FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Alpha Flight Services Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1434

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DIRECTOR OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS VICTORIA Applicant | |

AND: | ALPHA FLIGHT SERVICES PTY LTD (ACN 064 142 418) First Respondent QANTAS AIRWAYS LIMITED (ACN 009 661 901) Second Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

A AGAINST ALPHA FLIGHT SERVICES PTY LTD ("Alpha")

Declarations (s 21 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (C'th) ("the FCA Act"))

Nano Magnetics Nanodots

1. Between 4 August 2013 and 14 September 2013, Alpha, by supplying, in trade or commerce, to consumers by way of sale in international flights operated by Qantas Airways Limited ("Qantas") 220 items of Nano Magnetics Nanodots, being small high-powered magnets ("Nanodots"), and being goods that are separable magnetic objects that are supplied in multiples of two or more where:

(a) at least two of those magnetic objects are each separately able to fit entirely into the small parts cylinder, as provided by the relevant safety standard; and

(b) at least two of those magnetic objects each separately have a magnetic flux index greater than 50 (kG)2 mm2, determined in accordance with the relevant safety standard; and

(c) the magnetic objects are marketed by the supplier as, or supplied for use as, a toy, game, puzzle, or construction kit -

contrary to, or in non-compliance with, or inconsistent with, the permanent ban on small, high-powered magnets imposed by Consumer Protection Notice No. 5 of 2012 and effective from 15 November 2012, has contravened sub-s 118(1) of the Australian Consumer Law ("the ACL") and/or sub-s 118(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (Victoria) ("the ACL (Vic)").

2. Between August 2013 and 14 September 2013, Alpha, by offering for supply, in trade or commerce, to consumers by way of sale in international flights operated by Qantas, through:

(a) its Qantas and Alpha co-branded "In Sky Shopping" catalogue available on international Qantas flights and Qantas airport lounges;

(b) its Qantas and Alpha co-branded "In Sky Shopping" website accessible directly at URL www.inskyshopping.com and also accessible by link through the Qantas website at URL www.qantas.com.au ("Inflight Duty Free", "shop before you fly"); and

(c) by inflight duty free sales services by Qantas crew members and videos regarding Qantas' duty free program as shown by Qantas on international flights -

items of Nanodots, being small high-powered magnets, and being goods that are separable magnetic objects that are supplied in multiples of two or more where:

(i) at least two of those magnetic objects are each separately able to fit entirely into the small parts cylinder, as provided by the relevant safety standard; and

(ii) at least two of those magnetic objects each separately have a magnetic flux index greater than 50 (kG)2 mm2, determined in accordance with the relevant safety standard; and

(iii) the magnetic objects are marketed by the supplier as, or supplied for use as, a toy, game, puzzle, or construction kit -

contrary to, or in non-compliance with, or inconsistent with, the permanent ban on small, high-powered magnets imposed by Consumer Protection Notice No. 5 of 2012 and effective from 15 November 2012, has contravened sub-s 118(2) of the ACL and/or sub-s 118(2) of the ACL (Vic).

3. Between August 2013 and 14 September 2013, Alpha, in or for the purposes of trade or commerce, possessed or had control of consumer goods, namely Nanodots, being small high-powered magnets, and being goods, the supply of which is prohibited by sub-s (1) of s 118 of the ACL and sub-s (1) of s 118 of the ACL (Vic), has contravened sub-s 118(3) of the ACL and/or sub-s 118(3) of the ACL (Vic).

Pecuniary Penalties (s 224 ACL (Vic))

4. Alpha pay to the State of Victoria a pecuniary penalty in the sum of $50,000 in respect of the contraventions by Alpha of ss 118(1), (2) and (3) of the ACL (Vic) as found by the Court to be established.

Non-Punitive Publication Order (s 246 ACL (Vic)) / Adverse Publicity Order (s 247 ACL (Vic))

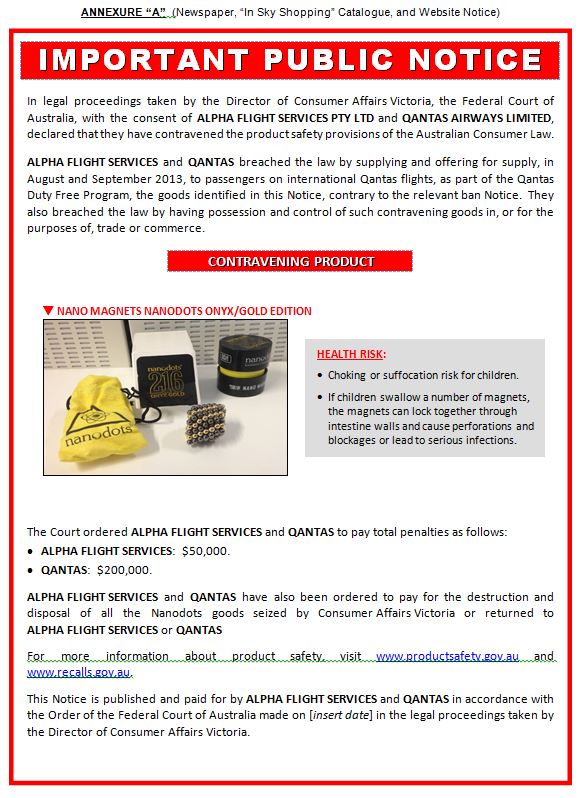

5. Alpha cause the Important Public Notice to be published, within 21 days of the date of the Order, in the form and with the content of Annexure "A" to the Order, on the Internet at the homepage of all websites which are owned, operated or maintained by or on behalf of Alpha, including the website accessible via Uniform Resource Locator ("URL") at the web address (URL) www.inskyshopping.com ("Alpha website") (or if any such URL is replaced or changed, the Internet home page of the corresponding website) and retain the Important Public Notice on the Alpha website, until the Alpha and Qantas In Sky Shopping catalogue identified in paragraph 6 below, is withdrawn or replaced and use its best endeavours to ensure that:

(a) the Important Public Notice is to be viewable by clicking through a "click-through" icon located on the Alpha website;

(b) the "click-through" icon referred to in the previous sub-paragraph is located in a central position on the page first accessed when the user opens to the home page of the Alpha website;

(c) the "click-through" icon must contain the words "PRODUCT SAFETY - IMPORTANT NOTICE ORDERED BY FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA" (in capital letters and use a minimum type size of 12 point Times New Roman or equivalent), clearly and prominently in red on a contrasting background and the words "Click Here"; and

(d) the Important Public Notice occupies the entire webpage which is accessed via the "click-through" icon referred to above.

6. Alpha, having contravened a provision of Chapter 3 of the ACL (Vic), as referred to in this Order, cause to be published in the next available co-branded Alpha and Qantas In Sky Shopping catalogue (in both print and electronic form) issued by or on behalf of Alpha or Qantas following the date of the Order, on the first right-hand page after the cover page, an Important Public Notice in the form and with the content of Annexure "A" to the Order. The Notice shall:

(a) be a minimum of a full catalogue page in size;

(b) use a minimum type size of 12 point Times New Roman or equivalent;

(c) be in full colour; and

(d) be available to Qantas international passengers for a period of not less than 3 months.

B AGAINST QANTAS AIRWAYS LIMITED ("Qantas")

Declarations (s 21 FCA Act)

Nano Magnetics Nanodots

7. Between 4 August 2013 and 14 September 2013, Qantas, by supplying, in trade or commerce, to consumers by way of sale conducted by Qantas crew members in international flights operated by Qantas 220 items of Nanodots, being small high-powered magnets, and being goods that are separable magnetic objects that are supplied in multiples of two or more where:

(a) at least two of those magnetic objects are each separately able to fit entirely into the small parts cylinder, as provided by the relevant safety standard; and

(b) at least two of those magnetic objects each separately have a magnetic flux index greater than 50 (kG)2 mm2, determined in accordance with the relevant safety standard; and

(c) the magnetic objects are marketed by the supplier as, or supplied for use as, a toy, game, puzzle, or construction kit -

contrary to, or in non-compliance with, or inconsistent with, the permanent ban on small, high-powered magnets imposed by Consumer Protection Notice No. 5 of 2012 and effective from 15 November 2012, has contravened sub-s 118(1) of the Australian Consumer Law ("the ACL") and/or sub-s 118(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (Victoria) ("the ACL (Vic)").

8. Between August 2013 and 14 September 2013, Qantas, by offering for supply, in trade or commerce, to consumers by way of sale in international flights operated by Qantas, through:

(a) its Qantas and Alpha co-branded "In Sky Shopping" catalogue for August 2013 to October 2013, available on international Qantas flights and Qantas airport lounges;

(b) its Qantas and Alpha co-branded "In Sky Shopping" website accessible directly at URL www.inskyshopping.com and also accessible by link through the Qantas website at URL www.qantas.com.au ("Inflight Duty Free", "shop before you fly"); and

(c) by inflight duty free sales services by Qantas crew members and videos regarding Qantas' duty free program as shown by Qantas on international flights -

items of Nanodots, being small high-powered magnets, and being goods that are separable magnetic objects that are supplied in multiples of two or more where:

(i) at least two of those magnetic objects are each separately able to fit entirely into the small parts cylinder, as provided by the relevant safety standard; and

(ii) at least two of those magnetic objects each separately have a magnetic flux index greater than 50 (kG)2 mm2, determined in accordance with the relevant safety standard; and

(iii) the magnetic objects are marketed by the supplier as, or supplied for use as, a toy, game, puzzle, or construction kit -

contrary to, or in non-compliance with, or inconsistent with, the permanent ban on small, high-powered magnets imposed by Consumer Protection Notice No. 5 of 2012 and effective from 15 November 2012, has contravened sub-s 118(2) of the ACL and/or sub-s 118(2) of the ACL (Vic).

9. Between August 2013 and 14 September 2013, Qantas, at its catering facilities and in carts used to carry and store duty free goods on Qantas' aircraft for international flights as part of Qantas' duty free program, in or for the purposes of trade or commerce, possessed or had control of consumer goods, namely Nanodots, being small high-powered magnets, and being goods, the supply of which is prohibited by sub-s (1) of s 118 of the ACL and sub-s (1) of s 118 of the ACL (Vic), has contravened sub-s 118(3) of the ACL and/or sub-s 118(3) of the ACL (Vic).

Pecuniary Penalties (s 224 ACL (Vic))

10. An order that Qantas pay to the State of Victoria pecuniary penalties in the sum of $200,000 in respect of the contraventions by Qantas of ss 118(1), (2) and (3) of the ACL (Vic) as found by the Court to be established.

Non-Punitive Publication Order (s 246 ACL (Vic)) / Adverse Publicity Order (s 247 ACL (Vic))

11. Qantas cause the Important Public Notice in the form and with the content of Annexure "A" to the Order to be published, within 21 days of the date of the Order, on the Internet in a central and prominent position on the first page of the website accessible via URL at the web address (URL) www.qantas.com.au ("Qantas website") (or if any such URL is replaced or changed, the Internet home page of the corresponding website), containing information about the Qantas Duty Free Program and retain the Important Public Notice on the Qantas website, until the Alpha and Qantas In Sky Shopping catalogue, identified in paragraph 6 above, is withdrawn or replaced and use its best endeavours to ensure that:

(a) the Important Public Notice shall be displayed by use of a "lightbox" technique, with the Important Public Notice occupying the majority of the webpage and darkening the remainder of the page on which it is displayed; and

(b) the Important Public Notice shall be introduced by the words "PRODUCT SAFETY - IMPORTANT NOTICE ORDERED BY FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA" (in capital letters and use a minimum type size of 12 point Times New Roman or equivalent), clearly and prominently on a contrasting background.

C AGAINST MORE THAN 1 RESPONDENT

Non-Punitive Publication Order (s 246 ACL (Vic)) / Adverse Publicity Order (s 247 ACL (Vic))

12. Alpha and Qantas, having contravened a provision of Chapter 3 of the ACL (Vic), as referred to in this Order, cause to be published within 21 days of the date of the Order:

(a) within pages 2 to 30 inclusive of The Australian newspaper; and

(b) within pages 2 to 30 inclusive of the Financial Review newspaper -

an Important Public Notice in the form and with the content of Annexure "A" to the Order. Each of the Notices:

(i) be a minimum size of one quarter of the printed areas of the relevant page of the newspaper;

(ii) use a minimum type size of 12 point Times New Roman or equivalent; and

(iii) be in full colour.

Refunds (s 232 ACL and ACL(Vic)

13. Pursuant to s 232(6)(a) of the ACL or ACL (Vic), Alpha and Qantas pay a full refund to all persons returning goods identified in the Important Public Notices.

14. Pursuant to s 232(1) of the ACL or ACL (Vic), Alpha and Qantas:

(a) notify on a monthly basis for 4 months, after publication of the Important Public Notices, an Officer designated by the Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria of the details of any goods returned to that company; and

(b) securely store all such returned goods for collection (destruction and disposal) by the Officer designated by the Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria, as soon as is convenient after the 4 month period, referred to in paragraph 19(a) above, has expired.

Destruction and disposal of the goods (s 232 ACL and ACL (Vic))

15. Pursuant to s 232(6)(d) of the ACL or ACL (Vic), the Applicant be permitted to destroy and dispose of the contravening goods, which were seized by the Applicant and contravening goods otherwise in the possession of or returned to Alpha or Qantas as provided for in paragraph 19 of the Application.

16. An order that Alpha and Qantas pay the Applicant the costs of and any costs incidental to the destruction and disposal of the contravening goods. Such payment is to be made by the Respondents to the Applicant within 7 days of a written request by the Applicant to the Respondents, quantifying the costs of, and any costs incidental to, the destruction and disposal of the contravening goods.

Costs

17. Alpha and Qantas pay a contribution towards the Applicant's costs fixed in the sum of $60,000.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 355 of 2014 |

BETWEEN: | DIRECTOR OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS VICTORIA Applicant

|

AND: | ALPHA FLIGHT SERVICES PTY LTD (ACN 064 142 418) First Respondent QANTAS AIRWAYS LIMITED (ACN 009 661 901) Second Respondent

|

JUDGE: | PAGONE J |

DATE: | 24 DECEMBER 2014 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 The Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria seeks the imposition of pecuniary penalties upon Alpha Flight Services Pty Ltd (“Alpha”) and Qantas Airways Limited (“Qantas”), and other orders, in respect of contraventions of product safety provisions concerning the supply, offering for supply, possession and control of certain goods, namely s 118 of the Australian Consumer Law (Cth) and s 118 of the Australian Consumer Law (Vic). The goods had been subject to a permanent ban upon their sale. Alpha and Qantas have admitted the contraventions but made submissions in respect of the amount of pecuniary penalty to be imposed and about the content of a publication notice to be ordered by the Court.

2 The parties were represented by counsel and tendered a statement of agreed facts for the purposes of the proceeding in reliance upon s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). They also relied upon eight affidavits made for the purposes of the proceeding to supplement the agreed facts, but not to derogate from them. The Director relied upon an affidavit by Mr Ian Anderson made 5 November 2014 and an affidavit by Mr Peter Hiland dated 8 December 2014. Mr Anderson was a passenger on a Qantas international flight to Hong Kong on 7 August 2013 when he noticed an advertisement in the “In Sky Shopping” catalogue for “Nano Magnetics Nanodots Onyx/Gold” (“Nanodots”) which he believed had been prohibited for sale under Australia’s product safety law as they were unsafe for children. It was Mr Anderson who first brought to the attention of Qantas that the Nanodots were potentially dangerous for children and that they ought not to have been available for sale. Mr Peter Hiland is an employee of the Director who gave evidence concerning the financial position of Qantas from publicly available information. Alpha relied upon an affidavit of Ms Melissa Jones dated 4 December 2014 and upon three affidavits made by Mr George Sakkas which were made, respectively, on 4, 9 and 16 December 2014. Ms Jones was the e-Commerce Executive of Alpha at the time of making the affidavit but from May 2011 had held the position of Training and Communications Executive at Alpha. Ms Jones was the person at Alpha who was informed by Qantas of the concerns which had been raised by Mr Anderson and who acted upon those concerns promptly. Mr Sakkas is the General Manager, Finance, of Alpha and was familiar with the business operations and financial position of Alpha during the relevant period. Qantas relied upon an affidavit of Ms Nicole Malone dated 4 December 2014 and an affidavit by Ms Kim Thomas dated 4 December 2014. Ms Malone was the senior legal counsel of Qantas with the overall responsibility for the Competition and Consumer Law Compliance Program of Qantas since December 2010. Ms Thomas was employed in the customer care department of Qantas in a role known as “Customer Care Executive”. She has been employed in Qantas for some 17 years since February 1998 and had been directly involved in responding to enquiries at the Qantas Contact Centre including, relevantly, the query by Mr Anderson in which he had raised with Qantas his concerns about the Nanodots for sale on Qantas flights. None of the evidence in the affidavits was contested or challenged.

3 The reliance upon agreed facts requires consideration of whether it is appropriate for the court to make declaratory orders by consent as sought by the Director. Declarations should generally not be made by a court “merely on admissions of counsel or by consent, but only if the Court is satisfied by evidence” that the judicial act of making declaratory orders is appropriate: see BMI Limited v Federated Clerks Union of Australia (1983) 51 ALR 401, 412-3; see also Forster v Jododex Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421, 437-8. The general rule that declarations by a court should not be granted by consent of the parties is a rule of practice and is not immutable: see Animatrix Limited v O’Kelly [2008] EWCA Civ 1415, [53]. The rule of practice exists to preserve the integrity of the court and the judicial process and will not be followed where necessary “to do justice between the parties”: see BMI Limited v Federated Clerks Union of Australia (1983) 51 ALR 401, 412-3; ACCC v Bridgestone Corporation (2010) 186 FLR 214, [17]; Animatrix Limited v O’Kelly [2008] EWCA Civ 1415, [54]. In ACCC v Dataline.net.au Pty Ltd (2006) 236 ALR 665 Kiefel J said at [58]-[59]:

58 The power to grant declarations (s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth)) is unconfined. Order 35A itself imposes no constraints upon the relief sought. Refusals to make declarations in cases of default are based upon a practice, not a rule of law. The practice is one of long standing and might be seen as derived from views about litigation which pre-date more recent concerns expressed by the courts as to the costs of unnecessary litigation, the management of cases and efficiency overall. Views expressed in older cases may not take account of the increase in the use made of declaratory orders in developing areas of law which may involve matters of public interest. A caution with respect to the use of older authority is made in the White Book Service 2003 to the English Civil Procedure Rules 1998 (40.20.2).

59 It may no longer be correct to have a practice which operates as a prohibition in every case of default and preferable to consider the circumstances pertaining to the particular case and the purpose and effect of the declaration. Millett J made declaratory orders in Patten v Burke Publishing Co Ltd [1991] 1 WLR 541 where justice to the plaintiff required it. The order however operated principally inter partes and it might be doubted whether it would be of interest to other persons. Cases such as this, involving the protection of consumers, are of public interest. Declarations are often utilised in such cases to identify for the public what conduct contributes a contravention and to make apparent that it is considered to warrant an order recognising its seriousness. It is however important that there be no misunderstanding as to the basis upon which they are made. This could be overcome by a statement, preceding the declarations, that orders are made ‘upon admissions which [the respondent in question] is taken to have made, consequent upon non-compliance with orders of the Court’.

Her Honour’s approach in this respect was described as “entirely appropriate” by the Full Court at (2007) 161 FCR 513, [92]. In the present case, the Court can be confident to make the orders sought by consent and based in part upon the agreed facts. The facts and the orders were agreed to between parties who had real and opposing interests in the litigation. One of those parties was a regulatory authority charged with public duties to be enforced by the Court. The agreed facts were all inherently probable and were supported by annexures containing reliable documentary evidence and were supplemented by affidavits and other supporting documentary evidence. The orders themselves are appropriate to the facts and to the contraventions disclosed by the facts.

4 The existence of the agreed facts and other material makes it unnecessary to make findings between contested facts, or to set out the facts except to the extent necessary to explain the reasons for the penalties and the orders. Alpha and Qantas, as previously mentioned, have accepted that they have contravened ss 118(1), (2) and (3) of the Australian Consumer Law (Cth) and the Australian Consumer Law (Vic). The section provides:

118 Supplying etc. consumer goods covered by a ban

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, supply consumer goods of a particular kind if:

(a) an interim ban on consumer goods of that kind is in force in the place where the supply occurs; or

(b) a permanent ban on consumer goods of that kind is in force.

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

(2) A person must not, in trade or commerce, offer for supply (other than for export) consumer goods the supply of which is prohibited by subsection (1).

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

(3) A person must not, in or for the purposes of trade or commerce, manufacture, possess or have control of consumer goods the supply of which is prohibited by subsection (1).

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

(4) In a proceeding under Part 5-2 in relation to a contravention of subsection (3), it is a defence if the defendant proves that the defendant's manufacture, possession or control of the goods was not for the purpose of supplying the goods (other than for export).

(5) A person must not, in trade or commerce, export consumer goods the supply of which is prohibited by subsection (1) unless:

(a) the person applies, in writing, to the Commonwealth Minister for an approval to export those goods; and

(b) the Commonwealth Minister gives such an approval by written notice given to the person.

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this subsection.

(6) If the Commonwealth Minister gives an approval under subsection (5), he or she must cause a statement setting out particulars of the approval to be tabled in each House of the Parliament of the Commonwealth within 7 sitting days of that House after the approval is given.

The first subsection prohibits the “supply” of goods in respect of which there is a permanent ban in force. The second subsection prohibits the “offer for supply” of those goods, and the third subsection makes it an offence for a person, amongst other things, to “possess” or “have control of” goods prohibited by the first subsection.

5 A permanent ban applied to the Nanodots by Consumer Protection Notice No. 5 of 2012 with effect from 15 November 2012. The permanent ban applied to small high powered magnets that are separable magnetic objects supplied in multiples of two or more where:

(a) at least two of those magnetic objects are each separately able to fit entirely into the small parts cylinder as provided by the relevant safety standard;

(b) at least two of those magnetic objects each separately have a magnetic flux index greater than 50 (kG2) mm2, determined in accordance with the relevant safety standard; and

(c) the magnetic objects are marked by the supplier as, or supplied for use as, a toy, game, puzzle, or construction kit.

The Nanodots fell within this ban and were sold, offered for sale, possessed and controlled by Alpha and Qantas during the period from 1 August 2013 to 14 September 2013 as part of the Qantas duty free program.

6 Qantas provides for sale a variety of goods on international flights as part of its duty free program. Qantas has outsourced its duty free program to Alpha since 20 April 2004 under an agreement for Alpha to manage and administer the Qantas duty free program and to provide related services on behalf of Qantas. A formal agreement governing the relationship and obligations between Qantas and Alpha was entered into commencing on 1 March 2005.

7 The Nanodots came to be acquired by Alpha as part of the Qantas duty free program between 1 August 2013 to 14 September 2013. During that period Alpha packed one or more units of the Nanodots onto carts for loading onto various Qantas aircraft for international Qantas flights departing from Australia. During that period Qantas had possession and control of carts received from Alpha which included the Nanodots. 220 units of Nanodots were sold during that period on Qantas flights between 4 August 2013 and 14 September 2013 at a unit price of $55. An additional three units were sold online through a website co-branded by Qantas and Alpha. Alpha and Qantas were left with some 507 units of Nanodots that were not sold.

8 Qantas came to be informed that Nanodots were being offered for sale on its international flights in potential contravention of Australian product safety laws by one of its passengers, Mr Anderson, around 8 August 2013. He had been a passenger the day before on a Qantas international flight to Hong Kong originating from Melbourne when he noticed an advertisement for the Nanodots in the “In Sky Shopping” catalogue in the utility pocket on the rear of the seat immediately in front of him. Mr Anderson had been involved in the Australian and international toy industry for more than 55 years and was familiar with the regime imposing restrictions on the sale of dangerous goods, including toys, in Australia. He has represented the Australian toy industry at a local level for over 30 years and became concerned that Nanodots were on sale which he believed to be subject to limitations imposed under Australia’s product safety law. On 8 August 2013 he contacted a colleague in Australia to confirm the details of what he understood to have been a permanent ban affecting the supply of small high power magnets such as the Nanodots. He then, around 8 August 2013, telephoned Qantas to express his concern.

9 Mr Anderson’s evidence concerning his telephone call to Qantas was different to, but was not inconsistent with, the evidence of Qantas. His account was that he spoke to a female customer services officer in which he asked whether Qantas was “aware that the Nanodots offered for sale in the duty free catalogue on Qantas aircraft [had] been banned in Australia”. His recollection is of having informed the person that these, and similar, magnets had been proven to be dangerous for children because of the risk of being ingested and that Qantas should remove them from sale. His recollection of the response was that the female person with whom he spoke said:

Qantas outsources this service to an outside provider for its duty free products and they handle its in-flight duty free goods. The outside provider is responsible to Qantas for ensuring the safety of the duty free goods.

I am not sure about your advice regarding the safety of the product, but I will refer your concerns to the appropriate people for their response.

Qantas did not have a record of a telephone call from Mr Anderson but did have a record of a contact from Mr Anderson raising concerns. There was no challenge to Mr Anderson’s account of how he made contact with Qantas and it is probable that whoever answered the phone at Qantas created an online enquiry to be dealt with by Qantas in accordance with the processes in place within Qantas. In any event it was clear that Mr Anderson contacted Qantas with his concerns around 8 August 2013 and that nothing was done about his concerns for six days.

10 On 14 August Mr Anderson received an email from a customer care executive at Qantas identified as “Kim”. That email acknowledged his earlier contact and indicated that his comments had been referred to Alpha for investigation and action. The evidence of Ms Kim Thomas is consistent with that of Mr Anderson, however the lack of action for six days between his first contact on 8 August and her response on 14 August was unexplained. Ms Thomas has been employed by Qantas since February 1998 and has held the role of Customer Care Executive since January 2004. The Qantas customer care department was responsible for general enquiries submitted to Qantas by its customers. Most of the enquiries are submitted using an online form accessible via the Qantas website, although some are made by letter or telephone. Ms Thomas came to know of Mr Anderson’s concerns as an online enquiry.

11 The standard procedure in place at Qantas during the period from August to September 2013 differed as between international and national travel. A supervisor would manually allocate online enquiries to Ms Thomas who, at the time, was working only three days a week from 8.30am to 4pm. Enquiries that could be fully addressed online would be marked as “closed” in the system by Ms Thomas but would be marked for “review” if a further response was required by a customer making a further enquiry. Ms Thomas was assigned on 8 August 2013 to respond to what had been identified as an online enquiry made by Mr Ian Anderson. Ms Thomas annexed a screenshot from the system showing an online enquiry and, to that extent, the evidence of Ms Thomas does not accord with that of Mr Anderson, although it is possible that Mr Anderson spoke with another person at Qantas who may have entered an online enquiry and, as indicated, the evidence of Mr Anderson is not challenged and is otherwise consistent with that of Ms Thomas. The difference is, in any event, of no significance and need not be resolved.

12 The evidence thereafter is consistent, namely, that nothing occurred until 14 August 2013 when Ms Thomas reviewed the enquiry. On that day Ms Thomas believed that she had referred Mr Anderson’s enquiry to Alpha and sent an email to Mr Anderson informing him to that effect. Her affidavit explained:

On 14 August 2013 I reviewed Mr Anderson’s Online Enquiry. In the system, I coded the Online Enquiry, by selecting from relevant drop down menus and selected ‘inflight’, ‘inflight products’, ‘duty free’ and ‘availability’. By coding the Online Enquiry in this way, I believed that I had directed the Online Enquiry to Alpha Flight Services (who I understood conducted all duty free operations on behalf of Qantas). I now understand that my belief at the time was incorrect and the system did not notify Alpha of Mr Anderson’s Online Enquiry.

Ms Thomas explained that she then sent an email to Mr Anderson using the generic customer care email address stating (as she believed) that she had passed on his comments to Alpha for their investigation and action.

13 Mr Anderson was next a passenger on a Qantas international flight on 25 August 2013 believing that his concerns had been addressed around 14 August 2013. On that flight, however, he obtained another copy of the Qantas inflight duty free catalogue and noticed that the Nanodots were still being offered for sale through the catalogue. On 3 September 2013 Mr Anderson sent an email to Qantas marked to the attention of “Kim” (with the reference number Qantas had given to his earlier enquiry) in relation to the concerns he had first raised on 8 August 2013. There was no response from Qantas for a further nine days.

14 Ms Thomas explained that the reason for that delay was that the 3 September email from Mr Anderson was not displayed on her review tab and that she did not become aware of it until 12 September 2013 when Mr Anderson sent a further response to the 14 August email. Indeed, Mr Anderson deposed to the fact that he had not received a response to the email he had sent on 3 September 2013 by 12 September 2013 and that at about 1pm on 12 September 2013 he sent another email to Qantas, again marked to the attention of “Kim”, quoting the Qantas reference number and raising his concerns that he had not been contacted about the Nanodots. That email also indicated that if he did not receive the information he was seeking by 18 September 2013 he would contact the Australian Competition and Consumer Commissioner, the press, and Choice magazine. That email resulted in a response from Ms Thomas and a review of why the 3 September email had not been displayed on her review tab. The reason for the latter, she discovered, was because the administrative assistant who had received and assigned the 3 September email had departed from the Qantas standard procedures by closing the file without reopening it or alerting Ms Thomas by a code that would cause the message to appear in her review tab.

15 The Director made no criticism of Ms Thomas personally and none is intended by these reasons. What the account of these facts reveal, however, is a system in Qantas that failed to operate appropriately in the context of concerns about products which were banned for sale and which posed potential risks for children. Consulting the Qantas inflight catalogue would have shown that the product had been identified as dangerous and as not suitable for children under 14 years of age. The product was displayed in the catalogue with the words “This product is not for children. Contains small magnets that can be dangerous if swallowed or inhaled. Ages 14 & up”. Mr Anderson’s expressions of concern had been about the potential danger of the products for children, and the systems then in place at Qantas led to two separate periods of delay that were only brought to an end on each occasion by external steps querying why Qantas had not taken action. This evidence reveals that at the time Qantas lacked an appropriate system to ensure that it complied with its obligations about product safety and that it would respond appropriately when breaches were drawn to the attention of Qantas staff.

16 The 12 September email from Mr Anderson did, however, result in Qantas doing something about his concern. Ms Thomas phoned Alpha on that day and spoke to Ms Melissa Jones who also made an affidavit in these proceedings. Ms Thomas informed Ms Jones of Mr Anderson’s concerns and Ms Thomas was advised by Ms Jones that she would undertake further investigation. Ms Thomas then phoned Mr Anderson and left a voicemail message advising him of her contact with Ms Jones and gave Mr Anderson Ms Jones’s telephone number. Ms Jones recalled that she had been telephoned by Ms Thomas between 2.30pm and 2.45pm on 12 September 2013 and that she was told that that Mr Anderson had been given Alpha’s telephone number. Ms Jones asked Ms Thomas for copies of the earlier emails and received a telephone call from Mr Anderson very soon after the call by Ms Thomas who told her that the Nanodots were a banned product. By shortly after 3.00pm that same day (that is, within around 30 minutes of Ms Jones having received a telephone call from Ms Thomas) Ms Jones instructed Alpha’s warehouse controller immediately to remove the Nanodots from carts because the product was the subject of a ban. At 3.28pm Ms Thomas emailed Alpha’s warehouse controller instructing him that Nanodots were to be removed from all outgoing duty free carts and from all future inflight and pre-order sales. One minute later she received an email from him in response. Eight minutes later she received an email from Alpha’s Bond Supervisor confirming that all Nanodots had been removed from the carts. One minute after that Ms Jones emailed Mr Anderson to inform him that the Nanodots would be removed from sale. The speed and appropriateness of Alpha’s action stands in stark contrast with that of Qantas.

17 The Director issued these proceedings on 30 June 2014. Alpha and Qantas admitted liability for the contraventions of s 118 and do not oppose declaratory relief and the making of publicity orders. Alpha and Qantas have since implemented a product safety compliance program satisfactory to the meet Director’s concerns who, accordingly, no longer presses for the injunctive relief initially sought in the application. The main outstanding issue between the Director and the respondents concerns the imposition and quantum of any pecuniary penalties to be imposed.

18 The amount of pecuniary penalty that may be imposed for “each act or omission” to which s 118 applies is an amount not to exceed $1.1 million. An issue which frequently arises when considering the amount of penalty to be imposed is how to treat actions which individually give rise to more than one offence and how to treat separate offending acts which arise from, or are due to, a common source of culpable conduct. Thus, for example, each of the 223 sales are separate acts in respect of which a penalty could be imposed. Each may also be seen as a breach of at least two, and possibly three, of the prohibitions in s 118; namely, the separate prohibitions against “supply”, “offer for supply”, and “possessing” or “controlling” of the goods. In some cases, however, it would be inappropriate (for the purposes of imposing penalties) to treat, for example, the offering for supply as separate from the actual sale which occurs only by reason of a purchaser taking action to buy the goods rather than from any additional positive action by the retailer: Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Dimmeys Stores Pty Ltd (2013) 308 ALR 296, 300-1. The conceptual complications which may arise should not, however, distract from the purpose for which a penalty is to be imposed, namely, to reflect the substance of the offending conduct. In some cases it may matter less that there have been multiple sales (and therefore multiple offences) than that they arose from a single cause over a confined period.

19 Different approaches to the imposition of penalty may be taken in respect of any particular situation and different circumstances will make some approaches more appropriate than others. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Ltd (2010) 188 FCR 238 Middleton J said at [250]-[251]:

250 A number of different approaches in this proceeding could be taken to imposing a penalty. The Court could look to each contravention, consider the appropriate penalty taking into account the totality principle, and then apply any appropriate discount. This was the approach submitted by the ACCC. The Court could group together each exchange or each State, or focus on each period of inability to gain access, and view the contraventions included within those groups as appropriately to be treated together for the purpose of assessing the appropriate penalty. Alternatively, the Court could treat the admitted contraventions as all following from the same cause, and with the maximum penalty being $10 million, and then consider the appropriate discount. This is the approach submitted by Telstra. Another approach would be to look at the capped sites and uncapped sites, and treat that as a basis for grouping the contraventions.

251 There is no scientific approach or arithmetic formula to be applied in determining the appropriate penalty. The circumstances of each contravention need to be looked at, taking into account all the circumstances pertaining to the contravention. I have already indicated what I regard as important and significant considerations, but the other matters I have raised are taken into account.

In some cases it may be appropriate to regard separate conduct as separate contraventions requiring distinct penalties to be imposed upon each: see Singtel Optus v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 287 ALR 249, [53]-[55]; see also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640, [61]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABB Transmission and Distribution Ltd (No 2) (2002) 190 ALR 169, [38]. In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v GE Capital Finance Australia [2014] FCA 701 Jacobson J said at [71]-[78]:

71 The factors identified by French J in TPC v CSR are to similar effect to those stated by Santow J in Re HIH Insurance Ltd (in prov liq); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Adler (2002) 42 ACSR 80 at [125]-[126] as providing guidance in the exercise of the discretion to impose a pecuniary penalty.

72 The overriding principle is that the Court must weigh all the relevant circumstances. The guiding principles stated by French J in TPC v CSR and by Santow J in ASIC v Adler may be applied to inform the exercise of the discretion but they should not be treated as a rigid catalogue of matters to be applied in every case.

73 The principal purpose of the imposition of a pecuniary penalty is to act as a specific deterrent and as a general deterrent to others who might be tempted to contravene the law: TPC v CSR at 52,152; ASIC v Adler at [125]; see also the authorities cited in Registrar of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations v Matcham (No 2) (2014) 97 ACSR 412 at [225]-[228].

74 Nevertheless, the role of deterrence in determining the amount of a pecuniary penalty is subject to the qualification that the amount should not be greater than is necessary to achieve the objective of deterrence. An appropriate balance must be struck to avoid oppression: NW Frozen Foods at 293; ASIC v Adler at [125].

75 The process of fixing the quantum of a penalty is not an exact science. The approach which should be adopted is one of “instinctive synthesis”: Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357. All of the circumstances must be weighed so as to mark the Court’s view of the seriousness of the offence. Attention must be paid to the maximum penalty fixed by the statute so as to compare the worst possible case with the one before the Court. The exercise is not a mathematical one, and there is no single correct penalty: see ATSIC v Matcham at [126]-[128].

76 In determining the appropriate penalty the Court should not leave room for any impression of weakness. Nor should there be any suggestion that the quantum of the penalty may be treated as an acceptable risk of doing business: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 304 ALR 186 at [65]-[66].

77 Separate contraventions arising from separate acts should ordinarily attract the imposition of a separate penalty appropriate for each contravention. The course of conduct principle is to be applied according to the facts of each case. The general objective of the course of conduct principle is to ensure that the penalty reflects the substance of the offending conduct, rather than a mathematical total for each separate offence: see the authorities cited in ATSIC v Matcham at [195]-[201].

78 The totality principle is to be applied as a final check to ensure that the penalty is appropriate for all of the offences: see Mill v The Queen (1988) 166 CLR 59 at 62-63; Mornington Inn Pty Ltd v Jordan (2008) 168 FCR 383 at [5] ff.

Care must be taken, therefore, to consider all relevant factors for the purpose of ensuring that the penalty reflects “the substance of the offending conduct”. It is the substance of the offending conduct which the penalty should reflect and it is relevant to that end to bear in mind the number and nature of the contraventions and the number of acts constituting contraventions and the time over which the contraventions occurred.

20 The conduct of Alpha and Qantas in this case gave rise to separate acts of supplying, offering to supply, possessing and controlling prohibited goods. Some of the acts gave rise to more than one offence and in some instances the acts were multiple and in others they occurred over a period of time. The importance of focusing upon the conduct that gave rise to the contraventions can be seen by the breadth of the discretion in s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law and the policy revealed in the section of matching the penalty to the culpable conduct. Subsection (1) provides that where the Court is satisfied of a contravention it “may order the person to pay” to the Commonwealth (or the State, as the case may be) “such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which this section applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate”. Subsection (2) provides:

(2) In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and the loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 of this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

Subsection (4) provides:

(4) If conduct constitutes a contravention of 2 or more provisions referred to in subsection (1)(a):

(a) a proceeding may be instituted under this Schedule against a person in relation to the contravention of any one or more of the provisions; but

(b) a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this section in respect of the same conduct.

It is the conduct which the legislature seeks to punish by these provisions rather than the number of contraventions which that conduct may have enlivened although the number of contraventions is a matter to be taken into account and in some cases may be determinative of the penalty.

21 Section 224(2) identifies three matters to be considered in determining the appropriate penalty which are similar to those to which regard had been required in the context of s 76(1) and 76E(2) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). In that context French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Limited [1991] ATPR 52,135 at 52,152-52,153 had identified a number of additional considerations relevant to the assessment of a pecuniary penalty under s 76. Those matters were approved by the Full Court in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285, 292 where the Court said:

The section itself lays down that the penalty is to be "appropriate having regard to all relevant matters", and then indicates certain matters which the legislature regarded as relevant, being:

"• the nature and extent of the act or omission.

• the nature and extent ... of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission.

• the circumstances in which the act or omission took place.

• whether the person [contravening] has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under [Part VI of the Act] to have engaged in any similar conduct."

The specified considerations do not necessarily exhaust "all relevant matters", but they do indicate considerations to which the Parliament turned its attention. In Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR 52,135 at 52,152-52,153, French J set out a checklist of matters to which judges have since frequently made reference. He added to those expressly mentioned in s 76 the following further points, which may be regarded as elaborations of the statutory requirement to consider "the circumstances in which the act or omission took place":

"• The size of the contravening company.

• The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

• The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

• Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

• Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

• Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention."

In CSR Ltd, French J said (at 52,152):

"The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act."

To these may be added other considerations depending upon the facts and circumstances of a particular case: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yellow Page Marketing BV (No 2) (2011) 195 FCR 1, 26-27.

22 The offending conduct in this case differs to some extent as between Alpha and Qantas, as do the reasons for the offending conduct having occurred in the case of each. Each has accepted that its conduct constituted offences under s 118 but the conduct that gave rise to the contraventions differed as between Alpha and Qantas. Each may have wrongfully supplied, offered to supply, possessed and controlled prohibited goods contrary to s 118, but the actions constituting their respective conduct, and the reasons that it occurred, were not the same.

23 The fundamental cause of both Alpha and Qantas contravening the provisions lay in the absence at the time in each company of a system and process which would have prevented the contravention and which would have ensured that each complied with the obligations imposed upon them by law. Each to some extent relied upon others to ensure that products complied with the relevant provisions. Neither was aware of the permanent ban in relation to the Nanodots, neither intended to contravene the provisions, and neither has previously been found by a court to have engaged in similar conduct. However, neither at the time had in place within their own organisations the necessary mechanisms to ensure that a product like the Nanodots, that is, that a product that was prohibited, would not come within their possession or control, would not be offered for sale, and would not be sold.

24 Alpha is a sizeable company and is part of a worldwide airline catering business trading under the name of Alpha Flight Services. Its operating profits after income tax for the year ended 31 December 2012 amounted to $16,550,961. Its duty free operation, however, is a relatively small part of its overall business. Its duty free operation in the financial year ended 30 June 2013 had a net turnover of $10.6 million and generated a net profit of $281,000. In the following year the net turnover was $11.1 million with a net profit of $336,000. Mr Sakkas estimated that the duty free operation contributed about 1.2% to Alpha’s net profit in each of the 2013 and 2014 financial years. The 220 units of Nanodots sold inflight were sold for a total combined price of $12,023 at a cost to Alpha of $5,093. The gross profit from the sales (before allocation of profit between Alpha and Qantas) was, therefore, approximately $5,500.

25 Senior management of Alpha had some involvement in the contravening conduct. On 22 May 2013 Ms Julie Holowinski, a buyer employed by Alpha, ordered 500 units of a product described as “Nano Dots” from a company called Scorpio Distributors Limited (trading as Scorpio Worldwide Limited in the United Kingdom) with the approval and authority of Mr Patrick Osborne who was Alpha’s General Manager for Sales, Marketing and Duty Free. On 23 May 2013 Ms Holowinski ordered a further 100 units of the Nanodots from Scorpio Worldwide with the approval and authority of Mr Osborne. A further 130 units were ordered by Ms Holowinski on 26 August 2013, again with the approval and authority of Mr Osborne. Neither of them, nor any other person at Alpha, was aware that the Nanodots acquired from the United Kingdom supplier contravened Australian legislation. Alpha did not have in place a product safety compliance program at the time of the contraventions which would have alerted them to that fact.

26 Alpha has expressed genuine regret about its contraventions and has acted with exemplary speed and appropriate actions as soon as it became aware that the products were banned. It has since promptly introduced a compliance program with training for employees on product safety compliance and has cooperated with the Director’s officers during the investigations, and with the Director in the efficient resolution of these proceedings. Alpha’s conduct, as the company responsible for the advertisements which appeared in the Qantas inflight catalogue, also revealed an appropriate appreciation of the need to warn potential buyers of dangers. Although Alpha was not aware of the ban at the time that advertisements were placed in the inflight catalogue, the advertisement for the Nanodots identified the product as “not suitable for children”. It gave as the explanation for that unsuitability, and warned potential buyers, that the product contained “small magnets that can be dangerous if swallowed or inhaled”. Someone at Alpha took the trouble to state this in the catalogue and indicated that the product should not be considered other than for children aged 14 or more. That may be seen to reveal both an appreciation of the need to prevent, and the need to warn about, danger in respect of goods thought to be permitted for sale. Counsel for Alpha stated to the Court its deep regret and that it was sorry for the circumstances which have occurred. The genuineness of that expression can more readily be accepted with confidence in light of Alpha’s actions when informed of the ban and by its actions subsequently. It may also be accepted with confidence in light of the submission made by Alpha of the amount that might be imposed by way of pecuniary penalty. Alpha’s submission of the appropriate range of penalty demonstrated its genuine regret and did not seek to minimise the significance of what had occurred by urging the imposition of an insignificant penalty.

27 Amongst the steps taken by Alpha to deal with the contravention has been the submission on 26 September 2013 of a recall notification in respect of the Nanodots to the ACCC after which a product recall notice was published in the recalls website. On 27 September 2013 Alpha contacted by email the customers who had purchased the Nanodots online, informing them of the recall and of the fact that the product was the subject of a ban. The customers were given a copy of the product recall notice. Alpha also complied with the requirement made of it in October 2013 by the Director to publish a copy of the product recall notice in every national newspaper in Australia. Alpha exceeded that requirement by publishing the recall notice not just once but twice in every national newspaper in Australia; once in weekly newspapers and once in weekend editions of those newspapers. Alpha also complied with the statutory notice served on it as part of the Director’s investigations by providing the information sought and by producing the documents required. Mr Osborne cooperated in the examination of him which was conducted as part of the Director’s investigations. Alpha has cooperated with, and engaged in, discussions with the Director’s office with a view to resolving questions about its liability and some of the issues relating to relief on a consensual, rather than a contested, basis.

28 The process of fixing the quantum of a penalty may require an “instinctive synthesis”: see Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357, 375; Australian Securities and Investment Commission v GE Capital Finance Australia [2014] FCA 701, [75]. By that what is meant is that all relevant factors must be taken into account to arrive at a single result: see Markarian, 374. On that approach the amount of penalty to be imposed upon Alpha should reflect the substance of the offending conduct bearing in mind the factors to which reference has been made, including the period of time over which the conduct occurred and Alpha’s exemplary conduct thereafter. The amount should be significant to leave no room for any impression of weakness. In this case, however, the court should also substantially reward Alpha’s exemplary and prompt behaviour. It is, in this case, appropriate to take into account that the amount which Alpha has submitted as the top of the range that might be imposed as a penalty was more than I would consider necessary in its case. This circumstance gives substance to its expression of contrition by making no attempt to minimise or seek to escape the imposition of a sizeable penalty. That, together with its actual conduct, and all of the other circumstances which I have set out above, leads me to impose a total penalty of $50,000.

29 The position of Qantas is different. Its role was described by counsel for the Director as essentially that of washing its hands of the obligations it had in respect of compliance with the relevant provisions. Qantas relied upon Alpha rather than to have taken steps of its own to ensure that it was complying with its obligations, although counsel for Qantas withdrew any submission to the effect that the reliance by Qantas upon Alpha was relied upon in mitigation of the penalty. The systems in Qantas, however, failed to respond swiftly when alerted to the fact of its non-compliance with its obligations at law and to a danger which its non-compliance posed to young children. Counsel for the Director was correct not to lay blame upon Ms Thomas because it was the responsibility of Qantas to have in place systems which ensured that its staff, including perhaps Ms Thomas, had complied with the obligations imposed upon Qantas and would deal swiftly and appropriately with concerns about compliance with product safety laws and the potential risks to children.

30 Counsel for Qantas adopted the submissions which had been made on behalf of Alpha and, in addition to the written submissions made on behalf of Qantas, drew attention to two matters by way of mitigation of penalty. The first was what counsel described as the more limited role of Qantas in the actual events constituting the contravention. The second was what counsel for Qantas described as the factor of contrition. In respect of the second counsel for Qantas said:

And, your Honour, I am instructed to say that Qantas understands and accepts that these contraventions are serious. It understands and respects the importance of the product safety standards, and it apologises unequivocally to the members of the public and to the court for the contraventions. Qantas takes its responsibility concerning the safety of the public and its employees and contractors very seriously, and, regrettably, your Honour, it did not have in place at the relevant time a product safety compliance program.

Counsel went on to refer to the fact that both Qantas and Alpha now have in place processes to comply with product safety standards.

31 The fact that Qantas may have had a more limited role than Alpha “in the activities which gave rise to the contraventions”, however, does little to advance a case of mitigation. The focus of inquiry for penalty is not the conduct that may be attributable to Alpha but, rather, the specific conduct of Qantas which gave rise to its failure to discharge its obligations. It is, therefore, not to the point to say that the activities of another person which gave rise to the liability of that other person for contraventions is greater than the activities of Qantas in respect of its contraventions. Furthermore, the submission in large part fails to address what was the essential criticism made by the Director, namely, that Qantas had “washed its hands” of the obligations to comply with the relevant provisions by “outsourcing” the duty free program to Alpha. The question of the appropriate penalty to be imposed upon Qantas must begin with focussing upon what it was that Qantas did, or should have done but did not do, so that the penalty may reflect the substance of its offending conduct. In that context it is not accurate to say that Qantas had a more limited role than Alpha in the contraventions. It may be that Alpha sourced the product and put it on the carts, but Qantas had its own obligations with which to comply and it was Qantas staff who sold all of the Nanodots on Qantas flights. Qantas crew were responsible for selling the products listed in the inflight catalogue and were paid commissions by Qantas for sales of products in the catalogue.

32 The Qantas Group annual report for the year ended 30 June 2014 shows a statutory loss after tax of $2.843 billion. The report shows that the group has strong liquidity of $3.6 billion including $3 billion in cash, but that it is subject to significant current liabilities and provisions, so that its net current assets as at 30 June 2014 were negative $2.593 billion. Mr Hiland’s affidavit updated that information by reference to a media release observed by him on 8 December 2014 in which Qantas announced that it expected to report an underlying profit before tax in the range of $300 million to $350 million in the first six months of the 2015 financial year. Its profit from the sale of the Nanodots was a share of the $5,500 previously referred to which is, in that context, insignificant.

33 Qantas is a large company with very substantial resources. Its size highlights the need for it to have effective systems to deal with situations such as that considered in this proceeding. Its substantial financial position might also be thought to suggest in that context that a substantial penalty should be imposed to reflect the fact that resources ought to have been appropriately allocated to ensure not only that situations such as that which arose would not have arisen, but that they would, in any event, have been dealt with swiftly and appropriately when they arose. Some of the other matters to which attention was drawn on behalf of Qantas might also be thought to point to the need for a substantial penalty rather than a lower penalty. It was said for Qantas, for example, that the contravening conduct had occurred without the knowledge or involvement of any of Qantas’ senior management, but that circumstance suggests that Qantas did not have systems to ensure that such contraventions would receive attention by senior management rather than that Qantas should not have a substantial penalty imposed upon it. The relevant employee responsible for the duty free program at Qantas at the time occupied the position of head of Qantas’ food and beverage business unit and did not report to the executive management team or to the board of Qantas and was not aware of or involved in any of the activities that gave rise to the contraventions. These circumstances, rather than mitigating the conduct for Qantas, revealed two further defects in the systems Qantas had at the time to ensure that compliance with the law would be dealt with along reporting lines that brought contraventions to the attention of management.

34 The cause of the contraventions by Qantas was essentially the absence at the time in Qantas of appropriate systems to ensure that it complied with its product safety obligations and responded appropriately when alerted to the fact of contravention. The contractual arrangements between Qantas and Alpha were insufficient to ensure that Qantas would comply with its obligations whatever might have been Alpha’s ability to comply with its own obligations. The systems Qantas had in place to deal with compliance upon receiving notification of a potential breach are set out above in relation to the receipt by Qantas of the expressions of concern by Mr Anderson. The systems then in place within Qantas were not adequate to ensure compliance upon being informed of the potential for contravention. On the other hand it can readily be accepted that Qantas did not intend to contravene the provisions and genuinely regrets having done so. It has not previously been found by a court to have engaged in similar conduct and, as one would expect, can be accepted to be committed to ensuring its compliance with product safety requirements.

35 On 22 August 2014 Qantas put in place a product safety compliance program for its duty free program which is acceptable to the Director. The program was developed by Ms Malone who is the senior legal counsel for Qantas with the overall responsibility for its Competition and Consumer Law Compliance Program. The program now in place requires all employees who have contact with suppliers or customers to complete mandatory product safety law compliance training every two years on an online course. 712 employees have completed that course between 20 September 2014 and 28 November 2014. The policy which Qantas now has in place also requires that all employees complete face-to-face training if they are considered to be at risk of encountering issues related to product safety law due to the nature of the role they have at Qantas. Ms Malone has identified a number of areas within Qantas where it was likely that employees would be at higher risk of encountering issues concerning product safety laws, and Qantas employees in those roles have undertaken face-to-face training with relevant staff across a range of divisions within Qantas and Jetstar airways. Ms Malone has also put in place a process to review the product safety law compliance process, commenced in December 2014, which will involve her contacting all staff referred to in the product safety law compliance procedure documents and requesting them to confirm that they have complied with their relevant procedures. Ms Malone’s responsibilities also include the preparation of a report on an annual basis to the General Counsel for Qantas concerning the compliance program. Qantas, like Alpha, has also cooperated with the Director in respect of compliance, and the Director’s investigation of the concerns, and has co-operated with the Director in the conduct of these proceedings.

36 I consider that the penalty appropriate to be imposed upon Qantas should be greater than that imposed upon Alpha. It had a direct and independent obligation to ensure compliance with relevant product safety laws and its direct contact with potential buyers of products was an additional reason for it to ensure that it was complying with its obligations. Its size made important the need for it to have in place appropriate systems in the discharge of its duties. Its conduct upon notification by Mr Anderson cannot be described as exemplary and does not warrant the substantial discount I have thought appropriate in the case of Alpha. In its case I will impose a penalty in respect of the totality of the conduct contravening the provisions at $200,000.

37 The only other issue for decision concerned the content of the public notice to be published concerning the outcome of these proceedings. The parties agreed about the notice in all but one respect. The disagreement was about whether the penalty amounts ordered by the Court should appear in the public notice. In my view it should. A factor in fixing the quantum of penalty is the effect the penalty will have as a deterrent to others. The quantum of the penalty can best, if not only, have a general deterrent effect if those intended to be deterred by the quantum know of the amount. It is not to be assumed that the lack of knowledge of the amount imposed by way of penalty is likely to have a greater deterrent effect than the publication of the amount determined by the Court as the amount intended to have that effect. Accordingly, the public notice shall include the amounts ordered to be paid, namely, $50,000 by Alpha and $200,000 by Qantas.

I certify that the preceding thirty-seven (37) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Pagone. |

Associate: