FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Toll Transport Pty Ltd v Fleiter (No 2) [2017] FCA 384

ORDERS

Prospective Applicant | ||

AND: | Prospective Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to Rule 7.23 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), within 17 days of the date of this order, the prospective respondent give discovery to the prospective applicant of the documents described in Schedule 1 to this order.

2. Pursuant to Rule 7.29(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the prospective applicant pay the prospective respondent’s reasonable costs and expenses of making discovery in accordance with paragraph 1 of this order, including any costs incurred by the prospective respondent in confirming the serial number or any other identifier of any external storage devices to assess whether those devices fall within the scope of Schedule 1 to this order.

3. As to the costs of the originating application filed on 23 December 2016:

(a) the prospective respondent pay the prospective applicant’s costs of and incidental to the preparation of its outline of submissions and of the appearance of counsel and solicitor at the hearing on 3 April 2017; and

(b) otherwise, there be no order as to costs in respect of the originating application.

Endorsement pursuant to Rule 41.06

To: The prospective respondent

You will be liable to imprisonment, sequestration of property or punishment for contempt if:

(a) for an order that requires you to do an act or thing – you neglect or refuse to do the act or thing within the time specified in the order; or

(b) for an order that requires you not to do an act or thing – you disobey the order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

schedule 1

LOGAN J:

1 On 3 April 2017, for reasons which I delivered ex tempore that day, I decided that Toll Transport Pty Ltd (Toll Transport) had established an entitlement to an order for preliminary discovery under r 7.23 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth): Toll Transport Pty Ltd v Fleiter [2017] FCA 376 (the principal judgment). Upon the delivery of those reasons, it proved both convenient and necessary to afford the parties an opportunity to consult in relation to the precise form of orders and to make related submissions on that subject as well as in relation to costs. I have now had the benefit, and benefit in each instance it truly was, of considering the resultant written submissions made on behalf of each of the parties by their respective counsel. These reasons for judgment must be read in conjunction with the principal judgment.

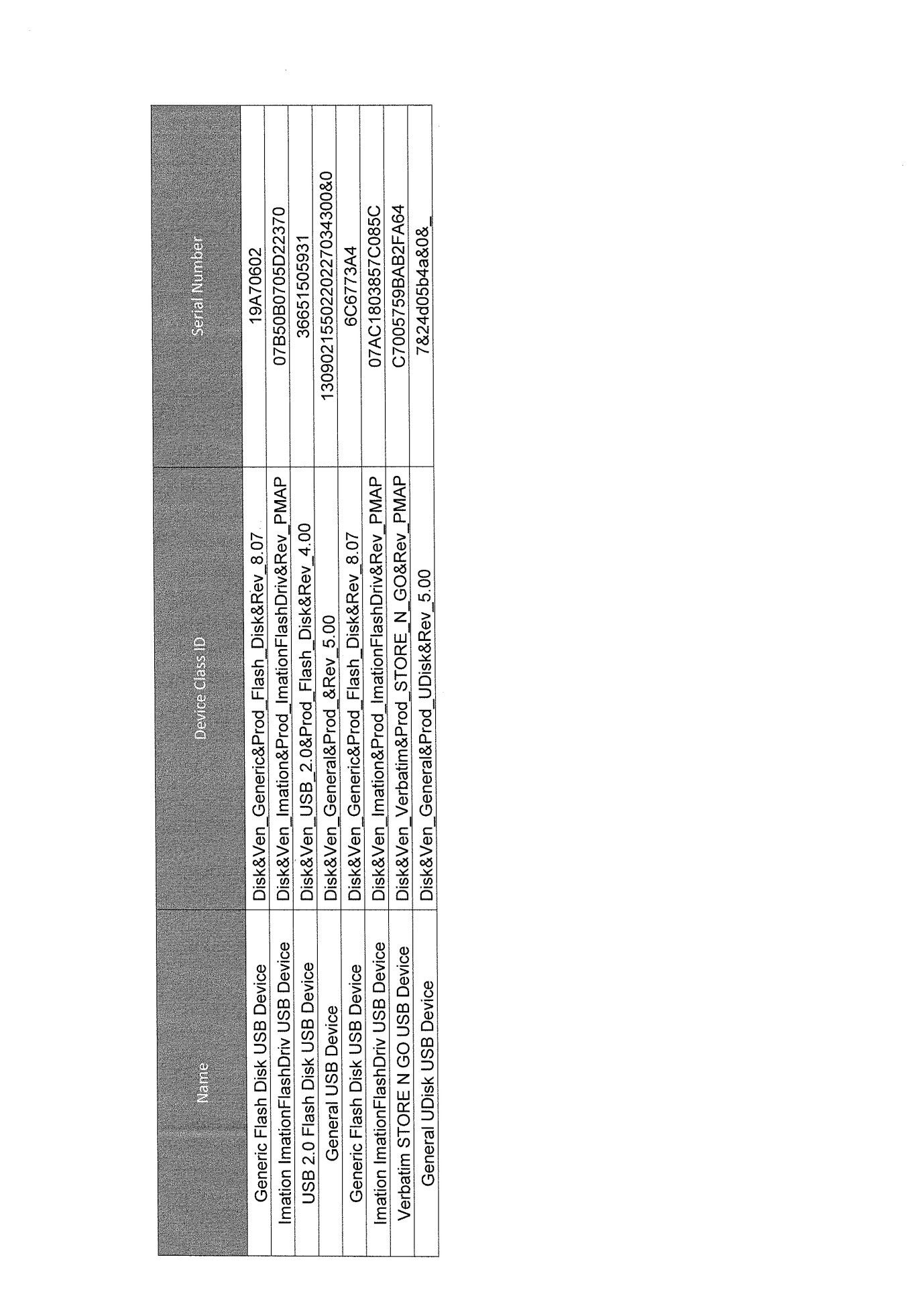

2 Omitting reference to the Schedule, which details the precise serial numbers of the external storage devices (USB) concerned, the orders proposed by Toll Transport are:

1. Pursuant to Rule 7.23 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), within 14 days of the date of this order, the prospective respondent give discovery to the prospective applicant of the documents described in Schedule 1 to this order.

2. Pursuant to Rule 7.29(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the prospective applicant pay the prospective respondent’s reasonable costs and expenses of making discovery in accordance with paragraph 1 of this order, excluding any costs incurred by the prospective respondent in confirming the serial number or any other identifier of any external storage devices to assess whether those devices fall within the scope of Schedule 1 to this order.

3. The prospective respondent pay the prospective applicant’s costs of the originating application filed on 23 December 2016 as agreed or assessed.

3 The reference to “assessed” in paragraph 3 of the proposed orders is inapt in respect of a proceeding in this Court. It reflects the different costs practice in the Queensland State jurisdiction. I have treated it as if the reference were to “taxed”.

4 Mr Fleiter does not take issue with the first of these proposed orders, but does with the second and third.

Second Proposed Order

5 Mr Fleiter’s difference with Toll Transport in relation to the second proposed order relates solely to the exclusion. The individual serial numbers of the USB by which each is identified in the Schedule to the proposed order are not, he submits, either printed on the USB concerned or otherwise physically marked on them. That identification information, he submits, is electronic in nature not accessible to a layperson such as he. The information technology evidence which was led in support of the application indicates that this is so.

6 Given this feature of a USB and that precision as to the USB in respect of which Mr Fleiter is to be ordered to give preliminary discovery is necessary, having regard to the basis upon which Toll Transport has succeeded in its application, he ought not, in my view, bear the expense of undertaking, via the assistance of a suitably qualified expert, the identification necessary to ensure that he complies with the obligation imposed by the Order. In the digital age, the expense of ascertaining the USB serial numbers is just part of searching for and collating the class of document in respect of which a person has been obliged to give discovery. In an earlier, wholly paper-based age to require a prospective applicant to pay the reasonable such costs of a prospective respondent would have been regarded as unremarkable. Further, as to the allowance of this type of cost, there are, in my view, analogies to be drawn with the position of a person subject to a third party discovery order or of a person subject to an obligation to produce documents pursuant to a subpoena. In respect of such persons and given this feature of a USB, expert assistance in the identification task would be regarded as a reasonable compliance cost, to be paid by the person who had sought the third party discovery order or the issuing of the subpoena.

7 For these reasons, I do not consider the proposed exclusion apt. Mr Fleiter ought also to have his reasonable costs of confirming that the serial number or any other identifier of any USB to assess whether those devices fall within the scope of the Schedule to the order.

Third Proposed Order

8 Mr Fleiter was wholly unsuccessful in opposing Toll Transport’s entitlement to preliminary discovery. As these reasons for judgment disclose, he has succeeded only to the limited extent of vindicating his position that his reasonable compliance costs ought to extend to expert assistance in confirming USB serial numbers. Does this mean that he must pay some or all of Toll Transport’s taxed costs in respect of the preliminary discovery application?

9 Rule 7.29(b) anticipates that a prospective respondent may apply for an order that the prospective applicant pay that person's costs and expenses but is silent as to whether those costs ought to include those in respect of an unsuccessful opposition to the making of an order for preliminary discovery under r 7.23.

10 What remains therefore is an issue for the exercise, pursuant to s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act), of the general discretionary power in respect of costs. It is frequently observed that this power must be exercised “judicially”. To some that might seem an odd qualification, given that the discretion necessarily falls to be exercised by a judicial officer. What is meant by the qualification is that the discretion must not be exercised whimsically or capriciously but rather reasonably, having regard to the circumstances of the particular case, including its outcome.

11 Examples of past exercises of the costs discretion in respect of applications for preliminary discovery were surveyed by Perry J in ObjectiVision Pty Ltd v Visionsearch Pty Ltd (No 3) [2015] FCA 304. If there is any conventional approach evident from that survey, it is only that it is usual for a prospective applicant to be ordered to pay a prospective respondent’s reasonable compliance costs. There is no settled approach to whether a prospective respondent who unsuccessfully opposes an application for preliminary discovery ought to be ordered to pay the costs of the prospective applicant in respect of the application.

12 In C7 Pty Ltd v Foxtel Management Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1864 (C7), Gyles J observed of the analogue in the former rules of the present r 7.23 at [50]:

It needs to be borne in mind that this is an extraordinary jurisdiction. It provides for compulsory access to the private affairs of members of the community in order that somebody else can determine if they have a case against that party and the threshold set by O 15A r 6(a) is not very high. There is much to be said for the view that a respondent in these circumstances is entitled to put the applicant to proof except in a clear case. Some judges have been disposed to make orders which, to a greater or lesser extent, leave costs to be determined after the result of preliminary discovery and inspection is known, and even to depend upon, to some extent, the fate of the litigation which ensues. I am not persuaded of the merit of that approach. An application pursuant to O 15A is a discrete application and may never lead anywhere. There is no reason why a party which is out of pocket because of costs should await some indefinite future event.

13 Leaving the costs of the application to depend to some extent on the fate of any resultant litigation has been described as the “contingent approach”. In the particular circumstances of C7, where the prospective applicant had largely succeeded in its application, over the opposition of the prospective respondents, this and the considerations mentioned in the passage quoted led Gyles J to determine that the appropriate order was that the prospective applicant pay 50% of the costs of the prospective respondents. In HC Foods Pty Ltd v Carmichael [2016] FCA 1214, Gilmour J ordered that a prospective respondent who had unsuccessfully opposed an application for preliminary discovery pay the prospective respondent’s costs of the application.

14 Interestingly, in England and Wales, where there exists an analogous jurisdiction to made orders for preliminary disclosure, the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 (Eng & W) (CPR) expressly provide for a “conventional approach” in respect of both the costs of the application and of compliance in the event that an order is made. The general position is that the person seeking the order must pay both, with no contingency condition. That is subject to the reservation of a discretion to make a different order in the event, materially, that the respondent has unreasonably opposed the granting of the order. Thus, r 48.1 of the CPR provides:

Pre-commencement disclosure and orders for disclosure against a person who is not a party

48.1

(1) This paragraph applies where a person applies—

(a) for an order under—

(i) section 33 of the Supreme Court Act 1981(1); or

(ii) section 52 of the County Courts Act 1984(2),

(which give the court powers exercisable before commencement of proceedings); or

(b) for an order under—

(i) section 34 of the Supreme Court Act 1981(3); or

(ii) section 53 of the County Courts Act 1984(4),

(which give the court power to make an order against a non-party for disclosure of documents, inspection of property etc.).

(2) The general rule is that the court will award the person against whom the order is sought his costs—

(a) of the application; and

(b) of complying with any order made on the application.

(3) The court may however make a different order, having regard to all the circumstances, including—

(a) the extent to which it was reasonable for the person against whom the order was sought to oppose the application; and

(b) whether the parties to the application have complied with any relevant pre-action protocol.

Given the evident absence of any conventional approach in Australia in respect of applications like the present, the model in the CPR may be worthy of consideration not in relation to the amendment of this court’s rules but for rules harmonisation.

15 There is no such default costs position either in the FCR or evident in the authorities. For that reason, no assistance is to be gained from recourse to English authorities in relation to r 48.1 of the CPR. In any event and inevitably, how the discretion falls to be exercised is always dependent on the circumstances of a given case.

16 It may be accepted that, compared with the hitherto prevailing position, the power to order preliminary discovery is aptly described as an “extraordinary jurisdiction”. An order under r 7.23 does interfere with the privacy of a person who may never become a respondent to a proceeding in the court. Nonetheless, it was neither suggested in the present proceeding nor, so far as I can ascertain, has it been previously suggested that the power conferred by the rule lies outside the rule making power conferred by s 59(1) of the FCA Act. Notably, the FCA Act expressly confers a power to make rules in respect of discovery: s 59(2)(c). Indulgent though the right may be, when all is said and done, an application under r 7.23 is just one to which any person may, for cause, be subject. It is a proceeding in the court. It is thus one subject to the over-arching purpose specified in s 37M of the FCA Act. The parties to such a proceeding, no less than in any other, each have a duty to act so as to facilitate the achievement of that over-arching purpose: s 37N of the FCA Act.

17 This statutory duty apart, the conduct of a party is always relevant to the exercise of discretion with respect to costs. Neither the statutory duty nor these more general considerations oblige a prospective respondent uncritically to acquiesce to a foreshadowed application for preliminary discovery. A prospective respondent is entitled to insist upon a proper case for such an order being put to it and to take advice on that subject. Further, as a preliminary step and in the absence of an apprehension as to the untoward disposal of the document sought, a prospective applicant ought, as matter of good practice, to propose that such discovery be given informally and candidly and in detail reveal to a prospective applicant the basis for the reasonable belief and view that the other elements found in r 7.23(1) are satisfied.

18 The solicitors for Toll Transport undertook preliminary correspondence with those acting for Mr Fleiter. These culminated in an exchange in late February and early March 2017 exhibited to an affidavit of Mr Zielinski of Minter Ellison, the solicitors for Toll Transport. This exchange makes it evident that the misconception as to the USB with the crucial metadata themselves being a document was then abroad in the thinking of those acting for Mr Fleiter. Other bases upon which the application came later unsuccessfully to be resisted are also evident. At that stage, some but not all of the affidavit material upon which Toll Transport came to rely had been served on Mr Fleiter. Mr Longmire’s and Mr Tierney’s affidavits, each of which was filed and read on behalf of Toll Transport on the hearing of the application, and which were influential in its outcome, were not made and filed until 13 March 2017. That was after the last exchange of correspondence.

19 Some assistance by analogy is, in my view, to be gained from the evolution in relation to orders for costs with respect to one practice which prevailed at common law in New South Wales under the Common Law Procedure Act 1899 (NSW). The view was taken that there was nothing in s 102 of that Act which compelled a party to an action to consent to an order for discovery. In the absence of consent, it was necessary for a party seeking discovery to apply to the court for an order for discovery. The view was taken that, where no consent was given and the application was not opposed, costs ought to be made costs in the cause: McLeod v Metayer (1901) 18 WN (NSW) 5 (McLeod v Metayer). Where, however, a party refused a request for discovery on a ground obviously insufficient such that an application was necessary and maintained the opposition on that ground an order for costs was made against the opposing party: Mitchell & Ors v Hore & Ors (1927) 44 WN (NSW) 49. As to this and referring to the order earlier made in McLeod v Metayer, Davidson J observed, at p 50:

The present practice in similar applications both in Equity, and at Common Law, as I understand it, is to visit with costs a litigant who unnecessarily takes up the time of the Court in opposing applications of this nature where there is no good ground of opposition. This practice does not necessarily apply when there are good grounds for taking the opinion of the Court.

His Honour then granted the order for discovery with costs to the applicant.

20 In my view, there is much to commend the adoption of a like approach in relation to an application for preliminary discovery. The costs of such an application ought not as a matter of course follow the event. Further, even in the event of a successful application, it does not follow that a prospective applicant ought to receive the whole of its costs. But there may come a point where continued opposition is not reasonable and results only in the unnecessary taking up of court time in the hearing and determination of an application. Further, like Gyles J in C7, I consider that the costs of a discrete application for preliminary discovery ought ordinarily to be determined by the judge who hears the application. For it is that judge who will be the most familiar with the merits of the issues raised. Further, so disposing of costs has the advantage of certainty and timeliness.

21 In my view, it was unreasonable for Mr Fleiter to have maintained his opposition to disclosure following the service on him of Mr Longmire’s and Mr Tierney’s affidavits. These fully revealed the factual basis for the application and gave complete context to the submission earlier made to his solicitors by those acting for Toll Transport that there was a case for preliminary discovery under r 7.23 of the USB as documents in their own right. None of the bases of opposition which came to be pressed on the hearing of the application had any merit. I do not, with respect, consider that this was a case where there were “good grounds for taking the opinion of the Court”. Had I been of that view then the costs sequel would probably have been different. As it is, I consider that Toll Transport ought to have its costs of the application but that these should be limited to the costs of and incidental to the preparation and filing of its outline of submissions and of the hearing of the application on 3 April 2017. As to the costs in relation to the form of orders and costs, each party has enjoyed an equal degree of forensic success in my view. I thus make no order as to costs in respect of that concluding stage of the proceeding.

I certify that the preceding twenty-one (21) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Logan. |

Associate: