Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Breast Check Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 190

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

| AND: | BREAST CHECK PTY LTD ACN 119 038 274 First Respondent ALEXANDRA BOYD Second Respondent |

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Court will receive submissions and hear from the parties as to the appropriate relief to be granted and the terms in which final orders in the proceeding should be made.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

| WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

| GENERAL DIVISION | WAD 515 of 2011 |

| BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant |

| AND: | BREAST CHECK PTY LTD ACN 119 038 274 First Respondent ALEXANDRA BOYD Second Respondent |

| JUDGE: | BARKER J |

| DATE: | 10 MARCH 2014 |

| PLACE: | PERTH |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 In 2010 and 2011, Breast Check (the first respondent), which employed Dr Boyd (the second respondent), offered a breast imaging service for reward at premises in Mosman Park, Western Australia.

2 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) (the applicant) alleges that:

from 18 October 2010 until around February 2011, Breast Check provided the breast imaging service using a device known as the Multifrequency Electrical Impedance Mammograph (MEM device) and various infrared imaging devices for digital thermography (thermography devices) (collectively the bundled imaging service).

from about February 2011 until a date unknown to it Breast Check provided the breast imaging service using thermography devices (the thermography service).

from about 18 October 2010 until at least July 2011, Breast Check provided customers (all women) who had purchased either the bundled imaging service or the thermography service with a breast health report and an information package which consisted of one or more of report information, a breast imaging pamphlet, a thermography pamphlet and a pamphlet describing the services offered by Breast Check.

from 18 October 2010 until around May 2011, Breast Check published and distributed “to the public”, a breast imaging pamphlet which, among other things, was made available at the reception area of the premises of Breast Check in Mosman Park for customers or potential customers who visited the business.

from at least around early May 2011 until around 19 May 2011, Breast Check similarly published and distributed “to the public” a pamphlet advertising the use of the thermography devices for breast imaging.

from around November 2010 until at least around August 2011, Breast Check similarly published and distributed “to the public” a pamphlet entitled “Our Services To You”.

3 ACCC alleges that by this conduct Breast Check represented that:

breast imaging done using a thermography device, either alone or in conjunction with a MEM device, could provide an adequate scientific medical basis for assessing whether a customer may be at risk from breast cancer and, if so, the level of such risk, when there was and is inadequate scientific medical basis for so representing (risk of cancer representation).

breast imaging using either a thermography device alone, or in conjunction with an MEM device, could provide an adequate scientific basis for assuring a customer that they do not have breast cancer, when there was and is inadequate scientific medical basis for so representing (assurance representation).

there is an adequate scientific medical basis for using either the thermography device alone, or in conjunction with an MEM device for breast imaging, as a substitute for mammography, when there was and is an inadequate scientific medical basis for so representing (substitute for mammography representation).

4 ACCC alleges that Breast Check thereby engaged in conduct in trade or commerce which was misleading or deceptive or which was likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1975 (Cth) (TP Act) (from 18 October to 31 December 2010) and s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (after 1 January 2011), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CC Act).

5 ACCC further alleges that each of the representations made by Breast Check represented that the devices used by Breast Check for breast imaging had performance characteristics, uses or benefits which they did not have and, in relation to the substitute for mammography representation, that the representation included the representation that the devices used by Breast Check for breast imaging were approved, when they were not, in contravention of s 53(c) TP Act (from 18 October to 31 December 2010) and s 29(1)(g) ACL (after 1 January 2011).

6 ACCC also alleges Dr Boyd was knowingly concerned in, or party to, each of Breast Check’s contraventions and is liable as an accessory for each contravention because she approved the contents of the promotional pamphlets and report information, prepared the breast health reports and knew that the representations alleged were false in that there was no adequate scientific medical basis for using a thermography device, either alone or together with the MEM device, for the purposes represented.

7 ACCC, by way of relief, seeks against the respondents declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), injunctions under s 232 of the ACL, an order for publication under s 86C TP Act and s 246 ACL, pecuniary penalties under s 76E TP Act and s 224 ACL, an order that a copy of the sealed reasons for judgment be retained by the Court for the purposes of s 137H of the CC Act and costs.

8 The respondents admit a number of allegations made against them including that at material times they offered a breast imaging service in trade or commerce but dispute a number of key allegations. As a result, the issues arising in this proceeding may be stated as follows:

(1) Whether the promotional pamphlets, breast health reports and report information were distributed “to the public”.

(2) Whether any of the three representations pleaded by the ACCC were conveyed by the conduct complained of.

(3) If the risk of cancer representation was conveyed, whether it was accurate. The respondents accept, however, that if the assurance representation and the substitute for mammography representation were conveyed, then it follows that those representations were inaccurate.

(4) Whether Dr Boyd was knowingly concerned in any proven contraventions.

were the promotional pamphlets, breast health reports and report information distributed to the public?

9 The respondents admit that Breast Check produced the promotional pamphlets, breast health reports and report information pleaded by the ACCC and that the breast health reports and report information were given to customers. They challenge the allegation, however, that these materials were distributed “to the public”.

10 The identification of the target audience – whether an individual or a section of the public – is important because, for example, conduct which may not mislead or deceive an individual with whom a respondent has had dealings, may possibly mislead or deceive a representative member of the public in a setting devoid of personal dealings.

11 At material times, s 52 TP Act and s 18 ACL provided that a corporation shall not, in trade or commerce “engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive”. Further, at material times, s 53(c) TP Act and s 29(1)(g) ACL provided that a corporation (s 53) and a person (s 29) shall not, or must not, respectively in trade or commerce in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services “represent that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits they do not have”. Each of these provisions is capable of applying to conduct that is directed to the public at large as well as to conduct involving individuals.

12 In Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd [1982] HCA 44; (1982) 149 CLR 191 (Parkdale), at 199, Gibbs CJ observed, in respect of s 52, that it did not expressly state what persons or class of persons should be considered as the possible victims for the purpose of deciding whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. Gibbs CJ added that it seems clear enough that consideration must be given to the “class of consumers likely to be affected by the conduct”. He added that the section must be regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class.

13 In Parkdale, the respondent had manufactured and sold under a particular name furniture of distinctive appearance and design. The appellant also made and sold furniture which closely resembled that made by the respondent. There was sewn into the front of each piece of Parkdale furniture a label identifying the range it came from, but the label could be tucked under the upholstery and would not then be visible and might be easily enough removed by cutting it off. It was the practice of manufacturers to label such furniture in that way and Puxu’s furniture bore labels of a similar kind but somewhat smaller. Puxu sued Parkdale alleging that Parkdale was engaging in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or which was likely to mislead or deceive and sought injunctions and damages. Gibbs CJ (at 199) considered that the persons likely to be affected by the conduct complained of were the potential purchasers of a suite of furniture costing about $1500 who would, if acting reasonably, look for a label, brand or mark if they were concerned to buy a suite of particular furniture. Gibbs CJ added that the conduct of a defendant must be viewed “as a whole”. Mason J (at 211) made a similar finding concerning a reasonable purchaser.

14 In Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 (Campomar) the appellants had manufactured and marketed cosmetics and toiletries outside Australia for many years. In 1986 the first appellant applied for and then obtained registration for the word “Nike” for perfume products. In 1992 it obtained registration for the word “Nike” for bleaching preparations. In 1993 the appellants began marketing their products using the word “Nike” in Australia. One of the products had a get-up featuring the expression “Nike sport fragrance”. By this time the respondents had built up a significant reputation in Australia for the manufacture and distribution of athletic footwear and sports clothing distinguished by the “NIKE” mark. In 1994 the respondents instituted proceedings against the appellants seeking to expunge the first and second registrations. They also contended the appellants’ marketing of their perfume products constituted misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 52. Amongst other things, the trial judge upheld the s 52 claim and by a majority the Full Federal Court dismissed an appeal against that finding. On further appeal the High Court also upheld the s 52 finding.

15 In Campomar, the Court (at [98] and following) dealt with the question of causation and erroneous assumption and (at [99]), said that the matter of contravention should not be considered in the abstract and regard must be had to the circumstances of the particular case and the remedies sought in respect of the contravention alleged either to have occurred or to be threatened.

16 The Court noted (at [100]) what Deane and Fitzgerald JJ had observed in Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 (Taco Bell), at 202, to the effect that whether or not conduct amounted to a representation was a question of fact decided by considering what was said or done “against the background of all surrounding circumstances”.

17 In Taco Bell their Honours also said that, in some cases, such as an express untrue representation made only to an identified individual, the process of deciding that question of fact may be direct and uncomplicated, but that in other cases the process would be more complicated.

18 In Campomar the Court (at [101]) said that the other classes of case which their Honours had in mind included those of “actual or threatened conduct involving representations to the public at large or to a section thereof”, such as prospective retail purchasers of a product the respondent markets or proposes to market.

19 The Court added (at [102]) that it is in cases of representations to the public that there enter the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of the class of prospective purchasers as those expressions were respectively used in Parkdale by Mason J and Gibbs CJ. The Court said that although a class of consumers may be expected to include a wide range of persons, “in isolating the ‘ordinary’ or ‘reasonable’ members of that class, there is an objective attribution of certain characteristics”. Thus, in Parkdale, Mason J had concluded it was unlikely an ordinary purchaser would notice slight differences in furniture but would attempt to look for a brand name.

20 The Court added (at [103]) that where the persons in question are not identified individuals to whom a particular misrepresentation has been made or from whom a relevant fact, circumstance or proposal was withheld, but are members of a class to which the conduct in question was directed in a general sense, it is necessary to isolate by some criterion a representative member of that class. The inquiry thus is to be made with respect to this hypothetical individual why the misconception complained of has arisen or is likely to arise if no injunctive relief be granted.

21 In Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Limited [2004] HCA 60; (2004) 218 CLR 592 (Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty), a suburban real estate agent produced a brochure which reproduced a survey diagram of waterfront land that was to be auctioned. The diagram inaccurately depicted a swimming pool as being entirely within freehold land partly demarcated by the mean high water mark. The brochure stated that the information within it had been obtained from other sources which the agent believed to be reliable, but that its accuracy could not be guaranteed and that interested persons should rely on their own inquiries. The agent provided the brochure to two interested persons and informed them that it contained everything that needed to be known about the property. Those persons later purchased the property at auction, after which they discovered that the swimming pool was not entirely within the land above the mean high water mark.

22 The majority of the Court (Gleeson CJ, Hayne and Heydon JJ) held that it followed from the nature of the parties, the character of the transaction contemplated, and the contents of the brochure that the agent had done no more than communicate what the vendor was representing, without adopting or endorsing it. Hence, the agent had not engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct within s 52 in distributing it to the purchasers.

23 The majority (at [36]) addressed the “relevant class addressed” issue. By reference to Campomar, they noted that questions of allegedly misleading conduct including questions as to what the conduct was, can be analysed from two points of view. One is employed in relation to members of a class to which the conduct in question is directed in a general sense and the other is employed where the objects of the conduct are “identified individuals”. Their Honours noted that the adoption of the former point of view requires isolation by some criterion or criteria of a representative member of the class.

24 The majority (at [37]) noted that the former approach is common when remedies other than those conferred by s 82 (or s 87 of the TP Act), as it then applied, were under consideration. But they added that the former approach is inappropriate, and the latter is inevitable, in cases like that then before the Court, where monetary relief is sought by a plaintiff who alleges that a particular misrepresentation was made to identified persons. In such a case a plaintiff must establish a causal link between the impugned conduct and the loss claimed. That depends on analysing the conduct of a respondent in relation to the applicant alone.

25 Accordingly, in Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty, the majority said (at [37]) it was necessary to consider the character of the particular conduct of the particular agent in relation to the particular purchasers, bearing in mind matters of fact each knew about the other as a result of the nature of their dealings and the conversations between them or which each may be taken to have known.

26 In Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; (2009) 238 CLR 304 (Campbell v Backoffice), the appellant, Mr Campbell, was a single shareholder and director of a company which conducted a water filtration business. He entered into a written agreement for the sale of one share to a company controlled by another person. He also entered into a shareholders agreement with that person and his company. The agreement contained warranties. The agreement did not, however, provide an effective mechanism for resolving disputes. Disagreement occurred and the other person and his company brought proceedings for the winding up of the company or for the compulsory acquisition of the share held by that company. They also claimed that the appellant had breached warranties and had contravened s 42 of the Fair Trading Act 1987 (NSW), dealing with misleading or deceptive conduct, in making representations about the company’s financial position and not correcting them.

27 So far as the s 42 claim was concerned, the Court held that the relevant representations had been of belief of truth, not accuracy, hence there had been no misleading or deceptive conduct.

28 Referring to Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty, the Court agreed that it is necessary to examine statements or actions alleged to constitute misleading or deceptive conduct in the context of the whole activity. French CJ noted (at [25]) that characterisation of conduct as misleading or deceptive is a task that generally requires consideration of whether the impugned conduct viewed as a whole has a tendency to lead a person into error, citing Parkdale at 198-199 per Gibbs CJ in particular. His Honour said that it may be undertaken by reference to the public or a relevant section of the public and that in cases of misleading or deceptive conduct analogous to passing off and involving reputational issues, the relevant section of the public may be defined, according to the nature of the conduct, by geographical distribution, age or some other common attribute or interest. On the other hand, his Honour noted, characterisation may be undertaken in the context of commercial negotiations between individuals. French CJ added that in either case it involves consideration of a notional cause and effect relationship between the conduct and the state of mind of the relevant person or class of persons, the test being necessarily objective.

29 French CJ said (at [26]) that the Court has drawn a practical distinction between the approach to characterisation of conduct as misleading or deceptive when the public is involved, on the one hand, and where the conduct occurs in dealings between individuals on the other. French CJ stated that in the former case, the sufficiency of the connection between the conduct and the misleading or deception of prospective purchasers (as in Campomar) is to be approached at a level of abstraction not present where the case is one involving an express untrue representation allegedly made only to identified individuals.

30 Both French CJ and the plurality (Gummow, Hayne, Heydon, Kiefel JJ) approached the case on the basis it involved conduct occurring in dealings between individuals.

31 In this proceeding, ACCC contends that the conduct of which it complains was directed to sections of the public, being: (1) those women who were interested in the breast imaging service offered by Breast Check, who could obtain the three promotional pamphlets; and (2) those women who made appointments and who had already received breast imaging.

32 ACCC rejects the respondents’ submission that the promotional pamphlets were not available to the public and were only given to existing customers or to those interested in the breast imaging offered by Breast Check and only after some detailed explanation had been given to them.

33 ACCC’s case is expressly advanced on the basis that a notional representative member of a class of customers or potential customers is likely to have been misled, not that any specific persons or members of a limited class or group of persons were misled by the conduct complained of.

34 ACCC says that, in this case, the relevant test is an objective test based on the assessment of: (1) either a reasonable hypothetical member of a general class of consumers for the promotional pamphlets; and (2) a reasonable hypothetical person in the position of a Breast Check customer for the breast health reports and the report information.

35 As to their attributes, ACCC contends that the reasonable hypothetical member of the audience of the promotional pamphlets, the first class of public contended for, should be regarded as a reasonable member of the wider public with an interest in breast imaging as a medical means of investigating breast cancer, but who has no special knowledge distinct from the wider public. ACCC submits that a reasonable member of that class is likely to correlate breast imaging in a health related, medical context, with investigations primarily concerned with detecting the presence or otherwise of breast cancer. Further, that such a person (a woman) would be aware in general terms that mammography is a recognised method of screening for breast cancer.

36 ACCC further contends that any distinction to be drawn between a reasonable hypothetical member of the audience of the promotional pamphlets, and that of the breast health reports and report information, the second class of public contended for, will depend on what further information was made known to a person who had received breast imaging from Breast Check and the extent to which the effect or likely effect of the conduct directed to that hypothetical person will differ as a result of such further information. That is to say, whether as a result of receiving further information that reasonable hypothetical individual has some special knowledge or understanding that changes the likely effect of the conduct directed towards them. It should be added that this submission depends, or appears to depend, on the members of this second class of the public having already read a relevant promotional brochure or reading it at the same time as receiving a breast health report or report information.

37 ACCC notes that Breast Check seeks to rely on a contention that those who had received breast imaging were provided with further information and had some special knowledge that would prevent the alleged misrepresentations arising. ACCC submits there is no evidence to support such a contention.

38 Breast Check (with whose submissions Dr Boyd generally agrees) notes that only two kinds of conduct are pleaded by ACCC: first, the provision to customers of the breast health reports (as to which see [9] amended statement of claim (statement of claim)); and secondly, “publication by distribution to the public” as alleged in [13], [16] and [19] statement of claim.

39 Breast Check says that while the allegation at [19] statement of claim involves the Our Services to You pamphlet by distribution to the public, the particulars go no further than its provision to customers with the breast health report, and there was no evidence suggesting the pamphlet was distributed in any other manner. Thus, the conduct with respect to that pamphlet should be assessed with that of providing the breast health reports to customers.

40 Breast Check submits that in the case of the other two promotional pamphlets, the breast imaging pamphlet and the thermography pamphlet, the allegation of publication by distribution to the public is confined by particulars to display in the reception of the clinic and sending or giving to members of the public who inquired about the services, as alleged in [13(iii)] and [16(iii)] statement of claim.

41 Breast Check says that each of the representations as pleaded is addressed to the efficacy of the thermography device alone or in conjunction with the MEM device, as per [22], [24] and [26] statement of claim. It submits that none of the representations as pleaded could have been conveyed by the literature in issue unless the women to whom the literature was published read the various references to “breast health profiling”, “a way of profiling your breast health”, “breast risk assessment”, “methods to monitor breast health”, “information that may reassure you in confirming the health of your breasts” and “complete physiological breast risk assessment profile” to be references to the use by Breast Check of its imaging devices alone. It further submits none of the conduct in issue conveyed a representation concerning the imaging devices alone and so none of the representations as pleaded was made.

42 Breast Check also submits that ACCC’s written closing submissions, at [67]-[68], attempt to depart from the pleaded case and so should be rejected. It is submitted the risk of cancer representation at [22] statement of claim is pleaded as being a representation of what “could” be an adequate basis for assessment, not what “would” be. The submission at [67]-[68], it submits, is a concession that the pleaded representation was not made.

43 As to the task of characterisation of the conduct, Breast Check contends that the conduct alleged in [9] and [19] statement of claim involves the provision of a report and pamphlets to customers who have undergone the breast health profiling procedure including the taking of full personal and family medical history, the conduct of various tests and observations (as to height, weight, blood pressure and other body measurements), thermographic imaging and a clinical breast examination. Each such customer will have had a consultation with the doctor before receiving the report and other pamphlets. Some had been referred for mammograms, ultrasound and/or biopsy before receiving the report and pamphlets.

44 Breast Check submits each breast health report contained information which was specific to the clinical findings with respect to the patient concerned and there is no complaint that any of those clinical findings were inappropriate.

45 It is in these circumstances, Breast Check notes, ACCC seeks to engage with the characterisation of this conduct by submitting that there exists a “class of the public” being “those who received the breast imaging, no doubt having also viewed a Promotional Pamphlet, and then received a Breast Health Report and Report Information” – as put in its written closing submissions at [15(b)].

46 Breast Check submits there are three difficulties with the submission made by ACCC, namely:

(1) It is artificial to describe the patients of an individual doctor as a “class of the public” and doing so obscures the real question of characterisation of conduct which differed from person to person;

(2) The evidence establishes that no woman received the breast imaging without also receiving other aspects of the breast health profiling as described by Breast Check;

(3) There is no evidence to support the proposition that customers generally viewed any pamphlets before undergoing the breast health profiling, and no basis to infer that that was the case.

47 Breast Check submits that, as French CJ indicated in Campbell at [26], the task of characterisation is not one involving a binary choice between “classes of the public” on the one hand and “dealings between individuals” on the other. Rather, in cases where the public is involved a degree of abstraction, as articulated in Campomar at [101], is as a practical matter appropriate; while in dealings between individuals it is not.

48 It is in those circumstances that the respondents submit that the conduct here is not directed in a general sense to the public and that this is a case where the dealings are both more targeted, and more intimate, than dealings with the public, but are also less targeted than those in Campbell v Backoffice. Accordingly, the pamphlets were directed “in a general sense” to all customers but each customer experienced conduct which was specific to her.

49 Breast Check submits that, by contrast, the cases of .au Domain Administration Limited v Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 424; (2004) 207 ALR 521 (.au Domain) and Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Exchange Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 955; (2003) 202 ALR 24 (National Exchange) were “paradigm cases” in which the conduct in question was in relation to members of a class to which the conduct was directed in a general sense. Each involved the use of bulk email and there were no dealings between the parties, other than the sending and receipt of those emails.

50 At a more general level, in relation to the allegations pleaded, Breast Check submits that, on the evidence led at trial, the Court should conclude that:

(1) the bulk of distribution of the brochures was to existing patients/customers who had, by the time of distribution, “experienced the process of breast health profiling” – and whose reasonable interpretation of the brochures could only have been equivalent to that of the breast health reports;

(2) any other distribution of the brochures was in response to specific inquiries and preceded by a conversation to the effect stated by Ms Robyn Coyle in her evidence;

(3) much of that other distribution was also preceded by the signature of the terms and conditions document that governed the relationship of the patient/customer with Breast Check.

51 Breast Check submits that in circumstances where a person has made a specific inquiry of a business and been informed of the scope of the breast health profiling service offered – including the taking of a history and detailed observations, the conduct of imaging, the conduct of a physical breast examination by the doctor and a consultation with the doctor at which the outcomes from all of that would be discussed – it would be unreasonable to read the various references to “breast health profiling” as being restricted to the use of the imaging devices alone. The respondents’ case is that none of the conduct complained of resulted in any representation being made concerning the imaging devices alone and so it follows that the representations alleged by ACCC were not made.

52 Breast Check, in advancing its case that each aspect of conduct complained of, including the publication and distribution of the three promotional pamphlets, must be seen in the context of a single profiling service, submits that the evidence of Dr Boyd (not at trial, but in her examination under s 155 of the TP Act and CC Act by ACCC) and Ms Coyle, who were both employed by Breast Check at material times, and Ms Kathleen Melia, an ACCC investigator, is relevant and is to the following effect:

The brochures were not distributed to the public at large, and were given only to existing customers of the clinic, or to people specifically inquiring about the services by telephone, or in person at the clinic (Coyle and Boyd).

The brochures were not printed in bulk – they were printed from the clinic computer as required (Coyle – exhibit 4, pg 32.37).

For telephone enquiries, a brochure would be sent following the provision of an explanation by the receptionist as to what the service involved (Coyle).

The substance of that explanation is described by Ms Coyle (transcript 70.05-25; 71.25-30).

Ms Melia’s evidence of what she was told when she enquired at the clinic in person is less detailed than but not inconsistent with Ms Coyle’s evidence; on those aspects of detail upon which Ms Melia might have differed from Ms Coyle, Ms Melia had no relevant recollection beyond the content of the note for file made by her on that day. Her evidence was not that “she was able to go into the reception area and pick up a pamphlet and take it away with nothing being said to her about it”. Her note for file was wholly inconsistent with that proposition.

Ms Coyle’s recounting of the conversation took no more than a minute or so. That is consistent with Ms Melia’s estimate of 40 seconds to a minute (transcript 55.27-29). On the other hand, Ms Melia’s estimate is inconsistent with the conversation being limited to words only to the effect set out in her affidavit at [6]-[8].

Ms Melia’s absence of detailed recollection provides no basis to reject Ms Coyle’s evidence of the system used by Breast Check and its application when members of the public called and enquired about the clinic’s services.

Ms Coyle was aware of only a small number of occasions when a person had enquired in person at the clinic (transcript 72.15-25). Apart from Ms Melia’s investigatory visit, there was no direct evidence of “in person” enquiries having occurred at all.

Ms Melia’s evidence about the physical characteristics of the clinic was inconsistent with that of Ms Coyle. There was no sign on the premises and no advertising in the vicinity. The only sign was directed to pointing customers who were otherwise seeking to enter the clinic to the entry door, which was in a side street. The location was not one with significant pedestrian traffic. The signage and other layout were all inconsistent with the operator of the clinic seeking to attract members of the public who may walk into the clinic.

When Ms Melia attended the clinic she walked directly to the reception desk. She understood that would be her first destination. Pamphlets were not available to her at that desk, rather she obtained them from a table in the waiting room – some five to six metres from the reception desk – a placement which was consistent with the pamphlets being made available to customers who had attended at the reception desk and received the explanation which Ms Coyle gave in evidence.

For the majority of existing customers attending the clinic, the brochure was only given after a consultation with Dr Boyd and then as part of an “information package” which included the written breast health reports (Coyle and Boyd).

It was the usual practice at the clinic (and before any imaging, consultation, report or brochure was provided) for customers to sign a terms and conditions acknowledgement (Coyle and Boyd).

The form of acknowledgement changed over time but examples can be seen on each of the ten customer files at TB 15-24.

In addition to the thermographic imaging, the majority of customers attending the clinic underwent a clinical breast examination by either Dr Boyd or Ms Coyle.

During the consultation with Dr Boyd she would discuss the service and any other health issues with the customer.

A substantial number of referrals were made by Dr Boyd for customers to attend for either ultrasound or mammogram tests (Boyd) and a number for surgical treatment (TB 25).

For the majority of customers attending the clinic, the report and brochures were hand delivered immediately following the consultation, but in some cases the materials were posted.

The breast health reports given to customers, along with the brochures, concluded with a written statement the form of which can be seen outlined in a red box at TB 15 pg 121.

53 ACCC contends that publication to the public, especially of the breast imaging pamphlet, is made out by the following evidence:

The availability of the promotional pamphlets, particularly the breast imaging pamphlet, to visitors at Breast Check’s premises which was confirmed by the evidence of Ms Coyle and Ms Melia.

The admission of Breast Check that it published each of the promotional pamphlets in the relevant periods.

Ms Coyle’s evidence that at relevant times either the breast imaging pamphlet or the thermography pamphlet was on display in the reception and were also sometimes kept on a table in the waiting area of the reception.

Ms Coyle’s evidence that if people came into the clinic they were able to pick up a pamphlet and take it with them.

Ms Melia’s evidence (in her affidavit and in her oral evidence) about her visit to the clinic on 24 February 2011: that her visit was one and a half to two minutes in duration; that she was given only general information on the procedure and was told she would have a consultation with a doctor; that her conversation with the staff member took “no more than a minute”; that she then left with the breast imaging pamphlet.

In cross-examination Ms Melia did not recall any further information or explanation being provided to her. Her interaction was not long enough for any such detailed explanation to have been given.

Ms Coyle’s evidence that she understood that the receptionist at Breast Check would provide information on the procedure to customers or potential customers enquiring about breast imaging. But she gave no evidence as to what was actually said by the receptionist. She did give evidence that she earlier prepared a detailed job description setting out the tasks to be performed by the receptionist and confirmed that the comprehensive list of tasks did not include giving detailed information on the breast imaging service to customers or anyone else enquiring about the services before they accessed its promotional pamphlets.

The evidence of Ms Melia and Ms Coyle that members of the general public would have easily been able to identify the Breast Check clinic, call in, pick up and take away a promotional pamphlet or read it while waiting in the clinic, and its promotion was not limited to existing customers.

Ms Coyle’s confirmation that the map on the back of the breast imaging pamphlet (also found on the back of the thermography pamphlet) was accurate and that the clinic was located in close proximity to the Mosman Park railway station and Stirling Highway.

There was prominent signage on Stirling Highway which consisted of two large, bright pink boards with a thermographic image and the text “Breast Check\Safe. No Pain”.

Ms Melia’s evidence that, while there was no sign on the clinic itself, the outside of the clinic was painted pink and there was a sandwich board sign in the carpark which read “Breast Check” and pointed to the door of the clinic.

Ms Coyle’s evidence that she could only recall two instances when members of the public came into the clinic without an appointment. However, much of her time was spent on nursing and other duties which she carried out in a private room or area in the clinic.

54 While the respondents submit that, having regard to the evidence Breast Check highlights, the Court should conclude that the bulk of distribution of the brochures was to existing patients/customers as described above, and that any other distribution of the brochures was in response to specific enquiries and preceded by a conversation to the effect stated by Ms Coyle in her evidence, and much other distribution was preceded by the signature on the terms and conditions document, ACCC submits that, having regard to the evidence it emphasises, the reasonable inference to be drawn is that no explanation was given by a receptionist as suggested and customers could take and read promotional pamphlets without more.

55 For the reasons which follow, I do not accept the respondents’ submissions that the persons or class or group of persons to whom the promotional brochures, particularly the breast imaging pamphlet, were distributed should be limited to existing patients/customers and that any other distribution was in response to specific enquiries and preceded by a conversation to the effect stated by Ms Coyle in her evidence and much other distribution was preceded by the signature on the terms and conditions document.

56 In this regard, it is important to observe that the Breast Check “clinic”, as the parties have referred to it, while located at Unit 2, 634 Stirling Highway, Mosman Park, was entered from the adjacent St Leonards Street. In her affidavit, Ms Melia stated that she attended at the premises and “saw a sign that read ‘Breast Check’ in the carpark”. She said that when she entered the building she noticed a reception desk and to its left a waiting area with a sofa and table. She said there was a pile of pamphlets on the table.

57 In cross-examination Ms Melia confirmed that she entered the premises from a side street although she could not then recall the name of the street. I infer having regard to the whole of the evidence including the breast imaging pamphlet which expressly refers to the address for visiting the clinic as “St Leonards Street, Mosman Park, Western Australia 6012” that the side street was St Leonards Street.

58 Ms Melia in cross-examination confirmed that the car she had travelled in to the clinic had been parked and then she had walked down the street and entered the premises “that way”, although she then added that the car was parked in the car park (she did not refer to a “street”).

59 In cross-examination Ms Melia agreed that there was no signage on the building to identify Breast Check, but that the building consisted of “pink brick”. She confirmed there was a sign in the carpark which identified Breast Check and agreed that it was in the nature of a portable triangular sign placed on the ground, pointing to the door. She called it a “small sandwich board sign”. She said on it appeared the words “Breast Check”.

60 I conclude that, by reason of the signage in the carpark and the pink paint on the external brickwork of the premises, an ordinary member of the public passing by, or looking for the premises, would have little difficulty in identifying the Breast Check clinic.

61 The evidence also discloses that any person wishing to enter the clinic was free to do so and to make an inquiry of Breast Check’s reception staff, just as Ms Melia and her colleague from the ACCC did on the occasion of their visit to the premises on 24 February 2011.

62 As noted above, Ms Melia said that when she entered the clinic she observed a reception desk and, to the left, a waiting room and a pile of pamphlets on a table in the waiting room near a sofa.

63 She said that she spoke to a female who was behind the reception desk but did not find out her name.

64 Ms Melia said that while she could not recall the exact words used, she said to the woman at reception words to the effect, “Can you tell me some details about the procedure?”. She said she was told words to the effect, “It involves taking an image of the breast then later discussing the results with the doctor at the clinic”.

65 Ms Melia said that she then said words to the effect, “What happens if any abnormalities are detected on the scan?”, to which she was told words to the effect, “The doctor based at the clinic will provide you with a consultation following the procedure”.

66 Ms Melia said that after asking about the cost of the scan and being told that the consultation could be bulkbilled to Medicare, she then picked up a pamphlet from the table by the sofa, being the Breast Check pamphlet identified above.

67 Ms Melia said that the woman at reception did not say anything to her when she picked up the pamphlet and did not offer any further information about the procedure.

68 Ms Melia finally said that she said to the woman at reception words to the effect, “I will review this pamphlet and will call to make an appointment later”, to which the woman replied with words to the effect, “The clinic is open on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays”.

69 Ms Melia then left the building with her colleague, taking the pamphlet with her.

70 Ms Melia’s evidence was tested in a number of respects during cross-examination. First, Ms Melia said she had a clear recollection of the waiting area because she remembered it was quite “shabby looking”.

71 She also said that she could not recall collecting pamphlets from the reception area, but took them from the table in the waiting area.

72 Ms Melia accepted that she went to the reception area directly when she walked into the premises but added that the whole area of the reception and the waiting area was a small area.

73 Ms Melia was insistent that the breast imaging pamphlet she took was the one produced in evidence attached to her affidavit. She said it was “quite distinctive” and the colours on it reminded her of the “breast cancer awareness ribbon”. She also remembered scanning it into the records at ACCC following her visit to the premises. She said she collected a number of pamphlets, the breast imaging pamphlet being one of them, all of them from the waiting room.

74 Ms Melia confirmed that she did not remember the exact words used when she spoke to the woman at reception. Whilst she made a file note subsequently, Ms Melia said she had not been trained to make file notes of such visits – “I just – I recorded the file note”. She was asked again whether she had been trained in how to make a file note after visiting premises and answered that, “In general terms I had been trained how to actually record a file note”. However she did not recollect being given guidance that she should record the actual terms of any conversation that occurred.

75 I construe the evidence about the file note recording given by Ms Melia to indicate that she had not received any particular training in how to go about recording any particular conversations she had on a visit to premises such as that of Breast Check, but understood that she needed to make a file note of them and later record the file note at ACCC.

76 It also became apparent during cross-examination that Ms Melia had indeed attended Breast Check’s business premises with another employee of ACCC and that she and her colleague had spoken “to two females at reception”. Her colleague had asked for details about the procedure and in the file note she (Ms Melia) had recorded:

Staff member stated that it involved taking an image of the breast and later discussing results with the doctor at the clinic.

77 She also accepted in cross-examination that her colleague had asked what would happen if any abnormalities were detected in the scan and that she (Ms Melia) had recorded in the file note:

Staff member stated that there the doctor based at the clinic who could provide a consultation following the procedure.

78 The file note also referred to the cost of the scan and bulkbilling to Medicare.

79 Ms Melia was adamant, when challenged in cross-examination, that while she could not recall the exact words used she did have a recollection of the conversation. I accept Ms Melia’s evidence in this regard. She was a very direct witness who was not dependent on the content of the file note for her evidence, while having had regard to it.

80 She also said that she asked about the procedure, “As I did with most of these places”, and was advised that an image or a scan (she could not remember the specific terminology used) would be taken and then she could speak to a doctor during a consultation.

81 She said, when the proposition was directly put to her by counsel for Breast Check, that she “… never heard the word ‘assessment’”. Counsel had suggested to her that it was not an image or scan, it was an “assessment service” that was the phrase used by the person in reception in the discussion. While Ms Melia said she could not rule out that “assessment service” was not used, she added that she certainly did not recall the word “assessment” being used. Similarly, she said, when asked, she could not recall the specific words “breast health assessment” being used. Further, Ms Melia said, when asked, she could not recall any conversation in which it was explained to her that the service would commence with the taking of a general medical history and pulse, blood and pressure check. Similarly, she said, when asked, she could not remember any words by way of explanation that, following the taking of general health details, she would be asked to disrobe for the taking of a thermographic image. She said she remembered the word “thermographic”, that is an image, being used but none of the other words put to her by counsel. She also said she did not recall it being explained to her that the thermographic imaging would be repeated following a “cold water challenge”.

82 Ms Melia also said, when asked in cross-examination, that she did not recall it being explained to her that she would then see the doctor to discuss the results and to have a physical breast examination and receive educational information from the doctor about breast massage and other aspects of breast care and health. She recalled only being told that she would have a consultation with a doctor following the scan or imaging procedure.

83 Ms Melia said that she later made an appointment for a couple of weeks afterwards and in fact went on a “second visit”, something not pursued in evidence by any party, but relied on by the respondents as to the inferences that may be drawn from the ACCC’s failure to lead evidence concerning the later appointments.

84 In re-examination Ms Melia was asked to estimate the distance between the reception area and the place where the brochures were laid out. Her response suggested a distance of about five average paces.

85 Ms Melia also confirmed in re-examination that she was not at the premises “very long at all”. She said she just generally asked about the procedure and was there “probably about 40 seconds up to a minute. No more than a minute, I wouldn’t think. Yes. I wasn’t in there very long”. When the question was pursued by counsel, Ms Melia extended the length of the visit to perhaps a minute and a half to two minutes – “maybe – not very long”.

86 On behalf of Breast Check, counsel also points to evidence given by Ms Coyle, a registered nurse who was employed by Breast Check at material times. It is sufficient to note that Ms Coyle said she had made efforts at improving some forms and systems and that receptionists had been trained to give an explanation as to what the service involved – at least for telephone enquiries. Counsel also referred to Ms Coyle’s evidence that it was the usual practice of the clinic to have customers sign a terms and conditions acknowledgement document.

87 I conclude from the evidence given by Ms Melia, however, that, while there may have been efforts to introduce general procedures of the sort described by Ms Coyle, they were not necessarily utilised or followed on all occasions and were not employed on the occasion that Ms Melia and her colleague visited the premises. Rather, on that occasion some very general information was provided by the woman at Breast Check’s reception but only in answer to questions asked by Ms Melia or her colleague.

88 Specifically, I find on the evidence that there was no controlled distribution of the materials that were available in the waiting room on the table, such that Ms Melia was only able to obtain the pamphlet she took after receiving some standard explanation of the type suggested by Ms Coyle as to the service provided by Breast Check or by signing a terms and conditions document.

89 I find the evidence given by Ms Melia to be reliable and that, having regard to her evidence, properly construed, Breast Check’s employee in the reception area:

did not speak about an “assessment service”;

did not say that the service was a “breast health assessment”;

did not say that the service would commence with the taking of a general medical history and pulse, blood and pressure check;

did not say that, following the taking of the general health details that “you would be asked to disrobe for the taking of a thermographic image”;

did not say that, the “thermographic imaging would be repeated following a cold water challenge”;

did not say words to the effect that you would see the doctor to discuss the results and to have a physical breast examination and receive educational information from the doctor about breast massage and other aspects of general breast care and health;

did not require Ms Melia (or her colleague) to sign a terms and conditions document at any time.

90 Rather, I find that Ms Melia and her colleague were able freely to enter the Breast Check clinic, easily able to locate the materials Ms Melia referred to, including the breast imaging pamphlet, and, finally, able to ask questions of the Breast Check staff member at reception. In response to the questions they asked, I find they received very general answers, as described by Ms Melia. Nothing as detailed as that suggested by Ms Coyle was in fact provided by way of response by any staff member to questions posed by Ms Melia or her colleague and neither was required to sign any terms and conditions document. Rather, Ms Melia left the clinic with the breast imaging pamphlet in her custody, and without, at that point, having made any appointment to receive the service offered.

91 I draw the inference, from the circumstances surrounding the visit by Ms Melia and her colleague to the Breast Check clinic, that what Ms Melia described was not an unusual event or contrary to the processes or procedures ordinarily undertaken by Breast Check’s reception staff at the clinic.

92 It is also clear from the evidence that promotional pamphlets would be disseminated by post to persons who would enquire of the business by telephone. There is nothing in the evidence to suggest that what Ms Coyle believed receptionists should impart by way of information was in fact imparted in some systematic or formal way.

93 I accept from the evidence taken as a whole and the respondents’ admissions (and notwithstanding the submission of Breast Check that the evidence does not support a finding of distribution in regard to the Our Services to You pamphlet) that the breast imaging pamphlet, the thermography pamphlet and the Our Services to You pamphlet were available at material times in the waiting room of the Breast Check clinic or provided to persons by mail who made telephone inquiries.

94 I find, therefore, as submitted by ACCC, that a section of the public, being female members of the public interested to enquire about the breast imaging service offered by Breast Check, were able, by personally calling at Breast Check’s business premises (as Ms Melia did), or by telephoning the business, to obtain these pamphlets at material times, and that persons so enquiring were not systematically provided with any information of any detail that qualified the content of any representations conveyed by the pamphlets.

95 I should add that nothing said by Dr Boyd during her s 155 examination detracts from this finding.

96 I reject, therefore, the respondents’ submission that these promotional pamphlets were not relevantly distributed “to the public” and were only given to certain individuals, namely existing customers or only to those interested in the breast imaging offered by Breast Check after they were given some detailed explanation or after they had signed a terms and conditions document governing the relationship of a patient/customer with Breast Check.

97 A further issue then arises, namely, whether there is relevantly a second class of members of the public, as contended for by ACCC, to whom pleaded materials were published, being those women who were not only interested in the breast imaging service offered by Breast Check but who had already received breast imaging. This class in particular also received the breast health reports and report information as pleaded. The ACCC in respect of this class also presumes that they had received and read the promotional brochures.

98 In the event, I am not satisfied that there is a further section or class of the public, being customers of Breast Check who had already received breast imaging, to whom the breast health reports, report information and other accompanying documents were separately published.

99 While it is possible in a factual sense to say that there is a class or category of women who, at material times, were customers of Breast Check and who had received the breast imaging service, who received breast health reports, report information and accompanying documentation, I am not satisfied that they relevantly constituted a section of the public to whom particular conduct was directed, in the sense discussed in the authorities such as Parkdale, Campomar, Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty and Campbell v Backoffice.

100 I think on the evidence it is more accurate to say, and I find, that the relevant conduct that ACCC complains of, including the publication of breast health reports to such women, involved Breast Check directing its conduct to individual customers, albeit that the relevant conduct in respect of individual customers had common features.

101 Unlike cases such as .au Domain and National Exchange where there was a single representation made to a class of persons in an existing relationship with the representor, here there is no single piece of conduct or representation made to all members of the class contended for. Each customer received a separate communication, at a separate point in time, following the provision of the breast imaging service to that particular customer, that included a breast health report tailored to their particular circumstances.

102 If it were the case that each breast health report, and the other documentation sent out in the pack, was relevantly identical (albeit with slight differences of content) then it might be argued that a case such as the present would be no different from the paradigm cases, as Breast Check’s counsel has described them. But here, in the opening “assessment” section of each of the breast health reports the subject of evidence, the particular personal circumstances of each woman who had received the service were set out. In some cases, it is clear that a woman has experienced difficulties or has a family history of breast cancer and that in some other cases a woman has undergone mammography or ultrasound testing; but not in all cases. It cannot be said that such information is irrelevant to any reading and understanding of the information conveyed in the relevant breast health report and accompanying materials in the pack.

103 In those circumstances, it is difficult to isolate the criterion or criteria by which a reasonable hypothetical class member can be identified, for the purpose of determining whether a reasonable hypothetical member of the class would be or might be misled or deceived by the representations made by the breast health report.

104 To develop this point, some women have undertaken the breast exam, a few may not have. Some may have received the breast exam from Ms Coyle, the nurse practitioner, and not from Dr Boyd. The breast health reports are not identical. How does one identify the reasonable hypothetical representative of the class contended for, when (for example) one report is in respect of a 30 year old female, who has not had children, with a family history of breast cancer, and another is in respect of a 45 year old female, who has not had children, with no family history of breast cancer, and, in some cases, some women have undertaken mammography and/or ultrasound and others have not? The uncertainties created by questions such as these, in my view, point to the conduct complained of by ACCC in this regard not being conduct directed to a section of the public, as such, but to individual customers.

105 In such cases, indeed in all cases involving alleged misleading or deceptive conduct of the kind under consideration, the whole of the circumstances must be considered in assessing whether there has been contravention. That has been the test since Parkdale and has been accentuated and emphasised in subsequent cases, such as Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty. There are different, albeit perhaps not extensive, circumstances that may be considered to exist from one breast health report to another, from one customer to another. It is not appropriate to effectively aggregate all customers and say that they are a relevant section of the public. Such a description is too loose, at least for the purposes of the TP Act and ACL in the circumstances we are here dealing with.

106 Nor is it open to conclude simply from the relief sought by ACCC, or its status as a “regulator” that some different view should be taken of the evidence or that a group of customers of Breast Check is automatically converted into a relevant section of the public for TP Act and ACL enforcement purposes.

107 I therefore accept the contention made on behalf of Breast Check that there is no second class of the public as ACCC contends and so the pleaded case that there was misleading conduct published in respect of a particular section of the public contended for must necessarily fail.

108 I note also the submission made by Breast Check that in this regard the case put in closing by ACCC differs from the case pleaded. In the pleaded case so far as the publication of the health reports is concerned, ACCC merely pleaded, at [9] statement of claim, that the publication was to customers. It did not expressly plead, as it did in the case of the promotional pamphlets, that the publication was “to the public”. Nonetheless, I consider it is open on the pleading for ACCC to contend, as it has, that the customers in question constituted a section of the public. Nonetheless, for the reasons given above, I am not satisfied that such conduct was directed to any relevant section of the public.

109 In summary, I find that the three promotional pamphlets pleaded, being the breast imaging pamphlet, the thermography pamphlet and the Our Services to You pamphlet were, on the evidence, published to a section of the public, being women interested in the breast imaging service offered by Breast Check, but there was no other relevant conduct directed to the public.

Did the promotional pamphlets convey the pleaded representations?

(1) Was the risk of cancer representation conveyed?

110 The ACCC relevantly pleads, by [22] statement of claim, that conduct, which includes the publication and distribution of the promotional pamphlets, represented that breast imaging using a thermography device, either alone or in conjunction with the MEM device, could provide an adequate scientific medical basis for assessing whether a customer may be at risk from breast cancer and, if so, the level of such risk, which it terms the “risk of cancer representation”.

111 ACCC submits the risk of cancer representation arose by reason of:

(1) the impression conveyed by each of the promotional pamphlets, including by particular statements in each of those documents; and

(2) by any combination of those documents and the statements made in them; and

(3) the context in which the information was received.

112 It is now relevant to consider whether the three promotional pamphlets I have found were published to the public conveyed the risk of cancer representation as alleged.

113 Each of the breast imaging pamphlet and thermography pamphlet was an A4 sized sheet printed in colour on both sides, with a layout that enabled the sheet to be easily folded into a smaller pamphlet. The Our Services to You pamphlets was an A4 sheet with coloured text on one side. The breast imaging pamphlet, on which ACCC primarily relies, is reproduced below.

114 Breast imaging pamphlet

115 ACCC submits that the reasonable consumer considering breast imaging would associate references to “risk” in such documents, in the context in which they were made, with the risk of breast cancer.

116 Examples of the statements concerning “risk” made that are relied upon by ACCC are as follows:

“Research has shown that Infrared Thermography can be a reliable predictor of breast cancer risk.” (Both breast imaging pamphlet and thermography pamphlet.)

In describing a thermographic image in their breast imaging pamphlet and thermography pamphlet it is stated:

Metabolic activity seen on the right breast was later confirmed to be breast cancer.

(Both breast imaging pamphlet and thermography pamphlet.)

117 ACCC submits it would be reasonable for the reasonable hypothetical customer to understand that the core purpose of any medical breast imaging would be to provide an assessment of their risk from breast cancer. Further, that such a reasonable consumer is unlikely to have in mind any other prominent risk posed by or to their breasts that require imaging. It is submitted this would be the case in any event but particularly so having regard to the statements made in the materials about breast cancer. The assessment of risk would not be understood with the same level of scientific inquiry as a trained medical professional who might understand risk to be associated with prognosis.

118 ACCC further submits that the overall impression of the breast imaging pamphlet, for example, would leave such a reasonable customer with little, if any, doubt that the devices used by Breast Check for breast imaging are used to assess the risk of breast cancer.

119 ACCC submits that the reasonable consumer who has already received breast imaging services from Breast Check who received the promotional pamphlets would construe the promotional pamphlets in the same way as the reasonable consumer falling within the stand-alone class of interested women.

120 By contrast, the respondents observe that the breast imaging and thermography pamphlets consistently refer to and promote not only breast imaging services and devices but also:

“Breast risk assessment using physiological methods”.

“Methods to monitor breast health”.

“An additional method of monitoring breast health”.

“A way of profiling breast health”.

“Management of breast health”.

“Breast health profiling”.

“Regular yearly breast health profiling”.

“Non-invasive breast risk assessment using physiological methods”.

“A complete physiological breast risk assessment profile”.

121 The respondents further submit that in addition to use of the devices and consideration of the images produced by them, the assessment/monitoring/profiling/management of breast health using “physiological methods” included a clinical breast examination followed by discussion of the results with the customer.

122 The respondents say the pamphlets also repeatedly referred to the possible need for further assessment procedures including mammogram and/or ultrasound. They say referrals for such procedures occurred with the results forming part of the respondents’ assessment, and were communicated to the customer in the reports which ACCC submits contained representations including the substitute for mammography representation.

123 The respondents contend the pamphlets do not assert unqualified or assured accuracy as the result of a breast health check and used qualified language (such as “may” or “can”, and not “does” or “will”) in a number of important respects, namely:

Breast imaging pamphlet

“may reassure you”

“can be a reliable predictor”

“some suspicious findings may require”

Thermography pamphlet

“can be a reliable predictor”

“some suspicious findings may require”

124 The respondents submit that whether read individually or in combination, what Breast Check was promoting in these pamphlets was a service for monitoring breast health which was aimed at providing women with additional information and opportunities to improve general breast health awareness.

125 Further, they submit, none of the documents suggests the use of either thermography or MEM as stand-alone measures; and that there are repeated references to plural technologies and risk assessment using physiological methods and references to Breast Check having developed “a way of profiling breast health”.

126 Thus, the respondents submit that in the context of Breast Check’s operations it is artificial to construe any of the promotional material or the breast health reports as referring to or advocating the use of either thermography or MEM as a stand-alone assessment tool.

127 Rather, they submit, none of the promotional material or the breast health reports can be fairly construed as offering any assurance that a customer does not have breast cancer and to infer such an assurance would be inconsistent with the repeated recommendations in favour of ongoing and regular monitoring.

128 In this regard, the respondents submit the offer of breast health assessment services is not analogous to mammogram screening but rather, when properly construed, is analogous to the widely recommended and commonly understood advantage of regular self or medically assisted physical breast examination. The respondents say Breast Check offered a breast health assessment that, although less stringent than structural tests, had perceived and arguable benefits in addition to physical breast examination alone.

129 The respondents submit none of the pamphlets suggests that the Breast Check service was a substitute for mammography; in fact the pamphlets expressly advert to mammography as one of a number of possible follow up procedures.

130 In my view, the submissions made on behalf of ACCC concerning the hypothetical class member (including at [35] above) and the pleaded risk of cancer representation should be accepted, save in respect of the Our Services to You pamphlet.

131 While the respondents refer to particular words, phrases and other statements made in the pamphlets in order to suggest that overall they simply promote a service for monitoring breast health, when read as a whole the risk of cancer representation as pleaded is made out.

132 The breast imaging pamphlet, under the heading, “How well do you know your breasts?”, relevantly states (emphasis added in each case save the last example):

“At Breast Check we use safe, non-invasive radiation-free devices that have the ability to scientifically measure metabolic indicators within the breast.”

“Each device measures different physiological parameters”.

“These technologies are now available to women of all ages especially the large number of younger women for whom conventional screening methods are not recommended”.

Then it is stated in a paragraph numbered (1) by reference to “breast health pofile (sic) uses”:

1. Bio impedance: maps the anatomy of breast tissue while measuring cell conductivity. Differences in conductivity between normal and malignant tissue can be measured.

A photograph is then shown of a device being held against a woman’s left breast.

Then, also in respect of “the breast health pofile uses”, it is stated:

2. Infrared thermography: research has shown that Infrared Thermography can be a reliable predictor of breast cancer risk.

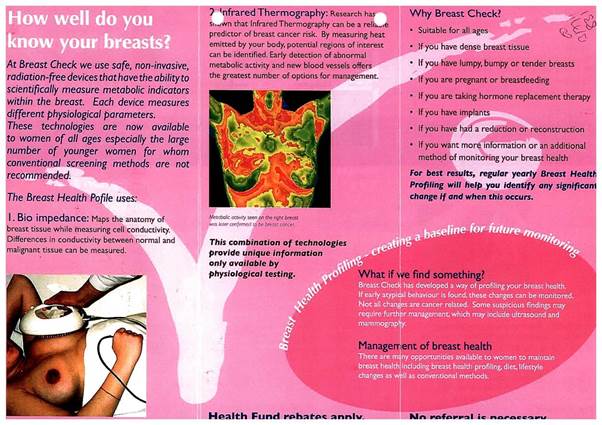

Below that paragraph is an image beneath which is stated: “Metabolic activity seen on the right breast was later confirmed to be breast cancer”.

This image is then followed by the statement:

This combination of technologies provide unique information only available by physiological testing.

(Emphasis in original.)

133 Similar statements are made in the thermography pamphlet.

134 I accept the submission made on behalf of ACCC that these various statements make no reference to the other matters Breast Check seeks to rely on, such as physical breast examination. The pamphlets refer to the use of the devices which in my view supports the risk of cancer representation pleaded. The idea that the pamphlets convey the representation that an assessment will be made utilising breast imaging in the advertised way as merely one technique in the process, along with others, is not made out.

135 The fact that in other parts of the breast imaging pamphlet the statement is made that “some suspicious findings may require further management, which may include ultrasound and mammography”, does not relevantly qualify or alter the primary representation made by the pamphlet as a whole, that thermography can detect the risk of cancer of the breast. Nor does the use of such permissive expressions as “may” and “can” qualify or remove that representation.

136 In short, each of the two pamphlets conveys the unqualified representation that breast imaging using a thermography device, either alone or in conjunction with the MEM device, could provide an adequate scientific basis for assessing whether a customer may be at risk from breast cancer and, if so, the level of such risk.

137 As to the submission made by Breast Check that the use of the word “could” in the risk of cancer representation carries no requirement as to accuracy, such that the representation can be read that thermography “would” or “may” provide a basis for assessment, I accept the submission of ACCC that such a meaning is not likely to be given to the word by an ordinary or reasonable member of the hypothetical class.

138 By contrast, the Our Services to You pamphlet says very little and it should be disregarded.

139 As to the question of the representation conveying that there is an adequate scientific or medical basis, I accept the submission made on behalf of ACCC that the word “adequate” should be taken in the sense by which it is generally understood. In the medical context that is that the service is provided according to evidence-based medical knowledge and that there is sufficient support in medical science for the use of the devices for the purposes represented. This is particularly so in the context of assessing whether or not a person may have or be at risk of breast cancer, which is clearly a question of medical science.

140 I also accept that a reasonable person looking to subject themselves to any form of testing or imaging relating to their health, and especially for something as potentially serious as breast cancer, would expect that there is a scientific medical basis to support the use of the equipment for those purposes.

141 In the context of a representation of a medical nature, as here, I accept ACCC’s submission that there is a clear “information asymmetry” between the maker of the representation and the audience. Thus, it would be entirely reasonable for a consumer to conclude that, where a service of a medical nature is being provided, there would be scientific medical evidence of a sufficient quality to support the use of the equipment used to provide such a service and that the use of breast imaging devices would not be promoted in a way as to be contrary to the state of scientific medical knowledge.

142 There can be no suggestion that a reasonable customer, having read the promotional pamphlets and other documents, would be obliged to take some reasonable care of their own interests. It would not be expected, for example, that customers should be obliged to conduct their own research as to whether or not there is a scientific medical basis for a thermography device and MEM device to be used for the purposes represented.

143 I find that the risk of cancer representation was conveyed by the breast imaging pamphlet and the thermography pamphlet as alleged.

(2) Was the assurance representation conveyed?

144 ACCC relevantly pleads that the breast imaging pamphlet and the thermography pamphlet, alone or together, represented that breast imaging using either the thermography device alone, or in conjunction with the MEM device, could provide an adequate scientific medical basis for assuring a customer that they do not have breast cancer.

145 The respondents contend that the representation pleaded cannot be made out.

146 ACCC submits that the assurance representation arises from the overall impression made by the breast imaging pamphlet and thermography pamphlet. It submits that if it is successful in establishing that the risk of cancer representation arises then it follows that the overall impression created is that the thermography device in isolation or in conjunction with the MEM device can also be used to identify customers not at risk from breast cancer and so provide them with an assurance that they did not have breast cancer.

147 I accept the submissions made in this regard by ACCC and find that the assurance representation was conveyed by the breast imaging pamphlet and thermography pamphlet in light of my finding above that those documents conveyed the risk of cancer representation.

148 The representation is ultimately made express, in my view, by the penultimate paragraph of the breast imaging pamphlet, which is repeated in the thermography pamphlet, under the heading “Your Visit”, where it is stated:

At Breast Check we provide information that may reassure you in confirming the health of your breasts.

149 For the reasons given above in relation to the question of an adequate scientific medical basis for such a representation, I also find that the representation included that there was an adequate scientific medical basis for the assurance representation conveyed.

150 I find that the assurance representation was conveyed by the breast imaging pamphlet and the thermography pamphlet as alleged.

(3) Was the substitute for mammography representation conveyed?

151 ACCC relevantly pleads that the breast imaging pamphlet and the thermography pamphlet in each case represented that there is an adequate scientific medical basis for using either the thermography device alone, or in conjunction with the MEM device for breast imaging, as a substitute for mammography.

152 The respondents deny the representation was so conveyed.

153 ACCC submits that the representation arises from the comparative advertising style of Breast Check’s material which compares and contrasts the known negative attributes of mammography with the features of its breast imaging devices.

154 ACCC contends that Breast Check has acknowledged that the series of dot points under the heading “Why Breast Check?” in the breast imaging pamphlet and the same points next to the checked boxes in the thermography pamphlet are all known contra-indicators of thermography.