FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2016] FCA 44

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | WOOLWORTHS LIMITED ACN 000 014 675 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Between 4 June 2012 and 4 July 2012, by continuing to offer the Abode 3 Litre Stainless Steel Deep Fryer, Model DF30BW (the Deep Fryer) for retail sale after it became aware that the side handles of the Deep Fryer may detach when the Deep Fryer was lifted, leading to a consequential hazard comprising oil spills and possible burn injuries if the appliance was moved while containing hot oil, by its silence and by refraining from:

(a) withdrawing the Deep Fryer from sale at its Big W stores; and

(b) recalling the Deep Fryer from its Big W stores;

once a reasonable period of time in which it could have identified, assessed and responded to this safety hazard had elapsed, Woolworths engaged in conduct (the Deep Fryer Silence Conduct) that was:

(c) misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(d) liable to mislead the public as to the suitability of the Deep Fryer for its purpose,

because:

(e) the side handles of the Deep Fryer may (and did on one known occasion prior to 4 June 2012) detach when the Deep Fryer was lifted, leading to a consequential hazard comprising oil spills and possible burn injuries if the appliance was moved while containing hot oil;

(f) Woolworths had knowledge of the matters stated in subparagraph (e) above; and

by the Deep Fryer Silence Conduct, Woolworths:

(g) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, which was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 18 of the ACL; and

(h) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, that was liable to mislead the public as to the suitability of the Deep Fryer for its purpose, in contravention of section 33 of the ACL

(the Deep Fryer Contravention).

2. Between in or about 25 August 2013 and in or about 20 March 2014, Woolworths, in offering the house brand consumer good Woolworths Select Drain Cleaner 1L (Select Drain Cleaner) for retail sale to consumers, with a cap that bore the text, “Close tightly while pushing down turn”, accompanied by two arrows directing an anti-clockwise motion, expressly and impliedly represented that the Select Drain Cleaner could only, within the ordinary range of uses of the product, be opened by applying downward pressure to the cap while turning it (the Select Drain Cleaner Opening Representation), which representation was:

(a) misleading and deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(b) a false or misleading representation that the Select Drain Cleaner was of a particular standard or quality and had certain performance characteristics; and

(c) liable to mislead the public as to the suitability for its purpose of the Select Drain Cleaner,

because the cap on the Select Drain Cleaner:

(d) was ineffective, in that it did not lock securely on the bottle; and

(e) could be opened or open without the application of downward pressure to the cap while turning it,

and thereby, Woolworths:

(f) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, which was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 18 of the ACL; and

(g) made a false or misleading representation, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of house brand home ware products, that the Select Drain Cleaner was of a particular standard or quality and had certain performance characteristics, in contravention of sections 29(1)(a) and 29(1)(g) of the ACL; and

(h) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, that was liable to mislead the public as to the suitability for its purpose of the Select Drain Cleaner, in contravention of section 33 of the ACL

(the First Select Drain Cleaner Contravention).

3. Between 24 February 2014 and 20 March 2014, by continuing to offer the Select Drain Cleaner for retail sale after it became aware that the Select Drain Cleaner was unsafe when deployed during ordinary or reasonably foreseeable uses of the product, because the cap on the Select Drain Cleaner was ineffective, in that it did not lock securely on the bottle and could be opened without applying downward pressure to the cap while turning it, by its silence and by refraining from:

(a) withdrawing the Select Drain Cleaner from Woolworths, Safeway, Food For Less, and Flemings stores; and

(b) recalling the Select Drain Cleaner from its Woolworths, Safeway, Food For Less, and Flemings stores,

once a reasonable period of time in which it could have identified, assessed and responded to this safety hazard had elapsed, Woolworths engaged in conduct (the Select Drain Cleaner Silence Conduct) that was:

(c) misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(d) liable to mislead the public as to the suitability of the Select Drain Cleaner for its purpose

because:

(e) when deployed during ordinary or reasonably foreseeable uses of the product, the cap on the Select Drain Cleaner:

(i) was ineffective, in that it did not lock securely on the bottle;

(ii) could be opened without applying downward pressure to the cap while turning it, which hazard in fact materialised; and

(f) Woolworths had knowledge of the matters stated in subparagraphs 3(e) above, and

by the Select Drain Cleaner Silence Conduct, Woolworths:

(g) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, which was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 18 of the ACL; and

(h) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, that was liable to mislead the public as to the suitability of the Select Drain Cleaner for its purpose, in contravention of section 33 of the ACL

(the Second Select Drain Cleaner Contravention).

4. Between 6 June 2012 and 28 June 2012, by continuing to offer the house brand 10 x 45 Homebrand Safety Matches (the Safety Matches) for retail sale after it became aware that the Safety Matches were unsafe when deployed during ordinary or reasonably foreseeable uses of the product because the Safety Matches suffered the defect that, in some instances, the head of the match may break or give off sparks upon ignition, and if that defect occurred the product may fail resulting in possible injury or property damage, including by causing the box of matches to ignite, by its silence and by refraining from:

(a) withdrawing the Safety Matches from Woolworths supermarket stores;

once a reasonable period of time in which it could have identified, assessed and responded to this safety hazard had elapsed, Woolworths engaged in conduct (the Safety Matches Silence Conduct) that was:

(b) misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(c) liable to mislead the public as to the suitability of the Safety Matches for their purpose;

because:

(d) the Safety Matches suffered the defect that, in some instances, the head of the match may break or give off sparks upon ignition;

(e) if that defect occurred the product may fail resulting in possible injury or property damage, including by causing the box of matches to ignite, which defect and hazard in fact materialised;

(f) Woolworths had knowledge of the matters stated in subparagraphs (d) and (e) above; and

by engaging in the Safety Matches Silence Conduct, Woolworths:

(g) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, which was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 18 of the ACL; and

(h) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, that was liable to mislead the public as to the suitability of the Safety Matches for their purpose, in contravention of section 33 of the ACL

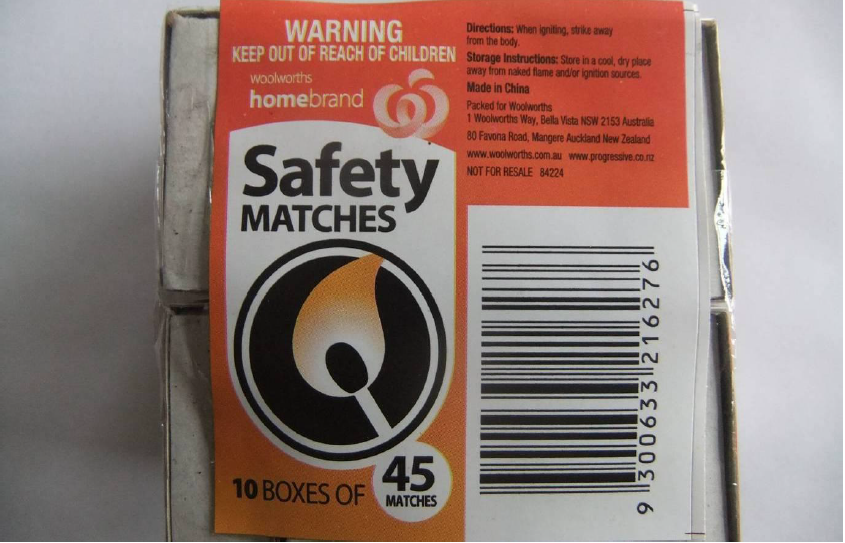

(the Safety Matches Contravention).

5. Between in or about 1 May 2012 and 31 August 2012, Woolworths, in offering the Padded Flop Chair for retail sale to consumers, made an express representation that the Padded Flop Chair was capable of bearing weights up to 115 kg, which representation was:

(a) misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(b) a false or misleading representation that the Padded Flop Chair was of a particular standard or quality and had certain performance characteristics; and

(c) liable to mislead the public as to the suitability for its purpose of the Padded Flop Chair,

because the Padded Flop Chair was not, in all cases, capable of bearing weights of up to 115 kg and, under testing, could reliably support no more than 92 kg, and thereby, Woolworths:

(d) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, which was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 18 of the ACL; and

(e) made a false or misleading representation, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of house brand home ware products, that the Padded Flop Chair was of a particular standard or quality and had certain performance characteristics, in contravention of sections 29(1)(a) and 29(1)(g) of the ACL; and

(f) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, that was liable to mislead the public as to the suitability for its purpose of the Padded Flop Chair, in contravention of section 33 of the ACL

(the Padded Flop Chair Contravention).

6. Between 31 August 2012 and 22 July 2013, Woolworths, in offering the Folding Stool for retail sale to consumers, made an express representation that the Folding Stool was capable of bearing weights up to 100 kg, which representation was:

(a) misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive; and

(b) a false or misleading representation that the Folding Stool was of a particular standard or quality and had certain performance characteristics; and

(c) liable to mislead the public as to the suitability for its purpose of the Folding Stool,

because the Folding Stool was not capable of bearing weights of up to 100 kg and, under testing, could reliably support no more than 90 kg, and thereby, Woolworths:

(d) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, which was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 18 of the ACL; and

(e) made a false or misleading representation, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of house brand home ware products, that the Folding Stool was of a particular standard or quality and had certain performance characteristics, in contravention of sections 29(1)(a) and 29(1)(g) of the ACL; and

(f) engaged in conduct, in trade or commerce, that was liable to mislead the public as to the suitability for its purpose of the Folding Stool, in contravention of section 33 of the ACL

(the Folding Stool Contravention).

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

7. In respect of the misleading or deceptive conduct Woolworths pay to the Commonwealth of Australia within 30 days a pecuniary penalty of $3,000,000 based on the following courses of conduct:

(a) the Deep Fryer contraventions $ 600,000

(b) the two Select Drain Cleaner courses of contraventions: $1,400,000

(c) the Safety Matches contraventions $ 400,000

(d) the Flop Chair contraventions $ 300,000

(e) the Folding Stool contraventions $ 300,000

8. In respect of the eight section 131 contraventions Woolworths pay to the Commonwealth of Australia within 30 days a pecuniary penalty of $57,000:

(a) the Deep Fryer s 131 contravention $ 10,000

(b) the Select Drain cleaner s 131 contravention $ 5,000

(c) the other six s 131 contraventions $ 42,000

9. Woolworths within 30 days prominently publish on the Internet homepage of Woolworths supermarkets, Big W, Masters Home Improvement and Ezibuy a link to an internet page in the form and terms set out in Annexure A.

10. Woolworths within 30 days or otherwise agreed with the ACCC prominently publish on the Woolworths supermarket Smartphone Application:

(a) details of products currently recalled by Woolworths and products recalled in the past 12 months; and

(b) a link to the Recalls Australia website.

11. Woolworths:

(a) implement the upgraded dedicated product safety compliance program in accordance with the requirements set out in Annexure B for the employees and other persons engaged in Woolworths’ business, being a program designed to minimise its risk of future breaches of sections 18, 29 and 33 of the ACL in relation to the safety of its products and of section 131 of the ACL (the Program), which would be provided to the ACCC within 3 months of the Orders being made;

(b) continue to develop and implement for a period of 3 years from the date of these orders the Program; and

(c) provide, at its own expense, a copy of any documents requested by the ACCC evidencing Woolworth’s implementation of the Program, including the documents referred to in clauses 4, 6, 12 of Annexure B.

12. Woolworths pay to the ACCC within 14 days of the date of this order the ACCC’s costs of the proceeding in the sum of $50,000.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

EDELMAN J:

[1] | |

[5] | |

[20] | |

[21] | |

[29] | |

[32] | |

[36] | |

[41] | |

[43] | |

[45] | |

[47] | |

[50] | |

[54] | |

[60] | |

[62] | |

[64] | |

[69] | |

[72] | |

[73] | |

[74] | |

[80] | |

Six additional failures to report incidents of serious injury or illness | [86] |

[87] | |

[88] | |

[89] | |

[90] | |

[91] | |

[92] | |

[93] | |

The category of contraventions concerning misleading or deceptive conduct and misrepresentations | [94] |

[100] | |

[102] | |

[103] | |

[104] | |

[105] | |

[106] | |

The category of contraventions concerning Woolworths’ failures to report | [107] |

[113] | |

[113] | |

[113] | |

[122] | |

[138] | |

[143] | |

[143] | |

[145] | |

The unintentional nature of the contraventions and Management’s knowledge | [146] |

[150] | |

Size of Woolworths, its financial position and the profits associated with its contraventions | [155] |

Co-operation with the ACCC, admission of culpability, compensation and contrition | [161] |

[168] | |

[178] | |

[178] | |

[185] |

1 The applicant – the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) – brought proceedings alleging that Woolworths contravened the Australian Consumer Law. Woolworths admitted to engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct, making false or misleading representations, and failing to report, or inadequately reporting, incidents of serious injury or illness. It cooperated with the ACCC, and agreed many of the facts described in these reasons.

2 Woolworth’s most significant contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law arose in relation to five different house brand products that Woolworths or its subsidiaries sold to consumers: a deep fryer, a drain cleaner, safety matches, a padded flop chair and a folding stool. In broad terms, Woolworths’ contraventions involved:

(1) a failure to withdraw and recall a Deep Fryer from sale when the side handles of the Deep Fryer could detach when it was lifted, potentially leading to burns from hot oil;

(2) misrepresentations on the text and directions on the cap of the Select Drain Cleaner which did not lock securely on the bottle and failing to withdraw the Select Drain Cleaner from sale;

(3) misrepresentations that Safety Matches were safe, and failing to withdraw them from the stores, when the head of the match could break or give off sparks upon ignition causing the box of matches to ignite;

(4) misrepresentations that a Padded Flop Chair was capable of bearing weights up to 115 kg when it could not reliably support any more than 92 kg; and

(5) misrepresentations that a Folding Stool was capable of bearing weights up to 100 kg when it could not reliably support any more than 90 kg.

3 During the periods of contravention many of these products were sold. The largest number of sales during a period involving a course of contraventions was 124,825 sales of Select Drain Cleaner during the first period of contraventions in relation to that product. The smallest number of sales was 1,840 sales of Folding Stools during the approximately eleven month period of contraventions. Some consumers suffered serious injury and illness as a result of using the products in question, particularly the Select Drain Cleaner. A man suffered permanent damage to his eyesight and could no longer work as a boilermaker. A baby girl suffered serious burns to her leg, requiring a skin graft and causing permanent scarring.

4 The parties agreed proposed non-pecuniary penalty orders and declarations. I consider those orders to be appropriate for the reasons explained in my conclusion to these reasons. The central issue in the proceeding was the amount of the pecuniary penalty to be imposed on Woolworths. For the reasons below, I consider the appropriate total penalty to be $3.057 million. This is comprised of $3 million for the six courses of conduct involving the products that I have described and $57,000 in relation to the contraventions concerning Woolworths’ reporting obligations under s 131. A breakdown of those amounts is provided in the conclusion to these reasons.

Woolworths’ quality review processes and their inadequacies

5 Woolworths is a household name. It is a national retailer with over 3000 stores located in Australia and New Zealand. Woolworths supplies a spectrum of low priced consumer goods including food, liquor, petrol, general merchandise, hardware, home improvement and hotel accommodation.

6 Woolworths is the owner in Australia of 931 supermarkets trading under (i) the “Woolworths” brand, (ii) the “Safeway” brand in Victoria, (iii) the “Flemings” brand and (iv) the “Food For Less” brand. Woolworths also owns a national chain of 182 discount department stores trading under the “Big W” brand and a national chain of 49 hardware and home improvement stores trading under the name “Masters Home Improvement”.

7 House brand goods are offered for sale at Woolworths supermarkets, Big W stores and Masters Home Improvement stores. Woolworths stocks more than 28,000 non-food house brand products across its trading divisions (i.e. supermarkets, Big W stores and Masters stores). Woolworths sources its house brand products globally from over 4500 factories.

8 At all relevant times Woolworths had a compliance system to ensure that officers and employees understood the obligations of the company and its officers and employees arising from the Competition and Consumer Act. That system included a Compliance Policy, a Code of Conduct and a compliance framework which identified compliance responsibilities throughout the Woolworths group. Woolworths also had, and has, a People Policy Committee which reports to the Board of Directors and covers the area of “Safety and Health” and an Audit, Risk Management and Compliance Committee which provides advice and assistance to the Woolworths Board with respect to the oversight of the management of risk and compliance, including areas such as health and safety, and Australian consumer law.

9 In 2010, Woolworths created a centralised Group Quality Assurance (QA) function. This was a change from the previously decentralised QA functions. That function was formed to monitor and ensure high standards of product quality at a reduced cost. The QA function was designed to ensure that all house brand goods sourced by Woolworths went through the QA evaluation process. During 2011 to 2014 all new house brand non-food goods (around 44,000 in total) went through Woolworths’ QA processes before being offered for sale by Woolworths. However, in some instances some products did not go through all the relevant steps.

10 Woolworths had a regime to internally assess the consumer incidents reported to it by reference to a severity scale. The severity scale was graded 1 to 3, in which Severity 1 incidents were classified in accordance with the language used in s 131 of the Australian Consumer Law. Under this scale:

(1) Severity 1 incidents were required to be escalated by a store feedback form, and included any complaint in regard to: actual or potential death; actual or potential serious injury or illness (i.e. requiring hospitalisation or medical attention by a doctor or nurse, or emergency dental work); any injury or illness involving a sensitive demographic (i.e. babies, children aged under 10, disabled, pregnant mothers, the elderly over 65); actual death to a pet; and any complaint that could cause national brand damage (i.e. talk back radio, national broadcast television, news etc.);

(2) Severity 2 incidents were required to be escalated if they could not be resolved, and included any complaint in regard to: mild injury or illness (i.e. a customer feeling unwell but not requiring medical treatment); injury or illness to pets (i.e. requiring medical attention by a vet); any complaint that could cause localised brand damage (i.e. community newspaper, low media coverage and enquiries, personal posts on social media etc.); and

(3) Severity 3 incidents were required to be escalated if they could not be resolved, and included any complaints that have no safety impact and would not lead to any brand/reputation damage.

11 During 2012 and 2013, the ACCC became aware of issues relating the safety of Woolworths’ house brand goods. The incidents included a Dick Smith Electronics portable DVD player which caught on fire due to a faulty battery causing severe burns to a child. That incident was the subject of correspondence between the ACCC and Woolworths (which then owned Dick Smith Electronics) referred to later in these reasons. There was also (i) an increase in withdrawals and product recall announcements made by Woolworths in relation to its house brand goods, (ii) an increase in complaints received by Woolworths regarding its house brand goods and (iii) a large number of mandatory reports relating to its house brand goods lodged by Woolworths with the ACCC under s 131 of the Australian Consumer Law (i.e. in 2012 Woolworths lodged 16 reports and in 2013 it lodged 59 reports).

12 During mid-2012 Woolworths commenced a review of its product quality processes. From this time, Woolworths also responded to concerns from the ACCC about the safety of Woolworths’ house brand goods and its QA processes. Woolworths maintained that it was continually striving to improve their quality management system and that it had made significant progress in the areas of product standards and supplier audits. Woolworths assured the ACCC that quality assurance process improvements were being planned. The planned improvements included a revised factory audit system, an improved customer complaints handling system, and improvements to the assessment of private label goods.

13 The outcome of the mid-2012 review by Woolworths was an internal, and confidential, Woolworths presentation titled “Creating daylight through Quality: Woolworths end-to-end quality management program”.

14 In that presentation, Woolworths recognises that its quality performance “is not where we want it to be. Recent recall figures are higher than most comparable benchmarks…with consequences to our customers ranging from inconvenience to injuries. Recent recalls analysis shows some potential areas to focus.” Indeed, Woolworths reported that withdrawals and recalls had increased in the period between 2010 to 2012. Woolworths reiterates six times in the presentation slides that its quality performance was not where it wanted it to be. Woolworths also identified that “Quality is not mentioned in Corporate Priorities”, that there was a “lack of clear roles within the business to investigate and follow-up with customer complaints”, and that “QA processes [were] by-passed on some occasions”. Woolworths also acknowledged that in “some cases, product testing not sufficient to ensure quality product” and that the “QA team [was] under resourced”; that there were “Significant inconsistencies in the way product specifications are given” and that “Previous recall analysis shows that product testing specifications are not sufficient to ensure the appropriate level of quality”.

15 Despite these observations, Woolworths said, in an isolated statement on one page, (which was accepted by senior counsel to be incorrect) that its “Risk and Assurance and Business Review structures provide good risk and safety management” and that it had “good recall and withdrawal processes”. I do not accept that this single statement in a very lengthy collection of detailed slides can be read in isolation to suggest that Woolworths’ management had no awareness of defects in its quality assurance processes that could bear upon its product representations and its withdrawal and recall procedures. This is particularly clear in light of Woolworths’ response to the 2012 review and the “Creating daylight through Quality” presentation.

16 Following the 2012 review of its product quality systems and processes, and the “Creating daylight through Quality” presentation, Woolworths made changes during the course of 2013 and 2014 as follows:

(1) in January 2013 Woolworths launched a Group Quality Program. This initiative was implemented by the leader of each business with the aim of improving product quality across the Woolworths Group;

(2) during 2013 Woolworths introduced improvements to its handling of customer complaints, including:

(a) in July 2013 Woolworths revised its Severity 1 Complaint Dashboard and established a Quality Excellence Steering Committee. This resulted in weekly reporting of significant Severity 1 incidents to the Head of Quality and Head of Commercial Teams for the relevant product;

(b) in December 2013 Woolworths launched a Severity 1 Closed loop process. This focussed on investigating, reviewing and actioning of high risk Severity 1 complaints;

(3) from late 2013 through 2014 Woolworths implemented a new “New Product Development” (NPD) program. That program was extremely costly and it involved the following:

(a) in September 2013 Woolworths established a “New product brief” and “New business rules” to support the NPD processes being developed and put in place;

(b) in November 2013 Woolworths signed off the NPD process;

(c) in January 2014 Woolworths published the new NPD framework and established a “New Sourcing Leadership” team;

(d) in July 2014 Woolworths’ divisions each signed off on the implementation of the NPD process;

(e) in August 2014 Woolworths implemented its NPD program framework and NPD tools which included a compliance requirement for product quality of house brand goods;

(4) in April 2014 Woolworths introduced a New Quality Governance Policy; and

(5) the implementation of the new QA function was completed in August 2014 which included an additional $12 million investment in QA resources to support the end to end NPD process across the business divisions.

17 In January 2013, Woolworths also produced a Supplier Manual which required all goods supplied to Woolworths to be inspected before shipping by an inspection company. The Manual required that goods should only be released for shipment once the pre-shipment report was approved by Woolworths Quality Assurance.

18 On 7 June 2013, the ACCC issued a notice under s 133D of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) to Woolworths seeking information about five private label consumer goods that had caused or had the potential to cause injury to consumers. Two of those goods were the house brand deep fryer and safety matches discussed below.

19 Although Woolworths had product quality processes and a compliance system in place, it failed to prevent product safety issues from occurring and continuing to occur during 2013 and 2014. In the period from January 2012 to November 2014, Woolworths issued 47 non-food product recalls for its house brand goods (i.e. 18 recalls in 2012, 8 recalls in 2013 and 20 recalls in 2014). Further, although Woolworths took steps in 2012 and 2013 to address shortcomings in its product quality processes, these steps were not fully implemented until August 2014. During the intervening period, the Select Drain Cleaner and Folding Stool contraventions occurred.

The Abode Deep Fryer incidents

20 Between approximately August 2011 and 9 July 2012, Woolworths offered a Deep Fryer for sale in its Big W stores. An image and the model number can be seen in Annexure 1 to these reasons. The Deep Fryer was intended for use in household cooking with a frying temperature range of between 130°C and 190°C. Woolworths sold 10,726 Deep Fryers during this time.

21 On 27 May 2012, Ms DW suffered serious burns when a side handle snapped off the Deep Fryer she had purchased from a Big W store in Lake Macquarie. At the time she was moving the deep fryer full of hot oil. The hot oil spilled onto her. She was treated at the John Hunter Hospital emergency department and subsequently by her general practitioner. She was absent from work for three days.

22 On 30 May 2012, Ms DW returned the Deep Fryer to Big W and notified Woolworths of the incident. Big W in Charlestown reported the incident internally:

Customer has returned an abode deepfryer kc 8230828, purchased 23/5/12 as they feel it is not fit for purpose. The deepfryer was used on 27/5/12 and then when attempted to move back to prevent children from being able to reach it the handles on the side snapped off spilling hot oil over the customer of which medical treatment was required. Customer is concerned it may happen to others and would like the product checked out as screws holding handles in place are very small and short.... (emphasis added)

23 On 1 June 2012, Woolworths’ Group Quality Assurance Department recorded concerns about the screws in internal emails:

I think the two screws alone is not sufficient to secure especially if one screw is not tight, the other alone is not strong enough.

Seems to be that initial design was with four screw but then the two on top of handle has been changed to be a guide for cost saving.

24 Woolworths’ Group Quality Assurance Department inspected the Deep Fryer returned by Ms DW and concluded that it was defective and that a withdrawal from sales was “likely”. The defects included problems with the handle where the pillar was too thin and the screws were too small.

25 On 4 June 2012, Woolworths completed an internal “Group Quality Assurance Product Incident Report”, based on a check of six new units, including two units with the same data code as the unit purchased by Ms DW, which stated that:

Checks of other new units from stock did not show any problem, and the handles are installed with the correct orientation. When filled to the maximum level with water, the handles did not come off when lifting the unit. Testing was also carried out with the handles installed the wrong way round. When secured properly, they still did not come off when lifting unit with water filled to maximum level.

From the above checks and tests, the handles are secure when fitted correctly. However, if the screws are loose and the handle is fitted with the wrong orientation, it is possible for the handle to flex away from the unit causing the pillars to crack when the unit is lifted.

No other unit has been found to have the handle installed incorrectly or loose, however it is recommended that the design be improved so that the handle cannot be incorrectly fitted. This could easily be achieved by changing the spacing so that the distance between the two screws is not the same as the distance between the two plastic pins. The number of screws on handle should also be increased...

26 On 5 June 2012, Woolworths informed Woolworths HK Procurement Ltd that the handle of the Deep Fryer needed to be modified and that the Deep Fryer should have a warning label on the front of the unit that contained the words:

Do not move the unit during use. Allow unit and oil to completely cool down prior to moving unit.

27 On 27 July 2012, Woolworths settled Ms DW’s claim for $8,000, including a payment of $110 for her medical expenses.

28 On or about 27 July 2012, Woolworths paid $110 to Whitebridge Medical Centre for Ms DW’s medical expenses, and on or about 23 August 2012 Woolworths provided Ms DW and her partner with a $100 WISH gift card as a gesture of goodwill.

The Second Deep Fryer Incident

29 On 2 July 2012, an 18 year old woman, Ms KA, suffered burns when the handle of a Deep Fryer snapped off when she tried to pick up and move the Deep Fryer full of hot oil. The Deep Fryer spilled hot oil on her. She described the pain as excruciating. The burn had already begun to blister on her way to hospital. The medical practitioners who treated her considered a skin graft but the skin had set within 24 hours. For six weeks she was heavily reliant on pain relief. She could not bend her leg and she was heavily reliant upon her sister for everyday living.

30 The photos of Ms KA’s burns are vivid. They extend over about 20cm of her upper left thigh. The burns continue to affect her life. For a year she was required to be very conscious of sunlight on her thigh. Her self-consciousness of the burn also affected her social life.

31 On 5 July 2012, Ms KA returned the Deep Fryer to the Big W store where she had purchased it and she informed Woolworths of the incident. On 23 December 2014, following a period of discussion between lawyers, Ms KA’s claim was settled by Woolworths making a payment to her of $44,000.

Withdrawal and recall of Deep Fryers

32 Immediately after the second incident, the Group Quality Assurance Manager withdrew the Deep Fryer from sale in Big W stores. The manager required further tests to be conducted on a larger sample size to re-assess the safety of the Deep Fryer.

33 After the internal tests, on 10 July 2012, the manager summarised the results in an email:

Two customer complaints were received where customers indicated the handle(s) of unit have come away when moving resulting in hot oil being spilt onto the customer which then required medical attention.

Subsequently QA completed testing on 24 samples from Stores and DC finding that 8 units had cracked pillars where the screw is secured on the handle and on 5 units the screw has stripped the plastic on the pillar. Both issues result in weakening the strength of the handle. It is therefore reasonable to assume this is how the injury to the customer occurred and therefore execution of a recall is necessary.

34 On 10 July 2012, Woolworths initiated a voluntary recall of the Deep Fryer. It notified the recall action to Big W stores and to the public, explaining the potential safety hazard where the side handles may detach when the Deep Fryer is lifted, and the risk of oil spills and possible burn injuries if the appliance is lifted or moved while containing hot oil.

35 On 10 July 2012, Woolworths notified the ACCC of its voluntary recall action, as required by s 128 of the Australian Consumer Law.

The Select Drain Cleaner incidents

36 From approximately 25 August 2013 until 20 March 2014, Woolworths offered for sale a house brand Select Drain Cleaner. The house brand Select Drain Cleaner was supplied to Woolworths by Pascoes Pty Ltd under a contract with Woolworths which contained express terms (i) requiring the safety of the product and (ii) an ability to terminate, in Woolworths’ absolute discretion, if an unacceptable number of complaints were received, or if Woolworths reasonably believed that there had been a breach of any term. Woolworths also had the ability to terminate, without cause, on one month’s written notice.

37 The Select Drain Cleaner and its model details are pictured at Annexure 2 to these reasons. It was sold through Woolworths, Safeway, Food For Less, and Flemings stores in Australia. Woolworths sold 124,825 units of Select Drain Cleaner.

38 The Select Drain Cleaner was intended for use in a domestic or household environment to unblock drains. It contained sodium hydroxide, non-ionic surfactants and water and was classified by the relevant criteria as a hazardous substance (2X), a dangerous good, and a Schedule 6 poison. Section 25(1) the Poisons Standard 2013 required the Select Drain Cleaner to be sealed with a child resistant closure conforming to Australian Standard 1928-2007 Child resistant packaging requirements and testing procedures for reclosable packages.

39 The Select Drain Cleaner had the following risks: severe burns; serious damage to the eyes; health damage from ingestion; and cumulative adverse effects from exposure. The following safety measures were therefore required during its use: it must be kept locked up; gas, fumes, vapour and spray must not be inhaled or breathed; users must avoid contact with the skin; users must avoid contact with the eyes; users must wear suitable protective clothing; users must wear suitable protective gloves; and users must wear eye/face protection.

40 The Select Drain Cleaner was sold in bottles which appeared to have a child resistant cap. The top of the cap read “Close tightly while pushing down turn” and there were two arrows directing an anti-clockwise motion for opening the bottle and a clockwise motion for closing the bottle. Each side of the bottle had the word “POISON” on it and the bottle contained the following text:

Warning: Corrosive. May produce severe burns. Attacks skin and eyes;

Caution: Keep out of reach of children. Read safety directions before opening or using; Safety: Wear eye protection when mixing or using. Wear protective gloves when mixing or using. Do not mix with hot water;

First Aid: For advice call Poisons Information Centre ...If swallowed, do not induce vomiting. If in eyes, hold eyelids apart and flush the eye continuously with running water. Continue flushing until advised to stop by the Poisons Information Centre or a doctor, or for at least 15 minutes. If skin or hair contact occurs, remove contaminated clothing and flush skin and hair with running water.

The first Select Drain Cleaner incident

41 On 2 February 2014, Ms VW dropped a bottle of Select Drain Cleaner at Woolworths, in Mountain View, Queensland. When Ms VW dropped the bottle, the cap came off and the contents splashed on her forehead, left eye and nostrils. Ms VW had medical treatment for a minor nose bleed, burns to the inner corner of her eyelid, her forehead and the inner lining of her nose.

42 On 24 February 2014, Ms VW informed Woolworths of the incident by an online Woolworths enquiry form. Woolworths classified the First Select Drain Cleaner Incident as a Severity 1 incident.

The second Select Drain Cleaner incident

43 On 22 February 2014, Ms MW was unpacking a trolley outside the Woolworths Gateways Store in Western Australia, when a bottle of Select Drain Cleaner fell over in her trolley. The cap of the bottle came off and the contents of the bottle splashed onto Ms MW’s legs and feet. Ms MW suffered a burn and blistering on her leg.

44 On 24 February 2014, Ms MW informed Woolworths of the incident by an online Woolworths enquiry form. Woolworths initially classified the Second Select Drain Cleaner Incident as a Severity 2 incident but, by mid April 2014, it was reclassified as a Severity 1 incident.

The third Select Drain Cleaner incident

45 On 18 March 2014, Mrs AL and her husband, Mr L, were at a residential premises when the cap came off a bottle of Select Drain Cleaner. The contents splashed onto the corners of Mr L’s mouth, causing burns to both corners of his mouth. The contents also spilled onto the carpet and Mr L’s mobile telephone, causing damage to both. Mrs AL told Woolworths about the incident the next day. Woolworths classified the Third Select Drain Cleaner Incident as a Severity 1 incident.

46 On 6 May 2014, Woolworths paid $500 as a contribution to Mr L’s medical expenses.

The fourth Select Drain Cleaner incident

47 On 19 March 2014, Mr TK was working at the Woolworths Ingleburn store in New South Wales as a night fill associate, stocking shelves. He lifted a bottle of the Select Drain Cleaner out of a box, holding the bottle by the lid. The cap came off the bottle. The contents of the bottle splashed into Mr TK’s eyes and burned his eyes and forehead. He washed his eyes with water and was taken by Woolworths’ staff to Campbelltown Hospital for observation and for treatment involving an eye flush. He later went to an ophthalmologist who diagnosed him as having severely burned and ulcerated eyes.

48 The damage to Mr TK’s eyes was permanent. There is permanent scarring to his right eye. More than a year later his eyes continue to be sensitive to bright light and they experience dryness and itching. He is unable to continue his work as a boilermaker due to the bright light involved in welding.

49 On 20 March 2014 the incident was reported through Woolworths’ incident management system, PULSE. Woolworths initially classified the Fourth Select Drain Cleaner Incident as a Severity 2 incident, but it was reclassified by mid April 2014 as a Severity 1 incident.

Withdrawal of Select Drain Cleaner from sale

50 On 20 March 2014, a Woolworths Category Manager sent an email to Woolworths Quality Assurance notifying them of the Fourth Select Drain Cleaner Incident and suggesting a product recall until Woolworths was certain that there was no safety risk.

51 On 20 March 2014, Woolworths staff checked the remaining Select Drain Cleaner stock at the store where the Fourth Select Drain Cleaner Incident occurred and found that 2 bottles had loose caps and a further 3 bottles had caps that had been leaking.

52 In the evening of 20 March 2014, Woolworths withdrew the Select Drain Cleaner from shelves in Woolworths, Safeway, Food For Less, and Flemings stores across Australia but did not initiate a recall of the product.

53 Between 21 and 31 March 2014, Woolworths was advised by Pascoes Pty Ltd (the supplier of the Select Drain Cleaner) that the bottle issue was caused by an inconsistency between the bottle heights and wall thickness of the neck. This inconsistency caused the cap to sit too high or crooked on the bottle. Pascoes Pty Ltd advised Woolworths of three changes to the packaging and manufacturing process to address the safety issues.

The fifth Select Drain Cleaner incident

54 On 2 April 2014, a baby girl accessed a bottle of Select Drain Cleaner at a residential home and removed the cap. The contents of the Select Drain Cleaner spilled onto the girl’s right leg and burned a hole in the girl’s leg. The girl’s mother took her immediately to hospital where the child was diagnosed with a serious chemical burn to her right knee. The girl had surgery involving a debridement and skin graft. The girl was required to keep her leg in a cast for 4 weeks following surgery and she had weekly visits to a burns clinic for 7 weeks.

55 On 3 June 2014, Woolworths was notified of the incident by a letter sent to Woolworths from the girl’s mother dated 26 May 2014.

56 In response to the incident, on 10 June 2014 Woolworths sent a letter to the girl’s mother expressing sympathies, and encouraging the mother to appoint a solicitor to protect her interests and to further her daughter’s claim. Woolworths did not receive a response to this letter. On 26 November 2014, Woolworths sent a follow up letter noting that no response had been received and enclosing the original. In December, the Woolworths Customer Direct team attempted to conduct the mother via other means. On 4 December 2014, an officer from the Customer Direct team received a telephone call from the mother. The officer encouraged the mother to seek legal representation, and to let her know what the mother’s out-of-pocket expenses were.

57 On 5 December 2014, Woolworths sent the mother a $500 gift card. After it was stolen, Woolworths arranged for a second $500 gift card to be sent, which was received. Woolworths subsequently paid an amount to the mother to refund her medical and associated expenses.

58 On 5 June 2014, Woolworths submitted a mandatory report form to the ACCC. Woolworths did not include: (i) information regarding when, and in what quantities, the Select Drain Cleaner was supplied in Australia; (ii) any detail regarding the nature of the injury suffered by the girl other than it was a “chemical burn”; or (iii) information regarding any action that Woolworths had taken or was intending to take in relation to the Select Drain Cleaner.

59 The failure by Woolworths to provide details of the injury meant that the ACCC was not aware of the seriousness of the girl’s injury until Woolworths, at the ACCC’s request, provided further information about the incident. Woolworths provided this further information by 12 June 2014.

ACCC inquiry and recall of Select Drain Cleaner

60 Following communications between 8 and 11 April 2014 between the ACCC and Woolworths about the Select Drain Cleaner, including the incidents and the safety of the product, on 14 April 2014, the General Manager Products and Quality at Woolworths sent an internal email which explained that Woolworths was recalling its Select Drain Cleaner after 4 incidents of caps leaking/coming off in store. The email described the background (which I have set out above) and said:

Further to the withdrawal the ACCC have contacted us to question why we did not follow mandatory reporting and formally report this to them (our risk teams assessment is that this was not required as the incidents happened in store). They also asked very leading questions about our risk assessment, focusing on the fact the cap does not meet legislative CRC requirements.

61 On 15 April 2014, Woolworths initiated a voluntary recall of the Select Drain Cleaner. Woolworths notified the ACCC of its voluntary recall action, as required by s 128 of the Australian Consumer Law. On 3 July 2014, Woolworths re-issued the Select Drain Cleaner recall following correspondence with the ACCC about the wording of the recall notice.

62 Between 1 April 2012 and 1 November 2012, Woolworths offered a house brand consumer good, Homebrand Safety Matches, for retail sale in Woolworths supermarket stores throughout Australia. During that period, Woolworths sold 300,000 packs of Safety Matches (each comprising 10 boxes with 45 matches in each box). An image of the Safety Matches is at Annexure 3 to these reasons.

63 Safety matches are described as being ‘safe’ because they are designed so that they do not spontaneously combust. In theory, they need to be struck against a special surface in order to ignite. When a lit safety match is touched against an unlit safety match there should be a delay of at least about five seconds before the unlit match ignites to prevent accidental ignition.

64 Between 4 May 2012 and 23 May 2012, Woolworths received three complaints concerning the quality and safety of the Safety Matches. Woolworths assessed these complaints as Severity 3 incidents.

65 On 6 June 2012, Ms SM complained online to Woolworths that she had struck a match and the entire box ignited. She wrote that her thumb was burned and it was very painful and swollen. She took photographs. She suggested that Woolworths consider a recall, describing the product as extremely dangerous. Woolworths assessed this complaint as a Severity 2 incident.

66 On 14 June 2012, Woolworths received a second complaint from an unidentified customer alleging that the Safety Matches did not comply with required standards and that after ignition the “shaft of the match continues to smolder glowing red and the tip of the match falls off at that section”. Woolworths rated the complaint as a Severity 3 incident.

67 On 17 June 2012, Woolworths received a third complaint from an unidentified customer who bought the Safety Matches. The customer described how the entire box of matches ignited when she lit a match. Woolworths rated the complaint as a Severity 2 incident.

68 On 27 June 2012, Woolworths received a fourth complaint from an unidentified customer who again said that when lighting a match the whole box caught fire, burning the customer’s finger and thumb. Woolworths rated the complaint as a Severity 1 incident.

Withdrawal of Safety Matches from sale

69 On 28 June 2012, a Woolworths employee who reviewed the third complaint said that excessive sulphur might have fallen off the struck match and ignited the others. The employee recommended that the vendor of the Safety Matches be contacted because a few samples were tested which ignited instantly.

70 On 28 June 2012, the same employee sent a further internal email saying that another complaint had been received and that the products should be removed from sale. The next day Woolworths withdrew the total stock of Safety Matches from retail sale across Australia.

71 During July 2012 Woolworths instructed the supplier of the Safety Matches to change the formulation of the head of the matches to reduce the sensitivity of ignition of the match head. Woolworths also instructed that the quality of the wood used in the matches be improved so that the matches do not snap when lit. The reformulated matches were tested for product quality, which took place between June and August 2012, and a new formulation was approved on or around 18 August 2012.

Further Safety Matches incidents

72 Between August and October 2012, Woolworths received another five complaints from customers, including allegations: from one customer that the Safety Matches were dangerous because the thinness of the wood required concentration to strike a match; from another customer that the entire box had ignited; from another that material fell off the matches when they were ignited; from another that they split and broke and had no ignition; and from another that the matches all broke and fell to the floor while alight.

The ACCC inquiry and the second recall of Safety Matches

73 On 11 October 2012, the ACCC contacted Woolworths in response to a customer complaint about the Safety Matches. The ACCC said it was concerned that Woolworths had received other complaints of this nature. Following communications with the ACCC, on 30 October 2012 Woolworths decided to recall the Safety Matches. Woolworths decided that the 11 complaints (including five after the first recall which were rated Severity 1) raised concerns about the safety of the product.

The Padded Flop Chair incidents

74 Between 1 May 2012 and 31 August 2012, Woolworths offered a house brand consumer good, a Padded Flop Chair, for retail sale in Woolworths and Big W stores. Woolworths sold 13,440 units of the Padded Flop Chair at those outlets. An image of the Padded Flop Chairs is at Annexure 4 to these reasons.

75 The Padded Flop Chair carried the following text on its packaging:

Comfortable support: Ideal for any room in your home

Sturdy Construction: Steel frame supports up to 115 kg

Design: Instantly add colour and style to any room in your home.

76 The Padded Flop Chair also had the following warning label attached to it:

WARNING

The maximum weight limit for this chair is 115 kg.

Do not exceed 115 kg or you may cause injury to yourself and or damage to the chair.

77 On 22 August 2012, Woolworths received a complaint by a customer that after he constructed the chair, the customer had sat on it, fallen straight back and hit his head on a metal garage door and on the concrete floor. The customer said that the chair was faulty because the locking pin on one of the legs did not lock in correctly.

78 An investigation by Woolworths revealed that all of the Padded Flop Chairs had the same fault. The locking pin was not locked in place so the hinge caused the chair to collapse when 92 kg of weight or more was placed on it.

79 On 31 August 2012, Woolworths initiated a voluntary recall of the Padded Flop Chair. From 1 May 2012 until this date, 107 Padded Flop Chairs have been returned to Woolworths as faulty goods.

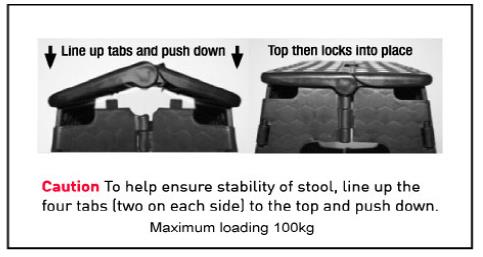

80 Between 31 August 2012 and 22 July 2013, Woolworths offered a house brand consumer good, a Plastic Folding Stool (the Folding Stool), for retail sale in Masters Home Improvement stores. Woolworths sold 1,908 units of the Folding Stool. An image of the Folding Stool is at Annexure 5 to these reasons.

81 The Folding Stool contained the following text:

Line up tabs and push down

Top then locks into place

Caution: To help ensure stability of stool, line up the four tabs (two on each side) to the top and push down

Maximum loading 100 kg.

82 On 18 July 2013, Woolworths received a complaint from a customer who fractured a vertebrae in her lower back when she fell to the floor while sitting on the Folding Stool. She was 75 kg.

83 On 22 July 2013, Woolworths withdrew the Folding Stool from sale. Between 31 August 2012 and 22 July 2013, consumers returned 75 Folding Stools to Woolworths.

84 On 13 August 2013, Woolworths performed a quality assurance check on 16 Folding Stools. Ten of the 16 units tested showed signs of failure across the hinge in the centre of the stool in less than a minute of loading 90 kg on the stool.

85 On 5 September 2013, following communication with the ACCC, Woolworths voluntarily recalled the Folding Stool.

Six additional failures to report incidents of serious injury or illness

86 For the six incidents listed below, Woolworths’ complaint handling systems recorded the customers’ complaints, which were then internally assessed. In each case, Woolworths failed to file the mandatory incident report required under the Australian Consumer Law.

The Multix Cling Wrap Premium Value 120m

87 Woolworths sold Multix Cling Wrap Premium Value 120 m at its Boronia supermarket. On 12 March 2011, Mrs CW told Woolworths that the previous week she had picked up this Cling Wrap at home and the serrated edge came off and hit her in the eye. Her doctor told her that her eye was scratched. It became swollen and subsequently infected. Woolworths failed to give a notice that complied with s 131(5) of the Australian Consumer Law.

88 Woolworths sold BBQ Chicken at its Dandenong supermarket. On 25 March 2011, Mr S told Woolworths that he ate some of the BBQ Chicken and approximately four hours later experienced severe vomiting. He went to hospital and was given Buscopan and injections to stop his vomiting. Woolworths failed to give a notice of this incident that complied with s 131(5) of the Australian Consumer Law.

The Homebrand Yellow Fruit Rings 400g

89 Woolworths sold a house brand consumer good, Homebrand Yellow Fruit Rings 400 g through its stores throughout Australia. On 17 May 2011, Ms TP told Woolworths that she had bought and eaten the Fruit Rings and subsequently developed welts and swelling on her face and body. Her doctor gave her an injection to stop the welts and swelling. Woolworths failed to give a notice about this incident that complied with s 131(5) of the Australian Consumer Law.

The Lamb, Herb, Garlic Cocktail K’Babs (10 Sticks pack)

90 From April 2008 until January 2010, Woolworths sold these Lamb K’Babs at its Baulkham Hills store. On 23 August 2011, Mr KP told Woolworths that after buying and eating the Lamb K’Babs from that store he began vomiting for 20 minutes and had difficulty breathing. His doctor gave him an injection and for the next week he had diarrhoea, stomach cramps, vomiting and was cold, shivering, unable to stand up straight or walk and lethargic. Woolworths failed to give a notice about this incident that complied with s 131(5) of the Australian Consumer Law.

The Arcosteel Coffee Plunger 6 Cup

91 Woolworths sold the Arcosteel Coffee Plunger 6 Cup at its Gosford supermarket. On 21 November 2012, Ms DW told Woolworths that after buying this Coffee Plunger she filled it with coffee and boiling water and when she stirred it, a two inch piece of glass blew out of the side of the Coffee Plunger. This caused boiling water and coffee to spill onto Ms DW’s hands and lower body. She suffered burns which blistered. Her doctor informed her that she had severe burns to 3% of her body. Woolworths failed to give a notice about this incident that complied with s 131(5) of the Australian Consumer Law.

92 Woolworths sold chicken thigh fillets at its South Melbourne supermarket. On 12 February 2013, Mr JM told Woolworths that the previous week he had purchased six of these Chicken Fillets and eaten three of them. He said that over the next three hours he began vomiting uncontrollably and had severe diarrhoea. His doctor said that he had food poisoning and administered an injection of Maxalon. Woolworths failed to give a notice about this incident that complied with s 131(5) of the Australian Consumer Law.

93 The precise description of the contraventions by Woolworths is set out in the declarations made. In summary, however, the contraventions by Woolworths can be divided into two broad categories. The first category broadly consists of its misleading or deceptive conduct including misrepresentations about the characteristics (including the safety) of products. The second category consists of its failures to report consumer goods associated with the death or serious injury or illness of any person.

The category of contraventions concerning misleading or deceptive conduct and misrepresentations

94 Woolworths admits to six courses of conduct giving rise to contraventions of the provisions of the Australian Consumer Law relating to misleading or deceptive conduct and false or misleading representations. The relevant provisions are ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33.

95 Section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law provides:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3‑1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

96 Section 29 of the Australian Consumer Law relevantly provides:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits…

97 In many cases, a breach of s 29 will also constitute a breach of s 18: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bunavit Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 6 [20] (Dowsett J). A breach of s 29 may attract a civil penalty, but a breach of s 18 will not.

98 Section 33 of the Australian Consumer Law provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any goods.

99 I accept Woolworths’ admissions (made for the purposes of these proceedings) and, based on my findings above, I conclude that Woolworths committed the following contraventions.

1. The Deep Fryer contraventions:

100 For the month between 4 June 2012 and 4 July 2012, Woolworths offered the Deep Fryer for retail sale although it was aware that the side handles of the Deep Fryer could detach when the Deep Fryer was lifted, leading to oil spills and possible burns if it contained hot oil.

101 Woolworths’ contraventions consisted of its failure to report the incidents to the ACCC within two days of the incidents occurring, and its failure to withdraw and recall the Deep Fryer from sale at its Big W stores after a reasonable period of time to identify and respond to this safety hazard. That conduct was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive (s 18); and it was liable to mislead the public as to the suitability of the Deep Fryer for its purpose, because the side handles of the Deep Fryer may detach when the Deep Fryer was lifted, leading to possible burns if it was moved while containing hot oil (s 33).

2. The Select Drain Cleaner labelling contraventions

102 Between 25 August 2013 and 20 March 2014 Woolworths offered the Select Drain Cleaner for sale. The text and directions on the cap of the Select Drain Cleaner, described above, were contraventions because they were: (i) misleading and deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive (s 18); (ii) a false or misleading representation that the Select Drain Cleaner was of a particular standard or quality and had certain performance characteristics (ss 29(1)(a) and 29(1)(g)); and (iii) liable to mislead the public as to the suitability for its purpose of the Select Drain Cleaner (s 33). Each of these contraventions arose because the instructions on the cap represented that the Select Drain Cleaner could only be opened, in ordinary use, by the application of downward pressure to the cap while turning it. In fact, the cap on the Select Drain Cleaner did not lock securely on the bottle and could be opened without the application of downward pressure to the cap while turning it.

3. The Select Drain Cleaner offer for sale contraventions

103 Between 24 February 2014 and 20 March 2014, Woolworths committed contraventions by offering the Select Drain Cleaner for retail sale when it was aware that the Select Drain Cleaner was unsafe during ordinary or reasonably foreseeable uses of the Select Drain Cleaner. It was unsafe because the cap did not lock securely on the bottle and could be opened without applying downward pressure to the cap while turning it. The contraventions committed by Woolworths were by its silence concerning this safety hazard and by refraining from withdrawing and recalling the Select Drain Cleaner within a reasonable time of identification, assessment and response to the hazard. These actions were misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive (s 18); and liable to mislead the public as to the suitability of the Select Drain Cleaner for its purpose (s 33).

4. The Safety Matches Contraventions

104 From 6 June 2012 until it withdrew them from sale on 28 June 2012, Woolworths offered the Safety Matches for sale when it was aware that the Safety Matches were unsafe when used during ordinary or reasonably foreseeable uses. This was because in some instances the head of the match could break or give off sparks upon ignition, causing possible injury or property damage, including by causing the box of matches to ignite. Woolworths’ contravening conduct was its silence in relation to this safety hazard and its failure to withdraw the Safety Matches from its stores once a reasonable period of time in which Woolworths could have identified, assessed and responded to these safety hazards had elapsed. This conduct was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive (s 18); and liable to mislead the public as to the suitability of the Safety Matches for their purpose (s 33).

5. The Padded Flop Chair Contraventions

105 Between 1 May 2012 and 31 August 2012, Woolworths offered the Padded Flop Chair for sale, making an express representation that the Padded Flop Chair was capable of bearing weights up to 115 kg. This representation was false because the Padded Flop Chair could not reliably support any more than 92 kg. This conduct involved the following contraventions: it was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive (s 18); it was a false or misleading representation that the Padded Flop Chair was of a particular standard or quality (s 29(1)(a)) and had certain performance characteristics (s 29(1)(g)); and it was liable to mislead the public as to the suitability for purpose of the Padded Flop Chair (s 33).

6. The Folding Stool Contravention

106 Between 31 August 2012 and 22 July 2013, Woolworths offered the Folding Stool for sale with an express representation that it was capable of bearing weights up to 100 kg. In fact, Woolworths was aware that under testing the Folding Stool could reliably support no more than 90 kg. The express representation involved the following contraventions: it was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive (s 18); it was a false or misleading representation that the Folding Stool was of a particular standard or quality (s 29(1)(a)) and had certain performance characteristics (s 29(1)(g)); and it was liable to mislead the public as to the suitability for its purpose of the Folding Stool (s 33).

The category of contraventions concerning Woolworths’ failures to report

107 In 2010, the Australian Consumer Law introduced a new national product safety regime, which commenced in January 2011. This regime built upon the product safety regime that Australia has had for decades by introducing a requirement of mandatory reporting of consumer goods associated with death or serious injury or illness of any person.

108 Woolworths admits to eight instances of failing to report incidents of serious injury or illness caused by the use of its consumer goods. This contravenes s 131 of the Australian Consumer Law. Under this section, suppliers must notify the Minister within two days of becoming aware of the incident. Section 131 of the Australian Consumer Law provides:

131 Suppliers to report consumer goods associated with the death or serious injury or illness of any person

(1) If:

(a) a person (the supplier), in trade or commerce, supplies consumer goods; and

(b) the supplier becomes aware of the death or serious injury or illness of any person and:

(i) considers that the death or serious injury or illness was caused, or may have been caused, by the use or foreseeable misuse of the consumer goods; or

(ii) becomes aware that a person other than the supplier considers that the death or serious injury or illness was caused, or may have been caused, by the use or foreseeable misuse of the consumer goods;

the supplier must, within 2 days of becoming so aware, give the Commonwealth Minister a written notice that complies with subsection (5).

109 The Australian Consumer Law defines serious injury or illness in s 2 to mean an acute physical injury or illness that requires medical or surgical treatment by, or under the supervision of, a medical practitioner or a nurse.

110 Section 131(4) provides for ways in which the supplier can become aware of the circumstances requiring a report. These include receiving the information from a consumer. Section 131(5) also provides for the matters that must be contained in the notice including: identification of the goods; the circumstances in which the death or serious injury or illness occurred; the nature of any serious injury or illness suffered by any person; the circumstances of the incident; action that the supplier has taken or is intending to take; and information known about the quantities manufactured in, or imported into, or exported from, Australia.

111 There are exceptions where s 131(1) does not apply, contained in s 131(2). These include where (a) it is clear that the death or serious injury or illness was not caused by the use or foreseeable misuse of the consumer goods; or (b) it is very unlikely that the death or serious injury or illness was caused by the use or foreseeable misuse of the consumer goods.

112 Woolworths committed eight contraventions of s 131(1):

(1) it failed to notify the ACCC within two days of becoming aware of the first Deep Fryer incident because notification did not occur until 1 June 2013;

(2) it failed to notify the ACCC of all the details required by s 131(5) within two days of becoming aware of the Fifth Select Drain Cleaner incident;

(3) it failed to notify the ACCC within two days of becoming aware of the Cling Wrap incident;

(4) it failed to notify the ACCC within two days of becoming aware of the BBQ Chicken incident;

(5) it failed to notify the ACCC within two days of becoming aware of the Fruit Rings incident;

(6) it failed to notify the ACCC within two days of becoming aware of the Lamb K’Babs incident;

(7) it failed to notify the ACCC within two days of becoming aware of the Coffee Plunger incident; and

(8) it failed to notify the ACCC within two days of becoming aware of the Chicken Fillets incident.

The course of conduct principle

113 A pecuniary penalty may be imposed at the Court’s discretion for any act or omission that contravenes ss 29, 33 or 131 of the Australian Consumer Law.

114 Section 224(3) of the Australian Consumer Law provides that the maximum civil pecuniary penalty for a body corporate:

(1) for each contravention of ss 29 and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law is $1.1 million; and

(2) for each contravention of s 131(1) of the Australian Consumer Law is $16,500.

115 Woolworths submitted that it engaged in six courses of conduct involving multiple contraventions. It submitted that the maximum possible penalty is $6.732 million ($1.1 million for each of the six courses of conduct and $16,500 for each of the eight s 131 contraventions).

116 There are two steps to assessing Woolworths’ submission that the maximum possible penalty is necessarily fixed at $6.732 million. The first step is whether the conduct in each course of conduct is the “same” conduct which contravenes two or more provisions. Where the same conduct contravenes two or more provisions, a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty in respect of the same conduct: s 224(4)(b) of the Australian Consumer Law.

117 Whether conduct is the “same” contravening conduct depends upon characterisation of the facts. That characterisation exercise focuses upon the level of generality at which the contravention is described. It is not a matter of how the contravention is pleaded. It is a matter of substance. If the conduct is characterised at a low, and particular, level of generality then the contravening conduct will often be different and multiple contraventions will not be the “same”. But as the conduct is characterised at higher levels of generality it becomes easier to say that the conduct is the “same” so that the person is liable for only one penalty for multiple contraventions.

118 Professor Schauer makes the same point by giving the example of saying to his friend “I own a 1990 White Subaru Legacy Station Wagon”. The friend might reply “I have the same car”. In this ordinary use of language the facts are characterised at a higher level of generality than an examination of whether the two cars are materially identical in all respects other than the described characteristics. As Schauer explains in “Instrumental Commensurability” (1998) 146 U Pa L Rev 1215, 1217:

The use of the word “same” often suggests not only that a number of relevant similarities exist even in the face of dissimilarities, but also that in the instant context these dissimilarities are immaterial.

119 It is unnecessary in this case to engage in the exercise of characterisation beyond saying that I am content to proceed upon the common assumption by counsel that the only conduct that was the same was where, within a course of conduct, the same facts were relied upon as establishing contraventions of multiple provisions. Senior counsel for Woolworths did not submit, for example, that the multiple infringements within a course of conduct were materially the “same” conduct. I am also prepared to proceed on that basis. Hence, it is not necessary to consider whether the maximum penalty is required to be limited to a total of $1.1 million for each course of conduct or a total of $16,500 for all the s 131 contraventions.

120 If conduct involving multiple contraventions, properly characterised, is not the “same” conduct then the next question is whether the conduct is so closely related that, as a matter of discretion, the maximum penalty for a single contravention should be treated as a guide, but not a limit, to the penalty to be imposed for all the related contraventions: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reebok Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 83 [160] (McKerracher J). In Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1, 13 [41], Middleton and Gordon JJ explained that the course of conduct principle is based in an underlying concern to avoid double punishment: it “recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, the court must ensure that the offender is not punished twice for the same conduct” (emphasis in bold added). The assumption of counsel in this case was that the notion of the “same” conduct is used here by Middleton and Gordon JJ in a broader sense than in s 224(4)(b) of the Australian Consumer Law. The concern to avoid double punishment in this context might also be seen as an aspect of what is sometimes described as the first limb of the “totality” principle: the total penalty should reflect the overall culpability involved.

121 The exercise of characterising the contravening conduct, at the (assumed) less strict standard of applying the course of conduct principle involves an evaluative judgment. In my view, each of the six courses of conduct involved, at least, a high degree of interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of the contraventions involved so as to fall within that principle. For each of the six courses of conduct the “course of conduct” principle is relevant and the maximum penalty of $1.1 million for a single contravention is appropriately part of the exercise of evaluation (as one factor to consider) in determining the appropriate total penalty for each course of contraventions involved. I do not consider that the principle has the same force in relation to the eight s 131 contraventions which involved different and unrelated circumstances even though they might all be related by a failure by Woolworths to have a system which ensured notification. Nor, after careful consideration, do I consider that the principle has the same force in relation the two courses of contraventions involving the Select Drain Cleaner even though the conduct involved in those courses of contravention was related both in character and in time.

The relevant factors and comparative cases

122 Section 224(2) of the Australian Consumer Law provides that in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

123 These mandatory considerations are only three of the matters to which the Court must have regard. Although other factors are commonly described as “discretionary factors” there is no real discretion involved. Once another factor is relevant, the Court is required to have regard to it.

124 Some of the commonly relevant matters other than those in (a) to (c) to which the Court must have regard if relevant were described by Perram J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd (No 4) [2011] FCA 761; (2011) 282 ALR 246, 250-251 [11] (a list which was referred to without objection on appeal: Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249, 258 [37] (the Court)):

(1) the size of the contravening company;

(2) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(3) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at some lower level;

(4) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act (or the new Australian Competition and Consumer Law) as evidenced by educational programmes and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(5) whether the contravener has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention;

(6) whether the contravener has engaged in similar conduct in the past;

(7) the financial position of the contravener; and

(8) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

125 Underlying many of these factors is what numerous authorities describe as the principal object of deterrence in the award of civil penalties. Deterrence can be “specific” to the particular person who committed the contravention and also “general” to persons in the same or similar circumstances to the person being subjected to the pecuniary penalty.

126 A consideration of deterrence, general and specific, also means that the following factors will also commonly be relevant:

(9) the extent of contrition;

(10) whether the contravening company made a profit from the contraventions;

(11) the extent of the profit made by the contravening company; and

(12) whether the contravening company engaged in the conduct with an intention to profit from it.

127 There was some dispute in this case about whether payments of compensation made by Woolworths is a relevant factor. As I explain later, I consider that this is a relevant factor to consider both directly and indirectly (as a matter which is relevant to contrition).

128 There are deep philosophical questions that underlie the process of reasoning to a conclusion by reference to multifarious factors and also by comparison with other cases. It is necessary to say something about these issues to explain why I do not accept a submission, powerfully pressed, by senior counsel for Woolworths.