Federal Court of Australia

Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2025] FCAFC 131

Appeal from: | Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited v Commissioner of Patents (No 3) [2024] FCA 212 |

File number(s): | NSD 506 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | BEACH, ROFE AND JACKMAN JJ |

Date of judgment: | 16 September 2025 |

Catchwords: | HIGH COURT AND FEDERAL COURT – question of correct approach to remittal and subsequent appeal – where equally divided decision of six High Court Justices resulted in preceding Full Federal Court decision being affirmed pursuant to s 23(2)(a) of Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) – where, on remitter of Full Court’s decision, the primary judge was to determine residual issues “in light of” Full Court’s reasons – where primary judge upheld Full Court’s reasoning – where High Court had unanimously rejected Full Court’s reasoning HIGH COURT AND FEDERAL COURT – whether primary judge was bound to follow Full Court’s reasoning – doctrine of precedent considered – only unanimous or majority decisions of High Court have binding authority – where no seriously considered dicta of a majority in High Court decision – primary judge was bound HIGH COURT AND FEDERAL COURT – whether this Full Court is bound to follow previous Full Court’s reasoning – where ‘compelling reason’ to depart from Full Court’s reasoning, being the High Court’s criticism – Full Court not bound APPEAL AND NEW TRIAL – whether appeal can be allowed without finding error on part of primary judge – legal principles considered – ‘constructive error’ found, as distinct from criticism of primary judge’s approach PATENTS – whether claimed computer-implemented invention is a manner of manufacture within meaning of s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) – approach of High Court’s allowing reasons adopted, as opposed to previous Full Court’s proposed alternative approach – where manner of manufacture depends on characterisation – where characterisation determined in light of specification as a whole – where appropriate approach to computer-implemented invention is whether subject matter is (i) an abstract idea manipulated on a computer; or (ii) an abstract idea implemented on a computer to produce an artificial state of affairs and useful result – claim 1 held to be a manner of manufacture – residual claims therefore also a manner of manufacture by analogy with claim 1 |

Legislation: | Patents Act 1990 (Cth) Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) Statute of Monopolies 1623 (UK) 21 Jac 1, c 3 |

Cases cited: | Algama v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2001] FCA 1884; (2001) 115 FCR 253 Allesch v Maunz [2000] HCA 40; (2000) 203 CLR 172 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2020] FCA 778; (2020) 382 ALR 400; 153 IPR 11 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2022] HCA 29; (2022) 274 CLR 115 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents (No 3) [2024] FCA 212; (2024) 177 IPR 73 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2024] FCA 987 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2025] HCADisp 7 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 735; (2015) 114 IPR 28 Australia Bay Seafoods Pty Ltd v Northern Territory of Australia [2022] FCAFC 180; (2022) 295 FCR 443 Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 63; (2001) 208 CLR 199 Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1833; (2001) 117 FCR 424 BVT20 v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs [2020] FCAFC 222; (2020) 283 FCR 97 CCOM Pty Ltd v Jeijing Pty Ltd (1994) 51 FCR 260 Colin R Price & Associates Pty Ltd v Four Oaks Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 75; (2017) 251 FCR 404 Commissioner of Patents v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC; (2021) 286 FCR 572 Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd [2020] FCAFC 86; (2020) 277 FCR 267 Commissioner of Patents v RPL Central Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 177; (2015) 238 FCR 27 Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 122; (2020) 279 FCR 631 D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc [2015] HCA 35; (2015) 258 CLR 334 Dei Gratia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2024] FCA 1145 Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd v Infotrack Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 161; (2019) 372 ALR 646 Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd [2007] HCA 22; (2007) 230 CLR 89 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v St Helens Farm (ACT) Pty Ltd [1981] HCA 4; (1991) 146 CLR 336 Federation Insurance Limited v Wasson [1987] HCA 34; (1987) 163 CLR 303 FKV17 v Minister for Home Affairs [2022] FCAFC 93; (2022) 292 FCR 201 Grant v Commissioner of Patents [2006] FCAFC 120; (2006) 154 FCR 62 Harvard Nominees Pty Ltd v Tiller [2020] FCAFC 229; (2020) 282 FCR 530 Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd v Motorola Solutions Inc [2024] FCAFC 168 In the Estate of Langley (Deceased); Langley v Langley [1974] 1 NSWLR 46 International Business Machines Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1991) 33 FCR 218 KMD v CEO (Department of Health NT) [2025] HCA 4; (2025) 421 ALR 469 Konami Australia Pty Ltd v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 103; (2016) 119 IPR 402 Lacey v Attorney-General (Queensland) [2011] HCA 10; (2011) 242 CLR 573 Lendlease Corporation Ltd v Pallas [2025] HCA 19; (2025) 423 ALR 23 Long v Chubb Australian Company Ltd [1935] HCA 11; (1935) 53 CLR 143 Milne v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1976] HCA 2; (1976) 133 CLR 526 Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZVFW [2018] HCA 30; (2018) 264 CLR 541 Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs v FAK19 [2021] FCAFC 153; (2021) 287 FCR 181 Monis v The Queen [2013] HCA 4; (2013) 249 CLR 92 Motorola Solutions Inc v Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd (Liability) [2022] FCA 1585; (2022) 172 IPR 221 National Disability Insurance Agency v Warwick [2025] FCAFC 100 National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents [1959] HCA 67; (1959) 102 CLR 252 Nguyen v Nguyen [1990] HCA 9; (1990) 169 CLR 245 Pallas v Lendlease Corporation Ltd [2024] NSWCA 83; (2024) 114 NSWLR 81 Perara-Cathcart v The Queen [2017] HCA 9l; (2017) 260 CLR 595 Re Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [2018] APO 45 Re Wakim; Ex parte McNally [1999] HCA 27; (1999) 198 CLR 511 Repipe Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2021] FCAFC 223; (2021) 164 IPR 1 Research Affiliates LLC v Commissioner of Patents [2014] FCAFC 150; (2014) 227 FCR 378 Tasmania v Victoria [1935] HCA 4; (1935) 52 CLR 157 Transurban CityLink Ltd v Allan [1999] FCA 1723; (1999) 95 FCR 553 UbiPark Pty Ltd v TMA Capital Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 885; (2023) 177 IPR 254 Unions NSW v New South Wales [2013] HCA 58; (2013) 252 CLR 530 Watson v Commissioner of Patents [2020] FCAFC 56; (2020) 150 IPR 207 P Herzfeld and T Prince, Interpretation (2nd ed, Thomson Reuters, 2020) |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Patents and Associated Statutes |

Number of paragraphs: | 144 |

Date of last submission/s: | 10 September 2025 |

Date of hearing: | 18 August 2025 |

Counsel for the Appellant: | Mr D Shavin KC with Mr P Creighton-Selvay |

Solicitors for the Appellant: | Gilbert + Tobin |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr C Dimitriadis SC with Ms M Evetts |

Solicitors for the Respondent: | Australian Government Solicitors |

ORDERS

NSD 506 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | ARISTOCRAT TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 001 660 715 Appellant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF PATENTS Respondent | |

order made by: | BEACH, ROFE AND JACKMAN JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 16 september 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be granted to the Appellant to amend its Notice of Appeal in the form handed up to the Court during the hearing of the appeal.

2. The appeal be allowed.

3. Orders 1 and 2 made on 12 April 2024 by the primary judge be set aside.

4. The decision made by the delegate of the Commissioner of Patents on 5 July 2018 to revoke:

(a) Claims 2–5 of Innovation Patent No. 2016101967;

(b) Claims 1–5 of Innovation Patent No. 2017101629;

(c) Claims 1–5 of Innovation Patent No. 2017101097;

(d) Claims 1–5 of Innovation Patent No 2017101098 (the Claims);

under s 101F(1) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Patents Act) be set aside.

5. The Commissioner of Patents is directed to issue, publish and register a certificate of examination in respect of each of the Claims in accordance with s 101E(2) of the Patents Act.

6. It is certified, pursuant to s 19(1) of the Patents Act, that the validity of the Claims as claiming an invention that is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act was questioned in this proceeding.

7. The Respondent pay the Appellant’s costs of the appeal and of the proceedings before the primary judge.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The fundamental issue in these proceedings is whether the claims in four patents concerning electronic gaming machines (EGMs) satisfy the requirement that they be a manner of manufacture within s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies 1623 (UK) 21 Jac 1, c 3 (Statute of Monopolies) as required by s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Patents Act). In the particular circumstances of this lengthy and complex litigation, however, the manner in which that issue is to be addressed depends on a series of questions concerning the doctrine of precedent which arise when a matter has been remitted to the Federal Court after the High Court was equally divided.

2 The patents in suit (the patents) are:

(a) innovation patent number 2016101967 (967 patent);

(b) innovation patent number 2017101097 (097 patent);

(c) innovation patent number 2017101098 (098 patent); and

(d) innovation patent number 2017101629 (629 patent).

Each of those patents is entitled “A system and method for providing a feature game” and has a priority date of 11 August 2014. The version of the Patents Act applicable to the patents is that which follows the commencement of the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth).

3 The patents are owned by Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd (Aristocrat). Aristocrat is part of the Aristocrat Leisure Limited group of companies, which is one of the largest gaming services providers in the world, and a manufacturer of EGMs. Each of the patents was granted and the Commissioner of Patents (the Commissioner) was asked to examine them pursuant to s 101A of the Patents Act. On 5 July 2018, a delegate of the Commissioner revoked the patents on the basis that none of the claims in any of the patents were a manner of manufacture: Re Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [2018] APO 45.

4 Aristocrat appealed from the decision of the delegate of the Commissioner pursuant to s 101F(4) of the Patents Act, and on 10 July 2020 the decision of the delegate was reversed: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2020] FCA 778; (2020) 382 ALR 400; 153 IPR 11 (Burley J) (PJ1). On 6 December 2021, the Full Court reversed that decision, with Middleton and Perram JJ giving one set of reasons for determining that the claims were not a manner of manufacture (majority decision) and Nicholas J providing separate reasons for the same conclusion (minority decision). The Full Court determined that the matter should be remitted to the primary judge for consideration of outstanding issues in light of its reasons: Commissioner of Patents v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC; (2021) 286 FCR 572

5 The High Court granted special leave to appeal. Six Justices heard the case and they were equally divided in opinion in the judgments delivered on 17 August 2022. Chief Justice Kiefel, Gageler and Keane JJ held that the claims were not a manner of manufacture and that the appeal should be dismissed (dismissing reasons), whereas Gordon, Edelman and Steward JJ held that the claims were a manner of manufacture and that the appeal should be allowed (allowing reasons): Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2022] HCA 29; (2022) 274 CLR 115.

6 The equal division in opinion in the High Court decision invoked s 23(2)(a) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) (the Judiciary Act), which provides in relation to the High Court:

(2) … when the Justices sitting as a Full Court are divided in opinion as to the

decision to be given on any question, the decision shall be decided according to the

decision of the majority, if there is a majority; but if the Court is equally divided in

opinion:

(a) in the case where … a decision of the Federal Court of Australia … is called in question by appeal or otherwise, the decision appealed from shall be affirmed…

7 Accordingly, the Full Court decision has been affirmed. An aspect of that decision was the order made by the Full Court that the proceedings be remitted to the primary judge (the remittal order):

…for determination of any residual issues in light of the Full Court’s reasons including any issues which concern the position of claims other than claim 1 of Innovation Patent No 2016101967 (referred to at [8] of the reasons of the primary judge dated 5 June 2020) and the costs of the hearings before the primary judge.

8 On 12 April 2024, on remittal, Burley J dismissed the appeal from the decisions of the Commissioner’s delegate, applying the reasons in the majority decision of the Full Court: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents (No 3) [2024] FCA 212; (2024) 177 IPR 73 (PJ2).

9 The present appeal is an appeal from PJ2. On 30 August 2024, O’Bryan J granted Aristocrat leave to appeal pursuant to s 158(2) of the Patents Act: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2024] FCA 987. On 6 February 2025, all seven Justices of the High Court refused an application by Aristocrat pursuant to s 40(2) of the Judiciary Act for removal of the whole of the cause pending in the Federal Court, being the present appeal: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2025] HCADisp 7. The reasons given by the High Court (at [2]) are as follows:

In the circumstances, the Appeal does not raise an issue of wide and significant public importance which requires urgent resolution and would justify the interruption of the appellate process of the Full Court of the Federal Court, the absence of the reasons of that Court, and allowing the applicant to by-pass the requirements of s 35A of the Judiciary Act.

The 967 patent

The specification

10 The 967 patent is entitled “A system and method for providing a feature game”. The field of the invention is said to relate to a gaming system and a method of gaming. The “Background of the Invention” states (page 1, lines 12–17):

In existing gaming systems, feature games may be triggered for players in addition to the base game. A feature game gives players an additional opportunity to win prizes, or the opportunity to win larger prizes, than would otherwise be available in the base game. Feature games can also offer altered game play to enhance player enjoyment.

A need exists for alternative gaming systems.

11 The “Summary of the Invention” contains a consistory clause in the same terms as independent claim 1 and dependant claims 2–5 (referred to below). There then follows a “Brief Description of the Drawings of the Invention”, being Figures 1–10B.

12 The “Detailed Description of a Preferred Embodiment of the Invention” commences as follows (page 3, lines 17–30):

Referring to the drawings, there are shown example embodiments of gaming systems having components which are arranged to implement a base game, from which may be triggered a feature game. In these embodiments, symbols are selected from a set of symbols comprising a plurality of configurable symbols and non-configurable symbols. The gaming system incorporates a mechanism that enables the symbols to be configured. In one example, the gaming system is configured so that a feature game is triggered when six of the configurable symbols are selected for display. The invention is not limited to triggering a feature game only when six configurable symbols are selected, however. In other embodiments, any number of configurable symbols may trigger the feature game.

Furthermore, each of the configurable symbols comprises a variable portion which is indicative of the value of a prize. When the feature game is triggered, the player is guaranteed to win the accumulated value of the prizes indicated by the variable portions of the configurable symbols.

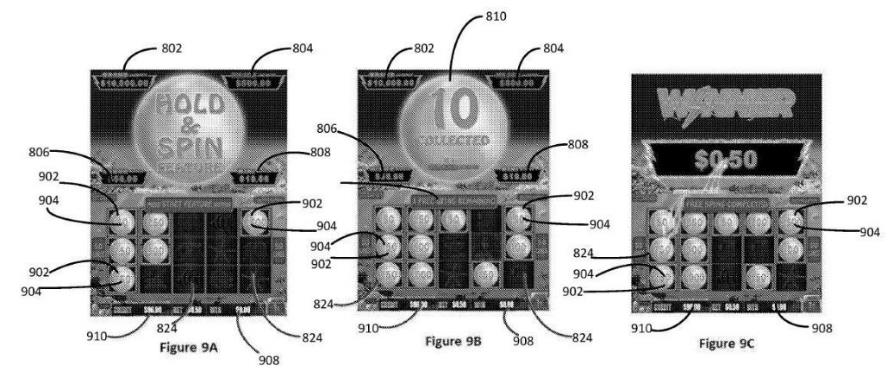

13 The concept of configurable symbols is elaborated upon later in the detailed description (page 9, line 36 – page 10, line 9), as being symbols that include a common component and a variable component as exemplified in Figures 9A–9C which are reproduced below:

The common component in figures 9A–9C is the pearl 902, and the variable component is the indicia 904 overlaying the pearl. In this particular example, the indicia numerals on the pearls directly indicate the value of the prize, but in other examples they may indirectly do so, such as by referring to “major” or “minor”, or the prize may be represented by an icon such as a representation of a car.

14 The specification identifies the “General construction of gaming system”. The specification says that gaming systems can take a number of different forms, one being a “standalone gaming machine” where all or most of the components required for implementing the game are present in a player operable EGM, and another being a distributed architecture where some of the components required for implementing the game are present in a player operable EGM and others are located remotely, such as by being networked to a gaming server (page 3, line 34 – page 4, line 13).

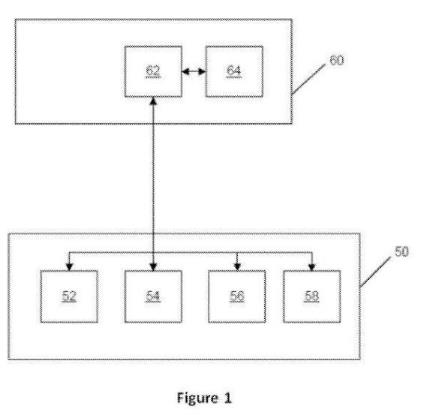

15 Figure 1 is the following diagram of the core components of a gaming system:

16 Those core components are described as follows (page 4, lines 15–24). The references to integers in the following paragraphs are references to the integers identified in the diagrams in the specification:

Irrespective of the form, the gaming system 1 has several core components. At the broadest level, the core components are a player interface 50 and a game controller 60 as illustrated in Figure 1. The player interface is arranged to enable manual interaction between a player and the gaming system and for this purpose includes the input/output components required for the player to enter instructions to play the game and observe the game outcome.

Components of the player interface may vary from embodiment to embodiment but will typically include a credit mechanism 52 to enable a player to input credits and receive payouts, one or more displays 54, a gameplay mechanism 56 including one or more input devices that enable a player to input gameplay instructions (e.g. to place a wager), and one or more speakers 58.

17 The specification describes the operation of the EGM as follows (page 4, lines 26–38):

The game controller 60 is in data communication with the player interface and typically includes a processor 62 that processes the gameplay instructions in accordance with game play rules and outputs game play outcomes to the display. Typically, the game play rules are stored as program code in a memory 64 but can also be hardwired. Herein the term “processor” is used to refer generically to any device that can process game play instructions in accordance with game play rules and may include: a microprocessor, microcontroller, programmable logic device or other computational device, a general purpose computer (e.g. a PC) or a server. That is a processor may be provided by any suitable logic circuitry for receiving inputs, processing them in accordance with instructions stored in memory and generating outputs (for example on the display). Such processors are sometimes also referred to as central processing units (CPUs). Most processors are general purpose units, however, it is also know[n] to provide a specific purpose processor using an application specific integrated circuit (ASIC) or a field programmable gate array (FPGA).

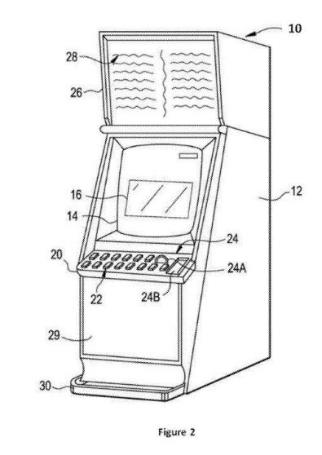

18 A gaming system in the form of a standalone gaming machine is illustrated in Figure 2, as follows:

The features include a console 12 having a display 14 on which are displayed representations of a game 16 in the form of a video display unit, for example a liquid crystal display plasma screen or the like. The bank of buttons 22 enables a player to interact during game play. There is a credit input mechanism 24, and the top box 26 may carry artwork 28 with pay tables and details of bonus awards.

19 The operative components of a typical EGM are described as including a game controller containing a processor mounted on a circuit board. Instructions and data to control operation of the processor are stored in a memory, which is in data communication with the processor. Hardware meters are also included for the purposes of ensuring regulatory compliance and monitoring player credit. A random number generator module generates random numbers for use by the processor. It is said that persons skilled in the art will appreciate that the reference to random numbers includes pseudo-random numbers.

20 Reference is made to the game controller including an input/output interface for communicating with peripheral devices including displays, a touch screen, credit input and output means and a printer. The EGM may include a communications interface such as a network card which may send status information, accounting information or other information to a bonus controller, central controller, server or database and receive data or commands from one or more of these. It is said that hardware may be added or omitted as required for the specific implementation. For example, it is said that while buttons or touchscreens are typically used in gaming machines to allow a player to place a wager and initiate a play of a game, any input device that enables the player to input game play instructions may be used, such as a mechanical handle or a touchscreen displaying virtual buttons which can be “pressed” by touching the screen where they are displayed (page 6, lines 10–17).

21 The main components of an exemplary memory are then illustrated and described, including RAM, EPROM and a mass storage device.

22 In one embodiment, a server remote from the EGM implements part of the game and the EGM implements another part of the game, such that the server and EGM collectively provide a game controller. A database management server may manage storage of game programs and associated data for downloading or access by the gaming devices, referred to as a “thick client embodiment”. In a “thin client embodiment”, the remote game server implements most or all of the game and the gaming machine essentially provides only the player interface. The specification states that other client/server configurations are possible, and incorporates by reference two other patents providing further details of a client/server architecture. It is said that persons skilled in the art will appreciate that in accordance with known techniques, functionality at the server side of the network may be distributed over a plurality of different computers (page 8, lines 5–6). Under the heading, “Further details of gaming system”, the specification states (page 8, lines 15–20):

The player operates the game play mechanism 56 to specify a wager and hence the win entitlement which will be evaluated for this play of the game and initiates a play of the game. Persons skilled in the art will appreciate that a player’s win entitlement will vary from game to game dependent on player selection. In most spinning reel games, it is typical for the player’s entitlement to be affected by the amount they wager and selections they make (i.e. the nature of the wager).

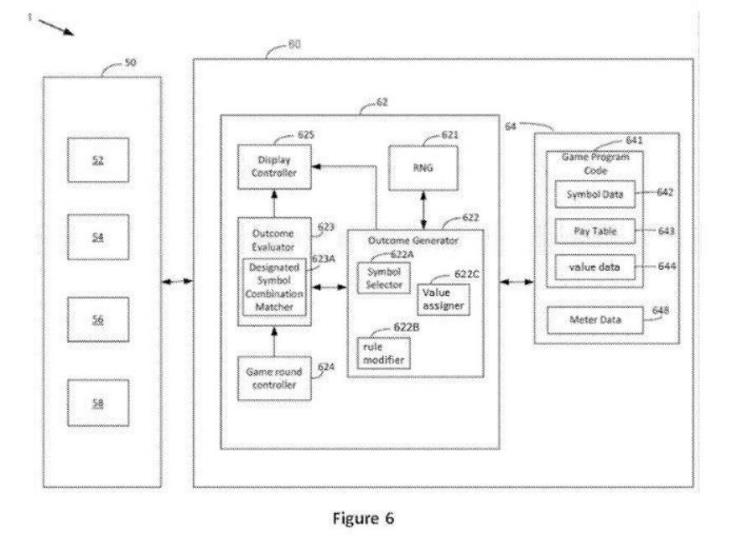

23 The specification refers to Figure 6, which is shown below:

The specification states that in Figure 6, the processes 62 of game controller 60 of gaming system 1 is shown implementing a number of modules based on game program code 641 stored in memory 64. It states that persons skilled in the art will appreciate that various modules could be implemented in some other way, for instance by a dedicated circuit (page 9, lines 7–9). In that figure, block 50 is the player interface.

24 Figure 7 is a flow diagram of one embodiment, showing a sequence of steps and decisions made during the course of a base game with a feature game that may be triggered. A base game is commenced using symbols that include configurable symbols. When a trigger event occurs, such as when a certain number of configurable symbols appear on the display, a free feature game is initiated by first holding the configurable symbols in their respective display positions and the additional feature game is then run. The feature game in operation may use symbols that include the configurable symbols and symbols from the base game, or different symbols. The feature game will play until it and any additional free games are played. Prizes are accumulated throughout the play of both the base game and the feature game.

25 The primary judge described that embodiment in the following terms (PJ1 at [67] and PJ2 at [52]):

In summary, the embodiment describes the steps whereby the EGM:

(a) holds the configurable symbols that triggered the feature game, during the rounds of the feature game;

(b) awards the player with a predefined number of rounds of the feature game;

(c) selects, via the symbol selector, and displays symbols for the display positions that do not currently hold a configurable symbol;

(d) for any configurable symbols that are selected, holds them during further rounds of the feature game;

(e) for each round of the feature game, increases or decreases the number of rounds remaining in the feature game according to whether an additional configurable symbol is displayed in that round;

(f) checks, using the outcome evaluator (which, the evidence discloses, is software programmed to perform this function), whether the number of configurable symbols displayed has reached a predefined number to trigger a jackpot;

(g) pays the accumulated value of the individual prizes as indicated by the variable components of the collected configurable symbols.

The primary judge said (PJ1 at [68] and PJ2 at [53]) that the steps described in (a) – (g) are performed on the EGM by the use of a computer system that is programmed to interface with the hardware and firmware elements of the gaming machine.

26 The specification provides a further example whereby, after a feature game is triggered, the game controller initiates a feature game using different reels to those used in the base game (page 15, lines 27–28). Depending on the embodiment, it is said that the trigger may be the configurable symbol trigger already described or some other trigger, for example a symbol combination. In this example, in the feature game, individual reels are associated with each of the symbol display positions, such that if there are fifteen symbol display positions, fifteen reels are used, with each of the reels comprising a mixture of non-configurable and configurable symbols.

27 The specification states that the program code in which the method may be embodied could be supplied in a number of ways, for example on a tangible computer readable storage medium, such as a disc or a memory device, or as a data signal, and different parts of the program code can be executed by different devices, for example in a client server relationship (page 16, lines l9–14).

The claims of the 967 patent

28 Claim 1 of the 967 patent, together with the integers and emphasis provided by the primary judge (at PJ1 at [69]) is as follows:

(1) A gaming machine comprising:

(1.1) a display;

(1.2) a credit input mechanism operable to establish credits on the gaming machine, the credit input mechanism including at least one of a coin input chute, a bill collector, a card reader and a ticket reader;

(1.3) meters configured for monitoring credits established via the credit input mechanism and changes to the established credits due to play of the gaming machine, the meters including a credit meter to which credit input via the credit input mechanism is added and a win meter;

(1.4) a random number generator;

(1.5) a game play mechanism including a plurality of buttons configured for operation by a player to input a wager from the established credits and to initiate a play of a game; and

(1.6) a game controller comprising a processor and memory storing (i) game program code, and (ii) symbol data defining reels, and wherein the game controller is operable to assign prize values to configurable symbols as required during play of the game,

(1.7) the game controller executing the game program code stored in the memory and responsive to initiation of the play of the game with the game play mechanism to:

(1.8) select a plurality of symbols from a first set of reels defined by the symbol data using the random number generator;

(1.9) control the display to display the selected symbols in a plurality of columns of display positions during play of a base game;

(1.10) monitor play of the base game and trigger a feature game comprising free games in response to a trigger event occurring in play of the base game,

(1.11) conduct the free games on the display by, for each free game, (a) retaining configurable symbols on the display, (b) replacing non-configurable symbols by selecting, using the random number generator, symbols from a second set of reels defined by the symbol data for symbol positions not occupied by configurable symbols, and (c) controlling the display to display the symbols selected from the second set of reels, each of the second reels comprising a plurality of non-configurable symbols and a plurality of configurable symbols, and

(1.12) when the free games end, make an award of credits to the win meter or the credit meter based on a total of prize values assigned to collected configurable symbols.

29 Claims 2–5 of the 967 patent are as follows:

2. A gaming machine as claimed in claim 1 wherein the second set of reels is the same as the first set of reels.

3. A gaming machine as claimed in claim 1, wherein the second set of reels comprises individual reels each corresponding to an individual display position.

4. A gaming machine as claimed in claim 3, wherein each reel of the first set of reels comprises configurable symbols and non-configurable symbols and wherein the game controller is configured to assign prize values to each displayed configurable symbol.

5. A gaming machine as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 4, wherein the game controller is configured to increase a number of free games remaining in response to the selection of one or more additional configurable symbols in at least one of the free games.

30 On remitter, the parties agreed that the residual issues referred to in the remittal order in relation to the 967 patent concerned whether claim 5 of the 967 patent (as dependent on claims 1, 3 and 4) is a manner of manufacture (PJ2 at [6]). The primary judge recorded (at PJ2 at [131]) that the parties agreed that claim 5 of the 967 patent, when dependent on claims 1, 3 and 4 (dependent claim 5 of the 967 patent) is as follows, with integer numbers added reflecting the claims from which it is derived:

(1.0) A gaming machine comprising:

(1.1) a display;

(1.2) a credit input mechanism operable to establish credits on the gaming machine, the credit input mechanism including at least one of a coin input chute, a bill collector, a card reader and a ticket reader;

(1.3) meters configured for monitoring credits established via the credit input mechanism and changes to the established credits due to play of the gaming machine, the meters including a credit meter to which credit input via the credit input mechanism is added and a win meter;

(1.4) a random number generator;

(1.5) a game play mechanism including a plurality of buttons configured for operation by a player to input a wager from the established credits and to initiate a play of a game; and

(1.6) a game controller comprising a processor and memory storing (i) game program code, and (ii) symbol data defining reels, and wherein the game controller is operable to assign prize values to configurable symbols as required during play of the game,

(1.7) the game controller executing the game program code stored in the memory and responsive to initiation of the play of the game with the game play mechanism to:

(1.8) select a plurality of symbols from a first set of reels defined by the symbol data using the random number generator;

(4.1) wherein each reel of the first set of reels comprises configurable symbols and non-configurable symbols and

(4.2) wherein the game controller is configured to assign prize values to each displayed configurable symbol.

(1.9) control the display to display the selected symbols in a plurality of columns of display positions during play of a base game;

(1.10) monitor play of the base game and trigger a feature game comprising free games in response to a trigger event occurring in play of the base game,

(1.11) conduct the free games on the display by, for each free game, (a) retaining configurable symbols on the display, (b) replacing non-configurable symbols by selecting, using the random number generator, symbols from a second set of reels defined by the symbol data for symbol positions not occupied by configurable symbols, and (c) controlling the display to display the symbols selected from the second set of reels, each of the second reels comprising a plurality of non-configurable symbols and a plurality of configurable symbols, and

(3.1) wherein the second set of reels comprises individual reels each corresponding to an individual display position.

(5.1) wherein the game controller is configured to increase a number of free games remaining in response to the selection of one or more additional configurable symbols in at least one of the free games.

(1.12) when the free games end, make an award of credits to the win meter or the credit meter based on a total of prize values assigned to collected configurable symbols.

The 097 patent

31 The specification for the 097 patent is substantially identical to the specification for the 967 patent with two exceptions. First, the consistory clause reflects the difference noted below in integer 1.10 of claim 1 in each of the patents. Second, the specification for the 097 patent contains additional descriptions of embodiments of the patent together with the additional Figures 11, 12A and 12B (page 14, line 17 – page 17, line 9), although the addition of that description is not material to the issues before us.

32 As to the claims in the 097 patent, integer 1.10 of claim 1 of the 967 patent is deleted and replaced with the following:

monitor play of the base game and trigger a feature game comprising free games in response to a trigger event using a Hyperlink system wherein the trigger event has a probability related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger events on the gaming machine.

33 On remitter, the parties agreed that the residual issues referred to in the remittal order in relation to the 097 patent concerned whether claim 5 of the 097 patent (as dependent on claims 1, 3 and 4) is a manner of manufacture (PJ2 at [6]). The primary judge helpfully set out claim 5 of the 097 patent, when dependent on claims 1, 3 and 4 (dependent claim 5 of the 097 patent) as follows, with integer numbers added reflecting the claims from which it is derived (at PJ2 at [143]):

(1.0) A gaming machine comprising:

(1.1) a display;

(1.2) a credit input mechanism operable to establish credits on the gaming machine, the credit input mechanism including at least one of a coin input chute, a bill collector, a card reader and a ticket reader;

(1.3) meters configured for monitoring credits established via the credit input mechanism and changes to the established credits due to play of the gaming machine, the meters including a credit meter to which credit input via the credit input mechanism is added and a win meter;

(1.4) a random number generator;

(1.5) a game play mechanism including a plurality of buttons configured for operation by a player to input a wager from the established credits and to initiate a play of a game; and

(1.6) a game controller comprising a processor and memory storing (i) game program code, and (ii) symbol data defining reels, and wherein the game controller is operable to assign prize values to configurable symbols as required during play of the game,

(1.7) the game controller executing the game program code stored in the memory and responsive to initiation of the play of the game with the game play mechanism to:

(1.8) select a plurality of symbols from a first set of reels defined by the symbol data using the random number generator;

(4.1) wherein each reel of the first set of reels comprises configurable symbols and non-configurable symbols and

(4.2) wherein the game controller is configured to assign prize values to each displayed configurable symbol.

(1.9) control the display to display the selected symbols in a plurality of columns of display positions during play of a base game;

(1.10) monitor play of the base game and trigger a feature game comprising free games in response to a trigger event using a Hyperlink system wherein the trigger event has a probability related to desired average turnover between successive occurrences of the trigger events on the gaming machine,

(1.11) conduct the free games on the display by, for each free game, (a) retaining configurable symbols on the display, (b) replacing non-configurable symbols by selecting, using the random number generator, symbols from a second set of reels defined by the symbol data for symbol positions not occupied by configurable symbols, and (c) controlling the display to display the symbols selected from the second set of reels, each of the second reels comprising a plurality of non-configurable symbols and a plurality of configurable symbols, and

(3.1) wherein the second set of reels comprises individual reels each corresponding to an individual display position.

(5.1) wherein the game controller is configured to increase a number of free games remaining in response to the selection of one or more additional configurable symbols in at least one of the free games.

(1.12) when the free games end, make an award of credits to the win meter or the credit meter based on a total of prize values assigned to collected configurable symbols.

The 629 patent

34 The specification for the 629 patent is substantially identical to the specification for the 097 patent, except that the consistory clause reflects the different claims made in the 629 patent. The additional material contained in the specification for the 097 patent which did not appear in the specification for the 967 patent is found in the specification for the 629 patent (page 15, line 17 – page 18, line 14).

35 The claims made in the 629 patent are as follows:

1. A gaming machine comprising:

a credit input mechanism configured to receive a physical item representing a monetary value for establishing a credit balance, the credit balance being increasable and decreasable based on wagering activity;

a manually operable player interface configured to, in accord with the wagering activity, initiate play of a base game;

a credit meter configured to monitor the credit balance;

an electronic display having a display area, said display area having a plurality of display positions;

a memory storing data indicative of a set of symbols, including a plurality of special symbols and a plurality of normal symbols;

a symbol selector configured to randomly select, via said data from the memory, and in accord with the wagering activity and the initiated play of a base game, a plurality of symbols from the set of symbols for display via said electronic display during play of the base game;

a display controller configured to cause the display to display the selected symbols;

an outcome evaluator configured to monitor play of the base game, and to trigger a feature game in response to a first count of the special symbols being displayed having reached a predefined number of the special symbols during the base game, said feature game comprising a variable number of free games;

a free game counter configured to generate a different second count representing a number of free games remaining to be played;

and wherein said outcome evaluator is configured to end the feature game when said different second count reaches a predetermined end count;

wherein, during the feature game, the symbol selector is configured for each free game to via the electronic display and the display controller:

1) hold at least some of the displayed special symbols appearing on the display;

2) remove at least one of the displayed normal symbols from the display;

3) select randomly a replacement symbol from the set of symbols to replace a removed normal symbol; and

4) replace the removed normal symbol with the selected replacement symbol,

and wherein the outcome evaluator is configured to revise the different second count of the free game counter and increment the first count of the special symbols being displayed if the selected replacement symbol is a special symbol; and

a payout mechanism configured to provide a payout associated with the credit balance.

2. A gaming machine according to claim 1, wherein the free game counter maintains the different second count of the number of free games to be awarded in the feature game; and wherein a predefined number of free games is initially awarded when the feature game is triggered.

3. A gaming machine according to claim 2, wherein the free game counter is reset to the predefined number of free games initially awarded each time a special symbol is selected for display in the feature game.

4. A gaming machine according to claim 2, wherein the free game counter is decremented each time no special symbols are selected for display in a free game.

5. A gaming machine according to claim 1, and further comprising a special symbol counter, said special counter being incremented each time a special symbol is selected for display in the feature game, and wherein a jackpot prize is awarded when the special symbol counter counts a predefined number of special symbols.

36 On remitter, the parties agreed that the residual issues referred to in the remittal order in relation to the 629 patent concerned whether claim 5 of the 629 patent (as dependent on claim 1) is a manner of manufacture (PJ2 at [6]). The primary judge helpfully set out the terms of claim 5 of the 629 patent when dependent on claim 1 (dependent claim 5 of the 629 patent) as follows, with integer numbers added reflecting the claims from which it is derived (PJ2 at [138]):

(1.0) A gaming machine comprising:

(1.1) a credit input mechanism configured to receive a physical item representing a monetary value for establishing a credit balance, the credit balance being increasable and decreasable based at least on wagering activity;

(1.2) a manually operable player interface configured to, in accord with the wagering activity, initiate play of a base game;

(1.3) a credit meter configured to monitor the credit balance;

(1.4) an electronic display having a display area, said display area having a plurality of display positions;

(1.5) a memory storing data indicative of a set of symbols including a plurality of special symbols and a plurality of normal symbols;

(1.6) a symbol selector configured to randomly select, via said data from the memory, and in accord with the wagering activity and the initiated play of a base game, a plurality of symbols from the set of symbols for display via said electronic display during play of the base game;

(1.7) a display controller configured to cause the display to display the selected symbols;

(1.8) an outcome evaluator configured to monitor play of the base game, and to trigger a feature game in response to a first count of the special symbols being displayed having reached a predefined number of the special symbols during the base game, said feature game comprising a variable number of free games;

(1.9) a free game counter configured to generate a different second count representing a number of free games remaining to be played; and

(1.10) wherein said outcome evaluator is configured to end the feature game when said different second count reaches a predetermined end count;

(1.11) wherein, during the feature game, the symbol selector is configured for each free game to via the electronic display and the display controller (1) hold at least some of the displayed special symbols appearing on the display; (2) remove at least one of the displayed normal symbols from the display; (3) select randomly a replacement symbol from the setoff symbols to replace a removed normal symbol; and (4) replace the removed normal symbol with the selected replacement symbol, and

(5.1) a special symbol counter, said special symbol counter being incremented each time a special symbol is selected for display in the feature game, and wherein a jackpot prize is awarded when the special symbol counter counts a predefined number of special symbols;

(1.12) wherein the outcome evaluator is configured to revise the different second count of the free game counter and increment the first count of the special symbols being displayed if the selected replacement symbol is a special symbol; and

(1.13) a payout mechanism configured to provide a payout associated with the credit balance.

The 098 patent

37 The specification for the 098 patent is substantially identical to the specification for the 097 patent, with the exception of the consistory clause which is drafted to reflect the different way in which the claims are expressed in the 098 patent. The new material which was added in the 097 patent specification, but which had not been included in the 967 patent specification is also included (page 14, line 1 – page 16, line 41).

38 The claims in the 098 patent are expressed as follows:

1. A gaming machine comprising:

a credit input mechanism configured to receive a physical item representing a monetary value for establishing a credit balance, the credit balance being increasable and decreasable based at least on wagering activity;

a credit meter configured to monitor the credit balance;

a manually operable player interface configured to, in accord with the wagering activity, initiate play of a base game;

an electronic display having a display area, said display area having a plurality of display positions;

a memory storing data indicative of a set of symbols including a plurality of symbols having a particular characteristic;

an evaluator configured to monitor the occurrence of a trigger event, and to trigger a feature game in response to the occurrence of a trigger event, said feature game comprising a variable number of free games;

a free game counter configured to generate a count representing a number of free games remaining to be played;

and wherein said evaluator is configured to revise said free game counter upon the occurrence of a defined outcome of a free game and to end the feature game when said count reaches a predetermined end count;

wherein during the feature game, the symbol selector is configured for each free game to:

1) hold at least some of the displayed symbols, having the particular characteristic appearing on the display;

2) remove at least one of the displayed symbols without the particular characteristic from the display;

3) select randomly a replacement symbol from the set of symbols to replace a removed symbol without the particular characteristic; and

4) replace the removed said one of the displayed symbols without the particular characteristic with the selected replacement symbol, and

wherein the outcome evaluator is configured to revise the count of the free game counter based on the selected replacement symbol in the outcome of a free game having said particular characteristic and including resetting the count of the free game counter.

2. A gaming machine according to claim 1, wherein the free game counter maintains

the count of free games to be awarded in the feature game, and wherein a predefined number of free games is initially awarded when the feature game is triggered.

3. A gaming machine according to claim 1, wherein said outcome evaluator is

configured to reset the count of the free game counter based on said another symbol having said particular characteristic.

4. A gaming machine according to claim 1, wherein said counter is reset to a

predefined number of free games.

5. A gaming machine according to claim 1, wherein the free game counter is

decremented each time the outcome of a free game does not have said another symbol with said particular characteristic.

39 On remitter, the primary judge noted that the 098 patent was not the subject of separate submissions by the parties (PJ2 at [7]).

The reasons in PJ1

40 The primary judge recorded the agreement between the parties that the specification of the 967 patent is sufficiently similar to the specifications of the other patents for the 967 patent to be used for the purpose of analysis, and the further agreement that if claim 1 of the 967 patent is a manner of manufacture, then so too are the rest of the claims in all of the patents in suit: PJ1 at [8]. Given the conclusion reached by the primary judge, it was not necessary to consider any claim other than claim 1 of the 967 patent: at [9].

41 The primary judge referred (at [83]) to s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act as providing that an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of an innovation patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim:

is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies.

His Honour said (at [84]) that the other requirements of s 18(1A) of novelty, innovative step, usefulness and that there be no secret use before the priority date are not relevant and are for present purposes to be assumed, citing CCOM Pty Ltd v Jeijing Pty Ltd (1994) 51 FCR 260 (CCOM) at 291 (Spender, Gummow and Heerey JJ). Thus, as the Full Court said in CCOM at 291, whilst a claim for a ballpoint pen would fail for anticipation and inventive step, it would still be a claim for a manner of manufacture: at [84].

42 The primary judge said that the task of construing the specification involves arriving at a characterisation of the invention claimed in order to determine whether or not it is in substance for a manner of manufacture: at [87]. At [89], the primary judge referred to a number of cases in which the question for consideration was whether or not a mere scheme or plan was nonetheless a manner of manufacture because invention lay not only in the scheme or plan, but also the means by which it was realised using computerisation: Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd [2020] FCAFC 86; (2020) 277 FCR 267 (Rokt); Grant v Commissioner of Patents [2006] FCAFC 120; (2006) 154 FCR 62 (Grant); Research Affiliates LLC v Commissioner of Patents [2014] FCAFC 150; (2014) 227 FCR 378 (Research Affiliates); Commissioner of Patents v RPL Central Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 177; (2015) 238 FCR 27 (RPL Central); Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd v Infotrack Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 161; (2019) 372 ALR 646 (Encompass); and Watson v Commissioner of Patents [2020] FCAFC 56; (2020) 150 IPR 207.

43 The primary judge then said (at [91]) that the reasoning in those cases involves an initial question of whether the claimed invention is for a mere scheme or business method of the type that is not the proper subject matter of a grant of letters patent. His Honour said that, once that question is answered in the affirmative, the subsequent enquiry becomes whether the computer-implemented method is one where invention lay in the computerisation of the method, or whether the language of the claim involves merely plugging an unpatentable scheme into a computer. The primary judge said that the second enquiry requires consideration of whether the invention claimed involves the creation of an artificial state of affairs where the computer is integral to the invention, rather than a mere tool in which the invention is performed. His Honour said that the second enquiry had spawned investigations in the cases to identify whether the contribution of the claimed invention is “technical in nature” or whether it solves a “technical” problem, or whether it merely requires “generic” computer implementation. However, in his Honour’s view, it was not necessary in the present case to consider those matters because the initial question should be answered in the negative: at [91].

44 The primary judge said that, central to Encompass, Rokt, Grant, Research Affiliates and RPL Central was the finding that after close examination of the specification and the claims in issue, the invention as disclosed and claimed was no more than a scheme or mere idea: at [94]. In the present case, however, the primary judge concluded that the invention described and claimed, when understood as a matter of substance, was not to a mere scheme or plan, but rather was to a mechanism of a particular construction, the operation of which involves a combination of physical parts and software to produce a particular outcome in the form of an EGM that functions in a particular way: at [95]. Accordingly, the primary judge said that it was unnecessary to consider the second enquiry: at [95].

45 The primary judge said that the invention as claimed has hardware, firmware and software components that were identified, and that the EGM is a physical device of a type that is played by those wishing to make a wager: at [96]. The primary judge described the specific components as including a display (integer 1.1) that must be able to show reels (integer 1.6(ii)), a credit input mechanism (integer 1.2) and meters (integer 1.3) recording the receipt of credits and recording wins and awarding prizes at the end of the game (integer 1.12), a gameplay mechanism with various buttons (integer 1.5), and a game controller comprising a processor and memory that stores software in the form of the game program code and symbol data defining the reels (integer 1.6), and having the functionality described in integers 1.7–1.11. The primary judge also referred to expert evidence to the effect that the skilled reader understands upon reading the specification that EGMs are subject to regulatory supervision which imposes various physical requirements on all EGMs: at [97].

46 The primary judge then expressed the following conclusion on the issue of characterisation (at [98]):

The result is that to the person skilled in the art, the invention may be characterised as a machine of a particular construction which implements a gaming function. It yields a practical and useful result. Simply put, the machine that is the subject of the claims is built to allow people to play games on it. That is its only purpose. In this regard, the physical and virtual features of the display, reels, credit input mechanism, gameplay mechanism and game controller combine to produce the invention. It is a device of a specific character.

The primary judge expressly disagreed with the approach to the characterisation of the invention taken by the Commissioner, insofar as that involved first identifying the “inventive concept” and then utilising that concept to conclude that the invention is a mere scheme: at [99]. The primary judge said that there was a danger of denuding an invention of patentability by prematurely discounting elements of the claim, in that any claim can be stripped back to remove all specific limitations so that at its core an abstract idea emerges; however, where the abstract idea is incorporated into a means for carrying it out, it may result in a manner of manufacture: at [101].

47 Further, the primary judge referred to the Commissioner’s acceptance of the proposition that if the EGM of claim 1 in the 967 patent were to have been implemented mechanically with cogs, physical reels and motors to create the gameplay, there is no doubt that it would be a manner of manufacture, and added that it is difficult to see why the development of an implementation of an EGM that utilises the efficiencies of electronic technology would be disqualified from patent eligibility when the old-fashioned mechanical technology was not: at [102]. His Honour said that such an approach would be antithetical to the encouragement of invention and innovation: at [102]. The primary judge also referred to the decision of Nicholas J in Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 735; (2015) 114 IPR 28 (Konami) at [223]–[224], which his Honour regarded as concerning a similar EGM, to the effect that the invention claimed was not a mere idea but a new and useful gaming machine and new and useful methods of operation producing new and improved results, and therefore was a manner of manufacture.

The reasons of the Full Court

The majority decision

48 In the majority decision, it was observed that the only inventive aspect of claim 1’s EGM was its feature game, and that it was in all other respects an unremarkable EGM: majority decision at [3]. The feature game was said to be provided for only by integer 1.11, although it was said to be useful to consider the feature game to be constituted by all of integers 1.10–1.12: at [10]. Integers 1.10–1.12 could be implemented in an infinite number of ways because a large number of rules were left wholly unspecified: at [13]. Their Honours said that the feature game defined by integers 1.10–1.12 may be seen either as a definition of a family of games with common attributes and akin therefore to the rules of the game, or as a method for increasing player interest in an EGM and hence for increasing revenue to the operator: at [14]. On either view, Middleton and Perram JJ said that integers 1.10–1.12 were an abstract idea: at [15].

49 The majority decision then stated that the prohibition on patents being granted in respect of ideas of this kind does not extend to inventions which physically embody an abstract idea by giving it some practical application: at [16]. The majority decision criticised the primary judge’s two-step approach, saying that it had the potential to convert the overarching inquiry as to whether the invention was patentable subject matter into a single question whether the invention was not a scheme: at [25].

50 Under the heading “Proposed alternative approach”, Middleton and Perram JJ said the following (at [26]–[27]):

In cases such as the present we would therefore respectfully favour the posing of these two questions in lieu of those advanced by the primary judge:

(a) Is the invention claimed a computer-implemented invention?

(b) If so, can the invention claimed broadly be described as an advance in computer technology?

If the answer to (b) is no, the invention is not patentable subject matter. Of course if the answer to (a) is no, one must then consider the general principles of patentability.

51 As to question (a), Middleton and Perram JJ gave the answer that the invention in claim 1 of the 967 patent is a computer-implemented invention: at [30]. That was said to follow from the proposition that an EGM is a computer, and the invention claimed in claim 1 is an invention consisting of the feature game in integers 1.10–1.12 implemented on the particular kind of computer which is an EGM. The majority decision emphasised that the invention disclosed by claim 1 differs from all other EGMs only by the feature game called for by integers 1.10–1.12, and thus it is said to be apparent that the invention disclosed by claim 1 is a computer implementation of the feature game in integers 1.10–1.12 where the computer in question is an EGM: at [31].

52 As to question (b), Middleton and Perram JJ said that the fact that integers 1.10–1.12 leave it entirely up to the person designing the EGM to do the programming which gives effect to the family of games which those integers define inevitably necessitates the conclusion that claim 1 of the 967 patent pertains only to the use of a computer, noting that claim 1 is silent on the topic of computer technology beyond that the person implementing the invention should use some: at [63]. Their Honours said that it was not to the point that the invention improves player engagement or increases subjective satisfaction: at [64]. Further, Middleton and Perram JJ said that changes in the reel structure (in claim 3 of the 967 patent) and the idea of configurable symbols may constitute advances in gaming technology but they are not advances in computer technology: at [65].

53 Accordingly, the majority decision was that the invention claimed in claim 1 of the 967 patent was not a patentable invention, although their Honours granted leave to appeal under s 158(2) of the Patents Act because the question which arises is a significant one.

54 A question then arose as to the disposition of Aristocrat’s notice of contention and whether it was appropriate that the matter be remitted. The notice of contention asserted that even if the primary judge was wrong to adopt his Honour’s two-step approach, or wrong to conclude that claim 1 was not a mere scheme, nonetheless the invention may be found to disclose patentable subject matter, including because it is technical in nature and solves technical problems in, and involves technical and functional improvements to, the operation of EGMs. The majority decision held that the Full Court was not in a position to decide the notice of contention in view of the lack of much of the relevant evidentiary material in the appeal papers, and said that the remitter had nothing to do with the merits of the notice of contention: at [96]. The majority decision held that it was appropriate that the matter be remitted to the primary judge to determine any residual issues in light of the Full Court’s reasons including any issues which concern the position of claims other than claim 1: at [97].

The minority decision

55 The minority decision of Nicholas J did not follow the two-step proposed alternative approach in the majority decision, and indeed proceeded on the basis that it was not appropriate to adopt an excessively rigid or formulaic approach to the question whether a computer-implemented scheme is a manner of manufacture: minority decision at [116]. Justice Nicholas said that that was especially true in situations where there may be no clear distinction between the field to which the invention belongs, and the field of computer technology, saying that there may well be a technological innovation in the field of technology to which the invention belongs even though it cannot be said that there has been some technological innovation in the field of computers: at [116]. The fact that a solution to a technical problem in a field other than that of computers may rely upon generic computing technology for its implementation does not necessarily render such a solution unpatentable: at [116].

56 According to the minority decision, for the purpose of determining whether the invention produces the artificially created state of affairs referred to in National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents [1959] HCA 67; (1959) 102 CLR 252 (NRDC) at 277, it will often be useful to ask whether the invention solves a technical problem or makes some other technical contribution to the field of the invention: at [117]. In particular, Nicholas J said (at [117]) that it may be useful to consider whether the invention solves a technical problem including one that exists “outside the computer”, whether the computer is utilised to produce “an unusual technical effect” or whether there is some ingenuity in the way in which the computer is utilised, citing RPL Central at [99], [104] and [109]. His Honour noted that mere business schemes, and abstract ideas or information, have never been regarded as sufficiently tangible in character to constitute patentable subject matter, and that implementing the scheme, idea or information in a generic computer, utilising its well-known and well-understood functionality, does not change its fundamental character: at [118]. However, once a scheme is given practical effect and transformed into a new product or process which solves a technical problem, or makes some other technical contribution in the field of the invention, it may no longer be considered a scheme: at [118].

57 The minority decision stated (at [119]):

Ultimately, the question is whether what may have begun as a mere scheme, an abstract idea or mere information, has been transformed in some definite and tangible way so as to result in a product or method providing the required artificial effect. There must be some technical contribution either in the field of computer technology (eg. an improvement in processor, memory or display technology) or in some other field of technology to which the invention belongs. As the authorities to which I have referred to [sic] make clear, that transformation is unlikely to be achieved by taking an inherently unpatentable scheme and implementing it utilising generic computer technology for its well-known and well-understood functionality that does not involve any ingenuity in the way in which the computer is utilised.

In the case of EGMs, Nicholas J said that patentable subject matter may be found to exist in a way in which a gaming system or machine functions even though a computer engineer may not consider that there has been any advance in the field of computer technology: at [120]. His Honour’s own decision in Konami was treated as a case in which a gaming machine or gaming system that provided a technical solution to a practical problem in the field of gaming technology was proper subject matter of a patent.

58 As to the 967 patent itself, Nicholas J said that the specification does not identify any specific problem to which the invention is directed or which the invention is said to provide a solution; rather, the invention is directed to providing a more enjoyable experience for the player, which may advantage the operator of the gaming machines by encouraging game play and thereby increasing the operator’s revenue: at [126]. His Honour referred to expert evidence that indicated that the configurable symbols, and in particular the presentation of prize values on their face, significantly enhanced user experience by allowing a player to visualise in real time potential rewards as play progressed towards the feature game: at [133]. The expert witnesses all gave evidence to the effect that they were not aware of configurable symbols with variable awards displayed over or on the symbol having been used in EGMs before the priority date: at [133]–[134].

59 The minority decision regarded it as appropriate to grant leave to appeal, criticising the primary judge’s two-step approach to the manner of manufacture issue for not engaging with the Commissioner’s submission that the invention as described and claimed was in substance a mere scheme or set of rules for playing a game implemented using generic computer technology for its well-known and well-understood functions: at [135].

60 The minority decision referred to claim 1 as describing an EGM consisting of physical components that are common to such machines, and said that the specification makes clear that the invention is for a gaming machine or gaming system which seeks to enhance player enjoyment by offering a feature game that may be triggered during play of the base game: at [136]. Nothing about the description of the physical components of the machine, or its capacity to trigger a feature game, is new: at [137]. The EGM described and claimed was said to be either a computer or an apparatus that incorporates a computer, and the substance of the invention resides in the game program code which embodies a computer-implemented scheme or set of rules for the playing of a game: at [138].

61 The question was then said to be whether there is anything about the way in which the game code causes the EGM to operate which can be regarded as having transformed what might otherwise be regarded as purely abstract information encoded in memory into something possessing the required artificial effect: at [140]. The minority decision stated that the specification does not identify any technological problem to which the patent purports to provide a solution, and nor did the expert evidence suggest that the invention described and claimed in the specification was directed to any technical problem in the field of gaming machines or gaming systems: at [141]. Rather, the minority decision held that the purpose of the invention is to create a new game that includes a feature game giving players the opportunity to win prizes that could not be won in the base game: at [141]. The purpose of the invention is to provide players with a different and more enjoyable playing experience, and the invention is not directed to a technological problem residing either inside or outside the computer: at [141].

62 The minority decision then considered the question whether the gaming machine described and claimed might be regarded as exhibiting an unusual technical effect due to the way in which the computer is utilised: at [142]. It was observed that the primary judge did not make any specific findings in relation to the use of configurable symbols and whether they were capable of amounting to a technological innovation, and there may well be ways in which the computer could be utilised that adds to the attractiveness of the game through the use of unconventional technical methods or techniques which might themselves give rise to patentable subject matter: at [142]. The minority decision referred to the extent to which the use of configurable symbols might amount to a technical contribution to the field of gaming technology as having been hardly touched on in oral argument before the Full Court, and referred to Senior Counsel for Aristocrat informing the Full Court that he did not consider that all of the evidentiary material relevant to that question was before the Full Court: at [143]. The minority decision regarded it as appropriate to remit the proceedings to the primary judge to consider whether claim 1 of the 967 patent, or any of the other claims in issue, is a manner of manufacture on the basis that it involves technical and functional improvements to EGMs through the use of configurable symbols of the kind more fully described in the specification: at [144]. However, Nicholas J agreed with the orders proposed by Middleton and Perram JJ, which included the remittal order formulated by the majority decision: at [144].

The reasons of the High Court

The dismissing reasons

63 The dismissing reasons of Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ treated NRDC as standing for the proposition that the terminology of “manner of manufacture” taken from s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies is to be treated as a concept for case-by-case development, applied in accordance with common law methodology, and was therefore not to be confined to the use of any verbal formula in lieu of “manner of manufacture”, such as “an artificially created state of affairs” as used in NRDC at 277: dismissing reasons at [23]. The dismissing reasons reviewed a number of Full Court decisions, beginning with CCOM, which concerned a claim for an invention which enabled a standard English keyboard to be used to generate Chinese characters for word processing purposes. Their Honours referred to the Full Court’s finding in CCOM that the claimed invention was capable of being a manner of manufacture because it was concerned with a mode or manner of achieving an end result which was an “artificially created state of affairs of utility in the field of economic endeavour”, that field being the use of word processing to assemble text in Chinese characters (CCOM at 295): at [26]. This was a “physically observable effect”, and the dismissing reasons said that there is no issue that CCOM, as so explained, was correctly decided: at [27]–[28]. By way of contrast, the dismissing reasons referred to Research Affiliates, Encompass, Rokt and Grant as relating to claimed inventions which were not patentable subject matter: at [29]–[30].

64 As to what is involved in an alleged manner of “new” manufacture within s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, the dismissing reasons said that the threshold requirement of an alleged invention will remain unsatisfied if it is apparent on the face of the relevant specification that the subject matter of the claim is, by reason of absence of the necessary quality of inventiveness, not a manner of new manufacture for the purposes of the Statute of Monopolies: at [68]. The threshold requirement of “an alleged invention” does not correspond with or render otiose the more specific requirements of novelty and inventive step (when compared with the prior art base) contained in s 18(1)(b), but simply means that, if it is apparent on the face of the specification that the quality of inventiveness necessary for there to be a proper subject of letters patent under the Statute of Monopolies is absent, one need go no further: at [68].

65 The dismissing reasons then turned to the question of characterising the claimed invention in the present case by reference to the terms of the specification having regard to the substance of the claim and in light of the common general knowledge: at [73]. Their Honours said the following (at [73]):

In the absence of a claim to some variation of or adjustment to generic computer technology to give effect to, or accommodate the needs of, the new game, there is no reason to characterise the claimed invention as other than a claim for a new system or method of gaming: it is only in relation to the feature game that the invention is claimed to subsist.

66 The dismissing reasons said that unlike CCOM, the present cannot be said to fall within a category of cases in which, as an element of the invention, “there [is] a component that [is] physically affected or a change in state or information in a part of a machine”, citing Grant at [32]: at [74]. Their Honours concluded that all members of the Full Court in the present case were right to conclude that the subject matter of Aristocrat’s claim is not patentable subject matter.

67 The dismissing reasons said that neither the primary judge nor the Full Court made any finding that any of the integers of claim 1 addressed the exigencies of the physical presentation of the operation of the game devised by Aristocrat, and it is not apparent from the terms of the specification of the 967 patent or claim 1 itself that there is a basis for such a finding (an apparent reference to the notice of contention which the Full Court did not entertain): at [76]. The dismissing reasons said that in the absence of such a finding, there is no basis for concluding that the claimed invention is patentable subject matter, and it is no more than an unpatentable game operated by a wholly conventional computer, using technology which has not been adapted in any way to accommodate the exigencies of the game or in any other way: at [76].

68 The dismissing reasons then criticised the two-step analysis proposed by the majority decision as unnecessarily complicating the analysis of the crucial issue: at [77]. The crucial issue was said to be as to the characterisation of the invention by reference to the terms of the specification, having regard to the claim and in light of common general knowledge. Their Honours said that it is not apparent in the present case that asking whether the claimed invention is an advance in computer technology as opposed to gaming technology, or indeed is any advance in technology at all, is either necessary or helpful in addressing that issue: at [77]. The issue was said not to be one of an “advance” in the sense of inventiveness or novelty, but whether the implementation of what is otherwise an unpatentable idea or plan or game involves some adaptation or alteration of, or addition to, technology otherwise well-known in common general knowledge to accommodate the exigencies of the new idea or plan or game.

69 The dismissing reasons then described the suggestion by the majority decision that the claimed invention may be an advance in gaming technology but not an advance in computer technology as “an unnecessary flourish”: at [78]. That was said not to be because an advance in gaming technology could not be patentable subject matter, because there is no reason to conclude from the terms of claim 1 of the 967 patent that it was claiming an advance in gaming technology other than the use of a generic computer to play its new game: at [78]. The dismissing reasons said that it was also neither necessary nor appropriate to speak of advances in gaming technology where one is concerned with a claimed invention that discloses no adaptation or alteration of, or addition to, apparatus well-known in common general knowledge in order to accommodate the exigencies of the new idea: at [78]. Their Honours said that a new idea implemented using old technology is simply not patentable subject matter: at [78]. Their Honours then said that there was no occasion for the Full Court to consider remitting the proceeding to the primary judge to enable findings to be made as to whether the claimed invention made any technical contribution to the common general knowledge of computerised gaming, and thus Nicholas J had no sufficient reason to think that the remitter which his Honour proposed was necessary or appropriate: at [78].