FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

De Rose v State of South Australia [2002] FCA 1342

NATIVE TITLE – application for a determination – Pastoral Leases containing reservations of rights in favour of Aboriginal people – whether the grant of Pastoral Leases extinguished native title – s 223 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) – whether rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed – whether the claimants ever had a connection with the claim area – whether the connection has been abandoned.

EVIDENCE – application for a determination of native title – subs 82(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) – when should the Court order that it is not bound by the rules of evidence.

Act, 1834 (4 and 5 William IV c. 95) ss 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 17-19

The South Australia Act, 1842 (5 and 6 Vict c. 61)

Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) ss 61, 64, 82, 84, 222-225, 228, 229, 237, 248A, 248B, 249C, 251B

Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 62, 63, 73, 74

Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) ss 9, 10

Federal Court Rules O 78 rr 1, 4

Pastoral Land Management and Conservation Act 1989 (SA) s 47, transitional provisions cls 5, 6

The Native Title (South Australia) Act 1994 (SA) ss 32, 33, 36F

Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Act 1981 (SA)

Pastoral Act 1893 (SA)

Pastoral Act 1936 (SA)

Aboriginal Heritage Act 1988 (SA)

Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 applied

Cooper v Stuart [1889] 14 App Cas 286 not followed

Fejo v Northern Territory of Australia (1998) 195 CLR 96 applied

Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 applied

The Wik Peoples v The State of Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1 applied

Western Australia v Ward (2002) 191 ALR 1 applied

Ward v State of Western Australia (2000) 159 ALR 483 cited

Western Australia v Ward (2000) 99 FCR 316 considered

Commonwealth of Australia v Yarmirr (2001) 184 ALR 113 applied

Western Australia v The Commonwealth (1995) 183 CLR 373 cited

Kogolo v Western Australia (2000) 102 FCR 38 followed

Subramaniam v Public Prosecutor [1956] 1 WLR 965 applied

Milirrpum v Nabalco (1971) 17 FLR 141 cited

Daniel v Western Australia (2000) 178 ALR 542 cited

Lardill v Queensland [2000] FCA 1548 cited

Yarmirr v Northern Territory (No 2) (1998) 82 FCR 533 considered

Semple v Noble (1988) 49 SASR 356 cited

Commonwealth of Australia v Yarmirr (2001) 184 ALR 113 applied

Attorney-General for the Northern Territory v Maurice (1986) 161 CLR 475 cited

Mason v Tritton (1994) 34 NSWLR 572 applied

Yanner v Eaton (1999) 201 CLR 351 considered

Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria (2000) 110 FCR 244 followed

Commonwealth of Australia v Yarmirr (1999) 101 FCR 171 considered

Kanak v National Native Title Tribunal (1995) 61 FCR 103 cited

R v Van Der Peet (1986) 137 DLR (4th) 289 cited

Hayes v Northern Territory (1999) 97 FCR 32 considered

Anderson v Wilson (2000) 97 FCR 453 considered

Wilson v Anderson (2002) 190 ALR 313 cited

Delgamuukuw v British Columbia (1997) 153 DLR (4th) 193 cited

Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v The State of Victoria [1998] FCA 1606 cited

Coe v Commonwealth (1993) 118 ALR 193 applied

Risk v National Native Title Tribunal [2000] FCA 1589 cited

Ngalakan People v Northern Territory of Australia [2001] FCA 654 cited

Russell v Bissett-Ridgeway [2001] FCA 848 cited

NB Tindale, Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution. Limits and Proper Names (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1974).

RM Berndt and CH Berndt, The World of the First Australians (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 1999).

GH Manning, Manning’s Place Names of South Australia (Adelaide: GH Manning, 1990).

RC Cockburn, South Australia; What’s in a name?, 3rd Ed, (Asciom Publishing, 1990).

Rev WH Edwards, “Patterns of Aboriginal Residence in the North West of South Australia” in Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia Vol 30, No 1 (1992), pp 2-32.

NB Tindale, “Results of the Harvard–Adelaide Universities Anthropological Expedition, 1938 – 1939: Distribution of Australian Aboriginal Tribes: A Field Study” in Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, Vol 64, No 1 (1990) pp 140-231.

AP Elkin, “Kinship in South Australia” in Oceania, Vol VIII, No 4 (1938), pp 419-452.

RM Berndt, “The concept of ‘The Tribe’ in the Western Desert of Australia” in Oceania, Vol XXX, No 2 (1959), pp 81-107.

PETER DE ROSE AND OTHERS v STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA AND OTHERS

NO SG 6001 OF 1996

O’LOUGHLIN J

1 NOVEMBER 2002

ADELAIDE

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| SG 6001 OF 1996 |

| BETWEEN: | PETER DE ROSE FIRST APPLICANT

OWEN KUNMANARA SECOND APPLICANT

PETER TJUTATJA THIRD APPLICANT

JOHNNY WIMITJA DE ROSE FOURTH APPLICANT

MICHAEL MITAKIKI FIFTH APPLICANT

RINI KULYURU SIXTH APPLICANT

PUNA YANIMA SEVENTH APPLICANT

JULIE TJAMI EIGHTH APPLICANT

SADIE SINGER NINTH APPLICANT

WHISKEY TJUKANKU TENTH APPLICANT

|

| AND: | THE STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA FIRST RESPONDENT

R D FULLER PTY LTD AND DOUGLAS CLARENCE FULLER SECOND RESPONDENTS

|

| DATE OF ORDER: | |

| WHERE MADE: |

1. The application for a determination of native title be dismissed.

2. There be liberty to apply.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

INDEX

| Heading | Paragraph No |

| INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| THE WITNESSES | 9 |

| THE CLAIMANTS’ CASE | 29 |

| THE PROPOSED DETERMINATION | 39 |

| THE TJUKURPA | 52 |

| The Kalaya Tjukurpa – The First Dreaming | 53 |

| Malu, Kanlaya and Tjurki Tjukurpa – The Second Dreaming | 62 |

| Pakalira Tjukurpa – The Third Dreaming | 66 |

| Papa Itari Tjukurpa – The Fourth Dreaming | 68 |

| The Seven Sisters Tjukurpa – The Fifth Dreaming | 72 |

| THE NGURARITJA | 75 |

| YANKUNYTJATJARA COUNTRY | 108 |

| ANTIKIRINYA | 117 |

| EUROPEAN DEVELOPMENT | 145 |

| THE CLAIM AREA | 197 |

| Agnes Creek | 208 |

| Paxton Bluff North | 221 |

| Paxton Bluff South | 223 |

| IMPROVEMENTS AND DEVELOPMENTS | 225 |

| LEGISLATION | 234 |

| THE STATUTORY LEASE? | 245 |

| ALLOWANCE FOR ABORIGINAL WITNESSES | 249 |

| HEARSAY | 260 |

| STAGES OF MANHOOD | 272 |

| SNOWY’S ACCIDENT | 277 |

| THE DEATH OF BOBBY | 284 |

| ETHNOGRAPHERS | 292 |

|

EXPERT WITNESSES |

|

| Associate Professor Cliff Goddard | 306 |

| Associate Professor Peter Veth | 314 |

| Dr Robert Foster | 317 |

| Mr Daniel Vachon | 322 |

| Dr John Willis | 332 |

| Mr Craig Norman Elliott | 347 |

| PROFESSOR KENNETH MADDOCK | 368 |

| SITE VISITS | 379 |

| Wantjapila and Intalka | 384 |

| Ilpalka | 391 |

| Wipa | 403 |

| Kantja | 411 |

| Apu Maru | 417 |

| Tiilkatkara | 426 |

| DOUGLAS CLARENCE FULLER | 430 |

| REX FULLER | 463 |

| LOCKED GATES | 478 |

| SECTION 223 OF THE NTA | 492 |

| EXTINGUISHMENT | 513 |

| OPERATIONAL INCONSISTENCY | 542 |

| CONNECTION | 559 |

| PETER DE ROSE | 572 |

| RILEY TJAYRANY | 600 |

| WHISKEY TJUKANKU | 621 |

| ALEC BAKER | 638 |

| WITJAWARA CURTIS | 648 |

| PETER TJUTATJA | 658 |

| TIM DE ROSE | 683 |

| SANDY PANMA WILLIAMS | 700 |

| ALAN WILSON (MANTJAKURA) | 705 |

| ROLEY MINTUMA | 713 |

| MABEL PEARSON | 726 |

| OWEN KUNMANARA | 736 |

| MICHAEL MITAKIKI | 761 |

| JOHNNY WIMITJA DE ROSE | 772 |

| CISSIE RILEY | 795 |

| MINNIE NYANU | 809 |

| EDIE ANGKALIYA | 817 |

| CARLENE THOMPSON | 824 |

| MAGGIE WARD | 829 |

| LILLY YUPUNA BAKER | 834 |

| JEANNIE KAMPUKUTA INPITI | 849 |

| TILLIE YALTJANGKI | 858 |

| SADIE SINGER | 860 |

| TANYA SINGER-DUCASSE | 867 |

| BERNARD SINGER | 871 |

| MONA TUR | 879 |

| REASONS FOR LEAVING | 888 |

| CONCLUSION | 897 |

| A SUGGESTED DETERMINATION | 916 |

| SECTION 251B OF THE NTA | 924 |

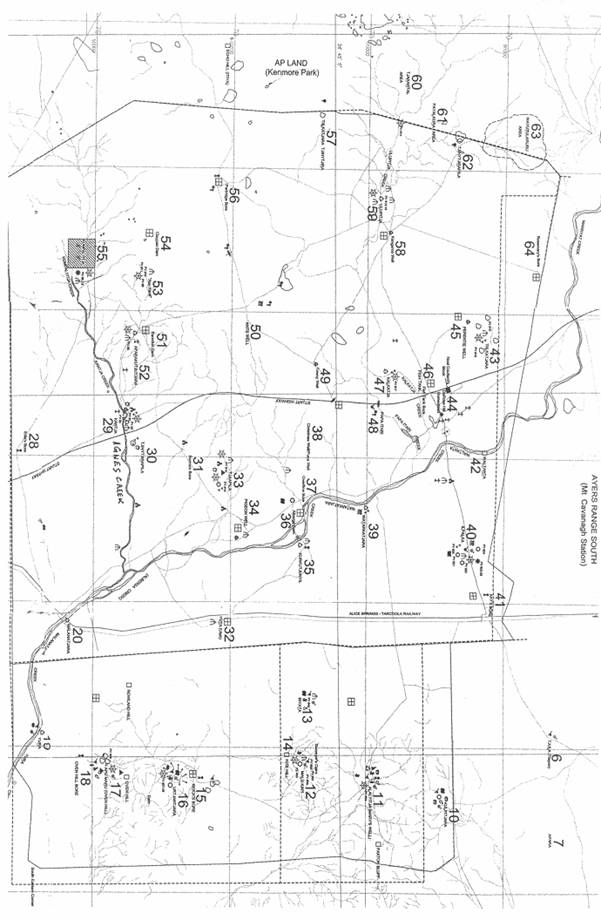

| MAP – EXHIBIT A2 | Page 393 |

| IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

| SG 6001 OF 1996 |

| BETWEEN: | FIRST APPLICANT

OWEN KUNMANARA SECOND APPLICANT

PETER TJUTATJA THIRD APPLICANT

JOHNNY WIMITJA DE ROSE FOURTH APPLICANT

MICHAEL MITAKIKI FIFTH APPLICANT

RINI KULYURU SIXTH APPLICANT

PUNA YANIMA SEVENTH APPLICANT

JULIE TJAMI EIGHTH APPLICANT

SADIE SINGER NINTH APPLICANT

WHISKEY TJUKANKU TENTH APPLICANT

|

| AND: | FIRST RESPONDENT

R D FULLER PTY LTD AND DOUGLAS CLARENCE FULLER SECOND RESPONDENTS

|

| JUDGE: | |

| DATE: | |

| PLACE: |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1 Ten Aboriginal men and women have applied for a determination of native title over the land that is contained in three pastoral leases that together comprise De Rose Hill Station (“the Station”). As presently constituted, the three leases are registered in the joint names of Douglas (“Doug”) Clarence Fuller and RD Fuller Pty Ltd, the second respondents in these proceedings (“the Fullers”). The first respondent is the State of South Australia (“the State”). When the application was first filed in the Federal Court on 1 November 1996, there were twelve applicants, but two have died in the intervening space of time. By consent, their names have been removed from the title of the proceedings. The Station, which is situated in the far north-west of South Australia, will sometimes be referred to as “the claim area” or as “De Rose Hill”. It is within the eastern extremity of a large area of land that was known to the early ethnographers as “the Western Desert Bloc”. It started life as a sheep station in the early 1930s when it was leased to one Thomas (“Tom”) Gregory O’Donoghue, but later it converted to a cattle station. For the purpose of taking the evidence of the Aboriginal witnesses, the Court was based in a marquee at a location known as Ilintjitjara which is on the northern bank of the Tarcoonyinna (also known as Tarkan) Creek. Ilintjitjara is a few kilometres to the south of the southern boundary of De Rose Hill Station. In addition to sitting at Ilintjitjara, the Court also took evidence in a community hall in Marla (because of inclement weather) and at numerous sites which were said to be sites of significance to the Aboriginal claimants.

2 I will refer to the applicants and the other persons for whom they claim native title over the claim area as “the claimants”. They have claimed in their application that they continue to follow the traditional laws and customs and that they maintain the necessary connection with the land and waters in the claim area that those laws and customs require. They have further claimed that they follow the traditional laws and customs which were followed for some time before the acquisition of sovereignty over the land by the British Crown.

3 Section 225 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (“the NTA”), entitled “Determination of Native Title”, is the particular provision that outlines the task that confronts the Court in native title proceedings. In the first place, it identifies a determination of native title as a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area of land or waters. That area is described in s 225 as “the determination area” but the term “the claim area” is also in common use and it is the one that I have chosen to use in these reasons. The second leg of s 225 identifies the five particular subject matters that must be addressed by the Court if it is to make a determination that native title exists in relation to the claim area:

· Who are the persons, or each group of persons, who hold the common or group rights that comprise the native title?

· What is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the claim area?

· What is the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the claim area?

· What is the relationship between the rights and interests that have been identified in answer to the two preceding questions (taking into account the effect of the NTA)? and

· To the extent that the land or waters in the claim area are not covered by a non-exclusive agricultural lease or a non-exclusive pastoral lease, whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native holders to the exclusion of all others?

4 The first two of those questions, the identities of those who comprise the native title claim group and the nature and extent of their rights and interests, are, of course, fundamental issues in these proceedings and must be addressed in some detail. If, upon an assessment of the evidence, it becomes apparent that native title rights and interests exist, it will be further necessary to identify and resolve the relationship between the competing rights and interests. The third question is, on the other hand, relatively easy to answer; the Fullers, in their capacity as the Crown lessees of the three pastoral leases, have rights and interests in relation to the claim area and the nature and extent of these rights and interests are to be found, primarily, in the terms and conditions of the three Crown leases and in the Pastoral Land Management and Conservation Act 1989 (SA) (“the 1989 Pastoral Act”). As to the fourth question, the claimants submitted that the relationship between their native title rights and interests and the rights and interests of the Fullers pursuant to the three Crown leases is governed by the terms of the Native Title (South Australia) Act 1994 (“the NT (SA) Act”) which, so it was claimed, mirrors certain of the terms of the NTA as to how the two sets of interests are be treated. That was a contentious proposition for the Fullers had submitted that the 1989 Pastoral Act had fully extinguished native title because it had created new leases.

5 The last of the five subject matters did not arise in these proceedings. It is quite clear that the claim area is covered by three pastoral leases, each of which is a non-exclusive pastoral lease. The terms “pastoral lease”, “exclusive pastoral lease” and “non-exclusive pastoral lease” are defined in ss 248, 248A and 248B of the NTA. A pastoral lease is defined in this manner:

“A pastoral lease is a lease that:

(a) permits the lessee to use the land or waters covered by the lease solely or primarily for:

(i) maintaining or breeding sheep, cattle or other animals;

or

(ii) any other pastoral purpose; or

(b) contains a statement to the effect that it is solely or primarily a pastoral lease or that it is granted solely or primarily for pastoral purposes.” (original emphasis)

An exclusive pastoral lease is either a Schedule Interest or a pastoral lease that confers a right of exclusive possession over the land and waters that are covered by the lease. The term “Schedule Interest” is defined by s 249C of the NTA as meaning (subject to some exceptions such as mining leases) the many interests that are set out in Sch 1 to that Act. I do not consider that any of the three Crown leases is either a “Schedule Interest” or a pastoral lease that confers a right of exclusive possession. In the first place, all leases were originally issued with a reservation of rights for the benefit of Aboriginal people. In the second place, when those rights were removed by the introduction of the 1989 Pastoral Act, they were immediately replaced with the statutory rights that s 47 of that Act gave to Aboriginal people. The last of the definitions, “non-exclusive pastoral lease” does no more than say that such a lease is a pastoral lease that is not an exclusive pastoral lease (s 248B).

6 The High Court in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 (“Mabo (No 2)”) held that the concept of native title is, and always has been, part of the common law of Australia. In coming to that conclusion, the Court rejected the advice of their Lordships in the Privy Council in Cooper v Stuart [1889] 14 App Cas 286 at 291. Lord Watson, who delivered that advice, said:

“There is a great difference between the case of a Colony acquired by conquest or cession, in which there is an established system of law, and that of a Colony which consisted of a tract of territory practically unoccupied, without settled inhabitants or settled law, at the time when it was peacefully annexed to the British dominions. The Colony of New South Wales belongs to the latter class.”

Those remarks would have had equal and like application to the then Colony of South Australia.

7 Paragraph 13(1)(a) of the NTA provides that:

“(1) An application may be made to the Federal Court under Part 3:

(a) for a determination of native title in relation to an area for which there is no approved determination of native title; or

(b) …”

Section 61 of that Act, which is to be found in Part 3, contains a table that sets out the nature of the applications that may be made to the Federal Court. The section also identifies the persons who may make each of those applications. Thus, so far as it is relevant to these proceedings, s 61 specifies that an application, as mentioned in subs 13(1) of the Act, for a determination of native title in relation to an area for which there is no approved determination of native title, may be made by:

“A person or persons authorised by all the persons (the native title claim group) who, according to their traditional laws and customs, hold the common or group rights and interests comprising the particular native title claimed, provided the person or persons are also included in the native title claim group; or …” (original emphasis)

Subsection 61(2) of the NTA then provides, inter alia, that, in the case of a native title determination application that is made by persons who are authorised to make the application by a native title claim group, those persons are to be identified jointly as the applicants.

8 Native title originates in the traditions and customs of the indigenous people. It is from them, and not from the common law, that it takes its content: Mabo (No 2) at 57 – 58 per Brennan J; at 110 per Deane and Gaudron JJ; at 178 per Toohey J; see also Fejo v Northern Territory of Australia (1998) 195 CLR 96 at 148 (“Fejo”) per Kirby J. The onus is upon the claimants to prove, to the satisfaction of the Court, that they have established their right to a determination in their favour.

THE WITNESSES

9 Twenty-six Aboriginal persons gave evidence as part of the claimants’ case. Seven of those had earlier been named as applicants in the proceedings. They were Peter De Rose, Owen Kunmanara, Peter Tjutatja, Johnny Wimitja De Rose, Michael Mitakiki, Sadie Singer and Whiskey Tjukanku. Three of the applicants did not, however, give evidence – Julie Tjami, Puna Yanima and Rini Kulyuru. The evidence of most of those twenty-six witnesses was directed towards establishing that most of them (and others who were claimants) were Nguraritja: the traditional owners of the claim area.

10 Peter De Rose, the first named of the applicants and the first of the witnesses for the claimants, would not agree that he and his wife Sylvia have been the main organisers of the Aboriginal people in their claim for a determination of native title. Neither would he agree that he is a spokesman for the Aboriginal people. Rather, he said, he deferred to the older people. It is not possible to make any findings about Sylvia. She did not give evidence in the trial. Peter was a different matter however. He was the dominant figure in the presentation of the claimants’ case. He was not only their principal witness, he was the individual who, more than any other person, was the one to whom the legal advisers turned for instructions. It might be the case that in matters of importance dealing with Aboriginal laws and customs, he had to defer to the old men. In such matters, Peter might only have been the spokesperson. But in the practical day-to-day handling of the case, he can quite properly be regarded as the leader of the Aboriginal claimants.

11 Peter De Rose said that he knew Julie Tjami as a person who had been born on De Rose Hill Station; she is younger than Peter. He could not express the difference in their ages in years, but he said that he was a grown man when she was born. According to Peter, she left De Rose Hill with her mother and her brother Richard Nginingini (otherwise known as Richard Yangki) when she was quite young and before she was old enough to work. If, for example, Peter De Rose was born in 1949 and if he was a grown man when she was born, it suggests that Julie could now be in her mid thirties. Her evidence would have been of value in assessing her generation’s views on native title. Julie had another brother Tima (otherwise know as Tim). Peter said that he regarded each of the siblings, Julie, Richard and Tima as Nguraritja, that is, as a traditional owner, for De Rose Hill based on the fact that they were each born in the area. Julie Tjami is listed as Nguraritjain an anthropological report that was prepared by Mr Craig Elliott as well as in the claimants’ closing submissions. She appears in Sheet 6a of Ms Woenne-Green’s genealogies as the daughter of Maggie Yilpi and Kunmanara Nginingini. That, however, would seem to be her only exposure in the case. Bearing in mind that she was presumably regarded as being a person of sufficient importance to be included as one of the original twelve applicants, it was puzzling that she did not give evidence and that no evidence was led to explain her absence. I can only infer that if she had given evidence, it would not have assisted the claimants’ cause: Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298.

12 Puna Yanima appears in the genealogies of Ms Woenne-Green as the daughter of Kunmanara Yanima.Johnny Wimitja De Rose (“Wimitja”) said that Puna had been born at Puna Well, which is a location on De Rose Hill Station. Wimitja also said that Puna was Nguraritja for De Rose Hill. The claimants put her forward as Nguraritja solely on the basis of her place of birth but without any explanation about her present whereabouts, her present connection (if any) to De Rose Hill or her absence as a witness.

13 Rini Kulyuru was identified as Nguraritja for the claim area on the basis of a long-term physical association. Ms Woenne-Green’s genealogies indicate that she is the daughter of Jeannie Kampukuta Inpiti, (“Kampukuta”) who is a claimant in this application and who was a witness in the trial. According to Kampukuta’s witness statement, Rini was born at Iranytjirany (a location to the west of the claim area) and now lives at Amata (Musgrave Park). Amata is about a further 100 kilometres to the west of Iranytjarany. It is, in my opinion, of some significance that Kampukuta considered that her son, Sammy, who she said was born on De Rose Hill, was Nguraritja, but she did not suggest in her witness statement that any of her other children (who were born outside the claim area) were Nguraritja for the claim area.

14 Three of the Anangu witnesses– Maggie Ward, Alan Wilson and Mona Tur – were not advanced as Nguraritja. Maggie Ward was born in about 1935 and was originally presented as a witness who was said to be Nguraritja for the claim area. However, in the course of her testimony it became clear that she repudiated the greater part of her witness statement, including, most importantly, any claim to being Nguraritja for the claim area. The claimants did not press her as Nguraritja in their closing submissions. Alan Wilson, who identified himself as a Pitjantjatjara man, was never put forward as Nguraritja for the claim area. He said that his country was further to the west of the claim area. Mona Tur identified herself as an Antikirinya woman. She was neither born on the claim area nor was she put forward as Nguraritja for the claim area.

15 I have divided the remaining twenty-three Aboriginal witnesses, who asserted some interest in the claim area, into three groups. The first and the largest group consists of those thirteen witnesses whose estimated ages exceeded sixty years. The oldest was Owen Kunmanara, who was born around 1910. The word “Kunmanara” was not part of his name; it is more like a title or a description. Owen’s other name happened to be the same as that of a man who had died recently. In accordance with Aboriginal tradition, the name of the deceased man could not be spoken. Instead, the living person is referred to as “Kunmanara” – which literally means “substitute name” – thereby identifying him or her as a person whose name could not be spoken because of the death of another who had the same name. The second or middle group are the eight witnesses who were aged in their fifties at the time when they gave evidence. Only two of the Aboriginal witnesses, Bernard Singer (aged thirty-five when he gave his evidence) and his younger sister, Tanya Singer-Ducasse, aged twenty-four, fell into the third category. It was, in my opinion, very disappointing and somewhat significant not to have received evidence from more young people. One is left wondering whether the members of the younger generations have the same interest in native title entitlements as their elders.

16 The twenty-three Aboriginal witnesses and their years of birth and groupings are as follows:

Name

Group A Approximate Year of Birth

Owen Kunmanara 1910

Peter Tjutatja 1912

Cissie Riley 1926

Jeannie Kampukuta Inpiti 1928

Riley Tjayrany 1930

Witjawara Curtis 1931

Alec Baker 1932

Johnny Wimitja De Rose 1933

Minnie Nyanu 1935

Mabel Pearson 1935

Lily Yupuna Baker 1938

Whiskey Tjukanku 1939

Edie Angkaliya 1940

Group B

Roley Mintuma 1943

Michael Mitakiki 1944

Sandy Panma Williams 1946

Tim De Rose 1948

Peter De Rose 1949

Tillie Yaltjangki 1949

Carlene Thompson 1950

Sadie Singer 1950

Group C

Bernard Singer 1966

Tanya Singer-Ducasse 1977

17 In addition to the Anangu witnesses, there were a number of other witnesses who gave evidence for the claimants. I will do no more than identify them at this stage; I will discuss their evidence at a later stage of these reasons. The first person who should be mentioned, however, did not give evidence. Ms Susan Woenne-Green is an anthropologist who was to have been, on my understanding, the main anthropological expert witness for the claimants. Two reports written by Ms Woenne-Green were marked for identification on the first day of the trial in anticipation of her giving evidence. Unfortunately she became quite seriously ill during the course of the trial and was unable to give evidence. Her reports were therefore not tendered, although, by consent, her genealogies with respect to the claimants and their ancestors were admitted as Ex A64. Ms Woenne-Green provided invaluable assistance to the court, the parties and the transcript providers by supplying spelling and pronunciation of Aboriginal words during the hearing. I am indebted to her for that very considerable help and I wish her a speedy recovery.

18 Associate Professor Cliff Goddard provided expert linguistic evidence for the claimants. Professor Goddard has written a Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara to English Dictionary, which is now in its second revised edition. The dictionary was relied upon quite extensively in the trial by the Court and the parties. Professor Goddard was asked to examine the differences between certain Yankunytjatjara and Antikirinya word lists. He concluded that there was little, if any, material difference between the two dialects.

19 Associate Professor Peter Veth provided archaeological evidence about the claim area. He holds a first-class Honours degree in Arts and a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Western Australia. Professor Veth has held a number of positions within government, academic and commercial spheres. He was asked to visit a number of sites on and around the claim area. His evidence related to pre-and post-colonial occupation of those sites by Aboriginal people.

20 Dr Robert Foster, a historian, examined a large number of documents (mainly government records) to piece together a history of the claim area and its surrounds from the time of the first European expeditions to the area until the mid 1960s.

21 Mr DA Vachon, a Canadian, completed a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in Anthropology and Psychology from the University of Windsor and a Master of Arts from the University of Toronto. He has had extensive experience in the Western Desert through his employment by the Pitjantjatjara Council as an anthropologist. His evidence was primarily concerned with the observations that he made in the late 1970s in the course of his research programme at Indulkana and its surrounds (which included De Rose Hill). He has also undergone several stages of initiation that Western Desert male Anangu are required by traditional law and custom to endure to become a Wati (an initiated man).

22 Dr John Willis obtained a Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in Anthropology and Sociology from the University of New South Wales. He was awarded a Master of Letters with Distinction in Sociology from the University of New England in 1989, and in 1997 he completed his PhD through the Tropical Health Program at the University of Queensland. His PhD involved extensive fieldwork at a variety of sites throughout the Western Desert. Dr Willis is a fully initiated Anangu. His evidence, the great majority of which was taken in closed session, centred on the ceremonial life of males and its importance within the Western Desert culture. However, he had virtually no specific knowledge of the practices within the claim area itself – his evidence was of the wider Western Desert rather than focusing on De Rose Hill.

23 Mr Craig Elliott became the main anthropological witness for the claimants following the illness of Ms Woenne-Green. He has had extensive experience in anthropological research into central Australian Aboriginal groups. Mr Elliot conducted research among the claimants on site to assess their current level of adherence to traditional laws and customs. He also described those laws and customs and reviewed previous ethnographic literature that was of relevance to the claim area.

24 The Reverend William Howell Edwards was called by the claimants to give evidence, primarily as a result of his experience at the Ernabella Mission. A Minister of the Presbyterian Church since 1958, he worked at the Ernabella Mission in the far north-west of the State from May 1958 to February 1972. He also worked at Fregon in 1973 and at Amata from 1976 to 1980. He was Acting Superintendent from September 1958 and became Superintendent at Ernabella in 1963. He has had a long and distinguished history in all aspects of Aboriginal affairs. He holds Bachelor degrees in Arts and Education, has completed a qualifying MA entry in Anthropology and is currently enrolled for a Master of Arts in History. At the time of giving his evidence, he held the position of Adjunct Lecturer in the Unaipon School at the University of South Australia, lecturing on matters relating to Aboriginal culture. He has conducted summer schools in the Pitjantjatjara language and he works as an interpreter in hospitals, courts and prisons.

25 The only witness called by the State was Professor Kenneth Maddock, an anthropologist. He provided two reports to the court, which were tendered as Exs S36 and S37; he also gave extensive oral evidence. Professor Maddock graduated with a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1960. Later, in 1964, he was awarded a Master of Arts with First Class Honours in Anthropology from the University of Auckland, New Zealand. He completed his PhD at the University of Sydney in 1969. He is currently Emeritus Professor in Anthropology at Macquarie University and, in the past, he has held a number of academic positions in Australia, Europe and South Africa. Professor Maddock has extensive experience working as a consultant on a number of land rights and native title claims and has published many articles and books since 1969. He is clearly an extremely learned and experienced anthropologist as was acknowledged by Mr Elliot.

26 There were three witnesses who gave evidence for the Fullers. They were Doug and Rex Fuller and Bruce Evans. Doug Fuller was ninety-two years of age when he gave his evidence. After working in the claim area for some years, including a period when he had an association with the O’Donoghue brothers (Tom and Mick), Doug became the sole proprietor of De Rose Hill Station. He worked on De Rose Hill for many years steadily developing its capacity as a cattle station. Although he has now retired to Beachport, a small town on the south-east coast of South Australia, he still retains a fifty percent interest in the three pastoral leases that today comprise De Rose Hill Station.

27 Rex Fuller is the only son of Doug Fuller. Following his father’s retirement to Beachport, he took over the position of Station Manager. He has continued the development of the improvements on De Rose Hill in order to maximise the cattle capacity and the efficiency of the station. His company, RD Fuller Pty Ltd owns the other half of the three leases.

28 Bruce Freebairn Evans was seventy-six years old when he gave his evidence. He has had extensive contact with the claim area and the surrounding country as a result of his former employment. From 1955 to 1960 and from 1963 to 1966 he was a Police Officer stationed at Oodnadatta. His patrol area, which was enormous, covered a number of pastoral stations in the north-west of the State, including De Rose Hill. From 1966 to 1985 Mr Evans, having left the police force, was employed by the South Australian Pastoral Board and worked as a pastoral inspector and Board member. His duties as an inspector required him to make regular inspections of De Rose Hill Station and other pastoral properties in the north-west of the State. As a result of his employment, first as a police officer and, later, as a pastoral inspector, Mr Evans was able to provide evidence about the conditions in the north-west with specific references to De Rose Hill, from the mid 1950s until the 1980s. He gave evidence that the De Rose Hill lease was one of the best improved cattle stations he had seen.

the claimants’ case

29 The claimantswere represented at the trial by Mr KR Howie SC, Mr AC Collett and Mr R Bradshaw of counsel, but Mr J Basten QC appeared during the course of closing submissions to address the Court on the issue of extinguishment of native title. Until his judicial appointment, Mr AJ Besanko QC led Ms GA Brown for the State. Mr GF Barrett QC, Ms R Webb and Ms E Strickland also represented the State during the later stages of the trial. Mr RJ Whitington QC, Mr CH Goodall, Mr JP Keen and, in the latter stages of the trial, Dr MA Perry appeared as counsel on behalf of the Fullers. Three interpreters were used in the trial. They were Mr Yami Lester, Ms Mary Anderson and Mr Alec Henry. Mr Lester and Ms Anderson divided the work based on the gender of the witness whilst Mr Henry was used only for the evidence of Johnny Wimitja De Rose. An avoidance relationship prevented Mr Lester acting as interpreter for Wimitja.

30 The claimants are said to be Nguraritja, that is, the traditional owners of the claim area according to the traditional laws and customs that are acknowledged and observed by the people of the region. They seek to be acknowledged as Nguraritja of the claim area, possessed of the rights and interests that have been outlined in the submissions that were made to the Court on their behalf.

31 Many of the witnesses, during the course of their evidence, referred to themselves as Yankunytjatjara people; others referred to themselves, or to one or both of their parents, as Pitjantjatjara, thereby holding out that Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara were two separate peoples. However, the name Yankunytjatjara did not appear in the application for a determination of native title. It was not, for example, propounded that the claimants were pursuing their claim for themselves and for the Yankunytjatjara people as a whole. Nor did the name Yankunytjatjara appear in the written outline that counsel for the claimants submitted as part of his opening address. Any reference to the word Yankunytjatjara was, initially, a reference to a dialect of the western desert language: see, for example, par 10 of the claimants’ outline of facts and contentions and par 37 of the claimants’ further and better particulars. On the other hand, from an early stage of the proceedings, the claimants filed documents which were headed:

“Peter De Rose and others on behalf of those Yankunytjatjara people who have historical, spiritual and ancestral relationship to the claim area.”

32 Furthermore, in par B21 of the claimants’ answer to the statement of facts and contentions that were filed on behalf of the State, a different emphasis was placed on the word Yankunytjatjara. Rather than using it in a dialectal context, it was there used to describe a people.

33 In their outline of facts and contentions, the claimants sought to place the claimant group within the larger “Western Desert Bloc”. For example, in par 10 they asserted that:

“Aboriginal people residing within this wider region speak dialects of the ‘Western Desert’ language which include Ngaanyatjara, Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara.”

In par 11 there was an asserted connection between the claimant group and the claim area:

“Claimants and the claimed land and water are a part of a regional network of classical and contemporary relationships shared with other Aboriginal people and land within what is known in anthropological writings as the ‘Western Desert bloc’ of Australian Aboriginal culture.”

That association with the Western Desert Bloc was further developed in pars 12 and 79:

“12. The system of rules binding upon claimants in respect of the claimed land and water is the system of rules shared with the other Aboriginal people within the ‘Western Desert bloc’ …”

…

79. The system of rules applicable to the wider social and cultural network integrates the claimed land and water with the wider region. The claimants and their land and water are recognised as being an integral component of the wider social and cultural network.”

Thus, the claimant group was not described in the claimants’ outline of facts and contentions as the Yankunytjatjara people (or as a discreet section or division of the Yankunytjatjara people) but, rather, as a group within the Western Desert Bloc, the members of which adhered to the same set of rules that prevailed throughout that Bloc. The case that the claimants developed in their pleadings was to the effect that there are groups within the Bloc who are connected by language, myth and their environment. In support of this proposition they relied upon some of the writings of Professor RM Berndt who was of the opinion that:

“Diagrammatically, the whole of the Western Desert could be seen as a series of overlapping interactory zones or as small communities.”

34 In their submissions in reply at par 1.3, the claimants presented themselves in a different fashion. They said:

“The claimants are a group of Aboriginal people. They are Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara speaking people. They acknowledge and observe traditional laws and customs. These laws and customs are the laws and customs of the broader Aboriginal Community or Society of the area known as the Western Desert, of which the claimant group is a part … The claimed land is within the region of the Western Desert.”

35 The intermix between Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara was made the more interesting because of the usage of certain words such as Anangu and Tjukurpa. The Pitjantjatjara people and the Yankunytjatjara people are closely related, both in language and culture. Anangu is the word for “person” or “people” in the Pitjantjatjara language. It is, historically, the word that the Pitjantjatjara use to refer to themselves but it would seem that it has become a word of extended usage and that it is now also used by Yankunytjatjara people to refer to themselves and other Aboriginal people. It will be convenient to use the word Anangu from time to time in the course of these reasons because of its frequent use in the evidence and exhibits. The relationship between the Anangu and their relationship with the land that they occupy is governed by a body of oral traditions, laws and customs (which non-Aboriginal people have called “the Dreamings”). The Dreamings are known to the Pitjantjatjara as the Tjukurpa and to the Yankunytjatjara as the Wapar, but it was the word Tjukurpa that was universally used by all the Aboriginal witnesses throughout the trial.

36 The first named of the claimants, Peter De Rose, gave his address in the application as Railway Bore, Indulkana, South Australia, but he now lives in his wife’s country at Papalangkuntja – otherwise known as Blackstone – in Western Australia, almost 500 kilometres from the claim area. Some of the claimants live in the Iwantja Community which is in the Indulkana area to the south of the claim area. Using the scale on Ex A1, one of the maps that was tendered by the claimants, it would seem that Indulkana and Iwantja are about twenty-five kilometres from the southern boundary of De Rose Hill Station. Those communities are north of the small township of Marla and to the west of the Stuart Highway and the Alice Springs Railway line. Other claimants live in the Amata Community, which is almost 200 kilometres to the west of the claim area; another claimant lives at Mimili, which is due west of Indulkana. Amata and Mimili were once cattle stations known as Musgrave Park and Everard Park respectively. Indulkana, Iwantja, Amata and Mimili are all within the boundaries of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands (“the AP Lands”).

37 At the end of the day, the claimants seemed to be arguing that each member of the claimant group is Nguraritja for the claim area and that the application for a determination of native title has been made by named individuals in their own right and on behalf of all other individuals who fulfil the criteria of Nguraritja according to traditional law and custom. In par 1.6 of their principal submissions the claimants submitted that the claimants are:

“… a group of people seeking a determination of their rights and interests as a group or aggregation of persons. The rights and interests claimed are not a communal title.”

38 Confusing as the claimants’ case was, it would appear that, in the end, they sought to establish the following propositions:

· the claim area is and always has been Yankunytjatjara country;

- Antikirinya and Yankunytjatjara are different names that are used to refer to the same people;

· the claimant group comprises those individual Anangu (Aboriginal people) who are Nguraritja (traditional owners) and who are connected with the claim area: that is, there is no claim on behalf of the entire Yankunytjatjara people; and

· the Nguraritja are part of the greater western desert culture.

the proposed determination

39 Some, but not all, of the Aboriginal witnesses were asked what it would mean to them if the claimants were to be successful in obtaining a determination of native title. Of those who were questioned on the subject, some did not have an answer. None of them gave detailed evidence that amounted to statements of intention to resume the observance of traditional customs or the maintenance and acknowledgement of traditional laws.

40 Johnny Wimitja De Rose was the first of the Aboriginal witnesses to be asked about his hopes and expectations for De Rose Hill, but he merely replied:

“I haven’t really given that much consideration to that far down the track.”

He was asked again: had he not thought about what might happen and he replied:

“I’m telling the truth, we haven’t thought that far down the track.”

41 Riley Tjayrany was asked what he thought it would mean if the Aboriginal people were to win. His answer, as recorded in the transcript was:

“I reckon its palya, good.”

42 Mr Whitington then explored with him what the likely consequences of winning the case would be for the Aboriginal people and for the Fullers. His first answer was to indicate a return to bush tucker and a return to traditional customs saying:

“We might have tawal-tawal, bush tomato; kampurara, other bush tomato; ili, the figs; and wangunu, the grass-seeds.”

Riley then switched his attention to meats referring to malu, the kangaroo, kalaya the emu and kipara, the wild turkey. Much seemed to depend on what Wapala (Peter De Rose) might do. If he were to go to live on the Station, Riley thought that others would follow him. Riley said that if Peter and the other Aboriginal people were to live on the station:

“We’ll tell the young people to do the cattle work and they can do the work. I’ll tell them.”

Asked what cattle would he use, Riley replied:

“Yes, if someone might help us out by buying the cattle for us, we will run that cattle.”

43 Riley said that he did not know what would happen to the “whitefellas” and their cattle, but he speculated that they might truck some away or they might leave some cows and calves. But, so he said, the “whitefellas” would not be able to stay there if the Aboriginal people were to live on the Station and run their own cattle. In other words, it was quite clear in Riley’s mind that he, at least, was seeking exclusive possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of De Rose Hill Station. Furthermore, it would seem that, whatever his reasons might be for wanting exclusive possession, they included the wish to carry on a commercial cattle operation. Despite these answers, however, Riley said that he had not spoken to any of the other Aboriginal people about what might happen if the claimants were to win the case.

44 Mr Whitington asked Roley Mintuma what he thought might be achieved if the Aboriginal people were to be successful in obtaining a determination of native title over the De Rose Hill Station. Mintuma said that “maybe if they win the case, then it will become Aboriginal land”. He was then asked, if it were to become Aboriginal land, what would happen to the cattle that are now on it. His evidence was as follows:

A “Maybe if it became Aboriginal land he might take his cattle to his own country.

Q If it becomes Aboriginal land, what do you think the Aboriginal people will do with it?

A Maybe the Aboriginal people do something – I don’t know – maybe they will get cattle or maybe they will make something.

Q Will some Aboriginal people go and live there?

A Yes, maybe they will work it out – I don’t know how they would work it out – to go there to live on that place. I don’t know they might work it out.

Q Will you go and live there?

A Yes, if I think I can go and live there, I will work it out, if I want to go there. Maybe if Wapala [Peter De Rose] goes there then I will have to think about going there and to live there, but I don’t know how we will work it out.

Q But if Wapala goes there, that may make you decide to go there too, is that right?

A Yes, if all the Nguraritja thinks that – and Wapala is a Nguraritja – and all the Nguraritja go back there, then we, that we grew up there, then we will think about maybe going there.

Q Are you a Nguraritja or not?

A Yes I am a Nguraritja. I grew up from a baby at that place.”

45 Jeannie Kampukuta Inpiti was asked to give her understanding of what benefits the Aboriginal people would enjoy if they were to win the present case. She replied saying:

A “Maybe people who they’re thinking that they might get that place, people who are born there.

Q And people who are Nguraritja?

A Yes, Nguraritja people might get that place and we might help and go there.

Q Do you think that you worked very hard on De Rose Hill for Doug Fuller, working with the sheep?

A Yes, I used to look after sheep for him.

Q Do you think that because of your hard work there you deserve to be Nguraritja?

A Yes.

Q Do you think because of your hard work that you are one of those people who might deserve to get De Rose Hill Station?

A Yes, maybe.

Q Would you like to live there if you could?

A Yes, maybe.”

46 Cissie Riley did not assist; she could only say that she would like to go back to De Rose Hill Station because it is:

“… our place. I don’t know. It might happen, it mightn’t happen.”

47 Although Sadie Singer claimed that she is Nguraritja for De Rose Hill because of her mother and her mother’s ancestors, she made it clear that she does not seek to live on the claim area in the event of the native title claim being successful. She claimed that she was participating in the application on behalf of other Aboriginal people and, presumably, her children. On the other hand, and contrary to the submissions that were advanced on behalf of the claimants, she said that she wanted the Fullers and their cattle off the property; she wanted exclusive possession for the Anangu.

48 During the course of his opening, Mr Howie SC, counsel for the claimants, made it clear that his clients were not seeking exclusive possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the claim area; they were, however, so he submitted, seeking more than that to which they are entitled under s 47 of the 1989 Pastoral Act. That section is in the following terms:

“47(1) Despite this Act or any pastoral lease granted under this Act or the repealed Act, but subject to subsection (2), an Aborigine may enter, travel across or stay on pastoral land for the purpose of following the traditional pursuits of the Aboriginal people.

(2) Subsection (1) does not give an Aborigine a right to camp:

(a) within a radius of one kilometre of any house, shed or other outbuilding on pastoral land; or

(b) within a radius of 500 metres of a dam or any other constructed stock watering point.”

“Aborigine” is defined in the 1989 Pastoral Act as meaning:

“… a descendant of the Aboriginal people who is accepted as a member by a group in the community who claim descent from the Aboriginal people.”

“Aboriginal people” is also a term that is defined in that Act. It means:

“… the people who inhabited Australia before European colonisation.”

It was common ground that the three leases with which these proceedings are concerned were pastoral leases to which s 47 of the 1989 Pastoral Act applied.

49 Whilst the claimants asserted that they are entitled to native title rights and interests over the claim area, they nevertheless acknowledged, from the outset, that their rights, in terms of possession, occupation, use and enjoyment, must be compatible with the rights, interests and obligations of the Crown lessees: see The Wik Peoples v The State of Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1 at 132-133 (“Wik”). They recognised that the terms of the original and the present crown leases deny them the right to exclusive possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the claim area. Expressed another way, the claimants acknowledged the rights of the crown lessees to possess, occupy, use and enjoy the claim area in terms that are compatible with the provisions of the relevant leases, subject always to the reservations of rights in favour of the Aboriginal people. So much was not, I think, in dispute; the dispute was centred upon whether the claimants have ever had a connection with the claim area, and if they did, whether they have retained that connection. If they have retained such a connection, the next question was what (if any) additional rights or interests, over and above those that are contained in the 1989 Pastoral Act, would be available for the Aboriginal people if a determination of native title were to be made in their favour?

50 The proceedings were concluded and judgment was reserved before the decision of the High Court in Western Australia v Ward (2002) 191 ALR 1 (“Ward”). However, as a result of that decision, further written submissions from all parties (“the supplementary submissions”) were received, by consent, by the Court during September and October 2002. The claimants had initially provided the Court with a statement of the native title rights and interests that were claimed on their behalf. That statement was provided, during the course of the trial on location at Ilinyjitjara in the far north-west of the State on 8 June 2001. It was later included as part of the claimants’ final submissions. The claimants have since revised their claims as a result of the High Court’s decision in Ward. They accept that any exclusive native title rights that may have once existed in respect of the claim area have been extinguished. However, they seek to establish that they have a non-exclusive right to make decisions about the use and enjoyment of the claim area. They submitted that the content of this non-exclusive right was the right to make decisions about the use and enjoyment of the claim area by people, other than the pastoral leaseholders and their employees, agents and invitees (who would be using the land and waters for pastoral purposes in accordance with the terms of the pastoral leases) and also other than people who would be exercising a statutory right in relation to the use of the land and waters in the claim area. The rights that are now claimed and the determination that the claimants now seek, as set out in their supplementary submissions, are as follows:

“PROPOSED DETERMINATION

THE COURT DETERMINES:

1. Native title exists in relation to the land and waters covered by Crown Lease Pastoral No. 2133, Crown Lease Pastoral No. 2138A and Crown Lease Pastoral No. 2190A (“the determination area”).

2. The persons who hold the group rights comprising the native title are the Aboriginal persons who are recognised as nguraritja of the land in the determination area under the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the Aboriginal people of the region, as common law holders.

3. The nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area are:

(i) The right to non-exclusive possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the land and waters of the determination area, including as incidents of the entitlement –

(a) the right to hunt on the land, to gather and use the products of the land such as food, medicinal plants, wild tobacco, timber, stone and resin, and to access and use water on the land;

(b) the right to live on the land, to camp, to erect shelters, and to move about the land;

(c) the right to engage in cultural activities on the land, to conduct ceremonies, to hold meetings, to teach the physical and spiritual attributes of places, to participate in cultural practices relating to birth and death;

(ii) the right to access, maintain and protect the sites of significance on the land of the determination area;

(iii) the non-exclusive right to make decisions about the use and enjoyment of the land and waters by people other than the pastoral leaseholders, their employees, agents and invitees (using the land and waters for pastoral purposes, in accordance with the terms of the pastoral leases) and others exercising a statutory right in relation to the use of the land and waters;

(iv) the non-exclusive right to refuse access to people other than the pastoral leaseholders, their employees, agents and invitees (who have a right of access to the land and waters for pastoral purposes, in accordance with the terms of the pastoral leases) and others who have a statutory right of access, and to grant access to Aboriginal people who are governed by the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the native title holders;

(v) the non-exclusive right to control the use and enjoyment of the resources of the land and waters by Aboriginal people who are governed by the traditional laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the native title holders *other than* the pastoral leaseholders, their employees, agents and invitees (using the land and waters for pastoral purposes, in accordance with the terms of the pastoral lease [sic]) and others exercising a statutory right in relation to the use of the land and waters;

*[In their supplementary submissions in reply, the claimants substituted the words “and who are not” for the words “other than” so as “to overcome the ambiguity”; they did not make like alterations in subpars (iii) and (iv) however.]

(vi) the right to prevent the disclosure otherwise than in accordance with traditional laws and customs of tenets of spiritual beliefs and practices (including songs, narratives, rituals and ceremonies) which relate to areas of land or waters, or places on the land or waters;

(vii) the right to be acknowledged as the owners of the land and waters in accordance with traditional laws and customs.

4. The nature and extent of other interests in relation to the determination area are the interests of Douglas Clarence Fuller and R D Fuller Pty Ltd as the holders of:

(i) Crown Lease No. 2133,

(ii) Crown Lease No. 2138A, and

(iii) Crown Lease No. 2190A

which interests are held subject to the Pastoral Land Management and Conservation Act 1989 (SA).

5. The relationship between the rights and interests of the native title holders and the rights and interests of the pastoral lessees is that of parties with co-existing rights and interests, which must be exercised having regard to the following principles:

(i) the Pastoral Land Management and Conservation Act 1989 and the pastoral leases [that] are the source of the rights and interests of the pastoral lessees;

(ii) section 47 of the Pastoral Land Management and Conservation Act 1989, which guarantees to Aborigines the right to enter, travel across and stay on the land for the purpose of following the traditional pursuits of Aboriginal people, but does not give a right to camp within a radius of one kilometre of any house, shed or other outbuilding, or within a radius of 500 metres of a dam or a constructed stock watering point;

(iii) the rights and interests of the pastoral lessees are of a limited character confined principally to the right to graze stock and the right to make improvements for that purpose;

(iv) as a consequence of s.44H of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and s.36I of the Native Title (South Australia) Act 1994 the rights and interests granted by the pastoral leases and the doing of any activity permitted by them prevail over the native title rights and interests, and are not prevented by the existence or exercise of the native title rights and interests;

(v) section 23 of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1988 prohibits any damage, disturbance or interference with any Aboriginal site, object or remains;

(vi) the coexisting rights of the native title holders and the pastoral lessees must be exercised by each party reasonably, having regard to the interests of the other.

AND THE COURT FURTHER ORDERS THAT

6. The native title is not to be held in trust.

7. An Aboriginal Corporation whose name will be provided within ‘X’ months is to:

(a) be the prescribed body corporate for the purposes of s.57(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); and

(b) perform the functions mentioned in s.57(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) after becoming a registered native title body corporate.”

51 The claim in subpar 3(vi) above to prevent improper disclosure of cultural information about the claim area was considered and accepted by Lee J at first instance in Ward v State of Western Australia (2000) 159 ALR 483. Lee J’s decision on that point was overturned by the majority decision of Beaumont and von Doussa JJ when the matter went on appeal: Western Australia v Ward (2000) 99 FCR 316 and the High Court did not interfere with that particular finding of their Honours. The claimants argued that the right to prevent the disclosure of spiritual beliefs and practices related to “places on the land”; they submitted that what they sought was different from that which had been rejected in Ward, arguing that the native title right that has been claimed in this case was not a broad claim of a right to protect cultural knowledge of the kind considered in Ward. In Ward the right that was sought was the “right to maintain, protect and prevent the misuse of cultural knowledge of the common law holders associated with the determination area”. In this case the claimed right, according to the claimants, was a limited right confined to disclosure of tenets of spiritual beliefs and practices (including songs, narratives, rituals and ceremonies) which relate to areas of land or waters, or places on the land or waters. I cannot see that there is a distinction. The decisions in the Full Court and the High Court have made it clear that matters of spiritual beliefs and practices are not rights in relation to land and do not give the connection to the land that is required by s 223 of the NTA.

the Tjukurpa

52 Peter De Rose was asked, during the course of his examination in chief, to explain the main Tjukurpa or Dreamings for his country; initially he replied that there were three, the first of which was his Tjukurpa. That was the Kalaya (emu) Tjukurpa – in the track of which he was born. The second Dreaming Track was to the east. It was the track of Malu (the red kangaroo), Kanyala (the euro) and Tjurki (the owl). Sometimes during the course of the trial a reference to this Tjukurpa was abbreviated so that it was simply called “the Malu Dreaming” or “the Malu Tjukurpa”. The third Dreaming was to the west and was one of great significance and secrecy to men; it was one about which Peter could not speak in mixed company. He did no more than name it – Pakalira. Later, as his evidence progressed, he referred to a fourth and fifth dreaming, Papa Itari and The Seven Sisters. In the ensuing discussion, references to the various places along the Tjukurpa paths will incorporate site references on the map, Ex A2, a copy of which is annexed to these reasons.

The Kalaya Tjukurpa –The First Dreaming

53 Peter De Rose said that the Kalaya Tjukurpa (or the emu Dreaming) started near Indulkana at a place called Kirara (site 26). Kirara is to the south of De Rose Hill Station. The emus, travelled north, entering De Rose Hill country where they travelled to Kantja (site 29). Kantja is where Peter’s story starts. At Kantja, the Kalaya met up with the local Kalaya and from Kantja they all then went to Tjinytjirapila (site 30), Tjaapila (site 33), Watarkatjara (site 39) and then on to Ilpalka (site 40). At Ilpalka they met up with other Kalaya who had come from Tiilkatjara (site 43). Yet another group of Kalaya had travelled from Kalkatja (site 47) and they, together with those who had come from Tiilkatjara, travelled through the area of the homestead of De Rose Hill Station and the ironwood tree under which Peter had been born until they arrived at Ilpalka. From Ilpalka, they all left De Rose Hill and travelled to Ngatiri (site 4) which is located on Ayers Range South. (Neither the oral evidence nor the maps that were tendered in evidence established whether Ayers Range South is a separate pastoral Station or, as I think, the southern section of Mt Cavenagh Station. It is not a matter of importance in the final determination of this case but there have been numerous references to Mt Cavenagh Station and only the occasional reference to Ayers Range South. I will refer to Mt Cavenagh Station in the belief that Ayers Range South is part of that Station.) From Ngatiri the Kalaya went to Wipa (site 5) which is directly to the east but located on Tieyon Station. Mt Cavenagh Station, known to the Anangu as “Watju” is to the north of De Rose Hill Station; Tieyon Station is to its east. Peter De Rose, speaking of Wipa, said:

“Wipa is very important place and at that place the Kalaya – all the Kalayas – they kill that devil dog called Kurpanga. They kill him there.”

And that is where Peter’s story ends – at Wipa. The story of the Kalaya Tjukurpa, as it unfolded in Peter’s evidence, was difficult to follow. In his initial answers to questions, he referred to the Kalaya as emus saying that there were many of them and that they had come from many different directions before joining up at Wipa. His counsel then put to him, in quite leading terms:

Q “Sometimes I have heard people say ‘Well, really they were men’. Have I misunderstood that or can you explain that to me?

A Tjukurpa, the story dreamtime, they were people – Wati, man, minyma, woman, tjitji, children – back in Tjukurpa, creation time.

Q Are you able to tell the court what they were doing when they were travelling along like that?”

Peter explained that he could only tell part of the story – being that part that women can hear. He then said in answer to the question:

“They weren’t only travelling; they were creating songs and dances.”

Peter said that he had learnt this story – and more which he could not disclose – from a lot of men, but his father, Snowy, was the one who first told him the story.

54 Peter Tjutatja gave evidence about this Dreaming when the Court took evidence on site at Kantja. He said that the Kalaya Tjukurpa starts from Kirara where it comes out of the ground. Tjutatja said that a male emu and some emu chicks travelled to Kantja from Kirara at which site restricted evidence had been taken earlier on the same day. When the emu and the chicks arrived at Kantja they introduced themselves to the local Kalaya. Tjutatja pointed to two trees at that stage – one to the south which represented the Kalaya who had travelled from Kirara and one to the north, a larger tree, representing the local Kalaya. After the Kalaya had introduced themselves, they joined together and travelled through the country near the De Rose Hill homestead to Ilpalka (site 40).

55 Tjutatja said that from Ilpalka, the Kalaya went further north to Warura (site 2). Warura is quite a distance to the north of De Rose Hill on Mt Cavenagh Station. Tjutatja said that he has been to Warura and he knows that the songs that have been sung at Kantja are the same as the songs that are sung at Warura; they are also the same as the songs that are sung at Ilpalka and at Kirara. However, Tjutatja said that his songs (Inma) finish at Wipa which is south of Warura, although north of Ilpalka. At Wipa, the Tjukurpa goes down into the ground and then off to some other place. He then said at par 31 of his witness statement:

“We are talking about many watis back then. The eggs hatched there at Kirara and the emus grew bigger and bigger.”

There is an interesting mixture of man and bird in those two sentences. Still referring to the Kalaya Tjukurpa, he said:

“They were young men moving in a northerly direction. They were singing (inma) of the places near the homestead, Tiilkatjara, Ilpalka – all the sites. It is a very important story. At Wipa they stomped the demon into the ground. They then went into the ground and went east. It becomes other people’s story from then on.”

He described the Kalaya Inma as a song to which only young married men can dance; it cannot be danced in mixed company. He added:

“I am the Mayatja [the boss] for the section Kirara to Wipa. I have done the Inma for Kalaya from Kirara through to Wipa.”

56 He learnt those songs from his uncles, Tjaapan Tjaapan, Old Panma and Jimmy Piti Piti. Those three old men came from Iranytjirany in the west but the songs came from Kirara in the south. According to Tjutatja, however, his uncles had learnt the songs at Iranytjirany. Tjutatja said that he also had learnt the Kalaya Inma at Iranytjirany, which is difficult to accept if his evidence is correct that he was only ten or twelve when he left Iranytjirany for Kantja. Tjutatja said that the Kalaya made ngaru ngaru at Ilpalka. Ngaru ngaru means more than one hole in the ground. Ngaru ngaru is also the word that is used for tjukula or a rock hole and there is a rock hole of significant size at Ilpalka.

57 In cross-examination, Tjutatja said that, in travelling from Kantja to Ilpalka, the Kalaya also stopped at Tiilkatjara (site 43). They always travelled from south to north and the places where they have stopped and the way in which they have travelled have always been the same. There are many songs for the Kalaya and the women can stay in the camp and can listen to the singing, but only the men can sing the Inma.

58 Riley Tjayrany agreed with Tjutatja that the two trees at Kantja represented the two groups of Kalaya. According to Riley, after the two groups of Kalaya had met and introduced themselves, they moved off together towards Ilpalka. That was in a north-easterly direction passing by a claypan that is called Tjinytjirapila (site 30). Riley said that the Kalayas stopped between Tjinytjirapila and Ilpalka but he could not remember the name of the place. He said that the Kalaya left rules at these places and the rules included the right of women to hear about the Inma.

59 In cross-examination, Peter De Rose recognised the three photographs in Ex F3 as photographs of a location known as Tiilkatjara (site 43). The photographs showed lines of small rocks in geometric patterns. Some of the lines have been broken and, according to Peter, that had been caused through cattle moving about in the area. Peter believed that the stones had been there from the creation days and the old men used to say that it was part of the Kalaya Tjukurpa. The rocks were said to be emu eggs. However, Peter had never seen a ceremony conducted at Tiilkatjara, nor had any of the old men, other than Johnny Wimitja De Rose, ever mentioned a ceremony being conducted there.

60 Johnny Wimitja De Rose gave evidence near the site of the De Rose Hill homestead. The homestead is not much more than a kilometre to the east of the Stuart Highway and the Court took evidence in a paddock a short distance to the west of the nearest outbuilding near a stand of mulga trees. Wimitja said that the location of the Court was on, or near, the path of the Kalaya Tjukurpa which had come from Kalkatja (site 47) and Tiilkatjara (site 43). The Dreaming track passed close by the homestead, following the line of a creek until it reached a swamp which is further to the east. From the swamp, the track went on to Ilpalka (site 40). At Ilpalka, the Tjukurpa had an Inma with another Kalaya who had come from Kirara (site 26) via Kantja (site 29), Tjinytjirapila (site 30), Tjaapila (site 33) and Watarkatjara (site 39) to Ilpalka. Wimitja said that there was only one emu but that he had a lot of little chicks with him. Wimitja also said that, originally, the track of the Tjukurpa could be seen in the shape of a line of ironwood trees to the west of the homestead. However, the trees are not there now; he does not know what happened to them but he is sad that they are gone.

61 Wimitja continued with his story. The Kalaya from each group joined together at Ilpalka and, together, they travelled to Ngatiri (site 4). That was where they met Kurpany (also called Kurpanga), the devil dog. One of them, Mala (the rufous hare – wallaby), was bitten by the dog. The Kalaya went to Wipa (site 5), and from there, two emus went out to meet the devil dog. The devil dog saw them and started to chase them, but luckily, he fell into a big hole that the Kalaya men had built. He died in that hole and, perhaps, said Wimitja, he is still there today. That was the end of Wimitja’s story. He did not know where the devil dog had come from; he had learnt that story from the old men - from his father, Jimmy Piti Piti, from Old Panma and Tjaapan Tjaapan and from the other old men who have since died. He said that the old men had shown him the Kalaya tracks. He knew that Tjaapan Tjaapan had been born at Katji Katji Tjara, far to the west but, as Wimitja said, referring to De Rose Hill, “he grew old here”. (T574)

Malu, Kanyala and Tjurki Tjukurpa – The Second Dreaming

62 Peter Tjutatja claimed that he is the “boss” for Malu. He described that Dreaming as coming from Indulkana through De Rose Hill on to the eastern side of the Station naming the following places through which it travelled: Yura (site 19), Apu Maru (site 17), Urtjantjara (site 16), Inyata (site 13), Malu Kapi (site 12), Alalyitja (site 11) and Kulpitjara (site 10). This description is not as complete as that of Peter De Rose (which is set out below) but I do not attach any significance to the small variations.

63 Tjutatja also said that there are special places on Iranytjirany for the Malu Tjukurpa and that he knew the stories and understood them. In addition, there are important places on Watju (Mt Cavenagh) and Wapirka (Victory Downs) and he knows the Tjukurpa for those places. Mt Cavenagh and Victory Downs are adjoining cattle stations in the Northern Territory immediately to the north of De Rose Hill Station.

64 Peter De Rose said that the Malu Tjukurpa comes “from long way but I’ll tell you from the close, close up in Granite Downs boundary …”. He commenced his evidence about the second Dreaming by referring to Wantjapila (site 23) Intalka (site 24) and Iwantja (site 25). These three locations are, as Peter indicated, within the boundaries of Witjintitja (Granite Downs Station) and to the south of De Rose Hill Station. From Iwantja, the Tjukurpa travels to Yura (site 19) which is in the south-eastern corner of De Rose Hill Station on the banks of the Alberga Creek. Thereafter, the Dreaming travels up the eastern side of De Rose Hill, passing through Apu Maru (site 17), Urtjantjara (site 16), Malu Kapi (site 12) and then on to Inyata (site 13) (which is due west of Malu Kapi). However, after passing through Inyata, the Dreaming doubles back to the north-east to Alalyitja (site 11) and then resumes its track to the north, passing through Kulpitjara (site 10). At Kulpitjara, it leaves De Rose Hill and travels to Tjula (site 6) before turning to the east where the story, for Peter, finishes at Arapa (site 8) on Tieyon Station. That, said Peter, is “where our country ends”. In giving this description of the Malu Tjukurpa, Peter explained that he had only mentioned those places where there was water; the Malu passed through other areas but as they had no water point he did not mention them. Peter’s ability to speak about the Malu was restricted. He said:

“… the women can talk about the water point and the name of the places and that’s OK. But I can’t tell you any more because its sacred secret things now, only for the men.”

65 In response to a question from his counsel, Peter said that he had learnt about the Malu Dreaming from Snowy (his step-father) and from those other elders who had given evidence in the trial. He named the witnesses Riley Tjayrany, Whiskey Tjukanku, Alec Baker and Peter Tjutatja but significantly, he failed to mention Owen Kunmanara whom he had, elsewhere in his evidence, named as a source of much information. Perhaps it was a case of a simple oversight. Peter was then asked what was his understanding of how these old men had learnt about the Dreamings. He answered saying:

“When they tell me and teaching me, telling me the stories they say they learned from their fathers and from their grandfathers and then they were teaching me.”

He added that he could not tell much more about the story, saying that “it started back in creation days and stays with this land, this country and it’s a law for this land for our country”.

Pakalira Tjukurpa – The Third Dreaming

66 Peter De Rose said that he could not speak about the third Dreaming, the Pakalira, in the presence of women. Asked what would happen if he talked about it openly, Peter said that the old people would not like it because it is a:

“… secret sacred thing and I can’t mention that. If I do I will get into trouble and they might kill me.”

The most that he was prepared to say was that some of the water points for the Pakalira Dreaming are to the west on the Kenmore Park boundary and that one of them was at Kumpalyitja (site 55) which is in the south western corner of De Rose Hill Station. The court subsequently took evidence in closed session at Kumpalyitja.

67 Wimitja, who said that old Panma had taught him the stories for the Tjukurpa Dreaming, said that the Pakalira Tjukurpa connects De Rose Hill with Ernabella. He also made reference to the Pakalira at Granite Downs. However, he did not give any details of the Dreaming in open evidence. Mitakiki also said that he understood the Pakalira Dreaming. He agreed that it was very miilmiilpa (very sacred) and only men could know the details of the story.

Papa Itari Tjukurpa – The Fourth Dreaming

68 Peter De Rose talked of a fourth Tjukurpa which he called Papa Itari. Papa Itari is also a location on De Rose Hill Station (site 48). It is a natural depression which has been bisected by the Stuart Highway. The Court took evidence about 200 metres to the east of the highway on a small sandy rise. Further to the east there were two small round depressions, both of which were covered with water and surrounded by samphire. Tim De Rose, who also gave evidence at this stage, said that he was authorised to speak for the place. He identified Papa Itari as words in the Yankunytjatjara language: “Papa” means “dog” and “Itari” means “to drag along the ground”. He said that he had been to the location on quite a few occasions because it was so close to De Rose Hill Station where he had worked as a young man.