Sandy on behalf of the Yugara People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2015] FCA 15

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Sandy on behalf of the Yugara People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2015] FCA 15

corrigendum

1 The list of parties on the cover page, Orders and Reasons pages has been amended.

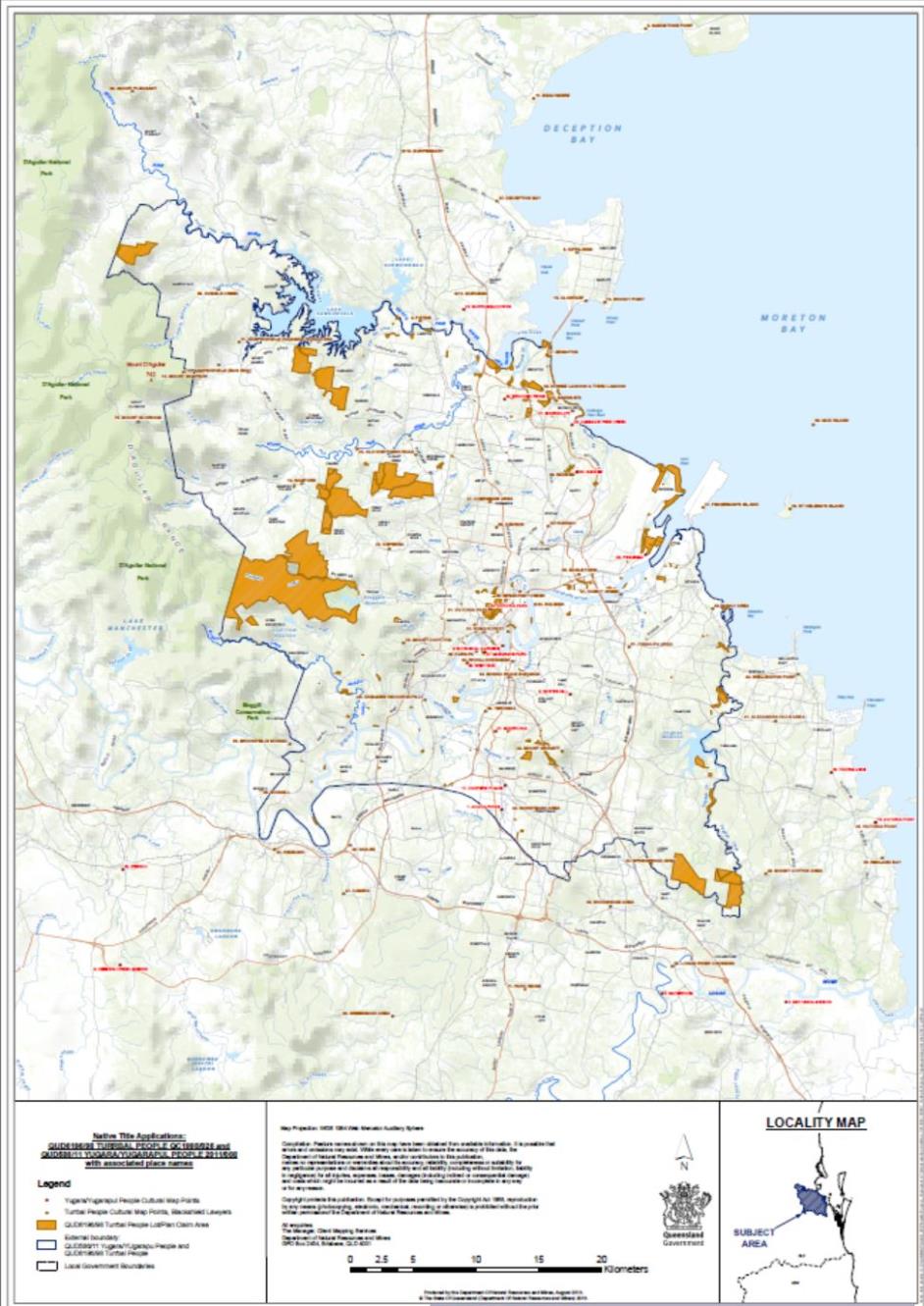

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Corrigendum to the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Jessup. |

Associate:

Dated: 2 February 2015

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: | Melbourne |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The questions referred to in the orders made on 30 October 2013 be answered as follows:

(a) No;

(b) Does not arise.

2. The proceeding be listed for further hearing in Brisbane at 2:15 pm on 11 February 2015.

3. Any party who, or which, proposes to submit that orders should now be made for the determination of the proceeding as a whole, file and serve a minute of the orders sought, and a brief memorandum in support of the making of the orders, on or before 6 February 2015.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 586 of 2011 QUD 6196 of 1998 |

BETWEEN: | DESMOND SANDY, RUTH JAMES and PEARL SANDY ON BEHALF OF THE YUGARA/YUGARAPUL PEOPLE First Applicants CONNIE ISAACS and MAROOCHY BARAMBAH ON BEHALF OF THE TURRBAL PEOPLE Second Applicants |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND First Respondent BRISBANE CITY COUNCIL Second Respondent MORETON BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL Third Respondent REDLAND CITY COUNCIL Fourth Respondent TELSTRA CORPORATION Fifth Respondent GARRY MURPHY Sixth Respondent BRISBANE PORT HOLDINGS PTY LTD Seventh Respondent EDDIE RUSKA Eighth Respondent LOGAN CITY COUNCIL Ninth Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Eleventh Respondent THE SHELL COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LTD (ACN 004 610 459) Twelfth Respondent INCITEC FERTILIZERS LTD Thirteenth Respondent MOONIE PIPELINE COMPANY PTY LTD Fourteenth Respondent CENTOR AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Fifteenth Respondent |

JUDGE: | JESSUP J |

DATE: | 27 JANUARY 2015 |

PLACE: | Melbourne |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 This proceeding arises from the consolidation, on 18 January 2013, of the following applications under s 61 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (“the Act”), each seeking a first determination of native title:

QUD 6196/1998, an application originally made by Connie Isaacs on 30 September 1998 on behalf of the Turrbal People; and

QUD 586/2011, an application made by Desmond Sandy, Ruth James and Pearl Sandy (“the Yugara applicants”) on 7 December 2011 on behalf of the Yugara, or Yugarapul (but referred to hereafter as the Yugara), People.

2 The State of Queensland (“the State”) is a respondent pursuant to s 84(4) of the Act. There are twelve other respondents but they did not participate in the hearing of so much of the case as is the subject of the reasons which follow.

3 On 11 March 2008, Ms Isaacs’ daughter, Maroochy Barambah, was added as an applicant on behalf of the Turrbal People, and, on the death of her mother on 8 May 2013, she became, and remains, the only such applicant. Despite that circumstance, Ms Barambah strongly resisted any suggestion that her mother’s name be removed from the record as an applicant in the case. In that resistance, she had the support of counsel for the State. In the circumstances, and despite my misgivings, I took no step to effectuate any such removal.

4 The subject of the present phase of the proceeding is defined by the terms of orders made by the court on 18 January, 23 May and 30 October 2013. On 18 January, and again on 23 May, it was ordered that all issues apart from extinguishment of native title be heard and determined prior to the hearing of any extinguishment issues. Then on 30 October, it was ordered that the following questions be determined at trial:

“But for any question of extinguishment of native title:

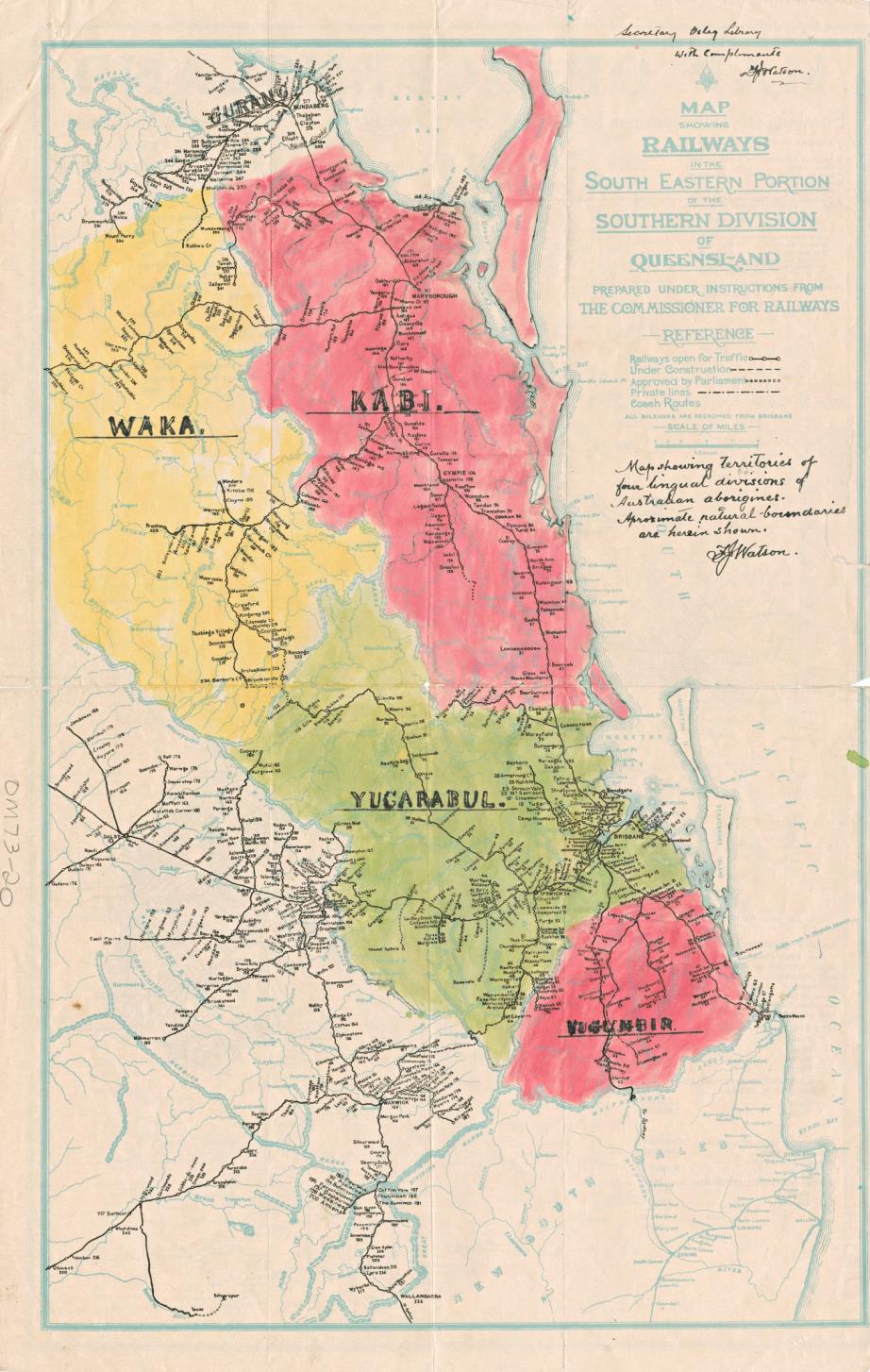

(a) does native title exist in relation to any and what land and waters of the claim area?

(b) in relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

i. who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title?

ii. what is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?”

5 The “claim area” is the area bounded by the dark blue line on the map in App A to these reasons. The Yugara application relates to the whole of that area. The Turrbal application relates to those parts of that area that are shown in brown on the map. As I understand the Turrbal case, the reason why parts only of the land bounded by the blue line on the map are claimed is the recognition that, in other respects, native title is likely to have been extinguished. Because I am not now concerned with the extent of extinguishment, Question (a) effectively requires me to take the same approach to the Turrbal application as I must in relation to the Yugara application. Ms Barambah contends that the question should be answered in the affirmative. She makes no discrimination as between different parts of the claim area. The effect of her submission is that, but for any question of extinguishment, native title exists in relation to all land and waters in the claim area. The Yugara applicants too contend that Question (a) should be answered in the affirmative, but they also make a submission in the alternative to which I shall come towards the end of these reasons. The State contends that Question (a) should be answered in the negative.

Native Title

6 What constitutes “native title” under the Act is the concern of s 223, subss (1) and (2) whereof provide as follows:

Common law rights and interests

(1) The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

Hunting, gathering and fishing covered

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), rights and interests in that subsection includes hunting, gathering, or fishing, rights and interests.

7 In Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 (“Yorta Yorta”), Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ referred to the three paragraphs of s 223(1) as setting up three “characteristics” of the rights or interests there mentioned (214 CLR at 440 [33]-[35]):

The first is that they are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the peoples concerned. That is, they must find their source in traditional law and custom, not in the common law (Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 at 66-67 [20]). It will be necessary to return to this characteristic.

Secondly, the rights and interests must have the characteristic that, by the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the relevant peoples, those peoples have “a connection with” the land or waters. Again, the connection to be identified is one whose source is traditional law and custom, not the common law.

Thirdly, the rights and interests in relation to land must be “recognised” by the common law of Australia ….

Their Honours said that the rights and interests referred to in s 223(1) –

… owed their origin to a normative system other than the legal system of the new sovereign power; they owed their origin to the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the indigenous peoples concerned.

(214 CLR at 441 [37])

8 With respect to the laws and customs referred to in paras (a) and (b) of s 223(1), their Honours said (214 CLR at 443 [42]):

Nonetheless, because the subject of consideration is rights or interests, the rules which together constitute the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed, and under which the rights or interests are said to be possessed, must be rules having normative content. Without that quality, there may be observable patterns of behaviour but not rights or interests in relation to land or waters.

And (214 CLR at 443 [43]):

Upon the Crown acquiring sovereignty, the normative or law-making system which then existed could not thereafter validly create new rights, duties or interests. Rights or interests in land created after sovereignty and which owed their origin and continued existence only to a normative system other than that of the new sovereign power, would not and will not be given effect by the legal order of the new sovereign.

And (214 CLR at 444 [44]):

Because there could be no parallel law-making system after the assertion of sovereignty it also follows that the only rights or interests in relation to land or waters, originating otherwise than in the new sovereign order, which will be recognised after the assertion of that new sovereignty are those that find their origin in pre-sovereignty law and custom.

9 With respect to the quality of the relationship between the laws and customs referred to as they existed at sovereignty and the laws and customs now identified as the source of the native title claimed, their Honours said in Yorta Yorta (214 CLR at 444-445 [46]-[47]):

A traditional law or custom is one which has been passed from generation to generation of a society, usually by word of mouth and common practice. But in the context of the Native Title Act, “traditional” carries with it two other elements in its meaning. First, it conveys an understanding of the age of the traditions: the origins of the content of the law or custom concerned are to be found in the normative rules of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies that existed before the assertion of sovereignty by the British Crown. It is only those normative rules that are “traditional” laws and customs.

Secondly, and no less importantly, the reference to rights or interests in land or waters being possessed under traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the peoples concerned, requires that the normative system under which the rights and interests are possessed (the traditional laws and customs) is a system that has had a continuous existence and vitality since sovereignty. If that normative system has not existed throughout that period, the rights and interests which owe their existence to that system will have ceased to exist. And any later attempt to revive adherence to the tenets of that former system cannot and will not reconstitute the traditional laws and customs out of which rights and interests must spring if they are to fall within the definition of native title.

10 Their Honours referred to what they described (214 CLR at 445) as the “inextricable link between a society and its laws and customs”. They said (214 CLR at 445 [49]) that “[l]aws and customs do not exist in a vacuum”. Their Honours continued (214 CLR at 445-446 [50]):

To speak of rights and interests possessed under an identified body of laws and customs is, therefore, to speak of rights and interests that are the creatures of the laws and customs of a particular society that exists as a group which acknowledges and observes those laws and customs. And if the society out of which the body of laws and customs arises ceases to exist as a group which acknowledges and observes those laws and customs, those laws and customs cease to have continued existence and vitality. Their content may be known but if there is no society which acknowledges and observes them, it ceases to be useful, even meaningful, to speak of them as a body of laws and customs acknowledged and observed, or productive of existing rights or interests, whether in relation to land or waters or otherwise.

And, a little later in their reasons (214 CLR at 446 [53]):

When the society whose laws or customs existed at sovereignty ceases to exist, the rights and interests in land to which these laws and customs gave rise, cease to exist. If the content of the former laws and customs is later adopted by some new society, those laws and customs will then owe their new life to that other, later, society and they are the laws acknowledged by, and customs observed by, that later society, they are not laws and customs which can now properly be described as being the existing laws and customs of the earlier society. The rights and interests in land to which the re-adopted laws and customs give rise are rights and interests which are not rooted in pre-sovereignty traditional law and custom but in the laws and customs of the new society.

11 The following lengthy passage, to be found later in their Honours’ reasons, is also essential reading for any court concerned to decide a question such as Question (a) as posed in the order of 30 October 2013 in the present case (214 CLR at 456-457 [86]-[89]):

Yet again, however, it is important to bear steadily in mind that the rights and interests which are said now to be possessed must nonetheless be rights and interests possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the peoples in question. Further, the connection which the peoples concerned have with the land or waters must be shown to be a connection by their traditional laws and customs. For the reasons given earlier, “traditional”' in this context must be understood to refer to the body of law and customs acknowledged and observed by the ancestors of the claimants at the time of sovereignty.

For exactly the same reasons, acknowledgment and observance of those laws and customs must have continued substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty. Were that not so, the laws and customs acknowledged and observed now could not properly be described as the traditional laws and customs of the peoples concerned. That would be so because they would not have been transmitted from generation to generation of the society for which they constituted a normative system giving rise to rights and interests in land as the body of laws and customs which, for each of those generations of that society, was the body of laws and customs which in fact regulated and defined the rights and interests which those peoples had and could exercise in relation to the land or waters concerned. They would be a body of laws and customs originating in the common acceptance by or agreement of a new society of indigenous peoples to acknowledge and observe laws and customs of content similar to, perhaps even identical with, those of an earlier and different society.

To return to a jurisprudential analysis, continuity in acknowledgment and observance of the normative rules in which the claimed rights and interests are said to find their foundations before sovereignty is essential because it is the normative quality of those rules which rendered the Crown’s radical title acquired at sovereignty subject to the rights and interests then existing and which now are identified as native title.

In the proposition that acknowledgment and observance must have continued substantially uninterrupted, the qualification “substantially” is not unimportant. It is a qualification that must be made in order to recognise that proof of continuous acknowledgment and observance, over the many years that have elapsed since sovereignty, of traditions that are oral traditions is very difficult. It is a qualification that must be made to recognise that European settlement has had the most profound effects on Aboriginal societies and that it is, therefore, inevitable that the structures and practices of those societies, and their members, will have undergone great change since European settlement. Nonetheless, because what must be identified is possession of rights and interests under traditional laws and customs, it is necessary to demonstrate that the normative system out of which the claimed rights and interests arise is the normative system of the society which came under a new sovereign order when the British Crown asserted sovereignty, not a normative system rooted in some other, different, society. To that end it must be shown that the society, under whose laws and customs the native title rights and interests are said to be possessed, has continued to exist throughout that period as a body united by its acknowledgment and observance of the laws and customs.

12 I would add that, as a matter of construction, the “aboriginal peoples” referred to three times in s 223(1) are the same peoples, and must necessarily be co-extensive with the claim group which is relevant in a particular case. This follows from the requirement in para (a) that the rights and interests “are possessed … by the Aboriginal peoples”, namely, those peoples who are mentioned in the introductory passage in the subsection, and those peoples who have the connection required by para (b). Further, the Act does not recognise the notion of interests in relation to land or waters abstracted from the identification of those who are possessed of them. Absent the legitimate claim of some other group, the failure of an applicant in a particular case to establish the title which he, she or the represented group holds will mean that native title does not exist in relation to the land in question.

13 It will be noted that Questions (a) and (b) above reflect the structure of s 225(a) and (b) of the Act. Counsel for the State submitted that neither the questions nor the section imply or implies a particular sequence in the intellectual exercise which such a determination requires. Rather, they identify the elements of the determination as made, or, in the present case, of the questions as answered. In particular, it was submitted, it would be both inappropriate and artificial to attempt to determine whether native title existed in relation to particular land without at the same time considering who were the individuals or groups who or which held that title. I accept that submission. As I have indicated, rights and interests of the relevant kind must of their nature be possessed by some person, persons or group.

14 It is also important, and in the present case it is crucial, that the relevant rights and interests be possessed under the traditional laws and under the traditional customs, referred to in the definition of “native title”. That is to say, the applicants must establish what those laws and customs said, and continue to say, on the question of entitlement to such rights and interests, and bring themselves within those entitling provisions. The importance of these considerations, in the present case, lies in the fact that, at least for relevant purposes, it was filiation that grounded the transfer of interests in relation to land and waters from one generation to the next. Absent the continuous existence of a visible society some of whose members were possessed of the relevant interests, it is inevitable that the applicants, in both applications, would seek to make good their claims that they are the ones now so possessed by reference to their biological descent. The present case has become the occasion to test the viability of those claims.

The Basis of the Applicants’ Claims

15 Each of the applicant groups claims native title on the basis of their biological descent from peoples who, at and immediately after sovereignty, formed part of aboriginal society in south-east Queensland. As will appear below, an aspect of the laws and customs of that society was that presently relevant interests in land and waters were held by members of local tribal groups. That is to say, when biological descent is invoked as the basis of present entitlement – as it is in this case – those presently claiming must establish descent from members of local tribal groups who themselves held the relevant interests in land the subject of the claim. To be descended from a local tribe whose members did not hold such interests would not be sufficient, even if there were, for example, a common language or the acknowledgement of the same body of laws or the observance of the same body of customs. In practical terms, this means that the applicant groups in the present case must establish that they are descended from members of tribal groups which inhabited the claim area, or parts of it.

16 The native title group on whose behalf the Turrbal application is made is defined as follows:

Connie Isaacs and her biological descendants, being the only known descendants of the Turrbal man known as the “Duke of York”, and the only known descendants of those people who comprised the Turrbal People as at 7 February 1788.

As will appear, the Duke of York was undoubtedly the leader of a tribe, or clan, of aboriginal people who inhabited the area to the north of the lower Brisbane River. It is readily to be inferred that the situation which the early settlers observed in this regard had existed at sovereignty (although the Duke of York himself had probably not been born by then). Subject to establishing descent (and subject also, of course, to the issue of continuity), Ms Barambah’s case conforms with the conceptual model to which I referred in the previous paragraph, at least in relation to the area of land in which the Duke of York and his followers had relevant interests.

17 The position occupied by the Yugara applicants is not so clear. The native title group on whose behalf their application is made is defined as follows:

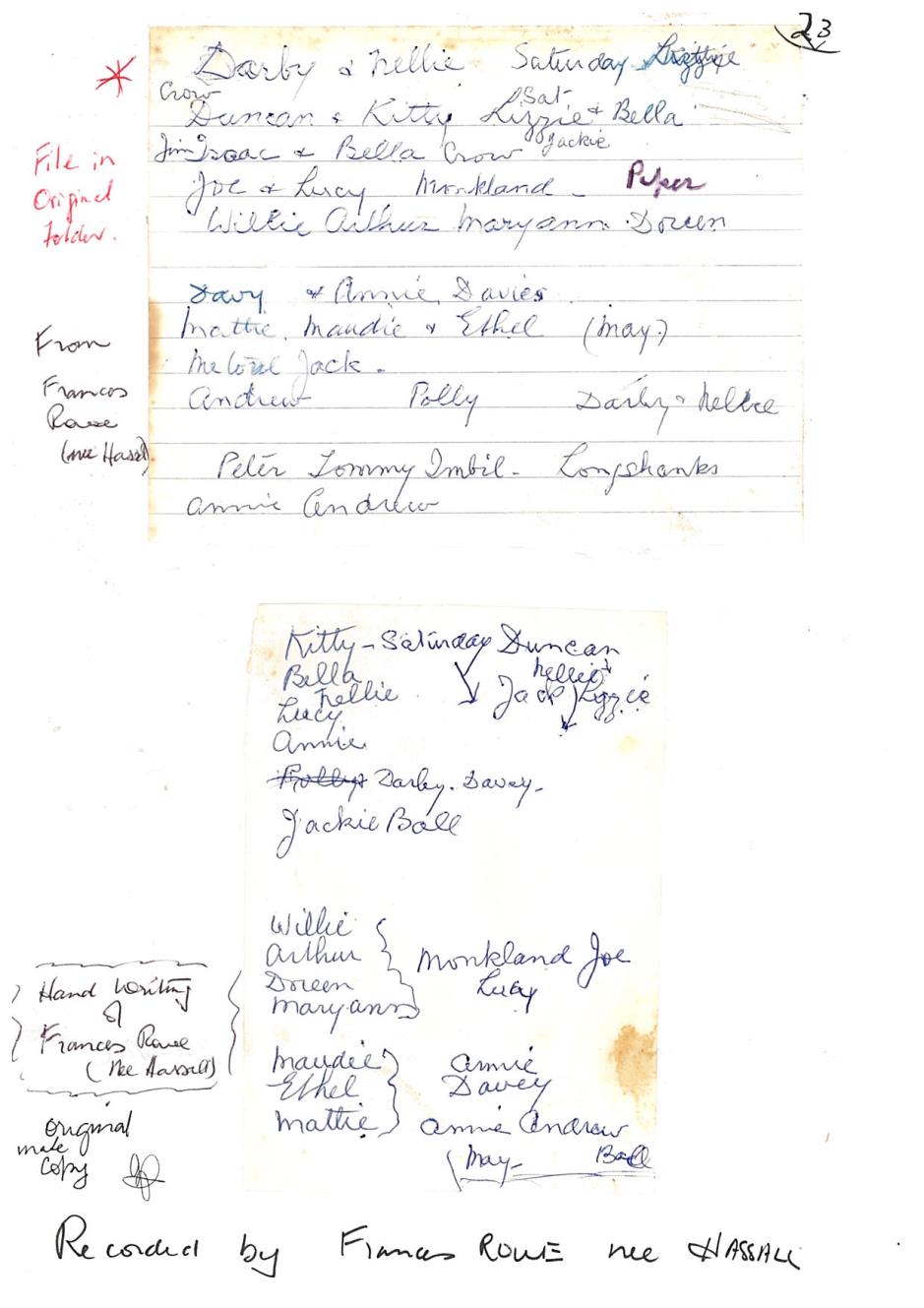

The biological and/or traditionally adopted descendants of the following people:

(i) Bilinba/Jackey (in particular Jackey Jackey/Kawae-Kawae and 3 wives Nellie, Mary and Sarah; and her brother-in-law Minnippi Rawlins)

(ii) Gairballie/Kerwalli/King Sandy (in particular his wife Naewin/Sarah)

(iii) Alexander/Sandy (Bungarr) and Paimba/Mary Ann Mitchell

(iv) John/Jack Bungaree (in particular his wife Mary Ann Sandy)

(v) Lizzie Sandy (in particular her husband William Mitchell)

(vi) Lizzie Sandy/Brown (in particular her son Billy Brown who married Topsy)

(vii) Kitty (in particular her daughter Molly and husband Ted Myers of Brisbane)

As will become apparent, there is a significant question as to the connection of these aborigines, or at least of most of them, to any land which lay within what is now the claim area. There are questions of descent in some cases, but in others the problem for the Yugara applicants is not so much the fact of descent as the relevance of descent to their claims in this case.

The Expert Witnesses

18 The subject of aboriginal society in the Brisbane area was dealt with in reports by anthropologists called by the parties. The Yugara applicants called Dr Fiona Powell, who graduated in 1968 with first class honours in anthropology and sociology, whose doctorate was awarded in 1976, whose special fields of interest are native title research, genealogical, historical and archival research, kinship systems and aboriginal history, whose areas of work experience include southern Queensland, and who has been the author of numerous reports on subjects within her area of expertise, including native title, since at least 1995. Despite the length of Dr Powell’s experience in relevant areas, it is clear from her curriculum vitae that she remains actively and regularly occupied in the provision of such reports.

19 In 2000, Dr Powell prepared a report for the FAIRA Aboriginal Corporation with respect to the connections of three indigenous families – Bell, Bonner and Sandy – to people and places in south-east Queensland, and to the Yugara language group. That report was in evidence in the present case. The Yugara applicants relied also upon two affidavits of Dr Powell affirmed in this case, one of 30 April 2012 and the other of 22 May 2012. The former was concerned substantially with answering Ms Barambah’s ancestry case (to which I shall refer in some detail below). The latter referred to the 2000 FAIRA report, and updated some details in relation to the Sandy family history. The most substantial – and, I would have to say, useful – evidentiary contribution made by Dr Powell, however, was her “Supplementary Anthropological Report” dated 3 December 2013, only eight days before she herself gave evidence and about a fortnight after the start of the trial. That dealt with a range of issues that were relevant to both major cases now before the court. I shall refer to it as required in my reasons below.

20 Ms Barambah called Dr Gaynor Macdonald, who graduated in 1981 in Social Science, whose doctorate was awarded in 1988, who is, and has since 1999 been, a senior lecturer and consultant anthropologist at the University of Sydney, whose work since 1981 has been focused within the Wiradjuri language territory and has involved research and publication primarily on contemporary aboriginal cultural and social life, with an emphasis on interpreting culture and change over time and the assessment of the extent to which traditions of aboriginal life have continued to impact on contemporary lives, who has conducted field work in diverse regions, including south-east Queensland, and who has published widely, and provided numerous research reports, in the area of her expertise.

21 Ms Barambah relied on a report dated September 2009 by Dr Macdonald titled, “The Boundaries of Turrbal-Speaking Territory: An Anthropological Assessment”, the subject of which is sufficiently indicated by that title. In June 2010, Dr Macdonald provided a further report on the subject “An Anthropological Assessment of Turrbal Connection”, which was also placed into evidence. That was a very substantial piece of work, and I shall refer to it as required below. Ms Barambah tendered a report, dated April 2011, which consisted of “Supplementary Details” with respect to Dr Macdonald’s earlier anthropological report. Dr Macdonald also provided a “Supplementary Anthropological Report” in October 2011, which was tendered by Ms Barambah. These three reports were prepared in the period when the Turrbal claim was the only relevant claim to the area now under consideration. Then, in the period subsequent to the filing of the Yugara application, Dr Macdonald affirmed an affidavit on 1 June 2012 in answer to Dr Powell’s affidavit of 30 April 2012. Finally, after the conference of the anthropologists, Dr Macdonald supplied a further supplementary report which was filed on 18 November 2013, about a week before the start of the trial.

22 The State called Dr Nancy Williams, who graduated (with distinction) from Stanford University, whose post-graduate degrees, including her doctorate, were obtained from the University of California (Berkeley), who has held a number of positions in universities and research institutions, most recently that of Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at the University of Queensland, who is now an Honorary Reader in Anthropology in the School of Social Science at that university, whose field of expertise includes aboriginal systems of land tenure and resource management and has involved research with aboriginal groups over a large area of northern Australia, and who has published widely in that field.

23 Dr Williams was engaged by the State to review the reports which had been filed by the other parties and to provide her opinion upon specific questions considered relevant to the case, under the headings “the normative system of law and custom”, “the claimant groups”, “continuity” and “connection”. She did so in a report dated 8 August 2013, which was tendered by the State. Dr Williams provided a second report, also tendered by the State, dated 15 November 2013.

24 The anthropologists referred to above participated in two conferences, the first on 29 August 2013 and the second on 9-10 October 2013. They provided a report in the form of a table with three columns, one for the views of each of them. The occasions upon which they had reached a tripartite consensus were few. This was, therefore, a joint report only in the documentary sense. Nonetheless, the report has been a valuable resource for the court so far as it goes. It was placed into evidence by the State, with the agreement of the other parties.

25 The specifically historical dimension of aboriginal society in the Brisbane area was also the subject of a report by Dr Rod Fisher, a historian whose undergraduate qualification was obtained in 1962, whose master’s degree was obtained in 1970 and whose doctorate was obtained in 1974. That report was provided to the Turrbal claim group in November 2009, and was tendered by Ms Barambah. However, Dr Fisher was not available for cross-examination, in consequence of which Ms Barambah had little choice but to accede to the other parties’ redaction requests in relation to the report. As heavily redacted, the report was received into evidence without objection.

26 The Yugara applicants also called two linguists, Dr Margaret Sharpe and Dr Sylvia Haworth. Dr Sharpe is an Adjunct Senior Lecturer in Behavioural and Cognitive Studies at the University of New England, and is an expert linguist in aboriginal languages. In 2000, she wrote a “Report to FAIRA on the Linguistic Literature of the Brisbane Region”. A copy of that report is annexed to Dr Sharpe’s affidavit of 9 April 2013, which was admitted into evidence. An earlier affidavit, made on 17 April 2012, is also in evidence. In it, Dr Sharpe refers to her 2000 report, and reiterates her opinion that a single language was spoken over, and in some respects more widely than, the present claim area.

27 Dr Haworth obtained her doctorate in 1995 and is an independent researcher of aboriginal languages. In her affidavit of 18 June 2013, she reports on her examination of “almost all known language records from south-east Queensland that are in the public domain”. She expresses a conclusion about the conformity of words and expressions used in parts of south-east Queensland with those used in other parts thereof. I shall refer to her conclusions in due course below.

Aboriginal Society in the Brisbane area at Sovereignty

28 The State accepted that it should be inferred, from what we know of aboriginal life and society at and after the earliest days of white contact (in the 1820s) that, at sovereignty, the claim area was occupied by aboriginal people who were united by their acknowledgement and observance of a body of law and customs. So far as it goes, that also reflects the position taken by both applicant groups. It is also common ground that this body of law and customs would have been acknowledged and observed over a wider, probably a much wider, area.

29 The anthropologists were asked for their opinions as to the extent of the society which then existed, and specifically whether there was anything in the laws and customs which marked out the claim area as distinguishable from areas around it. Dr Williams said:

For me the most productive way to look at the area is in terms of networks of interacting groups. It’s an interactive network of groups, all of whom share the same laws and customs … from which their rights in the country were derived. … It was an area … in respect of this region which included the language groups, Wakka Wakka, Gubbi Gubbi, Yugara and the subgroups within there. … [Y]ou could see the limits of it in terms of all the people who attended the Bunya festivals. And they would have shared the same laws and customs that would have been operating through the region.

Dr Powell agreed that there was a “regional system of law and custom” which extended well beyond the claim area across the whole of what is now known as south-east Queensland. Within that region, there were “territorial groups”, each under a “headman”, but the content of the laws and customs was substantially uniform over the whole of the region. Dr Macdonald said that the people living in all of the territorial divisions potentially of present relevance were “part of a highly regionalised ceremonial and belief system”. Within such a system, there were local territories in which peoples were organised under their various headmen, but “they [were] all part of one society, one system of law and custom”. The anthropologists were agreed that, if there was something which marked out the claim area as different from the areas around, and outside, it, it was not the existence of a separate system of laws and customs.

30 For reasons which will become clear, the present case cannot be resolved by reference only to the conclusions reached in the previous paragraph. It will be necessary next to consider the local, or territorial, groupings which inferentially existed within, and surrounding, the claim area. Commencing at a high level of generality, one discriminator which was discussed extensively in the expert evidence was language.

31 The anthropologists agreed that language is an important aspect of any consideration of the composition of a pre-sovereignty indigenous society within a defined area. Usage of a common language implies both a common society, at least at a high level of identification, and a sense of attachment to the land in question. Dr Macdonald said:

So the language is not simply understood as a form of communication, which I think is what most of the discussion has been about; language is, in fact, an incredibly important form of identification regardless of whether you actually speak it or not. The land and language are one consubstantiated reality, if you like.

32 Dr Powell said:

From my experience, people who say they – who identify themselves as language owners, not necessarily users, but owners because it’s their right – they have a birth right that’s inalienable. They – it’s to own the language of their forebears. That’s what I mean when I say language groups, and they don’t necessarily have to be able to speak that language, but they have a right under Aboriginal law and custom to say that’s my language and they take their identity from it.

Asked about the relationship between the use of a language and connection to the land over which that language was used, Dr Powell said that use of a language was –

… demonstrating your ownership of a dual right to own that land … that connects you to that language country. You have a right. So, if you’re not – you have a birth right and it’s come – it’s one of the rights that have descended to you.

Dr Powell made it clear, however, that the fact that a common language was used in a known area did not, of itself, establish that everyone who used that language would have rights to land over the whole of the area. She said:

[It] will depend then … where your ancestors come from … because that’s how people take their country.

33 Dr Williams said:

Well, for a whole range of historical circumstances, some of which have only been implied, some of which have been assumed, historical changes in the context of Australian history, people have been dislocated, they’ve moved, but they still recognise that they own a language. So they may no longer be able to speak it, or maybe only a few words, but that’s their language. They own it. It’s a part of their patrimony, it’s part of what comes with the land with which they’re associated, and their ancestors have been associated.

34 In a paper written by FJ Watson entitled “Vocabularies of Four Representative Tribes of South Eastern Queensland”, published as a supplement to Vol 48 of the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia (Queensland) in 1944, the author said:

In South East Queensland, that is, between the Pacific Ocean in the East, the Great Dividing Range in the West, the Burnett River in the North, and the Macpherson Range in the South, including Great Sandy, or Fraser’s Island and Bribie’s Island, but excluding Moreton and Stradbroke Islands, of whose people and language but little seems to have been recorded, there were but four distinct lingual divisions or tribes.

These tribes were the Kabi, Wakka, Yugarabul, and Yugumbir. The territory of the Kabi practically coincided with the basins of the Mary and Burrum Rivers, as well as those of the smaller streams that drain the Blackall Range on its eastern slope. It also included Great Sandy and Bribie’s Islands.

The Wakka tribe occupied the basins of the tributaries of the Upper Burnett River. The territory of the Yugarabul was the basins of the Brisbane and Caboolture Rivers, and that of the Yugumbir was the basins of the Logan and Albert Rivers.

The territories overlapped these areas in some places, but not to any great extent.

The names of these tribes, which were identical with the names of their individual languages, were derived from the negative word of each language, the words kabi, wakka, yugar and yugum each having the meaning of no, nothing, nowhere, etc.

….

The tribes were subdivided into locality groups, each group occupying a portion of the tribal territory which was generally recognised as its peculiar right.

Each group had a distinctive name, which, in many cases, was derived from some outstanding feature of the group’s territory, either of its geography, geology, flora or fauna.

An instance of this is the Taraubul group of the Yugarabul tribe, whose territory included the site of the City of Brisbane. This name has been rendered by historians, variously, as Turrbul, Turubul, Turrabul, and Toorbal, the difference in spelling being, no doubt, due to its peculiar pronunciation by the aborigines. The word tarau, which is common to the Yugarabul and Yugumbir tribes means stones, referring particularly to loose stones, and the name Taraubul is evidently derived from the geological nature of the Brisbane area, the formation of which is almost entirely of brittle schist.

35 Watson also prepared a map which showed the four broad “lingual divisions” to which he referred in his paper. That map is reproduced here. The “Kabi” and “Waka” divisions correspond very approximately with the “Gubbi Gubbi” and the “Wakka Wakka” language groups referred to by Dr Williams in the passage set out above (see para 29).

36 Dr Williams agreed with Watson’s map, at least as an approximation. So did Dr Macdonald, but only in the purely linguistic sense. She did not accept that the aborigines themselves, before or immediately after sovereignty, would have connected with their own territory in these terms. In particular, I understand Dr Macdonald to take issue with any proposition that would equate connection, in the native title sense, with the very large area of land marked as “Yugarabul” on Watson’s map. She stressed, quite appropriately in my view, the differences in dialect that seemingly existed within that area, and which had the capacity to indicate different centres of connection to land that might today be relevant to questions of native title. Dr Powell, too, as I understand her, was content to accept the broad outlines of Watson’s divisions, save that she had reservations about the reliability of his depiction of the Yugumbir division, a controversy which may be left for another day.

37 What Watson referred to as “the Taraubul group of the Yugarabul tribe” was a reference to the Turrbal people on whose behalf Ms Barambah makes her present application. She does, of course, contest the suggestion that this group was no more than a group within the Yugarabul division, but it is clear that Watson was referring to this group. Dr Sharpe expressed the view that Watson’s explanation of the origin of the name of the group as related in some way to the geology of the Brisbane area was most likely correct.

38 I mention next the historical writings of Constance Petrie, the daughter of Thomas Petrie who arrived as a six year-old with his parents at Moreton Bay in 1837. As a boy, he spent much time with the aborigines in that vicinity. In his adult life, he secured a property in the North Pine area, and again had extensive contact with the aborigines. He conversed with them in their own language. Based on conversations which she had had with her father, Constance Petrie contributed a series of articles about the aborigines in the Brisbane and North Pine areas which were published in The Queenslander. In 1904, these articles were collected together in a book under her name titled Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland.

39 In a forenote to the book, there is set out a letter to the editor of The Queenslander by Dr Walter Roth, author of Ethnological Studies and, in 1904 at least, Chief Protector of Aboriginals in Queensland, as follows:

It is with extreme interest that I have perused the remarkable series of articles appearing in the Queenslander under the above heading, and sincerely trust that they will be subsequently reprinted. . . . The aborigines of Australia are fast dying out, and with them one of the most interesting phases in the history and development of man. Articles such as these, referring to the old Brisbane blacks, of whom I believe but one old warrior still remains, are well worth permanently recording in convenient book form – they are, all of them, clear, straight-forward statements of facts – many of which by analogy, and from early records, I have been able to confirm and verify – they show an intimate and profound knowledge of the aboriginals with whom they deal, and if only to show with what diligence they have been written, the native names are correctly, i.e. rationally spelt. Indeed, I know of no other author whose writings on the autochthonous Brisbaneites can compare with those under the initials of C.C.P. If these reminiscences are to be reprinted, I will be glad of your kindly bearing me in mind as a subscriber to the volume.

Although Petrie’s Reminiscences was the subject of some reservations on the part of the expert witnesses who gave evidence in this case, generally it was accepted as an authoritative account of the characteristics, habits and lives of the aborigines who inhabited the Brisbane area in the nineteenth century. I shall be referring to it in a number of contexts below.

40 Petrie consistently referred to a “Turrbal” language. In the first chapter of his Reminiscences, the following appears (remembering that this is in the hand of his daughter):

Queensland is a large country, and the tribes in the North differ in their languages, habits, and beliefs from the blacks about Brisbane. Father was very familiar with the Brisbane tribe (Turrbal), and several other tribes all belonging to Southern Queensland who had different languages, but the same habits, etc. The Turrbul language was spoken as far inland as Gold Creek or Moggill, as far north as North Pine, and south to the Logan, but my father could also speak to and understand any black from Ipswich, as far north as Mount Perry, or from Frazer, Bribie, Stradbroke, and Moreton Islands.

In the present case, there is a question whether the “Turrbal language” identified by Petrie was a language in its own right confined to the area to which he referred, or was a component within – perhaps a dialect of – the language spoken over the broader area identified by Watson.

41 The evidence of both of the linguists was to the effect that the same language was spoken over the whole of the claim area, and much to the south as well. Consistently with Watson, this has been referred to as the Yugara or “Yugarabul” language. In her 2000 report, Dr Sharpe said:

Firstly, the reader should note that I refer to the ‘language of the Brisbane area’ as Yagara. (The issue of what constitutes a language will be discussed below.) Yagara was the word for ‘no’ in some of the dialects of this language. Some sources call the whole language Turrubul, Turrbal, etc. This language in its various dialects was spoken in the Brisbane area, in North Stradbroke Island and southern Moreton Island, as far south on the coast as Pimpama, north and west of the Logan River, perhaps nearly to Beaudesert, in Ipswich area and down the Fassifern Valley to Boonah, and possibly as far west as Gatton.

Dr Haworth said:

My consideration of these materials found that the known lists associated with the region from the north bank of the Brisbane to the Pine River valley agree substantially, as regards vocabulary and syntax, with the lists collected from the area from the south bank of the Brisbane to the north bank of the Logan, and also from west as far as Gatton and south and west as far as Coochin Coochin station (Bell) and Hardcastle’s material, and with the material recorded from Stradbroke. They agree with those lists far more than they agree with anything else.

The linguists were prepared to accept that there were different dialects in different parts of the broad area over which this language was spoken, but they rejected the notion that the language as such differed in any part from that spoken in any other part.

42 To the extent that we may follow Watson and suppose that both language and tribe names as used by the aborigines themselves were linked to words used to denote the negative (albeit that none of the experts wanted to place too much store by this supposition), it may be noted that, in a short word list in the back of Petrie’s own book, the word for “no” is given as “Yaggaar”. Ms Barambah points out, with some justification, that there are indications that the word “baal” was sometimes used for “no” in the Moreton Bay area, but both of the linguists indicated that this was a word in use in the Sydney area, and the possibility that it had made its way to Moreton Bay overland, even as a result of usage by whites, cannot, it seems, be discounted.

43 On the basis of the evidence to which I have referred, I would accept that a single language, albeit probably involving different dialects, was spoken over a region much more extensive than the claim area. Petrie’s observation (in the passage to which I refer at para 44 below) is not inconsistent with that. Nothing turns on the name by which we may identify that language, but, if we follow the “sources” referred to by Dr Sharpe (of which, it seems Petrie himself was one) in calling the language “Turrbal” or similar, that should not imply that there was a separate language spoken by the aborigines in the claim area. As indicated above, I think that the better view is that there was not. To this extent, identifying the language as “Yugara” or similar would have at least have the advantage of implying a geographical spread of the language which recognises two relatively uncontroversial circumstances: that it differed from that spoken to the north by the Wakka Wakka and the Gubbi Gubbi peoples, and that its use extended well to the south of the claim area, broadly as indicated on Watson’s map.

44 From the very high level indications of identity provided by a common language, it is necessary to move to a consideration of the “interacting groups”, or “territorial groups” referred to by the anthropologists in the evidence mentioned in para 29 above. It is convenient to commence with Petrie’s description of such groups. In his Reminiscences, Petrie said (through his daughter Constance, whose contribution will henceforth be assumed rather than mentioned specifically each time):

Each tribe had its own boundary, which was well known, and none went to hunt, etc., on another’s property without an invitation, unless they knew they would be welcome and sent special messengers to announce their arrival. The Turrbal or Brisbane tribe owned the country as far north as North Pine, south to the Logan, and inland to Moggill Creek. This tribe all spoke the same language, but, of course, was divided up into different lots, who belonged some to North Pine, some to Brisbane, and so on. These lots had their own little boundaries. Though the land belonged to the whole tribe, the head men often spoke of it as theirs.

The outer boundaries of what Petrie here referred to as “the Turrbal or Brisbane tribe” provided at least an approximate guide for the definition of the claim area in the original Turrbal application in this proceeding.

45 It should be noted that Petrie used the term “tribe” in two senses: one to refer to the overall group of peoples who inhabited the area to which he gave approximate definition, and one to refer to the smaller groupings, eg “some to North Pine, some to Brisbane, and so on”. Petrie also noted that the North Pine tribe “formed a part” of “the old Brisbane or Turrbal tribe”. The distinction between the different senses of this term is an important one in the context of this case, and Petrie’s easy, story-telling, style is not calculated to make the discriminations which will be necessary. Subject to that qualification, one may see, in the passage set out above, a recognition of the existence of these smaller groupings and their significance as centres of identity in relation to rights and interests in land.

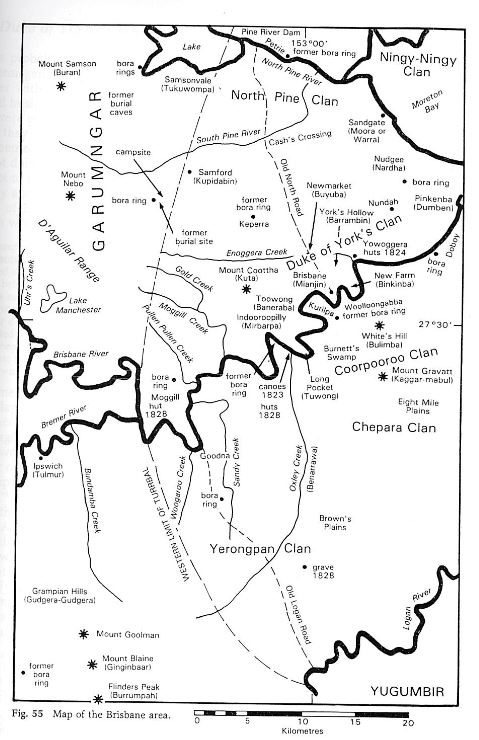

46 In his book published in 1983, Aboriginal Pathways in Southeast Queensland and the Richmond River, (which Dr Fisher regarded as “the most comprehensive and reliable work” on the history of aboriginal tribes, languages, boundaries and customs in south-east Queensland) JG Steele accepted Petrie’s statement of the scope of the Turrbal area. He identified five “clans” within that area (while acknowledging that other clans “no doubt inhabited the area”):

• the “Duke of York’s” clan, occupying the Brisbane metropolitan area on the north side of the river;

• the North Pine or Petrie clan;

• the Coorpooroo clan on the south bank of the Brisbane River;

• the Chepara clan of Eight Mile Plains; and

• the Yerongpan clan of Oxley Creek.

I have reproduced Steele’s map, on which are marked the locations of the five clans referred to, as well as the line marking the western boundary of the Turrbal country as he represented it. However, as stressed by the State in its submissions, this map cannot be regarded as anything more than indicative apropos Steele’s own identification of the clans. The anthropologists did not accept it as an accurate representation of the limits of the regions in which these clans existed. Subject to that reservation, the map is a convenient point of reference for a discussion of the evidence so far as it relates to the various aboriginal groups, and their leaders, who inhabited south-east Queensland in the early years after white settlement.

47 I will commence with the “Duke of York’s Clan”. Dr Fisher described the Duke of York as “the head man on the north side of the Brisbane River”.

48 According to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Capt Foster Fyans became commandant at Moreton Bay two years after his appointment as captain of the guard on Norfolk Island, which was in early 1833. As an approximation, therefore, he may be taken to have become commandant in 1835. In September 1837, rather than return to India with his regiment, Fyans “sold out, and … sailed for Port Philip as first police magistrate of Geelong”. In 1853, by then retired and living on a property at Geelong, Fyans began what became “500 pages of instructive and entertaining recollections”. Relevant extracts of those recollections are in the evidence.

49 According to one entry in those recollections, there was a day at the Moreton Bay settlement on which “the tribe of natives came in”. As it happened, a group of Quakers were visiting at the time, and they were introduced to the natives. The latter consisted of a group of “fifty males, chiefly boys and young men”. They were led by the Duke of York, whom Fyans described as “the great chief of the now Brisbane tribe”. The “now” part of this extract reflects the circumstance, I would infer, that the area in question was not known as “Brisbane” at the time, but was by the time that Fyans came to write down his recollections in the period following 1853. Fyans proceeded to describe the Duke of York as “aged about forty years; … a stout-looking old fellow; … the elder of the tribe, but the remains of a fine old man.” No party suggested that Fyans was mistaken in what he said, from which it is safe to say that, in the mid-1830s and thereabouts, there was a tribe of natives in what we now know as the Brisbane area, and that they were under the leadership of a man known to the whites as the Duke of York.

50 The Duke of York was referred to in a report, published in The Colonial Observer, of an expedition to the north by two missionaries from a German Mission in August 1841. As will be evident from events at York’s Hollow in late 1846, the Duke of York was still about in the Moreton Bay area at that time. Then, in June 1853, the Moreton Bay Courier published a mistaken, premature, obituary of him in which it described him as “a well known Brisbane black” (for which mistake the Courier later published an apology).

51 There is, therefore, a reliable record of the existence of this aboriginal leader over a period of about 20 years from the 1830s to the 1850s. Curiously, he is not mentioned by name in Petrie’s Reminiscences, notwithstanding that Petrie must, for reasons to which I shall refer below, have known who he was. Regarding the extent of the territory over which he was the acknowledged leader, there is nothing in the evidence that would permit me to go beyond Dr Fisher’s assessment that this was to the north side of the Brisbane River, roughly as indicated by Steele. I understand that Fisher was here referring to the lower Brisbane River, or what Steele equated with what is now the metropolitan area on that side of the river.

52 The North Pine clan referred to by Steele is mentioned frequently by Petrie in his Reminiscences. It will be noted that Steele gives this clan an alternative name, the “Petrie clan”, doubtless because it was the area in which Petrie settled as a young man and thereafter spent the rest of his life. At about 28 years of age (ie in about 1859), Petrie was advised to take up land for cattle. He knew an aboriginal, then about 60 years of age, called Dalaipi, whom he described as “the head man of the North Pine tribe”. Dalaipi told Petrie that he should take his (Dalaipi’s) son Dal-ngang with him for the purpose of identifying suitable land, and “any you pick on I will give you…. When you make up your mind to settle, I will go with you, and protect you and your cattle, or any one belonging to you.” (Petrie quoting Dalaipi) Petrie said that Dalaipi often came to Brisbane (indeed, as a boy, Petrie played with his son), but it is evident that he had leadership over a clan, or tribe, in the North Pine area which was separate from that of the Duke of York and which involved interests in relation to land. According to Petrie’s Reminiscences, Dalaipi was as good as his word: Petrie’s property and his stock were always protected, and never subjected to raids or the like by the aborigines of the area.

53 With respect to the area south of the Brisbane River, the evidence does not clearly demonstrate the existence of the three clans demarked by Steele. There are indications that the Chepara clan was an entity of much wider significance than Steele’s map implies. A source quoted by Dr Powell in her supplementary report had it as follows:

The ‘Chepara’ was the head clan. Its district was to the south of Brisbane inland and chiefly coast – It was the clan from which all the clans derived their common name as a tribe.

And:

The principal clan, and gave its name to the whole tribe. Its country was to the south of Brisbane, somewhat inland, but also along the coast. … The names of the clans were derived from local associations, as, for instance, Chepara means the coast … The Chepara was, so tradition says, originally the whole tribe, but in consequence of internal feuds it became broken into the clans mentioned. This however seems, notwithstanding the positive assertions of the Chepara informants, to require some corroboration, which cannot now be given. The oldest of the native informants, a man of about fifty years of age in the year 1880, spoke with certainty of this tradition, and said that after a time the clans became again friendly, and had during the whole of his lifetime considered the Chepara the principal clan.

54 In App B to her supplementary report, Dr Powell reproduced an undated map which she placed in the early 1880s. She said that it showed the “Chepara” clan’s country as extending along the coast from Caboolture River to Point Danger, and (in Dr Powell’s words) “inland to encompass the Logan and Albert catchments and the middle and lower reaches of the Brisbane catchment”. It seems that the informant referred to in the extract above was an aboriginal man of about 50 years of age in 1880. He said that Chepara was the principal clan, and that the area was made up of subordinate clans which Dr Powell identified (doing the best she could in the cases of some records which were only in handwriting) as follows:

• Chepara (discussed above);

• Mungulkabultu [Uulgunkabultu] in the Pimpana [Pimpama] district;

• Munnadali [Uunnadali], about the sources of the Albert River [head of Albert River];

• Kuttibul, about the sources of the Logan River [head of Logan river];

• Yungurpan, in the Coomera and Merang [Nerang] districts;

• Birrin at the Tweed River;

• Burginmeri, in the Cleveland district; and

• Chermanpura, the district along the coast [coast district].

55 There is nothing else in the evidence to suggest that the Chepara clan extended as far north as Caboolture River, but it is possible that the distinction between a clan as such and a “head clan”, or “tribe”, might be relevant to that question. What is of interest for present purposes, however, is the circumstance, which appears tolerably clearly from all of the evidence, that, at least as an approximation, the area south of the Brisbane River was distinct from the area to the north under the Duke of York.

56 A significant aboriginal leader to the south of the river, was the man called Mulroben, a contemporary of the Duke of York. He had what Dr Powell described as “a huge area”, also extending to the west as far as Ipswich. Subject to Dr Powell’s expansive opinion, it seems tolerably clear that Mulroben’s clan was that described by Steele as the Coorpooroo Clan.

57 A correspondent to the Jubilee Number of The Queenslander, 7 August 1909, apparently speaking from his own recollection as a young man, spoke of the situation 60 years previously as follows:

Among the South Brisbane tribe of aboriginals were many quaint personalities: one tribe was up to fully 400 strong. They were then healthy and in the full possession of their native agility, prowess, and arts. Their head man, or fighting chief, was “Molrubin”; his dusky queen was called “Gulpin”. He was killed treacherously in a family feud.

Consistently, a correspondent to the Colonial Times and Tasmanian, writing on 18 May 1850, mentioned “Molrooben, a celebrated chieftain, whose hunting grounds extended from the Dividing Range to the Logan River”. (Of some interest on the question of the interactions between clans in the Brisbane area is this correspondent’s description of a “great fight” which took place between the coastal tribes and the mountain tribes. The former were led in the fight by the leader of the Amity Point tribe, EulopÈ, who had three seconds, including the Duke of York and “Molrooben”.)

58 With respect to the “Yerongpan” clan, Dr Powell referred to a word list compiled by Archibald Meston, the Southern Protector of Aboriginals for Queensland from 1898 to 1903, most probably on information provided by an aborigine called Yoocum Billy (or “Lumpy Billy”), whom Meston first met in 1870. On that list, “Yeerompan” was a reference to Browns Plains. Steele considered Meston’s Yeerompan to be the same clan (as he called it) as the “Yerongpan tribe” the subject of a paper presented by a Dr Joseph Lauterer to a meeting of the Royal Society of Queensland on 19 March 1891. The title of the paper was the “Yaggara dialect, spoken in the ‘sandy country’ (Yerongpan) between Brisbane and Ipswich”. The imprecision of these indications is, if anything, exacerbated by the terms of a letter by Meston’s son LA Meston to the Courier Mail published on 14 November 1935 (referred to by Dr Powell in her supplementary report):

The Yerong-pan tribe, whose territory was on the sandy country between Brisbane and Ipswich, and included Eight Mile and Brown’s Plains and Yeerongpilly, gave us Yeronga or Yarunga, meaning ‘sandy’ and Yeerongpilly, meaning ‘a sandy creek or gully.’

However indicative, and approximate, Steele’s map may be, it is difficult to advance any interpretation of it that would have Eight Mile Plains and Yeerongpilly in the territory of the Yerongpan clan. LA Meston’s letter was concerned substantially with language, as distinct from territory or tribal regions, and I would place little store by the passage extracted from it above, particularly having regard to the derivative character of the information on which it was based.

59 Making allowances for the difficulties facing the parties in establishing the nature, and placement, of the tribal divisions which inferentially characterised the claim area at and after sovereignty, I consider that the following findings might be made on the probabilities. I shall use the word “clan” as the relevant descriptor, not only because Steele did so, but because, as will become clear presently, Ms Isaacs herself used the word. The five clans identified by Steele were distinct from each other. The geographic lines of demarcation between them were not precise and, especially further south, cannot be known even to an approximation at this substantial remove in point of time, but distinct clans there were. The fairly extensive historical references to the “leaders” of at least three of these clans – North Pine, Duke of York and Coorpooroo – is consistent with no other conclusion. There were, I would find, the “interacting groups” to which Dr Williams referred in the passage set out at para 29 above, or the “territorial groups” under “headmen” referred to there by Dr Powell and Dr Macdonald.

60 It is uncontroversial that the clan regions just discussed would have shared the same laws and customs. What did those laws and customs have to say on the subject of rights and interests in relation to land and waters? In addressing that question, it will not be necessary to separate out, or to give specific attention to, the content of the rights and interests which presumptively then existed, for example, the right to be present on land, to cross over land, to hunt or fish on land, to harvest the fruits of trees and bushes on land, and the like. For reasons which will become clear, the present case is susceptible of resolution at a higher level than would involve an examination of these rights and the differences between them.

61 Rather, the critical issues in the case are, first, what was the nature of the connection with particular land that would give rise to rights and interests in it, and secondly, by what principle, rule or custom would such rights and interests be possessed by people coming later in time who may not have been part of the original community when it was in direct occupation of the lands in the traditional way. In other words, who originally possessed these rights and interests, and who were their successors in future generations?

62 As to the first issue, in the State’s closing written submissions it was contended that “rights in relation to land were not conferred generally across the whole of the language territory – rather, differential rights were held amongst local groups, and within local groups”. In a footnote, the evidence relied on for this contention was three pages in Dr Macdonald’s report of June 2010. For my own part, I cannot see the issue either clearly presented or clearly resolved in those pages, and the State’s oral submissions contained no relevant elaboration. Dr Macdonald was concerned to discuss the quality and content of the norms which related to land rights and interests, but, other than in relation to specific cultural rights, the identification of those who would enjoy them was assumed rather than articulated.

63 More directly on point was Dr Macdonald’s report of September 2009, which was concerned principally with the boundaries of Turrbal-speaking territory. Although presenting her analysis in the framework of her conclusion that the Turrbal-speaking people were part of a “Riverine cultural bloc” (which was not accepted by the other anthropologists), Dr Macdonald dealt in some detail with the attributes of what she called “local territories”. Such a territory was recognisable as being under the control of a “headman”. Dr Macdonald said:

There is a consistent picture in the literature of each local group having a clearly bounded territory within which economic activities were pursued and others had to ask permission to enter and, if staying, would be told where they could hunt. This territory is understood economically and politically, as a hunting and gathering territory over which particular people had rights. Within it are an individual’s sites.

And:

The headman had the right to exclude people, although would rarely do so. However, it was imperative that he be asked permission to enter, camp, forage or even pass through. It was this respectful recognition that affirmed his authority.

If a small company sought and obtained permission to travel through another tribal territory, they must of course not hunt for food while so passing through, and as evidence of their bona-fide that must keep very strictly in a straight line behind each other. Such a party would consist of only six, possibly ten, men (Langevad 1982:29).

Of course, such a group could also ask for permission to hunt. But not to ask a headman for permission was tantamount to a denial of his rights over the territory (cf. Myers 1982). Someone disregarding such fundamental etiquette did so at their own risk as it would be assumed they had dangerous intentions. Trespassers could be put to death in some cases and in all cases a fight would result. These local dialect areas therefore corresponded with economic and political rights. Only those identified as having primary rights (senior owners/custodians) had the right to extend usufractory rights to visitors. There would be people identified with other territories, such as spouses and in-laws, who were resident and had the daily rights of residents, but did not have the right to grant permissions. They too had to defer to those with the right to call themselves by the name of that territory.

Dr Macdonald was not challenged on these views.

64 On this subject, Dr Powell said:

[I]t is my understanding that each territorial group indeed did have a headman who handled matters within the area of each group. But there was an overarching organisation connected with the religious system, and the list [sic] was paramount … over all the groups. … [Y]ou could become like a local group, a territorial group headman, and then according to what I’ve read, you’ve got other men to help you and you formed a council of senior men who handled matters within the territory your group was associated with. But on top of that uniting all these different territories there was what was called the bora – in the literature the bora council, and they could – if one of these headmen wasn’t up to scratch, so to speak, they could have him removed.

However, with respect to the rights of people who were associated with a particular local territory to enter upon, and to exploit, land within another local territory, Dr Powell was more guarded:

I don’t have the information to say that. … I really don’t know. Moreover, Petrie does say that all these groups were linked to each other through intermarriages, so that – and that people quite happily moved from one area to another and were – were friends and hunted and gathered and did things together. So … I would hesitate to say that somebody who we might think is with the Chepara in that area had no rights and interests, say, up at the North Pine which was the Duke of York’s. We don’t – I don’t know.

65 The passage from Petrie’s Reminiscences set out in para 44 above is not free of ambiguity on this subject, in the sense that it is not clear whether the “tribe” first referred to was to be understood as the whole Turrbal tribe as Petrie described it, or as each of the local tribes which he mentioned elsewhere in the book (North Pine, Brisbane, etc). I think that the latter is the more natural sense of this passage, but because of the easy conversational style in which this information is rendered, and Petrie’s evident lack of concern with the distinction now under consideration, it would be unwise to place too much store by it. Dr Powell agreed in the interpretation proffered by counsel for the State, namely, that Petrie was “talking about an overall tribe and then, within that, … the smaller groups” but, for my own part, I confess to an inability to appreciate which interpretation Dr Powell was being asked to favour.

66 In this state of the evidence, I find on the probabilities that rights and interests in relation to land and waters were possessed by reference to membership of each local group, under the leadership of a particular headman, or what Steele would call a “clan”. Dr Macdonald was clear in her evidence that such rights and interests were not enjoyed more widely. Dr Williams, as I read her evidence, was substantially of the same opinion. Dr Powell was able to put it no higher than that she did not know. In concrete terms, this means, for example, that rights and interests in relation to land and waters immediately to the north of the lower Brisbane River were possessed by members of the Duke of York’s clan, that rights and interests in relation to land and waters to the south of the river were possessed by members of the Coorpooroo clan, and so on. Interestingly, this perspective has the strong support of evidence given by Ms Isaacs herself. In a statement attached to her affidavit of 20 January 2006, she said that, within the various tribes that existed years ago, there were “particular clanlands”. Special permission had to be sought from the relevant clan and tribal authorities to enter into their territories. She continued: “Clan rights of clan areas are stronger than the tribes”. Expressed in the lexicon of native title, what Ms Isaacs was here saying, in my reading of it, was that rights and interests in relation to land and waters were specific to the members of the clan which occupied, or had the relevant connection with, that land and those waters.

67 For example, a member of the Coorpooroo clan would not have rights or interests in relation to the land and waters occupied by the Duke of York’s clan. Any suggestion that rights and interests in relation to land and waters within the claim area were held by people whose only connection with that area was that they spoke a common language, or that they acknowledged common laws or observed common customs, must be rejected.

68 As to the second issue, it seems clear that the intergenerational rule of succession to rights and interests in land was filiation. Dr Powell and Dr Williams took the view that patrifiliation was the rule, while Dr Macdonald considered that “filiation (patrifiliation and matrifiliation) was the primary and non-negotiable way in which proprietary rights to country were acquired and transmitted.” I do not need to proceed henceforth on the footing that filiation was the inflexible rule. There may, it seems have been other ways to acquire rights and interests in land, such as marriage and the adoption of an erstwhile outsider into the tribe or community in question, but these special cases do not need to be considered here.

69 In her 2010 report, Dr Macdonald in particular stressed the importance of descent by blood in the transmission and acquisition of rights and interests of the kind presently of concern. She said:

Filiation was the ascribed and non-negotiable foundation for the acquisition of rights in a specific territory. No one could claim Turrbal, Gabi Gabi or any other territorially-based (spatial) identity except where it was known that his or her parent made such a claim and was accorded the right to do so. A filial relationship established a person’s right to identity as ‘Turrbal’ and thus the right to be known as a member of the Turrbal land-owning group.

By “filiation”, Dr Macdonald meant “rights obtained by virtue of birth to a father and/or mother who themselves hold such rights”. She distinguished between “filiation” and “descent” in the following terms:

Filiation required only the active identification with rights held by one parent. The filial relationship required no verification because one’s parent’s claims to Turrbal identity would already have been recognised/legitimised by both Turrbal and non-Turrbal kin. Most people would have known their grandparents, and know that at least one of them also claimed the same right, and was recognised as having done so, hence the right of the parent to do so. Beyond grandparents are the ‘ancestors’ from whom such rights descended. Identifying specific ancestors beyond grandparents was not culturally important.

However:

If the rule of filiation has been applied in every generation, it can be expected that a person will be able to trace filial relations in each generation to an ‘apical ancestor’. However, it is not customary that this knowledge is retained and to do so, most people today would be required to rely upon written records [of uneven quality] in order to test the application of the law of filiation over time.

I have referred to Dr Macdonald’s views particularly on this subject since, as will be seen, it represents a crucial aspect of the Turrbal case.

70 In the life of an existing, vibrant, aboriginal tribe or community, it may have been sufficient, for an interest in land to arise, for that interest to have been held by one’s parent. It may not, in Dr Macdonald’s words, have been necessary “to test the application of the law of filiation over time”. But this is a court proceeding held many decades after the disappearance of such tribes and communities in the claim area – a matter dealt with in the next section of these reasons. To know whether, over that period, the rule of filiation has been at work transferring rights and interests in land and water from one generation to the next, it will be necessary, as it seems to me, to look at what Dr Macdonald refers to as descent. This was the unambiguous premise by reference to which both applicant groups conducted their cases.

71 The other dimension of the content of traditional laws and customs in relation to rights and interests in land that must be considered is how those laws and customs dealt with land that had been depopulated. Such land is sometimes referred to as “orphaned country”, but the anthropologists in the present case were agreed that this was “a problematic concept”. In their joint report, they said:

… Aboriginal people don’t see country as orphaned. Land may be de-populated but this does not render country without ownership.

Ownership was assumed to be transmitted through filiation. Where this was no longer possible, other principles came into play, such as those arising from kinship and propinquity.

Aside from “kinship and propinquity” – which, because of the specific ways in which both claim groups define themselves, do not need to be considered in the present case – this passage keeps our focus on filiation, regardless of whether the various generation-to-generation holders of the rights and interests in question were actually inhabiting the claim area.

Continuity of Society

72 There seems no doubt but that the aboriginal tribes which occupied the claim area at the time of first white settlement had been displaced – either by whites or by other aborigines – by about the end of the nineteenth century at the latest. Indeed, on the probabilities, this had happened by, say, the end of the 1850s. Although the redactions in Dr Fisher’s report compromise to an extent its utility in this regard, the sense of his conclusion is clear enough:

My interpretation of this evidence is that, as white settlement expanded, the [redacted] people were increasingly repressed and excluded by whites and blacks alike. The Duke of York’s group was driven from their Yorks Hollow camping-ground by the early 1850s, followed by other [redacted] groups later in the decade. The early pastoralists aided by the Native Police force (est. 1848) were largely responsible in rural areas, including the Sandgate, Pine River and Logan districts, as well as the Fassifern [redacted] valleys further afield.

73 Dr Fisher wrote that, before “European settlement”, the aboriginal population in the area bounded by the Pine River, the Dividing Range and the Logan River was about 5,000. By 1861, this had fallen to 2,000. Of the Brisbane tribe itself, Dr Fisher wrote:

At the Native Police inquiry in 1861, businessman Capt. Richard Coley testified regarding ‘the Brisbane tribe’, which numbered about 250 in 1842: ‘They are all gone since then – they are all extinct’. At the same time Magistrate Richard B. Sheridan of Maryborough, who took a great interest in Aboriginal affairs, attested that ‘I have not seen one of the North Brisbane tribe since my arrival here this time’.

Turning to the [redacted] people as a whole, Tom Petrie testified in 1861 that the old Brisbane tribes ‘are nearly all dead now: there are only about five of them left’. Other less informed witnesses said likewise. By 1901, Petrie knew of ‘one or two old men being left alive’. By this he meant members of ‘the old original tribe who camped at North Brisbane, and who were boys when I was a boy’.

By the time that Petrie gave his daughter the benefit of his recollections, he was aware of only one of “the old Brisbane or Turrbal tribe, of which the North Pine formed a part” who was still alive.

74 In her report of November 2013, Dr Macdonald said that, by the end of the nineteenth century, “people living within Turrbal language-territory had suffered a massive population decline”. Even as at the 1850s, Dr Macdonald accepted that, “[e]verybody was driven out of what became central Brisbane”.