FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Benwell v Gray, Electoral Commissioner [1999] FCA 1532

INJUNCTION – Order sought requiring segregation of ballot-papers at referendum – complaint that Electoral Commissioner’s Handbook misapplied the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth) – whether serious issue to be tried – balance of convenience

Constitution, s 128

Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth), ss 24, 89, 90, 92, 93, 97, 98, 100, 102, 142A

Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth), s 39B(1)

Kane v McClelland (1962) 111 CLR 518, followed

Boland v Hughes (1988) 83 ALR 673, followed

PHILLIP BENWELL v WILFRED JAMES GRAY, ELECTORAL COMMISSIONER

N 1258 OF 1999

JUDGE: SACKVILLE J

DATE: 5 NOVEMBER 1999

PLACE: SYDNEY

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

N 1258 OF 1999 |

|

BETWEEN: |

PHILLIP BENWELL Applicant

|

|

AND: |

WILFRED JAMES GRAY, ELECTORAL COMMISSIONER Respondent

|

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application be dismissed.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

N 1258 OF 1999 |

|

BETWEEN: |

Applicant

|

|

AND: |

WILFRED JAMES GRAY, ELECTORAL COMMISSIONER Respondent

|

|

JUDGE: |

|

|

DATE: |

|

|

PLACE: |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1 The applicant is the National Chairman of the Australian Monarchist League, an organisation which supports the retention of the Monarchy under the Constitution. He has instituted proceedings claiming relief in relation to the two proposed laws to be submitted to the referendum to be held on Saturday, 6 November 1999. The first is a proposed law

“to alter the Constitution to establish the Commonwealth of Australia as a republic with a President chosen by a two-thirds majority of the members of the Commonwealth Parliament.”

The second is a proposed law

“to alter the Constitution to insert a preamble.”

2 The referendum questions to be put to the electorate on 6 November 1999 follow the form specified in Schedule 1 to the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth) (“Referendum Act”). The questions are as follows:

“DIRECTIONS TO VOTER

Write Yes or No

in the space provided

opposite the question set out below

A PROPOSED LAW: To alter the Constitution to establish the Commonwealth of Australia as a republic with the Queen and the Governor-.General being replaced by a two-thirds majority of the members of the Commonwealth Parliament.

|

DO YOU APPROVE THIS

PROPOSED ALTERATION?

WRITE “YES”

OR “NO”

DIRECTIONS TO VOTER

Write Yes or No

in the space provided

opposite the question set out below

A PROPOSED LAW: To alter the

Constitution to insert a preamble.

|

DO YOU APPROVE THIS

PROPOSED ALTERATION?

WRITE “YES”

OR “NO””

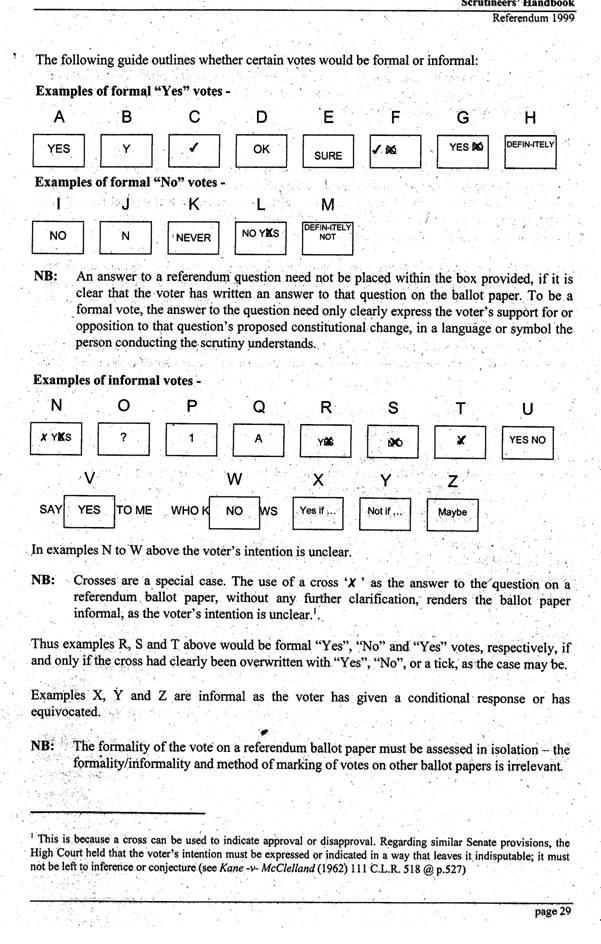

3 The applicant’s concern is that a document published by the respondent (“the Commissioner”), known as the “Scrutineers Handbook” (the “Handbook”), gives instructions to scrutineers which are not in accordance with the requirements of the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth) (the “Referendum Act”). In particular, he claims that the guidelines included in the Handbook, if followed, would result in informal ballots being counted as formal “YES” votes.

4 The applicant commenced proceedings on 2 November 1999. The application sought the following relief:

“1. A declaration that the section of the Scrutineers Handbook (“handbook”) issued by the Respondent with respect to the referendum to be held on 6 November 1999 under the heading “Formality checks” is ultra vires the powers of the Respondent pursuant to the provisions of the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984, as amended.

2. An order restraining the Respondents from issuing or otherwise distributing or acting upon that section of the said handbook.

3 An order requiring the Respondent to segregate at the scrutiny votes on which a returning officer exercises a discretion to allow a vote as formal under the provision of section 92(1) of the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984, as amended from other formal votes and return the same as a separate number.”

5 The matter first came before me at 12.30 pm on Wednesday, 3 November 1999. At that time, the applicant sought leave for short service of a claim for interlocutory relief. I was informed that the applicant intended to seek, by way of interlocutory relief, an order restraining the Commissioner from distributing or acting on the Handbook. The applicant also intended to seek an order requiring the Commissioner to segregate votes which a returning officer allows as formal under s 92 of the Referendum Act.

6 I made orders for short service of the application, which was made returnable at 2.15 pm on 4 November 1999. At that time, Mr Davidson, who appeared for the applicant, asked for the application to be determined on a final basis and foreshadowed proposed amendments to the application. The foreshadowed amendments included a claim for an order that the Commissioner reject as informal any ballot-paper cast at the referendums which does not contain the words “YES” or “NO” in the space provided.

7 The Solicitor-General for the Commonwealth, Mr Bennett QC, who appeared with Mr Robertson SC and Mr Johnson for the Commissioner, objected to a departure from the course proposed at the initial hearing, that is that the case be dealt with on an interlocutory basis only. I declined to entertain the application for final relief.

8 Mr Davidson then pursued a claim for interim relief on behalf of the applicant, but on a narrower basis than that previously foreshadowed. The only interim relief now sought by the applicant is an order in the following form:

“An order that the Respondent segregate at the scrutiny ballot-papers cast at each referendum to be held on 6 November 1999 which contain any of the markings indicated under Categories “B” to “M” [other than “I”] of the Scrutineers Handbook issued by the Respondent with respect to the referendum to be held on 6 November 1999 under the heading “Formality checks”.

9 The applicant submitted that the Court had jurisdiction to entertain the application pursuant to s 39B(1) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). The respondent accepted that the Court had jurisdiction. Mr Bennett expressly disclaimed any objection to the applicant’s standing for the purposes of the interlocutory application. The Commissioner reserved his position on the question of standing at a final hearing.

The Handbook

10 In order to understand the relief sought by the applicant, it is necessary to refer to the Handbook. The Handbook was published by the Commissioner on 20 September 1999. Since that date it has been available in printed form to the public. It has also been available since that date on the Internet. A total of 35,000 printed copies of the Handbook have been published, while to date at least 710 copies have been down-loaded from the Internet.

11 Material in the Handbook provides the basis for manuals provided to Officers in Charge (“OIC’s”) of the 7,712 polling places in Australia. Manuals are also provided to Declaration Issuing Officers (“DIO’s”) and (in a more summary form) to the polling staff who number over 60,000.

12 Section 8 of the Handbook deals with “Formality of Votes”. The information in Section 8 is said to be based on Parts 3 and 6 of the Referendum Act. Scrutineers are advised to refer to the legislation itself for the exact provisions.

13 Section 8.2 of the printed version of the Handbook is headed “Formal Votes”. It is as follows:

8.2 FORMAL VOTES

Formality checks of ballot papers fall into two categories:

• one comprising tests of whether the ballot paper is an authentic one which does not

identify the voter; and

• the other comprising tests of whether the voter has marked their vote on the ballot paper

and their intention is clear.

[s.93 RMPA]

Authenticity tests

To be accepted as authentic the ballot paper must:

• be authenticated by the official mark or by the initials of the Presiding Officer, or must, in

the opinion of the DRO deciding the question, be an authentic ballot paper; and

• not have any writing on it by which the voter can be identified.

Formality checks

To be accepted as formal, an authentic ballot paper must have a single unambiguous vote marked

on it.

Although electors are required to express their vote by writing the word "Yes" or "No” in the

space provided on the ballot paper there are other markings that can be accepted as a formal vote

if the elector's intention is clear.

14 It should be noted that the down-loaded version of Section 8.2 of the Handbook is slightly different, for technical reasons. The down-loaded version of Categories F, G and L are as follows:

“ F G L

3NXO YES NO

NXO YXS”

The Legislation

15 The issues raised by the application turn principally on what appears to be a tension between ss 24 and 93 of the Referendum Act. Section 24 provides for the manner of voting in apparently mandatory language:

“24. Manner of voting

The voting at a referendum shall be by ballot and each elector shall indicate his or her vote:

(a) if the elector approves the proposed law – by writing the word “Yes” in the space provided on the ballot-paper; or

(b) if the elector does not approve the proposed law – by writing the word “No” in the space so provided.”

16 Section 93 provides for informal ballot papers, as follows:

“93. Informal ballot-papers

(1) A ballot-paper is informal if:

(a) …

(b) it has no vote marked on it or the voter’s intention is not clear;

(c) …

(d) …

…

(8) Effect shall be given to a ballot-paper of a voter according to the voter’s intention, so far as that intention is clear.”

17 Part 6 of the Referendum Act provides for the scrutiny of a referendum. Section 89 provides for the appointment of persons as scrutineers by the Governor-General, the Governor of each State, the Administrator of the Northern Territory and an officer of each registered political party. Scrutineers appointed under s 89 are permitted to inspect all proceedings at the scrutiny: s 90(1). Section 92 of the Referendum Act provides for the allowance or rejection of informal ballots. Section 92(1) states as follows:

“If, at the scrutiny, a scrutineer appointed under section 89 objects to a ballot-paper as being informal, the officer conducting the scrutiny shall mark the ballot-paper “allowed” or “rejected” according to his or her decision to allow or reject the ballot paper.”

Timing of the Application

18 Because the Commissioner relied on the delay of the applicant in instituting proceedings, it is important to trace the history of the applicant’s complaint about the Handbook. This also assists in identifying the nature of the applicant’s complaint.

19 As I have noted, the Handbook was published on 20 September 1999. On 11 October 1999, the applicant down-loaded a copy from the Internet. It was not until 24 October 1999, five weeks after the Handbook was publicly available and thirteen days after the applicant obtained a copy, that he wrote a letter to the Commissioner.

20 The letter of 24 October 1999 complained that the introduction to Section 8.2 suggested that the scrutineer had a discretion to treat a clear indication of voter’s intention as an acceptable alternative to “YES” or “NO” (as the case may be) and was a departure from “what is legally required”. The letter also expressed concern that the guidelines appeared to favour the “YES” case, in particular by accepting a tick as a “YES” vote, but rejecting a cross as a “NO”. Other complaints, not presently relevant, were made.

21 The Commissioner replied on the following day, 25 October 1999. The reply drew attention to the terms of ss 24 and 93 of the Referendum Act. It continued:

“[I]n deciding on whether a ballot paper has been marked in the manner prescribed by section 24 of the Referendum Act, the AEC must … take into account whether the voter’s intention is clear, and will favour the franchise where possible.

The “Scrutineers’ Handbook” is provided by the AEC to all scrutineers to assist them in their duties, and information is provided on how various marks on ballot papers will be interpreted by electoral officials during the scrutiny of ballot papers, in accordance with legal advice from the Attorney-Generals’ Department.

This information is published in advance of the ballot, for the benefit of scrutineers, so that disputes at the scrutiny over formality of ballot papers can be dealt with efficiently and in accordance with legal advice previously obtained by the AEC. The Attorney-General’s Department has advised the AEC that whilst a tick can be interpreted as a “Yes”, it cannot be interpreted as a “No”.”

22 It was not until eight days after the Commissioner sent his reply that the present proceedings were instituted. They were commenced only three days before the referendum day.

The Applicant’s Submissions

23 The applicant submitted that there was a serious issue to be tried as to whether the Commissioner, by instructing OIC’s, DIO’s and polling staff to follow the guidelines in Section 8.2 of the Handbook, had misconstrued ss 24 and 93(8) of the Referendum Act. Mr Davidson put this submission on three alternative bases:

(i) Section 93(8) could not be read as qualifying the mandatory language of s 24.

(ii) If s 93(8) did qualify s 24, it required a ballot paper to be given effect only where the voter’s intention to write the words “YES” or “NO” (as the case may be) was clear but that intention had been imperfectly realised (as where the voter records the letters “YE” in the space provided). It was not enough to attract s 93(8) that a voter’s intention to approve or disapprove of the proposed law was expressed clearly on the ballot-paper.

(iii) Even if the test was whether the voter had clearly expressed an intention to approve or disapprove of the proposed law, none of the illustrations given in the Handbook (that is, examples “B” to “M”, other than “I”) constituted a sufficiently clear expression of that intention.

24 Mr Davidson contended that the balance of convenience lay in granting the interlocutory order sought by the applicant. He argued that the order had practical utility, notwithstanding that s 100 of the Referendum Act provides that only the Commonwealth, the States or the Northern Territory can dispute the validity of any referendum or of any return or statement showing the voting at a referendum. (See also s 102 permitting the Electoral Commission to file a petition disputing the validity of a referendum.) According to Mr Davidson, the practical utility in the interim relief lay in the possibility that the applicant could secure final relief, in the form of an order that the Commissioner reject as informal any ballot-paper cast at the referendum which is not in conformity with the requirements of the Referendum Act.

25 Mr Davidson appeared to accept that any such final relief would have to be obtained before the return of the writ (s 98) or the preparation of a statement by the Australian Electoral Officer for a State or Territory specifying the votes in favour and not in favour of the proposed law (s 97). He did not explore the practical difficulties of completing the litigation within the required time frame and in a manner that would not seriously delay counting of votes.

Serious Issue to Be Tried

26 In my opinion, neither of the first two ways in which the applicant puts his case raises a serious issue to be tried. It cannot be correct to suggest that the effect of s 24 is that a ballot is formal if, and only if, the voter writes either the word “YES” or “NO” in the ballot paper. To take this view would be to deny any effect at all to the language of s 93(8). Clearly that sub-section is intended to ensure that effect is given to a ballot-paper of a voter according to the voter’s clear intention, even if he or she writes neither the word “YES” nor “NO” on the ballot-paper. So much at least flows from the reasoning of the High Court, in relation to analogous provisions in the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth), in Kane v McClelland (1962) 111 CLR 518, at 527.

27 Nor, in my opinion, is the narrow construction of s 93(8) advanced by Mr Davidson correct. The intention referred to in s 93(8) is not confined to an incompletely realised intention to write the words “YES” or “NO” on the ballot-paper. The point of the referendum, as shown by the prescribed form of ballot-paper (Schedule 1, Form B), is to ascertain whether sufficient voters approve of the proposed alteration to the Constitution to satisfy the requirements of s 128 of the Constitution. The intention with which s 93(8) is concerned is the voter’s intention to express approval or disapproval of the proposed alteration. It follows that s 93(8) of the Referendum Act will apply to give effect to a ballot-paper of a voter where the voter’s intention to approve or disapprove the proposed law is sufficiently clear.

28 Nonetheless, on the broader construction of s 93(8), the test that must be satisfied is a stringent one. In Kane v McClelland (at 528), the Court, in relation to a provision equivalent to s 93(8), said (at 527) that a clear indication of the voter’s intention meant an “unmistakable” indication of that intention.

29 It seems to me that the better view is that of the examples of formal “YES” and “NO” votes identified in Section 8.2 of the printed version of the Handbook contain unmistakable indications of the hypothetical voter’s intention. Examples B, C, F, G and H seem to me to convey sufficiently a clear intention to approve the proposed law. It is difficult to see, for example, what other intention could lie behind a voter’s use of a tick (with or without the word “NO” crossed out) or the word “DEFINITELY”. Similarly, examples J, K and M appear to convey an unmistakable intention to disapprove the proposed law.

30 There may be slightly more doubt about examples D, E and L. The expressions “OK” and “SURE” are perhaps less clear-cut expressions of approval than the other examples. Nonetheless, I am inclined to the view that the expression of intention to approve the proposals would be sufficiently clear.

31 Mr Davidson pointed out that the down-loaded version of the Handbook set out some of the examples somewhat differently from the printed version. I think it clear enough that the differences are simply attributable to the technical difficulty of reproducing faithfully all the examples in the printed version. To the extent that the down-loaded version differs from the printed version, it is unlikely that examples in the latter will be reproduced by voters on their ballot-papers. It is difficult to believe for example that many voters will use “3NXO” to record their vote. I do not think that the differences in the down-loaded version of the Handbook materially advance the applicant’s case.

32 In the result, I doubt that the applicant has established that there is a serious issue to be tried as to whether the Handbook incorrectly applies the provisions of the Referendum Act. It is not necessary, however, to resolve this question. Even if there is a serious issue to be tried, I think the balance of convenience is clearly against the grant of any relief to the applicant.

Balance of Convenience

33 There are a number of factors which tell against the grant of interim relief in the form sought by the applicant.

34 First, Mr Wydeman, the Deputy Electoral Officer for New South Wales, gave evidence of the very considerable, if not insuperable difficulties that would be involved in changing the instructions to OIC’s, DIO’s and polling staff throughout Australia at such a late stage. Mr Wydeman was cross-examined, but the cross-examination did not, in my view, detract from his account of the practical difficulties that would be encountered in communicating accurately and effectively changed arrangements affecting over 60,000 personnel who have already been given detailed instructions for the conduct of the referendums. There is a real risk of confusion and of inconsistency in the carrying out of hastily revised instructions.

35 Mr Davidson attempted to counter this difficulty by suggesting that the segregation of ballot-papers disputed by the applicant could be undertaken after referendum night (when ballots cast on the day of the referendums are expected to be counted). But Mr Wydeman’s evidence shows that such a course is likely to delay the final counting of votes and to involve substantial duplication of work and additional cost. From the applicant’s point of view, the task of identifying and segregating disputed ballot-papers (that is, ballot-papers the applicant wishes to dispute) must be carried out very soon after the referendums take place. Otherwise there would be no possibility of obtaining final relief before return of the writs (which is expected to occur, in the ordinary course, on about 22 November 1999). The difficulty is that the earlier the task of segregating ballot-papers is undertaken the greater the risk of delay in counting and in finalising the referendums.

36 Secondly, there have been lengthy unexplained delays on the part of the applicant in instituting proceedings. They were ultimately commenced only three days before the referendums were scheduled to be held. That promptness in applications of this kind is important is shown by Boland v Hughes (1988) 83 ALR 673. There, Mason CJ rejected a last-minute attempt to postpone a referendum partly on the ground of the applicant’s significant delay. It may be that if the present proceedings had been brought much earlier some or all of the practical difficulties attested to by Mr Wydeman could have been overcome, or at least systematically addressed. The delays count heavily against the applicant.

37 Thirdly, it is highly speculative as to whether the issue raised by the applicant (assuming that his legal arguments have substance) will have any practical significance. Mr Davidson accepted that the number of ballot-papers answering the description of the examples in the Handbook might well be relatively small. There is nothing in the evidence to suggest that it is likely that ballot-papers of the classes disputed by the applicant will make a difference to the outcome of the referendums.

38 Fourthly, if the ballot-papers disputed by the applicant ultimately become important to the outcome of the referendums, Part 8 of the Referendum Act provides a mechanism whereby the validity of the referendums or any returns can be challenged. It is true that the applicant himself is unlikely to have the standing to mount such a challenge. But others do have standing. As Mason CJ said in Boland v Hughes (at 675) what is important is that the validity of the referendums or the returns can be challenged in appropriately constituted proceedings. There is no risk that the classes of ballot-papers identified by the applicant will be destroyed, since s 142A of the Referendum Act requires the ballot papers to be preserved for at least six months.

39 For these reasons the balance of convenience lies against the grant of interim relief to the applicant.

Conclusion

40 The application for interim relief should be dismissed.

|

I certify that the preceding forty (40) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Sackville. |

Associate:

Dated: 5 November 1999

|

Counsel for the Applicant: |

Mr I E Davidson |

|

|

|

|

Solicitor for the Applicant: |

Dennis Cooney Solicitors |

|

|

|

|

Counsel for the Respondent: |

Mr D M J Bennett QC with Mr A Robertson SC and Mr J Johnson |

|

|

|

|

Solicitor for the Respondent: |

Australian Government Solicitor |

|

|

|

|

Written submissions: |

4 November 1999 |

|

|

|

|

Date of Judgment: |

5 November 1999 |