FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Ltd v Bayer Australia Ltd [2015] FCA 35

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

NOVARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 004 244 160) Applicant | |

AND: | BAYER AUSTRALIA LIMITED (ACN 000 138 714) Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or before 20 February 2015, the parties are to identify which parts of the reasons they contend should not be published because of confidentiality and file a proposed form of orders.

2. The parties are to endeavour to agree the figure to be included in [366] of these reasons.

3. If the applicant wishes to contend that costs should not follow the event, it should file and serve by 20 February 2015 a written submission of no more than three pages in support of that contention. If the applicant files such a written submission, the respondent is to file and serve by 28 February 2015 its written submission of no more than three pages in response.

4. The proceedings be listed at 9.30 am on 6 March 2015 for the making of orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 314 of 2013 |

BETWEEN: | NOVARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 004 244 160) Applicant |

AND: | BAYER AUSTRALIA LIMITED (ACN 000 138 714) Respondent |

JUDGE: | ROBERTSON J |

DATE: | 6 FEBRUARY 2015 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

Introduction

1 These proceedings concern two medicines for the treatment, by intra-vitreal injection, of neovascular (wet) age-related macular degeneration (wet AMD or wAMD), a medical condition which results in loss of vision. Each medicine involves ongoing treatment.

2 Lucentis® (Lucentis), the Novartis product, has been available for sale in Australia since 2007. It is only available on prescription and is, and has been since 2007, administered only by ophthalmologists. Its active ingredient is ranibizumab and it is sometimes referred to by that name.

3 Eylea® (Eylea), the Bayer product, has been marketed and sold in Australia since 2012. It also is only available on prescription and is administered only by ophthalmologists. It too is administered via intra-vitreal injection. Its active ingredient is aflibercept and it is sometimes referred to by that name.

4 It is common ground that Lucentis and Eylea are in direct competition with each other as prescription-only medicines indicated for use in Australia for the treatment of wet AMD.

5 In February 2007, Lucentis was registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods and in August 2007 it was listed on the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits (PBS Schedule).

6 On 7 March 2012, Eylea was registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods. On 1 December 2012, Eylea was listed on the PBS Schedule.

7 Novartis pleads that in approximately 46 acts of publication, which I list below, and in detailing conduct, Bayer made the following representations:

(a) that in clinical use, in accordance with the approved dosage, the Novartis product, Lucentis, is administered monthly for all patients (First Representation);

(b) that, for each and every patient, Lucentis will only be a clinically effective treatment if administered monthly (Second Representation);

(c) that the Lucentis Product Information specified, without qualification, that it was to be administered monthly (Third Representation);

(d) that in accordance with approved dosages, all Eylea patients receive fewer injections than all Lucentis patients (Fourth Representation).

In its reply submissions, Novartis said that the heart of the case centred on the Fourth Representation.

8 Bayer denies that the representations were conveyed but admits that, if they were, each is false — that is, an incorrect statement of fact — but denies that they were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

9 Novartis claims that Bayer breached ss 18, 29(1)(a) and/or 29(1)(g) of the Australian Consumer Law, which sections were as follows:

18 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

Note: For rules relating to representations as to the country of origin of goods, see Part 5-3.

…

29 False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits; …

…

Section 29 was in Part 3‑1—Unfair practices: see s 18(2) above.

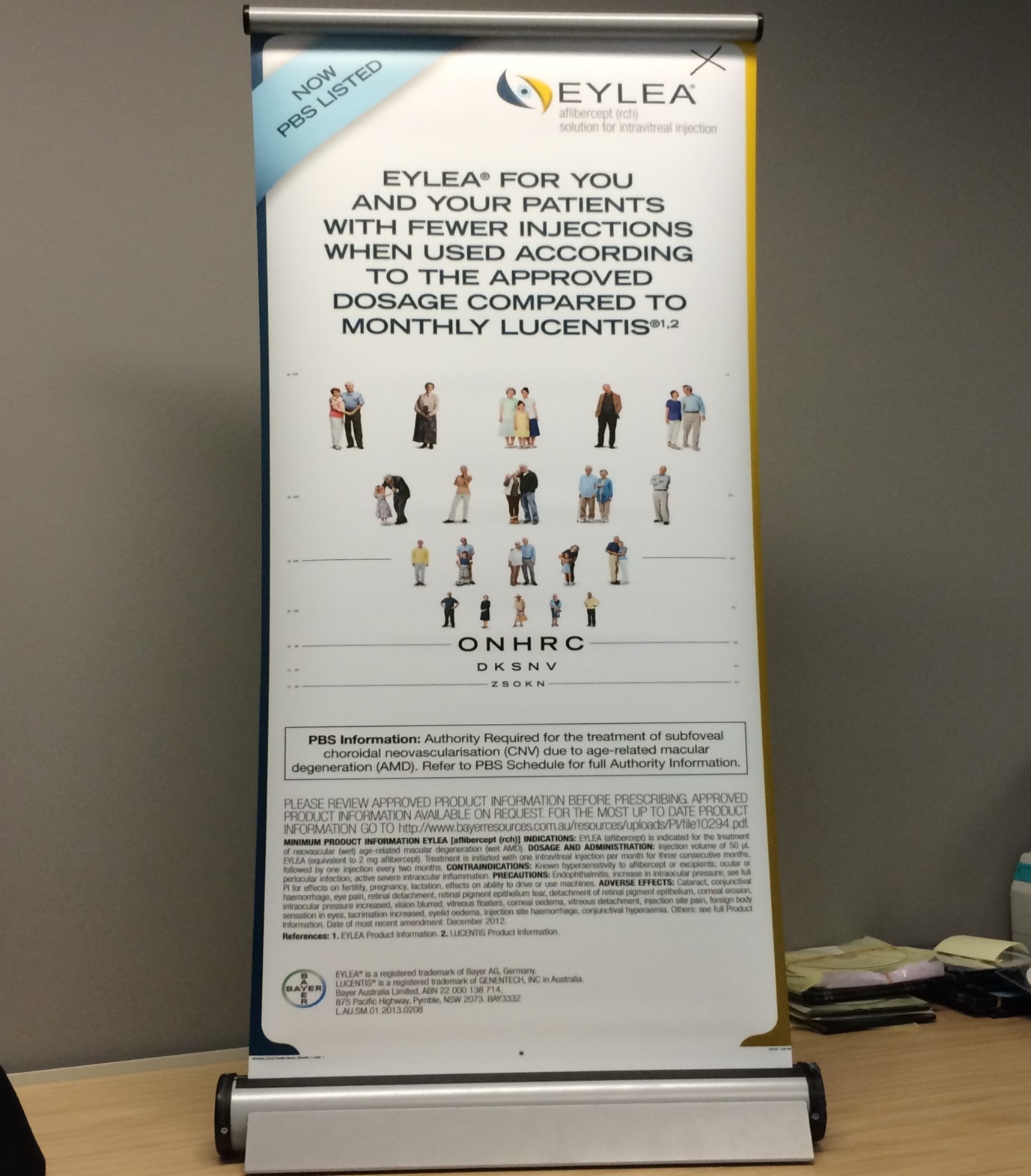

10 By way of example, the content of one of Bayer’s acts of publication, by baby banner (second form), was:

11 The central issues for decision are as follows:

(i) Were the four pleaded representations conveyed by the acts of Bayer? As I have said, Novartis pleaded approximately 46 acts of publication and detailing conduct, occurring on various dates up to mid-May 2013, but with one further publication in June 2013;

(ii) If so, was that conduct misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, or false or misleading?

(iii) If so, what is the appropriate remedy, if any? In particular, has Novartis proved that it suffered loss or damage because of Bayer’s conduct and, if so, in what amount, and is other relief, in the form of declarations, injunctions and corrective advertising, appropriate?

12 It is necessary to approach these issues with an appreciation of the context, in particular the regulatory context, and the identification of the relevant class of addressees and the education, training, experience and state of knowledge of a (hypothetical) reasonable member of that class.

The words used and the acts of publication

13 The acts of publication were alleged to have been by poster, which was a large banner designed to stand on the floor, being approximately 2.13 m wide and 2.19 m high; by baby banner which was smaller than a poster, say for a desk top, being approximately 40 cm wide and 95 cm high; by detailing conduct which meant the detailing, i.e. communications by Bayer company representatives with ophthalmologists and/or optometrists, during which the ophthalmologists and/or optometrists were shown Detail Aids (on an iPad), which included words in terms substantially similar to those otherwise complained of by the applicant Novartis; advertisements in the journal Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology and in mivision magazine; and by displaying and disseminating an attendee workbook at the Eylea product launch events in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide. Bayer accepts that it published magazine advertisements, published and had on display certain posters and baby banners at meetings and events, and that its sales representatives engaged in certain detailing conduct with an electronic document on an iPad. It also accepts that it provided the attendee workbook.

14 The magazine mivision is a monthly industry publication which is provided as a free subscription to ophthalmologists and optometrists and their practices in Australia and New Zealand 11 times a year on the first Monday of every month (except for January). In September 2012 the audited distribution for the magazine was 7265, made up of optometrists and optical shops (3793 recipients), ophthalmologists (1176 recipients) and ophthalmologists’ practices and staff (216 recipients). The journal Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology is a clinical journal produced by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) and distributed to RANZCO members, ophthalmologists, as part of their membership.

15 I next set out the words used of which complaint is made.

16 It is alleged that, by displaying a poster, Bayer published, amongst other words, the following words:

“EYLEA® HELPS YOU AND YOUR

PATIENTS WITH FEWER INJECTIONS

WHEN USED ACCORDING TO THE APPROVED

DOSAGE COMPARED TO MONTHLY RANIBIZUMAB 1, 2

…

References: 1. EYLEA® Product Information. 2. LUCENTIS® Product Information.”

17 This was the form for the poster (first form), the baby banner (first form), the Detail Aid and the attendee workbook.

18 It is next alleged that Bayer caused advertisements to be published in the same form.

19 This was the form used for the advertisements (first form).

20 Another form (second form) is alleged as follows:

“EYLEA® FOR YOU AND YOUR PATIENTS

WITH FEWER INJECTIONS WHEN USED

ACCORDING TO THE APPROVED DOSAGE

COMPARED TO MONTHLY LUCENTIS®1, 2

…

References: 1. EYLEA Product Information. 2. LUCENTIS Product Information.”

21 This was the form for the poster (second form), the baby banner (second form) (see [10] above) and the advertisements (second form).

22 The references to first form are to “Eylea helps …” (larger font) “when used …” (smaller font), and the references to second form are to “Eylea helps/for you and your patients …”, “when used … ” (same font).

23 Next I set out in chronological order the numbered acts of publication contended for by the applicant.

Date | Form of publication and event | |

1. | 28 July 2012 | Baby banner (first form) displayed by Bayer at the Sydney Eye Hospital Alumni Associate’s Ninth Biennial Conference held at the Sofitel Wentworth, Sydney |

2. | 3, 4 August 2012 | Poster (first form) displayed at Bayer’s trade display booth at a meeting of the Queensland branch of RANZCO |

3. | 6 August 2012 | Baby banner (first form) displayed by Bayer at an educational meeting held at Hobart Eye Surgeons, Hobart |

4. | September 2012 | Advertisement (first form) in Volume 40, Issue 7 of the journal Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology |

5. | October 2012 | Advertisement (first form) in Issue 73 of mivision magazine |

6. | 24 October 2012 | Attendee workbook (first form) displayed and disseminated at the Eylea product launch hosted by Bayer at Four Points by Sheraton, Sydney |

7. | 24 October 2012 | Poster (first form) displayed at Eylea product launch at Four Points by Sheraton, Sydney (respondent denies and says it displayed the baby banner (first form)) |

8. | 24 October 2012 | Attendee workbook (first form) displayed and disseminated at the Eylea product launch hosted by Bayer at the Sebel & Citigate Albert Park, Melbourne |

9. | 24 October 2012 | Attendee workbook (first form) displayed and disseminated at the Eylea product launch hosted by Bayer at the Sebel & Citigate King George Square, Brisbane |

10. | 24 October 2012 | Attendee workbook (first form) displayed and disseminated at the Eylea product launch hosted by Bayer at Hotel Grand Chancellor on Hindley, Adelaide |

11. | 24 October 2012 | Baby banner (first form) displayed by Bayer at the launch event at the Sebel & Citigate Albert Park, Melbourne |

12. | 24 October 2012 | Baby banner (first form) displayed by Bayer at the Sebel & Citigate King George Square, Brisbane (not admitted by respondent) |

13. | 27 October 2012 | Baby banner (first form) displayed by Bayer at a meeting attended by ophthalmologists at the Hotel Grand Chancellor, Hobart |

14. | November 2012 | Advertisement (first form) in Volume 40, Issue 8 of the journal Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology |

15. | November 2012 | Advertisement (first form) in Issue 74 of mivision magazine |

16. | 24 to 28 November 2012 | Poster (second form) displayed at Bayer’s trade display booth at a national meeting of RANZCO |

17. | December 2012 | Advertisement (second form) in Issue 75 of mivision magazine |

18. | December 2012 | Advertisement (first form) in Volume 40, Supplement S1 of the journal Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology |

19. | December 2012 | Advertisement (second form) in Volume 40, Issue 9 of the journal Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology |

20. | January 2013 | Advertisement (second form) in Volume 41, Issue 1 of the journal Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology |

21. | 9, 10 January 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at a training conference for registrar ophthalmologists held at the Sydney Eye Hospital |

22. | February 2013 | Advertisement (second form) in Issue 76 of mivision magazine |

23. | 1, 2 February 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at a meeting of the Tasmanian branch of RANZCO held at the Henry Jones Art Hotel, Hobart (not admitted by respondent) |

24. | 12 February 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an educational event held at the Lions Eye Institute, Nedlands, Western Australia |

25. | 26 February 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an optometrists’ referral meeting held at venue of the Victorian Eye Surgeons, Paisley Street, Footscray |

26. | March 2013 | Advertisement (second form) in Issue 77 of mivision magazine |

27. | 5 March 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at a referral meeting held at the Empire Grill, Geelong |

28. | 22, 23 March 2013 | Poster (second form) displayed by Bayer at its trade display booth at a meeting of the New South Wales branch of RANZCO |

29. | April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at a Luxottica educational meeting attended by optometrists held at the Novotel in Darling Harbour, Sydney (not admitted by respondent) |

30. | April 2013 | Advertisement (second form) in Volume 41, Issue 3 of the journal Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology |

31. | April 2013 | Advertisement (second form) in Issue 78 of mivision magazine |

32. | 3 April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an educational meeting for Luxottica optometrists held at the Mercure Hotel, Perth |

33. | 5-7 April 2013 | Poster (second form) displayed at Bayer’s trade display booth at the Australian Vision Convention, a meeting of the Optometrists’ Association of Australia held on the Gold Coast |

34. | 10 April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an optometrist referral meeting held at the Norwest Eye Clinic, Norwest, NSW |

35. | 10 April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an educational meeting attended by optometrists hosted by Outlook Eye Specialists held at the Vibe Hotel, Surfers Paradise |

36. | 10 April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an educational meeting for Luxottica optometrists held at the Amora Hotel, Richmond, Melbourne (not admitted by respondent) |

37. | 16 April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an educational meeting for Luxottica optometrists held at the Mercure Hotel, Geelong |

38. | 17 April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an educational meeting attended by optometrists held by Luxottica at the Old Woolstore Hotel, Hobart, Tasmania |

39. | 26 April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at a referral meeting attended by optometrists held at the consulting rooms of the Northern Eye Consultants, Victoria |

40. | 29 April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an educational meeting attended by optometrists held by Luxottica at the Lion Hotel, North Adelaide |

41. | 30 April 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at a retinal meeting held at the University Club at the Crawley campus of the University of Western Australia |

42. | May 2013 | Advertisement (second form) in Issue 79 of mivision magazine |

43. | 3 May 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an educational meeting attended by optometrists hosted by Central Queensland Eye held at the Mercure Hotel, Barney Point, Queensland |

44. | 7 May 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an optometrist referral meeting held at the Metwest Eye Clinic Blacktown, NSW |

45. | 14 May 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at an educational meeting attended by optometrists held by Luxottica at the Mantra in Chatswood, NSW |

46. | June 2013 | Baby banner (second form) displayed by Bayer at a Luxottica educational meeting attended by optometrists held at the Mantra Hotel in the Australian Capital Territory (not admitted by respondent) |

Various Dates (Novartis) Between May 2012 and May 2013 (Bayer) | Detailing Conduct (first form) |

24 I note that the first form ceased to be published at or about the time Eylea was listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and therefore became, practically, available for prescription. Novartis submitted that the first form applied at the critical time leading up to and through the national product launch, when minds were being won. On or about 15 May 2013, Bayer gave an undertaking that it would cease publishing or otherwise communicating the promotional material on a without admissions basis.

25 I consider at [227]–[233] below the disputed acts of publication.

The regulatory context

26 Under s 25(4) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (the TGA), as in force at the relevant time, the Secretary had a discretion to register therapeutic goods after an evaluation under s 25. If the Secretary decided so to register the goods and they were “restricted medicine” as defined, he or she was required to approve product information in relation to the medicine. Section 3(1) of the TGA defined “product information” in relation to therapeutic goods to mean: “information relating to the safe and effective use of the goods, including information regarding the usefulness and limitations of the goods.”

27 Under s 7D(1) of the TGA, a form was approved for providing product information to accompany the application for registration in accordance with s 23(2)(ba) of the TGA. That form required product information set out under certain specified headings including clinical trials and dosage and administration.

28 Under the Therapeutic Goods Regulations 1990 (Cth) (the TG Regulations), by reg 9A the sponsor of therapeutic goods (specified in Part 1 of Schedule 10) must not supply the goods if the sponsor does not supply with the goods written information about the goods that meets the requirements for a patient information document set out in Schedule 12 to the TG Regulations. By reg 9A(2), information must be provided in the primary pack in which the therapeutic goods are supplied or in another manner that will enable the information to be given to a person to whom the goods are administered or otherwise dispensed.

29 Schedule 12 to the TG Regulations provided, so far as relevant:

A patient information document about a medicinal product must be:

…

• consistent with product information about the product.

A patient information document must include the following:

1. Identification

The name of the medicinal product, which is the name given to the product by the sponsor, including or followed by the non-proprietary name(s) of the active ingredient(s) and the dosage form or strength, or both, of the product.

A statement of the active ingredients expressed quantitatively and excipients expressed qualitatively, using their common names, in the case of each presentation of the product.

The pharmaceutical form and the contents by weight, volume or number of doses of the product, in the case of each presentation of the product, together with its identifying Australian Register number.

2. What the product is used for and how it works

The therapeutic indications, unless a competent authority determines that dissemination of such information may have serious disadvantages for the patient.

The pharmaco-therapeutic group, or type of activity, if there is a term that is easily comprehensible for the patient. If not, a simple description of what the medicinal product is for and how it works, in 1 or 2 sentences.

3. Advice before using the medicinal product

A list of factors that are useful to consider before taking the medicinal product, including, if appropriate:

• contraindications, including consideration of whether the patient has experienced previous allergic reactions

• precautions for use, taking into account the particular condition of certain categories of users, such as the elderly, children, infants, pregnant or breastfeeding women, persons with specific pathological conditions

• potential effects of the medicinal product on the ability to drive vehicles or to operate machinery

• interactions with other medicinal products or other forms of interaction (for example with alcohol, tobacco, foodstuffs) which may affect the action of the product

• special warnings, such as effects on sensitivity to sun exposure.

4. How to use the medicinal product properly

The necessary and usual instructions for proper use of the medicinal product, in particular:

• the dosage, together with an indication that this may not always apply and may be modified by the prescriber

• the method and, if necessary, route of administration

• the frequency of administration, specifying, if necessary, the appropriate time at which the medicinal product should or must be used

In addition, depending upon the nature of the therapeutic goods:

• the duration of treatment, if it should be limited

• the expected effect of using the medicinal product

• what to do if 1 or more doses have not been taken

• the way the treatment should be stopped, if stopping the treatment may lead to withdrawal or other adverse effects. …

30 In order for a medicine to be listed on the PBS, the company must lodge a submission with the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) in accordance with the PBAC Guidelines: Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. The Guidelines applicable at the relevant time ran for nearly 300 pages. The overview of a major submission required: section A to establish the context for the submission, including a description of the proposed drug, its intended use on the PBS, and the therapies that would be co-administered or substituted (the therapy likely to be most replaced by prescribers in practice being the “main comparator”); section B to provide the best available evidence comparing the clinical performance of the proposed drug with that of the main comparator, preferably from direct randomised trials, and details to be provided about the trials, the section concluding with a comparative therapeutic assessment of the proposed drug; section C to describe the methods used in pre-modelling studies to translate the results of the evaluation of the clinical studies to the context of the requested listing; section D to provide an economic evaluation focused on changes in health outcomes and in the provision of healthcare resources due to the proposed drug; section E to include financial analyses for the PBS/Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and government health budgets; and section F (optional) to present any additional information of relevance to the major submission.

31 In the PBS Schedule the “dispensed price for maximum quantity” (the amount the Commonwealth government pays for the medicine so as to make it available at a government-subsidised price) was $1431.37 for Eylea and also for Lucentis. From 1 January 2013, the co-payment amount by a patient was $36.10 or, if the patient had a pensioner concession card, $5.90.

32 The Medicines Australia Code of Conduct edition 16 came into effect on 1 January 2010 (the Code). It stated it should be viewed as the minimum set of standards required to promote prescription products in Australia and did not in any way prohibit more stringent and comprehensive requirements being applied by individual companies. The Code complements the requirements of the TGA and the TG Regulations. Both Bayer and Novartis were members of Medicines Australia.

33 It was common ground that under the law in Australia it was illegal to advertise prescription-only medicines to the general public.

34 As I have said, Lucentis has been available for sale in Australia since 2007. It was approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration and was registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods in February 2007. From August 2007, Lucentis was listed on the PBS Schedule.

35 The Product Information for Lucentis contained the following:

Treatment of Wet AMD

The recommended dose of Lucentis is 0.5 mg (0.05 mL) or 0.3 mg (0.03 mL) given as a single intravitreal injection.

Lucentis is given monthly. The interval between two doses should not be shorter than 1 month. Although less effective, treatment might be reduced to one injection every 3 months after the first three injections (e.g. if monthly injections are not feasible) but, compared to continued monthly doses, dosing every 3 months may lead to an approximate 5-letter (1-line) loss of visual acuity benefit, on average, over the following nine months. Patients should be evaluated regularly.

36 The Consumer Medicine Information for Lucentis stated:

The usual dose is 0.05mL or 0.03mL

(equivalent to 0.5mg or 0.3mg). The

interval between two doses should

not be shorter than one month.

If you are treated for wet age-related

macular degeneration, the injection is

given once a month. If given less

frequently, the full benefit may not

be obtained or benefits already

obtained might be lost (that is your

vision might be less sharp or even).

37 On 7 March 2012, Eylea was registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods.

38 Between March and April 2012, Bayer sales representatives attended an 8 week training course including training in relation to anatomy, macular degeneration and wet AMD treatment options. On 23 March 2012, there was a “Marketing strategy & activities 2012” presentation to Bayer sales representatives.

39 Between May 2012 and May 2013, there was detailing conduct.

40 Eylea was launched on 24 October 2012.

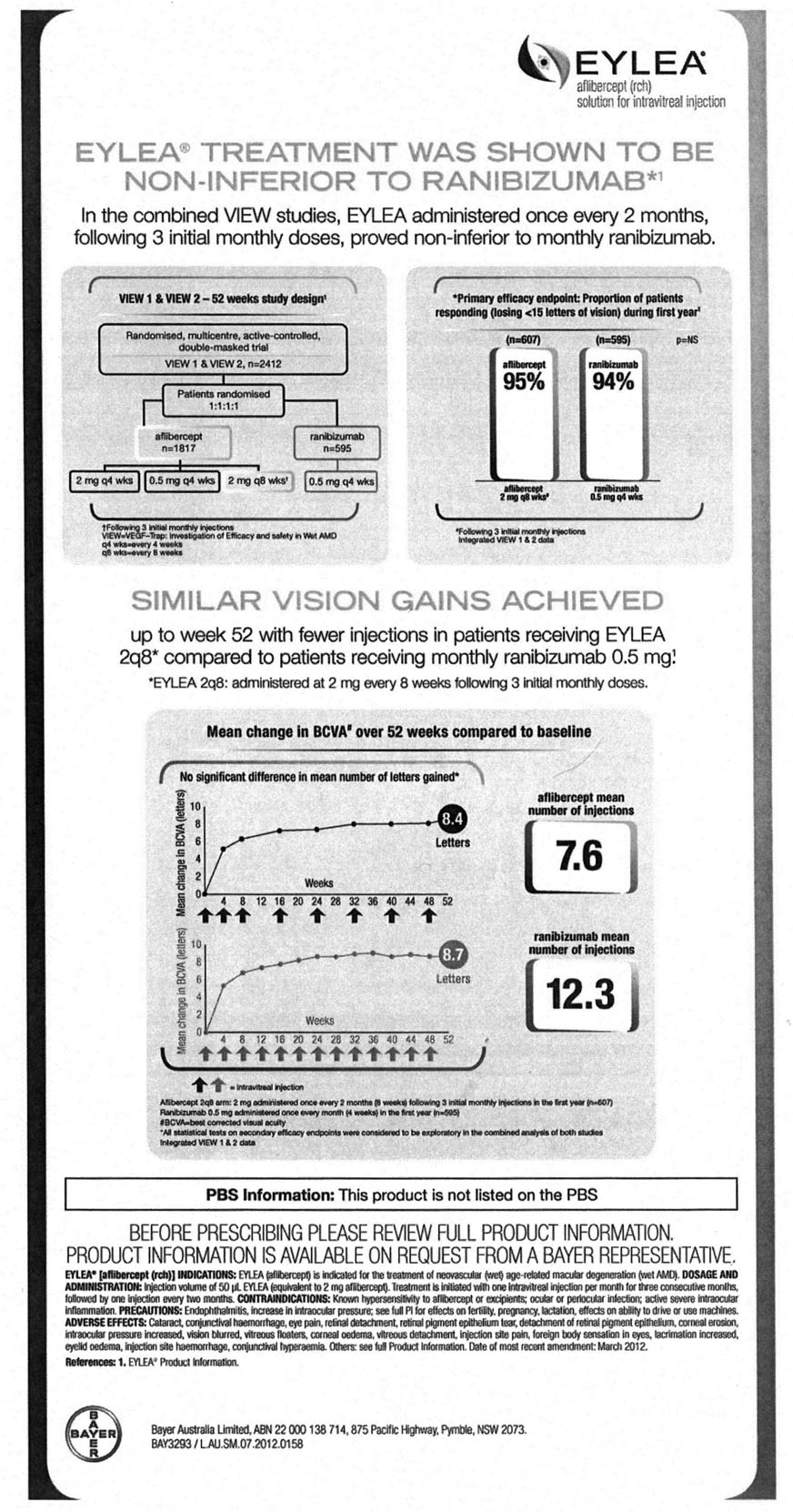

41 In December 2012, VIEW 1 and 2 year 1 trial results were published in Heier et al, ‘Intravitreal Aflibercept (VEGF Trap-Eye) in Wet Age-related Macular Degeneration’, Ophthalmology 2012; 119: 2537–2548. The summary objective, results and conclusions were stated as follows:

Objective: Two similarly designed, phase-3 studies (VEGF Trap-Eye: Investigation of Efficacy and Safety in Wet AMD [VIEW 1, VIEW 2]) of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) compared monthly and every-2-month dosing of intravitreal aflibercept injection (VEGF Trap-Eye; Regeneron, Tarrytown, NY, and Bayer HealthCare, Berlin, Germany) with monthly ranibizumab.

…

Results: All aflibercept groups were noninferior and clinically equivalent to monthly ranibizumab for the primary end point (the 2q4, 0.5q4, and 2q8 regimens were 95.1%, 95.9%, and 95.1%, respectively, for VIEW 1, and 95.6%, 96.3%, and 95.6%, respectively, for VIEW 2, whereas monthly ranibizumab was 94.4% in both studies). In a prespecified integrated analysis of the 2 studies, all aflibercept regimens were within 0.5 letters of the reference ranibizumab for mean change in BCVA; all aflibercept regimens also produced similar improvements in anatomic measures. Ocular and systemic adverse events were similar across treatment groups.

Conclusions: Intravitreal aflibercept dosed monthly or every 2 months after 3 initial monthly doses produced similar efficacy and safety outcomes as monthly ranibizumab. These studies demonstrate that aflibercept is an effective treatment for AMD, with the every-2-month regimen offering the potential to reduce the risk from monthly intravitreal injections and the burden of monthly monitoring.

42 On 1 December 2012, Eylea was listed on the PBS Schedule.

43 The product information for Eylea contained the following:

Pharmacodynamic effects

…

In patients treated with EYLEA (one injection per month for three consecutive months, followed by one injection every 2 months), retinal thickness decreased soon after treatment initiation, and the mean CNV lesion size was reduced, consistent with the results seen with ranibizumab 0.5 mg every month.

Dosage regimen

The injection volume is 50 μL of EYLEA (equivalent to 2 mg aflibercept).

EYLEA treatment is initiated with one injection per month for three consecutive months, followed by one injection every two months. (See CLINICAL TRIALS for dosing experience).

The clinical trials referred to were the VIEW 1 and VIEW 2 studies, which were summarised at pages 5 to 8 of the Eylea product information.

44 The Consumer Medicine Information for Eylea contained the following:

The recommended dose of EYLEA

is 50 μL (microlitre).

The interval between two doses

should not be shorter than one

month.

If you are being treated for wet

AMD:

The injection is given once a month

for the first 3 months followed by

one injection every 2 months.

The witnesses

45 The applicant relied on the evidence of the following witnesses:

(a) three affidavits of Ms Sweta Ghelani, affirmed 2 May 2013, 24 July 2013 and 30 August 2013;

(b) two affidavits of Dr Benjamin Waterhouse, sworn 14 August 2013 and 13 March 2014;

(c) two affidavits of Mr Paul Hodgkinson, sworn 23 August 2013 and 14 March 2014;

(d) four affidavits of Mr David Moore, health economist, affirmed 26 August 2013, 10 January 2014, 17 March 2014 and 12 April 2014; and

(e) three affidavits of Mr Tony Samuel, chartered accountant, affirmed 11 September 2013, 23 December 2013 and 17 March 2014.

46 The respondent relied on the evidence of the following witnesses:

(a) an affidavit of Dr Allan Ared, optometrist, affirmed 28 June 2013;

(b) two affidavits of Dr Paul Mitchell, retinal ophthalmologist, affirmed 28 June 2013 and 3 March 2014, the latter being supplemented by a report in the form of a letter to the respondent’s solicitors dated 10 April 2014;

(c) two affidavits of Dr Andrew Crawford, ophthalmologist, affirmed 28 June 2013 and 21 February 2014, and a report in the form of a letter dated 24 March 2014;

(d) an affidavit of Dr Jan Twomey, affirmed 8 November 2013;

(e) an affidavit of Ms Emel Elibol, affirmed 8 November 2013;

(f) an affidavit of Ms Radmila Grabovac, sworn 8 November 2013;

(g) an affidavit of Ms Naomi Leonard, sworn 8 November 2013;

(h) an affidavit of Ms Michele Doyle, sworn 8 November 2013;

(i) an affidavit of Mr John Burstow, sworn 8 November 2013;

(j) an affidavit of Mr Larry Hodges, affirmed 8 November 2013;

(k) an affidavit of Ms Cecilia Martinek, sworn 8 November 2013;

(l) two affidavits of Ms Susan Adams, affirmed 8 November 2013 and 19 December 2013;

(m) an affidavit of Ms Alena Reznichenko, affirmed 8 November 2013;

(n) an affidavit of Mr Andy Kuo, sworn 19 November 2013;

(o) an affidavit of Dr Philip Williams, economist, sworn 17 February 2014; and

(p) an affidavit of Mr Terence Potter, chartered accountant, sworn 14 February 2014.

47 Ms Ghelani was the marketing manager (wAMD) for Lucentis and had held that position since September 2012. In that role she was responsible for the oversight and coordination of the Lucentis marketing team. In July 2011, she began working as a member of the Lucentis cross-functional team in the role of Senior Brand Manager with her main responsibility being to optimise the commercial potential of Lucentis, including the development of marketing plans and sales material. In her affidavit of 24 July 2013, Ms Ghelani gave more detailed evidence of her experience as a pharmacist and in the marketing of pharmaceutical products. She has a Masters of Business (specialising in Marketing) from RMIT University, which she obtained in 2003. She said that as of April 2012, the International Council of Ophthalmology estimated on its website that there were approximately 763 ophthalmologists in Australia.

48 Much of her evidence was not controversial.

49 She gave her understanding of Lucentis as an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy and said that it was the only such therapy available for sale in Australia during the period 2007 to 2012. During the period 2007 to November 2012, Lucentis was the only anti-VEGF product available for sale in Australia which was registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods, listed on the PBS, and administered through intra-vitreal injection.

50 Ms Ghelani gave the monthly ex-factory sales of Lucentis by unit for the period January to November 2012. She then gave the sales figures for Lucentis for the period December 2012 to April 2013 following the launch of Eylea. It was in October 2012 that the Minister for Health announced that the proposed PBS listing for Eylea would be amended to allow the switching of existing Lucentis patients to Eylea. She also set out a table showing the relative market share (as measured by sales from wholesalers to pharmacies) for Lucentis and Eylea determined by reference to the data contained in a report by IMS, a company which provided industry market data. The figures for the monthly ex-factory sales of Lucentis by unit were substantially lower following the launch of Eylea and so was the share of the age-related macular degeneration (AMD) market in Australia held by Lucentis. A comparison of the monthly ex-factory sales of Lucentis by unit (vials) was 17,000 units in April 2012 against 8574 units in April 2013, and the market share for Lucentis in October 2012 was 99.9% (19,136 units) against 58.3% (9916 units) in February 2013, with Eylea having a market share in February 2013 of 41.7% (7090 units).

51 In her third affidavit, Ms Ghelani deposed that optometrists may detect evidence of wet AMD during a routine eye examination, and a patient who was having difficulty with their vision will often present to an optometrist, but optometrists may not diagnose or treat the condition. Consequently, they refer their patients to ophthalmologists who may make a diagnosis and then treat wet AMD, sometimes with intra-vitreal anti-VEGF injections such as Lucentis or Eylea. Both the Lucentis product information and the Eylea product information stated that the medicine must only be administered by a qualified ophthalmologist or physician experienced in administering intra-vitreal injections. The relevant entries on the PBS Schedule required that the intra-vitreal injections be administered by an ophthalmologist in order for reimbursement to be made. Consequently, Novartis focused its advertising, promotion and visits to optometrists on education in relation to identification of wet AMD, so as to facilitate diagnosis, and the importance of early referral to an ophthalmologist for definitive diagnosis and treatment as appropriate. For ophthalmologists, Novartis focused more directly on Lucentis and the science surrounding its features and would delve more deeply into the scientific literature in that regard.

52 Ms Ghelani deposed that after the initial scientific studies which established the safety and efficacy of Lucentis, many of the subsequent studies had attempted to determine whether, and the extent to which, the interval between injections of Lucentis could be extended beyond monthly.

53 In her oral evidence, Ms Ghelani said that most clinicians would know about the clinical trials in the product information document. She was speaking specifically of the ANCHOR and MARINA studies referred to in the Lucentis product information. She agreed that the exchange of scientific information with the clinician occurred very frequently. Ms Ghelani agreed that, in her perception, the ophthalmologists and optometrists she was visiting for Lucentis were aware in 2011 of Eylea on the horizon and that they were aware of clinical studies for Eylea either taking place or being reported as a precursor to the PBS launch of Eylea. Her understanding was that ophthalmologists and optometrists had their own sources of information about the coming of the Eylea product, including the obtaining by them of clinical study material and other scientific papers about aflibercept and its qualities. Before the first publication in issue in the proceedings, before July 2012, her understanding was that many ophthalmologists and optometrists already had a great deal of detailed information about the qualities of Eylea that was coming to market.

54 Ms Ghelani also agreed that Novartis’ marketing for Lucentis very regularly adopted the practice of footnoting a claim and the footnotes referred to product information documents as well as other clinical trials. She said whatever the claim, it must be supported by a form of evidence and it was usually either a clinical paper or the product information. It was her understanding that ophthalmologists and optometrists understood the procedure of footnoting product information documents.

55 More generally in relation to the product information document, her working assumption in her role was that the marketing of Lucentis had as one of its main facts that it conveyed to ophthalmologists what the approved product information document said about dosage and administration.

56 Ms Ghelani was taken in cross-examination to a Novartis marketing document prepared some time in the period April to July 2011 which contained the statement “A MONTHLY REGIMEN OF LUCENTIS DEMONSTRATED THE BEST VA OUTCOMES IN THE CLINICAL TRIALS”, with a footnote reference to a study published in 2009. She accepted that it was her understanding that the intention of the statement was to encourage a monthly regimen of Lucentis because it gave the best results and that if doctors took up the suggestion of a monthly regimen it would be good for sales as patients who are dosed monthly consume more vials and are materially more profitable to Novartis than patients who have intra-vitreal injections less frequently.

57 Ms Ghelani agreed that at the conferences there was a variety of information, including clinical studies and product information, which was available to conference delegates and that material was distributed as ophthalmologists or optometrists expressed an interest in it or they would sometimes pick it up. It was standard practice to have such material for people to pick up. As part of the Code, the product information must be available on the stand and the sponsor may also have available a clinical paper.

58 Ms Ghelani was taken to a Novartis document dated February 2013 referring to most clinics where clinicians practice (centres) having trialled aflibercept (at different rates), “mainly switching existing LUC[entis] patients not responding and/or patients who cannot be extended out further than 4–5 weeks [with or without] fluid on the retina”. Ms Ghelani accepted that in this analysis in the summary, the point was being made that two reasons were put forward for clinics switching existing Lucentis patients. She added there was a third reason given being extending out further than four or five weeks. She said that: “[i]n some cases as the extension occurs, sometimes the fluid returns. But in some cases clinicians may have wanted to extend the patient out further for other reasons, such as where they lived, or impact on carers to bring them into the clinic. So there potentially are other reasons other than purely efficacy.” She added it may be fluid was one of the reasons that the clinician did not want to extend the patients out but it may also be that the clinician just wished to extend the patient out further if they could and the clinician would have a clinical discussion with the patient around: “you might not get as great vision, but we’re going to extend you out to eight weeks because we know that you are coming from Dubbo into the clinic, and that’s a long way for someone to come for an injection in the eyeball.” She said her understanding of the reason an ophthalmologist would regard an existing Lucentis patient as not being able to be extended, and therefore should be switched, was that it could be the visual acuity outcomes were not as great or it could be fluid. She said that she knew that ‘treat and extend’ was the most predominant regimen in Australia and that had been verified by a number of quantitative sources of data as well, but accepted that she had not addressed that question or brought forward material to support it in her affidavits. In re-examination, she said that the Commonwealth’s drug utilisation sub committee in 2012 showed that in the first year, Lucentis patients were on 7.42 injections, which, she said, clearly indicated that those patients were not being dosed monthly. She also referred in re-examination to a touch responder pad of about 100 retinal specialists at a weekend conference, held usually in June of most years. Their response was that around 80% of clinicians used treat and extend, 10% use a PRN (i.e. as required) and the balance would be monthly.

59 She agreed that the marketing document attributed the switching as mainly being for the two reasons of non-responsiveness of Lucentis patients to Lucentis, on the one hand, and those who could not be extended without fluid on the retina on the other. She added another reason as well, being just simply not being able to extend the patient out. The same document set out qualitative feedback from the top ten prescribing doctors and in the headline stated that usage of aflibercept was mostly in non-responders and patients on four weekly Lucentis. Ms Ghelani said there were varying definitions as to what constituted a non-responder. She agreed that the reasons that Novartis was provided at the time by these clinicians were good clinical reasons for adopting Eylea as a treatment for wet AMD. The same document contained a statement that the sales of aflibercept for the first few months from December 2012 were identical to Lucentis at launch for the first few months from August 2007. The document also contained pages setting out “qualitative field insights and Novartis response”, being information that had become apparent to Novartis employees, predominantly the sales team, reporting back to Novartis. The document described three complaints and none of them was to the effect that Bayer’s advertising said of Lucentis that it was administered monthly for all patients. Ms Ghelani’s recollection was that there was no complaint at all about any reference to monthly Lucentis. In re-examination she was asked whether her thinking changed from the views there expressed and she said that what changed was that the switching did not just stop at patients at four weeks but patients at 5 to 11 plus weeks were being switched to Eylea and this was not anticipated: certainly people eight weeks and more were not anticipated by Novartis in its marketing assumptions. Novartis did not anticipate that clinicians would switch patients who had been extended and who were not having high volumes of injections.

60 Ms Ghelani was taken in cross-examination to a printout of the digital screens from the iPad sales aid deployed by sales and marketing representatives of Novartis in their meetings one-on-one with ophthalmologists and optometrists. She accepted that in Novartis’ promotion to ophthalmologists Novartis always put the particular mandatory statement as to the ANCHOR and MARINA trials, which involved Lucentis administered on a fixed monthly basis. The sales aid also included the statement “less than monthly dosing* can sustain VA improvements in some patients vs baseline at 12 months … *Lucentis® is given monthly. Although less effective, treatment might be reduced to one injection every three months after the first three injections (e.g. if monthly injections are not feasible).” Ms Ghelani did not accept that the iPad sales aid involved the regular frequent presentation to ophthalmologists of the proposition coming from Novartis that Lucentis was given monthly. She said she thought the page was about less than monthly dosing sustaining VA improvements but Novartis had “put the mandatory there because we want to be clear about what’s in our label”. She accepted that what she called “the mandatory” was something that appeared frequently and regularly in the sales aid iPad material that Novartis was providing to ophthalmologists in 2012 and 2013.

61 Ms Ghelani agreed that the Consumer Medicine Information for Lucentis included the words: “[i]f you are treated for wet age-related macular degeneration, the injection is given once a month. If given less frequently, the full benefit may not be obtained or benefits already obtained might be lost (that is your vision might be less sharp or even)” and was included in that Consumer Medicine Information at all times during 2012 and 2013.

62 Ms Ghelani was taken to a March 2013 report and accepted that, as there stated at that time, the uptake of Eylea in Australia was similar to Japan on the basis of comparing units and the uptake in Australia was similar to the United States on the basis of comparing patients. She accepted that the uptakes in Japan and in Australia in those initial months were similar and the uptakes in the United States and Australia were not dissimilar.

63 Subject to one exception, I accept Ms Ghelani’s evidence. In particular, I give weight to her understanding that most clinicians would know about the clinical trials in the product information document; that the exchange of scientific information with the clinicians occurred very frequently; her perception that the ophthalmologists and optometrists she was visiting for Lucentis were aware in 2011 of Eylea on the horizon and that they were aware of clinical studies for Eylea either taking place or being reported as a precursor to the PBS launch of Eylea; and her understanding that ophthalmologists and optometrists had their own sources of information about the coming of the Eylea product, including the obtaining by them of clinical study material and other scientific papers about aflibercept and its qualities, such that before 28 July 2012, the date of the first publication in issue in the proceedings, many ophthalmologists and optometrists already had a great deal of detailed information about the qualities of Eylea that was coming to market.

64 I also accept Ms Ghelani’s evidence as to the role of optometrists in relation to the detection of wet AMD, that is, that a patient having difficulty with their vision will often present to an optometrist, but optometrists may not diagnose or treat the condition. Consequently they refer their patients to ophthalmologists who may make a diagnosis and then treat wet AMD, sometimes with intra-vitreal anti-VEGF injections such as Lucentis or Eylea. This evidence is entirely consistent with that of Dr Ared, an optometrist called by the respondent. It establishes, and I so find, that any impact of the respondent’s conduct on optometrists is at best indirect because optometrists do not make any choice between Lucentis and Eylea. My finding is confirmed by Ms Ghelani’s evidence that Novartis focused its advertising, promotion and visits to optometrists on education in relation to identification of wet AMD, so as to facilitate diagnosis, and the importance of early referral to an ophthalmologist for definitive diagnosis and treatment as appropriate.

65 The exception to my acceptance of Ms Ghelani’s evidence, to which I have referred at [63] above, is that I do not accept that the Novartis sales aid was about less than monthly dosing sustaining VA improvements: in my opinion the statements in the sales aid should be taken as conveying, to those who read them, that the product information stated that Lucentis was given monthly and, although less effective, treatment might be reduced to one injection every three months after the first three injections (e.g. if monthly injections are not feasible).

66 Dr Jan Twomey was the medical director for Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, a division of Bayer, since August 2010. She graduated from medicine at Flinders University at the end of 1991. She had full general registration as a medical practitioner and had held this continuously since 1993. In 2004, she was appointed Acting Medical Director for the phase 1 clinical trials unit at GlaxoSmithKline Limited for a short period before holding the position of Associate Medical Director at Wyeth Limited, now part of Pfizer Limited. In August 2005, she was appointed Area Medical Director/Director of Global Clinical Operations for Australia and New Zealand at Schering Plough and held that position until February 2010. As Medical Director she was responsible for: Medical Affairs (which was responsible, amongst other things, for compliance review of all promotional material for pharmaceutical products); Medical Information (which was responsible for providing medical information requested by internal staff, healthcare professionals and consumers); Pharmacovigilance; Regulatory Affairs; and Clinical Operations.

67 Dr Twomey had ultimate autonomy and authority to review, reject and, if appropriate, approve marketing materials. She said it was her practice to approve marketing materials only if she was satisfied that they complied with all applicable Australian or New Zealand medical and compliance requirements, including the scientific veracity of any such campaigns. This involved ensuring such promotional materials met the relevant requirements set out in the Code and the TGA and the TG Regulations.

68 Dr Twomey said that clinical papers and academic articles formed an important part of the way that Bayer promoted prescription medicines, including Eylea, to doctors and educated doctors on the mechanism of action, efficacy and dosage strength and regimen for medicines. She said that part of the training of Bayer’s Eylea sales representatives included training given by Bayer’s medical affairs department on eye diseases and the structure and mechanism of action of Eylea, including the associated clinical trials and academic papers. As part of the training, sales representatives were instructed to take copies of clinical papers and academic articles to meetings with ophthalmologists or arrange for a copy to be sent to a doctor who asked for a paper or article the sales representative did not have to hand.

69 Dr Twomey listed a number of such clinical papers and academic articles which were referred to in the process of preparing the marketing materials for Eylea, including:

(a) VEGF-Trap: A VEGF blocker with potent antitumor effects, 99(17) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (2002), August 2002, Holash et al (2002) (Holash et al);

(b) VEGF Trap complex formation measures production rates of VEGF, providing a biomarker for predicting efficacious angiogenic blockade, 104(47) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (2007), November 2007, Rudge et al (Rudge et al);

(c) Predicted biological activity of intravitreal VEGF Trap, 92 British Journal of Ophthalmology (2008), March 2008, Stewart et al;

(d) VEGF Trap-Eye for Exudative AMD, Retinal Physician (2009), April 2009, Heier (Heier);

(e) Binding and neutralization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and related ligands by VEGF Trap, ranibizumab and bevacizumab, Angiogenesis (2012), February 2012, Papadopoulos et al (Papadopoulos et al);

(f) Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular (wet) age-related macular degeneration, 13(4) Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy (2012), March 2012, Ohr et al (Ohr et al);

(g) Intravitreal aflibercept (VEGF Trap-Eye) in wet Age-related macular degeneration, 119(12) Ophthalmology (2012), December 2012, Heier et al (Heier et al, elsewhere referred to as the VIEW study);

(h) Different antivascular endothelial growth factor treatments and regimens and their outcomes in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a literature review, 0:1-11 British Journal of Ophthalmology (2013), August 2013, Lanzetta et al (Lanzetta et al);

(i) Visual and anatomical outcomes of intravitreal aflibercept in eyes with persistent subfoveal fluid despite previous treatments with ranibizumab in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration, 33(8) The Journal of Retinal and Vitreous Diseases (2013), September 2013, Kumar et al (Kumar et al); and

(j) Conversion to aflibercept for chronic refractory or recurrent neovascular age-related macular degeneration, American Journal of Ophthalmology (1 July 2013), Yonekawa et al (Yonekawa et al).

70 Dr Twomey said she was responsible for approving and overseeing the approval of the marketing and educational materials for the Eylea campaign. She said this included a wide range of materials. She summarised examples of some of those materials, all of which were approved either by her or by staff within the medical department acting under her supervision. Her summary included: the first Detail Aid (from about May 2012 to around late June 2013); the second Detail Aid (from or around late June 2013); a document titled ‘Attendee Workbook’ that was to be made available for ophthalmologists attending the Eylea product launches in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and South Australia on 24 October 2012; various speeches and presentations made at the Eylea product launches on 24 October 2012; and a large pull-up banner for use by the territory managers. I have reproduced this banner at [110] below.

71 Dr Twomey gave her understanding of the term ‘me too’. She said it referred to a medicine that was a copy of an existing drug with only minimal differences — i.e. structurally very similar, with a very similar mechanism of action, dosing regimen, method of administration and therapeutic effect to the existing medicine. In particular, it offered no real clinical advantage or disadvantage over the existing medicine. She said that Eylea was not a ‘me too’ medicine in relation to Lucentis, in particular: it had a different active ingredient; it had a different mechanism of action; and it had a different dosing regimen.

72 In cross-examination, Dr Twomey agreed that the clinical papers she had listed — set out at [69](g), (h), (i) and (j) above — post-dated the particular set of marketing materials she had referred to in her affidavit and so were not referred to or considered for the purposes of approving those marketing materials. She said she had identified those four papers because they had been used in ongoing preparation of marketing materials.

73 Dr Twomey was asked about the term ‘me too’. She agreed it was a term used in pharmaceuticals but did not have a technical or fixed meaning. She agreed that one would not describe a generic drug as a ‘me too’ drug: it would be called a generic drug. She agreed that ‘me too’ was an expression used to describe similar drugs, but minds could legitimately differ in terms of the spectrum of similarity. She said that some people might have a different interpretation of whether a drug is ‘me too’ or not and agreed that the core concept was similarity and the area for different opinions was on the extent of similarity.

74 Very little of Dr Twomey’s affidavit evidence was challenged in cross-examination. There was some question as to how much of the materials for the Eylea campaign Dr Twomey approved or was responsible for approving. In her affidavit, at [39], she said she was responsible for approving and overseeing the approval of the marketing and educational materials for the Eylea campaign and said that she summarised examples in the following paragraphs. But the details of her approval or responsibility for or oversight of the approval of most of the material at issue in these proceedings was not tested. Her evidence was given in a matter of fact and responsive manner. I accept Dr Twomey’s evidence. In particular, I find that the emphasis of the training of Bayer’s sales representatives given by Bayer’s medical affairs department was on eye diseases and the structure and mechanism of action of Eylea, including the associated clinical trials and academic papers. I also find that Eylea was not a ‘me too’ drug in the sense that it was not relevantly the same as Lucentis: it had a different active ingredient; it had a different mechanism of action; and it had a different standard dosing regimen.

The Bayer sales representatives

75 I come now to the written and oral evidence of the sales representatives called by Bayer.

76 The first Bayer sales representative to give oral evidence was Ms Radmila Grabovac, the territory manager for the city of Melbourne and north-west Victoria. She had tertiary qualifications in business marketing. There were approximately 140 ophthalmologists in her territory and of those about 45 were injectors. She was given extensive product training on Eylea, and on anatomy and macular degeneration. She also gave evidence that she read textbooks on her own as well as having face-to-face training. She spent most of April and May 2012 in training including a few weeks in Sydney, training as a team with other territory managers. She also received training on how to use a presentation about Eylea on her iPad (Detail Aid). She said that she was aware that the proceedings involved a dispute about two pages of the Detail Aid (the disputed pages). She also referred to a database used by Bayer, called Cortex, to record sales calls. She said that whenever she made a sales call to an ophthalmologist or optometrist, she entered details of the call into Cortex. It was her practice to put in “the main crux” of her discussion with the doctor, anything interesting that they mentioned and the objective of the next call. She exhibited these notes to her affidavit. She said that she only used the Detail Aid in an arranged face-to-face meeting, called a “sit down call”, and then where she had the opportunity unless there was a time restriction or the ophthalmologist made it clear they were not interested in seeing it. She said that in the time between approximately May and September 2012 the only other information she had to use was the Eylea product information. After using the Detail Aid once or twice in the first or second call with a doctor, she did not generally use it again. Occasionally she used it to stress or explain a particular point in relation to clinical information or to answer administration questions on storage or vial size, for example. She estimated that the number of ophthalmologists to whom she showed the Detail Aid was between 63 and 72, but that figure may have been too high. She said it was rare for her to show the disputed pages to ophthalmologists, and an ophthalmologist would only have seen those slides by accident and in passing on one of the rare occasions when she opened the Detail Aid during the actual sales call instead of having it already open at the MOA (mode of action) tab where it was her practice to have the Detail Aid ready. She estimated that this would have happened with a maximum of 3 to 4 ophthalmologists. She did not think that any doctor would have seen only the disputed pages. Once the VIEW study clinical paper was published in December 2012/January 2013, she said it was her practice to build on the information about that study in the Detail Aid by referring to the actual VIEW study clinical paper and handing it out. She also handed out other clinical studies to ophthalmologists in sales calls. Those studies included: Ohr et al; Holash et al; Kumar et al; and Yonekawa et al.

77 In her oral evidence, Ms Grabovac said there was a national sales manager and there were eight representatives who reported to the national sales manager directly. Each of them worked solely in relation to the selling of Eylea. During her training she was not provided with a sales manual or any document identifying key selling messages and there were not key selling messages she took into the field. She was familiar with the phrase but said “we were not given key selling messages for the Eylea role”. She said she had a training manual that looked at anatomy, clinical papers, a lot of clinical information because “our role was to provide clinical information to doctors.” She disagreed that her role was to sell as many products as possible. She said there were no specific messages she was given to give the doctors regarding Eylea. The training was based around product information, the VIEW study, predominantly, and that was the main crux of the information that the sales representatives were giving to doctors. She denied that she had in mind when she met doctors in the field a key selling message or key selling messages in respect of Eylea. When taken to a reference to “key selling messages” in the notes of one of her sit down calls, on 10 May 2013, Ms Grabovac said “key selling messages” would have referred to reducing the burden for patients, which appeared in the VIEW study in several cases, reducing the burden for patients with less injections, and that would be supported with information, and perhaps she would have spoken about less visits and less chance of an adverse event, which was also highlighted and supported by the VIEW study and product information. She said she believed she would have spoken about key selling messages but there would have been a lot of other clinical information that was delivered and she believed that she spoke about the way the doctor treated and also the growth of his practice and how he managed patients. Ms Grabovac was next taken to another reference in her Cortex notes to key selling messages. She was asked what the key selling messages were and she said that to the best of her recollection “I would have assumed that it would be reducing — perhaps reducing the burden, which is also in the VIEW paper; providing, perhaps, less injections, as demonstrated in the VIEW study; perhaps less cost for the patient. And … Less visits … and less cost.” She agreed that the benefits she had identified all resulted from fewer injections. She agreed that one of her responsibilities was to grow sales. She also agreed that when she actually had a product, at the beginning of December 2012, she did have a sales target and one of her responsibilities was to achieve that sales target. She said she did not remember a clear marketing message being given based on anything outside the clinical information. She said she was told to discuss information that was in the product information and the VIEW paper because there was not a product for the first year. She denied that she had been seeking to convince ophthalmologists about the benefits of fewer injections of the product since at least May or June 2012. She said the discussion she had with ophthalmologists initially, from what she recalled, was information gathering, discussing the product information and developing relationships. She was taken to her Cortex notes for a sit down call on 3 July 2012 with an ophthalmologist. She agreed that what she did with that ophthalmologist, after discussing the MOA, efficacy and administration was to discuss the benefits of Eylea for patients and less injections. She agreed that what she was doing from July 2012, as one facet of what the role entailed, was laying the platform for future sales. She also agreed that one of the ways she sought to lay the platform was to impart the message of less injections. She said the comparison was with Lucentis, because in the VIEW study that was the comparison.

78 Ms Grabovac was next taken to a sit down sales call for an ophthalmologist on 21 May 2012. The notes recorded: “[w]ent through MOA, efficacy, admin and discuss benefits to the patient of less injections but with optimal treatment.” After first denying that she was seeking to convince ophthalmologists of the merits of Eylea over Lucentis, she accepted that that was one of the components of her discussions. She said she would never say to a doctor “Eylea helps you and your patients with fewer injections” without drawing reference to a clinical paper or product information because that was actually contrary to Medicines Australia. She agreed it was part of her task to talk about clinical equivalence based on the VIEW study because the VIEW study did demonstrate clinical non-inferiority to the current standard of treatment and it was equivalent in efficacy and safety.

79 Ms Grabovac said she called on optometrists on a couple of occasions only, although she went to lots of meetings where ophthalmologists were presenting to optometrists. She agreed that some optometrists wanted to know about treatment options for discussion with their patients. She also accepted that she spent time with an optometrist and she had a hope of a referral meeting. She said the reason there were referral meetings was not always about education of Eylea: it was relationship building and it was also educational support for doctors, ophthalmologists and their referrers. She accepted that she would be happy for optometrists to discuss the product because optometrists on occasion have close relationships with ophthalmologists.

80 Ms Grabovac was asked for her understanding on whether ophthalmologists were not in fact required to administer either Eylea or Lucentis in accordance with what was said about dosing in the product information. She was aware of the practice of treating other than on guidelines. She said this seemed to be the practice of therapy that was tailored specifically towards the needs of the patient in terms of interval. She needed to discuss Eylea treatment intervals on label which was what was approved in TGA guidelines. If the doctor chose to treat at different intervals, that was his or her choice. Some doctors did PRN, some did treat and extend, and some treated on label, whether it be monthly or two monthly. It was really a tailor-made approach for each patient based on the discussion and the evaluation the doctor would make with his or her patient. It was their choice how they treated their patient. Some had the discussion that they extended out over eight or 12 weeks. There was a range of practices.

81 In relation to the Detail Aid (iPad) Ms Grabovac’s evidence was that it was rare for her in sales calls to show the disputed pages (which were under the “Home” and “Summary” tabs). To the question whether the mode of action of Eylea was being explained to explain why there were fewer injections required with Eylea, Ms Grabovac answered “On occasion, yes”. She could not estimate the number of such occasions.

82 It is not a straightforward matter to evaluate Ms Grabovac’s evidence. Plainly she was nervous and uncomfortable giving evidence and volunteered that it was her first time in a court. Also she had some difficulties in understanding the more complex questions she was asked. On occasions she appeared reluctant to accept the obvious and was overly cautious in her answers. She was overly keen, in my view, to emphasise the informational aspects of her work rather than the selling of Eylea. But I find that she was truthful and I accept her evidence. In particular, I find that in her dealings with ophthalmologists and optometrists Ms Grabovac did not refer to fewer injections in the abstract but with reference to the product information, or a clinical paper, and the VIEW study paper once it became available. As to the disputed pages of the Detail Aid, I find that three or four ophthalmologists saw those pages in passing in the course of Ms Grabovac’s visits but in the context of the balance of the pages.

83 The second Bayer sales representative to give oral evidence was Ms Elibol. In her affidavit she said her sales territory was eastern Victoria. She replaced Ms Reznichenko as the Eylea territory manager for eastern Victoria when Ms Reznichenko was promoted. (Ms Reznichenko also gave evidence, which I consider below.) Ms Elibol said there were approximately 128 ophthalmologists in her territory and she shared approximately 15 of those with Ms Grabovac. She has a Bachelor of Science, a Diploma of Health — Medical Laboratory, and a Graduate Diploma in Business Systems. She said she had two weeks of training, including formal training from Bayer. She was shown how to use the Detail Aid on the iPad. From December 2012 to January 2013 she said the vast majority of her time spent with ophthalmologists and clinic support staff was spent answering logistical questions from doctors and clinic support staff such as: (a) How do I obtain Eylea? (b) How do I write a prescription for Eylea? (c) How many repeats do I need to prescribe? (d) How do I fill out the Medicare form? (d) What temperature is it stored at? and (e) What is Eylea’s shelflife/expiry date? Ms Elibol also annexed to her affidavit her Cortex notes. Her Cortex summary showed that she visited a total of 60 ophthalmologists and had at least one sit down call with each ophthalmologist during the period from 7 May 2012 to 21 June 2013. She said she did not recall using the Detail Aid at all during her first six months with Bayer from October 2012 to March 2013. She estimated she had used the Detail Aid approximately 3 to 4 times in sit down calls with ophthalmologists since March 2013. She did not recall ever using the “Summary” or “Home” tabs or the disputed pages within them. She said it was her practice only to use the Detail Aid in a reactive way, that is, if an ophthalmologist had a question. It was her practice to use the product information and clinical and academic papers about Eylea to answer any questions asked of her by ophthalmologists. She said she used the following clinical and academic papers as they became available: Holash et al; Ohr et al; Heier et al; Kumar et al; Yonekawa et al; and Lanzetta et al.

84 Ms Elibol estimated that approximately half the ophthalmologists in her territory injected for wet age-related macular degeneration. She said she did not conduct sales calls on optometrists and therefore did not show the Detail Aid to any optometrist.

85 In cross-examination, Ms Elibol was asked whether the statement “Eylea helps you and your patients with fewer injections” was the key marketing message for the sale of Eylea. She said she could not really answer that with a full yes or no because when she spoke about key messages she spoke about higher binding affinity, different molecule, that the eight weekly dose gave the same results as the four weekly dose. She said the key message of fewer injections with Eylea did not make sense to her. She said she would not discuss and say just there were fewer injections with Eylea. That needed an explanation. It depended entirely on the doctor and what the doctor was interested in: whether he or she wanted to know about the molecule, the mode of action, the trial design, the type of patients he was treating. The relevant transcript was as follows:

Q … So what you needed to do in order for ophthalmologists to consider switching over to your company’s product, EYLEA, was to point to some key difference in the products which he or she might find persuasive, a persuasive reason to change their existing practices. Do you agree with that?

A Because you mentioned key differences – I’ve pointed out key differences, because there has been patients that don’t respond to Lucentis that can respond to EYLEA because of difference in molecule design, difference in higher binding affinity, longer duration. So it’s - - -

Q Yes. Yes. Longer duration – can I ask you about longer duration? … If you pointed out longer duration, what you’re pointing out is that there would need to be fewer injections, because it lasts longer? Is that right?

A Yes, because it has got a higher binding affinity. It has got a lower dissociation constant … So once it binds, it doesn’t let go.

Q Yes. So did – can I just suggest to you - - -?

A But not in all patients. I’ve got to just – it’s not in all patients. It’s just what’s in the study…

Q But you did point out from time to time, can I suggest to you, to ophthalmologists, that this product requires fewer injections than Lucentis?

A Whenever I have pointed that out, it has been in reference to the VIEW trial or to the product information.

Q Yes. Yes. Yes. I’m just asking whether you did point that out?

A Yes. It’s in the trial – yes … It’s mentioned several times in the trial.

Q Yes. But you did point it out regularly, did you not, in your interactions with ophthalmologists, that EYLEA meant fewer injections for the ophthalmologist’s patients?

A Did I mention it regularly? … How would you define regularly? Sorry. Because I really concentrate on – I concentrate on my trial design, I talk about, again, the molecule design, it’s a human fusion protein, I – it’s level 1 evidence, the type of patients that were involved in the trial, how it might work for some patients where Lucentis doesn’t respond. So – I mean, I wouldn’t just go in there and just talk about fewer injections, fewer injections – it would have to come after a discussion.

Q Yes. And you’re not saying, are you, to his Honour that you never told a single ophthalmologist that EYLEA meant fewer injections – “Helps you and your patients with fewer injections”?

A Have I not – have I - - -

Q You’re not saying, are you, that you never said that to an ophthalmologist?

A No, I have said it.

…

Q Just focusing on the words, “EYLEA helps you and your patients with fewer injections.” Is it your evidence, Ms Elibol, that that statement – just that statement, “EYLEA helps you and your patients with fewer injections,” is misleading?

A Just that sentence, is that misleading? “EYLEA helps you and your patients with fewer injections.”

…

A What’s my belief? Like, what I think it is?

Q Yes. Yes?

A “EYLEA helps you and your patients with fewer injections,” I would like to know what is that compared to, personally, myself, if I saw that statement. Fewer injections compared to what?

Q Yes. Well – Lucentis?

A Okay. Fewer – in what way, I would want to know. Like, fewer injections in what way? How do you – what do you mean by fewer injections? That’s what I would want to know.

Q All right. Thank you. Because that statement may be misleading?

A Well, it just wouldn’t - - -

…

Q The statement, “EYLEA helps you and your patients with fewer injections,” just that statement?

A And so don’t look at the other thing – when you used according to – don’t look at that?

Q Yes. Yes?

A It wouldn’t make sense to me.

Q Right. Why?

A Because I - - -

Q Because you don’t know what it’s comparing it to?

A Yes. Like – yes. Comparing it to and how dosing - - -

Q All right. Well, just let me ask you this: it would be obvious, wouldn’t it – no. I will just leave that. I will leave that topic.

86 Ms Elibol was asked whether it was her understanding that a key message to communicate to physicians was that Eylea had comparable efficacy and safety to ranibizumab with fewer injections and she answered “Yes”.

87 Ms Elibol was asked whether she became aware of the summary results of the VIEW extension study soon after she started with Bayer. She said only from what she heard a few times from doctors from what they had heard from Novartis.

88 I found Ms Elibol to be a frank, forthright and truthful witness. I accept her evidence. In particular, I find that whenever she pointed out that Eylea required fewer injections than Lucentis it was with reference to the VIEW trial or to the product information. As to her use of the disputed pages, I find that she did not show the disputed pages to the ophthalmologists she visited and those ophthalmologists would not have seen those pages during her visits to them.

89 Ms Susan Adams was the third Bayer sales representative to give oral evidence. She was employed by Bayer as an Eylea territory manager between May 2012 and July 2013. Her territory was southern New South Wales and the ACT. Her customer base was made up of all the retinal specialists in her territory and some general ophthalmologists who managed patients with wet AMD. She has a Bachelor of Science and a Diploma of Education. She said she did not receive the same level of formal training as the rest of the team because she joined late and already had a very good knowledge of the treatment of wet AMD from her previous employment. She received an iPad with information about Eylea on it (Detail Aid) and she thought she received some training on the iPad but did not remember the details. She also exhibited to her affidavit her Cortex notes. She said that she made sales calls on 86 different ophthalmologists. She listed 24 where she was fairly confident that she did not show the Detail Aid to them and of the remaining 62 ophthalmologists she could not recall how many had seen the iPad presentation, although it was certainly not all. She said that the retinal specialists she dealt with were very well informed about Eylea and the timelines for its availability from data presented at congresses, international educational meetings and journal papers. She said their general reaction to Eylea was that they were pleased to have more than one drug available so as to have an alternative to Lucentis. She said she was told by some ophthalmologists that between “about 10% and 30% of their patients” were confined to monthly Lucentis and could not be “stretched out”. She was informed by retinal specialists that they were looking forward to the possibility of being able to extend treatment for these patients with Eylea. In relation to the Detail Aid she said to the best of her recollection she did not open the “Summary” tab but ophthalmologists may have seen pages under the “Home” tab when she was opening up the presentation, but that was rare and never intentional. To the best of her recollection, no doctor only saw the disputed pages. Ms Adams made a second affidavit as to her possession and use of the two baby banners.

90 In cross-examination, Ms Adams was first asked about the use of the poster and the baby banners.