FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Stone & Wood Group Pty Ltd v Intellectual Property Development Corporation Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 820

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the respondents’ costs of the proceeding (other than the cross-claim) including any reserved costs, to be taxed if not agreed.

3. If any party seeks a variation of the costs order, it may give written notice to the Court and the other parties within two business days.

4. In relation to the cross-claim, the parties submit agreed minutes of proposed orders to give effect to these reasons within seven days. If the parties cannot agree, each party provide its minutes of proposed orders, together with a short outline of submissions, within seven days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 The applicants (together, Stone & Wood) operate breweries in the Byron Bay and Murwillumbah areas of New South Wales. Stone & Wood launched its first beer in 2008 – it was known as ‘Draught Ale’. In November 2010, the Draught Ale was re-named ‘Pacific Ale’ (Stone & Wood Pacific Ale). Stone & Wood decided to change the name when it started to sell this beer in bottles – it seemed odd for a beer named ‘draught’ to be available in bottles. Stone & Wood chose the name ‘Pacific Ale’ for two reasons. First, it reflects the place where the beer is brewed and the story behind the brewery. Secondly, the word ‘Pacific’ generates (in the words of one of the directors) a “calming, cooling emotional response”. Over time, the range of beers brewed and sold by Stone & Wood has increased. The four main beer products now produced by Stone & Wood are Pacific Ale, Green Coast, Jasper Ale and Garden Ale. Since the brewery was established in 2008, sales of Stone & Wood beers have steadily increased. Stone & Wood sells its products mostly across the eastern seaboard of Australia, in particular in the Northern Rivers area of New South Wales, South East Queensland, Sydney and Melbourne. The Pacific Ale beer is Stone & Wood’s best-selling product, accounting for approximately 80-85% of Stone & Wood’s beer sales.

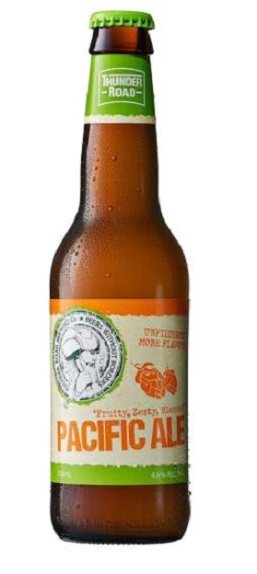

2 The second respondent (Elixir) operates a brewery in Brunswick, Melbourne, Victoria. It began brewing production operations in May 2010. Elixir distributes and sells beer under a number of brands, including ‘Thunder Road’. The Thunder Road logo is used in conjunction with a stylised image of Thor, the Norse god of thunder, a shield and, sometimes, the slogan, ‘Beer Without Borders’. Elixir produces a number of different beer products under the Thunder Road brand, including Pilsner, Golden, Pale Ale and Amber. In about January 2015, Elixir launched a beer named ‘Pacific Ale’ under the Thunder Road brand (Thunder Road Pacific Ale). Later, following letters of demand from Stone & Wood, this beer was re-named ‘Pacific’ (Thunder Road Pacific). Elixir sells its Thunder Road beer products in both ‘on premise’ and ‘off premise’ channels in Victoria, New South Wales, Western Australia and Tasmania. The ‘on premise’ channels consist of hotels, restaurants, cafes and bars, where the product is sold both in kegs and in packaged (bottle) format. The ‘off premise’ channels include bottle shops. Through this channel, the Thunder Road beers are sold in bottles.

3 Both Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and Thunder Road Pacific Ale may be described as ‘craft beers’. The craft beer market is difficult to define. Craft beer has come to be regarded by the market as beer which is outside of the traditional mainstream beer category, which comprises primarily pale lagers made by large multinational brewing businesses; the term ‘craft’ tends to describe beers (and brewers) that put greater emphasis on the flavours of a beer’s ingredients and that are made using less industrialised brewing processes.

4 Images of the 330 ml bottles of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale are set out below. (The bottle for Thunder Road Pacific, set out later in these reasons, was similar to the Thunder Road Pacific Ale bottle.)

|

|

5 Images of the six-packs for the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale are set out below:

|

|

6 Images of the beer tap ‘decals’ (affixed to the taps in licensed venues selling draught beer) for the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific are set out below:

| |

|

7 Stone & Wood claims that Elixir and the first respondent (Intellectual Property Development Corporation), which is an intellectual property holding company related to Elixir, have engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct (or conduct likely to mislead or deceive) and made false or misleading representations in contravention of ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law (being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (Australian Consumer Law) and have engaged in passing off. Stone & Wood contends that these causes of action are made out in two ways.

(a) First, Stone & Wood submits that it is likely that the respondents’ use of the names ‘Pacific Ale’ and ‘Pacific’ will lead consumers to order or buy the Thunder Road beer when they intend to order or buy Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

(b) Secondly, Stone & Wood submits that the respondents’ use of the names ‘Pacific Ale’ and ‘Pacific’ represents to consumers that there is a connection or association between the Thunder Road beers (and, consequently, the respondents) and Stone & Wood or Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. As there is no such connection, it is submitted that this is an actionable misrepresentation which will cause damage to Stone & Wood’s reputation and goodwill.

8 In support of these causes of action, Stone & Wood contends that Stone & Wood Pacific Ale has been promoted and sold on an extensive scale around Australia; that Stone & Wood has developed a substantial reputation and goodwill in relation to Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the mark ‘PACIFIC ALE’ (both alone and when used with the (predominantly) orange and green get-up of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale); and that Stone & Wood Pacific Ale is known and referred to by members of the trade and many consumers as ‘Pacific Ale’.

9 Also, the first applicant (Stone & Wood Group) claims that, through the respondents’ use of the names ‘Pacific Ale’ and ‘Pacific’ in relation to the Thunder Road beer, the respondents have infringed its registered trade mark under s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (Trade Marks Act), namely the following mark which is registered in class 32 in respect of beer (the Registered Trade Mark):

10 Elixir has cross-claimed against Stone & Wood contending that Stone & Wood made groundless threats to bring an action for infringement of a registered trade mark, within the meaning of s 129 of the Trade Marks Act. Stone & Wood relies on s 129(4) and (5) to resist the cross-claim, contending that: the acts of the threatened person (Elixir) in respect of which Stone & Wood threatened to bring an action constitute an infringement of the Registered Trade Mark; further or alternatively, Stone & Wood with due diligence began and has pursued an action against the threatened person (Elixir) for infringement of the trade mark.

11 In summary, my conclusions with respect to the claims and the cross-claim are as follows:

(a) In relation to Stone & Wood’s claims that the respondents have engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct (or conduct likely to mislead or deceive) and made false or misleading representations in contravention of the Australian Consumer Law, and engaged in passing off, I conclude that these claims are not made out. In order to make good these causes of action, it is necessary for Stone & Wood to establish that the representations alleged in its pleading were made by the respondents. The first alleged representation is to the effect that the Thunder Road Pacific Ale (or the Thunder Road Pacific) is Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. The second, third and fourth alleged representations are to the effect that there is an association or connection between the relevant Thunder Road products and Stone & Wood or the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. Stone & Wood has not established that the respondents made the alleged representations. There is no reference to Stone & Wood on any of the labels or packaging of the Thunder Road products. The labels and packaging of the Thunder Road products look very different to the labels and packaging of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. The colours used in the labels and packaging are quite different. I do not think the adoption of the name ‘Pacific Ale’ or ‘Pacific’ conveys an association or connection between the Thunder Road products, on the one hand, and Stone & Wood or Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, on the other.

(b) In relation to Stone & Wood Group’s claim that the respondents have infringed the Registered Trade Mark, I conclude that this claim is not made out. In my view, the words ‘Pacific Ale’ and ‘Pacific’, which have been used by the respondents in relation to beer, are not deceptively similar to the Registered Trade Mark.

(c) I conclude that Elixir’s cross-claim based on s 129 of the Trade Marks Act is made out. Stone & Wood threatened to bring an action against Elixir for infringement of the Registered Trade Mark. Stone & Wood has not established that either s 129(4) or (5) applies. Specifically, it has not established that the acts of Elixir constituted an infringement of the Registered Trade Mark; nor has Stone & Wood established that with due diligence it began and pursued an action against Elixir for infringement of the trade mark.

Procedural background

Parties

12 The parties to the proceeding are as follows. The first applicant is Stone & Wood Group. This company owns the assets (including intellectual property) associated with the business known as ‘Stone & Wood’. Stone & Wood Group is and has at all material times been the registered owner of Australian trade mark number 1395188 for the device set out in paragraph [9] above in class 32 in respect of beer. Stone & Wood Group uses the Registered Trade Mark in connection with Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. The second applicant (Stone & Wood Brewing) is the trading entity which operates the business known as ‘Stone & Wood’. Stone & Wood Brewing is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Stone & Wood Group. As noted above, in these reasons, I will refer to the applicants together as Stone & Wood.

13 The first respondent is Intellectual Property Development Corporation. This company is an intellectual property holding company and does not otherwise trade. The second respondent is Elixir. This company manufactures, distributes and sells beer. The respondents are related entities.

14 The cross-claimant is Elixir. The cross-respondents are Stone & Wood Group and Stone & Wood Brewing.

Pleadings

15 The proceeding was commenced on 20 May 2015. The applicants subsequently amended the originating application and the fast track statement. By the amended originating application dated 24 July 2015, Stone & Wood seeks:

(a) declarations that the respondents have contravened ss 18, 29(1)(g) and 29(1)(h) of the Australian Consumer Law;

(b) permanent injunctions restraining the respondents from making certain representations by using in any manner in the promotion or presentation of beer the trade mark ‘PACIFIC ALE’ or any trade mark which is misleadingly or deceptively similar to the trade mark ‘PACIFIC ALE’, including the name ‘PACIFIC’ – it should be noted that the references in the amended originating application to the trade mark ‘PACIFIC ALE’ are not to the Registered Trade Mark, which is the subject of separate treatment, described below;

(c) further or alternatively to (b), a permanent injunction restraining the respondents from engaging in such conduct in conjunction with a get-up prominently incorporating the colours green and orange;

(d) damages and compensation pursuant to ss 236 and 237 of the Australian Consumer Law;

(e) declarations that the respondents have engaged in passing off;

(f) permanent injunctions restraining the respondents from engaging in passing off (in various ways described in the originating application) by using in any manner in the promotion or presentation of beer the trade mark ‘PACIFIC ALE’ or any trade mark which is misleadingly or deceptively similar to the trade mark ‘PACIFIC ALE’, including the name ‘PACIFIC’;

(g) further or alternatively to (f), a permanent injunction restraining the respondents from engaging in such conduct in conjunction with a get-up prominently incorporating the colours green and orange;

(h) damages or equitable compensation for passing off;

(i) exemplary damages for passing off;

(j) further or alternatively, an account of profits;

(k) a declaration that the respondents have infringed the Registered Trade Mark –it is to be noted that the claims in relation to the Registered Trade Mark were introduced when the originating application was amended;

(l) a permanent injunction restraining the respondents from infringing the Registered Trade Mark, in particular, by using the Registered Trade Mark or any mark which is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the Registered Mark, in respect of any of the goods in respect of which the Registered Trade Mark is registered, any goods of the same description as the registered goods, or any services that are closely related to any of the registered goods (not manufactured or provided by or under the licence or authority of Stone & Wood Group);

(m) damages and additional damages for infringement of the Registered Trade Mark;

(n) further or alternatively, an account of profits for infringement of the Registered Trade Mark;

(o) delivery up of certain goods as described;

(p) alternatively, a mandatory order for destruction of certain goods as described;

(q) costs and interest.

16 In its amended fact track statement dated 24 July 2015 (Fast Track Statement), Stone & Wood describes the nature of the dispute, stating that the dispute concerns Stone & Wood’s rights in the trade mark ‘PACIFIC ALE’ (which is subsequently referred to in that document as the “Pacific Ale Trade Mark”). The Pacific Ale Trade Mark as so defined is to be distinguished from the Registered Trade Mark, which is referred to separately in the Fast Track Statement.

17 The Fast Track Statement states that Stone & Wood promotes, distributes and sells a beer under or by reference to: the Pacific Ale Trade Mark and a get-up prominently incorporating the colours green and orange (which is defined in that document as the “Pacific Ale Get Up”). The Fast Track Statement states that Stone & Wood’s Pacific Ale beer incorporating those features will be referred to as the “Pacific Ale Beer”; however, to avoid confusion, in these reasons I will refer to this as Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. The Fast Track Statement states that Stone & Wood contends that it has a significant reputation in Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Pacific Ale Trade Mark (both alone and in conjunction with the Pacific Ale Get Up).

18 The Fast Track Statement refers to Stone & Wood Group’s ownership of the Registered Trade Mark and then sets out images of the relevant products. (As with the amended originating application, the claims relating to the Registered Trade Mark were introduced when the document was amended.)

19 It is then contended that the respondents have commenced promoting, distributing and selling a beer under or by reference to: the Pacific Ale Trade Mark, or one or more trade marks which are misleadingly or deceptively similar to the Pacific Ale Trade Mark; and a get-up prominently incorporating the colours green and orange. The Fast Track Statement refers to the respondents’ impugned beer as the “Respondents’ Pacific Beer”. I will adopt this terminology in summarising the Fast Track Statement, but elsewhere in these reasons I will refer to Thunder Road Pacific Ale and Thunder Road Pacific.

20 The Fast Track Statement sets out more detailed contentions relating to Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, including the way in which it is sold by Stone & Wood and the geographical areas where it is sold. Stone & Wood contends that, as a result of these matters:

(a) the Pacific Ale Trade Mark in Australia means, and distinctively and exclusively indicates, Stone & Wood, Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or an association with them;

(b) Stone & Wood has developed a valuable reputation and substantial goodwill among distributors, wholesalers, re-sellers and consumers of beer in Australia in relation to Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Pacific Ale Trade Mark;

(c) the Pacific Ale Trade Mark used in conjunction with the Pacific Ale Get Up in Australia means, and distinctively and exclusively indicates, Stone & Wood, Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or an association with them;

(d) Stone & Wood has developed a valuable reputation and substantial goodwill among distributors, wholesalers, re-sellers and consumers of beer in Australia in relation to Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Pacific Ale Trade Mark used in conjunction with the Pacific Ale Get Up.

21 The Fast Track Statement contends that the respondents have promoted, distributed and sold the Respondents’ Pacific Beer to licensed venues in kegs for re-sale as a draught beer to on-premise customers, and to licensed venues and liquor retailers in bottles, without the licence or authority of Stone & Wood. Stone & Wood contends that the respondents selected the name ‘PACIFIC ALE’ for their beer to capitalise on the reputation and goodwill which Stone & Wood has developed in Australia in connection with Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Pacific Ale Trade Mark. Further, it is contended that the respondents selected an orange and green colour scheme for the packaging and branding of the Respondents’ Pacific Beer to capitalise on the reputation and goodwill which Stone & Wood has developed in Australia in connection with Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, the Pacific Ale Trade Mark and the Pacific Ale Get Up.

22 Stone & Wood contends in the Fast Track Statement that, by reason of the conduct referred to in the document, the respondents have represented that:

(a) the Respondents’ Pacific Beer is Stone & Wood Pacific Ale;

(b) the Respondents’ Pacific Beer is promoted, distributed and/or sold with the licence or authority of Stone & Wood;

(c) the Respondents’ Pacific Beer has the sponsorship or approval of Stone & Wood; and

(d) the respondents have the sponsorship or approval of, or an affiliation with, Stone & Wood.

These four representations are defined in the Fast Track Statement as the “Representations”.

23 After alleging that the conduct of the respondents was engaged in in trade or commerce (which is not contentious), Stone & Wood alleges that the Representations were misleading, deceptive and false because:

(a) the Respondents’ Pacific Beer is not Stone & Wood Pacific Ale;

(b) the Respondents’ Pacific Beer is not promoted, distributed and/or sold with the licence or authority of Stone & Wood;

(c) the Respondents’ Pacific Beer does not have the sponsorship or approval of Stone & Wood; and

(d) the respondents do not have the sponsorship or approval of, or an affiliation with, Stone & Wood.

24 On the basis of these contentions, it is alleged that the respondents have engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct, or conduct likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, and that the respondents have made false or misleading representations in contravention of ss 29(1)(g) and 29(1)(h) of the Australian Consumer Law.

25 Stone & Wood next contends that the conduct of the respondents is and was calculated to injure, has injured and is likely to injure the reputation and goodwill of Stone & Wood, Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, and the Pacific Ale Trade Mark (whether alone or used in conjunction with the Pacific Ale Get Up); and that by reason of the reputation that Stone & Wood has in Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Pacific Ale Trade Mark (whether alone or used in conjunction with the Pacific Ale Get Up), the respondents, by their conduct have passed off, are passing off and/or threaten to pass off:

(a) the Respondents’ Pacific Beer as Stone & Wood Pacific Ale;

(b) the Respondents’ Pacific Beer as a beer which is promoted, distributed and/or sold with the licence or authority of Stone & Wood;

(c) the Respondents’ Pacific Beer as having the sponsorship or approval of Stone & Wood; and

(d) themselves as having the sponsorship or approval of, or an affiliation with, Stone & Wood.

26 By amendment, Stone & Wood incorporated in the Fast Track Statement contentions that: the respondents have promoted, distributed and sold or caused to be promoted, distributed or sold the Respondents’ Pacific Beer to: (a) licensed venues in kegs for re-sale as a draught beer to on-premise customers; and (b) licensed venues and liquor retailers in bottles, bearing a mark which is deceptively similar to the Registered Trade Mark, without the licence or authority of Stone & Wood Group; and by reason of this conduct, the respondents have infringed, are continuing to infringe and/or threaten to infringe the Registered Trade Mark under s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act.

27 In the amended fast track response (Fast Track Response), the respondents state that Elixir distributes and sells beer under the brand name ‘Thunder Road’, described as ‘Pacific Ale’ (when sold to customers in bottles) and ‘Pacific’ (when sold to customers from a beer tap). (These are referred to together in the Fast Track Response as “THUNDER ROAD Pacific Ale”. However, for the sake of clarity, I will refer to Thunder Road’s relevant beers as Thunder Road Pacific Ale or Thunder Road Pacific (depending on the name used) and refer to them together as Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific.)

28 The respondents admit that Stone & Wood Brewing, the second applicant, has distributed and sold Stone & Wood Pacific Ale to licensed venues and liquor retailers for re-sale in bottles, and to licensed venues in kegs for re-sale as draught beer, but deny that these activities have been on an extensive scale throughout Australia. The respondents contend that:

(a) the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale has been sold under and by reference to the prominent ‘Stone & Wood’ brand name, not the term ‘Pacific Ale’ or the colours green and orange (defined in the document as the “Claimed Colours”);

(b) the term ‘Pacific Ale’ has been used, in conjunction with the term ‘Handcrafted’, in a subsidiary position by Stone & Wood Brewing on its labelling, to describe certain characteristics of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, namely, that it is a handcrafted pacific ale;

(c) Stone & Wood has repeatedly confirmed that ‘Pacific Ale’ is a description of a style of beer and not a brand name;

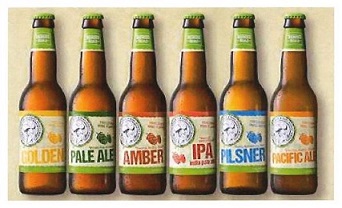

(d) the term ‘Pacific Ale’ has been used on the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale in the same position as Stone & Wood has used other descriptions of beer styles, such as ‘Lager’, ‘Pale Lager’ and ‘Draught Ale’ (the former name of ‘Pacific Ale’), to describe the style of beer being sold, as illustrated in following images:

29 In the Fast Track Response, the respondents deny that the Pacific Ale Trade Mark in Australia means and distinctively and exclusively indicates Stone & Wood, Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or an association with them, and contend that: other traders have, in Australia, used the term ‘Pacific Ale’ to describe the style of their beer; other traders throughout the world have used the term ‘Pacific Ale’ in a generic form to describe the style of their beer; and the term ‘Pacific Ale’ is used in Australia to describe a relatively fruity style of beer, often characterised by the use of Australian Galaxy hops or similar style New Zealand hops.

30 The respondents deny that the Pacific Ale Trade Mark used in conjunction with the Pacific Ale Get Up in Australia means and distinctively and exclusively indicates Stone & Wood, Stone & Wood Pacific Ale or an association with them, and contend that:

(a) the predominant colour used by Stone & Wood in connection with Stone & Wood Pacific Ale is a mustard colour not the Claimed Colours;

(b) other traders have in Australia used the Claimed Colours and/or a yellow or mustard colour in connection with their beer.

31 The respondents in the Fast Track Response deny they selected the name ‘Pacific Ale’ to capitalise on the reputation and goodwill which Stone & Wood has developed in Australia in connection with Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Pacific Ale Trade Mark, and contend that:

(a) the name of Thunder Road’s beer is not ‘Pacific Ale’ or ‘Pacific’ simpliciter, but ‘THUNDER ROAD Pacific Ale’;

(b) the terms, ‘Pacific Ale’ and ‘Pacific’ are used:

(i) as a geographical indicator, to reinforce the Australian/Pacific roots of Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific and Elixir; and

(ii) to describe the style of beer being offered for sale, namely, a beer with an “uplifting aroma of passionfruit from Australian Galaxy hops” (as explained on the bottle of Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific);

(c) before Elixir commenced any use of the terms ‘Pacific Ale’ or ‘Pacific’, the person who was then the head brewer for Elixir informed Elixir that ‘Pacific Ale’ is a style;

(d) the term ‘Pacific Ale’ is used in respect of bottles of Thunder Road Pacific Ale in precisely the same way as the terms ‘Pilsener’, ‘Pale Ale’, ‘Amber’, ‘Golden’ and ‘IPA’ are used in respect of other bottles of Thunder Road beers, namely to describe the style of beer being offered for sale, as illustrated by the following image:

32 The respondents deny that they selected an orange and green colour scheme for the packaging and branding of their beer to capitalise on the reputation and goodwill which Stone & Wood has developed in Australia in connection with Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, the Pacific Ale Trade Mark and the Pacific Ale Get Up, and contend that:

(a) the colours used by Elixir in connection with Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific are, in roughly equal proportions, green, orange, white and cream;

(b) the colour green is used by Elixir as a corporate colour, across the range of Thunder Road beers;

(c) in addition to the use of the corporate colour green, the use of white in the Thunder Road logo, and the use of cream as a background colour, Elixir also uses, across the range of Thunder Road beers, a separate colour for each style of beer to operate as a style differentiator (for example, amber for Amber Ale, gold for Golden Ale and green for Pale Ale);

(d) the colour orange is used by Elixir in connection with Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific as a style differentiator, consistent with the style of that beer, namely, “Fruity, Zesty, Blonde” (as explained on the bottle).

33 In response to the allegations described in paragraph [22] above, the respondents refer to matters already contended in the Fast Track Response and also contend that:

(a) the brand name ‘Thunder Road’ is used prominently on the caps, necks, fronts and backs of bottles of Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific; all packaging concerning Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific; beer taps from which Thunder Road Pacific is served at licensed venues;

(b) Elixir has a substantial and valuable reputation in the brand name ‘Thunder Road’ by reason of, inter alia: Elixir has sold beer under and by reference to the brand name ‘Thunder Road’ on an extensive scale, in bottle form and on tap, since 2011; Elixir has engaged in extensive promotional and marketing activities under and by reference to the brand name ‘Thunder Road’ since 2011; Elixir is recognised within the beer industry and the broader community as one of the leading brewers of craft beer in Australia;

(c) the ‘Stone & Wood’ brand name is not, and never has been, used in respect of Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific;

(d) the overall impression and look and feel of Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific bottles bears no similarity or resemblance to Stone & Wood Pacific Ale bottles, and is entirely distinctive;

(e) the overall impression and look and feel of the packaging in which Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific bottles are sold bears no similarity or resemblance to the packaging in which Stone & Wood Pacific Ale bottles are sold, and is entirely distinctive;

(f) the overall impression and look and feel of Thunder Road Pacific beer taps bears no similarity or resemblance to Stone & Wood Pacific Ale beer taps, and is entirely distinctive.

34 The respondents deny the claim of infringement of the Registered Trade Mark, and contend in the Fast Track Response that neither of the respondents has used the terms ‘Pacific Ale’ or ‘Pacific’ as a trade mark; and the terms ‘Pacific Ale’ and ‘Pacific’ are not deceptively similar to the Registered Trade Mark. The respondents also contend that they have not infringed the Registered Trade Mark because Elixir has, within the meaning of s 122(1)(b)(i) of the Trade Marks Act, only used the terms ‘Pacific Ale’ and ‘Pacific’ in good faith to indicate the matters referred to in paragraph [31](b) above.

35 In the fast track cross-claim dated 18 June 2015, Elixir contends that:

(a) Stone & Wood Brewing distributes and sells, under the brand name ‘Stone & Wood’, beer described as ‘Pacific Ale’;

(b) Stone & Wood Group is the registered owner of the Registered Trade Mark;

(c) prior to the commencement of this proceeding, Stone & Wood alleged that Elixir had, by distributing and selling under the brand name ‘Thunder Road’ beer described as ‘Pacific Ale’, infringed the Registered Trade Mark;

(d) Stone & Wood has not pursued any claim for infringement of the Registered Trade Mark; Elixir has arranged, at its own expense, for branding to be modified to describe the beer as a ‘Pacific’ beer rather than as a ‘Pacific Ale’, which it did without any admission of liability;

(e) by alleging, prior to the commencement of this proceeding, that Elixir had infringed the Registered Trade Mark, Stone & Wood made groundless threats within the meaning of s 129 of the Trade Marks Act.

36 Elixir in the cross-claim seeks declaratory relief, injunctive relief and damages.

37 After the cross-claim was filed and served, Stone & Wood amended the originating application and the fast track statement to incorporate a claim that the respondents have infringed the Registered Trade Mark, as described above.

38 In its fast track response to cross-claim, Stone & Wood denies the allegations in the cross-claim on the basis that:

(a) there were grounds for making any threats that Stone & Wood made;

(b) the impugned conduct of Elixir constitutes an infringement of the Registered Trade Mark; and

(c) Stone & Wood Brewing (that is, the second respondent) has not made any relevant threats.

Stone & Wood refers to ss 129(2) and (4) of the Trade Marks Act in relation to these responses.

39 Stone & Wood also contends that, by the amended originating application and the Fast Track Statement, Stone & Wood Group has alleged that Elixir has infringed the Registered Trade Mark; accordingly, Stone & Wood contends that the cross-claim should not proceed, relying on s 129(5) of the Trade Marks Act.

40 Elixir filed a fast track reply to the response to cross-claim. By this document, Elixir admits that, in the amended originating application and the Fast Track Statement (following the amendments), Stone & Wood Group has alleged that Elixir has infringed the Registered Trade Mark, but says that the cross-claim should proceed because Stone & Wood Group did not begin and pursue “with due diligence” an action for infringement of the Registered Trade Mark, within the meaning of s 129(5) of the Trade Marks Act.

Trial

41 It was ordered that issues of liability be heard and determined separately and prior to any issues of quantum. Evidence in chief was mostly by affidavit.

42 Stone & Wood adduced evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Jamie Cook, a director of both Stone & Wood Group and Stone & Wood Brewing. He gave evidence about the business known as ‘Stone & Wood’ and the history, marketing and sale of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

(b) Matthew Kirkegaard, a freelance beer writer, commentator, educator and consultant focused on the craft beer market. He gave expert evidence about the craft beer market in Australia, beer styles and the significance of the name ‘Pacific Ale’ in the craft beer market.

(c) Professor Lawrence Lockshin, who holds the positions of Professor of Wine Marketing and Head of School of Marketing at the University of South Australia. He gave expert evidence relating to the marketing of consumer goods and consumer behaviour.

(d) Matthew Coorey, the Managing Director of the Boardwalk Tavern, a venue located in Hope Island on the Gold Coast, Queensland. He is a co-owner of the Boardwalk Tavern.

(e) Corey Crooks, the Managing Director and co-owner of The Grain Store Craft Beer Café in Newcastle, New South Wales.

(f) Jessica McGrath, a director and co-owner of a company trading as the Palace Hotel in South Melbourne.

(g) James Omond, the solicitor for Stone & Wood. He gave evidence about some instances of the promotion of Thunder Road Pacific Ale. He was not cross-examined.

43 The respondents adduced evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Philip Withers, the Managing Director of the respondents.

(b) Peter Camilleri, who holds the positions of Senior Vice President of the ICB Group (which group includes the respondents) and General Manager of Marketing for Elixir.

(c) Alan Jane, the Managing Director of Disegno, a creative brand development agency. He gave expert evidence in relation to brand design.

(d) Domenic Piperno, who owned and operated two liquor stores specialising in craft beer and specialty wine, one in Brunswick, Melbourne and the other in Carlton North, Melbourne. He has worked in the retail liquor industry for approximately 40 years.

(e) Greg Curran, one of the owners of Sunshine Coast Brewery, which is a boutique brewery based in Kunda Park on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast.

(f) Tasos Eleftheriadis, a freelance web developer and brand designer. He was not cross-examined.

(g) Ian Morton, a graphic designer. He was not cross-examined.

(h) Adrian Cleaver, the National Sales Manager for Thunder Road beer, employed by Elixir. He was not cross-examined.

44 Each of the witnesses who gave evidence in this case did so honestly and their evidence was, in my view, generally reliable. To the extent that there were differences between Mr Withers’s evidence and that of Mr Camilleri regarding the choice of the name ‘Pacific Ale’ and the branding of Thunder Road’s product, I give more weight to Mr Camilleri’s evidence as he appeared to have a clearer recollection of the relevant decisions.

45 Parts of Stone & Wood’s affidavit material were read on a provisional basis, as those parts were responsive to parts of the respondents’ affidavit material which were the subject of objection (which objections had not been ruled on at the time the Stone & Wood witnesses were giving evidence). I have treated this provisional material as not having been read where the paragraph of the respondents’ material to which it responded was not admitted into evidence.

46 At trial, both sides adduced confidential evidence relating to sales. It is not necessary to disclose the confidential evidence in these reasons. To the extent that I refer to evidence about sales, I will refer to it in the same way as it was referred to in open court and in the parties’ submissions, which does not disclose the confidential information.

Factual findings

47 In this section I set out my factual findings based on the affidavit evidence and oral evidence at trial. Where I do not indicate an evidentiary source, the factual finding is based on affidavit material which was unchallenged or propositions which were put to witnesses in cross-examination which they accepted (and thus appear to be uncontentious).

Stone & Wood

48 Stone & Wood operates breweries in the Byron Bay and Murwillumbah areas of New South Wales. It produces a range of beers (both in draught and bottled formats) which it markets and distributes throughout Australia. Mr Cook is a co-founder of Stone & Wood and has been a director of Stone & Wood Group and Stone & Wood Brewing since March 2007, when the companies were formed. He has about 30 years of experience working in brewing companies in Australia; much of his working life has been spent promoting both commercial beers and craft beers.

49 In 2008, the Stone & Wood Brewery brewed its first beer for sale to market – the ‘Draught Ale’. It was given this name because it was originally sold in kegs only. It was re-branded ‘Pacific Ale’ in November 2010, as described below. Stone & Wood launched its second beer, called ‘Pale Lager’, in 2009. That beer was re-branded ‘Lager’ in November 2010 and was re-branded again (in June 2015) to ‘Green Coast’. Over time, the range of products manufactured and sold by Stone & Wood has grown. The four main beer products now produced by Stone & Wood are Pacific Ale, Lager (now Green Coast), Jasper Ale and Golden Ale.

50 Since the brewery was established, sales of Stone & Wood beers have steadily increased and the business has grown as a consequence. Stone & Wood now employs approximately 50 people, including 39 at its breweries in Byron Bay and Murwillumbah. In late 2008, sales were largely limited to the area around the brewery (namely, the Northern Rivers and South East Queensland). In about mid-2009, the brewery launched its products in the Melbourne and Sydney markets. In about mid to late 2010, Stone & Wood began making sales through national accounts, including through Dan Murphy’s, First Choice Liquor and Vintage Cellars (large chains of liquor outlets). Stone & Wood also supplies its beers for sale at independent bottle shops throughout Australia.

51 Stone & Wood sells its products mostly across the eastern seaboard of Australia. The approximate geographical breakdown of sales is currently (and has been since 2010):

(a) Northern Rivers and South East Queensland: 40-45%;

(b) Sydney: 25%;

(c) Melbourne: 20%;

(d) Other parts of Australia: 5-10%.

52 Since about 2009, Stone & Wood has had a significant online and social media presence, through which it promotes its products including the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. The combined total of social media followers and newsletter subscribers is approximately 34,000. In addition to social media, Stone & Wood has also operated a website since about 2008 through which it has promoted its products (including the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale). Between August 2014 and July 2015, the website has averaged approximately 8,200 unique visits each month.

53 Mr Withers accepted during cross-examination that Stone & Wood has and had (at the time of the launch of Thunder Road Pacific Ale) a good name in the craft beer market. I accept this evidence.

Elixir and Thunder Road

54 Elixir commenced its brewing business in 2010. Mr Withers said during cross-examination (and I accept) that his background is in the manufacture of fast-moving consumer goods, including household consumer products such as garbage bags, cling wrap and aluminium foil; he is also involved in the manufacture of gloves and a business in America that makes environmental cleaning products; he has invented a number of products which have been patented; intellectual property is a key driver of the business; and he entered the liquor market with an interest in diversifying the business.

55 The trading name ‘Thunder Road Brewing Company’ was chosen in-house, as a result of a collaborative process. Mr Withers said during cross-examination (and I accept) that the Thor symbol was chosen for the Thunder Road range after the team looked at hundreds of different visuals; he said, “We thought that was a pretty powerful image. … A guardian of quality.” Elixir sells its Thunder Road beer products in both ‘on premise’ and ‘off premise’ channels in Victoria, New South Wales, Western Australia and Tasmania. The ‘on premise’ channels consist of hotels, restaurants, cafes and bars, where the product is sold in both kegs and packaged format. The ‘off premise’ channel includes bottle shops. Through this channel, the Thunder Road beer products are sold in a packaged format. Elixir began manufacturing beer under the Thunder Road name in bottles in 2014 and launched its bottled beer in 2015. The bottled beer is brewed in Belgium. One of the reasons for this is that Elixir does not have a bottling facility in Brunswick.

56 Thunder Road was a major trophy winner at beer awards in 2014 and 2015. It won a gold medal and was a finalist for best Australian-style lager as well as receiving the most medals of any one single brewery. Mr Withers said during cross-examination (and I accept) that Thunder Road has established a good name in the craft beer market in Australia.

57 In addition to the Thunder Road products referred to above, Elixir sells a number of other beers using the Thunder Road logo, including Brunswick Bitter. Elixir also sells another line of beer under the brand name ‘Globe Brewing Company’. Elixir sells some beer directly to consumers in re-usable bottles.

The craft beer market

58 The craft beer market is difficult to define. Mr Kirkegaard in his first affidavit stated that craft beer has come to be regarded by the market as beer which is outside of the traditional mainstream beer category, which comprises primarily pale lagers made by large multinational brewing businesses; the term ‘craft’ tends to describe beers (and brewers) that put greater emphasis on the flavours of a beer’s ingredients and that are made using less industrialised brewing processes. Mr Kirkegaard also stated that, in his experience, craft brewers are often regarded as brewers that are independent of the larger, multinational brewing businesses; however, to some other consumers, a number of the smaller brands which are fully owned by the large brewers, such as James Square (Lion) and Matilda Bay (CUB), can be included in some definitions of craft beer.

59 Mr Kirkegaard stated in his first affidavit that the current craft beer movement in Australia started very slowly, tracing back to the late 1990s; having slowly gained momentum, the craft beer movement has grown quickly and substantially over the last two to three years, with a wider range of venues opening specifically to offer craft beer; consumer awareness and demand for the beer has grown dramatically.

60 Mr Kirkegaard accepted during cross-examination that ‘craft beer’ is a “kind of shorthand for a boutique-style beer”. He added that, “You could spend a considerable period of time discussing exactly what it means”. He accepted that it is a premium product. He said the breweries tend to be smaller breweries. He also said that recently the number of such breweries in Australia has reached the hundreds, as craft beer has become more popular; craft beers are to be contrasted with mainstream beers, such as Carlton & United; mainstream beers include mainstream premium beers.

61 Mr Kirkegaard also said during cross-examination that most of the ‘imported’ beers are in fact brewed under licence in Australia these days. He said that there are a large number of such beers that would be called craft beers.

62 In his first affidavit, Mr Kirkegaard said that, in his experience, the sudden growth of craft beer over recent years has largely been driven by two broad groups.

(a) The first comprises younger consumers looking to drink something different from the generic lagers. These consumers are often well informed about the products and could be described as ‘involved’ consumers.

(b) The second is a more general group of beer consumers. In Mr Kirkegaard’s experience, these consumers are looking for a premium (perhaps ‘boutique’) experience, but have less interest in, or understanding of, the issues relating to craft beer. These consumers are less likely to research brewery ownership and brewing practices and more likely to rely on a brewery’s marketing and brand image to form their view of whether a beer is ‘craft’ or satisfies their “non-flavour demands”. This part of the consumer base for craft beers has grown considerably as craft beers have become more widely available alongside mainstream beers.

During cross-examination, Mr Kirkegaard accepted that the first group he had described were “very much in tune with … what’s called the Brewery Story”. With respect to the second group, Mr Kirkegaard said during cross-examination that they “can be swayed by what they read on the bottle” and are quite willing to make purchasing decisions based on this. He believed this group “would be people who would look at the bottle carefully and would look at the packaging”. He accepted that these consumers were looking for a premium experience and that this “means they’re engaged in a thought process of trying to select a premium product”.

63 In his first affidavit, Mr Kirkegaard said that, in his experience, many consumers of craft beer are not only motivated by how the beer tastes; they are interested in what a brand promises in terms of independence, local production, small batch production and other ancillary aspects of the brand. In this context, ancillary aspects of the brand are marketing features that target personal preferences, but do not relate to how the beer actually tastes. In craft beer, many consumers are drawn to the independence of small breweries (and the stories behind them), being small local companies, or their ‘anti-establishment’ attitudes. During cross-examination, Mr Kirkegaard accepted that Stone & Wood communicates a brand promise, which was “[v]ery much from the northern rivers of New South Wales, very laidback lifestyle, very plugged into the community”.

64 Mr Kirkegaard said during cross-examination that, while it is very hard to pigeonhole craft beer consumers, they tend to be willing to spend more than the mainstream beer consumer. He also said that:

… particularly in the craft beer sphere, people tend to be very experimental and they will – if they like a particular class or style or flavour profile of beer, the brand isn’t necessarily what they’re buying for. They’re buying to experience others in that style.

65 Mr Withers said during cross-examination that the craft beer market constitutes four to five per cent of the total beer market in Australia. He said that the value of the beer market is $5.9 billion and the value of the craft beer market, depending on how you define it, is approximately $160 to $200 million. He also said it was growing steadily, from a low base.

66 I accept the evidence of Mr Kirkegaard as set out in paragraphs [58]-[64] above. There was no real challenge to this evidence by the respondents; indeed, parts of this evidence were embraced by the respondents in their submissions. Mr Kirkegaard’s description of the craft beer market and the different broad groups of consumers of craft beer provides important context in which to consider the legal issues that arise in this case. I also accept the evidence of Mr Withers set out in paragraph [65] above.

Stone & Wood Pacific Ale

67 As noted above, in November 2010, Stone & Wood re-named Draught Ale as ‘Pacific Ale’; Stone & Wood decided to change the name when it started to sell this beer in bottles – it seemed odd for a beer named ‘draught’ to be available in that format. At the time it was launched, the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale was the only beer sold in Australia named ‘Pacific Ale’.

68 The description of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale on the label on the side of the bottle reads:

Born and raised in Byron Bay, Stone & Wood take a fresh approach to brewing handcrafted beer in the Northern Rivers of NSW, one of the greatest places on earth. Inspired by our home on the edge of the Pacific Ocean and brewed using all Australian barley, wheat and Galaxy hops, Pacific Ale is cloudy and golden with a big fruity aroma and a refreshing finish.

69 Mr Cook in his first affidavit stated that, based on his experience in the brewing industry, the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale is a distinctive beer; it is cloudy and golden with a big fruity aroma and a refreshing finish. He also stated that it is brewed using Australian wheat, barley and Galaxy hops (which are grown in Tasmania and north east Victoria).

70 Mr Kirkegaard in his first affidavit said that, when it was released as ‘Draught Ale’, what is now known as Stone & Wood Pacific Ale was, in his view, a distinctive beer and significantly different from other beers on the market. He described the character of the beer in the following way in paragraph 63 of his first affidavit:

The Stone & Wood Pacific Ale incorporated a bursting hop aroma of tropical fruit more commonly experienced in beer styles such as American Pale Ale or India Pale Ale, but over a much lighter, crisper body more closely associated with an Australian Pale Ale. The hop aroma was very distinctive, showcasing the signature passionfruit and lychee notes of Galaxy hops but in a much bolder manner than other beers that had used that variety of hops.

71 Mr Cook said in his first affidavit (and I accept) that Stone & Wood chose the name ‘Pacific Ale’ for its product for two reasons. First, one of the Stone & Wood breweries is located in Byron Bay (the only Stone & Wood brewery that was in operation in 2010), which is the most easterly part of Australia and is situated on the Pacific Ocean; the story behind the brewery, including its location, is very important to the overall Stone & Wood brand, and the name ‘Pacific Ale’ is a reflection of that. Secondly, the use of the word ‘Pacific’ in the name was also designed to generate a calming, cooling emotional response in consumers, consistent with the idea behind (and flavour of) the Pacific Ale product. Mr Cook said during cross-examination (and I accept) that from his experience in marketing and promoting beer, he understood the importance of emotional branding as a marketing tool, which he regarded as considerable. In cross-examination, Mr Cook accepted that he wanted consumers to be aware of the story of the brewery, and that the brewery would be known to consumers as Stone & Wood.

72 In an article on Stone & Wood’s website entitled, “What’s in a Name?” and dated 30 November 2010, the change in name from Drought Ale to Pacific Ale was explained as follows:

Back in November 2008 when we proudly rolled out our first brew we were hell bent on keeping things simple. Brewed to no existing style, our cloudy, dry hopped ale was to be a draught only beer. We didn’t want to give it some crazy quirky critter name, we just called it what it was, an ale drawn fresh from the tank and available only on draught – so Draught Ale it was.

Over the next year and a half or so of pumping out the hoppy goodness we were constantly asked to have our Draught Ale available in bottles. Rolling out a Draught Ale in bottles seemed a bit weird but hey, we had a whole bunch of people who knew the beer as Draught Ale, so the same beer out of the tank was put into kegs and bottles and away we went.

On another angle, ever since we launched our ale, people have continually been asking us, “what style of beer is it?”

As independently minded brewers we don’t want to be limited to brewing beers from an existing style register. There is nothing stopping brewers from developing new approaches, and using new ingredients to create new styles of beer that don’t fit the strict criteria of traditional beer styles. That’s the mindset that drives our approach to brewing, and its what led us to develop our ale.

After a couple of years of living and brewing in this little town and watching people enjoying our Draught Ale here and afar, we are convinced that it has developed its own style, its own special place in the small beer world. So we have changed the name of our Draught Ale but the beer remains the same.

Our ale deserves a name that speaks to where it is created, its home, a name that helps it establish its own place and its own beer style. The answer has been staring us in the face all along. It’s now called Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

Inspired by our home on the edge of the Pacific Ocean and brewed using all Australian barley, wheat and Galaxy hops, Pacific Ale is cloudy and golden with a big fruity aroma and a refreshing finish.

So when someone asks us “what style of beer is it?”, we will simply say it’s a Pacific Ale.

73 On 3 December 2010, “Australian Brews News”, an online publication, published an article by Mr Kirkegaard titled, “A rose by any other name”. The article quoted Mr Cook in relation to the change in name from Draught Ale to Pacific Ale; his statements were to similar effect as the article on the Stone & Wood website set out above. Statements to similar effect were also made by Mr Cook as quoted in an article in “The Crafty Pint” dated 29 November 2010.

74 Mr Kirkegaard was asked during cross-examination whether ‘Pacific’ was an apt descriptor for Stone & Wood’s ale product. He answered, “It’s an apt descriptor for where the brewery is located, I guess”.

75 Stone & Wood Pacific Ale is sold both in bottles and in kegs (that is, as draught beer). There are two bottle sizes, 330 ml and 500 ml. Bottle sales have been predominantly of the 330 ml size.

76 Since November 2010, Stone & Wood has promoted and sold the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale as shown in paragraphs [4], [5] and [6] above. The branding has remained largely unchanged during this period. Some minor changes were made to the packaging and labelling of the product in 2013, but those changes did not impact the overall appearance of the product.

77 During cross-examination it was put to Mr Cook, but he did not accept, that the use of a mustard colour on the label for the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale “creates a kind of traditional look”; that the copper look of the lid was designed to create a “rather traditional look around the bottle”; and that the use of the symbol ‘&’ rather than the word ‘and’ was designed to “give a sense of establishment or tradition around the branding Stone & Wood”. Mr Cook did not accept the proposition that the way the ‘&’ passes through the two Os of ‘wood’ looks like a very established brand, and said that the ampersand was “designed to hook the three Os together in the way there were three founders”.

78 Mr Cook accepted during cross-examination that the way in which the words ‘Pacific Ale’ and ‘Handcrafted’ appear on the bottle of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale is consistent with the way in which Stone & Wood refers to the other beer products in its range. He was taken to the image which is reproduced in paragraph [28] above and accepted that the way in which ‘Pacific Ale’ is presented on the label of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale is typical of the way in which Stone & Wood presents the reference to the type of beer on its other products. He said that the same branding is used on Jasper Ale and Garden Ale.

79 Mr Cook was asked during cross-examination what the reference to ‘handcrafted’ meant and answered that “it evokes an imagery in people’s minds that the beer is carefully manufactured, carefully brewed”. He accepted that in reality the beer is produced using modern machines with skilled staff who work the machines.

80 Stone & Wood has received several awards for the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, both in Australia and internationally.

81 Stone & Wood Group is the registered owner of Australian Trade Mark number 1395188 in class 32 in respect of beer for the mark set out in paragraph [9] above.

82 On the basis of the facts and evidence set out in paragraphs [67]-[81] and my own observations of the bottles, packaging and decal which were in evidence as physical exhibits, I make the following findings in relation to the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale:

(a) I accept the evidence of Mr Cook, supported by Mr Kirkegaard’s description, that the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale is cloudy and golden with a big fruity aroma and a refreshing finish. I accept that it is brewed using Australian wheat, barley and Galaxy hops (which are grown in Tasmania and north east Victoria) – these matters did not appear to be contentious. I accept the evidence of Mr Cook and Mr Kirkegaard that, when it was launched, the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale had a distinctive character.

(b) I accept that the word ‘Pacific’ was chosen because of the location of the Stone & Wood brewery and to generate a “calming, cooling emotional response”.

(c) Based on my observation, the dominant feature of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale bottle is the Stone & Wood logo. The name ‘Pacific Ale’ is much smaller and occupies a subsidiary position. The same is true of the packaging for the six-pack and the decal for the beer taps. The dominant colour on the bottle label is the background colour. In my view, this colour is aptly described as a mustard colour (which may be considered to be a type of orange). The same or a similar colour is used on the six-pack packaging and the decal.

(d) The format of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale bottle is the same as for the other main beers in the Stone & Wood range, namely, Lager (now Green Coast), Jasper Ale and Golden Ale (the format is indicated by the image in paragraph [28] above). In each case, the dominant feature is the Stone & Wood brand and the name of the product appears in smaller print underneath the logo.

Stone & Wood Pacific Ale sales

83 In the 2014-2015 financial year, Stone & Wood sold in excess of 45,000 kegs, 200,000 cartons of 24 x 330 ml bottles and 22,000 cartons of 12 x 500 ml bottles of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

84 There was confidential evidence comprising the sales figures for Stone & Wood Pacific Ale for the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 financial years (CB 1038, 1039) and the aggregate sales of Draught Ale and Pacific Ale to date (Ex A9). Without disclosing confidential material, it is possible to say that Stone & Wood’s sales of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale are substantial and have increased significantly in recent years.

85 Mr Cook said in cross-examination (and I accept) that the bottled product has represented about half, or a little more than half, of the sales of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale; and that sales of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale represent and have represented between about 80 and 85 per cent of Stone & Wood’s total sales.

Stone & Wood Pacific Ale marketing

86 Mr Cook gave evidence in his first affidavit that, since its establishment, Stone & Wood has promoted its products (including Stone & Wood Pacific Ale) throughout Australia. During cross-examination, Mr Cook gave the following further evidence: the expenditure on communications is primarily for advertising; this includes advertising in magazines and on websites; Stone & Wood also attends consumer beer festivals at which it provides free tastings; and Stone & Wood supports local charities in the Byron Bay area through a community donation program and sponsors events such as the Mullumbimby music festival and surfing events. Mr Cook accepted in cross-examination that a “strong portion” of the sponsorship expenditure related to the Byron Bay area. He also accepted in cross-examination that all of the marketing activity is conducted by reference to the Stone & Wood brand. Mr Cook was taken during cross-examination to an advertisement in the “Echo”, the local newspaper in Byron. He accepted that the advertisement was primarily an advertisement for Stone & Wood (although the product depicted in the advertisement is Stone & Wood Pacific Ale).

87 Mr Cook was taken in cross-examination to posters showing a glass of beer, with the words ‘Stone & Wood’ on the glass and a circle with the text, “$5 Pacific Ale”. He said that these posters were for promotion in bars, and that they could be posted in the bar or on tables. He said that the posters promoted “both our primary brewer brand and our secondary beer brand”. He was also taken to an image called a “bottle shop screen”, showing two bottles of beer, the Stone & Wood Lager and the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. Mr Cook said that these images were of packaging which highlights “our parent brand and our sub-brand”. In response to a further question about this image, Mr Cook accepted that the word ‘lager’ was being used as a style not a brand.

88 Mr Cook was taken during cross-examination to a picture of a “venue blackboard” from a bar in Melbourne, in 2013, which was annexed to his affidavit. The blackboard referred to Thunder Road Pacific Ale and then, a few rows below, to Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. He accepted that it was clear that the customer was being told that there was a brand of beer sold under the name Thunder Road and there was a brand of beer being sold under the name Stone & Wood.

89 Mr Cook was taken during cross-examination to some photographs annexed to his affidavit of the set-up for certain events, such as a food festival event. The boards for these events had the name ‘Stone & Wood’ at the top of the board and then listed various products beneath this. Mr Cook accepted that Stone & Wood promoted the brands or products “by reference to the brand Stone & Wood in quite a distinctive way”.

90 In paragraph 58 of his first affidavit, Mr Cook estimated that the total reach at all of the festivals and major events attended by Stone & Wood since 2009 would be in excess of 1.1 million visitors. He accepted during cross-examination that the calculation was based on figures told to him by others or obtained from a website. He accepted that there was no evidence of the visual displays at the festivals and that the displays may have been different at each place and from year to year.

91 On the basis of the evidence referred to in paragraphs [80], [83]-[85] and [86]-[90] above, I find that the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale has, and had (in January 2015), a substantial reputation in the craft beer market. In relation to Stone & Wood’s marketing activities, on the basis of the evidence referred to in paragraphs [86]-[90] above, I find that Stone & Wood undertakes marketing activities for the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale in Australia generally; that the ‘Stone & Wood’ brand name is a significant focus of these activities; and that the words ‘Pacific Ale’ appear in conjunction with ‘Stone & Wood’ (rather than on their own) in almost all cases.

Thunder Road Pacific Ale

92 In about January 2015, Elixir launched the Thunder Road Pacific Ale in the bottled format. Later, in about May 2015, Elixir launched the keg format of the beer, but as ‘Thunder Road Pacific’ (see below). From about September/October 2015, Elixir started selling the bottled format of the beer as ‘Thunder Road Pacific’ (see below).

93 Thunder Road Pacific Ale formed part of Thunder Road’s ‘double fermentation’ series of beer. The series comprises products referred to as Golden, Pale Ale, Amber, IPA, Pilsner and Pacific Ale: see the image in paragraph [31](d) above. The Pacific Ale was the last to be added to the series.

94 The label on the back of the bottle of the Thunder Road Pacific Ale describes the beer as follows:

Thunder Road Pacific Ale is designed with thirst crunching drinkability in mind. An uplifting aroma of passionfruit from Australian Galaxy hops leads into a mild bitterness. We use two rare yeast strains in our double fermentation process for more flavour and stability. …

95 Mr Withers said in his first affidavit that the Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific is a light bodied beer made from Australian Galaxy hops and is characterised by a distinct hop aroma, with pineapple, passionfruit and citrus notes.

96 Mr Piperno (who, as noted above, owned two liquor stores which specialised in craft beer and specialty wines) gave evidence during cross-examination about the characteristics of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and Thunder Road Pacific Ale. He said that “this whole new craft beer segment, … whether it’s a Golden Ale, Bright Ale or Summer Ale, Pacific Ale, they tend to have the same characteristics like … jam-packed full of passionfruit, tropical flavours, melon, grapefruit. … It’s really, really hard to distinguish one from another, from my perspective”. He said that the “taste profile” of the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and the Thunder Road Pacific Ale were probably identical. He said that, insofar as the taste and aroma are concerned, they are “[p]retty much the same”.

97 In his first affidavit, Mr Withers said that he selected the name ‘Pacific Ale’ because the terms ‘Pacific Ale’ and ‘Pacific’ are used: (a) as a geographical indicator, to reinforce the Australian/Pacific roots of Elixir; (b) to describe the style of beer being offered for sale, namely, a beer with an “uplifting aroma of passionfruit from Australian galaxy hops” (as explained on the bottles of Thunder Road Pacific Ale / Thunder Road Pacific); and (c) because he was aware that some American breweries were describing their beers with new fruity Australian hops (such as galaxy hops) as pacific ale styles (eg, Sweet As Pacific Ale). Mr Withers said in his first affidavit that before Elixir commenced any use of the terms ‘Pacific Ale’ or ‘Pacific’, he was keen to ensure that using the name Pacific was not going to cause any confusion in the market place with Stone & Wood’s beer; that the Thunder Road brand is a successful brand in its own right and he had no desire for it to be associated with a competitor; he asked Colin Paige, who was at the time Head Brewer for Elixir and is now Head of Production for Stone & Wood, to confirm that it was acceptable to use ‘Pacific Ale’ as a descriptor of a style of beer; Mr Paige sent an email to Mr Withers on 26 August 2014 which stated in its subject header, “Pacific ale = style” and stated in the body of the email (below a link) that, “One of the founders admitting Pacific Ale is a style”; Mr Withers understood the reference to “one of the founders” to mean one of the founders of Stone & Wood; the link was to an article by Mr Kirkegaard in “Australian Brews News” dated 3 December 2010. (The article is described in paragraph [73] above.) The respondents contend that an adverse inference (Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298) should be drawn from the failure of Stone & Wood to call Mr Paige to given evidence. However, I do not think an adverse inference is to be drawn from the failure to call Mr Paige. The position is complicated because Mr Paige used to work for Elixir but now works for Stone & Wood. In these circumstances, I do not think it can be assumed that Mr Paige would divulge to Stone & Wood matters pertaining to his previous employment. One of the circumstances in which an adverse inference is not to be drawn is where the party “may not be sufficiently aware of what the witness would say to warrant the inference that, in the relevant sense, he feared to call him”: Fabre v Arenales (1992) 27 NSWLR 437 at 449-450 per Mahoney JA, Priestley and Sheller JJA concurring; Heydon JD, Cross on Evidence (10th ed, LexisNexis Butterworths, 2015), [1215]. Further and in any event, the email speaks for itself and thus it was unnecessary for Stone & Wood to call Mr Paige.

98 Mr Withers accepted during cross-examination that at the time Elixir launched the Thunder Road Pacific Ale, he knew about the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. He said that he knew Stone & Wood were very visible in the market place, but he did not know what level of success they had achieved. He said he thought they were a medium-sized player in the craft beer market. Mr Withers said during cross-examination that he did not know that Pacific Ale was “by far and away the most popular” of the Stone & Wood beers. He accepted that he knew it was a successful beer.

99 The label on the bottle and the packaging for the Thunder Road Pacific Ale use green, orange and beige colours. The format follows the same design as the other bottles in the ‘double fermentation’ series. Green is the colour used for the Thunder Road brand generally. Mr Withers said in cross-examination that the bright green colour was used because it was a unique colour, which distinguished the brand from other beer brands, and because it was “a green that symbolises what we represent, which is high quality freshness”. He said the beige colour (which is used in relation to the ‘double fermentation’ series generally) “gives it that craft aspect”. In addition, each product in the series has a particular colour.

100 Mr Eletheriadis was retained by Elixir to design the labelling and packaging for the ‘double fermentation’ series except Pacific Ale. He stated in his affidavit that, apart from the company’s signature green colour, the main purpose of the colours used in the design was to differentiate between the beer varieties within the range of beer in the ‘double fermentation’ series; each beer variety was assigned a different colour; each colour was also intended to match the flavour of the beer. His evidence was unchallenged and I accept it.

101 Mr Morton was retained by Elixir to design the labelling and packaging for the Thunder Road Pacific Ale, using the style guidelines created by Mr Eleftheriadis for the ‘double fermentation’ series. Mr Morton stated in his affidavit that he was asked by Mr Camilleri only to change the descriptor that appeared on the label and packaging to ‘Pacific Ale’ and to change the colour to orange; and that the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and its colours were not mentioned by Mr Camilleri when he briefed him to carry out this work. Mr Morton’s evidence was unchallenged and I accept it.

102 Mr Withers was asked questions during cross-examination about the choice of the colour orange in the get-up for Thunder Road Pacific Ale. He accepted that other colours can be used to identify something that is tropical or has passionfruit, pineapple and citrus notes. In response to a question about why purple, for example, had not been chosen, Mr Withers said that purple does not relate to the flavour profile – pineapple, citrus, passionfruit – and does not have a tropical connotation. Mr Withers during cross-examination described the Thunder Road Pacific Ale colour as “fluoro orange”. It was put to Mr Withers during cross-examination that the colours of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale and Thunder Road Pacific Ale look similar and that he chose the same colours (orange and green) as Stone & Wood Pacific Ale because he knew that these things can operate as a hook for consumers. He rejected this.

103 Mr Withers was taken during cross-examination to an image of the packaging, the bottles and the six-pack for the Thunder Road Pacific Ale. He agreed with the proposition that ‘Pacific Ale’ is very prominent on the packaging. It was put to him that this was the ‘hook’ for the consumer; he responded that it is the descriptor. He said that the total get-up was designed to be a fifty-fifty split between the ‘Thunder Road’ and ‘Pacific Ale’. In reference to the bottle, he said “there’s clearly a strong Pacific Ale and there’s clearly a strong Thor”. Mr Withers accepted during cross-examination that at the time Elixir launched the Thunder Road Pacific Ale, the Pacific Ale style had come to be closely associated with Stone & Wood as a style. It was put to him that Elixir had emphasised the word ‘Pacific’ in its decal, its marketing on the packaging and on the bottles, because Mr Withers knew that Stone & Wood had established a good name in respect of the Pacific Ale style. He rejected this and said: “We are promoting a style of beer from Thunder Road. The entire range is about Thunder Road with a descriptor of styles. ... One of those is a Pacific Ale”. Mr Withers rejected the proposition that he knew that ‘Pacific Ale’ was an important name for consumers because they associated it with the Stone & Wood Pacific Ale.

104 It was put to Mr Withers during cross-examination that his evidence that the Australian/Pacific roots of Elixir were a reason the name ‘Pacific’ was chosen, was inconsistent with the bottled beer being produced in Belgium. He responded that “this is a Australian style beer from an Australian brewery and we brew on the basis of our philosophy, as is shown in the label[,] Beers Without Borders, wherever it’s best. Just as Stella brews a Belgium [lager] in Melbourne. So we’re promoting … Thunder Road’s Australian roots. … All our beers have Australian hops in them.” It was put to Mr Withers that the reason the word ‘Pacific’ was chosen was not because he wanted the consumer to draw a link between the product and Galaxy hops. He responded that the recipe with Galaxy hops was up to the brewers; they identified the new, emerging style, Pacific Ale; and they said, “You need to have one of these new beers, they’re getting very popular all over the world and it’s highlighting a new style of hops”. Mr Withers said:

… I didn’t disagree with them [the brewers] that we needed, in addition to the classical beer styles, new emerging beer styles, because, at the end of the day, that’s what craft beer is all about, is, you know, bringing out to the market new and exciting things, new evolving beer styles that are coming out all the time.

105 The following exchange took place between senior counsel for Stone & Wood and Mr Withers during cross-examination in relation to the choice of the name ‘Pacific Ale’:

And because you thought it was highly descriptive, what I want to suggest to you is you were happy to springboard off Stone & Wood’s reputation that it [had] built up in the market place in connection with Pacific Ale; what do you say?---Well, I – I say that we’re promoting a beer style in a … typical way that will attract craft beer consumers to a new type of beer that, not only we wanted to – to launch, but others were doing so.

But you knew it was advantageous for you that Stone & Wood had done the hard work and developed the name “Pacific Ale” in the market place?---No. No.

You deny that, do you?---I … deny that Stone & Wood was referenced in any significant way in the decision to launch [an] additional style … called “Pacific Ale.”

106 It was put to Mr Withers during cross-examination that he “chose the Pacific Ale name to suggest an association with Stone & Wood Pacific Ale”. He rejected that proposition. It was also put to him that “you chose the name Pacific Ale, because you wanted to fast-track the sale of your Thunder Road Pacific Ale beer jumping on Stone & Wood’s good name in connection with that beer”. He also rejected that proposition.

107 Mr Camilleri said in his affidavit and during cross-examination that when Elixir released the Pacific Ale product, he was aware that Stone & Wood was producing a Pacific Ale. Mr Camilleri accepted during cross-examination that, at the time of the launch of Thunder Road’s product, he knew that there were a lot of consumers in the craft beer market who, when they saw the name Stone & Wood, would think of Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. In accepting this proposition, Mr Camilleri noted that the Pacific Ale had “more distribution” than Stone & Wood’s other products. Mr Camilleri accepted that, at the time Thunder Road launched its Pacific Ale, the only company selling beer in Australia under the name ‘Pacific Ale’ was Stone & Wood. He said that there were other Pacific Ales around the world.

108 Mr Camilleri said in his affidavit that, in developing the colours, labels and packaging for Thunder Road Pacific Ale no regard was had to Stone & Wood Pacific Ale, except to ensure that Thunder Road Pacific Ale did not have any similarities in appearance to Stone & Wood Pacific Ale. He accepted during cross-examination that he had seen Stone & Wood’s packaging, branding styles and colours. He said that the Stone & Wood colours were an olive green and a mustard colour. He said that Thunder Road’s shades were different. He was asked why orange was chosen and said: “When we developed the double-fermentation range, Pacific was one of the last of the styles that we developed and we had, more or less, gone through the colour palette”. He also said that they were “looking for something that was going to communicate a refreshing, fruity, sort of, flavour” and hence they decided on “this particular vibrant orange”.

109 Mr Camilleri accepted during cross-examination that at the time Elixir launched Thunder Road Pacific Ale, the name ‘Pacific Ale’ was unique to the beer produced by Stone & Wood in Australia; that the name ‘Pacific Ale’ had come to be very closely associated with Stone & Wood in Australia; and that he knew that Stone & Wood Pacific Ale had a good reputation in the craft beer market. He also said that he thought consumers had become familiar with the style ‘Pacific Ale’ through Stone & Wood, and recognised it as a different style of beer; “there was some recognition that this was a new and emerging style”. Mr Camilleri rejected the proposition that he was seeking to use “clever marketing” to “springboard” off Stone & Wood Pacific Ale’s reputation. The following exchange took place between senior counsel for Stone & Wood and Mr Camilleri during cross-examination:

Do you think there’s any possibility consumers might think that Thunder Road is selling its ale, its Pacific Ale, in collaboration with Stone & Wood?---None whatsoever.

Why?---Because they look completely different, and there’s not one mention of Stone & Wood on any of our packaging.

110 On 6 May 2015, Mr Kirkegaard sent an email to Mr Withers headed, “Trade marks”. The email stated:

Hope you’re well. I saw the new labels – very sharp! I was surprised to see a “Pacific Ale” amongst the range though…apart from Stone & Wood’s trademark application, don’t you consider that it’s clearly identified with their brewery? Given your history of trademark battles, I am surprised you have chosen this name…

111 Mr Withers asked Terry Alberstein, who was assisting Elixir in relation to social media, to respond to the email. On 7 May 2015, Mr Alberstein sent the following email to Mr Kirkegaard:

Hi Matt –

Please note our response below and please feel free to quote me as communications director if you are working on a piece by any chance. Thanks and might give you a call to discuss in more detail. Cheers.

Terry