FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia [2015] FCA 9

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

BARRY CROFT AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE BARNGARLA NATIVE TITLE CLAIM GROUP Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA AND OTHERS First Respondent |

DATE: | |

WHERE MADE: |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[10] | |

[34] | |

[38] | |

[49] | |

[56] | |

[73] | |

[73] | |

(B) Existence of a Barngarla society and Identification of Barngarla laws and customs at sovereignty | [87] |

[91] | |

[93] | |

[97] | |

[101] | |

[125] | |

[140] | |

[144] | |

[271] | |

[285] | |

[290] | |

[297] | |

[302] | |

[309] | |

[310] | |

[311] | |

[313] | |

[328] | |

[331] | |

[332] | |

[334] | |

[335] | |

[336] | |

[337] | |

[338] | |

[339] | |

[340] | |

[341] | |

[342] | |

[343] | |

[344] | |

[345] | |

[346] | |

[347] | |

[348] | |

[349] | |

[350] | |

[351] | |

[352] | |

[353] | |

[354] | |

[355] | |

[356] | |

[357] | |

[358] | |

[359] | |

[361] | |

[363] | |

[364] | |

[365] | |

[366] | |

[367] | |

[369] | |

[369] | |

[370] | |

[387] | |

[409] | |

[429] | |

[436] | |

[437] | |

[441] | |

[443] | |

[452] | |

[455] | |

[460] | |

[461] | |

[465] | |

[473] | |

[485] | |

[499] | |

[511] | |

[513] | |

[514] | |

[527] | |

[536] | |

[541] | |

[543] | |

[545] | |

[547] | |

[551] | |

[552] | |

[553] | |

[554] | |

[561] | |

[561] | |

[570] | |

[585] | |

[586] | |

[602] | |

[608] | |

[625] | |

[626] | |

[633] | |

[633] | |

[635] | |

[637] | |

[645] | |

[652] | |

[665] | |

[674] | |

[684] | |

[685] | |

[691] | |

[694] | |

[702] | |

[708] | |

[709] | |

[710] | |

[711] | |

[714] | |

[723] | |

[735] | |

[750] | |

[767] | |

[771] | |

[776] | |

[777] | |

[801] | |

Whether the Nauo-Barngarla boundary at settlement was the same as that at sovereignty | [807] |

[814] | |

[824] | |

[825] | |

[825] | |

[826] | |

Character of rights possessed under traditional laws and customs | [834] |

[839] | |

167 | |

APPENDIX A – SCHEDULE OF PARTIES | 168 |

SOUTH AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | SAD 6011 of 1998 |

BETWEEN: | BARRY CROFT AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE BARNGARLA NATIVE TITLE CLAIM GROUP Applicant |

AND: | STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA AND OTHERS First Respondent |

JUDGE: | MANSFIELD J |

DATE: | 22 JANUARY 2015 |

PLACE: | ADELAIDE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

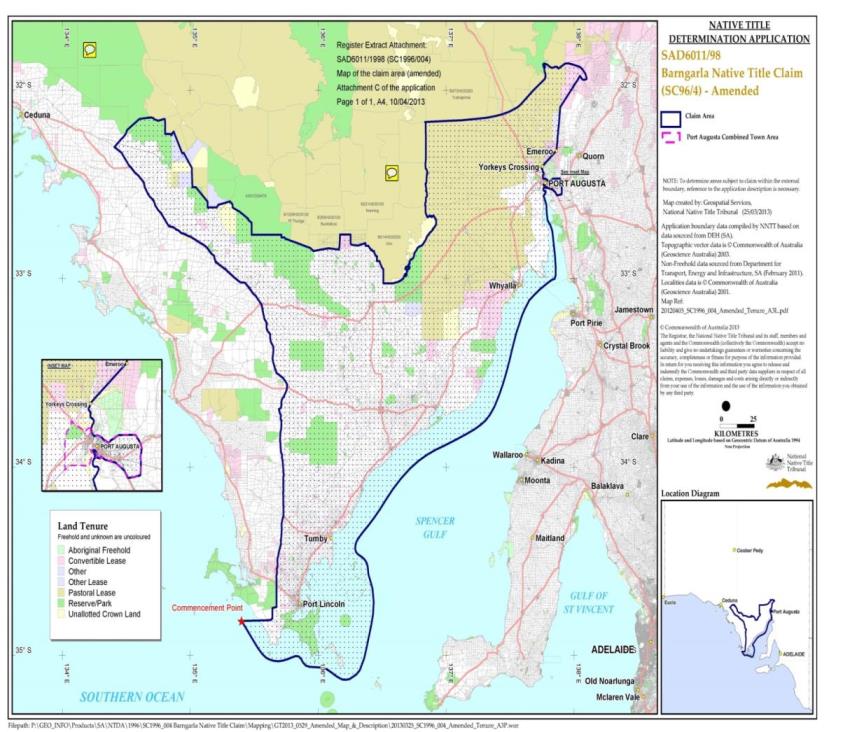

1 This matter is an application for a determination of native title over certain lands and waters in the vicinity of the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia specified in Appendix A to these reasons (the claim area).

2 In broad terms, the claim area is now over the eastern half of the Eyre Peninsula, but extending in a broad finger north-west of Kyancutta. In the lower part of the Eyre Peninsula, it abuts the Naou Native Title Claim (SAD 6021 of 1998), and as it extends north and west it abuts the Wirangu No 2 Native Title Claim (SAD 6019 of 1998) on its southern side. At its western extremity it abuts the area recognised as the native title lands of the Far West Coast people: see Far West Coast Native Title Claim v State of South Australia (No 7) [2013] FCA 1285. Along its northern side running from its western extremity it abuts the southern boundary of the area recognised as the native title lands of the Gawler Ranges people: see McNamara on behalf of the Gawler Ranges People v State of South Australia [2011] FCA 1471.

3 At a point roughly north of Cowell, at the area known as Lake Gilles, the claim area extends northwards (abutting part of the eastern boundary of the native title lands of the Gawler Ranges people) to the southern boundary of the lands now recognised as the native title lands of the Kokatha Uwankara people: see Starkey v State of South Australia [2014] FCA 924, and it extends to the east abutting that boundary to the southern point of Lake Torrens. That part of the claim area, as the map Annexure A indicates, extends north-east again in a finger shape to abut the southern boundaries of the Country of the Adnyamathanha People, and then it runs roughly south to Port Augusta and down the eastern boundary of the Spencer Gulf to a point roughly opposite Whyalla. That part of the claim area abuts the claim area of the Nukunu People Native Title Claim (SAD 6012 of 1998).

4 As can be seen, the claim area extends substantially over the waters of the Spencer Gulf along the eastern side of the Eyre Peninsula. In the vicinity of Port Lincoln, the claim area is more extensively into those waters, taking in the many islands and reefs in that vicinity. Along the eastern side of the Eyre Peninsula (below the line from about Port Germein to Port Bonython) to about Tumby Bay, the distance between the shoreline and the outer boundary of the claim area is about 15-20 km, and south of that around the southern end of the Eyre Peninsula the widest point between the shoreline and the external claim boundary is about 50-55 km.

5 There are no overlapping claims under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NT Act), save for the area of Port Augusta itself. The Nukunu people claim also overlaps the boundaries of the Port Augusta Town Area, and it is described in detail and depicted in Attachments H and H1 to the application as ultimately amended. It is not necessary to address that overlapping area because it is agreed that, for the purposes of the present hearing and determination, the Court should exclude the Port Augusta Town Area. It is anticipated by the applicant, by the applicant in the Nukunu people claim, and by the native title representative body for South Australia, South Australian Native Title Services (SANTS) that that area will be the subject of some agreement, to be reflected in an Indigenous Land Use Agreement under the NT Act.

6 On 29 May 2012, I ordered that the issue of the existence of native title over the claim area be separated from the issue of whether any such native title found to exist has subsequently been extinguished. Evidence was led and argument heard on the issue of the existence of native title over 22 hearing days from November 2012 to September 2013. This judgment contains the reasons for my determination in relation to the claim.

7 The Commonwealth’s interest, as reflected in its written submissions, was confined to whether – in the event that the Court accepted that the Barngarla people should be recognised as holding native title rights and interests over the claim area for the purposes of s 223(1) of the NT Act – such rights and interests extend over that part of the claim area which consists of land and waters below the high water mark in an area of sea adjacent to the eastern and southern coast of the Eyre Peninsula (the sea claim area).

8 The Commonwealth contends that it is not shown that, at the time of sovereignty, the Barngarla people possessed rights and interests under their traditional laws and customs over the land and waters on the sea claim area that extend beyond the intertidal zone (that is, between the high water mark and the low water mark) and adjacent waters (that is, the deeper waters that were able to be accessed from the adjacent shallower waters of the intertidal zone). It also contends that, in any event, the evidence does not show that any rights and interests in the sea claim area included (as asserted) a right to trade in marine resources. Finally, it says that, if any rights and interests in the sea claim area existed at sovereignty, if they were exclusive rights, they are not rights and interests recognised by the common law of Australia: cf Commonwealth of Australia v Yarmirr (2001) 208 CLR 1 at [99]-[100] (Yarmirr); Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 at [388] (WA v Ward).

9 The only other entity to make written submissions was BHP Billiton Olympic Dam Corporation Pty Ltd, and then only to preserve its entitlement to participate in any subsequent hearing concerning issues of extinguishment and of non-native title rights and interests which should be provided for in any determination.

HISTORY OF THE BARNGARLA CLAIM

10 Like many native title determination applications, this matter has had a protracted history. The Barngarla Native Title Claim (Barngarla claim) was commenced on 4 April 1996 in the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT). That original application encompassed a much greater area of land than the land that is presently claimed. The claim area extended much further north. It extended as far north-east as the town of Leigh Creek, and in the north-west, it encompassed Lake Gairdner and the town of Kingoonya, and was bordered by the Central Australian Railway as far north as Ingomar Homestead, about 70 kilometres south of Coober Pedy. In the south-east, the claim area extended past Port Augusta, as far east as Orroroo, and in the south, just north of Port Germein. In the west, the claim area extended to the western coast of the Eyre Peninsula up to Streaky Bay.

11 Upon the commencement of the Native Title Amendment Act 1998 (Cth) on 30 September 1998, the claim converted into an application in this Court by virtue of the amendments to the NT Act contained within that Act. A year later, on 7 October 1999, the application was amended so as to reduce the size of the claim area. In the north, much of the original north-west portion of the claim area was not pursued. The north-western border now ran along the eastern side of Lake Gairdner, and then roughly followed the 136th parallel up to the original northern-most boundary. That alteration removed the claim’s overlap with the land which is recognised as the native title land of the Gawler Ranges people. It comprises a combined claim group of Wirangu, Kokatha and Barngarla people.

12 In the south-west, the boundary line was brought in from the western coast of the Eyre Peninsula to the Port Lincoln-Ceduna railway line. That alteration removed the claim’s overlap with the Nauo Native Title Claim, which had been lodged on 17 November 1997, and the Wirangu No 2 Native Title Claim, which had been lodged on 28 August 1997.

13 The two excisions left the claim area with an irregular roughly finger shaped wedge extending out in its west. That shape has since remained unchanged in the present claim area.

14 On 14 September 2001, the size of the claim area was further reduced by O’Loughlin J’s order that the Barngarla claim be struck out pursuant to s 84C of the NT Act in respect of Crown Lease Volume 962 Folio 34, being land the subject of a commercial lease granted to Caltex Petroleum Pty Ltd. That order was made with the consent of the applicant. The relevant land was only about two square kilometres in size and situated near Whyalla.

15 On 6 August 2002, the Court was notified that the NNTT had accepted the Barngarla claim for registration pursuant to s 190A of the NT Act. The NNTT noted in its reasons for decision that there were at that time eight native title determination applications whose claim area overlapped with that of the Barngarla claim, but that three of those overlaps were only “technical”.

16 On 8 December 2003, the Court referred the claim to the NNTT for mediation. Two broad main areas of overlap emerged. The first area centred around the Lake Torrens area and concerned (at least initially) the claims of the Kokatha and Kuyani people (SAD 6013 of 1998 and SAD 6004 of 1998). The second area centred around the Flinders Ranges National Park and concerned two claims of the Adnyamathanha people (Adnyamathanha No 1 and Adnyamathanha No 2), and the claim of the Nukunu people referred to above. The Two Adnyamathanha claims subsequently are the subject of recognition in: Adnyamathanha No 1 Native Title Claim Group (No 2) v The State of South Australia [2009] FCA 359.

17 The NNTT, the State of South Australia (State) and the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement (ALRM) (now SANTS) were attempting to resolve native title claims through a process known as the “state-wide ILUA process”. The Barngarla claim became a part of that process, and specifically became a part of a strategy for resolution of native title claims called the “Central Western South Australia Mediation Strategy”. That Strategy was aimed, as far as the Barngarla claim was concerned, at resolving the Barngarla-Kokatha-Kuyani overlap. The Barngarla-Adnyamathanha-Nukunu overlap was dealt with in separate negotiations.

18 On 30 June 2004, the NNTT recommended that its mediation of the Barngarla claim cease to the extent that it concerned that part of the Barngarla claim which overlapped with the Kokatha and Kuyani native title claims, and that that part of the claim be listed for hearing. This recommendation was made mainly because an important meeting in 2004 at Spear Creek Caravan Park, near Port Augusta, and follow-up meetings, had been unsuccessful in resolving the groups’ differences. The State opposed that recommendation, saying that the more appropriate course was to persevere with the “state-wide ILUA process”. On 22 July 2004, the Court adopted the NNTT recommendation and ordered that that overlapping part of the Barngarla claim be removed from mediation.

19 Meanwhile, the NNTT reported at the same time that strong progress was being made on the resolution of the Adnyamathanha-Barngarla overlap, and that the Barngarla and Nukunu had agreed to negotiate their overlap, but would not be able to do so at that time because of insufficient funding available to ALRM.

20 On 13 October 2004, the Court ordered that the Kokatha-Barngarla overlap be referred back to mediation by the NNTT. That order was made because it had emerged that an in-principle agreement to share the area of the overlap might be able to be finalised.

21 On 27 January 2005, the Kuyani Native Title Claim was struck out by Finn J: McKenzie v South Australia (2005) 214 ALR 214. A second Kuyani Native Title Claim briefly emerged in early 2006, only to be discontinued several months later: Kokatha People v South Australia [2007] FCA 1057 at [9] per Finn J.

22 By this time, the Kokatha-Barngarla overlap had been affected by a third claim over the relevant land, the Arabanna Peoples Native Title Claim (SAD 6025 of 1998). On 15 April 2005, the Court referred the Arabana Peoples Native Title Claim to mediation by the NNTT, limited to that part of the claim which overlapped with the Kokatha and Barngarla claims. The consequent negotiations were not successful.

23 On 8 September 2005, the Court ordered that that part of the Barngarla claim that overlapped with the Kokatha and Arabana Peoples Native Title Claims was to be dealt with in a separate “overlap proceeding”. At that time, the NNTT had reported that there was a clear willingness for the Barngarla, Kokatha and Arabanna claimants to resolve the overlaps.

24 On 9 February 2006, the Court ordered that the ongoing NNTT mediation should focus on resolving overlaps between the Barngarla claim and the Adnyamathanha Peoples No 1 and No 2 Native Title Claims (SAD 6001 and 6002 of 1998 respectively). Negotiations between those groups had been on hold at the NNTT for several years, as the NNTT, ALRM and the State prioritised, inter alia, the Kokatha-Barngarla-Arabanna peoples overlap negotiations.

25 The Nukunu overlap area with the Barngarla claim also overlapped with the Dieri Native Title Claim (SAD 6017 of 1998) and the Arabanna Peoples Native Title Claim. Negotiations in regard to this overlap had not been successful. On 14 September 2006, it was ordered that that part of the Barngarla claim that overlapped the Nukunu, Dieri and Arabanna Peoples Native Title Claims should be removed from NNTT mediation.

26 On 1 July 2007, a resolution of the overlaps between the Barngarla and Arabanna Peoples Native Title Claims was finalised. The Barngarla Native Title Claim would withdraw its claim over the overlapping land.

27 Meanwhile, through 2006 and 2007, the NNTT mediation of the Barngarla overlaps with the two Adnyamathanha Peoples Native Title Claims, now collectively known as the “Adnyamathanha Peoples Proceeding”, continued. An agreement was eventually reached in around December 2007, and resulted in the determinations referred to above.

28 In consequence of the above agreements with both the Adnyamathanha peoples and Arabanna peoples, on 30 May 2008, a further amended application was filed by the applicant. The new application further reduced the claim area, bringing in the claim area’s north-eastern boundary to the eastern border of Lake Torrens.

29 A further agreement was reached on 14 December 2008 at a meeting at the Standpipe Hotel, Port Augusta, between the Barngarla, Kokatha and Kuyani peoples to pursue jointly a claim over Lake Torrens and the area to its west. That claim was lodged as the Kokatha Uwankara Native Title Claim on 18 June 2009, and in part has been resolved by the judgment referred to above, leaving its claim over the area of Lake Torrens unresolved.

30 On 13 July 2009, Finn J gave leave for the Barngarla claim to be further amended. The new application reduced the claim area yet further. That reduction was made in accordance with the 2008 agreement, and it abandoned the claim over the area that became the claim area of the Kokatha Uwankara Native Title Claim. The new application removed a large part of the remaining northern part of the claim area. Lake Torrens and almost all the land west of it were taken from the claim area. The new northern-most border of the claim area was a line that ran roughly from the southern tip of Lake Torrens to the southern tip of Lake McFarlane. However, a small, roughly triangular-shaped piece of land in what had been the far north-western corner of the claim area was not abandoned. The claim area therefore now consisted of two separate pieces of land – the first encompassing the eastern side of the Eyre Peninsula and some land to the north-west and north-east; the second encompassing a small triangle far north of the first piece of land.

31 Further overlaps with the Adnyamathanha and Nukunu claims remained at this point unresolved. It was not until 2012 that an agreement was reached in respect of those overlaps. On 2 April 2012, the Barngarla applicants were again given leave to file an amended application. The new application brought in the eastern border of the claim area so that it now constituted a line roughly level with, and encompassing, the town of Port Augusta. On 31 January 2012, however, the Court noted that the town of Port Augusta constituted the remaining area of overlap with the Nukunu claim, but would be the subject of joint negotiations between the Barngarla and Nukunu claimants and the relevant respondents, with a view to resolving that part of the claim by way of an Indigenous Land Use Agreement rather than a determination of native title. As noted, it is agreed that this judgment will not deal with the overlapping claims over the area of the Port Augusta Town Area.

32 After the resolution of the Nukunu overlap, the Court ordered on 29 May 2012 that the Barngarla claim be listed for hearing, but on the basis that: “the issues of the existence of native title and the extinguishment thereof be separated, so that evidence as to the existence of native title be heard and a determination be made thereon before evidence is adduced and a determination made as to the extinguishment thereof.”

33 Finally, on 10 April 2013, a further amended application was lodged by the Barngarla applicant, pursuant to leave granted by the Court on 11 December 2012. That application reduced the claim area by abandoning the claim over the separate small triangle of land far to the north of the rest of the claim area. That small triangle is now the subject of another joint claim, the Kokatha Uwankara No 2 Native Title Claim (SAD 270 of 2012). Hence, the present judgment deals with the claim area as broadly described above, and includes a decision on the whole of the claim as presently pursued by the Barngarla applicant on behalf of the Barngarla people, other than the Port Augusta Town Area.

THE BARNGARLA CLAIM AND THE HEARING

34 The present extent of the claimed lands and waters is set out on a map in Appendix A to these reasons, and described in broad terms above.

35 The description of the claim group contained in the present application cannot be said to be well-drafted. Nonetheless, it appears that the claim group consists of those people who “have a connection with the claim area in accordance with the traditional laws and customs of the Barngarla native title claim group” and who are biological descendants of the following asserted Barngarla apical ancestors:

Percy Richards;

Susie Richards;

Maudie Blade;

Bob Eyles;

Harry Croft;

Jack Stuart; and

Arthur Davis and his sons Andrew, Jack, Stanley and Percy;

as well as those people who are “of Aboriginal descent” and have been “adopted into the [Barngarla] group by a custom of descent other than biological.”

36 Anyone who is a member of the claim group in the Nukunu Native Title Claim (which still overlaps the Barngarla claim insofar as both claims concern the town of Port Augusta Town Area) is specifically excluded from the Barngarla claim group, but only “whilst that claim continues to overlap the Barngarla native title claim.”

37 The native title rights and interests that the applicant alleges the claim group holds in respect of the claim area are as follows (as set out in the application as finally amended):

the right to possess, occupy, use and enjoy the area;

the right to make decisions about the use and enjoyment of the area;

the right of access to the area;

the right to control the access of others to the area;

the right to use and enjoy resources of the area;

the right to control the use and enjoyment by others of resources of the area;

the right to trade in resources of the area;

the right to receive a portion of any resources taken by others from the area;

the right to maintain and protect places of importance under traditional laws, customs and practices in the area;

the right to maintain, protect and prevent the misuse of cultural knowledge associated with the area; and

the right to conduct burial ceremonies on the area.

38 The hearing of the issue of the existence of native title over the claim area proceeded over 22 hearing days from November 2012 to September 2013.

39 There were 21 lay witnesses called by the applicant over the hearing days from 19 November 2012 to 11 December 2012. They were: Howard Richards, Brandon McNamara Snr, Edith Burgoyne, Brandon McNamara Jr, Lynne Smith, Elizabeth Richards, Eric Paige, Linda Dare, Roddy Wingfield, Barry Croft, Simon Dare, Harry Dare, Dawn Taylor, Amanda Richards, Troy McNamara, Lorraine Briscoe, Maureen Atkinson, Yvonne Abdulla, Vera Richards, Rosalie Richards, Evelyn Dohnt, and Bill Lennon. Only two witnesses were not members of the claim group: Rosalie Richards and Bill Lennon.

40 Most witnesses gave evidence in the courtroom in Adelaide or, in some cases, Whyalla. On-country evidence was given by Elizabeth Richards, Brandon McNamara Snr and Howard Richards at Winters Hill and Caralue Bluff, by Howard Richards at Northside Hill, by Brandon McNamara Snr at Pildappa Rock, Turtle Rock, Waddikee Rock and Hummock Hill, by Eric Paige and Linda Dare at Lake Umeewarra, by Roddy Wingfield, Barry Croft and Brandon McNamara Snr at Fitzgerald Bay, by Barry Croft at Black Point and Iron Knob Cemetery, by Helen Smith and Edith Burgoyne at Pine Creek, by Eric Paige and Brandon McNamara Snr at Erappa, and by Eric Paige at Mt Laura.

41 Gender-restricted evidence was received from Brandon McNamara Snr, Howard Richards, Eric Paige, Bill Lennon, Elizabeth Richards, Linda Dare, Helen Smith, Edith Burgoyne, Yvonne Abdulla, Vera Richards and Rosalie Richards.

42 Apart from the oral evidence of the lay witnesses at the hearing, the applicant also relies on representations from deceased persons admissible pursuant to s 64 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and received into evidence. Those deceased persons were: Ms Dare (recently deceased), Randolph Richards, Harry Eyles, Henry Croft, and Leroy Richards.

43 No lay witnesses were called by any party other than the applicant.

44 The Court received expert reports into evidence and heard oral evidence from the expert linguists Dr David Rose and Mr Kim McCaul, called by the applicant and the State respectively. The expert linguist reports relied on by the applicant are the reports of Dr Rose of 1 November 2012 (Rose 2012 Report), and 3 June 2013 (Rose 2013 Report). The State relies upon the expert linguist report of Mr McCaul of 24 June 2013 (McCaul Linguist Report).

45 The Court also received expert reports into evidence and heard oral evidence from the expert anthropologists Professor Peter Sutton, Dr Timothy Haines, Mr McCaul and Dr David Martin. The first two expert anthropologists were called by the applicant, the latter two by the State. The applicant relies upon the expert anthropologist reports of Dr Haines of 4 October 2012 (Haines 2012 Report) and 30 April 2013 (Haines 2013 Report), as well as that of Professor Sutton of 25 April 2013 (Sutton Report). The State relies upon the expert anthropologist reports of Mr McCaul of 26 October 2012 (McCaul 2012 Anthropology Report) and 22 May 2013 (McCaul 2013 Anthropology Report), and of Dr Martin of 2 November 2012 (Martin 2012 Report) and 20 May 2013 (Martin 2013 Report).

46 The oral evidence of each set of experts (that is, the linguists and the anthropologists) was given concurrently over four days, from 30 July 2013 to 2 August 2013.

47 Finally, oral submissions were made by the parties over two days, 16 and 17 September 2013. The oral submissions were supplemented by written submissions.

48 While there are many parties to this application, only the applicant, the State, and the Commonwealth were represented at the hearing.

49 The State submits that the evidence adduced by the applicant is incapable of satisfying the criteria required for a determination of native title under the NT Act in favour of the Barngarla people over any part of the claim area. Specifically, it submits that the applicant is unable to establish the fact of continuity from sovereignty to the present day of a society “united in and by its acknowledgement and observance of a body of law and customs”: Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 at 445 [49] (Yorta Yorta) per Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ (Yorta Yorta).

50 The State submits that the traditional laws and customs that are said to have “comprised” a Barngarla society at sovereignty are today either not acknowledged or observed, or if they are in some sense acknowledged or observed, the laws and customs either:

(a) are acknowledged or observed only as a result of a revival following substantial interruption or discontinuity;

(b) are acknowledged or observed in a form substantially different from the form in which they were acknowledged and observed at sovereignty; and/or

(c) do not perform a normative or regulative role in contemporary Barngarla relations and at best represent merely observable patterns of behaviour, but not rights or interests in relation to land.

51 The complex factual issue of whether there has been since sovereignty a continuous acknowledgment and observance of the traditional Barngarla laws and customs under which rights and interests in land and waters are possessed is the primary issue to be determined in these reasons. In the event that it is found that there has been such continuous acknowledgement and observance, then there are several further issues to be determined.

52 First, the State submits that in any event the Barngarla people never possessed, and do not today possess, native title rights or interests in respect of those parts of the claim area to the south and west of the town of Port Lincoln.

53 Second, the State made a short, undeveloped submission that in any event, the claimants have not maintained a connection by their laws and customs with particular mainland parts of the claim area.

54 Third, as noted, the Commonwealth submits that the applicant is unable to establish, at sovereignty:

(a) that the Barngarla people possessed rights and interests under their traditional laws and customs over that part of the claim area which consists of an area of sea adjacent to the east and south coast of the Eyre Peninsula that extends beyond the intertidal zone (that is, the land and waters between the high water mark and the lowest astronomical tide) and adjacent waters (that is, deep waters accessible from the adjacent shallows of the intertidal zone); or

(b) that the Barngarla people possessed a right to trade in marine resources.

55 Fourth, also as noted, the Commonwealth submits that any rights and interests possessed by the Barngarla people over any seas cannot be exclusive rights as a matter of common law, even if they may have been exclusive rights at sovereignty.

56 To properly understand the State’s position regarding the principal issue in this matter, the continuity of acknowledgement and observance of traditional Barngarla laws and customs giving rise to rights and interests in lands and waters, a brief exegesis of the relevant law is called for.

57 Section 225 of the NT Act relevantly states that:

A determination of native title is a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area … of land or waters …

58 Section 223(1) provides the definition of “native title” and “native title rights and interests”:

The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples … in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples …; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples …, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

59 The seminal judgment in Yorta Yorta established much of the relevant jurisprudence on the interpretation of s 223(1)(a). It is therefore necessary to address that judgment at some length.

60 In Yorta Yorta, Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ discussed at length between [32]-[56] the elements of s 223(1)(a) of the NT Act. It is not really possible usefully to select a few parts only of that analysis. The submissions referred, amongst other passages, to the following at [49] and [50]:

Law and customs do not exist in a vacuum. … Law and custom arise out of, and, in important respects, go to define a particular society. In this context, “society” is to be understood as a body of persons united in and by its acknowledgement and observance of a body of law and customs. …

To speak of rights and interests possessed under an identified body of laws and customs is, therefore, to speak of rights and interests that are the creatures of the laws and customs of a particular society that exists as a group which acknowledges and observes those laws and customs. And if the society out of which the body of laws and customs arises ceases to exist as a group which acknowledges and observes those laws and customs, those laws and customs cease to have a continued existence and vitality. Their content may be known but if there is no society which acknowledges and observes them, it ceases to be useful, even meaningful, to speak of them as a body of laws and customs acknowledged and observed, or productive of existing rights or interests, whether in relation to land or waters or otherwise.

61 It is clear that Yorta Yorta stands for the proposition that s 223(1)(a) requires proof of the continuous existence of a “society”. Examination of the content of the definition of the terms “laws” and “customs” further elicited the following observations from the plurality at [41] and [42]:

To speak of … rights and interests being possessed under, or rooted in, traditional law and traditional custom might provoke much jurisprudential debate about the difference between what HLA Hart referred to as “merely convergent habitual behaviour in a social group” and legal rules. …

… the [NT Act] refers to traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed. Taken as a whole, that expression, with its use of “and” rather than “or”, obviates any need to distinguish between what is a matter of traditional law and what is a matter of traditional custom. Nonetheless, because the subject of consideration is rights or interests, the rules which together constitute the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed, and under which the rights or interests are said to be possessed, must be rules having normative content. Without that quality, there may be observable patterns of behaviour but not rights or interests in relation to land or waters.

62 This point, about the necessity of the existence of “rules having normative content” rather than merely “observable patterns of behaviour”, was reiterated by their Honours when they came to address the use of the term “traditional” as a qualifier of the nouns “laws” and “customs” in s 223(1)(a) at [46] of the judgment:

… “traditional” is a word apt to refer to a means of transmission of law or custom. A traditional law or custom is one which has been passed from generation to generation of a society, usually by word of mouth and common practice. But in the context of the [NT Act], “traditional” carries with it two other elements in its meaning. First, it conveys an understanding of the age of the traditions: the origins of the content of the law or custom concerned are to be found in the normative rules of the Aboriginal … societies that existed before the assertion of sovereignty by the British Crown. It is only those normative rules that are “traditional” laws and customs.

The requirement of “normative rules” was commented upon by Finn J in Akiba v Queensland (No 2) (2010) 270 ALR 564 at 610 (Akiba) where his Honour clarified that a rule need not be informed by any spiritual or religious dimension in order to be normative:

[In this case,] [u]nlike mainland Aboriginal cases, there is little in the laws and customs relied upon that has any informing spiritual dimension at all … Much appears simply utilitarian; much seems prosaic. … Yet it needs to be recognised that normative beliefs can be held about ordinary behaviour, as the fierce dispute over how properly to open soft boiled eggs in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels suggests.

63 The plurality in Yorta Yorta referred to the second of the two other elements, the concept of the rights and interests being “possessed” at [47]:

… [T]he reference to rights or interests in land or waters being possessed under traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the peoples concerned, requires that the normative system under which the rights and interests are possessed … is a system that has had a continuous existence and vitality since sovereignty. If that normative system has not existed throughout that period, the rights and interests which owe their existence to that system will have ceased to exist. And any later attempt to revive adherence to the tenets of that former system cannot and will not reconstitute the traditional laws and customs out of which rights and interests must spring if they are to fall within the definition of native title. (original emphasis)

64 That passage introduced the concept of “continuity” to native title jurisprudence. The “normative system” of laws and customs must have had a “continuous existence and vitality since sovereignty” in order for it to be able to be said that the laws or customs under which the rights and interests to the land exist are traditional laws or customs.

65 However, the plurality in Yorta Yorta at [83] went on to clarify that in order to have a “continuous existence and vitality”, laws and customs need not necessarily have had an unchanging existence since sovereignty:

… [S]ome change to, or adaptation of, traditional law or custom or some interruption of enjoyment or exercise of native title rights or interests in the period between the Crown asserting sovereignty and the present will not necessarily be fatal to a native title claim. Yet both change, and interruption in exercise, may, in a particular case, take on considerable significance in deciding the issues presented by an application for determination of native title. … The key question is whether the law and custom can still be seen to be traditional law and traditional custom. Is the change or adaptation of such a kind that it can no longer be said that the rights or interests asserted are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the relevant peoples when that expression is understood in the sense earlier identified?

66 The plurality made these further remarks on this important issue of the permissibility of change to and adaptation of traditional laws and customs at [87]:

… acknowledgement and observance of those laws and customs must have continued substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty. Were that not so, the laws and customs acknowledged and observed now could not properly be described as the traditional laws and customs of the peoples concerned. That would be so because they would not have been transmitted from generation to generation of the society for which they constituted a normative system giving rise to rights and interests in land as the body of laws and customs which, for each of those generations of that society, was the body of laws and customs which in fact regulated and defined the rights and interests which those peoples had and could exercise in relation to the land or waters concerned. They would be a body of laws and customs originating in the common acceptance by or agreement of a new society of indigenous peoples to acknowledge and observe laws and customs of content similar to, perhaps even identical with, those of an earlier and different society.

67 It is important, and of particular relevance to the present case, to note their Honours’ qualification at [89] to the above passage:

In the proposition that acknowledgement and observance must have continued substantially uninterrupted, the qualification “substantially” is not unimportant. It is a qualification that must be made in order to recognise that proof of continuous acknowledgement and observance, over the many years that have elapsed since sovereignty, or traditions that are oral traditions is very difficult. It is a qualification that must be made to recognise that European settlement has had the most profound effects on Aboriginal societies and that it is, therefore, inevitable that the structures and practices of those societies, and their members, will have undergone great change since European settlement. Nonetheless, because what must be identified is possession of rights and interests under traditional laws and customs, it is necessary to demonstrate that the normative system out of which the claimed rights and interests arise is the normative system of the society which came under a new sovereign order when the British Crown asserted sovereignty, not a normative system rooted in some other, different, society. To that end it must be shown that the society, under whose laws and customs the native title rights and interests are said to be possessed, has continued to exist throughout that period as a body united by its acknowledgement and observance of the laws and customs.

68 In the same vein, Finn, Sundberg and Mansfield JJ held in Bodney v Bennell (2008) 167 FCR 84 at [120]-[121] (Bodney):

… [W]hen determining whether rights and interests are traditional, the proper enquiry is whether they find their origin in pre-sovereignty law and custom, and not whether they are the same as those that existed at sovereignty. Clearly laws and customs can alter and develop after sovereignty, perhaps significantly, and still be traditional. …

It may be that the true position is that what cannot be created after sovereignty are rights that impose a greater burden on the Crown’s radical title. For example, in this proceeding, the evidence demonstrated that the claimants had never fished in the sea. The Crown’s radical title over the sea was therefore not, at sovereignty, burdened by any native title rights to fish. If a practice of fishing in the sea had developed since sovereignty, no native title rights could attach to that practice since any such rights would constitute a greater burden on the radical title than existed at sovereignty. By definition such rights could not be traditional. On the other hand, where the Crown’s radical title was burdened at sovereignty with a right to fish, a change in the number and identity of people whose rights so burden it does not necessarily mean that those current rights cannot be traditional.

69 Hence, it is clear that s 223(1)(a) will be fulfilled only where there is proof that a society acknowledges and observes rules under which rights and interests in land are possessed that have normative content and that find their real origins in the same pre-sovereignty society. The acknowledgement and observance of those normative rules must have continued substantially uninterrupted from the time of sovereignty. However, the qualification indicated by the use of the adverb “substantially” recognises both the difficulty of proving continuous acknowledgement and observance of oral traditions and the inevitability of change to the structures and practices of Aboriginal societies in the light of European settlement.

70 The focus in Yorta Yorta on the word “society” can give the impression that some inquiry, separate from the above inquiry into traditional laws and customs, must be conducted in order to establish whether a “society” exists. Jagot J in Wyman on behalf of the Bidjara People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2013] FCA 1229 at [469] observed that “for the purposes of the [NT Act], it is the continued acknowledgement and observance of pre-sovereignty laws and customs that enables it to be said that the relevant society itself has continued.” That was not intended to indicate that the society which presently exists is a continuation of the society which existed pre-sovereignty.

71 The proper interpretation of s 223(1)(b) was discussed by the plurality in Yorta Yorta at [33]-[35]. It was also considered in Bodney by the Full Court at [165]-[179]. The Court set out five matters to be kept in mind when applying s 223(1)(b):

First, the inquiry required by s 223(1)(b) is distinct from that required by s 223(1)(a), and they should not be “fused” or “confused”. That is because “connection is not simply an incident of native title rights and interests … The required connection is not by the Aboriginal peoples’ rights and interests. It is by their laws and customs.”

Second, because the laws and customs which provide the requisite connection are traditional laws and customs, the acknowledgement and observance of those laws and customs must have continued substantially uninterrupted and the connection itself must have been substantially maintained since the time of sovereignty.

Third, the inquiry required by s 223(1)(b) involves two steps: (i) identification of the content of the traditional laws and customs; and (ii) characterisation of the effect of those laws as constituting a connection of the people with the land. It should be noted that connection can often be proven merely by proving continued acknowledgement and observance of traditional laws and customs, because those laws and customs presuppose or envisage direct connections with land or waters or link community members to each other and to the land in a complex of relationships. However, that will always depend on the particular content of the traditional laws and customs as established by the evidence.

Fourth, to establish connection for the purposes of s 223(1)(b), the connection must involve a continuing internal and external assertion by the claimants of their traditional relationship to the country, as that relationship is defined by its laws and customs. That assertion may be expressed by physical presence on the relevant country, or by other means.

Fifth, the inquiry required by s 223(1)(b) can have a “particular topographical focus” within the claim area – that is to say, it may be found that there is no evidence of sufficient connection with a particular part of the claim area, despite there being evidence of sufficient connection in other parts of the claim area.

72 It is to those matters, dictated by s 223(1)(a) and (b) as explained in Yorta Yorta, that consideration must now be given.

BARNGARLA SOCIETY AT SOVEREIGNTY

(A) Early European contact and conquest of the claim area

73 This brief account of early European contact with Aboriginal people in the claim area is primarily based on the submissions of the applicant and the State, and on the material to which they have referred.

74 In 1770, at least part of Australia was claimed for the Crown by Lt James Cook RN, who named the new territory New South Wales: Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 at 77-78 per Deane and Gaudron JJ (Mabo (No 2)).

75 In 1788, New South Wales was established as a penal colony: An Act to enable his Majesty to establish a Court of Criminal Judicature on the Eastern Coast of New South Wales, and Parts adjacent (Imp) 27 Geo III, c 2. On 26 January 1788, Governor Phillip founded the colony of New South Wales. At this time, the colony of New South Wales encompassed all land to the east of the 135th meridian. Thus, most of the claim area fell within the colony of New South Wales (the 135th meridian intersects the claim area such that a very small portion of it lies to the west of the 135th meridian).

76 The first Europeans to set foot on the claim area appear to have been the crew of the English vessel HMS Investigator, captained by Matthew Flinders, in 1802. Flinders landed at the southern tip of the Eyre Peninsula, in a harbour he named Boston Bay, and which remains so named to the present day. He named the locality he landed at “Port Lincoln”, after his native Lincolnshire, a name that also remains to the present day. Flinders wrote of hearing Aboriginal people calling in the Port Lincoln area, and of observing their bark huts and paths by the shore.

77 In the 1820s or thereabouts, there was a whaleboat crew of sealers stationed on Thistle Island, off the coast of the Eyre Peninsula and south-east of Port Lincoln. At some stage, the sealers took Aboriginal women from neighbouring areas. There is evidence to suggest that some of these women were from the Port Lincoln area. There are various other accounts from this time of sealers stationed on other islands such as Kangaroo Island and Saint Peter Island in the Great Australian Bight, taking women believed to be from the Port Lincoln area to be their “wives”. There is some reference to the “wives” maintaining their hunting and gathering practices.

78 In 1825, the borders of the colony of New South Wales were expanded to encompass all land east of the 129th meridian by Letters Patent issued by the King: Letters Patent, 16 July 1825. The whole claim area now fell within the colony of New South Wales.

79 In 1836, another British colony was established in Australia, the colony of South Australia. It was established pursuant to the South Australia Act 1834 (Imp) 4 & 5 Wm IV, c 95. The entire claim area now comprised part of the colony of South Australia.

80 In 1839, Governor Gawler proclaimed the whole of the Eyre Peninsula area as the “District of Port Lincoln”. A settlement was established at Port Lincoln in that year, populated by a small number of European settlers. The first fulltime Protector of Aborigines, Dr Matthew Moorhouse, was appointed in 1839. In 1841, Moorhouse appointed Clamor Schürmann, a Lutheran missionary, as Deputy Protector of Aborigines for the District of Port Lincoln. In 1844 Schürmann published a vocabulary of the local Aboriginal language, which he called “Parnkalla”. In 1846 he published a work on the life, manners and customs of the “Aboriginal tribes of Port Lincoln”, by which apparently he meant both the “Parnkalla” tribe and the “Nauo” tribe (1846 article). The material suggests a significant Aboriginal population in the lower area of the Eyre Peninsula at that time.

81 From 1839-1840, over two journeys, Edward Eyre explored the peninsula that would eventually bear his name. Through these journeys he came into contact with Aboriginal people. Eyre in his Journal of Expeditions of Discovery (1845) asserted that the Aboriginal people he had come into contact with had a real concept of attachment to and interest in land.

82 Various reports from this time suggest that the claim area bore witness to a not insignificant amount of frontier violence between settlers and Aboriginal people. In the early 1840s, it appears that there had been a number of attacks by local Aboriginal people against pastoral outstations. A party of armed settlers took it upon themselves to carry out reprisal raids against the Aboriginal population. Not long afterwards, a military presence was established by the Governor to protect the settlers from the Aboriginals. The soldiers also carried out reprisal attacks. Schürmann lamented the indiscriminate nature of these raids, saying that the tribe responsible for the violence was the “Battara Yurarri”, a division of the larger “Parnkalla” tribe, but that the military were carrying out reprisal attacks against the “Nauo” tribe. Through the 1840s and 1850s, many more recorded examples of violence between settlers and Aboriginal people in the claim area could be given. Through the same period, there are also records of diseases afflicting the local Aboriginal population, causing a high mortality rate. The settler pastoralists slowly established pastoral stations further and further north from Port Lincoln.

83 The contemporary records of the decades following in essence the first and progressive formalised settlement of the Eyre Peninsula by Europeans confirm a significant existing Aboriginal occupation and significant violence by Aboriginal people against those who were European settlers in the area and violent reprisals by the settlers, especially in the Port Lincoln area. It is a fair inference to describe it as “frontier violence”, as the applicant does in the submissions.

84 The material tends to support the same picture, perhaps with less violence, as the settlers took interest in land progressively to the north of Port Lincoln during those decades.

85 There can be little doubt that at sovereignty there were Aboriginal people living in the lower part of the Eyre Peninsular in significant numbers, and as the subsequent history shows, they were also living in the mid and upper areas of the Eyre Peninsula, as considered by the progressive exposure of settlers to them as the settlers’ interests expanded geographically. That includes the Port Augusta area, where Port Augusta was established as a regional town centre in 1854.

86 In 1847, George French Angas also wrote on the Barngarla tribe, again referring to them as the “Parnkalla”, as did Charles Wilhelmi in 1861. Both writings heavily rely, however, upon Schürmann’s earlier writings.

(B) Existence of a Barngarla society and Identification of Barngarla laws and customs at sovereignty

87 The question of the existence of a Barngarla society and the identification of the Barngarla laws and customs as they stood at the time of the conquest of Australia by Europeans is a matter that can only be answered by reference to historical material and to the analysis of that material by the expert witnesses.

88 The question was principally addressed in the McCaul 2013 Anthropology Report and the Haines 2012 Report of 4 October 2012. The question was also the subject of comment in the reports of Professor Sutton and Dr Martin, and some matters of relevance to this question also arise from the linguist reports of both Dr Rose and Mr McCaul. In those circumstances, I have included reference to the reports and oral evidence of the expert witnesses. The question was dealt with at some length at the hearing of the expert evidence (the relevant part of the transcript being pages 1582-1652).

89 The historical material drawn upon can be broadly summarised as follows: there is, first, the writings of Clamor Schürmann, Lutheran missionary, who had substantial contact with the Barngarla people in the 1840s and wrote about their society and their language. Second, information can be garnered from various data collected by later anthropologists from Barngarla and non-Barngarla informants. Notable amongst this category of historical material is the work of Norman Tindale. Third, inferences can be made from the work of anthropologists such as A.P. Elkin and A.W. Howitt about the organisation of the “Lakes Group” of Aboriginal tribes generally (of which the Barngarla are generally considered to be a part). It is noted that some attributes assigned to the “Lakes Group” tribes generally ought to be assigned to the Barngarla tribe specifically.

90 The various aspects of Barngarla society at sovereignty are set out under a number of different headings below. It must be noted that there is a great deal of artificiality in attempting to describe a society in this manner. Barngarla at-sovereignty society, like any society, is unlikely to be comprehensively encapsulated within a number of discrete modules with abstract headings such as “kinship system” and “land tenure system”. Indeed, the attempt to explain Barngarla at-sovereignty society in these terms might well render it unrecognisable to its members. Nonetheless, for the purpose of these reasons, it is necessary to approach the task in this fashion.

91 As has been noted above, the British Empire claimed sovereignty over most of the claim area in 1788, and over the remaining western part of the claim area in 1825. Strictly speaking, those dates are therefore the relevant dates at which time the “traditional laws and customs” of the Barngarla people must be ascertained. That obviously presents evidentiary problems, because, as also noted above, there was no actual contact of any kind between Aboriginal people and in particular the Barngarla people and Europeans until 1802 at the very earliest, and there was no substantive contact and settlement of the claim area until the very late 1830s.

92 However, in this case it can be accepted that, in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, it is permissible to infer that the laws and customs and rights thereunder of the Barngarla people that were recorded to exist at or shortly after the time of substantive contact in the late 1830s, existed at the time of sovereignty: see, eg, Banjima People v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2013] FCA 868 per Barker J at [82] and Daniel v Western Australia [2003] FCA 666 per Nicholson J at [428].

Notion of the “Barngarla people” as a distinct society

93 It is clear and uncontentious that there existed at the time of sovereignty an identifiable group that called themselves the “Barngarla”. (Martin T1584, l.37; Haines Report 1, p 10; T1755, l.10-12)

94 Schürmann described the word “Parnkalla” (as he renders it) in 1844 as the “national name of the native tribes inhabiting the eastern coast of Spencer’s Gulf and the adjacent country.” In 1846 article, he wrote:

The Parnkalla dialect … is spoken by the tribe of the same name, inhabiting the eastern coast of [the Eyre] peninsula from Port Lincoln northward probably to as far as the head of the Spencer’s Gulf.

95 It will be noted, of course, that Schürmann does not use the ambiguous word “tribe” with any precision. In the earlier quotation, he indicates that “Parnkalla” is a “nation” consisting of a number of “tribes”, while in the latter quotation, “Parnkalla” is a single tribe. Despite the semantic imprecision, it is clear enough that there was a group known as “Parnkalla” on the Eyre Peninsula in the 1840s.

96 Professor Sutton summed up the general view amongst the experts on this topic when he stated:

[T]he notion of a Barngarla self as a collective self, I think, certainly was there. At least, Schürmann’s informants referred to Barngarla matta, and matta … is a collective noun which suggests “group”, which suggests a norm for belonging and norms for excluding, so I think in essence that broad category of Barngarla can be assumed to have been there as a landed identity, a territorial identity, at sovereignty… (T1607, ll6-19)

Language of the Barngarla people

97 As indicated by Schürmann’s above quotation, the Barngarla group was not united only in their identification under a common name. The Barngarla group also spoke a common Barngarla language.

98 A Barngarla dictionary was composed by Schürmann in 1844 (1844 dictionary). It is obvious that that dictionary was based on the Barngarla language as spoken in the Port Lincoln area, where Schürmann resided. The question arose in the proceedings as to whether the Barngarla language consisted of a number of dialects at sovereignty.

99 Mr McCaul was of the opinion that “there is indicative evidence that there were distinct forms of speaking Barngarla – distinct dialects that were associated with particular parts of the country” at the time of sovereignty. Dr Rose did not completely agree with that assessment, saying that “within the Barngarla, while there … appear to have been shades of difference in the particular terms and sound[s] people might have used across the Barngarla language territory, there’s no evidence of specific language dialectal communities or dialectal distinctions.”

100 In my view, the disagreement here is a technical one, and one of little import so far as the application for a determination of native title is concerned. Both linguistic experts agreed that the Barngarla people all spoke the same language at the time of sovereignty. Both linguistic experts agreed that, as one would expect over such a large area of land and where modern modes of transport and communication did not exist, there were regional differences in the Barngarla language. The only disagreement was as to whether those differences amounted to distinct dialects of the Barngarla language or not. That question of nomenclature may be of interest from a linguistic perspective, but I do not regard it as relevant to the present proceeding. That is based upon an overview of the two linguist experts and the analysis below about whether there were separate and different societies or one society.

101 It is agreed by the parties that at sovereignty, the Barngarla people were not a “unitary society”, but were divided into some form of “sub-groups”. By “sub-group”, what is meant in broad terms is some sort of land-holding group of Barngarla people of a size less than the entire Barngarla population. There appears to be some difference, however, between the parties and the experts as to whether these “sub-groups” were akin to “estate groups” and “patriclans” that are recorded to exist in other so-called “Lakes Group” Aboriginal societies such as the Dieri, or whether the “sub-groups” that existed were wider “dialect groups”.

102 There is a significant amount of conflicting evidence on the question of the existence of “sub-groups” amongst the Barngarla people at sovereignty.

103 Schürmann recorded in a letter in 1842 that:

The Parnkalla [sic] tribe are spread over a [great] extent of country from Port Lincoln to the northward beyond Franklin Harbour and over the greater part of the interior country. They divide themselves again into two smaller tribes, viz. Wambirri yurarri, i.e. coast people and Battara yurarru, i.e. gum tree people, so called from their living in the interior country where the gum is plentiful. It is to be understood, however, that these tribes are not so entirely separated as not to mix occasionally, on the contrary they often visit each other in small numbers …

104 The Wambirri-Battara bifurcation of Barngarla society is also recorded in Schürmann’s 1844 dictionary, but not in his 1846 article. In his 1844 dictionary, Schürmann also wrote at II:4-5 (and recognised at [39] of the Sutton 2013 Report):

The natives of Port Lincoln have four distinct words in their language descriptive of the bearings of their Peninsular country, and totally unconnected with the directions of the heavens. They are: -

iata, North East coast and country

worrtatti, South East country

wailbi, South West country

wayalla, North Western, and Northern country

They use entirely different words to express the directions of the winds.

105 Later in his 1844 dictionary, Schürmann at one point gives a telling example phrase at II:29:

… marruntu wanggatanna iata matta, the north eastern people speak differently.

106 The Sutton 2013 Report at [41] notes that elsewhere, the word matta, translated as “people” above, means “tribe” or “nation”.

107 Tindale (as recognised in the Haines 2012 Report at 28-29) recorded the following information about the Barngarla people’s sub-divisions:

… [T]he Banggala [sic] tribe was divided into several sections – and these are named: -

Warta Banggala NE

Wirangu Banggala West

Malkari Banggala Sth West

The Warta Banggala are the people of the eastern side of the Head of Spencers [Gulf] ranging north to beyond Parachilna but not to Beltana (except in modern times) and taking in Edeowie, Hookina, Hawker, Yarrah and Uno Bluff. They visited the other sections of the tribe for meetings, for trade and marriage.

The Malkari Banggala ranged from Oakden Hills and Yeltacowie … south through Uno Bluff, Yudnapinna, Carriewerloo and Hesso; in “very ancient times” they came no further south, but since before the white man came, they have been moving further south.

108 Tindale elsewhere makes a somewhat cryptic mention of the existence of a group called the “Kaltadjula Banggala” who “went west to Streaky Bay indefinite”, (Haines 2012 report at p.29) and also mentions a “Nhawu Parnkala” (presumably Nauo-Barngarla) and “Kwiabi Parnkala”, or “Kooapidna”, or “Kooapudna” (McCaul 2012 Anthropology Report at [112]).

109 Charles Mountford, interviewing two Barngarla men, Percy and Walter Richards in 1944, recorded the Barngarla’s country, but in doing so referred to two sets of (unnamed) “Bangala [sic] people” (Mountford 1944:2).

110 Hercus in 1999 identified three Barngarla dialects: Parnkalla, Pangkarla and Arra-Parnkalla (Hercus 1999: 12, McCaul 2012 Anthropology Report at [116]). By 2005, Hercus and Gara appeared to have refined this theory and introduced a hypothesis of identifiable sub-groups:

Moonie Davis [a Barngarla man, said] that there were three Barngarla dialects, which he differentiated as Nyawa Barngarla, Banggarla [sic] and Arrabarngarla. The Banggarla, according to Moonie, lived in the southern Flinders Ranges and the country north of Port Augusta, and Arrabarngarla country was down the eastern side of Eyre Peninsula. (Gara & Hercus 2005: 93; McCaul 2012 Anthropology Report at [116])

111 Dr Haines, in his 2012 Report at p 30 maintains that the terms recorded by Tindale, “Warta Banggala” and “Malkari Banggala” do not relate to specific sub-groups, but are rather merely “geographic descriptors or locators, so that people visiting other regions of Barngarla territory would be able to place themselves in relation to their hosts”. Dr Haines suggests that Schürmann’s division of the Barngarla into two sub-groups in his 1842 letter was erroneous, and that is why the division is not mentioned in his 1846 article on the native tribes of Port Lincoln. Dr Rose comes to the same general conclusion in his 2012 Report at [22], [24] and [59], that these various groupings are merely geographical or dialectal indicators, not social units.

112 Mr McCaul expressed a different opinion in his 2012 Anthropology Report at [121]-[122]:

I agree with Drs Haines and Rose that the precise nature of these groups is unclear, but I would not be inclined to dismiss their traditional significance as readily. …

The traditional break up of larger “language communities” into localised dialect groups is well documented (e.g. Hercus 1994, for the Arabana, Howitt 1996 for the Dieri and Breen 2004 for the Yandruwandha). The ethnography on the issue from other groups suggests, in my opinion, that these localised dialectal groups were the primary land using and land owning group. … It is within such local groups that people would have received their primary socialisation and education about the land. Therefore, it is in my opinion incorrect to state that they had little social or political significance.

113 Professor Sutton, in turn, disagreed with McCaul’s assessment in his Report at [47]-[49]:

[The] labels for different segments of the Barngarla people discussed above] are not primary land-holding units … They are sub-regional ethnicities usually comprised of members of a plurality of descent groups who themselves severally hold land and waters collectively and in perpetuity but at a very small scale both geographically … and in terms of membership …

In the absence of concrete evidence to the contrary I am … unable to agree with Mr McCaul when he writes … that ‘localised dialect groups were the primary land using and land owning group’. In general [in Aboriginal Australia], with some well known exceptions, the primary land owning group was a descent group or clan … that had an enduring membership, while a land using group was [merely] a band of fellow-campers … [I]n a mobile hunter-gatherer society the two categories (of owners v users) are never likely to be the same. …

To merge the two kinds of group is [a] fallacy …

It is usually the descent groups or clans that are the most critical building blocks of the society when it comes to land ownership in classical Aboriginal Australia [with some exceptions]. The lands they own, their estates, are thus the usual building blocks for wider territorially-associated entities such as dialect groups and environmental typifier groups and groups defined in terms of the cardinal directions.

114 Dr Martin in his 2013 Report at [46] endorses Professor Sutton’s opinion on this issue. The weight of the expert opinions thus clearly favours the view that the various labels applied to different segments of the Barngarla people that appear in the literature were not land-holding groups or primary social units. I am satisfied that the shared view of Dr Martin and Professor Sutton is the correct one. Mr McCaul did not forcefully press a contrary view during the concurrent evidence. I have made some general observations about the expert evidence later in these reasons.

115 That, however, does not dispose of the issue of the nature of Barngarla society at sovereignty. There remain two competing hypotheses: first, that the Barngarla society was a “unitary” society – that is to say, the primary land-holding unit was the entire society as a whole; second, that the primary land-holding units in Barngarla society were “estate groups” or “patriclans” – small groups of families attached to a relatively small area of land, similar to those that existed in many neighbouring Aboriginal groups.

116 Dr Haines held the former view in his 2012 Report, where at [51] he states:

[T]he Barngarla were effectively a unitary society, with no real structural divisions apart from geographic indicators.

And at [47D] he says:

It is my view that there was, at the time of sovereignty, a society of people with the ethonym … “Barngarla” … united by a body of laws and customs, who were co-resident on and circulated within a common territory of land and waters …

117 Dr Martin, on the other hand, holds the latter view. He wrote in his 2012 Report at [59] that Dr Haines’ opinion “would appear to be manifestly inconsistent with the ethnography available to Dr Haines.” The ethnography in question is the work of a number of early anthropologists such as A.W. Howitt, A.P. Elkin and Otto Seibert.

118 Howitt wrote in his 1904 work, The Native Tribes of South-East Australia, of the Lake Eyre group of Aboriginal tribes. He took the Dieri people as his “prototype” of that group of Aboriginal tribes, but asserted that all the Lake Eyre group tribes were similar societies, and that the “Parnkalla” tribe was a member of that group. Martin explains Howitt’s theory of tribal organisation at [31] of his 2012 Report:

Howitt saw the ‘tribe’ as a whole exclusively occupying a specified geographic area. This entity was divided into smaller and named groups living in a defined portion of the tribal country, and these again were subdivided until what Howitt saw as the basic residence unit was reached; one, or perhaps a few, families hunting and gathering on their own particular inherited area. The essential model is one of named clans linked together in regional associations.

119 Elkin, drawing upon Howitt inter alia, wrote a seminal paper for the Oceania journal in 1931 entitled “The Social Organisation of South Australian Tribes”. In that paper, he coined the term ‘”Lakes Group” to describe the Lake Eyre group of tribes described by Howitt. Elkin describes a division of these tribes into, inter alia, “ceremonial clans” under a system he calls “patrilineal ceremonial totemism” at [58]:

Each man inherits from his father a totem name[,] … a piece of country with which this totem and a Mura-mura [dreaming story] or culture-hero were associated in the past, a myth enshrining the story of this, and a ceremony the performance of which usually brings about an increase of the totemic species concerned… (Elkin 1931: 58)

120 It should be noted that Elkin is not certain that every tribe of the Lakes Group practised “patrilineal ceremonial totemism”. Elkin notes at [57] that the kinds of totemism he describes, including patrilineal ceremonial totemism, existed “in the [Lakes Group] tribes around Lake Eyre and on the Cooper and Diamentina. [But] [i]t is now too late to decide whether they were all formerly present in the southern part of the area.” It seems likely that Elkin meant to include the Barngarla people in his reference to the tribes of the “southern part of the [Lakes Group] area”.

121 In any event, it is clear that both Elkin and Howitt are describing the existence of small land-holding groups existing within larger tribes that sound similar to the “estate groups” that are recorded to exist within many Aboriginal groups in Australia.

122 Once the views of Howitt and Elkin are considered, it is Dr Martin’s opinion in his 2012 Report at [61] that:

[T]he ethnographic record clearly indicates that in all probability (since they were recorded in other groups in the Lakes cultural region), there were Barngarla subgroups which were not simply environmental or geographic referents, but landed groups comprising clans with interests in particular areas … ([61], 2012 report)

123 Professor Sutton, as indicated in his Report at [47], generally supported that view. Dr Haines in the oral hearing admitted that he was willing to concede that, though he maintained there was a “paucity of evidence” to infer the existence of any land-holding group other than a “unitary society”, “in all probability in each area [of Barngarla country] … there [were] people with a preponderance of rights, if you like, in their respective areas…” and that it is permissible to infer from evidence of the social organisation of neighbouring societies at sovereignty what the social organisation of Barngarla society was likely to have been at sovereignty. (T1645, 125-1646,120)

124 On the balance of probabilities, therefore, I think that Dr Martin’s opinion ought to be accepted – that is, that at sovereignty, the Barngarla people were divided into small land-holding sub-groups, and were neither “unitary” in the sense, as Professor Sutton put it in oral evidence, that they were not “interspersed throughout each other’s lives in a kind of ‘flat universe’”, (T1627, ll32-33) nor were they divided into dialect groups that formed some kind of separate social or political unit.

125 The above finding of the probable existence of estate groups in at-sovereignty Barngarla society leads inexorably to considerations of land tenure.

126 There was little dispute between the parties as to the nature of the land tenure system of Barngarla society at sovereignty. There is very little direct evidence of the content of that system, but both the applicant and the State submitted that, in accordance with the opinions of the expert witnesses, it was permissible to make inferences about the Barngarla land tenure system from the observations of Siebert, Howitt and Elkin, inter alia, as to the land tenure systems of other “Lakes Group” societies, in particular the Dieri (as noted in the McCaul 2012 Anthropology Report at [100].

127 There are two key questions to be asked in analysing the Barngarla system of land-holding: first, what kinds of rights or interests to land were recognised by the Barngarla? Second, how were those rights or interests acquired?

128 Turning first to the question of the nature of the rights or interests in land recognised by the Barngarla, it is agreed between the parties that the rights of Barngarla at-sovereignty people to land are collective rights, at least within the estate group. Mr McCaul summarised the general view in oral evidence thus:

It’s clear that [rights to land under the at-sovereignty Barngarla land tenure system] were held by more than the individual, but … if we are to assume [the existence of] some form of ... descent-based local group … then the rights of the members of that group in their own lands would not be the same as the rights that they would hold across other parts of Barngarla lands … They would be held differently as to ritual status, gender and so forth. … [So rights to land would have been] differentiated but held by groups or aggregates of people rather than by individuals, yes. (T1612, l6)

129 Next, it is not contentious that Barngarla rights to land were at sovereignty inalienable. Professor Sutton stated in his Report at [34]:

… Barngarla country, under the rules of its people, is nowhere described as a chattel that can be marketed or gifted but is, at least by implication, inalienable.

130 Now turning to the second question: how were rights in land acquired in the at-sovereignty Barngarla land tenure system? Howitt, after explaining the system of estate groups, or “patriclans”, that has been described in the section on “sub-groups” above, goes on to say at 34:

These groups have a local perpetuation through the sons, who inherit the hunting grounds of their fathers.

131 Elkin, writing several decades later, is also clear that the inheritance of rights is patrilineal. That is of course made explicit in his appellation for the system: “patrilineal ceremonial totemism”. In a passage on estate groups already quoted in the “sub-groups” section, Elkin refers to men “inheriting” a “piece of country” from their fathers.

132 Further, Otto Siebert explains the Dieri land tenure system in a similar vein at 48:

Every person inherits from his father a particular association to a mura-mura … [E]very person also inherits a place, which is considered the home of the mura-mura; this place can be a larger or smaller district, which is regarded as the possession of the respective person. A father will describe to his children the country thus belonging to them with words such as:

‘This your country. My mura-mura created it. My mura-mura lived here.’ …

This through the father inherited relationship to the mura-mura and everything that comes with it is called pintara. …

133 So it is very clear that so far as Elkin, Howitt and Siebert observed, the Dieri land tenure system was patrilineal. Dieri society is considered a “Lakes Group” society, as is Barngarla society. Martin notes that Barngarla society is considered a “Lakes Group” society primarily because there is evidence that at sovereignty it shared a common moiety system with other Lakes Group societies. But there is very little direct evidence that Barngarla society shared the land tenure system the Dieri called pintara. In oral evidence, Mr McCaul drew attention to some scant direct evidence to support that inference:

…[W]e do have in the 1930s A.P. Elkin and Tindale recording both … matriary [sic] and patriary [sic] totems for four or five Barngarla individuals and again in 1965 or so Luise Hercus is recording Stanley Davis [a Barngarla man] talking about totem and … what his totem is. And so I would from that infer that it was an important feature of Barngarla society in the past. (T1604, ll5-10)

134 Elkin recorded the following details from conversations with Barngarla informants about the Barngarla land tenure system at 59:

… I found that the Wailpi and Yadliaura [tribes now commonly referred to collectively as the Adnyamathanha people] used to have the [Dieri] pintara type of totem which they called budlanda, and that the present Pankala [sic] men knew all about this form of totemism and though that budlanda ceremonies must have been performed by the Pankala in the past, though not in their own time. One Pankala informant said that the local term for budlanda was wibma, that his wibma was the same as his father’s, and that it included a Mura-mura myth.

135 In any event, the parties agree in their written submissions that a system essentially the same as Elkin’s patrilineal ceremonial totemism operated in Barngarla society at sovereignty. I so find.