FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Mercedes Holdings Pty Ltd v Waters (No 3) [2011] FCA 236

FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Mercedes Holdings Pty Ltd v Waters (No 3) [2011] FCA 236

CORRIGENDUM

1. The appearance for the solicitor for the Thirteenth Respondent should read “Tucker & Cowen Solicitors”.

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Corrigendum to the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Perram. |

Associate:

Dated: 3 May 2011

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA | |

| First Applicant MAX INVESTMENTS (AUST) PTY LIMITED Second Applicant MANSTED ENTERPRISES PTY LTD Third Applicant MICHELLE O'GARR Fourth Applicant JM CUSTOMS & FREIGHT SERVICES PTY LIMITED Fifth Applicant OSVON PTY LIMITED Sixth Applicant ADAM JOHN THORN & GRAHAM DEAN Seventh Applicant MARK ROBERT HODGES & JANET ANNE HODGES Eighth Applicant | |

AND: | First Respondent MICHAEL JOHN ANDREW Second Respondent WELLINGTON INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT LIMITED Third Respondent OCTAVIA LIMITED Fourth Respondent GUY HUTCHINGS Fifth Respondent JOHN ARTHUR WHATELEY Sixth Respondent JACK SIMON DIAMOND Seventh Respondent CRAIG ROBERT WHITE Eighth Respondent DEBORAH BEALE Ninth Respondent STEVEN KRIS KYLING Tenth Respondent STUART ROBERTSON PRICE Eleventh Respondent MICHAEL GORDON HISCOCK Twelfth Respondent MICHAEL CHRISTODOULOU KING Thirteenth Respondent PAUL JOSEPH MANKA Fourteenth Respondent IAN ZELINSKI Fifteenth Respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Dismiss the applicants’ notice of motion filed 5 July 2010 with costs.

2. Direct any party wishing to file an application to dismiss the balance of proceedings summarily to do so by Friday 22 April 2011.

3. Direct the applicants to file any application to amend the proceedings to pursue a claim in negligence against the first and second respondents by Friday 22 April 2011 in the form of a notice of motion supported by an affidavit.

4. Direct the applicants to deliver only one version of the proposed pleading and not to deliver any further drafts of any proposed pleadings after Friday 22 April 2011 with the intent that the applicants are to deliver the final pleaded version of the case by Friday 22 April 2011 come what may.

5. Direct the applicants that any pleading delivered by them pursuant to Orders 3 and 4 not exceed 50 pages in length.

6. Order the applicants to pay the costs of the fifth, eleventh and thirteenth respondents associated with the abandoned claim for accessorial liability.

7. The application for leave to discontinue against the fifteenth respondent is dismissed.

8. The confidential exhibit on the discontinuance motion may be returned.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules. The text of entered orders can be located using Federal Law Search on the Court’s website.

NEW SOUTH WALES DISTRICT REGISTRY | |

GENERAL DIVISION | NSD 324 of 2009 |

BETWEEN: | MERCEDES HOLDINGS PTY LIMITED First Applicant MAX INVESTMENTS (AUST) PTY LIMITED Second Applicant MANSTED ENTERPRISES PTY LTD Third Applicant MICHELLE O'GARR Fourth Applicant JM CUSTOMS & FREIGHT SERVICES PTY LIMITED Fifth Applicant OSVON PTY LIMITED Sixth Applicant ADAM JOHN THORN & GRAHAM DEAN Seventh Applicant MARK ROBERT HODGES & JANET ANNE HODGES Eighth Applicant

|

AND: | ANDREA JANE WATERS First Respondent MICHAEL JOHN ANDREW Second Respondent WELLINGTON INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT LIMITED Third Respondent OCTAVIA LIMITED Fourth Respondent GUY HUTCHINGS Fifth Respondent JOHN ARTHUR WHATELEY Sixth Respondent JACK SIMON DIAMOND Seventh Respondent CRAIG ROBERT WHITE Eighth Respondent DEBORAH BEALE Ninth Respondent STEVEN KRIS KYLING Tenth Respondent STUART ROBERTSON PRICE Eleventh Respondent MICHAEL GORDON HISCOCK Twelfth Respondent MICHAEL CHRISTODOULOU KING Thirteenth Respondent PAUL JOSEPH MANKA Fourteenth Respondent IAN ZELINSKI Fifteenth Respondent

|

JUDGE: | PERRAM J |

DATE: | 18 MarCH 2011 |

PLACE: | SYDNEY |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

I

1 The applicants bring suit on their own and others’ behalf for events arising out of the affairs of a property trust known at the relevant times as the MFS Premium Income Fund which is now known as the Premium Income Fund. I shall refer to it as the Fund. The applicants have previously applied to amend their statement of claim but that application was refused because of various difficulties with the pleading: Mercedes Holdings Pty Ltd v Waters (No 2) (2010) 186 FCR 450 (Mercedes (No 2)). The applicants have regrouped and they now again apply by motion for leave to amend their statement of claim. At the same time, they seek leave to discontinue against the fifteenth respondent, Mr Zelinski. Leave is required because the representative nature of the proceeding engages s 33V(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and thereby the necessity of the Court’s sanction for its discontinuation. For the reasons which follow both applications should be refused. The applicants must bear the costs of the application to amend. It is convenient in the first instance to commence with the amendment application.

II

The application to amend: the evidence and the various parties

2 The applicants proceeded on a notice of motion filed on 5 July 2010 which sought generally a grant of leave to file an amended statement of claim and a further amended application. In support of that application Mr Martin SC who, with Mr Drew of counsel, appeared for the applicants, read an affidavit of Mr George Robert Charles Hoddle sworn 9 July 2010. This affidavit exhibited earlier iterations of the proposed pleading which, as events have turned out, have been largely superseded by later versions and those exhibits were not placed before me. Ultimately the only significance of Mr Hoddle’s evidence was to prove that a box of five lever arch folders of papers known as the Core Documents were the set of documents referred to in a letter written on the applicants’ behalf on 4 June 2010. These Core Documents – and their origins – are of considerable importance to one set of the issues to be resolved on the present application and I return to them below. The five folders of Core Documents and the box containing them formed Exhibit 2.

3 The final version of the proposed further amended application and the proposed amended statement of claim ultimately filled two lever arch folders and became Exhibit 1. The proposed pleading is 676 pages in length. Its predecessor, leave to file which was refused in Mercedes (No 2), was 571 pages in length. Of that document I was moved on the last occasion to remark that it was “prolix, repetitious and frequently obscure” (Mercedes (No 2) at 453 [6]), a sentiment which I apprehend has left the pleader of the present document largely unmoved. I should record, however, that on this occasion the proposed pleading was accompanied by a 13 page aide-mémoire to assist me in understanding, and perhaps better appreciating, the apparent necessity for what appears to be, at least at first blush, a document of extraordinary length.

4 Mr Martin SC also tendered, without objection, an affidavit which had previously been filed on behalf of the third respondent, Wellington Investment Management Limited, being the affidavit of Ms Jennifer Joan Hudson sworn 29 October 2009, and it was received, perhaps unusually but without objection, as Exhibit 3. Ms Hudson’s affidavit throws some light on the nature of the Core Documents.

5 The respondents are broken into a number of camps for the purposes of the amendment application. The first camp consists of the Fund’s former auditor and the firm of which she is a partner. On the application to amend they were represented by Mr Lockhart SC and, with him, Mr Arnott of counsel. They did not seek to lead any evidence confining themselves instead to legal submission. I will refer to the auditor and her firm as the auditors although this is strictly inaccurate as the first respondent alone filled that position.

6 The second camp consists of the sixth, seventh and ninth respondents, Mr Whateley, Mr Diamond and Ms Beale, who were three directors of the former responsible entity of the Fund which was known at the relevant time as MFS Investment Management Ltd (MFSIM). This camp was represented by Mr Jackman SC who appeared with Mr Colquhoun of counsel. Mr Jackman SC tendered, on the basis that it contained admissions, an affidavit of Mr John Walker dated 2 December 2009. Mr Walker is an officer of a litigation funder standing behind the applicants. Mr Walker’s affidavit was received as Exhibit 4.

7 There were then a series of directors of the former responsible entity who were separately represented. Of these members, at this stage, mention need only be made of the thirteenth respondent, Mr King, and the twelfth and fourteenth respondents, Messrs Hiscock and Manka. For Mr King an affidavit of Mr Daniel Davey of 2 August 2010 was read. The burden of that affidavit was to show that Mr King had entered into a personal insolvency agreement the effect of which was, so Mr Ash of counsel, who appeared for Mr King, submitted, to extinguish the applicants’ claims against him.

8 For Messrs Hiscock and Manka, Mr Horton, the solicitor who appeared on their behalf, read his own affidavit which, after successful objection, did not say anything of substance. He also tendered a letter dated 16 July 2010 from his own firm to the applicants’ solicitors and another letter from those same solicitors to him dated 22 July 2010. These I admitted as Exhibits 5 and 6 respectively. Mr Kidd of counsel appeared for the present responsible entity who is the third respondent. Ms Taylor, solicitor, appeared for Mr Hutchings, the fifth respondent and Mr Cohen, solicitor, appeared for Mr White, the eighth respondent. Mr Goodman of counsel appeared for the eleventh respondent.

II

The issues

9 Unsurprisingly, given the length of the proposed pleadings and the presence of a dozen legal practitioners (including three senior counsel) at the bar table, the parties joined issue on a broad range of matters. In outline these were as follows:

(a) the standing issue

10 The applicants claim that the value of their units in the Fund was diminished by the actions of the respondents. The auditors, and a number of the other respondents, submit that any loss was suffered by the responsible entity which alone has standing to sue. This complaint was made about the previous pleading and, on that occasion, I rejected it: Mercedes (No 2) at [112]. The applicants say therefore that the question should not be revisited.

(b) the failure to carry out an audit issue

11 Part of the applicants’ case against the auditors is that they did not carry out an audit of MFSIM’s compliance with the compliance plan for the years 2005, 2006 and 2007 in contravention of s 601HC(3)(b)(i) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The auditor and her firm submit that the particulars provided to support that allegation are not sufficient which is denied by the applicants.

(c) the knowledge of the compliance plan failures issue

12 The applicants seek to make a case that the auditor was aware of circumstances that she had reasonable grounds to suspect amounted to a contravention of s 601FC(1)(h) of the Corporations Act 2001 which requires the responsible entity of a managed investment scheme to comply with the scheme’s compliance plan. The applicants say that the auditor was aware of such circumstances because she had read a number of specified categories of documents relating to the affairs of the Fund. However, these documents did not include amongst their number any which indicated the existence of any resolution by the manager to establish a compliance committee, a compliance committee charter or a credit committee, nor certain other matters. It followed, so the applicants’ pleading contends, that the auditor was aware of circumstances suggesting non-compliance with the compliance plan. The auditor and her firm submit that this allegation is illogical.

(d) the constructive knowledge issue

13 The applicants’ pleading contends that the auditor was aware of certain related party transactions because she had read the Fund’s financial statements which revealed their existence. The pleading goes on to suggest that with that knowledge she then abstained from further inquiry about those transactions because she knew that such further inquiry would provide her with reasonable grounds to know or suspect the various matters alleged in paragraphs 433 to 438 of the pleading. This allegation forms part of the applicants’ case that the auditor breached s 601HG(4) of the Corporations Act 2001 which requires an auditor to inform the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) of circumstances of which the auditor is “aware” and which the auditor has reasonable grounds to suspect amount to a contravention of the Act. The auditor and her firm submit that the word “aware” in s 601HG(4) requires actual knowledge and that constructive knowledge, as pleaded, does not suffice.

(e) the duty of care issue

14 The applicants sue the auditor in her capacity as the Fund’s auditor for the financial years 2005-2007. In the proposed pleading the applicants contend for the existence of a duty of care owed by the auditor to persons who became members of the Fund up until 29 January 2008 when redemptions of units in the Fund were frozen. The auditor submits that the proposed pleading does not disclose a relationship between her and unit holders who acquired their units after the completion of the 2007 audit so that, as pleaded, no duty of care could arise.

(f) the Core Documents issue

15 The applicants’ case against the sixth, seventh and ninth respondents centres around a series of allegations that they breached their general law and statutory duties as directors of the responsible entity by failing to do certain things or take certain steps in respect of 11 sets of impugned transactions. The broad way in which the pleading puts this case is to allege: first, that the applicants have been given access to a selection of the Fund’s documents by the current responsible entity (known as the Core Documents); secondly, that nothing in the Core Documents suggests that the things were done or the steps taken; and, thirdly, that it should be inferred from the nature of the Core Documents that the absence of any such material suggests that those things were not done and that those steps were not taken. Mr Jackman SC submits that an examination of the Core Documents together with the surrounding context in which they were provided to the applicants demonstrates that such an inference cannot reasonably be drawn. Accordingly, so he submits, the pleaded case is doomed to fail and hence is unviable. The third, fifth, eighth and eleventh to fourteenth respondents adopt this submission.

(g) the case management issues

16 The sixth, seventh and ninth respondents submit that it is appropriate, in considering an amendment application, to take account of case management issues such as delay and expense. They submit that the present pleadings have been amended seven times and, even on the most beneficent view of affairs, there will inevitably be more amendments together with the incurring of further expense. They say this provides an independent reason for declining leave to amend even if the pleading is otherwise in order. This submission was adopted by the fifth and eleventh to fourteenth respondents.

(h) The overlength/incomprehensibility issue

17 The third, fifth, sixth, seventh, ninth, twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth respondents each criticised the great length of the proposed pleading and emphasised some of its obscurities. They submitted that these considerations, too, provided a basis upon which to decline leave to amend.

(i) the immediate payment of costs issue

18 The sixth, seventh, ninth and twelfth and fourteenth respondents submit that there is a high likelihood that the pleading will need to be amended again even if leave is now granted and that this process of amendment is likely to be expensive and time consuming. In view of the history of the matter they submit that if leave to amend is to be granted then it should be on condition that all of their costs to date be payable forthwith.

(j) the discontinued applicants issue

19 Should leave be granted, the applicants seek to remove the first to seventh applicants as parties. The eleventh respondent seeks to ensure the continuing efficacy of costs orders already made against them. This submission is adopted by the fifth respondent and the thirteenth respondent.

(k) the bankruptcy issue

20 On 4 August 2009 the thirteenth respondent entered into a personal insolvency agreement. He argues that s 229 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) has the effect of barring any further proceedings against him by the applicants. The thirteenth respondent also submits that the applicants’ conduct in pursuing him after being made aware of the agreement warrants an indemnity costs order.

(l) the summary dismissal issue

21 The sixth, seventh and ninth respondents, supported by the fifth and thirteenth respondents, submit that not only should leave not be granted but that the proceedings should be dismissed summarily.

(m) some non-issues

22 Because of the complexity of the pleading and also of some of the submissions it is useful to record some matters upon which there was, by the time of the hearing, some agreement. First, the sixth, seventh and ninth respondents formally repeated their argument that, in light of Mesenberg v Cord Industrial Recruiters Pty Ltd (1996) 39 NSWLR 128, the applicants had no standing to pursue a remedy under s 1325(2) of the Corporations Act 2001. However, they accepted that my previous determination to the contrary when rejecting the applicants’ last attempt to amend resolved the issue for the purposes of the present application: cf Mercedes (No 2) at 463 [49]. Secondly, the applicants accepted the force of two submissions contained in the auditor’s written submissions at paragraph 4(b) and (c) which I do not need to resolve. Thirdly, the applicants accepted that they were obliged to pay the costs of the fifth, eleventh and thirteenth respondents in meeting a subsequently unpursued claim for accessorial liability.

23 It is convenient to deal with these issues in turn.

III

Standing

24 The proposed pleading alleges that if the auditor had performed her duties as auditor correctly then the former responsible entity would not have entered into a series of transactions described as “the Wrongful Transactions”. At paragraph 486 of the proposed pleading the applicants allege that “[a]s a result of allowing MFSIM… to enter into the Wrongful Transactions, the Fund has suffered loss and damage”. Of course, loss to the Fund is not the same as loss to the unit holders. Proposed paragraph 487 however, then alleges that “[b]y reason of the matters referred to in paragraph 486” the value of the units in the Fund held by each member of the class have been “substantially diminished and/or rendered worthless” and that they have, therefore, suffered “substantial” loss and damage. A similar allegation was made in the applicants’ previous proposed pleading.

25 At the time that the applicants sought leave to file that earlier pleading the auditors objected that such an allegation was one which sought to recover what has come to be called, in the authorities, reflective loss. Particular reliance was placed by the auditors upon the English Court of Appeal’s reasoning in Prudential Assurance Co Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd (No 2) [1982] 1 Ch 204 which holds, generally speaking, that a shareholder may not recover against a third party who has done a wrong to a company by means of a suit alleging a corresponding diminution in the value of the shareholder’s shares (at 222-223). For the purposes of the previous amendment application I distinguished cases about reflective loss involving corporations from those, as here, involving trusts: Mercedes (No. 2) at 476 [111]-[112]. I did so because I concluded that part of the reasoning in Prudential rested upon a concern to avoid unauthorised returns of capital, a notion having little applicability in the case of a trust.

26 Accordingly, I determined that the reflective loss principle was not a sufficient reason to decline to grant leave to amend (although, for other reasons leave was not, in any event, granted).

27 The auditor and her firm now submit that leave should be declined to the applicants to file the new version of the proposed pleading; again, on the basis of the reflective loss principle. Two broad questions arise: first, is this a course precluded by my prior rejection of the same argument in Mercedes (No. 2); and, secondly, if not, what is the status of the reflective loss principle on a claim by the unit holders of a unit trust.

(a) Revisiting Mercedes (No. 2)

28 The auditors argue that the applicants have brought a new application and, that being so, they are free to resist it by any means at their disposal. Alternatively they submit that the basis upon which Mercedes (No. 2) ostensibly rests – the need to avoid unauthorised reductions in capital – was not the subject of argument and that they should be permitted to argue against that conclusion.

29 The applicants submit that the question of whether leave to amend should be denied because of the reflective loss principle was determined in Mercedes (No. 2) and that authority suggested that it was not open to the auditors to seek to recanvas that prior interlocutory ruling: Brimaud v Honeysett Instant Print Pty Ltd (1988) 217 ALR 44 at 46 per McLelland J. They also say that the issue of unauthorised capital reductions was argued in Mercedes (No. 2).

Consideration

30 The submissions of the auditors are to be preferred.

31 It is generally not open to a party who has lost a substantial interlocutory argument to seek to reventilate the same issue once more. Whilst it is true that a court always retains the power to vary, set aside or discharge interlocutory orders that power is subject to the overriding public interest in avoiding the deployment of the court’s processes in an abusive fashion. When a substantive argument has been had and determined then, absent fresh material not available at the time of the original hearing, it will generally be impermissible to seek to argue the matter once more. Were it otherwise, the Court and the parties might well be vexed by an endless array of never ending interlocutory disputes. As McLelland J remarked in Brimaud v Honeysett Instant Print Pty Ltd (1988) 217 ALR 44 at 46 of a case involving an interlocutory order made following substantive argument with the understanding that the order would apply for the balance of the proceeding “…the rule of practice is that an application to set aside, vary or discharge the order must be founded on a material change of circumstances since the original application was heard, or the discovery of new material which could not reasonably have been put before the court on the hearing of the original application”. Of course, that is not quite the present situation for it is not sought to vary a prior order. Nevertheless, the same principles apply to substantive interlocutory determinations generally and not just to those embodied in orders.

32 In this case there is no doubt that the auditors were heard on the question of reflective loss as the applicants correctly submit. However, to put the matter that way is to ignore the rather more critical point that they did not have the opportunity to make submissions on whether the principle was distinguishable because of the different implications of capital reductions in the law of trusts. I reject the applicants’ argument that the capital reduction point was argued. The words were said but there is a difference between that and running an argument about the concept. I accept, therefore, that the auditors should be permitted to argue that leave should be refused on the basis of the reflective loss principle.

(b) The status of the reflective loss principle

33 The auditors submit that it is a well established principle of company law that a shareholder cannot sue to recover loss caused to the value of its shares by reason of harm to the company. Such losses are merely a reflection of the losses suffered by the company: Prudential Assurance Co Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd (No 2) [1982] 1 Ch 204 at 222-223 per Cumming-Bruce, Templeman and Brightman LJJ. They admit the possibility of a shareholder being permitted to recover loss and damage which is distinct from the harm to the company but not otherwise. In this case, however, they submit that the loss claimed by the unit holders is plainly a reflective one. Such a claim should not be permitted to go forward because, so they submit, the policy reasons underlying the principle in the case of corporations apply with equal force to trusts. Further, the English Court of Appeal has determined that the principle does apply to trusts: Webster v Sandersons Solicitors (A Firm) [2009] EWCA Civ 830 at [31] per Lord Clarke of Stone-cum-Ebony MR, Arden and Lloyd LJJ.

34 As far as the policy considerations were said to go the auditors submit that the principle prevents double recovery by ensuring that the company and shareholders do not recover concurrently from the same defendant. There was no reason not to apply that policy consideration to trusts where precisely the same problem was likely to arise. The related potential for a multiplicity of suits by different shareholders – possibly even in different jurisdictions – was equally a problem in the case of a trust, and, so the auditors submit, both carried the identical risk of generating inconsistent verdicts. Apart from that risk, there was the allied risk that the damages in each suit might transpire to be assessed on different bases. There were other problems too. The Court might need to have detailed regard to the terms of the trust in order to fashion the nature of any relief. This was because prohibitions in the trust instrument on returning capital to unit holders were not to be outflanked, Maginot-style, by a suit for reflective loss. Worse still, there was the possibility that the Court would be placed in the situation where it might have to work out what the trustee would have done in exercising powers under the trust. The conclusion in Mercedes (No. 2) at 476 [112] that the principle of reflective loss did not apply to trusts because there was no prohibition on unauthorised capital reductions in trusts law was, so the auditors submit, an incomplete statement. Whilst it was true that a trustee remained liable to creditors even if all of the assets of the trust were paid away, this was unlikely to mean much in the real world if the trustee was a company with no assets. Whilst trusts and companies were obviously not the same, each of these considerations operated in both areas in the same way. Accordingly, the auditors’ submission was that the English Court of Appeal’s conclusion in Webster was sound as a matter of policy and should be followed.

35 The applicants saw things somewhat differently. The loss they were claiming was not a reflective loss but a loss to their actual property in the units which was specifically a class of claim permitted even on the basis of the Prudential principle. Trusts stood in a fundamentally different position to companies and there were many distinguishing features. The beneficiaries plainly had vested property interests in the corpus of the trust whereas a shareholder had no interest in the property of the company. In that regard the unit holders’ interests might rise even as high as an equitable tenancy-in-common in the trust property. Theirs was not merely a right to participate in the affairs of the company linked (in some cases) to a right to share in profits; rather, it was an equitable interest in the very trust property itself. The position too of creditors was fundamentally different as they remained entitled to recover from the trustee even if the trust assets had been entirely depleted. Indeed, in contradistinction to the position obtaining in the case of the creditors of a company, permitting unit holders to recover for the loss and damage to their units caused no prejudice to creditors because the value of their units necessarily was the value of the assets of the trust less its liabilities. In any event, it was established that beneficiaries of a trust could pursue third parties who had harmed trust property. The applicants instanced the situation where a beneficiary sued a person who had knowingly participated in a breach of trust contrary to the rule in Barnes v Addy (1874) LR 9 Ch App 244. There could be no suggestion in a case of that kind that the beneficiaries could not themselves sue and this case was to be seen in a similar light. Even if that were wrong, it was established that beneficiaries could sue for harm to the trust property when the trustee refused to do so. In this case, the present trustee had contractually agreed with the applicants not to pursue the former responsible entity or its officers. Accordingly, the applicants fell within that exception. The applicants also submit that their claim under s 1325 of the Corporations Act 2001 is one in which the provision itself should be seen as giving them standing and they submit that they are supported in that argument by the decision of Gummow J in Poignand v NZI Securities Australia Ltd (1992) 37 FCR 363. They deny there are any difficulties arising from the risk of double recovery. If the trustee recovers first the harm to the units is correspondingly reduced; if the unit holders recover first notions of res judicata will restrain the trustee from also recovering inconsistently. As to the English Court of Appeal’s decision in Webster, the applicants submit that it can, and should, be distinguished.

Consideration

36 The application before the Court is an application for amendment pursuant to Order 13 rule 2 of the Federal Court Rules. Generally speaking, it would be inappropriate to permit an amendment which was bound to fail. It will be inappropriate to permit an amendment which would, for example, be liable to be struck out under Order 11 rule 16(a) as not disclosing a reasonable cause of action. That kind of power, as has often been noted, is one to “be exercised with great care and should never be exercised unless it is clear that there is no real question to be tried”: Fancourt v Mercantile Credits Ltd (1983) 154 CLR 87 at 99; applied in Spencer v Commonwealth (2010) 241 CLR 118 at 131 per French CJ and Gummow J. This is a high standard. There are statements to the effect that it is not easy for that standard to be achieved where a difficult question of law is involved (“[t]he jurisdiction to give summary judgment should not be exercised “where a difficult question of law is raised”…” Theseus Exploration NL v Foyster (1972) 126 CLR 507 at 514 per Barwick CJ). No hard and fast rule about this exists but such sentiments most likely reflect the forensic reality that difficult areas of the law rarely reveal themselves in categorical outline.

37 In this case two matters disincline me to refuse to permit the applicants’ proposed amendments because of the principle of reflective loss. The first is that whilst I accept the existence of the Prudential principle in relation to corporations, I do not accept that it has been clearly established in the case of trusts. There are important distinctions between trusts and corporations which make it difficult to be dogmatic about the outcome. Secondly, some of the questions which arise turn on the nature of each unit holder’s interest in the Fund and the terms of the trust. These were not before me.

38 There is no doubt that the principle that bars claims for reflective loss by shareholders presently forms part of the law of this country: Prudential Assurance Co Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd (No 2) [1982] 1 Ch 204 at 222; Gould v Vaggelas (1984) 157 CLR 215 at 219-20 per Gibbs CJ; Johnson v Gore Wood & Co (a firm) [2002] 2 AC 1 at 35 per Lord Bingham of Cornhill; Chen v Karandonis [2002] NSWCA 412 at [35]-[44] per Beazley JA; Gardner v Parker [2004] EWCA Civ 781 at [33] per Neuberger LJ; Thomas v D’Arcy [2005] 1 Qd R 666 at 675 per McPherson JA; Jakeman v Hawkins [2006] QSC 289; Ballard v Multiplex Ltd (2008) 68 ACSR 208 at [32]-[41] per McDougall J; Webster v Sandersons Solicitors (A Firm) [2009] EWCA Civ 830 at [37]; Groeneveld Australia Pty Ltd v Nolten [2010] VSC 249 at [36] per Ferguson J.

39 However, that is not the question on the present application. That question is instead whether the same principle applies in the case of trusts. No Australian authority to which I was taken has as its ratio decidendi that the beneficiaries of a unit trust cannot bring suit for harm done to the value of their units. Nor was I taken to any Australian obiter dictum to that effect. Of course it is established that, exceptional circumstances aside, the beneficiaries of a trust may not sue on the trust’s behalf whether on an equitable claim (Ramage v Waclaw (1988) 12 NSWLR 84 at 91 per Powell J; Alexander v Perpetual Trustees WA Ltd (2004) 216 CLR 109 at [55] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ) or a common law count (Lidden v Composite Buyers Ltd (1996) 67 FCR 560 at 564 per Finn J; Lamru Pty Ltd v Kation Pty Ltd (1998) 44 NSWLR 432 at 436-437 per Cohen J; Jacobs’ Law of Trusts in Australia (7th ed, Butterworths, 2006) § 2303, pp 622-623; Mercedes (No 2) at 474 [105]-[106]). There is no reason to think that Finn J’s reasoning from the Judicature Act 1873 (UK) system does not apply to statutory counts too.

40 However, that rule has no direct application here because the applicants do not seek to recover the harm done to the trust fund, but instead only the harm done to the value of their individual units. This is not a case, therefore, where the beneficiaries seek “to stand in the room” of the trustee: Parker-Tweedale v Dunbar Bank plc (No 1) [1991] Ch 12 at 19 per Nourse LJ, Woolf LJ and Purchas LJ agreeing.

41 I accept that the English Court of Appeal in Webster v Sandersons Solicitors (A Firm) [2009] EWCA Civ 830 applied the Prudential principle to a trust. The reasons of the Court on this issue were as follows (at [31]):

The pension fund is not a corporate body but a trust, whose assets are vested in the trustees for the time being. Similar principles apply. If there is a cause of action against a third party for causing loss to the trust fund, it is vested in the trustees for the time being. It can be asserted by them and, normally, only by them. The proceedings commenced in November 2007 were brought on this basis. Exceptionally, if the trustees fail to pursue such a claim, it may be open to a beneficiary to assert the claim in proceedings to which the trustees are also parties as defendants: see Hayim v Citibank [1987] AC 730. This has some similarity to a derivative action in company law, but it does not require further consideration here, since the claimant does not say that the trustees have failed to bring proceedings, and indeed he has in fact brought separate proceedings in his capacity as one of the trustees, together with the other trustee. A beneficiary under a trust does not have a direct cause of action in negligence against a person who may be liable to the trustees: see Parker-Tweedale v Dunbar Bank plc (No 1) [1991] Ch 12.

42 There are two things one may, with respect, say about this. First, the Court did not cite any authority for the proposition it asserted, or consider any of the features which might arguably be thought to distinguish the situation of a trust from that of a corporation. Its reasoning consists of the terse but pithy statement that “[s]imilar principles apply”. Secondly, the case cited by the Court of Parker-Tweedale v Dunbar Bank plc (No 1) [1991] Ch 12 is authority for two propositions: (a) that where a trustee unreasonably refuses to sue, a beneficiary may sue on behalf of the trustee; and (b) that, generally speaking, a mortgagee of trust property does not owe a common law duty of care to the beneficiaries of the trust when exercising its power of sale. Neither of those principles has anything to say, so it seems to me, about whether the corporate principle that denies recovery of reflective loss by shareholders applies to trusts.

43 Contrary to the submission of the applicants, however, I do not accept that Webster is distinguishable for it was concerned precisely with a claim by a beneficiary for harm done to his interest in a trust fund. It is true that he was the sole beneficiary but I do not see that that makes a difference.

44 It was once accepted that where there was no Australian authority controlling the outcome of a case trial courts and intermediate appellate courts should, as a general rule, follow decisions of the English Court of Appeal: Public Transport Commission (NSW) v J Murray-More (NSW) Pty Ltd (1975) 132 CLR 336 at 341 per Barwick CJ and 349 per Gibbs J; Viro v The Queen (1978) 141 CLR 88 at 120-121 per Gibbs J. However, since Cook v Cook (1986) 162 CLR 376 at 390 per Mason, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ it has been accepted that “the precedents of other legal systems are not binding and are useful only to the degree of the persuasiveness of their reasoning.” Viewed through that prism, I am bound to say that I do not think Webster carries one very far because there is no illumination thrown on why the principle applies to trusts; one is simply told that it does.

45 Nor have I found the various policy matters to which the auditors referred especially compelling at the level of an amendment debate. The auditor and her firm submit that there are four policy considerations underlying the principle and, contrary to my previous conclusion in Mercedes (No. 2), these are just as applicable to trusts as they are to corporations. The first policy consideration was identified by Lord Millett in Johnson v Gore Wood & Co (a firm) [2002] 2 AC 1 at 62 and that was the risk of double recovery. Just as permitting shareholders to recover a loss suffered by a company exposes the defendant to the peril of being sued again by the company so, the auditors submit, permitting the unit holders in a trust to do something similar poses much the same risk: that is, that the defendant will remain exposed to a suit by the trustee. The risk of double recovery requires, however, careful analysis. When the trustee (or indeed the company) recovers first no such risk arises for, as the applicants correctly point out, the value of the units (or shares for that matter) will be augmented by what has been recovered by the trustee or company prior to the suit seeking recovery for reflective loss. The risk, in fact, only exists when the unit holders (or shareholders) recover first. In that case there is no reduction in the trustee’s (or company’s) claim merely by reason of the fact that the unit holders (or shareholders) have recovered.

46 The applicants’ initial response to this issue was simply to assert that this was not a problem because the plaintiff trustee’s claim would be reduced by the amount of whatever had been recovered, by that stage, by unit holders. The mechanism at law or equity which achieved this miraculous reduction was, however, left unexplained. Ultimately, after more mature reflection the applicants submitted that the beneficiaries of a trust and the trustee were privies for the purposes of the law of res judicata so that, to the extent that the beneficiaries recovered a reflective loss, the trustee was bound by that outcome: cf. Gleeson v J Wippell & Co [1977] 1 WLR 510 at 515 per Megarry VC (“…in relation to trust property I think there will normally be a sufficient privity between the trustees and their beneficiaries to make a decision that is binding on the trustees also binding on the beneficiaries”). Ultimately, this may prove to be a two-edged sword for the applicants. It raises at once the issue of whether a shareholder and a company are privies for res judicata purposes. There are statements in both directions. The Full Federal Court in Effem Foods Pty Ltd v Trawl Industries of Australia Pty Ltd (1993) 43 FCR 510 proceeded on the evident assumption that the shareholders of a company were not its privies for res judicata purposes. The learned author of the 4th edition of Spencer Bower and Handley: Res Judicata suggests at [9.47] footnote 6 that Effem stands for the proposition that privity between a company and a shareholder is now widely accepted but I confess that is not how I read the decision. On the other hand, it certainly seems clear that the courts in some countries have accepted the possibility that, with appropriate facts, a shareholder, or even a manager, might be a company’s privy: cf Wire Supplies Ltd v CIR [2006] 2 NZLR 384 at 395 – 398 per Courtney J (affirmed [2007] 3 NZLR 458 at 465 (CA)); Laughland v Stevenson [1995] 2 NZLR 474 at 477 per Hillyer J applying Shiels v Blakeley [1986] 2 NZLR 262 at 268.

47 In this country, however, the decision in Ramsay v Pigram (1968) 118 CLR 271 has usually been thought to mean that privity of interest is only made out when it is shown that the privy claims “under or through the person of whom he is said to be a privy” (at 279 per Barwick CJ). For my part, I would have thought that until Ramsay is reconsidered there are difficulties in embracing the notion that a shareholder can be, simpliciter, the privy of a company.

48 It follows that the different treatment for res judicata purposes of beneficiaries and trustees, on the one hand, and shareholders and corporations on the other, means that the applicants may well have a point worth trying in relation to the ability of trustees and beneficiaries to bind each other in their respective litigation and hence prevent the double recovery problem adverted to by Lord Millett. However, there may be analytical difficulties in determining how, at the level of drawing up judgments and orders in favour of a trustee, the previous orders in favour of a beneficiary are to be accounted for.

49 Given this suite of diverting and difficult questions I do not accept that the policy considerations concerning double recovery in the case of companies are necessarily sufficiently identical to warrant the conclusion that Lord Millett’s reasoning in Johnson inevitably applies in the case of trusts.

50 The second policy matter the auditors pointed to as assisting them was the risk to creditors posed by permitting unit holders to recover reflective losses. In Mercedes (No. 2) I concluded (at 476 [111]) that whilst permitting shareholders to recover reflective losses posed the risk of an unauthorised capital reduction with a concomitant risk to a company’s creditors, this was not so in the case of a trust since the trustee’s liability to creditors was unaffected by a reduction in the capital of a trust. The auditors submit that this conclusion need not be correct and that the position of a large scale corporate unit trust is, in practice, likely to be very similar to that of a corporation. This was said to be so because such trust companies were unlikely to have any substantial assets beyond their indemnity out of the trust assets.

51 I do not think that observation draws near to establishing, at the requisite level, that the capital reduction problem is the same in the case of corporations and trusts. Indeed, it is, in substance, a factual assertion about some trusts. The auditors submit that the analogy was complete because the trustee was a corporation with limited liability. I do not see how this assists. The creditors of a corporation are limited in what they may recover to the assets of the company. To the extent that the assets are not sufficient and a shareholder has not paid up their part of the capital, they can be required to contribute on a winding up. In contradistinction, the creditors of a trust are not limited to the assets of the trust but instead to the assets of the trustee. The concept of the assets of the trustee has no analogue in company law. On the argument articulated by the auditors the real question concerns, I think, the asset position of the trustee. If the trustee has assets beyond its right of indemnity out of the trust assets then the argument that the capital reduction problem is the same in both cases is simply wrong. In any event, the limited liability of the trustee company’s shareholders does not connect with that argument. I do not accept in that circumstance that there is any reason to depart from my prior conclusions about this.

52 The auditors then suggest that the Prudential principle should be applied by analogy because the position of a trust deed was “directly comparable” to the position of the constitution of a company, particularly, so it was said, in the case of a unit trust. This was because the autonomy of the directors of a company and the trustee in the case of a trust were equally undermined by permitting shareholder or unit holder claims for reflective loss. Those in control of the company (or the trustee) might have good reasons for taking the decision not to sue a third party. By permitting unit holder claims, the autonomy of the nominated decision-making agent was reduced and this was potentially contrary to the decisional architecture contemplated by the relevant constitutive documents. There is force in this point. Unit holders hold their units subject to the terms of the trust constituting them and those terms specify the arrangements governing how decisions are to be made in relation to the trust property. The trustees of a trust may well decide that the interests of the unit holders are best served by not pursuing a particular suit. Permitting unit holders, via a reflective loss suit, to undermine the integrity of such decisions is potentially inconsistent with the terms of the trust.

53 The matter is complicated, however, because unlike the case of a share in a corporation, a unit in a unit trust is generally constituted by an aliquot equitable interest in the corpus of the trust. What the directors of a company control is the legal and equitable property of the company and, viewed from that perspective, their autonomy is not hindered by any possibility of interference from other property co-owners. The situation is not so tidy in the case of unit trusts, for the trustee does not own the beneficial interest in the trust assets. It may be that ultimately this is not a distinction of sufficient moment but I do not accept that the auditors are inevitably correct about this. Further, another answer may be that prohibitions contained in a trust deed on returns of capital may equip a defendant with a defence to a reflective loss suit. Any consideration of that family of issues would, however, require an examination of the terms of trust, an endeavour which has not been embarked upon on this application.

54 The fourth policy matter pointed to by the auditors was the potential for there to arise unfairness amongst the unit holders inter se. If a unit holder recovered on one basis and subsequently the trustee recovered on some lesser basis, the unit holder who pursued his or her own action would end up in a preferred position. So too, if after a unit holder’s successful suit and recovery a defendant became insolvent, this would result in the trustee in any later suit having to prove as a creditor, giving rise to much the same effect.

55 I accept this is a possible consequence of permitting claims for reflective loss. For myself, it may prove ultimately to be a good reason for extending the Prudential principle to unit trusts. However, I do not accept that, as an observation, it is sufficient to prevent the point even being raised so that it may be argued at trial.

56 For these reasons I am not prepared to say that application of the Prudential principle to trusts is inevitable. There are sufficient significant distinguishing features between a trust and a corporation which make it impossible to say, at the level of an amendment application, that a claim based on reflective loss must inevitably fail in the case of a trust. Whilst there is force in some (but not all) of the points made by the auditors, they are of a nature which is properly to be resolved at trial. More generally, I do not see how such a debate of the kind which the auditors wish to have can occur without an examination of the terms of the trust in question. There may be provisions in the trust which assist the auditors; on the other hand, there may not be. No party directed me to any instrument containing the terms of the trust, although evidence tendered suggested such a document may have been available to the parties. Paragraph 29 of the proposed pleading tells one that the Fund was originally constituted by a deed poll dated 23 November 1999. However, it goes on to plead in paragraph 30 that there was something called the Fund’s “constitution” from 2 June 2003. I assume that that must be some species of trust instrument although what I cannot presently say. What it says about capital reduction, the role of unit holder suits and so on is entirely unknown. This would, no doubt, be different at trial.

IV

The failure to carry out an audit issue

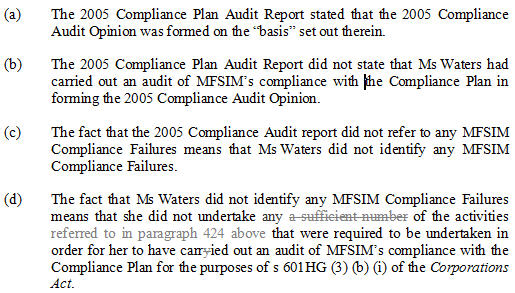

57 The proposed pleading alleges at paragraphs 425-427 that the auditor failed to carry out an audit in the financial years 2005 to 2007. This is not an allegation that an audit was conducted negligently, but, instead, an allegation that there was no audit at all. The particulars for each year are essentially the same. I will use the 2005 year as an exemplar:

58 For completeness one needs to know that paragraph 424 (referred to in (d)) sets out a list of 42 activities (listed over 18 pages) which, it is said, need to be undertaken by an auditor in order to audit a responsible entity’s compliance with its compliance plan. Armed with that knowledge the case disclosed is, I think, as follows:

(a) the audit report produced by the auditor of the responsible entity’s compliance with its compliance plan was formed on the basis set out in that report;

(b) in the course of writing her report, the auditor had not said that she had carried out such an audit;

(c) the auditor should be taken not to have identified any of the responsible entity’s compliance failures because her report did not identify any; and

(d) since she had failed to identify any of the compliance failures she cannot have carried out any of the 42 necessary activities.

59 With respect, step (b) is fanciful. One could no more conclude, from the fact that an auditor’s report did not expressly say that an audit had been performed, that such an audit had not been performed than one could say any of the following:

(a) a written submission which does not say it has been prepared following consideration of the law and the facts gives rise to an inference that it was not so prepared;

(b) a novel not containing the statement “This was produced as a result of creative activity” gives rise to an inference that it was not so prepared.

60 Leave to advance such a case would be frivolous and I will not permit it.

61 I am prepared to accept, on an amendment application, the logic of step (c). It is a plausible inference that that which was not referred to was not detected. However, I am unable to bring myself to embrace the ungainly logic of step (d). It does not follow as a matter of principle that any particular breach of duty can be inferred from the auditor’s failure to detect the alleged breaches by the former responsible entity of its compliance plan. One could not say, for example, that a termite inspector had not carried out any termite inspection at all just because he did not locate a nest of termites in the foundations. And this is so whether one divides the various duties of a termite inspector into a myriad of individual duties or not. In this case, the 42 duties alleged in the fearsomely proscriptive paragraph 424 demonstrate that very problem. For example, particular (f) provides that it is the duty of an auditor to:

develop and document an engagement plan that describes the expected scope and conduct of each engagement;

But it is logically impossible to deduce from the auditor’s (alleged) failure to detect the former responsible entity’s breach of its compliance plan a breach of this duty. Many other activities alleged have the same quality of exhibiting no logical connexion between the non-detection of compliance failures and the failure to carry out the activity, such as, for example, activities (b), (c), (d), (g), (h) and (j).

62 Those observations make the allegations in paragraphs 425-427, that no audit of compliance with the compliance plan had been conducted in the years 2005-2007, untenable. The provided particulars cannot conceivably demonstrate that no audit was conducted. Indeed, I feel bound to observe that there is something distinctly surreal about an allegation that an auditor did not conduct any audit at all which relies upon the audit report apparently produced as a result of the audit which did not happen. The applicants are, of course, correct when they emphasise that the purpose of particulars is to put the opposing party on notice of how its case will be put. The present difficulty is not, however, with their ability adequately to foreshadow what the case is; rather, the nature of the case to be put is plain but hopeless. There should be no grant of leave in respect of this set of allegations.

V

The knowledge of the compliance plan failure issue

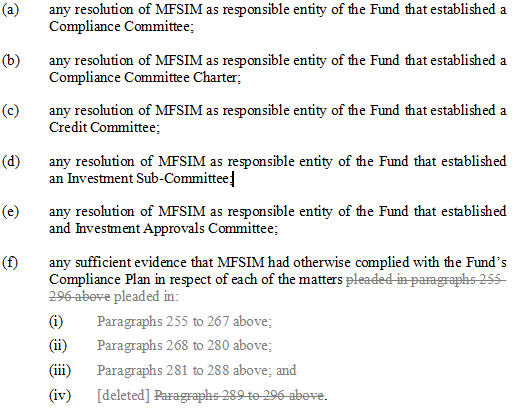

63 The auditor was under an obligation imposed by s 601HG(4)(a)(i) of the Corporations Act 2001 to inform ASIC of circumstances of which she was aware and which she had reasonable grounds to suspect amounted to a breach of the former responsible entity’s duties. The applicants seek to contend that the auditor was aware of the responsible entity’s compliance failures. This they do by making three further allegations. First, they say the auditor read a number of specified documents which, broadly speaking, consisted of various registers and minutes of the meetings of various committees. Secondly, at paragraph 437 they allege none of those documents contained:

64 The matters referred to in (f) are paragraphs 255-288 which (with one set of exceptions) are said, in paragraph 297, to constitute the former responsible entity’s compliance failures. This is important because the third allegation, in paragraph 438, is that the auditor’s awareness of those failures is to be inferred from the matters which were not contained in the documents seen by her.

65 I do not think that any such inference could be drawn from the fact that the documents the auditor saw did not contain those matters in (a)-(e). Paragraph (f) amounts to an assertion that the auditor was aware of circumstances which suggested a compliance breach because she had not seen any sufficient evidence to the contrary. But that effectively summons a case out of nothing. To use an example suggested by Mr Lockhart SC, the compliance failure alleged in paragraph 264(a) is a failure by the board of the former responsible entity to make any assessment of the application for MFS PECS Trust approval “as required by the terms of clause 3.1 of the Compliance Plan”. It is impossible to conclude, based on what is alleged in paragraph 437, that the auditor was aware of such a matter merely because she had not seen “sufficient” evidence to the contrary. I decline to permit this allegation to go forward.

VI

The Constructive Knowledge Issue

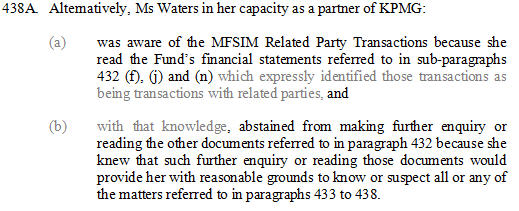

66 The obligation imposed upon the auditor by s 601HG(4)(a)(i), to inform ASIC of particular circumstances, extended only to those circumstances of which she was aware. In Mercedes (No. 2) I concluded that the word “aware” in s 601HG(4)(a)(i) meant actually aware and did not cover a situation where it could only be said that the auditor should have been aware (at 467 [70]). The applicants now propose this pleading:

67 The point made in this paragraph was that the auditor was aware from the financial statements that there were related party transactions. No one suggests that knowledge of those matters would, by itself, constitute awareness of breaches by the former responsible entity of its own compliance plan. This is because related party transactions may be lawful in certain circumstances.

68 My previous reasoning about this was as follows:

71 The plaintiffs submitted that the words “ought to be aware” in paragraph 432 were “infelicitous” and what had really been intended by the pleader was an invocation of the kind of a constructive knowledge referred to by Lord Esher in English and Scottish Mercantile Investment Company Ltd v Brunton [1892] 2 QB 700 at 707-708:

When a man has statements made to him, or has knowledge of facts, which do not expressly tell him of something which is against him and he abstains from making further inquiry because he knows what the result would be – or, as the phrase is, he “wilfully shuts his eyes” – then judges are in the habit of telling juries that they may infer that he did know what was against him.

72 I am prepared to assume in the plaintiffs’ favour that such a principle might be able to be applied in a case concerning s 601HG(4)(a)(i). However, the difficulty is that the present form of the pleading makes no such allegation. It merely alleges that certain documents ought to have been read. If the dictum were actually to be invoked it would be necessary to allege a good deal more. For example, it would be necessary to allege that the auditors were actually aware of matters of such a kind that their subsequent non-reading of the documents in question could be seen as a deliberate course of conduct intended to avoid finding out more. The present form of the pleading does not make that kind of allegation. Paragraph 432 is, as the auditors submit, embarrassing.

69 The applicants say that they have merely complied with that statement. I do not agree. What is required is effectively wilful blindness and that, in turn, requires there to be something about the material which is, in fact, known and which points inevitably down one path which the person involved then deliberately refrains from taking. But that is not what this pleading alleges. Instead there is a blanket allegation that the auditor simply knew that further inquiry would lead her to know or suspect circumstances which she would have to report. What the pleading does not disclose is why the auditor knew this. This is an allegation that a professional person deliberately eschewed further inquiry specifically so as not to find something out. It is an allegation of fraud or, at the very least, of serious misconduct. This makes it essential that the pleader – no doubt conscious of his or her own professional obligations not to make such allegations without a proper basis – identify the basis upon which it is said that the auditor was consciously acting this way. The pleading simply leaves unanswered the question of why the auditor should be found deliberately to have eschewed further inquiry. I will not permit this allegation to go forward.

VII

The duty of care issue

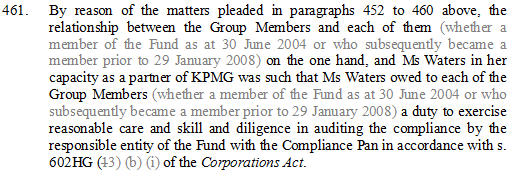

70 The applicants also contend that the auditors breached a duty of care owed to Group Members in carrying out the relevant audits in 2005, 2006 and 2007. The pleading makes no complaints about the 2008 audit so that defaults which are alleged to have been committed by the responsible entity in 2008 are not the subject of a damages claim. Paragraph 461 alleges:

71 The auditors’ submission on this issue is straightforward. By itself the mere act of holding units at 29 January 2008 establishes no relationship with the auditor in 2005, 2006 and 2007. This argument was advanced by the auditor on the last occasion in relation to 2005 and 2006 and I accepted it: Mercedes (No. 2) at 471 [92].

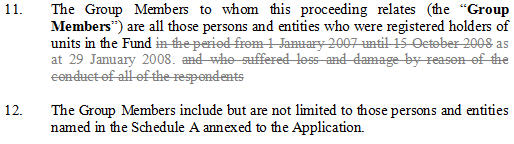

72 However, matters are now more complex. Whilst it is true that I previously accepted this complaint it is also true that, at that time, the definition of the group constituting the applicants was different. At that time, the group was defined in what was then proposed paragraphs 11 and 12 which were as follows:

73 One of the difficulties with this class definition was that it included unit holders who might never have suffered any loss. The applicants allege that in the six month period to 31 December 2007 the Fund was exhibiting signs of distress. For example, it is alleged in paragraph 139 that during that period the Fund was confronted with redemption applications totalling $210.398 million but, during the same period, only $90.326 million in cash applications for units and a further $11.021 million in reinvestment applications. Together it might be surmised that this suggested a net cash outflow of about $110 million. The applicants also allege (paragraph 139(b)) that the Fund in the same period borrowed about $200 million. The pleading does not allege that the loan proceeds were used to meet the redemptions.

74 What the pleading does allege is this: on 23 January 2008, trading in the shares of the parent company of the responsible entity was suspended (paragraph 141) which, the pleading alleges, only increased the number of redemptions (paragraph 142). This in turn resulted in material uncertainty about the recoverability of the Fund’s credit and equity exposures to the group of companies owned by MFS Limited (paragraph 143). Shortly thereafter, on 29 January 2008, the former responsible entity resolved to place a 180 day moratorium upon redemptions (paragraph 144). The responsible entity then called on its parent for support pursuant to a contractual entitlement but that proved ineffective (paragraph 145). On 10 March 2008, the former responsible entity extended the moratorium on redemptions to 360 days. By 13 March 2008 it had received redemption applications for 177,038,186 units in the Fund. Subsequently a restructuring took place. The constitution of the Fund was altered on 15 October 2008 to extinguish all unit holders’ rights of redemption and to enable the units then to be listed on the Australian Stock Exchange. The listing took place on 16 October 2008.

75 The consequence of the former class definition was that it was conceivable that there were unit holders as at 29 January 2008 who might have acquired their units at a price which reflected the considerable uncertainties surrounding the Fund by that date. Of this problem I said in Mercedes (No. 2) at 471 [92]:

It is true that many members of the class may have held units during the 2005 and 2006 financial years but that is not connected to the class definition. As things stand, there is no logical reason why the auditors in financial years 2005 and 2006 would owe duties to persons having no connexion with the Fund. It is possible, for example, that a unit holder may have acquired its units on 28 January 2008 at a deep discount, reflecting the loss suffered in those years. Without tying the class definition to some actual relationship with the auditors the claim cannot be permitted.

76 The proposition that unit holders might have acquired their units at such a discount was repeated before me on the present occasion by Mr Lockhart SC. However, the current version of the pleading presents a difficulty for that argument. The applicants now propose paragraph 12B which is in these terms:

12B. Up to 29 January 2008, the Group Members and each of them:

(a) acquired their units in the Fund by paying to MFSIM an application price of $1.00 for each unit; and

(b) were entitled to redeem their units in the Fund at a redemption price of $1.00 for each unit.

77 That allegation renders untenable the proposition that there could exist a class of unit holders who had acquired their units at a discount prior to 29 January 2008. It follows that the reasoning in [92] is no longer apposite.

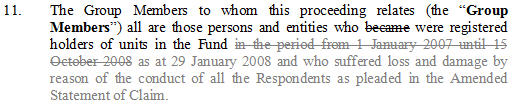

78 The applicants submit that there is a sufficient relationship between the unit holders and the auditors to justify, at least at the level of an amendment application, the existence of a duty of care. Mr Lockhart SC was critical, in that regard, of the new class definition which he submitted, did not advance the application. The new class definition is in paragraph 11 and is as follows:

79 The auditors emphasised, with some force, that this tied the class to those who had suffered loss and damage by reason of the conduct of all of the respondents and not just the auditors. Although foreshadowing the possibility that this definition also had difficulties in terms of class specification this was not pursued, by itself, as an objection to the amendment.

80 However, it seems to me that once the possibility is excluded that there might be unit holders who have acquired the units at a price not reflecting any loss, the auditors objection – at least at the level of a pleading debate – largely falls away. I do not think that I can say that the allegation that such a duty exists is untenable.

VIII

The Core Documents Issue

81 The applicants have brought a claim against a number of persons who were formerly directors of the responsible entity. In essence the case proposed against these directors is that they failed to do a number of things which they should have done and that if those things had been done the Fund would have avoided making a number of, what have transpired to be, somewhat infelicitous investments.

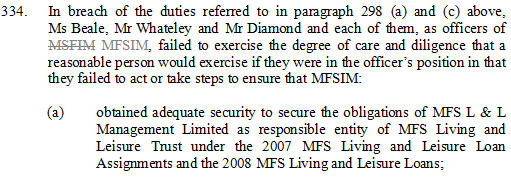

82 The question which now arises concerns the method by which the applicants propose to prove in a courtroom that the directors did not do these things. The sixth, seventh and ninth respondents had the primary carriage of this argument although the other directors joined in the mêlée. To give the flavour of the problem it is worthwhile setting out, as an example, one of the allegations against Mr Jackman SC’s clients. Paragraph 334(a) is in the following terms:

83 Paragraph 334 is not accompanied by any particulars. However, it follows on the heels of an allegation against the responsible entity in paragraph 154 which is accompanied by particulars. I infer – as Mr Jackman SC did – that in the case of each allegation the particulars provided of the responsible entity’s breach of duty are also to serve as particulars of the directors’ breaches.

84 The particulars are as follows:

(i) the Applicants’ solicitor has been provided by the present responsible entity of the Fund with the Core Documents referred to [in] the letter from the Applicants’ solicitor to each of the Respondents dated 4 June 2010;

(ii) the Core Documents do not disclose that any information of that kind was provided to, reviewed or assessed by MFSIM’s Investment Committee or the Investment Approval Committee, or alternatively MFSIM’s board of directors, for the purposes of any of the MFS Living and Leisure Approvals and Transactions (as defined in paragraph 59 above).

(iii) it is to be inferred:

(1) from the range and nature of the Core Documents, and

(2) by reason of the categories of documents agreed to be provided by the present responsible entity of the Fund pursuant to its agreement dated 24 June 2009 and with the Applicants’ solicitor, and

(3) by reason of the production of documents by the present responsible entity of the Fund pursuant to its agreement dated 24 June 209 with the Applicants’ solicitor,

that the fact that the Core Documents do not disclose that such information was provided to, reviewed or assessed by MFSIM’s Investment Committee or the Investment Approval Committee, or alternatively MFSIM’s board of directors, means that such information was not provided to, reviewed or assessed by MFSIM’s Investment Committee or the Investment Approval Committee, or alternatively MFSIM’s board of directors, for the purposes referred to in sub-paragraph (ii) above;

85 The capacity of the Core Documents to sustain this inference depends on their nature. Mr Jackman SC submits that when full account is taken of that nature and of the manner in which they were garnered it is apparent that the inference has no prospects of ever being drawn. The applicants’ primary submission in response focused on the purpose of particulars as being, in general, the facilitation to the opposing parties of a degree of procedural fairness in knowing the case they were required to meet.

86 That argument may be dispatched at the outset. None of the directors’ complaints were of that kind. Their point was that the case thus particularised had no prospects of succeeding. It is not an answer to that argument to characterise it as a complaint about the adequacy of particulars and then successfully to overcome that (unadvanced) complaint.

87 The Core Documents were placed in evidence before me. It is necessary to say something of how they came into being. The former responsible entity vacated that office on 15 October 2008 when it was replaced by the present one, Wellington Capital Ltd. Perhaps unfortunately, the administration and control of the electronic data of the Fund and the former responsible entity were undertaken by Octaviar Administration Pty Ltd (in liquidation) and the parent of the former responsible entity then known as MFS Limited but now known as Octaviar Ltd (in liquidation) (collectively “Octaviar” in these reasons). Since 2008 the electronic and physical documents belonging to the Fund have been in the control of the external managers of those businesses. The external managers were at some stages administrators but now appear to be liquidators.

88 The situation, therefore, is that the present responsible entity does not have physical possession of the documents of the Fund. That state of affairs has created considerable inconvenience for the applicants in drawing their allegations. In an attempt to overcome those problems negotiations were entered into between the applicants’ solicitors and the present responsible entity with a view to giving the former access to as much documentation in possession of the latter as was possible.

89 By 26 June 2009, the negotiations about the documents had fructified into an executed written agreement. The agreement was in these terms:

…

1. Wellington Capital Limited as responsible entity of the Premium Income Fund (formerly the MFS Premium Income Fund) (subject to its’ obligations as responsible entity) will:

(a) for the purposes of section 177(1A)(b) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), approve the use by the applicants in these proceedings (including their agents, legal representatives and parties who may provide litigation funding) of any information obtained from the register kept under Chapter 2C of the Corporations Act 2001 to contact or send information to existing or former unitholders about and concerning the proceedings; and

(b) permit, facilitate and co-operate in good faith to make available for examination by nominated representatives of the applicants during normal business hours, at least the following documents in the custody, possession or control of Wellington Capital Limited:

(i) the books and records of the fund evidencing or recording the related party transactions (within the meaning of part 5C.7 of the Corporations Act 2001) entered into by or on behalf of the fund (“the related party transactions”) in the period from 1 January 2005 until 15 October 2008 (“the period”);

(ii) the books and records of the fund evidencing or recording any deliberations and decisions concerning the entering into of each of the related party transactions during the period;

(iii) the books and records of the fund evidencing or recording compliance with the fund’s Constitution in respect of each of the related party transactions during the period;

(iv) the books and records of the fund evidencing or recording compliance with the fund’s Compliance Plan in respect of each of the related party transactions during the period; and

(v) the books and records of the fund evidencing or recording compliance with s 208(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (as modified by s 601LC) in respect of each of the related party transactions during the period, and

(c) undertake not to commence, nor permit any of its related entities to commence, proceedings in any court in relation to or concerning the subject matter of these proceedings, for so long as these proceedings remain on foot.

2. In consideration for the matters referred to in paragraph 1 above, the applicants will forthwith discontinue these proceedings as against the third respondent (Wellington Investment Management Limited) with no order as to costs.

…

90 I will return in a moment to chart how this agreement was carried into effect and how eventually it came to an end. It is worthwhile noting at this juncture, however, the very large number of the documents which are involved. The firm which presently has custody of the documents is Deloitte Touche Tomatsu (Deloitte). Deloitte have indicated that the electronic records occupy 6 terabytes of data, which is, on any view, a very large quantity. It is not clear which documents are owned by Octaviar and which by the Fund. The solicitors acting for the external managers have expressed the view that in order to consider all of the documents so as to determine which were owned by the Fund and which by its former parent would take about 8 months and cost around $2 million.

91 Knowledge of these considerable obstacles, however, did but lie in the future when the present responsible entity sought to perform its side of the above agreement. This involved the present responsible entity approaching Octaviar to see what could be obtained. At the Octaviar end, the relevant persons involved were a Mr Harwood (one of the administrators of Octaviar) and an employee, Ms Bennett. At the responsible entity’s end, the relevant person was Ms Snow.

92 After some initial wrangling of the usual kind, Ms Snow was eventually able to attend the offices of Octaviar to inspect some of the documents. This inspection had occurred as a result of requests by the present responsible entity to obtain access to the historical documentation of the Fund. The documents sought were extensive but may be summarised as being a set of historical documents dealing with related party transactions for the period 1 January 2005 to 9 June 2008.

93 Deloitte informed the present responsible entity that there was only one set of physical documents and that Ms Bennett had been assigned to retrieve them. The original request was not, in fact, limited only to physical documents but it is apparent that it was only physical documents that Deloitte were proposing to make available. On 10 July 2009, Ms Snow attended the offices of Octaviar. She was granted access to 16 boxes each of which contained a number of folders relating to investments of the Fund. Ms Snow read the files contained in the boxes and whenever a related party transaction was identified she had the documentation copied and brought back to the offices of the present responsible entity.

94 It is that material extracted by Ms Snow on her visit to Octaviar which now comprises the Core Documents in Exhibit 2. Pursuant to the agreement with the applicants’ solicitors the Core Documents were handed over to them at a meeting held on 16 July 2009. The applicants, it might fairly be said, were underwhelmed at the five volumes presented to them. Contentious correspondence ensued. The difference between the parties concerned the issue of whether the present responsible entity, by reason of its right to compel its predecessor to disgorge the Fund’s documents to it, was in possession, custody or control of those documents or whether, as it contended, it only had possession of the five volumes.

95 This debate – well-known to, if not well loved of, most litigators – took on increased importance because it was in return for the provision of such documents that the applicants had agreed to discontinue these proceedings against the present responsible entity (see clause 2 set out above). In the course of this debate the solicitor for the applicants, betraying an evident sense of frustration, described the provision of the five folders as “manifestly inadequate”, words which have been used against him on this application. The present responsible entity demurred, contending that it had supplied the Fund’s documents which were in its possession, custody or control. The applicants demanded the responsible entity obtain the documents from Deloitte and Deloitte, for its part, pointed to the $2 million it would cost to ascertain which documents belonged to the Fund. A stalemate had been reached. Thereafter, the present responsible entity applied to have the applicants’ proceedings against it discontinued on the basis of the agreement, which application I refused: Mercedes Holdings Pty Ltd v Waters (No 1) (2010) 77 ACSR 265 (Mercedes (No 1)). The debate having fully run its course, all that now remains are the Core Documents themselves.

96 What can one infer from Ms Snow’s five volume set? I accept as a fact that there are approximately 6,000 archive boxes of documents at a document repository on the Gold Coast. Mr Walker is an executive director of IMF (Australia) Limited which is the applicants’ funder. He was present at the meeting with Ms Snow on 16 July 2009 at which the Core Documents were provided to the applicants. He swore an affidavit on the applicants’ behalf in which he said that Ms Snow had said there were 6,000 archive boxes. I accept also that there are 6 terabytes of electronic material held by parties whose present inclination towards the applicants is not one of co-operation. There is no avoiding, in those circumstances, the proposition that the Core Documents are a very small sample of the universe of available documents.