FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited [2014] FCA 1157

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

|

AND: |

AIR NEW ZEALAND LIMITED (ARBN 000 312 685) Respondent |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Vary Order 1 of 1 May 2013 in the manner foreshadowed at paragraph 1287 of these reasons.

2. The application be dismissed.

3. Direct the parties to file and exchange written submissions on costs by 4:15 pm on Friday 19 December 2014 together with any affidavit upon which reliance is placed.

4. Stand the matter over for a hearing on costs at 10.15 am on Wednesday 4 February 2015.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

NSD 955 of 2009 |

|

BETWEEN: |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

|

AND: |

P.T. GARUDA INDONESIA LTD (ARBN 000 861 165) Respondent |

|

JUDGE: |

PERRAM J |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

31 OCTOBER 2014 |

|

WHERE MADE: |

SYDNEY |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Vary Order 1 of 1 May 2013 in the manner foreshadowed at paragraph 1287 of these reasons.

2. The application be dismissed.

3. Direct the parties to file and exchange written submissions on costs by 4:15 pm on Friday 19 December 2014 together with any affidavit upon which reliance is placed.

4. Stand the matter over for a hearing on costs at 10.15 am on Wednesday 4 February 2015.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

|

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

NSD 534 of 2010 |

|

BETWEEN: |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

|

AND: |

AIR NEW ZEALAND LIMITED (ARBN 000 312 685) Respondent |

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

|

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

|

GENERAL DIVISION NSD 955 of 2009

|

|

|

BETWEEN: |

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

|

AND: |

P.T. GARUDA INDONESIA LTD (ARBN 000 861 165) Respondent |

|

JUDGE: |

PERRAM J |

|

DATE: |

31 October 2014 |

|

PLACE: |

SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (‘the Commission’) sues Air New Zealand Limited (‘Air NZ’) and P. T. Garuda Indonesia Limited (‘Garuda’) alleging collusive behaviour in the fixing of surcharges and fees on the carriage of air cargo from overseas into Australia, allegedly contrary to the combined effect of ss 45 and 45A of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). The two airlines are not said to have acted alone but instead in the company of a large number of other international airlines. Whilst there were proceedings on foot against many of those airlines at an earlier time, all of those proceedings had been settled or were in the process of being settled prior to the present trial commencing.

2 Involved are four different kinds of charge:

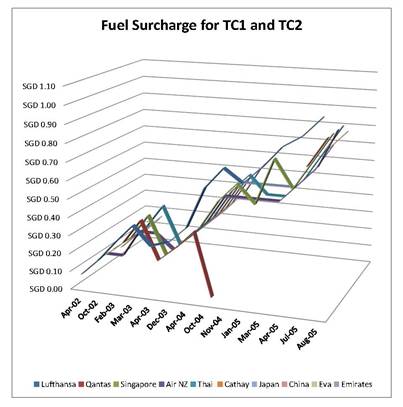

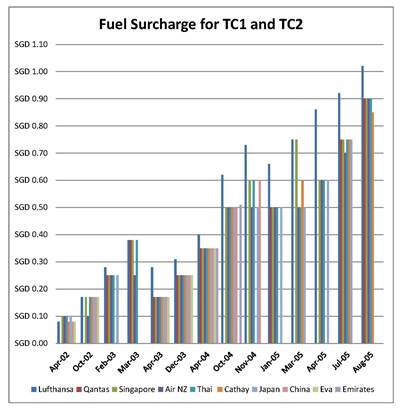

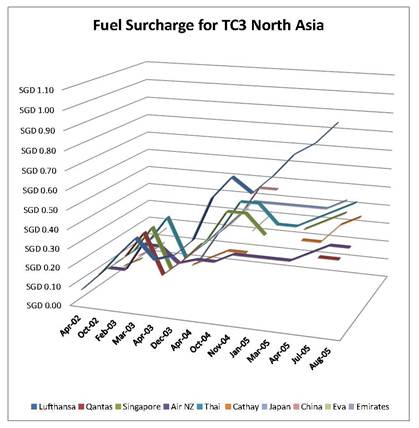

(a) a fuel surcharge: This was a charge usually calculated by reference to the weight of cargo and was designed to compensate airlines for fluctuations in the price of aviation fuel. The significance of it being levied as a surcharge was that it appeared as a separate charge on air waybills rather than being absorbed invisibly in an overall freight charge. An air waybill is the basic document of carriage in the air cargo market.

(b) an insurance and security surcharge (‘ISS’): This was a surcharge designed to compensate airlines for increased insurance costs in the wake of the attacks on the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001. Again it was charged by reference to weight and appeared as a separate charge on an air waybill.

(c) a customs fee: This fee was imposed by the Indonesian Government on airlines by reference to the number of air waybills contained in a cargo manifest. The airlines passed this fee on to their customers. There were only two such fees imposed in this case and their role is peripheral. These also appeared on the air waybill.

(d) a freight rate: There was a single example in Indonesia where it was alleged that Garuda had been involved in fixing an overall freight rate.

3 The Commission’s case was that anti-competitive conduct, including price fixing, had occurred in the markets in which cargo was flown into Australia from:

(a) Hong Kong;

(b) Singapore; and

(c) Indonesia.

4 With one minor exception, the Commission’s case was not concerned with the imposition of surcharges or fees on flights out of Australia. As will be seen, this is significant.

5 As a matter of industry structure, the airlines imposed the fuel and insurance surcharges at the airport of origin. The customs fee in Indonesia, however, was imposed on flights both out of and into Indonesia, including from Australia.

6 In each of the three jurisdictions above, most international airlines were members of industry representative bodies which had so-called ‘cargo sub-committees’. In Hong Kong, the relevant body was the Hong Kong Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Sub-Committee (‘the HK BAR CSC’) and it met in Hong Kong. In Singapore, the equivalent body was the Singapore Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Sub-Committee (‘the Singapore BAR CSC’), whilst in Indonesia it was known as the Air Cargo Representative Board (‘the ACRB’).

7 Air NZ and Garuda, together with very many other international carriers, were members of these three industry bodies.

8 The Commission’s basic contention is that the HK BAR CSC, the Singapore BAR CSC and the ACRB became forums in which the airlines were either able directly to engage in price fixing with respect to the surcharges and customs fees or that they provided an environment in which such conduct was facilitated.

9 The personnel of the airlines was not the same in each of the three jurisdictions although there was some overlap. Consequently, the Commission’s case in each jurisdiction is different. Further, the internal mechanics of its case in the three jurisdictions is also different. Those differences require an appreciation of the common element in all three cases, ‘the Lufthansa Index’, also sometimes referred to as the ‘Lufthansa Methodology’. I will use both expressions interchangably.

10 Beginning in around the mid-1990s international airlines had sought to impose fuel surcharges to compensate them for fluctuations in the price of aviation fuel. This was organised initially by the International Air Transport Association (‘IATA’). It adopted a resolution, known as ‘resolution 116ss’, which specified an appropriate level of fuel surcharge depending upon the average of five spot prices for aviation fuel (Singapore, US Gulf, US West Coast, Rotterdam and Italy). The appropriate level was expressed as a percentage of the baseline price in June 1996 and each level indicated a specified or particular surcharge once that percentage was reached. If resolution 116ss had come into force, it would have provided a system in which international airlines charged the same fuel surcharges at the same time. In other words, it would have provided a framework which allowed the airlines to move in unison in the face of fluctuations in the price of aviation fuel.

11 Of course, many airlines have hedging programmes to protect against just such fluctuations. On that basis, and other bases too, on 14 March 2000 the United States Department of Transport declined to give IATA or the airlines anti-trust immunity (the complex regulatory rÉgime is discussed below in Chapter 3). This prevented resolution 116ss from being given effect to in the United States. IATA consequently did not formally promulgate resolution 116ss. It notified its members of this development and warned them against publishing their own indexes, no doubt for anti-trust reasons.

12 Despite this, Lufthansa then began publishing an identical index to the, now defunct, resolution 116ss, which it did on its publicly available website. This index has given rise to a large amount of anti-trust litigation in many jurisdictions. In effect, a common theme has been that the Lufthansa Index facilitated price fixing by international carriers of fuel surcharges.

13 The Commission’s case in this litigation arises out of that general concept. However, there are significant variations.

14 In Hong Kong, the Commission alleges that the Lufthansa Index (and a later index created within the HK BAR CSC) was used as the basis for making joint applications to the Hong Kong Civil Aviation Department (‘the HK CAD’). That body’s approval was necessary for the imposition of any surcharge on flights out of Hong Kong and, through the HK BAR CSC, the airlines lodged joint applications for the approval of the Lufthansa (and later) indexes. The Commission alleges that this was price fixing. Both Air NZ and Garuda deny that they engaged in price fixing. They also say that they were obliged to lodge joint applications by Hong Kong law. I have concluded that they did engage in some, but not all, of the conduct alleged against them and that they were not required to act as they did by the law of Hong Kong.

15 In Singapore, only Air NZ was pursued. It was not directly alleged that Air NZ or other airlines had used the Lufthansa Index to set their surcharges. Instead, it was said that the approach of the index’s trigger points as the price of aviation fuel fluctuated provided multiple occasions for the airlines to discuss what surcharge they were going to impose and that this led to price fixing. Even if this practice was not price fixing in itself it was, so the Commission alleged, a practice which substantially lessened competition. In addition to its case about fuel surcharges, the Commission also alleged that the airlines had colluded on the imposition of an ISS.

16 I have concluded that the Commission has not demonstrated that Air NZ was involved in collusive practices with respect to the fuel surcharges in Singapore although it did engage in price fixing with respect to the ISS.

17 In Indonesia, the Commission pursued only Garuda. It was said that Garuda had engaged in price fixing with the other airlines using the Lufthansa Index as a means to determine fuel surcharges. This was alleged to have occurred at meetings of the ACRB. With one minor exception, I have accepted this case. I have also concluded that similar collusion took place with respect to the customs fee on outbound but not inbound flights.

18 Garuda argued that it was required to act as it did by Indonesian law or practice. This contention was of no substance.

19 Both airlines pursued a large number of technical defences. I have rejected all of these, including an ambitious submission that international commercial aviation in Australia is not subject to regulation under the Trade Practices Act 1974. These arguments were, in the main, of little merit and occupied much of a trial which spanned over six months.

20 Despite that, I have concluded that one of the airlines’ defences ought to be accepted. The Commission alleged conduct contrary to s 45 in respect of each act of collusion. Section 45 applies only to competition in a market in Australia. Because the Commission’s case was limited (in all but one minor case) to flights from airports outside Australia into airports inside Australia I have concluded that no market in Australia was involved. The evidence showed that the surcharges were imposed and collected at the origin airports. The competition which occurred between the airlines and which the surcharges interfered with was competition in markets in Hong Kong, Singapore and Indonesia and not competition in any market in Australia. Prices may well have been affected in Australia by the conduct but that does not mean the market in which the airlines were competing was located here.

21 In this regard, it is worth noting that the ‘market in Australia’ requirement is quite different to the effects doctrine in the United States under the Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 USC §§ 1 – 7 (1890) (USA) (‘the Sherman Act’), where a price effect in the United States will suffice to bring that legislation into play. That is not what the Trade Practices Act 1974 does.

22 Accordingly, the actions will be dismissed. I will hear the parties on costs.

23 These reasons are set out as follows:

|

[1003] | |

|

11.2.3.5 Communications between the airlines to settle on co-ordinated increases of FSCs |

[1045] |

|

11.2.3.6 The extraordinary meeting of the BAR CSC on 8 December 2003 |

[1049] |

|

[1056] | |

|

[1057] | |

|

[1059] | |

|

[1061] | |

|

[1066] | |

|

[1069] | |

|

[1070] | |

|

[1072] | |

|

[1074] | |

|

[1077] | |

|

[1078] | |

|

[1079] | |

|

[1087] | |

|

[1092] | |

|

[1106] | |

|

[1107] | |

|

[1109] | |

|

[1110] | |

|

[1111] | |

|

[1112] | |

|

[1128] | |

|

[1129] | |

|

[1129] | |

|

[1133] | |

|

[1133] | |

|

[1140] | |

|

[1141] | |

|

[1141] | |

|

[1149] | |

|

[1156] | |

|

[1177] | |

|

[1178] | |

|

[1179] | |

|

[1180] | |

|

[1190] | |

|

[1205] | |

|

[1209] | |

|

[1214] | |

|

[1217] | |

|

[1227] | |

|

12.3.14 The January 2003 Indonesia Security Surcharge Understanding. |

[1230] |

|

[1231] | |

|

[1233] | |

|

12.3.17 The July 2005 Indonesia Security Surcharge Understanding |

[1235] |

|

[1237] | |

|

[1244] | |

|

[1273] | |

|

[1280] | |

|

[1280] | |

|

[1287] |

2 THE INTERNATIONAL CARGO INDUSTRY – A GENERAL DESCRIPTION

24 The industry involves a considerable amount of terminology. The purpose of this section is to introduce that terminology and also to highlight some structural aspects of the industry. This section is heavily drawn from the parties’ agreed statement of facts. In addition to the description below I will set out the acronyms often used in these reasons:

|

ACRB |

Air Cargo Representative Board (Indonesia) |

|

Air NZ |

Air New Zealand Limited |

|

ANA |

Air Navigation Act 1920 (Cth) |

|

ANR |

Air Navigation Regulations 1947 (Cth) |

|

ARBN |

Australian Registered Business Number |

|

ASA |

Air Services Agreement |

|

AWB |

Air Waybill |

|

BAR CSC ExCom |

Hong Kong Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Sub-Committee Executive Committee |

|

BARINDO |

Board of Airline Representatives in Indonesia |

|

BSA |

Block Space Agreement |

|

CAB |

Civil Aviation Board (USA) |

|

CAD |

Civil Aviation Department (USA) |

|

CASA |

Civil Aviation Safety Authority (Australia) |

|

CASS |

Cargo Account Settlement System |

|

CIF |

Cost Insurance Freight |

|

EDN |

Export Declaration Number |

|

FSAG |

Fuel Surcharge Action Group |

|

FSC |

Fuel Surcharge for Cargo |

|

FOB |

Free On Board |

|

GSA |

General Sales Agents |

|

GSSA |

General Sales and Service Agents |

|

Garuda |

P.T. Garuda Indonesia Limited |

|

HAFFA |

Hong Kong Association of Freight Forwarding Agents Limited |

|

HAWB |

House Air Waybill |

|

HK BAR CSC |

Hong Kong Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Sub-Committee |

|

HK BAR CSC Ex Com |

Hong Kong Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Sub-Committee Executive Committee |

|

HK CAD |

Hong Kong Civil Aviation Department |

|

HMT |

Hypothetical Monopolist Test |

|

IATA |

International Air Transport Association |

|

IASC |

International Air Services Commission |

|

Indonesia ASA |

Australia-Indonesia Air Services Agreement |

|

ISC |

Insurance Surcharge for Cargo |

|

ISS |

Insurance and Security Surcharge |

|

LIDC-C |

Singapore Local Industry Development Committee - Cargo |

|

MAWB |

Master Air Waybill |

|

Qantas |

Qantas Airways Ltd |

|

Singapore BAR CSC |

Singapore Board of Airline Representatives Cargo Sub-Committee |

|

SPA |

Special Prorate Agreement |

|

SQ |

Singapore Airlines Ltd |

|

SSNIP |

Small but Significant Non-Transitory Increase in Price |

|

SWG |

Surcharge Working Group |

|

TACT |

The Air Cargo Tariff |

|

TC1 |

IATA Cargo Tariff Conferences - Area 1 |

|

TC2 |

IATA Cargo Tariff Conferences - Area 2 |

|

TC3 |

IATA Cargo Tariff Conferences - Area 3 |

|

the Commission |

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission |

|

the Conferences |

IATA Cargo Tariff Conferences |

|

ULD |

Unit Load Device |

2.1 International transportation of cargo

2.1.1 Demand from consignors and consignees

25 There is a requirement for the transportation of cargo on the part of persons who wish to send cargo from a place of origin to an international place of destination and on the part of persons who wish to receive cargo at an international place of destination sent from an international place of origin.

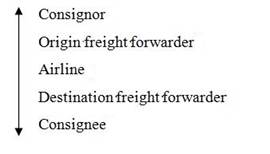

26 Within the international cargo transport industry, a person who sends cargo, or from whom cargo is sent, is typically referred to as the ‘consignor’. A person to whom cargo is sent is typically referred to as the ‘consignee’. The consignor and consignee may be the same person or related bodies corporate. The transport of cargo between a consignor and consignee does not necessarily involve the sale of the cargo by one to the other or any commercial transaction between them.

27 The international transportation of cargo involves the following activities (amongst others):

(a) transport of the cargo from the consignor to the sea or air port from which the cargo will be transported internationally;

(b) when necessary, storage at the port;

(c) transport from the origin port to the destination port;

(d) customs handling at the destination port;

(e) when necessary, storage at the destination port; and

(f) transport of the cargo from the destination port to the consignee.

28 If there is a sale of the cargo involved then the terms of sale between a consignor and consignee relating to the transport of cargo may include terms as to risk and responsibility for arranging the transport and payment. Within the international cargo transport industry, there are a number of common arrangements, including ‘ex-works’, ‘free on board’ (‘FOB’) and ‘cost insurance freight’ (‘CIF’). The effect and nature of these arrangements are defined in the Incoterms published by the International Chamber of Commerce. For ex-works and FOB, the consignee is ordinarily responsible for making the arrangements for the cargo to be transported from the place of origin or the origin port as applicable to the place of destination and is liable for the cost and risk. For CIF, the consignor is ordinarily responsible for making the arrangements for the cargo transport and is liable for the cost and risk.

29 Most consignors or consignees who wish to transport cargo only require the transportation of the cargo in one direction, that is, from a specific place of origin to a specific place of destination. The uni-directional nature of nearly all cargo transport is materially different to passenger transportation. The vast majority of passengers acquire transport services from a place of origin to a place of destination and a return service back to the place of origin, although not necessarily from the initial destination.

2.1.2 Modes of international cargo transport

30 Cargo is transported internationally by air, land (road and rail), sea and combinations of these modes of transport. Cargo can only be transported to or from Australia by sea or air. The key differences between sea, air and land modes of international cargo transport include speed and cost. In respect of transport between Australia and other countries, sea transport is almost always the slower mode of international cargo transport and the lower cost mode of international cargo transport for high volume and/or heavy weight cargo. In respect of transport between Australia and other countries, air transport is almost always the quicker mode of international cargo transport and the higher cost mode of international cargo transport for most types of cargo.

31 Air transport is generally the preferred mode for the international transport of time-sensitive cargo (including perishable cargo) and cargo that is high value, low volume and/or low weight. In the relevant period there were frequent and material fluctuations in the cost of fuel used for transportation of air cargo between other countries and Australia.

32 The decision whether to transport cargo by sea or air between Australia and other countries is affected by a number of factors including:

(a) relative transport costs, including to and from relevant ports and airports;

(b) the value, size and weight of the cargo;

(c) whether the delivery of the cargo is time-sensitive;

(d) the delay in reaching the destination port; and

(e) the distance between the place of origin and the place of destination and the directness of the available sea and air services.

33 Types of cargo that are frequently transported by sea:

(a) to Australia, by weight, include coal tar, pitch and other crude oils; ores; and inorganic chemicals and, by FOB value, include motor vehicles, parts and accessories; coal tar, pitch and crude oil; and engines and motors; and

(b) from Australia, by weight, include iron and other ores; mineral fuels; and unmilled grains and, by FOB value, include mineral fuels; iron and other ores; and fresh meat.

34 Types of cargo that are frequently transported by air:

(a) to Australia, by weight, include engines and machines; motors and electrical appliances; and polymer plastics and, by FOB value, include motors and electrical appliances; engines and machines; and pharmaceutical goods;

(b) from Australia, by weight, include fresh meat; fresh fruits and nuts; and seafood and, by FOB value, include precious stones and metals; medical products; and office machinery.

2.1.3 Categories of international air cargo

35 General air cargo is all cargo other than specialised air cargo and mail. Specialised air cargo are items which by their nature require special handling on the ground or in the air and includes items such as live animals, and oversize items such as boats or cars. Certain types of specialised cargo must be transported on freighters such as oversized items and some dangerous goods.

36 General air cargo is in turn usually classified as:

(a) perishable cargo (that is, cargo that will deteriorate over a short period of time or if exposed to adverse temperature, humidity or other environmental conditions); and

(b) non-perishable or dry cargo.

37 Perishable cargo ordinarily requires particular handling on the ground and/or in the air (e.g. cold storage) or may be subject to particular time pressures. The time-sensitivity of the transport of non-perishable cargo depends upon the nature of the cargo and the circumstances of the particular shipment. Transport of non-perishable cargo may also be required to occur quickly, for example when parts are required regularly or urgently for a production process that uses the part or otherwise required for urgent repairs. Certain types of goods need to be stored in particular conditions such as securely or at a particular temperature during transportation. The proportion of air cargo exported from Australia which is non-perishable is higher than the proportion of air cargo imported into Australia which is perishable.

2.2.1 Services supplied by freight forwarders

38 Freight forwarders offer to supply, and when engaged, do supply consignors and/or consignees with services associated with the transport of cargo from a place of origin to a place of destination. When these activities are performed by freight forwarders they are usually supplied by a freight forwarder located at the place of origin and a separate or related freight forwarder located at the place of destination.

39 Depending on the nature of the goods to be transported and the requirements of the consignor/consignee, freight forwarders endeavour to combine different shipments into one, larger, shipment, a process known as ‘consolidation’. Freight forwarders prefer to consolidate if practicable because the per kilogram cargo rate payable to an airline to carry the consolidated shipment usually decreases as the chargeable weight of a consignment increases. If a forwarder combines several small shipments into one large shipment the per kilogram rate payable by the freight forwarder is usually lower based on the total chargeable weight of the consolidated shipment. In addition, if a heavy, low volume consignment can be combined with a light, large volume consignment, the amount payable to the airline to carry the consolidated shipment is usually less than the amount that would be payable for the two shipments separately. Accordingly, consolidated cargoes usually qualify for better overall rates, by leveraging the volume and weight ratios of different cargo shipments. A freight forwarder may agree with another freight forwarder to consolidate cargo being handled by the two freight forwarders.

2.2.3 Customs clearance services

40 When cargo is delivered to an origin airport, customs clearance services are required to process the cargo through customs. For example, an export declaration must be submitted to Australian customs for cargo being transported from Australia. The Export Declaration Number (‘EDN’) assigned by customs is normally placed on the air waybill (in this chapter, ‘AWB’) in the box entitled ‘Accounting Information’. Australian Customs require the airline to lodge a main manifest within three working days after departure which lists all cargo loaded on the aircraft.

41 When cargo is delivered to the airport where the airline relinquishes possession, customs clearance services are required to process the cargo through customs. All cargo must be cleared at that airport by an entity authorised by the applicable customs authority to provide customs clearance services. This can be performed by a customs broker, integrator or a freight forwarder.

42 Freight forwarders monitor the cargo’s progress from the place of origin to the place of destination. Most freight forwarders provide tracking facilities on their websites which enable a user with access to the relevant AWB number to monitor the progress of transportation.

2.2.5 Types of freight forwarders

43 Freight forwarders range from multinational firms with staff and branches throughout the world to firms that operate in a single country or city. To enable freight forwarders effectively to provide their services to consignors and consignees across several countries, freight forwarding companies generally establish, or participate in, freight forwarding networks. The type of network depends on the type of freight forwarder:

(a) multinational freight forwarders generally operate and have offices in a number of countries. An example is DB Schenker, which has a worldwide network comprised of subsidiary companies. Some multinational freight forwarders operate only within particular regions. For example, the New Zealand-based company Mainfreight has a regional network in Asia, with some offices in the United States;

(b) national or local freight forwarders are locally based companies without an established international presence. Such freight forwarders have arrangements with other freight forwarders, situated at various locations internationally.

44 Some freight forwarders have separate ‘export’ and ‘import’ divisions. Others will divide their business in terms of ‘sea’ and ‘air’ cargo and/or ‘perishable’ and ‘non-perishable’ cargo. There are also specialist freight forwarders for particular industries. Some freight forwarders operate as wholesale freight forwarders, providing services to other (often non-IATA-accredited) freight forwarders.

2.2.6 Transactions between freight forwarders and consignors/consignees

45 Major freight forwarders may approach major consignors or consignees at their global or regional headquarters to promote the services they provide. Where a consignor is responsible for initiating a shipment and it does not have a standing arrangement in place, it usually contacts one or more freight forwarders located at the place of origin to negotiate and contract for the acquisition of services (the origin freight forwarder). The origin freight forwarder provides the services required of it at the place of origin and in turn contacts a freight forwarder at destination (a destination freight forwarder) to provide services required of them at the place of destination.

46 Where a consignee initiates the shipment it may contact either a freight forwarder at the place of origin or the place of destination to negotiate and contract for the acquisition of services. Where it contacts the destination freight forwarder, the destination freight forwarder provides the services required at the place of destination and, in turn, contacts an origin freight forwarder to arrange the necessary services (including arranging for freight to be carried by air) at the place of origin. These origin and destination freight forwarders may be part of one multinational group, members of an alliance of independent freight forwarders or simply parties that deal with each other on a regular or ad hoc basis.

47 Where the origin freight forwarder and the destination freight forwarder are not part of the same company, the forwarder which transacts with the consignor or consignee (as the case may be) usually pays the other freight forwarder for the services provided by it. The amount paid by one freight forwarder to another in such circumstances depends upon the terms agreed between them.

48 Following this contact the freight forwarder may offer its standard rates to the consignor/consignee or, where the consignor or consignee sends or receives shipments regularly, the freight forwarder may offer a particular rate or rates to apply to those shipments (together, fixed rates). Fixed rates may apply for several months or a few weeks and change depending on the size of the shipment (larger or regular shipments attracting better rates) and the requirements of the consignor or the consignee.

49 Alternatively, where the consignor/consignee requires a price for a particular shipment, the freight forwarder may prepare a specific quote. Quotes are most often provided in relation to large orders where no fixed rates have been agreed with the consignor/consignee or unusual orders, such as transporting unusual cargo or transporting to an unusual place of destination. Quotes may be provided in a form which shows the various components of the quote.

50 On occasions, some consignors and consignees tender for, and then contract for, services they require from freight forwarders for set periods of time. Different rates may apply for faster or slower services, direct and indirect routes, dangerous goods or depending on other relevant considerations such as the nature of the services required (door-to-door, door-to-airport, airport-to-door, etc).

51 The price for the carriage of freight by air is normally based on the ‘chargeable weight’ of a shipment. The chargeable weight of cargo is the higher of the actual weight (in kilograms) or the volumetric weight of the cargo. Volumetric weight (sometimes also known as ‘dimensional weight’) is a measure of the volume or space that a consignment takes up, converted to be expressed in kilograms. Different freight forwarders may apply different conversion rates. AWBs have the two weights (i.e. actual weight and volumetric weight) identified in respect of any consignment.

52 Once the shipment is delivered to its final place of destination, the origin freight forwarder invoices the consignor or the destination freight forwarder invoices the consignee depending on whether it is the consignor or consignee that arranged the freight transaction and is responsible for payment of the overall freight cost.

53 If the consignor is responsible to the freight forwarder for the freight cost, it pays the origin freight forwarder for the overall freight cost. If the consignee is responsible to the freight forwarder for the freight cost, the consignee pays the freight cost to the origin or destination freight forwarder. The freight forwarders will then settle amongst themselves for their respective services.

2.2.7 IATA accreditation of freight forwarders

54 Freight forwarders may apply for accreditation with IATA. IATA accreditation is given to a freight forwarder in respect of its outbound cargo operations within a specified country, being the preparation of cargo for air carriage from that country. On accreditation, IATA assigns the freight forwarder a numeric code which covers the forwarder’s outbound cargo operations throughout the country concerned. In order to obtain accreditation with IATA, freight forwarders must meet certain minimum criteria including staff qualifications, financial requirements, suitability of premises and cargo handling equipment and appropriate licenses to trade. IATA accreditation enables freight forwarders to utilise IATA’s Cargo Account Settlement System (‘CASS’) clearing house and settlement system to remit transaction details and make payments to airlines (which is discussed later).

55 Integrators may also use contracted space on freighter or passenger aircraft of third party airlines on particular routes and/or at particular times, according to demand and the capacity of the integrator to meet demand using capacity in its own aircraft.

2.4.1 Substitutable airports at which the airline first takes or relinquishes possession

56 The carriage of freight by air is more often than not undertaken by an airline from the airport closest to the place of origin of the cargo (primary origin airport) and to the airport closest to the place of destination of the cargo (primary destination airport). The carriage of freight by air may be undertaken by an airline to or from an airport other than the airport closest to the place of origin of the cargo (alternative origin airport) or to an airport other than an airport closest to the place of destination (alternative destination airport). Accordingly, the airport at which the international airline first takes possession or relinquishes possession of the cargo may not be the origin airport or destination airport respectively. Some international airlines use land transport between various airports selected by them so they can accept cargo from and to airports where they do not fly. For example, during the relevant period some international airlines accepted cargo to and from Brisbane but only flew to Sydney and used overnight road transport to transport cargo between Brisbane and Sydney and vice versa.

57 Whether an alternative origin or destination airport is a substitute for the primary origin or destination airport depends on factors such as the cost, timeliness, availability and capacity of the alternatives including the availability of land transport between alternative airports. In some cases where the carriage of freight by air is undertaken by an airline from an alternative origin airport and/or to an alternative destination airport the cargo does not arrive at its place of destination as quickly as if the cargo had been transported between the primary origin airport and the primary destination airport.

2.4.2 Substitutable intermediate airports

58 The carriage of freight by air between a particular origin airport and destination airport may involve:

(a) no stops at intermediate airports;

(b) a stop without change of planes at one or more intermediate airports which means that cargo continues to its destination airport without being unloaded; or

(c) a stop and change of aircraft at one or more intermediate airports, in which case the cargo must be unloaded and reloaded.

59 Where the carriage of freight by air involves a stop at an intermediate airport, in most cases the cargo does not arrive at its destination airport as quickly as if the cargo had been transported on a non-stop service.

2.5.1 Services supplied by airlines

60 In order to carry freight by air, an airline requires at least the following rights, facilities and services:

(a) aircraft operated by it (which includes both aircraft that are leased or owned);

(b) the right to fly aircraft of a specified capacity on specific routes pursuant to the applicable Air Services Agreements (‘ASAs’);

(c) the right to access the international airports on specific routes (origin airport, destination airport and any intermediate airport used) including:

(i) air traffic control services; and

(ii) landing slots (the right to schedule an aircraft arrival or departure, on a specific day within a specific time);

(d) ground handling;

(e) engineering services; and

(f) sales and marketing staff and office facilities.

61 Ground handlers provide all ground handling for airlines, including receipt of export cargo for carriage, loading and unloading of the aircraft, warehousing (when required) and handling relevant documentation. The generic term ‘ground handlers’ includes ‘cargo terminal operators’ and ‘ramp’ handlers. Airlines may engage different companies to supply cargo terminal or ramp handling services.

62 Cargo terminal operators accept freight, and prepare freight for export on each flight. They also handle and release imported freight. Cargo terminal operators also provide warehousing when required. Ramp handlers are responsible for loading and unloading the aircraft, which includes the delivery and collection of freight to or from the ground handler’s warehouse.

2.5.2 Types of airlines and aircraft

63 Airlines carry freight by air using the cargo hold (also known as the bellyhold) of international passenger aircraft or dedicated air freighter aircraft. For international passenger aircraft, passengers are seated on the main deck of the aircraft and passenger luggage is stowed in the bellyhold of the plane. Remaining space in the bellyhold is available for the transport of cargo capable of being transported in the bellyhold.

64 For freighter aircraft, both the main deck and the bellyhold of the aircraft are available for cargo transport. Freighter aircraft by reason of the dimensions of their main deck allow for the loading and unloading of oversized and irregular cargo including, for example, cars. The revenue earned by airlines from carrying passengers on international passenger aircraft is greater than the revenue that is earned from the transport of cargo on the aircraft.

65 Airlines which carry freight by air can be divided into the following categories:

(a) bellyhold only airlines;

(b) cargo only airlines; and

(c) combination airlines.

66 Cargo only airlines are airlines that operate only freighter aircraft. Cargolux is an example of a cargo only airline. Neither Air NZ nor Garuda operated as a cargo only airline during the relevant period.

67 Combination airlines operate both passenger aircraft (with cargo capacity in the bellyhold) and freighter aircraft. Air NZ was a combination airline. Garuda was not.

68 Wide-bodied aircraft are capable of carrying large Unit Load Devices (‘ULDs’). Examples of wide-bodied aircraft are the Boeing 777, Boeing 767, Boeing 747 and the Airbus A380. Narrow-bodied aircraft have less storage space than wide-bodied aircraft. For most narrow-bodied aircraft, cargo and baggage has to be stowed in the hold by hand. An exception to this is the A320 which is capable of carrying small ULDs. Examples of narrow-bodied aircraft are the Boeing 737 and Airbus A320. On both narrow-bodied or wide-bodied aircraft, part of the cargo holds may be kept at a special temperature for the transport of sensitive cargo requiring lower or higher temperatures, such as perishable cargo (as referred to in paragraphs 36 – 37 above).

69 During the relevant period, Garuda operated only wide-bodied passenger aircraft to and from Australia, Indonesia and Hong Kong. Air NZ operated narrow-bodied and wide-bodied aircraft between Australia and New Zealand during the relevant period.

2.5.3 Designation and capacity grants to airlines

70 An individual airline is not entitled to carry freight by air between two international airports unless the relevant traffic rights have been granted to it. The airline must first be designated under the ASA by one of the countries which is a party to the ASA in respect of the route, and then must be allocated capacity on the route by the relevant governmental authority of the designating country, and must hold the necessary regulatory approvals.

71 During the relevant period, some ASAs provided that signatories could refuse designation if, by way of example, the airline was not incorporated in a contracting state, did not have a principal place of business in a contracting state, was not substantially owned by entities domiciled in a contracting state or effective control was not vested in a contracting state. Except in the case of the Australia-Hong Kong ASA, the ASAs between each of New Zealand and Indonesia and Australia allowed a signatory to refuse designation if substantial ownership and control of the airline was not vested in the other party, or its nationals. The Australia-Hong Kong ASA provides that each signatory may refuse designation of an airline in its country where it is not satisfied that the airline is incorporated and has its principal place of business in the other signatory’s country.

72 Once designated by its ‘home’ country, an airline wishing to operate a service on a route governed by an ASA to which its ‘home’ country is a party must apply to the regulatory authority in its home country to obtain capacity rights.

73 In Australia, applications by Australian airlines for capacity to operate services on routes governed by ASAs to which Australia is a party, are made to a Commonwealth entity, the International Air Services Commission (‘IASC’). The IASC makes determinations on the allocation of scheduled international air route capacity to Australian airlines on public benefit grounds. Determinations allocating capacity are usually made for a period of five years for routes where capacity or route entitlements are restricted. In cases where capacity entitlements and route rights are unrestricted, determinations may be issued for a period of 10 years. In either case, the IASC has the discretion to make interim determinations, which are for a period of three years.

74 Airlines that intend to operate non-scheduled international air services need to obtain the approval of the aeronautical authorities in each country to be served. An airline usually has to be licensed by its home country to operate non-scheduled international air services. Non-scheduled international air services are not licensed in Australia. In Australia, foreign airlines may be required to obtain non-scheduled flight approvals in accordance with the Air Navigation Act 1920 (Cth).

2.6 Domestic regulation of international transportation of cargo

75 Domestic regulations in Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore and Indonesia also control the carriage of freight by air to or from those countries. Such regulations govern matters including licensing, the granting of capacity for scheduled services and permission for non-scheduled services. Each of Australia, Hong Kong, Singapore and Indonesia has enacted legislation and regulations governing the operation of scheduled air services.

76 An airline seeking to provide international scheduled services to or from a country for the first time is required to seek multiple approvals from regulatory authorities in all countries involved. By way of example, any airline (whether Australian or foreign) seeking to operate international scheduled air services to or from Australia must:

(a) obtain an International Airline Licence from the Department of Infrastructure and Transport.

(b) obtain Civil Aviation Safety Authority (‘CASA’) clearances in accordance with the Civil Aviation Act 1988 (Cth). Operators (Australian and foreign) seeking to commence scheduled international air services to and from Australia are also required to apply to CASA for an Air Operator’s Certificate or Foreign Aircraft Air Operator’s Certificate together with a certificate in respect of airlines liability insurance. CASA is responsible for all operational and safety approvals pertaining to civil aviation in Australia;

(c) obtain the approval of the Office of Transport of the Department in accordance with the Aviation Transport Security Act 2004 (Cth); and

(d) obtain timetable approval from the Department. Timetable details include the type of aircraft to be used for each scheduled international air service in accordance with regulations 16 and 20 of the Air Navigation Regulations 1947 (Cth).

77 Airports are constrained by the physical capacity of their facilities (the main constraint being the capacity of the terminal building and the number of runway slots available for landing or take-off) or restrictions in the form of night curfews. Further, some international airports have reached their capacity. Where, in practice, a constraint limits arrival and departure times, slot allocation is required and slot parameters are employed.

78 Once an ASA is negotiated between Australia and another country and an airline has obtained a licence from the Department, the airline then needs to arrange times to take-off and land at the airports it intends to serve in Australia and the other country. This is managed by the airports and airlines commonly using an IATA protocol for allocation of take-off and landing slots.

79 Decisions about whether to operate on a particular route and, if so, the frequency and aircraft type on the route are decisions made by the head office of an airline. Most routes operated by Air NZ and Garuda for passenger aircraft are to and from an airport or airports in their home countries. Such airports are described as the airline’s ‘hub’. The location of the hub is primarily determined by the ‘flag’ or nationality of the airline, and the availability of air traffic rights for air services between countries.

80 The factors that are relevant to a decision to operate a passenger aircraft on a particular route include but are not limited to (with varying degrees of significance):

(a) potential passenger demand on the route (both to and from the destination airport) and the revenue likely to be earned from carrying passengers, which is a primary factor in deciding whether to operate the service on routes;

(b) whether the airline holds or is able to acquire traffic rights to operate a service on the route (if the appropriate ASAs are in place or can be negotiated) and the time it may take to acquire these rights (if possible), particularly in relation to new routes;

(c) the availability of necessary airport infrastructure;

(d) the nature and capacity of services offered by competing airlines on the route; and

(e) indirect revenue or marketing effects arising from a change to the route network or schedule or linkages with other routes serviced by the airline.

81 The total revenue earned by airlines from carrying passengers on an aircraft is greater than the total revenue that is earned from the transport of cargo on the aircraft. For that reason, in relation to passenger aircraft, passenger rather than freight revenue considerations primarily determine routes, schedules and capacity.

82 Freighter aircraft routings can differ from passenger aircraft routings in that they often follow a scheduled sequence of stops within a multi-stage routing. Factors that are relevant to a decision to operate a freighter aircraft from a particular airport (as part of the freighter aircraft’s routing) include but are not limited to (with varying degrees of significance):

(a) potential freight requirements from that airport and other airports on the routing and the revenue likely to be earned from carrying cargo;

(b) whether the airline holds or is able to acquire traffic rights to operate a service on the route (if the appropriate ASAs are in place or can be negotiated) and the time it may take to acquire these rights (if possible), particularly in relation to new routes;

(c) the availability of necessary airport infrastructure;

(d) the nature and capacity of services offered by competing airlines from that airport; and

(e) indirect revenue or marketing effects arising from a change to the route network or schedule or linkages with other routes serviced by the airline.

83 Similar factors to those listed in paragraphs 79 to 82 are relevant to a decision to increase, reduce or remove capacity on a particular route.

2.9 Inter-airline arrangements

84 Airlines carry the majority of freight by air using aircraft operated by that airline. Airlines commonly refer to airports serviced using aircraft they operate as online airports. Airlines also have the option to and do carry freight by air by using another airlines’ capacity to carry freight by air. This practice is commonly known as interlining. Interlining occurs when:

(a) an airline wishes to carry freight by air to or from an airport to which the airline does not operate its own aircraft (offline airport) including where it does not have the relevant traffic rights and/or slots; or

(b) an airline is unable to carry freight by air on its own aircraft on a particular route at a particular time because of capacity constraints.

85 Interline agreements between airlines can take a number of different forms including:

(a) a Special Prorate Agreement (‘SPA’), which is an agreement between two airlines that specifies the rates that one party will charge the other for the carriage of cargo on given sectors of its network, and vice-versa. Alternatively, though far less frequently, the agreements set a minimum amount for the sector to be paid to the operating carrier. It does not include any space commitment by either party; or

(b) a Block Space Agreement (‘BSA’), which is a specific agreement between two airlines similar to an SPA but that includes a reservation of space (either hard or soft) on one or more specific sectors covered by the agreement.

86 Some international airlines share capacity on a freighter aircraft or share the operations of a freighter aircraft.

2.9.2 Code share arrangements and airline alliances

87 Code share arrangements enable one airline, which does not itself operate on a route (or if it needs more capacity), to sell space on a flight operated by another airline on that route under the first airline’s designated IATA code. The non-operating airline also requires traffic rights under the relevant ASA.

88 Airline alliances involve varying levels of marketing and/or operational cooperation.

2.10 Prices charged by airlines

89 The price charged for carrying freight by air is a combination of the air cargo rate plus any applicable surcharges.

90 There are four categories of air cargo rates charged by airlines:

(a) ‘standard’ rates;

(b) ‘contract’ or ‘special’ rates;

(c) ‘ad hoc’ rates; and

(d) ‘TACT’ rates.

91 Normally, air cargo rates are expressed in terms of a rate per kilogram based on the ‘chargeable weight’ of each consignment. Airlines typically offer a range of different rates based on:

(a) different types of cargo (e.g. general or perishable);

(b) different chargeable weights of consignments; and

(c) different airports at which the airline first takes possession and the airport at which the airline relinquishes possession (or destination regions).

92 In addition, different rates may be offered for specific routings and particularly time sensitive cargo (the most time sensitive cargo is usually described as ‘express’ cargo, which has the shortest delivery or collection cut off times before the flight), for ULDs and valuable goods (e.g. bullion), or where special handling is required (e.g. live animals, human remains or flowers).

93 Airlines also impose a minimum charge per consignment. Air cargo rates per kilogram usually decrease with increasing chargeable weight.

94 Each local cargo sales office of Air NZ and Garuda publishes, from time to time, its standard rates as ‘tariff’ or ‘rate’ sheets or schedules for carrying freight by air from the airport at which that office is located to the airport at which the airline relinquishes possession. Standard rates are generally quoted in the local currency at the place of origin. Sometimes the standard rates of airlines operating in particular origins (especially those exhibiting high currency volatility) are published in US dollars or Euros. Standard rates are generally reviewed between one and four times a year (on a seasonal basis), depending on the airline.

95 Contract rates are rates that have been agreed between an airline and a specific freight forwarder for cargo transported by the airline from a place of origin to places of destination. Mostly such agreements about contract rates do not include an obligation on the part of the freight forwarder to purchase any services from the airline. Contract rates are usually less than standard rates.

96 Contract rates are often agreed where there is a regular need for capacity leading to the possibility of higher volumes or in relation to cargo that has some special feature that means it does not fall under ‘standard’ rates, such as a requirement for special handling.

97 Contract rates that are offered to freight forwarders may be negotiated by email, telephone or at meetings with the staff of the local cargo sales office of an airline, who are based at the airport at which the airline first takes possession, with the relevant origin freight forwarder.

98 Ad hoc rates (also referred to as ‘spot rates’) are rates negotiated in respect of carrying a particular shipment of freight by air. Ad hoc rates may be affected by immediate supply and demand conditions including capacity on available flights at the required time.

99 During the relevant period TACT rates were the rates shown in the TACT Manual published by IATA. TACT is an acronym for ‘The Air Cargo Tariff’. Generally, airlines only used these rates for unusual types of cargo (for example, human remains). Airlines may also use TACT rates as the basis for interlining, although only where no SPA was agreed between the airlines.

100 At various times during the relevant period, Air NZ and Garuda applied surcharges, including fuel surcharges and also ISSs which were charged after September 2001 and which are described variously as security, insurance, war risk or crisis surcharges.

101 In some countries including Hong Kong and Japan, and in Dubai, the relevant aeronautical authorities required surcharges to be approved before they could be imposed on the transport of cargo by air from that country.

102 The air cargo rates offered by airlines for the transport of air cargo between two airports usually differ according to the direction of travel. Air cargo rates (both standard and contract rates) usually vary depending on route and carrier.

103 In locations where the airline’s cargo business volume is too small to justify dedicated cargo sales and marketing staff, the airline may appoint General Sales Agents (‘GSAs’) or General Sales and Service Agents (‘GSSAs’). GSAs perform some or all of an airline’s own sales and marketing function. The GSA may be a dedicated sales agent or, in some cases, another airline or an IATA freight forwarder. A GSSA is a GSA that also performs ground handling services.

104 Each of Air NZ and Garuda has a general website which can be viewed from anywhere in the world and which contains marketing and promotional information, including in relation to carrying freight by air. It was common for international airlines generally to have such a website.

105 Some international airlines have (at varying times) introduced functional website services accessible from Australia and other countries relating to carrying freight by air. The nature of these website services varies widely between airlines. Some provide only limited services such as general product and service information, flight timetables and shipment tracking. It is not clear whether this was done either by Air NZ or Garuda.

106 Some international airlines during at least part of the relevant period provided an online service available to Australian based freight forwarders registered with the particular airline to request capacity for cargo being transported from Australia (e.g. SQ, Cathay and Emirates). These services, among other things, allowed freight forwarders to enquire whether space was available for shipment on a particular day or flight and request capacity of the airline. Bookings could be made including by email and telephone.

107 Freight forwarders contact station employees (or the GSAs) of an airline by telephone, email or fax to make an enquiry about space and price for a particular shipment (and, where available, an enquiry about space through the airline’s website or other portals). The information provided to an airline for the purposes of carrying freight by air usually includes:

(a) a general description of the cargo making up the shipment;

(b) estimates of the weight and dimensions of the shipment (this information is required for pricing and logistics, i.e. how the shipment will be packed and loaded on to the aircraft);

(c) the preferred date of shipment;

(d) whether the cargo will be delivered to the cargo facility ready for loading onto the aircraft or will require further packing by the airline’s cargo terminal (e.g. loading onto a pallet or into a ULD with other cargo);

(e) any specific packaging or handling requirements (e.g. for dangerous or perishable cargo);

(f) when the shipment will be delivered to the ground handler for processing;

(g) the level of service required (e.g. whether the freight forwarder requires an express service or guaranteed uplift on a particular flight); and

(h) the airport at which the cargo is to be collected.

108 When a freight forwarder books the carriage of freight by air, it may be booked either in blocks or on an ad hoc basis:

(a) Pre-purchased block space (hard block space): ‘block space’ is available to be purchased from airlines. Pursuant to a BSA a freight forwarder has access to a pre-allocated amount of cargo capacity. Freight forwarders acquire block space on busy routes where they have regular demand and where there are limits on available capacity to carry freight by air. Under a hard BSA the freight forwarder must pay for the pre-allocated space regardless of whether or not the space is filled. Freight forwarders may also acquire hard block space on less busy routes where they have reliable, regular shipments or to ensure price stability;

(b) Pre-booked space (allocation space): some airlines offer ongoing (but not necessarily guaranteed) bookings for regular air cargo shipments, which can be cancelled a few days prior to flight. This is sometimes referred to as a ‘space allocation arrangement’ or ‘soft’ BSA. A freight forwarder may have an ongoing forward booking for a pallet from the airport at which the airline first takes possession to the airport at which the airline relinquishes possession for regular freight. The freight forwarder has to notify the airline a few days in advance of each flight whether the freight forwarder requires that pallet. Unlike hard block space, pre-booked space is only paid for if it is used; and

(c) Ad hoc space: where space has been neither pre-purchased nor pre-booked, transport of single or consolidated cargo is on an ad hoc basis and depends on the availability of space on a particular flight. Rates for ad hoc space are normally more variable than for pre-purchased or pre-booked space depending on demand and how far in advance a booking is made prior to departure. For ad hoc shipments, the freight forwarder contacts the airline at the place of origin, seeking a price as well as confirmation that space is available and that the required delivery time can be met. Such requests can be made as late as three or four hours prior to departure time.

109 The degree to which freight forwarders use BSAs is dependent upon the place of origin, the route and the characteristics of the consignors and consignees. Airlines and freight forwarders typically negotiate ‘hard block space’ and/or ‘soft block space’ agreements separately for each route (e.g. Sydney to Singapore).

110 Any additional terms on which the freight is carried by air are as negotiated between the airline and the freight forwarder. They may be recorded in a formal agreement such as a BSA, or recorded in a less formal document such as an email. Ordinarily, an airline which offers to carry freight by air has in place standard terms and conditions which are applicable to carrying freight by air.

111 The principal international standard document for carrying freight by air is the AWB. The AWB is prima facie evidence of the conclusion of a contract, the receipt of cargo, and conditions of carriage. Either an AWB or a substitute for an AWB is required before cargo can be loaded at the place of origin. Paper AWBs accompany the cargo to the destination airport where the airline relinquishes it.

112 There are two forms of AWB in use. An airline AWB contains the airline’s logo and unique AWB numbers printed on it. Neutral AWBs are template documents which have the same format and layout as an airline AWB but do not bear any logos and do not have AWB numbers printed on them. In respect of neutral AWBs, airlines issue freight forwarders with a range of valid AWB numbers, which the forwarders will then use to generate, or ‘cut’, the AWB for shipments to be consigned on that airline.

113 Airlines operating services from a particular airport of origin provide airline AWBs or a series of AWB numbers for use with neutral AWBs to authorised freight forwarders at the place of origin. Each AWB has an 11 digit serial number, commencing with a three digit code identifying the airline, which enables the issuing airline (and any other airlines participating in the carriage) to identify and account for all AWBs. This serial number provides a unique reference used to manage every shipment of cargo across all parties involved in the delivery of the shipment, including making bookings and checking the status of delivery and position of a shipment.

114 The freight forwarder ‘cuts’ or ‘raises’ the AWB at the place of origin. The AWB includes the following information:

(a) airline details and AWB number (as noted above);

(b) ‘shipper’ details – a name and address for the person or entity making available the cargo from the place of origin, who may also be the party sending the freight (for the purposes of the AWB, the person who makes the cargo available is also known as the ‘shipper’). Where cargo is consolidated by the freight forwarder, the ‘shipper’ named on the AWB is always the freight forwarder and this is sometimes the case for non-consolidated shipments;

(c) ‘issuing agent’ or ‘issuing airline’s agent’ details – the person authorised to hold the airline’s AWB stock and therefore to authenticate and issue the AWB on the airline’s behalf. The issuing agent is almost always the freight forwarder;

(d) ‘consignee’ details – a name and address for the person or entity who is the recipient of the cargo at the airport at which the airline relinquishes possession. This can be either a freight forwarder (and always is where cargo is consolidated) or the consignee;

(e) weight and dimensions of cargo (i.e. the weight and size of the shipment that will be physically loaded on the aircraft);

(f) general description of the cargo;

(g) the nature of the cargo and any special handling requirements;

(h) payment details – whether the shipment is ‘total prepaid’ (paid to the AWB issuing airline) or ‘charge collect’ (paid to the airline completing the carriage to the airport at which the airline relinquishes possession). The majority of shipments of Garuda and Air NZ are ‘prepaid’ with the freight forwarder paying the AWB issuing airline; and

(i) certification by the ‘shipper’ that the contents of the AWB are correct and a specific declaration concerning dangerous goods.

115 The AWB for each cargo shipment is signed by the freight forwarder on behalf of the person sending the freight and the air cargo carrier at the airport at which the airline first takes possession.

116 AWBs for cargo are only ever issued for one way shipments. In those exceptional cases where cargo is transported to one country and then returned to the country of origin, a separate AWB is issued in respect of each of the two shipments by the freight forwarder at each airport at which the airline first takes possession.

117 The AWB also records on its face particular rates for the shipment and various other charges. Ordinarily, the rate shown on an AWB is the IATA TACT rate, although in most cases that is not the rate actually being charged by the airline. The AWB never incorporates any benefit, incentive or rebate paid by the airline to the freight forwarders.

118 Where a freight forwarder consolidates various shipments of cargo received from a number of consignors into one consolidated shipment or consignment, the freight forwarder delivers a Master Air Waybill (‘MAWB’) to the airline at the airport at which the airline first takes possession. ‘MAWB’ is simply the terminology used to denote an AWB that is used for a consolidated shipment. The MAWB always describes the ‘shipper’ as the freight forwarder and the bulk shipment simply as ‘consolidated’. In such instances the freight forwarder separately issues its own ‘House Air Waybill’ (‘HAWB’) to the consignor of each of the individual shipments comprising the consolidated shipment. The HAWB incorporates or makes reference to the terms and conditions between the person sending the freight and freight forwarder.

119 For non-consolidated cargo, freight forwarders may still either automatically generate a HAWB number and/or create the HAWB (as well as a MAWB – known as ‘back to backs’ i.e. the single HAWB is attached to the back of the MAWB). This is because many freight forwarders rely on HAWB numbers to drive their billing systems, even if no actual HAWB is printed or created.

120 Airlines do not generally see HAWBs. During the relevant period, HAWBs were generally sealed in an envelope with invoices and other relevant documentation, which was then attached with the MAWB and transported with the cargo. The HAWBs contain information confidential to the freight forwarder and thus are not seen by the airlines.

2.16 Payments for air cargo transport

121 In most cases, the origin freight forwarder is obliged to pay the airline for air cargo transport charges. Payment is usually made in local currency of the place of origin. In some countries with high currency volatility payment may be required in another currency. In the industry, this is generally known as ‘prepaid’.

122 Some shipments may be ‘charges collect’, in which case the destination freight forwarder pays on delivery.

123 The charges which are payable to airlines for carrying freight by air by freight forwarders, whether prepaid or charges collect, are not conditional upon the freight forwarder receiving payment from the consignor or consignee, as the case may be, for the freight forwarder’s services.

124 The freight forwarder makes the payment to the airline for the cost of carrying freight by air including via the IATA-operated CASS (where that system is available in the country of origin). As noted above, CASS is an accounts settlement system that facilitates the interaction and exchange of information and remittance between freight forwarders and airlines.

125 Freight forwarders are able to use CASS if they are accredited agents/intermediaries or non-accredited IATA ‘associates’. In order to obtain IATA accreditation freight forwarders must meet certain financial criteria. The requirements for associateship are less stringent than for accreditation. However, associateship still requires a freight forwarder to provide a financial undertaking and a bank account in the country of origin (and in certain circumstances, a bank guarantee).

126 Between 2000-2006, in those countries where CASS operated, freight forwarders were able to settle the invoices issued by airlines in that country in a single payment to CASS. CASS then made a single payment to each airline in that country covering such invoices for all freight forwarders. The airline charges for carrying freight by air for most cargo transported from Australia are paid for using this system.

127 CASS is available in a number of countries. However, its implementation has been gradual. If CASS is not available in a particular origin country (for example, India), payment is made directly by the freight forwarder to the airline. In those circumstances, some airlines will contract with some freight forwarders based in that country only if it supplies a bank guarantee or other security for payment.

128 Having clarified these matters of terminology it is useful to begin with the airlines’ legal arguments as to the non-applicability of the Trade Practices Act 1974.

3 THE APPLICATION OF THE TRADE PRACTICES ACT 1974 TO INTERNATIONAL COMMERCIAL AVIATION

129 Garuda, supported by Air NZ, submitted that Part IV of the TPA had no application to the regulation of international commercial aviation under the Air Navigation Act 1920 (Cth) (‘the ANA’). There were five arguments in all:

(a) the background to the regulation of international commercial aviation showed that at the time of the introduction of the TPA, the majority of bilateral air transport agreements provided for rate fixing machinery;

(b) a consideration of the terms of the ANA showed that the TPA could never apply to international commercial aviation;

(c) alternatively, the TPA could not apply where Australia had entered into an ASA with another nation which required or permitted rate or tariff fixing;

(d) consequently, the TPA could not apply to the conduct alleged against the airlines in the period 2001-2006;

(e) further, the TPA did not apply to the service provided by the airlines which was not the carriage of goods by air but instead the provision to consumers of bundles of contractual rights.

130 It is convenient to deal with these in turn.

3.1 Background to the regulation of international commercial aviation

131 Garuda began its argument by drawing attention to the nature of the regulation of international civil aviation at the time at which the TPA came into force on 24 August 1974. At that time, the regulation of international civil aviation was quite different to the situation which presently obtains and reflected arrangements which had been reached between a large number of nations in the aftermath of World War II.

132 That aftermath had left the United Kingdom and the European nations with substantially weakened economies and the United States in a very much stronger economic position. Further, the end of the war had seen the United States having left over from its war efforts not only a very large number of air freighters which were readily suitable to being converted to commercial airliners but also a large number of pilots with which to fly them. Although the United Kingdom also had a significant number of pilots following its war effort it had not been involved in operating air freighters to the extent that the United States had. In addition, the United States’ economy in 1946 was, in stark contrast to the economy of the United Kingdom, in a position to continue manufacturing even more planes.

133 There was a general sense towards the end of the second world war that given the great advances in aviation technology in the preceding six years, international civil aviation would need to be regulated afresh and this led rapidly to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, signed 7 December 1944, 15 UNTS 295 (entered into force 4 April 1947) (‘the Chicago Convention’). Although the Chicago Convention achieved many things it did not achieve a consensus on the economic issues which arose between the various states. A multilateral agreement reached at the same time, the International Air Services Transit Agreement, signed 7 December 1944, 84 UNTS 389 (entered into force 8 February 1945) (‘the Air Transit Agreement’), recognised what are termed the first and second freedoms. These are respectively: the right of the civil aircraft of one country to fly over the territory of another without landing provided advance notice is given and approval given (the first freedom); and the right to land in another country for technical reasons such as maintenance or refuelling but without offering commercial services (the second freedom). Despite multilateral agreement on those matters no equivalent multilateral agreement could be reached about the operation of purely commercial services between states or through several states.

134 The reasons for this were related to the economic matters just mentioned. The United States, with its much greater economic position favoured ‘open skies’ and free trade, whereas the Europeans, and particularly the United Kingdom, were concerned that untrammelled competition with United States carriers would see their national air industries overrun.

135 The consequence of this impasse was that the terms on which international civil aviation operations were to be conducted between any two given states required bilateral agreement, a multilateral approach having failed at Chicago in 1944.

136 The first and most important of these bilateral agreements was that reached between the United Kingdom and the United States. Officials from these two countries met in Hamilton, Bermuda between 15 January and 11 February 1946. This meeting resulted in the Agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom relating to Air Services, signed 11 February 1946, 3 UNTS 253 (entered into force 11 February 1946), sometimes also known as the Original Bermuda Agreement or, amongst the cognoscenti of bilateral air transport treaties, more often as ‘Bermuda I’. I will call it ‘Bermuda I’, although I do not mean by that to suggest that I am one of those cognoscenti. Its significance is that it has served as a template for many other bilateral air service agreements subsequently reached between other states.

137 The provisions of Bermuda I dealt with five principle issues: entry, capacity, rates, discrimination and dispute resolution. For present purposes only the issue of rates is relevant.

138 Paragraphs (a) to (e) and (h) of Annexure II to Bermuda I were as follows:

(a) Rates to be charged by the air carriers of either Contracting Party between points in the territory of the United States and points in the territory of the United Kingdom referred to in this Annex shall be subject to the approval of the Contracting Parties within their respective constitutional powers and obligations. In the event of disagreement the matter in dispute shall be handled as provided below.

(b) The Civil Aeronautics Board of the United States having announced its intention to approve the rate conference machinery of the International Air Transport Association (hereinafter called (“I.A.T.A.”), as submitted, for a period of one year beginning in February 1946, any rate agreements concluded through this machinery during this period and involving United States air carriers will be subject to approval by the Board.

(c) Any new rate proposed by the air carrier or air carriers of either Contracting Party shall be filed with the aeronautical authorities of both Contracting Parties at least thirty days before the proposed date of introduction; provided that this period of thirty days may be reduced in particular cases if so agreed by the aeronautical authorities of both Contracting Parties.

(d) The Contracting Parties hereby agree that where-

(1) during the period of the Board’s approval of the I.A.T.A. rate conference machinery, either any specific rate agreement is not approved within a reasonable time by either Contracting Party, or a conference of I.A.T.A. is unable to agree on a rate, or

(2) at any time no I.A.T.A. machinery is applicable, or

(3) either Contracting Party at any time withdraws or fails to renew its approval of that part of the I.A.T.A. rate conference machinery relevant to this provision,

the procedure described in paragraphs (e), (f) and (g) hereof shall apply.