FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Scandinavian Tobacco Group Eersel BV v Trojan Trading Company Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 1086

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

SCANDINAVIAN TOBACCO GROUP EERSEL BV First Applicant SCANDINAVIAN TOBACCO GROUP AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Second Applicant | |

AND: | TROJAN TRADING COMPANY PTY LTD Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed with costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 568 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | SCANDINAVIAN TOBACCO GROUP EERSEL BV First Applicant SCANDINAVIAN TOBACCO GROUP AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Second Applicant |

AND: | TROJAN TRADING COMPANY PTY LTD Respondent |

JUDGE: | ALLSOP CJ |

DATE: | 9 October 2015 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

ALLSOP CJ

Introduction

1 This is an application for injunctive and other relief by Scandanavian Tobacco Group Eersel BV (STG Eersel), and Scandanavian Tobacco Group Australia Pty Ltd (STG Australia). I will refer to the applicants as STG, unless a distinction needs to be made between them.

2 STG claims that the respondent, Trojan Trading Company Pty Ltd (Trojan), has infringed registered Australian trade marks of STG Eersel for the word marks “CAFÉ CRÈME”, “HENRI WINTERMANS” and “LA PAZ” under the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act) in respect of cigars, and has engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in breach of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (ACL) and the tort of passing off.

3 The case raises a number of interesting issues as to the operation of ss 120 and 123 of the Act in the context of parallel importing of tobacco products now that the Commonwealth Parliament has required plain packaging of, with graphic photographs of diseased parts of the body on, all tobacco products. The alleged infringement concerns the importation by the respondent of cigars manufactured by, or with the consent of, STG Eersel in Belgium and Holland. The cigars are imported in packaging and bearing the trade marks placed thereon by STG Eersel. In order to comply with Australian law concerning the packaging of tobacco products sold in Australia, the respondent unpacks the cigars and re-packages them in packaging compliant with the relevant legislation. As part of that re-packaging, the marks in question are placed on the packaging by Trojan. There is no suggestion in the packaging or otherwise by its conduct that the trade marks are used to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods and Trojan.

4 A concise summary of the applicant’s case is as follows:

(a) Trojan is applying the trade marks CAFÉ CRÈME, HENRI WINTERMANS and/or LA PAZ to or in relation to cigars without the control or consent of the trade mark owner, then selling such products. It has also used those trade marks in its price lists and invoices to refer to such products no longer controlled by the trade mark owner. Such conduct amounts to trade mark infringement and no relevant defence applies.

(b) Ordinary retailers and consumers who know and seek out the applicant’s products by reference to the brand names and trade marks CAFÉ CRÈME, HENRI WINTERMANS and LA PAZ are misled by Trojan’s conduct to think that its products bearing those trade marks are authorised by the owner of those trade marks, and/or packaged under its authorisation. Such purchasers would not know or suspect the truth that those products had been unpacked by hand and re-packaged by Trojan into packaging relevantly different from the applicant’s packaging, without the knowledge, control or authorisation of the owner of those trade marks.

5 The claim for infringement under the Act can be divided into three parts – that Trojan, without the consent of STG Eersel (a) used the trade marks by applying them to or in relation to the cigars in the course of re-packaging them; (b) used the trade marks by selling the products to retailers with the trade marks so applied; and (c) used the trade marks in relation to the goods by issuing price lists, invoices and other communications for such products.

6 Pursuant to an order made at case management, the trial was ordered to be conducted on the basis that it be limited to the question of liability. At the hearing, by consent, the scope of the trial was further narrowed to exclude the applicants’ passing off case in so far as they are required to prove the likelihood of damage.

7 The controversy raised five issues: first, whether STG Australia had standing under s 26 of the Act to bring its trade mark suit; secondly, whether the uses of the mark constituted infringing use as a trade mark by Trojan under s 120 of the Act; thirdly, if prima facie infringement be made out under s 120, whether s 123 of the Act was engaged; fourthly, whether the defence under s 122(1)(b) of the Act was made out; fifthly, treating the passing off and misleading or deceptive conduct cases as one issue, whether either or both was or were made out.

8 For the reasons that follow, I would answer these questions as follows: first, STG Australia has standing; secondly, whilst I consider there to be a degree of force in the arguments of Trojan, I consider myself to be precluded by authority from concluding otherwise than that s 120 is engaged and prima facie infringement occurred subject to s 123 and s 122; thirdly, s 123 is engaged, that is, if it is to be viewed as a defence, it is made out; fourthly, the defence under s 122(1)(b) is not made out; and fifthly, the claims for passing off and under s 18 or s 29 of the ACL are not made out.

9 In these circumstances, the application should be dismissed with costs.

Background

10 For the most part, the facts are not in dispute. For many years, Scandanavian Tobacco Group A/S (STG A/S) located in Denmark, has carried on international business in the manufacture and sale of both hand and machine made cigars. STG A/S owns and controls various companies around the world, including STG Eersel and STG Australia, that operate around the world in the manufacture, distribution and wholesale of its range of cigars. The group is the product of the merger in or about 2011 of two groups known as Swedish Match and Scandinavian Tobacco.

11 STG Eersel manufactures machine made cigars for the STG Group in factories in Holland, Belgium and Indonesia. Machine made cigars destined for the Australian market, in particular those branded Henri Wintermans, Café Crème and La Paz are manufactured by STG Eersel in Holland and Belgium. These are the products to which are applied the registered trade marks including the word marks: “CAFÉ CRÈME” (registration number 761892), “HENRI WINTERMANS” (nos. 179680 and 1529889) and “LA PAZ” (no. 643779). The parties agree that the question of infringement can be determined simply by reference to these word marks: 179680, 643779 and 761892.

12 STG Australia is the sole distributor and wholesaler, with the authority to import, market, promote, sell and distribute these brands of cigars to which the trade marks relate in Australia. STG Australia is conferred with that authority by way of various distribution agreements, the relevant terms of which are discussed below.

13 STG Eersel has, at least since early 2013, packaged the authorised products at its factories in Europe for compliance with local Australian plain packaging laws: Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth) (TPP Act) and the Tobacco Plain Packaging Regulations 2011 (Cth) (TPP Regulations). The relevant provisions of the TPP Act and TPP Regulations prescribing the use of brand names and regulating plain retail packaging for tobacco products (see ss 17 to 27A of the TPP Act and r 1.1.2 of the TPP Regulations) came into effect in 2012.

14 Prior to 2013, there appear to have been instances where STG Australia had, under STG Eersel’s directions, undertaken some re-packaging of products manufactured and packaged in a non-conforming way overseas. This was said to have been done in light of a transition period when the plain packaging legislation was being introduced. It is sufficient to say that at least since early 2013, STG Eersel has at all times controlled the manufacture, packaging and distribution of the products sold in Australia by STG Australia: all authorised products pre-destined for Australia since early 2013 have been pre-packaged overseas by STG Eersel to conform with Australian law.

15 As apparent from the current retail packaging of authorised products, various packaging and methods appear to have been employed for each of the products. The La Paz cigars are sold individually in metal tubes, with the brand name “La Paz Gran Corona” affixed around the tube with relevant barcode and relevant distributor (STG Australia), manufacturer (STG Eersel) and point of origin (Holland) details. Upon removal of the cigar from the tube each is individually cellophane wrapped. Each cigar has been fitted with a paper “band” with the name “La Paz” and the words “Gran Corona”. Lots of ten tubes are packaged in each box.

16 The Café Crème cigars are sold in lots of ten in a cellophane wrapped metal box, with the relevant brand name appearing on the front of the box, and with relevant barcode, batch codes and again relevant details of the distributor, manufacturer and place of origin. Each cigar therein is not individually wrapped. The Henri Wintermans cigars are packaged in much the same way, except the cigars are individually cellophane wrapped, and the retail packaging is made of cardboard material, containing five cigars each.

17 The respondent, Trojan, imports, re-packages, markets and sells in Australia to retailers and wholesalers, the same three products. Although it is accepted by STG that the imported products are genuine in the sense manufactured by STG Eersel, the direct source of the cigars is unknown and was not a subject of evidence as relevant to the issues. Given that Trojan admits to subsequently re-packaging the imported products for compliance with the plain packaging laws for on-sale, it may be inferred that the original packaging was non-compliant in this regard.

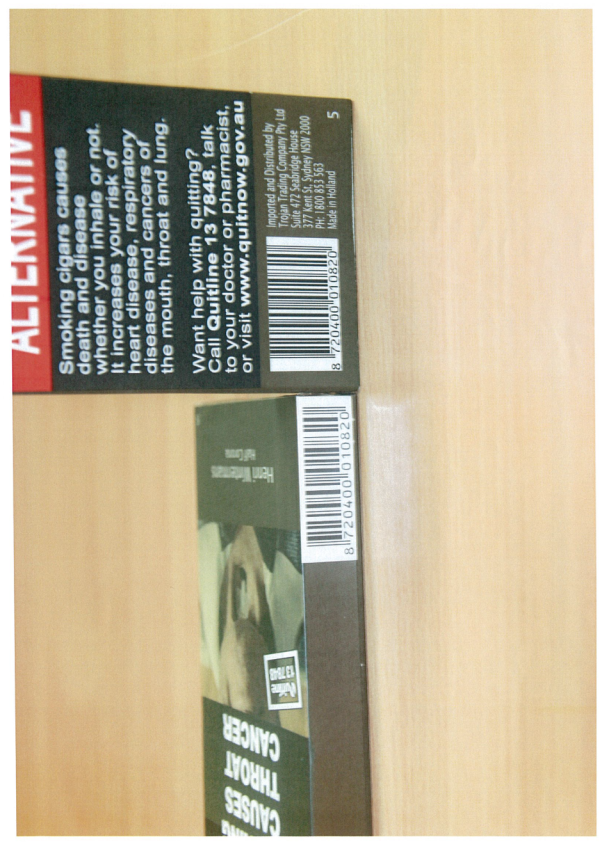

18 It is not in dispute that Trojan, upon acquisition of the cigars, removes the cigars from the original packaging and transfers them individually to compliant retail plain packaging that it sources independently. Again, the source of such packaging was not relevant for the proceedings. Trojan then applies the relevant word marks on the compliant packaging on the prescribed area and portion of the package. It also places on the packaging information concerning the relevant distributor (Trojan), manufacturer (STG Eersel) and point of origin (Holland) details on the outer packaging, as well as the barcodes identical to the ones employed by STG Eersel.

19 Upon examination, some differences in the packaging and packaging methods employed as a manifestation thereof can be observed on the imported products compared to what I will call the authorised products: omission of diacritic (e.g. above “Café Crème”); omission of batch codes; absence of cellophane wrapping on individual cigars and retail packaging; discrepancies in the number of individual retail packs in wholesale packages. Trojan, however, appears to have retained the original barcodes used by STG Eersel. None of these differences has any effect on the reasoning that is dispositive of the application.

20 Trojan was first challenged as to its conduct by a letter from the applicants’ solicitors dated 4 October 2012, titled “Parallel Importation of Tobacco Products”. In that letter, it was asserted that “for some time, our clients have been aware that your company has been importing and selling…products in packaging bearing STG’s trade marks without our clients’ permission”. Subsequent letters were sent to Trojan on 28 June 2013 and 8 April 2014, alleging trade mark infringement, breach of the ACL, and the tort of passing off.

21 On 1 October 2014, the applicants commenced proceedings in the Court. By its originating application, the applicants seek declarations that Trojan’s conduct constitutes:

1.1 infringement of the First Applicant’s (STG Eersel’s) Australian registered trade marks CAFÉ CRÈME (761892), HENRI WINTERMANS (nos 179680 and 1529889) and LA PAZ (no 643779) (the Trade Marks);

1.2 passing off the cigars so sold by Trojan to its customers as cigars packaged and authorised by the Scandanavian Tobacco Group; and

1.3 misleading representations to those customers in breach of ss 18 and 29 (1)(g) of the Australian Consumer Law that the cigars so sold by Trojan are approved by and were packaged by the Scandanavian Tobacco Group;…

22 In addition, the applicant seeks an injunction restraining Trojan from using any of the trade marks in relation to cigars or other tobacco products which have been unpacked and removed from the packaging and vacuum wrapped seal including by way of:

1.1 using the Trade Marks in:

1.1.1 advertisements published on a website located at the internet address www.trojantrading.com.au;

1.1.2 price lists published to customers of Trojan (“customers”) from time to time;

and delivering the Trojan Cigars to customers following orders made by then [sic] referring to the Trade Marks as so used;

1.2 using the Trade Marks to refer to the Trojan Cigars orally in telephone conversations with customers;

1.3 using the Trade Marks in email communications with customers to refer to the Trojan Cigars;

1.4 using the Trade Marks in invoices referring to Trojan Cigars delivered by Trojan to customers; and

1.5 using barcodes on packaging which, when scanned by retailers at the point of sale, cause one or more of the Trade Marks to be displaced so as to identify the Trojan Cigars to reference to the Trade Marks.

23 It is not part of the case of the applicants that the imported products are in any way different in composition or blend from the authorised products, nor that the quality or integrity of cigars have been affected in some way by Trojan’s conduct. Trojan also does not dispute that the characteristics of machine made cigars are susceptible, to some degree, to degradation by external factors, including friction, vapours and odours, humidity and light. But complaints in this regard are not a basis of the claims of the applicants.

24 Notwithstanding the above, there were some factual matters the subject of proof: what measures STG Eersel had taken to ensure quality control at point of packaging the products pre-destined for Australia; whether STG Eersel does in fact impose conditions on STG Australia in relation to the storage and handling of cigars; and what measures Trojan had taken in the repackaging procedure to ensure quality control.

Evidence for STG

25 Prior to and at the trial, the parties agreed that various affidavits would not be read. The remaining affidavits sought to be relied on were those of Mr Garcia affirmed on 3 March 2015, Mr King sworn on 3 March 2015, and Mr Nikolovski affirmed on 7 April 2015. Further, by consent of the parties, various paragraphs in Mr Garcia’s evidence were not read. ([24], [32], [56], [73], [81] and parts of [55], [64], [71]).

26 At the hearing, Mr Garcia, managing director of STG Australia, gave oral evidence. Mr Garcia provided in his affidavit (Annexure APG-7) the distribution agreements containing the following:

2 Appointment. Scope of Agreement

2.1 The Supplier hereby appoints the Distributor as its distributor in the Territory regarding distribution and sales of the Products.

…

3 General responsibilities of the Distributor

3.1 The Distributor is responsible for:

3.1.1 All necessary formalities as regards importation, distribution and sale of the Products according to laws of the Territory, including obtaining any certification, authorisation…

3.1.2 Storage and insurance of the Products in warehouses…

3.1.3 Delivery of Products to its customers;

3.1.4 Handing trade credits…

3.1.5 Certain sales and promotion related activities…

…

6 Legal Requirements

…

6.2 The Supplier shall ensure that the Products and all packaging materials fulfil prevailing regulations governing the production and sale of the Products, incl. health warnings, declarations of contents etc. The Distributor shall keep the Supplier informed about any such regulations on a current basis.

…

8 Infringement of the Supplier Trade Marks

Nothing in this Agreement shall be interpreted or otherwise construed as giving the Distributor any rights to any of the Supplier Trade Marks. The Distributor shall inform the Supplier of any Infringements of the Supplier Trade Marks of which the Distributor becomes aware. Prosecutions for infringements shall be at the Supplier’s discretion and cost, but the Distributor shall offer all reasonable assistance. Any damages received shall be credited to the Supplier.

…

27 Other clauses impose various obligations on STG Australia: to use its best efforts to actively distribute, promote and procure sales of the Products throughout the Territory (cl 4); submit forecasts and place orders accordingly (cl 5); and inform the STG Eersel on market conditions (cl 6). In return, STG Australia is provided an annually fixed price on STG Eersel’s products.

28 Mr Garcia further provided in his affidavit evidence that throughout his time as managing director of STG Australia, STG Eersel had controlled the production, packaging and distribution of the cigars it manufactures by enacting strict environmental and hygienic controls at its factories in Holland and Belgium, including by regulating temperature and humidity, and ensuring that the production and packing process involves minimal human contact with the cigars, prominently by use of machines in the packaging process.

Evidence for Trojan

29 Mr Nikolovski was employed by Trojan as an administrative officer and warehouse supervisor. He gave oral evidence in addition to his affidavit. Mr Nikolovski had knowledge of Trojan’s repackaging protocols and procedure applicable generally to tobacco and cigar products that it distributed, including the imported products. He gave evidence (see para 3 of his affidavit) that:

(e) The repackaging rooms are humidity and temperature controlled.

(f) Repackaging occurs on a “single produce at a time” basis so that different tobacco products are not located in the repackaging room at the same time.

(g) Prior to commencement of repackaging, the compliant packaging is laid out in the repackaging room ready for use.

(h) Usually between 8 to 12 employees are used for repackaging, depending on the volume. All employees are required to wear gloves, hairnets, facemasks and aprons.

(i) Each employee has a [sic] designated tasks. Those tasks are generally described as involving unwrapping “outers” (bulk packaging of a number of retail packets / tins) opening retail packaging, removal of the tobacco products, replacement of missing or damaged items with the same product sourced from the same batch, placement of the tobacco products into compliant retail packaging, grouping retail packets into “outers”, shrink wrapping the “outers” and placement of the repackaged goods back into stock.

The standing of STG Australia

30 Section 26 of the Act is now relevantly in the following terms:

(1) Subject to any agreement between the registered owner of a registered trade mark and an authorised user of the trade mark, the authorised user may do any of the following:

…

(b) the authorised user may (subject to subsection (2)) bring an action for infringement of the trade mark:

(i) at any time, with the consent of the registered owner; or

(ii) during the prescribed period, if the registered owner refuses to bring such an action on a particular occasion during the prescribed period; or

(iii) after the end of the prescribed period, if the registered owner has failed to bring such an action during the prescribed period;

…

(2) If the authorised user brings an action for infringement of the trade mark, the authorised user must make the registered owner of the trade mark a defendant in the action. However, the registered owner is not liable for costs if he or she does not take part in the proceedings.

31 In 2001, s 26(1)(b) in its then form was amended by item 3 of schedule 1 to the Trade Marks and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2001 (Cth) (No 99 of 2001). The form of s 26(1)(b) from 1995 to 2001 was as follows:

(b) The authorised user may (subject to subsection (2)) bring an action for infringement of the trade mark if the registered owner refuses or neglects to do so within the prescribed period;

32 The amendment was explained in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill, as follows:

This item substitutes a new paragraph 26(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act to provide that an authorised user of a registered trade mark can bring an action for infringement of the trade mark: at any time, with the consent of the registered owner; or within the prescribed period, where the registered owner has refused on any occasion in that period to bring the action; or after the end of the prescribed period, if the registered owner has failed to bring the action during that period. This amendment is necessary because prior to amendment paragraph 26(1)(b) did not allow the authorised user to bring the legal action before the end of the prescribed period – even with the consent of the registered owner, or where the registered owner has refused to bring the action.

33 Relevantly, r 3.2 of the Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (Cth) defines the “prescribed period” as 2 months from the day on which the authorised user of a trade mark asks the registered owner of the trade mark to bring an action for infringement of the trade mark.

34 The predecessor to s 26 in the former Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth) (1955 Act) was to be found in s 78:

(1) Subject to any agreement subsisting between the registered user of a trade mark and the registered proprietor of the trade mark, the registered user is entitled to call upon the registered proprietor to take proceedings for infringement of the trade mark, and, if the registered proprietor refuses or neglects to do so within 2 months after being so called upon, the registered user may institute proceedings for infringement in his own name as if he were the registered proprietor and shall make the registered proprietor a defendant.

(2) A registered proprietor so added as a defendant is not liable for costs unless he enters an appearance and takes part in the proceedings.

35 Thus, historically neither the Act nor its predecessor had a provision equivalent to s 26(1)(b)(i).

36 The submission of Trojan was that the reach of s 26(1)(b) after the amendment should be understood by the reach of the original provision and the reason for the amendment. It was submitted that before 2001, the authorised user could not sue alongside the registered owner; and was required to wait for the whole of the prescribed period before commencing proceedings if the registered owner refused or neglected to bring proceedings within that prescribed period. It was only this temporal problem (the requirement to wait even if one knew early in the prescribed period that the registered owner would not sue) that the amendment was intended to cure. Thus, it was submitted, the new provision should not be read as altering the position, beyond curing the inability to bring suit promptly if the registered owner consents.

37 There are at least two problems with this submission. First, it is not plain at all that s 26 in its pre-2001 form prohibited the registered owner and an authorised user propounding claims together. Section 26(2) contemplates the registered owner taking part in the proceedings in a way that would subject it to costs. If a registered owner initially did not wish to bring a claim, would s 26 prohibit it doing so if it changed its mind but the authorised user had actually commenced? Or would the authorised user’s suit lose statutory authority if the registered owner began a later suit?

38 Secondly, the words of s 26(1)(b)(i) are plain and unconstrained by the posited refusal or failure that appear in paras (ii) and (iii), respectively. There is no reason in the words of the provision to construe or imply a limitation into the words “at any time, with the consent of” of “as long as the registered owner does not”.

39 It was also argued that cl 8 of the licence agreements denied the existence of the consent. I reject that. First, cl 8 does not have that effect of preventing suit. Secondly, even if the words of the agreement were to be construed as contractually preventing STG Australia from suing, I would infer from the facts before me that the parties have agreed otherwise thereafter.

Section 120 – Is there use as a trade mark by Trojan that is prima facie an infringement?

40 In order to appreciate fully the issues as to use, it is helpful to have regard to a representative example of the package. Annexed are pages 92 and 93 from Mr Garcia’s affidavit. Page 92 contains a photograph of the front of exhibits C2 and C1 being, respectively, the authorised and the Trojan packaging; and page 93 contains a photograph of the back of exhibit C1 (the Trojan pack) showing the information concerning the distributor, Trojan.

41 It is unnecessary to set out the terms of the plain packaging legislation. It suffices to say that with some care and precision, it requires retail packaging of tobacco products to comply with the TPP Act and TPP Regulations. It does so not just by proscribing things, but also by prescribing things. Section 18 of the TPP Act deals with the physical features of retail packaging. Some examples are that there must be no decorated ridges, embossing etc: s 18(1)(a); glue must not be coloured: s 18(1)(b); the pack must be cardboard, rectangular without rounding or bevelling, with straight edges: s 18(2); the pack must have certain dimensions, with a flip top lid with straight edges: s 18(3). Section 19 deals with colour and finish of retail packaging. All outer and inner surfaces and the lining of the pack must be of matt finish and in “drab dark brown”, except the health warnings and the text of the brand, business or company name or variant name. Section 20 prohibits trade marks and marks generally appearing on retail packaging. Except as provided by s 20(3), no trade mark may appear anywhere on the retail packaging of tobacco products: s 20(1) of the TPP Act. Also except as provided by s 20(3), no mark (defined as including any line, letters, numbers, symbol, graphic or image) may appear on any retail packaging of tobacco products: s 20(2). By s 20(3), the following may appear on the retail packaging of tobacco products:

(a) the brand, business or company name for the tobacco products, and any variant name for the tobacco products;

(b) the relevant legislative requirements;

(c) any other trade mark or mark permitted by the regulations.

42 The TPP Regulations have detailed provisions concerning the form and placement of health warnings and the graphic pictures of diseased teeth, gums, toes etc.

43 The trade marks in question here were thus permitted to be used on the front of the pack by the TPP Act and TPP Regulations. All the other markings on the packets were either required by the TPP Act and TPP Regulations or by State or Commonwealth legislation concerning detail such as distribution, place of manufacture, etc.

44 There was a dispute at the hearing as to whether Trojan could have put on the packet “Dutch cigars” or some similar anodyne phrase. It is to be noted that “Gran Corona”, not a trade mark, appears. It is unnecessary to resolve this dispute.

45 The above is the context of the use of the trade marks.

46 A “trade mark” is defined in s 17 of the Act as “…a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods…dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.” The function or essential characteristics of a trade mark is to distinguish goods of the registered owner from the goods of others and indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods and the registered owner: see E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd [2010] HCA 15; 241 CLR 144 at 162-163 [42].

47 Upon registration of the trade marks, STG Eersel was conferred with “exclusive rights” to either “use the trade mark” (s 20(1)(a)) or “to authorise other persons to use the trade mark” (s 20(1)(b)) in relation to the goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered. There was no allegation here of Trojan infringing the trade mark by using the trade marks “in relation to services”. Rather, it is the use of the trade mark in relation to the imported products that is at issue.

48 Section 120(1) of the Act is in the following terms:

A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

49 “Use of a trade mark” in relation to goods is defined in s 7(4):

In this Act:

"use of a trade mark in relation to goods " means use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods (including second-hand goods).

(Emphasis retained)

50 “Use” so defined captures inter alia, use of the trade mark on packaging, signage, advertising or promotional items, as well as on price lists and correspondence: see Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380; 275 ALR 526 at 553 [141]; The Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; 109 CLR 407 at 422; Thunderbird Products Corporation v Thunderbird Marine Products Pty Ltd [1974] HCA 51; 131 CLR 592 at 600; Angoves Pty Ltd v Johnson [1982] FCA 119; 43 ALR 349 at 359-360.

51 As the Full Court noted in Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721; 96 FCR 107 at 115 [19] (Black CJ, Sundberg and Finkelstein JJ), s 120 expressly incorporates the requirement that the “use” be a use “as a trade mark”, whereas the repealed 1955 Act did not expressly stipulate as such; but in Shell Co v Esso Standard Oil 109 CLR 407 at 422-424 it was said to be implied in both s 58(1) and s 62(1) of the 1955 Act that the "use" there referred to is limited to use "as a trade mark". See also Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Limited v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Limited [1991] FCA 402; 30 FCR 326 at 333-334, 342-343 and 347-349.

52 Use as a trade mark means:

use of the mark as a “badge of origin” in the sense that it indicates a connection in the course of trade between goods and the person who applies the mark to the goods:see Johnson & Johnson Aust Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd [1991] FCA 310; (1991) 30 FCR 326 at 341, 351. That is the concept embodied in the definition of “trade mark” in s 17 - a sign used to distinguish goods dealt with in the course of trade by a person from goods so dealt with by someone else.

See Coca-Cola v All-Fect Distributors 96 FCR at 115 [19] expressly approved by French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ in E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia 241 CLR at 163 [43].

53 Trojan accepted that the use of the trade marks was to act as a badge of origin in the sense discussed in cases such as Mark Foy's Ltd v Davis Coop & Co Ltd [1956] HCA 41; 95 CLR 190 at 204-205; the Shell Case at 425, Johnson & Johnson at 347-348, 351; Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co [1994] FCA 163; 49 FCR 89 at 134-145; and Musitor BV v Tansing [1994] FCA 541; 52 FCR 363 at 372. Thus, it accepted that there was “use as a trade mark”. It argued, however, that the use was not by it, but by STG Eersel. This was so, it was submitted, because the connection in trade was between the goods and the manufacturer, not between the goods and Trojan. In this respect, Trojan referred to and relied in particular on what Gummow J said in Wingate Marketing v Levi Strauss 49 FCR at 134-135; and Smithers J in Atari Inc v Fairstar Electronics Pty Ltd (1982) 50 ALR 274 at 277.

54 Trojan’s argument had echoes of the debates and disagreements before 1995 about parallel importing simpliciter, if I may use that expression. Under the repealed 1955 Act, the legislation did not contain separate defences for “parallel importers” (cf s 123 under the current Act as discussed below). The only relevant question was whether the trade mark had been infringed under s 62 of the 1955 Act. Under that provision, the “exhaustion of rights” doctrine propounded by Clauson J in Champagne Heidsieck et cie Monopole Society Anonyme v Buxton [1930] 1 Ch 330 was often raised as a defence to trade marks infringement by parallel importers: see R & A Bailey & Co Ltd v Boccaccio Pty Ltd and Others; R & A Bailey & Co Ltd v Pacific Wine Co Pty Ltd (1986) 4 NSWLR 701 and Atari Inc and Futuretronics Australia Pty Ltd v Fairstar Electronics Pty Ltd 50 ALR 274, see below.

55 In Champagne Heidsieck, the defendant sought to import wine into England which had been manufactured by the plaintiff specifically (being a sweeter variant) for the French market. The plaintiff argued that pursuant to the Trade Marks Registration Act 1875 (UK) (1875 Act (UK)) and repealing provisions in the Trade Marks Act 1905 (UK) (1905 Act (UK)) that the legislation (at 338):

…had the further effect of vesting in the owner the right to object to any person selling or dealing with the goods produced by the owner of the trade mark with the trade mark affixed, except on such terms and subject to such conditions as resale, price, area of market, and so forth, as the owner of the trade mark might choose to impose.

56 Relevantly the definition in s 3 in the 1905 Act (UK) provided:

A “trade mark” shall mean a mark used or proposed to be used upon or in connexion with goods for the purpose of indicating that they are the goods of the proprietor of such trade mark by virtue of manufacture, selection, certification, dealing with or offering for sale.

57 The common law position prior to the introduction of statutes was to “prevent others from selling wares which are not his marked with that trade mark in order to mislead the public and so incidentally injure the person who is the owner of the trade mark”: Farina v Silverlock (1856) 6 De G M & G 214 at 217; 43 ER 1214 at 1216 per Lord Cranworth. Thus, in effect the argument was that the nature of a trade mark had fundamentally changed from one being a badge of origin to a badge of control, and that the registered owner had the right to full control over the goods, except in cases where consent, whether expressed or implied, had been given to release the control. Clauson J refused to accept that the language of the 1875 Act (UK) and the 1905 Act (UK) “operated to extend the rights of the proprietor of a trade mark from a right to prevent deception as to the origin of goods into a right to control dealings with the goods” (at [340]). His Lordship went on to hold at 341 by reference to Kerly on Trade Marks:

[T]he use of a mark by the defendant which is relied on as an infringement must be a use upon goods which are not the genuine goods, i.e., Those upon which the plaintiffs’ mark is properly used, for anyone may use the plaintiffs’ mark on the plaintiffs’ goods, since that cannot cause the deception which is the test of infringement.

58 In Revlon Inc v Cripps & Lee Ltd [1980] FSR 85 the English Court of Appeal subsequently cited Champagne Heidsieck with approval (see 115), although, the decision ultimately was one based on a finding of implied consent upon piercing the corporate veil between the two registered owners of the trade marks (see 116 and 117) in the United Kingdom and United States, and where consent was a valid defence under s 4(3)(a) of the Trade Marks Act 1938 (UK) then in force.

59 Champagne Heidsieck was considered under the 1955 Act in Atari Inc v Dick Smith Electronics Pty Ltd (1980) 33 ALR 20, by Starke J. His Honour considered whether the plaintiff was entitled to an interlocutory injunction against the defendant dealing with genuine goods, which were identical and where the goods bore the trade mark not as a forgery but because they had been imported in that form. Starke J refused to apply Champagne Heidsieck on the basis that there were differences in the English and Australian definitions of “trade mark”, the former being concerned with “indicating that they are the goods of the proprietor of the trade mark” (under s 3 of the 1905 Act (UK)) , whereas the latter was expressly concerned with “connexion in the course of trade between the goods and a person who has the right either as a proprietor or as a registered user to use the mark” (under s 6 of the 1955 Act) (at pages 22-23).

60 In Atari Inc and Futuretronics Australia Pty Ltd v Fairstar Electronics Pty Ltd (1982) 50 ALR 274, Smithers J dealt with substantially identical facts as those before Starke J, again dealing with genuine goods, to which the trade mark had already been applied by the registered owner. Smithers J expressly declined to follow Starke J and held that Clauson J’s proposition in Champagne Heidsieck as to the description of the “fundamental nature” of a trade mark was correct, in interpreting s 62 of the 1955 Act as to whether the defendant had “used” the mark in an infringing way (at 277) :

…once a manufacturer puts a trade mark on his goods and sends them into the course of trade on the billowing ocean on trade, wherever people bona fide deal with those goods under that name and by reference to that trade mark, not telling any lies or misleading anyone in any way at all, they are simply not infringing the trade mark. They are not ‘using’ the trade mark in the relevant sense. The Act is to be read by considerations such as these and these must be the considerations which ultimately support the Champagne case.

61 In R & A Bailey & Co Ltd v Pacific Wine Co Pty Ltd, Young J considered whether the plaintiff’s (manufacturer of Baileys Original Irish Cream) registered trade mark had been infringed by an unauthorised parallel importer of the same product but originally destined as apparent on the labelling, for retail sale in Holland. Central to the defendant’s submission was that a registered proprietor’s rights are virtually exhausted once the mark is affixed to the genuine goods, and subsequently sold, wherever the product was pre-destined. In his Honour’s view, a contrary finding would have been to give effect to trade marks being a badge of control, and as a corollary, accepting the so called “territorial” theory pressed by the plaintiffs. In acceding to the defendant’s submission, his Honour expressly approved Champagne Heidsieck and Atari v Fairstar 50 ALR 274 for the proposition that (at 707) :

… [It] rejects a construction of the Trade Marks Act which would change the nature of the mark from a badge of origin to a badge of control and also rejects the view that a remarkable alteration in the concept of a trade mark took place when trade marks became statutory.

62 Young J held that “a right to exclusive use” conferred by s 58 of the 1955 Act (equivalent to now s 20 of the TM Act) upon the registered owner to the trade mark in relation to goods only operated to prevent the sale in Australia of goods which are not the proprietor's but which are marked with the proprietor's mark. The right did not enable the registered proprietor to prevent the sale in Australia of its goods marked with its mark, even though it had projected the goods, as the labels indicated, into the Dutch market and not into the Australian market. Young J’s decision in Bailey was approved in Delphic Wholesalers Pty Ltd v Elco Food Co Pty Ltd (1987) 8 IPR 545 by McGarvie J in the Supreme Court of Victoria.

63 In Wingate 49 FCR 89 the appellant imported second-hand clothing bearing the respondent’s trade mark “LEVI’S”, which were subsequently treated or altered in various ways, and sold under the trade mark “REVISE” in addition to the extant “LEVI’S” mark. Gummow J allowed the appeal (with the plurality, Sheppard J and Wilcox J concurring) in so far as it related to the issue of the appearance of the respondent’s trade mark on jeans that had been substantially altered. After framing the essential question for infringement as per the Full Court in Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd 30 FCR at 347, his Honour said (49 FCR at 135):

In testing the question of infringement, it is proper to have regard to the very goods in question in their condition at the time of the allegedly infringing acts. The continued appearance of the Levi Strauss marks upon the goods as sold by Wingate, after what one might call their conditioning, is an illustration of the class of case referred to by Viscount Maugham in the quotation set out above from Aristoc Ltd v Rysta Ltd. Namely, these marks were intended by the manufacturer to indicate origin and thus indicate a character or quality of the goods. This may be displaced having regard to the degree of change wrought by the activities of Wingate.

….. The Levi Strauss trade marks appear on the goods not for the purpose of indicating or so as to indicate a connection between the garments and Wingate…but to indicate by comparison or contrast the origin of the goods. That is the purpose and nature of the alleged trade mark use by Wingate of the Levi Strauss trade marks. Use of that character is not a trade mark use: CF Irving’s Yeast-Vite Ltd v Horsenail (1934) RPC 110.

(emphasis added)

Part of the above passage is also relevant for Trojan’s argument about s 122(1)(b). For present purposes its importance is its standing as one of these cases which identify infringing use as a trade mark as requiring a purpose of connection between the goods and someone other than the registered owner.

64 Notwithstanding this line of authority, various obiter statements from the High Court in “non-use” cases suggested that use by a retailer of imported goods would prima facie constitute a use of the trade mark, contrary to the exclusive rights conferred under s 58: see Pioneer Kabushiki Kaisha v Registrar of Trade Marks [1977] HCA 56; 137 CLR 670 at 688; W D & H O Wills (Australia) Ltd v Rothman Ltd [1956] HCA 15; 94 CLR 182 at 188 (see also Estex Clothing Manufacturers Pty Ltd v Ellis & Goldstein Ltd [1967] HCA 51; 116 CLR 254), because a trade mark remains “in the course of trade” as long as it is sold under the trade mark, whether it is with or without the knowledge of the registered owner.

65 Prior to the introduction of the Act, a working party considering the proposed legislative changes were largely in favour of parallel importing (see Working Party to Review the Trade Marks Legislation, Recommended Changes to the Australian Trade Marks Legislation (Australian Government Publication Service, 1992 at 76)). Section 123 was introduced into the Act at least in part in order to deal with parallel importing. However, the legislature did not fully embrace the draft provision proposed by the Working Party. Subsequent reports also recommended further changes to the Act in favour of parallel importing, but no such changes have been accepted by the Parliament. (See Intellectual Property and Competition Review Committee, Parliament of Australia, Review of Intellectual Property Legislation under the Competition Principles Agreement: Final Report to Senator the Hon Nicholas Minchin, Minister for Industry, Science and Resources and the Hon Daryl Williams AM QC MP Attorney-General (2000) 188.)

66 The notion that there is infringing use as a trade mark by dealing in goods bearing the mark in circumstances that indicate a connection between the goods and the registered owner has a degree of counter-intuitiveness. The High Court in E & J Gallo Winery 241 CLR 144, did not deal with submissions relying on Champagne Heidsieck that an importer (Beach Avenue) was not using the trade mark as a trade mark, and as a corollary, an argument that it must lead to the necessary conclusion that the registered owner (Gallo) had “used” the trade mark in the non-use context – an argument in respect of which Gallo had succeeded before the Full Court: see E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 27; 175 FCR 386 at 403-404 [57]-[58]. The decision of the plurality in the High Court was expressed to be based on a different ground and “the only relevant question” (at [53]) being whether Gallo had used the trade mark under s 17.

67 It is, however, not for me to question the proposition that absent s 123 being engaged, the mere sale of goods already marked by the registered owner (a fortiori if a mark is applied by someone other than the registered owner) would be an infringing use of the mark by the importer. Four Full Courts can be seen so to have said in the context of the Act: Transport Tyre Sales Pty Ltd v Montana Tyres Rims & Tubes Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 329; 93 FCR 421 at 440 [94]; Paul’s Retail Pty Ltd v Sporte Leisure Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 51; 202 FCR 286 at 295 [66]; Paul’s Retail Pty Ltd v Lonsdale Australia Limited [2012] FCAFC 130; 294 ALR 72 at 82 [65]; and Gallo 175 FCR at 403-404 [57]-[58].

68 Under the newly introduced Act, the Full Court in Transport Tyre Sales Pty Ltd v Montana Tyres Rims & Tubes Pty Ltd 93 FCR at 440 [94] held that if a parallel importer imports and offers to sell, and sells genuine tyres manufactured overseas by a registered owner of the trade marks and advertises under those trade marks, it would constitute a use “as a trade mark” under s 120 unless s 123 applied: see also Paul’s Retail Pty Ltd v Sporte Leisure Pty Ltd 202 FCR at 295 [66] and Paul’s Retail Pty Ltd v Lonsdale Australia Ltd 294 ALR 72. In reaching that view in Montana, the Full Court did not find the need to mention Champagne Heidsieck in its reasons.

69 In Paul’s Retail v Sporte Leisure 202 FCR 286, the Full Court rejected leave for the appellant to withdraw a concession made at trial to raise the argument that in light of E & J Gallo Winery 241 CLR 144 there may be a subset of uses by a parallel importer that may not fall under s 120. Nevertheless, it discussed obiter that “it is most unlikely…that, as a matter of ordinary construction, the Act would leave open the application of the Champagne Heidsieck principle beyond its specific enshrinement under s 123”. It then remarked that the High Court in Gallo did not disapprove of the view reached by the Full Court in E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd 175 FCR at 404 [58] which had included the following, as noted by the Full Court in Paul’s Retail 202 FCR at 295 [66]:

…As Branson J said in Parfums Christian Dior (Australia) Pty Limited v Dimmeys Stores Pty Limited (1997) 39 IPR 349 at 353-354, citing Revlon Inc v Cripps & Lee Ltd [1980] FSR 85, it is reasonably argued that the philosophical basis for the rule in Champagne is that the registered proprietor consents to the use of its trade mark in those circumstances. That is entirely consistent with the introduction in the 1995 Act of s 123. That section provides that a defence to infringement is that the mark was applied to the goods with the consent of the registered proprietor. That is to say, it is a statutory recognition that absent s 123 the mere sale by an importer of goods already marked would be an infringing use of the mark by the importer.

70 The Full Court in Paul’s Retail v Lonsdale 294 ALR 72 also considered this point at [64]-[65], reaching the same view as the Full Court did in Paul’s Retail v Sporte Leisure, and expressly approving E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd 175 FCR at 403-404 [58] quoted in Paul’s Retail v Sporte Leisure 202 FCR at 295 [66]. Their Honours continued at [66]:

In our respectful opinion, the view expressed by this Court in these decisions is correct. It is hardly surprising that there is no authority supporting the proposition that a trader in goods who imports and sells goods distinguished from other goods by a particular trade mark is not using the trade mark when he or she sells the goods in the course of trade. Where an importer of marked goods is a trader in, rather than a consumer of, marked goods, it is no more than an ordinary and natural use of language to say that the importer has used the mark in the course of its trade: See WD & HO Wills (Australia) Ltd v Rothmans Ltd (1956) 94 CLR 182 at 188; see also Pioneer Kabushiki Kaisha v Registrar of Trade Marks (1977) 137 CLR 670 at 688.

71 Further, if one necessarily accepts that the “exclusive rights” conferred upon registration of a trade mark to the registered owner under s 20 is a “distinct species of property rights”, and “neither protection of goodwill nor deceptive conduct are the primary concern of the action for trademark infringement”: see Wingate Marketing v Levi Strauss & Co 49 FCR at 118 then the “[t]he surest guide to the nature and extent of the proprietary right created by the registration of a trade mark under the Act is the text of the Act.”: Paul’s Retail v Lonsdale 294 ALR at 82-83 [67] and [68].

72 Here, the process of re-packaging involved applying the three trade marks in relation to the cigars (on the boxes containing them) for the purposes of s 9(1)(b)(i). That and the sale to the retailer was the use of the trade mark “upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods”: s 7(4). That is the exclusive right of the registered owner: s 20(1). Infringement falls to be assessed by s 120(1). For the reasons above, subject to the application of ss 123 and 122, there was infringement.

The question whether s 123 is engaged

73 Section 123(1) is in the following terms:

In spite of section 120, a person who uses a registered trade mark in relation to goods that are similar to goods in respect of which the trade mark is registered does not infringe the trade mark if the trade mark has been applied to, or in relation to, the goods by, or with the consent of, the registered owner of the trade mark.

74 The section finds its place in the Act in Part 12 dealing with infringement. There was no equivalent provision in the 1955 Act. It is a provision that applies naturally to parallel importing and second-hand goods: see Davison M and Horak I, Shanahan’s Australian Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off (5th Ed , Thomson Reuters, 2012) at 677-679.

75 The difference between the parties in their construction of s 123(1) was as to whether the application to, or in relation to, the goods by, or with the consent of, the registered owner focuses upon the act of application physically present in the circumstances of alleged infringement (STG’s argument) or focuses upon the application at the time of manufacture so as to then characterise the goods (Trojan’s argument).

76 The difference can be seen in the following competing expressions of reasoning. STG says: The sale of the goods in the re-packaged form was an infringement under s 120 (see above); the trade marks in question have not been applied to, or in relation to, the goods in these packets by, or with the consent of, STG Eersel, but rather by Trojan without consent. Trojan, on the other hand, assuming that it has lost the argument under s 120 (see above) says: The very goods in question (the cigars) have had the trade mark applied to, or in relation to, them, by STG Eersel. That is to say, the trade mark has been applied to, or in relation to, the very goods by STG Eersel – in the original manufacture and packaging so it is free to apply the trade marks in relation to those very goods by placing them on the packets and using the trade marks by selling the goods and doing the associated activities involving invoices, etc.

77 The hearing was conducted on the basis that the goods in question were goods originally manufactured and packaged in Holland or Belgium and the trade marks were applied to the cigars, or in relation to the cigars, by STG Eersel; what was not applied by STG Eersel, but by Trojan, were the trade marks on the re-packaging.

78 STG says that its construction of s 123 is supported by an appreciation of the need for control by the registered owner of its trade marks. Section 8 dealing with authorised use was said to support this:

Definitions of authorised user and authorised use

(1) A person is an authorised user of a trade mark if the person uses the trade mark in relation to goods or services under the control of the owner of the trade mark.

(2) The use of a trade mark by an authorised user of the trade mark is an authorised use of the trade mark to the extent only that the user uses the trade mark under the control of the owner of the trade mark.

(3) If the owner of a trade mark exercises quality control over goods or services:

(a) dealt with or provided in the course of trade by another person; and

(b) in relation to which the trade mark is used;

the other person is taken, for the purposes of subsection (1), to use the trade mark in relation to the goods or services under the control of the owner.

(4) If:

(a) a person deals with or provides, in the course of trade, goods or services in relation to which a trade mark is used; and

(b) the owner of the trade mark exercises financial control over the other person’s relevant trading activities;

the other person is taken, for the purposes of subsection (1), to use the trade mark in relation to the goods or services under the control of the owner.

(5) Subsections (3) and (4) do not limit the meaning of the expression under the control of in subsections (1) and (2).

79 STG emphasised that though the rights in a trade mark were a species of statutory property now not dependent on goodwill, the question of control of the trade mark and its central commercial place in modern commerce made the constructional choice involved one that favoured its argument. Otherwise, it was submitted, trade mark owners would lose all control over secondary get up and packaging so important to modern commerce; and they would be placed in a difficult position as to cancellation under s 88 of the Act based on deception or confusion because of that lack of control.

80 Trojan submitted that the above argument impermissibly intruded questions of business goodwill and get up into the construction of a provision that was directed to the protection of the use of the trade mark, such as in invoices and the like when the goods in question had a certain status brought about when the trade mark has been applied to or in relation to the goods.

81 Thus, here, if the Australian Parliament had not passed the plain packaging legislation, Trojan could have sold the cigars in the boxes or packets with packaging placed on them by STG Eersel. But Trojan could not do so because of the plain packaging legislation. Thus, it replaced the packaging in order to conform with the law and in doing so placed the trade marks on the packets to disclose the connection between the goods and the registered owner (not it).

82 During argument, I posited to Mr Heerey, counsel for STG, an example: a tie with trade mark Z woven into the tie, in a pink box with trade mark Z embossed on the box. Both trade marks have been applied by the registered owner. The shop owner advertises his stock of Z ties with a sign outside bearing trade mark Z and invoices customers with a document bearing the same mark. Mr Heerey accepted that there would be no infringement in the use of the advertising and invoices even though such use would be use as a trade mark because of the operation of s 123: Facton Ltd v Toast Sales Group Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 612; 205 FCR 378 at 398-404 [112]-[145]. (It is to be noted, and Trojan emphasised this point in its submissions, that Middleton J in Facton said at [132] that “a natural reading of the words used in s 123 suggest that the only time at which the issue of consent is to be assessed is the time of the application of the trade mark to goods.”) I then posited a change to the facts. The shop owner preferred selling the tie in a blue box (fitting in with a blue theme to his shop) upon which he faithfully and accurately placed the trade mark Z. The tie was taken out of the pink box (which was discarded) and put in the blue box for display and sale. STG submitted that the step of placing the Z trade mark on the blue box would not be protected by s 123, but accepted that the sign and invoices remained protected. That was so, it was submitted, because of an implied consent by the registered owner of the trade mark to the advertising and invoices in the light of the trade mark on the tie. Yet, should the difference be governed by the existence of weaving on the tie? Has not the trade mark already been applied in relation to the good (the tie) by embossing on the pink box?

83 A further difficulty arises in the facts here if one focuses on the application of the trade mark on to the new packets, rather than focusing, as Mr Heerey did in argument, on the sales to the wholesaler or retailer. Looking at the circumstances of the application by Trojan on to the packets, before they were unwrapped, it was undoubtedly the case that there were trade marks on the non-conforming box that had been applied in relation to these goods by or with the consent of the registered owner of the trade mark. Unwrapping takes place. The state of affairs described in the previous sentence remains true. The use of the trade mark by Trojan by its application on to the packet and thus in relation to the goods appears to fall squarely within the words of s 123, even using STG’s emphasis on the very application in question. But once the trade marks are applied by Trojan on the packets in relation to the goods, the infringing use by the sale by Trojan to the wholesaler or retailer is, on STG’s argument, not a sale of goods in relation to which the trade marks have been applied by the registered owner. Yet, why should the sale to the retailer be any different in terms of infringement to the application of the trade marks on to the packets?

84 I prefer the submission of Trojan. The natural reading of s 123 is one that looks to (a) the use of a trade mark in relation to goods (b) the similarity of the goods to those in respect of which the trade mark is registered (c) an enquiry whether the trade mark has been applied to, or in relation to, the very goods as in (a); and (d) whether that application was with the consent of the registered proprietor. If one undertakes that enquiry, one finds that Trojan has used the trade marks in relation to cigars, being goods the same (and so similar: s 14(1)(a) of the Act) as those in respect of which the trade mark is registered, and the trade mark has been applied in relation to those very goods with the consent of the owner at the time of original packaging.

85 This construction more naturally conforms with a purpose in s 123 of protecting as non-infringing use that which does no more than draw a connection between the goods and the registered owner, and does not draw a connection between the goods and the person using the trade mark being someone other than the registered owner. This would be seen as conformable with vindicating that very idea found in Wingate Marketing v Levi Strauss 49 FCR at 134-135; and in Atari Inc v Fairstar Electronics Pty Ltd 50 ALR 274 at 277.

86 The status of s 123 as a defence or as a qualification to s 120 was not argued.

87 In my view, s 123 was engaged. That is an answer to the case under the Act.

The defence under s 122(1)(b)(i)

88 In these circumstances it is strictly unnecessary to deal with s 122. Trojan’s argument was based necessarily on my coming to the view that I should not follow Mansfield J in Britt Allcroft (Thomas) LLC v Miller [2000] FCA 699; 49 IPR 7. In the circumstances that anything that I say would be obiter dicta, it is not appropriate to embark on an analysis of his Honour’s reasons.

89 The circumstances here bear no real similarity to those in Wingate where one can understand from the surrounding facts how what was otherwise a trade mark (the Levi mark) took its place on the garments after their conditioning as a description of origin and thus in those circumstances indicated something as to characteristic, kind or quality: cf Wingate at 135. Here, the use of the marks was not to indicate the matters in s 122(1)(b)(i), but to indicate a trade connection between the goods and the registered proprietor. There is an absence of the descriptive character of the indication discussed in such cases as Mark Foy’s Ltd v Davies Coop & Co Ltd [1956] HCA 41; 95 CLR 190 at 202; FH Faulding & Co Ltd v Imperial Chemical Industries of Australia and New Zealand [1965] HCA 72; 112 CLR 537 at 543; Dr Martens Australia Pty Ltd v Figgins Holdings Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 461; 44 IPR 281 at [437]; and Britt Allcroft.

90 It should be noted that there was no submission put that Trojan had not proved that its use was in good faith, and thus I take it that there was no issue about “good faith” for the purposes of s 122(1)(b).

Passing off

91 The question of passing off was put in terms of the three core concepts in passing off: reputation, misrepresentation and damage: ConAgra Inc v McCain Foods (Aust) Pty Ltd [1992] FCA 176; 33 FCR 302 at 355-356.

92 As to reputation, Mr Garcia’s affidavit contained evidence as to the significant business of the STG Group in Australia and around the world. It is the world’s largest manufacturer of cigars and pipe tobacco. STG Australia is one of the largest tobacco wholesalers in Australia. Café Crème is the “number one” small cigar brand in the world; La Paz is one of the world’s five highest selling brands of machine made cigars. Henri Wintermans is also a successful brand in Australia and around the world.

93 There was an attempt in the opening submission of Trojan to contest this evidence of reputation as weak. No oral submissions were put about it.

94 I am prepared to accept that STG has a relevantly significant reputation in these three cigars in Australia.

95 The question of whether Trojan has made a misrepresentation is at the core of the complaint. STG’s complaint is not that Trojan is passing off its (Trojan’s) cigars as those of STG. Clearly it is not. The misrepresentation is that re-packaged in the way they are, the cigars look as though they have been packaged in this way with the authority of the person who originally packed them in an authorised way.

96 One difficulty for this submission is that there is no express representation to that effect. To be made out, it must be that in all the circumstances, the public or retailers would so clearly assume it to be so that not to disavow association with the original manufacturer would mislead people.

97 The evidence does not permit the conclusion that anyone would assume that any packaging or re-packaging required in order that there be compliance under the plain packaging legislation would necessarily be carried out under some unidentified process of authorised activity. There may well be some types of product or particular circumstances that would raise the relevant necessary assumption in the minds of the public or wholesalers or retailers. I see no basis to conclude that this is the case for machine-made cigars of this kind.

98 I therefore find no misrepresentation.

99 The passing off claim fails.

The Australian Consumer Law

100 Sections 18(1) and 29(1)(a) and (g) are in the following terms:

18(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

…

29(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use;

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits;

101 The focus of these provisions is different to that of passing off. Passing off is a commercial tort the essence of which is the protection of the business reputation of the applicant. Sections 18 and 29 are part of legislation the purpose of which is to protect the public from deception. That difference in rationale may become important. Here, the relevant question should be understood from that different perspective. Would any relevant segment of the public work on an assumption that the products distributed by Trojan were necessarily packaged or re-packaged under the authority and control of the original manufacturer. If so, in order not to mislead or deceive, it may be necessary for some communication to be made to deal with such assumption. Once again, one can contemplate types of products or circumstances that might lead to such an assumption. But, I do not consider, on the evidence before me, that there is in reality anything misleading about the sale of these products to the public. I do not consider that such an assumption would be made.

102 I do not consider the claims under ss 18 or 29 as made out.

103 For these reasons, the application should be dismissed. There is no apparent reason why costs should not follow the event.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and three (103) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Chief Justice Allsop . |

Associate:

P 92 of the Affidavit of Antonio Paiva Garcia sworn 3 March 2015

P 93 of the Affidavit of Antonio Paiva Garcia sworn 3 March 2015