FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v National Rugby League Investments Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 34

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v National Rugby League Investments Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 34

CORRIGENDUM

1. In paragraph 105 of the Reasons for Judgment, in the fourth line the word “then” should read “than”.

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Corrigendum to the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Rares. |

Associate:

Dated: 26 March 2012

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 1 February 2012 |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The parties confer and prepare draft declarations and orders to give effect to these reasons.

3. The proceedings be relisted on 3 February 2012 at 9.30 am for the making of orders to give effect to these reasons and directions.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 1430 of 2011 |

BETWEEN: | SINGTEL OPTUS PTY LTD (ACN 052 833 208) First Applicant and Cross-Respondent OPTUS MOBILE PTY LTD (ACN 054 365 696) Second Applicant and Cross-Respondent |

AND: | NATIONAL RUGBY LEAGUE INVESTMENTS PTY LIMITED (ACN 081 778 538) First Respondent and Cross-Claimant AUSTRALIAN RUGBY FOOTBALL LEAGUE LIMITED (ACN 003 107 293) Second Respondent and Cross-Claimant AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE (ACN 004 155 211) Third Respondent and Cross-Claimant TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED (ACN 051 775 556) Cross-Claimant

|

JUDGE: | RARES J |

DATE: | 1 FEBRUARY 2012 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 The operators of two of Australia’s popular football codes, the Australian Football League (AFL), the third respondent, and the National Rugby League partnership (between the first and second respondents) (NRL) own the copyright in broadcasts on free to air television of games played between teams in their respective competitions. Telstra Corporation Ltd is the AFL’s exclusive licensee of broadcasts of the footage of AFL games in respect of communicating them to the public on, or via, the internet and mobile telephony enabled devices. Telstra also has a similar licence from the NRL.

2 In mid July 2011, Singtel Optus Pty Ltd and its subsidiary, Optus Mobile Pty Ltd, began a new service called “TV Now”. I will refer to both companies simply as “Optus”, as did the parties. The “TV Now” service offers Optus’ private and small to medium business customers in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth the ability to record free to air television programs, including AFL and NRL games and play them back on any one or more of the following four types of device (compatible devices) operated by a user of the service (user), namely:

a personal computer operating on Microsoft Windows or an Apple system including iPads or tablets (collectively a PC), by accessing TV Now through a web browser, such as Internet Explorer, at the TV Now website using specified URLs (the TV Now website);

iPhone or iPad devices using Apple’s iOS TV & Video App that could be downloaded from Apple’s AppStore (an Apple device);

Android mobile devices, including a tablet, using the Android TV & Video App that could be downloaded from Google’s Android Market Place or the Optus Application Store (an Android device) ;

most 3G mobile devices, including Android devices, but not Apple devices (a 3G device) using that device’s web browser application to access the TV Now websites using specified URLs (the TV Now 3G website).

3 The user of the TV Now service could select a program to record from an electronic program guide that would appear on any one of those four kinds of device. Unknown to the user, Optus’ technology then caused a set of four unique recordings to be made of the program its user had selected, for the sole use of that person. Each of those four recordings in the set was in one of the four respective formats necessary to enable the user to view the recorded program on any one of the four kinds of device supported by the TV Now service. If several users selected the same program to record, the TV Now service made separate, unique sets of four copies (one in each format) for each of those users.

4 The facts and issues are largely agreed because of the commendably sensible approach that the parties have taken in bringing these complex questions to trial quickly. The resolution of the controversy will depend on the construction of a number of provisions of the Copyright Act 1966 (Cth) and their application to the facts.

5 The central issue in these proceedings is whether Optus, through the operation of its TV Now service, infringed the copyright interests of the AFL, NRL and Telstra (the rightholders) in the free to air broadcasts of some live and filmed AFL and NRL games played in September 2011. The rightholders alleged that Optus made cinematograph films within the meaning of the Act, being infringing copies, of those broadcasts and later communicated those films to users of the service. The users had utilised the TV Now service to record and later play the films on their compatible devices. Optus contended that the users, rather than it, had made the films or copies and played them without any infringement of copyright because of the exception for private and domestic recording in s 111 of the Act.

6 The parties agreed that there were seven issues for determination. I will set these out later, but it suffices to say that they focus on whether and how Optus, or the user, made, or later viewed, cinematograph films or copies of the broadcasts. I will first identify the principal relevant provisions of the Act, then set out the facts and then the issues.

The statutory context

7 The key provision of the Act that is engaged in these proceedings is s 111 which provides:

“111 Recording broadcasts for replaying at more convenient time

(1) This section applies if a person makes a cinematograph film or sound recording of a broadcast solely for private and domestic use by watching or listening to the material broadcast at a time more convenient than the time when the broadcast is made.

Note: Subsection 10(1) defines broadcast as a communication to the public delivered by a broadcasting service within the meaning of the Broadcasting Services Act 1992.

Making the film or recording does not infringe copyright

(2) The making of the film or recording does not infringe copyright in the broadcast or in any work or other subject-matter included in the broadcast.

Note: Even though the making of the film or recording does not infringe that copyright, that copyright may be infringed if a copy of the film or recording is made.

Dealing with embodiment of film or recording

(3) Subsection (2) is taken never to have applied if an article or thing embodying the film or recording is:

(a) sold; or

(b) let for hire; or

(c) by way of trade offered or exposed for sale or hire; or

(d) distributed for the purpose of trade or otherwise; or

(e) used for causing the film or recording to be seen or heard in public; or

(f) used for broadcasting the film or recording.

Note: If the article or thing embodying the film or recording is dealt with as described in subsection (3), then copyright may be infringed not only by the making of the article or thing but also by the dealing with the article or thing.

(4) To avoid doubt, paragraph (3)(d) does not apply to a loan of the article or thing by the lender to a member of the lender’s family or household for the member’s private and domestic use.” (bold emphasis added)

8 Importantly, the earlier version of that section had been repealed and the current s 111 enacted by the Copyright Amendment Act 2006 (Cth) along with a number of other provisions. Those included the definition in s 10(1) of “private and domestic use” which, unless the contrary intention appears, “means private and domestic use on or off domestic premises”. Relevantly, s 10(1) also contains the following definitions that apply unless the contrary intention appears:

cinematograph film means the aggregate of the visual images embodied in an article or thing so as to be capable by the use of that article or thing:

(a) of being shown as a moving picture; or

(b) of being embodied in another article or thing by the use of which it can be so shown;

and includes the aggregate of the sounds embodied in a sound-track associated with such visual images.

communicate means make available online or electronically transmit (whether over a path, or a combination of paths, provided by a material substance or otherwise) a work or other subject-matter, including a performance or live performance within the meaning of this Act.

copy, in relation to a cinematograph film, means any article or thing in which the visual images or sounds comprising the film are embodied.

infringing copy means:

…

(b) in relation to a sound recording—a copy of the sound recording not being a sound-track associated with visual images forming part of a cinematograph film;

(c) in relation to a cinematograph film—a copy of the film;

(d) in relation to a television broadcast or a sound broadcast—a copy of a cinematograph film of the broadcast or a record embodying a sound recording of the broadcast; and

(e) …

being an article (which may be an electronic reproduction or copy of the work, recording, film, broadcast or edition) the making of which constituted an infringement of the copyright in the work, recording, film, broadcast or edition …

sound recording means the aggregate of the sounds embodied in a record.

…

television broadcast means visual images broadcast by way of television, together with any sounds broadcast for reception along with those images.”

9 Next, s 22 deals with the making of literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works, sound recordings, including of live performances and, pertinently provides:

“22 Cinematograph films

(4) For the purposes of this Act:

(a) a reference to the making of a cinematograph film shall be read as a reference to the doing of the things necessary for the production of the first copy of the film; and

(b) the maker of the cinematograph film is the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the making of the film were undertaken.

Broadcasts and other communications

(5) For the purposes of this Act, a broadcast is taken to have been made by the person who provided the broadcasting service by which the broadcast was delivered

(6) For the purposes of this Act, a communication other than a broadcast is taken to have been made by the person responsible for determining the content of the communication.

(6A) To avoid doubt, for the purposes of subsection (6), a person is not responsible for determining the content of a communication merely because the person takes one or more steps for the purpose of:

(a) gaining access to what is made available online by someone else in the communication; or

(b) receiving the electronic transmission of which the communication consists.

Example: A person is not responsible for determining the content of the communication to the person of a web page merely because the person clicks on a link to gain access to the page.” (emphasis added)

10 Part IV of the Act (comprising ss 84-113C) makes specific provisions for copyright in subject matter other than literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works. In addition to s 111, Pt IV relevantly provides:

“85 Nature of copyright in sound recordings

(1) For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a sound recording, is the exclusive right to do all or any of the following acts:

(a) to make a copy of the sound recording;

(b) to cause the recording to be heard in public;

(c) to communicate the recording to the public;

(d) to enter into a commercial rental arrangement in respect of the recording.

…

86 Nature of copyright in cinematograph films

For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a cinematograph film, is the exclusive right to do all or any of the following acts:

(a) to make a copy of the film;

(b) to cause the film, in so far as it consists of visual images, to be seen in public, or, in so far as it consists of sounds, to be heard in public;

(c) to communicate the film to the public.

87 Nature of copyright in television broadcasts and sound broadcasts

For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a television broadcast or sound broadcast, is the exclusive right:

(a) in the case of a television broadcast in so far as it consists of visual images—to make a cinematograph film of the broadcast, or a copy of such a film;

(b) in the case of a sound broadcast, or of a television broadcast in so far as it consists of sounds—to make a sound recording of the broadcast, or a copy of such a sound recording; and

(c) in the case of a television broadcast or of a sound broadcast—to re‑broadcast it or communicate it to the public otherwise than by broadcasting it.

…

90 Cinematograph films in which copyright subsists

(1) Subject to this Act, copyright subsists in a cinematograph film of which the maker was a qualified person for the whole or a substantial part of the period during which the film was made.

(2) Without prejudice to the last preceding subsection, copyright subsists, subject to this Act, in a cinematograph film if the film was made in Australia.

…

91 Television broadcasts and sound broadcasts in which copyright subsists

Subject to this Act, copyright subsists in a television broadcast or sound broadcast made from a place in Australia:

(a) under the authority of a licence or a class licence under the Broadcasting Services Act 1992; or

(b) by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation or the Special Broadcasting Service Corporation.

…

101 Infringement by doing acts comprised in copyright

(1) Subject to this Act, a copyright subsisting by virtue of this Part is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia, or authorizes the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright.

…

103 Infringement by sale and other dealings

(1) Subject to sections 112A, 112C, 112D and 112DA, a copyright subsisting by virtue of this Part is infringed by a person who, in Australia, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright:

(a) sells, lets for hire, or by way of trade offers or exposes for sale or hire, an article; or

(b) by way of trade exhibits an article in public;

if the person knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the making of the article constituted an infringement of the copyright.

….

(3) In this section:

article includes a reproduction or copy of a work or other subject‑matter, being a reproduction or copy in electronic form.”

11 Finally, s 202 enables a person threatened with proceedings for breach of copyright to sue the person making the threats and the latter to counterclaim, in order to determine whether an infringement of copyright occurred to which the threats related.

How Optus provides TV Now at the retail level

12 The decision to approve capital expenditure to establish the infrastructure to conduct the TV Now service was recorded in an Optus executive capital board minute of a meeting held on 28 February 2011. The business case explanation for the service included that it was “a key component of Optus’ Digital Life Entertainment pillar” enabling Optus to be first to market with the product. The business case argued that the TV Now service would establish a leading position for Optus in “the fast moving digital TV industry. [The TV Now service] delivers the customer value proposition ‘record and watch my favourite TV shows on the go’”. The business case gave a brief financial analysis to support the proposal.

13 The TV Now service is available to Optus’ existing Optus 3G mobile prepaid and account individual customers or subscribers. It is also available to those employees of small to medium business subscribers of Optus 3G mobile services who have a mobile device that is supported by the business’ subscription. However, other Optus business customers and their employees cannot gain access to the TV Now service through the business’ subscription. For simplicity I will refer to a person who can utilise the TV Now service as a “user” and the contract that provides the facility as a “subscription”.

14 First, a user must sign up for the service by logging into the Optus myZoo portal through one of the TV Now or TV Now 3G websites or the TV & Video App, using a PC or compatible mobile device. Once logged into the myZoo portal, the user clicks on the “TV & Video” or “Find TV Shows & Record” buttons and is directed to a web page entitled “Optus TV & Video”. This page displays a number of links calculated to attract a user’s interest in utilising the ability to look at a TV show or video. One large part of this web page is entitled “What’s on TV today” and contains a portion of an electronic program guide featuring programs that will be shown later on free-to-air channels for a particular time period. This portion has a link that advises the user above a button titled “Get it for Free”:

“Record & Watch TV Shows on your Mobile or PC

1. Find a show in the Guide.

2. Press Record [and the webpage displays the “record” button].

3. Watch your recorded show.”

15 Next, the user navigates to the Optus TV Now webpage which invites him or her to sign up for one of three plans: a basic plan for 45 minutes recording space for free, a standard plan for about $7 per month for 5 hours recording space or a premium plan for about $10 per month for 20 hours recording space. Next, the user sees:

“Step 2: Tell us your current home address:

To ensure you get the TV shows broadcast in your area, we need you to provide us the below details of your home address. It is a breach of copyright to make a copy of a broadcast other than to record it for your private and domestic use. Optus accepts no responsibility for copyright infringement.” (emphasis added)

16 The user must fill in details of his or her home address and is then told to read and agree to the terms and conditions that include the following:

“Optus TV Now allows you to record and store television shows. You can then access those recordings for a limited period of time on your compatible Optus mobile or PC.

…

You may view one Optus TV Now recording at a time.

Are there any special liability issues?

Optus TV Now is for your individual and personal use. You must not sell an Optus TV Now recording, let it for hire, by way of trade offer or expose for it for sale or hire, distribute it for the purpose of trade, cause it to be seen or heard in public or use it for broadcasting. You must not use Optus TV Now for any unlawful or illegal activity. You must not knowingly take any action that would cause Optus TV Now to be placed in the public domain. You must not modify, copy, reproduce, publish, republish, frame, upload to a third party, communicate, re-communicate, post, transmit, re-distribute or distribute any content contained in Optus TV Now in any way or by any method whatsoever. Optus accepts no responsibility for content within the Service. Optus accepts no responsibility for lost content or program recordings. You are advised that it is a breach of copyright to make a copy of a broadcast other than to record it for your private and domestic use by watching the material broadcast at a more convenient time. You must not copy any information from Optus TV Now or from the Electronic Program Guide. Optus accepts no responsibility for copyright infringement. You indemnify Optus against claims for copyright infringement from copyright owners.

□ I agree to the Optus TV Now Terms & Conditions”

(italicised emphasis in original, bold emphasis added)

17 This web page also informs the user that:

the TV Now service is only available for a user whose home address is in one of the five capital city broadcast regions for free to air channels in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth and then only for those channels in that user’s home address broadcast region;

he or she can both schedule and watch recordings using a mobile or computer;

he or she can delete, re-record and watch as many times as desired;

“Optus stores the recorded shows in the cloud instead of on your phones or computer”;

recordings expire after 30 days.

How the user chooses to record a program

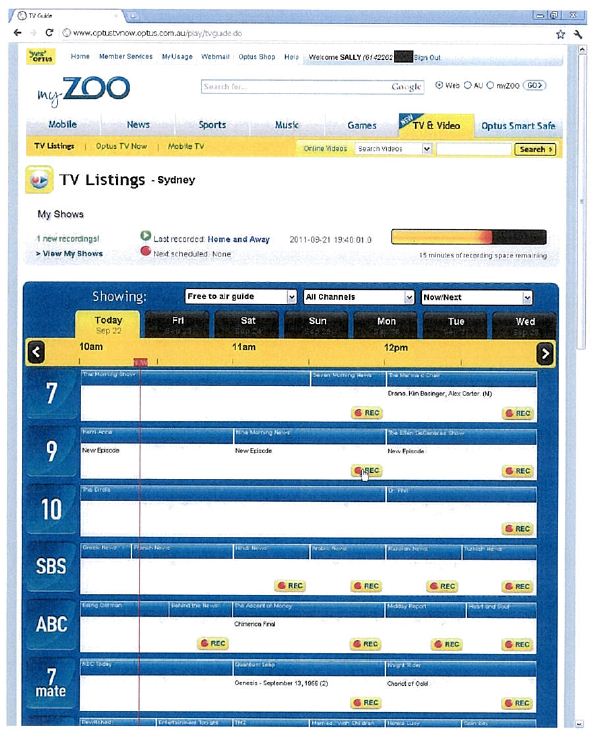

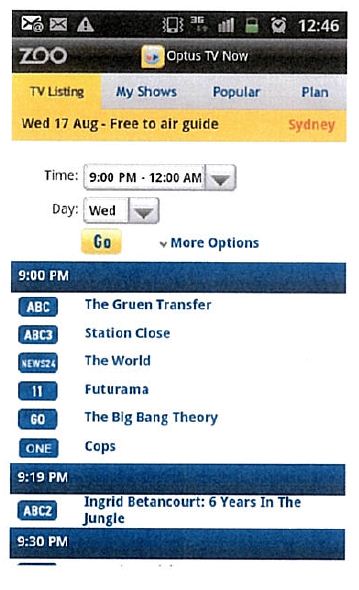

18 Once signed up for the TV Now service, a user logs in and is directed to the electronic program guide. He or she navigates that guide to look for and select the program to be recorded. The user cannot use the TV Now service when in another capital city to record any broadcasts that are not made in his or her home address broadcast region. A user is only able to change his or her home address details once every two months. The TV Now service can only record a program that a user wishes to record if the broadcast of the program has not yet commenced. Thus, a user cannot begin any recording once a program has commenced being put to air. The program guide appears on the screen of a PC as follows:

19 A user who has an Apple or Android device must download the appropriate TV & Video App or application suitable for that device in order to use the TV Now service. He or she then navigates to the equivalent screen to that above for a mobile device, an example of which is shown below:

20 The TV Now service calculates when a recording will begin using a clock in one of the two MACF (media application control framework) servers that control the system. These are programmed to commence recording 2 minutes before, and cease 10 minutes after, the scheduled broadcast times so as to allow for variations in the television station’s schedules.

21 In essence, from the user’s point of view, the TV Now system is simplicity itself. After logging in, he or she looks at the electronic program guide, decides what he or she wants to record and clicks the record button. Next, a pop up box appears on the screen displaying further information about the chosen program. This box invites the user to click on the “Record” button it displays to confirm that he or she wishes to record the program. That is the last the user does from then until he or she wants to play the recording. Users of the TV Now service can cancel a scheduled recording by clicking on an appropriate button. They can also change their TV Now service plan if they choose.

22 I will describe the complex system that the TV Now service uses to make and transmit recordings later in these reasons. However, from the user’s perspective, his or her involvement is similar to programming a recording device connected to a home television to record a program in advance and then playing it later at his or her leisure; indeed, the TV Now system is apparently easier for a user to employ than some of the technologies available to record programs that can be viewed on the user’s own equipment, such as a DVD recorder, DVR (digital video recorder) or VCR (video cassette recorder).

How the user watches a recorded program

23 When the user wants to watch a recorded program, he or she can do so on any of the four kinds of compatible device supported by the TV Now service. Once the user logs into the service and seeks to view a recording, the TV Now system detects the particular kind of device the user is then utilising and transmits a stream of data in the form suitable for that device from one of the four recordings of the program held in Optus’ datacentre. If the user subsequently wants to watch some or all of the same recording on another compatible device, the TV Now system will stream data to that device from another of those four recordings that is appropriate for the device.

24 If the user wishes to watch a recorded program using a PC, he or she logs into the TV Now website and is presented with the “My Shows” web page. That brings up the “Recorded Shows” tab. It lists the programs or shows that have been recorded and remain available (i.e. within 30 days of the original broadcast) with “play” and “delete” buttons next to them. If the user clicks “play”, a web page appears with a video player that the user can control to watch, pause, advance or rewind the recording as he or she wishes.

25 If the user wishes to watch a recorded program using a 3G device, he or she must use it to access the TV Now 3G website, and click on the “My Shows” button. He or she will see the “Recorded” tab. By clicking on that, a menu of all recorded programs (less than 30 days old) appears. The user then selects the desired program and a screen appears with information about it together with a “Watch now on your Mobile” button. If the user clicks on that, a mobile video screen appears and he or she can watch, pause, advance, rewind or delete the recording.

26 A similar process applies for Android devices and, with one important difference, for Apple devices. Both of these types of device use a TV & Video App and operate in much the same way as a 3G device. However, the Apple devices allow a user to view a recording of a television program within about 2 minutes from the commencement of the free to air broadcast of that program. That is, the Apple devices can be used to see a program such as an AFL or NRL game selected for recording on the TV Now service “almost live”. All of the other devices can only access recordings of programs made by the TV Now service after the whole program has finished being broadcast.

How Optus provides the TV Now service at the technical level

27 Optus’ expert witness, Rodney McKemmish, gave a precise technical description of Optus’ infrastructure system and its components in his detailed report. It is not necessary to descend too far into that detail in order to describe the essential features of this infrastructure that are relevant.

28 Australia uses a format known as DVB-T (digital video broadcasting - terrestrial) for its digital free to air television broadcasts. These broadcasts are made using an audio visual compression computer format known as MPEG-2 (motion picture experts group). This format is used to send a stream of digitised data that reception equipment, such as television sets or set top boxes, can convert or process into what the viewer sees as a television program at, or nearly at, the same time as the data is received by the device. The data in a DVB-T signal are split into several streams using a number of frequencies in a particular range for that signal.

29 Optus has established TV antennae and three DVB-T receivers in each of the five capital cities in which it offers the TV Now service. The antennae receive the total of 15 digital signals broadcast in the MPEG-2 format by each free to air channel in each city. The antennae are connected by coaxial cable to the DVB-T receivers.

30 Each of the three DVB-T receivers is configured so that, between them, they will receive signals from the 15 free to air channels in each city. The receivers then convert the radio frequency DVB-T signal to a packet-based stream of data, also in MPEG-2 format, and transmit that stream of data to the transcode servers. Each of those transcode servers has significant RAM (random access memory) and hard drive memory capacity. Those servers run a program known as “transcoding”. This digitally converts the MPEG-2 signal into four specifications that are designed so that the program can be played back on the different types of users’ devices that support the TV Now service. These data streams are called “output profiles”. The transcoders convert the MPEG-2 signal into seven different data streams. One combined audio and video stream is for data in the QuickTime HTTP Live Streaming proprietary format used by Apple devices (QuickTime Streaming). The way in which QuickTime Streaming operates could give rise to a discrete issue that may need to be decided later. I will explain this at the end of these reasons (see: “Conclusion” at [114]-[115]). The remaining six streams comprise three sets of an audio and a separate visual stream of data. Each set is in particular formats suitable for playback on one of the other three types of device capable of using the TV Now service.

31 Optus keeps a significant number of servers in its datacentre in Sydney. All the output profiles from Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth are sent as streams of data to the Sydney datacentre, as are the output profiles that are converted by the Sydney transcoders. The datacentre has the following equipment:

two MACF servers that control the TV Now service;

routers that direct data from the network of computers in each of Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide (each known as a local area network (LAN)), to the LAN in Sydney, via a virtual private LAN;

recording controllers or servers;

a QuickTime Streaming server;

a flash streaming server;

a network attached storage (NAS) computer that is connected to and manages a large number of hard drives. The recording controllers and QuickTime Streaming server are connected and write data to the NAS;

an electronic program guide engine;

a user database.

How the datacentre carries out a user’s instruction to record a program

32 The MACF servers display the electronic program guide for the TV Now service available in the five capital cities. When a user clicks on the “record” button for a program in the guide, that instruction is sent to the MACF servers which, in turn, enter this data in the user database. The MACF server enters or creates a schedule ID in respect of the program selected and the user’s unique identifying number (user ID). Every time a user instructs the TV Now service to record a program the MACF server generates both a new schedule ID for that user’s individual instruction and the user ID is entered against the schedule ID for each request.

33 The recording controllers ask or poll the user database once a minute enquiring whether any users have scheduled the recording of any programs due to be broadcast at the time of polling. If a user has instructed that a recording be made, the MACF server informs the recording controllers which then causes four recordings to be made on the NAS, one in each of the four output profiles for the user who gave that instruction. The recording controller notifies the MACF server, once a recording has begun, that the television program in relation to each particular schedule ID is being recorded. Thus, the user database contains the instructions of each user of the TV Now service to record a program for that user when it is later broadcast.

34 The MACF server then allocates an individual recording ID to each such recording and makes an entry in the user database linking the particular recording ID to the user ID associated with the instruction to make that recording. Thus, the MACF server is able to ascertain which particular recording was made for, and on the instruction of, which particular user. The MACF server will display information to the user about the recordings made for him or her or when the user next accesses the TV Now service. On the other hand, if no user has instructed that a program be recorded, no recording occurs (other than for no more than 60 seconds before deletion in the case of the Apple QuickTime Streaming server. The consequence of this exception is an issue that was separated from the issues that I am now determining.).

How the datacentre responds to a user’s play instruction

35 The following occurs when a user decides to play a program he or she caused the TV Now service to record during the 30 day period before it is automatically deleted. The user clicks the “play” button for the desired program displayed in a list of recorded programs on the device he or she is using. This causes the MACF server to look up the recording ID associated with that user’s ID in the user database. The equipment recognises the type of device that the user is then operating. It then causes the relevant streaming server to send to the device the compatible version of the output profile that is stored with the recording ID associated with the relevant user ID. There are two types of streaming servers; flash streaming servers that work with PCs and Macs and RTSP/iPhone streaming servers that work with iPhones and 3G mobile devices.

36 The flash streaming server instructs the storage server in the NAS to provide an IP stream of the recording in the required one of the four output profiles. The recording controller causes the NAS to transmit to the flash streaming server a stream of IP packets in that output profile. The flash streaming server sends this streamed playback data via the user’s internet connection to the IP address of the device the user is employing. The user sees the recording as it is streamed into, and processed by, his or her device. No data is stored in any permanent form in this process. The user then views, and controls his or her viewing of, the streamed program on that device.

37 Similarly, if the RTSP/iPhone streaming servers receive such an instruction, the flash streaming server responds by instructing the NAS to provide an IP stream of the recording in the output profile format connected to the recording ID for that user that is best suited to the user’s device making the play request. That streamed data is sent to the user’s device’s IP address via an internet connection without storing data in any permanent form. However, if the appropriate output profile uses QuickTime Streaming, it is transmitted in 10 second segments. The user’s device interprets the data sent in these streams and displays the program on the device. The device does not store a copy of the program in a permanent form. Rather, the program data is displayed by the device almost immediately it is received as data and not retained by it.

38 If the user presses the “rewind”, “pause” or “advance” buttons, the device sends the instruction back to the datacentre where it is processed and given effect by the streaming server. The user can log into the TV Now service on any compatible device any time during the 30 days following the broadcast and continue, or repeat, viewing it on that or another such device. The Optus equipment will use the same process with any necessary adaption to suit whatever compatible device is employed by the user.

39 If the user is using a PC, 3G device or Android device to access the TV Now service a recording will not appear there as available for viewing until the broadcast of the program has been completed and the recording has finished. However, if the user employs an Apple iOS device to access the TV Now service, the recording will appear as available for viewing approximately two minutes after the broadcast commenced. Thus, a user with an Apple iOS device will be able to play the recording in “near real time” i.e. within about two minutes of the scheduled start of the broadcast and watch the program continuously to its end. Nonetheless, the recording controllers will have caused four different copies, one in each of the four formats supported by the TV Now service, of the one program to be recorded for each recording ID.

Agreed facts

40 The parties agreed on the following facts:

(1) Channel Seven and Channel Ten companies operating in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth:

made cinematograph films and sound recordings of AFL matches in Australia (AFL films), each of which was a cinematograph film within the meaning of the Act; and

made television broadcasts of AFL matches on free to air television using the AFL films (AFL broadcasts), each of which was a television broadcast within the meaning of the Act.

(2) Copyright subsisted in each of the AFL broadcasts and AFL films.

(3) The AFL owned the copyright in each of the AFL broadcasts and AFL films.

(4) Telstra was the exclusive licensee of the copyright in the AFL broadcasts and AFL films in Australia for the internet and mobile telephony and it exploited that copyright by providing access to AFL broadcasts and AFL films to its subscribers of those services.

(5) Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (Channel 9):

made cinematograph films and sound recordings of NRL matches in Australia (NRL films), each of which was a cinematograph film within the meaning of the Act; and

made television broadcasts of NRL matches using NRL films (NRL broadcasts), each of which was a television broadcast within the meaning of the Act.

(6) Copyright subsisted in each of the NRL broadcasts and the NRL films.

(7) The NRL owned the copyright in the broadcasts, cinematograph films and sound recordings of NRL matches made by Channel 9 (collectively NRL footage).

(8) Telstra was the exclusive licensee of the copyright in the NRL footage in Australia for the internet and mobile telephony and it exploited that copyright by providing access to the NRL footage to its subscribers of those services.

41 The parties also agreed that particular TV Now users selected the following football matches for recording by the TV Now service and that when each of these was recorded a cinematograph film was made of it within the TV Now service infrastructure in the way described above:

(a) on 23 September 2011 the Manly Sea Eagles v Brisbane Broncos preliminary rugby league final was broadcast in Sydney at approximately 19:30 (the first NRL program);

(b) on 24 September 2011 the Melbourne Storm v New Zealand Warriors preliminary rugby league final was broadcast in Sydney at approximately 19:30 (the second NRL program);

(c) on 4 September 2011 the program “Nine’s Sunday Football: Brisbane Broncos v Manly Sea Eagles” was broadcast in Sydney at approximately 15:30 (the third NRL program);

(d) on 23 September 2011 the Collingwood v Hawthorn AFL premiership preliminary final was broadcast:

(1) in the Melbourne television area at approximately 19:30 local time (the first AFL program);

(2) in the Perth television area at approximately 18:30 local time (i.e. about 1 hour later than the first AFL program) (the second AFL program).

42 Various identified users watched the above five programs at times that were also agreed facts. For example, the first NRL program was watched by user A twice, once on 23 September at about 22:30 and again the next day at about 13:20, while user B watched it on numerous occasions between about 22:15 on 23 September to 18 October. However, it is not apparent whether the users necessarily watched the whole program when they accessed it. Thus, user B is recorded as having watched this program four times on 18 October at about 10:00, 15:39, 15:44 and 15:45. Obviously, user B could not have watched the whole, or even very much, of the program on 18 October at the second and third of those times.

43 The first AFL program, broadcast on 23 September at 19:30, was watched on that night by user I at about 19:49, user J at about 19:41, 20:06, 21:47 and 22:02 and user L at about 19:31. Each of these three users must have had an Apple device because they were able to watch the match as the broadcast was occurring. User J seems to have either paused or stopped and re-started the program to have a break, perhaps to get a refreshment, or to have had difficulty with the internet or mobile connection, at least in respect of his or her second connection at about 20:06. User L appears to have been aware of the ability to use his or her Apple device to obtain a near live streaming of the match. However, it is not clear how long any of these persons watched. User L is recorded as having played the same film 14 more times, although a number of these had such short breaks between them that user L must either have paused or stopped and re-started the program or had difficulty maintaining his or her internet or mobile connection.

44 In addition, two persons, users O and P, watched the second AFL program in Perth respectively, two and four days after it went to air and in doing so must have viewed a recording of the broadcast, i.e. a cinematograph film of it.

The issues for present determination

45 After they began on 26 August 2011, these proceedings developed as contemplated by s 202 of the Act. Optus pleaded that the AFL and NRL had alleged that the TV Now service infringed their copyright and had made unjustifiable threats, within the meaning of s 202, that they would seek to restrain Optus from continuing to provide the service. Telstra was joined as a cross-claimant to enable it to assert its rights as an exclusive licensee of the AFL. The parties sought only declaratory relief against each other in the present phase of the proceedings that is concerned to determine a number of separate issues arising on the amended cross claims and defences of the AFL, NRL and Telstra. The parties agreed that the following issues required determination separately and before any others in their controversy:

1. Who did the acts involved in recording the NRL broadcasts, AFL broadcasts and AFL films (Copyright Works or, for simplicity “film”) for the operation of the TV Now service:

the user (Optus’ primary position);

Optus (the rightholders’ position and Optus' alternate position); or

Optus and the user (the rightholders’ alternate position and Optus' further alternate position)?

2. Does s 111 mean that the recording was not an infringement of copyright? If s 111(2) does not apply, is Optus liable for copyright infringement by way of authorisation?

3. When the recording was viewed, who did the acts of electronically transmitting the Copyright Works:

the user (Optus’ primary position);

Optus (the rightholders’ position and Optus' alternate position); or

Optus and the user (the rightholders’ alternate position and Optus’ further alternate position)?

4. When recordings were streamed to a user, was this a communication “to the public”? Optus says it was not, and therefore was not an infringement of copyright. The rightholders say it was, and therefore was an infringement.

5. Did Optus make the Copyright Works available online?

6. If the answer to 5 is “yes”, was this to the public?

7. Is the digital file comprising the NRL footage streamed to users an “article” within the meaning of s 103 or an “article or thing” within the meaning of s 111(3)(d) and, if so, was it distributed for the purpose of trade? (This issue was pressed only by the NRL.)

46 Conceptually, the first six issues can be distilled as follows. The first substantively concerns identifying who is the person who made the films stored in Optus’ NAS computer. The second is whether or not s 111(2) excludes that person from liability for infringing the rightholders’ copyright by making the films. The third, fourth, fifth and sixth issues concern whether the user, or Optus, or both, made the transmission of a streamed film to the user and whether, by that transmission, the film was a communication “to the public” or made available online “to the public” under ss 86(c) or 87(c) within the defined meaning of “communicate” as used in ss 10(1), 22(6) and (6A).

47 On 20 December 2011 I ordered, by consent, that the issues arising on the amended cross claims and defences of AFL, NRL and Telstra be determined separately and before all other issues, so as to give substantial certainty to all the parties as to the legally and commercially crucial aspects of their controversy before the 2012 football season commences. Each of the parties agreed, at my suggestion, that I should also grant any unsuccessful party leave to appeal from any orders I make reflecting my decision.

48 I will discuss the issues for the sake of simplicity by focusing on the position of the AFL. That is illustrative of the cases of each of the NFL and Telstra, since there is no difference in substance between the positions of the AFL and NRL as owners of the Copyright Works, or of Telstra as exclusive licensee. Also, for simplicity, I will treat the rights to make or broadcast or copy as incorporated in the equivalent rights in the Act in respect of a (cinematograph) film.

Issue 1 : Who did the acts involved in recording the Copyright Works?

49 The AFL had the exclusive right to make a cinematograph film and sound recording of the second AFL program (s 87(a) and (b)) and to make a copy of the film (s 86(a)). These are rights, in substance, to reproduce a broadcast or film. The second AFL program was broadcast in Perth an hour after the live game had commenced being broadcast in Melbourne. Thus, the second AFL program exploited the AFL’s right under s 87(a) and (b) to make a film of the (live) television broadcast of the premiership preliminary final match that had commenced earlier on 23 September 2011.

50 When Optus’ equipment recorded the broadcast of the first AFL program in the four formats, it brought into existence four (identical) films of that broadcast. This recording was within the AFL’s exclusive right to make a film of a television broadcast under s 87(a) and (b). And, when that equipment recorded the broadcast of the film that one of the Channel Seven or Channel Ten companies had made of the second AFL program, Optus’ equipment brought into existence four (identical) copies of the broadcast film. This recording was within the AFL’s exclusive right to make a copy of a film under s 86(a).

51 Optus contended that, in each case, the user, by pressing the “record” button or instruction on the screen of his or her compatible device using the TV Now service, made each film of the live broadcast of the game and the subsequent broadcast of the film of the game within the meaning of s 111(1) and (2).

52 The rightholders argued that, for the purpose of s 111, Optus “made” any film when it recorded a program in the four formats. They argued that this was because Optus owned and operated the complex system that picked up the free to air broadcast in MPEG-2 form, ultimately recorded it in the four formats and later was able to stream one of those recordings to a user. The rightholders contended that TV Now was a recording service that Optus provided to a user and the user took no part in the complex recording process. They contended that the act of “making” a film could occur as an automated computer process that involved no human intervention, citing Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Ltd (2011) 194 FCR 285 at 320-322 [151]-[158] per Emmett J and 363-364 [328]-[329] per Jagot J. The rightholders also asserted that the TV Now service was best characterised as one in which the user asked Optus to copy a program on his or her behalf. They argued that s 111(1) required that the person who made the film had to do so for the sole purpose of his or her own private and domestic use by watching or listening to the material broadcast at a time more convenient than the time of the broadcast.

Legislative history of s 111

53 The Copyright Amendment Act 2006 (No 158 of 2006) repealed the former s 111 and substituted the present section. In the initial second reading speech, for an earlier version of what is now s 111, the Minister had said (Hansard: The Senate: 6 November 2006 at p 136):

“First, the reforms recognise that common consumer practices of ‘time-shifting’ of broadcasts and ‘format-shifting’ of some copyright material should be permissible.

This bill will amend the Copyright Act to make it legal for people to tape TV or radio programs in order to play them at a more convenient time.

It will be legal to reproduce material such as music, newspapers and books into different formats for private use—meaning people can transfer music from CDs they own onto their iPods and other music players. As a result of these changes, millions of consumers will no longer be breaching the law when they record their favourite TV program or copy CDs they own into a different format.

These reforms are innovative and technology is changing rapidly.” (emphasis added)

54 The Explanatory Memorandum for this draft of the Bill referred to the then lack of provision to enable copying for private or personal use. It explained that this situation was increasingly out of step with consumer attitudes and behaviour. It noted that copying for personal use was particularly popular in two areas: time-shifting and format-shifting (where an individual buys copyright material such as music, and then copies it to other devices that he or she owns that are capable of replaying it, even if the devices use different formats). The Explanatory Memorandum recognised that a range of new consumer devices was being marketed “… to simplify and encourage the private copying of television broadcasts” and that such acts usually infringed copyright. It continued:

“Many ordinary Australians do not believe that ‘format-shifting’ music they have purchased or ‘time-shifting’ a broadcast for personal use should be legally wrong with a risk of civil legal action, however unlikely. Failure to recognise such common practices diminishes respect for copyright and undermines the credibility of the Act.

The failure to recognise the reality of private copying is also unsatisfactory for industries investing in the delivery of digital devices and services. Eg, the supply of personal recording devices by broadcasters of subscription television services is proving to be important for the development of digital television. The availability of personal recording devices is also likely to be important for digital radio.” (emphasis added)

55 The Explanatory Memorandum said that specific exceptions should be introduced into the Act to permit both time-shifting and format-shifting to restore credibility to the Act. It saw this step as giving certainty to copyright owners, users and “industries that provide products and services that assist consumers carry out these copying activities. It said that this approach would “facilitate the growth of digital television and radio services”. The Explanatory Memorandum also considered that the recognition of these present practices would be likely to have negligible market impact.

56 During the second reading debates, two important amendments were made that affected the proposed cl 111(1) as first introduced in the Bill. First, the definition of “private and domestic use” was added to s 10 in the Senate at the same time as what became s 111(3)(e) and (f) and s 109A. Soon after, cl 111(1) was amended by deleting the words “in domestic premises and” that had appeared immediately before “solely for private and domestic use”. In moving these amendments in the Senate, the Minister said of the new definition of “private and domestic use” (Hansard: The Senate: 30 November 2006 at p 145):

“The bill adds new copyright exceptions that permit the recording or copying of copyright material for private and domestic use in some circumstances. This amendment makes it clear that private and domestic use can occur outside a person’s home as well as inside. The amendment ensures that it is clear that, for example, a person who under new section 109A copies music to an iPod can listen to that music in a public place or on public transport. (emphasis added)

57 The Minister then explained in the Senate, repeating the words of the Further Supplementary Explanatory Memorandum, why cl 111(1) had been reworded saying (ibid):

“This relates to time shifting. ... This amendment substitutes a new section 111(1), which removes the requirement that a recording of a broadcast under section 111 must be made in domestic premises. This amendment provides greater flexibility in the conditions that apply to time-shift recording. The development of digital technologies is likely to result in increasing use of personal consumer devices and other means which enable individuals to record television and radio broadcasts on or off domestic premises. The revised wording of section 111 by this amendment enables an individual to record broadcasts as well as view and listen to the recording outside their homes as well as inside for private and domestic use.” (emphasis added)

Issue 1 : Consideration

58 A person needs to employ technical equipment to make a film of a broadcast. Section 111(1) does not require the person who makes the film to have any particular relationship, such as ownership, to the equipment by which it is made. The Parliament must have contemplated that a variety of techniques and technical equipment could be used by a person to make a film of a broadcast. Since the 1980s households have had an evolving array of recording equipment capable of making a film, or in popular parlance “copying”, what is broadcast on television. Since the House of Lords decided CBS Songs Ltd v Amstrad Consumer Electronics Plc [1988] AC 1013, copyright legislation has had to balance the legitimate interests of the makers of original works and of ordinary citizens who use technological advances to copy those works for their own use in their private or domestic lives. In that case their Lordships refused to prohibit sales of blank tapes, recorders or similar electronic equipment that were capable of making copies of another’s copyright work merely because people might use these in their own homes to make copies of such work, rather than work not protected by copyright. Mere sale of articles that have lawful uses does not constitute authorisation of infringement of copyright, even if the manufacturer or vendor knows that there is a likelihood that the articles will be used for an infringing purpose, such as home recording, so long as the manufacturer or vendor has no control over the purchaser’s use of the article: Australian Tape Manufacturers Association Ltd v Commonwealth (1993) 176 CLR 480 at 498 per Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane and Gaudron JJ.

59 As Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ acknowledged in Stevens v Kabushiki Kaisha Sony Computer Entertainment (2005) 224 CLR 193 at 213 [54], because of the complex nature of the intangible form of property that it creates, copyright legislation in Australia and elsewhere gives rise to difficult questions of construction. The task of construction requires the Court to discern where the Parliament drew an enforceable line between the exclusive rights to exploit the proprietary interest it created and conferred on the owner of copyright in a work and the ability of others to use and copy that work. Amstrad [1988] AC 1013 recognised the somewhat symbiotic love-hate relationship between the entertainment industry, the electronics and communications industries and the consuming public. The entertainment industry, of which the AFL and NRL are part, wants to exploit and maintain its exclusive rights over its output. The electronics and communications industries want to sell their products and services to enable the public to see and hear and, of course, copy what the entertainment industry is exploiting. The public want to utilise the latest that technology has to offer to see and hear the entertainment as often as they desire, using whatever medium is most convenient.

60 The daily life of persons in Australia and many other countries has transformed over the last 20 years with advances in technology. Indeed, the subject matter of these proceedings would have been unimaginable two decades ago. Now, a person using a mobile phone, that can sit in the palm of his or her hand, can watch a recorded, or even near live, football game or other entertainment program that had been, or is being, broadcast on free to air television. The technology used by the TV Now service does not allow a user to download or copy any recorded, or near live, program onto his or her compatible device. The technology does allow a copy to be created, at the instance of the device’s owner or user, and stored by Optus’ infrastructure.

61 A person who makes a recording of a broadcast for his or her personal and domestic use, solely for the purpose of viewing or listening to it at a more convenient time, is described as having “time-shifted” the broadcast: cf: Laddie, Prescott & Vitoria, The Modern Law of Copyright and Designs (Vol 1, 4th ed, LexisNexis, 2011) at p 913 [21.107].

62 Who “makes” the copy for the purposes of the Copyright Act in a situation like that provided by the TV Now service? In some ways, this question resembles the old conundrum of which came first: the chicken or the egg? Different courts confronted by a similar dilemma to that presented here have approached it by recognising that identification of a policy choice may be a key to construing whether an infringement of copyright has occurred: cp, on the one hand, Network Ten Pty Ltd v TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 273 at 287 [29] per McHugh A-CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ; Cartoon Network LP, LLLP v CSC Holdings Inc 536 F 3d 121 at 138 (2008: CA 2), Record TV Pte Ltd v MediaCorp TV Singapore Pte Ltd [2011] 1 SLR 830 at 859-860 [69] per VK Rajah JA with, on the other hand, the view of the district judges in Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation v Cablevision Systems Corporation 478 F Supp 2d 607 (2007 SD NY) at 617-620 (who was reversed by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in Cartoon Network 536 F 3d 121), and Arista Records LLC v Myxer Inc (C.D. Ca unreported 1 April 2011; 2011 US Dist LEXIS 109668) at p 19.

63 I am of opinion that the user of the TV Now service makes each of the films in the four formats when he or she clicks on the “record” button on the TV Now electronic program guide. This is because the user is solely responsible for the creation of those films. He or she decides whether or not to make the films and only he or she has the means of being able to view them. If the user does not click “record”, no films will be brought into existence that he or she can play back later. The service that TV Now offers the user is substantively no different from a VCR or DVR. Of course, TV Now may offer the user a greater range of playback environments than the means provided by a VCR or DVR, although this can depend on the technologies available to the user.

64 The ordinary and natural meaning of “makes” and “making” in the sense in which those words are used in s 111(1) and (2) is “to create” by initiating a process utilising technology or equipment that records the broadcast. No doubt a director could be said to “make” a film as his or her creation of an original work in the sense of “make”, as that word is used in s 22(4). But, s 111 is dealing with an individual creating a film, being a copy of a broadcast by using some available technology or equipment to reproduce someone else’s original work. The complexity of making a recording or film of a broadcast requires the person referred to in s 111(1) to use a means external to himself or herself to do so. The concept of “making a film or recording” employed by s 111(1) and (2) is concerned with the creation by one person of a copy of a second person’s original work so that, as a result, a film or recording is brought, somehow, into existence by the first person’s action. The concept is not concerned about the technological or other means by which that result is created. It is unlikely that the Parliament intended to confine, in a presumptive way, the technology or other means available to be used by a person who wished to make a film solely for private or domestic use and subject to the other conditions in s 111.

65 The legislative materials do not support the rightholders’ argument that, in effect, the user could only utilise technology or equipment with which he or she had some greater connection than the “record” button on the TV Now electronic program guide. The Parliament intended that an individual should be able to time-shift by making a copy of a broadcast that he or she could watch or listen to at a more convenient time. The TV Now service provides the user with a means for him or her to make a film of a broadcast. As the Minister said in moving the amendment of s 111, it was intended to provide greater flexibility in the conditions that apply to time-shifting, allowing recording of films by individuals inside or outside their homes. VK Rajah JA, giving the judgment of the Singapore Court of Appeal in Record TV [2011] 1 SLR at 841 [21], described the differences between “traditional” VCRs and DVRs, on the one hand, and technology similar to that in Optus’ infrastructure for the TV Now service on the other, as follows:

“The fundamental objective of time-shifting is to allow a show to be recorded on a storage medium so that it may be viewed or listened to at the consumer’s convenience after it is broadcast. This is a perfectly legitimate activity so long as it does not constitute copying copyright-protected material or communicating such material to the public contrary to copyright laws.”

66 Here, the only person who could cause the Optus datacentre to bring into existence or create the films in the four formats was the user who clicked the instruction “record” on his or her compatible device. I agree with the reasoning of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in Cartoon Network 536 F 3d at 131 that there is no real or sufficient distinction between the characterisation of a user of a service, like TV Now, to record a film of a broadcast and a person who uses a VCR (or DVR) to do so, as the person who makes the copy of the work alleged to be an infringement of another’s copyright. The Court of Appeals did not consider that a service provider should be made liable for directly infringing a rightholder’s copyright simply by offering a service that makes copies automatically upon a user’s command.

67 Moreover, because of the way the TV Now service is designed, a film cannot be made unless a user clicks the “record” button. In University of New South Wales v Moorhouse (1975) 133 CLR 1 the High Court held that a student had infringed the copyright of an author by photocopying part of his book on a photocopier provided by the University in its library. However, the Court also held that the University was secondarily liable for authorising the infringement. That was because it had power to control the copying activity on its machines but failed to take steps to prevent infringement, while providing potential infringers with copyright material and the use of its machines by which infringing copies could be made: Australian Tape Manufacturers 176 CLR at 498 per Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane and Gaudron JJ; Moorhouse 133 CLR at 17 per Gibbs J, 22-23 per Jacobs J with whom McTiernan ACJ agreed. Critically, for present purposes, Gibbs J said that it was “impossible to hold” that the University did the act of photocopying when the student copied the part of a book in its library (133 CLR at 11).

68 In my opinion, there is a reasonable analogy between the University’s provision of the photocopier and Optus’ provision of the TV Now service. Each of them provided a means for a third person – a student or a user – to make a copy or a film. But, as Gibbs J reasoned, it was impossible to say that the University did the act of photocopying by providing the photocopier, just as, in my opinion, it is impossible to say that Optus makes any of the films in the four formats that are created when a user clicks “record” and its datacentre carries out that instruction.

69 The rightholders made a faint submission, that became much fainter in oral argument, that s 22(4) supported their argument that Optus made the films in the four formats. They accepted that the original purpose of s 22(4) was to deal with the subsistence and ownership of copyright in films. Having regard to the legislative history of s 111 and its evident purpose, I do not consider that s 22(4) is of particular assistance in construing “makes” and “making” as those words are used in s 111(1) and (2). Section 22(4) deals with who first “makes” a cinematograph film and thus is entitled to copyright in his or her original work. Unlike its purpose in enacting s 22(4) to identify who made the very first version of a cinematographic film, the Parliament did not intend to give copyright under s 111 to individuals who made or copied films of others’ copyright material. Section 111 deals with the position of a member of the community who “makes” what would otherwise be an infringing film by relieving him or her of the consequences of infringement if particular conditions are fulfilled. It is clear enough that the maker referred to in s 22(4) could never be the same as the person referred to as a maker in s 111(1) and (2) because such a result would fly in the face of the operation of s 111(3). That provision negates a person’s exemption from infringing copyright under s 111(2), if he or she does any of the acts it specifies. The acts specified in s 111(3) quintessentially comprise aspects of the right to exploit one’s own copyright. The person referred to as the “maker” of a film and the concept of “making” a film used in provisions such as ss 22(4), 90, 98 and 99 has all of the rights do what s 111(3) prevents the “maker” of a film referred to in s 111(1) doing with it.

70 I am of opinion that when s 111(1) and (2) refer to the “maker” and “making” they are dealing with individuals who are creating films or copies in the process of time-shifting. The use of the words “maker” and “making” elsewhere in the Act is different, namely, the latter use is the technical means of identifying the subsistence and ownership of copyright. Rather, in s 111(1) and (2), those words are used in the more colloquial sense, indeed in their natural and ordinary meaning, in order to identify who is to have the benefit, not of copyright in the film or copy, but of the exemption from liability for infringing another’s copyright: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v DB Management Pty Ltd (2000) 199 CLR 321 at 338 [34]-[35] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ.

71 For these reasons, I am of opinion that the user alone did the acts involved in recording the copyright works. It follows that Optus did not do any of those acts.

Issue 2 : Was recording the films an infringement of copyright?

72 Optus informed users in two separate places in the subscription process for the TV Now service that it was a breach of copyright to make a copy of a broadcast other than to record it for the user’s private and domestic use. In the second of those places, within the terms and conditions, Optus added that the copy also had to be recorded for use by watching the material broadcast at a more convenient time. I have emphasised these two warnings in [15] and [16] above. Also in the terms and conditions:

Optus promised the user that he or she could access the recordings on the user’s “compatible Optus mobile or PC”; and

the user promised that the TV Now service was for his or her “individual and personal use” and that he or she, in effect, would not breach any of the conditions in s 111(3).

73 The rightholders submitted that Optus had failed to prove that any of the films were made “solely for private and domestic use by watching or listening to the material broadcast at a time more convenient than when the broadcast is made” within the meaning of s 111(1). They contended that there was no evidence of any user’s purpose, let alone his or her having the sole purpose required by s 111(1) . The rightholders said that the making of four films in each compatible format negated the sole permissible purpose in s 111(1) because it had not been proved, and in any event was unlikely, that each user had all four kinds of compatible device. They contended that there was no need for more films to be made than the one necessary for the user to satisfy a desire to time-shift the broadcast for the convenience of his or her viewing. They argued that this gave the user significant freedom of choice as to the format for viewing. In addition, they argued that s 111(1) used the indefinite article “a” in the expression “makes a cinematograph film or sound recording” to denote that only one film or recording was authorised by the statute. Next, the rightholders argued that the evidence showed that users L and J had the first AFL program streamed to them within only about 1.5 and 11 minutes of the commencement time of the broadcast and that this did not amount to time-shifting of the broadcast. And, they argued that the use by small to medium businesses was outside the scope of the purpose in s 111(1) because such a business could not have a private or domestic use for such films.

Issue 2 : Consideration

74 The purpose of the exception in s 111(1) and (2) was to accommodate, to some degree, the law to the realities of modern life. Copying for private and domestic use is so much a commonplace that it is not difficult to infer that a user who made a film, by clicking “record”, was doing so for such a use. Indeed, the rightholders did not suggest how anyone, for example, watching a broadcast or film of a football game or television program, on his or her mobile device or PC would be doing so for some reason other than personal pleasure or interest. Similarly, even though small to medium business subscribers could sign on for the TV Now service, as a matter of practicality, the persons who could obtain access would be employees of, or individuals concerned in, those businesses. After all, a corporation, being an abstract creation of the law, cannot look at a film; only individuals are capable of that or of operating a mobile device or PC for that purpose So, whoever signed up for the TV Now service must have been an individual. That person’s use, not the corporation’s or business’s, is what is relevant for the purposes of s 111(1). Of course, if the person used the film for a business, non-personal or non-domestic purpose such as those proscribed in s 111(3), then s 111(1) and (2) would not apply to that use.

75 Here, the users agreed with the terms and conditions of the TV Now service that limited their use of it to a non-infringing use that complied with the purposes in s 111(1). Those terms and conditions expressly stipulated that the service was for the user’s “individual and personal use” and noted that the user would infringe copyright by making a copy of a broadcast other than to record it for his or her private and domestic use by watching it at a more convenient time. And, the only use that Optus authorised a user to make of the film was to play it at a time of his or her choosing within 30 days of the broadcast on mobile devices or PCs which are, of their nature, private. Optus also required a user to provide his or her own home address as a condition of signing onto the TV Now service. And, the user can only watch one recording from the TV Now service at a time.

76 The infringements complained of are that films of broadcasts of football matches were made in breach of the rightholders’ copyright. Each film of each broadcast remained in existence for only 30 days from the time of the original broadcast. There is no evidence that on the occasions in the agreed facts, any user had a purpose other than that of wanting to watch that game for his or her own private and domestic use and pleasure. Indeed, some of them replayed or revisited the recording on a number of a occasions. I infer that their purpose in playing (as well as in recording) the copyright works was for their own private and domestic use. That inference is conformable with the terms and conditions on which Optus provided the users with the TV Now service, and with which they agreed. Such an inference is also a recognition of the ordinary experience of life, that was assumed by the Parliament in ensuring that time-shifting of the kind provided for in s 111(1) and (2) would not be an infringement of copyright.

77 There is no evidence or other reason to suggest that individuals, such as the users of the TV Now service, were not making films solely for their own private and domestic use and had departed from their agreement only to use the TV Now service in that way. In these circumstances, a court should be slow to infer that those individuals have infringed the Act or copyright by making films having regard to s 111 and in circumstances such as those of the TV Now service. The value of the exception created by the Parliament, that is designed to give greater flexibility to individuals so as to take advantage of technological advances, would be seriously eroded if a service provider, who has structured a service as carefully as TV Now, had to lead evidence about each user’s individual purpose on each occasion of use: cf Record TV [2011] 1 SLR at 851 [46] ff.

78 However, the circumstances of the two users L and J and the facility offered by the TV Now service of being able to view broadcasts “near live” on Apple devices, require further consideration. As the rightholders submitted, there is a tension between “near live” viewing and a purpose of watching the material broadcast “at a time more convenient than the time when the broadcast is made” (s 111(1)).

79 The rightholders accepted in argument that recording technology generally available to individuals now allows a viewer of a television program to record it and, as it is being broadcast, the viewer can pause the live reception of the broadcast while continuing to record it so that he or she can, for example, make a cup of tea or coffee, or do something else in the house. When the viewer returns to where he or she has been watching, he or she will then play the recording from the moment when it was paused and no longer see the “live” program being broadcast. In this way the show may be watched “near live”, because it was a more convenient time to do so, since the viewer had been able to attend to whatever had made him or her pause the previously contemporaneous recording.

80 One feature of the Apple devices is that they permit a person to view a film of a broadcast “near live”. That raises the questions of why would someone want to watch a broadcast, not on a television, but using a mobile device or PC, and not “live” but only “near live”? First, the ability to time-shift creates a choice for a user of the time to view a film of a broadcast. In ordinary experience, the choice of the time a person does something is either because that is when the person wants to do it or he or she cannot do it at another time; i.e. the choice suits the person’s convenience. The meaning of the expression “a time more convenient than the time when the broadcast is made” in s 111(1) does not preclude watching a film “near live” if the viewer finds that to be more convenient. The section must be concerned with what the viewer subjectively thinks is a more convenient time for him or her. And, the convenience of a time for a person can be affected by other circumstances.

81 If a person can watch a broadcast “near live”, away from a television, that may enable him or her to do something else. For example, the person may want to finish a task at work in the time it would take to travel home, because he or she knows that, once he or she finishes the task, he or she can view the broadcast “near live” when travelling home late or while still at work. Such a purpose is consistent with the definition of “private and domestic use”. Moreover, the rightholders accepted that pausing the contemporaneous recording of a broadcast to allow a user to do something else, even momentarily, can entail that the recording is made for use immediately after the viewer finishes the distracting event because that is a time more convenient than the time when the broadcast is made.

82 In the circumstances, and in the absence of any other evidence, I infer that users L and J made their films and viewed them “near live” solely for private and domestic purposes by watching them at a more convenient time than that of the live broadcast.

83 I am not persuaded by the rightholders’ argument that the user cannot have made the films in the four formats solely for his or her private and domestic use within the meaning of s 111(1) because he or she did not know that more than one copy would be created. The user is indifferent to the process that creates a film or films that only he or she can gain access to, so long as the TV Now service delivers a streamed film to whatever compatible device he or she chooses to use to watch the recorded film. The protection afforded by s 111(2) to a person who makes a film and satisfies the conditions in s 111(1), operates primarily in respect of the liability for infringement of copyright that would otherwise be created by s 101: cf Network Ten 218 CLR at 288-289 [34]. That is because broadcasts and films are principally dealt with in Pt IV of the Act. Provided that the user satisfies the requirements in s 111(1), each of the films in the four formats that he or she causes some technology or equipment to make, will not infringe copyright by force of s 111(2) unless one of the circumstances in s 111(3) has occurred.

84 I reject the rightholders’ argument about the use of the indefinite article in the expression “makes a cinematograph film” in s 111(1). The Act does not evince a contrary intention to the presumption of statutory construction that words in the singular number include the plural and vice versa as provided in s 23(b) of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth). The exception from infringement provided in s 111 was intended to accommodate the development of technologies and the ordinary ways in which individuals can avail themselves of them. The user need not be confined to using the TV Now service on one type of compatible device. He or she may have access to at least a compatible mobile phone and a PC. The user may also visit a friend and want to see the film with that person on the friend’s compatible device by logging into his or her TV Now subscription.

85 For these reasons, I am satisfied that, by force of s 111(2), the users referred to in the agreed facts did not infringe copyright in any of the rightholders’ broadcasts or films.

Issues 3 and 5 : Does Optus communicate the film when the user plays it?