FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

De Satge on behalf of the Butchulla People #2 v State of Queensland [2014] FCA 1132

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

De Satge on behalf of the Butchulla People #2 v State of Queensland [2014] FCA 1132

CORRIGENDUM

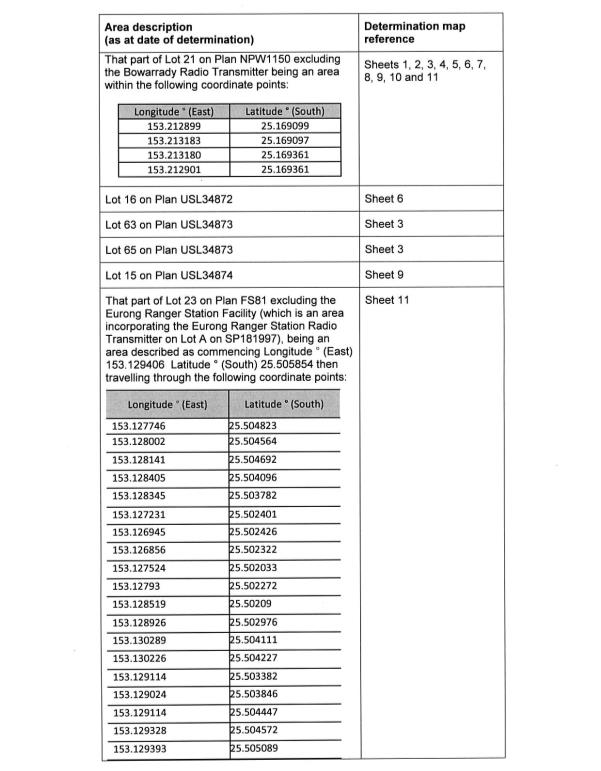

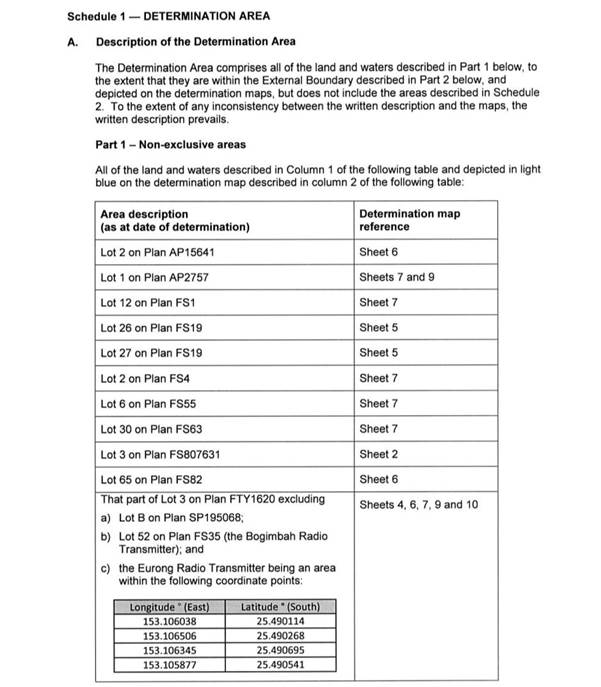

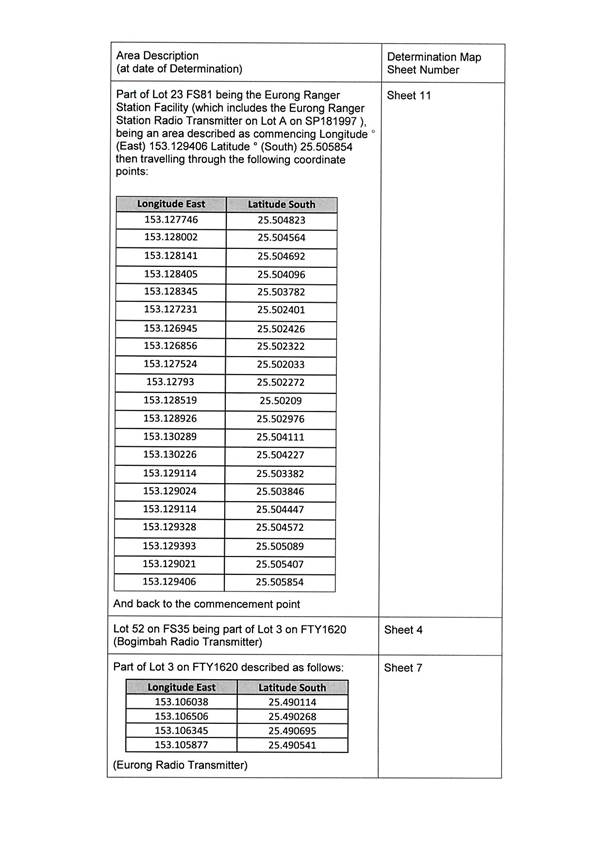

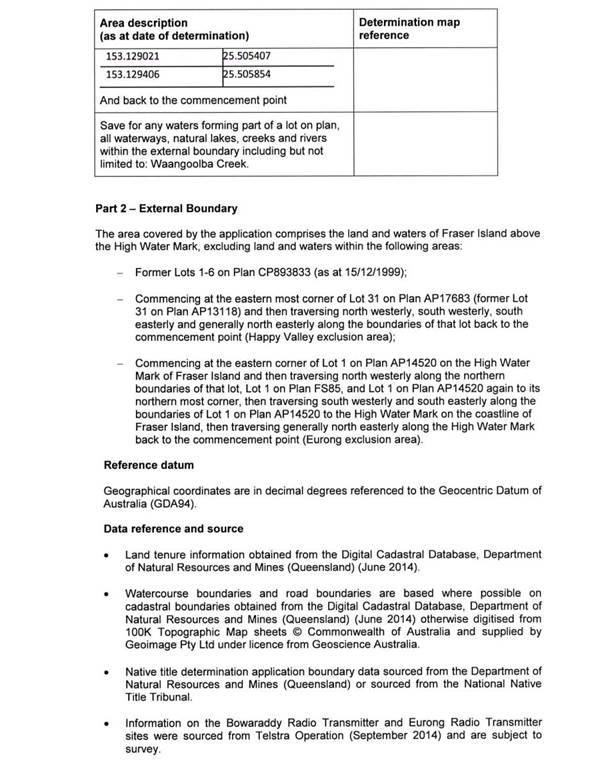

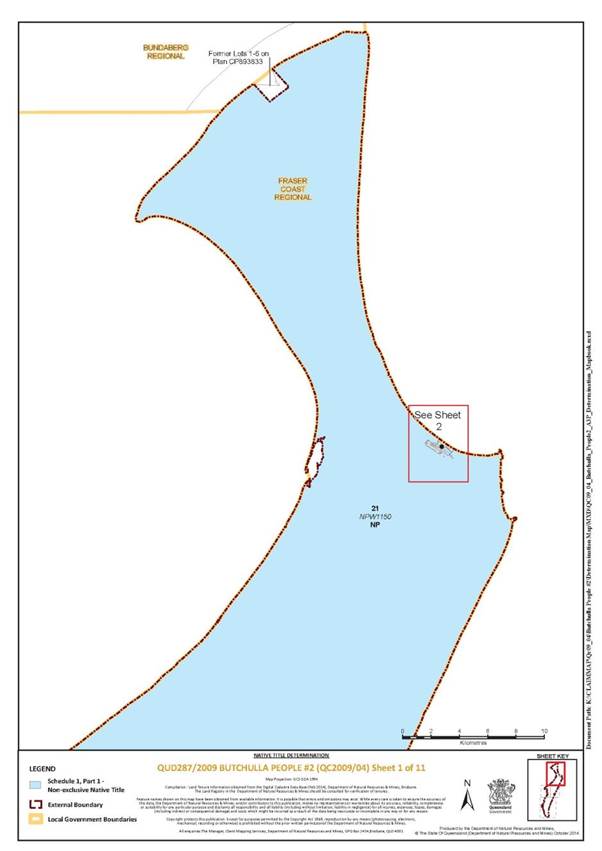

1 Page 8 of the Orders, Schedule 1 – DETERMINATION AREA, is incorrect and should be replaced with the document headed “Area description (as at date of determination)”, attached to this Corrigendum.

2 In paragraph 15 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the second last sentence, “Mr Shawn Foley” should read “Mr Shawn Wondunna-Foley”.

3 In paragraph 37 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the first sentence of the quote, “26 July 2802 on” should read “26 July 1802 in”.

4 In paragraph 47 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the last sentence of item 4, “Dr Backett” should read “Dr Sackett”.

5 In paragraph 48 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the fourth dot point, “Willy Wondanna” should read “Willy Wondunna”.

6 In paragraph 54 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the first dot point, “Darren Gene Black” should read “Darren Gene Blake”.

7 In paragraph 55 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the first sentence, “Butchella people” should read “Butchulla people”.

8 The heading above paragraph 56 and in paragraph 56, of the Reasons for Judgment, “Mr Darren Black” should read “Mr Darren Blake”.

9 In paragraph 57 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the first sentence, “Mr Black” should read “Mr Blake”.

10 In paragraph 75 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the fifth line of the quote, “news” should read “new”.

I certify that the preceding ten (10) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Corrigendum to the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Collier. |

Associate:

Dated: 5 November 2014

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

BEING SATISFIED that an order in the terms set out below is within the power of the Court, and it appearing appropriate to the Court to do so, pursuant to s 87 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth):

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The parties agree that the Military Hiring Area is an area within the external boundary of the application that was subject to an order under regulation 54 of the National Security (General) Regulations 1939 (Cth) (“Regulation 54”), as amended at the relevant time.

B. The State of Queensland’s position is that the making of an order under Regulation 54 in relation to an area wholly extinguishes any native title rights and interests in relation to that area.

C. The Full Federal Court has held that the making of an order under Regulation 54 in relation to an area does not wholly extinguish any native title rights and interests in relation to that area: see Congoo and Others on behalf of the Bar-Barrum People #4 v State of Queensland (2014) 218 FCR 358.

D. The State of Queensland filed an application for special leave to appeal to the High Court of Australia (“High Court”) in respect of that decision: see State of Queensland v Congoo and Others on behalf of the Bar-Barrum People #4 and Others (B15/2014).

E. Notwithstanding the decision of the Full Federal Court, the State of Queensland intended that this application be resolved by the making of orders pursuant to s 87A and s 94A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), on the basis that the Military Hiring Area would not be included in the Determination Area.

F. On 2 June 2014, the applicant requested that the State of Queensland change this position and consent to a determination of native title pursuant to s 87 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) including the Military Hiring Area in the Determination Area on the basis that an application to vary the determination may be made in the event that the High Court overturns the decision of the Full Federal Court. On 5 June 2014, the State agreed to the applicant’s request.

G. On 4 September 2014, the High Court granted the State of Queensland’s application for special leave to appeal the decision of the Full Federal Court.

H. Subject to paragraphs I to K of these notations below, the parties have agreed that the Military Hiring Area be included within the Determination Area.

I. The parties have agreed that the State Minister (under the title the “State of Queensland”) may seek to vary the Determination Area in accordance with ss 13(1)(b) and (5) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) by removing the Military Hiring Area, in the event that the High Court decides that an order made under Regulation 54 in relation to an area wholly extinguishes any native title rights and interests.

J. Subject to paragraph K of these notations below, if the State Minister makes a revised native title determination application, seeking to vary the Determination in accordance with paragraph I above, the parties agree to orders being made:

a. that provide for the revised native title determination to be served on the parties to this proceeding and the Butchulla Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC; and

b. that any party wishing to respond to the revised native title determination application will, within 28 days of the service of the application, file a notice of address for service; and

c. that any party that does not file a notice of address for service within the stated 28 days will not be a party to the revised native title determination application; and

d. that any party that files a notice of address for service will consent to the revised native title determination application being argued on its merits.

K. For the avoidance of doubt:

a. nothing in paragraph J above of these notations or otherwise prevents any party from opposing a variation to the Determination on the basis of the merits of such application; and

b. nothing in paragraphs I and J above of these notations or otherwise is or will be an admission by any of the parties that if the High Court makes a decision of the nature referred to in those paragraphs, the State Minister will necessarily be entitled to a variation of the Determination.

BY CONSENT THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in the terms set out below (“Determination”).

2. Each party to the proceeding is to bear its own costs.

BY CONSENT THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

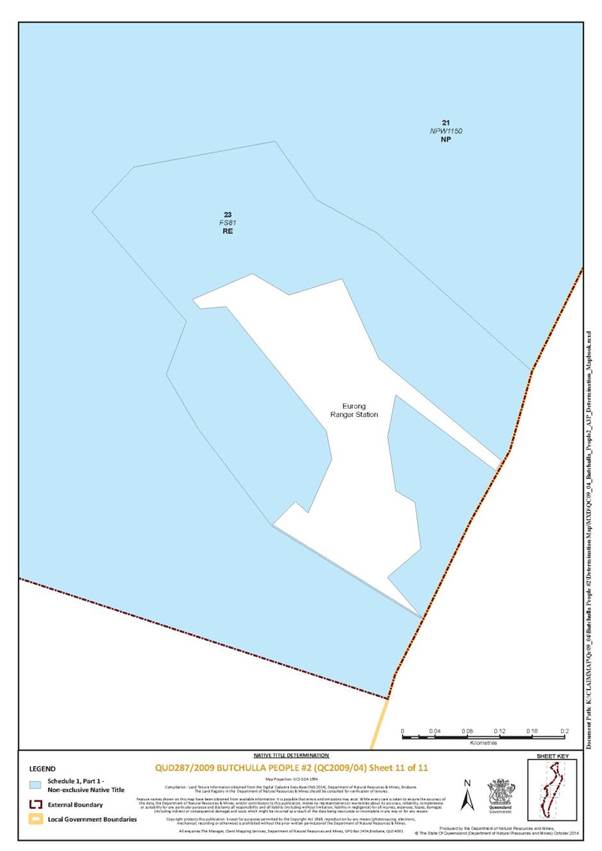

3. The determination area is the land and waters described in Schedule 1, and depicted in the maps attached to Schedule 1 (“Determination Area”).

4. Native title exists in the Determination Area.

5. The native title is held by the Butchulla People described in Schedule 3 (“native title holders”).

6. Subject to paragraphs 7, 8 and 9 below the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the Determination Area are the non-exclusive rights to:

(a) access, be present on, move about on and travel over the area;

(b) camp, and live temporarily on the area as part of camping, and for that purpose build temporary shelters;

(c) hunt, fish and gather on the land and waters of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(d) take, use, share and exchange Natural Resources from the land and waters of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(e) take and use the Water of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(f) conduct, and participate in, rituals and ceremonies on the area, including those relating to initiation, birth and death;

(g) be buried on and bury native title holders within the area;

(h) maintain places of importance and areas of significance to the native title holders under their traditional laws and customs and protect those places and areas from physical harm;

(i) teach on the area the physical, cultural, and spiritual attributes of the area;

(j) hold meetings on the area; and

(k) light fires on the area for personal and domestic purposes including cooking, but not for the purpose of hunting or clearing vegetation.

7. The native title rights and interests are subject to and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the Laws of the State and the Commonwealth; and

(b) the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the native title holders.

8. The native title rights and interests referred to in paragraph 6 do not confer possession, occupation, use or enjoyment of the Determination Area to the exclusion of all others.

9. There are no native title rights in or in relation to minerals as defined by the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) and petroleum as defined by the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) and the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld).

10. The nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the Determination Area (or respective parts thereof) as they exist at the date of this Determination are set out in Schedule 4 (“Other Interests”).

11. The relationship between the native title rights and interests described in paragraph 6 and the Other Interests is that:

(a) the Other Interests continue to have effect, and the rights conferred by or held under the Other Interests may be exercised notwithstanding the existence of the native title rights and interests;

(b) to the extent the Other Interests are inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of the native title rights and interests in relation to any part of the Determination Area, the native title rights continue to exist in its entirety but the native title rights and interests have no effect in relation to the Other Interests to the extent of the inconsistency for so long as the Other Interests exist; and

(c) the Other Interests and any activity that is required or permitted by or under, and done in accordance with, the Other Interests, or any activity that is associated with or incidental to such an activity, prevail over the native title rights and interests and any exercise of the native title rights and interests, but will not extinguish them.

DEFINITIONS AND INTERPRETATION

12. In this determination, unless the contrary intention appears:

“External Boundary” means the boundary described in Part 2 of Schedule 1;

“High Water Mark” means the ordinary high-water mark at spring tides;

“land” and “waters”, respectively, have the meaning given in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth);

“Laws of the State and the Commonwealth” means the common law and the laws of the State of Queensland and the Commonwealth of Australia, and includes legislation, regulations, statutory instruments, local planning instruments and local laws;

“Military Hiring Area” means the area described in Schedule 5;

“Natural Resources” means:

(a) any animal, plant, fish and bird life found on or in the lands and waters of the Determination Area; and

(b) any clays, soil, sand, gravel or rock found on or below the surface of the Determination Area,

that have traditionally been taken and used by the native title holders, but does not include minerals as defined in the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) or petroleum as defined in the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) and the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld);

“Water” means:

(c) water which flows, whether permanently or intermittently, within a river, creek or stream;

(d) any natural collection of water, whether permanent or intermittent;

(e) water from an underground water source; and

(f) tidal water.

Other words and expressions used in this Determination have the same meanings as they have in Part 15 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

13. The native title is not held in trust.

14. The Butchulla Aboriginal Corporation, ICN 8107, incorporated under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth), is to:

(a) be the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of s 57(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); and

(b) perform the functions mentioned in s 57(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) after becoming a registered native title body corporate.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LIST OF SCHEDULES

Schedule 1 — DETERMINATION AREA……………………………………………….…..7

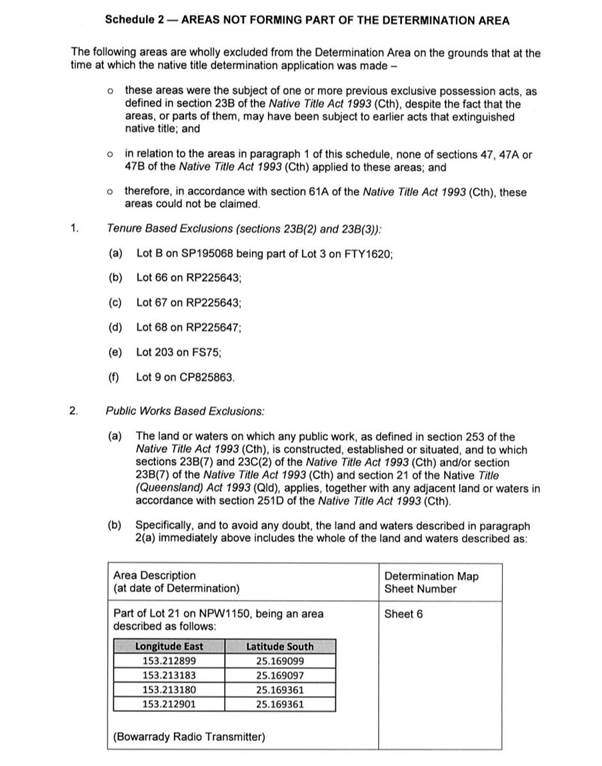

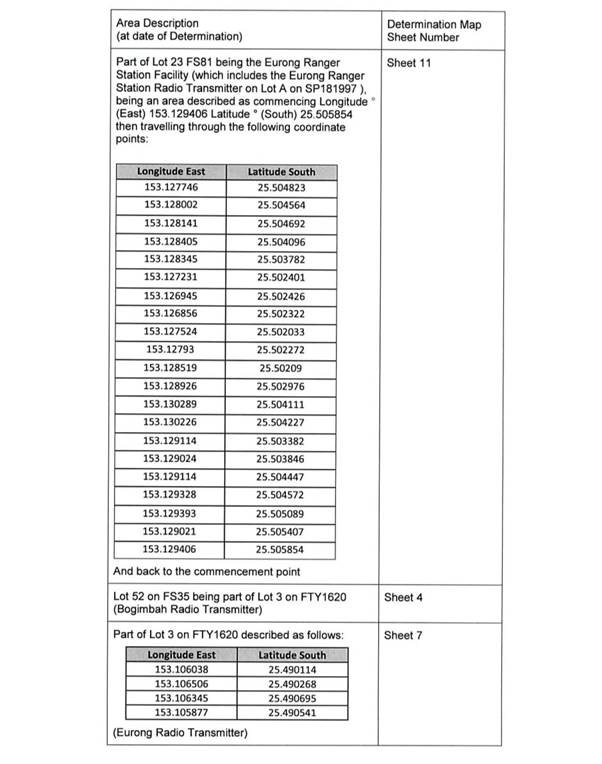

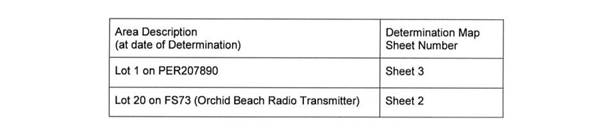

Schedule 2 — AREAS NOT FORMING PART OF THE DETERMINATION AREA……23

Schedule 3 — NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS…………………………………………………25

Schedule 4 — OTHER INTERESTS IN THE DETERMINATION AREA………………...26

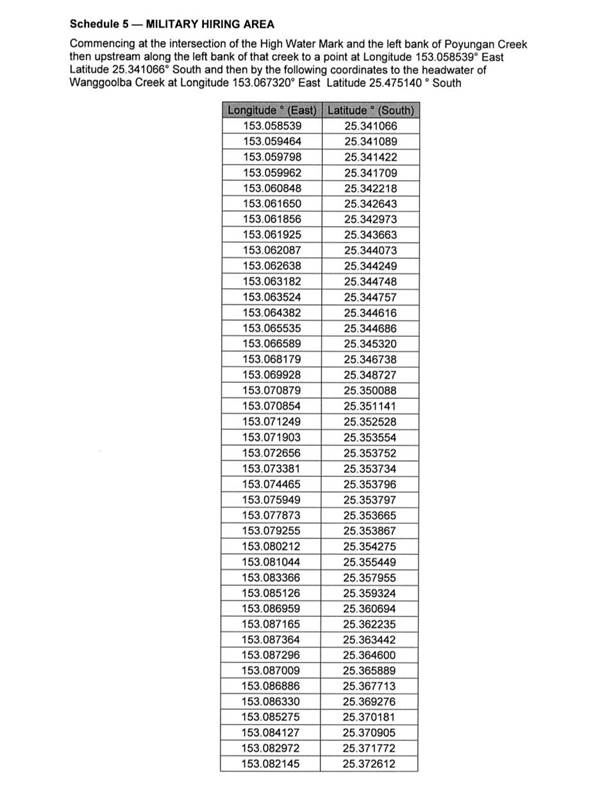

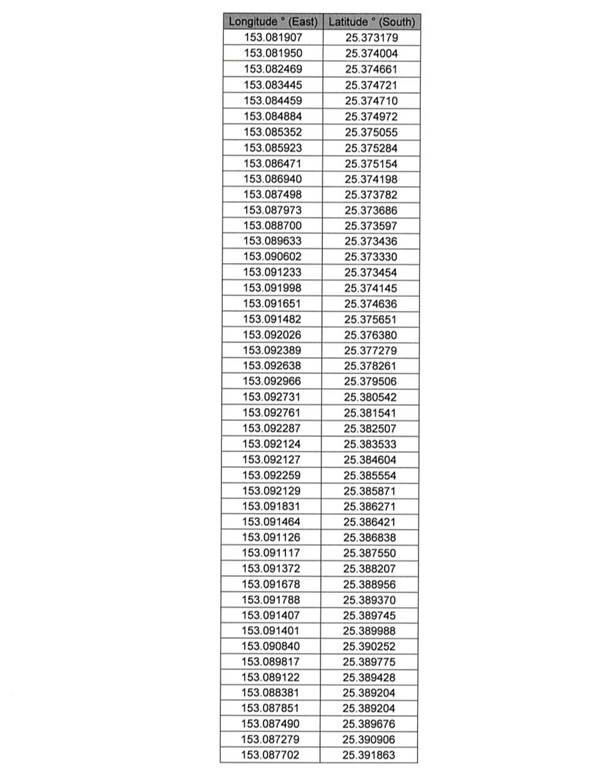

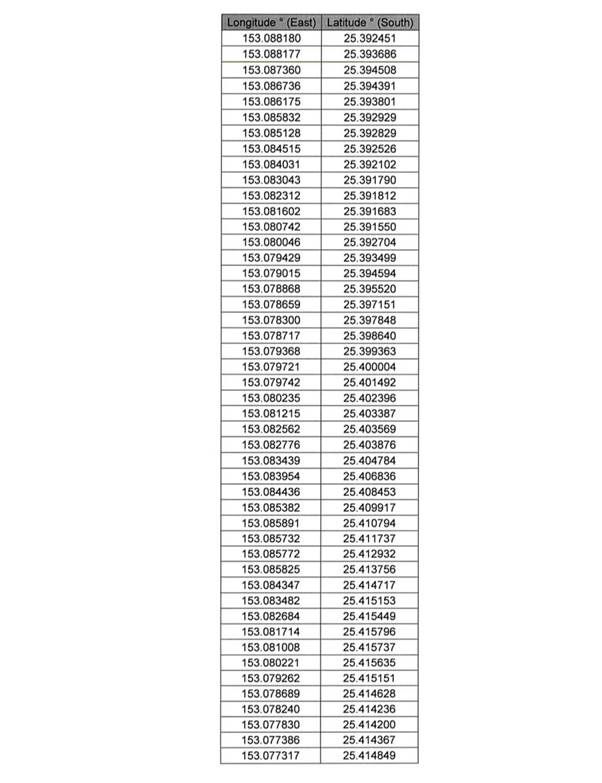

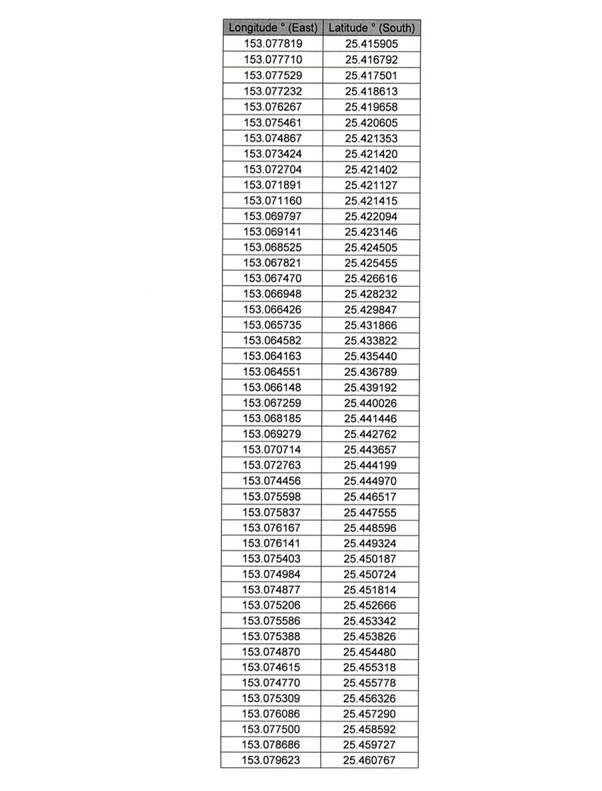

Schedule 5 — MILITARY HIRING AREA…………………………………………………29

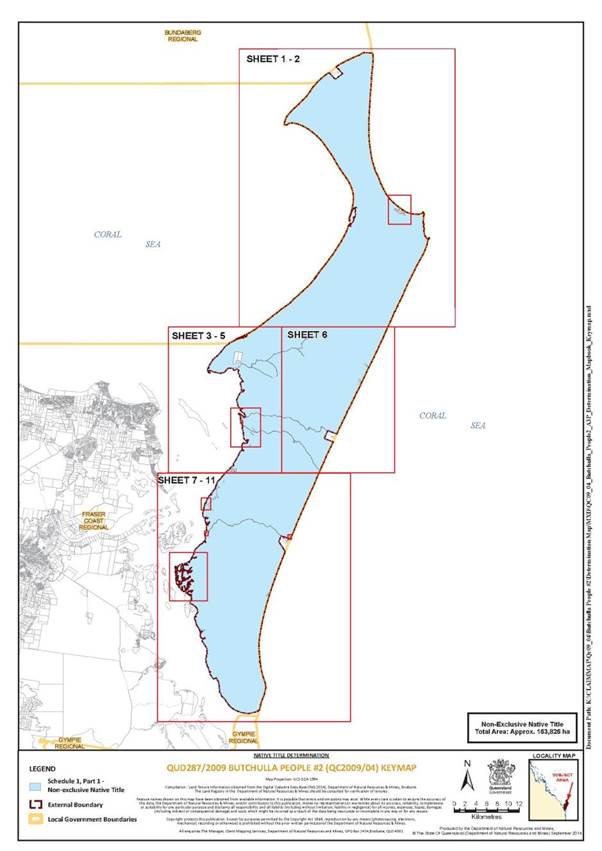

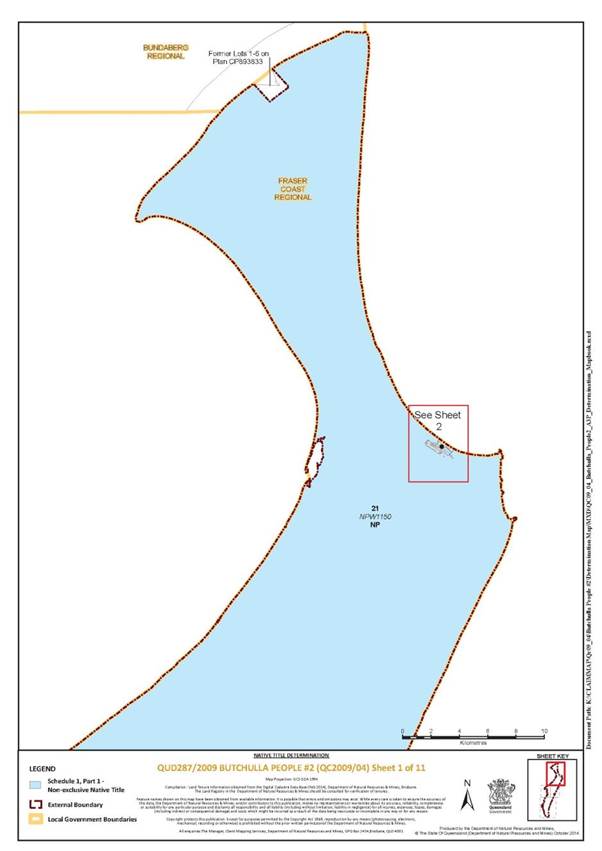

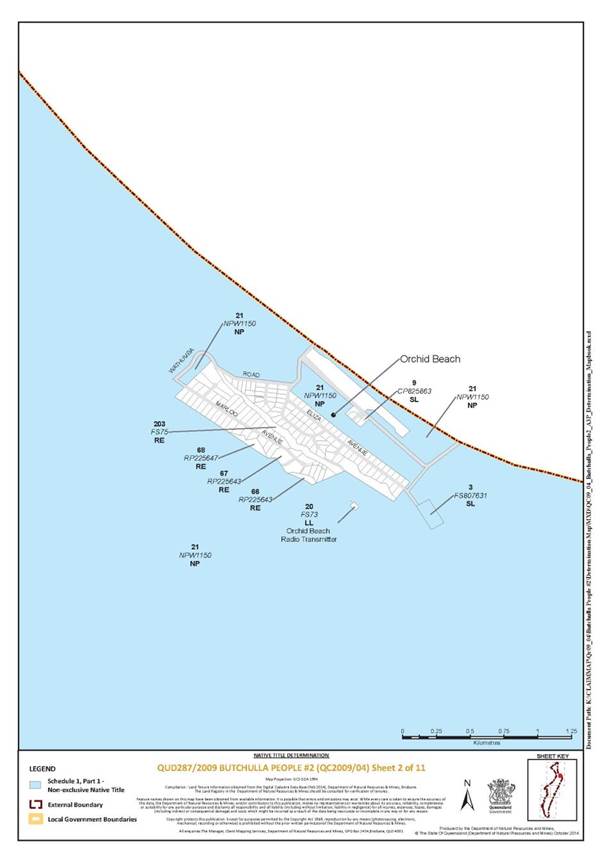

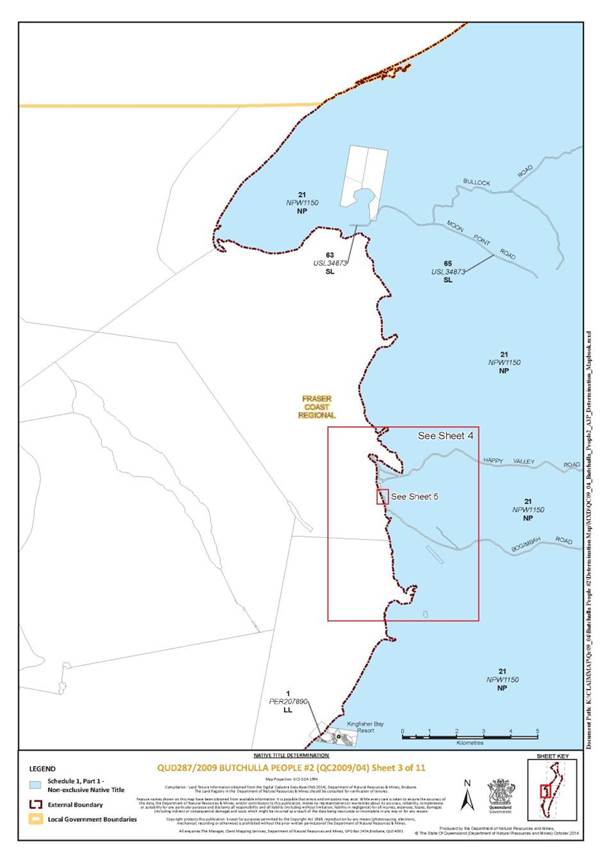

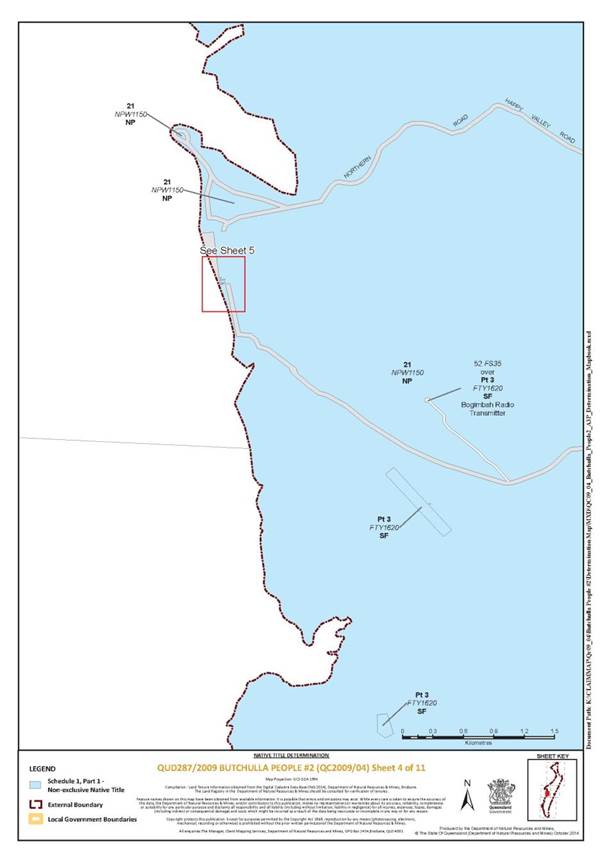

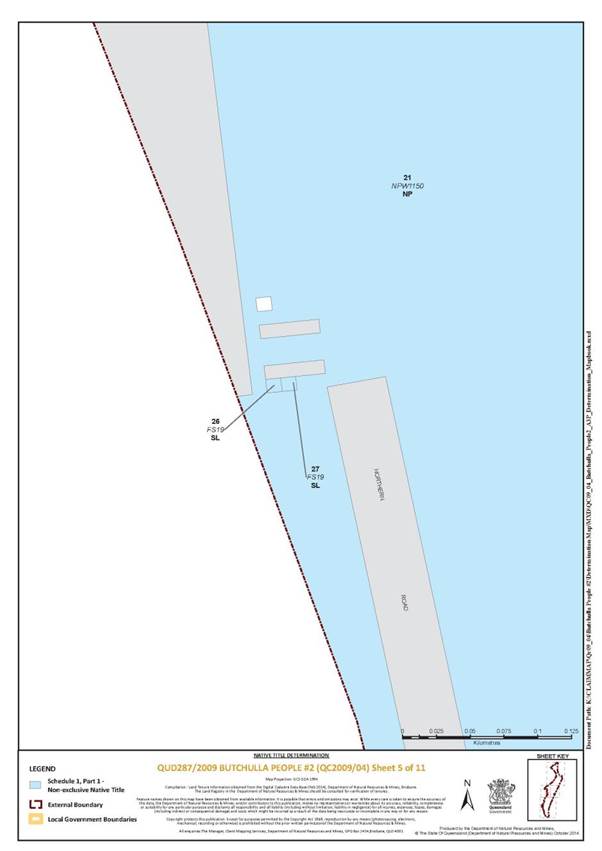

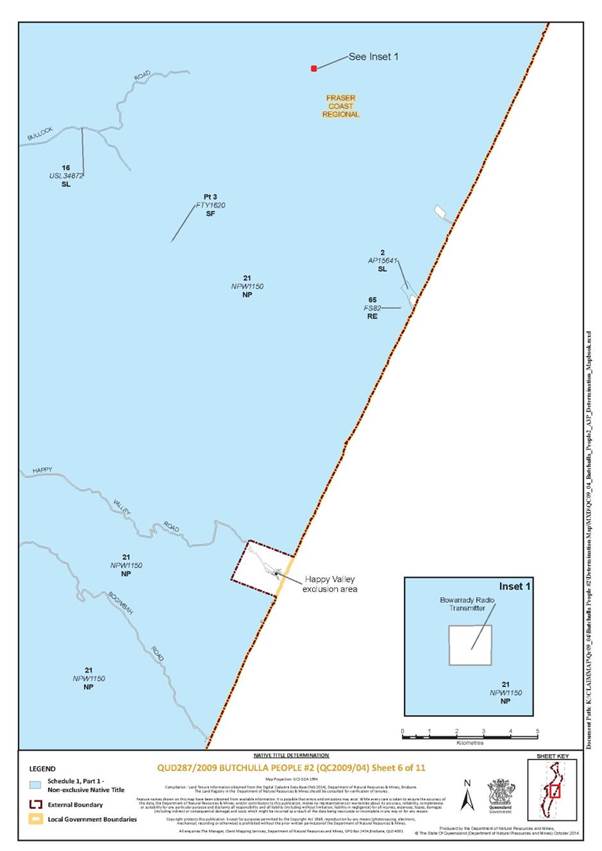

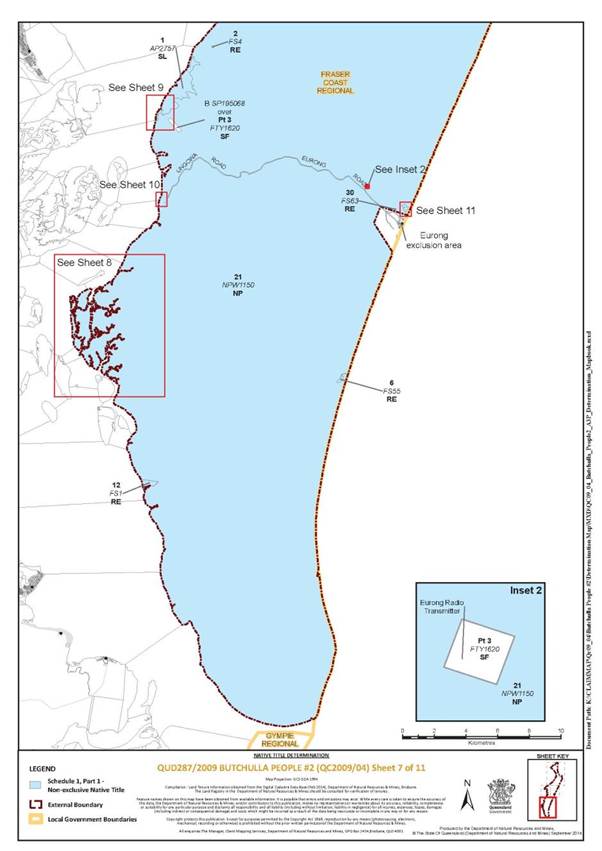

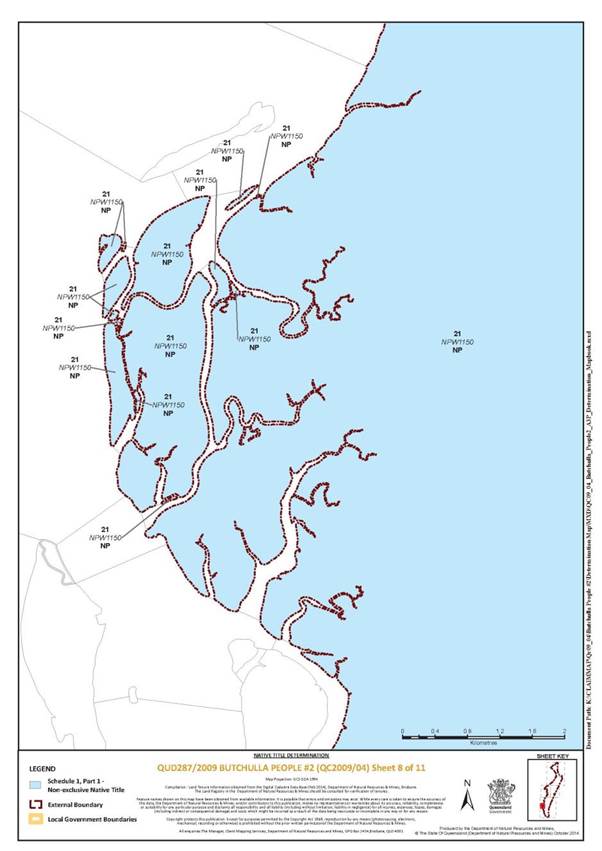

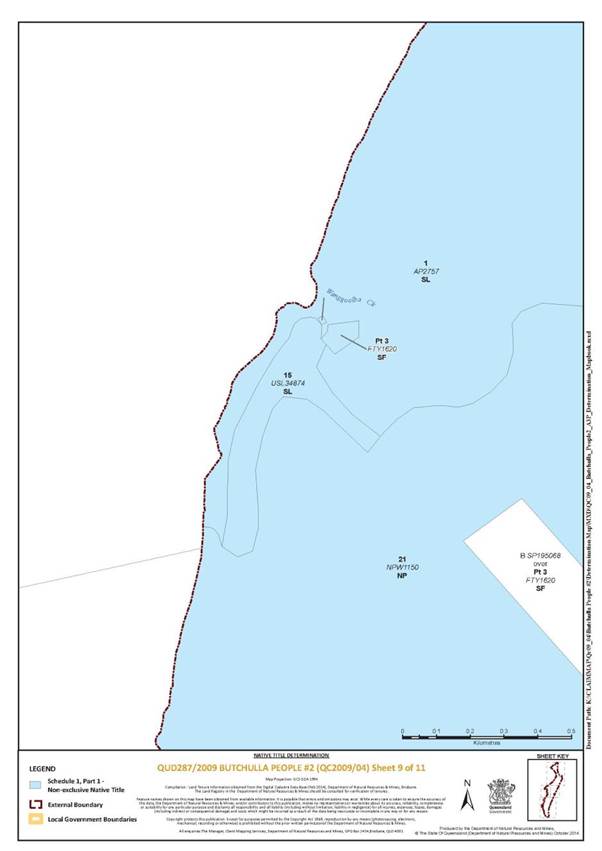

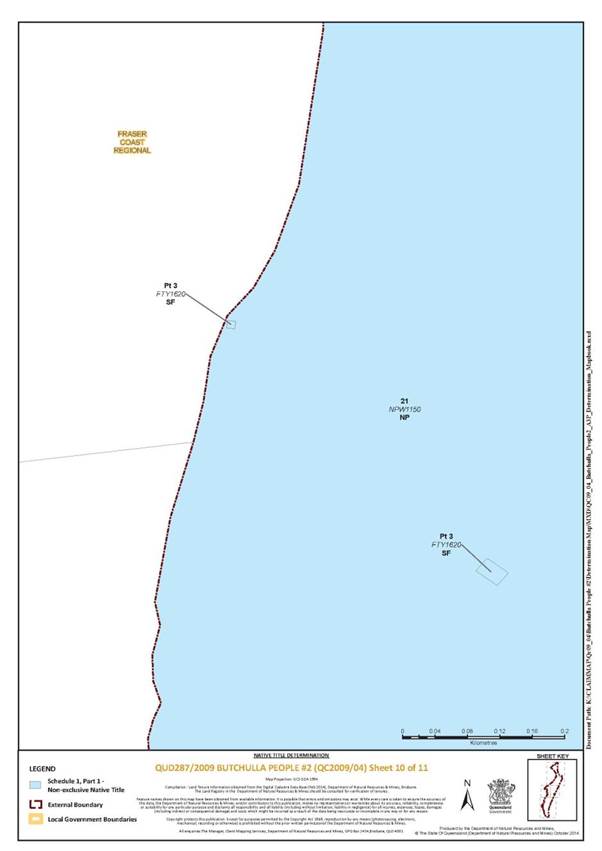

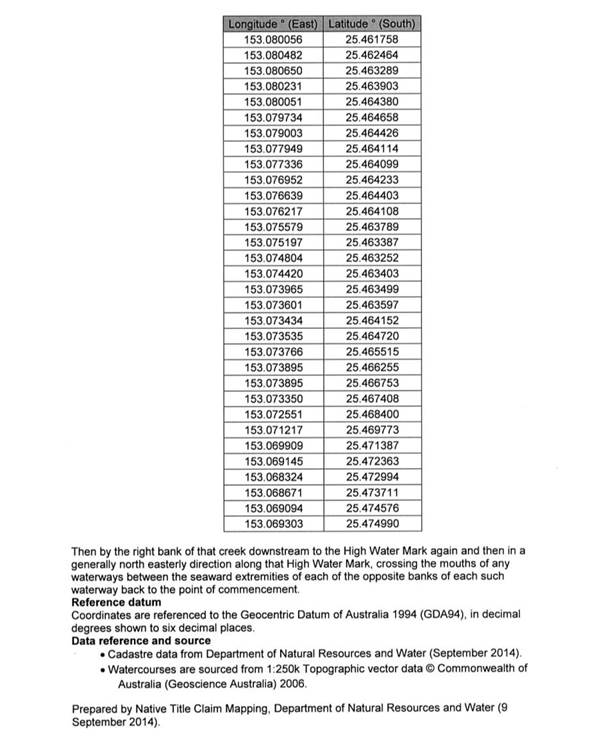

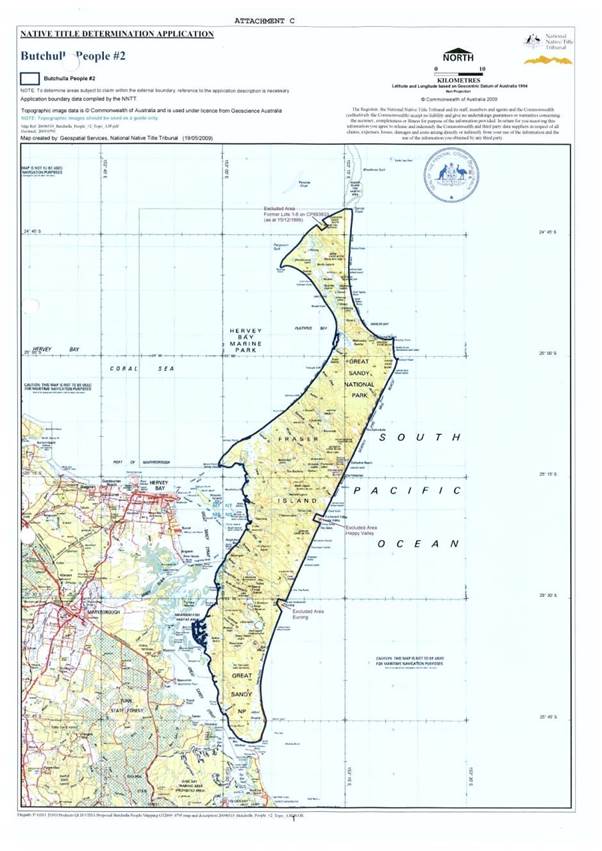

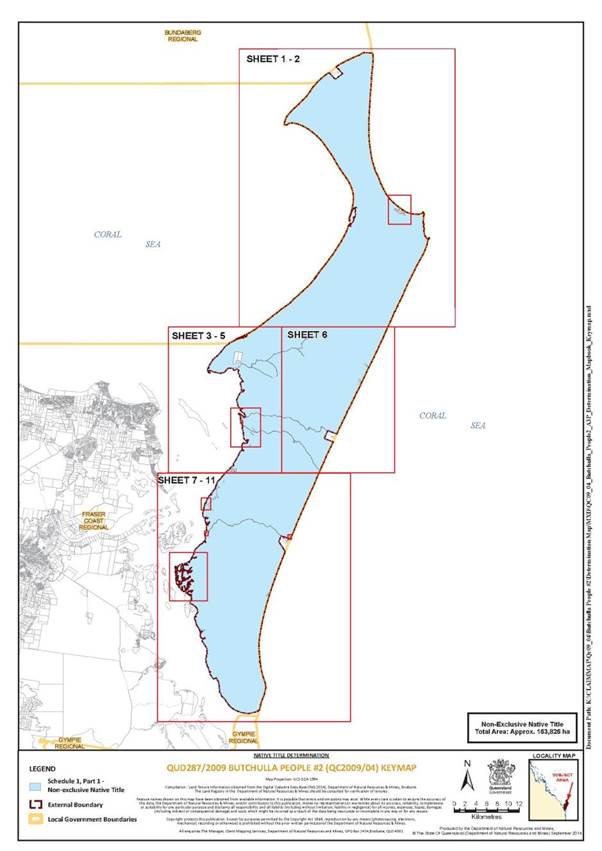

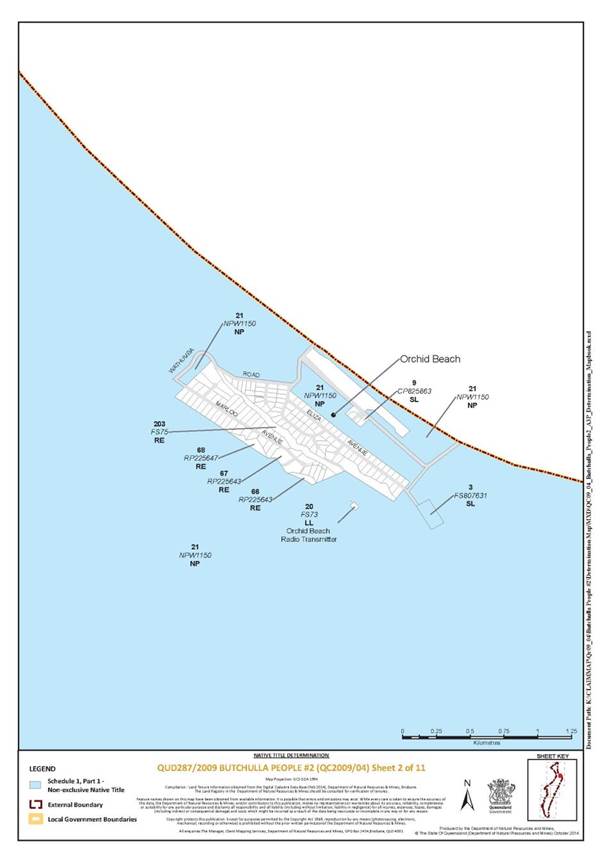

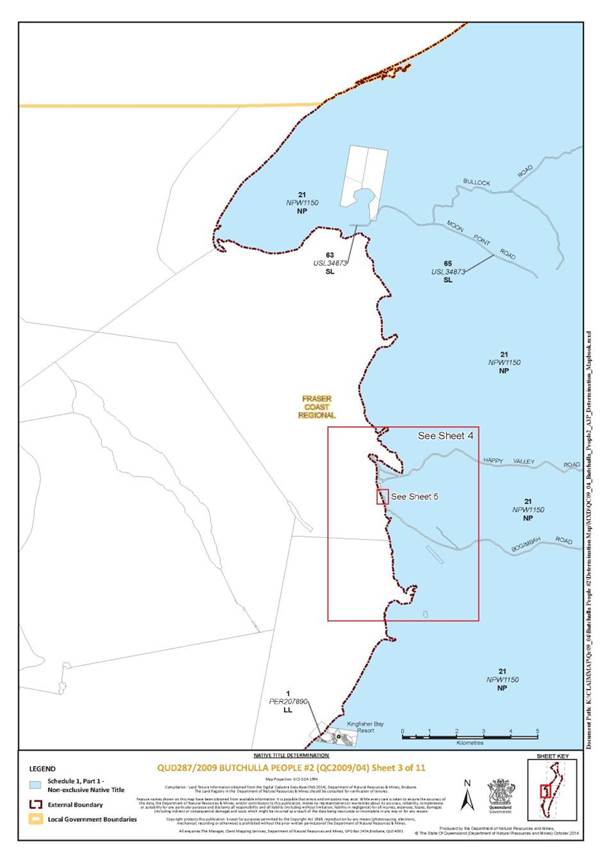

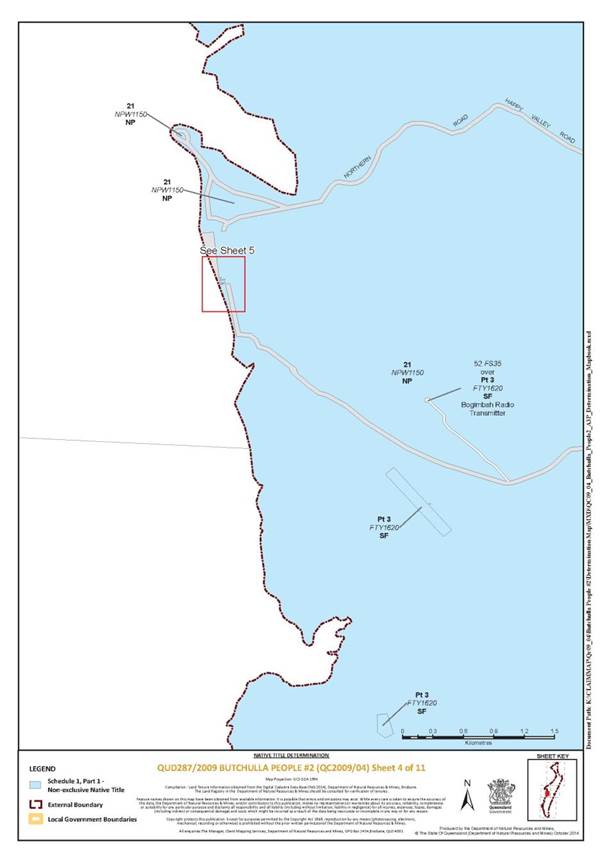

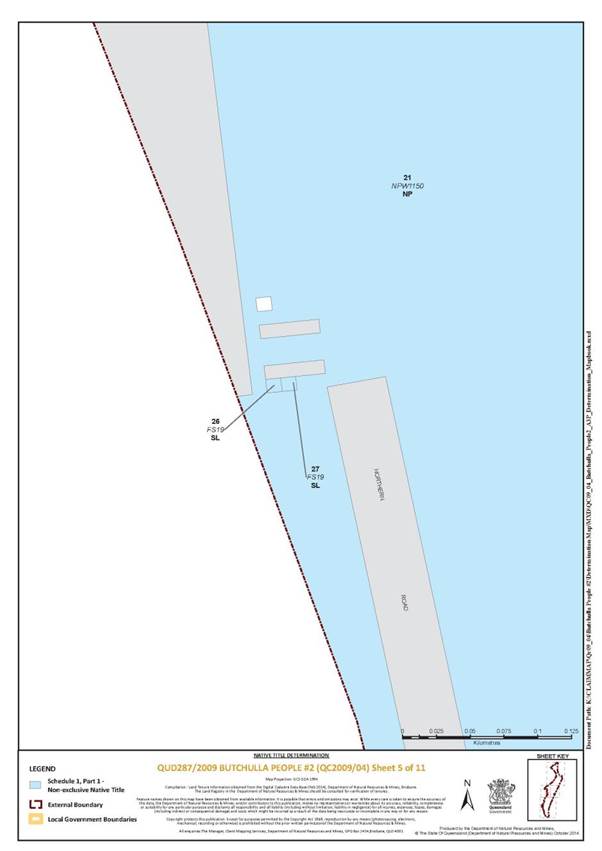

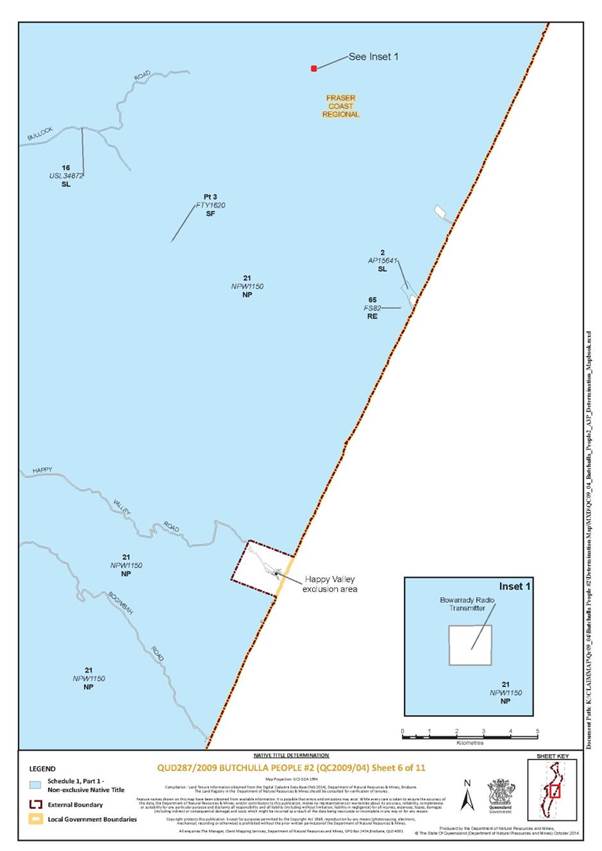

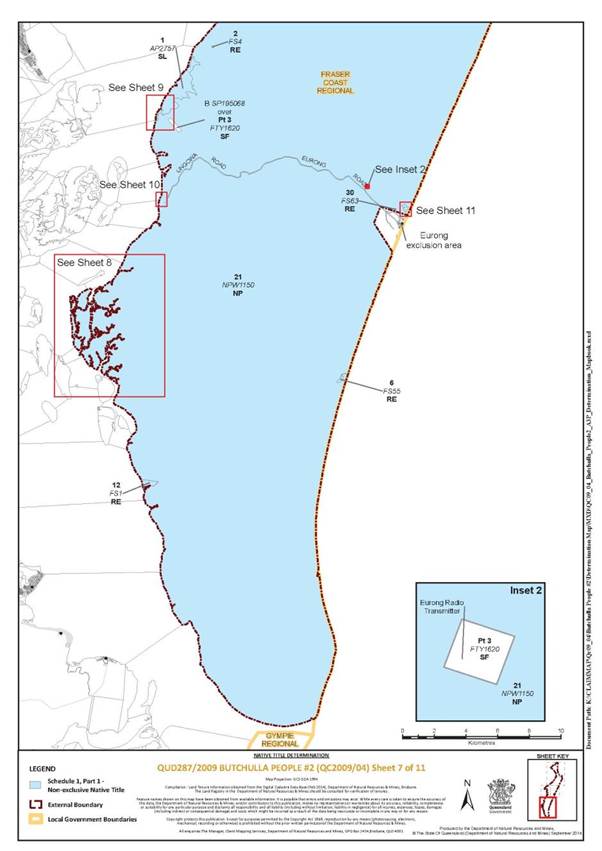

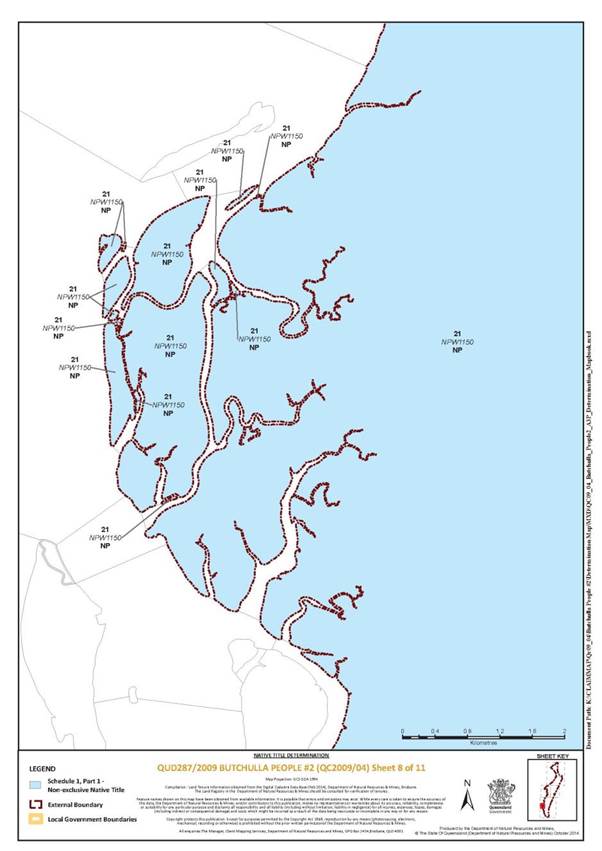

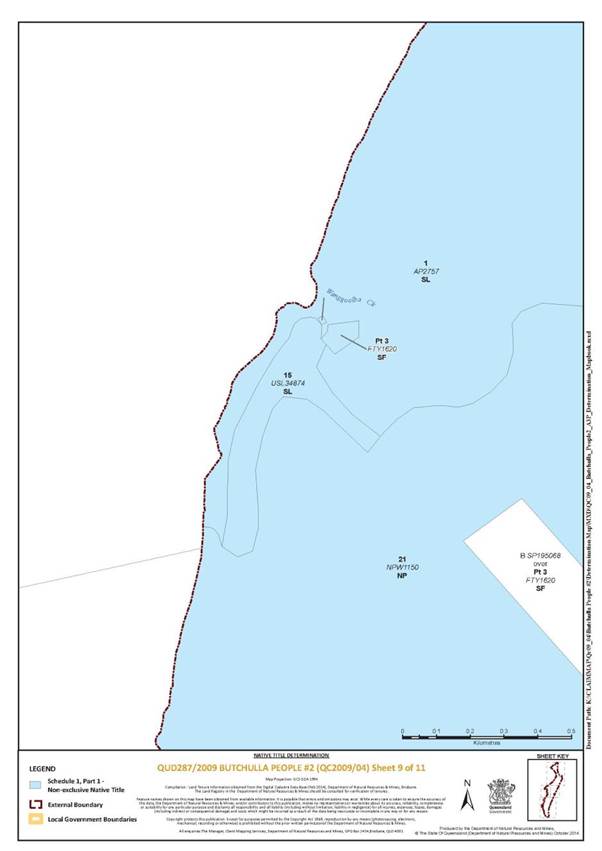

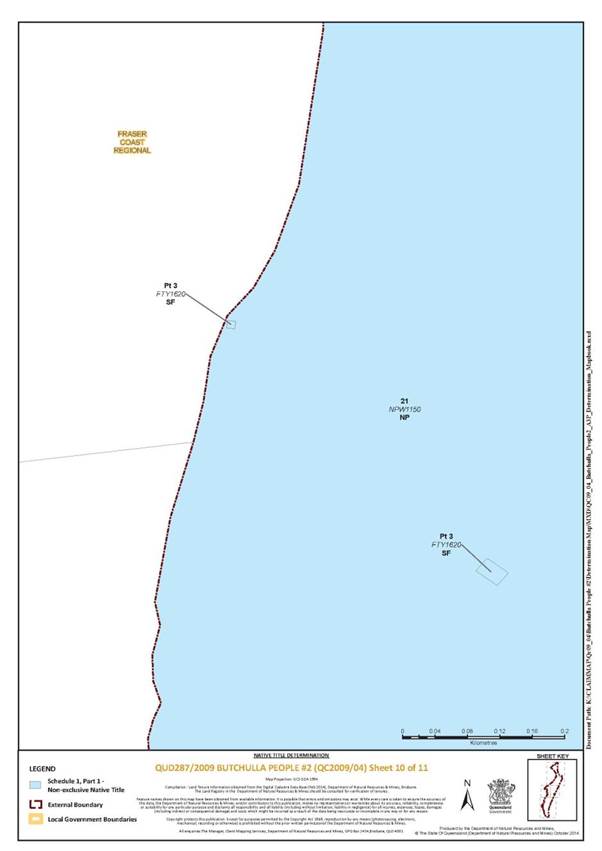

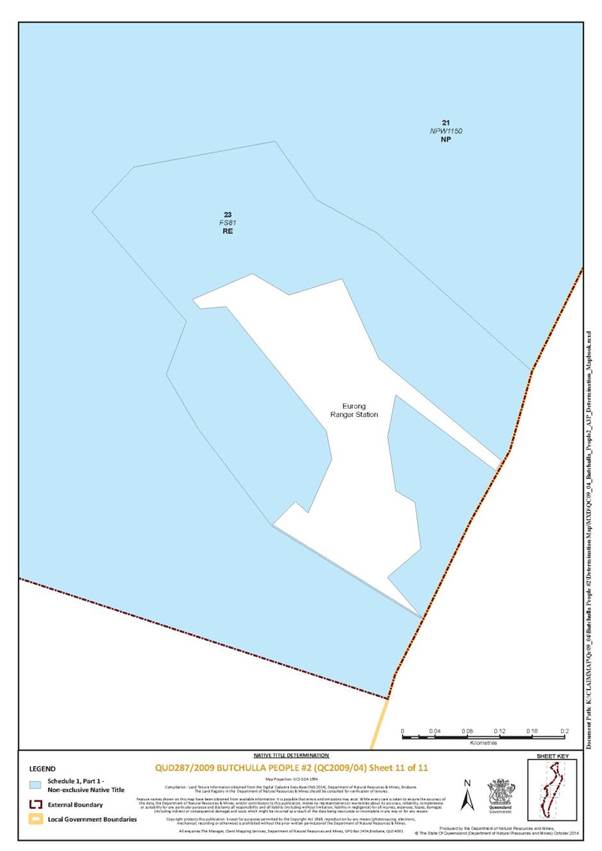

B. Maps of Determination Area

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 287 of 2009 |

BETWEEN: | BRONWYN DE SATGE, RODERICK TOBANE, BELINDA BARROWCLIFFE, SHIRLEY BLAKE, GEMMA CRONIN, SANDRA PAGE, LURLINE LILLIAN BURKE, CEPHA ROMA AND BRETT NUTLEY ON BEHALF OF THE BUTCHULLA PEOPLE #2 Applicant

|

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND First Respondent FRASER COAST REGIONAL COUNCIL Second Respondent TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED Third Respondent KINGFISHER BAY RESORT VILLAGE PTY LTD Fourth Respondent

|

JUDGE: | COLLIER J |

DATE: | 24 OCTOBER 2014 |

PLACE: | FRASER ISLAND |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 Before me is a further amended application (“the application”) filed pursuant to the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (“the Act”) in accordance with orders of this Court on 25 September 2014. The applicant, collectively Bronwyn de Satge, Roderick Tobane, Belinda Barrowcliffe, Shirley Blake, Gemma Cronin, Sandra Page, Lurline Lillian Burke, Cepha Roma, and Brett Nutley on behalf of the Butchulla People, has applied for a determination of native title under s 61(1) of the Act in respect of Fraser Island off the coast of central Queensland, subject to certain exclusions to which I will return shortly (“the determination area”).

2 That the pleading before me is a further amended application reflects the fact that there have been earlier versions of this application brought on behalf of the Butchulla People under s 61(1) of the Act. In my view it is unnecessary to detail the history of the amendments to the pleading currently before the Court other than to note that the original application in this proceeding was filed on 27 November 2009. It is common ground that these applications were authorised and made in accordance with the Act.

3 I note that the Butchulla People have also brought another application referable to a broader area including the inter-tidal zone surrounding Fraser Island, the Hervey Bay Marine Park, and contiguous mainland areas (Butchulla People Land & Sea Claim #2 QUD 288 of 2009). I understand that discussions are continuing in respect of that claim. I need make no further comments concerning that claim for the purposes of the matter currently before me.

4 It is not in dispute that the determination area is not the subject of any previously approved determination of native title.

5 All parties to this application are legally represented, and I understand that they have been legally represented throughout the proceeding. I note that the applicant is represented by Queensland South Native Title Services, which has also played a significant part in respect of the organisation of authorisation meetings of the native title claimant group and the negotiation of the agreement currently before the Court.

6 On 30 September 2014 the applicant filed submissions in support of orders sought pursuant to s 87 of the Act. On 10 October 2014 the applicant filed an agreement under s 87 of the Act, signed by all parties, in which the parties agreed to the making of orders (including orders recognising native title in the determination area in the Butchulla People) by consent.

7 The issues before me are:

whether the Court is satisfied that it has power to make orders in, or consistent with, consent orders proposed by the parties for a determination of native title (s 87(1)(c)); and

whether it appears to the Court to be appropriate to make the orders sought by the parties (s 87(1) and (2)).

8 In my view the proposed orders are within the power of the Court, and it is appropriate for me to make the orders sought. My reasons for forming this view are as follows.

THE DETERMINATION AREA

9 I have already noted that the application for determination of native title currently before the Court is referable to Fraser Island. More specifically – although subject to certain additional exclusions to which I will return – the determination area comprises the land and waters of Fraser Island above the high water mark, excluding the following land and waters:

former Lots 1-6 CP893833 (as at 15/12/1999);

commencing at the eastern most corner of Lot 31 on AP 13118 and extending north westerly, south westerly, south easterly and generally north easterly along boundaries of that lot back to the commencement point (Happy Valley exclusion area);

commencing at the eastern most corner of Lot 1 on AP 14520 on the high water mark of Fraser Island and extending north westerly along northern boundaries of that lot, Lot 1 on FS85, again Lot 1 on AP 14520 to its northern most corner; then south westerly and south easterly along boundaries of that lot to the high water mark of the coastline of Fraser Island, then generally north easterly along that high water mark back to the commencement point (Eurong exclusion area).

10 The external boundary of the determination area is represented in the map annexed as attachment “C” to the application, and which is set out immediately below:

11 More detailed maps of the determination area have been submitted by the parties and are as follows:

12 The assertion of native title over Fraser Island is, however, complicated by the existence of areas on Fraser Island which, during the Second World War, were made subject to military orders pursuant to reg 54 of the National Security (General) Regulations 1939 (Cth). The Full Court of this Court in Congoo and Others on behalf of the Bar-Barrum People #4 v State of Queensland [2014] FCAFC 9 has found that the making of an order under reg 54 in relation to an area did not wholly extinguish any rights and interests in that area. I understand that the State of Queensland has filed an application for special leave to appeal to the High Court of Australia from that decision, and while special leave to appeal was granted on 4 September 2014 the appeal has not yet been determined by the High Court. In the circumstances the parties before me have agreed that, should the Court be minded to make the determination sought, areas the subject of orders under reg 54 should be included within the determination area, subject to the right of the State of Queensland to seek to vary the determination in accordance with ss 13(1)(b) and (5) of the Act by removing those areas in the event that the High Court allows the appeal in Bar-Barrum.

13 As I note later in this judgment, in my view this is a practical and appropriate solution to a potentially difficult obstacle hindering a determination of native title by consent.

BACKGROUND

The native title claim group

14 The native title claimants acknowledge themselves as being, collectively, Butchulla People. In the application the native title holders for the determination area are described as the Butchulla People who are the biological descendants of the following people:

(a) Father/Mother of Gracie and Maudie Daramboi

(b) Mother of Jessie Aldridge’s mother and Lappy

(c) Mother of Charles Richards

(d) Garry Owens

(e) Annie Morris/Anna Gala nee Morris

(f) Granny Polcus/Jenny Brown

(g) Willy Brown/Mamboo/Namboo

(h) George Gundy

(i) Willy Wondunna

(j) Jack Morris

(k) Mary Ann (mother of Susan Rooney)

(l) Roger Bennett

(m) Percy Coulson

(n) Mother of John and Rosie Broome

(o) Mother of Clara, Henry, Percy and Lucy Wheeler.

15 Mr Edward Doolan in his affidavit affirmed 20 March 2013 deposes that he was taught that the Butchulla People comprised three families, namely Ngulungbara, Badjala and Dulingbara, even though these families were all under the umbrella of the Butchulla people. Ms Fiona-Lee Foley in her affidavit affirmed 18 November 2011 gave evidence that the prominent family groups she recalled around the Hervey Bay area who were Butchulla People from Fraser Island were the Wondunnas, the Owens clan, the Blackmans and the Galas. There is further evidence before the Court that certain families in the Butchulla People group are associated with particular areas on Fraser Island – in this respect I note evidence of Mr Doolan, Mr Malcolm Burns, Mr Garry Smith, Mr Shawn Foley and Ms Fiona-Lee Foley. So for example Mr Smith deposed that the Owens clan is associated with the middle of Fraser Island. Ms Foley gave evidence that historically the Wondunna family had a house on the western side of Fraser Island.

16 All witnesses are unanimous however that irrespective of association by different people with particular families and parts of Fraser Island, they all identified as being Butchulla People.

History and Anthropology

17 An historical report and three anthropological reports have been filed in these proceedings.

18 The expert historical report filed on 29 September 2014 was prepared by Dr Fiona Skyring. In summary, Dr Skyring was requested to address, in relation to both this claim and the Butchulla Land and Sea Claim #2, the following issues:

Pre-sovereignty society.

Continuity of connection from sovereignty to the present.

The principal factors and situational changes which have affected indigenous people in the determination area since sovereignty having regard to their interaction with non-indigenous societies.

Whether there is evidence to suggest that indigenous people were present and have remained in or in the immediate vicinity of the claimed lands throughout the period between settlement and the present day.

19 Expert anthropological reports were prepared and filed as follows:

A report dated November 2011 entitled “Butchulla Native Title Claims: Consolidated Genealogies” by anthropologist Ms Susan O’Brien filed 29 September 2014.

A second report by Ms O’Brien dated November 2011 entitled “Butchulla Native Title Claims – Consolidated Genealogies; Additional Genealogy: Wheeler Family Genealogy” filed 29 September 2014.

A detailed and lengthy report dated December 2011 entitled “Butchulla Native Title Claims: Anthropologist’s Report” by anthropologist Dr Lee Sackett, filed on 1 October 2014.

20 Dr Sackett noted in his report that, in respect of relevant genealogies, he relied heavily on the material produced by Ms O’Brien.

21 I shall return to consideration of these reports.

Nomination of prescribed body corporate

22 On 10 October 2014 the applicant filed submissions supporting the nomination of Butchulla Aboriginal Corporation ICN 8107 as the prescribed body corporate for the purposes of s 57(2)(a) of the Act. In doing so the applicant relied on the affidavit of Ms Kyleigh Currie, a member of the native title claim group, sworn 26 September 2014.

23 Ms Currie deposed that at a meeting of the Butchulla People in Hervey Bay on 10 August 2014 members of the claim group unanimously passed a resolution that the proposed Initial Members approve the adoption of the proposed Rule Book presented at the meeting as the constitution of the Butchulla Aboriginal Corporation and agree to its incorporation and registration with the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations. The meeting also nominated Ms Currie as the applicant and contact person on registration of the Butchulla Aboriginal Corporation.

24 Ms Currie also deposed that the Butchulla Aboriginal Corporation had been registered, that she nominated it to be the agent prescribed body corporate to perform the functions specified in s 57(3) of the Act with respect to the determination of native title in this matter, and that the Butchulla Aboriginal Corporation had consented to its nomination.

25 A certificate of registration of the corporation, its Rule Book and the consent to the nomination dated 26 September 2014 were annexed to Ms Currie’s affidavit.

Orders sought

26 The parties to the application have agreed on orders they seek in relation to the determination area, and have filed an agreement in writing setting out the terms of the agreement reached.

27 Importantly, the parties ask the Court to make consent orders pursuant to s 87 of the Act acknowledging that native title exists in respect of the determination area.

28 The orders sought by the parties are lengthy and, in addition to acknowledgement of the reservation of the position concerning the State and specific places within the determination area potentially subject to extinguishment as a result of military orders, require findings that:

native title exists in all areas of the determination area other than those identified;

any rights granted are subject to limitations concerning the exercise of native title rights and interests, and acknowledgement that any native title rights and interests granted do not confer possession, occupation, use or enjoyment of the determination area to the exclusion of all others;

there are no native title rights in or in relation to minerals as defined by the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) and petroleum as defined by the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) and the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld);

the relevant native title rights and interests are not to be held on trust; and

the relevant native title rights and interests are non-exclusive rights to engage in activities such as access and travel over the land; camp and live on the land; hunt, gather and otherwise use the natural resources of the land; conduct and participate in rituals and ceremonies on the area; access, maintain and protect places and areas of importance; teach on the area; hold meetings on the area; and light fires for personal and domestic purposes.

RELEVANT LEGISLATION

29 The jurisdiction of the Court in these proceedings, being proceedings in respect of which the parties seek a consent determination, is found in s 87 of the Act. Materially, s 87 provides as follows:

Power of Federal Court if parties reach agreement

(1) This section applies if, at any stage of proceedings after the end of the period specified in the notice given under section 66:

(a) agreement is reached between the parties on the terms of an order of the Federal Court in relation to:

(i) the proceedings; or

(ii) a part of the proceedings; or

(iii) a matter arising out of the proceedings; and

(b) the terms of the agreement, in writing signed by or on behalf of the parties, are filed with the Court; and

(c) the Court is satisfied that an order in, or consistent with, those terms would be within the power of the Court.

(1A) The Court may, if it appears to the Court to be appropriate to do so, act in accordance with:

(a) whichever of subsection (2) or (3) is relevant in the particular case; and

(b) if subsection (5) applies in the particular case – that subsection.

(2) If the agreement is on the terms of an order of the Court in relation to the proceedings, the Court may make an order in, or consistent with, those terms without holding a hearing or, if a hearing has started, without completing the hearing.

Note: If the application involves making a determination of native title, the Court’s order would need to comply with section 94A (which deals with the requirements of native title determination orders).

30 Section 94A, to which reference is made in the note to s 87(2), provides:

An order in which the Federal Court makes a determination of native title must set out details of the matters mentioned in section 225 (which defines determination of native title).

31 In turn, s 225 provides:

A determination of native title is a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area (the determination area) of land or waters and, if it does exist, a determination of:

(a) who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are; and

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area; and

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area; and

(d) the relationship between the rights and interests in paragraphs (b) and (c) (taking into account the effect of this Act); and

(e) to the extent that the land or waters in the determination area are not covered by a non exclusive agricultural lease or a non exclusive pastoral lease--whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

Note: The determination may deal with the matters in paragraphs (c) and (d) by referring to a particular kind or particular kinds of non native title interests.

32 It is not in dispute that the relevant notification period under s 66 of the Act has expired and that no approved determination of native title has previously existed in respect of the determination area.

33 In light of these provisions and the common ground I have identified, I now turn to the evidence before me.

EVIDENCE BEFORE THE COURT

34 As I noted earlier in this judgment, a considerable volume of material has been filed to support the native title determination application in both its original and amended forms. In particular, historical, anthropological and affidavit evidence has been produced and filed to substantiate the claim of the applicant that the Butchulla People have native title rights and interests in respect of the determination area within the meaning of the Act. It is appropriate to examine this evidence in more detail.

Historical report

35 Dr Skyring has produced a detailed and, it must be observed, fascinating account of the history of the European contact with the Butchulla People of Fraser Island. Indeed it appears that European contact with the Butchulla People coincided with not just early contact, but the very earliest European contact with the indigenous peoples of Australia. At paragraphs 12-14 of her report Dr Skyring writes:

12. The first written reports of the presence of Aboriginal people in the claim areas were from Captain James Cook in 1770. Cook sailed northwards along the eastern coast of Australia from April to June of 1770 in the ship the Endeavour, after circumnavigating and mapping the coast of New Zealand. He and his crew did not land on Fraser Island, nor did they realise it was an island. Cook’s published chart of the Queensland coastline showed his ship’s passage from Double Island Point and Wide Bay on the southern boundary of the Butchulla Land and Sea #2 claim area northwards. He mapped Sandy Cape and Break Sea Spit as being part of the mainland, when later maritime expeditions found that the Great Sandy Island was separated from the mainland by a narrow strait. Cook wrote in his journal for 20 May 1770 that in the evening they sailed past,

a black bluff head or point of land, on which a number of Natives were Assembled, which occasioned my naming it Indian Head.

13. It was the convention at the time for British explorers to refer to all Indigenous inhabitants of the South Seas as ‘Indians’; it was clear that here Cook and his crew saw Aboriginal people on Fraser Island. As he sailed along the coast and mapped Sandy Cape, Cook wrote,

From this last the land Trends a little more to the Westward, and is low and Sandy next the Sea, for what may be behind it I know not; it must be all low, for we could see no part of it from the Mast head. We saw people in other places besides the one I have mentioned; some Smokes in the day and fires in the Night.

Cook chartered Break Sea Spit and Hervey Bay before continuing north-west along the coastline.

14. What Cook and his crew did not realise was that the Aboriginal people on Fraser Island whom he called ‘Indians’ had followed his ship’s passage along the eastern shore of the Island. In 1923 Edward Armitage, one of the first pastoral station owners in the Butchulla claim areas, translated a corroboree song about Cook’s passage. Back in 1868 Armitage had been adopted as a member of a group he called the Wide Bay or Ginginbarra tribe, and was one of only four white men given the honorific of Bunda. This was the name of one of the four sections of the tribe, as Armitage described it ‘for the regulation of marriages and the avoidance of consanguinity. Linguist and ethnographer F.J. Watson, who published this and other Fraser Island corroboree songs, considered that Armitage’s translations were ‘very broad and derived from translation by the aborigines. This was the translation of the song:

These strangers where are they going?

Where are they trying to steer?

They must be in that place, Thoorvour, it is true.

See the smoke coming in from the sea.

These men must be burying themselves like the sand crabs.

They disappeared like the smoke.

(Footnotes omitted.)

36 Dr Skyring writes in her report that this song has been interpreted by some as referring to the passage of Captain Cook, the reference to “Thoorvour” being to Thoorvour shoal which the local people was aware was a dangerous shoal near what is now known as Indian Head on Fraser Island.

37 Dr Skyring then refers to the expeditions of explorer Matthew Flinders, and notes that in Flinders’ published account Flinders M, A Voyage to Terra Australis: undertaken for the purpose of completing the discovery of that vast country, and prosecuted in the years 1801, 1802, and 1803 in His Majesty’s ship the Investigator (First published 1814, Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia, 1966) the explorer recounts in detail his visit to Fraser Island in 1802. Dr Skyring writes as follows:

18. … On 26 July 2802 on the ship the Investigator, Flinders and his crew arrived at Wide Bay, and continuing around the bay discovered that there was a narrow opening leading to ‘a piece of water like a lagoon.’ At this opening to the Great Sandy Strait, Flinders observed that,

Upon the northern side of the opening there was a number of Indians, fifty as reported, looking at the ship, and near Double-island Point ten others had been seen, implying a more numerous population than is usual to the southward. I inferred from hence that the piece of water at the head of Wide Bay was extensive and shallow; for in such places the natives draw much subsistence from the fish which there abound, and are more easily caught than in deep water.

Flinders steered northward, sailing towards the eastern shore of Fraser Island, and wrote that

Nothing however can well be imagined more barren than this peninsula; but the smokes which arose from many parts, corroborated the remark made upon the population about Wide Bay; and bespoke that fresh water was not scarce in this sandy country. Our course at night was directed by the fires on the shore.

19. By daylight they had arrived at Indian Head then sailed on to Sandy Cape, and searched for a passage through Break Sea Spit into Hervey Bay, but the water was too shallow so Flinders anchored off Fraser Island to wait for Lieutenant Murray in the Lady Nelson. The ship’s botanist, Mr Brown, went ashore near Sandy Cape and Flinders recorded that

… some natives being seen upon the beach, a boat was sent to commence and acquaintance with them; they however retire and suffered Mr Brown to botanise without disturbance.

Along with a party of naturalists, another was sent ashore to collect wood. Flinders led a party of six, including his ‘native friend’ Bongaree, and headed towards Sandy Cape:

Several Indians with branches of trees in their hands, were there collected; and whilst they retreated themselves were waving to us to go back. Bongaree stripped off his clothes and laid aside his spear, as inducements for them to wait for him; but finding they did not understand his language, the poor fellow, in the simplicity of his heart, addressed them in broken English, hoping to succeed better. At length they suffered him to come up, and by degrees our whole party joined; and after receiving some presents, twenty of them returned with us to the boats, and were feasted upon the blubber of two porpoises, which had been brought on shore purposely for them. At two o’clock the naturalists returned, bringing some of the scoop nets used by the natives in catching fish; and we then quitted our new friends, after presenting them with hatches and other testimonials of our satisfaction.

(footnotes omitted.)

38 In her report Dr Skyring writes of the next expedition to the area led by Captain William Edwardson, who also wrote of seeing indigenous people, and of runaway convicts and shipwreck survivors who spent time on Fraser Island with the Butchulla People (including Captain Fraser and his wife Eliza Fraser who survived the shipwreck of the Stirling Castle in 1836). She also refers at paragraph 38 of her report to the writings of pioneer Andrew Petrie in 1842, including the following:

The blacks are very numerous on Fraser Island; there is a nut they find on it which they eat, and the fish are very plentiful… The Wide Bay River is navigable…the country on its banks is a good sheep country, and the farther you proceed to the westward the better the land. The blacks informed me there is a river about ten miles beyond the Wide Bay River, and another more to the north-westward, and pointed a long way to the interior to where the water came from… They also informed us that there was a beautiful country about forty miles from Bahpal Mountain [Bauple Mountain], extending quite to the ocean, and abounding in emus and kangaroos. According to their account, this country is thinly wooded.

(footnotes omitted.)

39 Dr Skyring notes at paragraph 45 of her report that in 1897 Queensland government administrator Archibald Meston had estimated that there were at least 2000 Aboriginal people on Fraser Island in 1836.

40 The historical report of Dr Skyring supports findings that, at the very least, indigenous people lived on Fraser Island in an observable pre-sovereignty society, and that those indigenous people were Butchulla People, being ancestors of the members of the claim group in these proceedings.

Anthropological reports

41 Three anthropological reports have been filed in these proceedings. The reports of Ms O’Brien provided detailed genealogical information relating to families in the Butchulla People native title claim group. A detailed anthropological report relating to connection was produced by Dr Lee Sackett. In his report, Dr Sackett comments on pre-sovereignty society including earlier reports, laws and customs of pre-sovereignty society, rights and interests, apical ancestors, and continuity of connection from sovereignty to the present. In considering the application before me it is useful to summarise key points addressed by Dr Sackett.

Pre-sovereignty society

42 First, Dr Sackett observed that the majority of claimants regularly spoke about Fraser Island, and about the Island being Butchulla country (at paragraphs 20, 456). He also notes (at paragraph 20) that this is consistent with the apparent views of a number of early commentators and locally influential views of recent commentators, and wrote in detail of the evidence concerning families being associated with specific areas on Fraser Island.

43 Dr Sackett also observed that some claimants had identified as Butchulla since childhood; some had identified as Butchulla when adults; and others had self-identified in a somewhat different way (for example Ms Cepha Roma identified as “Batjala”). However Dr Sackett noted at paragraph 147:

Whatever the case, I can report that the great bulk of the people I spoke with overall came across as certain and forceful in their Butchallaness, regardless of whether their awareness and knowledge came from their parents and/or grandparents, from Tindale’s genealogy sheets, from documents provided by Community and Personal Histories, or in some other manner.

Laws and Customs of pre-sovereignty society

44 In considering laws and customs of pre-sovereignty Butchulla society, Dr Sackett included reference to earlier works by writers including John Green (1851-1862), James Green (1890), Harry Aldridge (1880s and 1890s), Edward M Curr (1887), RH Mathews (1898), Alfred Howitt (1904), John Mathew (1910), Caroline Tennant Kelly (early 1930s), Norman Tindale (1940) and Lindsay Winterbotham (1950s).

45 Dr Sackett reported, inter alia at paragraphs 466-624 of his report:

Butchulla People traditionally believed in a supreme being, namely a sky-god, although many claimants with whom Dr Sackett spoke were Christians.

Butchulla People believed in totems. Anthropologist Norman Tindale wrote that in Butchulla society, totems were inherited through the mother, although the totem of the father was treated with respect. Totems were animals including dolphins, ducks, kites, honey bees and carpet snakes as well as plants including the cypress pine tree. There was some inconsistency in research as to whether totems could be eaten.

Circumcision or knocking out of teeth of young men was not practised, although other initiation rites were practised in relation to young men including trial by fire.

Young women on reaching puberty would be taken away into the bush, and ritually instructed in relation to marriage and mating.

Children joined the land holding units of their fathers.

A person is a Butchulla person because they are born as a Butchulla person. Many claimants referred to it as “bloodline”.

Permission was required from Butchulla People before persons from other countries accessed Butchulla land. Failure to seek permission was tantamount to trespass, and traditionally was punishable by, for example, spearing. Dr Sackett noted that the concept of requesting permission to enter Butchulla land was maintained by current members of the claim group.

Kin relationships guided interpersonal behaviour such that, for example, certain relationships were within proscribed boundaries of consanguinity and that marriage within such relationships was forbidden.

Rights and interests

46 Dr Sackett noted in his report that, in the application, the Butchulla People claimed eleven rights and interests, namely:

1. Hunt, fish, harvest, collect and in general use, take and enjoy the natural resources and attributes of the claim area for customary purposes;

2. Use the claimed area for all social, ritual and economic purposes, including the right to rear, socialise and educate their children on the claimed area;

3. Inherit native title rights and interests;

4. Bestow and acquire native title rights and interests;

5. Resolve amongst themselves any disputes concerning the claimed area;

6. Move freely about the claimed area;

7. Live on and erect residences and other infrastructure on and in the claimed area;

8. Manufacture materials, tools, artefacts, objects and weapons from the natural resources in the claimed area;

9. Dispose of products of the claimed area and manufactured products derived from the claimed area by trade, exchange or gift;

10. Manage, conserve and care for the claimed area;

11. Conduct funerals and ceremonies on and in relation to and to bury members and ancestors of the native title claim group on the claimed area.

47 Dr Sackett observed that the rights and interests asserted by the Butchulla claimants are delineated and grounded, where possible, through indicative instances of early and ongoing practice (at paragraph 630). To that extent there is a very distinct link between the backdrop of law and custom developed over time in the Butchulla community, and the rights and interests asserted. After considering the detailed material before him Dr Sackett opined, in summary:

1. The evidence supported the idea that Butchulla people have the right to freely access and move about Butchulla country, at least to the extent that such access and movement does not take them into areas that are deemed sensitive, off limits or dangerous (at paragraph 641).

2. To his knowledge no Butchulla People lived on Fraser Island at the time of claim research. A few Butchulla people worked there, but many camped there and sometimes for extended periods. Dr Sackett considered that although the evidence was limited, it supported the idea that Butchulla People, as Butchulla People, have the right to live and camp on Butchulla country (at paragraph 647).

3. In relation to the exploitation of the natural resources of the area:

(a) some practices were no longer maintainable because they were now illegal, including hunting turtle and dugong;

(b) however the exploitation of marine resources was most consistently and continuously engaged in, although claimants had on occasion spoken of gathering plant resources and hunting game. Dr Sackett noted that one claimant remarked on the earlier use of dingoes by Butchulla People to chase kangaroos (at paragraph 666).

4. Artefacts made historically by Butchulla People including nets, spears, and bark canoes appear to have been replaced substantially by European tools. Dr Sackett observed, however that baskets continued to be made, if only for sentimental reasons (at paragraph 681). To that extent, Dr Backett considered that the evidence supported the idea that Butchulla people have the right to make artefacts in the wider sense of the term from resources in the determination area (at paragraph 683).

5. In relation to the right to exchange and trade the resources of the area, Dr Sackett noted that he had difficulty distinguishing between exchange and trade. He noted that more recently Butchulla People had exchanged or traded things from Butchulla country for money, for example mangrove worms harvested by older men which were sold to non-Aboriginal fishermen (at paragraph 689). Further Dr Sackett noted that exchanges of different types of food (for example, meat in return for vegetables) “probably goes on constantly amongst claimants. It almost certainly went on amongst claimants’ ancestors” (at paragraph 694). Dr Sackett considered that selling of worms for cash, as well as the selling of art from and of the country, were “trade” (at paragraph 697).

6. Dr Sackett noted that there was strong evidence to support the belief of the Butchulla People that they had an obligation to care for their country, and in particular that there would be repercussions if the country was not cared for. He quoted one claimant, Ms Lillian/Lurline Burke, who said that part of being Butchulla was “Respect country. Care for country.” (at paragraph 702).

7. In respect of the right to hold ceremonies on Butchulla land, Dr Sackett noted activities in relation to a bora ring, smoking people and places, and naming children. He was unsure whether some of these ceremonies were traditional or more recently adopted, however he also noted that claimants seemed, at least at times, to be performing these rites on Butchulla country (at paragraph 713).

8. Dr Sackett referred in his report to the importance to the Butchulla People of passing knowledge down to succeeding generations and the associated right of the Butchulla People to teach others about Butchulla country. He noted that this tradition was being carried on, not only orally (with stories recorded on computer) but in published form. In this respect Dr Sackett referred to publications of two children’s books by claim group member Mr Shawn Wondunna-Foley Dingo Finds a Friend and Deadly Red Roo (paragraphs 714-716).

9. In relation to the right to acquire and transmit rights and interests in Butchulla country, Dr Sackett noted that Butchulla People were Butchulla through descent (paragraphs 724-725).

Apical ancestors

48 In his report Dr Sackett analysed information concerning named Butchulla apical ancestors and their descendants, being the Butchulla People. As I noted earlier in this judgment, Dr Sackett acknowledged that he relied heavily on the Butchulla genealogies prepared by Ms O’Brien, which were based largely on the knowledge and recollections of Butchulla claimants and reports of staff at the Community and Personal Histories section of the Queensland Department of Communities. After detailed consideration Dr Sackett opined that the Butchulla People were the biological descendants of those apical ancestors. In summary, Dr Sackett observed:

A combination of evidence and surmise points to some of those named apical ancestors or their immediate forebears being in or around Butchulla country either before or during the early moments of effective sovereignty, which he took to be marked by the 1842 opening up of the area to settlement (at paragraph 939).

Some ancestors and descendants were directly linked to or associated with the country (for example Billy Daramboi and his wife were strongly identified as Butchulla people from Fraser Island) (at paragraph 940).

Some ancestors and descendants were linked to or associated with places that were taken as laying in Butchulla country (at paragraph 941).

There are descendants of some apical ancestors who have maintained clear ongoing connections to Butchulla country, in particular the descendants of Garry Owens and Willy Wondanna (at paragraph 942), while some descendants did not maintain those connections.

The descendants having little or no ongoing connections with Butchulla country nonetheless remained Butchulla in the eyes of the Butchulla People with whom Dr Sackett spoke (at paragraph 944).

Continuity of connection from sovereignty to the present

49 This is clearly a critical aspect of the application before me. In considering this issue, Dr Sackett also took into account Dr Skyring’s report, factors which have affected the group, group members’ interaction with one another, and members’ interaction with country.

50 First, Dr Sackett’s evidence was that the claimants acknowledged and observed a body of law and custom as they relate to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of lands and waters, having their roots in the normative system existing at sovereignty (at paragraph 992). While the group no longer practised “increase” ceremonies, nonetheless members interviewed by Dr Sackett averred that they shared Butchulla lands with the overseeing and protecting spirits of Butchulla dead (paragraph 993). Identification as Butchulla by descent from apical ancestors was a strong component of membership of the claim group. Dr Sackett gave evidence that the fundamentals of descent-based membership and country links continued, as did the concept of the necessity of permission to access and exploit Butchulla lands. Further, Dr Sackett gave evidence that elders continued to guide decisions regarding Butchulla country, and that this seemed in line with traditional practice (paragraph 993).

51 Second, Dr Sackett had earlier observed in his report that descendants of a number of apical ancestors had maintained little or no physical connection with the area of the claims, whereas descendants of other apicals had maintained relatively solid physical connection to the area of claims (in particular the descendants of Garry Owens and Willy Wondunna). The dislocation of some Butchulla people from their country resulted from a number of causes including:

the settlement of non-Aborigines in the area beginning in the 1840s, accompanied by increasing competition for resources and violence between indigenous and non-indigenous people;

the gradual incorporation of the local population into the pastoral and timber industries as unskilled labour;

the establishment of a mission on Fraser Island in 1897;

the removal of many local indigenous people to Yarrabah in 1904 as well as other removals (paragraph 996).

52 In light of this dislocation Dr Sackett opined that it was not surprising that relatively few members of the Butchulla People had been able to maintain ongoing physical connection with their country.

53 Overall, however, Dr Sackett was satisfied that fundamental laws and customs continued to be acknowledged by Butchulla claimants, which meant that crucial aspects of Butchulla society were transmitted from generation to generation.

Affidavits filed in support of the amended application

54 Affidavits in support of the application have been affirmed or sworn by members of the native title claim group, namely:

Darren Gene Black, affirmed 20 March 2013;

Edward Christian Claude Doolan, affirmed 20 March 2013;

Fiona-Lee Foley, affirmed 18 November 2011;

Garry Owen Smith, affirmed 21 March 2013;

Ian Wallace Wheeler, affirmed 21 March 2013;

Malcolm John Frederick Burns, sworn 18 November 2011;

Marie Jessie Wilkinson, affirmed 21 March 2013;

Peter James Martin, affirmed 15 March 2013;

Shawn Wondunna-Foley, affirmed 18 November 2011.

55 The material in these documents attests to the basis of the witness’ identification as a member of the Butchella people and of their connection to the claim area under their traditional laws and customs. They are compelling reading. All witnesses deposed as to the aspects of Butchulla culture they had learned from elders, recounted traditional stories, and gave evidence of sacred places, totems and rules. Some of this evidence is relevant to areas outside the determination area, in particular on the mainland, but which the witnesses depose is also Butchulla country. I have extracted a number of paragraphs from these affidavits in which the witnesses give evidence particularly referable to Fraser Island and the interests of the Butchulla People there.

Mr Darren Black

56 In his affidavit Mr Darren Black deposed as to his ancestry, and to his early years growing up in Hervey Bay and Gladstone with his grandmother. He stated that his grandmother and his Aunty Olga told him everything he knows about Butchulla country. In particular he deposed:

16. I am from Fraser Island. My people are from there and they live all over the place, but mostly in the Bay. Nanna used to take me down to the Bay nearly every weekend to see my family – my brother, sister, cousins, aunts and uncles. Nan always told me that this is where I am from.

57 Mr Black gave evidence of sites and areas of significance (including men’s and women’s areas), rituals of acknowledgement when he visits Fraser Island, resource use (including only taking enough fish for himself and the family), and eating native foods including witchetty grubs and midgen berries. He also gave evidence concerning ceremonies and permission protocols, for example:

41. Nanna taught me not to take things from where they belong on country. One of the rangers, a white fella, took a whale bone from the western side of the island and he was telling us (Aboriginal rangers) about it. I told him, “Oh, no, mate. We better take that back, we’ll take that back.” He understood after that because, straight away, he wanted to take that bone back to where he took it. He was finding some discomfort at night. He never usually got nightmares, but he was getting nightmares. That is what happens when you take things from country. The ancestors, the spirits of the trees or animals, will bother you.

Mr Edward Doolan

58 Mr Doolan gave evidence that he was a “Badjala” man, through his mother and his mother’s family. He said that his maternal grandmother was born around 1875 on Fraser Island, and his maternal grandfather was from Sandy Cape on Fraser Island. He deposed:

7. I have always had a keen sense of who I am and who my mob are. I have always known the Island as my country. My country includes not only K’Gari but also parts of the mainland and the waters in between. My mother, my father and my grandparents told me this. They told me to be proud of my heritage. They taught me our history.

8. Granny Mabel and my mother taught me that our mob is made up of three (3) tribes – Ngulungbara, Badjala and Dulingbara. When I say “tribe”, I mean mobs off families, or just families belonging to certain areas. It does not matter. We are all the same. We are all similar people, coming under the big umbrella of Badjala (saltwater people), even though we belong to different areas of our country. Whilst we have our home areas (the areas that we have exclusive responsibilities for), we can move and roam freely, and use other areas on the Island, all of the country, as well. However, if something was to happen on your home turf, like firing up country, people need to consult with and ask you first.

59 In relation to boundaries, Mr Doolan said:

14. Granny Mable [sic] and my mother taught me about the boundaries. They taught me that the Ngulungbara traditional estate goes from north of Boomerang Hill to the northern end of K’Gari, and includes Corroboree Beach. The Badjala occupy the middle of the Island and the contiguous areas of the Great Sandy Straits and its other islands, including Hervey Bay on the mainland as well as all of the watershed areas of the Moonaboola (“Mary River”) and Tinana Creek, south to the mouth of Kauri Creek. The Dulingbara occupy the gundar (“the bottom”), the southern end of the Island, from Eurong on the east to Wangoolbver Creek on the west, taking in the Wondunna estate below Kingfisher Bay Resort & Village, all of the southern part of the Island. Duling means “nautilus shell”, so Dulingbara means “shell people or people of the nautilus shell” …

60 Further, Mr Doolan gave extensive evidence concerning places on Fraser Island, the Butchulla language, authority structures and decision-making, totems and management of natural resources, passing on knowledge, ceremonies and teaching them to the younger generation. He deposed that he visited the Island about three times a year, and further:

61. When I step on country, whether it is the Island, the sea or the mainland, I talk to my ancestors and pay respect. I talk lingo to them and I let them know to expect us there. We also do a bit of a corroboree and we have a fire. If I am taking my nieces, nephews or grandchildren along, I tell them to sing out to the ancestors, to respect the place. I also tell them that if they feel funny, that they should let me know straight away. If they feel funny that does not mean that they have to get out, it just means that the spirits know that one of them might not be Badjala and so I have to talk some more to appease the ancestors.

61 Mr Doolan said that there were sacred sites on the Island, both for men and women, and that Platypus Bay is a “very, very sacred place” as is Lake Carree, Black Lake. He commented on the dingoes on Fraser Island, and said that the Butchulla People have a plant which they use that destroys a dingo’s sense of smell, causing them not to smell food.

Ms Fiona-Lee Foley

62 Ms Foley deposed that she was a Butchulla woman through her mother’s line, and that her apical ancestor was Willy Wondunna. She said that her parents moved from the Hervey Bay area when she was a child because of racism displayed towards her parents because her father, a non-indigenous man, had married her mother.

63 Ms Foley deposed that growing up she always understood that she was of the Butchulla People, and that she was taught by her mother, aunties, and grandmother that “when people come over to your country, people need to show respect”. She said:

27. There are creation stories for the island. My brother, Shawn, has illustrated signs for parks up at Cathedral Beach. There is the story of how the coloured sands came into being. It is an old story about a young girl being promised to an old man. She used to go down and fraternise and meet with the rainbow. Her promised husband got jealous and did not like her meeting him. The old husband caught him out and threw his boomerang at the rainbow and shattered the rainbow. That is how the coloured sands came into being.

28. There is also the story about Yindingie, the rainbow serpent, how he created this hollowed out place in one of the boundaries at Mount Bauple. It is quite a sharp drop in the mountain. I was told that that was where he took off from the earth and went straight up into the sky, leaving a hollow. That was one of the places he would have been. I was told that he would have been in different places at different times through his travels across our country. There was a footprint at Urangan Beach on the rocks, which I have been told relates to Yindingie. That is where he would have travelled through leaving his mark.

…

31. There are places, waterholes, hills and rivers where dreamtime spirits are still present. We say that Little Wabby is a gundil lake which meant it is a bad place. It is next to Big Wabby on Fraser Island. Lake Wabby on the island is now a tourist attraction, and right next to it is Little Wabby. It is overcrowded with bush and growth, so not many people know that the lake is there. But if you to go to its edge, you certainly pick up a sense that it’s very eerie. It’s a sacred lake, and that’s how it’s marked on the map, but it’s a place where you’re not allowed to swim, because it has bad spirits in it. Tourists don’t swim in that lake. I’ve never seen anyone swim in that lake. You can swim in Big Wabby.

Mr Garry Smith

64 Mr Smith is a Butchulla man through his mother, and a descendant of Garry Owens. He deposes that he has lived in Hervey Bay for most of his life, and from the age of 20 worked for nine years on Fraser Island in the forestry industry. He deposed that his grandmother told him creation stories about Butchulla country and how Butchulla People came to the land. He gave evidence as to the importance of respect for elders, and totems. In particular he said:

30. I was taught by my grandparents that each member of the tribe was allocated a eurie (totem) which represented a plant or animal. I was taught that we are not allowed to hunt, eat or harm our totem or our family’s totem. For that, we need special permission from our elders. I was also taught that if someone else wanted to take, kill or eat your totem, they would need your permission, and vice versa… If someone messes with your totem without your knowledge and permission, you are bound to be very sick because it is a part of you, like your brother or sister.

31. My eurie is yul’lu (dolphin). That is the Badjala tribal totem.

32. I was taught that our totemic laws ensure our resources never die out.

65 Mr Smith also spoke of women’s areas where he is not allowed to go on Fraser Island, including Wangoolbver Creek, Puthoo Creek, and the Pinnacles area. Similarly there are men’s areas on the Island which are forbidden to uninitiated men and women, including Lake Wabby, the area between Hook Point and Eurong on the eastern side of the Island, the men’s area near Lake Boemingen on the north-west side of the Island, and the boras south of Markwell’s Lookout.

Mr Ian Wheeler

66 Mr Wheeler deposed that he was a Butchulla man through his father, and that his family had been fishermen for at least five generations. He learned a great deal about his culture from his grandfather. Much of his evidence details his experiences on the coast of Fraser Island, including fishing with his family. He concludes:

45. No matter whether we are one people, or three tribes, whether we spoke all different dialects, it really does not matter. To me, we are all the same mob of Butchullas. We are all just families living together on country. One thing is for sure though, we did not see ourselves as Kabi or Gabi.

Mr Malcolm Burns

67 Mr Burns deposed that he was a Butchulla man through his mother, and that his apical ancestor was Garry Owens. He lived with his maternal aunt and her husband from when he was five years old. He grew up knowing he was Butchulla.

68 He deposed:

12. My uncles and great-uncles fished all the time so when I was growing, we had lots of seafood to eat. We would go fishing all the time. We also went hunting in the bush. We always had turtle, porcupine, and bandicoot. My grandfather and uncles were great fishermen. They knew the waters here in Hervey Bay, going up to Great Keppell Island, and then further up to Townsville and down to Brisbane …

69 Later in his affidavit he said:

21. When people talk about law and custom, I immediately think that if you do the wrong thing, you would get speared. I am talking about going onto other people’s country without permission. I was taught that if you try and go onto somebody else’s country, you have to ask permission. You have to respect that country. I was brought up knowing that you do not go onto somebody else’s country without asking. I was taught that you certainly do not steal or take their women or their food. You have to ask otherwise there would be big fights or war. People can come onto our country, do things or take things from my country but they need to get my permission first. They know they are coming onto strange country. They have to have respect for my country …

22. There are rules about who you should or should not marry in our culture. You cannot marry blood, or someone from the same moiety. People should marry the right way and not too close. It is very hard to work that out nowadays. People are marrying non-Aboriginals. I was taught by my Elders that in the olden days, you would get thrown out of the tribe for not observing rules about proper marriage. You basically were exiled …

70 At paragraph 26 Mr Burns said:

… My grandfather told me stores about how there used to be big gatherings on Fraser Island. All the neighbouring groups used to come over for feasting, just days and days of fishing and fishing. I was told that at special times during a big “out” (big tides being out) you could walk over to the island. My grandfather got those stories off my Nanna’s father. My great grandfather told my grandfather, my grandfather told us and my Nanna. We used to sit down in the old house in Miller Street and they would be testing us while we were all sitting around the fire, testing us to see what we knew, asking us how we knew, making little hints, hitting us with questions whilst we sat as kids around the fire waiting for the porridge to cook.

Ms Marie Wilkinson

71 Ms Wilkinson is a Butchulla woman through her father and in that respect is a member of the Blackman family. She has lived in Hervey Bay most of her life. She deposed:

19. Dad always was adamant that he knew who was Butchulla and who was not. When somebody came along and we would go to Dad to ask if he knew them, he would say, “Yes, they are such and such’s family”, or, “No, I do not know them.” He knew who was who in the line, he knew everyone. If he said someone was not Butchulla, they were not. Dad always told us though, “You show respect to whoever it is but they are not belonging to this tribe.” It did not matter what tribe or who they were or where they came from. I was taught you have got to show respect to your own people and also other people out there. It did not matter their colour or creed or who they were, that was our Law. I learnt that from our elders, our old people, like Granny and my father. He was my elder. With all the old people down in the Bay, whether they were Butchulla or otherwise, you had to respect them.

72 Ms Wilkinson deposed that the boundaries of Butchulla country encompassed Fraser Island.

Mr Peter Martin

73 Mr Martin’s evidence is that he is Butchulla through his mother, although he has only in recent years come to understand his cultural heritage as a Butchulla person. In particular he deposed as follows:

62. I will say a few words about the island because to me, it is all one country – the island, the bay and the mainland. All of the island, every part of the island, is sacred. I went to the island for the first time when I was about 8 or 9 years old with Grandad. I know it is sacred because Grandfather told me it is sacred. He said, “This whole island is a sacred island. It’s a spirit.” It is actually K’Gari. As the story goes, K’Gari created all the mainland and all the oceans between here, and then she decided to lay down, so the island is actually a spirit, a female spirit, a female island. You cannot get away from that.

63. Lake Wabby is a culturally significant area. That is a women’s area.

64. Then there is Black Lake, I am not really sure whether I should talk about that one but it is down near the university camp, near Dili Village. We call it Black Lake because the water is just black and very cold. There were the tracks going down there and a few of the older fellas. Alfie Blackman (who has passed away now) and Uncle Eddie Doolan went over and closed the all [sic] the tracks because that lake was an initiation area for Batajala men and boys. I cannot say as I have never been there. I just know where it is because my grandfather and great grandad told me where it is and that it is only initiated men that go in there …

65. Whenever we go to the island before we can set foot on the island, we have to say ‘hello’ to the island. That is when we arrive, and when we leave, we also have to say ‘goodbye’ to the island. That is how we respect K’Gari, the spirit. Not that we do knock a lot of trees over but everything has got a spirit and so we are supposed to talk to the tree and just say that we wish the tree well and we would need to cut it.

66. Even when we are hunting, we have to talk to the animal and apologise for killing it and sending its spirit to a good place.

Mr Shawn Wondunna-Foley

74 Mr Wondunna-Foley is the brother of Ms Fiona-Lee Foley, and like her identifies as a Butchulla person through his mother. Mr Wondunna-Foley deposed as to his understanding of the boundaries of Butchulla country, and the importance of passing on knowledge to his children. Like many other witnesses he identified the general “clan” totem as the dolphin. He deposed:

25. I recall stories where we were told that you do not spit into the fire or you will bring gundils or evil spirits, don’t whistle at night because you will bring evil spirits, you don’t talk bad, you don’t say someone’s name who is dead or you don’t refer to somebody’s mother, you don’t say their name, these are all little bits and pieces that we still practise as a family.

26. We were told to have respect for places on the island – the coloured sands going to the lakes, Indian Head – up the rocks there, there is a pretty spiritual place. That was also the site of the massacre of 1851. There are men’s initiation sites. There is one on the island at Lake Barrowdy.

75 He concludes:

31. Responsibilities to country still remain strong within our group. It is a bit hard to do it by yourself when there are 300,000 people using Fraser Island each year. Whilst industries and government try to incorporate an indigenous understanding, they don’t really understand. For our culture, laws and customs to survive, it is about combining traditional knowledge with news assets and resources to make a different future. I do believe though that if you don’t look after country, you will get sick and your connection will degrade.

CONCLUSION

76 I am satisfied that orders in the terms agreed by the parties to these proceedings are within the power of the Court. In particular, I am satisfied that the material filed by the parties in these proceedings evidences native title rights and interests in the claim group as defined by s 223(1) of the Act. Section 223(1) provides that “native title” or “native title rights and interests” means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

77 Material in the historical report of Dr Skyring, the anthropological reports of Dr Sackett and Ms O’Brien, as well as lay evidence before the Court, support the conclusion that the applicant has native title rights and interests in the determination area.

APPLICATION OF SECTION 87: IS THE ORDER APPROPRIATE?

78 In Brown (on behalf of the Ngarla People) v State of Western Australia [2007] FCA 1025, Bennett J observed:

[22] The exercise of the Court’s discretion pursuant to s 87A imports the same principles as those applying to the making of a consent determination of native title under s 87. The discretion conferred by s 87A and by s 87 must be exercised judicially and within the broad boundaries ascertained by reference to the subject matter, scope and purpose of the Act (Hughes at [8] citing Lota Warria (on behalf of the Poruma and Masig Peoples) v Queensland (2005) 223 ALR 62 at [7]).

(emphasis added.)

79 That an order recognising native title is good as against all third parties, as well as the specific parties to the application, is an important factor in determining whether an order is appropriate for the purposes of s 87 of the Act.

80 More recently however Keane CJ in King v South Australia (2011) 285 ALR 454 reviewed the approach to be adopted in determining whether orders under s 87 were appropriate. There his Honour noted the processes in which the States and territories engage to determine whether they are satisfied that native title rights and interests exist within the meaning of s 223 of the Act. His Honour then observed at [19]:

Although the court must, of course, preserve to itself the question whether it is satisfied that the proposed orders are appropriate in the circumstances of each particular application, generally the court reaches the required satisfaction by reliance upon those processes.

81 His Honour then referred to comments of North J in Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v Victoria [2007] FCA 474 at [36]-[37 where his Honour said:

36. The focus of the section is on the making of an agreement by the parties. This reflects the importance placed by the Act on mediation as the primary means of resolving native title applications. Indeed, Parliament has established the National Native Title Tribunal with the function of conducting mediations in such cases. The Act is designed to encourage parties to take responsibility for resolving proceedings without the need for litigation. Section 87 must be construed in this context. The power must be exercised flexibly and with regard to the purpose for which the section is designed.

37. In this context, when the Court is examining the appropriateness of an agreement, it is not required to examine whether the agreement is grounded on a factual basis which would satisfy the Court at a hearing of the application. The primary consideration of the Court is to determine whether there is an agreement and whether it was freely entered into on an informed basis: Nangkiriny v State of Western Australia (2002) 117 FCR 6, Ward v State of Western Australia [2006] FCA 1848. Insofar as this latter consideration applies to a State party, it will require the Court to be satisfied that the State party has taken steps to satisfy itself that there is a credible basis for an application: Munn v Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109. There is a question as to how far a State party is required to investigate in order to satisfy itself of a credible basis for an application. One reason for the often inordinate time taken to resolve some of these cases is the overly demanding nature of the investigation conducted by State parties. The scope of these investigations demanded by some States is reflected in the complex connection guidelines published by some States.

82 The case before me, in which the State has been deeply involved in the negotiation of consent orders in respect of a determination of native title, appears to satisfy the criteria outlined by Keane CJ and North J in King and Lovett respectively.

83 In summary, in this case:

I am satisfied from the evidence I have summarised that the applicant has “native title rights and interests” as defined in s 223(1) of the Act, and as agreed by the parties in the section 87 agreement before the Court, in the determination area.

I am satisfied that:

o the material provided by the applicants to identify the native title claim group and its society satisfies the requirements of the Act;

o there is sufficient evidence of continued connection to the claim area by members of the claim group;

o there is continued adherence by members of the claim group to its laws and customs;

o members of the claim group are still actively engaged in and affected by their traditions;

o members of the claim group engage in the activities identified as rights and interests included in the application; and

o these rights and interests arise from traditional law and customs.

All parties to the application are legally represented and, I understand, have been legally represented throughout the proceedings up to and including execution of the section 87 agreement.

It is not in dispute that the State of Queensland has played an active role in the negotiation of the proposed orders, after extensive investigation of the merits of the native title application before me. An agreement pursuant to s 87 of the Act has been signed by the State as well as the second, third and fourth respondents.

There is sufficient material filed in these proceedings for the respondents, and in particular the State, to be satisfied that there is a credible basis for this application. Further, I accept that the State and the other respondents have taken appropriate steps to be so satisfied.

There are no other proceedings before the Court relating to native title determination applications that cover any part of the determination area which would require orders pursuant to s 67 of the Act.

84 Further, I am satisfied that an order is appropriate in the terms proposed by the parties in respect of the reservation of the State’s position concerning military firing areas within the determination area.