FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Lyoness Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 1129

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding is dismissed.

2. The Applicant is to pay the costs of the Respondents.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 884 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

AND: | LYONESS AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED First Respondent LYONESS ASIA LIMITED (HONG KONG COMPANY NUMBER 1619260) Second Respondent LYONESS UK LIMITED (UK COMPANY NUMBER 06932198) Third Respondent LYONESS INTERNATIONAL AG (SWISS COMPANY NUMBER CHE-114.950.380) Fourth Respondent |

JUDGE: | FLICK J |

DATE: | 23 OCTOBER 2015 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 On 28 August 2014 the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (the “Commission”) filed in this Court an Originating Application and a Statement of Claim.

2 There were four Respondents named in that proceeding, being:

Lyoness Australia Pty Limited (“Lyoness Australia”);

Lyoness Asia Limited (“Lyoness Asia”);

Lyoness UK Limited (“Lyoness UK”); and

Lyoness International AG (“Lyoness International”).

Of these entities, relevantly:

Lyoness International owns and controls Lyoness Asia;

Lyoness Asia owns and controls Lyoness Australia; and

Lyoness UK is owned and controlled by yet another entity, namely Lyoness Europe AG.

3 The relief which is sought by the Commission against one or other of the four Respondents is founded upon alleged contraventions of the prohibitions on pyramid selling and referral selling set forth in ss 44 and 49 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the “Competition and Consumer Act”). Section 44 is directed at “pyramid selling schemes”; s 49 is directed at “referral selling”.

4 In support of its case, the Commission relied upon affidavits either sworn or affirmed by:

Ms Shannon Friedman;

Mr John Raemond Neill;

Ms Teri Bartolo;

Mr Trevor Deutsher; and

Ms Margot Rylah.

None of these witnesses were called for cross-examination. But there were objections taken, for example, on the basis that one witness purported to give an account of what that witness had been told by another person not called as a witness. Not surprisingly, objection was taken if that account was sought to be relied on as proving the truth of the matters recounted to the witness. The Respondents prepared a Schedule of the objections and the bases upon which objections were made. The hearing continued without the need to resolve at the outset the merit of each objection. Care must nevertheless be taken when considering that evidence which was the subject of objection. In addition to the evidence of these witnesses and the Annexures and Exhibits to their affidavits, both the Commission and the Respondents tendered documents. Some of those documents had been produced on discovery. It became relevant to consider the description given to some of those documents in the affidavits of discovery in order properly to consider what the document purported to be. Other documents which were tendered were obtained upon the execution on 19 September 2013 of a search warrant which had been issued pursuant to s 154X of the Competition and Consumer Act.

5 It is concluded that the proceeding should be dismissed with costs.

PYRAMID & REFERRAL SELLING – THE LEGISLATIVE PROVISIONS

6 Commonwealth legislative provisions directed to “pyramid selling” schemes and “referral selling” were included from the outset in the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (the “Trade Practices Act”).

7 The Commonwealth legislature has long formed the view that such conduct should be proscribed. The legislative provisions have been variously said to be directed to inherent “vices” and to “evils”.

8 The view has thus long been taken that “pyramid selling” schemes should be “stamp[ed] out”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Worldplay Services Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1138, (2004) 210 ALR 562 at 583 (“Worldplay Services”). Finn J there observed:

[94] It has, in my view, rightly been said that the apparent purpose of the pyramid selling provisions of legislation in this country is to “stamp out” such schemes: Hawkins v Price [2004] WASCA 95 at [15]. Given the serious losses that have been inflicted both in this country and world-wide by pyramid schemes: see Heydon, Trade Practices Law, Law Book Co, Sydney, at [14.10] and the notes thereto; and given the declared consumer protection object of the TP Act (see s 2), it is unsurprising that there should be such a legislative purpose. The legislation is beneficial in character and for this reason should be construed purposively …

In Australian Communications Network Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2005] FCAFC 221, (2005) 146 FCR 413 at 425 (“Australian Communications Network”) Heerey, Merkel and Siopis JJ outlined the “vice” in pyramid schemes as follows:

[43] … the vice inherent in pyramid selling schemes is the reward that, as a matter substance, is given directly or indirectly, for the introduction of new participants, rather than a reward based on sales or other such activities by a participant or others introduced by participants …

Their Honours continued:

[46] The real vice inherent in pyramid selling schemes appears to be that the rewards held out are substantially for recruiting others, who in turn get their rewards substantially for recruiting still more members, and so on. If there is no underlying genuine economic activity the scheme must ultimately collapse and many people will have been induced to pay money for nothing. We see the purpose of the legislation as directed at proscribing schemes where the real or substantial rewards held out are to be derived substantially from the recruitment of new participants, as distinct from rewards for genuine sales of goods or services.

9 In respect to “referral selling”, Lindgren J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Giraffe World Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [1999] FCA 1161, (1999) 95 FCR 302 at 311 (“Giraffe World”) similarly observed:

[30] The section is directed against the evil that a person might be induced to buy goods or services by an expectation that he or she will subsequently receive a rebate, commission or other benefit (after this, simply “commission”) for assisting the supplier to supply its goods or services to other consumers, when there is no assurance that the commission will in fact be received because receipt of it is subject to a contingency. The contingency is something over and above the rendering of the assistance or the doing of any other act by the consumer alone.

The objective of proscribing “referral selling”, it has been said, is to “shield members of the public”: Sherman as liq of Giraffe World Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] NSWSC 996, (2003) 47 ACSR 505 at 511 per Barrett J. His Honour was there considering the aftermath of the orders made by Lindgren J. When considering the terms of the former s 57 of the Trade Practices Act, Barrett J explained the “aim” of the section as follows:

[12] … The aim of s 57 is, clearly enough, to shield members of the public from attempts to persuade them to enter into transactions of a certain kind under which they will, in expectation of rebates, commissions or other benefits, assist in the introduction of prospective customers. The legislative policy works on the premise that such transactions should not be undertaken by corporations and, therefore, that people should not be put into a position in which they may effect introductions and thereby receive rebates, commissions or other benefits. In the particular circumstances considered by Lindgren J, future payment of commissions to members of Giraffe World (or a representation as to such payment) was an element of the course of conduct found to be unlawful. The illegal conduct consisted, in part, of drawing persons into introducing further potential purchasers by promise of reward. If the reward were to be given, the statutory purpose of ensuring that corporations do not, by creating an expectation of that reward, induce persons to solicit participation by others would be defeated. I am of the opinion that s 57 should be seen as impliedly precluding both the giving and the receiving of rebates, commissions and other benefits of the kind central to the success of the conduct the section makes it unlawful for corporations to undertake.

In the United States, the opposition has been such that even in the absence of legislation expressly dealing with referral selling, a scheme has been held unlawful as amounting to an illegal lottery: Sherwood & Roberts-Yakima Inc v Leach 409 P 2d 160 (1965). The purchaser of a fire-alarm was there told that he would not have to pay if he obtained 12 additional purchasers. If each purchaser obtained 12 additional purchasers, the market would become saturated with almost 250,000 purchasers being required by the fifth round of sale.

10 The current legislative provisions in respect to “pyramid schemes” are found in Pt 3, Div 3 of the Australian Consumer Law. That Division contains three sections – ss 44, 45 and 46. Div 5, also within Pt 3, deals with “Other unfair practices”, including “referral selling”. These provisions should be construed in a manner which promotes, rather than frustrates, the legislative intent to “stamp out” retail practices which properly fall within the reach of the prohibition.

11 Each of the relevant provisions within Pt 3 should be briefly but separately considered.

Pyramid selling schemes

12 With reference to pyramid selling in Div 3, it should be noted that no provision within that Division seeks to define the term “scheme”.

13 Section 45(1) of the Australian Consumer Law sets forth two “characteristics” of a “scheme” – but the term itself remains undefined. Nor was the term defined in the Trade Practices Act. With reference to the former legislative provisions, Finn J in Worldplay Services was content to adopt the meaning given to that term by Mason J in Australian Softwood Forests Pty Ltd v Attorney-General (NSW); Ex rel Corporate Affairs Commission (1981) 148 CLR 121 at 129, namely that “all that the word ‘scheme’ requires is that there should be ‘some programme, or plan of action’”: [2004] FCA 1138 at [86], (2004) 210 ALR at 581. The same broad meaning of the term “scheme” should also be applied to the current s 45.

14 Within that context, s 44 provides as follows:

Participation in pyramid schemes

(1) A person must not participate in a pyramid scheme.

(2) A person must not induce, or attempt to induce, another person to participate in a pyramid scheme.

(3) To participate in a pyramid scheme is:

(a) to establish or promote the scheme (whether alone or together with another person); or

(b) to take part in the scheme in any capacity (whether or not as an employee or agent of a person who establishes or promotes the scheme, or who otherwise takes part in the scheme).

Justice Finn in Worldplay Services also directed attention to the phrase common to both the predecessor provision to s 44 and s 44(3)(b) itself, namely the phrase “to take part in the scheme”. His Honour there observed:

[97] … the question whether a person takes part in such a scheme is to be determined by reference to the nature of that person’s involvement (if any) in the actual program or enterprise that constitutes the scheme. To make that determination it will ordinarily be necessary to understand the scheme itself: how is it structured? How and by whom are its products and/or services developed and provided? How is the scheme conducted? How is it promoted? Etc. The obvious reason why such an analysis is necessary is that the definition is directed at taking part in any capacity “in the scheme”: (2004) 210 ALR at 583.

The phrase “to take part in the scheme” is also repeated in s 45(1)(a). The guidance suggested by Finn J remains equally applicable to the construction and application of that same phrase when employed in the current legislation.

15 Section 45 sets forth the meaning of a “pyramid scheme” as follows:

Meaning of pyramid scheme

(1) A pyramid scheme is a scheme with both of the following characteristics:

(a) to take part in the scheme, some or all new participants must provide, to another participant or participants in the scheme, either of the following (a participation payment):

(i) a financial or non-financial benefit to, or for the benefit of, the other participant or participants;

(ii) a financial or non-financial benefit partly to, or for the benefit of, the other participant or participants and partly to, or for the benefit of, other persons;

(b) the participation payments are entirely or substantially induced by the prospect held out to new participants that they will be entitled, in relation to the introduction to the scheme of further new participants, to be provided with either of the following (a recruitment payment):

(i) a financial or non-financial benefit to, or for the benefit of, new participants;

(ii) a financial or non-financial benefit partly to, or for the benefit of, new participants and partly to, or for the benefit of, other persons.

(2) A new participant includes a person who has applied, or been invited, to participate in the scheme.

(3) A scheme may be a pyramid scheme:

(a) no matter who holds out to new participants the prospect of entitlement to recruitment payments; and

(b) no matter who is to make recruitment payments to new participants; and

(c) no matter who is to make introductions to the scheme of further new participants.

(4) A scheme may be a pyramid scheme even if it has any or all of the following characteristics:

(a) the participation payments may (or must) be made after the new participants begin to take part in the scheme;

(b) making a participation payment is not the only requirement for taking part in the scheme;

(c) the holding out of the prospect of entitlement to recruitment payments does not give any new participant a legally enforceable right;

(d) arrangements for the scheme are not recorded in writing (whether entirely or partly);

(e) the scheme involves the marketing of goods or services (or both).

Section 45 had its predecessor in various manifestations in the Trade Practices Act, including s 65AAD. Two aspects of s 45(1)(b) should be noted.

16 First, the phrase “entirely or substantially” now appearing in s 45(1)(b) should be interpreted in the same manner as the same phrase formerly appearing in s 65AAD and as Finn J explained in Worldplay Services:

[108] If there is a difference between the parties as to what is signified by “substantially induced” — and it is the operative formula in this matter — that difference is one of degree.

…

…

[110] The use of the composite formula in s 65AAD recognises that there may be a number of inducements to make a participation payment, and if such be the case, their relative significance must be considered. A participation payment could, for example, be induced substantially by the s 65AAD “prospect” held out while another and lesser inducement was the use or enjoyment of the goods or services being provided. Where multiple prospects are held out, if a particular prospect is to be characterised as the substantial inducement, it must be the predominant inducement: cf Graovac at [11]. This said, I consider it is unlikely to be helpful to engage in further adjectival elaboration of the word “substantially” in this setting bearing in mind that what one is characterising is a reason for action: (2004) 210 ALR at 585 to 586.

See also: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jutsen (No 3) [2011] FCA 1352 at [108], (2011) 206 FCR 264 at 289 per Nicholas J.

17 Second, the phrase “in relation to the introduction to the scheme of further new participants” requires there to be “a relevant, sufficient or material connection or relationship, rather than merely a causal connection or relationship”: Australian Communications Network [2005] FCAFC 221 at [29], (2005) 146 FCR at 421. There in question was whether compensation payable by the Australian Communications Network to independent representatives amounted to payments “in relation to the introduction to the scheme of further new participants”. In a joint judgment, Heerey, Merkel and Siopis JJ reviewed an array of reference materials, the decision at first instance of Selway J, and the decision of Finn J in Worldplay Services, and concluded:

[29] It follows from the foregoing that, in determining the requisite connection or relationship between the payment or benefit described as the “recruitment payment” and the introduction to the scheme of further new participants, the question is whether there is a relevant, sufficient or material connection or relationship, rather than merely a causal connection or relationship. Accordingly, we do not agree with the views expressed by Finn J in Worldplay at [114]–[116], and applied in the present case by Selway J, that under s 65AAD(1)(b):

(a) “a relationship, whether direct or indirect, between the two subject matters” is sufficient; and

(b) accordingly, the question is whether the benefits in question “are received in consequence of the introduction of new members whether or not the benefits are paid for the introduction as such or are paid as a result of the subsequent activities of the members introduced”.

Their Honours thereafter went on to consider the relevance of “post-introduction activities” of persons introduced to the scheme:

[33] It is clear from the text of s 65AAD(1)(b) that a payment for the introduction to the scheme of further new participants will be a payment in relation to the introduction of the new participants. Also, it is clear from the Explanatory Memorandum that it was intended that a payment that is, in substance, a payment for the introduction of new participants is an aspect of the vice or mischief aimed at by the legislative scheme. But the question of whether payments made, for example, under a multi-level marketing scheme as a result of post-introduction activities of the members introduced by participants were also intended to be recruitment payments requires consideration of whether such payments were also considered to be part of that vice or mischief.

Their Honours concluded:

[43] The above references are consistent with the view that is apparent in s 61AAD(1)(b)and in the Explanatory Memorandum and the examples given in it, that the vice inherent in pyramid selling schemes is the reward that, as a matter of substance, is given directly or indirectly, for the introduction of new participants, rather than a reward based on sales or other such activities by a participant or others introduced by participants. In the present case, the ACCC was not able to refer the court to any material or cases that suggest that the latter activities, which the ACCC itself described as a legitimate multi-level marketing scheme, were an aspect of the vice or mischief aimed at by the legislative prohibition of pyramid selling schemes. Indeed, the ACCC was not able to point to any economic or social vice or mischief involved in a multi-level marketing scheme that would warrant such a scheme falling within the prohibition of pyramid selling schemes proscribed by Div 1AAA.

[44] True it is, the marketing of goods and services may be involved in a pyramid selling scheme, as subs (3)(e) makes clear. But the converse does not follow; the fact that there is multi-level marketing of goods and services does not necessarily mean there is a “pyramid selling scheme”.

[45] The relevant provisions have to be applied case by case to infinitely variable fact situations. The statutory purpose would not be served either by a construction in which:

(a) it is sufficient that there is an element of introduction, even though that is not enough in itself to earn any reward, and no matter what else has to be done subsequently to earn a reward, and no matter how genuine or competitive the goods or services being sold; or, on the other hand;

(b) the recruitment payment must be solely for introduction, no matter how worthless the prospect of selling goods or services under the scheme.

The first construction would criminalise commercial activity which the material to which we have referred, including the ACCC’s own public statements, does not recognise to be illegitimate. The second would open the door to artificial evasion, and could not be reconciled with s 65AAD(3)(e).

[46] The real vice inherent in pyramid selling schemes appears to be that the rewards held out are substantially for recruiting others, who in turn get their rewards substantially for recruiting still more members, and so on. If there is no underlying genuine economic activity the scheme must ultimately collapse and many people will have been induced to pay money for nothing. We see the purpose of the legislation as directed at proscribing schemes where the real or substantial rewards held out are to be derived substantially from the recruitment of new participants, as distinct from rewards for genuine sales of goods or services.

These paragraphs place in context the earlier reference made with respect to paras [43] and [46], to the “vice” against which the statutory prohibition is directed.

18 It should finally be noted that the concern of provisions such as s 45 (and its predecessor provisions) has not been to proscribe what their Honours in Australian Communications Network referred to as “legitimate multi-level marketing scheme[s]”. Lehane J had recognised as much in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Destiny Telecom International Inc (1997) ATPR 41-588 when his Honour concluded that the trading scheme there contravened s 61 of the Trade Practices Act as that section was then drafted:

The material makes two things very clear: one is that the principal benefit available to the participant, stressed by the documents, is the receipt of the commissions. It is the ability to make large sums of money which is quite plainly described as the principal attraction of participation. Undoubtedly the benefits of the card itself, and the various telephone services to which it will give access, are stressed also, but there is in my view no question that the principal benefit of participation in the scheme is said to be the receipt of money - indeed, the receipt of very large sums of money.

Additionally, and this I think has some significance, it is made clear that there is particular benefit in early participation, and in participation as an initial participant rather than as somebody introduced by an initial participant because, it is said (and having regard to the nature of what is proposed, there is obvious logic in it) by participating at the top and early one is likely to make more money than if one were to participate further down or later. It is said that even participants introduced later may make a satisfactory return from participation: (1997) ATPR at 44,116.

The scheme there involved a participant paying an initial sum of $100 and receiving two benefits. One was a telephone card which enabled the making of telephone calls and the other was the receipt of commissions. See also: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v World Netsafe Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1827. Similarly, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Golden Sphere International Inc (1998) 83 FCR 424 a scheme was struck down which did not involve the sale of any genuine product.

19 The concern of the legislature, at its most simple and subject to the statutory language employed, has been throughout to catch pyramid selling which did not generate income for members through the sale of genuine products as opposed to the redistribution of money from members of the scheme who later joined for the benefit of the few who originated it: Corones, Pyramid selling schemes caught by the Trade Practices Act: some much needed clarification, (2001) 29 Aust Bus L Rev 348.

20 Section 46 provides:

Marketing schemes as pyramid schemes

(1) To decide, for the purpose of this Schedule, whether a scheme that involves the marketing of goods or services (or both) is a pyramid scheme, a court must have regard to the following matters in working out whether participation payments under the scheme are entirely or substantially induced by the prospect held out to new participants of entitlement to recruitment payments:

(a) whether the participation payments bear a reasonable relationship to the value of the goods or services that participants are entitled to be supplied with under the scheme (as assessed, if appropriate, by reference to the price of comparable goods or services available elsewhere);

(b) the emphasis given in the promotion of the scheme to the entitlement of participants to the supply of goods or services by comparison with the emphasis given to their entitlement to recruitment payments.

(2) Subsection (1) does not limit the matters to which the court may have regard in working out whether participation payments are entirely or substantially induced by the prospect held out to new participants of entitlement to recruitment payments.

Referral selling

21 Division 5, also within Pt 3 of the Australian Consumer Law, deals with “Other unfair practices”, namely “referral selling” and “harassment and coercion”.

22 Within Div 5, s 49 provides as follows:

Referral selling

A person must not, in trade or commerce, induce a consumer to acquire goods or services by representing that the consumer will, after the contract for the acquisition of the goods or services is made, receive a rebate, commission or other benefit in return for:

(a) giving the person the names of prospective customers; or

(b) otherwise assisting the person to supply goods or services to other consumers;

if receipt of the rebate, commission or other benefit is contingent on an event occurring after that contract is made.

As the terms of s 49 make apparent, the section is directed against the making of representations inducing consumers to acquire goods or services in the expectation that they will receive a rebate, commission or other benefit. A contravention of the section may result in both the imposition of a pecuniary penalty and a claim for damages. Section 49 had its counterpart provision in s 57 of the Trade Practices Act.

23 In addition to identifying the legislative objective sought to be achieved by the former s 57 ([1999] FCA 1161 at [30], (1995) 95 FCR at 311), Lindgren J in Giraffe World construed s 57 such that the comparable reference to “that contract” in the concluding words of s 57 was a reference “back to the ‘contract’ expressly referred to in the section, that is, the contract for the acquisition of goods or services made by the original consumer”: [1999] FCA 1161 at [32], (1999) 95 FCR at 311. His Honour later observed:

[74] While a case where the individual was not induced at all by the holding out of the prospect of earning commission would not be caught by s 57, I do not think that section requires that the representation described in it should be the sole or even the dominant inducement operating on the consumer's mind. In my view, it suffices that it be a “real” or “significant” inducement. The section is intended to compel corporations to ensure that they do not encourage consumers to acquire goods or services for a certain price while thinking that the “true price” will ultimately prove to be less, because of commissions to be received, when there is no certainty that they will be received at all because their receipt is contingent on the occurrence of later events outside the consumer's control. It would be consonant with this objective to understand the notion of “induce” in the section in the manner that I have indicated, and it would be discordant with it to understand it as activated only where the prospect of receiving commissions was the sole or dominant inducement.

24 These same conclusions are equally applicable to the construction of the current s 49.

THE LYONESS LOYALTY PROGRAM

25 The manner in which pyramid selling schemes operate, it has been said, can be “complex and elusive”: Worldplay Services [2004] FCA 1138 at [87], (2004) 210 ALR at 581 per Finn J.

26 The present Lyoness Loyalty Program is no exception.

27 For present purposes it is sufficient to note that Lyoness Asia operates a loyalty shopping program in Australia which has three levels of participants, namely:

Lyoness Asia and Lyoness Australia;

those merchants with whom Lyoness Australia has entered an agreement, described as Loyalty Merchants; and

consumers who are Members of the Lyoness Loyalty Program.

At its heart is the concept that Members who purchase goods or services from a Loyalty Merchant receive a discount and potentially other benefits.

28 The Lyoness program itself was originally founded in July 2003 and is active in more than 40 countries. As of 2015 it has well over 3,000,000 registered Members world-wide.

29 The Australian Lyoness program commenced in April 2012. The facts relevant to the resolution of the present proceeding, however, pre-date April 2012.

30 The complexity of the program is such that it is necessary separately to examine:

the events preceding April 2012; and

post-April 2012.

31 For the purposes of seeking to establish contraventions of ss 45 and 49 of the Australian Consumer Law, the Commission seeks (inter alia) to place considerable reliance upon the manner in which parts of the program were promoted to potential future Members; the Respondents seek (inter alia) to focus attention upon the terms and conditions regulating the rights and benefits of prospective Members and persons who became Members. The Commission seeks to focus upon what is described in its pleadings, repeated in the terms and conditions regulating the rights and entitlements of Members, as “Premium Members”.

32 Of particular relevance are:

the steps which must be undertaken to become a Member and to become a Premium Member;

the benefits which a Member may receive in the form of “Cashback” and “Friendship Bonuses”; and

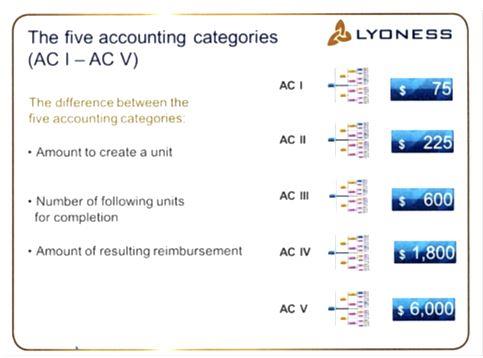

the manner in which a Member may become entitled to “Extended Member Benefits”, including (inter alia) a “Loyalty Commission”; “Loyalty Cash”; a “Loyalty Credit”; a “Loyalty Commission Bonus” and “Bonus Units”.

In very general terms, the entitlement of any Member to receive “Extended Member Benefits” would depend upon the number of “units” held in a particular category of a matrix called the “Accounting Program”. There were five different categories of “units” in the “Accounting Program”. The contractual terms and conditions which described these entitlements were set forth in the Additional Terms and Conditions which could be signed by an existing Member. Although strictly speaking it was a concept existing only after April 2012, there was an uneasy tension in the submissions of the Commission between repeated references to both “membership” and “premium membership” prior to that date.

33 In addition to Members receiving discounts on purchases, it is also of relevance to note:

the manner in which a Member could proceed through different “Career Levels” and the manner in which cash payments could also be received, being cash payments made to the nominated bank account of a Member.

Repeated reference was made in the materials relied upon by the Commission to the prospect of Members receiving “income” or “passive income”.

34 Although the analysis of the factual material involves complexity and detail, it is not necessary to master it in its entirety in order to understand the manner in which the Commission seeks to advance its case. Nor is a mastery of that complexity and detail necessary to resolve many of the factual allegations advanced on behalf of the Commission.

35 Some understanding of the manner in which the Lyoness Loyalty Program operated and the volume of the business activities being undertaken nevertheless remains essential. It is thus necessary to:

initially set forth the relevant factual material being available to Members and prospective Members; and to

set forth the content of what was referred to as the “Lyoness Movie”.

It is also necessary to set forth:

the content of the forms needed to be completed by prospective Members and the contractual terms and conditions prior to April 2012; and

membership post-April 2012, including the contractual terms and conditions then in place.

These issues roughly follow the chronology of events whereby the Loyoness Loyalty Program was initially promoted to persons in Australia, and the establishment of that program thereafter. It is also necessary to have some understanding as to:

the volume of shopping and the value of benefits both prior to, and subsequent to, April 2012.

It is only against that factual and contractual context that the application of ss 44 and 49 of the Australian Consumer Law then can be meaningfully assessed.

The “unique opportunity” of Lyoness membership prior to April 2012

36 Prior to the launch of the Australian Lyoness program in April 2012, the Lyoness Loyalty Program was promoted by a group of four residents of the United Kingdom, described as the “Global Go Getters”. The Global Go Getters were Mr Phil Watts, Ms Sally Watts, Mr Andy Hansen and Ms Wendy Hansen.

37 What assumed some importance throughout the hearing was the encouragement being extended to persons in Australia to become Members of the Lyoness Loyalty Program – the opportunity to become such Members prior to the launch of the program in Australia in April 2012 was repeatedly referred to as a “unique opportunity”. The encouragement took the form of material distributed in the form of “webinars”, promotional material, meetings with the Global Go Getters, materials generated by persons in Australia who became Members, and a “Lyoness Movie”.

38 In setting forth the encouragement being extended to those instrumental in establishing the Lyoness Loyalty Program in Australia, it is prudent to set forth not merely the text of at least some of the conversations that occurred but also the graphic depiction of what was sought to be achieved. In many instances, the graphic depiction of the program displays more easily the manner in which the program was to operate, than do the verbal explanations. The verbal communications, of course, may not have the same impact upon a reader and potential Member as the more “glossy” pictorial representations. In now reproducing some of these depictions, it is to be acknowledged that some are more easily read than others. The “originals”, with respect, are “no better” than those now reproduced.

39 A number of presentations of the program were then available on “the web” and were described as “webinars”.

40 There were in evidence various versions of the different “webinars”.

41 Two of the Australian persons who became Members, and who gave evidence on behalf of the Commission, were Ms Rylah and Mr Neill. Ms Rylah recruited Mr Neill and numerous other persons as Members. Thereafter, Ms Rylah and Mr Neill and those other Members in turn secured the membership of further persons in Australia to participate in the Lyoness Loyalty Program in advance of its launch in April 2012.

42 Ms Rylah was a registered nurse in the State of Queensland. She made what was known as a “Down Payment” in September 2011 and thereby became a Lyoness Member. In about August/September 2011 Ms Rylah was in regular contact with Mr Craig Wotton, who appears to have been approached to assist in the Australian launch of Lyoness. Mr Wotton forwarded to Ms Rylah material to assist her in the promotion of Lyoness. Part of that material was information on “how to start a conversation about Lyoness” with potential new Members. The information provided the text and suggestions about how to relate to the prospective new Member. An extract from that information included the following:

43 Ms Rylah also gave evidence of watching “webinars” between August 2011 and March 2012. In mid-March 2012 she gave evidence of making her own presentations in order to secure new Members, during which she would say words to the following effect:

Well, I think you can see how excited Phil and all the team in the UK are about Lyoness in Australia. This is a great opportunity and a great time to be starting in Lyoness. We are in one of the best international teams, with Phil and Sally and Andy and Wendy. They have enormous experience and can give us all, as a team, the support we need to start up a great business to earn passive income.

Objection was taken to parts of Ms Rylah’s evidence, including the above account of what she told prospective new Members. The references to Phil, Sally, Andy and Wendy were references to members of the Global Go Getters.

44 Ms Rylah also gave evidence of attending a Lyoness Training Workshop in August 2012 during which a Lyoness “leader”, Mr Matthias Mueller, gave a motivational address saying words to the following effect (without alteration):

Now, the loyalty commission bonus: - and you should do this with your directs by looking at the back office – the rule is that there is always a benefit when you support your lifeline

Your first goal is to help everyone find 4 directs who make downpayments and that will give them belief. Once they have 4 directs that gives them eligibility, to start picking up the bonuses. As soon as they see the money, they will understand, they will “get it”.

After Sensation, (in September) there will be a change in the training program so that they will also be able enable to start with 3/1/1 and that will be enough to enable them to go to Workshop 1.

To become Premium Members, they either have to save or just work on it.

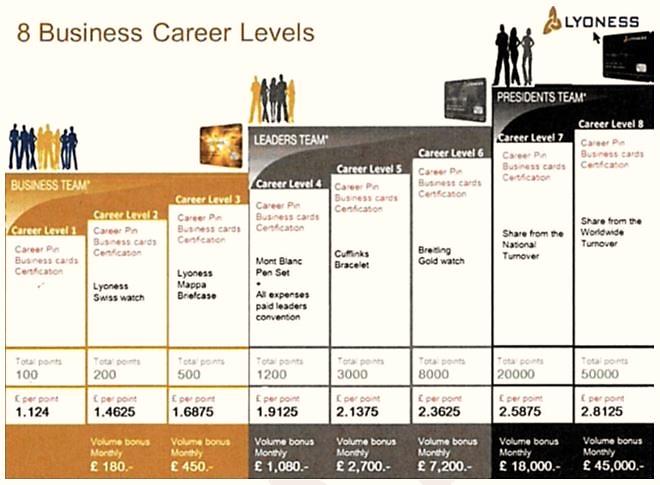

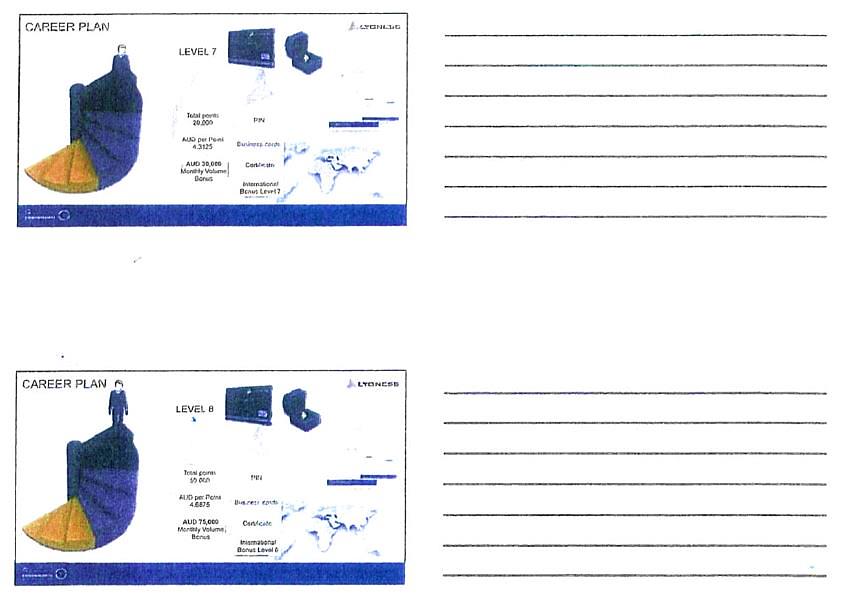

The thrust of this address was, obviously enough, to convey the potential benefits of membership. The reference to “directs’, it may presently be noted, was a reference to those further Members “directly” introduced by an existing Member. Exhibited to the affidavit of Ms Rylah was one version of one of the presentations given. Although she could not recall the date upon which she recorded that version, an extract provided as follows:

I’m going to start at career level 8 because that’s always the first place everybody looks on the screen. Career level 8 is the highest level in the Lyoness shopping community. It gives you a share of the worldwide turnover of Lyoness, and at this level you’d be generating 50,000 points in any given calendar month. But these 50,000 points could be as simply as 25,000 shoppers generating two of those £45 shopping units per month. And at this level you will be reimbursed at a maximum rate of £2.81 per point per month. Plus in addition, every month that you re-qualify for level 8 you will receive an additional £45,000 by way of your volume bonus monthly. Now please remember ladies and gentlemen this is just two of our ten income streams.

On the next page appeared the following diagram depicting what was intended to be conveyed:

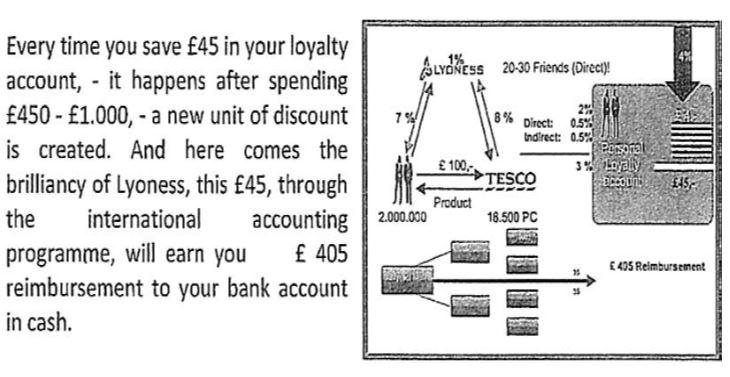

45 Another of the “webinars” exhibited to the affidavit of Ms Rylah set forth the following text (without alteration):

Now I look at an example in Australia, there’s actually a member in Australia who in the first 30 days made $5,500. That’s not enough money to retire but it certainly is a big difference. It could be the difference between keeping your house or losing it, it could be the difference between having a great Christmas or not, it could be the difference in not having to worry about sending your partner out to work or whatever. So the Lyoness shopping community we’re not into selling anything, we’re just leveraging what happens anyway. We build our team with benefits and the loyalty card. You can actually generate a substantial income for months if you just follow the system, plug it to your leaders, listen to your leaders and then they can advise you on how you develop your own team.

...

And this is a passive residual income that once we’re into phase 3 and 4 you cannot stop. As long as consumers around the world want to buy the products, goods and services and get cash back that we offer, and members, you will receive a passive residual income.

That “webinar” also set forth the following depiction, including a quantification of the “amount of resulting reimbursement” given certain assumptions being made about the various “Accounting Categories”:

46 Mr Neill also gave evidence of having a meeting in London in mid-September 2011 when he met the Managing Director of Lyoness UK (Mr John French) and the Global Go Getters. Prior to going to London he watched a number of the “webinars”. Albeit in a passage in his affidavit to which objection was taken, Mr Neill maintains that during one of these “webinars” Mr Wotton described, as follows, the manner in which the program was to be introduced into Australia and that the “founding members” would be part of a “unique opportunity”:

The information in this webinar has been authorised and approved by Lyoness head office.

The launch in Australia will be a phased program. Phase 1 will be complete when 500 foundation members are in place. The second phase will be the opening launch in Australia.

Phase 3 is rolling out of the small medium enterprise (SME) program, and issuing of cashback cards to get shopping underway. Phase 4 involves Lyoness conducting a mass media advertising campaign, which will benefit the founding members.

Once Australia reaches 500 founding members, Lyoness will put in 1,000,000 customers through a very aggressive mass media advertising campaign. These founding members will have the privilege of 1,000,000 new customers being divided amongst them, benefiting from the result of the advertising program. This is a unique opportunity and we are a privileged few to be part of the launch.

In another passage in his affidavit to which objection was taken, Mr Neill also maintains that in another “webinar” Mr Andy Hansen “focused on the importance of recruiting new members, and recommended a process of approaching a potential member or ‘prospect’”. Mr Neill’s account of what Mr Hansen said was as follows:

You move up career levels with units accumulating from your team, which means that you earn more money. You should introduce 5 people to Lyoness as premium members, and teach these 5 people to introduce another 5 people as premium members. To achieve career level 3, you guide your direct recruits to teach their 5 people to recruit another 5 premium members.

Give the prospect a sentence about Lyoness, and then invite them to an information webinar. You cannot expect a prospect to understand Lyoness from the first webinar. You should follow up with them a few days after the webinar, and either invite them to another webinar or meet with them to discuss Lyoness.

47 During the meeting in London, Mr Neill maintains that he had the following exchange with the managing director of Lyoness UK, Mr John French:

French: So, what do you like about Lyoness? What do you think you can achieve?

Neill: There is a great opportunity in being one of the first 500 members in Australia. Being part of the launch, there are obvious benefits in the advertising campaign.

Thereafter, Mr Neill maintains that either Mr Hansen or Mr Watts said:

If you get a team together quickly, with the best people you can find, then you will get to the first 500 members quickly.

Thereafter, the following exchange took place between Mr Neill and Mr Hansen:

Neill: How many lines do I need in my team?

Hansen: Find your best 5 people and introduce them to Lyoness, and then get them to do the same thing. There has to be 500 premium members to open up Australia.

Thereafter, Mr Neill commenced recruiting other persons as Members and, in doing so, said to the prospective new Members words to the following effect:

“I have been looking at a company called Lyoness, and they have a program that gives cashback to members. We are looking to have 500 premium members before Lyoness will launch in Australia. When Lyoness starts in Australia, there will be an advertising campaign. The original 500 premium members will benefit by having the customers recruited through the advertising campaign allocated underneath them. You should look at a webinar about Lyoness.”

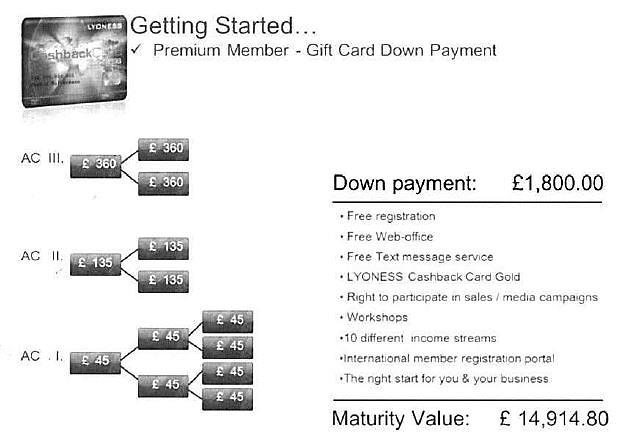

As he became more familiar with the Lyoness Loyalty Program, in October 2011 Mr Neill developed his own “flipchart” set of slides which he in turn used when seeking to recruit other consumers into the program. One of those slides was as follows:

The “10 different income streams” referred to is a reference to the ten different types of rebates that may be received under the scheme, being:

The “10 different income streams” referred to is a reference to the ten different types of rebates that may be received under the scheme, being:

cash back;

friendship bonus;

loyalty cash;

loyalty credits;

loyalty commissions;

loyalty partner bonus;

bonus units;

category re-booking;

volume commissions; and

volume bonus.

48 In a further passage in his affidavit, to which objection was taken by the Respondents, Mr Neill maintains that a further part of the words he would use when seeking to recruit new Members were the following:

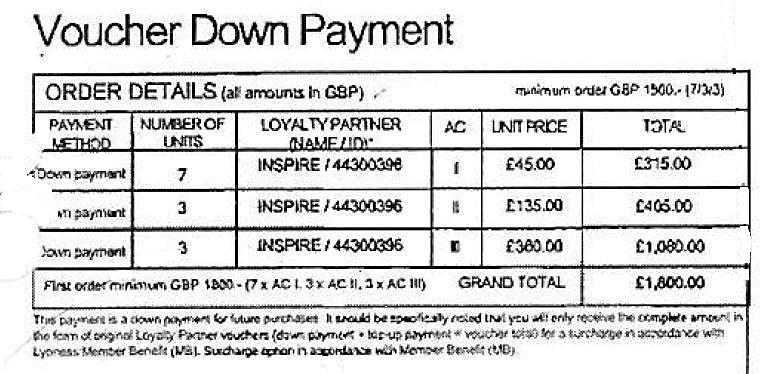

If you look at slide 8, entitled “Immediate + Remaining Discount in Customer Account” say you started shopping today, it would take some considerable time for you to create a sizeable income. So we have a fast start program such that you make in advance some down payments: you purchase units that are already complete and they go into the accounting program. So here you’re purchased a total of 7 units, £45 units in accounting level 1, £335 units in accounting 2 and £360 units in accounting 3 and that all totals up to £1,800 so they are, they call them down payments. You’ve actually pre-purchased those units and they’re sitting there, and when other units to in behind your units as we’re already shown you that moves through and it starts off your shopping program once we open the shopping program here in Australia. Now when those units move through the matrix, that £1,800 investment – which is in effect what it is – as well as giving you free registration and a website and text message servicing, the Lyoness cards, access to workshops and all the other income streams, that £1,800 that converts into £14,000 nearly £15,000.

Unique to the language employed by Mr Neill was his use of the term “investment”. Although described by Senior Counsel for the Respondents as a “maverick”, the fact remains that this was the language he employed. But nothing turns, with respect, upon this sole use of that term by Mr Neill.

49 Reference should also be made (merely by way of example) to the following reference to “Career Income” that a Member could achieve upon attaining “Career Level 6”:

This depiction comes from part of the material used in “Business Workshop 1” and is dated as being the September 2013 version.

50 Many of these graphic depictions of the manner in which the Lyoness Loyalty Program was to operate are scattered throughout many of the documents – be those documents annexed to the affidavits of witnesses called by the Commission or in documents produced on discovery by the Respondents or obtained as a result of the search warrant executed in September 2013.

The Lyoness Movie & scripts – March 2012

51 Prior to April 2012 was a conference held in Macau, in or around March 2012. Those attending were the “Lyoness Leaders”. A new means of securing membership in Australia was then released in the form of a Lyoness Movie in relation to the Lyoness Loyalty Program of approximately 15 minutes duration. That movie was available to be viewed by any member of the public on the internet site of Lyoness Australia. In or around March 2012, Lyoness International also produced written materials in relation to the Lyoness Loyalty Program and provided information which was available to the public in relation to that program.

52 Parts of the “scripts” that accompanied the Lyoness Movie again referred to the different “Career Levels” that could be achieved and the benefits that could be received. Albeit omitting parts of those scripts, parts of one script included the following:

53 Also released after the Macau conference was an extended Lyoness Movie of some 30 minutes in length. The longer Lyoness Movie was only available to Premium Members.

54 A “still” from part of that Lyoness Movie was as follows:

55 Part of that which was said during the longer version of the Lyoness Movie was the following:

Right now Lyoness is still in the process of introducing the cash back card in the market and this presents a great opportunity. Once this card is accepted at the most [well-known] businesses that become loyalty merchants things are going to happen very fast. After that everyone will want to have this card. Those who are ready to participate and communicate the benefits to others have a great future ahead of them. There is a great opportunity that still many people don’t have the cash back card. If everyone already had the card it would be too late to build a substantial business by recommendations.

56 In addition to the two versions of the Lyoness Movie and the scripts, by no later than May 2012 Lyoness International produced “training materials”.

Membership & terms and conditions prior to April 2012

57 Although the Commission placed greater reliance upon the steps being taken to encourage persons to become Members, the Respondents placed greater reliance upon the contractual terms and conditions which regulated the rights and entitlements of Members.

58 However these competing stances may ultimately be resolved, it remains of obvious relevance to in fact set forth those contractual rights and entitlements.

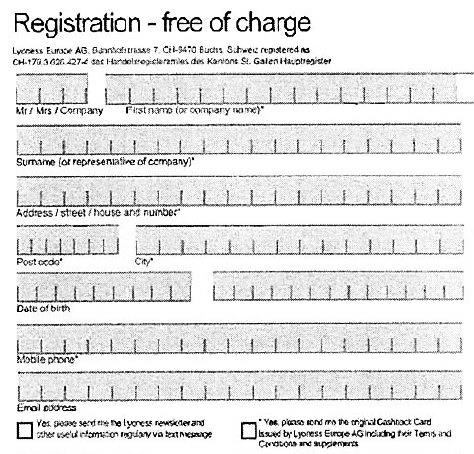

59 The form of application to be completed by prospective Members prior to April 2012 was set forth in a pamphlet titled “Australian Team Members Registration Process”. The pamphlet outlined “the new process for registering new members in Lyoness who live in Australia”.

60 The form of application there set forth titled “Initial order and registration” stated at the outset the following:

After successful registration and initial order placement you will receive your Lyoness Cashback Card by post. The cost of £1.80 for your initial order will be paid for by your recommender. (sponsor).

Please pay attention to the phase status of your country when placing your initial order. Phase 1 countries (National subsidiary not yet established or is not yet active)

• (Voucher order not yet possible)

• Minimum voucher Down Payment £1,800. (7/3/3)

The form of document then set forth the information required to be provided by an applicant. Part of that information was the following:

Further information required to be provided also included:

The form of document also provided for “Bank Details” to be provided. At the foot of the document was the following notation:

Important Notice: Should no payment be made by the new Member within 21 days after the date of signature of the Customer Agreement, no registration is possible. The recommender must ensure that there are enough funds in his/her purchase account to cover the costs of the registration for the new member. If this money has not been received within 21 days then the new member will not be registered.

In many of the forms which had been otherwise completed, no bank details were provided; in some of the forms, the details under “Voucher Down Payment” were left blank.

61 The contractual terms and conditions that governed membership in Australia prior to April 2012 were set forth in the UK General Business Terms for Lyoness Customers in the United Kingdom. Clause 2.1 provided as follows:

2. The relationship between the Customer and LYONESS

2.1 Nothing in these General Business Terms nor in any agreement between a Customer and LYONESS shall render a Customer an employee, servant, worker agent or partner of LYONESS nor shall any Customer hold himself out as such.

Clause 9.1 provided as follows:

9. Charges

9.1 Participation by the Customer in the LYONESS System is always free of charge unless specific provisions provide for a charge for particular services. No special administrative charges will therefore be made against the Customer for purchases made.

Clause 15 addressed “Down Payments”. Clause 15.1 provided as follows:

15. Down payments

15.1 In addition to the possibility of generating positions through purchases (remaining profit margin), the Customer also has the opportunity of obtaining positions through down payments (minimum first order: 3 positions in business category 1). These are down payments on future purchases, i.e. the profit margin in advance which offer the opportunity to save for planned future purchases and generate further reimbursements. Save as set out in paragraph 10.5A of Appendix 1 to these General Business Terms, it is not possible for the down payment to be refunded, as the profit margins which have arisen will have been included in the account and paid. However, the Customer has the opportunity to top up his down payments at any time, until the position pays out (shopping voucher) in the respective business category as set out in Clause 10.3. By topping up according to the relevant profit margin code for the desired Partner Company, the down payment becomes a full payment and the Customer receives the full amount in the form of vouchers from the Partner Company (down payment + top up payment = voucher value). If this is the case and the position (created by down payments) changes the Customer’s status to a full payment, this has the consequence that, after achieving the position pay out in the respective business category, the respective reimbursement (purchase reimbursement) will be paid out, less the original prepayment.

Appendix 1 to these UK General Business Terms thereafter addressed “Lyoness Reimbursements” and “Types of Payment”. That Appendix also referred to the benefits of purchasing a “Business Package”.

62 No provision of these UK General Business Terms referred to a “Premium Member”.

Membership post-April 2012

63 The Australian Lyoness Loyalty Program commenced in April 2012.

64 Once again, a consumer could become a Member by being recommended by an existing Member and by completing an application form on-line. The existing Member paid a $1.50 application fee; the applicant joined for free.

65 By signing the application form, the consumer acknowledged that he became bound by the General Business Terms and Conditions. Those General Business Terms and Conditions constituted an agreement between the new Member and Lyoness Asia. The introduction to those terms and conditions provided as follows:

Introduction

Lyoness Asia Limited, with its registered office at Suite 2607-12, 26th Floor, Tower 2, The Gateway, Harbour City, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong, and company number 1619260 registered with the Registrar of Companies of Hong Kong (Lyoness Asia) is a member of the Lyoness Group of companies which operate an international shopping community which offers Lyoness Members (Members) the opportunity to receive benefits (“Lyoness Loyalty Program”) through the purchase of goods and services from approved Lyoness retailers or service providers called Loyalty Merchants (“Loyalty Merchants”).

This Agreement is between the Member and Lyoness Asia.

Clause 1.1 provided as follows:

1. Object of the Agreement

1.1. To the extent permitted by these General Terms and Conditions (Agreement) you are entitled to participate in the Lyoness Loyalty Program with Lyoness Merchants using the types of shopping available through Lyoness Loyalty Program and you have the opportunity to benefit (“Member Benefits”). You may also recommend the Lyoness Loyalty Program to others, being Direct or Indirect Members within the meaning of Clause 7.3 (“Recommending Person”) but you are under no obligation to recruit further members to participate in the Lyoness Loyalty Program.

Clause 3.1 described the relationship as follows:

3. Legal Relationship

3.1 Nothing in this Agreement will be construed as to create a relationship of employment, agency or partnership between Lyoness and the Member (including, for the avoidance of doubt, when a Member is acting as Recommending Person). There is no obligation on a Member at any time to participate in the Lyoness Loyalty Program or to recommend or recruit further Members, and the Member acting in the capacity of Recommending Person acts independently of Lyoness. Given a Recommending Person’s independent obligations and responsibilities, the Recommending Person must comply with all applicable laws (including privacy laws and consumer protection laws) and codes of conduct.

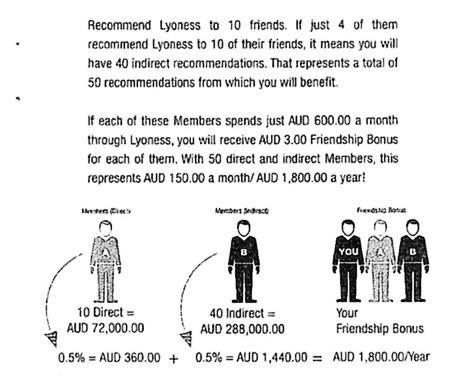

66 By becoming a Member, a consumer was entitled to receive a “Cashback” for purchases and a “Friendship Bonus”. A “Friendship Bonus” arose where the existing Member had introduced a new Member (described as a “Direct” Member), and also where that Direct Member had in turn introduced a further new Member (described as an “Indirect” Member) and where either or both of the Direct and Indirect Members undertook shopping with Lyoness Loyalty Merchants. A brochure forwarded from the solicitors for Lyoness in September 2013 depicted this relationship as follows:

The General Business Terms and Conditions described the relationship as follows in cll 7.2 and 7.3:

7.2. Cashback: for Purchases which are recorded by Lyoness in the Lyoness Loyalty Program, the Member receives up to 2% Cashback. The percentage specified by the respective Loyalty Merchant at www.lyoness.com.au (login area) is valid for Cashback. Cashback payments take place in accordance with Clause 7.4.

7.3. Friendship Bonus: Members have the opportunity to benefit from the Lyoness Friendship Bonus. For every Purchase made through the Lyoness Loyalty Program with Loyalty Merchants by your Direct and Indirect Members, a Member has the opportunity to receive:

a) Up to 0.5% direct friendship bonus (for Purchases made by your Direct Members, namely Members who were directly introduced by you as an existing Member)

b) Up to 0.5% indirect friendship bonus (for Purchases by Indirect Members ie those Members who have been introduced by your Direct Members) – a Friendship Bonus does not accrue for other Indirect solicited Members.

67 A Member could also sign what were described as the Additional Terms and Conditions. No fee was payable in the event that an existing Member chose to sign these additional terms. These Additional Terms and Conditions regulated both:

the manner in which a Member could become a “Premium Member” (cl 5.4); and

the entitlement of a Member to receive “Extended Member Benefits” (cl 7).

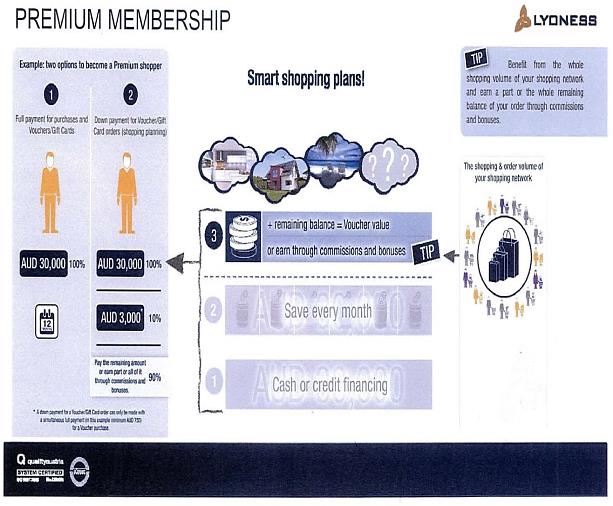

68 Clause 5 provided for the transition from membership to “Premium Membership”. That clause, in its entirety was as follows (without alteration):

5.) Voucher Down Payments and Premium Membership

5.1. As well as making Purchases through the Lyoness Loyalty Programme, the Member also has the opportunity to generate Loyalty Benefits by making a binding Down Payment order for Vouchers/Gift Cards, in this case the same amount of credit will be booked into the Member’s personal Loyalty Account for the Down Payment as was booked for the purchase in Clause 4.2 above. However, no Cashback or Friendship Bonus is paid for a Down Payment.

5.2. The Member has the opportunity to make a binding Down Payment order for Vouchers/Gift Cards. The Down Payment must be at least the relevant benefit percentage for Member Benefits for the chosen Loyalty Merchant. The GTCs and the ATCs do not give right for a claim for reimbursement of the Down Payment.

5.3. Any Down payments for Voucher/Gift card orders do not expire. Until the point that full payment is received for the Voucher/Gift Card orders, the Member may change the Loyalty Merchant they originally chose. This could however mean that the Member Benefit will also change, as it varies depending on the Loyalty Merchant, as explained in Clause 4.3.

5.4. A Member can become a Premium Member if they have fulfilled the following criteria:

Fully paid (and booked) Purchases using the Cashback Card, Vouchers and/or Online Shopping of AUD 30,000 within 12 months.

If a purchase volume of AUD 30,000 has not been achieved in accordance with 5.5 a) then the Member can make up the difference using Down Payments (booked) for Voucher Orders/Gift Cards, whereby the Down Payment amount should be multiplied by ten (a Down Payment of AUD 1,500 represents e.g. a purchase volume of AUD 15,000).

Made (and booked) Down Payments for Vouchers/Gift Cards of AUD 3,000 (Premium Voucher Down Payment)

5.5. Down Payments of up to AUD 2,925 can be accepted if the Member has made Purchases of at least AUD 300, or makes a simultaneous Voucher order for this amount (fully paid) at the same time that he makes the Down Payment. Down Payments of AUD 3,000 can be accepted if the Member has made Purchases of at least AUD 750, or makes a simultaneous Voucher order for this amount (fully paid) at the same time that he makes the Down Payment. If a Member has already made Down Payments of AUD 3,000 then further Down Payments are only possible if the Member has made an equal amount of Purchases as the amount of Units (inc. the new Down Payment).

5.6. Premium Members receive additional service support in the Lyoness Loyalty Programme (including without limitation Gold Cashback Card, Cashback Magazine).

Clause 5.4, it may be noted, provided for a number of ways in which a Member could become a Premium Member. This was depicted in the Lyoness promotional material as follows:

Clause 5.6, it will be noted, provided for the benefits of premium membership.

69 Clause 7 of the Additional Terms and Conditions provided for “Extended Member Benefits”. These Extended Member Benefits were in the form (inter alia) of a “Loyalty Commission”, “Loyalty Cash”, “Loyalty Credit”, “Loyalty Commission Bonus” and “Bonus Units”. Every Member who signed the Additional Terms and Conditions had the opportunity to obtain Extended Member Benefits.

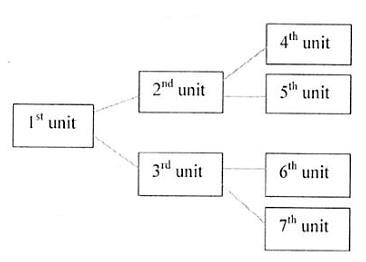

70 The entitlement of any Member to receive Extended Member Benefits depended upon the number of “units” held in the “Accounting Program”. A Member qualified for units upon accumulating a certain number of credits. The amount of credits in turn depended upon either cash purchases or the making of “Down Payments”. Each time a Member obtained a new unit in a designated Accounting Category, the new unit would sit behind or “follow” the existing unit as follows:

71 Depending upon the Accounting Category to which a Member belonged, a Member could become entitled to a payment of a Loyalty Commission. A Member, for example, in Accounting Category 1 would receive a $12 payment if he had 6 units; a Member in Accounting Category V would receive $6,000 when he had accumulated 50 units.

72 Similarly, a Member could become entitled to a Loyalty Cash payment direct to his bank account. A Loyalty Credit could accrue through the Member’s own shopping, which would then entitle him to receive vouchers in the dollar amount of that credit.

73 The number of units dictated a Member’s “Career Level”.

The volume of shopping & benefits – prior to and subsequent to April 2012

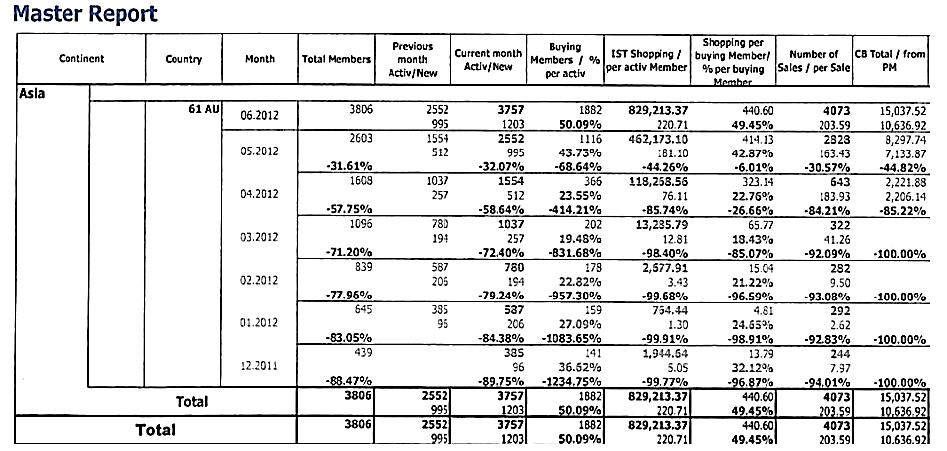

74 The volume of shopping and benefits to Australian Members prior to April 2012 was addressed in part in a series of internal Master Reports and Sales Reports.

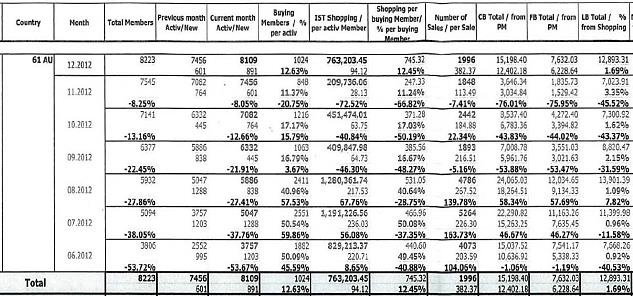

75 For the period prior to April 2012, a Master Report produced on discovery by the Respondents provided as follows:

This Master Report was described in the affidavit of discovery as recording (inter alia) the “volume and value in Euro per month (IST) of shopping (gift cards, or fully paid purchases online or instore) by members, with associated ratios, and number of shopping transactions per month”.

76 If reference is made, for example, to the figures in the column headed “CB Total/from PM”, the percentages track the changes in “Cashback” from one month to the next. Thus the 44.82% was calculated as follows:

$15,037.52 |

$ 8,297.74 |

= $ 6,739.78 |

The difference was said to represent the change from the period from May to June 2012. The percentage was calculated as follows:

$6,739.78/ $15,037.52 = 44.82% |

So much seems to flow naturally from the Report itself.

77 For the period from June through to December 2012, another Master Report records in part the following:

The figure of 1.69% in the column headed “LB Total / % from Shopping” also seems to have been derived from performing the following calculation:

$ 12,893.31/$763,203.45 = 1.69% |

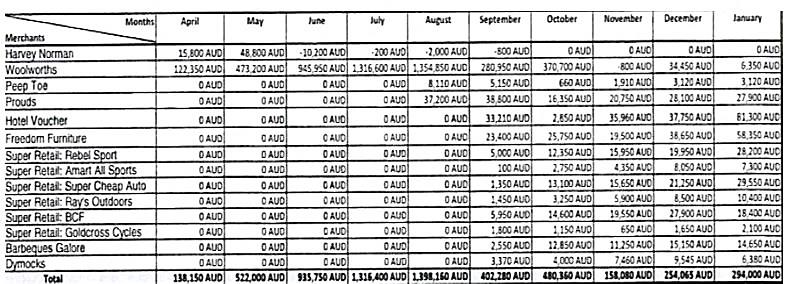

78 Part of the Australian Sales Report for the period from April 2012 through to January 2013 records as follows the value in Australian dollars of shopping at those Loyalty Merchants identified:

There were like details for other periods of time.

79 The Australian Sales Report for the period from April 2012 through to December 2014 again records the following total volume of sales in respect to those Loyalty Merchants identified:

Months Merchants | Total |

Harvey Norman | 0 AUD |

Woolworths | 0 AUD |

Peep Toe | 0 AUD |

Prouds | 336,550 AUD |

Hotel Voucher | 471,370 AUD |

Freedom Furniture | 452,400 AUD |

Super Retail: Rebel Sport | 285,650 AUD |

Super Retail: Amart All Sports | 101,350 AUD |

Super Retail: Super Cheap Auto | 391,650 AUD |

Super Retail: Ray’s Outdoors | 93,800 AUD |

Super Retail: BCF | 311,350 AUD |

Super Retail: Goldcross Cycles | 14,750 AUD |

Barbeques Galore | 227,400 AUD |

Dymocks | 87,105 AUD |

Coles | 14,794,500 AUD |

Kmart | 982,400 AUD |

Liquorland | 1,188,550 AUD |

Coles Express | 5,510,850 AUD |

Marks & Spencer | 15,810 AUD |

Target | 293,700 AUD |

Dick Smith | 128,800 AUD |

Toyworld | 11,425 AUD |

Total | 25,699,410 AUD |

80 In lieu of Loyalty Agreements being produced in respect to each of the Small/Medium Enterprises, a Schedule was compiled by the parties showing those enterprises participating in the Lyoness Loyalty Program and the dates upon which such agreements were entered into.

CONTRAVENTIONS OF SECTIONS 44 & 49

81 In very summary form, the case advanced on behalf of the Commission in its Amended Statement of Claim in respect to pyramid selling alleges that:

the making of “Down Payments” were “participation payments” for the purposes of s 45(1)(a) of the Australian Consumer Law;

and (inter alia) that:

“Premium Members were induced to become Premium Members by making Down Payments by the prospect held out to them that they would thereby become entitled to receive financial benefits being Extended Member Benefits of a higher value than those Down Payments”; and that

such benefits were “recruitment payments” for the purposes of s 45(1)(b) of the Australian Consumer Law.

The Commission concludes in this respect that the Lyoness Loyalty Program was a “pyramid scheme” within the meaning of s 45. The Commission further alleges (inter alia) that:

Lyoness Australia, Lyoness International, Lyoness Asia and Lyoness UK were each “participants” in the Lyoness Loyalty Program and therefore contravened s 44.

82 Again in very summary form, the case advanced on behalf of the Commission in its Amended Statement of Claim in respect to referral selling was that:

the “receipt of Direct Friendship Bonus and Indirect Friendship Bonus by a Premium Member was contingent on shopping by Members with Units Down Line from Units held by the Premium Member…”;

the “amount of Loyalty Commission, Loyalty Commission Bonus, Volume Commission or Volume Bonus which a Premium Member might receive was contingent on Down Payments made by Members with Units Down Line from the Units held by the Premium Member”; and

persons were induced to “become Premium Members by acquiring Units in the Lyoness Accounting Program” by representations that “each such Member would receive benefits in return for recommending new Members…”.

The Commission concludes in this respect that the Lyoness Loyalty Program constituted “referral selling” within the meaning of s 49. The Commission thereafter alleges that:

Lyoness Australia and Lyoness Asia engaged in referral selling and, in the alternative, that Lyoness Australia was knowingly concerned in or party to the contravention by Lyoness Asia within the meaning of s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law.

83 It is relevantly concluded that the Commission’s case in respect to “pyramid selling” fails primarily because:

even had there been a “participation payment” that fell within s 45(1)(a), any “recruitment payment” which was thereafter made was not a payment “in relation to the introduction to the scheme of further new participants” as required by s 45(1)(b).

It has also been concluded that:

there has been no holding out to persons that they “will be entitled, in relation to the introduction to the scheme of further new participants” to be provided with a “recruitment payment” for the purposes of s 45(1)(b).

Another difficulty in the path of the Commission, it is respectfully considered, was its failure to make good the following allegations in its Amended Statement of Claim, namely its allegations in:

para [39] that “a person could become a Member in Australia only by making a Down Payment”;

para [40] that in order to become a Premium Member it was a “practical requirement that a Down Payment be made … because there did not exist any realistic alternative”; and

paras [42] and [43] that the value of benefits “was due to Down Payments”.

The failure to establish paras [39], [40], [42] amd [43] of course, only provides further reason to reject the “pyramid selling” allegations.

84 It is further concluded that the Commission’s case in respect to “referral selling” also fails, primarily because:

the phrase appearing in s 49, namely that a consumer “will … receive a rebate, commission or other benefit in return for” (relevantly) “giving … the names of prospective customers…” should be construed in a manner comparable to the phrase in s 45 (namely, “in relation to the introduction to the scheme of further new participants”) and that the phrase in s 49 requires a “relevant, sufficient or material connection or relationship” between the giving of the names and the receipt of the benefit, and that that relationship has not been made out.

It is also further concluded that the Commission has most probably failed to make good the allegations in:

paras [68] and [69] of the Amended Statement of Claim, namely the allegations that Lyoness Asia and Lyoness Australia induced persons to become Premium Members “by representing that each such Member would receive benefits in return for recommending new Members…”.

Although the decision of the Full Court in Australian Communications Network was a decision in respect to “pyramid selling”, it is respectfully further considered that their Honours’ insistence upon the need for “the real or substantial rewards held out … to be derived substantially from the recruitment of new participants, as distinct from rewards for genuine sales of goods or services” ([2005] FCAFC 221 at [46], (2005) 146 FCR at 425) applies equally to both ss 45 and 49.

85 Notwithstanding these being the principal bases upon which the claims for relief advanced by the Commission are to be dismissed, it is nevertheless prudent to address – albeit perhaps in briefer form than may otherwise have been required – a number of the other competing submissions advanced for resolution. It is also prudent initially to address the manner in which amendments were made throughout the hearing to the allegations being advanced for resolution and to the claims for relief.

Questions as to the pleadings & particulars

86 The case as initially advanced for resolution by the Commission raised the prospect that the case, as it was opened by Senior Counsel on its behalf, departed in at least two material respects from the case as pleaded.

87 The first potential departure went to the very heart of its case. As pleaded, the “scheme” which was expressly identified as the “pyramid scheme” the subject of challenge was the “Lyoness Loyalty Program in Australia”. So much expressly followed from at least the introductory heading to paras [39] and [40] of its Statement of Claim. Those paragraphs provide (in part) as follows:

The Lyoness Loyalty Program in Australia

39. Until 26 April 2012 a person could become a Member in Australia only by making a Down Payment.

40. Further to paragraph 39 at all relevant times, in order for a person in Australia to become a Premium Member it was a practical requirement that a Down Payment be made to or for the benefit of Lyoness Asia or Lyoness Europe AG as the case may be, because there did not exist any realistic alternative.

Paragraphs [42] to [50] thereafter proceed to address the significance sought to be attached by the Commission to the making of the “Down Payment” as the “participation payment” and the “inducements” held out which resulted in the “recruitment payments”. Thereafter para [52] provides as follows:

52. In the premises, the Lyoness Loyalty Program in Australia was a pyramid scheme within the meaning of section 45 of the ACL:

(a) At all times from September 2011;

(b) In the alternative at all times from April 2012;

(c) In the further alternative from September 2011 to April 2012.

Annexure A to the Originating Application, moreover, identified the scheme in respect to which declaratory relief was sought as the “Lyoness Loyalty Program”. An injunction, for example, was sought restraining the Respondents “from establishing, promoting, taking part in or otherwise participating in the Lyoness Loyalty Program inside or outside of Australia”.

88 The potential departure from this identification of the “pyramid scheme” the subject of challenge in Senior Counsel’s opening on the first day of the hearing was to confine the “pyramid scheme” to only that part of the “Lyoness Loyalty Program” whereby “Members” (at least after April 2012) could become “Premium Members”.

89 If there were a contravention of s 45, as alleged by the Commission, there was at least the prospect of disharmony between that conduct which constituted the contravention alleged and relief which attached to the Lyoness Loyalty Program as a whole.

90 Such a shift in focus, it was then suggested, required an amendment to the Statement of Claim and an amendment to the form of relief as identified in the Originating Application.

91 The second potential departure from the pleadings in the Statement of Claim which occurred in the opening of the Commission’s case focussed attention on the introductory words to s 45(1)(a), namely the characteristic that “some or all new participants must provide” a participation payment.

92 The case for the Respondents was (inter alia) that:

cl 5.4 of the Additional Terms and Conditions provided for three ways in which a Member could become a Premium Member and that contractually the making of a “Down Payment” of $3,000 was but one of the ways; and

as a factual matter there were a number of Members who became Premium Members after April 2012 other than by way of making a “Down Payment”.

That factual matter, so the Commission submitted, mattered not. It was sufficient to satisfy the terms of s 45(1) if “some” of the existing Members fell within the terms of s 45(1)(a).

93 That, again, at least raised the prospect that there was further disharmony between the case as pleaded and the case as opened on behalf of the Commission. As pleaded, there was certainly no express allegation that only “some” of the existing Members became Premium Members by the making of a “Down Payment” and the allegations that were made were drafted in terms which suggested that the allegation applied to “all” Members.

94 Leave was granted on the second day of the hearing to amend the Originating Application and the Statement of Claim. Annexure A to the Originating Application, in particular, was then the subject of revision. No amendment of the pleading was sought expressly contending that “some” of those persons made a “participation payment”. The Defence as first filed was taken to be a Defence to the Statement of Claim as amended.

95 A final matter which occasioned some attention on the first day of the hearing was the provision of further particulars by the Commission by way of a letter dated 23 July 2015 in respect to:

para [44] of the Statement of Claim, namely that paragraph which identified those “Premium Members who were induced to become Premium Members by making Down Payments” – the July 2015 letter providing a list of the names of a further 63 such Members; and

para [54], namely that paragraph which identified by name those “people in Australia who were recruited as Premium Members by the Global Go Getters” – the July 2015 letter stating that by “20 February 2012, 658 Premium Members had been so registered” and that by “27 February 2012, over 800 Premium Members had been so registered…”.