FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fortis Bank (Nederland) N.V v “MSC Sumatra” [2003] FCA 524

ADMIRALTY – arrest of ship on time charter – whether property in bunkers retained by charterer – whether property in reefer spare parts retained by charterer – whether bunkers and provisions consumed subsequent to arrest are an expense of the Marshal

Den Norske Bank (Luxembourg) SA v The Ship “Martha II”, Sheppard J, unreported, 6 March 1996 cited

The “Span Terza” [1984] 1 Lloyd’s Law Reports 119 followed

Fraser Shipyard and Industrial Centre Ltd v The “Atlantis II” (1999) 170 FTR 1 distinguished

Den Norske Bank (Luxembourg) SA v The Ship “Martha II” [2000] FCA 241 cited

“The Honshu Gloria” [1986] 2 Lloyd’s Law Reports 63 cited

Osborn Refrigeration Sales & Service Inc v The “Atlantean I” [1979] 2 FC 661 cited

M Wilford, Time Charters, 4th edn, Lloyd’s of London Press Ltd, 1995

N Meeson, Admiralty Jurisdiction and Practice, 2nd edn, LLP, 2000

FORTIS BANK (NEDERLAND) N.V. v THE SHIP “MSC SUMATRA”

W52 OF 2003

LEE J

30 MAY 2003

PERTH

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

W52 OF 2003 |

IN ADMIRALTY

|

BETWEEN: |

FORTIS BANK (NEDERLAND) N.V. PLAINTIFF

|

|

AND: |

THE SHIP “MSC SUMATRA” DEFENDANT

|

|

LEE J |

|

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

PERTH |

THE COURT ORDERS AND DECLARES THAT:

1. The bunkers on board the defendant ship at the time of arrest on 7 March 2003 are and remain the property of the intervenor, MSC Mediterranean Shipping Company SA (“MSC”).

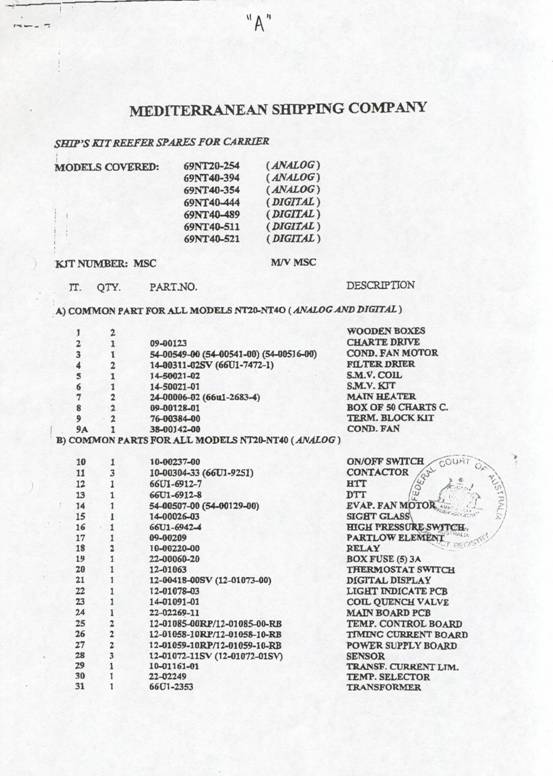

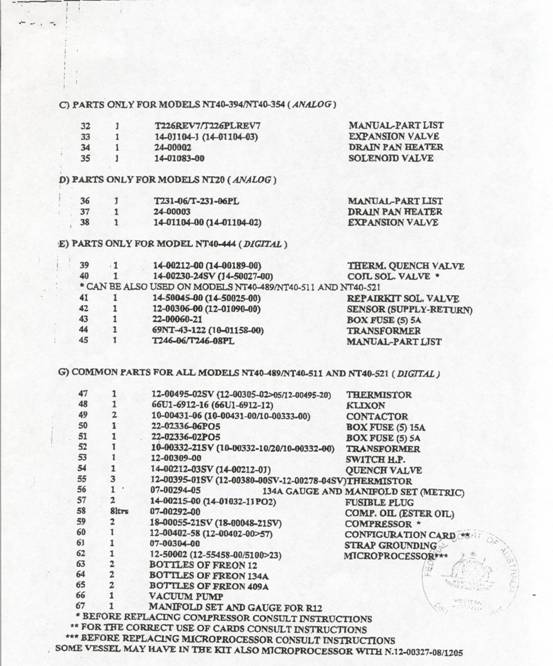

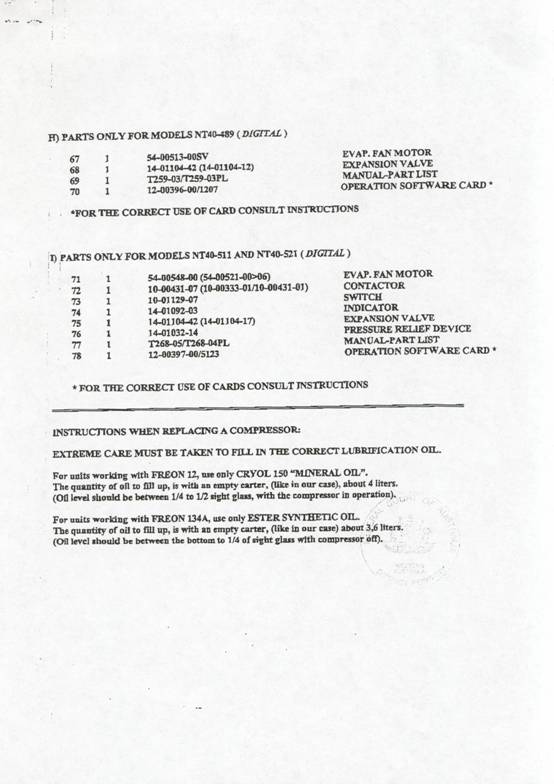

2. The reefer spare parts on board the defendant ship as itemised in Schedule “A” attached hereto are and remain the property of MSC.

3. MSC and/or its nominated representatives are permitted to board the defendant ship to take such steps as are reasonably necessary to remove the reefer spare parts referred to in item 2 above.

4. So much of the bunkers referred to in item 1 above as has been consumed between the arrest and re-bunkering of the vessel is an expense incurred by the Marshal to be paid by the Marshal to MSC before release of the vessel from arrest.

5. Costs be reserved.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

W52 OF 2003 |

IN ADMIRALTY

|

BETWEEN: |

FORTIS BANK (NEDERLAND) N.V. PLAINTIFF

|

|

AND: |

THE SHIP “MSC SUMATRA” DEFENDANT

|

|

JUDGE: |

LEE J |

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

23 MAY 2003 |

|

WHERE MADE: |

PERTH |

THE COURT ORDERS AND DECLARES THAT:

- At all material times MSC has had leave to intervene and make application for orders in respect of property in the bunkers.

- The extracted form of the orders made on 10 April 2003 be recalled and item 4 thereof amended to conform with the orders pronounced by the Court on that day. Further item 4 thereof, and item 5 of the orders made on 1 April 2003, be varied to provide that the period in which calculation of the amount of the bunkers consumed between the arrest and rebunkering of the vessel commence from the time MSC completed the discharge of cargo from the vessel pursuant to the order made on 11 March 2003.

3. By 28 May 2003 MSC is to file a minute of the calculation made pursuant to item 2 above.

- By 28 May 2003 the Marshal is to file an affidavit setting out the costs incurred by the Marshal for the sale by the Marshal of the bunkers of MSC, and for the sale of the vessel.

5. By 28 May 2003 MSC is to file submissions on orders for costs of MSC’s application. The plaintiff to file submissions in reply by 3 June 2003.

- The matter is adjourned to 4 June 2003 at 2.15pm.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

WESTERN AUSTRALIA DISTRICT REGISTRY |

W52 OF 2003 |

IN ADMIRALTY

|

BETWEEN: |

FORTIS BANK (NEDERLAND) N.V. PLAINTIFF

|

|

AND: |

THE SHIP “MSC SUMATRA” DEFENDANT

|

|

JUDGE: |

LEE J |

|

DATE: |

|

|

PLACE: |

PERTH |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 This is an interlocutory application by an intervening third party, MSC Mediterranean Shipping Company SA (“MSC”), in a proceeding in rem in admiralty commenced by a writ for the arrest of the defendant ship “MSC Sumatra” (“the vessel”). The writ was issued by the plaintiff (“the mortgagee”) on 7 March 2003. On the same day the Admiralty Marshal of the Court arrested the vessel at its berth in the Port of Fremantle, shortly before the vessel was due to sail for foreign ports to deliver cargo. The vessel is a cargo ship of approximately 17,300 gross registered tonnes.

2 Under a loan agreement dated 11 July 1995, made between the owner of the vessel, Dexlex Shipping Company Limited (“Dexlex”), and others, as borrowers, and the mortgagee and another, as lenders, the lenders agreed to lend to the borrowers a sum of US$85 million. The borrowers agreed to provide security for that loan by mortgages to the lenders over the vessel and other vessels owned by the borrowers.

3 As “Security Trustee” under the loan agreement, the mortgagee was authorised to commence this proceeding on behalf of the lenders.

4 In October 1995 the borrowers drew-down US$81,250,000 of the sum agreed to be advanced by the lenders. Pursuant to the loan agreement, the borrowers reduced the sum borrowed by quarterly payments. Payments by the borrowers ceased in early 2002. At that time the sum outstanding was US$25 million. In 2002 the borrowers sold five ships mortgaged to the lenders and applied the proceeds of sale in reduction of the loan debt. Thereafter the borrowers were unable to make any further payments as they fell due under the loan agreement. As at 29 January 2003, the sum outstanding was US$13,786,103.

5 On 6 March 2003 the lenders gave notice to the borrowers that they were in default under the loan agreement and on 7 March arrested the vessel. Subsequent to the arrest Dexlex did not file an appearance nor did it attempt to provide security for release of the vessel.

6 At the time of arrest the vessel was on time charter to MSC, an operator of a fleet of cargo ships. The form of charterparty executed by MSC and Dexlex was described as “Approved by the New York Produce Exchange” (1946 revision). The parties excised some provisions from the form and added others. The vessel was chartered for a period of one year from 17 March 2002. Pursuant to the terms of the charterparty, Dexlex provided, and was responsible for the provisioning of, the Master and crew of the vessel. The Master and crew were of Russian nationality. On 11 March 2003, MSC applied to the Court, under r 49(3) of the Admiralty Rules, for an order permitting MSC to unload eighty containers of cargo from the vessel whilst it remained at its berth at the port and to land the containers on the wharf. Seventy-seven of those containers had been loaded at Fremantle and three at Sydney. The cargo in the containers included potatoes, flour and frozen meat. It was the intention of MSC that the containers be loaded on another vessel operated by MSC that was due to berth at the port within several days.

7 The application was not opposed by the mortgagee which foreshadowed that it would be seeking an order that the vessel be sold. In all the circumstances it was appropriate that such an order be made in respect of the cargo. (See: Den Norske Bank (Luxembourg) SA v The Ship “Martha II”, Sheppard J, unreported, 6 March 1996). Accordingly, on 11 March an order was made that MSC be permitted to remove the containers from the vessel, subject to MSC filing a further affidavit deposing that the shippers of the cargo agreed with the proposed action and that steps had been taken to provide safe and adequate storage for the cargo, particularly refrigerated goods, pending transhipment. In due course the containers were removed from the vessel.

8 On 12 March MSC filed a caveat against release of the vessel from arrest, formally giving notice of its interest as time-charterer of the vessel.

9 On 26 March the mortgagee applied for orders, inter alia, that the Marshal have the vessel appraised and sold; that the vessel be moved from the harbour berth to a safe anchorage; that only a “skeleton” crew be retained pending sale of the vessel; that the entitlements of the crew be paid and that the surplus crew be repatriated to St Petersburg. On 28 March orders were made for the Marshal to pay and repatriate part of the crew; for the vessel to be moved by the Marshal from the port to a safe place of anchorage; and for the expenses of the Marshal in respect of the foregoing to be covered by the undertaking provided by the mortgagee for reimbursement of the Marshal for costs and expenses incurred by the Marshal in the course of the arrest.

10 On 31 March MSC applied for an order that there be a declaration that the bunkers and the reefer spare parts on the vessel remained the property of MSC and that it be ordered that the Marshal reimburse MSC for the amount of bunkers consumed since the arrest.

11 On 1April an order was made that the Marshal have the vessel appraised and sold. It was also ordered that the Marshal consult with the Master, the mortgagee, MSC, and with a providor that had supplied provisions to the vessel before the arrest on terms on which the providor retained ownership in the goods pending payment therefor, and compile an inventory of the property on board the vessel that was property owned by persons other than Dexlex, and, therefore, excluded from sale of the vessel. It was also ordered that so much of the bunkers, and of the provisions supplied by the providor, consumed since the arrest, be an expense of the Marshal payable to the owner of that property from proceeds of sale of the vessel.

12 On 3 April, in default of an appearance by Dexlex, the mortgagee applied for judgment in the sum of US$13,786,103. On 4 April it was ordered that summary judgment be entered against Dexlex in that sum, the borrowers being jointly and severally liable to the lenders under the loan agreement.

13 On 10 April it was declared that the bunkers on board the vessel at the time of arrest and the reefer spare parts, were the property of MSC. It was ordered that MSC be permitted to remove the reefer spare parts from the vessel. In respect of the bunkers, MSC advised the Court that it was taking steps to ascertain whether arrangements could be made to remove from the vessel, bunkers that were the property of MSC. The Court was asked to refrain from making any further order in respect of the bunkers pending those negotiations. On 1 May the orders made on 10 April were varied by adding a further order that on behalf of MSC the Marshal sell the property of MSC in the bunkers. On 16 May the Marshal sold the vessel, and the property of MSC in the bunkers, to the same purchaser.

14 At about that time solicitors for MSC were informed by the Court that the extracted form of the orders made on 10 April did not conform with the orders pronounced by the Court, insofar as the extracted form of the order provided that the mortgagee had been ordered jointly and severally with the Marshal to pay MSC for the cost of bunkers consumed after the date of arrest of the vessel and that the extracted order must be amended. Further, the parties were invited to make submissions on why the orders made on 1 and 10 April should not be varied to provide that the calculation of the amount of the bunkers that had been consumed subsequent to the arrest commence from the time MSC completed the discharge of cargo from the vessel on or after 11 March and not from the time of arrest on 7 March.

15 On 23 May, after hearing the parties on the issue of amendment of the orders made on 1 and 10 April, I was satisfied that pursuant to O 35 r 7(2)(c) of the Federal Court Rules amendment to the interlocutory orders made was necessary to prevent the occurrence of an injustice. Whether MSC obtained a benefit or advantage from the use of its bunkers between the time of arrest of the vessel and the time of discharge from the vessel of cargo MSC had contracted to carry on board the vessel, was not an issue addressed by the parties at the time the order was made. (See: Allstate Life Insurance Co v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group (1995) 133 ALR 667 per Lindgren J at 675.) Accordingly I directed, first, that the extracted form of the order made on 10 April be amended to conform with the orders pronounced by the Court on that day and, second, that the orders made on 1 and 10 April be further amended by varying the period in which the amount of bunkers of MSC consumed by the vessel after the arrest was to be calculated by stipulating that the commencement of the period be the time at which MSC completed the discharge of cargo from the vessel pursuant to the order in that regard made on 11 March.

16 I turn now to the reasons for the foregoing orders as to property in the bunkers and reefer spare parts and that the bunkers and provisions consumed subsequent to arrest be an expense of the Marshal to be reimbursed by the Marshal to MSC, and the providor, out of the proceeds of sale of the vessel.

17 I am satisfied by the evidence adduced that the reefer spare parts on the vessel were parts MSC had acquired and placed on the vessel for use in the carriage of cargo on behalf of MSC in the course of the charter. Property in the reefer spare parts remained with MSC at all times. MSC should be permitted, at its cost, to remove those parts from the vessel.

18 In regard to the issue of property in the bunkers on the vessel at the time of arrest, it is necessary to have regard to the terms of the charterparty. The charterparty provided that MSC was to pay Dexlex for bunkers delivered with the vessel at the commencement of the charter and MSC was to be reimbursed by Dexlex for bunkers on board when the vessel was redelivered to Dexlex on completion of the charter. Under the charterparty MSC undertook to redeliver the vessel with the quantity of bunkers supplied by Dexlex at the commencement of the charter, namely, approximately 500 tonnes of fuel oil and fifty tonnes of “gas oil”. In the period of the charter MSC was to provide and pay for all bunkering. The value of bunkers on board the vessel at the time of arrest was approximately $250,000.

19 The vessel consumes about three to four tonnes of fuel per day at sea and consumes about three tonnes per day of “gas oil” in maintaining the operating systems of the vessel. The arrest was an event for which Dexlex was responsible and the vessel may be taken to have been “off hire” from the time of arrest (see: M Wilford, Time Charters, 4th edn, Lloyd’s of London Press Ltd, 1995, p 387). However, the vessel was not “redelivered” to Dexlex by the act of arrest. Insofar as the vessel was “off hire”, the rights and obligations of the parties to the charterparty continued notwithstanding the arrest. (See: Wilford pp 222, 377; N Meeson, Admiralty Jurisdiction and Practice, 2nd edn, LLP, 2000, par 4-054)

20 The charterparty required MSC to acquire all fuel installed in the bunkers during the course of the charter. The bunkers were used for the purposes of MSC as charterer of the vessel. The charterparty did not provide that MSC supply Dexlex with fuel for the bunkers, the fuel to become the property of Dexlex for use by Dexlex for the purposes of MSC. As charterer MSC had control of, and property in, the fuel it brought on board the vessel, notwithstanding that Dexlex, through the Master and crew, had permission to take and use that fuel to propel and operate the vessel.

21 Whilst the vessel was under arrest the Marshal, and persons deputed by him to take care of the vessel, had custody of the vessel. Custody was obtained by the Marshal as an officer of the Court in furtherance of the Court process commenced by the mortgagee. Although it may be said that the Marshal did not obtain possession of the vessel upon arrest (see: Meesonpar 4-054), in taking custody of the vessel the Marshal controlled the vessel, and did so, in relevant respects, to the exclusion of Dexlex.

22 In the instant case the arrest of the vessel continued until sale of the vessel had been effected. If the charterparty were terminated by reason of the arrest there was no provision in the charterparty to the effect that Dexlex would succeed to the property of MSC in the bunkers, Dexlex thereafter becoming liable in personam to MSC to account and pay for the bunkers so acquired.

23 If the arrest of a ship by reason of default of the owner results in termination of a charterparty by the charterer, the charterer would be entitled to recover its property from the vessel forthwith and any right of possession in respect of that property that the owner may have had as bailee would come to an end. (See: Wilford, p 228). Where the property is a bulk liquid in the bunkers of the vessel, the charterer may have difficulty, and incur expense, in attempting to recover its property but such a circumstance would not oblige a conclusion in law that the property of the charterers in the bunkers passed to the owner.

24 The provisions of the New York Produce Exchange form of charterparty were considered by the House of Lords in The “Span Terza” [1984] 1 Lloyd’s Law Reports 119. Their Lordships held that proper construction of clauses similar to those considered in this case was that property in the bunkers remained with the charterer at all material times. In particular it was held that the termination of the charterparty by the charterer after arrest of the vessel did not constitute redelivery of the vessel to the owner nor pass property in the bunkers to the owner. Their Lordships held that upon termination of the charterparty in such a circumstance any right the owner had, through the Master and crew, to use and consume the bunkers for the purpose of the charterparty also came to an end. (See: The “Span Terza” per Lord Diplock at 122-123). Unless the charterparty clearly provided otherwise in respect of the consequences of arrest of the vessel, it would seem to be consonant with the statement of their Lordships to conclude that when, by reason of the arrest of the vessel caused by the default of Dexlex, MSC lost the use of the vessel as charterer, Dexlex thereupon obtained no right to use the property of MSC in the bunkers for application by Dexlex to the purpose of the Marshal.

25 Under the charterparty MSC gave directions to the Master and crew as to its requirements for use of the vessel and the charterparty contemplated that the property of MSC in the bunkers became available to Dexlex for use in service of that purpose. Clause 20 of the charterparty also provided that whilst the vessel was “off hire” Dexlex was permitted to use bunkers supplied to the vessel by MSC and account to MSC for that use. However, that clause was predicated on the assumption that when the vessel was “off hire” Dexlex resumed control of the use of the vessel until resumption of the charter. In its terms, the clause had no effect where the vessel came “off hire” by reason of arrest of the vessel caused by an act or default of Dexlex. Upon such an arrest the Marshal took custody of the vessel to the exclusion of Dexlex and thereafter directed the Master and crew as to management and control of the vessel. That is to say the Master and crew became subject to the direction of the Marshal, not Dexlex, in respect of the use of the vessel.

26 The Marshal had custody of the vessel to preserve it for the purpose of the litigation. It may be said, subject to the further comments made below in respect of preservation of the cargo, that from the time of arrest, which resulted in MSC losing the use of the vessel and the ability to exercise its rights under the charterparty, consumption of the bunkers thereafter served the purpose of the Marshal in carrying out his duty of protecting and preserving the vessel for the mortgagee, and others, and not the purpose of MSC.

27 The mortgagee did not “actively oppose” the application by MSC to obtain a declaration as to its property in the bunkers and in the reefer spare parts but did oppose MSC’s application for an order that the Marshal reimburse MSC for bunkers consumed whilst the vessel was in the custody of the Marshal pursuant to the arrest.

28 Whilst the vessel was at the harbour berth and the cargo loaded by MSC remained on board, the vessel’s systems were operated by the Master and crew, under direction of the Marshal, for purposes that included, in significant respects, the purposes of MSC. MSC had an interest in the cargo it had loaded being duly cared for and secured, in particular the refrigerated goods and perishables. Maintaining the operating systems of the vessel was necessary for that purpose to be effected. Whether the interest of MSC in that outcome arose out of contractual obligations with, or a duty of care owed to, cargo owners or shippers, or out of a desire by MSC to preserve any reputation it may have as an efficient and reliable carrier of such cargo was immaterial. Consumption of “gas oil” by the vessel subsequent to the arrest and up to the point of discharge of the containers onto the wharf by MSC, should be taken to have been necessary in a material degree to serve the interests of MSC and, therefore, should not be taken to be a liability to MSC incurred by the Marshal. It was not submitted by any party that the “gas oil” so consumed could, or should, be apportioned.

29 In respect of the bunkers used in moving the vessel from the harbour berth to a place of anchorage, that step was taken pursuant to an order obtained by the mortgagee to preserve the vessel for sale and to further the interests of the mortgagee. Therefore, the fuel consumed for that purpose should not be treated as fuel used for the purpose or benefit of MSC.

30 In opposing the order sought by MSC that the Marshal reimburse it in respect of fuel consumed after arrest, the mortgagee relied upon a decision of the Prothonotary of the Federal Court of Canada in Fraser Shipyard and Industrial Centre Ltd v The “Atlantis II” (1999) 170 FTR 1 at [41] – [52] in which the learned court officer held that bunkers owned by a charterer and consumed whilst the chartered vessel was under arrest at Vancouver was fuel used by the owner of the vessel, against whom the charterer could maintain a claim in personam in respect of the cost of the fuel used. Alternatively, it was held that if the fuel consumed were treated as fuel supplied by the charterer to the arrested vessel, recovery of the cost of that fuel would be a right in rem held by the charterer against the vessel, being a right of no higher priority than other claims against the vessel. In the instant case, as in The “Atlantis II”, the secured claims of the mortgagee will absorb the entire proceeds of sale and no claims against the vessel, other than claims superior in priority to that of the mortgagee, will be paid from those proceeds.

31 The foundation for the Prothonotary’s conclusion was that whilst the charterers had rendered a valuable service to the vessel, the charterer had done so “outside…the framework of a marshal’s supervision or of any court order”. The circumstances considered in The “Atlantis II” may be distinguished from those that apply in the instant case, where it may be said that the bunkers were consumed under the Marshal’s supervision.

32 Under r 47 of the Admiralty Rules, and under admiralty law and practice at the time of arrest, the Marshal became responsible for the safety and care of the vessel and property, including cargo. (See: Den Norske Bank (Luxembourg) SA v The Ship “Martha II” [2000] FCA 241 at [41]). That duty included an obligation to make arrangements for the supply of fuel to the vessel if the owner of the vessel had no fuel on board. The Marshal could not direct the Master and crew to use bunkers that were not the property of Dexlex, being property that Dexlex no longer had a right to use under the charterparty. It followed that the Marshal could not convert MSC’s right in the property to an in personam right against Dexlex in respect of the bunkers consumed for purposes of the Marshal. If an order of the Court had been sought by the Marshal, to enable the Marshal in all the circumstances, to use the property of MSC, it would have been a term of that order that the Marshal reimburse MSC for the cost of the bunkers consumed. That outgoing would have been an expense of the Marshal to be met by the Marshal from the proceeds of sale of the vessel or from the undertaking to indemnify the Marshal provided to the Marshal by the mortgagee.

33 As to the alternative postulation that MSC “supplied” fuel to the vessel whilst the vessel was under arrest, MSC did not make its property available to the Marshal. It gave early notice of its claim to property in the bunkers. Although an application to the Court for declaratory orders did not follow until some days later, there was no reason to treat bunkers consumed prior to the application as other than an expense incurred by the Marshal. It was not the case that that cost would only become a Marshal’s expense from the point where the mortgagee had the opportunity to object to it upon an application for that purpose being made. (See: “The Honshu Gloria” [1986] 2 Lloyd’s Law Reports 63 at 65). Even if it could be said that MSC “supplied” fuel to the vessel it would have been a “supply” that occurred after arrest notwithstanding that the fuel was already on board the vessel, and would have been a “supply” that occurred in response to a request by the Marshal for access to the property of MSC. It would follow that the fuel so “supplied” to the vessel would have been a usual expense incurred by the Marshal whilst the vessel was under his control, resulting in a liability to reimburse MSC for the cost of the fuel consumed.

34 For these reasons I am satisfied that after the containers were unloaded from the vessel onto the wharf, consumption of the bunkers thereafter was to the detriment, not the advantage, of MSC and was done to further the purpose of the arrest. Accordingly it should be treated as an expense incurred by the Marshal being within the category of outgoings the Marshal would be expected to authorize to further the purpose of arrest and the sale of the vessel.

35 With regard to the provisions supplied by the providor immediately before the arrest, title in which goods remained with the providor until payment had been made, the providor, at the time of arrest, became entitled under its contract with Dexlex to remove from the vessel so much of the goods as had not been appropriated by the Master and crew. At the time of arrest Dexlex could not meet its obligation to pay for the goods. In effect, after the arrest Dexlex abandoned the vessel to the care of the Marshal, Dexlex not being able to pay for the provision of supplies or to maintain the vessel. The inference should be drawn that at the time the provisions were delivered at the order of the Master, Dexlex was aware it was not in a position to pay for those goods and that it would have no right to derogate from the providor’s title to the goods by appropriating them to the use of Dexlex. In carrying out his duties, the Marshal could not authorize the Master and crew to appropriate the property of the providor. It followed that before the Marshal could treat the providor’s goods as goods supplied to the vessel and available for use by the persons under his control, the Marshal had to make arrangements with the providor for payment for the goods then on board the vessel or obtain goods for the crew from another supplier.

36 Therefore, the goods of the providor consumed after arrest, should be treated as a cost incurred by the Marshal pursuant to the arrest. That is to say, the expense involved in appropriating the goods of the providor was the type of expense that the Marshal would have incurred, or would have authorized, in the course of his control of supplies to the vessel pursuant to the arrest. (See: Osborn Refrigeration Sales & Service Inc v The “Atlantean I” [1979] 2 FC 661, 688).

|

I certify that the preceding thirty-six (36) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Lee. |

Associate:

Dated: 30 May 2003

|

Counsel for the Plaintiff: |

I R Freeman |

|

|

|

|

Solicitor for the Plaintiff: |

Phillips Fox |

|

|

|

|

Counsel for the Caveator: MSC Mediterranean Shipping Company SA: |

P A Saraceni |

|

|

|

|

Solicitor for the Caveator: |

Cocks Macnish |

|

|

|

|

Date of Hearing: |

10 April 2003, 23 May 2003 |

|

|

|

|

Date of Judgment: |

30 May 2003 |

SCHEDULE “A”