FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Homeopathy Plus! Australia Pty Limited [2014] FCA 1412

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | HOMEOPATHY PLUS! AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED First Respondent FRANCES MERCIA SHEFFIELD Second Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1) The First Respondent and the Second Respondent have in trade and commerce:

a) engaged in conduct that was misleading and deceptive or was likely to mislead and deceive, in contravention of section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”); and

b) in connection with the supply or possible supply of homeopathic treatments or products (“Homeopathic Treatments”), and in connection with the promotion of the supply of Homeopathic Treatments, made false or misleading representations that the vaccine publicly available in Australia for whooping cough (“Vaccine”) is of a particular standard or quality in contravention of sections 29(1)(a) and (b) of the ACL,

by publishing, or causing to be published, on the website www.homeopathyplus.com.au (“Website”):

c) from 1 January 2011 until around 26 April 2012, an article entitled “Whooping Cough – Homeopathic Prevention and Treatment” (the “First Whooping Cough Article”) in which a representation was made to the effect that the Vaccine is short-lived, unreliable and no longer effective in protecting against whooping cough;

d) from 11 January 2013 until around March 2013, an article entitled “Whooping Cough – Homeopathic Prevention and Treatment” (the “Second Whooping Cough Article”) in which a representation was made to the effect that the Vaccine may not be the best solution for, is of limited effect, and is unreliable at best, in protecting against whooping cough; and

e) from 3 February 2012 until around March 2013 an article entitled “Government Data Shows Whooping Cough Vaccine a Failure” (the “Government Article”) in which a representation was made to the effect that the Vaccine is largely ineffective in protecting against whooping cough;

when, in fact, the Vaccine is effective in protecting a significant majority of people who are exposed to the whooping cough infection from contracting whooping cough.

2) The First Respondent and the Second Respondent have in trade or commerce:

a) engaged in conduct that was misleading and deceptive or was likely to mislead and deceive, in contravention of section 18 of the ACL;

b) in connection with the supply or possible supply of Homeopathic Treatments, and in connection with the promotion of the supply of Homeopathic Treatments, made false or misleading representations that the Homeopathic Treatments are of a particular standard or quality in contravention of section 29(1)(a) and (b) of the ACL; and

c) in connection with the supply or possible supply of Homeopathic Treatments, and in connection with the promotion of the supply of Homeopathic Treatments, made false or misleading representations that Homeopathic Treatments have a use or benefit in contravention of section 29(1)(g) of the ACL,

by publishing, or causing to be published, on the Website:

d) the First Whooping Cough Article;

e) the Second Whooping Cough Article; and

f) the Government Article in conjunction with the Second Whooping Cough Article,

in which representations were made to the effect that there was a reasonable basis, in the sense of an adequate foundation, in medical science to enable it or them (as the case may be) to state that Homeopathic Treatments are a safe and effective alternative to the Vaccine for the prevention of whooping cough when, in fact:

g) there is no reasonable basis, in the sense of an adequate foundation, in medical science to enable the First Respondent and the Second Respondent to state that Homeopathic Treatments are safe and effective as an alternative to the Vaccine for the Prevention of Whooping Cough; and

h) the Vaccine is the only treatment currently approved for use and accepted by medical practitioners in Australia for the prevention of whooping cough.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

3) The matter is listed for directions at 9.30 am on Wednesday 4 February 2015 in order to set a timetable for any further evidence on the question of penalties and submissions including on the injunctive and other final orders sought by the Applicant.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 256 of 2013 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant

|

AND: | HOMEOPATHY PLUS! AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED First Respondent FRANCES MERCIA SHEFFIELD Second Respondent |

JUDGE: | PERRY J |

DATE: | 22 DECEMBER 2014 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 The first respondent, Homeopathy Plus! Australia Pty Ltd (“Homeopathy Plus”), is an Australian proprietary company limited by shares which was registered in New South Wales on 20 November 2008. It is not in dispute that, among other activities, Homeopathy Plus sells homeopathic products and treatments through its website at www.homeopathyplus.com.au (“the Website”).

2 The second respondent, Mrs Frances Sheffield, has been the sole director of the first respondent since 18 November 2009. It is common ground that she is the author of three articles which she uploaded onto the Website, namely:

(a) “Whooping Cough – Homeopathic Prevention and Treatment” (“First Whooping Cough Article”);

(b) “Whooping Cough – Homeopathic Prevention and Treatment” (“Second Whooping Cough Article”); and

(c) “Government Data Shows Whooping Cough Vaccine a Failure” (“Government Article”)

(collectively referred to as the “Three Articles”).

3 The domain name of the Website is registered to Mrs Sheffield and her husband.

4 The applicant (“the ACCC”) seeks declarations, injunctions, penalties and ancillary orders in respect of alleged contraventions by the Respondents of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”), being Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (“CCA”). The CCA and ACL came into force on 1 January 2011. The contraventions are said to arise from statements made in the Three Articles published on the Website.

5 This judgment addresses only the question of whether the alleged contraventions have taken place. As foreshadowed before the trial and confirmed at the hearing with the parties, the hearing covered all matters relating to the alleged contraventions of the ACL, the circumstances in which they occurred and the severity of those contraventions. The issues addressed by these reasons are similarly confined. That approach leaves open the option to the parties for evidence to be led otherwise in mitigation of penalty and the like, and for separate submissions to be made as to the pecuniary penalty, injunctive relief and other final orders sought by the ACCC aside from the declaratory relief sought which I will grant for the reasons I explain in the conclusion.

6 The dispute centres upon the proper characterisation of the representations made in the Three Articles and whether those representations were made in trade and commerce. The ACCC alleges that the Three Articles contained false, misleading and/or deceptive representations contrary to ss 18 and 29(1)(a), (b) and (g) of the ACL concerning:

(a) the effectiveness of the Vaccine publicly available in Australia for the prevention of whooping cough; and

(b) the safety and effectiveness of homeopathic treatments as an alternative to the Vaccine for the prevention of whooping cough.

7 No allegations are made with respect to any statements as to the effectiveness of homeopathic treatments for the treatment, as opposed to prevention, of whooping cough, or as a complementary treatment more broadly, or in respect of any vaccine other than that for Whooping Cough (“the Vaccine”).

8 Section 18 of the ACL provides that:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

9 Section 29 has more specific elements and relevantly provides that:

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

(b) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular standard, quality, value or grade; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits;…

10 The ACCC alleges that Homeopathy Plus and Mrs Sheffield engaged in the impugned conduct as principal contraveners. For the reasons I set out below, I find the contraventions of the ACL alleged by the ACCC to be established.

2.1 The ACCC’s primary contentions

11 The ACCC alleges that Homeopathy Plus and/or Mrs Sheffield, made representations to the effect that the Vaccine:

(a) is short-lived, unreliable and no longer effective in protecting against whooping cough (“the First Vaccine Representation”);

(b) may not be the best solution for, is of limited effect and is unreliable at best, in protecting against whooping cough (“the Second Vaccine Representation”); and

(c) is largely ineffective in protecting against whooping cough (“the Third Vaccine Representation”);

(together the “Vaccine Representations”).

12 The ACCC contends that the Vaccine Representations are false, misleading and/or deceptive in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1)(a) and (b) of the ACL because the Vaccine is, in fact, effective in protecting a significant majority of people who are exposed to whooping cough infection from contracting whooping cough.

13 The ACCC further alleges that, by publishing, or causing to be published, the First and Second Whooping Cough Articles and the Government Article in conjunction with the Second Whooping Cough Article, the Respondents made representations to the effect that there was a reasonable basis, in the sense of an adequate foundation in medical science, to enable it or them, as the case may be, to state that homeopathic treatments are a safe and effective alternative to the Vaccine for the prevention of whooping cough (the “Homeopathy Alternative Reasonable Basis Representation”). This representation is also alleged to be false, misleading and/or deceptive in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1)(a), (b) and (g) of the ACL on the grounds that:

(a) there is no reasonable basis in medical science to allow the Respondents to state that homeopathic treatments are safe and effective as an alternative to the Vaccine for the prevention of whooping cough; and

(b) the Vaccine is the only treatment currently approved for use and accepted by medical practitioners in Australia for the prevention of whooping cough.

14 In determining these claims, it was not in issue that the Court should construe the Three Articles, including the key notions said to be conveyed by them, in the plain English sense in which the public would understand them. In this regard, the ACCC submitted (and I do not understand it to be in issue) that, based upon the Oxford English Dictionary and Macquarie Dictionary (5th edition) definitions, the meaning of these key notions were as follows:

“Unreliable” means not able to be relied upon. “Reliable” in turn means consistently good in quality or performance, able to be trusted. “Ineffective” means not producing any or the desired effect. “Solution” means the act of solving a problem, or state of being solved; a particular instance or method of solving. “Short-lived” means lasting only a short time; or living or lasting only a little while.

15 In support of its contentions that each of the representations were false, misleading or deceptive, the ACCC relied upon the expert evidence of three witnesses:

a) Dr Nicholas Wood, Staff Specialist, General Medicine at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead and a Senior Research Fellow at the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases;

b) Dr Nigel William Crawford, Medical Head of Immunisation Services (which recommends and administers vaccines to high-risk children, including whooping cough, according to the schedule) and a Paediatrician at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne; andProfessor Kerryn Phelps AM, General Practitioner, who was the President of the Australian Medical Association from 2000-2003, and the President of the Australasian Integrative Medicine Association from 2009-2012.

16 Ultimately, no expert evidence was relied upon by the Respondents that materially contradicted the evidence of these witnesses; the evidence of Dr Mark Donohoe called by the Respondents being consistent with that of the experts called by the ACCC. Nor was the expertise of Dr Wood, Dr Crawford and Professor Phelps to give evidence on the matters addressed by them in their reports in issue.

17 In their defence, the Respondents contend that:

(a) the statements in the Three Articles were not made in trade and commerce but “were uploaded for general information and education purposes and were a contribution to an ongoing public debate of scientific and political interest which is an activity regularly undertaken by [Homeopathy Plus]”;

(b) the statements in the Three Articles were not false, misleading and deceptive as there is a reasonable basis in homeopathic science for the statements as to the effectiveness of homeopathy in the prevention of whooping cough; and/or

(c) the statements in the Three Articles were not false, misleading and deceptive even if measured against orthodox medical science.

18 The Respondents summarised the primary elements of their defence in their submissions in closing as follows:

I. When corporations conceived with an advocacy purpose participate in public debates about science and politics it does not necessarily follow that their conduct is commercial simply because they are corporations. The intention of the alleged contravener is important to assess during the trade and commerce test (i.e. the design of the representations). The representations were not centrally conceived or designed with a trading or commercial purpose and did not amount to conduct in trade or commerce. When qualified assertions, which are accurate summations of a position within a wider debate, are made not about ‘products’ but rather the roll-out of a complicated Government schedule and its effectiveness then those assertions bear a non-commercial character.

II. Those same qualified assertions, even if they were sufficiently commercial in character so as to attract the jurisdiction of the ACL, are factually well-founded insofar as they relate to the vaccines. This is based on a plain reading of the words themselves rather than an unnecessarily medico-technical one based on the insertion of concepts of efficacy foreign to the readers of the website.

III. The commentary on homeoprophylaxis has been shown to fall within the accepted definitions of that modality and cannot be considered misleading when read in their context as emanating from a homeopathy publication (the name Homeopathy Plus! across all banners and weblinks relevant to this proceeding is not merely suggestive, but overt, with regard to the framework within which the statements are made). There is a clear differentiation between the two epistemological frameworks and Homeopathy Plus! never passed off ‘mainstream acceptance’ as per the allegations of the Applicant.

(emphasis in original)

19 Preliminary issues arose as to the bulk of the expert evidence which the Respondents sought to lead in support of the second and third primary grounds of their defence. These are considered below.

3. The Respondents’ expert evidence

20 The Respondents initially sought to rely upon reports of Dr Isaac Golden, Dr Jurgen Schulte, and Dr Donohoe.

21 The ACCC objected to much of that evidence on the grounds that the expert opinions were irrelevant, conclusionary, argumentative, disclosed no reasoning, and were incapable of being tested intelligibly in cross-examination, and that the underlying studies were hearsay and not attached to the report.

22 The report of Dr Schulte was excluded in its entirety on the ground of relevance.

23 As a result of rulings at trial and of concessions made by the Respondents, substantial parts of the reports of Dr Golden and Dr Donohoe were also not received in evidence (albeit that some of that material was nonetheless received as submission). The reports were in patently inadmissible form with no apparent regard to the rules of evidence and, in particular, to s 79 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (“Evidence Act”). An application by the Respondents at trial under s 190(3)(b) of the Evidence Act to dispense with the rules of evidence insofar as they precluded the admission of substantial parts of Dr Golden’s report was also refused.

24 Dr Donohoe was a general medical practitioner with 26 years’ experience who retired in 2003. He did not purport to be an expert in the prevention of disease or in the prevention or treatment of whooping cough. He had little clinical experience with cases of infant pertussis in the past decade although he had seen many adult and adolescent cases in this period. Insofar as his evidence was admitted, Dr Donohoe’s evidence was largely consistent with that given by the experts called by the ACCC, as I later explain.

25 Dr Golden is an Honorary Research Fellow at the School of Science, Information Technology and Engineering at the University of Ballarat. He holds a Doctor of Philosophy from Swinburne University of Technology awarded in 2004 on the topic of Potential value of Homeoprophylaxis in the Long-Term Prevention of Infectious Diseases and the Maintenance of General Health in Recipients, together with diplomas in naturopathy and homoeopathy from the Melbourne College of Naturopathy in 1990 and the Melbourne College of Homoeopathy in 1989 respectively. To the extent that Dr Golden’s report was admitted, it was largely confined by orders under s 136 of the Evidence Act to a description of the philosophical approach of homeopathy to the treatment and prevention of disease as opposed to evidence on the effectiveness of homeopathy in preventing whooping cough. The closing submissions for the Respondents repeatedly overlooked the limited basis on which Dr Golden’s evidence was admitted, submitting that it showed that there is a reasonable basis in homeopathic science for the representations about homeoprophylaxis. However, given the terms of the order, his evidence simply could not be put to that use.

3.2 Admissibility of expert opinion evidence under the Evidence Act

26 Given the extent of the apparent difficulties with the Respondents’ expert evidence and the potential impact of excluding such evidence upon the Respondents’ case, I delivered detailed reasons in the course of the trial for ruling inadmissible sample passages from the report of Dr Golden. It is helpful to repeat the substance of those reasons here. These reasons were illustrative of the difficulties found in the bulk of the Respondents’ expert reports.

27 By s 76(1) of the Evidence Act, the general rule is that “evidence of an opinion is not admissible to prove the existence of a fact about the existence of which the opinion was expressed”. This rule is known as the “opinion rule”. Section 79 of the Evidence Act exempts evidence of certain opinions of experts from the general rule in s 76(1) and provides that:

If a person has specialised knowledge based on the person’s training, study and experience, the opinion rule [in s 76(1)] does not apply to evidence of an opinion of that person that is wholly or substantially based on that knowledge.

28 As Lindgren J held in Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v Western Australia (No 2) (2003) 130 FCR 424 (“Harrington-Smith”) at 427 (an authority relied upon by the Respondents):

By providing for an exception to the inadmissibility created by the opinion rule, s 79 goes to admissibility… the section poses an objective test; no discretion is involved; a party raising an objection to admissibility on the ground that the section is not satisfied is entitled to a ruling on the objection…

29 The test which must be applied in determining whether expert opinion evidence is admissible under s 79 was considered by the High Court in Dasreef Pty Limited v Hawchar (2011) 243 CLR 588 (“Dasreef”). The joint judgment in that decision of French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ established in my opinion the following matters.

30 First, the expert opinion rule directs attention as to why the party tendering the evidence says that it is relevant, that is, as to the finding that the tendering party wishes the Court to make. Thus, in considering the operation of s 79(1), their Honours held at 602 [31] that it is “…necessary to identify why the evidence is relevant: why it is ‘evidence that if it were accepted, could rationally affect (directly or indirectly) the assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue in the proceedings.’”

31 Secondly, as Gleeson CJ pointed out in HG v The Queen (1999) 197 CLR 414 at 427 [39] in a passage approved in Dasreeef at 604 [36], “…by directing attention to whether an opinion is wholly or substantially based on specialised knowledge based on training study or experience, [s 79] requires that the opinion is presented in a form which makes it possible to answer that question”. Thus, as their Honours in Dasreef later explained in their joint reasons, “[t]he point which is now made is a point about connecting the opinion expressed by a witness with the witness’ specialised knowledge based on training, study or experience.” (at 605 [41]).”

32 Thirdly, their Honours in Dasreef held that a failure to demonstrate that an opinion expressed by a witness is based on the witness’ specialised knowledge based on training, study or experience “…is a matter that goes to the admissibility of the evidence, not its weight.” (Dasreef at 605 [42]; see also Honeysett v The Queen (2014) 88 ALJR 786 (“Honeysett”) at 794 – 795 [44]-[46] (the Court). Thus in Dasreef, the evidence of the witness’ estimate as to the volume of respirable silica dust to which the plaintiff was exposed over time in the course of his employment lacked reasons. The absence of reasons in turn was held to point inexorably to the lack of any sufficient connection between a numerical or quantitative assessment or estimate, on the one hand, and relevant specialised knowledge, on the other hand (Dasreef at 605 [42]). In this regard, I reject the Respondents’ submission that the Court in Dasreef was not concerned with the absence of reasons in the expert’s report, but rather there had been a failure to demonstrate that the expert’s opinion had a foundation in his specialised knowledge in some other way, which the Respondents did not clearly articulate. In my view, the need to demonstrate the connection between the specialised knowledge and its application is inconsistent with the Respondents’ submission: see also e.g. Honeysett at 794–795 [44]–[46]. Reasons provide the mechanism, in other words, by which the connection is exposed. In this regard, Heydon J in his separate judgment in Dasreef also makes the point with respect to the need for the reasoning to be stated, that “[t]he opposing party is not to be left to find out about the expert’s thinking for the first time in cross-examination” (ibid at 623 [91]) and further that “[t]he requirement that the opinion be based wholly or substantially on specialised knowledge is an explicit precondition of admissibility. Like other preconditions under s 79, it is to be established by the party tendering the evidence. It is to be established in evidence in chief… not in cross-examination …” (ibid at 626 [99]).

3.3 Admissibility of the evidence

33 At its heart, the difficulty with Dr Golden’s report was that it cast no light upon the reasoning by which the opinions given were reached. Crucially, just as the figure reached in Dasreef as to the likely level of exposure to dust lacked reasons by which the connection between the specialised knowledge and the evidence was demonstrated, equally no such connection between the evidence as to the alleged efficacy of homeoprophylaxis in the prevention of whooping cough (or other diseases) and the application of specialised knowledge was identified by Dr Golden’s report. As such, the evidence fell well short of meeting the requirements of s 79 of the Evidence Act. In those circumstances, I had no discretion. The passages in question were not admissible.

34 The Respondents sought to rely upon the breadth of Dr Golden’s curriculum vitae, submitting generally that:

I would put it so high as to say this is one of the most eminently qualified homeopaths in Australia and he has got dozens and dozens of articles published, many of them are relevant to international trends and experience and I just wonder if we’re going to take the approach of seeing whether or not every single statement has a proper basis without reference to the curriculum vitae, then not only will it take a long time, but I will certainly feel, your Honour, that perhaps there has been some disenfranchisement going on here with the expert witness.

35 In a similar vein, the Respondents further submitted that:

…perhaps, my rather abstract and tangential opening submissions on the decision in Dorber, insofar as it may be that Dr Golden is being indirectly punished in the sense that the way he references in material, and the self-referential aspects like referring to his own studies do appear to be markedly from the approaches taken by Dr Woods and Dr Crawford.

In some sense, that’s the nub of the problem for our expert witness, is trying to feed their evidence through this orthodox medical paradigm and all I’m saying is let’s not confuse the orthodox medical paradigm with regard to how references are attached and how they’re referred to for the test under the Evidence Act, because they’re two separate things, and there is a danger of conflation insofar as you have eminent evidence-based medical practitioners appearing for the applicant and doing expert reports in the way you would expect of an orthodox evidence-based medical practitioner, as against a homeopath, I’m unsure of his experience with regard to building documents like this.

36 However, these submissions suffer from the same fallacies as those identified by Lindgren J in Harrington-Smith. Specifically, Lindgren J held at 427 that:

Unfortunately, in the case of many of the experts’ reports, little or no attempt seems to have been made to address in a systematic way the requirements for the admissibility of expert opinion. Counsel protested that, in order to ensure that the requirements of admissibility are met, lawyers would have to become involved in the writing of the reports of expert witnesses. In the same vein, counsel said in supporting the admission of certain parts of a report, that they were written in the way in which those qualified in the particular discipline are accustomed to write.

Lawyers should be involved in the writing of reports by experts: not, of course, in relation to the substance of the reports (in particular, in arriving at the opinions to be expressed); but in relation to their form, in order to ensure that admissibility is attracted by noting more than the writing of a report in accordance with the conventions of an expert’s particular field of scholarship. So long as the Court, in hearing and determining applications such as the present one, is bound by the rules of evidence, as the Parliament has stipulated … the requirements of s 79 (and of s 56 as to relevance) of the Evidence Act are determinative in relation to the admissibility of expert opinion evidence.

(emphasis in original)

37 Nothing in that approach is inconsistent with the decision in Dasreef; indeed, in my view, the decision in Dasreef emphasises the correctness of the approach.

38 In short, the reason why the evidence in question was excluded was not because it was product of, to use the words of counsel for the Respondents, a science which operates in a different paradigm from orthodox medical science. Nor was it excluded because, as the Respondents also submitted, “…automatic superiority and automatic preference [is] given to one paradigm over the other either at the admissibility level or the weight level …” The evidence was excluded because the Respondents’ evidence must comply with the same rules of evidence as those which apply to all parties under the Evidence Act, relevantly, the requirements for the admissibility of expert opinion evidence under s 79. Responsibility for ensuring that evidence is put before this court in admissible form lies with the legal representatives. It is no answer, as Lindgren J has said, to say that the expert is unaccustomed or untrained in presenting evidence in an admissible form; nor that the form in which the evidence is presented reflects the way in which material might customarily be presented within the field of expertise in question.

4. Background concepts and facts

39 The expert evidence led by the ACCC as to the nature and seriousness of whooping cough, the nature of the Vaccine and recommended schedule for its administration and the essential precepts of Evidence Based Medicine were not contentious.

4.1 Pertussis – the disease and potential complications

40 Pertussis, otherwise known as whooping cough, can be a serious respiratory disease and is caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis (“pertussis”). It is an exclusively human pathogen spread by respiratory droplets. It is highly infectious, spreading to 90% of “susceptible household contacts”, being individuals who are not immune and live in the same house as the infectious person. Pertussis is known for the uncontrollable and violent paroxysms (bouts) of coughing experienced by those suffering from the disease at the end of which, the patient needs to take a deep breath resulting in a “whooping” sound.

41 “Classical pertussis” typically has an incubation period of 7 to 10 days followed by three phases of illness:

(a) The first phase is catarrhal. This is a non-specific nasal congestion illness accompanied by a mild cough, lasting one to two weeks.

(b) The second phase is paroxysmal: namely, a spasmodic cough, post-cough vomiting and inspiratory whoop which lasts for four to six weeks or longer. Facial suffusion (redness/congestion) with prominent eyes and protrusion of neck veins may be seen during these paroxysms. It can also affect infant’s feeding.

(c) The final phase is convalescent during which the symptoms slowly improve over one to two weeks, although the phase may persist longer. The cough may persist for a number of weeks or months and future episodes of upper respiratory tract infections may restimulate the coughing paroxysms.

42 If untreated, a person with whooping cough is contagious for at least 21 days. Whooping cough is treated by ten day course of antibiotics, after the first five days of which there is minimal chance of transmitting the disease. This means, as Dr Crawford explained, that early treatment is an important public health measure for decreasing the risk of further contact cases. However the antibiotic treatment will not stop or improve the cough.

43 Professor Phelps explained that transmission of the disease from mother to child is thought to be responsible for 38% of cases of whooping cough in children, with fathers responsible for further 17% and siblings, 41%. Dr Wood also identified infected parents and siblings as the most important source of infection to infants, stating that:

Individuals with pertussis disease are most infectious during the initial catarrhal period and for the first 2 weeks of spasmodic cough, but can remain infectious for up to 6 weeks, especially in the case of non-immune infants. A probable scenario is that adults and adolescents, who become infected because of waning vaccine or disease induced immunity, act as reservoirs for infection and transmit infection to unvaccinated or partially vaccinated infants. In Australia, a national study identified a presumptive source of infection in 60% of 110 hospitalised infants, of whom 60% were parents. (Elliot E, McIntyre P, Ridley G et al. National study of infants hospitalised with pertussis in the acellular peturssis (sic) vaccine era. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004; 23: 246-252) In a recent study by Jardine et al in 2010, siblings have also identified as a source of infection for young infants. (Jardine A et al. Who gives pertussis to infants? Source of infection for laboratory confirmed cases less than 12 months of age during an epidemic, Sydney, 2009. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2010 Jun;34(2):116-21).

44 The symptoms in older children, adolescents and adults can range from classic pertussis to a mild cough or even no cough. Young infants may present with apnoea only or an apparent life-threatening event characterised by shallow/absent breathing, slowing heart rate and cyanosis (i.e. appearing blue due to lack of oxygen).

45 Serious complications can arise from pertussis but are more common in non-immune young infants and very young infants. As Dr Crawford explained:

Respiratory complications are frequent with a pneumonitis (lung inflammation), commonly seen. The secondary pneumonia (chest infection) may also occur due to B.pertussis or a secondary bacterial infection. Occasionally the pneumonia may be of a severe necrotizing form, which is the major cause of death. Atelectasis (airway mucous plugging) may occur. Severe air leak complications relate to damage to the lungs following rupture of the alveoli. They include pneumothoraces, which is air between the lung and the pleura (lining of the lung) and if large may require intervention with an underwater sealed drain. Interstitial emphysema (damage to the lungs) and pneumomediastinum (air in the chest, but outside the lung) may also occur. Bronchiectasis or damage to the airways caus[ing] them to widen and become infected is a rare late complication. Su[b]conjunctival hemorrhages of the eye, rectal prolapse or inguinal (groin) hernia may occur due to the increase in intra-abdominal pressure. Cerebral anoxia (lack of oxygen), with associated convulsions, can occur in young children and an encephalopathy (global brain dysfunction) is seen in approximately 1 in 10,000 cases.

46 Younger infants under six months are more likely to have complications such as apnoea (breath-holding) and require hospitalisation. Most deaths secondary to pertussis also occur in children under six months of age and especially those under one month old. The infection can also result in death among adults, especially the very elderly.

47 Individuals can become immune to pertussis either by naturally acquiring pertussis or following receipt of a pertussis Vaccine.

48 All vaccines available in Australia, including that for pertussis, are approved for use and regulated by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (“TGA”) under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth). The stated object of the Therapeutic Goods Act is to create “a national system of controls relating to the quality, safety, efficacy and timely availability of therapeutic goods” that are, relevantly, used in Australia: s 4, Therapeutic Goods Act. It prohibits the importation, exportation, manufacture and supply of therapeutic goods in Australia for use in humans save where the goods are registered, listed, exempt, or approved/authorised under s19 or s 19A: see ss 19(4) and 19D(1). Therapeutic goods include goods for use in “preventing, diagnosing, curing or alleviating a disease, ailment, defect or injury in persons” (see the definition of “therapeutic good” and related definition of “therapeutic use” in s 3(1), Therapeutic Goods Act).

49 The TGA has published guidelines for the registration of prescription medicines, including vaccines, in the Australian Regulatory Guidelines for Prescription Medicines, June 2004.

50 Before a product can be registered under the Therapeutic Goods Act, the sponsoring company must make an application with data to support the quality, safety and efficacy of the vaccine for its intended use. Dr Wood explained that the data requirements are largely based on those applying in the European Union, supplemented where necessary by Australia–specific requirements. In the case of vaccines, the premarket evaluation data includes: the quality and quality control aspects of the manufacture; pre-clinical data designed to assess the toxicological profile of the vaccine, including safety when tested in animals: and clinical (i.e., human) trial data to support the safety and efficacy of the vaccine in humans. Information from equivalent regulators in other jurisdictions that undertake a similar approval process, such as the Food and Drug Administration in the United States, may also be requested.

51 In determining whether to allow an application for registration of the therapeutic product, the Secretary must evaluate the goods for registration having regard to a number of matters including “whether the quality, safety and efficacy of the goods for the purposes for which they are to be used have been satisfactorily established”: s 25(1)(d), Therapeutic Goods Act. The term “safety” has, in my view, been used in its ordinary meaning to refer to “the quality of being unlikely to cause hurt or injury; the quality of not being dangerous or presenting a risk’”: Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Ltd v Minister for Health and Ageing (“Aspen”) [2012] AATA 362 at [19]-[20]; see also the Oxford English Dictionary (1.a. The state of being protected from or guarded against hurt or injury; freedom from danger”); Macquarie Dictionary (6th Ed; 2013) (“the state of being safe; freedom from injury or danger”).

52 Similarly, I consider that the word “efficacy” is likely used in s 25(1)(d) in its ordinary sense, namely, the “‘ability to bring about the intended result’ … that is, effectiveness to bring about the intended therapeutic result for which the goods have been registered…”: Aspen at [21]; see also the Oxford English Dictionary (“1. Power or capacity to produce effects; power to effect the object intended”); and the Macquarie Dictionary (“capacity for serving to produce effects; effectiveness”). This view is also consistent with the statement in the Second Reading Speech for the Therapeutic Goods Bill 1989 (Cth) that, “[t]hree parameters are used to define the acceptability of a product for therapeutic use... The third parameter is the product’s efficacy, or its effectiveness in fulfilling its intended purpose” (Hansard 5 October 1989, page 1612) (emphasis added). It is true that in a technical medical sense, the term “efficacy” is used in the context of randomised control trials which constitute best evidence (as I later explain at [68]-[70]). However, it seems unlikely that the Parliament would have intended to limit the concept to its technical meaning in the context of the Therapeutic Goods Act given that other data may be relevant, including that obtained by subsequent observation of the use of the drug in other countries.

53 In undertaking the balancing exercise required by s 25(1), a high level of safety is required from vaccines, which unlike most medications, are generally given to healthy people, to prevent illness and death. Dr Crawford explained that a fever in the first twenty-four hours is an expected and common side effect from the administration of a vaccine because the vaccine operates to stimulate the system to produce a new protection.

4.3 Administration of the Vaccine under the National Immunisation Program

54 The Vaccine is administered in Australia as part of the National Immunisation Program (NIP), in common with the majority of vaccines. All of the pertussis vaccines under the NIP are acellular pertussis vaccines (“Pa”), containing three or more purified components of B.pertussis. The change from a whole cell pertussis to acellular vaccines took place in the late 1990s. The vaccine is injectable and usually given as part of a combination vaccine including diphtheria (D) and tetanus (T) (“DTPa”), and may also include hepatitis B, polio and Haemophilus influenzae type b.

55 In line with the requirements earlier outlined, the Vaccine had to be approved as a medication by the TGA before it could be included on the NIP. Dr Crawford explained the process following TGA approval by which a vaccine is added to the NIP:

The vaccine is then reviewed by the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI), who will make recommendations about the utility of adding a vaccine to the NIP. The vaccine then requires a cost effectiveness evaluation through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC)… This assessment will take into account the efficacy/effectiveness of the vaccine on available evidence and the price proposed by the pharmaceutical company. These recommendations then go to the federal government for approval through the Department of Health in Canberra before a new vaccine can be added onto the NIP. State health departments are involved in the introduction of vaccines onto the NIP program.

56 The pertussis vaccine is generally included in a combined vaccine administered by injection, the type of which varies depending on the recipient’s age.

57 While pertussis vaccination schedules differ around the world, Dr Wood explained that none currently started earlier than six weeks of age. The schedule recommended by the World Health Organisation is six, ten and fourteen weeks for primary immunisation.

58 The recommended schedule in Australia is administration of the vaccine:

(a) at 6 – 8 weeks, 4 and 6 months of age (the primary schedule);

with boosters at:

(b) at 3.5 – 4 years; and

(c) during adolescence (11 – 13 years); and

(d) adulthood (recommended for those who wish to reduce the likelihood of becoming ill with pertussis, such as parents of young infants, and at 50 years of age);

(collectively, “the Vaccine”: see Australian Government Department of Health and Aging, The Australian Immunisation Handbook (10th Ed, 2013) at 4.12.7 (the “Australian Immunisation Handbook”)).

59 In relation to the recommended schedule, the Australian Immunisation Handbook advises that the booster dose at 3.5 years of age “is essential as waning of pertussis immunity occurs following receipt of the primary schedule.” The Handbook also advises that the optimal age for administration of the second booster dose is 11 to 13 years “due to waning antibody response following the 1st booster dose recommended at 4 years of age. This 2nd booster dose of pertussis – containing vaccine is essential for maintaining immunity to pertussis (and diphtheria and tetanus) into adulthood.”

60 In the case of adults, the Australian Immunisation Handbook recommends vaccination for any adult who wishes to reduce the likelihood of becoming ill with pertussis which is particularly important where an adult falls within a special risk group, such as health care workers and adults working with infants and young children aged less than four years. With respect to those in contact with infants, the Handbook advises that “[t]here is significant morbidity associated with pertussis infection in infants <6 months of age, particularly those <3 months of age, and the source of infection in infants is often a household contact.” As a consequence, pertussis vaccination of the close contacts of young infants (the “cocoon strategy”) is recommended for women planning pregnancy or during pregnancy and other adult household contacts and carers of infants less than six months of age. As Professor Phelps explained:

The recognition that pertussis immunity can wane with time and the urgency of protecting newborns from infection are the reasons that Australia has had active public health programs in place to encourage prospective parents, new parents and grandparents to make sure they have booster immunization to reduce the risk of exposure of unprotected infants.

61 Thus, for example, the Vaccine is available for women in public maternity units in New South Wales for the opportunistic postpartum (i.e. after childbirth) vaccination of new mothers, if they have not received a pertussis vaccine in the previous five years. The Vaccine is also available free in the Northern Territory to parents and close family members when administered within seven months of the birth of the child.

62 Dr Donohoe referred to additional strategies that may enhance the effectiveness of the Vaccine including removing susceptible children from exposure to the disease where a person such as a sibling or parent has been diagnosed with whooping cough, active surveillance of adults with children who may be carriers of pertussis, and higher awareness on the part of medical practitioners that mild forms of pertussis, even following vaccination, may provide a vector for transmission.

63 Evidence Based Medicine (“EBM”) is a movement which aims to increase the use of high quality clinical research in clinical decision-making. It has been described in the literature as the “conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research”: Sackett, DL, et al (1996) “Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t”, BMJ; 312:71-72 (as quoted and adopted by Professor Phelps in her report).

64 The Cochrane Collaboration was formed out of this movement and its systematic reviews of primary research in human health care and health policy are internationally recognised as the highest standard in evidence-based health care – the “gold standard in terms of evidence-based research in health care”, as Professor Phelps explained. The Cochrane Reviews (to which I return later) investigate the effects of interventions for prevention, treatment and rehabilitation. Dr Crawford explained that the Cochrane reviews “are a meta-analysis of robust clinical trials with clear justifications for studies included. If an individual study does not fully meet the rigorous criteria it will be excluded. In some instances, there will be insufficient data for the Cochrane review to make a firm statement on the effectiveness of an invention.”

65 The National Health and Medical Research Council (“NHMRC”), established under s 5B of the National Health and Medical Research Council Act 1992 (Cth) (“NHMRC Act”), is the national body responsible relevantly for raising public and individual health standards and fostering medical research: NHMRC Act, s 3(1). Its functions include responsibility for issuing guidelines, and advising the community, on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of disease, and public health research and medical research: NHMRC Act, s 7(1)(a).

66 The NHMRC develops guidelines based on consultation with experts, expert bodies and the community in accordance with the requirements of s 13 of the NHMRC Act and does so in line with a rigorous nine step based approach. Given these matters and the statutory role of the NHMRC, I accept Dr Wood’s evidence that the NHMRC guidelines about levels of evidence for intervention are the accepted standard for clinical practice, including prevention such as vaccination, in Australia.

67 The standard taxonomy of levels of evidence for intervention studies based on the NHMRC guidelines and starting with the highest quality of evidence, is as follows:

Level I: evidence obtained from a systematic review of Level II studies;

Level II: evidence obtained from at least one properly designed randomised controlled trial of appropriate size;

Level III-1: evidence obtained from well-designed pseudo-randomised controlled trials;

Level III-2: evidence from comparative studies (including systematic reviews of such studies) with concurrent controls being a non-randomised experimental trial, a cohort study, an interrupted time series or matched case-controlled study;

Level III-3: evidence from a comparative study without concurrent controls, being a historical control study, two or more single arm studies (i.e. case series from two studies), or a well-designed interrupted time series trial without a parallel control group from more than one centre or research group or from case reports; and

Level IV: evidence obtained from a case series, either post-test or pre-test/post-test outcomes.

68 A “randomised controlled trial” is a trial designed to test the efficacy of a vaccine or medication by assigning the subjects of the trial randomly into those to whom the medication or vaccine is administered, on the one hand, and a control group, the members of which receive a placebo, on the other hand. The efficacy of the vaccine or medication can then be assessed by comparing the results of each group.

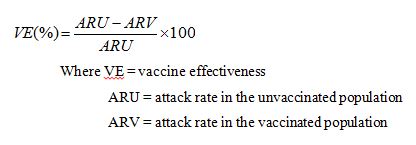

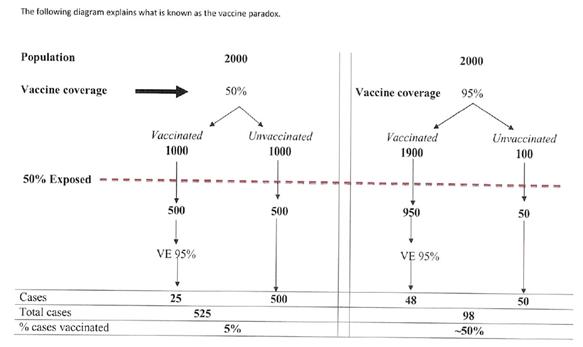

69 In this context, the term “efficacy” bears a technical meaning and is used in contradistinction to “effectiveness”. The difference between the two concepts was explained by Dr Crawford in the following terms:

Vaccine Efficacy (VE) is the percentage reduction in disease incidence attributable to vaccination. When this relative reduction is incidence measured in an individually randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial, the term vaccine efficacy is used. When it is measured through observational studies under program conditions (e.g. retrospective cohort or case control studies; or through outbreak investigations), the term vaccine effectiveness is used.

70 Thus, while “vaccine efficacy” is applied in the context of randomised controlled trials, “vaccine effectiveness” is concerned with how a vaccine is observed to perform in the real world. The differences between the two means of assessing effectiveness means that efficacy rates tend to exceed rates for vaccine effectiveness. This is because randomised controlled trials are conducted under very strict conditions with the subjects following a strict protocol, while the real world performance of a vaccine will be affected by variables which may impact adversely on its effectiveness, such as late compliance with the recommended NIP schedule or missed booster doses.

71 Homeopathy is said to be a system of treatment first practiced by the German physician and pharmacist, Dr Samuel Hahnemann, in 1783.

72 Dr Golden identified two principles as central to the practice of homeopathy:

a) the selection of medicines using the Principles of Similars (a matching of symptoms to be treated or prevented with the symptoms of the remedy which had been determined by controlled testing (provings) and/or clinical experience); and

b) the administration of medicines using the Principle of Minimum Dose (the use of the minimum amount of remedy needed to produce either a curative or a preventative effect).

73 These were described to be “the fundamental tenets of both homoeopathic practice as well as homoeopathic immunisation.” In short, as Burke J explained in Rose v Health Commission (NSW) (1986) NSWCCR 32, at [3], homeopathy can be described as a “method of treating disease by drugs, given in minute doses, which produce in a healthy person symptoms similar to those of the disease.”

74 Dr Golden explained that “homoeopathic medical science significantly differs from pharmaceutical medical science in that it is based on fundamental principles taken from a detailed and expert observation of the natural world by not only Dr Hahnemann but others before him such as Hippocrates.” On the basis that, unlike pharmaceutical medical science, “homoeoprophylaxis is based on observable and consistent Principles in the natural world and so its method of use has remained consistent over 200 years…”, Dr Golden argued that “information regarding homoeoprophylaxis [i.e. homeopathic treatment intended to prevent disease] needs to come from the homoeopathic medical literature, and not the pharmaceutical medical literature, as they relate to two completely different scientific paradigms”. The evidence of Dr Golden makes it clear that the principles underpinning the administration of homeoprophylaxis as explained by Dr Golden stand in stark contrast to the principles underpinning conventional, science-based medical treatment.

75 There are a number of homoeopathic professional bodies and groups within Australia. The single national registration body which is recognised by most homoeopathic professional associations is the Australian Register of Homoeopaths (“AROH”).

76 Finally, as at October 2013, there were no NHMRC levels of evidence regarding homeoprophylaxis. However, the NHMRC was reviewing the evidence for the effectiveness of homeopathy and a working group had been established to that end. Dr Wood explained that that review comprised “a systematic review of available systematic reviews on the effectiveness of homeopathy in treating a variety of clinical conditions in humans.”

5. Publication of the Three Articles

77 Homeopathy Plus was first registered as Homeolink Australia by Mrs Sheffield’s husband in around 2001, and re-registered from January 2009 under the name Homeopathy Plus. Mrs Sheffield became the sole director of Homeopathy Plus towards the end of 2009. I accept that one of the purposes of Homeopathy Plus is to advocate for homeopathy. More specifically, one of its main purposes is to change public health authority attitudes towards homeopathy prophylaxis and Mrs Sheffield has for several years promoted the prophylactic qualities of homeopathy through Homeopathy Plus. For example, at the time that the First Whooping Cough Article was published, the Website also called upon governments to look into the effectiveness of Vaccines as against homeopathy on a page headed “Immunisation Issues” under the heading “Isn’t it time?”. However, I do not accept that advocacy on such matters was the sole purpose of Homeopathy Plus. It is apparent from the Website that Homeopathy Plus was also engaged relevantly in the sale of homeopathy products.

78 Mrs Sheffield also runs a private homeopathy practice in her own name where she sees patients and provides homeopathy advice and treatment. She treats an average of 25 patients per week. It was her evidence that the “advocacy organisation” and the “homeopathic patient care business” with which she is involved “have distinct and separate purposes, even though there is a cross-over in the subject matter.”

79 Mrs Sheffield had also previously lobbied for changes in government policies in the homeopathy prophylaxis area as the founding member of a political lobby group and its spokesperson in 2007-2009. Further, Mrs Sheffield had written to state and federal members of parliament with an involvement in health policy on the issue in July 2007.

80 Mrs Sheffield has maintained the Website from around 2001. She collates the content for the Website and also contributes her own articles. While her husband has been a co-registrant of the Website, he does not have any involvement in producing or editing its content which is a task undertaken solely by Mrs Sheffield. She was responsible for all of the content uploaded to the Website and has promoted the prophylactic qualities of homoeopathy through Homeopathy Plus for several years.

81 Mrs Sheffield started offering free subscriptions to a homeopathy information newsletter several years ago, initially by posting hard copies and now by sending it online to subscribers using a group e-newsletter service. As at 28 June 2013, there were 12,041 subscribers to the email newsletter which contains articles written by Mrs Sheffield and others on the practice, science, history, current trends and politics around homeopathy.

82 The content and design on the Website as at the various dates on which the contraventions are alleged to have occurred are not in dispute.

5.2 Publication of the First Whooping Cough Article

83 Mrs Sheffield wrote the First Whooping Cough Article at some time during 2009. The article was published on a section of the Website entitled the “Treatment Room”. I accept that Mrs Sheffield intended in part that the Treatment Room section of the Website would educate visitors on how common homeopathic remedies are used for different symptom profiles and increase understanding of the discipline of homeopathy. I accept also that there were no direct links within the body of the text of the Three Articles to products available from the Online Shop. However, I do not accept that advertising had no role in the inclusion of information uploaded to the Treatment Room given that all such information, including the First Whooping Cough Article, were located on pages which included a menu with click-button access to the Online Shop and the sale of homeopathic products was one of the purposes of Homeopathy Plus. Furthermore, as Mrs Sheffield accepted, visitors to the Website could, by clicking through a series of two or three links from the First Whooping Cough Article commencing with the online shop button, reach a page where they could purchase Drosera which was referred to in the First Whooping Cough Article as a remedy for the prevention of whooping cough (see [148]). I do not, however, accept the ACCC’s submission that I should infer that Pertussinum was also available for sale through the Website shop. It would have been a simple matter for the ACCC to prove that fact, and its failure to do so cannot be remedied by evidence that a different product was available for sale through the Website.

84 On 13 April 2012, Ms White, who is an Assistant Director in the Enforcement Operations, at the ACCC, visited the Website and navigated to the section of the Website entitled “Treatment Room”. She then clicked on the First Whooping Cough Article and printed out a copy. The printout of the webpage where the First Whooping Cough Article was located included a toolbar which formed part of a constant frame within which all pages of the website were displayed. By clicking on one of the links on the toolbar, the user could navigate to other pages of the Website. Those links were displayed as follows:

Join Our Newsletter

Sign Up |

Main Menu |

Home |

Flu Watch |

Tutorials |

Answers |

Treatment Room |

Library |

Clinic Cases |

Immunisation Issues |

Research |

Political Issues |

Videos |

Agrohomeopathy |

Quick Tips |

Podcasts |

Your Story |

Latest News |

Contact Us |

Appointments |

Alerts |

Treatment for Autism |

Newsletter |

Newsletter Archives |

Letters to Editor |

Shop |

Simplex Remedies (Pills) |

Complex Remedies (Liquids) |

Kits and Bottles |

Agrohomeopathy Remedies |

Tissue Salts |

Bach Flowers |

Books |

Shop Notes |

Subscribe to our feed |

Search our Site |

Go! |

Follow Us On [facebook] [twitter] |

85 However, the physical printout of the webpage where the First Whooping Cough Article was located omitted to print the banner at the top of the webpage. It was common ground that at that time the banner read:

86 In contrast to the banner when the Second and Third Whooping Cough articles were published, the banner did not refer to the online shop.

87 From 20 April 2012, the ACCC corresponded with Mrs Sheffield for the purpose of requesting that the First Whooping Cough Article be removed from the Website. The First Whooping Cough Article was removed from the Website on 26 April 2012 following a verbal undertaking given by Mrs Sheffield to the ACCC in a telephone conversation earlier that day. In the course of that conversation she said words to the effect that “I will remove the article until I have time to check whether any of it needs to be changed. I will put it back up again when I am happy with it.” I also accept that she had always intended to re-upload the First Whooping Cough Article when she had undertaken further research.

5.3 Publication of the Second Whooping Cough Article

88 In the fortnight after removing the First Whooping Cough Article in April 2012, Mrs Sheffield read further material on the Vaccine, as well as prevention and treatment of whooping cough by homeopathic means.

89 At this time she asked her son, who assisted Homeopathy Plus with IT, to arrange for a “members’ area” to be added to the Website. There had been problems in the past with establishing such an area which was an “on-again and off-again project” during the second half of 2012 due to time constraints and their lack of familiarity with the software, WishList Member, which Homeopathy Plus had purchased for this purpose. Once WishList Member was ready to facilitate content uploads, Mrs Sheffield instructed her son to upload to the Website articles about homeopathy prophylaxis which had been temporarily removed pending establishment of the members’ area. The Second Whooping Cough Article was among several articles that her son was asked to upload. This was a revised version of the First Whooping Cough Article and contained direct links to two other articles under the heading “Further Reading”, namely, “Bordetella pertussis: Strains with increased toxin production associated with pertussis resurgence”, Emerging Infectious Diseases (2009) v 15(8) at 1206-1213 (the “2009 Emerging Infectious Diseases article”), and an online article by the Chicago based homeopath, Heidi Stevenson, entitled “Whooping Cough Outbreaks in Vaccinated Children Become More and More Frequent’ (the “Stevenson online article”) Mrs Sheffield’s son told her, and she believed, that he had placed the requested material within the members’ area. She therefore believed that the Second Article would not be accessed outside the members’ area on the Website.

90 Before being able to access material contained within the members’ area, a visitor was required to accept terms and conditions of access set out on a sign-up page. Mrs Sheffield compiled the terms and conditions for the members’ area after reviewing other medical sites on the internet and included those terms which she considered might be relevant and applicable to her Website.

91 The Website had been redesigned since publication of the First Whooping Cough Article and, at the time of the Second Whooping Cough Article, bore a different banner as follows which referred expressly to the online store:

“

92 Mrs Sheffield accepted that the words under the Homeopathy Plus banner were chosen as they were “the three encompassing things for websites”, and that those things included the provision of an online store.

93 The toolbar, which was previously located down the side of the page, was now placed horizontally below the banner but continued to form part of the frame within which all pages constituting part of the Website appeared. The toolbar provided the following links:

Latest News Tutorials Treatment Room Homeoprophylaxis/Vaccination Library Shop

Videos/Podcasts Contact Us What We REALLY said Members

94 Unlike the toolbar on the Website at the time that the First Whooping Cough Article was published, the toolbar no longer referred to a separate page for “Political Issues”.

95 On 15 January 2013, Ms White visited the Website and navigated to a page upon which the Second Whooping Cough Article appeared without having to accept the terms and conditions for the members’ area.

96 Following her discovery of the Second Whooping Cough Article on the Website, Ms White endeavoured to contact Mrs Sheffield between 15 and 17 January 2013 by telephone and email. Mrs Sheffield received an email from Ms White on 15 January 2013 referring to Mrs Sheffield’s agreement to remove the Second Whooping Cough Article and that she would attempt to revise the page in a manner that would satisfy the ACCC’s concerns about a breach of the ACL. In the email, Ms White advised that she had recently reviewed the “Whooping Cough – Homeopathic Prevention and Treatment” page and had some concerns which she would like to discuss.

97 The email from Ms White prompted Mrs Sheffield to visit the Website on 15 January 2013 where she saw that the Second Whooping Cough Article was not only visible in the members’ area, but also on the public area of the Website where it had been accessible for the past four days. On the same day, Mrs Sheffield asked her son to remove the Article from the public area of the Website so that it would be accessible only within the members’ area after viewing the front “disclaimer” screen. Mrs Sheffield then investigated the problem and found that in order to limit material to the members’ area, it was necessary to select a check box at the time of uploading an article. Mrs Sheffield’s son complied with her request as a result of which the article was accessible thereafter only in the members’ area of the Website after viewing a front page and accepting the terms and conditions. The front page contained text written by Mrs Sheffield and read:

“Oops! This Content is Members Only”

Looking for this content?

It’s now in our free member’s area – just follow the link.

Why has it been moved there?

Some people think you shouldn’t know about homeopathy – especially in relation to this particular problem.

They have lodged complaints with various government departments against Homeopathy Plus! and this website to stop the information entering the public domain.

We think this behaviour is silly, short-sighted and against the public interest.

It also makes it difficult for you to research potentially valuable information on homeopathy.

So, to reduce the complaints and protect your access to information we have moved this “shocking” content to a free member’s area where you can still read it and form your own opinion.

To access the information just click the link, accept the terms of membership and start reading.

98 A disclaimer (“the Stand Alone Disclaimer”) appeared beneath this text which is set out at [282] below.

99 The terms and conditions relevant to the current proceedings are set out at [286] below.

100 On 17 January 2013, Ms White spoke with Mrs Sheffield who advised that she intended to record the conversation. Ms White consented to that course. I accept Mrs Sheffield’s detailed evidence as to the content telephone conversation which ensued as follows:

[Ms White] said: I just wanted to check, I am not sure if you manage the website content yourself and whether you do know what the statements on the pages are at the moment?

[Mrs Sheffield] said: I went, when I got your email yesterday I went off and had a look at the article and it’s off in the member’s area. Now apparently when you came across it it wasn’t. Now these things happen sometimes because I have a web manager, and I said to put this, this, this and this article in the member’s area. And of course the whooping cough article wasn’t moved off into the member’s area, it was made public, for some reason or another, by accident of course, but it’s now in the member’s area now.

[Ms White] said: OK. But how can it be accessed in the member’s area? Can anybody find what can be accessed there?

[Mrs Sheffield] said: Yes, but they sign agreements going in that they are aware that it’s information that’s not accepted by the orthodoxy. It’s from the homoeopathy perspective only.

[Ms White] said: OK.

[Mrs Sheffield] said: And that it’s not to be removed out of that member’s area.

[Ms White] said: Right. Well, yeah, that’s what I thought may have been the case. It was on the page so I really just wanted to check that.

[Mrs Sheffield] said: Yeah, well thanks for that. I wasn’t… I went off and had a look and thought, what, well of all the articles that was the one that slipped through.

[Ms White] said: Yeah, [laughing], well OK at this stage that’s all I wanted to check with you. Um, well I think we still have to consider whether [inaudible] from our end, with the page, but I’ll give you a call.”

101 I accept Ms White’s evidence that at the end of the conversation she stated words to the effect that, while the content may be moved to another area, this would not necessarily allay the ACCC’s concerns over the potentially misleading nature of the statements made on the ‘Whooping Cough’ page. However, I am not prepared to find that Mrs Sheffield in fact heard anything further than that which is recorded in evidence as set out above.

102 Later on 17 January 2013, Ms White visited the Website and observed that the Second Whooping Cough Article did not appear and that the webpage directed readers to the “Members” area of the “Website”. She also observed that in order to sign up as a “Member”, readers had to agree to certain terms and conditions.

103 On the following day, another employee of the ACCC who is not Ms White, visited the Website again and signed up as a “Member” by inputting her name and email address on the Website and agreeing to the terms and conditions. She then accessed the Second Whooping Cough Article.

5.4 Publication of the Government Article

104 On 3 February 2012, Mrs Sheffield read an article entitled “Whooping cough in Australian children – how many were vaccinated?” by Greg Beattie. As a consequence of reading the article, Mrs Sheffield sent a newsletter “Alert” to the Homeopathy Plus subscription list. The content of that email was also uploaded to the Website on the same day and constitutes the Government Article. I accept that Mrs Sheffield’s motives in uploading the Government Article were in part to advocate for a change in the government’s approach to what she considered to be a whooping cough epidemic because in her view, “the current policies were inappropriately one sided”. However, I also consider that she was intending to promote her online shop.

105 Ms White visited the Website on 22 January 2013 and performed a search for “whooping cough” on the Website search engine. The website directed her to the Government Article which she printed. It was not necessary for Ms White to become a member of the Website before she was able to access the Government Article. It was freely accessible to any member of the public who visited the Website.

106 Subsequently, on 29 January 2013, Ms White placed an order for a product through the Website and received a tax invoice.

6. Elements of the statutory causes of action: overview

107 The ACCC alleges contraventions of ss 18 and 29(1)(a) and (b) of the ACL. I have earlier set out the terms of these provisions at [8] and [9] above. It is helpful, however, to briefly explain the elements of the two causes of action.

6.1 A person for the purposes of the ACL

108 There is no issue that each Respondent is “a person” within ss 18 and 29 of the ACL.

109 The ACL applies to the conduct of corporations by virtue of s 131 of the CCA and therefore to Homeopathy Plus.

110 Mrs Sheffield conceded that the ACL applied to her as an individual by operation of s 6(3)(b) of the CCA. Section 6(3)(a) provides (relevantly) that Parts 2-1 and 3-1 of the ACL, which include ss 18 and 29 respectively, apply as if:

(a) those provisions … were …. confined in their operation to engaging in conduct to the extent to which the conduct involves the use of postal, telegraphic or telephonic services … and

(b) a reference in those provisions to a corporation included a reference to a person not being a corporation.

111 The concession by Mrs Sheffield was correctly made, in my view, as the Three Articles were published on the internet and access to the internet involves the use of telephonic services: Seafolly Pty Ltd v Madden (2012) 297 ALR 337 at [76]-[79] (Tracey J); ACCC v Jutsen (No 3) (2011) 206 FCR 264 at 287 [100] (Nicholas J); ACCC v Jones (No 5) [2011] FCA 49 at [6] and [10] (Logan J).

112 Nor is it in dispute that both Respondents “engag[ed] in conduct” within s 18 of the ACL by making representations contained in the Three Articles and publishing those on the Website. By s 4(2)(a) of the CCA, a reference to “engaging in conduct” is to be read as a reference to “doing or refusing to do any act…”. Conduct can include making a statement which is misleading or deceptive: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 (“Global Sportsman”) at 88 (the Court). Any omission alleged to constitute “conduct” within s 18 must be deliberate, as s 4(2)(c) suggests in providing that the phrase includes a reference to “refraining (otherwise than inadvertently) from doing that act.”

113 The remaining elements that must be established under s 18 of the ACL are that:

(a) the conduct engaged in occurred “in trade or commerce”; and

(b) the conduct “is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.”

114 The scope of s 29 of the ACL is more narrow. While certain elements overlap with those in s 18, s 29 is concerned with “representations” only. A representation is a statement made orally or in writing or which is implied from words or conduct (see Given v Pryor (1978) 39 FLR 437 at 440-441).

115 The elements specified in s 29 require that a representation is made “in trade or commerce” and is false or misleading, in common with s 18. In addition:

(a) the representation must be made “in connection with”:

(i) the supply or possible supply of good or services; or

(ii) the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services; and

(b) the representation must be a representation of the kind caught by one of the subsections.

7. Were the alleged representations false, MISLEADING or deceptive?

7.1 What is meant by “misleading or deceptive”?

116 Sections 18 and 29 of the ACL are in effectively the same terms as their predecessor provisions, ss 52 and 53 of the Trade Practices Act 1975 (Cth) (“TPA”), save that the phrase “[a] person must not” is used in the ACL rather than the phrase “[a] corporation shall not” in the TPA. That difference is not of any relevant consequence here, as was also the case in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 (“TPG Internet”) at 645 [11] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ). As such, the consideration by authorities of whether conduct was “misleading or deceptive” conduct for the purposes of ss 52 and 53 of the Trade Practices Act is equally applicable to ss 18 and 29 of the ACL.

117 The principles to be applied in determining whether conduct is misleading or deceptive can conveniently be summarised as follows. In so summarising the relevant principles, it must be emphasised that they are interrelated.

118 First, in common with its predecessor provision, s 18 of the ACL:

… is concerned with the effect or likely effect of conduct upon the minds of those by reference to whom the question of whether the conduct is or is likely to be misleading or deceptive falls to be tested. The test is objective and the Court must determine the question for itself: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87 (the Court) (citations omitted).

119 As French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ explained more recently in TPG Internet at [49], the characterisation of conduct as misleading or deceptive or as likely to mislead or deceive “generally requires consideration of whether the impugned conduct viewed as a whole has a tendency to lead a person into error” (citing Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at 318 [24] (French CJ) with approval)). “That is to say…”, as their Honours had earlier explained in their joint reasons at [39], “there must be a sufficient causal link between the conduct and error on the part of persons exposed to it.”

120 Secondly, the test being an objective one, it follows that intention is not an element of s 18 (or s 29) of the ACL notwithstanding that intention may be relevant to the question of whether it may be inferred that a representation is misleading or deceptive or likely to be so: TPG Internet at [55]-[56] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

121 Thirdly, conduct is “likely” to mislead or deceive if there is “a real or not remote chance or possibility regardless of whether it is less or more than fifty per cent’”: Global Sportsman at 87 (the Court) (citations omitted). This enquiry in turn focuses upon the time of publication: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kaye [2004] FCA 1363 (Kenny J) at [105].

122 In the fourth place, where the impugned conduct is constituted by the making of a statement, the question of whether the statement has a tendency to lead into error can meaningfully be addressed only once the class of persons likely to be affected and their relevant attributes have been identified. Only then can the effect of the representations on persons acting reasonably in all of the circumstances be assessed. As Gibbs CJ held in Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 (“Puxu”) at 199:

…consideration must be given to the class of consumers likely to be affected by the conduct. Although it is true, as has often been said, that ordinarily a class of consumers may include the inexperienced as well as the experienced, and the gullible as well as the astute, the section must in my opinion by [sic] regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class. The heavy burdens which the section creates cannot be have been intended to be imposed for the benefit of persons who fail to take reasonable care of their own interests. What is reasonable will or [sic] course depend on all the circumstances.