FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Chrisco Hampers Australia Limited [2015] FCA 1204

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | CHRISCO HAMPERS AUSTRALIA LIMITED ACN 080 852 535 Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties to confer on a timetable for evidence and submissions concerning a hearing on penalty and consequential issues.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 683 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

AND: | CHRISCO HAMPERS AUSTRALIA LIMITED ACN 080 852 535 Respondent |

JUDGE: | EDELMAN J |

DATE: | 10 NOVEMBER 2015 |

PLACE: | BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 This trial concerned three alleged classes of contravention by the respondent, Chrisco, of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (the ACL). The comprehensive submissions by counsel addressed three sections of the ACL about which there appears to be very little authority relevant to these circumstances.

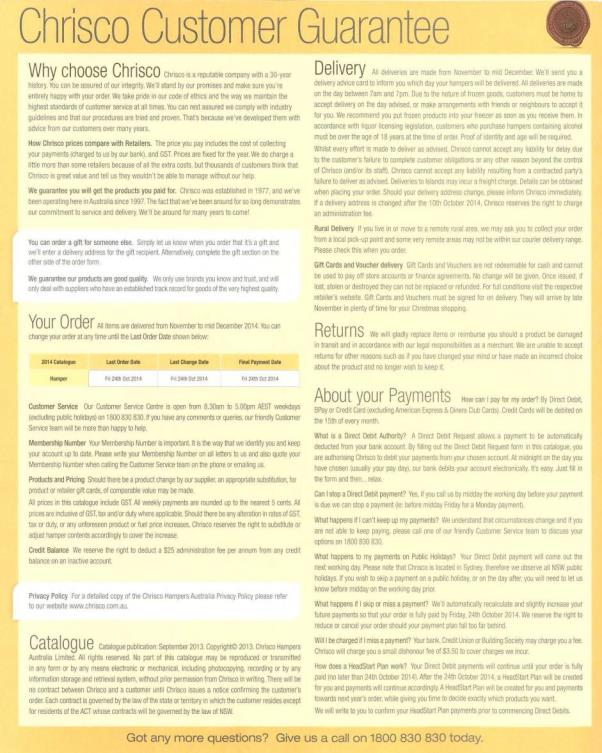

2 The applicant, the ACCC, claimed that Chrisco contravened the ACL in the course of Chrisco’s business. Chrisco’s business included supplying customers with Christmas hampers. The goods in Chrisco’s hampers were usually priced above retail prices. But the customers paid Chrisco for the hampers by instalments over periods of up to a year. Chrisco said that many of its customers had told Chrisco that “they wouldn’t be able to manage without our help”.

3 Chrisco’s contracts with its customers contained a term (called the HeadStart term) that required the customers to allow Chrisco to continue withdrawing funds from the customer’s bank account even after the customer had made full payment for the goods. The term would apply unless the customer opted out of it. The money withdrawn from the customer’s bank account would be used for any future order made by the customer but the customer would not obtain any discount on a future order and if the customer did not place an order, but requested a refund of the money paid, the money would be refunded without interest.

4 The first issue concerns whether the HeadStart term is an “unfair term” within the meaning of s 24 of the ACL. The essential issue in this case is whether the HeadStart term caused a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract. One of Chrisco’s submissions was that the demographic of its customers, some of whom were described as “unsophisticated”, was such that it was an advantage for them to have money removed from their accounts prior to placing another order unless they elected to the contrary or sought a refund. Chrisco submitted that the removal of the money from the customers’ accounts without interest, and without any discount on a prospective order, conferred a benefit on the customers. Chrisco said that the benefit was that the customers were given the ability to pay for prospective orders by smaller instalments over a longer period of time (albeit at a higher cost taking into account the time value of money). As I explain in the body of these reasons, such a “benefit” is not substantial. I consider that in all of the circumstances of the HeadStart term and Chrisco’s contract the term was unfair.

5 The second issue concerns the meaning and application of the duty in s 97(3) of the ACL upon a supplier who is a party to a lay-by agreement to “ensure” that the amount of a termination charge is not more than the supplier’s reasonable costs in relation to the agreement. Chrisco charged its consumers a “cancellation charge” which, during one period of time, could have been as much as 50% of the cost of the order (if only one Christmas hamper had been ordered the price could have been more than $2,000).

6 The ACCC did not lead any evidence of Chrisco’s actual charges in relation to any agreement. Instead, its submission was that Chrisco had failed to ensure that it had a proper system in place for estimating reasonable costs in relation to the contract even if the application of that criterion meant that Chrisco would never have actually imposed a termination charge which exceeded its reasonable costs in relation to the agreement.

7 The ACCC’s approach to s 97(3) is inconsistent with the words of s 97(3), it is inconsistent with their context, and, in comparison with Chrisco’s construction, it operates to the detriment of the consumer and contrary to the purpose of s 97(3). Chrisco’s construction should be accepted: s 97(3) is contravened only when a supplier’s termination charge exceeds its reasonable costs in relation to the agreement. On the evidence before the Court, the ACCC did not prove that Chrisco contravened s 97(3).

8 The third issue concerns whether Chrisco contravened s 29(1)(m) of the ACL by making a false or misleading representation that a consumer could not cancel his or her lay-by agreement once an order was fully paid and before delivery of the goods. Chrisco’s only submission was that s 96(3), and the definition of “lay-by” is concerned with an agreement for the supply of particular goods upon a condition of full payment and not with an agreement which provides for the possibility of the supply of alternative goods if full payment has not been made. There is no warrant in the terms or the purpose of s 96(3) to construe the definition of “lay-by” so narrowly.

9 My ultimate conclusion on this trial of liability is that the ACCC succeeds in relation to the matters raised in the first and third issues, but not in relation to the second.

10 Most of the facts in this case were uncontroversial. A broad background, deriving from the agreed facts, is as follows.

11 Chrisco is a company incorporated in New Zealand. It operates from Regents Park in New South Wales. It has approximately 114-126 permanent staff. It is in the business of the supply of goods.

12 The goods supplied by Chrisco include food, beverages, and domestic and household products. The goods are packaged and typically delivered from 1 November to 10 December each year, as a hamper (the Christmas hamper), to customers across Australia.

13 The goods that constituted the Christmas hamper were goods of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household use or consumption; and the acquisition of which was wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household use or consumption.

14 Chrisco offered the Christmas hampers principally through catalogues. For example, for the 2014 year, Chrisco offered Christmas hampers through the Chrisco 2014 Christmas Hamper Catalogue. Chrisco’s catalogues were available to customers on Chrisco’s website, and as hard copies, sent via post, including upon request.

15 Chrisco’s prices for the supply of items that could be selected for inclusion in a Christmas Hamper were fixed for each year. The price for each item available for selection by a customer for inclusion in a Christmas hamper was published in the catalogue for that year.

16 The distribution of customers who ordered Christmas hampers in 2014 was approximately 46% based in metropolitan areas and 54% based outside metropolitan areas. There was some evidence that Chrisco’s customers were from the low to middle income demographic.

17 Since 1 January 2011, Chrisco published a series of pro forma documents headed “Order Form” (Order Form). The Order Form was published in Chrisco catalogues and on Chrisco’s website. Chrisco also published terms and conditions of orders in each of its catalogues and on its website.

18 Customers could place orders with Chrisco for Christmas hampers in one of the following three ways:

(1) returning the completed Order Form published in a Chrisco catalogue;

(2) submitting the Order Form published on Chrisco’s website; or

(3) placing an order by telephone with a Chrisco representative.

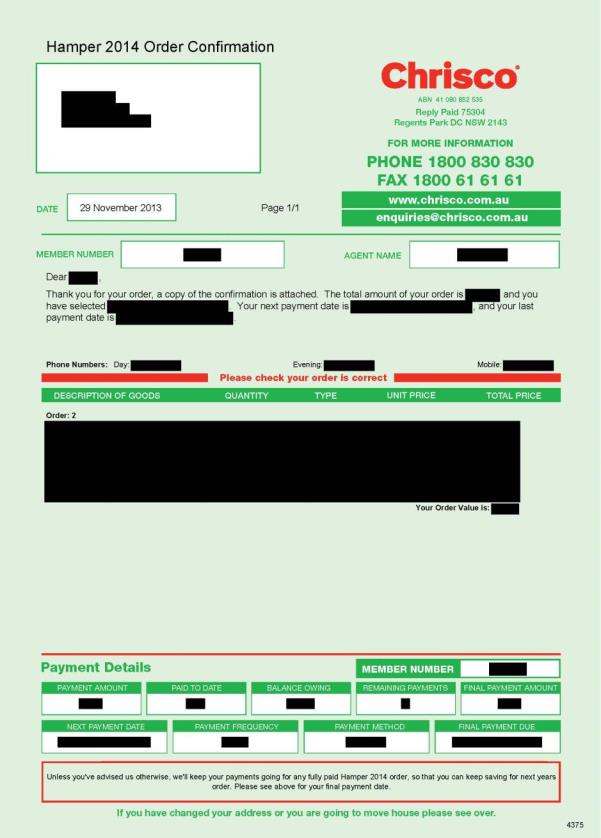

19 After Chrisco had received a completed Order Form from a customer, or the customer had placed an order by telephone, Chrisco sent a document titled “Order Confirmation” to the customer (Order Confirmation).

20 When Chrisco entered into an agreement with a customer, the terms of the agreement included a term to the effect that the customer would make regular payments to Chrisco. Those payments were calculated by reference to the following matters: (i) the total amount payable, (ii) the chosen date for payments to start, (iii) the chosen frequency of payments, and (iv) the “Final Payment Date”.

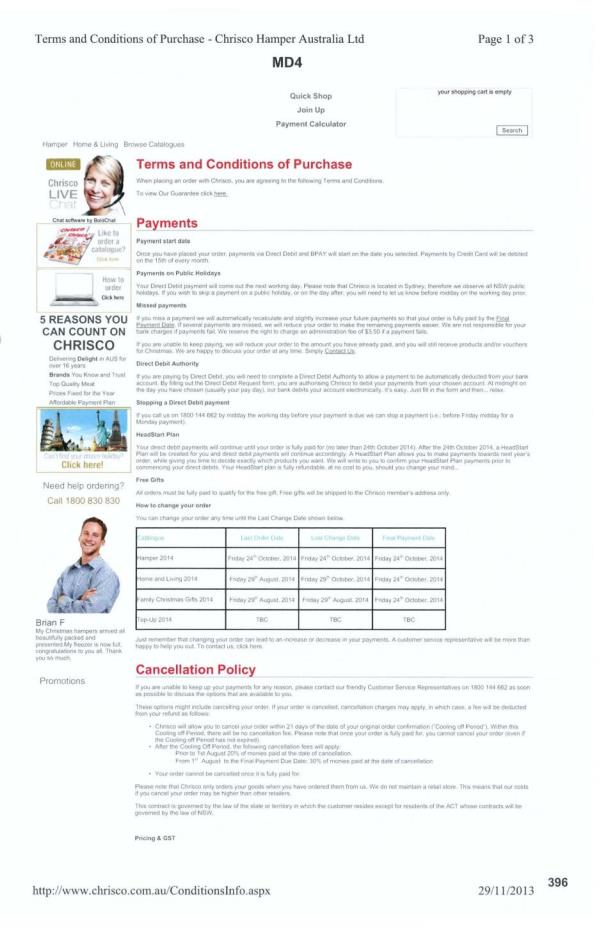

21 Between 1 January 2011 and about December 2014, the website terms and conditions included terms to the effect that:

(1) the “Final Payment Date” for any order is a specified date, which for each of the relevant years was in the last or second last week of October of the year the goods were to be delivered;

(2) a customer can change their order at any time until the “Last Change Date”;

(3) the “Last Change Date” is a specified date, which for each of the relevant years was in the last or second last week of October of the year the goods were to be delivered;

(4) if a customer misses a payment, Chrisco will automatically recalculate and slightly increase the customer’s future payments so that the customer’s order is fully paid by the “Final Payment Date” identified in the agreement;

(5) if a customer misses several payments, Chrisco will reduce the customer’s order to make the remaining payments easier;

(6) if a customer is unable to keep paying, Chrisco will reduce the customer’s order to the amount that the customer has already paid and the customer will still receive products and/or vouchers for Christmas; and

(7) Chrisco will deliver the goods to the customer during the period November to mid-December.

22 Between 1 January 2011 and about December 2014, the catalogue terms and conditions included terms to the effect that:

(1) if a customer skips or misses a payment, Chrisco will automatically recalculate and slightly increase the customer’s future payments so that the customer’s order is fully paid by a date identified in the agreement that, for each of the relevant years, was in the last or second last week of October of the year the goods were to be delivered;

(2) Chrisco understands that circumstances may change such that the customer is unable to keep paying and, if that occurs, the customer should call a Chrisco representative to discuss the options available to the customer; and

(3) Chrisco will deliver the goods to the customer during the period November to mid-December.

23 The 2014 Christmas Hamper catalogue also contained terms to the effect that a customer can change their order at any time until the “Last Order Date” which was Friday 24 October 2014.

24 The Chrisco agreements for the 2014 year included a term, on the website and in the catalogue referring to the HeadStart Plan, for payments to continue towards a 2015 order after the 2014 order had been fully paid. That term is discussed in more detail below as the 2014 HeadStart term.

25 Between 1 January 2011 and about December 2014, between 99% and 100% of sales made by Chrisco were pursuant to agreements on terms that had the effect that the price of the goods was to be paid by three or more instalments.

26 It was common ground that, since January 2011, each agreement between Chrisco and a customer for the supply of a Christmas hamper was a consumer contract within the meaning of s 23(3) of ACL and a standard form contract within the meaning of section 27 of ACL. Chrisco’s customers were all consumers.

27 There were three issues at trial that concerned the potential liability of Chrisco for three different types of contravention of the ACL. The three issues were broadly as follows:

(1) Was the 2014 HeadStart term an “unfair term” within the meaning of s 24 of the ACL with the effect that, due to s 23, the term was void?

(2) Did Chrisco’s cancellation charges contravene s 97 of the ACL?

(3) Were Chrisco’s agreements lay-by agreements within s 96(3) of the ACL?

Issue 1: Was the 2014 HeadStart term an “unfair term” within the meaning of s 24 of the ACL?

The documents that comprise the contract

28 The parties’ submissions concerning the process by which the contract was formed evolved during the trial. By the conclusion of the trial it was common ground, and I proceed on the basis, that the contract between Chrisco and a consumer was formed in the following way.

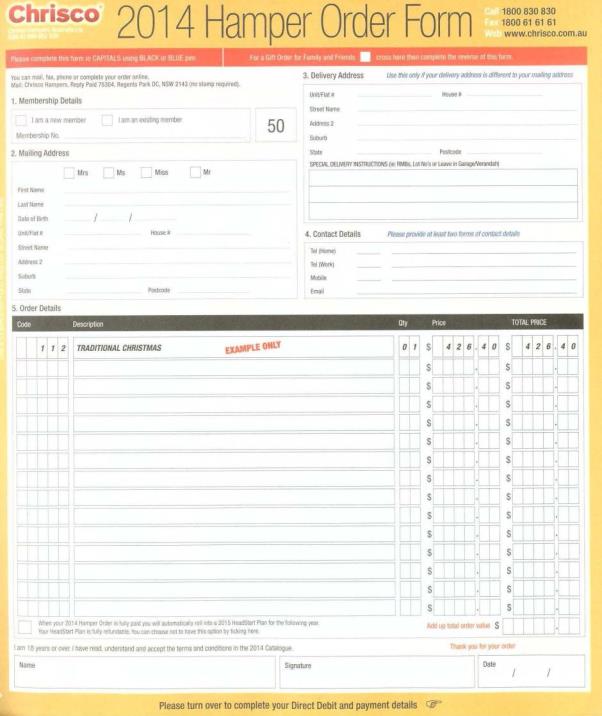

29 In the case of an order that was placed by completing the order form contained within the middle four pages in the Chrisco Christmas catalogue,

(1) the consumer’s completed order form amounted to an offer to Chrisco on the terms contained in the order form and the accompanying three pages. Those pages are annexed to these reasons as Annexure 1.

(2) Chrisco’s “Order Confirmation”, which is Annexure 3 to these reasons, contained additional terms, including cancellation fees, and amounted to a counter-offer.

(3) The counter-offer was accepted by the consumer’s conduct, although there were no submissions made about the conduct of the consumer that involved such acceptance.

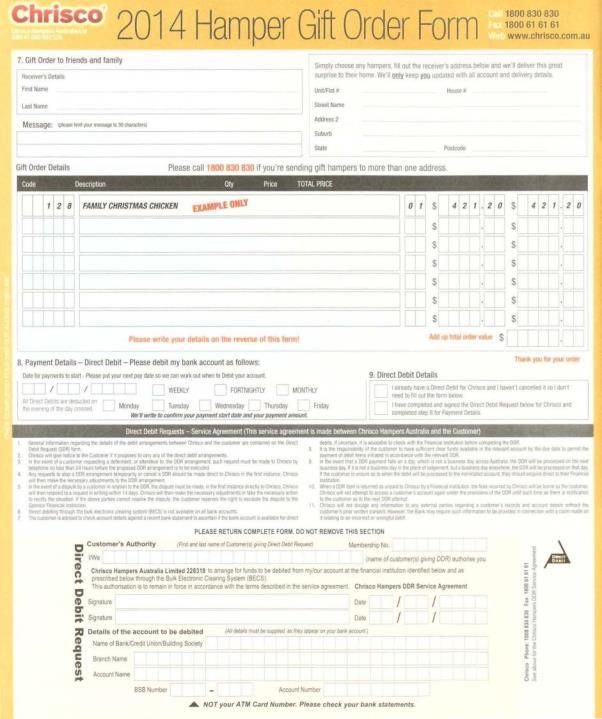

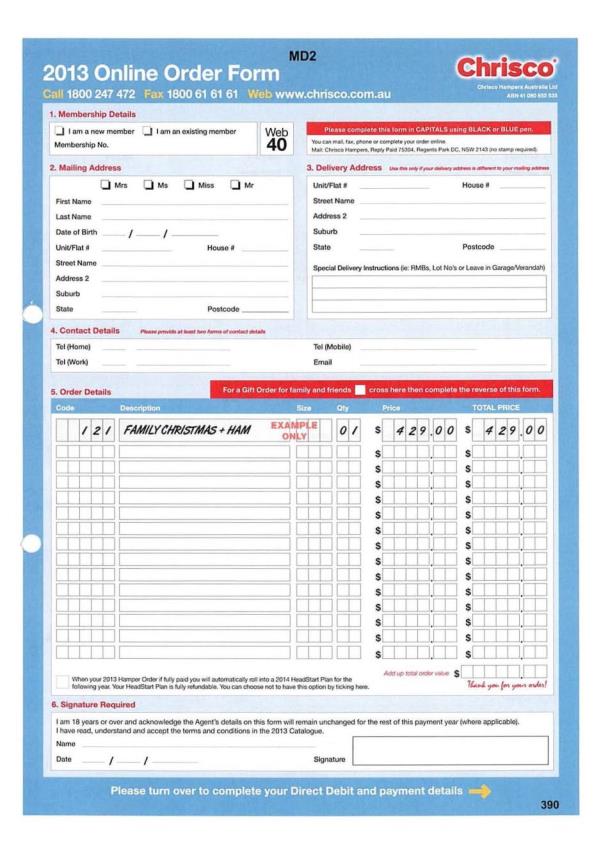

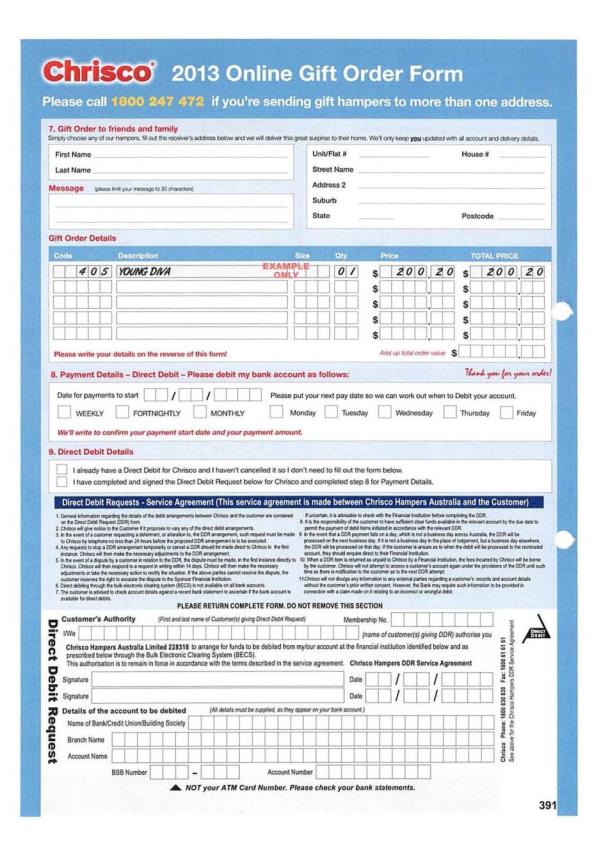

30 In the case of an order that was placed by completing the order form contained on Chrisco’s website:

(1) the consumer’s completed online order form amounted to an offer to Chrisco on the terms contained in the online material. Those pages are annexed to these reasons as Annexure 2.

(2) Chrisco’s “Order Confirmation”, which is Annexure 3 to these reasons, was either an acceptance of that offer or a counter-offer which was accepted by later conduct of the consumer (again, the parties’ assumption was that there was conduct by the consumer amounting to acceptance of any counter-offer).

31 The 2014 HeadStart term which the ACCC alleged to be unfair is set out below. It was pleaded in paragraphs 10 and 11 of the ACCC’s statement of claim, and admitted to be a term by Chrisco.

32 As to orders made from Chrisco’s catalogue:

When your 2014 (…) Order is fully paid you will automatically roll into a 2015 HeadStart Plan for the following year. Your HeadStart Plan is fully refundable. You can choose not to have this option by ticking here.

and

How does a HeadStart Plan work? Your direct Debit payments will continue until your order is fully paid (no later than 24th October 2014). After the 24th October 2014, a HeadStart Plan will be created for you and payments will continue accordingly. A HeadStart Plan will be created for you and payments towards next year’s order, while giving you time to decide exactly what products you want.

We will write to you to confirm your HeadStart Plan payments prior to commencing Direct Debits.

33 As for orders made from Chrisco’s website, for the 2014 year, the website terms and conditions relevantly provided:

When your 2014 (…) Order is fully paid you will automatically roll into a 2015 HeadStart Plan for the following year. Your HeadStart Plan is fully refundable. You can choose not to have this option by ticking here.

and

HeadStart Plan

Your direct debit payments will continue until your order is fully paid for (no later than 24th October 2014). After the 24th October 2014, a HeadStart Plan will be created for you and direct debit payments will continue accordingly. A HeadStart Plan allows you to make payments towards next year’s order, while giving you time to decide exactly which products you want. We will write to you to confirm your HeadStart Plan payments prior to commencing your direct debits. Your HeadStart Plan is fully refundable at no cost to you, should you change your mind.

34 Although the paragraphs above describe the whole of the pleaded unfair term, they contain material which strictly goes beyond the “term”. There are aspects of the paragraphs pleaded which are not part of any contractual “term”. The “opt-out” statement that “You can choose not to have this option by ticking here” is not a contractual term. Instead, it determines what the contract term will be. It is part of Chrisco’s form by which the consumer’s offer might be made. Nevertheless, the parties conducted this trial on the assumption that this statement in Chrisco’s offer could be considered together with the alleged unfair term. The opt-out option is plainly a matter that I consider relevant to the assessment of whether the HeadStart term is unfair under s 24(1) (see the relevancy criteria in s 24(2)) so I am content to proceed on the same basis.

35 A separate term of the contract, which the ACCC did not allege to be unfair but which is relevant in the consideration of the terms of the contract as a whole, is the provision in the Order Confirmation. For the 2014 year, the Order Confirmation also provided in relation to a HeadStart Plan:

Unless you’ve advised us otherwise, we’ll keep your payments going for any fully paid Hamper 2014 order, so that you can keep saving for next years order. Please see above for your final payment date.

36 The Hamper 2014 Order Confirmation identified the final payment date as a date in late October 2014.

Section 24 of the ACL: the meaning of an unfair term

37 Section 24 of the ACL provides as follows:

Meaning of unfair

(1) A term of a consumer contract is unfair if:

(a) it would cause a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract; and

(b) it is not reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term; and

(c) it would cause detriment (whether financial or otherwise) to a party if it were to be applied or relied on.

(2) In determining whether a term of a consumer contract is unfair under subsection (1), a court may take into account such matters as it thinks relevant, but must take into account the following:

(a) the extent to which the term is transparent;

(b) the contract as a whole.

(3) A term is transparent if the term is:

(a) expressed in reasonably plain language; and

(b) legible; and

(c) presented clearly; and

(d) readily available to any party affected by the term.

(4) For the purposes of subsection (1)(b), a term of a consumer contract is presumed not to be reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term, unless that party proves otherwise.

38 Section 24(1) of the ACL requires the three elements in (a) to (c) to be satisfied before a term of a consumer contract is unfair. Each is addressed below after some broad observations about the operation of s 24.

39 Section 24 of the ACL is an example of a legislative technique that was historically less familiar to the common lawyer than it was to the civilian lawyer. It is a technique which creates broad evaluative criteria to be developed incrementally. In Plevin v Paragon Personal Finance Ltd [2014] UKSC 61; [2014] 1 WLR 4222, the United Kingdom Supreme Court considered a legislative provision that permitted reopening of credit transactions where the relationship between the creditor and the debtor was “unfair”. Speaking of the provision, Lord Sumption in the leading judgment said, at 4227 [10], that it was not possible to state a precise or universal test for its application.

40 As Justice Leeming has explained, open-ended statutes which turn on broadly expressed concepts “naturally and indeed necessarily attract a more purposive and less minutely textual mode of construction”: M Leeming “Equity: Ageless in the ‘Age of Statutes’” (2015) 9 Journal of Equity 108, 116. The legislative concept of “unfairness” in s 24, with elaboration through the three elements of unfairness, might be described as a guided form of open-ended legislation. In relation to the Victorian version of the same unfairness provisions as arise in this case, in Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2015] FCAFC 50 [363] – [364], Allsop CJ (Besanko and Middleton JJ agreeing) emphasised the evaluative nature of the assessment of unfairness, to be carried out with a close attendance to the statutory terms. The Chief Justice also observed that “unjustness and unfairness are of a lower moral or ethical standard than unconscionability”.

41 The Explanatory Memorandum to the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Bill (No 2) 2010 (Cth) [5.2]-[5.4] explained that the regime which contained s 24 was introduced following an agreement between the Council of Australian Governments to establish a national law. The national law had been recommended by the Productivity Commission and proposed by the Ministerial Council on Consumer Affairs. The Productivity Commission had noted that common unfair contract provisions had been adopted in the United Kingdom and Victoria: Productivity Commission Inquiry Report, Review of Australia’s Consumer Policy Framework Volume 2 – Chapters and Appendices (No 45, 30 April 2008) p 159.

42 Despite the origin of much of the unfair contract term definition in the UK regulations, Parliament departed from the precise terms of the UK provision. In particular, reference in UK to the requirement of “good faith” was removed from the Australian provision. The Regulation Impact Statement in Chapter 11 of the Explanatory Memorandum (pages 133 and 135) described the unsettled status of good faith in Australia and proposed that the definition should not make reference to “good faith” given that uncertainty.

43 In his eloquent submissions, senior counsel for Chrisco emphasised a number of matters concerning the construction of s 24, all of which I accept:

(1) for a term to be unfair it must satisfy the requirements of all of s 24(1)(a) to (c);

(2) the onus is upon the applicant to prove the matters in ss 24(1)(a) and 24(1)(c) but it is upon the respondent in relation to s 24(1)(b);

(3) s 24(2)(a) only requires the Court to consider transparency in relation to the particular term that is said to be unfair and only in relation to the matters concerning that term in s 24(1)(a) to (c);

(4) similarly, the assessment of the contract as a whole in s 24(1)(c) only requires the Court to consider the contract as a whole in relation to the particular term that is said to be unfair and only in relation to the matters concerning that term in s 24(1)(a) to (c);

(5) as the Explanatory Memorandum to the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Bill (No 2) 2010 (Cth) provided at [5.39], “if a term is not transparent it does not mean that it is unfair and if a term is transparent it does not mean that it is not unfair”; and

(6) guidance can be had to s 25 which provides examples of unfair terms.

44 Although there was some dispute about (5), a contextual approach to statutory interpretation cannot ignore the matters provided in s 25 which are specifically provided for the purpose of giving examples of potentially unfair terms: see also Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd v Free [2008] VSC 539, [110] and [114] (Cavanough J); Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank Plc [2001] UKHL 52; [2002] 1 AC 481, 481 [17] (Lord Bingham). Further, the Explanatory Memorandum to the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Bill (No 2) 2010 (Cth) in which these provisions were introduced, provided in [5.44] that the examples in s 25 “provide statutory guidance on the types of terms which may be regarded as being of concern. They do not prohibit the use of those terms, nor do they create a presumption that those terms are unfair”. See also the second reading speech of the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Bill) 2009, Hansard, House of Representatives, 24 June 2009, 6986 (Dr Emerson).

45 Section 25 of the ACL provides examples of unfair terms as follows:

Examples of unfair terms

(1) Without limiting section 24, the following are examples of the kinds of terms of a consumer contract that may be unfair:

(a) a term that permits, or has the effect of permitting, one party (but not another party) to avoid or limit performance of the contract;

(b) a term that permits, or has the effect of permitting, one party (but not another party) to terminate the contract;

(c) a term that penalises, or has the effect of penalising, one party (but not another party) for a breach or termination of the contract;

(d) a term that permits, or has the effect of permitting, one party (but not another party) to vary the terms of the contract;

(e) a term that permits, or has the effect of permitting, one party (but not another party) to renew or not renew the contract;

(f) a term that permits, or has the effect of permitting, one party to vary the upfront price payable under the contract without the right of another party to terminate the contract;

(g) a term that permits, or has the effect of permitting, one party unilaterally to vary the characteristics of the goods or services to be supplied, or the interest in land to be sold or granted, under the contract;

(h) a term that permits, or has the effect of permitting, one party unilaterally to determine whether the contract has been breached or to interpret its meaning;

(i) a term that limits, or has the effect of limiting, one party’s vicarious liability for its agents;

(j) a term that permits, or has the effect of permitting, one party to assign the contract to the detriment of another party without that other party’s consent;

(k) a term that limits, or has the effect of limiting, one party’s right to sue another party;

(l) a term that limits, or has the effect of limiting, the evidence one party can adduce in proceedings relating to the contract;

(m) a term that imposes, or has the effect of imposing, the evidential burden on one party in proceedings relating to the contract;

(n) a term of a kind, or a term that has an effect of a kind, prescribed by the regulations.

46 In the Explanatory Memorandum to the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Bill (No 2) 2010 (Cth) [5.49]-[5.57], it is explained that:

(1) Paragraphs 25(1)(a), (b), (d), (e), (f), (g), and (h) are examples of types of terms that allow a party to make changes to key elements of a contract, including terminating it, on a unilateral basis.

(2) Paragraphs 25(1)(i), (k), (l), and (m) are examples of types of terms that have the effect of limiting the rights of the party to whom the consumer contract is presented.

(3) Paragraph 25(1)(c) refers to terms that penalise, or have the effect of penalising, one party for a breach or termination of the contract (reflecting the common law concept of penalties); and

(4) Paragraph 25(1)(j) refers to terms that allow for a party to assign the contract to the detriment of the other party, without that party’s consent.

(a) Would the HeadStart term cause a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract?

47 Both parties proceeded on the common ground that the approach to be taken to this element was the approach taken by Lord Bingham in Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank Plc [2001] UKHL 52; [2002] 1 AC 481, 481 [17]:

The requirement of significant imbalance is met if a term is so weighted in favour of the supplier as to tilt the parties’ rights and obligations under the contract significantly in his favour. This may be the granting to the supplier of a beneficial option or discretion or power, or by the imposing on the consumer of a disadvantageous burden or risk or duty.

48 These remarks were made by Lord Bingham in the context of regulation 5(1) of the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contract Regulations 1999 (UK) which was a response to the European Community’s Council Directive 93/13/EEC on unfair terms in consumer contracts. Regulation 5(1) provided:

A contractual term which has not been individually negotiated shall be regarded as unfair if, contrary to the requirement of good faith, it causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract, to the detriment of the consumer.

49 I proceed on the basis that Lord Bingham’s definition is an appropriate meaning to be given to the notion of “significant imbalance”. But the focus remains on the terms of the section. This is particularly the case in circumstances in which the UK regulations are not identical to the terms of s 24 and, as I have explained above, were not intended to be identical.

50 I also proceed on the basis that the lack of individual negotiation of the contracts between Chrisco and its customers is not relevant to whether the HeadStart term caused a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract: see Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd v Free [2008] VSC 539 [112] (Cavanough J); Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2014] FCA 35 [331] (Gordon J).

51 An assessment of this first element of unfairness requires consideration of the HeadStart term together with the parties’ other rights and obligations arising under the contract in order to assess whether the HeadStart term causes a significant imbalance in the rights and obligations arising under the contract.

52 The first point of note about the HeadStart term, which I consider to be a “relevant matter” under s 24(2), is that the HeadStart term is a term from which the consumer could “opt out”. Although the Headstart term required the consumer to permit Chrisco to remove money from the consumer’s account for an order that might never be placed, the consumer had the power to opt out of that obligation.

53 The second point of note is that the HeadStart term gave a right to Chrisco to withdraw money from the consumer’s account, after the conclusion of the consumer’s order, without any substantial corresponding right to the consumer. A right is the correlative of a duty. But what duty is imposed upon Chrisco which corresponds to the consumer’s duty to permit Chrisco to withdraw money from his or her account?

54 Several possible formulations of a consumer’s corresponding right can be considered.

55 One formulation by senior counsel for Chrisco was that the HeadStart term gave the consumer (ts 112) “a right to place an order for delivery of a hamper of their choosing within the amount … contributed at any time up to the delivery date and they retain the option to get their money fully back if they do not place that order”.

56 But this is no right at all. A consumer had the power to place an order for a delivery of a hamper whether or not the HeadStart term applied. The consumer could place an order for an amount which would otherwise have been collected under the HeadStart term, or an amount more or less than that. I do not accept that the consumer obtained a substantial corresponding right to be repaid upon demand, prior to placing an order, without interest, and assuming the continuing solvency of Chrisco, the same sum of money that Chrisco had withdrawn earlier. As I explain below, there is also a lack of clarity about the operation of any such “right”.

57 Another attempted formulation of a right of a consumer under the HeadStart term corresponding to the obligation to have money withdrawn from the consumer’s account was that the consumer had a right to place an order for a Chrisco hamper without having to pay the larger weekly or larger monthly contribution if the payments were made over a shorter period. But the “larger weekly” or “larger monthly” contribution was not a larger overall payment because the price of the hamper did not change. In fact, taking into account the time value of money, this alleged “right” is for the consumer to pay more, by making payments of the same total amount but starting at an earlier point in time.

58 In effect, the HeadStart term involved a savings plan by which (unless they opted out or sought a refund) consumers were required to save, interest free, with Chrisco, towards the purchase of Chrisco’s goods in 2015 which were generally priced above retail prices and which the consumers might not decide to purchase.

59 At various points in oral submissions both counsel proceeded from the assumption that the consumers involved suggests that Chrisco’s consumers were generally from low to middle incomes. The limited evidence concerning the demographic of consumers supports that as a general, although not universal, matter. There was evidence describing anecdotal information that this was Chrisco’s class of consumer (TB 794). Chrisco’s “Customer Guarantee” also described how “thousands of customers … tell us they wouldn’t be able to manage without our help”.

60 Senior counsel for Chrisco submitted that there was no imbalance, or no substantial imbalance, in the parties’ rights because the sums of money lost as a result of the consumers’ payments being interest free were likely to be small. Even if the assumption were made that the sums of money involved were likely to be small (which I do not accept, for reasons explained below at [65]-[68]), I do not accept that there would be no imbalance in the parties’ rights as a result of the interest free transfer of the consumer’s money to Chrisco.

61 Chrisco’s assumption of very small sums of money being lost as a result of interest free payments can be tested with an example. The example might be a consumer who orders Chrisco’s Australia Zoo Family pass hamper for $185 from the 2014 Chrisco catalogue. This requires weekly payments of $3.60 rather than a lump sum payment or larger payment, before 24 October 2014, of $185 (which Chrisco’s general acknowledgment in its marketing material might be an amount which is more than retail prices).

62 The submission by Chrisco was effectively that such an “unsophisticated” consumer who did not have the “discipline” to budget to pay $185 for the purchase of the same hamper for the following Christmas, in December 2015, would benefit from Chrisco’s savings plan at very little cost to the consumer. In other words, this unsophisticated consumer, who cannot budget for himself or herself to save $3.60 per week, would not suffer any significant financial disadvantage by having Chrisco withdraw that amount of money from the consumer’s account on a monthly basis after 24 December 2014.

63 In oral submissions, senior counsel for Chrisco accepted that a hypothetical consumer might have credit card debt which would accumulate at a greater rate due to Chrisco’s withdrawals. But, he submitted, it might only be 25% of these small sums that would have been incurred as a cost (ts 114).

64 The example given by senior counsel for Chrisco is based on the assumption that consumers who provide Chrisco with a direct debit authority might have a credit card debt. That is an appropriate assumption. The possibility that a consumer might have credit card debt is a matter upon which judicial notice could be taken just as easily as the judicial notice invited by Chrisco that low interest rates are paid on savings accounts. Indeed, Chrisco’s own terms and conditions provided that an order can be paid by credit card and that “Credit Cards will be debited on the 15th of every month”. Although the ACCC’s case focused only upon the direct debit payments rather than the credit card payments by consumers, Chrisco’s intention to debit credit cards as well as savings accounts provides a further basis for the inference that Chrisco’s customers might have credit card debt.

65 It takes only a little reflection, and a calculator, to see that in the hypothetical example above the Chrisco withdrawals could cost this hypothetical consumer up to $25 in interest. This calculation is made using only monthly compounding. In other words, in the hypothetical example, the “unsophisticated” consumer who did not have the “discipline” to budget $3.60 a week, could incur an additional cost of $25 on a $185 purchase. Although this is only a hypothetical example, and might be the outer limit of cost to the consumer, it illustrates that the sums of money involved due to the interest free nature of a consumer’s payments over periods of up to 11 months is not necessarily a small amount in relation to the hamper purchase.

66 In any event, I do not accept the assumption by Chrisco that only small sums of money were involved in the expenditure on Christmas hampers.

67 First, although senior counsel submitted that the average hamper cost was between $80 and $750, there were certainly hampers that cost more than $750. For instance, at page 34 there was a “Mega Christmas” hamper for $962. At page 40 there was a large foldout of a “Summer holiday” hamper for $2249. There was no evidence concerning the average size of an order.

68 Secondly, the assumption that orders would be in the lower end of a range of $80 to $750 is based upon the premise that consumers would order only one hamper. But the order form permitted a consumer to order multiple hampers. Indeed, the considerable number of boxes to complete on the order form for different hampers (see instruction number 5), and the provision for a “quantity” of each different hamper, suggests that an order of more than one hamper might not have been unusual. Gift hampers could also be ordered for other people.

69 Ultimately, it suffices to say that the sums of money lost by Chrisco’s withdrawals from the consumer’s account, without any obligation upon Chrisco to pay interest and with no discount for the consumer who subsequently chose to place an order, involved a significant detriment to the consumer. That detriment was not balanced by any substantial corresponding right that the consumer obtained against Chrisco.

70 By itself, it is not necessarily determinative that there is no substantial right to a consumer, or duty upon Chrisco, that corresponds with the consumer’s obligations under the HeadStart term. The evaluative exercise involves consideration of the contract as a whole to determine whether there is a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract. I have mentioned the particular importance of the provision which permits the consumer to opt out of the HeadStart term. The evaluative exercise also requires consideration of the extent to which the HeadStart term was transparent.

71 I turn to a consideration of the extent to which the HeadStart term was transparent and the terms of the contract as a whole.

72 The Explanatory Memorandum to the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Bill (No 2) 2010 (Cth) at [5.38] described a lack of transparency in the terms of a consumer contract as a matter that may be “a strong indication of the existence of a significant imbalance in the rights and obligations of the parties under the contract”.

73 Dr Harder has argued that a lack of transparency might go further and “itself cause an imbalance”: S Harder “Problems in interpreting the unfair contract terms provisions of the Australian Consumer Law” (2011) Aust Bar Rev 306, 317. He gives as an example of this a situation in which the parties’ rights and obligations directly depend upon the acquirer being aware of the term such as a fixed-term contract that provides for an automatic extension unless one of the parties gives notice.

74 It is unnecessary to decide whether a lack of transparency could itself create an imbalance which does not otherwise exist. However, in the example given by Dr Harder it might be thought that the term itself could potentially involve an imbalance (assessed in the context of the contract as a whole) because of its weighting of the extension in favour of the supplier. Whether that imbalance is significant in the context of the whole of the contract might depend upon an assessment of the extent to which the term is transparent.

75 The considerations relevant to assess the extent of transparency of the HeadStart term involve whether it is expressed in reasonably plain language; legible; presented clearly; and readily available to the consumer.

76 As for catalogue orders, the location of the HeadStart term, which can be seen in Annexure 1 to these reasons, is at the bottom of the Chrisco Customer Guarantee page under the heading “How does a HeadStart Plan Work?” The Chrisco Customer Guarantee was one of only four removable pages in the middle of the Chrisco Christmas catalogue. In the catalogue, the HeadStart term was directly opposite the box to be ticked by a consumer to opt out of the HeadStart Plan. That box was at the bottom of the Hamper Order Form, next to the column for the total price (which the consumer would need to calculate) and above the signature panel.

77 As for website orders, the location of the HeadStart term can be seen in Annexure 2 to these reasons. Although described as the 2013 order form, the relevant year for the unfair contract terms is orders placed prior to 24 October 2014. Again, there is an “opt out” clause on the order form in a similar place to the catalogue order form and the HeadStart term is under the subheading “HeadStart Plan” in a section entitled Payments.

78 I do not consider that the HeadStart term in the catalogue or on the website was wholly lacking in any transparency. The matters I have described above show that the term was not hidden, and that the option to opt out of the clause was in a place where it might be noticed.

79 However, there are matters concerning the HeadStart term that reduce its transparency.

80 First, the language of the HeadStart term is not plain in three respects.

81 The first respect in which the HeadStart term is not plain is that, as the ACCC set out in its amended pleading at [13A], the HeadStart term does not clearly identify the amounts that will be direct debited by Chrisco under the HeadStart term or the means by which those amounts would be determined.

82 The HeadStart term provides that payments to Chrisco from the consumer’s account will “continue accordingly”. It is the taking of these payments without any corresponding right that the ACCC alleges caused the significant imbalance between the rights of the consumer and the rights of Chrisco. But what are the payments that will be taken? The HeadStart term contains no information on this point. The direct debit request to be completed by the consumer does not resolve this lack of transparency because it does not provide for any particular amount to be debited. It provides only that Chrisco “will give notice to the Customer if it proposes to vary any of the direct debit arrangements”.

83 The lack of transparency on this point might have been easily resolved by reference to the contract as a whole if the amount to be withdrawn from the consumer’s account is clearly provided elsewhere in a contemporaneous document. But, prior to the “Order Confirmation” (which is part of the contract although it is not expressed in that way), it was not clear what the amount would be that would be withdrawn from the consumer’s account to “continue” the payments. For the notion of “continuing” payments to be transparent the consumer must be able to know what payment was being “continued”.

84 One possibility is that the payments being “continued” were the payments that the consumer had made immediately prior to the order being fully paid. But, there was also a term that permitted Chrisco “slightly [to] increase your future payments” if the consumer skipped a payment or missed a payment. It is also unclear whether the amount of the increase would include Chrisco’s “dishonour fee” of $3.50 for a missed payment which was said “to cover charges we incur”.

85 Senior counsel for Chrisco submitted that a proper construction of the term was that the payments that would “continue” would not be the previous higher payments but the lower, earlier payments. I am prepared to accept that this may be the best construction. But the point would not be plain to a consumer. At the very least, it is very difficult to describe the lower payments as “continuing” from the series of higher payments. There also remains the difficulty, not addressed in submissions, of whether the lower, earlier payments would also apply in a circumstance where the consumer missed several payments and Chrisco adjusted the consumer’s order to be a smaller order (see [21] above).

86 The second respect in which the HeadStart term is not plain is closely related to the first. It concerns the sentence in the catalogue and website terms and conditions which provided “We will write to you to confirm your HeadStart Plan payments prior to commencing Direct Debits”. It would not be plain to a consumer whether this was an indication that Chrisco would write to confirm whether the consumer intended to proceed with a scheme of having his or her account debited before an order was placed or whether it was an indication that Chrisco would write to confirm the amount of the payments that it would take.

87 The Order Confirmation, when it was subsequently received, would have revealed to any consumer that it was the latter. Only at this time would any doubts be removed concerning the precise amount of payments for the consumer who had not opted out of the HeadStart Plan. But, at this later time, the consumer would also discover that the “confirmation” was effectively a formal notice rather than a request by Chrisco to withdraw the money from the consumer’s account.

88 The third respect in which HeadStart term was not plain was that, as the ACCC pleaded, it did not explain to the consumer “the means by which the consumer could cancel the HeadStart Plan” and obtain a refund. Numerous uncertainties might arise:

(1) Could the consumer cancel the HeadStart Plan at any time prior to the final order date in October the following year?

(2) What would happen if the consumer did not do so? (It appears that Chrisco developed a practice of “auto-converting” a HeadStart Plan to an order in February or March the next year: See exhibit MD 8, question 29, scenario 3).

(3) Would direct debit payments continue even if the payments for the previous year’s hamper had been made over a short period (say, from August 2014) so that the total amount of the 2014 total payment had already been collected by January 2015?

(4) In (3), if Chrisco assumed that the consumer intended to order a larger hamper and continued the direct debits then how long would those direct debits continue?

(5) Could Chrisco, as the ACCC asserted, “charge the consumer termination charges in the event he or she cancels the HeadStart Plan after it has been converted to a new order without the benefit of having a 21 days Cooling off period”? If so, could the same termination charges apply where Chrisco “auto-converts” the HeadStart Plan into an order by the consumer for similar goods as the consumer had ordered the previous year?

89 Secondly, the HeadStart term could have been presented in a manner which was far more legible, much clearer, and more readily available to the consumer. The font size of the HeadStart term was very small. It was less than half of the size of the main heading “About your payments”. There was nothing about this term that drew it to the consumer’s attention beyond any of the 20 other paragraphs on the same page.

90 In comparison, in the catalogue order form and “Customer Guarantee”, Chrisco employed various techniques to bring other matters specifically to the attention of the consumer. For instance, a bright red colour was used to the statement “Add up total order value”. Blue italics, and a larger font, was used for the request “Please provide at least two forms of contact details”. And a box in white starkly against a yellow background, and bold font, was used for statements like “We guarantee our products are good quality”. The HeadStart term, which permits money to be withdrawn from the consumer’s account, without interest, and before any order is placed, is in the same font as every other term on the densely packed page of small print terms and conditions.

91 Another difficulty with the legibility, clarity and availability of the HeadStart term is that although the HeadStart term and the opt-out provision were opposite each other in the four pages of the catalogue there was no reference in either to the other. The opt-out box to be ticked did not refer to the HeadStart term on the previous page nor did it explain what was involved in the HeadStart Plan. And the HeadStart term on the previous page did not refer to the possibility of opting out.

92 A further difficulty with the legibility, clarity and availability of the HeadStart term is that the provision that the “HeadStart Plan is fully refundable” is not contained in the terms and conditions in the catalogue at all. Instead, this term is contained in the opt-out box on the form which would be sent to Chrisco. Unless the consumer made a copy of the order form, the consumer who consulted the terms and conditions would not be aware that the HeadStart Plan is fully refundable. Although the ACCC did not allege that Chrisco had breached s 97(1)(b) by failing to ensure that “a copy of the agreement is given to the consumer to whom the goods are, or are to be, supplied”, s 97(1)(b) emphasises the lack of transparency that arises due to the absence of this term being in the possession of the consumer who orders by catalogue.

93 In considering the contract as a whole (s 24(2)(b)), Chrisco also pointed to the provision in the Order Confirmation (Annexure 3) that “Unless you’ve advised us otherwise, we’ll keep your payments going for any fully paid Hamper 2014 order, so that you can keep saving for next year’s order. Please see above for your final payment date.”

94 As I have explained, the Order Confirmation was one of the communications that constituted the contract. It was a communication of a contractual obligation upon the consumer to make payments to Chrisco. It provided the consumer with some additional clarity. But the communication did not remind the consumer that the continued payments can be refunded, without penalty, at any time that the consumer wishes before placing an order. It did not inform the consumer that the consumer could immediately notify Chrisco, if he or she wished, to cease taking payments from the consumer’s account, without penalty. The lack of availability of this information in the Order Confirmation is not assisted by the use of the past tense in the statement that payments would be continued “unless you’ve advised us otherwise” (emphasis added).

95 I have focused above upon the considerations particular to the HeadStart term as pleaded. This was the primary focus of the parties in submissions. The evaluative exercise, however, requires the HeadStart term to be considered in the context of the contract as a whole in order to determine whether it would cause a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations arising under the contract. I take into account that both the HeadStart term and the contract as a whole were designed to be convenient to the consumer. In many respects a consumer who entered into the contract with Chrisco may have sought this convenience, particularly given Chrisco’s acknowledgement that the prices were generally more than retail prices. This convenience also included the lack of a charge for the collection of instalment payments and the lack of any separate packing, administration, or delivery (other than to remote areas or for oversized or overweight items) charge for items that could be selected for inclusion in a Christmas Hamper.

96 I also take into account that the HeadStart term is neither listed as an example of an unfair term in s 25 nor does it fall into any of the categories of potential unfair terms described in s 25. But neither those terms, nor those categories, are exhaustive.

97 Overall, for the reasons I have expressed, and as an evaluative assessment of all the circumstances relevant to the HeadStart term including its transparency and the contract as a whole, the HeadStart term caused a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations arising under the contract.

(b) Was the HeadStart term not reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of Chrisco as a party advantaged by it

98 There is a rebuttable presumption in s 24(4) that a term of a consumer contract is presumed not to be reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term. Chrisco made no submission to suggest that the term was reasonably necessary to protect its legitimate interests. This requirement of an unfair term was satisfied.

(c) Would the HeadStart term cause detriment to a party if it were to be applied or relied on?

99 Counsel for the parties made few submissions concerning this requirement of an unfair term. They assumed, correctly, that in the circumstances of this case, considerations of detriment were also an important part of the consideration of whether the HeadStart term caused a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations arising under the contract.

100 As I have explained above at [60]-[68], the primary manner in which the HeadStart term would cause detriment to a consumer if it were to be applied or relied on is that it would impose a significant financial detriment upon the consumer without any significant corresponding benefit. This conclusion is also fortified by the considerations concerning transparency discussed above at [72]-[92].

101 The first issue concerned those consumers who placed orders, either by Chrisco’s Christmas hamper catalogue or online, for delivery of hampers in the November to December 2014 period. I am satisfied that the HeadStart term in those contracts was an unfair term. Since it was common ground that (i) the contracts between Chrisco and its customers were consumer contracts and (ii) the contracts were standard form contracts, the effect of s 23(1) is that the HeadStart term was void for customers placing orders in the November to December 2014 period online or by the catalogue order form.

Issue 2: Did the cancellation charges contravene s 97 of the ACL?

The cancellation charge provisions

102 There were three different provisions, over time, in Chrisco’s agreements which were concerned with cancellation charges. The effect and meaning of those terms were agreed facts as set out below.

103 The first was in the period between January 2011 and about December 2013. During that period, any agreement between Chrisco and a consumer for the supply of a Christmas hamper included a term to the effect that after the cooling off period of 21 days from the date of the original order confirmation, and provided the order was not fully paid:

(a) if the order was cancelled prior to 1 August, a cancellation fee of 20% of the monies paid at the date of cancellation would be charged; and

(b) if the order was cancelled on or after 1 August, a cancellation fee of 50% of the monies paid at the date of cancellation would be charged.

104 The second term arose between December 2013 and November 2014, where any agreement for the supply of a Christmas Hamper for the 2014 year included a term to the effect that:

After the Cooling off Period, Chrisco will charge you a cancellation fee, which will not be more than Chrisco’s reasonable costs in relation to your order. Facts that may be taken into account in calculation the cancellation fee include, but are not limited to:

• if Chrisco has ordered the goods and must resell the goods at a discounted price due to seasonal changes or technology upgrades;

• if Chrisco has ordered the goods and is unable to resell the goods within a reasonable time;

• if Chrisco has incurred any other reasonable cost which cannot be recovered in relation to your order; and

• how close to the anticipated date of delivery you cancel your order. The cancellation fee will be higher the closer to that date you cancel your order. For example, depending on the goods you have ordered, if your order is cancelled:

• before 1 August, your cancellation fee might be 20% of monies paid at the cancellation date;

• after 1 August, your cancellation fee might be 50% of monies paid at the cancellation date”.

105 The third term occurred after November 2014, where any agreement between Chrisco and a consumer for the supply of a Christmas Hamper for the 2015 year included a term to the effect that after the cooling off period of 21 days from the date of the original order confirmation:

(a) if the order was cancelled prior to 1 August, a cancellation fee of 20% of the monies paid at the date of cancellation would be charged, up to a maximum cancellation fee of $200.00; and

(b) if the order was cancelled on or after 1 August, a cancellation fee of 50% of the monies paid at the date of cancellation would be charged, up to a maximum cancellation fee of $500.00.

106 Section 97 of the ACL provides as follows:

Termination of lay-by agreements by consumers

(1) A consumer who is party to a lay-by agreement may terminate the agreement at any time before the goods to which the agreement relates are delivered to the consumer under the agreement.

(2) A supplier of goods who is a party to a lay-by agreement must ensure that the agreement does not require the consumer to pay a charge (a termination charge) for the termination of the agreement unless:

(a) the agreement is terminated by the consumer; and

(b) the supplier has not breached the agreement.

(3) A supplier of goods who is a party to a lay-by agreement must ensure that, if the agreement provides that a termination charge is payable, the amount of the charge is not more than the supplier's reasonable costs in relation to the agreement.

The parties’ submissions on construction of s 97(3)

107 The dispute between the parties concerned the construction of s 97(3) of the ACL. The ACCC initially submitted that s 97(3) could be contravened in two different ways. One way would be if a supplier failed to have a system to ascertain its reasonable costs in relation to the agreement. The other way would be if, in a particular case, the cancellation charge exceeded the supplier’s reasonable costs in relation to the agreement. Chrisco submitted that s 97(3) could only be contravened in the latter way. Both parties agreed that the “reasonable costs in relation to the agreement” were the costs actually incurred by the supplier, in relation to the agreement, at the time of termination.

108 The ACCC did not submit that Chrisco had contravened s 97(3) by imposing a charge that was more than Chrisco’s reasonable costs. The ACCC called no evidence concerning Chrisco’s charges nor any evidence concerning its reasonable costs.

109 It is difficult to identify the precise reason why, on the ACCC’s case, Chrisco was said to have contravened s 97(3).

110 The ACCC’s submission appeared to be that whether or not Chrisco’s cancellation charges had actually exceeded its reasonable costs in relation to the agreement, Chrisco had failed to ensure that the cancellation charges would not exceed its reasonable costs. The ACCC pointed to the definition of “ensure” in the Oxford English Dictionary which, in its latest online version, provides that, as a verb, the word relevantly means to “make (a person) mentally sure; to convince, render confident”. In oral reply submissions, however, senior counsel for the ACCC positively disclaimed any submission that “ensure” involved any subjective issue at all. Senior counsel said that “we say ensure means, as a matter objectively: is the system that the supplier has adopted one which ensures?” (ts 126). In other words, as he clarified, the obligation was upon a supplier to adopt a system which the Court considers will ensure that a cancellation charge will not exceed reasonable costs. Ultimately, senior counsel for the ACCC accepted that (ts 125):

If the system [for calculating reasonable costs in relation to the contract] is a system which meets the criterion “must ensure” and if, as it turns out, the application of that criterion results in something which exceeds reasonable costs then the section is not contravened.

111 In relation to this submission, the ACCC relied on the following agreed facts:

(1) Chrisco did not ascertain its reasonable costs in relation to the cancellation of each of its agreements, where the cancellation occurred during the different periods identified in the terms of cancellation;

(2) Chrisco did not separately estimate its costs for each of the agreements it entered into with a consumer between January 2011 and December 2014 when it entered into that agreement; and

(3) Chrisco did not keep a separate account of its costs attributable to the management of each agreement that it entered into with a consumer between January 2011 and December 2014.

Reasons why I do not accept the ACCC’s construction of s 97(3)

112 As the ACCC’s submissions developed, the curiosity of its submissions became that the ACCC’s construction of s 97(3) would operate significantly to the detriment of the consumer compared with the approach by Chrisco. There are five reasons why I do not accept the ACCC’s submission that that s 97(3) could be contravened if a supplier fails to have a system in place to ascertain its reasonable costs in relation to the agreement.

113 First, the ACCC’s construction ultimately depended upon the obligation upon the supplier as being one to “ensure” that a charge that was more than Chrisco’s reasonable costs. But the ACCC disclaimed the literal meaning of “ensure” and proposed a non-literal meaning that would create an obligation with which it would be impossible for most suppliers to comply.

114 If “ensure” were to be given its literal meaning of being “rendering confident” then there would be no contravention of s 97(3) if a cancellation charge exceeded the supplier’s reasonable costs provided that the supplier had in place a system which made the supplier mentally sure, or rendered it confident, that the cancellation charge would not exceed reasonable costs. But, as I have explained above, Chrisco denied that “ensure” involved any subjective element.

115 Another possible meaning of “ensure” which was advanced by senior counsel for the ACCC during oral submissions was that the supplier “must make certain” that the charge imposed by the agreement is not more than the supplier’s reasonable costs in relation to the agreement (ts 59). The difficulty with this construction is that it imposes an obligation with which very few, if any, suppliers could ever comply. At the time when terms and conditions are agreed, very few suppliers could ever know for certain what their reasonable costs in relation to the agreement will ultimately be. Consider the example of a retailer. The retailer’s costs might fall. When a consumer cancels an order with the retailer, the wholesaler might agree to waive any charges arising from consequential cancellation by the retailer.

116 During oral argument, I asked senior counsel for the ACCC for an example of a clause in a supplier’s agreement that, on the ACCC’s construction, would comply with s 97(3). The only example given of a clause which would satisfy s 97(3) was a clause that said “We will be entitled to charge you a termination charge which equals our reasonable costs in respect of your agreement as at the date of termination” (ts 66). Later, he accepted that this clause would be void for uncertainty (ts 123). Whether or not this is correct, it would be very surprising if the only way that s 97(3) could be satisfied was by a clause where the “amount of the charge” could not be calculated until after termination.

117 In contrast with the ACCC’s construction of “ensure”, Chrisco’s construction is both consistent with the meaning of “ensure” in s 97(2) (ie “must not”) and is an obligation with which a supplier could reasonably comply. At the time when a supplier required payment of a charge for a cancelled order the supplier would know, or be able to ascertain with a degree of certainty its reasonable costs in relation to the agreement. If the cancellation charge imposed by the agreement were more than the supplier’s reasonable costs then the supplier would contravene s 97(3) unless it ensured that the amount of the charge actually imposed was not more than its reasonable costs.

118 Secondly, the approach of the ACCC would operate to the considerable prejudice of consumers. The difficulty for a supplier to predict its future cancellation costs would be likely to cause a supplier to adopt a formula for cancellation costs rather than a fixed amount. This would mean that s 97(3) would usually have the effect that a consumer who entered a contract with the supplier would never know what cancellation costs he or she would incur upon cancellation until after cancelling. The detriment to a consumer of a cancellation clause that provided only a formula but no “amount” compares with s 101 which requires a supplier of services, upon request, to provide a transparent, itemised bill within 30 days from the date that the consumer receives an account from the supplier.

119 Thirdly, there is an internal inconsistency in the ACCC’s construction. On the ACCC’s construction, a contractual clause imposing a termination charge could be valid at one point in time (such as when the agreement entered into effect) but invalid at a later point in time (such as when the termination occurred). A supplier could not know whether a clause was valid or not until termination. This inconsistency arises because the ACCC’s construction involves a comparison between the amount of the charge in the contract clause at the date of contract with the amount of the termination cost at the later date (ts 123-124).

120 At various points in oral submissions the ACCC’s approach shifted. However, as I have quoted above, by the ACCC’s reply submissions its position was that it did not matter whether the amount of the charge actually exceeded reasonable costs provided that the supplier had “taken sufficient steps to form the proper view that the charge it will impose will not exceed reasonable costs at the time it is imposed” (ts 125). This would radically transform the terms of s 97(3) to the detriment of the consumer. It would mean that the supplier need only have a proper system in place so that a proper view could be formed (by the Court, not the supplier) that the charge would not exceed the supplier’s reasonable costs in relation to the agreement. The supplier would not be required to ensure the result that the amount of the charge did not exceed the reasonable cancellation costs. If it turned out that the cancellation charges did exceed reasonable costs in relation to the agreement then the consumer would bear that cost.

121 Fourthly, the ACCC’s construction is inconsistent with the use of the word “amount” in s 97(3). The use of that word in s 97(3) directs attention to the quantification of the charge at the date of termination not the formula used in ascertaining the charge.

122 Fifthly, the ACCC’s construction is not contextual. If the purpose of s 97(3) were to require that the agreement did not require the consumer to pay a termination charge which exceeded reasonable costs then that could easily have been accommodated by adding a s 97(c) which provided that “the charge does not exceed the supplier’s reasonable costs”.

123 In contrast with these five reasons, the construction for which Chrisco contended (i) is consistent with the words of s 97(3), (ii) is consistent with s 97(2), (iii) operates to the benefit of a consumer, and (iv) does not place the supplier under an impossible burden.

124 The effect of Chrisco’s construction is that at the time of termination a supplier must not charge a termination charge which exceeds its reasonable costs. At the time of termination the supplier will be in a position to make an accurate assessment of its reasonable costs in relation to the agreement. If the contractual term permits the supplier to charge a greater amount than its reasonable costs in relation to the agreement then the supplier contravenes s 97(3) if it imposes the contractual charge.

125 Contrary to the submissions of the ACCC, this conclusion does not mean that a supplier would be likely to include in contractual agreements a termination charge without adopting a system which is designed to minimise the risk that the termination charge is less than the supplier’s reasonable costs in relation to the agreement. A supplier who took such an approach would be extremely likely to contravene s 97(3).

126 Consider the following hypothetical example. Suppose a flat termination charge of 20% of the cost of an order were imposed. Suppose also that a consumer placed an order in November 2014 for a 2015 Christmas hamper to the value of $2000. Then suppose that the consumer cancelled the order 22 days’ later and before Chrisco had ordered any of the goods from its supplier. It might be seriously questioned whether a cancellation fee of $400 would be less than Chrisco’s reasonable costs in relation to the agreement, although this would be a matter for evidence. Of course, Chrisco could avoid liability under s 97(3) in such a case by waiving some or all of the cancellation charge. But, in the absence of any evidence about waiver of the charge, an inference might be drawn that the contractual amount had been charged.

Reasons why the ACCC’s case fails even on the ACCC’s construction of s 97(3)

127 Even if the ACCC’s construction of s 97(3) were accepted, the subsection would not have been contravened by Chrisco. Senior counsel for the ACCC submitted, in reply, that Chrisco would not have contravened s 97(3) if it had engaged in the following process (ts 69):

If it had done a proper evaluative exercise based on facts, applying appropriate principles, taking into account the proper things, arrived at a figure based upon a proper exercise then said, “Well, we will charge a small fraction of that figure.” Then that would, in our submission, be capable of satisfying the requirement it must ensure.

128 The flourish about a “small fraction” can be put to one side. There is no such requirement in the text of s 97(3). Nor could it be implied that s 97(3) was intended to have the effect that most of the costs of cancellation by a terminating consumer should be passed on to other consumers or absorbed by a supplier. The “small fraction” flourish is also inconsistent with the rest of the ACCC’s construction of s 97(3), which is whether Chrisco had put in place “a system which meets the criterion ‘must ensure’”. As senior counsel for the ACCC submitted, the case for the ACCC was based on a submission that “Chrisco had no method, system, procedure” (ts 56) or that Chrisco “must both have a method which enables it to ascertain its reasonable costs and apply that method” (ts 59) or that “it contravened the section because of the complete absence of system” (ts 66) (emphasis added).

129 The ACCC did not prove that Chrisco had failed to put any such system in place. As I explain below, three matters of evidence establish that Chrisco did have a system. Although the system that Chrisco had was not one which estimated costs at the level of the individual contract, that level of detail was not required even on the ACCC’s case. The ACCC did not suggest that a requirement of estimation of costs at the level of the individual contract in every case must be a further implication beyond the implication it sought of a requirement for a system generally. Indeed, the ACCC accepted (ts 127) that in some cases a supplier could “adopt a method of looking at its overall costs based on uniform agreements and derive a formula which was relevant to each agreement”.

130 Although the ACCC submitted that a generalised system was not adequate in this case, it did not provide any evidence to suggest that the generalised system used by Chrisco would ever have produced a result by which the cancellation charge imposed by Chrisco exceeded Chrisco’s reasonable costs.

131 The three matters of evidence that support the existence of a general system used by Chrisco are as follows.

132 The first example of evidence of Chrisco’s system was at TB 825, where Chrisco responded to a question, in an answer admitted into evidence and accepted as true. Chrisco was asked to describe the factors that it uses to determine the termination charge that Chrisco would typically impose on a consumer when they terminate a Chrisco lay-by agreement, including an itemised account of Chrisco’s incurred costs that are incorporated, or taken into account, in the termination charge. Chrisco responded that these factors include:

• The costs Chrisco incurs in marketing its products, including advertising and the cost of developing its catalogues;

• The costs Chrisco incurs in:

• receiving and processing orders from customers, which can be placed online, by fax, mail or telephone;

• confirming customers’ orders (including the payment details); and

• placing orders with suppliers to correspond to customers’ orders;

• the fact that in confirming orders with suppliers, Chrisco will typically contractually commit itself to receive the orders;

• the nature of the goods a customer has ordered;

• the requirements imposed by suppliers for orders to be confirmed by certain dates in order for Chrisco to be able to deliver customers’ orders on time. For example:

• in relation to meat products, some suppliers require confirmation as early as March in the year in which they are to be delivered; and

• orders from Chinese suppliers typically need to be confirmed by the last week of May in the year in which they are to be delivered;

• how close to the anticipated date of delivery the customer terminates the agreement;

• the need to store product while it awaits delivery; and

• the difficulties which Chrisco typically encounters in allocating a cancelled order to another customer, or selling surplus stock, particularly if it is out of season or has been superseded by technological change.

133 Chrisco acknowledged that it does not maintain activity based accounting and so was unable to provide an itemised account of Chrisco’s incurred costs.

134 The second example of evidence that Chrisco had a system was that Chrisco was also asked whether it calculates its lay-by termination charges inclusive of ‘HeadStart’ plan payments. It responded:

The following two scenarios illustrate how Chrisco calculates lay-by termination charges where ‘HeadStart’ plan payments have commenced.

Scenario 1

Assume that a customer has ordered a 2014 Christmas hamper. By late October 2014, the customer has fully paid for that hamper. During November 2014, payments begin to be made under the 2015 ‘HeadStart’ plan. At the end of November 2014, the customer terminates the agreement relating to the 2014 Christmas Hamper.

In those circumstances:

• Chrisco will impose a termination charge in relation to the 2014 Christmas hamper; and

• its calculation of that termination charge will not include the payments made during November 2014 under the 2015 ‘HeadStart’ plan. It will only include the payments made by the customer in relation to the cancelled 2014 Christmas hamper.

Scenario 2

Assume that a customer has a 2014 ‘HeadStart’ plan, under which payments started in November 2013. The customer contacts Chrisco in January 2014 and confirms that they wish to ‘convert’ their ‘HeadStart’ plan into an order for a 2014 Christmas hamper. At the end of May 2014, the customer terminates the agreement relating to the 2014 order.

In those circumstances:

• once the ‘HeadStart’ plan has been ‘converted’ into an order, the ‘HeadStart’ payments are allocated to that order and payments continue as normal; and

• Chrisco will impose a termination charge in relation to the 2014 order calculated by reference to all payments, including the ‘HeadStart’ amount transferred to the order when it was ‘converted’.

135 The third example of evidence of a system used by Chrisco was the evidence, again accepted as true, that (TB 795):

The orders that Chrisco places with its suppliers are generally not required to be confirmed until July/August of the year in which the order is to be delivered. Some orders must be confirmed earlier in the year. Meat orders are confirmed from March. Orders from the Family Christmas Gifts catalogue that are sourced from China must be confirmed by the last week of May and other big imported goods are ordered from April onwards. Once orders are confirmed, Chrisco is committed to receiving the goods ordered. This is the reason for distinguishing between orders cancelled before and after 1 August in any year. Before 1 August, 20% is a reasonable estimate of the largely administrative costs that Chrisco will have incurred in relation to any order that is cancelled.

136 I reiterate that it was no part of the ACCC’s case that Chrisco’s system had led or would lead, in any individual case, to a cancellation charge which exceeded Chrisco’s reasonable costs. Nor did the ACCC make any submission that alleged that any of the matters to which Chrisco took account in this system were not legitimate components for an estimation of reasonable costs. The ACCC’s only case was that Chrisco was required to adopt a system which estimated reasonable costs in relation to each individual agreement, including keeping a separate account of its costs attributable to the management of each agreement that it entered into with a consumer. But even on the assumption (which was not proved) that the reasonable costs in relation to each agreement were not uniform, the ACCC has not proved that the broad, generalised approach adopted by Chrisco might even possibly have estimated a cancellation fee which exceeded reasonable costs in any individual case.

137 After these matters of evidence were addressed in Chrisco’s oral submissions, senior counsel for the ACCC submitted in reply that this defence was not open to Chrisco. He said that the point had taken him by surprise. He submitted that it had not been pleaded as a defence by Chrisco and that it was not open to Chrisco to submit that it had a general system in place to ensure that its calculation of its cancellation fees did not exceed reasonable costs. I do not accept that submission.