FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Wotton v State of Queensland (No 5) [2016] FCA 1457

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 75, first sentence, “the conduct of the respondents” has been changed to “the conduct of QPS officers”. | |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 394, “has” has been changed to “have” in the first sentence and “it has” has been changed to “they have” in the second sentence. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 718, “three” has been changed to “there” in the second sentence and “DS Webber” has been changed to “DI Webber” in the fourth sentence. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 725, “respondents’ conduct” has been changed to “conduct of QPS officers”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 738, “judgment” has been changed to “judgement”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 739, “in” has been deleted after the words “critical to”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 740, “has contributed” has been changed to “have contributed”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraphs 1126 and 1358 and in the list of cases, the word “Commonwealth” has been deleted from the title of Eastman v Director of Public Prosecutions (ACT) [2003] HCA 28; 214 CLR 318. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 1468, “of” has been added to the phrase “members of the public”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 1568, second sentence, “Caroll” has been changed to “Carroll”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 1579, a typographical error has been corrected in “referring”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 1613, “ no such proportion” has been changed to “ no such proposition”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 1734, a typographical error has been corrected in “Lockhart J”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 1759, a typographical error has been corrected in “Spigelman CJ”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 1768, “at first instance” has been deleted after “assault and battery claims”. |

21 December 2016 | In paragraph 1780, “Federal Circuit Court” has been changed to “Federal Magistrates Court” |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 255, eighth paragraph of the quote, the letter “L” has been changed to “K”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 274, seventeenth paragraph of the quote, “be” has been changed to “he”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 344, penultimate sentence, “have” has been added before “wanted”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 351, subparagraph (7), a typographical error has been corrected in “Berna”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 359, last sentence before the quote, “impact” has been added before “munitions”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 433, sixth sentence, “a” has been added before “stoic”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 436, third paragraph of the quote, “10” has been deleted after “access”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 441, penultimate sentence, “riots” has been changed to “strike”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 461, last sentence, “the” has been added before “three”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 760, first sentence of the quote, “anyway” has been changed to “away”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 807, first sentence of the quote, “island” has been changed to “Island”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 814, sixth sentence, “is” has been added between “exaggeration” and “in part”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 861, last paragraph of the quote, the letter “L” has been changed to “K”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 973, second sentence, “SS Leafe” has been changed to “Sergeant Leafe”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1000, penultimate paragraph of the quote, “5” has been deleted after “Aboriginality of”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1045, second sentence of the quote, a closing quotation mark has been added after “next one,”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1086, first sentence, “not” has been added before “employed”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1144, first sentence, “of” has been deleted before “the emergency”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1193, first sentence, “evening” has been changed to “morning”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1260, fourth sentence, “above” has been deleted after “As I have noted”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1346, second sentence, “attested” has been changed to “arrested”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1413, first sentence, “three” has been changed to “two”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1458, penultimate sentence, “of” has been deleted before “being shot”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1529, the text before the quote has been changed to correct a grammatical error. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1660, last sentence of the quote, “In” has been changed to “in” and “Issues” has been changed to “issues”. |

18 January 2017 | In paragraph 1711, seventh sentence, “appellants” has been changed to “applicants”. |

ORDERS

First Applicant AGNES WOTTON Second Applicant CECILIA ANN WOTTON Third Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent COMMISSIONER OF THE POLICE SERVICE Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. In relation to the applicants and group members as defined in the further amended originating application filed 25 August 2015, Detective Inspector Warren Webber, Detective Senior Sergeant Raymond Joseph Kitching and Inspector Mark Williams committed unlawful discrimination, in contravention of section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth), by failing to treat Senior Sergeant Christopher Hurley as a suspect in the death of Cameron Doomadgee and by allowing Senior Sergeant Hurley to continue to perform policing duties on Palm Island between 19 and 22 November 2004.

2. In relation to the applicants and group members, between 19 and 22 November 2004, Detective Inspector Webber and Detective Senior Sergeant Kitching committed unlawful discrimination, in contravention of section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act, in their treatment of Aboriginal witnesses interviewed, and in their treatment of information supplied by those witnesses, for the purposes of the investigation by the Queensland Police Service into the death of Cameron Doomadgee.

3. In relation to the applicants and group members, between 19 and 22 November 2004, Detective Senior Sergeant Kitching committed unlawful discrimination, in contravention of section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act, in submitting inaccurate information to the coroner, and in failing to supply relevant information to the coroner, for the purposes of the coronial investigation into the death of Cameron Doomadgee.

4. In relation to the applicants and group members, the failure of any officer of the Queensland Police Service with appropriate command responsibilities, including Inspector Gregory Strohfeldt and Acting Assistant Commissioner Roy Wall, to suspend Senior Sergeant Hurley from active duty on Palm Island after the death of Cameron Doomadgee on 19 November 2004 constituted unlawful discrimination in contravention of section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act.

5. In relation to the applicants and group members, the failure of any officer of the Queensland Police Service with appropriate command responsibilities on Palm Island between 22 and 26 November 2004, including Inspector Brian Richardson and Senior Sergeant Roger Whyte, to communicate effectively with the Palm Island community and defuse tensions within that community relating to the death in custody of Cameroon Doomadgee, and the subsequent police investigation, constituted unlawful discrimination in contravention of section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act.

6. In relation to the applicants and group members, Detective Inspector Webber, in making at 1.45 pm on 26 November 2004 and continuing until 8.10 am on 28 November 2004 a declaration of an emergency situation under section 5 of the Public Safety Preservation Act 1986 (Qld) engaged in unlawful discrimination in contravention of section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act.

7. In using officers of the Special Emergency Response Team to carry out the arrest of the first applicant on 27 November 2004, officers of the Queensland Police Service with command responsibilities for the police operations on Palm Island at that time, including Detective Inspector Webber, Inspector Steven Underwood and Inspector Glenn Kachel, engaged in unlawful discrimination in contravention of section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act.

8. In using officers of the Special Emergency Response Team on 27 November 2004 to carry out the entry and search of the house of the first and third applicants, officers of the Queensland Police Service with command responsibilities for the police operations on Palm Island at that time, including Detective Inspector Webber, Inspector Underwood and Inspector Kachel, engaged in unlawful discrimination contrary to section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act.

9. In using officers of the Special Emergency Response Team on 27 November 2004 to carry out the entry and search of the house of the second applicant, officers of the Queensland Police Service with command responsibilities for the police operations on Palm Island at that time, including Detective Inspector Webber, Inspector Underwood and Inspector Kachel, engaged in unlawful discrimination contrary to section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act.

10. Pursuant to section 18A of the Racial Discrimination Act, the Racial Discrimination Act applies in relation to the first respondent as if the first respondent had engaged in the conduct of the officers of the Queensland Police Service referred to in paragraphs 1 to 9 above, and the first respondent is taken to have contravened section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act in the manner there set out.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The first respondent pay to the first applicant damages in the total sum of $95,000.

2. The first respondent pay to the second applicant damages in the sum of $10,000.

3. The first respondent pay to the third applicant damages in the total sum of $115,000.

4. Paragraphs 1 to 3 of these Orders are stayed pending the determination by the Court of the matters set out in paragraphs 1 to 4 and paragraph 6 of the Directions given by the Court on 5 December 2016.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MORTIMER J:

1 Section 9(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (RDA) provides:

It is unlawful for a person to do any act involving a distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of any human right or fundamental freedom in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

2 This is a representative proceeding brought under Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) in which the applicants allege various contraventions of s 9(1) by reason of the conduct of members of the Queensland Police Service (QPS) on Palm Island, Queensland in November 2004. The applicants are Mr Lex Wotton, Mrs Agnes Wotton and Ms Cecilia Wotton. They have brought this proceeding on their own behalf and on behalf of Indigenous people who were ordinarily resident on Palm Island on 19 November 2004 and who remained ordinarily resident there until 25 March 2010. I will refer to the persons in this group as the group members. The three named applicants also represent a subgroup of the group members, constituted by those persons who were affected (in one or more of four ways set out at [4] of the applicants’ third further amended statement of claim) by entries and searches conducted by members of the QPS, including members of the Special Emergency Response Team (SERT), on 18 homes on Palm Island during the period 27 to 28 November 2004. Those entries and searches led to the arrests of 11 people, including two arrests made at a place called Wallaby Point on 29 November 2004. The respondents are the State of Queensland and the Commissioner of the QPS, who is sued as Commissioner and as representing the members of the QPS who engaged in the conduct impugned by the applicants.

3 For the reasons set out below, the applicants have established some but not all of the contraventions of s 9(1) of the RDA which they alleged. I set out a summary of my findings in favour of the applicants at [1540] below.

4 The events and conduct with which this proceeding is concerned begin with the death in police custody of a 36-year-old man now known as Mulrunji at approximately 11 am on 19 November 2004. Before he died, Mulrunji was known as Cameron Doomadgee and in some of the contemporaneous evidence he is called by that name. Unless the context otherwise requires, it is appropriate to use his traditional name, Mulrunji. On the morning of 19 November 2004, Mulrunji had been arrested and placed in custody in what was called the “watchhouse” by Senior Sergeant Christopher Hurley, the Officer in Charge of the Palm Island Police Station. Police Liaison Officer Lloyd Bengaroo, an Aboriginal man employed by the QPS, assisted with the arrest. However, it was SS Hurley who brought Mulrunji into the watchhouse and it was SS Hurley’s physical interactions with Mulrunji that would become the subject of scrutiny. The impugned events and conduct end approximately 11 days later when the large contingent of police officers who had come to the island over the course of that period returned to the mainland.

5 The applicants allege contraventions by the respondents of s 9(1) of the RDA in the investigation of Mulrunji’s death and the conduct of policing operations on the island during this 11-day period. The respondents have accepted that all the allegations of conduct by individual officers of the QPS occurred in the course of the employment of those officers, alternatively in circumstances where those officers were acting as agents of the State of Queensland. Accordingly, vicarious liability under s 18A of the RDA was accepted if the applicants’ allegations were otherwise proven.

6 There have been a considerable number of proceedings and inquiries (including three coronial inquests) into the events with which this proceeding is concerned. Race, and the circumstances and treatment of Aboriginal people on Palm Island, may have featured in some of those previous proceedings and inquiries, but it was intermingled with many other matters. In this proceeding, the role of race in the events on Palm Island between 19 November 2004 and approximately 29 November 2004 is the central issue. At certain times during the course of the proceeding, it appeared the applicants concentrated on failures and shortcomings in police conduct in general (including the issue of its lawfulness), without a clear set of contentions regarding how that conduct contravened s 9(1) of the RDA. However, the Court’s jurisdiction arises because this is a claim under s 9(1) of the RDA and a focus on the issues raised by the terms of that provision must be steadily maintained.

7 The applicants’ claims may be divided broadly into three groups of issues. The first involves the manner in which the QPS conducted the investigation into Mulrunji’s death. The QPS officers with principal responsibility for the investigation were Detective Inspector Warren Webber and Detective Senior Sergeant Raymond Joseph (“Joe”) Kitching. Inspector Mark Williams was a member of the Ethical Standards Command of the QPS and also participated in the investigation. I use the term ‘investigation’ in a broad sense, because this aspect of the applicants’ claims really covers a number of events from very shortly after Mulrunji’s death on 19 November 2004 until just before the civil unrest that saw the burning down of the Police Station and other buildings on Palm Island on 26 November 2004. The applicants allege that, in a number of specific ways, the conduct of the investigation was substandard, inadequate and flawed, and that these failures, omissions and inadequacies occurred because QPS officers were dealing with the death of an Aboriginal man, in an Aboriginal community, and more particularly the Aboriginal community of Palm Island. In the third further amended statement of claim these allegations are made in Parts H and I, and cover the period 19 to 24 November 2004. Many of these allegations begin with a premise that police conduct was unlawful, although in my opinion that premise is not as central to a potential contravention of s 9 as the applicants’ approach suggested.

8 The second group of issues involves the lead-up to events that have sometimes been described as the “riots” that took place on Palm Island on 26 November 2004, as well as the police reaction to those events. On that day, the wider community on Palm Island was given some information about a preliminary autopsy report regarding the injuries that caused Mulrunji’s death. It was the provision of this information that triggered the events of 26 November 2004. The word “riot” is one I have decided to avoid, although on the evidence before me it was the description of choice used by the media at the time. The word “riot” also forms part of the criminal offences with which some Palm Islanders were charged. Some people were acquitted of those charges, some were convicted, and some had charges withdrawn. To use the word “riot” may indicate this Court has formed a view about those charges, which is not the case. It is the case that there were protests about Mulrunji’s death, the police investigation and perceived police inaction and bias, and those protests became violent at some points through activities such as rock-throwing and yelling abuse. There were also fires, which were deliberately lit and caused serious property damage, although no individual was convicted of arson. To use the word “riot” to describe these events would be to convey an impression that does not reflect my view of the evidence before me. I have used the composite phrase “protests and fires” in these reasons to describe what happened on 26 November 2004. In like manner, I describe the conduct of QPS officers on 27 to 29 November 2004 as “arrests, entries and searches” rather than as “raids”, which was a term used by the applicants and the media at the time.

9 In this second group of issues about the lead up to the protests and fires, the applicants allege a series of failures, inadequacies and omissions by the QPS, including:

(a) the failure to suspend SS Hurley from duty pending the outcome of the investigation;

(b) the making of an emergency declaration under s 5 of the Public Safety Preservation Act 1986 (Qld) (PSP Act);

(c) the entries and searches of the homes of subgroup members; and

(d) the arrests of subgroup members in relation to offences said to have been committed on 26 November 2004.

10 It is alleged, broadly, that the police would not have conducted themselves as they did (including by deploying SERT officers to effect the arrests and conduct the searches of the homes) if this were not an Aboriginal community. In the third further amended statement of claim, these allegations are made in Parts J, K and L and cover the period 22 November 2004 to 28 November 2004. Again, many of these allegations begin with the premise that police conduct was unlawful, and again in my opinion that premise is not as central to a potential contravention of s 9 as the applicants’ approach suggested.

11 In their pleadings the applicants raised a third issue, concerning what was described in Part L of the third further amended statement of claim as “systemic and institutional discrimination”. These allegations centred on the policies, orders and procedures issued or continued by the second respondent (the Commissioner) being, to borrow a phrase, not fit for the purpose of policing in an Aboriginal community, and specifically in the Aboriginal community of Palm Island. This aspect of the applicants’ case was, ultimately, not pressed at trial. On the last day of evidence, senior counsel for the applicants informed the Court that these allegations were not pressed, along with a series of factual allegations which she then identified. Accordingly, those matters are not the subject of any express findings in these reasons.

12 In final submissions, and with greater focus on s 9 of the RDA as I had requested, the applicants provided a short summary of their key contentions that somewhat reorganised the first and second groups of issues into four main categories of claims. I have adopted that structure in these reasons. The four categories of claims are:

(a) the police conduct in the investigation of Mulrunji’s death;

(b) the police conduct during the ‘intervening week’ after Mulrunji’s death and prior to the protests and fires of 26 November 2004;

(c) the emergency declaration issued under the PSP Act;

(d) the use of SERT in the arrests, entries and searches carried out between 27 and 28 November 2004.

13 The applicants seek declaratory relief, an apology, compensation, and aggravated and exemplary damages.

THE COMPLAINT TO THE COMMISSION, THIS PROCEEDING AND ITS HISTORY

14 Although this proceeding is brought as a representative proceeding pursuant to Pt IVA of the Federal Court Act, it comes to this Court pursuant to s 46PO of the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) (AHRC Act) after termination of a complaint made to the Australian Human Rights Commission.

15 The applicants lodged a written complaint with the Commission on 25 March 2010 on behalf of themselves and the group members. In the complaint letter, the applicants alleged that the first respondent – the State of Queensland – contravened s 9 of the RDA through various acts and omissions after Mulrunji’s death, and through the subsequent protests and fires and the police response to them. The applicants divided the police acts and omissions into four heads of discrimination. The matter did not resolve at the conciliation conference facilitated by the Commission on 16 February 2012 and a delegate of the President of the Commission issued a notice of termination under s 46PH of the AHRC Act on 13 June 2013.

16 The applicants filed their originating application on 9 August 2013. On 20 November 2014, Dowsett J fixed the matter for trial for four weeks, to take place in two tranches from 31 August 2015 to 11 September 2015 and from 21 September 2015 to 2 October 2015.

17 The matter was allocated to my docket in April 2015 and the parties appeared before me for a directions hearing on 28 April 2015. I made orders on this date varying the trial dates so that the trial would run from 7 September 2015 to 2 October 2015, to enable the trial to proceed in a single tranche, and requiring the respondents to discover certain documents by 5 May 2015.

18 It is agreed between the parties that both the group members and the subgroup members as so defined number more than seven people. It is also agreed that, at all relevant times, the applicants and group members as identified by the applicants were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander persons. When referring to the community on Palm Island, the parties used the descriptor “Aboriginal” in their pleadings and submissions. Accordingly, that is the term I have adopted in these reasons. I accept there may be Torres Strait Islanders on Palm Island, but there was no specific evidence adduced on that issue, nor did the applicants submit it was necessary specifically to refer to Torres Strait Islanders.

19 The applicants have made several changes to their pleadings throughout these proceedings. I summarised the changes made up until 21 August 2015 in Wotton v State of Queensland [2015] FCA 910 at [6]-[11], but will briefly repeat them here. The applicants filed the first version of their statement of claim on 22 October 2013. Throughout 2014, they filed three further iterations of the statement of claim: an amended statement of claim filed on 28 January 2014; a further amended statement of claim filed on 29 May 2014 (together with an amended originating application); and a second further amended statement of claim filed on 1 August 2014. The respondents filed a defence on 3 October 2014 and the applicants a reply on 24 October 2014.

20 On 11 August 2015, less than a month before the trial was scheduled to commence, the applicants filed an interlocutory application to make substantial amendments to their amended originating application and second further amended statement of claim. The application was heard on 19 August 2015 and, on 21 August 2015, I granted leave to the applicants to make some, but not all, of the amendments they had sought leave to make: see Wotton [2015] FCA 910. In order to provide the respondents with a proper opportunity to consider and respond to the amended pleadings, the hearing dates from 7 to 18 September 2015 were vacated. It was determined that the Court would sit on Palm Island on the week commencing 21 September 2015 and in Townsville in the week commencing 28 September 2015 and that a further tranche of trial would be scheduled at a later date as required. The applicants filed a further amended originating application and third further amended statement of claim on 25 August 2015.

21 Further interlocutory applications were made after the commencement of the trial. The respondents objected to the admission of expert reports of Dr Rosalind Kidd and Emeritus Professor Jon Altman on the basis of relevance. On 23 September 2015, I made orders that the reports be admitted and delivered brief reasons for my decision. On 28 September 2015, I refused an application by the applicants for closed court orders and suppression orders in respect of evidence concerning the psychological condition of the first and third applicants. On 28 September 2015, the applicants applied to adduce further oral expert evidence from sociolinguist Dr Diana Eades about specific parts of the evidence given by four Aboriginal witnesses in an attempt to explain what the applicants seemed to consider might otherwise be seen as credibility issues with their evidence. On 29 September 2015, I refused that application for reasons given orally at the time which need not be rehearsed here.

22 The first week of the trial was, as foreshadowed, conducted on Palm Island. The Court sat in the hall of the local school – the same school that was used as the police command post from 26 November 2004. During that week, the Court conducted, with the agreement and cooperation of the parties, a view of places on Palm Island which would feature in the evidence. Those places included the mall area in which community meetings took place during the week of 22 November 2004; the police station, which was destroyed in the protests and fires but has since been rebuilt in the same location; the hospital; the houses of the applicants and of certain members of the subgroup; and other locations at which events occurred which are the subject of this proceeding. A note of the view, which includes photographs of the locations visited by the Court, is an exhibit in the proceeding. I have drawn certain inferences from the view, as s 54 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) contemplates. Those inferences are set out at various places in these reasons. The view was material to many of the findings I have made. An understanding of the nature of Palm Island, and its community, is critical to the resolution of many contested issues in this proceeding. The view also informed my understanding of the contemporaneous evidence, including (but not limited to) the contemporaneous video evidence.

23 The applicants’ claims in this proceeding cannot be understood without first appreciating the particular history of Palm Island and its community. The particular features of this community form part of the circumstances which existed on the island in November 2004. They are not mere matters of history, consigned to the past without relevance to the present as it was in November 2004. My findings in this section are drawn from the agreed facts; from the report of Dr Kidd, an expert called on behalf of the applicants, together with the annexed historical documents upon which her report was based; and from the report by Professor Altman, which was co-written with Dr Nicholas Biddle. Professor Altman was another expert called on behalf of the applicants. I discuss the evidence given by Dr Kidd and Professor Altman, and their qualifications, at [441] and [450] below. In that section I have made some findings about Dr Kidd which affect the weight I give to parts of her report. Given my reservations, I have relied more on the source material than on the commentary in Dr Kidd’s report. Where I have relied on Dr Kidd’s summaries, these were aspects of her report that were not challenged in cross-examination.

24 On the basis of the facts agreed between the parties, the population of Palm Island in 2006 was approximately 1,855 people, 93.5% of whom identified as Indigenous. The 2001 census recorded the population as being approximately 1,949 people, 90.8% of whom identified as Indigenous. I infer that in November 2004 the population, and the proportion of Indigenous people, was somewhere around or in between these two sets of figures. It was common ground between the parties that the overwhelming majority of non-Aboriginal people who lived on Palm Island were involved in providing goods or services to the Aboriginal community. It is also necessary to acknowledge, soberly, that the Palm Island community shares characteristics of disadvantage with other Aboriginal communities in Queensland and in other parts of Australia.

25 Gageler J provided a useful overview of the governance history of Palm Island in Maloney v The Queen [2013] HCA 28; 252 CLR 168 at [255]:

Palm Island comprises a group of ten islands forming part of Queensland situated about 70 km north of Townsville. Palm Island was established as an Aboriginal reserve under Queensland legislation in 1914 and retained that or a similar status under subsequent Queensland legislation until 1986. Title to Palm Island was then granted in trust under the Land Act 1962 (Qld) to the Palm Island Aboriginal Council, an Aboriginal council under the Community Services (Aborigines) Act 1984 (Qld) (the Aboriginal Communities Act), and Palm Island became a “trust area” (subsequently redesignated a “community area”) within the jurisdiction of the Palm Island Aboriginal Council under the Aboriginal Communities Act. In 2004, by force of the Local Government (Community Government Areas) Act 2004 (Qld) (the Community Government Areas Act), as well as being continued as a community area within the meaning of the Aboriginal Communities Act as then amended, Palm Island was declared to be a “local government area” and by virtue of that also became a “community government area” to which provisions of the Local Government Act 1993 (Qld) thereafter applied and the Palm Island Aboriginal Council was continued in existence as the Palm Island Shire Council.

(Footnotes omitted.)

26 From 1897 until the early 1970s, the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 (Qld) empowered the Queensland government to remove any Aboriginal person from rural and town areas and confine them to Aboriginal reserves. From approximately 1914, the government operated an Aboriginal reserve at what was known as Hull River on the northern coast of Queensland, now known as Mission Beach. This was the reserve to which Aboriginal people in northern Queensland were initially forcibly removed. Reasons included their unemployment and an assessment that they were in need of ‘protection’. Removals occurred in circumstances where the demands of expanding white occupation of land in Queensland rendered the occupation by Aboriginal people of their country incompatible or inconvenient for white settlers.

27 Soon after its establishment, the Hull River reserve experienced sufficient problems that the Queensland government began to look for alternative locations for the reserve. In 1916, the government attempted to clear Palm Island of its original Aboriginal inhabitants, being the traditional owners of the land and waters at Palm Island. When the Hull River settlement was destroyed by a cyclone in 1918, John Bleakley, the then ‘Chief Protector of Aboriginals’, ordered that the salvaged building materials and the inmates who had not died or escaped during and after the cyclone be relocated to Challenger Bay on Palm Island. While there was little evidence in this proceeding about the descendants of the original inhabitants of the island, it is apparent that some of the traditional owners retained their connections and still comprise part of the Palm Island community: see, eg, The Manbarra People and Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority [2004] AATA 268; 82 ALD 573 at [10].

28 Thus, Palm Island was occupied by Aboriginal people before it was identified as a place for forced confinement and punishment. Dr Kidd reports that European awareness of the original Palm Islanders dates from a sighting by Captain James Cook in June 1770. She gives the following summary of what historical records say about these people, and how they came to be tricked into leaving the island (although a few of the original male inhabitants were transported back to assist in building the settlement for other Aboriginal people who were to be forcibly removed there):

Reports survive of periodic attacks by Palm Islanders on traders in bêche-de-mer, trochus shell and sandalwood who visited Challenger Bay to recruit or kidnap men and women. In 1877 it was suggested that Great Palm Island be declared an Aboriginal reserve to prevent European incursions and protect Islanders from exploitation.

Around the turn of last century there were around 50 men, women and children living on Palm Island although others were said to be working on bêche-de-mer and fishing boats. Reports of the Northern Protector and Chief Protector of Aboriginals record similar populations in the years to 1914. Families on the island reportedly lived well having their own cutter and two dinghies, well built gunyahs of thatched grass, hunting dogs to catch wild pig, and ample supply of bush foods and fresh water.

In 1913 the Townsville protector described Great Palm Island as a ‘regular native camp and hunting ground’[.] On his suggestion most of the area was gazetted an Aboriginal reserve in June 1914.

In 1916 superintendent John Kenny, from the Hull River settlement reported that Challenger Bay would be a good site for a new settlement.

The families on Palm Island were enticed to visit the Hull River settlement in 1916 with promises that they could return if they did not like it. Twenty-two men, women and children were removed, but refused permission to return.

(Footnotes omitted.)

29 Palm Island’s remote geographical location made it a convenient place for the government to send people considered problematic, including those who had completed jail sentences or deserted compulsory labour contracts. The island was described as a “punishment island”, but it was used for other social and governmental purposes as well. This extract from Joanne Watson, Becoming Bwgcolman: Exile and Survival on Palm Island Reserve, 1918 to the Present (PhD thesis, The University of Queensland, 1994) at 72, which Dr Kidd provided with her report, captures the thinking at the time:

From 1897 the development of a punitive reserve on Badjala land at Fraser Island would serve as a prototype to the later institution on Palm. Murri ex-prisoners were sent to Fraser Island from Brisbane, Rockhampton, Roma, Townsville and Cardwell. By 1899 Roth, as Northern Protector, perceived Fraser Island as a place suited for the isolation of ‘troublesome’ or ‘dangerous characters’. The island was under the surveillance of the armed physical presence of the Mestons and a lock-up and police force soon established there. Those who were removed from their homelands developed an earth-eating disease. Before its closure in 1905 the reserve had become ‘a vast burial ground’ where those who fell ill believed they were ‘doomed to die’.

It was in the context of this historical background, combined with increasing numbers of removal orders, that Palm Island was gazetted for reserve purposes. By 1916 Bleakley as Chief Protector complained to the Under Secretary that neither Hull, Taroom nor Barambah could cope with the growing numbers of Murris under the Act, and that a reserve was needed ‘suitable for use as a penitentiary’, to confine ‘the individuals we desire to punish’. Bleakley decided to take advantage of Kenny’s removal of Wulgurugaba people to Hull River, to carry out an inspection of the island, and the following year he reported that in ‘Being an island’ Palm ‘also provided the security from escape required with such characters’.

(Footnotes omitted.)

30 Dr Kidd also included an extract from Bill Rosser, Dreamtime Nightmares (1985) at 144-45. In this extract, Fred Clay, who lived on Palm Island in the 1970s and was head of the island’s Aboriginal Council, describes what happened when as a fifteen-year-old boy he tried to get off Palm Island to work in Cairns, and then to make his way elsewhere, but was recaptured. I refer to this extract because it is also a good example of the long and fraught relationship between Palm Island people and the Queensland Police Service:

‘When they first opened the settlement over there, they didn’t have jails but, by gee, they used to handcuff them to a tree, you know. They used to have them in a chain-gang. In the early days,’ [Fred] explained, ‘they used to do all the clearing of the scrub by hand. There were no machines in those days’. He gave a short laugh. ‘Only a pick and shovel and the axe, grubbing trees out. They cleared all the settlement there’. He was silent again, probably thinking of the harsh conditions which he and his mates suffered in those far-off days. He stirred and said, ‘I wasn’t conscious of the Act until I left school. I was old enough to go to jail. That’s when I realised that we had no hope on the island. It was then that I realised the superintendent’s powers.’

‘And you rebelled against it, even at that age?’

‘Yes, I did. Yes. I took off from Palm when I was fifteen. I went to work in Cairns under an agreement. I had my money sent to Palm. We didn’t see the amount, they just filled it in – the Superintendent. We signed it. Each week I worked in Cairns, I got twenty-five shillings [$2.50] pocket money. So, I worked there for a year, then I jumped a train down to Ingham. I got in with a contractor, cutting cordwood for a sugar mill there. I was going bloody good, too, for about two months. Then, one dinner hour, a bloody big cop turned up.’ Fred winced at the memory, shrugged his shoulders and then continued with his story.

‘The cop was looking for a “Fred Clay”. I said, “I’m Fred Clay”. He said, “Ah, I’ve got a warrant for your arrest and an order from the Department of Native Affairs to escort you back to Palm Island”. This is when I was fifteen! I was going to go “bush”, but I saw this bloody big pistol handle sticking out of his pocket and I wasn’t going to give the bastard a chance to shoot me. No way! He would have, I think. So, he took me to Ingham and put in the jail there, to wait for an escort to take me to Palm Island.’

‘They put you in jail – at fifteen?’

‘Yes. On the third day, this tracker turned up from Palm Island – my escort. He took me down to the railway station and handcuffed me to the seat. They didn’t give him a key for the handcuffs. The police in Townsville had it. They were waiting for us.’

Fred interrupted his story to look for a cigarette and was still wandering around when he resumed speaking. ‘When we got to Townsville a big cop came and released me from the seat and led me by the handcuffs. I stayed back in the watchhouse for three or four days before I was taken back to the island. There, I went to jail first for fourteen days, for absconding from the job in Cairns where I was under agreement with the Department of Native Affairs. After the fourteen days, I was given another six months punishment in the timber camp; that’s around the back of the island. I wasn’t allowed to come into the settlement for six months.’

‘That was a bit rugged’, I remarked.

‘Yes, it was rugged all right,’ Fred agreed. ‘When I came back to the settlement, I was put to work on the wood camp, cutting wood for the white people on the island.’

‘What pay did you get for that?’ I asked.

‘Heck! I wasn’t on pay.’

‘No pay. Only rations?’

‘Yes, only rations. I didn’t go on wages for about three years, I think, when I was eighteen. …’

31 In 1919, a magistrate from Ingham was called to Palm Island following an assault by the Superintendent of the island, Robert Curry, on a German storeman.

32 The magistrate reported on the terrible conditions he observed on the island and made a number of recommendations. Reference to one of them suffices to indicate the extremity of the living conditions, and attitudes, on the island at that time:

That provision be made for such free issue that will allow unfinancial natives a change of clothing. As it is the gins at least some of them and some of the children have only what they stand up in and often after remaining unadorned while the said garment is being washed they put it on before it is properly dry thus leading to colds, pneumonia and other chest complaints.

33 Dr Kidd provides an overview of the layout of the settlement in the 1920s, including the poor living conditions:

By 1923, after five years’ development, the Palm Island population was around 730, including 200 children. Over half the children were kept in ‘dormitories’ comprising two tin sheds; there was neither school nor school teacher. Nor was there a qualified medical practitioner, and even the monthly visits by the Ingham doctor had ceased. When the Queensland’s Governor Thatcher visited Palm that year, inmates protested their entrapment on poor rations comprising flour, occasional sweet potato, and 450 grams of meat weekly. Governor Thatcher criticised the policy of sending 100 able-bodied men to external employment to bring in revenue instead of using them for building and farming. He supported their complaints in a letter to the minister, but nothing changed.

By 1929, despite continuing substandard conditions and chronic illnesses on the Island, the government’s aggressive removal policy had increased the population to almost 1000 people.

(Footnotes omitted).

34 The conditions on the island were deplorable and substandard in many areas of life over several decades. Dr Kidd’s report identifies, for example, a critical shortage of food and resulting malnutrition, which was particularly dire during the second world war; limited education and other opportunities for youth; widespread lethal diseases; very high infant mortality rates; chronic overcrowding in houses and dormitories; unsafe water and defective sanitation; poor and oppressive management and policing by authorities on the island; and very poor quality medical facilities.

35 Although an education system was eventually established on the island, and children received schooling until the age of 14 years, their life and employment prospects remained extremely limited after they finished their schooling. Teenage boys were sent back into the community without trades or other practical skills and teenage girls were either contracted to work on remote properties or, if unmarried, confined in dormitories for decades. Mrs Agnes Wotton’s own history, as recounted in her evidence, is an example.

36 In the 1920s, Robert Curry, an ex-serviceman, was in charge of the Palm Island settlement as Superintendent. Curry imposed and enforced strict curfews for the community and, armed with a revolver, patrolled the island with “native police” who were authorised to dispense punishments and break up meetings. Curry worked groups of “troublemakers” in chain gangs clearing scrubs and trees. There were allegations that he interfered with Aboriginal girls and he was officially reprimanded for severely flogging an Aboriginal girl. In 1930, a few months after his wife died in childbirth, Curry killed his son and stepdaughter, shot the local doctor and his wife, set fire to several staff homes, and blew up administrative buildings. An Aboriginal man named Peter Prior shot Curry and fatally wounded him during this rampage, acting under the instructions of state police. Incredibly, Prior was later arrested for murder and jailed in Townsville for several months before the charges against him were dropped.

37 In the 1940s, regulations were introduced to legitimise intensive control of Aboriginal people. Dr Kidd reports that:

Inmates could be ordered to any section of a reserve or to another settlement, they had to obey all orders, cease dancing or card playing if commanded, surrender to the superintendent any property which might ‘disturb the harmony, good order or discipline of the reserve’. It was an offence ‘to commit a nuisance’, to act ‘in a manner subversive to the good order’ of the reserve, to be on a reserve or leave a reserve without permission, to refuse to work 32 hours per week. Superintendents could censor mail and demand any correspondence be given to him. Superintendents appointed, dismissed, and made the rules for, community police who had powers to arrest and imprison those who breached the regulations. Superintendents could pass sentence, and dictate behaviour and work of gaol inmates.

38 There were significant interferences with residents’ personal autonomy and freedom of movement. In her report, Dr Kidd discusses a 1948 petition from a Palm Island woman which highlights the plight of the girls and women kept in dormitories:

[The petition] implored the government to save her from her imprisoned existence where girls and women were locked up from 5 pm until 6 am, their only freedom a small patch of fenced grass. They could not shop or go to the weekly film show unless under police escort. For this ‘free’ show two shillings was deducted from the ten shillings ($18.30) earned by the few dormitory monitors. While single girls were allowed 45 minutes once a week to speak to boyfriends under police supervision, this small privilege was denied the writer, a widow. She blamed the suffocating confinement for girls becoming ‘unbalanced’ and running away after which, she said, ‘the rope is tightened all the more’ for those who remained trapped for life. (She didn’t raise this with the visiting justice, declared the deputy director of Native Affairs, therefore ‘she has no grounds for complaint’.) Nothing changed.

(Footnotes omitted).

39 Dr Kidd’s summary of this source document is slightly inaccurate in parts. For example, the petition itself, poignantly written by one of the women living in the dormitory in 1948, states that the author was “a divorced woman” rather than a widow.

40 Nonetheless, the 1948 petition, the role of Robert Curry and other “Superintendents” on the island, and the role of the “native police” give a flavour of the overwhelming, controlling and at times abusive role of the police in the lives of Palm Islanders: in this case, they were operating as guards to the young women.

41 After noting in detail the appalling restrictions imposed on the women, and the quarantining and expropriation of the paltry sums they earned for working, the author of the petition notes that any transgressions (such as stepping past lines intended to impose constraints on where the girls could move outside the dormitory buildings) would result in jail. She then states:

Sir, being Minister for Health and Home Affairs, do you consider these rules all above board, or do you think them a little inhuman, which is my point of view. We look to the white officials for advice, help and protection. When we are in trouble we go to our Superintendent and he does try to right our wrong, yet I blame these rules over us girls which make some of them unbalanced and which cause them to break out of the Dormitory and run away.

When one girl runs away the rope is tightened all the more. It is the ones that do try to live by the rules and help the staff on this Island who suffer most. I myself have done my best, but as these rules stand I’m afraid I will break them by running away too.

One girl at this moment has been gone now for a fortnight. When they get her she will get 6 weeks jail or maybe more, on bread and water, but the girl is not at all to blame. Should we get a little more freedom without having the police over us all the time I’m sure the girls will be more contented. This is all I am going to say. I hope you will do something for us. Thanking you.

42 The poor medical facilities on Palm Island were documented in 1944 when, given the infant mortality rate on the island was 15 times the infant mortality rate for Queensland generally at that time, a senior Health Department officer was sent to investigate the facilities and conditions on the island. Dr Kidd summarises the officer’s findings, as well as the findings of other Department staff who visited the island around this time in the following terms:

He reported hospital practices were so defective that several child patients developed septic sores; the diet was grossly deficient in milk, vegetables, and fruit. He said the resident doctor’s belligerent treatment of Aboriginal mothers was a major factor in the non-reporting of illness. (A visiting magistrate confirmed the doctor had struck a female patient but said action against him would not succeed.) Perhaps seeking an acceptable internal assessment, the department sent the matron from its Cherbourg settlement. She reported the hospital was in a filthy and neglected condition with many patients sleeping on old and soiled mattresses. Children’s cots and mattresses were filthy and crawling with cockroaches, the food store rooms were unventilated and full of flies and uncovered slops, and the labor ward was cramped and unhygienic.

(Footnotes omitted).

43 Once again, this summary embellishes somewhat upon the source document. In it, the officer does not state that the diet on the island was “grossly deficient in milk, vegetables, and fruit”, although he does recommend that the matron should exercise vigilance to make sure each patient receives an adequate diet. Nevertheless, the document clearly shows the deficiencies in health care and practice that existed on the island.

44 The chief state health officer, Dr Abraham Fryberg, visited the island in July 1945 and gave the following summary of living conditions, which starkly illustrates how Aboriginal people were forced to live. I leave the language in its original form.

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH, QUEENSLAND

BRISBANE

13th July, 1945.

The Deputy Director-General.

Re Palm Island

As directed I visited Palm Island arriving there on June 15th and leaving Fantome Island on June 19th.

Palm Island was built as the result of a cyclone demolishing the settlement – at the mouth of the Hull River. 150 natives were transferred there and this number has grown to approximately 1200 by –

1. natural increase

2. transfer of natives of New Guinea

3. transfer of incorrigibles from all over Queensland

Accommodation

Varies from the type made from pandanus leaves to up to date cottages. The poorest type of hut is occupied by the poorest type of native. As many as five people live in a room 10 x 12 ft. There is no space for furniture nor is there a kitchen in the poorer type.

Every encouragement should be given to the inhabitants to improve their positions; many of the natives do make something out of their poor cottages. In such cases the authorities should assist them to get a better house. This would give the natives something to strive for and would improve the general morale on the Island.

Kitchens

Only provided in the better type of cottage. Cooking is carried out in the open. Cooking utensils are not provided. Equipment such as stores and pans are bought by natives who are earning money. No provision of safes to keep food.

Latrines.

Daily pan service. Practically no latrines are fly-proof. The burial ground is situated at the waterfront a short distance from the jetty. There is a native sanitary squad under the command of a native overseer. At the time of inspection the work for the day had been completed but faeces in big trenches had not been covered. A new burial ground has been selected and will be put into use when a road has been made.

Ablutions.

The sea. No bath houses as water supply is inadequate.

Laundry facilities. Nil

Water supply

From shallow wells. No treatment. Hospital has tanks which will not hold water. Iron tanks holding 4470 gallons which originally cost £220 are available for £75. in Townsville from the Army Disposals Board. The Director of Native Affairs will inspect these tanks when he goes North on his next visit. In the dry season fresh water is in short supply.

Hospital

Consists of a male, female and maternity ward and operating theatre which is only used in extreme urgency. It is an old building and is far too small. It is suggested a new hospital might be erected from the Fantome Island buildings. In fairness to the staff I must report the building was clean. I did not see sufficient of the staff to comment on their efficiency.

Dairy.

The dairy is a worthy institution but the hygiene is of a low standard, even though the utensils are clean. The utensils are stored in the open; the brass strainers are worn out and I was advised brass gauze could not be procured.

A building is required to house the utensils.

The resting yard and bales have an earth floor and in the wet weather become a quagmire. No drains are provided. The floor of the bales and part of the resting yard should be concreted.

Farm.

There is a super-abundance of vegetables at this time of the year but in the summer they will not grow on account of the heat.

A few acres of land grown tomatoes, sweet potatoes and other vegetables are now under cultivation.

The farm, which is under the supervision of Mr. Sturgess, who is doing an excellent job, is irrigated.

Unfortunately Mr. Sturgess can only give a limited amount of time to it as he has too many other duties.

Medical

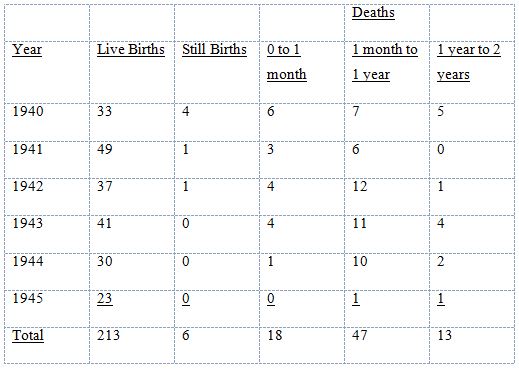

A matter of concern on the medical side is the infantile mortality rate, as is seen by the following figures.

The deaths include 12 from prematurity, excluding still births.

Total Deaths – 78.

Regular ante-natal treatment is not carried out. Facilities for child welfare are not provided as a regular thing.

45 Poor health issues continued. In 1973, there was a severe outbreak of gastroenteritis amongst the children on Palm Island, leading to about 40 children being affected and many being hospitalised in Townsville. Doctors treating the children likened them to Biafran children in Africa.

46 State police were permanently stationed on Palm Island from 1968, with one sergeant and one constable. In a 1980 report, Patrick Killoran, the director of the Department of Aboriginal and Islander Advancement, stated that it was “common gossip at Palm Island that the Police Station was totally ineffective”, with the station being shut on weekends and police officers taking extended weekends for fishing trips and spending long hours playing chess in public view while on duty. Killoran also commented that problems were caused by quick promotions within the police force, which resulted in reasonably junior officers being promoted to sergeant positions when posted to Palm Island, quite often leading to personality clashes, culture shock, and other forms of discord between the inexperienced officers and the community.

47 Dr Kidd reports that from the early years of the Palm Island settlement, an Aboriginal community police force played a central role in policing the island. They assisted in controlling public disorder and drunken violence and in identifying and locating people the state police were looking for in relation to various civil matters. The existence of such a “native” force is apparent from the source documents to which I have already referred. However, Dr Kidd notes that Aboriginal police officers often had difficult relationships with their own communities, and this was reflected in a 1981 report titled ‘The Position of Aboriginal Police on Queensland Reserves’. That report also found that the state and Aboriginal police did not operate as a cohesive unit and that Aboriginal police officers were regarded as a separate and inferior agency. Dr Kidd states that:

Aboriginal police received no training, and were limited by poor literacy. Unlike state police who were supplied with a private home, and ‘all of the police benefits, allowances, overtime etc’, the native police were on call nights, weekends and public holidays on minimum wages while denied penalty rates, and were housed on Palm Island in a small poorly furnished room behind the cells. These detrimental conditions underlay the lack of job experience expressed in a turnover of 62 workers for the nine positions. Native policing was ‘fraught with danger’ and their positions often untenable given ‘problems of inter-family relationships and long-standing friendships’ from childhood. These conflicts would not be faced by a state police officer, who would ‘not normally’ be assigned to serve ‘in the country town of his birth and upbringing.’

(Footnotes omitted.)

48 Dr Kidd reports that a 1991 review of the Community Services (Aborigines) Act 1984 (Qld) revealed that community complaints about the behaviour of state police were extensive and longstanding at that time. The community was frustrated that police were not accountable to them and that there was no way they could effect changes to inappropriate police behaviours.

49 There has also been a long history of interference with workers’ rights on Palm Island, including rights to equal pay. Dr Kidd’s report describes how, pursuant to regulations in 1919, every able-bodied person on Palm Island was required to work. However, no wage was set for government workers. Aboriginal workers usually worked long hours with poor conditions for no or very little pay. The poor working conditions and unequal pay for Aboriginal workers on Palm Island resulted in a strike in 1957, where all workers (except those providing essential services) ceased work for approximately five days. Some witnesses in this proceeding gave evidence about their parents having been involved in the strike.

50 While new regulations were introduced in 1972 which declared that all Aboriginal workers must be paid an award wage, these regulations did not apply to workers on government reserves such as Palm Island, where payment was labelled a “training allowance”, despite many employees having worked for decades. Other legal reforms in the 1970s did not improve conditions for Aboriginal workers. Dr Kidd reports that:

After the 1975 … federal Racial Discrimination Act made it illegal to underpay workers on the basis of race, the Queensland government continued its policy. Correspondence in mid-1978 put the state’s profit at the expense of community workers at $3.6 million ($11 million) compared to the state mandatory minimum wage and $6.85 ($21 million) if award wages were paid where due.

51 Finally, in 1986, facing numerous union-funded wage challenges, the Queensland government agreed that award rates would be paid within existing budget levels. Further constructive changes occurred on Palm Island in the 1980s. After the Community Services (Aborigines) Act signalled the transfer of local government functions to community councils after a three-year training period, the Palm Island community Council assumed local government functions in 1986. The local Council gained title to Palm Island under a Deed of Grant in Trust, but at the same time the community lost the benefit of government infrastructure such as shops, a timber mill and farming equipment.

52 Palm Island’s history also manifested itself in continuing socioeconomic disadvantage. Professor Altman and Dr Biddle’s report provides some information about the socio-economic circumstances of Palm Islanders at times close to November 2004. Professor Altman and Dr Biddle used ABS census data from 2006 as the basis of their analysis – the 2006 national census being the census closest to 2004. Professor Altman explained this use in his evidence:

The way that the census data is presented in community profiles … is a summation of information for all the individuals on that community that have been counted during the census collection day or period. It depends on which methodology is used, and so what I’ve, in fact, referred to quite correctly is a – some summary statistics about that community which – which constitutes a summation, and then median information on – on Indigenous and non-Indigenous members of that community.

Yes. The report uses data obtained from the 2006 census. Is that correct?---Yes. I chose to use the 2006 census because I thought this was an appropriate census to use, given that the issues that were under discussion occurred in 2004. I could have used the 2001 census, or the 2006 census, or the 2011 census, but the 2006 census appeared the most proximate.

All right. And do I take from that you considered using the 2001 census, but you thought that was perhaps a little too early in time for 2004; 2006 was closer in time. Is that the thinking?---Yes, it was a lot closer. Yes.

Yes. All right. And did you, in fact, look at the - - -?---Would it – I would add one other thing.

Sure?---Is that experience tells us that census collection is – is continually improving, and so in some ways the later the census one uses, the better, although if I had used 2011 I think that would have been too far away from 2004.

53 In an analysis of the geographic distribution of socioeconomic outcomes for the Indigenous population Australia-wide, Palm Island was ranked 475th out of 531 areas. With 1 being the most advantaged area and 531 the most disadvantaged, this put Palm Island in the 89th percentile, and therefore one of the most disadvantaged Indigenous communities in Australia in 2006. Professor Altman and Dr Biddle commented on the “marked disparity” in 2006 between median individual cash income for Indigenous people aged over 15 years on Palm Island ($216 per week) compared to $911 per week for non-Indigenous Palm Island residents, who were mostly professionals, teachers, police, and health services providers.

54 Professor Altman and Dr Biddle report that the unemployment rate in 2006 for Indigenous people on Palm Island was 17%, compared with 0% for non-Indigenous Palm Island residents, 13.1% for Queensland Indigenous people generally, and 4.7% for Queenslanders generally. The employment/population aged over 15 years ratio (35.7%) and the labour force participation rate (43.1%) for Indigenous people on Palm Island were also low compared to 83.3% and 83.3% respectively for non-Indigenous Palm Island residents, 48.9% and 56.2% respectively for Queensland Indigenous people generally, and 58.9% and 61.8% respectively for Queenslanders generally.

55 Professor Altman and Dr Biddle concluded that:

These statistics despite arguments that they inevitably highlight Indigenous deficits because they reflect western norms reflected in social indicators, nevertheless indicate that Indigenous residents of Palm Island are as a group among the most socioeconomically disadvantaged in Australia. Disparities are most clearly evident in a comparison between Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents of Palm Island which can be an acute source of community tension.

But equally compared to Indigenous people elsewhere in Australia, Palm Islanders appear to be relatively badly off (ranking 475 out of 531 regions in 2006) an outcome that cannot just be explained by isolation and locational disadvantage given Palm Island’s relative proximity to the city of Townsville.

(Footnotes omitted).

56 In November 2004, the matters which I have described were in the living memory of many residents of Palm Island. In the contemporaneous video evidence adduced in this proceeding, the number of elderly people in the Palm Island community is easily visible. In 2004, people such as Agnes Wotton had personal, lived experience of some of the events, living conditions, and police behavior that is the history of Palm Island. Those people knew, through their parents and grandparents, of the earlier abuses and deprivations inflicted on Aboriginal people on Palm Island, to which I have referred. In November 2004, the children and grandchildren of people such as Agnes Wotton were the young people one sees in the contemporaneous video evidence. The history of the Palm Island community was a living history. Places around the island still went by names which resonated with that history – many witnesses called the area in which the mall, police station, Council building and store were located “the Mission”, because that is where the dormitories were located. The area where Mr Wotton and his family lived is called “The Farm”, because that is where, in the early days of forced settlement on Palm Island, a dairy farm was established. The historical experiences of families on the island with the police is informed by the kinds of matters to which I have referred. Police were the ones who acted as guards, who placed locals in jail for minor infringements of rules applying only to Aboriginal people, who sought out those who fled the island and brought them back to be placed in jail. Control and subordination on a racial basis was central to the way this community had always been compelled to function. These matters were part of their lives, not simply entries in the history books and archives.

57 The pattern of arrests for minor infringements was, on the evidence, still occurring in 2004.

58 My overwhelming impression of the (current or former) QPS members who gave evidence in this proceeding was that they knew little or nothing about the history of Palm Island. Most freely admitted this. They also paid no real attention to the particular history and characteristics of Palm Island and its people in the approach they took to the investigation of Mulrunji’s death and their subsequent interactions with local people, with elders and with the Council. Yet it is clear in the contemporaneous video evidence that the palpable sense of powerlessness and injustice felt by people attending the community meetings is connected with the history of Palm Island, and the histories of their own families.

59 If content is to be given to the obligation, contained in sections of the QPS Operational Procedures Manual (OPM) as it applied in November 2004, to consider “cultural needs”, then in the case of Palm Island those cultural needs could not possibly be understood or met in any genuine way without a good working appreciation of the racism and oppression that characterised the island’s history.

THE PARTIES’ COMPETING CONTENTIONS

60 Before descending into the resolution of the significant number of factual and legal issues in this proceeding, it is necessary to make some preliminary comments on the parties’ competing contentions on both facts and law, as they were developed in final submissions. It is also convenient to address a number of connected issues, including the scope of the applicants’ case on the pleadings, the standard of proof to be applied in assessing the evidence, the nature of the findings I make regarding the conduct of SS Hurley, and the matters that are not in contest between the parties.

The approach I have taken to the parties’ competing contentions, as expressed in final submissions

61 It is easy to get lost in the detail of a proceeding such as this, and to pay insufficient attention to the real controversy between the parties. In the present case, and almost despite the detail, the real controversy between the parties, while acute, is not difficult to summarise: see [7]-[12] above.

62 At this point, the approach taken by Allsop J in Baird v Queensland [2006] FCAFC 162; 156 FCR 451 should be recalled. Dealing with issues of ambiguity and lack of clarity in the pleadings in that case, his Honour said at [17]:

The pleading is to be understood in its context. It is not to be read divorced from counsel’s opening and how the case was otherwise litigated. This is not to say that the pleadings are other than central to understanding what was fought below and thus what can be raised on appeal. But to the extent that context may cure or ameliorate ambiguity or lack of clarity, it is not to be ignored.

63 When his Honour then came to identify the allegations made in relation to s 9 of the RDA in that case, he took the following approach (at [25]-[29]):

A number of matters appear to flow from, and can be said in consequence of, the above outline of the presentation of the case. First, read in their context, the amended application and the Consolidated Statement of Claim contain a case based on s 9 of the RD Act not dependent upon any finding that the appellants were employed by the State.

Secondly, the case put forward was in effect that determining and paying the grants in the amounts that were fixed had the effect of at least impairing the enjoyment of a relevant human right (the right to equal pay for equal work, by reference to applicable award rates) because the grants did not permit or did not enable the Church to pay award rates or because the grants effectively determined the amount to be paid in wages by the Church.

Thirdly, the reference to the payments of the grants as the “acts” for s 9 incorporated, from time to time, notions of decisions concerning how the grants were calculated. The primary case of the appellants was to the effect that the State in fact and in practical reality calculated the amount of the wages to be paid in the calculation of the grants. This threw up for consideration, as a central issue in the case, how the grants were calculated and the relationship between the calculation and payment of the grants and the payment of below award-wages.

Fourthly, there was a degree of imprecision and confusion in the identification of the distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference for the purposes of s 9(1) and the relationship of such with race. What can be said, it seems to me, is that within the pleading and submissions can be found the assertions that the acts of calculating and paying the grants involved taking into account that the funds would be required to fund below-award wages as distinct from award wages and that the calculation of the grants was made on that basis. This occurred, so it was said, because the ultimate recipients of the below-award wages were Aboriginals.

Fifthly, in fairness to the pleader, some of the difficulty in enunciating how the case fits into s 9 on the hypothesis that the State was not the employer of the appellants can be seen to flow from the almost elusive simplicity of s 9(1), the content of which can be described as “vague and elastic”: see Gibbs J in Gerhardy v Brown (1985) 159 CLR 70 at 86. Nevertheless, what was thrown up for debate and consideration were the calculation of the grants, the relationship between the amounts of the grants fixed upon and paid, the payment of below-award wages, the reasons why the appellants were paid below-award wages, and why the amounts of the grants were calculated as they were.

64 I have extracted these paragraphs in their entirety to make good the following proposition. Although, especially in a large and wide-ranging proceeding such as this, it is important to hold a party to the party’s ‘case’ (including, as a cornerstone, the pleadings), in order to do justice between the parties, the Court must strive to ascertain, as Allsop J put it, what is “thrown up for debate and consideration” by the case as it has been framed. At times, the respondents’ approach in final submissions was, in my opinion, too narrow and sought to have the Court quarantine and assess in isolation the applicants’ factual allegations. In my opinion, the approach taken by the applicants in final submissions remained broadly consistent with their pleadings and properly grouped the conduct of QPS officers into four categories. Within each category there may be several “acts” for the purposes of s 9 of the RDA, but it is appropriate to deal with the applicants’ allegations in a more holistic way than the respondents’ submissions suggested.

65 For example, the respondents submitted, on the basis of the Full Court’s decision in Iliafi v The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Australia [2014] FCAFC 26; 221 FCR 86 at [44], that there were a number of “elements” to s 9(1), and in their written submissions, set out what they said the applicants had to prove in the following way:

(a) the officer did an act;

(b) the act:-

(i) involved a distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference;

(ii) based on race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin; and

(c) the act:-

(i) had the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing of a right of the applicants;

(ii) which right was a human right or fundamental freedom in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

66 It is correct that this is how Kenny J (with whom Greenwood J and Logan J agreed) in Iliafi set out what the appellants had to prove in the case before her. I do not understand this paragraph of her Honour’s reasons as doing more than that. In particular, I do not read her Honour’s reasons as suggesting that the division of s 9(1) into a series of smaller elements is a necessary part of s 9(1). In Iliafi, the respondent, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Australia, had discontinued its Samoan-speaking worship groups so that the appellants were no longer able to worship publicly as a group in their native Samoan language at services conducted by the Church. As Kenny J observed at [46] the central issue was whether or not the appellants had in fact identified a right that could be properly described as “a human right or fundamental freedom in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life”, within the meaning of s 9. Her Honour held that the three rights in Arts 5(d)(iii), (vii) and (viii) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) neither separately nor together gave rise to a right to worship publicly as a group in the appellants’ native language at the Church’s services of public worship. Therefore, the appellants failed to establish that there was a “human right or fundamental freedom ... of a kind referred to in Article 5 of the Convention” that engaged s 9: at [110].

67 There was no dispute in Iliafi about what constituted the “act” for s 9 purposes. The appellants submitted that the “act” was the Church’s decision to cease Samoan language services, or alternatively to require services to be conducted in English (see [21]), and the Full Court did not have cause to comment on the correctness of that characterisation in its reasons.

68 In the present case, the respondents’ submissions respond to the applicants’ case at the level of itemised conduct of each individual QPS officer. Such a narrow and granular focus is not always required. The applicants’ case, as disclosed through the pleadings and final submissions, takes the conduct of QPS officers at both a broad and a particular level.

69 The applicants’ factual contentions traverse a wide range of conduct by QPS officers. Sometimes the contentions do descend into great detail, and examine police conduct at quite a minute level, including by copious references to sections of the OPM and alleged non-compliance by QPS officers with those sections. In circumstances such as these, it is likely (and has proven to be the case in my opinion) that contraventions of s 9 will not be made out at such a detailed level, measuring each individual piece of conduct against s 9. It is also true that where there is a serious allegation of individual conduct it may well sustain a contention that the conduct contravenes s 9, and this has also proven to be the case in this proceeding.

70 The detail in the applicants’ allegations and arguments tended to overwhelm the general narrative and thrust of their case. To that extent, the respondents cannot fairly be criticised for taking the plethora of allegations of individual conduct and dealing with them one by one. Rather, the point I am making is that a more holistic approach to s 9 is required, if it is to be properly understood.

71 Prior to final submissions, and in order to ascertain what was really “thrown up for debate and consideration”, I asked the parties to provide a summary, limited to 3 pages, of their contentions on the specific contraventions of the RDA alleged by the applicants (with cross-references to the pleadings and submissions). This was to encourage closer focus on how it was that conduct of QPS officers was said to contravene the RDA, rather than how it was said to be generally substandard, or non-compliant with various procedural requirements such as those set out in the OPM.

72 Those summary documents proved most helpful in re-focusing the parties’ arguments on contraventions of the RDA and in identifying the principal conduct impugned by the applicants. In that regard, I note that the applicants pleaded that the second respondent, the Commissioner, had a general “prescribed responsibility” pursuant to subs 4.8(1) and (2) of the Police Service Administration Act 1990 (Qld) (PSA Act) for the efficient and proper administration, management and functioning of the QPS, including its “priorities” and the conduct and discipline of its members. However, in final submissions the applicants did not press this as an independent ground of liability, focusing instead on the actions of individual officers for whose conduct the first respondent is vicariously liable.

Two aspects of the legal contentions