FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Global Brand Marketing Inc v Cube Footwear Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 852

PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – application to amend pleading – trade mark infringement – whether trade mark claim is arguable – whether manufacture of goods constitutes infringing use.

Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth): ss 10, 120(1)

Federal Court Rules: O 20 r 2

Hunter Douglas Australia Pty Ltd v Perma Blinds (1970) 122 CLR 49, cited

Advanced Switching Services Pty Limited v State Bank of New South Wales t/as Colonial State Bank (2001) ATPR 41‑848, applied

General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) (1964) 112 CLR 125, applied

Spotwire Pty Limited v Visa International Services Inc (2003) ATPR 41‑949, cited

The Shell Company of Australia Limited v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Limited (1963) 109 CLR 407, applied

MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd and Ors (1998) 90 FCR 236, cited

Fraser Henleins Pty Ltd v Cody (1945) 70 CLR 100, cited

Ex parte O’Sullivan; Re Craig (1944) 44 SR (NSW) 291, cited

Polaroid Corporation v Sole N Pty Ltd [1981] 1 NSWLR 491, cited

Southern Cross Refrigerating Company v Toowoomba Foundry Proprietary Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592, cited

Levi Strauss & Co v Wingate Marketing Pty Limited (1993) 43 FCR 344, cited

Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 365, cited

de Cordova v Vick Chemical Coy (1951) 68 RPC 103, considered

Powell v Glow Zone Products Pty Ltd (1997) 39 IPR 506, considered

BP Plc v Woolworths Ltd ((2004) 62 IPR 545, considered

Coca‑Cola Company v All‑Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107, considered

Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd (1999) 91 FCR 167, considered

Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd (2000) 100 FCR 90, considered

GLOBAL BRAND MARKETING INC v CUBE FOOTWEAR PTY LTD

(ACN 059 140 304) & ORS

VID 267 of 2004

GOLDBERG J

23 JUNE 2005

MELBOURNE

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

VID 267 of 2004 |

|

BETWEEN: |

GLOBAL BRAND MARKETING INC Applicant

|

|

AND: |

CUBE FOOTWEAR PTY LTD (ACN 059 140 304) First Respondent KAM WING DIU Fifth Respondent SHIRLEY MEI MEI HAU Sixth Respondent KITTY MIAO YUN LIU Seventh Respondent SHERITON FOOTWEAR PTY LTD (ACN 072 648 821) Eleventh Respondent KAHLON ENTERPRISES PTY LTD (ACN 098 616 507) Twelfth Respondent GURPREET SINGH KAHLON Thirteenth Respondent

|

|

GOLDBERG J |

|

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

23 JUNE 2005 |

|

WHERE MADE: |

MELBOURNE |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to the filing of Diesel SpA’s consent to be added as an applicant in the proceeding, the applicant be granted leave to add Diesel SpA as an applicant to the proceeding.

2. The applicant be granted leave to file and serve a Fourth Amended Application and a Fourth Amended Statement of Claim generally in the terms of the Fourth Amended Statement of Claim which is exhibit “LME‑11” to the affidavit of Lisa Maree Egan sworn 27 April 2005 within seven days of the date of this order.

3. The applicant pay the respondents’ costs of and incidental to the applicant’s motion filed on 19 April 2005 and any costs of the respondents thrown away by reason of the filing of a Fourth Amended Application and a Fourth Amended Statement of Claim.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

VICTORIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

VID 267 of 2004 |

|

BETWEEN: |

GLOBAL BRAND MARKETING INC Applicant

|

|

AND: |

CUBE FOOTWEAR PTY LTD (ACN 059 140 304) First Respondent KAM WING DIU Fifth Respondent SHIRLEY MEI MEI HAU Sixth Respondent KITTY MIAO YUN LIU Seventh Respondent SHERITON FOOTWEAR PTY LTD (ACN 072 648 821) Eleventh Respondent KAHLON ENTERPRISES PTY LTD (ACN 098 616 507) Twelfth Respondent GURPREET SINGH KAHLON Thirteenth Respondent

|

|

JUDGE: |

|

|

DATE: |

23 JUNE 2005 |

|

PLACE: |

MELBOURNE |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

introduction

1 The applicant, Global Brand Marketing Inc, applies by way of Notice of Motion to join Diesel SpA (“Diesel”) as an applicant to the proceeding and to amend the statement of claim by including a claim for trade mark infringement. The first, fifth, sixth, seventh and eleventh respondents (“the respondents”) oppose the application.

background

2 The proposed amendment should be considered against the following background. The initial statement of claim, filed on 3 March 2004, pleaded infringement of a registered design, copyright infringement, conduct in breach of ss 52 and 53 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), passing off and breach of agreement. There were three applicants named: World Brands Management Pty Ltd, Diesel and Global Brand Marketing Inc (“the original applicants”). An amended application and statement of claim was filed on 29 April 2004. The original applicants subsequently applied for leave to file and serve a Further Amended Application and Statement of Claim, and on 4 June 2004 Heerey J made orders granting leave to do so.

3 On 4 August 2004 the original applicants filed a Further Amended Application and Statement of Claim, which abandoned the claims of infringement of a registered design, conduct in breach of ss 52 and 53 of the Trade Practices Act and passing off. On 9 September 2004 World Brands Management Pty Ltd and Diesel discontinued their claims in the proceeding. On 17 September 2004 Merkel J made orders striking out the Further Amended Statement of claim and granting leave for the filing and service of a Third Amended Statement of Claim, which was subsequently filed on 13 October 2004. The Third Amended Statement of Claim contained claims for copyright and breach of agreement.

4 On 25 October 2004 the first respondent filed a motion for dismissal of the proceeding and to strike out the Third Amended Statement of Claim. I heard the notice of motion on 29 October 2004 and judgment was reserved. On 19 April 2005 the applicant filed a notice of motion seeking leave to join Diesel to the proceeding and to file and serve a Fourth Amended Application and Statement of Claim, which would include a claim for trade mark infringement.

5 On 22 April 2005 I dismissed the first respondent’s motion to strike out the statement of claim and for dismissal of the proceeding. The applicant’s motion to join Diesel to the proceeding and to include a claim for trade mark infringement was heard on 29 April 2005.

Registration of Diesel’s trade marks

6 On 29 January 2004, trade mark applications were lodged in the name of the applicant for the sole pattern of a shoe (“the sole mark”) and for the three‑dimensional shape of a shoe (“the shape mark”). On 11 June 2004 the applicant assigned the trade marks to Diesel. The sole mark was registered on 20 January 2005 and the shape mark was registered on 3 March 2005. However both marks are effectively registered from 29 January 2004, the date of the application to register. The significance of this is that at the time of the first respondent’s application to strike out the remaining cause of action for infringement of copyright an application for registration of a trade mark had been lodged. When Diesel discontinued the proceeding on 9 September 2004, it had applications for registration of trade marks pending and it was therefore open to Diesel to bring proceedings for trade mark infringement, albeit without the ability to obtain relief in the proceeding until registration of the marks: see Hunter Douglas Australia Pty Ltd v Perma Blinds (1970) 122 CLR 49 at 59.

7 The applicant now seeks to include in the statement of claim a cause of action for infringement of the sole mark and shape mark. The sole mark (No 986709) comprises a pattern for the sole of a shoe and is registered in the class concerning footwear. It comprises a cross‑hatched sole pattern, that is a pattern of angled lines that criss‑cross the sole of the shoe so as to give the effect of a series of equilateral triangles with raised dots at the corner of each triangle. At the heel end of the shoe there is a rectangle inserted into the sole, displacing the triangles, with a stylised letter “D” in the rectangle. The mark is depicted thus:

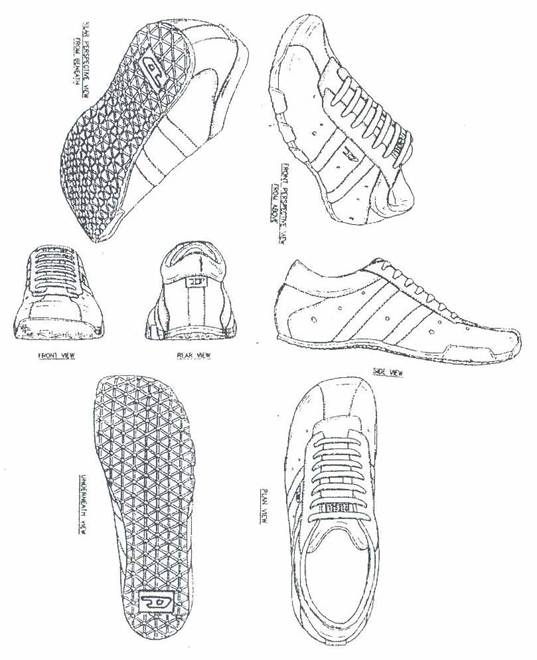

8 The three-dimensional shape mark (No 986713) comprises the sole mark, and six other visual angles of the shoe that show the shape of the footwear. The shape mark comprises a combination of the shape of a shoe and the stylised letter “D” and is also registered in the class concerning footwear. The registration of the shape mark is endorsed in the following terms:

“The trade mark consists of a combination of the stylised letter D together with the shape of a SHOE including its features as depicted in the representations accompanying the application form. The stylised letter D appears on the rear and outer side of the shoe; the sole comprises a rubber cross-hatched pattern with a square containing the stylised letter D; and two oblique stripes on either side of the shoe and one vertical stripe on the rear.”

The mark is depicted thus:

9 The solicitors for the applicant approved the above endorsement by a letter dated 13 October 2004 to the Trade Marks Examiner, in response to a second examination report that had declined to accept the registration. The letter stated:

“Thank you for your second examination report dated 11 October 2004.

We note that you are prepared to accept the above trade mark application if it is made clear that the application claims a combination of elements depicted on the representations of the shoe accompanying the application.

In accordance with the recommendation in your examination report, we request that the current application be amended to include the following revised endorsement clarifying the nature of the trade mark and the extent of the claim:

“The trade mark consists of a combination of the stylised letter D together with the shape of a SHOE including its features as depicted in the representations accompanying the application form. The stylised letter D appears on the rear and outer side of the shoe; the sole comprises a rubber cross-hatched pattern with a square containing the stylised letter D; and two oblique stripes on either side of the shoe and one vertical stripe on the rear.”

We trust this amendment satisfies all the issues identified in your examination report and we look forward to confirmation that the mark has been accepted.”

10 The respondents submitted that the joinder and amendment should not be allowed for the following reasons:

· The new claim for relief does not arise out of any facts or matters that have occurred or arisen since the commencement of the proceeding

· The proposed pleading of the cause of action in trade mark infringement is hopeless and unarguable.

· The selling of the footwear by the respondents does not constitute use of a trade mark

· In the circumstances, the Court should not exercise its discretion to allow the amendment:

o Diesel did not have proper title to sue at the date of issue of this proceeding in March 2004

o The applicants have delayed in bringing the claim, as the applicant could have brought the claim whilst registration was pending or in the time following registration

o The applicant’s conduct borders on an abuse.

11 The power to order joinder is found in O 6 r 8 and the power to order amendment to pleadings is found in O 13 r 2. The relevant principle to apply was re‑stated by Hely J in Advanced Switching Services Pty Limited v State Bank of New South Wales t/as Colonial State Bank (2001) ATPR 41‑848, at 43,486:

“Where a party satisfies a court that the party genuinely desires to amend the pleading so as to alter an existing claim or to introduce a new claim, leave should be granted, subject to proper terms, unless the proposed amendment is obviously futile or would cause substantial injustice which cannot be compensated for.”

12 Ordinarily a joinder and amendment will be allowed if the cause of action is arguable. Insofar as the respondents argue that the cause of action is hopeless, and should not be allowed, they are in effect relying upon O 20 r 2 of the Federal Court Rules and the principles set out in General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) (1964) 112 CLR 125 at 129 (“General Steel”). In Spotwire Pty Limited v Visa International Services Inc (2003) ATPR 41‑949, Bennett J summarised the manner in which the test in General Steel has been applied (at 47,410, par [10]):

“Such an order would only be made where it is clear that there is no real question to be tried (SmithKlein Beecham (Australia) Pty Ltd v Chipman[2002] FCA 674; Douglas v Tickner (1994) 49 FCR 507) or that it is hopeless and bound to fail (Orchard v Comrie(1998) 80 IR 76) or clearly untenable (Faessler v Neale (1994) 29 IPR 1) or hopeless to the extent that it should not be permitted to go to trial (Bray v F Hoffman‑La Roche (2003) ATPR 41‑946; [2003] FCAFC 153 per Carr J). It must be plain and obvious that the impugned portions of a statement of claim are unarguable (Murex Diagnostics Australia Pty Ltd v Chiron Corp (1995) 55 FCR 194) or it must be very clear that there is no issue deserving of a hearing (Anderson v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [1995] FCA 787). However, proceedings will not be dismissed summarily merely on the ground that it appears, at the hearing of the motion, that the claim may fail (Australia Building Industries Pty Ltd v Stramit Corp Ltd [1997] FCA 1318).”

In short, the joinder and amendment should not be allowed if I consider that such amendment would be hopeless and the cause of action cannot succeed.

Substantially identical or deceptively similar

13 In order to establish trade mark infringement under s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) the applicant must establish that the respondent has used as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the applicant’s trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

14 In order to determine whether the respondents’ marks are “substantially identical” or “deceptively similar” the Court must apply two separate tests: first, in respect of substantial identity, whether there is similarity when viewing the marks side by side; and secondly, in respect of deceptive similarity, whether the hypothetical consumer’s recollection of the marks in a trade context would cause them to wonder whether the goods shared the commercial origin of the registered trade mark. These tests were conveniently set out by Windeyer J in The Shell Company of Australia Limited v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Limited (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 414‑415 (“Shell v Esso”):

“In considering whether marks are substantially identical they should, I think, be compared side by side, their similarities and differences noted and the importance of these assessed having regard to the essential features of the registered mark and the total impression of resemblance or dissimilarity that emerges from the comparison. ‘The identification of an essential feature depends’ it has been said, ‘partly on the Court’s own judgment and partly on the burden of the evidence that is placed before it’: de Cordova v Vick Chemical Co. Whether there is substantial identity is a question of fact: see Fraser Henleins Pty Ltd v Cody, per Latham CJ and Ex parte O’Sullivan; Re Craig, per Jordan CJ, where the meaning of the expression was considered.

…

On the question of deceptive similarity a different comparison must be made from that which is necessary when substantial identity is in question. … The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. ... It is between, on the one hand, the impression based on recollection of the plaintiff’s mark that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have; and, on the other hand, the impressions that such persons would get from the defendant’s television exhibitions. To quote Lord Radcliffe again: ‘The likelihood of confusion or deception in such cases is not disproved by placing the two marks side by side and demonstrating how small is the chance of error in any customer who places his order for goods with both the marks clearly before him… It is more useful to observe that in most persons the eye is not an accurate recorder of visual detail, and that marks are remembered rather by general impressions or by some significant detail than by any photographic recollection of the whole’: de Cordova v Vick Chemical Co. And in Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd Dixon and McTiernan JJsaid: ‘In deciding this question, the marks ought not, of course, to be compared side by side. An attempt should be made to estimate the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers by the mark or device for which the protection of an injunction is sought. The impression or recollection which is carried away and retained is necessarily the basis of any mistaken belief that the challenged mark or device is the same.” [footnotes omitted]

15 Windeyer J’s decision in Shell v Esso was reversed on appeal. The appeal, however, concerned only the use of the mark and did not question the tests espoused by Windeyer J. The Full Federal Court has subsequently applied Windeyer J’s test for deceptive similarity as outlined above: MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd & Ors (1998) 90 FCR 236 at 245.

16 Determining whether marks are substantially identical requires a “test of resemblance”, which is a question of fact: Fraser Henleins Pty Ltd v Cody (1945) 70 CLR 100, per Latham CJ at 114‑115; Ex parte O’Sullivan; Re Craig & Anor (1944) 44 SR (NSW) 291, per Jordan CJ at 298; Polaroid Corporation v Sole N Pty Ltd [1981] 1 NSWLR 491.

17 Pursuant to s 10 of the Trade Marks Act, deceptive similarity is defined in the following manner:

“For the purposes of this Act, a trade mark is taken to be ‘deceptively similar’ to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion.”

18 Deceptive similarity requires a test related to the recollection of the consumer of the mark as it appears in its trade context. It is necessary for the Court first to determine the essential features of the trade mark and of the alleged infringing mark in any consideration of whether the infringing mark is deceptively similar.

19 The question is whether there is a real risk that the alleged infringing use will result in a significant number of persons being caused to wonder whether there is some association in the provenance of the goods: Southern Cross Refrigerating Company v Toowoomba Foundry Proprietary Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592 at 608; Levi Strauss & Co v Wingate Marketing Pty Limited (1993) 43 FCR 344 at 359. One aspect of the deceptive similarity test is that the consumer’s recollection will be imperfect. The degree of confusion required was articulated by the Full Federal Court in the following terms (Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 365 per French, Branson and Tamberlin JJ at 382 [50]):

“ To show that a trade mark is deceptively similar to another it is necessary to show a real tangible danger of deception or confusion occurring. A mere possibility is not sufficient.”

Are the respondents’ shoes substantially identical?

20 I have had the benefit of photographs of the alleged infringing footwear and footwear bearing the registered marks and the benefit of examining the footwear itself.

21 The soles of the respondents’ shoes disclose a cross hatched pattern of lines so as to form equilateral triangles in much the same manner as in the applicant’s sole mark. At the corners of each equilateral triangle sit embossed rubber dots. This pattern covers the whole of the shoe and there is no other mark on the sole.

22 If I apply the substantially identical test set out by Windeyer J in Shell v Esso I consider there is a strong case for saying that the soles of the respondents’ shoes are not substantially identical to the applicant’s sole mark. It may be said that the visual impression of each of them is quite different. For example, one sees prominently on the respondents’ shoes the absence of any rectangle and stylised “D”.

23 However, as Windeyer J pointed out, the identification of an essential feature depends not only on the Court’s own judgment but also on the burden of the evidence that is placed before it. It seems to me that Windeyer J was leaving open the opportunity for evidence to be led in respect of the issue of substantial identity. His Honour referred to the observation of the Privy Council in de Cordova v Vick Chemical Coy (1951) 68 RPC 103. Lord Radcliffe, delivering the opinion of the Privy Council, said at 106:

“The identification of an essential feature depends partly on the Court’s own judgment and partly on the burden of the evidence that is placed before it. A trade mark is undoubtedly a visual device; but it is well‑established law that the ascertainment of an essential feature is not to be by ocular test alone.”

Windeyer J also relied on the observation of Latham CJ in Fraser Henleins Pty Ltd v Cody (supra) at 115 that the question of substantial identity must be determined “as a question of fact”. See also Ex parte O’Sullivan; Re Craig (supra) at 298.

24 These observations make it clear that it is open to the owner of the trade mark to lead evidence in relation to the issue of the essential features of the registered trade mark and the issues of substantial identity. In these circumstances notwithstanding the tentative view which I expressed based upon my own judgment, I do not consider it appropriate to form a concluded view on the issue of substantial identity at this stage as the owner of the registered mark may wish to lead evidence on this issue. In such circumstances where the issue of the calling of evidence is open it is not appropriate to form a conclusion that the cause of action cannot be maintained on the issue of substantial identity.

25 I have formed the same conclusion in relation to the shape mark which is a combination mark. On one view it may be said that on the basis of a visual side‑by‑side comparison one sees two different shoes. It may be said that the absence of the stylised “D” or indeed any stylised letter at all, on various parts of the shoe and the differences in the sole patterns to which I have already referred, might lead to the conclusion that the respondents’ shoes are not substantially identical to Diesel’s marks. However this is a matter to which evidence may be addressed and I consider that it is not appropriate to form a concluded view on the viability of this cause of action at this stage.

26 I reach a similar conclusion at this stage of the proceeding in relation to the cause of action based upon deceptive similarity. Although there are significant issues in relation to the distinguishing features of the two marks I do not think that those issues can be resolved on what is in substance a strike out application.

27 The applicant submitted that the cross‑hatched pattern on the sole of the shoe may be a distinguishing feature of the sole mark, and that the use of that pattern on the infringing shoes could be use of the mark, notwithstanding the absence of the stylised letter “D”. The applicant relied on Powell v Glow Zone Products Pty Ltd (1997) 39 IPR 506 at 519, where Lehane J commented, in obiter, that the mark “GLO CAPS” could still infringe the appellant’s registered trade mark “CAPS THE GAME”, even if part of the infringing goods indicated a trade origin other than the appellant. In BP Plc v Woolworths Ltd (2004) 62 IPR 545 at 555 [23] (“BP”), Finkelstein J considered the trade mark in the colour green in respect of BP and found that in order to establish that green was a distinctive feature of the BP mark, BP must establish:

“…first, that it has used the particular shade of green as a trade mark and, second, that in the minds of the public the primary significance of that shade of green, when used in connection with the supply of petroleum products or the provision of petroleum services, identifies the source of those goods or the provider of those services as originating from a particular trader, though not necessarily from an identified trader.”

In that case expert evidence in marketing and psychology was led in order to understand the perception of the colour green in the retail context. His Honour found that the colour green, owing to its predominance in BP’s get up, was a badge of origin (at [62]). The applicant submitted that the cross‑hatched sole pattern could be similarly distinctive.

28 The applicant also relied upon Coca‑Cola Company v All‑Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107 (“Coca‑Cola”), a case concerning the shape mark in the well known Coca Cola bottle. In that case the Full Federal Court stated the question as being whether consumers are being invited to purchase the alleged infringing product which is to be distinguished from that of other traders partly because they have the features of the sign or mark: at 118 par [26] and cases there cited. The applicant submitted that consumers of the infringing footwear are being invited to purchase such footwear on the basis that it contains the cross‑hatched sole pattern that is a feature of the sole mark.

29 The respondents submitted that the Court must consider which elements of the mark confer distinctiveness and that it is clearly the stylised letter “D” that is distinctive of Diesel’s marks. The respondents submitted that the absence of the stylised “D” on the respondents’ footwear would therefore be a strong indicator of lack of distinctiveness.

30 The respondents distinguished the cases relied upon by the applicants. The respondents contended that Powell v Glow Zone Products Pty Ltd (supra) did not concern an endorsement and the factually distinctive element of the mark was “CAPS”, which was used by the infringing mark. BP was a case of acquired distinctiveness, which the applicant does not allege in the present case. Similarly, Coca‑Cola concerns a famous mark with an enormous reputation, and the same cannot be said of the sole mark.

31 The respondents submitted that in order for the applicant to succeed it must prove that the cross‑hatching was sufficiently distinctive of the sole mark such that its use on the alleged infringing footwear, without the stylised letter “D”, constitutes use of the mark. This is a difficult case to prove, and the difficulty, according to the respondents, is indicated by the fact that the applicant has previously abandoned claims based on reputation, namely the Trade Practices claims and passing off.

32 There is substance in the respondents’ submissions, but although the applicant has a difficult case to prove in relation to the sole mark and the shape mark, I am not satisfied that the case is unarguable or hopeless or bound to fail in the manner set down by the High Court in General Steel. In any event, I do not need to determine the point finally, because the question of deceptive similarity is one to be determined at trial.

33 The test necessarily concerns consumers’ recollection of the marks in a trade context. It is by its nature therefore not a matter that can be determined at this stage. The applicant conceded that the absence of the stylised D makes its case difficult, but contended that evidence may establish that the cross‑hatched sole pattern is the distinctive feature of the sole mark. According to the applicant, it is therefore necessary for the Court to hear evidence of consumers’ recollections and impressions of the marks and the relevant footwear, and any expert evidence as to the manner in which consumers perceive brands, before the Court is in a position to understand whether any consumers might be deceived by the infringing footwear. The shoes in question appeal to a particular group of consumers, and the Court should have evidence from the relevant consumers, presumably young people, of the fad and whether the brand is distinguished by the cross‑hatched sole pattern in the absence of the stylised D.

34 Counsel for the respondents also acknowledged that whether there is deception in any similarity is a matter to be determined according to evidence. The respondents contended that they branded their shoes differently and that the shoes were markedly different in other ways, such that it was a fanciful possibility at best that there would be any deception.

35 I consider that the factual question of the deceptive similarity of the mark and the respondents’ shoes is therefore a matter of fact that is to be determined on the evidence led at trial. It is never appropriate for the Court to strike out a claim where the ultimate resolution of the question relies upon disputed matters of fact: Unilan Holdings Pty Ltd and Ors v Kerin (1992) 35 FCR 272 at 275 per Hill J.

Use as a Trade Mark

36 The respondents submitted that in any event their conduct does not amount to use as a trade mark in the necessary manner. The conduct alleged against the respondents is merely the sale of the shoe, and not any ancillary marketing, brochures or packaging. A problem encountered in the protection of shape marks is that the distinctive aspects of the mark that distinguish the commercial origins of the goods can be protected, but the functional shape cannot. In Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd (1999) 91 FCR 167 at 182 [44] (“Philips v Remington”), Lehane J considered the nature of the use that will constitute infringement:

“The legal test is not in doubt. There are a number of well known formulations and there is no need to repeat a large selection of them. The test derives from the definition of “trade mark” itself:

‘With the aid of the definition of “trade mark” in s 6 of the Act, the adverbial expression may be expanded so that the question becomes whether, in the setting in which the particular pictures referred to were presented, they would have appeared to the television viewer as possessing the character of devices, or brands, which the appellant was using or proposing to use in relation to petrol for the purpose of indicating, or so as to indicate, a connection in the course of trade between the petrol and the appellant…. (Shell at 425)’”

37 The sale of the shoes in this case, must therefore indicate a connection in the course of trade between the infringing goods and Diesel. The respondents submitted that as the alleged infringing shoes do not bear the stylised letter “D”, and therefore effectively do not contain branding, their sale cannot indicate any connection with Diesel and therefore that sale does not amount to an infringement of the sole mark (or the shape mark). Put another way, the respondents have not used the stylised D, the essential element of the mark, as a sign to establish any trade connection with Diesel.

38 In Philips v Remington Lehane J considered the sale and marketing of a triple headed rotary shaver, in which Philips claimed trade mark monopoly. Lehane J found that the manufacturing of the alleged infringing shaver by Remington alone did not constitute trade mark use, as it was not a use of the shape to denote origin (see pars [49]‑[50]).

39 The respondents therefore submitted that the mere creation of the functional shape of a mark is not to use it as a trade mark. The applicants must prove reputation in the distinctive shape, here the distinctive cross‑hatched sole pattern, such that the creation of that pattern on the sole of the respondents’ shoes could denote that the origin of the respondents’ shoes is in fact Diesel.

40 On appeal in Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd (2000) 100 FCR 90 (“Philips on appeal”), Burchett J noted at 100 [12]:

“In my opinion, merely to produce and deal in goods having the shape, being a functional shape, of something depicted by a trade mark (here the marks do depict, one more completely than the other, a working part of a triple rotary shaver) is not to engage in a “use” of the mark “upon or in physical or other relation to, the goods” within s 7(4), or to “use” it “in relation to the goods” within s 20(1). “Use” and “use”, in those contexts, convey the idea of employing the mark, (first) as something that can be “upon” or serve in a “relation” to the goods, and (and secondly) so as to fulfil a purpose, being the purpose of conveying information about their commercial origin. The mark is added, as something distinct from the goods. It may be closely bound up with the goods, as when it is written upon them, or stamped into them, or moulded onto them … But in none of these cases is the mark devoid of a separate identity from that of the goods. The alternative ways of using a trade mark in relation to goods do not include simply using the goods themselves as the trade mark. The reason is plain: it is to be assumed that goods in the mark are useful, and if they are useful, other traders may legitimately wish to produce similar goods (unless, of course, there are, for the time being, subsisting patent, design or other rights to prevent them from doing so), and it follows that a mark consisting of nothing more than the goods themselves could not distinguish their commercial origin, which is the function of the mark: Johnson & Johnson at 342 and 348‑9.”

41 The endorsement contained on the shape mark suggests that something more than the functional shape is required in order to constitute infringement. The absence of the stylised D on the infringing footwear, which is an essential element of the mark by the terms of the endorsement, indicates that the reproduction of the goods themselves, the footwear, cannot distinguish the commercial origin of the infringing footwear and is therefore not use of the mark.

42 The applicants submitted that shape marks can be registered where the goods remain distinct from the mark, and that Philips on appeal stated that the mark may be “closely bound up with the goods” (at par [12] per Burchett J). The applicant relied upon Coca‑Cola and BP and again submitted that the Court must determine whether the shape sufficiently distinguishes the goods to the extent that it becomes a mark in its own right. This determination requires a consideration of context and representations of the cause of origin that would be the subject matter of evidence at trial.

43 The respondents submitted that the cause of action for trade mark infringement was bound to fail because merely trading in a product bearing a shape did not amount to trade mark use. It was submitted that there could be no suggestion of infringing a trade mark merely by selling shoes bearing the shape the subject of the trade mark. The respondents relied upon Philips v Remington and Philips on appeal. In Philips on appeal, Burchett J said at 103‑104 (par [16]):

“It does not follow that a shape can never be registered as a trade mark if it is the shape of the whole or a part of the relevant goods, so long as the goods remain distinct from the mark. Some special shape of a container for a liquid may, subject to the matters already discussed, be used as a trade mark, just as the shape of a medallion attached to goods might be so used. A shape may be applied, as has been said, in relation to goods, perhaps by moulding or impressing, so that it becomes a feature of their shape, though it may be irrelevant to their function. Just as a special word may be coined, a special shape may be created as a badge of origin. But that is not to say that the 1995 Act has invalidated what Windeyer J said in Smith Kline. The special cases where a shape of the goods may be a mark are cases falling within, not without, the principle he expounded. For they are cases where the shape that is a mark is ‘extra’, added to the inherent form of the particular goods as something distinct which can denote origin. The goods can still be seen as having, in Windeyer J’s words, ‘an existence independent of the mark’ which is imposed upon them.”

(See also Coca‑Cola at pars [24], [25]‑[36], [39]‑[41]; BP at pars [23], [60], [62] and [65]).

44 The applicant put its submission in the following terms:

“The issue becomes one of determining whether the shape sufficiently distinguishes the goods as to become a mark in its own right, being fundamentally an issue for trial after consideration of context and in particular representations as to source of origin.”

I am disposed to accept this submission at the present stage. I consider it too early to determine whether the matter can simply be resolved, as the respondents put it, on the basis simply that “merely trading in a product bearing a shape does not amount to trade mark use”. It may well be that there are issues of evidence in context which are relevant in the determination of this issue.

Discretion to grant amendment

45 The respondents raised a number of issues which they submitted should be taken into account when exercising discretion to amend the pleadings. These issues are:

· delay in bringing the proceeding following registration;

· the earlier discontinuance of the proceeding by Diesel;

· a retrospective assignment of registration of the trade mark

· the pleadings do not disclose matters that have arisen since the commencement of the proceeding.

46 Although there has been delay in seeking to bring the proceeding for trade mark infringement following the application for registration of the marks I do not consider that that delay should be determinative of the application for leave to join Diesel and amend the statement of claim. I make the same observation in relation to the earlier discontinuance of the proceeding by Diesel and the fact that the amendment discloses matters which have existed for some time. If I were to refuse the joinder and the amendment it would only result in a further proceeding being commenced with the desirability thereafter of consolidation of the two proceedings. It seems to me that this is only productive of extra costs and not efficiency.

47 I have taken these matters into account in the exercise of my discretion, and do not consider that they are determinative of the application. The interests of justice require that the applicant be given the opportunity to raise arguable claims in court. On these bases I will order that subject to compliance with O 6 r 8(2) of the Federal Court Rules, the filing of Diesel’s consent to be joined as an applicant, Diesel be joined as an applicant in the proceeding and that leave be granted to file and serve an amended statement of claim in the form exhibited to the affidavit of Lisa Egan (LME‑11).

costs

48 The usual costs rule on an application for joinder and amendment is that the party seeking the amendment pays the costs of the application for leave to join and amend and occasioned by and thrown away by virtue of the amendment in any event unless the application is unreasonably opposed by the respondent. In effect the applicant has sought an indulgence. Although I have not accepted a number of the respondents’ submissions, I do not consider that their objections to the joinder and amendment were unreasonable, having regard to the sequence of events in this proceeding to which I have referred earlier. The respondents should have their costs of the application to join and amend and any costs thrown away by the amendment.

|

I certify that the preceding forty‑eight (48) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Goldberg. |

Associate:

Dated: 23 June 2005

|

Counsel for the Applicant: |

C Golvan S.C. |

|

|

|

|

Solicitor for the Applicant: |

Middletons |

|

|

|

|

Counsel for the First, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh and Eleventh Respondents: |

G McGowan S.C. |

|

|

|

|

Solicitor for the First, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh and Eleventh Respondents: |

West & Co |

|

|

|

|

Date of Hearing: |

29 April 2005 |

|

|

|

|

Date of Judgment: |

23 June 2005 |