Wyman on behalf of the Bidjara People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2013] FCA 1229

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

KEVIN ALBURY AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE KARINGBAL PEOPLE #2 Applicant |

|

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND AND OTHERS Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application, to the extent it relates to the “overlap area” as identified in the reasons for judgment published today, be dismissed.

2. Order 1 be stayed as follows:

(a) if no notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the time for the giving of that notice has expired; or

(b) if such notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the determination whether any further order should be made is published.

3. Grant leave to the State of Queensland to notify the Court and other parties within 7 days whether it wishes to seek a further order determining that native title does not exist in relation to the overlap area.

4. If the State of Queensland seeks such a determination, the State file and serve a short written submission in support of the making of such a determination with its notice in accordance with order 2 above.

5. Any other party wishing to be heard in respect of that application may file and serve a short written submission in reply within a further 7 days thereafter.

6. Any application for costs shall be made by interlocutory application to be filed within 14 days of these orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

QUD 216 of 2008 |

BETWEEN: |

BRENDAN WYMAN AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE BIDJARA PEOPLE Applicant |

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND AND OTHERS Respondent |

JUDGE: |

JAGOT J |

DATE OF ORDER: |

6 december 2013 |

WHERE MADE: |

BRISBANE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application, to the extent it relates to the “overlap area” as identified in the reasons for judgment published today, be dismissed.

2. Order 1 be stayed as follows:

(a) if no notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the time for the giving of that notice has expired; or

(b) if such notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the determination whether any further order should be made is published.

3. Grant leave to the State of Queensland to notify the Court and other parties within 7 days whether it wishes to seek a further order determining that native title does not exist in relation to the overlap area.

4. If the State of Queensland seeks such a determination, the State file and serve a short written submission in support of the making of such a determination with its notice in accordance with order 2 above.

5. Any other party wishing to be heard in respect of that application may file and serve a short written submission in reply within a further 7 days thereafter.

6. Any application for costs shall be made by interlocutory application to be filed within 14 days of these orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

QUD 245 of 2011 |

BETWEEN: |

CHARLES STAPLETON AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE BROWN RIVER PEOPLE Applicant |

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND AND OTHERS Respondent |

JUDGE: |

JAGOT J |

DATE OF ORDER: |

6 December 2013 |

WHERE MADE: |

BRISBANE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application, to the extent it relates to the “overlap area” as identified in the reasons for judgment published today, be dismissed.

2. Order 1 be stayed as follows:

(a) if no notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the time for the giving of that notice has expired; or

(b) if such notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the determination whether any further order should be made is published.

3. Grant leave to the State of Queensland to notify the Court and other parties within 7 days whether it wishes to seek a further order determining that native title does not exist in relation to the overlap area.

4. If the State of Queensland seeks such a determination, the State file and serve a short written submission in support of the making of such a determination with its notice in accordance with order 2 above.

5. Any other party wishing to be heard in respect of that application may file and serve a short written submission in reply within a further 7 days thereafter.

6. Any application for costs shall be made by interlocutory application to be filed within 14 days of these orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

QUD 301 of 2012 |

BETWEEN: |

CHARLES STAPLETON AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE BROWN RIVER PEOPLE #2 Applicant |

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND AND OTHERS Respondent |

JUDGE: |

JAGOT J |

DATE OF ORDER: |

6 december 2013 |

WHERE MADE: |

BRISBANE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application, to the extent it relates to the “overlap area” as identified in the reasons for judgment published today, be dismissed.

2. Order 1 be stayed as follows:

(a) if no notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the time for the giving of that notice has expired; or

(b) if such notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the determination whether any further order should be made is published.

3. Grant leave to the State of Queensland to notify the Court and other parties within 7 days whether it wishes to seek a further order determining that native title does not exist in relation to the overlap area.

4. If the State of Queensland seeks such a determination, the State file and serve a short written submission in support of the making of such a determination with its notice in accordance with order 2 above.

5. Any other party wishing to be heard in respect of that application may file and serve a short written submission in reply within a further 7 days thereafter.

6. Any application for costs shall be made by interlocutory application to be filed within 14 days of these orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

QUD 310 of 2012 |

BETWEEN: |

KEVIN ALBURY AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE KARINGBAL PEOPLE #3 Applicant |

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND AND OTHERS Respondent |

JUDGE: |

JAGOT J |

DATE OF ORDER: |

6 december 2013 |

WHERE MADE: |

BRISBANE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application, to the extent it relates to the “overlap area” as identified in the reasons for judgment published today, be dismissed.

2. Order 1 be stayed as follows:

(a) if no notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the time for the giving of that notice has expired; or

(b) if such notice is given by the State of Queensland under order 3 below, until the determination whether any further order should be made is published.

3. Grant leave to the State of Queensland to notify the Court and other parties within 7 days whether it wishes to seek a further order determining that native title does not exist in relation to the overlap area.

4. If the State of Queensland seeks such a determination, the State file and serve a short written submission in support of the making of such a determination with its notice in accordance with order 2 above.

5. Any other party wishing to be heard in respect of that application may file and serve a short written submission in reply within a further 7 days thereafter.

6. Any application for costs shall be made by interlocutory application to be filed within 14 days of these orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

QUD 23 of 2006 QUD 216 of 2008 QUD 245 of 2011 QUD 301 of 2012 QUD 310 of 2012 |

BETWEEN: |

KEVIN ALBURY AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE KARINGBAL PEOPLE #2 First Applicant BRENDAN WYMAN AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE BIDJARA PEOPLE Second Applicant CHARLES STAPLETON AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE BROWN RIVER PEOPLE Third Applicant CHARLES STAPLETON AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE BROWN RIVER PEOPLE #2 Fourth Applicant KEVIN ALBURY AND OTHERS ON BEHALF OF THE KARINGBAL PEOPLE #3 Fifth Applicant

|

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND Respondent

|

JUDGE: |

JAGOT J |

DATE: |

6 december 2013 |

PLACE: |

BRISBANE |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 These reasons for judgment concern the following questions which on 7 May 2013 I ordered be decided separately from all other questions in the proceedings:

But for any question of extinguishment of native title:

(a) does native title exist in relation to any and what land and waters of the overlap area?

(b) in relation to any part of the overlap area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

(i) who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title?

(ii) what is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

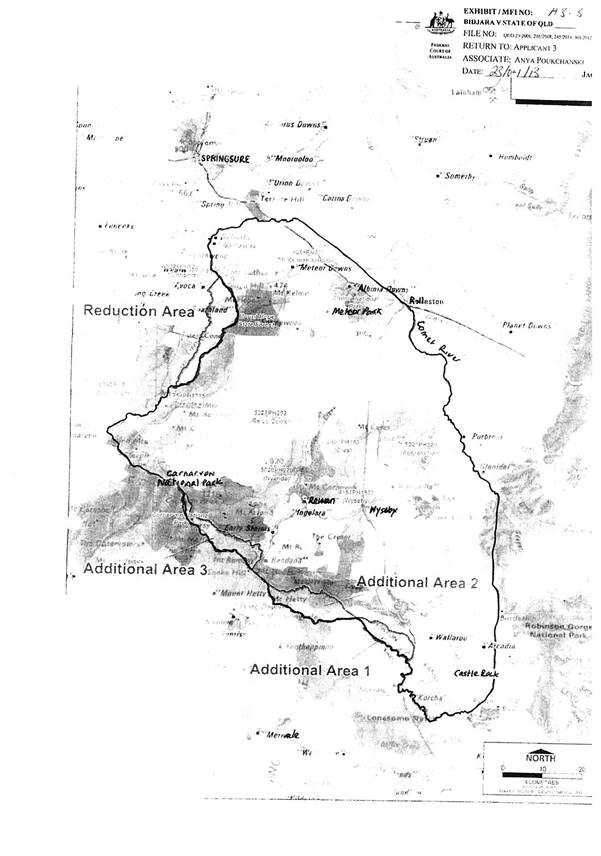

2 The “overlap area” is an area of land where the claims of the Bidjara (QUD 216 of 2008), the Brown River People (QUD 245 of 2011 and QUD 301 of 2011) and the Karingbal (QUD 23 of 2006 and QUD 310 of 2012) overlap. The overlap area includes the Arcadia Valley, Carnarvon Gorge and parts of Carnarvon National Park in Queensland. The area is shown on the map which is annexed.

3 The Bidjara and the Brown River People (or BRP) contend that they hold native title rights and interests in the whole of the overlap area to the exclusion of the other.

4 The BRP identify as Karingbal people but separated themselves from the Karingbal claim when they decided that an apical ancestor included in that claim, Jemima of Albinia, and her descendants were not in fact Karingbal.

5 The descendants of Jemima of Albinia, the active participants in the Karingbal claim, contend that they are Karingbal and, accordingly, enjoy the same native title rights and interests in the whole of the overlap area as claimed by the BRP.

6 The State of Queensland (the State) contends that while it is open on the evidence to find that the persons associated with the overlap area at sovereignty were a group of people who identified as Karingbal and that a group of persons who identified as Bidjara were, traditionally also associated with a part of the overlap area at sovereignty, being Carnarvon Gorge and Carnarvon National Park, an area which was co-held under the traditional normative system with the Karingbal / Garingbal people, the rights and interests now asserted to be held by the descendants of both the Karingbal and Bidjara ancestors in the overlap area are not capable of being recognised as “native title rights and interests” within the meaning of s 223(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA), because they are not rights and interests possessed under traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed, substantially uninterrupted, since sovereignty.

7 As explained below, I have concluded that the State’s submissions should be accepted other than that the weight of the evidence supports the inference that at sovereignty Carnarvon Gorge and Carnarvon National Park, within the overlap area, were Bidjara country in which other tribes, including the Karingbal, had rights in respect of both burials and ceremonies.

8 In these reasons for judgment the following references are used.

Breen (1973): Breen, G Bidyara and Gungabula: Grammar and Vocabulary (Linguistic Communications 8). Clayton: Monash University.

Breen (2009): Breen, G 2009 The Biri Dialects and Their Neighbours. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 133:219-256.

Cameron (1904): Cameron, A 1904 On Two Queensland Tribes. Science of Man 7(2):27-29.

Capell (1963): Capell, A 1963 Linguistic Survey of Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies

Curr (1887): Curr, E (ed) 1887 The Australian Race (Volume III). Melbourne: John Ferrer, Government Printer.

Davidson (1938): Davidson, D 1938 A Preliminary Register of Australian Tribes and Hordes. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society: Appendix 13; and Davidson, D 1938 An Ethnic Map of Australia. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 79:649-679.

Holmer (1983): Holmer, N 1983 Linguistic Survey of South-eastern Queensland (Pacific

Linguistics Series D – No. 54). Canberra: Australian National University.

Rita Huggins and Jackie Huggins (1994): Huggins, R and J Huggins 1994 Auntie Rita. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Jefferies (2006): Jefferies, T 2006 The Maric Dialects of Fitzroy River Basin (Part One) (Unpublished Report held by Queensland South Native Title Services, Brisbane).

Bill and Lynette Oates (1970): Oates WJ and L Oates 1970 A Revised Linguistic Survey of Australia, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra.

Tennant Kelly (1935): Tennant Kelly, C 1935 Tribes on Cherbourg Settlement, Queensland. Oceania 4:461-474.

Terrill (1993): Terrill, A 1993 Biri: A Salvage Study of a Queensland Language (Unpublished BA Honours Thesis). Canberra: Australian National University.

Tindale (1940): Tindale, N 1940 Distribution of Australian Aboriginal Tribes: A field Survey. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 64:140-231.

Tindale (1974): Tindale, N 1974 Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits and Proper Names. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Walsh (1999): Walsh, G 199 Carnarvon and Beyond. Carnarvon Gorge: Takarakka Nowan Kas Publications.

9 I also refer to the Bonzle Digital Atlas of Australia (©2013 Digital Atlas Pty Limited), accessible at http://www.bonzle.com/c/a (Bonzle). With the consent of all parties I used Bonzle to ascertain the relative locations of the places referred to in the evidence.

10 Otherwise, it should be noted that the spelling of various words in Aboriginal languages varies. I have usually adopted the spelling the witness has used except where clarity demands some other spelling.

11 I deal first with the preserved evidence in section 4. This comprises statements and testimony that was taken in 2001 in respect of two claims made by the Bidjara in circumstances where the primary witnesses were elderly and the evidence might otherwise have been lost. Section 5 deals with the evidence of all of the lay witnesses. Section 6 deals with historical material. Section 7 concerns the evidence of the anthropologists and section 8 concerns the archaeologists. Section 9 deals with some other miscellaneous material. After dealing with the statutory provisions and applicable principles in sections 10 and 11, I turn to my overall analysis in the subsequent sections.

12 In 2001, over a period of five days, Ryan J heard evidence in respect of two claims by the Bidjara (Proceeding No QG 6133 of 1998 and No QG 6169 of 1998) known as the Bidjara No 2 and No 4 claims. By consent this evidence was admitted in these proceedings. The evidence consists of statements of Reginald (Rusty) Fraser, often referred to as Uncle Rusty, Robert (Bob) Mailman, Elizabeth (Betty) Charlotte Saylor, and Ronald Thomas (Ritchie) Fraser, their oral evidence and certain maps. Exhibit Q1, a map marked up during Uncle Rusty’s oral evidence, cannot now be located. To assist in understanding these reasons for judgment I refer to these witnesses by the names most often used to identify them in other evidence. No disrespect is intended by doing so.

13 To the extent that it was submitted for the Bidjara that this evidence should be understood to have been limited to the areas to which those proceedings related, the submission should be rejected. The purpose of the taking of the evidence in 2001 was to preserve the evidence of Bidjara elders so that their evidence about Bidjara country (that is, all Bidjara country) and Bidjara laws and customs would be available and able to be used in all claims by the Bidjara for native title rights and interests.

14 Uncle Rusty’s evidence is important for many reasons. All of the Bidjara people who gave evidence during the hearing in 2013 acknowledged that Uncle Rusty was a highly respected and knowledgeable elder. They all accepted that Uncle Rusty knew Bidjara country. Keelen Mailman and Patricia Fraser, in particular, gave first-hand evidence about Uncle Rusty’s involvement in drawing up the boundaries of the Bidjara No 3 claim which extends in an easterly direction to Rolleston and beyond Injune into the Expedition Ranges. Keelen Mailman and Patricia Fraser also gave evidence that Uncle Rusty was very upset that he had to reduce the area of land claimed to be Bidjara country, apparently by (then) legal representatives. The thrust of this evidence was that Uncle Rusty should be understood to have been saying that Bidjara country extended east at least to Rolleston and, indeed, east again to the Expedition Ranges, thereby encompassing (and extending beyond) the whole of the overlap area.

15 The best evidence about Uncle Rusty’s identification of Bidjara country is Uncle Rusty’s own words. Uncle Rusty’s own words are available through his written statement and, more importantly, his oral evidence. Uncle Rusty’s oral evidence is a better source of information than his written statement for a number of reasons. Although the statement reads as it might be imagined Uncle Rusty would speak and thus shows little sign of drafting by lawyers, it is still a statement in writing rather than Uncle Rusty’s own direct speech. Keelen Mailman read the statement to Uncle Rusty (he could not read or write and at the time he lived at Mount Tabor which Keelen Mailman manages) and he swore it was true, but the fact remains that the words are written rather than spoken. This is not to say Uncle Rusty’s statement is not important. It is important. But if there is any inconsistency between the written statement and Uncle Rusty’s oral evidence, the oral evidence should generally be seen as more reliable.

16 Uncle Rusty’s oral evidence is highly reliable for a number of reasons. Uncle Rusty was giving the evidence on oath. He gave the evidence over five days on various locations throughout country he identified as Bidjara country. When he gave the evidence he regarded himself as being on Bidjara country. He was rarely interrupted giving the evidence. He had a full opportunity to speak and, it appears, took that opportunity. His evidence about Bidjara country is detailed and consistent. Although it might seem repetitive to examine the parts of his evidence which appear to deal with the same topic and unnecessary to the extent that he deals with land outside the overlap area, it is the very consistency of his evidence that lends it a high degree of reliability. I set out the evidence below so the detail and consistency of description should be readily apparent. It should also be apparent from these extracts that Uncle Rusty was describing all Bidjara country.

17 In his written statement Uncle Rusty described Bidjara country as follows:

Bidjara country starts around Beechal Creek and then goes to Adavale and then to Wyandra. It runs from Wyandra to Charleville, from Charleville to Augathella, Augathella up to Boggarella, and from Boggarella right up to Babbiloora, and from Babbiloora to Carnarvon Ranges – and that’s all Bidjara Country. And it runs right across to Blackall and towards Barcaldine. That’s Bidjara country. That’s where Black’s Palace is – on the other side of Aramac.

….

So Bidjara go from near Roma to Injune, from Injune to the turn off to the Carnarvon National Park. A different tribe own the country at Roma, going from Roma, that’s as far as we go then. Bidjara go into – go off the main road there – and go into the National Park, Carnarvon National Park, that’s Bidjara Land. Carnarvon National Park is Bidjara Land. We go from there then across to Mount Moffat, and then we go from Mount Moffat up to Lethbridge. That’s all Bidjara country. And you can go from the Arch, not far to the Lethbridge Pocket, that’s all Bidjara Country, that’s all on Mount Moffat country. And, coming back this way, - Mount Tabor is Bidjara, Babbiloora and Boggarella, all Bidjara. Babbiloora, Boggarella – all Bidjara country, right up to Carnarvon Ranges, that’s all Bidjara Country. That’s the lot.

…

I get upset about Carnarvon Gorge. It’s a special place. White people are walking all over it. I was there not long ago and a white person asked me what I was doing there, at Carnarvon Gorge. I said “what do you mean, this is my country”.

18 In his oral evidence Uncle Rusty returned to the extent of Bidjara country many times.

19 At Charleville, Uncle Rusty said:

That Mount Tabor Station, is that your country?---Yeah, belong to - yeah, our country. Yeah, that's Bidjara country, yeah, right up to Carnarvon.

…

Have you sung those songs at other places on your country?---Yeah, I sung - oh, yeah, sing Sydney. We sing in Sydney and everywhere with it. Go right down to what-d'ye-call-im - right up Blackall and right up to Longreach and all around there.

We dance all around Longreach and everywhere, around Barcaldine.

What about - - - ?---As far as the Bidjara country run through there, far as - as far as Barcaldine I think, Aramac.

What about Carnarvon Gorge? Do you sing those songs there?---Yeah, we sung there for four nights there.

…

But what about if an Aboriginal mob from New South Wales, right, wanted to come and do their songs and their dances in Carnarvon Gorge?---What you mean? What, they come into our country to dance?

Yes?---They can't do it, though.

…

What about - like, is Roma on your country?---No. Roma's in a different country.

Different country?---Yeah.

…

Yeah, that all Bidjara country runs right down from here, right down to Wyandra and across to Beechal Creek from there. Go right up to Mitchell. This is all Bidjara country, see…

Because I had to walk it. I walked it from - from Mitchell right to Beechal Creek, right past what-d'ye-call-im, past - we walked there. We had to watch our country, see. They can't go over the tribal ground, see. He want to go over the tribal ground. Bloke said, "We going to go" - "No," I said, "I'll ring the government people." They come out. "No," they say, "can't go over. That's a tribal ground, see. You can't go over it." "You can't go over the tribal ground," he says.

…

We're on Bidjara country. This is Bidjara country here. It run right past Adavale, right up - right up to what-d'ye-call-im, right up to - runs right up to Barcaldine, see. That's our boundary there. Finish then with our boundary. I don't know who owns that next lot then from there on. I don't know who owns that country then.

20 At a place called One Mile Gully near Augathella Uncle Rusty said:

This is our country. This is Bidjara country, you see.

21 In another location close to Augathella Uncle Rusty said:

…Yeah, I was working on Mount Playfair then. That's where that Water Snake is, on Mount Playfair.

MR MAURICE: Yes. Is that Bidjara country?

RUSTY FRASER: Eh?

MR MAURICE: Is that Bidjara country?

RUSTY FRASER: Oh, yeah, Bidjara country, yeah. Bidjara country run right back - right back to - right back to what-d'ye-call-im, I suppose, right back to Springsure.

…

This here land, it belong to us, belong to Bidjara land this is, yeah…

We can put a paddock up here. Well, they can't - no one can come in here, see, in this land, because it's Bidjara land, see. It belong to the Bidjara. The camps, old camps, see, they old Bidjara camps, see. They can't come into old Bidjara camps, see.

…

RUSTY FRASER: I worked on Chesterton, and I worked on Mount Tabor, and worked on Attica. I work all that country years ago, yeah.

…

MR MAURICE: Is that all Bidjara country?

RUSTY FRASER: Bidjara country, yeah, all Bidjara country. Bidjara country runs right up to Carnarvon.

22 At Caroline Crossing, to the north-east of Augathella, Uncle Rusty said:

MR MAURICE: Yes. Whose country is this?

RUSTY FRASER: It's Bidjara country. Belong to me.

23 On Mount Tabor Station, which is also to the north-east of Augathella, Uncle Rusty said:

This is the one we call the Rock City, this one here, the Rock City. That's where - the Aboriginals around here years ago, I suppose, when they travel all round this country around here. That's how they got the marks there, see. See all the marks there? They been put there thousand and thousands of years ago, I suppose. Those marks been put there by the Aboriginals. Bidjara mob, I suppose, been around here, see, years ago. All the Bidjara mob been around. They do all them what-d'ye-call-im there, see, through there, and marks there, all the marks.

All this country belong to the Bidjara, see. Bidjara country all this here. Bidjara land, see, because the olden time told me - the olden time Murris told me, old George Muthers and all those, this all country belong to us, see, belong to the Bidjara mob, see. No other people allowed to come up in this country, you know, what-d'ye-call-im. This is Bidjara country, see. But a lot of people come here, the tourists.

…

MR MAURICE: Who should look after this place?

RUSTY FRASER: Well, me, I suppose. I'm the eldest Bidjara, eh, so I'll have to look after it, I suppose, all the country and everything. I've been looking after it all the time. Me and Floyd [Floyd Robinson] been looking after it, all up in Carnarvon, up in Carnarvon National Park, Carnarvon National Park and all this.

…

Up at Carnarvon National Park they done it too, and I went for them because they had no - the bloke said to me, "What are you doing up here?" I said, "This is my country," I said. "This is Bidjara country." I said, "What you white fellas doing here," I said. "You shouldn't be here." I said, "This belong to Bidjara. This is Bidjara country." The Bidjara should be looking after it, eh. The Bidjara mob should be looking after it, not the other blokes looking after it.

…

I walked it right from Mitchell right up to - to Wyandra and out to - out to our boundary, see, out to Beechal Creek, our boundary there. I walked it, see.

24 On Babbiloora Station, which is also to the north-east of Augathella, heading towards the Carnarvon Ranges, Uncle Rusty said:

MR MAURICE: Whose country is this one?

RUSTY FRASER: This is Bidjara country.

MR MAURICE: Right.

RUSTY FRASER: Our country, right - right up to Carnarvon, right over to Springsure, our country, yeah.

…

RUSTY FRASER: This on Babbiloora, yeah. Babbiloora all Bidjara country, see, right through, right up to - Babbiloora and right over to what-d'ye-call-him, then it runs right across then, right across to - up to Blackall and around that way, Longreach and all around that way, you know.

…

And Barcaldine.

…

RUSTY FRASER: Mount Moffatt, see. You got to go past Dooloogarah and then you go past the arch then, big arch there, big mountain like that. They meet together like that. And not far from there to go up to the Lethbridge Pocket then. They wanted to take the country off us but they couldn't take it off us because it was Bidjara country, see.

…

See, "Lethbridge Pocket all our country," I said. Not far from Carnarvon, see, up there.

…

That's the Maranoa River, that one there, Maranoa River.

MR MAURICE: Who owns that river?

RUSTY FRASER: Eh?

MR MAURICE: Who owns that river?

RUSTY FRASER: Well, he supposed to be all belongs to Bidjara - all supposed to belong to Bidjara.

MR MAURICE: Yes.

RUSTY FRASER: But those what-d'ye-call-him, they claiming it. The Gunggari's claiming it, but they can't - they can't take it because what-d'ye-call-him. If it come to law, we can take the country off them, because we own - that's our country, see.

25 On Carnarvon Station, which is also to the north-east of Augathella heading into the Carnarvon Ranges, Uncle Rusty said:

Well, Bidjara mob. Bidjara mob owns the - owns the land. They own the land around here. That's Bidjara land here, see. It goes right across to Carnarvon - right across to what-d'ye-call-him - right over to - right over to what-d'ye-call-him, and out this way. You can go up this way too, across to Springsure. Right over to Springsure, that's Bidjara country all the way, see.

MR MAURICE: Yes. Are we in the Carnarvons now? These mountains here, are these the Carnarvons?

RUSTY FRASER: Carnarvon Ranges, yeah. This is Carnarvon - Carnarvon Ranges, all them mountain you see around. See them all?

26 This evidence continued as follows:

RUSTY FRASER: Mount Lambert, yeah. That one there. See that mountain there, yeah. That's Mount Lambert that one, yeah.

MR MAURICE: Yes. Has it got a Murri name?

RUSTY FRASER: Eh?

MR MAURICE: Murri name?

RUSTY FRASER: Yeah, that's the name of it, Mount Lambert, but Murri call - Murri got a name for it too. They call it - - -

BOB MAILMAN: Murrubu.

RUSTY FRASER: Eh?

BOB MAILMAN: Murrubu.

RUSTY FRASER: Murrubu. Murrubu mountain, see. Murrubu.

MR MAURICE: Say that one again?

RUSTY FRASER: Murrubu mountain they call it.

MR MAURICE: Murrubu?

RUSTY FRASER: Yeah, Murrubu, yeah, the Murri call this.

27 At Torres Park, to the east of Babbiloora and to the north of Boggarella (which is between Augathella and Babbiloora), Uncle Rusty said:

MR MAURICE: This country here. Who belongs to this?

RUSTY FRASER: Belong to Bidjara country. Belong to the Bidjaras. Go right around up to Carnarvon, right over to Springsure. That's all Bidjara country.

28 At Carnarvon National Park, Uncle Rusty said:

Well, this is Bidjara country.

…

Well, they had a look at the country, I suppose, Bidjara country.

…

[About the sewage problem at Takkarakka, just outside Carnarvon Gorge National Park] Destroying the Bidjara land here, see. Destroying the Bidjara land. And a lot of these tourist people come here and they go out here, out to caves out here. See, lot of caves out here, all them places where all these tourist go, and they writing their names. They're destroying that Bidjara land, eh, doing them sort of things. We went down to hold a court about that too, trying to stop them, you know, from doing them sort of things.

…

Mitchell is Bidjara country too, see. When we walked there, we walked it from there right down to Wyandra and across to - across to Beechal Creek, see. That's our boundary down there.

…

MR MAURICE: Which way is Springsure from here? Is that out towards the east?

RUSTY FRASER: No. Springsure is back here.

MR MAURICE: Back here?

RUSTY FRASER: You know where we come in the turn-off?

MR MAURICE: Yeah, off the main road.

RUSTY FRASER: Well, you go across and you come to what-d'ye-call-im. Then Springsure is further on then. Little town come there and then you go to Springsure and you can go to what-d'ye-call-im, this other way. You can go to Rolleston. You go from Rolleston, you can go into Springsure, and you can go back that way, and there's a turn-off into Woorabinda, and you can go straight on, you know, straight on, go straight on then into Rockhampton.

MR MAURICE: Right.

RUSTY FRASER: Go straight up to Rockhampton then.

MR MAURICE: This country out here going out towards Springsure, right - - -

RUSTY FRASER: Eh?

MR MAURICE: This country out here going out towards Springsure: whose country is that?

RUSTY FRASER: That's Bidjara country right to Springsure.

MR MAURICE: Is it?

RUSTY FRASER: All Bidjara country, yeah. This here - they call this Carnarvon Creek here. Well, he runs down, then runs down, and when he gets further down there they call it the what-d'ye-call-im. They call it what-d'ye-call-im then. It goes into Burnett then, Burnett country, see, up into what-d'ye-call-im. I don't know who own that country up that way then, see.

…

And he said to me - this fella said, "What are you doing up here?" I said, "This is my country here," I said. "I come up to have a look at my country here," I said. "You white fellas," I said, "shouldn't be in the country," I said. "This is our country," I said, "Bidjara country this," I said. John said - John Long said, "Get into them, Rusty," he said. "Uncle," he said, "get into them." He had to put me out, see, because I just come up to have a look around up here. He never said no more. He went inside then. He went inside.

MR MAURICE: You've got a right to be on your country, have you?

RUSTY FRASER: Oh, yeah, course I have. Must have a right. It's my country, eh. Got to look after your country.

…

MR MAURICE: Do you like coming back here?

RUSTY FRASER: Yeah, like coming back here, yeah. Well, it's my country, eh. It's my country, so I like coming back to it. Yeah, I like coming back here.

…

MS BOWSKILL: So, Mr Fraser, if you could walk us around the boundaries of what you call the Bidjara country?---Well, the boundaries - well, the boundary starts from - our boundary, the Bidjara boundary, starts from Wyandra to Charleville, Charleville to Augathella, and Augathella up to Babbiloora, and Babbiloora to - Boggarella to Babbiloora, and Babbiloora to Carnarvon.

HIS HONOUR: Just slow down a bit, Mr Fraser. It's a bit hard for everyone to keep up with this. I think we got up to Babbiloora.

MS BOWSKILL: Where next from Babbiloora?---Babbiloora to Carnarvon here.

And then going to the - where does it go to the east?---Carnarvon to - then it runs to Springsure. That's the last Bidjara country.

What about south from Springsure?---What's that?

Does the boundary go - where does it go south from Springsure?---What you say?

What you call Bidjara country, where's the next point in the boundary which is south of Springsure?---And it runs right across from - it runs right across from Springsure right across then to what-d'ye-call-im there - right across to - right across to Barcaldine. That's other side of Blackall, Barcaldine is.

All right. And does that describe the whole of the boundary?---Yeah.

And that area includes Mount Tabor?---Mount Tabor, yes. It's Bidjara country too, yes. It's just down from Carnarvon, what-d'ye-call-im is - Mount Tabor. We own Mount Tabor. That's our country. We own it too. We own the station too. It belongs to the Bidjara traditional owners, see.

Does the boundary include Mitchell, Mr Fraser?---What's that?

Does the boundary include Mitchell?---Barngo Lagoon?

Mitchell. Does the boundary include - - -?---Mitchell, yeah. Yeah, Mitchell is Bidjara country too, yeah. It belong to Bidjara too. They reckon it's not though, but it is though. It's Bidjara country, see. It's where I walked the pipeline, from old Amby, see, old Amby. There's a siding there, railway siding, and I walked it from there right through to - right to Wyandra and across to Beechal Creek. That's our boundary, Beechal Creek. That's our boundary that side then, see.

And Injune: is that part of the boundary?---Yeah.

Injune: is that part of the boundary of what you call Bidjara?---Beechal Creek is, yeah. That's the last boundary. We walked it right to there and then what-d'ye-call-im took it on then. Cunnamulla mob took it on and what-d'ye-call-im mob then. Some more mob come in then. I don't know where they went to, but Cunnamulla, see.

…

Could you tell the court why Mount Tabor is special to you? Mount Tabor - could you tell me why Mount Tabor is special to you?---Yeah. Well, it's Bidjara country, see, all Bidjara country right up to Carnarvon. Mount Tabor is Bidjara country.

…

And how would the Gungabulla feel about Mount Tabor? Is Mount Tabor important?---See, they can't take Mount Tabor because it belong to Bidjara, but they can take it too, I suppose. They got lot to do with it too, see. All the same, see. They're the same, same mob.

…

And did they [your grandparents] live on Bidjara country?---Oh, yeah. Used to work on Babbiloora when he was - when he worked there at Babbiloora he was only about 14 or 15. Worked on Carnarvon, see, Carnarvon Station.

…

Your mother, Ada: was her mother Bidjara?---Yeah. She born there. She Bidjara, yes. She Bidjara too.

And did she live on Bidjara country?---Yeah, lived on Bidjara - that's Bidjara country, that Yarrawonga. That's where they reared up there, Yarrawonga Station.

[About other people entering Mount Tabor] Got to ask me. I'm the boss of the country, see. I'm a Bidjara, see. I'm the boss of the country.

…

Did anyone ever tell you that you couldn't be on Mount Tabor?---No, no one can't tell me because I own they country. They can't hunt me off the country. Can't hunt you off your country, can they. If it's your country, well, they can't hunt you off it, eh.

…

You were born in Augathella?---I was born in 1921, yeah, in Augathella, yeah, on Bidjara country. That's where I born.

…

Mr Fraser, when did you first come to Carnarvon Gorge, this place? When did you first come here?---I don't know. When I was born. That's our country. That's our country there, Bidjara country, see. All Bidjara country. That's all Bidjara country here too.

…

When you used to come to Carnarvon Gorge, this area around here, it was when you were working?---Yeah. Used to belong to Carnarvon, all the country round here too. It's all Bidjara country, see.

…

How do you know where Bidjara country is?---Well, I know. You start from Wyandra, runs right up to - Wyandra to - Wyandra to Charleville, Charleville to Augathella, Augathella to - Augathella up to Carnarvon then, Carnarvon, Babbiloora and Boggarella and all them places, see, and it runs right over to - far as - past what-d'ye-call-im - runs out then far as other side of Blackall - what's that place there now - Barcaldine. I think that's as far as it goes, Barcaldine. Hey, Robert, it goes far as Barcaldine, doesn't it, Bidjara country? It goes far as Barcaldine.

…

We're here on Carnarvon Gorge?---Yeah.

This Carnarvon area, the Carnarvon Gorge?---Mm.

It was a meeting place for a number of tribal groups?---Eh?

It was a meeting place, Carnarvon Gorge?---Yeah.

Different tribes used to come here?---Yeah. Only one tribe come. No different tribes come.

And what was that tribe that came here?---Well, the Bidjara mob, see. Only the Bidjara mob can come there, see.

So no other tribes were in Carnarvon Gorge?---I don't know no other tribe. Only the Bidjara tribe. That's all. That's all I know.

The Karinbal tribe?---Eh?

The Karinbal tribe: weren't they in Carnarvon?---No.

What about the Nuri?---No.

Or the Kairi?---No, they don't come up there. They wouldn't be game enough to come up there anyway. They wouldn't come up there.

… So if I'm in Carnarvon Gorge, no other Aboriginal peoples apart from Bidjara can come into Carnarvon?---No.

Wasn't there other Aboriginal tribes in Carnarvon?---No.

…

Mr Fraser, there are markings in the caves here that aren't anywhere else in Bidjara country. Those markings were put by other Aboriginal tribes?---No, put there by Bidjara mob, I suppose. Bidjara mob put it in there, those marks. This country belong to Bidjara, see.

…

MR O'BRIEN: Mr Fraser, you talk about Springsure being Bidjara country?---Yeah, Springsure, yeah.

It's Kairi country, isn't it?---No, Bidjara country. Belong to Bidjara, Bidjara and Gungabulla. Gungabulla and Bidjara both own it, own that country.

You talk about Barcaldine. That's Wadjabanji country, isn't it?---No, no.

Blackall is also in Wadjabanji country?---Who reckon that?

Well - - -?---You reckon it? Well, you make a mistake then. It belong to Bidjara country.

I'm asking for what you think, Mr Fraser?---Well, it's Bidjara country. I'm telling you. It's Bidjara country. The Gunggari wanted to take Mount Moffatt. "You can't take Mount Moffatt. That's our country," I said, "Bidjara country." I said, "You can't take that country. If you carry on," I said, "then I'll take you to court." Soon as I mentioned the court, "No," they said, "you take the country. You own it." I said, "We own it all right," I said.

Mount Moffatt: it's Nuri country, isn't it?---No, it belongs to the what-d'ye-call-im - Bidjara country.

And where we are here in Carnarvon, that's Karinbal country.

MR MAURICE: I don't think he answered that, your Honour. He shook his head.

MR O'BRIEN: I was about to say - -

MR O'BRIEN: I was about to say - - -?---Who that tribe that owns that then you reckon?

Karinbal. Karinbal own Carnarvon Gorge, don't they? Mr Fraser, could you just indicate yes or no because - - -

HIS HONOUR: You have to say yes or no so we can record it?---No, they don't own it. It's Bidjara country. They don't own the country.

MR O'BRIEN: Augathella, Mr Fraser: that's Kunja country, isn't it?---No, Bidjara country.

And Charleville: that's also Kunja country?---No. I don't know this Kunja country. Kunja? Kunja? Who them people? I never ever heard of them. That's what they say in that paper there. That's only just say it on the paper, see, in that what-d'ye-call-im. I never heard the name before.

You've never come across those other tribes?---No, I never. They must have been here years and years ago. I know the Bidjara. That's all I know. Bidjara own the country. Bidjara own this country on Carnarvon and right down to Wyandra. They own that country. That Bidjara country, see.

…

Where is Gungabulla country?---Eh?

Where is Gungabulla country?---Well, Springsure, but they're the same. They talk same lingo as we talking now, see. We both talk the lingo. They talk the same - sing the same songs and everything.

They're a different tribe, though?---No, they're the same tribe. Gungabulla and Bidjara the same.

Gungabulla doesn't have - does Gungabulla have its own country?---Gungabulla the name of the tribe.

Do they have their own country apart from Bidjara?---No.

The Gungabulla tribe: where's their land?---Well, they must be here with us. Same mob as us, Gungabulla, Gungabulla and Bidjara.

…

These white fellas here shouldn't be here, see, up here, up at the what-d'ye-call-im up here. There shouldn't be any white fella working at all. Should be black people working, not white people work. This is Bidjara land, see.

…

Are there any other places that are significant to Bidjara people - - - ?---Yeah.

…

Only round Carnarvon here, round Carnarvon, and all round our country. That's all. There's no other places around.

…

Only around Carnarvon here, up here at Carnarvon, then you go down to what-d'ye-call-im, down to Mount Tabor and around there. That's the only places where you see the sites, all the Aboriginal sites. A lot of places in Mount Tabor there, a lot of caves there with a lot of what-d'ye-call-im, old camps and everything around there, you know. You see the nardoo stones and all that where they grind the what-d'ye-call-im on.

…

Talking about those boundaries of Bidjara country, right?---Yeah.

You've told us where that country is?---Yeah, I told you, yeah.

This lady over here, she asked you about Injune, right?---Yeah.

She asked you about Injune, whether that was in Bidjara country?---Injune?

Injune?---No, Injune not Bidjara country, no.

Not Bidjara country?---No, not Bidjara country, no. Bidjara country this side of that.

Just this side of it?---Yeah. Yeah just see that in your - you remember that written statement we did for you, that written statement?---Yeah, yeah.

It says there that:

Bidjara go from near Roma to Injune and from Injune - - -

?---Yeah, near Roma, yeah.

Continuing:

...to Injune, from Injune to the turn-off to the Carnarvon National Park.

?---Yeah.

But they don't actually go quite to Injune; is that right?---No. Out this side of Injune. I don't know how far out.

This side of Injune?---Good way out of Injune before you get to Bidjara country.

Let me get that clear. But definitely, definitely, Injune is not in Bidjara country?---No.

Okay?---No, not Bidjara county, not Injune is, no. Dundandanji [Mandandanji] or something name of - own that country.

…

And that snake: now he's at Mount Playfair?---He's over - yeah, over Mitchell Camp. We've got to go over there yet to have a look at that one, you know. Good hole that one, Mitchell Camp. Big hole there.

And that's on Bidjara country?---Yeah, Mitchell Camp, yeah. Big hole there. Not far from down there to go to Cungelella then. That's Mantuan Downs country then.

Is that Bidjara?---No, no - I don't know. Yeah, it would be Bidjara country.

…

Jimmy Lawton and Ted Lawton and Joe Lawton, right: are they Gungabulla?---Yeah, they all Gungabulla, all them Lawtons.

Gungabulla?---Yeah.

All those Lawtons Gungabulla?---But don't make no difference. They're Bidjara just the same. Well, Gungabulla and Bidjara the same, see.

I hear what you say?---They talk the same lingo and sing the same songs.

…

Is Mount Tabor their country?---No. They can't - they can't take Mount Tabor because Mount Tabor belongs to the - belong to us, see, belong to Bidjara.

Yes. What about - - - ?---The Gungabulla can't take it, see.

Right?---Can't take it, can't take the Bidjara country, see. Might be Gungabulla, but they can't take the Bidjara country, see.

What about Boggarella and Babbiloora?---No.

No?---They're all Bidjara country, see.

29 Burnett, which Uncle Rusty referred to, is best understood as a reference to the Burnett River. The Burnett River is many hundreds of kilometres to the east of the overlap area. Locations which Uncle Rusty said were not Bidjara country, such as Injune and Roma, are situated between the overlap area and the Burnett River. When specifically asked about Injune, it will be recalled that Uncle Rusty said “No, Injune not Bidjara country, no…[Not Bidjara country?]---No, not Bidjara country, no. Bidjara country this side of that”. It is obvious that by “this side of that” Uncle Rusty meant that Bidjara country was to the west of Injune. When asked about Roma, Uncle Rusty said “[a] different tribe own the country at Roma, going from Roma, that’s as far as we go then”. Together, this evidence clearly discloses that that Uncle Rusty was setting a very firm boundary for the eastern extent of Bidjara country. Bidjara country did not extend as far east as Injune or Roma but it did include Springsure and Carnarvon Gorge and Carnarvon National Park. The notion that Uncle Rusty was claiming the land between Carnarvon Creek and the Burnett River as Bidjara country is plainly untenable. It is also apparent that, when located in Carnarvon Gorge, Springsure (which Uncle Rusty was claiming to be Bidjara country) is to the north and, if anything, slightly west of the Gorge. The overlap area, in contrast, is to the east of the Gorge and to the east of the eastern-most extent of land Uncle Rusty described as Bidjara country.

30 The other witnesses who gave evidence in 2001 said a few things about Bidjara country but not in anything like the detail Uncle Rusty was able to give.

31 At Carnarvon National Park, Bob Mailman said:

I was only small, but they used to talk a lot about this country, and, well, Bidjara country, and many of the bushrangers, like when the Kenniffs were around here and duffing and all that, stealing cattle.

…

You say, Mr Mailman, that Mount Tabor and Carnarvon are part of Bidjara country. What do you understand to be Bidjara country? What are the boundaries of Bidjara country?---Now, well, that's where you got me, see. All I know is - I don't know where the boundary is, you know - well, the stones or the, you know, the fence line or the line, you might say. I don't know where they are, but I know it covers a fair bit of ground, from what I'm told, eh.

The Carnarvon Gorge - - - ?---Definitely Bidjara country.

It wasn't the Karinbal country?---Who?

Karinbal, Karinbal---Never heard of them.

Did you ever see any other Aboriginal tribes when you came - - - ?---No.

Any other Aboriginal people when you'd come to Carnarvon Gorge?---No. Well, it's only a few months ago - yeah, only a few months ago since I first come here.

So the first time you came here was a couple of months ago?---Yeah.

…

And Mount Moffatt: it's in Nuri country, isn't it? It's not Bidjara country?---Oh, I don't know. Couldn't tell you, see.

Right. Augathella: that's Kunja country, isn't it, Kunja country, Augathella?---No, Bidjara.

Bidjara country?---Yes.

What about Blackall? Blackall is Wadjabanji country, isn't it?---Well, that's what I say. I don't know the boundary fences, see, the boundary lines or anything.

Springsure: Springsure is in Kairi country, isn't it?---Well, I'm told it's in Bidjara country, eh. Could be. I don't know, see, as I said. Like black and white. There's a lot of half-castes, you know. The less you knew about the black fella law and country, like, the better.

32 This oral evidence must be weighed up when considering the statement that Mr Mailman provided in March 2001, which forms part of the preserved evidence. Mr Mailman said that said he was descended from Lucy Long and Charles Mailman on his father’s side and Nellie Combo and Bill Geebung on his mother’s side. He said they were all born and lived in Bidjara country. According to the records, Nellie Combo was born near Augathella and William Geebung was born near Springsure at Orion Downs and they lived mostly near Babbiloora Station, whereas Lucy Long was associated with the Upper Warrego area. These areas are all west of the overlap area on land which Uncle Rusty identified as Bidjara country.

33 Mr Mailman also said the largest artwork he had done was a painting which depicts the Mandagharra (the rainbow serpent) and its journey across Bidjara country. The journey starts at the bottom right hand corner representing the “16 mile and Carnarvon and the Pump hole near the head of the Warrego”. The head of the Warrego is in the Great Dividing Range (which I infer Mr Mailman referred to as “Carnarvon”), well to the west of Carnarvon Gorge and the overlap area. At the top left hand corner is the “water well at the Babbiloora mission”. Babbiloora is yet further to the west again. In the bottom left hand corner is a representation of the Barngo Lagoon. Barngo is located between Babbiloora and the head of the Warrego (that is, north-east of Babbiloora but west of the head of the Warrego). Across the middle of the canvas is the Mandagharra.

34 Mr Mailman said that there is a Bidjara legend about the Mandagharra that it had lived in Barngo lagoon but left it “when all of the blackfellas were killed, died, or moved off their land …in 1944 or 1945”. The water then all dried up in the lagoon. In the top right hand corner of the canvas is a representation of Lake Nuga Nuga near Springsure. This “is where the Mandagharra went and continues to watch the Bidjara country”. There are “small white dots around the painting representing the slithery movement of Mandagharra away from the area”. “Mandagharra’s tracks across the earth heading northeast away from Barngo Lagoon in the direction of Springsure can be seen in the landscape today”. There are also small black dots on the painting that represent the footprints of the Bidjara people.

35 Contrary to the submission that was put, I do not see this description as suggesting that Lake Nuga Nuga is part of Bidjara country. In fact, I consider that Mr Mailman was explaining that Lake Nuga Nuga was not Bidjara country. As I understand the legend he is describing, it is that the Mandagharra lived in Barngo Lagoon which is Bidjara country until the Aboriginal people were driven off their land. The Mandagharra then left Barngo Lagoon which had dried up and slithered to the north-east to Lake Nuga Nuga so the Mandagharra could continue to look over Bidjara country (that is, the country to the west of Lake Nuga Nuga). This is consistent with not only Mr Mailman’s description of Bidjara country (Babbiloora, Barngo Lagoon, the head of the Warrego) but Uncle Rusty’s description of Bidjara country running from the west up to but no further than the Carnarvons.

36 At Carnarvon National Park, Ritchie Fraser said:

MR MAURICE: So she told you she came over here?

RICHIE FRASER: Oh, yes, they used to come over here, apparently quite often, from the stories that she used to tell me. I can't remember the stories, but she used to always - I can remember stories that she used to tell us about Carnarvon Gorge.

MR MAURICE: Right. And did she say whose country it was?

RICHIE FRASER: Bidjara, all Bidjara country.

MR MAURICE: And how does it feel, coming here, for you?

RICHIE FRASER: Fantastic.

Mr Fraser, can you tell us the boundaries of Bidjara Station - of Bidjara property?---No, I cannot do that. I cannot do that.

Did you - - - ?---I know it goes from the Carnarvon homestead down to Augathella, back to Mitchell, Springsure, and I didn't think it got quite to as far as Barky.

That's Barcaldine, is it?---Barcaldine I meant, yeah, Barcaldine.

Yes, sorry?---I didn't think it got quite that far, but apparently it does, I hear, and then back up through Blackall and back to Tambo, that way.

Did your father tell you where Bidjara country was?---Not really, no. I can't remember. He could have done.

So you're not really sure of the areas that it covers?---No, only just what I told you then. I don't know what these other things they have drawn up since then. They've drawn maps everywhere, I think.

This Carnarvon Gorge: is it Karinbal country? Do you know whether it's - well, is it Karinbal country?---?---Who's Karinbal?

Karinbal is another tribe that was in Carnarvon Gorge?---No, no, never heard of them.

Springsure?---Well, I thought Springsure was in it but apparently it doesn't quite - it doesn't come in. I don't know. Could be wrong. As I say, when I first looked at it it was more or less straight-forward, but everything - there's more lines. There's more lines, I think.

37 There is no map in evidence which shows all of the locations and land features Uncle Rusty identified. Certain things are clear from his evidence. For example, Uncle Rusty was firm that Injune and Roma are not part of Bidjara country. He was equally firm that Bidjara country includes Carnarvon Gorge up to Springsure. The way Uncle Rusty consistently described Bidjara country when asked to do so is also apparent. He consistently described Bidjara country by reference to his current location, extending out from that location to certain boundaries. Locations described as boundaries are repeatedly identified as Beechal Creek, Blackall, Barcaldine, Wyandra, Mitchell, and the Carnarvons up to Springsure. When describing the boundary running between Wyandra and Carnarvon Uncle Rusty linked Wyandra to Charleville, Charleville to Augathella, Augathella to Bogarella, Bogarella to Babbiloora, Babbiloora to Carnarvon, Carnarvon to Springsure, with Springsure being “the last Bidjara country”. When asked to describe Bidjara country south of Springsure, Uncle Rusty described the boundary running back to the west from Springsure towards Barcaldine with Beechal Creek being the boundary on that (western) side.

38 The mapping service Bonzle shows the coherence of Uncle Rusty’s descriptions. Starting in the south, Wyandra is south of Charleville. Heading west from Wyandra you meet Beechal Creek which runs generally in a north-south direction. You can then travel in a generally northerly direction along Beechal Creek in the direction of Blackall and thence Barcaldine. Heading north and east from Wyandra you will reach Charleville. If you continue in a north-easterly direction you will travel through Augathella, Bogarella, Babbiloora, the Carnarvon Ranges including Carnarvon Gorge and thence to Springsure.

39 Some observations can be made about the eastern extent of Bidjara country as described by Uncle Rusty. As noted, Uncle Rusty was clear that neither Roma nor Injune were Bidjara country. He described the Maranoa River, however, as Bidjara country. The Maranoa River aligns generally north-south and extends from the Chesterton Range in the north to far beyond Mitchell (a southerly extent of Bidjara country in this location according to Uncle Rusty) in the south. Uncle Rusty said you had to be a good way out of (that is, west of) Injune before you reached Bidjara country. In context, this can only mean that Bidjara country ended to the west of Injune but to the east of the Maranoa River. If, as Uncle Rusty said, Springsure is a boundary of Bidjara land then it is a boundary to both the north and the east. Uncle Rusty said that the boundary from Springsure ran west to Barcaldine but he did not suggest the boundary extended any further to the east. Eastern locations mentioned by Uncle Rusty as Bidjara country, as noted, are the Maranoa River, Carnarvon Gorge, Carnarvon National Park and Springsure. While he mentioned Rolleston in describing locations Uncle Rusty did not say Rolleston was in Bidjara country. He expressly said Roma and Injune were not Bidjara country. Rolleston is to the east (and south) of Springsure. It is to the north of Injune but in a similar easterly location as Injune.

40 From this analysis it is apparent that Uncle Rusty’s evidence in his own words identifies the eastern-most extent of Bidjara country as ending, in the south, somewhere to the east of Mitchell (but not as far east as Roma), in the middle to the east of the Maranoa River (but not as far east as Injune), and in the north at Springsure. The only matter not clarified by his evidence is the location of the eastern boundary of Bidjara country somewhere to the east of Mitchell and running up to Springsure, other than that the Maranoa River is inside Bidjara country, as are Takkarakka and Carnarvon Gorge, whereas Injune and Roma are outside Bidjara country. If Uncle Rusty believed that Rolleston was part of Bidjara country it was apparent from his evidence he would have said so when he mentioned Rolleston. He had no hesitation in identifying what was and was not Bidjara country. Once his evidence is considered as a whole it is impossible to understand Uncle Rusty to be saying Rolleston is Bidjara country. He did refer to Carnarvon National Park in the context of Bidjara country. This is consistent with the fact that the majority of the national park is to the north-west of Injune and, in particular, Carnarvon Gorge and Takkarakka are west of Injune and Rolleston. All of Uncle Rusty’s evidence points to Bidjara country ending a good distance to the west of Injune and to the west of Rolleston, as well as at Springsure. This is consistent with the fact that Uncle Rusty does not mention, as part of Bidjara country, the Expedition Ranges, the Arcadia Valley, Lake Nuga Nuga, the Kongabula Range, or Rolleston. These places are all located to the east of the Carnarvon Ranges, Carnarvon Gorge, Takkarakka, as well as to the east of both Mitchell and Springsure.

41 Uncle Rusty’s evidence discloses his deep knowledge of Bidjara country. The difference in detail between his knowledge of the boundaries of Bidjara country and that of the other Bidjara people who gave evidence in 2001, Bob Mailman, Betty Saylor, and Ritchie Fraser, is obvious. When comparing the weight to be given to Uncle Rusty’s oral evidence given at various locations throughout Bidjara country compared to the evidence in his written statement and the inferences which should be drawn from his involvement in drawing up the boundaries of the Bidjara No 3 claim, it should be apparent that his oral evidence is far more likely to be reliable for many reasons. As noted, Uncle Rusty’s written statement was read to him. While he signed off on the statement as accurate he corrected it in his oral evidence by saying that Injune is not Bidjara country. The fact that Uncle Rusty could not read or write (as he said in his oral evidence) would have made it very difficult for him to use a map to draw up the boundaries of Bidjara country. By contrast, while on Bidjara country he could describe by direction, in a great level of detail, places that link one to the other, all generally moving from the western part of Bidjara country (Wyandra and Barcaldine) towards the eastern part of Bidjara country (up to the Carnarvons and Springsure). Uncle Rusty’s repeated descriptions of Bidjara country as extending “up to” the Carnarvons and Springsure, in the context of his evidence as a whole, can mean only that Uncle Rusty was saying that these places are the eastern-most extent of Bidjara country. Carnarvon Gorge and Takkarakka, which he referred to expressly as Bidjara country, are generally within the scope of this eastern-most scope of Bidjara country. However, they are located in the western part of the overlap area. The overlap area extends well to the east of Carnarvon Gorge and Takkarakka across the whole of the Arcadia Valley into Expedition National Park, east beyond Lake Nuga Nuga, east beyond the Kongabula Range and the Comet River and Clematis Creek, and to Rolleston. Uncle Rusty’s evidence cannot be understood on a rational basis as suggesting that these areas are Bidjara country. To the contrary, his words about Bidjara country going up to the Carnarvons and up to Springsure, in the context of moving from west to east, and not extending to or even close to Injune, confirms that Bidjara country as identified by Uncle Rusty does not extend as far east as Injune, the Arcadia Valley, Lake Nuga Nuga, or Rolleston. Bidjara country does extend as far east as the Maranoa River, the Carnarvon Gorge, Takkarakka, and the area which might be described as the western part of the Carnarvon Range.

42 In other words, the general shape of the boundary of the Bidjara claim, which extends further to the east in the southern part and then cuts back to the west towards Springsure in the northern part is consistent with Uncle Rusty’s evidence but the entire line representing the eastern claim boundary starts too far to the east to be consistent with his evidence. His evidence leaves work for inference about the actual eastern boundary of Bidjara country but, as I have said, Uncle Rusty clearly identified Mitchell in the south and Springsure in the north as two relevant locations being Bidjara country, the Maranoa River as being in Bidjara country, and Injune being quite a distance to the east of Bidjara country. This enables an inference to be drawn that Bidjara country, as identified by Uncle Rusty, must be west of the Carnarvon Highway, incorporating the main western parts of the Carnarvon National Park (and Carnarvon Gorge and Takkarakka) and the western parts of the Great Dividing Range in this area.

43 The hearing in 2001 also produced valuable evidence about Bidjara culture. Again, Uncle Rusty’s evidence is the most detailed of all of the witnesses. Given that Uncle Rusty was the eldest Bidjara at this time (80 years of age) this is perhaps unsurprising. It is also apparent that Uncle Rusty had the benefit of time with his father, a Bidjara man, and another Bidjara man who was much older than his father, George Muthers, as well as Uncle Billy Peters (a man with six fingers whom the Bidjara, including Uncle Rusty, associated with rock art in Bidjara country, including at Carnarvon Gorge). Uncle Rusty was taught how to hunt, sing and dance the Bidjara way by these men from when he was six or seven years old.

44 Uncle Rusty and other Bidjara people would hunt and eat kangaroo, wallaby, snake, emu, possum, porcupine, goanna, and collect burumu bushes (a wild currant), yika (a wild orange) and lots of other bush tucker such as emu eggs, witchetty grubs and fresh-water crayfish. Uncle Rusty could sell the skin but not eat possum, however. He explained:

He's my meat too, possum is. I can't eat the possum because it's my meat, see. They my meat, them fellas, the possum. And my father the red kangaroo.

45 Betty Mailman said her father told her that other people needed permission from the Bidjara to hunt on Bidjara country. All of Bidjara country was their hunting ground. Other people needed permission to cross Bidjara country as well, even if not hunting.

46 Uncle Rusty said he was possum from his mother and red kangaroo from his father. Bob Mailman was also red kangaroo from his father so their fathers were brothers. He also gave this evidence about marriage:

MR MAURICE: But tell me this, Rusty. Can a red kangaroo person marry a red kangaroo person? Is that right?

RUSTY FRASER: No, can't do that. No, you can't do it. You got to marry a different mob, see. Say that I want to get married now. Well, I can marry a what-d'ye-call-im. I can marry a red kangaroo, see. I can marry red kangaroo.

MR MAURICE: Because you're a possum?

RUSTY FRASER: I'm a possum, yeah.

HIS HONOUR: But no possum?

MR MAURICE: You can't marry a possum, Rusty?

RUSTY FRASER: I can't marry possum. No, you can't marry. They kill you for that. Years ago, even if you sit on your sister's bed or anything like that, they can kill you for that too. They point a bone. They get a bone from here. They point it at you like that and you're dead, dead in a few minutes. They kill you straight away with that thing.

…

RUSTY FRASER: Lot of them, they can bleed you - cut you there, that vein there, and they put it over the fire and sing this song then, sing a song, and you're gone then.

…

RUSTY FRASER: Oh, yeah, you're gone. You can go to all the doctors in the world. They can't cure it. They can't cure it because you got to get a bloke that's clever bloke to cure it. Doctor can't cure it. No chance, doctor.

47 Uncle Rusty later explained the rules about marriage in more detail, as follows:

You can't marry a Bidjara woman, you know. You got to marry a different tribe, see, different tribe. You can marry a different tribe but you can't marry a Bidjara. You can't marry into your tribe or your relation. See, lot of people now, they get married and they might be cousins or something. That's not the law, see. The law won't allow it, see. They kill you for that years ago. Years ago they kill you. If you went with your cousin or something like that, well, they'll put the bone into you or something, kill you, yeah.

48 Uncle Rusty said he had taught younger Bidjara men traditional songs and dances. These had been sung and performed in “Sydney and everywhere with it. Go right down to what-d'ye-call-im - right up Blackall and right up to Longreach and all around there. We dance all around Longreach and everywhere, around Barcaldine”, as well as at Carnarvon Gorge. Uncle Rusty explained that other Aboriginal people could not dance in Carnarvon Gorge unless they first asked the Bidjara as that is part of Bidjara country. So too Bidjara people would have to ask the Gunggari mob if the Bidjara wanted to dance in Roma as Roma is not Bidjara country. Near Carnarvon Gorge Uncle Rusty said people who were not Bidjara could not sing and dance with Bidjara. Uncle Rusty also said near Carnarvon Gorge:

Not many what-d'ye-call-im now, half caste, can sing a Murri song. I been taught by the olden times see, old George Muthers and my father. One of the best singers in the back country, them fellas. When they singing you can hear them miles away singing, them fellas, when they hit the bilkan, you know. They call him bilkan, you know. Hit him like that, sticks together. And making a fire, see. Lot of people - lot of white people die now if they went in bush. You got bush here, but Murri, they'll survive, Murri will, because he knows how to make the fire, see. You get that stick and make a fire. They made the fire the other day. You seen that?

…

Well, you can make it with any sort of stick too, but they made it with that bunbulbul. They call it bunbulbul. He grows here in the Carnarvon Ranges, see.

…

That's why you get that medicine from here. They call it mila mila medicine. You drink him up. I drink a lot of gumbi gumbi. I drink it all the time. That's why I'm well all the time, see. My nephew, he drinks it too, that fella over there. Sugar, he drinks it. Good stuff for you, gumbi gumbi. If you drink too much of it, it make you drunk too, but if you take him up there like that up there, that fine. Drink him up. Next thing, you right as rain. You get crook from the cold or any flu or anything, he kill him straight away. You got all cures here, all black fella cures.

49 At Ambathala Lake near Augathella Uncle Rusty explained that the Bidjara snake, Mundangarra, lived in the lake. This snake would not hurt Bidjara people as the snake was a Bidjara snake but would hurt other people if they went in the lake. The snake knew they were at the lake and caused a big whirlywind while they were there to let them know. The same Bidjara snake (the rainbow serpent) could be seen in the sky after it rained and also lived in other places such as at Boggarella and near Mount Playfair, as well as (in the past) Tambo Bridge. The snake was dangerous and would kill other people. At Tambo Bridge Uncle Rusty said:

Oh, well, you get crook. You might die. See, you'll die too. Oh, yeah, they can kill you. He can kill you, Mundangarra can. He's all colours of the rainbow, he is. You see when it rain? Well, that's him. He's up in the air - sky. But he went from here. I don't know where. He could have went to Mitchell Camp; he could have went anywhere, see. They travel around, you know.

50 Betty Mailman said:

That's the Rainbow Snake. When Aborigines used to see that snake, they used to be frightened. They used to get a terrible fright out of it, because it used to make them sick, Mundangarra. It was the Rainbow Snake. Aborigines was very terrified of that snake when they used to see it. You can go to a water hole - you see a water hole there, never been dry, because that's when you know when a Mundangarra is there, because that water hole will never dry up while that snake is there. That is true.

51 At Torres Park Uncle Rusty said:

Well, that used to be where that Mundangarra used to be. That's that what-d'ye-call-im. Used to be big spring there one time. Water running there. Used to be big spring there, but it all dried up now. I don't know what happened to it.

MR MAURICE: Was that Mundangarra there when you were working on the place?

RUSTY FRASER: Oh, yeah, he was there, yeah. When all the dark fella left, he might have left too. He might have went somewhere else. He might have went to Mitchell camp. He could've gone anywhere. They go anywhere, that Rainbow Snake. You heard Betty say this morning once they go in the water it never dry, the water. That Ambathalla never dry, you know.

52 Uncle Rusty said about the birds around them in one location:

[some birds]…They all black fella one time, these birds, here, yeah. See that crow then. He had a fight with a galah then, a galah. He threw the galah in the fire. That's why it's all red now, see. He's all red all over him now. That's from the fire, see, when they threw him in the fire. And the bowerbird and the happy family. They do it then. He chopped the bowerbird in the back of the neck there. When you see the red in the back of his neck there, well, that's where he chopped him with that - with a tommyhawk, see.

53 Uncle Rusty said nothing could be touched in a cave at Mount Tabor or else the person might get sick, and it is apparent that he believed no-one should go in the cave. Bidjara people who had died had been wrapped in Budjeroo bark and placed in the caves. Later Uncle Rusty said about the Lost City on Mount Tabor:

There's a lot of printing there too, but you can't go there. You know, you can't do what you like there. You can't go without - well, my nephew, Sugar's boy there, Robert, Robert's son what-d'ye-call-im in the cave there, he went in the cave and had a look, and it's a woman's cave, see. There's woman cave and men cave. It'll kill you, you know, make you sick. Well, he got in this woman. People walking around on the roof and all round there, you know. Haunted him all night. He reckons there's some fella in there, see, another Bidjara, see. If you're not Bidjara, well, you can't go in there, anything like that, or touch anything, you know. If you're not Bidjara, you'll get very sick or it'll kill you all right.

Is that Floyd that you're talking about?---Yeah, Floyd. He said to me, "Uncle," he said, "I don't know," he said. "This thing haunting me down here." He reckon there's things haunting him, walking round on top of the roof. I said, "It might have been a possum or something walking." "No," he said, "it's rock. You can hear him walking on it, see."

54 At Babbiloora Uncle Rusty looked for the six fingered sign he had seen before and explained why it was important:

Oh, yes. Must - might be my uncle, see. He got six fingers and six toes, my uncle, Billy Peters, see. He had - he had six fingers and six toes. He must have been up here too, see, draw the marks like that on the - on the rocks like that, see.

55 When a stone was taken from Carnarvon Gorge Uncle Rusty said it had to be taken back there. He said:

…they took one stone away. There's my nephew there now. There's Robert there now. They took one stone away from here and we had to bring that stone - my brother brought it right back here and give it over there to what-d'ye-call-im - Grahame Walsh. He still had that stone there when we come up here last time. I come up to see Grahame Walsh. He still that stone out at Takarakka there, see. I said, "Where's that stone?" He said, "I got it in here," he said. So he brought it out then and he showed it to us. I said, "That's the stone all right," I said.

…

Yeah, somebody took it away. Some of them tourist people took it away down New South Wales or somewhere down there, or Sydney somewhere. They traced that stone back. They knew where the stone come from, see. Come from here, so they bring it right back. You can ask him. Dusty brought it back then, eh? He sent Dusty back with it.

…

He still got it there. Grahame Walsh got that stone. It belong to here, see. That stone belong to here. I don't know whether they put it back in the cave again, but I don't think so. I think he still got it.

…

Belong to here. Belong to Bidjara. Belong to Bidjara mob. Belong to Bidjara mob, yeah.

56 He said also that there were lots of Jun-juddie (little hairy men) in the Carnarvon ranges. As Uncle Rusty explained:

Oh, well, if you camp anywhere and you make a fire anywhere - you might be having a yarn. If you left your tobacco, they take tobacco, anything. They take it on you, take him away and smoke him.

…

Mm. Another fella here too. He lay on top of you. Yunji. Yunji. He lay on top of you too. He kill you too. Same as the Rainbow Snake. When it rains, you see that rain. Well, you see him there in the sky, you know. In the night-time you can see him up here. Lot of them can't get along in the night-time, but I'm a better bushman in the night-time than what I am in the day-time, see.

57 Uncle Rusty then said:

Calliwong, yeah, what-d'ye-call-im. He's a calliwong, that fella. Murri call him karabarka. Karabarka, Murri call him, that fella singing out there. That's a calliwong, that one, calliwong. When the calliwong come flying down from the mountain, then they start dancing then, you know. That's what Murri said.

…

Yeah. Oh, they cheeky fellas, them fellas. That's the fella put the tommyhawk into the what-d'ye-call-im - cut the bower bird in the back of the neck there, and now you see the red. You get a bower bird and he got red in the back of the neck. Well, he chop him with a tomahawk.

…

Happy family chop him with a tommyhawk. Cheeky little bird, that one. They all black fellas one time, all them fellas.

…

Old Murri told me. All black fellas here.

…

That crow? He got all the gilayi. He got all the gilayi and he threw him in the fire and that's why he's all red now. He's all red now, see, from the fire.

58 The Calliwong you could eat but you could not eat the “happy family bird”.

59 The Curlew or Guylban, Uncle Rusty said, is:

…a death bird. If my people die, well, I know when they die because he come there. One on his own, he dangerous, because he tell you that - he'll go the same way. Where your people died, well, he'll sing out and go the same way, and he knock off then. He sing out about two or three times and he go the same way where the people die. Well, you know there's a death, see. He's a death bird, see. He's a death bird, see.

60 Uncle Rusty said:

Do you teach Floyd about the stories that George Muthers told you?---Yeah, yeah, sometimes I teach him. I try and teach him. See, somebody got to take this place when I die, see. I'm 80 years of age, see, and when I die, well, I got to get someone else to take over then, you know, to take over.

And who else do you teach?---I teach Floyd. He might be all right for that. You know, he understands.

Do you teach other young Bidjara people as well?---Eh?

Do you teach other young fellas as well?---Yes. I teach them everything, you know. I teach a lot of them dancing, Bidjara dances and everything. I teach them all how to dance.