FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Gawirrin Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (No 2) [2005] FCA 1425

NATIVE TITLE – determination of native title – form of determination – issues as to extent of native title rights in inter-tidal zone – whether public right to fish extends into tidal waters that are not navigable

JUDGES – when judge unavailable to make orders after delivering reasons for judgment

Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)

Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth)

Aboriginal Councils and Associations Act 1976 (Cth)

Native Title (Prescribed Bodies Corporate) Regulations 1999 (Cth)

Customs Act 1901 (Cth)

Fisheries Act 1988 (NT)

Aboriginal Land Act 1978 (NT)

Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1989 (NT)

Aboriginal Land Act 1978 (NT)

Water Act (NT)

Fisheries Act 1988 (NT)

Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1989 (NT)

Brennan v Brennan (1958) 89 CLR 129 applied

R v Toohey; Ex parte Meneling Station (1982) 158 CLR 327 cited

Yorta Yorta v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 followed

Northern Land Council v Olney (1992) 34 FCR 470 cited

Pareroultja v Tickner (1993) 42 FCR 32 cited

Commonwealth v Yarmirr (1999) 101 FCR 171 followed

Harper v Minister of Sea Fisheries (1989) 168 CLR 314 considered

New South Wales v Commonwealth (1975) 135 CLR 337 considered

Anderson v Alnwick District Council [1993] 1 WLR 1156 considered

Minister for Primary Industry and Energy v Davey (1993) 47 FCR 151 considered

Attorney-General for British Columbia v Attorney-General for Canada [1914] AC 153 considered

Yanner v Eaton (1999) 201 CLR 351 followed

Passi v State of Queensland [2001] FCA 217 cited

Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 followed

Attorney-General (NT) v Ward (2003) 134 FCR 16 applied

De Rose v South Australia (2003) 133 FCR 325 cited

Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 followed

De Rose v State of South Australia (No 2) [2005] FCAFC 110 cited

Attorney-General (NT) v Ward (2003) 134 FCR 16 cited

Wandarang People v Northern Territory (2000) 104 FCR 380 cited

Erubam Le v Queensland [2003] FCAFC 227 cited

GAWIRRIN GUMANA, DJAMBAWA MARAWILI, MARRIRRA MARAWILI, NUWANDJALI MARAWILI, DAYMAMBI MUNUNGGURR, MANMAN WIRRPANDA AND DHUKAL WIRRPANDA (ON BEHALF OF THE YARRWIDI GUMATJ, MANGGALILI, GUMANA DHALWANGU, WUNUNGMURRA (GURRUMURU) DHALWANGU, DHUPUDITJ DHALWANGU, MUNYUKU, YITHUWA MADARRPA, GUPA DJAPU, DHUDI DJAPU, MARRAKULU 1, MARRAKULU 2, WANAWALAKUYMIRR MARRAKULU, DJARRWARK 1, DJARRWARK 2 AND NURRURAWU DHAPUYNGU (DHURILI/Durila) GROUPS) v NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA and COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA and NORTHERN TERRITORY SEAFOOD COUNCIL INC and ARNHEM LAND ABORIGINAL LAND TRUST and TELSTRA CORPORATION LTD and AMATEUR FISHERMENS’ ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY

NTD 6035 of 2002

ARNHEM LAND ABORIGINAL LAND TRUST and NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL and GAWIRRIN GUMANA, DJAMBAWA MARAWILI, MARRIRRA MARAWILI, NUWANDJALI MARAWILI, DAYMAMBI MUNUNGGURR, MANMAN WIRRPANDA AND DHUKAL WIRRPANDA (ON BEHALF OF THE YARRWIDI GUMATJ, MANGGALILI, GUMANA DHALWANGU, WUNUNGMURRA (GURRUMURU) DHALWANGU, DHUPUDIJ DHALWANGU, MUNYUKU, YITHUWA MADARRPA, GUPA DJAPU, DHUDI DJAPU, MARRAKULU, DJARRWARK 1, DJARRWARK 2, AND NURRURAWU DHAPUUYNGU (DHURILI/DURILA) GROUPS) v NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA and DIRECTOR OF FISHERIES (NT) and COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA and AMATEUR FISHERMENS’ ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY

NTD 12 of 2003

MANSFIELD J

11 OCTOBER 2005

YILPARA

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

NORTHERN TERRITORY DISTRICT REGISTRY |

NTD 6035 OF 2002 |

|

BETWEEN: |

GAWIRRIN GUMANA, DJAMBAWA MARAWILI, MARRIRRA MARAWILI, NUWANDJALI MARAWILI, DAYMAMBI MUNUNGGURR, MANMAN WIRRPANDA AND DHUKAL WIRRPANDA (ON BEHALF OF THE YARRWIDI GUMATJ, MANGGALILI, GUMANA DHALWANGU, WUNUNGMURRA (GURRUMURU) DHALWANGU, DHUPUDITJ DHALWANGU, MUNYUKU, YITHUWA MADARRPA, GUPA DJAPU, DHUDI DJAPU, MARRAKULU 1, MARRAKULU 2, WANAWALAKUYMIRR MARRAKULU, DJARRWARK 1, DJARRWARK 2, AND NURRURAWU DHAPUYNGU (DHURILI/DURILA) GROUPS APPLICANTS

|

|

AND: |

NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA FIRST RESPONDENT

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA SECOND RESPONDENT

NORTHERN TERRITORY SEAFOOD COUNCIL INC THIRD RESPONDENT

ARNHEM LAND ABORIGINAL LAND TRUST FOURTH RESPONDENT

TELSTRA CORPORATION LTD FIFTH RESPONDENT

AMATEUR FISHERMENS’ ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY INTERVENOR

|

|

MANSFIELD J | |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

11 OCTOBER 2005 |

|

WHERE MADE: |

YILPARA |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in the terms of the determination set out below.

2. The native title is not to be held on trust.

3. An Aboriginal corporation whose name is to be provided within 12 months, or such other time as the Court may allow, is to:

(a) be the prescribed body corporate for the purposes of subs 57(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (‘the Act);

(b) perform the functions outlined in subs 57(3) of the Act after becoming a registered native title body corporate.

4. Each party and the intervenor bear their or its own costs of the proceeding.

THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

The Determination Area

1.1. Native title exists in the areas of land and waters depicted on the map comprising Schedule B and described in Schedule A hereto (‘the determination area’), the determination area being made up of:

(a) the areas described in item 1(a) of Schedule A (‘the land and inland waters’);

(b) the areas described in item 1(b) and (c) of Schedule A (‘the inter-tidal zone’); and

(c) the areas described in item 1(d) of Schedule A (‘the outer waters’).

1.2. In the event of inconsistency between Schedules A and B, Schedule A prevails.

1.3 In this determination, unless the contrary intention appears:

(1) ‘land’ and ‘waters’ bear the meanings given by s.253 of the Act;

(2) ‘low water mark’ and ‘high water mark’ refer to the mean low water mark and the mean high water mark;

(3) ‘resources’ does not include minerals, petroleum, natural gas and any other natural resource to the extent to which native title has been extinguished or affected pursuant to valid laws of the Northern Territory and Commonwealth of Australia.

The native title holders

2. The whole of the determination area comprises parts of the estates of the eight Yirritja Moiety clans and the seven Dhuwa Moiety clans known as:

(a) Yirritja moiety clans: (1) Yarrwidi Gumatj, (2) Manggalili, (3) Gumana Dhalwangu, (4) Wunungmurra (Gurrumuru) Dhalwangu, (5) Dhupuditj Dhalwangu, (6) Munyuku, (7) Yithuwa Madarrpa, (8) Manatja.

(b) Dhuwa moiety clans: (1) Gupa Djapu, (2) Dhudi Djapu, (3) Marrakulu 1, (4) Marrakulu 2, (5) Djarrwark 1, (6) Djarrwark 2, (7) Galpu.

3. The persons who hold the communal, group and individual rights comprising the native title are the Aboriginal persons who:

(a) are members of one of the fifteen clans referred to at 2 by virtue of descent through his or her father’s father or by virtue of adoption into the clan;

(b) are the guardians of or successors to the rights of a clan and its members in relation to a clan’s estate;

(c) have kinship connections to one or more of those clans by virtue of the fact that his or her mother (ngandi) or mother's mother (mari) is or was a member of such clan;

(d) are spouses of persons referred to in sub-par (a); or

(e) have non-descent based connections to part or parts of the determination area by virtue of:

(1) his or her place of spirit conception being in the determination area;

(2) being a member of a clan (other than one of the fifteen clans referred to at 2), which clan has one or more estate areas adjacent to one or more of the estate areas that comprise the determination area and that person has relations with one or more of the fifteen clans and their estates through kinship or marriage; or

(3) related spiritual (wangarr) affiliations or ritual authority in or related to the determination area;

(4) being a member of one of the clans known as Ngaymil, Datiwuy, Guyula Djambarrpuyngu and Marrangu who are at times entitled to access places in the determination area associated with ceremony and known as ringgitj places.

Native Title Rights in Land and Inland Waters

4. In relation to the land and inland waters, the native title rights and interests that are possessed under the traditional laws and customs are, subject to the traditional laws and customs that govern the exercise of the native title rights and interests by the native title holders, possession, occupation, use and enjoyment to the exclusion of all others.

Other Interests in Land and Inland Waters

5. The other interests in relation to the land and inland waters are:

(a) the interests of the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust under the two deeds of grant dated 30 May 1980 made under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth);

(b) the rights of a holder of a permit granted under Part II of Aboriginal Land Act 1978 (NT) and the rights of a person to otherwise enter or remain on or use the area permitted by ss.69-71 of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth), Part II of the Aboriginal Land Act 1978 (NT) and Parts IV and V of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1989 (NT);

(c) the rights and interests of Telstra Corporation Limited:

(1) as the owner and operator of telecommunications facilities installed within the determination area, being, the Warralwuy Radio Site situated on Northern Territory Portion 5748(A), the Durabudboi Radio Site situated on Northern Territory Portion 5752(A), and certain customer radio terminals and as the holder of a carrier licence under the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth), including the right for its employees, agents or contractors to have access to the telecommunications facilities for the purposes of maintaining and operating the telecommunications facilities; and

(2) pursuant to the lease to Telstra Corporation Limited from the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust in relation to NT Portion 5748(A), registered 31 May 2000, in respect of the Warralwuy Radio Site.

(d) rights of access by an employee, servant, agent or instrumentality of the Northern Territory, Commonwealth or other statutory authority as required in the performance of his or her statutory duties;

(e) the interests of persons to whom valid and validated rights and interests have been:

(1) granted by the Crown pursuant to statute or otherwise in the exercise of its executive power; or

(2) otherwise conferred by statute.

6. The relationship between the native title rights and interests and the other interests in relation to the land and inland waters is as follows:

(a) the other interests and the doing of any activity required or permitted to be done by or under the other interests, prevail over the native title rights and interests, but do not extinguish them, and the existence and exercise of the native title rights and interests do not prevent the doing of the activity;

(b) to the extent that the other interests are inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of the native title rights and interests, the native title continues to exist in its entirety, but the native title rights and interests have no effect in relation to the other interests during the currency of those interests;

(c) if those other interests are later removed or otherwise cease to operate, either wholly or partly, the native title rights and interests will again have effect.

Native Title Rights in the Inter-Tidal Zone and Outer Waters

7. In relation to the inter-tidal zone and outer waters the native title rights and interests that are possessed under the traditional laws and customs are, subject to the traditional laws and customs that govern the exercise of the rights and interests by the native title holders, rights of access to, and use of resources in or on, clan estate areas, being:

(a) the right to hunt, fish, gather and use resources within the area (including the right to hunt and take turtle and dugong) for personal, domestic or non-commercial exchange or communal consumption for the purposes allowed by and under their traditional laws and customs;

(b) the right to access, use and travel over and visit any part of the area in accordance with and for the purposes allowed by and under their traditional laws and customs, including:

(i) to access the area for religious, spiritual or cultural purposes or to engage in religious, spiritual or cultural practices;

(ii) to visit, have access to, and maintain sites, places and areas of religious, spiritual or cultural importance or significance within the area;

(c) the right to make decisions about access to and use and enjoyment of the area by Aboriginal people who recognise themselves as governed by the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the native title holders.

8. The native title rights and interests do not confer on the native title holders possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the inter-tidal zone and outer waters to the exclusion of others.

Other Interests in the Inter-tidal Zone

9. The other interests in the inter-tidal zone are:

(a) the interests of the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust under the two deeds of grant dated 30 May 1980 made under theAboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth);

(b) the rights of a holder of a permit granted under Part II of the Aboriginal Land Act1978 (NT) and the rights of a person to otherwise enter or remain on or use the area permitted by ss.69-71 of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth), Part II of the Aboriginal Land Act 1978 (NT) and Parts IV and V of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1989 (NT);

(c) the rights of the persons holding licences to fish granted under the Fisheries Act 1988 (NT) and the regulations made thereunder or any other legislative scheme for the control, management and exploitation of the living resources within the area;

(d) the right of members of the public to fish otherwise than under the rights specified at (c) above;

(e) the rights of members of the public to navigate;

(f) rights of access by an employee, servant, agent or instrumentality of the Northern Territory, Commonwealth or other statutory authority as required in the performance of his or her statutory duties;

(g) the interests of persons to whom valid and validated rights and interests have been:

(1) granted by the Crown pursuant to statute or otherwise in the exercise of its executive power; or

(2) otherwise conferred by statute.

10. The relationship between the native title rights and interests and the other interests referred to at 9(a) (b), (c) (f) and (g) in relation to the inter-tidal zone is as follows:

(a) the other interests and the doing of any activity required or permitted to be done by or under the other interests, prevail over the native title rights and interests, but do not extinguish them, and the existence and exercise of the native title rights and interests do not prevent the doing of the activity;

(b) to the extent that the other interests are inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of the native title rights and interests, the native title continues to exist in its entirety, but the native title rights and interests have no effect in relation to the other interests during the currency of those other interests;

(c) if those other interests are later removed or otherwise cease to operate, either wholly or partly, the native title rights and interests will again have effect to that extent.

11. The relationship between the native title rights and interests and the other interests referred to at 9(d) and (e) in relation to the inter-tidal zone is as follows:

(a) the other interests co-exist with the native title rights and interests;

(b) the determination does not affect the validity of those other interests;

(c) to the extent of any inconsistency, the native title rights and interests yield to the other interests.

Other Interests in the Outer Waters

12. The other interests in the outer waters are:

(a) the rights of the persons holding licences to fish granted under the Fisheries Act 1988 (NT) and the regulations made thereunder or any other legislative scheme for the control, management and exploitation of the living resources within the area;

(b) the right of members of the public to fish otherwise than under the rights specified at (a) above;

(c) the right of members of the public to navigate;

(d) rights of access by an employee, servant, agent or instrumentality of the Northern Territory, Commonwealth or other statutory authority as required in the performance of his or her statutory duties;

(e) the interests of persons to whom valid and validated rights and interests have been:

(1) granted by the Crown pursuant to statute or otherwise in the exercise of its executive power; or

(2) otherwise conferred by statute

13. The relationship between the native title rights and interests and the other interests referred to at 12 in relation to the outer waters is as follows:

(a) the other interests co-exist with the native title rights and interests;

(b) the determination does not affect the validity of those other interests;

(c) to the extent of any inconsistency, the native title rights and interests yield to the other interests;

Other Matters

14. The native title rights and interests are subject to and exercisable in accordance with the valid laws of the Northern Territory of Australia and the Commonwealth of Australia.

15. There are no native title rights and interests in:

(a) minerals as defined in s.2 of the Minerals Acquisition Act 1953 (NT);

(b) petroleum as defined in s.5 of the Petroleum Act (NT);

(c) prescribed substances as defined in s.5 of the Atomic Energy Act 1953 (Cth) and s.3 of the Atomic Energy (Control of Materials) Act 1946 (Cth).

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

Schedule A

The Determination Area

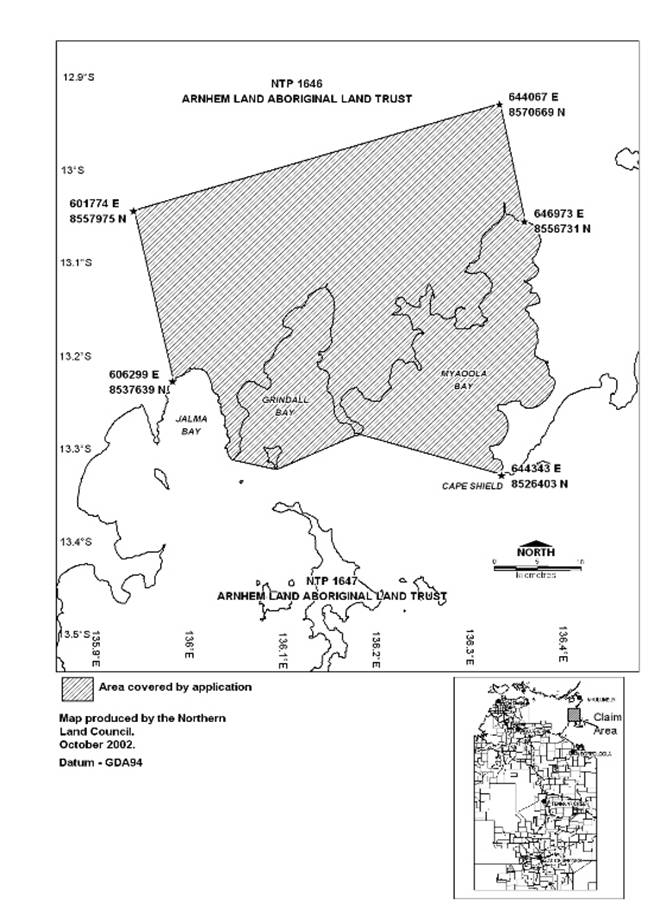

1. The determination area is portrayed by way of illustration on the map contained in Schedule B and comprises all that land and waters bounded by the bold lines on the map, being:

(a) Land and waters above the high water mark of the foreshore of the coastlines of Jalma, Grindall and Myaoola bays and of Round Hill Island within the bounded lines, including rivers, streams and estuaries that are not affected by the ebb and the flow of the tides;

(b) Land and waters of the foreshore of the coastlines of Jjalma, Grindall and Myaoola Bays and of Round Hill Island within the bounded lines that are between the low water mark boundaries of the deeds of grant referred to at 3 and the high water mark generally parallel or adjacent to those boundaries;

(c) Land and waters of rivers, streams and estuaries intersecting the coastlines of Jalma, Grindall and Myaoola bays within the bounded lines landward of the low water mark boundaries of the deeds of grant that are affected by the ebb and flow of the tides;

(d) Waters and seabed adjoining and seaward of the low water mark boundary lines of the deeds of grant and within the outer seaward bounded lines of the determination area drawn across the bights of Grindall Bay and Myaoola Bay.

2. The said boundary lines are:

(1) The south-western point of the boundary commences at a point on the coastline of Jalma Bay at about 135.56.19e and -13.02.33n and thence proceeds in a generally south easterly direction along the low water mark of the coastline of Jalma Bay until it reaches the southern most point at low water mark at Grindall Point.

(2) From Grindall Point the boundary proceeds generally in an easterly direction across the bight of Grindall Bay to the southern most point of Round Hill island at low water mark, and thence continues across the bight of Grindall Bay until it reaches the southern most point at low water mark at Point Blane.

(3) From Point Blane the boundary continues in a generally easterly direction across the bight of Myaoola Bay until it reaches the southern most point at high water mark at Cape Shield at about 136.19.58e and -13.19.34n.

(4) From Cape Shield the boundary follows generally the high water mark of the coastline of Myaoola Bay until it reaches a point in Myaoola Bay at about 136.21.20e and –13.03.07n and then proceeds inland generally in a north – westerly direction to a point near Wyonga River at about 136.19.41e and – 12.55.34n.

(5) From the point near Wyonga River the boundary proceeds inland generally in a south-westerly direction to a point near Gan Gan at about 135.56.19e and –13.02.33n, and from there the boundary proceeds inland generally in a southerly direction until it reaches the south-western point of the boundary of the determination area on the coastline of Jalma Bay at about 135.56.19e and -13.02.33n.

3 The low water mark boundary lines of the determination area correspond with the low water mark boundary lines specified in two deeds of grant of fee simple made under ss.10 and 12 of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) held by the Arnhem land Aboriginal Land Trust, namely:

(a) the Deed of Grant encompassing the mainland in the claim area known as the Arnhem Land (Mainland) Deed of Grant (the Mainland Grant);

(b) the Deed of Grant encompassing islands in the claim area known as the Arnhem Land (Islands) Deed of Grant (the Islands Grant);

registered in Volume 23, Folios 135 and 136 of the register maintained by the Registrar General of the Northern Territory. Without limiting the low water mark boundary lines so identified, they may be described as:

(i) in relation to the Mainland Grant, a line along the low water mark of the seacoast of the determination area but excluding from the said line those parts along the low water mark of all intersecting rivers, streams and estuaries inland from a straight line joining the seaward extremity of each of the opposite banks of each of the said rivers, steams and estuaries so that the aforesaid boundary line follows that part below low water mark of each of the aforesaid straight lines across each of the aforesaid rivers, streams and estuaries;

(ii) in relation to the islands grants, a line along the low water mark of Round Hill Island.

SCHEDULE B

MAP OF CLAIM AREA

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

NORTHERN TERRITORY DISTRICT REGISTRY |

NTD 12 OF 2003 |

|

BETWEEN: |

ARNHEM LAND ABORIGINAL LAND TRUST FIRST APPLICANT

NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL SECOND APPLICANT

GAWIRRIN GUMANA, DJAMBAWA MARAWILI, MARRIRRA MARAWILI, NUWANDJALI MARAWILI, DAYMAMBI MUNUNGGURR, MANMAN WIRRPANDA AND DHUKAL WIRRPANDA (ON BEHALF OF THE YARRWIDI GUMATJ, MANGGALILI, GUMANA DHALWANGU, WUNUNGMURRA (GURRUMURU) DHALWANGU, DHUPUDITJ DHALWANGU, MUNYUKU, YITHUWA MADARRPA, GUPA DJAPU, DHUDI DJAPU, MARRAKULU 1, MARRAKULU 2, WANAWALAKUYMIRR MARRAKULU, DJARRWARK 1, DJARRWARK 2, AND NURRURAWU DHAPUYNGU (DHURILI/DURILA) GROUPS THIRD APPLICANTS

|

|

AND: |

NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA FIRST RESPONDENT

DIRECTOR OF FISHERIES (NT) SECOND RESPONDENT

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA and AMATEUR FISHERMENS’ ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY INTERVENORS

|

|

JUDGE: |

MANSFIELD J |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

11 OCTOBER 2005 |

|

WHERE MADE: |

YILPARA |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicants have leave to amend the amended application dated 26 August 2004 by the insertion of par 1E in the following form:

‘The Fisheries Act 1988 (NT):

(1) is not a law regulating or prohibiting the entry of persons into, or controlling fishing or other activities in, waters of the sea adjoining, and within 2 kilometres of, Aboriginal land within the meaning of and for the purposes of s 73(1)(d) of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth);

(2) has no application in relation to waters of the sea that are seaward of and adjoining, and within 2 kilometres of, the boundary lines described in the said grants; and

(3) is invalid and of no effect in so far as it relates to waters of the sea that are seaward of and adjoining, and within 2 kilometres of the boundary lines described in the said grants.’

2. The applicants file and serve the further amended application within seven days.

3. The application, as further amended, is dismissed.

4. Each party and intervenor bear their or its own costs of the proceedings.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

NORTHERN TERRITORY DISTRICT REGISTRY |

NTD 6035 OF 2002 |

|

BETWEEN: |

GAWIRRIN GUMANA, DJAMBAWA MARAWILI, MARRIRRA MARAWILI, NUWANDJALI MARAWILI, DAYMAMBI MUNUNGGURR, MANMAN WIRRPANDA AND DHUKAL WIRRPANDA (ON BEHALF OF THE YARRWIDI GUMATJ, MANGGALILI, GUMANA DHALWANGU, WUNUNGMURRA (GURRUMURU) DHALWANGU, DHUPUDITJ DHALWANGU, MUNYUKU, YITHUWA MADARRPA, GUPA DJAPU, DHUDI DJAPU, MARRAKULU 1, MARRAKULU 2, WANAWALAKUYMIRR MARRAKULU, DJARRWARK 1, DJARRWARK 2, AND NURRURAWU DHAPUYNGU (DHURILI/DURILA) GROUPS APPLICANTS

|

|

AND: |

NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA FIRST RESPONDENT

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA SECOND RESPONDENT

NORTHERN TERRITORY SEAFOOD COUNCIL INC THIRD RESPONDENT

ARNHEM LAND ABORIGINAL LAND TRUST FOURTH RESPONDENT

TELSTRA CORPORATION LTD FIFTH RESPONDENT

AMATEUR FISHERMENS’ ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY INTERVENOR

|

AND

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

| |

|

NORTHERN TERRITORY DISTRICT REGISTRY |

NTD 12 OF 2003 | |

|

BETWEEN: |

ARNHEM LAND ABORIGINAL LAND TRUST FIRST APPLICANT

NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL SECOND APPLICANT

GAWIRRIN GUMANA, DJAMBAWA MARAWILI, MARRIRRA MARAWILI, NUWANDJALI MARAWILI, DAYMAMBI MUNUNGGURR, MANMAN WIRRPANDA AND DHUKAL WIRRPANDA (ON BEHALF OF THE YARRWIDI GUMATJ, MANGGALILI, GUMANA DHALWANGU, WUNUNGMURRA (GURRUMURU) DHALWANGU, DHUPUDITJ DHALWANGU, MUNYUKU, YITHUWA MADARRPA, GUPA DJAPU, DHUDI DJAPU, MARRAKULU 1, MARRAKULU 2, WANAWALAKUYMIRR MARRAKULU, DJARRWARK 1, DJARRWARK 2, AND NURRURAWU DHAPUYNGU (DHURILI/DURILA) GROUPS THIRD APPLICANTS

| |

|

AND: |

NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA FIRST RESPONDENT

DIRECTOR OF FISHERIES (NT) SECOND RESPONDENT

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA and AMATEUR FISHERMENS’ ASSOCIATION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY INTERVENORS

| |

|

JUDGE: |

MANSFIELD J |

|

DATE: |

11 OCTOBER 2005 |

|

PLACE: |

YILPARA |

REASONS FOR ORDERS

introduction

1 On 7 February 2005 Selway J published reasons for judgment in this matter (the reasons for judgment). His Honour intended that the parties should have some time to address the final orders which should be made in the light of those reasons. Unfortunately, his Honour’s death occurred before that process had been completed. With the consent of the parties, I have completed the hearing (see Brennan v Brennan (1953) 89 CLR 129). See also Halsburys Laws of Australia, Vol. 8, 236, 158 [125-280]; Halsburys Laws of England, 4ed (1995), Vol.10, 331-332 [726].

2 The parties are also agreed that, although there are a number of matters arising from the reasons for judgment which require consideration, I should do so by proceeding from the reasons for judgment of Selway J of 7 February 2005 and should give full effect to them. I agree that I should proceed accordingly. My task is to make such final orders as are appropriate in accordance with the reasons for judgment. Consequently, these reasons for orders are to be read with the reasons for judgment. I will not repeat that which is in the reasons for judgment, except to the extent necessary to identify and address particular issues. I shall also endeavour to consistently adopt the definitions of terms in the reasons for judgment.

3 The reasons for judgment identified the essential issue raised in the proceeding as being whether, and to what extent, the traditional owners of parts of Blue Mud Bay in north-east Arnhem Land can exclude fishermen and others from the inter-tidal zone of the claim area and from the adjacent sea, including certain sites in the inter-tidal zone and in the sea. That issue arose in two claims:

(1) a claim for determination of native title rights under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA), and

(2) a claim for declarations that, by reason of land grants to the applicants under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (the Land Rights Act) and the provisions of that Act, the Northern Territory lacks the legislative and executive power to issue fishing licences over the inter-tidal zone and the adjacent sea within two kilometres of the low water mark (the Judiciary Act matter).

4 As to those two claims, his Honour concluded at [2] and [3] of the reasons for judgment that it was inappropriate to make any of the declarations sought by the applicants in the Judiciary Act matter. He concluded in [3] in respect of the NTA claim that:

(i) As to the “land” other than the inter-tidal zone (which term refers to the area of the foreshore between the low and high water mark and to the area of rivers and estuaries affected by the ebb and flow of the tides) – the applicants have a native title right of exclusive possession:

(ii) As to the sea and the inter-tidal zone – the applicants have native title rights similar to those identified in Yarmirr: see Commonwealth v Yarmirr (2001) 208 CLR 1 at 144-145 [327] as further explained in Lardil Peoples v Queensland [2004] FCA 298.’

I shall adopt Yarmirr and Lardil as shorthand references to those two cases hereafter.

5 It is convenient to deal with the Judiciary Act matter immediately. The parties are agreed that the Court should give leave to the applicants to further amend the application to expressly raise an argument in respect of s 73(1)(d) of the Land Rights Act. Upon that amendment, the application is to be dismissed. It is agreed that each party and the intervenors should bear their or its own costs of the proceedings.

6 Before turning to the issues remaining between the parties as to the appropriate form of determination in the light of the reasons for judgment, there are two additional matters which need to be addressed.

7 In the reasons for judgment, at [275(b)], Selway J raised a question whether those persons who are in groups having relevant traditional interests in the claim area pursuant to Aboriginal traditions, and who are not ‘represented’ by the individual applicants, should be given a further and separate opportunity to be heard before the making of the final orders.

8 Sections 61 and 225 of the NTA contemplate that the persons the Court finds to be the native title holders may include persons other than the native title claim group. However, there are extensive notification processes under the NTA before a determination of native title can be made. An application under s 61 must promptly be given to the Native Title Registrar, who must then give the notifications required by s 66. Those notifications include notification to any representative bodies for any part of the claim area, any registered native title claimant, or any registered native title body corporate in relation to any part of the claim area. They also include any person whose interests the Registrar considers may be affected by a determination in relation to the application. They further include notification to the public at large. The notification given must include detail as to the means by which any person interested may become a party to the application under s 84 of the NTA.

9 The determination to be made will require the establishment of a prescribed body corporate under the Aboriginal Councils and Associations Act 1976 (Cth). That prescribed body corporate will then perform the functions specified under s 57 of the NTA and under the Native Title (Prescribed Bodies Corporate) Regulations 1999 (Cth). The determination will give effect to a duly authorised application, and one which was certified by the Northern Land Council as the relevant representative body under s 203BE of the NTA as an application which the applicants had authority to make. The certification was given after the NLC had undertaken consultation on the application including the facilitation and assistance functions required of the Northern Land Council by s 203BB and s 203BC of the NTA. It is apparent therefore that the applicants have authority to speak for the country of the 15 clans and for all those persons who hold native title in that country, including persons such as spouses and those with kinship or special responsibilities for the country of the claim area, or who have ceremonial relations closely connected to the 15 clans. As the reasons for judgment indicate at [133]-[140], it would not be possible to list all such persons by name, and so it is appropriate to identify those persons by group description.

10 The persons to whom his Honour was referring have had the opportunity to be informed of the claim, and to participate in the hearing to the extent that they wished to assert matters different from those put forward by the applicants on behalf of the claimants. That they have not done so is very probably because, being aware of the claim, they agree with the course of the conduct of the proceeding as presented by the applicants on behalf of all those persons who, it is to be determined, have native title rights and interests in the claim area.

11 In those circumstances, I am satisfied that it is appropriate to proceed to final determination without further notification to those persons.

12 The second matter raised by Selway J in the reasons for judgment at [275(e)] was whether the land and boundaries within the land grants under the Land Rights Act should be included in the native title determination area or whether such determination would be ‘advisory and hypothetical’ only. The context of his Honour’s concern in particular was that the claim area had been identified on a ‘relatively arbitrary basis’ so that the specific relevant issues might be determined (see reasons for judgment at [28]) as well as whether the determination would have any utility.

13 Despite those concerns, I think it is appropriate to proceed to such determination of the native title rights and interests as the applicants may be entitled to under the NTA upon his Honour’s findings generally. In doing so, the Court will be applying the legal principles established under the NTA to the facts as found before his Honour. Those matters were contentious in the current proceeding. The contentions were not contrived.

14 The application for determination of native title was duly instituted under s 61(1) of the NTA. It is the function of the Court under s 225 then to make such determination as is appropriate. The provisions of the NTA, in particular ss 47A and 61A(4), have particular significance in addressing the effects of past extinguishing acts. Section 210 of the NTA specifically contemplates that the determination of native title under the NTA will operate without affecting rights or interests under the Land Rights Act (and certain other specified legislation). Section 23B(9) of the NTA excepts the grant of a freehold estate granted for the benefit of Aboriginal peoples from those grants of freehold estates which, prior to 23 December 1996, would constitute a previous exclusive possession act and so preclude an application under s 61 over such land being made. There is therefore no apparent legislative intent that a grant under the Land Rights Act should thereby exclude the area of that grant from being the subject of a determination of native title under the NTA. The contrary is the apparent legislative intent.

15 There is also, as senior counsel for the Commonwealth pointed out, utility in granting the relief sought. The utility is not found simply in the need to address and resolve a dispute between the parties in an application which has been properly brought before the Court. It is also found in practical considerations associated with fulfilling the object in s 3(a) of the NTA of providing ‘for the recognition and protection of native title’. The nature of the grant of native title rights and interests under the NTA is conceptually different from those rights granted under the Land Rights Act (see e.g. R v Toohey; Ex parte Meneling Station (1982) 158 CLR 327 at 357-359). The recognition of native title and the recognition of traditional Aboriginal ownership of land under the Land Rights Act are separately defined in the respective enactments. A grant under the Land Rights Act is not predicated upon the existence of Aboriginal traditions and rights and interests held under those traditions which have their origin in pre-sovereignty laws and customs: see e.g. Yorta Yorta v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422. Nor does such a grant require the continuous existence and vitality of a normative system of traditional laws and customs since sovereignty under which those rights and interests are possessed. The definition of ‘traditional Aboriginal owners’ and of ‘Aboriginal traditions’ in s 3(1) of the Land Rights Act illustrates that its provisions are applied in the present tense: see e.g. Northern Land Council v Olney (1992) 34 FCR 470 at 485-486. Hence, the ‘status’ of persons recognised as holders of native title having a native title right of exclusive possession over particular land may be different from persons who are beneficiaries of a grant under the Land Rights Act in respect of the same land. The potential absence of such a necessary correspondence in identity, and of such a necessary correspondence in the rights and obligations which flow from a land grant under the Land Rights Act compared to a grant of native title under the NTA, was recognised in Pareroultja v Tickner (1993) 42 FCR 32 at 42.

16 A determination of native title in favour of native title holders determines finally the existence and nature of native title rights and interests with respect to particular land. On the other hand, a grant under the Land Rights Act to Aboriginal persons can be surrendered to the Crown (s 19(2) of the Land Rights Act), or may be revoked or acquired. In such circumstances, native title might nevertheless survive, including the rights which arise with respect to future acts in relation to the land.

17 Finally, I note that there is an issue, which need not be finally determined, but which provides another reason to consider that the proposed determination is not merely theoretical. Under the grants under the Land Rights Act, certain roads over which the public had right of way as at 21 January 1997 and 30 May 1980 are expressly excluded from the grants. There may, however, in the light of the proposed determination, be certain of those roads where native title rights and interests may be found to exist because one issue which the Court was asked to address is whether the construction or establishment of certain roads in the claim area (which were excluded from the land grants under the Land Rights Act) are previous exclusive possession acts, or otherwise totally extinguished all native title that had previously existed over those areas.

18 Accordingly, in my view, there is utility in proceeding to determination in respect of the area the subject of the claim under the NTA claim in the light of the matters litigated in the present proceeding and the findings made in the reasons for decision, including in respect of that land landward of the low water mark, that is the land subject to the land grants and which is also the subject of an application for determination of native title.

19 I return to address the issues specifically raised by the parties concerning the appropriate form of the determination arising out of the reasons for decision. There were six issues of substance which arose between the parties in relation to the reasons for judgment. I shall deal with them in turn. Generally, but not in all respects, the respondents adopted a common position. I have therefore referred to them collectively as ‘the respondents’ although I have endeavoured to identify those instances where one or other of the respondents adopted a position different from the others.

The Determination Area - Rivers, Streams and Estuaries

20 The first issue concerns the inter-tidal zone, as defined in [30] of the reasons for judgment. The description of the determination area in the proposed determination of the applicants refers to Schedule A (and the Map in Schedule B). It distinguishes between ‘land and inland waters’ on the one hand and ‘the inter-tidal zone’ and the ‘outer waters’ or seas adjacent to the inter-tidal zone on the other by the subclauses of par 1 of Schedule A. The reason for the distinction is that the reasons for judgment determines that the native title rights are affected by the public rights to fish and to navigate that may be exercised in the inter-tidal zone and in the adjacent waters, so that in those areas they are not exclusive.

21 The applicants’ proposed determination, apparently in an attempt to reflect the reasons for judgment, has defined the inter-tidal zone to include the land and waters of rivers, streams and estuaries intersecting the coastline of the claim area landward of the low watermark boundaries of the grants under the Land Rights Act that are navigable and are affected by the ebb and flow of the tides (my emphasis). The applicants, consistently, then define the land and inland waters to include rivers, streams and estuaries that are tidal but are not navigable.

22 The disputed issue concerns whether the public right to fish extends into tidal waters that are not navigable.

23 As noted, in the reasons for judgment, his Honour at [3(i)] and [275(d)(i)] defined the term inter-tidal zone to refer to the area of foreshore between the low and high water mark and to the area of rivers, streams and estuaries ‘affected by the ebb and flow of the tides’. It was that area in which it was found that the applicants had non-exclusive native title rights. That was because his Honour regarded himself as bound by the decision of the Full Court of this Court in Commonwealth v Yarmirr (1999) 101 FCR 171 (Yarmirr FC) to hold the fee simple in the foreshore granted by the grants under the Land Rights Act was qualified so as not to exclude those exercising public rights to fish and to navigate in that area, nor by s 70 of the Land Rights Act. His Honour concluded also at [87] that the decision in Yarmirr FC also applied to ‘those parts of estuaries or navigable rivers where the waters are affected by the flow or ebb of the tide.’

24 The applicants accept that conclusion applies to all estuaries and rivers capable of navigation and subject to the ebb and flow of the tides. The issue is whether the wider expression ‘tidal waters’ (to connote any waters affected by the tides, whether navigable or not) was used in the reasons for judgment so as to convey the full extent of the public right to fish, or whether that right is confined to the areas which in the reasons for judgment are called ‘arms of the sea’ (to connote tidal waters which are navigable).

25 The first step is to determine whether Selway J resolved that point, or whether the question as to whether the public right to fish extends to the non-navigable parts of tidal waters in rivers, streams and estuaries was left unresolved. If it was not resolved by his Honour, it will be necessary to do so.

26 In the reasons for judgment at [80] Selway J concluded that the decision in Yarmirr FC required him:

‘… to hold that the grant of the fee simple to the Land Trust over the inter-tidal zone does not confer on the Trust the exclusive right to control access to the sea over the tidal foreshore and/or that persons exercising public rights to fish or navigate can come onto the inter-tidal zone without breaching s 70 of the Land Rights Act.’

No distinction was then drawn between those parts of the inter-tidal zone which were navigable and those which were not. That conclusion, his Honour found at [87], should be extended to those parts of estuaries or navigable rivers where the waters are affected by the flow or ebb of the tide. Paragraph [87] reads:

‘I note that the orders and reasons in Yarmirr did not deal with tidal waters in estuaries and rivers and to that extent I am not strictly bound to follow the Full Court in that regard. However, I am unable to discern any sustainable distinction between the application of the public rights to fish or navigate in the foreshore or in respect of other tidal waters, whether such waters are in estuaries, in rivers or elsewhere. I do not see how the principle established by the Full Court in Yarmirr FC can be limited to the foreshore. It also must extend to the “arms of the sea”. Accepting that I am bound by the principle as applied in Yarmirr FC, it follows, in my view that the applicants do not have a right pursuant to the grant to exclude persons exercising the public rights to fish or navigate from the waters between the high and low water marks or from those parts of estuaries or navigable rivers where the waters are affected by the flow or ebb of the tide. Nor are they excluded by the operation of s 70 of the Land Rights Act.’

27 As counsel for the applicants pointed out, the reasons for judgment do not consistently use the alternative ‘or’ when referring to ‘arms of the sea’. For example, at [66], the arms of the sea as distinct from the foreshore were referred to as ‘estuaries and rivers capable of navigation and subject to the ebb and flow of the tide’.

28 His Honour’s reasoning on this topic firstly recognised that the prerogative rights of the Crown with respect to the foreshore (the area between the mean high and low water marks) were subject to the separate common law rights of the public to fish and to navigate in the water above that land (at [61]-[65]), and to the arms of the sea (at [66]). The next step was to reach the provisional view that the public rights to fish and to navigate in the foreshore and in the rivers and estuaries of Blue Mud Bay were abrogated by the land grants under the Land Rights Act [67]-[73]. However, as noted above, his Honour then felt bound by Yarmirr FC to conclude at [80]-[87] that the grants under the Land Rights Act did not abrogate the public rights to fish or to navigate. In all that discussion, his Honour recognised that the public right to fish and the public right to navigate in the foreshore and the arms of the sea were separate public rights. That is also apparent in his Honour’s consideration of whether the licences under the Fisheries Act 1988 (NT) are different in nature from the public right to fish (at [90]-[92]). That being so, there is no reason to think that his Honour intended to limit the public right to fish by reference to the navigable waters of the foreshore or of the arms of the sea simply because, by definition, the public right to navigate is confined to the navigable waters of the foreshore or of the arms of the sea.

29 I do not find in the reasons for judgment cause to conclude that the common law public right to fish in tidal waters was confined to tidal navigable waters. His Honour at [63] relied upon four authorities for the proposition that the prerogative rights of the Crown were subject to the common law public right to fish (and the common law public right to navigate). The first of those cases was Harper v Minister of Sea Fisheries (1989) 168 CLR 314 where Brennan J at 329-331 described the public right to fish as extending to tidal waters generally, although at one point his Honour used the expression ‘tidal navigable waters’. His Honour’s views were agreed with generally by Mason CJ, Deane and Gaudron JJ at 325, and by Dawson, Toohey and McHugh JJ generally at 336. In New South Wales v Commonwealth (1975) 135 CLR 337, Stephen J at 423 referred to Hale’s De Jure Maris as stating that the shore between ‘the flux and reflux of the tide’ was subject to the public right of fishing, and Jacobs J at 489 also referred to the ‘public rights of fishing in tidal waters’. Anderson v Alnwick District Council [1993] 1 WLR 1156 at 1166-1170 also referred to the public right to fish as extending to ‘areas of tidal waters’ without confining that right to navigable tidal waters. So too did Burchett J in Minister for Primary Industry and Energy v Davey (1993) 47 FCR 151 at 168.

30 It is correct, as counsel for the applicants pointed out, that the public right to fish is said to have resembled in origin the right to navigate the sea and navigable rivers (see e.g. Attorney-General for British Columbia v Attorney-General for Canada [1914] AC 153 at 169). It is also correct to point out that his Honour in the reasons for judgment did not seek to distinguish between the extent of tidal waters affected by the public right to fish and those affected by the public right to navigate. Counsel put that, if there is a coincidence in their extent, because by definition the public right to navigate can only be in tidal navigable waters, the public right to fish was intended also equally to be so confined.

31 However, for the reasons given, in my view the reasons for judgment indicate that the public right to fish as identified by his Honour was exercisable in the inter-tidal zone, including tidal waters, whether those waters are navigable or not. The public right to navigate is necessarily confined to tidal waters which are navigable.

32 Consequently, I propose to give effect to that ruling by deleting from the applicants’ proposed determination defining the extent of the determination area in Schedule A from the proposed par 1(a) the words ‘or that are affected by the ebb and flow of the tides, but are not navigable’ and from the proposed par 1(c) in Schedule A the words ‘are navigable and’. That will have the effect of excluding from the defined areas comprising the land and inland waters those parts of rivers streams and estuaries that are affected by the ebb and flow of the tides even if they are not navigable, and on the other hand of extending the inter-tidal zone to include those parts of the rivers, streams and estuaries that are affected by the ebb and flow of the tides, whether or not they are navigable.

Native Title - Inland Waters

33 Paragraph 4 of the applicants’ proposed determination provides regarding land and inland waters as follows:

‘In relation to the land and inland waters, the native title rights and interests that are possessed under the traditional laws and customs are, subject to the traditional laws and customs that govern the exercise of the native title rights and interests by the native title holders, possession, occupation, use and enjoyment to the exclusion of all others.’

34 The respondents contend that par 4 should reflect the rights recognised in the reasons for judgment separately with respect to the land (which are accepted as being accurately expressed in the proposed determination as flowing from the reasons for judgment) and with respect to water on that part of the land. The respondents contend that native title rights in accordance with the reasons for judgment with respect to water over or on land and inland waters is simply the right to use it for their own needs. They submit that the reasons for judgment did not intend to recognise, as par 4 of the proposed determination suggests, that native title holders have exclusive property in the inland waters themselves.

35 The starting point is [3(i)] of the reasons for judgment set out in [4] above.

36 His Honour recognised at [70] that normally the owner of land does not ‘own’ everything physically on it. Hence he said the ‘ownership’ of free flowing water is not sensible. The owner has a right to control access to that water and to use it for his or her own purposes.

37 Then at [185] in discussing the propensity of certain evidence to be misunderstood, his Honour recognised that ‘ownership’ or the ‘belonging’ of objects such as free flowing water meant (according to the applicants’ evidence) the right to use the water whilst present on the claimant’s country rather than a right of dominion over it. See also Yanner v Eaton (1999) 201 CLR 351 at 368.

38 The form of the proposed determination is the same as that made in Passi v State of Queensland [2001] FCA 697, and as recognised in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 at 217. Hence, the applicants contend that par 4 by declaring exclusive possession of the land and inland waters operates within a legal framework that the owner of the land has only the rights to control access to the waters thereon and to take and use those waters whilst on the land.

39 The respondents contend both as a matter of law and common expression that ownership of land or exclusive possession of land does not carry with it other than riparian rights in respect of the water that overlies and traverses the land. They are concerned that par 4 as expressed might be understood as recognising a sui generis native title right of a more expansive nature, if par 4 were read literally.

40 There is no real dispute between the parties as to the nature of the right which is intended to be conveyed. They are agreed that the reasons for judgment determines that, in respect of the land comprised in the land and inland waters, the applicants should have possession, occupation, use and enjoyment to the exclusion of all others. They are agreed further that his Honour did not intend to determine the existence of a native title right by way of ‘ownership’ in the waters on that part of the land and inland waters area of the claim, in the sense of an exclusive right to ownership of those waters. They are agreed that, by virtue of the exclusive right to possess that part of the claim area, the applicants are intended to have the right to control access to the waters on that part of the claim area, and to have the right to use and enjoy (that is take and use) those waters while they are on that part of the claim area. It becomes a matter of drafting as to how that state of affairs should properly be reflected in the proposed determination.

41 In Attorney-General (NT) v Ward (2003) 134 FCR 16 at 25 (Attorney-General (NT) v Ward), the Full Court (Wilcox, North and Weinberg JJ) recognised that native title holders cannot obtain exclusive water rights with respect to free flowing or subterranean waters. Their Honours felt it appropriate to make explicit reference to water rights to avoid any possible dispute. In this matter the applicants contend that it is unnecessary to do so given the findings in the reasons for judgment to which I have referred.

42 In determining the appropriate form of determination, it is important to recognise, as his Honour intended, that the native title rights and interests over the land and inland waters, should be expressed so as to include the exclusive right to control access to water on that part of the claim area (it being contained within the claim area over which there is such an exclusive right) and to use and enjoy that water. The factual issue as to the existence of such exclusive rights was ventilated by the pleadings and in the course of evidence, and resulted in the findings to which I have referred.

43 In my view, his Honour’s intentions as discernable from the reasons for judgment are consistent with the expression of par 4 of the applicants’ proposed determination. It does not mean that they have some additional or unique form of right in respect of subterranean or flowing water on that part of the claim area within the defined section ‘land and inland waters’. It means simply that, in respect of that part of the claim area they have the exclusive right to control access to the water within that part of the claim area and to use and enjoy it. It is apparent from the reasons for judgment that his Honour was not seeking to create some new or additional right to ‘possess’ flowing or subterranean water in a way which extended beyond that recognised in other authorities. I do not think the proposed par 4 of the proposed determination has that meaning. The term ‘the land and inland waters’ is defined by par 1(a) of Schedule A as a geographical area but not in terms indicating some special and peculiar interest in the waters on that part of the claim area. In my view par 4 appropriately reflects the reasons for judgment.

Other Interests: Land and Inland Waters

44 At [142] of the reasons for judgment, Selway J said:

‘Finally it is necessary to mention one further problem that was referred to in the submissions. It relates to the obvious possibility (at least in claims involving co-existing rights) that a right or title which might otherwise limit the native title right might be overlooked in the determination. Plainly it was not the intention of the Parliament that the NTA would create rights inconsistent with the ordinary system of land tenure except to the extent it does so expressly: see Lansen v Northern Territory (2004) 211 ALR 365 at 378 [34]. On the other hand, the effect of a determination which created inconsistent rights would or may be to “extinguish” other rights or titles, including, for example, a right or title under the torrens system, contrast Hillpalm Pty Ltd v Heaven’s Door Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 59 at [53]. In order to avoid any such possibility all parties submitted to me that any determination should include a “catch-all” qualification of the sort often used in such determinations: see for example pars 8(c)-(f) of the draft determination in De Rose v South Australia (2003) 133 FCR 325 (De Rose) at 375.’

45 To give effect to that, the proposed determination in par 5(a) and par 5(c) recognises the interests of the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust under the two deeds of grant of 30 May 1980 made pursuant to the Land Rights Act, and the rights and interests of Telstra Corporation Ltd. Paragraph 5(c) is in terms acceptable to the fifth respondent.

46 Paragraph 5(b) of the applicants’ proposed determination recognises as other interests rights of the holder of a permit granted under Pt II of the Aboriginal Land Act 1978 (NT) (the Aboriginal Land Act) and the rights of a person to otherwise enter or remain on or use the area permitted by ss 69-70 of the Land Rights Act, Pt II of the Aboriginal Land Act and Pts IV or V of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1989 (NT). According to the respondents, par 5(b) does not comprehensively describe the other interests that exist in the determination area and so additional sub-pars 5(d) and 5(e) are proposed. They are to read:

(d) rights of access by an employee, servant, agent or instrumentality of the Northern Territory, Commonwealth or other statutory authority as required in the performance of his or her statutory duties;

(e) the interests of persons to whom valid and validated rights and exercise have been:

(1) granted by the Crown pursuant to statute or otherwise in the exercise of its executive power; or

(2) otherwise conferred by statute.

47 The applicants contend that such concerns are adequately accommodated by the proposed formulation of par 5(b) and by par 14 of their proposed determination which provides that the native title rights and interests are subject to and exercisable in accordance with the valid laws of the Northern Territory and of the Commonwealth.

48 The concerns of the Northern Territory and of the Commonwealth relate to persons who may enter the determination area under a number of Commonwealth or Northern Territory enactments. It would be unsafe to endeavour to provide an exhaustive list of such enactments, lest some relevant statutory provision might be overlooked. There are, as pointed out, persons who may enter and remain on Aboriginal land under s 7 of the Aboriginal Land Act. They may do so without a permit (for instance, the Administrator, elected politicians to the Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory or of either house of the Commonwealth Parliament or candidates for those offices). Moreover, the prohibition under the s 4 of the Aboriginal Land Act on persons entering on Aboriginal land without a permit is subject to ‘any provision to the contrary in a law of the Territory’, so that persons who may enter the determination area under certain enactments also do not need a permit. Finally, the Northern Territory refers to s 6 of the Aboriginal Land Act which permits a Minister to authorise entry onto Aboriginal land by persons beyond those who have statutory rights of entry, including persons employed under an enactment who have a ‘need’ to do so in performance of their duties.

49 The Northern Territory contends that its proposed par 5(e) is necessary to capture rights and interests under statute not arising by virtue of the performance of the statutory duty. Examples are provided of rights exercisable under s 9(2) of the Water Act (NT), and access rights of Aboriginal persons to enter upon Aboriginal land in accordance with Aboriginal tradition, which do not necessarily correlate with native title access rights, and the like.

50 The applicants resist that proposed change to their proposed determination for two main reasons. The first is that par14 of their proposed determination provides the ‘catch all’ to meet the concern in the reasons for judgment at [142] and the requirements of s 225 of the NTA. The second is that the amendment suggested by the respondents may undermine the workings of the future act regime in the NTA because the changes would, or could, extend to certain and unknown specified interests and would not be limited to extant interests.

51 As to the first point, I observe that s 225(c) of the NTA, in conjunction with s 94A, requires a determination to provide details of ‘the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area’. Par 14 of the proposed determination does not provide such details of the nature and extent of any other ‘interests’ in relation to the determination area except in the most general way. The word ‘interests’ is defined in s 253 broadly. It is not confined to legal and equitable interests in land. A statutory right of access to land would fall within par (b)(i) of the definition and so should be described in the determination: s 225(c). Such rights are not included in par 5(b) of the applicants’ proposed determination. They arise by virtue of the relevant Commonwealth or Northern Territory statute, and not because of a permit granted under Pt II of the Aboriginal Land Act. They may be exercised whether or not a permit for the entry authorised by the relevant enactment has been obtained under the Aboriginal Land Act. In any event, on this aspect, the more detailed expression suggested by the Northern Territory will (as the applicants acknowledge) have at the worst from the applicants’ perspective no greater significance than par 14 of the proposed determination of the applicants.

52 I also do not accept that the applicants’ second reason for opposing that suggested change to their proposed determination should lead to its rejection. The suggested change or addition is confined to those exercising statutory rights or privileges. They do not extend to any members of the public purporting to exercise any rights at common law. I do not think they encompass any persons who could later seek access to the claim area pursuant to any interests which would be, or would arise from, invalid future acts under the NTA. They would not impinge on any independent exclusory entitlement of the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Land Trust, by virtue of the land grants under the Land Rights Act.

53 Finally, I am influenced to include the Northern Territory’s proposed additions to par 5 of the determination because, in my view, that is what Selway J contemplated in [142] of the reasons for judgment. His Honour referred to pars 8(c)-(f) of the draft determination in De Rose v South Australia (2003) 133 FCR 325 at 375, which are in similar terms. It is clearly more detailed and specific than par 14 of the applicants’ proposed determination.

54 The determination will therefore incorporate recognition of those additional other interests.

Native title rights in the inter-tidal zone and outer waters

55 The respondents variously complained to some degree regarding the extent of the applicants’ proposed determination of native title rights in the inter-tidal zone and the outer waters. One issue concerned the applicants’ proposal that their native title rights extend beyond hunting, fishing and gathering resources to their ‘use’. Another relates to the use of the word ‘resources’, which the Northern Territory contends should be limited to ‘living and plant resources’. A third issue relates to the applicants’ proposal that it is only in the case of the outer waters that their rights should be confined to non-commercial purposes. The respondents also are concerned that the proposed rights include accessing the area for ‘cultural’ purposes or ‘to engage in religious, spiritual or cultural practices’, and to ‘maintain or protect’ special sites. Finally, the respondents oppose an order declaring or determining the existence of a right to make decisions about access to and use and enjoyment of the area by Aboriginal people who are governed by the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the native title holders. It is necessary to address each of those issues in turn.

56 As noted, the reasons for judgment indicate that the applicants have native title rights ‘similar to those identified in Yarmirr, as further explained in Lardil’. However, whilst his Honour indicated that he would make a determination of native title rights similar to those granted in Yarmirr and Lardil, in my view it is apparent that he did not intend that the determination in this matter should verbatim follow the determinations in either of those matters. That is apparent from his Honour’s reasons at [214] where he indicated that it was unnecessary to make findings on particular evidence before him, before determining what rights the applicants enjoyed. The need to do so was obviated in part by the concessions or agreements of the parties, and in part by the agreement of the anthropologists to a significant number of propositions which his Honour recorded in Appendix 1 to the reasons for judgment. Clearly, he did so for a purpose.

57 The respondents’ concern about the word ‘use’ as part of par 7(a) of the proposed determination of the applicants’ non-exclusive native title rights in the formulation ‘the right to hunt, fish, gather and use’ resources springs from the absence of that word in the determinations in Yarmirr and Lardil. Counsel for the applicants confirmed that the word ‘use’ was not intended to recognise some right greater than or different from the rights recognised in those two cases. There is no foundation in the reasons for judgment for adopting any contrary view. However, the anthropologists are agreed that the applicants rights include the right to use the resources of the claim area (Proposition 14(d)), and in the light of that material I consider par 7(a) in this respect reflects the reasons for judgment. In addition, in the reasons for judgment at [216], Selway J adopted a section of the submissions of the Commonwealth as describing ‘appropriately’ the various rights in the claim area. Those submissions included the right to use resources on the claim areas. I therefore consider that the formulation of the applicants is consistent with and reflects his Honour’s reasons for decision. I do not propose to delete that word.

58 The Northern Territory, but not the Commonwealth, was also concerned at the definition of ‘resources’ in par 1.3(3) of the proposed determination, and then the use of that defined term. It submitted the reasons for judgment confined the right, as an incident of the right of exclusive possession (save to the extent it was not recognised by the common law), to hunt, fish, gather and use living and plant resources. The words ‘living and plant’ qualify or explain the term ‘resources’ in the Lardil determination.

59 Again, I consider the formulation proposed by the applicants reflects the reasons for judgment. The extent of ‘resources’, that is whether they were confined to living and plant resources, does not appear to have been an issue specifically addressed. But the adoption of the Commonwealth submission as a description of the rights in the claim area, including the wider word ‘resources’, leads me to the view that his Honour had in mind a determination such as that the applicants propose. That is also consistent with Appendix 1 to the reasons for judgment, recording the propositions with which the anthropologists agreed, in particular in Proposition 14 where the word ‘resources’ is used in an unqualified or unrefined way. The definition of ‘resources’ in par 1.3(3) in the applicants’ proposed determination ensures the use of that word does not extend inappropriately.

60 Paragraph 7(b) of the applicants’ proposed determination is also expressed, in a few respects, in terms wider than the respondents consider proper having regard to the reasons for judgment. They refer to certain wording put forward by the applicants which is not drawn from the determinations in Yarmirr or Lardil.

61 In my view, the proposed rights to access this area for cultural purposes, and to visit sites and places of significance reflect his Honour’s reasons for judgment. As noted, he adopted the device of an appendix to the reasons for judgment recording the propositions upon which the anthropologists agreed. The applicants’ Proposition 14 contained a number of specific claims upon which there was no dispute, and which (in the context of the reasons for judgment) indicate that his Honour had in mind that ultimately the determination might reflect them. With one qualification, I do not propose to vary the proposed par 7(b)(i) or (ii).

62 The qualification is to delete from par 7(b)(ii) the words ‘or protect’ in relation to significant sites in this part of the claim area. That claimed right is based on one of the propositions upon which the anthropologists agreed: Proposition 14, item (i). There is such a right in the Yarmirr determination, but not in the Lardil determination. In the reasons for judgment at [243], in this respect Selway J specifically adopted the Lardil determination because, in this matter also, a right to ‘maintain or protect’ such sites would include the right to exclude others from those sites. That entitlement would be inconsistent with the public rights to fish and to navigate. I do not consider that the maintenance of a particular site involves the assertion of an exclusive right in the claimants inconsistent with those public rights, but the protection of a particular site would have that effect. See also Yarmirr per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJat 67-68, [94]-[100]. I will therefore remove the words ‘or protect’ from the proposed par 7(b)(ii).

63 The next concern of the respondents was that the applicants are seeking a determination of rights which includes hunting, fishing, gathering and using the resources of the inter-tidal zone for commercial purposes. They point out that the determinations in Yarmirr and Lardil each confined the relevant right to non-commercial purposes.

64 The applicants contend firstly that the evidence, but more specifically the reasons for judgment, supports the claimed right to fish for commercial purposes in the inter-tidal zone, and so the present circumstances are different from those found in Yarmirr (where there was no traditional right found to exist to control access to the relevant area).

65 The reasons for judgment do not expressly find, or indeed address, the existence of a traditional right to fish for commercial purposes in the inter-tidal zone. The applicants support their contention by reference to Proposition 14 in the propositions upon which the anthropologists agreed in Appendix 1 to the reasons for judgment. One part of Proposition 14 is that the claimants have the right to ‘share, exchange and trade’ the resources of the claim area and of the right of senior clan members to receive a portion of the resources taken from the claim area. Two of the three anthropologists accepted that proposition (or really a combination of propositions). The other had ‘reservations about the concept of “trade”’ but otherwise also agreed. No other propositions are so directly relevant to the present issue.

66 In the light of that material, although I have in some other instances been prepared to regard his Honour’s recording of the agreed propositions as some indication that a determination as sought would reflect the reasons for judgment and his Honour’s intention, I am not able to do so in this instance. I do not think the factual foundation is shown to exist in or from the reasons for judgment to expressly determine that the applicants enjoy the native title right to fish for commercial purposes in the claim area. It is not a matter of being satisfied that such a traditional right existed, and either was extinguished (but for the operation of s 47A or s 47B) or was not recognised by the common law. It is simply that I do not consider that such a native title right according to traditional laws and customs was one that Selway J found to have existed, and to continue to exist.

67 It is therefore unnecessary to address the application of s 47A as argued by the applicants. The foundation for its possible application is not shown to exist. I do not regard his Honour’s acceptance of the applicants’ general entitlement, according to their traditional laws and customs, to control access to the inter-tidal zone in the claim area (which he then regarded as one not recognised under the common law) as providing a sufficiently specific foundation to so proceed.

68 In each of Yarmirr and Lardil, it was found that, as a consequence of the assertion of sovereignty that marked the imposition of a new source of authority, there could be no continuing traditional rights of exclusive possession in relation to waters of the sea and, by virtue of the public common law rights to fish and to navigate in the inter-tidal zone, in that area also.

69 His Honour at [243] said that a traditional right to exclude from an area of the sea or the inter-tidal zone is inconsistent with the common law public rights to fish and to navigate. His Honour further said at [247] that to the extent that the claimants or their ancestors possessed any exclusive or commercial right to fish, that right was extinguished in part by the various statutes dealing with fisheries which were applicable from time to time in the Northern Territory, so that what remained to the claimants was a non-exclusive right to take fish for non-commercial purposes. He went on to find at [251] that the extinguishing effects of any statutes relevantly could be disregarded, in particular of the fisheries legislation, over the whole of the area for grant including the inter-tidal zone by reason of s 47A of the NTA. That did not have the effect that ‘non-recognition’ by the common law of the traditional right of exclusive occupation of the tidal zone, by reason of the public rights to fish and navigate, is to be disregarded for the purpose of making a determination of native title.

70 In my view, the consequence of those findings is that his Honour regarded any rights possessed under traditional laws and customs to use the waters of the inter-tidal zone and outer waters for commercial purposes were simply rights which were not recognised by the common law, and so should not be the subject of a determination. In my view it would be inconsistent with his Honour’s reasons to include in the proposed determination that it is only in the case of the outer waters that fishing and other like activities could not exist for other than commercial purposes. However, I consider his Honour’s reasons recognise that fishing gathering and using resources within the area would include the exchange of those resources. That would have regard to the extent of the agreement between the anthropologists as recorded in Appendix 1 to the reasons for judgment.

71 I therefore propose, in this respect, to determine the applicants have the right to hunt, fish, gather and use resources within the area (including the right to hunt and take turtle and dugong) for personal, domestic or non-commercial exchange or communal consumption for the purposes allowed by or under their traditional laws and customs.