FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Robinson v Goodman [2013] FCA 893

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| Applicant | |

AND: | First Respondent RIVERS (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD Second Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

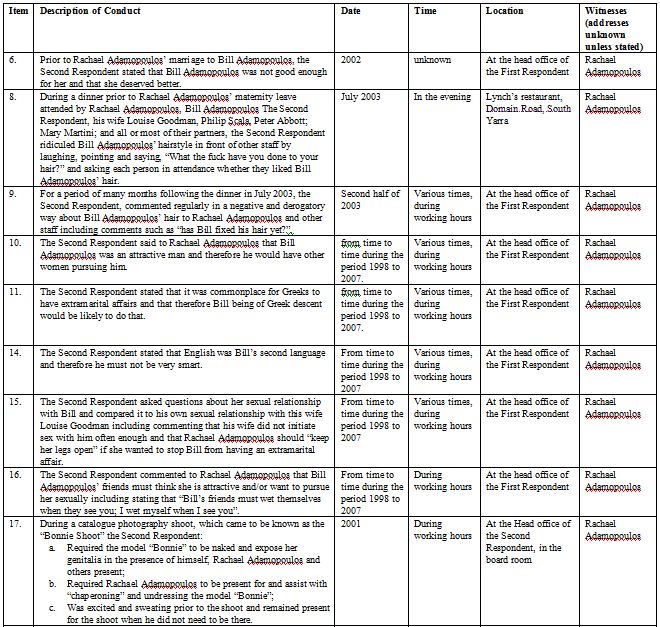

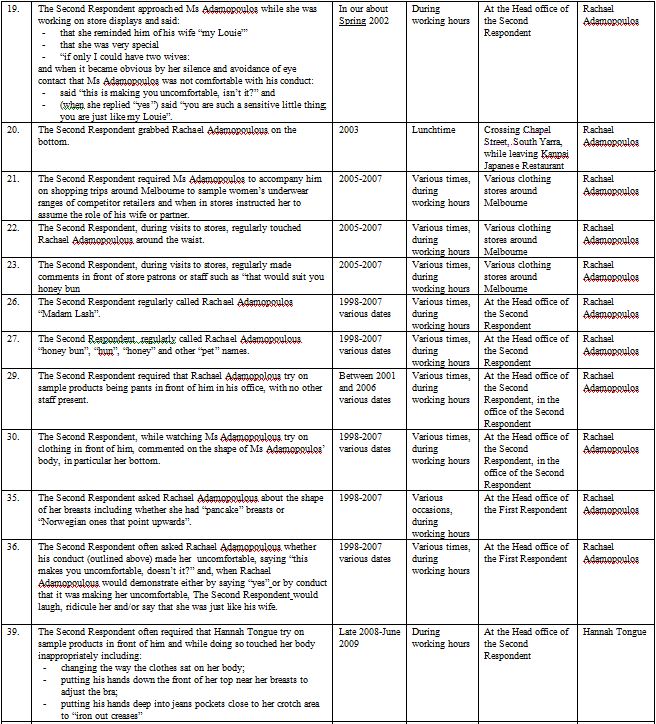

1. Items 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 26, 30 and 35 of the amended Notice to Adduce Tendency Evidence served by the applicant, in respect of the evidence of Ms Rachael Adamopoulos, are admissible under s 97 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

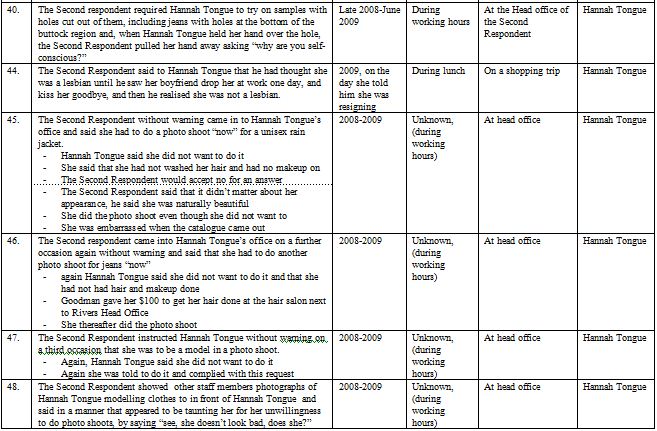

2. Item 39 of the amended Notice to Adduce Tendency Evidence served by the applicant, in respect of the evidence of Ms Hannah Tongue, is admissible under s 97 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | VID 61 of 2011 |

BETWEEN: | SALLYANNE ROBINSON Applicant

|

AND: | PHILIP HARRY GOODMAN First Respondent RIVERS (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD Second Respondent

|

JUDGE: | MORTIMER J |

DATE: | 2 SEPTEMBER 2013 |

PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTERLOCUTORY JUDGMENT ON TENDENCY EVIDENCE

1 The applicant has applied to adduce tendency evidence from two witnesses in this proceeding. By order of Gray J, the trial is being conducted by adducing viva voce evidence from all witnesses, on the basis of outlines of evidence filed in respect of each witness.

2 The first witness from whom it is sought to adduce tendency evidence is Rachael Adamopoulos. Ms Adamopoulos is an applicant in her own proceeding in this Court and has brought a claim against the first and second respondents alleging sexual harassment contrary to the provisions of the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth). That matter has not yet been listed for trial. In this proceeding, a detailed outline of evidence has been filed on behalf of Ms Adamopoulos. That outline states that Ms Adamopoulos was an employee of the second respondent between 1992 and 2007. The outline contains statements about conduct of Mr Goodman (the first respondent) towards Ms Adamopoulos, and comments made by him to Ms Adamopoulos and others, between approximately 1999 and October 2007.

3 The second witness from whom it is sought to adduce tendency evidence is Ms Hannah Tongue. An outline of evidence has been provided on behalf of Ms Tongue. That outline indicates Ms Tongue was an employee of the second respondent from late 2008 to June 2009, for a period of approximately eight months. The outline contains statements about the conduct of Mr Goodman towards Ms Tongue, and statements he is alleged to have made to her and to others, during her employment.

4 The applicant gave notice of her intention to adduce this evidence by an amended Notice filed after the matter was discussed at a directions hearing before me on 9 August 2013. It is this Notice on which the applicant seeks to have the evidence adduced.

5 I have decided that some of the evidence sought to be adduced is relevant, and admissible under s 97. I do not propose to exclude that evidence under s 135. Most of the evidence is however neither relevant nor admissible under s 97. My reasons for those conclusions are as follows.

APPLICABLE PRINCIPLES

6 Before reaching s 97 itself, ss 55 and 56 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) must be considered. The evidence sought to be adduced from Ms Tongue and Ms Adamopoulos must meet the test of relevance. That is, their evidence must affect the probability of the existence, or non-existence, of a fact in issue. Relevant evidence is admissible unless another provision of the Evidence Act excludes it, or confers a discretion on the Court to do so.

7 Section 97 of the Evidence Act is a contingent exclusionary rule. It excludes the tendency evidence unless the preconditions set out in subss (a) and (b) are met. There was a change in the language of s 97 in 2008, by the Evidence Amendment Act 2008 (Cth). The changes are discussed by Reeves J in Richards v Macquarie Bank Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 1403 at [30]–[31]. His Honour did not consider that the change in language changed the substantive law. After the amendment, it is certainly clear that the onus is on the moving party to persuade the Court the evidence will have significant probative value: see Astram Financial Services Pty Ltd v Bank of Queensland Ltd [2010] FCA 1010 at [235]–[239]. As Mr Borenstein SC submitted in argument for the respondents, it is possible to see the changes as having had a more substantive effect than that. That is not a matter I need decide. It is enough to say that the applicant must persuade me that the evidence is relevant, and meets the criteria in s 97 so as to avoid the exclusion contained in it.

8 Finally, the respondents have relied on the general exclusionary power in s 135 of the Evidence Act. Even if the evidence is relevant, and admissible under s 97, the respondents submit I should exercise my discretion in s 135 to exclude it because the probative value of the evidence is outweighed by the danger the evidence might be unfairly prejudicial to the respondents, or result in an undue waste of time. I consider those submissions in more detail below.

9 There was some debate before me about whether I should look more closely at the authorities in a criminal trial, or in civil proceedings. The applicant submitted that, although this is a civil proceeding, it is most similar to the circumstances in which tendency has been sought to be adduced in prosecutions for sexual offences. Mr Borenstein submitted that was not the correct approach and that this case, as a civil proceeding, should be approached as just that, so that the authorities in this Court, principally from the trade practices area, are most relevant.

10 In my opinion, considering whether to follow one particular line of authority or another is a distraction. This case is obviously a civil proceeding: for that reason, additional rules about tendency evidence such as s 101 of the Evidence Act do not apply. However, it is also about allegations of conduct of a sexual nature and it is a case which to a great extent turns on an allegation by the alleged victim and a denial by the alleged perpetrator. In its subject matter it has some similarity with sexual offences trials and that may mean that some of the analysis in the criminal cases is of assistance. Although I accept the principles developed in this Court in the trade practices area are of central importance, the fact all of those cases deal in the end with the making of representations means the approach taken may not be entirely comparable. In any event, applications of this kind turn very much on considerations particular to the proceeding in issue. Authorities on s 97 from both the criminal and civil jurisdictions are of assistance.

11 In Jacara Pty Ltd v Perpetual Trustees WA Ltd (2000) 106 FCR 51, Sackville J described at [61] and [62] the kind of evidence to which the limited exception in s 97(b) is directed:

61 The critical question in a case in which the tendency rule stated in s 97(1) is said to apply to evidence of conduct is whether the evidence is relevant to a fact in issue because it shows that a person has or had a tendency to act in a particular way. To adopt the language of Cowen and Carter, the question is whether the evidence of conduct is relevant to a fact in issue via propensity: insofar as the evidence establishes the propensity of the relevant person to act in a particular way, is it a link in the process of proving that the person did in fact behave in the particular way on the occasion in question?

62 This approach is consistent with the manner in which the Commission used the term “propensity” in its reports on Evidence. It defined the word this way (Interim Report, Vol 1, par 785):

Propensity. This word is defined by the Concise Oxford Dictionary to mean “inclination or tendency”. It seems that this is the way it is used in the law, a tendency to act, think or feel in a particular way. Usually the propensity will be evidenced by specific conduct, leading (like character) to the inference that the person will behave in conformity with that propensity.

12 Putting to one side the question of reasonable notice (which is not in dispute in this application), there are two steps in the application of s 97. First, the Court must be satisfied that the evidence sought to be adduced is within the scope of the provisions. This, in turn, requires the Court to identify: first, the facts in issue in this proceeding in terms of Mr Goodman’s conduct and statements; second, the precise evidence sought to be adduced under s 97; and, third, whether it can be said that evidence is capable of proving a tendency in Mr Goodman to behave in the way alleged, or to say the things alleged.

13 The second step is consideration of whether the Court thinks the evidence has “significant probative value”. Only if the Court forms this opinion of the particular evidence may it be admitted.

14 In determining the second step, the Court must assess as a matter of logic and experience the impact the tendency evidence is capable of having on the existence or non existence of the facts in issue about Mr Goodman’s conduct and statements: (see DSJ v Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) (2012) 215 A Crim R 349; [2012] NSWCCA 9 at [7]–[10]). The term “probative value” is defined in the Dictionary to the Evidence Act as “the extent to which the evidence could rationally affect the assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue”.

15 In determining “the extent” to which the evidence can affect the assessment of which the Dictionary definition speaks, the Court can consider the cogency of the evidence, the strength of the inference or inferences that can be drawn from the evidence as to the tendency of a person to act, speak or think in a particular way, and the extent to which the tendency evidence increases the likelihood that a fact in issue did or did not occur: Jacara 106 FCR 51 at [76]. A number of factors have been identified as indicators of the strength of inferences which could be drawn from proposed tendency evidence. They are collected in Odgers S, Uniform Evidence Law (10th ed, Thomson Reuters, 2012) pp 460–461 and deal with matters such as the numbers of occasions of conduct relied upon, time gaps between them, specificity of the tendency evidence, and the degree of similarity of the conduct and circumstances in which it occurred.

16 Many of these factors may contribute to a conclusion that the evidence bears a “striking similarity” to the evidence to be given in the instant case, or has “unusual features” like the evidence in the instant case. Those descriptions are still applied, including in civil proceedings, although they are derived from the approach in criminal cases as set out in Hoch v The Queen (1988) 165 CLR 292: see Richards [2012] FCA 1403 at [41]; Twynam Pastoral Co Pty Ltd v AWB (Australia) Ltd [2008] FCA 1922 at [36] per Jagot J.

17 However, as Sackville J cautioned in Jacara, it is important not to replace the statutory language in s 97 with common law descriptions of the correct approach. It is not necessary that the evidence sought to be adduced bears “striking similarity” to the conduct alleged, nor that it have “unusual features”: see Jacara 106 FCR 51 at [82]; see also FB v The Queen [2011] NSWCCA 217 at [27].

18 Rather, the applicant must establish that the evidence possesses a degree of relevance to the events alleged, such that it could be said that it was “important or of consequence”: see FB v The Queen [2011] NSWCCA 217 at [25]. Another expression of this can be found in the judgment of Lehane J in Zaknic Pty Ltd v Svelte Corporation Pty Ltd (1995) 61 FCR 171 at 175–176, where the extent to which the evidence must be capable of affecting the probability of a fact in issue was described as “to a significant extent; [that is], more is required than mere statutory relevance”. However, the standard is no higher than that.

19 In the end, these are but factors which, in combination, are capable of increasing or decreasing the probative value of evidence. Rather than relying on them as a checklist, a Court should reflect on how, in combination, they affect the probative value of the evidence sought to be adduced, as those terms are defined in the Evidence Act, and in the circumstances of the particular proceeding.

THE FACTS IN ISSUE

20 As Mr Borenstein submitted, close attention to the facts in issue in the proceeding is needed to undertake this exercise. The ultimate fact in issue is, relevant to the tendency argument, whether Mr Goodman engaged in sexual harassment of Ms Robinson contrary to the provisions of the SDA. To pick up the language of s 28A of the SDA and take the “fact in issue” to the next and more specific level, the facts in issue are whether Mr Goodman made unwelcome sexual advances to Ms Robinson, or engaged in other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature in relation to Ms Robinson in circumstances in which a reasonable person, having regard to all the circumstances, would have anticipated the possibility that Ms Robinson would be offended, humiliated or intimidated. As in a criminal trial where the elements of each offence will be facts in issue, in civil proceedings dealing with statutory causes of action, so each of the elements of the relevant statutory definition will be facts in issue. Here, relevantly, that is the definition in s 28A.

21 Sitting at a level below the facts in issue (in the sense of elements of an offence or of a statutory definition) are many issues about facts relevant to the ultimate one: see Smith v The Queen (2001) 206 CLR 650 at [7].

22 Mr Borenstein was correct to submit that, in a case conducted by pleadings, if a fact in issue or a fact relevant to a fact in issue is asserted and admitted by the opposing party, there is no dispute as to the existence of that fact. He submitted that meant the fact was no longer “in issue”. If that were so, his argument continued, tendency evidence was not admissible in respect of that fact. I note that the logical extension of this argument is that, by reason of the provisions of s 55 of the Evidence Act, the evidence may not be admissible at all.

23 In some cases, and depending on the quality and specificity of the pleadings, that may be so. But the proposition has no application to the pleadings in the current case, nor to the cause of action of sexual harassment alleged in them. That is because the “elements” of sexual harassment in s 28A involve composite phrases. For example, the key fact in issue in respect of which the tendency evidence is to be admitted is whether Mr Goodman “engaged in conduct of a sexual nature” or made “sexual advances”. The aspect of “unwelcome” is to be determined only in respect of Ms Robinson, and the “reasonable person” aspect of the definition was not said to be engaged in the question of the admission of the tendency evidence.

24 It is true that various allegations are pleaded as constituting the conduct of a sexual nature, or the sexual advances. It is true, as Mr Borenstein pointed out, that they might well have been better pleaded as material facts rather than as particulars. But it does not follow, in my opinion, that simply because one allegation, or a part of one allegation, is admitted, a fact is no longer in issue for the purposes of admissibility questions. It may be that a fact relevant to a fact in issue is not disputed. But that is a different matter. On the question of admissibility, evidence affecting the probability of whether Mr Goodman engaged in conduct of a sexual nature towards Ms Robinson will be admissible, nonetheless because Mr Goodman admits to some conduct but says it is not of a sexual nature. The statutory phrase is a composite one and is itself an element of the definition and therefore a fact in issue. To determine whether the evidence establishes conduct of a sexual nature involves a question of characterisation, which is neither answered nor avoided by an admission that particular words were uttered or a particular event occurred.

25 A further consideration is that Ms Gladman, in her submissions on behalf of the applicant, made it clear that the applicant’s case included a submission that Mr Goodman’s course of conduct towards Ms Robinson, as particularised, was cumulatively “conduct of a sexual nature” for the purposes of the definition in s 28A. It is difficult to see this allegation clearly made in the pleadings. I have not had the opportunity to revisit Senior Counsel’s opening to see if it was expressly raised then. However, at [11] of the outline of submissions filed on behalf of the applicant in advance of trial, there is a submission that Mr Goodman’s actions “were part of an overall pattern of sexual behaviour, which colours any individual allegation that, when viewed on its own, may not seem sexual in nature”. Authority for that proposition is said to be the case of Shiels v James [2000] FMCA 2 at [72]. The passage referred to in Shiels may provide modest support for the proposition. In my opinion, greater support may simply be found in the language of s 28A itself. There is nothing to suggest, by the use of the word “conduct”, that the statute intends to limit the meaning of that word to a single incident. In context, and to advance the purposes of the Act, it is capable of extending to a course of conduct. This is also supported by the fact that other aspects of the definition in s 28A are in the plural (eg “sexual advances”). I am satisfied that the submission at [11] of the outline of submissions makes tolerably clear that, viewed cumulatively and as a whole, and in context, Mr Goodman’s conduct is alleged to be of a sexual nature even if, when broken up and viewed separately, a different impression might initially be formed. That is an approach to s 28A which I am prepared at the moment to accept is at least open to the applicant, whether or not it is ultimately made out.

26 I have spent some time on this issue because in my opinion it is a part of the applicant’s case which needs to be borne in mind in considering the tendency evidence, and when considering Mr Borenstein’s submission about some facts not being in issue.

THE EVIDENCE SOUGHT TO BE ADDUCED

27 The evidence sought to be adduced by the applicant narrowed as the argument developed, after having already been narrowed from the first Tendency Notice which was served on the respondents. That was a sensible course. Reasonable notice under s 97(a) was not disputed by the respondents.

28 The contents of the Tendency Notice relied on by the applicant (amended to reflect what was not pressed), service of which in accordance with s 97(1)(a) was not disputed by the respondents, is attached to these reasons for judgment.

29 The applicant submits this evidence establishes a tendency in Mr Goodman to engage in a “calculated pattern of sexual pressure and harassment”, or a modus operandi of treating some of his female employees. The applicant submits the pattern or modus operandi is demonstrated by:

• Touching female employees’ bodies without their consent.

• Calling female employees pet names or nicknames that were unwelcome, of a sexual nature and/or insulting.

• Making unwelcome statements about female employees’ sex lives, the sex lives of their partners or relatives, or his own sex life.

• Requiring some female employees to adopt the role of his wife or partner during sample shopping trips, including using such occasions to purportedly legitimise other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature including calling them names such as “hun”, “honey bun” and “honey” and touching, asking about or commenting on their bodies in a suggestive, sexual way.

• Requiring or requesting some female employees to try on or model clothing samples including but not limited to jeans, underwear and swimwear in front of him at the premises of the second respondent, at times or in locations when other staff were not present, despite their hesitation or objections.

• Requiring certain female employees to be present at and assist with photography shoots featuring naked models, where a reasonable person in all the circumstances would have anticipated the possibility that the employees would be offended, humiliated or intimidated.

• Discussing what Mr Goodman perceived to be particular sexual characteristics of races or classes of people to which the employees’ family members belonged, in order to comment inappropriately on them.

• Commenting on employees’ relationships with their partners or spouses including making unwelcome and/or insulting comments about their partners.

CONSIDERATION

30 So far as I am aware, this is the first case in which the Court has been asked to decide on the admission of contested tendency evidence in a proceeding dealing with allegations of sexual harassment. As I have stated above, in my opinion authorities from both this Court in the trade practice areas, and from the field of the criminal law, can assist in considering this application.

31 In the area of sexual offences, there is clear authority for the proposition that the details of the tendency evidence sought to be led may differ from the alleged facts in the proceeding, but if the overall circumstances are sufficiently similar, that may give the evidence enough importance to be characterised as having significant probative value: see R v Harker [2004] NSWCCA 427 at [55]. However these kinds of conclusions will be specific to the proceedings in issue and the nature of the tendency evidence. Nevertheless I have gained some assistance from the analysis in Harker. Especially where reliance is placed on a sequence of conduct, said to constitute a pattern and said to at least in the alternative gain its colour as conduct of a sexual nature by looking at the overall circumstances, it is important in making a determination under s 97 to look at the similarities in the overall circumstances, as well as the close detail of the evidence.

32 Here, those broader matters include: the status of Ms Adamopoulos and Ms Tongue as employees of Rivers, Mr Goodman’s position as their boss, the owner of the company and the person in control of the operations of the business, their female gender, their asserted attractiveness, and the occurrence of the same kind of events as those deposed to by Ms Robinson (eg buying trips, fit sessions, photo shoots).

33 I recognise that the approach taken by Reeves J in Richards was one which looked in great detail at each of the representations sought to be adduced. Richards was a trial where there were detailed witness statements, unlike the present proceeding. However, in a case such as the one with which his Honour was concerned, the precise nature of the representations is critical to the cause of action itself and contemporaneity of other representations may also be critical. It was, for example, a critical aspect of Jagot J’s admission of other representations pursuant to s 97 in Twynam. In Richards, the tendency evidence consisted of representations made by different financial advisers than the ones who advised the applicant. They had different content and were spread out over long time periods, which in those circumstances clearly reduced their probative value in proving the representations made to the applicant in the terms alleged.

34 In circumstances of allegations of conduct of a sexual nature, the evidence is more likely to be primarily that of the complainant and the respondent. That is the case here. Also here, where some of the conduct is admitted, it is the characterisation of it as sexual (and sexualised) which is in issue. I consider that, by hearing from other female employees about their experiences of similar alleged conduct by Mr Goodman, the probability that the conduct is correctly characterised as sexual may be affected. Indeed, in some respects that is precisely the kind of evidence the respondents are seeking to lead from Ms Mo and Ms Thompson, as I understand the position. Finally, the issue of a pattern of sexual conduct is raised by Ms Robinson in this proceeding, and that feature is not present in the trade practices cases.

35 In my opinion the following evidence is admissible pursuant to s 97. In respect of this evidence, I am satisfied it is of a kind which reveals a propensity in Mr Goodman to act in a particular way towards his female employees, and to say particular things. For the reasons I set out in relation to each Item, I am also satisfied the evidence has significant probative value.

36 Item [17]. This is evidence about the “Bonnie shoot”, which has already been the subject of the evidence in chief and cross-examination of Ms Robinson. A photograph from the shoot has been tendered by the respondents. One of the key incidents said to constitute conduct of a sexual nature is alleged to be a re-creation of the “Bonnie shoot”. Whether this incident, or the one at which Ms Robinson was present, had sexual connotations or overtones so that it could be said to be conduct of a sexual nature is a key issue before me. The nature of the ultimate photo is very similar. The conduct of the shoot also seems similar. Mr Goodman will, I understand, say such events are a regular feature of the way he prefers to produce his promotional shots. Ms Robinson has a very different view of them. I consider that hearing from Ms Adamopoulos about her participation in the “Bonnie shoot” is capable of affecting the probability of one of the accounts of one of Ms Robinson or Mr Goodman about the shoot where Ms Robinson was present being accurate.

37 Item [20]. This is a remarkably similar allegation of impermissible and inappropriate touching by Mr Goodman, as that made by Ms Robinson. It is a single event, as is the one alleged by Ms Robinson.

38 Items [21], [22] and [23]. This is also remarkably similar, but that is less notable because Mr Goodman admits to a husband/wife pretence when visiting competitors’ stores looking at samples. However, the fact in issue is whether this conduct was of a sexual nature. Ms Robinson’s case is that it was, because the pretence was carried further than it needed to be by Mr Goodman and because of what he said during this pretence, whether about how clothes looked on her or by calling her pet names. Ms Adamopoulos’ account of the details of how Mr Goodman behaved when he underwent the same pretence with her is capable of being important in determining how to characterise this conduct, in terms of whether it was of a sexual nature or not. The evidence about touching I consider capable of affecting the probability that Mr Goodman touched Ms Robinson in public on such occasions (including the bottom-grabbing allegation and the stroking of her face while trying on glasses).

39 Item [26] — the “Madam Lash” comment. Although the making of this is not disputed, it is an unusual name to use. Repetition of it with other female employees may be capable of suggesting a sexual connotation more than isolated use of it with one female employee.

40 Item [30]. The kind of statements made by Mr Goodman in these contexts, and what he conveyed by making them, is in issue in this proceeding. Mr Goodman seeks, as I understand it, to put a business characterisation on them, as relating to assessing the fit of the products. Ms Robinson in contrast emphasises the comments were about her body and not the product and, thus, were of a sexual nature. Ms Adamopoulos’ evidence goes over some time, but there is a clearly similar theme to that given by Ms Robinson. Since it is the characterisation of the conduct which matters, I consider the evidence of Ms Adamopoulos is capable of affecting — to a degree which meets the test of significant probative value — the probability of one characterisation or another.

41 I consider Item [35] is admissible. There are several aspects of Ms Robinson’s allegations which involve Mr Goodman commenting on her breasts. Once again, as I understand the way in which Ms Robinson’s cross-examination has proceeded, Mr Goodman will deny some of those comments, but will otherwise contend Ms Robinson initiated the conversation topic. Ms Robinson’s allegations include Mr Goodman talking about breast augmentation and then commenting about (and touching) Ms Robinson’s breasts, as well as comments to Ms Robinson about her breasts during a fit session. Ms Adamopoulos’ evidence is quite specific in its subject matter and the nature of the comments alleged to have been made. It is not specific as to times and dates but I find, in relation to this kind of evidence, that timing issue is less critical. They are unusual enough kinds of comments for Mr Goodman to be able to deal with by way of recollection.

42 Item [39] is admissible. It relates to allegations of the same kind of conduct by Mr Goodman as Ms Robinson alleges: namely, inappropriate and sexualised touching of female employee’s bodies during “fit” sessions. That different kinds of clothes may have been involved is not at all to the point. Once again, these allegations are unusual enough for Mr Goodman to be able to deal with by way of recollection.

43 The remaining evidence is inadmissible.

44 Item [6], although it relates to Ms Adamopoulos’ husband, is evidence about a comment about his hair. It relates to an event more than 10 years ago. It is not sufficiently similar to any of the facts pleaded as material to the facts in issue under s 28A. There is no possible sexual connotation. The same is true of Items [8], [9] and [14].

45 Item [10] is more similar to allegations made about Mr Goodman’s comments about Ms Robinson’s then boyfriend. However, the evidence ranges over more than 14 years and is unspecific.

46 Item [11] calls to mind Ms Robinson’s evidence about Mr Goodman’s comments to her about affairs and the English “upper class”. It might be said this evidence shows a tendency to talk about sexual conduct — that is, affairs, using the ethnicity of a female employee’s partner as the purported subject matter. However, again it ranges over 14 years and is still at such a level of generality that I do not find it important enough to affect the probability that Mr Goodman made comments to Ms Robinson about the English upper class and affairs they might have.

47 Item [15], although it seems to deal with discussion about sexual matters, is not sufficiently similar to any of the allegations made by Ms Robinson. There is no particular allegation about Mr Goodman speaking about his wife in the way Item [15] asserts. It also ranges over a long period of time. The same is true of Items [16] and [19].

48 Although Ms Robinson makes a similar allegation to Item [27], hers is centred on the use of these phrases while she and Mr Goodman are out on buying trips. Ms Adamopoulos’ evidence is about what occurred in the workplace. The context is too different, and the terms are far less unusual than the “Madam Lash” comment.

49 Item [29] is spread over a range of years, is far too general in nature and insufficiently related to facts relevant to facts in issue, let alone to any facts in issue themselves.

50 Item [36] is spread over the entirety of Ms Adamopoulos’ employment with Rivers. It is insufficiently probative of the issue whether Mr Goodman’s conduct was sexual in nature and is too general. It is also not sufficiently similar to any evidence given by Ms Robinson. The same is true of Item [40], especially given there is no remotely similar allegation by Ms Robinson.

51 I find Items [44], [45], [46], [47] and [48], in relation to proposed evidence from Ms Tongue, to be in the same category. It is insufficiently probative of the sexual nature of the conduct alleged against Mr Goodman in the present proceeding. The allegations are about different kinds of conduct altogether, and cannot contribute to the proof of any “pattern” as alleged in this proceeding.

52 I have considered whether any of the evidence I have decided is admissible under s 97 should be excluded under s 135. Mr Borenstein made two submissions on this aspect. First, the age of the evidence meant it would be unfairly prejudicial to Mr Goodman to admit it: it lacked any certainty, and it would be very difficult for him to remember events from such a long time ago. Second he submitted the taking of the evidence could result in an undue waste of time in the proceeding — not only because of the time taken to adduce and cross-examine on it, but because there may be other witnesses who would need to be called to respond.

53 Aside from Item 35, most of the evidence I have decided is admissible is from the latter parts of Ms Adamopoulos’ employment with Rivers. Indeed, most of it is some years after the “Bonnie shoot” (2001), which is a matter to be introduced into evidence by Mr Goodman. I have excluded the older and more general kind of evidence which the applicant sought to adduce from Ms Adamopoulos. Item 35 is a specific allegation and, because of its content, in my opinion it should stand out in the memory of both Ms Adamopoulos and Mr Goodman, one way or the other. In my opinion, Mr Goodman’s ability to recall the events on which Ms Adamopoulos and Ms Tongue will give evidence is a matter I can take into account in assessing the weight I will give to the women’s evidence, if it cannot be properly tested because Mr Goodman cannot give evidence and instructions about what they say. However, I doubt that will be the case. The evidence about the pretence of having female employees pose as his wife, his practices of using female employees as models for “fit” and photography sessions, how he behaved with those individuals during those sessions and whether he engaged in conduct such as grabbing the bottom of a female employee, are all matters which in my opinion one can reasonably expect a person in the position of Mr Goodman to be able to recollect and deal with in the evidence. I am confident he will be able to deal with the “Bonnie shoot” evidence because that has been the subject matter of cross-examination of Ms Robinson, on his instructions.

54 As to the second submission, this trial has been set down for three weeks. It seems to me the applicant’s evidence is likely to finish by the middle of the second week, at the latest. I consider within the allocated time there will be sufficient time for these two witnesses. Mr Borenstein did not elaborate on who the other witnesses might be and what they might say, nor how long their evidence might take. Without any such details, this aspect of the second submissions lacked persuasive force.

OTHER RELEVANT EVIDENCE?

55 Outside the evidence which is tendency evidence, it was submitted by counsel for the applicant that both Ms Tongue and Ms Adamopoulos could give other evidence which was relevant. However, when pressed, she did not identify any in the outlines of the two witnesses.

56 In respect of the tendency evidence I propose to admit, it may of course be necessary for each witness to give some contextual background to her evidence, including personal details, perhaps work experience, and the course of her employment at Rivers, at least in broad outline.

57 Beyond this, my present view is that nothing else in the proposed outline of evidence of each witness is admissible because there does not appear to be anything else in their evidence which is relevant. Should counsel for the applicant seek to put specific submissions about specific aspects of either witness’ evidence, I will hear those submissions. Unless and until that occurs and a ruling is made, each of Ms Tongue and Ms Adamopoulos will be permitted to give only the evidence referred to at [35] above, together with the necessary background evidence to which I have referred at [56].

I certify that the preceding fifty-seven (57) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Mortimer. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE A