FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Nona and Manas v State of Queensland [2006] FCA 412

VICTOR NONA AND JOHN MANAS ON THEIR OWN BEHALF AND ON BEHALF OF THE BADUALGAL AND MUALGAL PEOPLE v STATE OF QUEENSLAND

QUD 6002 of 2002

DOWSETT J

13 APRIL 2006

BRISBANE

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

QUEENSLANDDISTRICT REGISTRY |

QUD 6002 OF 2002 |

|

BETWEEN: |

VICTOR NONA AND JOHN MANAS ON THEIR OWN BEHALF AND ON BEHALF OF THE BADUALGAL AND MUALGAL PEOPLE APPLICANT

|

|

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND RESPONDENT

|

|

JUDGE: |

DOWSETT J |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

13 APRIL 2006 |

|

WHERE MADE: |

BRISBANE |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The applicant has made a native title determination application No QUD 6002 of 2002 (“the application”) in relation to the area identified in order 1 below (the “determination area”).

B. The applicant and the State of Queensland (“the parties”) have reached an agreement as to the terms of a determination of native title to be made in relation to the determination area.

C. The parties have agreed to make application to the Federal Court of Australia for a consent order for a determination that native title exists in relation to the determination area.

Being satisfied that a determination in the terms sought by the parties would be within the power of the Court, and it appearing appropriate to the Court that the application be disposed of in this way.

BY CONSENT THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

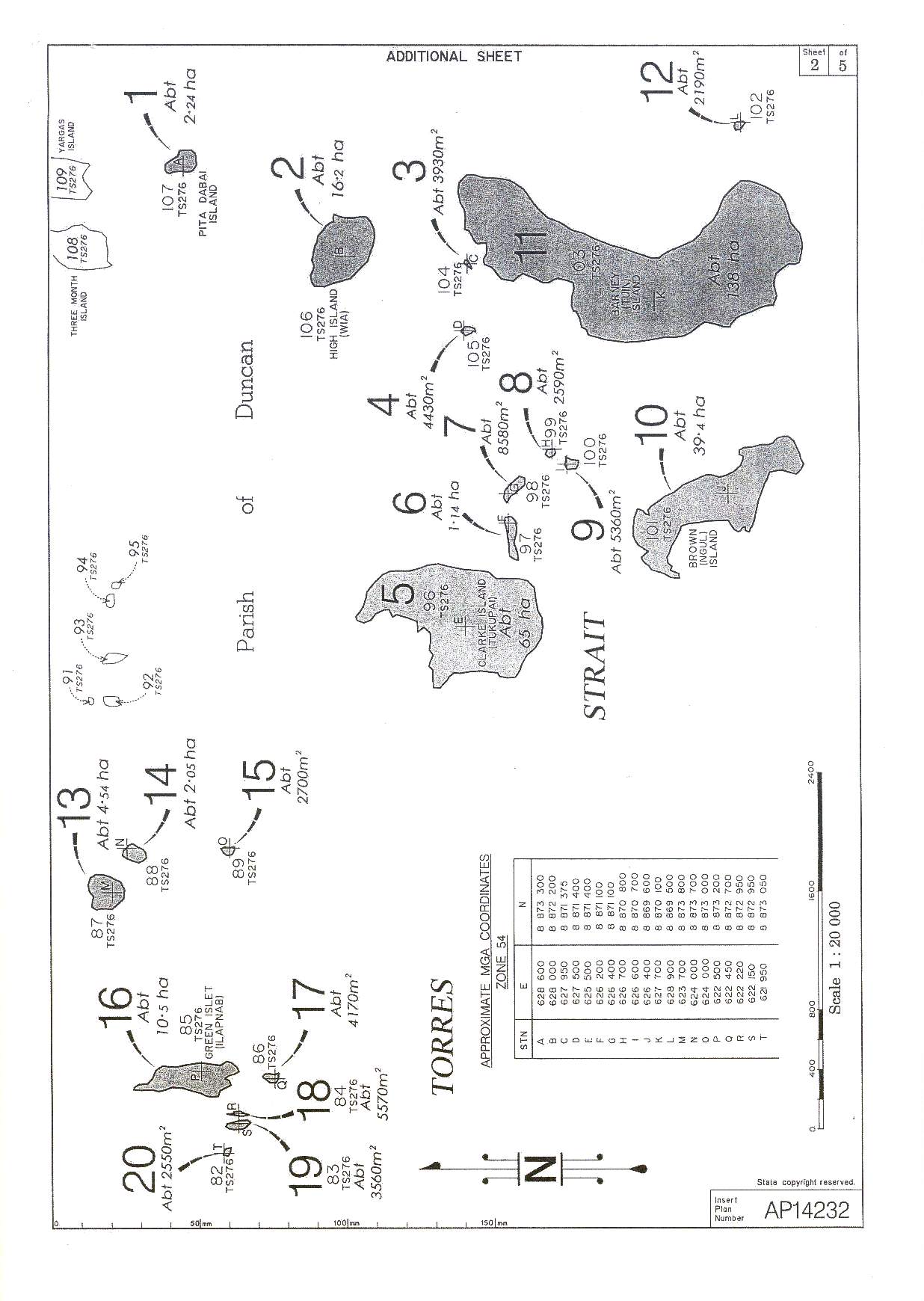

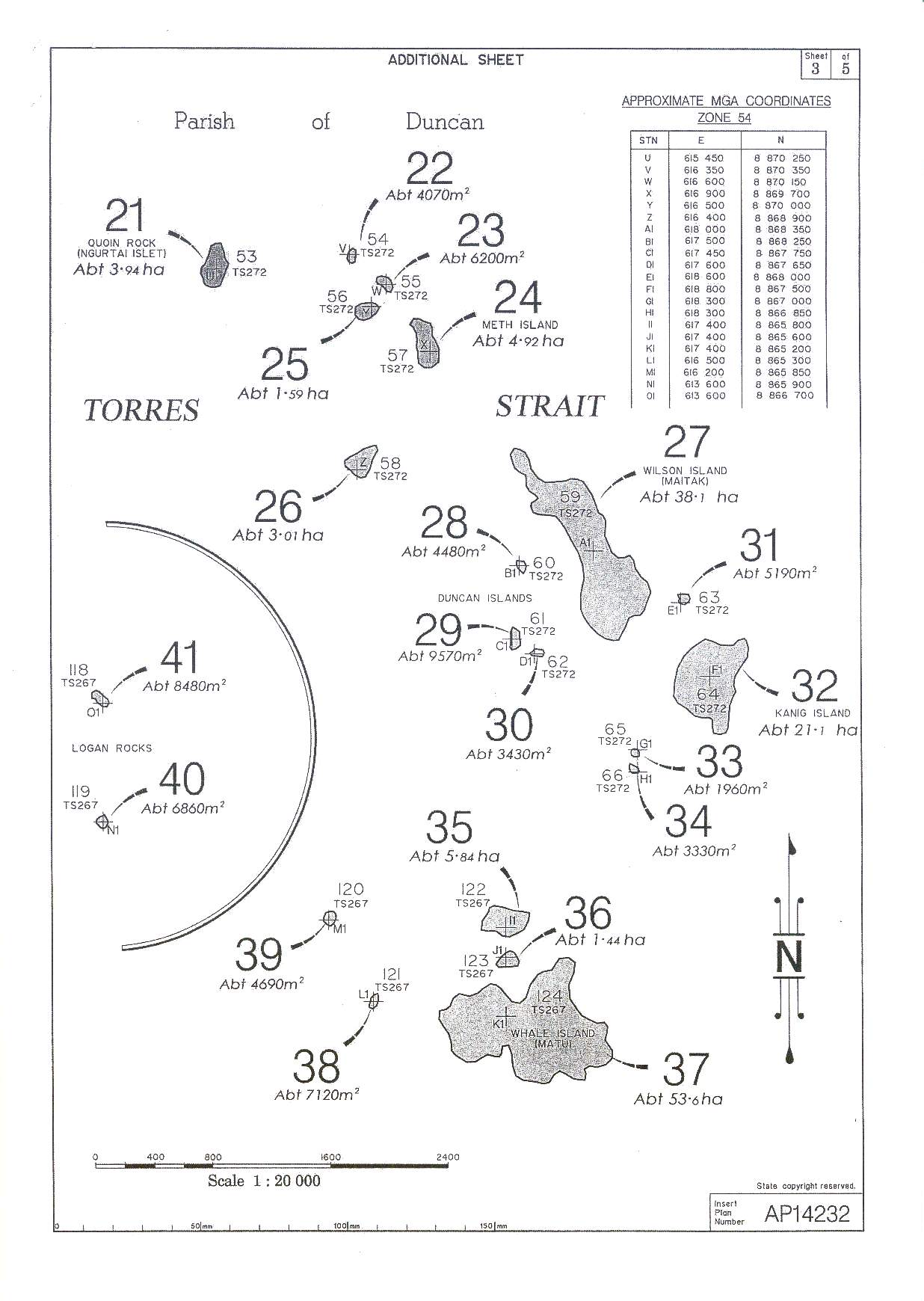

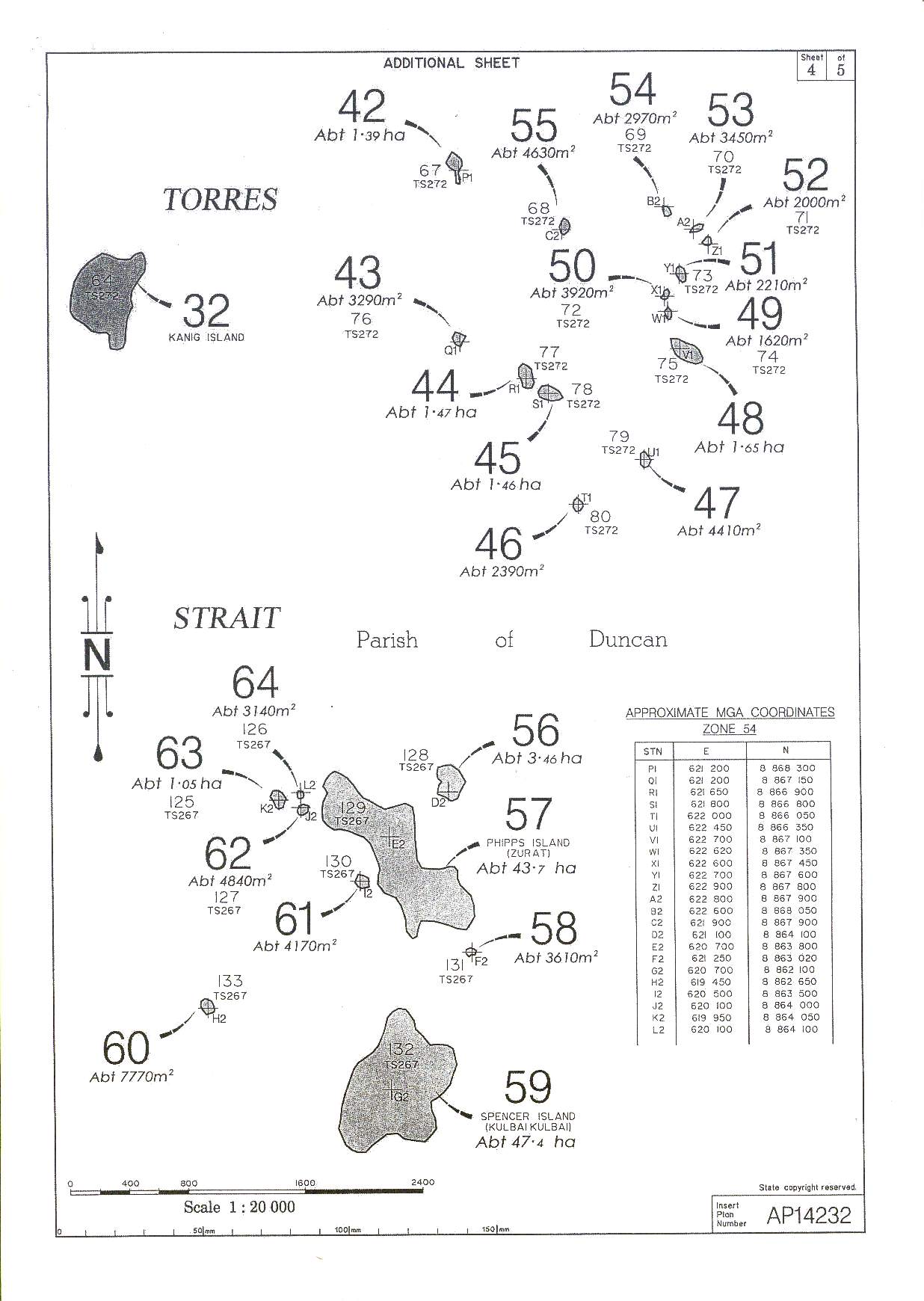

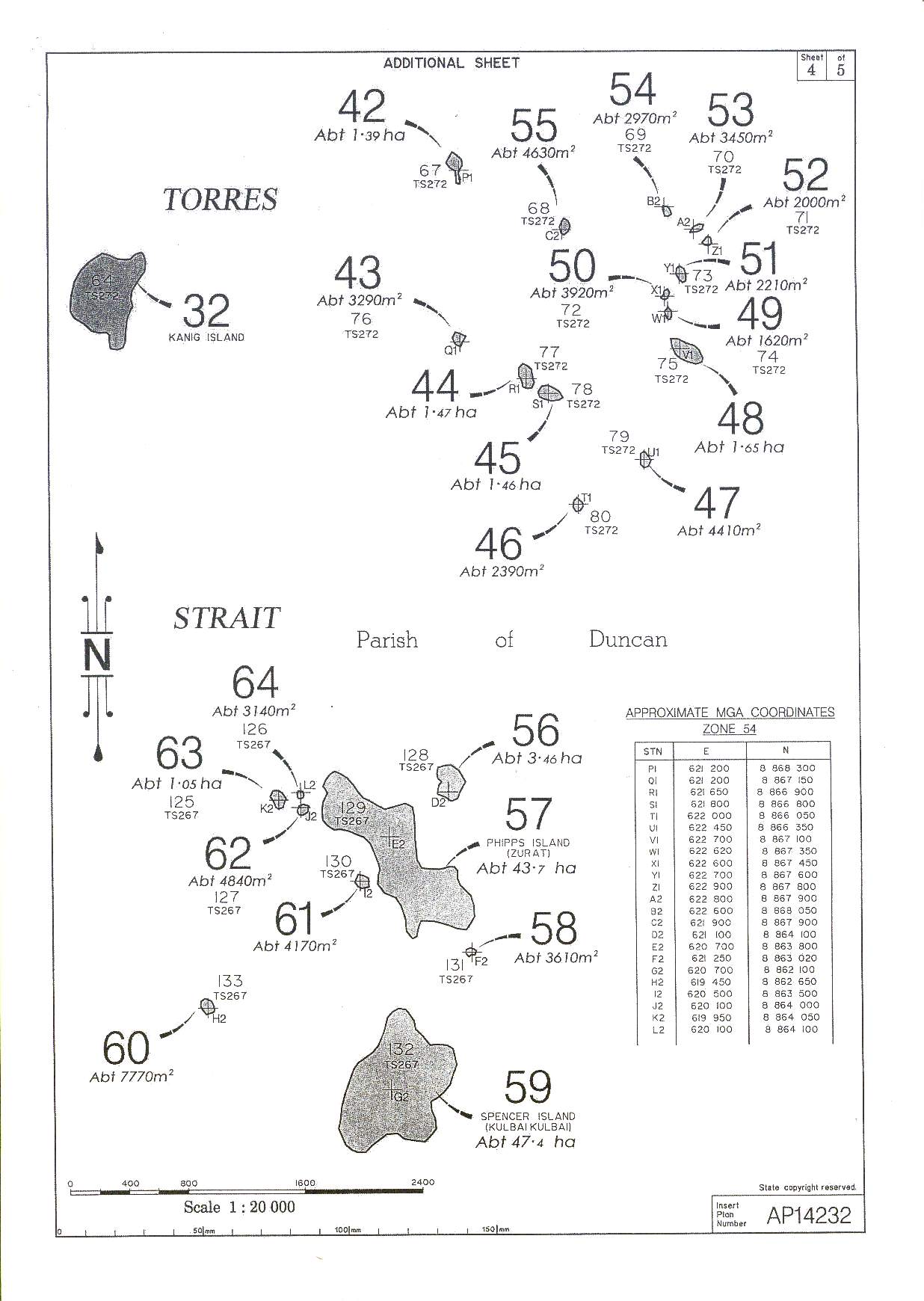

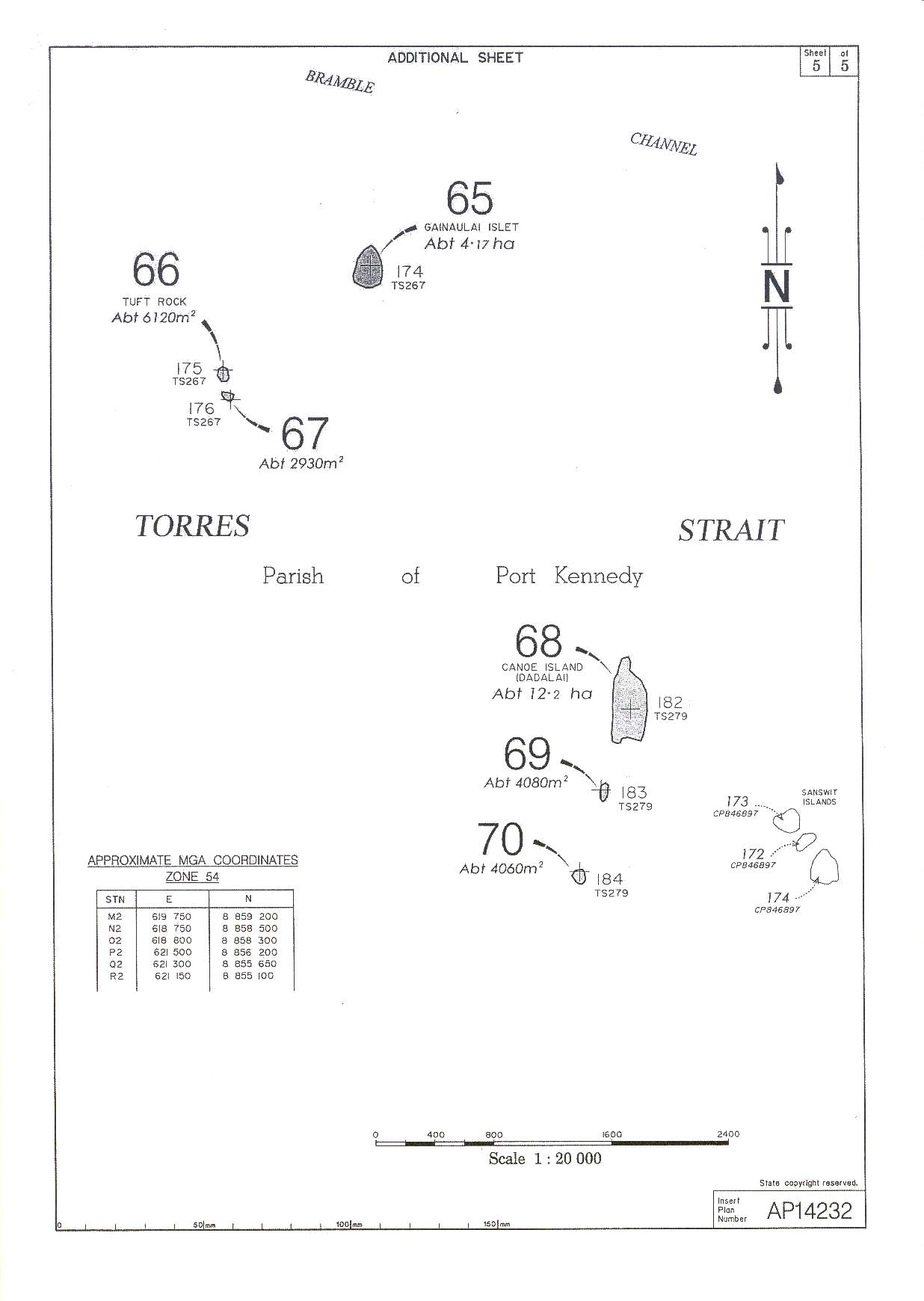

1. Native title exists in relation to the land and waters on the landward side of the High Water Mark of Lot 124 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Matu Island (also referred to as Whale Island), Lot 129 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Zurat Island (also referred to as Phipps Island), Lot 132 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Kulbai Kulbai Island (also referred to as Spencer Island), Lot 53 on Crown Plan TS272 known as Ngurtai Island (also referred to as Quoin Island), Lot 59 on Crown Plan TS272 known as Maitak Island (also referred to as Wilson Island), Lot 64 on Crown Plan TS272 known as Kanig Island (also referred to as Duncan Island), Lot 85 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Ilapnab Island (also referred to as Green Island), Lot 96 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Tukupai Island (also referred to as Clarke Island), Lot 101 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Ngul Island (also referred to as Browne Island), Lot 103 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Tuin Island (also referred to as Barney Island), Lot 106 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Wia Island (also referred to as High Island), Lots 118 and 119 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Logan Rocks, Lots 120-123 on Crown Plans TS267, Lots 125-128 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 130, 131 & 133 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 174 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Gainaulai Island, Lot 175 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Tuft Rock, Lot 176 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 54-56 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 57 on Crown Plan TS272 known as Meth Islet, Lot 58 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 60-63 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 65-80 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 82-84, 86-89, 97-100, 102, 104, 105 and 107 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 182 on Crown Plan TS279 known as Dadalai Island (also referred to as Canoe Island) and Lots 183-184 on Crown Plan TS279 and shown on the plans in Schedule 1 (“the Determination Area”) as shown on the plan in Sch 1 to this order.

2. The persons holding the communal or group rights comprising the native title are set out in Sch 2 to this order.

3. The nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area are:

(a) to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of all land in the determination area to the exclusion of all others; and

(b) in relation to all water in the determination area, the right to:

(i) hunt and fish in or on, and gather from, the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs; and

(ii) take, use and enjoy the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs

provided that such right to water does not confer any right to possession, use or enjoyment thereof to the exclusion of others.

4. Such native title is subject to, and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland including the common law;

(b) traditional laws acknowledged, and traditional customs observed, by the native title holders; and

(c) other interests in relation to the determination area as set out in Sch 3 to this order, the relationship between the native title and those other interests being that:

(i) such other interests continue to have effect, and the rights conferred by, or held thereunder, may be exercised notwithstanding the existence of the native title; and

(ii) such other interests and any activity done in exercise of the rights conferred by, or held thereunder, prevail over the native title and any exercise of the native title.

5. If a word or expression is not defined in this order, but is defined in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), then it has the meaning given to it in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). In addition to the other words defined in this order:

(a) “high water mark” has the meaning given to it in the Land Act 1994 (Qld);

(b) “laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland” means the common law and the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland;

(c) “local government” has the meaning given to it in the Local Government Act 1993 (Qld); and

(d) “water” has the meaning given to it in the Water Act 2000 (Qld).

6. The native title be held in trust by the Badu Ar Mua Migi Lacal (Torres Strait Islanders) Corporation for the benefit of the native title holders.

7. Each party to the proceedings is to bear its own costs.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

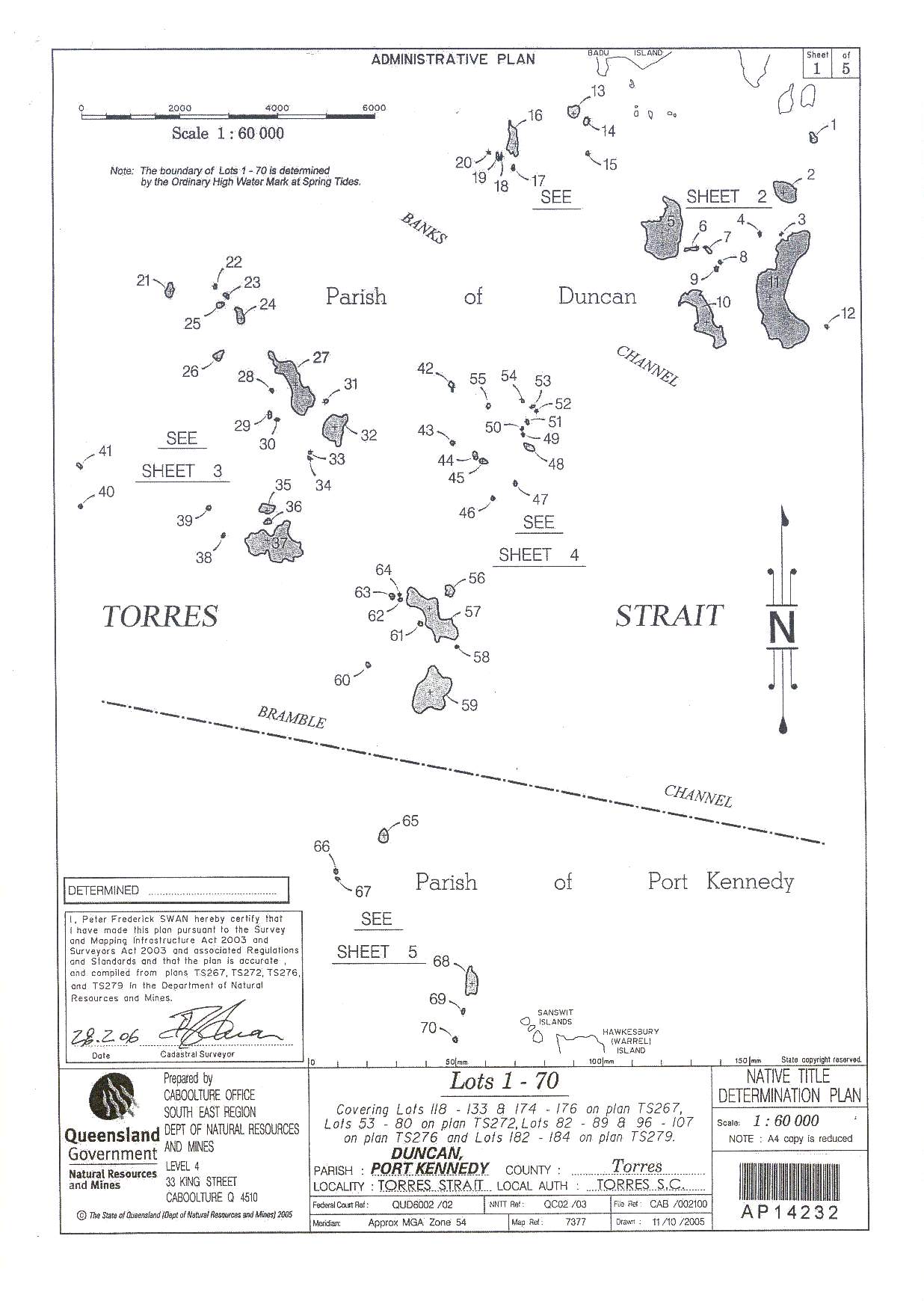

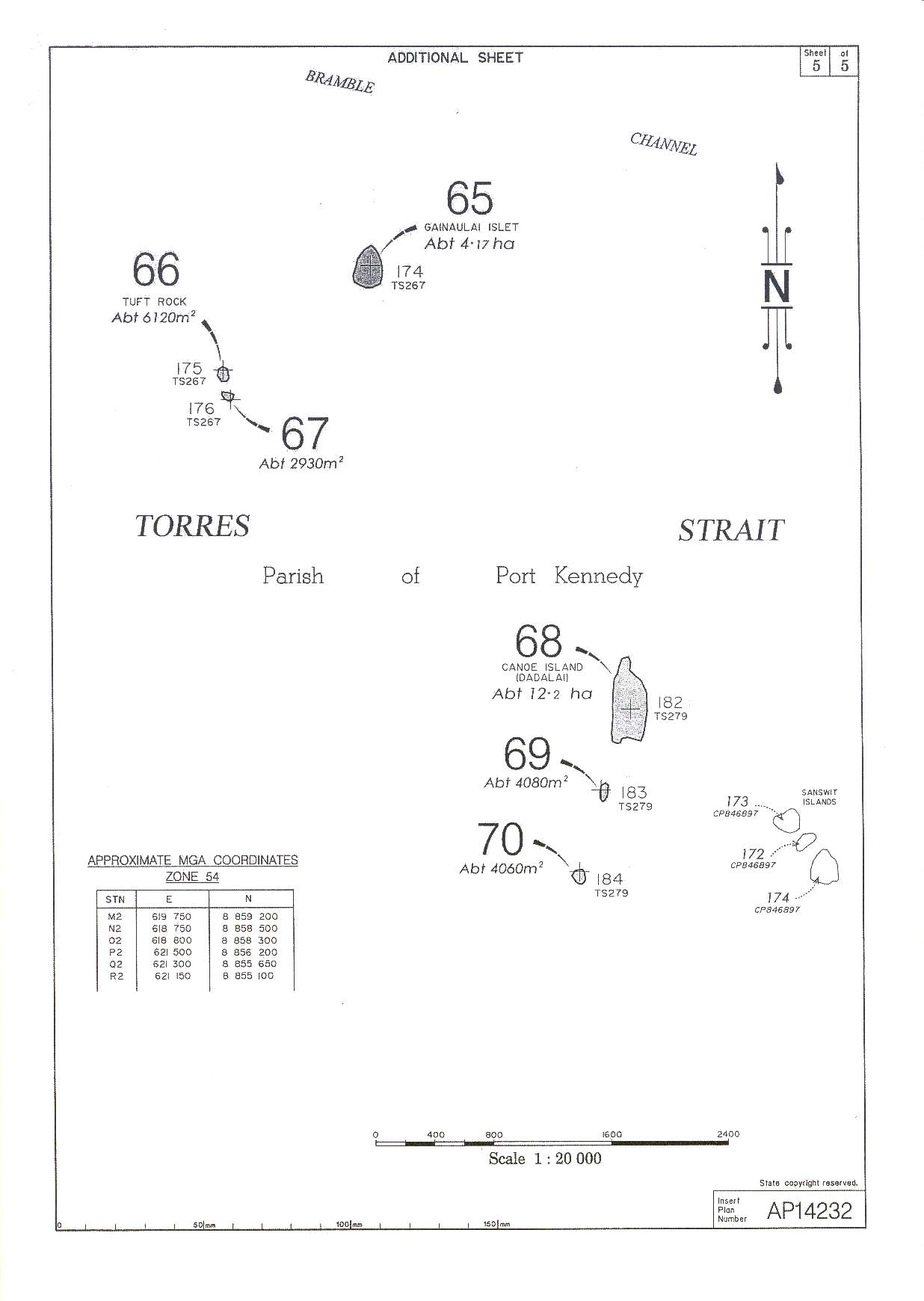

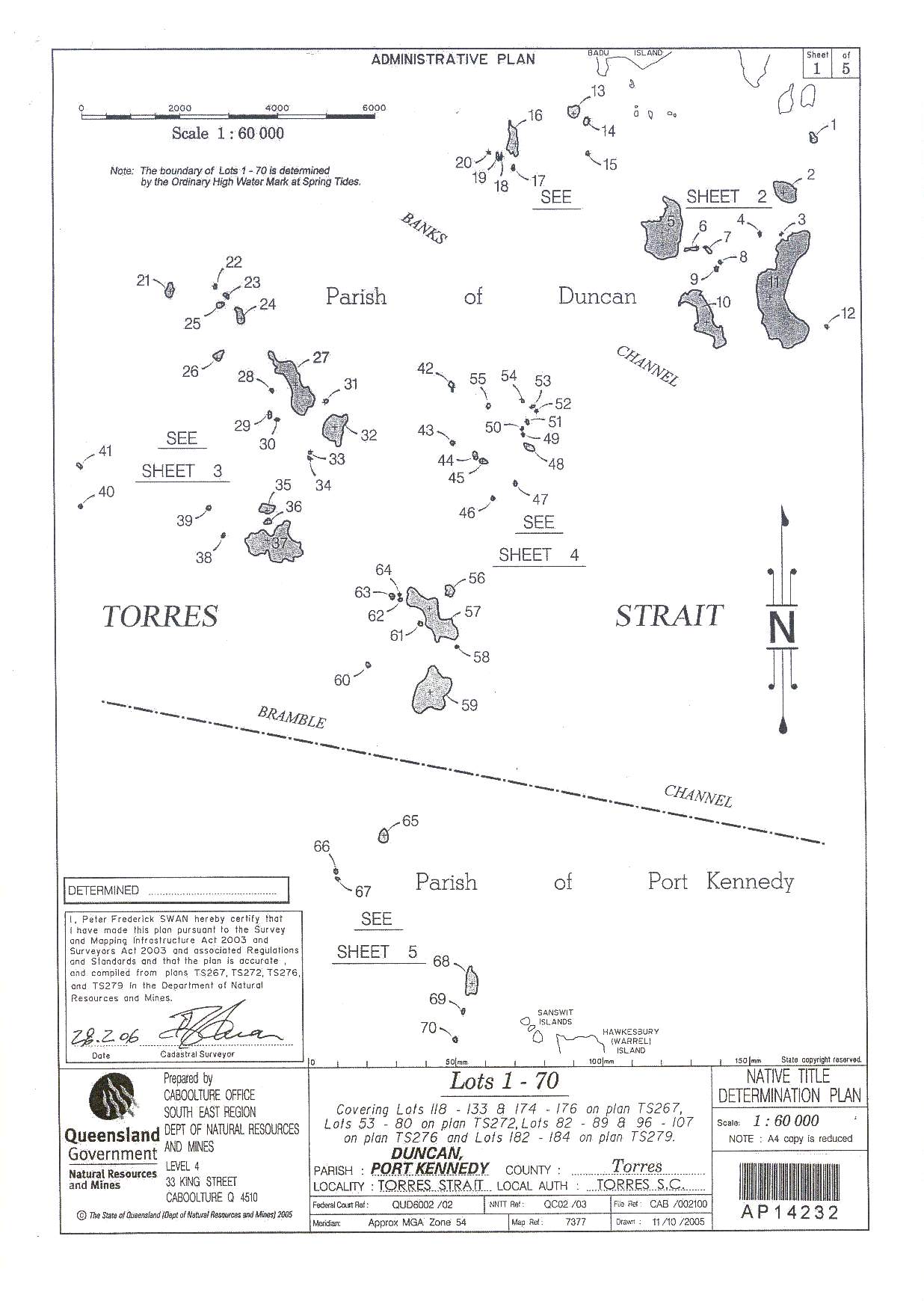

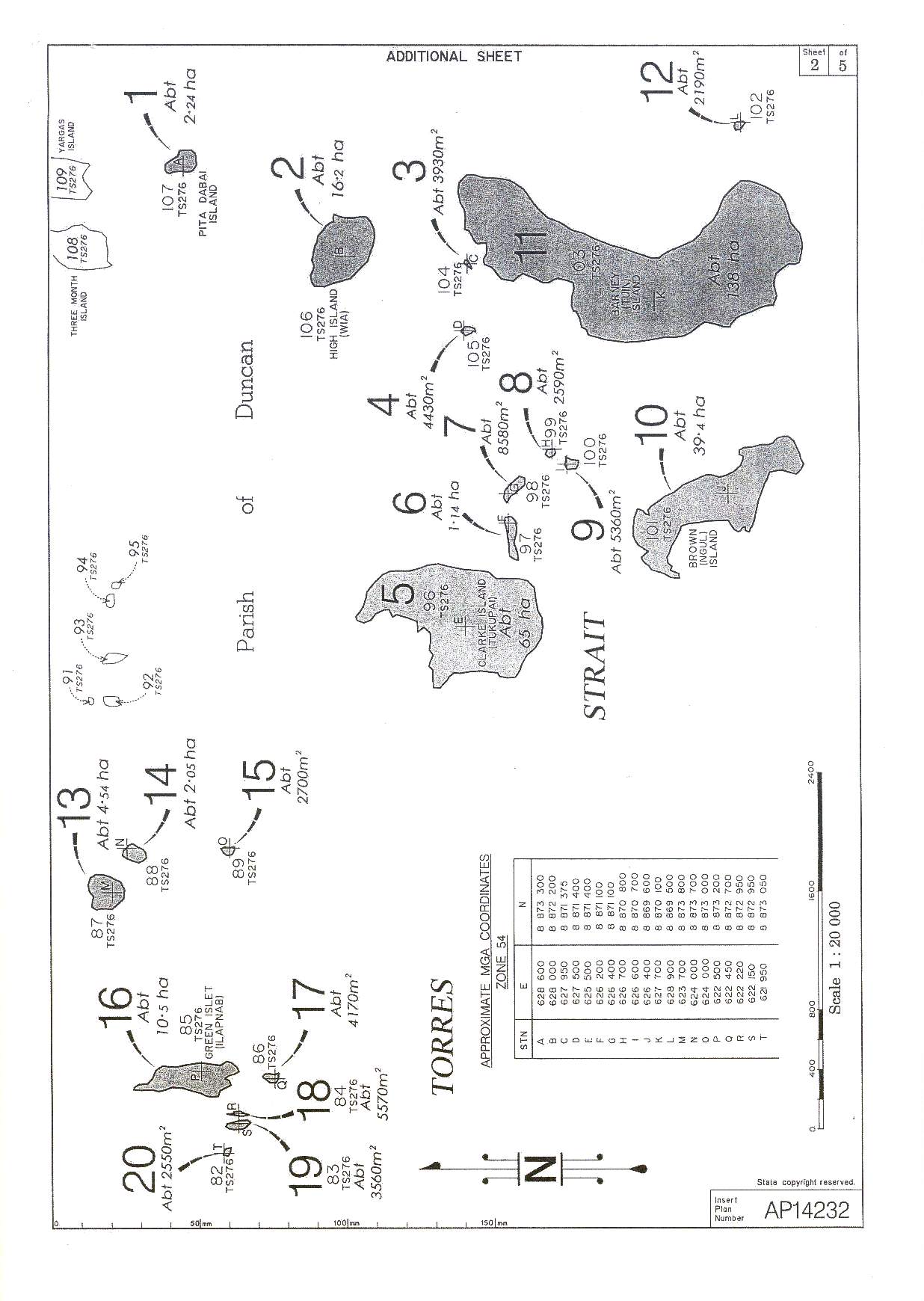

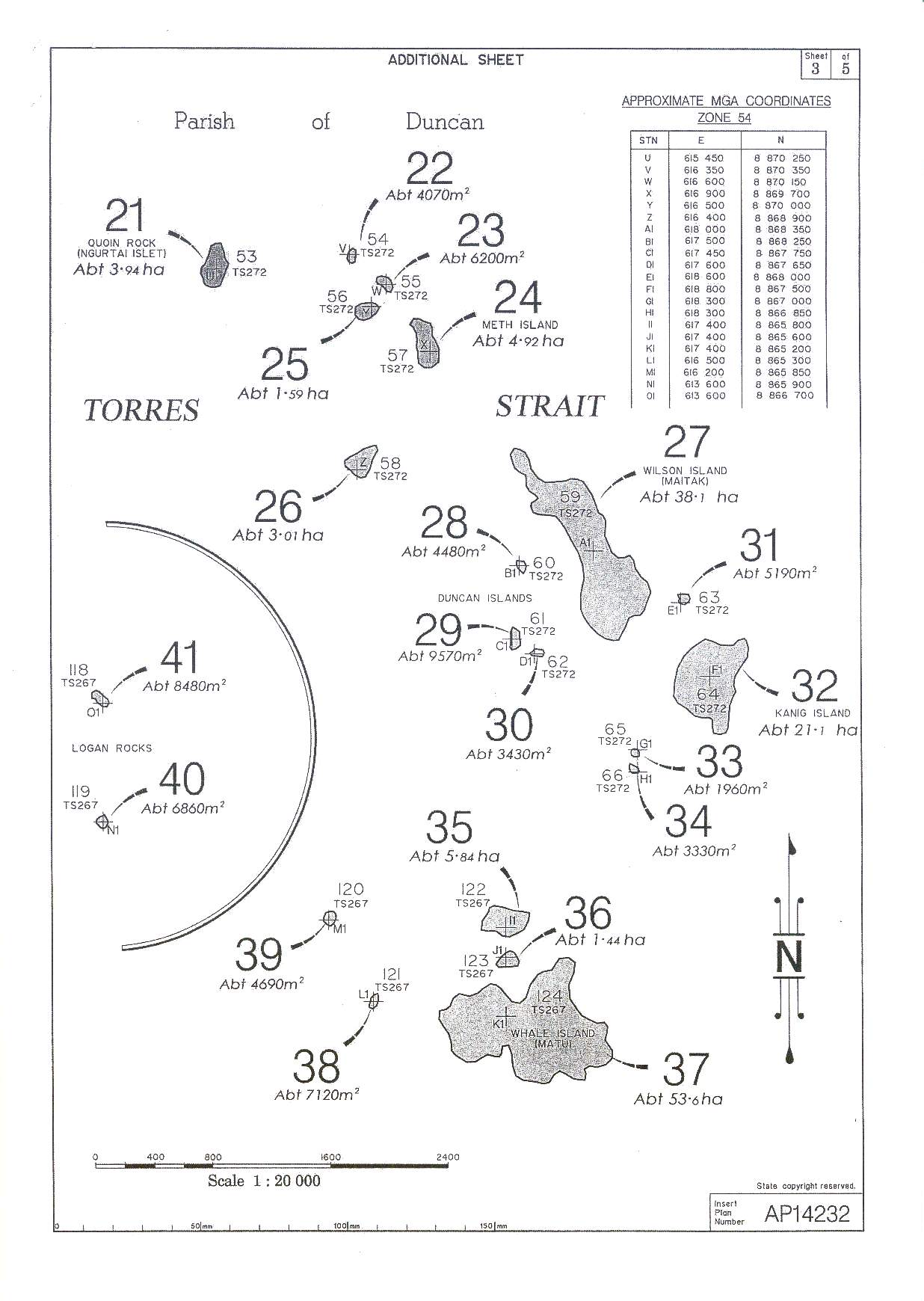

SCHEDULE 1

NATIVE TITLE DETERMINATION PLAN

SCHEDULE 2

NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS

The Badualgal and Mualgal Peoples, being:

(a) the descendants of one or more of the following apical ancestors:

Getawan, Sagul, Uria, Baira, Inor, Zimoia, Newar, Sagigi, Jawa, Wairu, Paipe, Waria, Kamui, Mabua, Laza, Gainab, Zaua, Walit, Namagoin, Alageda, Mariget, Bazi, Ugarie, Karud, Dauwadi, Gizu, Aupau, Zarzar, Samukie and Tuku, Babun, Kupad, Goba, Maga, Kanai, Kulka, Anu Namai, Maiamaia, Gai, Nakau, Iaka/Aiaka and Dadu, Waina and Jack Moa and Koia; and

(b) Torres Strait Islanders who have been adopted by the above people in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by those people.

SCHEDULE 3

OTHER INTERESTS

The nature and extent of the other interests in relation to the determination area are:

(a) the interests of the State of Queensland in the following reserves, the interests of the persons in whom they are vested and the interests of the persons entitled to access and use those reserves for the respective purposes for which they are reserved:

(i) Reserve 215 over Lot 124 on Crown Plan TS267; and

(ii) Reserve 222 over Lot 129 on Crown Plan TS267;

(iii) Reserve 221 over Lot 132 on Crown Plan TS267;

(iv) Reserve 92 over Lot 53 on Crown Plan TS272;

(v) Reserve 216 over Lot 59 on Crown Plan TS272;

(vi) Reserve 217 over Lot 64 on Crown Plan TS272;

(vii) Reserve 77 over Lot 85 on Crown Plan TS276;

(viii) Reserve 79 over Lot 96 on Crown Plan TS276;

(ix) Reserve 81 over Lot 101 on Crown Plan TS276;

(x) Reserve 80 over Lot 103 on Crown Plan TS276; and

(xi) Reserve 78 over Lot 106 on Crown Plan TS276.

(b) the interests, powers and functions of the Torres Shire Council as Local Government for Lot 124 on Crown Plan TS267; Lot 129 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 132 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 53 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 59 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 64 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 85 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 96 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 101 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 103 on Crown Plan TS276, and Lot 106 on Crown Plan TS276, Lots 118 and 119 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 120-123 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 125-128 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 130, 131 & 133 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 174 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 175 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 176 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 54-56 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 57 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 58 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 60-63 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 65-80 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 82-84, 86-89, 97-100, 102, 104, 105 and 107 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 182 on Crown Plan TS279 and Lots 183-184 on Crown Plan TS279.

(c) the interests recognised under the Treaty between Australia and the Independent State of Papua New Guinea concerning Sovereignty and Maritime Boundaries in the area between the two Countries, including the area known as Torres Strait, and Related Matters signed at Sydney on 18 December 1978 as in force at the date of this order including the interests of indigenous Papua New Guinea persons in having access to the determination area for traditional purposes; and

(d) any other interests that may be held by reason of the force or operation of the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia or the State of Queensland including the common law.

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

QUEENSLAND DISTRICT REGISTRY |

QUD 6002 OF 2002 |

|

BETWEEN: |

VICTOR NONA AND JOHN MANAS ON THEIR OWN BEHALF AND ON BEHALF OF THE BADUALGAL AND MUALGAL PEOPLE APPLICANT

|

|

AND: |

STATE OF QUEENSLAND RESPONDENT

|

|

JUDGE: |

DOWSETT J |

|

DATE: |

13 APRIL 2006 |

|

PLACE: |

BRISBANE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1. Victor Nona and John Manas have applied on their own behalf and on behalf of the Badualgal and Mualgal Peoples for a determination of native title over numerous uninhabited small islands, islets and rocks located south of Badu Island and south-west of Mua Island in the Torres Strait in the State of Queensland (the “determination area”).

BACKGROUND

2. This application was filed with the Federal Court of Australia on 1 March 2002 pursuant to s 61(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (“the Act”). The application was made over land and waters on the landward side of the High Water Mark of Lot 124 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Matu Island (also referred to as Whale Island), Lot 129 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Zurat Island (also referred to as Phipps Island), Lot 132 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Kulbai Kulbai Island (also referred to as Spencer Island), Lot 53 on Crown Plan TS272 known as Ngurtai Island (also referred to as Quoin Island), Lot 59 on Crown Plan TS272 known as Maitak Island (also referred to as Wilson Island), Lot 64 on Crown Plan TS272 known as Kanig Island (also referred to as Duncan Island), Lot 85 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Ilapnab Island (also referred to as Green Island), Lot 96 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Tukupai Island (also referred to as Clarke Island), Lot 101 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Ngul Island (also referred to as Browne Island), Lot 103 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Tuin Island (also referred to as Barney Island), Lot 106 on Crown Plan TS276 known as Wia Island (also referred to as High Island), Lots 118 and 119 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Logan Rocks, Lots 120-123 on Crown Plans TS267, Lots 125-128 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 130, 131 & 133 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 174 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Gainaulai Island, Lot 175 on Crown Plan TS267 known as Tuft Rock, Lot 176 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 54-56 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 57 on Crown Plan TS272 known as Meth Islet, Lot 58 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 60-63 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 65-80 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 82-84, 86-89, 97-100, 102, 104, 105 and 107 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 182 on Crown Plan TS279 known as Dadalai Island (also referred to as Canoe Island) and Lots 183-184 on Crown Plan TS279 and shown on the plans in Schedule 1 (“the Determination Area”). The area is further identified in the plan which is Sch 1 to these reasons.

3. The National Native Title Tribunal (“the Tribunal”) gave notice of the application pursuant to, and in accordance with, s 66 of the Act. However the State of Queensland is the only respondent. On 15 July 2003 the matter was referred to the Tribunal for mediation pursuant to s 86B of the Act.

4. On 14 February 2006 the appellants sought leave to amend the application. On 24 February 2006 leave was granted. The amendments included a change to the description of the native title claim group to include two further apical ancestors, Zaua and Alageda.

5. The parties have reached agreement upon the terms of a draft determination. That agreement confers exclusive rights on the Badualgal and Mualgal Peoples to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the land in the determination area to the exclusion of all others. The native title in relation to water is a right to:

(a) hunt and fish in or on, and gather from, the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs; and

(b) take, use and enjoy the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs.

The native title in relation to water does not confer upon the native title holders the right to possession, use or enjoyment of the water to the exclusion of others.

6. The agreement is subject to the Court being satisfied that it has the power to make orders in, or consistent with, the terms as sought by the parties and that it is appropriate to do so: s 87 of the Act.

POWER OF THE COURT

7. Pursuant to s 13 of the Act, applications for the determination of native title may be made to the Federal Court in relation to areas for which there is no approved determination of native title. Part 3 of the Act sets out the rules for making such applications to the Court. Part 4, Division 1C of the Act provides that some or all of the parties involved in native title proceedings may negotiate an agreed outcome for that application or part of that application. Section 87 of the Act empowers the Court, if it is satisfied that such an order is within its power, to make an order in, or consistent with, the terms of the parties’ written agreement without holding a full hearing.

8. Where the Court makes an order in which a determination of native title is made, s 94A of the Act requires that it set out in the order details of the matters mentioned in s 225. Section 225 of the Act provides as follows:

‘A determination of native title is a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area (the determination area) of land or waters and, if it does exist, a determination of:

(a) who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are; and

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area; and

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area; and

(d) the relationship between the rights and interests in paragraphs (b) and (c) (taking into account the effect of this Act); and

(e) to the extent that the land or waters in the determination area are not covered by a non-exclusive agricultural lease or a non-exclusive pastoral lease – whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.’

CONSIDERATION OF AGREEMENT AND DRAFT DETERMINATION

9. I have examined an anthropological report prepared by Dr Garrick Hitchcock. The report was annexed to an affidavit of David Glen Saylor filed on 9 February 2006. Dr Hitchcock is an anthropologist employed by the Torres Strait Regional Authority. The report contains the anthropological research prepared by Dr Hitchcock dealing with the connection of the Badualgal and Mualgal claim group to the determination area and is based on his own studies, reports of consultant anthropologists and discussions with elders of the native title claim group. In particular, it relies upon earlier reports of Mr Murphy and Dr Powell.

10. Dr Hitchcock’s report describes the existence of organised Torres Strait Islander occupation and possession of the determination area since before the assertion of British sovereignty over the area in 1872. The report also confirms the continuity of an identifiable society of Torres Strait Islander people having a connection with the lands and waters of the determination area in accordance with traditional laws which they acknowledge and traditional customs which they observe.

11. Dr Hitchcock records that:

‘In 1872 all islands located with 60 miles of the mainland coast were annexed to Queensland by the Crown. This incorporated Badu, Mua and the claim islands. The majority of the remaining islands in Torres Strait were subsequently annexed to Queensland in 1879 (Lumb 1990:161-163; van der Veur 1966:23-24). Annexation was directly linked to a desire to control the maritime frontier in Torres Strait, which began in the mid-1860s, and expanded dramatically with the discovery of pearlshell in 1869.

…

The annexation of the Torres Strait Islands to Queensland, and the influx of Europeans and others into the Strait to participate in the maritime industries, did not dispossess the Islanders of their home islands or their other territories (e.g. Beckett 1983:202). Indeed, the continued participation of Island men in these fisheries, in particular the pearl shell industry, enabled them to continue to visit the claim islands, and full maintain their connections with them. For example, Mua Passage, the narrow and rock-studded channel between Badu and Mua, was a favoured pearlshelling ground. In 1872, several hundred Pacific Islanders were working there (Mullins 1995:72).’

12. Dr Hitchcock continues:

‘Historian and archaeologist David Moore (1979) reconstructed the information provided to O.W. Brierly and other crew (e.g. MacGillivray 1852) of HMS Rattlesnake by Barbara Thompson, a Scottish castaway who lived with the Kaurareg people from December 1844 until her rescue in October 1849, principally on Muralag (Prince of Wales Island).

…

The smaller vessels accompanying the Rattlesnake expedition, Bramble and Asp, commenced a surveying excursion northward into the Western Islands on 21 October 1849, possibly going as far as the New Guinea coast, and returning to Evans Bay a month later. Modern charts show ‘Bramble Channel’ lying immediately south of the large east-west reef, Umiayab6, Lagaumazaor Dollar Reef, and ‘Asp Reef’, both to the south of Mua.

During the trip any Badu or Mua people in this area who saw them, hid or paddled away. The well-known Victorian scholar T.H. Huxley was with this party, but records in his diary only the sentence: ‘Went away in the Asp with Bramble and pinnace to the Badoo Islands’ (Huxley 1935:248). MacGillivray was not present, but says ‘The boats held no intercourse with any of the natives, except a small party of Kowraregas, the inhabitants of Mulgrave [Badu] and Banks [Moa] Islands having carefully avoided them’ (1852, I:307).’

Brierly says:

‘They had not seen much of the natives who appeared to regard them with fear. At one time a number of canoes were seen together near where none of the Bramble’s boats with Mr Yule was at anchor, but upon the pinnace and the Asp pulling down towards them they retreated (Moore 1979:112).’

13. According to Dr Hitchcock Mrs Thompson related details of an attack on three white sailors. After providing a report of the incident Dr Hitchcock continues:

‘The significance for this report is the demonstration of relations between Mua and Badu, at least of people with ties of kinship to one another …’

Dr Hitchcock continues at page 10 of the report:

‘The “master boats” period described by Ganter (1994) covers the years between 1899 and 1931, when most Islanders worked as divers for non-Indigenous captains. There is also the important period of the “company boats”, skippered and crewed by Torres Strait Islanders, although some continued to work on ‘master boats’ under the command of Asians.10

The ‘company boats’ were community-island based and operated, meaning that their crews were relatively homogenous, and knew their local waters intimately. The company boat system afforded the crews opportunities to incorporate traditional activities into their work practices, such as visiting the claim islands for hunting and gathering, when voyages took them into the vicinity.

…

During the Second World War, the European and ‘half-caste’ population of Thursday Island was evacuated to the Australian mainland, and the region came under military administration. Almost all able-bodied Torres Strait Islander men joined the Torres Strait Light Infantry, based on Horn Island, while their families remained on the outer islands (Fuary 1993:173). The women, children and elderly of Mua continued to occupy the island during this time, camping in the bush to avoid detection by Japanese aircraft (Powell 1998:38-39; Teske 1991:19).

…

The limited historical information that relates to the claim group demonstrates that at contact, the Badu-Mabuiag alliance was ascendant, compared to the Mua-Kaurareg grouping, with whom they often fought. However, simple ‘us-them’ categories do not accurately reflect the complex, nature of social interactions described by some European observers, and the oral history of the claimants, with oscillation between friendship and headhunting. For example, it is clear that trade and intermarriage were common between both groups, as evidenced by the observations of Barbara Thomson, and the genealogical records compiled by the members of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Torres Straits. With regard to the people of Badu and Mua, it is recorded that they had generally good relations with the Mualgal clans living on the eastern side of Mua, with marriages occurring between the groups (Haddon 1935:63-64)

The oral traditions of the claimants state that both groups have enjoyed rights and interests in the claim area, since ‘beforetime’ (i.e. since time immemorial, and before the annexation of the area by the British Crown). Badulgal and Mualgal elders also assert that throughout the period after annexation, the Badu and Mua people continued to visit the claimed islands, and that their participation in the marine industries and the Second World War in no way impeded or extinguished the exercise of their traditional rights and interests in the islands under claim (Oza Bosen, pers. Comm., 5 April 2005; Fr John Manas, pers, comm., 1 April 2005; Joshua Nawie, pers. Comm., 23 April 2005; Walter Nona, pers. Comm. 21 April 2005).

Just as they did before contact with Europeans and the assertion of British sovereignty, the Badulgal and Mualgal had and continue to have a rich tradition of ownership, visitation, use, and toponomy (a system of place names) in relation to the claim area, which demonstrates that the islands were indeed part of their territories. 11 Each of these points will be elaborated upon below, to substantiate the Applicant’s claim. It will be shown that the shared rights and interests of the Badualgal and Mualgal are drawn from a common heritage of Western Torres Strait Islander laws and customs.’

14. Dr Hitchcock continues at page 12 of the report:

‘The Badulgal are the descendants of the Indigenous inhabitants of Badu, and the Mualgal are the descendants of the Indigenous inhabitants of Mua.

…

Recruitment to both groups occurs primarily by birth, or by traditional Torres Strait Islander adoption. Whether natural born or adopted, all such children automatically acquire a community identity, which in turn confers native title rights and interests in the community’s traditional estate (for further information, see Murphy 2000:16-17; Powell 1998:44-48,51-55).

The State of Queensland has previously assessed the connection report by Murphy (2000) and Powell (1998) in support of the original Badu and Mua native title claims. The State found that these reports satisfactorily furnished evidenced identifying these groups as the traditional owners of Badu and Mua respectively, prior to the establishment of British sovereignty, and consented to determinations of native title over their respective claim areas.

…

A number of anthropologists, archaeologists and others have since worked among the Badulgal and Mualgal. Ethnomusicologist Dr Wolfgang Laade (1962-1964) visited Torres Strait in the early 1960s and recorded a number of stories from Badu Islanders. Dr Jeremy Beckett worked on Badu at roughly the same time (e.g. Beckett 1963, 1987). Folklorist Margaret Lawrie visited Badu and Mua in the 1960s and collected a number of myths, which appear in her well-known books (Lawrie 1970, 1972). Booklets written by Teske (1986, 1991) for north Queensland schools also contain information on the history and cultural heritage of the Mualgal. A team of archaeologists from Monash university have been active on both Badu and Mua for several years, working with these communities to document and manage their cultural heritage (e.g. Brady et al. 2003, 2004; David et al. 2004a, 2004b). the author has read each of these works as part of the literature review for this connection report.

…

On the basis of linguistic and cultural similarities, a history of interaction, and relations to the claim area, the claim group is a single group. In relation to their respective community islands they are two separate communities or societies, with many similarities, a history of close interaction, and which, along with Mabuaig, Boigu, Dauan and Saibai, form part of a wider system again, that of Western Torres Strait.

…

Indigenous oral testimony asserts, and written evidence supports the view, that there is not, and has never been, a self-assigned name to describe the native title group as it relates to the islands under claim. Rather, in relation to the claim area the claim group (that is, the Badulgal and Mualgal) defines itself with reference to rights and interests in the islands, based as thy are on commonly acknowledged and observed traditions and customs. These similarities are a reflection of the abovementioned linguistic and cultural affinities.

…

The contemporary existence of seemingly self-contained, autonomous Island communities, each with their own Island council (since 1936) and now in the native title era, their respective Prescribed Body Corporate, can obfuscate the traditional relationships that have existed, and continue to exist, between these sociocultural groups. At a higher level of inclusiveness, and one that is directly linked to commonly observed laws and customs, the two communities fall into two dialect groups, which were arbitrarily identified in the fifth volume of the Cambridge Reports as the ‘Gumulaig’ (comprising the people of Mabuiag and Badu) and the ‘Kauralaig’ (comprising the people of Mua, and the people of Muralug in southwest Torres Strait).’

15. Dr Hitchcock continues at page 17 of the report:

‘Badulgal and Mualgal tradition and custom, from which their native title rights and interests derive, share much in common with other Western Torres Strait Islander groups, and indeed, all Torres Strait Island societies. Many aspects of the relationship between the communities forming these groups continue today, and members of the claim group continue to acknowledge the closeness between the communities forming each larger group (e.g. dialect group), and their wider identification as Western Torres Strait Islanders.

Badulgal and Mualgal also identify as a member of their Torres Strait ‘cluster group’ – in this case the Western (or Central Western) Islands, comprising Mua, Badu and Mabuiag. Following pacification and missionization in the early 1870s, relations between Mualgal and Badu (and Mabuiag) people have been strong and deeply held. Intermarriage has also continued to take place; for example, a number of Badu people have married into the Mualgal community and reside at Kubin. The cluster grouping has an important role in local social and political activity in the region. Cooperation and sharing between the islands, and participation in each other’s ceremonies are part of normal, everyday life. Sporting teams and events, lobby groups, and political representation often occurs along cluster groups lines. The Western cluster group is not merely a proximal label, but reflects ongoing relationships and customary practice, and demonstrates the continuity of these more inclusive levels of social identity and organisation.

…

The above discussion is intended to clarify the nature of the claimant group. Simply put, the claim is made by two present-day communities – Badu and Mua – who acknowledge and observe traditional laws and customs, and exercise and enjoy common rights and interests in the claim area. With respect to the claim area, which is held as common ground, and their observable commonalities as Western Torres Strait Islanders (in terms of shared language, kinship systems and customs, alliance and intermarriage), they together form a native title holding group.

…

The acknowledgement by Badulgal and Mualgal of common rights and interests in the claimed islands, exclusive of all others, reflects this past and contemporary Islander custom, grounded in normative rules (i.e. traditional laws and customs). It reflects the assertion by the claimants that these islands are part of the traditional territory or estate of both communities, with members of both groups offering oral testimony as evidence of intergenerational rights and interests held by them since before annexation (e.g. Horace Baira, pers. Comm., 21 April 2005; Oza Bosen, pers. Comm., 5 April 2005; Fr John Manas, pers. Comm., 1 April 2005; Walter Nona, pers. Comm., 21 April 2005; Joshua Nawie, pers. Comm., 23April 2005).

…’

16. Dr Hitchcock continues at page 20 of the report:

‘The State of Queensland has previously been furnished extensive genealogical data relating to the claimant group, in the form of genealogies (‘family trees’) which accompanied the connection reports written for the Badu and Mua native title claims (Murphy 2000; Powell 1998).

The State accepted that these genealogies demonstrate that the Badulgal and Mualgal of today are the direct descendants of the traditional owners of Badu and Mua prior to the establishment of British sovereignty, have maintained continuity of connection with their estates, and continue to possess and exercise native title rights and interests over them. The Mua claim was the subject of a consent determination by the Federal court of Australia on 12 February 1999, while the Badu claim determination too place on 14 December 2004.

…

During the author’s research in 2005, interviews were conducted with various members of the claim group, in particular Badulgal elders Walter Nona and Horace Baira, and Mualgal elders Oza Bosen, Fr John Manas and Joshua Nawie. They explained that for as long as anyone could remember, the claim islands have formed part of Badu’s and Mua’s traditional estate, that is, it is common ground for both groups. From this author’s research, the existing ethnographic and historical literature, and the arguments presented in this report, it is reasonable to infer that the claim group has used and enjoyed the claim area since before the assertion of sovereignty by the Crown, and to state that its members continue to use and enjoy it today. This is supported by the fact that both groups assert that they have maintained physical, cultural and spiritual connection with the claim area since before 1872, and continue to do so.

…

The claimants identify as the Badulgal or Mualgal. This identity is not only a function of descent from their respective Badulgal and Mualgal forebears, it is fundamentally related to their connection to their home island, and the surrounding land and sea territories that make up each group’s estate. Membership of either community confers rights and interests in the claim islands, which have been handed down from ancestors alive at and before 1872, through succeeding generations to the existing claimants. Al the claim areas, their contiguous reefs, and the surrounding sea country are intimately known. The Badulgal and Mualgal have the same Western Torres Strait language names for the islands, and have associated stories and historical episodes pertaining to them.

Since 1872, these peoples continue to maintain and visit the claim area, even in the face of severe environmental and economic difficulties, including the early and disruptive impacts of colonialism, missionary and government directions to settle in a single village, and the Second World War. The claim islands are surrounded by lucrative pearling grounds, and members of the Badulgal and Mualgal were able to regularly visit the islands as part of their work in the maritime industries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (known in Torres Strait as ‘lugger days’), ensuring their continued connection to these lands after annexation.

In more recent decades, many Torres Strait Islander families have moved away from their home islands to elsewhere in Torres Strait or to the Australian mainland. However, their knowledge of their rights in land has been retained, and is activated when they return to their community island for visits. All members of the Badu and Mua communities, wherever they reside, continue to assert their ownership of the lands and resources within their traditional estate, including the claim area, and many have visited the islands for subsistence and cultural purposes.

…

… physical connection is demonstrated by members of the claim group today visiting the shared islands to use them as bases for exploiting particular marine resources in their seasons (e.g. pearl shells, crayfish, particular fish species) and as weekend camps.

The native title claimants aver that they and their ancestors have continued to visit the islands periodically, since before the assertion of British sovereignty, primarily for subsistence purposes including dugong and turtle hunting, and voyages for the collection of turtles, turtle eggs, and other food resources (see discussion below). The Cambridge Reports noted that Torres Strait Islanders visited uninhabited islands for such purposes:

There are in Torres Straits numerous low islets without a permanent

Population, as well as sand-banks raised just above the surface of the water, and mainly about the end of October and during November the

natives make expeditions to them to hunt for turtles’ eggs (Haddon

1912:161).

Given that the people of Torres Strait were expert seafarers, and the proximity of most of the claim area to Badu and Mua, it is reasonable to infer, in the absence of detailed historical or ethnographic accounts, that visits to the islands were in fact made in the period prior to annexation. This is supported by the oral testimony of elders within the community.

The native title claimants have never been dispossessed of their home islands, and have a documented history of continuous connection to them that predates 1872 (Murphy 2000; Powell 1998:50). This fact has been recognised by the State of Queensland and the Federal Court of Australia, with a determination of native title over Moa in 1999, and Badu in 2004. the claimants have the same history of connection to the smaller, offshore islands which lie to the south of Badu and southwest of Mua, which the have recognised as common ground since time immemorial, and are considered to be an integral part of Badu and Mua, and hence a fundamental component of their respective identities.

…

Continuity of connection has been maintained by the native title claim group since the establishment of British sovereignty over the islands in 1872. In the physical sense, it was maintained through continuous visitation to the islands. These were made possible by traditional, double-outrigger canoes (gul) up to around 1900, which were later superseded by luggers and wooden dinghies, followed, since the 1960s, by aluminium dinghies.

…

The body of laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the native title claim group is traditional, in that it has been passed from generation to generation within the group, in the form of verbal instruction and common practice. Powell (1998:57) notes that ‘an unbroken physical connection to their island has facilitated the continuation of many Mualgal cultural traditions’. Similarly, unbroken physical connection to the claim area has resulted in the Mualgal being able to continue to exercise native title rights and interest there. The same pertains for the Badulgal, who were never dispossessed of their home island, and who have continued to visit the claim area since before annexation, up until today.’

17. In summary Dr Hitchcock writes:

‘The present claim is over a number of offshore islands located south of Badu and southwest of Mua, in which both groups, and both groups alone, possess exclusive native title rights and interests, in accordance with Western Torres Strait Islander traditional law and custom. These rights and interests are recognised by all other Torres Strait Islanders. The rocks, islets and islands making up the claim area are either Unallocated State Lands or Reserves for the use of the Aboriginal Inhabitants of the State, and the State of Queensland is the only party to the claim. The Badualgal and Mualgal have never been dispossessed of the claim are, and continue to exercise their native title rights and interests in the claimed islands in accordance with a normative system of traditional law and custom, that predates the establishment of British sovereignty in 1872.

…

It is submitted that this report provides relevant historical facts, and expert opinion based on historical facts, sufficient to conclusively identify the native title claimants as the descendants of the traditional owners exercising native title rights and interests over the islands under claim prior to the establishment of British sovereignty in 1872. Furthermore, this information and evidence also demonstrates that the native title claimants have maintained a continuity of connection with the claim area, since before 1872 and up until today. Finally, this body of information and evidence also identifies the nature of the native title claimants’ rights and interests, and identifies these as being derived from their traditional laws and customs; a normative system of Torres Strait custom that predates annexation, has been substantially maintained, and is extant today, though somewhat modified.’

18. I infer that the State of Queensland has taken such advice as it considers appropriate and, in light of such advice, has chosen to seek this consent determination.

19. The evidence demonstrates that the claim group members are descendents of people who have lived on their respective islands for a very long time. They were, and are, seafarers who would almost certainly have visited neighbouring islands, islets and rocks, searching for food. It is probable that over the centuries, they have come to regard the determination area as being theirs. The anthropological evidence supports this view, but it is really based on observations of human nature. This connection pre-dates the first assertion of British sovereignty.

20. Based on this material I am satisfied that native title exists in relation to the lands and waters identified in Sch 1 to these reasons and, pursuant to s 225, find that:

· the persons holding the communal or group rights comprising the native title are as set out in Sch 2 to these reasons;

· the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area are:

· to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of all land in the determination area to the exclusion of all others; and

· in relation to water the right to:

(a) hunt and fish in or on, and gather from, the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs; and

(b) take, use and enjoy the water for the purpose of satisfying personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs,

provided that such right to water does not confer any right to possession, use or enjoyment thereof to the exclusion of others.

· such native title is subject to, and exercisable in accordance with:

· the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland including the common law;

· traditional laws acknowledged, and traditional customs observed, by the native title holders; and

· other interests in relation to the determination area as set out in Sch 3 to these reasons, the relationship between the native title and those other interests being that:

· such other interests continue to have effect, and the rights conferred by, or held thereunder, may be exercised notwithstanding the existence of the native title; and

· such other interests and any activity done in exercise of the rights conferred thereby, or held thereunder, prevail over the native title and any exercise of the native title.

21. The orders will contain the following definition clause:

‘If a word or expression is not defined in this order, but is defined in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), then it has the meaning given to it in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). In addition to the other words defined in this order:

(a) “high water mark” has the meaning given to it in the Land Act 1994 (Qld);

(b) “laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland” means the common law and the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Queensland;

(c) “local government” has the meaning given to it in the Local Government Act 1993 (Qld); and

(d) “water” has the meaning given to it in the Water Act 2000 (Qld).’

22. I order that the native title be held in trust by the Badu Ar Mua Migi Lacal (Torres Strait Islanders) Corporation for the benefit of the native title holders.

23. Each party to the proceedings is to bear its own costs.

24. These orders are consistent with the terms agreed by the parties. They recognise that the Badulgal Peoples, as the common law holders of native title in the determination area, are entitled to the exclusive use and enjoyment of the land above the high water mark in accordance with their traditional laws and customs and to the non-exclusive use and enjoyment of water above the high water mark.

SCHEDULE 1

NATIVE TITLE DETERMINATION PLAN

SCHEDULE 2

NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS

The Badualgal and Mualgal Peoples, being:

(a) the descendants of one or more of the following apical ancestors:

Getawan, Sagul, Uria, Baira, Inor, Zimoia, Newar, Sagigi, Jawa, Wairu, Paipe, Waria, Kamui, Mabua, Laza, Gainab, Zaua, Walit, Namagoin, Alageda, Mariget, Bazi, Ugarie, Karud, Dauwadi, Gizu, Aupau, Zarzar, Samukie and Tuku, Babun, Kupad, Goba, Maga, Kanai, Kulka, Anu Namai, Maiamaia, Gai, Nakau, Iaka/Aiaka and Dadu, Waina and Jack Moa and Koia; and

(b) Torres Strait Islanders who have been adopted by the above people in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by those people.

SCHEDULE 3

OTHER INTERESTS

The nature and extent of the other interests in relation to the determination area are:

(a) the interests of the State of Queensland in the following reserves, the interests of the persons in whom they are vested and the interests of the persons entitled to access and use those reserves for the respective purposes for which they are reserved:

(i) Reserve 215 over Lot 124 on Crown Plan TS267; and

(ii) Reserve 222 over Lot 129 on Crown Plan TS267;

(iii) Reserve 221 over Lot 132 on Crown Plan TS267;

(iv) Reserve 92 over Lot 53 on Crown Plan TS272;

(v) Reserve 216 over Lot 59 on Crown Plan TS272;

(vi) Reserve 217 over Lot 64 on Crown Plan TS272;

(vii) Reserve 77 over Lot 85 on Crown Plan TS276;

(viii) Reserve 79 over Lot 96 on Crown Plan TS276;

(ix) Reserve 81 over Lot 101 on Crown Plan TS276;

(x) Reserve 80 over Lot 103 on Crown Plan TS276; and

(xi) Reserve 78 over Lot 106 on Crown Plan TS276.

(b) the interests, powers and functions of the Torres Shire Council as Local Government for Lot 124 on Crown Plan TS267; Lot 129 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 132 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 53 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 59 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 64 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 85 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 96 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 101 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 103 on Crown Plan TS276, and Lot 106 on Crown Plan TS276, Lots 118 and 119 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 120-123 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 125-128 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 130, 131 & 133 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 174 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 175 on Crown Plan TS267, Lot 176 on Crown Plan TS267, Lots 54-56 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 57 on Crown Plan TS272, Lot 58 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 60-63 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 65-80 on Crown Plan TS272, Lots 82-84, 86-89, 97-100, 102, 104, 105 and 107 on Crown Plan TS276, Lot 182 on Crown Plan TS279 and Lots 183-184 on Crown Plan TS279.

(c) the interests recognised under the Treaty between Australia and the Independent State of Papua New Guinea concerning Sovereignty and Maritime Boundaries in the area between the two Countries, including the area known as Torres Strait, and Related Matters signed at Sydney on 18 December 1978 as in force at the date of this order including the interests of indigenous Papua New Guinea persons in having access to the determination area for traditional purposes; and

(d) any other interests that may be held by reason of the force or operation of the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia or the State of Queensland including the common law.

|

I certify that the preceding twenty-four (24) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Dowsett. |

Associate:

Dated: 13 April 2006

|

Solicitor for the Applicant: |

Mr D Saylor (Torres Strait Regional Authority) |

|

Solicitor for the Respondent: |

Ms A Cope (Crown Solicitor) |

|

Date of Hearing: |

13 April 2006 |

|

Date of Judgment: |

13 April 2006 |