FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Acohs Pty Ltd v Ucorp Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 577

|

Citation: |

Acohs Pty Ltd v Ucorp Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 577 |

|

|

Parties: |

ACOHS PTY LTD (ACN 009 572 187) v UCORP PTY LTD (ACN 062 768 094) and BERNARD BIALKOWER |

|

|

File number: |

VID 873 of 2004 |

|

|

Judge: |

JESSUP J |

|

|

Date of judgment: |

10 June 2010 |

|

|

Catchwords: |

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY – Copyright – Literary work – Material Safety Data Sheet generated electronically from database each time viewed on computer – Whether constitutes original copyright work – Whether constitutes a compilation.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY – Copyright – Material Safety Data Sheet – Data entered into electronic database by transcription – Whether new work thereby created original. INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY – Copyright – Whether an electronic database can be regarded as literary work – Whether data selected by applicant – Whether original work in nature of compilation.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY – Copyright – Infringement of copyright – Reproduction – Material Safety Data Sheets required to be provided for hazardous substances and dangerous goods – Ready access required to be given – Copying contemplated by regulations – Electronic access contemplated – Where copyright subsists in Material Safety Data Sheets, whether reproduction implicitly licensed by law. |

|

|

Legislation: |

Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 10, 21, 32, 35, 78, 79 National Occupational Health and Safety Commission Act 1985 (Cth) Occupational Health and Safety (Safety Standards) Regulations 1994 Dangerous Goods Safety Management Regulations 2001 (Qld) Dangerous Goods Safety (Storage and Handling of Non-explosives) Regulations 2007 (WA) Dangerous Goods (Storage and Handling) Regulations 2000 (Vic) Dangerous Substances (General) Regulations 2004 (ACT) Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 2001 (NSW) Occupational Health, Safety and Welfare Regulations 1995 (SA) Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 2007 (Vic) Occupational Safety and Health Regulations 1996 (WA) Workplace Health and Safety Regulations (NT) Workplace Health and Safety Regulation 2008 (Qld) Workplace Health and Safety Regulations 1998 (Tas) |

|

|

Cases cited: |

Acohs Pty Ltd v R A Bashford Consulting Pty Ltd (1997) 144 ALR 528 Acohs Pty Ltd v Ucorp Pty Ltd (No 2) (2009) 82 IPR 493 Beck v Montana Constructions Pty Ltd (1963) 5 FLR 298 Express Newspapers plc v Liverpool Daily Post and Echo plc (1985) 5 IPR 193 IceTV Pty Ltd v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 239 CLR 458 Ladbroke (Football), Ltd v William Hill (Football), Ltd [1964] 1 All ER 465 Lamb v. Evans [1893] 1 Ch 218 Redwood Music Ltd v B Feldman & Co Ltd [1979] RPC 385 Roland Corporation v Lorenzo and Sons Pty Ltd (1991) 22 IPR 245 Telstra Corporation Ltd v Phone Directories Company Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 44 T R Flanagan Smash Repairs Pty Ltd v Jones (2000) 172 ALR 467 Victoria Park Racing and Recreation Grounds Co Ltd v Taylor (1937) 58 CLR 479 William Hill (Football) Ltd v Ladbroke (Football) Ltd [1980] RPC 539 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dates of hearing: |

31 August, 1-4 September, 7-11 September, 16-18 September and 7 October 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Date of last submissions: |

7 October 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Place: |

Melbourne |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Division: |

GENERAL DIVISION |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Category: |

Catchwords |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of paragraphs: |

148 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Counsel for the Applicant: |

Mr J Burnside QC and Mr G Dalton |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Solicitor for the Applicant: |

Murray Round, Corporate Solicitor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Counsel for the Respondents: |

Mr R Garratt QC, Mr P Wallis and Mr S Rebikoff |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Solicitor for the Respondents: |

Holding Redlich |

|

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

VID 873 of 2004 |

|

ACOHS PTY LTD (ACN 009 572 187) Applicant

|

|

AND: |

UCORP PTY LTD (ACN 062 768 094) First Respondent

BERNARD BIALKOWER Second Respondent

|

|

JUDGE: |

|

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

10 JUNE 2010 |

|

WHERE MADE: |

MELBOURNE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

2. Subject to any order as to costs previously made, the applicant pay the respondents’ costs, including reserved costs.

3. The operation of the previous order be stayed for 21 days, during which period the parties have liberty to apply on the matter of costs.

Note:Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

The text of entered orders can be located using Federal Law Search on the Court’s website.

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

|

|

GENERAL DIVISION |

VID 873 of 2004 |

|

BETWEEN: |

ACOHS PTY LTD (ACN 009 572 187) Applicant

|

|

AND: |

UCORP PTY LTD (ACN 062 768 094) First Respondent

BERNARD BIALKOWER Second Respondent

|

|

JUDGE: |

JESSUP J |

|

DATE: |

10 JUNE 2010 |

|

PLACE: |

MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 In this proceeding, the applicant, Acohs Pty Ltd (“Acohs”), sues the first respondent, Ucorp Pty Ltd (“Ucorp”), and the second respondent, the director of Ucorp, Bernard Bialkower, for alleged infringement of copyright under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (“the Copyright Act”), for declarations, damages and injunctions for alleged breaches of ss 52 and 53 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), in passing off, and for alleged infringement of trade mark. At trial, only the copyright aspects of Acohs’ claims were pursued, and I shall say nothing further about its other causes of action. As so limited, the case is about copyright in relation to particular kinds of electronic information sheets which must be prepared and provided with respect to hazardous substances and dangerous goods. The respondents deny that the things in which the applicant claims copyright are literary works, and deny that they are original works of which employees of Acohs were the authors. In the alternative, they say in relation to some of the so-called works that the copyright, to the extent that it existed, was assigned to Acohs’ customers. They say that, if (which is not substantially in issue) they did reproduce any works in which Acohs held copyright, they did so pursuant to an implied licence. They also raise some other objections to Acohs’ claim to which, because of the way I have decided the points so far mentioned, I need not consider further.

Legislative requirements for Material Safety Data Sheets

2 Pursuant to the terms of regulations to which I shall refer in more detail presently, the manufacturer, importer or supplier (“MIS”) of certain substances (described variously as “dangerous” or as “hazardous”) must prepare a Material Safety Data Sheet (“MSDS”) which sets out prescribed categories of information about the substance in question. Any person to whom the substance is supplied must be provided with a copy of the MSDS. Employers, and the occupiers of certain premises, using, or having on-site, a substance of this kind must have readily accessible a copy of the relevant MSDS. In use across Australia, there are thousands of dangerous or hazardous substances to which obligations of this kind would attach. The need for users of these substances, and for employers and their staff, to have ready access to the relevant MSDSs has led to the emergence of business undertakings of the kind with which this proceeding is concerned.

3 The provision and content of MSDSs has, however, not always been the subject of regulation. Originally, it seems, there was a certain ad hocery about the provision of MSDSs by MISs and, where they were provided, about their format and content. In 1986, the National Occupational Health and Safety Commission (established under the National Occupational Health and Safety Commission Act 1985 (Cth)) (“the NOHSC”) published a “guidance note” for completion of an MSDS, which provided general instructions on how to compile an MSDS, with standard content and format, and containing the minimum information which was relevant and suitable for use in Australia. However, the system thereby produced had its shortcomings, and in 1994 the NOHSC published three things: the National Code of Practice for the Preparation of Material Safety Data Sheets (“the 1994 preparation code”); the National Model Regulations for the Control of Workplace Hazardous Substances (“the model regulations”); and the National Code of Practice for the Control of Workplace Hazardous Substances (“the 1994 control code”).

4 The model regulations came to have a substantial influence on the content of the regulations made in the States and Territories. The Commonwealth’s own regulations were the Occupational Health and Safety (Commonwealth Employment) (National Standards) Regulations 1994, recently renamed the Occupational Health and Safety (Safety Standards) Regulations 1994 (“the safety standards regulations”). As at 1999, reg 6.05(2) provided as follows:

(2) An MSDS must:

(a) set out the name, and Australian address and telephone numbers (including an emergency number), of the manufacturer or importer; and

(b) for the hazardous substance to which it relates:

(i) clearly identify the substance in accordance with the National Code of Practice for the Preparation of Material Safety Data Sheets [NOHSC:2011 (1994)]; and

(ii) set out its recommended uses; and

(iii) describe its chemical and physical properties; and

(iv) disclose information relating to each ingredient to the extent prescribed by regulation 6.07; and

(v) set out the substance’s risk and safety phrases and any relevant health hazard information about the substance that is reasonably practicable for the manufacturer to provide; and

(vi) set out information concerning the precautions to be followed in relation to its safe use and handling.

5 The 1994 preparation code was advisory only. It provided (in cl 5.2) as follows:

MSDS are used internationally to provide the information required to allow the safe handling of substances used at work. MSDS assist employers to discharge their general duty of care to employees by providing them with information on the hazardous substances that they are working with and the hazards associated with those substances. The MSDS provides information on:

(a) identification:

(i) product name,

(ii) physical description and properties,

(iii) uses, and

(iv) composition;

(b) health hazard information;

(c) precautions for use; and

(d) safe handling information.

The code provided “general guidelines” for the preparation of MSDSs. It identified “core information”, which was essential information that should always be included in an MSDS, and “conditional information”, which was information which should be included where relevant and available. Under the heading “format” the guidelines provided that an MSDS was “not a fixed length document”. The amount of information to be provided in the major sections of an MSDS was variable, “so that if there is a great deal of relevant information on one item, that section can be expanded”.

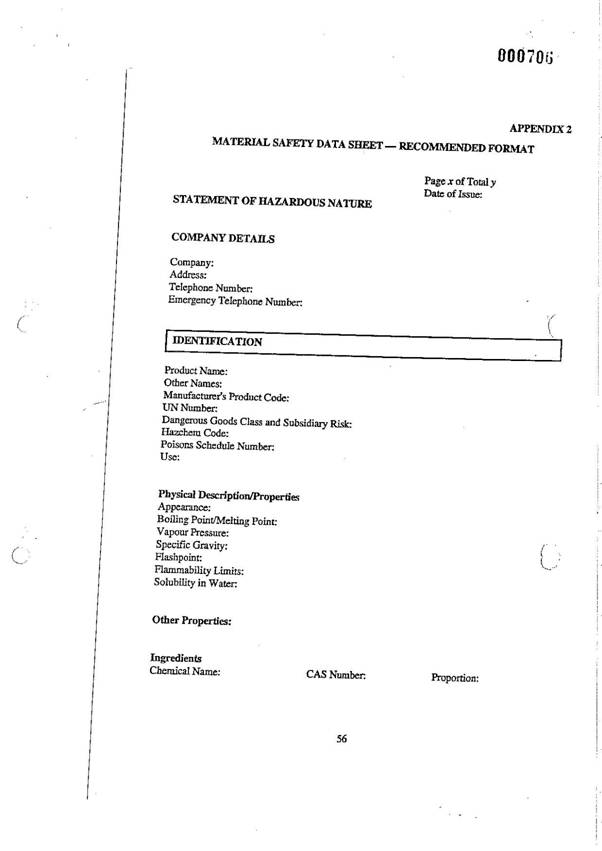

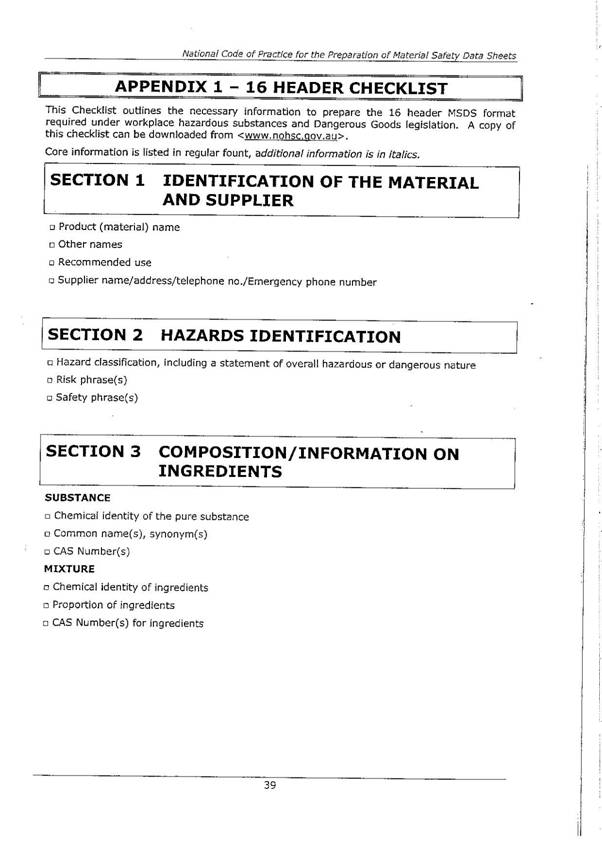

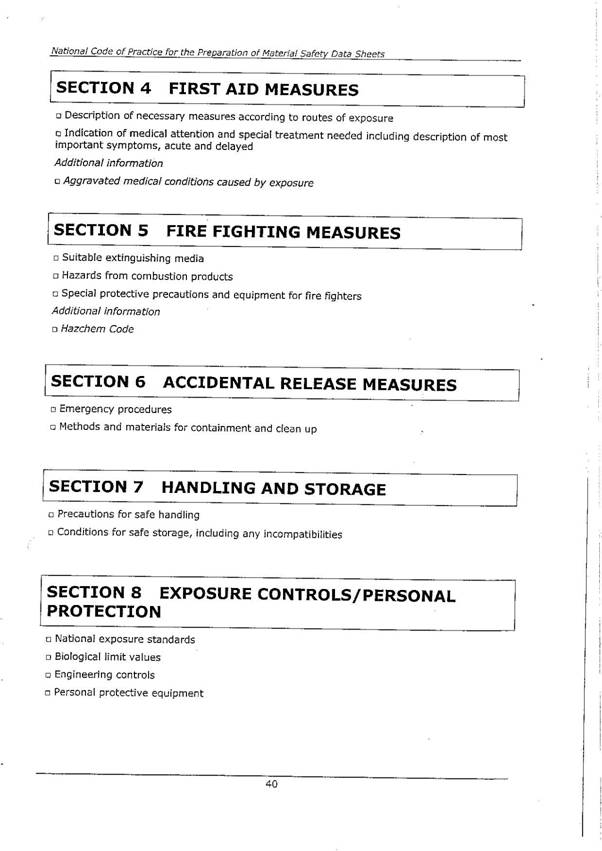

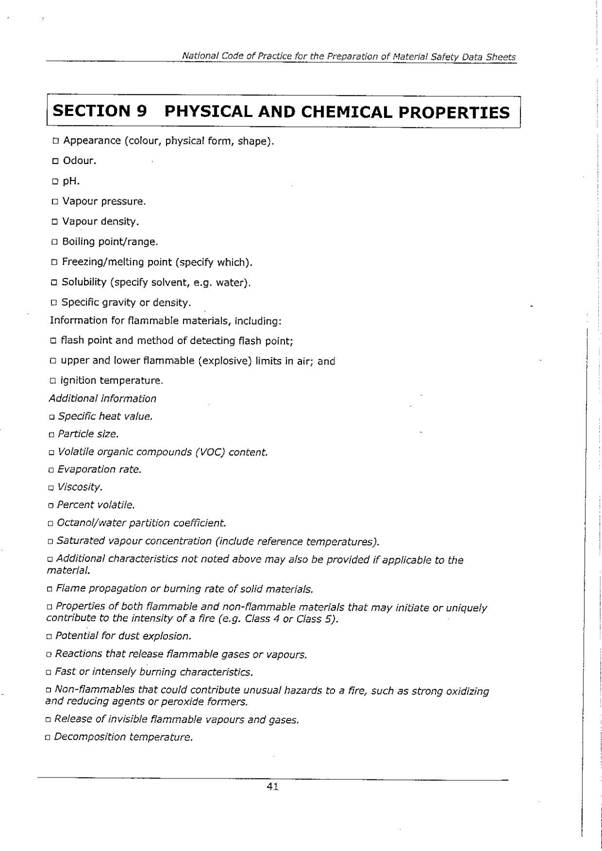

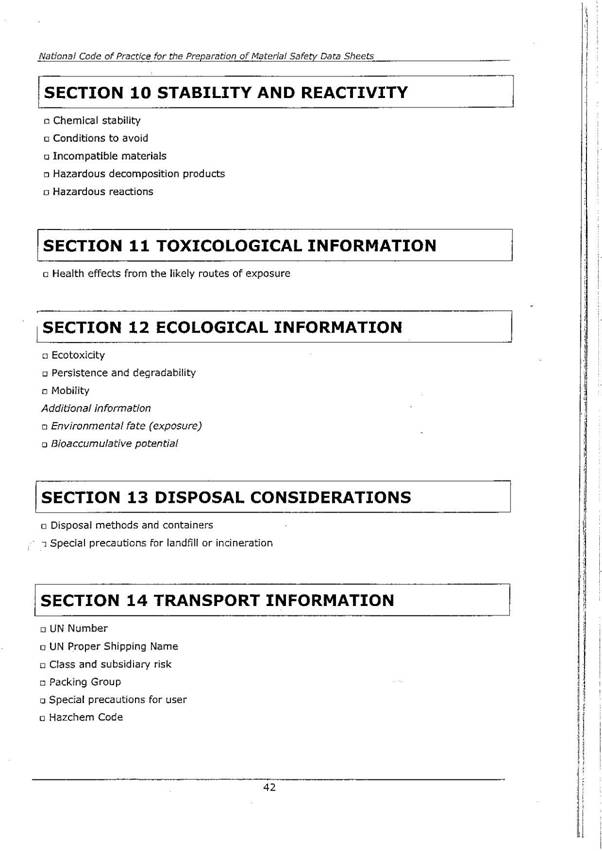

6 The guidelines set out a “recommended format” for an MSDS. A copy of that format is set out in Appendix 1 to these reasons. As will be seen, there were four main sections of substantive information in such an MSDS, under the headings Identification, Health Hazard Information, Precautions for Use and Safe Handling Information. The 1994 preparation code provided detailed, and quite extensive, guidance as to the completion of the particulars required in each of these sections of an MSDS. This recommended format came to be known as the “4-section” (or “4-header”) format for MSDSs.

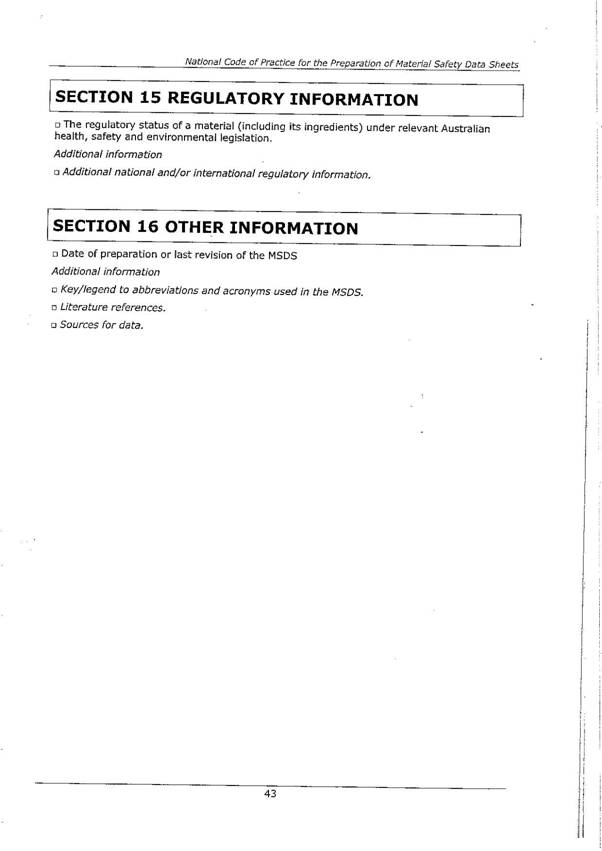

7 The 1994 preparation code was replaced in 2003 by the National Code of Practice for the Preparation of Material Safety Data Sheets, 2nd Edition (“the 2003 preparation code”). It introduced a 16-section (or 16-header) format. A copy of the recommended format appended to the code is set out in Appendix 2 to these reasons. Under the heading “Document format”, the code stated that an MSDS was “not a fixed length document”. The length of the MSDS was to be commensurate with the hazard of the material, and the information available. The code provided detailed particulars of the categories of information that were required to be included (the “core information”), and that might, where relevant, be included (“additional information”), under each of the 16 headers in the recommended format.

8 In 2006, reg 6.05(2) of the safety standards regulations was amended and now provides that an MSDS must be in accordance with the 2003 preparation code. As a result, use of the 16-section structure became mandatory. Notwithstanding the now prescriptive nature of the 2003 preparation code, and of the structure for MSDSs required thereby, Ian Cowie, the director of Acohs, gave the following evidence, upon which he was not challenged:

The [4-header] structure and the 16 Header structure do not dictate the layout presentation and appearance of MSDS. In my experience, MSDS authored in accordance with each structure vary considerably in the way they look by reason of the author’s choice of formatting variables such as heading font sizes, spacing, underlining, type faces, the use of sub-headings and tables and many other variables.

9 Obligations as to the preparation and provision of MSDSs, and requiring their availability in particular industrial settings, arise under the safety standards regulations and corresponding regulations in the States and Territories. I shall summarise the effect of those regulations, referring first (in each of the main subject-matter areas) to the position in New South Wales, and following with a brief note on the extent to which the regulations in each other jurisdiction differ in material respects.

10 In New South Wales, under cl 150(1) of the Occupational Health and Safety Regulation 2001, a manufacturer of a “hazardous substance” must prepare an MSDS for the substance before it is supplied to another person for use at work. A like obligation arises under cl 174J(1) in relation to “dangerous goods”, save that the MSDS must be prepared before the goods are supplied to another person, whether or not “for use at work”. A person who imports a hazardous substance, or dangerous goods, manufactured outside New South Wales for supply to others, or for the person’s own use, must ensure that the responsibilities of a manufacturer under cl 150(1) or cl 174J(1), as the case requires, are met: see cll 148(2) and 174F respectively.

11 Obligations broadly similar to those referred to in the previous paragraph arise under:

- Reg 4.1.5(1) of the Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 2007 (Vic) (concerned with hazardous substances, where the MSDS must be prepared before the substance is first supplied to “a workplace”) and reg 306(1) of the Dangerous Goods (Storage and Handling) Regulations 2000 (Vic) (concerned with dangerous goods);

- Section 190(1)(a) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations 2008 (Qld) (concerned with hazardous substances) and s 12(1)(a) of the Dangerous Goods Safety Management Regulations 2001 (Qld) (concerned with dangerous goods) (in both of which cases the MSDS must be prepared before the substance, or the goods, is or are manufactured or imported, or as soon as practicable thereafter);

- Reg 4.1.5(1) of the Occupational Health, Safety and Welfare Regulations 1995 (SA) (concerned with hazardous substances);

- Reg 5.5(1)(a) of the Occupational Safety and Health Regulations 1996 (WA) (concerned with hazardous substances, where the MSDS must be prepared with respect to a substance that has been manufactured or imported “for use at a workplace”) and reg 18 of the Dangerous Goods Safety (Storage and Handling of Non-explosives) Regulations 2007 (WA) (concerned with dangerous goods);

- Reg 70(1)(a) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations 1998 (Tas) (concerned with hazardous substances, where the MSDS must be prepared with respect to a substance that has been manufactured or imported “for use at a workplace”);

- Reg 67(1)(a) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations (NT)(concerned with hazardous substances, where the MSDS must be “produced” with respect to a substance “for use at a workplace”, and where the obligation falls upon the “supplier”, defined to mean a person who imports, manufactures, wholesales or distributes the substance, but [not including] a retailer”);

- Section 215(1)(a) of the Dangerous Substances (General) Regulations 2004 (ACT) (concerned with “dangerous substances”, where the MSDS must be prepared before the substance is manufactured or imported, or as soon as practicable thereafter);

-

Reg 6.05(1) of the safety standards regulations (concerned with hazardous substances, where a relevant MSDS must be prepared before a substance which the manufacturer knows, or ought reasonably to expect, will be used by employees at work is supplied to the employer of the employees).

12 Under cl 150(6) of the Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 2001 (NSW), the manufacturer of a hazardous substance “must review and revise the MSDS as often as is reasonably necessary to keep it up to date and, in any event, at intervals not exceeding 5 years”. A like obligation arises under cl 174J(3) in relation to dangerous goods. Similar obligations arise under:

- Reg 4.1.7 of the Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 2007 (Vic) and reg 306(1) of the Dangerous Goods (Storage and Handling) Regulations 2000 (Vic) (in each case the obligation being to “review” only); Dangerous Goods Safety (Storage and Handling of Non-explosives) Regulations 2007 (WA)

- Section 190(1)(b) and (c) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations 2008 (Qld) and s 12(1)(b) and (c) of the Dangerous Goods Safety Management Regulations 2001 (Qld) (in each case the obligation being to “amend the MSDS whenever necessary to ensure it contains current information”, and to review at least every 5 years);

- Reg 4.1.5(3) of the Occupational Health, Safety and Welfare Regulations 1995 (SA);

- Reg 5.5(1)(c) of the Occupational Safety and Health Regulations 1996 (WA) and reg 19(1) of the Dangerous Goods Safety (Storage and Handling of Non-explosives) Regulations 2007 (WA);

- Reg 70(1)(b) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations 1998 (Tas);

- Reg 67(1)(b) and (c) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations (NT);

- Section 215(1)(b) and (c) of the Dangerous Substances (General) Regulations 2004 (ACT);

-

Reg 6.05(3) and (4) of the safety standards regulations.

13 Under cl 151 of the Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 2001 (NSW), the manufacturer of a hazardous substance must provide a copy of a current MSDS for the substance to any person who supplies the hazardous substance for use at work, to any person who “claims to be associated with the use of the hazardous substance at work and who asks to be provided with a copy of the MSDS”, and to any medical practitioner or health practitioner who requires it for the purpose of providing emergency medical treatment. The first situation is concerned with the interface between the manufacturer and a (subsequent) supplier. The second situation is concerned with the circumstances of a person to whom an MSDS may not have been provided in the normal course but who is associated with the use of the substance at his or her work. And the third situation contemplates a medical emergency where a practitioner of the kind indicated might need the MSDS for the purposes, say, of treatment being administered by him or her. Like obligations arise under cl 174K in relation to dangerous goods.

14 Clause 155 of the NSW regulations is concerned with the obligations of a supplier (as distinct from a manufacturer). Under that clause, a person who supplies a hazardous substance to an employer for use at work must ensure that a current MSDS prepared by the manufacturer is provided on the first occasion the substance is supplied to the employer, on the first occasion the substance is supplied following a revision of the MSDS, to any person who claims to be associated with the use of the substance at work and who asks to be provided with a copy of the MSDS, and to any medical practitioner or health practitioner who requires the MSDS for the purpose of providing emergency medical treatment. Like obligations arise under cl 174M(1) in relation to dangerous goods.

15 Save for the obligation to provide an MSDS to a medical or health practitioner, analogous, but not always closely similar, obligations to those referred to in the two preceding paragraphs arise under:

- Reg 4.1.8(1) of the Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 2007 (Vic) (concerned with hazardous substances, where the obligation falls upon the manufacturer or supplier and is to ensure that a copy of the current MSDS for the substance is provided to any person to whom the substance is supplied on or before the first occasion that the substance is supplied to that person, to any person to whom the substance is supplied on or before the first occasion that the substance is supplied to that person after a review, and to any employer who intends to use that hazardous substance in a workplace, on request) and reg 309(1) of the Dangerous Goods (Storage and Handling) Regulations 2000 (Vic) (concerned with dangerous goods, where the obligation is the same as that arising under the Occupational Health and Safety Regulations, save that, in place of the obligation to provide a copy to the employer in the third situation mentioned above, there is an obligation to provide a copy “on request, to an occupier of any premises where those dangerous goods are stored and handled”);

- Section 191 of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulation 2008 (Qld) (concerned with hazardous substances, where the obligation is closer to the Victorian format than to the NSW format, save that, in place of the obligation to provide a copy to the employer, there is an obligation to provide a copy to a “relevant person” – defined in s 28(1) of the Workplace Health and Safety Act 1995 (Qld) as “any person … who conducts a business or undertaking” – and to a “worker or worker’s representative at a workplace where the substance is, or is to be, used”) and s 15(1) of the Dangerous Goods Safety Management Regulation 2001 (Qld)(concerned with dangerous goods, where the obligation is similar to that arising under the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations, save that, in place of the obligation to provide a copy to a relevant person (etc), there is an obligation to provide a copy, on request, to “the occupier of a major hazard facility, dangerous goods location or workplace where the goods are stored and handled”);

- Reg 4.1.5(4) of the Occupational Health, Safety and Welfare Regulations 1995 (SA) (where the obligation is to provide a current MSDS on the first occasion that the substance is supplied to a person who purchases the substance from the supplier, and at any other time, “on the request of a person who reasonably requires a copy” of the MSDS);

- Reg 5.5(8) of the Occupational Safety and Health Regulations 1996 (WA) (concerned with hazardous substances, where the obligation is to provide the MSDS to a person who purchases the substance from the supplier on the first occasion of the person obtaining the hazardous substance from the supplier, whether or not on that person’s request, to a person who purchases the substance from the supplier on a subsequent occasion, or who purchases the substance from someone who obtained the substance from the supplier, on that person’s request, to a person who is a “potential purchaser” of the substance and who intends to purchase the substance from the supplier, or from someone who obtained the substance from the supplier, on that person’s request) and reg 20(1) of the Dangerous Goods Safety (Storage and Handling of Non-explosives) Regulations 2007 (WA) (concerned with dangerous goods, where the obligation is to ensure that the current MSDS is provided to any person to whom the goods are supplied for the first time by the MIS, and, on request, to the operator of any “dangerous goods site” on which the goods are stored or handled, to the operator of any “dangerous goods pipeline” in which the goods are conveyed, and to any person engaged by the operator to work on such a site or pipeline);

- Reg 70(1)(d), (3) and (5) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations 1998 (Tas) (concerned with hazardous substances, where the obligation falling upon the manufacturer or importer is to “ensure that the MSDS is readily available to any member of the public who requests a copy”, and where the obligations falling upon the supplier are provide a current MSDS to a person on the first occasion that the person purchases the substance from the supplier and to any person who “reasonably requires a copy”);

- Reg 67(2) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations (NT) (concerned with hazardous substances, where the obligation is to ensure that the current MSDS is provided to a person on the first occasion that the substance is supplied to the person, and “on request”);

- Section 217(1) of the Dangerous Substances (General) Regulation 2004 (ACT) (concerned with hazardous substances, where the obligation is to ensure that a copy of the current MSDS is provided to a person on or before the first occasion the substance is supplied to the person for use, on or before the first occasion the substance is supplied to the person after an amendment of the MSDS, and, on request, to the person in control of any premises where the substance is handled);

-

Reg 6.06(1) of the safety standards regulations (concerned with hazardous substances, where the obligation falls upon the supplier and is to give a copy of the current MSDS to the relevant employer – ie one whose employees the supplier knows, or ought reasonably to expect, will use the substance at work – on the first occasion that the substance is supplied to the employer, and at any later time “on request”).

16 Under cl 162(1) of the Occupational Health and Safety Regulation 2001 (NSW), for each hazardous substance supplied to an employer’s place of work, the employer must obtain from the supplier an MSDS for the substance before or on the first occasion on which it is supplied, must ensure that the MSDS is readily accessible to an employee who could be exposed to the substance, and (with a presently immaterial exception) must ensure that the MSDS is not altered. Similar obligations arise under:

- Regs 4.1.15, 4.1.17 and 4.1.18 of the Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 2007 (Vic) (in addition to which there is an obligation upon the employer under reg 4.1.16 of those regulations to make reasonable inquiries as to the currency of an MSDS obtained by the employer if it was prepared more than 5 years before the substance to which it relates was supplied to the employer, and the MSDS had not been reviewed during that 5-year period);

- Sections 199(1) and 200(2) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulation 2008 (Qld) (where the obligation of a “relevant person” (see para 15 above) is, first, in the case where he or she does not receive an MSDS for the substance, to ask the supplier if the substance is a hazardous one and, if it is, to ask the supplier for a copy of its current MSDS, and, secondly, where he or she is an employer, to keep a copy of the MSDS close enough to where the substance is being used to allow a worker who may be exposed to the substance to refer to it easily);

- Reg 4.1.9(1) of the Occupational Health, Safety and Welfare Regulations 1995 (SA);

- Reg 5.11(1) of the Occupational Safety and Health Regulations 1996 (WA) (where the obligations fall not only upon an employer, but also upon “the main contractor or a self-employed person”, and include an obligation to consult with all persons who might be exposed to the substance at the workplace about the intention to use, and the safest method of using, the substance at the workplace; and in which the obligation is to ensure that the MSDS is “readily available” to any person who might be exposed to the hazardous substance at the workplace);

- Reg 75 of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations 1998 (Tas);

- Reg 68(1) of the Workplace Health and Safety Regulations (NT) (where the obligation is to ensure that an MSDS provided by the supplier is “available” and is “readily accessible to a worker with potential for exposure” to the substance concerned);

-

Reg 6.12(1), (2) and (4) of the safety standards regulations.

17 In the 1994 control code, the following provisions appear:

8.5 At each workplace, employees and employee representatives shall have ready access to MSDS for the hazardous substances used. Copies shall be readily accessible to employees who are required to use or handle the hazardous substance, as well as to employees who are supervising others working with the hazardous substance.

8.6 Access to MSDS may be provided in a number of ways including:

(a) paper copy collections of MSDS;

(b) microfiche copy collections of MSDS with microfiche readers open to use by all employees; and

(c) computerised MSDS databases.

8.7 Depending on the needs of the workplace, any of the methods in section 8.6 of this national code of practice may be used. In each case, the employer should ensure that:

(a) the current MSDS are available;

(b) any storage or retrieval equipment is kept in good working order;

(c) employees are trained in how to access the information; and

(d) where information is displayed on a screen, there are means of obtaining a paper copy of that information.

The parties conducted their cases by reference to the assumption that “computerised MSDS databases” as referred to in s 8.6(c) of this code were within the contemplation of the various State and Territory regulations that required MSDSs to be readily accessible (etc). Consistently, I was referred to cl 16.3 of the Code of Practice for Hazardous Substances approved under s 55 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act 1985 (Vic), which contains the following:

Access to MSDS may be provided in a number of ways including:

- paper copy collections of MSDS;

- microfiche copy collections of MSDS with microfiche readers open to use by employees; and

-

computerised MSDS databases.

You may wish to discuss these options with your supplier. In each case, the employer should ensure that:

- any storage or retrieval equipment is kept in good working order;

- employees know how to access the information; and

-

there are means of obtaining a paper copy of information contained in a computerised database.

Commercially available computerised MSDS databases made available by another party are acceptable provided they contain the manufacturer’s or importer’s current MSDS. You need to ensure that the MSDS obtained from such a database is the authorised version prepared by the manufacturer or importer.

I was not referred to any similar provision in another jurisdiction, but the parties conducted their cases by reference to this provision of the Victorian code, as though I should regard it as more or less typical.

18 With certain presently immaterial exceptions, under cl 174ZG the Occupational Health and Safety Regulation 2001 (NSW), the occupier of premises must obtain from the supplier of dangerous goods stored or handled on the premises an MSDS before or on the first occasion on which the goods are supplied, must ensure that the MSDS is readily accessible to any person at the premises who could store or handle the goods, and (with a presently immaterial exception) must ensure that the MSDS is not altered. Similar obligations arise under:

- Reg 438(1) of the Dangerous Goods (Storage and Handling) Regulations 2000 (Vic) (where the MSDS must be “readily accessible to persons engaged by the occupier to work at the premises, to the emergency services authority and to any other person on the premises”);

- Section 40(1) of the Dangerous Goods Safety Management Regulation 2001 (Qld) (where “occupier” is defined as the occupier of a “major hazard facility” or a “dangerous goods location”, and where the MSDS must be “readily accessible to persons at the facility or location and to emergency services”);

-

Regs 79(1), 114 and 131(1) of the Dangerous Goods Safety (Storage and Handling of Non-explosives) Regulations 2007 (WA) (where the obligation exists with respect to a “dangerous goods site”, a “a dangerous goods pipeline” and “a rural dangerous goods location or small quantity dangerous goods location”, and where, in any of those situations, there appears to be no obligation to ensure that an MSDS is not altered).

The businesses of Acohs and Ucorp

19 Acohs and Ucorp produce MSDSs, or copies of MSDSs, for MISs and for the users of substances to which MSDSs relate. There are two principal contexts in which this might be done. The first is the creation of an MSDS for a particular substance on behalf of the MIS concerned. As will become clear, that is not a simple task, and requires both a qualification in science or a like discipline and much experience in the practical task of expressing information about the substance of interest in a way that will be compliant with the relevant regulations and readily intelligible in a broad range of industrial settings. This task is described by Acohs as “authoring” an MSDS, and it is a service which both Acohs and Ucorp provide to MISs. The second context is where the service is provided not to MISs but to those who would use, or would need to have access to, an MSDS – most typically in this context, to a large number of MSDSs. For example, a large industrial concern may store, and use in its operations, many potentially hazardous chemicals and other substances. Rather than making contact with the numerous MISs of these substances (or relying on the original paper versions of MSDSs obtained at the time of acquisition of the substances), the concern may engage Acohs or Ucorp to provide it with electronic access to all the relevant MSDSs. A further advantage of so proceeding is that the user may rely on Acohs or Ucorp to keep the MSDSs up to date.

20 Although both Acohs and Ucorp deal in electronic MSDSs (ie rather than paper ones), the means by which they create, store and disseminate MSDSs are different in ways which go to the centre of the dispute in the present case. When Ucorp authors an MSDS for an MIS, it will create an electronic document as such, which will then be stored in its electronic library, which it calls “the Collection”. Documents may be stored, and viewed electronically, in various formats (ie as HTML files, as PDF files or as word processor files). A user who secures access to such an MSDS will view the document as it is stored. When Ucorp is required to give access to an MSDS of which it has not been the author for the relevant MIS, it will locate the MSDS on the Internet (and/or by direct communication with the MIS), download the MSDS as an entity and then store it as part of the Collection, from where any of its non-MIS customers who might require access to the MSDS could, under appropriate commercial relationships with Ucorp, achieve that access. Necessarily, such an MSDS will be identical in content and appearance to the “original” MSDS from which it was derived.

21 The Acohs system of producing MSDSs is very different. Acohs does not maintain a library of MSDSs as such. Rather, it maintains a large relational database (described in the evidence as a “network of databases”, but for present purposes use of the singular will be sufficient) called the “Central Database” or “CDB”. All the data required to generate a particular MSDS (indeed, all the data required to generate some 200,000 MSDSs overall) are stored in the CDB. When access to a particular MSDS is required, the Acohs software calls up the necessary components from this database, and assembles them in a way which is represented on the user’s screen as the MSDS of interest. As Mr Cowie put it in his affidavit sworn on 3 July 2008:

An essential feature of the design of the Infosafe System is that it does not store discrete documents. It stores only the raw data which the programs call upon in response to a user request to compile or generate the report required.

22 It follows that, in the case of Acohs, there is no function which corresponds directly to Ucorp’s copying of MSDSs for storage in the Collection. Rather, what happens at Acohs is that elements of data which are required to make up MSDSs are entered into the CDB. When Acohs “authors” an MSDS, a member of its “Professional Services Group” (“PSG”) enters data into the CDB in response to prompts given by the computer program which controls the database. When Acohs needs to copy an existing MSDS (eg for the purposes of a customer who is an industrial user of the substance in question), a “transcriber” will, again in response to prompts from the program, enter the exact content of the existing MSDS into the CDB. I shall refer in more detail to each of these processes below, as they bear importantly upon the issues of authorship and originality which are contentious in this proceeding. There is a third means by which the data for a new MSDS may be entered into the CDB, which involves Acohs’ MIS customers undertaking their own authoring. This involves a further layer of sophistication in the Acohs system, and I shall refer to it too below.

The Infosafe System

23 The system by which Acohs authors, transcribes and supplies MSDSs is called the “Infosafe System”. Every MSDS produced by this system is given a unique number, its “Infosafe” number. Fundamental to the determination of Acohs’ copyright claims in this case is an understanding of how the Infosafe system works.

24 The technical centre of the Infosafe System is a computer program – written in Visual Basic code – which has the functions of receiving a request for the generation of a particular MSDS, of calling up the data and other elements from the CDB, of compiling the relevant HTML source code, and of sending that code to the user’s computer. To do this, the program uses “routines” called “GETHTML”, “Generate_MSDSReport” and “GenerateHTML”. These routines are in turn run by a fourth routine, “WebClass_Start”. The source code will then cause the MSDS to appear as intended on the user’s screen, in the conventional way of web pages generally. The source code will contain all the content of the electronic document which is to appear on the screen (ie the “data”), as well as the “tags” and other instructions necessary to give a particular layout, presentation and appearance to an MSDS. Thus, for example, the instruction that finds its way into the source code of the MSDS to require a heading to be placed within a box will be an element of the routine. The routine will combine that instruction with data retrieved from the CDB (in this case, the heading itself). The same instruction – to apply the box – will be used time and again with different headings as may be appropriate to the situations of different MSDSs being electronically generated.

25 Authoring of MSDSs is a service which Acohs offers to its customers who are MISs. Such authoring is carried out by Acohs employees in the PSG who have qualifications in science or science-related disciplines. The means by which new MSDSs are created by the authors employed by Acohs were explained by one of them, Nga Dam, a chemical engineer who has been employed by Acohs since 2002. To author an MSDS, Ms Dam uses the editor module in the Infosafe software. This program displays a menu of items and categories on Ms Dam’s computer screen, by reference to which the appropriate data are entered. The menu of items reflects the 16 headers in the format for MSDSs mandated by the 2003 preparation code. Each of those items may be expanded to reveal a list – and in some cases a very extensive list – of subheadings. When Ms Dam selects one of the headings or subheadings on the menu, the body of the screen provides the visual environment for the entry of the appropriate data. In some cases, the data will be entered by reference to preset categories, whilst in others a short passage of text must be used. In the latter respect, Ms Dam has access to an extensive collection of standard risk phrases, which are part of the software.

26 At no stage while Ms Dam is entering data in the way described above does the partially-completed MSDS itself appear on the screen. She is not in the position of someone conventionally writing a new document by way of a word processor, for example. Rather, what appears to her is a series of data-entry screens by reference to which she enters the content that will ultimately make up the MSDS. However, having completing the task of entering data for a new MSDS, Ms Dam will exit from the editor module of the Infosafe software, and will call up the completed MSDS on her screen, for the purpose of ensuring “that I had completed the MSDS in accordance with the regulations and that the MSDS is internally consistent and accurate.”

27 A separate, but similar, function which Ms Dam performs as author is the review of existing Acohs MSDSs. Under reg 6.05(4) of the safety standards regulations – and under corresponding regulations in the States and Territories – it is the obligation of every MIS to review its MSDSs at least every five years. When she is called upon to review an existing MSDS, Ms Dam will again use the editor module, but this time, when brought up on her screen, that function of the Infosafe software will reveal, under the appropriate menu items, the data which is relevant to the existing MSDS. Ms Dam must consider the contemporary accuracy and appropriateness of that data, and make such changes as are necessary. She made it clear in her evidence that she did not regard the process of reviewing an MSDS as involving any less responsibility, or any less onerous obligations, than the process of creating a new MSDS.

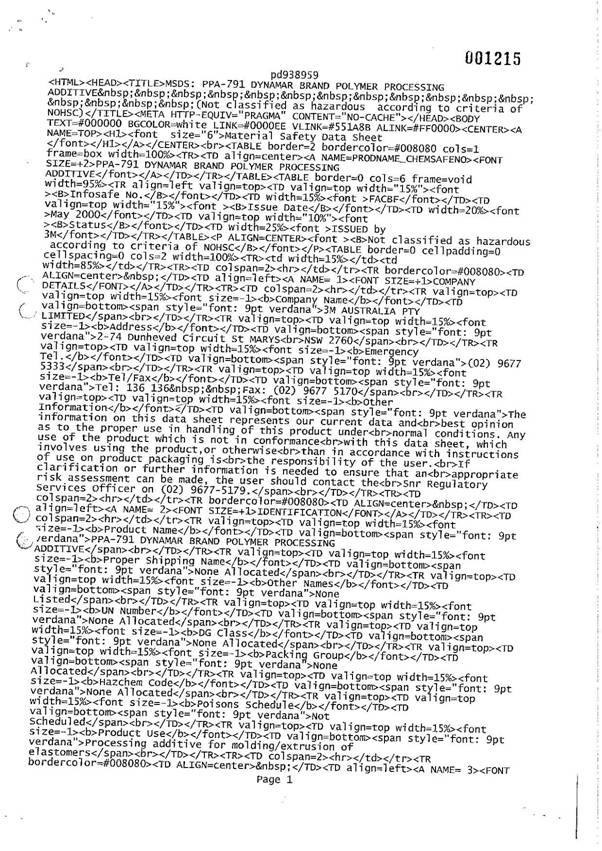

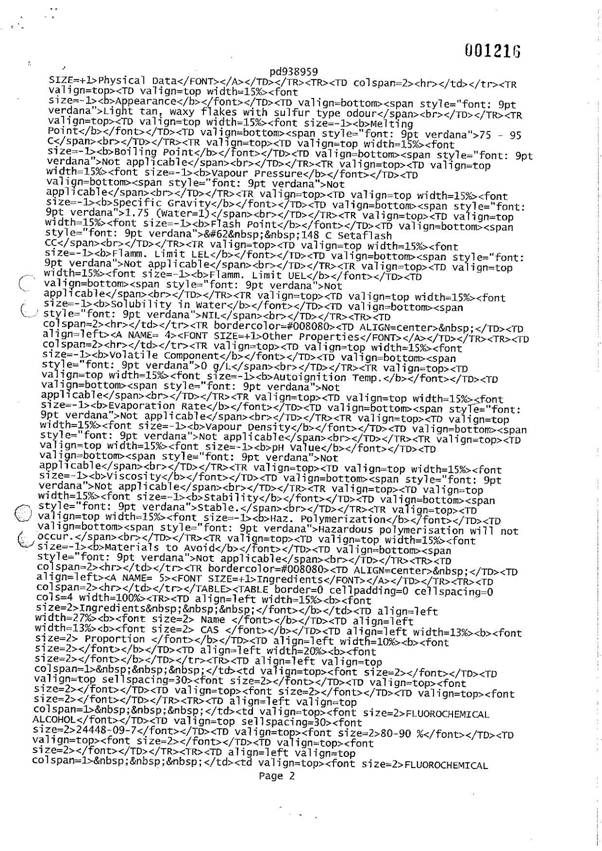

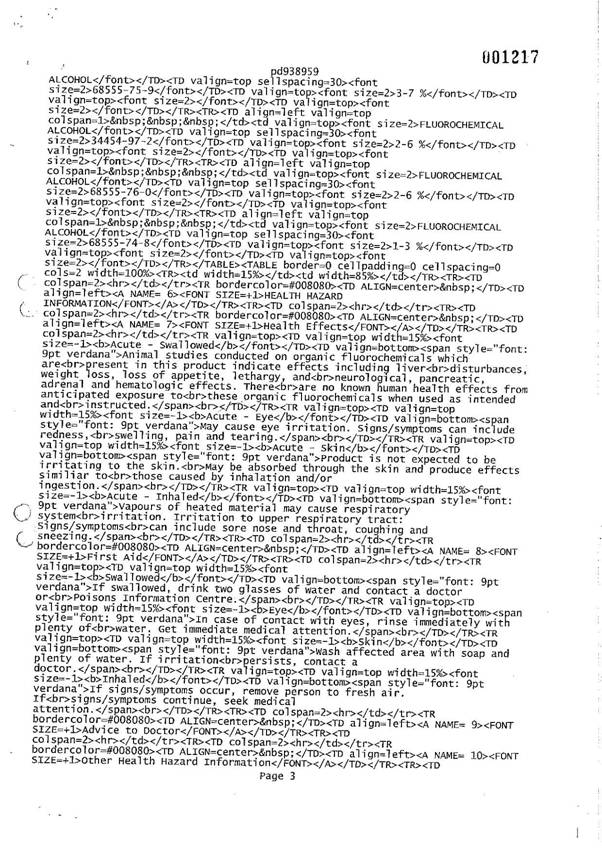

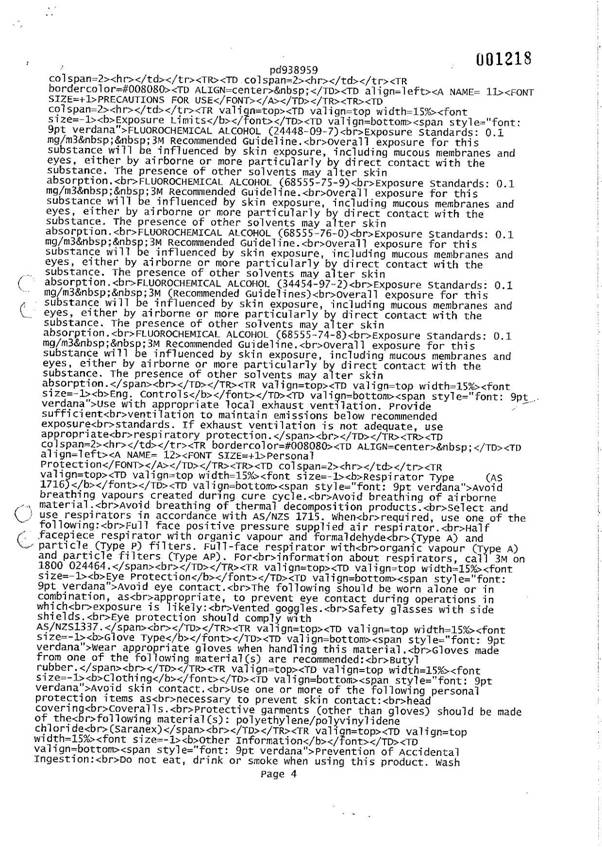

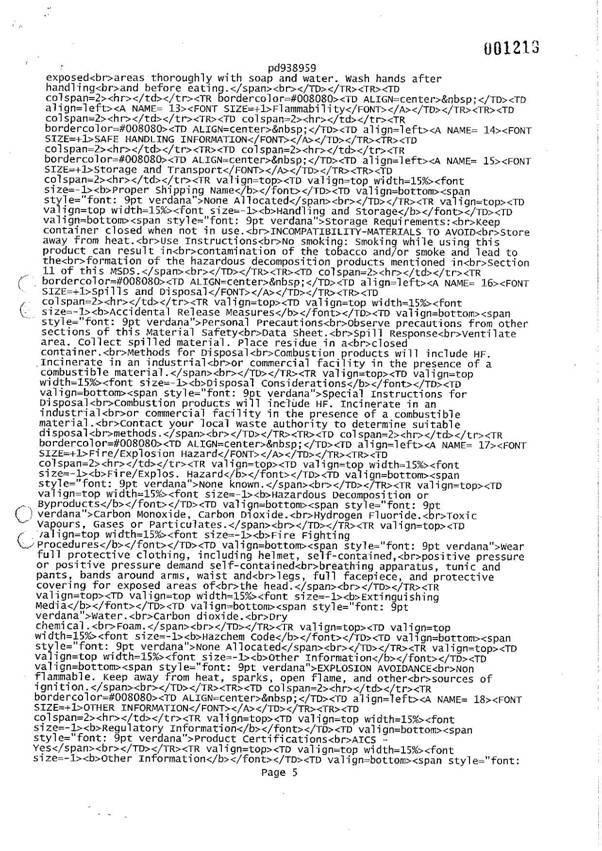

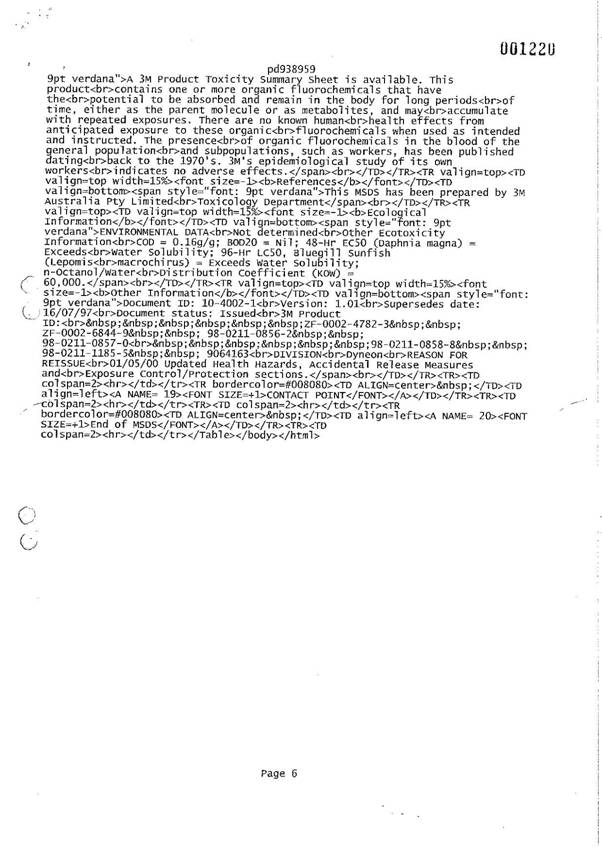

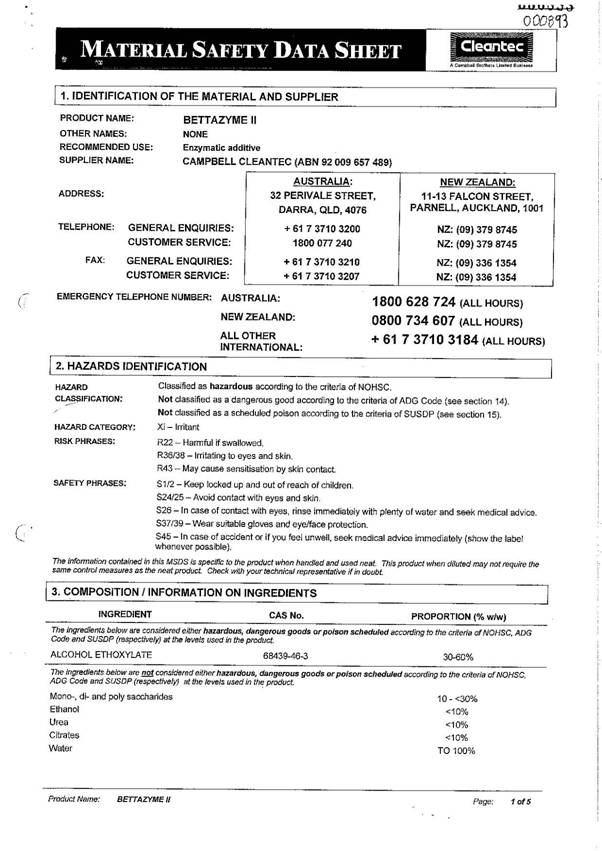

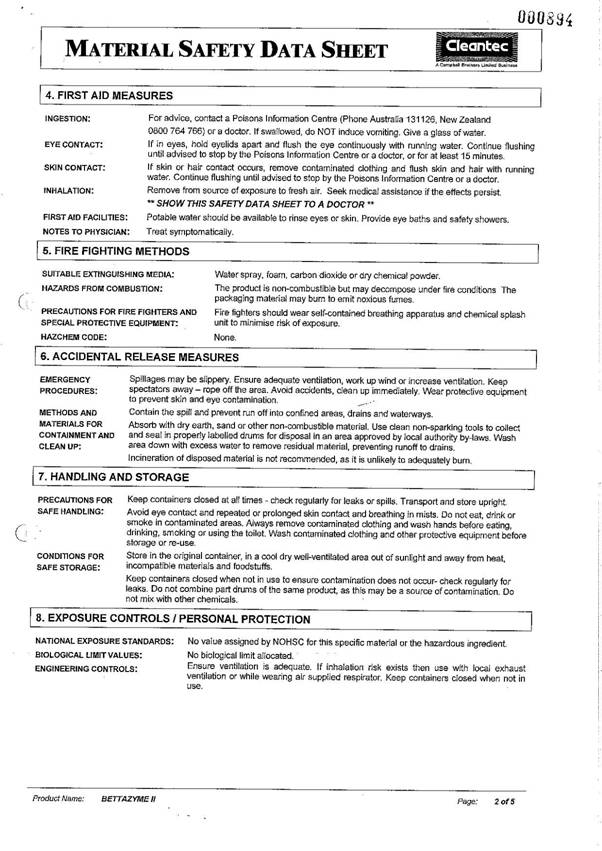

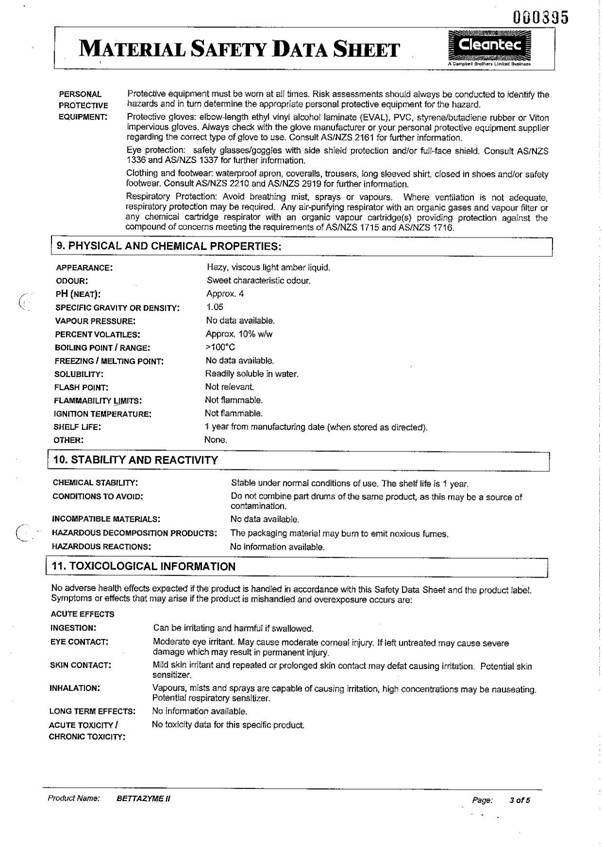

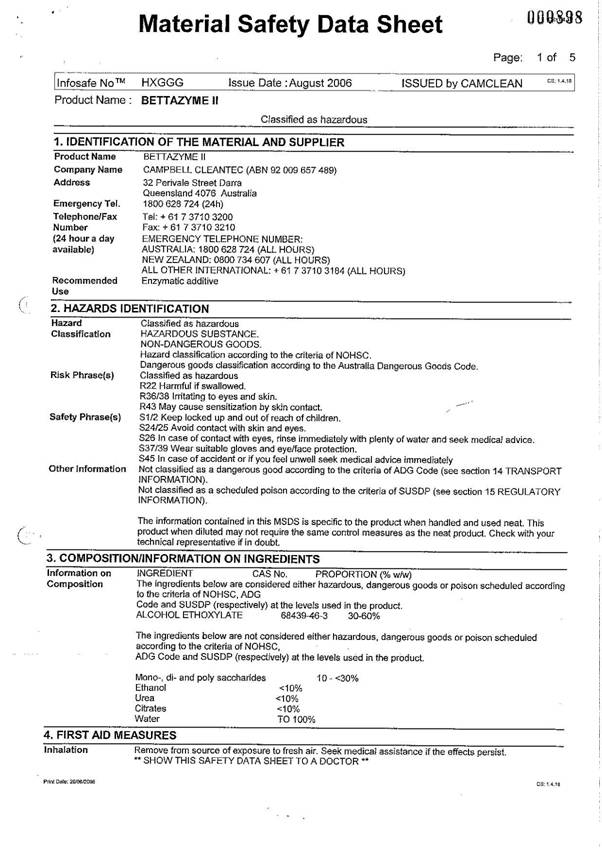

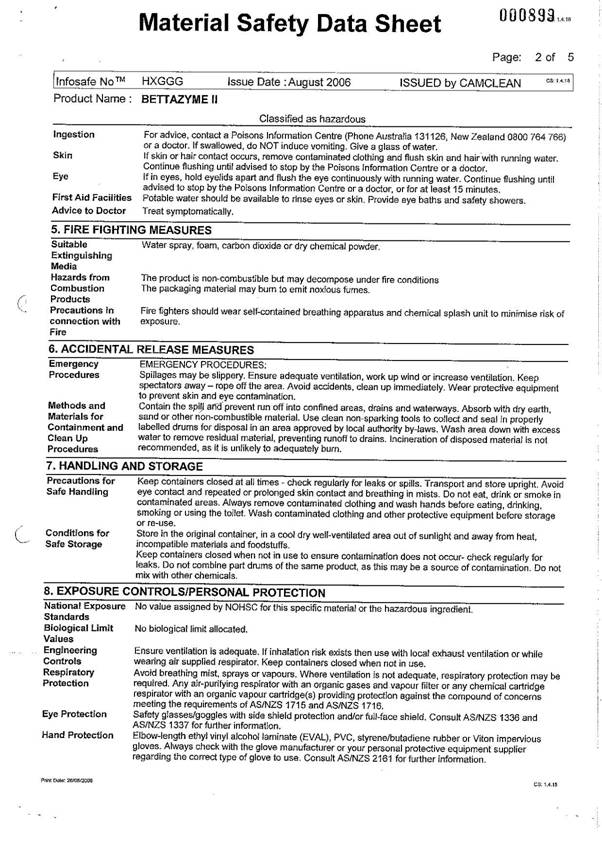

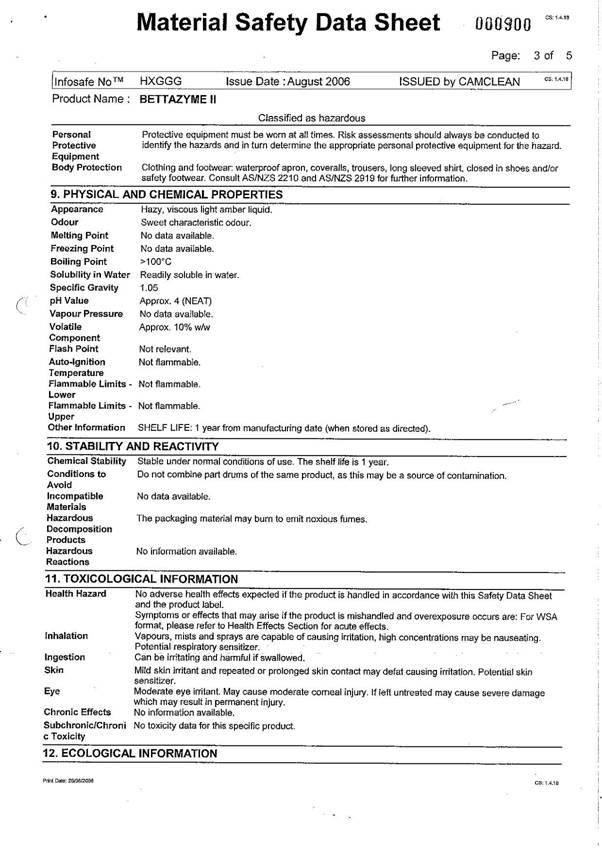

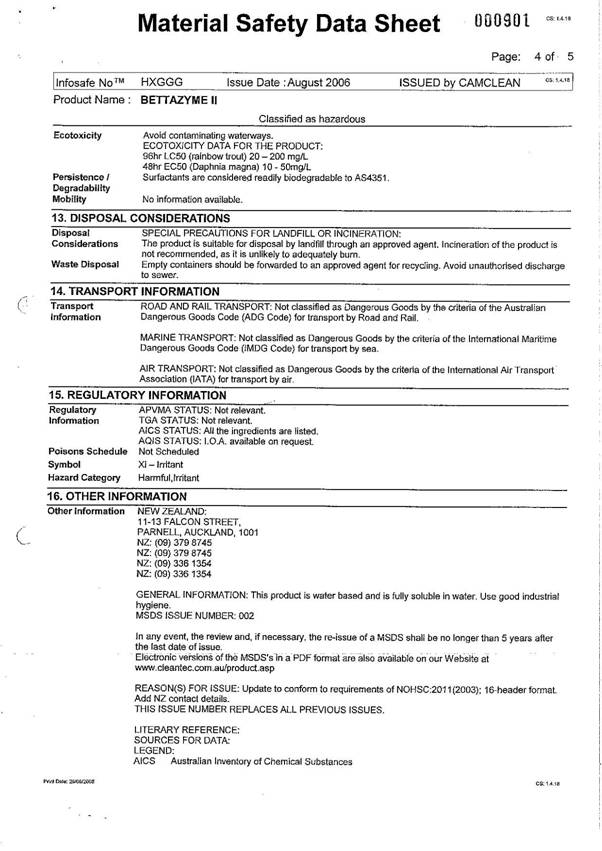

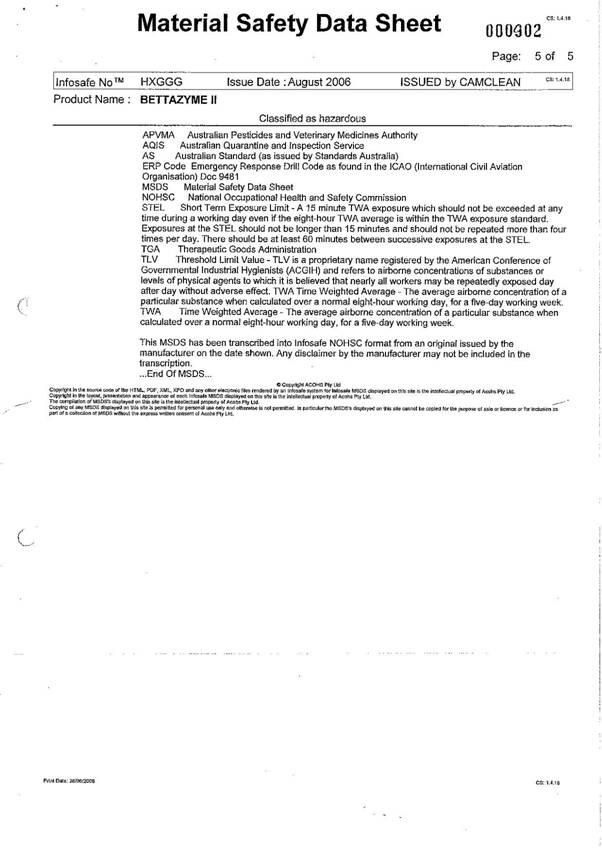

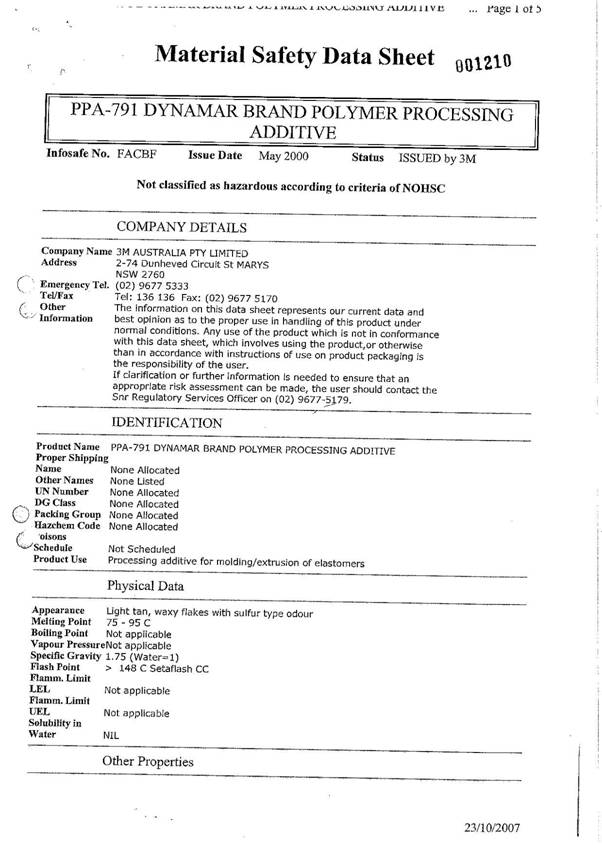

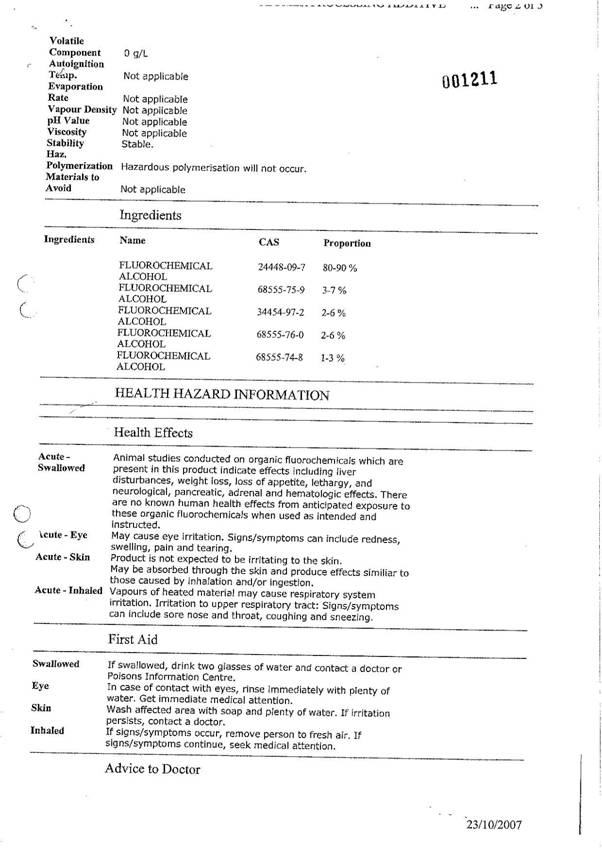

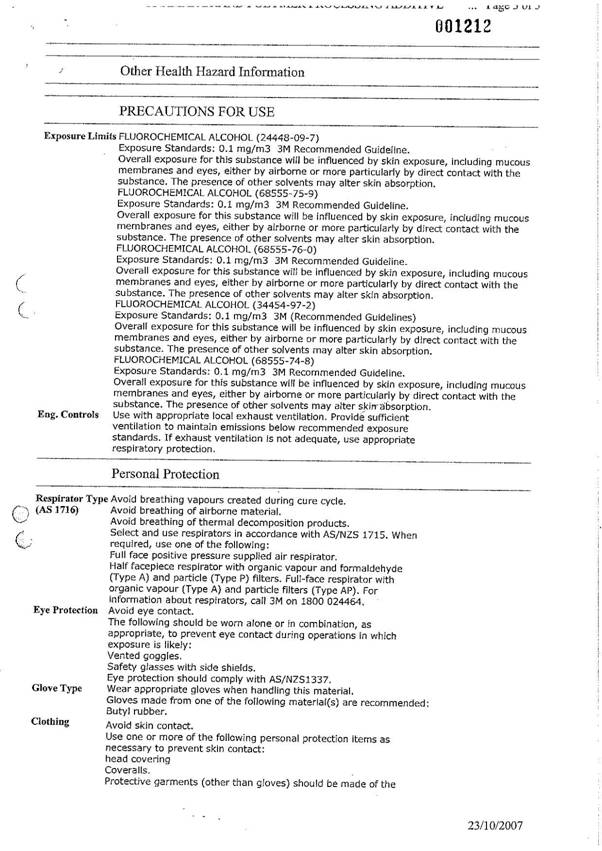

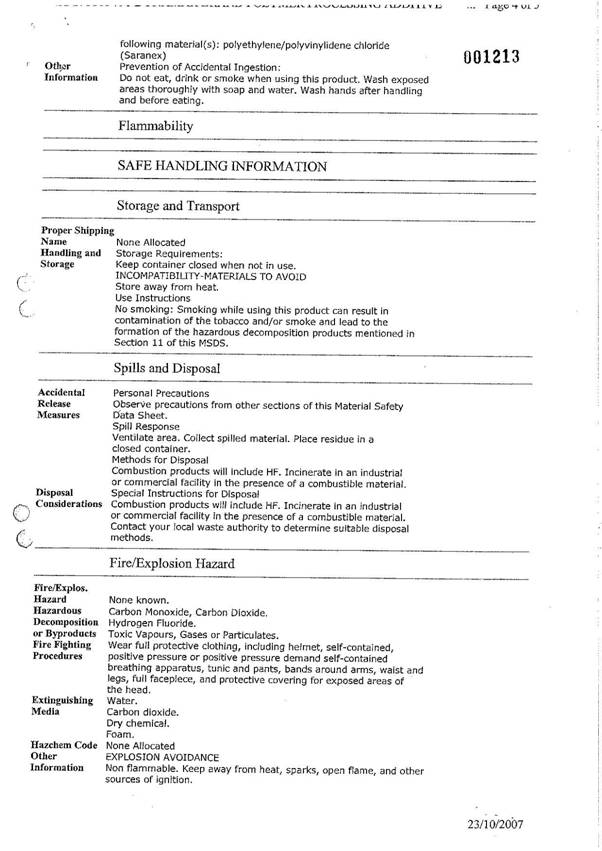

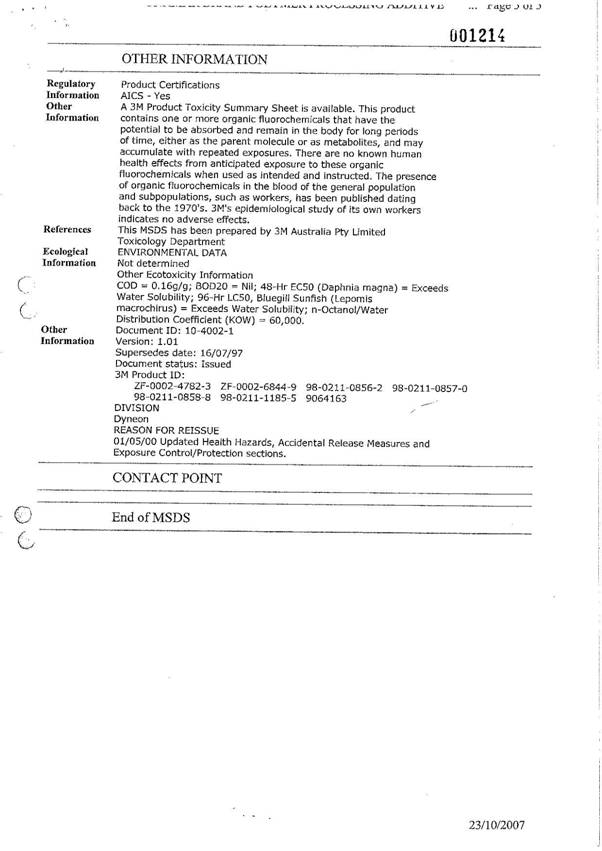

28 The second means by which a new Infosafe MSDS might come into existence is “transcription”. Here transcribers employed by Acohs (or, since about 2003, by Acohs (Shanghai) Information and Technology Pty Ltd) will take an existing MSDS (ie a non-Acohs MSDS) and, using the editor module, faithfully enter into the CDB every piece of information which is set out on the existing MSDS. This is because neither Acohs nor the customer for whom it transcribes has the authority to alter an MSDS as issued by the MIS. Thus, when the Acohs version of the MSDS is called up from the CDB, it will be identical in point of content and expression with the original, but will have the general appearance, layout and presentation of all Acohs MSDSs. In his affidavit sworn on 3 July 2008, Mr Cowie provided several examples of MSDSs as issued by the original MIS, and as generated by the Infosafe system after transcription by Acohs’ staff. Appendices 3 and 4 to these reasons are, respectively, the MSDS for a product called “Bettazyme II” as issued by the MIS and the corresponding MSDS generated by the Infosafe System. It will be seen that the layout and appearance of the version generated by Infosafe differs somewhat from the original. There is, however, no difference in the content.

29 Acohs has two commercial applications to which its customers may subscribe for the purpose of viewing (and, in some cases, creating) an MSDS. They are known as Infosafe 2000 Web (“I2000W”) and Infosafe 2000 Client Server (“I2000CS”). In the case of I2000W, a user (for example, an employer seeking access to the MSDS of an MIS) will have on-line access to the MSDSs covered by its subscription. Without having to go to the web site of the MIS concerned, the user may call up the MSDS of interest electronically from the CDB. The Infosafe program will then cause the elements of the HTML source code for the MSDS in question to be collected from the CDB, assembled and sent down the line to the user’s computer. In the case of I2000CS, selected elements of the CDB of relevance to the user will, together with the necessary application software, be installed on the user’s own computer, so that the user may view all MSDSs of interest without going on line. I2000CS also contains the editor module, enabling a customer who is the relevant MIS to author its own MSDSs, and to modify an MSDS from time to time, whether the MSDS had been authored originally by it or by Acohs for it. It may, but need not, transfer the data it entered – whether on the original creation of an MSDS or on a variation – to Acohs for inclusion in the CDB. This is the third means by which a new Infosafe MSDS might come into existence. Another feature of I2000CS is that an MSDS may be presented on the user’s screen not only in HTML format, but also in PDF format, by means of a program (which is part of the installed software) called “Crystal Reports”.

30 The Visual Basic program was originally written over the period 1996 – 1998 by Danny Lau, a consultant (or whose company was a consultant – the detail of this is not clear in the evidence) to Acohs. Towards the end of the project, he was assisted by Chien Yu Lee and Sei Nghi Trang, programmers employed by Acohs. Mr Cowie gave Mr Lau instructions as to the layout, presentation and appearance which he wanted for the Infosafe MSDSs. With his programming skills, and with his understanding of the technology being used to retrieve elements of an MSDS from the CDB, Mr Lau wrote the Visual Basic code used by Acohs. This code has been updated many times since. In his affidavit, Mr Cowie said that the Infosafe 2000 applications were “continually being upgraded” and that the software routines which enabled the system to generate MSDSs were “also continually being updated”. In each case, the upgrading and updating is done by programmers in the employ of Acohs.

The development of Acohs’ copyright claim

31 The means by which Acohs identified the MSDSs upon which it would sue ultimately involved complete reliance on the respondents’ discovery. That is to say, the respondents gave discovery of all the MSDSs in the Collection that could be shown to have come from Acohs (eg, and most commonly, by bearing the words “Infosafe No”), and Acohs then treated them as the works upon which it sued. The result of this, quite evidently, was that Acohs’ reproduction allegations were almost tautological. But that is to anticipate a subject to which I shall turn below.

32 Acohs’ identification of the copyright works on which it sued was originally problematic, and gave rise to difficulties which were resolved only by an amendment for which I considered I had no choice but to give leave on what transpired to be the penultimate day of the trial: see Acohs Pty Ltd v Ucorp Pty Ltd (No 2) (2009) 82 IPR 493. It is not presently necessary to go further back than Acohs’ Fifth Further Amended Statement of Claim, filed on 13 December 2007. The copyright claim, set out in para 8 thereof, was in the following terms:

Acohs is the owner of the copyright subsisting in the Infosafe System which includes (but is not limited to) the copyright subsisting in the following original literary works:

(a) the source code of each of the HTML and PDF files for MSDS rendered by the Infosafe System;

(b) the layout, presentation and appearance of each Infosafe MSDS rendered by the Infosafe System;

(c) a compilation of data which, in combination with the Infosafe management programmes, generated and rendered the MSDS as required by Blackwoods pursuant to the License [sic] Agreement set out in paragraph 10 below (the Blackwoods Compilation).

Particulars were annexed.

33 The respondents’ Defence (filed on 17 June 2008) to para 8 of Acohs’ pleading was both complex and lengthy. It included the following in relation to the layout claim in sub-para (b):

(a) in relation to the layout, presentation and appearance of each Infosafe MSDS referred to in sub-paragraph (b) of the Claim:

(i) each MSDS as a whole, including the words and data in the MSDS and the manner in which the words and data are laid out, presented and appear in the MSDS, constitutes a single literary work for the purposes of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (“Copyright Act”);

(ii) the “layout, presentation and appearance” of each MSDS does not constitute a separate literary work from the literary work constituted by the MSDS as a whole, including the words and data in the MSDS;

34 In a Reply filed on 2 July 2008, Acohs responded to these aspects of the Defence in terms which included the following:

Further to sub-paragraphs 8(a)(i) and (ii) thereof it says that:

(a) each MSDS in Annexure A to the Fifth Further Amended Statement of Claim (the statement of claim) is a separate literary work and a separate compilation being a literary work;

(b) The Applicant has, in paragraph 8 of the statement of claim (and the Particulars of Ownership thereto) set out the main (and relevant) original contributions made by the Applicant to the creation of the works in suit (being those in Annexures A and B to the statement of claim);

(c) the reference in paragraph 8 of the statement of claim to the Applicant’s original contributions to the creation of the works does not limit the scope of the copyright subsisting in the works in suit nor the scope of the copyright owned by the Applicant (as made clear in the Particulars of Ownership last paragraph), but merely focuses upon those aspects of reproduction and infringement in respect of which the Applicant sues and seeks relief;

Relevantly to Acohs’ layout claim (that made in para 8(b) of its pleading) this represented the parties’ positions during most of the trial of the case.

35 The particulars of copyright ownership on which Acohs went to trial were those annexed to its Fifth Further Amended Statement of Claim. Those particulars were divided into four parts. The first contained a general explanation of the Infosafe System; the second dealt with source code; the third dealt with the “layout, presentation and appearance” of Acohs’ MSDSs; and the fourth dealt with the “Blackwoods Compilation”. It was in these particulars that one found the essence of Acohs’ copyright ownership claim.

36 Under “the Infosafe System”, the particulars commenced as follows:

The Infosafe System comprises software applications and relational database repositories which work together to generate and render MSDS in electronic formats that can be viewed and printed by use of a computer. The Infosafe System includes web based applications, known as Infosafe 2000 Web, which generate and render MSDS in HTML and/or PDF format for delivery over the world wide web and client server applications, known as Infosafe 2000 Client Server, which generate and render MSDS in HTML and/or PDF format.

The particulars then stated that the development of the software applications, described as “management computer programs”, began in 1988, and they named the persons by whom the software was written and designed. It was said that the applications “have been updated from time to time since”. The “software routines” that call for and retrieve the data and generate the required source code which was said to “reflect the templates” were identified by name. The particulars then continued:

The relational database repositories in the Infosafe System have been made principally by ACOHS employees coding, collating and feeding data into [the CDB]…. In addition, some of ACOHS’ customers who use the Infosafe System enter data into their own database repositories.

37 Under the heading “source code”, the particulars stated that the HTML and PDF files for MSDSs in which the applicant claimed copyright were set out in a DVD annexed thereto. The organisation of those MSDSs on the DVD was explained in the particulars. Annexure A on the DVD contained two folders, the first of which contained 10,748 MSDSs generated for Blackwoods and the second of which contained 48,826 MSDSs generated in other circumstances. In each case, the MSDSs were either authored by Acohs, authored by Acohs and its licensees or transcribed. The MISs for whom Acohs authored MSDSs, and in conjunction with whom the applicant authored MSDSs, were identified by name. It was said that Acohs was unable to identify the customers for whom it transcribed MSDSs. In September 2009, as a result of further discovery given by the respondents, Acohs amended its particulars by adding a further DVD on which, set out by the reference to the same categories, in Annexure A1, were an additional 12,599 MSDSs for which it claimed copyright.

38 The break-up as between the different categories of MSDSs in Annexures A and A1 to Acohs’ particulars were as follows (I have included the MSDSs in Annexure A1 under “other”):

Blackwoods

Other

Authored by Acohs

3,772

47,889

Authored by Acohs and customers

9,164

11,361

Transcribed

6,060

2,175

39 The particulars next identified the sense in which Acohs claimed copyright in the layout, presentation and appearance of the MSDSs, as follows:

ACOHS claims copyright in the particular layout, presentation and appearance of MSDS rendered by the Infosafe System. All MSDS generated and rendered by the Infosafe System comprise data from the database repositories as compiled by the Infosafe System’s software applications into the particular layout, presentation and appearance of Infosafe MSDS which is determined by the templates within the software applications. Each particular layout presentation and appearance of MSDS rendered by the Infosafe System in which the Applicant claims copyright in this proceeding appears in Annexure A and in Annexure B (the Templates Annexure) contained in the DVD annexed hereto, Annexure B being the Applicant’s bare templates populated with sample data.

It was said that the particular layout, presentation and appearance of these MSDSs were authored by Mr Cowie and Mr Lau. The particulars continued:

The authorship of the layout, presentation and appearance of the MSDS involved the arrangement and division of headings, devising of data fields, selection of font sizes, styles, colours and highlights; horizontal and vertical spacing; margins; borders; heading styles; boxes and tables and other formatting (as can be seen from Annexure B) from an almost infinite combination of choices so as to present the information in the MSDS in an original, useful, informative, regulation-compliant, attractive, accessible and distinctive manner.

Each time an MSDS is generated or rendered by the Infosafe System it appears in the particular layout, presentation and appearance determined by the Infosafe MSDS source code at that particular time. Variations in the source code between versions of the Infosafe System may cause the display of the same MSDS to be viewed slightly differently as disclosed by the MSDS templates in Annexure B. Differences between internet browser applications that interpret the source code may cause the same MSDS to be viewed slightly differently.

40 Under the heading “The Blackwoods Compilation”, the following particulars were provided:

Pursuant to the License Agreement referred to in paragraph 10 hereof, the Blackwoods Compilation was created exclusively by ACOHS employees. The MSDS and their underlying HTML files generated and rendered by the Infosafe software applications in conjunction with the Blackwoods Compilation are contained in the folder entitled “Blackwoods” in Annexure A. From time to time during the currency of the License Agreement, ACOHS updated the Blackwoods Compilation by removing some MSDS and adding or updating others in response to instruction from Blackwoods as to the MSDS required and in response to changes in the content of MSDS issued by the manufacturer, importer or supplier of the substance to which the MSDS relates. The compilation of data in the folder entitled “Blackwoods” in Annexure A is the Blackwoods Compilation downloaded by the Respondents on or about 3 September 2003 from the Acohs Blackwoods Website. ACOHS has not kept historical versions of the Blackwoods Compilation. The changes to the Blackwoods Compilation made during the currency of the License Agreement did not substantially alter the Blackwoods Compilation.

41 After having said that the Infosafe System was made exclusively by employees of Acohs pursuant to the terms of their employment, and having referred to s 35(6) of the Copyright Act, the particulars concluded as follows:

For the avoidance of doubt, ACOHS makes no claim to the bare unformatted data contained in the individual MSDS generated and rendered by the Infosafe System but ACOHS reserves its rights in relation to other aspects of the Infosafe System.

42 Returning to the pleadings as such, at trial the respondents contended that the layout, presentation and appearance of a document could not constitute a literary work. They did so at two levels. Their first point was a matter of the identification of the work: either the document as a whole was literary work or it was not. The indentation of sub-headings and the use of a particular colour and style of text boxes in a document, for example, could not be a work as such. Their second point related to the intrinsic concept of a literary work: features such as these could not be literary because they did not convey semiotic meaning. Acohs’ response to the first point was not forthcoming until final submissions were being made in the case. It applied to amend its (then) Sixth Further Amended Statement of Claim by the replacement of para 8(b) with the following:

(b) each MSDS in Annexure A and Annexure A1 having its layout, presentation and appearance in accordance with one or other of the templates in annexure B;

As I have said, that amendment was allowed. Unsurprisingly, the respondents’ initial reaction to that development was to anticipate the need to re-open their evidentiary case. I allowed them an adjournment so that they might consider their position.

43 During the adjournment, the respondents’ solicitors wrote to Acohs’ solicitor in terms which referred to the old and the new states of the pleadings, and to the aspects of Acohs’ particulars which I have set out in paras 37-39 above. They made the point, implicitly if not expressly, that Acohs’ disavowal of any claim to the “bare unformatted data” had the potential to present rather differently if it were an MSDS as such, rather than the layout, presentation and appearance thereof only, which was held out as the copyright work. The respondents’ solicitors required “clear and unambiguous answers” to the following questions:

1. Does the expression “bare unformatted data” in the Ownership Particulars mean all of the words, figures and symbols in each MSDS the subject of the Claim, including all of the headings and subheadings?

2. If the answer to question 1 is “no”, please identify precisely which words, figures and symbols in each MSDS the subject of the Claim Acohs contends fall outside the meaning of “bare unformatted data”.

3. Does Acohs make any claim of originality in respect of the words, figures and symbols (if any) identified in response to 1 and 2 above in determining the originality of each MSDS as a literary work for the purposes of subsistence of copyright?

4. Does Acohs contend that the Court should otherwise have regard to any originality of the words, figures and symbols in each MSDS (ie the words, figures and symbols that Acohs contends fall within the meaning of “bare unformatted data”) in determining the originality of each MSDS for the purposes of subsistence of copyright?

44 Acohs’ solicitor did answer those questions, in the following terms:

1. No. It means the variable data which is inserted into the template of an Infosafe MSDS. As is apparent from Annexure B to the Statement of Claim, each template includes headings and sub-headings of fixed content. Those headings and sub-headings are presented and arranged as appears in the template. The arrangement and selection of those headings and sub-headings is part of the original content of Infosafe MSDS.

2. The headings and sub-headings which appear in the templates in Annexure B to the Statement of Claim are not comprehended by the expression “bare unformatted data”. See 1 above.

3. Acohs does not claim that the headings and sub-headings are original, but that their selection, arrangement and layout are original. The selection, arrangement and layout are a function of the operation of the Infosafe system as described by Mr Cowie’s affidavit of 2 July 2008.

4. No.

He provided the following further elaboration as to his client’s understanding of “bare, unformatted data”, and added a comment in relation to “layout, templates and content”:

The layout of a document is organised by structural rules or instructions, (HTML for example), that identify headings, sections, lists and forms, and where words are placed on the relevant page.

The content or data which might be put into the document is ordered by the layout structure and is platform independent subject to minor idiosyncrasies of (in the case before us) of web browsers.

Templates, insofar as they relate to the web, are predesigned webpages which are divided into specific structural and content areas. The Infosafe templates, which are set out in Appendix B, contain various headings and subheadings as to where content and, in some cases logos, dropdown menus, footers, and instructions as to where content will appear in the document.

As you are well aware, the templates in Appendix B were authored by the Applicant’s employees and are generated by the Applicant’s source code which is written in the visual basic language.

In addition to the above, the appearance of the layout of the Infosafe MSDS is influenced by the use of typography, fonts and placement of headings etc. The Respondents called evidence in relation to both layout and appearance.

The content or data in the Infosafe MSDS is, as I have said, ordered by the predetermined layout of the Infosafe MSDS. That order is controlled by spaces, tabs, carriage returns etc in order to present the content in the predetermined layout on the web.

As can be seen from Mr Moody’s affidavit the presentation of the content or data, without control is an unbroken string of words.

Thus bare unformatted data in an Infosafe MSDS is the variable data which appears in an MSDS, and which does not have spaces, tabs, carriage returns or other controlling instructions, whether those instructions be in HTML or Crystal Report PDF or HTML converted to PDF. As the Applicant has made clear, it has not sought to claim copyright in the bare unformatted data.

On the strength of that response from Acohs’ solicitor, the respondents chose not to apply to re-open their evidentiary case.

The HTML source code as an original literary work

45 As appears from para 8(a) of Acohs’ pleading, copyright is asserted in “the source code of each of the HTML and PDF files” for Infosafe MSDSs. However, in final submissions made on its behalf, Acohs confined its claim to HTML source code. As I understand it, the source code for an MSDS rendered in PDF format would never have been written by an individual, and would be unintelligible even to the programmers employed by Acohs. Rather, that source code will be machine-generated as part of the “Crystal Reports” function when a customer of Acohs uses I2000CS to produce an MSDS in PDF format. However these aspects may be, Acohs’ final submissions were, as I have said, confined to HTML source code, and my reasons will be likewise.

46 I have referred to the means by which the source code for a particular MSDS is generated, and the use to which it is put, at paras 24 and 29 above. To give some idea of what source code contains, and how it is related to the relevant MSDS as the latter would appear on a computer screen, I have included, as Appendices 5 and 6 to these reasons, a copy of an MSDS as it appears on the screen and the source code for that MSDS, respectively.

47 There is no a priori reason to deny a body of source code such as that set out in Appendix 6 the status of a literary work. It consists of words, letters, numbers and symbols which are intelligible to someone skilled in the relevant area, and which convey meaning. It has a discrete existence as an entity in its own right, with a definite point of commencement and definite point of conclusion. It is fairly described as a set of statements or instructions to be used in a computer in order to bring about the appearance on the screen of the corresponding MSDS, and therefore as a “computer program”, and thus a literary work, within the meaning of the Copyright Act. But even without recourse to that definition, I consider that the source code referred to has all the necessary attributes of a literary work in the traditional copyright sense, remembering always that the test is not literary quality, and that quite mundane, functional expressions may be literary works in the statutory sense.

48 The more difficult question is whether the source code for an Acohs MSDS is an original literary work. In IceTV Pty Ltd v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 239 CLR 458, six members of the High Court provided, in two separate judgments, firm reminders of the importance of authorship in bringing an original copyright work into existence. French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ said (239 CLR at 470-471 [22]-[24]):

The “author” of a literary work and the concept of “authorship” are central to the statutory protection given by copyright legislation, including the Act.

Undoubtedly, the classical notion of an individual author was linked to the invention of printing and the technical possibilities thereafter for the production of texts otherwise than by collective efforts, such as those made in mediaeval monasteries. The technological developments of today throw up new challenges in relation to the paradigm of an individual author. A “work of joint authorship”, as recognised under the Act, requires that the literary work in question “has been produced by the collaboration of two or more authors and in which the contribution of each author is not separate from the contribution of the other author or the contributions of the other authors”. As in other cases where the facts resemble those under consideration here, the Weekly Schedules (and the Nine Database) were the result of both a collaborative effort and an evolutionary process of development, involving in this instance both manpower and the use of computers. However, nothing in these reasons turns on any conclusion as to the precise identity of the author or authors of those works.

In assessing the centrality of an author and authorship to the overall scheme of the Act, it is worth recollecting the longstanding theoretical underpinnings of copyright legislation. Copyright legislation strikes a balance of competing interests and competing policy considerations. Relevantly, it is concerned with rewarding authors of original literary works with commercial benefits having regard to the fact that literary works in turn benefit the reading public.

Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ said (239 CLR at 496 [105]):

A generally expressed admission or concession by one party to an infringement action of subsistence of and title to copyright may not overcome the need for attention to these requirements when dealing with the issues immediately in dispute in that action. This litigation provides an example. The exclusive rights comprised in the copyright in an original work subsist by reason of the relevant fixation of the original work of the author in a material form. To proceed without identifying the work in suit and without informing the enquiry by identifying the author and the relevant time of making or first publication, may cause the formulation of the issues presented to the court to go awry.

Quite apart from the question whether the putative author was a “qualified person”, and allowing for the possibility, in some cases, of a work having multiple authors, as a general proposition the need for a work to spring from the original efforts of a single human author is a fundamental requirement of copyright law. I use the expression “original efforts”, of course, in the sense explained by French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ in IceTV (239 CLR at 474 [33]).

49 The point at which the need arises to identify the author is (in the case of an unpublished work) the moment when the work is first reduced to a material form or (in the case of a published work) the moment when the work was first published in Australia (IceTV, 239 CLR at 495 [103]). In the present case, Acohs submitted:

The HTML source code for the Infosafe MSDS in Annexure A was in each case reduced to a material form over the period from the writing of the HTML generating routines in the Infosafe System and to the end of the process of creating the particular MSDS so that the HTML source code was able to be generated to enable the MSDS to be viewed. It is during that period that the HTML source code was reduced to a form of storage from which it was capable of being reproduced. That is, it is reduced to a material form for the purposes of the Act: Roland Corporation v Lorenzo & Sons Pty Ltd (1991) 33 FCR 111.

And:

Once the author or transcriber of an MSDS completes the process of authorship or transcription using the Editor Module, they view the completed MSDS on the screen and conduct a formal check to endure it is accurate and internally consistent. Where the MSDS is viewed by an author or transcriber on the screen in HTML, the completed HTML source code is stored in a file named “Default.htm”. That HTML source code contains other HTML source code that creates internal hyperlinks that are not present in the HTML source code of an HTML MSDS produced by Infosafe 2000 Web or Client Server. For that reason it is not identical to the final HTML source code. However, in order to view the MSDS in HTML it is necessary that the corresponding HTML file exists somewhere in the computer. It is submitted that the HTML source code for each MSDS is stored as a complete source code when the author or transcriber checks the MSDS at the end of the process of authorship or transcription.

Aside from such issues as may arise from the existence of the internal hyperlink referred to in this passage, it is at least clear that Acohs contends that the source code said to be a literary work is first reduced to a material form at the point when the author or transcriber has completed his or her task and checked the appearance of the completed MSDS on his or her screen.

50 If it were Acohs’ case that the author of the source code for each MSDS was the author or transcriber who undertook that task, the case would immediately confront the problem that he or she did not write the code, either in a traditional way or using a computer. Rather, the author or transcriber was, at least for the most part, engaged in the task of entering data into the CDB, it being the routine in the Infosafe System which gathered together the elements needed for the source code in question. As Acohs put it, the source code was “generated” by the system. This difficulty is not overcome by the circumstance that an author of an Acohs MSDS will frequently be required to devise a new phrase or expression for a particular MSDS: the question is whether the complete source code as a work is original, not whether some parts of it are. It may be accepted that, had the source code been written as such by an Acohs author, its originality would not necessarily be compromised by the existence of much material drawn from other places – even from material stored in databases. The problem is more that the source code as a work – ie as a complete entity – was not written by any single human author. It was generated by a computer program.

51 Acohs sought to overcome this difficulty by proposing that the computer used by authors and transcribers was “no more than a tool”, relying upon the interlocutory and, it seems, ex tempore judgment of Whitford J in Express Newspapers plc v Liverpool Daily Post and Echo plc (1985) 5 IPR 193 in this respect. In that case, the task of devising a series of numbers in grids was undertaken by writing a program by which a computer would produce the desired result. Speaking of the person held to be the author, his Lordship said (5 IPR at 196):

What Mr Ertel says is that he started off by seeing whether he could work out these grids by just writing down appropriate sequences of letters. It soon became apparent to him that, although this could be done, and done without too much difficulty when just producing a small number of grids, if you are going to produce sufficient for a year’s supply or something of that order, it becomes a very different matter indeed. It was immediately apparent to him that the labour involved in doing this could be immensely reduced by writing out an appropriate computer program and getting the computer to run up an appropriate number of varying grids and letter sequences.

….

The computer was no more than the tool by which the varying grids of five-letter sequences were produced to the instructions, via the computer programs, of Mr Ertel. It is as unrealistic as it would be to suggest that, if you write your work with a pen, it is the pen which is the author of the work rather than the person who drives the pen.

52 I am disposed to agree with Pincus J that the analogy between the computer and the pen is “rather [unconvincing]”: see Roland Corporation v Lorenzo and Sons Pty Ltd (1991) 22 IPR 245, 252. However that may be, the analogy would not in any event justify the conclusion that the authors and transcribers in the present case used the computer to write the source code for each MSDS in the same way as Mr Ertel used his computer to produce grids in Express Newspapers. It was not as though the authors and transcribers, having in mind the source code they desired to write, used the computer to that end. They were not computer programmers, and there is no suggestion that they either understood source code or ever had a perception of the body of source code which was relevant to the MSDSs on which they worked.

53 At this point of the argument, Acohs introduced the contribution of the programmers who wrote the Visual Basic code which controls the operation of the Infosafe System. It submitted that they wrote the individual elements of source code that would ultimately find their way into the desired body of source code that caused each MSDS to appear on the screen when required. It was they who used the computer as a tool; and they well understood what a body of source code – relevant to a particular MSDS – would look like when it was generated by the program which they wrote. In my view, however, it would be artificial to regard the programmers as involved in the task of writing the source code for thousands of MSDSs yet to take a material form merely because they wrote, and amended, the program which, when prompted, would put together a selection of the fragments of source code which they did write with other fragments later contributed by the authors and transcribers.

The question of joint authorship of the HTML source code

54 This leads me to the way that Acohs in fact conducted its case in this proceeding. It did not submit that either the programmers or the authors/transcribers were, alone, the authors of the relevant source code in the copyright sense. Rather, it submitted –

…that the authors of the HTML source code for each MSDS in Annexure A were:

(a) Danny Lau … and/or Feng Liu Yang …, Chien Yu Lee … and Sai Nghi Tran …, who were the computer programmers who wrote the ‘GenerateHTML’ routines including the HTML instruction tags that are retrieved by the Infosafe System and placed into the HTML source code for the MSDS; and

(b) the individual who ‘authored’ or transcribed the data for each MSDS into the Infosafe System.

That is to say, Acohs’ case was one of joint authorship, and it is to that concept that I must now turn.

55 Under s 10 of the Copyright Act, a “work of joint authorship” is defined as:

…a work that has been produced by the collaboration of two or more authors and in which the contribution of each author is not separate from the contribution of the other author or the contributions of the other authors.

The questions, then, are whether the source code for a particular MSDS was written by the Visual Basic programmers (of the one part) and the particular author or transcriber, as the case may be (of the other part), in collaboration with each other; and whether the contribution of each was not separate from that of the other or others.