FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fanatics, LLC v FanFirm Pty Limited [2025] FCAFC 87

Appeal from: | FanFirm Pty Limited v Fanatics, LLC [2024] FCA 764 |

File number(s): | NSD 1030 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | BURLEY, JACKSON AND DOWNES JJ |

Date of judgment: | 9 July 2025 |

Catchwords: | TRADE MARKS – infringement – s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) – use as a trade mark – whether use on information labels is use as a trade mark – whether use on a website is use in relation to goods or use in relation to online retail services – whether goods are of the same description. TRADE MARKS – defences to infringement – s 122(1)(a)(i) of the Act – good faith use of own name – where infringer had knowledge of prior use of mark – whether good faith use established. TRADE MARKS – defences to infringement – s 122(1)(f) and (fa) of the Act – whether person using the infringing mark would obtain registration – s 44(3) of the Act – honest concurrent use – whether honest use established – application of s 58 and s 60 of the Act to honest concurrent use defence. TRADE MARKS – defences to infringement – s 122(1)(e) of the Act – exercising a right to use a trade mark given under the Act – whether products infringed fall within scope of right to use trade mark. TRADE MARKS – cancellation of registered trade marks – s 88(2)(a) of the Act – application to cancel marks on grounds on which registration could have been opposed – s 58 of the Act – whether owner of the mark as at the filing date. TRADE MARKS – cancellation of registered trade marks – s 88(2)(a) of the Act – application to cancel marks on grounds on which registration could have been opposed – s 44 of the Act – substantially identical or deceptively similar to registered mark – whether ss 44(3) or (4) made out in defending cancellation under s 44 – whether honest concurrent or prior use established. TRADE MARKS – cancellation of registered trade marks – s 88(2)(a) of the Act – application to cancel marks on grounds on which registration could have been opposed – s 60 of the Act – whether, because another trade mark had acquired a reputation in Australia, registration would be likely to deceive or cause confusion. TRADE MARKS – cancellation of registered trade marks – s 88(2)(c) of the Act – whether trade mark likely to deceive or cause confusion. TRADE MARKS – cancellation of registered trade marks – s 89 of the Act – whether discretion ought to have been exercised against rectification of the Register of Trade Marks. CONSUMER LAW – alleged breach of s 18 and s 29 of the Australian Consumer Law – passing off. |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Schedule 2, ss 18, 29 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 37M Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) ss 6, 7(4), 17, 20(1)(a), 44(1), 44(2)(a)(i), 44(3), 44(4), 58, 60, 88(1), 88(2)(a), 88(2)(c), 89, 120, 120(2)(a), 122(1)(a)(i), 122(1)(e), 122(1)(f), 122(1)(fa) Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (Cth) reg 8.2 |

Cases cited: | Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; (2018) 261 FCR 301 Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Limited v ACPA Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 6; (2018) 259 FCR 514 Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Ltd v ACPA Pty Ltd (No 3) [2015] FCA 1436; (2015) 116 IPR 159 Anheuser-Busch v Budejovicky Budvar [2002] FCA 390; (2002) 56 IPR 182 Baume & Co Ltd v AH Moore Ltd [1958] Ch 907 Bohemia Crystal Pty Ltd v Host Corporation Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 235; (2018) 354 ALR 353 Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2023] FCA 1258 Carnival Cruise Lines Inc v Sitmar Cruises Ltd [1994] FCA 68; (1994) 31 IPR 375 Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721; (1999) 96 FCR 107 Deckers Outdoor Corporation Inc v Farley (No 2) [2009] FCA 256; (2009) 176 FCR 33 Dunlop Aircraft Tyres Limited v The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company [2018] FCA 1014; (2018) 262 FCR 76 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd [2010] HCA 15; (2010) 241 CLR 144 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Pty Ltd (No 2) [2008] FCA 1005; (2008) 78 IPR 334 Estex Clothing Manufacturers Pty Ltd v Ellis and Goldstein Ltd [1967] HCA 51; (1967) 116 CLR 254 FanFirm Pty Limited v Fanatics, LLC (No 2) [2024] FCA 826 FanFirm Pty Limited v Fanatics, LLC [2024] FCA 764 Firstmac Limited v Zip Co Limited [2025] FCAFC 30 Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 235; (2016) 118 IPR 239 Goodman Fielder Pte Ltd v Conga Foods Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1808; (2020) 158 IPR 9 House v The King [1936] HCA 40; (1936) 55 CLR 499 Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Py Ltd [1991] FCA 402; (1991) 30 FCR 326 Killer Queen, LLC v Taylor [2024] FCAFC 149; (2024) 306 FCR 199 Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 876; (2000) 100 FCR 90 McCormick & Co Inc v McCormick [2000] FCA 1335; (2000) 51 IPR 102 Optical 88 Limited v Optical 88 Pty Limited (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380; (2010) 275 ALR 526 Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 130; (2011) 197 FCR 67 PDP Capital Pty Ltd v Grasshopper Ventures Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 128; (2021) 285 FCR 598 Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; (1998)194 CLR 355 RB (Hygiene Home) Australia Pty Ltd v Henkel Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 10; (2024) 302 FCR 285 Re Alex Pirie & Sons Ltd’s Application (1933) 50 RPC 147 Re Parkington & Co (1946) 63 RPC 171 Seiko Epson Corporation v Calidad Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1403; (2017) 133 IPR 1 Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; (2023) 277 CLR 186 Seven Network (Operations) Ltd v 7-Eleven Inc [2024] FCAFC 65; (2024) 181 IPR 210 Solahart Industries Pty Ltd v Solar Shop Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 700; (2011) 281 ALR 544 Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd [1954] HCA 82; (1953) 91 CLR 592 Sports Warehouse, Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 664; (2010) 186 FCR 519 The Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; (1963) 109 CLR 407 Vivo International Corp Pty Ltd v Tivo Inc [2012] FCAFC 159; (2012) 99 IPR 1 Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co [1994] FCA 163; (1994) 49 FCR 89 Yarra Valley Dairy Pty Ltd v Lemnos Foods Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1367; (2010) 90 IPR 117 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Trade Marks |

Number of paragraphs: | 306 |

Date of hearing: | 5 – 6 November 2024 |

Counsel for the Appellant: | Mr AJL Bannon SC, Mr L Merrick SC and Ms M Evetts |

Solicitor for the Appellant: | King & Wood Mallesons |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr C Dimitriadis SC and Ms S Ross |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Sparke Helmore Lawyers |

ORDERS

NSD 1030 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | FANATICS, LLC Appellant | |

AND: | FANFIRM PTY LTD Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | FANFIRM PTY LTD Cross-Appellant | |

AND: | FANATICS, LLC Cross-Respondent | |

order made by: | BURLEY, JACKSON AND DOWNES JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 9 July 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and supply draft short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons (marked up with any points of difference) together with submissions on the question of costs (limited to 5 pages), to the chambers of Burley, Jackson and Downes JJ by 4 pm on 30 July 2025.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[1] | |

[9] | |

[15] | |

[25] | |

[27] | |

[28] | |

[28] | |

[30] | |

[54] | |

[54] | |

[59] | |

[61] | |

[76] | |

[76] | |

[78] | |

[113] | |

[113] | |

[114] | |

[124] | |

[124] | |

[132] | |

[144] | |

3.4 Consideration – s 122(1)(a)(i) Good faith use of own name | [148] |

3.5 Consideration – ss 122(1)(f) and (fa) and s 44(3) Honest concurrent use | [177] |

3.6 Application of s 58 and s 60 in the context of ss 122(1)(f) and (fa) | [186] |

[188] | |

[200] | |

[210] | |

[210] | |

[210] | |

[214] | |

[219] | |

[225] | |

[228] | |

[233] | |

[256] | |

[256] | |

[259] | |

6 NOTICE OF CONTENTION AND APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A CROSS APPEAL | [264] |

[264] | |

[271] | |

[271] | |

[281] | |

[283] | |

[296] | |

[296] | |

[304] |

THE COURT:

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 The appeal proceedings

1 This proceeding, like many others brought primarily under the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (Trade Marks Act), raises too many duplicated claims and arguments. At its heart, the dispute concerns the trade mark entitlements of two parties who have decided to use the word “Fanatics” as a trade mark and who, after a period of apparent co-existence, have decided to sue each other for trade mark infringement, each contending that various trade marks of the other are infringed or invalid.

2 Broadly, the case advanced before the primary judge followed a familiar course. The applicant below and respondent on the appeal, FanFirm Pty Ltd, alleged infringement of two of its registered trade marks. The respondent below and present appellant, Fanatics, LLC, contended that the impugned sign was not used as a trade mark within the scope of goods or services of the trade mark registration. Fanatics contended that for those uses of impugned signs that did amount to trade mark use, it was entitled to rely on four affirmative defences available under the Trade Marks Act. As a fall back, in its cross-claim Fanatics contended that the FanFirm trade marks were invalid and ought to be removed from the Register of Trade Marks. It also alleged that FanFirm had itself infringed its registered trade marks. In response, FanFirm contended that it was entitled to rely on various defences under the Trade Marks Act and also contended that the trade marks asserted should be revoked. Both parties also contended that the other had acted in breach of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) and engaged in passing off.

3 Ultimately, Fanatics was found by the primary judge to be liable for trade mark infringement. Her Honour rejected various defences advanced by Fanatics and dismissed its cross claim; FanFirm Pty Limited v Fanatics, LLC [2024] FCA 764.

4 The learned primary judge picked her way through the welter of issues raised, including duplicated defences and cross-claims for revocation, and found that FanFirm should succeed on its case for trade mark infringement, rejecting defences raised under ss 122(1)(a)(i), 122(1)(f) and 122(1)(fa) (and via those provisions, ss 44(3), 58 and 60), and partially rejecting a defence under s 122(1)(e). She also found that aspects of the trade marks owned by Fanatics should be cancelled under s 88(2)(a) having regard to grounds for opposition under ss 44, 58, 59, 60 and 88(2)(c), and declined to exercise the discretion under s 89(1) not to give effect to the cancellation.

5 In its Amended Notice of Appeal, Fanatics identifies 19 grounds of alleged error that present as a scattergun of challenges to legal and factual findings of the learned primary judge. Fortunately, Fanatics’ submissions were corralled into four categories that are more coherent, namely, that the primary judge erred as follows. First, in making findings of infringement in favour of FanFirm. Secondly, in finding that three of Fanatics’ own trade marks should be cancelled in relation to class 35 services. Thirdly, in dismissing its cross claim for trade mark infringement against FanFirm. Fourthly, in dismissing Fanatics’ cross claims brought under the ACL and for passing off against FanFirm. Fanatics also contends that the primary judge erred in awarding FanFirm its costs of the proceedings.

6 FanFirm relies upon a Further Amended Notice of Contention which advances five bases upon which it contends the primary judge ought also to have found in its favour. The first concerns the application of the defences under s 122(1), the second the characterisation of Fanatics as a trade rival or competitor, the third the application of s 122(1)(e) as a defence to infringement to the benefit of Fanatics, the fourth the sale by FanFirm of clothing in the nature of third-party licensed merchandise prior to 2012 and the fifth the availability to FanFirm of a defence to infringement of Fanatics’ trade marks pursuant to ss 122(1)(f) and (fa). FanFirm sought leave to rely on a Notice of Cross-Appeal on the second day of the hearing of the appeal. We address that in section 6 of these reasons.

7 The principles relevant to consideration of a decision under appellate review are well established and set out in Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; (2018) 261 FCR 301 at [2]–[10] (Allsop CJ) and [45]–[53] (Perram J).

8 Unless stated otherwise, references to sections in these reasons are to the Trade Marks Act and references to paragraphs are to the primary judgment.

1.2 The trade marks

9 FanFirm sued on two marks (the FanFirm Marks), being no. 1232983 for the word “FANATICS” in classes 9, 16, 24, 25, 32, 38 and 39 and having a priority date of 2 April 2008 (FanFirm Word Mark) and no. 1232984 for the word “FANATICS” and device in classes 9, 16, 24, 25, 32, 38 and 39 (FanFirm Device Mark) and having a priority date of 2 April 2008, the device being:

10 The FanFirm Marks are both registered in the following classes:

Class 9: Motion picture films (recorded); for use in multi media (not limited to recordings for television; world wide web and DVD).

Class 16: Printed material used for advertising and promotional material (although not limited to); postcards, books, bumper stickers, calendars, posters, printed publications and printed matter and photographs; paper flags.

Class 24: Banners; flags (not of paper), including textile flags; woven and non-woven textile fabrics; textile material; textiles made of linen, cotton, silk, satin, flannel, synthetic materials, velvet or wool; cloth.

Class 25: Clothing, footwear and headgear, shirts, scarves, ties, socks, sportswear.

Class 32: Mineral and aerated waters and beer.

Class 38: Providing telecommunication services including content and entertainment; television broadcasts and Internet communication; press or information agencies (news).

Class 39: Organisation of transport and travel facilities for tours; functions; sporting and entertainment events for people and products.

11 In its cross claim, Fanatics asserted that FanFirm infringed two of its trade marks (the FANATICS Word Marks) being no. 1288633 for the word “FANATICS” in classes 35 and 42 and having a priority date of 10 September 2008 (633 TM) and no. 1905681 for the word “FANATICS” in classes 35 and 42 and having a priority date of 9 January 2018 (681 TM).

12 In addition, the following trade marks owned by Fanatics were relevant to the case before the primary judge: no. 1288632 for the words “FOOTBALL FANATICS” in class 35 and having a priority date of 10 September 2008 (632 TM), no. 1680976 for the words “SPORT FANATICS” in class 35 and having a priority date of 18 May 2010 (976 TM), and no. 1894688 for the word “Fanatics” and device as shown below, in classes 35 and 42 and having a priority date of 15 November 2017 (688 TM or FANATICS Flag Mark):

13 The trade marks owned by Fanatics which are listed above are registered in the following classes (subject to some slight variations in the specifications, which are not relevant to the present appeal), save that the FOOTBALL FANATICS and SPORTS FANATICS marks are only registered in class 35 ([22]):

Class 35: Business marketing consulting services; customer service in the field of retail store services and on-line retail store services; on-line retail store services featuring sports related and sports team branded clothing and merchandise; order fulfillment services; product merchandising; retail store services featuring sports related and sports team branded clothing and merchandise.

Class 42: Development of new technology for others in the field of retail store services for the purpose of creating and maintaining the look and feel of web sites for others, not in the field of web site hosting; computer services, namely, creating and maintaining the look and feel of web sites for others, not in the field of web site hosting services; computer services, namely designing and implementing the look and feel of web sites for others, not in the field of web site hosting services; computer services, namely, managing the look and feel of web sites for others, not in the field of web site hosting.

14 We refer to the FANATICS Word Marks and the FANATICS Flag Mark together as the FANATICS Marks.

1.3 Background findings of the primary judge

15 The primary judge summarised the origins of the FanFirm business from 1997, when Mr Warren Livingstone proposed the idea of a travelling cheer squad for the Australian tennis squad wearing the word or logo “Fanatics” while giving enthusiastic support for Australian sports teams and players ([23]). This developed into organised tours, where attendees wore “FanFirm branded” t-shirts and caps ([25]). Initially, the business focussed on organising tour and event services for particular sporting events and in 2002 the business expanded to providing organised tour and event services for a wide range of non-sport related events including skiing trips to France and Japan, and Anzac Day in Gallipoli ([27]). Many thousands of people have attended such event tours over the years ([27]).

16 In September 2004, Mr Livingstone incorporated FanFirm and offered the same goods, services and activities that he had personally ([29]). FanFirm has a database of its customers and subscribers who have purchased FanFirm branded merchandise and/or purchased and participated in tours organised by FanFirm. FanFirm had around 160,000 members on the database ([30]). In addition to sending newsletters to customers on the database, FanFirm operated a loyalty and rewards program from its inception, which entitled customers to participate in online communities operated at the website www.fanatics.com and receive benefits ([31]). FanFirm began operating from this domain name and also had registered www.fanatics.com.au and thefanatics.com.au from at least 2003 ([32]). Until around 2020 the primary website of the FanFirm business was www.fanatics.com, with traffic to www.thefanatics.com.au being redirected to that website ([34]).

17 The primary judge noted the evidence given by Mr Livingstone and Mr Fenton Coull (a former sports executive who had business dealings with FanFirm and Mr Livingstone while employed at Tennis Australia) that Mr Livingstone, and FanFirm since its incorporation, sold clothing, including third party licensed merchandise, online via the www.thefanatics.com website from 1998 (and later via www.thefanatics.com.au and www.fanatics.com.au), and that branded merchandise was sold in the lobbies of hotels where the tour groups were staying ([37]–[38]). The primary judge considered in section 4.1.1 the evidence adduced by FanFirm of sales of merchandise and in 4.1.3 details of its social media presence.

18 In section 4.1.4, the primary judge addressed the reputation of FanFirm. FanFirm submitted before the primary judge that as at least December 2010 it had a valuable reputation in the word “Fanatics” with respect to sporting and other events tour services and also sports merchandise, including clothing, headgear, sportswear and footwear ([83]). This was not disputed by Fanatics in relation to the use of the word “Fanatics” in connection with the business of promoting and providing sporting and event tour services ([84]). Nor did Fanatics dispute that as part of its tour services business FanFirm supplied items of clothing and headgear to attendees. The dispute concerned whether or not FanFirm has a reputation in relation to the promotion and sale of merchandise under the FanFirm Word Mark other than as an adjunct to its sporting and event tour service business ([85]).

19 The primary judge considered:

(1) the length of operation of FanFirm’s tours business ([88]);

(2) the evidence of annual gross income for each year from 1997 ([89]);

(3) the size of the database (around 160,000 contact details) of customers ([90]);

(4) the visibility of large numbers of Fanatics supporters who attended prominent events, such as the Davis Cup in 2003 where between 1,000 and 1,300 Fanatics supporters attended ([93]);

and determined that FanFirm had established that as at December 2010 it had a reputation in the FanFirm Marks, including the word “Fanatics”, with respect to sports merchandise including at least clothing, headgear and footwear, which was separate to and not merely an adjunct of its tour business ([99]).

20 The primary judge then turned to consider the business of Fanatics, noting that it had begun trading as “Football Fanatics” in 1995 as a traditional store selling sporting merchandise related to the Jacksonville Jaguars NFL team in Jacksonville, Florida, before moving to become an online retail store in 1997 ([106]–[107]). After addressing the history of the names used by Fanatics (to which we refer further below) the primary judge found that Fanatics changed its corporate name and brand to “Fanatics” simpliciter on 7 December 2010 ([115]).

21 The primary judge noted that in addition to its online sale of officially licensed sports merchandise and apparel, another aspect of Fanatics’ business is the design, implementation, maintenance and management of third party partner e-commerce stores (Partner Stores) for sporting teams, leagues and media brands in the United States and other countries such as England ([117]). Fanatics has also offered a rewards or loyalty program called “FANATICS MVP” since 2004 ([122]) and has offered “FANATICS LIVE” events connecting fans with athletes since 2018 (which has since been renamed to “FANATICS PRESENTS”) ([120]).

22 The primary judge found that Fanatics has sold products to customers in Australia since 2000, initially under the “FOOTBALL FANATICS” brand, with confidential sales figures showing that the volume of sales into Australia slowly increased each year from 2014 to 2020 but has since dropped off. The volumes have been “meaningful but not overwhelming” ([124]). Mr Zohar Ravid, an executive with Fanatics, gave evidence that prior to 2020, Fanatics’ activity in Australia was limited to selling and shipping merchandise to persons present in Australia, but since that date, Fanatics has pursued Australian-based sporting leagues and teams to offer its partner services, including the development of Partner Stores ([125]).

23 In section 4.3, entitled “Coexistence prior to 2020”, the primary judge found that other than legal skirmishes in the Australian Trade Marks Office in 2010, 2013 and 2019 – when one or the other of the parties opposed the other’s trade mark applications – the parties largely coexisted until 2020, finding at [137]:

…The respondent has since 2010, operated an online retail store selling licensed third-party team apparel for a wide variety of sports, initially focussing on US sporting leagues, such as the NFL and the NBA, and then expanding to every major sporting code around the world. The applicant operated a tour and events company which sold merchandise both directly related to those events and third-party licensed merchandise relating to Australian national sporting teams such as the Wallabies, Socceroos and Matildas.

24 Her Honour found that the parties were operating in “the same broad field”, with both targeting sports fans and their enthusiasm for sport and selling merchandise to them over the internet. Prior to 2020, FanFirm had a narrower focus on Australian customers and licensed sports apparel for Australian national teams, and Fanatics did not specifically target Australian customers, instead selling sporting merchandise primarily relating to US sporting teams and codes and European football leagues and teams ([138]). The coexistence was possible because, her Honour found, they operated in slightly different “lanes” that did not overlap. However, the status quo changed in 2020 when both moved out of their lanes: Fanatics by making deals with the Australian retailer Rebel Sport and the Australian Football League (AFL), and FanFirm by launching a “retail store” ([140]).

1.4 The Orders made

25 On 17 July 2024 the primary judge:

(1) made a declaration to the effect that Fanatics has infringed the FanFirm Word Mark by using the FANATICS Word Marks and the FANATICS Flag Mark (together, the Infringing Marks), in relation to clothing, headgear, sportswear, sports bags, scarves, water bottles, towels and blankets.

(2) granted an injunction that Fanatics be permanently restrained:

…from using the FanFirm Word Mark or any signs that are substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the FanFirm Word Mark, including the Infringing Marks, in relation to the goods and services in respect of which the FanFirm Word Mark is registered, without the permission, authority or licence of [FanFirm].

(3) ordered that the Register be rectified by removing the Infringing Marks in respect of the services in class 35 in which they are registered and that Fanatics’ 976 TM (“SPORT FANATICS”) be removed from the Register.

(4) ordered that the Register be rectified by removing the FanFirm Word Mark and FanFirm Device Mark in respect of goods in classes 9, 16 and 32 and services in class 38.

(5) ordered that FanFirm’s claim be “otherwise dismissed” (Order 6).

(6) ordered that Fanatics’ cross claim be dismissed.

(7) ordered that Fanatics pay FanFirm’s costs of the proceedings, including the cross claim.

26 Issues arise in this appeal concerning the orders referred to in (1) (2), (3), (5), (6) and (7). The orders for the rectification of the Register in (3) and (4) have been stayed pending the determination of this appeal (FanFirm Pty Limited v Fanatics, LLC (No 2) [2024] FCA 826).

1.5 Summary of conclusions in the appeal

27 For the reasons set out below, we have found that:

(1) the primary judge erred in her evaluation that the packaging labels or care labels used on certain Fanatics goods, in the absence of other Fanatics branding, constitute use of the word “Fanatics” as a trade mark (section 2.3);

(2) with the exception of the Corporate Goods (as defined below) and the “Fanatics Branded” goods sold by Fanatics on its website (as described below), which were correctly found to infringe, the primary judge erred in finding that the use of the FANATICS Marks on Fanatics’ websites constituted use in relation to class 24 and 25 goods and thus infringed the FanFirm Word Mark (section 2.4);

(3) the primary judge erred in finding that towels and blankets fall within FanFirm’s class 24 registration for the FanFirm Marks (section 2.5);

(4) Fanatics has not demonstrated error in the finding that it could not rely on the defence of ‘good faith use of its own name’ under s 122(1)(a)(i) in respect of its infringement of the FanFirm Word Mark in relation to the Infringing Goods (as defined below) (section 3.4);

(5) Fanatics has not demonstrated error in the finding that it could not rely on the defence of ‘honest concurrent use’ under ss 122(1)(f) or (fa) and s 44(3) in respect of its infringement of the FanFirm Word Mark in relation to the Infringing Goods. However, her Honour erred in finding that s 58 would prevent Fanatics from relying on the defence in respect of the FANATICS Flag Mark (sections 3.5 and 3.6);

(6) Fanatics has not demonstrated error in the finding that the FANATICS Marks should be cancelled pursuant to s 88(2)(a), on grounds under ss 44, 58 (in respect of the FANATICS Word Marks only) and 88(2)(c). However, her Honour erred in finding that s 60 provided an additional ground for cancellation of the FANATICS Marks pursuant to s 88(2)(a) (section 4);

(7) as we have upheld the primary judge’s finding that the FANATICS Marks should be cancelled, it was not necessary to consider Fanatics’ appeal regarding its infringement case against FanFirm (section 5.1);

(8) Fanatics has not established error in the finding rejecting its claims under the ACL and passing off (section 5.2); and

(9) the primary judge erred in finding that the defence under s 122(1)(e) was available to Fanatics in respect of its infringement of the FanFirm Word Mark in relation to the Infringing Goods, and erred in making Order 6 otherwise dismissing FanFirm’s claim (section 6).

2. APPEAL FROM FINDINGS OF TRADE MARK USE BY FANATICS

2.1 Introduction

28 On the question of infringement, Fanatics contends that the primary judge erred in finding:

(1) that its use of the word “Fanatics” in relation to certain swing tags, care label information and packaging amounted to use as a trade mark (information label issue);

(2) that its use of “Fanatics” on the websites fanatics.com and fanatics-intl.com amounted to trade mark infringement (the website issue); and

(3) that certain goods sold by Fanatics were “goods of the same description” as the goods in respect of which the FanFirm Word Mark was registered (the goods of the same description issue).

29 In its written submissions, Fanatics parenthetically refers to grounds 1–4 and 7–13 as relevant to these three subjects. We deal with Fanatics’ appeal from the primary judge’s findings on its defences to infringement in section 3 below.

2.2 The primary judge’s findings

30 There was no dispute before the primary judge that the FanFirm Word Mark, which has a priority date of 2 April 2008, is substantially identical to the FANATICS Word Marks ([223]). The primary judge also found that the FANATICS Flag Mark was deceptively similar to the FanFirm Word Mark ([237]), and this was not challenged on appeal. As noted above, we refer to the FANATICS Word Marks and the FANATICS Flag Mark together as the FANATICS Marks.

31 FanFirm’s infringement case before the primary judge involved allegations first, that Fanatics had used its FANATICS Marks in Australia in relation to clothing, headgear, sportswear, umbrellas, sports bags, scarves, water bottles, towels, flags, footwear and blankets (Impugned Goods) to indicate a connection between the goods and Fanatics ([169]), and that second, Fanatics had offered and promoted loyalty and reward services and services whereby it connected fans to athletes (Impugned Services) in Australia under and by reference to the FANATICS Marks in order to indicate a connection between those services and Fanatics ([170]). The primary judge rejected the allegations of infringement by reference to the Impugned Services ([264], [271]–[272]).

32 At [160]–[163] the primary judge set out relevant parts of ss 120, 17 and 6 of the Trade Marks Act, and at [166] quoted the decision of the High Court in Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; (2023) 277 CLR 186 as follows:

23 Use of a trade mark in relation to goods means use of a trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, those goods, and so can include use of the mark on product packaging or marketing such as on a website. There is a distinction, although not always easy to apply, between the use of a sign in relation to goods and the use of a sign as a trade mark. A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods dealt with by one trader from goods dealt with by other traders; that is, as a badge of origin to indicate a connection between the goods and the user of the mark.

24 Whether a sign has been “use[d] as a trade mark” is assessed objectively without reference to the subjective trading intentions of the user. As the meaning of a sign, such as a word, varies with the context in which the sign is used, the objective purpose and nature of use are assessed by reference to context. That context includes the relevant trade, the way in which the words have been displayed, and how the words would present themselves to persons who read them and form a view about what they connote. A well known example where the use was not “as a trade mark” was in Irving’s Yeast-Vite Ltd v Horsenail, where the phrase “Yeast tablets a substitute for ‘Yeast-Vite’” was held to be merely descriptive and not a use of “Yeast-Vite” as a trade mark. Therefore, it did not contravene the YEAST-VITE mark.

25 The existence of a descriptive element or purpose does not necessarily preclude the sign being used as a trade mark. Where there are several purposes for the use of the sign, if one purpose is to distinguish the goods provided in the course of trade that will be sufficient to establish use as a trade mark. Where there are several words or signs used in combination, the existence of a clear dominant “brand” is relevant to the assessment of what would be taken to be the effect of the balance of the label, but does not mean another part of the label cannot also act to distinguish the goods.

(Footnotes omitted)

33 Her Honour noted that there were three categories of dispute going to the question of trade mark infringement by the Impugned Goods.

34 The first category concerned Fanatics’ use of the FANATICS Marks on branded corporate merchandise ([172(a)], section 6.2.2.1).

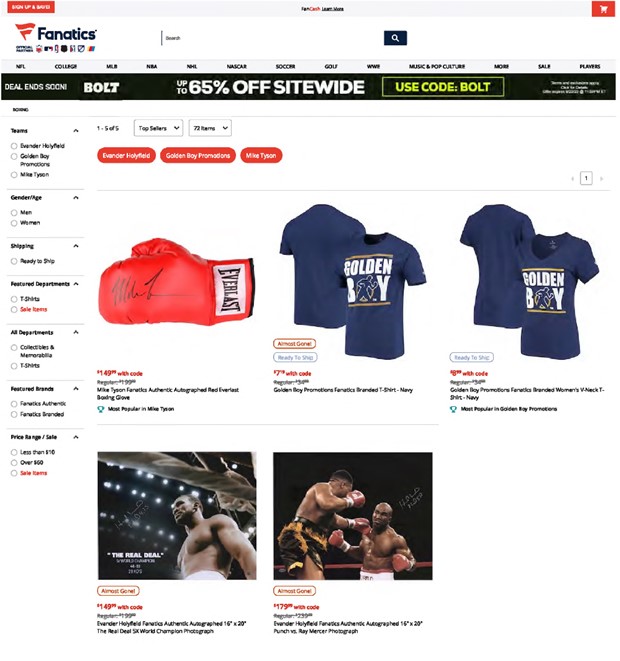

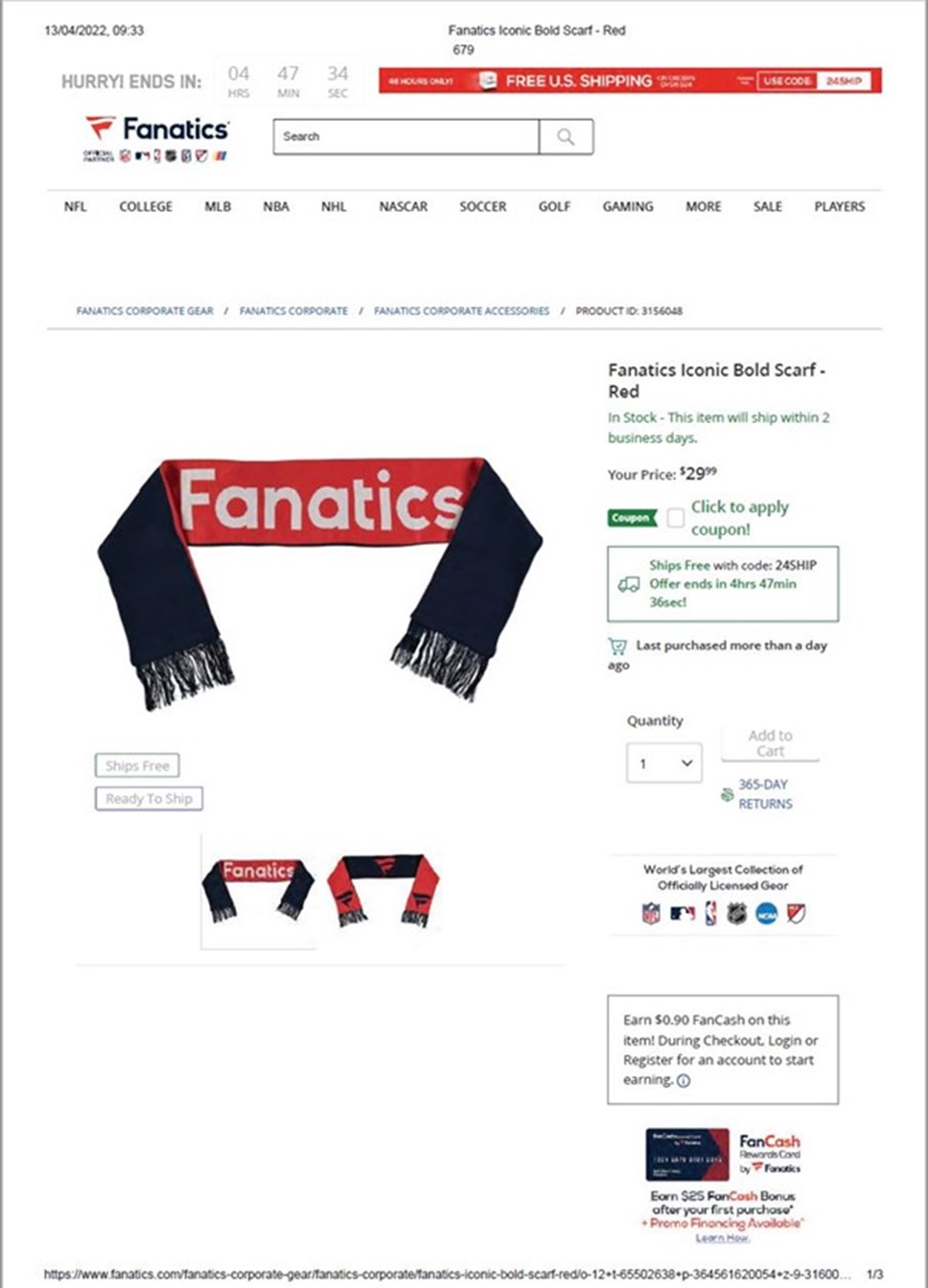

35 The primary judge considered a number of examples of trap purchases tendered as evidence of corporate goods acquired from the Fanatics website at www.fanatics.com in April 2022 and July 2023 ([181]), and screenshots of the purchasing process ([184]–[185]). Her Honour described the homepage showing the FANATICS Flag Mark displayed at the top left corner of the page and a navigation bar above the product listing on the webpage which included references to “FANATICS CORPORATE GEAR” and the like. Using the menu, the trap purchaser navigated to a navy t-shirt located under “Fanatics Corporate T-Shirts” and a scarf under “Fanatics Corporate Accessories” ([185]). The scarf bears the word “Fanatics” on it in large letters.

36 Three website pages from www.fanatics.com are reproduced in the primary judgment at [185], displaying various items of clothing with labels referring to them as “Fanatics Corporate” clothing, as follows:

37 The primary judge found at [186] that “the above items”, referring, as we understand it, to all of the items identified in [185], are examples of Fanatics using its FANATICS Word Marks as a trade mark in relation to clothing, including sports apparel.

38 Although in ground 10 of its Notice of Appeal Fanatics contends that the primary judge erred in her conclusions in this section, it addressed no submissions to the primary judge’s findings in this category and we address that ground no further.

39 The second category of use by Fanatics concerned “third party licenced merchandise” where the argument addressed was as follows:

187 The applicant contends that the respondent has advertised and sold clothing, including third party licensed merchandise, by reference to the FANATICS Word and Flag Marks because:

(a) some of the goods bear one of the FANATICS Marks on the goods themselves, such as on the label, barcode, swing tag or packaging labels; and

(b) the goods are displayed on, and are accessible via, the respondent’s websites at www.fanatics.com and www.fanatics-intl.com and those websites prominently bear the FANATICS Marks.

40 Her Honour noted that trap purchases were made by a solicitor, Mr Alastair Cockerton, of a “Hawthorn Fanatics Shirt” from the AFL store at www.aflstore.com.au (the Hawthorn Football Club Shirt) and a red Men’s Kansas City Chiefs Hoodie from the “Fangear” section of the Rebel Sport website at www.rebelsport.com.au. Her Honour set out observations made by Mr Cockerton about the product page for the Hoodie and statements on the “Frequently Asked Questions” page on the Rebel Sport website at [189] and [190]. Her Honour also noted at [191] that the Hoodie as tendered had a care label sewn into the garment that referred to, amongst others, FANATICS International and FANATICS (Germany).

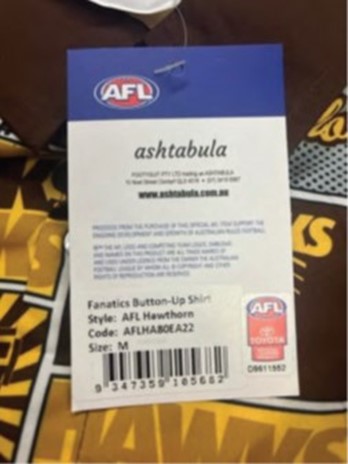

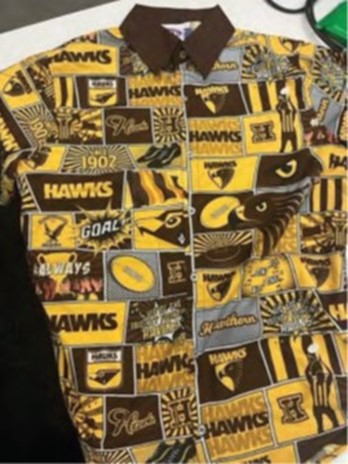

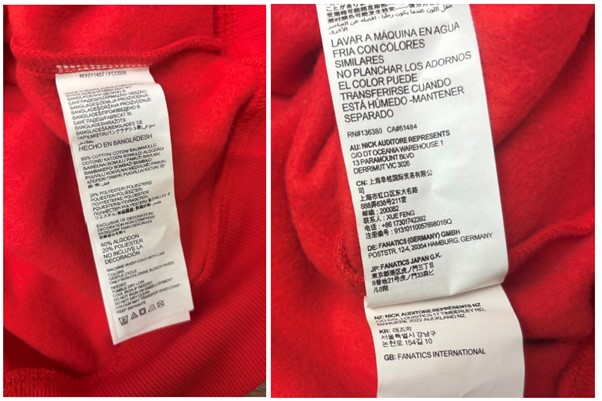

41 At [192] her Honour produced images of the Hawthorn Football Club Shirt and noted Mr Cockerton’s observation that it arrived in packaging labelled “Fanatics Button-up Shirt” and with a swing tab as depicted:

|

|

42 The primary judge also referred to a further purchase from the www.fanatics.com website made by Mr Cockerton in September 2023 of a turquoise football jersey described as “Australia Women’s National Team Nike Women’s 2023 Away Stadium Replica Jersey – Turquoise” (at [193]).

43 The primary judge found at [194]:

I consider that the role of the FANATICS Marks on the clothing (stitched or printed on the back) and care labels is to denote the manufacturer of those goods. Mr Swallow said in relation to the FANATICS branded goods: “you can think of ‘Fanatics-branded’ in the same way that we look at, say, an Adidas or a Nike. It’s just that’s the name that we call our own branded merchandise, Fanatics”…

(Emphasis added)

44 The primary judge rejected a contention advanced by Fanatics that the use of the FANATICS Marks on labels or swing tags does not amount to trade mark use because they are not acting as badges of origin in any relevant sense ([195]). The primary judge relevantly held:

198 It would be apparent to any reasonable Australian consumer that the Hawthorn Football Club (or any sporting club) does not manufacture clothing, and that the Hawthorn indicia are part of the design of the shirt material. The use of the FANATICS Marks in these instances are being used as “a badge of origin” to distinguish the respondent’s relevant good from goods manufactured by other sports clothing manufacturers such as Nike or Adidas: E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144 at [41]–[42] (per French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ).

199 The fact that, in some circumstances, the FANATICS Marks are not physically on the clothing itself, but on a tag or label attached to the garment, is not decisive. The phrase “used as a trade mark … in relation to goods” in s 120(1) of the Act does not require the goods be physically branded with the mark but “can include use of the mark on product packaging or marketing such as on a website”: Self Care at [23].

200 In this case, the FANATICS Marks on the FANATICS branded goods are being used as a badge of origin and thus the use constitutes trade mark use. The fact that other marks are present on the clothing, such as the logo of the relevant sporting team or league, does not matter. Dual branding is “nothing unusual” and does not have the effect that one of the marks is not being used as a trade mark: see Allergan Australia Pty Ltd v Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd (2021) 162 IPR 52 at [66] (per Jagot, Lee and Thawley JJ) and the cases there cited (these comments were not disturbed on appeal in Self Care). See also Anheuser at [189] and [191] (per Allsop J).

45 On appeal, Fanatics does not dispute that where the FANATICS Word Mark or Flag Mark appears stitched into the inside collar of a shirt the finding of trade mark use is properly made. However, it contends that the primary judge erred in finding that use of the word “Fanatics” on various care labels, packaging barcodes, swing tags or postage packaging (which Fanatics describes as information label use) could, on the evidence in this case, be described as “trade mark use” within the authorities.

46 The third category concerns third party licensed merchandise sold on the Fanatics websites that are not visibly branded with the FANATICS Marks, such as jerseys for a football team manufactured by Nike or Adidas ([201]).

47 The primary judge found that the vast majority of goods sold by Fanatics are not themselves branded with FANATICS Marks ([203]) and noted that the point of departure between the parties was that whereas Fanatics accepted that the domain name www.fanatics.com constitutes use of the FANATICS Word Marks as a trade mark in relation to its online retailing services, it disputed that the domain name constitutes use of the FANATICS Marks in relation to the clothing and apparel offered for sale at that site ([207]).

48 The primary judge cited a number of first instance decisions concerning the question of whether online use of a sign may amount to trade mark use in relation to goods that it promotes as well as services, noting at [213] that Fanatics’ use of FANATICS on its website was not limited to its use as part of the domain name, and included displays of the FANATICS Flag Mark on the top left of each page and employing the word FANATICS in relation to the goods displayed for sale on the website.

49 The primary judge found:

201 The next issue is whether third party licensed merchandise sold on the FANATICS websites that are not FANATICS branded goods, such as jerseys for a football team manufactured by Nike or Adidas, are being sold by reference to the FANATICS Marks. Namely, whether use of a domain name can constitute trade mark use in relation to goods sold on that website.

202 For the reasons set out below, I consider the respondent’s sale of third party licensed merchandise to be a sale of goods by reference to the FANATICS Marks and to constitute use of FANATICS as a trade mark.

…

214 I consider that the use of FANATICS in the respondent’s domain name and on its website on the webpages displaying goods for sale constitutes use of the FANATICS Word Marks as a trade mark. However, the question remains as to whether these uses are simply use in respect of online retail services, as the respondent contends, and whether that is a different use to use in respect of the goods depicted on the website.

….

220 The respondent invites consumers to visit its website at www.fanatics.com. At that website, goods are available for purchase under the name FANATICS as part of the domain name, displayed in page headings and in references to products. I consider that this constitutes use of the FANATICS Marks as trade marks in relation to the goods for which the applicant’s FanFirm Marks are registered, including clothing, sportswear and headgear.

(Emphasis added)

50 Fanatics contends on appeal that the primary judge erred in reaching this conclusion, which we address below as the “website issue”.

51 The primary judge next relevantly considered whether the uses by Fanatics of the impugned signs amounted to use in relation to goods or services of the same description as or closely related to those in respect of which the FanFirm Word Mark is registered. In relation to services, the primary judge found that the services that Fanatics offers under the FANATICS MVP sign are not services of the “same description” as the services that FanFirm’s Marks are registered for, and are also not “closely related” to any of the goods FanFirm’s marks are registered for ([257], [264]). While her Honour found that the services provided under Fanatics’ FANATICS LIVE mark fell within FanFirm’s registration for class 38, she noted her earlier finding that neither FANATICS MVP nor FANATICS LIVE is deceptively similar to the FanFirm Word Mark, and hence it followed that there was no infringement by those marks ([271]–[272]). These findings are not the subject of appeal.

52 However, Fanatics takes issue with the findings of the primary judge in relation to goods of the same description at [242]–[256]. There was no dispute before the primary judge that clothing, headgear, sportswear, scarves, flags and footwear as promoted and sold by Fanatics fell within the goods in respect of which the FanFirm Marks were registered ([243]). However, the parties disagreed as to whether or not umbrellas, sports bags, water bottles, towels and blankets fell within the scope of the registration.

53 The primary judge cited the decisions in Goodman Fielder Pte Ltd v Conga Foods Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1808; (2020) 158 IPR 9 at [277]–[286] (Burley J) and McCormick & Co Inc v McCormick [2000] FCA 1335; (2000) 51 IPR 102 (Kenny J) at [18] and concluded that blankets, throws and towels are goods of the same description as “woven and non-woven textile fabrics; textile material; textiles made of linen, cotton, silk, satin, flannel, synthetic materials, velvet or wool; cloth” (being part of the class 24 registration) ([245]) and that sports bags and water bottles are goods of the same description as “sportswear” (being part of the class 25 registration) ([251]–[253]). Fanatics challenges these findings on appeal, which we address below as the “goods of the same description issue”.

2.3 The information label issue

2.3.1 The relevant law concerning use as a trade mark

54 Section 17 of the Trade Marks Act provides that a trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.

55 Subsection 7(4) provides that “use of a trade mark in relation to goods” means “use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods (including second-hand goods)”.

56 The word “sign” is defined in s 6 of the Trade Marks Act as follows:

sign includes the following or any combination of the following, namely, any letter, word, name, signature, numeral, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, aspect of packaging, shape, colour, sound or scent.

57 The authorities establish that context is all-important. Not every use of a sign that is identical with or deceptively similar to a registered trade mark will infringe within s 120 of the Trade Marks Act. In The Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; (1963) 109 CLR 407, Kitto J (Dixon CJ, Taylor and Owen JJ agreeing) noted at 425 that the question becomes whether, in the setting in which the particular pictures referred to were presented, they would have appeared to the viewer as:

… possessing the character of devices, or brands, which the appellant was using or proposing to use in relation to petrol for the purpose of indicating, or so as to indicate, a connexion in the course of trade between the petrol and the appellant.

58 That statement has been followed on many occasions. The test has also been framed as a question of whether or not the use in question has been use as a “badge of origin”: E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd [2010] HCA 15; (2010) 241 CLR 144 at [43]; Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721; (1999) 96 FCR 107 at [19]; Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 876; (2000) 100 FCR 90 at 103 [15]–[16] per Burchett J (Hill and Branson JJ agreeing); RB (Hygiene Home) Australia Pty Ltd v Henkel Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 10; (2024) 302 FCR 285 at [53]. As we have noted above, the primary judge set out considerations relevant to the question as most recently formulated by the High Court in Self Care.

2.3.2 The submissions

59 Fanatics contends that the primary judge erred in finding that reference to the name “Fanatics”, on care labels, packaging barcode labels, stickers on swing tags and postage packaging relating to third party licensed merchandise, whether alone or with other words such as a corporate name, was use in a trade mark sense. It submits that such information labels could not function as a trade mark because they could not be seen in the course of trade, all of them being visible only after an online order had been placed and delivery made. It submits that the primary judge failed to make an objective and contextual assessment of the use made and exemplifies the error by reference to the care labels sewn into the inner seam of garments, the barcode stickers and stickers applied to packaging materials. Taking the Hawthorn Football Club Shirt as an example (at [192]), Fanatics submits that a reasonable consumer would regard Hawthorn (Hawks) or the AFL as the brands indicating the trade source of the product and that the reference to Fanatics would not be perceived to be used as a badge of origin.

60 FanFirm defends the approach of the primary judge. It submits that the nature and purpose of the word “Fanatics” on the information labels is to identify or connote the source of the goods and that not only what precedes the customer’s receipt of the clothing, but also the receipt of the labels themselves, is important. It submits that when proper regard is had to the context it is plain that the examples relied upon by Fanatics were being used to indicate a connection between the goods and the user of the mark.

2.3.3 Consideration

61 The contention advanced on appeal is that the primary judge erred in finding that the use of the word “Fanatics” on swing tags, barcodes and packaging labels amounted to trade mark use. As a preliminary point we note that although there may be some ambiguity in her Honour’s reasons in this regard at [220], FanFirm does not dispute that the primary judge’s findings, and the declaratory and injunctive relief ordered, encompass each such uses where the word “Fanatics” appears independently of other uses in relation to the goods in question (that is, each use of “Fanatics” on the swing tags, barcodes, care and packaging labels is an independent instance of trade mark use).

62 The distinction between use of a sign in relation to goods and use of a sign as a trade mark is not always easy to apply. Whether a sign has been used in a relevant trade mark sense is to be assessed objectively by reference to the context in which it is used in the relevant trade. Paraphrasing the passage from Shell Co at 425, the question becomes whether, in the setting in which the particular words referred to were presented, they would have appeared to the consumer as possessing the character of devices, or brands, which Fanatics was using in relation to the goods in respect of which the FanFirm Marks were registered, or so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between those goods and Fanatics.

63 Fanatics first submits that the primary judge erred by taking into account the appearance of the goods after they had been purchased online and had been delivered. By that time, it submits, the course of trade had been completed and an acquisition had been made. FanFirm submits that in the online context a collection of goods are offered for sale on the website and the consumer can select them and make a purchase, and the first time that the consumer sees the particular goods is when they are delivered. Only then does the purchaser receive the packaging and is able to handle the goods, thereby revealing (for the first time), the swing tag, the bar codes and the care labels. It submits that in online retailing, returns are provided, and were offered on the website under consideration, and until a return period expires the goods remain in the course of trade.

64 In Gallo the question of where the course of trade may be said to start and when it stops was considered. The High Court at [46] approved the following reasoning of Windeyer J in Estex Clothing Manufacturers Pty Ltd v Ellis and Goldstein Ltd [1967] HCA 51; (1967) 116 CLR 254 at 266–267:

[W]hen it is said that a trade mark is used to distinguish the goods of one man from those of another, that abbreviated statement obviously does not refer to the goods of the owner of the mark in the sense of goods which he owns or possesses. After the goods have been sold by him his mark may still, using the definition of trade mark in the Act, be used in relation to those goods for the purpose of indicating a connexion in the course of trade between them and him, the registered proprietor of the mark. The manufacturer who sells goods, marked with his mark, to a warehouseman, wholesaler or retailer does not, in my view, thereupon cease to use the mark in respect of those goods. The mark is his property although the goods are not; and the mark is being used by him so long as the goods are in the course of trade and it is indicative of their origin, that is as his products. Goods remain in the course of trade so long as they are upon a market for sale. Only when they are bought for consumption do they cease to be in the course of trade.

65 The High Court in Gallo went on to dismiss the notion that either Windeyer J or the Full Court of the High Court upholding the decision on appeal meant that the trade mark owner in such a circumstance must knowingly project its trade mark into other markets (at [48]–[49], [51]). It is apparent from the final sentences of this passage that, regardless of intermediate transfers from wholesale to warehouse to retail, once goods are bought for consumption, they cease to be in the course of trade. Put another way, from that point they cease to perform the task of distinguishing the goods of the registered owner from the goods of others. That is because upon the completion of a retail sale, the goods are no longer on the market.

66 FanFirm submits that goods remain in the course of trade where, in the online context, the consumer has an opportunity to return them after they are received. It cites Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co [1994] FCA 163; (1994) 49 FCR 89 as supporting the proposition that where goods are sold but subsequently re-enter the market as second hand goods, they are still in the course of trade. However, in our view this authority provides no analogous assistance to FanFirm. The Full Court (per Sheppard J, Wilcox J agreeing) found that when Wingate, who reconditioned LEVIS branded jeans and re-labelled them REVISE, put the REVISE branded jeans on the market, they did so to “put them back into the course or flow of trade” (at 104). The continuum of the course of trade having ceased at some point upon sale and consumption or use by the consumer and being revived later. That is not the present position. Nor do we consider that the circumstances of online sales are materially different to in-store physical sales such as to alter the analysis. The stimulus that leads a consumer to purchase an item online is the material presented to them on the relevant website promoting the sale. It is at that point that there will be trade mark use. The fact that after a sale the consumer may prefer to return the good once it is received and unwrapped cannot distract attention from the fact that the purchasing decision is made on the basis of the stimulus made available online.

67 The primary judge did not in her reasons explicitly consider the question of whether it was appropriate to have regard to post-sale materials. This was perhaps because, amongst the welter of issues raised by the parties, this issue did not receive top billing. However, contrary to the submission advanced by FanFirm, we do consider that the point was sufficiently made in oral submissions that the information label uses would not have reached a consumer until after the transaction was completed and that accordingly they did not amount to a trade mark use.

68 This finding is sufficient to allow the appeal in relation to the information labels.

69 However, Fanatics makes the further submission that, even if one were to take into account the goods that were delivered after an online purchase was complete, each of the uses of the word “Fanatics” on the care labels, packaging and swing tags alone would be insufficient to amount to trade mark use. We agree.

70 In our respectful view, the primary judge erred in her evaluation that the packaging labels or care labels would be regarded objectively by a reasonable consumer as involving use of the word “Fanatics” as a trade mark.

71 We take first as an example the Hoodie. Fanatics provided during the course of argument photographs of exhibit A2 which include the uses of “Fanatics” on the care label, and on the packaging (as the return sender) in which the parcel arrived. The care label is partially depicted below. It is located on an inside seam and consists of three separate tags or pages, stitched together into the seam. The tags bear dense writing in multiple languages providing care instructions. A number of different names are mentioned on the fifth and sixth pages as depicted in the right hand image below. The Hoodie otherwise has on its collar an NFL emblem and a swing tag with the same emblem and a reference to “NFL.com”. The front of the Hoodie bears the name of the Kansas City Chiefs.

72 In our view the obscurely placed care label that bears reference to the words: “DE: Fanatics (Germany) GMBH”, “JP: Fanatics Japan G.K.” and “GB: Fanatics International” would not, in the context of a garment not otherwise bearing the word “Fanatics”, be regarded by a consumer as being a use of that word as a trade mark. In this regard the position is analogous to that in Seiko Epson Corporation v Calidad Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1403; (2017) 133 IPR 1 (Burley J) at [327].

73 An example of the packaging, also depicted in photographs of exhibit A2 and provided during argument on appeal is as follows:

74 In our view, the reference to “Fanatics” as providing the return to sender address on the packaging would not be regarded by a consumer as use of the word as a trade mark in relation to the contents of the packaging. It is not a use as a trade mark having regard to when the consumer would see it (after sale and shipping) or how they would see it (on the exterior of a grey plastic package).

75 Finally, the swing tag appearing on the Hawthorn Football Club Shirt is depicted in section 2.2 above. The collar of the shirt bears the logo of the AFL as does the swing tag, which also contains the word “ashtabula” and a corporate name. Beneath these, a sticker has been added to the swing tag bearing the words “Fanatics Button-Up Shirt”. We recognise, as her Honour did at [196], that the use of a word may have more than one purpose and that a product may have more than one trade mark on it: Anheuser-Busch v Budejovicky Budvar [2002] FCA 390; (2002) 56 IPR 182 at [189]. However, having regard to its size, position and the fact that it is placed on a sticker just on the swing tag, in our view a consumer would be more likely than not to consider that this is a Hawthorn Hawks shirt made with the approval of the AFL by Ashtabula of a style known as a “Fanatics Button-Up Shirt” (that is, using the word “Fanatics” descriptively to refer to the style of shirt as being for dedicated followers). We do not consider that the small sticker appearing on the swing tag would be perceived by the consumer as a trade mark used on or in relation to the shirt.

2.4 The website issue

2.4.1 The submissions

76 Fanatics submits that the primary judge erred in finding that the use of the FANATICS Marks as branding for its websites constituted use in relation to the merchandise retailed on those sites. It submits that the primary judge failed to consider the context of the use of the word on the website which, from a consumer’s perspective, indicates that the branding was of use not in relation to goods but as an online retail service, citing Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 130; (2011) 197 FCR 67. It submits that objectively considered, an online retailer does not present to the consumer as the manufacturer of the products but as the retailer from which the products can be purchased, even though the use on the website displays not only the retailer’s trade mark but also trade marks of the products offered for sale. It submits that where a consumer views the site, unless the goods themselves bear the retailer’s trade mark, the use will not be in relation to goods but to online retail services.

77 FanFirm defends the reasoning of the primary judge and distinguishes Optical 88. It submits that in the present case there is a range of goods promoted for sale on the Fanatics websites which is all under the Fanatics brand, including “Fanatics Branded” goods, and the FANATICS Marks are applied to all of these goods by way of the branding on the website. Accordingly, there is no clear line between use in relation to online retail services and use in relation to goods and it was open to the primary judge to find that an online retail service selling goods is nothing more than the sale of goods via a website (at [158], [431]).

2.4.2 Consideration

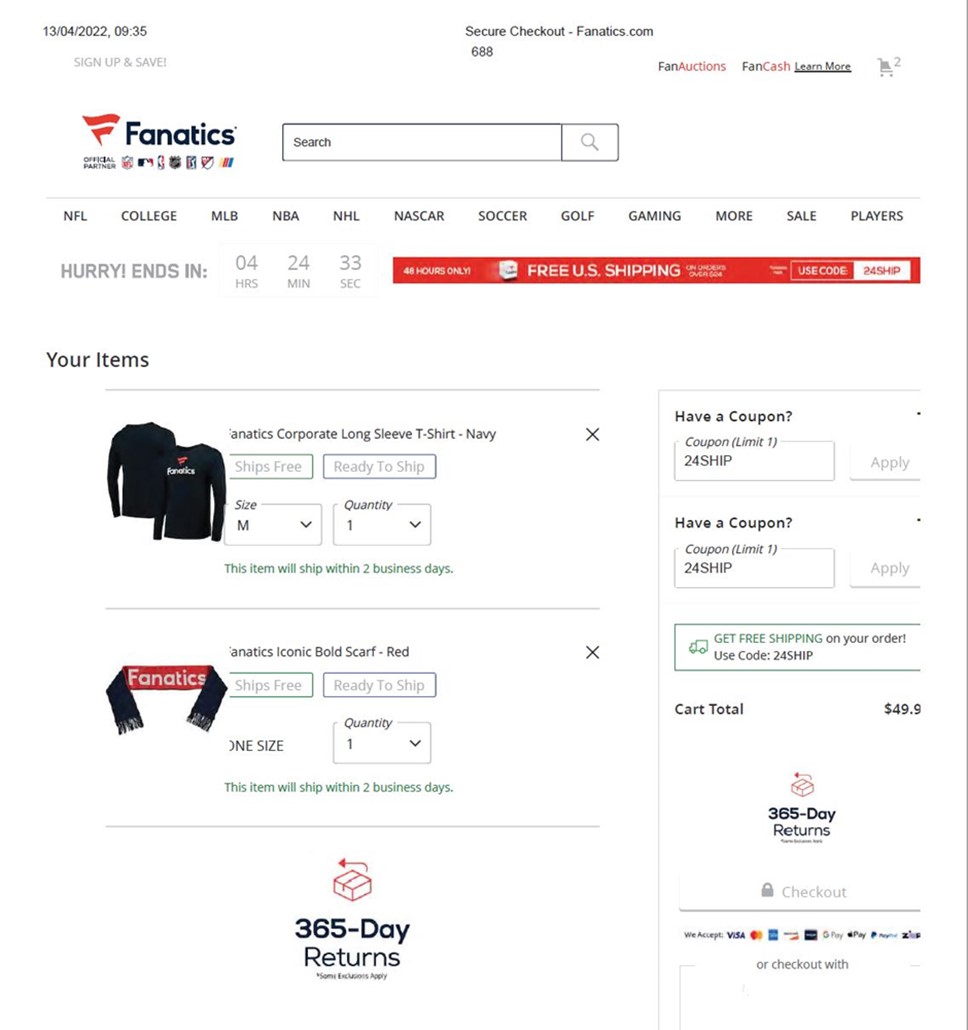

78 The case advanced before the primary judge was that by reason of its use of the word “Fanatics” in its web address and also in various forms on the website operated by Fanatics from time to time, Fanatics had engaged in conduct in breach of s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act, which requires that the infringing trade mark be used “in relation to goods or services in respect of which the [allegedly infringed] trade mark is registered” ([174], [201]). The FanFirm Marks were not registered in respect of online retail services. Accordingly, the question considered by the primary judge was whether Fanatics’ use of the word “Fanatics” as part of its website address and in various forms on the website was use in relation to goods advertised and sold, or whether it was use only in respect of retail services. The question of whether the particular goods sold on the website fell within the classes of goods in respect of which the FanFirm Word Mark was registered was considered separately (at [242]–[256]).

79 There is no dispute that the use of a domain name or uniform resource locator, either alone or together with language used on a website, may amount to trade mark use either for goods or services, depending on the content of the website in question and the likely perception of consumers. In that sense, the analysis is technology neutral, and the same considerations identified in Shell Co (which were articulated in the context of the then novel use (in 1961) of moving images in advertising) to which we have referred in section 2.3.1 above will apply; see Sports Warehouse, Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 664; (2010) 186 FCR 519 at [146]; Solahart Industries Pty Ltd v Solar Shop Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 700; (2011) 281 ALR 544 at [50]; Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 235; (2016) 118 IPR 239 at [58]–[62].

80 It was not in dispute before the primary judge that the use by Fanatics of the word “Fanatics” on its website in various forms amounted to trade mark use, at least in relation to online retail services, by reason of a combination of its use in the web addresses and also the use of the word on the website itself. Although the primary judge characterised the question before her as being whether use of a domain name per se can constitute trade mark use in relation to goods sold on that website (at [201]), after answering that theoretical question in the affirmative, the primary judge went on to consider whether or not the Fanatics website should be characterised as involving use of the word “Fanatics” on or in relation to goods depicted on the website, as FanFirm contended, or whether it was limited to use in respect only of online retail services, as Fanatics contended (at [214]).

81 The primary judge made a general finding that FanFirm had established its case that Fanatics had used the word “Fanatics” in relation to goods as well as online retail services at [220].

82 On appeal, Fanatics challenges the generality of that finding. It accepts that there are parts of the website that involve use of the word “FANATICS” as a trade mark in respect of its own corporate branding (within the first category of trade mark use found by the primary judge at [180]–[186]) and that a finding that this constitutes use of the FANATICS Marks in respect of clothing is apposite. However, it challenges the balance of the finding at [220], namely that “goods are available for purchase under the name FANATICS as part of the domain name, displayed in page headings and in reference to products” where the goods promoted are not branded with the word “Fanatics”, but which bear other marks such as Adidas or Nike.

83 The dispute may be understood by reference to several of the many web page screenshots in evidence. Three are included within the judgment at [185] and are reproduced in section 2.2 above. These are located on the www.fanatics.com website.

84 As the primary judge explains at [185], a navigation bar above the product listing on the webpage includes references to “FANATICS CORPORATE GEAR”, “FANATICS CORPORATE” and “FANATICS CORPORATE ACCESSORIES”. Using the menu, Mr Cockerton had selected “Fanatics Corporate Gear”, then “Fanatics Corporate”. The navy t-shirt pictured in [185] of the primary judgment was located under “Fanatics Corporate T-shirts” and the scarf under “Fanatics Corporate Accessories”. The primary judge found that these uses on and in relation to the Fanatics “Corporate Goods” amounted to trade mark use in relation to clothing, including sports apparel, within the scope of the goods in respect of which the FanFirm Marks are registered ([186]). As we have noted, although included within its grounds of appeal, in oral submissions Fanatics made clear that no challenge is made to that finding.

85 However, numerous other items of clothing are promoted for sale on the Fanatics website beyond the Corporate Goods, and the central submission advanced by Fanatics in this aspect of the appeal is that the primary judge erred in failing to explain how a use in relation to an online retail service for the sale of goods is use in relation to goods. We were taken to a number of web pages during the course of argument, but the point advanced by Fanatics may be made having regard to the following.

86 An example of a Fanatics landing page in May 2014 is below:

87 It will be seen that multiple products are promoted, with drop down menus displaying more options.

88 In April 2020 one page of the website was as follows (the top part of the page is depicted on the left):

|

|

89 It may be seen that the FANATICS Flag Mark appears on the top left of the page. The goods displayed bear no visible Fanatics trade marks but do display other trade marks, including a prominent Adidas logo and the names of sporting teams and sponsors. At the conclusion of the page are the words “MLS Shop: MLS Apparel and Gear from Fanatics” with the words:

Keep up with the exciting chase to for the MLS Cup this season by browsing the MLS Shop at Fanatics.com. Regardless of which MLS team you call your own, you’ll find the MLS Apparel and Gear you need to support your club 2019 MLS Jerseys in adidas styles for every club and player, like a MLS home jersey or away kit. Find all the top sellers of MLS Gear for clubs like the New York Red Bulls, Portland Timbers and Philadelphia Union. Fans can also find jerseys for their favorite players, including top stars like Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Carlos Vela or any other MLS player. Fanatics is your best match for top-rate customer service and free shipping options on officially licensed MLS Gear for your favorite club, so snatch up the best sellers and head to the pitch in team spirit.

90 Beneath these words are three columns, the third including the heading “Information” and a click-through menu for a list of items, including “FanCash Rewards” and “Fanatics Presents”. Next to this column is a trade mark for ticketmaster and the FANATICS Flag Mark.

91 This page, considered as a whole, would appear to the consumer to be promoting the sale, via the website, of goods that are not Fanatics products, but rather are shirts and other third party branded apparel offered for retail sale at a Fanatics website. That impression is confirmed by the heading “MLS Shop” and reinforced by the language in the paragraph that follows, which advises that “adidas styles” are available – drawing attention to goods not manufactured by or with the involvement of Fanatics.

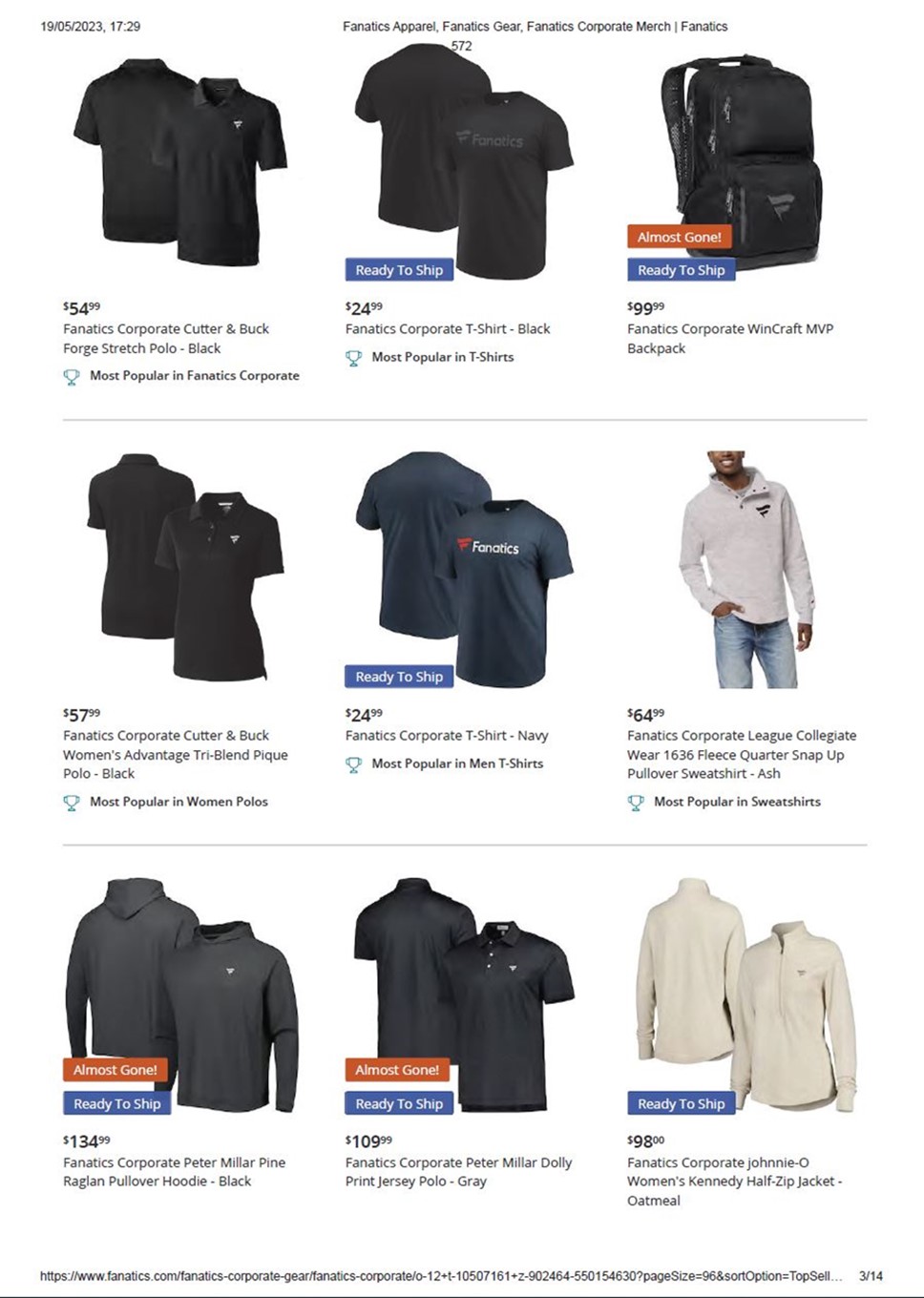

92 We note that there are, or at some point were, products offered on the Fanatics websites which were described as “Fanatics Branded”, which are not the Corporate Goods. In September 2023, one page of the www.fanatics.com website was as follows (which has been cropped to show the relevant goods):

|

93 It may be seen that the FANATICS Flag Mark appears on the top left of the page, and three category headings are shown above the displayed goods, being “Evander Holyfield”, “Golden Boy Promotions”, and “Mike Tyson”. Five goods are displayed, including two shirts. What appears to be the product name is displayed beneath each shirt, being “Golden Boy Promotions Fanatics Branded T-Shirt – Navy” and “Golden Boy Promotions Fanatics Branded Women’s V-Neck T-Shirt – Navy” respectively. The front of each shirt contains a ‘Golden Boy’ logo, and they do not have any visible Fanatics branding.

94 On the left-hand side of the page, there is a column listing categories by which the products may be sorted. This includes a category named ‘Featured Brands’, below which are ‘Fanatics Authentic’ and ‘Fanatics Branded’.

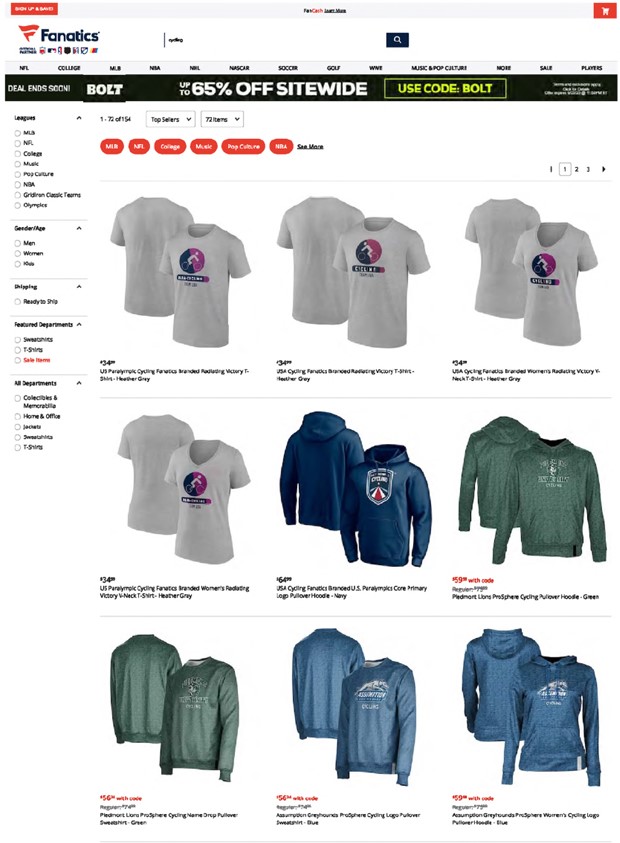

95 Also in September 2023, one page of the www.fanatics.com website, appearing to be the search results for the term ‘cycling’ on the website, was as follows (again, cropped to show the relevant goods):

96 The first five goods appearing in the search are shirts and a hoodie, each bearing the words ‘CYCLING’ or ‘PARA-CYCLING’ and ‘TEAM USA’, accompanied by an image of a cyclist or para-cyclist (with the exception of the hoodie, which bears no image). Once again, the product name is displayed beneath each good and includes the phrase ‘Fanatics Branded’. For example, the first shirt is named “US Paralympic Cycling Fanatics Branded Radiating Victory T-Shirt – Heather Gray”.

97 Other than these first five products, the remaining goods displayed on the search page bear third-party brands both on the product and in the product name, and their product names do not include the words “Fanatics Branded”. For example, the sixth good appearing is a hoodie named ‘Piedmont Lions ProSphere Cycling Pullover Hoodie – Green”, which bears the Piedmont University logo on its front.

98 FanFirm submits that, in relation to goods such as those extracted above at [92] and [95], even though the Fanatics brand does not appear on the goods they are described as “Fanatics Branded”. FanFirm argues that there is an intermingling of these “Fanatics Branded” goods with other clearly third-party branded goods (such as those extracted above at [88]) offered on the Fanatics website.

99 We note that these “Fanatics Branded” goods do not fall in the same category as the Fanatics branded Corporate Goods, as unlike the Corporate Goods the “Fanatics Branded” goods do not visibly bear the word “Fanatics”. Rather, the words “Fanatics Branded” are used solely in the name of the product and in some instances their categorisation on the website.

100 Fanatics appeared (during argument) to accept that where it has told the consumer a good is “Fanatics Branded” on the website by way of the product name and category, that good is indeed a product of Fanatics. Fanatics argues that this establishes that the remaining goods, such as the shirts set out above at [88], are not being offered by reference to the Fanatics brand.

101 We have set out in section 2.2 above [201], [202], [214] and [220] of the primary judge’s reasons. For convenience, we repeat [220]:

The respondent invites consumers to visit its website at www.fanatics.com. At that website, goods are available for purchase under the name FANATICS as part of the domain name, displayed in page headings and in references to products. I consider that this constitutes use of the FANATICS Marks as trade marks in relation to the goods for which the applicant’s FanFirm Marks are registered, including clothing, sportswear and headgear.

(Emphasis added)

102 The difficulty with this passage is that it does not differentiate the types of use in contemplation. As we have explained, the primary judge found that the goods promoted online characterised as the Corporate Goods which included the FANATICS Marks on them infringed. In the third category (see [46] above) her Honour was considering third party licensed merchandise, being goods that were not visibly branded with the word “FANATICS”.

103 The evidence that we have surveyed above indicates that within this category are two sub-categories. The first, and vastly larger sub-category, is goods branded by third parties’ trade marks that are merely sold via the appellant’s online store. The second, much smaller sub-category, is of goods branded by third parties’ trade marks which are referred to on the website as “Fanatics Branded” goods. There is no dispute on appeal that use in the latter sub-category is infringing use. However, the appellant challenges any finding of the primary judge that may be suggested in the reasoning at [220] or the form of injunction granted that the first sub-category amounts to a trade mark use within the scope of the respondent’s trade mark registrations. That suggestion finds traction in [430] of the primary judgment. In the different context of s 122(1)(e), the primary judge considered whether FanFirm can defend an allegation of infringement of the FANATICS Word Marks in class 35 by its use of that mark in relation to “clothing” in class 25. Her Honour said at [430]–[431]:

… I see no difference between selling goods by displaying them for sale, and taking orders and payment on a website, and online retail services involving the online sale of sports merchandise.

Accordingly, I consider that the applicant’s registration of the FanFirm Word Mark in class 25 in respect of goods, including sports merchandise, includes the sale of goods online by reference to that mark.

104 For the reasons set out below, to the extent that the primary judge found that the use of the FANATICS Marks in the domain name, on the heading of the webpages and otherwise on the website to promote the retail sale of items on the website was infringing use, we consider that her Honour erred. In our view, such use did not amount to trade mark use in respect of the goods for which the FanFirm Marks were registered.

105 Sections 7(4) and (5) of the Trade Marks Act provide:

(4) In this Act:

use of a trade mark in relation to goods means use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods (including second-hand goods).

(5) In this Act:

use of a trade mark in relation to services means use of the trade mark in physical or other relation to the services.

106 Section 9 of the Trade Marks Act provides:

(1) For the purposes of this Act:

(a) a trade mark is taken to be applied to any goods, material or thing if it is woven in, impressed on, worked into, or affixed or annexed to, the goods, material or thing; and

(b) a trade mark is taken to be applied in relation to goods or services:

(i) if it is applied to any covering, document, label, reel or thing in or with which the goods are, or are intended to be, dealt with or provided in the course of trade; or

(ii) if it is used in a manner likely to lead persons to believe that it refers to, describes or designates the goods or services; and

(c) a trade mark is taken also to be applied in relation to goods or services if it is used:

(i) on a signboard or in an advertisement (including a televised advertisement); or

(ii) in an invoice, wine list, catalogue, business letter, business paper, price list or other commercial document;

and goods are delivered, or services provided (as the case may be) to a person following a request or order made by referring to the trade mark as so used.

(2) In subparagraph (1)(b)(i):

covering includes packaging, frame, wrapper, container, stopper, lid or cap.

label includes a band or ticket.

107 The question of whether or not an impugned use of a sign amounts to use in relation to the goods or services in respect of which a trade mark is registered is a question of mixed fact and law, having regard to the particular circumstances of the case; Optical 88 at [21]. The fact that there has been use of a trade mark in relation to retail services for goods does not automatically mean that there will be use of the same mark in relation to goods; Optical 88 at [10], [21]. Although FanFirm sought in its submissions to distinguish Optical 88 on its facts, the legal proposition to which we have referred was not, as we understand it, challenged. It is, in our respectful view, plainly correct.

108 In each case it will be a question of consideration of the statutory test in the context of the goods and services in respect of which the asserted trade mark is considered. In this respect, this court is in a position on appeal to evaluate whether or not the use of FANATICS Marks on the Fanatics website, including in the domain name and in page headings, constituted use in relation to the goods which displayed no visible Fanatics branding (such as the examples described above at [86]–[97]).

109 The evidence indicates that the Fanatics websites aggregate and sell an extensive range of third party branded products. It is true that, as her Honour found at [220], Fanatics invites consumers to visit its website and acquire goods for purchase. But that invitation is to acquire a large range of apparel much of which has no Fanatics branding on it.

110 Many of the products, like the shirts set out above at [88], are plainly branded with other prominent brands including Adidas and Nike. We do not consider that a consumer is likely to perceive that the use of Fanatics branding on the website extends beyond branding relevant to the online retail sale of clothing in relation to these products.

111 Some of the products, like those set out above at [92] and [95], have no Fanatics branding on them but are named and categorised as “Fanatics Branded” on the websites. Fanatics appears to have accepted in oral submissions, and we agree, that the naming of the goods using the words “Fanatics Branded” (even if the goods themselves bear no Fanatics branding) constitutes trade mark use in relation to those products.

112 However, unless the consumer’s attention is specifically drawn to the particular products that are either the “Fanatics Branded” goods or the Corporate Goods, we do not consider that a consumer is likely to perceive that the general use of Fanatics branding on the website extends beyond branding relevant to the online retail sale of clothing. With the exception of those goods – which Fanatics accepts amounts to a use of the mark in respect of clothing – we find that Fanatics succeeds on this ground.

2.5 The goods of the same description issue

2.5.1 The submissions