FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Anglo Coal (Dawson Services) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2015] FCA 265

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

CONSTRUCTION, FORESTRY, MINING AND ENERGY UNION First Applicant STEPHEN BYRNE Second Applicant | |

AND: | ANGLO COAL (DAWSON SERVICES) PTY LTD Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

The amended originating application filed 28 May 2014 be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

FAIR WORK DIVISION | QUD 198 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | CONSTRUCTION, FORESTRY, MINING AND ENERGY UNION First Applicant STEPHEN BYRNE Second Applicant |

AND: | ANGLO COAL (DAWSON SERVICES) PTY LTD Respondent |

JUDGE: | COLLIER J |

DATE: | 26 MARCH 2015 |

PLACE: | BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 Before the Court is an amended originating application filed on 28 May 2014 brought by the applicant union and Mr Stephen Byrne (“the applicants”) against the respondent, in respect of alleged conduct of the respondent as the employer of Mr Byrne. The applicants seek a number of orders relating to the decision of the respondent to terminate the employment of Mr Byrne, a decision which the applicants claim was in contravention of provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (“FW Act”). While it is necessary to shortly turn to examine the facts of this case in greater detail, I note in particular that Mr Byrne was at material times the Lodge President of the union at the Dawson Mine, and involved in extensive negotiations with the respondent on behalf of the union. I also note that the termination of Mr Byrne’s employment arose in circumstances where his application for annual leave in April 2013 was refused by management, but where he nonetheless claimed that he was ill and was absent from work at that time. Much of the evidence and many of the submissions relate to these particular facts.

2 In the circumstances of this case, for reasons I will explain in greater detail, I am of the view that the amended originating application should be dismissed.

CLAIM AGAINST THE RESPONDENT

3 In an amended originating application filed on 28 May 2014 the applicants made the following claims on the grounds stated in the affidavit sworn by Mr Byrne and filed with the application, namely:

1. A declaration that the respondent has contravened section 340 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the “FW Act”) in respect of Stephen Byrne by threatening to take adverse action against him because he had and/or had exercised and/or had proposed to exercise a workplace right, namely the taking of personal leave.

2. A declaration that the respondent has contravened section 340 of the Fair work Act 2009 (Cth) (the “FW Act”) in respect of Stephen Byrne by terminating his employment because he had and/or had exercised and/or had proposed to exercise a workplace right, namely the taking of personal leave on 23 April 2014 and 24 April 2014.

3. A declaration that the respondent has contravened section 346 of the FW Act in respect of Stephen Byrne by terminating his employment because he had engaged in industrial activity.

4. A declaration that the respondent has contravened section 352 of the FW Act in respect of Stephen Byrne by terminating his employment because he was temporarily absent from work because of illness or injury on 23 April 2014 and 24 April 2014.

4A. A declaration that by terminating the employment of Stephen Byrne on 12 May 2014 the Respondent breached the contract of employment with Mr Byrne.

4 The applicants sought the imposition of penalties on the respondent pursuant to s 546 of the FW Act as well as the following orders:

5. An order requiring the respondent to treat as null and void the termination of the employment of Stephen Byrne.

6. An order requiring the respondent to reinstate Stephen Byrne to his former employment on the same terms and conditions that applied prior to 12 May 2014.

6A. Further, and in the alternative, an order that the respondent specifically perform the contract of employment with Stephen Byrne by treating as null and void the termination of the employment of Stephen Byrne on 12 May 2014 and by reinstating Stephen Byrne to his former employment on the same terms and conditions that applied prior to 12 May 2014.

7. An order pursuant to section 545 of the FW Act requiring the respondent to pay compensation to Stephen Byrne.

…

12. An order that the respondent pay damages to Stephen Byrne.

BACKGROUND FACTS

5 Mr Byrne affirmed affidavits in this proceeding on 14 May 2014, 6 June 2014 and 21 July 2014.

6 In summary, Mr Byrne has worked at the Dawson Mine (“the mine”) at Moura in central Queensland since 1 August 2011. At material times he was employed by the respondent as a Mine Employee Level 2, which he deposed meant that he was a multi-skilled operator. In November 2012 he was elected to the position of Lodge President of the union at the mine. From April 2013 until approximately November 2013 Mr Byrne was involved in negotiations with, inter alia, the respondent in respect of the replacement enterprise agreement applicable to workers at the mine. Mr Byrne deposed that his activities during that period included:

conducting meetings of the union members to consider the respondent’s offer, and encouraging them not to accept the offer; and

advocating the taking of protected industrial action by union members.

7 Mr Byrne also participated in regular meetings with representatives of other unions and the respondent, and in internal disciplinary hearings conducted by the respondent involving union members.

8 It is not in dispute that:

On 21 April 2014 Mr Byrne applied for annual leave, which he wished to take on 24 and 25 April 2014.

This application was refused by his superintendent at the mine, Mr Andrew Lawn.

Mr Byrne did not attend work on 24 and 25 April 2014.

Mr Byrne attended a meeting with Mr Lawn and human resources manager, Ms Kaitlyn Britton on 30 April 2014. After that meeting Mr Lawn decided that Mr Byrne should be stood down immediately, and that he should be required to attend a further meeting on 1 May 2014.

A show cause letter, signed by the general manager at the mine, Mr Aaron Puna, was issued by the respondent and given to Mr Byrne at a meeting on 1 May 2014. The letter invited Mr Byrne to show cause why disciplinary action should not be taken against him.

Mr Byrne attended a meeting with human resources manager, Ms Amanda Baker and mine operations manager, Mr Tony Power on 9 May 2014.

Mr Byrne was dismissed by letter dated 12 May 2014 in a letter signed by Mr Power.

9 The details of the events of 21, 22, 23 and 24 April 2014 so far as they concerned Mr Byrne and the respondent are however in dispute, and are critical to the current application. It is helpful to consider the evidence tendered by both parties in this respect.

EVIDENCE OF THE APPLICANT

Mr Stephen Byrne

10 Materially, Mr Byrne’s evidence as deposed in his affidavit of 14 May 2014 was as follows:

Mr Byrne is an asthmatic who has suffered periodic breathing difficulties arising from that condition. An example given by Mr Byrne was that on 20 April 2013, he cleaned the oven at his home, using an oven cleaner which emitted fumes, and experienced such breathing difficulties that he was taken by ambulance to Rockhampton hospital where he subsequently spent three days in intensive care.

In respect of the type of leave taken by employees at the mine, Mr Byrne deposed:

29. At the Dawson Mine it is not uncommon for employees who are unwell to apply for annual leave rather than taking sick leave. This is because each year the company allows workers to cash out their untaken sick leave. Employees are not permitted to cash out their untaken annual leave. Further, I am aware that unplanned absenteeism is a performance metric which is measured by the company. As a consequence I endeavour to take annual leave when sick so as to improve the rates of unplanned absenteeism.

He was rostered to work day shifts on 21 and 22 April 2014, and night shifts on 24 and 25 April 2014. A shift change day was rostered for 23 April 2014.

For several days prior to and including 21 April 2014 he suffered symptoms of a head cold, and he was beginning to suffer symptoms of a chest cold. On 21 April 2014 he became concerned about working the night shifts for which he had been rostered later that week. This was particularly so in light of the fact that the weather was cold. In his experience cold air exacerbates his asthma symptoms.

On 21 April 2014 he approached his supervisor, Mr Gavin Horn, to identify whether it would be possible to take annual leave on 24 and 25 April 2014 when he was rostered to work night shifts. Mr Horn said that he would need to consult with the superintendent, and later advised that Mr Byrne’s application had been refused.

On 22 April 2014 Mr Byrne approached the superintendent, Mr Lawn, who informed him that “the quota” was full in respect of employees seeking to take leave on those dates. Mr Byrne deposed that the conversation between them was as follows:

40. I then said in words to the following effect:

“The reason I asked for annual leave is that I am not feeling well and I am concerned that I will be sick and that working night shift will make my asthma worse.”

41. Mr Lawn then said in words to the following effect:

“If you don’t come in there will be ramifications for you.”

He felt progressively more ill on 22 April 2014. At 3 pm on that day he attended a meeting with Ms Baker and Mr Graeme Thompson (a union member) during the course of which the following conversation took place between him and Ms Baker:

45. … Ms Baker said in words to the following effect:

“You look terrible are you okay?”

46. I then said in words to the following effect:

“I’m not feeling very well I’ve had a head cold that I can’t shake for a few days. I think I am going to need to take Thursday and Friday off as I am worried about working nightshift. I don’t want a repeat of last year happening again.”

47. Ms Baker then said in words to the following:

“No we definitely don’t want that. You really don’t look well you should go home now.”

48. I then said in words to the following effect:

“I will finish the shift.”

On 23 April 2014 Mr Byrne attended upon his doctor, Dr Vahid Farahmand. Dr Farahmand advised Mr Byrne not to attend work on Thursday and Friday evenings, prescribed him antibiotics, and issued a medical certificate certifying that he was unfit for duty on those days.

At approximately 4.45 pm on 23 April 2014 Mr Byrne telephoned his supervisor, Mr Russell Gurney. Mr Byrne informed Mr Gurney that he was unwell and would not be attending work for the night shifts on 24 or 25 April 2014. He also communicated with Ms Baker via text message and informed her of the terms of the medical certificate prepared by Dr Farahmand.

Mr Byrne did not return to work until 30 April 2014. On the previous day he obtained another medical certificate from Dr Farahmand certifying him as fit for duty.

At approximately 2 pm on 30 April 2014 Mr Byrne was advised to attend a meeting with Mr Lawn and Ms Britton. Mr Lawn challenged Mr Byrne concerning the leave that Mr Byrne had taken and said words to the effect:

The issue is that you applied for annual leave and when that was knocked back you took sick leave.

Mr Byrne said that he had told Mr Lawn that he was sick, however Mr Lawn responded that he did not believe that Mr Byrne was sick. Mr Lawn then gave Mr Byrne a letter advising him that he had been stood down on full pay pending an investigation.

At a meeting on 9 May 2014 with Mr Power and Ms Baker, Mr Byrne provided a copy of his response to the show cause correspondence. Ms Baker stated that she did not agree with specific parts of the response. Mr Byrne reminded Ms Baker that she had seen him on 22 April 2014 and knew that he was sick, and Ms Baker responded that she did not know that Mr Byrne had previously applied for annual leave.

On 12 May 2014 Mr Byrne’s employment with the respondent was terminated.

Dr Vahid Farahmand

11 In his affidavit dated 14 May 2014, Dr Farahmand gave evidence supporting that of Mr Byrne as to Mr Byrne’s illness when Dr Farahmand saw him on 23 April 2014. In particular, Dr Farahmand said that he knew Mr Byrne, that he had seen Mr Byrne at his practice on 23 April 2014 and on that date he had observed Mr Byrne exhibiting symptoms which were compatible with asthma exacerbation and a lower respiratory tract infection. Dr Farahmand also described the medications he had prescribed Mr Byrne, and stated that while Mr Byrne was not fit to work on 24 and 25 April 2014, Mr Byrne was fit to return to work from 29 April 2014.

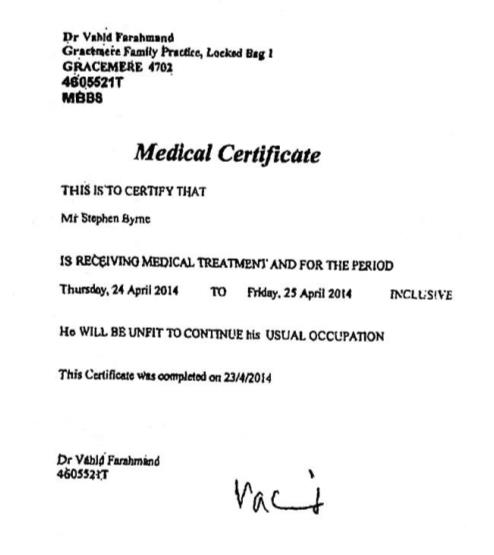

12 The medical certificate issued by Dr Farahmand for Mr Byrne on 23 April 2014 was as follows:

Mr Graeme Thompson

13 Mr Thompson attended a meeting with Mr Byrne and Ms Baker on 22 April 2014. Mr Thompson had appointed Mr Byrne his representative and support person for that meeting. In his affidavit affirmed 15 May 2014 Mr Thompson gave the following evidence:

6. During the first 20 or 30 minutes of the meeting Stephen was coughing and sniffling and wheezing and looked sick.

7. Toward the end of the meeting, after about 20 or 30 minutes of discussion, Ms Baker told Stephen that he was ill and should go home. Stephen said that he could complete the balance of his shift but could not work the next night shift.

8. Ms Baker advised Stephen that he should seek medical advice as he was ill.

Ms Kylie Byrne

14 Ms Byrne is Mr Byrne’s wife. In her affidavit affirmed 5 June 2014 Ms Byrne gave evidence that was consistent with that of Mr Byrne, in respect of his illness at the relevant times. In particular, Ms Byrne emphasised that Mr Byrne was sufficiently ill on 23, 24 and 25 April 2014 that he slept each evening on the couch.

Mr Troy Deeth

15 At material times Mr Deeth was an operator at the mine. In early to mid 2012 he took a position as relief supervisor for D crew. Relevantly, he deposed in his affidavit affirmed 18 July 2014:

5. It has been my practice, whilst employee of Anglo Coal, that if I was unwell I would contact my supervisor and ask to take annual leave instead of sick leave. If sufficient annual leave was available the supervisor would allow me to take annual leave. I did this as it meant that when the sick leave was paid out annually in August I would receive more pay than if I had taken sick leave.

6. When I acted as the relief supervisor for D Crew I, subject to annual leave being available, approved employee’s [sic] taking leave in this manner. In my experience at the mine it is common for employees who are sick to first request the taking of annual leave rather than personal leave or sick leave.

EVIDENCE OF THE RESPONDENT

Ms Rebecca Taumalolo

16 Ms Taumalolo was employed by the respondent as an employee relations specialist. In her affidavit dated 19 May 2014 Ms Taumalolo deposed that she had had a telephone conversation on 30 April 2014 with Ms Britton and a human resources superintendent, Ms Stephanie Elliot. In particular at [14] of her affidavit Ms Taumalolo deposed:

In relation to Mr Byrne, I was informed that it was alleged that an incident had occurred on 21 April 2014 as follows:

(a) Mr Byrne had requested annual leave for the period of 24 April 2014 and 25 April 2014 (inclusive);

(b) Andrew Lawn (Production Superintendent) had denied the request on the basis that there were already too many people rostered to take annual leave at that time;

(c) When Mr Lawn informed Mr Byrne that his annual leave request was refused, Mr Byrne had become agitated and said words to Mr Lawn to the effect of “regardless of what happens, I won’t be here”.

Mr Andrew Lawn

17 Mr Lawn was employed by the respondent as a mining superintendent at the mine. He deposed that he has worked in the coal mining industry since 2006, and at material times was responsible for managing approximately 213 employees at the mine. In his affidavits of 4 July 2014 and 16 July 2014 Mr Lawn deposed in summary:

The practice employed at the mine in relation to the taking of annual leave is that employees are usually required to submit annual leave requests at least 28 days before they wish to take the leave. This policy is documented in the Dawson Mine Collective Enterprise Agreement 2010 Questions and Answers and in his experience it is well-known among the workers. At material times the process for an employee wishing to take annual leave was to submit an annual leave request form, which was checked by either Mr Lawn or a supervisor to see if the annual leave request could be accommodated having regard to the planned operational requirements of the mine.

The 28-day notice period is important to ensure that there are enough employees at the mine each day to meet the operational requirements of the mine. In order to minimise the disruption caused by employees being away a policy of allowing up to one in eight employees to be absent at any one time is generally applied by the mine.

He had a very brief conversation with Mr Byrne on the evening of 21 April 2014 and did not see any indication that Mr Byrne was unwell.

On 22 April 2014 on arriving at work he saw Mr Byrne’s application for annual leave but declined it having regard to the available crew numbers in the relevant period. Later that morning Mr Byrne came to Mr Lawn’s office and they had a conversation to the following effect:

Mr Byrne: Have you signed my annual leave off yet?

Mr Lawn: I have done the annual leave. It has been declined due to overall crew numbers.

Mr Byrne: Well, you can’t decline it due to the new enterprise agreement, it’s only about annual leave numbers. The leave is within the numbers, you have to approve it.

Mr Lawn: It’s been declined.

Mr Byrne: (Repeatedly) No, you can’t decline it. The leave is within the numbers, you have to approve it.

Mr Lawn: No, it’s declined. If I have made an accounting error, I will get Julie to check and I will get back to you.

Mr Byrne: You have to approve it. The leave is within the numbers, I’ve checked.

Mr Lawn: I said, if I have made an accounting error, I will get Julie to check and I will get back to you.

Mr Byrne: Fine, I’m going to be sick anyway.

Mr Lawn: Mate, you have asked for annual leave, it is not within the time period, it’s not approved.

Mr Byrne: I will get a medical certificate. You will find that very hard to challenge.

Mr Lawn: If you get a certificate from a medical practitioner, that is fine but you have already told me that you are going to be sick. If you take sick leave, we will have to have a completely separate discussion based on the discipline policy.

Mr Lawn deposed that during that conversation Mr Byrne appeared quite agitated. Further, during that conversation and a subsequent conversation with Mr Byrne, Mr Byrne was not exhibiting any signs of being unwell.

Mr Lawn then deposed:

60. I returned back to the Mine on 29 April 2014.

61. When I arrived back at the Mine, I was told (I do not recall who by) that Mr Byrne had not turned up for work on 24 and 25 April 2014 and that instead he had called in and said that he was sick and was not coming to work.

62. Having received this information, I formed the view, based on my conversation with Mr Byrne on 22 April 2014 as referred to in paragraph 46 above, that:

(a) Mr Byrne was being dishonest about having being [sic] sick on 24 and 25 April 2014, and that in fact, he just wanted to have those days off even though I had declined his annual leave request; and

(b) That by being dishonest in this way, Mr Byrne had conducted himself, and continued to conduct himself, in a way which was inconsistent with company values.

63. I therefore decided that a meeting needed to be held with Mr Byrne when he returned to work (he was due back on 30 April 2014). The purpose of the meeting was to determine what course of action to take in relation to Mr Byrne’s conduct.

Mr Lawn arranged a meeting to be held with Mr Byrne and Ms Britton on 30 April 2014. A discussion at that meeting was as follows:

Mr Lawn: We want to discuss the conversation that you and I had last week. Why did you want annual leave?

Mr Byrne: No reason in particular. It coincided with night shift and I wanted the days off anyways. Plus, taking annual leave instead of sick leave financially benefits me in August when sick leave is paid out. It helps the company anyway because that way the absenteeism figures are lower.

Mr Lawn/Ms Britton: The way you have conducted yourself is not in accordance with our values.

Mr Byrne: But I have a medical certificate.

Mr Lawn: I’m not here to challenge a medical certificate. We are here to talk about process and values and the conversation we had last week.

Having regard to Mr Byrne’s responses and Mr Lawn’s own experience, Mr Lawn did not accept Mr Byrne’s statement about wanting to assist the respondent have lower absenteeism figures. He also concluded that Mr Byrne had been dishonest about being sick on 24 and 25 April 2014.

Mr Lawn deposed that it was his decision that a show cause letter be issued to Mr Byrne, and the letter was given to Mr Byrne at a meeting on 1 May 2014. The meeting was also attended by Mr Heath Timmins as Mr Byrne’s representative, Ms Britton and Ms Elliott. Mr Lawn deposed that at that meeting there was a conversation which included words to the following effect:

Mr Byrne: How have I been dishonest? I asked for annual leave and that was declined but then I took the leave because I was sick and Amanda noted that I was sick. This process is boarding [sic] on an adverse action claim however that is a different meeting.

Mr Timmins: I don’t understand how his behaviour was dishonest.

Ms Elliott: We are not challenging the validity of the medical certificate.

Mr Timmins: There was a meeting with Amanda and she said that Stephen was sick and suggested for him to go home. Stephen was trying to help the company by improving the leave statistics and figures. There is no dishonesty. We will attend the show cause meeting.

Mr Lawn deposed at [99] of his first affidavit that he was not aware of a practice at the mine whereby employees who were unwell applied for annual leave rather than take sick leave, and or employees endeavoured to take annual leave to improve the rates of unplanned absenteeism.

Mr Lawn also deposed that Mr Byrne’s position with the union, his union activities, and his temporary absence from work because of illness or injury, had no bearing on his decision to refuse Mr Byrne’s application for annual leave.

Mr Gavin Horn

18 Mr Horn commenced work as a Production Officer at the mine in approximately March 2014. He was relief supervisor of D Crew on the day shift on 21 April 2014. In his affidavit of 4 July 2014 Mr Horn relevantly deposed that he had told Mr Byrne to speak with the superintendent about taking annual leave on 24 April 2014 and 25 April 2014. He further deposed in response to Mr Byrne’s affidavits:

18. As to paragraphs 34 to 35 of the May Byrne Affidavit, I deny that during my discussion with Mr Byrne on 21 April 2014:

(a) Mr Byrne said that he was not feeling well and thought it was a good idea to take annual leave on his upcoming rostered night shifts;

(b) I said to Mr Byrne that I would check with the Superintendent about his leave request and get back to him;

(c) I later approached Mr Byrne and said that the Superintendent had refused his leave request.

19. I say further that Mr Byrne appeared to be in good physical health at that time of our conversation on 21 April 2014 and that I did not observe that Mr Byrne:

(a) was coughing or spluttering;

(b) was wheezing or short of breach;

(c) had watery eyes; and/or

(d) had any other physical symptoms consistent with a head cold.

20. In relation to paragraph 29 of the May Byrne affidavit, I am not aware of any current practice at the Mine whereby employees who are unwell apply for annual leave rather than sick leave. I am also unaware, based on my nine years of working at the mine, of such a practice occurring in the past.

Mr Tony Power

19 Mr Power commenced as Mine Manager at the mine on 5 May 2014, following the events giving rise to the show cause letter issued to Mr Byrne. He had previously worked at the mine as Mine Manager from 28 March 2011 to 19 August 2012 but deposed in his affidavit dated 4 July 2014 that he could not recall any interaction with Mr Byrne during that time.

20 Relevantly, Mr Power deposed that he dismissed Mr Byrne on 12 May 2014. Mr Power deposed that he had a conversation with Mr Lawn during the week commencing 5 May 2014 in which Mr Lawn said words to the effect of:

19. … I had a couple of conversations with Stephen Byrne. He had applied for annual leave and wanted to know where his application was. Later on in the day, I told him that the leave was declined because we were at numbers and then he told me that it didn’t matter whether the annual leave was granted or not because he was not going to come to work and he would go and get a medical certificate which would mean his absence from work could not be challenged.

21 Mr Power also understood that a mining superintendent, Mr Peter Hutchings, had overheard the conversation between Mr Lawn and Mr Byrne and had verified Mr Lawn’s account of what had occurred.

22 Mr Power deposed that he had reviewed the Anglo American Consequences Model (“the Consequences Model”), which is a tool for managers in assessing appropriate disciplinary outcomes. He also formed the view that Mr Byrne’s attitude was a serious one because it demonstrated an attitude of “I will do what I like and when I like it” (at [22]).

23 In his affidavit Mr Power detailed events including his presence at the show cause meeting also attended by Mr Byrne, and the discussions he had with other mine employees including Ms Baker, Ms Taumalolo, and Mr Puna. At [55] of his affidavit he set out his reasons for concluding that the allegations against Mr Byrne were substantiated and that Mr Byrne had wilfully absented himself from work on 24 and 25 April 2014 after his request for annual leave had been declined, as follows:

(a) I did not believe that it was true that Mr Byrne had tried to take annual leave rather than sick leave so as not to impact the absenteeism levels or his crew, because this is not to my knowledge normal process at the Mine and is not otherwise something that I have ever heard of happening during the course of my career in mining.

(b) Absenteeism statistics do not impact on any individual’s performance or even on a crew’s performance and it was my belief that Mr Byrne was likely to have known that this was the case.

(c) I had no reason to believe that Mr Lawn was being anything but honest about his account of the conversation that he had with Mr Byrne on 22 April 2014.

(d) I had no reason to believe that Mr Hutchings was being anything but honest about his account of the conversation that he had overheard between Mr Lawn and Mr Byrne on 22 April 2014.

(e) I formed the view that Mr Byrne had in effect threatened Mr Lawn with a sick certificate and had indicated to Mr Lawn that he would use a sick certificate to get what he wanted and that by doing so he would put himself above reproach by Mr Lawn or his employer. My view in this regard was supported by the fact that Mr Byrne had agreed during the Show Cause Meeting that he had said to Mr Lawn that Mr Lawn would have difficulty challenging a sick certificate if Mr Byrne produced one.

(f) I judged that it was likely that Mr Byrne had just expected that his request for annual leave on 24 and 25 April would be approved and then, when it was not, decided that he was going to do what he wanted anyway, and take the leave in any event, without any regard for the impact of his conduct on his colleagues or his employer. In particular, he appeared to me to have had no regard for the fact that it is important for annual leave to be managed carefully at the Mine because it has an impact on productivity and operations at the Mine and it puts pressure on other employees when too many people are away at any given time.

(g) In my view, as at 22 April 2014, when Mr Byrne’s annual leave request was refused, he conducted himself in a manner which showed that he intended to be dishonest with his actions and take sick leave when he was not in fact sick.

(h) I believed that Mr Byrne had not actually been unfit to come to work and perform work on each of 24 and 25 April 2014.

(i) I believed that Mr Byrne had obtained a medical certificate for those [sic] 24 and 25 April only because his request for annual leave had been declined and that, in my view, Mr Byrne got a sick certificate as he thought that was an easy way to circumvent the refusal of his annual leave request.

(j) In my experience, it is very easy for an employee to go to a doctor and get a medical certificate even if they are in fact not unfit to work, and that many medical practitioners do not necessarily impose any rigor around the process involved in giving a person a medical certificate. Again in my experience, this is because doctors usually rely to a great degree upon what people tell them about their symptoms in order to issue medical certificates. For that reason I did not attach any significance to the fact that Mr Byrne had obtained a medical certificate, and I did not consider that the fact that he had done so was a reason not to hold the belief described in (h).

(k) During my career, there has been at least one other instance which I recall where I challenged an employee’s medical certificate. That employee had asked for domestic leave and the application was refused. The employee then took sick leave and obtained a medical certificate for that sick leave. The employee, on the employee’s own admission, was not genuinely sick when the employee obtained the medical certificate. I ultimately dismissed that employee from employment (that employee also worked at the Mine) for matters including that the employee had taken sick leave when not genuinely sick.

(l) During the meeting, Mr Byrne did not show any remorse for his conduct or otherwise accept that his conduct was not appropriate.

(m) The attitude that Mr Byrne exhibited during the meeting showed contempt and disdain for his employer and its processes. Mr Byrne’s attitude led me to believe that Mr Byrne thought that his behaviour was acceptable and he did not understand why it was problematic.

24 Importantly, at [56] Mr Power also deposed:

My ultimate conclusion was that, to my mind, if the conversation between Mr Byrne and Mr Lawn had not occurred, then there would not have been any issue with the fact that Mr Byrne had taken sick leave.

25 In relation to the termination decision Mr Power deposed:

60. I came to the conclusion that terminating Mr Byrne’s employment was the appropriate outcome in the circumstances for the following reasons, and for no other reasons:

(a) My belief that Mr Byrne had acted dishonestly by putting in his annual leave application at short notice, and then when that was declined, telling his superintendent that he was not coming to work in any event and that he was going off to get a doctor’s certificate; and

(b) My belief that Mr Byrne had acted dishonestly during the Show Cause Meeting in saying that he was worried about crew statistics and that was why he wanted to take annual leave rather than sick leave.

26 The letter dated 12 May 2014 as signed by Mr Power, by which Mr Byrne’s employment was terminated, was as follows:

Dear Steve

Termination of Employment

You attended a meeting with Dawson Mine Management (“the Company”) representatives on 9 May 2014 to show cause why your employment with the Company should not be terminated in relation to your misconduct.

We have now taken into consideration your response. It is the Company’s position that your behaviour is unacceptable. Steve, you made it clear that regardless of the Company’s rejection of your leave application, you would not be in attendance for your rostered shifts and you then did not subsequently attend your rostered shifts.

The Company considers that your conduct is in breach of your terms and conditions of employment and has irreparably damaged and undermined the employment relationship.

Given the seriousness of your misconduct, the Company has decided to terminate your employment at Dawson Mine effective immediately. You will be paid one week in lieu of notice and all entitlements owing. Your termination pay will be transferred within seven (7) business working days.

The Company will continue to allow you access to the Employee Assistance Program … for a period of one month.

27 Mr Power also deposed that he was not aware of a practice at the mine whereby employees who were unwell applied for annual leave rather than sick leave, or a practice whereby Mr Byrne and his colleagues endeavoured to take annual leave so as to improve the rates of unplanned absenteeism. He also said that he was unaware of any such practice anywhere in the coal mining industry (at [73]).

Ms Amanda Baker

28 Ms Baker swore an affidavit on 9 July 2014 in which she deposed that until 27 June 2014 she was the Human Resources Manager at the mine. Her evidence was that she had worked for several years in human resources at the mine, as well as other mines in Queensland.

29 Ms Baker deposed that she knew Mr Byrne and had had a number of dealings with him in his capacity as President of the Moura Mine Lodge of the union. Further, between approximately June 2013 and December 2013 Ms Baker represented the respondent in negotiations for the Dawson Mines Enterprise Agreement 2014. Mr Byrne also participated in those negotiations. She gave evidence that the negotiations for this enterprise agreement progressed in an orderly fashion.

30 In relation to the meeting with Mr Byrne on 22 April 2014 Ms Baker deposed as follows:

30. On Tuesday 22 April 2014 at approximately 2.30pm (although I cannot recall the time precisely), I met with Mr Graeme Thompson (Mine Employee Level 2 – Operator), Mr Peter Hutchings (Production Superintendent) and Mr Byrne. This meeting took place in my office located at the Dawson Mine main administration complex.

31. The meeting related to an incident of misconduct by Mr Thompson. Mr Thompson had been issued with a “major breach” by the respondent and was disputing the respondent’s decision to issue the breach through the dispute settlement procedure in the Agreement. At that stage, the matter was currently at level 3 of the dispute settlement procedure.

32. Mr Byrne attended the meeting as a support person for Mr Thompson.

33. My office is approximately 4m by 6m. It contains a circular table which is located in the middle of the room. There are also six chairs situated around the table.

34. I recall that when Mr Byrne entered my office, I was already standing next to one of the chairs which was adjacent to the wall and the furthest from the door. Mr Byrne walked towards me and stood approximately 60cm to 80cm away. He gestured that he wanted to take the chair next to me.

35. As Mr Byrne entered the room and moved towards me, he made a coughing noise and did not attempt to cover his mouth with his hand. I remember feeling like Mr Byrne had coughed over me, because he was only 60 cm to 80 cm away and hadn’t covered his mouth.

36. I was surprised that Mr Byrne had intended to sit so close to me because there were other chairs available and because Mr Byrne has attended my office on a number of occasions previously and had never attempted to sit so close to me before. Normally, Mr Byrne would position himself opposite me, or as close to oppose as possible.

37. When Mr Byrne coughed, I said to him:

You should keep your distance. My son is going into hospital next week so I need to be well.

38. When saying that, I gestured to an empty seat opposite me on the other side of the table.

39. To give this comment context, my son suffers from bulbar palsy and has a low immune system and a history of chest infections. As a result of his illness, I am particularly concerned about hygiene issues such as people coughing without covering their mouth.

40. I then had the following conversation with Mr Byrne:

Me: If you’re sick go home, because you know if you’re ill you should go home and rest.

Mr Byrne: I’m planning on going home after this meeting.

41. I did not take a great deal of notice of Mr Byrne’s response because at the time, I was focused on what I needed to say to Mr Thompson.

42. I do not recall saying anything further to Mr Byrne about his health.

43. I then proceeded to speak to Mr Thompson about the disciplinary matters which concerned him.

44. The meeting continued for approximately 30 minutes.

45. Once the meeting commenced, Mr Byrne was actively involved in the discussions between me and Mr Thompson. I recall that on one occasion, I actually had to say to Mr Byrne that he needed to stop talking and let Mr Thompson speak.

46. At the conclusion of the meeting, after I had spoken to Mr Thompson about the disciplinary matter, Mr Byrne, Mr Hutchings and I had the following conversation:

Mr Byrne: What’s happening with our flu needles this year?

Me: There will be a communication coming out about this from safety.

Mr Byrne: I should have had mine by now.

Me: As a high risk asthma person, you would be able to get your needle for free from the doctor. You can get it from some pharmacies for $12.95.

Mr Hutchings: If you have medical insurance, which we all have, you’ll get it for free anyway.

47. I knew Mr Byrne suffered from asthma as a result of my previous dealings with him.

48. I recall that the meeting concluded shortly after this exchange.

49. During the course of the meeting on 22 April 2014, Mr Byrne did not physically look any different to me than how I would, in the ordinary course, consider him to look. Although Mr Byrne coughed at the very start of the meeting, I do not recall that he continued to cough for the remainder of the meeting.

50. Throughout the duration of the meeting, Mr Byrne:

(a) actively participated in the meeting and did not appear to be struggling to do so;

(b) was not sneezing;

(c) was not sniffling;

(d) did not have a runny nose;

(e) did not have watery eyes;

(f) did not use a tissue or a handkerchief; and

(g) did not appear to be suffering from any other flu like symptoms.

51. At the end of the meeting, and after Mr Byrne and Mr Thompson had left the room, Mr Hutchings said:

I know what that discussion about the flu needles was about. I’ll tell you about it later.

52. I cannot recall Mr Hutchings saying anything further to me about this on 22 April 2014.

31 In her affidavit at [53]-[102], Ms Baker also gave evidence including to the following effect:

On 23 April 2014 Ms Baker received a text message from Mr Byrne in relation to an apology for a meeting and a doctor’s certificate he had received. Mr Byrne expressed some concern in relation to the wording of the certificate, and Ms Baker agreed that if the language of the medical certificate was inaccurate it should be corrected.

Sometime after 23 April 2014 Mr Hutchings asked Ms Baker “How did you go with Mr Byrne and his medical certificate?” At that point Ms Baker learned that Mr Byrne had applied for annual leave and that had been refused.

Ms Baker returned to work on 1 May 2014.

Ms Baker led the discussion on behalf of the respondent at the show cause meeting of 9 May 2014 with Mr Byrne. At that meeting:

o Ms Baker admitted that she had spoken with Mr Byrne on 22 April 2014 but said that she is not a doctor, and that she had only made a comment in relation to his coughing;

o Ms Baker also admitted that she had received a text message from Mr Byrne but did at that stage did not understand the context and that he had previously asked for annual leave;

o Ms Baker expressed the opinion to Mr Byrne that he had acted with wilful intent, namely that he had wilfully disregarded the fact that his annual leave application had been declined due to crew numbers and had taken the days he wanted to take off anyway.

32 Ms Baker gave detailed evidence concerning the annual leave approval process at the mine. In relation to the evidence of Mr Byrne and Mr Thompson concerning employees taking annual leave rather than sick leave, she deposed at [124] of her affidavit:

(a) I am not aware of any custom or practice at the Mine where employees request to take annual leave instead of personal/carer’s leave to improve the respondent’s unplanned absenteeism records. Given my role as Human Resources Manager and my employment history at the Mine, if any such custom or practice existed, I would expect to know of it.

33 Ms Baker said that she did not recall saying to Mr Byrne at the meeting on 22 April 2014 either or both of the following:

“You look terrible are you okay?”; or

“You really don’t look well you should go home now.”

34 Ms Baker positively deposed that Mr Byrne did not inform her at any stage of the meeting on 22 April 2014 that he required time off work the following day.

Mr Peter Hutchings

35 In his affidavit affirmed 4 July 2014 Mr Hutchings deposed that he was employed by the respondent as a Dragline Supervisor at the mine, and that he had worked at the mine for a period of eight and a half years in a number of roles.

36 In his affidavit Mr Hutchings gave evidence as to the effect of the conversations between Mr Byrne and Mr Lawn on 22 April 2014, which he said that he heard because he was seated in a cubicle outside Mr Lawn’s office. In particular Mr Hutchings deposed:

13. At approximately 6.30am, I saw Mr Byrne walk up to Mr Lawn’s office and stand in the doorway to the office. I did not see Mr Byrne knock or otherwise greet Mr Lawn.

14. I then overheard words as follows:

Mr Byrne: Have you approved my annual leave?

Mr Lawn: I haven’t, I’ve declined it because of crew numbers.

Mr Byrne: Well I saw the numbers yesterday and I know there are only two people off on annual leave and we are allowed eight off at any given time and so there are still six spare spots.

Mr Lawn: That’s not right, it’s declined due to overall crew numbers.

15. I could see and hear both Mr Lawn and Mr Byrne while this conversation was occurring.

16. Mr Byrne then left Mr Lawn’s office.

17. Shortly afterward, Mr Byrne returned to Mr Lawn’s office. Again, I did not see Mr Byrne knock or otherwise greet Mr Lawn.

18. I then overheard words as follows:

Mr Byrne: Can I take the annual leave?

Mr Lawn: I told you before, the crew numbers don’t allow for the leave due to overall numbers

Mr Byrne: Well, I’m not going to be here one way or the other.

Mr Lawn: Mate, if you are not here, we will be having a completely different conversation.

Mr Byrne: Well, I’ll get a medical certificate and I will be bringing that, you will have trouble challenging a medical certificate.

19. I could see both Mr Lawn and Mr Byrne while this conversation was occurring.

20. I then saw Mr Byrne walk away from Mr Lawn’s office.

21. I made some notes of what I had heard in my diary shortly afterward …

37 In relation to the meeting of 22 April 2014, Mr Hutchings deposed materially:

32. I recall that at the start of the meeting, Mr Byrne coughed a couple of times and I recall he said “I’ve been feeling a bit crook”. I also recall that Ms Baker said at one stage to Mr Byrne “Are you ok? Don’t cough on me”.

33. Mr Byrne also said the following during the course of the meeting:

You know sometimes when people get frustrated or annoyed they say things that they wouldn’t normally say. I spoke to my superintendent this morning in a manner which I wouldn’t normally do.

34. I understood that Mr Byrne was making a direct reference to the conversations that he had had with Mr Lawn earlier that day and to the way he had spoken to Mr Lawn during those conversations.

35. Mr Byrne did not look to me to be ill at that point and he did not exhibit any signs that I would normally associate with someone being ill. Mr Byrne was not “nasally” or blocked up. He was not wheezing, his eyes were not watering and he was not having trouble breathing. Mr Byrne’s cough was not wheezy in character or a deep, chesty cough.

36. After the meeting ended I remained in Ms Baker’s office and Mr Byrne and Mr Thompson left. I then had said to Ms Baker:

You know what, Stephen just asked for annual leave and it got declined and he said that he didn’t care, he was going to go off and get a medical certificate. He’s coughing all over you, he’s preconditioning you for the medical certificate you’re going to get.

38 In relation to taking annual leave instead of sick leave, Mr Hutchings deposed:

44. As to paragraph 29 of the 14 May Byrne Affidavit, to my knowledge, I am not aware of a practice at the Mine whereby employees who are unwell apply for annual leave rather than taking sick leave or a practice where Mr Byrne and his colleagues endeavour to take annual leave so as to improve the rates of unplanned absenteeism. There have been instances in the past where an employee has submitted a leave form and attempted to claim annual leave instead of sick leave but because I have known that the employee has actually been sick, I have changed the type of leave to sick leave and then approved the leave. This is to ensure that the annual leave and sick leave statistics are correct and employees are taking the correct type of annual leave.

Mr Aaron Puna

39 I have also considered the evidence of Mr Puna. His evidence is consistent with that of the other witnesses for the respondent, and adds nothing of substance to the evidence I have already recounted.

RELEVANT LEGAL PRINCIPLES

Relevant legislation

40 The applicants rely on ss 340, 346 and 352 of the FW Act. These sections provide:

340 Protection

(1) A person must not take adverse action against another person:

(a) because the other person:

(i) has a workplace right; or

(ii) has, or has not, exercised a workplace right; or

(iii) proposes or proposes not to, or has at any time proposed or proposed not to, exercise a workplace right; or

(b) to prevent the exercise of a workplace right by the other person.

Note: This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

…

…

346 Protection

A person must not take adverse action against another person because the other person:

(a) is or is not, or was or was not, an officer or member of an industrial association; or

(b) engages, or has at any time engaged or proposed to engage, in industrial activity within the meaning of paragraph 347(a) or (b); or

(c) does not engage, or has at any time not engaged or proposed to not engage, in industrial activity within the meaning of paragraphs 347(c) to (g).

Note: This section is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

…

…

352 Temporary absence--illness or injury

An employer must not dismiss an employee because the employee is temporarily absent from work because of illness or injury of a kind prescribed by the regulations.

Note: This section is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

41 “Adverse action” is defined by Item 1 of s 342(1) of the FW Act to include if an employer:

(a) dismisses the employee; or

(b) injures the employee in his or her employment; or

(c) alters the position of the employee to the employee's prejudice; or

(d) discriminates between the employee and other employees of the employer.

42 Further, I note that s 360 of the FW Act provides:

For the purposes of this Part, a person takes action for a particular reason if the reasons for the action include that reason.

43 The respondent accepts that terminating the employment of Mr Byrne constituted “adverse action” within the meaning of s 342 of the FW Act. It also accepts that, by reason of s 361 of the FW Act, it has an onus to demonstrate that its reasons for terminating Mr Byrne’s employment did not include any of the prohibited reasons alleged by the applicant union in its amended originating application.

44 The respondent does not accept that, in his conversation with Mr Byrne on 22 April 2014, Mr Lawn – and therefore the respondent – threatened to take adverse action against Mr Byrne because Mr Byrne (inter alia) was proposing to exercise a workplace right, namely the taking of sick leave.

45 The leading cases dealing with identification of the reasons for adverse action are Board of Bendigo Regional Institute of Technical and Further Education v Barclay (2012) 248 CLR 500 (“Barclay”) and more recently Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Coal Pty Ltd [2014] HCA 41; (2014) 314 ALR 1 (“CFMEU v BHP”). Before turning to consideration of the facts of the case before me it is useful to consider the principles explained by the High Court in Barclay and CFMEU v BHP.

Barclay

46 In Barclay the employee was an employee of the appellant, as well as the president of the sub-branch of the Australian Education Union consisting of all union members employed by the appellant. The employee sent an email to all members of the sub-branch of the union, inter alia referring to reports of members having witnessed and being asked to participate in the production of false and fraudulent documentation in respect of a statutory audit for re-accreditation of the appellant. The appellant’s chief executive officer decided to suspend the employee and asked him to show cause why he should not be subject to disciplinary action for serious misconduct. The employee and the union sought declarations from the Federal Court that the appellant had contravened s 346 of the FW Act by taking adverse action against the employee for the reason or for reasons including that the employee was an officer of the union and had engaged in industrial activity. The chief executive officer gave sworn evidence detailing her concerns about the conduct of the employee and her reasons for taking the actions that she did. She denied that she took any of the action because of the employee’s membership of the union, or because of his role in the union, or because he had engaged in any industrial activity. The trial judge accepted this evidence and dismissed the application. The employee and the union appealed to the Full Court of the Federal Court, which allowed the appeal. In particular, in addressing s 346 and s 347 of the FW Act the majority of the Full Court said:

The determination of those questions involves characterisation of the reason or reasons of the person who took the adverse action. The state of mind or subjective intention of that person will be centrally relevant, but it is not decisive. What is required is a determination of what Mason J in Bowling … called the ‘real reason’ for the conduct. The real reason for a person’s conduct is not necessarily the reason that the person asserts, even where the person genuinely believes he or she was motivated by that reason. The search is for what actuated the conduct of the person, not for what the person thinks he or she was actuated by. In that regard, the real reason may be conscious or unconscious, and where unconscious or not appreciated or understood, adverse action will not be excused simply because its perpetrator held a benevolent intent. It is not open to the decision-maker to choose to ignore the objective connection between the decision he or she is making and the attribute or activity in question.

Barclay v Board of Bendigo Regional Institute of Technical and Further Education (2011) 191 FCR 212 at 221.

47 The majority of the Full Court found that the employee had, inter alia, engaged in industrial activity in respect of his actions, and further found that the action taken by the chief executive officer of the appellant was taken for an unconscious reason or a reason which was not appreciated by her, which reason was prohibited.

48 The appellant sought and obtained special leave to appeal to the High Court from the decision of the Full Court.

49 The High Court allowed the appeal.

50 As French CJ and Crennan J said at 506, the task of a court in a proceeding alleging a contravention of s 346 of the FW Act is to determine, on the balance of probabilities, why the employer took adverse action against the employee, and to ask whether it was for a prohibited reason or reasons which included a prohibited reason.

51 French CJ and Crennan J noted that the question of why an employer took adverse action against an employee is a question of fact arising from the operation of interdependent provisions of the FW Act, which provisions must be construed together in accordance with the principles of statutory construction established by the High Court (at 516). Their Honours observed that determining why an employer took adverse action against an employee involved consideration of the decision-maker’s “particular reason” for taking adverse action and consideration of the employee’s position with the relevant union and engagement in the relevant industrial activity at the time of the adverse action (at 516). There is no reason for treating the word “because” in s 346, or the statutory presumption in s 361 of the FW Act, as requiring only an objective inquiry into the employer’s reason for taking adverse action. As their Honours explained at 517:

The imposition of the statutory presumption in s 361, and the correlative onus on employers, naturally and ordinarily mean that direct evidence of a decision-maker as to state of mind, intent or purpose will bear upon the question of why adverse action was taken, although the central question remains “why was the adverse action taken?”

The question is one of fact, which must be answered in light of all the facts established in the proceeding … However, direct testimony from the decision-maker which is accepted as reliable is capable of discharging the burden upon an employer even though an employee may be an officer or member of an industrial association and engage industrial activity.

(footnotes omitted.)

52 Later their Honours observed (at 523):

… it is erroneous to treat the onus imposed on an employer by s 361 as being made heavier (or rendered impossible to discharge) because an employee affected by adverse action happens to be an offer of an industrial association. Further, the history of the relevant legislative provisions reveals no reason why the onus must now be different if adverse action is taken while an employee engages in industrial activity – like a person who happens to be an officer of an industrial association, a person who happens to be engaged in industrial activity should not have an advantage not enjoyed by other workers.

53 In that case, the employee’s status as an officer of an industrial association engaged in lawful industrial activity at the time industrial action was taken against him was not inextricably entwined with that adverse action (at 523).

54 At 534 Gummow and Hayne JJ noted:

The application of s 346 turns on the term “because”. This term is not defined. The term is not unique to s 346 …

The use in s 346(b) of the term “because” in the expression “because the other person engages … in industrial activity”, invites attention to the reasons why the decision-maker so acted.

55 At 535 their Honours continued:

An employer contravenes s 346 if it can be said that engagement by the employee in an industrial activity comprised “a substantial and operative” reason, or reasons including the reason, for the employer’s action and that this action constitutes an “adverse action” within the meaning of s 342.

56 In relation to the question whether a “subjective” or “objective” ought be applied, Gummow and Hayne JJ said at 540-541:

… to engage upon an inquiry contrasting “objective” and “subjective” reasons is to adopt an illusory frame of reference. Such an inquiry into the “objective” reasons risks the substitution by the court of its view of the matter for the finding it must make upon an issue of fact. Here, that finding was made by Tracey J and it was an error of law to displace it in the way seen in the reasons of the Full Court majority.

57 Their Honours later continued at 542:

In determining an application under s 346 the Federal Court was to assess whether the engagement of an employee in an industrial activity was a “substantial and operative factor” as to constitute a “reason”, potentially amongst many reasons, for adverse action to be taken against that employee. In assessing the evidence led to discharge the onus upon the employer under s 361(1), the reliability and weight of such evidence was to be balanced against evidence adduced by the employee and the overall facts and circumstances of each case; but it was the reasons of the decision-maker at the time the adverse action was taken which was the focus of the inquiry.

Whilst it is true to say, as do the respondents, that there is a distinction between discharging the onus of proof and establishing that the reason for taking adverse action was not a proscribed reason, there is nothing to suggest that the conclusions drawn by the primary judge, and the findings and reasons upon which these were based, did not take this into consideration. As Lander J concluded, if the reasons for the conclusions and the facts for which they were formulated are not challenged, then the contravention of s 346 cannot be made out. This proposition should be accepted. To hold otherwise would be to endorse the view that the imposition of an onus of proof on the employer under s 361(1) creates an irrebuttable presumption at law in favour of the employee.

(Footnotes omitted.)

58 In a separate judgment at 546 Heydon J said:

To search for the “reason” for a voluntary action is to search for the reasoning actually employed by the person who acted. Nothing in the Act expressly suggests that the courts are to search for “unconscious” elements in the impugned reasoning of persons in Dr Harvey’s position. No requirement for such search can be implied. This is so if only because it would create an impossible burden on employers accused of contravening s 346 of the Act to search the minds of employees whose conduct is said to have caused the contravention. How could an employer ever prove that there was no unconscious reason of a prohibited kind? …

Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Coal Pty Ltd (2014) 314 ALR 1

59 In this case the employee worked for BHP Coal Pty Ltd, and participated in a lawful protest organised by the union at a mine. During the protest the employee held signs supplied by the union reading “No principles SCABS No guts”. The employee was terminated by BHP Coal Pty Ltd on the basis that the use of the word “SCABS” was a flagrant violation of the workplace policy. The manager whose decision it was to dismiss the employee said that the fact that he was an active member of the union only entered his mind to the extent that he knew the decision would be controversial. The primary judge accepted the manager’s evidence that the employee was not dismissed because he was a member of the union, however his Honour concluded that the employee was dismissed because he had engaged in industrial activity within the meaning of s 347(b)(iii) and (v) of the FW Act, and therefore contravened s 346(b) of the FW Act. On appeal, the Full Court of the Federal Court allowed the appeal by the employer.

60 The union appealed the decision of the Full Court to the High Court of Australia, however the appeal to the High Court was dismissed (by French CJ and Kiefel and Gageler JJ, Hayne and Crennan JJ dissenting).

61 French CJ and Kiefel J observed at [6] that s 346 of the FW Act directs attention to the reason why the manager took the adverse action. Their Honours referred to Barclay and continued:

[10] None of the reasons given by Mr Brick, and accepted by the primary judge as true in fact, was a reason prohibited by s 346(b). Mr Brick did not dismiss Mr Doevendans because he participated in the lawful activity of a protest organised by the CFMEU (s 347(b)(iii)), nor did he dismiss Mr Doevendans because, in carrying and waving the sign, Mr Doevendans was representing or advancing the views or interests of the CFMEU (s 347(b)(v)), as the CFMEU alleged. Mr Brick’s reasons related to the content of Mr Doevendans’ communications with his fellow employees, the way in which he made those communications and what that conveyed about him as an employee. Mr Brick’s reasons included his concern that Mr Doevendans could not or would not comply with the standards of behaviour which Mr Brick was attempting to instil in employees at the mine.

62 In finding that the conduct of the employee in waving the sign with the offending word had to be associated with the industrial activity and that accordingly this association was the reason for the termination of his employment, their Honours considered that the reasoning of the primary judge was analogous to that of the majority of the Full Court in Barclay which the High Court had held to be incorrect. In this case it could only be said that the adverse action had a connection, in fact, to the industrial activity in which the employee was engaged, and while that connection could necessitate some consideration as to the true motivations of the manager it could not itself provide the reason why the manager took the action he did (at [22]).

63 Gageler J said:

[88] The majority in the Full Court of the Federal Court in the present case was correct to treat Barclay as foreclosing the mode of analysis adopted by the primary judge in the present case to conclude that BHP Coal’s dismissal of Mr Doevendans was because he had engaged in industrial activity within the meaning of s 347(b)(iii) and (v).

[89] In a case where the totality of the operative and immediate reasons for one person having taken adverse action against another person are proved, the question presented by s 346(b) is whether any one or more of those reasons answers the description of the other person having engaged in any one or more of the industrial activities listed in s 347(a) or s 347(b). The specific question presented by s 346(b) in its application to s 347(b)(iii) is whether any one or more of those reasons was that the person had, or had not, encouraged or participated in some lawful activity organised or promoted by an industrial association. The specific question presented by s 346(b) in its application to s 347(b)(v) is whether any one or more of those reasons was that the person had, or had not, represented or advanced some view, claim or interest of an industrial association.

[90] In the present case, the totality of the operative and immediate reasons for BHP Coal having taken adverse action against Mr Doevendans were proved by the evidence of Mr Brick about his own process of reasoning. The fact that Mr Doevendans held and waved the signs while participating in the protest organised by the CFMEU was not an operative part of Mr Brick’s reasoning. Nor was the fact that the signs represented or advanced the views or interests of the CFMEU. The correct answer to the question presented by s 346(b) in those circumstances was that given by the majority in the Full Court: BHP Coal’s dismissal of Mr Doevendans was not because he had engaged in industrial activity within the meaning of s 347(b)(iii) and (v) and therefore did not contravene s 346(b).

SUBMISSIONS OF THE PARTIES

64 In summary, the applicants submit as follows:

The rule in Browne v Dunn (1893) 6 R 67 is relevant in respect of the evidence of Mr Byrne, Dr Farahmand and Ms Byrne.

There is no evidence cited by the respondent to support its contention that Mr Byrne attended Dr Farahmand’s surgery only for the purpose of obtaining a medical certificate.

Reference should be made to the evidence of Mr Deeth in relation to the practice at the mine of taking annual leave rather than sick leave.

The reasons for the adverse action taken against Mr Byrne should not be limited only to the reasons of Mr Power. Regard should also be had to the involvement of Mr Lawn, Mr Puna, Ms Taumalolo and Ms Baker. It is also significant that not all human resources staff who were involved in advising Mr Puna, and ultimately Mr Power, were either identified or called to give evidence.

Mr Power chose, without explanation, not to put a range of matters to Mr Byrne in the show cause meeting, and chose further to conduct a procedure in relation to the show cause meeting which was inadequate. In particular, no questions relating to Mr Byrne’s illness, fitness to attend work or views concerning work statistics were put to Mr Byrne at the show cause meeting.

Mr Power was not a credible witness, in that his recollection was fundamentally flawed, he changed his evidence and he did not investigate matters. The matters identified by the respondent as allegedly motivating Mr Power in his decision were not referred to by Mr Power.

No evidence was put on by the respondent concerning the absence or otherwise of the necessary degree of trust and confidence as between Mr Byrne and the respondent in the workplace.

65 The respondent submits, in summary:

The reason Mr Byrne’s employment was terminated was not that he took leave, but his defiance and dishonesty.

By 22 April 2014 Mr Byrne knew that he would not be attending work on 24 and 25 April 2014.

Mr Byrne attended Dr Farahmand in order to get a medical certificate, not for medical treatment.

Mr Byrne knew that the practice (if it had ever existed) of taking annual leave rather than sick leave in case of illness had ceased by the time of these events.

Mr Byrne swore that, on 22 April 2014, he was ill and went to bed early. This was clearly untrue, as he subsequently corrected this statement by saying that he attended a union meeting. Further in his first affidavit he swore that on 24 April 2014 he stayed at home and recuperated, whereas in his second affidavit he admitted that he had travelled to Rockhampton for a two and a half hour shopping trip. His evidence was a series of reconstructions to retrospectively justify his position, and his evidence shifted.

Dr Farahmand’s evidence was based on what Mr Byrne had told him.

The decision-maker was Mr Power, and it is his reasons for making the decision to dismiss Mr Byrne that are relevant. None of the reasons given by Mr Power, or the evidence in this case, supports the applicants’ case.

The evidence demonstrates that Mr Byrne exercising a right to take personal leave was not the reason for the decision to terminate his employment.

CONSIDERATION

66 In respect of the claims of the applicants against the respondent the applicants concede, correctly, that they are required to establish the necessary facts from which it can be concluded that the adverse action was taken for prohibited reasons. These facts are:

1. That Mr Byrne was employed by the respondent; and

2. That he was an officer and member of the applicant union; and/or

3. That he had a workplace right, in this case to take sick leave; and/or

4. That as an officer of his union he had engaged in industrial activity; and/or

5. That he was absent from work for two days because of illness; and

6. That the respondent took adverse action against him, in this case the threat to take adverse action and his dismissal from his employment.

67 If the applicants are able to establish facts 1, 6 and any of facts 2-6, the onus shifts to the respondent to rebut the presumption in s 361 of the FW Act that the relevant adverse action was taken for the alleged proscribed reason related to facts 2-5.

68 In turn, the respondent concedes facts 1-4 and 6. It does not concede that Mr Byrne was absent from work for two days because of illness. Further, while conceding that it bears the onus under s 361 of the FW Act of proving that the adverse action taken against Mr Byrne was not for a proscribed reason or reasons, the respondent claims that it has discharged that onus.

69 While the applicants also claim breach of contract and seek an order for specific performance of Mr Byrne’s contract, the submissions of the parties primarily focused on the position under the FW Act.

70 Before turning to the question of breach of contract, it is first convenient to examine the three key issues in controversy under the FW Act, namely:

whether Mr Byrne was ill on 24 and 25 April 2014;

whether the statement of Mr Lawn to Mr Byrne on 22 April 2014 was a threat to take adverse action under the FW Act; and

on the basis that the dismissal of Mr Byrne constituted adverse action, the reason or reasons for dismissal for Mr Byrne and whether those reasons were proscribed reasons under the FW Act.

Was Mr Byrne ill on 24 and 25 April 2014?

71 A great deal of evidence was given by the parties during the course of the trial relating to the question whether Mr Byrne was ill on 24 and 25 April 2014 as he claimed. The reasons for this are clear:

the applicants claimed in this proceeding that Mr Byrne was absent on 24 and 25 April 2014 because of his illness on the relevant two days;

it is not in dispute that an employee who is unfit for duty has a workplace right to claim sick leave within the terms of the relevant industrial instrument; and

under s 352 of the FW Act the dismissal of an employee because the employee is temporarily absent from work as a result of illness or injury of a kind prescribed by the regulations is prohibited, and liable to give rise to a civil penalty.

72 The respondent strongly argued that:

Mr Byrne was not ill on 24 and 25 April 2014;

the evidence of employees of the respondent was that he did not appear ill when he was at work on 22 April 2014;

he planned to take those dates as leave irrespective of the position of the respondent to the extent that he had asked for annual leave in respect of those dates; and

he dishonestly relied on a medical certificate he persuaded Dr Farahmand to provide for him.

73 In my view there are a number of fundamental flaws in the respondent’s arguments concerning the medical condition of Mr Byrne on 24 and 25 April 2014.

74 First, in my view Dr Farahmand was a credible witness, and in particular was credible in relation to his belief that Mr Byrne was unwell at the time Mr Byrne attended the surgery on 23 April 2014. I also note that the evidence of Dr Farahmand is uncontested, in the sense that there is no medical evidence before me to rebut it.

75 The respondent seeks to make much of the fact that Dr Farahmand’s diagnosis was, to some extent, based on the information provided to him by Mr Byrne as to how Mr Byrne was feeling at the relevant time. I do not see this as undermining the value of Dr Farahmand’s evidence. Inevitably the view of a medical practitioner must, to some extent, be guided by the symptoms described by the patient. In any event however it cannot be said that, in forming his opinion concerning Mr Byrne’s state of health, Dr Farahmand relied exclusively on information supplied to him by Mr Byrne. As was clear from his evidence Dr Farahmand was aware from Mr Byrne’s medical history that Mr Byrne was “very susceptible” to respiratory tract infections and that Mr Byrne had been “coping with asthma” for a number of years. Dr Farahmand examined Mr Byrne on both 23 April 2014 and 29 April 2014. On 23 April 2014 Dr Farahmand formed the view that Mr Byrne had, inter alia, a “wheezy chest” and prescribed him medication. In response to questions from Mr Neil SC, Dr Farahmand explained:

… I ask him to stay home for the rest of the week which means that the Thursday and Friday and come back after actually – after … actually week day, first of all to check his chest if he is … start his job, I issue actually a certificate to actually come back to the work, otherwise definitely I have to do some further investigation and maybe blood tests, chest x-ray and maybe a specialist referral.

(transcript 30 July 2014 p 19 ll 13-19.)

76 Dr Farahmand also rejected the proposition that his assessment of Mr Byrne as sick depended on what Mr Byrne had told him, rather than his own observations of Mr Byrne (transcript 30 July 2014 p 23 ll 8-10).

77 Further, while I note that this Court is not obliged to accept without reservation a medical certificate provided by a medical practitioner excusing conduct of this nature, I note the uncontested evidence of Dr Farahmand that he is:

… very strict, very strict about issuing the medical certificate.

(Transcript 30 July 2014 p 22 l 18.)

78 I am satisfied that on 23 April 2014 Dr Farahmand formed the view that Mr Byrne was ill, that Mr Byrne should take time off work to rest, and that it was for that reason that Dr Farahmand provided the relevant certificate.

79 The respondent has directed my attention to the decision in Anderson v Crown Melbourne Ltd [2008] FMCA 152, a case in which a Melbourne-based, self-described fanatical supporter of an Australian rules football club had obtained a medical certificate to support his absence from work on a day on which the applicant’s football team was playing in Perth. The employer terminated the employee’s employment in respect of that absence. In that case the Federal Magistrate was satisfied that the applicant was not ill on any relevant day, was further satisfied that the applicant had procured an accommodating medical practitioner to issue a medical certificate to excuse his absence from work on the day his team played in Perth, and declined to accept the validity of the medical certificate. However that case is somewhat different from the one before me, in which there is evidence not only of an underlying medical condition of Mr Byrne but evidence of himself, Ms Byrne, Dr Farahmand, and to a lesser extent Mr Thompson, to support Mr Byrne’s claim of illness at that time.

80 Second, I found Mr Byrne a credible witness in relation to his evidence that he was developing a chest cold on 22 April 2014 and was sick on 24 and 25 April 2014. It is not in dispute that Mr Byrne is an asthmatic, and that he suffered a serious attack of asthma in April 2013. He was responsive to the questions put to him by Mr Neil SC at the hearing, and to the extent that his memory was faulty he made appropriate concessions (for example at p 81 of the transcript of 31 July 2014 in relation to the attendance of Mr Spencer at the union meeting). I accept Mr Byrne’s evidence that, in light of his previous experiences with asthma:

he was concerned that he was developing a chest cold, and that he would be required to work at night for the next few days because working in a cold temperature could exacerbate his asthma;

he preferred to see his own doctor; and

it would have been a waste of time for him to see the nurse at the mine because she would have been unable to prescribe him any medication.

81 Third, I found Ms Byrne a credible witness. Her evidence concerning Mr Byrne’s illness on 23 April 2014 and events of the following two days was firm and unshaken under cross-examination.

82 Fourth, I note the evidence of witnesses for the respondent – in particular Ms Baker, Mr Horn, Mr Lawn and Mr Hutchings – that Mr Byrne did not appear to be ill when they saw him on 21 and 22 April 2014. However in my view this evidence should be given less weight than the evidence of Mr Byrne, Ms Byrne and Dr Farahmand in deciding whether, as a fact, Mr Byrne was actually ill or becoming ill on 22 April 2014 and was actually ill on 24 and 25 April 2014. Simply because a person appears well enough to function in the workplace does not necessarily mean that they are “well”. Mr Byrne’s evidence was that he could feel a chest cold developing and he was anxious that it might develop into something more serious because of his underlying asthma. I accept this evidence. I also give greater credence to the evidence of Ms Byrne, in describing, in some detail, Mr Byrne’s condition on 24 and 25 April 2014, than to the casual impressions formed by the respondent’s witnesses as to Mr Byrne’s state of health on 21 and 22 April 2014.

83 In my view the respondents’ witnesses were not in a position to comment with any authority as to whether Mr Byrne was actually ill or developing a medical condition, on those dates. I do not discount their evidence entirely however – indeed I consider this evidence of greater relevance in determining the reasons of the respondent in terminating Mr Byrne’s employment. I shall return to this issue later in the judgment.

84 On the evidence before me I am satisfied that Mr Byrne was ill on 24 and 25 April 2014.

85 For completeness in respect of this point however, I also note that I do not accept the contention of the applicants that the rule in Browne v Dunn applies so far as concerns the evidence of Dr Farahmand, Mr Byrne and Ms Byrne. That the respondent’s case was that Mr Byrne had fabricated his illness and sought, after the event, to create the false impression that he was sick, was in my view obvious from the evidence of its witnesses (several of whom deposed that, so far as they knew, Mr Byrne was not sick in the days prior to 24 and 25 April 2014) and the outline of the respondent’s submissions filed on 29 July 2014. The applicants knew, well in advance of the hearing, that Mr Lawn and subsequently Mr Power had formed the view that Mr Byrne had been dishonest in his claim of illness. In this light, to paraphrase the Full Court in Kraus v Menzie [2012] FCAFC 144 at [40]:

… the rule in Browne v Dunn did not require the … respondent to put his allegations in chapter and verse to the [applicant] and [it] was not deprived of procedural fairness.