FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Hatfield on behalf of the Darumbal People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2016] FCA 723

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

BEING SATISFIED that an order in the terms set out below is within the power of the Court, and it appearing appropriate to the Court to do so, pursuant to s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)

THE COURT ORDERS BY CONSENT THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in the terms set out below (the determination).

2. The determination will take effect upon the agreements referred to in paragraph 1 of Schedule 4 being registered on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements.

3. In the event that the agreements referred to in paragraph 2 are not registered on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements within six (6) months of the date of this order or such later time as this Court may order, the matter is to be listed for further directions.

4. Each party to the proceedings is to bear its own costs.

THE COURT DETERMINES BY CONSENT THAT:

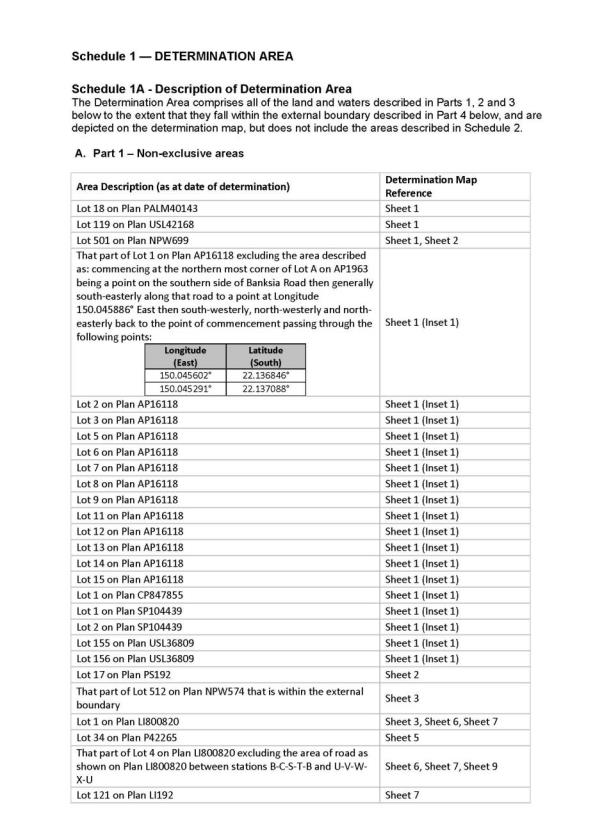

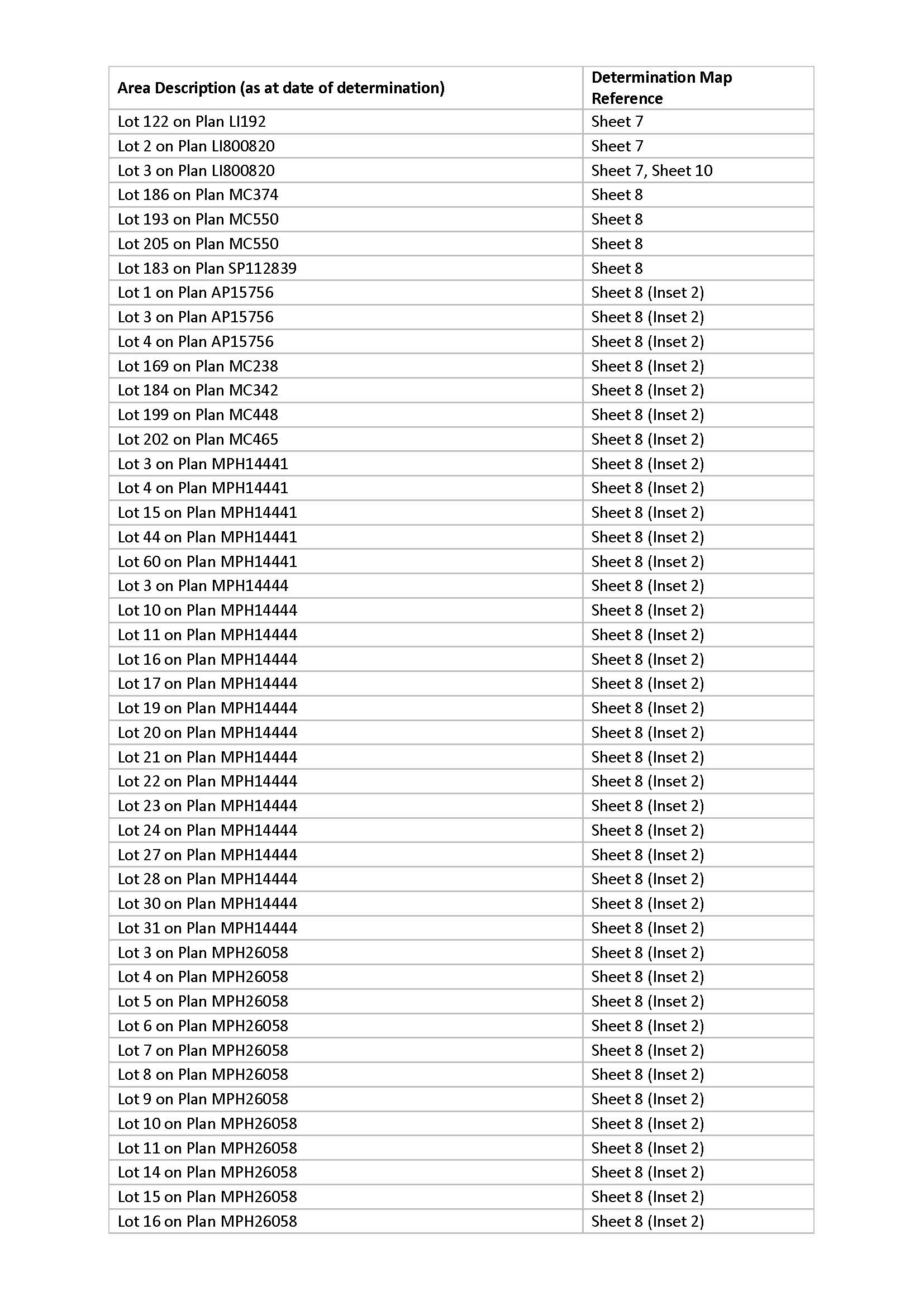

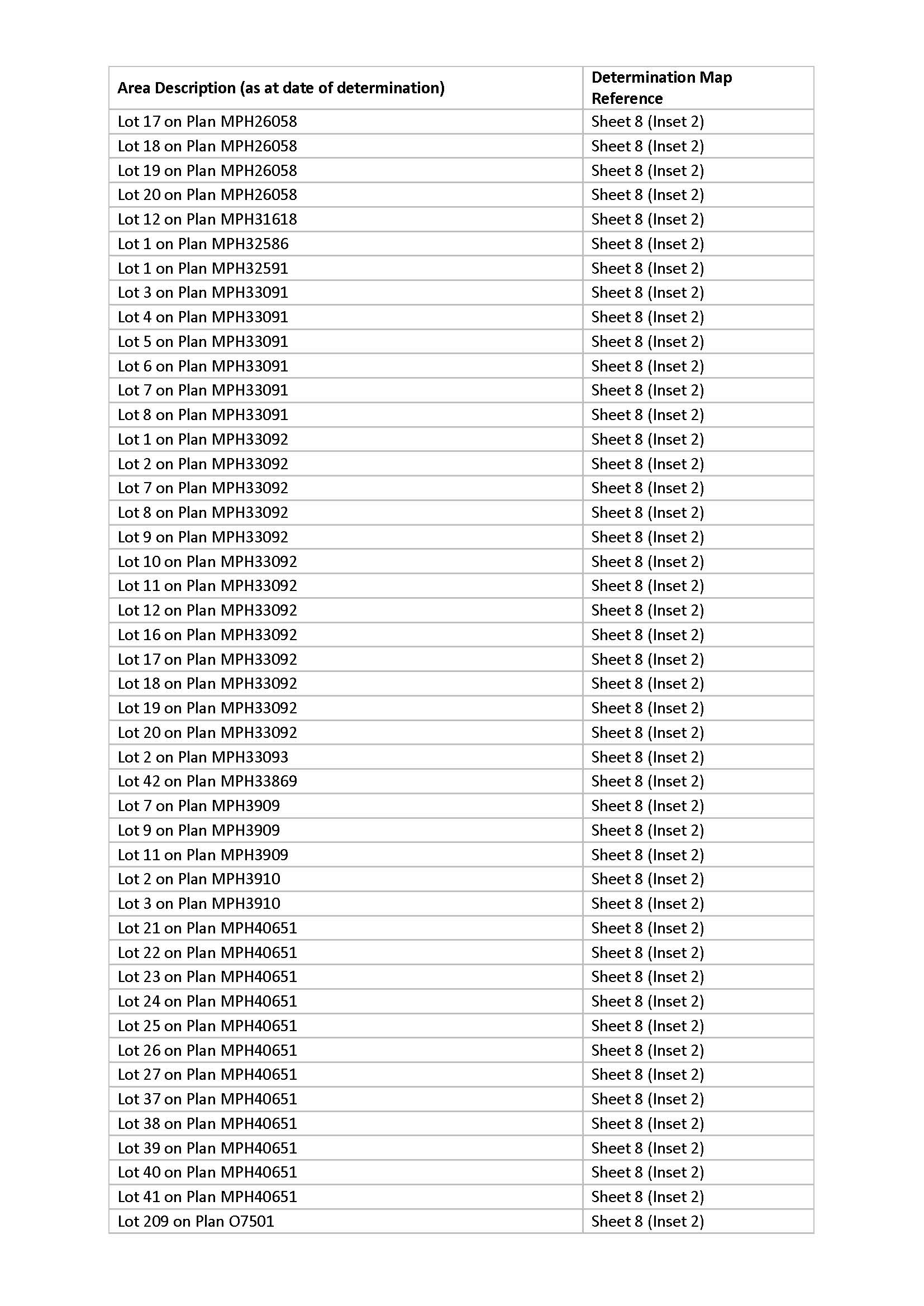

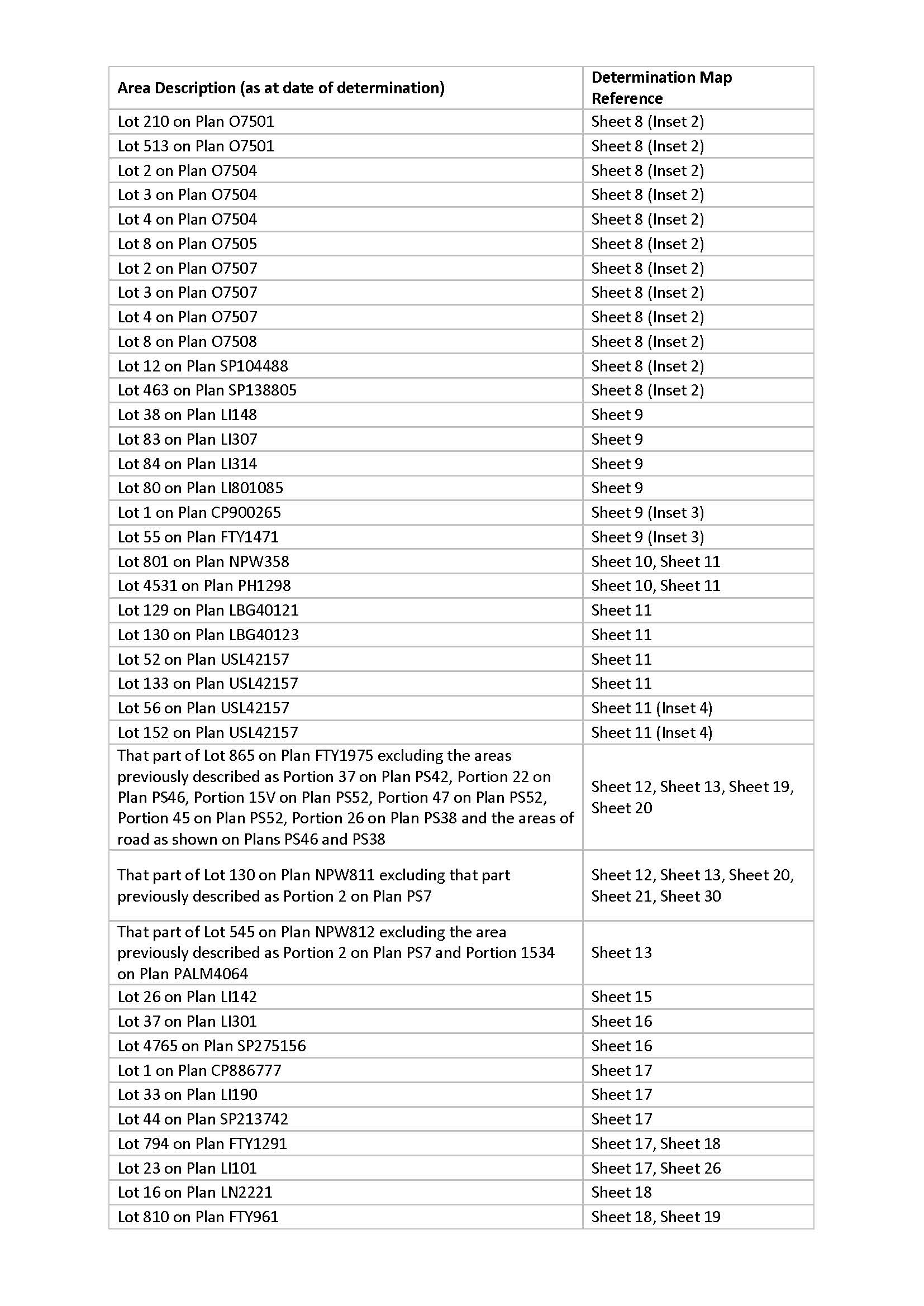

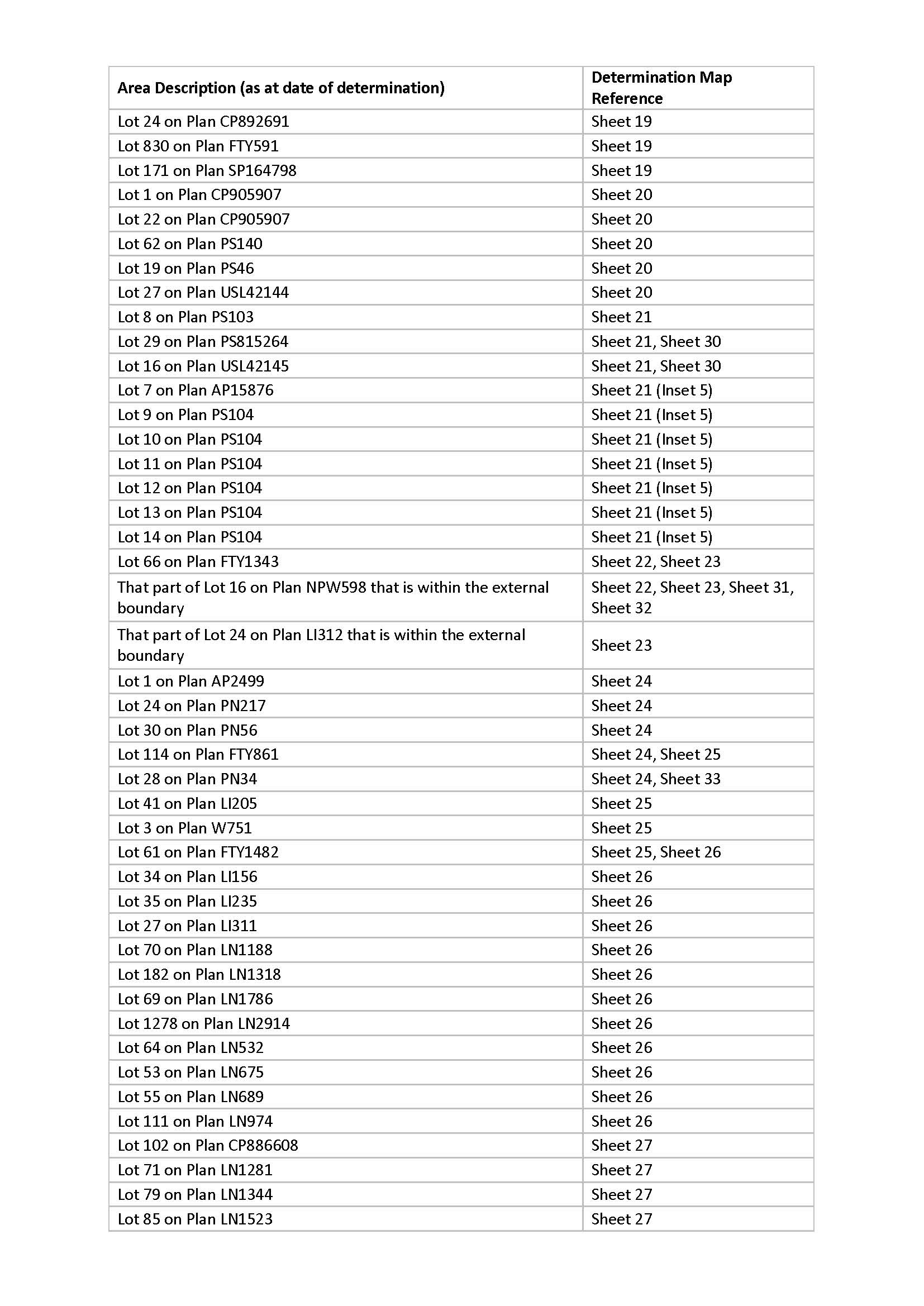

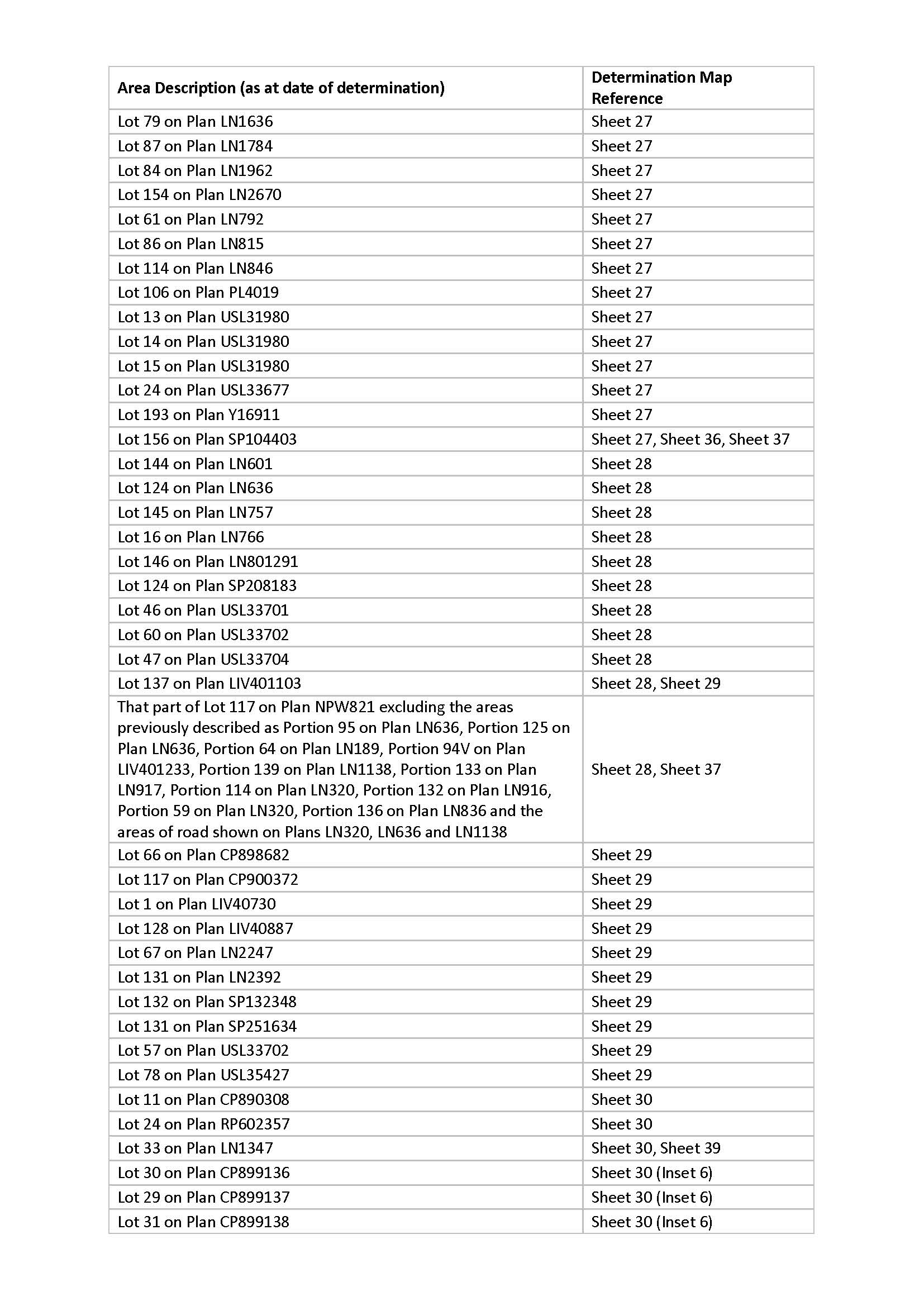

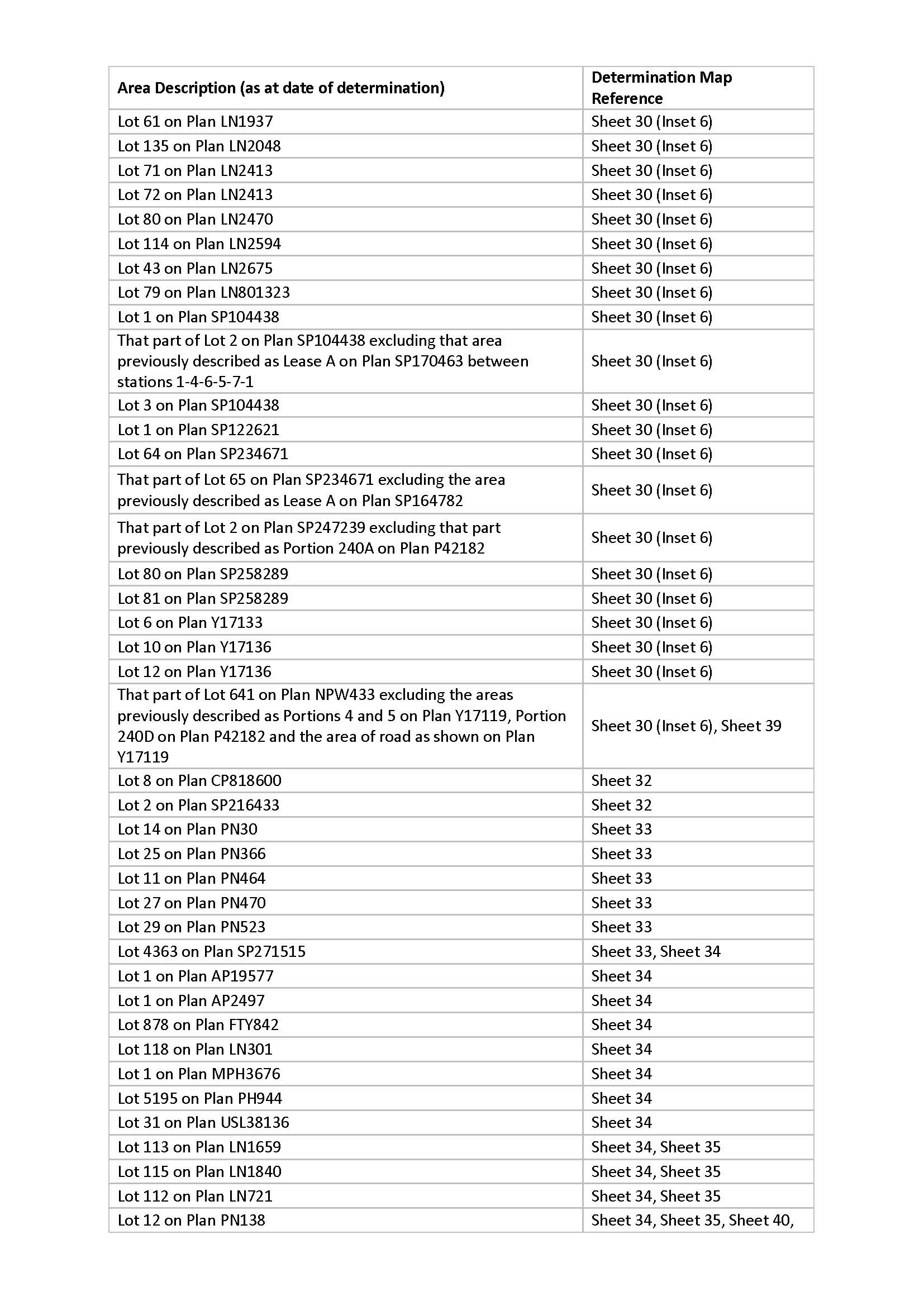

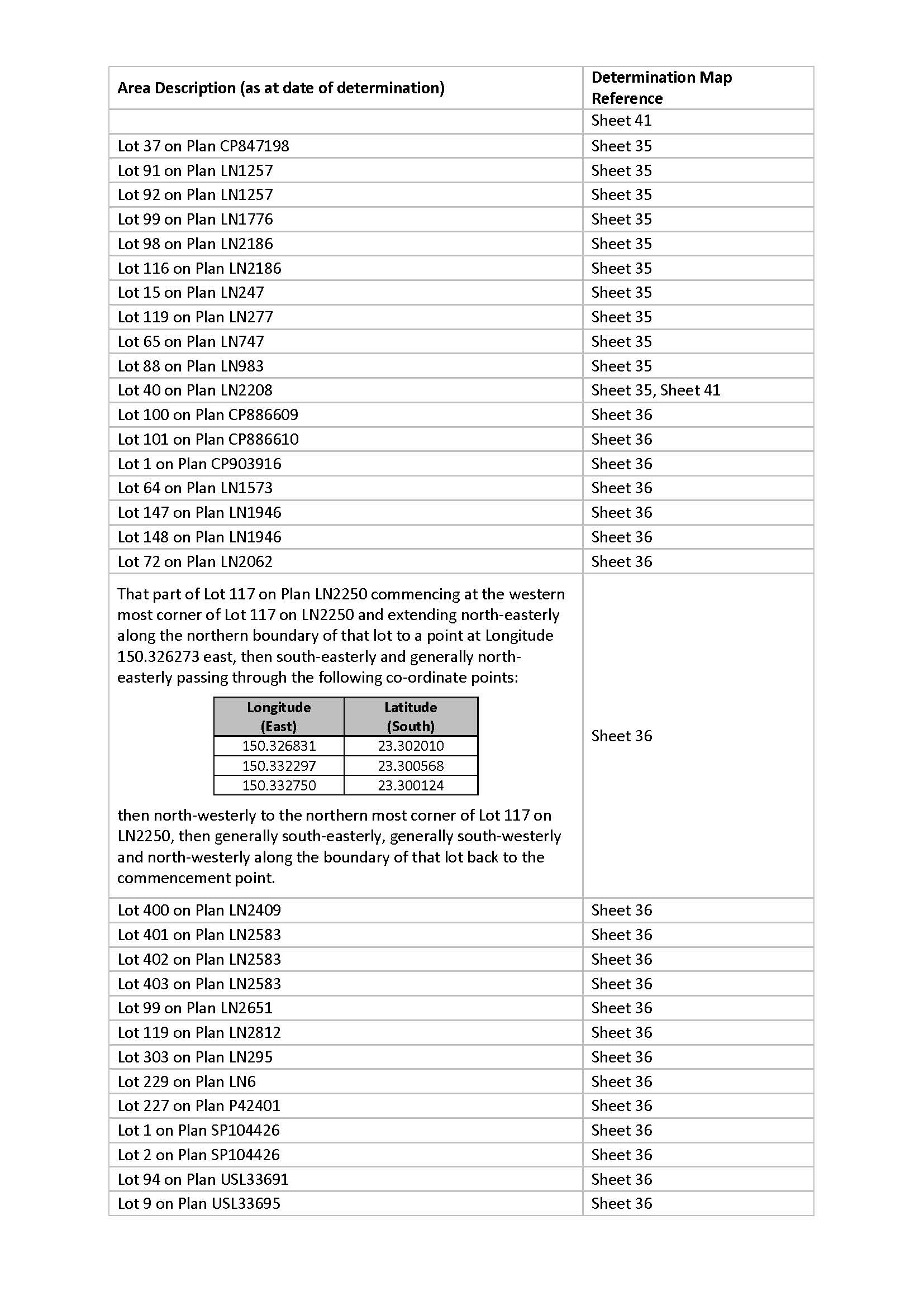

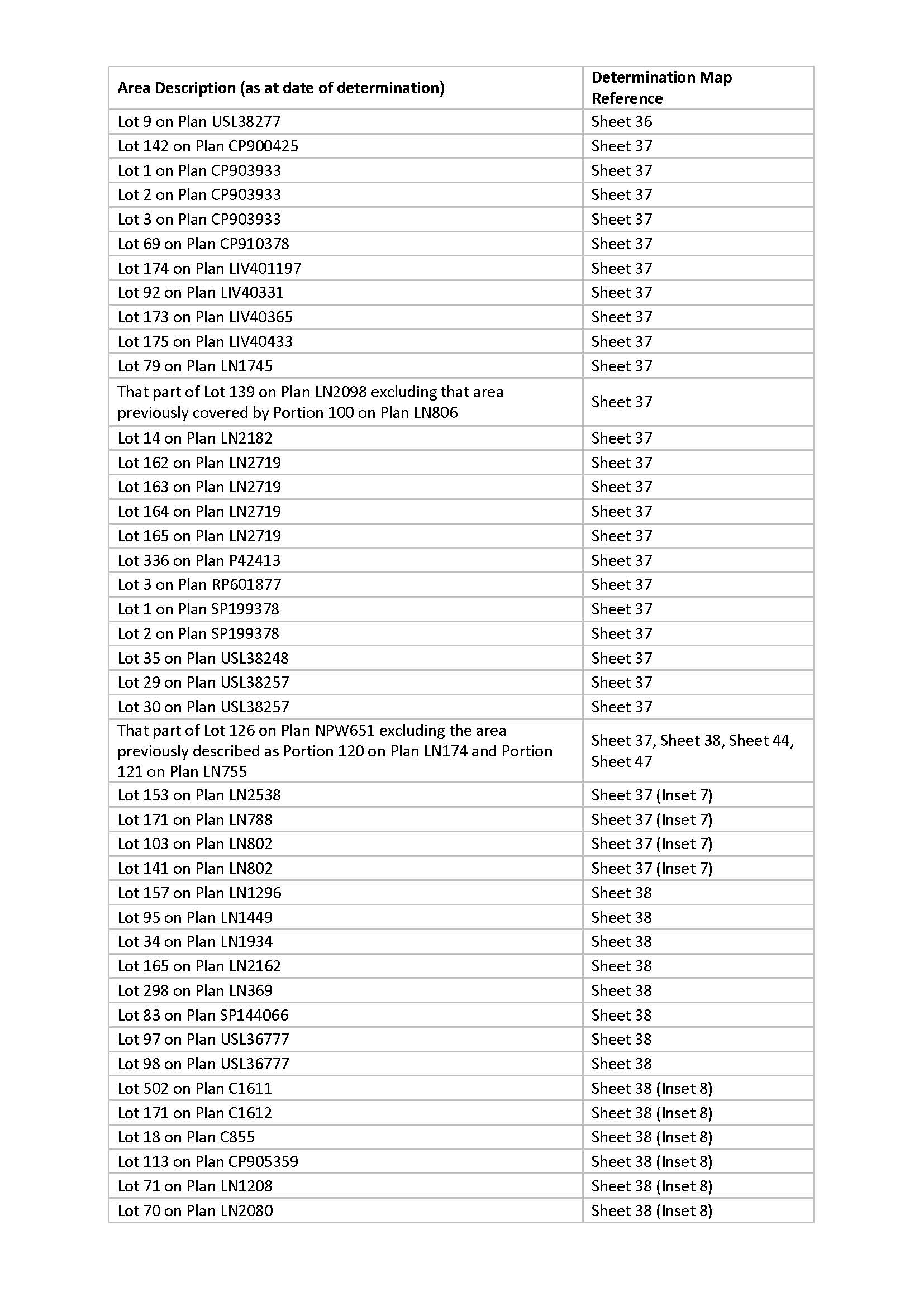

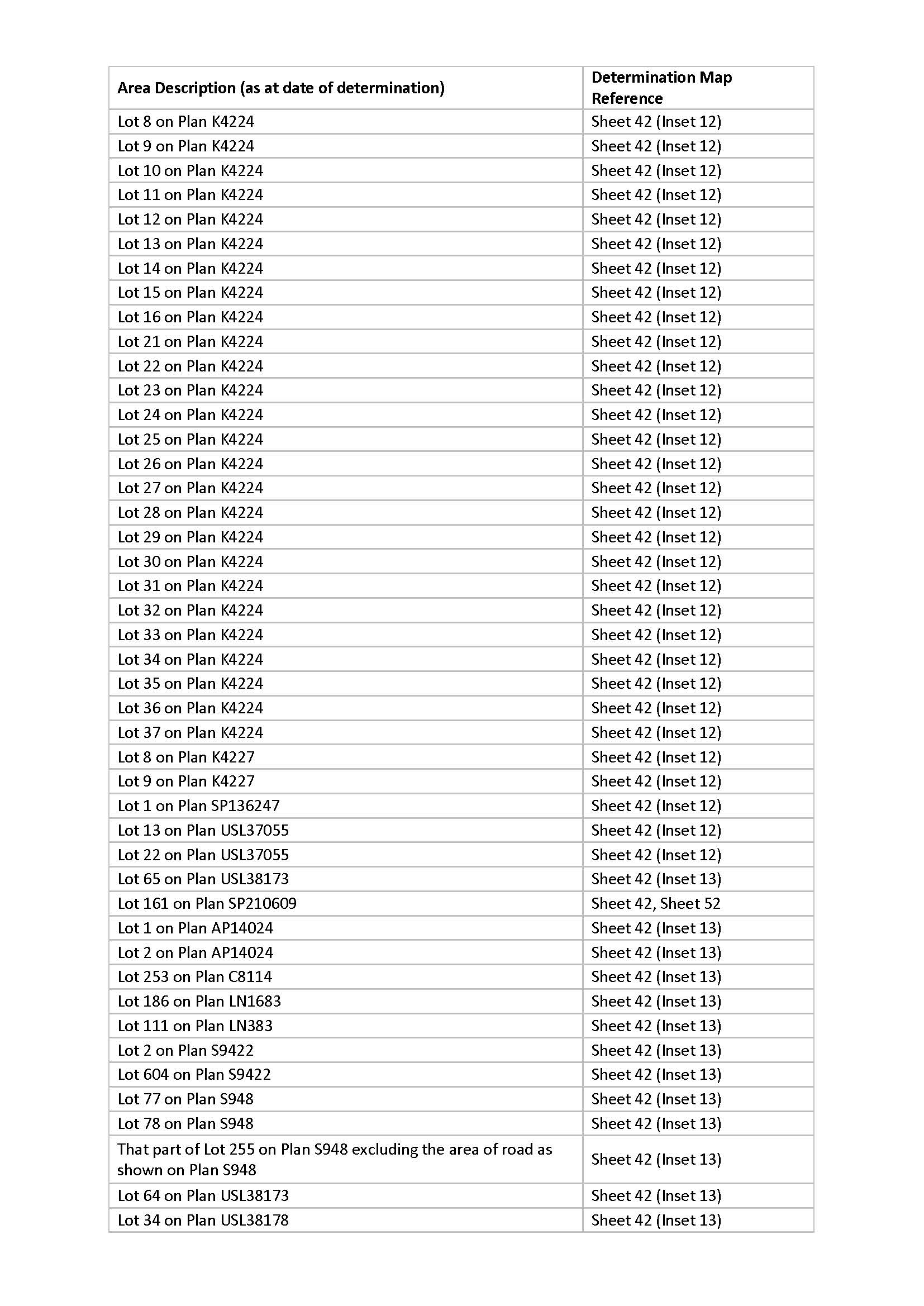

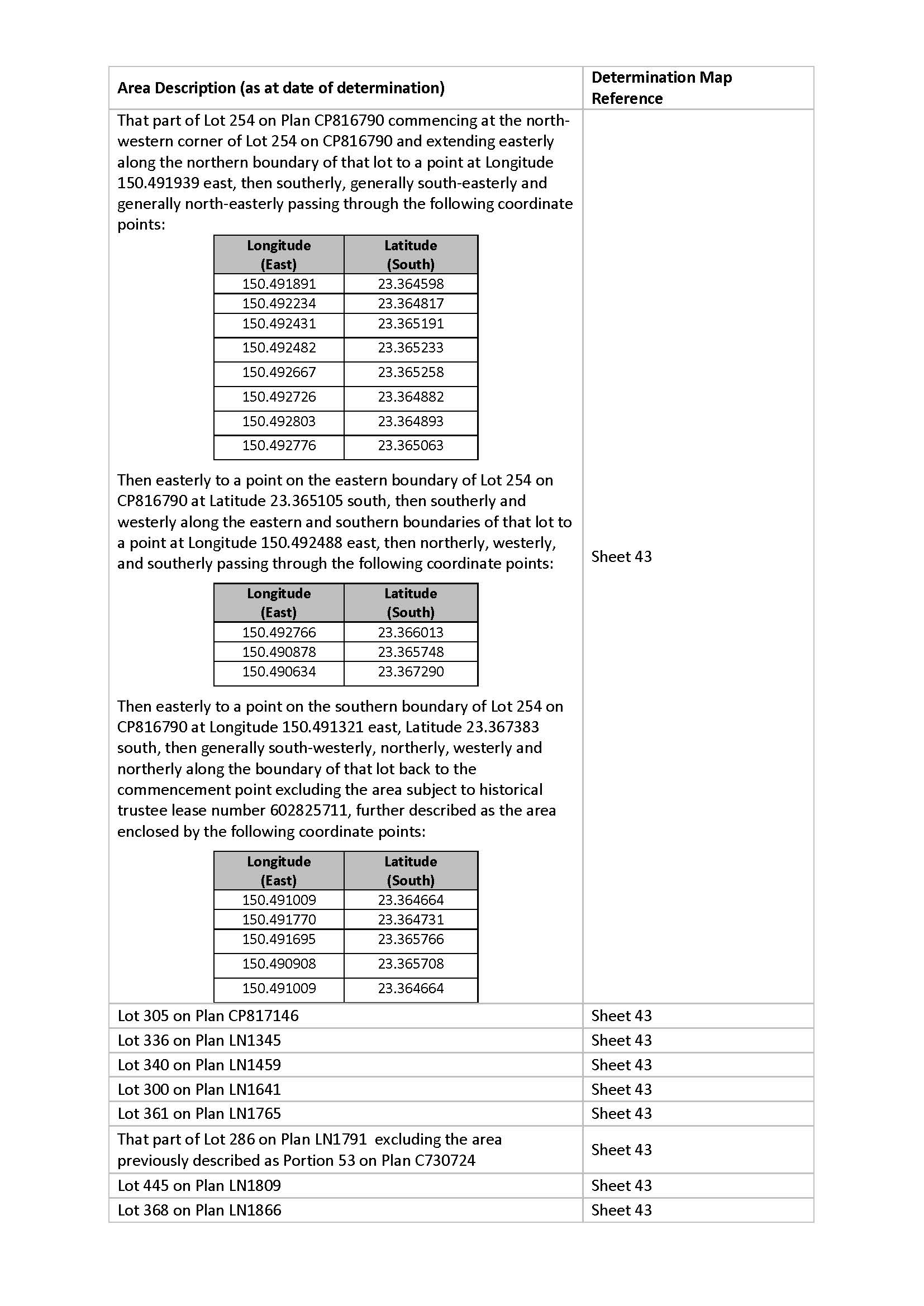

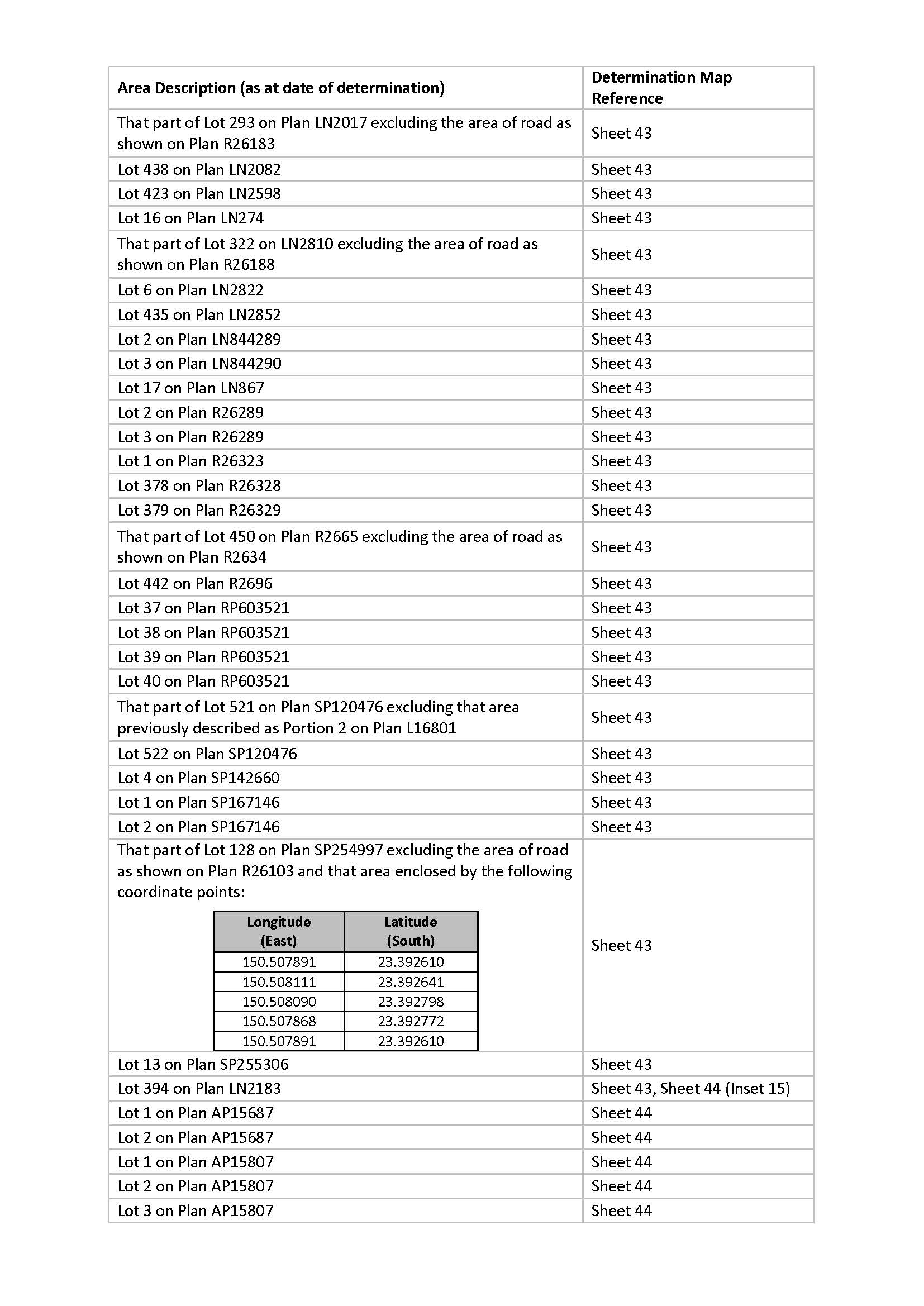

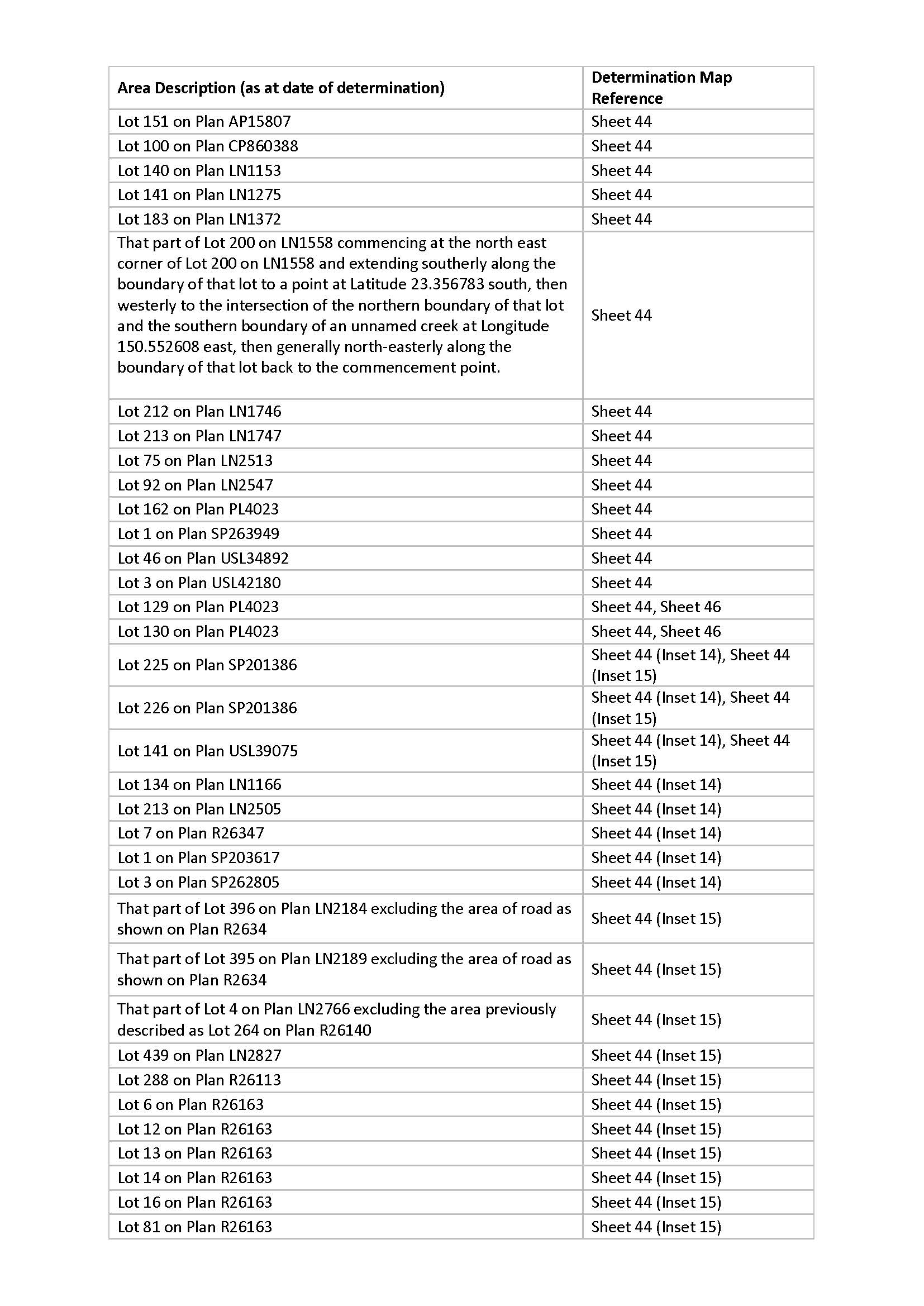

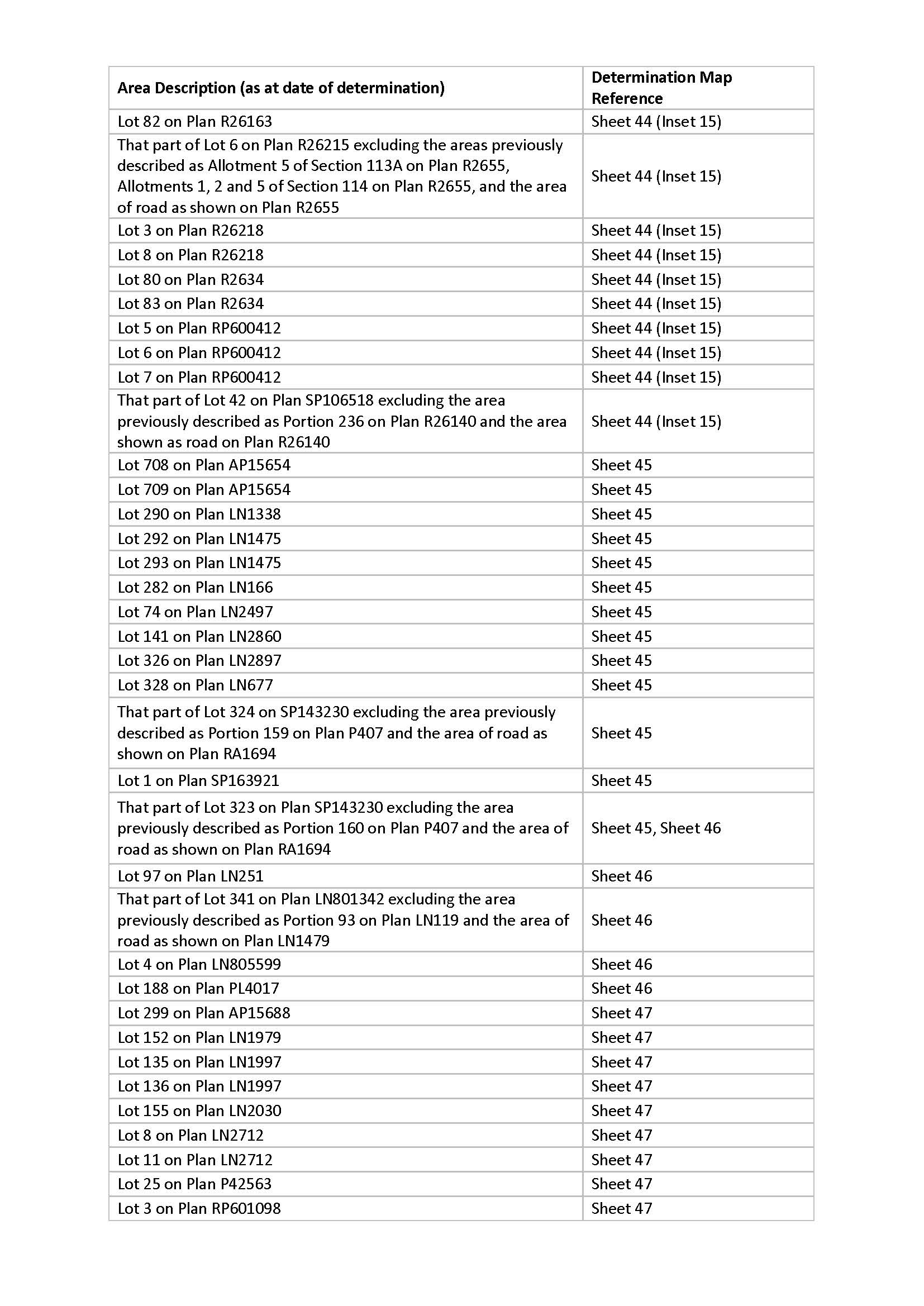

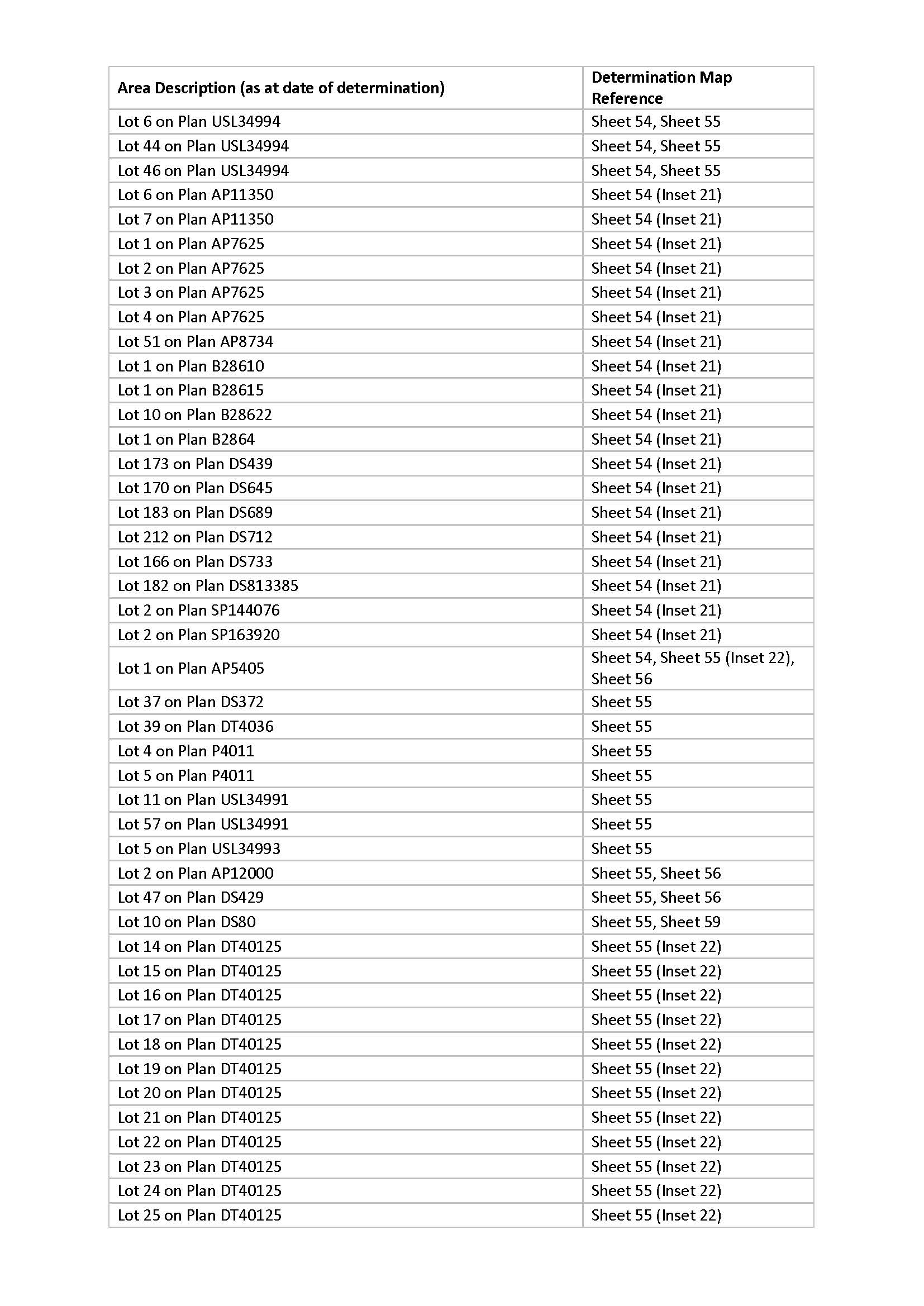

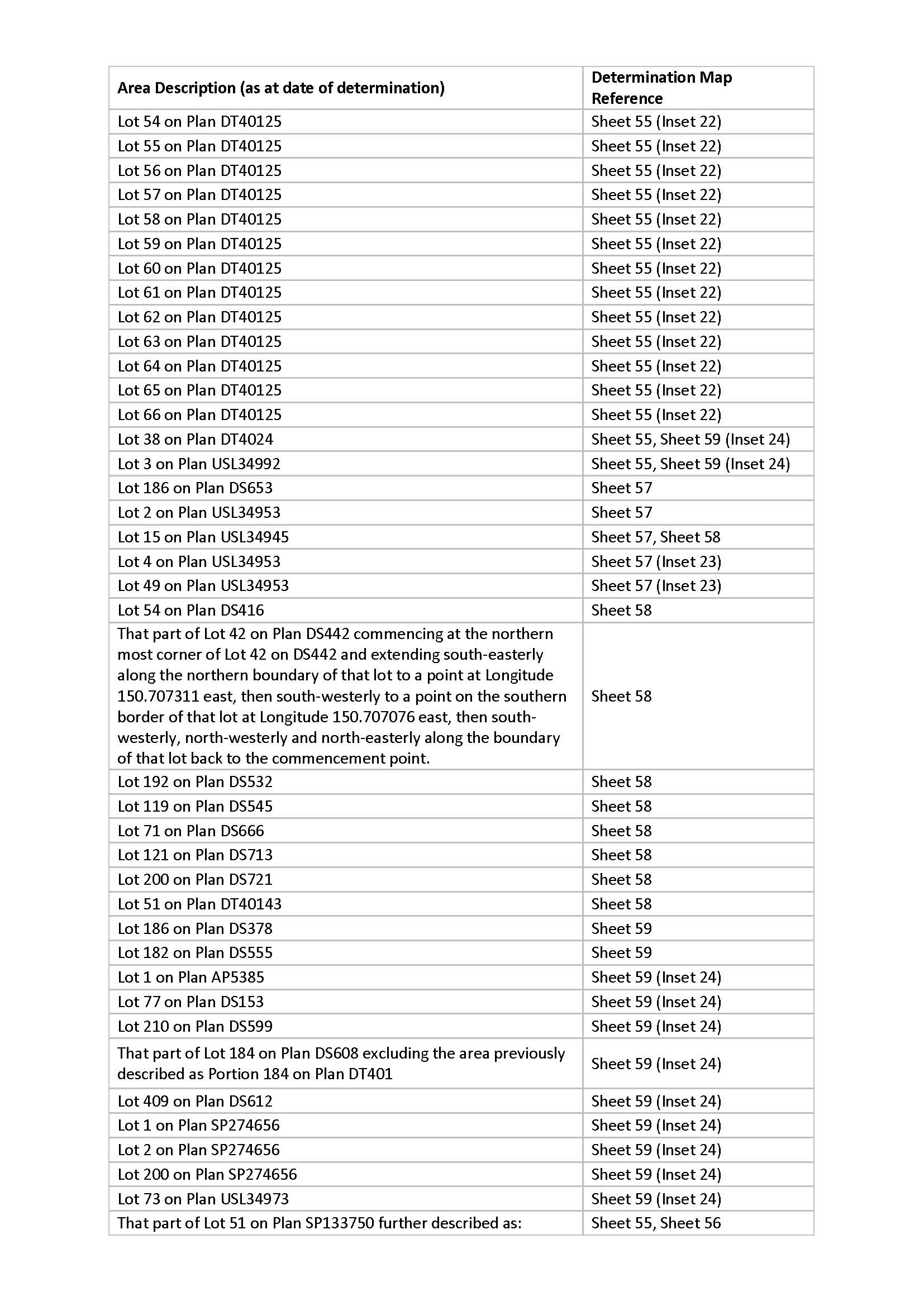

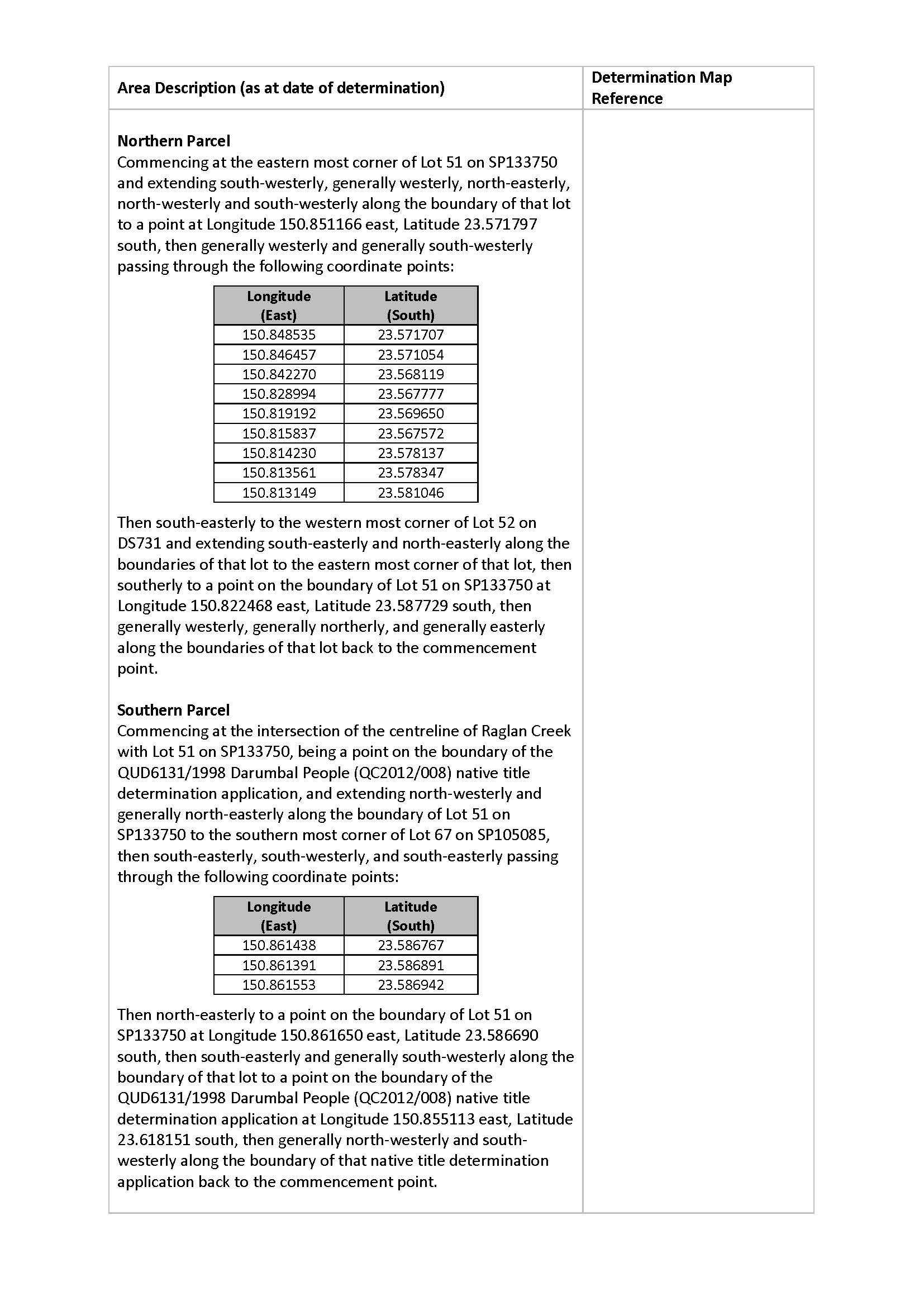

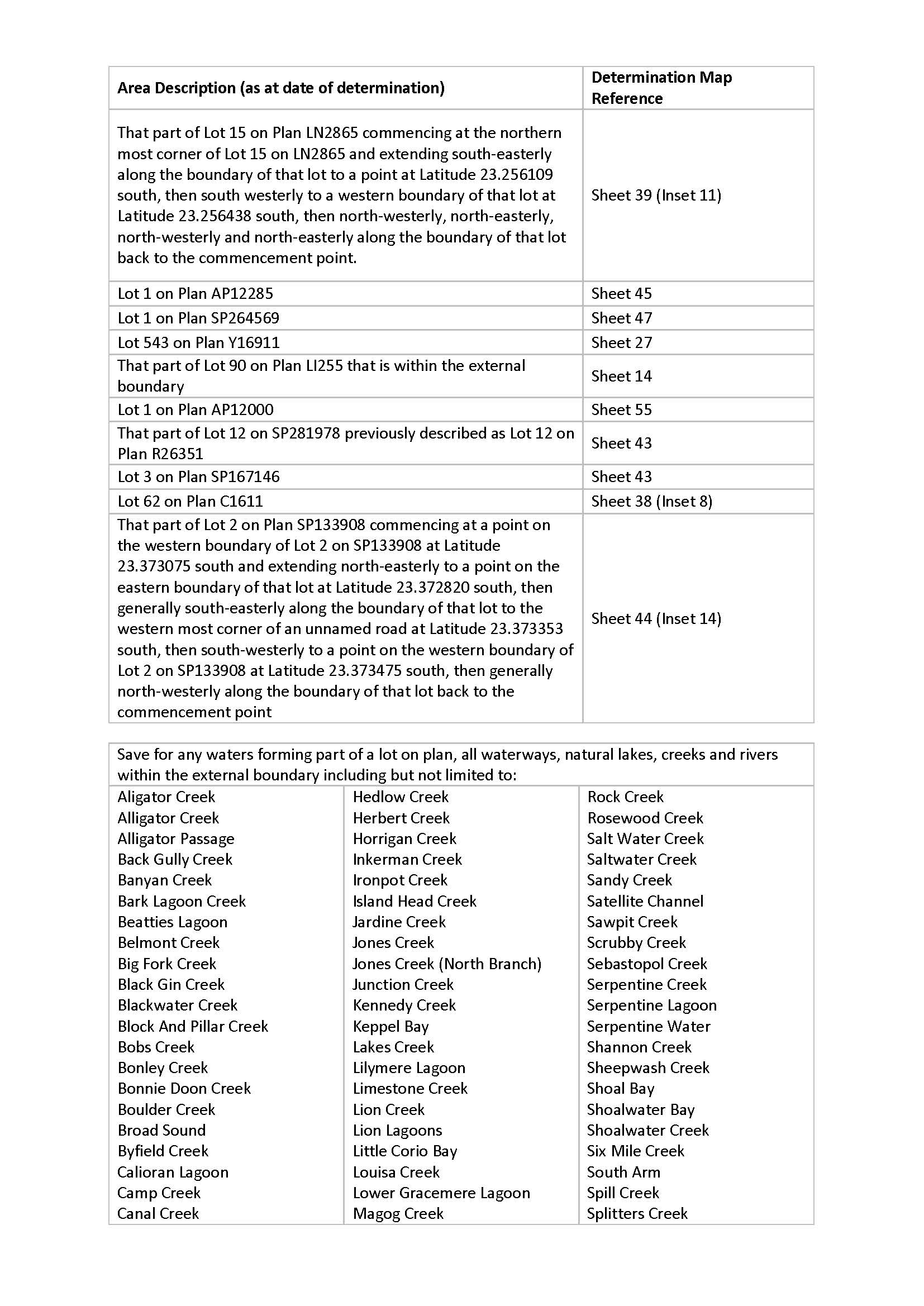

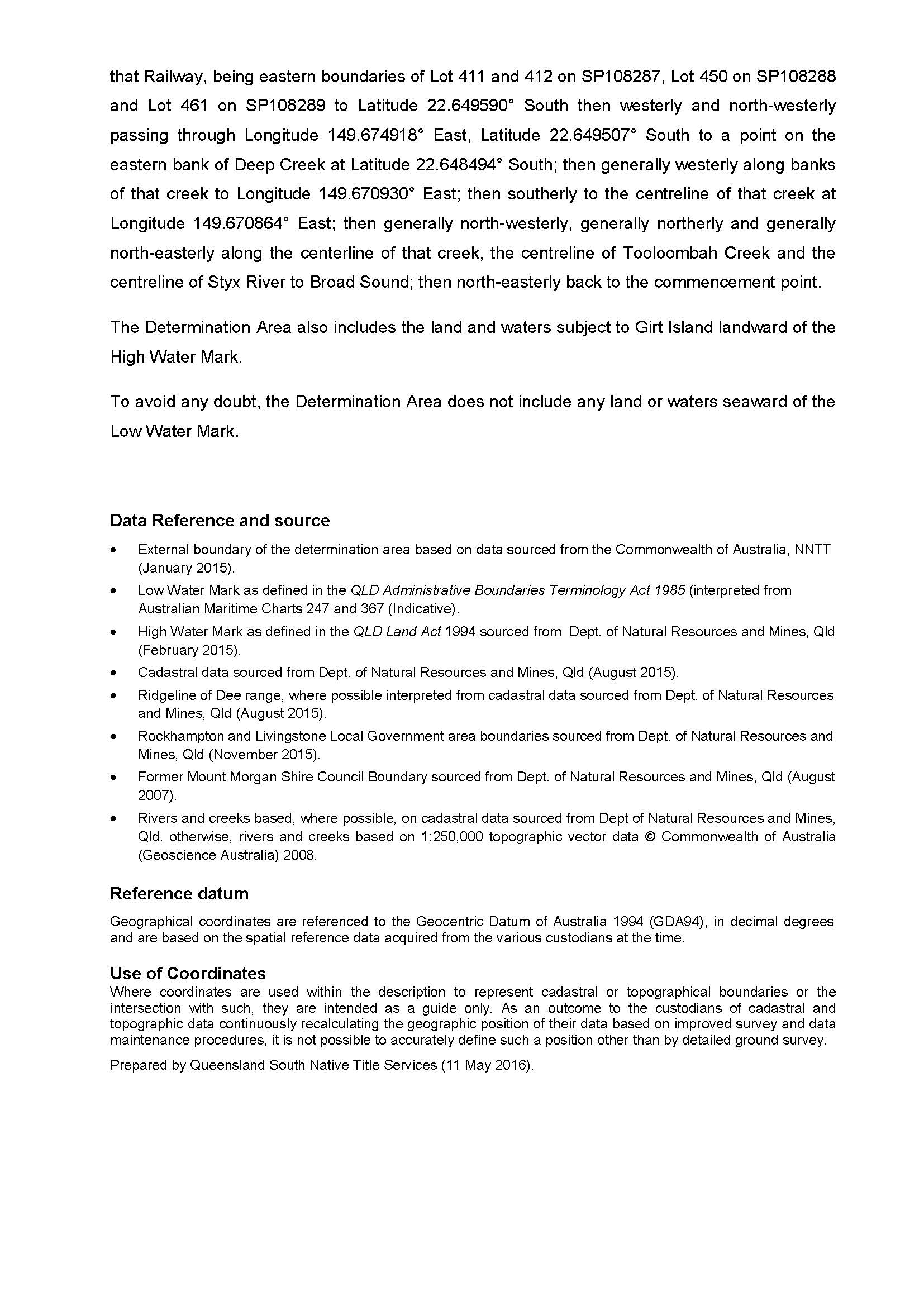

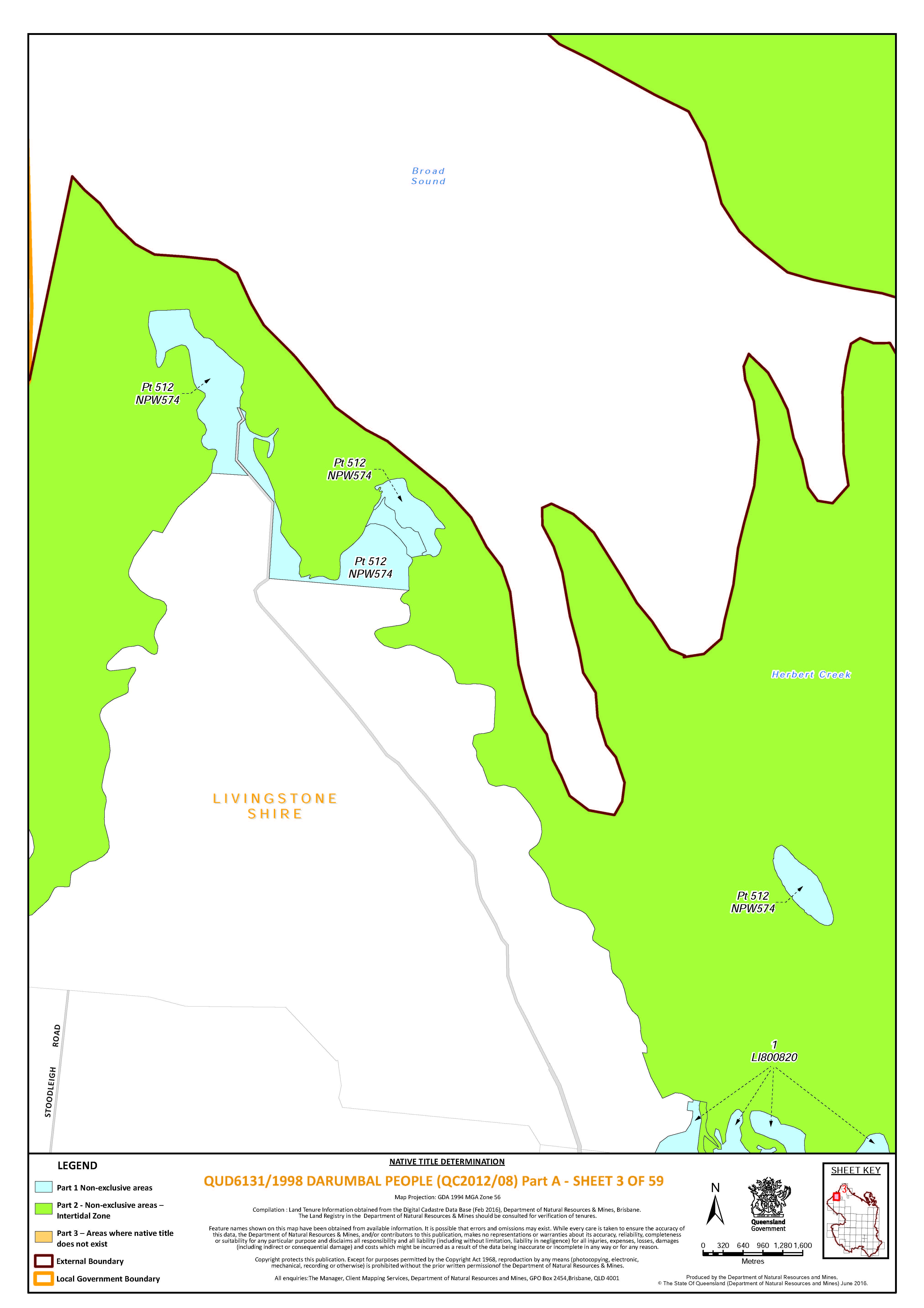

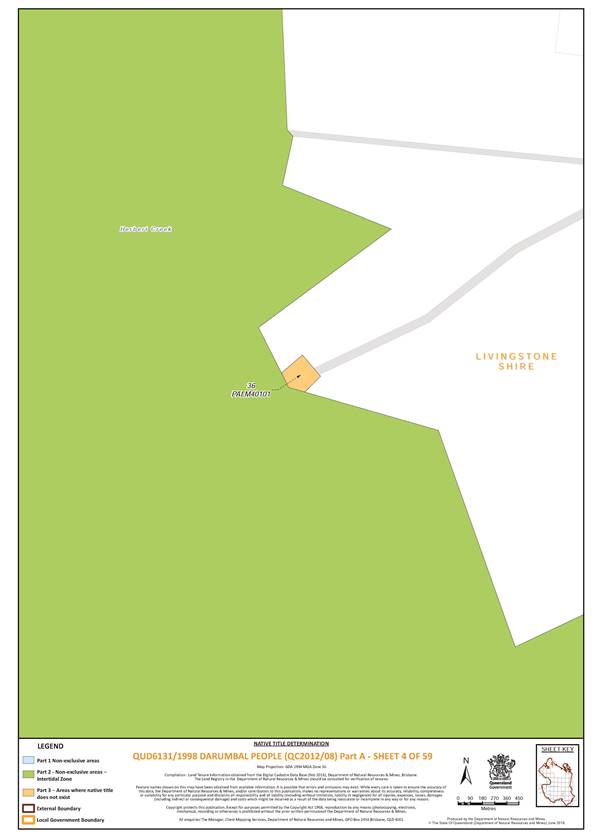

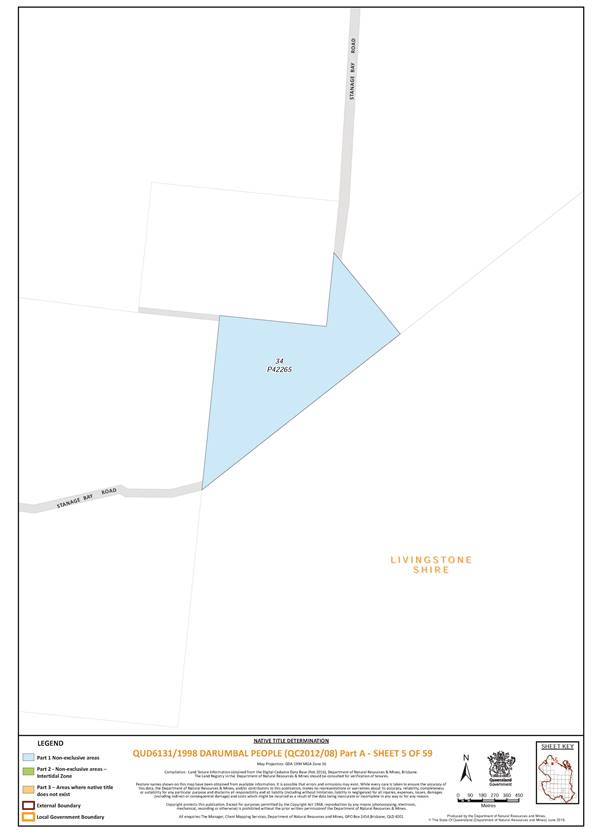

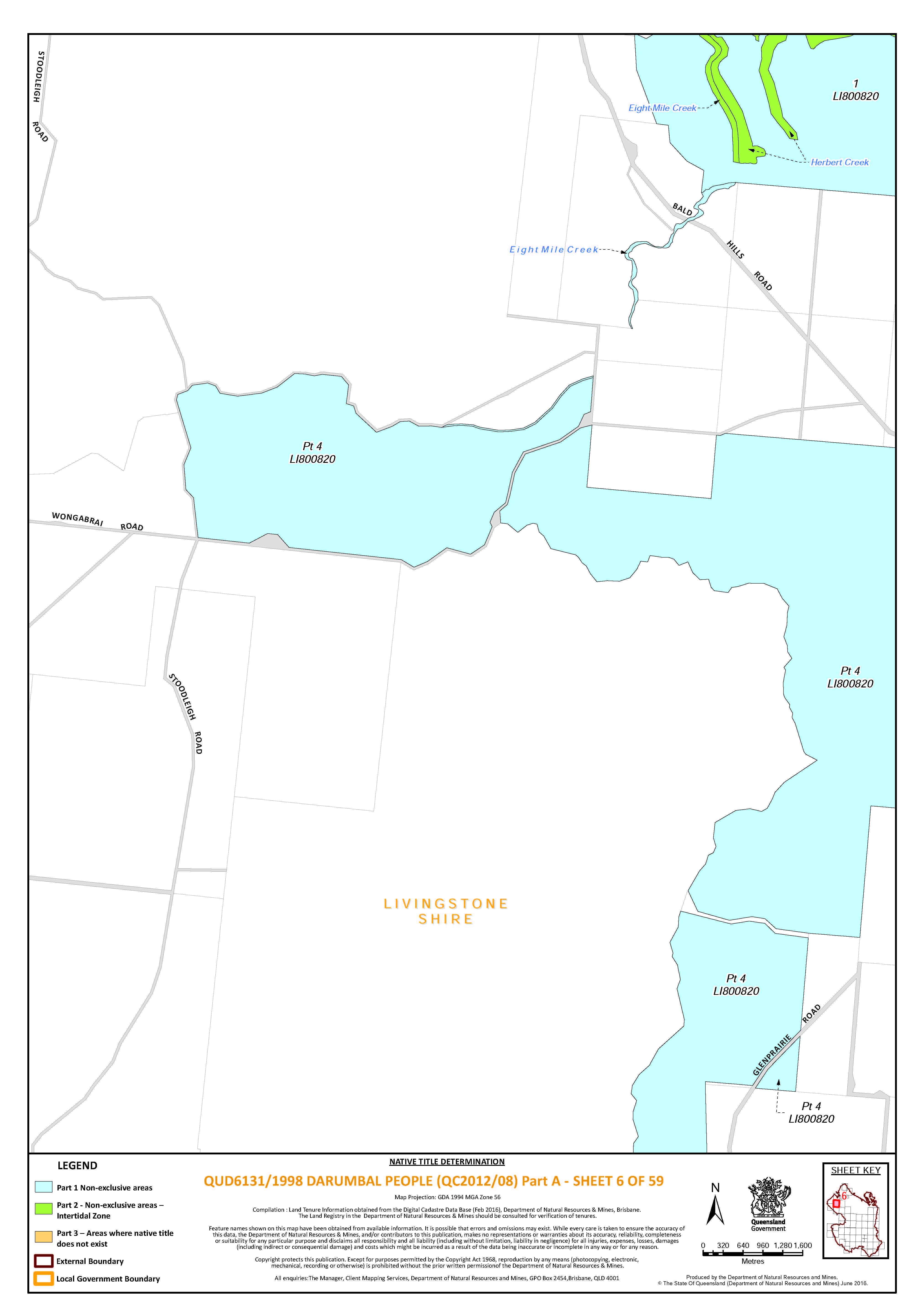

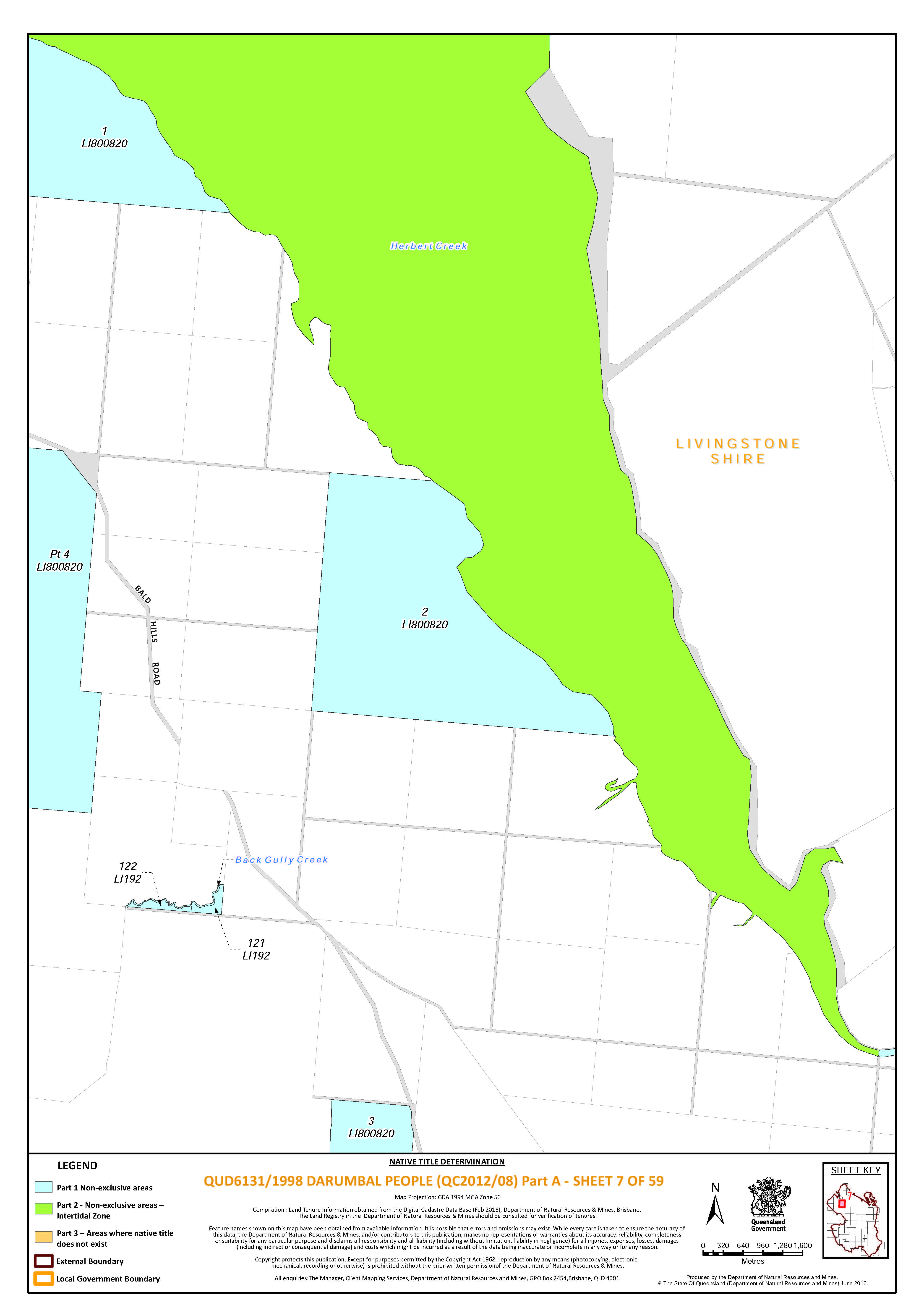

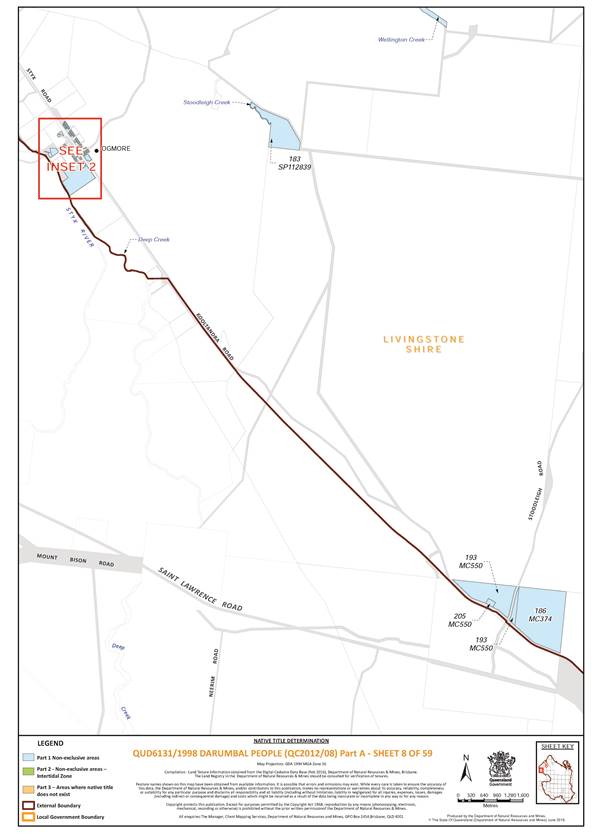

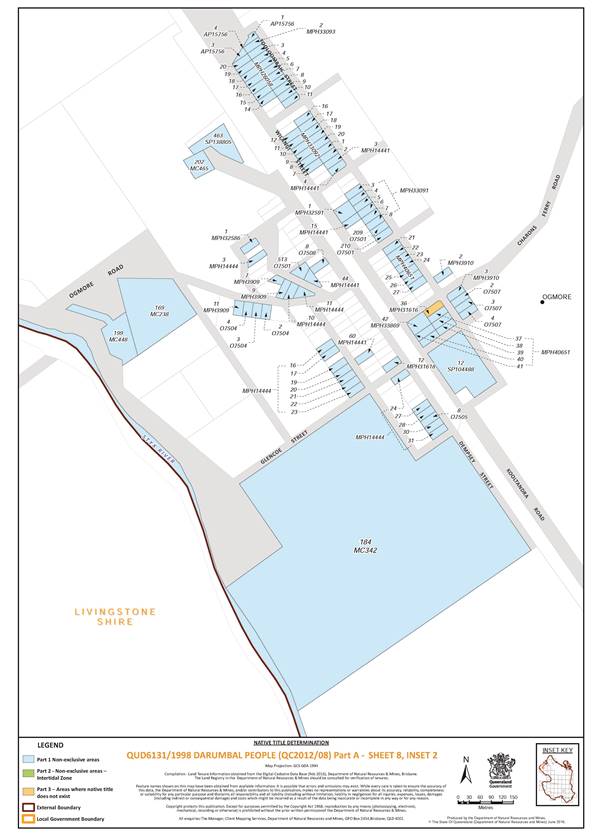

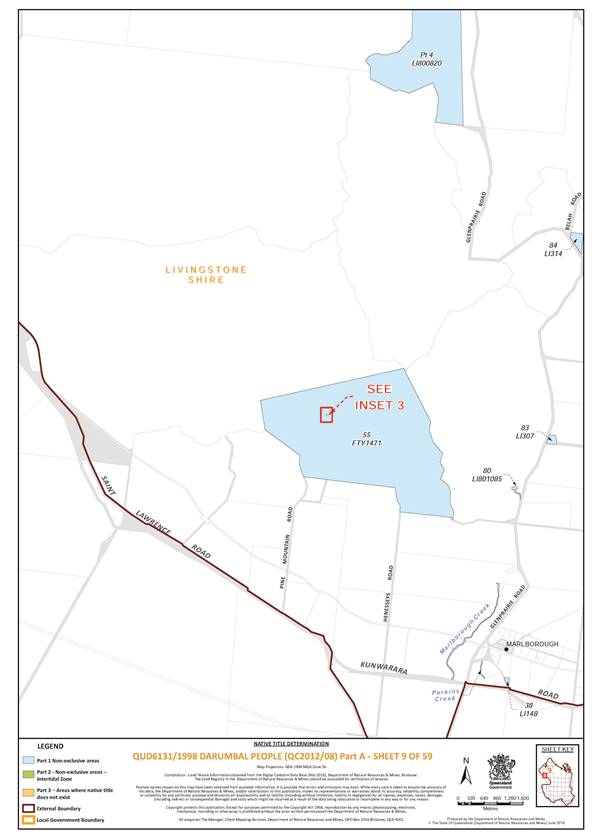

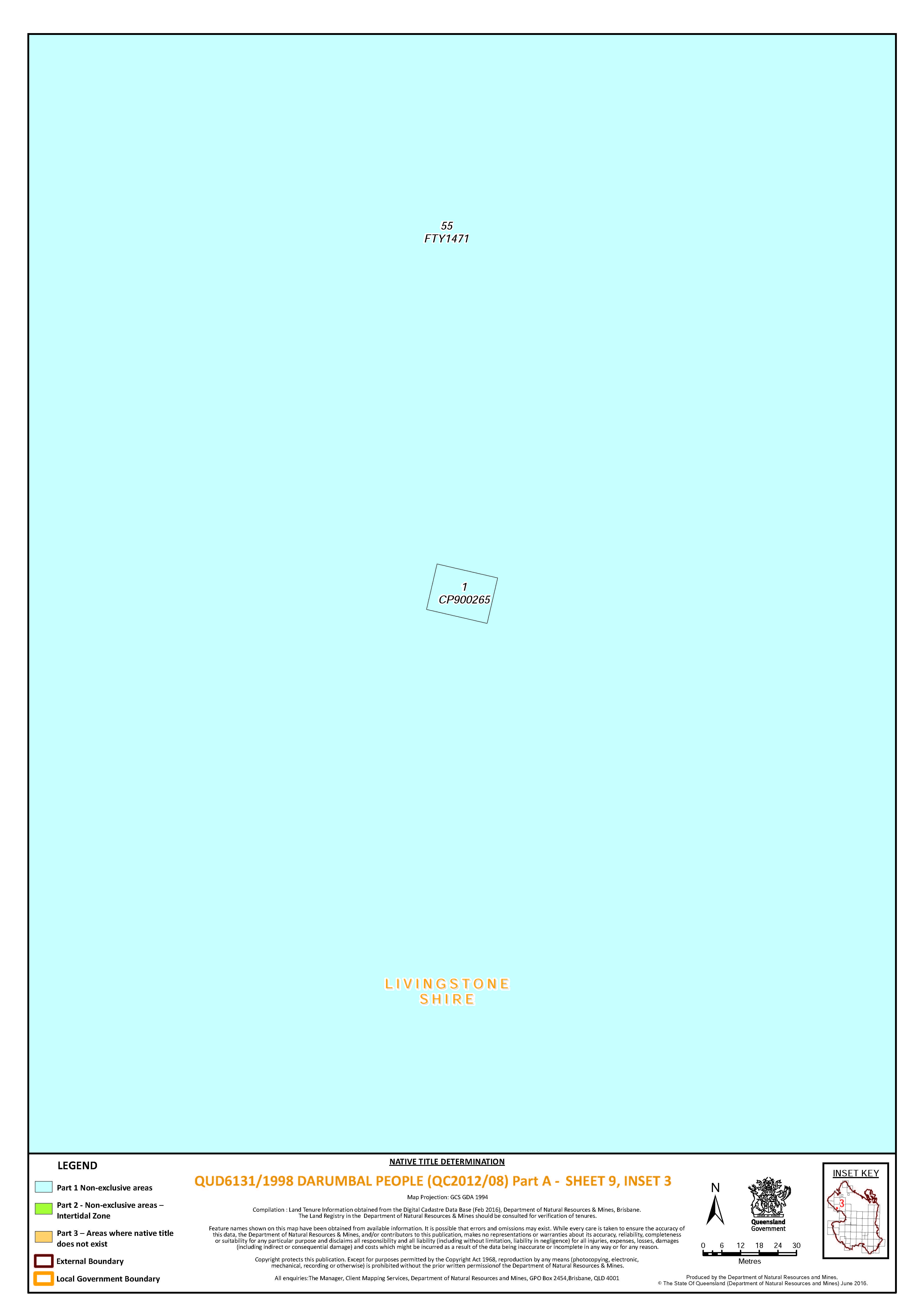

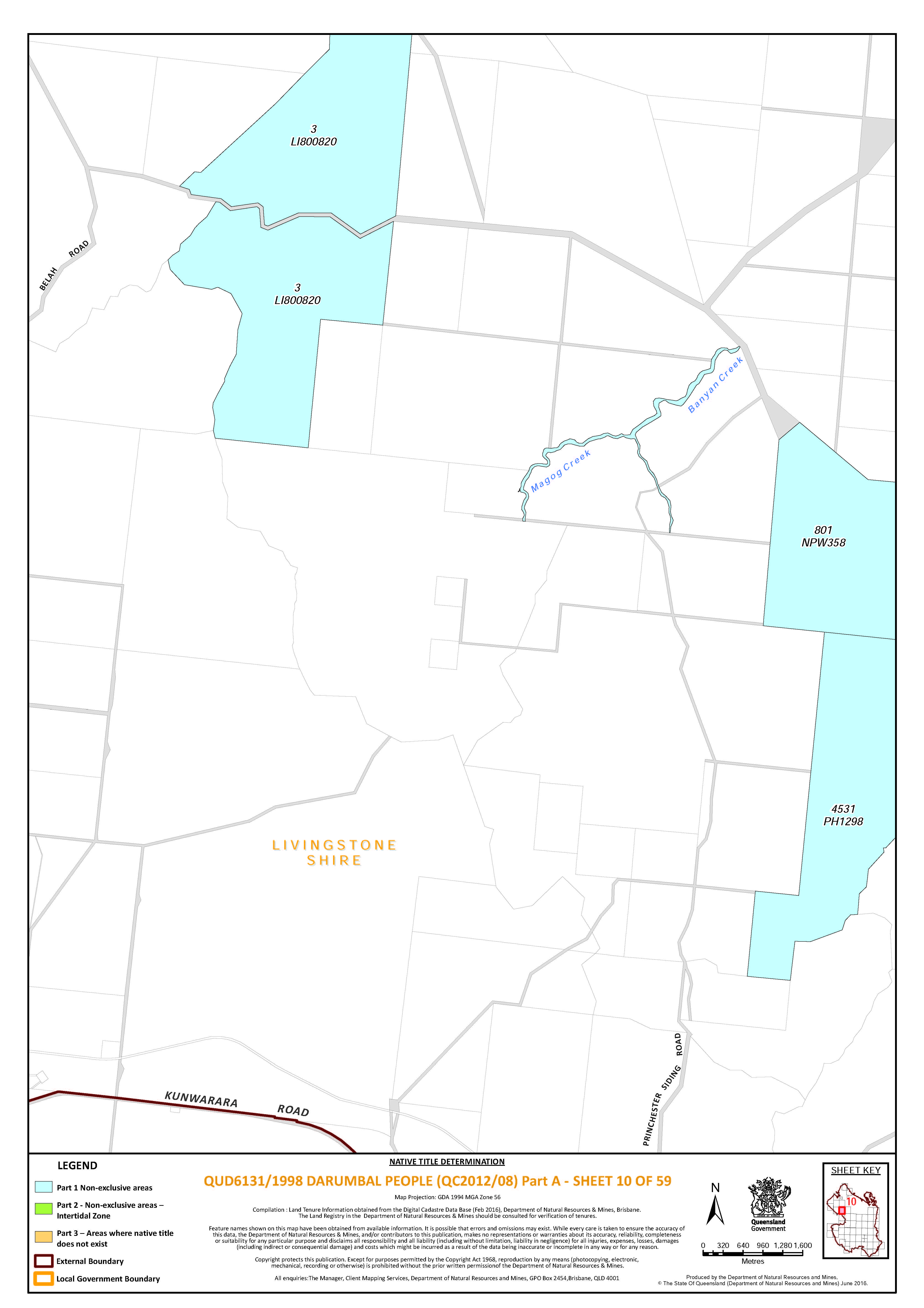

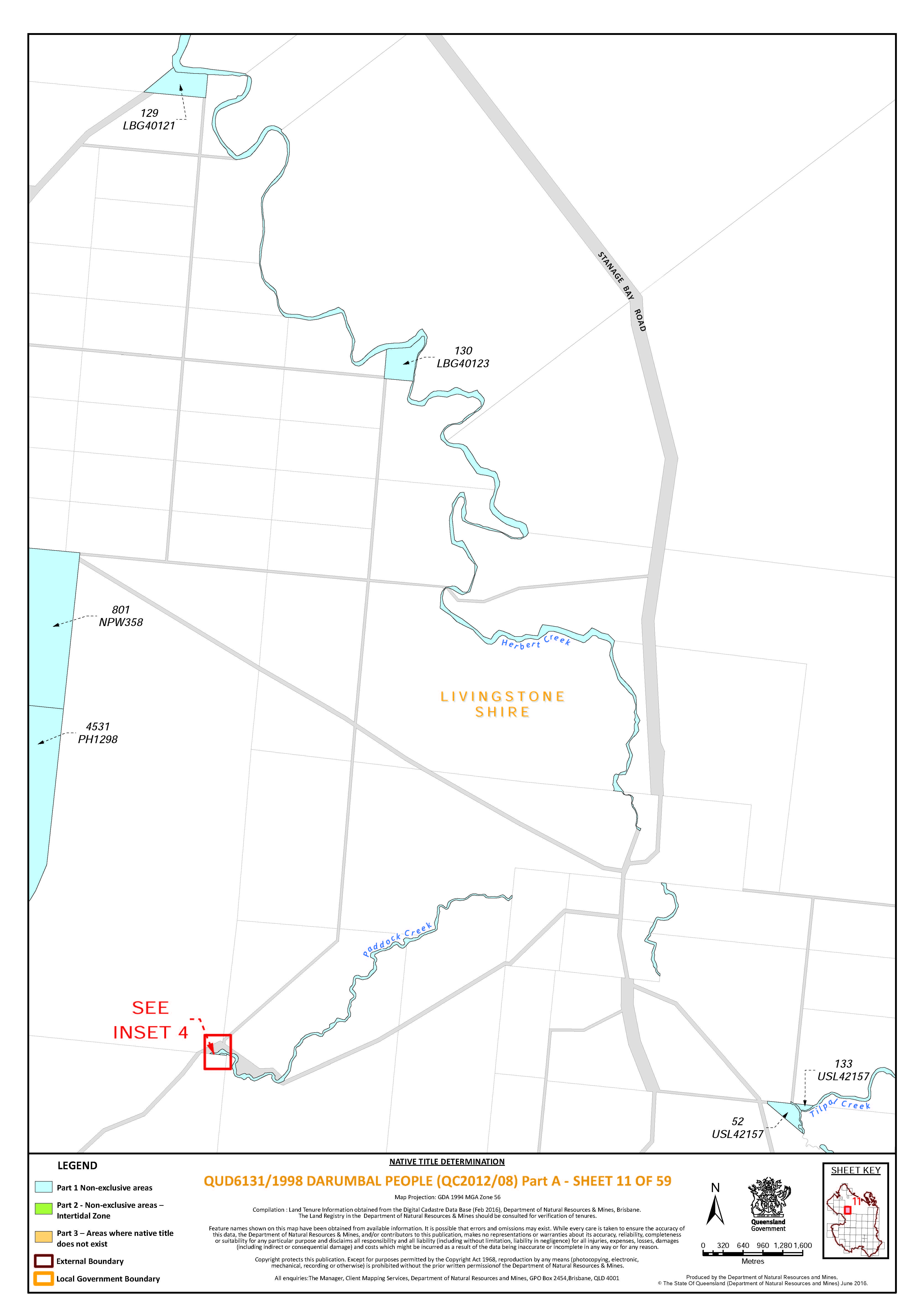

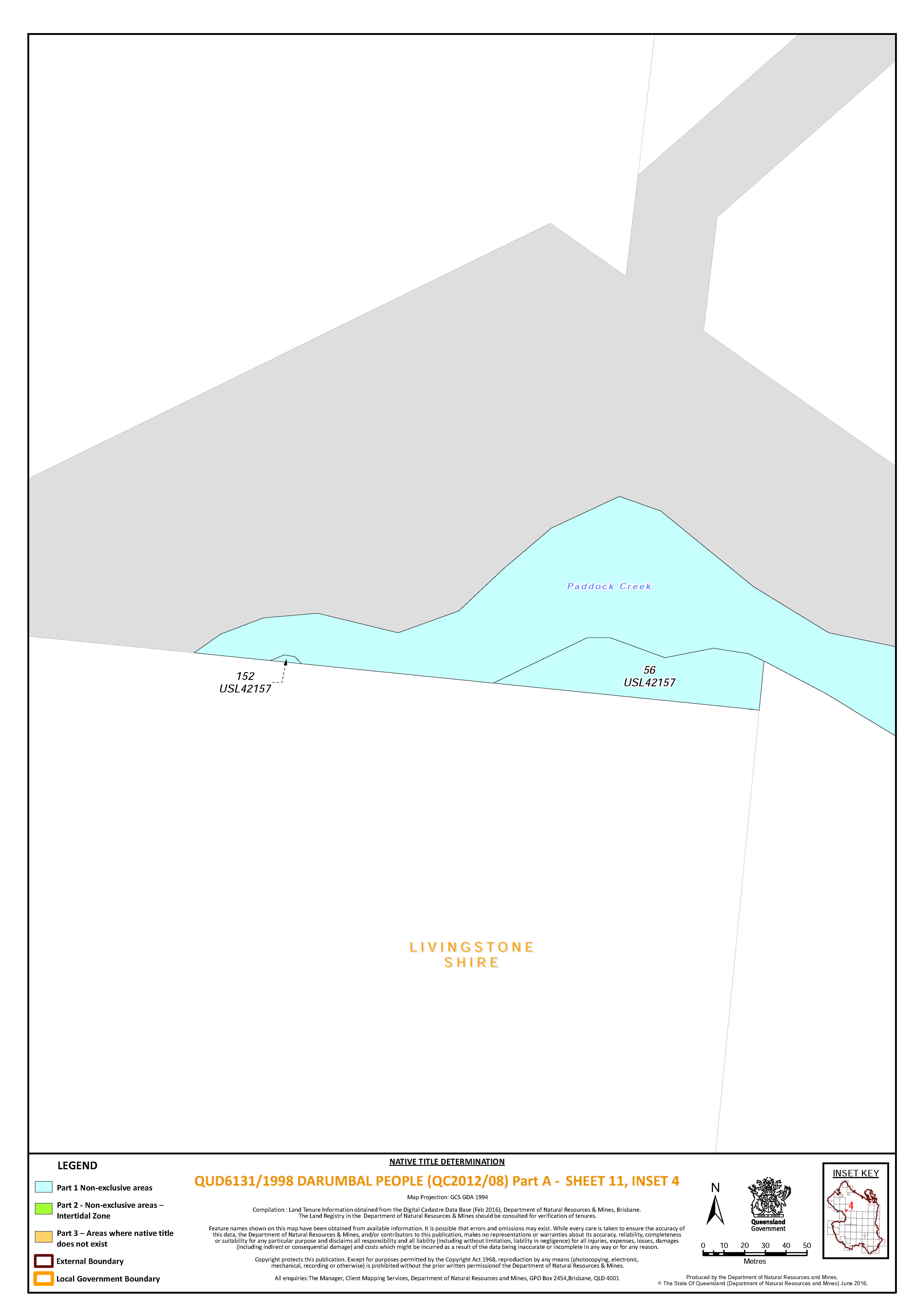

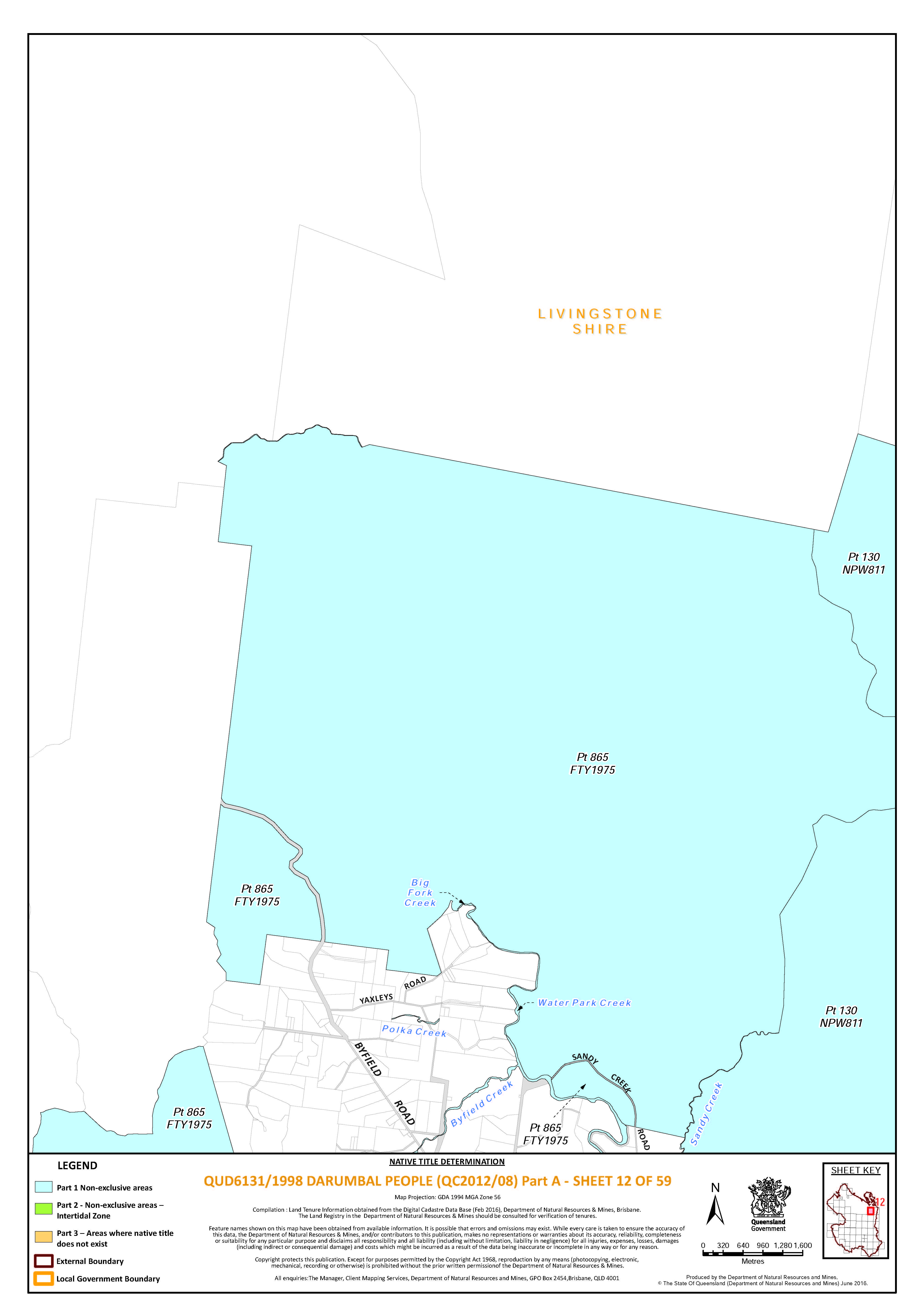

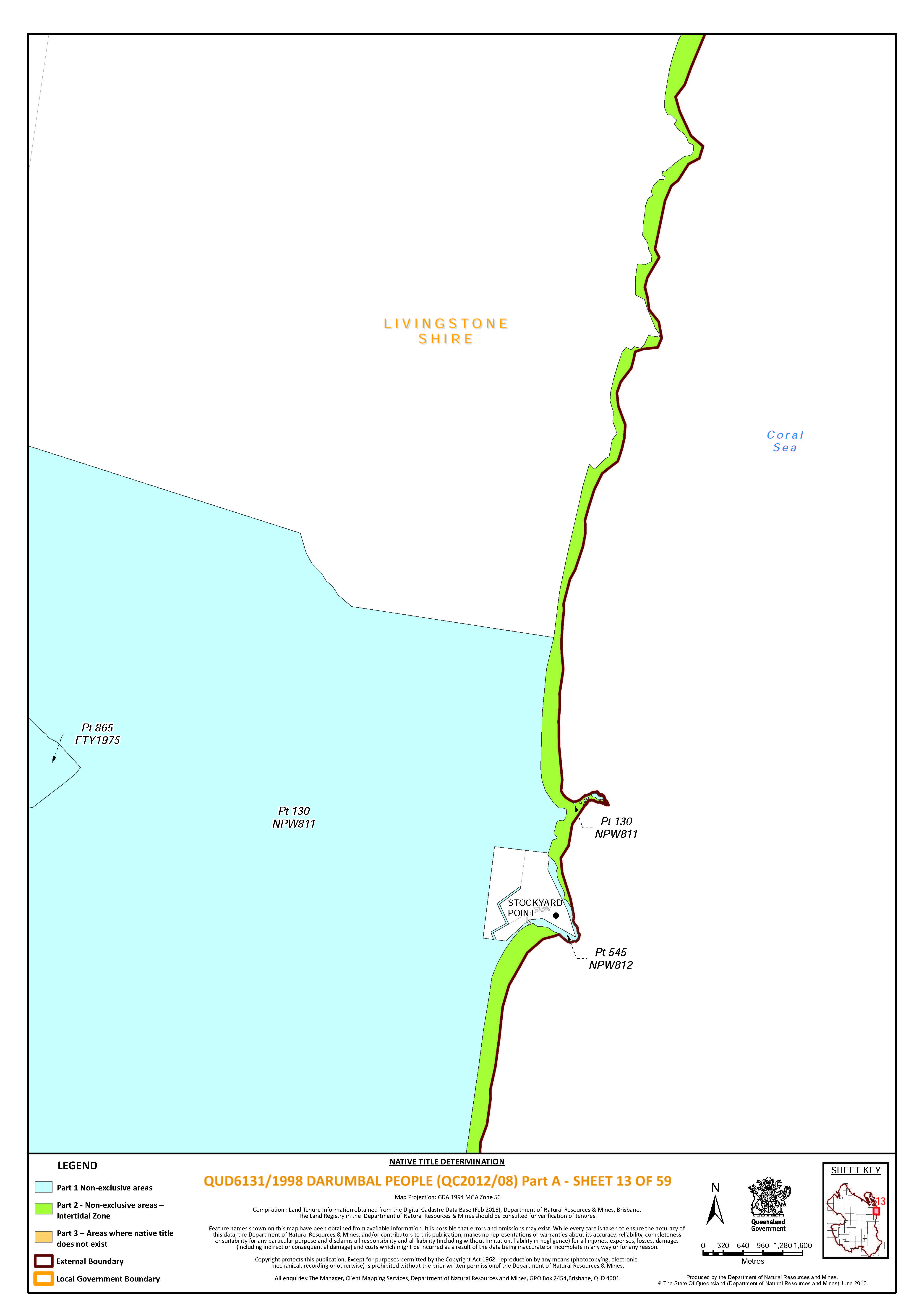

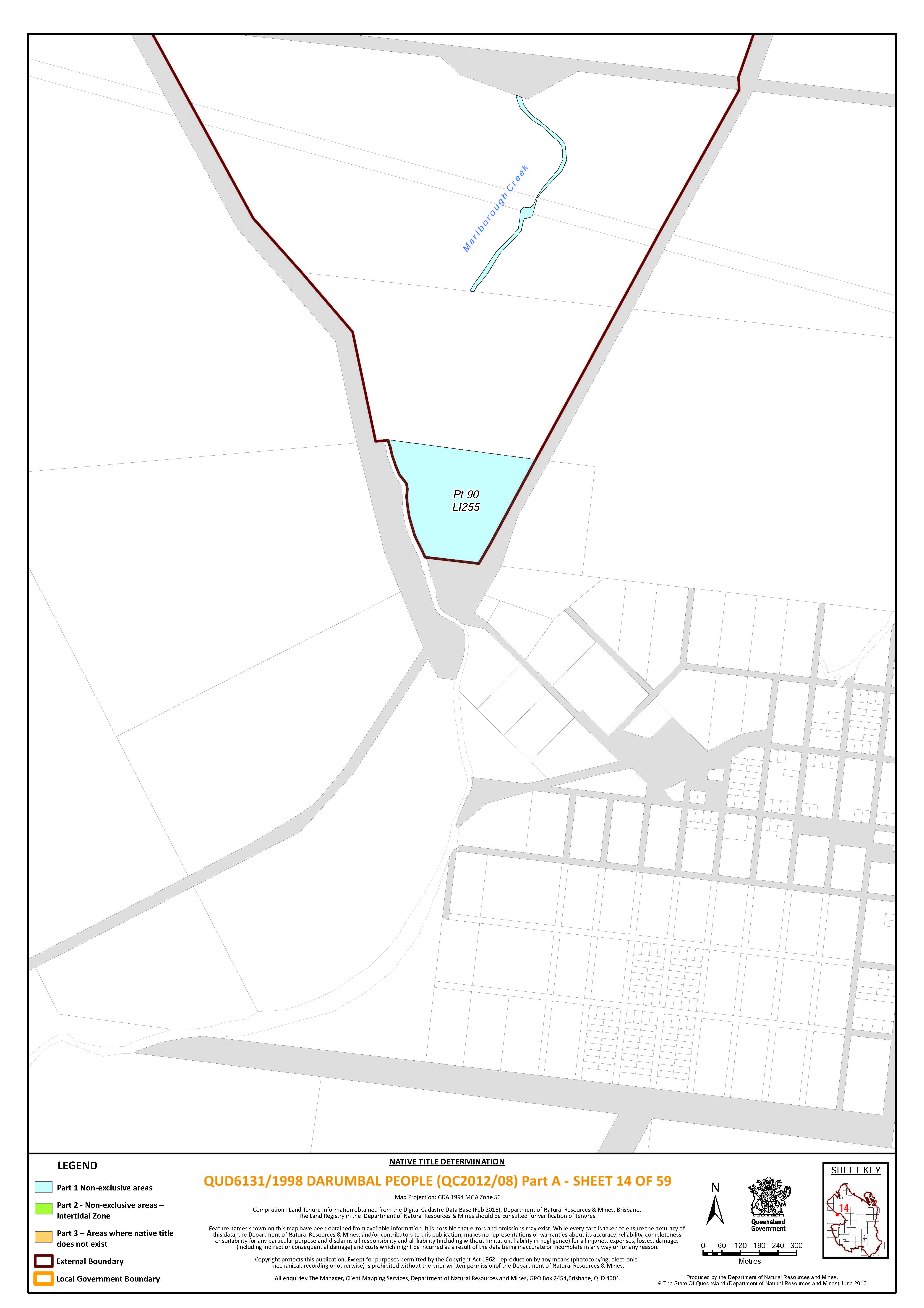

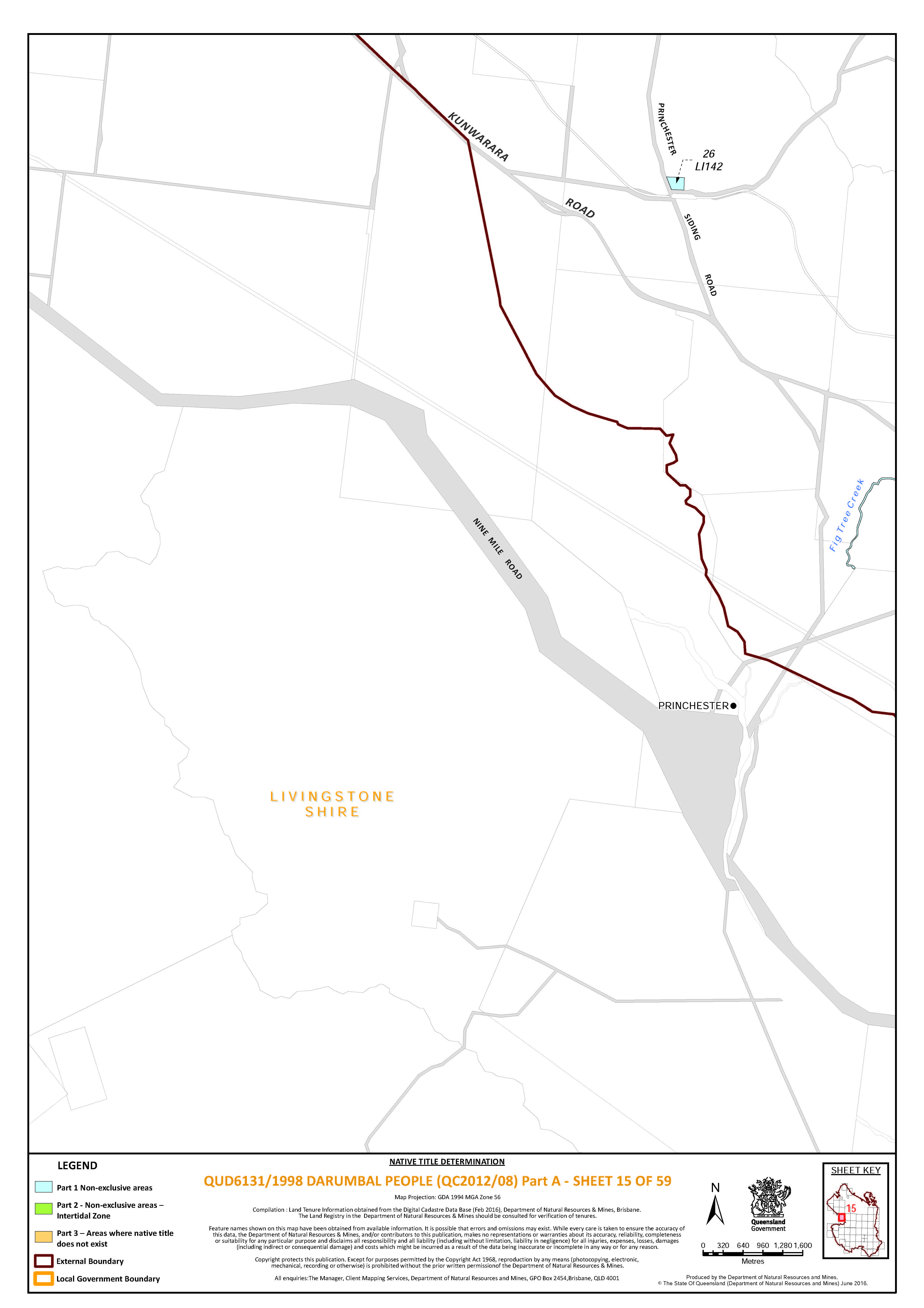

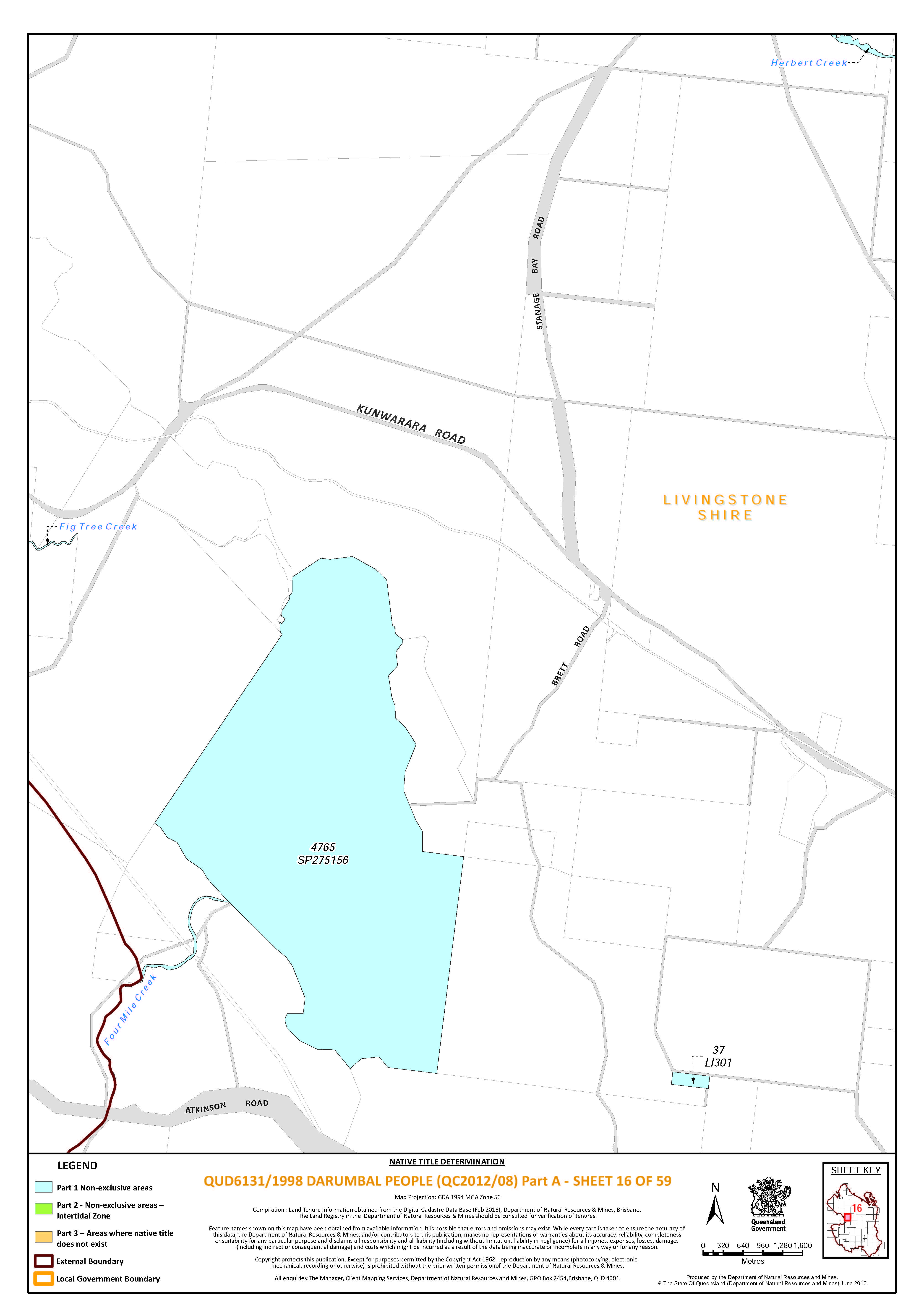

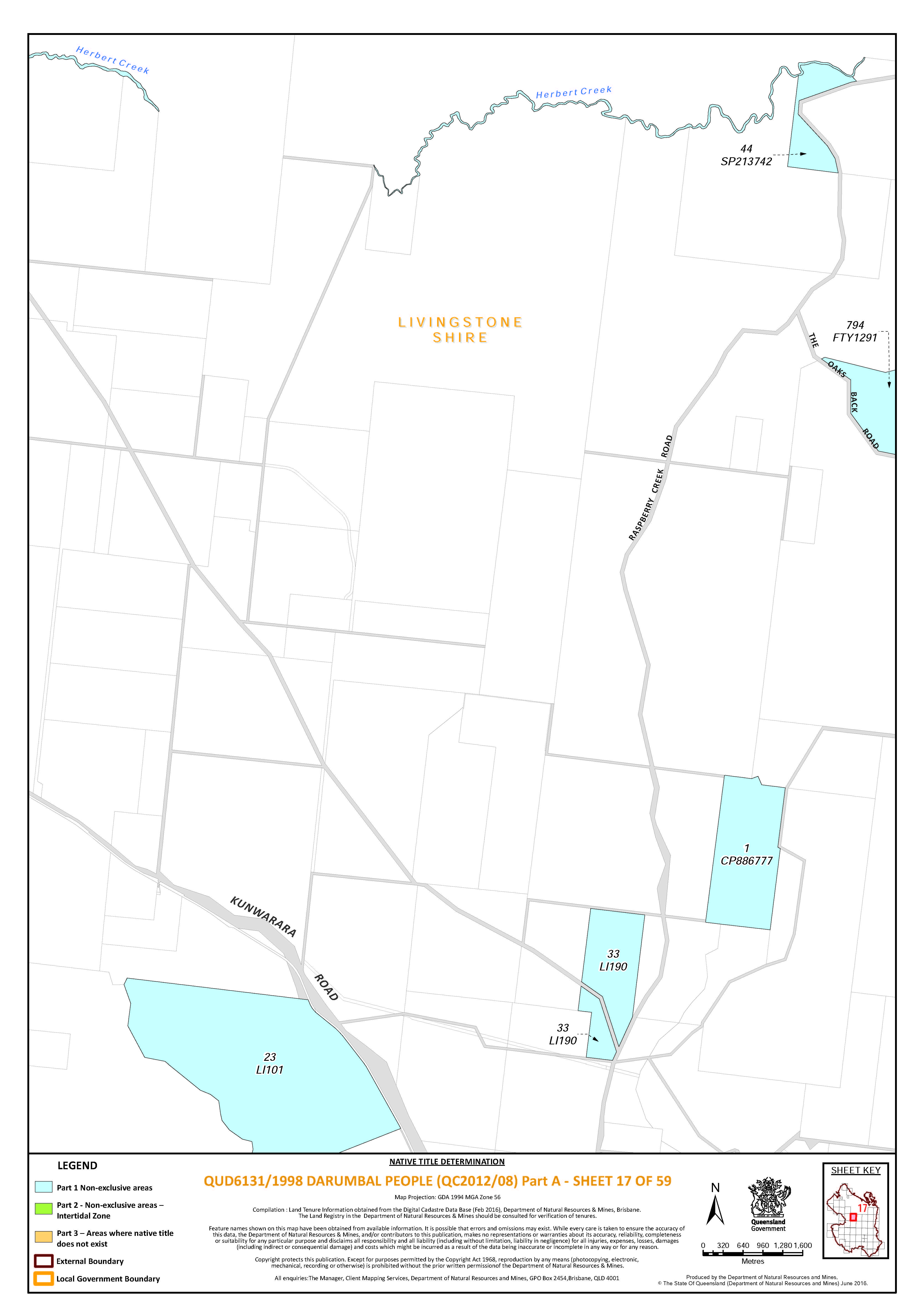

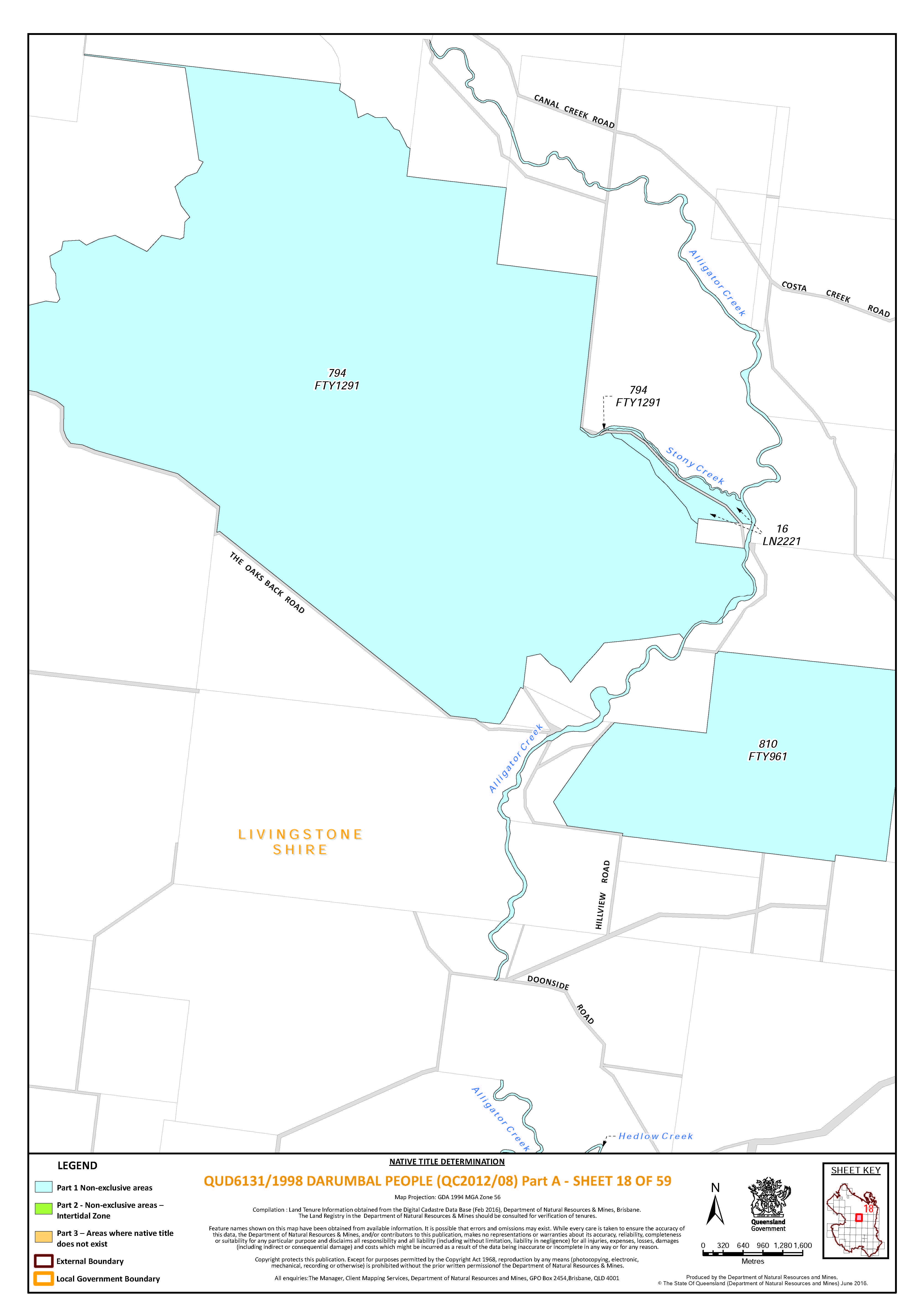

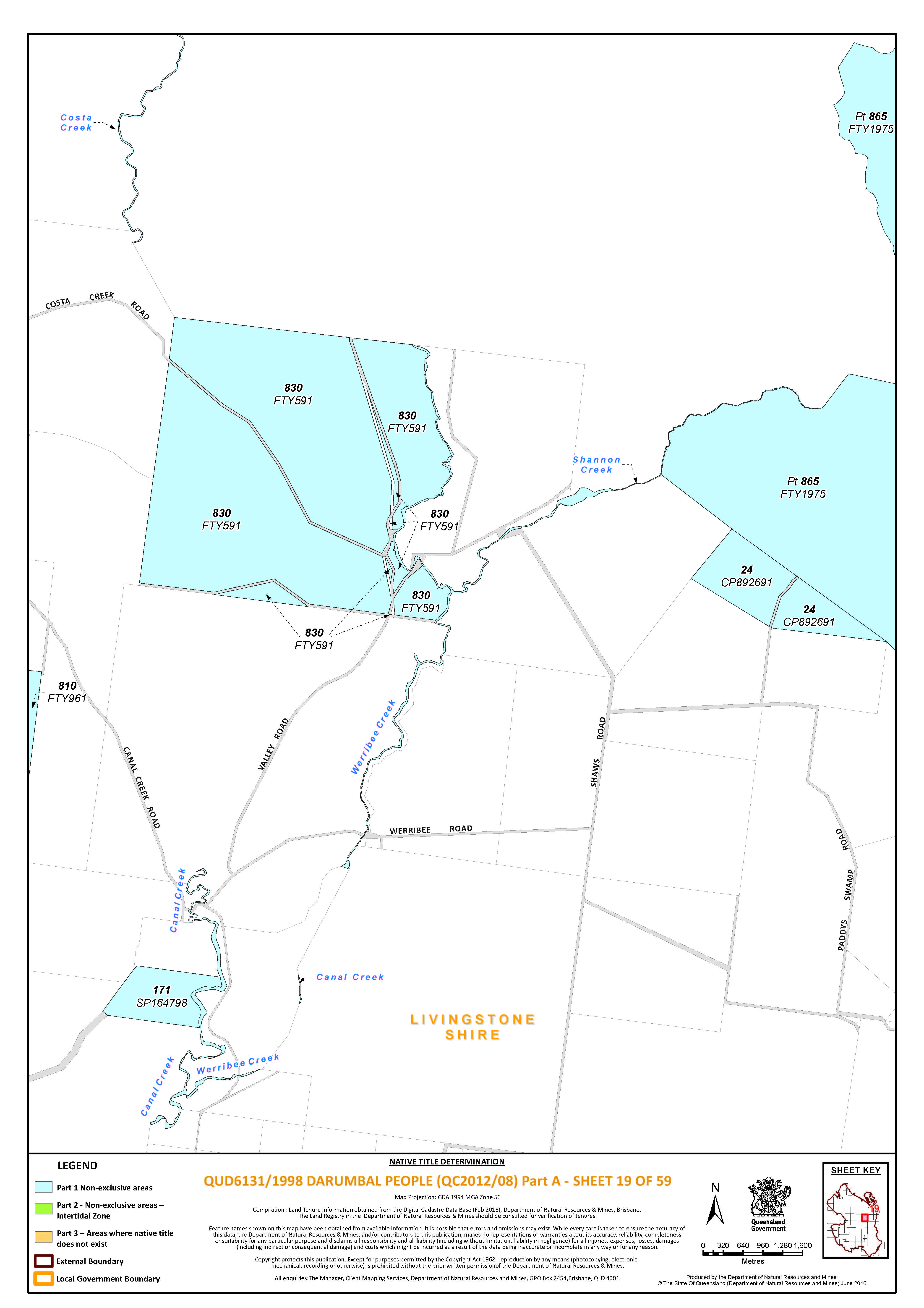

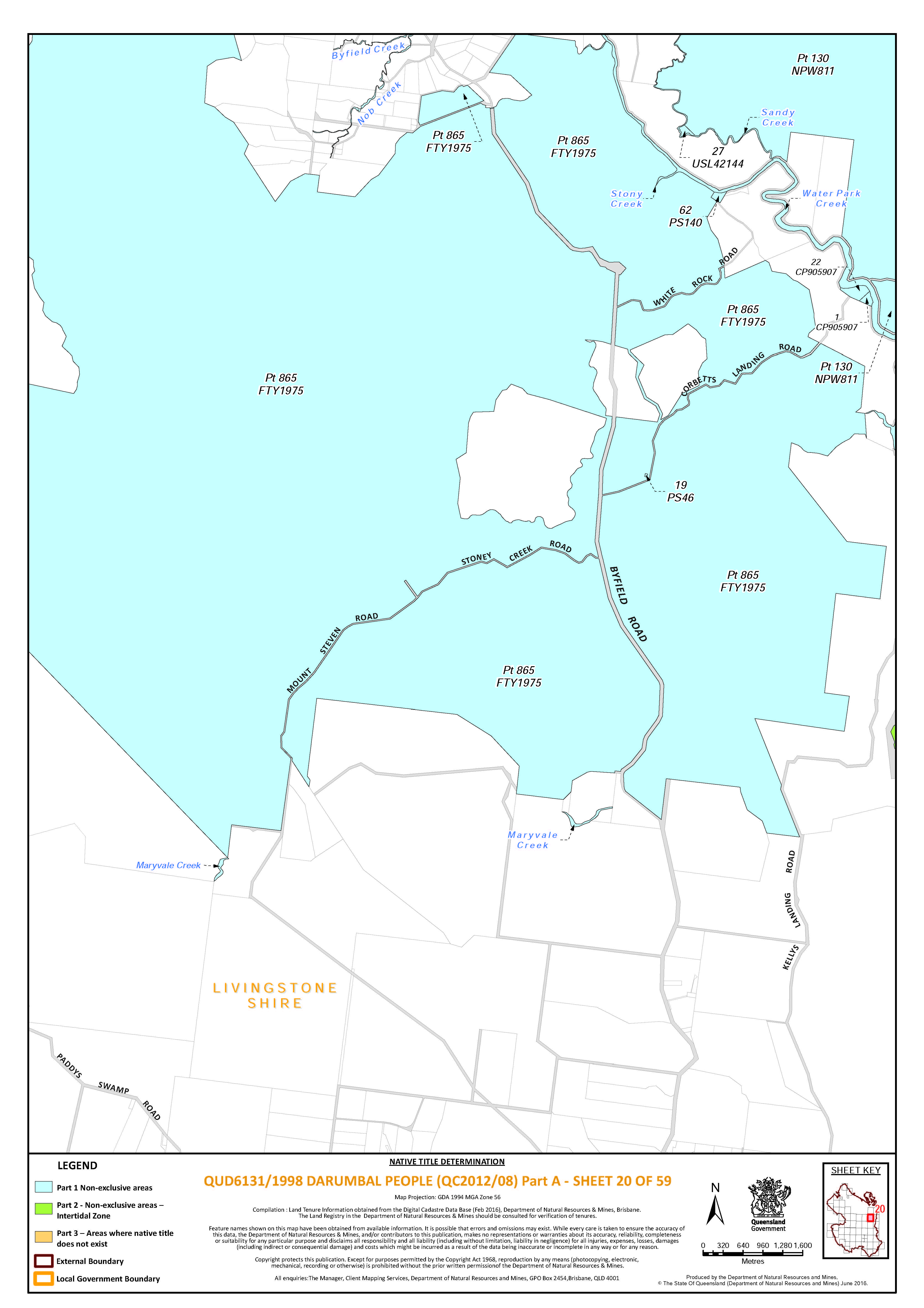

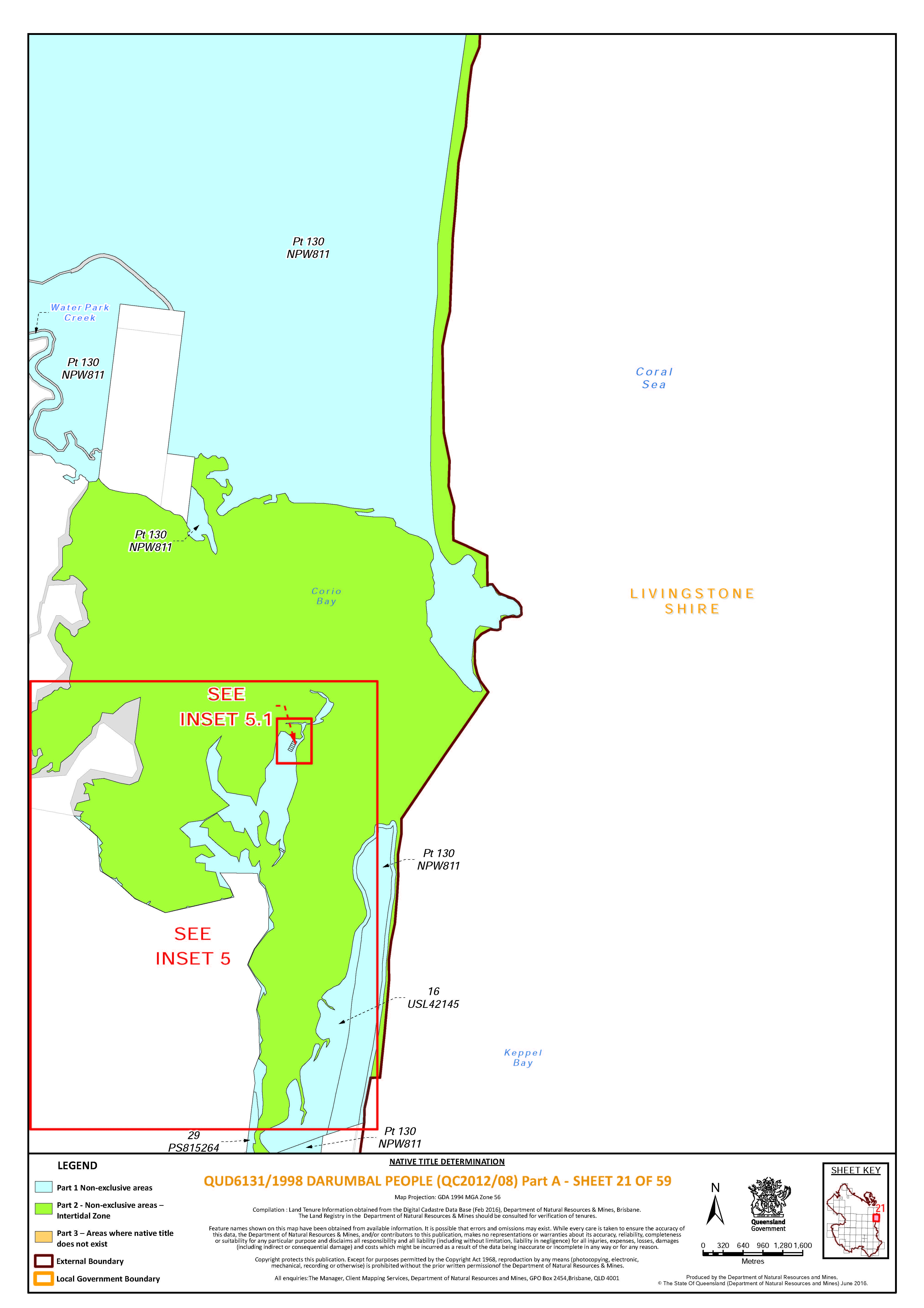

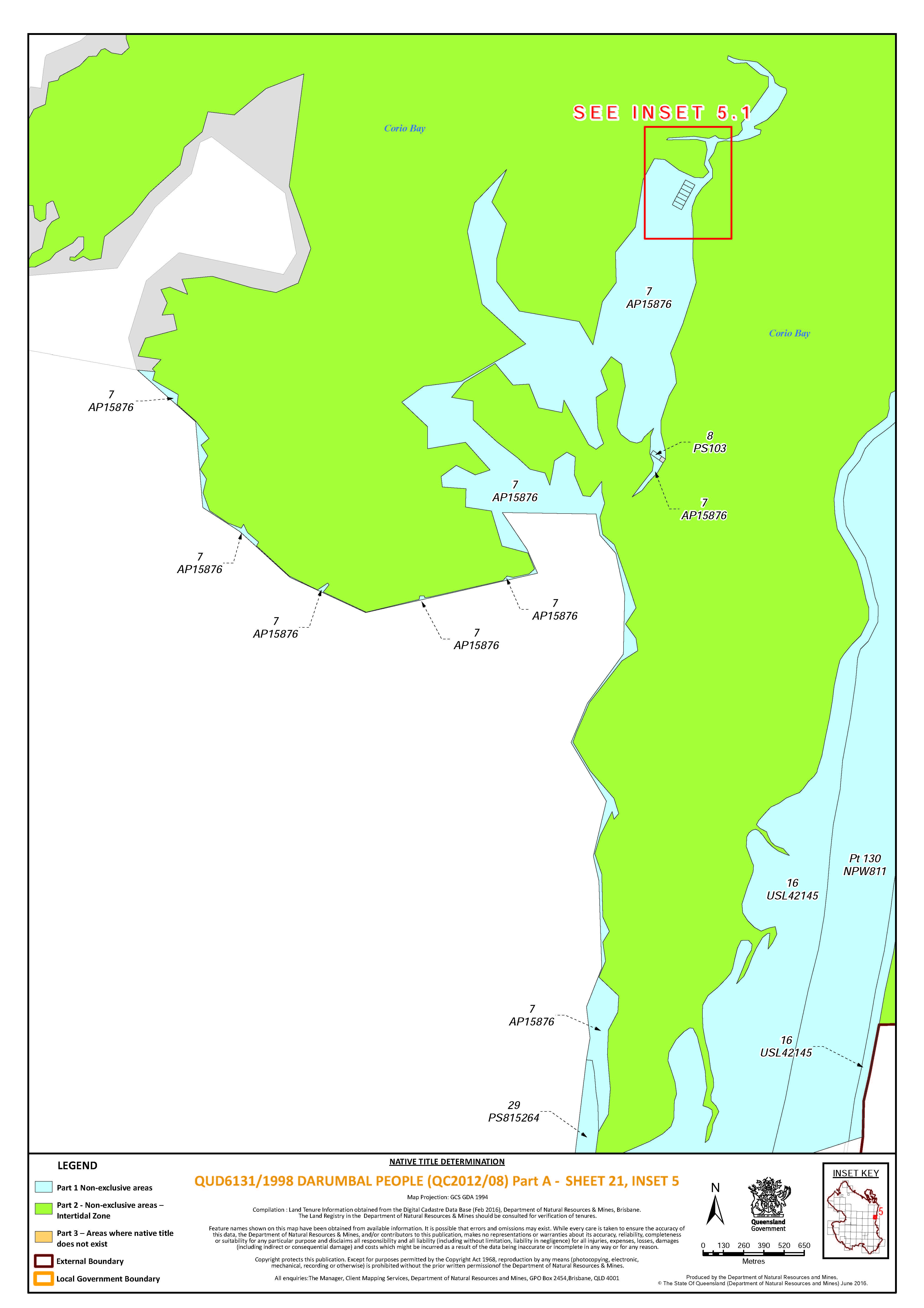

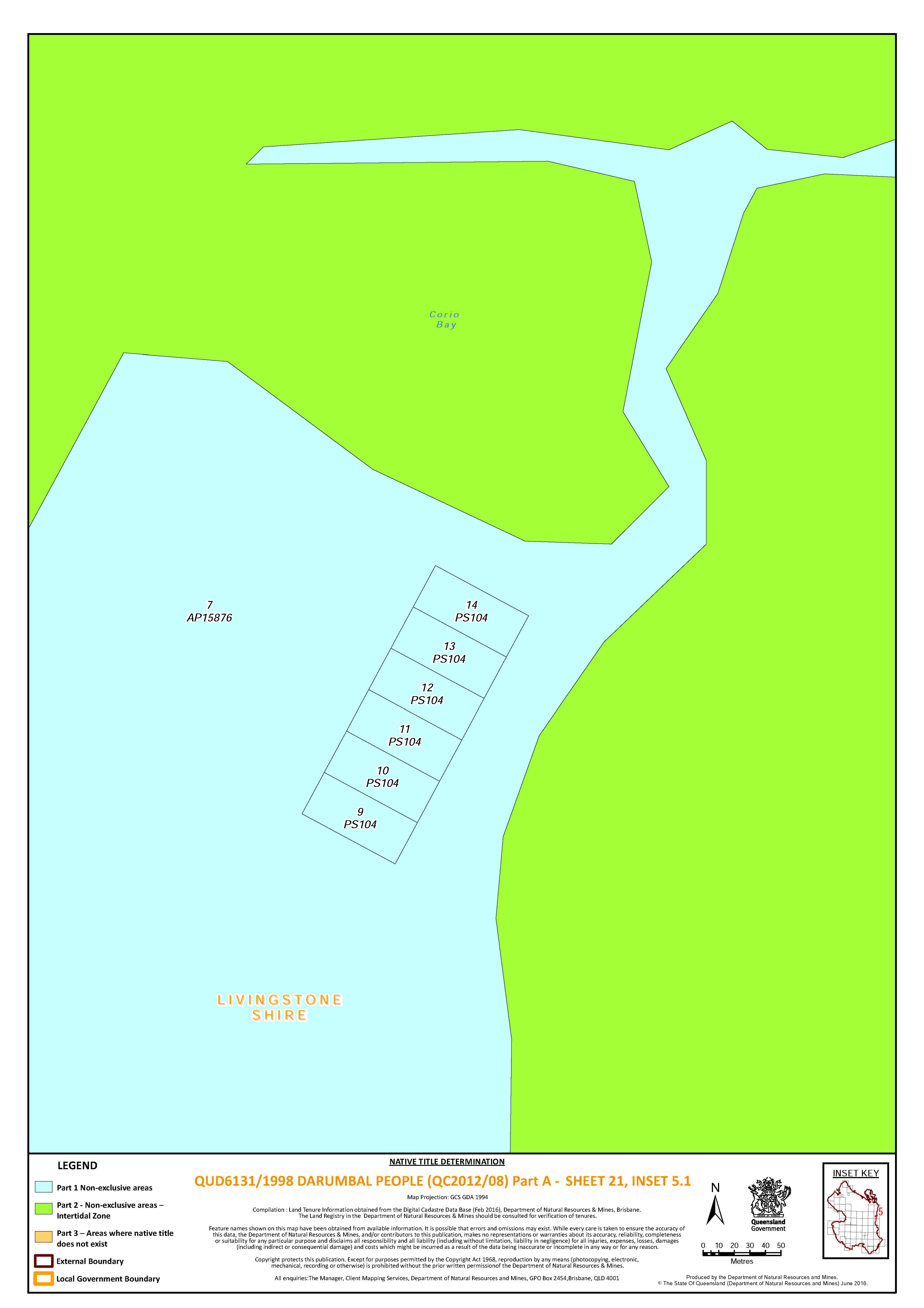

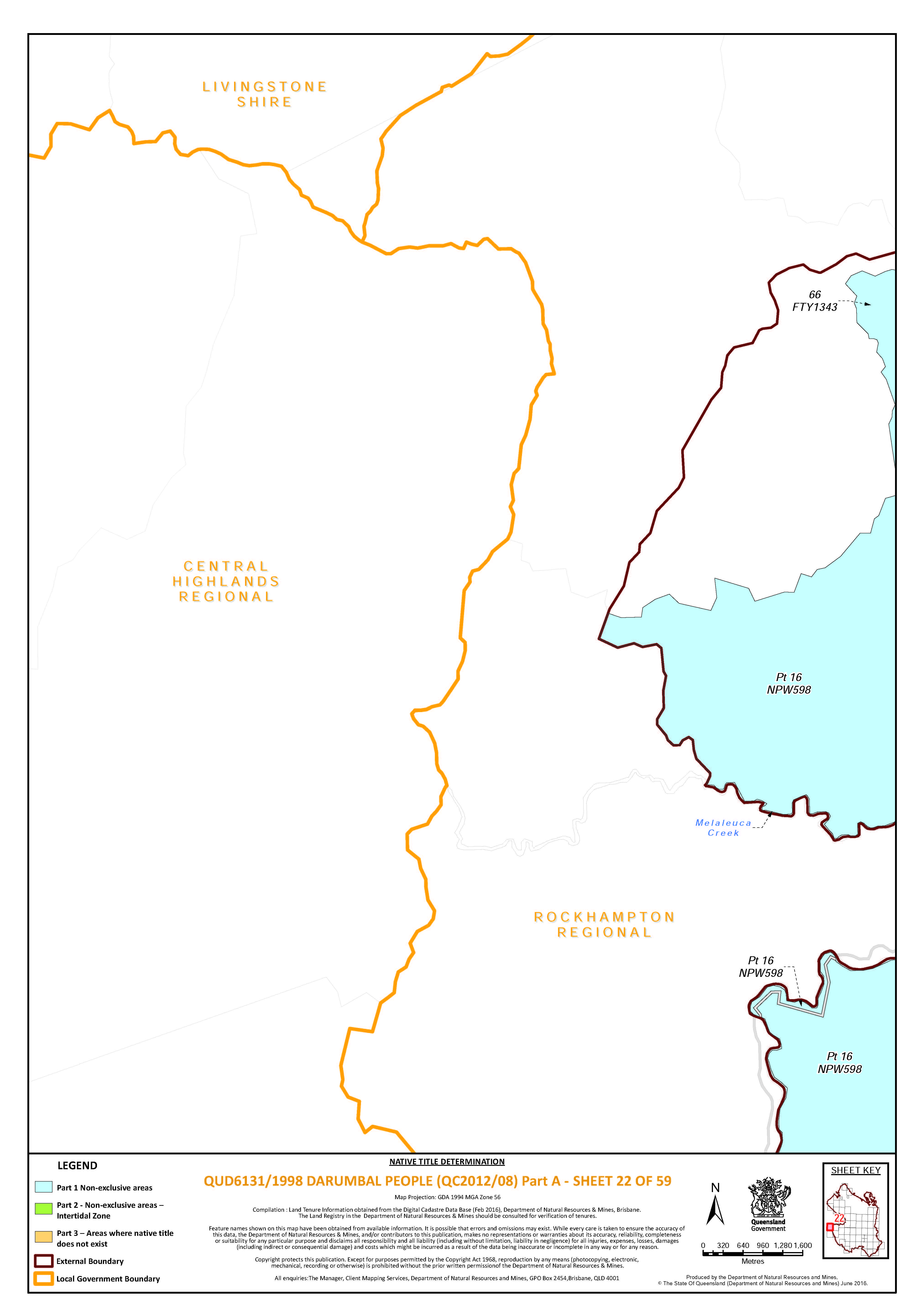

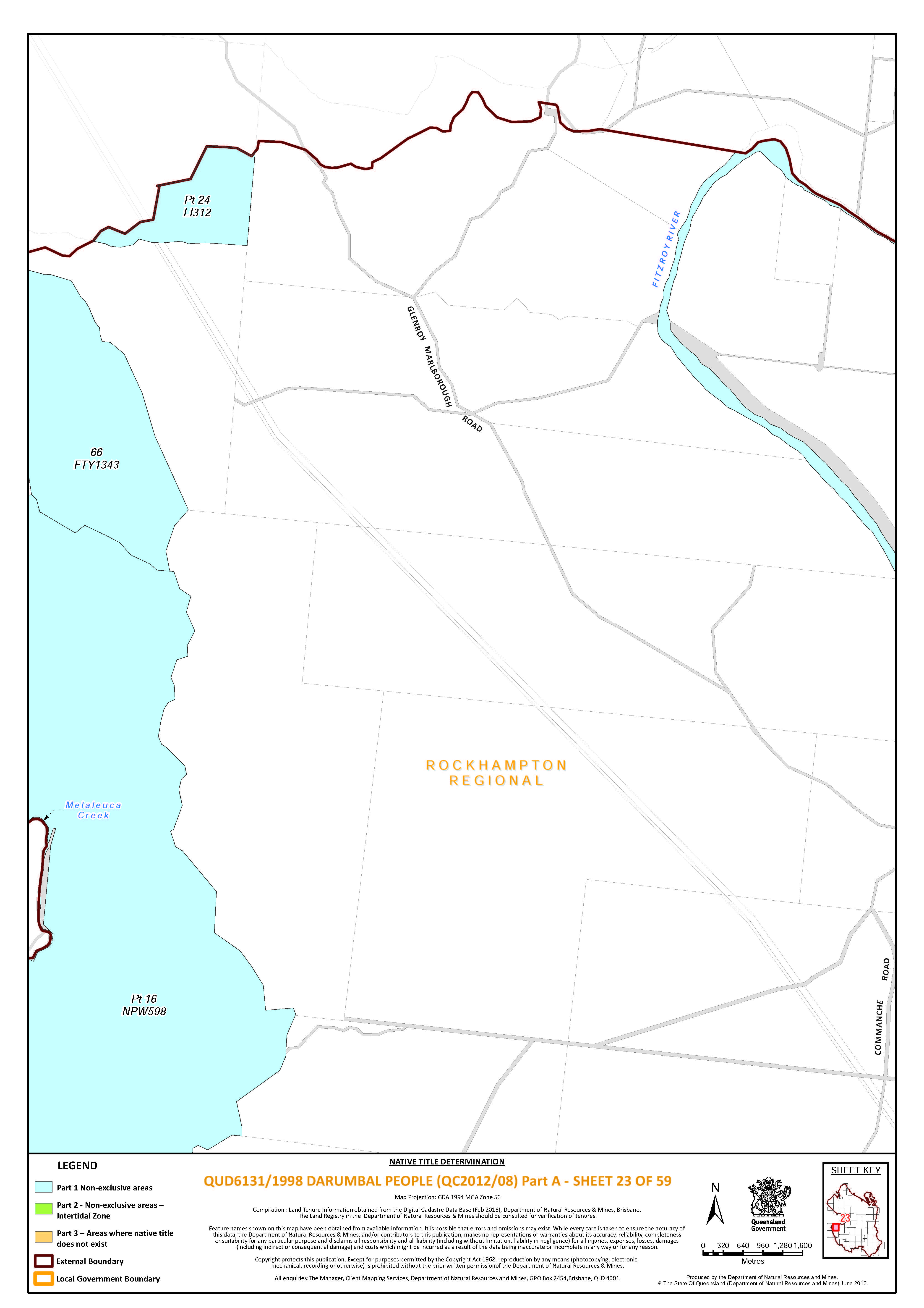

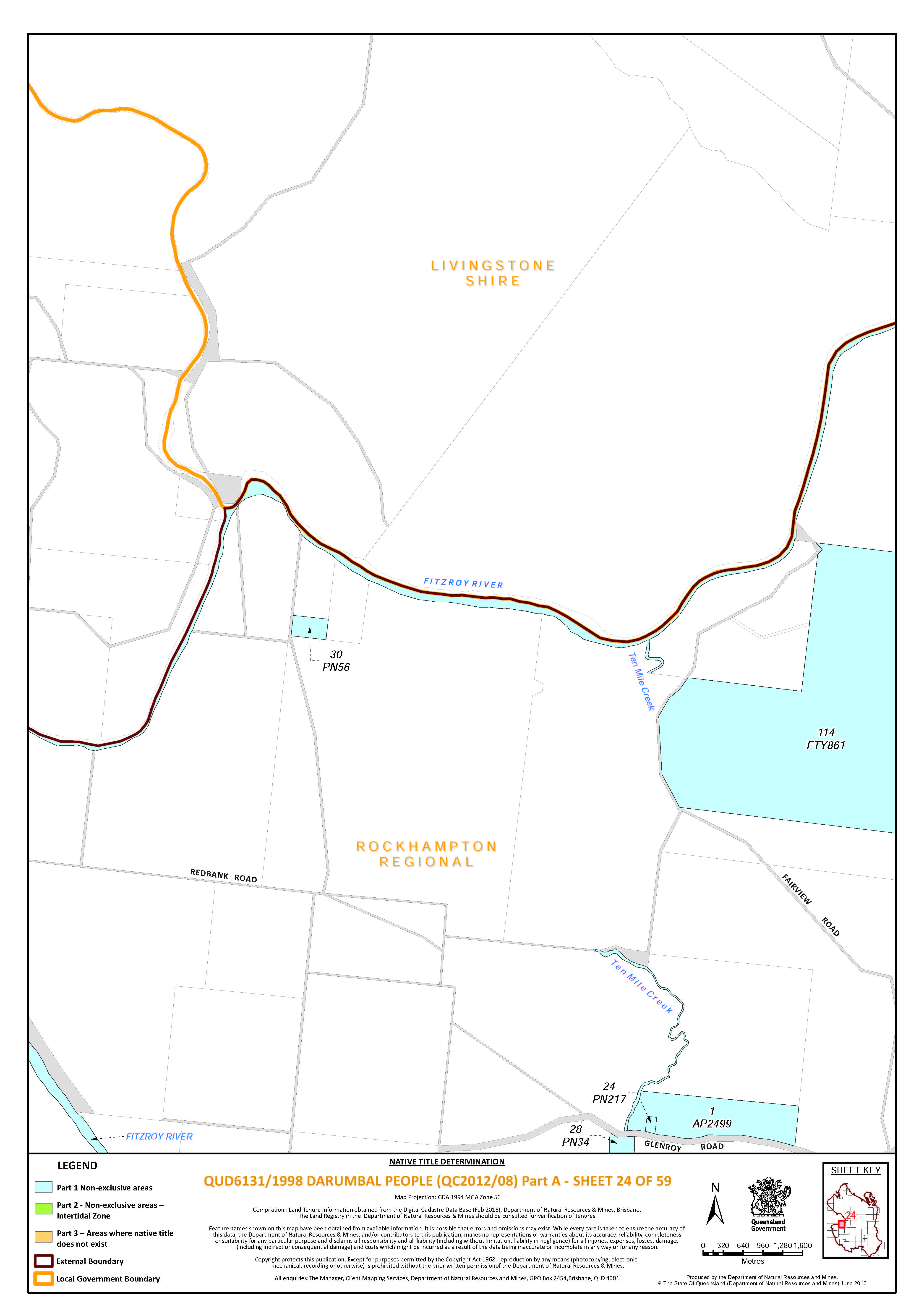

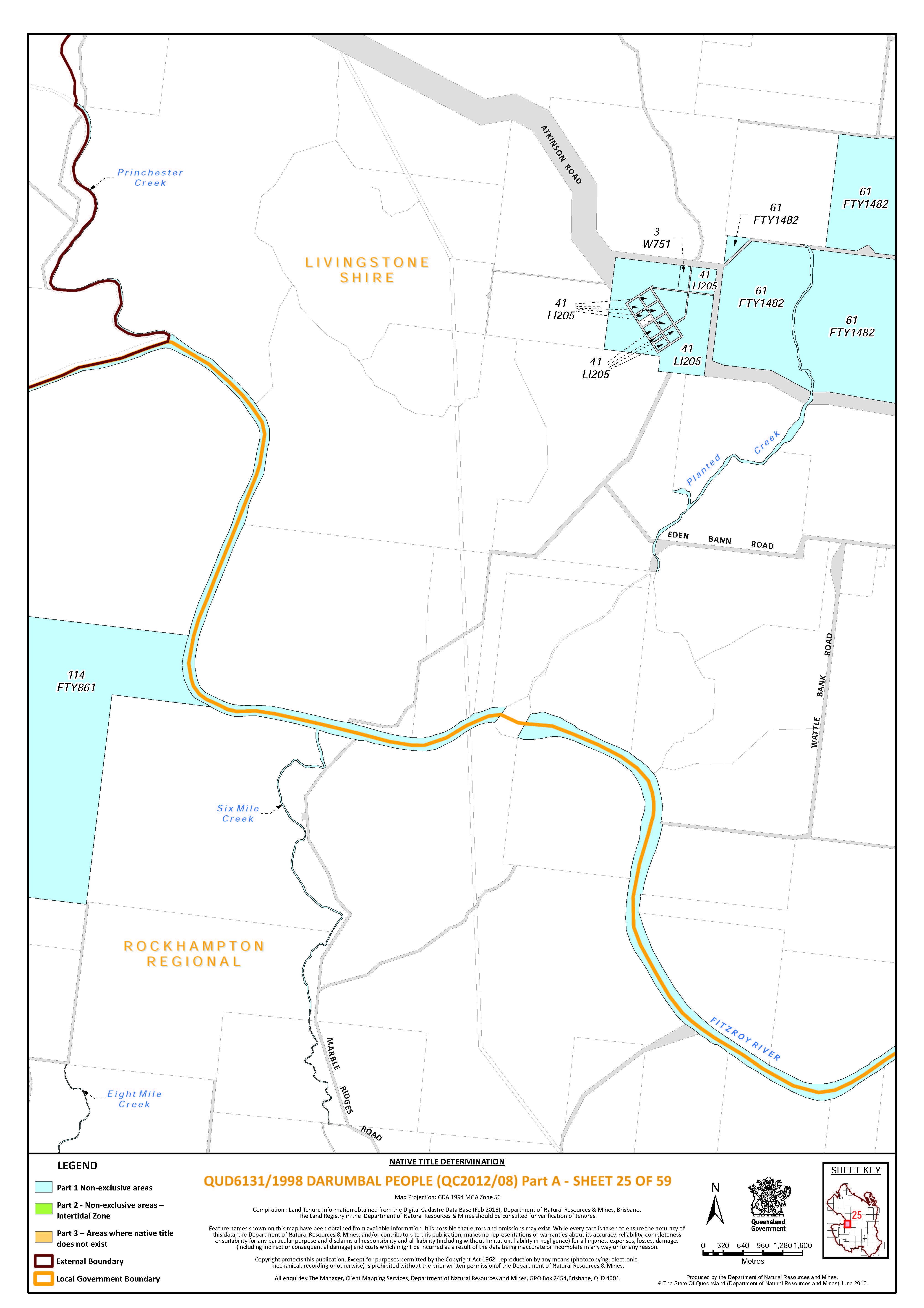

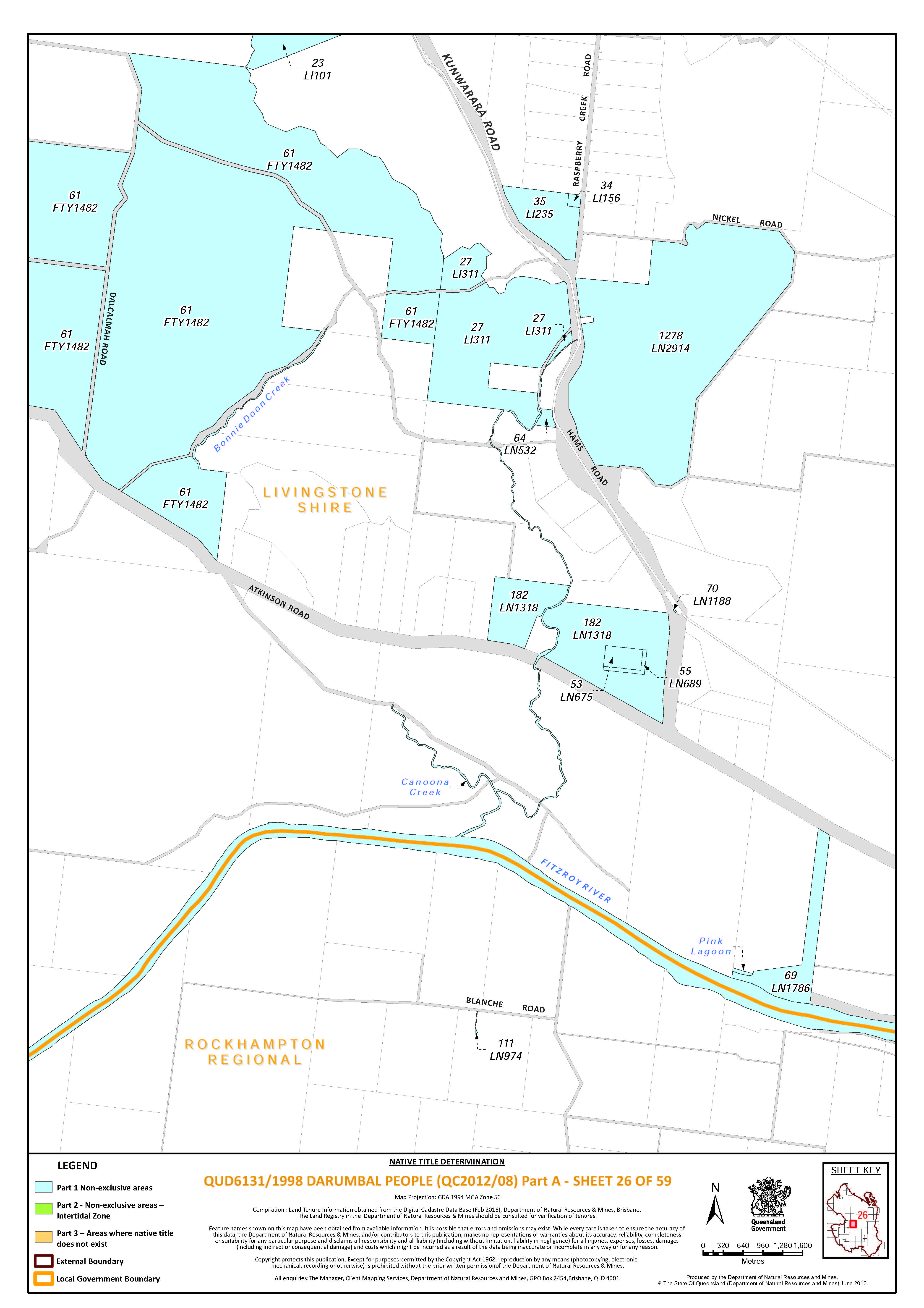

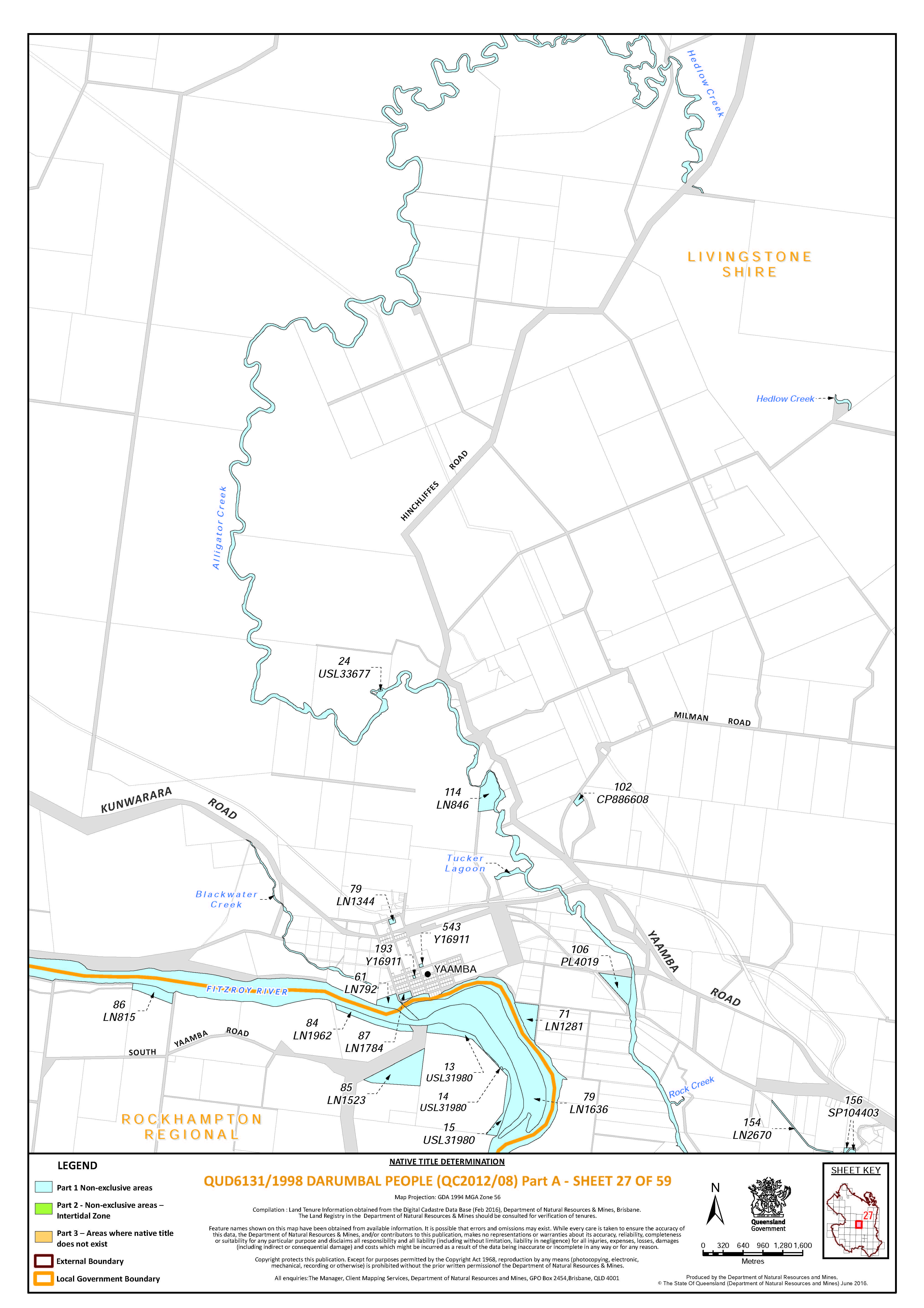

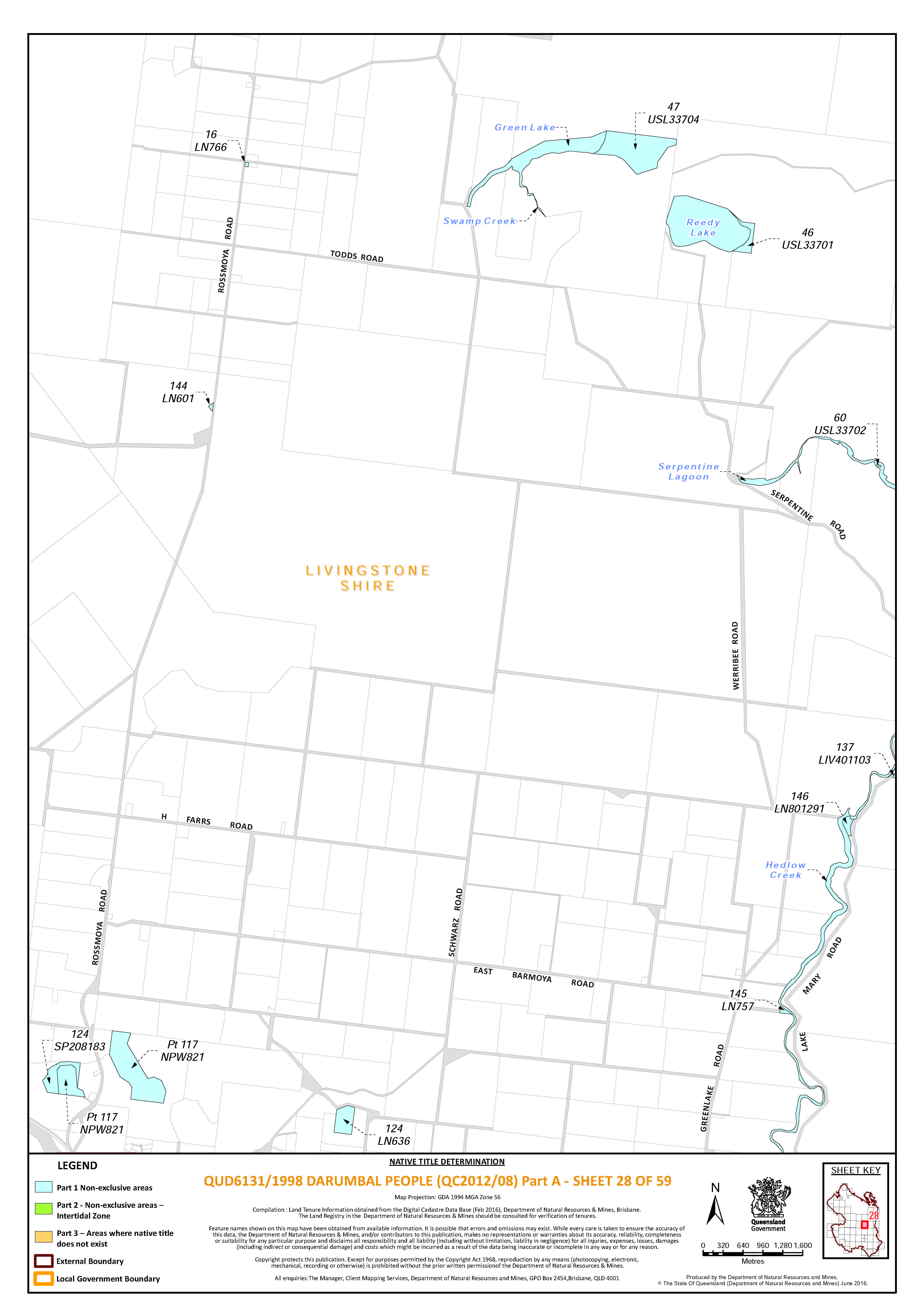

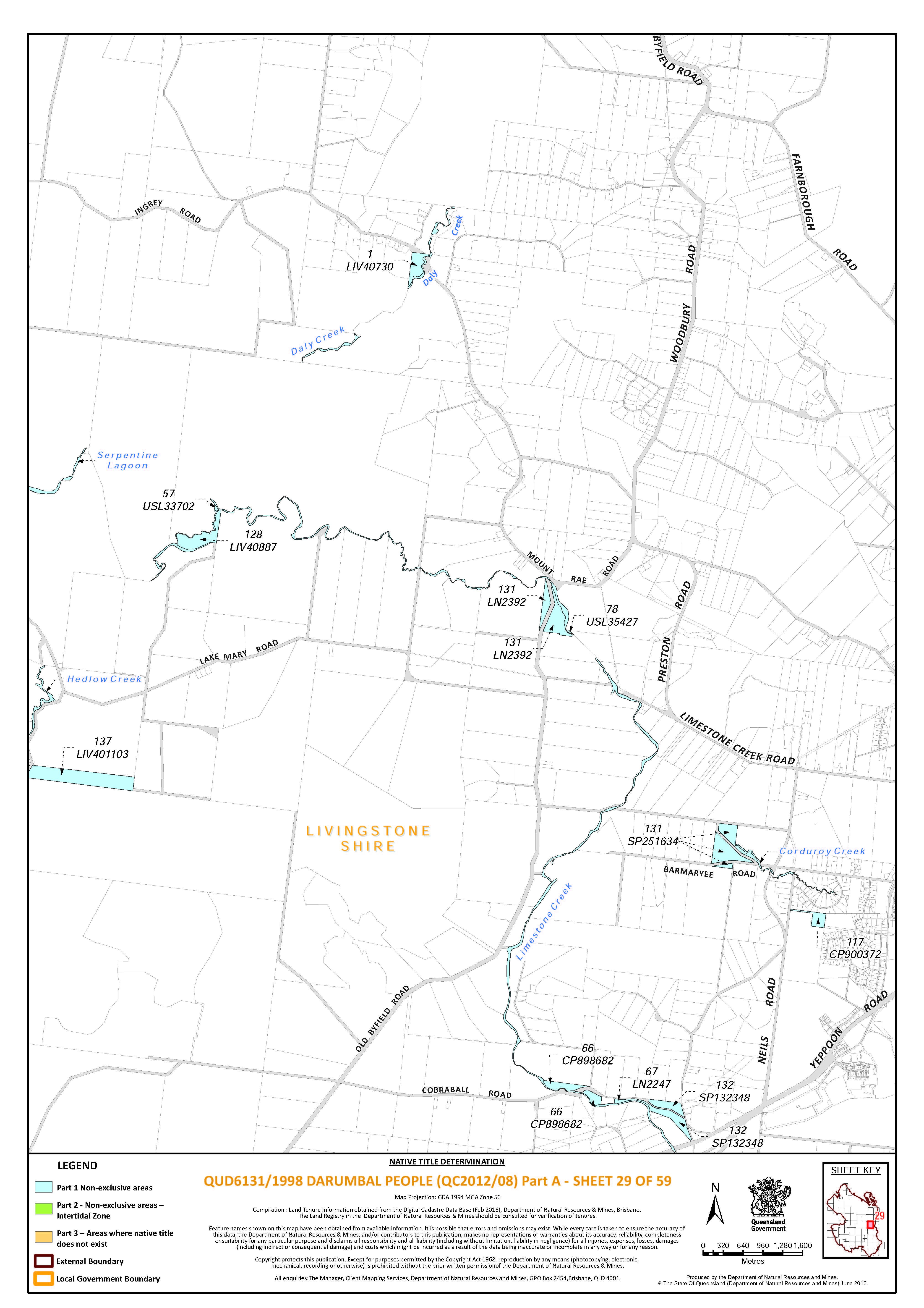

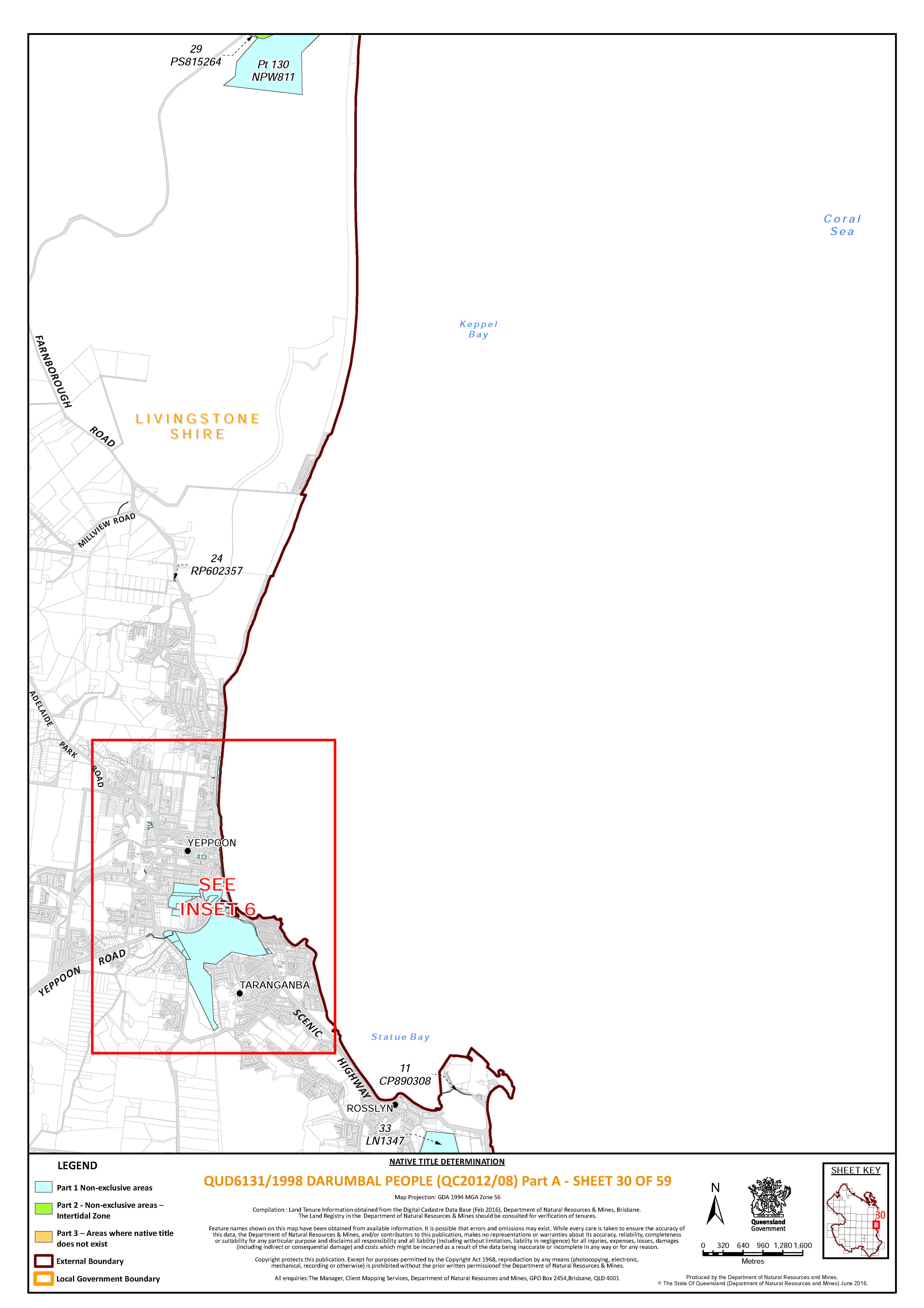

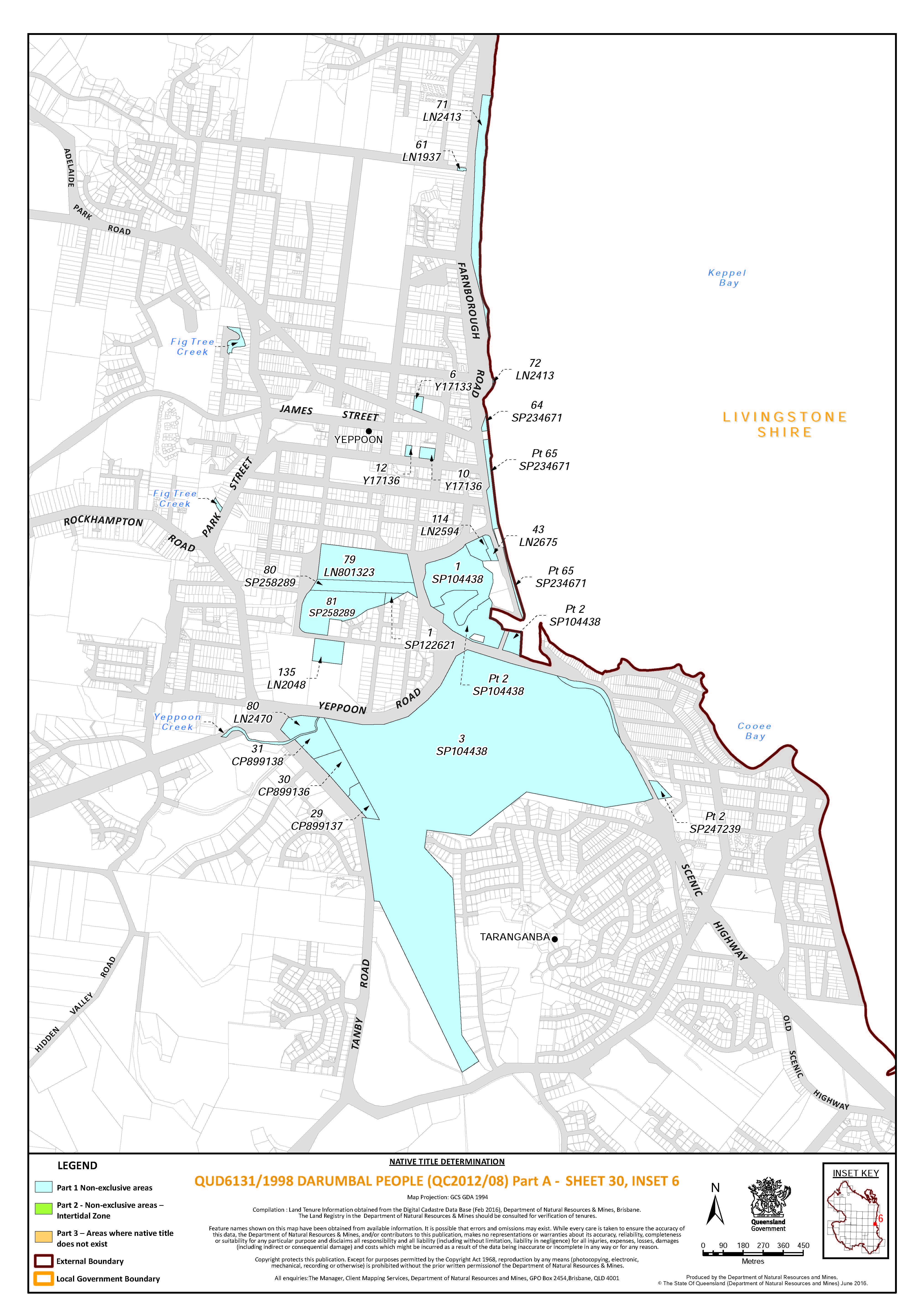

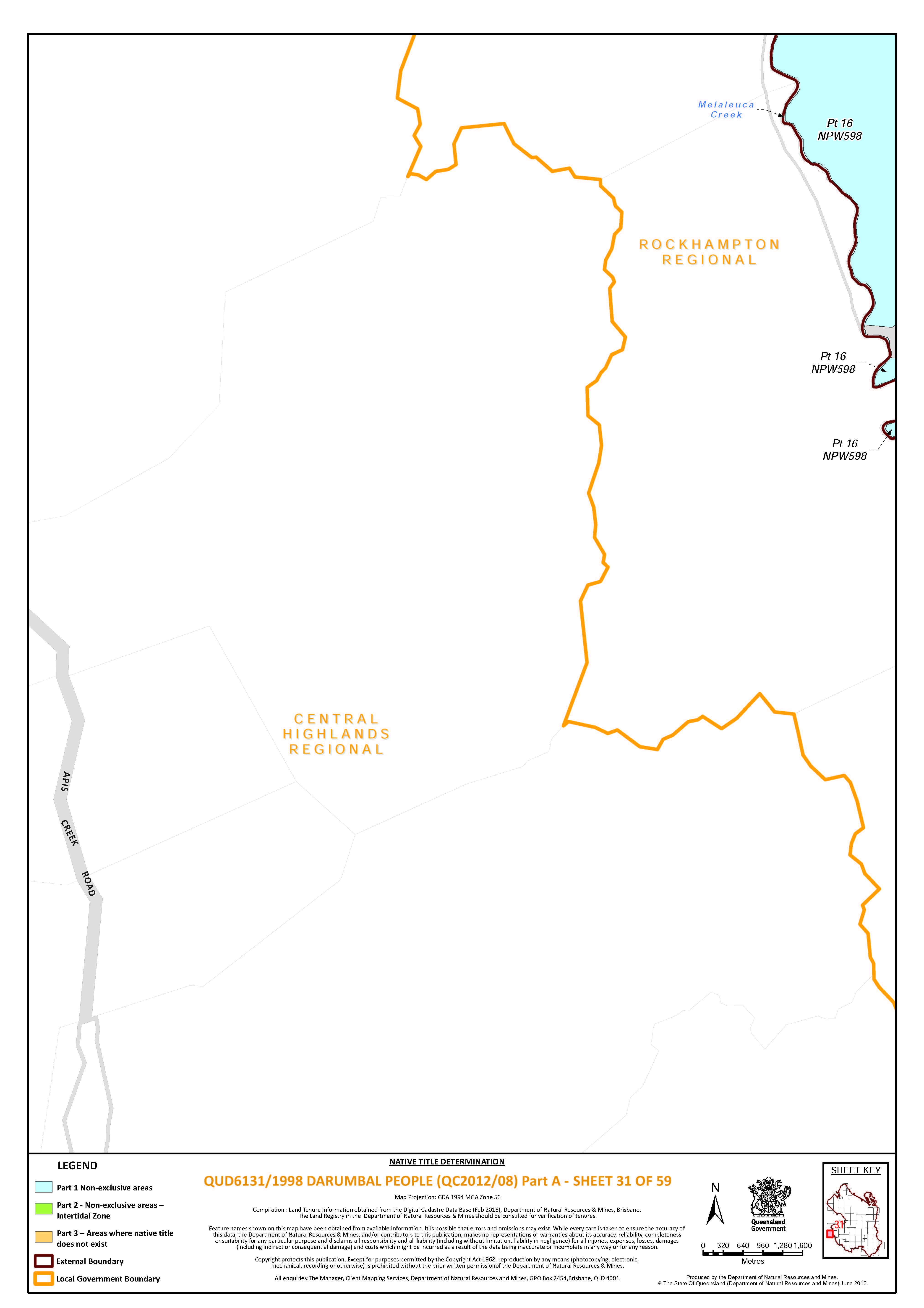

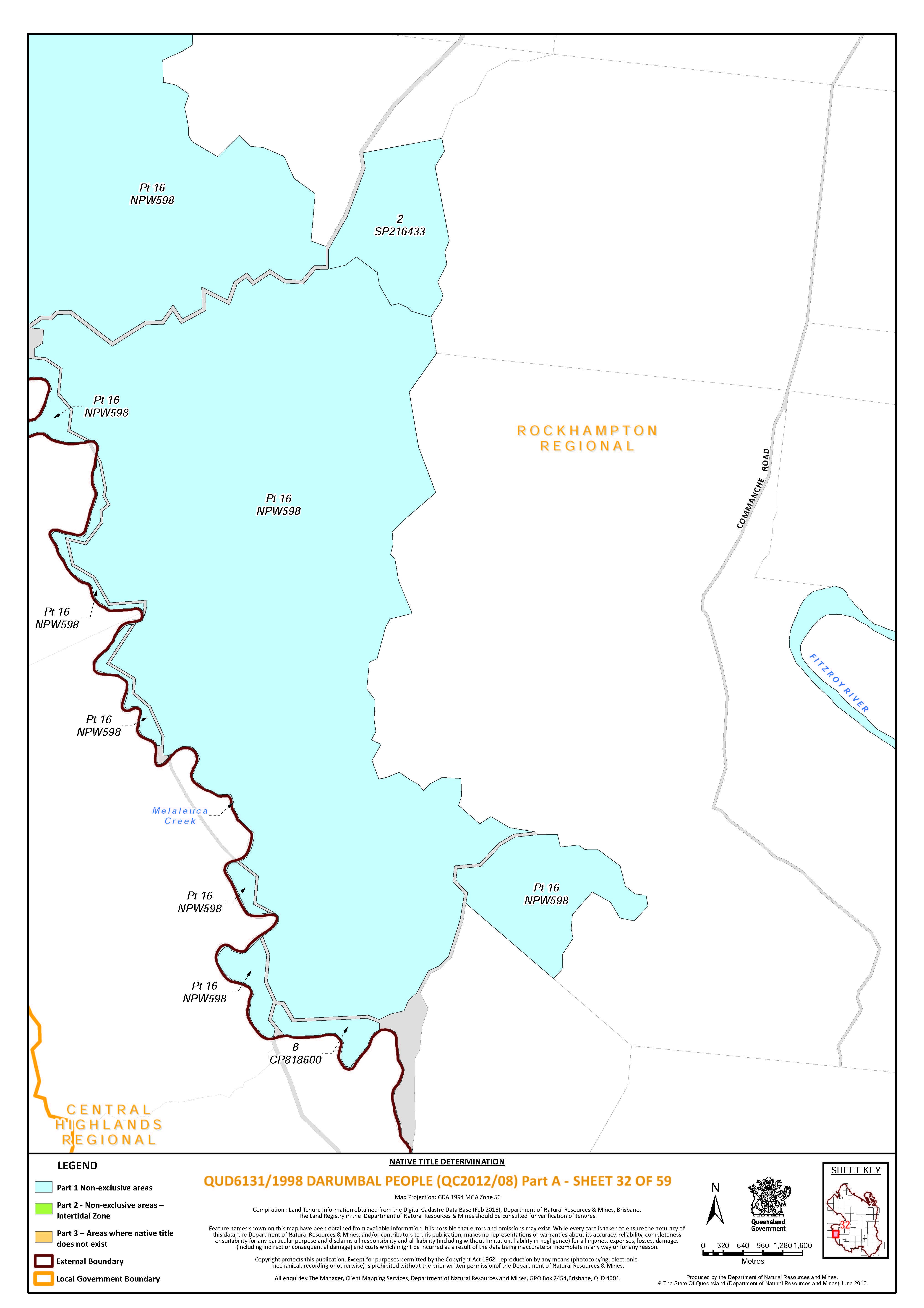

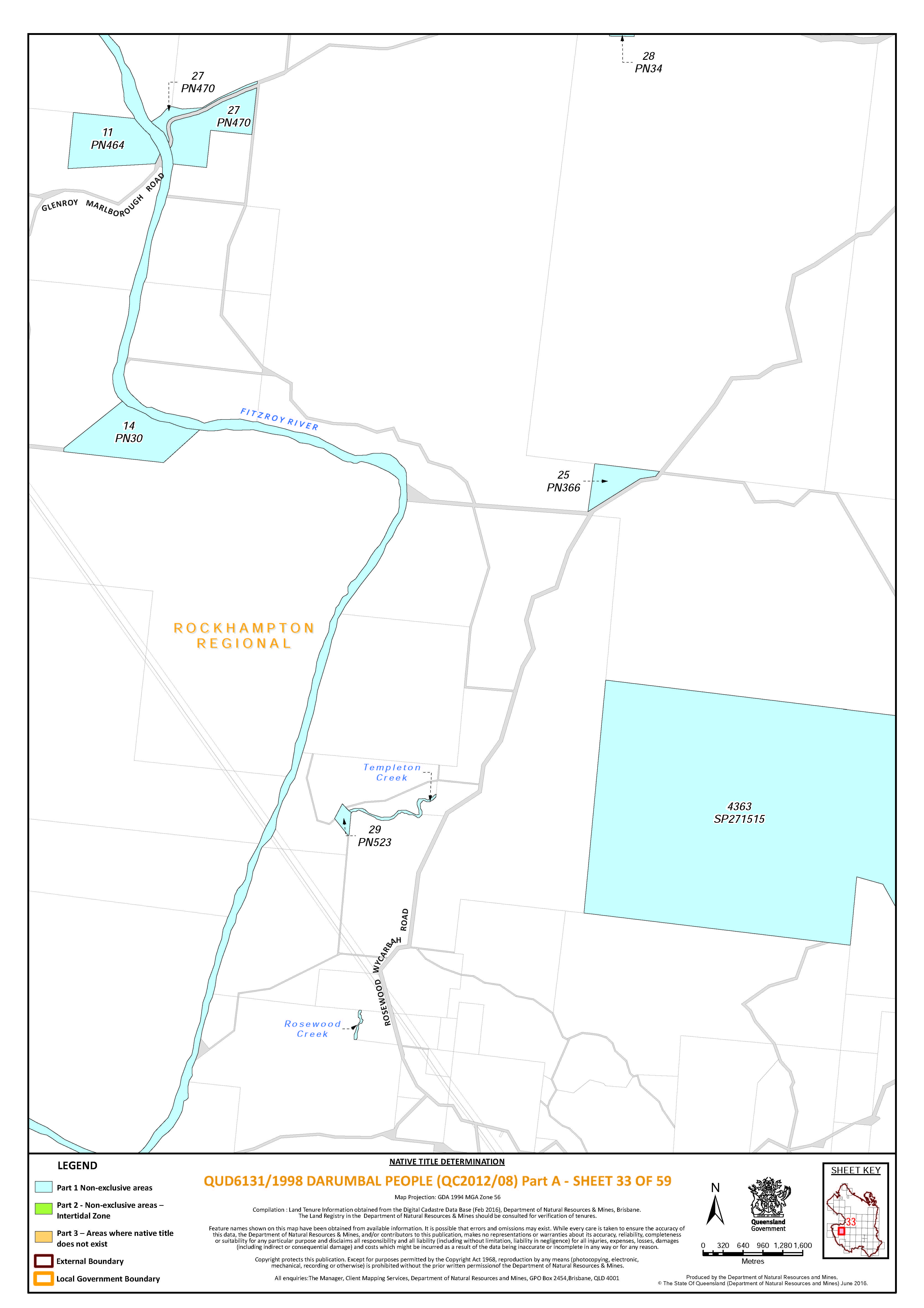

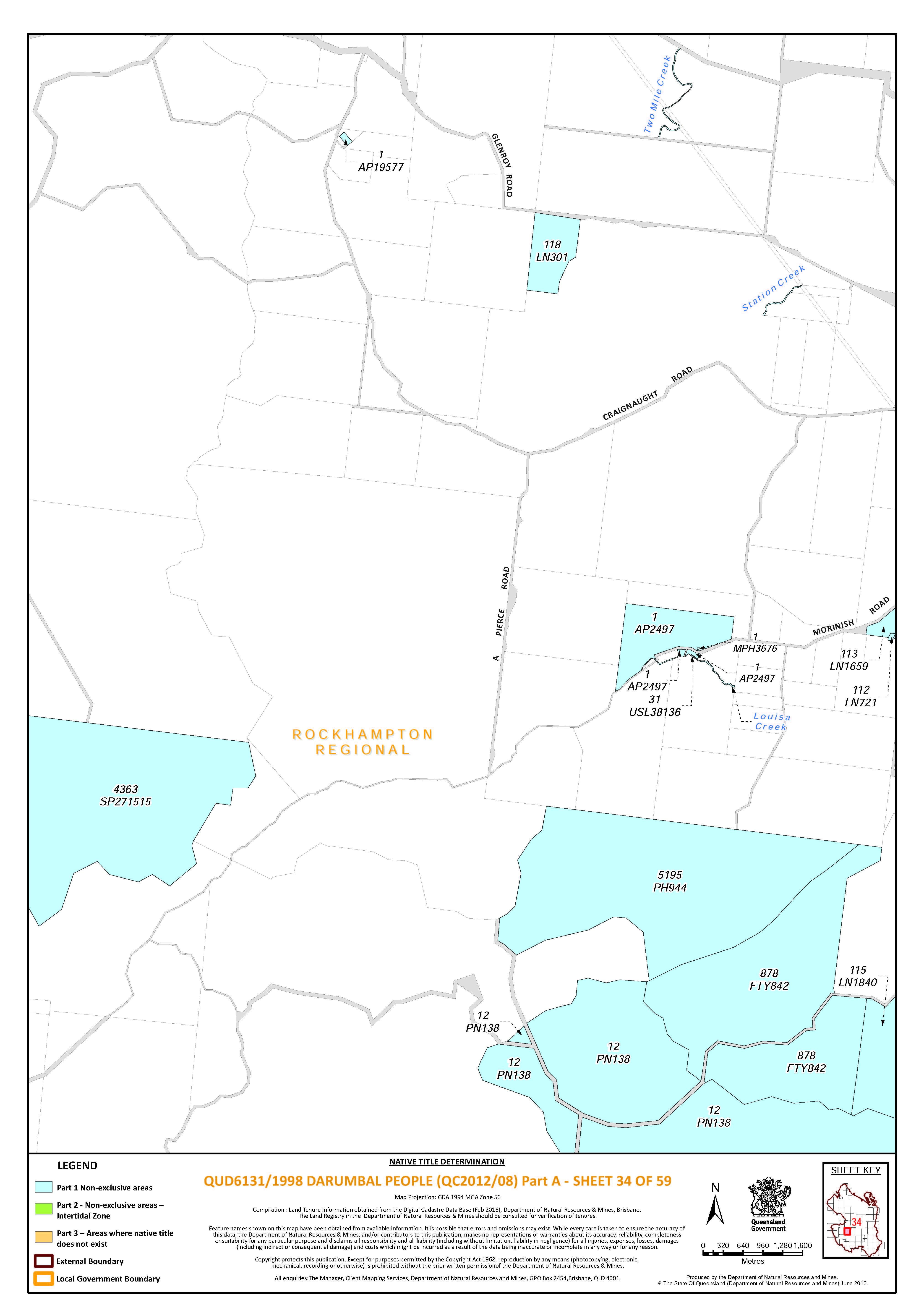

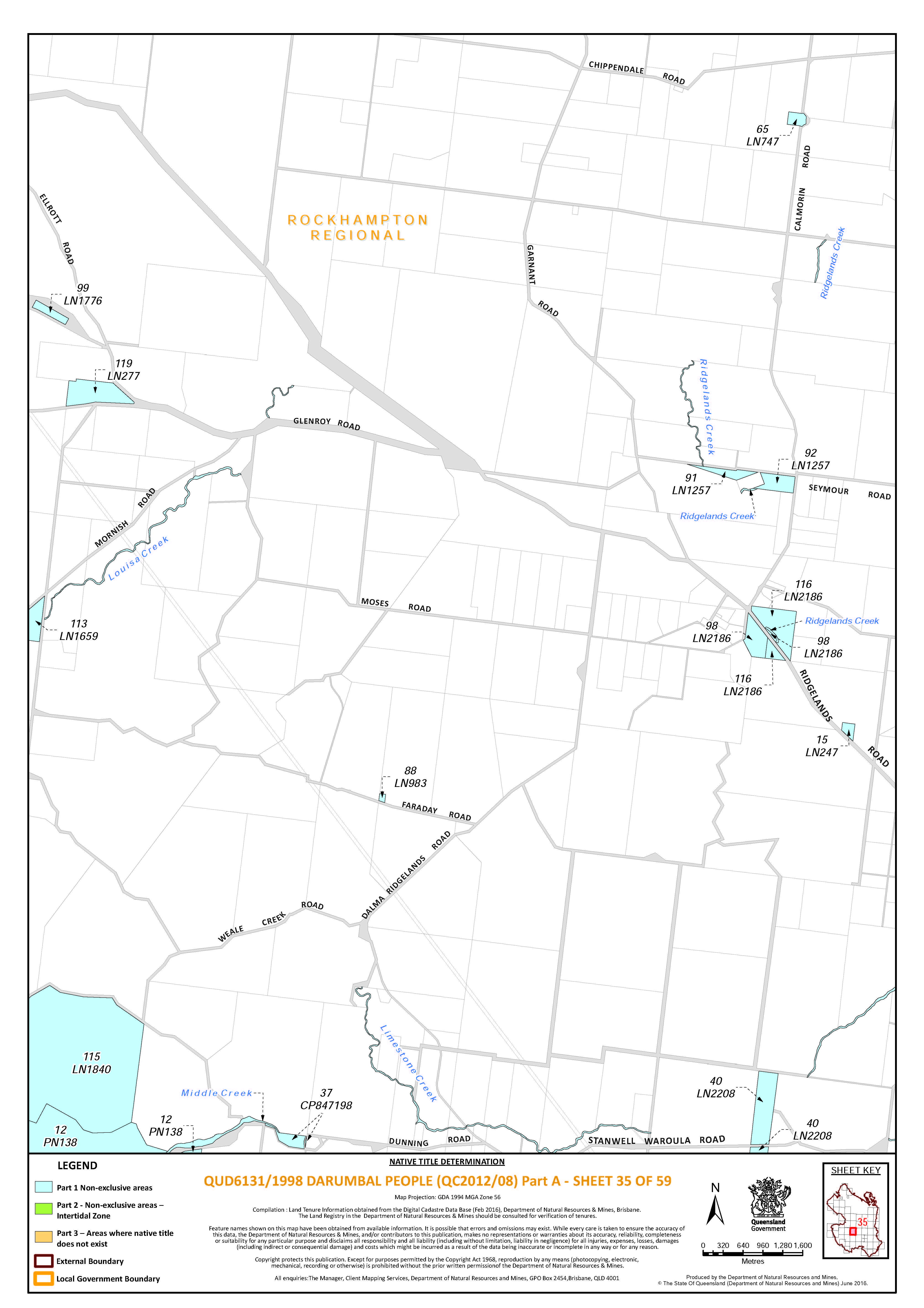

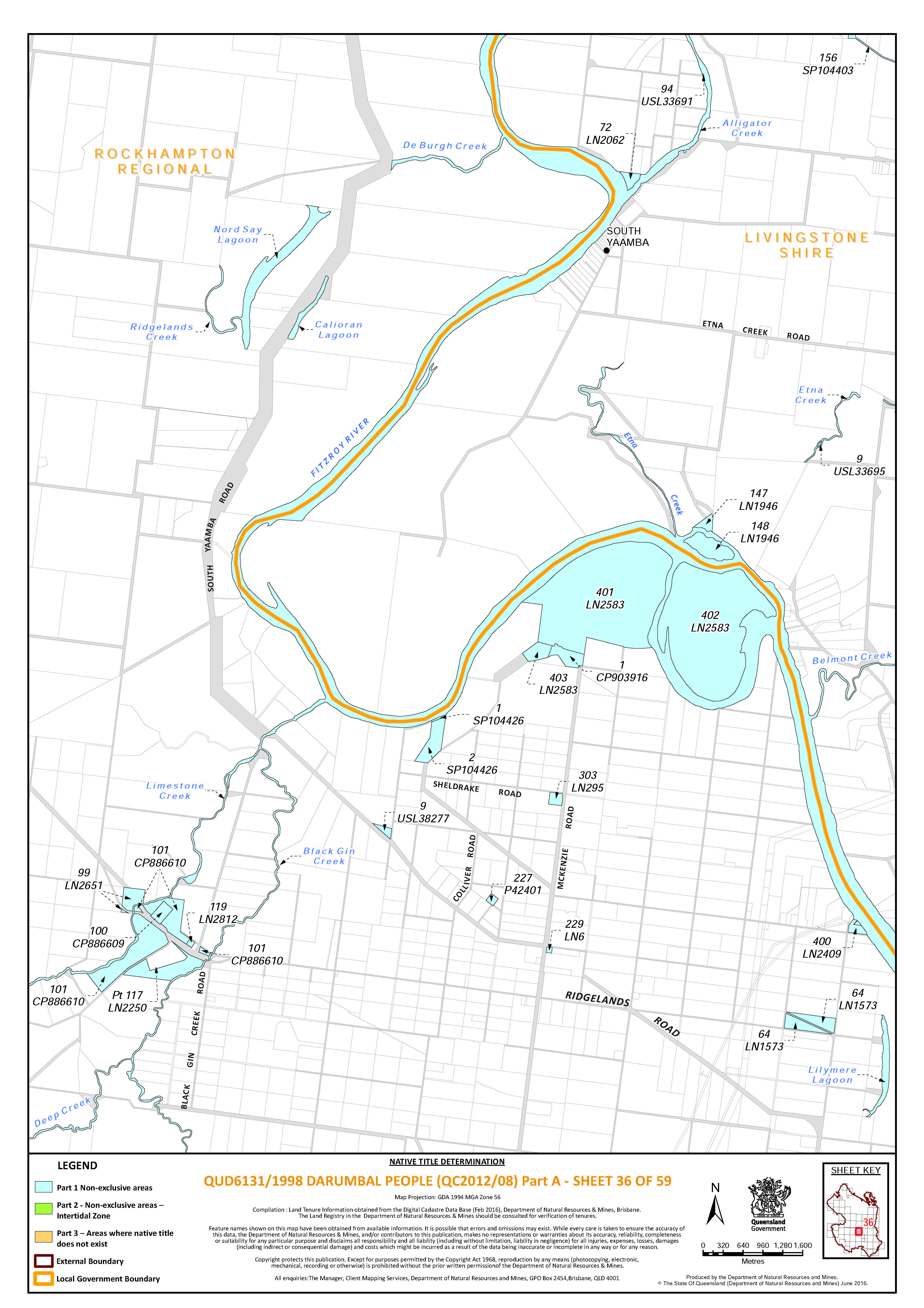

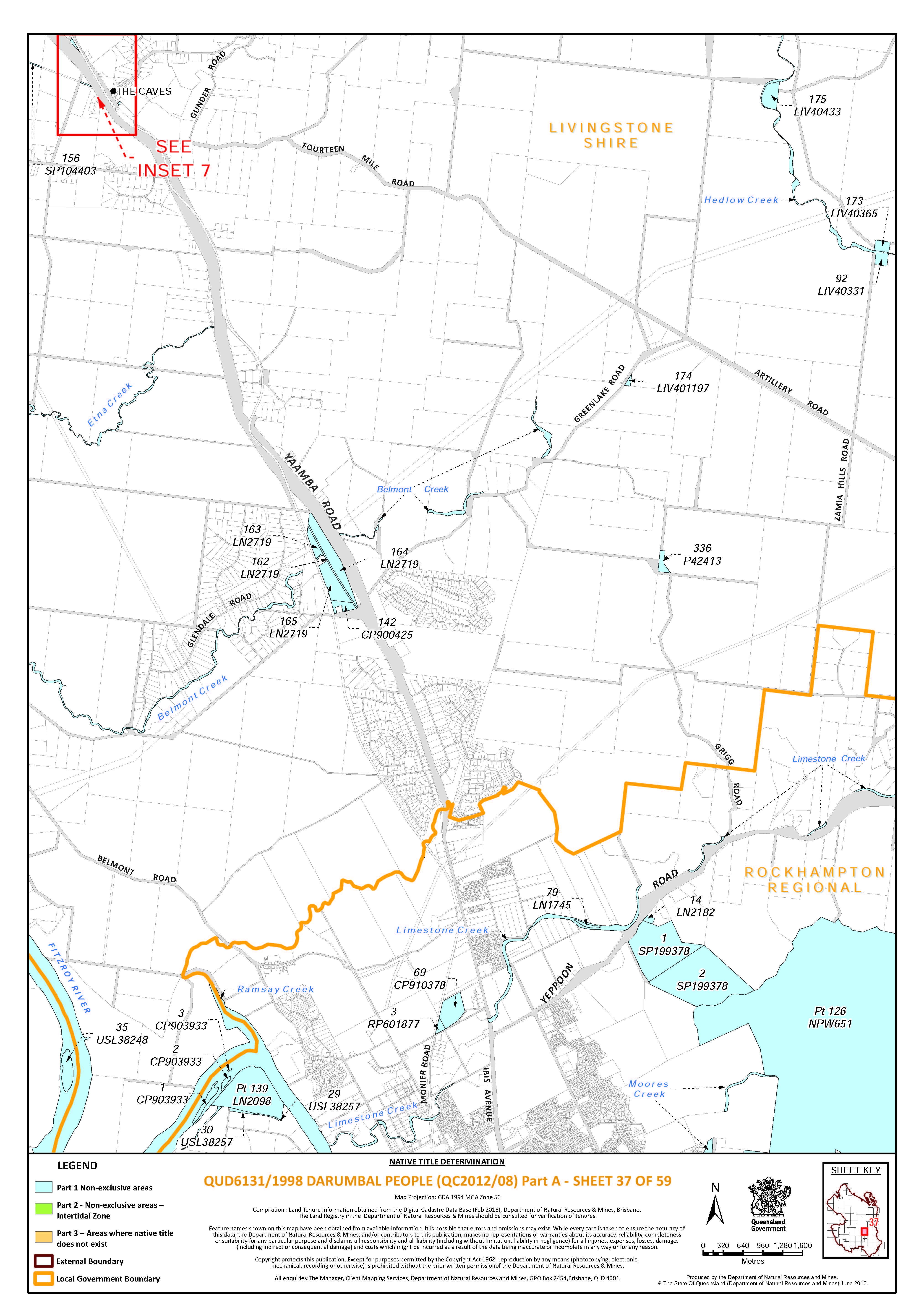

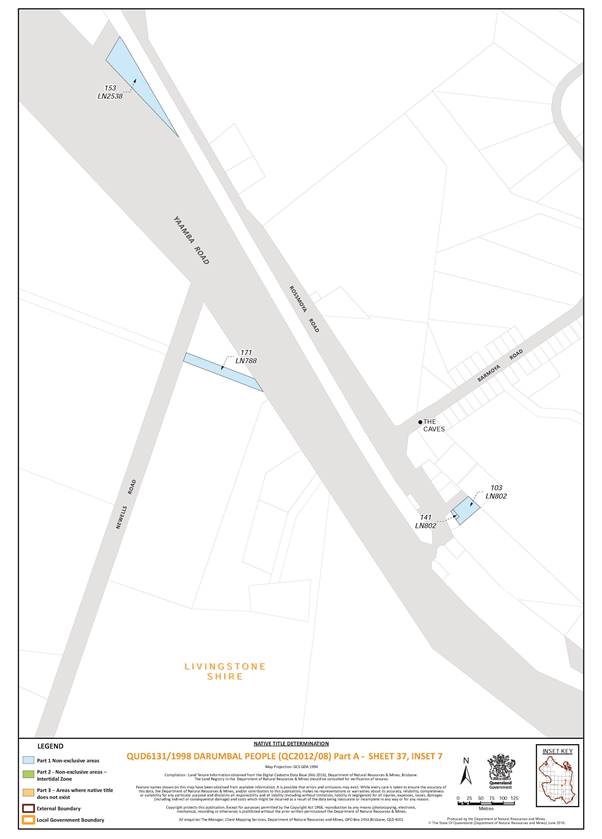

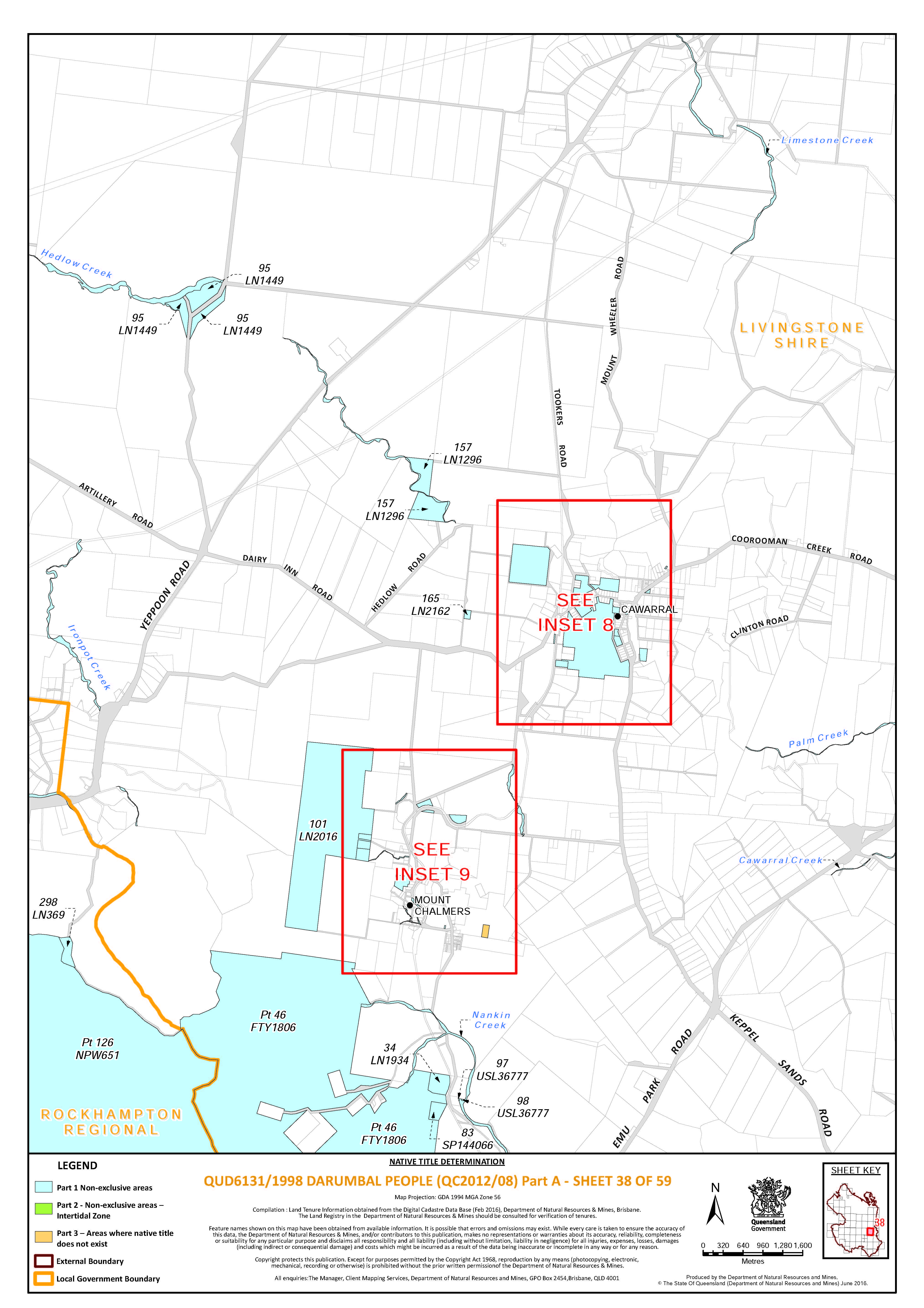

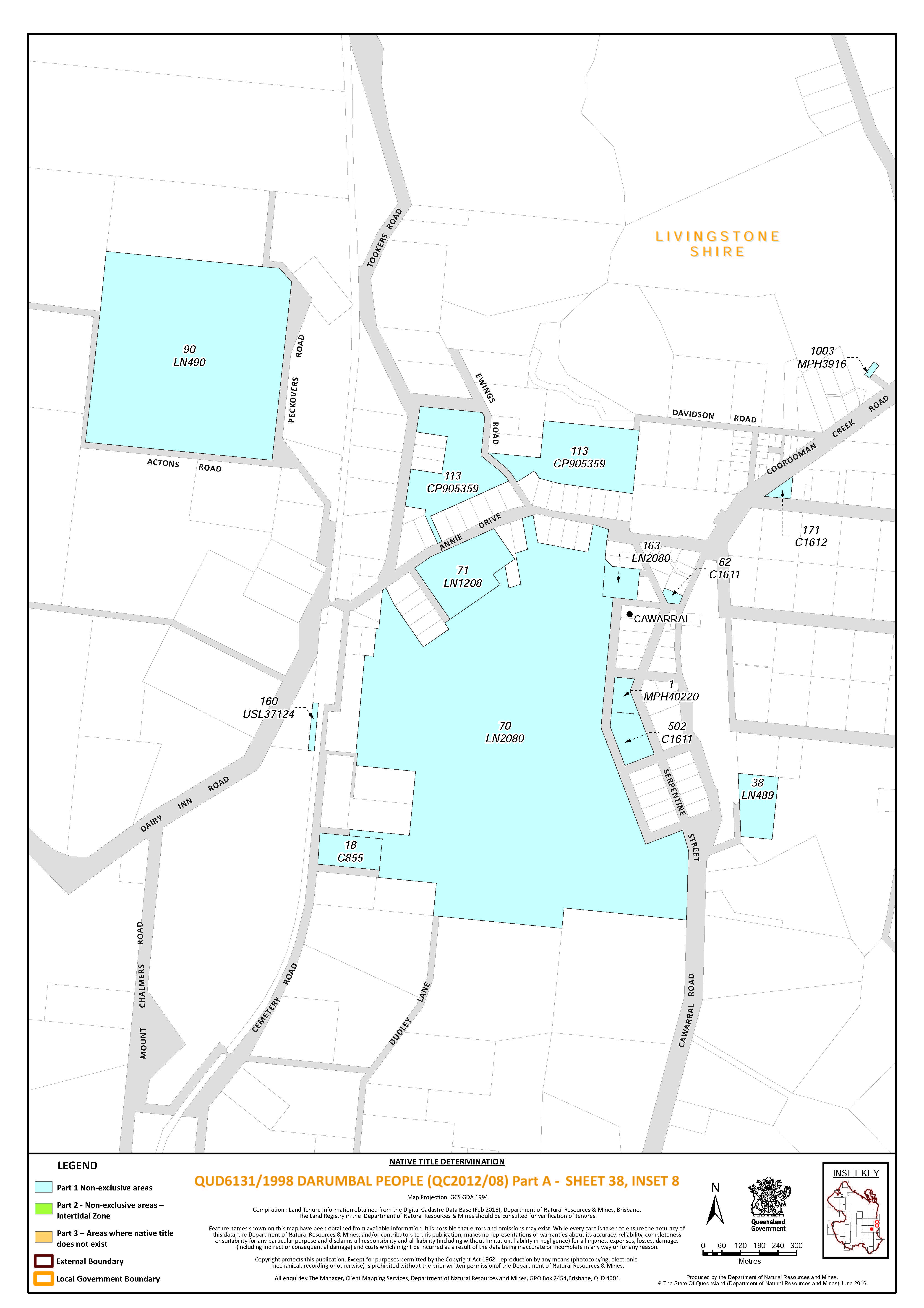

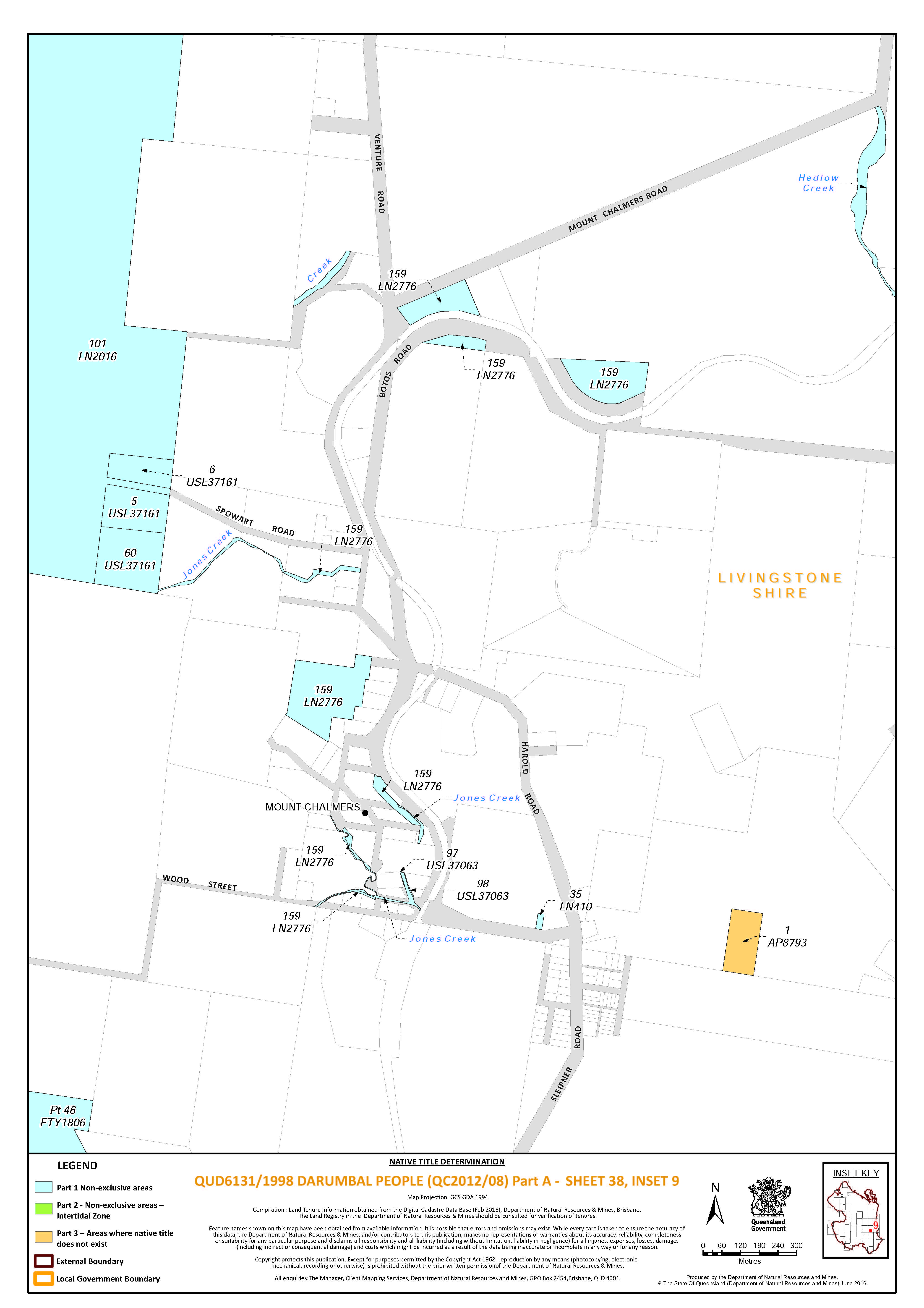

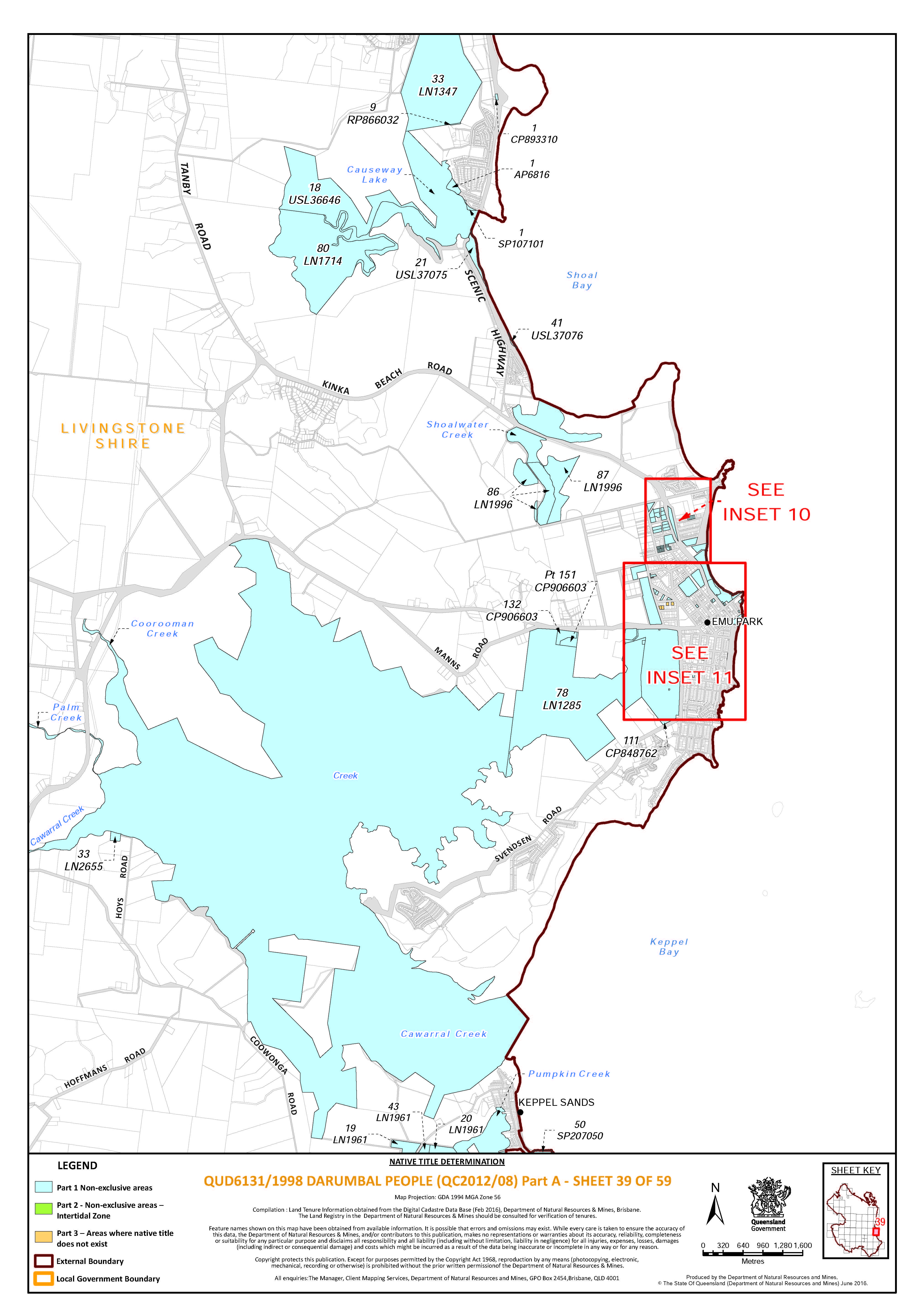

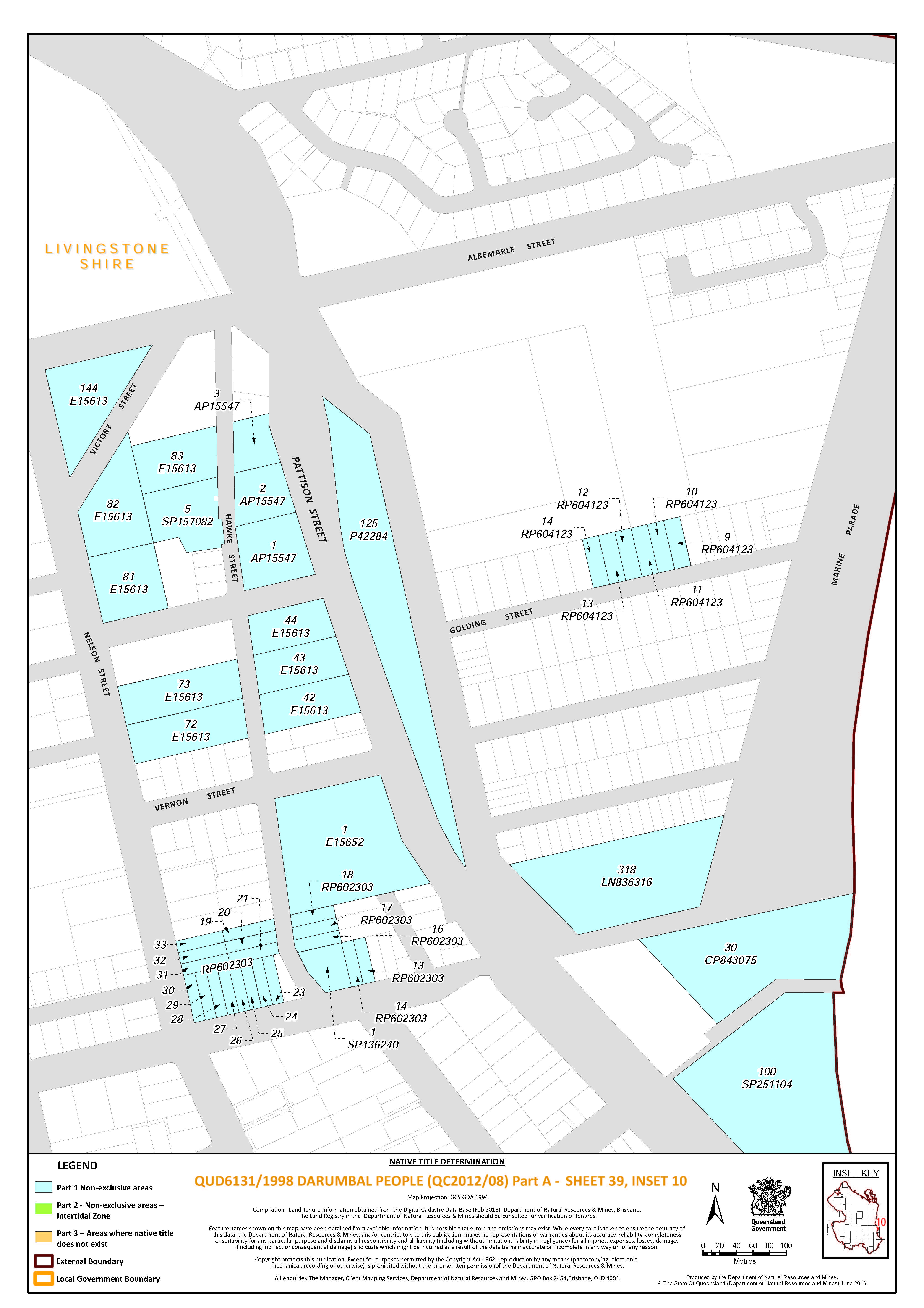

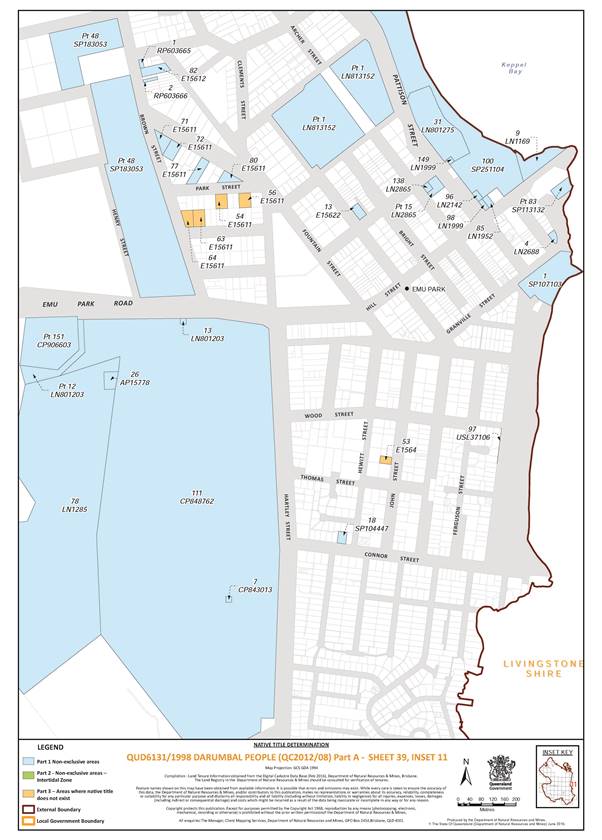

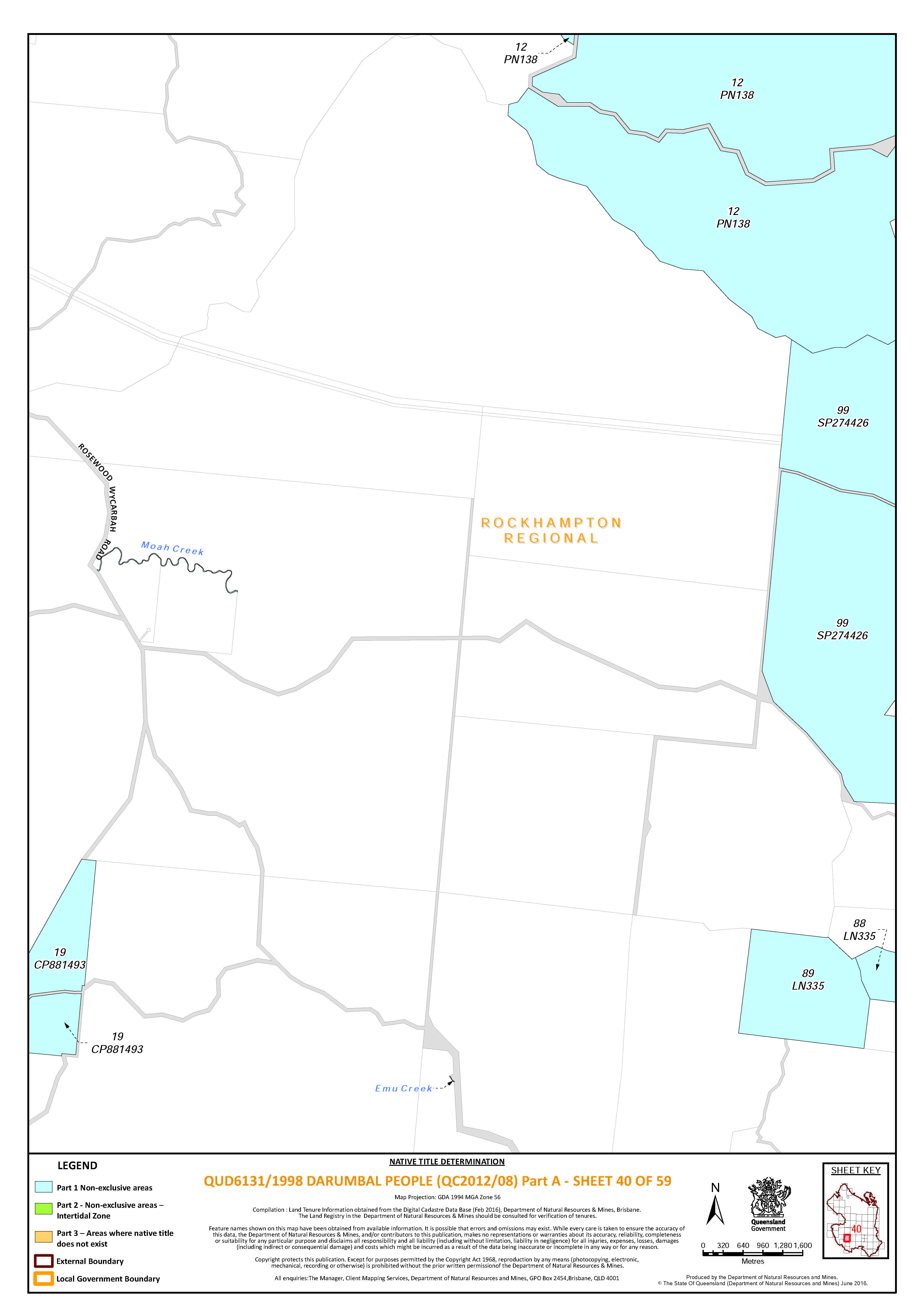

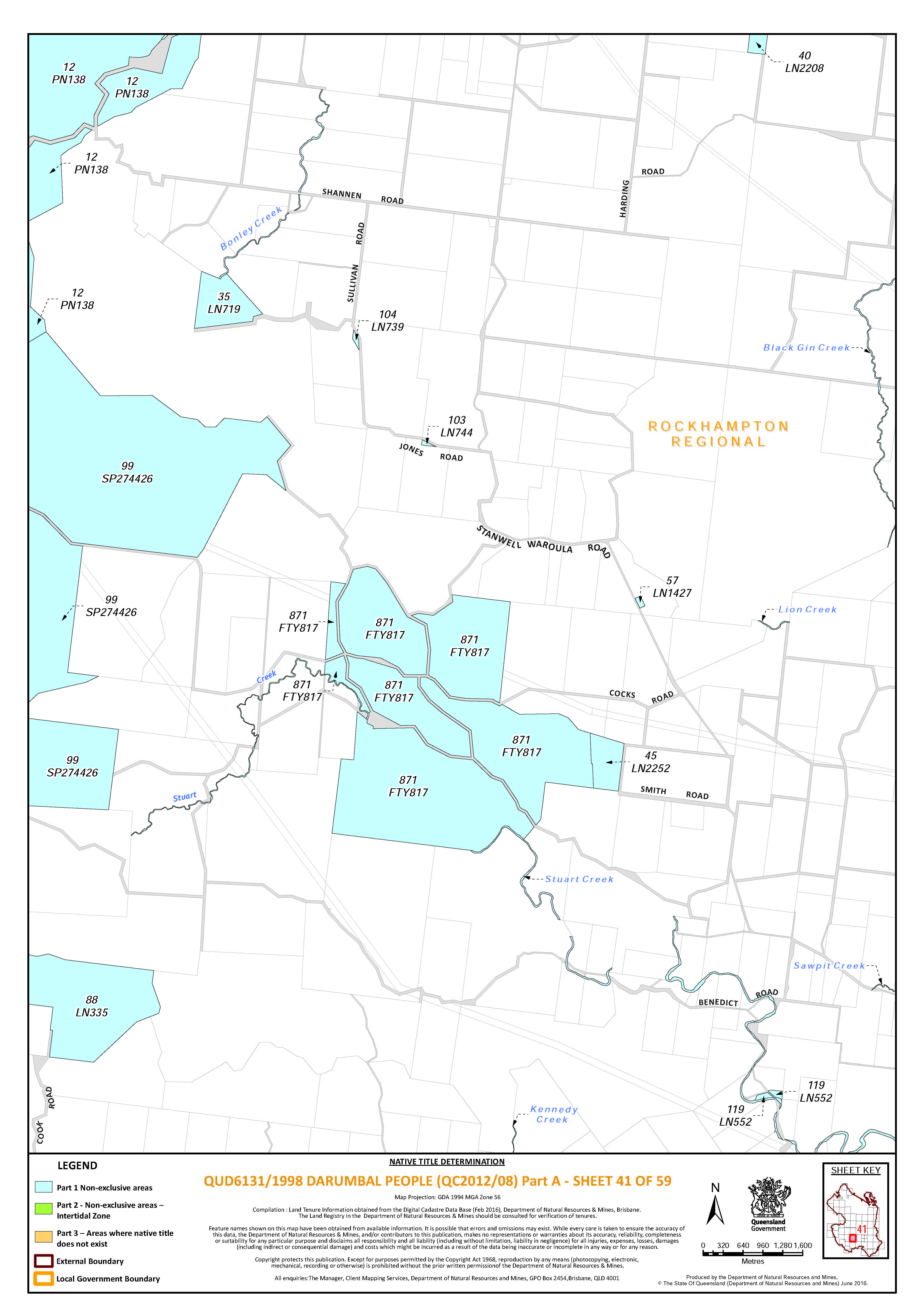

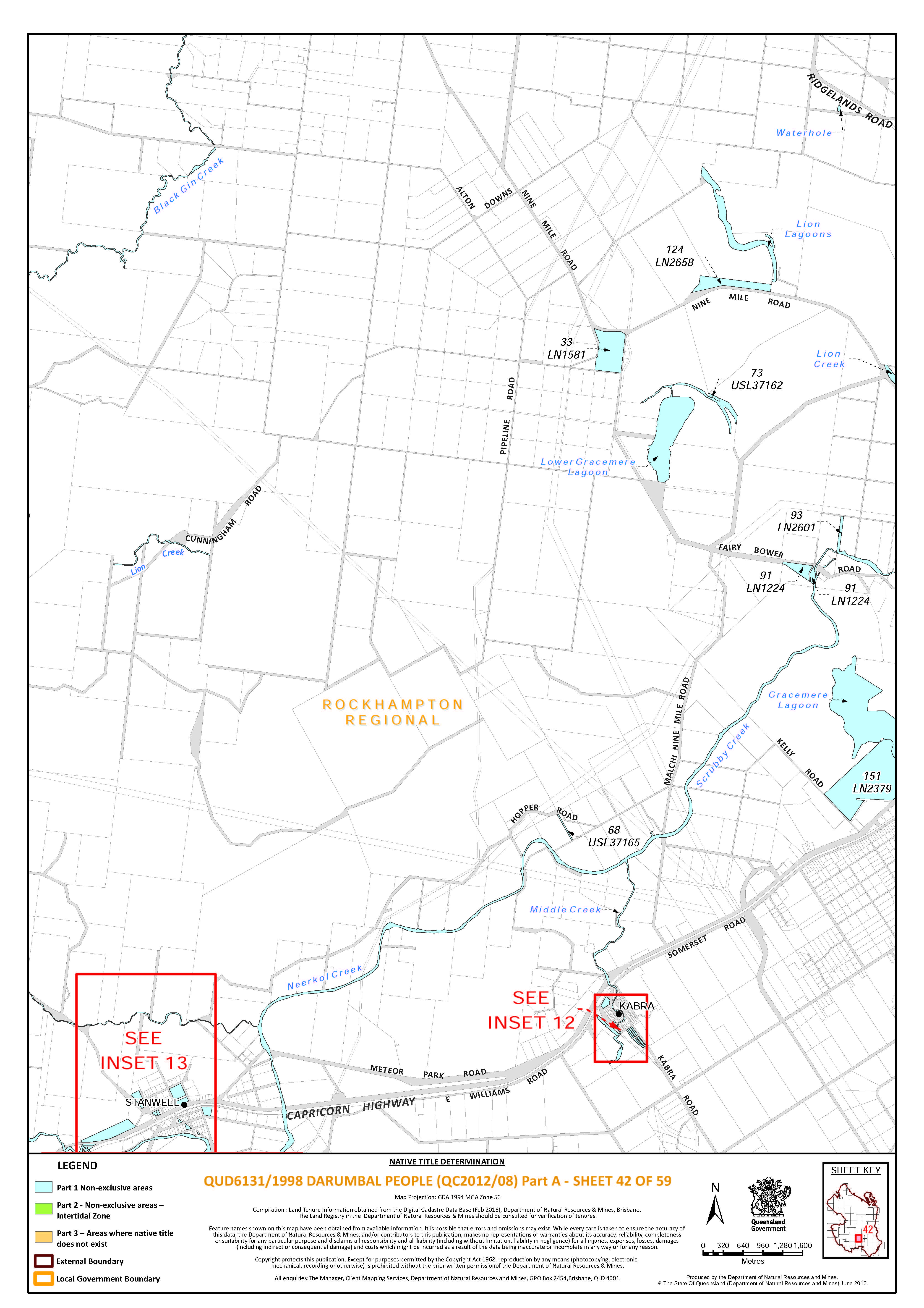

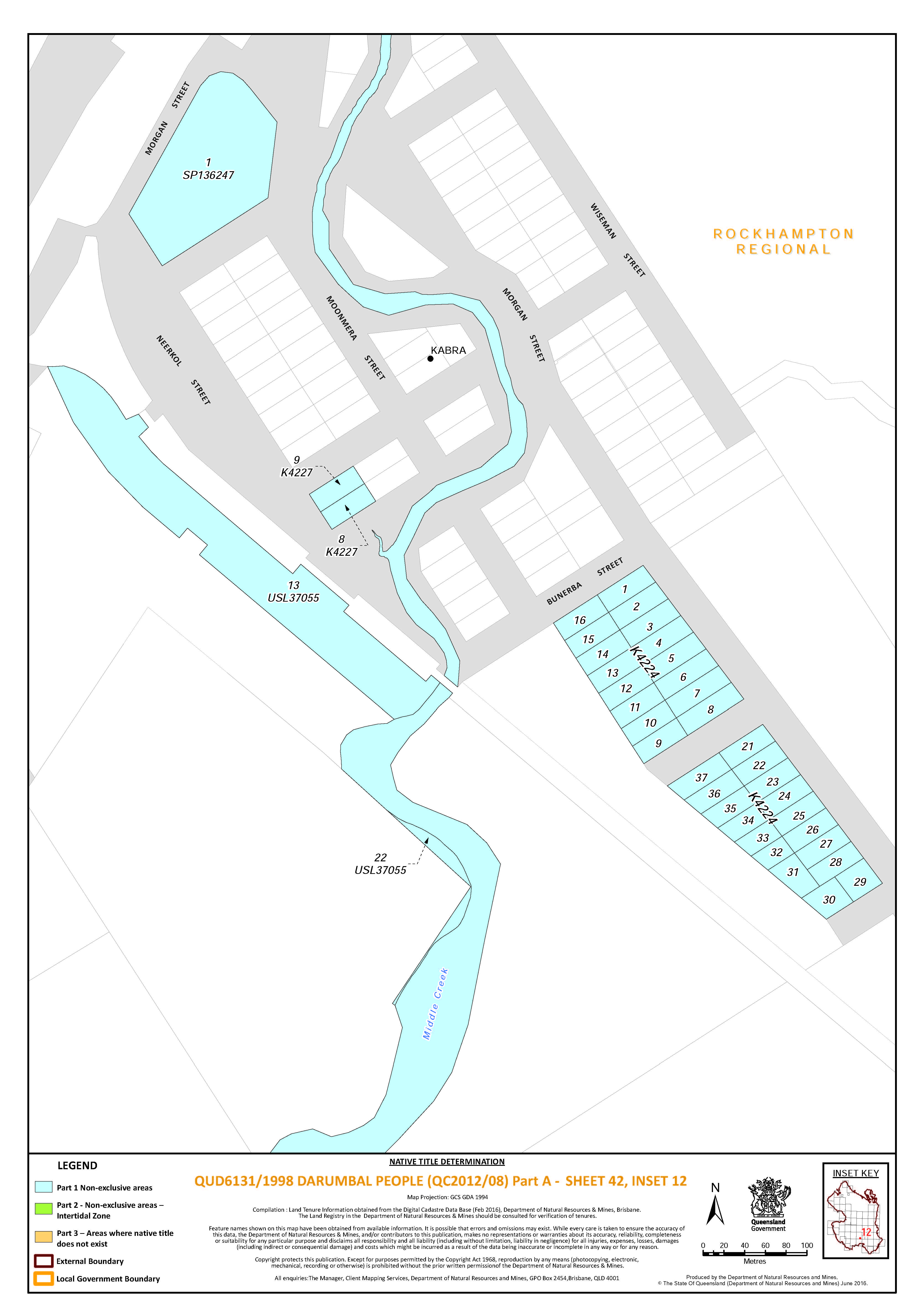

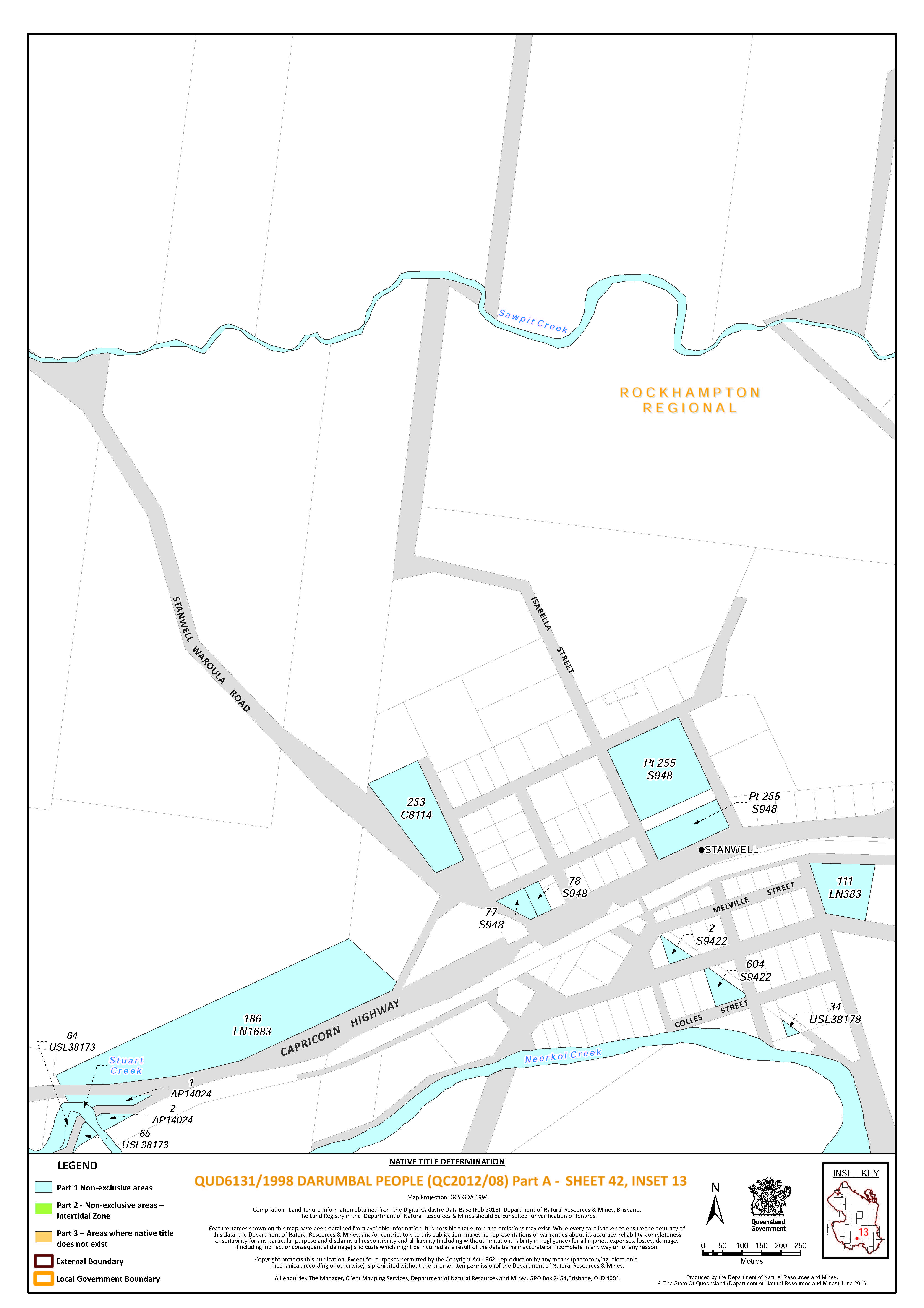

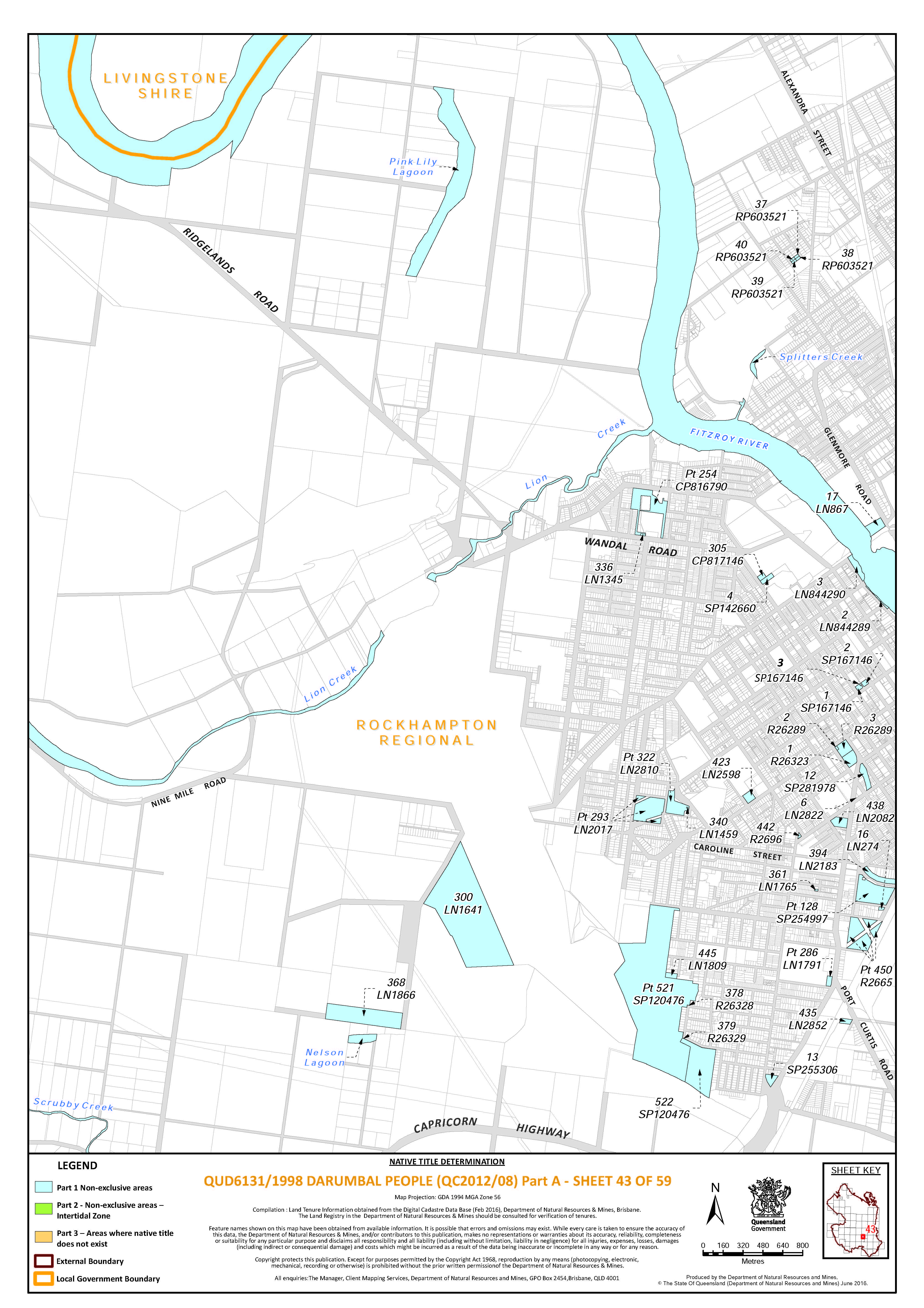

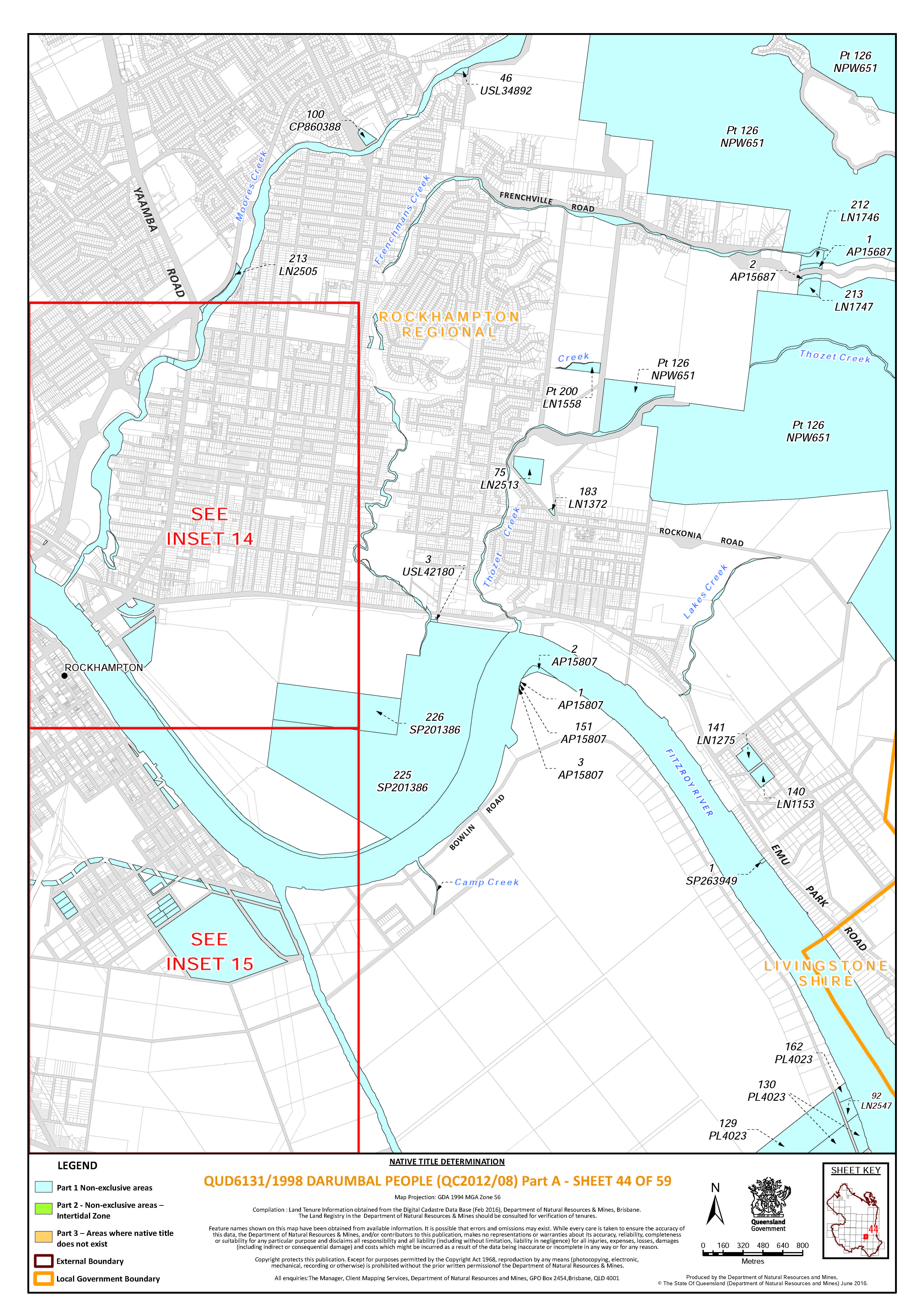

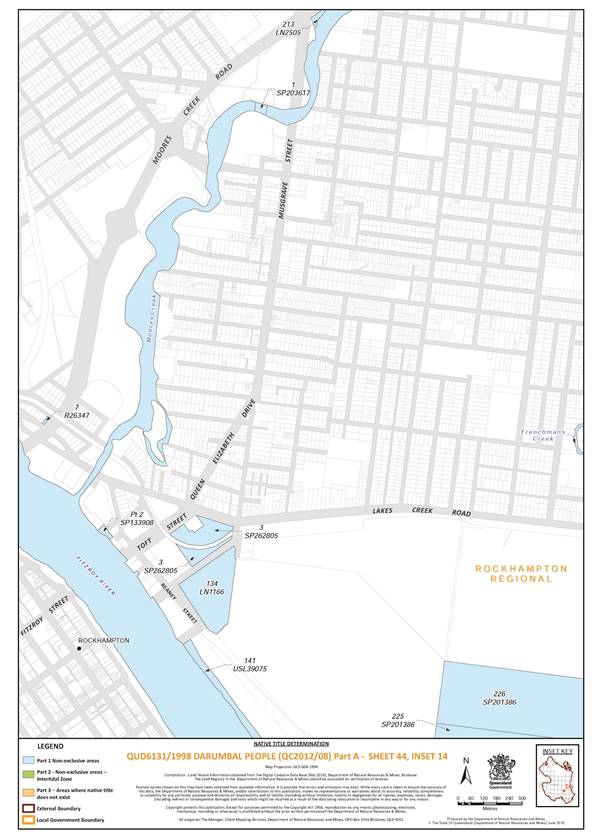

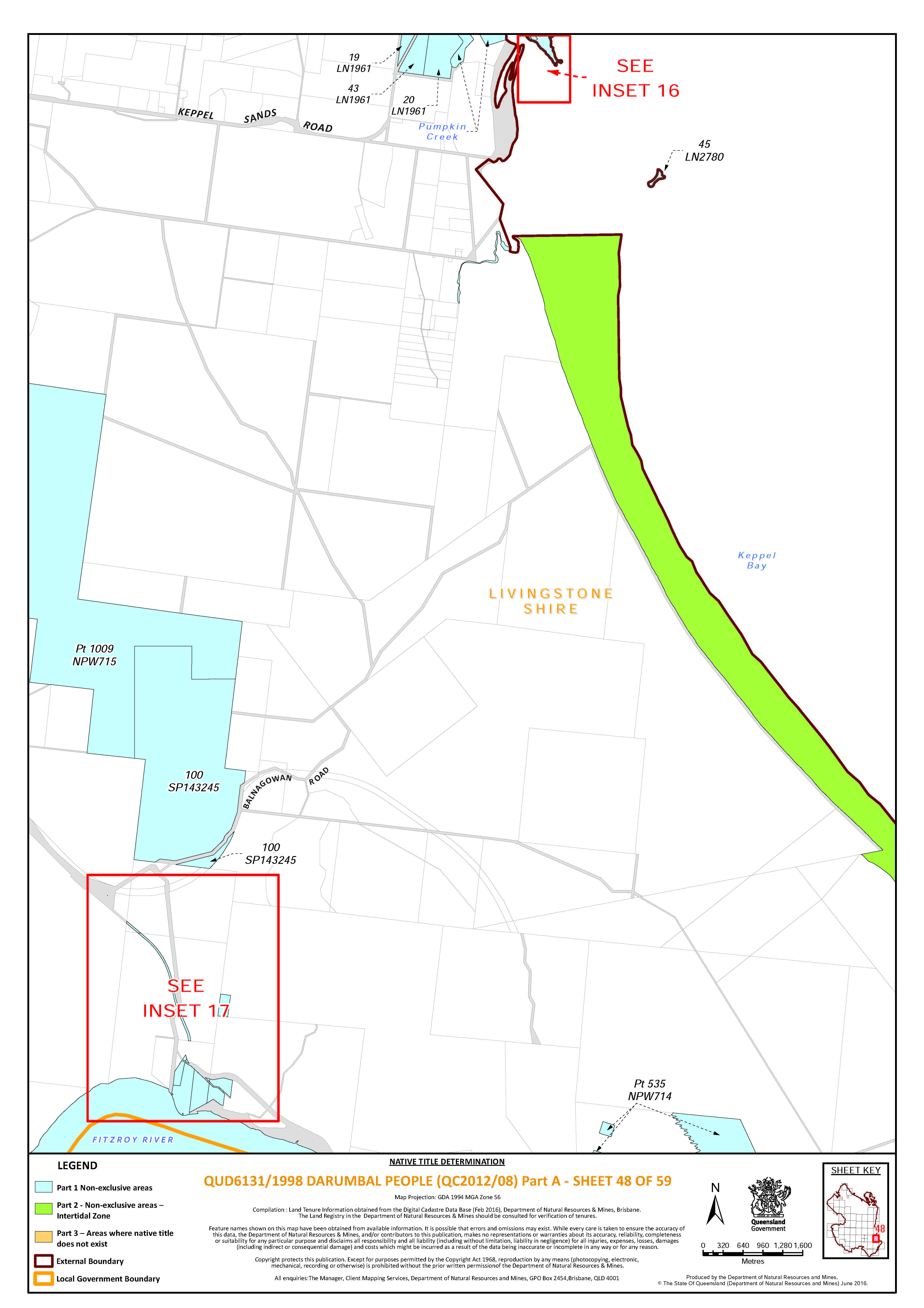

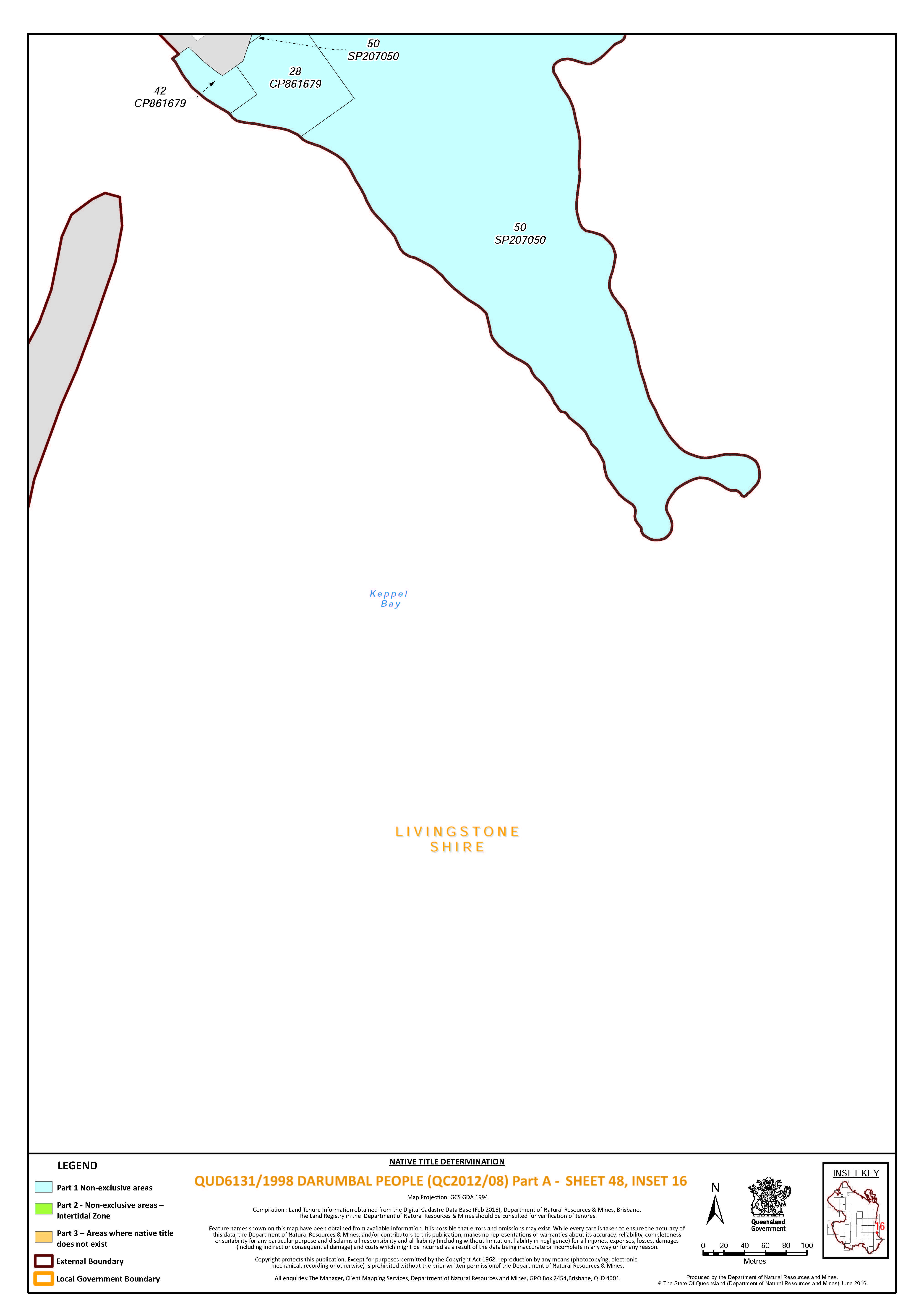

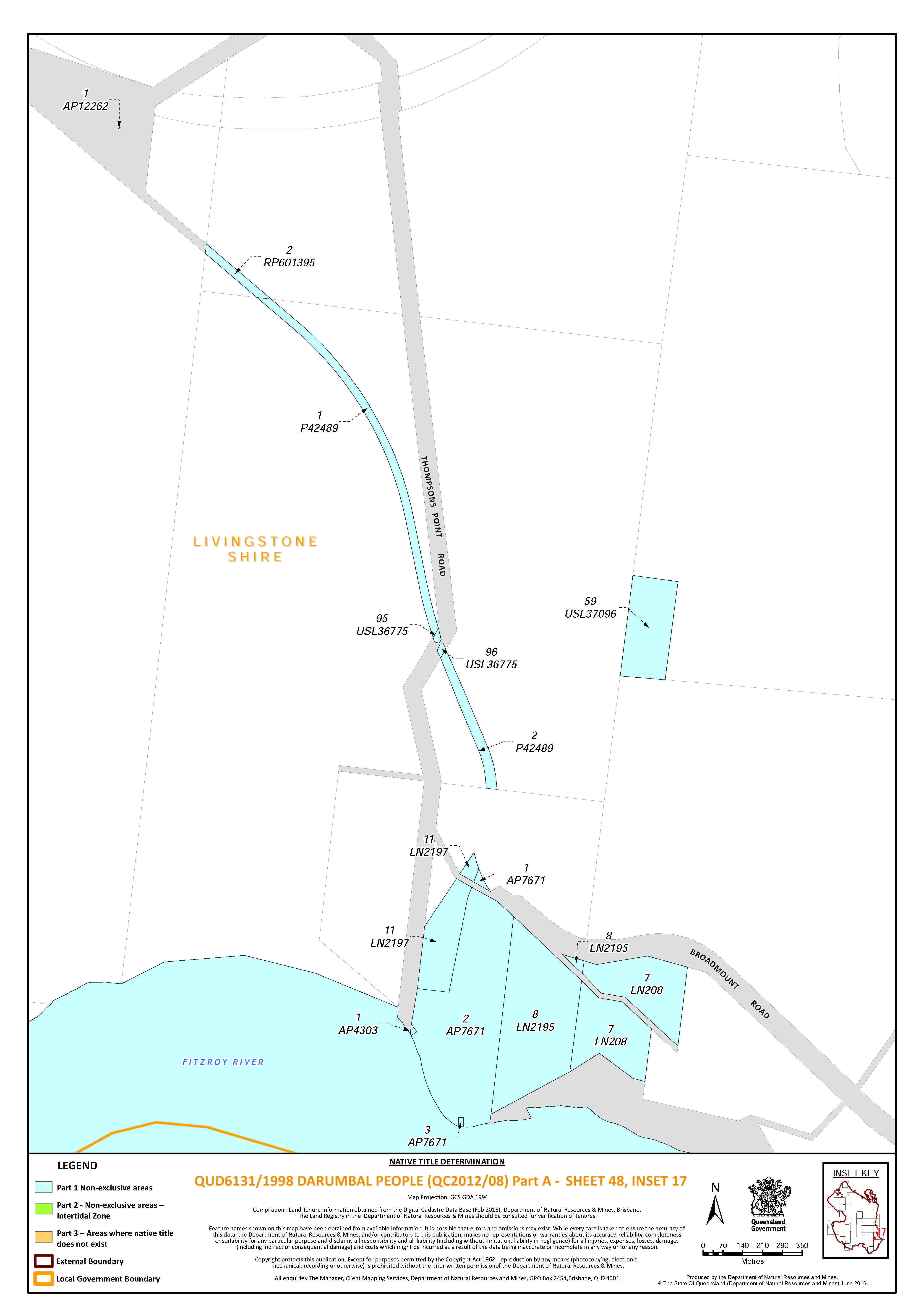

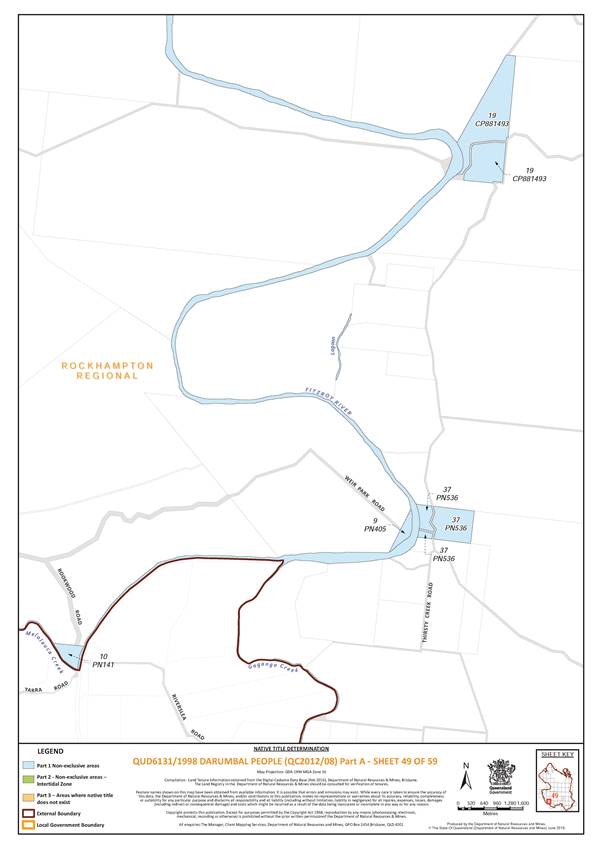

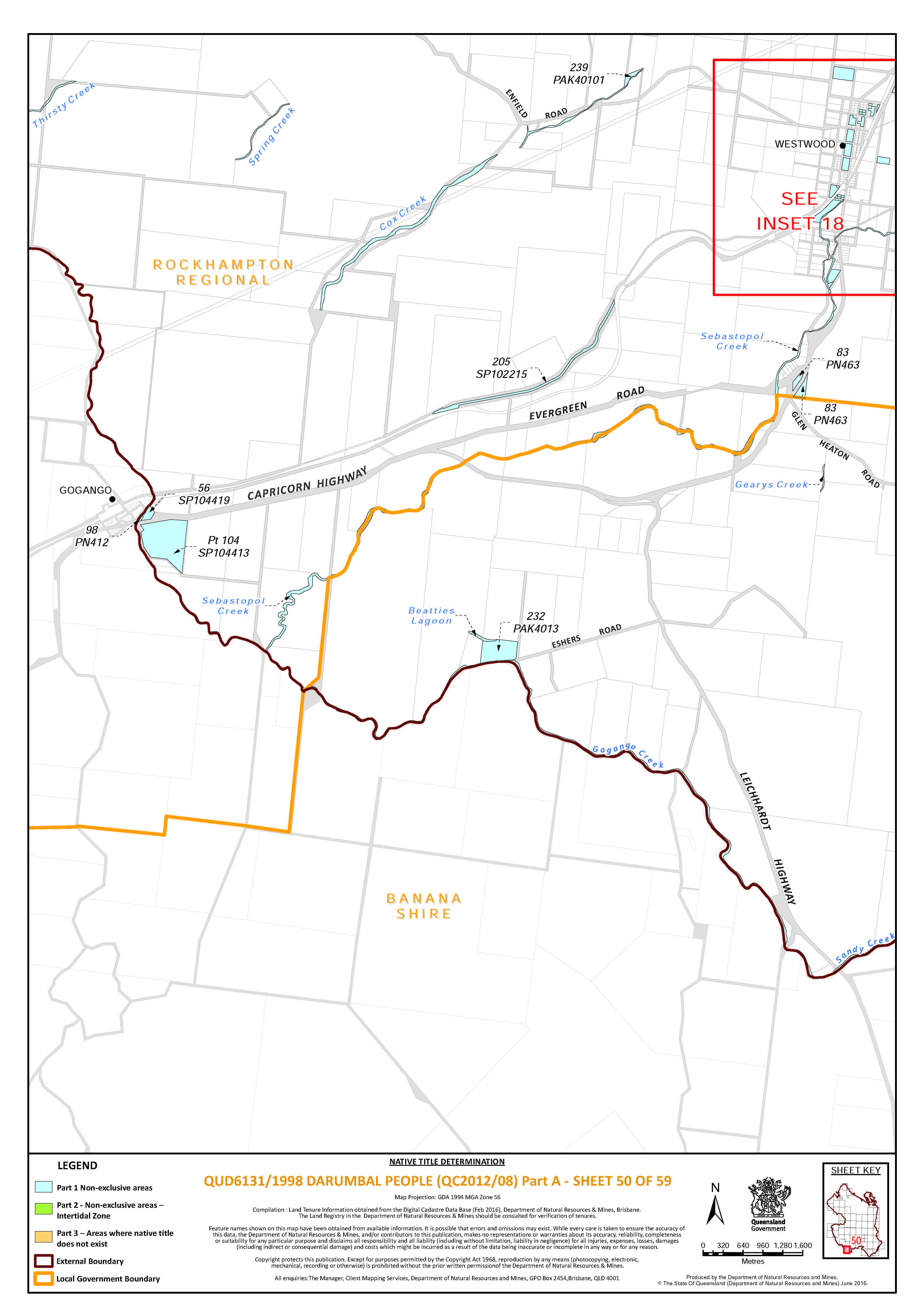

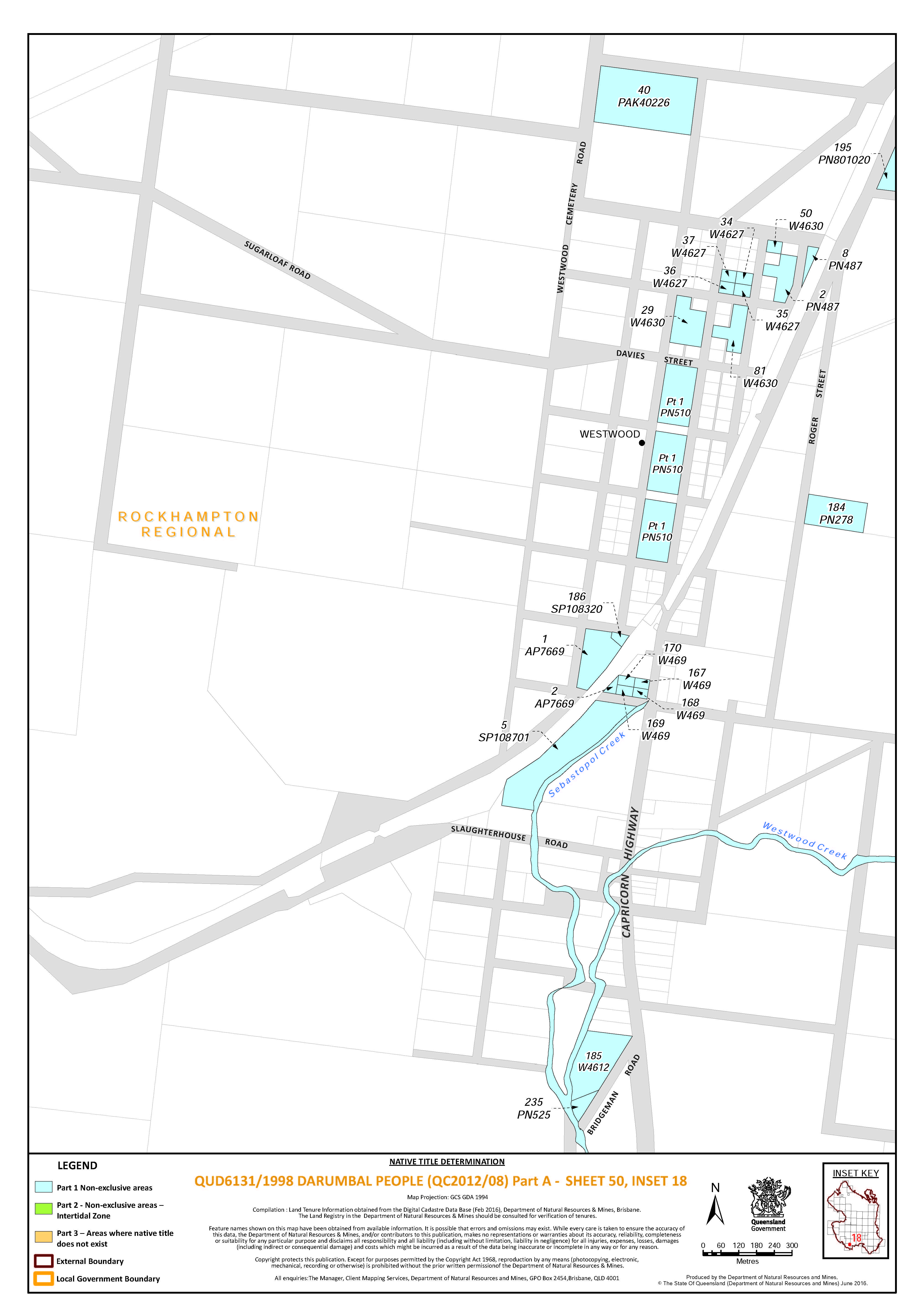

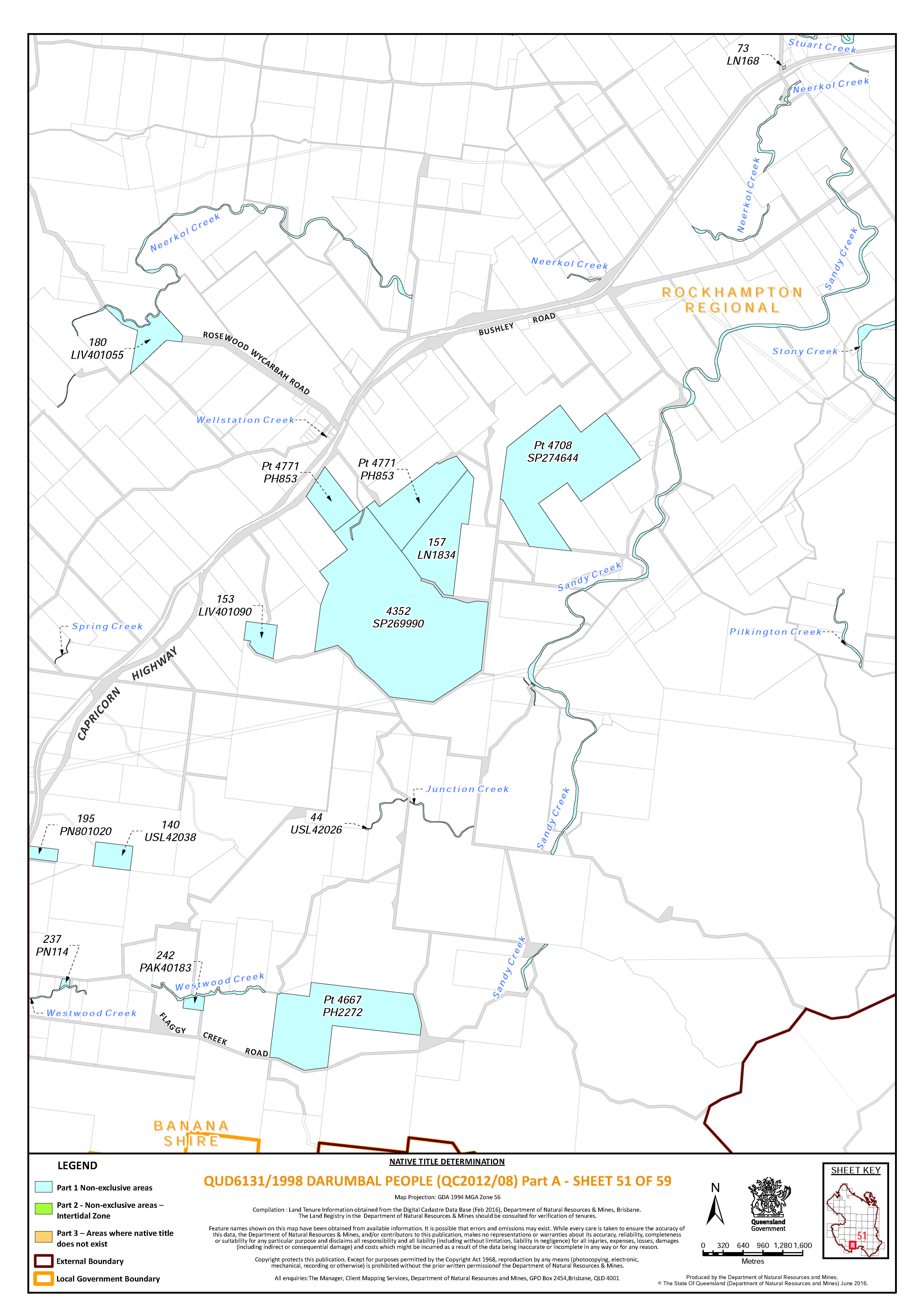

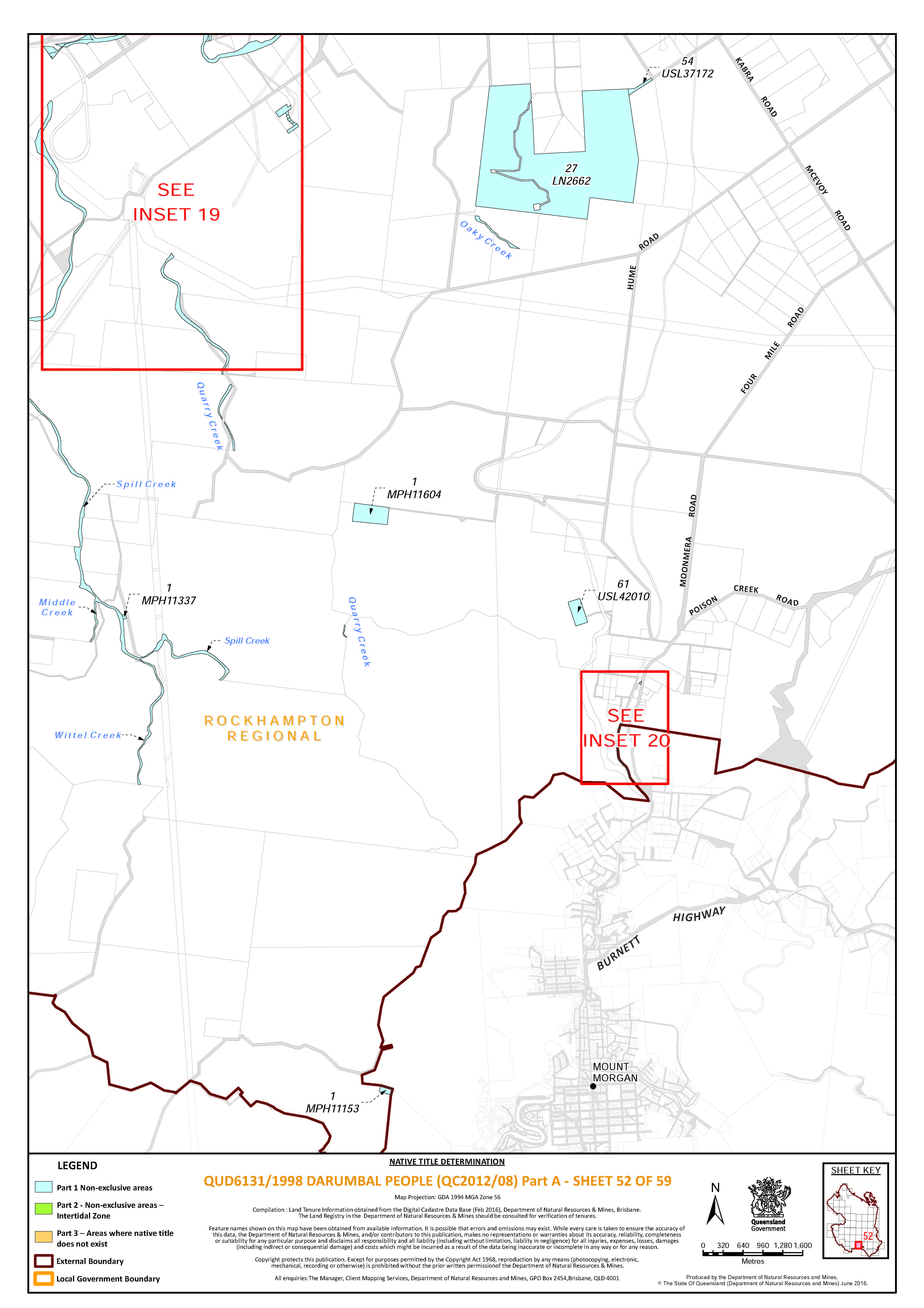

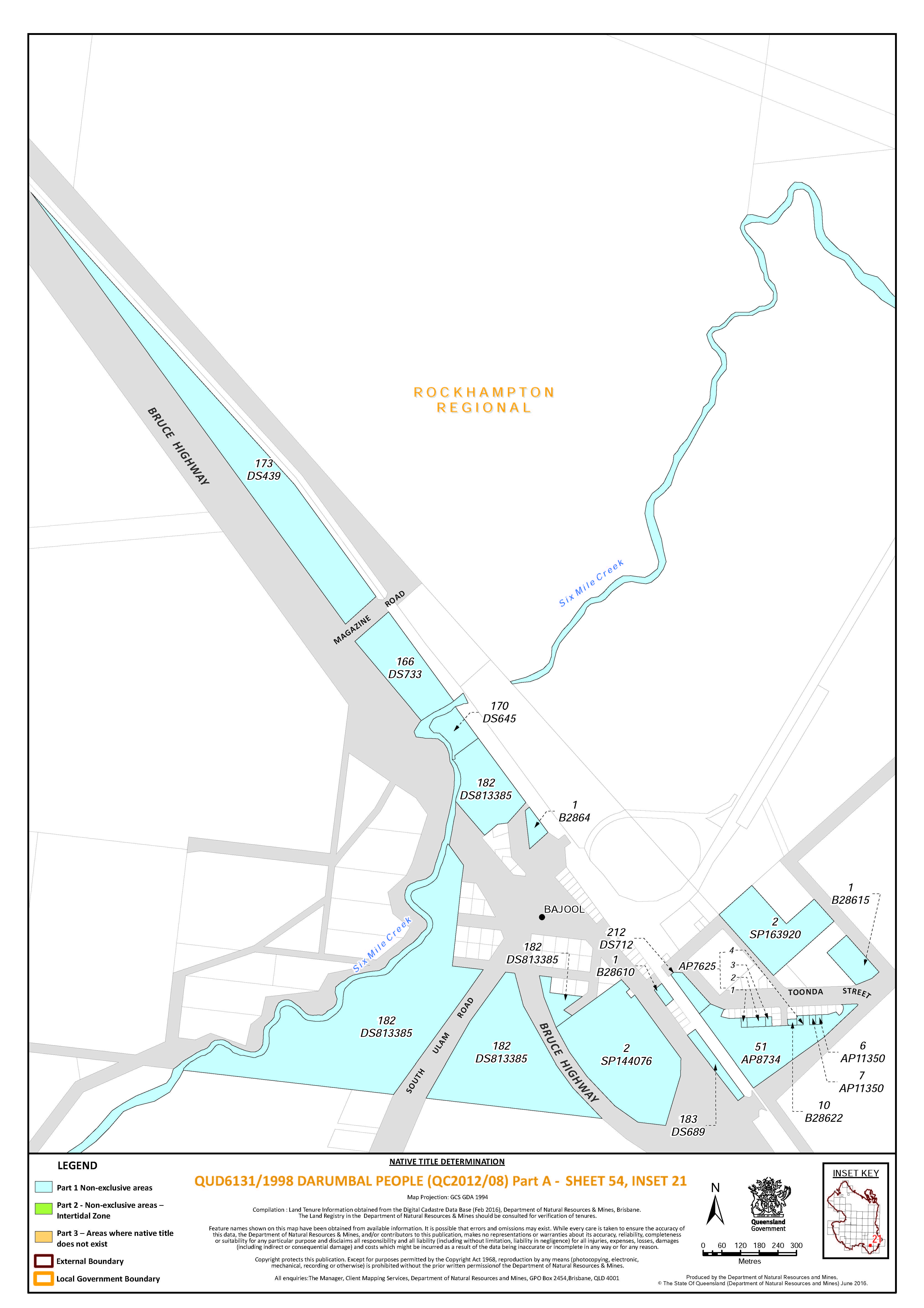

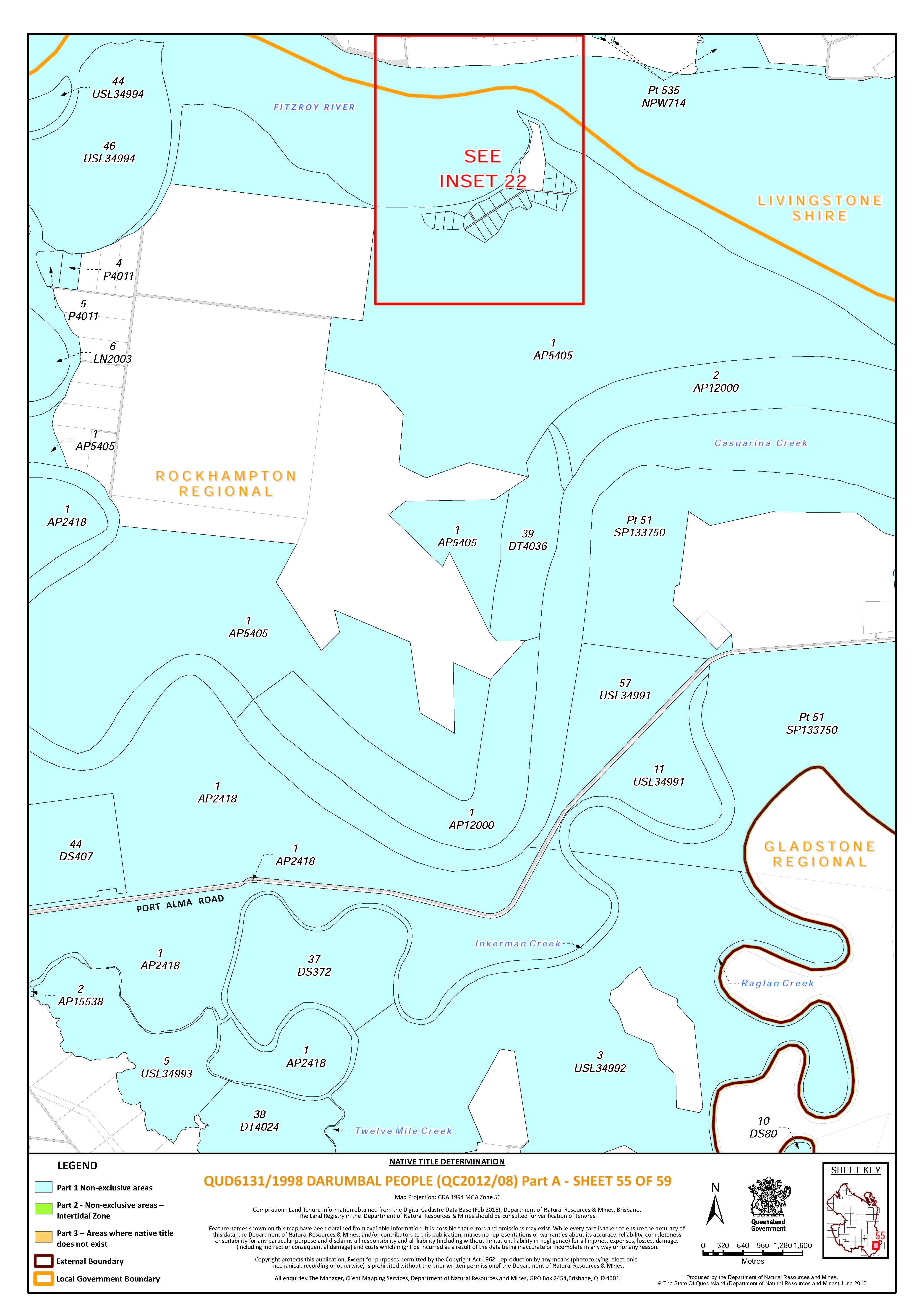

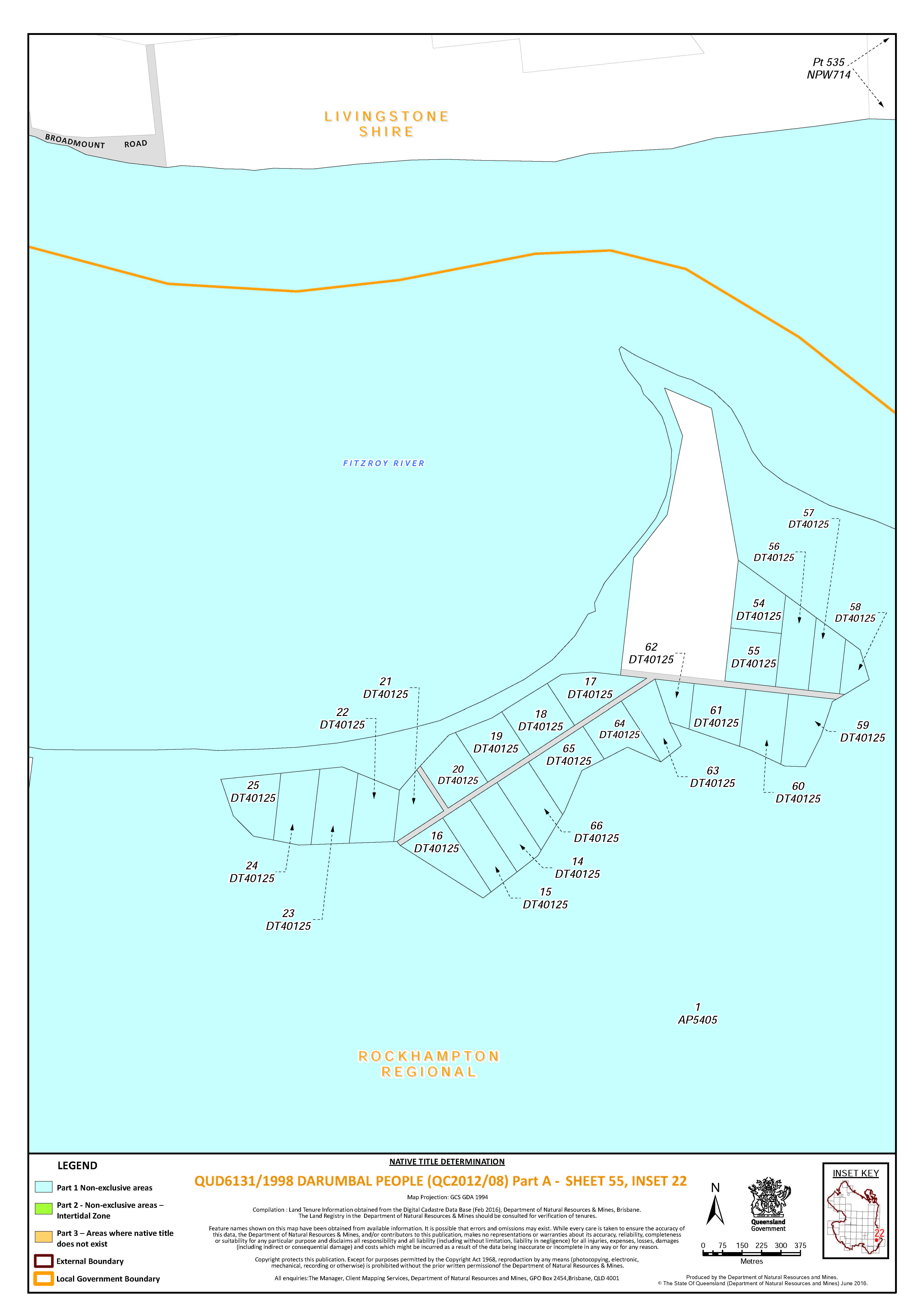

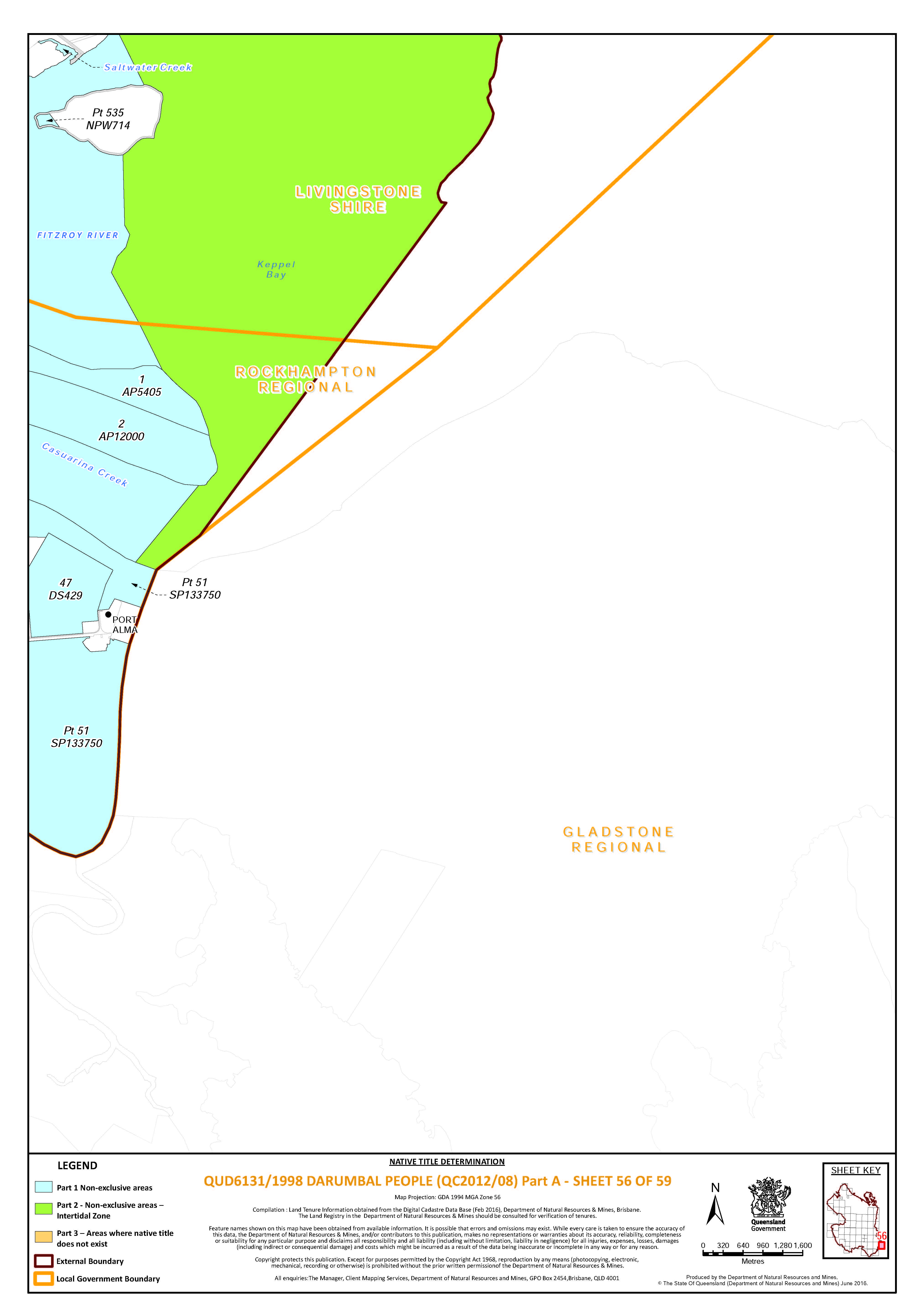

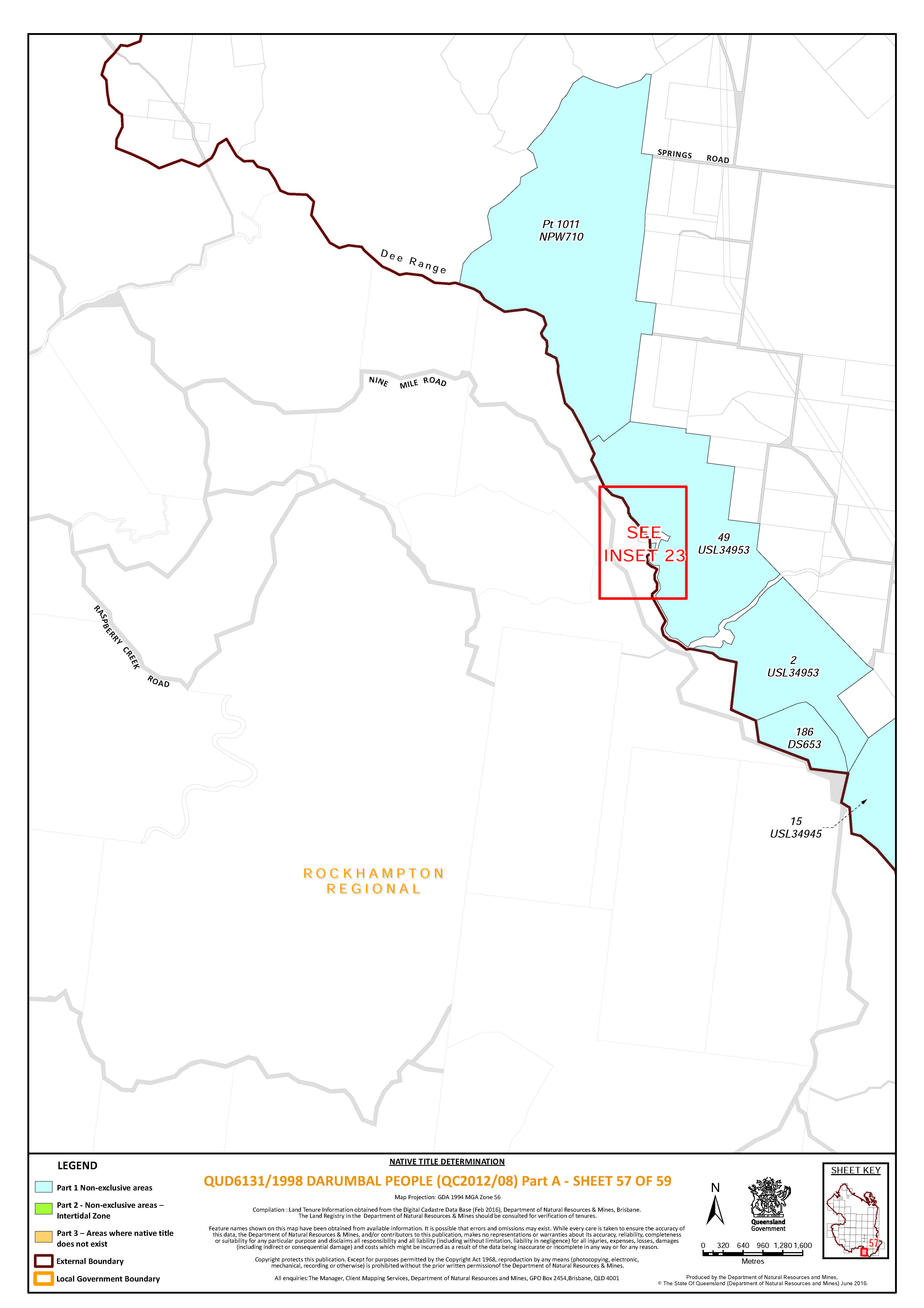

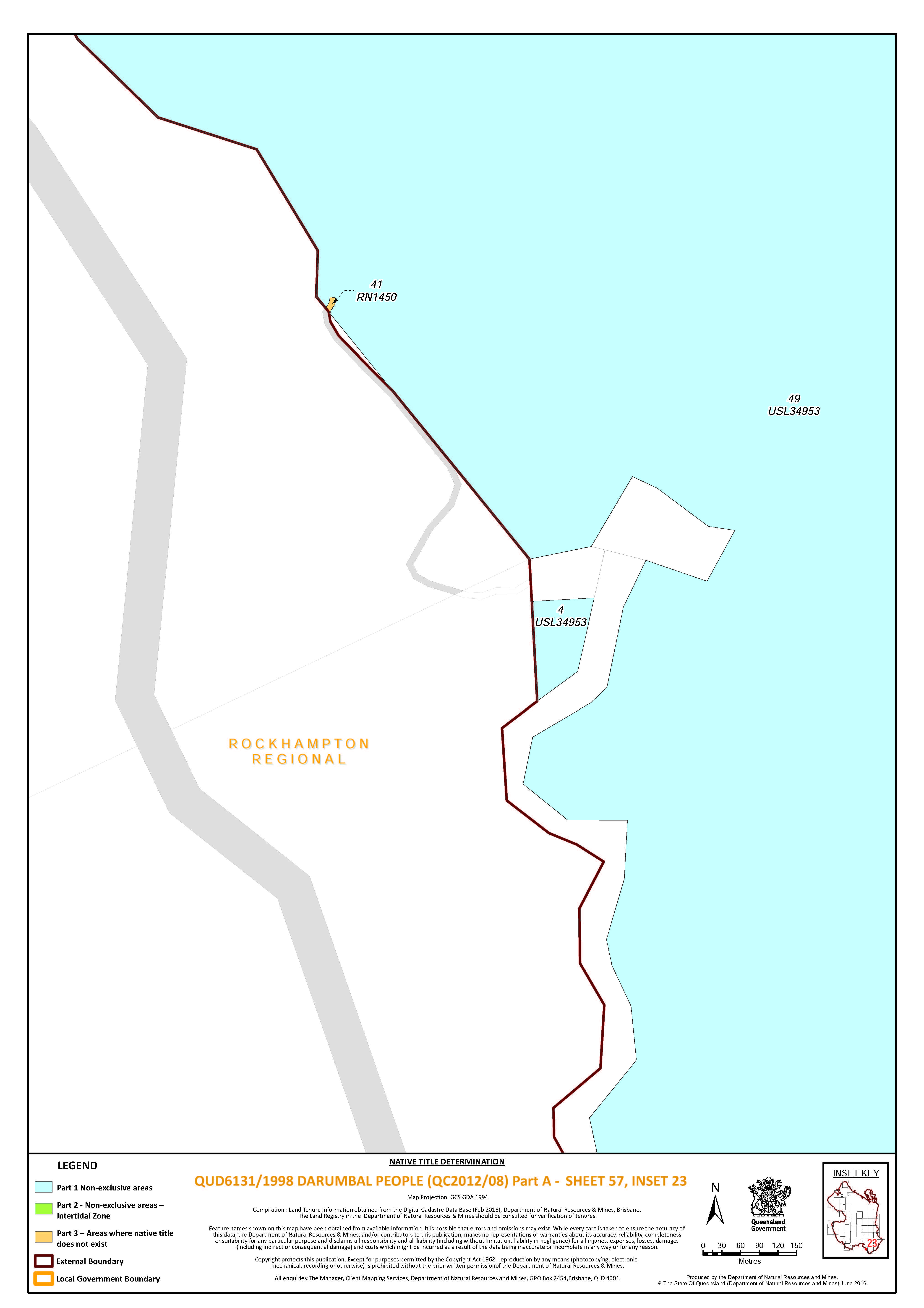

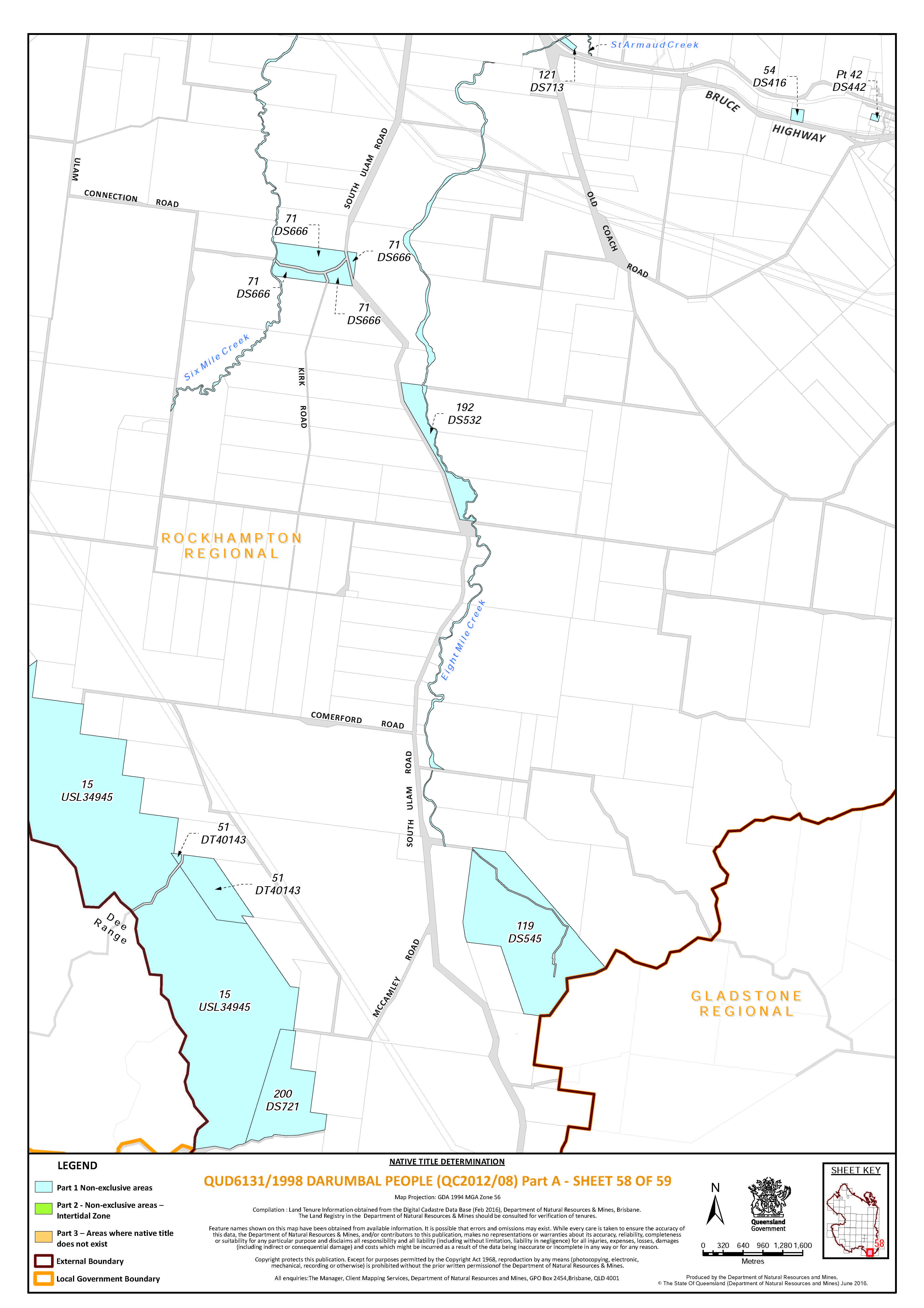

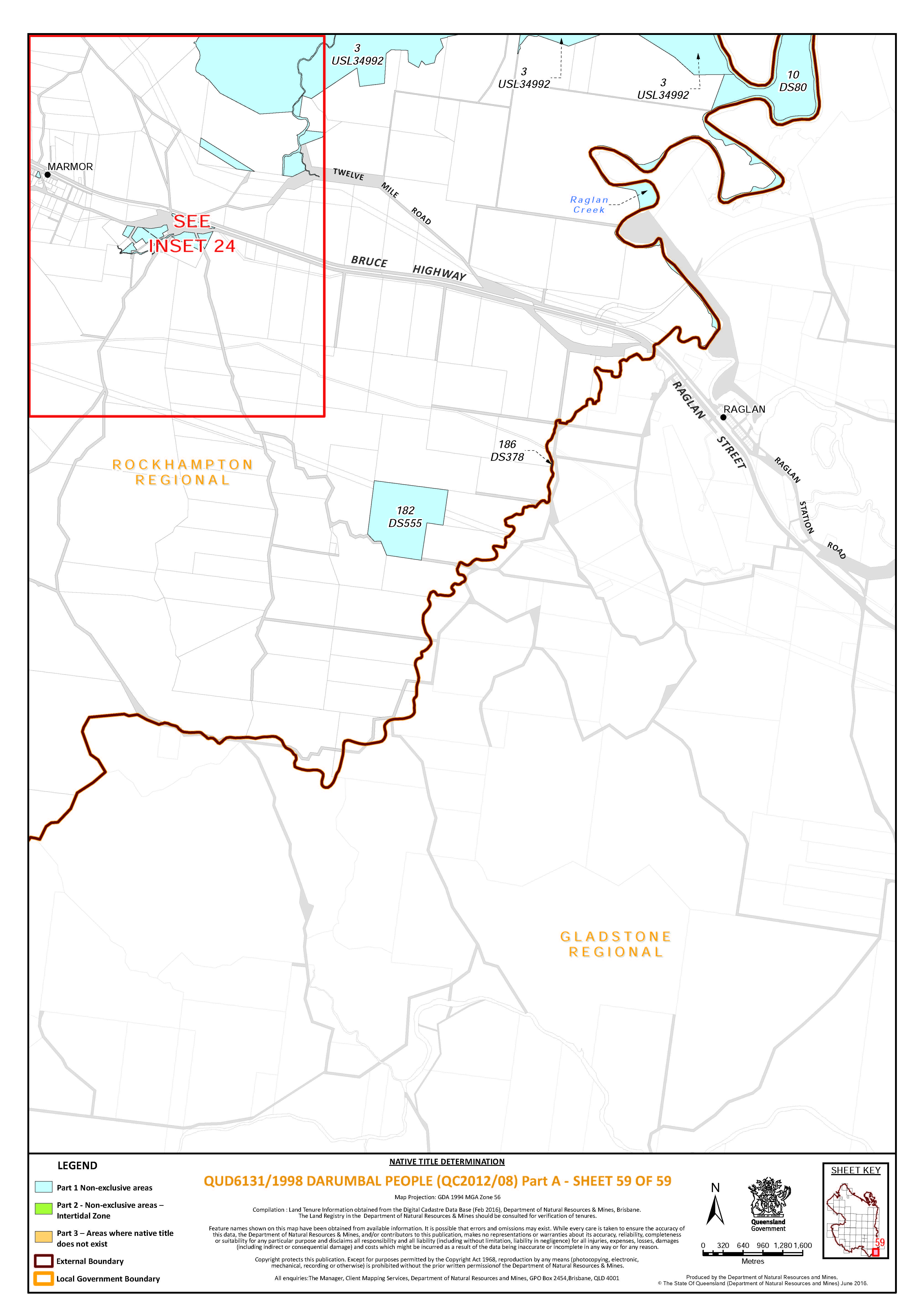

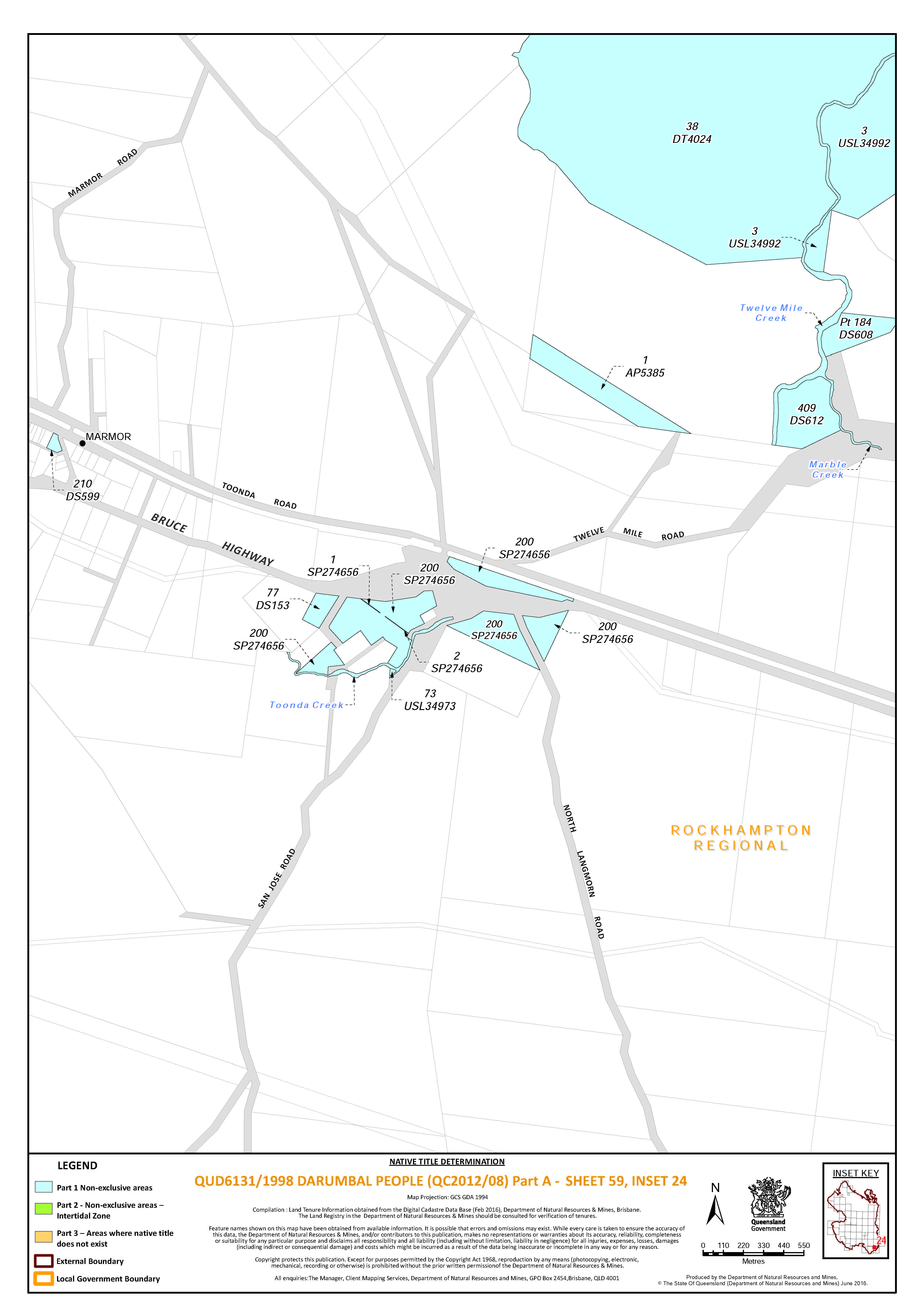

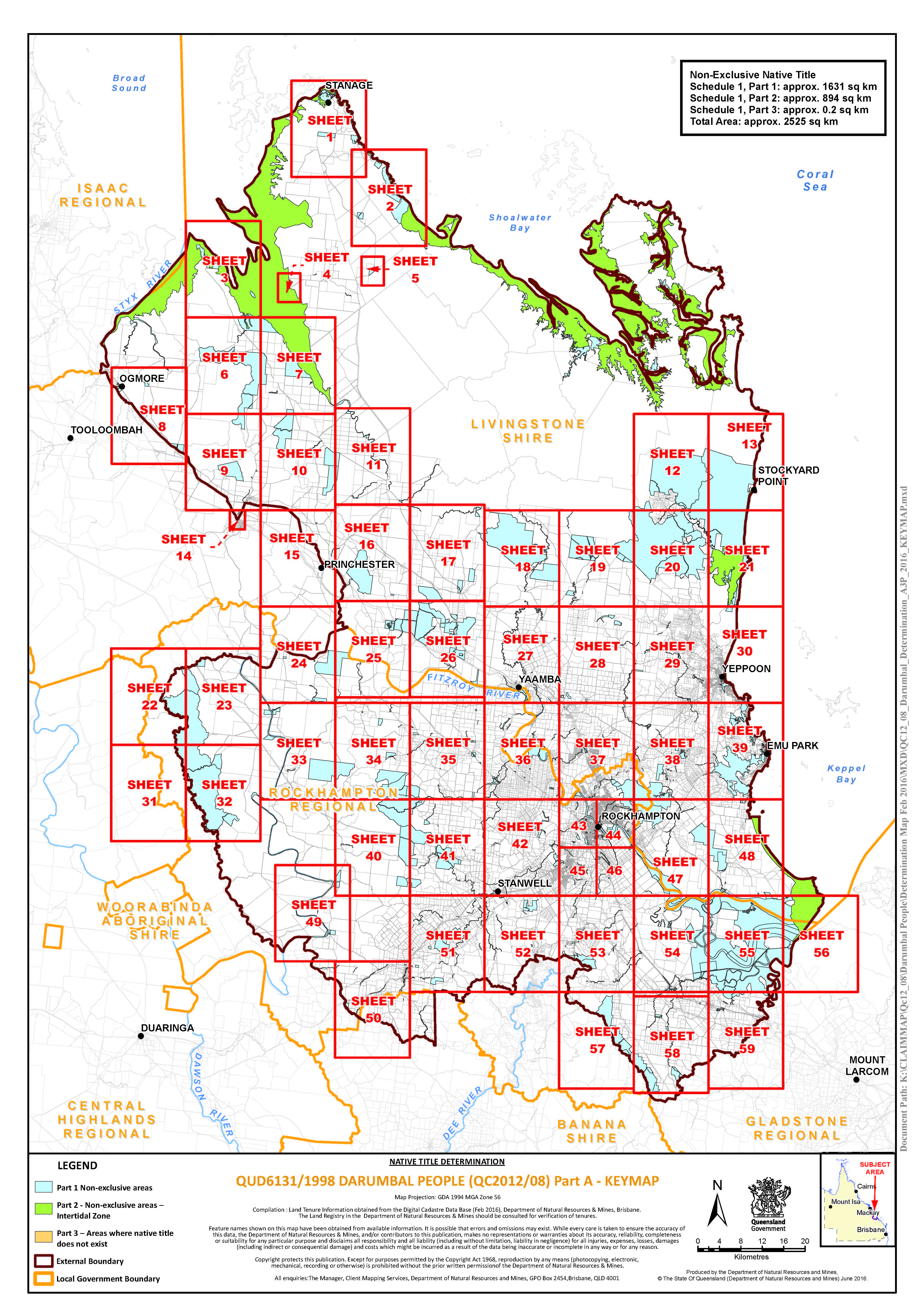

5. The Determination Area is the land and waters described in Schedule 1A and depicted on the map attached to Schedule 1B. To the extent of any inconsistency between the written description and the map, the written description prevails.

6. Native title exists in relation to the Determination Area described in Part 1 and Part 2 of Schedule 1A. Native title does not exist in relation to the Determination Area described in Part 3 of Schedule 1A.

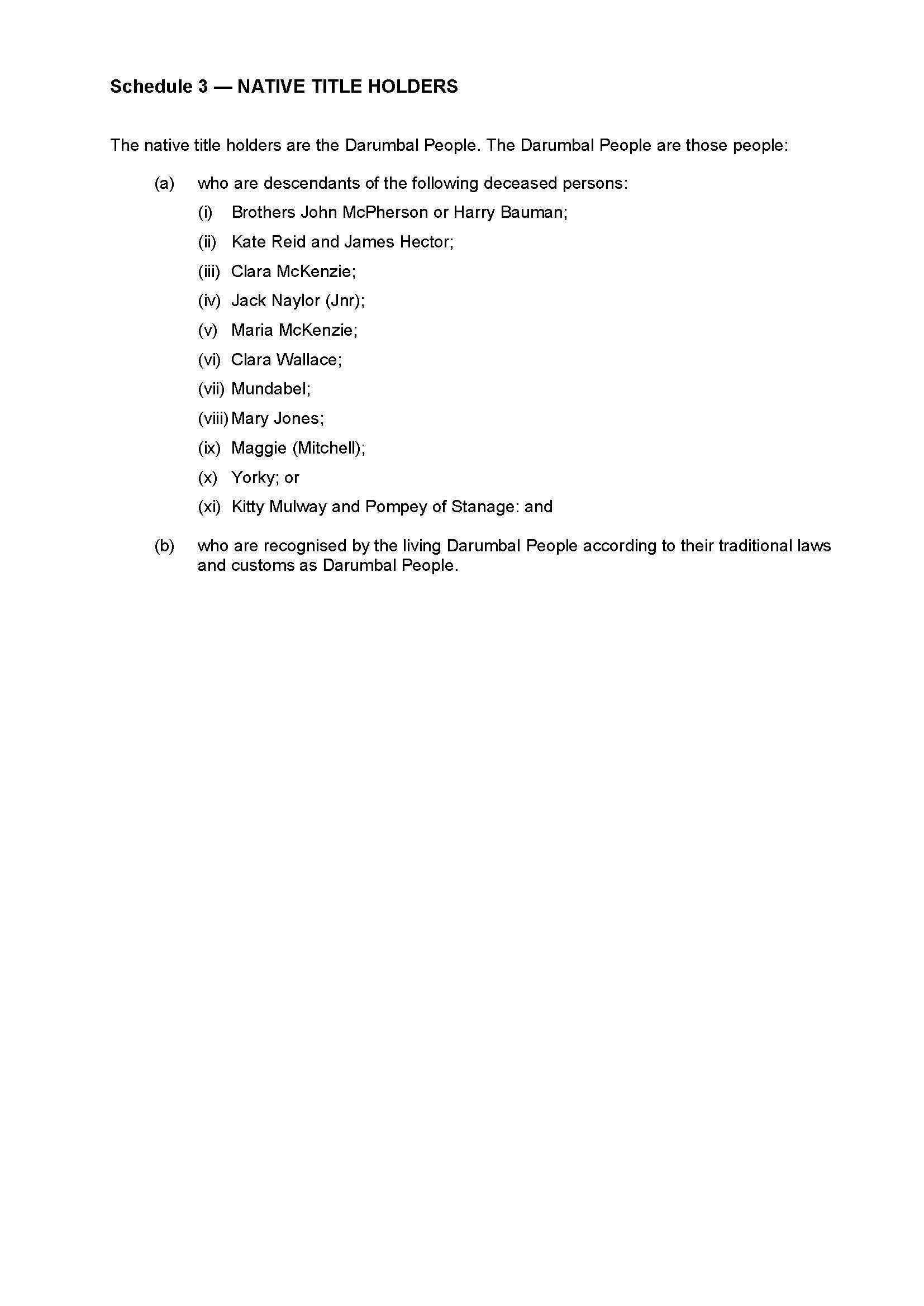

7. The native title is held by the Darumbal People described in Schedule 3 (the native title holders).

8. Subject to paragraphs 10, 11 and 12 below, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters described in Part 1 of Schedule 1A are the non-exclusive rights to:

(a) access, be present on, move about on and travel over the area;

(b) camp, and live temporarily on the area as part of camping, and for that purpose build temporary shelters on the area;

(c) hunt, fish and gather on the land and waters of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(d) take, use and share Natural Resources from the land and waters of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(e) take and use the Water of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(f) conduct smoking, welcome and cleansing ceremonies and ceremonies associated with repatriation of remains on the area;

(g) be buried and bury native title holders within the area;

(h) maintain and protect places of importance and areas of significance to the native title holders under their traditional laws and customs;

(i) teach on the area the physical, cultural and spiritual attributes of the area;

(j) hold meetings on the area; and

(k) light fires on the area for personal and domestic purposes including cooking, but not for the purpose of hunting or clearing vegetation.

9. Subject to paragraphs 10, 11 and 12 below, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters described in Part 2 of Schedule 1A are the non-exclusive rights described in paragraphs 8(a), (c), (d), (h) and (i) above.

10. The native title rights and interests are subject to and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the Laws of the State and the Commonwealth; and

(b) the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the native title holders.

11. The native title rights and interests referred to in paragraphs 8 and 9 do not confer possession, occupation, use or enjoyment of the Determination Area to the exclusion of all others.

12. There are no native title rights in or in relation to minerals as defined by the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) and petroleum as defined by the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) and the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld).

13. The nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the Determination Area (or respective parts thereof) as they exist at the date of this Determination are set out in Schedule 4 (Other Interests).

14. The relationship between the native title rights and interests described in paragraphs 8 and 9 and the Other Interests described in Schedule 4, with the exception of JUMP Station RKH1, is that:

(a) the Other Interests continue to have effect, and the rights conferred by or held under the Other Interests may be exercised notwithstanding the existence of the native title rights and interests;

(b) to the extent the Other Interests are inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters of the Determination Area, the native title continues to exist in its entirety but the native title rights and interests have no effect in relation to the Other Interests to the extent of the inconsistency for so long as the Other Interests exist; and

(c) the Other Interests and any activity that is required or permitted by or under, and done in accordance with, the Other Interests, or any activity that is associated with or incidental to such an activity, prevail over the native title rights and interests and any exercise of the native title rights and interests, but will not extinguish them.

15. The relationship between the native title rights and interests in paragraph 8 and JUMP Station RKH1 referred to in paragraph 7 of Schedule 4 is that JUMP Station RKH1 is:

(a) wholly inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of the native title rights and interests;

(b) the native title continues to exist but has no effect in relation to JUMP Station RKH1;

(c) if JUMP Station RKH1 or its effects are wholly removed or otherwise cease to operate the native title rights and interests again have full effect;

(d) if JUMP Station RKH1 or its effects are removed to any extent or otherwise cease to operate only to any extent, the native title rights and interests again have effect to that extent.

DEFINITIONS AND INTERPRETATION

16. In this determination, unless the contrary intention appears:

“land” and “waters”, respectively, have the same meanings as in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth);

“Laws of the State and the Commonwealth” means the common law and the laws of the State of Queensland and the Commonwealth of Australia, and includes legislation, regulations, statutory instruments, local planning instruments and local laws;

“Local Government Act” has the same meaning as in the Local Government Act 2009 (Qld);

“Local Government Area” has the same meaning as in the Local Government Act;

“Natural Resources” means:

(a) any animal, plant, fish and bird life found on or in the lands and waters of the Determination Area; and

(b) any clays, soil, sand, gravel, rock or ochre found on or below the surface of the Determination Area

that have traditionally been taken and used by the native title holders, but does not include:

(a) animals that are the private personal property of another;

(b) crops that are the private personal property of another; and

(c) minerals (except ochre taken in accordance with the traditional laws and customs of the native title holders) as defined in the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) or petroleum as defined in the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) and the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld);

“Reserves” means reserves that are dedicated or taken to be reserves under the Land Act 1994 (Qld);

“Water” means:

(a) water which flows, whether permanently or intermittently, within a river, creek or stream;

(b) any natural collection of water, whether permanent or intermittent; and

(c) water from an underground water source.

Other words and expressions used in this Determination have the same meanings as they have in Part 15 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

17. The native title is held in trust.

18. The Darumbal People Aboriginal Corporation (ICN: 8405), incorporated under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth), is to:

(a) be the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of s 56(2)(b) and s 56(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); and

(b) perform the functions mentioned in s 57(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) after becoming a registered native title body corporate.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LIST OF SCHEDULES

Schedule 1 — DETERMINATION AREA………………………………………………..vii

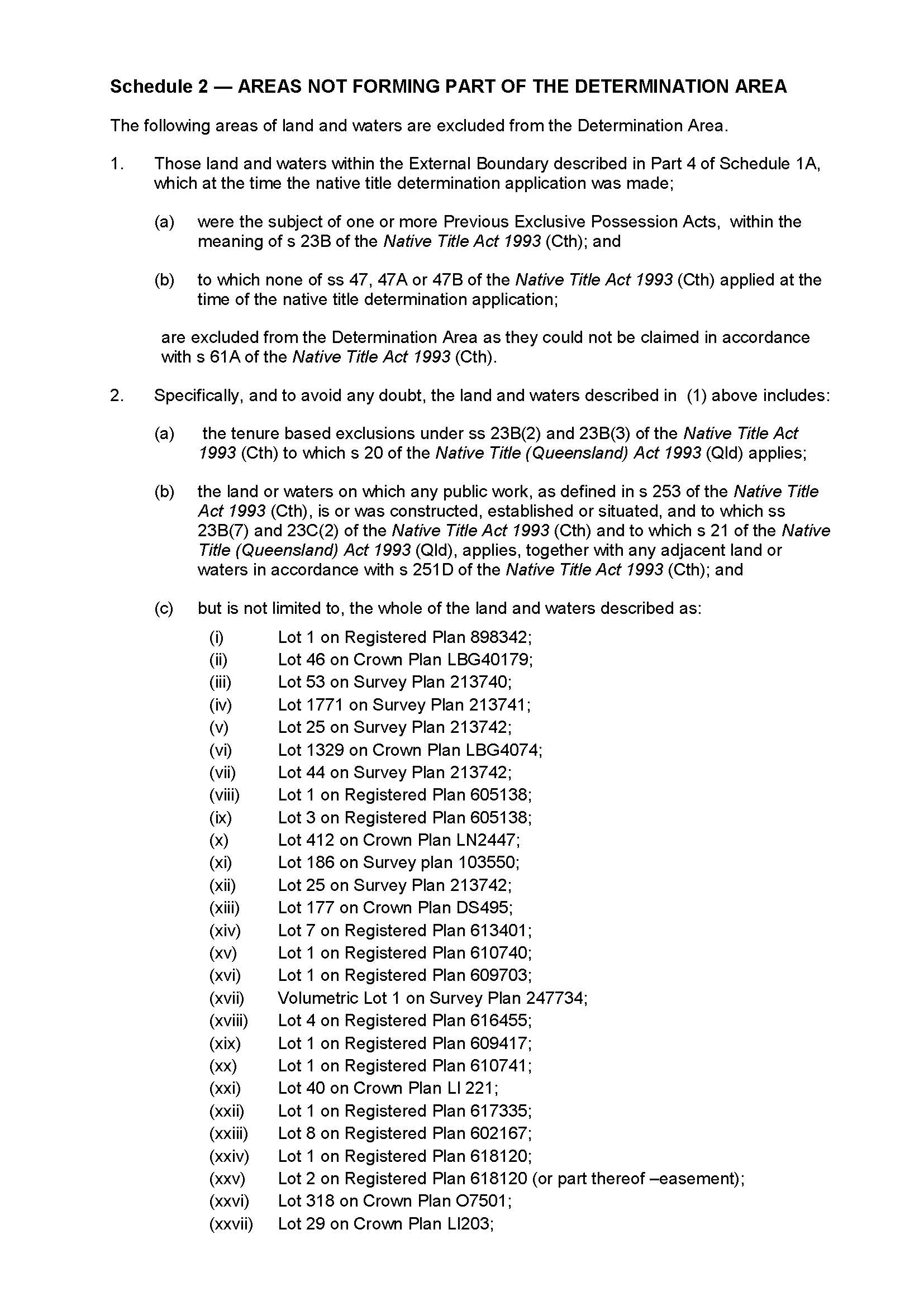

Schedule 2 — AREAS NOT FORMING PART OF THE DETERMINATION AREA……………………………………………………………………...……………..…cxx

Schedule 3 — NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS…………………………………….……...cxxii

Schedule 4 — OTHER INTERESTS IN THE DETERMINATION AREA….……..cxxiii

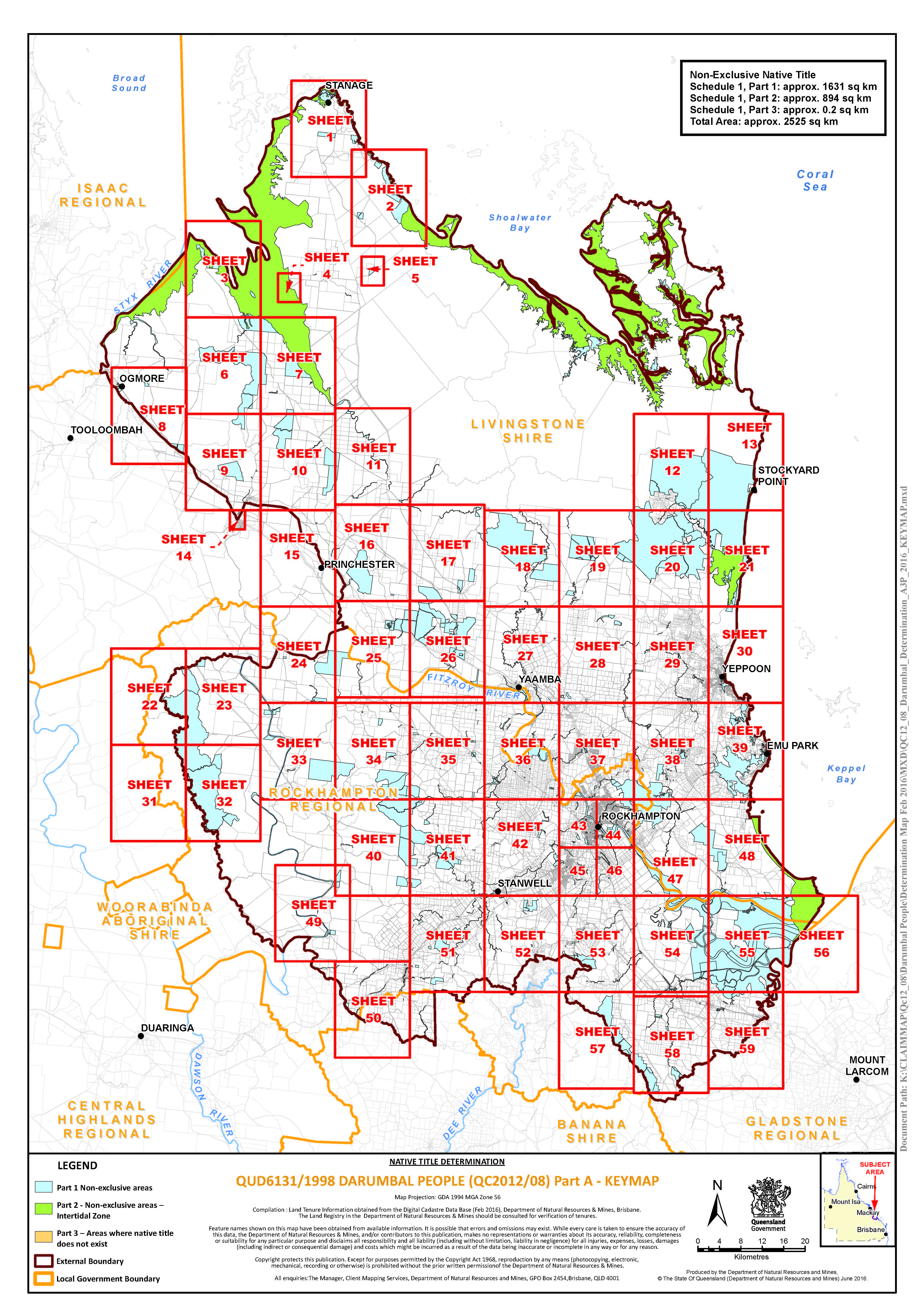

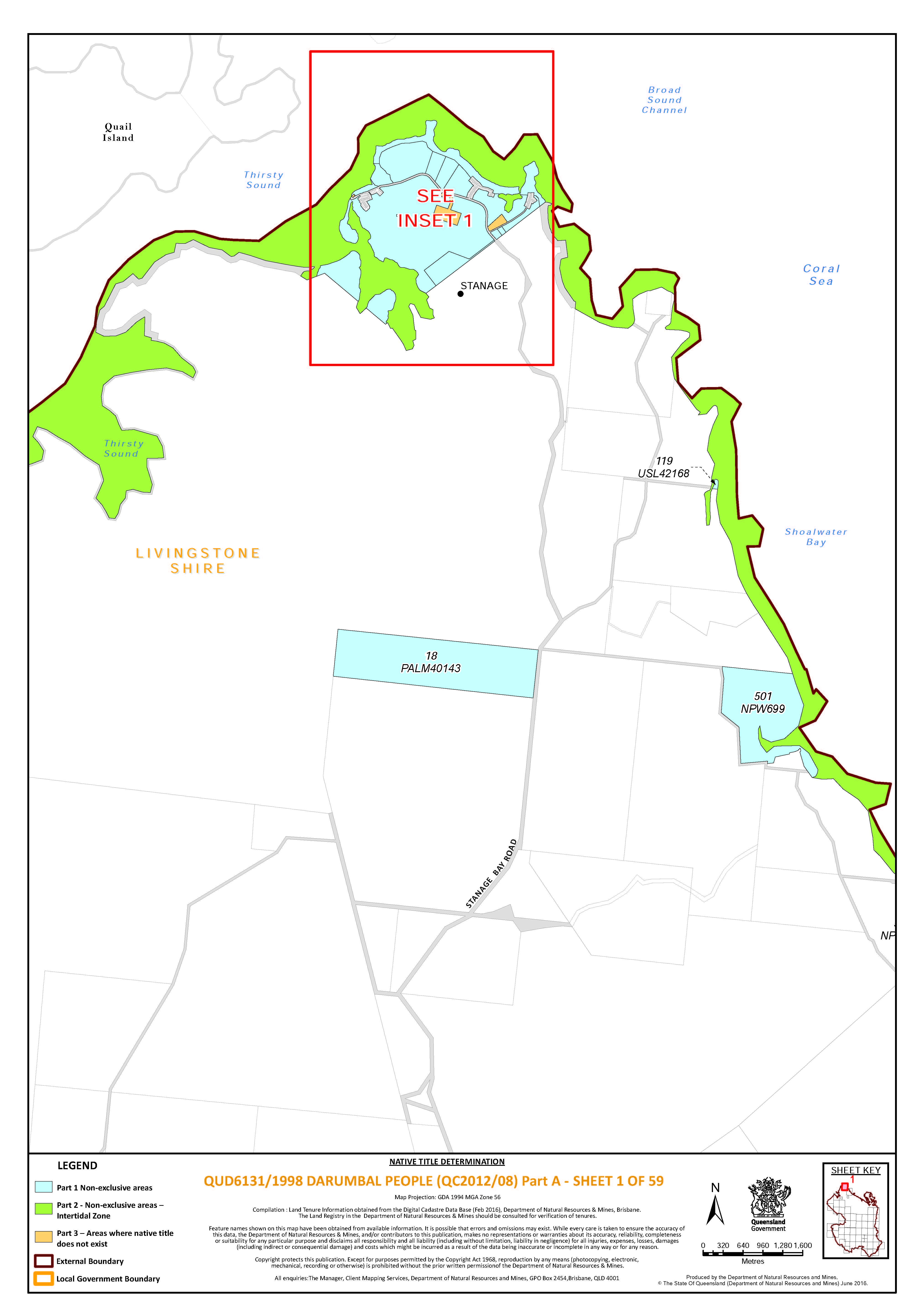

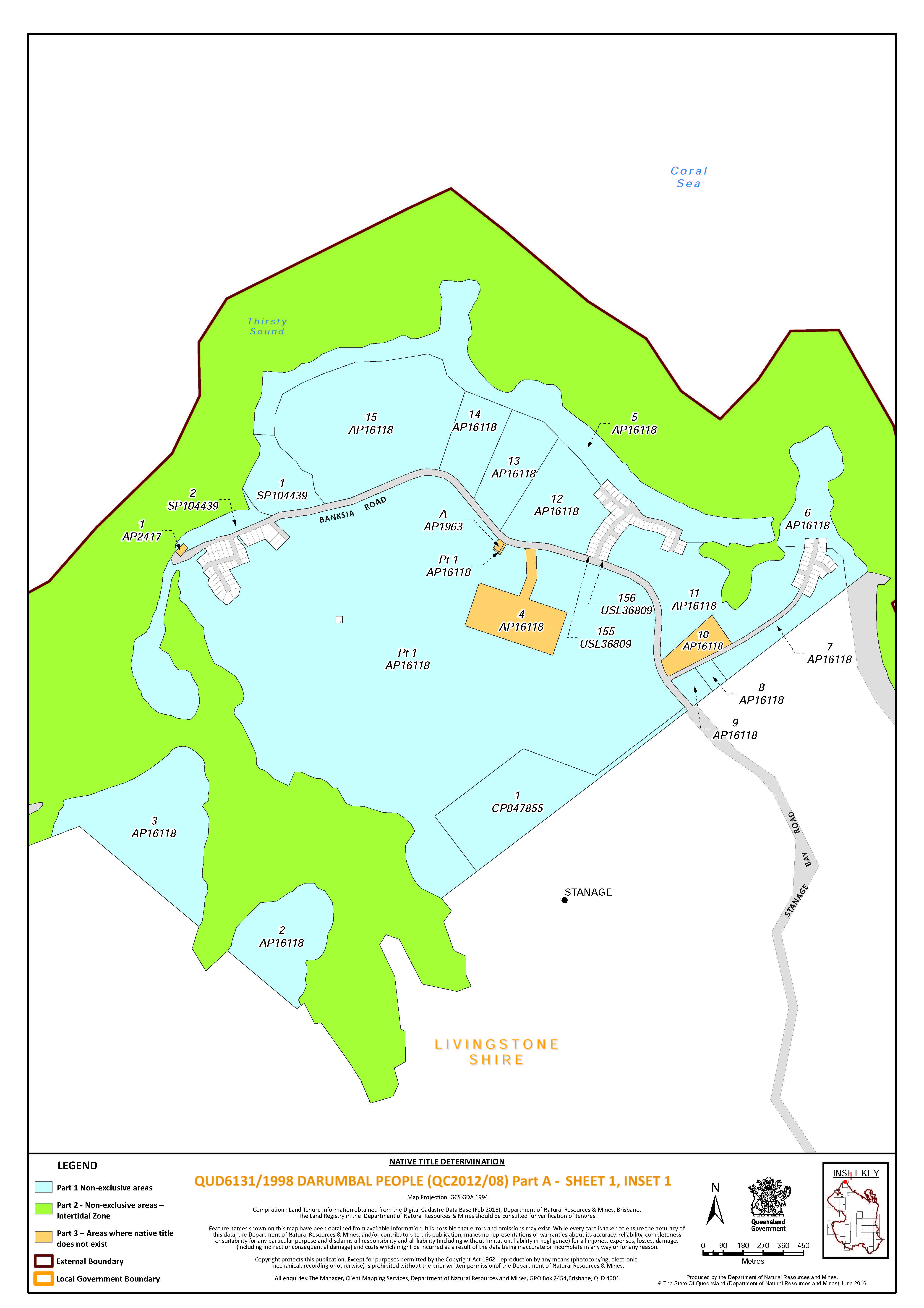

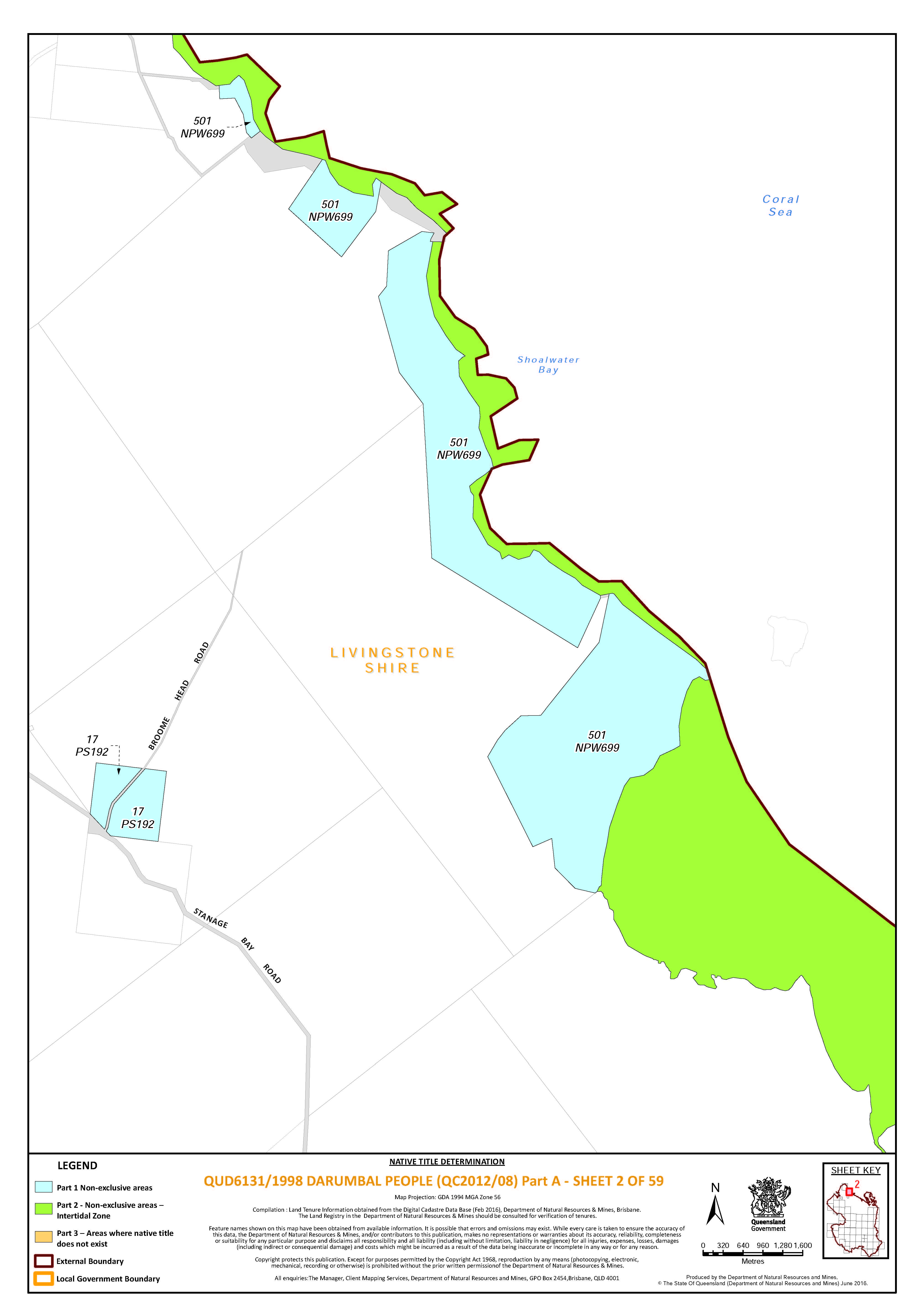

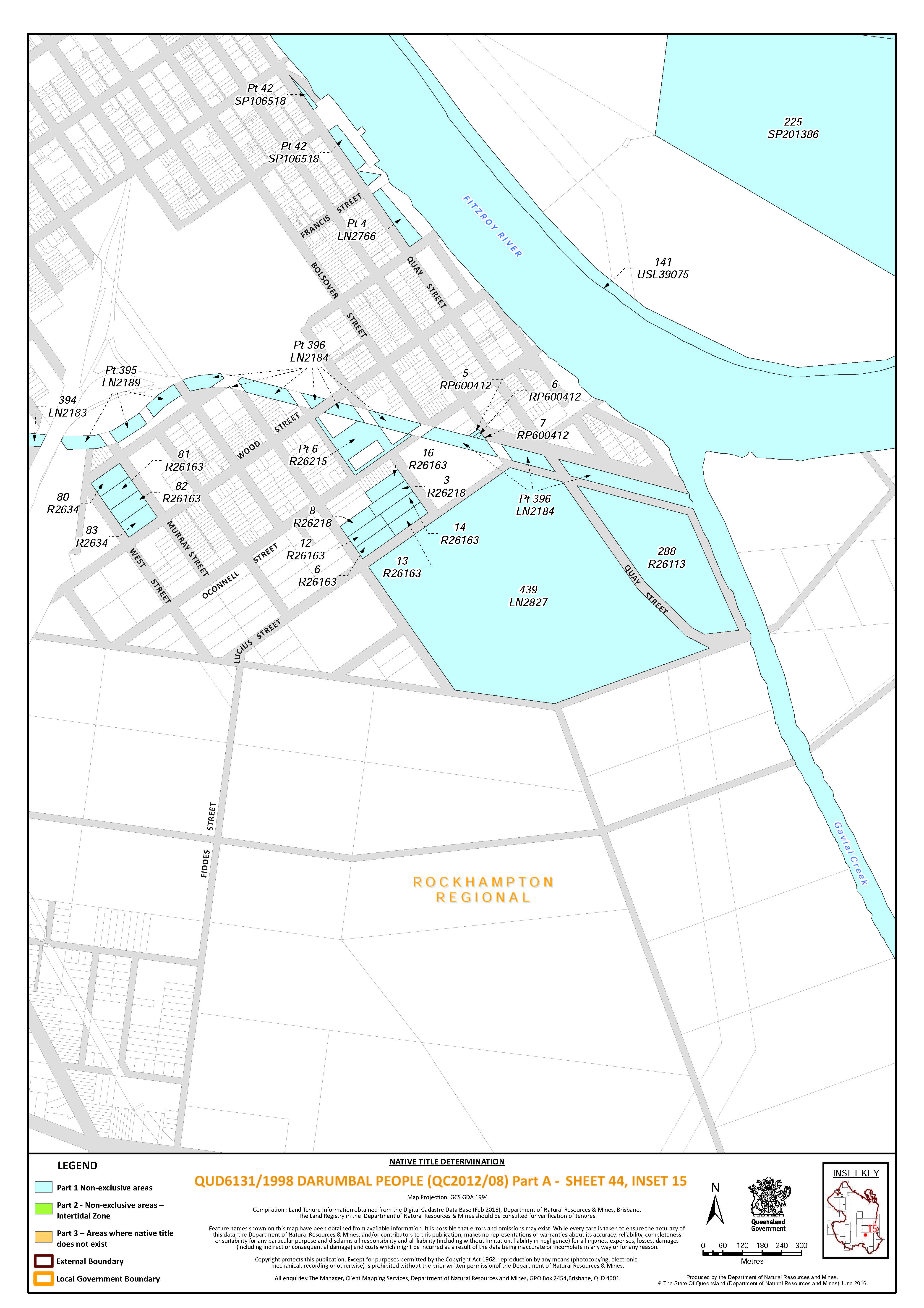

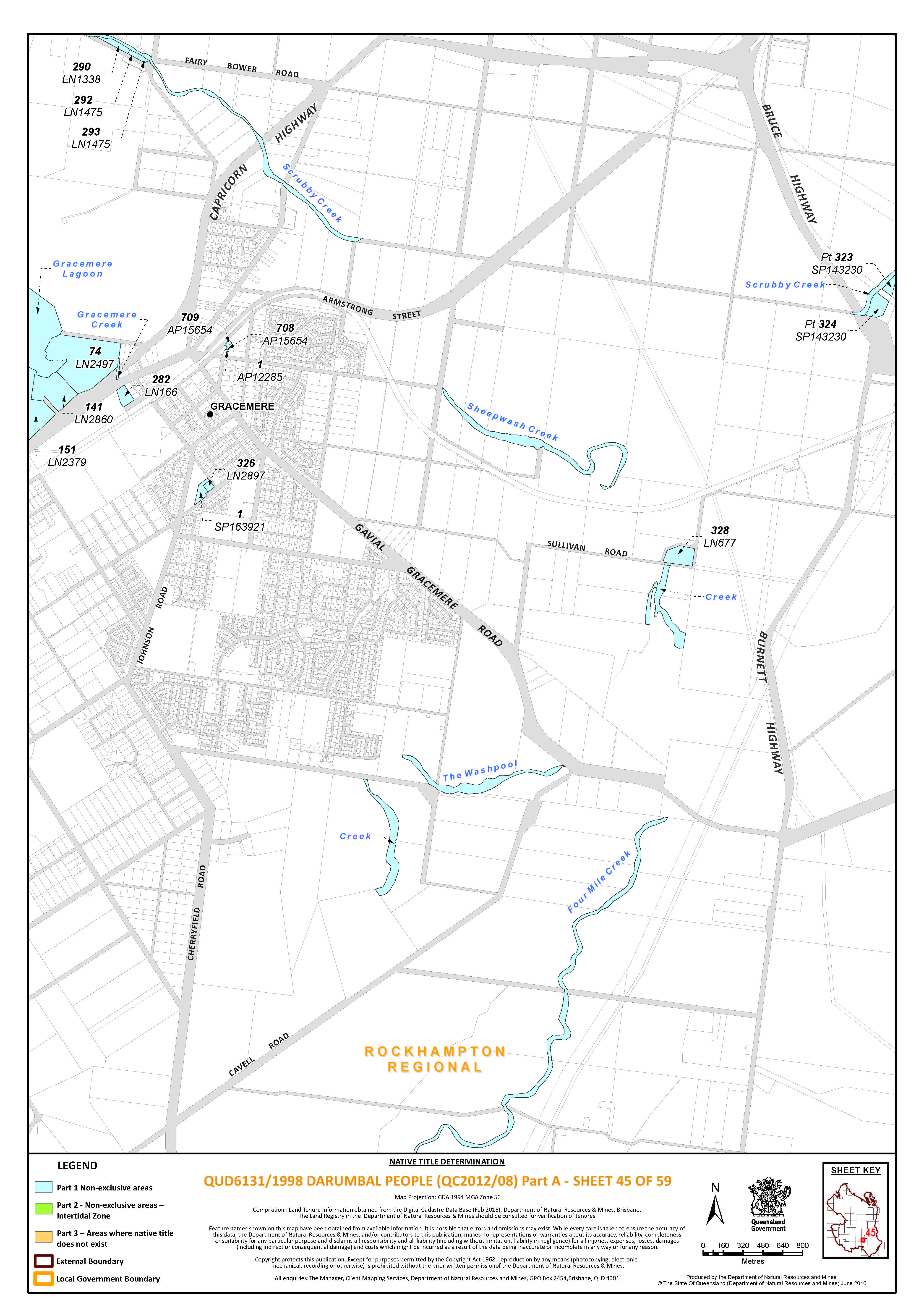

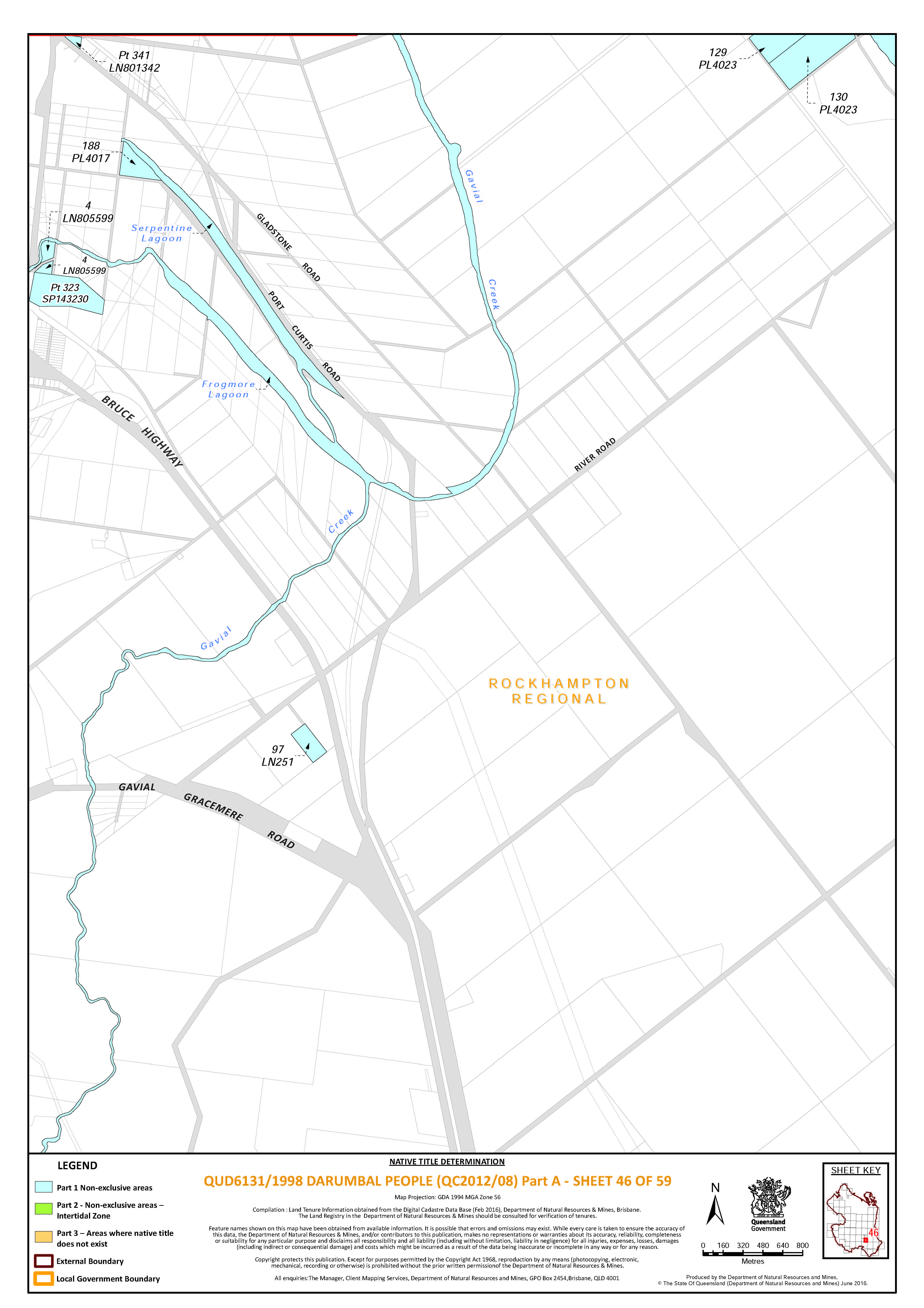

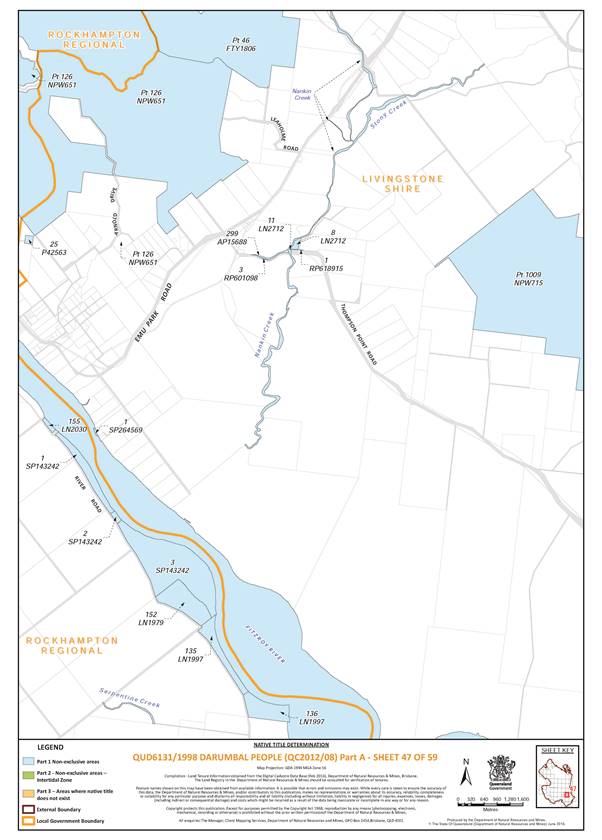

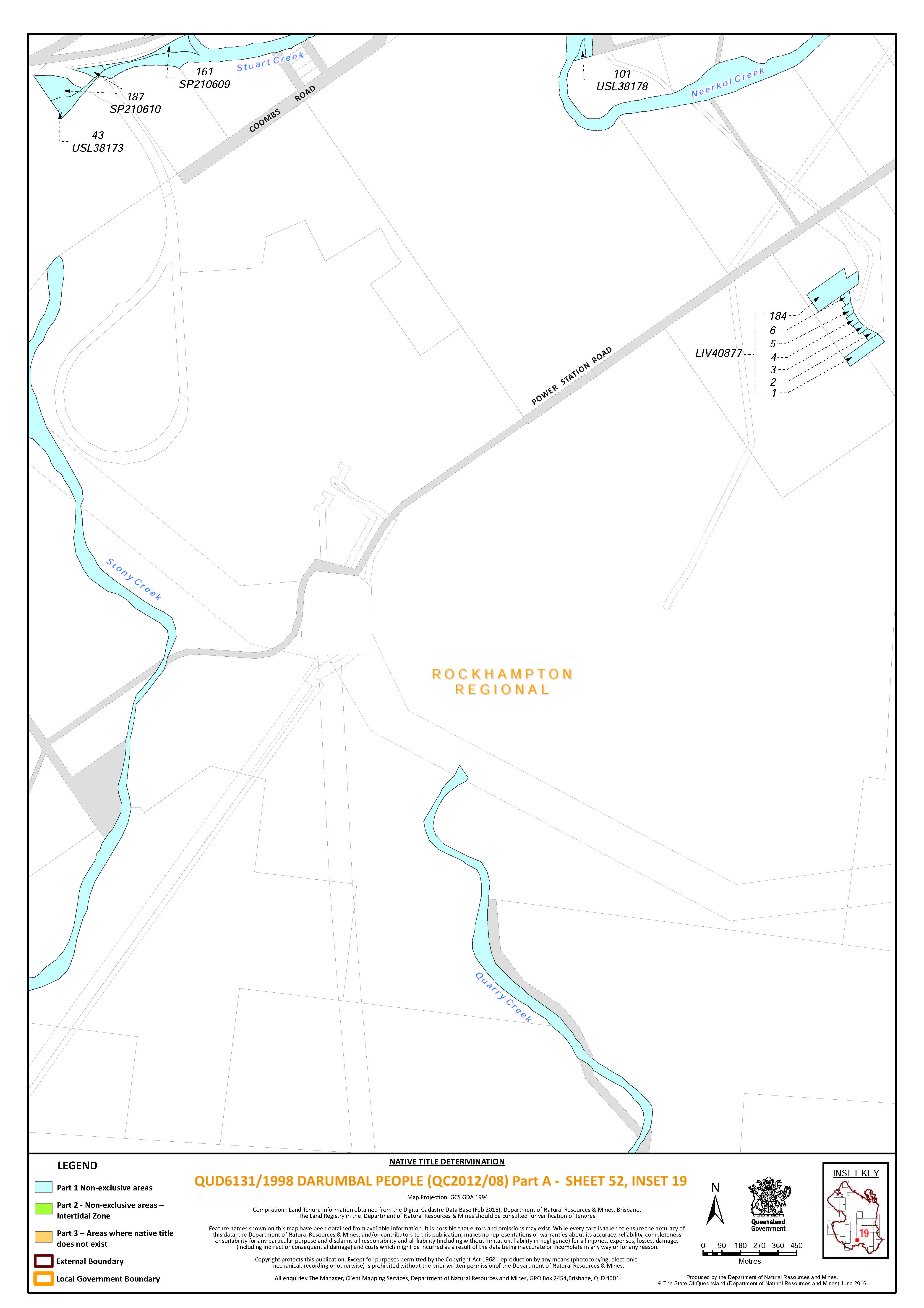

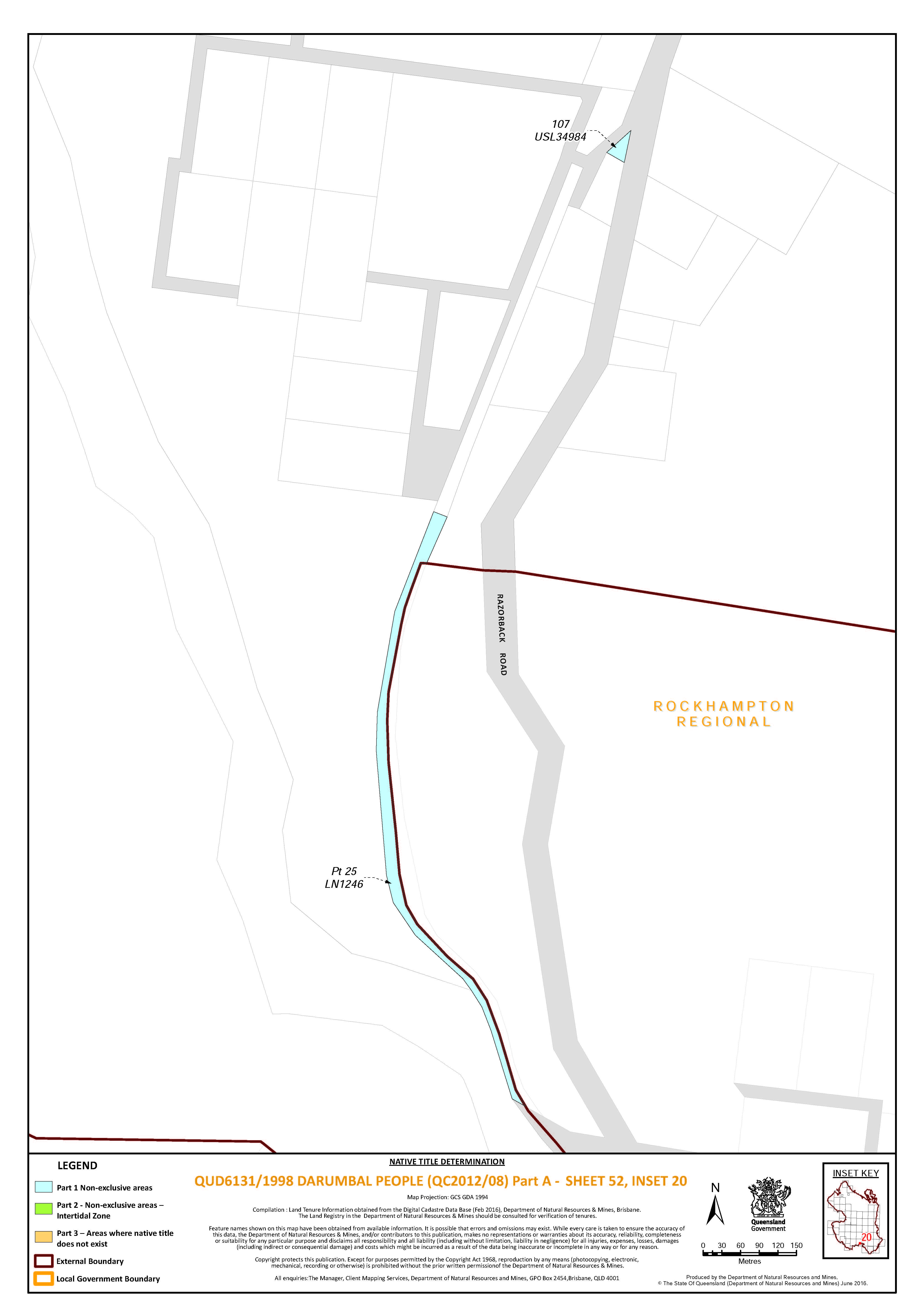

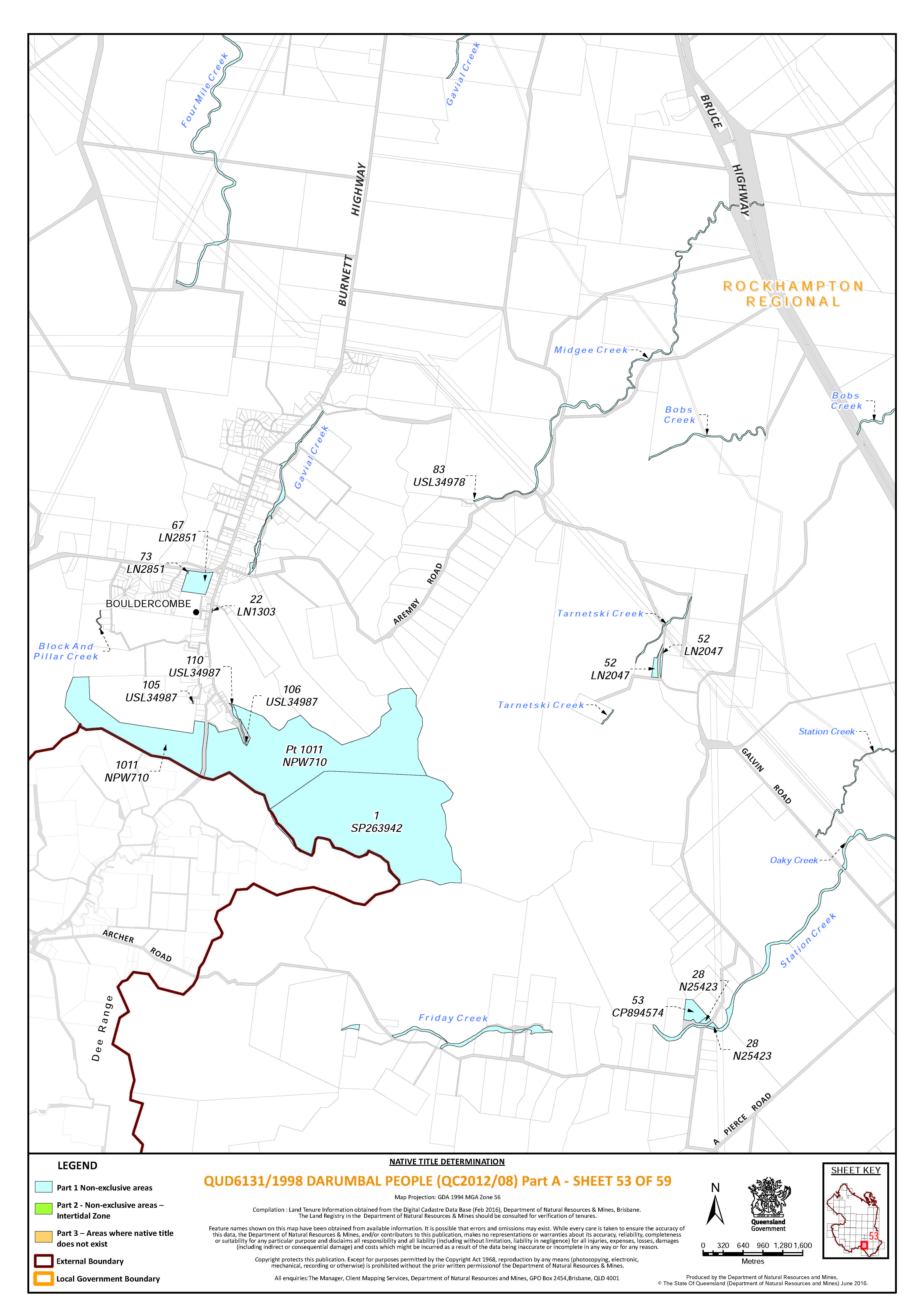

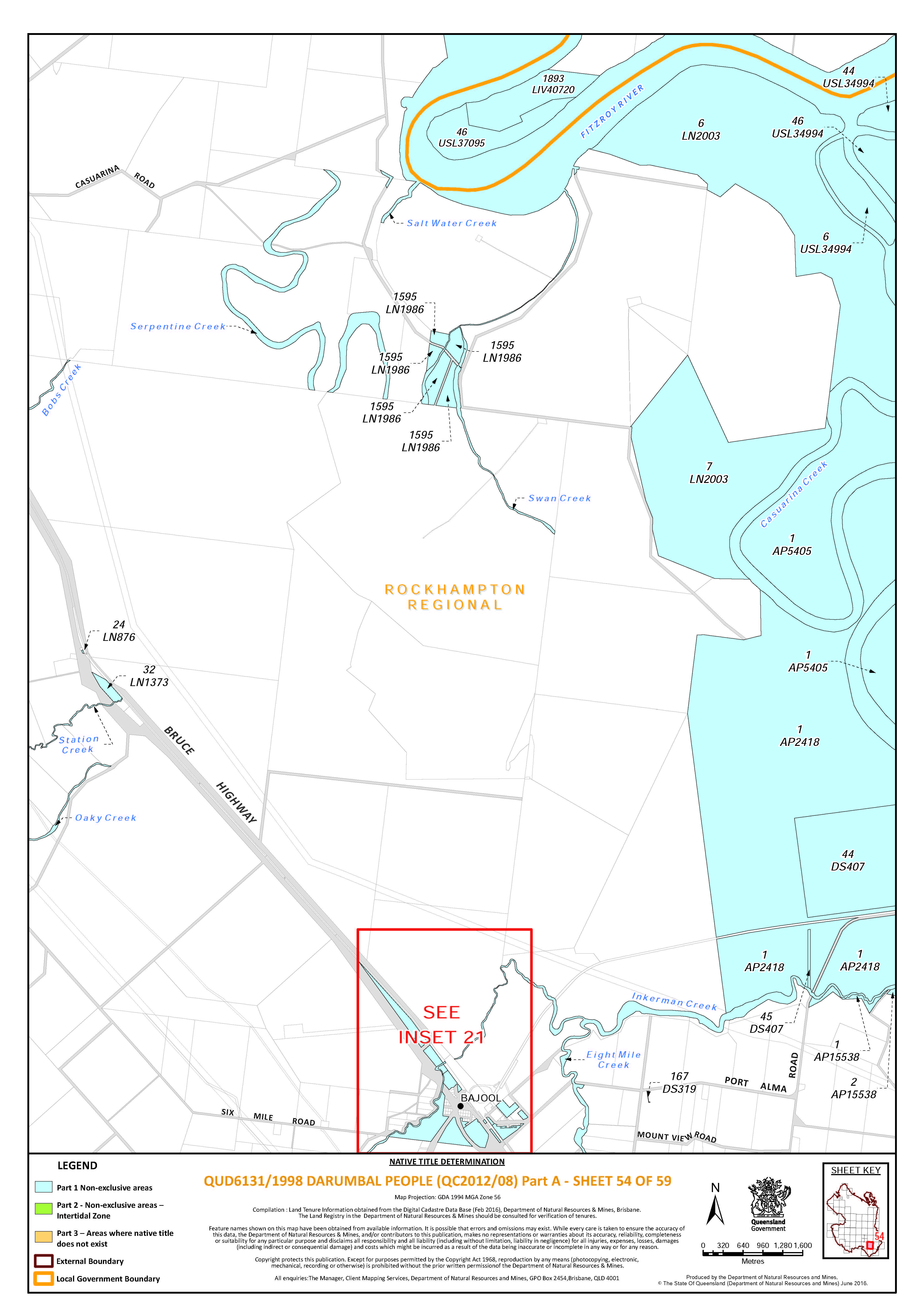

Schedule 1B - Map of Determination Area

COLLIER J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The applicant before me, collectively Alan Douglas Hatfield, Pauline Cora, Warren John Malone, Rodney William Mann, Amanda Meredith and Vanessa Ross on behalf of the Darumbal People, has applied for a determination of native title under subs 61(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Native Title Act) in respect of an area of land and waters along the central coast of Queensland in the region of the city of Rockhampton. The applicant relies on a second further amended application filed on 24 November 2015. Notwithstanding the relative recentness of this application, it is clear from the history of the native title claim of the Darumbal People that the procedural path to judgment has been lengthy and complex. It is unnecessary in my view to detail this history minutely – suffice to say that:

An application was lodged by the Darumbal people with the National Native Title Tribunal on 27 June 1997, and deemed to be filed in the Federal Court as at 30 September 1998. The original application covered approximately 52,380 square kilometres of land, off-shore waters and a number of islands. The application was accepted for registration on 5 July 2000 and notified on 22 August 2001.

A second application for a determination of native title was filed on behalf of the Darumbal People on 22 January 1999, and accepted for registration on or about 23 February 1999.

An area of land in the western part of the Darumbal claim area was the subject of competing assertions by another native title claim group, the Yetimarala People. Agreement was reached between the two claim groups as to the boundary area and as to shared country.

The two Darumbal applications were combined and conducted under file QUD 6131/1998 on 26 July 2012.

On 27 March 2013 the proceedings were split into Darumbal Part A and Part B, with Part B representing the area that is asserted to be shared Darumbal-Yetimarala country. Part B is now the subject of a wholly overlapping claim by the Barada Kabalbara Yetimarala People.

The Part A proceeding continued separately. The parties ultimately reached an in-principle agreement resolving all issues arising between them in relation to connection. The Court granted the applicant leave to file the second further amended application which accorded with the agreement reached by the parties, and which in particular refined the description of the native title claim group, the nature of the rights and interests claimed, and contracted the seaward extension of the external claim boundary to the intertidal zone.

2 It is the area in Darumbal Part A, identified following the in-principle agreement reached between the parties, in respect of which the applicant seeks a determination of native title (the determination area). I note that there is no material before the Court to indicate that the determination area is the subject of any previously approved native title determination.

3 On 14 June 2016 the applicant filed submissions in support of a minute of proposed consent determination. On the same date the applicant filed an agreement under s 87A of the Native Title Act, signed by all parties, in which the parties agreed to the making of attached orders by consent (the section 87A Agreement).

4 All parties to this application are legally represented with the exception of two individual respondents, Mr Hollier and Mr Brownlow. I note, however, that all parties including Mr Hollier and Mr Brownlow have signed the section 87A Agreement before the Court. I also understand that the State of Queensland and the Commonwealth of Australia were the only respondent parties which actively participated in the separate question of connection, and both respondents have at all times been legally represented by experienced lawyers.

SECTION 87A

5 Section 87A of the Native Title Act provides as follows:

Power of Federal Court to make determination for part of an area

Application

(1) This section applies if:

(a) there is a proceeding in relation to an application for a determination of native title; and

(b) at any stage of the proceeding after the end of the period specified in the notice given under section 66, agreement is reached on a proposed determination of native title in relation to an area (the determination area) included in the area covered by the application; and

(c) all of the following persons are parties to the agreement:

(i) the applicant;

(ii) each registered native title claimant in relation to any part of the determination area who is a party to the proceeding at the time the agreement is made;

(iv) each representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander body for any part of the determination area who is a party to the proceeding at the time the agreement is made;

(v) each person who holds an interest in relation to land or waters in any part of the determination area at the time the agreement is made, and who is a party to the proceeding at the time the agreement is made;

(vi) each person who claims to hold native title in relation to land or waters in the determination area and who is a party to the proceeding at the time the agreement is made;

(vii) the Commonwealth Minister, if the Commonwealth Minister is a party to the proceeding at the time the agreement is made or has intervened in the proceeding at any time before the agreement is made;

(viii) if any part of the determination area is within the jurisdictional limits of a State or Territory, the State or Territory Minister for the State or Territory if the State or Territory Minister is a party to the proceeding at the time the agreement is made;

(ix) any local government body for any part of the determination area who is a party to the proceeding at the time the agreement is made; and

(d) the terms of the proposed determination are in writing and signed by or on behalf of each of those parties.

Proposed determination may be filed with the Court

(2) A party to the agreement may file a copy of the terms of the proposed determination of native title with the Federal Court.

Certain parties to the proceeding to be given notice

(3) The Registrar of the Federal Court must give notice to the other parties to the proceeding that the proposed determination of native title has been filed with the Court.

Orders may be made

(4) The Court may make an order in, or consistent with, the terms of the proposed determination of native title without holding a hearing, or if a hearing has started, without completing the hearing, if the Court considers that:

(a) an order in, or consistent with, the terms of the proposed determination would be within its power; and

(b) it would be appropriate to do so.

Note: As the Court’s order involves making a determination of native title, the order needs to comply with section 94A (which deals with the requirements of native title determination orders).

(5) Without limiting subsection (4), if the Court makes an order under that subsection, the Court may also make an order under this subsection that gives effect to terms of the agreement that involve matters other than native title if the Court considers that:

(a) the order would be within its power; and

(b) it would be appropriate to do so.

(6) The jurisdiction conferred on the Court by this Act extends to making an order under subsection (5).

(7) The regulations may specify the kinds of matters other than native title that an order under subsection (5) may give effect to.

Objections

(8) In considering whether to make an order under subsection (4) or (5), the Court must take into account any objections made by the other parties to the proceedings.

Agreed statement of facts

(9) If some or all of the parties to the proceeding have reached agreement on a statement of facts, one of those parties may file a copy of the statement with the Court.

(10) Within 7 days after a statement of facts agreed to by some of the parties to the proceeding is filed, the Registrar of the Court must give notice to the other parties to the proceeding that the statement has been filed with the Court.

(11) In considering whether to make an order under subsection (4) or (5), the Court may accept a statement of facts that has been agreed to by some or all of the parties to the proceedings but only if those parties include:

(a) the applicant; and

(b) the party that the Court considers was the principal government respondent in relation to the proceedings at the time the agreement was reached.

(12) In considering whether to accept under subsection (11) a statement of facts agreed to by some of the parties to the proceedings, the Court must take into account any objections that are made by the other parties to the proceedings within 21 days after the notice is given under subsection (10).

6 The applicant submits, and I accept, that:

the Court has jurisdiction under either s 87 or 87A of the Native Title Act to make the order sought by the parties in relation to Part A without holding a hearing; but

where both sources of power are available, it is preferable to use s 87A because an order under that provision will give rise to other measures that will assist in promoting expeditious resolution of claims, including automatic amendment of the claim and exemption from the registration test being reapplied to the amended claim.

7 The applicant refers me to comments of McKerracher J in Smirke on behalf of the Jurruru People v State of Western Australia [2015] FCA 939 at [28]-[30]. I also note relevant statements in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Native Title Amendment Act 2007 (Cth) at [2.62], to which his Honour also refers.

8 In these circumstances, it follows that, in terms of s 87A, the Court needs to be satisfied that:

there is a proceeding in relation to an application for a determination of native title (s 87A(1)(a));

agreement has been reached on a proposed determination of native title in relation to an area included in the area covered by the application (s 87A(1)(b));

all relevant persons are parties to the agreement (s 87A(1)(c));

the terms of the proposed determination are in writing and signed by or on behalf of each of those parties (s 87A(1)(d));

it has power to make orders in, or consistent with, the minute of proposed consent determination of native title (s 87A(4)(a)); and

it is appropriate to make the orders sought by the parties (s 87A(4)(b)).

9 I am satisfied of all of these matters. I now turn to the broader question whether the orders proposed by the parties are within the power of the Court, and appropriate for the Court to make.

THE DETERMINATION AREA

10 Earlier in this judgment I briefly described the determination area. The section 87A Agreement describes the determination area in extensive detail. Part 4 of Schedule 1 of the section 87A Agreement identifies the external boundary of the determination area, and it is useful to set out this description, which is as follows:

Commencing at a point in Broad Sound at Longitude 149.784740° East, Latitude 22.395110° South and extending northerly along a line drawn to Longitude 149.873617° East, Latitude 22.039361° South to its intersection with the Low Water Mark; then generally south-easterly, generally north-easterly, again generally south-easterly and generally southerly along that Low Water Mark to Latitude 23.000000° South; then west to the High Water Mark; then generally southerly along that High Water Mark to Latitude 23.365037° South at Longitude 150.791624° East; then east to again the Low Water Mark; then again generally southerly along that Low Water Mark to its intersection with a line drawn between Longitude 151.282503° East, Latitude 23.080228° South and a point on the south eastern boundary of the Rockhampton Regional Council boundary at Longitude 150.875392° East, then south-westerly to that point; then generally south-westerly along that regional council boundary to a corner at Longitude 150.596570° East, Latitude 23.826429° South; then generally north-westerly along the ridgeline of Dee Range, further described as generally north-westerly along western boundaries of Lot 15 on USL34945, southern and western boundaries of Lot 186 on DS653, western boundaries of Lot 2 on USL34953, Lot 174 on DS475, Lot 4 on USL34953 and Lot 178 on DS534 to the north-western corner of that lot, being a point on the boundary of the former Mount Morgan Shire Council; then generally north-westerly, generally northerly and generally westerly along that former shire council boundary to the southernmost corner of Lot 120 on LN422, being a point on the boundary of the Rockhampton Regional Council; then generally westerly along boundaries of that regional council to a corner at Longitude 150.209131° East, Latitude 23.652751° South; then southerly to the centerline of Sandy Creek at Longitude 150.209130° East, then generally westerly and generally north-westerly along the centerline of that creek and the centerline of Gogango Creek to the centerline of the Fitzroy River; then generally westerly and generally south-westerly along the centerline of that river to its intersection with the centerline of Melaleuca Creek; then generally north-westerly along the centreline of that creek to its intersection with an unnamed tributary at Longitude 149.736249° East; then generally northerly and generally westerly along the centerline of that tributary to Longitude 149.719940° East, then north-easterly to the headwaters of again an unnamed tributary at Longitude 149.721750° East, Latitude 23.146380° South; then generally north-easterly along the centerline of that unnamed tributary and the centerline of Ten Mile Creek to Longitude 149.857870° East; then easterly to the centreline of the Fitzroy River at Longitude 149.880542° East and generally easterly along the centreline of that river to the centerline of Princhester Creek; then generally northerly along the centreline of that creek and the centerline of Four Mile Creek to Latitude 22.964422° South; then generally north-westerly passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude (East) | Latitude (South) |

150.060063 | 22.961660 |

150.059233 | 22.960414 |

150.058392 | 22.959567 |

150.056083 | 22.954114 |

150.053984 | 22.949499 |

150.052514 | 22.947191 |

150.046427 | 22.938801 |

150.043278 | 22.935235 |

150.039919 | 22.934816 |

150.036770 | 22.932928 |

150.034041 | 22.931879 |

150.030053 | 22.929991 |

150.023755 | 22.927054 |

Then westerly to again the centreline of Princhester Creek at Latitude 22.926040° South; then generally north-westerly along the centreline of that creek to an unnamed tributary at Latitude 22.894070° South; then generally north-westerly along the centreline of that tributary to its headwaters at Longitude 149.982867° East, Latitude 22.873790° South; then northerly to the northern boundary of the Bruce Highway (Kunwarara Road) at Longitude 149.978446° East; then generally westerly along boundaries of that highway to its intersection with the western boundary of Marlborough Road; then generally south-westerly along boundaries of that road to the eastern boundary of the western severance of Lot 90 on LI255; then generally south-westerly, westerly and generally north-westerly along boundaries of that severance to its north-western corner; then westerly to a point on the eastern boundary of an unnamed Road at Latitude 22.845050° South; then generally north-westerly along boundaries of that road and onwards to the northern boundary of the Bruce Highway (St Lawrence Road) at Latitude 22.813738° South; then generally north-westerly again along boundaries of that Highway to Latitude 22.760299° South; then north-westerly to a point on the eastern boundary of the North Coast Railway at Latitude 22.753842° South; then generally north-westerly along boundaries of that Railway, being eastern boundaries of Lot 411 and 412 on SP108287, Lot 450 on SP108288 and Lot 461 on SP108289 to Latitude 22.649590° South then westerly and north-westerly passing through Longitude 149.674918° East, Latitude 22.649507° South to a point on the eastern bank of Deep Creek at Latitude 22.648494° South; then generally westerly along banks of that creek to Longitude 149.670930° East; then southerly to the centreline of that creek at Longitude 149.670864° East; then generally north-westerly, generally northerly and generally north-easterly along the centerline of that creek, the centreline of Tooloombah Creek and the centreline of Styx River to Broad Sound; then north-easterly back to the commencement point.

The Determination Area also includes the land and waters subject to Girt Island landward of the High Water Mark.

To avoid any doubt, the Determination Area does not include any land or waters seaward of the Low Water Mark.

11 A pictorial representation of the determination area is annexed to the section 87A Agreement, and is set out immediately below:

12 The section 87A Agreement sets out areas not forming part of the determination area, as well as other interests in the determination area. I will return to these issues later in this judgment.

MATERIAL RELIED ON BY THE APPLICANT

13 The applicant relies primarily on affidavit evidence of members of the claim group, and an expert anthropologists’ report dated 15 August 2014 prepared by Dr Peter Blackwood and Professor Paul Memmott (followed by a supplementary expert anthropological report prepared by Dr Blackwood and Professor Memmott and filed 24 October 2014). I note that the evidence of members of the claim group relates primarily to their own personal experiences as Darumbal people, whereas the material prepared by the anthropologists is referable to a number of issues put to them by Queensland South Native Title Services (QSNTS), which represented the applicant. Those issues were:

a) As at 1788, did the ancestors of those people now known as Darumbal people constitute or belong to a body of persons united in and by its acknowledgement and observance of a body of laws and customs, particularly laws and customs governing the use and occupation of land and waters within the claim area (the “native title society”).

b) If so, describe the content of that body of law and customs, particularly in relation to the holding of rights and interests in land within the claim area, and how they could be transmitted.

c) Have the laws and customs of the pre-sovereignty society continued to be acknowledged and observed by members of each generation of that native title society and in particular by the descendants of the original indigenous inhabitants of the claim area, to the present time? If so, please explain whether, and if so how, the laws and customs have been transmitted from generation to generation.

d) Has there been any significant alteration to, or adaptation of, the acknowledgement and observance of the laws and customs of the native title society, and if so, what and how? Can the laws and customs presently acknowledged and observed nevertheless be described as substantially the same laws and customs as those acknowledged and observed by the members of the pre-sovereignty native title society?

THE NATIVE TITLE CLAIM GROUP

14 The native title claimants acknowledge themselves as collectively being the Darumbal People. In Schedule 3 to the section 87A Agreement they describe themselves as being those people:

(a) who are descendants of the following deceased persons:

(i) Brothers John McPherson or Harry Bauman;

(ii) Kate Reid and James Hector;

(iii) Clara McKenzie;

(iv) Jack Naylor (Jnr);

(v) Maria McKenzie;

(vi) Clara Wallace;

(vii) Mundabel;

(viii) Mary Jones

(ix) Maggie (Mitchell);

(x) Yorky; or

(xi) Kitty Mulway and Pompey of Stanage; and

(b) who are recognised by the living Darumbal People according to their traditional laws and customs as Darumbal People.

15 The anthropologists Dr Blackwood and Professor Memmott agreed that the claim group was comprised of persons descended from these apical ancestors. The report contains claim group genealogies referable to these apical ancestors, including indications of intermarriage between relevant claim group families. Dr Blackwood and Professor Memmott acknowledged that the genealogies presented in their report were based upon a review of previous research, particularly earlier work of Professor Memmott in 1994, that of anthropologists Seton & Hagen in 2009, and the outcomes of a large meeting of the claimants in July 2009 which considered the findings of the Seton & Hagen report. That earlier work was supplemented with additional data prepared by Dr Blackwood in 2012 and 2014. Interestingly, the anthropologists observe:

337. Because of intermarriages among some descent groups in earlier generations, there are many claimants who are able to trace descent through more than one Darumbal ancestor, and may therefore be members of more than one descent group. They may not, therefore, immediately identify as a member of a particular descent group, even though they appear on genealogies for that group, because they have grown up regarding their Darumbal identity as deriving from the parent or grandparent who belongs to another descent group …

…

339. Because the genealogies of many of the descent groups have a time depth that has been reconstructed from documentary sources, they extend back to apical ancestors whose identity may only be known from these sources, and therefore may not be readily known to all claimants today. Certainly they are generally not known from what has been passed down to claimants orally and even where they have come to know about these ancestors from their own research and/or earlier anthropology reports, sometimes names and other details may have slipped from emmory. For this reason we have endeavoured to list as apical ancestors those individuals who are the most widely known among claimants today as forebears of the particular group. These may be of a more recent generation than the ‘ultimate’ apical ancestors who establish genealogical connection back to the time of European settlement and who appear on the genealogies …

16 Further, and more specifically, the anthropologists noted (in summary):

While there was some evidence that John McPherson and Harry Baumann may originally have had primary connections with areas and groups to the west of Darumbal country, it is clear that the descendants of both men considered them (and themselves) Darumbal, that they were associated with Darumbal people (for example, the wife of John McPherson, Minnie, was a Darumbal woman, being the daughter of apicals Kate Reid and James Hector), and other Darumbal people knew and regarded them as Darumbal men. Accordingly, it was appropriate that John McPherson and Harry Baumann be named as apical ancestors for the purposes of the claim.

It is clear that Kate Reid and James Hector were Darumbal ancestors, as were their children Nellie Hector, Alf Hector and Minnie Hector.

While Seton & Hagen expressed doubt as to whether Clara McKenzie was a Darumbal woman, Dr Blackwood and Professor Memmott considered decisive the understanding of her descendants that she was Darumbal. Certainly there was evidence from anthropological records of Norman Tindale that Clara McKenzie was born a “fullblood Darumbal of Rockhampton district”. Members of the claim group accept that Clara McKenzie was Darumbal, as are her descendants.

Jack Naylor Jnr’s identity as Darumbal was recorded by Norman Tindale, and the anthropologists consider that he was Darumbal, in particular through his mother.

While there was some suggestion that Maria McKenzie was a member of the family of Kate Reid and James Hector, nonetheless Seton & Hagen suggested that Maria McKenzie be listed as a separate apical. The anthropologists accepted her as Darumbal on the basis of her birth place, Westwood, being in the claim area, and the fact that her descendants were accepted as being part of the contemporary Darumbal community.

Despite sharing a surname, the anthropologists were satisfied that Clara Hector was not related to Katie Reid and James Hector. However she was born in the Marlborough area, spent all her life in the claim area, and was known to her descendants as having been a Darumbal woman. Her descendants have continued to live in the district and are active in Darumbal affairs.

Relevantly, Mundabel appeared in newspaper reports and official correspondence in the early 1900s as “a native of Rockhampton”. He is accepted as a Darumbal man by the claim group.

Mary Jones was associated with Mt Morgan, Rockhampton and Gracemere. The claim group accepts her as a Darumbal woman.

Seton & Hagen concluded that Maggie (Mitchell) was a Darumbal woman, probably born in the 1860s or early 1870s.

Yorkie appeared in press reports of the late 1800s as a “native of Rockhampton”, and was identified by Tindale as a Darumbal man. He is accepted by claimants as a Darumbal apical, although there was some discussion regarding those who might claim Darumbal identity through him because they were descended from his social rather than biological daughter. The anthropologists noted however that members of those families who claim descent from Yorkie accept social parenthood as a legitimate traditional form of filiation and descent through which full Darumbal rights and interests may be passed on.

The anthropologists noted the identification by Seton & Hagen of Kitty Mulway and Pompey of Stanage as Darumbal ancestors. Kitty Mulway was identified as a “full blood of Torilla Station”. Sunny, the daughter of Kitty Mulway and Pompey of Stanage, was an important Darumbal person born in the 1870s and was widely known in the Darumbal community.

17 Significantly, the anthropologists also noted that social parenthood was broadly accepted among the Darumbal people, and formed a legitimate and licit basis for filiation and the descent of native title rights and interests. In making this observation, the anthropologists also had regard to statements of members of the claim group including Trevor Hatfield, Vanessa Ross, Billy Mann, Nikki Hatfield and Doug Hatfield.

HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY

18 In their report Dr Blackwood and Professor Memmott describe, in detail, the occupation and use of the claim area by indigenous people from circa 5200BP (“Before Present”). It is instructive to note highlights of this research.

Pre-colonial occupancy of the claim area

19 Between 25 and 31 May 1770 Captain James Cook in the Endeavour sailed the coast from Curtis Island, through the inner coastal islands of the claim area and on past Cape Palmerston to north of the claim area. Captain Cook and his crew did not make contact with the people living in the area, however they observed signs of occupancy including smoke, fireplaces, remnants of cooked meals, and burnt country.

20 Archaeological surveys revealed, inter alia, sites dated around 5200BP, 3250BP and 2510 BP, including middens, fish traps, ceremonial sites and other evidence of occupation.

21 Explorer Matthew Flinders made expeditions in August and September 1802 along the central coast of Queensland. It is likely that members of his crew were the first Europeans to make contact with Aboriginal people in the claim area. Flinders himself recorded seeing Aboriginal people in a canoe, and evidence of their use of the land including remnants of meals and fireplaces.

22 Captain Phillip King anchored at Port Clinton in the claim area in 1820, and had a friendly encounter with two Aboriginal men. A less friendly encounter occurred in July 1820 between members of King’s crew and indigenous people. Similarly in 1843 Captain Price Blackwood and his crew in the Fly anchoring in Port Clinton observed a small hut and a man’s step in the sand leading to it. Subsequently Blackwood’s party had extended contact with a group of over 20 local men and boys who approached the mariners’ boat and shore camp. These men and boys had spears, fishing nets and baskets.

23 A violent incident took place in 1854-55 on Percy Island involving the deaths of both Aboriginal people and the party of a botanist, Walter Hill.

24 Dr Blackwood and Professor Memmott observe:

69. These maritime contacts and observations record Aboriginal people on the islands of the claim in the months of March, June, August and September, and from October through to January, from which it has been inferred that the islands were in year-round use by groups from the neighbouring mainland, a pattern of use which is distinctive for this region compared with southern Australia, where island use tends to be seasonal, targeted towards specific resources and limited to islands requiring much shorter sea crossings … These observations are consistent with the archaeological record reviewed in the first part of this chapter.

European settlement

25 The first Europeans to venture by land into the claim area were pastoralists Charles and William Archer in August 1853. In January 1854 the pastoral district of Port Curtis was proclaimed by the New South Wales Government, substantially encompassing the claim area. The Archer brothers returned to the Fitzroy River in August 1855 and took up Gracemere Station. According to a descendant of the brothers, the lake near the station site contained “evidence of extensive pre-settlement Aboriginal use and occupancy in the form of summer and winter campsites, and associated material cultural items such as grindstones” (paragraph 85 of the expert report).

26 As the anthropologists note, news of good pastoral country on the Fitzroy river quickly spread, and within five years almost the whole of the mainland portion of the claim area west of a line from Rockhampton north to Broad Sound had been taken up and was operating as pastoral runs, and what was to become the urban area of Rockhampton. A gold rush in the Rockhampton area in the late 1850s brought thousands of people into the area, and in 1860 the Municipality of Rockhampton was declared.

27 While the initial contact with Europeans could be described as amicable curiosity and guarded acceptance on the part of the indigenous people of the claim area, as the anthropologists noted this rapidly changed to resistance to the new settlers, resulting in hostility from the indigenous people and murderous reprisals by the Native Mounted Police and station people. Certainly, it appears that the original white settlers considered themselves “at war” with the local indigenous people, while it appears equally that the indigenous people considered the settlers invaders who had unceremoniously invaded the territory of the indigenous people and claimed it as their own. The anthropologists detail numerous incidents of hostile interaction between settlers and the indigenous people, in which deaths occurred on both sides.

28 Dr Blackwood and Professor Memmott refer to evidence that during the late 1850s, the 1860s and the 1870s indigenous people were present in large numbers throughout the district. One example is a letter published in the “Rockhampton Bulletin” in 1864 referring to a camp of nearly 200 Aborigines at Woodend in Rockhampton. There was also a policy adopted by some of the pastoralists of “letting in” – namely not objecting to the presence of Aboriginal people whom the pastoralists considered “belonged” to the country occupied by the station.

29 By the mid-1870s indigenous people in the region had been largely incorporated into the pastoral economy, either as servants or living on the fringes of stations. The anthropologists observed that this was the beginning of a long period of “dual occupancy” during which Aborigines were permitted by the leaseholders to continue to live on and use their traditional lands, while providing local knowledge and labour to the stations. The anthropologists noted:

119. Up until at least the early 1880s local coastal groups and the marine economy, including the use of sea-going canoes, were still intact. Both Flowers and Lumholtz witnessed dugong hunts from traditional bark canoes and using traditional harpoons in Shoalwater Bay during 1878/9 and 1881 …

30 Similarly, there are records of large scale hunts by local indigenous people.

31 In the early 1860s semi-sedentary station camps were being established, which by the 1890s were the dominant form of Aboriginal residence in the area. The Yaamba station camp was described as the tribe’s “main camp”, as well as other camps in and around Rockhampton.

Post-settlement until 1950

32 The anthropologists discuss in detail the period following European settlement. They note that the decade 1934-1945 was critical to current views of the continuity of native title in the region, because Darumbal people alive at that time who provided information to contemporary anthropologists “bridged the gap” between the generation born before the arrival of Europeans and the senior generation of the descendants today. A limitation on this information is that, in some cases, the information was provided by indigenous people from the region who had been removed to Cherbourg and Woorabinda (for example, Sunny Sunflower), namely away from their country and daily contact with countrymen and relatives remaining in the claim area. At the same time, as the anthropologists note there had been a steep decline in the original population of the claim area – possibly up to around 90% by 1898 compared with the population at the time of sovereignty – arising from conflicts, disease, and removal. Further decline into the twentieth century caused by disease and poverty depleted the existing indigenous population.

33 The anthropologists note that:

509. The local response to this decline and to the loss of country which accompanied it, was for Aboriginals from throughout the region to congregate in semi-permanent camps on friendly stations, and in and around towns; and in our view, to activate wider regional social capital networks to facilitate social interaction, marriage prospects and maintenance of traditional laws and customs

34 Certainly a number of apical ancestors – for example Mundabel, Yorkie and John McPherson – were resident in these camps at various times.

35 Further, the anthropologists note that the Darumbal people who were removed to Cherbourg continued to retain their identity and retained knowledge of their origins; that kinship, section and totemic systems continued to be in use as the basis for reckoning identities, relationships and marriage preferences at Cherbourg; and that a number of people who had been removed managed to return to the claim area.

1950 until the present day

36 The anthropologists note the ongoing “sense of community” underwritten by real social relations among the families who can trace descent from apical ancestors, who in turn were part of the native title society for the claim area at or soon after the arrival of the first European settlers in the late 1850s. In summary, I note that these social relationships continued in the form of:

such descendants of the old dialect tribes remaining on country in semi-sedentary stations and town camps, maintaining inter-familial connections through, inter alia, visiting and annual walkabout;

off-country knowledge was conserved among those who had been removed to Barambah/Cherbourg and whose descendants continued to live there into the 1950s and 1960s;

consolidation of a residential base of Darumbal people in Rockhampton from 1950 until the present day. The anthropologists profiled seven Darumbal households in Rockhampton in the period 1940-1970 which regularly hosted other Darumbal people, in particular the household of Douglas and Nancy McPherson (and later their daughter Irene Hatfield) in Quay Street Rockhampton.

Society and laws

37 The anthropologists noted that tribes within the claim area appeared to be autonomous, socio-political and territory-owning groups with their own languages. They note further that historically the Darumbal language was distinguishable from that of other groups in the region, although closely related to Kuinmurrburra and Warrabal dialects.

38 Earlier anthropological research, accepted by Dr Blackwood and Professor Memmott, found that there was a fluidity of movement and interdependency throughout the region involving networks of economic, ritual and marriage relations, as well as regional governance through formalised mechanisms of inter-tribal dispute resolution (at [230]). In their report they observe:

232. As well as identifying each tribe’s ‘main camp’ Roth also described the ‘walkabouts of several. Kuinmurburra, for example, “owned the coast country” as described above, of which Torilla was the head camp, from where they “would travel down the coast to Emu Park and inland to Yaamba and Rockhampton” (Roth 1898:6). Yeppoon was known as a meeting place where the tribes from Torilla (Kuinburrburra), Rockhampton (Tarumbal), Yamba (Warrabal) and Mt HJedlow (an extinct Tarumbal sub-tribe) “would exchange courtesies” with each other (Roth 1898:3, 5)

233. These walkabouts do not define areas of territorial interests, but essentially networks of inter-tribal communication, based around trade and ceremonial activities (see, e.g. Winterbotham 1982:72) …

234. These ‘walkabouts’ involved not only trade, but also large intertribal gatherings, ceremony and dispute resolution such as through duelling …

39 This did not mean that there was a single, bounded regional society in the anthropological sense between the people of the claim area – it did mean however that the people there were:

329. … with respect to their interests in land … united in and by their common acknowledgement and observance of a body of law and custom which defined and regulated interests in the land throughout the region and could thus be said to comprise a native title society.

40 That body of law and custom was summarised by the anthropologists as follows:

330. At the time of European settlement the essential laws of possession of land for Tarumbal, Warrabal, Kuinmurrburra and Ningebal who occupied the greater part of the claim area, and of the neighbouring Yettimaralla and Urambal whose country may have also extended into the claim area… were three-fold. Firstly, the laws set out in the myths of their shared cosmology, and made visible and enduring in the landscape as specific sites associated with the beings and events recounted in the stories, by which the land was populated by man and species and enculturated with language, sites and ritual, and which bequeath these creations to a particular group of people who thenceforth hold them as their own. Secondly, land was held collectively by groups, almost certainly these were primarily the language ‘main tribes’ described by Flowers and Roth, but it is likely the local ‘burra’ groups also held rights to localised clan estates. Thirdly, the laws of filiation by which membership of the groups and their sub-divisions, and inheritance of rights and interests in land, passed from generation to generation, and validated anew for each generation the group’s possession of its territory, its sites, its rites and its language. While there is not sufficient description in the early sources to be able to describe the system of laws and customs in specific detail, there is, in our opinion, sufficient to be able to say that the Aboriginal people living on the claim area at the time of first settlement, and by inference at sovereignty, had a system of law and custom relating to the possession of land, that this system had at its heart these three sources of law (i.e. mystical charter, group ownership and filiation), and that such a system is comparable with those that are known in greater detail for other similar groups in northern Australia.

41 Other important and ongoing social aspects of Darumbal society include:

respect for country and the spirits in it;

respect for elders and ancestors;

marriage laws, including not marrying someone from the same totem, or family;

collective ownership of land rather than individual members;

the requirement that non-Darumbal people seek permission to come on to country, and pay respects to the old people and spirits of the country;

smoking rituals, being a means of cleansing and protection from the spirits of the dead and bad spirits;

totems, being an affiliation of a person to another species (for example green frogs and eaglehawks). The anthropologists noted that totemic affiliation continues to be an important part of Darumbal society, and that Darumbal society had a system of matrilineal moiety totemism;

the importance of burial on country;

avoidance of certain places (for example, women avoiding traditional men-only sites).

42 As the anthropologists concluded:

921. We find that there is plentiful evidence of the continuing practice by Darumbal people today of the three key laws identified in Chapter 6, namely the fundamental role of the stories, beliefs and sites of the mythological era in anchoring people to country and validating their connection; the role of filiation and descent in determining a person’s group identity and their rights and interests in country; and the fact that while a person’s connection to country may be very personal (for example, through connection to particular Old People), their rights and interests are held collectively with other Darumbal People. The rule of filiation, in particular, establishes the threat of continuity which ties Darumbal people today to ancestors who occupied and used the country comprising the claim area from around the time of first settlement and earlier. This thread of connection is also evident in beliefs about the continuing spiritual presence of Old People in the country, which links people today to the creative forces of the mythological era, and as such to the creation of the Aboriginal world itself, with all its species, technology, languages, human groups and natural phenomena …

922. As well as those laws and customs which in our model confer and regulate rights and interests in land, we have also found that there are a range of other laws and customs which have persisted, including totemism and its role in marriage, kinship behaviours, decision making and authority structures, respect for elders and transmission of knowledge …

CONTINUITY

Genealogical continuity of Darumbal native title holders

43 In their report the anthropologists refer in detail to continuity of engagement with the determination area by descendants of Darumbal apical ancestors. In particular I note the following statement in the report:

441. … Looking back over this history, what can be seen is that the threads of descent through filiation which define the membership of the claim group have persisted like an unbroken cable, anchoring successive generations to the country of their forebears, even where these have been removed from the country for several generations. Swirling around this cable of connection have been dramatic changes wrought by colonisation, including near catastrophic demographic and economic disruption, which have required dynamic adjustments in social organisation and identity in order to conserve as much as possible of the old order of things. Thus while there have been transformations over time in the structure and identity of the primary traditional land holding groups, including by succession and by the ‘re-branding’ of affiliation group identities, the group of native title holders for the claim area has remained stable throughout this period. by historical and anthropological research we are able to show that to a great extent the members of the Darumbal native title claim group today are descended from forebears who were born within the claim area or at known locations in its proximity, around the time of the first European settlement. This research confirms the emic model put forward by the claimants themselves, which is based upon what they have been told by close kin in their parental and grandparental generations, and which they in turn now pass down to their children and grandchildren.

(emphasis added.)

44 Later in the report, and in my view importantly, the anthropologists identify critical continuities as including:

635. a) Physical connection with the claim area through several generations within those descent groups whose members have remained substantially on country, residing in home-based camps on stations and in towns.

b) Centres of transmission of traditional knowledge and identity, both on-country in the station and town camps, and among diaspora families living in regionally organised camps on government settlements. There were a number of key individuals who are today remembered as having played pivotal roles in the transmission of knowledge, identity and connection to country. A number of members of the senior generation of today’s claimants can recall some of these individuals as being grandparents who were actively involved in their upbringing as children, and from whom they learnt about their Aboriginal identity and connection to country, as well as practical bush skills for living from and caring for the country.

c) Social connection among families within the home-based community through visitation between camps, such as during the annual lay-off walkabouts and movement between stations for work purposes.

d) Social connection between the home-based and diaspora communities by visitation and work release on to stations in the region.

e) Demonstrated genealogical continuity between individuals who are named in written sources from the late 19th century as members of the Aboriginal society in the claim area at that time and who would have been born prior to or around the time of first settlement, through their descendants named in sources from the mid 20th century, to members of the contemporary claim group who are known descendants.

f) Corroborees continuing to be performed by senior Darumbal men into at least the 1940s.

g) Other ritual practices, such as smoking houses following a person’s death were also being practiced in this period, such as those reported being performed by Sunny Sunflower in the 1950s among diaspora families living on Cherbourg.

45 The anthropologists also conclude:

636. In summary, the historical pattern for this period shows a simultaneous maintenance of a continuous presence on traditional country by various members of the claimant descent groups, who we refer to as the home based community, as well as a social interaction of these people to those other various members of the claimant descent group who were moved off country.

Continuity of connection, law and custom within the Darumbal native title group

46 The anthropologists state that, based primarily on the data in claimant affidavits, interviews and earlier anthropological research, they are satisfied that myths and sacred histories continue to be the basis of Darumbal traditional ownership of the claim area and of the native title rights interests of the group. Aspects of these beliefs include the following:

there is some evidence that among Darumbal people there is a belief in a supreme or pre-eminent creator;

there are marks left on the land by ancestral beings from the Dreamtime, including:

o the whale, which forms clouds by surfacing to expel air;

o Moonda-ngutta the Rainbow Serpent, a spiritual being which dwells in the waterways and deepest waterholes of the Fitzroy River and other river systems in Darumbal country, and whose actions cause floods;

o Moon and the Seven Sisters, a story linked to locations around Torilla;

o Koala and Kangaroo, and the story of how the koala lost its tail;

o Gai-i and Baga, two men who fought over a Darumbal girl, and who turned into local mountains Mt Wheeler and Mt Crow.

47 The anthropologists were also satisfied of historical and continuing activities of Darumbal people in the determination area, including:

hunting, fishing and gathering activities;

camping, and erecting shelters and other structures in the area;

access, being present on, moving about on and travelling over the claim area. The anthropologists note that archaeological records demonstrate the presence of Aboriginal people on the islands and coastal parts of the claim area for thousands of years;

exclusive possession of the land, allied with responsibilities and obligations associated with the land;

using, sharing and exchanging natural resources from the claim area, including fish, game or manufactured items such as weapons, baskets and fishing gear;

taking and using water of the claim area;

observation of ritual actions associated with spiritual presences and powers in the land, including calling out to spirits, smoking and welcome to country;

burial of deceased Darumbal people within the claim area;

maintenance of places of importance and areas of significance;

teaching on the claim area about the physical and spiritual attributes of the area;

holding meetings on the claim area;

lighting fires on the claim area for domestic purposes but not for the purpose of hunting or clearing vegetation;

caring for country and managing its resources, including speaking for country;

controlling access of non-Darumbal people on to country, and ensuring their well-being.

EXPERT REPORT OF DR DALLEY AND DR MORTON

48 I note that there is also filed in these proceedings an expert anthropologists’ report prepared by Dr Cameo Dalley and Dr John Morton dated September 2014. While ultimately the parties did not rely on the expert report of Dr Dalley and Dr Morton (which had been prepared for the State of Queensland), it is appropriate to note this report and the obviously extensive work undertaken by the authors in its preparation. Indeed I note that there was significant agreement between all anthropologists in respect of the existence of native title rights and interests in the claim area.

AFFIDAVITS FILED IN SUPPORT OF THE AMENDED APPLICATION

49 Affidavits in support of the application have been affirmed or sworn by the following witnesses:

Alan Douglas Hatfield, affirmed 10 June 2014;

Kristina Ann Hatfield, affirmed 5 June 2014;

Warren John Malone, affirmed 3 June 2014;

Vanessa Ruth Ross, affirmed 4 June 2014;

Trevor Leslie Hatfield, affirmed 4 June 2014;

Tosie William Cora, affirmed 4 June 2014;

Tanya Maree Mitchell, affirmed 1 June 2014;

Selena Michele Edmund, affirmed 3 June 2014;

Rodney William Mann, affirmed 2 June 2014;

Pauline Joyce Cora, affirmed 4 June 2014;

Pamela Meredith, affirmed 11 June 2014;

Nyoka Myra Hatfield, affirmed 3 June 2014;

Naticia Carleigh Jeanine Meredith, affirmed 10 June 2014;

Roeina Sarah Vea Vea, sworn 10 June 2014;

Barry John Mann, affirmed 4 June 2014;

Cepha Maria Roma, affirmed 12 June 2014;

Malcolm Lyle Mann, affirmed 5 June 2014;

Amanda Melanie Meredith, affirmed 23 June 2014.

50 Each of these affidavits sets out evidence of the connection of claim group members to Darumbal country, and refers to their identification as members of the Darumbal people. The affidavits are detailed and moving, and illustrative of claim members’ strong relationship with Darumbal culture and the determination area. The witnesses give evidence as to the boundaries of Darumbal country and in many cases teachings which they learned from elders and family members (including traditional stories and rules, sacred places and totems). I have extracted some of this evidence and set it out below.

Mr Alan Douglas Hatfield

51 Mr Hatfield deposed that he is Darumbal through his mother and grew up in Rockhampton. He stated that growing up his family would teach him about Darumbal heritage and culture through stories. In relation to boundaries, Mr Hatfield said:

73. My parents and grandparents never drew a line on a map and told me this was the boundary of our country. However, my parents, grandparents, great aunts and uncles always taught us kids who our people were and where they were from so I always had a general idea of the boundaries. For example, Mum told me about how Great grandmother Minnie used to walk and camp all around in the Shoalwater Bay area and even out as far as Torilla. Sonny Sunflower was from that way and his family were closely related to the McPhersons. I understood those connections and I knew where people were from so I understood what area was part of our country. I hadn’t actually been to the Shoalwater Bay area before the inquiry because it had been a defence area and closed off since about 1965. But I had grown up hearing the old people talking about these places. For example, my grandfather’s brother, Henry McPherson, used to live on Raspberry Creek Station and he would talk about that country when he came and stayed with my family at Quay Street.

74. Many of our old people who stayed at Quay Street would talk about different places and say that is “my country”. It was through hearing those stories and knowing who my family was connected to and where they were from that I had an understanding of the extent of Darumbal country. I grew up hearing about my old people being at Craiglea Station, Princhester Station, Kunwarara, Redrock, Glen Geddes, and lots of other places in the claim area. My parents and Nanna McPherson would refer to someone as their “countrymen” when they came from places in the Rockhampton area like Yaamba or Shoalwater Bay.

Ms Katrina Hatfield

52 Ms Hatfield is Darumbal through her father’s side, through her great-grandmother. She said that her family has lived in Rockhampton for many generations and that they continue to live in Rockhampton. She recounts many teachings of her family, such as the following:

16. I was always taken out into the bush with Mum and Dad (Trevor Hatfield) and Uncle Tosie (my mother’s brother, Tosie Cora). We used to go fishing and we were taught how to keep track of the time and watch the country so that we would not get stuck by the tide. I was taught to use the shadows of the trees to tell the time. We could tell when the tide was coming in or going out. My family goes up to Freshwater Bay in Shoalwater Bay. There is a little island off Freshwater Beach which you can walk when the tide is out. It is about a 30 – 50 metre walk. In about 1988 or 1989 my brothers got stuck on that little island because they were too busy fishing and weren’t paying attention to the tide. The kids in our family have got kayaks now so they don’t have to walk over at low tide and they can paddle all the way around the island.

17. When we (Darumbal People) drive to the beach at Yeppoon we tell the kids the story about Mount Jim Crow and Mt Wheeler. That is a story about how the mountains were formed – two aboriginal men fighting over a woman. Mum has told me the story many times. Mum and Dad told me about that story. Uncle Tosie (Cora) has also told the story to the kids when we take them out doing the program. I know the story but it is for my parents to tell to others. I don’t tell the story without their permission.

53 Further she said:

52. At Darumbal meetings I have heard some people talk about how “you have to be bloodline” to be Darumbal but I think that is wrong. If people grow up as Darumbal and are accepted as Darumbal then they are Darumbal and it is disrespectful to tell them otherwise. Aboriginal people always raise other people’s children and those children are family whether or not they are “blood”. I can’t think of any Darumbal People who were “adopted” into a family but I was not taught any rule about “bloodline”.

Mr Warren Malone

54 Mr Malone deposed that he is a Darumbal through his mother and that growing up he spent most time with his mother’s family. He said that while he moved around as a child, he always understood that he was a Darumbal man. Mr Malone said:

29. I only ever knew that I was Darumbal and I have always identified as Darumbal through my mother. I have known that since I was a child. We didn’t live on Dad’s country and he did not talk to us about his country. My father never talked about his mob or his side of the family at all …

55 Mr Malone explained what he had learnt growing up about being a Darumbal and how he had learnt it. He learnt most about being Darumbal from his grandfather and uncle. His grandfather was an important Darumbal elder and when he died, Mr Malone’s uncle continued his teachings. Such teachings included what land was Darumbal country. He knew what was Darumbal country because his uncle told him. Mr Malone said:

45. When my family moved to Stanwell, I knew we were on our own county because Uncle Mervyn told me. Uncle Mervyn had also told me that you had to ask permission to hunt on someone else’s county. I never saw anyone in my family ask for permission to hunt or fish in places like Gracemere or Yaamba, and this reinforced my sense that these areas were also part of my county. We always hunted and fished in these places.

56 Further, he deposed:

19. My family moved to Stanwell and we lived in Stanwell for about 5 years. At the time, we were the only Aboriginal family in town. It was a pretty small place – there was a shop and maybe ten houses. Uncle Mervyn came and visited us at Stanwell too … It was Uncle Mervyn who told me that Stanwell was part of my country too. He would say, “You’re back on your own country now”.

Ms Vanessa Ross

57 Ms Ross is a Darumbal woman through her mother, and was raised by her great-grandmother while her mother was away working. While they moved around, she and her mother visited Rockhampton “all the time”. Ms Ross stated:

30. When we visited Rockhampton, Mum would say “This is home. This is my country”. I was only young when Mum started telling me all of this, before I was even a teenager. I remember one time when we passed Gracemere, Mum said that that’s where her Aunty Grace (Grandfather Ross’ sister) got her name from. Mum used to tell us kids that all this area here – Gracemere, Rockhampton – was ours. She said we come from this area and that this is all where we’re part of. I had a real sense of belonging here (Rockhampton area). I understand that all of Mum’s mob belonged to this land.

58 Ms Ross recalled many of the teachings of her mother and great-grandmother. She described how she was taught creation stories and how to look after the land. Materially Ms Ross said:

69. Right from when I was growing up, I was told about Mundagatta, the Rainbow Serpent. I was taught that he is the keeper and creator of our land. Nan Tilly used to say to me that Mundagatta makes the river, and that’s where you get your food from fish, and that he came on the land and planted all the trees and that.

70. Mundagatta goes a long way. He was at Clermont and Cherbourg too. All the old people would say that. When I was at Cherbourg, there was a place on the creek where we couldn’t go because the Mundagatta would get you and take you away. There was the same thing in Clermont - a place you couldn’t go swimming or fishing because the Mundagatta will get you there. Lots of people would say that, but it was my Nan Tilly who drummed that into my head. I know that Mundagatta is in Darumbal country but I don’t know the place where he appears.

59 She also stated that her mother did not talk about the boundaries of Darumbal country. Her mother recounted and described different areas within Darumbal country. In particular, Ms Ross said:

42. Mum used to always talk about the black orchids at Gracemere. Granny Cissie used to do something with the black orchids. Mum said they were on her country and were special to that area. Mum used to use a language name for the orchids but I can’t remember it. Mum used to speak some language words that I think were Granny Cissie’s language. I used to be able to speak Gunggari with Nan Tilly because that was her language. I can’t remember much of it anymore but when I hear it I know what is being said. Whenever I see a black orchid I point it out and tell my children.

Mr Trevor Hatfield

60 Mr Hatfield deposed that he is a Darumbal man through his mother’s line and grew up in Rockhampton. While he knew many other Aboriginal people, he knew he was Darumbal.

61 He stated:

24. I always knew I was Darumbal. From a very young age when I was a child, Mum told me and instilled what I now teach my children and grandchildren – the fact that we are Darumbal. Mum knew where she was from and who she was. She was always emphasising family connections to us. She knew she was from the Rockhampton area. She talked often about “being from here” and that “Grandad (McPherson) was from here”, and “it is our land and we are from here”. I had always understood my mother to be saying that the land was part of us – that is what it means to be “from here”. When my mother told us who our family were, she always told us where they were from. I was taught that if you have a parent or grandparent who is a Darumbal person, then you are a Darumbal person. That includes being reared up by a Darumbal person and accepted as their child or grandchild. It is the family who decides whether another person is part of their family.

62 Later in his affidavit he said:

39. Although I have connection to Barada through my father’s side, I don’t speak for Barada and my father accepts this. My father told me that I can go through either my mother (Darumbal) or my father (Barada) but I can only go one way.

40. My connection is stronger to Darumbal because Rockhampton is on Darumbal country. My mother and her ancestors are from the Rockhampton area, and I have lived here all my life. I have an emotional attachment to Darumbal country and Rockhampton in particular.

Mr Tosie Cora

63 Mr Cora is a Darumbal man through his mother. He worked and lived on Darumbal country for most of his life. Mr Cora deposed that it was his mother who taught him about Darumbal country and that he continues to teach his children and grandchildren what his mother taught him. He said:

32. My mother would also show us different plants and tell us when you could pick and eat them. There was a small plant found at the base of hills. It grows where the water lies for a short period of time. It’s a little seed that goes from green to white. When it turns white that is when you can eat it. It’s really good to eat and there is a lot of it around.

33. I teach my kids and my grandkids what my mum told me. I remember going out and getting wild passion fruit. Most of my grandsons today love it. You’ve got to get it at the right time, along the Fitzroy River there is an abundance of it. I would take my boys fishing and when the passionfruit was ripe they would get into it.

…

40. I have taken my children out fishing and today I also take my grandchildren out fishing. If there is bush tucker around I’ll show them that too, for example wild passionfruit and anything else that is eatable …

Ms Tanya Mitchell

64 Ms Mitchell’s evidence is that she is a Darumbal woman through her father who was Darumbal through his mother and grandmother. While it was only after returning to Rockhampton in 2011 that Ms Mitchell first heard the word “Darumbal” and first began learning about her Darumbal heritage, she has also known that she was part of a distinct “mob”. In particular she deposed:

43. It is only since I moved back here to Rocky in 2011 that I have started to learn more. Whenever I have questions or get confused about something I ask Kristina (Hatfield).

…

45. I honestly can’t remember hearing the word “Darumbal” being used when I was growing up but I knew who was the same “mob” as me because I lived with them and I grew up with them – they were family. When people came to visit, Nanna Hatfield or someone would say, “This is your family from ...” and tell me where they were from. From that I understood that Rockhampton and the surrounding areas were where my family was from.

65 Since her return to Rockhampton in 2011 is has also began learning the native language and has been educating her children in Darumbal culture. She said:

78. I am learning the language myself and know the basics. I vaguely remember Nanna Mac speaking language but I can’t remember Nanna Hatfield speaking language other than using words occasionally like when she was looking for nits in my hair. I use words with my children and grandchildren like:

“yarma” – No

“youi” – Yes

“Goodamulli” – Hello

“Yumajungu” – goodbye

“yaddaba” – respect

79. My kids have been learning the language at school from Aunty Nicky and outside of school with Aunty Nicky and Kristina (Hatfield). My children go to Crescent Lagoon School in Rockhampton and Aunty Nicky had language classes at the school every Friday. Outside of school she teaches them too.

Ms Selena Edmund

66 Ms Edmund is Darumbal through her mother’s side, namely through her mother, grandmother and her mother’s grandmother. She grew up in Rockhampton and has lived there most of her life. Like many other claim members, Ms Edmund did not know the name “Darumbal” before this claim started, however she has always known that she and her family belonged to the Darumbal area. Darumbal traditions and culture still play a great role in her life and in the life of her family. She outlined that growing up she would catch crabs and “crawchies” (freshwater crayfish) and that she teaches her grandchildren these skills. She also outlined tradition Darumbal sites that remain of great importance to her and her family.

67 In particular Ms Edmund stated:

76. Gawula is very spiritual because that is where the massacre was. I learnt about Gawula and the spiritual significance from my mum when I was in my late 20’s. It used to be called Mt Wheeler (after that trooper). It is spiritual because a lot of souls were lost there. I always knew that those mountains were significant but because other people had rights to that area (miners and other people) we never knew if we were allowed to go there. You can stand anywhere and see Gawula, as long as you can see it you can feel it and you know you’re safe. Sally and Billy (Mann) found out the process in order to change the name and get the land back. The land was actually given back and we had a celebration. We reclaimed it and then we were legally able to go there … Being able to go there legally and actually having some say in it has made it more special to us.

77. My family and Billy (Mann), we all go up there and when we do we feel better. The birds start singing and the wind starts blowing and you can see the formation of our ancestors in the rocks. They show themselves on the rocks and sometimes you may see them and sometimes you may not. But you know that they are there watching you … We know a lot of ancestors were lost there and if we go there it is like letting them know that we remember them. I was only out there a few weeks ago. I went with my grandchildren; Billy Mann and his wife Venita and their grandchildren; my sister Sally and her son Jason as well as her grandchildren. My family and I went out there to check on the area and get everything ready for this year’s NAIDOC week.

78. I was also always drawn to the beach at Yeppoon. Through research I learnt about the massacre that happened there and then I knew why I was drawn to the place.

Mr Rodney Mann

68 Mr Mann is Darumbal through his father and while his family moved around when he was a child, he has spent most of his life in Darumbal country. Much of his evidence details how his father taught him to live off the land and how to hunt. Mr Mann also deposed that his father continued to teach the children about the Darumbal culture through stories. In particular, he said:

59. My father taught me a lot of things – things that were just part of my everyday life and which I never really thought of as “culture” at the time. For example, he taught me all about the land – how to read it, live from it, and respect it by looking after it – even though he didn’t tell me where his country was.

61. I was taught by my father to preserve animals and not to kill too much. He taught me to just take what you need to look after your family. He didn’t talk about it being a Darumbal rule or an Aboriginal rule. It was just how we were to things and how to behave.

65. I teach my kids busy crafts that I know, and respect for country. My daughter talks about it all the time, about me teaching all the different stuff in the bush, knowing your season. I try to teach my kids not to take things out of season, all that sort of stuff.

69 Later he stated:

115. I maintain my connection to the country to this day by spending as much time as I can in the bush and by passing on the knowledge and respect for the country to my children and grandchildren. My kids have grown up with me taking them hunting and fishing and camping, and teaching them all the things I learnt from my father.

Ms Pauline Cora

70 Ms Cora’s deposed that she is a Darumbal woman through her father’s side and has spent the majority of her life around the Rockhampton region. Growing up her parents and grandparents taught her the importance of country. She states: