept the gift of capital of $700,000. It was further resolved to accept delivery of promissory note in satisfaction of the gift.

(g) On a date or dates unknown:

i. Lake Mylor Pty Ltd as trustee of the Zebra Capital Trust lends $1,191,000 to Cleary Hoare Principals and associated entities including entities associated with the applicant

ii. who in turn makes corresponding payments to or on behalf of the applicant.

68 The sequences of events reproduced above from [102(c)], [102(d)] and [102(f)] of the Commissioner’s third further amended appeal statement, and the terms of [102(g)] of that statement (the last stage of the flowchart) were not accepted by Mr Hart. However, the asserted correct sequences were not pleaded and no argument was advanced as to how or why the unstated correct sequences made any difference given that all the events described at [102(c)] took place on 6 June 1997, all the events described at [102(d)] took place on 30 June 1997 and all the events described at [102(f)] took place on 2 July 1997. Moreover, the Commissioner did not in terms ultimately rely upon any particular sequence of events on those days, and Mr Hart did not ultimately dispute any particular sequence of events on those days.

The Practice Trust NVI Scheme and the Income Earning Trusts NVI Scheme

69 The Commissioner characterised both sets of NVI arrangements utilised by Mr Hart as being contrived, artificial and devoid of any commercial rationale. For the purposes of the Part IVA argument, the Commissioner’s case was that on all the evidence, the obtaining of a tax benefit for Mr Hart by way of the avoidance of the payment of income tax on his share of the income earned by the Practice Trust and the Income Earning Trusts was the only objective purpose by which his participation in those two applications of the NVI Scheme could be explained.

70 In large measure, Mr Hart did not join issue on, or even question, the transactions that the Commissioner relied upon or the description of what had taken place, or even its pejorative characterisation, which he apparently regarded as legally irrelevant. As noted above, the non-acceptance of the sequence of events was not relied upon in any discernible way and most likely did not matter, at least as the case and issues unfolded. Apart from an explanation of asset protection, no rationale was advanced to explain the transactions by Mr Hart. Nor did Mr Hart provide objective evidence as to the alternative arrangements available to him in lieu of the NVI Scheme, or any other like scheme to which Part IVA clearly would not apply, as opposed to subjective assertions in general terms as to what he would not have done, which were properly objected to and rejected. It was not in doubt that Mr Hart did not want to pay income tax on any of this money, or at all. His declared income was for a minuscule and nominal sum. The main part of his case was that the NVI Scheme, as applied to both the Practice Amount and the IET Amount, was legally effective and beyond the reach of Part IVA. As considered in some detail below, Mr Hart’s answer to the trust distribution means of treating the Practice Amount as assessable income was that the money was never received as income at all, but rather as a loan, and accordingly could never be assessable income.

71 Consideration of both the trust distributions issue and the Part IVA issue requires some closer consideration of key facts and evidence going beyond the general summary above. However that is best done in each after a consideration of the relevant statutory provisions and case law in order to appreciate better the legal significance of the facts in issue.

The issues as articulated by the parties at trial

72 Opening written submissions for the Commissioner suggested that the specific issues that arose for determination from the facts and law in this case could be addressed by reference to a series of specific questions as follows (per original):

[1] In relation to the Practice Trust only:

(a) whether the amount of $220,398 (or some lesser amount) should be included in the Applicant’s assessable income for the 1997 income year under ss 97 and/or 101 of the ITAA 1936 by reason of:

(i) the Applicant being a Special Unitholder in the Practice Trust; or

(ii) alternatively, by reason of the Outlook Trust being a unitholder in the Practice Trust and the Applicant being a beneficiary of the Outlook Trust;

(b) in the alternative:

(i) whether a person or persons who entered into or carried out the Practice Trust NVI Scheme did so with the sole or dominant purpose of enabling the Applicant to obtain a tax benefit;

(ii) whether the Applicant obtained a tax benefit in connection with the Practice Trust NVI Scheme; and

(iii) whether Pt IVA of the ITAA 1936 accordingly applies to include the amount of $220,398 (or some lesser amount) in the Applicant’s assessable income for the 1997 income year.

[2] In relation to the Income Earning Trusts only:

(a) whether a person or persons who entered into or carried out the Income Earning Trusts NVI Scheme did so with the sole or dominant purpose of enabling the Applicant to obtain a tax benefit;

(b) whether the Applicant obtained a tax benefit in connection with the Income Earning Trusts NVI Scheme; and

(c) whether Pt IVA of the ITAA 1936 accordingly applies to include the amount of $275,481 (or some lesser amount) in the Applicant’s assessable income for the 1997 income year.

[3] In relation to both the Practice Trust and the Income Earning Trusts:

(a) whether the assessment dated 3 December 2004 and the amended assessment dated 26 April 2006 are excessive for the purposes of s 14ZZK(b)(i) of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (TAA);

(b) whether penalties were correctly imposed under the former s 226 of the ITAA 1936 at the rate of 50%; and

(c) whether the penalties imposed on the Applicant should be remitted in whole or part.

73 Thus the questions at (1)(a) above address the trust distributions issue, while the questions at (1)(b) and (2) above address the Part IVA issue. The resolution of question (1) on either basis and question (2), and the reasons for reaching those conclusions, necessarily had a substantial and potentially determinative effect on the penalty issues addressed by the questions at (3) above. There was some degree of nuance in relation to these questions in the Commissioner’s closing submissions, which framed the issues and questions somewhat differently, but in substance they were the key points of contention and constitute the way in which the conclusions to these reasons are framed.

74 I did not understand Mr Hart to take issue with the formulation of the above questions as being appropriate to address the issues in dispute, although as noted below his senior counsel suggested that answering slightly different and simpler questions addressing the nub of the same issues would lead to the resolution of the dispute. Senior counsel for Mr Hart characterised the case as coming down to two questions which would resolve both of the issues in the appeal as follows.

75 The first question for resolution posed on behalf of Mr Hart, addressing the trust distributions issue and therefore only the Practice Amount, was whether Mr Hart had persuaded the Court that he did not receive $220,398, or indeed any amount, having the legal character of income from either the Practice Trust or the Outlook Trust in the 1997 income year. On Mr Hart’s case, the payments made and moneys received had the legal character of a loan, not trust distributions, and therefore not income at all and therefore not taxable income. In support of that question being resolved in Mr Hart’s favour, the Court was invited to consider the references provided on his behalf to the evidence in the form of financial statements and tax returns that were said to demonstrate that moneys were advanced by way of loan in the 1997 income year, and also Mr Hart’s evidence to that effect. Mr Hart’s case was that all of the submissions put on behalf of the Commissioner, including as to the entries in the bank statements suggestive of income payments and other indicia of distribution as income, could not overcome the legal character of the payments to be ascribed by the resolutions of the trustees and the terms of the trust deeds. It was accepted that Mr Hart had to discharge the onus of satisfying the Court that the Practice Trust amount was in fact received as a loan.

76 The second question posed by senior counsel for Mr Hart, addressing the Part IVA issue, and therefore both the Practice Amount (in the alternative) and the IET Amount, was whether Mr Hart had persuaded the Court that, absent any scheme, neither the Outlook Trust, nor any of the Income Earning Trusts, nor the Practice Trust, would have distributed their income to him personally or through the Outlook Trust in the 1997 income year. The substance of Mr Hart’s case is that absent the NVI Scheme, Mr Hart would not instead have caused taxable trust distributions to be made to him personally, but rather that a different, but unspecified non-scheme, tax effective process would instead have been deployed.

trust distributions issue (Practice Trust amount only)

77 In this section, I consider whether the Practice Amount constituted a trust distribution under the ITAA 1936.

Sections 95A(1), 97(1) and 101 of the ITAA 1936

78 An important part of this issue turns on the meaning, operation and interaction between ss 95A(1), 97(1) and 101 of the ITAA 1936. Those provisions are as follows:

95A Special provisions relating to present entitlement

(1) For the purposes of this Act, where a beneficiary of a trust estate is presently entitled to any income of the trust estate, the beneficiary shall be taken to continue to be presently entitled to that income notwithstanding that the income is paid to, or applied for the benefit of, the beneficiary.

…

…

97 Beneficiary not under any legal disability

(1) Where a beneficiary of a trust estate who is not under any legal disability is presently entitled to a share of the income of the trust estate:

(a) the assessable income of the beneficiary shall include:

(i) so much of that share of the net income of the trust estate as is attributable to a period when the beneficiary was a resident; and

(ii) so much of that share of the net income of the trust estate as is attributable to a period when the beneficiary was not a resident and is also attributable to sources in Australia;

…

…

101 Discretionary trusts

For the purposes of this Act, where a trustee has a discretion to pay or apply income of a trust estate to or for the benefit of specified beneficiaries, a beneficiary in whose favour the trustee exercises his discretion shall be deemed to be presently entitled to the amount paid to him or applied for his benefit by the trustee in the exercise of that discretion.

79 It may be seen that s 95A(1) of the ITAA 1936 contains a deeming provision in relation to when a beneficiary of a trust estate, for the purposes of s 97(1), is presently entitled to income of that trust estate. I address below a complaint made by senior counsel for Mr Hart concerning the Commissioner’s reliance on s 95A(1) in closing submissions.

80 There was no issue of Mr Hart being other than a resident of Australia for taxation purposes during the 1997 income year, nor of moneys the subject of the assessment being sourced from anywhere outside Australia, nor of him being under any legal disability. With those considerations removed, the plain words of s 97(1) mean that the assessable income of a presently entitled beneficiary of a trust comprises the beneficiary’s share of the net income of the trust estate. The dispute between the parties concerns whether or not Mr Hart was “presently entitled” to any part of the Practice Amount. Specifically, given the onus, the issue was whether Mr Hart had established that the Commissioner was in error in raising an assessment for the Practice Amount in the sum of $220,398.

81 There is no universal definition in the ITAA 1936 for the phrase “presently entitled”, although the phrase is used repeatedly in that Act. Its ordinary meaning therefore must be derived from the general law.

82 In Harmer v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1991) 173 CLR 264, consideration was given to the meaning of “presently entitled” in 97(1)(a) of the ITAA 1936 as follows (at 271; citations omitted, emphasis added):

The parties are agreed that the cases establish that a beneficiary is “presently entitled” to a share of the income of a trust estate if, but only if: (a) the beneficiary has an interest in the income which is both vested in interest and vested in possession; and (b) the beneficiary has a present legal right to demand and receive payment of the income, whether or not the precise entitlement can be ascertained before the end of the relevant year of income and whether or not the trustee has the funds available for immediate payment.

83 That passage was quoted without any qualification specifically in respect of s 97(1) in Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia v Bamford [2010] HCA 10; (2010) 240 CLR 481 at 505 [37] and was followed as a definitive statement on the meaning of “presently entitled” in Colonial First State Investments Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2011] FCA 16; (2011) 192 FCR 298 at 306 [22] and 307 [24]. Mr Hart did not suggest that there was any reason not to apply that definition.

84 In Walsh Bay Developments Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1995) 130 ALR 415, the above passage from Harmer was quoted by Beaumont and Sackville JJ (with whom Jenkinson J agreed) before turning to consideration as to what was meant by the terms “vested in interest” and “vested in possession” as follows at 427:

A vested interest is one where the holder has an “immediate fixed right of present or future enjoyment”: Glenn v Federal Commissioner of Land Tax (1915) 20 CLR 490 at 496, per Griffith CJ. In relation to land, an estate is vested in possession where there is a right of present enjoyment, as where A has a life estate or fee simple estate in the land. An estate is vested in interest where there is a present right of future enjoyment. Thus where T holds in trust for A for life and then in trust for B in fee simple, B’s equitable fee simple estate is vested in interest during A’s lifetime. The estate will vest in possession on A’s death: Glenn v Commissioner, at 496; Dwight v FCT [(1992) 37 FCR 178], at FCR 192.

85 Earlier, in East Finchley Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1989) 90 ALR 457, Hill J considered entitlements under discretionary trusts and the operation of ss 95A(1) and 97(1) at 477:

A discretionary trust deed may provide a discretion in the trustee to determine, in respect of the income of a particular year, who among a class of beneficiaries is to be entitled. If that determination were made prior to 30 June in a year of income and was irrevocable the consequence would be under s 98 that there would be as at the end of the year of income (that being the relevant time to determine the issue) present entitlement under s 97. There would be no need to have any deemed present entitlement in such a class of case assuming, for present purposes, that there had been no payment of any amount to the beneficiary. In the class of case where there had been a payment, then s 95A(1) would deem the beneficiary to continue to be presently entitled to the income and thus keep s 97 of the Act applicable: cf per Barwick CJ in Union-Fidelity Trustee Co of Australia Ltd v FCT (1969) 119 CLR 177 at 182.

Where on the other hand a discretionary trust deed provides that the trustee has a discretion to pay or apply income of the trust estate to or for the benefit of beneficiaries at his discretion and where there has been a payment there would not (at least in the absence of s 95A(1) which was introduced in 1979) be present entitlement at the end of the year of income, nor in the event that income had been applied in favour of a beneficiary would there have been such present entitlement because, looking at the matter as at the end of the year of income, there would have been no right in the beneficiary to sue the trustee for his share of income, that right having been satisfied by the payment or application already made under s 101. Thus it is doubtful that s 101 was intended to cover the entire field. For almost all purposes (and perhaps indeed for all purposes) it will be irrelevant whether a beneficiary is presently entitled under s 97 or 98 or merely deemed to be presently entitled by force of s 101. …