FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

LED Builders Pty Ltd v Eagle Homes Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 584

COPYRIGHT – infringement – copyright in floor plans for project homes – whether copying of a substantial part – whether houses built in accordance with floor plans which infringed applicant’s copyright also infringed that copyright – no evidence that houses built exactly in accordance with infringing floor plans or other evidence of appearance of houses – quantum of profits where houses built in accordance with infringing floor plans – whether part of building profit included – quantum of damages where no houses built in accordance with infringing floor plans –whether applicant entitled to additional damages.

ACCOUNT OF PROFITS – infringement of copyright in floor plans for project homes – construction of houses in accordance with infringing floor plans – proper measure of account of profits – whether respondent must account for all profits made from construction of houses in accordance with infringing floor plans – whether respondent must account only for saving made through use of infringing floor plans – whether profits should be apportioned – proper basis for apportionment – whether allowance should be made for overheads – whether construction of houses in accordance with infringing floor plans involved opportunity cost – whether overheads should be allowed on an incremental or absorption basis – whether overheads should be allocated on basis of revenue or average cost – whether applicant can be awarded additional damages where it elects for an account of profits in respect of an infringement.

Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 21 (3), 115

Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 51A

Eagle Homes Pty Ltd v Austec Homes Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 138, applied

Bradbury, Agnew & Co v Day (1916) 32 TLR 349, considered

Chabot v Davies [1936] 3 All ER 221, considered

LB (Plastics) Ltd v Swish Products Ltd [1979] RPC 551, referred to

Ogden Industries Pty Ltd v Kis (Australia) Pty Ltd [1982] 2 NSWLR 283, referred to

S W Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466, considered

Dyason v Autodesk Inc (1990) 24 FCR 147, considered

Lend Lease Homes Pty Ltd v Warrigal Homes Pty Ltd [1970] 3 NSWR 265, applied

Ancher, Mortlock, Murray & Woolley Pty Ltd v Hooker Homes Pty Ltd [1971] 2 NSWLR 278, considered

Robert J Zupanovich Pty Ltd v B & N Beale Nominees Pty Ltd (1995) 59 FCR 49, considered

Burke and Margot Burke Ltd v Spicers Dress Designs [1936] Ch 400, considered

Colbeam Palmer Ltd v Stock Affiliates Pty Ltd (1968) 122 CLR 25, applied

Sheldon v Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corp 309 US 390 (1940), applied

My Kinda Town v Soll [1982] FSR 147, considered

Potton Ltd v Yorkclose Ltd [1990] FSR 11, distinguished

Peter Pan Manufacturing Corp v Corsets Silhouette Ltd [1964] 1 WLR 96, distinguished

Siddell v Vickers (1892) 9 RPC 152, distinguished

Dart Industries Inc v Décor Corporation Pty Ltd (1993) 179 CLR 101, applied

Leplastrier & Co Ltd v Armstrong-Holland Ltd (1926) 26 SR (NSW) 585, referred to

Levin Bros v Davis Manufacturing Co 72 F (2d) 163 (8th Cir, 1934), referred to

Tremaine v Hitchcock & Co (“The Tremolo Patent”) 90 US 518 (1874), referred to

Sheldon v Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corp 106 F 2d 45 (2nd Cir, 1939), applied

Warman International Ltd v Dwyer (1995) 182 CLR 544, referred to

Wilkie v Santly Bros Inc 139 F 2d 264 (1943), considered

Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd v Apand Pty Ltd (No 2) (1998) 83 FCR 466, applied

Manfal Pty Ltd v Longuet (1986) 8 IPR 410, referred to

New England Country Homes Pty Ltd v Moore (1998) AIPC ¶91-410, referred to

Autodesk Australia Pty Ltd v Cheung (1990) 94 ALR 472, considered

Amalgamated Mining Services Pty Ltd v Warman International Ltd (1992) 111 ALR 269, considered

Columbia Pictures Industries Inc v Luckins (1996) 34 IPR 504, considered

Bailey v Namol Pty Ltd (1994) 53 FCR 102, considered

Redrow Homes Ltd v Bett Brothers Plc [1999] 1 AC 197, applied

Concrete Systems Pty Ltd v Devon Symonds Holdings Ltd (1978) 20 SASR 79, considered

International Credit Control Ltd v Axelsen [1974] 1 NZLR 695, not followed

Wellington Newspapers Ltd v Dealers Guide Ltd [1984] 2 NZLR 66, not followed

Raben Footwear Pty Ltd v Polygram Records Inc (1997) 145 ALR 1, referred to

Autodesk Inc v Yee (1996) 139 ALR 735, referred to

Cala Homes (South) Ltd v Alfred McAlpine Homes East Ltd (No 2) [1996] FSR 36, referred to

Prior v Lansdowne Press Pty Ltd (1975) 29 FLR 59, applied

Ravenscroft v Herbert & New English Library Ltd [1980] RPC 193, applied

International Writing Institute Inc v Rimila Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 250, applied

Warman International Ltd v Dwyer (1992) 46 IR 250, distinguished

Beloit Canada Ltd v Valmet Oy (1995) 61 CPR (3d) 271, considered

LED BUILDERS PTY LIMITED v EAGLE HOMES PTY LIMITED

NG 817 of 1993

NG 862 of 1994

LINDGREN J

7 MAY 1999

SYDNEY

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

NG 862 OF 1994 |

|

BETWEEN: |

LED BUILDERS PTY LIMITED (ACN 002 351 957) Applicant

|

|

AND: |

EAGLE HOMES PTY LIMITED (ACN 002 800 115) Respondent

|

|

DATE OF ORDER: |

|

|

WHERE MADE: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

(1) The proceedings be stood over to 21 May 1999 at 9.30 am for the making of orders, including orders as to costs.

(2) The applicant notify the respondent and the Associate to Lindgren J by 14 May 1999 if the applicant wishes to make submissions in relation to the issue raised at paras 181-184 of the Reasons for Judgment published this day.

(3) The parties submit to the Associate to Lindgren J by 20 May 1999 agreed short minutes of the orders to be made or, if agreement has not by then been reached, short minutes of the orders for which they will respectively contend and an outline of their respective submissions in support.

Note: Settlement and entry of orders is dealt with in Order 36 of the Federal Court Rules.

|

IN THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA |

|

|

NG 817 OF 1993 NG 862 OF 1994 |

|

BETWEEN: |

LED BUILDERS PTY LIMITED (ACN 002 351 957) Applicant

|

|

AND: |

EAGLE HOMES PTY LIMITED (ACN 002 800 115) Respondent

|

|

JUDGE: |

|

|

DATE: |

|

|

PLACE: |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

INTRODUCTION

1 The applicant (“LED”) sues the respondent (“Eagle”) for infringement of copyright. LED and Eagle carry on the business of building project homes, Eagle under the name “Eagle Homes” and LED under the name “Beechwood Homes”. The copyright in question is in LED’s floor plans for such homes.

2 Both proceedings have, throughout, been heard together. There was a hearing on liability before Davies J from 4 to 8 March 1996 resulting in his Honour’s publishing Reasons for Judgment on 29 July 1996, and a further hearing before his Honour on 15 August 1996 followed by the publication of Supplementary Reasons on 27 August 1996. In conformity with the Reasons and Supplementary Reasons, his Honour made orders in each proceeding on 27 August 1996. He

· declared that Eagle had infringed LED’s copyright in the drawings for nine floor plans for houses identified in the orders, “by the [nine] floor plans for the respondent’s houses [identified in the orders]”;

· ordered that Eagle be restrained from infringing by reproducing either the same nine LED plans or the same nine infringing Eagle plans, or by building or authorising the building of any of the eighteen houses identified (LED’s nine and Eagle’s nine) or any house “with the same floor plan, or a substantial part thereof, [as] any of those [18] houses” or, in substance, promoting the sale of any of the eighteen houses “or any house with the same floor plan, or a substantial part thereof, as any of those houses”; and

· directed Eagle to file and serve by 13 September 1996 affidavit evidence “setting out”, in respect of the same eighteen identified houses “or any substantial reproduction thereof”, the total number of houses built by Eagle and their location, contract price and construction cost (with respect, the terms of the direction are not entirely clear).

The question of pecuniary relief was reserved for a further hearing. It is this hearing that has now taken place before me.

BACKGROUND FACTS

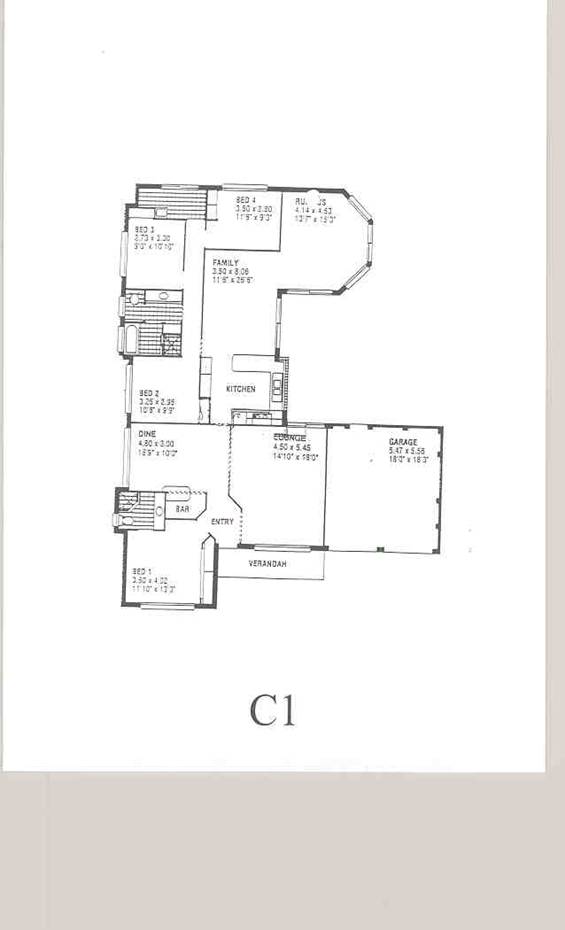

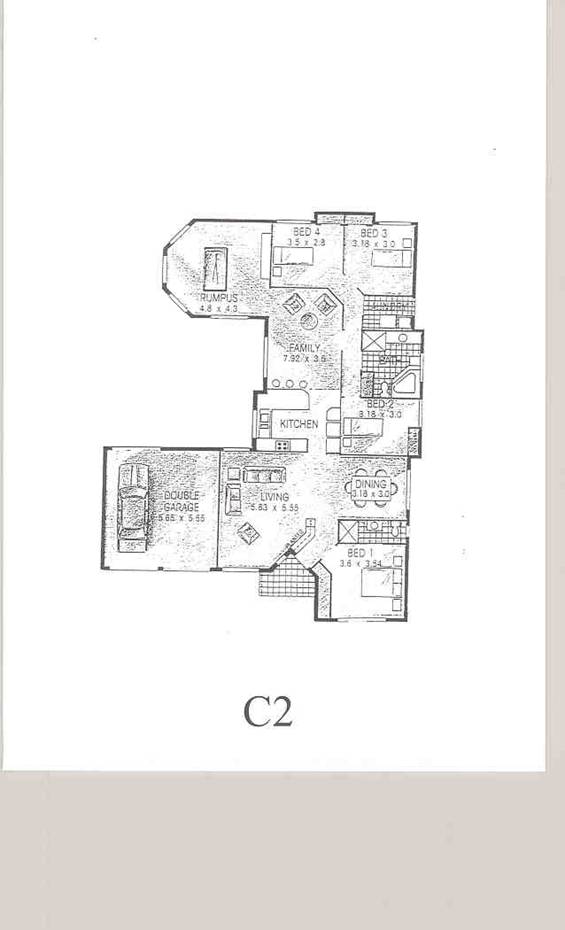

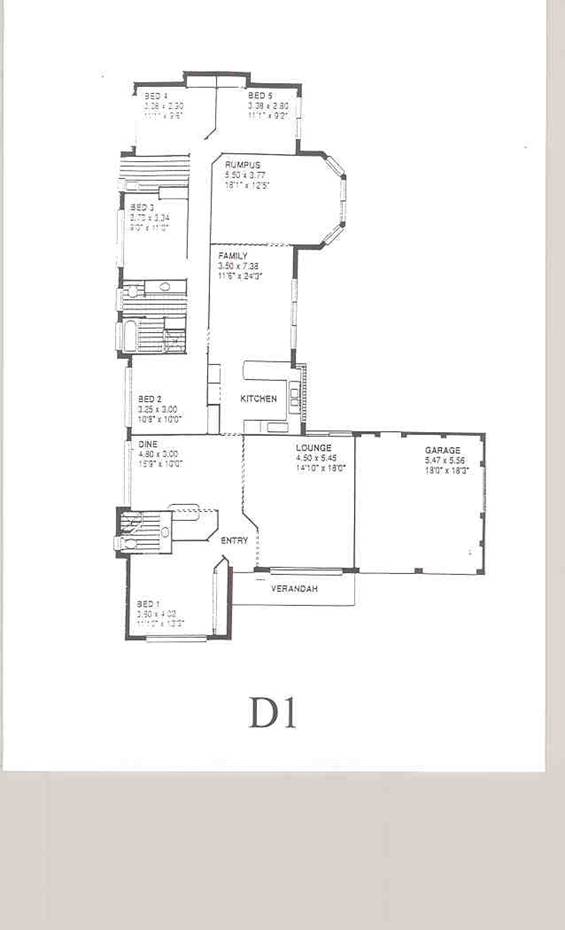

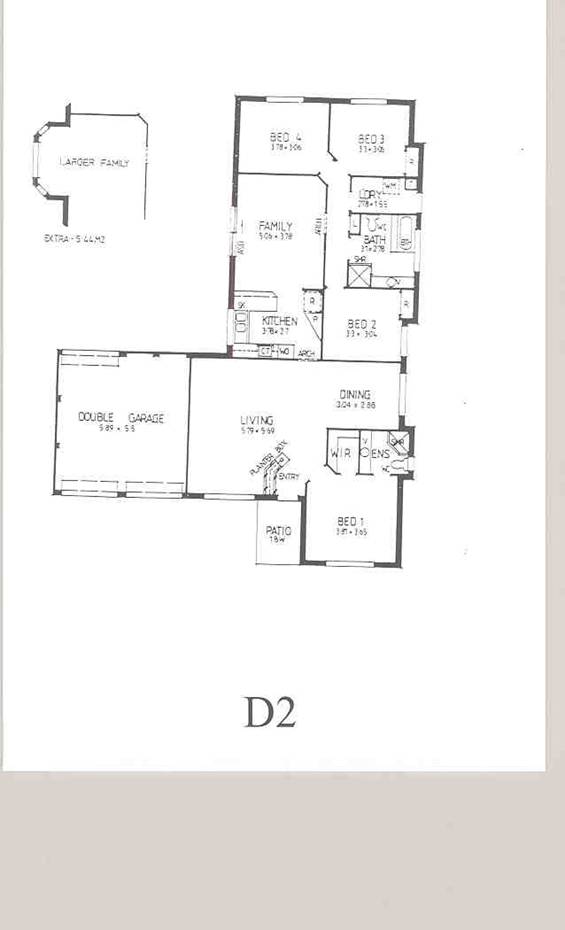

3 In the first proceeding, NG 817 of 1993, Davies J dealt with plans for two of LED’s project homes and in the second proceeding, NG 862 of 1994, he dealt with plans for three of them. Accordingly, in his original Reasons for Judgment, his Honour addressed five drawings of LED and the five drawings of Eagle which were said to infringe them. The five pairs of drawings were identified by the letters A, B, C, D and E.

4 One of the infringing drawings the subject of the first proceeding was that for Eagle’s “Flamingo Premier”. A dispute arose in relation to the plans for four further houses in Eagle’s “Flamingo” range. This led to the supplementary hearing to which I referred and the inclusion in the orders made in proceeding NG 817 of 1993 of four further pairs of house plans (identified by the letters F, G, H and J), in addition to the original two pairs of plans (the A pair and the B pair) in that proceeding.

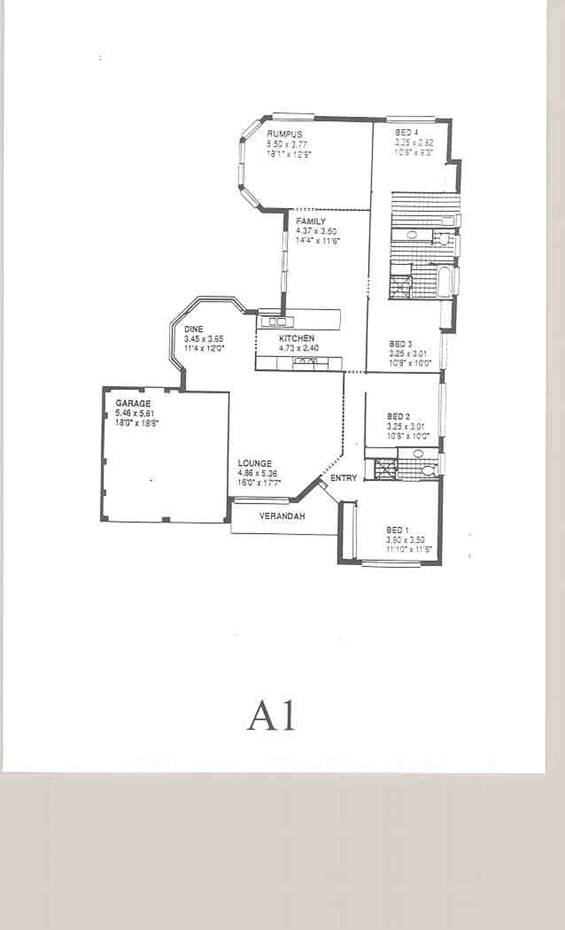

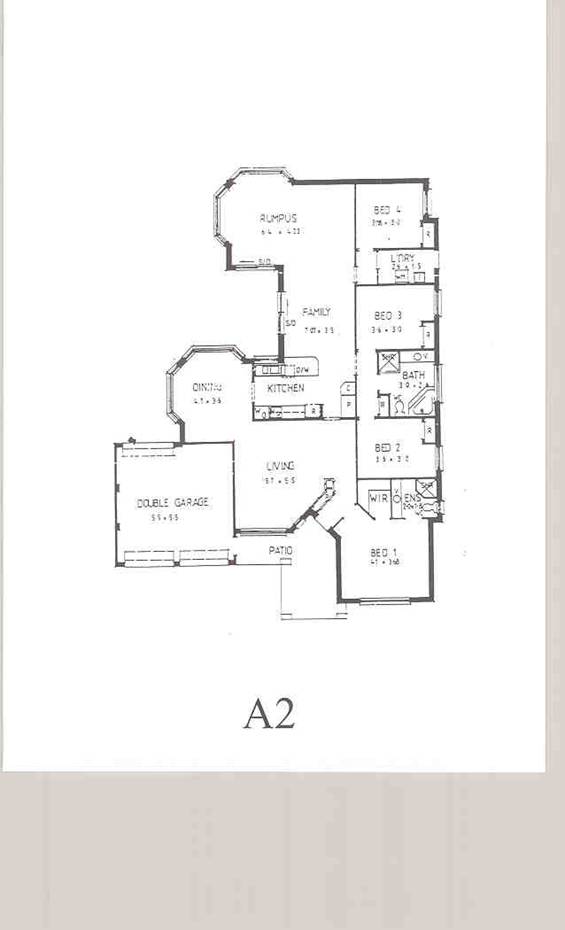

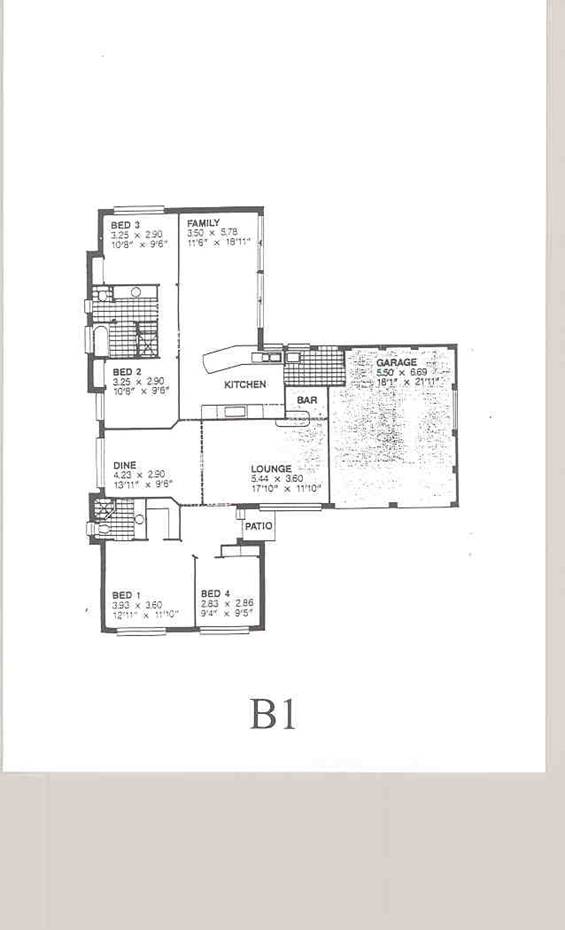

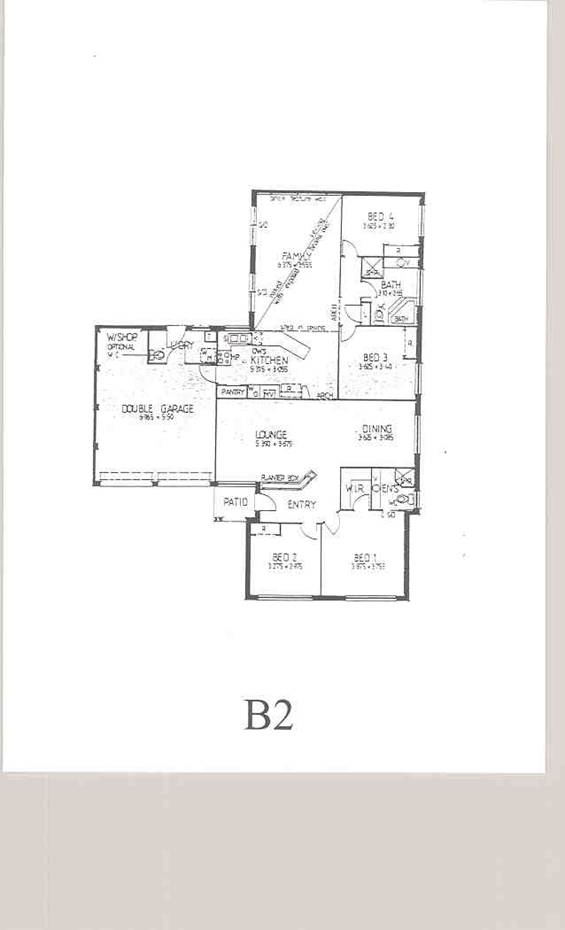

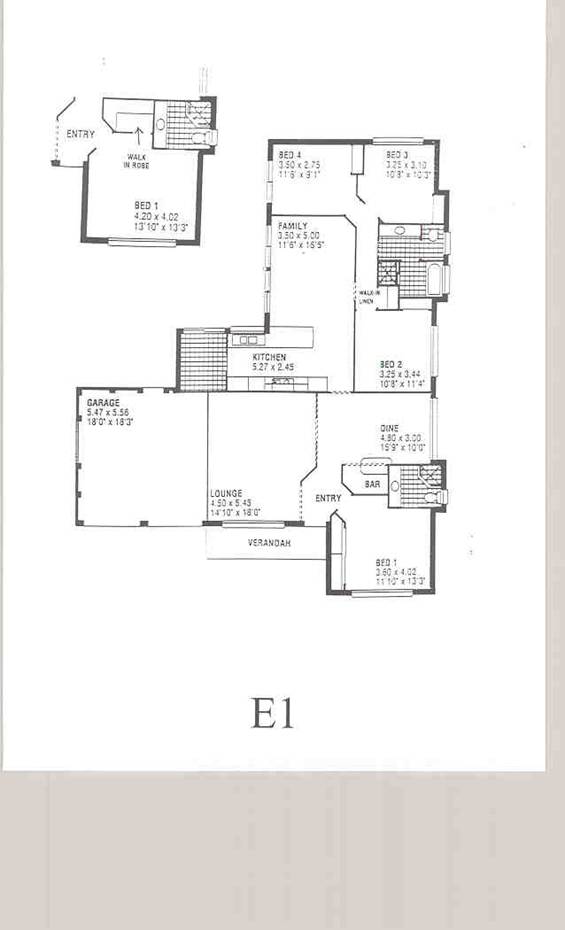

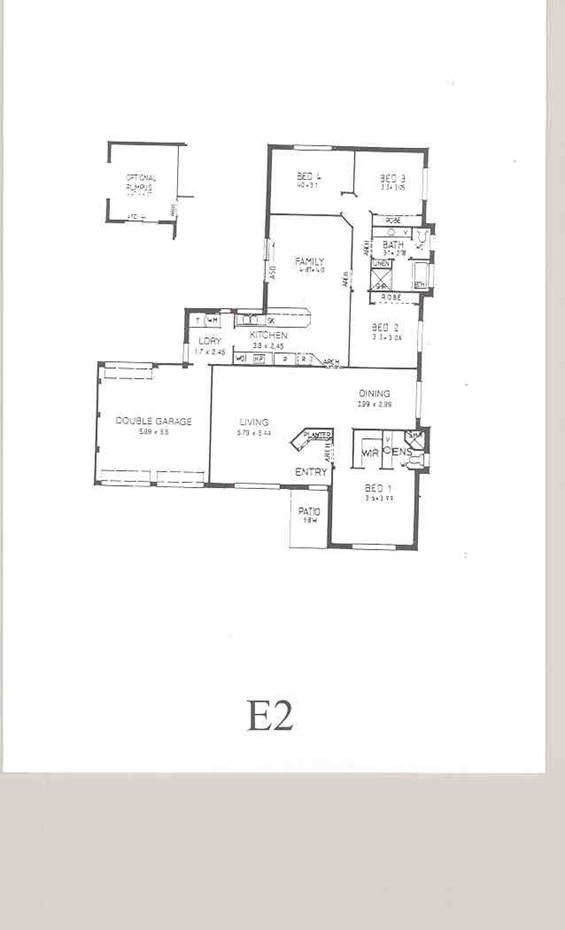

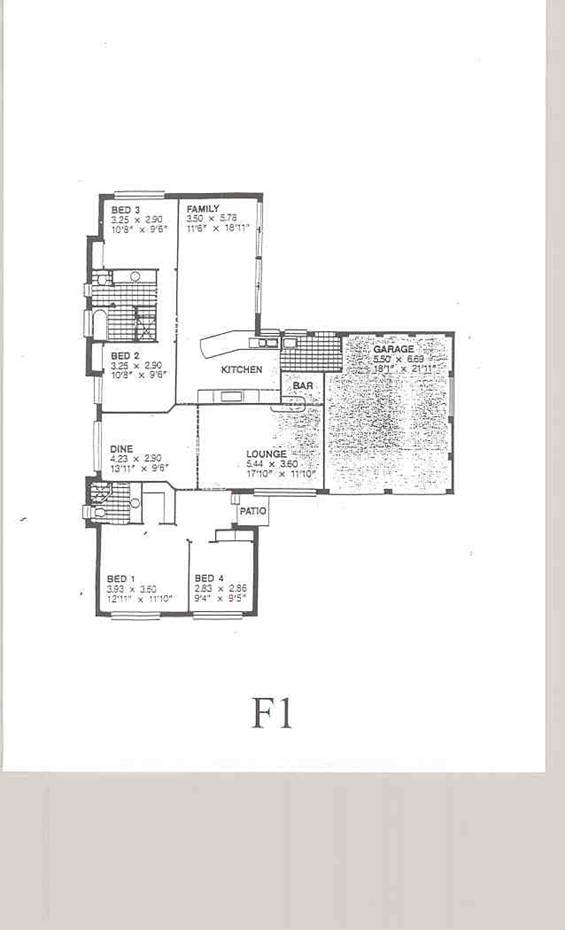

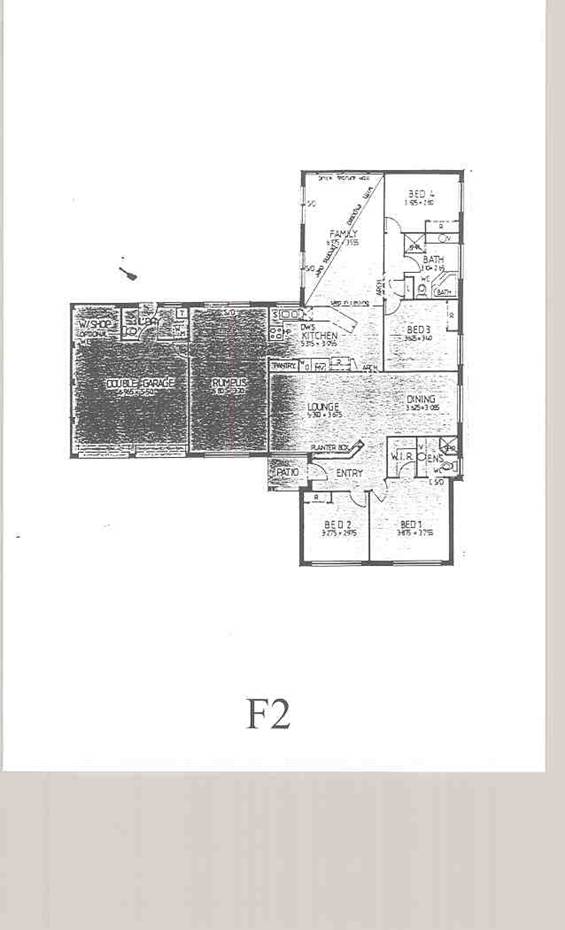

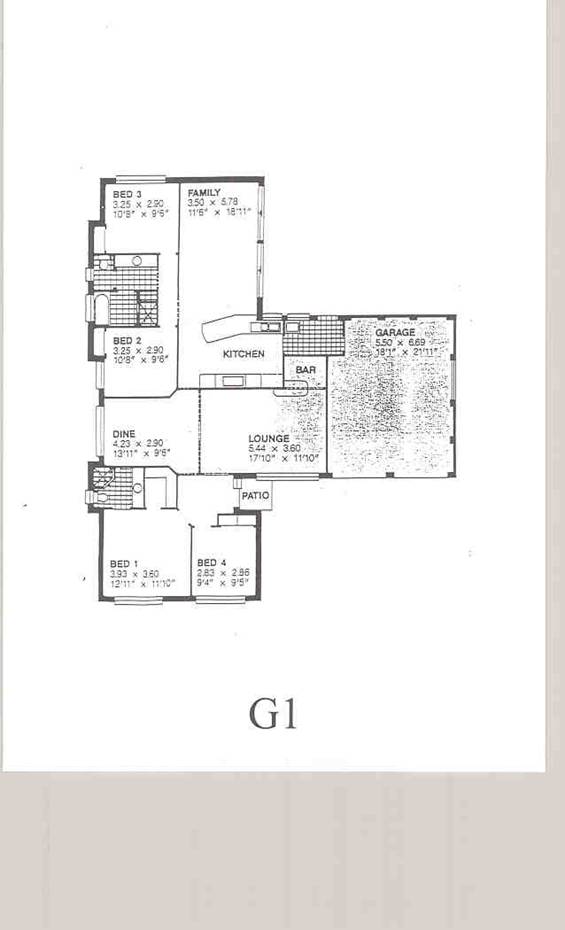

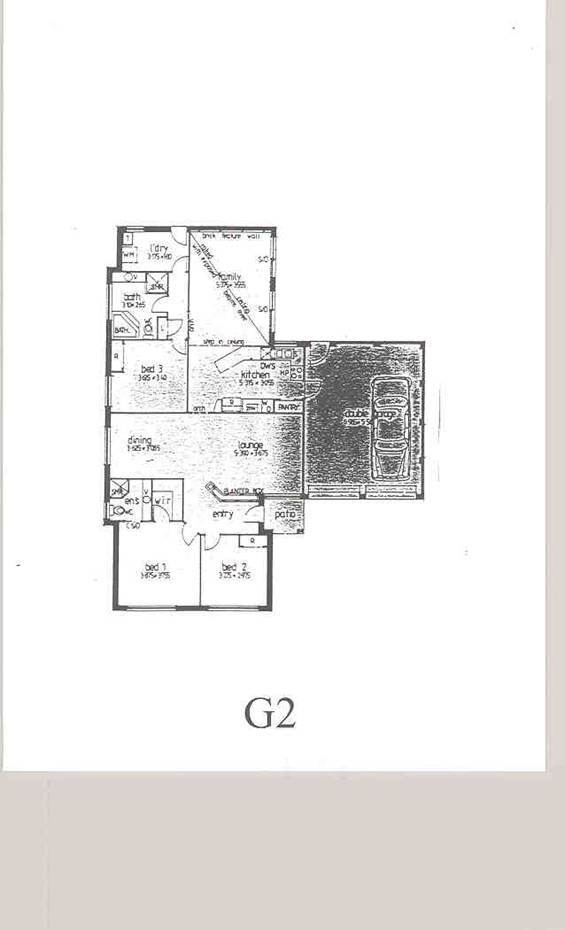

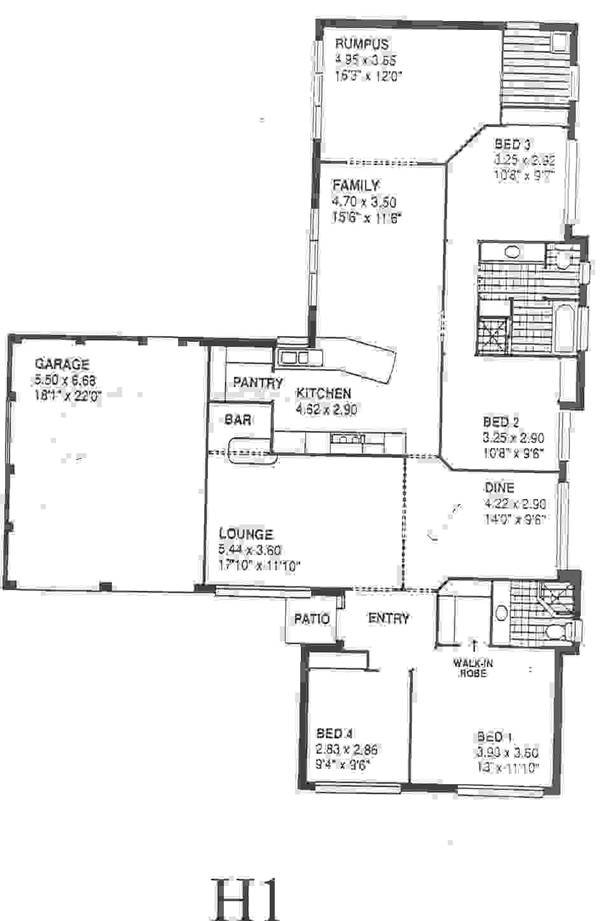

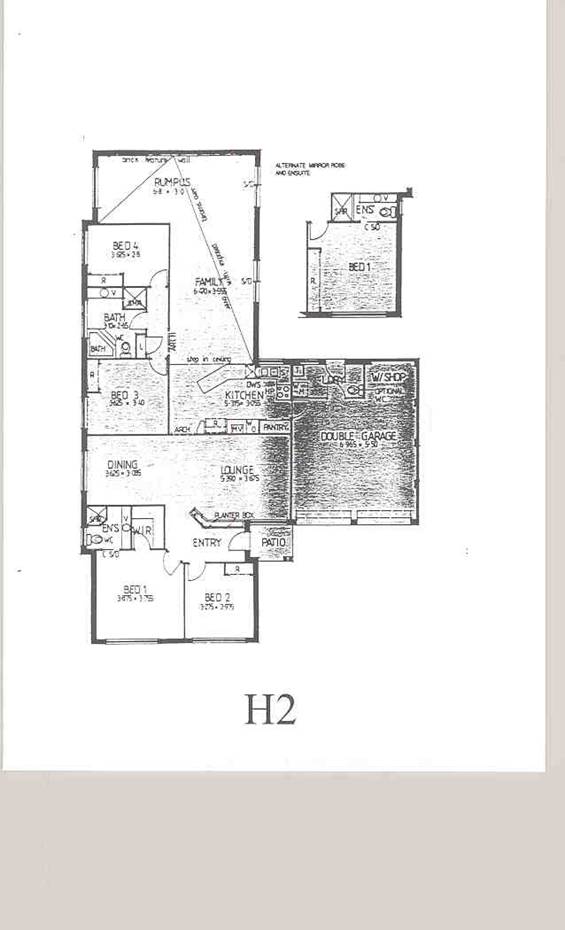

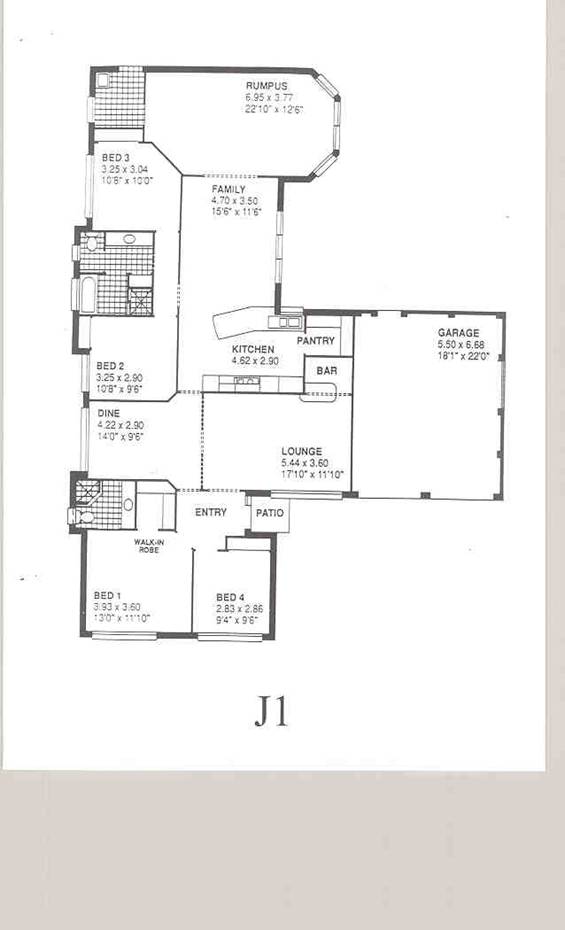

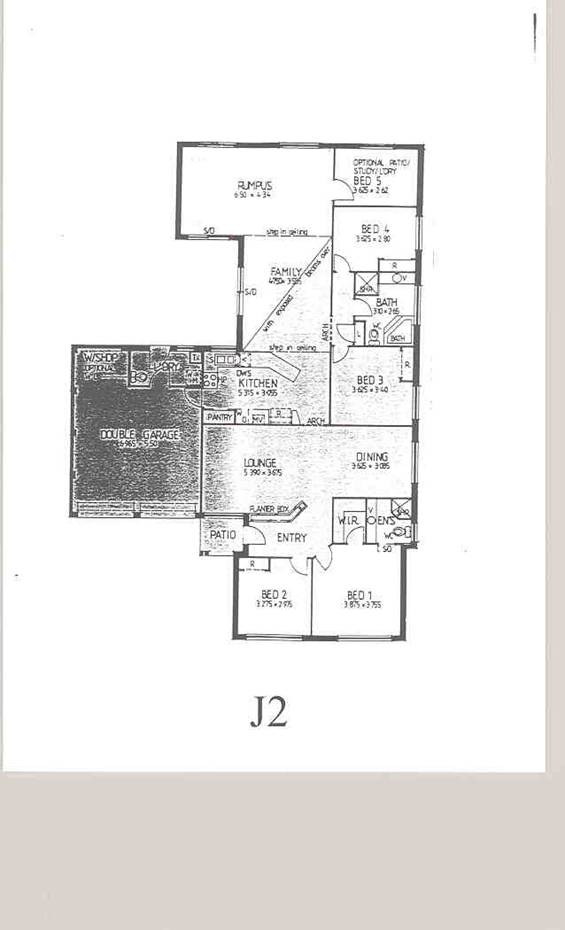

5 The orders which his Honour made in the two proceedings referred to copies of the LED and Eagle drawings in question which were annexed to his orders. In each case, LED’s plan was identified by the numeral “1” while Eagle’s infringing plan was identified by the numeral “2”. Annexed to these present Reasons are copies of all nine pairs of plans, identified as they were in his Honour’s orders. They are as follows

Order made on 27 August 1996 in NG 817 of 1993

|

LED’S PLAN |

ANNEXURE |

EAGLE INFRINGING PLAN |

ANNEXURE |

|

Sussex 4 Bedroom Rumpus/ Solarium [also called “Beechwood Sussex 1992” with solarium and dining bay windows]

|

A1 |

Regal Royale (or Regal Series I) |

A2 |

|

Freemont 4 Bedroom [also called “Beechwood Freemont 88” with four bedrooms]

|

B1 |

Flamingo Premier |

B2 |

|

Freemont 4 Bedroom [see above]

|

F1 |

Flamingo Classic |

F2 |

|

Freemont 4 Bedroom [see above]

|

G1 |

Flamingo Regular |

G2 |

|

Freemont 4 Bedroom [see above] with Rear Rumpus

|

H1 |

Flamingo Deluxe |

H2 |

|

Freemont 4 Bedroom [see above] with Rear Rumpus/Solarium |

J1 |

Flamingo Royale |

J2 |

Order made on 27 August 1996 in proceeding NG 862 of 1994

|

LED’S PLAN |

ANNEXURE |

EAGLE INFRINGING PLAN |

ANNEXURE |

|

Essington 4 Bedroom with Side Rumpus/Solarium [also called “Beechwood Essington 1991” with four bedrooms and rumpus solarium at side]

|

C1 |

Regal Supreme (or Regal Series II) |

C2 |

|

Essington 5 Bedroom with Side Rumpus/Solarium [also called “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms and rumpus/solarium]

|

D1 |

Oriole 4 Mk I |

D2 |

|

Clovelly 4 Bedroom [also called “Beechwood Clovelly 1991”] |

E1 |

Oriole 4 Mk II |

E2 |

(References to the LED plans often include the prefix “Beechwood”, and references to the Eagle plans often include the prefix “Eagle”.)

6 The nine pairs of house plans were not the only ones before Davies J but they are the only ones which he considered. He said in the final paragraph of his original Reasons for Judgment:

“ ... I am satisfied that LED succeeds on the question of liability with respect to the specific drawings, copies of which I have attached and that it has established that the copying was deliberate .... Counsel should be able to agree as to which of the remaining drawings in issue have breached the applicant’s copyright.” (emphasis supplied)

Agreement was not to eventuate.

7 Pursuant to his Honour’s direction, on 13 September 1996 Eagle filed an affidavit of John Valeri (“Valeri”) of that date identifying fifty seven houses which Eagle had constructed and which, according to the affidavit, “depict[ed] the [Eagle] plans” to which Valeri referred in the affidavit. The plans to which Valeri referred were in fact the nine Eagle drawings referred to in the orders of Davies J. The fifty seven houses were listed by addresses. In summary they were as follows:

Eagle infringing plan Number of

Houses built

Regal Royale (or Regal Series I) 12

Flamingo Premier 7

Flamingo Classic 2

Flamingo Regular 3

Flamingo Deluxe 10

Flamingo Royale 2

Regal Supreme (or Regal Series II) 3

Oriole 4 Mark I 9

Oriole 4 Mark II 9

___

57

8 Eagle accepted that the plans for the fifty seven houses built at the addresses identified in Valeri’s affidavit were the very nine Eagle plans which Davies J had held infringed LED’s copyright in its own nine plans mentioned earlier.

9 By the time of and during the hearing before me, Eagle conceded that in accordance with his Honour’s Reasons, more of its drawings infringed LED’s copyright in the nine LED drawings specified in Davies J’s orders. LED relies on the course of events by which this concession emerged in support of a claim by it for aggravated damages. It is convenient to sketch that course of events at this stage.

10 On 18 August 1997, Speed & Stracey, the solicitors for LED, wrote to Castrission & Co, the solicitors for Eagle, suggesting that Valeri’s affidavit may not have listed “all the infringing houses”. They asserted that two specified display homes, in particular, should have been included. They further claimed that an election which LED had made in favour of an account of profits applied only to the fifty seven houses disclosed in the affidavit, and reserved LED’s right to elect as between damages and an account of profits in respect of any further infringements which might come to light. They also asked for confirmation that the two display homes should have been disclosed and that there were “no other houses built by Eagle Homes which infringe[d] [LED’s] copyright.”

11 Castrission & Co replied on 3 September. They advised that Valeri had understood that “only the buildings under contract to customers were required to be disclosed”. The letter disclosed five “display homes” and advised that Valeri was not aware of any other homes which should be disclosed.

12 The number of houses disclosed by Eagle had therefore now risen from fifty seven to sixty two. Not being satisfied, Speed & Stracey wrote to Castrission & Co on 8 September 1997 referring to two further display homes which had been referred to in an earlier affidavit of Mr Paul Cardile (“Cardile”), a director of Eagle. The homes were in the Flamingo range and were at Lot 501 Stockdale Crescent, Abbotsbury and Lot 107 Wilson Road, Hoxton Park. After inspection of the drawings for those houses, Pasquale Romano (“Romano”), the design and purchasing manager for LED, in an affidavit sworn 11 December 1997, stated that in his opinion the display home at Abbotsbury “infringe[d] [LED’s] copyright” while that at Hoxton Park did not. From that time, LED has not pressed any claim in respect of the house at Lot 107 Wilson Road, Hoxton Park. On the other hand, on the hearing before me, Eagle has conceded that, consistently with Davies J’s reasoning, the drawings for the Abbotsbury display home infringed LED’s copyright in its floor plan for the Freemont 4 Bedroom.

13 By serving notices to produce and other procedures, LED continued to explore the possibility that there were further instances of infringement. On Eagle’s side, by an affidavit sworn 23 September 1997 Valeri explained the course which he had followed with a view to identifying infringements. On 7 October 1997, I ordered by consent that Eagle make available to LED’s solicitors and Romano for inspection, the plans from its customer files drawn since January 1987. The inspection took place at Eagle’s office on or about 27 and 28 October 1997. Prior to the inspection LED had obtained from Construction Research of Australia (“Con Res”) a list of addresses of houses for which Eagle had obtained building approvals from local councils in New South Wales in the period January 1988 to October 1995. The Con Res list is in evidence.

14 On 30 October, Speed & Stracey wrote to Castrission & Co enclosing a copy of the Con Res list and asserting that the list showed that Eagle had obtained building approvals for 164 houses since 1 January 1988. The letter requested that all drafting companies retained by Eagle make available for inspection all building plans drawn for Eagle from 1 January 1988 to 31 October 1995. As well, the letter asserted that three further particular houses “infringe[d] [LED’s] copyright” and should be the subject of the accounting for profits. Inspection took place of building plans produced by various councils pursuant to subpoenas issued on behalf of LED and of plans produced by Eagle’s drafters.

15 In his affidavit sworn 11 December 1997, Romano expressed the opinion that there were at least forty six plans of houses built by Eagle which “infringe[d] [LED’s] copyright” which had not been disclosed in Valeri’s affidavit of 13 September 1996. Annexure “Q” to his affidavit was a list of the forty six houses and Exhibit “PR2” to the affidavit comprised the associated forty six plans.

16 LED conceded that of the forty six house plans, one (number forty one) had in fact already been disclosed by Valeri as part of the original fifty seven in his affidavit of 13 September 1996, with the result that the effective number of additional infringements claimed by LED was reduced from forty six to forty five.

17 In an affidavit sworn 18 December 1997, Valeri conceded that in accordance with Davies J’s Reasons, nine of these forty five house plans “should form part of the Judgment in these Proceedings”. This increased the number conceded from fifty seven to sixty six. In relation to the remainder (numbering thirty six), he referred to “variations” which constituted his reasons for claiming that they did not infringe. In respect of ten of these, Valeri’s annotation was “Did not proceed” indicating that construction had not proceeded. LED did not immediately accept the correctness of this annotation in all ten cases. It wished to satisfy itself on the matter and even where it became satisfied that construction had not proceeded, it claimed damages in respect of the infringement constituted by the production of the plan. In one case, his annotation was “Not built by Eagle Homes”. That house (which was built in accordance with plan number 23) was apparently built by a Mr Vidic or his company “Petmar Homes” pursuant to an agreement with Cardile.

18 It is convenient to note here that in all cases but one, where construction proceeded LED has elected for an account of profits and in those where construction has not proceeded it has elected for damages. (In the one exceptional case, LED made no profit but a loss, with the result that it seeks damages rather than an accounting for profits in that case.)

19 Annexed to these Reasons is a table (“the Table”) which lists all forty six house plans and accompanying statements of Eagle’s position. These include the one, number forty one, which had been included in Valeri’s original fifty seven. The remaining forty five and Eagle’s responses to LED’s claim in respect of them can be classified as follows:

(a) “Conceded” (Eagle concedes that a house was built in accordance with its plan and that in conformity with Davies J’s Reasons that plan would be held to infringe LED’s copyright in an LED plan)

1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 19, 28, 29, 30, 35, 37, 45, 46.

Total: 18

(b) “Submit not infringe” (Eagle concedes that a house was built in accordance with its plan but it is in issue whether that plan infringes LED’s copyright in an LED plan)

4, 5, 6, 10, 18, 20, 21, 22, 25, 27, 31, 32, 34, 36, 39, 43, 44

Total: 17

(c) “Not built [accepted by LED] submit plan not infringe” (LED accepts that no house was built in accordance with Eagle’s plan but there is an issue whether the plan itself infringes LED’s copyright in an LED plan) (A house was built in accordance with plan 23 but not by Eagle)

7, 14, 23, 24, 26, 38, 40.

Total: 7

(d) “Not built [accepted by LED] concede plan” (LED accepts that no house was built in accordance with Eagle’s plan but Eagle concedes that in conformity with Davies J’s Reasons the Eagle plan would be held to infringe LED’s copyright in an LED plan)

13, 33, 42.

Total: 3

Grand total: 45

20 In addition, there were the fifty seven houses disclosed in Valeri’s affidavit of 13 September 1996, the plans for all of which, Eagle conceded, infringed LED’s copyright in LED plans. In the result, Eagle conceded that seventy eight of its house plans infringed LED’s copyright, made up as follows:

Disclosed in Valeri’s affidavit 57

Category (a) above 18

Category (d) above 3

__

78

==

It was in issue whether twenty four of Eagle’s plans infringed LED’s copyright, as follows:

Category (b) above 17

Category (c) above 7

__

24

==

ISSUES

21 The parties agreed that the following issues fall for determination by me:

“I. RESPONDENT’S LIABILITY

A. EAGLE’S PLANS – TWO DIMENSIONAL

1. Are any of the disputed plans from “the 46” [sic] reproductions in a material form of a substantial part of the Applicant’s drawings? The disputed plans are the 17 in the “submit not infringe” category and the 7 in the “not built, submit plan not infringe” category.

B. EAGLE’S HOUSES – THREE DIMENSIONAL

2. Did his Honour Justice Davies hold that the Respondent’s houses (the 57) are versions in a three-dimensional form of a substantial part of the Applicant’s drawings? If not, can that finding be made at this stage of the proceedings? If so, are the 57 houses versions in a three-dimensional form of a substantial part of the applicant’s drawings?

3. Are any of the 35 houses built (inferentially built in accordance with the Respondent’s – not the Applicant’s – drawings) versions in three- dimensional form of a substantial part of the Applicant’s drawings?

C. APPLICANT’S ‘TRACING’ SUBMISSION

4. The Applicant contends that the issue is whether Eagle is liable to account in respect of the 17 additional houses (built) (not conceded by Eagle to infringe) on the basis that they were derived from, and would not have come into existence but for, the infringing plans which preceded them.

5. The respondent contends that the issue is whether Eagle is liable to account in respect of any of:

(a) the 18 houses built where the plans are conceded to infringe (category 1); or

(b) the 17 houses built where the plans are not conceded to infringe (category 2),

on the basis that they were derived from, and would not have come into existence but for, the infringing plans which preceded them, whether or not the plans in category 2 are held to infringe, and whether or not the respective houses have been or will be held to be reproductions of the drawings.

II. QUANTUM

D. DAMAGES

6. With respect to plans held to infringe, where there are no houses built in accordance with the plans, what is the appropriate measure of damages?

E. CALCULATION OF ACCOUNT OF PROFITS ON INFRINGING HOUSES

7. Whether profits can be said to be derived by Eagle on any or all of site preparation, appliances and PC items and contract variations and extras. If so, whether the profits for which Eagle is liable to account include profits on any or all of site preparation, appliances and PC items and contract variations and extras.

8. Has the respondent discharged the onus of establishing that an allowance should be made for overheads.

9. If so, the applicant contends that the issue is whether that allowance should be calculated on an incremental basis or an absorption basis. The respondent contends that the issue is whether the absorption basis is a reasonable basis of allocation.

10. If the allowance is to be calculated on an absorption basis, then should overheads be allocated on the basis of revenue or average cost?

11. Whether, and if so by how much, an apportionment should be made for the following matters:

(a) as submitted in 2 and 3 above, no three dimensional infringements have been or should be held (as to the 57) or should be held (as to the 35) to have occurred,

(b) even if (a) is wrong, all the activities and factors which give rise to Eagle’s profit, including, inter alia, the selling, marketing and contract supervision activities of Eagle and factors which influence purchases of project homes such as price, facades, internal and external finishes and the reputation of the builder,

(c) whether or not (a) is wrong, the fact that copyright protects only the skill and labour of the draftperson’s expression of ideas and not the ideas themselves – and does not confer a monopoly in the presence or absence of rooms or in their general arrangement.

F. ADDITIONAL DAMAGES

12. Given that [LED] has, in respect of the original 57 houses, elected for an account of profits:

(a) is it also entitled to claim additional damages?

(b) if additional damages are available is this an appropriate case for additional damages and what matters inform the court’s discretion in assessing them?

(c) what is the appropriate amount of additional damages?”

REASONING

Issue 1

1. Are any of the disputed plans from “the 46” [sic - 45] reproductions in a material form of a substantial part of the Applicant’s drawings? The disputed plans are the 17 in the “submit not infringe” category and the 7 in the “not built, submit plan not infringe” category.

22 As noted above, Eagle concedes that in addition to the original fifty seven plans, twenty one of the additional forty five plans infringe LED’s copyright (categories (a) and (d) above). In relation to the remaining twenty four plans (“the Disputed Plans” – categories (b) and (c) above) Eagle does not submit that Davies J’s finding of deliberate copying is not applicable; rather, it submits that, regarded objectively, none of the twenty four reproduces an LED plan or a substantial part of an LED plan.

23 The twenty four Disputed Plans differ as between themselves and are alleged to infringe various of the nine LED plans. In view of their number, I have not annexed them to these Reasons for Judgment. Nor do I think it necessary, in order to expose my reasoning, to deal separately with the differences and similarities between each Disputed Plan and the LED plan relevant to it.

24 The Table identifies Eagle plans from which the respective Disputed Plans were derived. Where appropriate, the Table also sets out the differences referred to in Valeri’s affidavit between a Disputed Plan and that Eagleplan. But a comparison between each Disputed Plan and an Eagle plan is not the test which the legislation requires. Rather, each Disputed Plan must be compared with the relevant LED plan in order to determine whether it reproduces the whole or a substantial part of that plan. However, the Table does give some idea of the differences between a Disputed Plan and that LED plan from which, through the Eagle plan referred to in Davies J’s orders, the Disputed Plan was ultimately derived.

25 Each Disputed Plan was produced by the making of alterations to one or other of the nine Eagle plans (the original nine “infringing Eagle plans”) which Davies J held infringed copyright in an LED plan. Valeri said that each Disputed Plan was produced when a potential client, upon seeing an Eagle display home and its corresponding floor plan, proposed variations. Valeri agreed that the starting point in the discussion with the prospective client was an infringing Eagle plan. Eagle conceded that the Disputed Plans would not have been drawn without the infringing Eagle plans preceding them. This derivation of the Disputed Plans from the infringing Eagle plans explains Eagle’s concession that Davies J’s finding of subjective copying is applicable to the Disputed Plans.

26 Certain principles relating to the issue of the reproduction of the whole or a substantial part of the plans of project home were discussed in Eagle Homes Pty Ltd v Austec Homes Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 138 in which judgment was delivered on 22 February 1999. In Reasons for Judgment with which Finkelstein J and Weinberg J agreed, I said (at 91):

“In no case concerning project homes of which I am aware where there has been ... a finding of actual copying, has it been held that nonetheless the copier will not have infringed copyright unless there is in addition an extraordinarily close resemblance between his or her drawing and the copyright work. Rather, I think that the issue of sufficient objective similarity simply poses in the case of project homes, as in other cases, the usual question whether the copyright drawing can still be seen embedded in the allegedly infringing drawing, that is, whether the allegedly infringing drawing has adopted the “essential features and substance” of the copyright work: Hanfstaengl v Baines & Co [1895] AC 20 at 31 (Lord Shand) (I exclude the exact replication of a discrete unoriginal part of the copyright work discussed earlier).”

27 Counsel for Eagle submits that Davies J fell into error in his Reasons for Judgment delivered on 29 July 1996 when he found sufficient objective similarity on the following basis:

“It will be seen from the attached drawings that, although there are some minor differences in the room sizes, the overall proportions are similar. The windows and doors are not all in precisely the same place and there are some minor variations in the external walls. There are also differences in the position of the laundry and the bathroom. Sometimes the laundry and bathroom are adjacent and sometimes they are separated by a bedroom. That is not a significant difference in the designs, however, representing, rather, a permissible variation. There are also minor differences in cupboards and fittings.

What stands out is that the overall positioning, orientation and design of the rooms, of the entry and of the garage are practically identical. So also is the general relationship between the house and its environs … .

Notwithstanding the differences which exist, it appears to me that the respective drawings depict the same design, at least in substance.”

28 According to Eagle’s submission, the commonplaceness of the ideas that are expressed in project home plans and the simplicity of those plans produce the result that a particularly close similarity is required in order for it to be found that one project home plan reproduces another. According to the submission, matters of detail take on considerable importance, otherwise the copyright owner will, in effect, have a monopoly over the ideas and concepts expressed in its plan as distinct from a monopoly in the drawing itself.

29 However, this submission ignores the significance of a finding of subjective copying, based on evidence other than the mere similarity of plans. Where there is such a finding, the remaining question is simply whether the copyright plan as a whole, or a substantial part of it, can be seen in the allegedly infringing plan. It is beside the point that the similarities between the two plans might not have been sufficiently strong to support an inference of subjective copying, or, to put the matter differently, might have been explicable as the product of two minds working independently of each other in the drawing of plans expressing commonplace ideas and concepts. The present issue was discussed in Eagle Homes Pty Ltd v Austec Homes Pty Ltd, cited above.

30 Again, the fact that Eagle has made additions to an LED plan (plan 1) in producing an Eagle plan (plan 2) does not preclude a finding that plan 1 or a substantial part of it has been reproduced. The question is whether the whole or a substantial part of plan 1 has been taken into plan 2, not whether what has been taken forms a substantial part of plan 2. Similarly, if plan 1 or a substantial part of it is still visible in plan 2 as a result of subjective copying, the drawing of plan 2 will have infringed LED’s copyright in plan 1 notwithstanding that Eagle has made design improvements. But it is otherwise if the effect of changes made by Eagle is to produce a plan so different from plan 1 that neither plan 1 nor a substantial part of it can any longer be seen in plan 2.

31 Romano gave evidence that the “Beechwood Sussex 1992” was derived from an earlier “Beechwood Sussex” which he drew in 1987; that the 1987 plan was based on the earlier “Beechwood Park Royal”; and that this was, in turn, based on the “Beechwood Oxford” and the “Accent Homes Panorama”. According to Romano, the “Beechwood Oxford” was derived from the “Beechwood Macquarie” which, in turn, was derived from the “Maxlin Homes Grevillea”. (Romano said that “Maxlin Homes Pty Ltd” was a “sister company” of LED and merged with LED after the “Grevillea” was developed but before the “Macquarie” was developed.) There were family trees for other LED plans, the copyright in which was allegedly infringed by Eagle. Romano was involved in drawing at least some of the plans in the family trees as well as the current plans.

32 Eagle does not suggest that the “Beechwood Sussex 1992” or any of its predecessors was developed in infringement of copyright or by the use of the plans of companies outside the “LED family”. However, Eagle does submit that in assessing whether a substantial part of the “Beechwood Sussex 1992” was copied by Eagle, less weight should be given to those parts of that plan which had been copied from earlier plans. This general approach was, however, rejected by the Full Court in Eagle Homes Pty Ltd v Austec Homes Pty Ltd, cited above, at paras 77 and 78.

33 I turn now to the twenty four Disputed Plans. I have studied them and have concluded that the following Eagle plans are reproductions of the whole or a substantial part of the LED plans from which they were respectively ultimately derived:

• plans 4, 5 and 6, which are modified versions of the Eagle “Regal Royale” which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Sussex 1992”;

• plans 10, 14 and 18, which are modified versions of the Eagle “Flamingo Premier” which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Freemont ’88”;

• plans 20, 21, 31 and 36, which are modified versions of the Eagle “Regal Supreme” which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Essington 1991 with four bedrooms”;

• plans 24 and 27, which are modified versions of the Eagle “Oriole 4 Mark I” which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Essington 1991 with five bedrooms”;

• plans 32 and 34, which are modified versions of the Eagle “Oriole 4 Mark II” which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Clovelly 1991”;

• plans 38, 39 and 40, which are modified versions of the Eagle “Flamingo Classic” which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Freemont ’88 with four bedrooms”; and

• plans 43 and 44, which are modified versions of the Eagle “Flamingo Deluxe” which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Freemont ’88 with four bedrooms and rear rumpus”.

34 Given Davies J’s earlier finding of deliberate copying, it follows that Eagle’s making of those nineteen of the twenty four Disputed Plans infringed LED’s copyright in its plans which I have mentioned. Accordingly, the infringing Eagle plans now number ninety seven comprising the fifty seven originally disclosed in Valeri’s affidavit sworn 13 September 1996, the twenty one conceded on the hearing and these further nineteen of the twenty four Disputed Plans.

35 As indicated earlier, I do not find it necessary, in order to expose my reasoning, to deal with the similarities and differences between each of these nineteen Disputed Plans and the LED plans from which they were respectively derived. The question is ultimately one of impression upon a close comparison of a Disputed Plan and the relevant LED plan in terms of the shapes, orientations, layout and interrelationship of rooms and other spaces and traffic flows. On some of the Disputed Plans, rooms have been added. On some, LED rooms have been omitted. Sometimes rooms have been relocated: for example, the bathroom or laundry has often been moved from one side of a bedroom to the other. There are often changes to the arrangement of bay windows or the entry. Some of these changes may be thought to be design improvements. However, in each case the Disputed Plan embodies the LED plan from which the intervening infringing Eagle plan was deliberately copied. The additions, subtractions and alterations do not persuade me that Eagle has not reproduced the relevant LED plan or a substantial part of it in each of these nineteen Disputed Plans. I will now refer to seven of them in more detail as being representative of my reasoning in respect of all nineteen.

36 First, I will take plan 4. Eagle produced plan 4 by making alterations to the its “Regal Royale” plan (A2) which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Sussex 1992” (A1). The main difference is that bedroom four and the rumpus room with its solarium are omitted from plan 4. Those rear two rooms were present in both the Beechwood Sussex 1992 and the Eagle Regal Royale the subject of his Honour’s judgment. Double bay windows are substituted in plan 4 for the solarium and are located on the outside corner of plan 4’s family room. What is left, however, is still strikingly similar to the “Beechwood Sussex 1992”. The front and most distinctive part of plan 4 is virtually identical to it in terms of layout, although there are differences of detail (for example, a walk-in wardrobe and a double bay window have been added to the master bedroom and a fixed wardrobe omitted, and alterations have been made to the patio and entry). In the rear of the house, the bathroom and laundry of the “Beechwood Sussex 1992” were between bedrooms three and four but by reason of the omission of bedroom four at the rear of the house, the bathroom of plan 4 is located in a position between bedrooms two and three and the laundry is not adjacent to the bathroom (it was not adjacent to it in the infringing Eagle Regal Royale) but is placed at the very rear of the house, separated from the bathroom by bedroom three.

37 When Eagle’s plan 4 and LED’s “Beechwood Sussex 1992” are looked at as a whole, despite the differences mentioned, it is apparent that the LED plan is to a substantial extent embedded in plan 4. The similarities between the two are striking. The differences between plan 4 and the “Regal Royale” which was dealt with by Davies J do not persuade me to find that plan 4 does not infringe although the “generic” Regal Royale does. I therefore consider that Eagle’s plan 4 infringes LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Sussex 1992” plan.

38 Plan 5 is also derived from Eagle’s “Regal Royale” (A2) which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Sussex 1992” (A1). In terms of layout and shape of rooms, the front half of plan 5 is the same as the front half of LED’s “Beechwood Sussex 1992”. The major difference at the rear of the house is the addition of a fifth bedroom with consequential lengthening of the family room and movement of the laundry from its position adjacent to the bathroom and between bedrooms three and four to a position at the rear of the house behind bedroom five. As in the case of the “Regal Royale”, the double bay windows in the rumpus room are at the top outside corner, substituting for the solarium at the end of that room in LED’s “Beechwood Sussex 1992”. There are differences of detail (for example, the addition of a walk-in wardrobe in the master bedroom, of built in wardrobes in the other four bedrooms and of an archway between the living and dining rooms). Like plan 4, however, plan 5 expresses the “Beechwood Sussex 1992” plan in the sense that it is recognisable as a version of that plan. It infringes LED’s copyright in that plan.

39 In the case of plan 6, again the front half is very similar to the “Beechwood Sussex 1992” (A1) save for the re-naming of bedroom 2 as a “study” and the relocation of the door of that room and a lateral extension of the garage. Part of the additional space has been used to add a bar which looks out into the living and dining rooms. At the rear of the house, a bedroom has been added “above” the family room and between bedroom four and the rumpus room. The rumpus room has been extended “downwards”, partly, I presume, to provide an entry to the family room. Again as with Eagle’s “Regal Royale” (A2), the double bay windows in the rumpus room are at the top outside corner rather than being a solarium at the side of the room. As in plan 5, there are differences of detail such as the addition of fixed wardrobes in bedrooms and of a pantry in the kitchen. Yet, again as in the case of plan 5, overall plan 6 reflects the “Beechwood Sussex 1992” plan and infringes LED’s copyright in that plan.

40 Plan 10 was derived from Eagle’s “Flamingo Premier” plan (B2) that Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Freemont ’88” plan (B1). The main differences are the omission from the rear of the house of bedroom three and part of the family room to make the house shorter and the omission of the bar and part of the lounge room to make the house narrower. The omission of the “divider” wall between the dining and living rooms would also have an impact on the “feel” of the house. There are other differences: for example, the laundry is now wholly confined to the garage area and the kitchen bench is straightened. Overall, however, the two plans are strikingly similar. The changes are not so great that one can no longer see that plan 6 is basically the “Beechwood Freemont ’88”. I therefore find that plan 10 infringes LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Freemont ’88” plan.

41 Plan 14 is also derived from the Eagle “Flamingo Premier” (B2). The major difference between plan 14 and the “Beechwood Freemont ’88” (B1) is that bedroom two has been omitted to enlarge the dining room and provide space for a bar (including a “cocktail sink”). The bar “under” the laundry adjacent to the garage in the “Beechwood Freemont ’88” has, of course, been omitted and the lounge room narrowed laterally as on plan 10. Also as on plan 10, the “divider” between the lounge and dining rooms has been omitted. Once again, however, the differences do not detract significantly from the overall striking similarity between plan 14 and the “Beechwood Freemont ’88”. I therefore find that plan 14 infringes LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Freemont ’88” plan.

42 Plan 18 is also derived from the Eagle’s “Flamingo Premier” (B2). The most significant difference between plan 18 and the “Beechwood Freemont ’88” (B1) is that the bar under the laundry and the garage have been omitted and the back half of what was the garage is now a work-shop while the front half is an extension of the lounge room. Again, the “divider” between the lounge and dining rooms has also been omitted. Overall, however, the plans are strikingly similar: the main change has simply been to convert the space previously dedicated to the garage to other uses. I find that plan 14 infringes LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Freemont ’88” plan.

43 Plan 20 was derived from the Eagle “Regal Supreme” (C2) plan which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Essington 1991” plan (C1). The main differences are that bedroom four on the “Beechwood Essington 1991” has been omitted and the resultant space has become part of the rumpus room, the laundry has been moved from a position above bedroom three to be adjacent to the bathroom and the solarium at the end of the rumpus room has been replaced by double bay windows at the top outside corner of the room. There are other small differences, such as the omission of the bar and the rearrangement of the entry. However, it is still apparent that plan 20 expresses the LED plan. I therefore find that plan 20 infringes LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Essington 1991” plan.

44 I have also compared the remaining twelve of the nineteen Disputed Plans carefully with the respective LED plans that they are said to reproduce. My approach to them is sufficiently indicated by my discussion of the seven Disputed Plans identified above.

45 I turn now to the remaining five Disputed Plans: plans 7, 22, 23, 25 and 26. In my opinion, these plans do not reproduce LED plans or a substantial part of them and therefore do not infringe LED’s copyright.

46 First, plan 7 was produced by the making of alterations to the Eagle “Regal Royale” (A2) which Davies J decided infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Sussex 1992” (A1). The most striking alterations are found in the rearrangement of the living areas. The entry leads directly into the middle of the house, rather than at a forty five degree angle towards a corridor outside bedroom two. The shape of the living room is quite different from that in plans A1 and A2. It has a distinctive projection at the front of the house. The garage does not protrude into the living and dining rooms as it does in plans A1 and A2. There is a new space behind the entry with a linen closet and coat closet. The layout and shape of the kitchen is also different and includes a walk-in pantry and an angle in the bench. The corridor outside bedrooms three and four and the bathroom between them in the “Beechwood Sussex 1992” now provides the only access to bedrooms two and three and the bathroom between them. The rumpus room has also been reduced in size to become little more than an extension of the family room. The “divider” between the family room and the rumpus room has been omitted. These changes are all changes to the layout of the house, not simply changes of detail. They give plan 7 an appearance so different from that of the “Beechwood Sussex 1992” that while some resonances of that plan can be detected, neither that plan nor a substantial part of it can be said to be embedded in plan 7. I therefore find that plan 7 does not infringe LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Sussex 1992” plan.

47 Second, plan 22 was produced by the making of alterations to the Eagle “Oriole 4 Mark I” plan (D2), which Davies J found infringed LED’s copyright in its “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms (D1). The front half of plan 22 is similar to the front half of the “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms, although, as on many of the plans, there is a difference in the entries. Moreover, unlike the LED plan the master bedroom has a walk-in wardrobe, and the plan has no bar facing into the dining room. The rear halves of the two plans are completely different. On plan 22 there is no bedroom between the bathroom and laundry and the absence of the fifth bedroom makes the house shorter. There are other minor differences in the bedrooms such as the addition of built-in wardrobes and the re-positioning of windows. The family and rumpus rooms are substantially different. The family room is much “squarer” while the rumpus room is in a rear top corner of the house. While the changes are perhaps not as extensive as those on plan 7 noted above, in my view their cumulative effect is to make plan 22 so different that one can no longer see in it, the “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms.

48 Third, plan 23 was also ultimately derived from the “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms (D1). However, the derivation is not apparent from a comparison of the plans. The entry is different; the master bedroom is differently arranged; the lounge room is “squarer”; there is no double garage; the dining room has been replaced by a bedroom; the kitchen seems to be larger; there is no rumpus room; there are no bedrooms across the top of the house; the family room is longer; and the laundry is accessed through the family room rather than through the corridor adjoining the other bedrooms and the bathroom. In my view the changes are such that it cannot be said that the whole or a substantial part of the “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms is reproduced in plan 23.

49 Fourth, plan 25 was, like plans twenty two and twenty three, derived ultimately from the “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms (D1). It is in fact almost a mirror image of plan 22, except for the fact that the entry is different and the rumpus room does not have a solarium or double bay windows. These differences do not make it any more like the “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms. Hence, for the reasons given in relation to plan 22, I do not consider that plan 25 contains the whole or a substantial part of that LED plan.

50 Fifth, plan 26 was also derived ultimately from the “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms (D1). However, the entryway has been altered; a walk-in wardrobe and an extra window have been added to the master bedroom and a fixed wardrobe has been omitted; the bar adjacent to the main bedroom’s ensuite and looking into the dining room has been omitted; the dining room has been omitted and a bedroom substituted for it; the kitchen appears to be larger and is arranged differently; there is no longer a bedroom between the bathroom and the laundry; there is no rumpus room; and there are only four bedrooms with only one of them at the rear of the house (there were two at the rear of the LED plan). These changes are such that despite some similarities, it is no longer possible to see the “Beechwood Essington 1991” with five bedrooms in Eagle plan 26.

51 In summary, therefore, the forty five plans discovered since Davies J delivered judgment (I omit plan 41 which was one of the fifty seven plans disclosed in Valeri’s original affidavit) can now be divided in to the following four categories:

(1) plans 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 43, 44, 45 and 46 (33 plans) infringe LED’s copyright and houses were built in accordance with them (bold plan identifying numbers indicate fifteen of the nineteen Disputed Plans that I have found infringed LED’s copyright);

(2) plans 13, 14, 24, 33, 38, 40 and 42 (7 plans) infringe LED’s copyright but no houses were built in accordance with them (bold plan identifying numbers indicate the other four of the nineteen disputed Plans that I have found infringed LED’s copyright);

(3) plans 22 and 25 (2 plans) do not infringe LED’s copyright but houses were built in accordance with them (bold plan identifying numbers indicate two of the five Disputed Plans that I have found do not infringe LED’s copyright);

(4) plans 7, 23 and 26 (3 plans) do not infringe LED’s copyright and no houses were built (at least not by Eagle) in accordance with them (bold plan identifying numbers indicate the other three of the five Disputed Plans that I have found do not infringe LED’s copyright).

Issues 2 and 3

“2. Did his Honour Justice Davies hold that the Respondent’s houses (the 57) are versions in a three-dimensional form of a substantial part of the Applicant’s drawings? If not, can that finding be made at this stage of the proceedings? If so, are the 57 houses versions in a three-dimensional form of a substantial part of the applicant’s drawings?

3. Are any of the 35 houses built [categories (a) and (b) of the additional 45 earlier] (inferentially built in accordance with the Respondent’s – not the Applicant’s – drawings) versions in three-dimensional form of a substantial part of the Applicant’s drawings?”

52 Prior to the Copyright Act 1911 (UK) (“the 1911 Act”), it was not an infringement of copyright to produce a three dimensional version of a two-dimensional copyright work. The 1911 Act, which was applied in Australia by the Copyright Act 1912 (Cth), provided for the first time that “copyright” meant “the sole right to produce or reproduce the [copyright] work or any substantial part thereof in any material form whatsoever” (s 1(2) - emphasis supplied). It was held that the expression “material form” was wide enough to encompass the production in three-dimensional form of a version of a two-dimensional work and vice versa: Bradbury, Agnew & Co v Day (1916) 32 TLR 349. In Chabot v Davies [1936] 3 All ER 221, Crossman J held that the copyright in a drawing of a plan and elevation of a shop front was infringed by the construction of the shopfront in that case.

53 The development described was given explicit recognition in the definition of “reproduction” in s 48 (1) of the Copyright Act 1956 (UK) and in s 21 (3) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (“the 1968 Act”). The latter is as follows:

“21 (3) For the purposes of this Act, an artistic work shall be deemed to have been reproduced:

(a) in the case of a work in a two-dimensional form - if a version of the work is produced in a three-dimensional form; or

(b) in the case of a work in a three-dimensional form - if a version of the work is produced in a two-dimensional form;

and the version of the work so produced shall be deemed to be a reproduction of the work.”

54 This provision does not appear to have altered the position under the 1911 Act as it had been judicially explained. However, the exclusive right to produce a version of a two-dimensional work in a three-dimensional form was qualified by s 71 (1) of the 1968 Act which provided as follows:

“71 (1) For the purposes of this Act –

(a) the making of an object of any kind that is in three dimensions does not infringe the copyright in an artistic work that is in two dimensions; ...

if the object would not appear to persons who are not experts in relation to objects of that kind to be a reproduction of the artistic work.”

55 This provision operated by way of defence after it had been found, relevantly, that the three-dimensional object was a version of the two-dimensional copyright work or a substantial part of it: LB (Plastics) Ltd v Swish Products Ltd [1979] RPC 551 at 622; Ogden Industries Pty Ltd v Kis (Australia) Pty Ltd [1982] 2 NSWLR 283 at 289. In applying the “non-expert” test, the judge was to make a direct visual comparison between the drawing and the allegedly infringing object: LB (Plastics) at 622; Ogden Industries at 289-290; Solar Thomson Engineering Co Ltd v Barton [1977] RPC 537 at 559; S W Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466 at 476 (Gibbs CJ), 487 (Wilson J).

56 The defence provided by s 71 (1) was criticised: see, for example, S W Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems, above at 475 (Gibbs CJ), 485-487 (Wilson J), but cf at 493-503 (Deane J). Section 71 was repealed by the Copyright Amendment Act 1989. The position with respect to three-dimensional infringement of a two-dimensional copyright work is now the same as it was under the 1911 Act. The question posed by the 1968 Act in the present case is simply that found in s 21 (3), that is, are the houses a version in three-dimensional form of LED’s nine plans?

57 The word “version” is not defined in the Act and has its ordinary meaning of a special or particular form or variant of something: Dyason v Autodesk Inc (1990) 24 FCR 147 at 155, 173, 196. The Court must approach the question whether a three-dimensional work produces a version of a two-dimensional work in the same manner as if the question were one of reproduction in two dimensions, that is, one must ask whether there is a causal connection between the copyright work and the allegedly infringing work and whether there is sufficient objective similarity between the two.

58 The question arises whether a house built “in accordance with” an infringing Eagle plan produced in a three-dimensional form a version of the copyright LED plan which the infringing Eagle plan had reproduced. If so, the house is itself a reproduction of the LED plan and Eagle will have infringed LED’s copyright in that plan: s 31(b)(i). The Eagle house need be a version in three-dimensional form of only a substantial part, as distinct from the whole, of the LED plan: s 14 (1).

59 I turn first to the houses built in accordance with infringing Eagle plans (Valeri’s original fifty seven houses and the thirty three additional houses in category (1) above – a total of ninety houses). LED submits that as the infringing Eagle plans reproduce the whole or a substantial part of one or other of the nine LED plans, it follows inexorably that houses built “in accordance with” those infringing Eagle plans are a version in three-dimensional form of one or other of the nine copyright LED plans or of a substantial part of it. Eagle, on the other hand, submits that there is no evidence that any houses were built exactly in accordance with the infringing Eagle plans or any other evidence that would show that the ninety houses are versions in three-dimensional form of LED’s plans. Eagle points out that in cases such as Chabot v Davies, above, Lend Lease Homes Pty Ltd v Warrigal Homes Pty Ltd [1970] 3 NSWR 265, Ancher, Mortlock, Murray & Woolley Pty Ltd v Hooker Homes Pty Ltd [1971] 2 NSWLR 278, and Robert J Zupanovich Pty Ltd v B & N Beale Nominees Pty Ltd (1995) 59 FCR 49 in which buildings were held to infringe the copyright in architectural plans, the court relied on evidence, either in photographic form or based on an inspection of the allegedly infringing building, when making a finding of three-dimensional infringement of two-dimensional works of the kind sought here by LED and that evidence of that kind is absent in the present case.

60 In the Lend Lease Homes case, Helsham J said (at 273):

“I believe that both on the authorities and for reasons to which I shall presently refer, the proof (by admission or otherwise) that a building has been erected in accordance with a floor plan is not itself sufficient successfully to claim that the building as so erected is a reproduction in material form of the plan in which copyright exists. Proof of the copying may be necessary, but it is not in my view conclusive.”

61 Lahore on Copyright and Designs (looseleaf) cites the Lend Lease Homes case as authority for the proposition that it is not sufficient to prove reproduction merely to show that the building was erected “in accordance with” the plans: “there must be visual resemblance” (at [34,390]). Helsham J went on to say (at 273-274):

“I consider there is adequate material before me to enable me to find a sufficient objective similarity between the floor plan of the plaintiff and the actual building erected by and for the defendants. It will be remembered that the floor plan of the plaintiff displayed the shape of the house by reference to exterior walls, the position and relative size of windows, the interior layout of rooms and doors, and the presence and position of a number of internal fitments. I know from the first defendant’s plan the similar position and relationship of the self-same features; I know from sworn evidence that the house was erected for all practical purposes in accordance with the first defendant’s plan, and I am assisted in this by a number of photographs of that house from which many of the features and their relative positions vis-à-vis the plaintiff’s plan are recognizable. Without actually visiting the house it is open to me to find that there is between it and the floor plan a similarity that could be seen and which would reveal, in accordance with the evidence, a reproduction of the features depicted on the floor plan by the actual features in situ.”(emphasis supplied)

62 It is true that the Lend Lease Homes case was decided by reference to the 1911 Act which contained no counterpart the present s 21 (3). However, as I have said earlier, I do not consider that s 21 (3) altered the position from what it was under the 1911 Act. It remains necessary, in my view, for there to be evidence of the appearance of the building, that is, its impact on the eye. It is only by means of some evidence of that kind that one can assess the similarity between the building and the plan. In my view, Helsham J’s comments in relation to proof that a three-dimensional object produces a version of a drawing remain relevant under the 1968 Act.

63 A quite different impression may be gained upon viewing a three-dimensional structure from that arising from inspecting a plan. I respectfully agree with the following comment on Chabot v Davies, above,in Copinger and Skone James on Copyright (13th ed, 1991) at 8-74:

“[In Chabot v Davies it was] held that an architect’s elevation representing a shop front was infringed by the erection of an actual shop incorporating the elevation, on the ground that the same was a reproduction of the elevation ‘in a material form.’ It is submitted that this decision is confined to cases in which the appearance of the complete building appeals to the eye as being a reproduction of what appears on the architect’s plan or elevation, and that it would not be an infringement of the copyright in a plan, such as a ground plan, to erect a building based thereon, if the resulting erection bore no resemblance to the plan except when dissected and measured. But if a completed structure appears to the eye to be a reproduction of what appears in a floor plan then it will be an infringement.” (emphasis added)

For the last proposition, the authors refer to the Lend Lease Homes case.

64 Reference may also be made to Burke and Margot Burke Ltd v Spicers Dress Designs [1936] Ch 400. In that case Clauson J found that the making of a frock was not a reproduction of a sketch depicting a frock worn by a lady. He distinguished Bradbury, Agnew & Co v Day, above, saying (at 406):

“That case would be binding on me; but it is not that, or anything like that, of which Mrs Burke complains. She complains that the defendants have brought into being a frock which no doubt when placed in a particular position upon a lady of a particular figure might be used to produce a living picture of [the sketch] but when I look at the frock, qua frock, either spread out on a table or held up to my view, it seems quite impossible for me to hold that that frock, qua frock, is a reproduction of the sketch ... . It is not like it at all. It is on the word ‘reproduction’ that Mrs Burke has based her case. The mere fact that the general design of the frock may have been derived from what the dressmaker saw in [the sketch] does not seem to me to assist the case. What I have to consider is whether the frock reproduces [the sketch] which is a sketch of a young lady wearing a frock seen from a particular view-point. The answer seems to me to be that it does not. Accordingly, in my view, Mrs Burke’s claim fails.”

65 In the present case, as noted earlier, Valeri annexed to his affidavit a list of fifty seven houses, their locations, the Eagle plans “relevant to them” (I use a neutral expression) and what he claimed were departures from those plans. His affidavit said that the fifty seven houses “depicted”, not the nine LED plans but the nine generic infringing Eagle plans. I do not construe the word “depicted” to signify that Mr Valeri meant that to the eye, the fifty seven houses produced in three-dimensional form even the nine generic Eagle plans. The affidavit was filed in response to Davies J’s direction, set out in full below, that Eagle file an affidavit setting out particulars of houses “in respect of” the eighteen floor plans “or any substantial reproduction thereof built by the respondent [sic]”. On any reckoning, the direction is one to file an affidavit particularising the houses built “in respect of” the eighteen floor plans or any substantial reproduction thereof! The question arises what Valeri’s affidavit signifies for present purposes.

66 There is no sworn testimony in terms that the houses were “erected for all practical purposes in accordance with” Eagle’s plans. There is no photographic evidence or expert testimony as to the appearance of the houses. Consistently with the approach taken by Helsham J, I do not think that a concession that the houses “reproduced” the LED plans is reasonably to be derived from Valeri’s affidavit, either standing alone or read with Davies J’s direction. Although he does not say so in terms, Valeri’s evidence probably signifies that the respective Eagle plans in evidence were given to the subcontractors who built the houses. One might also infer that it is unlikely that the subcontractors departed from the plans except in minor respects. But in the absence of any evidence whatever as to the appearance of the houses to the human eye, I am simply not in a position to find that the houses are sufficiently similar to the copyright LED plans from which the infringing Eagle plans were derived to amount to a production of a version of those LED plans or of a substantial part of them.

67 I also do not accept LED’s submission that Davies J explicitly or implicitly found that houses built “in accordance with” the nine infringing Eagle plans considered by him necessarily infringed LED’s copyright in those plans. Given that there was apparently no evidence before his Honour of the kind mentioned above, it would be surprising for him to have intended to make such a finding.

68 LED’s pleading was of infringement in three-dimensional as well as two-dimensional form. In his Reasons for Judgment delivered on 29 July 1996, his Honour noted (at page 2) that LED claimed that its copyright had been breached by “the making of drawings, the issuing of brochures and the building of houses” (emphasis supplied). He also said (at pages 5 to 6) that LED was “entitled to succeed if it [could] prove that Eagle’s drawings, brochures or houses reproduce a substantial part of LED’s drawings”. However, he did not separately consider the question whether the houses, as distinct from the plans, did so, and his finding (at page 21) was only that LED had succeeded “on the question of liability with respect to the specific drawings” (emphasis supplied). His Honour’s Supplementary Reasons delivered on 27 August 1996 were also limited to findings in relation to Eagle’s plans. The declaration in each proceeding was that Eagle had infringed LED’s copyright “in the drawings for the floor plans of each of [LED’s] houses … by the floor plans for [Eagle’s] houses …” (emphasis supplied).

69 His Honour’s declaration, orders and direction made on 27 August 1996 in each proceeding were relevantly as follows:

“THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The respondent has infringed the applicant’s copyright in the drawings for the floor plans of each of the applicant’s houses shown in the table below (and annexed hereto and marked as shown respectively below) by the floor plans for the respondent’s houses shown respectively in the table below (and annexed hereto and marked as shown respectively below):

.............................................................................................................................

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The respondent [Eagle] be restrained from, by itself its servants or agents:

(a) reproducing or authorising the reproduction of the whole or a substantial part of any of the drawings of the floor plans of the houses referred to in paragraph 1 above [which listed LED’s nine plans and the corresponding nine infringing Eagle plans] (whether of the applicant’s plans or the respondent’s plans listed in paragraph 1); or

(b) building or authorising the building of any of the houses referred to in paragraph 1 above or any house with the same floor plan, or a substantial part thereof, as any of those houses (whether of the applicant’s plans or the respondent’s plans listed in paragraph 1); or

(c) advertising or offering for sale or opening to the public any exhibition or display home of any of the houses referred to in paragraph 1 above or any house with the same floor plan, or a substantial part thereof, as any of those houses

in infringement of the applicant’s said copyright, save for the completion of the Regal Royale house currently being constructed under contract for Mr D Dinic and Ms A Cako at Lot 1228 Whitsunday Circuit in Hinchinbrook in the State of New South Wales and the house contracted to be constructed for Mr & Mrs Ram, Lot 4154 Christabel Pl, Cecil Hills.

3. Within twenty eight (28) days of the giving of judgment on issues of pecuniary relief, the respondent deliver up to the applicant on oath all sketches, drawings, working drawings, master drawings, diagrams and brochures in its possession or control being reproductions of the whole or a substantial part of any of the floor plans referred to in paragraph 1 above.

.............................................................................................................................

THE COURT DIRECTS THAT:

The respondent file and serve an affidavit or affidavits by 13 September 1996 setting out in respect of the houses referred to in paragraph 1 above or any variation or substantial reproduction thereof built by the respondent (“the houses”):

(a) the total number of houses;

(b) the location of each of the houses;

(c) the contract price for the construction by the respondent of each of the houses; and

(d) the costs to the respondent of the construction of the houses.”

70 Several observations can be made about these orders and the direction. Order 2(b) refers to the “building of any of the houses referred to in para 1”, but it must be remembered that para 1 was a declaration of infringement which referred only to “plan to plan reproduction”. Apart from the exception at the end of order 2, the orders do not refer to any house built by LED or by Eagle at any particular site. It is clear that it was intended to restrain the building of houses “with” either the nine LED plans or the nine infringing Eagle plans or “with” a substantial part of any of them “in infringement of [LED’s] said copyright” (emphasis supplied). The “said copyright” is that referred to in the declaration and is LED’s copyright in its nine plans. The qualification which I have just emphasised tells against a construction that Davies J implicitly foundthat building houses “with” or “on the basis of” or “in accordance with” any of the eighteen plans would necessarily infringe LED’s copyright. In any event, it would not be proper to decide what findings Davies J intended to make merely from the terms of that injunctive relief that his Honour granted.

71 The direction was clearly directed towards providing LED with information on which it might decide whether or not to seek an account of profits. As noted earlier, with respect the direction could be better expressed. It was directed to identification of houses actually built by Eagle, a matter with which his Honour had not been concerned in his Reasons, which were of the kinds listed in the tables in his orders “or any substantial reproduction thereof”. As indicated earlier, I do not think that disclosure by Eagle of built houses pursuant to the direction constitutes an admission by it that the building of those houses itself constituted an infringement of the copyright in the nine LED plans referred to in his Honour’s orders. However, for reasons which appear below, the fact that there was no finding by his Honour or admission by Eagle to that effect does not signify that the direction was redundant. Therefore, the giving of the direction does not indicate an implicit finding of three-dimensional infringement.

72 It is not necessary for me to decide whether it is too late for LED to raise the issue whether houses built by Eagle infringed LED’s copyright in its drawings. As noted earlier, LED pleaded that they did and Davies J’s Reasons for Judgment record that from the outset LED submitted that they did. But there is still no evidence of the appearance of any of the houses to the human eye on which to make such a finding, and, for the reasons given above, I would not make a finding of infringement by reproduction in three-dimensional form of LED’s plans in the absence of evidence of that kind.

Issues 4, 5, 7 and 11

“4. The Applicant contends that the issue is whether Eagle is liable to account in respect of the 17 additional houses (built) (not conceded by Eagle to infringe) on the basis that they were derived from, and would not have come into existence but for, the infringing plans which preceded them.”

“5. The respondent contends that the issue is whether Eagle is liable to account in respect of any of:

(a) the 18 houses built where the plans are conceded to infringe (category [(a)]); or

(b) the 17 houses built where the plans are not conceded to infringe (category [(b)]).

on the basis that they were derived from, and would not have come into existence but for, the infringing plans which preceded them, whether or not the plans in category [(b)] are held to infringe, and whether or not the respective houses have been or will be held to be reproductions of the drawings.”

“7. Whether profits can be said to be derived by Eagle on any or all of site preparation, appliances and PC items and contract variations and extras. If so, whether the profits for which Eagle is liable to account include profits on any or all of site preparation, appliances and PC items and contract variations and extras.”

“11. Whether, and if so by how much, an apportionment should be made for the following matters:

(a) as submitted in 2 and 3 above, no three dimensional infringements have been or should be held (as to the 57) or should be held (as to the 35) to have occurred,

(b) even if (a) is wrong, all the activities and factors which give rise to Eagle’s profit, including, inter alia, the selling, marketing and contract supervision activities of Eagle and factors which influence purchases of project homes such as price, façades, internal and external finishes and the reputation of the builder,

(c) whether or not (a) is wrong, the fact that copyright protects only the skill and labour of the draftperson’s expression of ideas and not the ideas themselves – and does not confer a monopoly in the presence or absence of rooms or in their general arrangement.”

73 These issues raise questions relevant to the remedy of an account of profits in respect of houses built, excluding questions relating to the treatment of overheads. Questions relating to the treatment of overheads arise from Issues 8, 9 and 10. Questions relating to damages and additional damages are raised by Issues 6 and 12 respectively.

74 The numbers of houses (or plans) which are referred to in Issues 4, 5 7 and 11 are now apt to mislead. Clearly, the parties have taken them from the summary of the parties’ positions reproduced at para 18 earlier. That summary preceded my findings. While it has been common ground that there are thirty five houses built in accordance with Eagle plans to which these Issues refer, the following change has now occurred:

· Originally conceded that plans infringed (parties’ category (a) earlier): 18.

· Now concluded that plans infringed (category (1) of my summary of findings): 33.

· Originally submitted that plans did not infringe (parties’ category (b) earlier): 17.

· Now concluded that plans did not infringe (category (3) of my summary of findings): 2.

75 Issues 4 and 5 relate to houses built in accordance with plans. Therefore they relate respectively to the thirty three houses referred to in my category (1) and the two houses referred to in my category (3) of the summary of the results of my findings. They also relate to the fifty seven houses which were built in accordance with the apparently unaltered nine infringing Eagle plans that were before Davies J and which were disclosed in Valeri’s affidavit sworn 13 September 1996 – a total of ninety two houses.

76 In their agreed statement of issues, the parties gave the heading “APPLICANT’S TRACING SUBMISSION” to Issues 4 and 5. The way in which Issues 4 and 5 have been formulated is not ideal. They are intended to raise, and were treated by the parties as raising, certain issues on the assumption that the actual building of the houses did not infringe LED’s copyright. The issues are whether there is nonetheless a liability to account for the whole or part of the building profit (and if part, what part) because of a causal connection between an LED plan and a house built by Eagle either in accordance with an infringing Eagle plan or even in accordance with a non-infringing Eagle plan that was derived from an intervening infringing Eagle plan. LED contends that Eagle is liable to account for the entire building profit in all cases because in all cases the house would not have come into existence but for the existence of an LED plan and an infringing Eagle plan.

77 I find it convenient to re-formulate Issues 4, 5, 7 and 11.

A. Must Eagle account to LED for the profits made from the construction of the ninety homes built in accordance with infringing plans?

78 A convenient starting point is the general proposition stated by Windeyer J in Colbeam Palmer Ltd v Stock Affiliates Pty Ltd (1968) 122 CLR 25 (at 42), that

“a person who wrongly uses another man’s industrial property —patent, copyright, trade mark—is accountable for any profits which he makes which are attributable to his use of the property which was not his”.

79 His Honour was dealing with a claim of infringement of the plaintiff’s trade mark on painting sets sold by the defendant and was concerned to emphasise that the profits to be accounted for were not all the profits made from the selling of the painting sets but only those made from the wrongful use of the mark. The aim in taking an account is not to inflict punishment but to make the wrongdoer disgorge the profit made from the infringement: Sheldon v Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corp 309 US 390 (1940) at 399; My Kinda Town v Soll [1982] FSR 147 at 156. In the present case, the infringement was the reproduction in two-dimensional form of the whole or a substantial part of LED’s plans. The proper inquiry then is what profit was made by Eagle from this conduct.