FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Streetworx Pty Ltd v Artcraft Urban Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1366

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

Applicant ARTCRAFT URBAN GROUP PTY LTD and another named in the schedule Respondents |

|

ARTCRAFT URBAN GROUP PTY LTD and another named in the schedule Cross Claimants STREETWORX PTY LTD Cross Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: |

18 December 2014 |

WHERE MADE: |

1. The applicant file and serve on or before 16 January 2015 proposed minutes of orders to give effect to these reasons including any submissions on costs.

2. The respondents file and serve on or before 23 January 2015 proposed minutes of orders to give effect to these reasons including any submissions on costs.

3. The further hearing of this proceeding be adjourned to 9.30 am on 30 January 2015 for the making of orders to give effect to these reasons, including orders for costs and for further directions as to the future disposition of this matter.

4. Costs reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

VID 853 of 2013 |

BETWEEN: |

STREETWORX PTY LTD Applicant ARTCRAFT URBAN GROUP PTY LTD and another named in the schedule Respondents ARTCRAFT URBAN GROUP PTY LTD and another named in the schedule Cross Claimants STREETWORX PTY LTD Cross Respondent |

JUDGE: |

BEACH J |

DATE: |

18 December 2014 |

PLACE: |

MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 This proceeding involves questions concerning the construction, validity and infringement of innovation patent claims for lighting assemblies known as luminaires for use in public areas, in particular street lighting.

2 On 22 August 2013, the applicant, Streetworx Pty Ltd (Streetworx) commenced proceedings against Artcraft Urban Group Pty Ltd (AUG) and Murray John Saint (Saint) alleging infringement of Australian Innovation Patent No. 2009101103 (the 103 Patent) and Australian Innovation Patent No. 2009101104 (the 104 Patent). The relief sought by Streetworx has included:

Declarations of infringement against the respondents;

Injunctions restraining the respondents from further infringement;

Damages or an account of profits (an election is still to be made);

Delivery up of all infringing articles;

Additional damages pursuant to s 122(2A) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act).

AUG and Saint deny infringement. Further, by way of cross-claim filed on 4 October 2013 they allege that various claims of the 103 Patent and the 104 Patent are invalid.

3 This trial has only dealt with issues of liability. An order has been made that liability be heard and determined separately from and prior to issues of relief.

4 In summary, in my view, none of the allegations of invalidity made by AUG and Saint have been made out. As to Streetworx’s case on infringement, it has been made good in relation to the three luminaires supplied by AUG. But in my view, Saint did not relevantly “authorise” such exploiting conduct of AUG within the meaning of s 13(1) of the Act.

I: The Parties, the Patents and the issues

5 Streetworx is a street lighting company. It is the registered proprietor under the Act of the 103 Patent and the 104 Patent for inventions described as lighting assemblies. Streetworx is part of the Ace group of companies, which includes Ace Energy Services Pty Ltd.

6 AUG has supplied and supplies lighting assemblies, including:

The Windowless Artcraft Luminaire (Artcraft model AUGT5) (Windowless Artcraft Luminaire) for several months in mid-2012;

The Artcraft Luminaire (Artcraft model AUGT5) (Artcraft Luminaire) from early May 2013 to December 2013; and

The Modified Artcraft Luminaire (Artcraft model AUGT5) (Modified Artcraft Luminaire) from about January 2014.

7 The ascription T5 refers to a type of lamp. “T” represents the shape of the lamp (tubular) and “5” represents the diameter of the fluorescent lighting tube in eighths of an inch. T5 lamps are reliable and have good energy efficiencies. The Windowless Artcraft Luminaire, Artcraft Luminaire and Modified Artcraft Luminaire are luminaires that utilise T5 lamps.

8 Until 2009, a division of Artcraft Pty Ltd known as “Artcraft Urban Group” traded in the design and manufacture of street lighting and street furniture. From 2009, that division of Artcraft Pty Ltd was established as a separate company, AUG. Saint transitioned from the general manager of that division to being a director and the general manager of AUG, with day-to-day control of its business. Saint indirectly held 20% of the shares in AUG. Rodney Wellington and Ronald Slabak were also directors and held indirectly 40% each of the shares in AUG.

9 AUG supplied to its customers AUG manufactured luminaires as well as luminaires manufactured by other companies such as the Pierlite T5 Greenstreet Luminaire. From August 2010 to sometime in 2013, AUG also supplied the Streetworx Enviro T5 Luminaire.

The 103 Patent – general

10 The 103 Patent is titled “Lighting Assembly” and has a priority date of 30 October 2009. The complete specification for the 103 Patent was published and became open for public inspection on 26 November 2009. The 103 Patent was examined and certified by the Commissioner of Patents on 15 February 2013, after which infringement proceedings could be pursued (s 120(1A) of the Act).

11 The abstract for the 103 Patent states:

The present invention provides an improved lighting assembly suitable for a range of uses, particularly in public areas and thoroughfares, which lighting assembly has reduced maintenance and servicing needs. In a particular preferred embodiment the lighting assembly has a casing comprising a main body defining a port for receiving a support and mains cable, and a visor, the casing enclosing;

- a reflector assembly for receiving at least one lamp, and

- a termination chamber for location of a PE cell.

wherein the visor is of unitary construction for covering both the reflector assembly and the termination chamber.

12 The complete specification for the 103 Patent provides the following description.

13 The invention relates to the field of lighting, in particular lighting assemblies and fixtures suitable for a range of uses outdoors, including street lighting as well as flood lighting and the illumination of stadiums for sporting events. In particular, the invention relates to a light assembly, being an electric device used to create artificial illumination.

14 The term “lighting assembly” includes a luminaire within its scope. A luminaire is a term of art that includes a lighting assembly comprising a light source (lamp), a reflector for directing the light, an aperture covered by a lens, an outer casing for lamp alignment and protection, an electrical ballast and a connection to a power source.

15 The use of electric street lighting dates back to the late 19th century, when carbon arc lamps employing alternating current were used to ensure the electrodes burned down at the same rate. By the start of the 20th century they had been replaced by incandescent light bulbs which remained in use until replaced by the high-intensity discharge lamps or high pressure sodium lamps used today. The use of compact fluorescent lamps has also become common.

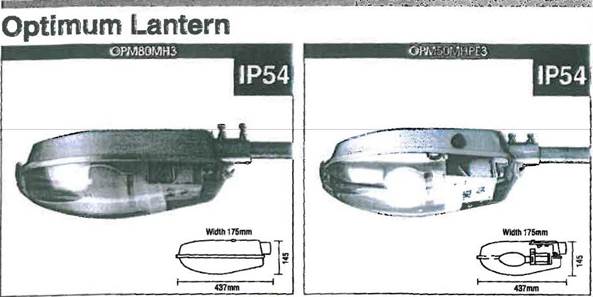

16 Street lights are located at the top of poles to maximise the light cast below. Street lighting has progressed from the use of straight vertical poles of 3-4 metres in height to up to 10 metres in height, often curved at the top, including a bracket to locate the light closer to the centre of the thoroughfare. Such street lights include those sold under the registered Australian trade mark Greenstreet® by Pierlite Pty Ltd; such street lights are described in Pierlite’s patent application AU 2004205200. The Pierlite Greenstreet product is portrayed in the following picture:

17 In lighting assemblies such as the Greenstreet®, there are often multiple parts for entry to internal portions of the lens or visor. Further, the component area may not be locked and can vibrate loose. Further, the fixture may not be attached with lanyard. Such issues may warrant increased ongoing maintenance. With additional parts included by having a separate cover arrangement, the apparatus may become loose and there is a potential for falling parts. This can be an occupational health and safety (OHS) issue. Further, these arrangements may allow a point of entry for vermin, spiders (webs), insects and other pests to enter the luminaire and may facilitate weather or pollution exposure (e.g. salt in coastal areas), which can then create potential risks such as fire, electrocution and OHS hazards.

18 Further, service and maintenance of street lighting incurs significant cost. The elevated position of each light contributes to the time, cost and difficulties associated with servicing and maintaining the light system. To save time and avoid interruption to service, street light systems are not usually turned off during maintenance or servicing. The lighting system is left “live” whilst the linesmen are at work. Typically, linesmen manually handle cables operating at 196-254V AC or 176-254V DC.

19 One of the problems with street lights is that they are time consuming for linesmen to maintain due to servicing occurring when the system is “live”. Linesmen must wear thick protective gloves which limit their dexterity. Further, the breakability of the components (due to them being brittle or corrosion), the size of the components (comparatively small) and the need to work at elevated heights all create difficulties. Further, the malfunctioning of photoelectric (PE) cells (e.g. failure to turn off, shortening the lifespan of the light components (day burners)) can be a problem. A PE cell is typically present in each street light. The PE cell controls the activation and deactivation of the street light based on ambient light level.

20 The objects of the invention embodied in the claims include reducing the maintenance and servicing requirements for lighting assemblies and improving the ease and speed of service and maintenance.

21 The claims defining the invention are:

1. A lighting assembly having a casing comprising a main body defining a port for receiving a mains cable, and a visor, the casing enclosing;

- a reflector assembly for receiving at least one lamp, and

- a termination chamber located laterally in relation to the reflector assembly,

wherein the visor is of unitary construction for covering both the reflector assembly and the termination chamber, at least part of the termination chamber and at least part of the reflector assembly being visible through the visor.

2. A lighting assembly according to claim 1 which includes at least one integral hinge that permits movement of the visor from a first, closed position to a second, open position permitting full access to the reflector assembly and termination chamber without the visor disengaging from the main body.

3. A lighting assembly according to claim 1 or 2 which includes a clip that is capable of independently supporting the visor on the main body.

4. A lighting assembly according to any one of the previous claims which includes at least one fastener comprising a first part that pivots on the main body of the casing but does not contact the visor, and a second part in operative connection with the first part, wherein the second part contacts the visor but does not contact the main body.

5. A lighting assembly according to any one of the previous claims wherein the reflector assembly and termination chamber are fastened by single throw turning lock screws.

The 104 Patent – general

22 The 104 Patent is also titled “Lighting Assembly” and has a priority date of 30 October 2009. The completed specification for the 104 Patent was published and became open for public inspection on 3 December 2009. The 104 Patent was examined and certified by the Commissioner on 19 March 2013.

23 The field of invention and prior art set out in the complete specification to the 104 Patent is identical to that of the 103 Patent.

24 In the 104 Patent specification, the claims defining the invention are:

1. A lighting assembly having a casing comprising a main body defining a port for receiving a mains cable, and a visor, the casing enclosing;

- a reflector assembly for receiving at least one lamp, and

- a termination chamber for location of a PE cell,

wherein the visor is of unitary construction for covering both the reflector assembly and the termination chamber and the portion of the visor covering the termination chamber is adapted to allow visual inspection of components within the termination chamber.

2. A lighting assembly according to claim 1 wherein the PE cell resides entirely within the casing.

3. A lighting assembly according to any one of the preceding claims wherein the visor is clear in an area adjacent the PE cell.

4. A lighting assembly according to any one of the preceding claims wherein the visor further includes a frosted region for preventing unwanted de-activation of the PE cell due to ambient artificial light.

5. A lighting assembly according to claim 1 and substantially as herein described with reference to the drawings.

Streetworx Enviro T5 luminaire

25 The lighting assembly developed, manufactured and intended by Streetworx to be made in accordance with and protected by the 103 Patent and 104 Patent is the Enviro T5 Luminaire. The “Enviro T5” was launched by Streetworx prior to June 2010. Of course, the claims of the 103 Patent and the 104 Patent are to be construed without regard to the Streetworx Enviro T5. But I describe the Streetworx Enviro T5 at this point only as background to the later discussion of the s 13(1) authorisation question concerning Saint’s conduct, where Saint had reference to this actual product.

26 According to Streetworx, its “Enviro T5” has the following integers:

• A visor of unitary construction;

• One or more integral hinges;

• The PE cell within the termination chamber;

• A non-opaque section of the visor over the termination chamber;

• The part of the visor over the termination chamber being frosted for preventing unwanted deactivation of the PE cell due to ambient artificial light;

• One or more two-part clips (fasteners) capable of independently supporting the visor;

• A clear window over the PE cell; and

• An ability to see into the termination chamber through the visor.

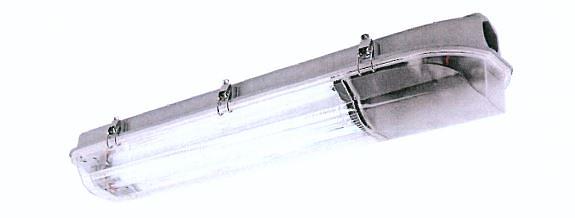

27 The Enviro T5 Luminaire is portrayed in the following picture:

28 As to the strictly separate matter of the integers of the relevant claims of the 103 Patent and the 104 Patent, Streetworx asserts that these are innovations that constitute important and economically valuable improvements over the prior art which reduce the need for, and improve the ease and safety of, maintenance and servicing of lighting assemblies.

Alleged infringement of the Patents

29 Streetworx contends that the supply of the Artcraft Luminaire and Windowless Artcraft Luminaire infringed each of claims 1 to 4 of the 103 Patent and claims 1 to 4 of the 104 Patent (except for claim 3 of the 104 Patent in respect of the Windowless Artcraft Luminaire).

30 Streetworx contends that the supply of the Modified Artcraft Luminaire infringes and has infringed each of claims 1 to 4 of the 103 Patent. It is not contended that the Modified Artcraft Luminaire infringes any of the claims of the 104 Patent.

Alleged infringement of 103 Patent and 104 Patent by Artcraft Luminaire

31 Since at least 7 December 2009 AUG developed and manufactured, and from early 2013 to about December 2013 supplied the Artcraft Luminaire.

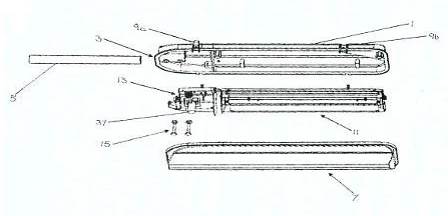

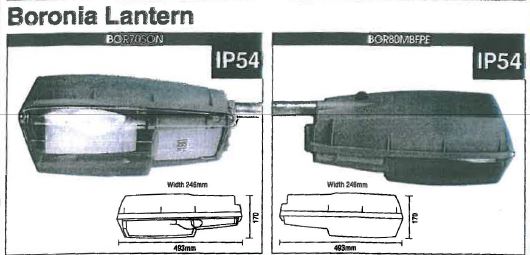

32 The Artcraft Luminaire is portrayed in the following pictures:

33 Streetworx alleges that AUG has without the licence or authority of Streetworx used, made or imported, offered for sale, sold or otherwise disposed of, kept for the purpose of selling or otherwise disposing of and authorised others to do each of such acts in respect of the Artcraft Luminaire in infringement of claims 1-4 of the 103 Patent and claims 1-4 of the 104 Patent. Further, it alleges that Saint authorised such conduct.

34 In these proceedings it has not been in dispute that AUG has imported, manufactured, offered for sale, sold, kept for the purpose of selling and authorised others to sell the Artcraft Luminaire in the patent area within the meaning of s 13(1) of, and the Dictionary to, the Act. What is in dispute is whether that product has taken all the integers of each of the relevant claims of the Patents, and whether Saint authorised AUG’s alleged infringing conduct.

35 Accordingly, the questions in respect of infringement are whether that product falls within the scope of each asserted claim of the Patents and whether Saint authorised the infringing conduct of AUG.

36 In respect of the 103 Patent, Streetworx has alleged that the Artcraft Luminaire:

(a) had all integers of claim 1, including a visor of unitary construction, with at least part of the termination chamber and at least part of the reflector assembly being visible through the visor (claim 1);

(b) had all integers of claim 1 and included an integral hinge that in an open position permitted full access to the reflector assembly and termination chamber without the visor disengaging from the main body (claim 2);

(c) had all integers of claim 1 or 2 and included a clip capable of independently supporting the visor on the main body (claim 3); and

(d) was a lighting assembly according to any one of the previous claims and included a multiple-part fastener which operated in a particular manner (claim 4).

37 In respect of the 104 Patent, Streetworx has alleged that the Artcraft Luminaire:

(a) had all integers of claim 1, including a visor of unitary construction with the portion of the visor covering the termination chamber adapted to allow visual inspection of components within the termination chamber (claim 1);

(b) had all integers of claim 1 wherein the PE cell resided entirely within the casing (claim 2);

(c) was a lighting assembly according to any one of the preceding claims wherein the visor was clear in an area adjacent to the PE cell (claim 3); and

(d) was a lighting assembly according to any one of the preceding claims wherein the visor further included a frosted region for preventing unwanted deactivation of the PE cell due to ambient artificial light (claim 4).

Alleged infringement of 103 Patent by Modified Artcraft Luminaire

38 Apparently, due to commercial concerns about the potential impact of the present litigation on AUG’s business with respect to contracts for the supply of T5 luminaire products to Victorian municipal councils, AUG introduced a modified T5 luminaire into the Australian market (the Modified Artcraft Luminaire), with modifications that were designed with the intention of avoiding any patent infringement.

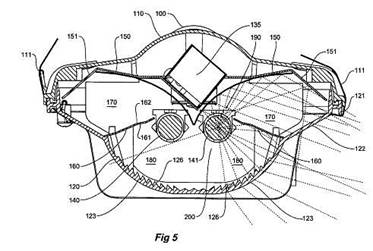

39 The key modification was to the design of the visor, being the acrylic/polycarbonate/polymer outer casing of the luminaire, with respect to coverage of the visor over the termination chamber, being the internal portion of the luminaire where the mains cable terminated, housing inter alia the PE cell (cf with the reflector assembly being the internal portion of the luminaire, housing inter alia the lamps which reflect emitted light).

40 In the Artcraft Luminaire, the PE cell was located in the termination chamber, completely enclosed within the visor with no part projecting through the visor. The portion of the visor located directly above the PE cell was a fully transparent oval shape of approximately 5 cms in diameter, allowing the PE cell and most of the termination chamber to be visible through the transparent portion. The remaining portion of the visor above the termination chamber was lightly frosted. Contrastingly, in the Modified Artcraft Luminaire the detector portion of the PE cell (approximately 1 cm at the tip of the PE cell) projected through an opening in the visor located over the termination chamber. The visor was designed so that the tip of the PE cell protruded through an aperture or sleeve in the visor in the shape of a circular cavity, which fitted closely around the PE cell (although there was approximately a 2 mm gap between the edge of the aperture and the PE cell). An insert in the visor, a semi-circle shaped depression, surrounded the aperture. There was no fully transparent portion of the visor above the termination chamber; the entirety of the visor in that region was frosted, in a slightly heavier opacity when compared to the Artcraft Luminaire.

41 The Modified Artcraft Luminaire is portrayed in the following pictures:

42 Streetworx alleges that from January 2014, AUG has without the licence or authority of Streetworx used, made or imported, offered for sale, sold or otherwise disposed of, kept for the purpose of selling or otherwise disposing of and authorised others to do such acts in respect of the Modified Artcraft Luminaire in infringement of claims 1-4 of the 103 Patent. Further, it alleges that Saint authorised such conduct.

43 In the present case, the dispute is whether the Modified Artcraft Luminaire has taken all the integers of the relevant claims of the 103 Patent, and whether Saint authorised AUG’s alleged infringing conduct, despite the Modified Artcraft Luminaire purportedly being developed by AUG to avoid any patent infringement.

44 In respect of the 103 Patent, Streetworx has alleged that the Modified Artcraft Luminaire in summary:

(a) had all integers of claim 1, including a visor of unitary construction, with at least part of the termination chamber and at least part of the reflector assembly being visible through the visor (claim 1);

(b) had all integers of claim 1 and included an integral hinge that in an open position permitted full access to the reflector assembly and termination chamber without the visor disengaging from the main body (claim 2);

(c) had all integers of claim 1 or 2 and included a clip capable of independently supporting the visor on the main body (claim 3); and

(d) was a lighting assembly according to any one of the previous claims and included a multiple-part fastener which operated in a particular manner (claim 4).

Alleged infringement of 103 Patent and 104 Patent by Windowless Artcraft Luminaire

45 The Windowless Artcraft Luminaire was a design of luminaire produced by AUG before the Artcraft Luminaire. In contrast to the Artcraft Luminaire, the portion of visor above the PE cell of the Windowless Artcraft Luminaire was completely frosted (albeit lightly frosted).

46 A small number of Windowless Artcraft Luminaire were produced by AUG, but the design was subsequently modified to introduce a clear window in the visor above the PE cell.

47 The Artcraft Luminaire was then produced by AUG and replaced the Windowless Artcraft Luminaire. In both designs, the PE cell was located inside the termination chamber, completely enclosed within the visor with no part projecting through the visor.

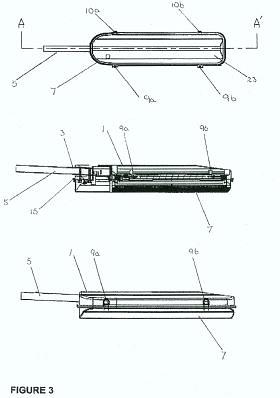

48 The Windowless Artcraft Luminaire is portrayed in the following pictures:

49 Streetworx alleges that AUG has without the licence or authority of Streetworx used, made or imported, offered for sale, sold or otherwise disposed of, kept for the purpose of selling or otherwise disposing of and authorised others to do such acts in respect of the Windowless Artcraft Luminaire in infringement of claims 1-4 of the 103 Patent and claims 1, 2 and 4 of the 104 Patent. Further, it alleges that Saint authorised such conduct.

50 As with the Artcraft Luminaire, the dispute is whether the Windowless Artcraft Luminaire took all the integers of the relevant claims of the Patents, and whether Saint authorised AUG’s alleged infringing conduct.

51 In respect of the 103 Patent, Streetworx has alleged that the Windowless Artcraft Luminaire in summary:

(a) had all integers of claim 1, including a visor of unitary construction, with at least part of the termination chamber and at least part of the reflector assembly being visible through the visor (claim 1);

(b) had all integers of claim 1 and included an integral hinge that in an open position permitted full access to the reflector assembly and termination chamber without the visor disengaging from the main body (claim 2);

(c) had all integers of claim 1 or 2 and included a clip capable of independently supporting the visor on the main body (claim 3); and

(d) was a lighting assembly according to any one of the previous claims and included a multiple-part fastener which operated in a particular manner (claim 4).

52 In respect of the 104 Patent, Streetworx has alleged that the Windowless Artcraft Luminaire in summary:

(a) had all integers of claim 1, including a visor of unitary construction with the portion of the visor covering the termination chamber adapted to allow visual inspection of components within the termination chamber (claim 1);

(b) had all integers of claim 1 wherein the PE cell resided entirely within the casing (claim 2); and

(c) was a lighting assembly according to any one of the preceding claims wherein the visor further included a frosted region for preventing unwanted deactivation of the PE cell due to ambient artificial light (claim 4).

Defence to infringement and cross-claim alleging invalidity

53 AUG denies any infringement of the Patents. Further, with respect to the involvement of Saint in the alleged infringements, Streetworx has asserted that Saint made the relevant decisions, undertook, delegated and outsourced the tasks in relation to the development, manufacture, importation, testing, promotion and sale of the allegedly infringing products. Streetworx says that Saint had the power to prevent AUG’s allegedly infringing conduct and failed to do so. Accordingly, it says that Saint authorised AUG’s infringing conduct within the meaning of s 13(1) of the Act. AUG denies that Saint authorised the allegedly infringing conduct of AUG and submits that at all times Saint was acting with the approval, sanction and authority of the board of directors of AUG and without any intention to infringe the Patents or to procure infringement.

54 Further, by way of a notice of cross-claim filed on 4 October 2013, AUG and Saint have also sought orders that the 103 Patent and the 104 Patent be revoked.

55 In their further amended particulars of invalidity dated 10 April 2014, the respondents assert that the 103 Patent was invalid on the basis of a lack of novelty, a lack of innovative step, a failure to constitute a manner of manufacture, a lack of utility, a lack of clarity and a lack of fair basing. In particular, the respondents assert that:

Claims 1-4 lack novelty as the alleged invention was not novel compared to prior art existing before the priority date of the claims.

The alleged invention in each of the claims 1-5 was not a patentable invention in that when compared to the prior art as it existed before the priority date of each claim it did not involve an innovative step.

The alleged invention in claim 2 (and claims 3-5 insofar as they are dependent on claim 2) and in claim 4 (and claim 5 as dependent) are not patentable inventions as they are not an “invention” or are not a “manner of manufacture” within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies 1623 (Imp). It is said that the invention in claim 2 is a mere collocation as there is no working relationship between the requirement in claim 2 that the hinge be of integral construction and the feature of visibility described in claim 1 on which claim 2 is dependent. It is also said that the invention in claim 4 is a mere collocation as there is no working relationship between the requirement in claim 4 that “at least one fastener comprising a first part that pivots on the main body of the casing but does not contact the visor, and a second part in operative connection with the first part, wherein the second part contacts the visor but does not contact the main body” and the features described in the claims on which claim 4 is dependent.

The alleged invention in claims 1-5 and dependent claims are not patentable as they are not useful. It is said that claim 1, and claims 2-5 as dependent claims, includes embodiments that do not give the asserted benefit of a linesman being able to carry out a visual inspection of components within the luminaire without having to remove any cover as stipulated in the specification. It is said that claim 3, and claims 4-5 insofar as they are dependent on claim 3, is not useful as it includes embodiments where the “independent” clip does not provide any maintenance advantage, namely embodiments where the integral hinge does not have a removable pin. It is said that claim 4, and claim 5 insofar as it is dependent, is not useful as the two part fastener described would not achieve a reduction in corrosion in the fastener. Further, the fasteners would not achieve a reduction in corrosion in the fastener, and the casings (when used with the relevant fasteners) would also not achieve a reduction in corrosion.

It is said that claim 3 (a lighting assembly according to claim 1 or 2 which includes a clip that is capable of independently supporting the visor on the main body) lacks clarity as claim 1 does not require the luminaire to have a hinge. Claims 4-5 are said to be unclear insofar as they rely on claim 3.

Further, it is said that claim 1 and its dependent claims are not fairly based. Further, claim 3 and each of its dependents are said not to be fairly based – “[t]here is no real and reasonably clear disclosure of the use of an ‘independent’ clip other than with an integral hinge that has a removable hingepin”. Further, claim 4 and each of its dependents are said not to be fairly based – “[t]here is no real and reasonably clear disclosure of the use of a two part fastener for luminaires that do not have a metal casing”.

56 Further, the respondents assert that the 104 Patent was invalid on the basis of lack of novelty, a lack of innovative step, a lack of utility and a failure to constitute a manner of manufacture. In particular, the respondents assert that:

Each of claims 1-5 lack novelty as the alleged invention was not novel compared to the prior art existing before the priority date of the claims.

The alleged invention in each of the claims 1-5 was not a patentable invention in that when compared to the prior art as it existed before the priority date of each claim it did not involve an innovative step.

The alleged invention in claim 2 (and claims 3-5 insofar as they are dependent on claim 2) is not a patentable invention as it is not an “invention” or a “manner of manufacture” as there is no working relationship between the requirement in claim 2 that the PE cell reside “entirely within the casing” (as distinct from merely being located inside the termination chamber) and the features of the visor that are identified in claim 1 or in claims 3-4.

The alleged invention in claims 3-4, and claim 4 insofar as dependent on claim 3, are not patentable as they are not useful. The features of claims 3 and 4, or some embodiments included within each of claims 3 and 4, do not:

ensure that the PE cell correctly detects the level of ambient light;

achieve a useful reduction in the level of unwanted de-activation of the PE cell due to reflected or early ambient artificial light; or

achieve a reduction in the incidence of “day burners”.

II: Construction

57 It is convenient to begin with questions of construction, as this is the foundation for considering the asserted grounds of invalidity, the asserted grounds under s 40(3) and, finally, the case for alleged infringement.

(a) Legal principles

58 The principles applicable to the construction of a claim are not in doubt. The proper construction of a claim is a question of law.

59 A claim is construed by the Court from the perspective of a person skilled in the relevant art as to how such a person would have understood the patentee to be using the words of the claim in the context in which they appear. Further, a claim is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge including the art before the priority date.

60 A generous measure of common sense should be used (Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (2013) 101 IPR 11 at [108] per Middleton J). Further, ordinary words should be given their ordinary meaning unless a person skilled in the art would give them a technical meaning or the specification ascribes a special meaning (Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Multigate Medical Products Pty Ltd (2011) 92 IPR 21 at [39] per Greenwood and Nicholas JJ).

61 In terms of how the body of the specification may be used in construing a claim:

The claim should be construed in the context of the specification as a whole even if there is no apparent ambiguity in the claim (Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa-Secure Pty Ltd (2012) 290 ALR 47 (Britax Childcare) at [222] per Middleton J and more generally Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 (Welch Perrin) at 616);

Nevertheless, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of the monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to these words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification (Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 86 (Jupiters) at [67]; Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron & Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 at [44]); and

More particularly, if a claim is clear and unambiguous, to say that it is to be read in the context of the specification as a whole does not justify it being varied or made obscure by statements found in other parts of the specification.

62 Now the specification may stipulate the problem in the art before the priority date and the objects of the invention that are designed to address or ameliorate this. It will also stipulate the preferred embodiments of the invention, including the best method. And no doubt the Court is to read the specification in the logical sequence of its structure. Nevertheless, what is being construed are the claims. The specified objects may be useful in construing a claim in context. Further, the specified objects may be useful in considering any lack of utility argument. Nevertheless, the specified objects are not controlling in terms of construing a claim; you cannot justify glosses drawn from the objects.

63 A claim should be given a “purposive” construction. To elaborate, words should be read in their proper context. Further, a too technical or narrow construction should be avoided. Further, the integers of a claim should not be considered individually and in isolation. Further, a construction according to which the invention will work is to be preferred to one in which it may not (Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly & Co (2005) 68 IPR 1 at [250]).

64 But to give a claim a “purposive” construction “does not involve extending or going beyond the definition of the technical matter for which the patentee seeks protection in the claims” (Sachtler GmbH & Co KG v RE Miller Pty Ltd (2005) 221 ALR 373 at [42] per Bennett J). To apply a “purposive” construction does not justify extending the patentee’s monopoly to the “ideas” disclosed in the specification (GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare (UK) Ltd (2013) 305 ALR 363 (GSK v Reckitt) at [60]).

65 A claim is to be construed from the perspective of how a person skilled in the art would have understood the patentee to be using the words, informed by the notional skilled addressee’s general knowledge and what has been disclosed in the specification.

66 But to consider such a perspective does not entail that the Court necessarily requires expert evidence to assist on construction. If it is clear that the claims are to be read according to their ordinary meaning with no special meaning given to any word or phrase, if the science or technical issues are easily comprehensible and if, more generally, the Court does not require expert assistance in understanding the context of the claims, then expert evidence on construction may not only be unnecessary, but unhelpful and distracting. The nature and complexity of the patent in suit and the issues raised will determine the utility or necessity for expert evidence on construction (Britax Childcare at [225] per Middleton J). But to say that expert evidence may not be required on construction does not entail that expert evidence may not in any event still be required on other issues such as novelty or innovative step, even if not necessary on construction per se.

67 The Court is to place itself in the position of a person acquainted with the state of the art and manufacture prior to the priority date. In terms of the skilled addressee, one is using a hypothetical construct. The following principles are applicable:

First, to identify the characteristics of the skilled addressee, the field to which the invention relates must be identified.

Second, the skilled addressee is taken to be a person of ordinary skill (as opposed to a leading expert) in that field and equipped with the relevant common general knowledge including the art before the priority date (Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Aust) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 (Minnesota Mining) at 293; Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [24]; Jupiters at [67]).

Third, the qualifications and experience of the skilled addressee will depend on the particular case, having regard to the nature of the invention and the relevant industry. Formal qualifications are not essential. Practical skill and experience in the field may suffice (Britax Childcare at [239] per Middleton J). A patent specification is addressed to those having a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention; such persons are those with practical knowledge and experience of the kind of work in which the invention is intended to be used.

Fourth, the hypothetical person skilled in the art may possess an amalgam of attributes drawn from a team of persons whose combined skills, even if disparate, would normally be employed in interpreting and carrying into effect instructions such as those contained in the specification (The General Tire & Rubber Co v The Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 (The General Tire) at 485).

Fifth, as the skilled addressee comes to a reading of the specification with the common general knowledge of persons skilled in the relevant art, they read it knowing that its purpose is to describe and demarcate an invention. But the person skilled in the art is not particularly imaginative or inventive (or innovative) (NSI Dental Pty Ltd v University of Melbourne (2006) 69 IPR 542 at 570).

68 Generally, the Court is to place itself in the position of such a skilled addressee, using such expert evidence that is of assistance to the construction task.

69 Finally, in construing a patent claim the Court should disregard any alleged infringing article. The Court should not construe a patent claim with an eye to alleged infringement. I accept this.

(b) Expert and industry evidence

70 The parties have adduced expert evidence on construction. Streetworx called Mr Sylvan Sherwood Browne (Browne), a registered patent attorney and partner at intellectual property firm FB Rice with approximately 16 years’ experience as an international and domestic patent practitioner in engineering-related fields. Browne also holds a degree in electrical engineering.

71 The respondents called Mr John Robert Rogers (Rogers), a consultant lighting engineer with qualifications in illuminating engineering and 56 years’ experience in the area of lighting including having worked at GEC from 1957 to 2010, primarily in the manufacture of commercial lighting including in management and technical roles. Rogers is a life fellow of the Illuminating Engineering Society of Australia and New Zealand and presently provides consulting services for a major consulting engineering company. He also conducts educational workshops for the lighting industry and has been and continues to be a member of a number of different lighting-related committees for Standards Australia.

72 Further, other witnesses called by the parties gave evidence relevant to construction, namely:

Mr Stephen James Furzey (Furzey), the technical manager of Sylvania Lighting Australasia Pty Ltd (one of the largest manufacturers of lighting in Australia), with approximately 49 years’ experience in the design and manufacture of lighting having worked in the UK lighting industry since 1965 and in the Australian lighting industry since 1983. Furzey was called by Streetworx. Furzey holds diplomas in electrical engineering and lighting design and has worked as Sylvania’s technical manager since about 1993 with responsibility for factory engineering including the engineering of street lighting. Furzey has been and continues to be a member of several Lighting Standards committees and advisory committees to the federal government on lighting trends and lamp efficacy, and has taught lighting subjects at the University of Sydney and the National Institute of Dramatic Arts. He is a life fellow of the Illuminating Engineering Society of Australia and New Zealand.

Mr Stephen Krueger (Krueger), a qualified linesman and the sole owner and director of B&M Towers Pty Ltd (a street lighting maintenance company subcontracted to Ace Energy Services Pty Ltd to provide street lighting maintenance and repairs) with more than 30 years’ experience as a linesman including working for the State Electricity Commission of Victoria for 16 years and Power Services Victoria. Krueger presently works as a linesman on a daily basis. Krueger was called by Streetworx.

Mr John Charles Joosten (Joosten), a leading hand/auditor at CD Patrols Pty Ltd (a street lighting maintenance company who holds an exclusive contract with Energex, a power authority responsible for the maintenance of public street lighting across South East Queensland) with approximately 25 years' experience performing maintenance of public street lighting, including as a linesman. Joosten’s present duties include the supervision and auditing of crews of linesmen during the installation and maintenance of street lighting. Joosten was called by the respondents.

73 In my view, the person skilled in the art for the purposes of the issues in the present case is one who possesses the general skills of a designer of street lights, with practical knowledge and experience of the way in which street lights are repaired and maintained and the issues which can arise in the course of such maintenance and associated service. This hypothetical person may comprise a team, for example a designer of street lights, a maintenance person and a linesman. In what I discuss below and in my statements and conclusions on questions of construction, such statements and conclusions are expressed from the perspective of how such a skilled addressee would construe the claims.

(c) Various integers

Visibility – Claim 1 (103 Patent)

74 Claim 1 uses the concept of visibility in the phrase “at least part of the termination chamber and at least part of the reflector assembly being visible through the visor”.

75 The word “visible” just looking at the language of claim 1 itself does not provide any express content or context. Visible from what perspective? The ground? An elevated work platform? Visible under what conditions? Further, “visible” is a relative term. Is it good visibility, poor visibility or any visibility? In other words, how clearly is a person to see through the visor? How clearly visible is a part of the termination chamber to be? How clearly visible is a part of the reflector assembly to be? Does the visor need to be completely transparent? Can it be frosted? And if so, to what degree? Further, it is to be noted that claim 1 does not expressly refer to any visibility of any components within either the termination chamber or reflector assembly (cf claim 1 of the 104 Patent).

76 In order to construe claim 1 in context, a number of features may be noted about the complete specification:

The invention is conveniently described in terms of street lighting (p 2).

Street lights are located at the top of the poles; at the time of the filing of the complete specification, poles up to 10 metres in height have been used, often “curved at the top or including a bracket to locate the light closer to the centre of a thoroughfare” (p 3).

There are many servicing and maintenance issues involving street lighting; moreover, visual inspections may be required at regular intervals (pp 3-4).

The elevated position of a street light contributes to the time, cost and difficulties associated with servicing and maintenance (p 4).

Street lights are serviced live; the necessity to wear thick gloves limits manual dexterity (p 4).

77 In dealing with the embodiments described under the heading “Summary of Invention”, the following may be noted:

An object of the embodiments of the invention is to reduce maintenance and servicing (p 5).

A further object of the embodiments of the invention is to improve the ease and speed with which lighting assemblies can be serviced or maintained (p 5).

In a first aspect of embodiments, there is provided a visor which incorporates within its structure a lens for optimising the casting of light from the lamp (p 6).

The second and third aspects of embodiments also incorporate a visor (pp 8-9).

In describing the third aspects of embodiments there is then said (p 10):

Preferably the components located within the termination chamber as well as the components of the reflector assembly are visible through the visor. For example, this part of the visor may be clear or lightly frosted compared to the remainder of the visor. Similar light fittings of the prior art have included a two part visor - a first part comprising a clear lens for the lamp and a second part comprising an opaque cover for the termination chamber. A preferred embodiment of the present invention allows a linesman to carry out a visual inspection of the components without having to remove any covers. Typically the part of the visor in the vicinity of the PE cell is clear so that the PE cell correctly detects the level of ambient light. Using frosting in other parts of the visor however may provide the advantage of preventing reflected or early ambient light impinging on the PE cell and causing it to prematurely deactivate. In particular, the use of frosting as in this preferred embodiment can avoid "day burners" (lights that are emitting 24 hours per day or at least into periods of the day not requiring artificial lighting). In related art systems, the avoidance of "day burners" was achieved by the addition of or attachment of a shield to the casing to shield the sensor or PE Cell. These shields were not attached to the lens/visor.

Then it is said that advantages provided by the lighting assembly of preferred embodiments comprise (pp 11-12):

• can be installed as part of a new lighting structure or retrofitted to existing lighting assemblies, structures or supports;

• requires less time for installation and routine maintenance;

• malfunctions are reduced;

• provides better access to components for repair and replacement,

• easier to maintain and service;

• lower occupational health and safety risks during installation, servicing and maintenance;

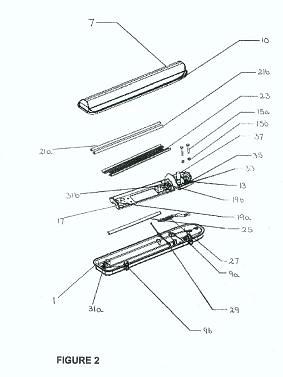

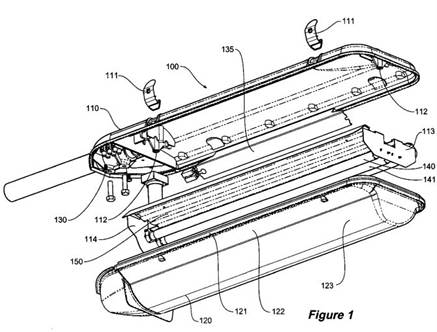

• can operate using “green” lamps adapted to reduce energy consumption.

78 In the section “Detailed Description” (pp 12-16) there is a discussion and explanations of Figures 1, 2 and 3, being accompanying drawings, but these are by way of illustration only (pp 18-20). Figures 1, 2 and 3 are represented as follows:

79 In terms of Figure 1, which is an exploded view of a preferred embodiment, there is a discussion of the visor in terms (p 13):

The visor (7) is of unitary construction and at least in the vicinity of the lamp it is conformed to act as a prismatic lens. The visor is typically made of acrylic, polycarbonate or other hard wearing polymer that can be made clear or translucent, however, other suitable materials may used as would be understood by the person skilled in the art. The components located within the termination chamber (13) as well as the components of the reflector assembly (11) are visible through the visor (7).

80 In terms of Figure 3, which illustrates the fully assembled lighting assembly of Figure 1 viewed from underneath, it is said (p 15):

Figure 3(a) illustrates the fully assembled lighting assembly of Figure 1 when viewed from underneath. This is the view that a person would have if they walked underneath the lighting assembly and looked up. In this view they would see through the visor (7) to the reflector tray (23) and lamps and the PE cell (37).

81 Finally, in terms of the preferred embodiments, it is said (p 15):

As the present invention may be embodied in several forms without departing from the spirit of the essential characteristics of the invention, it should be understood that the above described embodiments are not to limit the present invention unless otherwise specified, but rather should be construed broadly within the spirit and scope of the invention as defined in the appended claims. The described embodiments are to be considered in all respects as illustrative only and not restrictive.

82 Streetworx has contended that in the context of the specification, the integer “at least part of the termination chamber ... being visible through the visor” means that one can see through the visor the presence of components located within the termination chamber, but not necessarily the components in detail. So, one can discern that there are components, but that one might not necessarily see or need to see what they are. So, parts of each of the termination chamber and reflector must be visually discernible, without necessarily being able to see components in detail. Streetworx contends that the need to see what the components are is encapsulated in the preferred embodiment of being able to conduct a visual inspection of the components.

83 Browne for Streetworx described the quality of visibility required in these terms, including by comparison to the more prescriptive requirement of “allowing visual inspection” discussed in the specification.

84 Although Rogers for the respondents questioned the reason for this requirement, he did not have any difficulty in understanding the meaning of “visible”. Further, when considering the construction of claim 1 of the 104 Patent, Rogers described differing levels of visibility required by the two expressions in the same manner as set out in the evidence of Browne. Rogers revealed under cross-examination (in the context of being asked about whether the solid control gear chamber in the Boronia met the visibility requirement of claim 1 of the 103 Patent) that he had originally construed the term alone, without reference to the body of the specification. That was not appropriate. When asked to consider what the term meant in light of the body of the specification, he agreed that claim 1 was directed to the language on p 10, lines 13-16 of the Patents which required visibility of the components but not necessarily needing to be able to discern what they were. That is a lesser requirement than the visibility required to perform a visual inspection of components as set out in claim 1 of the 104 Patent.

85 The respondents fixed upon a preferred embodiment (p 10) of the claimed invention (that the visor allows a linesman to carry out a visual inspection of the components of the termination chamber). But for construction purposes, all features of a claim must be considered, not just those which relate to what has been identified as a preferred embodiment.

86 The respondents said that Streetworx’s position on limited “visibility” was at odds with the purpose explained in the Patents at p 10:

Preferably the components located within the termination chamber as well as the components of the reflector assembly are visible through the visor. For example, this part of the visor may be clear or lightly frosted compared to the remainder of the visor. Similar light fittings of the prior art have included a two part visor - a first part comprising a clear lens for the lamp and a second part comprising an opaque cover for the termination chamber. A preferred embodiment of the present invention allows a linesman to carry out a visual inspection of the components without having to remove any covers.

and, in relation to the drawing which is Figure 1 (p 13):

The components located within the termination chamber (13) ... are visible through the visor (7).

87 But the respondents have paid little attention to the words “[in] a preferred embodiment” in the last sentence of the quote, which described the level of visibility required in claim 1 of the 104 Patent not claim 1 of the 103 Patent. A “preferred embodiment” of an invention is a narrower form of the invention described.

88 The respondents submit that the word “visible” must be understood in the context of the specification as a whole, and in a purposive sense, as involving visibility assessed by reference to there being a practical level of visibility into the termination chamber, sufficient to allow an inspection of the internal components by persons, such as linesmen, maintaining the luminaire.

89 I accept that the word “visible” must be understood in the context of the specification as a whole as involving visibility assessed by reference to there being a practical level of visibility into the termination chamber. But I do not accept that the level of visibility must be sufficient to allow an inspection of the internal components by persons, such as linesmen, maintaining the luminaire.

90 In my view, the construction advanced by Streetworx is correct when seen through the perspective of a skilled addressee. Although there must be a practical level of visibility into the termination chamber, particularly from an EPV, it is not required that there be sufficient visibility to allow an inspection of the internal components. The wording of the integer does not stipulate for such a requirement. Further, it is incorrect to take the meaning from a preferred embodiment. Further, Streetworx’s construction conformably fits with the specification as a whole. In terms of a purposive construction, it is consistent with making the invention work.

Termination Chamber – Claim 1 (103 Patent)

91 Claim 1 uses the description of “a termination chamber”. This is not defined in the specification.

92 In terms of that description, the following may be said on the question of construction. First, the termination chamber appears to be something separate from the reflector assembly. In claim 1, both descriptions are separately used, and this is also reinforced by the phrase “a termination chamber located laterally in relation to the reflector assembly”. Second, it is apparent that the termination chamber is not a chamber to receive a lamp; by inference, this is the function and design of the reflector assembly. Third, the termination chamber is, of course, part of the lighting assembly. The lighting assembly consists of a casing and a visor. The casing is said to “enclos[e]” the termination chamber. Thus the termination chamber is enclosed on one side by the casing and covered on the other side by the visor. It is not apparent, just considering the language of claim 1 only, as to whether “chamber” is just a space enclosed on one side by the casing and on the other side covered by the visor or is itself separately physically bounded so that it becomes a separated space within a space. It is also not apparent, just considering the language of claim 1 only, what is contemplated by the descriptor “termination” or the composite phrase “termination chamber”.

93 Reference to the terms of the complete specification provides the following context:

In the first aspect of embodiments, there is reference to “attaching the termination chamber to the main body of the casing and/or the reflector assembly to the termination chamber”;

In a second aspect of embodiments there is reference to “the termination chamber being at least 20-25% of the volume of the casing”;

There is also reference to “the non-conductive envelope” comprising of a combination of, inter alia, a “Terminal block”;

It is also said that the “increased volume of the termination chamber… allows easier manual handling of the mains cable and easier manipulation of other parts and components within the casing such as the PE cell and the terminal block…”; this suggests that the termination chamber may include within it the PE cell (or at least part of it) and terminal block, at least in a particular preferred embodiment (see the abstract as well); the third aspect of embodiments refers expressly to “a termination chamber for location of a PE cell”.

There is also the possible suggestion that the control gear is also to be located in the termination chamber, although there is some uncertainty and this is an unlikely reading, a matter I discuss later. It is said (p 9) that:

Furthermore, the increase in volume of the termination chamber is preferably also due to increased depth of the casing. This assists in dissipating heat and reducing the operating temperature. In particular it keeps the control gear cooler by locating it further away from the casing surface. Most lighting assemblies have electronic ballast components rated to 50°C however it is common for sun exposure to cause the storage and/or radiation of heat in excess of 60°C. Optionally, the addition of a reflective coating to the exterior surface of the main body of the casing may further reduce operating temperature.

Preferably the lighting assembly includes an equaliser that acts as a heat valve to dissipate excess heat.

However, another and more likely reading is that the increased volume has this effect, but with the control gear behind the reflector assembly (i.e. not in the termination chamber).

The termination chamber is to be contrasted with the reflector assembly which is described to include “a reflector tray adapted to receive a single, double or compact fluoro lamp or more than one lamp without restriction on wattage”.

In referring to “[s]imilar light fittings of the prior art” (p 10) it is implied that that part of the casing which includes the termination chamber does not include the lamp.

Figure 1 separates out the reflector assembly (11) from the termination chamber (13); Figure 1 shows the termination chamber with the PE cell.

Figure 2 shows the reflector assembly with a gear tray having lamp holders, a reflector tray, an electronic ballast (also known as control gear, which controls and potentially limits current and regulates current fluctuations), and a 3-way terminal socket and lanyard; in the embodiment illustrated, the reflector assembly is adapted to support the electronic ballast and two lamps.

Then there is a more fulsome description of the termination chamber in terms (p 14):

The termination chamber (13) includes a terminal tray (33), a terminal block (35) of plastic or other suitable material and is adapted to hold a PE cell (37). The termination chamber is at least 25% of the volume of the casing. This is combined with improved layout of the components within the termination chamber (13). For example, the port (3) is elongated to provide additional stability for the light fitting when located on the support (5), and in addition, this makes it easier for the linesman to thread the live main cable into the light fitting. Furthermore, the terminal block (35) is of increased size to make it easier for the linesman to connect the mains cable, which is typically a twin cable of large gauge (6 mm²) and is relatively inflexible and resistant to bending.

The PE cell (37) is seated in the terminal tray (35)…

Figure 3 shows the fully assembled lighting assembly of Figure 1 viewed from underneath including in a particular cross-section (Figure 3(b)) which shows the termination chamber consistently portrayed as previously described.

94 Furzey gave evidence to the effect that the “termination chamber” is a separate, enclosed area as opposed to a compartment which is not necessarily enclosed or segregated. Furzey explained that this is based on the meaning of the terms “termination” and “chamber” and the industry understanding of what constitutes a “chamber”. The evidence is not clear whether the term “termination chamber” itself is widely used, but according to Furzey it was understood to mean a closed area where the mains cable terminated. Other similar terms were in use such as “terminal chamber” in technical documents, for example the Pierlite Greenstreet instructions.

95 It is apparent that the term “chamber” (and each of the terms “lamp chamber” and “control gear chamber”) has a specific meaning to a person skilled in the art. Australian Standard AS1158.6 (the Australian Standard) provides for different ingress protection (IP) ratings in respect of different chambers found within a street light and refers expressly to the concepts of “lamp chamber” and “control gear chamber” (see at section 2.2.2), but not “termination chamber” in terms. If a chamber was not fully enclosed, the concept of different IP ratings for different chambers would be meaningless. Accordingly, a “termination chamber” would be properly understood by a person skilled in the relevant art as defining an enclosed space, not one that is necessarily airtight, but an enclosed space separate to the remainder of the luminaire.

96 Furthermore, in my view a “termination chamber” in the context of the specification ought not to be construed as a chamber with control gear in it. Furzey accepted that interpretation, which is consistent with the Patents. Rogers also appeared to accept that a chamber with control gear in it would most likely be called a control gear chamber. Further, technical documents such as the Pierlite Greenstreet instructions separately refer to a “lamp and gear chamber” and a “terminal chamber” as present in that luminaire.

97 Streetworx has submitted that for “termination chamber” to overcome its natural and technically understood meaning of a chamber that would not include control gear, it would be necessary for the Patents to clearly and precisely disclose that it was intended as an option that control gear could be in that chamber. I am inclined to agree.

98 Further, the preferred embodiment discloses control gear behind the reflector assembly, not in the termination chamber. Now Rogers explained how he relied on the language of the first two sentences of the paragraph at p 9, line 13 of the specification as meaning that a termination chamber might include control gear. But Furzey held a different view. The passage at p 9, lines 13-20, as I have set out earlier, reads:

Furthermore, the increase in volume of the termination chamber is preferably also due to increased depth of the casing. This assists in dissipating heat and reducing the operating temperature. In particular it keeps the control gear cooler by locating it further away from the casing surface. Most lighting assemblies have electronic ballast components rated to 50°C however it is common for sun exposure to cause the storage and/or radiation of heat in excess of 60°C. Optionally, the addition of a reflective coating to the exterior surface of the main body of the casing may further reduce operating temperature.

99 When the first two lines are read in the context of the paragraph as a whole and the paragraphs that follow, in my view the person skilled in the art would understand that the first sentence leads into a new topic, namely the increased depth of the casing. It is the depth of the casing (the whole casing) which is the object of the next two sentences. This is how the paragraph would naturally be read by the skilled addressee. Other features of the specification confirm that position:

The only way control gear is expressly disclosed as being located in a position that keeps it “further away from the casing surface” is on a gear tray behind the reflector tray.

There is no exemplification of control gear in the termination chamber.

The electronic ballast disclosed in the specification is long and thin and would not naturally fit within the termination chamber.

100 Now I accept that the Australian Standard would not necessarily exclude the possibility of a “termination chamber” including control gear if the Australian Standard otherwise referred to a “termination chamber”. Furzey confirmed that for the requirement to achieve an ingress protection rating of IP54 for the “lamp chamber”, what is of concern is to identify and test a sealed area that contained the lamps, but it did not matter for that analysis whether other components, including the control gear and/or the terminal block, were contained within that same chamber. Similarly, an analysis of whether the “gear chamber” met the requirement of IP24 involves looking at the chamber that contains the control gear, but it may contain other components. Further, the gear chamber may, for the purpose of the Australian Standard, relevantly be the same chamber as the “lamp chamber” that was assessed for its IP rating (of course they will then have the same rating). The respondents contended that so extending that logic to what a “termination chamber” would mean if it was otherwise included in the Australian Standard, it could include a chamber containing the terminal block, and it would not matter if the chamber also enclosed the lamps and the control gear. Such reasoning may be correct in its hypothetical generality. But the specification and its context does not support a construction that the “termination chamber” includes the control gear.

101 More generally, the respondents say that the term “termination chamber” contemplates a chamber containing the mains cable, terminal block, PE cell and other components. So much may be accepted.

102 Rogers explained that a “termination chamber” is the part of a luminaire in which the mains cables terminate within the luminaire. He said that it is not a precise term and can refer to any sort of enclosure where this occurs. He said in some luminaires the termination chamber can be separate from the optical chamber (which contains the lamp) but in other luminaires it may not be separate. In my view, whatever be the position with some luminaires, in the present case, what is described in the relevant claim in the context of the specification is something separate and enclosed as described by Furzey.

103 Krueger said that “termination chamber” was not a term that he would typically use, but understood it to mean a place where the power supply wire connects to the light fitting.

104 In summary, in my view a skilled addressee would construe “termination chamber” such that:

(a) it needed to be an enclosed area;

(b) it is an area separate from the reflector assembly;

(c) it is enclosed on one side by the casing and on the other side by the visor;

(d) it does not include the control gear;

(e) it contains the terminal block; and

(f) it may include the PE cell (I note that this is expressly stipulated in claim 1 of the 104 Patent).

Visor of “unitary construction” – Claim 1 (103 Patent)

105 Claim 1 refers to a visor of unitary construction for covering both the reflector assembly and the termination chamber. What is meant by “unitary construction”?

106 In considering the context, in the complete specification there is a discussion of problems and deficiencies in the prior art in terms (p 3):

In lighting assemblies such as the Greenstreet® apparatus there is often multiple parts for entry to internal portions of the lens/visor, the component area may not be locked and could vibrate loose. Also the fixture may not be attached with lanyard. These issues may contribute to warranting increased ongoing maintenance. With the additional part(s) included by having a separate cover arrangement, there is an opportunity for the apparatus to be loose, moving and a potential for falling parts, which can be a serious OHS issue. These arrangements allow a point of entry for vermin, spiders (webs), insects/pests to enter the light and allows weather/pollution exposure and effects (e.g. salt in coastal areas). Risk introduced because of the above include that of fire, electrocution and general OHS hazards.

107 Other aspects to note are the following:

The description “visor” seems to be interchangeable with “lens”, although sometimes it is said that “[t]he visor incorporates within its structure a lens”;

There is only one covering (on the side other than the casing) for both the reflector assembly and the termination chamber, described as “the visor”;

Occasionally there is reference to a “unitary visor” and one of its advantages is said to be “ease of replacement if the visor is broken”;

It is also said that in a preferred embodiment there is a clip capable of independently supporting the visor;

Further, it is said that there is a “gasket of silicon or neoprene or other suitable material” which is “provided along at least part of the interface between the visor and the main body”;

Further, in describing a third aspect of embodiments, reference is made to similar light fittings of the prior art, which have included “a two part visor - a first part comprising a clear lens for the lamp and a second part comprising an opaque cover for the termination chamber”;

In reference to Figure 1, there is a description in the following terms (p 13):

The visor (7) is of unitary construction and at least in the vicinity of the lamp it is conformed to act as a prismatic lens. The visor is typically made of acrylic, polycarbonate or other hard wearing polymer that can be made clear or translucent, however, other suitable materials may used as would be understood by the person skilled in the art. The components located within the termination chamber (13) as well as the components of the reflector assembly (11) are visible through the visor (7).

The main body (1) and visor (7) are held together by two clips (9a, 9b) and two integral hinges (10a, 10b not shown) located in corresponding positions on the other side of the main body and visor, thus permitting movement of the visor (7) from a first, closed position to a second, open position permitting full access to the reflector assembly (11) and termination chamber (13).

108 The specification describes a visor or lens in one piece rather than multiple parts. Does “unitary construction” mean an end product that is one unit? Or does it look to the anterior assembly or construction to see whether there was only one part used for construction rather than multiple parts that were then transformed into one unit?

109 Originally, Browne, Furzey and Rogers agreed that a visor of unitary construction for covering both the reflector assembly and termination chamber meant a visor that was constructed or made during the manufacturing process as one piece. But at trial, Rogers came to a different view on the meaning of the phrase “visor of unitary construction”. He accepted that if a piece was constructed in a factory in a manner which was plainly not intended to be taken apart (e.g. if the parts were glued, welded or riveted together) then that piece would be of unitary construction.

110 Streetworx now accepts Rogers’ interpretation. Further, it points to the fact that the specification raises a concern about two part visors such as found in the Pierlite Greenstreet (mentioned on p 3, line 21 and inferentially at p 10, lines 16-18) and the problems that arise from multiple parts dislodging or falling off the luminaire, particularly the problem with the cover over the component area not being locked and vibrating loose (p 3, lines 23-25).

111 Streetworx now says that Furzey concentrated on simplicity of manufacture in his interpretation of the term “visor of unitary construction”, but that this was not a stated object.

112 Streetworx further contends that a visor which has a part added to it (such as a gasket, an end-cap or an insert around the PE cell), but which still covers the termination chamber and reflector assembly, is a visor of unitary construction within the meaning of claim 1 of each Patent. It is asserted that it is a visor of unitary construction even if it is not moulded of one piece, as long as it is not designed to be taken apart. Of course, if one has a gasket or end-cap, that is quite consistent with having a visor of unitary construction; you are simply adding something to it.

113 The respondents contend that the expression “unitary construction” is to be understood as meaning a part that has been formed as a single unit in the construction process, such as a single moulded part. They say that this interpretation accords with the ordinary meaning of the words, construed in the context of the specification as a whole. They say that if the patentee had intended simply to refer to a visor which covered both the termination chamber and the reflector assembly (and opened as one piece) it would have been more natural to refer to “unitary visor”. The word “construction”, on the other hand, indicates that it is to be constructed as one piece. This is the construction given to the expression by Browne. It is also the view of Furzey. Unsurprisingly, the respondents do not agree with the revised construction of Rogers.

114 It is apparent that the parties have flip-flopped in their respective positions on this aspect, which has not greatly assisted me. In my view, the skilled addressee would take the expression “unitary construction” to focus on the visor as an end product. So, if the visor was constructed in a factory in a manner such that the end product could fairly be said to be one unit, then that would be sufficient. That accords with the plain language. It also accords with a purposive approach. Further, I can see little sense in the alternative construction. Moreover, how atomistic would one need to go on the alternative construction? In one sense, all manufacturing processes have a composite aspect at some particular level. Streetworx’s contention is to be preferred.

Reflector assembly – Claim 1 (103 Patent)

115 The reflector assembly is the group of parts in the luminaire which reflect light emitted from the light source (which is a separate component). In my view, it is a separate group of parts from the casing since the casing is said to “enclose” the reflector assembly. Rogers accepted that the natural meaning of the term assembly was a group of parts, that a fair reading of “reflector assembly” in the Patents was as separate to the casing, and further: “The way I read is the - is it a part - it's a part that's fitted into - into the casing”.

116 Although the respondents suggested that there was an issue between the experts as to whether the casing or body of the luminaire can be a reflector if it performs a reflective function, Rogers' evidence reveals that he considered that a reflector was a different component from the body of the luminaire, as did Furzey. I accept their construction. Furthermore, a reflector assembly must be something made of more than one part, otherwise the term “assembly” is otiose. It cannot simply be the casing. In my view the skilled addressee would similarly so construe “reflector assembly”.

Integral Hinge – Claim 2 (103 Patent)

117 Claim 2 describes an integral hinge as included within the lighting assembly according to claim 1. Browne, Rogers and Furzey agreed that an integral hinge was one built into the visor and main body and formed part thereof.

118 In the first aspect of embodiments this is described in the following terms (pp 5-6):

Preferably the casing includes at least one integral hinge that permits movement of the visor from a first, closed position to a second, open position permitting full access to the reflector assembly and termination chamber, without the visor disengaging from the main body. This avoids the problem associated with prior art lighting assemblies which have a hinge separate to the casing and a plurality of parts that are prone to coming apart and disengaging from the casing. Further, the integral hinge portion prevents excess freedom of movement of the visor/lens with respect to the casing, which can result in misalignment of the two parts upon closing up of the light assembly at the end of maintenance and/or service.

119 Further, in a discussion of Figure 1 reference is made as to how the main body and visor are held together in one particular embodiment, in terms (p 13):

The main body (1) and visor (7) are held together by two clips (9a, 9b) and two integral hinges (10a, 10b not shown) located in corresponding positions on the other side of the main body and visor, thus permitting movement of the visor (7) from a first, closed position to a second, open position permitting full access to the reflector assembly (11) and termination chamber (13).

120 Streetworx contended that claim 2 of the 103 Patent requires the result that when the visor is in an open position, there is immediately full access to the reflector assembly and termination chamber with the visor still attached to the main body. The respondents submit that claim 2 is describing the attributes of the hinge – i.e. it permits full access to these areas without the visor disengaging from the main body. I agree with Streetworx’s position which flows naturally from the language of claim 2. A skilled addressee would so construe it. I expand on this later when discussing the Boronia luminaire.

Independent Clip – Claim 3 (103 Patent)