FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Griffiths v Northern Territory of Australia (No 3) [2016] FCA 900

Table of Corrections | |

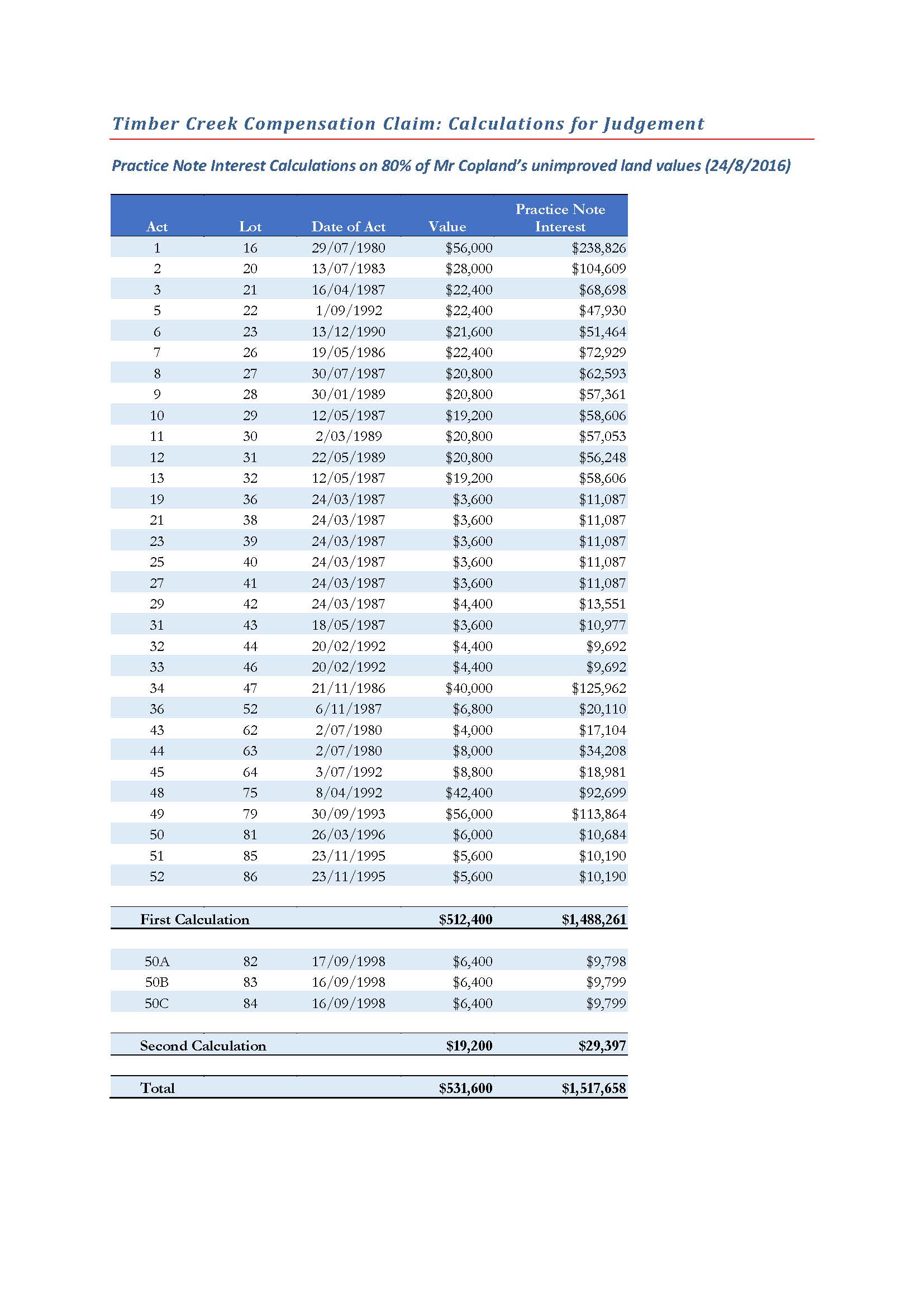

In Order 3(a) and (b), the amount “$512,000” is replaced with “$512,400”. | |

12 September 2016 | In Order 3, the Totalling amount “$3,300,261” is replaced with “$3,300,661”. |

12 September 2016 | In paragraph 466(a) and (b), the amount “$512,000” is replaced with $512,400”. |

12 September 2016 | In paragraph 466, the Totalling amount “$3,300,261” is replaced with “$3,300,661”. |

13 September 2016 | The appearance for Counsel for the Second Respondent “S Lloyd SC and N Kitson” be replaced with “S Lloyd SC and N Kidson”. |

13 September 2016 | The appearance for Counsel for the Intervener: Attorney-General for the State of Queensland “P Dunning SC” be replaced with “P Dunning QC and AD Keyes. |

ORDERS

ALAN GRIFFITHS AND LORRAINE JONES ON BEHALF OF THE NGALIWURRU AND NUNGALI PEOPLES Applicant | ||

AND: | NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA First Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

In this Order:

A. “past act”, “previous exclusive possession act” and “non-extinguishment principle” have the meaning given by the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Act);

B. “exclusive native title”, “non-exclusive native title” and “native title holders” have the meaning given by the Interim Statement of Agreed Facts dated 2 May 2012 at [2], [3] and [4];

C. the numbered acts referred to in these orders are the subject of the compensation claims in the Applicant’s Amended Particulars dated 17 October 2012;

D. the Applicant has withdrawn the claims for compensation made for acts 35, 42, 49A and 55.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The native title holders are entitled to compensation, to be assessed, in relation to acts 1 to 34, 36, 40 to 41, 43 to 50, 51 to 54 and 56 to 59; and:

Grants that are category D past acts that impair native title

(1) each of acts 1, 3, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 36 and 41 is a category D past act attributable to the Respondent to which the non-extinguishment principle applies that impaired non-exclusive native title at the time of the grant (or dedication in the case of act 41) the subject of the act, and for the duration of the granted (or dedicated) interest (subject to (2) below), and compensation is payable by the Respondent under s 20 of the Act:

(2) in the case of acts 3, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27 and 29, the non-exclusive native title in the land concerned that was impaired by those acts was later extinguished by acts 4, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28 and 30 respectively referred to at (3) and (4) below;

Grants that are previous exclusive possession acts that extinguish native title

(3) each of acts 2, 4 to 13, 31 to 33, 40, 45, 48, 49, 50 and 51 to 54 is a previous exclusive possession act attributable to the Respondent that extinguished non-exclusive native title at the time of the grant the subject of the act and compensation is payable by the Respondent under s 23J of the Act;

Works that are previous exclusive possession acts that extinguish native title

(4) each of acts 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 43, 44, 46, 47, 56, 57 and 59 is a previous exclusive possession act attributable to the Respondent that extinguished non-exclusive native title at the time when establishment of the works the subject of the act began and compensation is payable by the Respondent under s 23J of the Act;

Works (act 58) that are a previous exclusive possession act that extinguishes native title if no earlier works

(5) subject to whether or not the land concerned (or any part) was covered by a previously established public work, act 58 is a previous exclusive possession act attributable to the Respondent that extinguished non-exclusive native title at the time when establishment of the works the subject of the act began and compensation is payable by the Respondent under s 23J of the Act;

Grants in Part A.1 area (act 34) that are a previous exclusive possession act and extinguishment not to be disregarded in compensation application

(6) notwithstanding the approved determination of native title made on 28 August 2006, as varied on 22 November 2007 and 21 December 2007, that exclusive native title exists in relation to the land affected by act 34 (Lot 47) by virtue of the application of s 47B of the Act, for the purposes of the Compensation Application, act 34 is to be treated as a previous exclusive possession act attributable to the Respondent and as extinguishing non-exclusive native title at the time of the grant the subject of the act and compensation is payable by the Respondent under s 23J of the Act.

2. The Compensation Application is dismissed in relation to acts 37, 38 and 39.

3. The compensation payable to the native title holders by reason of the extinguishment of their non-exclusive native title rights and interests arising from the said act is:

(a) Economic value of the extinguished native title rights: $512,400;

(b) Interest on the said sum of $512,400 assessed in accordance with the reasons for judgment: $1,488,261;

(c) Allowance for solatium of $1,300,000;

Totalling $3,300,661.

THE COURT FURTHER NOTES:

A. Section 94 of the the Act provides that when the Court makes an order that compensation is payable, the order must set out the things in paragraphs (a), (b) and (c).

B. The Court has determined that the groups and persons comprising the native title holders (as set out in order [5] below) are entitled to the compensation that is payable.

C. Pursuant to s 58(c) of the Act and the Native Title (Prescribed Bodies Corporate) Regulations 1999 (Cth) (the Regulations) the agent prescribed body corporate for the native title holders (the PBC), Top End (Default PBC/DLA) Aboriginal Corporation, has certain functions to hold and invest the compensation that is payable.

D. Pursuant to s 60 of the Act and the Regulations an agent prescribed body corporate may be replaced in certain circumstances, in which event the functions referred to at C devolve to the replacement PBC.

THE COURT FURTHER ORDERS

4. Payment of the compensation to the PBC on behalf of the native title holders shall be taken as full discharge of the liability to pay compensation.

5. The persons entitled to the compensation are the native title holders, being:

(1) the Ngaliwurru and Nungali persons who are members of the estate groups Makalamayi, Wunjaiyi, Yanturi, Wantawul and Maiyalaniwung by reason of:

(a) descent through his or her:

(i) father’s father;

(ii) mother’s father;

(iii) father’s mother;

(iv) mother’s mother; or

(b) having been adopted or incorporated into the descent relationships referred to in (a);

(2) other Aboriginal persons who in accordance with traditional laws and customs, have rights in respect of land and waters of the relevant estate group, being:

(a) members of estate groups from neighbouring estates;

(b) spouses of estate group members;

(c) members of other estate groups with ritual authority.

6. The amount or kind of compensation to be given to each person, and any dispute regarding the entitlement of a person to an amount of the compensation, shall be determined in accordance with the decision making processes of the PBC.

AND THE COURT DETERMINES

7. Pursuant to ss 13(2) and 225(1) of the Act, the Court determines that, at the time at which the determination of compensation is made:

(1) native title does not exist in the compensation claim area (as defined in the further amended compensation application dated 17 August 2015), other than as identified below;

(2) in relation to Lots 52 and 60 (subject to acts 36 and 41):

(a) there exists native title comprising the rights referred to in par [3] of the statement of agreed facts dated May 2012;

(b) there are other interests in that land comprising:

(i) a freehold estate granted to the Commonwealth over Lot 52; and

(ii) the reservation of use as a cemetery over Lot 60,

to which the non-extinguishment principle applies.

AND THE COURT FURTHER DECLARES

8. Pursuant to s 213(2) of the Act, the Court declares in relation to Lots 82 to 84 (subject to acts 50A to 50C), acts 50A to 50C are invalid future acts within ss 24AA(2) and 233 of the NTA.

9. The damages payable by the Northern Territory to the PBC on behalf of the native title holders for the invalid future acts (calculated in accordance with the reasons for judgment) is $48,597 comprising the value of the native title rights imposed by those acts of $19,200 and pre-judgment interest thereon of $29,397 and totalling $48,597.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MANSFIELD J:

INTRODUCTION

1 This is a claim for compensation, principally under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA), involving important issues of principle, and about the application of well-established rules about the valuation of compulsorily acquired land under legislation such as the Lands Acquisition Act (NT) (LAA) to the loss or impairment of the traditional rights and interests of Aboriginals in this country.

2 The NTA is seminal legislation addressing the progressive dispossession of Aboriginal peoples from their land by European and related settlement. It followed the decision of the High Court in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 (Mabo) that the common law of Australia recognises the native title of Aboriginal people in their traditional country in accordance with their traditional laws and customs.

3 The NTA, by its Preamble, is to ensure that Aboriginal people “receive the full recognition and status within the Australian nation to which history, their prior rights and interests, and their rich and diverse culture, fully entitle them to aspire”.

4 To that end, it provides for the recognition of ongoing native title rights and interests in land in the prescribed circumstances, and where acts have extinguished or partially extinguished native title and are validated or allowed, it provides for compensation for that extinguishment on just terms.

5 This claim is for compensation for the partial extinguishment of native title rights and interests. It concerns land within the Township of Timber Creek.

6 It is necessary to refer to the particular claim and its background to identify the issues which arise.

The Claim

7 By a Further Amended Compensation Application dated 17 August 2015 (the Amended Application), the Applicants apply for a determination of compensation under s 61(1) of the NTA. They also claim compensation under the general law for three invalid future acts. I am satisfied that the Court has jurisdiction to deal with those three claims, on the basis that each involves a matter arising under the NTA: see s 213(2) of the NTA and s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). The application was first made on 2 August 2011.

8 In broad terms, compensation is claimed over the land and waters in Timber Creek for acts attributable to the Territory which occurred after the commencement of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (RDA) on 31 October 1975 which have extinguished native title in whole or in part, or have impaired or suspended native title where it still exists.

9 The application follows from an earlier proceeding.

10 The earlier native title proceeding concerned three applications for a determination of native title to vacant Crown land within the boundaries of the proclaimed town of Timber Creek. The native title claims were made by Narpijawuk/Yitipiari (Alan Griffiths) and Kalwaying (William Gulwin now deceased) as representatives of the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples: Griffiths v Northern Territory of Australia (2006) 165 FCR 300 (Griffiths SJ).

11 The trial judge determined that native title existed and held that s 47B of the NTA applied to the claimed land, with the result that any prior extinguishment by the grant of pastoral leases over the land must be disregarded. He then determined that the native title comprised non-exclusive rights to access and use the area: Griffiths SJ at [705].

12 The Full Court varied the determination of native title to provide that, in relation to those parts of the claim area to which s 47B applied, the native title comprised a right, on the part of the native title holders, to exclusive possession, use and occupation of that part of the claim area: Griffiths v Northern Territory of Australia (2007) 165 FCR 391 (Griffiths FC).

13 The native title holding group is a set of five descent based Yakpali (country or estate) groups, being Makalamayi, Wunjaiyi, Yanturi, Wantawul and Maiyalaniwung. The native title holding group is now the compensation claim group (the Claim Group).

14 It was found that at the time each of the compensable acts occurred, native title existed in relation to the relevant parcel affected by the act and involved the following rights in accordance with traditional laws and customs of the claim group:

(1) to travel over, move about and have access to the land;

(2) to hunt, fish and forage on the land;

(3) to gather and use the natural resources of the land such as food, medicinal plants, wild tobacco, timber, stone and resin;

(4) to have access to and use the natural water of the land;

(5) to live on the land, to camp, to erect shelters and structures;

(6) to engage in cultural activities, conduct ceremonies, to hold meetings, to teach the physical and spiritual attributes of places and areas of importance on or in the land, and to participate in cultural practices related to birth and death, including burial rights;

(7) to have access to, maintain and protect sites of significance on the application area;

(8) to share or exchange subsistence and other traditional resources obtained on or from the land (but not for any commercial purposes).

15 By an earlier decision in this matter: Griffiths v Northern Territory of Australia [2014] FCA 256 (Compensation Decision Part 1), I decided a number of issues requiring to be addressed in this claim.

16 The current claim is conveniently addressed at this point as covering three categories of area:

(1) areas where native title had been found to exist and was exclusive of other interests because s 47B of the NTA applies to those areas;

(2) areas where native title had been found to exist and was non-exclusive because s 47B did not apply to those areas; and

(3) areas where there had been no determination of native title in the Griffiths SJ and Griffiths FC decisions as they had not been addressed: Lots 16, 22 and 49 were expressly excluded from that earlier claim, and all other land and waters within Timber Creek simply not included in that earlier claim.

17 Compensation is, of course, not sought in relation to those areas where exclusive native title has been found to exist. The compensation claim is confined to the areas (2) and (3) referred to in the preceding paragraph. It is not now necessary to refer in detail to the Compensation Decision Part 1. There were a number of issues required to be addressed, focusing on whether (in respect of the land in (3) of the preceding paragraph) native title had been extinguished or partly extinguished, either by historic tenure grants and reservations, or by public works, and whether that extinguishment had occurred prior to the RDA coming into effect. There were other subsidiary issues addressed.

18 The Compensation Decision Part 1 proceeded on agreed facts about the existence of native title (apart from extinguishment issues), and on the occurrence of acts said by one or both of the Applicant and the Northern Territory (the Territory) to affect native title. The disagreement as to the effect of certain acts on native title was resolved by that decision, and the parties agreed that the native title rights and interests were in terms that mirror the earlier determination of native title in Griffiths SJ as altered by Griffiths FC.

19 The effect of the Compensation Decision Part 1 and certain ancillary matters was reflected in a Draft Order (not formally made) which set out those parts of the land and waters in Timber Creek to which an entitlement to compensation was found to exist, in addition to those areas in Timber Creek to which an entitlement to compensation exists by reason of Griffiths SJ and Griffiths FC.

20 The Draft Order is attached to these reasons at Annexure A.

21 The provisions of the NTA, read with the provisions of the Validation (Native Title) Act (NT) (VNTA), govern both the entitlement to compensation and the quantum of that entitlement.

22 There is of course a significant background to the present application. It can largely be drawn from the judgment of Weinberg J in Griffiths SJ. The Applicant applied to the Court to adopt and receive under s 86 of the NTA in this proceeding those findings. Their adoption and receipt initially was disputed by the Territory and by the Commonwealth. In the result, there was little dispute about them. I see no reason why I should not accede to the application to receive them as evidence capable of being adopted. The findings which follow broadly reflect that decision. It was only in a very limited respect that the Commonwealth in its submissions specifically disagreed with the Applicant’s use or understanding of those findings, and the Territory in its submissions did not point to any particular finding which it disputed. Where there is a dispute, I have not acted on the finding relied on by the Applicant without specifically addressing the dispute.

BACKGROUND

European contact in Ngaliwurru-Nungali country

23 Timber Creek is a tributary of the Victoria River in the north-western corner of the Northern Territory. Augustus Gregory explored the Victoria River district in the mid-19th Century and established a camp in the area of Timber Creek. He published an account of his expedition, which described Indigenous people visiting his camp, and on one occasion as having displayed hostility, where shots were fired.

24 Gregory’s exploration made known the potential extent of grazing land in the region, and at the end of the 19th Century a number of pastoral leases were granted in the Victoria River district. Stocking of the various holdings did not commence until several years later. After the arrival of the first permanent European settlers, Timber Creek became a focus for the supply of cattle stations. Indigenous inhabitants of the area found themselves being excluded from their traditional lands by cattle station owners, and as recorded in Griffiths SJ at [50]:

During these early years of settlement, relations between the local indigenous groups and the European settlers ranged from open warfare, and massacres, to what was at times friendly co-operation.

25 In the early 1900s, some station managers began to encourage Aboriginal people to settle at the various homesteads and outstations, but while the open conflict may have ended, cattle spearing and theft from station stores and unoccupied camps continued, and again as recorded in Griffiths SJ at [51]:

This situation quickly degenerated into a kind of guerrilla warfare, with Aborigines striking opportunistically and then retreating into rough range country.

26 Indigenous people in the region became increasingly involved in station work, and the period roughly 1920 to 1960 saw little change in their conditions where, at the beginning of the wet season, stock camps closed down and most Aboriginal workers returned to the bush, walking across country to visit relatives and engage in traditional ceremonies. One effect of World War II was that many white station employees enlisted in the armed forces and Indigenous persons began to play a greater role in the cattle station economy. Victoria River district Aborigines became aware that improved work conditions were possible, but when the war ended, station life for Aborigines reverted, more or less, to what it had been in earlier times.

27 In 1966, local dissatisfaction on the part of Aboriginal persons finally came to a head at Wave Hill where Aboriginal employees walked off the job, and camped in the Victoria River bed. Their initial demands for full wages and improved conditions were soon overtaken by others, including a demand for land rights, and by 1972 Aborigines from other stations had joined the strike. The Wave Hill strike contributed to the enactment of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (the Land Rights Act), which ultimately resulted in Indigenous groups gaining grants of land in the northern Victoria River region, including the areas surrounding Timber Creek in the Territory.

Makalamayi – Timber Creek

28 The township of Timber Creek was proclaimed on 10 May 1975. It is within Yakpali (country) known as Makalamayi, named after a focal site of significance to the Ngaliwurru-Nungali Peoples at the junction of Timber Creek and Victoria River. It is also known as Lamaparangana’s country, an apical ancestor of the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples.

29 The township is bounded to the north by Victoria River and to the west, south and east by Aboriginal land granted under the Land Rights Act. Land within the boundaries of the proclaimed township was unavailable for claim under the Land Rights Act, but the area surrounding the proclaimed boundaries was claimable, and was granted on the findings of the Aboriginal Land Commissioner (Justice Maurice) that six descent based country or estate groups of the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples were traditional Aboriginal owners of the area, that is (using the definition in s 3(1) of the Land Rights Act):

… a local descent group of Aboriginals who:

(a) have common spiritual affiliations to a site on the land, being affiliations that place the group under a primary spiritual responsibility for that site and for the land; and

(b) are entitled by Aboriginal tradition to forage as of right over that land.

30 Each of the groups was associated with a separate tract of land in the region of which the claim area formed part, those groups being Makalamayi, Wunjayi, Yanturi, Wantawul, Maiyalaniwung and Kuwang, who are the native title holding subgroups constituting the Claim Group.

31 Further areas in the vicinity of Timber Creek available for claim under the Land Rights Act have also been granted as a result of findings by successive Aboriginal Land Commissioners that the Ngaliwurru-Nungali are the traditional Aboriginal owners of the claimed land: they are the former Fitzroy Pastoral Lease, Stokes Range Pastoral Lease, and Kidman Springs and Jasper Gorge Pastoral Leases.

Development of the Town and the compensable acts

32 The Town of Timber Creek has a population of about 231. Aboriginal people make up about two thirds of the Town population, drawn principally from the native title holders, who are about 336 in number. The economy of the Town relies on tourism and associated services, and regional service delivery. The principal buildings are a road house and general store, a hotel and caravan park, local council offices, a police station, primary school and health clinic.

33 The Town is an area of about 2362 hectares. As noted, that area was declared as a Town and set the area apart as Town lands under s 111 of the Crown Lands Ordinance 1931 (NT) by Proclamation made on 10 May 1975.

34 A consequence of that Proclamation was that land set apart as Town lands could then be leased for various purposes by public auction or offered for sale upon payment of a reserve price, and leases of Town lands could be granted for particular purposes. Many of the compensable acts involve grants of that kind (development leases: see below).

35 Another consequence of setting apart the area as a Town was that, on the later enactment of the Land Rights Act, the area of the Town could not be the subject of a claim under that Act, which provides for the grant of unalienated Crown land in the Territory as traditional Aboriginal land. Where Crown land becomes Aboriginal freehold land under that Act, interests in the land cannot be granted without the consent of the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land. As noted, largely the area surrounding the Town including south of Victoria River was the subject of a claim and report under that Act, and was granted as Aboriginal freehold land.

36 Compensation is claimed for acts attributable to the Territory occurring after the commencement of the RDA that have extinguished native title in the area where native title no longer exists and for acts that have impaired or suspended native title in the areas where native title still exists.

37 Inevitably, because the application for compensation was brought in respect of 63 acts numbered 1-59 (including 49A, 50A, 50B and 50C) and because the claim as presented concerns those acts, by reference to identified lot numbers within the Town of Timber Creek, the factual circumstances are somewhat complex. The difficulty of refining and confining the issues is, it is fair to say, compounded by the complexity of the legislation itself. The Court has been greatly assisted in identifying the appropriate focuses for its consideration, and to address the issues, by the exchange of points of claim and points of defence between the Applicants, the Territory and the Commonwealth, and by the very helpful and thorough written submissions of the parties, together with the oral submissions made on their behalf by counsel.

38 In the course of the exchange of the pleadings, the claims for acts numbered 35 (Lot 48), 42 (Lot 61), 49A (Lot 79), and 55 (Victoria Highway Public Works) have been withdrawn. Consequently, the application now concerns 56 acts, which were validated under the terms of the NTA and the VNTA (the compensable acts), and three acts which were invalid (the invalid acts). The invalid acts are those numbered 50A, 50B and 50C.

39 To understand the context for the detailed statutory analysis which is required to address the principal issues, it is probably convenient to provide an introductory summary to how those issues arise beyond the recognition of the native title rights and interests of the claim group.

OVERVIEW

40 In short, the claim for compensation is said to be payable in respect of:

(1) 53 compensable acts, being acts numbered 1-34, 36, 40-41, 43-50, 51-54 and 56-59;

(2) 3 acts in relation to which the application for compensation was dismissed by the Compensation Decision Part 1, being acts 37, 38 and 39 (in respect of Lots 56-57, 73 and 109) (dismissed acts); and

(3) 3 invalid future acts, being acts 50A, 50B and 50C (in respect of Lots 82-84) (invalid acts).

As the Territory in its submissions suggested, I shall adopt the collective description of those acts as the “determination acts”.

41 Each of the determination acts is accepted as being attributable to the Territory within the meaning of s 239 of the NTA.

42 In respect of each of the determination acts, the Applicant on behalf of the Claim Group claims compensation under the following heads of loss:

1. economic loss;

2. non-economic/intangible loss; and

3. pre-judgment interest.

43 Given the complexity of the legislation, the Applicant’s quantification of those losses depended to a degree on a series of contingencies and alternatives.

44 On its primary case, sometimes called its “just terms case”, the economic loss is said to constitute:

(a) for all the determination acts (except those to which the non-extinguishment principle applies and which were followed by later extinguishing acts, and acts in respect of infrastructure lots) the value of the extinguished native title rights and interests assessed as at 10 March 1994 for which the improved freehold land value at that date is an appropriate proxy; and

(b) for all the determination acts (except extinguishing acts following an earlier act to which the non-extinguishment principle applies, and acts in respect of infrastructure lots) the value of the impaired enjoyment of the native title rights and interests between the date of the acts and 10 March 1994 for which market rental value is an appropriate proxy.

45 Secondly, as part of the primary claim, interest is sought to be awarded on the economic loss determined by reference to the freehold value at 10 March 1994 calculated on a compound basis at superannuation rates, or alternatively on a compound risk free rate, or alternatively on a simple interest rate in accordance with Practice Note CM 16 of the Federal Court Practice Notes.

46 Thirdly, there is claimed an in globo award of not less than $2m for non-economic loss to give effect to the diminution or disruption in traditional attachment to country and the loss of rights to live on, and gain spiritual and material sustenance from, the land.

47 That case is opposed by both the Territory and the Commonwealth, starting from the first proposition that the valuation of the extinguishment of native title rights and interest should be assessed at 10 March 1994, rather than the date of the act which constituted the extinguishing act.

48 The date 10 March 1994 is selected as it is said to be the date of the validation of the determination acts, previously invalid by removing native title rights unlawfully having regard to the RDA. The validation was effected by the NTA and the VNTA. I note that the Applicant says certain validated acts were validated only at a later point in time, but adopts a consistent (and the earliest) date of validation in the submissions. That step was uncontroversial in the sense that the Territory and the Commonwealth agree that is a sensible starting date for the assessment, if the primary contention of the Applicant is correct. That is a contention they firmly dispute.

49 The Applicant’s alternative case (sometimes called its “statutory claim”) is for economic loss:

(a) for all determination acts (except those to which the non-extinguishment principle applies which were followed by a later extinguishing act and acts in respect of infrastructure lots), the value of the extinguished native title rights and interests assessed as at the date of the act for which the unimproved/improved freehold land value is an appropriate proxy; and

(b) for acts 3, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27 and 29 (to which the non-extinguishment principle applies and which were followed by later previous exclusive possession acts), the value of the impaired enjoyment of the native title rights and interests between the date of the act and the later extinguishing act for which market rental value is an appropriate proxy.

50 Interest is claimed on the starting valuation of economic loss calculated on the three descending options referred to in [45], and again an in globo award of not less than $2m for non-economic loss is also sought.

51 The Territory’s case is that the Claim Group is entitled to the economic value of the native title rights and interests which were either actually or effectively extinguished by the determination acts, for which an appropriate proxy of value is a usage value (according to its expert Wayne Lonergan) plus 50% of the excess of freehold value over usage land value. It says that any interest should be calculated in accordance with Practice Note CM 16 on economic loss. It accepts that there should be a modest in globo award in the nature of solatium for the loss of the native title rights and interests. It also says that any compensation in respect of the dismissed acts should be determined on the same basis. Finally, it contends that there is no entitlement under s 51 of the NTA to compensation in respect of the invalid acts.

52 The Commonwealth’s position is a little different.

53 It ultimately submitted that the value of the non-exclusive rights should be valued at 50% of the freehold value of the allotments, having regard to a comparison between the full range or bundle of rights which constitutes freehold title, the bundle of rights which comprises exclusive native title, and the bundle of rights which the non-exclusive native title of the Claim Group in fact enjoyed at the time of the determination acts.

Primary areas of dispute

54 There are four principal, but somewhat related, areas of dispute.

55 The first is in respect of the “timing” issue under the NTA. As noted, the disagreement is as to whether the valuation date is that on which the native title rights and interests were extinguished (as the Territory says, in the sense of a divestiture of property) or whether it is the date at which the Claim Group’s native title as extinguished was validated. The Territory contends that the proper focus and identification on the timing issues and their resolution are inseparable from resolution of the question whether the formulation of the Applicants’ primary case involves a double counting of loss.

56 On the first area of dispute, the Commonwealth has adopted the same position as the Territory.

57 The second area of dispute is in respect of the value which should be ascribed to the native title rights and interests which have been extinguished, whatever the timing. That is, the Applicants’ claim that the value of the extinguished rights should be determined by reference to valuation of freehold title as an appropriate proxy for the valuation, whereas the Territory and the Commonwealth do not accept that. Within that dispute, the following issues have been identified:

(a) the application of economic principle to the valuation of non-exclusive native title rights and interests;

(b) the application of anthropological fact and opinion to the valuation of non-exclusive native title rights and interests; and

(c) the construction, prioritisation and application of legal norms governing the value of economic loss for the purposes of determining compensation under the NTA.

It is fair to say the third of those points is of major significance.

58 The Commonwealth has propounded a somewhat different method of the valuation of non-exclusive native title rights which have been extinguished, but in the end result it does not appear that its method, as distinct from that of the Territory produces a significantly different outcome.

59 The third area of dispute concerns the manner and extent to which traditional attachment to the land should be reflected in the award of compensation. That concerns the “solatium” calculation, using the term used by the Territory. Although both the Territory and the Commonwealth adopt a somewhat different position on this issue, again, the outcome of applying their respective positions is not significantly different.

60 The fourth main area of dispute concerns the manner and extent to which the effluxion of time between the various dates in which the entitlement to compensation arose and the date of judgment should be reflected in the award of compensation. The major dispute concerns the issue of pre-judgment interest. The Commonwealth agrees with the Territory in its approach to this issue, as noted above.

61 The Territory has pointed out, and I accept, that the differences on those issues principally concern the proper understanding and construction and application of the NTA and related legislation. I therefore adopt the approach which it has suggested, namely to address the construction issues by reference to the evidence in the hearing, and separately then to address the application of the outcome of those considerations to the quantification process including evidentiary matters, some interpretative differences, and the calculations which will result in the final orders.

62 I note also that the Commonwealth has raised an issue under s 94 of the NTA as to the terms of the appropriate order which should be made, bearing in mind the status and character of the Claim Group. That is addressed as a fifth and separate issue at the conclusion of these reasons for judgment.

63 I also note that in the Applicants’ opening submissions, there were six issues addressed, or identified. The additional issues to which I have not referred concern the quantification of compensation for occupation and use of land (impairment), dependent upon the rejection or acceptance of its primary contention as to the date at which the primary quantification should take place. In the course of submissions, that element of its contentions was absorbed into, and for the purposes of this decision conveniently it is absorbed into, the first issue.

64 The Applicants also raised the issue of compensation for economic loss under s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution, raising concern that the Territory or the Commonwealth might argue that s 51A of the NTA (to be referred to shortly) imposed a restriction on the upper level of compensation inconsistent with the statutory or constitutional provisions. That submission was ultimately not put by either the Territory or the Commonwealth and does not require separate consideration. Nevertheless, s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution is an important element in the Applicant’s claims for economic loss on either its primary case or its alternative case. It is considered in that context.

65 It is worth noting, at this point, that the Applicant’s statutory claim for economic loss for impairment of native title, that is its alternative claim if the loss is not to be assessed at the date of the validation of the determination acts, is as follows:

(1) Where native title has been impaired before it is extinguished by a later act, the applicant’s claimed economic loss for the impairment of native title is reasonable remuneration for occupation or use of land for the period of impairment, measured by reference to reasonable market rental, or receipts.

(2) Where native title is impaired by an act of indefinite and perpetual duration, the applicant’s claimed economic loss for this impairment is assessed by reference to the freehold value of the land at the date of the act. The same measure is claimed in relation to the three invalid future acts.

(3) The Applicant claims non-economic loss to be assessed on an in globo basis in reference to all of the lots and road areas as a whole, having regard to the factors listed in the Points of Claim at [11].

66 The primary claim is made in reliance on the provision in s 53 of the NTA, which appears to provide for “just terms” to the extent required to avoid invalidity under s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution. These claims are referred to as “constitutional compensation” in the Applicant’s submission. These claims only arise if, and to the extent that, the compensation assessed in accordance with ss 51 and 51A of the NTA (statutory compensation) does not provide “just terms” within the meaning of s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution for the acquisition of any property. As noted, that constitutional issue depends on the constructional premise that the validation and confirmation provisions fix the date for assessing compensation at a time earlier than the legal divestiture of the native title.

Applicant’s evidence

Economic loss

67 The Applicants rely on the following evidence in support of the claims for economic loss:

(1) “Expert valuation report – Timber Creek Township” by Glenn Miller dated 15 May 2015 (Miller Report);

(2) “Expert Valuation Report – Timber Creek Compensation Claim” by Brian Dudakov and Les Brown dated 12 August 2015 (Dudakov and Brown First Report), and “Supplementary Expert Valuation Report – Timber Creek Compensation Claim” by Brian Dudakov and Les Brown dated 2 September 2015 (Dudakov and Brown Second Report);

(3) Expert Economists’ Report by Barry Lewin and Kuo Ning Ho dated 27 July 2015 (SLM First Report), and Expert Economists’ Supplementary Report by Kuo Ning Ho dated 25 August 2015 (SLM Second Report);

(4) Affidavit of John Hofmeyer sworn on 23 July 2015;

(5) Affidavit of Rebecca Hughes sworn on 23 July 2015;

(6) Affidavit of Mark Lewis sworn on 17 August 2915;

(7) Affidavit of Lorraine Jones sworn on 14 October 2015;

(8) The documents referred to in the Particulars of Receipts.

Non-economic loss

68 The Applicants rely on the following evidence in support of the claims for non-economic loss, as outlined in the Notice on Non-Economic Loss:

(1) Affidavit of Alan Griffiths sworn on 7 July 2015;

(2) Affidavit of Jerry Jones sworn on 7 July 2015;

(3) Affidavit of Lorraine Jones sworn on 7 July 2015;

(4) Witness statement of Josie Jones dated 17 August 2015;

(5) Witness statement of Roy Harrington dated 17 August 2015;

(6) Expert Anthropologists’ Report – Timber Creek Native title Compensation Application, by Kingsley Palmer and Wendy Asche November 2012 (Palmer and Asche 2012 Report);

(7) Expert Economists’ Report – by John Altman dated 17 August 2015 (Altman Report); and

(8) The s 86(1) evidence and findings referred to in the s 86 Notice, and the Notice on Non-economic Loss.

Pre-judgment interest

69 The applicant relies on the following evidence in support of the claims for pre-judgment interest:

(1) SLM First Report and SLM Second Report;

(2) Dudakov and Brown First Report, and Dudakov and Brown Second Report.

70 The Applicants also rely generally on the lay evidence given on-country in and around Timber Creek by Alan Griffiths, Jerry Jones, Josie Jones and Lorraine Jones, Roy Harrington, and Chris Griffiths (listed in the sequence they gave evidence on country.

Continuing Agreed Starting Point

71 For the purposes of the current reasons, it is convenient to record that the parties agree that, at the time of an act for which compensation is claimed:

(1) Native title (within the meaning of s 223 of the NTA) existed in relation to the land and waters comprising Timber Creek.

(2) Where the native title had not been wholly or partially extinguished by an earlier act, the native title rights and interests that existed were rights and interests in accordance with traditional laws and customs to the possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the Timber Creek area to the exclusion of all others.

(3) Where the native title had not been wholly extinguished, but had been partially extinguished by an earlier act, the native title rights and interests were the following non-exclusive rights in accordance with traditional laws and customs:

1. the right to travel over, move about and to have access to the application area;

2. the right to hunt, fish and forage on the application area;

3. the right to gather and to use the natural resources of the application area such as food, medicinal plants, wild tobacco, timber, stone and resin;

4. the right to have access to and use the natural water of the determination area;

5. the right to live on the land, to camp, to erect shelters and other structures;

6. the right to:

(a) engage in cultural activities;

(b) conduct ceremonies;

(c) hold meetings;

(d) teach the physical and spiritual attributes of places and areas of importance on or in the land and waters; and

(e) participate in cultural practices relating to birth and death, including burial rights;

7. the right to have access to, maintain and protect sites of significance on the application area; and

8. the right to share or exchange subsistence and other traditional resources obtained on or from the land or waters (but not for any commercial purposes).

(4) The persons who held the native title were:

1. the Ngaliwurru-Nungali persons who are members of the estate groups Makalamayi, Wunjaiyi, Yanturi, Wantawul and Maiyalaniwung by reason of:

(a) descent through his or her:

(i) father’s father;

(ii) mother’s father;

(iii) father’s mother;

(iv) mother’s mother; or

(b) having been adopted or incorporated into the descent relationships referred to in (a);

2. other Aboriginal persons who in accordance with traditional laws and customs, have rights in respect of land and waters of the relevant estate group, being:

(a) members of estate groups from neighbouring estates;

(b) spouses of estate group members;

(c) members of other estate groups with ritual authority.

(5) The native title rights and interest were subject to and exercisable in accordance with the valid laws of South Australia, the Northern Territory of Australia and the Commonwealth of Australia.

72 That agreement on the facts is subject to the contentions which the parties make at the hearing as to:

(1) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the application area, including in respect of the waters and the beds and banks of Timber Creek and the Victoria River;

(2) the relationship between the native title rights and the other interests (taking into account the effect of the NTA), and any contention by the Territory as to the nature and effect of the other rights; and

(3) the existence of any native title rights and interests in:

(a) minerals (as defined in s 2 of the Minerals (Acquisition) Act 1953 (NT));

(b) petroleum (as defined in s 5 of the Petroleum Act 1984 (NT)); and

(c) prescribed substances (as defined in s 3 of the Atomic Energy (Control of Materials) Act 1946 (Cth) and s 5(1) of the Atomic Energy Act 1953 (Cth)).

Matters not in contest

73 It is common ground that:

(1) the application was brought in respect of 63 acts numbered 1 to 59 (including 49A, 50A, 50B and 50C);

(2) the claims for Act 35 (Lot 48), Act 42 (Lot 61), Act 49A (Lot 79) and Act 55 (Victoria Highway public works) have been withdrawn;

(3) the application now concerns 56 acts which were validated under the terms of the NTA (the compensable acts), and three acts which were invalid (the invalid acts);

(4) the compensable acts were attributable to the Northern Territory within the meaning of s 239 of the NTA;

(5) the compensable acts were pasts acts within the meaning of s 228 of the NTA, except for Acts 50, 51, 52, 53 and 54;

(6) the past acts were validated on 10 March 1994;

(7) Acts 50, 51, 52, 53 and 54 were intermediate period acts within the meaning of s 232A of the NTA;

(8) the intermediate period acts were validated on 1 October 1998;

(9) the compensable acts were previous exclusive possession acts within the meaning of s 23B of the NTA, except for Acts 1, 3, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 36 and 41;

(10) native title was extinguished by each of the previous exclusive possession acts;

(11) Acts 1, 3, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 36 and 41 were category D past acts within the meaning of s 232 of the NTA;

(12) the non-extinguishment principle applies to the category D past acts;

(13) Acts 3, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27 and 29 were followed by subsequent previous exclusive possession acts affecting the same Lots which extinguished native title over the relevant Lots;

(14) Acts 1, 36 and 41, affecting Lots 16, 52 and 60 respectively, were not followed by any subsequent act affecting native title and the non-extinguishment principle continues to apply in respect of those Acts;

(15) the native title holders are entitled to compensation pursuant to s 23J of the NTA in respect of the compensable acts which are previous exclusive possession acts;

(16) the native title holders are entitled to compensation pursuant to s 20 of the NTA in respect of the compensable acts which are category D past acts;

(17) the Applicants seek damages under the general law in respect of the invalid acts.

74 In relation to category (5) above, s 228 relevantly means that a past act is an act which was done before 1 July 1993 (for legislative acts) or 1 January 1994 (for non-legislative acts) and was, apart from the NTA, invalid to any extent but would have been valid to that extent if the native title did not exist. The validation of past acts took place by operation by s 19 of the NTA and s 4 of the VNTA.

75 The reference to “intermediate period acts” in (7) above refers to the definition which generally, and relevantly, means an act which took place between 1 January 1994 and 23 December 1996, and which was invalid to any extent but would have been valid to that extent if native title did not exist, and which was not a past act. The validation of those acts took place by operation of s 22F of the NTA and s 4A of the VNTA.

76 For the purposes of the previous exclusive possession acts referred to in (9) above, they are defined by s 23B of the NTA relevantly as comprising a certain type of act which took place before 23 December 1996 which is valid (because it was validated by s 14(1) of the NTA or s 4 of the VNTA or by s 22A of the NTA and s 4A of the VNTA). The extinguishment of native title by each of the previous exclusive possession acts was effected by s 23E of the NTA and ss 9H and 9J of the VNTA. Section 23C(3) of the NTA and s 9G of the VNTA mean that where a particular act is either a past act or an intermediate period act, and also a previous exclusive possession act, the extinguishment of native title is effected by the previous exclusive possession act provisions.

77 To this point, therefore, the prescriptive legislative provisions mean that the compensable acts which were past acts and previous exclusive possession acts (that is those listed in category (9) above) extinguished native title because they were previous exclusive possession acts, and the remainder of the compensable acts (other than acts 50, 51, 52, 53 and 54) were past acts which were validated on 10 March 1994, and acts 50, 51, 52, 53 and 54 were intermediate period acts which were validated on 1 October 1998. As noted, the Applicant is prepared to treat the date of validation of all determination acts as 10 March 1994.

78 To revert to the list above, the past acts which were also previous exclusive possession acts, were also category D past acts within the meaning of s 232 of the NTA. That categorisation arises because, by definition, category D past acts are past acts that are not category A past acts (generally, certain freehold grants, certain types of leases, and certain public works as defined by s 229 of the NTA), and are not category B past acts (generally, certain leases as defined by s 230 of the NTA), and are not category C past acts (comprising mining leases as defined by s 231 of the NTA). They fall within the default category. As a consequence, the non-extinguishment principle as defined in s 238 of the NTA applies to them.

79 However, all but acts 1, 36 and 41 of those category D past acts were followed by subsequent previous exclusive possession acts affecting the same lots, and which extinguish native title over those lots: that occurs by operation of s 23E of the NTA and ss 9H and 9J of the VNTA. For the purposes of later cross-referencing, and the application of the compensation principles as subsequently determined by reference to the principal issues, I note that acts 3 and 4 affect Lot 21, acts 15, 16, 17 and 18 affect Lot 34, acts 19 and 20 affect Lot 36, acts 21 and 22 affect Lot 38, acts 23 and 24 affect Lot 39, acts 25 and 26 affect Lot 40, acts 26 and 28 affect Lot 41, and acts 29 and 30 affect Lot 42.

80 The remaining category D past acts, that is acts 1, 36 and 41, affecting Lots 16, 52 and 60 respectively, were not followed by any subsequent act affecting native title so that the non-extinguishment principle continues to apply to them.

81 The grouping in (15), (16) and (17) above therefore identifies the compensable acts, and the invalid acts to which the entitlement to compensation is said to arise.

THE LEGISLATION

82 Section 23J of the NTA (appearing in Div 2B) provides:

23J Compensation

Entitlement

(1) The native title holders are entitled to compensation in accordance with Division 5 for any extinguishment under this Division of their native title rights and interests by an act, but only to the extent (if any) that the native title rights and interests were not extinguished otherwise than under this Act.

Commonwealth acts

(2) If the act is attributable to the Commonwealth, the compensation is payable by the Commonwealth.

State and Territory acts

(3) If the act is attributable to a State or Territory, the compensation is payable by the State or Territory.

83 Section 20 of the NTA (appearing in Div 2) provides, so far as is relevant to the application:

20 Entitlement to compensation

Compensation where validation

(4) If a law of a State or Territory validates a past act attributable to the State or Territory in accordance with s 19, the native title holders are entitled to compensation if they would be so entitled under subsection 17(1) or (2) on the assumption that section 17 applied to acts attributable to the State or Territory.

…

Recovery of compensation

(3) The native title holders may recover the compensation from the State or Territory.

…

84 Section 17 of the NTA provides relevantly in relation to category D past acts that the native title holders are entitled to compensation for the act if the native title affected by the act is in relation to an onshore place (and the application area in this case is entirely an onshore place) and the act could not have been validly done on the assumption that the native title holders instead held ordinary title to any land concerned and the land adjoining or surrounding any waters concerned (s 17(2)(a), NTA).

85 Section 51 of the NTA provides, so far as is relevant to the application:

51 Criteria for determining compensation

Just compensation

(1) Subject to subsection (3), the entitlement to compensation under Division 2, 2A, 2B, 3 or 4 is an entitlement on just terms to compensate the native title holders for any loss, diminution, impairment or other effect of the act on their native title rights and interests.

…

Compensation not covered by subsection (2) or (3)

(4) If:

(a) neither subsection (2) nor (3) applies; and

(b) there is a compulsory acquisition law for the Commonwealth (if the act giving rise to the entitlement is attributable to the Commonwealth) or for the State or Territory to which the act is attributable;

the court, person or body making the determination of compensation on just terms may, subject to subsections (5) to (8), in doing so have regard to any principles or criteria set out in that law for determining compensation.

Monetary compensation

(5) Subject to subsection (6), the compensation may only consist of the payment of money.

…

86 Section 51A or the NTA imposes a limit on compensation in the following terms:

51A Limit on compensation

Compensation limited by reference to freehold estate

(1) The total compensation payable under this Division for an act that extinguishes all native title in relation to particular land or waters must not exceed the amount that would be payable if the act were instead a compulsory acquisition of a freehold estate in the land or waters.

This section is subject to section 53

(2) This section has effect subject to section 53 (which deals with the requirement to provide “just terms” compensation).

87 Section 53(1) provides for an additional entitlement to compensation whenever that is required to avoid invalidity by reason of s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution. It is as follows:

Entitlement to just terms compensation

(1) Where, apart from this section:

(a) the doing of any future act; or

(b) the application of any of the provisions of this Act in any particular case;

would result in a paragraph 51(xxxi) acquisition of property of a person other than on paragraph 51(xxxi) just terms, the person is entitled to such compensation, or compensation in addition to any otherwise provided by this Act, from:

(c) if the compensation is in respect of a future act attributable to a State or a Territory – the State or Territory; or

(d) in any other case – the Commonwealth;

as is necessary to ensure that the acquisition is made on paragraph 51(xxxi) just terms.

88 The term “paragraph 51(xxxi) acquisition of property” is defined in s 253 of the NTA as an acquisition of property within the meaning of s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution, and “paragraph 51(xxxi) just terms” is defined as just terms within the meaning of s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution. Section 51(xxxi) of the Constitution provides for the power to acquire property on just terms.

89 There is a compulsory acquisition law for the Northern Territory in the form of the LAA. Section 5 requires the LAA to be read so as to provide for the acquisition of land on just terms.

90 The expression “the date of acquisition” used in the LAA, including in the Compensation Assessment Rules in Sch 2 means, when land is compulsorily acquired, the date on which a notice of acquisition of land is published in the Gazette: s 4(1).

91 Compensation bears interest from the date of acquisition to the date on which payment is made to the claimant: s 64(1)(a). The rate of interest is the rate from time to time fixed by the Minister after consultation with the Treasurer: s 65. The Territory has advised in correspondence that no rate of interest has been set under the LAA. That is accepted by the Applicants and by the Commonwealth.

92 Section 66 of the LAA provides relevantly that in assessing compensation the relevant Tribunal must have regard to, but is not bound by, the Rules set out in Schedule 2 (as modified in respect of the acquisition of native title rights and interests).

93 Schedule 2 provides relevantly:

Schedule 2 Rules for the assessment of compensation

1. VALUE TO THE OWNER

Subject to this Schedule, the compensation payable to a claimant for compensation in respect of the acquisition of land under this Act is the amount that fairly compensates the claimant for the loss he has suffered, or will suffer, by reason of the acquisition of the land.

1A. RULES TO EXTEND TO NATIVE TITLE RIGHTS AND INTERESTS

To the extent possible, these rules, with the necessary modifications, are to be read so as to extend to and in relation to native title rights and interests.

2. MARKET VALUE, SPECIAL VALUE, SEVERANCE DISTURBANCE

Subject to this Schedule, in assessing the compensation payable to a claimant in respect of acquired land the Tribunal may take into account:

(a) the consideration that would have been paid for the land if it had been sold on the open market on the date of acquisition by a willing but not anxious seller to a willing but not anxious buyer;

(b) the value of any additional advantage to the claimant incidental to his ownership, or occupation of, the acquired land;

(c) the amount of any reduction in the value of other land of the claimant caused by its severance from the acquired land by the acquisition; and

(d) any loss sustained, or cost incurred, by the claimant as a natural and reasonable consequence of:

(i) the acquisition of the land; or

(ii) the service on the claimant of the notice of proposal,

for which provision is not otherwise made under this Act, other than costs incurred as a result of attending, participating in or being represented at consultations for the purposes of section 37(1) or mediation under section 37(4).

…

8. MATTERS NOT TO BE TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT

The Tribunal shall not take into account:

(a) any special suitability or adaptability of the acquired land for a purpose for which it could only be used:

(i) in pursuance of a power conferred by law; or

(ii) by the Commonwealth or the Territory, a statutory corporation to which the Financial Management Act applies, or a council constituted under the Local Government Act;

(b) any increase in value of the acquired land resulting from its use or development contrary to law;

(c) any increase or decrease in the amount referred to in rule 2(a) arising from:

(i) the carrying out; or

(ii) the proposal to carry out,

the proposal; or

(d) any increase in the value of the land caused by construction, after the notice of proposal was served on the applicant, of any improvements on the land without the approval of the Minister.

9. INTANGIBLE DISADVANTAGES

(1) If the claimant, during the period commencing on the date on which the notice of proposal was served and ending on the date of acquisition:

(a) occupied the acquired land as his principal place of residence; and

(b) held an estate in fee simple, a life estate or a leasehold interest in the acquired land,

the amount of compensation otherwise payable under this Schedule may be increased by the amount which the Tribunal considers will reasonably compensate the claimant for intangible disadvantages resulting from the acquisition.

(2) In assessing the amount payable under subrule (1), the Tribunal shall have regard to:

(a) the interest of the claimant in the land;

(b) the length of time during which the claimant resided on the land;

(c) the inconvenience likely to be caused to the claimant by reason of his removal from the acquired land;

(d) the period after the acquisition of the land during which the claimant has been, or will be, allowed to remain in possession of the land;

(e) the period during which the claimant would have been likely to continue to reside on the land; and

(f) any other matter which is, in the Tribunal’s opinion, relevant to the circumstances of the claimant.

CONSIDERATION: CONSTRUCTIONAL CONTENTIONS

Preliminary

94 As a starting point, I refer to my earlier reference to the Preamble of the NTA. It recognises that the dispossession of Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders from their lands occurred largely without compensation, and that successive governments have failed to reach a lasting and equitable agreement with Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders concerning the use of their lands. It is also unexceptional to observe that, if acts have extinguished native title and are to be validated or allowed, justice requires that compensation on just terms be provided to the holders of native title whose rights have been extinguished.

95 Hence it is that s 10 provides that native title is recognised and protected in accordance with the NTA, and s 11 says that native title is not able to be extinguished contrary to the NTA. The circumstances in which legislation of the Commonwealth, or of a State or Territory, may extinguish native title is circumscribed by the requirements of s 11(2). After 1 July 1993, such legislation may only extinguish native title in accordance with Div 2B (which deals with the confirmation of past extinguishment of native title), or Div 3 (which deals with future acts and native title) of Pt II, or by validating past acts and intermediate period acts in relation to native title in accordance with Div 2 and 2A of Pt II of the NTA.

96 It is in that context that the NTA provides for compensation in respect of native title rights and interests which have been extinguished, at least since acts undertaken after the commencement of the RDA.

97 It is, therefore, not surprising that the criterion for determining compensation in s 51 of the NTA described a standard of entitlement by reference to “just terms”. Nor is it surprising that the parties accept that “just terms” as there expressed is coterminous with the meaning of “just terms” in s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution.

98 The standard is one of fair dealing: Nelungaoo Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1952) 85 CLR 545 at 600 per Kitto J. In the context of a challenge to the validity of a lease of Aboriginal land granted under the Land Rights Act, pursuant to the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 (Cth), in Wurridjal v The Commonwealth (2009) 237 CLR 309 the High Court used a like expression at [190] per Gummow and Hayne JJ (Wurridjal).

99 In the NTA, the standard of just terms compensation does not prescribe any particular framework for the determination of the compensation payable, save that in the circumstances of this application by the operation of s 51(4) of the NTA, assistance may be derived from the framework under Sch 2 to the LAA.

100 In Wurridjal a statutory right to “reasonable compensation” was interpreted as conferring whatever compensation was necessary to provide “just terms” within s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution.

101 The Applicant submits that the “just terms” requirement necessarily means that the compensation be assessed at the time of validation in 1994, rather than at the time of the act which has been validated. That is a matter which is addressed in considering the “timing issue” below. However, I did not discern from the submissions of the Territory or of the Commonwealth that it was contended (or accepted) that, to assess the compensation at the time of the compensable act itself rather than of its validation, would or could routinely or necessarily lead to the compensation being other than on “just terms”. The contrary was the case.

102 As to the RDA itself, s 7(1) of the NTA provides that it is intended to be read and construed subject to the provisions of the RDA. However, it goes on to explain that that expression means only that the provisions of the RDA apply to the performance of functions and the exercise of powers conferred by or authorised by the NTA, and so that any ambiguous terms in the NTA should be construed consistently with the RDA if that would remove the ambiguity. Section 7(3) specifically said that those explanations do not affect the validation of past acts or intermediate period acts in accordance with the NTA.

103 In my view, neither the RDA itself, nor the RDA taken in light of s 7 of the NTA, necessarily prescribes that native title rights generally cannot be valued at less than freehold title, or that the native title rights and interests which were extinguished or impaired by one or more of the determination acts the subject of the present proceedings, necessarily must be treated as “relevantly exclusive”. Nor does it mean that the divestiture of the native title rights and interests, or their extinguishment, occurred at the time of the validation rather than at the time of the act itself.

104 So long as the provisions of the NTA or of the VNTA in relation to validation of past acts or intermediate period acts are valid, the general principle should apply that as a later enactment contemplated and made by the Parliament, they would prevail: Goodwin v Phillips (1908) 7 CLR 1 at 7 per Griffiths CJ. Indeed, in my view that was made explicit in Western Australia v Commonwealth (1995) 183 CLR 372 at eg 484 in the joint judgment of Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ (Native Title Act case). There is no basis for qualifying their proper construction or application by reason of any primacy of the RDA or its terms.

105 Section 7(3) in any event makes that clear.

106 There is no dispute that there are four categories of acts which attract, or are said to attract, the entitlement to compensation. There is an overlap in the first three, because previous exclusive possession acts are or may be also past acts and/or intermediate period acts.

107 The break-up of those categories is set out in more detail earlier in these reasons, but because it requires specific consideration in this context, it is convenient to repeat them. They are:

(1) past acts under s 20 of the NTA which, read with ss 5-8 of the VNTA, entitle the Applicants to compensation under s 17(1) including where the non-extinguishment principle applies under s 17(2);

(2) intermediate period acts: the entitlement to compensation arises under s 22G of the NTA, read with s 22B of the NTA and ss 9B-9E of the VNTA, and for other intermediate period acts to which the non-extinguishment principle applies;

(3) previous exclusive possession acts: the entitlement to compensation arises under s 23 of the NTA, read with ss 23E and 23I of the NTA and ss 9H-9JB of the VNTA, as they apply to previous exclusive possession acts and previous non-exclusive possession acts and, as noted, where a previous exclusive possession act is also a past act or an intermediate period act, the entitlement to compensation is in respect of its status as a previous exclusive possession act, as s 23J then confers the entitlement to compensation for extinguishment; and

(4) invalid future acts: generally, a future act will be valid if it is covered by a provision in Div 2 of the NTA and it is invalid if it is not: s 24AA(2), as the VNTA does not deal with future acts.

108 The VNTA commenced on 10 March 1994, and validated past acts attributable to the Territory. It was amended on 1 October 1998 to provide for the validation of intermediate period acts, and the confirmation of extinguishment of native title by previous exclusive possession acts: Validation of Titles and Actions Amendment Act 1998 (NT).

109 The Applicant’s primary case is that the assessment of just terms compensation must be by reference to the date of validation of past acts: 10 March 1994, but on its alternative or statutory contention on the dates when the acts occurred. However, as noted, although the intermediate period acts were validated later, on 1 October 1998, for the purposes of assessing compensation for those acts, the Applicants are content to adopt the 10 March 1994 date. It is accepted that any further and more precise breakdown, by reference to the operative dates of extinguishment and impairment in relation to individual lots, is not likely to affect the overall assessment of loss.

110 The non-extinguishment principle in s 238 of the NTA provides for the suspension of what otherwise would be native title rights and interests, so that whilst they continue to exist, to the extent of any inconsistency they have no effect in relation to the act in question. The inconsistency precluding the exercise or enjoyment of native title rights may itself be entire or partial and will last until the act or its effects are later removed or cease to operate.

111 As also noted, the Territory accepts that it is liable for the acts about which compensation is sought. Section 239 of the NTA provides that an act is attributable to the Territory if it is done by the Crown in light of the Territory or by any other person under a law of the Territory. This captures acts done by the Territory after its establishment as a body politic on 1 July 1978 by the Northern Territory (Self-Government) Act 1978 (Cth).

The Claim for Economic Loss

112 The Applicants claim economic loss under the following heads:

(1) for previous exclusive possession acts – the freehold value of the land at the time of the compensable act, including any improvements;

(2) for category D past acts – reasonable remuneration for the occupation or use of the land in the nature of mesne profits evidenced by market rental or receipts for use of the land from the time of the compensable act until native title was extinguished by a later act, or for an indefinite period where there was no later extinguishing act;

(3) for all the compensable acts – reasonable remuneration for the wrongful occupation or use of the land in the nature of mesne profits evidenced by market rental receipts for use of the land from the time of the compensable act until the act was validated on 10 March 1994;

(4) for compensable acts where native title was extinguished – the freehold value of the land at the date of validation on 10 March 1994, including any improvements; and

(5) for compensable acts to which the non-extinguishment principle continues to apply – reasonable remuneration for the occupation or use of the land in the nature of mesne profits evidenced by market rental or receipts from 10 March 1994 for an indefinite period.

113 The claims described in subparagraphs (3), (4) and (5) immediately above are said to be brought on the concession or contingency first that the entitlement to compensation under ss 20, 23J and 51 of the NTA is to be assessed at the date the compensable act happened rather than at the date of validation; second that the limitation imposed by s 51A(1) the NTA operates on the entitlement to compensation under ss 20, 23J and 51 of the NTA; and third on the basis that if the Claim Group are not entitled to those species of compensation under ss 20, 23J and 51 of the NTA, they are entitled to that additional compensation from the Commonwealth by operation of s 53 of the NTA.

114 The Applicant through counsel put its proposition at the commencement of closing submissions on this topic which is repeated as follows:

1. Compensation for economic loss is to be assessed by reference to the market value of the affected native title rights and land at the time of validation of the past acts (10 March 1994), and include compensation for the invalid occupation and use of the land by others in the intervening period between date of act and validation.

(a) Validation for the purposes of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (as a permitted exception to the protection of native title) does not remove the historical fact that the acts were invalid by the overriding operation of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) at the time of grant and in the intervening period until validation.

(b) Validation effected a divesture (acquisition) of the native title rights in relation to the land that were recognised by the common law and protected by the NTA or the RDA, and resulted in the Northern Territory gaining a benefit in having its underlying radical title to the land cleared of the burden or qualification of the native title rights and in its invalid dealings in the land validated, and in grantees acquiring valid titles.

(c) The lead compensation provision is s 51(1) of the NTA by which the native title holders are entitled to be compensated on just terms. This involves assessment or compensation by reference to the value of the affected rights and land at the time of the acquisition, or at least at a time that is not remote from the time of acquisition, irrespective of retrospective validation of acts that occurs for the purposes of the NTA.

CONSIDERATION: Date for the assessment of compensation

115 The validation of the past acts occurred on 10 March 1994 when s 4 of the VNTA commenced operation, but it provides expressly that each act to which it applies is taken always to have been valid.

116 The validation of the intermediate period acts occurred on 1 October 1998 when s 4A of the VNTA commenced operation, but again it provides that each act to which it applies is taken always to have been valid.

117 It is common ground that the NTA does not expressly provide for the date upon which the entitlement to compensation arises, or the date at which the value of the interest being acquired or extinguished is to be determined.

118 The critical question is whether compensation is to be assessed as at the date of each of the acts effecting the extinguishment or divestiture of the relevant native title rights and interests, or at the date of the validation of that act of extinguishment or divestiture.

119 Both the NTA at ss 14 and 22B provides respectively that a past act and an intermediate period act by the Commonwealth are, by the operation of those sections, valid and are taken always to have been valid. The same expression applies to past acts of the Territory: ss 19 and 22F of the NTA and s 4 of the VNTA. The entitlement to compensation arises by ss 20 or 23J ( in respect of previous exclusive possession acts).

120 The entitlement to compensation is for “the act” itself. As s 8 of the VNTA provides for the non-extinguishment principle to apply to the act, the entitlement to compensation under s 20 arises for a past act that extinguishes or suppresses native title. In the case of a previous exclusive possession act, s 23J gives rise to the entitlement to compensation for the act which extinguishes the native title and ss 9H and 9J of the VNTA provide that the Act is “taken to have happened when the act was done”. In the case of a public work, it is taken to have happened when the construction or establishment of the public work began.

121 As a matter of construction, in my view, because the relevant provisions deemed the extinguishing act to have been valid from the time of the act, or to have been done at the time of the act, it is the date of the act which fixes the date at which compensation is to be assessed.

122 That conclusion is consistent with the views of Sackville J in Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCA 150 (Jango SJ). That case concerned a claim for compensation under Div 2 and Div 2B of the NTA and the corresponding provisions of the VNTA. The issue of liability (that is, the establishment of native title held by the claimants upon which the extinguishing acts were said to have effected an extinguishment of native title) was first heard and determined.

123 As that issue was decided adversely to the claimants, it was not strictly necessary for Sackville J to address the issues concerning the claim for compensation, including the issue as to the date upon which the compensation was to be assessed. However, his Honour made some carefully considered observations on the topic.

124 The claimed compensable acts consisted of public works (including Connellan Airport), fee simple grants and a Crown Lease, each of which was attributable to the Territory and found by his Honour to have been previous exclusive possession acts within Pt 3B of the VNTA.

125 Sackville J specifically considered the question as to when the extinguishment should be taken to have occurred: at [742]. I shall not repeat his Honour’s careful review of the legislative history of the 1998 amendments to the NTA, including his references to the Explanatory Memorandum. Having regard to the clear language of s 23C, noted above, Sackville J found that the effect of the deemed date of extinguishment when read with s 23J of the NTA is that the right to compensation under s 23J: “arises (or is taken to arise) when the extinguishment is taken to have happened”: at [774].