FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited [2025] FCAFC 63

Appeal from: | Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (No 5) [2024] FCA 477 Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (No 6) [2024] FCA 1097 |

File numbers: | VID 572 of 2024 NSD 815 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | MURPHY, MOSHINSKY AND BUTTON JJ |

Date of judgment: | 7 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | CORPORATIONS - continuous disclosure – whether the respondent (the Bank) breached its continuous disclosure obligations under s 674 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and rule 3.1 of the ASX Listing Rules – where, over a period of about three years (from November 2012 to September 2015), the Bank failed to provide approximately 53,000 threshold transaction reports (TTRs) to AUSTRAC as required by law – where the Bank subsequently lodged the TTRs in September 2015 – where the Bank did not disclose that failure to the market at any time up to 3 August 2017 – where, on 3 August 2017, AUSTRAC commenced a proceeding against the Bank about several matters including that failure – where the Bank’s share price then dropped substantially – where the primary judge decided that the Bank did not have awareness of certain aspects of the pleaded information at the times alleged – where the primary judge decided that the pleaded information was not complete and accurate – where the primary judge concluded that the pleaded information, if considered with contextual matters, was not material – where the primary judge decided that the applicants had not established causation or loss – whether the primary judge erred in reaching those conclusions |

Legislation: | Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (Cth), ss 5, 6, 43, 81, 82, 83, 85, 162, 175, 184, 191, 197 Banking Act 1959 (Cth) Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), ss 674, 677, 111AE, 111AC, 111AL Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Rules Instrument 2007 (Cth) Federal Court Rules 2011, r 16.08 |

Cases cited: | Allen v The Queen [2014] VSCA 180 Armory v Delamirie (1722) 1 Stra 505; 93 ER 664 Australian Energy Regulator v AGL Retail Energy Ltd [2024] FCA 969 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (No 2) [2023] FCA 1217 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Big Star Energy Limited (No 3) [2020] FCA 1442; 389 ALR 17 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Fortescue Metals Group Ltd (No 5) [2009] FCA 1586; 264 ALR 201 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vocation Limited (in liq) [2019] FCA 807; 136 ACSR 339 Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2024] FCAFC 128 Baden v Société Générale pour Favoriser le Développement du Commerce et de l’lndustrie en France SA [1993] 1 WLR 509; [1992] 4 All ER 161 Banque Commerciale SA, En Liquidation v Akhil Holdings Ltd [1990] HCA 11; 169 CLR 279 Berry v CCL Secure Pty Ltd [2020] HCA 27; 271 CLR 151 Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1833; 117 FCR 424 CCL Secure Pty Ltd v Berry [2019] FCAFC 81 Cessnock City Council v 123 259 932 Pty Ltd [2024] HCA 17; 418 ALR 304 Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited [2018] FCA 930 Commonwealth v Amann Aviation Pty Limited [1991] HCA 54; 174 CLR 64 Coulton v Holcombe [1986] HCA 33; 162 CLR 1 Crowley v Worley Limited [2022] FCAFC 33; 293 FCR 438 Crowley v Worley Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 1613; 171 ACSR 410 Cruickshank v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2022] FCAFC 128; 292 FCR 627 Cubillo v Commonwealth (No 2) [2000] FCA 1084; 103 FCR 1 Fink v Fink [1946] HCA 54; 74 CLR 127 Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] HCA 39; 247 CLR 486 Gould v Mount Oxide Mines Ltd [1916] HCA 81; 22 CLR 490 Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Ltd (in liq) [2015] FCA 149; 322 ALR 723 Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Ltd (in liq) [2016] FCAFC 60; 245 FCR 402 James Hardie Industries NV v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2010] NSWCA 332; 274 ALR 85 JLW (Vic) Pty Ltd v Tsiloglou [1994] 1 VR 237 Jubilee Mines NL v Riley [2009] WASCA 62; 40 WAR 299 Keys Consulting Pty Ltd v CAT Enterprises Pty Ltd [2019] VSCA 136 Kismet International Pty Ltd v Guano Fertilizer Sales Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 375 Longden v Kenalda Nominees Pty Ltd [2003] VSCA 128 MA & J Tripodi Pty Ltd v Swan Hill Chemicals Pty Ltd [2019] VSCA 46 Masters v Lombe (Liquidator); In the Matter of Babcock & Brown Limited (in liq) [2019] FCA 1720 Metwally v University of Wollongong [1985] HCA 28; 60 ALR 68 National Australia Bank Ltd v Pathway Investments Pty Ltd [2012] VSCA 168; 265 FLR 247 Placer (Granny Smith) Pty Ltd v Thiess Contractors Pty Ltd [2003] HCA 10; 196 ALR 257 R v Myer [2023] QCA 144 Re HIH Insurance Ltd (in liq) [2016] NSWSC 482; 335 ALR 320 Sanda v PTTEP Australasia (Ashmore Cartier) Pty Ltd (No 7) [2021] FCA 237 TPT Patrol Pty Ltd v Myer Holdings Limited [2019] FCA 1747; 293 FCR 29 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Corporations and Corporate Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 621 |

Date of hearing: | 18 – 21 November 2024 |

Counsel for the Appellants: | Mr JT Gleeson SC with Mr WAD Edwards KC, Mr DJ Fahey, Ms C Winnett and Ms S Chordia |

Solicitor for the Appellant in VID 572 of 2024: | Maurice Blackburn |

Solicitor for the Appellants in NSD 815 of 2024: | Phi Finney McDonald |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr N Hutley SC with Ms E Collins SC, Mr I Ahmed SC, Mr T Kane and Ms S Crosbie |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Herbert Smith Freehills |

ORDERS

VID 572 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | ZONIA HOLDINGS PTY LTD Appellant | |

AND: | COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED Respondent | |

order made by: | MURPHY, MOSHINSKY AND BUTTON JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 May 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days, the parties provide any agreed minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Full Court’s reasons and in relation to costs.

2. If the parties cannot agree, then:

(a) within 21 days, each party file and serve its minute of proposed orders and a written submission (of no more than five pages) in support of those orders;

(b) within a further seven days, each party file and serve any responding written submission (of no more than two pages); and

(c) the issues of the form of orders and costs be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 815 of 2024 | ||

BETWEEN: | PHILIP ANTHONY BARON First Appellant | |

JOANNE BARON Second Appellant | ||

AND: | COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED Respondent | |

order made by: | MURPHY, MOSHINSKY AND BUTTON JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 May 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days, the parties provide any agreed minute of proposed orders to give effect to the Full Court’s reasons, and in relation to costs.

2. If the parties cannot agree, then:

(a) within 21 days, each party file and serve its minute of proposed orders and a written submission (of no more than five pages) in support of those orders;

(b) within a further seven days, each party file and serve any responding written submission (of no more than two pages); and

(c) the issues of the form of orders and costs be determined on the papers.

[Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

1 INTRODUCTION

1 These appeals relate to two representative proceedings that were commenced by shareholders of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (the Bank) against the Bank. In each proceeding, the applicants alleged that the Bank contravened its continuous disclosure obligations under s 674 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and rule 3.1 of the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Listing Rules (the Listing Rules), by not disclosing to the market operated by the ASX (on which the Bank’s shares (CBA shares) were traded) information that was said to be material.

2 The information that it was alleged the Bank should have disclosed comprised (in summary) information that:

(a) from around November 2012 to 8 September 2015, the Bank had failed to give threshold transaction reports (TTRs) on time for approximately 53,506 cash transactions of $10,000 or more processed through Intelligent Deposit Machines (IDMs);

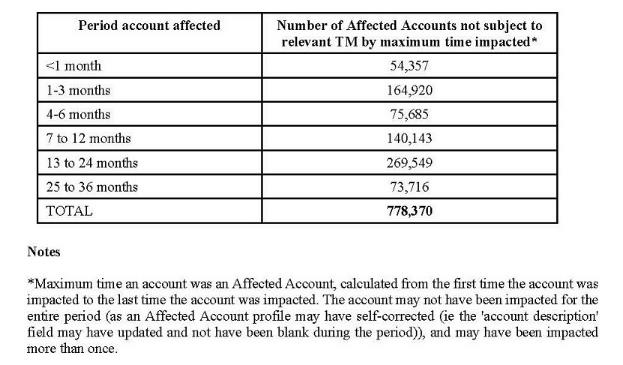

(b) from at least October 2012 to 8 September 2015, the Bank had failed to conduct account level monitoring with respect to 778,370 accounts;

(c) in the period prior to the roll-out of the Bank’s IDMs in May 2012, and subsequently, the Bank had failed to carry out any assessment of money laundering/terrorism financing (ML/TF) risk in relation to the IDMs; and

(d) the Bank was potentially exposed to enforcement action by the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC) in respect of allegations of serious and systemic non-compliance with the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (Cth) (the AML/CTF Act), which might result in the Bank being ordered to pay a substantial civil penalty.

3 The Bank did not disclose the pleaded information in the period up to 3 August 2017.

4 On 3 August 2017, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of AUSTRAC commenced a proceeding against the Bank seeking civil penalties and other relief (the Civil Penalty Proceeding) in relation to the failures identified in (a), (b) and (c) above and two other matters. The CEO also published a Tweet, with a link to a media statement about the commencement of the proceeding, which media statement had a link to AUSTRAC’s concise statement as filed in this Court on 3 August 2017 (the Concise Statement). In the immediate aftermath of the commencement of the proceeding, the Bank’s share price dropped substantially. Subsequently, in the Civil Penalty Proceeding, the parties jointly proposed, and the Court made orders for the Bank to pay, a pecuniary penalty of $700 million for the contraventions of the AML/CTF Act.

5 The applicant in one of the proceedings at first instance was Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd (Zonia) (the Zonia proceeding). The applicants in the other proceeding at first instance were Philip Baron and Joanne Baron (the Barons) (the Baron proceeding). Zonia and the Barons purchased CBA shares during the “relevant period” in the proceedings (see below).

6 The subject matter of the two proceedings overlapped and they were case managed together. The proceedings were not consolidated, but the pleadings were harmonised, such that the allegations in the two proceedings were substantially the same. The proceedings were heard together by the primary judge, and his Honour delivered a single judgment dealing with both proceedings: Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (No 5) [2024] FCA 477 (the Reasons), delivered on 10 May 2024. The primary judge decided that the applicants’ case against the Bank failed at a number of levels. In summary, the primary judge found that:

(a) the Bank was not “aware” of many of the forms of the pleaded information as at the relevantly pleaded dates, but found that the Bank was aware of some of the forms of the pleaded information on some of the relevantly pleaded dates: Reasons, [561], [565];

(b) all forms of the pleaded information were incomplete and, in some respects, misleading. Therefore, his Honour was not satisfied that Listing Rule 3.1 required the Bank to disclose that information in that form to the ASX: Reasons, [631]. The applicants’ case therefore failed before one even considered the “materiality” of the pleaded information;

(c) the exception to rule 3.1 contained in rule 3.1A of the Listing Rules did not apply: Reasons, [639];

(d) although the conclusion in (b) meant that the applicants’ case failed, the primary judge went on to consider the applicants’ case on materiality. The primary judge was not satisfied that the pleaded information, in any of its forms, was information that, if disclosed at the relevantly pleaded times, would (or would be likely to) influence persons who commonly invest in securities in deciding whether to acquire or dispose of CBA shares. Further, his Honour was not satisfied that the pleaded information, in any of its pleaded forms, was information that a reasonable person would expect, if the information were generally available at the relevantly pleaded times, to have a material effect on the price or value of CBA shares: Reasons, [1030];

(e) even if the applicants had succeeded in their case on contravention, he would not have found that their case on causation was established: Reasons, [1245]; and

(f) leaving to one side the fact that the applicants’ case had failed at a number of levels (so that one never gets to the assessment of damages), he concluded that their case on the assessment of damages also failed: Reasons, [1246].

7 The primary judge made orders in each proceeding to give effect to those reasons on 28 May 2024. The orders included that the proceeding be dismissed and that the common questions be answered as set out in the orders.

8 Zonia and the Barons (the appellants) appeal to this Court from the judgment and orders of the primary judge. The two appeals were heard together over a period of four days. The same lawyers represented Zonia and the Barons in both appeals. The same lawyers represented the Bank in both appeals. The issues raised by the two appeals are essentially the same, and the parties’ submissions generally did not differentiate between the two appeals. Consistently with this, we will deal with the two appeals together and generally will not differentiate between them.

9 The appellants’ case on appeal is in some respects narrower than their case at first instance. The period of time relied upon is shorter. At first instance, the “relevant period” for the purposes of the applicants’ case was from 16 June 2014 to 1.00 pm on 3 August 2017, but on appeal the appellants rely on the period from 8 September 2015 to 1.00 pm on 3 August 2017. Relatedly, some aspects of the pleaded information relied upon by Zonia and the Barons at first instance are no longer relied upon. When we refer to the “pleaded information” in the following summary of the issues on appeal, we are referring only to the aspects of the pleaded information that are relied upon on appeal. In light of the narrowing of the appellants’ case, the appellants accept that Zonia’s personal claim should be dismissed irrespective of the outcome of the appeal.

10 The Bank has cross-appealed from one of the orders made by the primary judge in each proceeding, namely the order in which his Honour ordered that one of the common questions, relating to the exception in rule 3.1A of the Listing Rules, be answered in a particular way. The Bank contends that the primary judge erred in concluding that the exception in rule 3.1A of the Listing Rules did not apply.

11 The issues raised by the appeals and cross-appeals may be summarised as follows:

(a) whether the primary judge erred in his findings relating to whether the Bank was aware, for the purposes of Listing Rule 3.1 and s 674(2) of the Corporations Act, of the pleaded information (the Awareness issue);

(b) whether the primary judge erred in dealing with the completeness and accuracy of the pleaded information as a threshold issue (rather than as part of the materiality analysis) and in concluding that the pleaded information was incomplete and, in some respects, misleading and therefore the Bank was not obliged to notify the ASX of that information (the Completeness and Accuracy issue);

(c) whether the primary judge erred in concluding that the exception in rule 3.1A of the Listing Rules did not apply to the pleaded information (the Rule 3.1A issue);

(d) whether the primary judge erred in finding that the pleaded information was not material for the purposes of Listing Rule 3.1 and ss 674(2) and 677 of the Corporations Act (the Materiality issue); and

(e) whether the primary judge erred in concluding that Zonia and the Barons had not established causation or loss (the Causation and Loss issue).

12 For the reasons that follow, we have concluded in summary that:

(a) No error is shown in the primary judge’s findings relating to the Bank’s awareness of the pleaded information.

(b) The primary judge erred in deciding as a threshold issue the question as to whether the pleaded information was complete and accurate.

(c) No error is shown in the primary judge’s conclusion that the exception in rule 3.1A did not apply.

(d) The primary judge erred in concluding that certain forms of the pleaded information were not material.

(e) No error is shown in the primary judge’s conclusion in relation to quantification of loss.

13 It follows from the above that the appeals are to be allowed in part (insofar as the answers to some of the common questions need to be changed to reflect the above conclusions), but the primary judge’s orders dismissing the proceedings at first instance remain undisturbed. Further, it follows that the cross-appeals are to be dismissed.

2 BACKGROUND FACTS

14 The facts are set out in detail in the Reasons at [49]-[351]. The following is a summary, drawn from the Reasons, of the key facts relevant to the issues raised by the appeals.

2.1 General matters

15 The Bank is, and was at all relevant times, Australia’s largest bank. For the years ended 30 June 2014 to 30 June 2017, the Bank’s total annual income was between $22 billion and $26 billion; its profit was between $8.6 billion and $9.9 billion. It employed approximately 52,000 staff members. The Bank operates (and, at all relevant times, operated) in a highly regulated market and processes a large volume of domestic and cross-border transactions.

16 The Bank is required to monitor certain transactions under AML/CTF legislation. As at May 2015, the Bank was monitoring approximately 7 million transactions per day with a value of $219 billion. At that time, peak volumes stood at 16 million transactions per day with a value of $570 billion. As at June 2016, the Bank was monitoring over 8 million transactions per day with a value of $300 billion. As at April 2017, the Bank was reporting approximately 3.1 million International Funds Transfer Instructions, 800,000 TTRs, and almost 9,000 Suspicious Matter Reports (SMRs) to AUSTRAC each year.

17 The Bank is, and was at all relevant times, licensed to carry on banking business in Australia and authorised to take deposits from customers as an Authorised Deposit-Taking Institution (ADI) under the Banking Act 1959 (Cth). It was subject to the AML/CTF Act and the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Rules Instrument 2007 (Cth) (the AML/CTF Rules).

18 The AML/CTF Act imposes obligations on ADIs that provide “designated services”. Those services are defined in s 6 of the AML/CTF Act. A “designated service” includes opening an account or allowing a transaction to be conducted in relation to an account. A person who provides a “designated service” is a “reporting entity”: s 5.

19 Part 3 of the AML/CTF Act contains reporting obligations for reporting entities. Relevantly to this proceeding, one obligation is to report a “threshold transaction” (as defined in s 5) to the AUSTRAC CEO: ss 43(2)-(3). A “threshold transaction” includes, for example, a transaction involving the transfer of physical currency, where the total amount of physical currency transferred is not less than $10,000. Section 43(2) is a civil penalty provision: s 43(4).

20 Section 81(1) of the AML/CTF Act provides that a reporting entity must not commence to provide a designated service to a customer if the reporting entity has not adopted and maintained an anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing program that applies to the reporting entity. Section 81(1) is a civil penalty provision: s 81(2). The program can be a standard AML/CTF program, a joint AML/CTF program, or a special AML/CTF program: s 83(1). The Bank adopted and maintained a joint anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism program. Such a program is divided into two parts—Part A (general) and Part B (customer identification): s 85(1).

21 The primary purpose of Part A (which is the Part of relevance for present purposes) is to identify, manage, and mitigate the risk that a reporting entity may reasonably face that the provision of designated services at or through its Australian operations might involve or facilitate money laundering or the financing of terrorism: s 85(2)(a). Section 82(1) provides that a reporting entity must comply with Part A of the program. Section 82(1) is a civil penalty provision: s 82(2).

22 As detailed in the Reasons at [73]-[79], there are a number of avenues open to the AUSTRAC CEO where AUSTRAC considers that there has been non-compliance with the AML/CTF Act, the Regulations, or the AML/CTF Rules. In summary:

(a) First, no formal action need be taken.

(b) Secondly, if there are reasonable grounds to think that there has been a contravention of an “infringement notice provision” (defined in s 184(1A)), an authorised officer can issue an infringement notice under s 184(1) requiring payment of a penalty.

(c) Thirdly, the AUSTRAC CEO can give a remedial direction under s 191(2) of the AML/CTF Act if satisfied that a reporting entity has contravened, or is contravening, a civil penalty provision.

(d) Fourthly, the AUSTRAC CEO can accept enforceable undertakings under s 197 of the AML/CTF Act.

(e) Fifthly, if the AUSTRAC CEO has reasonable grounds to suspect that a reporting entity has contravened, is contravening, or is proposing to contravene the AML/CTF Act, Regulations, or AML/CTF Rules, a written notice can be given under s 162 of the AML/CTF Act requiring the reporting entity to appoint an external auditor to carry out an audit of, and report on, the reporting entity’s compliance with the AML/CTF Act, Regulations, or AML/CTF Rules.

(f) Sixthly, the AUSTRAC CEO can commence proceedings under s 175 of the AML/CTF Act seeking a civil penalty order for the contravention of a civil penalty provision.

23 In its published Enforcement Strategy 2012 – 2014, AUSTRAC stated that it generally chooses to use a supervisory approach to secure reporting entity compliance before proceeding to “more formal enforcement activities”.

24 Before 3 August 2017, AUSTRAC had taken 33 enforcement actions. Only one was for a civil penalty order, namely the Tabcorp proceeding (see below).

2.2 Events in 2012

2.2.1 The roll-out of IDMs (May 2012)

25 In about May 2012, the Bank began rolling out its fleet of IDMs, being a type of automated teller machine (ATM), with additional functionality, which are part of the Bank’s NetBank platform. IDMs allow customers to deposit cash or cheques into their accounts without the need to enter the branch itself. Cash deposits are automatically counted and credited instantly to the nominated recipient account. This means that these funds are then immediately available for transfer to other domestic or international accounts.

26 During the relevant period, the Bank’s IDMs could accept up to 200 notes per deposit (i.e., up to $20,000 per cash transaction). The Bank did not limit the number of IDM transactions a customer could make each day. A card was required to activate and make a deposit through an IDM. The card could be issued by any financial institution, but the funds could only be deposited to one of the Bank’s account holders.

27 The IDM channel favours anonymity and there is no mechanism to identify the person who activates the machine and performs the transaction. IDMs can also be used to structure transactions in which large cash amounts can be deposited in smaller quantities. The primary judge found (and there is no issue about this on appeal) that IDMs present a high inherent ML/TF risk.

28 At the commencement of the relevant period for the proceedings at first instance (16 June 2014), the Bank had 245 active IDMs and 3,147 active ATMs. At the end of the relevant period (3 August 2017), the Bank had 904 active IDMs and 2,522 active ATMs.

29 Before rolling out the IDMs in May 2012, the Bank did not conduct a formal risk assessment in relation to the designated services provided through this channel. Instead, the Bank relied on the risk assessment conducted for ATMs generally. At first instance, the Bank accepted that it had not carried out a formal risk assessment in relation to the designated services provided through the IDM channel, and also that such an assessment was not made before July 2015. The Bank accepted that, by not conducting the required risk assessment before rolling out the IDMs, it failed to comply with its AML/CTF Program. The primary judge referred to this as the IDM ML/TF risk assessment non-compliance issue.

30 This is not to say, however, that the Bank did not have regard to AML/CTF risks in respect of IDMs at the time they were rolled out. In a business requirements document, the Bank considered the need to report threshold transactions to the AUSTRAC CEO and the means by which this would be done through IDMs. TTR reporting and transaction monitoring were considered to be mandatory requirements as part of the IDM roll out project, and TTR reporting functionality was built and linked to IDMs. IDM deposits were also linked to automated transaction monitoring rules that targeted certain practices.

31 The primary judge found that the failure of the Bank to carry out a risk assessment in relation to the IDMs before they were rolled out, or in the period before July 2015, had no direct consequences. On appeal, the appellants contest that finding.

2.2.2 The introduction of code 5000 (November 2012)

32 When the IDMs were introduced, the Bank’s processes relied on two transaction codes to generate TTRs (codes 5022 and 4013). Then, in November 2012, the Bank introduced an additional transaction code (code 5000) for a sub-set of IDM transactions to clarify a deposit message that was visible to customers via the NetBank platform. The new transaction code fixed the message problem, but it was not factored into the downstream process by which threshold transactions were identified for reporting. In short, a “flag” in the system for TTR reporting was missing.

33 This problem was not discovered, and its implications brought home to officers of the Bank, until much later (August-September 2015). In 2013, a potential problem, with an association with code 5000, was identified by the Bank’s staff, but unfortunately it was not fully investigated and rectified: see the Reasons at [118]-[139]. The primary judge found (and there is no issue about this on appeal) that as at 24 October 2013, no-one in the Bank had identified that transactions which should have been flowing through to TTR reporting were not flowing through and being reported to AUSTRAC.

2.2.3 Project Juno

34 The Bank’s Financial Crimes Platform (FCP) contained data about the Bank’s customers, accounts and transactions, which were sourced from different upstream systems. The platform was used by the Bank to undertake various functions, including:

(a) certain kinds of fraud detection, in particular internal fraud by the Bank’s employees, cheque fraud, and application fraud;

(b) automated politically exposed person and sanctions screening of customers; and

(c) automated transaction monitoring for AML/CTF purposes.

35 In 2012, the Bank commenced an internal project known as Project Juno. This project related to enhancing the Bank’s ability to monitor and detect potential instances of internal fraud. It was not focused on the Bank’s AML/CTF systems, but it did impact on the FCP, which was used for both fraud monitoring and automated transaction monitoring.

36 One aspect of Project Juno involved integrating a new process called the “Associate Web” into the FCP. The Associate Web sourced data from the Group Data Warehouse (GDW) and the FCP to identify potential linkages between the Bank’s staff and their customer profiles, the accounts they held, and any accounts that were related to them. For example, the Associate Web identified accounts that were registered with the same address or telephone number as a Bank staff member, or where an account was shared by a Bank staff member. This data was then used to populate a field in the FCP which flagged whether an account was “employee-related” or not. The rules in the FCP could then automatically run internal fraud monitoring rules to identify instances where Bank employees had initiated transactions involving accounts that had been identified as “related” to them.

37 In the course of updating account profiles in the FCP with data from the Associate Web, an error arose. In that process, the ACCOUNT_TYPE_DESC field for some accounts was populated with a null value (i.e., it was left blank). Over time, this caused the ACCOUNT_TYPE_DESC field in the FCP to be left blank, for a period, for certain “employee related” account profiles (i.e., accounts that were intended to be flagged as accounts belonging to a Bank employee or related to a Bank employee). This occurred even though the process of integrating data from the Associate Web with the FCP was not intended to make any changes to the ACCOUNT_TYPE_DESC field. The consequence was that the automated transaction monitoring rules that depended on this field being populated did not operate for so long as the field was not populated. In short, some account monitoring did not occur in respect of some “employee related” accounts. The primary judge referred to this as the account monitoring failure issue.

38 Not all “employee-related” accounts were affected and the accounts that were affected were still monitored for financial crime screening (they were monitored against sanctions, politically exposed persons, and terrorists lists). Further, only some of the affected accounts were not subject to customer level transaction monitoring in the FCP.

2.3 Events in 2014

39 In mid-June 2014, the account monitoring problem was identified by a Bank employee, Mr Dhankhar (who was engaged in Financial Crime Analytics), in the course of developing rules for the FCP. On 17 June 2014, Mr Dhankhar circulated an email in which he identified seven issues with FCP data, one of which concerned the ACCOUNT_TYPE_DESC field. This was given the incident number IM0809261. By late August 2014, this issue (amongst other issues) was recorded in the Bank’s risk management platform, RiskInSite, as “Medium Impact”.

2.4 Rectification of the account monitoring issue (2014-2016)

40 On about 18 September 2014, the FCP was updated with a change that resolved the error so that, on updating the account profile, the ACCOUNT_TYPE_DESC field was updated with the relevant data as part of a “self-correct” process, and not left blank. Implementation of the Bank’s usual data updating processes resulted in approximately 75% of the affected accounts (being active accounts) self-correcting by 30 November 2015. A manual update of the ACCOUNT_TYPE_DESC field in respect of inactive affected accounts (approximately 25% of the affected accounts) was completed by 27 September 2016.

41 In total, 778,370 accounts were affected in the period 20 October 2012 to 30 November 2015. The accounts were affected over varying time periods. For example, some accounts (54,357 accounts) were affected for a period of less than one month (for example, the period could have been one day); some accounts (73,716 accounts) were affected for a period of between 25 to 36 months. However, a significant percentage of accounts (representing, in number, 195,000 accounts) were not active accounts.

2.5 Events in 2015

2.5.1 Tabcorp proceeding (July 2015)

42 On 22 July 2015, AUSTRAC announced that it had commenced proceedings against Tab Limited, Tabcorp Holdings Limited, and Tabcorp Wagering (Vic) Pty Ltd (collectively, Tabcorp) (the Tabcorp proceeding) for “extensive, significant and systemic non-compliance with Australia’s anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing legislation”.

2.5.2 AUSTRAC raises concerns (July 2015)

43 On 30 July 2015, the Bank met with AUSTRAC to provide a “general monthly update”. It seems that, beforehand, AUSTRAC and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) had met and discussed an audit report of May 2015. That audit report was one of APRA’s requirements notified in an APRA report of 5 September 2014. The report was prepared by Group Audit (at the Bank) and focused on the completeness of data captured in the Bank’s systems used for centralised AML/CTF screening and the processes it used for the maintenance of “AML/CTF rules”.

44 At the meeting with the Bank, AUSTRAC said that it had “serious concerns around” the audit. AUSTRAC made the overarching comment that, on the face of it, the 2015 audit report was “very concerning” and was “raising questions internally within AUSTRAC” and that, potentially, AUSTRAC “would … consider if enforcement action would be necessary”.

2.5.3 Identification of the TTR problem (August–September 2015)

45 On 11 August 2015, AUSTRAC asked the Bank to locate TTRs relating to “two ATM deposits”. The Bank could not locate these reports and it realised that they had not been made. On investigation, it was found that the deposits were processed under code 5000, but that code 5000 had not been linked to TTR reporting, as it should have been. It was then found that this resulted in the non-reporting of 51,637 threshold transactions from November 2012 to 18 August 2015. The number of affected transactions represented approximately 2.3% of the overall volume of TTRs provided by the Bank over the same period.

46 By the morning of 4 September 2015, the late TTR issue had been escalated to Mr Narev (the Managing Director and CEO of the Bank), who had asked for a “short briefing paper”. By the afternoon, Mr Byrne (the Bank’s Head of Group Financial Crime Compliance, Regulatory Liaison & Complex Matters) had prepared a briefing paper. The briefing paper said that it had been discovered that the two deposits (which had been referred to the Bank by AUSTRAC) had not been reported “because of a system coding error dating back to November 2012” and that, at that stage, “the investigation has identified that 51,637 TTRs were not reported to AUSTRAC” which represented “approximately 2.5% of the total reportable transactions for the same period (November 2012 to 18 August 2015)”. A prefatory section of the report noted that failure to comply with the obligation to lodge TTRs “can result in reputational damage and regulatory enforcement including fines and remedial action”.

47 On 6 September 2015, an email exchange took place between Mr Narev and Mr Comyn (the Group Executive for Retail Banking Services). In that exchange, Mr Comyn said that “the full extent of the issue is [being] investigated”. In response, Mr Narev said that he had spoken to Mr Alden Toevs (Group Executive – Risk Management) that day. He continued:

It goes without saying that we need to take this extremely seriously. I have let Alden know that he should personally be in touch with Austrac about this, and offer up a discussion with me. We need to adopt a similarly senior posture with AFP, though I suspect David Cohen (also copied) may be the better contact with them given that there are current legal proceedings.

Whilst this is as a result of unintentional coding related errors, the circumstances warrant very senior oversight.

We need also to make sure that:

- we are going through all relevant transactions to check for other problems

- we have fixed the problem, and

- no-one within the Group had knowledge of/concern about this issue. I understand we have no cause for concern about this, but I want to know that there was no avoidance of the issue/reluctance to escalate.

48 Mr Comyn replied on 7 September 2015 that the matter was being taken “very seriously” but that he had “zero concerns about the reluctance to escalate”.

2.5.4 Rectification of the TTR problem (September 2015)

49 By 8 September 2015, the error that had caused the TTR problem had been rectified.

50 On 8 September 2015, Mr Toevs sent a letter to AUSTRAC notifying it that 51,637 TTRs had not been lodged for the period November 2012 to 18 August 2015. The letter advised AUSTRAC of the root cause of the problem and informed it of the “extensive remediation program” that the Bank would implement in response. This included the Bank retrospectively submitting “all of the reportable TTRs that resulted from the missing transaction code”.

51 The primary judge accepted Mr Narev’s evidence to the effect that, in early September 2015, he thought that the TTR issue posed a risk of AUSTRAC taking regulatory action: Reasons, [260].

52 By 24 September 2015, the outstanding TTRs had been lodged with AUSTRAC. There were 53,506 TTRs so lodged. The primary judge referred to this as the late TTR issue.

53 The reason why the number of TTRs lodged (53,506) is higher than the figure referred to in the Bank’s letter to AUSTRAC dated 8 September 2015 (51,637) is that the 53,506 figure relates to a slightly longer period: Reasons, [462]. The higher figure was included in a spreadsheet prepared by the Bank on 22 September 2015: Reasons, [463]

2.5.5 October 2015

54 On 12 October 2015, Mr Toevs, Mr Dingley (the Chief Operational Risk Officer) and Ms Williams (the Chief Compliance Officer) prepared a report for the Bank’s Risk Committee which, after noting the outcome of the 2015 audit report, included the following:

3.4.2. Group Operational Risk and Compliance (GORC) has accepted the outcomes of the Internal Audit reviews and is driving a series of initiatives to deliver effective end-to-end governance over the control environment.

3.4.3. An example of the outcomes of these control issues and their ongoing rectification is that, following a recent investigation undertaken by the Bank into two unreported threshold transaction reports (TTRs) to AUSTRAC, it was identified that between November 2012 and August 2015, 51,637 cash deposits of over $10,000 conducted through intelligent deposit machines (IDMs) were unreported to AUSTRAC. This arose because of a coding error.

3.4.4 While there is no formal breach reporting requirement under the AML/CTF Act, the breach has been reported to AUSTRAC and the non-compliance remediated. We have also taken steps to ensure better assurance processes are in place to detect these types of failures going forward. By taking steps to rectify the reporting failure and improving our control environment we reduce the risk of any regulatory action being taken by AUSTRAC.

55 The report noted that, in Australia, regulatory action had been taken against Barclays Bank, Mega Bank and Tabcorp for AML/CTF breaches, resulting in enforceable undertakings being given and (in the case of Tabcorp) “Federal Court action”.

56 The Bank’s Board was informed of the late TTR issue at its meeting on 12 and 13 October 2015.

57 On 12 October 2015, AUSTRAC responded to the Bank’s communications of 8 and 24 September 2015. In a letter to Mr Toevs, AUSTRAC expressed its “serious concerns” about the scale of the Bank’s non-compliance with s 43 of the AML/CTF Act and the period over which those contraventions had occurred.

58 AUSTRAC sought further details from the Bank in the form of information and documents. Among the documents sought was “any ML/TF risk assessment the CBA conducted on the IDMs before rolling out these machines in May 2012”. AUSTRAC sought a response by 26 October 2015.

59 The Bank provided that response by letter on 26 October 2015. In relation to the request for documents of any ML/TF risk assessment before rolling out IDMs, the Bank said:

CBA considers that IDMs were an enhancement of the existing ATM functionality as a channel to provide designated services. As a result, CBA has relied upon the ML/TF risk assessments conducted on ATMs as a channel for providing designated services.

60 The Bank also said:

No changes have been made to IDMs since 2012 to warrant any further risk assessment.

There were no additional high rated ML/TF risks raised in relation to the roll out of IDMs that required escalation to the Board or senior management. IDMs were intended to provide deposit functionality (similar to that of Branches) and the existing AML transaction monitoring controls and TTR reporting were applied to deposits via IDMs.

2.6 Events in 2016

2.6.1 Board meeting with AUSTRAC on 14 June 2016

61 On 14 June 2016, a lunch meeting took place attended by the Bank’s Board, several members of the Bank’s management, Mr Jevtovic (the AUSTRAC CEO) and Mr Clark (the Deputy CEO).

2.6.2 The statutory notices

62 On 22 June 2016, AUSTRAC gave a notice to the Bank under s 167(2) of the AML/CTF Act seeking the production of information and documents (the first statutory notice). The notice was circulated to Mr Comyn and others by an email dated 23 June 2016. The content of the notice (and the background to it) was described by Mr Keaney (General Manager, Group Financial Crime Services) in a further email dated 13 July 2016 that was sent to various people, including Mr Comyn:

On 22 June 2016, a statutory notice was received from AUSTRAC for the production of information and documents. Information collected under this notice could be used by AUSTRAC in civil penalty proceedings against the Group, although at this stage AUSTRAC is silent on its intentions. The notice is wide ranging but primarily relates to CBA’s compliance with AUSTRAC’s customer on-boarding and ongoing customer due diligence requirements. There is a particular focus on on-line account opening procedures, including electronic verification of customer identities, and the monitoring of transactions through Intelligent Deposit Machines. The notice also seeks detailed information in relation to 59 customers and 120 accounts, and asks for AML-related audit reports (over multiple years) as well as minutes of Board meetings where those reports were considered.

This incident is related to the non-reporting of Threshold Transaction Reports for transactions undertaken through Intelligent Deposit Machines which was detected and self-reported to AUSTRAC in August 2015. Issues relating to that incident are largely closed out. The root cause for regulatory interest in relation to our customer on-boarding and ongoing customer due diligence processes more generally is not yet known. Further information on the root cause may be determined over the course of responding to the notice.

Should AUSTRAC launch Federal Court proceedings against the Group (as in the case of Tabcorp) there will be reputational impacts. In addition, the Group would incur costs in defending such action. The maximum penalty that could potentially be applied by a court is $18 million per breach. Based on the CEO of AUSTRAC’s description to the CBA Board just weeks ago that he has no concerns about the CBA’s intention to be fully compliant with AML legislation, and his belief that the Group is a diligent manager of AML Risk (against a backdrop of significant business and technology complexity) it is hard to believe that AUSTRAC intends to impose significant penalties on the Group – especially given that the CEO Mr Jevtovic would have known about this imminent notice at the time he met with our Board and yet didn’t raise it to offset his praise of the Group in relation to the management of financial crime.

63 Mr Keaney’s email was forwarded to Mr Narev on the same day.

64 At the request of the Bank’s Legal Services team, a project team was formed to assist in maintaining confidentiality and legal privilege in respect of responses to the first statutory notice. This was part of a project called Project Concord (the project being the Bank’s response to AUSTRAC’s investigation as reflected in the first statutory notice).

65 On 2 September 2016, AUSTRAC gave a second notice to the Bank under s 167(2).

66 On 14 October 2016, AUSTRAC gave a third notice to the Bank under s 167(2) (the third statutory notice).

67 On 17 October 2016, a report was prepared by an Executive Committee of the Bank seeking endorsement of a proposal to execute a program of work that would “establish the fundamentals for the Group to manage its financial crime risk effectively and efficiently over the next three years”. The report commenced by noting:

1.1. The Executive Committee is aware of the Group’s exposure to financial crime risk, including money-laundering, sanctions-violations and bribery and corruption, and of consequences of non-compliance, including fines by onshore and offshore regulators.

1.2. Notwithstanding the Group’s investment in financial crime compliance in recent years, there is still a way to go, as recently confirmed by Group Audit.

1.3. The potential for fines or other regulatory action seem elevated in light of AUSTRAC recently issuing the Group with an Enforcement Notice, stemming from breaches in Threshold Transaction Reporting from branch-based Intelligent Deposit Machines.

1.4. Group Security is taking a leadership role in improving the Group’s management of financial crime and is now returning to ExCo to provide an update and plan for the way forward.

68 The primary judge accepted Mr Narev’s evidence to the effect that, by October/November 2016, he thought that there was a serious risk of AUSTRAC taking regulatory action in relation to the late TTR issue, but he did not consider it likely that AUSTRAC would commence civil penalty proceedings: Reasons, [282].

2.6.3 The Bank’s internal audit report 2016

69 In the meantime, on 28 September 2016, Group Audit delivered a report on a further internal audit in relation to the Bank’s AML/CTF framework (the 2016 audit report). The 2016 audit report gave an overall “red” rating based on an “unsatisfactory” rating for “Control Environment” and a “marginal” rating for “Management Awareness & Actions”.

70 In its Audit Conclusion, Group Audit noted (amongst other things) that:

A large number of AML/CTF issues continue to exist across the Group, with weaknesses identified across Business Unit’s (sic) … and Group-wide AML/CTF processes. A number of repeat issues were identified due to inadequate implementation of action plans. Many of the prior issues remain open, with projects currently underway or due to commence to revisit the AML/CTF operating model and completeness of AML/CTF data flows.

71 Group Audit also said:

As part of this Audit, Internal Audit conducted an independent review of the Group’s Part A AML/CTF Program as required by the AML/CTF Rules … Whilst we found that the Bank’s AML/CTF framework covered all of the key requirements of an effective AML/CTF framework, we noted a number of gaps in the development of the program (for example, mapping of compliance obligations), and the implementation and operationalisation of the program …

72 Group Audit noted that the Group had been “slow to address many of the previously identified issues and associated root causes” and that a “number of significant issues from our Audits in 2013 and 2015 remain unaddressed and are either still being remediated … have been reopened due to inadequate remediation … or are yet to be addressed …”.

2.7 Events in 2017

2.7.1 Meeting with the AUSTRAC CEO on 30 January 2017

73 On 30 January 2017, Ms Livingstone (the Chair of the Bank’s Board) had a meeting with Mr Jevtovic. Ms Livingstone did not give evidence in the proceeding at first instance, but her handwritten note of the meeting was in evidence. The note records, amongst other things, the following matters.

74 First, the note records Mr Jevtovic’s view that the Bank’s relationship with AUSTRAC was professional “outside of IDMs”. The apparent concern in that regard appears to have been the Bank’s failure to lodge TTRs, as discussed above. However, the note records that, while that matter “warrants close scrutiny”, the Bank did respond to “the systems issue”.

75 Secondly, the note records that AUSTRAC was concerned about whether the Bank had done sufficient work on understanding AML/CTF risk, refers to the 2015 internal audit, and appears to question the Bank’s “risk culture” (noting the Bank’s “poor performance” as against other banks).

76 Thirdly, the note records that AUSTRAC was concerned about the Bank’s lack of reporting, its poor risk assessment, its slow response to risk assessment, and the fact that its IDMs had been compromised by organised crime.

77 Fourthly, the note refers to the issue of the three statutory notices, but records AUSTRAC’s view that the Bank had responded adequately to the notices.

78 Fifthly, the note records that AUSTRAC had made no decision on what action “it may or may not take”. The note appears to indicate that AUSTRAC would make a decision in that regard within two weeks, and that there were “options”.

79 On 31 January 2017, Mr Narev (who, at this time, was concerned that the late TTR issue had been “dragging on” with AUSTRAC and that AUSTRAC might be considering taking action, such as an enforceable undertaking, which he wanted to avoid) sent Ms Livingstone an email in which he said:

I am keen to get your instincts on how, if at all, you believe we can engage with [AUSTRAC] in advance of the final determination to influence it.

2.7.2 The development of Project Concord

80 The further action, if any, that AUSTRAC might take as a consequence of the late TTR issue remained a matter of abiding concern for the Bank. The Bank continued to consider the causes and impacts of that issue.

81 By 7 February 2017, Project Concord had expanded to include “an internal and external communications plan to be used in the event of public dialogue from AUSTRAC on the TTR matter”. The concern appears to have been that, through various means, the fact that AUSTRAC was investigating the Bank in relation to the late TTR issue might or would become public knowledge. The Bank was concerned about bad publicity. One of the aims of the management of this issue was to seek to influence, to the extent possible, how the Bank’s customers and investors would react upon becoming aware of the investigation of the late TTR issue. However, at that time, the plan did not envisage that AUSTRAC would commence proceedings against the Bank.

82 On 14 February 2017, Ms Watson (the Executive General Manager, Group Security and Advisory) sent an email to Mr Craig (the Bank’s Chief Financial Officer), stating (amongst other things):

- No new information from AUSTRAC

- AUSTRAC have knocked back multiple requests for clarity

- Paul Jevtovic has declined two invitations to meet with the CBA Board this week (invited May and June – no to both)

- Latest update is Catherine Livingstone’s where Paul said “I will let you know soon…”

- Action could include:

• Civil penalties following court proceedings

• Enforceable undertaking style action

• External review/audit of our financial crime arrangements.

There would likely be a media overlay to any of these actions.

2.7.3 Tabcorp civil penalty (February-March 2017)

83 On 16 February 2017, The Australian newspaper reported that Tabcorp had revealed the terms of a settlement with the AUSTRAC CEO in which it had agreed to pay a pecuniary penalty of $45 million. A copy of the article was sent, by internal email, to Mr Cohen (the Bank’s Chief Risk Officer). Mr Cohen’s response was:

Yes saw that today – this will potentially embolden AUSTRAC in its issue with us.

84 Ms Watson sent an email to Mr Comyn and others attaching a media release and articles explaining the settlement. Mr Comyn’s response was:

Jeez, that’s a lot of money. Can you please remind me of the nature of their breach. I hope it’s much more severe than us?

85 On 16 March 2017, in the Tabcorp proceeding, this Court ordered Tabcorp to pay a civil penalty of $45 million.

2.7.4 Meeting with AUSTRAC on 7 March 2017

86 On 7 March 2017, Ms Watson and Mr Keaney met with AUSTRAC. Ms Watson summarised the meeting in an email to Mr Craig on 8 March 2017, as follows:

Matt Keaney and I met with AUSTRAC yesterday. They described their view of the TTR and associated matters as “serious, significant and systemic”. They also said our failure to immediately and proactively tell them about these and other problems (here they were talking about control weaknesses over multiple years, etc) is a show of bad faith which leads them to wonder what else is broken across CBA’s financial crime landscape.

They said they have not made a determination but it isn’t far off. And in either a slip or a deliberate signal they said “we will tell you before we go public or to media.”

Legal is helping draft a defence outline so we can work out what we do under a civil penalty scenario in particular. I didn’t get any sense of them being interested in us putting an EU to them - they told me that the ball is in their court and they’re going to make a decision then either advise or consult with us.

87 A copy of the email found its way to Mr Narev. Mr Narev forwarded Ms Watson’s email to Ms Livingstone, saying:

Obviously not good news here, though also not surprising.

The judgment call we need to make from here is whether at the Chair/CEO level we ought to reach out again before a final determination?

88 Ms Livingstone responded:

Agree – not good news. Paul didn’t say anything on Monday and in fact could not have been more friendly.

It might be a good idea if you and I together seek a meeting with Paul. If they speculate publicly about ‘what else is broken’ it will play into the very convenient culture rhetoric. We must make sure that we are dealing with facts and not supposition.

89 The primary judge stated that he understood the reference to “Paul” in Ms Livingstone’s email to be to Mr Jevtovic.

2.7.5 Meeting with AUSTRAC on 21 March 2017

90 On 21 March 2017, Mr Narev and Ms Livingstone met with Mr Jevtovic and Mr Clark.

91 Mr Narev gave evidence of the discussion at the meeting. After recounting statements made by Mr Jevtovic and Mr Clark about the general nature of the engagement between the Bank and AUSTRAC, Mr Narev gave this evidence of the discussion:

Mr Jevtovic: We have been looking into the information which CBA had been providing to us, and we have found some other things beyond the non-reporting of the TTRs. As recently as January, something happened that concerned us. We are looking into possible failures to lodge reports, submit reports linked to investigations, do some ongoing customer due diligence, and undertake adequate risk assessment of the IDMs.

We think this is serious because of the scale of the IDMs, which should have prompted an earlier risk assessment than what was undertaken in mid-2016. Internal advice had highlighted the risk of IDMs.

I wonder whether CBA’s investment has necessarily been in the right place. We think accounts have remained open without follow-up. We also think that CBA’s SMR policy may contradict the Act. There is a written policy which suggests that once SMRs had been submitted, further SMRs did not need to be.

In terms of next steps, AUSTRAC is going to take an evidence-based approach. The options for us are an external auditor, a remedial direction, seeking an Enforceable Undertaking, or instituting civil penalty proceedings.

We think it will take approximately one more month until we decide which path we want to follow.

As we consider our options, CBA’s leadership approach will be critical. This is the first time that a Chair and CEO have ever come personally to AUSTRAC, and that makes a difference. We are also very encouraged by Philippa’s leadership and her relationship with Peter.

Ms Livingstone: I have met with Paul prior to this meeting, on matters unrelated to these issues.

We acknowledge that the issues you are now raising are serious, and that CBA needs to do better.

We do think it is important that the path forward be constructive. Beyond the regulatory issues, there are potential reputational issues that are important to CBA, and it is key to us that it is not portrayed that CBA has a cavalier and disrespectful approach.

It is clear that this is about systems, policy and capability, not bad intent. Our priority is to make sure this process sticks to the facts.

Mr Jevtovic: We are not interested in adding to “bank bashing”, and in fact all the major banks have been important and constructive partners for us.

We will give you advance notice once we have decided what path to go down. We will definitely not do anything without telling CBA first, and we’ll allow CBA time to consider what AUSTRAC is going to do.

The work that CBA has done in recent times will be instrumental in shaping AUSTRAC’s thinking about which path it will take.

Ms Livingstone: We will have Philippa Watson articulate CBA’s vision today and walk that over.

92 The primary judge stated that Mr Narev’s evidence in this regard was not challenged substantively in cross-examination. The primary judge noted that AUSTRAC was still referring to “options”, which not only included civil penalty proceedings, but other regulatory action which was available to it. In cross-examination, Mr Narev accepted that it was fair to say (apparently based on his understanding of the matter) that AUSTRAC was seriously considering all options, including civil penalty proceedings. Even so, Mr Jevtovic had made it clear that AUSTRAC had not made a decision about “the path we want to follow”. He had also made it clear that AUSTRAC would give the Bank “advance notice once we have decided what path to go down” and provide the Bank with an opportunity to consider what AUSTRAC was going to do.

93 Mr Narev accepted during cross-examination that, at that time, his thinking was that it was “highly likely”, but not inevitable, that AUSTRAC would be seeking a “fine” from the Bank.

2.7.6 March to August 2017

94 In the period from the 21 March 2017 meeting to 3 August 2017, there were no substantive updates from AUSTRAC.

95 On 13 April 2017, the Bank responded to a request from AUSTRAC (made on 1 March 2017) for further information in relation to two matters arising from the Bank’s responses to the first and third statutory notices in respect of the account monitoring failure issue. In its request dated 1 March 2017, AUSTRAC requested:

Please confirm the exact number of CBA profiles that were not picked up by FCP/Pegasus and the dates between which these profiles were not being picked up by FCP/Pegasus.

96 In response to that request, the Bank provided a table in its letter of 13 April 2017, which recorded that, in total, 778,370 accounts were affected:

97 In relation to that information, the primary judge made the following findings (at [499]):

… the number of the accounts affected by the account monitoring issue varied over time. The numbers are given in the analysis undertaken in March/April 2017 and reported to AUSTRAC at that time. In its letter to AUSTRAC dated 13 April 2017, the Bank pointed out that, in respect of the affected accounts, the account monitoring failure was intermittent for periods that varied between one day and 36 months; not all employee-related accounts were affected by the issue; and approximately 25% of the affected accounts were inactive. The applicants do not challenge these facts.

98 On 23 June 2017, Mr Narev had a meeting with the Minister for Justice and Minister Assisting the Prime Minister on Counter Terrorism, the Honourable Michael Keenan. Mr Narev wanted to meet Mr Keenan prior to any further developments with AUSTRAC. In an email (which included Mr Craig and Ms Watson as recipients), Mr Narev described the meeting as “very valuable” and reported:

… Key points are as follows:

- The Minister is aware of Austrac’s investigations

- This is very much Austrac’s process, ie he does not expect to have significant involvement

- He has heard directly that Austrac considers us to have a partnership approach. He noted specifically that he was made aware that Catherine and I had made the effort to go and visit

- In that sense it was considered a different type of issue than Tabcorp

- Although of course there is currently a leadership change, he believes these views are shared by the level below Paul as well, ie the key acting leaders.

Whilst of course this does not alter the seriousness with which we should take all this, nor remove the risk, it does show that the approach we are taking in our interactions is unquestionably the right one.

99 By 22 March 2017, Project Concord had reached the stage of formulating a communications strategy should AUSTRAC commence proceedings against the Bank, described as a “worst case scenario”. The strategy was based on the events attending the Tabcorp proceeding. It also focused on AUSTRAC’s investigation of the late TTR issue.

2.7.7 AUSTRAC commences proceedings against the Bank (3 August 2017)

100 At about 10.18 am on 3 August 2017, Mr Narev received a message that Mr Clark (at this time, the Acting CEO of AUSTRAC) needed to speak to him “quite urgently”. Shortly after receiving the message, Mr Narev telephoned Mr Clark, who, according to Mr Narev, said:

AUSTRAC is issuing civil proceedings against CBA in around 15 minutes. We will arrange service of the relevant court documents and this will be followed shortly after by a media release from AUSTRAC.

101 Mr Narev’s response to Mr Clark was:

This is exactly what you said you wouldn’t do.

102 Mr Clark replied:

I hope this doesn’t harm the relationship AUSTRAC has with CBA.

103 The primary judge found that Mr Clark’s message took Mr Narev (and the Bank) by surprise, in that AUSTRAC had informed the Bank on a number of occasions that it would give advance notice of any action it decided to take to enable the Bank to consider its position. No doubt, from the Bank’s perspective, adequate notice would have provided it with the opportunity to make further representations to AUSTRAC.

104 At 12.26 pm on 3 August 2017, AUSTRAC posted a Tweet stating that it had “initiated civil penalty proceedings against CBA for serious non-compliance with AML/CTF Act”. The Tweet linked to the following media release posted on AUSTRAC’s website (AUSTRAC’s media statement):

AUSTRAC seeks civil penalty orders against CBA

3 August 2017

Australia’s financial intelligence and regulatory agency, AUSTRAC, today initiated civil penalty proceedings in the Federal Court against the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) for serious and systemic non-compliance with the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (AML/CTF Act).

AUSTRAC acting CEO Peter Clark said that this action follows an investigation by AUSTRAC into CBA’s compliance, particularly regarding its use of intelligent deposit machines (IDMs).

AUSTRAC’s action alleges over 53,700 contraventions of the AML/CTF Act. In summary:

• CBA did not comply with its own AML/CTF program, because it did not carry out any assessment of the money laundering and terrorism financing (ML/TF) risk of IDMs before their rollout in 2012. CBA took no steps to assess the ML/TF risk until mid-2015 - three years after they were introduced.

• For a period of three years, CBA did not comply with the requirements of its AML/CTF program relating to monitoring transactions on 778,370 accounts.

• CBA failed to give 53,506 threshold transaction reports (TTRs) to AUSTRAC on time for cash transactions of $10,000 or more through IDMs from November 2012 to September 2015.

• These late TTRs represent approximately 95 per cent of the threshold transactions that occurred through the bank’s IDMs from November 2012 to September 2015 and had a total value of around $624.7 million.

• AUSTRAC alleges that the bank failed to report suspicious matters either on time or at all involving transactions totalling over $77 million.

• Even after CBA became aware of suspected money laundering or structuring on CBA accounts, it did not monitor its customers to mitigate and manage ML/TF risk, including the ongoing ML/TF risks of doing business with those customers.

Mr Clark said that today’s action should send a clear message to all reporting entities about the importance of meeting their AML/CTF obligations.

“By failing to have sound AML/CTF systems and controls in place, businesses are at risk of being misused for criminal purposes,” Mr Clark said.

“AUSTRAC’s goal is to have a financial sector that is vigilant and capable of responding, including through innovation, to threats of criminal exploitation.”

“We believe this can be achieved by working collaboratively with and supporting industry. We will continue to work in this way with our industry partners who also share this aim and demonstrate a strong commitment to it.”

As we have said, AUSTRAC’s media statement included a link to the Concise Statement that AUSTRAC filed in this Court on that date.

105 The primary judge defined the cumulative information provided in AUSTRAC’s Tweet, its media statement and the Concise Statement as the “3 August 2017 announcement”. We refer to the combined package of AUSTRAC’s 3 August 2017 Tweet, media statement and linked Concise Statement as the 3 August 2017 AUSTRAC announcement, and will refer to AUSTRAC’s media statement and the Concise Statement separately when discussing either part. The appeal proceeded on the basis that AUSTRAC’s media statement was to be read with the Concise Statement.

106 It may be noted that AUSTRAC’s media statement referred to five issues:

(a) the IDM ML/TF risk assessment non-compliance issue;

(b) the account monitoring failure issue;

(c) the late TTR issue (the third and fourth bullet points);

(d) the Bank’s failure to report suspicious matters (either on time or at all) for transactions totalling over $77 million; and

(e) the Bank’s failure to monitor customers even after becoming aware of suspected money laundering or structuring in respect of accounts held with the Bank.

107 While the first three issues formed part of Zonia and the Barons’ case below, the fourth and fifth issues did not. As we go on to explain, the Concise Statement contained significant additional information, both in respect of the first three points, and the additional points. This is significant for the purposes of some of the issues on appeal, because it calls into question whether (as the appellants contend) the market’s reaction to the commencement of the proceeding is representative of what would have happened if the Bank had disclosed the pleaded information.

108 The Concise Statement, which was set out in a Schedule to the Reasons, is relevant to some of the issues raised by the appeal. In particular, again, it calls into question whether the market’s reaction to the commencement of the proceeding is representative of what would have happened if the Bank had disclosed the pleaded information.

109 The primary judge noted that, even though Mr Clark had told Mr Narev after 10.18 am on 3 August 2017 that AUSTRAC would be commencing proceedings, the Concise Statement had, in fact, been lodged with the Court for filing at 9.39 am on that day. In other words, AUSTRAC had taken steps to commence enforcement proceedings seeking pecuniary penalties against the Bank without prior warning or, indeed, the advance notice that AUSTRAC said that it would give to the Bank when it had arrived at a decision as to the action, if any, it intended to take. Contrary to the expectation that AUSTRAC had engendered, the Bank did not have an opportunity to consider its position in relation to AUSTRAC’s decision. The primary judge stated that that consideration would have included whether steps could, or should, be taken by the Bank to attempt to dissuade AUSTRAC from taking its chosen course.

110 On 3 August 2017, the Bank issued the following media release:

Commonwealth Bank today acknowledges that civil proceedings have been brought by the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC). The proceedings relate to deposits made through our Intelligent Deposit Machines from 2012.

We have been in discussions with AUSTRAC for an extended period and have cooperated fully with their requests. Over the same period we have worked to continuously improve our compliance and have kept AUSTRAC abreast of those efforts, which will continue.

We take our regulatory obligations extremely seriously and we are one of the largest reporters to AUSTRAC. On an annual basis we report over four million transactions to AUSTRAC in an effort to identify and combat any suspicious activity as quickly and efficiently as we can.

We have invested more than $230 million in our anti-money laundering compliance and reporting processes and systems, and all of our people are required to complete mandatory training on the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act.

Money laundering undermines the integrity of our financial system and impacts the Australian community’s safety and wellbeing. We will always work alongside law enforcement, intelligence agencies and government authorities to identify, disrupt and prevent this type of activity.

We are reviewing the nature of the proceedings and will have more to say on the specific claims in due course.

The applicants’ pleadings define the 3 August 2017 AUSTRAC tweet and media statement and the Bank’s media release as the “3 August Corrective Disclosure”. We adopt that definition.

111 The primary judge considered it noteworthy that the Bank’s media release referred to AUSTRAC’s action against it as relating to “deposits made through our Intelligent Deposit Machines from 2012”. The primary judge observed that the proceeding commenced by AUSTRAC against the Bank concerned non-compliance that was far more extensive than the late TTR issue.

2.8 Zonia and the Barons’ shareholdings

112 As at 3 August 2017, Zonia held 17,213 CBA shares. It had acquired 718 of those shares on 18 September 2015 under the Bank’s dividend reinvestment plan (DRP). Notwithstanding the 3 August 2017 announcement, Zonia continued to hold its shares. On 16 August 2017, within two weeks of the announcement, it purchased 593 PERLS IX hybrid securities (subject to a mandatory exchange for CBA shares in 2024) for $60,248.80. Further, on 17 August 2017, Zonia elected to participate in the Bank’s DRP under which it was allotted 522 CBA shares for a payment of $39,531.06. Zonia did sell some of its CBA shares on 29 September 2017, along with some of its PERLS IX hybrid securities on 11 October 2017. The reason for these disposals was not explained in the evidence below.

113 On 21 August 2014, 19 February 2015, and 20 August 2015, the Barons acquired shares under the Bank’s DRP. On 18 September 2015, they acquired shares under the 2015 Entitlement Offer and, on 29 May 2017, they made an on-market acquisition of shares. As at 3 August 2017, their portfolio included 3,757 CBA shares. Notwithstanding the 3 August 2017 announcement, the Barons continued to hold those shares. It was not until 14 May 2019 that they made a relatively small divestment.

114 The primary judge stated that the evidence supported an inference that Zonia and the Barons were indifferent to the disclosures in the 3 August 2017 announcement and simply took no notice of it in relation to their holding and, in Zonia’s case, further acquisition, of CBA shares. The primary judge considered that this supported an inference that Zonia and the Barons would also have been similarly indifferent to the disclosure of any of the pleaded forms of the information. The primary judge stated that, as Zonia elected not to call evidence from any officer of the company, and as the Barons elected not to give evidence, he could more safely draw, and did draw, those inferences: Reasons, [1229].

3 THE KEY RELEVANT PROVISIONS

115 The provisions of the Corporations Act are set out as at 3 August 2017 (based on the compilation prepared as at 1 July 2017).

116 It is uncontentious that at all relevant times the Bank:

(a) was included in the official list of the financial market operated by the ASX (i.e., listed on the ASX);

(b) had issued shares being “ED securities” (short for “enhanced disclosure securities”) for the purposes of s 111AE of the Corporations Act, which shares were able to be acquired and disposed of by investors on the financial market operated by the ASX;

(c) was a “disclosing entity” within the meaning of s 111AC(1) and a “listed disclosing entity” within the meaning of s 111AL(1) of the Corporations Act.;

(d) was subject to and bound by the Listing Rules; and

(e) was by reason of the above matters and ss 111AP and/or 674(1) of the Corporations Act, an entity to which s 674(2) of the Act applied.

117 Section 674 of the Corporations Act relevantly provided:

674 Continuous disclosure—listed disclosing entity bound by a disclosure requirement in market listing rules

Obligation to disclose in accordance with listing rules

(1) Subsection (2) applies to a listed disclosing entity if provisions of the listing rules of a listing market in relation to that entity require the entity to notify the market operator of information about specified events or matters as they arise for the purpose of the operator making that information available to participants in the market.

(2) If:

(a) this subsection applies to a listed disclosing entity; and

(b) the entity has information that those provisions require the entity to notify to the market operator; and

(c) that information:

(i) is not generally available; and

(ii) is information that a reasonable person would expect, if it were generally available, to have a material effect on the price or value of ED securities of the entity;

the entity must notify the market operator of that information in accordance with those provisions.

Note 1: Failure to comply with this subsection is an offence (see subsection 1311(1)).

Note 2: This subsection is also a civil penalty provision (see section 1317E). For relief from liability to a civil penalty relating to this subsection, see section 1317S.

Note 3: An infringement notice may be issued for an alleged contravention of this subsection, see section 1317DAC.

118 Section 677 provided:

677 Sections 674 and 675—material effect on price or value

For the purposes of sections 674 and 675, a reasonable person would be taken to expect information to have a material effect on the price or value of ED securities of a disclosing entity if the information would, or would be likely to, influence persons who commonly invest in securities in deciding whether to acquire or dispose of the ED securities.

119 The relevant provisions of the Listing Rules as set out in these reasons are from the compilation provided by the parties in the joint bundle of authorities. Rules 3.1 and 3.1A provided:

General rule

3.1 Once an entity is or becomes +aware of any +information concerning it that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of the entity’s +securities, the entity must immediately tell ASX that information.

Note: Section 677 of the Corporations Act defines material effect on price or value. As at 1 May 2013 it said for the purpose of sections 674 and 675 a reasonable person would be taken to expect information to have a material effect on the price or value of securities if the information would, or would be likely to, influence persons who commonly invest in securities in deciding whether or not to subscribe for, or buy or sell, the first mentioned securities.

…

Exception to rule 3.1

3.1A Listing rule 3.1 does not apply to particular +information while each of the following is satisfied in relation to the information:

3.1A.1 One or more of the following 5 situations applies:

• It would be a breach of a law to disclose the information;

• The information concerns an incomplete proposal or negotiation;

• The information comprises matters of supposition or is insufficiently definite to warrant disclosure;

• The information is generated for the internal management purposes of the entity; or

• The information is a trade secret; and

3.1A.2 The information is confidential and ASX has not formed the view that the information has ceased to be confidential; and

3.1A.3 A reasonable person would not expect the information to be disclosed.

The plus sign appearing before certain expressions indicates that the expression is defined in chapter 19 of the Listing Rules.

120 Chapter 19 (Interpretation and definitions) included:

Definitions

19.12 The following expressions have the meanings set out below.

…

aware an entity becomes aware of information if, and as soon as, an officer of the entity (or, in the case of a trust, an officer of the responsible entity) has, or ought reasonably to have, come into possession of the information in the course of the performance of their duties as an officer of that entity.

…

information for the purposes of Listing Rules 3.1 3.1B, information includes:

(a) matters of supposition and other matters that are insufficiently definite to warrant disclosure to the market; and

(b) matters relating to the intentions, or likely intentions, of a person.

121 These provisions were considered in James Hardie Industries NV v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2010] NSWCA 332; 274 ALR 85 (James Hardie); Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Ltd (in liq) [2016] FCAFC 60; 245 FCR 402 (Grant-Taylor); Crowley v Worley Limited [2022] FCAFC 33; 293 FCR 438 (Crowley (FC)); and Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2024] FCAFC 128 (ANZ v ASIC).

4 THE PROCEEDINGS AT FIRST INSTANCE

4.1 Overview