Federal Court of Australia

Levitt v Luke in his capacity as the co-executor of the estate of Luke (Deceased) [2025] FCAFC 79

Appeal from: | Luke v Aveo Group Limited (No 3) [2023] FCA 1665 |

File number: | VID 59 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | MOSHINSKY, BUTTON and SHARIFF JJ |

Date of judgment: | 12 June 2025 |

Catchwords: | REPRESENTATIVE PROCEEDING – appeal from a decision approving a settlement under s 33V of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) – where primary judge disallowed a portion of claimed legal fees on basis that solicitor for the lead applicants failed to act with due expedition in preparation and filing of expert evidence and that matter would have settled earlier at a mediation – no error in primary judge’s finding that there were inadequate explanations for the delay in the preparation and finalisation of expert evidence – primary judge erred in finding that the matter would likely have settled at mediation had solicitor acted with due expedition – no reason to disturb orders made by the primary judge on a re-exercise of discretion under s 33V – appeal dismissed |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Sch 2 (Australian Consumer Law) ss 18, 21, 236, 237 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 33V, 33V(1), 33V(2), 37M, 37M(1), 37N, 37N(2) |

Cases cited: | Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; (2018) 261 FCR 301 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Chats House Investments Pty Limited (1996) 71 FCR 250 Barnes v Addy (1874) LR 9 Ch App 244 Bellamy’s Australia Ltd v Basil [2019] FCAFC 147 Blairgowrie Trading Ltd v Allco Finance Group Ltd (Receivers & Managers Appointed) (in liq) (No 3) [2017] FCA 330 Camilleri v Trust Company (Nominees) Ltd [2015] FCA 1468 Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; (2003) 214 CLR 118 Gill v Ethicon Sàrl (No 11) [2023] FCA 229 House v R [1936] HCA 40; (1936) 55 CLR 499 Impiombato v BHP Group Ltd [2025] FCAFC 9 Lendlease Corporation Limited v Pallas [2025] HCA 19 Luke v Aveo Group Limited (No 3) [2023] FCA 1665 Matthews v Ausnet Electricity Services Pty Ltd [2014] VSC 663 McDonald v Commonwealth of Australia [2025] FCA 380 Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZVFW [2018] HCA 30; (2018) 264 CLR 541 Modtech Engineering Pty Ltd v GPT Management Holdings Ltd [2013] FCA 626 Parkin v Boral Ltd [2022] FCAFC 47; (2022) 291 FCR 116 Petersen Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd v Bank of Queensland Ltd (No 3) [2018] FCA 1842; (2018) 132 ACSR 258 Redfern v Mineral Engineers Pty Ltd [1987] VR 518 Warren v Coombes [1979] HCA 9; (1979) 142 CLR 531 Wheelahan v City of Casey [2011] VSC 215 Williams v FAI Home Security Pty Ltd (No 4) [2000] FCA 1925; (2000) 180 ALR 459 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Commercial Contracts, Banking, Finance and Insurance |

Number of paragraphs: | 144 |

Date of hearing: | 22 April 2025 |

Counsel for the Appellant | Mr PD Herzfeld SC with Mr SD Puttick |

Solicitor for the Appellant | Levitt Robinson Solicitors |

Counsel for the Fifth Respondent | Mr BA McLachlan |

Solicitor for the Fifth Respondent | Arnold Bloch Leibler |

Contradictors | Mr LWL Armstrong KC with Mr TA Rawlinson |

ORDERS

VID 59 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | STEWART LEVITT TRADING AS LEVITT ROBINSON SOLICITORS Appellant | |

AND: | MICHAEL ROBERT LUKE (IN HIS CAPACITY AS THE CO-EXECUTOR OF THE ESTATE OF ROBERT COLIN LUKE, DECEASED) First Respondent MEREDITH ANNE LUKE (IN HER CAPACITY AS THE CO-EXECUTOR OF THE ESTATE OF ROBERT COLIN LUKE, DECEASED) Second Respondent ANN MARY STROUD (IN HER CAPACITY AS THE CO-EXECUTOR OF THE ESTATE OF JOAN MARY COLOMBARI, DECEASED) (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | MOSHINSKY, BUTTON AND SHARIFF JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 12 June 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. There be no order as to costs.

3. Pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), on the ground in s 37AG(1)(a), the publication of the redacted parts of [115]–[116] are suppressed and not to be published or disclosed until 5.00pm on 12 June 2030 without prior leave of the Court to any person other than: (a) the Court; (b) the appellant; (c) the appellant’s legal representatives; (d) the first respondent; (e) the first respondent’s legal representatives; (f) the second respondent; (g) the second respondent’s legal representatives; (h) the third respondent; (i) the third respondent’s legal representatives; (j) the fourth respondent; (k) the fourth respondent’s legal representatives; (l) the fifth respondent; (m) the fifth respondent’s legal representatives; (n) group members who have provided an appropriate acknowledgement of their obligations under this order; (o) counsel appointed as Contradictor; (p) Galactic Aveo LLC; and (q) Galactic Aveo LLC’s legal representatives, with such permitted disclosures to be on terms that none of those persons or entities disclose the material or any part of it to any person or entity other than those listed in this order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 This appeal relates to the approval of the settlement of representative proceedings under s 33V of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the FCA Act) and, specifically, whether the primary judge erred by disallowing certain legal fees claimed by the legal practice that acted for the lead applicants.

2 The appellant, Mr Stewart Levitt trading as Levitt Robinson, acted in the proceedings below for the Luke Applicants and the Colombari Applicants (together referred to as the Lead Applicants). The Lead Applicants brought claims on their own behalf and on behalf of approximately 2,700 current and former owners of freehold or leasehold interests in units in retirement villages operated by the fifth respondent (Aveo), a major operator of retirement villages in Australia.

3 The proceedings settled after the conclusion of the sixth day of the trial. The settlement sum was $11 million inclusive of interest, legal fees and disbursements (for convenience referred to together as legal fees or fees) and settlement administration costs (Settlement Sum). As part of the approval, Levitt Robinson sought approval for the payment of an amount of $10,999,558 in respect of legal fees claimed up to the date of settlement and $251,450 in respect of the legal fees claimed in relation to the settlement approval. If the settlement had been approved on these terms, the result would have been that the group members would have received nothing from the Settlement Sum.

4 The approval of the settlement was not opposed by Aveo. The primary judge appointed a costs consultant, Ms Elizabeth Harris, as a referee to inquire into and report on the reasonableness of the legal fees that had been claimed by Levitt Robinson, and also appointed Mr Armstrong KC and Mr Loxley of Counsel as contradictors in respect of the approval of the proposed settlement (Contradictors).

5 The primary judge concluded that the amount of legal fees claimed by Levitt Robinson should be reduced by $1,334,864 on account of the difference between the fees claimed and those assessed by Ms Harris to be fair and reasonable (Disallowed Costs): Luke v Aveo Group Limited (No 3) [2023] FCA 1665 (the primary judgment or PJ) at [134], [153].

6 The primary judge also concluded that the legal fees claimed by Levitt Robinson should be further reduced by an amount of $1,141,078 on the basis that this amount represented legal fees claimed by Levitt Robinson that were avoidable (Avoidable Costs): PJ [153]. It is the primary judge’s findings and conclusions relating to Avoidable Costs which are the subject of the appeal. In concluding that the Avoidable Costs should not be allowed, the primary judge reasoned that:

(a) the case was unlikely to settle until the parties had the benefit of the competing expert evidence: PJ [137], [150];

(b) the appellant did not act with due expedition and was seriously inefficient between November 2021 and July 2022 when pre-trial timetables required the filing and service of the lead applicants’ expert evidence: PJ [144]–[145], [149];

(c) had the appellant acted with due expedition and efficiency, it is likely that both the applicants and Aveo would have filed and served their respective expert evidence prior to a mediation that was scheduled to be held in December 2022: PJ [14], [144];

(d) it is likely that the proceedings would have settled at that scheduled mediation in December 2022: PJ [150]; and

(e) the amount of $1.141 million in fees claimed from the end of 2021 to the trial (up to and including entry into the settlement deed) would have been avoided.

7 By leave to appeal granted by the Court on 23 May 2024, Levitt Robinson appeals from order 1(a) of the orders made by the primary judge on 22 December 2023. In its Notice of Appeal, Levitt Robinson contends that the primary judge erred by disallowing the Avoidable Costs by finding that:

(a) the appellant did not act with due expedition between November 2021 and July 2022 by failing to file and serve the applicants’ expert evidence (Ground 1); and

(b) it was likely that the case would have settled at the mediation scheduled to occur in December 2022 if the appellant had acted with due expedition (Ground 2).

8 For the purpose of the appeal, Mr Armstrong KC and Mr Rawlinson of Counsel were appointed as contradictors (with their costs borne by Levitt Robinson). For convenience, they are also referred to in these reasons as the “Contradictors”.

9 For the reasons that follow, Ground 2 should be upheld. However, in re-exercising the discretion under s 33V(2) of the FCA Act, we have concluded that the claimed fees should be reduced by the amount of $1,141,078 (being the same amount as determined by the primary judge), albeit for reasons that are in part different from those of the primary judge. Accordingly, the appeal is to be dismissed. In making orders dismissing the appeal, we will also make orders under s 37AF of the FCA Act that parts of these reasons at [115]–[116] that refer to the confidential opinions expressed by the Lead Applicants’ legal representatives, which have been suppressed by earlier orders made by the Court, be redacted, suppressed and not be published or disclosed for a period of five years without prior leave of the Court, other than to the parties and the Contradictors.

2. THE APPLICABLE STANDARD OF APPELLATE REVIEW

10 There was no dispute that a decision under s 33V(2) of the FCA Act to make “such orders as are just as to the distribution of money paid under a settlement” involves the exercise of discretion and is therefore subject to appellate review in accordance with the principles in House v R [1936] HCA 40; (1936) 55 CLR 499 at 504–5 (Dixon, Evatt and McTiernan JJ). However, Levitt Robinson submitted that its grounds of appeal involved challenges to findings of fact that were anterior to the exercise of the discretion, as opposed to the appeal involving a challenge to the exercise of that discretion. Specifically, it was submitted that the primary judge’s finding at PJ [149] that Levitt Robinson had not acted with due expedition and was seriously inefficient between November 2021 and July 2022 and the further finding at PJ [150] that it was likely that the proceedings would have settled in December 2022 were findings of fact that were governed by the correctness standard of appellate review: see Warren v Coombes [1979] HCA 9; (1979) 142 CLR 531 at 551-552 (Gibbs ACJ, Jacobs and Murphy JJ); Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZVFW [2018] HCA 30; (2018) 264 CLR 541 at [41] (Gageler J).

11 The Contradictors did not dispute that the appeal was to be conducted by way of rehearing in which the Court is required to determine whether the primary judge’s findings of fact involved error and that the Full Court was “in as good a position as the primary judge to make findings of fact on the evidence that was adduced at the hearing”: citing Impiombato v BHP Group Ltd [2025] FCAFC 9 at [193] (Beach and O’Bryan JJ). The Contradictors, however, submitted that it remained necessary for error to be established and that “mere disagreement” did not equate with error: citing Impiombato at [345] (Lee J). The Contradictors further relied upon Lee J’s judgment in Impiombato at [345] to contend that “some findings of fact … are based upon evidence aspects of which can sometimes point in different directions (and over which different tribunals of fact, acting rationally, can reach a different conclusion without recognisable error)”.

12 The differences between Levitt Robinson and the Contradictors as to the standard of appellate review to be applied were slight, and at the margins. They both agreed that the present appeal involves challenges to findings of fact that are governed by the principles set out in Warren v Coombes. Given that no witnesses gave oral testimony and no witnesses were cross-examined, the Full Court is in as good a position as the primary judge to make findings of fact on the evidence that was adduced at the hearing before the primary judge: Warren v Coombes at 552; Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; (2003) 214 CLR 118 at [25] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ); SZVFW at [41]; Impiombato at [193] (Beach and O’Bryan JJ). For such an appeal to be successful, a finding of error is indispensable, and a mere disagreement on a finding of fact is ordinarily insufficient: Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; (2018) 261 FCR 301 at [45] (Perram J, with whom Allsop CJ and Markovic J agreed).

13 In determining whether there has been an error of fact, the Court must engage in a “real review” of the evidence that was before the primary judge: Fox v Percy at [25]; SZVFW at [32]. As a result, it is necessary to consider the uncontested facts and the salient evidence in determining the grounds of appeal.

3. THE RELEVANT FACTS

3.1 An overview of the claims made in the proceedings

14 The proceedings were commenced in September 2017.

15 The Lead Applicants were persons who held freehold and leasehold interests in retirement villages operated and managed by Aveo. The subject matter of the proceedings related to the alleged impairment and diminution in the value of the freehold and leasehold interests held by the Lead Applicants and group members which were said to have been brought about by the introduction of the “Aveo Way Programme” (AWP) which Aveo began implementing in about 2014 and 2015. The Luke Applicants were representative of those persons who held freehold interests. The Colombari Applicants were representative of those who held leasehold interests.

16 By the time of the commencement of the trial on 16 March 2023, the relief sought by the Lead Applicants was set out in the Further Amended Originating Application dated 5 February 2021 (FAOA) and their case was pleaded in the Third Further Amended Statement of Claim filed on 3 November 2021 (3FASOC). As set out below, on the first day of the trial, the Lead Applicants pressed an application to further amend the FAOA and the 3FASOC, which was rejected.

17 The gravamen of the case pleaded in the 3FASOC was that prior to the introduction and implementation of the AWP, Aveo had sold to the Lead Applicants and group members their rights to occupy retirement village units upon certain contractual terms (referred to as “legacy contracts”), commonly as freehold but also leasehold interests with lower deferred management fees and the prospect of capital gains when disposing of those interests. It was claimed that by introducing and implementing the AWP, Aveo altered the terms on which incoming residents were to be offered units such that it impaired and diminished the value of the pre-AWP interests (referred to as pre- and post-AWPIs) held by the Lead Applicants and group members. It was alleged that the relevant changes had the effect of altering the quantum of deferred management and other fees, and diminished the expected or actual capital gain that an incoming resident could generate from the post-AWPIs. It was claimed that, as a result, incoming residents would pay less for the interests held by outgoing residents such that Aveo had engaged in conduct that devalued the economic interests held by the Lead Applicants and group members.

18 The causes of action pleaded in the 3FASOC were far from a model of clarity. Essentially, there were two broad causes of action pleaded as to unconscionability and misleading or deceptive conduct, together with accessorial liability claims. Broadly speaking, the claims made were that in introducing and implementing the AWP, Aveo had engaged in:

(a) unconscionable conduct within the meaning of s 21 of Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (Australian Consumer Law); and

(b) misleading or deceptive conduct contrary to s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law.

19 In respect of each of these claims, it was pleaded that Aveo was liable as a primary contravener of the relevant provisions of the Australian Consumer Law or, alternatively, was an accessory to contraventions engaged in by others including managers involved in the development and implementation of the AWP and a related entity known as Aveo Real Estate Pty Ltd (Aveo Real Estate).

20 There were various aspects of the operation and implementation of the AWP that were said to have been tantamount to unconscionable conduct or gave rise to an “unconscionable system”. One such aspect was the assertion that an element of the AWP required outgoing residents that held a freehold interest to appoint a real estate agent to sell that interest but without disclosing that the ensuing transaction would involve a sale of that freehold interest to Aveo itself in circumstances where Aveo would then convert that freehold interest into a leasehold interest granted to an incoming resident. It was claimed that a conflict of interest arose where the outgoing resident appointed Aveo Real Estate as their agent in circumstances where it was a wholly-owned subsidiary of Aveo and earned commissions for selling the outgoing resident’s freehold interest to its holding company, Aveo.

21 As further explained below, the Lead Applicants later submitted that this conduct gave rise to breaches of fiduciary duty by Aveo Real Estate and knowing involvement on the part of Aveo in those breaches. An application was made shortly before the commencement of the trial to amend the 3FASOC to plead a claim of knowing involvement as against Aveo. In order to place these later developments in context, it is convenient to observe that the case pleaded in the 3FASOC cast the alleged breaches of fiduciary duty as an element of the AWP that made it unconscionable. Relevantly, the 3FASOC at [174] pleaded the following:

174 The Aveo Way System had the following characteristics:

…

(l) ARE, and Aveo Way Managers that acted as real estate agent in relation to sal1es by System Group Members of Pre-AWls (which included the surrender of Pre-AWLIs [pre-Aveo Way Leasehold Interests] and the attendant entry into an AWI by an incoming resident), breached fiduciary duties owed to System Group Members, in that:

(i) where Pre-AWIs were to be sold or surrendered to the Respondent or to a Relevant Aveo Manager, rather than sold or assigned (or otherwise disposed of) on the open market, non-disclosure of that matter, and of the matters in paragraphs 20 to 20B, and the charging of commission involved the agent:

(A) preferring its own interests to its duty to the principal;

(B) wrongfully profiting from the agency relationship;

(ii) implementing the Aveo Way System required that the real estate agent procure the cost-equivalency required by the Mechanism (described in paragraph 168(b)(ii) above), whereas the real estate agent's duty to its principal was:

(A) to not allow its own interests, or the interests of a third party, to conflict with the interests of the owner of the Pre-AWI;

(B) to not prefer its own interests, or the interests of a third party, over the interests of the owner of the Pre-AWI;

(C) accordingly:

(1) to seek to procure the highest price for the Pre-AWI that was available; and

(2) not to withhold any information from the owner of the Pre-AWI that might influence or impact upon any decision by them to accept or reject any offer made to acquire their Pre-AWI, including the matters pleaded in paragraphs 17, 17B, 17C, 20A and 20B above;

(iii) in each of the cases pleaded in paragraph 174(l)(i) and (ii) above, the breach of fiduciary duty caused loss or damage to the relevant System Group Member.

Particulars

…

Loss or damage includes:

(A) the difference between the price in fact paid for the Pre-AWI, and the fair market value of the Pre-AWI, or the actual market value of the Pre-AWI; and

(B) the quantum of any commission payment to the real estate agent: and

(C) any fees or other costs incurred by reason of the prolongation of the period in which the Pre-AWI was sold as a resulted of the Aveo Way Programme.

(Underlining from the original.)

22 It was pleaded at [175] of the 3FASOC that the “Aveo Way System” was unconscionable within the meaning of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law by reason of a number of matters including those alleged in [174] (which included the paragraphs extracted above).

23 It will be apparent from the above that there was no standalone claim of breaches of fiduciary duty, or knowing involvement in them under one or other limb of Barnes v Addy (1874) LR 9 Ch App 244. Rather, the case pleaded was that the alleged breach of fiduciary duty by Aveo Real Estate was an element of the “unconscionable system” and that Aveo was thereby liable as a primary contravener or an accessory to a contravention of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law.

24 Based on the claims pleaded in the 3FASOC, the Lead Applicants claimed that they and group members were not able to sell as attractive a set of rights to incoming residents as the rights they had themselves originally purchased. As noted above, it was claimed that the value of the pre-AWPIs was therefore materially diminished and Aveo unconscionably took advantage of its bargaining power in order to shift the Lead Applicants and group members over to being required to sell their existing rights under the AWP. In respect of these matters, the FAOA sought orders for damages or compensation under ss 236 and 237 of the Australian Consumer Law. That claim included a claim for payment by way of compensation in respect of the commissions paid to real estate agents (as particularised at [174] of the 3FASOC).

3.2 An overview of the relevant procedural history of the proceedings

25 The proceedings were initially allocated to the docket of the primary judge.

26 As recorded at PJ [46], the “centrality of loss” being proved was obvious from early in the conduct of the proceedings. Aveo took the position from very early on in the proceedings that the question of loss should be determined as a separate question and before any other question raised in the proceedings.

27 On 30 July 2019, the primary judge referred the proceedings to a National Judicial Registrar of the Court to assist the parties in identifying and agreeing upon a separate question for determination: PJ [47]–[48].

28 Eventually, on 12 February 2021, Aveo filed an application for the determination of separate questions which broadly related to loss: PJ [49].

29 On 2 September 2021, the primary judge made orders dismissing Aveo’s application for determination of separate questions and listed the initial trial of the proceeding to commence on 1 March 2023 with an estimate of five weeks. This allowed for a period of 18 months for the parties to complete the remaining pre-trial steps. The applicants were required to provide Aveo with a proposed timetable for the further steps in the litigation by 16 September 2021. The orders provided for Aveo to respond to the proposed timetable by 30 September 2021, and for the parties to confer in an attempt to agree to the timetable by 7 October 2021.

30 On 11 October 2021, orders were made fixing a timetable for the completion of the core pre-trial steps (first pre-trial timetable). The first pre-trial timetable required the completion of a range of pre-trial steps between late 2021 and late 2022. This included the filing and service of a further amended pleading by the Lead Applicants (by 11 October 2021), points of claim for sample members (by 24 December 2021), points of defence (by 25 March 2022), as well as expert evidence in chief (by 29 July 2022) and reply (by 28 October and 25 November 2022). The orders also required the parties to confer and seek to agree on categories of discovery by 6 December 2021, failing which an application could be made by 1 April 2022 to be heard at an interlocutory hearing listed on 21 April 2022. Importantly, the first pre-trial timetable required a mediation to occur and to be conducted by no later than 16 December 2022.

31 In relation to the orders made relating to discovery, it should be observed that the parties had already given discovery during 2018 in accordance with orders made on 14 March 2018. That discovery was completed by 3 October 2018 and occurred at a time when no claims had been made in the proceedings in relation to residents who held leasehold interests. The Luke Applicants reviewed the documents produced under Aveo’s discovery and it led to them making amendments to the (then) pleadings to make claims on behalf of residents who held leasehold interests as represented by the Colombari Applicants.

32 There were multiple instances of non-compliance with the first pre-trial timetable. The Lead Applicants effected service of the 3FASOC on 14 October 2021 (which was three days late) and, on 1 November 2021, Aveo advised that it consented to the filing of the pleading in the form provided. Aveo then filed its defence to the 3FASOC on 26 November 2021. A period of five months then elapsed and, in early April 2022, the Lead Applicants eventually served Aveo with proposed points of claim in respect of four of five sample group members. This was almost four months out of time. The Lead Applicants then filed an interlocutory application on 14 April 2022, by which they sought discovery and variations to the first pre-trial timetable including for leave to be granted to file the points of claim.

33 At a hearing before the primary judge on 21 April 2022, there was a dispute between the parties as to the date by which Aveo was to give discovery. The primary judge made further orders which introduced further items to the pre-trial timetable and extended the time for compliance with certain existing orders (second pre-trial timetable). Amongst other things, the parties were granted approximately one additional month to complete and serve their expert evidence. The expert evidence in chief was now required to be filed on 19 August 2022 with Aveo’s expert evidence in response due by 18 November 2022, and any reply to that evidence due by 9 December 2022. As a result, the second pre-trial timetable contemplated that all expert evidence would be served prior to the time scheduled for mediation of 16 December 2022. The Lead Applicants were also granted an extension to serve the last of the sample group members’ points of claim.

34 The second pre-trial timetable also contained several orders governing the discovery process. The categories of discovery required to be produced by Aveo were set out in Annexure A to the orders. The Lead Applicants’ application for further discovery dated 14 April 2022 was listed for hearing on 2 June 2022.

35 In the period that followed, the proceedings were transferred to the docket of the trial judge (Anderson J) and his Honour listed the proceeding for a case management hearing on the same day as the interlocutory hearing relating to the Lead Applicant’s further discovery application, being 2 June 2022.

36 On 2 June 2022, the trial judge made further timetabling orders. By these orders, the Lead Applicants were granted leave to file the points of claim for all five sample group members that had been provided to Aveo throughout the course of April. Orders were also made to fix 24 June 2022 and 29 July 2022 as the respective dates by which Aveo was to file and serve its points of defence and to give discovery of a new category of discovery (Category 21). An order was also made appointing an amicus curiae to represent the interests of group members who had not entered into a litigation funding agreement. Importantly, there were no changes made to the orders requiring the Lead Applicants to file their expert evidence in chief by 19 August 2022.

37 On 9 June 2022, the Lead Applicants filed and served their points of claim in relation to four of the five sample group members. The points of claim for the final sample group member were then served on 14 June 2022. The delay was attributed to the need to correct minor errors.

38 On 24 June 2022, the parties were each due to give discovery in respect of the sample group members. Although the Lead Applicants and Aveo each discovered some documents by this deadline, they were ultimately late in discharging their obligations under the second pre-trial timetable. The solicitors for Aveo provided an incomplete tranche of documents and advised that they would provide a supplementary tranche within a week, which was then provided on 28 June 2022. Levitt Robinson likewise provided a supplementary tranche of documents on 28 June 2022 and supplied a further tranche on 1 July 2022.

39 On 4 July 2022, at the Lead Applicants’ request, the Court issued 29 subpoenas that were said to be directed to assisting the preparation of their expert evidence. Of the subpoenas, five were issued to external advisors of Aveo and 20 were issued to retirement villages that neighboured the retirement villages at which sample group members resided. The first return date of the subpoenas was 13 July 2022.

40 On 7 July 2022, Aveo filed its points of defence. This was two weeks late. Upon reviewing this document, Levitt Robinson identified a document that had been referred to but not discovered to the applicants. This was brought to Aveo’s attention by way of correspondence dated 19 July 2022 and resulted in further correspondence and disputation as to the completeness of Aveo’s discovery in respect of the sample group members. Ultimately, Aveo produced further documents and also provided a further tranche of documents which had been due for production by 29 July 2022.

41 On the expert evidence front, Levitt Robinson sent a letter dated 12 July 2022, acknowledging the 19 August 2022 deadline for the Lead Applicants’ expert evidence and stating that the preparation of that evidence was underway.

42 On 29 July 2022, Aveo was required to complete its discovery under the second pre-trial timetable and the further orders of the trial judge dated 2 June 2022 but informed the Lead Applicants that it would not complete discovery until 26 August 2022.

43 On 5 August 2024, Aveo completed discovery regarding the sample group members, including further discovery that was requested by Levitt Robinson, which was 42 days late. Aveo also produced tranches of documents that had been due on 29 July 2022 and which were produced seven days late.

44 On 8 August 2022, Aveo’s lawyers wrote to Levitt Robinson proposing an extension on the balance of discovery to 31 August 2022 and proposing that the service of the Lead Applicant’s expert evidence be extended to 9 September 2022.

45 On 9 August 2022, the application regarding the form of opt-out notice was heard by the trial judge.

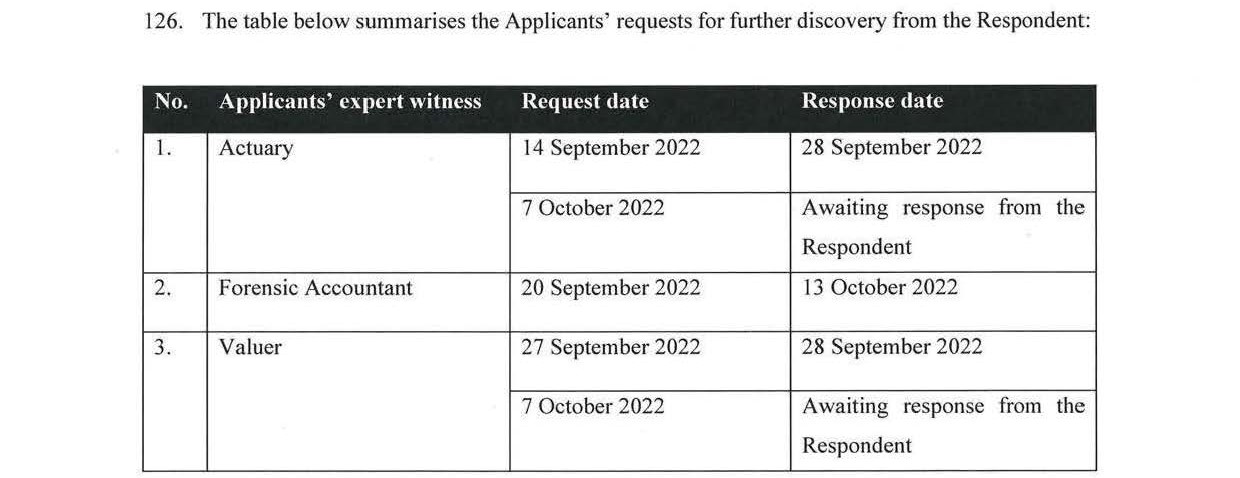

46 On 1 September 2022, Aveo completed discovery under the second pre-trial timetable and the orders made on 2 June 2022. However, between 14 September and 13 October 2022, the Lead Applicants made several further requests regarding discovery said to be relevant to instructing its experts.

3.3 The failed application to vacate the trial date in October 2022

47 On 29 September 2022, Levitt Robinson formed the view that compliance with the pre-trial timetable was unachievable, and the Lead Applicants would not be in a position to proceed with the trial scheduled to commence in March 2023.

48 On 24 October 2022, the Lead Applicants made an application to vacate the trial date (October 22 Vacation Application). In support of that application, the Lead Applicants relied upon, amongst other things, an affidavit of Mr Levitt dated 21 October 2022 (the October 22 Levitt Affidavit).

49 In the October 22 Levitt Affidavit, Mr Levitt explained that a primary reason why the trial date should be vacated was due to delays in finalising the Lead Applicants’ expert evidence. Mr Levitt deposed as follows:

72 The following factors have contributed to the Applicants’ not having filed their expert evidence by the time required by the April 2022 Orders or at all:

72.1 by way of context, the pleading amendments in February 2021 to include the Unconscionable System Claims and in November 2021 to include the special value claim and the introduction of sample group member claims, resulted in:

i. the Applicants seeking further discovery by the Respondent;

ii. the Applicants subpoenaing a number of entities for the purpose of obtaining documents to instruct its expert witnesses with; and

iii. the need for Applicants to call expert evidence in respect of the new allegations.

72.2 delays in the Respondent producing the documents responsive to the various categories of discovery…;

72.3 the need to issue subpoenas to numerous entities, and delays incurred by the process of obtaining production of documents sought under subpoena (including, the following three matters):

i. the access regime whereby the Respondent required first access to documents produced by certain addressees to enable it to make claims of privilege;

ii. the application of redactions and negotiating confidentiality undertakings in relation to certain documents produced pursuant to the subpoenas;

iii. amendments made to the addressee details of certain subpoenas due to difficulties in identifying the correct entity;

72.4 the large volume of material produced under subpoena and during discovery, which has resulted in a significant document review process, simultaneously with other work required in the proceeding; and

72.5 additional or further requests by the Applicants for information to address deficiencies in the discovery or non-compliance with discovery or subpoena obligations, or other material they have required in order to instruct their expert witnesses.

50 Mr Levitt elaborated upon some of these matters. The principal explanations given were that there had been delays:

(a) in identifying and selecting sample group members and preparing their points of claim (at [17]–[26]);

(b) arising from the subpoenas issued to Aveo’s external advisors (at [74]–[79]);

(c) arising from Aveo’s insistence upon a first access regime in respect of documents that were produced under subpoenas (at [80]–[87]);

(d) arising from Aveo’s claims relating to privilege and confidentiality over produced documents (at [88]–[95]);

(e) arising from requests for additional materials to produce from Deloitte under a subpoena issued to it (at [96]–[104]);

(f) arising from subpoenas issued to other retirement village operators (at [105]–[110]);

(g) arising from the discovery process (at [111]–[123]);

(h) arising from the need to make further requests for additional documents required to instruct the Lead Applicants’ experts (at [124]–[132]);

(i) occasioned by reviewing the documents that had been produced under subpoenas and discovered (at [133]–[135]); and

(j) arising due to turnover in the counsel retained for and on behalf of the Lead Applicants (at [136]–[137]).

51 It will be necessary to return to these explanations later in these reasons.

52 On 17 November 2022, the trial judge heard and refused the Lead Applicants’ application for leave to vacate the trial date. In coming to this conclusion, the trial judge was not satisfied as to the adequacy of the explanations provided by the Lead Applicants including by way of the October 22 Levitt Affidavit. The trial judge’s concerns in this regard emerge from the following exchanges with the Senior Counsel who appeared for the Lead Applicants:

HIS HONOUR: What’s the reason for the late retaining of experts? That’s the thing that troubles me the most.

SENIOR COUNSEL: Yes, your Honour.

HIS HONOUR: I mean, why wouldn’t you retain experts well in advance? I mean, what seems to have happened here, on the affidavit evidence, is that your instructing solicitor has been worried about documentation, obtaining more and more documentation, amending the case numerous times, and not turning their mind to, well, do we need any expert evidence, and if so, from what disciplines and who do we retain? So rather than turn their mind to that, the issues in the case, and retain the experts, been worried about getting these – all these documents, and then – it’s effectively cart before the horse. You get all the documents and then you retain the experts. Why didn’t you get the experts and ask them, “What documents do you need to perform your function?

SENIOR COUNSEL: Your Honour, in respect of – your Honour would have seen there’s three experts that are now engaged.

HIS HONOUR: But am I right? What are the dates upon which you retained them?

SENIOR COUNSEL: The actuary was engaged well before the current timetable.

HIS HONOUR: So why isn’t his report completed?

SENIOR COUNSEL: His report is very well advanced.

…

SENIOR COUNSEL: And so to answer your Honour’s question directly, he was engaged well before the current time period we’re concerned with. He was well advanced with doing the work and preparing the reports, but there were certain documents that he required which, of course, formed part of the discovery process and there has then been some delay with…

…

HIS HONOUR: Just identify for me, property evaluation. I mean, why does that involve a lot of documentation. It’s just not clear to me why.

SENIOR COUNSEL: Your Honour, your Honour would see from the affidavit material that there was, obviously, the delay in the sample group members’ claims coming on.

HIS HONOUR: Yes.

SENIOR COUNSEL: Then there were subpoenas - - -

HIS HONOUR: But that was – that rests fairly at your – and I don’t mean you personally, but your instructing solicitor’s [feet]. That’s – or the delay there.

SENIOR COUNSEL: That’s true, your Honour, but, with respect, it’s portrayed as being, in a sense, a voluntary move.

HIS HONOUR: But it’s five years since this proceeding was commenced. Five years.

SENIOR COUNSEL: I do appreciate that, your Honour. The thing is that that five years is - - -

HIS HONOUR: It’s not reflective of the complexity of this case.

SENIOR COUNSEL: It’s reflective of the approach by the parties to the complexity of this case in the sense that - - -

HIS HONOUR: It’s reflective of, from what I can see, too many applications to amend the claim brought by the group members without enough thought.

SENIOR COUNSEL: There’s certainly – had we had human perfection from the outset, it might have been possible to articulate the claims we now have, identify the experts we now have and get the hearing on sooner. But…

HIS HONOUR: So the reason for this, as I understand your submissions and the affidavit for wanting to vacate the trial date, is the inability to put on expert evidence. That’s the issue, isn’t it?

SENIOR COUNSEL: It’s – that’s what’s – that was the critical point we got to which made it apparent.

53 Although the trial judge did not publish reasons for refusing the application to vacate the hearing dates, his Honour’s essential reasoning is apparent from the following parts of the transcript:

HIS HONOUR: …I will just be very direct with you. I’m not satisfied, subject to hearing your submissions, that the proper explanation has been given for the delay.

SENIOR COUNSEL: Yes, your Honour.

HIS HONOUR: And what I see, when I read the affidavit material – when I look at the file, having been a judge that has come in to this recently, I see a lot of applications. I see a lot of delay. I see a lack of focus on getting on with the job. That – if you – there’s a responsibility of solicitors acting on behalf of group members and that’s a wider responsibility than when they’re acting in relation to individual clients because they’re acting for the class. And it’s incumbent upon the solicitors to act with due diligence and expedition. And the one thing I see when I read the file, and I’ve read it, is a lack of application, diligence and expedition.

I see numerous applications being made for what it seems to me to be matters which go to the periphery rather than the heart of getting the case on for trial. I see a massive amount of costs being run-up for what I can see to be not much benefit to date. We’re five years down the track and you’re saying, “I’m not ready to go to trial” and you were told a year ago when the trial date was. Now, what am I missing?

SENIOR COUNSEL: Your Honour, in terms of the five years, there is an initial period of roughly two years where, I accept, not very much appears to have occurred.

HIS HONOUR: Okay. We’ve got three years to go.

SENIOR COUNSEL: Then there’s a two-year period which, in effect, is our learned friends floating the prospect of a separate question.

HIS HONOUR: Yes.

SENIOR COUNSEL: That going to a registrar, coming back and then nothing occurring on the separate question application.

…

HIS HONOUR: So it works this way. We go five and a half years and there has been a lot of delay, much of which is unexplained or an unacceptable explanation is given for delay. In October, you say. We’ve acted since then. We’ve acted with due haste and expedition, and that means that I should take that into account, even though the conduct prior to October is lamentable delay.

…

HIS HONOUR: I’m not satisfied with the explanations that have been given for the delay. The delay has not been properly explained in my view. I have a serious concern that this matter is just dragging on far too long. It’s causing distress to 10 elderly people who should, you know, at that stage of their life not be troubled with matters like this and it needs to be resolved.

…

…I won’t be vacating the trial date. What I want to try and ascertain is what is possible.

3.4 Further pre-trial orders and a failed mediation

54 On 2 December 2022, the trial judge made further pre-trial orders. Those orders relevantly extended the time by which the Lead Applicants were required to file their expert evidence to 16 January 2023 and required Aveo to file expert evidence in response by 24 February 2023.

55 On 16 January 2023, in accordance with the orders made on 2 December 2022, the Lead Applicants served the following expert evidence:

(a) a report of Dennis Barton, an actuary;

(b) seven reports of Nicole Adamson, a property valuer; and

(c) a further report of Mr Barton.

56 On 24 February 2023, a mediation was held between the parties. At this time, Aveo had not served its expert evidence in response. The mediation was unsuccessful.

57 On 24 February 2023, after the mediation had concluded, Aveo served one expert report, but other expert reports remained outstanding.

58 On 27 February 2023, the Lead Applicants applied again to vacate the trial date. The trial judge (again) refused the application and instead made further pre-trial orders. Those orders relevantly included the following:

1. The trial of this proceeding, listed to commence on 2 March 2023, be relisted to commence on 14 March 2023.

…

4. The time in order 14 of the orders made on 2 December 2022 (providing for the Respondent to serve an expert report of any expert witness whose evidence it intends to adduce at the trial) be extended to 10 March 2023.

3.5 The late application to amend the FAOA and 3FASOC to plead a fiduciary duty claim

59 On 13 March 2023, the Lead Applicants filed an application seeking leave to amend the FAOA and the 3FASOC to specifically plead a breach of fiduciary duty claim. In support of that application, the Lead Applicants relied upon an affidavit of Mr Brett Imlay dated 13 March 2023. In that Affidavit, Mr Imlay deposed as follows:

7. The Applicants already plead that a feature of the Aveo Way System was that ARE and other Aveo-controlled entities that acted as real estate agents breached fiduciary duties that they owed to outgoing residents (3FASOC [174(1)]), and that Aveo directed or controlled or knew or ought to have known about, that conduct (3FASOC [174(n)]). They already plead that those breaches of fiduciary duty caused loss or damage (3FASOC [174(l)(iii)]), and that Aveo profited from the introduction of the Aveo Way System (3 F ASOC [ 173(b)]).

8. At present, those facts are relied upon in support of a claim of statutory unconscionability. The amendments sought amount to introducing, based on the same facts, a characterisation of the same conduct as constituting the procuring or inducing (by Aveo) of breaches of fiduciary duty-an equitable wrong. This would, if leave were granted and if the claim were substantiated, cause equitable relief (equitable compensation or an account of profits, at election) to be available.

60 Aveo opposed the proposed amendments.

3.6 Other pre-trial steps

61 Prior to the commencement of the trial, the Lead Applicants made an application seeking leave to issue further subpoenas, but the trial judge refused to grant such leave.

62 Aveo served the balance of its expert evidence, including a supplementary report of its valuation expert and a report of an economist, Mr Houston. The latter evidence was not anticipated by Levitt Robinson. Aveo also served further lay evidence.

63 In accordance with the (then) pre-trial timetable, the parties exchanged detailed written opening submissions on liability, and also separately on damages.

3.7 The conduct of the trial

64 The trial commenced on 16 March 2023.

65 During the course of the Lead Applicants’ oral opening submissions, the trial judge made a number of comments that sought to test aspects of the claims that were being advanced. For example, the trial judge observed that, in implementing the AWP, Aveo did not appear to have forced residents to change their contractual arrangements, and the residents had a choice as to whether to do so or not: see T34.27–44. The trial judge also observed that the relevant communications that were sent to the residents only expressed a “belief” as to what Aveo considered to be the benefits of the new arrangements, as opposed to asserting them as matters of fact: T35.6–14. The trial judge further observed that the evidence indicated that outgoing residents were not forced to appoint Aveo Real Estate as a selling agent of their interests and were able to, and did in fact, appoint other agents: T36.6–38.

66 During the afternoon of the first day of the trial, the Lead Applicants pressed their application to amend the FAOA and the 3FASOC: T74.25ff. The trial judge rejected the application as it had come “far too late” in proceedings that were “issued five years ago” and that the proposed amendments sought to advance “a different case” from the case that had been put: T81.13–18. The trial judge did not accept that the amendments merely added a new remedy to the claims that had been pleaded to that point: T74.18–22.

67 Following the conclusion of oral opening submissions, the lay evidence was called. The lay witnesses called in the Lead Applicants’ case were not required for cross-examination. Aveo then called its lay witnesses, and they were cross-examined.

68 During the fifth day of the trial (22 March 2023), a former employee of Aveo Real Estate, Mr Spencer, was cross-examined by one of the Senior Counsel retained by the Lead Applicants. Mr Spencer was a sales manager for the Queensland North region from 2014 until April 2016: T375.37–38. However, he had been employed by Aveo Real Estate, including (according to his belief) as a real estate agent: T376.17; T377.27–28. Mr Spencer was asked a series of questions in cross-examination as to Aveo Real Estate owing duties in its capacity as a real estate agent to outgoing residents in their capacity as vendors to obtain the highest possible price for the sale of freehold interests: T378.1ff. Mr Spencer was next asked questions about the bundle of features and rights associated with interests held by outgoing residents including deferred management fees, capital gain percentages, buy back entitlements and the like: T378.22–33. Mr Spencer was then asked questions about sales training and instructions that had been provided by Aveo to real estate agents in respect of the sale of interests in Aveo’s retirement villages to incoming residents. He was asked about the features that such incoming residents found valuable. At this point, an objection was taken on the basis that Mr Spencer was not an expert on the behaviour or psychology of incoming residents and, more generally, an objection was taken to the line of questions on the basis that they did not seem to be “related to the pleaded case”: T379.5–9.

69 The trial judge observed that the line of questions appeared to be a “new twist” that had been raised in the opening about the fiduciary duty of the real estate agents: T378.16–17. There followed rival submissions in which Senior Counsel for the Lead Applicants relied upon the pleadings in the 3FASOC at [174(l)] (as set out above): T380.24–384.40. The trial judge ruled that he would permit questions being asked about Aveo Real Estate pursuing the best price and interests of the outgoing residents because they were “relevant on the pleading” but would disallow questions asking Mr Spencer about the needs and wants of incoming residents: T384.35–385.4. However, after a further short exchange, the trial judge ruled that he would allow such questions if they were asked by reference to specific documents: T385.19–26.

70 The cross-examination then continued but shortly thereafter, Senior Counsel for Aveo took another objection to a question asked of Mr Spencer about the materials that were marketed to incoming residents: T387.18–28. There followed a further exchange of oral submissions about the scope of the case pleaded in the 3FASOC: T387.34–400.47. An examination of this part of the transcript discloses that Senior Counsel for the Lead Applicants made it clear that the line of examination he wished to pursue was aimed at establishing that Aveo Real Estate failed to discharge its fiduciary duties to outgoing residents by effectively limiting the market and pool of purchasers because it preferred Aveo’s interest in selling to purchasers the new form of interest reflecting the AWP. Senior Counsel for the Lead Applicants submitted that the case being advanced was that the agents employed by Aveo Real Estate had been trained and instructed by Aveo to sell to incoming residents only the new AWP contracts, which were less beneficial than the legacy contracts, and thereby had limited the pool of prospective purchasers. It was submitted that by engaging in this conduct Aveo Real Estate had a conflict and was not acting in the best interests of the outgoing residents. Senior Counsel for Aveo submitted that this was a new case that had not been pleaded.

71 The trial judge ruled that, notwithstanding that some of the matters relating to breaches of fiduciary duty had been raised during the course of opening submissions, there was no case pleaded that the relevant breach of duty involved Aveo Real Estate limiting the pool of potential buyers (i.e. potential incoming residents) as purchasers of an outgoing resident’s interests by reason of them preferring Aveo’s interests to those of the outgoing residents. The short point is that the trial judge accepted that the 3FASOC had pleaded a case that the system implemented by Aveo had allegedly given rise to a conflict of interest that was not disclosed to them but was not satisfied that the 3FASOC pleaded that the relevant breach of duty was caused by Aveo Real Estate limiting the pool of purchasers. After a short adjournment, the cross-examination of Mr Spencer continued but without any questions being asked on the topic that been ruled on by the trial judge.

72 The balance of the fifth and the sixth days of the trial were taken up in the cross-examination of the remainder of Aveo’s lay witnesses. Settlement was reached after the conclusion of the sixth day of the trial when the cross-examination of the lay evidence had concluded.

3.8 The application for approval of the settlement

73 On 28 April 2023, the Lead Applicants filed an application for approval of the proposed settlement under s 33V of the FCA Act. In support of that application, the Lead Applicants relied upon the following affidavits:

(a) an Affidavit of Mr Levitt sworn 26 April 2023 (First Levitt Affidavit);

(b) an Affidavit of Mr Brett Imlay sworn 26 April 2023;

(c) an Affidavit of Mr Levitt sworn 28 September 2023 (Second Levitt Affidavit);

(d) a confidential Affidavit of Mr Levitt sworn on 28 September 2023 (Third Levitt Affidavit);

(e) a confidential Affidavit of Mr Levitt sworn on 29 September 2023 (Fourth Levitt Affidavit); and

(f) an Affidavit of Mr Levitt sworn 29 September 2023 (Fifth Levitt Affidavit).

74 The First Levitt Affidavit and Mr Imlay’s Affidavit largely addressed procedural matters relating to the settlement that had been reached and set out the legal fees that were claimed. In the Second Levitt Affidavit, Mr Levitt set out a history of the proceedings and the events leading to the settlement of the proceedings, largely in support of the claim for payment of fees and disbursements from the Settlement Sum. In the Third Levitt Affidavit, Mr Levitt, amongst other things, deposed that during 2019 and 2020 he had encountered difficulties in identifying a valuation expert who did not have any conflict with Aveo and was willing to accept an engagement. Mr Levitt further said that a relevant expert that had been identified in Western Australia was unable to complete his engagement due to lockdowns associated with COVID-19 and travel restrictions. Mr Levitt said that eventually a different valuation expert had been retained but did not state when this had occurred. The Fourth Levitt Affidavit exhibited a copy of the Confidential Opinion that had been prepared by trial counsel. The Fifth Levitt Affidavit made a correction to the contents of one paragraph of the Second Levitt Affidavit.

75 The Contradictors’ outline of written submissions in chief were filed and served on 16 October 2023 (Contradictors’ Primary Submissions). Relevantly, the Contradictors submitted that the deduction of the Avoidable Costs was warranted in circumstances where Levitt Robinson and the litigation funder, Galactic Aveo LLC (Galactic) did not conduct the litigation with the “efficiency that the Court would expect”. Whilst the Contradictors acknowledged that the evidence before the Court was “sparse”, it was submitted that the evidence indicated that there were delays in the preparation of the expert evidence, especially critical expert evidence as to valuation. The Contradictors observed that Levitt Robinson had sought to explain away these delays by reason of the alleged delays in Aveo’s production of documents on discovery but noted that the trial judge was “critical of the applicants’ explanations” in the adjournment application in late 2022. The Contradictors also submitted that an inference could be drawn that funding problems with Galactic were “a reason” (emphasis added) why the pre-October timetables for service of expert evidence were not met (although we note that this suggestion receded by the time of the hearing before the primary judge, in light of the further evidence of Mr Levitt to which we refer below). Nevertheless, the Contradictors submitted that it was appropriate that some of the fees claimed by Levitt Robinson not be allowed due to the “apparent undue prolongation of the litigation, resulting from the delays in the critical process of expert reports”. It was submitted that better management of the proceedings would “probably have resulted in the case being settled in late 2022 or very early 2023” and the fees claimed during 2023 “may be characterised as unnecessary or disproportionate to the outcome…” (emphasis added).

76 Met with these submissions, Levitt Robinson filed both submissions and evidence in reply. In so far as the evidence was concerned, Levitt Robinson served the October 22 Levitt Affidavit (referred to above) and a confidential affidavit of Mr Levitt sworn 2 November 2023 (Sixth Levitt Affidavit). Reliance was also placed on two further affidavits of Mr Imlay but these largely related to procedural and other matters.

77 In the Sixth Levitt Affidavit, Mr Levitt deposed that:

(a) it was his opinion that in order to be able to negotiate the resolution of the claims made by the Lead Applicants “based upon a full and proper appraisal of the value” of their claims it was “necessary for [their] damages to be quantified and also, for a considered, informed and educated opinion to be reached as to the prospects of success with respect to each claim made…”;

(b) some of 2021 was taken up with, and the proceedings were progressed having regard to, Aveo’s application for a separate trial;

(c) between 2019 and mid-2021, there were difficulties in retaining a suitable forensic valuation expert with expertise in the valuation of retirement villages;

(d) the discovery given by Aveo was extensive in terms of its volume and the delays in production impacted on the ability to instruct expert witnesses and to propound further amendments to the 3FASOC;

(e) there were also delays in the production of documents issued under subpoenas which impacted on the information that could be provided to experts including as to comparable sales at neighbouring retirement villages;

(f) the COVID lockdowns caused protracted interruptions during 2020 and 2021 particularly in relation to interstate travel and access to aged care accommodation facilities which meant that the “valuation process was substantially delayed, for the better part of two (2) years”;

(g) much of September 2022 was taken up with attending to the Opt-Out process, which coincided with the period during which Aveo provided its discovery and occasioned the need to work intensively with experts whilst also attending to other interlocutory disputes and preparing for the impending hearing;

(h) he could not recall there being any proposal for mediation “emanating” from Aveo;

(i) at the end of 2019, the ownership of Aveo changed and it transitioned from being an ASX listed company to being delisted;

(j) based on a without prejudice discussion held with one of Aveo’s lawyers, Mr Levitt perceived that a derisory view had been formed by that representative as to the Lead Applicants’ case;

(k) it was impracticable to enter into any negotiations with Aveo until such time as there could be a level of confidence as to the quantum of damages which were sought to be proved in respect of each pleaded cause of action, whether there were reasonable prospects of success and the degree of discount to be conceded in relation to each tenable claim;

(l) by the time of the mediation that was conducted on 23 February 2023, losses had been quantified at approximately $113 million in respect of those group members who had sold their interest net of agent’s commissions charged by Aveo Real Estate and approximately $154 million inclusive of those commissions. The “commission claim” was valued at approximately $41 million (excluding interest);

(m) it was the prevalent view among the lawyers acting for the Lead Applicants that the “commission claim” was “strong” especially in relation to the position prevailing with Victorian based residents;

(n) after the failed mediation in February 2023, there was no reasonable opportunity to engage with Aveo in negotiations as a result of the strict timetable then in place in the lead up to the commencement of the trial;

(o) there had been regular changes in the Counsel retained for and on behalf of the Lead Applicants due to matters beyond Levitt Robinson’s control; and

(p) there continued to be a manageable working relationship between Levitt Robinson and Galactic until early March 2023.

78 In its written submissions responding to the Contradictor’s Primary Submissions, Levitt Robinson contended that the totality of the evidence did “not sustain the inference that the relational difficulties” between Galactic and Levitt Robinson “actually mattered” as to the “material reason why the pre-October timetable for expert evidence was missed”. As to the question of the Avoidable Costs and the prospect of earlier settlement, Levitt Robinson submitted that the Contradictor’s Primary Submissions advanced arguments that were speculative. It contended that the “corpus of evidence” demonstrated that the matter had settled on the sixth day of the trial as a result of the forensic environment having shifted by reason of (a) the two failed applications for adjournments that were made prior to the commencement of the trial (including the October 22 Vacation Application), (b) Aveo’s service of its lay evidence in late December 2022 and as late as March 2023 and its service of expert evidence in early 2023, and (c) the trial judge’s adverse comments made during the course of oral openings and in making rulings on objections to evidence which essentially foreclosed the Lead Applicants’ fiduciary duty claims.

79 In response to Levitt Robinson’s materials, the Contradictors filed submissions in reply. In those submissions, the Contradictors contended that what remained unclear and “inadequately explained” in the materials relied upon by Levitt Robinson was why the expert evidence was not “prepared more expeditiously in accordance with the timetable originally ordered by the Court”. The Contradictors further pointed out that the trial judge had been critical of the explanations that had been provided and that the further material in the Sixth Levitt Affidavit “still [did] not adequately explain the delay in the Applicants’ progress of the case, particularly through the first ten months of 2022”. It was further submitted that Levitt Robinson had misunderstood the Contradictors’ submissions as to the prospect of an earlier settlement. The Contradictors emphasised that “the Court need not find, as a matter of fact, that the earlier exchange of expert evidence would have resulted in an earlier settlement” and that the relevant question was one of “onus, and whether Levitt Robinson has now answered Anderson J’s concerns that there had in fact been a lack of application, diligence and expedition on the Applicant’s part during 2022”.

80 With this review of the evidence in mind, it is next necessary to address Levitt Robinson’s grounds of appeal.

4. GROUND 1

81 By Ground 1, Levitt Robinson contended that the primary judge erred in finding that the appellant did not act with due expedition and showed serious inefficiency in the period between November 2021 and July 2022.

82 The primary judge’s finding at PJ [149] as to Levitt Robinson’s “lack of application, diligence and expedition in relation to the critical task of filing and serving the applicants’ expert evidence” (PJ [149]) and other similar findings at PJ [139] need to be viewed in the context of the submissions that were advanced by the Contradictors and other critical aspects of the primary judge’s reasoning.

83 As set out above, in the proceedings before the primary judge, the Contradictors submitted that Levitt Robinson had provided an inadequate explanation as to the delay in the filing of expert evidence in accordance with the first and second pre-trial timetables. The only evidence that Levitt Robinson had relied upon to explain those delays was the October 22 Levitt Affidavit and the Sixth Levitt Affidavit. It is to be recalled that these Affidavits were relied upon by Levitt Robinson in the application for approval of the settlement after the Contradictors had served their Primary Submissions. As the Contradictors pointed out, the explanations that Mr Levitt raised in each of these Affidavits were ones which were not accepted by the trial judge in dismissing the October 22 Vacation Application.

84 At PJ [148], the primary judge accepted the Contradictors’ submission that there was a “lacuna” in the evidence upon which Levitt Robinson sought to rely to “explain away its failure to serve the applicants’ expert evidence in accordance with the first or second pre-trial timetables”. Thus, a critical aspect of the primary judge’s reasoning which informed the findings made at PJ [139] and [149] was that there was an inadequacy in the evidence upon which Levitt Robinson had relied to explain the delays. The primary judge’s acceptance that there was an inadequate explanation for the delay has to be further viewed in the context that similar observations were made by the trial judge in refusing the October 22 Vacation Application (as set out above). At PJ [146]–[147], the primary judge agreed with the observations made by the trial judge that an assessment of the relevant materials demonstrated a lack of application, diligence and expedition on the part of Levitt Robinson.

85 The primary judge also observed at PJ [147] that, whilst it was appropriate to focus on the seven-month period between November 2021 and July 2022 relied upon by the Contradictors, the broader context was that the proceedings had been commenced in September 2017 and the Court’s file demonstrated repeated failures by Levitt Robinson to comply with Court-ordered timetables. The primary judge’s findings in this regard were reinforced by the matters enumerated at PJ [148(a)–(e)] including that Levitt Robinson had some 10 months to put on its expert evidence which should have been readily achievable in circumstances where the case had been on foot for four years by the time those orders were made.

86 As will be evident from the above, the primary judge’s findings at PJ [149] were informed by the paucity and inadequacy of evidence relied upon by Levitt Robinson to explain the delays in the preparation and finalisation of the expert evidence in the period from November 2021 to July 2022 in view of the overall context of the proceedings having been on foot since September 2017.

87 In the appeal, Levitt Robinson contended that the conclusion reached by the primary judge was erroneous in that it was not factually correct that Levitt Robinson had showed a lack of application, diligence and expedition in serving the Lead Applicants’ expert evidence in the period from November 2021 to July 2022. Levitt Robinson advanced four primary reasons in support of this contention:

(a) first, Levitt Robinson submitted that the delay in serving expert evidence was partly attributable to the difficulties associated with, and delays arising from, the preparation of points of claim for sample group members including by reason of the identification of appropriate sample group members and the investigation of their respective claims: AS [10];

(b) second, Levitt Robinson pointed to Aveo’s own delay in filing its defensive points of claim which was said to have had an impact on the balance of the first and second pre-trial timetables including the preparation and service of the Lead Applicants’ lay evidence which, in turn, impacted upon the service of Aveo’s lay evidence: AS [11];

(c) third, and principally, Levitt Robinson relied upon the delays arising from the need to obtain and review documents produced under subpoena from third parties and discovery from Aveo. It was submitted that each of these processes was affected by further delays arising from production regimes that were insisted upon by Aveo including as to first access, as well as claims for privilege and confidentiality: AS [12]. In oral submissions, it was emphasised that discovery was critical to the finalisation of the Lead Applicants’ expert evidence; and

(d) fourth, Levitt Robinson pointed to challenges that had been confronted due to changes in the Counsel team.

88 None of these contentions demonstrate error. The submissions failed to grapple with the fact that the evidence (such as it was) that had been relied upon by Levitt Robinson was inadequate.

89 First, as to the delays arising in the finalisation of the points of claim, the first pre-trial timetable required these to have been filed on or by 24 December 2021. A period of five months then elapsed until in early April 2022, Levitt Robinson served Aveo with proposed points of claim in respect of four of five sample group members. The final points of claim were served in late April 2022. In the October 22 Levitt Affidavit, Mr Levitt gave the following explanation for this delay:

18. Under the October 2021 Orders, the Applicants were to file and serve the Points of Claim by 24 December 2021. The Points of Claim were served in early April 2022 (and on 29 April 2022 in the case of Julie Pirie) rather than 24 December 2021 (around 3 ½ months later than required by the October 2021 Orders).

19. Despite the late provision of those Points of Claim, the date for the trial, as set by the October 2021 Orders, was not altered.

20. I refer to my affidavit sworn 14 April 202[2] (my April affidavit) which was relied on by the Applicants for the purposes of the CMH.

21. In my April affidavit I explained why the Points of Claim were late, including the following:

21.1. the steps taken in the selection of sample group members (which involved considerations such as the availability of relevant documents, the State in which the village was located, and the different time periods in which units were sold);

21.2. the reasons for the selection of the sample group members for whom the Applicants have since served Points of Claim;

21.3. information sought from the Respondent during the sample group member selection and points of claim processes, and delays in the Respondent supplying that information;

21.4. the steps taken by the Applicants when they realised that they would not be in a position to comply with the 11 October 2021 orders (including proposing orders amending the timetable to trial on 21 December 2021);

21.5. communications with the Respondent about the timetable delays; and

21.6. the causes of the delays leading to the Applicants' non-compliance with the October 2021 Orders.

90 As will be evident from the above, Mr Levitt referred to an earlier affidavit sworn on 14 April 2022. This affidavit was not before the primary judge in the application for approval of the settlement and was not before the Full Court. Accordingly, a full explanation as to the delays associated with the preparation of the points of claim was not put before the primary judge in the approval application. In any event, at best, Mr Levitt’s evidence provided an explanation as to the late service of the points of claim for sample group members. Those matters, of themselves, did not explain why or how these delays had specifically impacted upon the preparation of expert evidence including any such evidence relating to the valuation of the loss claims advanced on behalf of the Lead Applicants. Nor did it explain why expert evidence directed to the valuation of the Luke Applicants’ claims or the Colombari Applicants’ claims were not able to be progressed. Ultimately, as far as can be ascertained from the Confidential Opinion, the evidence led in relation to the sample group members largely followed the same theme as those of the Lead Applicants. The essential rationale of the valuation of the primary losses claimed by the Lead Applicants and the sample group members was the determination of the differential in value as between a counterfactual sale of their respective interests to incoming residents under Aveo’s “legacy contracts” and under the AWP-based contracts.

91 In any event, even if the delays caused by the finalisation of the points of claim caused Levitt Robinson’s failure to comply with the first pre-trial timetable, the evidence did not explain the delays that were caused after 21 April 2022 when the second pre-trial timetable was made. Under the second pre-trial timetable, the Lead Applicants were required to file and serve expert evidence on or by 19 August 2022 (an extension of approximately a month). This gave Levitt Robinson a period of four months in which to prepare and finalise the expert evidence including in circumstances where the sample group members had been identified, and their claims had been able to be articulated in points of claim that had been served on Aveo.

92 Second, Levitt Robinson’s contention that there were delays arising from Aveo’s late filing of its defence to the points of claim, and the late service of lay evidence by both parties, did not explain how these delays impacted on the failure to obtain and finalise the expert evidence. The evidence in this regard was cast at a high level of generality without seeking to draw a connection between how any of those delays bore upon the preparation and finalisation of the expert evidence.

93 Third, Levitt Robinson’s contention that delay in the preparation and finalisation of expert evidence was occasioned by reason of delays arising from production of documents under subpoenas and discovery requires closer examination.

94 As to delays arising from documents produced under subpoenas, in the October 22 Levitt Affidavit, Mr Levitt deposed that:

The Applicants sought leave to issue subpoenas to five of the Respondent's external advisors who were engaged to undertake advisory work, such as audit and valuation services. The subpoenas were subsequently issued on 4 July 2022. The first return date was 13 July 2022. However, the Applicants are still yet to receive all the documents production of which is required by subpoena.

95 As will be apparent from this evidence, Levitt Robinson first sought to issue subpoenas on 4 July 2022. Mr Levitt provided no explanation as to why it had taken until 4 July 2022 to seek to issue these subpoenas. Mr Levitt’s explanations that there were subsequent delays caused by reason of the volume of materials produced by the subpoena recipients, the access regimes insisted upon by Aveo and the need for Levitt Robinson to request and review further documents, all pointed to delays occurring after July 2022. This evidence did not explain why it had taken from November 2021 to July 2022 to seek to issue the subpoenas. The evidence did not disclose when Levitt Robinson first sought to identify, and did in fact identify, the external advisors to whom the subpoenas were to be issued.

96 Mr Levitt also stated that a further 20 subpoenas were issued upon retirement villages in areas neighbouring those at which the sample group members had resided. Again, those subpoenas were issued on 4 July 2022, and no explanation was given as to why it had taken that period of time to seek to issue those subpoenas. As noted above, the points of claim had largely been finalised and served on Aveo during April 2022. There was no explanation given why the subpoenas were not issued at that point in time, or earlier.

97 Thus, the evidentiary position before the primary judge was that Levitt Robinson had taken until 4 July 2022 to seek to issue subpoenas in circumstances where it had known since November 2021 that under the first pre-trial timetable, expert evidence was due to be filed in July 2022, and, under the second pre-trial timetable, it had known since 21 April 2022 that the time for filing expert evidence had been extended to 19 August 2022.

98 As to delays caused by the process of discovery, again, the evidence before the primary judge was cast at a high level of generality, as were the submissions advanced on Levitt Robinson’s behalf. As noted above, the further discovery that was sought in April 2022 was a second tranche of discovery, with earlier discovery having already occurred in relation to the Luke Applicants’ claims. There was no explanation given in the evidence or submissions before the primary judge as to why or how the further categories of discovery impacted upon the finalisation of the expert evidence.

99 A close examination of the categories of discovery ordered on 21 April 2022 (as set out in Annexure A of those orders) discloses that:

(a) Category 1 sought production of the standard form of management agreements in place in respect of leasehold group members prior to the introduction of the AWP;

(b) Category 2 sought production of documents brought into existence since the time of the first tranche of discovery in relation to a limited set of categories;

(c) Category 3 sought production of documents from January 2014 produced to Aveo’s board or senior management recording or summarising the effect of the introduction of the AWP on the returns generated on Aveo’s assets and the net present value of those assets, as well as documents relating to Aveo’s operational control of units within retirement villages;

(d) Category 4 sought documents relating to the implementation of the AWP at the retirement village at which the Colombari Applicants resided;

(e) Categories 5 to 16 sought production of documents relating to the property leased by the Colombari Applicants and its sale;

(f) Category 17 sought production of documents relating to the methods, protocols, guidelines, procedures, instructions, directions or policies (however described) since 8 May 2014 in relation to the appointment of real estate agents when a resident of Aveo gave notice of an intention to surrender their relevant interest;

(g) Category 18 sought production of documents from January 2014 that were produced to Aveo’s board or senior management recording or summarising the effect of the introduction of the AWP on various matters including the rate of accrual of deferred management fees, membership fees and exit fees; and