FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Comcare v Commonwealth of Australia [2009] FCA 700

PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – civil proceedings – use of victim impact statements

INDUSTRIAL LAW – occupational health and safety – breach of duty of employer to take all reasonably practicable steps to protect the health and safety of employees – group of cadets lost overnight without proper communication equipment – request for adjournment based on the applicant considering that an appropriate undertaking is in force – whether Court must be satisfied undertaking is reasonable

Occupational Health and Safety Act 1991 (Cth) ss 5, 9(5), 10, 16(1), 40(2), 41(1)(b), 53(1), Sch 2 cl 2, cl 14, cl 16

Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic) Pt 6 Div 1A

Comcare v Commonwealth (2007) 163 FCR 207; [2007] FCA 662 (Trooper Lawrence) applied

Comcare v Post Logistics Australasia Pty Ltd (2008) 178 IR 200; [2008] FCA 1987 cited

Director of Public Prosecutions v Amcor Packaging Australia Pty Ltd (2005) 11 VR 557; [2005] VSCA 219 discussed

Director of Public Prosecutions v DJK [2003] VSCA 109 approved

Director of Public Prosecutions v Yarra Valley Water Limited (2006) 159 IR 395; [2006] VSCA 279 discussed

Lawrenson Diecasting Pty Ltd v Workcover Authority of New South Wales (Inspector Ch’ng) (1999) 90 IR 464 applied

R v Dowlan [1998] 1 VR 123 discussed

R v Medini [2002] VSC 12 cited

R v Propsting [2009] VSCA 45 applied

Veen v R (No 2) (1988) 164 CLR 465; [1988] HCA 14 applied

Workcover Authority of New South Wales v Profab Industries Pty Ltd (2000) 49 NSWLR 700 applied

COMCARE v COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA

VID 409 of 2008

NORTH J

30 JUNE 2009

MELBOURNE

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | VID 409 of 2008 |

| COMCARE Applicant

| |

| AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Respondent

|

| JUDGE: | |

| DATE OF ORDER: | 30 JUNE 2009 |

| WHERE MADE: | MELBOURNE |

THE COURT DECLARES BY CONSENT THAT:

1. On 29 March 2007 at the Wombat State Forest near Gisborne in Central Victoria, the respondent, acting through the Chief of Army as the employing authority of members of the Australian Army Cadets (‘AAC’), contravened cl 2(1) of Sch 2 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act 1991 (Cth) by reason of having breached s 16(1) of the said Act in the course of conducting a three day training course known as Bivouac 2007 in that it:

(a) supplied Cadet Nathan Fazal Francis, Cadet Nivae Anandaganeshan and Cadet Gene van den Broek with one-man combat ration packs (CRP’s) containing a satay beef food pouch which contained peanuts or peanut protein for their consumption despite having been informed that the said cadets were allergic to peanuts;

and, in so doing, it failed to:

(b) warn parents of the AAC cadets about the contents of the CRP’s;

(c) warn AAC cadets about the contents of CRP’s;

(d) warn AAC cadets with pre-existing food allergies of the contents of CRP’s;

(e) make appropriate use of information provided by AAC cadets and parents of AAC cadets regarding pre-existing or known allergic conditions and correlate that information with the potential risk of being exposed to allergies through the supply of food contained in CRP’s;

(f) ensure that the contents of CRP’s allocated to AAC cadets did not include food products or allergens that may have triggered allergic responses by removing or requiring the removal of peanut-based food products from CRP’s;

(g) prevent distribution or provision of peanut-based food products to AAC cadets with pre-existing allergic reactions by:

i. inspecting the contents of CRP’s to be allocated to those individual AAC cadets who had given notice of allergic conditions;

ii. isolating cadets with pre-existing medical conditions and / or notified food allergies at the time of distribution of CRP’s and issuing them with CRP’s that did not contain peanut products or other food allergens;

iii. removing all CRP’s known to contain peanut protein or other food allergens from circulation amongst AAC cadets;

iv. requiring all AAC cadets with notified allergic conditions to provide their own food supplies;

(h) issue any or any adequate instructions or provide adequate supervision regarding distribution of CRP’s;

(i) issue any adequate instructions or provide adequate supervision regarding consumption of contents of CRP’s;

(j) prevent the consumption of CRP’s containing food allergens by AAC cadets with food allergies;

(k) distribute CRP’s after consulting or considering pre-existing medical conditions; and

(l) take into consideration the findings of a report dated 22 November 1996 by the Australian National Audit Office entitled ‘Management of Food Provisioning in the Australian Defence Force’.

2. The Commonwealth entity to which the conduct related is the Chief of Army.

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to cl 4 of Sch 2 of the said Act, the respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a penalty of 1910 penalty units equating to $210,100.

AND BY CONSENT ORDERS THAT:

2. The respondent is to pay the applicant’s costs.

3. The Amended Application dated 16 September 2008 insofar as it relates to paragraphs 20 – 33 of the Statement of Claim dated 6 June 2008 stands adjourned until 10.15 am on 1 April 2010.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

The text of entered orders can be located using eSearch on the Court’s website.

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY | VID 409 of 2008 |

| BETWEEN: | COMCARE Applicant

|

| AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Respondent

|

| JUDGE: | NORTH J |

| DATE: | 30 JUNE 2009 |

| PLACE: | MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

introduction

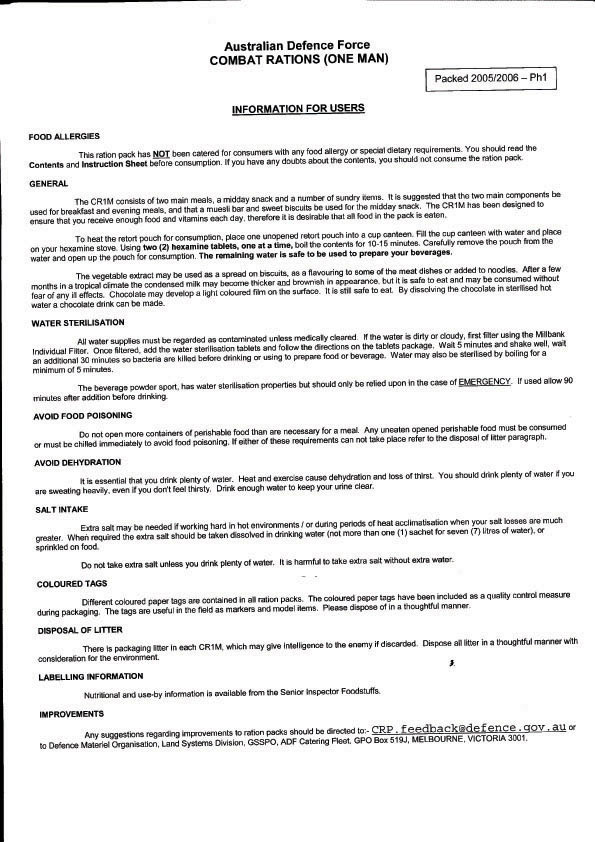

1 This case arises from the tragic death of Nathan Francis who died on a Scotch College cadet camp. He was 13 years old. He died from the effects of anaphylactic shock after taking a mouthful of food containing peanut. The food was supplied to him by the staff of Scotch College then acting as officers of the Scotch College Cadet Unit. The food containing peanut was supplied to him despite his parents having advised that Nathan had a severe peanut allergy. He died because those responsible for his health and safety failed in their duty to take all reasonably practicable steps to protect his health and safety. That duty arose under s 16(1) of the Occupational Health and Safety Act 1991 (Cth) (the Act). The Court is asked to make a declaration of contravention, and to impose a pecuniary penalty on the respondent, the Commonwealth of Australia (the Commonwealth), for the contravention.

2 At the same Scotch College cadet camp six cadets were lost in the bush for 18 hours. The person with a radio who was supposed to remain with them in the bush left them alone, taking the radio with him. Again, those responsible for the health and safety of these six cadets failed to take all reasonably practicable steps to protect their health and safety and thereby contravened s 16(1) of the Act. The Court is asked to adjourn the proceedings in relation to this incident because written undertakings relating to the fulfilment of obligations under the Act have been given to and accepted by Comcare.

The relevant statutory provisions

3 The statutory context is provided by the objects of the Act which are:

(a) to secure the health, safety and welfare at work of employees of the Commonwealth, of Commonwealth authorities and of non‑Commonwealth licensees; and

(b) to protect persons at or near workplaces from risks to health and safety arising out of the activities of such employees at work; and

(c) to ensure that expert advice is available on occupational health and safety matters affecting employers, employees and contractors; and

(d) to promote an occupational environment for such employees at work that is adapted to their needs relating to health and safety; and

(e) to foster a co‑operative consultative relationship between employers and employees on the health, safety and welfare of such employees at work; and

(f) to encourage and assist employers, employees and other persons on whom obligations are imposed under the Act to observe those obligations; and

(g) to provide for effective remedies if obligations are not met, through the use of civil remedies and, in serious cases, criminal sanctions.

4 The central duty relating to occupational health and safety is contained in s 16(1) as follows:

An employer must take all reasonably practicable steps to protect the health and safety at work of the employer’s employees.

5 The Act provides for both civil and criminal remedies for contraventions of the Act (Sch 2). The civil remedies available are declarations of contravention (cl 2), pecuniary penalty orders (cl 4), injunctions (cl 14), remedial orders (cl 15) and undertakings (cl 16). In this proceeding Comcare seeks declarations of contravention, a pecuniary penalty order, and an adjournment of part of the proceedings following the giving and acceptance of a written undertaking. The relevant provisions relating to the relief sought are as follows:

2 Declarations of contravention

(1) If a court considers that a person has breached one of the following provisions, or was involved in such a breach, it must make a declaration that the person has contravened this subclause:

(a) subsection 16(1) (duties of employers in relation to their employees etc.);

…

(3) A declaration of contravention made under subclause (1) must specify the following:

(a) the court that made the declaration;

(b) that the subclause was contravened;

(c) any provision that the person who contravened that subclause breached or was involved in breaching;

(d) the person who contravened that subclause;

(e) the conduct that constituted the contravention;

(f) the Entity, Commonwealth authority or non‑Commonwealth licensee to which the conduct related.

3 Declaration of contravention is conclusive evidence

A declaration of contravention is conclusive evidence of the matters referred to in subclause 2(3).

(1) If a court has declared, under subclause 2(1), a contravention of that subclause by a person because the person breached, or was involved in the breach of, a provision listed in that subclause, the court may order the person to pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty.

6 Clause 4(2) relevantly provides that the maximum penalty for breach of s 16(1) is 2,200 penalty points (cl 4(2) item 1) which equates to $242,000 (s 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth)). Schedule 2 continues:

5 Who may apply for declaration or order?

Application by Comcare or investigator

(1) Comcare or an investigator may apply for a declaration of contravention or a pecuniary penalty order.

…

16 Undertakings

(1) Comcare may accept a written undertaking relating to the fulfilment of an obligation under this Act, if the undertaking is given in writing to Comcare by a person who is required to fulfil the obligation.

(2) The person must not withdraw or vary the undertaking without the written consent of Comcare.

(3) If proceedings relating to whether a declaration should be made against a person under clause 2 have commenced, the court may adjourn the proceedings if Comcare requests the court to do so on the grounds that Comcare considers that an appropriate written undertaking by the person under subclause (1) is in force.

(4) If the court considers that a person has breached a term of an undertaking, or that the person has withdrawn or varied the undertaking without the written consent of Comcare, the court may, if it thinks fit:

(a) revive any proceedings adjourned under subclause (3); or

(b) make an order directing the person to comply with the term (regardless of whether the person has withdrawn or varied the undertaking) and any consequential orders it considers appropriate.

(5) Comcare or an investigator may apply to a court for an order under paragraph (4)(b) if the person has breached, is breaching, or proposes to breach the undertaking.

7 Criminal proceedings may also be brought for a contravention of the Act, including for breach of the duty established by s 16(1). However, in order to prove criminal liability it must be established that the breach caused death or serious bodily harm, and that the perpetrator was negligent or reckless. The maximum penalty which may be imposed for a criminal contravention is significantly higher than the penalty which may be imposed for a civil contravention. For instance, the maximum penalty for criminal liability for breach of s 16(1) is 4,500 penalty units equating to $495,000, rather than the maximum civil penalty available which is $242,000.

The parties to the proceeding

8 Comcare is a body established under s 68 of the Safety, Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 1988 (Cth), and is entitled to institute proceedings for a breach of the Act (s 77(1) of the Act).

9 The duty under s 16(1) is stated to be imposed on an employer. Section 5 defines employer relevantly to mean the Commonwealth.

10 The duty is imposed in favour of employees. The Act deems cadets undertaking cadet activities to be employees so that the Commonwealth is made liable for any failure to comply with s 16(1) in respect of the cadets. This result flows from s 9(5) of the Act which provides:

(5) The Minister may, by notice in writing, declare:

(a) that a person who is included in a class of persons specified in the notice, being a class of persons who engage in activities or perform acts:

(i) at the request or direction, for the benefit, or under a requirement made by or under a law, of the Commonwealth; or

(ii) at the request or direction, or for the benefit, of a Commonwealth authority;

is, for the purposes of this Act, to be taken to be employed by the Commonwealth, or by that authority, as the case may be;

and

(b) that the employment of the person is, for those purposes, to be taken to be constituted by the performance by the person of such acts as are specified in the notice;

and such a declaration has effect accordingly.

11 On 25 November 1999, the Minister for Employment, Workplace Relations and Small Business made a declaration under s 9(5) of the Act that the Commonwealth was the employer of members of the Australian Army Cadets for all acts performed in connection with cadet activities. Section 10 of the Act imposes duties on the Commonwealth as employer of cadets and specifies that such duties are to be performed by a particular person or body as the employing authority. Anything done by that person or body in their capacity as employing authority has the effect as if it had been done by the Commonwealth (s 10(1)(b)). Section 5 of the Act defines “employing authority” as the person or body specified in the regulations to be the employing authority in relation to a class of Commonwealth employees. Item 3 of reg 4(1) of the Occupational Health and Safety (Safety Arrangements) Regulations 1991 (Cth) specifies the Chief of Army as the employing authority of members of the Australian Army Cadets.

12 The Scotch College Cadet Unit is a unit of the Australian Army Cadets. During activities undertaken by the cadet unit, the cadets are, in law, treated as employees of the Commonwealth. As a result it was the Commonwealth which owed to cadets a duty to take all reasonably practicable steps to protect their health and safety during activities as cadets. It was the Chief of Army who, as employing authority, had to perform the duties imposed by the Act.

13 This proceeding has two separate parts. One is concerned with the death of Nathan Francis, and the other is concerned with the loss of the six cadets in the bush. That part of the proceeding concerned with the death of Nathan Francis will be dealt with first.

The death of nathan francis

The facts

14 Nathan was born on 16 August 1993. When he was one year old he was diagnosed with having asthma. When he was about 4 years old he was diagnosed as having a severe allergy to peanuts.

15 He started at Scotch College in 2005 in year 7. It was compulsory to join one of several activities. The cadets was not Nathan’s first choice. It was his third. He joined in March 2007. In order to be accepted as a cadet he had to attend a medical examination and submit a record of the outcome of it to the cadet unit. The medical examination record form asked for any advice that may assist in the treatment of the child if any medical condition exists. Nathan’s mother wrote in response to this question “Use of EpiPen for peanut allergy”.

16 A cadet camp named Bivouac 2007 was organised by the Scotch College Cadet Unit for 29 to 31 March 2007 at the Wombat State Forest near Gisborne in Central Victoria. Before the cadet camp Nathan’s parents were required to complete a number of forms including a parental authorisation form. In a section dealing with medical conditions, Mrs Francis wrote “yes” next to the word “allergies”. In answer to the question “Does your child have any severe allergies (if yes, please state each one)” Mrs Francis circled “Yes” and wrote “PEANUTS – but all nuts to be avoided”.

17 The Australian Army Cadets Policy Manual 2004 published by the Army governed the procedures of cadet units and required the compilation of a list of medical conditions including allergies of all cadets attending camps. The manual stipulated that the list was to be available in the event of a medical emergency on a camp, and also required it to be sent to central Army administration. It did not require the medical information to be circulated in relation to the distribution of food to cadets.

18 From the forms returned by the parents of cadets Ms Joanne Fisher, a member of staff of Scotch College and the administrative secretary to the cadet unit, compiled a list of the medical conditions of each of the cadets who were to attend the camp. She was assisted by Mr Robert Papuga, a teacher at Scotch College who was a Lieutenant in the cadet unit. He was in charge of A Company to which Nathan belonged, and was responsible for producing a list of the medical conditions of each cadet in that company. He was assisted by another teacher, Mr Geoffrey Dans, who was a Second Lieutenant in the cadet unit and an advisor to A Company. The final form of the list showed that Nathan suffered from asthma and peanut allergy and noted that all nuts were to be avoided. A composite list which showed medical issues in relation to all cadets attending the camp indicated that six other cadets also suffered from peanut allergy. Mr Papuga sent a copy of the final form of the list to Mr Peter Riley. Mr Riley was also a teacher at Scotch College and was a Major in the cadet unit. He was Second in Charge and Safety Officer of the camp.

Food Instructions from the Cadet Unit to Parents

19 The instructions for the cadet camp which were distributed with the forms required to be returned by parents included the following:

Cadets should not bring any food with the exception of a very small amount of sweet energy food. They are to be reminded that a large amount of time and money has been invested into the menu for Bivouac. Cadets are not expected to feed themselves…

The Food Supplied to the Cadets

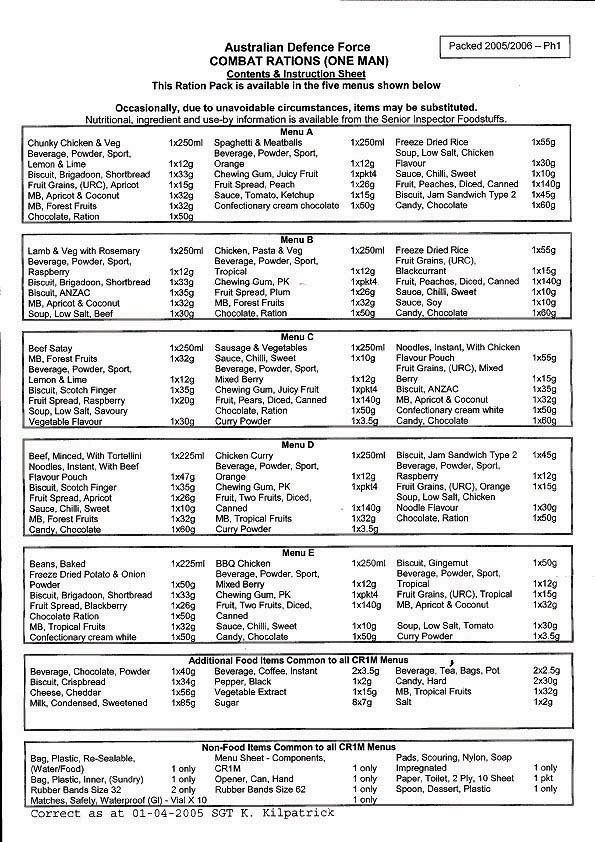

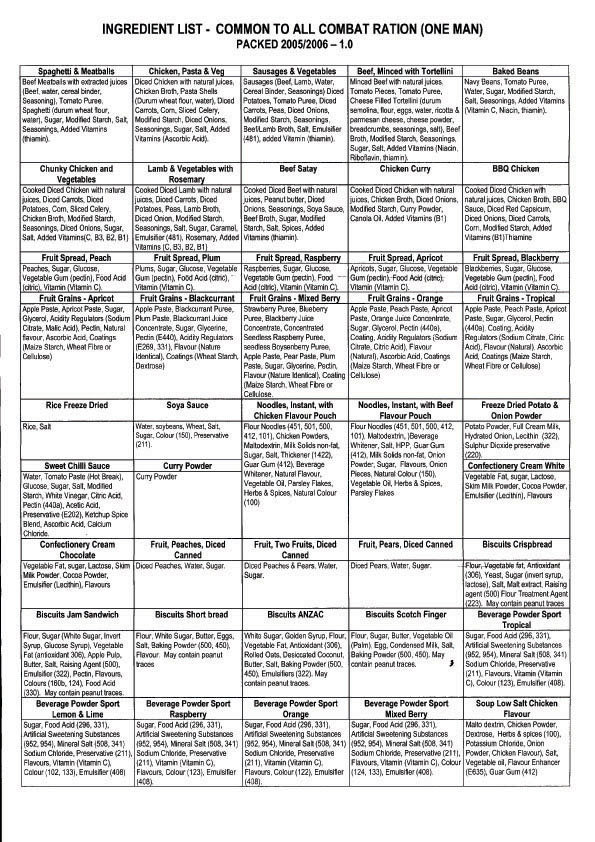

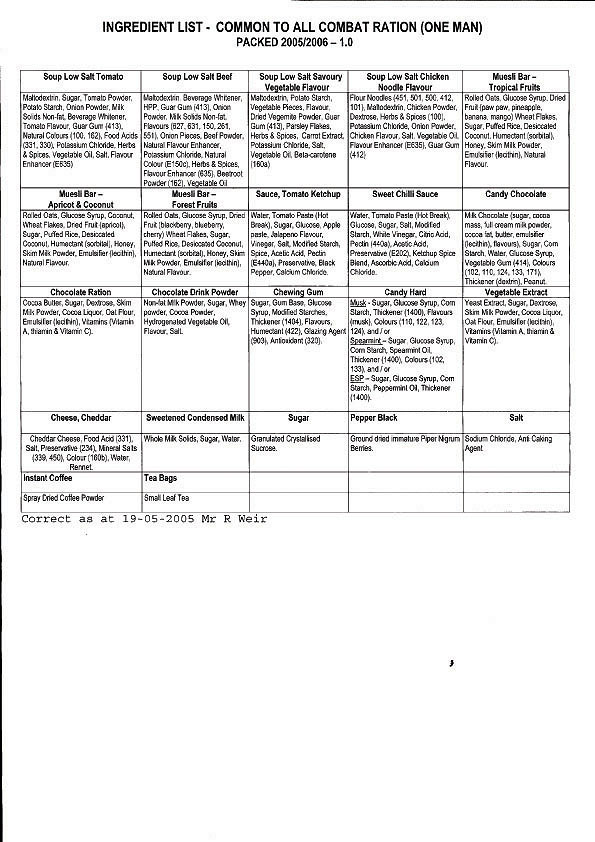

20 The Army supplied one man combat ration packs for the cadet camp. The ration pack was a plastic bag packed tightly with items of food contained in tubes, tins, packets and pouches. The ration packs contained two main courses. These were in pouches. On the outside of each pouch was a stamp with the name of the food inside that pouch.

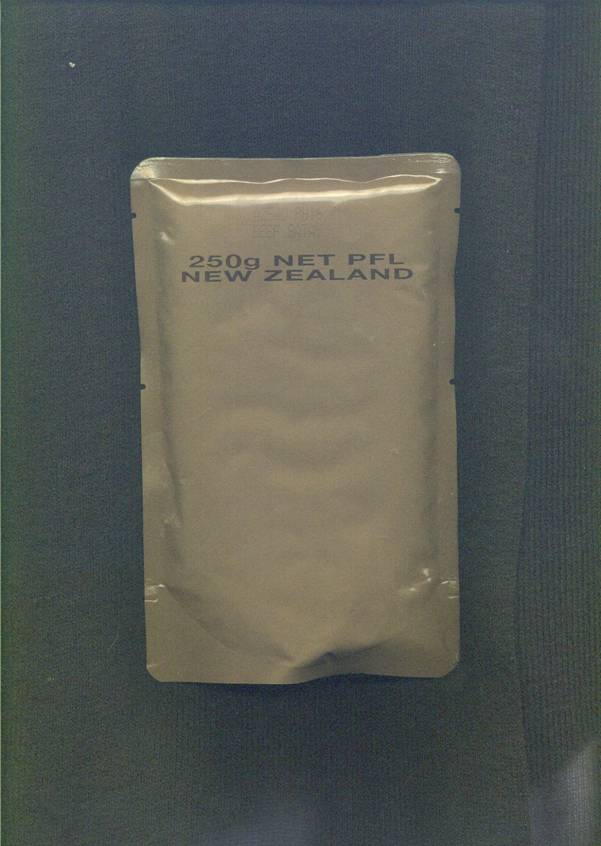

21 There were five different ration packs designated by letters from A to E. The C pack contained a main meal pouch stamped with the words “Beef Satay” and another stamped with the words “Sausages & Vegetables”. These descriptions were barely legible. They were stamped in a light grey colour on a fawn background. A copy of the front of the beef satay pouch is appended to these reasons as Schedule A.

22 Whilst the description on the pouches did not identify the ingredients of the food in the pouch, there were, within the tightly packed plastic bag containing the food, two A4 sheets folded together into a small rectangle. One sheet set out the menus or contents of each of the five different ration packs. The other set out the ingredients of all of the foods in all five of the ration packs. A copy of each of these sheets is appended to these reasons as Schedule B.

23 The ration packs are designed for use by Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel in the field. People with allergies are not permitted to join the ADF. Food labelling legislation does not apply to the ration packs as they are produced for use by the ADF internally and are not for sale.

The Distribution of Food to the Cadets

24 Just before the buses left for camp on 29 March 2007 the cadets assembled at the Lithgow centre on the Scotch College campus where they were issued with the ration packs. The distribution to about 300 cadets took about 20 minutes and was supervised by Mr Norman Bain. He was assisted by several cadets.

25 The ration packs were distributed at random. The cadets were not given any information about the contents of the packs apart from being told that E packs were suitable for vegetarians.

26 The medical information required to be and in fact supplied by parents was not provided to Mr Bain to identify cadets who had allergies to food or any other special requirements.

27 C packs were issued to Nathan and also to Nivae Anandaganeshan, and Gene van den Broek. Each of these cadets had notified that they had peanut allergy. The C pack contained beef satay which was made with peanut butter.

28 Mr Bain had been employed by Scotch College for 23 years as the College Marshall. That position involved a number of jobs which teachers did not do such as holding detentions and acting as Fleet Manager. Before that he had been in the Regular Army for 21 years including time as a recruiter. There he became aware that the ADF did not allow people with food allergies to join. Mr Bain was a Major in the cadet unit and acted as one of the Quarter Masters.

Disaster Strikes

29 Friday 30 March 2007 was the first full day of the camp. After a morning navigation exercise Nathan returned to the campsite with members of his section. At about 1.30 pm they sat down to prepare lunch. Ryan Melville, a year 10 student and the Corporal in the section, was near Nathan. He described what happened then:

Nathan ended up sitting by himself in a corner, I started eating and turned around to see Nathan spit out a mouthful of his food, and quickly jump up and start drinking a lot of water, and then he sat down. He looked very panicked so I went over to him and asked him what was wrong. I was standing probably about 5 metres away from him. Nathan said “I’m allergic to peanuts, and I think I just ate something with peanuts in it”. Because my brother is allergic to peanuts I knew what to look for and through first aid training I knew the symptoms.

I asked Nathan if he was feeling alright, he said that his lips and tongue were tingling and I could see that his lips were slightly swollen. I asked him if he had an Epipen with him, which he said he did. I asked him where it was and he said it was in his webbing, which was on the ground beside him, and he got it out from his front right ammo pouch. He then gave me the Epipen, so he could put his webbing on which was still on the ground, he put his webbing on while I moved his ration pack which was a “C” pack and was sitting on the other side of where he was sitting. I asked him if it was his ration pack and he said yes that it was. It was definitely a “C” pack. …

Nathan and I both walked up to the headquarters[,] he was unaided, I asked Nathan twice along the way if he was finding it hard to breathe, the first time I asked him he said he was finding it a little harder to breathe, he then took a puff of his asthma puffer and the second time he said, it was the same as before. While we’re walking Nathan told me [he] had swallowed one mouthful of his lunch and that he spat the second one out. When we got up to the A company HQ I sat him down on a chair, and removed his japara, and jacket, [and] he removed his webbing. I put his EpiPen down on a table on top of the first aid kit and alerted everyone to its position.

30 From the Company Headquarters Nathan was driven to the Unit Headquarters. That took less than a minute. He arrived there at 2.05 pm. Dr Anne Waterhouse, the voluntary medical officer at the camp, administered Nathan’s EpiPen. Nathan was transferred into a vehicle to be taken to hospital. An ambulance was called. At 2.11 pm Nathan became unconscious. At 2.48 pm the ambulance arrived from Daylesford. The ambulance officers observed that Nathan exhibited no signs of life. At 3.42 pm Nathan was taken by air ambulance helicopter to the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne. He arrived at 4.20 pm. Dr Simon Young pronounced him dead on arrival.

Some Subsequent Events

31 On 3 April 2007, Dr Noel Woodford, the Senior Forensic Pathologist at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine conducted an autopsy on Nathan and found that the probable cause of death was anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis is a serve acute allergic response which may cause severe asthma like symptoms as well as shock leading to cardiorespiratory arrest.

32 On 8 May 2007 the Acting Chief of the Defence Force issued an order prohibiting the use or consumption of ration packs by cadets. He also ordered a review of the sufficiency of food warning and labelling standards for ration packs and the adequacy of ADF and cadet policies regarding the management of people, particularly children, with severe food allergies. Major General Grant Cavenagh conducted the review and reported on 22 June 2007.

33 On 30 March 2007 the Army notified Comcare of Nathan’s death. Section 41(1)(b) of the Act provides that an investigator who is a member of the staff of Comcare may conduct an investigation concerning a breach or possible breach of the Act. Stewart Williams had been appointed as a Comcare Occupational Health and Safety Investigator under s 40(2) of the Act. Between 3 April 2007 and 29 May 2008, Mr Williams conducted an investigation into Nathan’s death. The investigation was undertaken in co-operation with Victoria Police acting on behalf of the Victorian State Coroner. Evidence collated during the investigation comprised witness statements, documents, reports and other material which occupied eight large lever arch folders. On the basis of this evidence Mr Williams prepared a report and gave it to Comcare on 29 May 2008 pursuant to s 53(1) of the Act.

The Allegations made against the Commonwealth

34 On 6 June 2008 Comcare commenced these proceedings.

35 The allegations concerning Nathan’s death pleaded against the Commonwealth in the Statement of Claim were as follows:

The Supply Breach

11. On 29 March 2007 the Respondent breached its duty to Cadets Francis, Anandaganeshan and van den Broek by supplying them with one-man 24-hour combat ration packs (“CRPs”) for consumption. The CRPs supplied contained a satay beef food pouch. The satay beef food pouch contained peanuts or peanut protein.

12. As a result Cadets Francis, Anandaganeshan and van den Broek were exposed to the risks to health and safety particularised at paragraph 15 below.

PARTICULARS

12.1 On 29 March 2007, the day of the scheduled departure for Bivouac 2007, all of the cadet members of the SCACU [Scotch College Army Cadet Unit] were allocated CRPs.

12.2 CRPs are made up of various food components and utensils for consumption by members of the ADF and AAC [Australian Army Cadets] over a 24-hour period. The one-man CRPs include five different menus, menu A to menu E. Each menu contains a different mixture of foods. At all relevant times, menu C included one pouched meal of beef satay which included peanuts in its ingredients. The CRPs were distributed to the AAC cadets by the SCACU Quartermaster, Major (AAC) Norman Bain.

12.3 Major (AAC) Bain was not aware that at least seven SCACU cadets (including Cadet Francis) had reported their peanut allergy status to the SCACU secretary.

12.4 Major (AAC) Bain supervised and conducted the random distribution of CRPs to the SCACU cadets without consideration of the potential risk of exposing the peanut allergic cadets to those CRPs which contained peanut products, namely the CRP C packs. Cadet Francis was issued with a CRP C pack as were Cadets Anandaganeshan and van den Broek.

12.5 From 1 to 30 March 2007, the Respondent through its employing authority, the Chief of Army had been made aware of Cadet Francis’ peanut allergy status as well as that of the other six AAC cadets referred to in paragraphs 10.7. No action was taken to correlate the information that was complied in the Nominal Medical Roll with the contents of CRPs.

The Consumption Breach

13. On 30 March 2007, the Respondent breached its duty to Cadet Francis by permitting the consumption of the satay beef food pouch supplied to him as part of the CRP on 29 March 2007.

14. As a result Cadet Francis was exposed to the risks to health and safety particularised at paragraph 15 below.

PARTICULARS

14.1 At about 1.30 pm on 30 March 2007, Cadet Francis joined other cadets at an open fire as they prepared and cooked lunches from their respective CRPs.

14.2 Cadet Francis was observed to take a pouch of beef satay meal from his CRP C pack and place it in the open fire. Shortly after heating the pouch Cadet Francis was observed to taste a mouthful of the beef satay meal before immediately reacting and spitting it out. Cadet Francis drank water immediately and requested assistance.

14.3 The corporal in charge of Cadet Francis’ platoon, a Year 10 student, Corporal (AAC) Ryan Melville immediately came to the assistance of Cadet Francis and escorted him to the tent housing the A Company headquarters.

14.4 From A Company headquarters, Cadet Francis was transported to the Unit Headquarters in a vehicle driven by Major (AAC) Peter Riley, an officer who was second in charge of Bivouac 2007. During this journey Cadet Francis informed Major (AAC) Riley that he had “eaten something”. Major (AAC) Riley had been given Cadet Francis’ EpiPen for use should it be necessary.

14.5 On arrival at Unit headquarters, Cadet Francis was immediately examined by a medical practitioner, Dr Anne Waterhouse.

14.6 Cadet Francis’ EpiPen was administered promptly by Dr Waterhouse, but within a period of a few minutes Cadet Francis had collapsed and was unconscious. Dr Waterhouse carried out emergency CPR treatment with the assistance of three SCACU officers, Major (AAC) Riley, Lieutenant (AAC) Demeris and Lieutenant (AAC) Collins. SCACU secretary Ms Fisher was present during the treatment.

14.7 The CPR was carried out while verbal instructions were provided by emergency ambulance service operators based at Rural Ambulance Victoria (“RAV”) in Ballarat initially to Major (AAC) Riley and then Ms Fisher, who relayed them to Dr Waterhouse, Major (AAC) Riley, Lieutenant (AAC) Demeris and Lieutenant (AAC) Collins.

14.8 Three additional EpiPens, obtained from other cadets present on Bivouac 2007, were administered to Cadet Francis, but despite this, ongoing CPR treatment and evacuation from the camp site by road ambulance and helicopter, Cadet Francis was declared dead on arrival at the Royal Children’s Hopsital at 4.20 pm on 30 March 2007.

…

16. Between 7 March 2007 and 31 March 2007, the Respondent, acting through the Chief of Army as employing authority breached its duty under section 16(1) of the OHS Act to take all reasonably practicable steps to protect the health and safety at work of the cadets participating in Bivouac 2007 in contravention of sub-clause 2(1) of Schedule 2, Part 1 of the OHS Act. The Respondent:

16.1 Failed to provide and maintain a work environment (including plant and systems of work) that was safe for its employees and without risk to their health;

16.2 Failed to ensure that the workplace was safe for its employees and without risk to their health;

16.3 Failed to ensure the safety at work of, and the absence of risks at work to the health of the employees in connection with the use of plant (i.e. the CRPs) or substances (i.e. the food in the CRPs);

16.4 Failed to provide its employees with information, instruction, training and supervision necessary to enable them to perform their work in a manner that was safe and without risk to their health;

16.5 Failed to take appropriate action to monitor employees’ health and safety at work;

16.6 Failed to monitor the condition of the workplace under its control;

16.7 Exposed Cadets Francis, Anandaganeshan and van den Broek to peanut-based food products; and

16.8 Exposed seven known peanut-allergic cadets to the risk of consuming peanut-based food products in the CRPs.

The Undertaking given by the Commonwealth to Comcare

36 It will be recalled that one of the civil remedies available for breach of s 16(1) is the giving of written undertakings to Comcare pursuant to cl 16 of Sch 2 of the Act.

37 On 8 April 2009, Comcare accepted an undertaking from the Commonwealth through the Chief of Army. In part the undertaking related to the death of Nathan.

38 By the undertaking the Commonwealth and the Chief of Army admitted liability for the breaches of s 16(1) alleged in [11], [12], [13], [14] and [16] of the Statement of Claim which are set out in [35] of these reasons.

39 Further, in relation to Nathan’s death, the Chief of Army undertook to do the things listed in Sch 1 of the undertaking and to report to Comcare concerning compliance with the undertaking. That part of Sch 1 relevant to Nathan’s death was in the following terms:

22. A warning will appear in AAC activity joining instructions:

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) is unable to provide a severe food allergy free environment (such as from peanuts) in relation to consumption of food during cadet activities. Such a risk may be life threatening for people who suffer from a severe food allergy. Parents may consider it is in their child’s best interest not to allow participation of their child in the proposed activity. In the event that the child is allowed to attend a catered cadet activity, the parents may choose to provide, at their own expense, sufficient food to cover the duration of the activity.

23. Not distribute, use or allow the use of ADF supplied combat ration packs during AAC activities or for non Service members, unless the following warning label is affixed to each inner bag in the combat ration pack:

CAUTION

FOOD ALLERGIES

This ration pack has NOT been constituted for consumers with

any food allergy or special dietary requirements.

You should read the contents & instruction sheet before

consumption. If you have any doubts about the contents, you

should not consume the ration pack.

Products used in ration packs which contain nuts or traces

of nuts include beef & chicken satay meals, biscuits & chocolate.

ADF supplied combat ration packs distributed, used or allowed by Service members are to have the above warning label affixed to the outside of the exterior cardboard packaging containing combat ration packs.

24. Restrict the distribution of combat ration packs that have been produced prior to 1 July 2008 to ADF personnel only and prohibit the distribution of such combat ration packs to members of the public and the AAC.

25. Provide compulsory pre-activity instructions and training for all current Army Cadet Staff (‘ACS’) by 15 December 2009 on the following topics:

25.1 potential food allergies;

25.2 signs of allergic reactions;

25.3 initial medical treatment of such conditions (including Epi-Pen use); and

25.4 the training referred to in 27.1 to 27.3 [sic] inclusive be provided within 12 months of appointment of all ACS appointed after the date of this Undertaking.

26. Apologise in writing to the family of Cadet Nathan Francis, which apology has been sent to the family on 17 December 2008 and copied to Comcare.

27. Pay for the publicity prepared by Comcare, including publication of an advertisement confirming the entering into of this Undertaking in a daily metropolitan newspaper in each capital city of each State and Territory of Australia.

28. Publish an appropriate statement in the ADF internal publications.

29. Develop and implement, at the ADF’s own cost, in respect of army cadets, an Anaphylaxis Policy by 30 June 2009. Such Policy is to be developed in conjunction with medical advisors (as agreed in consultation between Comcare and the ADF) who specialise in allergens, immunology and respiratory diseases.

The Declaration of Contravention

40 It will be further recalled that another civil remedy provided by cl 2 of Sch 2 of the Act is the making of a declaration of contravention by the Court. Comcare sought a declaration of contravention, and the Commonwealth agreed to the Court making a declaration in the following terms:

On 29 March 2007 at the Wombat State Forest near Gisborne in Central Victoria, the respondent, acting through the Chief of Army as the employing authority of members of the Australian Army Cadets (‘AAC’), contravened cl 2(1) of Sch 2 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act 1991 (Cth) by reason of having breached s 16(1) of the said Act in the course of conducting a three day training course known as Bivouac 2007 in that it:

(a) supplied Cadet Nathan Fazal Francis, Cadet Nivae Anandaganeshan and Cadet Gene van den Broek with one-man combat ration packs (‘CRP’s’) containing a satay beef food pouch which contained peanuts or peanut protein for their consumption despite having been informed that the said cadets were allergic to peanuts;

and, in so doing, it failed to:

(b) warn parents of the AAC cadets about the contents of the CRP’s;

(c) warn AAC cadets about the contents of CRP’s;

(d) warn AAC cadets with pre-existing food allergies of the contents of CRP’s;

(e) make appropriate use of information provided by AAC cadets and parents of AAC cadets regarding pre-existing or known allergic conditions and correlate that information with the potential risk of being exposed to allergies through the supply of food contained in CRP’s;

(f) ensure that the contents of CRP’s allocated to AAC cadets did not include food products or allergens that may have triggered allergic responses by removing or requiring the removal of peanut-based food products from CRP’s;

(g) prevent distribution or provision of peanut-based food products to AAC cadets with pre-existing allergic reactions by:

(h) inspecting the contents of CRP’s to be allocated to those individual AAC cadets who had given notice of allergic conditions;

(i) isolating cadets with pre-existing medical conditions and / or notified food allergies at the time of distribution of CRP’s and issuing them with CRP’s that did not contain peanut products or other food allergens;

(j) removing all CRP’s known to contain peanut protein or other food allergens from circulation amongst AAC cadets;

(k) requiring all AAC cadets with notified allergic conditions to provide their own food supplies;

(l) issue any or any adequate instructions or provide adequate supervision regarding distribution of CRP’s;

(m) issue any adequate instructions or provide adequate supervision regarding consumption of contents of CRP’s;

(n) prevent the consumption of CRP’s containing food allergens by AAC cadets with food allergies;

(o) distribute CRP’s after consulting or considering pre-existing medical conditions; and

(p) take into consideration the findings of a report dated 22 November 1996 by the Australian National Audit Office entitled ‘Management of Food Provisioning in the Australian Defence Force’.

Pecuniary Penalty Orders

41 The final civil penalty relevant to this aspect of the proceeding is the pecuniary penalty order which is provided for by cl 4 of Sch 2 of the Act. Comcare sought such an order against the Commonwealth.

42 Having admitted liability for contravention of s 16(1) in relation to Nathan’s death, the Commonwealth agreed that a pecuniary penalty should be imposed. There was however no agreement between the parties as to the amount of the penalty. Comcare argued that the contravention was in the worst case category and should attract a pecuniary penalty in the range of $220,000 to $242,000. The Commonwealth accepted that a substantial penalty was appropriate but contended that the case was not in the worst case category.

Material before the Court

43 Comcare tendered an Agreed Statement of Facts dated 3 April 2009 as the basis for the relief it sought. The Agreed Statement of Facts is cross referenced in many places to the report of Mr Williams, the Comcare Investigator. When the application came on for hearing on 9 April 2009 the Court indicated that it would be appropriate for the Court to have access to the report of Mr Williams. Following this indication Comcare arranged for the eight folders constituting the evidence upon which the report was based as well as the final report to be sent to the Court. It has been used in these reasons to amplify and explain some of the agreed facts.

44 The Commonwealth relied on an affidavit sworn on 8 April 2009 by David Thomas Mulhall.

45 In the course of submissions by counsel for Comcare it appeared that there might be some further evidence which could assist the Court in determining the appropriate level of the pecuniary penalty including evidence from Nathan’s parents, Mr and Mrs Francis, evidence concerning the state of knowledge at the time in the school community about peanut allergy, and evidence as to the knowledge of Scotch College about peanut allergy and any steps taken by the school to address the issue. The parties assisted the Court by supplementing the evidence in these areas.

The evidence of Mr and Mrs Francis

46 Initially the Court had not heard the voices of Nathan’s parents, Brian and Jessica Francis. Whilst the pain of the loss of a 13 year old son is, on the one hand, obvious, and, on the other hand, indescribable, it seemed wrong for the Court not to hear from those most closely affected. There was a danger that the result of the proceedings being based on a largely agreed outcome could be seen as bypassing those left who are most closely affected by the events. It was likely that Mr and Mrs Francis could give the Court a deeper understanding of the context of the events and the events themselves, as well as some evidence of any steps taken by the Commonwealth to ease their pain and demonstrate acceptance of responsibility for Nathan’s death.

47 In the case of victims of criminal acts, legislation now provides for courts to hear their voices through victim impact statements: for example see Div 1A of Pt 6 of the Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic). That legislation broadened the type of evidence which a court could consider in the course of sentencing in criminal cases: R v Dowlan [1998] 1 VR 123 at 138-9 per Charles JA. But even at common law a criminal court was entitled to take into account the impact on a victim in order to assess the severity of criminal conduct: R v Medini [2002] VSC 12 at [45]. In Director of Public Prosecutions v DJK [2003] VSCA 109 (DJK) Vincent JA explained the value of victim impact statements in a way which is equally applicable to evidence given by those affected by the failure of employers to comply with their occupational health and safety obligations. He said at [17] - [18] that such statements:

17 … constitute a reminder of what might be described as the human impact of crime. They draw to the attention of the judge who would of necessity have to consider the possible and probable consequences of criminal behaviour, not only its significance to society in general but the actual effect of a specific crime upon those who have been intimately affected by it. The statements provide an opportunity for those whose lives are often tragically altered by criminal behaviour to draw to the court’s attention the damage and sense of anguish which has been created and which can often be of a very long duration. For practical purposes, they may provide the only such opportunity. Obviously the contents of the statement must be approached with care and understanding. It is not to be expected that victims will be familiar with or even attribute significance to the many considerations to which a sentencing judge must have regard in the determination of a just sentence in the particular case. Nor would it normally be reasonable or practicable for a sentencing judge to explore the accuracy of the assertions made. Nevertheless, there has been an increasing level of appreciation by the courts of the value of victim impact statements. In my view they play an important role with respect to an aspect of the criminal law to which reference is not often made. They play their part in achieving what might be termed social and individual rehabilitation. Rehabilitation, in this sense, is not perceived from the perspective of the offender, but from that of those persons who have sustained loss and damage by reason of the commission of an offence.

18 … It seems to me that the process of social and personal recovery which we attempt to achieve in order to ameliorate the consequences of a crime can be impeded or facilitated by the response of the courts. The imposition of a sentence often constitutes both a practical and ritual completion of a protracted painful period. It signifies the recognition by society of the nature and significance of the wrong that has been done to affected members, the assertion of its values and the public attribution of responsibility for the wrongdoing to the perpetrator. If the balancing of values and considerations represented by the sentence which, of course, must include those factors which militate in favour of mitigation of penalty, is capable of being perceived by a reasonably objective member of the community as just, the process of recovery is more likely to be assisted. If not, there will almost certainly be created a sense of injustice in the community generally that damages the respect in which our criminal justice system is held and which may never be removed. Indeed, from the victim’s perspective, an apparent failure of the system to recognize the real significance of what has occurred in the life of that person as a consequence of the commission of the crime may well aggravate the situation.

48 Counsel for Comcare indicated that an invitation had already been extended to Mr and Mrs Francis to give evidence but had not been taken up. He said that Comcare would facilitate their attendance if they now wished to give evidence. In view of the tragic circumstance of Nathan’s death the Court indicated that Mr and Mrs Francis could give their evidence in less formal surroundings than the courtroom, and that a certain level of privacy could be arranged at the time when the evidence was given.

49 Although the Court could provide a degree of privacy to Mr and Mrs Francis when they gave evidence, it was made clear to them that a transcript would be taken of their evidence, the parties would be able to question them at a later date on the transcript, and the transcript would be publicly available in the usual way. These requirements follow from the entitlement of the parties to the proceeding to natural justice, and from the open nature of Court proceedings.

50 Mr and Mrs Francis took up this invitation. On 15 May 2009, they gave evidence in a small conference room in the presence only of myself, my Associate and the transcript operator. The parties and Scotch College had access to the transcript and decided not to question Mr and Mrs Francis.

51 Mr and Mrs Francis’ evidence has been of considerable assistance to the Court. Nobody can fail to understand the depth of the grief that Mr and Mrs Francis feel but the trouble they took to tell the Court about that grief has added a further dimension to the Court’s understanding of the context in which this decision must be made. They explained the enormous gap in their family resulting from the loss of Nathan. Mrs Francis said:

It sounds silly and simple but things like we used to always sit down to dinner across the table and all of a sudden, you know, after – we actually went to sit down and realised well, it doesn’t work anymore, there’s a seat missing.

52 Mr Francis described his loss of faith, his loss of motivation and his loss of social interaction. Mrs Francis vividly explained how she felt when she reflected on the fact that Nathan’s death was preventable. She said:

I went through a stage that, to me, it was like they’ve killed – it was murder, they killed my son, and I wanted to – I wanted to physically go in and kill one of those teachers, you know, I had nightmares that I was ..... them.

And I actually had to tell them – we arranged a meeting with one of the – with the chaplain, and we sat like we are sitting now, and I just looked at him and said “I’m sorry, I have to tell you that I want to kill you, you know, because if I don’t tell you this, I’m going to bottle it up, and I’m going to hurt myself”. So it’s this feeling of frustration. It should not have happened, and you know, we gave – I can understand if they were camping and a tree fell on him; he fell off a cliff, God forbid; he was in a car accident or something. You can almost understand that. If a child is sick in hospital with an illness, you understand what’s going to happen, you expect the death, you have got time – you know, there’s a bit more – it’s never okay, but it’s – there’s a reasoning. But there was no reasoning with Nathan’s death. You know, there was so much – you know, there was so many people involved. Even if one person showed a bit of initiative, he would have been okay. There were four packs. If he got any of the other ones, he’d still be okay. It wasn’t as if he made the choice, or you know, he made a wrong choice. They took – you know, it was given to him.

There was no control about – you know, we had letters come back from the school to say great care has been taken in the preparation of the meals and the food for this camp, and so we had no reason to worry about his allergy. You know, he’d been on camps before, so there was no reason to even suspect that there would be a problem with his meals, because it was – they knew about it, and so, for us, that’s the hardest thing for me, and I’m sure for Brian, is that it just should not have happened. We should be enjoying Nathan in year 11.

53 Mr and Mrs Francis were critical of Scotch College. Mr Francis said:

We subsequently found out – we spoke to Gordon Donaldson, who was the Headmaster at the time – the Principal is now no longer there, but he had no understanding of the ramifications of an allergic reaction to peanuts. The school had no peanut allergy policy, so there was no – the school tuck shop, at the school, there was no ban on any peanut products whatsoever. The school was utterly ignorant to the consequences of ingestion of peanuts to someone who had an allergic reaction to it.

54 Mr Francis later said:

That’s why you send them to a good school, … . We feel very betrayed by that and we want to make sure that schools like Scotch College don’t rely upon their 150-odd year history but they are on the curve or ahead of the curve. You would expect them to be ahead of the curve. So for the Principal of the school to say we have no policy, we don’t understand, yet a State school out in the outer suburbs does have a policy in place. I have a sister-in-law who is a teacher, who was both a teacher in the State system and now in the private system. These policies were in place. Scotch College didn’t have that policy.

55 Mrs Francis expressed concern that Scotch College had not learned from Nathan’s death. She related that about six months after his death the junior school held an international day. At this time her younger son, Justin, attended the junior school. The boys were to bring food representing all parts of the world as part of an international food fair. As Mrs Francis had not received any notice about avoiding peanuts in the food to be brought to the school, she rang and then went to see the teacher in charge. As a result the event was cancelled on the day, and the food which had been brought to school was thrown out. To Mrs Francis this demonstrated that the junior school had not learned from Nathan’s death.

56 In relation to the efforts of Scotch College to extend sympathy and understanding to them, Mr Francis said:

[O]ne of the grievances I had with – and I did say it to Gordon Donaldson, the Headmaster, the Principal of the school – he never, ever visited our house, from the time Nathan died to the day of his funeral. Never.

MRS FRANCIS: Or after.

MR FRANCIS: Or after. Never. Never. And I think that’s something he should be very ashamed of.

57 Mr and Mrs Francis said that the Vice Principal and the Chaplain did visit. They said that the Chaplain had been superb and the new Principal, Mr Ian Batty, recently came to their home and was most understanding on the occasion of the second anniversary of Nathan’s death.

58 Throughout their evidence Mr and Mrs Francis referred to the responsibility of Scotch College and of its conduct and the conduct of its teachers rather than the conduct of the Army. The Court commented ‘you keep talking about the school, the case keeps talking about the Army’. In his response Mr Francis said:

The Army does have a role to play, undoubtedly, but the school are the people who are running this event.

59 And Mrs Francis said:

… I haven’t used the word “Army” because when I have spoken to Stewart [Williams – the Comcare Investigator], and asked him questions – there was no Army personnel involved, so to speak. There was not one Army personnel at that camp, there was not one Army personnel who took the papers, there was not one Army personnel who issued meals. So that’s why I say “school”.

60 Later Mr Francis said:

[T]he anger I have – at least I think we both – I think the anger is not really to the Army, but to the school, because they were the people who… fell under the authority of the Army, but were really there representing Scotch College.

61 The transcript of the evidence of Mr and Mrs Francis was available to the parties and to the solicitor for Scotch College. The Court fixed a time within which they had to indicate whether or not they required to question Mr and Mrs Francis. Each indicated that they did not wish to do so.

62 The evidence of Mr and Mrs Francis is a good example of the purpose of such evidence as explained by Vincent JA in DJK [2003] VSCA 109. The extent to which their evidence is directly relied upon in the sentencing process is described later in these reasons.

Evidence concerning the state of knowledge in the community about peanut allergy

63 The second issue on which the Court sought further assistance from Comcare was the state of knowledge in March 2007 about peanut allergy in the community generally and in the school community in particular. Initially the only prior knowledge of peanut allergy on which Comcare relied against the Commonwealth was the Australian National Audit Office Report in 1996 which was in limited in its terms and will be discussed later. But general knowledge suggested that peanut allergy awareness was a very live issue in the school community by March 2007. Comcare responded to the Court’s request by filing an affidavit sworn on 11 May 2009 by Dr Jo Ann Douglass. Dr Douglass is a specialist physician and Head of the Department of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Service at the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne. She was a member of the Allergy and Anaphylaxis Working Party established in 2006 by the Victorian Department of Health Services. The Working Party was chaired by Dr Robert Hall, the Chief Health Officer for Victoria, and included paediatric allergy physicians, representatives of general practitioners, consumer advocacy groups, representatives of the Office for Children and the Department of Education and Training. It held its first meeting on 13 September 2006. The working party developed guidelines which were published in November 2006 by the Office of School Education and entitled “Anaphylaxis Guidelines: A resource for managing severe allergies in Victorian Government schools” (the Guidelines). The document acknowledges the contributions of various bodies including the Association of Independent Schools of Victoria. The Guidelines address how anaphylaxis can be prevented as follows:

The key to prevention of anaphylaxis in schools is knowledge of those students who are at risk, awareness of triggers (allergens) and prevention of exposure to these.

Schools need to work with parents and students to ensure that certain foods or items are kept away from the student while at school.

64 The Guidelines then outline a number of prevention strategies for school camps and remote settings as follows:

· Schools must have in a place a risk management strategy for students at risk of anaphylaxis for school camps, developed in consultation with the student’s parents/carers.

· Camps must be advised in advance of any student with food allergies.

· Staff should liaise with parents/carers to develop alternative menus or allow students to bring their own meals.

· Camps should avoid stocking peanut or tree nut products, including nut spreads. Products that ‘may contain’ traces of nuts may be served, but not to students who are known to be allergic to nuts.

· Use of other substances containing allergens should be avoided where possible.

65 Dr Douglass said that the Guidelines together with a practice EpiPen were distributed to all schools in Victoria in the first half of 2007.

Evidence concerning the state of knowledge of Scotch College about peanut allergy

66 The third issue on which the Court sought further assistance was the knowledge of peanut allergy at Scotch College and what actions had been taken to address the issue. This request arose from the fact that the cadet camp was run entirely by people who were teachers or other staff of Scotch College even though, for the period of the camp, the Commonwealth was responsible for their actions or omissions in safeguarding the health and safety of the cadets for the purposes of s 16(1) of the Act.

67 In response to this request Scotch College filed an affidavit sworn on 13 May 2009 by Ian Thomas Batty. Mr Batty is the Principal of Scotch College. He explained the medical management system in place at the school. Entrants to the senior school in 2006 had to complete a medical card. One question asked was whether the student suffered from allergic reactions. The medical cards were transferred to the school health centre. Hard copy medical alert lists were generated from this information and distributed to year level coordinators who in turn passed on the information to classroom teachers. The form of the card was changed for 2007 entrants by adding a section as follows:

Anaphylaxis: Yes/No EPIPEN: Yes/No

Medication (if EPIPEN not required): ________________ Dose: _____________ Type ____________________

68 It is likely that the change in the form arose as a result of the heightened awareness of the dangers of peanut and other nut allergies in about 2006 at the time the Victorian government convened the working party referred to by Dr Douglass.

The proper approach to assessing penalty

69 In Comcare v Commonwealth (2007) 163 FCR 207; [2007] FCA 662 (Trooper Lawrence) Madgwick J said at [116] – [123]:

116. The overriding principle in assessing penalty is that the amount of the penalty should reflect the Court’s view of the seriousness of the offending conduct in all, the relevant circumstances: Coochey v Commonwealth (2005) 149 FCR 312 and the cases there cited.

117. The relevant circumstances will vary from case to case and by reference to the objects of the particular legislation which has been contravened.

118. Pursuant to s 3 of the OHS Act the objects of the Act include:

(a) to secure the health, safety and welfare at work of employees of the Commonwealth and of Commonwealth authorities; and

…

(d) to promote an occupational environment for such employees at work that is adapted to their needs relating to health and safety;

…

(f) to encourage and assist employers, employees and other persons to whom obligations are imposed under the Act to observe those obligations; and

(g) to provide for effective remedies if obligations are not met, through the use of civil remedies and, in serious cases, criminal sanctions.

119. The applicant contends that guidance may be had from decisions relating to penalty under State occupational health and safety laws which import like obligations on employers.

120. Decisions under the cognate New South Wales Act refer to the following considerations among others:

(i) the penalty must be such as to compel attention to occupational health and safety generally, to ensure that workers whilst at work will not be exposed to risks to their health and safety;

(ii) it is a significant aggravating factor that the risk of injury was foreseeable even if the precise cause or circumstances of exposure to the risk were not foreseeable;

(iii) the offence may be further aggravated if the risk of injury is not only foreseeable but actually foreseen and an adequate response to that risk is not taken by the employer;

(iv) the gravity of the consequences of an accident does not of itself dictate the seriousness of the offence or the amount of penalty. However the occurrence of death or serious injury may manifest the degree of the seriousness of the relevant detriment to safety;

(v) a systemic failure by an employer to appropriately address a known or foreseeable risk is likely to be viewed more seriously than a risk to which an employee was exposed because of a combination of inadvertence on the part of an employee and a momentary lapse of supervision;

(vi) general deterrence and specific deterrence are particularly relevant factors in light of the objects and terms of the Act;

(vii) employers are required to take all practicable precautions to ensure safety in the workplace. This implies constant vigilance. Employers must adopt an approach to safety which is proactive and not merely reactive. In view of the scope of those obligations, in most cases it will be necessary to have regard to the need to encourage a sufficient level of diligence by the employer in the future. This is particularly so where the employer conducts a large enterprise which involves inherent risks to safety;

(viii) regard should be had to the levels of maximum penalty set by the legislature as indicative of the seriousness of the breach under consideration;

(ix) the neglect of simple, well-known precautions to deal with an evident and great risk of injury, take a matter towards the worst case category;

(x) the objective seriousness of the offence, without more may call for the imposition of a very substantial penalty to vindicate the social and industrial policies of the legislation and its regime of penalties.

121. The applicant contends that the above approach is particularly relevant in the context of the subject OHS Act. The evident purpose of making the Commonwealth liable to a penalty for a breach of s 16(1) of the OHS Act is to mark the seriousness of the conduct and act as a deterrent to the Commonwealth, Commonwealth agencies and other persons who may be subject to the OHS Act.

122. The respondent submitted:

Care must be taken in the use of criminal cases arising under occupational health and safety legislation in the various State jurisdictions. Unlike subsection 16(1) of the OHS Act, the New South Wales equivalent imposes an absolute obligation on an employer to secure the health and safety of its employees, a circumstance that has guided the New South Wales courts in their approach to penalties in criminal proceedings under the NSW legislation. Subsection 11(2) of the OHS Act very deliberately excludes the Commonwealth and Commonwealth authorities (other than Government business enterprises) from liability for prosecution for an offence under the Act. The reasons for this exclusion must go beyond simply easing the procedural and evidentiary burdens faced by Comcare and its investigators in making the Commonwealth accountable for occupational health and safety breaches. As Giles JA observed in Adler v ASIC [2003] NSWCA 131; (2003) 46 ACSR 504, [658]: “Civil penalties can be regarded as punitive, with a resemblance to fines imposed on criminal offenders, but the resemblance is not identity”.

123. I nevertheless consider that, despite the differences between the New South Wales and the Commonwealth legislation, and bearing in mind that these are civil and not criminal proceedings, the considerations enumerated above, mainly enunciated in decisions of the New South Wales Industrial Commission, provide useful, analogical, general guidance as to the approach to be taken in consideration of penalties under the Commonwealth Act.

Both parties accepted that these remarks provided useful guidance in assessing the amount of a pecuniary penalty in the present case.

70 Comcare also relied on the following passage from Workcover Authority of New South Wales v Profab Industries Pty Ltd (2000) 49 NSWLR 700 at 714 (quoting with approval from Lawrenson Diecasting Pty Ltd v Workcover Authority of New South Wales (Inspector Ch’ng) (1999) 90 IR 464):

[T]he primary factor to look at in relation to the penalty to be imposed is the objective seriousness of the offence. Particularly in cases involving a serious breach of the OH & S Act, subjective factors, such as a plea of guilty, co-operation with the investigation and subsequent measures taken to improve safety, must play a subsidiary role in determination of penalty to the gravity of the offence itself.

See also Director of Public Prosecutions v Amcor Packaging Australia Pty Ltd (2005) 11 VR 557; [2005] VSCA 219 (Amcor) at [35] where this passage was cited.

71 Subject to the overriding caution expressed by Flick J in Comcare v Post Logistics Australasia Pty Ltd (2008) 178 IR 200; [2008] FCA 1987 at [38] in the passage which follows, these statements reflect the proper approach to assessing penalty:

Care must be taken to ensure that any listing of potentially relevant considerations do not themselves become an impermissible substitute for considering the terms of the legislation in issue or an unnecessary constraint upon a discretion conferred in otherwise unconfined terms.

The Submissions of Comcare

72 Mr Rozen, who appeared as counsel for Comcare, submitted that the contraventions in this case were in the worst category.

73 He argued that the risk of a cadet suffering an allergic reaction to peanuts contained in a ration pack was both foreseeable and foreseen. This was, he argued, a significant aggravating factor. The Australian National Audit Office report in 1996 drew attention to the risk of ADF personnel suffering allergic reactions as a result of lack of awareness of the ingredients in the ration packs. The report recommended:

… that Army needs to provide greater assurance that personnel are aware of the contents of ration packs prior to issue so that individuals can make alternative arrangements where medical circumstances warrant. Army could also investigate the development of alternative components to allow use by personnel with medical conditions that preclude consumption of current components.

It seems from an affidavit sworn on 5 June 2009 by Alfred John Purvis, Director, Health System Program Office, Defence Material Organisation, that the ADF responded to this report by including the ingredients list in ration packs from 1997. However, there was no warning of the dangers of food allergy on the ration packs, and no indication of the ingredients on the beef satay pouch in the ration packs provided to Nathan and Nivae Anandaganeshan and Gene van den Broek.

74 Then, Mr Rozen contended that the grave consequences, particularly Nathan’s death, but also the exposure of Nivae Anandaganeshan and Gene van den Broek to the danger of death, pointed to the seriousness of the risk to safety that arose from the contravention of s 16(1).

75 Next, it was contended that the threat to safety in this case arose from a systemic failure rather than from the inadvertence of the victim or a momentary lapse of supervision. Here, parents were required to advise the camp organisers of any medical conditions of the cadets. The cadets were not permitted to bring their own food on the camp. The medical details were collated but the list was not given to those responsible for distributing food to the cadets. There was thus a failure to have a system whereby the medical details relating to food allergies were available to those distributing the ration packs, and no sufficient attention was given to the potential risk to cadets with food allergies.

76 Comcare accepted that the Commonwealth did not consciously or deliberately disregard the safety of cadets. There was no conscious decision to flout the law. Mr Rozen said that in Trooper Lawrence 163 FCR 2007 Madgwick J held that, absent such features, a case could not fall within the worst category. Mr Rozen, however, contested this view and argued that the absence of such features did not remove the case from the worst category.

77 In Trooper Lawrence 163 FCR 2007 Madgwick J said at [125]:

I cannot impose the maximum penalty for the reason suggested by Mr Maurice QC for the respondent, namely that there was no conscious decision to flout the law, this is not quite in the worst class of case. The seriousness of the breaches of the law mean, however, that the case is close to being in the worst class. There were systemic failures of the most serious kinds.

78 His Honour was referring to the circumstances of the particular case before him. I doubt that he was seeking to lay down a general principle concerning the operation of the section. Such a reading would not sit comfortably with the approach of his Honour expressed in [116] – [117]. There His Honour emphasised that the overriding principle in assessing penalty is that the amount should reflect the Court’s view of the seriousness of the offending conduct in all the circumstances. It is possible to imagine cases of the extreme end of seriousness, perhaps involving multiple fatalities, where the maximum penalty would be ordered even though there was no deliberate flouting of the law.

79 In the criminal law it is established that a maximum penalty prescribed for an offence is intended for cases falling within the worst category of cases for which that penalty is prescribed. In Veen v R (No 2) (1988) 164 CLR 465 at 478; [1988] HCA 14, Mason CJ, Brennan, Dawson and Toohey JJ said:

That does not mean that a lesser penalty must be imposed if it be possible to envisage a worse case; ingenuity can always conjure up a case of greater heinousness.

In R v Propsting [2009] VSCA 45, Vincent JA said at [15]:

There is a stage at which conduct becomes so egregious that it must be regarded as being of a kind attracting the imposition of a very substantial, if not the maximum, penalty for the commission of the offence involved regardless of whether a more serious example could be imagined.

80 This approach is equally applicable to the assessment of a pecuniary penalty for contravention of s 16(1).

Submissions of the Commonwealth

81 Mr Livermore, who appeared as counsel for the Commonwealth, commenced the written submissions as well as the oral submissions to the Court with the following acceptance of responsibility by the Commonwealth:

1. The Army apologises to the family and friends of Nathan Francis. His death was a tragedy – a shock and deep loss keenly felt in the Defence, Cadet and wider communities.

2. Army failed in its duty to ensure that cadets in the circumstances of Nathan Francis did not consume combat ration packs containing ingredients to which they were allergic.

3. This was a preventable death. The death of Nathan Francis exposed systemic faults involving the procedures and policies relating to the supply and permitted consumption of foodstuffs that might contain food allergens, namely Combat Ration Packs, to food allergic persons.

82 In oral submissions Mr Livermore explained that the Commonwealth accepted liability for contravention of the Act and also accepted that the contravention was a serious breach of the duty imposed by the Act. Following enquiry from the Court he said that the level of seriousness could properly be reflected in a pecuniary penalty of 75% of the maximum, that is, $181,500. He also submitted that it would be appropriate to discount that figure by between 10-25% to allow for the Commonwealth’s early acceptance of liability and cooperation in the conduct of this proceeding. The resulting figure would be in the range of $136,125 to $163,350.

83 Mr Livermore argued that this case was not in the worst category. He relied on the following factors to support this conclusion.

84 The first step taken by the Army following Nathan’s death was to prohibit the use of ration packs by cadets. This was done promptly on 8 May 2007. At the same time the Acting Chief of the Defence Force ordered a review into the sufficiency of food warning and labelling standards for ration packs, as well as the adequacy of ADF and cadet policies regarding the management of people, particularly children, with severe food allergies. The review was undertaken by Major General Cavenagh who reported on 22 June 2007 with recommendations concerning improved labelling of ration packs and improved management of food allergy in cadet units. Further, the undertaking accepted by Comcare obliges the Commonwealth to take a number of steps including improved labelling of ration packs produced in the future, limitation of use to the ADF of ration packs already produced, prohibition on the use of ration packs by cadets unless properly labelled, and the development and implementation of an anaphylaxis policy for cadets by 30 June 2009.

85 The Commonwealth also relied on evidence that the Army had taken a number of actions which showed it was a generally responsible organisation attentive to its obligations to protect the health and safety of its members and responsive to the matters which resulted in Nathan’s death. In his affidavit Brigadier Mulhall set out some proactive initiatives to improve safety including the establishment of the Directorate of Army Safety Assurance with eight full-time staff, the establishment of the Directorate of Army Health to provide leadership and accountability ensuring that soldiers receive the highest standard of health care possible in prevailing circumstances, the establishment of the Army SAFE Advisory Service with the role of completing biennial safety system audits and the engagement of 65 part-time staff, the development of an Army Incident Management System, the development of a 17 element Occupational Health and Safety Management System, the development of military risk management and the inclusion of safety competencies within the Army’s training continuum. Further, the Army has employed ten full-time Occupational Health and Safety staff within the Army cadet organisation and will address leadership, governance and assurance and risk management issues in the Army cadet organisation. Finally, the Army will conduct a trend analysis of reported incidents and update the Army cadet’s risk profile annually in March each year. These matters were put before the Court to demonstrate that the Commonwealth was serious in its commitment to health and safety, and has devoted significant resources to the issue. The evidence, so it was said, assists to take the case out the worst category. One marker of the worst category case would be the general approach of an employer which demonstrated a cavalier approach to health and safety.

86 In a similar vein, Mr Livermore relied upon features of the incident in question to show that, whilst the contraventions were undoubtedly serious, the context in which it occurred demonstrated that it was an isolated failure within a general pattern of care and attention for the health and safety of the cadets. Thus, there were comprehensive procedures in place, and carried out, for the camp to be conducted safely. For instance, a risk management plan was compiled and local ambulance, hospital and police were notified of the intention to hold the camp. Further, although not formally required, an experienced medical practitioner attended the camp. A medical roll was compiled and, although not supplied to Mr Bain at the critical time of distribution of the ration packs, it was a valuable tool available at the camp in the case of medical emergencies. Additionally, although the individual food pouches were not labelled, a list of ingredients was included in the ration pack. Then, Mr Livermore pointed out that Nathan was competently attended to in the course of the emergency.

87 A further part of the general background of responsible practice of the Army in health and safety issues was the fact that the ADF did not recruit people with food allergies because it could not guarantee the provision of safe food. If a member of the ADF was found to have a serious food allergy they would be presented to a Medical Review Board with a view towards discharge. Finally, Mr Livermore noted that there had been no previous incident of a fatality in the ADF from an allergic reaction to food from the ration packs.