FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Fisher & Paykel Customer Services Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1393

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and file and serve proposed minutes of order reflecting these reasons within 28 days of the date of these reasons. In the event that the parties are unable to agree, the parties should have the matter listed for directions as soon as possible.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 2309 of 2013 |

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION First Applicant SCOTT GREGSON, CURRENTLY THE EXECUTIVE GENERAL MANAGER, CONSUMER ENFORCEMENT OF THE AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Second Applicant

|

AND: | FISHER & PAYKEL CUSTOMER SERVICES PTY LTD (ACN 003 335 171) First Respondent DOMESTIC & GENERAL SERVICES PTY LTD (ACN 127 221 032) Second Respondent

|

JUDGE: | WIGNEY J |

DATE: | 19 DECEMBER 2014 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 In 2011 and 2012, Fisher & Paykel Customer Services Pty Ltd (F & P Customer Services) and Domestic & General Services Pty Ltd (Domestic & General) engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct and made false or misleading representations to consumers concerning the need for extended warranties, and the existence and effect of statutory consumer guarantees in the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). In doing so, they contravened ss 12DA, 12DB(1)(h) and 12DB(1)(i) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act).

2 The Australian Competition and Consumer Competition (the Commission) applies for relief in relation to those contraventions. The relief sought includes declarations, injunctions, pecuniary penalties and other non-punitive orders. The parties are largely in agreement as to the relief that the Court should grant in relation to these contraventions. It nevertheless falls to the Court to determine the appropriate relief, including the scope of any injunctions (about which there is some dispute) and the appropriate amount of the pecuniary penalties, in accordance with established principles. These reasons address the relevant principles, the application of those principles to the facts and the appropriate relief to grant in relation to the contraventions.

Facts relevant to the contraventions

3 There is no dispute between the parties in relation to the relevant facts. The parties tendered a Joint Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions (Joint Statement) signed by their respective legal advisers. By reason of s 191(2)(a) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) evidence is not required to prove the existence of the facts agreed in the Joint Statement. The Court can also proceed to judgment and make orders on the basis of admissions contained in the Joint Statement: r 22.07 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

4 Following is a brief summary of the facts as agreed or admitted in the Joint Statement.

5 F & P Customer Services, as its name suggests, carries on the business of providing after sales service to customers who have purchased Fisher & Paykel electrical home appliances. It is part of a group of companies (the Haier Group) one or more members of which are responsible for manufacturing this well-known brand of appliances.

6 Domestic & General carries on the business of providing, amongst other things, marketing and administration services to clients in respect of warranty protection for domestic electrical products and appliances. In 2011 and 2012, F & P Customer Services was one of Domestic & General’s clients. Under terms of an agreement entered into in 2008, Domestic & General agreed to provide a number of services to F & P Customer Services, including issuing extended warranties on behalf of F & P Customer Services and providing marketing services in relation to the provision and offer of extended warranties.

7 Between January 2011 and December 2012 Domestic & General, as agent for F & P Customer Services, sent a letter (the extended Warranty letter(s)) to each of approximately 48,214 purchasers of Fisher & Paykel appliances, including ovens, cookers, dishwashers, refrigerators, freezers, washing machines and dryers. The extended warranty letters were sent to purchasers 12 months after they had purchased a Fisher & Paykel appliance. They were on a letterhead bearing the words “Fisher & Paykel” and were signed by a person above the words “Customer Care, Fisher & Paykel”.

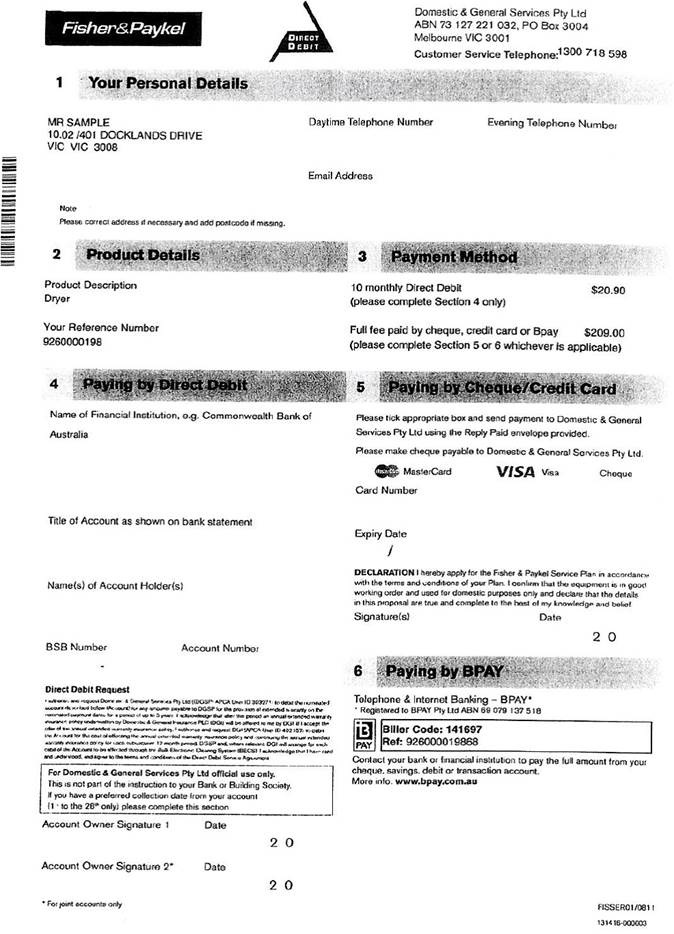

8 The extended warranty letters contained an offer or invitation to the recipient of the letter, the purchaser of a Fisher & Paykel appliance, to purchase an extended warranty in relation to that appliance. The main text of each letter was in the following terms:

When you purchased your Dishwasher it came with a warranty protecting you against the cost of repairs for a total of 2 years. Your Dishwasher is now a year old, which means you have 12 months remaining - after that your appliance won’t be protected against repair costs. Fisher & Paykel can help.

We have teamed up with Warranty Specialists, Domestic & General to offer you an extra 2 years of protection with our Service Plan. With the Fisher & Paykel Service Plan you can enjoy the peace of mind and convenience of protection against unexpected repair bills even as your appliance gets older.

Unlimited number of repairs - or a brand new replacement

Quite simply, if your product breaks down within the 4 years covered (from the purchase date), we’ll fix it. You won’t even have to fill in a claim form since the bill is normally settled directly for you. Plus if we can’t fix your product economically we will happily give you a brand new replacement. There is no limit to the number of repairs.

Join by Direct Debit and spread the cost

To ease the household budget, you can even spread the fee of $209.00 over 10 monthly instalments of $20.90 by Direct Debit. There are no forms to complete – just give us a call on 1300 718 598 or use one of the other payment options shown below.

Your payment will indicate your acceptance of this offer. Your plan will commence at the end of the manufacturer’s warranty. As confirmation, you will receive plan documents by mail within 28 days of application. Please be sure to read the Terms and Conditions accompanying this letter prior to taking up this offer and put it in a safe place for future reference.

9 On the right hand side of the letter was a highlighted box which contained the following:

How does the Fisher & Paykel Service Plan work?

1. It extends your warranty to 4 years and protects you against electrical and mechanical faults

2. If something goes wrong with your product, all you need to do is call our customer care team

3. Repairs by our approved engineers will be quality-guaranteed and free of charge

4. You could receive a brand new replacement if your product can’t be fixed

5. You can use the service as many times as you need, potentially saving hundreds of dollars

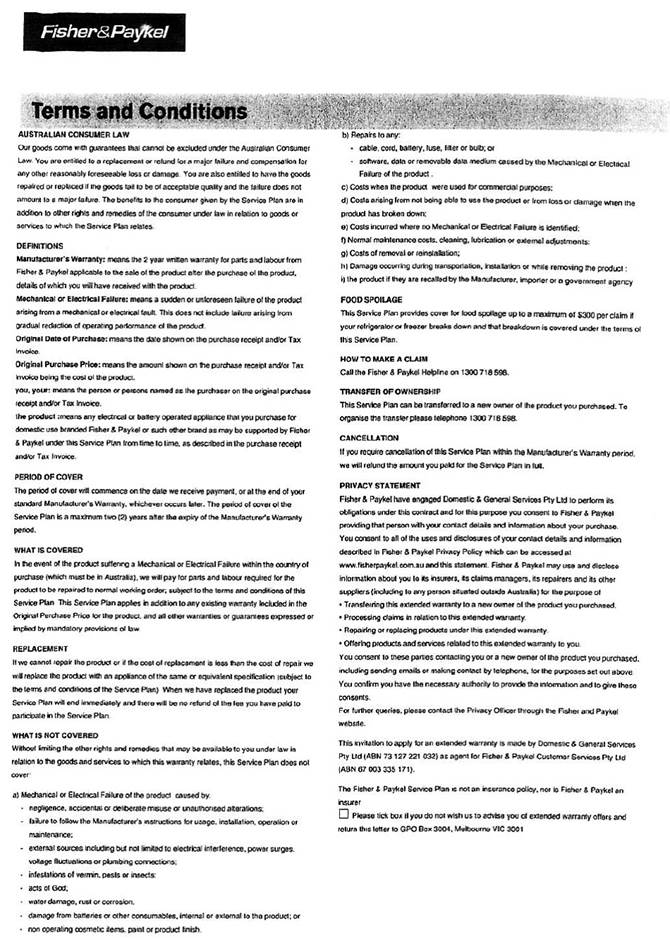

10 The reverse side of the letter contained the terms and conditions adverted to in the last paragraph of the main text of the letter. The first paragraph of the terms and conditions was in the following terms under the heading “AUSTRALIAN CONSUMER LAW”:

Our goods come with guarantees that cannot be excluded under the Australian Consumer Law. You are entitled to a replacement or refund for a major failure and compensation for any other reasonably foreseeable loss or damage. You are also entitled to have the goods repaired or replaced if the goods fail to be of acceptable quality and the failure does not amount to a major failure. The benefits to the consumer given by the Service Plan are in addition to other rights and remedies of the consumer under law in relation to goods and services to which the Service Plan relates.

11 The terms and conditions contain some other references to guarantees, warranties, rights and remedies that may be available to the consumer aside from the extended warranty. Under the heading “WHAT IS COVERED”, the following appears:

… This Service Plan applies in addition to any existing warranty included in the Original Purchase Price for the product, and all other warranties or guarantees expressed or implied by mandatory provisions of law.

12 Likewise, under the heading “WHAT IS NOT COVERED”, the following words appear before a relatively long list of exclusions:

Without limiting the other rights and remedies that may be available to you under law in relation to the goods and services to which this warranty relates, this Service Plan does not cover: …

13 Other provisions of the terms and conditions make it plain that the offer of the extended warranty was made by Domestic & General as agent for F & P Customer Services.

14 The letter enclosed an application form. The terms of the application form are of no particular relevance, other than that they again make it clear that the extended warranty was provided by Domestic & General as agent for F & P Customer Services.

15 The layout and format of the extended warranty letter and the terms and conditions is of relevance to the overall impression or representation conveyed to the recipient of the letter. Accordingly, an image of a sample letter (including the terms and conditions on the reverse side of the letter), is at Appendix A to these reasons. The short point is that the statements in the main text of the letter and in the highlighted box on the front page of the letter are prominent, whereas the references to the ACL in the terms and conditions are in relatively fine print on the reverse side of the letter. The references to the ACL in the fine print in the terms and conditions on the reverse side of the letter are by no means prominent.

16 F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General admit and agree that the extended warranty letter that was sent to the consumers, despite the references to the ACL in the terms and conditions, represented to the consumers that the consumer would not be protected against repair costs for the appliance after a period of two years from the date of purchase of the appliance unless the consumer purchased the extended warranty. F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General also agree and admit that this representation was false or misleading and the making of it was conduct that was misleading or deceptive. That admission, which is properly made, flows from the fact that the effect of various provisions of the ACL, which are considered below, is that consumers may, in certain circumstances, be protected under the ACL against repair costs in respect of an appliance after a period of two years from the date of purchase even if the consumer did not purchase an extended warranty.

Relevant provisions of the ACL

17 The ACL is Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA). It applies as a law of the Commonwealth as provided in Pt XI of the CCA.

18 Section 54 of the ACL creates a statutory guarantee of the acceptable quality of goods. It relevantly provides as follows:

(1) If:

(a) a person supplies, in trade or commerce, goods to a consumer; and

(b) the supply does not occur by way of sale by auction;

there is a guarantee that the goods are of acceptable quality.

(2) Goods are of acceptable quality if they are as:

(a) fit for all the purposes for which goods of that kind are commonly supplied; and

(b) acceptable in appearance and finish; and

(c) free from defects; and

(d) safe; and

(e) durable;

as a reasonable consumer fully acquainted with the state and condition of the goods (including any hidden defects of the goods), would regard as acceptable having regard to the matters in subsection (3).

(3) The matters for the purposes of subsection (2) are:

(a) the nature of the goods; and

(b) the price of the goods (if relevant); and

(c) any statements made about the goods on any packaging or label on the goods; and

(d) any representation made about the goods by the supplier or manufacturer of the goods; and

(e) any other relevant circumstances relating to the supply of the goods.

19 The effect of s 64 of the ACL is that, amongst other things, the guarantee as to acceptable quality in s 54 cannot be excluded, restricted or modified by a term of a contract.

20 Section 259 of the ACL creates a right of action against a supplier in respect of, amongst other things, non-compliance with a guarantee of acceptable quality under s 54 of the ACL. The available remedy for non-compliance depends on whether or not the failure is a major failure which cannot be remedied. Section 259 relevantly provides as follows:

(1) A consumer may take action under this section if:

(a) a person (the supplier) supplies, in trade or commerce, goods to the consumer; and

(b) a guarantee that applies to the supply under Subdivision A of Division 1 of Part 3-2 (other than sections 58 and 59(1)) is not complied with.

(2) If the failure to comply with the guarantee can be remedied and is not a major failure:

(a) the consumer may require the supplier to remedy the failure within a reasonable time; or

(b) if such a requirement is made of the supplier but the supplier refuses or fails to comply with the requirement, or fails to comply with the requirement within a reasonable time – the consumer may:

(i) otherwise have the failure remedied and, by action against the supplier, recover all reasonable costs incurred by the consumer in having the failure so remedied; or

(ii) subject to section 262, notify the supplier that the consumer rejects the goods and of the ground or grounds for the rejection.

(3) If the failure to comply with the guarantee cannot be remedied or is a major failure, the consumer may:

(a) subject to section 262, notify the supplier that the consumer rejects the goods and of the ground or grounds for the rejection; or

(b) by action against the supplier, recover compensation for any reduction in the value of the goods below the price paid or payable by the consumer for the goods.

21 These provisions applied to Fisher & Paykel appliances purchased by the consumers who were sent the extended warranty letters by Domestic & General as agent for F & P Customer Services. The appliances were goods for the purposes of s 54 of the ACL, were supplied in trade and commerce and were not acquired by way of sale by auction.

22 The right of action under s 259 of the ACL contains no time limit. A consumer can take action under s 259 at any time so long as the terms of s 259 are satisfied. The right of action does not cease two years after purchase, or upon the expiry of any warranty provided by the manufacturer or supplier.

23 It is for this reason that the representation that F & P Consumer Services and Domestic & General admit was conveyed by the extended warranty letter was false or misleading. The making of that representation also amounted to misleading or deceptive conduct.

The ASIC Act Contraventions

24 The provisions of the ACL dealing with misleading and deceptive conduct and false and misleading representations do not apply to the supply or possible supply of services that are financial services, or of financial products: s 131A of the CCA. The extended warranty offered by Domestic & General, as agent for F & P Customer Services, was a financial product as defined in subss 12BAA(1) and (5) of the ASIC Act because it was a facility through which, or through the acquisition of which, a person (the consumer) managed financial risk by managing the financial consequences to them of particular circumstances happening. The relevant circumstances and financial consequences to the consumer here were the financial consequences of their Fisher & Paykel appliance having a defect or otherwise breaking down after the expiry of the manufacturer’s warranty.

25 Issuing a financial product, or arranging to issue a financial product, constitutes a dealing in a financial product and therefore amounts to providing a financial service: s 12BAB(1)(b), (7)(b) and (8) of the ASIC Act. Arranging for a person to apply for a financial product also constitutes the provision of a financial service: s 12BAB(1)(b), (7)(a) and (8) of the ASIC Act.

26 The combined operation of these provisions of the ASIC Act is that the conduct of F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General in sending the extended warranty letters involved or related to the provision, and therefore the supply or possible supply, of financial services. It concerned the application for, or issue of, or arranging for the application for, or issue of, a financial product (the extended warranty).

27 Section 12DA(1) of the ASIC Act provides that:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct in relation to financial services that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

28 Section 12DB(1) of the ASIC Act relevantly provides that:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of financial services:

…

(h) make a false or misleading representation concerning the need for any services; or

(i) make a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including an implied warranty under section 12ED);

…

29 The agreed and admitted facts demonstrate that, in sending the extended warranty letters to consumers F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General contravened ss 12DA and 12DB(1)(h) and (i) of the ASIC Act. That is because, as earlier indicated, the letters represented that the consumer would not be protected against repair costs for the appliance after a period of 2 years from the date of purchase of the appliance unless the consumer purchased the extended warranty. That representation was false or misleading because, by reason of ss 54, 64 and 259 of the ACL, the consumer may have been protected under the ACL against repair costs for the appliance after a period of 2 years from the date of purchase of the appliance, even if the consumer did not purchase the extended warranty.

30 The representation in the letter concerned the need for services (the provision of the extended warranty) (s 12DB(1)(h) of the ASIC Act) and the existence and effect of a guarantee (being the guarantee arising from s 54 of the ACL) (s 12DB(1)(i) of the ASIC Act). The conduct involved in sending the letters containing the false or misleading representation was conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive (s 12DA(1) of the ASIC Act).

31 F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General admit that their conduct amounted to contraventions of s 12DA and 12DB(1)(h) and (i) of the ASIC Act. The contraventions are accordingly made out.

Facts relevant to the appropriate relief

32 The Joint Statement contains a number of agreed or admitted facts that are relevant to the appropriate relief, in particular the appropriate amount of any pecuniary penalty.

33 The extended warranty letters were sent over a 23 month period from 1 January 2011 to 10 December 2012.

34 There is no evidence that (and no agreed or admitted fact to the effect that) either F & P Customer Services or Domestic & General intended to mislead or deceive the recipients of the extended warranty letter, or intended to misrepresent the rights of the recipients as consumers. Nor can that intention be inferred from any agreed or admitted fact. The matter should accordingly be approached on the basis that there was no such intention.

35 F & P Customer Services did not itself prepare or send the extended warranty letters, though senior officers were responsible for the operation of the program and the engagement of Domestic & General. Senior officers of Domestic & General were involved in supervising the drafting, finalising and sending of the letters.

36 The number of consumers who purchased extended warranties was 1,326. The price of the extended warranty varied between $100 and $220. The total amount paid by consumers was therefore quite large. Domestic & General received the payments and paid a fixed fee per warranty to F & P Customer Services. This amount, which was F & P Customer Services’ revenue from the extended warranty program, was fairly modest. F & P Customer Services’ profit from the program was even more modest. Domestic & General was responsible for the costs of the program. It was also responsible for paying refunds to consumers who purchased extended warranties (as explained later). After taking into account the costs and refunds, Domestic & General’s profit from the extended warranty program was relatively modest.

37 F & P Customer Services was informed that the Commission was investigating their conduct in relation to the extended warranty program from about late November 2012. It immediately notified Domestic & General to cease all activities in relation to the extended warranty offers.

38 Between June 2013 and September 2013 F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General undertook a voluntary consumer refund program. This arose after F & P Customer Services became aware of the Commission’s investigation relating to the extended warranty letters and met with the Commission in relation to it. All consumers who received the extended warranty letter and purchased an extended warranty were unconditionally offered a full refund. All consumers who responded to the offer of a refund were given a full refund. There were 107 refunds provided. It is unclear why so few consumers claimed a refund. Because so few refunds were claimed, the total amount refunded was fairly modest.

39 F & P Customer Services at all times fully cooperated with the Commission’s investigation. It voluntarily provided information and documents sought by the Commission in the course of its investigation. It met with the Commission prior to the commencement of these proceedings and offered to resolve the matter by way of administrative action.

40 Domestic & General also fully cooperated with the Commission’s investigation. It voluntarily contacted the Commission after it became aware of the investigation, provided information and documentation sought by the Commission, voluntarily offered to refund consumers and offered to provide an undertaking under s 87B of the CCA.

41 These proceedings were commenced on 12 November 2013. Shortly thereafter both F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General entered into discussions with the Commission with a view to resolving the dispute by consent. Ultimately, however, agreement in relation to the resolution of the proceedings was not reached until shortly prior to the date that the matter was listed for hearing. Notwithstanding this, the cooperation of both parties and the ultimate resolution of the matter saved the Commission, the Court, and ultimately the community, the cost and burden of a fully contested hearing.

42 Neither F & P Customer Services nor Domestic & General have previously been found by a court to have contravened any provision of the ACL or to have engaged in conduct similar to the contravening conduct.

43 F & P Customer Services is a wholly owned subsidiary of Fisher & Paykel Australia Pty Ltd. Since November 2012 both companies have been ultimately owned or controlled by the Haier Group. The revenue of the Haier Group in 2013 was US $29.5 billion. Fisher & Paykel is a leading brand in Australia for kitchen and laundry appliances. F & P Customer Services provides after sale service in relation to Fisher & Paykel appliances. The sales revenue and net profit figures for F & P Customer Services for the 2012 and 2013 financial years are commercially confidential. They were disclosed to the Court on a confidential basis. It is unnecessary to detail them in these reasons. Suffice it to say that sales revenue was significant, though net profit was fairly modest in the circumstances.

44 Domestic & General is part of the Domestic & General group of companies (D & G Group), which includes companies that specialise in providing warranty services in relation to breakdown protection for consumer electronics and domestic electrical products. Domestic & General provides such services to clients in Australia. The revenue of the D & G Group in the year ended 31 March 2013 was £574.8 million. The sales revenue and net profit figures for Domestic & General for the 2012 and 2013 financial years are commercially confidential. Again, these figures were provided to the Court on a confidential basis. It is unnecessary to detail them in these reasons. Suffice it to say that both the revenue and the net profit figures were substantial.

45 F & P Customers Services has had a compliance program in place for over 10 years. Upon the introduction of the ACL in January 2011, F & P Customer Services undertook a thorough ACL compliance review of those areas of its business for which F & P Customer Services was directly responsible. However, the conduct the subject of this proceeding indicates that, at the time of the contravening conduct, F & P Customer Services obviously did not have appropriate processes in place to ensure that material prepared by its agent in relation to the extended warranty program was consistent with the ACL and was not misleading or deceptive.

46 Domestic & General also had a compliance program in place at all relevant times. With the introduction of the ACL in January 2011, Domestic & General undertook an ACL compliance review. However, the conduct the subject of this proceeding again indicates that, at the time, Domestic & General did not have appropriate processes in place to ensure that materials prepared by it on behalf of F & P Customer Services in relation to the extended warranty plan complied with the ACL and the ASIC Act.

Relief

47 The parties jointly submitted that, in relation to the contravening conduct of both F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General, the Court should:

(a) make declarations pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act);

(b) order injunctions under s 12GD of the ASIC Act;

(c) make non-punitive orders under s 12GLA of the ASIC Act relating to their respective compliance programs;

(d) order that both parties pay a pecuniary penalty in respect of the contraventions under s 12GBA of the ASIC Act; and

(e) order that the parties pay a fixed sum contribution to the Commission’s costs of and incidental to the proceedings.

48 With one exception, the parties agree and consent to the terms of the declarations and orders. The exception is, in the case of Domestic & General, the precise terms of the injunction. That issue will be addressed later in these reasons.

49 When deciding whether to make orders that are consented to by the parties, the Court must be satisfied that it has the power to make the orders proposed and that the orders are appropriate: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Real Estate Institute of Western Australia Inc (1999) 161 ALR 79 at [20] (REIWA). Determining the appropriateness of the orders must involve the application of established principles to the particular facts of the case. There is authority to the effect that the Court should exercise a degree of restraint when scrutinising consent orders which represent terms of settlement between legally represented parties: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Target Australia Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1326 at [24]; REIWA at [20]-[21]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths (South Australia) Pty Ltd (trading as Mac’s Liquor) (2003) 198 ALR 417 at [21]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2007) ATPR 42-140; [2006] FCA 1730 (ACCC v CFMEU) at [4]. If, however, the consent orders are found to be appropriate upon an application of established principles to the facts, there would in any event be little, if any, need for such restraint.

Declarations

50 The Court has a wide discretionary power to make declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court Act: Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 437-438 (Forster); Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (No. 2) (1993) 41 FCR 89 at 99.

51 Before making declarations, the Court should be satisfied that the question is real, not hypothetical or theoretical, that the applicant has a real interest in raising the issue and that there is a proper contradictor: Forster at 437-438 (Gibbs J citing Russian Commercial and Industrial Bank v British Bank for Foreign Trade Ltd [1921] 2 AC 438 at 448). Each of these requirements is satisfied here. The issue concerning the contraventions of the ASIC Act by F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General is a real, not theoretical, issue. The Commission as the relevant regulator has a real interest in raising this issue and F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General are appropriate contradictors: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (2012) 201 FCR 378.

52 The facts necessary to support the declaration may be established by agreed facts (under s 191 of the Evidence Act) and admissions: Minister for Environment, Heritage and the Arts v PGP Developments Pty Ltd (2010) 183 FCR 10. The Joint Statement provides a proper factual basis for the declarations sought by the Commission and agreed to by the parties.

53 Declarations relating to contraventions of legislative provisions are likely to be appropriate where they serve to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the applicant’s claim that the respondent contravened the provisions, assist the regulator to carry out its duties and deter other persons from contravening the provisions: ACCC v CFMEU at [6] and the cases there cited. That is the situation here. The declarations are of utility and are an appropriate exercise of the Court’s discretion to grant declarations. The declarations sought by the Commission and agreed to by F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General contain sufficient particulars of how and why the conduct amounted to contraventions of the ASIC Act: cf. Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 216 CLR 53 at [90].

54 Accordingly, the Court will make declarations in the terms sought by the Commission and consented to by the other parties.

Injunctions

55 Section 12GD(1) of the ASIC Act relevantly provides that if the Court is satisfied that a person has engaged in conduct that constitutes a contravention of Pt 2 Div 2 of the ASIC Act (which includes ss 12DA and 12DB) the Court may grant an injunction “in such terms as the Court determines to be appropriate”. The power of the Court to grant an injunction restraining a person from engaging in conduct may be exercised whether or not it appears to the Court that the person intends to engage again, or to continue to engage, in conduct of that kind, whether or not the person has previously engaged in conduct of that kind and whether or not there is an imminent danger of substantial damage if the person engages in conduct of that kind: s 12GD(5) of the ASIC Act.

56 The text and legislative history of s 12GD of the ASIC Act indicate that the authorities dealing with s 1324 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act), s 80 of the CCA and s 232 of the ACL are likely to be of assistance in determining the relevant principles to apply in relation to the grant of injunctive relief under s 12GD. Section 80 of the CCA has been described as a “widely drawn remedial provision available to restrain conduct which may impinge upon that public interest by contravention of provisions of the Act”: ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1992) 38 FCR 248 (ICI) at 268. The remedy is flexible and may be applied in service of a variety of functions to support the policy of the Act: ICI at 268.

57 The jurisdiction to order an injunction under s 12GD is a statutory jurisdiction and is not confined by the principles applicable to the jurisdiction of courts of equity to grant injunctions: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mauer-Swisse Securities Ltd (2002) 42 ACSR 605 (Mauer-Swisse Securities) at 613 [36]. Traditional doctrine surrounding the grant of injunctive relief was developed primarily for the protection of private proprietary rights, whereas public interest injunctions are different: ICI at 256. An injunction granted under s 12GD is a public interest injunction. The traditional equitable doctrines are not, however, entirely irrelevant: ICI at 256-257. They may represent a sound basis for undertaking a preliminary assessment which should be reviewed against the statutory role the relevant regulator plays and the wider question of what is “desirable” in the statutory context: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Triton Underwriting Insurance Agency Pty Ltd (2003) 48 ACSR 249 at [25].

58 Amongst the considerations which the Court will take into account in an application for an injunction under s 12GD are the wider issues as to whether the injunction would have some utility or would serve some purpose within the contemplation of the ASIC Act: Mauer-Swisse Securities at 613 [36]. An injunction may be appropriate if directed to achieve an end such as enforcing and giving effect to the relevant statute: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Pegasus Leveraged Options Group Pty Ltd (2002) 41 ACSR 561 at [109]. Where there is an appreciable, not fanciful, risk of particular future contraventions of the ASIC Act by the defendant, it would serve a purpose within the contemplation of the ASIC Act that the Court may grant an injunction restraining such conduct: Mauer-Swisse Securities at 613-614 [36].

59 The issue between the Commission and Domestic & General here is not whether or not an injunction should be granted. Rather, the dispute is as to the duration of the injunction and its terms. The Commission submits that the injunction should operate for three years whereas Domestic & General submits that two years is appropriate. Perhaps more significantly, the scope and particularity of the injunction proposed by the Commission is significantly broader than the terms of the injunction that Domestic & General submits is appropriate.

60 In this respect, it is clear that the injunctive relief should be appropriate to the occasion and care should be exercised to avoid “casting the net too wide”: ICI at 261. Each case must be examined on its own facts to determine the aptness of a particular form of an injunction: Commodore Business Machines Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1990) 92 ALR 563. There must be a sufficient nexus or relationship between the factual circumstances that gave rise to the proceedings and the terms of the injunction: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Z-Tek Computer Pty Ltd (1997) 78 FCR 197 at 203-204; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Albert (2005) 223 ALR 467 at [45]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Artorios Ink Co Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCA 1292 (Artorios Ink) at [61].

61 It does not necessarily follow, however, that the injunction must correspond exactly to the particular contravention the subject of the proceedings. An injunction should not be so precisely expressed as to “encourage evasion of the spirit but not the letter” of the injunction: ICI at 261. It may in some circumstances be appropriate for the injunction to prevent conduct to the like effect, or a contravention in a similar manner to that which gave rise to the proceedings: ICI at 261; BMW Australia Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2004) 207 ALR 452 at [36]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v IPM Operation and Maintenance Loy Yang Pty Ltd (2006) 157 FCR 162 at [229].

62 The injunction should also be expressed in clear and precise terms so that it is capable of being obeyed without the respondent being required to make an evaluative judgment or subjective assessment about its scope or coverage: Melway Publishing Pty Ltd v Robert Hicks Pty Ltd (2001) 205 CLR 1 at [60]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd (2007) 161 FCR 513 at [112]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Seven Network Ltd (2007) 244 ALR 343 at [108]; ICI at 259; REIWA at [26].

63 The Commission’s primary submission is that an injunction in the following terms is appropriate:

Pursuant to section 12GC(1)(a) of the ASIC Act, for a period of 3 years from the date of this order, [Domestic & General], whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from representing, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply, possible supply or promotion by any means of the supply or use of financial services in relation to extended warranty plans:

that a consumer will not be protected against the costs of repairing or replacing an appliance in the event of a mechanical or electrical fault after a certain period from the date of purchase of the appliance in the absence of an extended warranty plan.

in circumstances where the consumer may be so protected under the Australian Consumer Law.

64 Domestic & General submits that the form of the injunction proposed by the Commission is both too wide and too uncertain. It points to the fact that, unlike the contraventions that gave rise to the proceedings, the injunction proposed by the Commission is not limited to printed material, not limited to Domestic & General’s relationship with F & P Customer Services and not limited to the precise terms of the extended warranty letter it sent on behalf of F & P Customer Services. Domestic & General submits that the form of injunction sought by the Commission is inappropriate because it goes well beyond the conduct involved in the established contraventions and thus lacks the necessary nexus with that conduct.

65 Domestic & General also submits that the proposed form of injunction is uncertain as it uses supposedly uncertain or unclear expressions such as “financial services”, “extended warranty plans” and “protected against the costs of”. It is also contended that the proposed terms of the injunction requires Domestic & General to make an evaluative assessment of whether a consumer “may have” protection under the ACL.

66 Domestic & General submits that the following form of injunction would be appropriate in the circumstances:

“Pursuant to section 12GD(1)(a) of the ASIC Act, for a period of two years from the date of this order, [Domestic & General], whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from sending to consumers in relation to the supply or possible supply of the Extended Warranty Plan as agent for and on behalf of Fisher & Paykel, the Mid-Warranty Mailer attached in Annexure A.

67 Whilst maintaining its primary submission that the form of injunction it proposes is both appropriate and sufficiently certain in the circumstances, the Commission advances the following alternative form of injunction that purports to meet some of the issues raised in Domestic & General’s submissions:

Pursuant to section 12GD(1)(a) of the ASIC Act, for a period of 3 years from the date of this order, [Domestic & General], whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from:

(a) issuing any mailer or other document to consumers in the form, or in a substantially similar form, to the Mid-Warranty Mailer; and

(b) issuing any mailer or other document to consumers in which words to the following effect are stated: “The appliance or good purchased by you will not be protected against repair costs after the conclusion of the warranty with respect to that appliance or good.

68 There is some merit in some of Domestic & General’s complaints concerning the terms of the injunction proposed by the Commission. In particular, the terms of the injunction should at the very least be limited to written representations of the sort the subject of these proceedings. It is not, however, appropriate to limit the terms of the injunction to printed material such as letters or “mailers”. The injunction should, for example, extend to emails. There should also be some further specificity as to the circumstances whereby the consumer may be protected under the ACL.

69 There are also some problems or disadvantages with the Commissions alternative form of injunction. It would be preferable to avoid having to annex a copy of the extended warranty letter. The use of the expressions “substantially similar form” and “to the following effect” may also require an evaluative assessment of the relevant mailer or other document. The injunctions proposed by the Commission are also not specifically limited to circumstances where ss 54, 64 and 259 of the ACL may operate.

70 However, the injunction proposed by Domestic & General is far too narrow. An injunction in the terms proposed by Domestic & General would permit, if not encourage, “evasion of the spirit but not the letter of the law”. It would allow a letter to be sent which contained essentially the same representation as that admitted to be false and misleading in these proceedings, but in slightly different terms. It would permit a letter to be sent to consumers in identical terms to the letter impugned in these proceedings, so long as Domestic & General was not sending the letter on behalf of F & P Customer Services. Domestic & General could send such a letter on behalf of any of its other clients or customers. Finally, the narrow terms of the proposed injunction would permit Domestic & General to send an identical letter on behalf of F & P Customer Services, so long as the extended warranty plan offered in the letter was not in identical terms to the plan the subject to these proceedings. An injunction in such narrow terms would have limited utility and would not serve the purposes of a public interest injunction, including deterrence. It is clear from the Joint Statement that an essential aspect of Domestic & General’s business is the provision of extended warranty plans to clients other than F & P Customer Services. It is in these circumstances both appropriate and desirable for the Court to order an injunction which would deter Domestic & General from engaging in like conduct involving other clients.

71 Domestic & General’s complaints concerning the breadth and uncertainty of expressions such as “possible supply”, “financial services,” “extended warranty plans” and “protected against the cost of” have no merit. These expressions are either used in the relevant legislation or are used by Domestic & General itself in the extended warranty letter that gave rise to these proceedings. These expressions are also used in the Joint Statement. They are sufficiently certain.

72 Domestic & General’s submission concerning the uncertainty of the expression “in circumstances where the consumer may be so protected by the ACL” is also rejected. The reason that the representation conveyed by the extended warranty letter is misleading is that it represents, in unqualified terms, that a consumer will not be protected after two years, whereas, under the ACL a consumer “may be” protected. That is precisely how the matter is framed in paragraph 30 of the Joint Statement. Domestic & General plainly had no difficulty understanding that point when it agreed to and admitted the facts in the Joint Statement. Nevertheless, as previously indicated, the terms of the injunction should perhaps provide some further specificity as to the circumstances in which a consumer “may be” protected having regard to the facts of the established contraventions.

73 Given the nature and gravity of the contraventions the subject of these proceedings, it is both appropriate and desirable that the injunction operate for a period of 3 years.

74 In all the circumstances, an injunction in the following terms would be both appropriate and desirable:

Pursuant to section 12GD(1)(a) of the ASIC Act, for a period of 3 years from the date of this order, DGS, whether by itself, its servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from sending to consumers, in trade or commerce, any written material in connection with the supply, possible supply or promotion of financial services in the nature of extended warranties in relation to domestic electrical appliances purchased by consumers where:

(a) the written material represents to the consumer that the consumer will not be protected against repair costs for the appliance after a certain period from the date of purchase of the appliance (the stated period) unless the consumer purchases an extended warranty plan; and

(b) the circumstances are such that the consumers may be protected against repair costs for the appliances after the stated period even if no extended warranty plan is purchased because a guarantee that the appliance is of acceptable quality applies by reason of s 54 of the ACL and, in the event of a failure to comply with that guarantee, the consumer may be able to take action under s 259 of the ACL after the stated period.

75 An injunction in the same terms should be made against F & P Customer Services.

76 The wording of the injunction is drawn essentially from the wording used in the Joint Statement. The only material variance is that the injunction is not limited to printed material sent by Domestic & General as agent for F & P Customer Services. Nor is it confined to the exact terms of the extended warranty letter or the exact terms of the extended warranty plan that are the subject of the established contraventions. In effect, the injunction will prevent Domestic & General from engaging in conduct in a similar manner, or to like effect, to the conduct involved in the established contraventions.

Non-punitive order - compliance program

77 Section 12GLA(2)(b) of the ASIC Act, read together with the definition of “probation order” in s 12GLA(4), empowers the Court to make an order for the purpose of ensuring that the person does not engage in the contravening conduct, similar conduct or related conduct during the period of the order. Such orders may include an order directing the person to establish a compliance program for employees or other persons involved in the person’s business, being a program designed to ensure their awareness of the responsibilities and obligations in relation to the contravening conduct, similar conduct or related conduct.

78 Both F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General had compliance programs in place prior to the contravening conduct. Plainly enough these programs were deficient to the extent that they did not prevent the contravening conduct. F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General consent to orders that require them to review their existing compliance programs, make any necessary amendments, maintain the programs for three years from the date of the amendments and provide the Commission with any documents which are required by the programs to be provided to the Commission.

79 Such orders are clearly within the scope of subss 12GLA(2) and (4) and are appropriate to the facts and circumstances.

Pecuniary penalties

80 Section 12GBA(1) provides that if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened, inter alia, a provision of Subdivision D (other than s 12DA), the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty as the Court determines to be appropriate. Section 12GBA(2) provides that in determining the appropriate penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters, including the nature and extent of the act or omission, any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission, the circumstances in which the act or omission took place and whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under Subdivision D to have engaged in any similar conduct.

81 The maximum penalty payable by a body corporate in respect of a contravention of s 12DB at the time of the contraventions by F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General was $1.1 million: s 12GBA(3) of the ASIC Act; s 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth). Section 12GBA(4)(b) provides that if conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more provisions in, relevantly, Subdivision D (which includes s 12DB), a person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty in respect of the same conduct.

Relevant principles – pecuniary penalties

82 The relevant legal principles in relation to the determination of the appropriate pecuniary penalty in respect of contraventions of civil penalty provisions in the ASIC Act and other similar legislation (including the Corporations Act and the ACL) are in most respects well settled.

83 The principal purpose of a pecuniary penalty is to act as a personal deterrent and a deterrent to the general public against repetition of like conduct: Australian Securities Commission v Donovan (1998) 28 ACSR 583 at 608; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Macdonald (No 12) (2009) 259 ALR 116 at [359]-[365]; Re HIH Insurance (in prov liq); ASIC v Adler (2002) 42 ACSR 80 at [125]. In Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd (1991) 13 ATPR 41-076; [1990] FCA 521 at [40]-[42] (TPC v CSR), French J (as his Honour the Chief Justice then was) referred to the primacy of the deterrent purpose in the imposition of pecuniary penalties and described deterrence, both specific and general, as the “principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties” (at [40]). His Honour described the determination of the appropriate penalty in terms of the assessment of a penalty of “appropriate deterrent value” (at [42]). This approach has been consistently followed and applied by the Full Court, including in the context of penalties for contravention of consumer protection provisions: see for example, Global One Mobile Entertainment Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 134 (Global One Mobile).

84 As already indicated, s 12GBA(2) of the ASIC Act provides that in determining the appropriate penalty the Court “must” have regard to “all relevant matters”. It then specifies three fairly obvious relevant matters relating to the nature and circumstances of the particular contravention and the existence of any prior contraventions. It is obviously not possible to provide an exhaustive list of all other matters that might be relevant to consider in arriving at the appropriate pecuniary penalty for contraventions of ss 12DA and 12DB of the ASIC Act. A number of authorities dealing with similar civil or pecuniary penalty provisions in other Acts have listed factors that are likely to be relevant: see in particular TPC v CSR; NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 292-294 (NW Frozen Foods); J McPhee & Sons (Aust) Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2000) 172 ALR 532 at [150]. These factors are likely to be relevant to contraventions under the ASIC Act unless the context of the specific provisions suggests otherwise: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology (No 2) (2011) 279 ALR 609 at [69]; Global One Mobile at [119]. These relevant factors include:

1. The size of the contravening company;

2. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

3. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level;

4. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with regulatory provisions, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

5. Whether the company has shown a disposition to cooperate with the regulator in relation to the contravention;

6. Whether the company has engaged in similar conduct in the past;

7. The company’s financial position; and

8. Whether the conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

85 The process to be applied in arriving at a particular penalty has been considered by the High Court in the context of criminal sentencing: Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357. This process has been held to be applicable to the assessment of pecuniary penalties in the context of consumer protection provisions: TPG Internet Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 210 FCR 277 at [145]. In simple terms, the assessment of the appropriate penalty is a discretionary judgment based on all relevant factors. Whilst careful attention to the maximum penalty will almost always be required, the process should not be approached in a staged, mechanical or mathematical way. Rather, it should be approached as a matter of “instinctive synthesis”: see Wong v The Queen (2001) 207 CLR 584 at [76]. The Court should have regard to all relevant facts and circumstances and arrive at a result which takes due account of, and balances, the many different and conflicting features.

86 The Commission, F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General jointly submit that the appropriate pecuniary penalty for each of the respondents is $200,000. Before dealing with the appropriateness or otherwise of these proposed pecuniary penalties, some brief observations should be made concerning the proper approach to take in respect of such joint submissions, or agreed penalties.

87 In NW Frozen Foods, Burchett and Kiefel JJ considered a number of authorities relating to agreed penalties in civil penalty cases and concluded that a regulator and respondent could jointly propose specific penalty amounts to the Court. It was emphasised, however, that it was necessary for the Court to be independently satisfied that the proposed amount was appropriate. Importantly, their Honours referred to the strong public interest in imposing the proposed agreed penalty even if the Court may otherwise have selected a different figure for itself.

88 The issue was given further detailed consideration by the Full Court in Minister for Industry, Tourism & Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd (2004) ATPR 41-993; [2004] FCAFC 72 (Mobil Oil). As a result of some criticism that had been made of the reasoning in NW Frozen Foods, the Full Court in Mobil Oil was specifically directed to consider the question whether, where the parties in civil penalty proceedings proposed an agreed amount as a penalty, the Court was bound by the decision in NW Frozen Foods to consider whether the proposed amount was within the permissible range in all the circumstances and, if so, impose a penalty of that amount. The Full Court answered that question in the negative, but observed that there was no error of principle in the reasons in NW Frozen foods.

89 The Full Court in Mobil Oil distilled the following six propositions from the reasoning in NW Frozen Foods (at [53]):

(i) It is the responsibility of the Court to determine the appropriate penalty to be imposed under s 76 of the TP Act in respect of a contravention of the TP Act.

(ii) Determining the quantum of a penalty is not an exact science. Within a permissible range, the courts have acknowledged that a particular figure cannot necessarily be said to be more appropriate than another.

(iii) There is a public interest in promoting settlement of litigation, particularly where it is likely to be lengthy. Accordingly, when the regulator and contravenor have reached agreement, they may present to the Court a statement of facts and opinions as to the effect of those facts, together with joint submissions as to the appropriate penalty to be imposed.

(iv) The view of the regulator, as a specialist body, is a relevant, but not determinative consideration on the question of penalty. In particular, the views of the regulator on matters within its expertise (such as the ACCC’s views as to the deterrent effect of a proposed penalty in a given market) will usually be given greater weight than its views on more “subjective” matters.

(v) In determining whether the proposed penalty is appropriate, the Court examines all the circumstances of the case. Where the parties have put forward an agreed statement of facts, the Court may act on that statement if it is appropriate to do so.

(vi) Where the parties have jointly proposed a penalty, it will not be useful to investigate whether the Court would have arrived at that precise figure in the absence of agreement. The question is whether that figure is, in the Court’s view, appropriate in the circumstances of the case. In answering that question, the Court will not reject the agreed figure simply because it would have been disposed to select some other figure. It will be appropriate if within the permissible range.

90 In Mobil Oil the Full Court made a number of points in relation to these propositions. Particularly significant is a point made in relation to the sixth proposition. The Full Court observed (at [56]) in relation to that proposition that it does not follow that the Court must commence its reasoning with the proposed penalty and limit itself to considering whether that penalty is within the permissible range. Whilst a Court may wish to take that approach, it would also be open to a Court, consistently with the reasoning in the NW Frozen Foods, “first to address the appropriate range of penalties independently of the parties’ proposed figure and then, having made that judgment, determine whether the [proposed] penalty falls within the range”.

91 There has, of late, been some a degree of controversy concerning the correctness of some of the reasoning in NW Frozen Foods and Mobil Oil. The reasoning was criticised by the Victorian Court of Appeal in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Ingleby (2013) 275 FLR 171 (Ingleby), though the decision in Ingleby has not been followed in this Court, where NW Frozen Foods and Mobil Oil continue to be regarded as binding authority: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Energy Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 336 (Energy Australia) at [135] and the cases there cited. It has also been observed that there may be little, if any, difference between the approach identified in Ingleby and the approach referred to in NW Frozen Foods as explained in Mobil Oil: Artorios Ink at [87]; Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Constriction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2013] FCA 1014 (Director v CFMEU) at [32]-[33].

92 It is unnecessary in the circumstances of this case to enter into this debate. There is, however, one observation that should be made concerning the reasoning in NW Frozen Foods and Mobil Oil. For reasons expanded on below, the Court is not obliged to take either of the approaches referred to by the Full Court in Mobil Oil to the extent that they involve determining whether the agreed penalty is within the “appropriate range”. Indeed, it may be preferable for the Court to approach the matter without addressing the “appropriate range” at all. Rather, there is much to be said for the view that the Court should simply approach the appropriate penalty by applying the established principles of law to all the relevant facts and circumstances, including penalties imposed in comparable cases. An appropriate figure can then be arrived at by the Court without the need to consider an “appropriate range”. In determining the appropriate amount, weight can be given to joint submissions that include an agreed penalty amount. However, the weight to be given to that submission, like any submission, will depend to a large extent on whether the submission persuasively justifies or explains the proposed agreed penalty having regard to the established principles and the relevant facts and circumstances. If the figure appears to have been simply “plucked out of the air”, or is not adequately explained or justified by reference to the applicable principles, comparable cases and the facts and circumstances of the case, no doubt the joint submission and the proposed agreed penalty would be given little or no weight by the Court.

93 Some weight can also be given to the agreement and the public interest in facilitating settlement of civil penalty cases. It is, however, at least doubtful that this consideration alone would warrant or justify the Court accepting an agreed penalty amount that it would not otherwise have arrived at by applying the principles to the facts and circumstances of the case. The agreed penalty or joint submissions relating to it can never operate as a fetter on the Court’s discretion. Nor should it distract from the Court’s overriding duty to determine the appropriate penalty.

94 This is consistent with the approach taken by Gordon J in Director v CFMEU and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Renegade Gas Pty Ltd (trading as Supagas NSW) [2014] FCA 1135. In the first of these cases, her Honour said (at [33]):

In the end, the principles to be applied may be simply stated. First, the question of an appropriate penalty for a proven contempt or an established breach of a statutory prohibition is a matter for, and function of, the Courts in the exercise of judicial power. Secondly, contrary to statements in some cases, the role of the Court in addressing an agreed penalty is not to exercise an “appellate” role: Ingleby at [29] and [99]. The role of the trial judge is to give such weight to an agreed penalty as is appropriate and to treat the joint submission as it is – a joint submission – to be considered as a factor, an important factor, in the exercise of judicial power of fixing the appropriate penalty in the circumstances of the particular case. These principles are consistent with the observations of Lockhart J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pioneer Concrete (Qld) Pty Ltd (1996) ATPR 41-457 at 41,581-41,582. The role of the Court is to assess what it would do itself based on the facts. Whether the Court assesses for itself what is the appropriate penalty and then tests that against the agreed penalty, or the Court asks itself whether the agreed penalty is broadly in accord with what the Court would have done acknowledging that the fixing of quantum – the task is not an exact science. The role of the Court is the same – to impose a penalty that is proportionate to the gravity of the contravening conduct. Much of the current debate about the appropriate approach has descended into a debate about which goes first – the Court assessing the penalty having regard to the agreed penalty or assessing whether the agreed penalty is within the appropriate range. For my part, that debate is distracting. It is distracting because it ignores the important role of the fundamental principles of sentencing that must be considered by a trial judge.

95 Whilst this approach, to some extent, eschews an approach which suggests that the Court should accept the proposed or agreed penalty if it’s “within the permissible range”, it is not inconsistent with Mobil Oil. The Full Court in Mobil Oil did not say that the Court was bound to take an approach which involved determining the appropriate or permissible range.

96 The debate concerning the approach the Court should take to joint submissions that propose an agreed penalty has, of late, taken on a new dimension following the decision of the High Court in Barbaro v The Queen (2014) 305 ALR 323; [2014] HCA 2 (Barbaro), a case concerning sentencing for criminal offences. In Barbaro, the High Court had cause to consider a particular practice that had been generally followed in criminal sentence proceedings in Victoria whereby the prosecution was permitted or required to submit to the sentencing judge the bounds of the range of sentences which may be imposed on the offender: cf. R v MacNeil-Brown (2008) 20 VR 677. The majority in the High Court said, in fairly emphatic terms, that this practice should cease.

97 Central to the reasoning of the majority was the proposition that a statement by the prosecution concerning the bounds of the available range of sentences is not a submission of law, but a mere statement of opinion. The majority said, at [7]:

The prosecution’s statement of what are the bounds of the available range of sentences is a statement of opinion. Its expression advances no proposition of law or fact which a sentencing judge may properly take into account in finding the relevant facts, deciding the applicable principles of law or applying those principles to the facts to yield the sentence to be imposed. That being so, the prosecution is not required, and should not be permitted, to make such a statement of bounds to a sentencing judge.

98 The majority elaborated on the difficulties inherent in prosecution sentences concerning the available range at [36]-[38]:

If a party makes a submission to a sentencing judge about the bounds of an available range of sentences, the conclusions or assumptions which underpin that range can be based only upon predictions about what facts will be found by the sentencing judge. In some cases, there may be little controversy about the facts. But that will not always be so. In the present cases, for example, counsel for Mr Zirilli told the sentencing judge that the prosecution accepted that Mr Zirilli’s guilty plea indicated his remorse. Presumably the range of sentences which the prosecution indicated in correspondence with Mr Zirilli’s lawyers reflected this view of the matter. But the sentencing judge did not accept that Mr Zirilli was remorseful. Necessarily, then, the range of sentences proffered by the prosecution was fixed on a false basis.

This serves to demonstrate that bare statement of a range tells a sentencing judge nothing of the conclusions or assumptions upon which the range depends. And if, as will often be the case, counsel who appears for the prosecution on a sentencing hearing was not responsible for deciding what range would be proffered, the judge will have little or no assistance towards understanding why the range was fixed as it was.

If a sentencing judge is properly informed about the parties’ submissions about what facts should be found, the relevant sentencing principles and comparable sentences, the judge will have all the information which is necessary to decide what sentence should be passed without any need for the prosecution to proffer its view about available range. If the judge is not sufficiently informed about what facts may or should be found, about the relevant principles or about comparable sentences, the prosecution’s proffering a range may help the sentencing judge avoid imposing a sentence which the prosecution can later say was manifestly inadequate. But it will not do anything to help the judge avoid specific error; it will not necessarily help the judge avoid imposing a sentence which the offender will later allege to be manifestly excessive. Most importantly, it will not assist the judge in carrying out the sentencing task in accordance with proper principle.

99 The question arises whether, in the context of entertaining submissions in relation to the appropriate pecuniary penalty in civil penalty cases, this Court is bound, in any respect, to follow or apply any principle emerging from Barbaro.

100 This question has not yet been decided by the Full Court. A number of single judges of the Court have, however, held that nothing said in Barbaro expressly or impliedly overrules NW Frozen Foods and Mobil Oil. Accordingly, it has been held that the Court is not bound to refuse to entertain such submissions: Energy Australia; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Mandurvit Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 464 (Mandurvit); Tax Practitioners Board v Dedic [2014] FCA 511; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v GE Capital Finance Australia, in the matter of GE Capital Finance Australia [2014] FCA 701 at [68]; Australian Communications and Media Authority v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2014) 221 FCR 502 at [89]-[93]; DP World Sydney Pty Ltd v Maritime Union of Australia (No. 2) [2014] FCA 596 at [23]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Titan Marketing Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 913. There would appear to be only one decision where a single judge considered that he was bound by Barbaro to decline to entertain submissions in relation to penalty: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Flight Centre (No 3) [2014] FCA 292 (ACCC v Flight Centre (No 3)) at [56]. However that decision was made soon after Barbaro was handed down and without the benefit of argument from the parties.

101 It is well established that a single judge of this Court should, as a matter of judicial comity and precedent, follow the decision of another single judge of this Court unless persuaded that the earlier decision is clearly or plainly wrong. Putting aside ACCC v Flight Centre (No 3), I am not persuaded that the decisions earlier referred to are wrong, let alone plainly wrong. The issue was particularly closely considered and persuasively analysed by McKerracher J in Mandurvit and Middleton J in Energy Australia. In the circumstances, I see little point or benefit in adding to the detailed analysis in those cases.

102 Whilst there are undoubtedly some similarities between the process involved in fixing an appropriate pecuniary penalty in a civil penalty proceeding and the sentencing process in a criminal proceeding, there are also some significant differences. The particular sentencing practice that was considered in Barbaro (a prosecutor nominating an available range within which there would effectively be no appealable sentencing error) is different in many important respects from the well-established practice of regulators making submissions (or joint submissions) in respect of the appropriate pecuniary penalty. There is nothing in Barbaro to suggest that the High Court intended to exclude the latter practice. It is not possible to conclude that the High Court implicitly overruled the Full Court decisions in NW Frozen Foods and Mobil Oil.

103 A perhaps more significant question is whether, even if it is accepted that the Court is not bound to apply Barbaro in the civil penalty context, the analysis in Barbaro of the role of a prosecutor’s submissions on sentence should cause the Court to re-evaluate the proper approach to be taken to agreed or joint penalty submissions in civil penalty cases. In light of the analysis in Barbaro, what is the exact status, relevance, admissibility and attributable weight of an agreement as to penalty in civil penalty cases? What is the status and attributable weight of a regulator’s submissions (or joint submissions of the regulator and a party) as to the appropriate penalty or appropriate range of penalties?

104 I would prefer to defer any detailed analysis of these questions until it directly arises in a different matter. That is so for a number of reasons. First, these questions may require a re-evaluation of some of the principles or propositions that emerge from NW Frozen Foods and Mobil Oil. Those Full Court decisions continue to bind a single judge. It accordingly would be more appropriate for any re-evaluation to be undertaken by the Full Court. Second, these questions were not the subject of any detailed argument or submission before me. The parties made joint submissions which addressed Barbaro, but given that all parties had an interest in having the Court accept the agreed penalty as the appropriate penalty, there was effectively no contradictor. Third, and perhaps most importantly, a detailed analysis is unnecessary in this case because, for reasons I will come to, in this matter the agreed penalty is soundly justified and supported by the application of otherwise well-established principles to the facts and circumstances of this case. The joint submissions of the parties, which comprehensively address the principles and apply them to the facts of the case, are persuasive.

105 I would, however, venture the opinion that a reconsideration of some of what was said in NW Frozen Foods and Mobil Oil is warranted. As discussed earlier, it may be appropriate in some cases to give some weight to the fact that the parties have agreed on a penalty amount so as to properly reflect the public interest in fostering the settlement of civil penalty proceedings. It may also be appropriate to give weight, in some cases significant weight, to submissions (including joint submissions) made by the regulator in respect of the appropriate penalty. In my opinion, however, it will rarely be appropriate, particularly in light of the observations in Barbaro, to approach the fixing of an appropriate penalty by either starting with the agreed penalty and considering whether it is within the “available range”, or working out the available range and then determining whether the agreed penalty falls within it. Either approach is likely to distract the Court from applying the applicable legal principles in relation to the determination of penalties to the facts and circumstances of the case. I also doubt that the Court should accept the agreed amount if it would, by applying the principle to the facts, have otherwise arrived at a different figure. That is so even if the agreed figure might be within an appropriate or acceptable range. To the extent that NW Frozen Foods and Mobil Oil suggest otherwise, in my opinion this may need to be reconsidered or re-evaluated. Whilst, as previously indicated, it was not suggested in Mobil Oil that the Court was bound to take an approach which involved accepting the agreed penalty if it was within the appropriate range, I would perhaps go further and say that such an approach should rarely, if ever, be taken.

106 The overriding principle, whether or not there is an agreed penalty or joint submissions, is that it is for the Court itself to determine the appropriate penalty having regard to established principles and the facts and circumstances of the particular case. If there are joint submissions that include a proposed agreed penalty, the appropriate weight to be given to those submissions will vary depending on the nature of the submissions and the facts and circumstances of the case. In light of the discussion in Barbaro concerning the problems with prosecution submissions in relation to available sentencing ranges, joint submissions in civil penalty cases that amount to little more than a joint statement of opinion or agreement about the appropriate penalty should be given little or no weight. If, however, the submissions address the applicable principles of law in relation to the imposition of penalties, the application of those principles to the facts as agreed or admitted and comparable sentences in previous cases, and demonstrate in a persuasive way how the application of the facts to the principles would or should lead the Court to impose a penalty in accordance with the agreed amount, it might be expected that the Court would accord significant weight to the submissions. It does not, of course, necessarily follow that the Court must accept the submissions and impose the agreed penalty. At the end of the day, a joint submission proposing an agreed penalty is just that – a submission. It can never operate as a fetter on the Court’s discretion.

What is the appropriate pecuniary penalty in this matter?

107 The starting point in determining the appropriate penalty is the maximum penalty, which provides a guidepost to the seriousness with which the legislature views contraventions of the relevant provisions of the ACL. The maximum penalty for contraventions of ss 12DA and 12DB at the relevant time was $1.1 million.

108 Regard must then be had to the s 12GBA(2) considerations, including the nature and extent of the acts or omissions that led to the contravention, the circumstances in which the contraventions occurred, any loss or damage arising from the contraventions and whether F & P Customer Services and Domestic & General have previously contravened these or similar provisions.

109 The conduct here unquestionably involves serious and significant contraventions of the ACL. The misleading representations concerned extended warranties for well-known consumer goods. The representations potentially misled or deceived thousands of consumers in respect of the supposed need for extended warranty plans. Those plans involved the outlay of not insignificant sums of money. Whilst there is no evidence that specific consumers were in fact misled by the representations, ultimately a relatively large number of consumers took up the relevant extended warranty plans.

110 On the other hand, it cannot be inferred or concluded that either F & P Customer Services or Domestic & General intended to mislead or that the contraventions were deliberate. Rather, the contraventions arose from a failure on the part of both companies to adequately consider the operation of ss 54, 64 and 259 of the ACL and a failure to properly scrutinise the terms of the extended warranty letter in light of those provisions. Had careful attention been given to those matters, the misleading nature of the letters would have been readily apparent. These failures occurred at a fairly senior level in both companies. Senior officers of both companies were involved in overseeing or supervising the extended warranty programs. That must have extended to scrutinising the terms of the extended warranty letters. If it did not, it should have. The contraventions have plainly exposed weaknesses in both companies’ compliance programs.

111 It is not possible to calculate with any certainty any loss or damage arising from the contraventions. Whilst a relatively large number of consumers ultimately took up the offer, it cannot be inferred that they necessarily did so as a result of the misleading nature of the extended warranty letters. Nevertheless, not insignificant sums of money were involved. It must also be acknowledged that consumers were offered refunds soon after the contravening conduct was identified by the Commission. If there was any loss or damage, consumers were able to obtain compensation for that loss.