FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

De Rose v State of South Australia [2013] FCA 687

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| First Applicant TJARUWA ANDERSON Second Applicant | |

AND: | First Respondent LYNDAVALE PTY LTD Second Respondent TIANDA RESOURCES (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD Third Respondent TIANDA URANIUM (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD Fourth Respondent TIEYON PASTORAL CO PTY LTD Fifth Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: | WARURA |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A The Applicant first filed Native Title Determination Application No. SAD 208 of 2010 with the Federal Court on 17 December 2010 in relation to lands and waters in northern South Australia.

B The Applicant, the State of South Australia and the other respondents have reached an agreement as to the terms of a determination of native title to be made in relation to the land and waters covered by the Application as described in Schedules 1 and 3. They have filed with this Court pursuant to section 87(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Native Title Act) an agreement in writing to seek the making of consent orders for a determination.

C The parties acknowledge that the effect of the making of the determination will be that the members of the native title claim group, in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by them, will be recognised as the native title holders for the Determination Area as defined by paragraph 3 of this Order.

D The parties have requested that the Court determine the proceedings without a trial.

Being satisfied that a determination in the terms sought by the parties would be within the power of the Court and it appearing to the Court appropriate to do so and by the consent of the parties:

THE COURT ORDERS, DECLARES AND DETERMINES BY CONSENT THAT:

Interpretation & Declaration

1. In this determination, including its schedules:

(a) unless the contrary intention appears, the words and expressions used have the same meaning as they are given in Part 15 of the Native Title Act;

(b) in the event of an inconsistency between a description of an area in a schedule and the depiction of that area on the map in Schedule 2, the written description shall prevail;

2. Native title exists in the areas described in Schedule 1 with the exception of those areas described in paragraphs 9, 11, 12 and 13 (the Determination Area).

Native Title Holders

3. Under the relevant traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert Bloc, the native title holders comprise those Aboriginal people who have a spiritual connection to the Tjayiwara Unmuru Determination Area and the Tjukurpa associated with it because:

(a) the Determination Area is his or her country of birth (which is also reckoned by the area where his or her mother lived and travelled during pregnancy); and/or

(b) he or she has had a long-term association with the Determination Area such that he or she has traditional geographical and religious knowledge of that country; and/or

(c) he or she has an affiliation with the Determination Area through a parent or grandparent with a connection to the Determination Area as specified in sub paragraphs (a) or (b) above; and

he or she is recognised under relevant Western Desert traditional laws and customs by other members of the native title holders as having rights and interests in the Determination Area;

Rights and Interests

4. Subject to paragraphs 5, 6 and 7, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the Determination Area are non-exclusive rights to use and enjoy in accordance with the native title holders’ traditional laws and customs the land and waters of the Determination Area, being:

(a) the right to access and move about the Determination Area;

(b) the right to hunt on the Determination Area;

(c) the right to gather and use the natural resources of the Determination Area such as food, medicinal plants, wild tobacco, timber, stone and resin;

(d) the right to use natural water resources of the Determination Area;

(e) the right to live, to camp and to erect shelters on the Determination Area;

(f) the right to cook on the Determination Area and to light fires for domestic purposes but not for the clearance of vegetation;

(g) the right to engage and participate in cultural activities on the Determination Area including those relating to births and deaths;

(h) the right to conduct ceremonies and to hold meetings on the Determination Area;

(i) the right to teach on the Determination Area the physical and spiritual attributes of locations and sites within the Determination Area;

(j) the right to maintain and protect sites and places of significance to members of the native title holders under their traditional laws and customs on the Determination Area;

(k) the right to be accompanied on the Determination Area by those people who, though not members of the native title holders, are:

(i) spouses of members of the native title holders; or

(ii) people required by traditional law and custom for the performance of ceremonies or cultural activities on the Determination Area; or

(iii) people who have rights in relation to the Determination Area according to the traditional laws and customs acknowledged by the native title holders; and

(l) the right to speak for country and make decisions about the use and enjoyment of the Determination Area by Aboriginal people who recognise themselves to be governed by the traditional laws and customs acknowledged by members of the native title holders.

General Limitations

5. The native title rights and interests are for personal, domestic and communal use but do not include commercial use of the Determination Area or the resources from it.

6. The native title rights and interests do not confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of those lands and waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of others.

7. Native title rights and interests are subject to and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the traditional laws and customs of the native title holders;

(b) the valid laws of the State and the Commonwealth, including the common law.

For the avoidance of doubt, the native title interest expressed in paragraph 4(d) (the right to use the natural water resources of the Determination Area) is subject to the Natural Resources Management Act 2004 (SA).

8. Native title does not exist in the areas and resources described in paragraphs 9, 11, 12 and 13 herein.

9. Native title rights and interests have been extinguished in respect of those parts of the Determination Area being any house, shed or other building or airstrip or any dam or other stock watering point constructed pursuant to the pastoral leases referred to in paragraph 15(a) below and constructed prior to the date of this determination. These areas include any adjacent land or waters the exclusive use of which is necessary for the enjoyment of the improvements referred to.

10. To be clear, paragraph 9 does not preclude the possibility of further extinguishment, according to law, of native title over other limited parts of the Determination Area by reason of the construction of new pastoral improvements of the kind referred to in paragraph 9 after the date of this determination.

11. Native title does not exist in those areas described in Schedule 3, as it has been extinguished.

12. Native title rights and interests do not exist in:

(a) minerals, as defined in s 6 of the Mining Act 1971 (SA); or

(b) petroleum, as defined in s 4 of the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000 (SA); or

(c) a naturally occurring underground accumulation of a regulated substance as defined in s 4 of the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000 (SA), below a depth of 100 metres from the surface of the earth; or

(d) a natural reservoir, as defined in section 4 of the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000 (SA), below a depth of 100 metres from the surface of the earth; or

(e) geothermal energy, as defined in section 4 of the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000 (SA) the source of which is below a depth of 100 metres from the surface of the earth.

For the purposes of this paragraph and the avoidance of doubt:

(i) a geological structure (in whole or in part) on or at the earth's surface or a natural cavity which can be accessed or entered by a person through a natural opening in the earth's surface, is not a natural reservoir;

(ii) thermal energy contained in a hot or natural spring is not geothermal energy as defined in section 4 of the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000 (SA);

(iii) the absence from this order of any reference to a natural reservoir or a naturally occurring accumulation of a regulated substance, as those terms are defined in s 4 of the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000 (SA), above a depth 100 metres below the surface of the earth or geothermal energy the source of which is above a depth of 100 metres below the surface of the earth is not, of itself, to be taken as an indication of the existence or otherwise of native title rights or interests in such natural reservoir, naturally occurring accumulation of a regulated substance or geothermal energy.

13. Native title rights do not exist in the areas covered by public works (including the land defined in s 251D of the Native Title Act) which were constructed, established or situated prior to 23 December 1996 or commenced to be constructed or established on or before that date.

14. Public works constructed, established or situated after 23 December 1996 have had such effect as has resulted from Part 2, Division 3, of the Native Title Act.

Other Interests & Relationship with Native Title

15. The nature and extent of other interests in the Determination Area are:

(a) the interests within the Determination Area created by the following pastoral leases:

Lease name | Pastoral Lease No | Crown Lease |

Portion of Tieyon | 2495 | CL 1628/19 |

Ayers Range South | 2491 | CL 1433/13 |

(b) the interests of the Crown in right of the State of South Australia;

(c) the interests of persons to whom valid or validated rights and interests have been granted or recognised by the Crown in right of the State of South Australia or by the Commonwealth of Australia pursuant to statute or otherwise in the exercise of executive power including, but not limited to, rights and interests granted or recognised pursuant to the Crown Land Management Act 2009 (SA), Crown Lands Act 1929 (SA), Mining Act 1971 (SA), Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000 (SA) and Opal Mining Act 1995 (SA), all as amended from time to time;

(d) rights or interests held by reason of the force and operation of the laws of the State or of the Commonwealth;

(e) the rights to access land by an employee or agent or instrumentality of the State, Commonwealth or other statutory authority as required in the performance of his or her statutory or common law duties where such access would be permitted to private land;

(f) the rights and interests of all parties to the following Pastoral ILUAs:

(i) Tieyon Station Pastoral ILUA; and

(ii) Ayers Range South Pastoral ILUA.

16. Subject to paragraph 5, the relationship between the native title rights and interests in the Determination Area that are described in paragraph 4 and the other rights and interests described in paragraph 15 (the Other Interests) is that:

(a) to the extent that any of the Other Interests are inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of the native title rights and interests, the native title rights and interests continue to exist in their entirety, but the native title rights and interests have no effect in relation to the Other Interests to the extent of the inconsistency during the currency of the Other Interests; and otherwise,

(b) the existence and exercise of the native title rights and interests do not prevent the doing of any activity required or permitted to be done by or under the Other Interests, and the Other Interests, and the doing of any activity required or permitted to be done by or under the Other Interests, prevail over the native title rights and interests and any exercise of the native title rights and interests, but, subject to any application of ss 24JA or 24IB of the Native Title Act, do not extinguish them;

(c) the native title is subject to extinguishment by:

(i) the lawful powers of the Commonwealth and of the State of South Australia; and/or

(ii) the lawful grant or creation of interests pursuant to the laws of the Commonwealth and the State of South Australia.

AND THE COURT MAKES THE FOLLOWING FURTHER ORDERS:

17. On this determination coming into effect, the native title is not to be held in trust.

18. Tjayiwara Unmuru Aboriginal Corporation ICN 7854 is to:

(a) be the prescribed body corporate for the purposes of s 57(2) of the Native Title Act; and

(b) perform the functions mentioned in s 57(3) of the Native Title Act after becoming a registered native title body corporate.

19. The parties have liberty to apply on 14 days notice to a single judge of the Court for the following purposes:

(a) to establish the precise location and boundaries of any public works and adjacent land and waters referred to in paragraphs 13 and 14 of this Order;

(b) to determine the effect on native title rights and interests of any public works as referred to in paragraph 14 of this Order; or

(c) to determine whether a particular area is included in the description in paragraph 99 of this Order.

Schedules

SCHEDULE 1 – Description of the external boundary of the Determination Area

Commencing at the north-western corner of Piece 3000 in Deposited Plan 35731, Out of Hundreds (Alberga), Pastoral Lease 2491 (Ayers Range South), being a point on the State Border between the State of South Australia and the Northern Territory of Australia; thence easterly to the north-eastern corner of the said Piece 3000; easterly to the north-western corner of Piece 3001 in Deposited Plan 35731, Out of Hundreds (Alberga), Pastoral Lease 2491 (Ayers Range South); easterly to the north-eastern corner of the said Piece 3001; easterly along the northern boundary of Section 1319, Out of Hundreds (Alberga) to the north-western corner of Piece 3002 in Deposited Plan 35731, Out of Hundreds (Alberga), Pastoral Lease 2491 (Ayers Range South); easterly to the north-eastern corner of the said Piece 3002; easterly to Longitude 133.900000° east, being a point on the northern boundary of Block 1227, Out of Hundreds (Abminga), Pastoral Lease 2495 (Tieyon); generally southerly to Longitude 133.850000° east, being a point on the southern boundary of the said Block 1227; westerly to the south-eastern corner of Block 1213, Out of Hundreds (Abminga); northerly to the north-eastern corner of Block 1212, Out of Hundreds (Abminga); westerly to the north-western corner of the said Block 1212; northerly to the south-eastern corner of the aforementioned Piece 3002; generally westerly to the south-western corner of the said Piece 3002; generally westerly to the south-eastern corner of the aforementioned Piece 3001; generally westerly to the south-western corner of the said Piece 3001; generally westerly to the south-eastern corner of the aforementioned Piece 3000; generally westerly to the south-western corner of the said Piece 3000; thence northerly along the western boundary of the said Piece 3000 to the point of commencement.

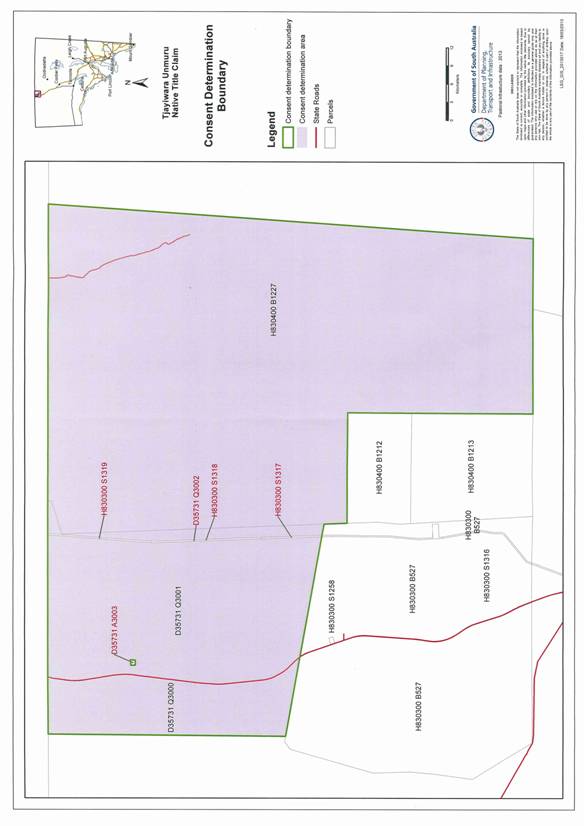

SCHEDULE 2 - Map of the Determination Area

SCHEDULE 3 – Areas within the external boundaries of the Determination Area where native title has been extinguished

The following areas within the external boundaries of the claim area are agreed to have been excluded from the Determination Area by reason of the fact that native title has been extinguished in those areas:

1. All roads including the corridor of the Stuart Highway which have been delineated in a public map pursuant to s 5(d)(ii) of the Crown Lands Act 1929 (SA) or s 70(3) or (4) of the Crown Land Management Act 2009 (SA) or which have otherwise been validly established pursuant to South Australian statute or common law as shown in red on the map at Schedule 2;

2. The land parcels comprising that portion of the Central Australian Railway excised from the native title claim area, namely, portion of section 1317 and sections 1318 and 1319 in OH (Alberga);

3. Allotment 3003 in Deposited Plan 35731.

The parties accept that in those areas, the native title holders would have had the native title rights and interests as recognised in Paragraph 4 of this Order but for the acts that extinguished native title.

SCHEDULE 4

No. 208 of 2010

Federal Court of Australia

District Registry: South Australia

Division: General

Applicants

Second Applicant: Tjaruwa Anderson

Respondents

Second Respondent: Lyndavale Pty Ltd

Third Respondent Tianda Resources (Australia) Pty Ltd

Fourth Respondent Tianda Uranuim (Australia) Pty Ltd

Fifth Respondent Tieyon Pastoral Co Pty Ltd

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SOUTH AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | SAD 208 of 2010 |

BETWEEN: | PETER DE ROSE First Applicant TJARUWA ANDERSON Second Applicant

|

AND: | STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA First Respondent LYNDAVALE PTY LTD Second Respondent TIANDA RESOURCES (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD Third Respondent TIANDA URANIUM (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD Fourth Respondent TIEYON PASTORAL CO PTY LTD Fifth Respondent

|

JUDGE: | MANSFIELD J |

DATE: | 16 JULY 2013 |

PLACE: | WARURA |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 This application for the determination of native title rights and interests under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Native Title Act) has proceeded much more quickly than past experience would have dictated. The application was made on 17 December 2010, so it is almost to the day two and a half years to its finalisation by the consent orders which are made with this judgment. That is a matter of great credit to the Tjayiwara Unmuru People, to Mr De Rose and Ms Anderson who bore the responsibility of progressing the claim on their behalf as their authorised representatives, to the State of South Australia, and to the pastoral lessees who have leases over part of the claim area, Lyndavale Pty Ltd and Tieyon Pastoral Co Pty Ltd and the two miners who have exploration licences over part of the claim area, Tianda Resources (Australia) Pty Ltd and Tianda Uranium (Australia) Pty Ltd.

2 The area to be the subject of recognition of native title is a significant area in the central northern part of South Australia, part of the much larger Western Desert region of Australia over which the Tjayiwara Unmuru People share traditional laws and customs with other Western Desert groups. It adjoins the area of the earlier De Rose Hill native title claim (SAD 253 of 2002).

3 The determination area is described in detail in Schedule 1 to the Orders and depicted in the map in Schedule 2 (the Determination Area). It is important to stress some important more general matters.

4 The first is that, by the determination of native title rights and interests over the Determination Area, the Tjayiwara Unmuru People are being recognised on behalf of all the people of Australia as the Aboriginal peoples who inhabited this country prior to European settlement. The preamble to the Native Title Act recognised, on behalf of all the people of Australia, that the Aboriginal peoples of Australia variously inhabited this country for many years prior to European settlement, and that they were progressively dispossessed of their lands. It recorded that by the overwhelming vote of the people of Australia, the Constitution was amended to enable laws such as the Native Title Act to be passed to facilitate recognition of the native title rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples in their land. The determination that the Tjayiwara Unmuru People were and are the traditional owners of the land we are on is a recognition of that status. It is important to emphasise that the Court does not grant that status. It declares that it exists, and has always existed at least since European settlement. The determination is made recognising the existence of native title rights and interests with the consent of the State of South Australia, and all the respondents whose interests might be affected by the orders made today. It is therefore a community recognition of that status.

5 It is also important to note that the Native Title Act by its Preamble recognises that European settlement did progressively dispossess Aboriginal peoples in whole or in part of their lands, largely without compensation, and in significant respects at least to date without reaching a lasting and equitable agreement with Aboriginal peoples concerning the use of their lands. The parties to this application have, following their negotiations, recognised that primary status of the Tjayiwara Unmuru People over this land and the significance of certain acts made before the 1993 Native Title Act which affected that status. All the parties present have obviously approached the negotiations in good faith to agree upon the Orders made today. Such a task was no doubt a challenging one. The Court encourages resolution of claims such as the present claim by giving effect to the agreement of the parties where it is appropriate to do so.

6 However, the Court must be satisfied in terms of s 87 of the Native Title Act, that it should make the determination of native title by consent as proposed. The Tjayiwara Unmuru People and the State have together filed the following documents:

1. Minute of proposed orders and determination of native title by consent;

2. Submissions of the Tjayiwara Unmuru People and of the State;

7 Section 87 enables the Court to make such a determination without a hearing under certain conditions. They are:

(a) the period specified in the notice given under s 66 of the Native Title Act has ended and there is an agreement between all the parties on the terms of a proposed order of the Court in relation to the proceedings (s 87(1)(a));

(b) the terms of the proposed determination agreement are in writing and are signed by or on behalf of the parties and filed with the Court (s 87(1)(b));

(c) the Court is satisfied that an order in, or consistent with, those terms would be within its power (s 87(1)(c)); and

(d) the Court considers that it would be appropriate to make the order sought (ss 87(1A) and (3)).

8 In addition, the Court should have regard to the following before making determinations of native title by consent orders:

(a) whether all parties likely to be affected by an order have had independent and competent legal representation;

(b) whether the rights and interests that are to be declared in the determination are recognisable by the law of Australia or the State in which the land is situated;

(c) whether all of the requirements of the Native Title Act have been complied with.

See generally Munn for and on behalf of the Gunggari People v Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109 at [29] and [31]-[32] per Emmett J.

9 The focus of the Court in considering whether the orders sought are appropriate under s 87 is on the making of the agreement by the parties. That is because the Native Title Act is designed to encourage parties to take responsibility for resolving proceedings without the need for litigation. That is why, when the Court is examining the appropriateness of an agreement, it is not required to examine whether the agreement is grounded on a factual basis which would satisfy the Court at a hearing of the application. The primary consideration of the Court is to determine whether there is an agreement and whether it was freely entered into on an informed basis. It will be influenced by whether the State party has taken steps to satisfy itself that there is a credible basis for an application.

10 Therefore, the Court does not need to embark on its own full inquiry of the merits of the claim made in the application to be satisfied that the orders sought are supportable and in accordance with the law: Cox on behalf of the Yungngora People v State of Western Australia [2007] FCA 588 at [3] per French J. However, it might consider that evidence for the limited purpose of being satisfied that the State is acting in good faith and rationally: Munn for and on behalf of the Gunggari People v Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109 at [29]-[30] per Emmett J.

11 State governments are necessarily obliged to subject claims for native title over lands and waters owned and occupied by the State and State agencies, to scrutiny just as carefully as the community would expect in relation to claims by non-Aborigines to significant rights over such land: Smith v Western Australia (2000) 104 FCR 494 at [38] per Madgwick J.

12 Reeves J in Nelson v Northern Territory (2010) 190 FCR 344; [2010] FCA 1343 at [12]-[13] said:

It is appropriate to make some comments about the difficult balance a State party needs to strike between its role in protecting the community’s interests, including the stringency of the process it follows in assessing the underlying evidence going to the existence of native title, and its role in the native title system as a whole, to ensure that it, like the Court and all other parties, takes a flexible approach that is aimed at facilitating negotiation and achieving agreement. In Lovett North J commented:

…

The power conferred by the Act on the Court to approve agreements is given in order to avoid lengthy hearings before the Court. The Act does not intend to substitute a trial, in effect, conducted by State parties for a trial before the Court. Thus, something significantly less than the material necessary to justify a judicial determination is sufficient to satisfy a State party of a credible basis for an application. The Act contemplates a more flexible process than is often undertaken in some cases.

See Lander v State of South Australia [2012] FCA 427 and the cases cited therein.

13 The State has developed a process for assessing the evidence in native title claims against the requirements of the Native Title Act. This process is outlined in the State’s policy document Consent Determinations in South Australia: A Guide to Preparing Native Title Reports (the State’s CD Policy).

14 Having assessed the evidence presented by the applicants (the Evidence) in accordance with the State’s CD Policy, the State is satisfied that a consent determination is appropriate for the Determination Area as set out in the consent determination. That material is available as required.

15 As noted, this claim is over an area that adjoins the determined De Rose Hill native title claim. It involves many of the same persons who have been determined to be native title holders in that area. It is sensible that both the applicants and the State have, therefore, relied on the extensive evidence given in the course of that matter. However, as the claim area is different and the composition of the claim group includes some other persons, it was nevertheless appropriate to procure and consider further evidence to validate the inclusion of the new claimants in the claim group and to substantiate the contemporary traditional activities and connection to the particular claim area.

16 The further evidence consisted of:

(a) the native title application Form 1, and in particular Attachment G with affidavits from Whiskey Tjukanku, George Kenmore, Peter De Rose, Lucy Waniwa Lester and Leroy Lester;

(b) a document entitled Draft Statement of Facts - Contemporary Connection (which asserts that the substantial evidentiary material provided during the De Rose claim establishes the claimants’ contemporary connection to the claim area),

(c) a Report on the Tjayiwara Unmuru Native Title Determination Application prepared by Susan Woenne-Green and additional statements from Peter De Rose, David Frank, Martin Thompson, Tjaruwa Anderson, Hughie Cullinan, Julie Anderson, Angkuna Baker, Christine De Rose, Jeannie Minungka and Tillie Yaltjangki.

Ms Woenne-Green is an anthropologist with extensive experience in the Western Desert Bloc and did much of the preparatory anthropological work for the De Rose claim. She has also had considerable professional experience with the De Rose Hill native title holders, conducting extensive fieldwork in the De Rose and Tjayiwara Unmuru claim areas and neighbouring Yankunytjatjara and Eringa areas.

(d) The assessment of the material by a consultant anthropologist, Mr Kim McCaul, engaged by the State. Mr McCaul was also closely involved in the earlier De Rose claim.

17 All of the evidence submitted by the applicants, as well as Mr McCaul’s assessment, was reviewed by independent counsel experienced in the requirements under the Native Title Act. His opinion is that a decision by the State to consent to Orders recognising native title in favour of the claim group over the claim area would be justifiable on the basis of the material before him.

18 A position paper explaining the basis for the State’s view was distributed to all other respondent parties in December 2012.

19 Section 223 of the Native Title Act defines native title as:

(1) ... the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples … in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples …; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples …, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

20 Section 223(1) of the Native Title Act has been considered extensively by the High Court, most notably in Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 (Yorta Yorta). Subsequently, several Federal Court judges have summarised the relevant principles, including in Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404 at [44]-[58] and Summary [8] (Risk).

21 A threshold requirement is that the evidence shows that there is a recognisable group or society that presently recognises and observes traditional laws and customs in the Determination Area. In defining that group or society, the following must also be addressed:

(a) That they are a society united in and by their acknowledgement and observance of a body of accepted laws and customs;

(b) That the present day body of accepted laws and customs of the society in essence is the same body of laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the ancestors or members of the society adapted to modern circumstances; and

(c) That the acknowledgement and observance of those laws and customs has continued substantially uninterrupted by each generation since sovereignty, and that the society has continued to exist throughout that period as a body united in and by its acknowledgment and observance of those laws and customs.

22 The claim group must show that they still possess rights and interests under the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by them, and that those laws and customs give them a connection to the land: Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 at [64]; Yorta Yorta at [84]-[86].

23 The native title claim group identifies themselves as Yankunytjatjara people with some Pitjantjatjara ancestry. The claim group membership substantially mirrors that found to hold native title in the De Rose determination. The congruence might be expected given the relatively small size of this claim and its shared border with the determined De Rose claim. The evidence suggests that the Yankunytjatjara people have always moved freely between the pastoral stations that make up the De Rose and Tjayiwara Unmuru areas.

24 The Yankunytjatjara are recognised as part of the Western Desert Bloc (WDB) society. This bloc consists of a number of groups of people who speak variants of a single language that are mutually intelligible (at least in the case of adjacent groups) and have similar culture. Their country includes vast areas of Australia’s interior from Western Australia, into the north-west of South Australia and the south-west of the Northern Territory.

25 The definition of the WDB society, as accepted by the Federal Court in De Rose v South Australia (No 2) (2005) 145 FCR 290 (De Rose (No 2)), recognises that persons are Nguraritja (traditional owners) by virtue of a number of principles, specifically:

(a) he or she was born on the claim area, or;

(b) he or she has a long-term physical association with the claim area, or;

(c) he or she possesses an ancestral connection to the claim area, or;

(d) he or she possesses geographical and religious knowledge of the claim area

and he or she is recognised as Nguraritja by the other Nguraritja.

26 The native title claim group in the Tjayiwara Unmuru claim differs slightly from the claim group in De Rose, and relates to land that was previously the subject of the Eringa native title claim. As Peter De Rose stated:

Tjayiwara Unmuru is Yankunytjatjara country. There is tjukurpa that marks our country, and there is tjukurpa east of Tieyon that is not our country. For example, there is a tjukurpa site east of Mount Irwin that is not in our claim. That is not Yankunytjatjara. That is not my ngura [country] over there.

Another example is Mungapiti. That is Yankunytjatjara tjukurpa and that is why it is in the Tjayiwara Unmuru claim, not the Eringa claim. That is why their country stops at Tjayiwara. It is the same tjukurpa, but their tjukurpa stops at Mungapiti. Yankunytjatjara takes over that tjukurpa from Mungapiti. They won’t know the ngintaka tjukurpa from Mungapiti.

27 Similarly, Martin Thompson stated:

Mungapiti is next to Tieyon. It is Ngintaka tjukurpa. There is a handover of who can speak for that country. That is called mayunganyi. Old people sing the songs, they come to a certain point, and then another person takes over and he has to start singing. That is called kanyinma, meaning someone else holding that law.

Mungapiti is also a common area though. Mungapiti is Yankunytjatjara Country and it belongs to the Tjayiwara mob. The Traditional Owners can go there.

There is Katukatu, or an overlap, because there is lots of tucker and water there. So it is a common area.

28 On specific inclusions in the Tjayiwara Unmuru claim, Martin Thompson continues:

Howard Doolan is from Tieyon, he was born in Tieyon, that dog place. That is why Howard is on the Tjayiwara Claim. He is Papa tjukurpa. Lucy Lester was also born there, she is also Papa tjukurpa. So, through them being born there, and through the tjukurpa, they are connected to Tieyon. Mt Cavenagh, Tieyon, is all ngura kutja, all one country.

29 Although that material might support the limitation of the claim group as expressed in the proposed determination by a further element of biological descent from named apical ancestors, other WDB determinations are in accord with the proposed description of the claim group and the Court is satisfied in the circumstances that it is both appropriate on fact and to properly identify a claim group capable of recognition by the State as part of the WDB society, and to satisfy the requirements of the Native Title Act.

30 Further negotiation with the claimants on the claim group description resulted in the amendment of the description to comply with the accepted principle-based formulation set out above at paragraph 25. Accordingly, the State is satisfied that there is an identifiable claim group capable of recognition by the State as part of the WDB society.

31 In De Rose (No 2) at [8], the Court summarised its findings in De Rose v South Australia (2003) 133 FCR 325 at [278]-[280] as follows:

The evidence amply supported the proposition that, whatever the degree of acknowledgment or observance of traditional laws and customs by the appellants themselves, Western Desert society had continued to exist since sovereignty and the traditional laws and customs of that society had been acknowledged and observed substantially uninterrupted throughout that period.

32 As undisputed members of the WDB society (and comprising many of the same people referred to as appellants by the Full Court in the above quotation), the Court agrees with the acknowledgment of the State that the contemporary native title claimants’ society is directly linked to the native title holders at sovereignty.

33 Moreover, the evidence supports the continued existence and observance of the traditional laws and customs. The claimants give accounts of travelling through the claim area, hunting and gathering traditional foods and being taught about the tjukurpa (dreaming) sites and the associated stories relating to how ancestral creatures created significant features of the landscape (such as waterholes) in the course of their progress across the land. From the time of sovereignty through until the present time, the claimants, their ancestors, and their descendants have continued to celebrate these tjukurpa narratives for the land.

34 This knowledge has been passed down from generation to generation and connects the claimants not only to one another but also to the physical and spiritual country of the land. In Peter De Rose’s words:

My father, …, would teach me all of these things. We would go around Tieyon all the time, at least once every year.

35 Similarly, Hughie Cullinan says of his traditional education:

I was taught about the country of Tjayiwara by [the father of Peter De Rose]. We would go around hunting for kangaroo, emu and perentie.

I still go hunting in Tieyon, especially for malu. [Mr Kunmanara De Rose] taught me where to go, so I know that place.

36 David Frank concurred stating:

The old people would tell me about the tjukurpa for Unmuru. That was only after I was made a man, not when I was a young fella. I had to go through the Law before I was told those things.

37 The evidence is that personal interpretations of the Nguraritja rule satisfy a person’s particular life circumstances and are consistent with the traditions of WDB people. These traditions provide for an individual’s ability to connect to multiple areas, a feature with high survival value in this highly arid country, and are also well attested for giving rise to sometimes intense internal controversy about interests in land.

38 Also relevant to this issue is the observation of the Court in De Rose (No 2) at [83] that:

… the findings and the evidence point strongly to a number of appellants … genuinely believing in the Tjukurpa and in the sacredness of particular sites.

The Court further observed at [90] that the evidence presented by Peter De Rose and a number of other members in the claim group demonstrated that they “… regarded themselves as bound at all times by the rules for determining Nguraritja for particular country” and as such continued to possess rights and interests in relation to the claim area under the traditional laws and customs of the WDB society.

39 Consequently, the Court agrees with the State that there is sufficient evidence of the continued existence and vitality of a system of law and custom, substantially uninterrupted since sovereignty, among the claim group.

40 In assessing the connection evidence provided by the claimants, Mr McCaul observed that daily life was focussed around the stations of Tieyon, Mt Cavanagh (Ayers Range South) and Sundown, with people using a wider area for hunting, gathering and camping. Mr McCaul acknowledged the existence of tjukurpa sites in the claim area, and concluded that there are a range of spiritual connections across the claim area, linking the Nguraritja to country.

41 For example, Tjaruwa Anderson describes her connection in the following terms:

The reason why this is our country is because one of our tjukurpa, the Ngintaka (Perentie) tjukurpa came through into our country north of Tieyon Homestead. The Ngintaka came into our country through the northeast corner of the Tjayiwara Unmuru claim boundary.

The tjukurpa, to me, is telling us where we belong on the country and what country belongs to us. What we know through our tjukurpa stops us from claiming country that belongs to other people even if it is through other parts of the same tjukurpa.

42 In a similar vein, Julie Anderson says of her connection:

When I say it makes me happy, it is like my heart is glad. That feeling comes from the tjukurpa, my tjukurpa, and also from good memories. When I am away from my country, it is like my heart is blocked. But when I got back to my country, it is like my heart is open and free.

43 Claimant David Frank is more pragmatic, describing his connection in bare terms:

There was always lots of bush tucker at Unmuru, including bush tomatoes, witchetty grub and honey ant. The women and the children would collect them. The men would go hunting for Malu, kangaroo.

There is lots of kapi, water, at Unmuru, and we would always drink that. That water would stay there for a long time for us to drink. We camped there because there was plenty of water that would stay for a couple of years. We would’ve all died without that water and the old people wouldn’t have taken us there unless we could camp.

44 It is a principle under WDB traditional law and customs that the claimants have responsibility for the tjukurpa and the sacred sites and ancestral tracks, and they exercise authority over other members of the WDB society in relation to them. These sites are linked to each other, to the country and to the claimants. In Martin Thompson’s words:

I look after the Tieyon area, I watch over those places because I have been shown that Country because I married [name deleted for cultural purposes]. Artumananyi means to look after and protect sites. It is like being a guardian over those places. That’s what I do for Tieyon.

45 Similarly, David Frank has said:

I am nguaritja for all that area. That is my place.

Because I am nguaritja, people must ask me for permission to go on to that Country. People can go hunting in the area but if they want to use a motor car, they need to ask permission. That is because they could damage the tjukurpa through that area. I have to look after that Country.

46 The tjukurpa and the associated sites within the Tjayiwara Unmuru area encompass the following major ancestral creatures:

(a) Kalaya (Emu);

(b) Kurpany (“Mamu”) and Mala (Rufous Hare Wallaby) which join together with Kalaya;

(c) Malu (Kangaroo), Kanyala (Euro) and Tjurki (Owlet Nightjar) (usually conflated when referring to it in public as “Malu”; and

(d) Kungkaralya (Seven Sisters);

(e) The Pakalira tjukurpa is represented within the claim area, but all information concerning the tjukurpa, except the name, is specifically restricted to senior male claimants and a number of other senior men;

(f) Maku (edible grub) tjukurpa. Both Maku locations on the land are restricted completely in terms of physical access, and both Pakalira and Maku sites and all associated tjukurpa are associated only with senior men at a “very high” (completely gender-restricted) level; and

(g) Ngintaka (Perentie) tjukurpa.

47 The evidence in De Rose and the statements and affidavits provided in connection with this claim indicate that under the relevant traditional laws and customs those who were Nguraritja in relation to land had rights and responsibilities in connection with the tjukurpa sites on the land, and that any claimants who possess rights and interests under the traditional laws and customs would be most unlikely to encounter any difficulty in demonstrating their connection to the land.

48 On consideration of the evidence provided, the Court agrees with the State that it is appropriate to accept that the native title claim group’s traditional laws and customs give them a connection to the claim area.

49 The rights and interests which it is contemplated will be recognised through a native title determination are set out at paragraph 4 of the consent determination.

50 These rights are consistent with rights recognised by the Federal Court elsewhere in South Australia and they align with those recognised by the Court in De Rose (No 2) at [112].

51 The evidence provides that a number of claimants have camped, hunted and gathered on the claim area. For example:

(a) In relation to camping, Peter De Rose said:

I would go to Ngatiri, Wipa, and Kulpitjara near Tjiti Tjiti. We camped near Kulpitjara. Sometimes we go out to that area for one day to get perentie.

Tillie Yaltjangki remembers that:

Our family used to travel between these places on my brother [Mr Kunmanarai De Rose’s] camels.

Angkuna Baker remembers travelling across the claim area:

We used to go between Sundown and Tieyon, and walk. It would take about one night and in between we camped and then we would get to the Station on the next day.

(b) in relation to hunting and gathering, Hughie Cullinan said:

We would usually go hunting in the northern part of Tjayiwara. We would get perentie where all the small rocks are. That is a good area for perentie.

Peter De Rose remembers gathering the bush tucker:

We would get lots of bush tucker like kangaroo, perentie, echidna, bush tomatoes, witchetty grubs and quandongs. Only men would hunt the kangaroo. But the women would still get sand goannas. The echidnas are everywhere and are very easy to catch; you can easily see their tracks and just grab them. Quandongs would be out in the spring time.

52 The claimants also continue to observe the laws in relation to the tjukurpa sites and teach the associated stories to the next generation. The division between men’s and women’s knowledge continues, as Peter De Rose explains:

There is also a tjukurpa that goes through the western part of the claim. I can’t talk about that though. It is for men and is too heavy to talk about; it is mens’ ngura millmillpa. [Mr Kunmanara De Rose] showed me that tjukurpa after I was made a man. Only men know and can talk about that tjukurpa. I need to talk to all the old men about this before I can share information about that tjukurpa.

53 Martin Thompson also provides an example:

There is another place near Tieyon Station, which isn’t on the maps that were made for De Rose Hill. I have been shown that place, but I am not allowed to talk about it.

54 Tjaruwa Anderson also provided an example of current practice in the observance of laws and customs:

So today, if people visit our country like our water points, before they drink water or camp close by they have to throw a small rock into the pool to let the spirit of the water and country know that they are visitors that they are only visiting for a short time or are passing through.

As traditional owners, we have the right to take the water or camp close by without doing these things.

55 All of the cultural sites and areas associated with tjukurpa on the land are linked with cultural sites, areas and tjukurpa which extend beyond the boundaries of the claim. In particular, the tjukurpa of Kalaya, Kurpany and Mala, Malu, Ngintaka, and Kungkaralya are associated with linked sites on ancestral tracks, which extend a considerable geographical distance beyond the Determination Area in all four directions.

56 The Court accepts, on the material, that the native title rights and interests claimed arise from the claimants’ traditional law and customs and that they have evolved from the native title rights and interests as they were likely to have been at sovereignty.

57 The State submits that there is no right or interest within the consent determination that would not be recognised by the laws of Australia.

58 Section 225 of the Native Title Act governs what the consent determination must include. The applicants and the State submit that the consent determination complies with each requirement. The consent determination defines the group of native title holders and the criteria by which they have group membership. Paragraphs 4 to 14 of the consent determination set out the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in the Determination Area. Paragraph 15 lists the nature and extent of other interests in the Determination Area. This has been the subject of some negotiation between the applicants and the State and various respondents. There has been ample opportunity for any other interest-holders in the area to identify themselves and join as parties to the claim, so it may be accepted as reliable especially as the State’s comprehensive tenure searches have not identified any other relevant interest holders in the area.

59 Paragraph 16 of the consent determination describes the relationship between the native title rights in Paragraphs 4 to 14 and those other rights in Paragraph 15.

60 Finally, the land and waters in the Determination Area are covered entirely by non-exclusive pastoral leases. There are no exclusive native title rights in the Determination Area.

61 It is clear that the requirements of s 225 are met.

62 Agreement has been reached between all parties to the proceedings on the terms of the consent determination and signed copies of that determination have been filed with the Court. As noted, the Tjayiwara Unmuru native title claim was filed on 17 December 2010. Full notification by the National Native Title Tribunal under section 66 of the Native Title Act closed on 15 February 2012. The Court is satisfied that all relevant interest holders in the area have had an opportunity to take part in the proceedings.

63 The Court notes that South Australian Native Title Services Ltd, the native title service provider for the Determination Area, is not a party to the proceedings, and that the Commonwealth is not a party to the proceedings.

64 All parties have had independent and competent legal advice in the proceeding from solicitors well versed in native title law.

65 Schedule 1 to the consent determination contains a detailed description of the external boundary of the Determination Area. Schedule 3 to the consent determination contains a detailed description of those areas within the external boundary which have been excluded from the Determination Area because native title has been extinguished.

66 Section 87 of the Native Title Act allows the Court to make a consent determination in the native title proceeding even though the proceeding has not been heard by the Court. In light of the above, the Court is satisfied that it is appropriate to make a final determination over the Determination Area on the basis of the evidence presented by the applicants and with the support of the other respondents.

Extinguishment

67 Also as noted, a tenure history of the claim area was provided by the State, and made available to all the parties to the claim. The State has carried out a detailed historical analysis of this tenure. It is accepted that exclusive native title has been extinguished in the Determination Area by the grant of non-exclusive pastoral leases. There is no reason to go behind that assessment.

Conclusion

68 The Native Title Act encourages the resolution by agreement of claims for determinations of native title. For the reasons set out above, the State and the applicants consider the consent determination is appropriate and should be made in this proceeding. By signing the agreement to the consent determination all other parties to the proceeding have indicated their agreement. The Court considers it entirely appropriate to make the determination of native title in the terms proposed.

69 Accordingly, the determination is made in the terms of the Orders which these reasons for judgment accompany.

I certify that the preceding sixty-nine (69) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Mansfield. |

Associate: