FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Murray on behalf of the Yilka Native Title Claimants v State of Western Australia (No 5) [2016] FCA 752

ORDERS | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 JUNE 2016 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. With respect to settling the form of the Determination or Determinations, the parties consult in relation to all matters that may be pertinent to a proposed form of Determination or Determinations to give effect to these reasons.

2. By 26 August 2016, the parties notify my Associate as to the form of Determination or Determinations if agreed, or if not agreed, each party is to notify my Associate of its proposed form of Determination.

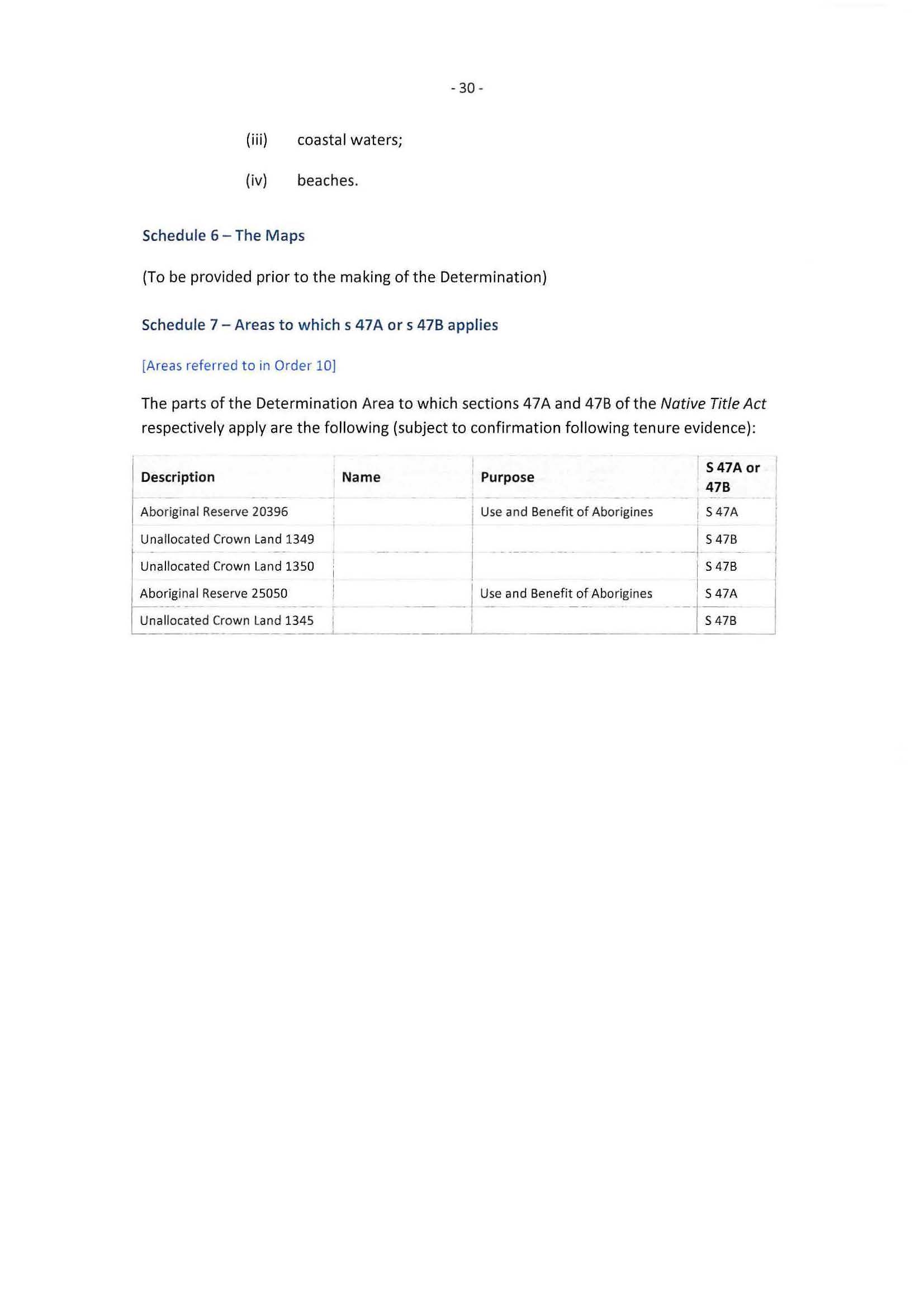

3. There be liberty to apply to vary these orders.

4. Any order dismissing the State’s interlocutory application dated 15 October 2012 be made at the date of making the Determination or Determinations.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Orders | |

WAD 498 of 2011 | |

BETWEEN: | GS (DECEASED), PATRICK EDWARDS AND MERVYN SULLIVAN Applicant |

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA First Respondent SHIRE OF LAVERTON Second Respondent CORINA BENNELL, LISA BENNELL, MATTHEW BENNELL, CENTRAL DESERT NATIVE TITLE SERVICES LTD, COSMO NEWBERRY (ABORIGINAL CORPORATION), BRETT DIMER, HILDA DIMER, JARED DIMER, SHAUN DIMER, SHONDELLE DIMER/GARLETT, RON HARRINGTON-SMITH, HARVEY MURRAY ON BEHALF OF THE YILKA NATIVE TITLE CLAIMANTS, ALISON TUCKER (NEE BARNES), DANIEL TUCKER, FABIAN TUCKER, KATHY TUCKER, MICHAEL TUCKER AND QUINTON TUCKER Third Respondents ELECKRA MINES LTD AND SASAK RESOURCES AUSTRALIA PTY LTD AND URANEX NL Fourth Respondents TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED Fifth Respondent GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LIMITED Sixth Respondent |

JUDGE: | MCKERRACHER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 JUNE 2016 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. With respect to settling the form of the Determination or Determinations, the parties consult in relation to all matters that may be pertinent to a proposed form of Determination or Determinations to give effect to these reasons.

2. By 26 August 2016, the parties notify my Associate as to the form of Determination or Determinations if agreed, or if not agreed, each party is to notify my Associate of its proposed form of Determination.

3. There be liberty to apply to vary these orders.

4. Any order dismissing the State’s interlocutory application dated 15 October 2012 be made at the date of making the Determination or Determinations.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS | |

WAD 303 of 2013 | |

BETWEEN: | HARVEY MURRAY ON BEHALF OF THE YILKA NATIVE TITLE CLAIMANTS Applicant |

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA First Respondent PATRICK EDWARDS AND MERVYN SULLIVAN Second Respondents |

JUDGE: | MCKERRACHER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 29 JUNE 2016 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. With respect to settling the form of the Determination or Determinations, the parties consult in relation to all matters that may be pertinent to a proposed form of Determination or Determinations to give effect to these reasons.

2. By 26 August 2016, the parties notify my Associate as to the form of Determination or Determinations if agreed, or if not agreed, each party is to notify my Associate of its proposed form of Determination.

3. There be liberty to apply to vary these orders.

4. Any order dismissing the State’s interlocutory application dated 15 October 2012 be made at the date of making the Determination or Determinations.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MCKERRACHER J:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 – CONNECTION – YILKA CLAIM

1 The Yilka applicant and the Sullivan Edwards applicant (Sullivan applicant) claim native title. The first respondent (State) opposes the claim. In these reasons, in four chapters, I have, for the most part, addressed issues raised by the parties in the same or similar order as an agreed list of issues that I directed the parties file and which their submissions, most helpfully, have addressed.

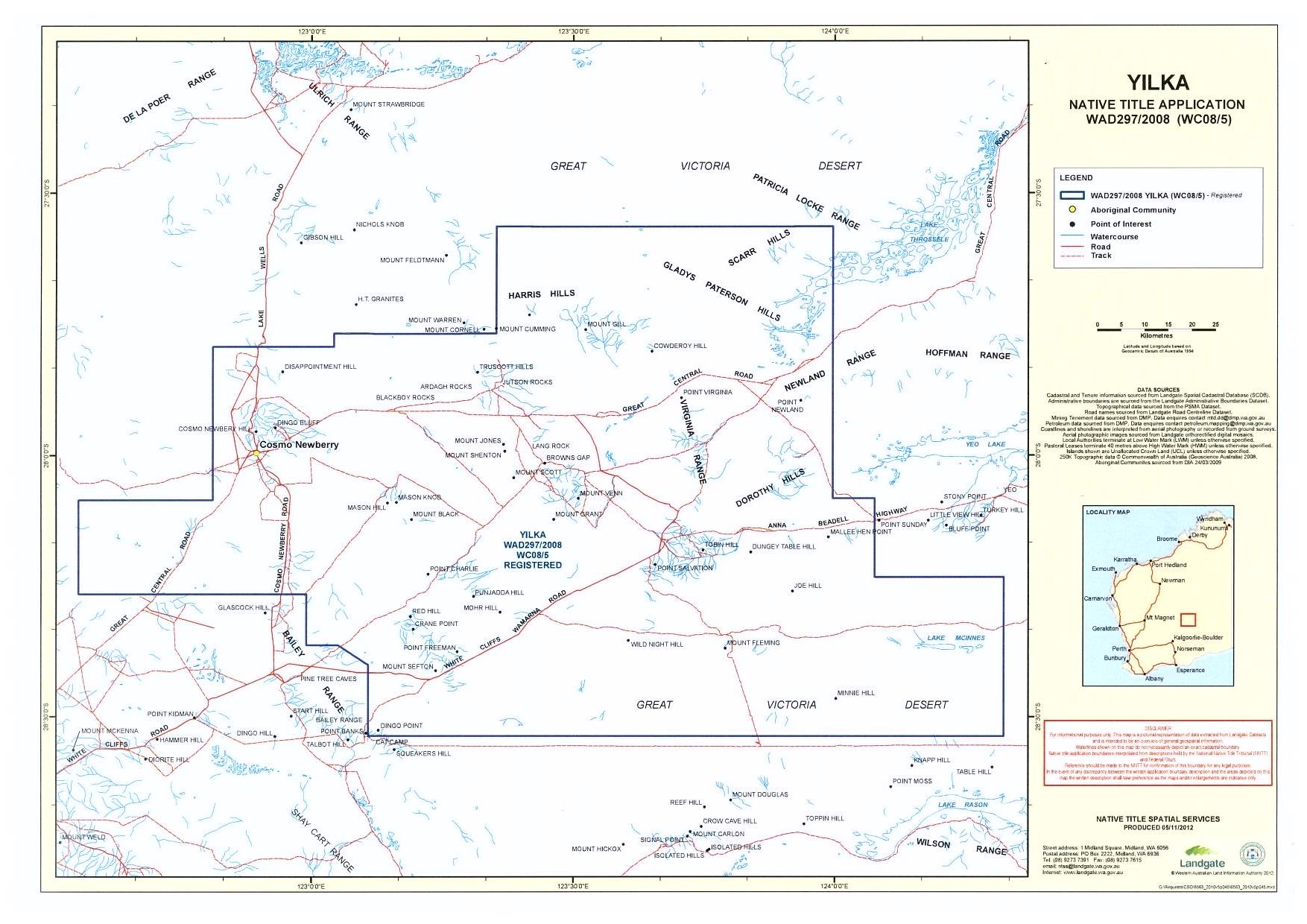

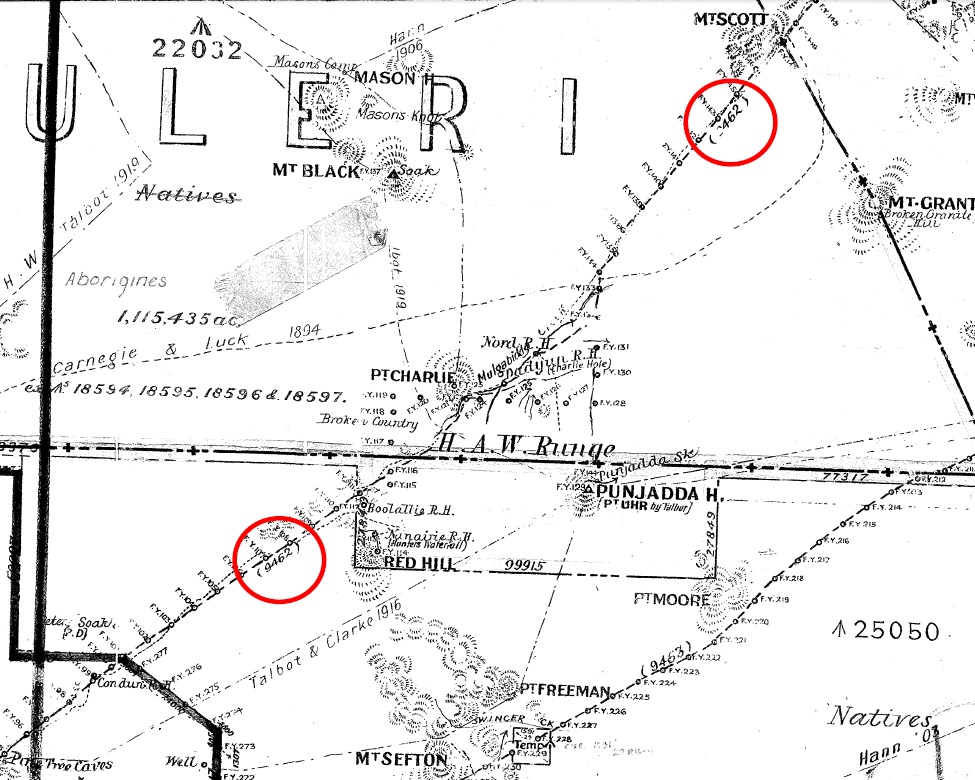

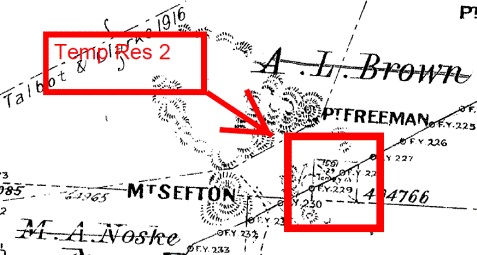

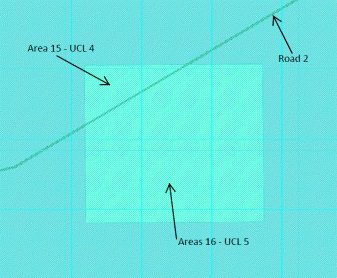

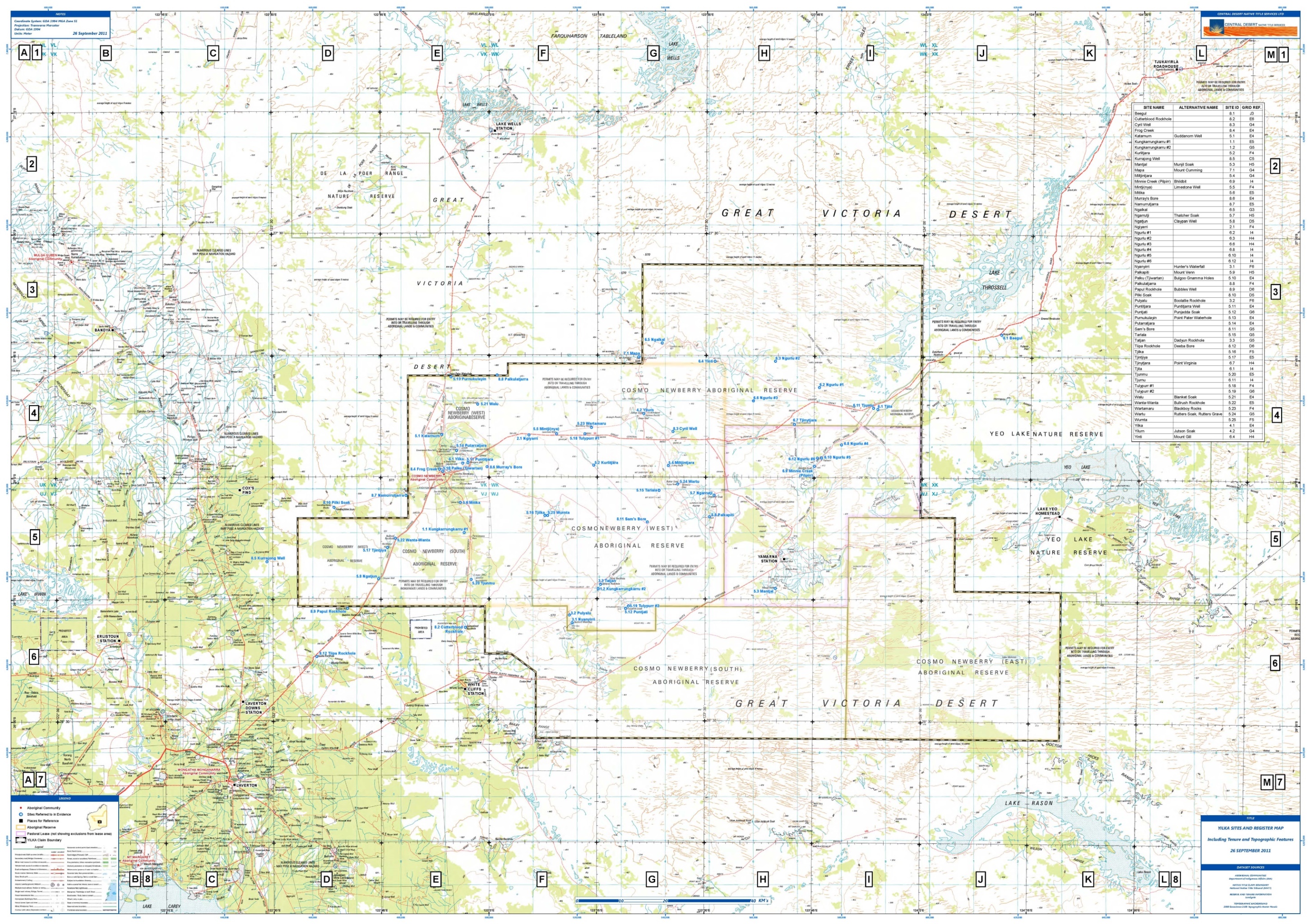

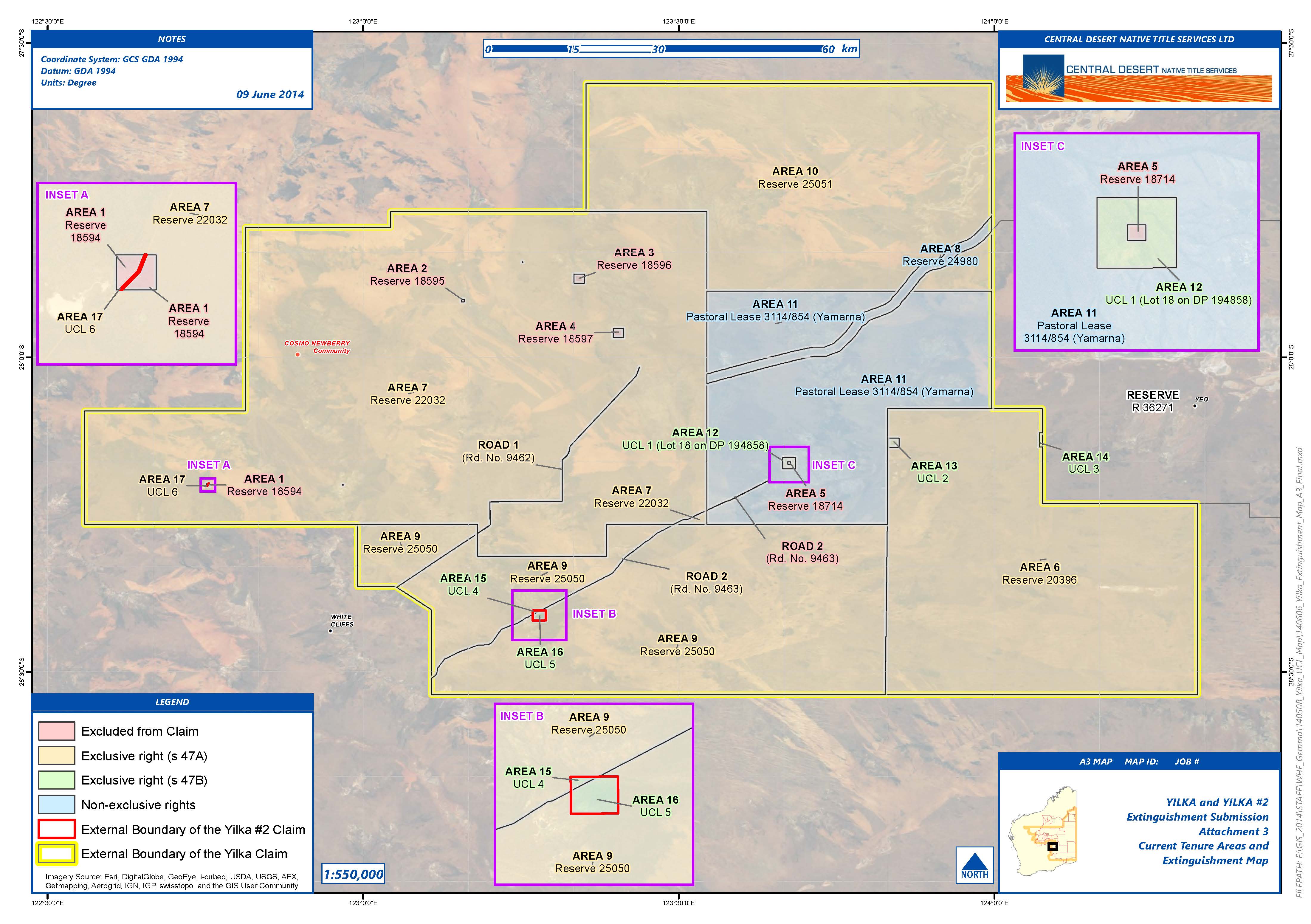

2 The Yilka No 1 claim (WAD 297 of 2008) was lodged on 15 December 2008. The Court and parties, including a not insignificant entourage first set foot (in this application) in the Claim Area on 31 October 2011 and extensive site evidence was heard in the course of hearing the Yilka applicant’s case. The Yilka No 2 claim (WAD 303 of 2013) was lodged on 1 August 2013, as a formality in order to attract the operation of s 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA), and partially overlaps the Yilka No 1 claim. As per Court orders dated 29 August 2013, the Yilka No 1 and Yilka No 2 claims were ordered to be heard together, so that pleadings and evidence in both matters stand as pleadings and evidence in the other proceeding. The Yilka No 1 and Yilka No 2 claims are referred to collectively as the Yilka claim, unless specified otherwise. Similarly, the terms Yilka applicant and Yilka claim area, being the area the subject of the Yilka claim refer to those entities in relation to both claims.

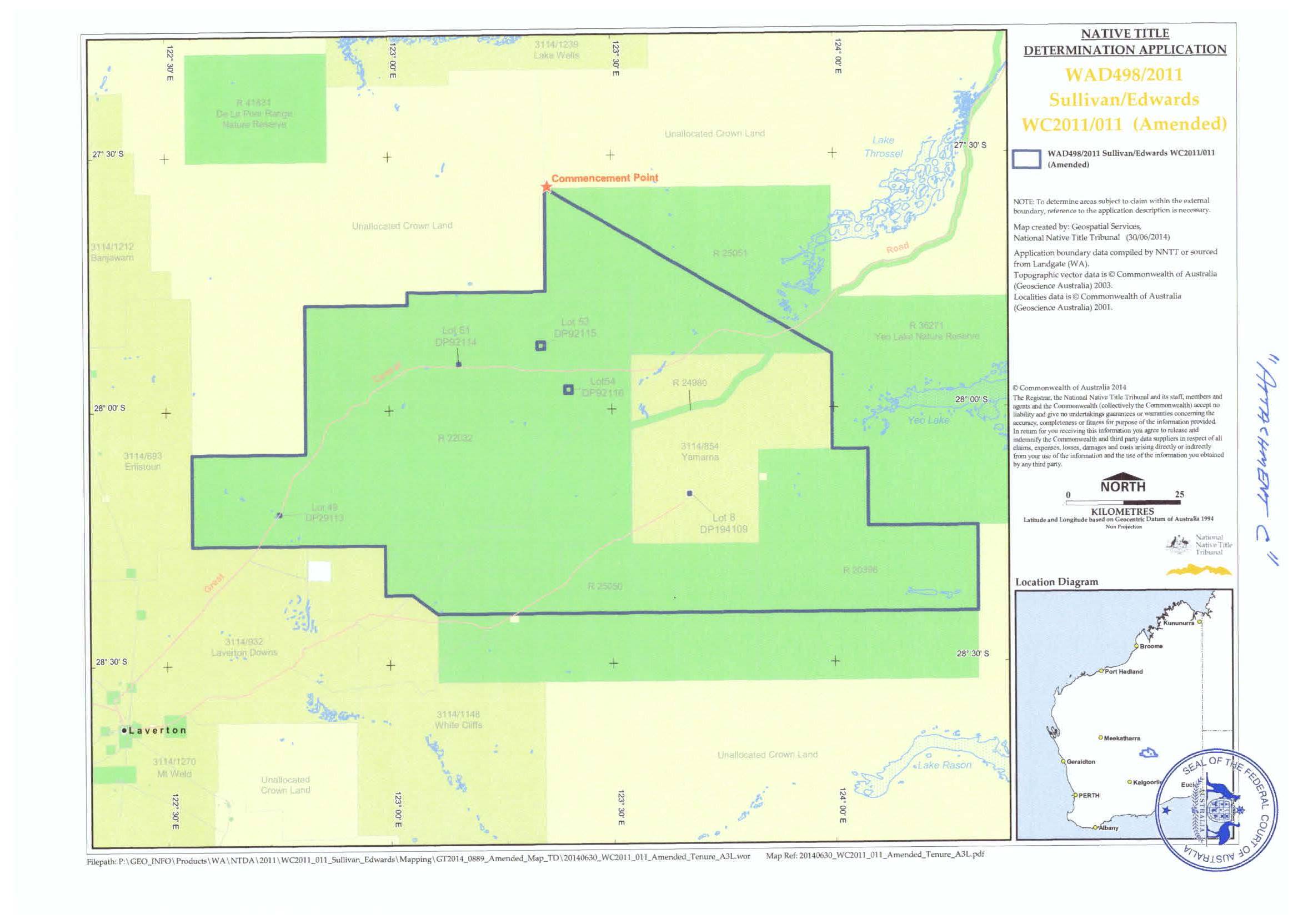

3 The Sullivan applicant did not join in the hearing until relatively late in the piece. The Sullivan Edwards claim (Sullivan claim) (WAD 498 of 2011) was lodged on 7 December 2011. The area the subject of the Sullivan claim is referred to as the Sullivan claim area. On 1 March 2012, I ordered that both the Yilka and Sullivan claims be heard together pursuant to s 67 NTA. The parties were subsequently joined as respondents in each other’s claim, as per orders of 26 April 2012. Prior to that time, the Sullivan applicant did not participate in the evidence called on behalf of the Yilka applicant.

4 The three claims are referred to collectively as the proceedings (and sometimes as these proceedings or the present proceedings) and the totality of the areas of the Yilka claim area and the Sullivan claim area is referred to as the Claim Area. The term Yilka claim group means the persons on whose behalf the Yilka claim is made, and its members are also referred to as Yilka claimants. Similarly, Sullivan claim group mans the persons on whose behalf the Sullivan claim is made, and its members are referred to as Sullivan claimants.

5 For the Yilka applicant, evidence was given by some 16 lay witnesses, together with seven witnesses who only gave evidence during site visits. Many others attended the site visits voluntarily. There were also many people who participated in a demonstration of the preparation of bush tucker at the second last open site visit location at Yilurn. The site visits were followed by many days of more formal evidence with the tender of affidavits, the leading of oral evidence where necessary, and the tender of statements of various deceased persons who were regarded as possessing right in the Claim Area.

6 The Yilka applicant named its native title claim after a significant place on the Claim Area. It includes the area of the Cosmo Newberry Aboriginal Community (Cosmo Newberry Community), a number of large reserves for the use and benefit of Aboriginal people, some small reserves of other kinds, some small areas of unallocated Crown land (UCL), and a pastoral lease.

7 The Sullivan applicant claims a similar area, but shortly prior to closing submissions, amended the claim to reduce it by excising a small portion of its original claim area.

8 As explained by senior counsel for the Yilka applicant, Mr Blowes SC, there are a number of distinct features of this claim. The first of those is that it is a contested claim involving people of the Western Desert and the laws and customs of the Western Desert, which poses some special considerations for the application of the NTA. The Yilka applicant argues that these issues are not insurmountable. Secondly, and again, unusually, it is a claim that follows previous claims involving, to some extent, similar people and, to some extent, a similar area. This has created special considerations, not only by reason of detailed abuse of process submissions advanced by the State, but also because all of the parties have relied to some extent on the evidence and/or reasons in the very substantial judgment of Justice Lindgren in Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1. As such, more than a passing familiarity with the evidence and reasoning in Wongatha has been necessary for the parties and the Court. A third feature of the claim is that not all claimants are resident in the Claim Area. The Yilka applicant argues this is not unusual; indeed, many claims have been determined where there are no residents in the claim area.

9 Since evidence was first given in the proceedings, two of the witnesses have passed away. Those two witnesses were Lincoln (Jayden) Smith (deceased), referred to as Jayden Smith, who was born near a location known as Minnie Creek, about which much evidence was given, on 30 June 1953, and the late Yinga Estelle Ross, referred to as Ms Ross whose mother was also born in that area in 1915.

10 There are two main lines of disputation in regards to the existence of native title, which are canvassed in this and the following chapter.

11 In respect of both the Yilka and the Sullivan claims, the State puts the applicants to proof and contends they have not come up to their pleaded cases. The State’s primary focus, however, has been on the contention that it is not open to advance either of the claims concerned due to findings in Wongatha. As will be seen, I do not consider that these arguments should be upheld. This is largely because I consider that these claims are entirely different claims from those argued and dealt with in Wongatha.

12 The other major dispute is between the Yilka applicant and the Sullivan applicant. Whereas, on the one hand, the Sullivan applicant simply says that the Sullivan claimants should have been included in the Yilka claim and has not objected to the Yilka claimants being included in its claim, the Yilka applicant strenuously maintains its position that the Sullivan claimants are not entitled to be within the Yilka claim. I have rejected that contention. The Yilka claim has been on foot for longer than the Sullivan claim and its presentation has been more detailed but, in substance, I have concluded that there is no reason why the Yilka claim should ever have excluded the Sullivan claimants. This is a conclusion which substantially accords with the views reached by the expert anthropologists in the case. While the Yilka applicant’s written submissions catalogue endless criticisms of and weaknesses in the Sullivan applicant’s evidence, to my mind, had such a microscopic analysis been taken to the Yilka case, similar problems would have arisen.

13 As a subsidiary issue, I can understand the State being confused as to exactly how the Yilka applicant was putting its case initially and, indeed, for some time. I do not think it has been as clear cut as the Yilka applicant’s indignation on that topic suggests. There has certainly been a significant argument over the issue of whether the claim simply constitutes an aggregation of individual claims, rather than a group claim.

14 This chapter deals with the existence of native title in respect of the Yilka claim. As such, while much of the discussion which follows is equally applicable to the Sullivan claim, the focus here is on the arguments put forward by the State in relation to the Yilka claim, and on the arguments made by the Yilka applicant in support of its claim.

15 An application for a determination of native title under the NTA is for rights defined by s 223(1) NTA. It is the NTA which governs consideration of the claim.

16 Section 223 NTA provides as follows:

223 Native title

Common law rights and interests

(1) The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

Hunting, gathering and fishing covered

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), rights and interests in that subsection includes hunting, gathering, or fishing, rights and interests.

Statutory rights and interests

(3) Subject to subsections (3A) and (4), if native title rights and interests as defined by subsection (1) are, or have been at any time in the past, compulsorily converted into, or replaced by, statutory rights and interests in relation to the same land or waters that are held by or on behalf of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, those statutory rights and interests are also covered by the expression native title or native title rights and interests.

Subsection (3) does not apply to statutory access rights

(3A) Subsection (3) does not apply to rights and interests conferred by Subdivision Q of Division 3 of Part 2 of this Act (which deals with statutory access rights for native title claimants).

Case not covered by subsection (3)

(4) To avoid any doubt, subsection (3) does not apply to rights and interests created by a reservation or condition (and which are not native title rights and interests):

(a) in a pastoral lease granted before 1 January 1994; or

(b) in legislation made before 1 July 1993, where the reservation or condition applies because of the grant of a pastoral lease before 1 January 1994.

17 In Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422, the majority of the High Court said (at [37]-[38]) (footnotes omitted):

37 First, it follows from Mabo (No 2) that the Crown's acquisition of sovereignty over the several parts of Australia cannot be challenged in an Australian municipal court. Secondly, upon acquisition of sovereignty over a particular part of Australia, the Crown acquired a radical title to the land in that part, but native title to that land survived the Crown's acquisition of sovereignty and radical title. What survived were rights and interests in relation to land or waters. Those rights and interests owed their origin to a normative system other than the legal system of the new sovereign power; they owed their origin to the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the indigenous peoples concerned.

38 When it is recognised that the subject matter of the inquiry is rights and interests (in fact rights and interests in relation to land or waters) it is clear that the laws or customs in which those rights or interests find their origins must be laws or customs having a normative content and deriving, therefore, from a body of norms or normative system – the body of norms or normative system that existed before sovereignty. Thus, to continue the metaphor of intersection, the relevant intersection, concerning as it does rights and interests in land, is an intersection of two sets of norms. That intersection is sometimes expressed by saying that the radical title of the Crown was "burdened" by native title rights but, as was pointed out in Commonwealth v Yarmirr, undue emphasis should not be given to this form of expression. Radical title is a useful tool of legal analysis but it is not to be given some controlling role.

18 The applicants carry both an evidential onus and an ultimate onus, or a burden of proof, to the civil standard, namely, on the balance of probabilities. As noted in Yorta Yorta, there are challenges in the forensic task of proving facts back to historical and pre-historical times. The majority said (at [80]):

It may be accepted that demonstrating the content of that traditional law and custom may very well present difficult problems of proof. But the difficulty of the forensic task which may confront claimants does not alter the requirements of the statutory provision. In many cases, perhaps most, claimants will invite the Court to infer, from evidence led at trial, the content of traditional law and custom at times earlier than those described in the evidence. Much will, therefore, turn on what evidence is led to found the drawing of such an inference and that is affected by the provisions of the [NTA].

19 Recently, in AB (deceased) (on behalf of the Ngarla People) v Western Australia (No 4) (2012) 300 ALR 193, Justice Bennett collected the case law helpfully where her Honour discussed the principles involved in drawing inferences in native title determination applications (at [106]-[108]):

106 In Yorta Yorta, Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ accepted that demonstrating the content of traditional law and custom may well present difficult problems of proof and that the court may be invited to infer, from evidence led at trial, the content of traditional law and custom at times earlier than those described in the evidence. They recognised that it may be especially difficult to demonstrate the content of traditional laws and customs in cases where it is recognised that the laws and customs have been adapted in response to European settlement. It was not possible to offer any single bright line test for deciding what inferences may be drawn or when they may be drawn (Yorta Yorta at [80] and [82]).

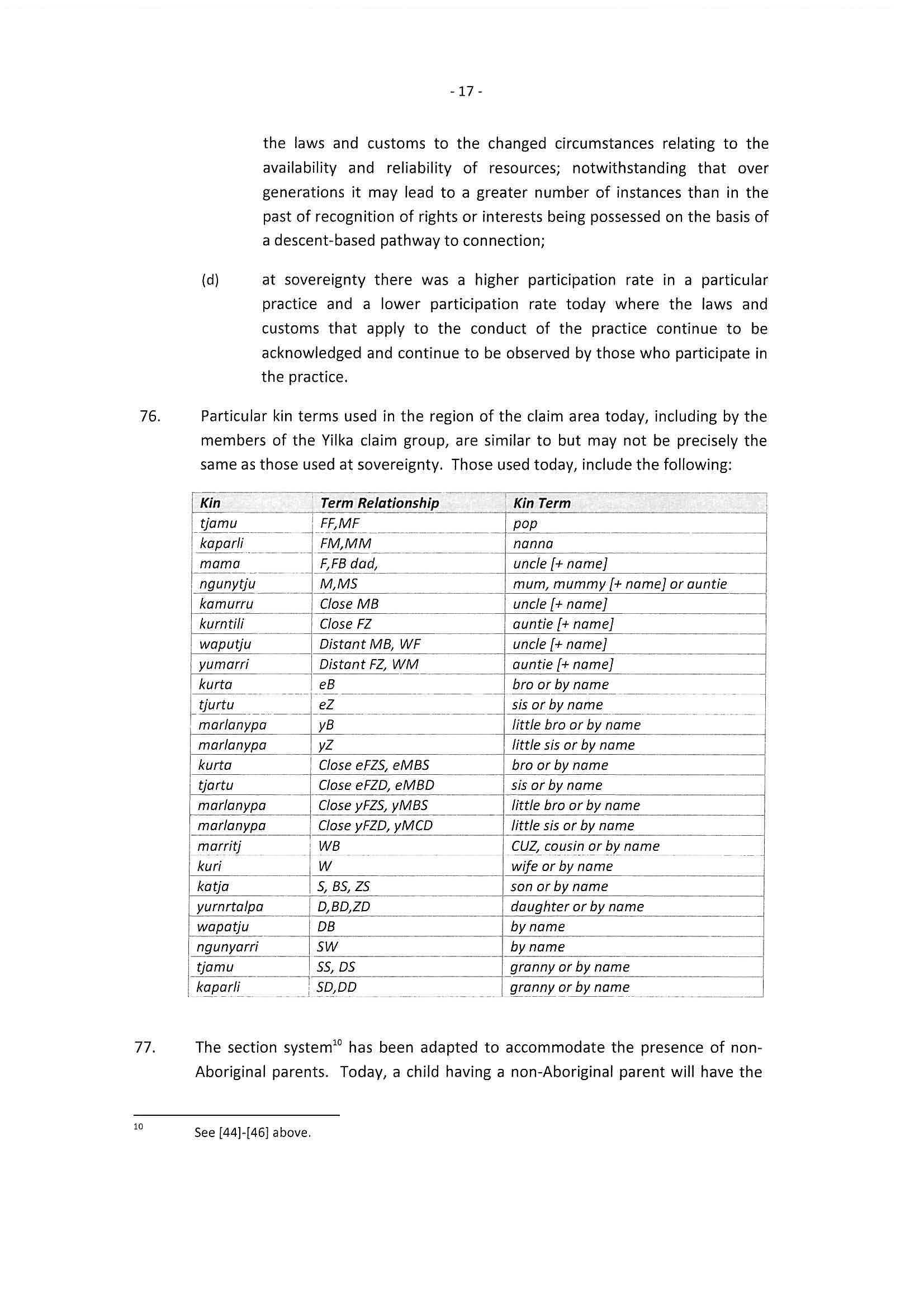

107 Justice Kirby in Mason v Tritton (1994) 34 NSWLR 572 concluded that inferences can be drawn in native title cases that a situation that exists at a particular time also existed at an earlier time. However, whether such an inference can be drawn depends upon whether the probabilities of the case favour the inference and whether intervening circumstances have occurred which would bring the situation to an end. His Honour noted that in more traditional Aboriginal communities the inference will be more easily drawn (at 887–889).

108 Similarly, in Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 141 FCR 457 (Gumana (2005)), Selway J held at [198]–[201] that there was no “obvious reason” in that case why evidentiary inference (of the kind discussed in Mason v Tritton) was not applicable for the purpose of proving the existence of Aboriginal custom and Aboriginal tradition at the date of settlement and the existence of rights and interests arising under that tradition or custom. However, Selway J continued to state that “[t]his does not mean that mere assertion is sufficient to establish the continuity of the tradition back to the date of settlement”. See also the application of Mason v Tritton in De Rose v South Australia [2002] FCA 1342 at [503]–[505] and [570].

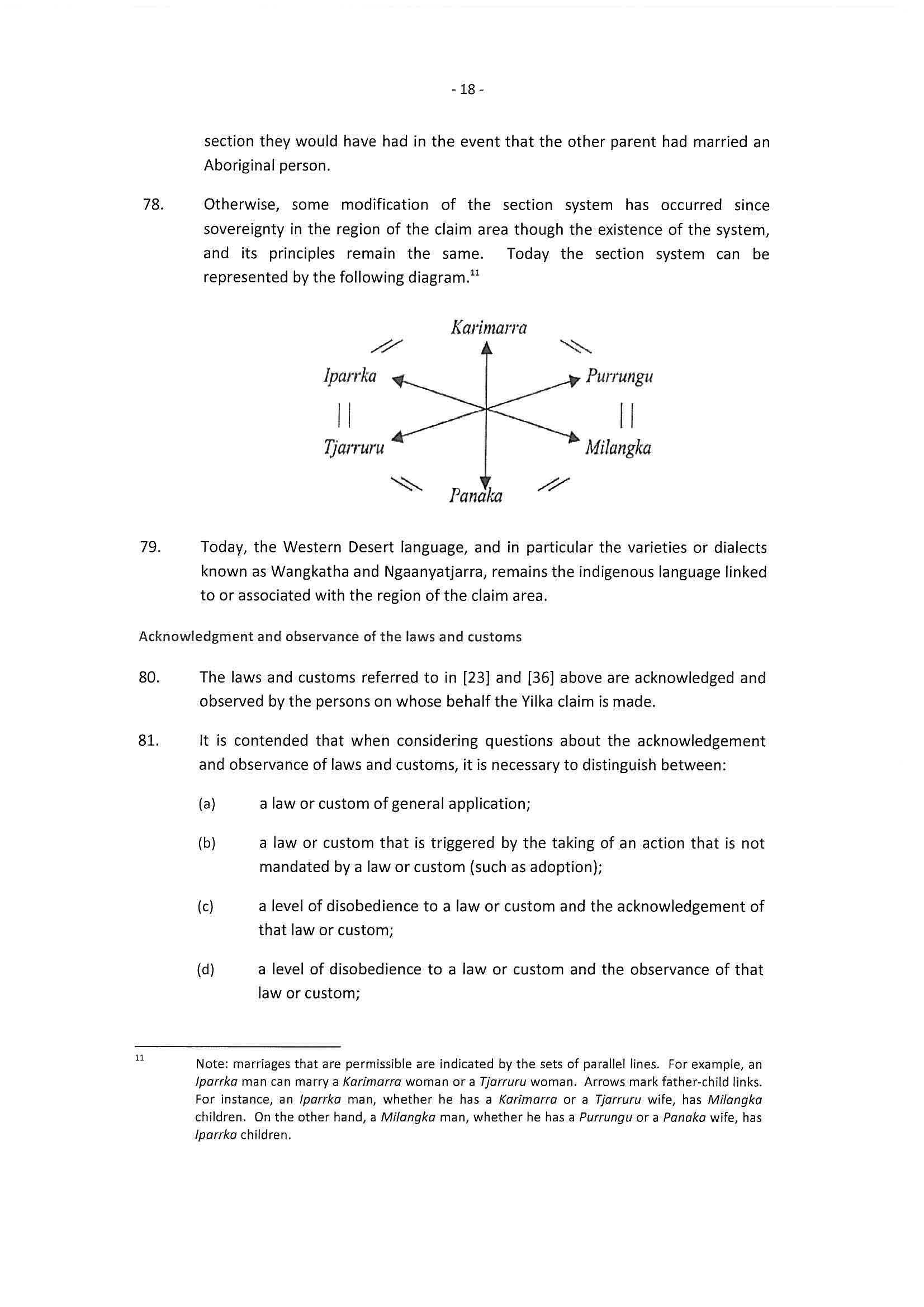

20 These matters are not in dispute. However, the State makes a number of submissions in relation to issues of proof.

21 First, the State seeks to emphasise the unique nature of those particular claims, making it clear that the proceedings here have much in common with the proceedings in Wongatha, in particular, proceedings WAD 144 of 1998 (Cosmo claim) and proceedings WAD 6005 of 1998 (Wongatha claim), two of the eight overlapping claims in Wongatha. The State draws attention to the fact that Harvey Murray (HM), who is the named Yilka applicant, in his capacity then as a Cosmo claimant, has lodged an appeal from Wongatha and that the present proceedings raise many questions which it says are, if not the same as the matters considered in Wongatha, not materially distinguishable. The State says, therefore, that it is not surprising that the considerations given by Justice Lindgren in Wongatha to comparable conditions will often provide potential guidance on questions arising in these proceedings. It is suggested that decisions made by Justice Lindgren on questions of law, questions of mixed law and fact, and questions concerning the application of principles should be followed unless plainly wrong.

22 The State makes the point that this difficulty is compounded by the reliance placed by the Yilka applicant’s expert and lay witnesses, including anthropologists, Dr Scott Cane and Dr Lee Sackett, on evidence given before Justice Lindgren in the Cosmo claim, the Court’s summaries of that evidence, the use and interpretation of that evidence and the findings in relation to that evidence, as if it were part of the process of information gathering or preparation for the present claim. The State submits that such an approach places this Court at a disadvantage to Justice Lindgren in that, whereas Justice Lindgren had before him a body of direct evidence as well as ethnographic and other documentary evidence, some parts of the evidence which was direct evidence before Justice Lindgren is now before the Court in the present proceeding in the form of a lifeless record of those proceedings. There is other evidence not before this Court at all. Significantly, the State says, a portion of the evidence received and summarised by Justice Lindgren has been considered without the advantage enjoyed by Justice Lindgren and used by expert and lay witnesses for the applicants as if it were ‘research’ or ‘advice’ for the purpose of providing a foundation of evidence in the present proceedings.

23 While there certainly are similarities between the Yilka claim and the Cosmo claim, that is a matter primarily for consideration in relation to the abuse of process argument which the State advances. The Yilka claim is pleaded differently and advanced with evidence directed to the pleaded claim. There is the further complication in relation to the Cosmo claim that Justice Lindgren ruled that he did not have jurisdiction (in the absence of authorisation) to consider the Cosmo claim. Nevertheless, for completeness and in light of the fact that the evidence had been adduced, his Honour did go on to consider the evidence. There is no doubt that, to the extent his Honour made findings (on the assumption that he was wrong about lack of jurisdiction), those were findings reached on the basis of the facts before his Honour, in turn moulded by the pleadings and arguments developed in that case. While the abuse of process arguments will be considered in due course, it should not be readily assumed that whatever findings that were reached by his Honour on the evidence, arguments and pleadings in Wongatha should be adopted in these proceedings.

24 The process of evidence taking in the Yilka claim involved visiting and hearing evidence at different sites in the Claim Area, including the significant area of Minnie Creek. Evidence adduced by witnesses in the Yilka claim has been of a quite different nature to that adduced in the Cosmo claim, directed, as it were, to the pleadings in the Yilka claim, which, as will be seen, were cast in a distinctly different way from the pleading in the Cosmo claim.

25 I would also discount the suggestion that the evidence from Dr Sackett and Dr Cane, as anthropologists, was significantly influenced by the material relied upon in the Cosmo claim. Although the expert anthropologists had access to material from the Cosmo claim when preparing their draft reports, the final reports were prepared with access to the first tranche of the claimants’ evidence, which Dr Sackett attended in full, from 31 October 2011 to 11 November 2011, after HM gave evidence on 5-6 December 2011; and following two expert conferences, the first on 22 July 2011, and the second across 24 July and 16 August 2012. Before they gave their evidence in September 2013, the expert anthropologists had attended and/or had access to the transcript of the entirety of the evidence advanced for the Yilka applicant in regards to the existence of native title.

26 Secondly, the State submits that the manner in which the applicants’ cases are put, being principally based on the claims of individuals, has a bearing upon the extent to which it is open to the Court to draw inferences relating to an entire population of a claim group from the evidence of individuals. The State submits that inclusion of particular individuals in a claimant group is not a sufficient basis to permit the drawing of inferences concerning one individual from attributes of some other individuals in that group. The State argues that if this were the case, then mere assertion that individuals constitute a group would amount to proof of the existence of the group and the attributes of all who are said to be included.

27 In this regard, the State emphasises that the Yilka claim group is said to comprise approximately 400 to 500 people whilst the evidence suggests it may be well over 1000 people, excluding any Sullivan claimants. There is, the State contends, a very large number and proportion of people about whom very little is known. The State complains that the number and proportion of witnesses whom have not been heard and whose circumstances are mostly unexplained is far greater than in the Cosmo proceedings where 15 from a total of 128 group members gave evidence.

28 Although the topic will be examined more fully, it is not clear that there is support for the State’s submission that if a claim is, as it describes it, an ‘individual claim’, evidence by an individual will not be capable of giving rise to inferences about any other person. The evidence in this case, as in many others, of individual witnesses includes direct evidence about many other persons, including deceased persons. There is no reason why inferences should not be drawn in relation to such evidence, whether the inference pertains to other individuals or the existence of groups.

29 Although the State’s submission does draw on a figure of well over 1000 people within the Yilka claim group, and therefore submits that the number of witnesses called to give evidence was insufficient, it is doubtful whether the number of persons within the claim group itself would be that high. The number of claimants referred to in the various genealogies adduced in evidence is less than 500. Given the detailed analysis in the genealogies, I consider that this would be a more reliable figure than an apparently un-researched estimate in oral evidence.

30 The Yilka applicant points to the fact that in Akiba (on behalf of the Torres Strait Islanders of the Regional Seas Claim Group) v Queensland (No 2) (2010) 204 FCR 1, Finn J found no difficulty in reaching conclusions in favour of the claim group extending to tens of thousands of people (at [27] referring to some 53,000 Torres Straight Islanders of whom 3,806 presently resided in the relevant islands of the Torres Straight) on the basis of the evidence of 26 witnesses, which included between one to four witnesses from each of the 13 island communities in question: Akiba (at [96]-[97]). The Yilka claim is in respect of a much smaller claim group. If only one or two witnesses had been called, then there would be some force in the complaint raised, but the proportion of witnesses and participants in relation to the number of claimants, as discussed above, was significantly higher than the State submission might suggest.

31 Finally, as to the question of drawing inferences, as discussed by Bennett J in Ngarla, the State submits that the applicants have failed to discharge the onus of establishing continuity in the acknowledgement and observance of law and custom which would lead to the drawing of the requisite inference. In relation to Gumana v Northern Territory (2005) 141 FCR 457, to which Bennett J referred to in Ngarla, Selway J (at [194]-[200]) considered whether evidence of witnesses which, on its face, may establish that the witnesses and relevant elders believed there was a long standing custom that predated them, could establish customs going back to an earlier time or time immemorial. In that instance, the custom under consideration was belief that the Law came from the land and the sea. Selway J referred to a number of common law cases and set out an extract from Hammerton v Honey (1876) 24 WR 603 (at 604) to the effect that the usual course taken is that where persons of middle or old age state that in their time, usually at least half a century, the usage has always prevailed, that is considered, in the absence of countervailing evidence, to show that the usage has prevailed from all time. The State emphasises that usual practice is expressed to be dependent on there being evidence that certain conduct ‘has always prevailed’ and perhaps, more importantly, in the absence of ‘countervailing evidence’. Selway J observed (at [201]):

There is no obvious reason why the same evidentiary inference is not applicable for the purpose of proving the existence of Aboriginal custom and Aboriginal tradition at the date of settlement and, indeed, the existence of rights and interests arising under that tradition or custom: see Lester G “Aboriginal Land Rights: the territorial rights of the Inuit of the Canadian Northwest Territories; a legal argument (1985) Repub vol 2, pp 884-906. Although no such inference would seem to have been relied upon in Millirrpum (see at ALR 110, 119-21; FLR 184, 197-8) Australian cases thereafter would seem to have relied upon such inferences, although without expressly acknowledging the common law authorities which plainly supported doing so: see, for example, Mason v Tritton (1994) 34 NSWLR 572 at 588; Yarmirr (FC) at [66]; De Rose at [259]; Lardil at [116] ff. This does not mean that mere assertion is sufficient to establish the continuity of the tradition back to the date of settlement: contrast [Yorta Yorta]. However, in my view where there is a clear claim of the continuous existence of a custom or tradition that has existed at least since settlement supported by creditable evidence from persons who have observed that custom or tradition and evidence of a general reputation that the custom or tradition had “always” been observed then, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, there is an inference that the tradition or custom has existed at least since the date of settlement. That was not the case in [Yorta Yorta]. It is the case here.

32 The State argues that the problem in transposing this reasoning into the present claims is that in key respects, such as the formation of intermediate groups such as the Yilka and Sullivan claim groups, the evidence is that the practices or laws and customs have, in fact, not always prevailed. The State also submits that in other respects, the conditions that have existed so lack constancy and stability as to leave doubts about whether conditions could reasonably be expected or assumed to have been sufficiently stable to permit the continuity which the applicant is asking the Court to infer. The impact of settlements and the consequential option of living in groupings larger than those that were viable in pre-sovereignty times was an example given by the State of dynamic rather than static conditions. Not only is there an absence of evidence of important customs or traditions always prevailing, but there is affirmative evidence, it is submitted, by the State that they have not always prevailed. The State refers to Griffiths v Northern Territory (2006) 165 FCR 300 in which Weinberg J found that it was reasonable to infer continuity of acknowledgement and observation of laws and customs, as there was nothing to suggest that the ritual and ceremonial practices observed since the middle of the nineteenth century, in a largely unbroken pattern, were suddenly created or radically transformed from what had immediately gone before (at [577]). Weinberg J noted the limits of the process of inference in relation to ancestral occupation (at [583]):

I accept that there will be some cases where the need to go back 30 or 40 years beyond the earliest extant genealogy would render the process too speculative to permit an inference of continuity or connection to be drawn. However, in the present case, the position seems to me to be different. It is known that indigenous people occupied the Timber Creek region at least as far back as the time of the earliest explorers. It is also known that inhabitants of that area adopted laws and customs that were, ethnographically, very similar to the laws and customs that indigenous people in other parts of Australia followed. A number of the ritual practices that are documented at least as far back as the latter part of the nineteenth century are, in significant respects, similar to those followed by Aboriginal people since well before European settlement in this country. It would be wrong, in my view, to approach the issue of connection by turning a blind eye to these historical realities.

33 Similarly, the State cites Jango v Northern Territory (2006) 152 FCR 150, where Sackville J (at [504]) observed:

If the indigenous evidence consistently favoured a particular set of laws and customs, an inference might well be available that the laws and customs described by the witnesses have remained substantially intact since sovereignty, or at least that any changes have been of a kind contemplated by presovereignty norms. The evidence is not, however, consistent. Accordingly, the force of any inference that might otherwise be available is much reduced. Indeed, the fact that in modern times people apparently have adhered to such different versions of law and custom rather suggests that the changes that have occurred since sovereignty are not mere “adaptations”.

34 Also, in Bennell v Western Australia (2006) 153 FCR 120 (at [457]) Wilcox J noted the following matters:

457 In addressing these questions, I am conscious of the possibility that a native title claim may fail because of a discontinuity in acknowledgement and observance of traditional laws and customs, even though there has been a recent revival of interest in them and there is current acknowledgement and observance. I have in mind cases such as Yorta Yorta and the decision of Mansfield J in Risk v Northern Territory of Australia [2006] FCA 404 (the Larrakia case). Before upholding a native title claim, the Court must be satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, of continuity of acknowledgment and observance, by the relevant community, from the date of sovereignty until the present time. Of course, there can never be direct evidence covering such a long time. However, inferences may be drawn, from evidence led at trial, concerning the situation in earlier times: see Yorta Yorta at [80] and [Gumana] at [195] – [201]. In the latter case, Selway J applied the principle enunciated by Jessell MR in Hammerton v Honey (1876) 24 WR 603 at 604:

It is impossible to prove the actual usage in all time by living testimony. The usual course taken is this: Persons of middle or old age are called, who state that, in their time, usually at least half a century, the usage has always prevailed. That is considered, in the absence of countervailing evidence, to show that usage has prevailed from all time.

35 However, the findings of continuity of the community, as opposed to the continuity of observance of law and custom, was subsequently found on appeal to have been erroneous: Bodney v Bennell (2008) 167 FCR 84 (at [70]-[78]) where the Full Court (Finn, Sundberg and Mansfield JJ) said:

70 The appellants contended that the questions the primary judge posed (quoted at [49]) are the wrong questions. The Commonwealth submitted that the correct question is whether acknowledgment and observance of traditional laws and customs has continued substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty. It is to be answered by ascertaining whether, for each generation of the relevant society since sovereignty, those laws and customs constituted a normative system giving rise to rights and interests in land, and in fact regulated and defined the rights and interests which those people had and could exercise in relation to the land and waters.

71 Since [Yorta Yorta] the approach propounded by the Commonwealth has been adopted in relation to the continuity issue. There at [87] the majority said:

acknowledgment and observance of those laws and customs must have continued substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty. Were that not so, the laws and customs acknowledged and observed now could not properly be described as the traditional laws and customs of the peoples concerned. That would be so because they would not have been transmitted from generation to generation of the society for which they constituted a normative system giving rise to rights and interests in land as the body of laws and customs which, for each of those generations of that society, was the body of laws and customs which in fact regulated and defined the rights and interests which those peoples had and could exercise in relation to the land or waters concerned.

(Emphasis in original.)

72 In Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404 at [97](c) (Risk TJ) Mansfield J said that applicants for native title must establish, amongst other things, that:

the acknowledgment and observance of the laws and customs has continued substantially uninterrupted by each generation since sovereignty, and the society has continued to exist throughout that period as a body united in and by its acknowledgment and observance of those laws and customs.

On appeal to the Full Court, the appellants did not attack that formulation, though they did unsuccessfully attack other parts of his Honour's summary of the requirements for establishing native title: Risk v Northern Territory (2007) 240 ALR 74 at [78]-[79]. The Full Court regarded the whole of his Honour's summary, including that quoted above, as an accurate statement of the effect of the cases, including [Yorta Yorta]: see at [78]-[98].

73 As appears from [49], the primary judge did not pose the continuity question in the form propounded by [Yorta Yorta]. Instead of enquiring whether the laws and customs have continued to be acknowledged and observed substantially uninterrupted by each generation since sovereignty, he asked whether the community that existed at sovereignty continued to exist over subsequent years with its members continuing to acknowledge and observe at least some of the traditional 1829 laws and customs relating to land.

74 The [Yorta Yorta] formulation concentrates on continued acknowledgment and observance of laws and customs because the rights and interests the subject of a determination of native title (s 225) are the product of the laws and customs of the society. It is not the society per se that produces rights and interests. Proof of the continuity of a society does not necessarily establish that the rights and interests which are the product of the society's normative system are those that existed at sovereignty, because those laws and customs may change and adapt. Change and adaptation will not necessarily be fatal. So long as the changed or adapted laws and customs continue to sustain the same rights and interests that existed at sovereignty, they will remain traditional. An enquiry into continuity of society, divorced from an inquiry into continuity of the pre-sovereignty normative system, may mask unacceptable change with the consequence that the current rights and interests are no longer those that existed at sovereignty, and thus not traditional.

75 Consistently with the primary judge’s formulation at [49], his Honour’s conclusion quoted at [67] is cast in terms of continuation of a society.

76 The primary judge’s focus on the continuity of a society rather than continued acknowledgement and observance of laws and customs is seen in his treatment of the change from an essentially patrilineal system of descent to a mixed patrilineal/matrilineal system.

77 His Honour did not engage in the [Yorta Yorta] and Risk TJ 240 ALR 74 enquiry as to whether the laws and customs relating to descent had continued to be observed by each generation from sovereignty to the present. He made no findings about that. Rather he seems to have proceeded on the basis that provided the pre sovereignty society continued to exist, its members would have continued to acknowledge and observe those laws and customs. At [777] he said:

The descent rules are undoubtedly of great importance. However, changes to them must have been inevitable, if the Noongar community was to survive the vicissitudes inflicted upon it by European colonisation and social practices. I think the move away from a relatively strict patrilineal system to a mixed patrilineal/matrilineal or cognative system should be regarded as not inconsistent with the maintenance of the previous-settlement community and the continued acknowledgement and observance of its laws and customs.

78 The primary judge adopted a similar approach to the breakdown of the estate system. At [784]-[785] he said:

counsel [for the State] rightly say the claims made by the witnesses in these cases do not distinguish between “home areas’, inhabited by estate groups, and “runs”, larger areas to which they have access without the need for permission. Each of the witnesses only identified a relatively large area of land, his or her boodja, or country, to which he or she had access (as a matter of Noongar law, although often not under wajala law) without the need for permission.

It seems to me that “home areas” have effectively disappeared. Today’s boodjas are similar in concept to - although probably larger in area than - the ‘runs’ of pre-settlement times. I agree this is a significant change. However, it is readily understandable. It was forced upon the Aboriginal people by white settlement. As white settlers took over, and fenced, the land, Aborigines were forced off their home areas; the “bands” or “tribes”, comprising several related families, were broken up. Surprisingly, the social links between those families seem to have survived, but the related families ceased to be residence groups, together occupying a relatively small area of land. The ability to maintain the “home area” element of the pre settlement normative system was lost.

36 The State extracts from Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 per Kitto J (at 305) the observation that one does not pass from the realm of conjecture into the realm of inference until some factors are found which positively suggests, that is to say provides a reason, special to the particular case under consideration, for thinking it likely that in that actual case a specific event happened or a specific state of affairs existed.

37 In relation to the State submission that key aspects of the Yilka claim include ‘the formation of intermediate groups’, which the State contends is a law or custom that has not always prevailed, the Yilka applicant submits that this premise, which apparently lies at the heart of the State case, ‘rests on persistent refusal to accept the plain statements of the Yilka applicant about the way the case is put’. The Yilka applicant refers to the explanatory paragraph in the document entitled ‘Yilka Applicant’s fourth amended Points of Claim’ (Yilka POC) at [4]):

Any reference in the Form 1 and [Yilka POC] to the persons on whose behalf the Applicant has made the Yilka claim as a ‘group’ or ‘claim group’:

(a) except where the context requires otherwise – is no more than the adoption of a term used in Item (1) in the Table of Applications in s 61 of the [NTA];

(b) is not intended as a statement that they constitute an enduring social entity constituted under laws and customs of the WDCB;

(c) is intended to convey that they are the several persons and several groups of persons who have in common that they are the present possessors under traditional laws and customs of the WDCB of rights and interests in all of [sic] part of the claim area;

(d) it is not intended to convey, in relation to the exercise of rights by those persons, that rights are not exercisable to an extent individually and to an extent communally with other holder of rights; or that in any event rights are not exercised in a broader social context among people who share in the acknowledgement and observance of the same laws and customs.

38 The Yilka applicant argues that the evidence is clear that the several persons and descent lines of the Yilka claim group are merely the persons who, under the relevant laws and customs, are the possessors for the time being of the rights and interests in the Claim Area. There is no evidence of any ‘formation’, to use the State’s term, of the Yilka claim group other than being the persons identified by the application of traditional law and custom to the Claim Area. Nor, if that makes it a ‘group’, is there any evidence of it being an ‘intermediate’ group, being a term used by the State.

39 In any event, to the extent that the State submissions are based on continuity of the population that is not the case put by the Yilka applicant. The NTA prescribes that native title will depend upon continuity of a normative system. The existence of native title does not depend upon the possession of rights by descent, but rather, on what the traditional laws and customs say about how rights and interests are acquired and possessed. If those laws and customs do not limit the possession of rights and interests to the descendants of an ancestor who possessed such rights, then the NTA will not do so either.

40 The Yilka applicant argues with some force that it is a matter of comfortable inference that the laws and customs of the relevant Western Desert Cultural Block (WDCB) society were in existence at sovereignty. For this, it relies upon the agreement of all expert witnesses on the proposition that the WDCB system of normative laws and customs has had, to varying extents, a continuous existence and vitality since sovereignty, together with assertions of the Aboriginal witnesses that it has always prevailed. Further, as noted by Weinberg J in Griffiths, it is reasonable to infer that the recent ancestors from whom the present claimants acquired their laws and customs ‘did not simply invent them’ (at [577]). I accept this and the submissions referred to in this paragraph.

41 It is clear that all of the elements of the definition of native title in s 223 must be established (Yorta Yorta (at [33]). This emphasis flows from the statute and in the discussion in the High Court in Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 (Ward HC) where Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ said (at [17]-[18]):

17. However, as indicated, the immediately relevant elements in the definition in s 223(1) of "native title" and "native title rights and interests" have remained constant. Several points should be made here. First, the rights and interests may be communal, group or individual rights and interests. Secondly, the rights and interests consist "in relation to land or waters". Thirdly, the rights and interests must have three characteristics: (a) they are rights and interests which are "possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed", by the relevant peoples; (b) by those traditional laws and customs, the peoples "have a connection with" the land or waters in question; and (c) the rights and interests must be "recognised by the common law of Australia".

18. The question in a given case whether (a) is satisfied presents a question of fact. It requires not only the identification of the laws and customs said to be traditional laws and customs, but, no less importantly, the identification of the rights and interests in relation to land or waters which are possessed under those laws or customs. These inquiries may well depend upon the same evidence as is used to establish connection of the relevant peoples with the land or waters. This is because the connection that is required by par (b) of s 223(1) is a connection with the land or waters "by those laws and customs". Nevertheless, it is important to notice that there are two inquiries required by the statutory definition: in the one case for the rights and interests possessed under traditional laws and customs and, in the other, for connection with land or waters by those laws and customs.

(emphasis added)

42 The State emphasises the passage from Ward HC (at [64]), where the majority stressed that what is required by s 223(1)(b) NTA is first an identification of the content of traditional laws and customs and, secondly, the characterisation of the effect of those laws and customs as constituting a ‘connection’ of the people with the land or waters in question. Their Honours further said that whether or not there is a relevant connection depends, in the first instance, upon the content of traditional laws and customs and in the second, upon what is meant by ‘connection’ by those laws and customs.

43 If there is to be a determination of native title made pursuant to the requirements of s 223(1) NTA, it is to be made under s 94A in accordance with s 225 NTA. Section 225 provides:

225 Determination of native title

A determination of native title is a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area (the determination area) of land or waters and, if it does exist, a determination of:

(a) who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are; and

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area; and

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area; and

(d) the relationship between the rights and interests in paragraphs (b) and (c) (taking into account the effect of this Act); and

(e) to the extent that the land or waters in the determination area are not covered by a non-exclusive agricultural lease or a non-exclusive pastoral lease - whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

44 The determination of native title must be viewed from the Aboriginal perspective: Western Australia v Ward (2000) 99 FCR 316 per North J (Ward FC) (at [783]). The majority in Ward HC in the High Court also spoke (at [76]) about a ‘bundle of rights’ having indicated (at [18]) that, as a question of fact, it is necessary, not only to identify the laws and customs said to be traditional laws and customs, but, no less importantly, to identify the rights and interests in relation to land or waters which are possessed under those laws or customs. The majority in Ward HC (at [95]) indicated that the metaphor of ‘bundle of rights’ is useful in two respects. It draws attention, first, to the fact that there may be more than one right or interest and, secondly, to the fact that there may be several kinds of rights and interests in relation to land that exist under traditional laws and customs. The Yilka applicant contends, in this case, that the rights in the asserted bundle of traditional rights are both specific and clear, even though they are broadly stated. As the Yilka applicant points out, there is no authority which precludes the claiming or a finding of broadly stated rights.

45 In Ward HC, the majority observed (at [14]) the evident difficulty of expressing a relationship between a community or group of Aboriginal people and the land in terms of rights and interests, but nonetheless, that was what was required by the NTA. It was pointed out that, in expressing this relationship the spiritual or religious is ‘translated’ into the legal. Their Honours said that this requires the fragmentation of an integrated view of the ordering of affairs into rights and interests which are considered apart from the duties and obligations which go with them. The notion of translation was reiterated in Northern Territory v Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakaya Native Title Claim Group (2005) 145 FCR 442, in the discussion of the Full Court (Wilcox, French and Weinberg JJ) (at [64]) of the idea of recognition which it said is central to the common law of native title and also to the NTA. Their Honours stated that the common law and the NTA define the circumstances in which recognition will be accorded to native title rights and interests and the conditions upon which it will be withheld or withdrawn. By this process, aspects of an indigenous society’s relationship to land and waters are ‘translated’ into a set of rights and interests existing under non-indigenous laws. The Full Court stressed that the term ‘recognition’ links it to the normative framework established by the common law and by the NTA as evidenced in its preamble. This process of translation was achieved by Finn J, through examination of the utility and practical outcomes of the relationship of people and their country and resources in Akiba (at [524], [525] and [529]) where his Honour said:

524 While there were customary and other constraints on the manner of taking things (for example, the method of taking dugongs – a matter not discussed in these reasons – or the widely but not uniformly accepted objection to using hookahs (diving apparatus) to catch crayfish), there were no constraints on what could be taken, though contrary views were expressed on whether dugong and turtle could be sold under customary law. Taking, I should add, was contrived in the main by considerations of utility. As Tom Jack Baira put it:

Our ancestors didn’t have a shop, they didn’t have money but they could use what they got from our area in whatever way was useful to them. Our ancestors did whatever they needed to do to survive. They lived off their areas, land and sea. We do the same.

So, for example, after shell meat had been used, the shells were used for decorative and aesthetic purposes, to collect water (if big) or as food bowls: Kris Billy. And among the things used were sand, shells, a vast range of marine species, coral, mangrove timber, etc. Or as the Applicant summarised it, basically everything edible or otherwise useful. I do not accept the State’s limitation that what can be taken are “living and plant resources”. It does not accord with the evidence.

525 While the Commonwealth has conceded the breadth of what could be accessed and taken, it has denied explicitly any “right to trade” or “to use for commercial purposes”. This is apparently for reasons of non-recognition by the common law. The right to trade in marine products of an area, it is said, presupposes exclusive possession of that area. I will return to this below. My present concern is with what, traditionally, were allowable uses of marine resources taken.

…

529 The point to be emphasised is that the fundamental resource-related right of use (cf Ward HC at [91]) was the right to take. Use of what was taken was unconstrained, save by considerations of respect, conservation and the avoidance of waste.

(emphasis added)

46 As the above paragraphs show, Finn J identified the practical effect of the relationship of people to their country, and ‘translated’ this into the right of use and the right to take.

47 Applying these principles to the current proceedings, the Yilka applicant asserts that the people who, under their traditional laws and customs, can call an area their ngurra, their country, may fully utilise and control access to that country and resources. There may be rules governing that right, but the overall effect of the relationship of the people to their country under their traditional laws and customs is, according to the Yilka applicant, ‘akin broadly to a notion of ownership and control’. It was emphasised in Akiba on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim Group v Commonwealth (2013) 250 CLR 209 (Akiba HC), that particular activities that may be conducted in accordance with a broadly described right could be regulated, even prohibited under non-indigenous law, without extinguishing the right (per Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ (at [613])). In this instance, a statutory prohibition against fishing for sale and trade without a licence was held not to extinguish the native title right to take resources for any purpose. The Yilka applicant argues that this supports the proposition that particular activities done in exercise of rights may be subject to particular rules under traditional law and custom without denying the existence of the right itself. There are some such rules apparent from the evidence in this case, such as rules against wastage of resources (as in Akiba: see [529] set out above), and rules about gender restricted access to sites etc, that may be regarded as simply regulation of the exercise of the right without detracting from its existence. The Yilka applicant argues, and the argument is supported by the Sullivan applicant, whose claim I discuss below, that laws and customs are what the people within the normative system say they are as recorded historically and as expressed by people today and also about their ‘remembered past’. If people are properly understood as saying it is, and according to their oral history it is, ‘theirs’, or that it ‘belongs to’ them, or that they are ‘owners’ of it, then that is what is to be regarded as the relevant law and custom under which their rights and interests are possessed, unless there is clear historical evidence to the contrary. The Yilka applicant submits that that is how their rights and interests properly are to be understood. There is, for example, no basis to inherently disbelieve claimants in relation to such matters, particularly when they are not challenged or contradicted.

48 There is also a distinction of some importance. While what people actually do as of right may well be an example of what they are entitled to do under their laws and customs, it will not necessarily be determinative of the scope of the right possessed under the laws and customs, unless the evidence is that those activities are all that they are entitled to do. For the Yilka applicant it is submitted that there is no basis or authority for confining rights and interests to particular activities apparently done as of right as at sovereignty or as at today. That would be to proceed incorrectly by reference to observable behaviour or activity or to wrongly assume and ignore evidence to the contrary that laws and customs only permit people to do what they actually did at a particular time in the past. In my view, this submission is correct. By analogy with common law freehold, the entitlement to use one’s land in a much broader way than one uses it, does not detract from the existence of the entitlement. The existence of a right will not depend on the right having been exercised in every manner possible.

1.1.4 Traditional laws and customs

49 As noted in Yorta Yorta (at [38]-[40] and at [43]-[45]), the rights and interests the subject of the NTA are those deriving from traditional laws and customs forming a body of norms that existed before sovereignty. Transmission of law or custom from generation to generation of a society is usually by word of mouth and common practice (at [46]). As noted in Yorta Yorta (at [46]), ‘traditional’ within the NTA context carries two other elements. First, it conveys an understanding of the age of the tradition, that is, if it existed pre-sovereignty and, secondly (at [47]):

… the reference to rights or interests in land or waters being possessed under traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the people concerned, requires that the normative system under which the rights and interests are possessed (the traditional laws and customs) is a system that has had a continuous existence and vitality since sovereignty. If that normative system has not existed throughout that period, the rights and interests which owe their existence to that system will have ceased to exist. And any later attempt to revive adherence to the tenets of that former system cannot and will not reconstitute the traditional laws and customs out of which rights and interests must spring if they are to fall within the definition of native title.

(emphasis in original)

50 The majority in Yorta Yorta also noted that there was no need to distinguish between the two terms in the expression ‘laws and customs’. However, the majority noted (at [42]):

… Nonetheless, because the subject of consideration is rights or interests, the rules which together constitute the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed, and under which the rights or interests are said to be possessed, must be rules having normative content. Without that quality there may be observable patterns of behaviour but not rights and interests in relation to land or waters.

51 In Akiba (at [171]-[173]) Finn J said:

171 Secondly, what are laws and customs? The plurality judgment in [Yorta Yorta] touched on this subject helpfully, but not conclusively: at [41]-[42]. Having noted the jurisprudential debates the “laws and customs” terminology might provoke, but also the lack of any need to distinguish between what is a matter of traditional law and what is a matter of traditional custom, the judges indicated (at [42]):

… the rules which together constitute the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed, and under which the rights or interests are said to be possessed, must be rules having normative content. Without that quality, there may be observable patterns of behaviour but not rights or interests in relation to land or waters.

In [Wongatha (at [996])], Lindgren J enlarged upon this by reference to the following comments of Professor H.L.A. Hart, in The Concept of Law (OUP New York, 1994) in relation to “rules” (at p 57):

What is necessary is that there should be a critical reflective attitude to certain patterns of behaviour as a common standard, and that this should display itself in criticism (including self-criticism), demands for conformity, and in acknowledgements that such criticism and demands are justified, all of which find their characteristic expression in the normative terminology of “ought”, “must”, and “should”, “right” and “wrong”.

172 The question whether much of what has been advanced by the applicant as laws and customs amounts at best to no more than “observable patterns of behaviour”, has been put in issue primarily by the State. A factor of which account needs to be taken in considering this is the distinctive context in which this issue arises. Unlike mainland Aboriginal cases, there is little in the laws and customs relied upon that has any informing spiritual dimension at all: cf Ward FC at [242]. Much appears simply utilitarian; much seems prosaic. As Mr Hiley QC put it, “the absence of the spiritual element … is almost probably unique to this case”. Yet, it needs to be recognised that normative beliefs can be held about ordinary behaviour, as the fierce dispute over how properly to open soft boiled eggs in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels suggests.

173 After discussion with counsel, I have settled upon the following working definition of “custom” as suited to the distinctive circumstances of this matter. It is that “customs” are accepted and expected norms of behaviour, the departure from which attracts social sanction (often disapproval especially by elders). I would note that reference to the sanction of public disapproval for deviant behaviour recurs in the evidence. I would also note in this regard Haddon’s comment (1908, 250; also to like effect, 1935, 130 and 288-289):

Rules of conduct were sufficiently defined and as far as possible enforced not by a special judiciary or executive body but by public opinion.

Judged by the above working definition, as will be seen, some number of the behaviours relied upon by the Applicant lacked, or were not shown to have, normative content.

(emphasis in original)

52 The word ‘society’ is not to be found in s 223 NTA (or elsewhere in the NTA). Wilcox, French and Weinberg JJ in Northern Territory v Alyawarr noted (at [78]):

78 The elements of a determination of native title are set out in s 225. It requires a determination of “who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are”. That requires consideration of whether the persons said to be native title holders are members of a society or community which has existed from sovereignty to the present time as a group, united by its acknowledgement of the laws and customs under which the native title rights and interests claimed are said to be possessed. That involves two inquiries. The first is whether such a society exists today. The second is whether it has existed since sovereignty. The concept of a “society” in existence since sovereignty as the repository of traditional laws and customs in existence since that time derives from the reasoning in Yorta Yorta. The relevant ordinary meaning of society is “a body of people forming a community or living under the same government” – Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. It does not require arcane construction. It is not a word which appears in the [NTA]. It is a conceptual tool for use in its application. It does not introduce, into the judgments required by the [NTA], technical, jurisprudential or social scientific criteria for the classification of groups or aggregations of people as “societies”. The introduction of such elements would potentially involve the application of criteria for the determination of native title rights and interests foreign to the language of the [NTA] and confining its application in a way not warranted by its language or stated purposes.

53 It is a term which evolves from the judgment of Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ in Yorta Yorta (at [49]) where their Honours said that law and custom arise out of and, in important respects go to define, a particular society, a word which they said was to be understood as being ‘a body of persons united in and by its acknowledgment and observance of a body of law and customs’. Their Honours said, albeit in a footnote, that they had chosen the word society rather than the word community in order to emphasise the close relationship between the identification of the group and the identification of the laws and customs.

54 The State also draws attention to remarks of Toohey J in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1, where his Honour stated that the relevant society must be ‘sufficiently organised to create and sustain rights and duties’. The State emphasises that although the word society is not defined in s 223 NTA, the emphasis in that section on ‘traditional’ laws and customs, and the inseparability of consideration of laws and customs from consideration of the society from which they derive, requires the Court to consider questions relating to the relevant society.

55 Further consideration of society is raised below in Pt 4 (note that throughout these reasons a reference to a Part is generally a reference to that Part within the same chapter unless otherwise specified).

56 The majority judgment in Yorta Yorta established the requirement of continuity of the society and of the acknowledgment and observance of the traditional laws and customs which are claimed to give rise to the rights and interests under s 223 NTA (Yorta Yorta at [45]-[56]). At [74] of the Yilka POC, the Yilka applicant claims:

[T]hat when considering the continuity of acknowledgement and observance of laws and customs, it is necessary to distinguish them between:

(a) change and adaptation of the laws and customs of the WDCB themselves;

(b) changes in the circumstances in which those laws and customs were acknowledged and observed;

(c) the social and demographic outcomes that may result from the acknowledgment and observance of unchanged laws and customs in different circumstances;

(d) where participation in a practice is not mandatory – the laws and customs that apply when the choice is made to engage in the practice and the numbers or proportions of persons who engage in the practice in a given generation;

(e) ‘regional variation’ in the laws and customs that are acknowledged and observed and regional variability in the numbers who participate in non-mandatory practices governed by laws and customs;

(f) ‘expectations’ that many or most will engage in or be the subject of a practice, a law or custom that represents an ‘ideal’ but is not mandatory and a law and custom that includes mandatory participation in a practice; and

(g) where participation in a practice is mandatory – practices that all must engage in, practices that a particular segment of the population must engage in, practices in relation to which mandatory participation is subject to exceptions, and practices in relation to which the circumstances under which participation is required occurs once in a lifetime, rarely, or as an everyday aspect of life.

57 And at [75]:

[T]hat no change or adaptation of the WDCB laws or customs necessarily is involved where:

(a) the descendants of a person who held rights or interests through a particular pathway to connection in one area move (or the person in his or her own lifetime moves) to and acquires rights or interests on the basis of another pathway to connection in another area within the broader area of the WDCB. Such is ordinarily merely an instance of the application of the laws and customs;

(b) a person who has a recognised connection to and rights or interests in a particular area successfully asserts rights or interests in adjoining or other places through another pathway to connection such that his or her ‘my country’ area is geographically extended over those adjoining places or to those other places. Such is ordinarily merely an instance of the application of the laws and customs;

(c) a number of persons who each have a pathway to connection to the area settle relatively permanently in and become recognised as possessing rights in an area where a reliable supply of resources is available. Such ordinarily merely involves instances of the application of the laws and customs to the changed circumstances relating to the availability and reliability of resources; notwithstanding that over generations it may lead to a greater number of instances than in the past of recognition of rights or interests being possessed on the basis of a descent-based pathway to connection;

(d) at sovereignty there was a higher participation rate in a particular practice and a lower participation rate today where the laws and customs that apply to the conduct of the practice continue to be acknowledged and continue to be observed by those who participate in the practice.

58 The Yilka applicant has attempted to distinguish and isolate non-relevant change and adaptation from the kind of change that will defeat a native title claim. Relevantly, in Yorta Yorta (at [56]), the majority said:

For these reasons, it would be wrong to confine an inquiry about native title to an examination of the laws and customs now observed in an indigenous society, or to divorce that inquiry from an inquiry into the society in which the laws and customs in question operate. Further, for the same reasons, it would be wrong to confine the inquiry for connection between claimants and the land or waters concerned to an inquiry about the connection said to be demonstrated by the laws and customs which are shown now to be acknowledged and observed by the peoples concerned. Rather, it will be necessary to inquire about the relationship between the laws and customs now acknowledged and observed, and those that were acknowledged and observed before sovereignty, and to do so by considering whether the laws and customs can be said to be the laws and customs of the society whose laws and customs are properly described as traditional laws and customs.

(emphasis in original)

59 The observations by the Full Court in Bodney (at [70]-[74]) are also pertinent to this analysis, where it was noted the importance of considering the continuity of observation and acknowledgment of traditional laws and customs, as opposed to merely considering the continuation of the society or community. Their Honours said:

70 The appellants contended that the questions the primary judge posed (…) are the wrong questions. The Commonwealth submitted that the correct question is whether acknowledgement and observance of traditional laws and customs has continued substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty. It is to be answered by ascertaining whether, for each generation of the relevant society since sovereignty, those laws and customs constituted a normative system giving rise to rights and interests in land, and in fact regulated and defined the rights and interests which those people had and could exercise in relation to the land and waters.

71 Since [Yorta Yorta] the approach propounded by the Commonwealth has been adopted in relation to the continuity issue. There at [87] the majority said:

acknowledgment and observance of those laws and customs must have continued substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty. Were that not so, the laws and customs acknowledged and observed now could not properly be described as the traditional laws and customs of the peoples concerned. That would be so because they would not have been transmitted from generation to generation of the society for which they constituted a normative system giving rise to rights and interests in land as the body of laws and customs which, for each of those generations of that society, was the body of laws and customs which in fact regulated and defined the rights and interests which those peoples had and could exercise in relation to the land or waters concerned.

(emphasis in original)

72 In Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404 at [97](c) (Risk TJ) Mansfield J said that applicants for native title must establish, amongst other things, that

the acknowledgment and observance of the laws and customs has continued substantially uninterrupted by each generation since sovereignty, and the society has continued to exist throughout that period as a body united in and by its acknowledgment and observance of those laws and customs.

On appeal to the Full Court, the appellants did not attack that formulation, though they did unsuccessfully attack other parts of his Honour’s summary of the requirements for establishing native title: Risk v Northern Territory (2007) 240 ALR 75 at [78]-[79]. The Full Court regarded the whole of his Honour’s summary, including that quoted above, as an accurate statement of the effect of the cases, including [Yorta Yorta]. See at [78] - [98].

73 … [T]he primary judge did not pose the continuity question in the form propounded by [Yorta Yorta]. Instead of enquiring whether the laws and customs have continued to be acknowledged and observed substantially uninterrupted by each generation since sovereignty, he asked whether the community that existed at sovereignty continued to exist over subsequent years with its members continuing to acknowledge and observe at least some of the traditional 1829 laws and customs relating to land.

74 The [Yorta Yorta] formulation concentrates on continued acknowledgment and observance of laws and customs because the rights and interests the subject of a determination of native title (s 225) are the product of the laws and customs of the society. It is not the society per se that produces rights and interests. Proof of the continuity of a society does not necessarily establish that the rights and interests which are the product of the society’s normative system are those that existed at sovereignty, because those laws and customs may change and adapt. Change and adaptation will not necessarily be fatal. So long as the changed or adapted laws and customs continue to sustain the same rights and interests that existed at sovereignty, they will remain traditional. An enquiry into continuity of society, divorced from an inquiry into continuity of the pre-sovereignty normative system, may mask unacceptable change with the consequence that the current rights and interests are no longer those that existed at sovereignty, and thus not traditional.

(emphasis in original)

60 It is clear that some change to, or adaptation of, traditional laws and customs or some interruption of enjoyment or exercise of native title rights or interests in the period between sovereignty and the present would not necessarily be fatal to a native title claim: Yorta Yorta (at [83]). The majority held that the key question is whether the law and custom can still be seen to be traditional law and traditional custom. That is, is the change or adaptation of such a kind that it can no longer be said that the rights or interests asserted are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the relevant people? The Full Court’s statement in Bodney (at [74]), that the changed or adapted laws will remain traditional so long as they continue to sustain the same rights and interests that existed at sovereignty, is relevant in considering this question.

61 The Yilka applicant would argue then that the increased reliance, for example, on the pathway of descent rather than birth on country is not a significant change to the acknowledgment and observance of laws and customs, but simply a result of the changed circumstances whereby a greater number of births now take place in hospitals rather than on country. Although the change involves considerable social change, it is not a change to the available pathways recognised by traditional law and custom, nor is it a change to the rights and interests possessed as consequence of the application of a pathway to a person. Although, as a matter of behaviour, births taking place on country is no longer the norm, it does not mean that the continuous acknowledgment and observance of the pre-sovereignty laws and customs and the acknowledgment of them as traditional laws and customs has ceased or changed. That will be a separate enquiry, on the available evidence. Of course, the evidence supporting the submission is to be examined, but as a matter of principle, I accept the submissions advanced by the Yilka applicant as noted in this paragraph.

62 The Full Court in Bodney (at [163]) identified the genesis of the term ‘connection’ in the NTA as being derived from the judgment of Brennan J in Mabo (at 59-60) where his Honour said: