FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Manas v State of Queensland [2006] FCA 413

JOHN MANAS ON HIS OWN BEHALF AND ON BEHALF OF THE MUALGAL PEOPLE v STATE OF QUEENSLAND

QUD 6003 of 2002

DOWSETT J

13 APRIL 2006

BRISBANE

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

QUEENSLANDDISTRICT REGISTRY |

QUD 6003 OF 2002 |

|

BETWEEN: |

JOHN MANAS ON HIS OWN BEHALF AND ON BEHALF OF THE MUALGAL PEOPLE APPLICANT

|

|

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND RESPONDENT

|

|

JUDGE: |

DOWSETT J |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

13 APRIL 2006 |

|

WHERE MADE: |

BRISBANE |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The applicant has made native title determination application No QUD 6003 of 2002 (“the application”) in relation to the area identified in order 1 below (the “determination area”).

B. The applicant and the State of Queensland (“the parties”) have reached an agreement as to the terms of a determination of native title to be made in relation to the determination area; and

C. The parties have applied to the Federal Court of Australia for a consent determination that native title exists in relation to the determination area.

Being satisfied that a determination in the terms sought by the parties would be within the power of the Court, and it appearing appropriate to the Court that the application be disposed of in this way.

BY CONSENT THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

1. Native title exists in relation to the land and waters on the landward side of the High Water Mark of Lot 185 on Crown Plan TS236 known as Murrabar Islet (also referred to as Channel Island, and Murbayl Islet) Lot 13 on Crown Plan TS247 known as Sarbi Islet (also referred to as Bond Island), Lot 14 on Crown Plan TS247 known as Iem Islet (also referred to as North Possession Island), Lot 116 on Crown Plan TS277 known as Zagarsup Islet (also referred to as Zagarsum and also known as Tobin Island), Lot 117 on Crown Plan TS277 known as Kulbi Islet (also referred to as Portlock Island), Lots 113-115 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 134 on Crown Plan TS277, Lot 10 on USL36708 known as Muknab Rock, and Lot 4 on USL36712 known as Kapril Rock and shown on the plan in Schedule 1 to this order.

2. The persons holding the communal or group rights comprising the native title are set out in Sch 2 to this order.

3. The nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area are:

(a) to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of all land in the determination area to the exclusion of all others; and

(b) in relation to water the right to:

(i) hunt and fish in or on, and gather from, the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs; and

(ii) take, use and enjoy the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs;

provided that such right to water does not confer any right to possession, use or enjoyment of the water to the exclusion of others.

4. Such native title is subject to, and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland including the common law;

(b) traditional laws acknowledged, and traditional customs observed by the native title holders; and

(c) other interests in relation to the determination area as set out in Sch 3 to this order, the relationship between the native title and those other interests being that:

(i) such other interests continue to have effect, and the rights conferred by, or held thereunder, may be exercised notwithstanding the existence of the native title; and

(ii) such other interests and any activity done in exercise of the rights conferred thereby, or held thereunder, prevail over the native title and any exercise of the native title.

5. If a word or expression is not defined in this order, but is defined in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), then it has the meaning given to it in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). In addition to the other words defined in this order:

(a) “high water mark” has the meaning given to it in the Land Act 1994 (Qld);

(b) “laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland” means the common law and the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland;

(c) “local government” has the meaning given to it in the Local Government Act 1993 (Qld); and

(d) “water” has the meaning given to it in the Water Act 2000 (Qld).

6. That the native title be held in trust by the Mualgal (Torres Strait Islanders) Corporation for the benefit of the native title holders.

7. Each party to the proceedings is to bear its own costs.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

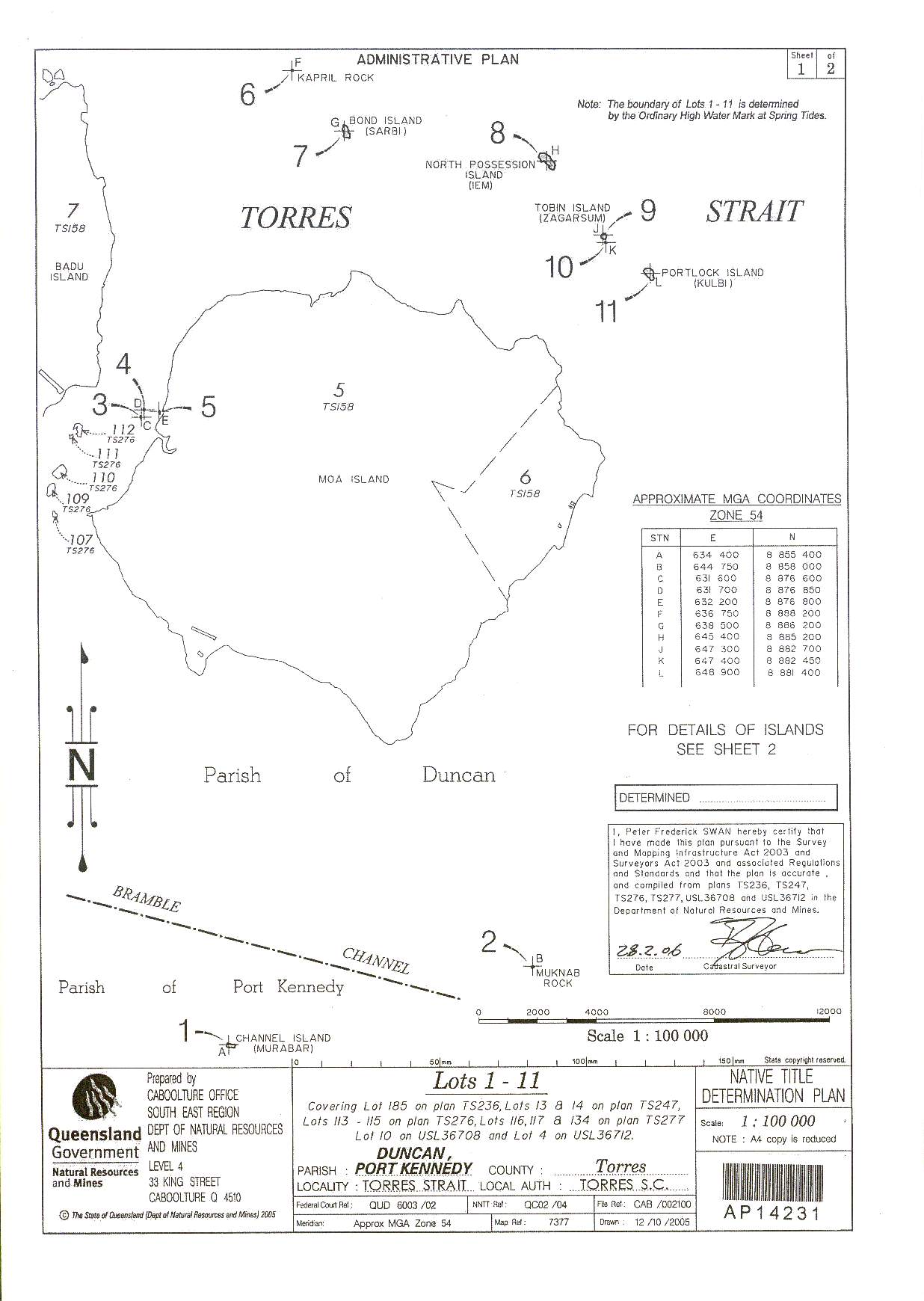

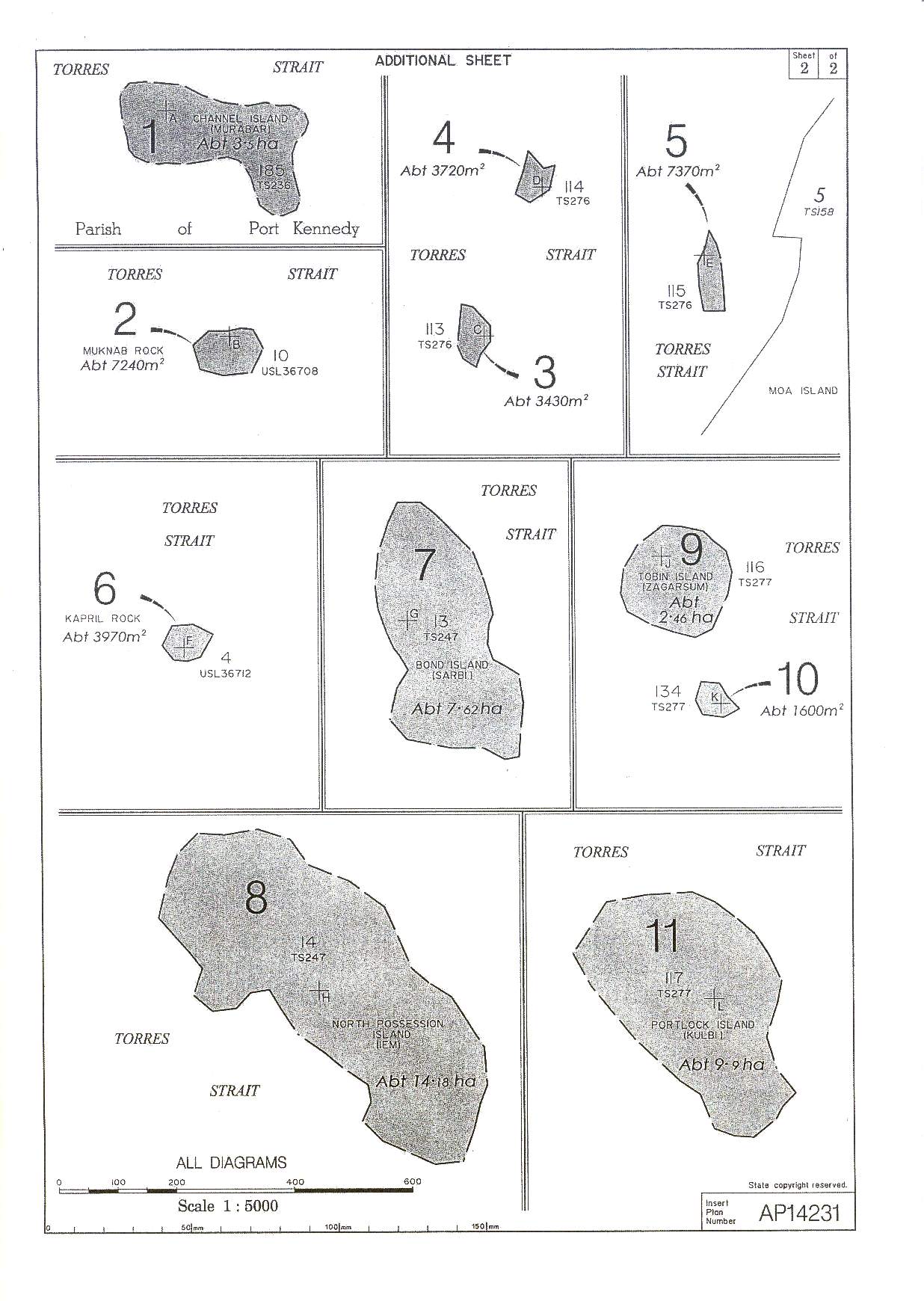

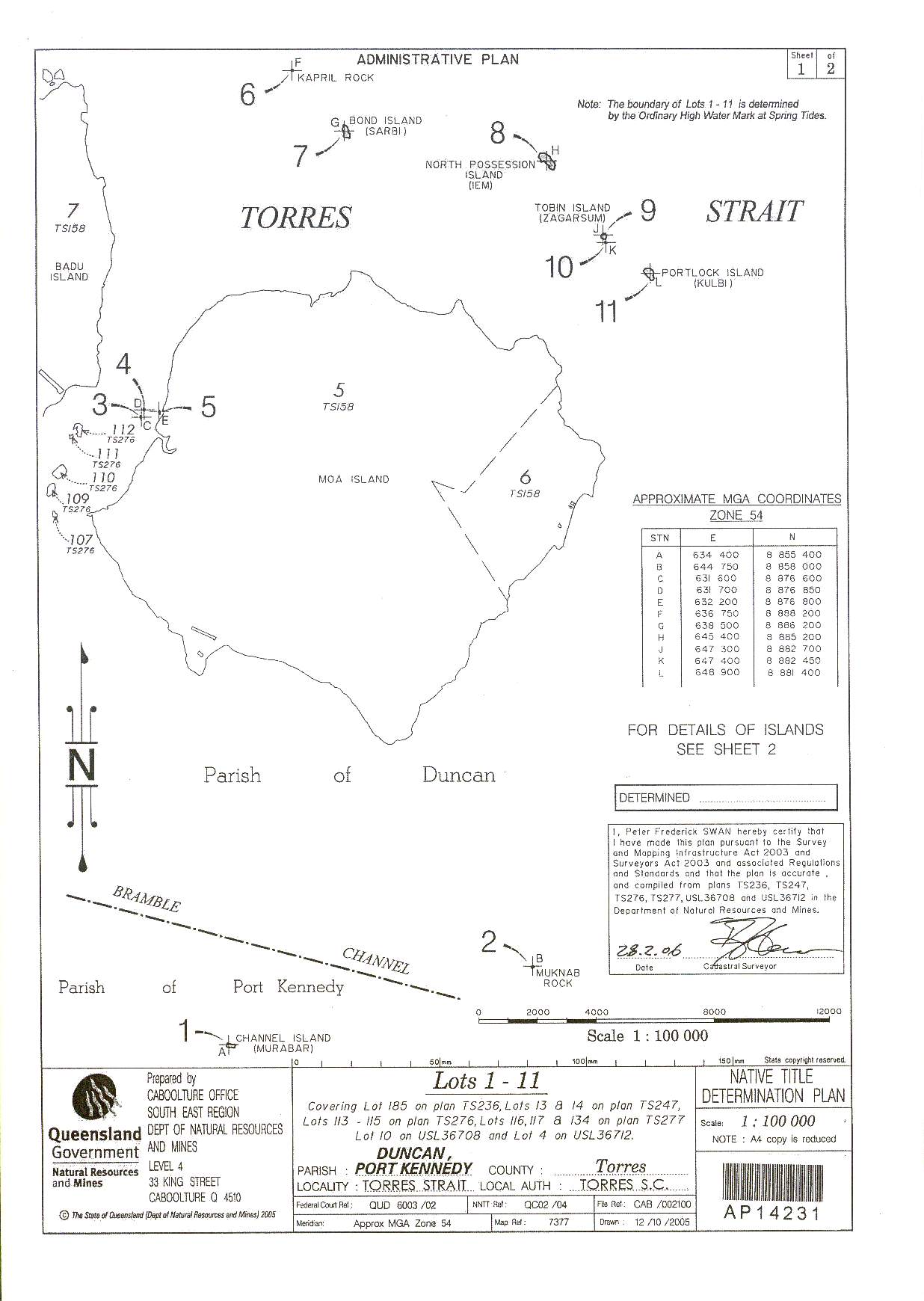

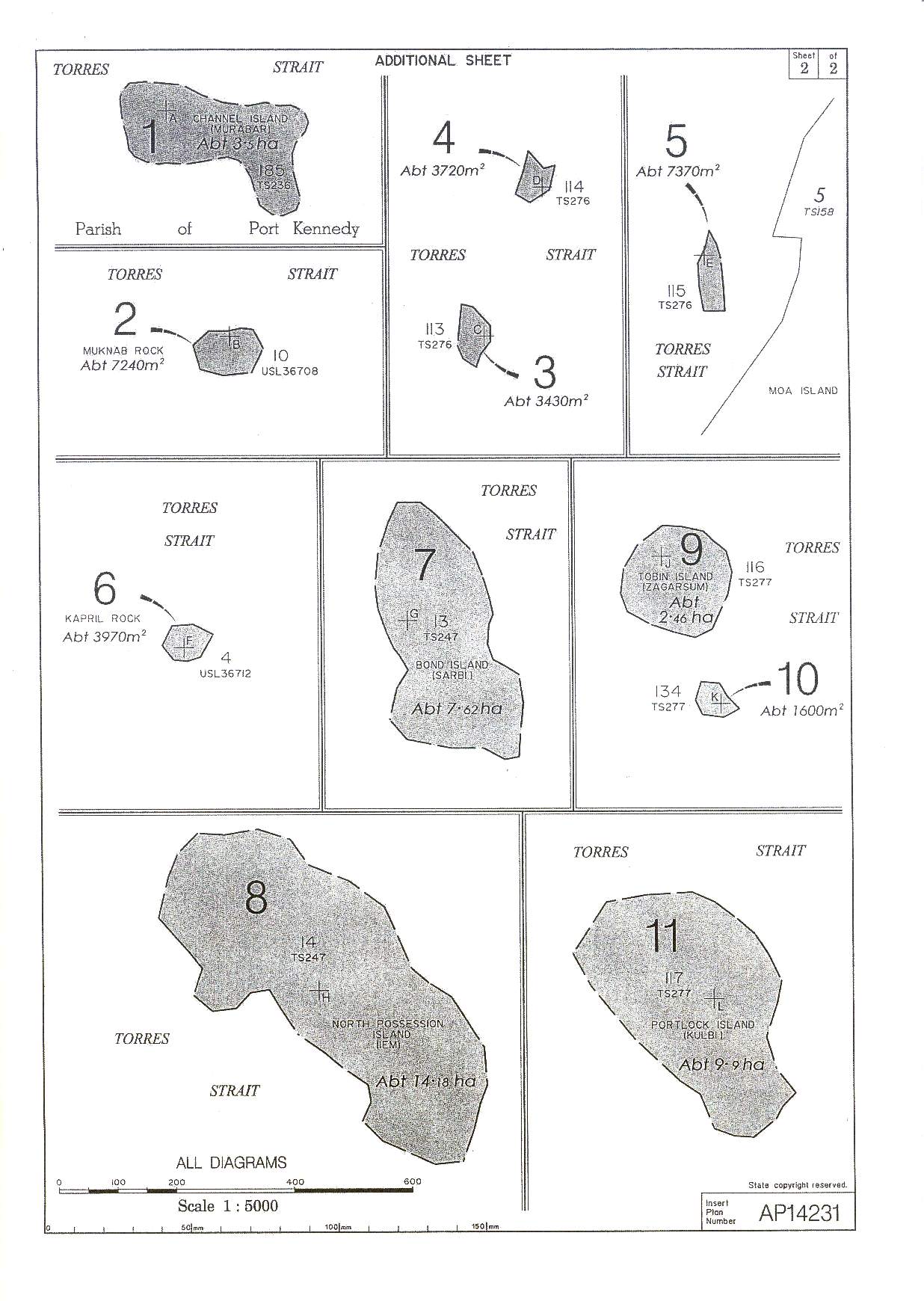

SCHEDULE 1

NATIVE TITLE DETERMINATION PLAN

SCHEDULE 2

NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS

The Mualgal People, being:

(a) the descendants of one or more of the following apical ancestors:

Samukie and Tuku, Babun, Kupad, Goba, Maga, Kanai, Kulka, Anu Namai, Maiamaia, Gai, Nakau, Iaka/Aiaka and Dadu, Waina and Jack Moa and Koia; and

(b) Torres Strait Islanders who have been adopted by the above people in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by those people.

SCHEDULE 3

OTHER INTERESTS

The nature and extent of the other interests in relation to the determination area are:

(a) the interests of the State of Queensland in the following reserves, the interests of the persons in whom they are vested and the interests of the persons entitled to access and use those reserves for the respective purposes for which they are reserved:

(i) Reserve 220 over Lot 13 on Crown Plan TS247; and

(ii) Reserve 91 over Lot 117 on Crown Plan TS277;

(b) the interests, powers and functions of the Torres Shire Council as Local Government for Lot 185 on Crown Plan TS236, Lot 13 on Crown Plan TS247, Lot 14 on Crown Plan TS247, Lots 113-115 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 116 on Crown Plan TS277, Lot 117 on Crown Plan TS277, Lot 134 on Crown Plan TS277, Lot 10 on USL36708 and Lot 4 on USL36712;

(c) the interests recognised under the Treaty between Australia and the Independent State of Papua New Guinea concerning Sovereignty and Maritime Boundaries in the area between the two Countries, including the area known as Torres Strait, and Related Matters signed at Sydney on 18 December 1978 as in force at the date of this order including the interests of indigenous Papua New Guinea persons in having access to the determination area for traditional purposes; and

(d) any other interests that may be held by reason of the force or operation of the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia or the State of Queensland including the common law.

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY |

QUD 6003 OF 2002 |

|

BETWEEN: |

JOHN MANAS ON HIS OWN BEHALF AND ON BEHALF OF THE MUALGAL PEOPLE APPLICANT

|

|

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND RESPONDENT

|

|

JUDGE: |

DOWSETT J |

|

DATE: |

13 APRIL 2006 |

|

PLACE: |

BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

APPLICATION

1 Father John Manas, on his own behalf and on behalf of the Mualgal People, has applied for a determination that native title exists over numerous uninhabited small islands, islets and rocks located in the vicinity of Mua Island in the Torres Strait within the boundaries of the State of Queensland.

BACKGROUND

2 The application was filed on 1 March 2002 pursuant to s 61(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the “Act”). It concerns land and waters on the landward side of the high water mark being Lot 185 on Crown Plan TS236 (Murrabar Islet, also referred to as Channel Island), Lot 13 on Crown Plan TS247 (Sarbi Islet, also referred to as Bond Island), Lot 14 on Crown Plan TS247 (Iem Island, also referred to as North Possession Island), Lot 116 on Crown Plan TS277 (Zagarsup Islet, also referred to as Zagarsum or Tobin Island), Lot 117 on Crown Plan TS277 (Kulbi Islet, also referred to as Portlock Island), Lots 113-115 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 134 on Crown Plan TS277, Lot 10 on USL36708 (Muknab Rock), and Lot 4 on USL36712 (Kapril Rock). The areas of land and water as described in the claim are hereinafter referred to as the “determination area”. They are further identified in the plan which is Schedule 1 to these reasons.

3 The National Native Title Tribunal (“the Tribunal”) gave notice of the application pursuant to, and in accordance with, s 66 of the Act. However the State of Queensland is the only respondent. On 15 July 2003 the matter was referred to the Tribunal for mediation pursuant to s 86B of the Act.

4 The parties have reached agreement upon the terms of a draft determination. The agreement recognizes the traditional rights of the Mualgal People to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the land in the determination area to the exclusion of all others. In relation to water the agreement recognizes a non-exclusive right to:

(a) hunt and fish in or on, and gather from, the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs; and

(b) take, use and enjoy the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic and non-commercial communal needs.

5 The parties ask the Court to make orders in, or consistent with, the terms of their agreement, provided that it is satisfied that it is appropriate to do so: s 87 of the Act.

POWER OF THE COURT

6 Pursuant to s 13 and Pts 3 and 4 of the Act, the Court may make determinations concerning native title in relation to areas over which there is no existing approved determination. Division 1C of Pt 4 of the Act provides that some or all of the parties to native title proceedings may negotiate an agreed outcome for an application or part thereof. Section 87 of the Act empowers the Court, if it is satisfied that such an order is within its power, to make an order in, or consistent with, the terms of the parties’ agreement without holding a full hearing. Where the Court makes a determination of native title, s 94A of the Act requires that it set out details of the matters mentioned in s 225 which provides:

‘A determination of native title is a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area (the determination area) of land or waters and, if it does exist, a determination of:

(a) who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are; and

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area; and

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area; and

(d) the relationship between the rights and interests in paragraphs (b) and (c) (taking into account the effect of this Act); and

(e) to the extent that the land or waters in the determination area are not covered by a non-exclusive agricultural lease or a non-exclusive pastoral lease – whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.’

AGREEMENT AND DRAFT DETERMINATION

7 I have examined an anthropological report prepared by Dr Garrick Hitchcock, an anthropologist employed by the Torres Strait Regional Authority. The report is based on his own studies, reports by consultant anthropologists and discussions with elders of the native title claim group. In particular he relies upon a report prepared by Dr Powell in connection with an earlier claim concerning Mua Island. Drummond J made a determination in connection with that claim on 12 February 1999. Mua is, and has traditionally been, inhabited. The present determination area surrounds Mua but the relevant islands, islets and rocks are not, and have not generally been, inhabited. The present claim is on behalf of the claim group which successfully demonstrated that they hold native title over Mua.

8 Dr Hitchcock describes organised Torres Strait Islander occupation and possession of the determination area since some time prior to the establishment of British sovereignty over the area in 1872. He also confirms the continuity of an identifiable society of Torres Strait Islander people having a connection with the lands and waters of the determination area in accordance with traditional laws which they acknowledge and traditional customs which they observe. Other groups in the Torres Strait appear also to recognize such connection.

9 Dr Hitchcock records that:

‘In 1872 the British Government extended the maritime boundary of Queensland to include all islands situated within sixty miles of the Queensland coast, including islands in the Torres Strait, and these were then annexed to the colony. The maritime boundaries of Queensland were again extended in 1879 to include most of the remaining Torres Strait Islands situated to the north of the 1872 boundary. Mua and the claim area came within the maritime boundary of 1872 (Mullins 1995:87-90, 139).

The Mualgal were among the first Indigenous people in Australia to obtain a consent determination of their native title rights and interests, on 12 February 1999. This claim, QC96120, originally covered the community or ‘home’ island, Mua, and surrounding areas:

‘The Mualgal Native Title Claim QC96120 covers Mua and surrounding seas, reefs and islands that comprise the traditional area of the Mualgal….One of the larger islands in Torres Strait, Mua’s coastline contains many long beaches, headlands and creek estuaries, and is surrounded by large reefs, islets and rocks. The whole island and its surrounding waters that contain these reefs, islets and rocks are part of the traditional territory of the Mualgal people (Powell 1998:6).’

10 Dr Hitchcock continues:

‘It is quite possible that Mua and the claim islands were seen by the Portuguese explorer Torres during his voyage through Torres Strait in 1606 (see Hilder 1980:78; Ingleton 1980:912; Stevens 1930). However, the first European documented as ‘discovering’ Mua and some of the claim islands was William Bligh, during his first transit of the Strait in 1789, in the Bounty’s launch. On this voyage, the south coast of Mua, and Mua’s highest peak, Mua Pad or Mt Augustus, were sighted in the distance from the south.

…

Historian and archaeologist David Moore (1978) reconstructed the information provided to O.W. Brierly and other crew (e.g. MacGillivray 1852) of HMS Rattlesnake by Barbara Thompson, a Scottish castaway who lived with the Kaurareg people from December 1844 until her rescue in October 1849, principally on Muralag (Prince of Wales Island).

While there is no indication that Mrs Thompson visited Mua itself, the people she referred with variants of the word Italgal, a Mualgal group inhabiting the southern part of Mua (‘Uttalaga’, ‘Ettalaga’, ‘Itallaga’, ‘Eet’, ‘Eetalaga’: Moore 1978:162-163, 172, 174, 203; Powell 1998:17, 57-58) were in regular contact with her Kaurareg hosts. Brierly himself met a woman of Mua origin on 29 November 1849, called Gadjiemali (Moore 1978:121).

This is worthy of comment in the present context, simply to show that the Mualgal were able to, and did in the normal course of their affairs, move around in the southwestern part of Torres Strait in the mid-nineteenth century, thus frequenting islands beyond Mua itself.’

11 Dr Hitchcock continues:

‘The annexation of the Torres Strait Islands to Queensland , and the influx of Europeans and others into the Strait to participate in the maritime industries, did not dispossess the Islanders of their home islands or their other territories (e.g. Beckett 1983:202). Indeed, the continued participation of Island men in these fisheries, in particular the pearl shell industry, enabled them to continue to visit the claim islands, and fully maintain their connections with them. For example, Mua Passage, the narrow and rock-studded channel between Badu and Mua, was a favoured pearlshelling ground. In 1872, several hundred Pacific Islands were working there (Mullins 1995:72).

…

During the Second World War, the European and ‘half-caste’ population of Thursday Island was evacuated to the Australian mainland, and the region came under military administration. Almost all able-bodied Torres Strait Islander men joined the Torres Strait Light Infantry, based on Horn Island, while their families remained on the outer islands (Fuary 1993:173). The women, children and elderly of Mua continued to occupy the island during this time, camping in the bush to avoid detection by Japanese aircraft (Powell 1998:38-39; Teske 1991:19).

…

Throughout the period after annexation, the claimants continued to visit the claimed area, and participation in the marine industries and the Second World War in no way impeded or interfered with the continued exercise of their traditional rights and interests in the islands under claim (Oza Bosen, pers. comm., 5 April 2005; Fr John Manas, pers. comm., 1 April 2005; Joshua Nawie, pers. comm., 23 April 2005).

Just as they did before contact with Europeans and the assertion of British sovereignty, the Mualgal had and continue to have a rich tradition of ownership, visitation, use, and toponomy (a system of place names) in relation to the claim area, which demonstrates that the islands were indeed part of their territories.

...

The native title claimant group can be characterised as a single Torres Strait people, community or group, the Mualgal, identified as the descendants of the Indigenous inhabitants of Mua. Schedule A of the Native Title Determination Application identified the claimant group as follows:

‘The native title holders are the Mualgal people, being those persons who are members of the cognatic descent groups deriving from the following apical ancestors: Samukie and Tuku, Babun, Kupad, Goba, Maga, Kanai, Kulka, Anu Namai, Maiamaia, Gai, Nakau, Iaka/Aiaka and Dadu, Waina and Jack Moa, and Koia.’

Recruitment to the above community occurs primarily by birth, or by traditional Torres Strait Islander adoption. Whether natural born or adopted, all such children automatically acquire a community identity, which in turn confers native title rights and interests in the community’s traditional estate (for further information, see Powell 1998:44-48).

The State of Queensland has previously assessed the connection report by Powell (1998) in support of the original Mua native title claim (QC96120). The State found that this report satisfactorily furnished evidence identifying the native title group as the descendants of the traditional owners of Mua prior to the establishment of British sovereignty, and consented to a determination of native title, which was duly made by the Federal Court of Australia.

…

In the Executive Summary of her report, Powell (1998:4) outlined the key features of Mua subsistence, settlement and social organisation, which share many features in common with other groups in Torres Strait:

‘Official records and oral histories describe how Mua was populated in the last century by indigenous people who were agricultural fisherfolk. They lived in small villages along the coast and in the interior where they had extensive gardens; and shifted residence from coast to interior according to the agricultural calendar. In addition, these people travelled to surrounding islands for social, cultural and political reasons. They had a diverse economy, based on shifting subsistence agriculture, freshwater, coastal and deep sea fishing and hunting. The island was divided into broad territorial divisions, each inhabited by clan or buai groups who maintained permanent villages and well established garden areas. The claims were connected to each other and to people on other islands by a complex web of kinship, trading and exchange relationships. The claims were exogamous, and polygyny was permitted, reflecting the wealth and status of men. Children and women were part of an exchange system which enabled claims to form lasting alliances with more distant groups. A rich cosmology connected the Mualgal with their surroundings, and linked them to the historical past, as well as the continuing spiritual present. Parts of the landscape were attributed with cosmological powers, some topographical features were the manifestations of totemic and legendary beings.’

…

Mualgal tradition and custom, from which their exclusive native title rights and interests in the claim area derive, shares much in common with their Kaurareg allies, other Western Torres Strait Islander groups, and indeed, all Torres Strait Island peoples. Many aspects of the relationship between the communities forming these groups continue today, and members of the claim group continue to acknowledge the closeness between the communities forming each larger group (e.g. dialect group), and their wider identification as Western Torres Strait Islanders. This is particularly so with reference to their traditional allies the Kaurareg. The two groups shared a dialect, traded, and intermarried with each other, and also with the Naghir people to the east.’

12 Dr Hitchcock continues:

‘The claimants identify as Mualgal. This identity is not only a function of descent from Mualgal forebears, it is fundamentally related to their connection to their home island, and the surrounding land and sea territories that make up the society’s estate. Membership of the Mualgal confers rights and interests in the claim islands, which have been handed down from ancestors alive at and before 1872, through succeeding generations to the existing claimants. All the claim areas, their contiguous reefs, and the surrounding sea country are intimately known. They have their own language names for the islands, and have associated stories and historical episodes pertaining to them.

…

The native title claimants aver that they and their ancestors have continued to visit the islands periodically, since before the assertion of British sovereignty, primarily for subsistence purposes (see discussion below). On the basis of ethnographic evidence relating to contemporary usage, it is reasonable to infer that visits to the claim islands were often seasonal, taking place during kuki, the northwest monsoon season (November-April) (Haddon 1912b:225). At this time the water is relatively calm, and ideal for dugong and turtle hunting, and voyages for the collection of turtles, turtle eggs, and other food resources.

…

Evidence of such visitation is provided by the observations of camping shelters and the remains of meals of turtle, made by members of William Bligh’s crew at Kulbi in 1792, in particular by Matthew Flinders (Lee 1920:193-196). This island, and others in the claim area, continue to be visited for picnics, and camping associated with hunting expeditions (Fr John Manas, pers. comm., 1 April 2005; Oza Bosen, pers. comm., 5 April 2005; Joshua Nawie, pers. comm., 23 April 2005).

…

Further evidence of continuity of physical connection was furnished during interviews with Mualgal elders. In every case, these men were able to accurately describe the islands, noting such things as the location of coconuts, former garden sites, and suitable anchorages. For example, they could provide specific information about their experiences visiting the claim area, detailing the flora and fauna present in their own language.

…

Cultural connection is evidenced by the fact that elders instruct younger people that the claim islands are part of the Mua traditional estate, relate stories about their use by past Mualgal (e.g. the well-known elder, Anu Namai), and take them to the islands in the course of visits for picnics and resource-gathering activities. In so doing, the continuity of connection between Mualgal and the claim area is ensured.

…

Continuity of connection has been maintained by the native title claim group since the establishment of British sovereignty over the islands in 1872. In the physical sense, it was maintained through continuous visitation to the islands. These were made possible by traditional, double-outrigger canoes (gul) up to around 1900, which were later superseded by luggers and wooden dinghies, followed, since the 1960s, by aluminium dinghies:

‘And people all time go, Mua people all time go and come, go and come. Exactly. Them island lo [belong to] Mua… We all, me myself too, we all sail in small boats, small dinghies, sailing boat [to those islands]. Just for picnic ground, fishing ground (Joshua Nawie, pers. comm., 23 April 2005).’

The islands under claim never supported permanent populations of Indigenous people (on account of their size and environmental constraints), and were located only a short distance from Mua. In this narrow sense was the native title group ‘separated’ from these lands. However, the claim group was never dispossessed of their home island by the State (it, along with some of the claim islands, were declared Aboriginal Reserves). They were thereby able to maintain a continuing connection to the sea and the claim area through continued access to watercraft. Today, Mualgal continue to visit the islands, as did their forebears who were alive prior to the establishment of British sovereignty.’

13 Dr Hitchcock concludes as follows:

‘The Mualgal are a distinct community or people of Torres Strait, have never been dispossessed of the claim area, and continue to exercise their native title rights and interests in the claimed islands in accordance with a normative system of Torres Strait Islander traditional law and custom. This system predates the establishment of British sovereignty in 1872, and has continued substantially uninterrupted up to today. In short, this report will demonstrate that the Mualgal are clearly the native title holders of the claim area.’

14 I infer that the State of Queensland has taken such expert advice as it deems appropriate and has chosen to recognize the applicant’s claim. In any event the objective facts of the case demonstrate the probability of continued connection between the people resident on Mua and the various islands, islets and rocks in the determination area. The Mua people were, and are, seafarers, able to travel to these features and further afield. There was, and is, good reason for them to visit them on a regular basis. Food is available there. It would be inconsistent with one’s experience of human nature if, over the centuries, successive generations had not come to view these islands, islets and rocks as their own. No doubt, over those same centuries, there have been challenges to their claims, but any such challenges must have been resolved in favour of those of whom the claim group are successors. I accept the anthropological evidence to the extent necessary to find that native title exists in relation to the lands and water identified in Sch 1 to these reasons. I further find, pursuant to s 225, that:

· the persons holding the communal or group rights comprising the native title are as set out in Sch 2 to these reasons;

· the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area are:

· to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of all land in the determination area to the exclusion of all others; and

· in relation to water the right to:

(a) hunt and fish in or on, and gather from, the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs; and

(b) take, use and enjoy the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs;

provided that such right to water does not confer any right to possession, use or enjoyment of the water to the exclusion of others;

· such native title is subject to, and exercisable in accordance with:

· the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland including the common law;

· traditional laws acknowledged, and traditional customs observed by, the native title holders; and

· other interests in relation to the determination area as set out in Sch 3 to these reasons, the relationship between the native title and those other interests being that:

· such other interests continue to have effect, and the rights conferred thereby, or held thereunder, may be exercised notwithstanding the existence of the native title; and

· such other interests and any activity done in exercise of the rights conferred thereby, or held thereunder, prevail over the native title and any exercise of the native title.

15 The order will contain the following definition clause:

‘If a word or expression is not defined in this order, but is defined in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), then it has the meaning given to it in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). In addition to the other words defined in this order:

(a) “high water mark” has the meaning given to it in the Land Act 1994 (Qld);

(b) “laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland” means the common law and the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland;

(c) “local government” has the meaning given to it in the Local Government Act 1993 (Qld); and

(d) “water” has the meaning given to it in the Water Act 2000 (Qld).’

16 I order that the native title be held in trust by the Mualgal (Torres Strait Islanders) Corporation for the benefit of the native title holders.

17 Each party to the proceedings is to bear its own costs.

18 These orders are consistent with the terms agreed by the parties. They recognise that the Mualgal People, as the common law holders of native title in the determination area, are entitled to the exclusive use and enjoyment of the land above the high water mark in accordance with their traditional laws and customs and to the non-exclusive use and enjoyment of water above the high water mark.

SCHEDULE 1

NATIVE TITLE DETERMINATION PLAN

SCHEDULE 2

NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS

The Mualgal People, being:

(c) the descendants of one or more of the following apical ancestors:

Samukie and Tuku, Babun, Kupad, Goba, Maga, Kanai, Kulka, Anu Namai, Maiamaia, Gai, Nakau, Iaka/Aiaka and Dadu, Waina and Jack Moa and Koia; and

(d) Torres Strait Islanders who have been adopted by the above people in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by those people.

SCHEDULE 3

OTHER INTERESTS

The nature and extent of the other interests in relation to the determination area are:

(e) the interests of the State of Queensland in the following reserves, the interests of the persons in whom they are vested and the interests of the persons entitled to access and use those reserves for the respective purposes for which they are reserved:

(i) Reserve 220 over Lot 13 on Crown Plan TS247; and

(ii) Reserve 91 over Lot 117 on Crown Plan TS277;

(f) the interests, powers and functions of the Torres Shire Council as Local Government for Lot 185 on Crown Plan TS236, Lot 13 on Crown Plan TS247, Lot 14 on Crown Plan TS247, Lots 113-115 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 116 on Crown Plan TS277, Lot 117 on Crown Plan TS277, Lot 134 on Crown Plan TS277, Lot 10 on USL36708 and Lot 4 on USL36712;

(g) the interests recognised under the Treaty between Australia and the Independent State of Papua New Guinea concerning Sovereignty and Maritime Boundaries in the area between the two Countries, including the area known as Torres Strait, and Related Matters signed at Sydney on 18 December 1978 as in force at the date of this order including the interests of indigenous Papua New Guinea persons in having access to the determination area for traditional purposes; and

(h) any other interests that may be held by reason of the force or operation of the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia or the State of Queensland including the common law.

|

I certify that the preceding eighteen (18) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Dowsett. |

Associate:

Dated: 13 April 2006

|

Solicitor for the Applicant: |

Mr D Saylor (Torres Strait Regional Authority) |

|

Solicitor for the Respondent: |

Ms A Cope (Crown Solicitor) |

|

Date of Hearing: |

13 April 2006 |

|

Date of Judgment: |

13 April 2006 |