FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited (Appeal) [2025] FCAFC 67

Appeal from: | Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited (No 41) [2023] FCA 555 | |||

File number: | NSD 689 of 2023 NSD 690 of 2023 NSD 691 of 2023 | |||

Judgment of: | PERRAM, KATZMANN AND KENNETT JJ | |||

Date of judgment: | 16 May 2025 | |||

Catchwords: | DEFAMATION – where respondents published articles making imputations that appellant committed serious criminal offences including war crimes while fighting with Australian forces in Afghanistan – where imputations of appellant’s involvement in murders and related matters found to be substantially true – where primary judge upheld defence of contextual truth in relation to other imputations – where alleged inconsistencies in, and other difficulties with, aspects of evidence of respondents’ witnesses, whether evidence as a whole sufficiently cogent to establish substantial truth of imputations – whether primary judge erred by giving insufficient weight to the presumption of innocence – whether “official” records supported appellant’s contention that killings were legitimate – where “official” records indicated killings were legitimate, whether primary judge erred by rejecting those accounts and preferring respondents’ evidence – where primary judge rejected evidence of appellant and his witnesses as untruthful and appellant makes no challenge to adverse credit findings and respondents carried burden of proof, whether adverse credit findings irrelevant – where alternative version of events propounded by appellant found to be fictitious, whether open to appellant to propound alternative hypotheses inconsistent with appellant’s evidence at trial EVIDENCE – tendency evidence –where no objection taken to evidence of appellant’s conduct during training exercises and no application made to limit its use, whether primary judge erred by relying on it as tendency evidence – whether primary judge engaged in tendency reasoning when taking into account findings concerning the appellant’s conduct on one mission to reject his account of his conduct on a subsequent mission | |||

Legislation: | Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) ss 11.2, 268.70 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 94, 97, 99, 136, 140 National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004 (Cth) Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, opened for signature 12 August 1949, 75 UNTS 287 (entered into force 21 October 1950) Gageler S, Truth and justice, and sheep, (2018) 46 Australian Bar Review 205 Pejic J, “Conflict Classification and the Law Applicable to Detention and the Use of Force” in E Wilmshurst (ed), International Law and the Classification of Conflicts (OUP, 2012) | |||

Cases cited: | Abalos v Australian Postal Commission [1990] HCA 47; 171 CLR 167 Amalgamated Television Services Pty Ltd v Marsden [2002] NSWCA 419 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Delta Automation Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 880 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 794; 160 FCR 321 Bale v Mills [2011] NSWCA 226; 81 NSWLR 498 Bradshaw v McEwans Pty Ltd (1951) 217 ALR 1 Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 Browne v Dunn [1893] 6 R 67 Channel Seven Sydney Pty Ltd v Mahommed [2010] NSWCA 335; 278 ALR 232 Commercial Union Assurance Company of Australia v Ferrcom Pty Ltd (1991) 22 NSWLR 389 Devries v Australian Railways Commission [1993] HCA 78; 177 CLR 472 Edwards Lifesciences LLC v Boston Scientific Scimed Inc [2018] EWCA Civ 673; [2018] FSR 29 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v SNF (Australia) Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 74; 193 FCR 149 Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; 214 CLR 118 Gonzales v The Queen [2007] NSWCCA 321; 178 A Crim R 232 Griffiths v TUI (UK) Ltd [2023] UKSC 48; [2025] AC 374; [2023] 3 WLR 1204 In re Coordinated Pretrial Proceedings in Petroleum Products Antitrust Litigation, 906 F 2d 432, 444–5 (9th Cir, 1990) Islam v Director-General, Justice and Community Safety [2022] ACTSC 124; 369 FLR 417 Jacara v Perpetual Trustees WA [2000] FCA 1886; 106 FCR 51 Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 Jones v Sutherland Shire Council [1979] 2 NSWLR 206 Kazal v Thunder Studios In (California) [2023] FCAFC 174; 416 ALR 24 Lee v Lee [2019] HCA 28; 266 CLR 129 Mayfair Wealth Partners Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2022] FCAFC 170; 295 FCR 106 Miller v Cameron (1936) 54 CLR 572 Mohammed v Ministry of Defence [2014] EWHC 1369 Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd (1992) 110 ALR 449 Pell v The Queen [2020] HCA 12; 268 CLR 123 Perish v The Queen [2016] NSWCCA 89; 92 NSWLR 161 R v Baden-Clay [2016] HCA 35; 258 CLR 308 R v Hillier [2007] HCA 13; 228 CLR 618 Reifek v McElroy (1965) 112 CLR 517 Rosenberg v Percival [2001] HCA 18;205 CLR 434 Seltsam Pty Ltd v McGuiness [2000] NSWCA 29; 49 NSWLR 262 Shepherd v The Queen (1990) 170 CLR 573 SS Hontestroom v SS Sagaporack [1927] AC 37 Steinberg v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1975) 134 CLR 640 The Queen’s Case (1820) 2 Brod & Bing 284; 129 ER 976 Warren v Coombes (1979) 142 CLR 531 | |||

Division: | General Division | |||

Registry: | New South Wales | |||

National Practice Area: | Other Federal Jurisdiction | |||

Number of paragraphs: | 1018 | |||

Date of hearing: | 5-9 and 12-16 February 2024 | |||

Counsel for the Appellant: | Mr B Walker SC with Mr A Moses SC, Mr M Richardson SC and Mr P Sharp | |||

Solicitor for the Appellant: | Mark O’Brien Legal | |||

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr N Owens SC with Mr C Mitchell and Ms H Ryan | |||

Solicitor for the Respondents: | MinterEllison | |||

Counsel for the Commonwealth: | Ms J Single SC with Mr J Edwards | |||

Solicitor for the Commonwealth: | Australian Government Solicitor | |||

Table of Corrections | |

9 September 2025 | In paragraph 753, the cross-reference to “[89]” is replaced with “[624]”. |

ORDERS

NSD 689 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | BEN ROBERTS-SMITH Appellant | |

AND: | FAIRFAX MEDIA PUBLICATIONS PTY LIMITED First Respondent NICK MCKENZIE Second Respondent CHRIS MASTERS (and another named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | PERRAM, KATZMANN AND KENNETT JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 16 MAY 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs.

3. Pursuant to s 37AF of the of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and on the grounds referred to in s 37AG(1)(b) and (c) of that Act, there be no disclosure, by publication or otherwise, of the reasons for judgment delivered in open court (open court reasons) until either the Commonwealth notifies the Court and the parties that it has no objection to publication of the open court reasons or 4pm on 20 May 2025 (whichever is the earlier).

4. Order 3 does not prevent disclosures of the open court reasons to and between Authorised Persons within the meaning of the orders made by his Honour Justice Besanko on 15 July 2020 (as most recently amended on 26 September 2023) under ss 19(3A) and 38B of the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004 (Cth).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 690 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | BEN ROBERTS-SMITH Appellant | |

AND: | THE AGE COMPANY PTY LIMITED First Respondent NICK MCKENZIE Second Respondent CHRIS MASTERS (and another named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | PERRAM, KATZMANN AND KENNETT JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 16 MAY 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs.

3. Pursuant to s 37AF of the of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and on the grounds referred to in s 37AG(1)(b) and (c) of that Act, there be no disclosure, by publication or otherwise, of the reasons for judgment delivered in open court (open court reasons) until either the Commonwealth notifies the Court and the parties that it has no objection to publication of the open court reasons or 4pm on 20 May 2025 (whichever is the earlier).

4. Order 3 does not prevent disclosures of the open court reasons to and between Authorised Persons within the meaning of the orders made by his Honour Justice Besanko on 15 July 2020 (as most recently amended on 26 September 2023) under ss 19(3A) and 38B of the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004 (Cth).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 691 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | BEN ROBERTS-SMITH Appellant | |

AND: | THE FEDERAL CAPITAL PRESS OF AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED First Respondent NICK MCKENZIE Second Respondent CHRIS MASTERS (and another named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | PERRAM, KATZMANN AND KENNETT JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 16 MAY 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs.

3. Pursuant to s 37AF of the of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and on the grounds referred to in s 37AG(1)(b) and (c) of that Act, there be no disclosure, by publication or otherwise, of the reasons for judgment delivered in open court (open court reasons) until either the Commonwealth notifies the Court and the parties that it has no objection to publication of the open court reasons or 4pm on 20 May 2025 (whichever is the earlier).

4. Order 3 does not prevent disclosures of the open court reasons to and between Authorised Persons within the meaning of the orders made by his Honour Justice Besanko on 15 July 2020 (as most recently amended on 26 September 2023) under ss 19(3A) and 38B of the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004 (Cth).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[14] | |

[15] | |

The nature of the appeal and the advantages of the primary judge | [28] |

The significance of the wholesale rejection of the appellant’s case | [37] |

[41] | |

[41] | |

[58] | |

[60] | |

[61] | |

The evidence of Person 18 concerning the man with the prosthetic leg | [64] |

Person 18’s examination of the bodies during the SSE process | [67] |

Person 18’s evidence concerning the weapons in the hay store | [68] |

Person 18’s evidence concerning the “blooding of the rookie” | [69] |

[71] | |

[78] | |

[81] | |

[82] | |

[92] | |

[95] | |

[100] | |

[105] | |

[106] | |

[107] | |

[113] | |

[115] | |

[119] | |

[130] | |

[131] | |

[133] | |

[137] | |

[138] | |

[149] | |

Did the primary judge err by failing to give weight to the official records (particulars 7 and 8)? | [154] |

[170] | |

[204] | |

[208] | |

[216] | |

[217] | |

[220] | |

[221] | |

[222] | |

[226] | |

[229] | |

Did the primary judge err in assessing the reliability of Person 14 (particular 11)? | [231] |

[234] | |

[242] | |

[270] | |

Did the primary judge err in assessing the reliability of Person 24 (particular 6, 7 and 8)? | [272] |

Did the primary judge err in assessing the reliability of Person 41 (particular 4)? | [273] |

[273] | |

[289] | |

[297] | |

Difficulties with the timing of the death of the old man (particular 1) | [303] |

[333] | |

[335] | |

[338] | |

[349] | |

[356] | |

[362] | |

[364] | |

[369] | |

[370] | |

[378] | |

[379] | |

[381] | |

Inconsistencies about whether a man with a prosthetic leg was brought out of the tunnel | [385] |

[386] | |

[387] | |

[391] | |

[392] | |

[393] | |

[394] | |

Error in concluding the evidence was reliable because each witness had no motive to lie | [405] |

[410] | |

[416] | |

[423] | |

The number of soldiers in the vicinity of the killing of the man with the prosthetic leg | [426] |

Inconsistencies on the part of the clothing by which the appellant was holding the man | [462] |

Inconsistencies on whether the man was dropped on his front or his back | [463] |

[464] | |

[465] | |

[466] | |

[467] | |

Was Person 4 known as the rookie and had he previously been blooded (particulars 14, 16 and 17)? | [469] |

[483] | |

[484] | |

[485] | |

[486] | |

[487] | |

[497] | |

[508] | |

Were the primary judge’s findings in respect of insurgent behaviour in error (particular 12)? | [518] |

[529] | |

[535] | |

[536] | |

[536] | |

[542] | |

[545] | |

[555] | |

[563] | |

[564] | |

[565] | |

[573] | |

[575] | |

[606] | |

[608] | |

[613] | |

[615] | |

[620] | |

[622] | |

Was insufficient weight given to discrepancies in the evidence of Mangul and Hanifa? | [641] |

[642] | |

[657] | |

[669] | |

[670] | |

[679] | |

[683] | |

[684] | |

[695] | |

[702] | |

[714] | |

[716] | |

[740] | |

[757] | |

[762] | |

[785] | |

[808] | |

[837] | |

[840] | |

Did the primary judge err by taking into account the findings about the murders at Whiskey 108 and the pre-deployment training to infer that the appellant had a tendency to execute persons he thought were or were likely to be Taliban (particular 26)? | [852] |

Did the primary judge err by by taking into account the findings in relation to pre-deployment training to infer that the appellant had a tendency to use “throwdowns” to conceal an unlawful kill (particular 28)? | [853] |

Did the primary judge err by finding that the appellant’s motive for killing Ali Jan was that he would execute persons he thought were Taliban or likely to be Taliban when it was not put to the appellant and the respondents’ case was that Ali Jan was a farmer and not a member of the Taliban (particular 27)? | [877] |

Did the primary judge err by making adverse credit findings about Persons 11 and 100 on the basis that, because they were unreliable witnesses about some specific matters, they were unreliable about all matters relating to Darwan (particular 29)? | [887] |

Did the primary judge fail to properly apply s 140 and Briginshaw (particular 30)? | [888] |

[891] | |

[892] | |

[892] | |

[893] | |

[908] | |

[920] | |

[927] | |

Did the primary judge err by finding that two caches were discovered (particular 31)? | [944] |

Did the primary judge err by failing to find that there was insufficient time for the events as related by Person 14 to have occurred (particular 32)? | [972] |

Did the primary judge err by relying on Person 14’s evidence about the troop sergeant’s reaction (particular 33)? | [987] |

[996] | |

[1015] | |

[1016] | |

Page 243 |

THE COURT:

INTRODUCTION

1 In 2018 the respondents published a number of articles about the activities of Australian special forces soldiers during the war in Afghanistan. Among other things, the articles contained sensational allegations that war crimes had been committed by soldiers in the Special Air Service Regiment (SASR), raising serious questions about the culture and command structure of the regiment. Although he was not named in the articles, the appellant instituted three proceedings claiming he had been defamed in them. The respondents contended that the defamatory imputations were substantially true and also relied on the defence of contextual truth. Following a lengthy trial, while the primary judge found that the appellant was defamed in the articles, he also found that most of the imputations were substantially true and upheld the defence of contextual truth with respect to the rest. In particular, his Honour found that the respondents had proved to the requisite standard the truth of the imputations that the appellant had committed or was complicit in murder on three separate occasions in 2009 and 2012. In this appeal the appellant claims that those findings should not have been made. He argues that the evidence was not sufficiently cogent to satisfy the respondents’ burden of proof.

2 The imputations which were found to have been conveyed and to be substantially true were that:

(1) the appellant, while a member of the SASR, murdered an unarmed and defenceless Afghan civilian, by kicking him off a cliff and procuring the soldiers under his command to shoot him;

(2) the appellant broke the moral and legal rules of military engagement and is therefore a criminal;

(3) the appellant disgraced his country, Australia, and the Australian Army by his conduct as a member of the SASR in Afghanistan;

(4) the appellant, while a member of the SASR, committed murder by pressuring a newly deployed and inexperienced SASR soldier to execute an elderly, unarmed Afghan in order to “blood the rookie”;

(5) the appellant, while a member of the SASR, committed murder by machine gunning a man with a prosthetic leg;

(6) the appellant, having committed murder by machine gunning a man with a prosthetic leg, is so callous and inhumane that he took the prosthetic leg back to Australia and encouraged his soldiers to use it as a novelty beer drinking vessel;

(7) the appellant, as deputy commander of a 2009 SASR patrol, authorised the execution of an unarmed Afghan by a junior trooper in his patrol;

(8) the appellant, during the course of his 2010 deployment to Afghanistan, bashed an unarmed Afghan in the face with his fists and in the stomach with his knee and in so doing alarmed two patrol commanders to the extent that they ordered him to back off;

(9) the appellant as patrol commander in 2012 authorised the assault of an unarmed Afghan, who was being held in custody and posed no threat;

(10) the appellant engaged in a campaign of bullying against a small and quiet soldier called Trooper M which included threats of violence; and

(11) the appellant assaulted an unarmed Afghan in 2012.

See Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited (No 41) [2023] FCA 555 (J) at J[11]–[13], J[2599]–[2600].

3 The appeal is concerned with the findings that the imputations set out in (1)–(7) and (9) above are substantially true. There is no challenge to the findings concerning the imputations set out in (8), (10) and (11).

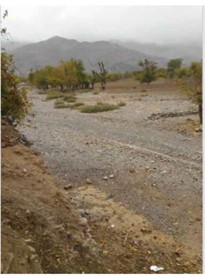

4 Two of the killings occurred at the village of Kakarak on 12 April 2009 at a compound known as Whiskey 108 or just W108. The third occurred on 11 September 2012 during an operation to capture a particular enemy combatant at Darwan. The fourth occurred on 12 October 2012 during a mission at Chinartu. It is convenient at this point to refer to the principal findings.

5 With respect to Whiskey 108, those findings were as follows. After the compound had been declared secure, two Afghan nationals were discovered in a concealed tunnel and brought out into a courtyard onto which the tunnel opened. One was an old man (referred to as EKIA56), the other a man with a prosthetic leg (referred to as EKIA57). Once most of the Australian soldiers in the courtyard had left it, the appellant made the old man kneel before Person 4 and ordered Person 4 to execute him. Person 4 did so with a single shot to the old man’s head fired from an M4 rifle fitted with a suppressor. Sometime after that, the appellant frogmarched the man with the prosthetic leg out of the compound to a point at its northwest corner, threw him on the ground and executed him with machine gun fire.

6 With respect to Darwan, his Honour found that, during the clearing of compounds by the appellant’s patrol, a soldier referred to as Person 11 and the appellant had murdered an Afghan man known as Ali Jan. His anterior findings included that Ali Jan was handcuffed and was being held by his shoulder by Person 11 when the appellant kicked him off a small cliff or steep slope into a dry creek bed below. His Honour found that at the appellant’s direction Person 11 and Person 4 carried Ali Jan to the opposite side of the creek bed and into the cornfield where, with the agreement of the appellant, he was executed by Person 11. Afterwards, Ali Jan’s handcuffs were removed, an ICOM (a two-way radio) was placed on his body, and photographs were taken to create the false impression that he was an enemy combatant.

7 With respect to Chinartu, his Honour’s principal findings were these. While the appellant was questioning an Afghan man in the presence of other soldiers, another member of his patrol, Person 14, discovered a cache of weapons and supplies in a perimeter wall outside the room where the questioning took place. In response to the discovery, through an interpreter the appellant directed Person 12, a commander of the Afghan partner forces, to shoot the Afghan man. After a discussion between the interpreter and Person 12, and then Person 12 and the Afghan partner soldiers, one of the Afghan soldiers then shot the Afghan man.

8 The primary judge was satisfied that each of the men who was killed at Whiskey 108, Darwan and Chinartu in the circumstances described above was a “Person Under Control” (PUC), that is to say, a person who was being detained or held by the SASR for the purpose of interrogation and/or processing. Consequently, each of the executions constituted offences against s 268.70 of the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) (Criminal Code or Code) which is entitled “War Crime – Murder”. Thus, the findings of the primary judge constitute findings that Person 4 and the appellant had committed that crime at Whiskey 108, that Person 11 had committed that offence at Darwan, and that an Afghan soldier had done so at Chinartu.

9 Section 11.2 of the Code is entitled “Complicity and Common Purpose”. It makes it an offence to aid, abet, counsel or procure the commission of an offence under the Code including s 268.70.

10 The primary judge found that the appellant ordered Person 4 to execute the old man, that he had agreed with Person 11 that Ali Jan should be executed at Darwan, and that he had ordered the commander of the Afghan partner forces at Chinartu to execute the Afghan man who was being questioned and so was complicit in, and responsible for, the executions. Each of these conclusions constituted findings that the appellant had committed the offence in s 11.2 as applied to s 268.70. The latter two executions would also satisfy the terms of s 11.2A, which commenced on 20 February 2010, after the events at Whiskey 108. That section provides that, where a person who enters into an agreement to commit an offence and an offence is committed in accordance with the agreement or in the course of carrying out the agreement, that person is taken to have committed the offence. The section makes it clear that the agreement may consist of a non-verbal understanding and may be entered into before, or simultaneously with, the conduct constituting the physical elements of the offence.

11 Although it has no direct legal significance in this litigation, it should be noted that these statutory provisions give effect to Australia’s obligations under Article 3 of the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, opened for signature 12 August 1949, 75 UNTS 287 (entered into force 21 October 1950) (Fourth Geneva Convention). Article 3 applies to hostilities which are not of an international character but which occur in the territory of a contracting party which was the case with Australia’s involvement in the hostilities in Afghanistan. Article 3 requires the humane treatment of persons taking no active part in hostilities including persons who have been taken into custody, and prohibits, among other things, acts of violence towards them, including murder and summary execution. .

12 It was common ground that at all relevant times the war in Afghanistan was “an armed conflict that is not an international armed conflict”, no doubt because at least at all relevant times it was not an armed conflict conducted between States. In Mohammed v Ministry of Defence [2014] EWHC 1369 (QB) at [231] Leggatt J observed that, since the overthrow of the Taliban in 2001 and the establishment of a new Afghan government pursuant to the Bonn Agreement, it is generally accepted that the fighting in Afghanistan was “a non-international conflict”. We interpolate that the Bonn Agreement was a reference to the “Agreement on Provisional Arrangements in Afghanistan pending the Re-establishment of Permanent Government Institutions”, dated 5 December 2001, which provided for the establishment of an Interim Administration in Afghanistan on 22 December 2001. Leggatt J went on to explain, citing J Pejic, “Conflict Classification and the Law Applicable to Detention and the Use of Force” in E Wilmshurst (ed), International Law and the Classification of Conflicts (OUP, 2012), p 82:

In the taxonomy of such conflicts, the situation in Afghanistan can be classified as a “multi-national non-international armed conflict”, i.e. one in which multi-national armed forces are fighting alongside the armed forces of a ‘host’ state, in its territory, against one or more organised armed groups.

13 Some of the evidence in this case is covered by the National Security Information (Criminal and Civil Proceedings) Act 2004 (Cth). The evidence which is subject to that Act cannot be disclosed in open court. Consequently, parts of the trial were conducted in a court closed to the public. The primary judge prepared public reasons in the usual way but he also prepared a set of closed court reasons portions of which cannot be disclosed publicly due to national security constraints. In this Court the same approach was taken. The parties made separate closed court submissions and, like the primary judge, we will also give separate closed court reasons. Where there are closed court reasons touching upon a subject matter discussed in the open court reasons, we will indicate as much.

SOME GENERAL REMARKS

14 Before going any further, it is useful to refer to some matters of law which bear upon the fact-finding process, the nature of the appeal, and the manner in which the issues it raises are to be decided.

The burden and standard of proof

15 As the Chief Justice of the High Court observed in a recent article, the legal concept of truth is not absolute; it is a matter of degree. “True or untrue”, his Honour wrote, “means proven or unproven, and proven or unproven is ultimately believed or not believed with the requisite degree of intensity”. His Honour explained:

When we speak in a civil case of proof “on the balance of probabilities” or “on the preponderance of the evidence”, just as when we speak in a criminal case of proof “beyond reasonable doubt”, we are expressly eschewing any notion that we can determine that a past fact happened or did not happen with absolute certainty. We are talking probabilistically. But we are not talking about objective probabilities; otherwise we would never find an improbable thing to have happened. We are talking about belief, and we are acknowledging that belief can be held with different degrees of intensity.

See Stephen Gageler, Truth and justice, and sheep (2018) 46 Australian Bar Review 205 at 207-8.

16 The difference between the criminal and civil standards of proof is “not a mere matter of words” but one of “critical substance”; in a civil case, “no matter how grave the fact which is to be found … the mind has only to be reasonably satisfied”: Reifek v McElroy (1965) 112 CLR 517 at 521. In a criminal case where circumstantial evidence is relied upon, especially to prove the accused’s state of mind, the prosecutor must exclude all reasonable explanations consistent with innocence: Shepherd v The Queen (1990) 170 CLR 573. But that is an aspect of the criminal standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt, “which has no analogue in relation to the civil standard of the balance of probabilities”, even in civil cases where serious wrongdoing, including criminal conduct, is alleged: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Delta Automation Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 880 (Delta) at [55] (Bromwich J). As Bromwich J went on to say in Delta at [56]–[57]:

[56] In a civil case, the combination of circumstances relied upon must do no more than raise “a more probable inference in favour of what is alleged”: see Shepherd per Mason CJ at 576 and per Dawson J at 581 (with whom Toohey and Gaudron JJ agreed), explaining a passage from Chamberlain v The Queen [No 2] (1984) 153 CLR 521 at 536 containing that phrase without adverse comment. The unquoted, but footnoted, source of that phrase in Chamberlain is Luxton v Vines (1952) 85 CLR 352 at 358, where Dixon, Fullagar and Kitto JJ quoted from the following passage in Bradshaw v McEwans Pty Ltd (1951) 217 ALR 1 at 5 (emphasis added to identify the phrase):

Of course as far as logical consistency goes many hypotheses may be put which the evidence does not exclude positively. But this is a civil and not a criminal case. We are concerned with probabilities, not with possibilities. The difference between the criminal standard of proof in its application to circumstantial evidence and the civil is that in the former the facts must be such as to exclude reasonable hypotheses consistent with innocence, while in the latter you need only circumstances raising a more probable inference in favour of what is alleged. In questions of this sort, where direct proof is not available, it is enough if the circumstances appearing in evidence give rise to a reasonable and definite inference: they must do more than give rise to conflicting inferences of equal degrees of probability so that the choice between them is mere matter of conjecture (see per Lord Robson, Richard Evans & Co Ltd v Astley (1911) AC 674 at 687). But if circumstances are proved in which it is reasonable to find a balance of probabilities in favour of the conclusion sought then, though the conclusion may fall short of certainty, it is not to be regarded as a mere conjecture or surmise: cf per Lord Loreburn, above, at p 678.

[57] It follows that the starting point is that the exclusion of alternative explanations forms no part of any civil law requirement for reaching the necessary state of satisfaction on the balance of probabilities, even if it might be analytically deployed as a process of reasoning. Although common, this is not a rule of law even in relation to jury directions in criminal cases and is sometimes not appropriate in such a case: Shepherd per Mason CJ at 575 and per Dawson J at 578. As Dawson J pointed out, while a direction of that kind is customarily given to a jury in circumstantial evidence cases, it is no more than an amplification of the rule that the prosecution must prove its case beyond reasonable doubt, such that in some cases such a direction may be confusing rather than helpful. Even in criminal proceedings, it is only the elements of an offence that must be proven beyond reasonable doubt, each fact relied upon to support the proof of that element need not be proven to that standard unless indispensable to the finding of guilt. Of course, sometimes a non-element component of a criminal case may need to be proven beyond reasonable doubt, such as identification.

(Emphasis in original in [56], emphasis added to [57].)

17 The primary judge cited the same passage in Bradshaw v McEwans as that which Bromwich J extracted in Delta at [56] (at J[168]).

18 In Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 (Briginshaw) at 361 Dixon J explained that, before a particular finding of fact can be made, the tribunal of fact “must feel an actual persuasion of its occurrence or existence” and no such finding can be made “as a result of a mere mechanical comparison of probabilities independently of any belief in its reality”. In a civil case, his Honour went on to explain at 362, “it is enough that the affirmative of an allegation is made out to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal”. His Honour continued:

But reasonable satisfaction is not a state of mind that is attained or established independently of the nature and consequence of the fact or facts to be proved. The seriousness of an allegation made, the inherent unlikelihood of an occurrence of a given description, or the gravity of the consequences flowing from a particular finding are considerations which must affect the answer to the question whether the issue has been proved to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal. In such matters “reasonable satisfaction” should not be produced by inexact proofs, indefinite testimony, or indirect inferences …

19 Later, at 363, his Honour remarked that, where a question arises in a civil proceeding as to whether a crime has been committed, “the standard of persuasion is … the same as upon other civil issues” but “weight is given to the presumption of innocence and exactness of proof is expected”.

20 Consequently, as the High Court observed in Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd (1992) 110 ALR 449 (Neat Holdings) at 450, authoritative statements have often been made to the effect that clear, cogent or strict proof is necessary where, for example, a court is asked to find “so serious a matter as fraud”.

21 These principles have effectively been codified in s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act). That section requires a Court, when determining whether a party who bears the burden of proof has discharged that burden on the balance of probabilities, to take into account the nature of the cause of action or defence, the nature of the subject-matter of the proceeding, and the gravity of the matters alleged.

22 The appellant argued that the primary judge failed to apply these principles and had failed to give weight to the presumption of innocence because he did not explain how he applied the principles and in what way the presumption had affected his view of the evidence.

23 We reject this argument. The primary judge discussed the relevant principles at length in the early part of his reasons and repeatedly reminded himself of them. Section 140 of the Evidence Act, for example, is mentioned nine times in the reasons for judgment, Briginshaw 10 times, Neat Holdings three times and the presumption of innocence seven times. These were no mere ritualistic incantations, as the appellant suggested. It is apparent that his Honour was acutely conscious of the seriousness of the findings the respondents called upon him to make and of the necessity that he be reasonably satisfied that the imputations were substantially true without resorting to inexact proofs, indefinite testimony or indirect inferences. Accordingly, he gave no weight to uncorroborated evidence and largely relied on eyewitness accounts. He expressly adverted to the appellant’s submission concerning the strength of the evidence required to discharge the respondents’ burden and the presumption of innocence (at J[114]). Still, he was satisfied that “the proof [was] clear and cogent” (J[115]).

24 It is manifestly clear from the reasons of the primary judge that, in reaching conclusions about contested facts, his Honour did not engage in any mechanical comparison of probabilities divorced from a belief in the occurrence or existence of the matters in dispute. That is perhaps best illustrated by his unwillingness to find that the imputations concerning the mission to Fasil on 5 November 2012 were substantially true, despite evidence from an SASR member (Person 16), which his Honour accepted in the face of the appellant’s denials, that the appellant had admitted to shooting a young, unarmed Afghan adolescent in the head and gloating about it. His Honour said at J[1686]:

Having regard to all the evidence, including the absence of an eyewitness to the alleged execution, and the nature of the allegations, I do not think the respondents’ case can succeed unless the Court is clearly satisfied that the deceased Afghan male shown in exhibit R105 is the young Afghan male detained by Person 16.

Exhibit R105 was a photograph of a deceased Afghan male.

25 While Person 16 identified the man in the photograph with “a high degree of confidence” as the man he had detained and the primary judge did not doubt the honesty of Person 16, his Honour did not consider that the identification evidence was “sufficiently clear and cogent” to support a finding that the deceased Afghan male in the photograph was the man detained by Person 16 (at J[1688]-[1692]).

26 Similarly, while his Honour did not accept the appellant’s evidence about any of the matters in dispute in relation to the allegations concerning the imputations relating to Person 17, who testified that she had been assaulted by the appellant, his Honour did not consider her evidence to be sufficiently reliable to make out the substantial truth of the imputations themselves (J[2226]).

27 The appellant also repeatedly criticised the primary judge for failing to consider the reliability of the testimony of witnesses, claiming that he focussed on credibility only. These criticisms are unwarranted. The reasons must be read as a whole. At J[162]–[166] his Honour discussed the fallibility of human memory, particularly with the passage of time, and the effect of imagination, emotion, prejudice and suggestion. The particular attention his Honour gave to the credibility of the witnesses was an inevitable result of the attention given to the matter in the submissions made on behalf of both the appellant and the respondents.

The nature of the appeal and the advantages of the primary judge

28 This is an appeal by way of rehearing. Speaking of appeals of this kind, Gibbs ACJ, Jacobs and Murphy JJ said in Warren v Coombes (1979) 142 CLR 531 at 551:

[I]n general an appellate court is in as good a position as the trial judge to decide on the proper inference to be drawn from facts which are undisputed or which, having been disputed, are established by the findings of the trial judge. In deciding what is the proper inference to be drawn, the appellate court will give respect and weight to the conclusion of the trial judge but, once having reached its own conclusion, will not shrink from giving effect to it.

29 The respect and weight to be afforded the conclusion of the primary judge is not limited to findings likely to have been affected by assessments of demeanour, as the appellant seemed to suggest. That is clear from what the High Court said in a number of cases.

30 As Lord Sumner observed in SS Hontestroom v SS Sagaporack [1927] AC 37 at 47 in a passage cited with approval by McHugh J in Abalos v Australian Postal Commission [1990] HCA 47; 171 CLR 167 at 178 (Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson and Gaudron JJ agreeing) and affirmed in many later authorities, including Devries v Australian Railways Commission [1993] HCA 78; 177 CLR 472 (Devries):

[N]ot to have seen the witnesses puts appellate judges in a permanent position of disadvantage as against the trial judge, and, unless it can be shown that he has failed to use or has palpably misused his advantage, the higher Court ought not to take the responsibility of reversing conclusions so arrived at, merely on the result of their own comparisons and criticisms of the witnesses and of their own view of the probabilities of the case. The course of the trial and the whole substance of the judgment must be looked at, and the matter does not depend on the question whether a witness has been cross-examined to credit or has been pronounced by the judge in terms to be unworthy of it. If his estimate of the man forms any substantial part of his reasons for his judgment the trial judge’s conclusions of fact should, as I understand the decisions, be let alone.

31 In Devries at 479-480 Deane and Dawson JJ remarked:

An appellate court which is entrusted with jurisdiction to entertain an appeal by way of rehearing from the decision of a trial judge on questions of fact must set aside a challenged finding of fact made by the trial judge which is shown to be wrong. When such a finding is wholly or partly based on the trial judge’s assessment of the trustworthiness of witnesses who have given oral testimony, allowance must be made for the advantage which the trial judge has enjoyed in seeing and hearing the witnesses give their evidence. The “value and importance” of that advantage “will vary according to the class of case, and, … [the circumstances of] the individual case” (Watt (or Thomas) v Thomas [1947] AC 484 at 488 per Lord Thankerton).

32 In Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; 214 CLR 118 (Fox v Percy) at [23] Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby J explained that, while an appellate court is obliged to give the judgment it considers should have been given at first instance:

[I]t must, of necessity, observe the “natural limitations” that exist in the case of any appellate court proceeding wholly or substantially on the record. These limitations include the disadvantage that the appellate court has when compared with the trial judge in respect of the evaluation of witnesses’ credibility and of the “feeling” of a case which an appellate court, reading the transcript, cannot always fully share. Furthermore, the appellate court does not typically get taken to, or read, all of the evidence taken at the trial. Commonly, the trial judge therefore has advantages that derive from the obligation at trial to receive and consider the entirety of the evidence and the opportunity, normally over a longer interval, to reflect upon that evidence and to draw conclusions from it, viewed as a whole.

(Footnotes omitted.)

33 The limitations to which their Honours adverted unquestionably apply to the present appeal.

34 Further, in Fox v Percy at [93] McHugh J observed:

[N]othing has occurred that would justify abandoning the current doctrines of appellate review, doctrines that have remained unchanged for over a century. The nature of the materials that appellate courts act on remain the same as they were in the last quarter of the nineteenth century when the principles of appellate review were formulated and developed. No persuasive research suggests that the interests of justice would be better served if appellate courts decided appeals on the printed record without regard to the advantage that the trial judge has in seeing and hearing the witnesses …

35 In Rosenberg v Percival [2001] HCA 18;205 CLR 434 at [41], McHugh J said:

One of the consequences of the “advantage” of seeing and hearing the witnesses is that the trial judge is in a far better position than an appellate court to know what individual weight should be assigned to the various factors — credibility, matters for and matters against — that must be evaluated in making the ultimate findings of fact in the case. Where a finding is based on credibility and other facts support the finding, the case would need to be exceptional before an appellate court could set aside the finding on the ground that, judging by the transcript, the trial judge gave insufficient weight or consideration to other facts and circumstances in the case. The common law tradition is an oral tradition. Trial by transcript can seldom be an adequate representation of an oral trial before a judge or an oral trial before a judge and jury.

36 That is particularly true of a case like this in which the trial ran for 110 days over a period of more than 13 months, in which 44 witnesses were called and over a thousand documents tendered, in which ferocious attacks were made on the credibility of key witnesses, and in which details matter. With respect to the latter, for example, it was commonplace for witnesses’ attention to be drawn to maps and photographs as they were giving their evidence. While counsel endeavoured to explain the witnesses’ annotations to and explanations of those documents, the primary judge had the advantage of seeing the witnesses mark these documents in real time. There is no substitute for being in the room and hearing the evidence as the case unfolds.

The significance of the wholesale rejection of the appellant’s case

37 In relation to each of the matters the subject of the appeal, the primary judge found that the appellant had presented false accounts of the events in question and rejected him and the witnesses he called to support it as witnesses of truth.

38 Of course, the mere fact that a witness is disbelieved does not prove the opposite of what the witness asserted: Steinberg v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1975) 134 CLR 640 at 694 (Gibbs J). Moreover, as Gibbs J observed in that case (also at 694), it is sometimes said that where a witness’s account is disbelieved, “the result is simply that there is no evidence on the subject”. Still, that is incorrect “as a universal proposition”. As his Honour explained:

There may be circumstances in which an inference can be drawn from the fact that the witness has told a false story, for example, that the truth would be harmful to him; and it is no doubt for this reason that false statements by an accused person may sometimes be regarded as corroboration of other evidence given in a criminal case: Eade v. The King [(1924) 34 CLR 153 at [158]; Tripodi v. The Queen [(1961) 104 CLR 1]. Moreover, if the truth must lie between two alternative states of fact, disbelief in evidence that one of the state of facts exists may support the existence of the alternative state of facts: Lee v Russell [[1961] WAR 103 at 109].

39 The respondents’ case was in part a circumstantial one. “Often enough”, in such a case, as the plurality observed in R v Hillier [2007] HCA 13; 228 CLR 618 at [48] (Gleeson CJ agreeing at [1]), “there will be evidence of matters which, looked at in isolation from other evidence, would yield an inference compatible with the innocence of the accused, [b]ut neither at trial, nor on appeal, is a circumstantial case to be considered piecemeal”. Of course this is a civil case, not a criminal one, but the same holds true here. In deciding whether a trial judge erred, a court is not entitled to disregard parts of the evidence. Yet that is what the appellant urged this Court to do. While he did not challenge any of the adverse findings of the primary judge about his own credit or that of his witnesses, he submitted that the Court was required to put those findings to one side and focus only on the evidence adduced by the respondents in their own case. Where, as here, however, a party who does not shoulder the burden of proof chooses to give evidence, the fact that that evidence was disbelieved does not mean that his testimony (and that of the witnesses he called to support it) can be put to one side. The Court cannot pretend that the evidence was not given. In the context of a murder case based on circumstantial evidence, the High Court explained in R v Baden-Clay [2016] HCA 35; 258 CLR 308 at [57]:

[T]he respondent chose to give evidence. To say that the respondent’s evidence was disbelieved does not mean that his evidence could reasonably be disregarded altogether as having no bearing on the availability of hypotheses consistent with the respondent’s innocence of murder. His evidence was important, even if it was disbelieved, because it was open to the jury to consider that the hypothesis identified by the Court of Appeal was not a reasonable inference from the evidence when the only witness who could have given evidence to support the hypothesis gave evidence which necessarily excluded it as a possibility.

40 How this principle applies is discussed further below.

WHISKEY 108

Introduction

41 The appellant was a member of G Troop. On the morning of 12 April 2009, G Troop established an overwatch position on the western side of the Deh Rafshan river. On the eastern side, the 7th Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment was being engaged by insurgents as part of the second Battle of Kakarak. The regiment was part of the broader Mentoring and Reconstruction Taskforce (MRTF). The insurgents were operating out of several compounds on the western side of the river. The word “compound” has a military connotation but the evidence shows that the compounds were very basic rural structures made from mud and used for mixed purposes including habitation and farming.

42 Two particular compounds were identified as harbouring insurgents. These were designated Whiskey 108 and Whiskey 109. During the morning, G Troop observed numerous insurgents manoeuvring against the MRTF from its overwatch position and engaged them with sniper fire. Three insurgents were observed entering Whiskey 108 over the course of the day. A drone located high above the battlefield also detected insurgents at Whiskey 108 and this intelligence was conveyed to G Troop.

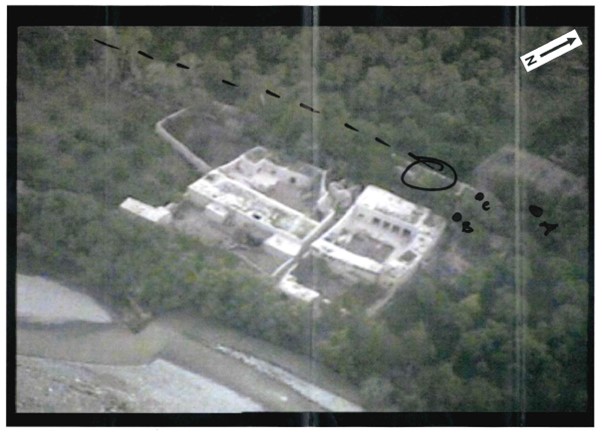

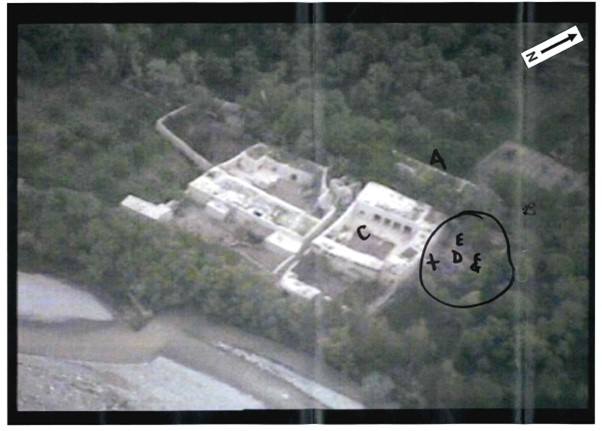

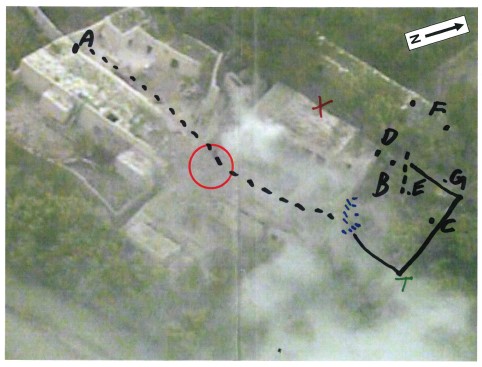

43 After the detection of insurgent activity at Whiskey 108, a 500lb bomb was dropped on the compound. This occurred at 12.21pm and caused extensive damage to its northern end. As the primary judge noted, there was a misunderstanding on the day of the mission concerning cardinal directions such that north (which is correctly displayed on the aerial photographic evidence of Whiskey 108) was thought by troops on the ground to be more parallel to the river. As a result the courtyard relevant to the events occurring at Whiskey 108 was described in the oral evidence as being at the northwestern end of the compound despite the photographs instead showing it more around the northeast. At any rate, the primary judge did not consider this misunderstanding created any confusion with the evidence and we, like his Honour, will proceed by reference to the cardinal points as they were understood on the day. A decision was then made that G Troop would clear Whiskey 108 and Whiskey 109 of insurgents. Orders to that effect were given to the patrol commanders of the troop by its captain, a person known in this proceeding as Person 81.

44 The troop itself was divided into five patrols and a headquarters unit. These were as follows:

(a) Headquarters – consisting of the captain, Person 81; the troop sergeant, Person 82; and an interpreter.

(b) Gothic 1 – consisting of a sergeant, Person 44; a corporal, Person 45; and four privates: Persons 27, 46, 47 and 48.

(c) Gothic 2 – consisting of a sergeant, Person 29; a corporal, Person 40; and four privates: Persons 35, 38, 41 and 42.

(d) Gothic 3 – consisting of a sergeant, Person 43; a corporal, Person 72; and four privates: Persons 3, 98, 108 and 109.

(e) Gothic 4 – consisting of a sergeant, Person 6; a corporal, Person 73; and four privates, Persons 14, 24, 68 and 80.

(f) Gothic 5 – consisting of a sergeant, Person 5; the appellant, who was then a lance corporal; and three privates: Persons 4, 18 and 52.

45 For the mission to Whiskey 108, the five patrols were given functions either as assault patrols or as cordon and security patrols. The role of the assault patrols was to enter Whiskey 108 and clear it of insurgents. The role of the cordon patrols was to provide a cordon around the compound and external security for the compound. The assault patrols were Gothic 2 and Gothic 5. During the assault phase, the cordon patrols were Gothic 1, Gothic 3 and Gothic 4.

46 The overwatch position which the troop occupied was known as the vehicle drop off point (VDOP). The troop stepped off the VDOP at around 3 pm. It proceeded in a formation known as open file which is essentially a wedge shaped formation with a single patrol leading the way at the wedge’s apex. The patrol at the front was Gothic 4.

47 The troop approached the compound from the south. On the approach, Gothic 4 engaged three insurgents and killed them. An insurgent killed in action is referred to as an enemy killed in action or “EKIA” or sometimes just as a “KIA”. The last of these insurgents was designated EKIA50. The body of EKIA50 was close to the northwest corner of the compound. Although he did not accept this at trial, the appellant now accepts that Gothic 4 was located off the northwest corner of the compound.

48 The two assault patrols entered the compound through an alleyway which opened up about half way along the compound’s western wall. The appellant’s patrol, Gothic 5, entered first followed by the other assault patrol, Gothic 2. The southern half of the compound was cleared first. On balance, the evidence indicated that there were local nationals (not insurgents) in the southern end of the compound. Having cleared the southern part of the compound, Gothic 2 and Gothic 5 then proceeded to clear the northern part of the compound.

49 At the western end of the northern edge of the compound there was an adjoining courtyard which was enclosed by walls and measured approximately 18 metres by 30 metres. Its precise purpose was not altogether clear. It may have been an animal pen, or perhaps a cooking area or even a latrine. The courtyard had two means of ingress and egress. One was through a gap in the compound wall. It was possible to pass through this gap in a northerly direction and thereby to gain access to the courtyard. The other was through a gap in the wall of the courtyard. Through this latter gap it was possible to gain access to the area outside the western wall.

50 It is convenient at this point to make an observation about nomenclature. The courtyard was treated as being part of the compound both in much of the evidence and in the primary judge’s reasons which was entirely appropriate since the courtyard forms part of the overall structure. It does have the consequence, however, that sometimes the northwest corner of the courtyard is referred to as the northwest corner of the compound and vice versa. The two corners are the same corner. We will refer to the corner as the northwest corner of the compound unless the context otherwise requires. Similarly, sometimes the western wall of the courtyard is referred to as the western wall of the compound (since it is part of the same wall). We will use the expression “the western wall of the compound” where what is being discussed does not directly concern the western wall of the courtyard but will use the latter expression where the subject matter concerns the courtyard.

51 Returning to the events on the day, once the compound had been cleared and declared secure, the duties of some of the patrols were reassigned. There were two kinds of duty. The first was maintaining cordon security around the compound and the second was conducting a process known as Sensitive Site Exploitation (SSE) within the compound and its local environs (such as nearby sheds). The SSE process involved a thorough search for items of interest such as explosives, weapons and the bodies of dead insurgents. This SSE process was documented in written and photographic records which were available at trial.

52 Once the formal declaration that the compound was secure had been made, Gothic 3 and Gothic 4 were given cordon duties. In the case of Gothic 4, this entailed that it remained off the northwest corner of the compound where it was already located having engaged EKIA50. Gothic 3 was at the southern end of the compound. Gothic 1 appears to also have been engaged in security duties. Gothic 2 and Gothic 5 were assigned SSE duties.

53 Another event which occurred when a compound is declared secure was a meeting between the troop commander, the captain (in this case Person 81), the troop sergeant (in this case Person 82), and each of the patrol commanders (in this case, the sergeants Persons 44, 29, 43, 6 and Person 5). This meeting was known as the RV meeting (the RV meeting). Although there was a dispute about this at trial it is no longer in dispute that the RV meeting occurred inside the compound.

54 It is now also uncontroversial that after the compound had been declared secured and during the SSE process which followed, a tunnel was discovered in the courtyard. The tunnel entrance was located about halfway along the northern wall of the courtyard. The discovery of the tunnel occurred at or around the time that the RV meeting was beginning.

55 At or just after the time the tunnel was discovered, it is no longer controversial that five soldiers called as witnesses by the respondents were present in the courtyard. These were Persons 18, 40, 41, 42 and a sergeant, Person 43, the patrol commander of Gothic 3. Also present in the courtyard at around that time were the appellant and four witnesses who testified on his behalf: Persons 5, 29, 35 and 38. Person 5 was the patrol commander of the appellant’s patrol, Gothic 5. Person 29 was the patrol commander of Gothic 2.

56 At trial these witnesses for the appellant gave evidence that they alone had discovered the tunnel before the compound was declared secure and that when they did so no persons had been discovered inside it. However, this evidence became untenable during the trial. The evidence became untenable because of the evidence of Persons 18, 40, 41, 42 and 43 all of whom gave evidence of having been in the courtyard at or around the time the tunnel was discovered and some of whom gave evidence that they saw men being brought out of the tunnel. The appellant accepted on appeal that each of these witnesses was in the courtyard at or around the time the tunnel was discovered. He also accepted that the tunnel was discovered after the compound was declared secure. Furthermore, he does not challenge the honesty of any of these witnesses.

57 The events which unfolded after the tunnel was discovered constitute the terrain of dispute between the parties. That dispute may be passed over for now. But it is useful to record an important fact which is no longer contested. The appellant has accepted that an old man was shot dead in the tunnel courtyard by Person 4 and that his body lay where it fell. What remains in dispute about the old man is not whether he was shot dead by Person 4 in the courtyard but rather whether the killing was a murder or a lawful engagement and, if the former, whether it was a murder carried out on the orders of the appellant. This is an important fact to keep in mind when the time comes to consider the appellant’s various submissions about the weaknesses and contradictions in the respondents’ case at trial.

The respondents’ case at trial

58 The respondents’ case was that after the tunnel was discovered the old man and the man with the prosthetic leg were discovered inside it and brought out. They were placed under control and taken by the appellant and Person 35 for tactical questioning. Subsequently, the old man was brought back into the courtyard and executed by Person 4 on the orders of the appellant. The appellant then left the courtyard. Sometime after that, he carried or frogmarched the man with the prosthetic leg out the gap in the western wall of the courtyard and carried him about five metres to a point just outside the compound off its northwest corner. There the appellant threw the man with the prosthetic leg on the ground and killed him with machine gun fire.

59 To prove this case the respondents called the following witnesses whose evidence touched directly on this case. They were Persons 4, 18, 40, 41, 42, 43, 14 and 24.

Person 18

60 Person 18 was a soldier in Gothic 5. Other members of Gothic 5 were its sergeant, Person 5, the appellant who was its second in charge (2IC) and two soldiers, Person 4 and Person 52. Person 18 gave evidence relevant both to the death of the old man and the death of the man with the prosthetic leg together with evidence on other topics.

Person 18’s evidence concerning the old man

61 Person 18’s patrol, Gothic 5, was one of the two patrols that had cleared the compound before it was declared secure and the SSE process commenced. Person 18 had a speciality in the SSE process. He described it as a process by which evidence was labelled and moved back to the base.

62 Once the SSE process commenced, Person 18 began to search the compound. He went back to the entry point on the western side of the compound (where the alleyway entrance was) and began searching the rubble (recalling that a 500lb bomb had been dropped on the compound some hours before). Person 18 then worked clockwise around the compound from that point. He recalled a cache of rockets having been found by someone in a wall. While he was doing this on the western side of the compound, he received a radio call that a tunnel had been found and that a person or persons had been pulled out of it. He recalled that at this time the meeting of patrol commanders (the RV meeting) was taking place. When he arrived at the courtyard, he saw an Afghan male wearing flexicuffs (handcuffs made of plastic straps), who was dressed in white, together with two or three soldiers. He did not think this was unusual as the finding of Afghan males in a compound was a regular occurrence. He went over to the tunnel and looked down into it. He recalled another soldier, Person 35, went down into the tunnel and Person 18 slid in after him so that he was up to his waist “inside the tunnel leaning on the stairs”.

63 Person 18 did not give any evidence of having seen the man with the prosthetic leg before undertaking the SSE process on his body.

The evidence of Person 18 concerning the man with the prosthetic leg

64 After his involvement in the clearance of the tunnel Person 18 returned to where he had been before the radio call and recommenced searching that area. This area consisted of some rooms on the western side of the compound. While there he heard a conversation between the appellant’s patrol commander, the sergeant Person 5, and the appellant. They were no more than three metres away from Person 18. The conversation was as follows:

Person 5: You’ve just done this – done this whilst the ISR is still flying above and may have recorded you?

The appellant: We need to find out if the ISR was still above us.

(ISR is an acronym for Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance. It is a drone.)

65 Person 5 then sent a message on the troop internal chat to the Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC) during which the following was said:

Person 5: Where is the ISR platform and was it recording?

JTAC: No, I pushed the ISR off station after we made entry and was – pushed into another area that was a threat area.

66 This conversation was consistent with records which showed that the drone was not above at this time. The primary judge accepted that the conversation recounted by Person 18 had occurred.

Person 18’s examination of the bodies during the SSE process

67 Person 18 subsequently conducted the SSE process on three bodies. This involved him searching the bodies and placing anything found in an evidence bag which was then placed on the body’s chest and photographed. He started with the body of EKIA50 which was off the northwest corner of the courtyard near a break in a wall, then the body of the man with the prosthetic leg (referred to in the records as EKIA57) and finally the body of the old man in the courtyard (referred to in the records as EKIA56). The body of the old man was located near the tunnel entrance. Person 18’s evidence was that the notation “NW corn tunnel” on the evidence bag meant that the body was located at the northwest corner in the vicinity of the tunnel.

Person 18’s evidence concerning the weapons in the hay store

68 It was after his conduct of the SSE process on the three bodies that Person 18 discovered some weapons in a hay store which he photographed. This evidence is relevant to part of the appellant’s case that the old man and the man with the prosthetic leg were armed insurgents that he had engaged as they ran around the outside of the compound. The appellant purported to identify the weapons he claimed the men had been carrying in the photographs taken by Person 18. If Person 18’s evidence was correct, this could not be right.

Person 18’s evidence concerning the “blooding of the rookie”

69 When the troop got back to the VDOP, Person 18 heard the appellant and Person 5 say that they had “blooded the rookie”. Person 5, one of the appellant’s witnesses, denied having had such a conversation and the appellant denied using or hearing the phrase “blooding the rookie”. They supported this contention by eliciting evidence that the word “rookie” was not used in the troop and that, even if it were, Person 4 had already been “blooded” in an earlier engagement in which he, that is Person 4, had killed a target known as Objective Depth-charger.

70 But the respondents elicited evidence from Person 18 that it was a running joke between him and Person 4 that Person 4 was known as the “rookie” since Person 4 was 20 years older than Person 18. He also gave evidence of having been asked by a regimental sergeant major in 2014 whether he had heard a rumour about blooding the rookie at Whiskey 108. The relevance of this evidence was to suggest that the expression “rookie” was in use in the SASR. In addition, Person 18 had himself been part of the mission during which Objective Depth-charger had been killed. His evidence was that Objective Depth-charger had been first engaged by Person 6 and next by him and Person 14 who were on a ladder next to a wall. After them, the next to engage the Objective was Person 73. Person 18 said that if anyone had engaged after that they would have been killing a dead body. He could not rule out that Person 4 had engaged the Objective but he had not heard of that as a possibility until the week before he was cross-examined.

Person 40

71 Person 40 was the 2IC of Gothic 2, one of the two assault patrols that had cleared the compound. He gave evidence relevant to the deaths of both the old man and the man with the prosthetic leg.

72 He said that a thorough search was conducted during the SSE process. He found a cache of weapons that was well hidden within a wall. He recalled there was a gathering of key personnel from the troop which was broadly in the courtyard area (probably the RV meeting of patrol commanders). He described himself as bouncing back and forth. While doing so someone told him that they believed there was “a tunnel there”. He went into the courtyard. He recalled there being present in the courtyard the patrol commanders for each patrol (Persons 44, 29, 43, 6 and 5) as well as the troop commander (the captain, Person 81), the troop sergeant (Person 82) and an interpreter. He also recalled the presence of the appellant, Person 35 and two women who were looking concerned. He was about five to seven metres from the tunnel. The two women and the interpreter were calling into the tunnel for the persons within it to come out.

73 Person 40 thought that it was Person 35 who was instrumental in persuading the individuals to come out of the tunnel. He said two men came out of the tunnel and were very frightened. One had a distinctive limp and this was the man with the prosthetic leg. He was an older man with a beard and no shoes. Person 40 did not recall anything significant about the second man other than that he had a beard and was baldish. (It is worth interpolating here that the man with the prosthetic leg was not old).

74 Person 40 said the two men were searched and then marched off to another area by the appellant and Person 35. Person 40 considered they were being taken for tactical questioning. He was unable to recall whether they were handcuffed, but he thought that they would have been since it was standard practice for this to be done.

75 Person 40 gave no evidence of having heard a single suppressed shot from an M4 rifle. The relevance of this is that, according to Person 41, the old man was shot dead by Person 4 using an M4 rifle fitted with a suppressor. It is not controversial that a suppressor reduces the sound of a shot but does not eliminate it.

76 After the two men were taken away, Person 40 went out of the compound to the northwest side and took up a defensive position. He was waiting for the next command when he heard a burst of machine gun fire from an LSW or F89 (also known as a Para Minimi). He was facing out and the sound came from his right and was quite close, about 30 metres away. Person 40 did not say how many rounds were in the burst of fire he heard. There was then initial confusion on the radio with people saying “What was that? Where did that come from?”.

77 Sometime later, as he left the compound, he saw the body of the man with the prosthetic leg outside the northwest corner of the courtyard. He recognised the body as being one of the men who had come out of the tunnel.

Conversations involving Person 40

78 We consider the evidence of Person 41 and Person 42 below. But it is useful to note at this point that both gave evidence of conversations with Person 40 on the day. Person 41 gave evidence that Person 40 had asked him “Do you know what happened to those two blokes that they pulled out of the tunnel?” to which Person 41 had replied “No mate, I was just in that cowshed there” (the cow sheds are discussed below). Person 43 gave evidence that Person 40 had asked him just as the troop was leaving Whiskey 108 where the PUCs were: Person 43 had replied “You know where they are”; and Person 40 had responded “That’s fucked”.

79 In addition to these two conversations, Person 40 himself recounted a conversation back at the base at Tarin Kowt where he had told Person 42 that what had happened was wrong.

80 The primary judge found that these witnesses had not colluded in giving their evidence and were reliable. He therefore found that these conversations occurred in the terms suggested.

Person 41

81 Person 41 was a member of Gothic 2, which it will be recalled was one of the two assault patrols that had cleared the compound. He was probably the most important witness in the case concerning Whiskey 108 as he gave direct testimony about both killings.

The killing of the old man

82 When Person 41 went to the courtyard for the first time, he saw the appellant and Persons 4, 5, 35 and 29. He had a bit of a look around and “there didn’t appear to be too much there”. At that point, someone – either Person 29 or Person 35 – discovered a tunnel entrance. Person 41 recalled standing around it with Persons 29 and 35. Person 29 started yelling down the tunnel and this went on for a short time. Person 41 did not see anyone come out of the tunnel. As he concluded that not much was going on there, he left the tunnel area to look at two rooms on the northwest of the courtyard. In the first room he saw batteries on a makeshift shelf together with a lot of wires. Damage to the walls caused by the 500lb bomb strike revealed hidden items in the walls such as wood, hacksaw blades and more wires. He concluded that the Afghan nationals must have been making improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in the room. He also observed two or three large bags of a black sticky substance which he later identified as opium.

83 He searched the room for “probably a minute or two”. This statement by Person 41 forms one of the appellant’s central points on appeal and we will return to it in more detail later. This point concerns how much activity could have occurred in the courtyard while Person 41 was away from it for “probably a minute or two”.

84 It was at this point that Person 41 heard some louder voices and “a bit of a commotion” outside in the courtyard. He stepped out of the room, which contained the IED components and the opium and back into the courtyard. He noticed the appellant and Person 4 standing to his immediate left. Just beyond them and squatting against the northeast wall near the tunnel entrance was an Afghan male who Person 41 described as an older male with short-cropped hair dressed in a traditional Afghan loose top with either white or very light-coloured clothing.

85 The appellant and Person 4 approached Person 41 and asked him whether they could borrow his suppressor. A suppressor suppresses the flash and noise of a rifle. Unlike a silencer, however, a suppressor does not make a weapon completely silent. He thought this a strange request but nevertheless complied. He thought it a strange request because Person 4 would have had his own suppressor. He thought that perhaps Person 4 was going down into the tunnel and needed the suppressor to muffle any sound made in the tunnel.

86 In any event, Person 41 removed the suppressor from his own M4 rifle and handed it to Person 4. Person 4 turned around and began fitting the suppressor to his M4. The appellant and Person 4 then began walking towards the old man who was still squatting against the wall. At this point Person 41 thought to himself “I think I know what’s about to happen here”.

87 Even so, he stood there and watched for a few seconds. He saw that Person 4 was facing the old man towards the tunnel entrance. Then the appellant walked down and grabbed the old man by the scruff of his shirt, picked him up and marched him a couple of metres until he was in front of Person 4. The appellant kicked the old man in the back of the legs just behind the knees until he was kneeling in front of Person 4. The appellant then pointed at the old man and said to Person 4 “Shoot him”. As he said this, the appellant stepped to the side.

88 By this time, Person 41 was about three metres from the old man, Person 4 and the appellant. Person 41 did not wish to witness what was about to occur, so he stepped back into the room where he had found the IED components. Within a second or two he heard a single suppressed shot which he knew was from an M4 rifle. He waited for 15 seconds or so and then stepped back out of the room and into the courtyard.

89 When he stepped into the courtyard there were only two people there: Person 4 and the old man he had previously seen by the wall who was now dead. It is implicit that the appellant had left the courtyard. Person 41 walked over to Person 4 who did not say anything. Person 4 then removed the suppressor from his rifle and gave it back to Person 41. The suppressor was warm so Person 41 knew that it had just been used to shoot the old man. Person 41 refitted the suppressor to his own M4, after which he walked over to look at the body of the old man.

90 The old man had been shot once in the head. A lot of blood was flowing around out of his head wound and he was lying on his back. Photographs taken of the old man by Person 18 during the SSE process (referred to above) show a large amount of blood around the head of the old man. Person 41 thought that Person 4 seemed to be “in a bit of shock”. It should be noted that although it was controversial at trial, the appellant has accepted that the old man was killed in the courtyard and that he was killed by Person 4.

91 The appellant no longer contends that the body of the old man had been moved from elsewhere. This contention was made impossible by the photographs of the old man’s body which, without dwelling on the detail, unquestionably show that he died where his body lay.

The killing of the man with the prosthetic leg

92 After he had looked at the body of the old man in the courtyard, Person 41 then walked out through the exit on the north-western side of the compound. He stopped on a footpad running alongside the wall of the compound which was about two metres wide. He looked to the front and noticed two small buildings just up a slight hill in front of him, not very far away. Person 41 later referred to these two structures as cowsheds. He decided to go and search these cowsheds when he noticed the appellant out of the corner of his eye to his right about five metres away from him, walking along the outside wall of the compound. The appellant was walking up towards him holding another Afghan male by the scruff of his clothing with his left arm and holding up a machine gun with his right arm. The Afghan male was wearing a dark coloured top. He described the appellant as frogmarching the man. At this point, Person 41 turned to face the appellant to see what was happening. He saw the appellant throw the man on the ground on his back. The appellant reached down, grabbed the man by the shoulder and flipped him over on to his stomach. The appellant then lowered his machine gun and shot approximately three to five rounds into the man.

93 After shooting the man, the appellant looked at Person 41 and said “Are we all cool? Are we all good?”. Person 41 replied “Yeah, mate, no worries”. Person 41 continued to look at the appellant who walked past him and back into the courtyard through the exit that Person 41 had himself come through.

94 Person 41 identified the man who had been shot as the man with the prosthetic leg. He then proceeded to the two buildings he had seen (up the slight hill). There he had a conversation with Person 40 who said to him “Hey [Person 41], do you know what happened to those two blokes they pulled out of the tunnel?”. Person 41 replied “No, mate, I was just in that cowshed there”.

Person 42

95 Person 42 was a soldier in the same assault patrol as Person 41, that is to say, Gothic 2. His evidence was relevant only to the death of the old man.

96 When Person 42 first entered the courtyard he recalled his whole patrol being present there. Person 42 said that there were women in the courtyard when the tunnel was discovered. They had been making a noise and indicating that there was something else within the courtyard. A more thorough search was then conducted and the tunnel was found. He recalled Persons 35 and 38 being present when the tunnel was found. He was unable to recall who else was present. He said that either he or another soldier were shouting down into the tunnel in broken Pashto. He believed it was Person 29 who called the men out of the tunnel but he was not completely sure of this.

97 After the tunnel had been discovered, members of his patrol (Gothic 2) had their weapons trained on it. Members of the patrol were shouting out to have anyone in the tunnel come out. He recalled men coming out of the tunnel. There were at least two men but there could have been three. He did not recall anything specific about the men’s physical appearance. They were unarmed and came out freely. They were subject to a pat down search. This was to ensure that they were not carrying concealed weapons or any type of suicide vest or fragmentation grenades.