FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

TICA Default Tenancy Control Pty Ltd v Datakatch Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 815

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties bring in orders giving effect to these reasons by Friday, 29 July 2016.

2. The matter be stood over for further directions on Tuesday, 9 August 2016 at 9.30am.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

1 For many years now Mr Philip Nounnis has conducted a business providing information to interested persons about tenants, such as whether they have defaulted on prior leases and what applications for previous tenancies they have made. This business has been conducted by him through various corporate entities, the most recent of which is, and has been since 1999, the present applicant (‘TICA’).

2 TICA’s business is conducted online via a website, and is provided to members who pay a yearly fee. Most of these members are real estate agencies. The service is also provided to members of the public who pay a one-off fee.

3 This case is chiefly about the software and databases which together underpin and constitute TICA’s website service. The claim is one of industrial theft. In the period between 26 March 2014 and 21 August 2014, three of TICA’s staff departed its employ. The first of these was Mr Anthony Nounnis, the son of Mr Philip Nounnis. Mr Nounnis Jnr was, at most material times, a director of TICA and was, on his evidence, ‘involved in all aspects of its business’. He departed TICA on or around 26 March 2014 following an irretrievable breakdown in the relationship with his father.

4 The second was Mr Nathan Portelli, who commenced working for TICA in September 2011 as a sales manager. He resigned on 11 August 2014.

5 The third former employee is Mr Reginald Joshua. He had two periods of engagement at TICA. The first was between around mid-1998 and 2003 (although for an early part of this period he was employed by one of TICA’s corporate predecessors, Tenancy Information Centre Australasia Holdings Pty Ltd). Mr Nounnis Snr says that Mr Joshua was hired at this time as the general manager of the business. In 2003, Mr Joshua left TICA, but he returned to it in 2009 although not, this time, as its employed general manager but instead as a contractor with a similar function on a full time basis. One issue which arises later in these reasons concerns Mr Joshua’s level of expertise as a computer programmer. For that purpose, it is useful to know that he studied for a Bachelor of Commerce for five years at the University of Western Sydney, majoring in Computer Information Systems but did not complete the degree because he left in his final year to set up his own business. Also relevant in that regard is his evidence that in the interregnum between 2003 and 2009, when he was not employed in Mr Nounnis Snr’s businesses, he acquired a detailed understanding of software programming, including code such as PHP (which features later in these reasons). Mr Joshua’s engagement as general manager was terminated by Mr Nounnis Snr on 21 August 2014 because Mr Nounnis Snr no longer trusted him.

6 Not long after, on 18 September 2014, a company called Datakatch Pty Ltd (‘Datakatch’) was incorporated. The shareholders were Mrs Elesha Nounnis (Mr Nounnis Jnr’s wife), Mr Joshua and Mr Portelli. Mr Joshua was the sole director and secretary.

7 Each of Datakatch, Mr Nounnis Jnr, Mr Joshua and Mr Portelli is a respondent to the current suit. The role of the fifth respondent, Datakatch International Pty Ltd, was not substantially explained in the evidence.

8 It is not in dispute that after September 2014, Datakatch took steps to develop a tenancy information business of its own under the name Datakatch. According to Mr Nounnis Jnr, he and Mr Joshua worked closely together to design the ‘look and feel’ of the Datakatch system in the period between September and November 2014, working apparently every day for three months. Mr Joshua was said to have done the computer programming, whilst Mr Nounnis Jnr had assisted with the design of the user interface.

9 The primary dispute between the parties is this: TICA alleges that Datakatch’s ‘system’ has been copied by it from TICA’s own system. Datakatch says this is not so and that the Datakatch system was written by Mr Joshua. The way the case is put, each of Mr Joshua, Mr Nounnis Jnr, Mr Portelli and Datakatch itself are said either to have done the copying or to have been involved in it.

10 This alleged copying by Datakatch is alleged to have involved both an infringement of the copyright owned by TICA in the TICA system, and also a misuse of its confidential information. In final address, it was accepted by Mr Smark SC, who appeared for TICA, that the confidential information claim was a subset of the copyright infringement case, at least at a factual level. The respondents’ primary defence was that there had been no copying by Datakatch or any other respondent of the TICA system, which had been written by Mr Joshua with Mr Nounnis Jnr. There was thus no infringement of copyright, and no taking of confidential information. Alternatively, the respondents denied that TICA owned the copyright in the TICA system. This contention turned largely on the identity of the employer of the author of the TICA system, an independent computer programmer, Mr Michael McCoy. This issue was complicated by the fact that the TICA system had been written over an extended period of time, and was subject to frequent revision. It was further complicated because the business being conducted by Mr Nounnis Snr was manifested through several corporate entities, because Mr Nounnis Snr was bankrupt for some of the time, and because some effort seems to have been made to keep the TICA system, qua asset, away from potential claims by creditors.

11 So far as the confidential information case was concerned the respondents did not accept that each element of the information relied upon was in fact ‘owned’ by TICA. In relation to some of it, the respondents submitted that it had been obtained by them quite legitimately, and certainly not from TICA.

12 A final part of the case turned upon allegations that Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr had breached various duties owed to TICA, arising from their positions at it, by copying the TICA system. Essentially, this was a rehearsal of the arguments just described. There was, however, a distinct variant of it. This variant turned upon a letter signed on TICA’s behalf by Mr Nounnis Jnr which granted Mr Joshua permission to work for other clients apart from TICA. The letter was dated 10 May 2012. It had been apparently prepared by Mr Joshua for Mr Nounnis Jnr’s signature. This was alleged by TICA to have involved a breach of fiduciary duty to the extent that it authorised Mr Joshua to set up Datakatch. The respondents denied that this was the effect of the letter.

13 These reasons are set out as follows:

1. Introduction

2. Did the respondents take the TICA system?

3. Copyright Infringement

4. The Confidential Information Claim

5. The Claim for Breach of Fiduciary and Related Duties

6. Mr Portelli and Datakatch International Pty Ltd

7. The Amendment Application

8. Conclusions

2. Did the respondents take the TICA system?

14 There are a number of issues calling for resolution under this heading. They are:

(a) What is the TICA system?

(b) What is TICA’s pleaded case?

(c) How TICA’s case was actually run – a case of circumstantial evidence;

(d) The elements of the circumstantial case:

(i) copying of TICA’s source code;

(ii) similarities in the schema of the Datakatch databases and those of TICA;

(iii) similarities in the stylesheets;

(iv) the presence of unique elements in both sets of databases;

(v) usernames and passwords;

(vi) the taking of the back-up CDs;

(vii) the letter of 10 May 2012; and

(viii) other matters.

(e) Has the circumstantial case been proved?

15 It is convenient to start with the TICA system.

16 I return below, when dealing with the question of whether TICA owned the copyright in some or all of the TICA system, to describe in more detail the various stages in the historical development of the TICA system. For present purposes, it is not necessary to dwell on that detail, and it is sufficient to describe in broad terms what the TICA system presently is.

17 At the highest level of generality, TICA runs its business through a web interface which is accessed by its customers. The software which runs the web interface has two distinct components. The first of these is the program which runs the outward appearance of the web interface which customers see. It mediates the relationship between the customer and the underlying databases which TICA maintain in relation to tenants. The second element of the software is an administration module, which is visible only at TICA’s end. It provides a control console which permits TICA to administer the website, the customers’ accounts and, to the extent necessary, the underlying databases themselves.

18 It will be apparent, therefore, that the TICA system has three components:

the user interface;

the administration console; and

the underlying databases.

19 The nature and content of these three elements has varied substantially over time although, with some minor exceptions, their designer has generally been Mr McCoy, the computer programmer referred to above. The first two components are programs written in a variety of source codes. The databases are currently maintained as MySQL databases (although at earlier times different formats were used).

20 To foreshadow some of the issues which lie ahead in respect of the copyright infringement claim, it is said that copyright subsists in the software constituting the user interface and the administration module. It is not claimed that copyright subsists in the contents of the various databases, but it is said that what was referred to as the schema of those databases (i.e. their layout) is a work in which copyright does subsist. The contents of the databases, despite not being alleged to be subject to copyright, are alleged to contain confidential information.

21 It is then useful to examine the various ways that TICA has advanced its case for, as will appear, there was a difference between its case as pleaded and its case as pursued. Nor is this to be thought merely a question of idle historical curiosity. One of the complaints made by TICA’s expert related to the degree of access he was given to Datakatch’s system for the purposes of preparing his report on whether it had been copied from TICA’s system. As will be seen, the extent of the access he was given was very much driven by the nature of the case as it was pleaded.

(b) What was TICA’s pleaded case?

22 It is a common enough feature of litigation of the present kind, where one firm alleges that another has stolen its programs or databases that the moving party may not know with any precision what it is that the defending party has actually done. This difficulty afflicted TICA in the present case as its pleading shows.

23 The version of the pleading which was before the Court at trial was the Further Amended Statement of Claim (the ‘FASOC’). It began with a general allegation contained at paragraph 12 that Datakatch had replicated the ‘TICA Business’ in various ways. The ‘TICA Business’ was defined in paragraph 1 to be the business of operating in Australia a national residential tenancy online history database. The various ways in which this business was said to have been replicated by Datakatch related to the offering for sale from its website of six specified services. These were set out in paragraphs 12(a)(i)-(vi) as follows:

(i) Profile Checks Analyser, which is a replication of the Applicant’s Enquiry Database;

(ii) Tenancy Database, which is a replication of the Applicant’s Tenancy History Database;

(iii) Property History Classification, which is a replication of the Applicant’s Property Comparison Database, that has been under development by the Applicant since around September 2013;

(iv) Approved Applications Index, which is a replication of the Applicant’s Virtual Manager;

(v) Private eMailing System, which a function of the Applicant’s replicated Virtual Manager and Tenancy History Database; and

(vi) Rental Serviceability Scoring, which is a replication of the Applicant’s Affordability Calculator, that has under development by the Applicant since about November 2013, and was launched on the Applicant’s website in about early December 2014.

(Errors in original).

24 Paragraph 12 made no allegation about the legal consequences of this replication, but merely asserted it as a fact. The legal consequences were instead set out in other parts of the pleading. Central to these, however, was a definition appearing at paragraph 3(c), where it was alleged that TICA had a ‘computer application’. This was defined in Part A of the appendix to the FASOC as follows:

Computer application (Application), the property of the Applicant, custom built and written by the Applicant’s computer programmer, forming part of and used by the Applicant for the purpose and in the course of the TICA Business, consisting of:

(a) databases containing all the information that the Application requires for its operation;

(b) the Web front end, being the component of the Application by which the end user (the Applicant’s members) accesses the Application; and

(c) the administration console, being the component of the Application required for the general administration, report writing, data export, accounting, Communication, record management, record compliance and business management.

The databases and Web front-end are comprised of 180,000 lines of source code written by the Applicant’s computer programmer. The administration console is comprised of 14,000 lines of source code written by the Applicant’s computer programmer. There are over 1,000 unique functions created in the administration console.

25 At paragraph 17 it was then alleged that Datakatch had reproduced the Application so defined. The particulars to paragraph 17 proceeded to repeat, inter alia, those appended to paragraph 12. The significant link with paragraph 12 was then underscored in paragraph 18 which was as follows:

18. From a date not presently known to the Applicant, and at least from October 2014, the Second to Fourth Respondents procured the First and/or Fifth Respondent to use, and the First and/or Fifth Respondent, by itself, its servants or agents, without the licence of the Applicant, has used, and continues to use, the Infringing Reproductions for the purpose of, and in the course of carrying on, the Datakatch Business.

Particulars

(a) The First Respondent’s carrying on of the Datakatch Business and the use of the Infringing Reproductions are to be inferred from services or products offered for sale and/or sold by the First Respondent on the First Respondent’s website described in paragraph 12(a) above, which services and products include the Applicant’s Replicated Services and Goods.

(b) The Fifth Respondent’s carrying on of the Datakatch Business and the use of the Infringing Reproductions are to be inferred from services or products offered for sale and/or sold by the Fifth Respondent on the First Respondent’s website described in paragraph 12(a) above, which services and products include the Applicant’s Replicated Services and Goods.

(c) The Applicant repeats paragraph 13 above.

26 The effect of particulars (a) and (b) was to connect this allegation back to the six matters set out in paragraph 12. There followed allegations, not necessary to recount, that these various actions involved an infringement of TICA’s copyright.

27 So understood, it will be seen that the copyright infringement case, as pleaded, rested upon an inference alleged in paragraph 18 and said to be drawn from the six identified features of the Datakatch website set out in paragraph 12. Such a case did not involve any need to examine either the Datakatch source code or the Datakatch databases. In terms, it required only an examination of the six features of the website pleaded at paragraph 12, from which it was then to be deduced that TICA’s copyright in the ‘Application’ has been infringed.

28 A simple case. It is now useful to turn to how the case was actually run.

(c) How TICA’s case was actually run – a case of circumstantial evidence

29 At trial, counsel for TICA, Mr Smark SC, opened a case which differed very substantially from the pleaded case. It was now said that the fact that Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr had taken the TICA system would be proved, in effect, by a circumstantial case. Not all of the elements of the circumstantial case were identified in opening. Many of them, in fact, emerged only during the evidence and some were touched upon only in closing address. Indeed, at no point during the trial were all of the elements of this case conveniently collected in a single location. However, by the time judgment was reserved, the circumstantial case seemed to my observation to have, at least, the following elements:

(i) the alleged copying of TICA’s source code;

(ii) similarities in the schema of Datakatch’s databases and those of TICA;

(iii) similarities in the stylesheets (a term explained later in these reasons);

(iv) the presence of unique elements of data in Datakatch’s databases which were also found in TICA’s databases;

(v) the fact that Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr accessed the TICA system after they had ceased working for TICA, using the usernames and passwords of certain of TICA’s clients;

(vi) the letter of 10 May 2012 (which purported to give Mr Joshua, inter alia, the right to work for other clients apart from TICA);

(vii) the poor relationship between Mr Nounnis Snr and Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr;

(viii) the fact of Datakatch having TICA’s mailing list; and

(ix) the allegedly dishonest nature of Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr’s evidence.

30 It will be observed that this case involved a substantial departure from the case as pleaded. When I first began to prepare these reasons, I was concerned about the procedural consequences of the case being pleaded on one basis and then run on another. However, no objection was taken to this course being adopted, and it was clear that the respondents were aware that the case they were facing was indeed a circumstantial one: see, e.g., T277.34-T278.11 and paragraph 37 of the respondents’ closing submissions (‘The case put by TICA is a circumstantial one’). This is, therefore, one of those cases where the parties have chosen to conduct the case on a different basis to the way in which it has been pleaded: Banque Commerciale S.A. en liquidation v Akhil Holdings Ltd (1990) 169 CLR 279 at 286-287 (‘...the circumstances in which a case may be decided on a basis different from that disclosed by the pleadings are limited to those in which the parties have deliberately chosen some different basis for the determination of their respective rights and liabilities.’)

31 Before turning to the elements of TICA’s circumstantial case, it is necessary to refer to three further matters. The first of these is to note that what the circumstantial case seeks to prove is that the Datakatch system has been copied from the TICA system. In this context it has been pointed out that where a plaintiff and defendant’s work are similar:

…there are four possible explanations: the defendant’s work was copied from the claimant’s; the claimant’s from the defendant’s; both from a common source; or mere chance or coincidence. It is only in the first case that an infringement of the claimant’s work can have occurred. Although the concept of copying is expressed differently in relation to the different categories of work, the underlying principle is that there can be no infringements unless use has been made, directly or indirectly, of the copyright work. Copyright is not a monopoly right and no infringement occurs by an act of independent creation. This is often expressed as saying there must be a causal connection between the copyright work and an infringing work. This is one of the ways in which copyright differs from true monopoly rights such as patents and registered designs. In the case of the latter rights, a person can infringe even though he has arrived at his result by independent creation.

(Footnotes omitted.)

(Copinger and Skone James on Copyright, 16th Ed, 2011 at p.426)

32 In a similar vein, Bennett J has observed, in the context of one computer program allegedly copied from another, that a work is reproduced ‘if there is a sufficient degree of objective similarity between the copyright work and the work said to infringe and there is ‘some causal connection’ between the form of the allegedly infringing work and the form of the copyright work’: CA Inc v ISI Pty Limited (2012) 201 FCR 23 at 54.

33 Secondly, in the present context, these issues are to be approached with an eye on the principles attending the proof of circumstantial cases. What is to be assessed is the weight which is to be given to all of the circumstances put together. The onus of proof is applied only at the end, and not to the individual circumstances. Authority for these propositions may be found in Palmer v Dolman [2005] NSWCA 361 at [41].

34 Thus, in what follows, the question is not whether any of the individual circumstances proves that Datakatch copied the TICA system; it is rather whether taken as a whole they do so.

35 Thirdly, the allegation that Datakatch illicitly copied TICA’s intellectual property is, I think, an allegation of some seriousness; in effect, an allegation of industrial theft. It is relevant in assessing whether the circumstantial case is proven to take account of the fact that what is alleged to have been done is quite improper (see s 140(2)(c) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336).

36 It is convenient to deal with the various alleged circumstances in the order I have set out above.

(d) The elements of the circumstantial case

(i) Copying of TICA’s source code

37 The evidence for copying by Datakatch of TICA’s source code was, by the conclusion of the trial, sparse. The expert called by TICA to opine upon it was Mr Rodney McKemmish. He examined several versions of the source code and many of the other elements of the TICA system. He did not himself think that the Datakatch source code had been directly copied from the TICA source code. However, there was a qualification to this. He was keen to emphasise that the version of the Datakatch system with which he had been provided for the purposes of his report was incomplete. This carried with it, I think, the sub silentio suggestion by Mr McKemmish that his inability to testify that the Datakatch system had been directly copied from the TICA system might itself need to be discounted. As will be shortly seen, I am not minded, despite this invitation, to approach his evidence in this circumspect manner.

38 There were two elements to the incompleteness, as he saw it. The first was that he had only been provided with the source code relating to the six components set out in paragraph 12(a) of the FASOC, and was not given a copy of the entire Datakatch system. However, this limitation emerged from the way in which TICA had pleaded its case. As I have explained above, TICA’s pleaded case was that Datakatch’s copying of its system was to be inferred from the six elements identified at paragraph 12 of the FASOC. It was hardly surprising, in that circumstance, that the orders requiring that Datakatch provide Mr McKemmish with access to its system were limited to the matters set out in paragraph 12. Those orders merely reflected the way in which TICA was formally putting its case. The actual orders made by the Court on this topic were made on 28 August 2015. The relevant order was order 3:

3. Subject to 4 below, directs that the First Respondent, by 11 September 2015, provide in native format to the Expert, such of the following as is in the possession, custody or control of the First Respondent:

(a) Copies of source code (stored procedures, scripts, etc.), including versions of source code, as pertains to the aspects of the First Respondent’s program/system identified in paragraph 12(a) of the Amended Statement of Claim (“the First Respondent’s Program”).

(b) Copies of databases, including past versions, as used or accessed by the First Respondent’s source code in the First Respondent’s Program;

(c) Copies of the database schema, including table structure, data dictionary and entity relationship mapping in the First Respondent’s Program;

(d) Copies of design and architecture documentation used in the development of the First Respondent’s Program;

(e) Copies of functional and technical specifications used in the development of the First Respondent’s Program;

(f) Copies of all versions of technical and operation manuals for the First Respondent’s Program.

(g) Copies of data used and accessed by the First Respondent’s Program.

39 I do not accept that the circumscribed nature of what Datakatch provided, at least in this first respect, is a cause either for complaint or for criticism. As its case was then articulated, TICA had no entitlement to examine all of Datakatch’s source code, because it did not propose to prove its case by reference to that code. Indeed, it could be said that if Datakatch had taken a more robust approach to the way the case against it had been pleaded by TICA (and I do not suggest that it should have done so), it might well have denied TICA any entitlement to see Datakatch’s source code at all without amending its particulars (although it is not necessary to express a concluded view on that matter). More importantly, given the pleading context, the limited nature of what Mr McKemmish was provided gives no credence to the idea that he was given only limited access for surreptitious reasons.

40 The second aspect of this complaint emerged from the terms of order 3(a) itself and, in particular, from its requirement that ‘versions’ of the software be disgorged. It is not in dispute that any such earlier versions were not handed over. But this seems to me to lack much significance when the very recent nature of Datakatch’s business is brought to account. As a matter of fact, it seems likely that the earliest date at which any of the Datakatch system was operating would have been in November 2014, and even then only in a fairly embryonic form. Then there is the further fact that the current proceeding was commenced in February 2015 in consequence of which Datakatch has not begun to operate its business pending the outcome of this litigation.

41 The access orders were made in August 2015 only six months later. It seems to me unlikely that a business which had not yet operated and was still in its start-up phase would be likely to have multiple versions of its software. I do not, therefore, think that its failure to produce more than one version signifies very much, at least in the absence of any evidence that there actually were earlier versions (of which there was none). In fact, the only available evidence about this issue came from Professor Rabhi, from the University of New South Wales School of Computer Science and Engineering, who was called by Datakatch as an expert and who, under cross-examination, gave this testimony:

…In terms of maintaining copies of the software, again, if it’s one person doing the coding and it’s not a teamwork, and you don’t maintain multiple versions, what happens is when you build software for other people, so you have customers, you have to have a version control system because customer has version one, another customer has version two, and the one who has version one wants changes and so on. So you have to – if you’re a software house, that’s essential. If you’re building software for your own use and you’re a one-man team or two-man team, it’s not good – it’s not good practice, but, as well, it’s not uncommon.

42 Given that evidence, and given the youthful nature of the business, I infer from the non-production of earlier versions that there were no such versions.

43 For those two reasons, I am not inclined to treat Mr McKemmish’s opinion that the Datakatch source code does not appear to be directly copied from TICA’s as a conclusion which is, in some way, to be used cautiously or to be regarded with some circumspection.

44 That evidence, which is, after all, TICA’s own evidence, throws up real obstacles in the path of accepting that the Datakatch source code was copied from the TICA source code. Of course, in this context one needs to understand that the case that the source code was copied was really just an element in TICA’s broader circumstantial case that the whole system (and not just the source code) had been copied. To keep that possibility alive, TICA submitted that the reason that the source code did not appear to have been copied was, perhaps, because between the commencement of the proceeding (in February 2015) and the time at which access to the source code was ordered (in August 2015), there was enough time for Datakatch to revise the source code so that it did not appear to have been copied. Viewed from this perspective, it might be possible also to view the failure to produce earlier versions of the Datakatch system in a more sinister light.

45 An interesting feature of this submission is that it thrives on the absence of any evidence that demonstrates it to be true. The fact that the source code did not appear to have been copied was, in fact, what proved that it had been. And concomitantly, the failure of Datakatch to provide earlier versions of the source code proved (a) that these earlier versions existed; and (b) that they had been suppressed to conceal the fact that the current source code had been altered to make it appear not to have been copied.

46 I reject this argument which suffers, at least, from the flaw of being a non-falsifiable hypothesis. Even apart from that methodological deficiency, Professor Rabhi expressed the opinion that such a reworking was unlikely for two reasons. The first of these was that it would be a very difficult thing to do and, even if attempted, traces of the original code would still remain. He gave this evidence:

…I would say changing the system would be very hard. Re-doing it, probably, would be the only possibility to – to change it completely. I think it would be very hard, within such a short time period, to change the system to a point where it bears no resemblance to the original system. There would still be some traces that you could notice from the code, or from the user interface.

47 The second reason was one of size and complexity. The TICA source code was large and complex, but the Datakatch code was much shorter. It was difficult to see that the smaller could have been generated, via a merely cosmetic process, from the larger.

48 I accept Professor Rabhi’s evidence about this. It is most unlikely that the Datakatch source code was copied from the TICA source code and then cosmetically altered to make it look different, particularly where the alleged cosmetic alteration effected a significant change in the size of the source code. I find that this did not occur and that the reason that the Datakatch source code does not appear to have been copied from the TICA source code is because it was not. It is implicit in that conclusion that I accept that the Datakatch system was substantially written by Mr Joshua. This is not difficult to do in light of the skills I have accepted he had above at [5].

49 This conclusion is fatal to so much of TICA’s case as depended on the copying of the source code. It does not dispose, however, of all of its case. The broader circumstantial case may yet prove to be sufficient to show that the schema of the databases, the so-called stylesheets or some of the data in the databases was copied. The mere fact that the source code cannot have been copied does not eliminate these other possibilities.

50 It is useful then to turn to the schema of the databases.

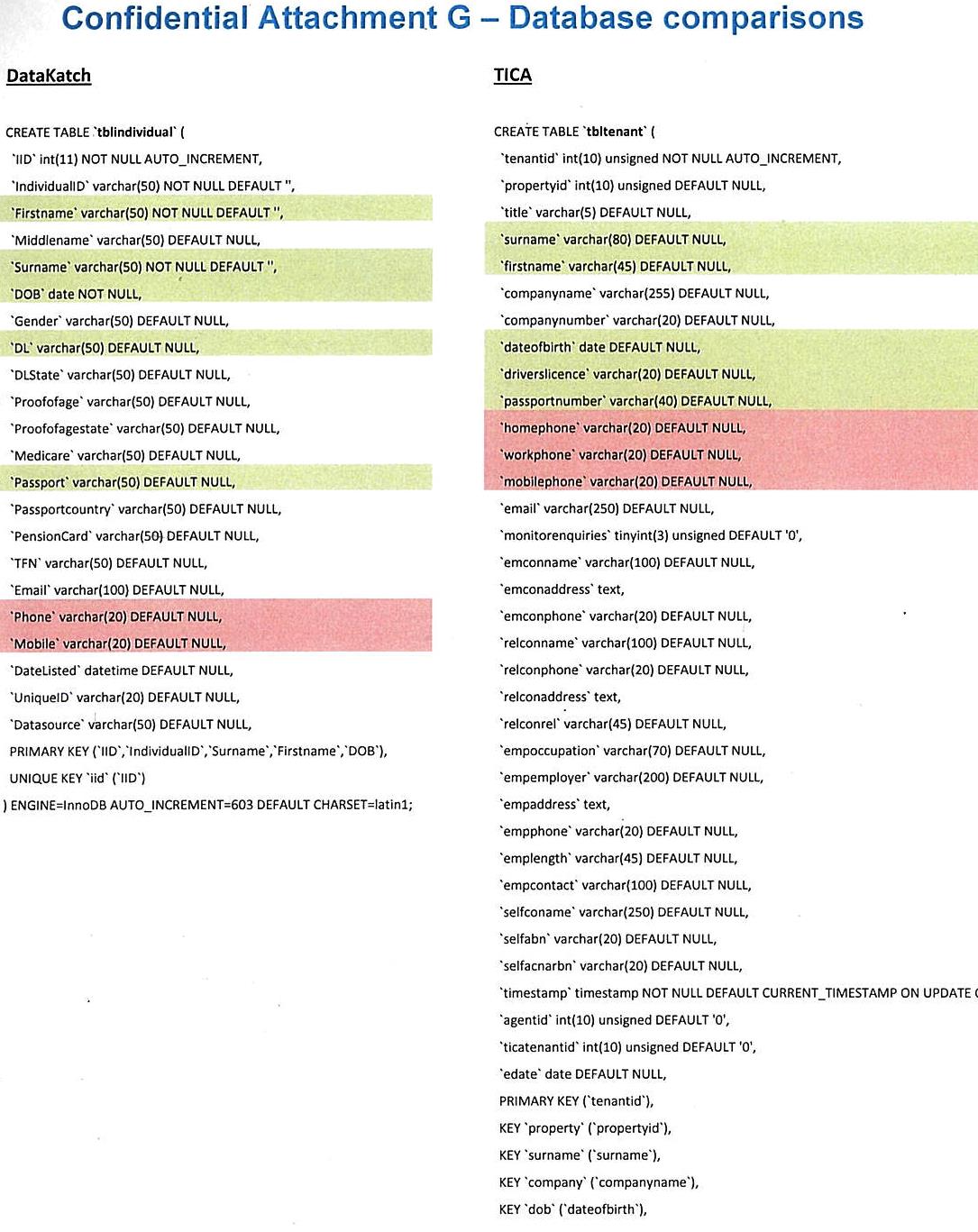

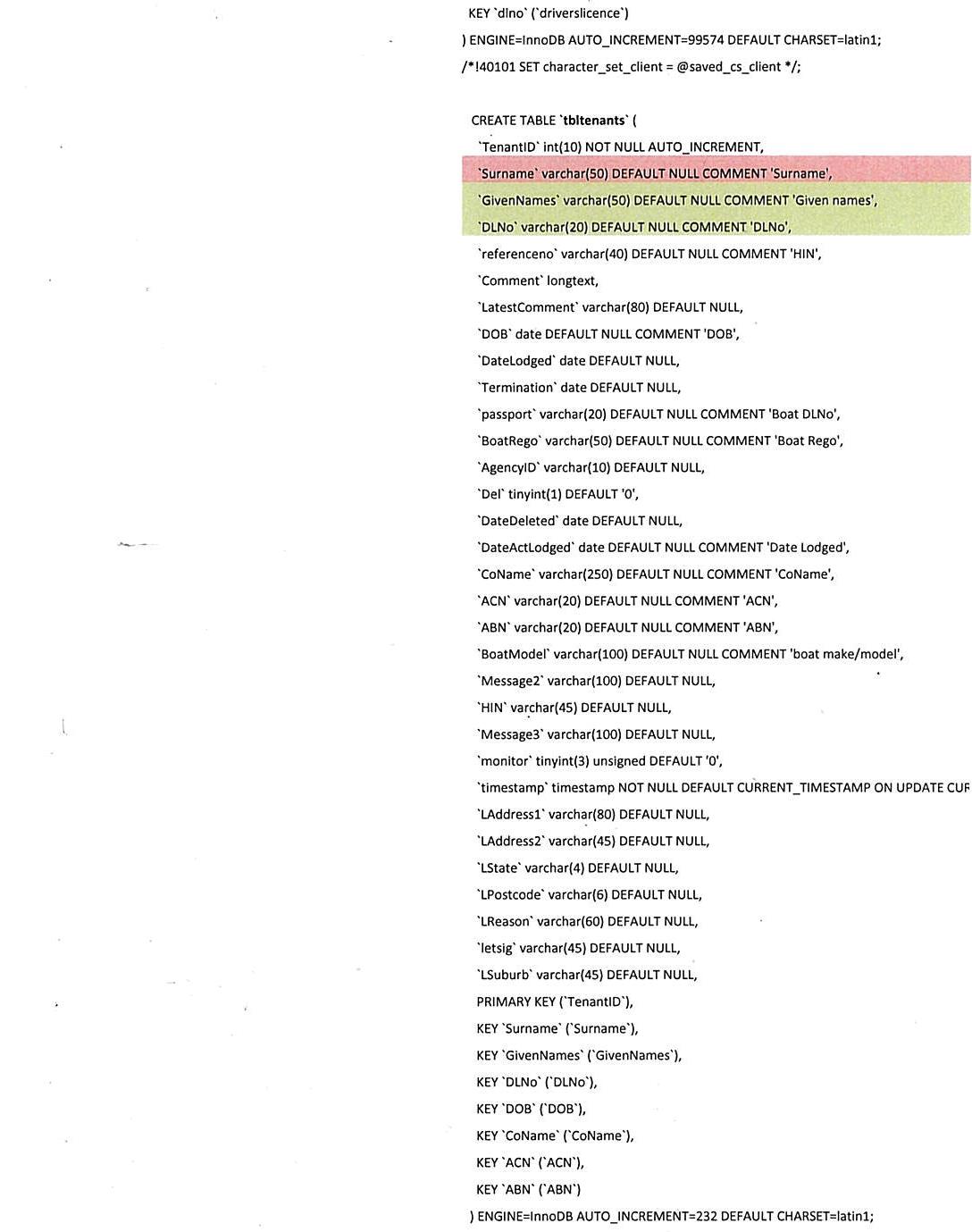

(ii) Similarities in the schema of the Datakatch databases and those of TICA

51 TICA’s case on this issue was as follows. The data supporting the TICA system was stored in seven separate databases, which comprised between them some 213 separate tables. Each table consisted of a number of records (i.e. rows) and fields (i.e. columns).

52 The Datakatch system, on the other hand, consisted of one database comprised of 20 tables. Mr McKemmish went through all of TICA’s 213 tables to identify those which were similar to Datakatch’s in terms of structure. He identified three tables in TICA’s system which he thought were sufficiently similar to three tables in Datakatch’s to justify the conclusion, in relation to at least two of them, that there was ‘a high degree of probability’ that the latter had been modelled on the former.

53 The three tables were called, in the TICA system:

‘tblindividual’;

‘tbllandlord’; and

‘tblproperty’.

54 One might begin with the proposition that in the context of two firms conducting the same business of keeping track of tenancies, the fact that they both have tables in their databases with words such as ‘landlord’ and ‘property’ in the title is far from surprising. To meet the challenge arising from that proposition, TICA submitted that the prefix ‘TBL’ was one thing which tended in the opposite direction. Further, Professor Rabhi agreed under cross-examination that there was ‘certainly no requirement’ for tables to be called by names prefixed with ‘TBL’ (I infer, as a matter of programming convention). On the other hand, calling a table ‘TBL’ is hardly a staggering event either. By itself, the fact that two of Datakatch’s 20 tables have similar or identical names to two of TICA’s 213 tables is equivocal.

55 But there was more. Mr McKemmish then examined the three tables in question more closely to see if he could find other evidence of copying. He believed that he could. His evidence worked this way.

56 Mr McKemmish first drew attention to the table entitled ‘tblindividual’ in Datakatch’s system and ‘tbltenant’ in TICA’s. He then prepared another table comparing them using colour codes. The entries in green denoted that the records in the two systems were similar, whilst those in pink denoted that the records were identical. Uncoloured entries denoted that the records in question were different. Mr McKemmish’s table was as follows:

57 I do not think that the similarities necessarily indicate copying. It is unremarkable that both tables have entries like ‘firstname’ and ‘surname’ or use subject matter nomenclature of that kind. By itself, this evidence would not persuade me that the Datakatch ‘tblindividual’ table was copied from the TICA ‘tbltenant’ table.

58 I reach the same conclusion in relation to the ‘tbllandlord’ and ‘tblproperty’ tables, which I do not need to set out. By itself, this material does not establish copying, although it is not inconsistent with it. I return to the issue of whether this part of TICA’s circumstantial case (equivocal in its own terms) might be proved in the context of the whole circumstantial case below at [121].

(iii) Similarities in the stylesheets

59 In this part of the case there were four propositions:

A. a piece of software known as a ‘miggibot’ existed which, if given access to a website, could make a copy of a website’s HTML code;

B. the webpages of the TICA site were available only to its members;

C. IP addresses associated with some of the respondents had been detected accessing TICA pages; and

D. there were similarities between some of Datakatch’s HTML code and TICA’s.

60 The inference which it was said should be drawn from the last step was that Datakatch had copied the visual form of TICA’s webpages, presumably using software such as a miggibot.

61 I accept that there is software which can copy the HTML code publicly presented by a website. However, as Mr McCoy accepted, such software cannot copy the underlying scripts because these cannot be accessed. In practical terms, I infer that this means that software such as a miggibot may download and copy the appearance of a given website as it then appears to the person accessing the website, but it cannot access any of the code which is operating behind the website. If one were to use a miggibot to create a facsimile of a website, it would only allow one to do so in relation to the question of final appearance. The person copying would still need to write the scripts behind the website for themselves.

62 As discussed in more detail below at [88]-[100], I accept that Mr Nounnis Jnr and Mr Joshua accessed the members’ section of TICA’s website after they had left TICA and whilst they were setting up the Datakatch system. I also accept that in doing so they improperly used confidential TICA client usernames and passwords Mr Nounnis Jnr had obtained in the course of his employment. I infer that Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr were accessing TICA’s pages as an aspect of their development of the Datakatch website. No other plausible reason why they would be accessing TICA’s website presents itself for consideration.

63 Returning to what the code shows, Mr McCoy compared some of the HTML code he acquired from the Datakatch website to HTML code he had himself written for TICA’s website two years beforehand. The HTML code in question generated ‘stylesheets’. A stylesheet is a piece of HTML code which, in effect, dictates the appearance of a website. For example, it is a stylesheet which provides for the appearance of the buttons on a website. Mr McCoy thought that the Datakatch HTML code for some of the stylesheets he examined had been copied from his own code.

64 Although initially sceptical of Mr McCoy’s claims in this regard, I have ultimately concluded that he is correct and that some of the Datakatch HTML code underlying the Datakatch stylesheets must have been copied from the TICA HTML code.

65 The reasons for this are as follows. Mr McCoy provided three sets of comparison code for different aspects of the HTML code underlying both sets of web pages. The first was concerned with ‘button style’ and was the code determining the general appearance of various buttons on both websites. Successive buttons were denominated by the letters ‘.btn’ followed by a number. Thus the first button in TICA’s HTML code was called ‘.btn1’. In both TICA and Datakatch’s HTML code the same nomenclature was used. Mr McCoy’s evidence was that the use of this nomenclature was not required by any programming convention. By itself, I would not accept that this was sufficient to prove that the Datakatch code had been copied from TICA’s. However, both sets of code also contain an entry for ‘.btn6a’. That does strike me as a curious coincidence, and that is so even though the actual code for ‘.btn6a’ is different in the TICA and Datakatch stylesheets.

66 If matters rested there, it would again be equivocal. However, Mr McCoy also gave evidence about the HTML code for some cell styles. As with the ‘.btn’ files, the same nomenclature has again been used by both sites: ‘.td1’. Two entries amongst the style cells are essentially identical. The first is ‘.td1’.

67 In TICA’s pages the HTML code reads:

.td1 {

font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif;

font-size: 9pt;

background-color: #5b5b5b;

color: #FFF;

68 In Datakatch’s it reads:

.td1 {

font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif;

font-size: 9pt;

background-color: #999999;

color: #FFF;

69 The only difference is the background colour and otherwise the code is identical. The second is ‘.td3’. TICA’s reads:

.td3{

font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif;

font-size: 9pt;

background-color: #E6E6E6;

color: #000000;

text-align: left;

70 Datakatch’s reads:

.td3{

font-family: Arial, Helvetica, sans-serif;

font-size: 9pt;

background-color: #E6E6E6;

color: #000000;

text-align: left;

71 This is identical. Taken together, I do not accept that these three very close similarities or identicalities in the HTML code (.btn6a, .td1 and td3) could be the product of coincidence. The range of colours in the case of .td1 and .td3 is enormous. The range of possible fonts is large although the range of font sizes is less so. Nevertheless, the likelihood of these entries being the result of chance seems to me to be so small as to require its rejection as a plausible hypothesis. It seems to me, therefore, that copying is the unavoidable conclusion. I return to the question of the extent of this copying below.

(iv) The presence of unique elements in both sets of databases

72 This element of the circumstantial cases was a remnant of TICA’s earlier, and broader, claim for breach of confidence. For the sake of completeness, it is useful briefly at this stage to outline what that case was.

73 Paragraphs 35 and 44 of the FASOC alleged that Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr used the ‘Confidential Information’ in breach of variously formulated obligations of confidence owed to TICA. Paragraphs 36 and 47 allege that Datakatch has suffered loss and damage as a result of these breaches. The ‘Confidential Information’ was defined in the Appendix to the FASOC this way:

Information of a confidential nature, the property of the Applicant, forming part of, and used by the Applicant for the purpose and in the course of, the Applicant’s Business, including the following:

(a) tenant data files;

(b) membership lists;

(c) mailing and marketing lists;

(d) strategic and business plans;

(e) marketing procedures;

(f) training manuals;

(g) procedure and policy manuals;

(h) technical data; and

(i) trade secrets.

74 Plainly, this was diffusely expressed. In TICA’s opening written submissions, the actual nature of the confidential information was not identified. But as the case was opened by Mr Smark, it did seem to have three elements:

the presence of a number of individuals in the databases of both TICA and Datakatch;

the use of usernames and passwords by Datakatch on TICA’s website after Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr had left TICA; and

the use by Datakatch of TICA’s mail out list.

75 The evidence elicited at trial was broader in the sense that Mr Nounnis Snr gave extensive evidence of a number of other categories of information which were confidential to TICA. The evidence, however, of alleged actual use by the respondents was narrower. It consisted only of:

evidence that some business cards had been removed from TICA’s premises;

some evidence that 45 back-up CDs had gone missing;

a suspicion that a mailing list had been taken; and

evidence from Mr McKemmish that there were common data entries in TICA and Datakatch’s databases.

76 In TICA’s closing submissions, only the following elements were pursued:

the usernames and passwords; and

the common data in the databases.

77 It was also said in closing oral submissions that the confidential information claim lay factually within the four corners of the copyright claim. I take that to mean that it is concerned only with the claim that the TICA system was taken (that is, the source code and databases). I do not think that the usernames and passwords issue is part of the copyright claim, but I also do not think that Mr Smark intended to abandon a case he had just advanced nor a case based on the taking of the back-up CDs. On the other hand, I do not think that the case based on the mailing list was pursued. It was never explained to me how it worked. In those circumstances, I propose to treat the claim for breach of confidence as having had only three extant elements by the end of the trial:

the presence of common data elements in the databases;

the use by Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr of confidential usernames and passwords on TICA’s website after they had left TICA’s employ; and

the taking of the back-up CDs.

78 These parts of the extant confidentiality claim are, potentially, relevant to the circumstantial case. I deal in this section with the common data allegation.

79 This was advanced by Mr McKemmish in his report. He compared the databases of TICA and Datakatch. As mentioned already, there was only one Datakatch database (although there were seven TICA databases). In the table within the Datakatch database called ‘.tblindividual’, Mr McKemmish located 82 records. Mr McKemmish thought that this was mostly test data consisting of a mix of actual and fictitious records. This is, of course, consistent with the then preliminary nature of Datakatch’s business.

80 He compared these 82 records with one of the databases in TICA’s system. He found that some of the first name, surname and date of birth records matched. He set out the matches in a document entitled ‘Confidential Attachment H’.

81 Recourse to this document shows that of the 82 records in ‘.tblindividual’, only 10 records matched. One of these records is Mr Nounnis Jnr himself which may, I think, be put to one side. Another is a repeat entry which can be treated in the same way. As Mr Katekar correctly submitted, that left only eight matching records.

82 In relation to those eight, evidence was given about each by Mr Joshua. In its theoretical structure, his evidence in relation to all eight was the same. It will suffice, therefore, to deal with only one in detail.

83 First, he identified a table of Datakatch’s subscribers. The list in this table contains 25 records. Thirteen of these are blank, and Mr Joshua explained that several of these were associated with those behind Datakatch. However, a number of entities listed in the table were authentic. They had become subscribers by reason of a free trial conducted by Datakatch between December 2014 and April 2015 (with one presently irrelevant exception). Each subscriber was associated with a unique identifier number.

84 Secondly, Mr Joshua then addressed the first common entry. Since this person has nothing to do with this litigation, I will anonymise her as ‘ABC’. The entry for ABC in the TICA records shows that it was generated by an inquiry made by a TICA client called ‘Your Portfolio Manager’ on 17 December 2014. That was, of course, after each of Mr Joshua, Mr Nounnis Jnr and Mr Portelli had left TICA. No mechanism was suggested to me which might explain how data entered in TICA’s databases after their departure might have found its way to Datakatch.

85 On the other hand, the entry for ABC in Datakatch’s .tblindividual was, in fact, different. To begin with, her middle name ‘B’ was omitted and she was recorded as ‘AC’ only. And, according to the Datakatch record, her entry had been added on 15 January 2015 following an inquiry by one of Datakatch’s genuine members, Palm Beach Holiday Resort.

86 It seems to me more likely that the entry for ‘AC’ in Datakatch’s records arose from a genuine inquiry made by one of its own customers than as a result of a taking from TICA.

87 I accept, therefore, that the presence of ‘AC’ in Datakatch’s ‘.tblindividual’ table does not prove that it was taken from TICA’s databases. I accept the validity of this conclusion for all of the common data in the ‘.tblindividual’ table.

88 The second element of the extant confidential information case consisted of the proposition that Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr had accessed the accounts of TICA’s members after their departure by using confidential usernames and passwords. Mr Nounnis Jnr admitted this, but sought to give an exculpatory account of himself (which I reject below). Mr Joshua did not respond to the allegation (no doubt because it was not pleaded), and the evidence against him on this aspect stands unanswered. I propose to proceed on the basis that he denies the allegation. The significance of the issue for present purposes is that it suggests that Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr had possession of, and did use, confidential information of TICA.

89 As will be seen shortly, I accept that this is so, and that they used the usernames and passwords to obtain access to TICA’s HTML code, which were then used as a rough base from which Datakatch generated its own HTML code by a process involving substantial modification.

90 I begin with the evidence of Mr Jeffery Ang. Mr Ang is TICA’s present general manager, and seems to have succeeded Mr Joshua. Not long after Mr Joshua had left TICA, Mr Ang decided to attempt to monitor the extent to which Mr Joshua, Mr Nounnis Jnr and Datakatch were accessing the TICA web pages. TICA already had in place systems which monitored the IP addresses of persons accessing its site as an ordinary measure to ensure that its members with multiple office locations were not undersubscribing by having only a single subscription.

91 By examining emails, Mr Ang, in concert with Mr McCoy, was able to obtain IP addresses for Datakatch and Mr Joshua. He was also able to obtain the IP address for one of Mr Joshua’s other clients called The Basket Factory.

92 With this information, Mr Ang was able to determine that the Datakatch IP address had been used to log on to the TICA website through the account of a TICA client, Century 21, on 13 November 2014. It would not have been possible to do this without Century 21’s username and secret password. On 28 November 2014, the Datakatch IP address accessed the account of Ray White on TICA’s system. Again this would not have been possible without the username and password. Likewise it is established that Mr Joshua’s IP address was used on two occasions to log on to client accounts on the TICA website (the Style Property account and the Define Property account). This occurred first on 28 August 2014, just after Mr Joshua had left, and then again on 3 September 2014. Mr Katekar submitted that the cross-examination of Mr McCoy showed that there had been no access to the website prior to 12 February 2015. I am not sure this is necessarily a complete statement but it does not matter as Mr Ang’s evidence certainly shows it.

93 Although the fact that a person’s IP address has been used to access a website does not necessarily prove that it was that person who did the accessing, in this case, I am prepared to infer that this is so. I can conceive of no reason why any other person would be using either the Datakatch IP address or Mr Joshua’s IP address to access the TICA website. I infer that the person using Mr Joshua’s IP address to do this was, in fact, Mr Joshua.

94 Because Mr Nounnis Jnr gave evidence that he did access the TICA website using the usernames and passwords, I infer that it was he who was in control of the Datakatch IP address when it was used to log on to the TICA web site through member accounts.

95 I also accept that Mr Joshua used the IP address of The Basket Factory to log on to the TICA website. I draw this inference because it does not appear to me that a firm with the name ‘The Basket Factory’ would have any reason to access a tenancy database.

96 I pause to note in passing that it is a federal criminal offence carrying a maximum penalty of two years imprisonment to obtain unauthorised access to data held in a computer to which access is restricted by an access control system: see Div 478 of the Schedule to the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth). A similar offence exists under New South Wales law: see s 308H of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW). In reaching the conclusion I have in relation to this issue, I have taken into account the apparent criminality of the conduct.

97 Mr Nounnis Jnr sought to explain his access through these members’ accounts on the following basis:

Mr McCoy gave him the usernames and passwords before he left TICA;

he remained an officer of another entity called TICA Training Pty Ltd. It had been providing training but it had been removed as a registered training organisation with the Australian Skills Quality Authority. He wished to be sure that TICA Training was not offering unlawful training through TICA’s website; and

it was for that reason that he used the member accounts.

98 I do not accept this evidence for two reasons. First, Mr McCoy gave evidence that contradicts Mr Nounnis Jnr’s account, and I accept Mr McCoy as a reliable witness. Mr McCoy denies giving Mr Nounnis Jnr the usernames and passwords, and he says that the TICA Training business was not an aspect of TICA’s business (with the corollary that Mr Nounnis Jnr would have had, therefore, no reason to be accessing the website for that purpose). Secondly, Mr Nounnis Jnr’s version strikes me as inherently unlikely. In order to remain in touch, or across, the TICA Training business it is obscure to me why one would use member accounts for that purpose.

99 I accept therefore that Mr Nounnis Jnr and Mr Joshua used TICA’s usernames and passwords to obtain access to its website after they had finished working at TICA. Further, I conclude that they did so for the purpose of designing their own Datakatch web interface. In Mr Joshua’s case, I infer this because I am satisfied that he accessed the website to copy TICA’s externally facing HTML which he then modified, to an extent I later discuss, to create the external appearance of the Datakatch website. I am satisfied, too, in Mr Nounnis Jnr’s case, because he was involved at this time with designing the Datakatch website with Mr Joshua and had good reason to be examining the form of the TICA website.

100 It is not altogether clear whether Mr Joshua obtained the usernames and passwords from Mr Nounnis Jnr, or whether he obtained them himself through an independent act of misappropriation whilst at TICA. Since the evidence is equivocal, I conclude that the least improper of these explanations should be embraced. Mr Joshua obtained the usernames and passwords from Mr Nounnis Jnr.

(vi) The taking of the back-up CDs

101 In his affidavit, Mr Nounnis Snr gave evidence of a process whereby at the end of each day a CD would be burnt containing a complete back up of TICA’s databases and software. There were around 1,000 to 1,400 of these CDs stored in six albums. In addition to these CDs, there were around 60 other CDs containing applications. Mr Nounnis Snr was of the view that at some point after Mr Nounnis Jnr left, the 1,000-1400 back-up CDs went missing. In light of an email between Mr Nounnis Jnr and Mr Joshua dated 5 August 2014, in which the former asked the latter for his DVDs and CDs back, he believed that this provided the explanation for where the CDs had gone.

102 I am not satisfied that the CDs were taken by Mr Joshua or Mr Nounnis Jnr. The reasons for this are practical. The process of backing up onto CDs ended in 2009, as Mr Nounnis Snr agreed under cross-examination. Thereafter the entire system was backed up on alternate days on to two external hard drives. The person responsible for this was Mr Joshua, who would take one hard drive home with him each other day (to secure it off site). This process continued until Mr Joshua left TICA.

103 It was not suggested that these two external drives were missing. Further, it is clear that it would have been very easy for Mr Joshua to have copied the external drives at any point before his departure. It seems to me unlikely that Mr Joshua would have bothered taking the 1,000-1400 CDs which contained very out-of-date data and, no doubt also, superseded software from 2009 (at the latest), when he had up-to-date software and databases in the form of the external hard drives at his home every night. I find that he did not do this and that Mr Nounnis Jnr did not do so either (largely for similar reasons).

104 At trial a case was not pursued based on the external hard drives (although Mr Nounnis Snr did refer to them in his affidavit), at least so far as I could tell. If it was (which is very unlikely) I reject it. It is inconsistent with TICA’s case that Mr Joshua used a miggibot to copy the HTML code from the TICA website by using client usernames and passwords. If Mr Joshua always had the whole application these activities would not have been necessary.

105 This leaves unresolved whether Mr Nounnis Snr’s evidence that the 1,000-1,400 CDs were missing is false or whether, instead, they have genuinely gone missing for reasons unrelated to the actions of the respondents. It is not necessary to resolve this issue.

(vii) The letter of 10 May 2012

106 In May 2012, Mr Nounnis Jnr was a director of TICA. According to Mr Nounnis Jnr and Mr Joshua, Mr Joshua prepared a letter dated 10 May 2012 about the terms of Mr Joshua’s employment at TICA and sought Mr Nounnis Jnr’s agreement to, and his signature upon, it. Mr Nounnis Jnr did agree and did sign. Mr Nounnis Jnr gives the following evidence about his signing of this letter:

6. Annexed to this affidavit and marked ‘APN-1’ is a letter attaching terms and conditions from Reginald Joshua to TICA dated 10 May 2012. At or about the date of that letter, I had a conversation with Reginald Joshua to the following effect:

He said: Can you please have a read of this. If you are okay with it please sign it.

I said: Okay.

7. I read the letter and saw no difficulty with it, I understood that the letter reflected the position that was in place as between TICA and Mr Joshua in the past. I saw no difficulty with it and signed it.

8. I left the signed letter on the desk of Marina Nounnis (who I understood at the time was a 100% shareholder of TICA). I subsequently spoke to Marina Nounnis about it, and we had a conversation to the following effect:

Marina said: What’s this?

I said: Reg needed it signed. You just need to file it.

9. I then saw Marina Nounnis read the letter. She did not say anything to me about it after that.

10. In light of the contents of the letter, which I understood were not controversial, I did not see the need to mention it to Philip Nounnis.

107 Mr Joshua gave no evidence in chief about the letter, although he was cross-examined about it. At trial, the respondents’ case was that the letter merely authorised Mr Joshua to continue working for other clients. It was not relied upon as any part of their defence. Its principle relevance for present purposes is, therefore, as part of TICA’s circumstantial case, and as part of its claim for breach of fiduciary duty. As will become apparent, it also has a secondary relevance in relation to the credit of Mr Nounnis Jnr and Mr Joshua.

108 It is now useful to set the letter out in full. It enclosed a long set of terms and condition. I will not set those out in full but only the relevant parts. The letter was as follows:

10th May 2012

TICA Default Tenancy Control Pty Ltd

P.O. Box 120

Concord NSW 2137

Re: Contractor Terms

Dear Anthony

As discussed earlier with you I am concerned with the fact that I will be coming on board full-time with TICA in July of this year and I am currently running a business (Coolification Enterprises) as well as providing contract services for other businesses.

Philip knows about Coolification Enterprises as well as the fact that I do work for other businesses. As he has suffered a major health issue and scare recently, I do not want to bother him with this matter and now that you have been made a Director of TICA Default Tenancy Control Pty Ltd I am presenting these concerns to you.

I would like an undertaking by TICA that no restrictions will be placed on me with respect to my current business or contract work I conduct now and into the future.

I have enclosed a copy of a standard contract Terms and Condition I use with my contract clients. I would like TICA to sign off on acceptance of these Terms and Conditions for all my contract work performed to date and continuing, as well as an undertaking that TICA will not impose any restrictions on me due to my full-time employment and my contract Terms and Conditions will remain effective and binding during and after my contract term or employment.

Regards

[Signed]

Reginal Joshua

I Anthony Nounnis a Director of TICA Default Tenancy Control Pty Ltd, agree and accept the Terms and Conditions supplied by Reginald Joshua who is a current contractor of the company. I also agree to undertake that TICA Default Tenancy Control Pty Ltd and its related entities will not impose any restrictions on Reginald Joshua during his full-time employment or into the future and the Terms and Conditions remain part of his employ.

Signature: [Signed] Date: 11-05-2012

109 The relevant parts of the terms and conditions were as follows:

1. Your relationship with Reginald Joshua

a. Your contract of services from Reginald Joshua and any related entities he owns is subject to the terms of a legal agreement between you and any related entity you own. This document explains how the agreement is made up, and sets out some of the Terms and Conditions of that agreement and is not limited to these Terms and Conditions which can be changed at anytime without notification to you or your entities.

…

…

4. Provision of the Services

…

b. You acknowledge and agree that the form and nature of the Services provided may change from time to time without prior notice to you. These changes will not effect these terms and conditions which will remain in effect during any change of circumstances.

c. As part of Reginald Joshua’s continuing innovation, you acknowledge and agree that the Services (or any derivatives of the Services) supplied to you remains the right for future use without restrictions by you. This includes but is not limited to all involvements with your business operations. Intellectual property rights for use between parties will not be claimed at anytime. In the event that you decide to permanently discontinue the use of Reginald Joshua’s service you have no claim to any works, knowledge, skills or developments.

…

8. Content in the Services

…

e. You will not have the rights to impose any restrictions of trade and use of any technologies and developments that arise from the Services conducted for you, and this knowledge will remain open for use by Reginald Joshua with other clients or for personal developments.

…

g. You the client have no rights to any works, material or content, in all forms, whether tangible or intangible in the possession of Reginald Joshua should services be terminated.

h. There will be no obligation to return data to you after the service is suspended or cancelled. If is your responsibility to supply only sample data for use and this data should have no other significance than for analysis, testing and development purposes. Should you supply sensitive data you do so at your own risk and no responsibility is place on Reginald Joshua.

9. Proprietary rights

a. You acknowledge and agree that Reginald Joshua will own all legal right, title and interest in and to any works Reginald Joshua may be involved in while providing the Service, including any Intellectual Property Rights which subsist (whether those rights happen to be registered or not, and wherever in the world those rights may exist). You further acknowledge that while providing the Services there may contain information which is designated confidential and that you shall not disclose such information without prior written consent.

b. All knowledge obtained while conducting Services including but not limited to all works of other contractors will form part of the general skills and knowledge Reginald Joshua will possess and open for free use always.

…

16. General legal terms

…

b. The Terms constitute the whole agreement between you and Reginald Joshua and govern your use of the Services provided.

…

…’

(Errors in original).

110 The major health issue referred to by Mr Joshua in the letter is a reference to Mr Nounnis Snr having gone into a coma for four days following an allergic reaction in December 2011, at least four months before the apparent date of the letter.

111 Mr Nounnis Snr’s evidence about this letter was quite different. He says that he became aware of the letter only in about October 2014, after both Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr had left. He thought it odd that Mr Joshua had prepared the letter for Mr Nounnis Jnr to sign when he, Mr Nounnis Snr, was regularly attending TICA’s offices notwithstanding his recuperation. There was, according to Mr Nounnis Snr, also no directors’ resolution authorising Mr Nounnis Jnr to sign such a letter. Further, in response to his son’s evidence about placing the letter on his wife’s desk, Mr Nounnis Snr said that Mr Nounnis Jnr would have needed to walk past his own desk to do so and having checked his emails, he believed he had been in the office on that day. Mrs Nounnis herself denied that this had occurred. Mr Nounnis Snr had also been unable to find any version of the letter in TICA’s system (which is perhaps not that surprising since it was written by Mr Joshua). He could not understand why Mr Nounnis Jnr did not think the contents of the letter controversial.

112 In my opinion, the terms of the letter are quite out of the ordinary, and I do not accept that had Mr Nounnis Jnr signed it on 11 May 2012 in the circumstances in which he says he signed it, he would not have thought so either. I think it most unlikely that Mr Nounnis Snr would have agreed to the letter, and I do not accept that he was not available to sign it on 11 May 2012.

113 More importantly, there was no reason on 11 May 2012 for Mr Joshua to be seeking the strong protections the letter conferred, which went beyond anything required as a result of his change of status. There was no reason, correlatively, for Mr Nounnis Jnr to be granting them. Mr Nounnis Jnr’s evidence that he did not think the letter did any more than reflect the current situation is implausible, as were Mr Joshua’s attempts under cross-examination to downplay the letter’s significance (‘…it was just saying I can still work for other clients…’). If it was as innocuous as Mr Nounnis Jnr says he thought, there was no reason for Mr Nounnis Snr not to sign it. Furthermore, and to Mr Nounnis Jnr’s direct discredit, any attention to the letter shows that it did not merely regularise the situation. Such a reading is so at variance with its terms that I cannot accept the view genuinely to be held.

114 All these circumstances point to the correctness of TICA’s submission that the document was created after Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr had left TICA and was backdated. This is a strong conclusion to reach but to do otherwise I would need to accept that:

Mr Nounnis Jnr did not understand the significant effect of the letter he was signing even though it was obvious;

the reason Mr Nounnis Snr was not asked to sign the letter was because of his health problems, when the coma event referred to had been four months earlier and when, in fact, he was readily available;

Mrs Nounnis’ denial is false;

Mrs Nounnis did not file the letter or it was otherwise inexplicably lost; and

the letter was a minor matter of just acknowledging what was already the case, even though it was being officially signed by Mr Nounnis Jnr as a director and enclosed eight pages of closely drafted and controversial contractual terms.

115 I am unable to accept any of these matters considered in isolation or, even less so, cumulatively. In relation to the position of Mrs Nounnis, whilst I explain below why I cannot accept her evidence on the question of who owned the copyright in the TICA system, this does not cause me not to accept her evidence on this issue.

116 Accordingly, I conclude that the letter was backdated by Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr after they had left TICA. I do not need to determine this, but it is likely that it was created after TICA first started sending letters of demand to Mr Joshua. In reaching that conclusion I take into account the fact, which I explain elsewhere, that none of Mr Nounnis Snr, Mrs Nounnis, Mr Nounnis Jnr or Mr Joshua were, in my view, especially reliable witnesses.

117 Also relevant to the circumstantial case are these matters. First, clearly the relationship between father and son is toxic. They had been estranged before the events giving rise to this litigation but then were reconciled. Now they are estranged again. It is not my role to assign blame in that aspect of this dispute. For my purposes it is enough to know that Mr Nounnis Jnr is most likely not well disposed towards his father and vice versa.

118 Secondly, I do not think that Mr Joshua or Mr Nounnis Jnr were completely honest in their evidence to me. Both lied about the letter of 10 May 2012. Mr Nounnis Jnr also lied about the circumstances which led him to access TICA’s website. Additionally, I found one particular aspect of Mr Joshua’s evidence unsatisfactory. It arose from a letter he wrote to TICA’s solicitors on 27 October 2014 in response to a letter of demand written by them. The letter is long and contains many complaints. On the second page, this was said:

…

Does “Confidential Information” include the racist attitude shown towards myself? I have a lot of witnesses in relation to this and who are happy to help me to pursue this matter vigorously and publicly. Does “Confidential Information” include the bullying in the workplace, breach of workplace practice or smoking in the workplace? As none of these things were mentioned in your letter I am assuming they are not included as part of the “Confidential Information” and as they are workplace issues cannot be included in any confidentiality agreement.

As for the “Trade secrets”, I would like your client to clarify what they mean by this term. Do trade secrets include falsifying of records to supply to government departments such as Privacy and Office of Fair Trading? Or deliberately slowing computer programs to extract extra monies from unsuspecting individuals? Or a teenager hacking the TICA system and downloading who knows what type of confidential information? Are these examples classed as “Trade Secrets” or would this information be classified as in the best interest of the public and a matter for the appropriate government departments to deal with? I have a lot more examples of what I may consider a secret but clarification by your client would be appreciated so I will know what to keep confidential.

…

119 Mr Joshua repeatedly refused to accept that this was a threat. I will not set the many pages of cross-examination out. They are at T138-143. There was no reason for Mr Joshua not to accept that his letter contained a threat, the delivery of which could be hardly surprising in a case such as the present. Whatever else it reveals about Mr Joshua, it shows a reluctance to embrace the truth about his own actions.

120 Thus were the elements of the circumstantial case.

(e) Has the circumstantial case been proved?

121 I accept that Mr Joshua and Mr Nounnis Jnr have used the usernames and passwords of some of TICA’s clients illicitly to access TICA’s website, and that they did so to assist in the design of Datakatch’s website. In Mr Joshua’s case, I am satisfied that he used the opportunity thus obtained to copy the HTML code from TICA’s website, which he then heavily modified. In the case of Mr Nounnis Jnr, his access was either to assist him with design concepts, or to provide Mr Joshua assistance with his endeavours. I also accept that both men were minded to use the resources of TICA for the benefit of Datakatch to the extent that they could.

122 Whilst I am satisfied that they would have copied TICA’s source code if given the opportunity I do not think that, beyond the HTML code, they had such an opportunity. This is because for the reasons already given, I do not think that they took the back-up CDs. Furthermore, a case that Mr Joshua had copied the application from the external hard drives was not advanced. It is not open to me, therefore, to conclude that Mr Joshua copied the source code from the external hard drives. The respondents were not called on to respond to such a case. Further, there are obvious inquiries which might be made about such a case including providing the external drives for examination.

123 I have previously concluded that, viewed in isolation, the case that some of the database schema were copied was equivocal. However, in assessing the circumstantial case, the individual circumstances are not to be assessed in isolation but rather as the Lord Chancellor explained in Re Belhaven and Stenton Peerage (1875) 1 App Cas 278 at 279:

… in dealing with circumstantial evidence, we have to consider the weight which is to be given to the united force of all the circumstances put together. You may have a ray of light so feeble that by itself it will do little to elucidate a dark corner. But on the other hand, you may have a number of rays, each of them insufficient, but all converging and brought to bear upon the same point, and, when united, producing a body of illumination which will clear away the darkness which you are endeavouring to dispel.

124 Even so, I remain unclear how this copying could have occurred in light of my conclusions about the back-up CDs and external hard drives. The best that I can do is that Mr Joshua might have recalled from the time of his employment at TICA some of the headings or layouts. However, in the end I am not satisfied that this has been demonstrated, rays of light notwithstanding. To put it another way, the applicant has not satisfied me that copying occurred.

125 In summary, I conclude that:

the source code was not copied;

some HTML code was copied, most likely using miggibot software;

database schema were not copied; and

no data was copied.

126 Before turning to the legal consequences of these conclusions, it is convenient to make some further observations about the extent of the copying that occurred.

127 In the case of the HTML stylesheets, I am not able to discern how much of the HTML code was copied by Mr Joshua. Even in the three examples which I have found were copied, I am unable to discern how much of the overall HTML code these represented. No comparison was performed either in relation to the overall HTML code (or the larger Datakatch code) or even a visual comparison of the appearance of the websites when the code was executed.

128 In those circumstances, I do not conclude that it has been demonstrated that the copying carried out by Mr Joshua was of a substantial part of the TICA system. It is not that it might not be the case; it is that it is not shown.

129 For the following reasons, the immediately preceding conclusion entails that TICA’s claim based on copyright infringement fails. The principles to be applied in a case such as the present are clear. Section 36(1) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (the ‘Copyright Act’) provides that the copyright in a ‘literary work’ is infringed by a person who, not being the owner and without the owner’s licence, ‘does… any act comprised in the copyright’. By s 10 ‘literary work’ is defined to include computer programs, tables and compilations. By s 31(1)(a) the right comprised in the copyright includes the exclusive right ‘to reproduce the work in a material form’. By s 10 the concept of an ‘adaptation’ is introduced in relation to a computer program as meaning ‘a version of the work (whether or not in the language, code or notation in which the work was originally expressed) not being a reproduction of the work’.

130 The definition of adaptation matters because ‘material form’ is defined in s 10 to include ‘in relation to a work or an adaptation of a work, … any form (whether visible or not) of storage of the work or adaptation, or a substantial part of the work or adaptation…’.

131 The consequence of this thicket of provisions is that TICA must show either that the respondents reproduced the TICA system or a substantial part of it. As Bennett J pointed out in CA Inc v ISI Pty Limited (2012) 201 FCR 23 at 55 the question of substantial reproduction in the context of a computer program is to be approached taking into account the importance of function: cf. Autodesk Inc v Dyason (1992) 173 CLR 330 at 346-347 per Dawson J. I am not satisfied that a substantial part of TICA’s software has been taken. The amount of code copied is trivial from a quantitative point of view, and no functional analysis was attempted. The infringement case fails.

132 That makes it strictly unnecessary to deal with the respondents’ contention that TICA was not the owner of the copyright in the TICA software. However, for the sake of completeness, I will record my view that the owner was TICA.

133 There were three substantive phases in the development of the TICA system. The first phase, in 1992, involved Mr Nounnis Snr engaging a programmer to write the original system. As with the composer of Greensleeves, the name of this programmer has been lost to history. This first version was then replaced by an entirely different second version in 1997, which was written by Mr McCoy. This second version was superseded in 2004 by a third version, using MySQL. I am satisfied that this was a different work to the earlier two versions.

134 As far as the substantive facts are concerned, the two earlier versions may be put to one side. At the time that Mr McCoy wrote the third version, TICA itself was in existence and was conducting the TICA business.

135 Mr McCoy plainly never regarded himself as owning the copyright. He felt that it was Mr Nounnis Snr who had owned it but, unsurprisingly, he could not recall the specific terms of any formal agreement with Mr Nounnis Snr to that effect. I say it is unsurprising because the events in question were many years ago, and related to a topic then of very little significance.

136 There is other evidence about the ownership of the copyright, but for reasons which I will shortly give, I do not regard any of it as reliable. This evidence was as follows:

Mr Nounnis Snr (and to an extent Mrs Nounnis) gave evidence suggesting that TICA owned the copyright in Mr McCoy’s 2004 work;

until 2013 there was an entry in TICA’s accounts for software as an asset; and