Queensland North Australia Pty Ltd v Takeovers Panel [2014] FCA 591

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. The costs of the first, second, third and fourth respondents of and incidental to this proceeding are to be paid by the applicants.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | QUD 526 of 2012 |

| BETWEEN: | QUEENSLAND NORTH AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 146 828 122) First Applicant CLOSERIDGE PTY LTD (ACN 010 560 157) Second Applicant CLIVE FREDRICK PALMER Third Applicant |

| AND: | TAKEOVERS PANEL First Respondent THE PRESIDENT’S CLUB LIMITED (ACN 010 593 263) Second Respondent PRESIDENT, TAKEOVERS PANEL Third Respondent AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Fourth Respondent |

| JUDGE: | COLLIER J |

| DATE: | 5 JUNE 2014 |

| PLACE: | BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 Before the Court is an amended originating application filed 30 July 2013 by the first applicant, Queensland North Australia Pty Ltd (“QNA”). QNA seeks judicial review under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (“ADJR Act”) of the following decisions and orders of the first respondent, the Takeovers Panel (“the Panel”):

1. the decision of the Panel dated 24 July 2012 to make a declaration under s 657A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“Corporations Act”) that circumstances constituted unacceptable circumstances in relation to the affairs of the second respondent (“The President’s Club”) arising out of:

the acquisition by QNA around July 2011 of 98% of the shares in Coeur de Lion Holdings Pty Ltd (“Lion Holdings”); and

the acquisition by QNA, in March 2012, of 221 shares in The President’s Club.

2. the decision of the Panel made 24 July 2012 to extend the time for The President’s Club to bring its application for relief to 26 June 2012.

3. the orders of the Panel made 27 July 2012 under s 657D of the Corporations Act.

4. the decision of the third respondent, the President of the Panel, not to revoke the direction appointing Mr Ewen Crouch as the President of the sitting Panel pursuant to s 185(2) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (“ASIC Act”).

2 Specifically, QNA seeks:

1. An order quashing or setting aside the decisions of the Panel.

2. An order setting aside the orders.

3. Further or alternatively, an order that the application be remitted to the Panel (differently constituted) to be dealt with according to law.

4. Such further or other orders as are appropriate.

5. Costs.

3 While the applicants did not specifically amend or abandon their challenge to the decision of the President of the Panel so far as concerned s 185(2) of the ASIC Act, I note that at the hearing they did abandon ground of review 18 which was specifically referable to s 185(2). Further the applicants continued to press their claim that the President of the Panel ought to have revoked the direction appointing Mr Crouch on the basis that his role on the Panel in this case gave rise to a reasonable apprehension of bias.

4 Overall, the primary protagonists in this litigation are on the one hand the applicants, and on the other hand The President’s Club and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (“ASIC”). In accordance with the principles articulated in R v Australian Broadcasting Tribunal; ex parte Hardiman (1980) 144 CLR 13 the Panel and its President appeared only for the purpose of submitting to such order as the Court may make, and otherwise made no submissions in respect of the merits of the matters in dispute.

5 Materially, s 5 of the ADJR Act limits the grounds upon which a person aggrieved by a decision to which the Act applies to seek an order of review on one or more of the following grounds:

(a) that a breach of the rules of natural justice occurred in connection with the making of the decision;

(b) that procedures that were required by law to be observed in connection with the making of the decision were not observed;

(c) that the person who purported to make the decision did not have jurisdiction to make the decision;

(d) that the decision was not authorized by the enactment in pursuance of which it was purported to be made;

(e) that the making of the decision was an improper exercise of the power conferred by the enactment in pursuance of which it was purported to be made;

(f) that the decision involved an error of law, whether or not the error appears on the record of the decision;

(g) that the decision was induced or affected by fraud;

(h) that there was no evidence or other material to justify the making of the decision;

(j) that the decision was otherwise contrary to law.

6 The background facts to this application are outlined in the Reasons for Decision of the Panel in The President’s Club Ltd [2012] ATP 10 published on 24 August 2012, and expanded in submissions of the applicants. It is useful to summarise those facts before turning to the grounds of review before the Court.

Background

Shareholdings and offers

7 The President’s Club is an unlisted public company. Its capital is divided into 7,488 ordinary shares and five subscriber shares. The subscriber shares are irrelevant to this case.

8 The President’s Club operates a time share scheme at the property previously known as the Hyatt Regency Coolum but now known as the Palmer Coolum Resort (“the resort”). The President’s Club is the tenant under two leases, both dated 21 December 1988 and each for a term of 80 years over all the lots in The President’s Club Golf Community Titles Scheme and The President’s Club Tennis Community Titles Scheme (“community titles schemes”).

9 The constitution of The President’s Club contemplated that each holder of ordinary shares in the company would hold one or more parcels of 13 ordinary shares, and would own an associated one-quarter interest as tenant in common in a lot (“a Villa Interest”) in either of the community titles schemes. The effect of a set of interlocking agreements was that a purchaser of one timeshare interest must become both:

a member of The President’s Club, holding 13 shares; and

the registered proprietor of a corresponding one-quarter interest in either of the community titles schemes.

10 Purchasers of timeshare interests were also required to execute:

a deed poll, binding them, if they sold their Villa Interest, to sell the corresponding shares in The President’s Club to the same person; and

an assignment of a letting pool agreement, under which their Villa Interest was made available with others as part of a pool.

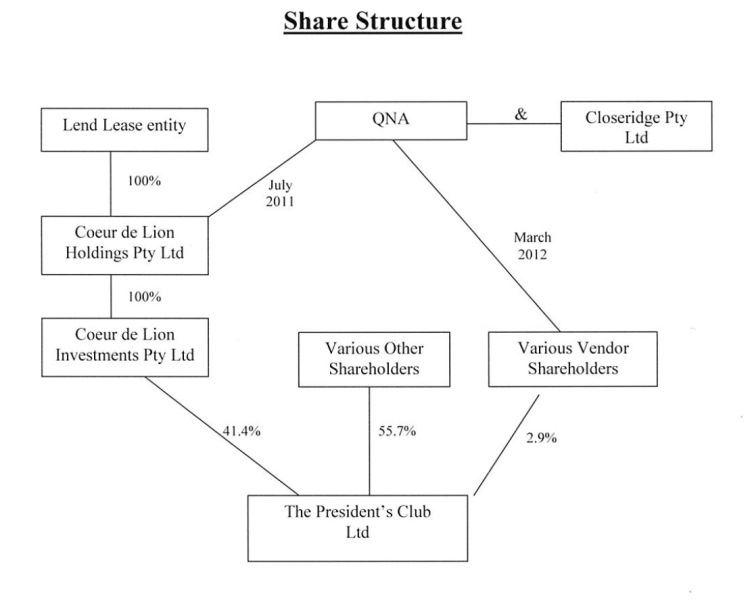

11 At all material times Lion Holdings was the sole shareholder of Coeur de Lion Investments (“Lion Investments”), which in turn owns 3107 or 41.4% of the shares in The President’s Club. Helpfully, the applicant tendered a diagram explaining the share structure of relevant entities, as follows:

12 On 31 January 2005 ASIC exercised its powers pursuant to s 601QA(1)(a) of the Corporations Act to conditionally exempt The President’s Club and Lion Investments from registration as a managed investment scheme under Ch 5 of the Corporations Act. The exemption was provided on the basis that Lion Investments entered into a deed poll (“the deed poll”) whereby Lion Investments covenanted that it would not exercise more than 10% of its voting rights on any resolution other than:

in circumstances consented to in writing by ASIC; or

in relation to a resolution to wind up the scheme.

13 Clause 4.2 of the deed poll allowed Lion Investments to revoke the deed poll upon providing to ASIC and The President’s Club at least 180 days prior written notice.

14 In July 2011 QNA acquired 98% of the shares in Lion Holdings from Lend Lease. The remaining 2% of shares were acquired by the second applicant, Closeridge Pty Ltd (“Closeridge”). Both QNA and Closeridge are companies associated with the third applicant, Mr Palmer.

15 By letter dated 15 September 2011, Lion Investments gave notice to ASIC and The President’s Club that it intended to revoke the deed poll. The revocation took effect on or about 13 March 2012, following expiry of the 180 day notice period required by cl 4.2 of the deed poll. It followed that, on this date, the ASIC exemption ceased to apply.

16 In or around March 2012, QNA acquired 221 additional shares in The President’s Club (plus corresponding Villa Interests) being 2.9% of the shares in that company. This took QNA’s direct or indirect interest in the President’s Club to approximately 44.3%.

17 On 14 March 2012 The President’s Club held an extraordinary general meeting to consider amending its constitution to cap the voting power of Lion Investments at a meeting to 10%, effectively replicating the covenant in the deed poll previously entered by Lion Investments. The relevant resolution was not carried.

18 On 12 April 2012, QNA lodged a bidder’s statement with ASIC, proposing a bid for all shares in The President’s Club and the corresponding Villa Interests. The bid was unconditional. The purchase price offered for each parcel of 13 shares and corresponding Villa Interest was $55,013 (being $1 per share for the 13 shares and $55,000 for the Villa Interest).

19 On 20 April 2012, ASIC wrote to QNA raising a number of concerns with the bidder’s statement, including inadequate disclosure, and a suspected ongoing contravention of s 606 of the Corporations Act. On 24 April 2012, QNA’s solicitors wrote to The President’s Club advising that QNA did not intend to proceed with its bid. ASIC was notified of this decision by letter of the same date.

20 On 26 April 2012, ASIC advised QNA’s solicitors that, having regard to s 631(1) of the Corporations Act, ASIC considered the bid to have been made public through the lodgement of the bidder’s statement with ASIC. Accordingly, QNA could not withdraw its bid and was required to proceed with the offer within two months from the announcement.

21 Section 631 of the Corporations Act provides:

631 Proposing or announcing a bid

(1) A person contravenes this subsection if:

(a) either alone or with other persons, the person publicly proposes to make a takeover bid for securities in a company; and

(b) the person does not make offers for the securities under a takeover bid within 2 months after the proposal.

The terms and conditions of the bid must be the same as or not substantially less favourable than those in the public proposal.

Note: The Court has power under section 1325B to order a person to proceed with a bid.

(1A) For the purposes of an offence based on subsection (1), strict liability applies to paragraph (1)(b) and to the requirement that the terms and conditions of the bid must be the same as or not substantially less favourable than those in the public proposal.

Note: For strict liability, see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

Proposals if takeover bid not intended

(2) A person must not publicly propose, either alone or with other persons, to make a takeover bid if:

(a) the person knows the proposed bid will not be made, or is reckless as to whether the proposed bid is made; or

(b) the person is reckless as to whether they will be able to perform their obligations relating to the takeover bid if a substantial proportion of the offers under the bid are accepted.

(3) Section 1314 (continuing offences) and subsection 1324(2) (injunctions) do not apply in relation to a failure to make a takeover bid in accordance with a public proposal under subsection (1).

Note: For liability and defences for contraventions of this section, see sections 670E and 670F.

22 On 11 May 2012 QNA sought an extension of time within which to lodge a supplementary and replacement bidder’s statement. On the same date ASIC granted the extension of time sought.

23 On 21 May 2012, QNA lodged a replacement bidder’s statement (replacement bidder’s statement). Again, QNA proposed to make an offer to purchase all the shares in The President’s Club and all Villa Interests. On the front page of the replacement bidder’s statement was the following statement:

The bid is being made for both your shares and your Villa Interest. It is not possible to accept the bid in relation to your shares only or in relation to your Villa Interest only.

24 On page 1 of the replacement bidder’s statement there appeared the following statement:

While there is no formal stapling of your President’s Club Shares to your Villa Interest, it is likely that you have executed a deed poll which obliges you to sell your shares if you sell your Villa Interest to the same person. Also clauses 6(b) and 6(c) of the Constitution require that a member of President’s Club must own a Villa Interest and a member’s shareholding is limited to the number of Villa Interests owned.

25 Later in the replacement bidder’s statement there appeared the following statement:

Because the ASIC Deed Poll was still current at the time of the Acquisition and therefore QNA’s voting power was limited to 10% of persons who actually vote, QNA did not acquire voting power of more than 20% at the time of the Acquisition. Accordingly, QNA was not required to make a takeover offer for the remaining shares in President’s Club or otherwise comply with the takeover provisions of the Corporations Act.

As CDLI has revoked the ASIC Deed Poll (and the revocation became effective on 19 March 2012) QNA’s voting power is no longer restricted …

26 (The “Acquisition” was defined in the replacement bidder’s statement as the transaction in July 2011 whereby QNA completed the acquisition from Lend Lease of 98% of the shares in Lion Holdings.)

27 On 1 June 2012 the solicitors for QNA advised the solicitors for The President’s Club that:

the replacement bidder’s statement would not be dispatched;

a further replacement bidder’s statement would be provided on 4 June 2012; and

QNA would propose further relief to ASIC to extent the dispatch period until 12 June 2012.

28 No further replacement bidder’s statement had been provided as of 26 June 2012 when The President’s Club lodged an application with the Panel for a declaration of unacceptable circumstances pursuant to s 657A and s 657C(2) of the Corporations Act.

Application to the Panel by The President’s Club for declaration of unacceptable circumstances

29 In its application to the Panel The President’s Club contended (in summary) that:

QNA appeared to have breached and continued to be in breach of s 606 of the Corporations Act. Inter alia, s 606 prohibits transactions which result in someone’s voting power in a defined company increasing from below 20% to above 20%, or increases from a starting point that is above 20% and below 90%.

The circumstances giving rise to a breach of s 606 first occurred when QNA acquired an initial 41.1% interest in The President’s Club through QNA’s acquisition of Lion Holdings in or about July 2011. QNA continued to hold a relevant interest in The President’s Club in excess of 20% without qualifying for an exemption under s 611.

QNA (together with its associates) had not lodged a bidder’s statement which complied with the minimum bid price principle set out in s 621(3) of the Corporations Act. Section 621(3) requires the bidder to pay all shareholders no less than it paid for shares during the four months before the date of the bid.

The bidder’s statement was materially deficient in that it included material which was misleading and/or confusing, and omitted information that shareholders of The President’s Club and their professional advisers would reasonably require to make an informed assessment of QNA’s offer. These deficiencies included:

o an absence of disclosure of QNA’s breach of s 606 of the Corporations Act and the possible effects of this on QNA and The President’s Club;

o misleading disclosure in relation to the revocation of the ASIC exemption;

o deficient disclosure in relation to the funding of the offer;

o deficient disclosure in relation to compliance with the resort administration agreement and QNA’s intentions for The President’s Club; and

o deficient disclosure in relation to the net asset value of shares in The President’s Club and the comparative value of the offer.

QNA appeared to have breached and continued to breach s 631(1) and s 633(1) of the Corporations Act by not lodging a complying bid within the time limits of the Corporations Act. Under s 631(1) it is an offence for a person who has publicly proposed to make a takeover not to proceed with offers within two months of that proposal. Circumstances relevant to breach of s 631(1) first occurred on or about 12 June 2012 when QNA failed to lodge a complying bid within two months of making a public proposal to make a takeover bid. Further, s 633(1) sets out the steps required of a bidder in order to make an effective off-market bid. Circumstances relevant to breach of s 633(1) first occurred on or about 7 June 2012 when QNA failed to dispatch a complying bidder’s statement to shareholders of The President’s Club as required by s 633(1).

30 The President’s Club sought both interim and final restraining orders. Interim orders sought were that QNA be restrained until the Panel determined the application from:

dispatching a second bidder’s statement; and

voting (with its associates) more than 20% of shares in The President’s Club.

31 Final orders sought by The President’s Club were that:

QNA and its associates be restrained from voting more than 20% of The President’s Club;

QNA proceed with its takeover bid for The President’s Club on terms no less favourable than in the original bidder’s statement;

QNA raise the offer price per share to $1.00 per share and the price per Villa Interest to $65,000, being the highest price paid in the preceding 4 months; and

QNA remedy the information deficiencies in a second replacement bidder’s statement.

Decision of the Panel

32 The Panel observed that ongoing circumstances in the nature of contraventions of the Corporations Act were alleged in the application before it, or alternatively that the Panel had extended the time for making the application to the date on which it was made by The President’s Club (that is 26 June 2012). The Panel decided to conduct proceedings.

33 In a detailed decision the Panel decided, in summary, that the circumstances of the acquisition of shares in The President’s Club in July 2011 were unacceptable having regard to:

The effect the circumstances had, were having, will have or were likely to have on:

o the control, or potential control, of The President’s Club; or

o the acquisition, or proposed acquisition, by a person of a substantial interest in The President’s Club; and

The purposes of Ch 6 as set out in s 602 of the Corporations Act; and

The fact that they constituted, constitute, will constitute or were likely to constitute a contravention of a provision of Ch 6.

34 Section 602 of the Corporations Act provides:

602 Purposes of Chapter

The purposes of this Chapter are to ensure that:

(a) the acquisition of control over:

(i) the voting shares in a listed company, or an unlisted company with more than 50 members; or

(ii) the voting shares in a listed body; or

(iii) the voting interests in a listed managed investment scheme;

takes place in an efficient, competitive and informed market; and

(b) the holders of the shares or interests, and the directors of the company or body or the responsible entity for the scheme:

(i) know the identity of any person who proposes to acquire a substantial interest in the company, body or scheme; and

(ii) have a reasonable time to consider the proposal; and

(iii) are given enough information to enable them to assess the merits of the proposal; and

(c) as far as practicable, the holders of the relevant class of voting shares or interests all have a reasonable and equal opportunity to participate in any benefits accruing to the holders through any proposal under which a person would acquire a substantial interest in the company, body or scheme; and

(d) an appropriate procedure is followed as a preliminary to compulsory acquisition of voting shares or interests or any other kind of securities under Part 6A.1.

Note 1: To achieve the objectives referred to in paragraphs (a), (b) and (c), the prohibition in section 606 and the exceptions to it refer to interests in “voting shares”. To achieve the objective in paragraph (d), the provisions that deal with the takeover procedure refer more broadly to interests in “securities”.

Note 2: Subsection 92(3) defines securities for the purposes of this Chapter.

35 The Panel considered that a declaration of unacceptable circumstances was warranted because, in summary:

Although QNA had not filed a notice of appearance, it was not denied natural justice by the Panel in that:

o the Panel properly required QNA to provide confidentiality and media canvassing undertakings in the form required by the Panel, in accordance with 10 years of Panel practice of ensuring private conduct of Panel matters.

O under s 194 of the ASIC Act, leave of the Panel is required for a party to be legally represented, and leave was not requested in this case by QNA.

O QNA and Lion Investments were provided with all relevant material and were invited to make submissions and rebuttals, which they did.

O it was not a denial of natural justice for the Panel to direct that proceedings before the Panel were confidential.

QNA had submitted that the Panel did not have jurisdiction to hear matters arising out of its offer for the Villa Interests, for which QNA had recently paid $65,000 each (in addition to $13 for each parcel of 13 shares). However the Panel considered that it did have jurisdiction because:

O Although complicated, the arrangement whereby shareholders in The President’s Club also had a corresponding Villa Interest, could only transfer shares together with that Villa Interest, and had a right to use the relevant villa because it was conferred by rights attached to the shares, clearly constituted rights in the form of a “stapled entitlement”.

O The allocation of the price between a Villa Interest and the related shares was arbitrary and it was commercially unrealistic to treat the shares and Villa Interests separately. Any bid for The President’s Club would also have to relate to the Villa Interests as well as the shares.

O The fact that Lion Holdings, as developer of the time share scheme, did not enter all the agreements and arrangements entered by the buyers, and entered into a different deed poll in favour of ASIC, was irrelevant.

O In any event it was inappropriate to ignore the rights attaching to the shares and simply allocate the shares a value of a nominal $1. Both the principle underpinning s 621(3) and the purpose of Ch 6 set out in s 602(c) are brought into play by the offers for shares and corresponding Villa Interests.

O Further, s 623 provides that a bidder must not during the offer period give or agree to give a benefit to a person unless the same benefit is offered to every offeree. QNA offered different prices for Villa Interests in March 2012, which meant that there may be a collateral benefits issue.

O QNA submitted that “the deed polls were only intended to regulate secondary sales of the timeshare scheme”, and that shares and Villa Interests were not stapled. However QNA’s acquisition of control over Lion Holdings did not involve the stapling arrangements, whereas all the other actual and proposed transactions under discussion were secondary sales.

O Although there had been a transfer during the Panel proceedings of a Villa Interest from Lion Investments to Mr Palmer while the associated shares remained with Lion Investments (which Mr Palmer controlled), this could be done because the stapling does not bind the Land Titles Office. It did not prove that a parcel of shares could be transferred without the corresponding Villa Interest.

It is clear that s 606 of the Corporations Act applies to The President’s Club.

The ordinary shares in The President’s Club were voting shares within the meaning of s 9 of the Corporations Act. “Voting share” is defined as:

voting share in a body corporate means an issued share in the body that carries any voting rights beyond the following:

(a) a right to vote while a dividend (or part of a dividend) in respect of the share is unpaid;

(b) a right to vote on a proposal to reduce the body’s share capital;

(c) a right to vote on a resolution to approve the terms of a buy back agreement;

(d) a right to vote on a proposal that affects the rights attached to the share;

(e) a right to vote on a proposal to wind the body up;

(f) a right to vote on a proposal for the disposal of the whole of the body’s property, business and undertaking;

(g) a right to vote during the body’s winding up.

This was not changed by a deed poll entered by Lion Investments with ASIC, revocable on 180 days’ notice: cf Cumbrian Newspapers Group Ltd v Cumberland and Westmorland Newspaper and Printing Co Ltd [1987] Ch 1.

The Panel did not accept QNA’s submission that, because of the covenant in the ASIC deed poll, neither Lion Investments nor QNA had a relevant interest in the shares which Lion Investments had covenanted not to vote and that, even if they did have relevant interests in those shares, they did not have commensurate voting power. Rather, Lion Investments had a relevant interest constituted by its power to exercise the right to vote the shares and by its power to dispose of the shares. This was because, inter alia:

O Any fetter on voting arose entirely from the covenant in the deed poll, and not from the constitution of The President’s Club.

O The rights attached to the shares as set out in The President’s Club constitution were the same for all voting shares.

O Lion Investments had power to vote the shares in breach of the deed poll even though such a vote would have been cast in breach of an obligation owed to ASIC: Re Fernlake Pty Ltd [1995] 1 Qd R 597.

O Lion Investments had unfettered power to dispose of 41.4% of the shares in The President’s Club, and none of the exclusions in s 609 applied to its interest in those shares.

O When QNA acquired control of Lion Investments, QNA acquired the same relevant interest in the shares in The President’s Club held by Lion Investments pursuant to s 608(3) of the Corporations Act.

At all relevant times Lion Investments’ relevant interest in the shares it held constituted 41.4% of the voting power in The President’s Club despite the covenant in the deed poll.

The Panel rejected QNA’s submission that Lion Investments only acquired its relevant interest in the shares in The President’s Club on expiry of the notice it gave ASIC of the revocation of the deed poll, by operation of law pursuant to item 15 of s 606 of the Corporations Act.

The acquisition by QNA of an additional 2.9% of the shares in The President’s Club and the corresponding Villa Interests by private treaty in March 2012, while technically falling within the parameters of the 3% creep rule as defined by item 9 of s 611 of the Corporations Act, nonetheless constituted unacceptable circumstances. This was because QNA contravened s 606 when it acquired 98% of the shares in Lion Holdings and therefore acquired control of Lion Investments.

The Panel had regard to the matters in s 657A(3), namely:

O the purposes of Ch 6 of the Corporations Act set out in s 602;

O the other provisions of Ch 6;

O the rules made under s 658C;

O the matters specified in regulations made for the purposes of para 195(3)(c) of the ASIC Act; and

O any other matters it considers relevant.

Control of The President’s Club effectively passed without a reasonable and equal opportunity being provided to all shareholders to participate in any benefits accruing from a proposal under which QNA acquired control of, or a substantial interest in, The President’s Club.

The acquisition of control over voting shares occurred in contravention of s 606 and was not in an efficient competitive and informed market.

Allegation of conflict

36 On 9 August 2012 the solicitors for QNA wrote to the Panel (inter alia) claiming as follows:

… we have been made aware that Allens Arthur Robinson (sic), the firm of which Mr Crouch is the Chairman, has acted since 2011 on behalf of a member of the CITIC Group of companies in an ongoing matter against Minerology, a company controlled by Professor Clive Palmer. We draw this to your attention as we note that Mr Crouch did not declare this matter at the time of his appointment to the Panel. We acknowledge that this is the first occasion on which we have drawn this to the Panel’s attention, but in that respect we submit that it was for Mr Crouch to conduct a full conflict search within Allens Arthur Robinson and declare his position regarding the above matter before agreeing to his appointment. Accordingly, we submit that the statement in the Panel’s Declaration of Interests dated 27 June 2012 that Mr Crouch “is not aware of any interest that could conflict with the proper performance of his functions in relation to this matter” may not have been accurate …

37 At [150]-[152] of the Panel’s Decision the Panel stated as follows:

[150] The President of the Panel considered the state of knowledge of [Mr Crouch], the stage of the proceedings at which the issue was raised, and the fact that (other than for completion of reasons) the Panel’s performance of its functions and exercise of its powers had been completed, and decided not to revoke the direction appointing Mr Crouch. In all the circumstances the President believed on reasonable grounds that the member’s interest is immaterial or indirect and will not prevent the member from acting impartially in relation to the matter.

[151] The parties and QNA were advised of the interest and the decision of the President, as was the sitting Panel.

[152] The President also considered that, on the test of a fair-minded, objective bystander having all the factual information, no reasonable apprehension of bias would arise.

Declaration of Unacceptable Circumstances

38 The Panel made the following declaration of unacceptable circumstances pursuant to s 657A of the Corporations Act:

CIRCUMSTANCES

1. The President’s Club Ltd (TPC) is an unlisted company with more than 50 members. Its capital is divided into 7,488 ordinary shares and 5 subscriber shares (the latter having no right, to dividends or to participate in the net assets of the company on a winding up).

2. Coeur de Lion Holdings Pty Ltd (CDLH) owns all the shares in Coeur de Lion Investments Pty Ltd (CDLI). CDLI owns 3.107 shares in TPC (approximately 41.4%).

3. Ordinary shares in TPC are voting shares. They carry voting rights beyond those in the definition of ‘voting share’ in section 9. This is not changed by a deed poll entered by CDLI, revocable on 6 months’ notice and which has been revoked, in favour of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission as follows:

Where [CDLI] and its associates are not disqualified and excluded from voting their interests at a meeting, [CDLI] covenants that any voting rights held by [CDLI] and its associates or any operator, manager, promoter in relation to each Scheme, must not be exercised in excess of 10% of the votes that may be cast (after deducting any votes not cast by anyone or more members) on a resolution by members of the relevant Club other than:

a. In circumstances consented to in writing by the ASIC; or

b. In relation to a resolution to wind up the relevant Scheme.

4. In or around July 2011, CDLI:

a. Was the holder of the shares.

b. Had power to exercise, or control the exercise of, a right to vote attached to the shares, and/or

c. Had power to dispose of, or control the exercise of a power to dispose of, the shares.

5. In or around July 2011, Queensland North Australia Pty Ltd (QNA acquired 98% of the shares in CDLH. The remaining 2% of the shares in CDLH were acquired by Closeridge Pty Ltd.

6. By reason of section 608(3)(a), or alternatively section 608(3)(b), in or around July 2011 QNA acquired a relevant interest in the shares in TPC that CDLI had a relevant interest in (first acquisition).

7. None of the exceptions in section 611 applied to the first acquisition. The first acquisition occurred in contravention of section 606.

8. Further in March 2012, QNA acquired 221 additional shares in TPC (2.9%) taking its relevant interest in TPC shares to approximately 44.4% (collectively, second acquisition). The second acquisition was the acquisition of a substantial interest in TPC.

9. The second acquisition occurred in purported reliance on item 9 of section 611. However, to the extent that item 9 was met, it was only by reason of the first acquisition, which contravened section 606.

10. It appears to the Panel that the circumstances of the first acquisition are unacceptable, having regard to:

a. The effect that the Panel is satisfied the circumstances have had, are having, will have or are likely to have on:

i. The control, or potential control, of TPC or

ii. The acquisition, or proposed acquisition, by a person of a substantial interest in TPC and

b. The purposes of Chapter 6 set out in section 602 and

c. Because they constituted, constitute, will constitute or are likely to constitute a contravention of a provision of Chapter 6.

11. Further it appears to the Panel that the circumstances of the second acquisition are unacceptable having regard to:

a. The effect that the Panel is satisfied the circumstances have had, are having, will have or are likely to have on

i. The control, or potential control, of TPC or

ii. The acquisition, or proposed acquisition, by a person of a substantial interest in TPC and

b. The purposes of Chapter 6 set out in section 602.

12. The Panel considers that it is not against the public interest to make a declaration of unacceptable circumstances. It has had regard to matters in section 657A(3)

DECLARATION

The Panel declares that the circumstances constitute unacceptable circumstances in relation to the affairs of The President’s Club Limited.

Orders of the Panel

39 In addition to making a declaration of unacceptable circumstances on 24 July 2012 in respect of the affairs of The President’s Club, the Panel made the following orders pursuant to s 657D of the Corporations Act:

1. The Associated Parties must not exercise any voting rights that attach to the Acquisition Shares

2. The Associated Parties must not make any further acquisitions of a relevant interest in shares in TPC, except:

a. With the consent of the Panel or

b. Pursuant to acceptances under a takeover offer referred to in Order 4 or

c. The acquisition by Mr Clive Palmer of the shares corresponding to Lot 64 on BUP 8874 recently acquired by Mr Palmer from CDLI.

3. The Associated Parties must not dispose of, transfer or charge any of the Acquisition Shares, except:

a. With the consent of the Panel or

b. For a disposal or transfer pursuant to the acquisition by Mr Clive Palmer of the shares corresponding to Lot 64 on BUP 8874 recently acquired by Mr Palmer from CDLI.

4. Orders 1, 2 and 3 cease if all of the following requirements are met:

a. QNA or an associate of it makes offers for all the shares in TPC under a takeover bid that complies with chapter 6 and which meets the following conditions:

i. The terms are no less favourable than those set out in the original Bidder’s Statement lodged with ASIC on 12 April 2012

ii. The offer price is no less than $65,013 for each parcel of shares and the corresponding villa interest

iii. The offer period is no less than 2 months and

iv. ASIC has confirmed in writing to the proposed bidder that it is otherwise satisfied with the terms of the offer and the disclosure in the bidder’s statement. This confirmation is not to be construed as ASIC’s approval of the bidder’s statement and

b. No less than 50% of the offers made for shares not already held by the Associated Parties are accepted and

c. All the accepting shareholders have been paid.

5. If QNA or an associate proposes to make a takeover bid under Order 4:

a. QNA and its associates must ensure that the proposed bidder provides ASIC with all reasonable assistance requested by ASIC and

b. Should ASIC be unable to settle terms or disclosure with the proposed bidder, either ASIC or the proposed bidder may refer the issue to the Panel for determination.

6. In these orders the following terms have the corresponding meaning:

Acquisition Shares 3,328 shares in TPC held:

(a) As to 3,107 shares, by CDLI or an associate and

(b) As to 221 shares, by QNA or an associate

Associated Parties CDLI, CDLH, Closeridge, QNA and each of their respective associates

CDLH Coeur de Lion Holdings Pty Ltd

CDLI Coeur de Lion Investments Pty Ltd

Closeridge Closeridge Pty Ltd

QNA Queensland North Australia Pty Ltd

TPC The President’s Club Limited

Grounds of Review

40 The grounds of application filed by the applicants and relied on at the hearing were relatively lengthy. Materially, they are as follows:

1. …

2. …

3. …

4. The declaration of unacceptable circumstances and the decision to extend time were made in circumstances where there was a breach of the rules of natural justice.

5. Further, and in the alternative, in determining that the application was made in time the Panel made an error of law in construing s 657B(a) of the Act as referring to continuing circumstances and not to the occurrence of the circumstances represented by the acquisitions by QNA in July 2011 and March 2012.

6. Further, and in the alternative, the Panel made the decision to extend time when there was no evidence or other material to justify doing so.

7. In making the declaration of unacceptable circumstances the Panel made an error of law in finding that the acquisition by QNA of 98% of the shares in Lion Holdings contravened s.606 of the Act.

8. The Panel made findings and acted upon them in making the declaration of unacceptable circumstances (arising out of the acquisition in July 2011) when there was no evidence or other material to justify doing so

9. The declaration of unacceptable circumstances was an improper exercise of the power conferred on the Panel by the Act in that the Panel took into account irrelevant considerations (at paragraph 107 of its reasons).

9A. The Panel made an error of law by stating conclusions without identifying and providing reasons which set out the findings of fact and reference to the evidence on which those findings were based (in paragraph 107 of its reasons).

10. In making the declaration of unacceptable circumstances the Panel made an error of law in finding that the acquisition by QNA, in March 2012, of 221 shares in the President’s Club contravened s. 606 of the Act.

11. In making the declaration of unacceptable circumstances (arising out of the acquisition in March 2012) the Panel (at paragraph 108 of its reasons):

i. Did not make any finding as to or identify the effect on the matters required by s657A(2) of the Act as preconditions to the making of the declaration;

ii. Accordingly, the declaration was not authorized by the Act.

12. Alternatively, the Panel made findings and acted upon them in making the declaration of unacceptable circumstances (arising out of the acquisition in March 2012) when there was no evidence or other material to justify doing as to the effect that the circumstances have had, are having, will have or are likely to have on:

i. The control, or potential control, of the President’s Club;

ii. The acquisition, or proposed acquisition, by a person of a substantial interest in the President’s Club.

13. The Panel made a finding and acted upon it that the shares and villa interests were “effectively stapled” and could only be transferred together when there was no evidence or other material to justify this finding.

14. In making the declaration of unacceptable circumstances and in the orders then made, the Panel made an error of law in concluding that it had jurisdiction to make orders which extended to villa interests.

15. The orders made by the Panel under s 657D of the Act were an improper exercise of the power because the nature of orders made was so unreasonable that no reasonable person could have so exercised the power and because the Panel failed to take into account the matters required by s 657D (2), and in failing to provide reasons which set out the findings of fact and reference to the evidence on which those findings were based.

16. Further the orders made by the Panel insofar as they are directed to entities other than the first and second applicants, and in particular the third applicant as an “associated Party” within the meaning of the Orders, were made in circumstances where there was a breach of the rules of natural justice and s 657D

17. The decision by the third respondent not to revoke the direction appointing Mr Ewen Crouch, as sitting President of the panel, involved a breach of the rules of natural justice.

41 As the applicant concedes there is some degree of overlap in respect of some of these grounds of review. It is convenient to group them as appropriate, and consider them accordingly.

Grounds 4, 5 and 6: timing of declaration of unacceptable circumstances

42 The applicants submit that the application to the Panel by The President’s Club for a declaration of unacceptable circumstances was out of time, and for that reason the decision of the Panel should be set aside. In particular, the applicants submit that although the second acquisition of shares of which The President’s Club complains took place in March 2012, the application to the Panel was made more than two months later on 26 June 2012, and was therefore out of time in the absence of an extension of time granted by the Panel pursuant to s 657C(3)(b) of the Corporations Act. To the extent that the Panel concluded that the circumstances were ongoing beyond March 2012 – because the applicants continued to hold the relevant shares – the applicants claim that the Panel fell into error in forming this view and deciding to conduct the proceedings.

43 Further, the applicants submit that the Panel denied them procedural fairness in extending the period of time for bringing the application before it without giving them notice of its intention to extend time, and without taking into account relevant considerations which bear upon a decision to extend time.

Consideration

44 Section 657B and s 657C(3) of the Corporations Act respectively impose limits on the power of the Panel to make a declaration of unacceptable circumstances, and the competence of a party to apply for such a declaration. These sections provide:

657B When Panel may make declaration

The Panel can only make a declaration under section 657A within:

(a) 3 months after the circumstances occur; or

(b) 1 month after the application under section 657C for the declaration was made;

whichever ends last. The Court may extend the period on application by the Panel.

657C Applying for declarations and orders

…

(3) [When an application may be made] An application for a declaration under section 657A can be made only within:

(a) two months after the circumstances occurred or;

(b) a longer period determined by the Panel.

45 The Panel’s decision to extend time was communicated first to the parties in an email from Ms Nicole Graham of the Panel to the parties on 18 July 2012, when the parties were informed that:

The Panel has met and is minded to declare that unacceptable circumstances exist in relation to the affairs of President’s Club.

…

Extension of time

The Panel considers that the circumstances of the acquisitions by QNA in or around July 2011 and March 2012 are continuing. For the avoidance of doubt, the Panel has extended the time for the application to be made by President’s Club, under s657C(3)(b) to 26 June 2012.

46 In its decision the Panel stated:

[40] In our view, there are alleged in the application contravention of the Corporations Act which are ongoing circumstances. Alternatively, in case it should be necessary we extended the time for making the application to the date on which it was made. On the alternative basis, we had one month within which to make a declaration, if one was to be made.

Decision of Panel in the alternative to extend time to The President’s Club to make application pursuant to section 657C(3)(b)

47 That the Panel is empowered by s 657C(3)(b) to extend the time in which an application for a declaration of unacceptable circumstances can be made beyond the two months prescribed by s 657C(3) is clear. However it is also clear that in doing do the Panel is required to accord procedural fairness to parties: s 195(4) ASIC Act, Australian Broadcasting Tribunal v Bond (1990) 170 CLR 321 at 367 per Deane J, cf Jackamarra v Krakouer (1998) 195 CLR 516 at 522, CP Ventures Pty Ltd v Withnall [1999] FCA 1437. Further, and specifically, the Panel must give each person to whom a proposed declaration relates, each party to the proceedings and ASIC the opportunity to make submissions in relation to the matter: s 657A(4) Corporations Act. This would, in my view, include making submissions as to whether an extension of time ought be granted by the Panel.

48 It appears from [40] of the Panel’s Reasons for Decision (“reasons for decision”) that the Panel, out of an abundance of caution, granted The President’s Club an extension of time to make its application for a declaration of unacceptable circumstances. In my view however, were such an extension of time necessary, the manner in which the Panel made this decision was contrary to the rules of natural justice. The decision was made cursorily, without providing the applicants the opportunity to make submissions in relation to such an order, and without reasons provided by the Panel. This can be contrasted with, for example, the careful consideration of a similar issue in the decision of the Panel in Re Austral Coal Limited [2005] ATP 14. In particular I note the comments of the Panel at [18] of Austral Coal where the Panel (correctly, in my view) observed:

[18] The Panel is given a discretion to extend the 2 month time limit set out in section 657C(3)(a) to make an application. The Panel considered that it should not lightly exercise that discretion. The time limit was set by the legislature to provide certainty to market participants in the context of takeovers that actions could not be challenged indefinitely.

49 In the reasons for decision before me it is not clear why the Panel decided that it was appropriate that time be extended to The President’s Club pursuant to s 657C(3)(b) to make its application.

50 In its submissions ASIC contends that QNA could have raised the issue of extension of time in response to the Panel’s email of 18 July 2012. However it is difficult to identify the utility of such a complaint by QNA at that time, when the Panel had already informed the parties that it had extended time to The President’s Club to make its application for a declaration of unacceptable circumstances.

51 Unless it was unnecessary for the Panel to extend time to The President’s Club to make its application because the relevant circumstances were ongoing (as the Panel actually concluded), the application was out of time and the Panel ought not to have conducted proceedings as it did.

Ongoing Circumstances

52 If it were open to the Panel to find that there were ongoing unacceptable circumstances, such that the unacceptable circumstances existed at the time of the declaration by the Panel, it was not necessary for the Panel to grant an extension of time to The President’s Club to make its application for a declaration. The application would not have been time-barred by s 657C(3)(a), and the decision of the Panel to conduct the proceedings was within its jurisdiction.

53 The primary complaints of the applicants in this respect however are that:

The Panel made an error of law in construing “circumstances” in s 657B(a) of the Corporations Act as referring to ongoing circumstances rather than the transactions in July 2011 and March 2012 when QNA acquired the relevant shares in the President’s Club; and

The Panel failed to provide reasons for its conclusion that the circumstances were ongoing.

54 I will examine each of these issues in turn.

Did the Panel err in law in finding that there were ongoing unacceptable circumstances?

55 Historically, the Panel has taken a broad view of “circumstances” for the purposes of its power to declare circumstances unacceptable (or not) pursuant to s 657A of the Corporations Act. Certainly in a number of decisions the Panel has found, on the facts of those cases, that unacceptable circumstances were ongoing. So, for example, in Re Trysoft Corporation Limited [2003] ATP 26 the Panel observed in the context of those particular facts:

[98] In these proceedings, the Panel considered that the relevant circumstances for the purposes of section 657C(3) of the Act were:

(a) the continued existence of the Agreements, the acquisitions of relevant interests under them and the associations existing pursuant to them, which had resulted in a breach of section 606 that had not been remedied; and

(b) the continuing failure by Mr Wong and the Shareholders to comply with their obligations under section 671B of the Act.

[99] These circumstances were still continuing as at the date of the Application, and so the Panel concluded that it had jurisdiction to hear the Application without the need to exercise its power under section 657C(3) to extend the period for making the Application.

(Emphasis added, footnotes omitted.)

56 In Re Anzoil NL [2002] ATP 19 the Panel observed, in the course of discussing the relevant facts:

[65] The evidence establishes clear contraventions of section 606 by IGM and Capersia, involving the purchase of a substantial interest at an 80% premium to market and offers to acquire more shares, which would have resulted in Capersia having voting power of not less than 30%, connected with proposals to change the board and intervene in the conduct of the company’s affairs. We are satisfied that these breaches, the willingness of the parties to carry forward the purchase from IGM by means other than the Agreement and the continued acting in concert regarding the composition of the Anzoil board constitute ongoing unacceptable circumstances in relation to the affairs of Anzoil.

57 In Re LV Living Limited [2005] ATP 5 at [128] the Panel concluded that the following matters constituted unacceptable circumstances in relation to the affairs of LV Living Ltd:

(a) the acquisition of shares in LV Living by each of Mr West, Peridon and ACP in breach of section 606;

(b) the on-market acquisitions of shares by Lidcombe and Mr Radford after 29 December 2004 in breach of section 606;

(c) in light of the acquisitions referred to in paragraphs (a) and (b), the continued holding by the Peridon Parties, ACP and the ACP Transferees of voting power in LV Living in excess of 20%; and

(d) the failure by the persons listed in Annexure D to lodge substantial holding notices which complied with the requirements of Chapter 6C.

(Emphasis added.)

58 That the Panel considers that it has broad powers to make a declaration of unacceptable circumstances is noted in the Panel’s Guidance Note 1 - Unacceptable Circumstances (http://www.takeovers.gov.au/content/DisplayDoc.aspx?doc=guidance_notes/current/001.htm) paragraph 17.

59 In this case, the Panel concluded at [40] that there were alleged in the application contraventions of the Corporations Act which were ongoing circumstances, and to that extent a declaration of unacceptable circumstances could be made without an extension of time.

60 That the Panel is a finder of facts, including the existence or otherwise of contraventions of the Corporations Act, and, in particular cases, unacceptable circumstances, in the context of Ch 6 of the Corporations Act, is clear: cf Attorney-General (Cth) v Alinta Ltd (2008) 233 CLR 542 at 574. Errors of fact made by the Panel in reaching a particular conclusion are generally not susceptible to challenge by way of judicial review. However it is also clear that if the Panel has made findings of fact as a result of an error of law, for example misconceiving the factual issue which it must ultimately determine, those findings are reviewable. In Waterford v The Commonwealth (1987) 163 CLR 54 at 77 Brennan J observed in the context of considering an appeal from a decision of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal:

The error of law which an appellant must rely on to succeed must arise on the facts as the AAT has found them to be or it must vitiate the findings made or it must have led the AAT to omit to make a finding it was legally required to make. There is no error of law simply in making a wrong finding of fact.

61 In my view it was open to the Panel to find that there were ongoing unacceptable circumstances, and indeed the Panel found that the unacceptable circumstances alleged by The President’s Club were ongoing. In forming this view I make the following observations.

62 First, I note comments of the Panel in Brickworks Limited (No.1) [2000] ATP 6 where the Panel said:

[30] A circumstance is distinct from the act or event which brings it into existence: circumstances are the relatively persistent background against which acts and events occur.

(Emphasis added.)

63 I accept the accuracy of this statement. Indeed, I am satisfied “circumstances” do not necessarily equate to an event or a specific transaction or transactions. Relevantly I note the following definition of “circumstances” in the Macquarie Dictionary:

2. (usually plural) the existing condition or state of affairs surrounding and affecting an agent: forced by circumstances to do a thing.

64 Further, in Alinta members of the High Court appeared to accept that “circumstances” in the takeovers context could extend to a general state of affairs relevant to a corporation rather than specific events. For example, at 552 Gleeson CJ said:

The purposes of the Chapter are declared in s 602, in terms that define the nature of the considerations at work in reaching a conclusion that circumstances in relation to the affairs of a company are unacceptable and that the public interest requires a certain form of regulatory intervention in the market.

(Emphasis added.)

65 Further, at 597 Kiefel and Crennan JJ observed:

The declaration is a statement of the Panel’s conclusion that, having regard to the circumstances created by the contravention and to the public interest, it considers something needs to be done about those circumstances. They are “unacceptable” in the sense that they cannot remain as they are and that they require consideration to be given to the orders that may be made under s 657D.

(Emphasis added.)

66 Comments of the High Court in Alinta in these cases as well as the Panel’s Guidance Note reflect s 657A(1) which empowers the Panel to declare circumstances in relation to the affairs of a company to be unacceptable circumstances.

67 Second, for the time limits prescribed by s 657B and s 657C to have meaning, there must be some certainty associated with definition of those “circumstances” to which the application relates and in respect of which a declaration of unacceptable circumstances may be made pursuant to s 657A. An absence of certainty in this respect would rob the time limits of any practical effect, and would cause ongoing uncertainty in the market in respect of the affairs of the particular company. However, these time limits should also be construed in conjunction with s 657A(2) which limits circumstances which may be declared unacceptable. So, for example, s 657A(2)(c) states that circumstances may only be unacceptable because they:

(i) Constituted, constitute, will constitute, or are likely to constitute a contravention of a provision of this Chapter or of Chapter 6A, 6B or 6C; or

(ii) Gave or give rise to, or will or are likely to give rise to, a contravention of a provision of this Chapter or of Chapter 6A, 6B or 6C.

68 In this respect, it appears that s 657A(2)(c) contemplates there being circumstances in particular cases which are in existence at the time of the application or indeed the declaration, in that the section specifically refers to presently-existing circumstances which – for example – constitute or give rise to a contravention of the legislation. Further, the reference in s 657A(2)(c) to circumstances which “constituted” or “constitute” a contravention suggests that the legislature recognised that a contravention could be ongoing rather than fixed to a particular point in time. The breadth of the terms of s 657A(2)(c) similarly supports a broad interpretation of the term “circumstances” for the purposes of Ch 6, and is consistent with the natural meaning of “circumstances” as set out earlier in this judgment.

69 A similar point may be made about s 657A(b) and (c) which refer to the effect the circumstances have had, are having, will have or are likely to have on control of the company or in relation to the company.

70 Third, the decision of the Panel should also be considered in light of the application made by The President’s Club which was before it. In its application The President’s Club had claimed, in summary, that the circumstances in respect of which it sought a declaration were as follows:

QNA and its associates had breached and continued to be in breach of s 606 of the Corporations Act.

There were extensive and material deficiencies in the bidder’s statement lodged by QNA with ASIC.

QNA had breached and continued to be in breach of s 631 and s 633 of the Corporations Act.

The circumstances giving rise to a breach of s 606 first occurred at the time of the first acquisition of shares, and those circumstances were continuing because QNA continued to hold a relevant interest in the company.

The circumstances giving rise to a breach of s 631(1) first occurred on 12 June 2012 when QNA failed to lodge a complying bid within two months of making a public proposal to make a takeover bid.

The circumstances giving rise to a breach of s 633(1) first occurred on or about 7 June 2012 when QNA failed to dispatch a complying bidder’s statement to The President’s Club shareholders.

The balance of the circumstances first occurred when the bidder’s statement was lodged with ASIC on 12 April 2012.

QNA had failed to lodge a replacement bidder’s statement, which circumstances were continuing.

71 The circumstances claimed by The President’s Club were clearly far broader than the share acquisitions in July 2011 and March 2012. It is appropriate to read the decision of the Panel, which found in favour of The President’s Club, with the application before it.

72 Fourth, as I have already observed, in order to make a declaration of unacceptable circumstances within the context of Ch 6 of the Corporations Act, those circumstances must be identified with some certainty. In Annexure A to the reasons for its decision (being the Declaration of Unacceptable Circumstances), the Panel declared:

[10] It appears to the Panel that the circumstances of the first acquisition are unacceptable having regard to:

(a) the effect that the Panel is satisfied the circumstances have had, are having, will have or are likely to have on:

(i) the control, or potential control, of TPC or

(ii) the acquisition, or proposed acquisition, by a person of a substantial interest in TPC and

(b) the purposes of Chapter 6 set out in section 602 and

(c) because they constituted, constitute, will constitute or are likely to constitute a contravention of a provision of Chapter 6.

[11] Further it appears to the Panel that the circumstances of the second acquisition are unacceptable having regard to:

(a) the effect that the Panel is satisfied the circumstances have had, are having, will have or are likely to have on:

(i) the control, or potential control, of TPC or

(ii) the acquisition, or proposed acquisition, by a person of a substantial interest in TPC and

(b) the purposes of Chapter 6 set out in section 602.

73 It is clear that the acquisitions of shares in July 2011 and March 2012 were at the core of claimed unacceptable circumstances in relation to the state of affairs of the company. However, it also appears from the terms of the declaration that the Panel was not confining the declaration to the specific transactions in which the relevant shares were acquired in July 2011 and March 2012. The Panel clearly considered that “the circumstances of” those acquisitions were unacceptable. In order to identify “the circumstances of” those acquisitions it is necessary to have regard to the reasons of the Panel.

74 Materially at [25]-[30] the Panel said:

[25] On 12 April 2012, QNA lodged a bidder’s statement with ASIC. Its proposed bid was for all the shares in TPC and corresponding villa interests and was unconditional.

[26] On 24 April 2012, QNA withdrew the bidder’s statement.

[27] On 11 May 2012, ASIC extended the time for QNA to make a bid.

[28] On 21 May 2012, it lodged a replacement bidder’s statement. Under its replacement bidder’s statement, QNA proposed to make an offer to purchase all the shares in TPC and all villa interests. The bidder’s statement said on the front page:

The bid is being made for both your shares and your Villa Interest. It is not possible to accept the bid in relation to your shares only or in relation to your Villa Interest only.

[29] On page 1 the following statement appeared:

While there is no formal stapling of your President’s Club Shares to your Villa Interest, it is likely that you have executed a deed poll which obliges you to sell your shares if you sell your Villa Interest to the same person. Also, clauses 6(b) and 6(c) of the Constitution require that a member of President’s Club must own a Villa Interest and a member’s shareholding is limited to the number of Villa Interests owned.

[30] At the time of the application, QNA had not dispatched offers to shareholders. It has since indicated that it will not do so.

75 At [103] the Panel said:

[103] It appears to us that the circumstances of the acquisition of TPC shares in July 2011 are unacceptable having regard to:

(a) the effect that we are satisfied the circumstances have had, are having, will have or are likely to have on:

(i) the control, or potential control, of TPC or

(ii) the acquisition, or proposed acquisition, by a person of a substantial interest in TPC and

(b) the purposes of Chapter 6 set out in section 602 and

(c) because they constituted, constitute, will constitute or are likely to constitute a contravention of a provision of Chapter 6.

76 After referring to observations of the High Court in Alinta, the Panel continued at [107]:

[107] The contravention of section 606 in this case gave effective control of TPC to QNA without other shareholders having an opportunity to decide if that should occur and without them having a reasonable and equal opportunity to participate in any benefits accruing to QNA through the proposal to acquire a substantial interest in TPC. We note that now a follow-on bid will not occur. We also agree with the application by TPC that the effect of the circumstances was that they were likely to inhibit an efficient, competitive and informed market in TPC shares since shareholders were not given information necessary for them to assess the merits of the proposal before it occurred. Further, in our view, based on our experience, any control premium for the shares of the remaining shareholders must now be considered unlikely, or at least significantly reduced in likelihood.

(footnote omitted.)

77 Further at [110] after referring to the second acquisition of shares in March 2012, the Panel observed:

[110] It appears to us that the circumstances of QNA’s subsequent purchases in reliance on the ‘creep’ provision in item 9 of section 611 are unacceptable. While they may not have involved a contravention, reliance was, in our view, based on a contravention (namely, the initial acquisition). The subsequent acquisitions consolidated QNA’s control of TPC. Moreover, had the initial acquisition been made by a takeover bid, the subsequent acquisitions would have occurred in circumstances in which the shareholders had information and a reasonable and equal opportunity to participate in any benefits. As it happened, the shareholders sold their shares (and villa interests) to QNA at different prices.

78 The acquisitions of shares in July 2011 and March 2012 were clearly, in the view of the Panel, contraventions of the Corporations Act. However as the reasons of the Panel also demonstrate, they were contraventions which:

Were ongoing, in that the applicants continued to maintain a relevant interest in those shares.

Had created a continuing state of affairs in respect of The President’s Club where the remaining shareholders were faced with a situation where QNA had achieved, and could continue to exercise, effective control of the company, without shareholder approval, or without the advantage of shareholders receiving an open bid.

Had created a state of affairs where a takeover bid by QNA for the remaining shares would have ameliorated the situation faced by the shareholders, but QNA had failed to make the bid despite preparation of two bidder’s statements (one of which was revoked in May 2012), and that state of affairs was continuing.

79 These circumstances were clearly distinguished by the Panel from the effects of the circumstances to which the Panel had regard, including the impact on the market and the control premium for the shares of the remaining shareholders. The Panel did identify the circumstances with certainty - namely the ongoing state of affairs in respect of the company created by the acquisitions of interests in shares in The President’s Club by the applicants in July 2011 and March 2012. In its submissions ASIC states:

The applicants’ contention that the relevant circumstances had all occurred by March 2012 at [33] focuses upon the facts giving rise to the circumstances, as opposed to the circumstances the subject of the application for a declaration.

80 I agree, and take the view that the applicants’ contention is, to that extent, flawed.

81 It follows that, in my view, it was open to the Panel and the Panel was entitled to make a finding that the application by The President’s Club had been made at a time when unacceptable circumstances were ongoing.

82 I do not consider that this view deprives the time limits prescribed by s 657B and s 657C of their meaning and effect. Obviously, there may be instances before the Panel where circumstances are not ongoing and the time limits will have commenced to run. However the facts before the Panel in this case support a finding that the relevant state of affairs was continuing and that the application was not time-barred. It follows that it was unnecessary for the Panel to grant The President’s Club an extension of time to make its application.

Reasons and submissions

83 The applicants claim that it is not clear from the reasons of the Panel why it concluded that the unacceptable circumstances were ongoing and therefore why the Panel was empowered to make a declaration.

84 It is well-settled that inadequate reasons given by an administrative body in respect of a decision can constitute an error of law: Adams v Yung (1998) 83 FCR 248 at 288, 301, Oberhardt v Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (2008) 174 FCR 157. However I note it is equally settled that, in reviewing the reasoning of an administrative body, the Court should not be concerned with looseness in language, nor unhappy phrasing, and that:

The reasons for the decision under review are not to be construed minutely and finely with an eye keenly attuned to the perception of error.

(Collector of Customs v Pozzolanic Enterprises Pty Ltd (1993) 43 FCR 280 at 287.)

85 Further, as the High Court observed in Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Wu Shan Liang (1996) 185 CLR 259 at 272:

These propositions are well settled. They recognise the reality that the reasons of an administrative decision-maker are meant to inform and not to be scrutinised upon over-zealous judicial review by seeking to discern whether some inadequacy may be gleaned from the way in which the reasons are expressed.

86 In this case, while the basis for decision of the Panel could perhaps have been more clearly articulated, it is also clear from its reasons for decision why the Panel considered the unacceptable circumstances before it to be ongoing. In particular, I note that the basis of the application of The President’s Club was ongoing unacceptable circumstances created by conduct of the applicants, and the reasons of the Panel were framed in those terms. A captious approach to examination of the reasons of the Panel is, as the High Court has observed in respect of judicial review of administrative decisions generally, improper.

87 Finally, I note the Panel’s observation at [120] that QNA had been permitted to participate fully in the Panel’s proceedings and had done so with legal representation throughout. In such circumstances the finding of the Panel that there had been ongoing unacceptable circumstances could have been no surprise to the applicants.

88 It follows that grounds 4, 5 and 6 are not substantiated.

Ground 7

89 The applicants contend that the Panel erred in concluding that the July 2011 acquisition of shares was a contravention of s 606 of the Corporations Act.

90 The key finding of the Panel with which the applicants take issue was [91] where the Panel said:

[91] “Voting power” is a concept defined by section 610. It looks only at the number of votes attached to the shares in which a person or their associate has a relevant interest. It is not concerned with the practicalities of whether the person can in fact cast those votes.

91 Importantly the Panel continued at [92]-[93]:

[92] A person’s voting power in a company is the percentage of the votes attached to voting shares in that company in which the person (with their associates) has relevant interests. Although CDLI’s covenant to ASIC largely prevented it from exercising the votes attached to approximately 31.4% or more of the shares it held (because it could vote only 10%), those votes remained attached to the shares.

[93] Therefore, in our view, at all relevant times CDLI’s relevant interest in those shares constituted 41.4% of the voting power in TPC, despite the covenant in the deed poll.

92 Earlier in its reasons the Panel had observed:

[83] In our view, CDLI has a relevant interest constituted by power to exercise the right to vote the shares. The fetter on voting arose entirely from the covenant in the deed poll, and not at all from TPC’s constitution. The rights attached to the shares as set out in TPC’s constitution are the same as for all voting shares (in contrast to the 5 Subscriber Shares).

93 In summary the applicants submit:

Although in July 2011 QNA acquired a relevant interest in 41.4% of the issued voting shares of The President’s Club, this did not mean that result in an increase in the voting power indirectly controlled by QNA from below 20% to more than 20%.

The deed poll prevented Lion Investments from exercising more than 10% of the voting power in The President’s Club, and this deed poll remained in effect immediately after the purchase by QNA of the shares in Lion Holdings in July 2011.

The deed poll was directly relevant to the issue of voting power, but was not treated as such by the Panel.

The Panel’s conclusion at [91] was inconsistent with the language of s 610 of the Corporations Act.

The exercise of a right under a deed poll is not itself a “transaction”.

The key issue was whether the votes could be cast. In this case they could not be cast because of the terms of the deed poll.

94 In response, The President’s Club submits that:

The argument that the July 2011 acquisition was not a contravention of s 606 was actually a challenge to a mixed conclusion of fact and law of the Panel, namely that:

o the Panel should have had regard to evidence (that is the deed poll by Lion Investments in favour of ASIC) in order to make a finding that Lion Investments could not in fact have cast more than 10% of the votes in The President’s Club; and

o that finding of fact should have led the Panel to find that the voting power acquired by QNA was only 10% and therefore no contravention.

alternatively the Panel correctly applied s 610 by having regard to votes which the shareholder was legally entitled to vote in respect of each share held. The deed poll between Lion Investments and ASIC could only be enforced by ASIC by application to Court: s 601QA(3).

The constitution of The President’s Club is legally binding as between the company and Lion Investments, and determines the votes that Lion Investments is legally able to cast at a general meeting of the company. The deed poll is not legally binding as between the company and Lion Investments.

In any event, if the deed poll meant that Lion Investments could only cast 10% of shares in The President’s Club, that situation changed when the deed poll came to an end on 13 March 2012. At this point the contravention of s 606(1) was complete.

95 Further, ASIC submits that s 610(1), in defining “voting power” by reference to a formula, is not concerned with limitations which a person may have placed on their right to exercise the total number of votes which they hold, and that there is nothing in s 610(2) to the contrary. I note that The President’s Club adopted this submission.

Consideration

96 Materially s 606 of the Corporations Act provides as follows:

606 Prohibition on certain acquisitions of relevant interests in voting shares

Acquisition of relevant interests in voting shares through transaction entered into by or on behalf of person acquiring relevant interest

(1) A person must not acquire a relevant interest in issued voting shares in a company if:

(a) the company is:

(i) a listed company; or

(ii) an unlisted company with more than 50 members; and

(b) the person acquiring the interest does so through a transaction in relation to securities entered into by or on behalf of the person; and

(c) because of the transaction, that person’s or someone else’s voting power in the company increases:

(i) from 20% or below to more than 20%; or

(ii) from a starting point that is above 20% and below 90%.

Note 1: Section 9 defines company as meaning a company registered under this Act.

Note 2: Section 607 deals with the effect of a contravention of this section on transactions. Sections 608 and 609 deal with the meaning of relevant interest. Section 610 deals with the calculation of a person’s voting power in a company.

Note 3: If the acquisition of relevant interests in an unlisted company with 50 or fewer members leads to the acquisition of a relevant interest in another company that is an unlisted company with more than 50 members, or a listed company, the acquisition is caught by this section because of its effect on that other company.

…

…

97 Section 610 defines “voting power” as follows:

610 Voting power in a body or managed investment scheme

Person’s voting power in a body or managed investment scheme

(1) A person’s voting power in a designated body is:

Person’s and associate’s votes x 100

Total votes in designated body

where:

person’s and associates’ votes is the total number of votes attached to all the voting shares in the designated body (if any) that the person or an associate has a relevant interest in.

total votes in designated body is the total number of votes attached to all voting shares in the designated body.

Note: Even if a person’s relevant interest in voting shares is based on control over disposal of the shares (rather than control over voting rights attached to the shares), their voting power in the designated body is calculated on the basis of the number of votes attached to those shares.

Counting votes

(2) For the purposes of this section, the number of votes attached to a voting share in a designated body is the maximum number of votes that can be cast in respect of the share on a poll:

(a) if the election of directors is determined by the casting of votes attached to voting shares-on the election of a director of the designated body; or

(b) if the election of directors is not determined by the casting of votes attached to voting shares-on the adoption of a constitution for the designated body or the amendment of the body corporate’s constitution.

Note: The Takeovers Panel may decide that the setting or varying of voting rights in a way that affects control of a designated body is unacceptable circumstances under section 657A.

(3) If:

(a) a transaction in relation to, or an acquisition of an interest in, securities occurs; and

(b) before the transaction or acquisition, a person did not have a relevant interest in particular voting shares but an associate of the person did have a relevant interest in those shares; and

(c) because of the transaction or acquisition, the person acquires a relevant interest in those shares;