FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation (No 3) [2017] FCA 465

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent AUSTRALIAN ARROW PTY LTD ACN 071 956 057 Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement

1. On 28 April 2003, Australian Arrow Pty Limited (AAPL) made an arrangement or arrived at an understanding with SEWS Australia Pty Limited (SEWS-A) in respect of a Request for Quotation (RFQ) issued by Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited (TMCA) to SEWS-A in connection with a minor model change to the 2002 Toyota Camry (2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement), the provisions of which

1.1 had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of the engine room main wire harness for the 2002 Toyota Camry to TMCA, by AAPL and SEWS-A, or by either of them, which were in competition with each other;

1.2 constituted exclusionary provisions, within the meaning of sections 4D and 45(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Act) and the Competition Code as applied as a law of Victoria by section 5 of the Competition Policy Reform (Victoria) Act 1995 (Competition Code);

1.3 had the purpose, effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining, or providing for the fixing, controlling or maintaining of, prices for the engine room main wire harness for the 2002 Toyota Camry supplied or to be supplied by AAPL or SEWS-A, or by either of them, in competition with each other; and

1.4 by operation of section 45A of the Act and the Competition Code (as in force at that time), had the purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the Australian Toyota Camry wire harness market,

and thereby:

1.5 contravened section 45(2)(a)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code; and

1.6 contravened section 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act and the Competition Code.

2. On 1 May 2003, by:

2.1 providing SEWS-A with the price at which AAPL then supplied the engine room main wire harness to TMCA (AAPL’s engine room main wire harness price);

2.2 discussing with SEWS-A the extent to which the price for the engine room main wire harness that SEWS-A would submit to TMCA in response to the Request for Quotation would exceed AAPL’s engine room main wire harness price;

AAPL gave effect to the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement, and thereby:

2.3 contravened section 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code; and

2.4 contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act and the Competition Code.

2003 Agreement

3. On 30 June 2003, Yazaki Corporation (Yazaki) made an arrangement or arrived at an understanding with Sumitomo Electric Industries Ltd (SEI) in response to a Request For Quotation issued by Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) for the supply of wire harnesses for the 2006 Toyota Camry (2003 Agreement), the provisions of which:

3.1 had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of the selected wire harnesses for the 2006 Toyota Camry to TMC or its related bodies corporate, including TMCA, by Yazaki and SEI, or by either of them, or by any bodies corporate related to either of them, in competition with each other;

3.2 constituted exclusionary provisions, within the meaning of sections 4D and 45(2) of the Act and the Competition Code,

and thereby contravened section 45(2)(a)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

4. By:

4.1 discussing and agreeing with SEI between 30 June 2003 and 7 July 2003 prices for wire harnesses for the 2006 Toyota Camry that they would submit in response to the Request For Quotation issued by TMC (2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices);

4.2 submitting the 2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMC in Japan on 7 July 2003;

4.3. directing AAPL to submit the 2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMCA in Australia between 17 September 2003 and 28 October 2003; and

4.4 causing AAPL, as an agent of Yazaki within section 84(2) of the Act, to submit the 2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMCA on 28 October 2003;

Yazaki gave effect to the 2003 Agreement and thereby contravened section 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

2008 Agreement

5. In or about late April 2008, Yazaki made an arrangement or arrived at an understanding with SEI in response to a Request For Quotation issued by TMC for the supply of wire harnesses for the 2011 Toyota Camry (2008 Agreement), the provisions of which:

5.1 had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of the selected wire harnesses for the 2011 Toyota Camry to TMC or its related bodies corporate, including TMCA, by Yazaki and SEI, or by either of them, or by any bodies corporate related to either of them, in competition with each other;

5.2 constituted exclusionary provisions, within the meaning of sections 4D and 45(2) of the Act and the Competition Code,

and thereby contravened section 45(2)(a)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

6. By:

6.1. discussing and agreeing with SEI between 9 and 28 May 2008 prices for wire harnesses for the 2011 Toyota Camry that they would submit in response to the Request For Quotation issued by TMC (2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices);

6.2. submitting the 2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMC in Japan on 29 May 2008;

6.3. directing AAPL to submit the 2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMCA in Australia between late May 2008 and mid-2008; and

6.4. causing AAPL, as an agent of Yazaki within section 84(2) of the Act, to submit the 2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMCA on 25 June 2008,

Yazaki gave effect to the 2008 Agreement and thereby contravened section 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

Overarching Cartel Agreement

7. By making or arriving at the 2003 and the 2008 Agreement, Yazaki gave effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement, the provisions of which:

7.1. had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of wire harnesses to TMC or its related bodies corporate, including TMCA, by Yazaki and SEI, or by either of them, or by any bodies corporate related to either of them, in competition with each other;

7.2. constituted exclusionary provisions, within the meaning of sections 4D and 45(2) of the Act and the Competition Code;

and thereby contravened section 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

8. Yazaki be restrained for a period of three years from the date of this order from making, arriving at, or giving effect to, any contract, arrangement or understanding with SEI for the supply of wire harnesses, containing provisions which have the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of wire harnesses by it, or its related bodies corporate or agents, to any customer in Australia, unless such conduct is authorised under section 88 of the Act or any other Australian statute in accordance with section 51 of the Act.

9. Under s 76(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 and the Competition Code as applied as a law of Victoria by s 5 of the Competition Policy Reform (Victoria) Act 1995, Yazaki pay the Commonwealth of Australia pecuniary penalties totalling $9,500,000 in respect of its contraventions of ss 45(2)(a)(i) and 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and Competition Code identified in paragraphs 5 and 6 above.

10. The respondents pay 85% of the applicant’s costs of the proceeding as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BESANKO J:

Introduction

1 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation (No 2) [2015] FCA 1304; (2015) 332 ALR 396, I held that Yazaki Corporation and Australian Arrow Pty Ltd had each contravened various provisions in s 45(2)(a) and (b) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) and the equivalent sections in the Competition Code of Victoria applied as a law of Victoria by s 5 of the Competition Policy Reform (Victoria) Act 1995 (Vic). I will refer to those reasons as the liability reasons. These reasons deal with relief, pecuniary penalties and costs. These reasons should be read with the liability reasons and I will use the abbreviations and descriptions I used in the liability reasons.

2 After I had delivered the liability reasons, the parties were given time to prepare for the hearing as to relief, pecuniary penalties and costs and to agree such facts as they were able to agree. The parties were able to agree a number of facts relating to the supply of WHs by AAPL to TMCA in Australia in relation to the 2011 Toyota Camry, the size and financial position of Yazaki, AAPL and TMC, the positions held by Yazaki employees involved in the contravening conduct and a compliance program implemented by Yazaki. A document entitled “Statement of Agreed Facts” was put before the Court. In addition, the ACCC relied on two documents which it had tendered at the trial. Yazaki and AAPL tendered four affidavits and two documents.

3 There are four agreements which are relevant in this proceeding and they are described in the liability reasons as the Overarching Cartel Agreement, the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement, the 2003 Agreement and the 2008 Agreement. As found in the liability reasons, AAPL’s contraventions relate to the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement, and Yazaki’s contraventions relate to the other three agreements.

4 The ACCC seeks declarations with respect to each of the contraventions and an injunction against Yazaki and against AAPL. Yazaki accepts that the declarations and injunction sought against it are appropriate, and AAPL accepts that the declarations sought against it are appropriate. However, AAPL submits that an injunction should not be made against it.

5 The ACCC seeks pecuniary penalties against Yazaki in relation to its conduct concerning the 2008 Agreement and the giving effect to of the Overarching Cartel Agreement. It is not open to the ACCC to seek pecuniary penalties in relation to the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement or the 2003 Agreement because this proceeding was not commenced within six years of the conduct constituting the contraventions in relation to those agreements (s 77(2) of the Act and Competition Code).

6 There are a number of issues between the parties as to the appropriate pecuniary penalty or penalties in respect of Yazaki’s conduct in 2008. The first issue is as to the amount of the maximum penalty. Section 76(1A) of the Act and Competition Code provides that the maximum penalty is the greatest amount of three alternatives. Those alternatives are the amount of $10 million or three times the value of the benefit reasonably attributable to the contraventions, or 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate and related bodies corporate during the 12 months ending at the end of the month in which the contraventions occurred. Neither the ACCC nor Yazaki have sought to prove the value of the benefit reasonably attributable to the contraventions and that alternative is not relevant. There is a dispute as to the amount of annual turnover to be attributed to Yazaki during the 12 months ending at the end of the month in which the contraventions occurred. The ACCC’s case is that the annual turnover is an amount in the region of $175 million and that this results in a maximum penalty in the region of $17.5 million for each contravention in 2008. Yazaki’s case is that the annual turnover is an amount in the region of $65 million and that this results in a maximum penalty in the region of $6.5 million in relation to this alternative. In the circumstances, on Yazaki’s case, the relevant maximum penalty is $10 million. The second issue relates to the contraventions found against Yazaki and whether by reference to the provisions of s 76 of the Act or the course of conduct principle or the totality principle, the contraventions should be treated as one contravention for the purposes of determining and applying the appropriate maximum penalty. The ACCC submits that there are five contraventions each carrying the appropriate maximum penalty, whereas Yazaki submits that the contraventions should be treated as if they were one contravention carrying a maximum penalty of $10 million. The third issue, which is affected by the resolution of the first two issues, relates to the total pecuniary penalty which is appropriate and should be imposed. The ACCC submits that the total pecuniary penalty which is appropriate is in the region of $42 million to $55 million, whereas Yazaki submits that the total pecuniary penalty which is appropriate is between $4 million and $6 million.

7 The ACCC seeks an order that Yazaki and AAPL pay its costs of the proceeding. Yazaki and AAPL submit that the ACCC failed on a number of issues and that, in the circumstances, the appropriate order as to costs is that each party bear its own costs of the proceeding.

Declarations (yazaki and aapl)

8 The parties agree that the following declarations reflect the conclusions I reached in the liability reasons and are appropriate:

The Court Declares that:

2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement

1. On 28 April 2003, Australian Arrow Pty Limited (AAPL) made an arrangement or arrived at an understanding with SEWS Australia Pty Limited (SEWS-A) in respect of a Request for Quotation (RFQ) issued by Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited (TMCA) to SEWS-A in connection with a minor model change to the 2002 Toyota Camry (2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement), the provisions of which:

1.1. had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of the engine room main wire harness for the 2002 Toyota Camry to TMCA, by AAPL and SEWS-A, or by either of them, which were in competition with each other;

1.2. constituted exclusionary provisions, within the meaning of sections 4D and 45(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Act) and the Competition Code as applied as a law of Victoria by section 5 of the Competition Policy Reform (Victoria) Act 1995 (Competition Code);

1.3. had the purpose, effect or likely effect of fixing, controlling or maintaining, or providing for the fixing, controlling or maintaining of, prices for the engine room main wire harness for the 2002 Toyota Camry supplied or to be supplied by AAPL or SEWS-A, or by either of them, in competition with each other; and

1.4. by operation of section 45A of the Act and the Competition Code (as in force at that time), had the purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the Australian Toyota Camry wire harness market,

and thereby:

1.5. contravened section 45(2)(a)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code; and

1.6. contravened section 45(2)(a)(ii) of the Act and the Competition Code.

2. On 1 May 2003, by:

2.1. providing SEWS-A with the price at which AAPL then supplied the engine room main wire harness to TMCA (AAPL’s engine room main wire harness price);

2.2. discussing with SEWS-A the extent to which the price for the engine room main wire harness that SEWS-A would submit to TMCA in response to the Request for Quotation would exceed AAPL’s engine room main wire harness price;

AAPL gave effect to the 2002 Toyota Camry Minor RFQ Agreement, and thereby:

2.3. contravened section 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code; and

2.4. contravened section 45(2)(b)(ii) of the Act and the Competition Code.

2003 Agreement

3. On 30 June 2003, Yazaki Corporation (Yazaki) made an arrangement or arrived at an understanding with Sumitomo Electric Industries Ltd (SEI) in response to a Request For Quotation issued by Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC) for the supply of wire harnesses for the 2006 Toyota Camry (2003 Agreement), the provisions of which:

3.1. had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of the selected wire harnesses for the 2006 Toyota Camry to TMC or its related bodies corporate, including TMCA, by Yazaki and SEI, or by either of them, or by any bodies corporate related to either of them, in competition with each other;

3.2. constituted exclusionary provisions, within the meaning of sections 4D and 45(2) of the Act and the Competition Code,

and thereby contravened section 45(2)(a)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

4. By:

4.1. discussing and agreeing with SEI between 30 June 2003 and 7 July 2003 prices for wire harnesses for the 2006 Toyota Camry that they would submit in response to the Request For Quotation issued by TMC (2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices);

4.2. submitting the 2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMC in Japan on 7 July 2003;

4.3. directing AAPL to submit the 2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMCA in Australia between 17 September 2003 and 28 October 2003; and

4.4. causing AAPL, as an agent of Yazaki within section 84(2) of the Act, to submit the 2006 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMCA on 28 October 2003;

Yazaki gave effect to the 2003 Agreement and thereby contravened section 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

2008 Agreement

5. In or about late April 2008, Yazaki made an arrangement or arrived at an understanding with SEI in response to a Request For Quotation issued by TMC for the supply of wire harnesses for the 2011 Toyota Camry (2008 Agreement), the provisions of which:

5.1. had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of the selected wire harnesses for the 2011 Toyota Camry to TMC or its related bodies corporate, including TMCA, by Yazaki and SEI, or by either of them, or by any bodies corporate related to either of them, in competition with each other;

5.2. constituted exclusionary provisions, within the meaning of sections 4D and 45(2) of the Act and the Competition Code,

and thereby contravened section 45(2)(a)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

6. By:

6.1. discussing and agreeing with SEI between 9 and 28 May 2008 prices for wire harnesses for the 2011 Toyota Camry that they would submit in response to the Request For Quotation issued by TMC (2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices);

6.2. submitting the 2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMC in Japan on 29 May 2008;

6.3. directing AAPL to submit the 2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMCA in Australia between late May 2008 and mid-2008; and

6.4. causing AAPL, as an agent of Yazaki within section 84(2) of the Act, to submit the 2011 Toyota Camry agreed prices to TMCA on 25 June 2008,

Yazaki gave effect to the 2008 Agreement and thereby contravened section 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

Overarching Cartel Agreement

7. By making or arriving at the 2003 and the 2008 Agreement, Yazaki gave effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement, the provisions of which:

7.1. had the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of wire harnesses to TMC or its related bodies corporate, including TMCA, by Yazaki and SEI, or by either of them, or by any bodies corporate related to either of them, in competition with each other;

7.2. constituted exclusionary provisions, within the meaning of sections 4D and 45(2) of the Act and the Competition Code;

and thereby contravened section 45(2)(b)(i) of the Act and the Competition Code.

The Court clearly has the power to make these declarations (Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 21). In my opinion, the declarations reflect the conclusions in the liability reasons and should be made.

Injunctions (YAZAKI AND aapl)

9 The parties agree that it is appropriate to make an injunction against Yazaki in the following terms:

The Court Orders that:

8. Yazaki be restrained for a period of three years from the date of the order from making, arriving at, or giving effect to, any contract, arrangement or understanding with SEI for the supply of wire harnesses, containing provisions which have the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of wire harnesses by it, or its related bodies corporate or agents, to any customer in Australia, unless such conduct is authorised under section 88 of the Act or any other Australian statute in accordance with section 51 of the Act.

In my opinion, this order is appropriate and should be made.

10 The ACCC also seeks an injunction against AAPL. It is in the following terms:

9. AAPL be restrained for the earlier of:

9.1. a period of three years from the date of the order,

9.2. until it ceases trading in Australia,

from making, arriving at, or giving effect to, any contract, arrangement or understanding with any of its competitors for the supply of wire harnesses, containing provisions which have the purpose of preventing, restricting or limiting the supply of wire harnesses by it, or its related bodies corporate or agents, to any customer in Australia.

11 It should be noted that the injunction sought against AAPL is not limited to SEI’s subsidiary in Australia, SEWS-A, but extends to “any of its competitors” and that it is not qualified by reference to authorised conduct. In these two respects, it is wider than the injunction sought against Yazaki. Counsel for the ACCC conceded that the injunction sought against AAPL should be qualified by reference to authorised conduct. I do not need to address the terms of the injunction because I have reached the conclusion that an injunction should not be made against AAPL.

12 It is not necessary to establish that the person against whom the injunction is sought intends to engage again or to continue to engage in the conduct before an injunction is granted (s 80(4)(a) of the Act and Competition Code). In BMW Australia Ltd v Australian Competition & Consumer Commission [2004] FCAFC 167; (2004) 207 ALR 452 at [39], the Full Court of this Court said that in deciding whether to grant an injunction it was relevant to ask whether the prohibited conduct was such as to call for the additional sanction of proceedings for contempt of court by failure to comply with an injunction. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Oceana Commercial Pty Ltd and Others (2004) 139 FCR 316 at [184] the Full Court of this Court said the fact that there is no continuing or threatened contravention is relevant to the discretion whether to grant relief under s 80 of the Act. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dermalogica Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 152; (2005) 215 ALR 482 (ACCC v Dermalogica) at [110], Goldberg J identified, albeit not in an exhaustive way, the following matters as being relevant to whether an injunction is granted: the scale of the prior contravening conduct, the contravener’s future intentions and the likelihood of damage to other persons as a result of further proscribed conduct.

13 The contravening conduct by AAPL occurred 14 years ago. The individuals involved in the conduct were Japanese expatriates. In addition, it is relevant to note that in the liability reasons, I found that the local employees of AAPL did not know of the 2003 Agreement (at [236]) or the 2008 Agreement (at [308]) and that AAPL did not know of those agreements.

14 It is an agreed fact that by the end of 2017, AAPL will cease all of its operations.

15 In my opinion, the chances of AAPL engaging in the conduct proscribed by the proposed injunction are very slim. In the circumstances, I do not think it appropriate to grant an injunction against AAPL.

The Pecuniary Penalty (yAZAKI)

16 This is the most contentious aspect of the relief sought. The starting point is s 76 of the Act which at the relevant time was in the following terms:

(1) If the Court is satisfied that a person:

(a) has contravened any of the following provisions:

(i) a provision of Part IV;

(ii) section 75AU or 75AYA;

(iii) section 95AZN; or

(b) has attempted to contravene such a provision; or

(c) has aided, abetted, counselled or procured a person to contravene such a provision; or

(d) has induced, or attempted to induce, a person, whether by threats or promises or otherwise, to contravene such a provision; or

(e) has been in any way, directly or indirectly, knowingly concerned in, or party to, the contravention by a person of such a provision; or

(f) has conspired with others to contravene such a provision;

the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate having regard to all relevant matters including the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission, the circumstances in which the act or omission took place and whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under this Part or Part XIB to have engaged in any similar conduct.

(1A) The pecuniary penalty payable under subsection (1) by a body corporate is not to exceed:

(a) for each act or omission to which this section applies that relates to section 45D, 45DB, 45E or 45EA—$750,000; and

(b) for each act or omission to which this section applies that relates to any other provision of Part IV—the greatest of the following:

(i) $10,000,000;

(ii) if the Court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate, and any body corporate related to the body corporate, have obtained directly or indirectly and that is reasonably attributable to the act or omission—3 times the value of that benefit;

(iii) if the Court cannot determine the value of that benefit—10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the period (the turnover period) of 12 months ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred; and

(c) for each act or omission to which this section applies that relates to section 95AZN—$33,000; and

(d) for each other act or omission to which this section applies—$10,000,000.

Note: For annual turnover, see subsection (5).

…

(3) If conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more provisions of Part IV, a proceeding may be instituted under this Act against a person in relation to the contravention of any one or more of the provisions but a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this section in respect of the same conduct.

(4) The single pecuniary penalty that may be imposed in accordance with subsection (3) in respect of conduct that contravenes provisions to which the 2 limits in paragraphs (1A)(a) and (b) apply is an amount up to the higher of those limits.

Annual turnover

(5) For the purposes of this section, the annual turnover of a body corporate, during the turnover period, is the sum of the values of all the supplies that the body corporate, and any body corporate related to the body corporate, have made, or are likely to make, during that period, other than:

(a) supplies made from any of those bodies corporate to any other of those bodies corporate; or

(b) supplies that are input taxed; or

(c) supplies that are not for consideration (and are not taxable supplies under section 72-5 of the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999); or

(d) supplies that are not made in connection with an enterprise that the body corporate carries on; or

(e) supplies that are not connected with Australia.

(6) Expressions used in subsection (5) that are also used in the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 have the same meaning as in that Act.

The Maximum Penalty

17 As I have said, the alternative of the value of any benefit that Yazaki and AAPL may have obtained, directly or indirectly, and that is reasonably attributable to the acts in 2008, is not relevant. The ACCC’s case is that the amount calculated in accordance with s 76(1A)(b)(iii) of the Act is approximately $17.5 million and is, therefore, the maximum penalty. Yazaki’s case is that the amount calculated in accordance with s 76(1A)(b)(iii) of the Act is approximately $6.5 million and, therefore, the maximum penalty is $10 million.

18 The structure of s 76(5) of the Act is that an initial calculation is to be made involving the sum of the values of the supplies that the body corporate and related bodies corporate have made or are likely to make during the specified period. In this case, that involves a consideration of the value of all supplies made by Yazaki and AAPL. Supplies made by Yazaki are not connected with Australia and are excluded, and that leaves for consideration supplies made by AAPL.

19 AAPL’s turnover during the turnover period as defined in s 76(1A)(b)(iii) of the Act includes the supply of WHs and EMDs (i.e., other automotive electronic components) to various motor vehicle manufacturers. Those motor vehicle manufacturers were, principally at least, TMCA, Holden and MMAL. The parties are agreed that supplies of WHs and EMDs are to be included in the calculation of the annual turnover as defined, but the ACCC submits that supplies by AAPL to all manufacturers are to be included, whereas Yazaki submits that supplies by AAPL to TMCA only are to be included. The resolution of this dispute turns on whether the supplies to Holden and MMAL are “made in connection with an enterprise that the body corporate carries on” (s 76(5)(d) of the Act). Before addressing this issue, I should say that the annual turnover of AAPL was established on the evidence and summarised in an aide memoire put before the Court by the ACCC. There are differences in the amounts depending on whether the preceding 12 month period is calculated from April or May or June 2008, but I do not need to detail those differences. The key point is that the annual turnover advanced by the ACCC is in the region of $175 million, whereas the annual turnover advanced by Yazaki is in the region of $65 million.

20 Prior to the passing of the Trade Practices Legislation Amendment Act (No 1) 2006 (Cth) (the Amendment Act) the relevant maximum penalty was $10 million. The Amendment Act introduced the provisions dealing with the value of the benefit reasonably attributable to the act or omission, and the alternative of 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate. The Amendment Act was preceded by the Report of the Trade Practices Act Review Committee dated 31 January 2003. The committee dealt with pecuniary penalties and noted the provisions of the Commerce Act 1986 (NZ). The committee said:

Accordingly, the New Zealand Act now provides for an increased pecuniary penalty for breaches of the equivalent of Part IV of our Act. It is, in the case of a corporation, the greater of - (I) NZ$10 million; or (II) either - (A) if it can be readily ascertained and if the Court is satisfied that the contravention occurred in the course of producing a commercial gain, three times the gain resulting from the contravention; or (B) if the commercial gain cannot be readily ascertained, 10 per cent of the turnover of the body corporate and all of its interconnected bodies corporate (if any). The Committee considers this to be a desirable provision and for that reason, and because it is in the interests of closer economic relations between the countries, it is of the view that the Australian Act should be amended along the same lines.

21 In the Second Reading Speech for the Bill, the Minister said:

The government has adopted recommendations made by the Dawson Review which provide that the maximum pecuniary penalty for corporations be raised to be the greater of $10 million or three times the gain from the contravention or, where gain cannot be readily ascertained, 10 per cent of the turnover of the body corporate and all of its interconnected bodies corporate, if any.

22 The ACCC submitted that this extrinsic material supported its interpretation of s 76(5) of the Act to the effect that the annual turnover as defined of AAPL includes all of its turnover and not only that turnover which relates to AAPL’s supplies to TMCA. The difficulty with this submission is that it does not take account of the fact that s 76(5)(d) of the Act refers to “the body corporate” and does not include a reference to “any body corporate related to the body corporate”. That is significant having regard to other features of s 76(5). There is express reference to the body corporate and any body corporate related to the body corporate in the first part of s 76(5) of the Act and s 76(5)(a) of the Act distinguishes between “any of those bodies corporate” and “any other of those bodies corporate”. I think that in the present case, body corporate is restricted to Yazaki.

23 It follows in my view, that one starts in this case with an annual turnover in the region of $175 million and then subtracts from that, (relevantly) the value of supplies that are not made in connection with an enterprise that Yazaki carried on.

24 An issue at the trial was whether Yazaki carried on business in Australia. I identified in the liability reasons 23 matters which the ACCC relied on to establish that Yazaki was carrying on the whole of the business of AAPL in Australia and I said that they were established on the evidence (at [333]-[334]). I identified matters which supported a conclusion that Yazaki exercised a fairly high level of control over AAPL (at [361]). Nevertheless, I found that Yazaki appeared not to have exercised any significant control over AAPL’s business with its other major customers, such as Holden and MMAL, and that it could not be said that it was not maintained as a distinct and separate entity (at [360]). In the result, I concluded that Yazaki and AAPL were conducting the business in Victoria/Australia of supplying WHs to TMCA, but not the whole of the business apparently conducted by AAPL (at [362]-[363]).

25 Yazaki submitted that “enterprise” in s 76(5)(d) of the Act meant business, and relying on the findings I have identified, supplies by AAPL to Holden and MMAL were not supplies made in connection with a business that Yazaki carried on.

26 The ACCC’s alternative submission to that even if body corporate in s 76(5)(d) encompasses only Yazaki, nevertheless the provision should be given a broad construction. First, it submits that the phrase “in connection with” is capable of embracing direct and indirect links. Secondly, it submits that the word “enterprise” is not limited to a particular business or product line. Finally, it points to the fact that s 76(1A)(b)(iii) is a default provision in the sense that it applies where the value of the benefit identified in s 76(1A)(b)(ii) cannot be determined. The ACCC submits that it would be unlikely in those circumstances that Parliament had in mind a prima facie position to be adjusted by what could be a complicated exercise of determining the precise business the body corporate carried on.

27 As far as the meaning of the word “enterprise” is concerned, by reason of s 76(6) of the Act, expressions used in s 76(5) of the Act have the same meaning as they have in the “A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999” (the GST Act). Section 9-20 of the GST Act defines an “enterprise” and it provides, relevantly:

9-20 Enterprises

(1) An enterprise is an activity, or series of activities, done:

(a) in the form of a business; or

(b) in the form of an adventure or concern in the nature of trade; or

(c) on a regular or continuous basis, in the form of a lease, licence or other grant of an interest in property; or

(d) by the trustee of a fund that is covered by, or by an authority or institution that is covered by, Subdivision 30-B of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 and to which deductible gifts can be made; or

(da) by a trustee of a complying superannuation fund or, if there is no trustee of the fund, by a person who manages the fund; or

(e) by a charitable institution or by a trustee of a charitable fund; or

(f) by a religious institution; or

(g) by the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory, or by a body corporate, or corporation sole, established for a public purpose by or under a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory; or

(h) by a trustee of a fund covered by item 2 of the table in section 30-15 of the ITAA 1997 or of a fund that would be covered by that item if it had an ABN.

(2) However, enterprise does not include an activity, or series of activities, done:

(a) by a person as an employee or in connection with earning withholding payments covered by subsection (4) (unless the activity or series is done in supplying services as the holder of an office that the person has accepted in the course of or in connection with an activity or series of activities of a kind mentioned in subsection (1)); or

Note: Acts done as mentioned in paragraph (a) will still form part of the activities of the enterprise to which the person provides work or services.

(b) as a private recreational pursuit or hobby; or

(c) by an individual (other than a trustee of a charitable fund, or of a fund covered by item 2 of the table in section 30-15 of the ITAA 1997 or of a fund that would be covered by that item if it had an ABN), or a partnership (all or most of the members of which are individuals), without a reasonable expectation of profit or gain; or

(d) as a member of a local governing body established by or under a State law or Territory law (except a local governing body to which paragraph 12-45(1)(e) in Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 applies).

(3) For the avoidance of doubt, the fact that activities of an entity are limited to making supplies to members of the entity does not prevent those activities:

(a) being in the form of a business within the meaning of paragraph (1)(a); or

(b) being in the form of an adventure or concern in the nature of trade within the meaning of paragraph (1)(b).

…

28 The ACCC submits that the definition of “enterprise” is doing no more than drawing a broad distinction between commercial activities on the one hand, and, for example, private recreational pursuits and local government activities on the other.

29 There is force in each of the ACCC’s submissions, but I do not think that they should prevail. In the circumstances of this case, I think the most natural meaning of the word “enterprise” is business, and Yazaki was not carrying on AAPL’s business of making supplies to Holden and MMAL. Even if “enterprise” means commercial activity, I do not think Yazaki was carrying on AAPL’s commercial activity of making supplies to Holden and MMAL.

30 It follows that I accept Yazaki’s submission that the maximum penalty is $10 million.

The Same Act or Conduct or a Single Course of Conduct

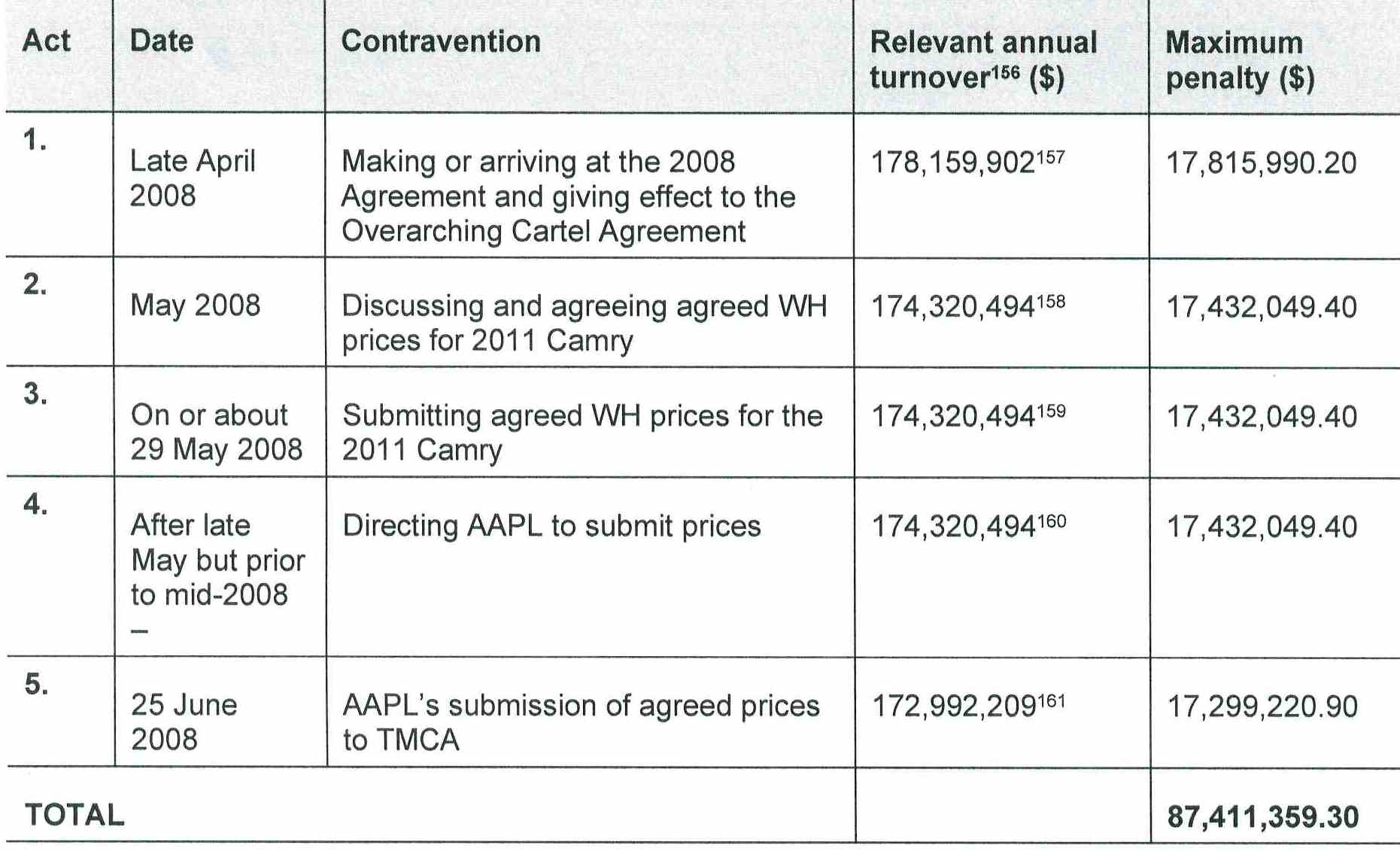

31 The next issue involves a determination of how many contraventions are subject to the maximum penalty of $10 million. The ACCC submits that there are five contraventions which are each subject to the maximum penalty. The following table summarises the ACCC’s case.

32 Yazaki submits that the power to impose a pecuniary penalty should be exercised on the basis that there was one act or the same conduct or a single course of conduct with the result that sentencing should be approached as if there was one maximum penalty of $10 million. It put its submission in various ways.

33 First, Yazaki submitted that the reference in s 76(1A)(b) of the Act to “each act or omission” should be read broadly and it referred to the decision of Goldberg J in ACCC v Dermalogica and, in particular, the following observations made by his Honour (at [55]):

By s 76(1A), the pecuniary penalty payable under s 76(1) by a body corporate for offences including offences against s 48 is not to exceed $10,000,000 for each act or omission. The phrase in s 76(1) (and in subs (1A)) ‘each act or omission’ should not be taken as requiring a separate pecuniary penalty to be awarded, for example, for each conversation, each letter and each offending phrase in the website information. The relevant ‘act’ is engaging in the course of conduct that constitutes the practice of resale price maintenance.

34 I do not think the five contraventions are one act in this sense. Whilst the approach identified by Goldberg J means that in the present case not every conversation about, for example, the allocation of supply and the fixing of prices would be treated as a separate act (see liability reasons at [257]-[258] and [263]), I do not think that the principle extends any further than this.

35 Secondly, Yazaki submitted that the five “contraventions” were all part of the same conduct within s 76(3) of the Act. It sought to rely on the following observations made by Gordon J as a member of this Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 at [127]:

In considering the maximum penalties, Coles is not liable for more than one pecuniary penalty in respect of the same conduct: s 224(4)(b) of the ACL. In determining what constitutes the same conduct, regard may be had to the “one transaction” or “one course of conduct” principle as explained by the majority of the Full Court in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill (2010) 194 IR 461 39 at [39] and [41]:

The principle recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality. That requires careful identification of what is “the same criminality” and that is necessarily a factual specific inquiry.

…

In other words, where two offences arise as a result of the same or related conduct that is not a disentitling factor to the application of the single course of conduct principle but a reason why a Court may have regard to that principle, as one of the applicable sentencing principles, to guide it in the exercise of the sentencing discretion. It is a tool of analysis which a Court is not compelled to utilise.

(Citations and emphasis omitted.)

36 Whatever the position may be under s 224(4)(b) of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act), I do not think the conduct in this case can be, or should be, characterised as the same conduct for the purposes of s 76(3) of the Act. Each act was carried out at a different time and at least some of the acts had a different quality from the others. The approach which is relevant in this case is that which applies in the case of a course of conduct. The approach is closely related to the totality principle.

37 The course of conduct or one transaction approach is engaged where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more contraventions. The application of the approach is designed to avoid double punishment (Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 at [39] per Middleton and Gordon JJ). The approach is closely allied to the totality principle (ACCC v Rural Press Ltd [2001] FCA 1065 (ACCC v Rural Press) at [19] per Mansfield J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 7) [2016] FCA 424 (ACCC v Reckitt Benckiser) at [24]- [29] per Edelman J; Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (No 3) [2017] FCA 10 at [27]-[28]). As the cases make clear, the course of conduct or one transaction approach is a guide to sentencing or a tool of analysis which a court is not bound to apply in a mechanical way. The application of the approach does not mean that a number of contraventions become one contravention, but rather, where it is appropriate to apply the approach, a number of contraventions may be treated as if they attract one penalty (Construction, Forestry, Mining, and Energy Union v Williams [2009] FCAFC 171; (2009) 262 ALR 417 at [31]). The aim is to avoid double punishment or a sentence which is not proportionate with the offending. One sees in this latter consideration, the overlap with the totality principle (Mill v The Queen (1988) 166 CLR 59 at 63). The Court is unlikely to sentence on the basis of a course of conduct if to do so does not reflect the gravity of the offending involved. Furthermore, as Edelman J said in ACCC v Reckitt Benckiser, the exercise of characterising the conduct to determine the number of courses of conduct requires an evaluative judgement about which reasonable minds might reach different conclusions. As his Honour noted, the outcome might depend on the level of generality deployed to resolve the issue.

38 Justice Young discussed the question in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v IPM Operation and Maintenance Loy Yang Pty Ltd (No 2) [2007] FCA 11 (ACCC v IPM Operation and Maintenance Loy Yang). After reviewing the relevant authorities, his Honour concluded that the conduct in the case before him was the same conduct within s 76(3) of the Act. His Honour said at [40]:

This is not a case where different actions were taken by the CEPU at different times and in relation to dealings with different persons or entities. In such a case, the most that could be said was that the conduct on each occasion was of a similar character: see Trade Practices Commission v Simpson Pope Ltd (1980) 30 ALR 544 at 548 per Franki J. On the findings I have made, the CEPU’s conduct was part and parcel of one transaction or episode that took place over the period between 9 August and 23 August 2001.

39 His Honour went on to consider the position in the event that he had concluded that s 76(3) of the Act did not apply. He said at [42]):

If the CEPU’s conduct that is relevant to Edison’s contravention of s 45EA can be distinguished from its conduct in relation to the s 45E(3) contravention, with the consequence that s 76(3) does not apply, I consider that the approach described in Allied Mills, Advance Bank and in McPhee at 584 [185] should be applied in the circumstances of this case. In substance, the CEPU engaged in a single course of conduct that was related and interlocking and which involved it in both contraventions. To my mind, it would be artificial to distinguish between the conduct that is relevant to the making of the arrangement and that which is relevant to Edison’s giving effect to the arrangement. The CEPU’s conduct in relation to the two contraventions is so interconnected that the appropriate course is to apply the totality principle to set a penalty for the CEPU’s accessorial conduct in respect of one breach and to take the CEPU’s involvement in the other breach into account. Adopting that approach, I have concluded that the appropriate penalty would not differ from that which I would impose on the basis that s 76(3) applies.

40 Unsurprisingly, the parties in this case emphasised different matters. The ACCC submitted that the making of the 2008 Agreement was quite a different act from giving effect to it. The conduct involved two different decisions and it was open to Yazaki not to give effect to the agreement and, in those circumstances, the agreement would have had no deleterious consequences. Furthermore, the ACCC submitted that invariably there will be a relationship between making an agreement and giving effect to it, and yet they are separate contraventions indicating (so it was submitted) that “these distinct forms of conduct may properly warrant separate penalties” (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 453; (2016) 336 ALR 1 at [800] as to the Tarong Contract; but see [810] as to the Millmerran Contract). Yazaki, on the other hand, pointed to the short period of time during which the conduct was carried out (i.e., April – June 2008), and to the fact that the agreement was with only one other party and that it related to one customer and one model of vehicle. Yazaki also pointed to the fact that the last three acts were only unlawful because of the first two acts (i.e., without more, submitting prices was not unlawful) and to the fact that the finding in relation to the fourth act (i.e., giving effect to the agreement by a direction to AAPL) was based on an inference and not direct evidence, and that the fifth act (i.e., giving effect to the agreement by submitting prices to TMCA) was described in the liability reasons as a formality (see, [363], [388]). Yazaki submitted that it would be artificial to treat a direction to one’s agent as a contravention, and also the agent carrying out the direction as a separate contravention for penalty purposes.

41 The ACCC responded to the various contentions made by Yazaki. For example, it pointed out, correctly in my view, that whilst it is true that there was only one other party to the agreement, the evidence was that there were very few participants in the market. Furthermore, although there might have been only one customer, it was a very sizeable contract.

42 I have not found the issue an easy one to resolve. At one level, there is a connection between all of the acts and there are cases where this Court has treated making the agreement and giving effect to it as a single course of conduct (ACCC v Rural Press; ACCC v IPM Operation and Maintenance Loy Yang; J McPhee & Son (Aust) Pty Ltd v ACCC [2000] FCA 365; (2000) 172 ALR 532 (J McPhee & Son v ACCC)). However, and at the risk of stating the obvious, each case needs to be considered having regard to its own particular facts.

43 I think Yazaki’s conduct can be divided into two broad categories. Those categories are the making of the agreement and activities between the contraveners on the one hand, and the submission of the prices to the proposed purchaser on the other. The quality of those two acts is different. Referring to the table put forward by the ACCC (at [31]), I characterise acts 1, 2 and 4 as one course of conduct, and acts 3 and 5 as a separate course of conduct. I propose to impose a pecuniary penalty for the first course of conduct and a second pecuniary penalty for the second course of conduct. However, the pecuniary penalty for the second course of conduct will be considerably lower than the pecuniary penalty for the first course of conduct to reflect the fact that to an extent, but not entirely, there is a connection between all of the conduct.

44 For the reasons set out below, I think that the appropriate pecuniary penalty in relation to the first course of conduct is $7 million, and the appropriate pecuniary penalty in relation to the second course of conduct is $2.5 million.

The Appropriate Penalty

45 The nature of the process of fixing a pecuniary penalty and the relevance of the maximum penalty to that process were considered by the Chief Justice of this Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 (ACCC v Coles) at [6] (see Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357 at [27]-[39] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ). I will not repeat what his Honour said. Section 76(1) of the Act requires the Court to impose such a penalty as it considers appropriate having regard to all relevant matters, including the four matters which are identified in the subsection. The authorities in this Court have long recognised a non-exhaustive list of additional relevant matters (see, for example, Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 762; [1991] ATPR 41-076 at 52,152-153 (TPC v CSR); NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 (NW Frozen Foods v ACCC) at 292-294 per Burchett and Kiefel JJ; J McPhee & Son v ACCC at [150] and following; ACCC v Dermalogica at [60]).

46 At the outset, it is to be noted that the High Court has made it clear that general deterrence and specific deterrence each play a primary role in assessing the appropriate pecuniary penalty in cases of this nature. Although the Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 was dealing with the provisions of the Australian Consumer Law, the plurality’s observations as to the significance of general deterrence and specific deterrence at [65] apply equally in this area (see also TPC v CSR at 52-153; NW Frozen Foods v ACCC at 292). As has been said a number of times, it is also important that the penalty acts as a deterrent and is not simply viewed by the contravening company and the third parties as the cost of doing business.

47 Yazaki submitted that special deterrence is less important in this case because it and its subsidiary, AAPL, will cease doing business in Australia at the end of 2017. I will take this matter into account, although it does not mean that special deterrence is irrelevant.

The nature and extent of the contravening conduct, the circumstances in which it occurred and the deliberateness of the conduct

48 The 2008 Agreement concerned the allocation of WHs for the 2011 Toyota Camry in relation to nine manufacturing locations, including Australia. It related to 15 WH parts. After the 2008 Agreement had been made, there were a number of meetings in late April or early May 2008 between SEI representatives and Yazaki representatives at which time the prices to be submitted to TMC were coordinated. I said the following in the liability reasons (at [263]):

… The aim of these meetings was to ensure that the prices of the party who was to lose were higher than the prices of the party who was to win (generally by about 2 – 3%), but not so much higher as to make the party who was to lose appear uncompetitive. The parties needed to analyse and simulate the implications of each adjustment on the component prices, assembly times and rate, and other pricing elements. Mr Nagano and either Mr Shida or Mr Nakai, or both, attended these meetings as representatives of SEI, and Mr Sudo and Mr Niimi attended as representatives of Yazaki. In addition to the meetings, there were a number of telephone conversations between Mr Shida and Mr Niimi about the prices to be submitted to TMC. A number of spreadsheets were created showing the prices of different parts in different locations and the prices in relation to components such as wiring, parts, manufacturing, administration, other and total costs.

49 This conduct may be described as deliberate, sophisticated and devious. The prices that were submitted by Yazaki to TMC related to 16 different WHs and seven geographical locations. Yazaki instructed AAPL to submit the prices for Australia to TMCA which AAPL did with the exception of one part.

50 The Overarching Cartel Agreement is not merely a relevant background circumstance. Whilst Yazaki is not to be punished for making the Overarching Cartel Agreement (that was not the ACCC’s case), it is to be remembered that the making of the 2008 Agreement also gave effect to the Overarching Cartel Agreement. An example of the significance of the Overarching Cartel Agreement is that the parties were discussing the RFQ for the 2011 Toyota Camry before it was issued (liability reasons at [253]).

51 I made findings in the liability reasons that the Overarching Cartel Agreement had the following features. First, the Agreement had been in place since at least the mid 1990’s which was the ACCC’s pleaded case and, in fact, the evidence suggested a date considerably earlier. Secondly, the Agreement related to WHs to be supplied by the parties to the Agreement and their subsidiaries or agents to TMC and its subsidiaries or agents. Thirdly, the Agreement related to all countries and not just Japan. The Overarching Cartel Agreement involved the same type of discussions about prices of parts and of their components as I have described in the case of the 2008 Agreement and again, it is appropriate to describe the conduct as deliberate, sophisticated and devious.

52 The ACCC submitted that the 2008 Agreement involved serious or “hard-core” cartel conduct which is now attended with criminal sanctions in Part IV Division 1 of the Act (Norcast S.ár.L v Bradken Ltd and Others (No 2) (2013) 219 FCR 14 at [209] per Gordon J). That submission is correct. Yazaki accepts that the contraventions are serious because they involved deliberate and covert cartel conduct.

53 As to the circumstances in which the contravening conduct took place, Yazaki submits that the degree of connection between the conduct and Australia is relevant to the quantum of the penalty and that the contravening conduct in this case had a very limited connection to Australia. Yazaki submits that the only conduct which occurred in Australia was AAPL’s submission of prices to TMCA and that that was a mere formality (see liability reasons at [363] and [388]). Yazaki points to the fact that the Court found that there was no relevant market for WHs in Australia and that such competitive activity as there was in connection with the supply of WHs in Australia took place in Japan. It also points to the fact that neither AAPL nor any representative of Yazaki in Australia was found to have any knowledge of the 2008 Agreement. Yazaki asks the Court to approach this case on the basis that it is unique in that: the contraventions do not relate to a market in Australia; there was no knowing participation by any Australian individual or company; and the only contravening conduct which took place in Australia was a formality.

54 The degree of connection to Australia is relevant to the quantum of penalty (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Qantas Airways Limited [2008] FCA 1976; (2008) 253 ALR 89 (ACCC v Qantas) at [39] per Lindgren J). Whilst Yazaki’s submission may be accepted to a point, the fact is that Yazaki’s conduct bore upon substantial financial transactions between substantial corporations in Australia, one of which provided goods to members of the Australian public.

The loss and damage caused by the contravening conduct and the profit gleaned from the conduct

55 TMCA’s initial forecast of the volume of the 2011 Toyota Camry for which AAPL would supply WHs to TMCA in Australia was between approximately 750,000 and 780,000 vehicles over five years of production, equating to 150,000 to 156,000 vehicles per annum. As at 25 June 2008, the forecast value of WHs to be supplied by AAPL to TMCA in Australia for the 2011 Toyota Camry was between AUD221,100,000 and AUD229,944,000, equating to a value of AUD294.80 per vehicle. Between August 2011 and 31 January 2016, AAPL supplied WHs to TMCA in Australia for the 2011 Toyota Camry in relation to 416,458 vehicles providing a revenue of AUD142.1 million, equating to a value of AUD341 per vehicle. The forecast figure for the period from February 2016 to the end of 2017 is 171,542 vehicles providing a revenue of AUD57.3 million equating to a value of AUD334 per vehicle.

56 The evidence from Yazaki establishes that once AAPL’s loss and YES’s profit is taken into account, the overall profit from the supply of WHs over the life of the 2011 Toyota Camry is in the region of $3.6 million.

57 The ACCC submits that the Court should infer from the longstanding cartel arrangements that the cartel conduct in relation to the 2011 Toyota Camry RFQ was for the benefit of Yazaki and SEI in terms of their profits and to the detriment of TMC and TMCA. Why else it may be asked, would they have engaged in the conduct? In the alternative, it submits that the absence of evidence of benefit or detriment is due to the anti-competitive conduct itself and the absence of evidence should not be considered a factor in Yazaki’s favour.

58 Yazaki submits that there is no evidence of loss and damage and the profit is modest. The agreed prices were only starting prices (see liability reasons at [170]-[178]), the cartel agreements were exposed before supply of the 2011 Toyota Camry commenced, and TMC is a very large customer which has significant market power.

59 I am prepared to conclude from the longstanding nature of the arrangement and the size of the transactions (see [55] above) that, at a general level, the contravening conduct caused loss and damage and enabled Yazaki or AAPL to secure a not insignificant profit or avoid a not insignificant loss. It is not possible to be more specific than that.

Previous contraventions of the Act

60 It is not suggested that Yazaki has committed any previous contraventions of the Act.

The deliberateness of the conduct

61 As I have already said, Yazaki’s contravening conduct was deliberate.

The size of the contravening company and its market share or power

62 Yazaki is the parent company of the Yazaki Group, which broadly comprises Yazaki, its subsidiaries, including AAPL, and its affiliate entities. The Yazaki Group is a large multinational supplier of automotive equipment, including WHs, gas meters and air-conditioning equipment.

63 Yazaki, through the Yazaki Group, was at all relevant times, and continues to be, one of the main suppliers of WHs globally. TMC and its subsidiaries around the world, including TMCA in Australia, are one of Yazaki Group’s main purchasers of WHs.

64 Yazaki’s total turnover (including sales to overseas affiliates, royalties from overseas affiliates and sales to group companies in Japan) in respect of the supply of WHs and all of its other operations for the year ending 30 June 2008 was approximately AUD7.5 billion, and the equivalent figure for the year ending 30 June 2015 was AUD4.5 billion. For the year ending 20 June 2008, the net sales of the Yazaki Group was JPY1,493 billion or approximately AUD15.5 million, and for the year ending 20 June 2015 the net sales of Yazaki and its consolidated subsidiaries was JPY1,662.3 billion or approximately AUD17.3 billion.

65 Yazaki estimates that its market share in respect of the supply of WHs in Japan for the 2008 calendar year was approximately 45%, and in respect of the 2014 calendar year, Yazaki estimates its market share was approximately 54%. The Yazaki Group estimates that its market share in respect of the global supply of WHs for the 2008 calendar year was in the range of approximately 23.5-30%, and the equivalent figure for the 2014 calendar year was approximately 27.6%.

66 As at 20 June 2008, Yazaki directly employed or engaged 3,385 people, and during the 2014/2015 financial year, the total number directly employed or engaged was 2,716 people. In terms of Yazaki’s Australian operations, AAPL employed or engaged all personnel. As at June 2008, the Yazaki Group employed or engaged approximately 200,000 people, and the equivalent figure as at June 2015 was approximately 279,800 people.

67 As far as AAPL is concerned, its turnover in respect of the supply of WHs and all of its other operations for the period from 1 May 2007 to 30 June 2008 was, with respect to WHs, AUD167,046,785 and with other operations (including sales to related bodies corporate) was AUD233,644,806 and its annual turnover for the 2014/2015 financial year, was with respect to WHs, AUD64,607,569 and with other operations was AUD67,251,817.

68 AAPL had an estimated 63% market share in respect of the supply of WHs in Australia for the 2008 calendar year. As at 1 June 2008, AAPL employed or engaged 400 permanent employees and an additional 35 people as either contractors or casual employees.

69 The relevance of the size of the contravening company was considered by Allsop CJ in ACCC v Coles. His Honour said (at [92]):

These authorities make it clear that Coles’ financial resources do not alone justify a higher penalty than might otherwise be imposed. However, they are clearly relevant to considering the size of the penalty required to achieve the end of specific deterrence and can be weighed against the need to impose a sum which will be recognised by the public as significant and proportionate to the seriousness of the contravention for the purposes of achieving general deterrence. Further, the resources of Coles are relevant to understanding whether it can pay (and not be crushed by) an appropriate penalty, especially when one takes account of revenue earned by products sold using the impugned phrases.

70 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Visa Inc [2015] FCA 1020; (2015) 339 ALR 413 (ACCC v Visa), Wigney J said (at [114]):

Perhaps the primary consideration, however, is specific and general deterrence. The penalty imposed in this matter should send a clarion call to large multinational corporations that have operations in Australia that whatever decisions may be made globally, Australia will not tolerate conduct that contravenes its competition laws and will not tolerate conduct that is likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition in Australian markets. Given the size of Visa Worldwide and the global Visa business, only a very sizeable penalty is likely to operate as an effective deterrent here. Only a very sizeable penalty is likely to ensure that in the future the risk of incurring a penalty for contravention of the Act will not be treated as a mere cost of doing business in Australia.

The involvement of senior management

71 The employees of Yazaki involved in the contravening conduct were Mr Ryoji Kawai, Mr Toshio Sudo and Mr Nobuyoshi Niimi. Those persons were all employed within Yazaki’s TBU. Their conduct and role is referred to in the liability reasons (at [254]-[263]). As at 21 June 2008, Mr Niimi was employed in the Lexus Sales Department of TBU. Mr Niimi did not have any subordinates reporting to him in that role. Mr Niimi was supervised by Mr Sudo. Mr Sudo’s title as at 21 June 2008 was Manager of the Lexus Sales Department of TBU. Mr Sudo was supervised by Mr Kawai. Mr Kawai’s title as at 21 June 2008 was Deputy Division Manager of the Sales and Marketing Division of TBU. Mr Kawai was supervised by Mr Hitoshi Hashimoto. Mr Hashimoto’s title as at 21 June 2008 was Division Manager of the Sales and Marketing Division of TBU.

72 Mr Kawai, Mr Sudo or Mr Niimi did not make written reports to their superiors regarding the price-coordination meetings and discussions with SEI representatives in relation to the 2011 Camry. To the best of Mr Kawai’s recollection, he believes that he spoke with Mr Tetsuro Suzuki about the discussions which he had had with SEI’s representatives after the 2008 Agreement was reached. Mr Suzuki was, at the time, a senior Yazaki employee whose title was General Manager of TBU.

A corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act

73 In 2008 when the contravening conduct occurred, Yazaki did not undertake specific compliance programs or provide training to its personnel in relation to compliance with the Prohibition of Private Monopolization and Maintenance of Fair Trade Act (Japan) (Anti-Monopoly Act) or the Trade Practices Act. Clearly, as the existence of the Overarching Cartel Agreement evidences, a culture of compliance did not exist within Yazaki.

74 After the anti-competitive arrangements with SEI were revealed, Yazaki implemented compliance and training programs in relation to the Anti-Monopoly Act. On 19 January 2012, the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) made a “Cease and Desist Order” in relation to the supply of WHs (including the 2011 model Camry WHs) and other products to Toyota. The Cease and Desist Order required Yazaki to do the following: implement measures necessary to ensure that its employees are thoroughly informed about their obligations under the Anti-Monopoly Act; implement regular training in relation to compliance with the Anti-Monopoly Act to those employees responsible for sales of WHs and other products to Toyota and other customers; ensure that its legal department conducted regular auditing in respect of these activities; and seek the prior approval of the JFTC in relation to the measures referred to above, and promptly report to the JFTC on any measures that have been implemented.

75 Prior to 30 March 2012 and in accordance with the order, Yazaki prepared a Plan for Implementing Reoccurrence Prevention Measures. The Plan has been approved by the JFTC. The Plan refers to “Rules Relating to Compliance with the Anti-Monopoly Act” and the “Code of Conduct Relating to Compliance with the Anti-Monopoly Act”. There is no suggestion that Yazaki voluntarily undertook any training programs.

Contrition and cooperation

76 There is no evidence of cooperation by Yazaki before this proceeding was commenced. In terms of its conduct in this proceeding, Yazaki did make certain limited admissions (see liability reasons at [187] and [265]), did not cross-examine unnecessarily and acted in a way which contributed to the efficient running of the trial. Yazaki did not put this forward as evidence of cooperation, perhaps aware of the decision of the Full Court of this Court in Rural Press Ltd and Others v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and Others (2002) 118 FCR 236 at [166] to the effect that cooperation at trial is not relevant to penalty, although it may bear on costs.

77 Subject to one matter, there is no evidence of contrition on the part of Yazaki. In a Social and Environmental Report published by Yazaki in 2011, it did express regret (apparently to its stakeholders) for its actions in contravening anti-trust laws and promised to implement measures to prevent a recurrence.

Double punishment

78 Yazaki asks the Court to take into account the punishment it has received in Japan under the Anti-Monopoly Act. The circumstances are as follows.

79 On 19 January 2012, the JFTC found that Yazaki had contravened the Anti-Monopoly Act in relation to the supply of automotive WHs and related products to five motor vehicle manufacturers, being Toyota, Daihatsu, Honda, Nissan and Fuji. The JFTC had commenced its investigation into Yazaki and others in February 2010 and the investigation related to anti-competitive conduct by Yazaki, SEI and another company and which, in the case of TMC, spanned the period from at the latest, September 2002 to June 2009. The JFTC issued five Cease and Desist Orders against Yazaki under the Anti-Monopoly Act and it made Surcharge Payment orders totalling over JPY9.5 billion against Yazaki under the Act. The Surcharge Payment order imposed on Yazaki under the Anti-Monopoly Act in relation to its dealings with TMC was in an amount of JPY4.9 billion approximately, and Yazaki has paid that amount. I was told that JPY4.9 billion is approximately AUD62 million. The conduct which led to these orders against Yazaki was, in relation to TMC, making and giving effect to allocation arrangements with SEI in connection with various RFQs issued by TMC for the supply of WHs between the period from no later than September 2002 to 1 June 2009.

80 Yazaki has also advanced evidence that two Yazaki employees “who were involved in the contraventions which are the subject of this proceeding” have been imprisoned in the United States for crimes involving contraventions of the anti-trust legislation in that jurisdiction. In or around March 2012, Mr Ryoji Kawai was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment and ordered to pay a fine of USD20,000. In or around September 2012, Mr Toshio Sudo was sentenced to 14 months’ imprisonment and ordered to pay a fine of USD20,000.

81 Yazaki is not to be punished twice for the same conduct and the Court should take into account penalties imposed by overseas countries in relation to the same conduct (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cargolux Airlines International SA [2009] FCA 342 at [21] per Lindgren J; ACCC v Qantas at [42] per Lindgren J). The difficulty for Yazaki in this case is that it is not clear that the conduct relating to the 2008 RFQ was the subject of punishment in Japan, and it is not clear that the conduct insofar as it related to motor vehicles manufactured in Australia (as distinct from Japan), was the subject of punishment in Japan. The former matter could be inferred, having regard to the fact that the 2008 RFQ is within the period which is the subject of the punishment. The latter matter is more difficult for Yazaki because the Cease and Desist Order refers to motor vehicles manufactured in Japan. It was within the power of Yazaki to make the position clear and its failure to do so means that I will not take the punishment in Japan into account.

The parity principle

82 Each party referred to pecuniary penalties imposed in other cases whilst recognising that the assistance to be obtained from such an exercise is limited (Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 at [60]; NW Frozen Foods v ACCC at 295 per Burchett and Kiefel JJ).

83 The ACCC referred to ACCC v Visa; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd (No 2) [2016] FCA 528 (ACCC v Colgate-Palmolive (No 2)); and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd (No 3) [2016] FCA 676 (ACCC v Colgate-Palmolive (No 3)).

84 ACCC v Visa involved a contravention of s 47(2) of the Act by the practice of exclusive dealing. The conduct related to conditions imposed on the provision of services involving participation in the Visa payment card network. The maximum penalty in the case was not in dispute. It was 10% of an admitted annual turnover of $331 million. I will not list all of the relevant factors in that case. Some are present in this case, such as the involvement of senior management and others, such as the fact that Visa had a culture of compliance at the time of the contravention are not. Wigney J imposed a penalty of $18 million.

85 ACCC v Colgate-Palmolive (No 2) involved contraventions of s 45(2)(a)(i) and (b)(i) and s 45(2)(a)(ii) and (b)(ii). The maximum penalty for the contraventions involving conduct in February 2009 was 10% of an annual turnover of AUD512.427 million (i.e., AUD51.2 million) and Jagot J imposed a penalty of $12 million. The maximum penalty for the contraventions in November 2008 was 10% of an annual turnover of AUD502.226 million (i.e., AUD50.2 million) and Jagot J imposed a penalty of $6 million. The penalties were penalties which had been agreed by the parties. I do not propose to list the relevant factors. They include the fact that Colgate-Palmolive had an “extensive trade practices and competition law compliance programme” and senior management were not involved in the contraventions.

86 ACCC v Colgate-Palmolive (No 3) involved the same proceeding, but a different respondent, Woolworths Limited. Woolworths admitted to being knowingly concerned in contraventions of s 45(2)(a)(i) and (b)(i) and the maximum pecuniary penalty was $13.08 million for each contravention, being the value of the benefit. Jagot J imposed a penalty totalling $9 million for both contraventions, being approximately 34% of the maximum of $26.16 million. The penalties imposed were penalties which had been agreed by the parties. There were similar differences between this case and that case as there were in the case involving Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd.

87 Yazaki referred to Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Prysmian Cavi E Sistemi Energia S.R.L. (No 5) [2013] FCA 294 (a penalty of $1.35 million); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v April International Marketing Services Australia Pty Ltd (No 8) [2011] FCA 153; (2011) 277 ALR 446 (penalties of $800,000 and $3.4 million); and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bridgestone Corporation and Others (2010) 186 FCR 214 (penalties between $675,000 and $3.2 million). I do not need to discuss these cases. They were put forward by Yazaki as support for the proposition that the ACCC’s proposed range of penalties of $42 to $55 million was disproportionate in terms of penalties in other cases. It will be clear from these reasons that, having regard to the approach I have taken, it is not necessary for me to consider that proposition.

Conclusion

88 The conduct in this case involved contraventions of a key provision in Part IV of the Act and Competition Code. The conduct was deliberate, sophisticated and devious. It included the manipulation of the prices and the components of the prices so as to avoid arousing suspicion. The conduct gave effect to a longstanding and broader anti-competitive agreement. The conduct was more serious than “mid-range” as Yazaki suggested. I think a pecuniary penalty of $7 million is appropriate for the first course of conduct. As I have said, because of the connection between the contravening acts, a lower penalty is appropriate for the second course of conduct. I impose a penalty of $2.5 million.

Costs

89 The ACCC succeeded on the issues identified in the declarations set out above.

90 The ACCC failed on the following issues:

(1) As far as Yazaki is concerned, the ACCC failed to establish that it contravened s 45(2)(a)(ii) and (b)(ii) of the Act and Competition Code because I found that there was not a market in Australia for the supply of Toyota WHs (liability reasons at [394]-[395]).

(2) As far as Yazaki is concerned, the ACCC failed to establish the fifth alleged provision of the 2003 Agreement against Yazaki (liability reasons at [164]-[166]) and the fifth alleged act of giving effect to the 2003 Agreement (liability reasons at [218]-[226]). Leaving aside the fact that there would have been additional contraventions by Yazaki, the significance of this is that had I found otherwise, some of the conduct would have fallen within the six year period for the imposition of a pecuniary penalty. The same conclusions apply with respect to the 2008 Agreement (liability reasons at [264]) with the qualification that there was no allegation in the case of that Agreement of a contravention by continuing to supply (liability reasons at [306]).

(3) As far as AAPL is concerned, the ACCC failed to establish that it gave effect to the 2003 Agreement (liability reasons at [228]-[240]) and the 2008 Agreement (liability reasons at [307]-[308]). Leaving aside the fact that there would have been additional contraventions by AAPL, the significance of this is that had I found otherwise, some of the conduct would have fallen within the six year period for the imposition of a pecuniary penalty.