FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Merchant v Commissioner of Taxation [2025] FCAFC 56

Appeal from: | Merchant v Commissioner of Taxation [2024] FCA 498 |

File number(s): | NSD 746 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | LOGAN, MCELWAINE AND HESPE JJ |

Date of judgment: | 22 April 2025 |

Catchwords: | TAXATION – schemes to reduce tax pursuant to Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) – where vendor incurs a substantial capital loss on related party share sale but there is no effective alteration of control – whether primary judge erred in considering s 177D matters by considering the subjective intent of the scheme participants – whether primary judge failed to consider all objective purposes in the s 177D(2) analysis – held no error established. DIVIDEND STRIPPING – s 177E – whether primary judge erred in concluding that two debt forgiveness schemes entered into between related companies were schemes having substantially the effect of a scheme by way of or in the nature of dividend stripping – whether the schemes had the requisite tax avoidance purpose – whether the schemes had the requisite substantive effect – appeal allowed in part. TAXATION OF FINANCIAL ARRANGEMENTS (TOFA) – meaning of the expression “contingent only on the economic performance of the business” in s 230-460(13) Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) – application to expired rights to receive certain milestone payments in a share sale agreement – no error demonstrated. |

Legislation: | Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) ss 2-10(2), 2-15(2), 230-15(2), 230-45, 230-55, 230-460(13), 294-35, 974-85(1), 974-60, 995-1 Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) ss 44, 177A(5), 177C, 177C(1)(a), 177D, 177D(1), 177D(2), 177E, 177E(1)(a), 177E(1)(a)(ii), 177E(1)(b), 177E(1)(c), 177F, 177F(1)(a), 177F(1)(c), 177F(3) New Business Tax System (Debt and Equity) Act 2001 (Cth) New Business Tax System (Thin Capitalisation) Act 2001 (Cth) Tax Laws Amendment (Taxation of Financial Arrangements) Act 2009 (Cth) Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) s 14ZZ Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) ss 34, 62, 65 Explanatory Memorandum, Income Tax Laws Amendment Bill (No. 2) 1981 |

Cases cited: | Automotive Invest Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2024] HCA 36; 98 ALJR 1245 B&F Investments Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2023] FCAFC 89; 298 FCR 449 Bahonko v Sterjov [2008] FCAFC 30; 166 FCR 415 Bblood Enterprises Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2023] FCAFC 114 British American Tobacco Australia Services Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2010] FCAFC 130;189 FCR 151 Commissioner of Taxation v Bamford [2010] HCA 10; 240 CLR 481 Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Press Holdings Ltd [1999] FCA 1199; 91 FCR 524 Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Press Holdings Ltd [2001] HCA 32; 207 CLR 235 Commissioner of Taxation v Hart [2004] HCA 26; 217 CLR 21 Commissioner of Taxation v Macquarie Bank Ltd [2013] FCAFC 13; 210 FCR 164 Commissioner of Taxation v News Australia Holdings Pty Ltd [2010] FCAFC 78 Commissioner of Taxation v Peabody [1994] HCA 43; 181 CLR 359 Commissioner of Taxation v Sleight [2004] FCAFC 94; 136 FCR 211 Commissioner of Taxation v Spotless Services Ltd [1996] HCA 34; 186 CLR 404 Commissioner of Taxation v Zoffanies [2003] FCAFC 236; 133 FCR 523 CPH Property Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (1998) 88 FCR 21 Cumins v Commissioner of Taxation [2006] FCA 43 Eastern Nitrogen Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2001] FCA 366;108 FCR 27 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Michael John Hayes Trading Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 80; 303 FCR 62 Futuris Corporation Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2010] FCA 935 Hancock v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1961) 108 CLR 25 Investment & Merchant Finance Corporation Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) [1970] HCA 1; 120 CLR 177 Kilgour v Commissioner of Taxation [2024] FCA 687 Lawrence v Commissioner of Taxation [2008] FCA 1497; 70 ATR 376 Lawrence v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2009] FCAFC 29; 175 FCR 277 Merchant and Commissioner of Taxation [2024] AATA 1102 Merchant v Commissioner of Taxation [2024] FCA 498 Minerva Financial Group Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2024] FCAFC 28; 302 FCR 52 News Ltd v South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Ltd [2003] HCA 45; 215 CLR 536 Noza Holdings Pty Ltd v FCT [2011] FCA 46; 82 ATR 338 PepsiCo Inc v Commissioner of Taxation [2024] FCAFC 86; 303 FCR 1 Rowdell Pty. Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1963] HCA 61; 111 CLR 106 Review of Business Taxation: A Tax System Redesigned (July 1999) |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Taxation |

Number of paragraphs: | 443 |

Date of hearing: | 7-8 November 2024 |

Counsel for the Appellants: | Mr D O’Sullivan KC with Mr M May |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Ms M Brennan KC with Mr D Ananian-Cooper and Ms N Derrington |

Solicitor for the Appellants: | HLS Tax Law |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Gadens |

Table of Corrections | |

22 April 2025 | In paragraph 94, “dismissed the review off” has been replaced with “set aside”. |

25 July 2025 | In paragraphs 155 and 391, “appellant’s” has been replaced with “appellants” |

25 July 2025 | In paragraph 395, “appellant” has been replaced with “appellants” |

25 July 2025 | In paragraph 219, “he” has been replaced with “they”. |

ORDERS

NSD 746 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | GORDON STANLEY MERCHANT First Appellant GSM PTY. LTD. ACN 074 508 124 Second Appellant | |

AND: | COMMISSIONER OF TAXATION Respondent | |

order made by: | LOGAN, MCELWAINE AND HESPE JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 April 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days the parties:

(i) Must file any agreed short minutes of orders to give effect to these reasons, including as to costs; or

(ii) Failing agreement, their competing proposed orders and their respective submissions (not exceeding three pages).

2. Subject to any further order, final orders will be made on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

LOGAN J:

1 I have had the benefit of reading in draft the reasons for judgment to be delivered by McElwaine and Hespe JJ (joint judgment).

2 The thoroughness with which the facts of this case, the reasons of the primary judge and the issues on the appeal are rehearsed in the joint judgment enables me to state relatively briefly why I would allow this appeal, except insofar as it relates to the Taxation of Financial Arrangements Provisions (TOFA) in the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (ITAA 1997). I would dismiss so much of the appeal as relates to the TOFA.

3 I refer to the facts only to the extent necessary to explain my conclusions.

SECTIONS 177D AND 177C OF THE INCOME TAX ASSESSMENT ACT 1936 (CTH)

4 In his youth, Mr Gordon Stanley Merchant was a surfer and a maker and repairer of surfboards. He travelled the world undertaking these activities. By the early 1970’s, when he was in his late twenties, Mr Merchant had settled in rented farmhouse accommodation in Springbrook in the Gold Coast hinterland. There he continued his business of building surfboards. During this time and through surfing, he met his future wife, Rena. Rena also then had a business serving the surfing community. She made bikinis and simple boardshorts, selling them to other surfers on the Gold Coast. In 1973, they decided to start making boardshorts at home and sell them to local surf shops on the Gold Coast. Together, they made about 20 pairs of boardshorts a week on their kitchen table.

5 Over time, the business so founded grew and evolved into the successful “Billabong” brand of surf ware. Billabong Limited (BBG), which came to conduct that business, was listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) on 11 August 2000.

6 Even before the listing of BBG on the ASX, there had been challenges for Mr Merchant in the conduct and direction of the Billabong business. These were created by the introduction of external shareholders (notably entities controlled by the Perrin brothers) and related tensions in corporate decision-making. These continued after the listing. A principal source of tension was Mr Merchant’s view that the Billabong business should continue to concentrate on wholesale, rather than, as more recently introduced shareholders wished, retail, operations.

7 In about August 2002, Mr Matthew Perrin, who was CEO of BBG at the time, sold a large block of BBG shares. This was controversial and caused a fall in BBG’s share price. Mr Perrin eventually stood down as CEO of BBG because of these events.

8 As at 1 March 2006, the Merchant Group, via Gordon Merchant No. 2 Pty Ltd (GM2) as trustee for the Merchant Family Trust (MFT), an entity controlled by Mr Merchant, held about 25% of the issued capital in BBG. This was significantly more than the next largest shareholder. The Merchant Group shareholding of BBG Shares represented a large proportion of Mr Merchant’s wealth. He was concerned about having such wealth concentration in BBG shares. So he decided to sell down the Merchant Group’s BBG shareholding. To this end, on 1 March 2006, MFT sold 13,403,000 BBG shares to Citigroup Global Markets Australia Pty Ltd for total consideration of $199,838,730. After that sale, the Merchant Group held approximately 15% of the issued capital in BBG. That share parcel meant that the Merchant Group remained the largest single shareholder in BBG. Retention of that status was important to Mr Merchant both as a founder of BBG and for the influence it gave him in BBG.

9 The selling down of the BBG shareholding allowed Mr Merchant to diversify his investments. However, the sale proved controversial. Mr Merchant was reprimanded by BBG’s then chairman, who told him that he was not happy that he had not told him he intended to sell the shares before he did so. The issues surrounding Mr Perrin's earlier sale of BBG shares made this a particularly sensitive issue. In combination, Mr Merchant’s observation of Mr Perrin’s fate after he sold his shareholding and his experience after he sold down MFT’s made him cautious from that time about BBG management and board members.

10 Although the selling down of MFT’s shareholding enabled greater wealth distribution for Mr Merchant, even before then the success of the BBG business had enabled Mr Merchant, or entities related to him, to acquire interests in entities carrying on other businesses.

11 So it was that, on 31 March 2005, MFT acquired 14% of the issued capital in Plantic Technologies Limited (Plantic). Mr Merchant was appointed as a director of Plantic.

12 Plantic was a “start up” company that developed technology for recyclable and reusable material in plastic packaging. It produced a “plastic-like” material made of corn starch, which formed a barrier said to work as effectively as glass. Plantic’s product was an invention of Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation but which Plantic owned and was seeking to commercialise.

13 Related to Plantic’s then status as a “start up” company, it was not then profitable. There was a need, met from entities within the Merchant Group which Mr Merchant controlled, to fund its operations until such time, as was then hoped and expected, it became profitable. As it turned out, Mr Merchant underestimated how much subsidising funding Plantic would require.

14 In November 2010, MFT acquired all the shares in Plantic under a scheme of arrangement. MFT paid approximately GBP 6.38 million (which was then approximately AUD $10.3 million) to acquire all the shares in Plantic. Plantic then had about $10 million in its bank account.

15 Entities within the Merchant Group continued to fund Plantic while it worked to become financially viable on its own. During the time that MFT owned shares in Plantic, it did not make a profit. It required regular, monthly funding from entities within the Merchant Group. Plantic generally required funding of at least $1 million each month from January 2011. However, it was difficult to predict Plantic’s funding requirements for a given month, because cash flow projections provided to Mr Merchant by Plaintic proved not to be accurate. An example of the variation is that, in August 2014, entities within the Merchant Group made loans to Plantic of $700,000; in September 2014, loans made to Plantic by entities within the Merchant Group amounted to $1.4 million.

16 Over time, Mr Merchant was forced to sell properties in Hawaii owned by entities he controlled to assist in funding Plantic, because other resources within the Merchant Group were insufficient.

17 Each year, the Merchant Group was required to provide a “comfort letter” to Plantic’s Board, containing assurances that it would continue to provide financial support to Plantic.

18 Entities within the Merchant Group continued to fund Plantic by loans until March 2015, when MFT sold all its shares in Plantic.

19 By the end of March 2015, loans made to Plantic from within the Merchant Group comprised the following:

(a) in the period between 1 January 2011 to 30 March 2015 GSM Pty Ltd (GSM), an entity within the Merchant Group, loaned Plantic - $50,192,000 (GSM Loan);

(b) in the period between 1 January 2011 to 30 June 2012 Tironui Pty Ltd (Tironui) loaned Plantic - $4,215,000 (Tironui Loan);

(c) in the period between 1 January 2011 to 30 June 2012 Kahuna Pty Ltd as trustee for the Angourie Trust (Angourie) loaned Plantic - $790,854.

(the Plantic Loans)

20 From around 2011, a number of companies expressed interest in Plantic’s technology and in acquiring the company. One such company was Sealed Air; another was Kuraray. Ultimately, by an agreement made in March 2015, Kuraray acquired all of the shares in Plantic from GM2 as trustee for the MFT.

21 A feature of the sale to Kuraray, as it had been in relation to earlier but ultimately failed negotiations with Sealed Air, was that amounts owed to various entities within the Merchant Group by Plantic were forgiven. In other words, Kuraray, as with Sealed Air before it, was interested only in acquiring shares in Plantic if that company were a “clean” company, free not only of any ongoing shareholding by MFT but free of debts to entities controlled by Mr Merchant.

22 Thus, on 2 April 2015, the Plantic loans were forgiven by GSM, Tironui and Kahuna as part of the transaction whereby MFT sold its shares in Plantic to Kuraray.

23 On 2 April 2015, Kuraray paid GM2, as trustee of the MFT, $59,803,400 cash for the whole of the shares in Plantic. The sale resulted in GM2 making a capital gain of $84,885,502.

24 This sale brought to an end the need of the Merchant Group to continue to fund Plantic’s operations.

25 The BBG share price was generally on a downward trend from around 2007. The global financial crisis of 2008 negatively affected BBG and more particularly led to reduced retail sales due to decreased consumer spending and currency movements. In the 2009 income year, BBG ended with underlying net profit after tax down by 9.2% on the 2008 income year.

26 At the end of 2011, BBG reviewed its capital structure. Following this review, BBG received proposals to purchase its issued capital. There were a number of trading halts placed on BBG during 2012. BBG also stopped paying dividends in 2012.

27 Even after BBG stopped paying dividends, Mr Merchant caused entities in the Merchant Group to continue to buy BBG shares. There were several, inter-related reasons for this. He believed that BBG would be successful again. He had always seen BBG as his personal venture and, related to that, had always believed in the Billabong brand. These beliefs were rooted in his knowledge of the business as a Board member and from his longstanding involvement with the business. In turn, Mr Merchant believed that BBG’s poor financial results were due to mismanagement by key staff. He wanted to retain a controlling stake in the company to prevent mismanagement in the future. He believed that if the necessary changes in the management approach were taken it was likely that BBG would become successful again.

28 The primary judge accepted that Mr Merchant had a unique and distinctive connection with the BBG business, which caused him to wish to retain, via entities he controlled, his shareholding in BBG (PJ 267).

29 On 2 September 2014, GSM Superannuation Pty Ltd (GSMS) as trustee for the Gordon Merchant Superannuation Fund completed an off-market purchase of 10,344,828 shares in BBG for $5,844,827.82 ($0.565 per share) from GM2 (BBG Share Transfer). The BBG Share Transfer crystallised a capital loss for GM2 of $56,561,940 in the 2015 income year.

30 Although a transaction between related parties, the primary judge found (PJ 295) that the BBG Share Transfer was at market value. Neither party questioned this finding on the hearing of the appeal.

31 The Commissioner expressly conceded on the hearing of the appeal that, had the BBG Share Transfer entailed a sale not to a related party but to an unrelated third party, consideration of the factors in s 177D(2) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) would not have led to a conclusion that the dominant purpose of any person in entering into or carrying out the scheme he posited would have been to obtain a tax benefit. He likewise expressly conceded that this would remain so even though a crystalised loss of the same amount would thereby have become available.

32 In my view, the appellants demonstrated that the reasoning of the learned primary judge with respect to s 177D was affected by an error of principle. His Honour approached (PJ 250(a)) s 177D(1) on the basis that it “provides an objective test used to determine actual purpose” and that it “requires a conclusion about the intention of a person who entered into or carried out the scheme or a part of it to be determined objectively by reference to the eight matters in s 177D(2): Commissioner of Taxation v Hart (2004) 217 CLR 216 (Hart) at [37]”.

33 The second proposition is correct; the first, with respect, is not. Another case referred to by the primary judge for these propositions was Commissioner of Taxation v Zoffanies Pty Ltd (2003) 132 FCR 523 (Zoffanies) in particular observations made by Hill J at [54]. Hill J there stated:

It is sometimes said that the conclusion under s 177D is a conclusion of objective purpose. That way of putting it is correct if what is meant by it is that the conclusion is not one drawn from evidence of the actual purpose of the relevant taxpayer or other taxpayers. It may perhaps contribute to confusion if it is suggested that the conclusion to be drawn is other than a conclusion about the actual purpose of the taxpayer. Particularly, the conclusion required to be drawn is not a conclusion about the transaction itself but the state of mind of a person. To this extent Pt IVA differs from the previous general anti-avoidance provision (s 260) which was concerned inter alia with the purpose of the contract agreement or arrangement of the kind to which the section referred and not the purpose of a person party thereto.

[Emphasis added]

34 This passage from the judgment of Hill J in Zoffanies reveals, with respect, a confusion of understanding about s 177D uncannily similar to that of the primary judge. That understanding was not shared by the other members of the Full Court in Zoffanies. This is evident in the judgment of Gyles J (with whom Hely J, at [84], materially agreed) in his Honour’s statement, at [91], “The difference between the actual purpose of a taxpayer, on the one hand, and the purpose which is to be imputed to the taxpayer based upon an exclusive set of criteria, on the other hand, is not without subtlety and has been misunderstood before”.

35 There was much evidence at trial about subjective motivations of Mr Merchant and others, including advice furnished by EY. This was in turn much rehearsed by the primary judge. Reading the reasons for judgment as a whole, it is tolerably clear, as the appellants submitted, that the end to which this rehearsal was directed was the drawing of a conclusion as to actual purpose. This is most stark in the following passage (PJ, at [362]):

Each of these documents, understood in the context in which they were written, make it plain that the real reason for the BBG Share Sale was to crystallise a capital loss in the MFT which was regarded as beneficial whether Plantic was sold by way of asset sale or by way of share sale.

36 Further, as the appellants also submitted, to focus upon the “real reason” is to depart from the language of s 177D, which requires an objective conclusion, having regard to the eight factors specified in s 177D(2), as to what was the dominant purpose of a person who was a party to the scheme.

37 Of course, by the extinguishment via capital losses crystalised by the BBG Share Sale of a capital gain made by GM2 as trustee for the MFT on the sale of its Plantic shares, a tax benefit was obtained by GM2. Objectively, at the time of the BBG Share Sale, it was possible that the Plantic shares might be sold when and on the terms which came about but it could hardly be said this was at that time a matter of reasonable expectation. The failure of the proposed sale to Sealed Air is proof perfect of that. In the Full Court in Peabody v Commissioner of Taxation (1993) 40 FCR 531, at 541, Hill J (with whom Ryan and Cooper JJ agreed) explained that in the expression “reasonable expectation” that, “the word ‘reasonable’ is used in contradistinction to that which is ‘irrational, absurd or ridiculous’. The word "expectation" requires that the hypothesis be one which proceeds beyond the level of a mere possibility to become that which is the expected outcome”. A later appeal to the High Court by the Commissioner was dismissed by the High Court: Commissioner of Taxation v Peabody (1994) 181 CLR 359 (Peabody HCA). The High Court did not gainsay the explanation offered by Hill J in the Full Court; indeed, the Full Court’s reasoning was affirmed: see, esp. at Peabody HCA, at 385-386. In the absence of a capital gain against which to offset those losses, there could be no tax benefit, only losses to carry forward. “Reasonable expectation” is an important element both of whether there is a “tax benefit” (s 177C(1)(a)) and predicating a change in financial position for the purposes of s 177D(2)(e) and s 177D(2)(f).

38 Hindsight is apt to confer an expectation that the timing and terms of the ultimate sale of the Plantic shares is likely. However, that expectation could not exist at the time when the BBG Share Sale actually occurred. At the time of the BBG Share Sale, and in terms of the change in financial position considerations in s 177D(2)(e) and s 177D(2)(f), the only change in financial position was the capital losses. Nothing more could then reasonably be expected. A sale of the shares in Plantic and certainly one which generated the capital profit concerned, was then but a possibility. Yet for the posited tax benefit to exist, the “scheme” necessarily, had to include the sale of the shares in Plantic: Hart, at [9].

39 Further, as Gleeson CJ and McHugh J stated in Hart, at [15], taking up a point made in Commissioner of Taxation v Spotless Services Ltd (1996) 186 CLR 404, at 416, as to the routineness of revenue law considerations influencing the form of commercial transactions, “even if a particular form of transaction carries a tax benefit, it does not follow that obtaining the tax benefit is the dominant purpose of the taxpayer in entering into the transaction”.

40 The Commissioner’s concession that losses so crystalised by a third party sale would not lead to a conclusion that the dominant purpose was securing a tax benefit by their application against a later capital gain recognised a pervasive reality of holding shares in ASX-listed companies. Sometimes share investments made for reasons thought good at the time in terms of an apprehended dividend yield and increase in share value prove good, sometimes they do not. When they do not, it can be prudent to cut one’s losses and to do so at a time when it is prudent to realise a capital gain on a share investment which has proved good. The Commissioner did not suggest that an application of s 177D to such a scenario would inexorably lead to a conclusion that the imputed purpose was the obtaining of a tax benefit by the application of the capital loss against the capital gain. Any such imputation would be difficult because an obvious additional purpose is just cutting one’s losses.

41 There was no difference between form and substance (s 177D(2)(b)) with respect to the BBG Share Sale. In form and in substance it was a sale at market value of shares in a company listed on the ASX. That exact symmetry is hardly a factor supportive of a conclusion that the dominant purpose was the obtaining of the tax benefit.

42 In terms of s 177D(2)(g), there were multiple other consequences of the BBG Share Sale, apart from crystalising capital losses. The sale was to the trustee of a superannuation fund, GSMS. Sale of shares in a company listed on the ASX was one of the permissible related party transactions for a superannuation fund trustee. Yet the sale maintained an overall interest in BBG by entities controlled by Mr Merchant. Maintenance of major shareholder status was a purpose and one singularly important to the founder of the BBG business. A sale to a third party would not have achieved this purpose. Selling to an entity controlled by Mr Merchant avoided the acrimony which had attended earlier sales of large parcels of shares in BBG by those involved in its governance or management. It could not be perceived as a vote of no confidence in BBG.

43 Another consequence of the BBG Share Sale was that GM2 as trustee of the MFT received an immediate cash benefit of $5.8m from GMSF. It was a permissible way for funds to be paid out from the GMSF. Given the Commissioner’s concession about the unremarkable quality of a sale to a third party at a like price (and thus a like cash injection of $5.8 million), it is just a distraction as to whether GM2 really then needed that cash. Further and in any event, care needs to be taken about the false wisdom of hindsight. Objectively and at the time of the BBG Share Sale, Plantic continued to need regular monthly injections of funds from entities in the Merchant Group to continue to operate. It bears repeating that when and on what terms there would be a sale of GM2’s shares in Plantic admitted of a possibility that this would occur, as it came to, but not of a “reasonable expectation”.

44 With all respect to those who have a contrary view, consideration of the factors specified in s 177D(2) should lead, inexorably, to a conclusion that the obtaining of the posited tax benefit was not a dominant purpose.

S 177E OF THE INCOME TAX ASSESSMENT ACT 1936 (CTH)

45 Section 177E creates a sui generis regime directed to dividend stripping. It is singularly important that its meaning not be affected by notions imported from s 177D or, in relation to what constitutes a tax benefit, from s 177C. The section creates a “supplementary code” applicable in circumstances where it is not likely that s 177D will be applicable: Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Press Holdings Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 235 (Consolidated Press Holdings), at [109].

46 I have concluded that s 177D is inapplicable. I do not in any event consider it appropriate to embark on a consideration of the applicability of s 177E influenced by a conclusion that s 177D was applicable. Further, a reason for the enactment of s 177E was, as mentioned, to serve as a “supplementary code”. The notion that it might be applicable in circumstances where s 177D was applicable is odd.

47 Rather than favour the so often futile endeavour of prescriptive definition, Parliament has in s 177E instead favoured concept-based drafting. Thus, there is no definition of what amounts to “dividend stripping” for the purposes of s 177E(1). Which is not to say, as is explained in Consolidated Press Holdings, that, when s 177E was enacted, what amounted to “dividend stripping” did not have certain well-understood characteristics. As to this, in Consolidated Press Holdings, at [105], the High Court (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ) cited with apparent approval an understanding of the term, as given in Halsbury’s Laws of England, which had commended itself to Windeyer J in Investment & Merchant Finance Corporation Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1970) 120 CLR 177, at 179:

Dividend stripping is a term applied to a device by which a financial concern obtained control of a company having accumulated profits by purchase of the company’s shares, arranged for these profits to be distributed to the concern by way of dividend, showed a loss on the subsequent sale of shares of the company, and obtained repayment of the tax deemed to have been deducted in arriving at the figure of profits distributed as dividend.

48 Subject to one caveat, the High Court also favoured in Consolidated Press Holdings, at [127], an explanation of “dividend stripping” offered by the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia:

The widely understood connotation [of the expression 'dividend stripping'] was explained in the pre-1981 case law to which we have referred. The so-called dividend stripping cases invariably had as their dominant, if not exclusive, purpose the avoidance of tax that otherwise would or might be payable by the vendor shareholders in respect of the profits of the target companies. The apparent exceptions ... are readily explicable on the basis that the particular scheme, insofar as it involved vendor shareholders, was complete before the dividend stripper began its operations and thus could not itself be described as a dividend stripping operation. The case law preceding the 1981 Act strongly supports the view that Parliament framed s 177E(1)(a) on the basis that dividend stripping operations necessarily involve a predominant tax avoidance purpose.

49 The caveat voiced by the High Court in Consolidated Press Holdings, at [129] was out of abundant caution and to avoid a possible misunderstanding of this statement. The High Court made clear that the Full Court’s view at intermediate appellate level in that case that “s 177E was intended to apply only to schemes which can be said to have the dominant purpose of tax avoidance”. Without being prescriptive, the High Court added that, also at [129], that the required tax avoidance purpose would ordinarily be that of the enabling vendor shareholders.

50 The test posited by each limb of s 177E(1) is outcome or result focussed and it is an objective one.

51 The primary judge stated (at PJ [506]):

No commercial and objective onlooker could sensibly conclude that the object of the structure was to permit GSM and Tironui to access the increase in value in the MFT. It is plain that Mr Merchant would not choose to make a capital distribution to GSM and Tironui, and thereby expose himself again to top up tax as a shareholder of those entities, rather than to distribute the profits to himself in a manner which avoided that consequence.

[Emphasis added]

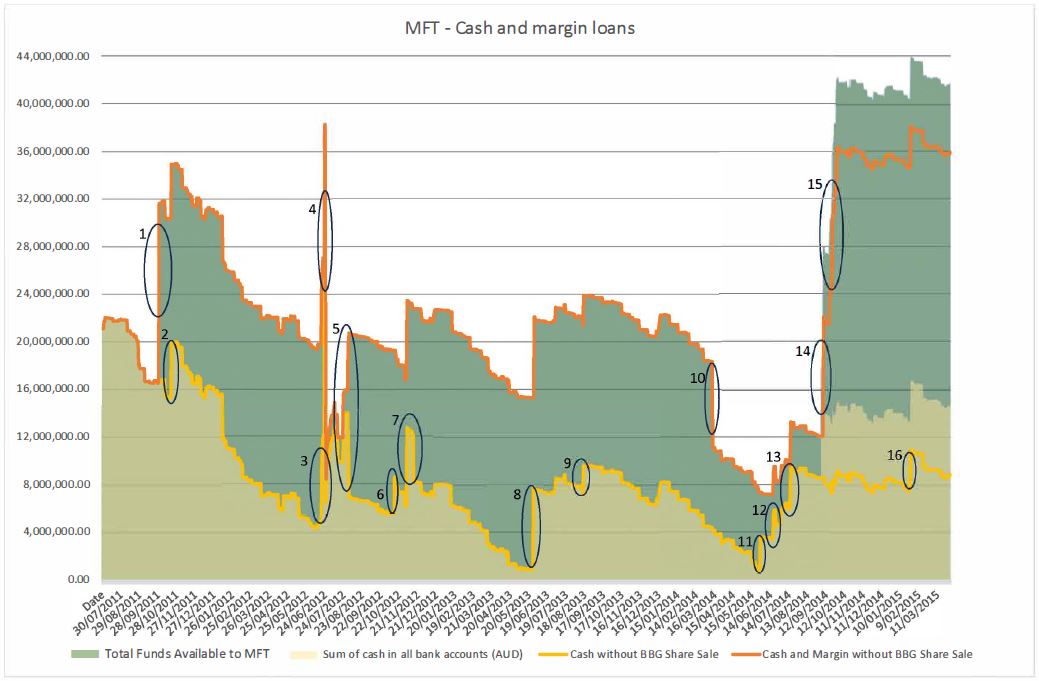

52 In the first sentence in the passage quoted, the primary judge has apparently proceeded on the basis that the test was an objective one. So to proceed would be correct. However, and with respect, whether that was indeed the basis upon which his Honour proceeded is immediately challenged by what is stated in the second sentence (emphasised). The appellants’ submission that the second sentence evinces an “actual purpose” error by his Honour analogous to that made with respect to s 177D should be accepted. An “actual purpose” analysis permeates the primary judge’s analysis of s 177E (see, especially, PJ 541, 548 and 549).

53 Objectively, the contemporaneous evidence disclosed, as the appellants correctly submitted, the dominant purpose of the debt forgiveness had nothing to do with “dividend stripping”. The relationship between GSM, Tironui, MFT and Mr Merchant was such that the forgiving of the Plantic loans benefited the MFT and, in turn, each of GSM and Tironui as beneficiaries of the MFT. The debt forgiveness just increased the amount of the capital gain that MFT made on the sale of the shares in Plantic. The reason why MFT did not derive a net capital gain for the year was because it had available to it, not as a result of the debt forgiveness, capital losses.

54 After the remaining capital losses are exhausted, the balance of the capital gain derived by MFT from the sale of its shares in Plantic remain as a potential source of income tax obligations. If there are no other available capital losses MFT will be faced with choices. If paid to GSM to extinguish in part its unpaid present entitlements, there will be income tax consequences. If it distributes the gain to GSM as capital, GSM will face a choice of paying the amount to Mr Merchant as either a dividend or a capital amount. In either case, as the appellants submitted, there will be income tax consequences. If the former, “top up” tax on a dividend at an effective rate of 27.14% after franking credits would be attracted. If paid to Mr Merchant as a capital amount, tax at an effective rate of 24.5% for a concessional capital gain would be attracted.

55 The point is that nothing about the debt forgiveness rendered the capital gain made on the Plantic shares “tax free”. The debt forgiveness increased the amount of the capital gain.

56 These features are difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile with a dominant purpose of “dividend stripping”. The practice of “dividend stripping” as explained in Consolidated Press Holdings, entails a conversion of corporate profits which might have been taxed into something that will not be taxed (in the absence of a measure such as s 177E). In these circumstances and as Consolidated Press Holdings, at [133] highlights, s 177E was inapplicable.

TOFA

57 In addition to provision for cash payments, the agreement for the sale of MFT’s shares in Plantic also included a range of economic performance clauses (termed “Future Payment Rights” by the primary judge).

58 Economic performance clauses of one sort or another are a not uncommon feature of corporate mergers and acquisitions and related share sale agreements. There is no one type of such clause.

59 Some such clauses take the form of an “earn out” arrangement whereby, in addition to lump sum consideration of the purchase of shares, an additional amount may become payable depending on whether specified income targets are met for a specified period or periods after settlement of the share sale. That type of clause can be attractive where it is desired that previous owners of the shares in a company continue to work for the company after its acquisition by new owners, although that is not their only use or attraction. An “earn out” provides an incentive for such persons not just to continue to work for the company but also to maintain or improve its profitability. Kilgour v Commissioner of Taxation [2024] FCA 687 was decided against a background which included such a clause.

60 Other such clauses in a share sale agreements focus upon post-settlement performance milestones in respect of sales or production volumes. Sometimes a feature of such clauses is that a failure to achieve a milestone triggers an obligation on the part of the vendor shareholder an obligation to refund a proportion of a lump sum previously paid by the purchaser to the vendor. Sometimes also a share sale agreement contains a combination of various types of economic performance clauses.

61 In each instance, an economic performance clause lends a contingent quality to the total consideration in respect of a share sale. But they provide a means by which, even in circumstances of some uncertainty about the value of shares, parties can nonetheless reach agreement with respect to their sale.

62 This share sale agreement contained a variety of economic performance clauses:

(a) Milestone Amounts (as detailed by the primary judge under a heading of that title at PJ 578 and following); and

(b) Earn Out Amounts (as detailed by the primary judge under the heading “Earn Out Amount” at PJ 589 and following).

63 The appellants submitted that the expression “contingent only on the economic performance of the business” in s 230-460(13) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) did not, as the primary judge considered the position to be, carry its ordinary meaning, but rather than a meaning “informed by” the meaning of the expression “contingent on the economic performance” as defined in s 974-85(1) of that Act. The effect of the latter expression is that a right is not relevantly contingent merely because it is contingent on “the receipts or turnover” of the entity.

64 A consideration which was said to support the construction promoted by the appellants was that Div 974 and Div 230 each formed part of a series of “reforms” progressively introduced into the Act with respect to the TOFA, Div 974 as part of the first stage and Div 230 as part of a combined third and fourth stages.

65 Considered at this level of abstraction, the submission made by the appellants is correct. It may also be said of the TOFA amendments generally that in such circumstances as they apply, they change the focus from legal form to economic substance. But that is where the commonality in the stages stops.

66 Division 974 was introduced by amendments made by the New Business Tax System (Debt and Equity) Act 2001 (Cth) and the New Business Tax System (Thin Capitalisation) Act 2001 (Cth). The amendments introduced rules for classifying financial instruments as debt interests or equity interests according to the economic substance of an instrument rather than its legal form. These rules can be seen to have a single organising purpose, which is that an instrument is a debt interest where an issuer has an effectively non-contingent obligation to return, to the investor, an amount at least equal to the amount invested. The wording of s 974-85(1) is adapted to that end. Further, unlike later stage TOFA reforms, Div 974 contains no direct taxing provisions. It just deals with the debt/equity classification of an instrument, leaving the resultant tax outcomes to be determined by taxation legislation elsewhere.

67 Division 230 was introduced by the Tax Laws Amendment (Taxation of Financial Arrangements) Act 2009 (Cth). It is directed to the tax treatment of gains and losses from “financial arrangements”. Where applicable, it permits a taxpayer to recognise the gains or, as the case may be, losses, over the life of a financial arrangement and to ignore distinctions between income and capital.

68 There are exceptions to the applicability of Div 230. These are found in Subdiv 230-H. One of these is that specified in s 230-460(13). The primary judge observed (PJ, at 636) of s 230-460(13) that it “addresses financial benefits arising from the sale of a business under an earn out arrangement”. I agree. The obvious purpose of the qualification “only” in the chaussette of that provision is to narrow the focus of the exception to arrangements based solely on economic performance rather than, for example, profitability.

69 Had parliament wanted s 974-85(1) to affect or supply the meaning of “contingent only on the economic performance of the business after the sale” in s 230-460(13), it would have been very easy to have stated this. Like the primary judge (PJ at 638), I find the difference in the text as between s 230-460(13) and s 974-85(1) reason enough not to regard s 974-85(1) as “informing” the meaning of s 230-460(13). Consideration of context and purpose, as discussed above, serves to confirm this.

70 It follows that I agree with the primary judge’s assumption that, assuming what his Honour termed the “Future Payments Rights” were “financial arrangements” to which division 230 would otherwise have applied, the rights were subject to the exception in s 230-460(13).

71 As with the primary judge, that conclusion means that it is strictly unnecessary to express a view on the subject. However, I respectfully agree with the primary judge, for the reasons his Honour gives, that each of what his Honour termed “the Expired Future Payment Rights” is a “financial arrangement” within the meaning of s 230-45.

72 More particularly, the use in the text of s 230-45(1) of “legal or equitable right” and “legal or equitable obligation” more naturally direct attention to the right or obligation itself, as described and sourced in a specific contractual provision, rather than to the contract in which that right or obligation is found as a whole. In turn, that meaning is congruent with s 230-55 (Rights, obligations and arrangements (grouping and disaggregation rules)) and with the reference to “right” in s 230-460(13).

73 I would therefore dismiss so much of the appeal as related to the TOFA provisions.

OUTCOME

74 In summary, if one steps back and examines events which transpired informed by the considerations specified in s 177D(2), a number of purposes are evident:

(a) crystallization of tax losses via a sale of BBG shares, which did not in itself confer any tax benefit, only the contingency that a benefit of uncertain nature and extent might in the future become available depending on whether and on what terms MFT’s shares in Plantic could be sold;

(b) a purchase at market value of those BBG shares by GSMS, bringing with it the benefit of retention under the control of Mr Merchant of an influential parcel of shares and without any potential for criticism for the sale to be construed as a loss of confidence by a founder in BBG’s business;

(c) liberation of funds from within a superannuation fund and bringing the shares within the superannuation regime;

(d) bringing to an end via the Plantic share sale of an investment that was occasioning a monthly haemorrhaging of funds by other entities with the Merchant Group (and it was not necessary in order to find an absence of dominant purpose that those entities be proved to already have been bled white financially).

75 So viewed and objectively, no single purpose is dominant.

76 If one adds to this consideration of s 177E, a debt forgiveness which maximises an assessable capital gain is, in itself, the antithesis of “dividend stripping”.

77 Subject to the TOFA related dismissal noted, I would, for the above reasons, allow so much of the appeal as relates to objection decisions which confirmed assessments grounded in determination under s 177F, based on the applicability of s 177D and s 177E. I would, to this extent, set aside the objection decisions and in lieu thereof order that the objections be allowed and the related assessments quashed. I would remit the matter to the Commissioner for reassessment accordingly.

78 In their written submissions in relation to s 177D, the appellants put that “one of the root problems with the Commissioner’s approach in this matter was that ‘schemes’ are filleted out for forensic reasons, divorced from their wider and non-fiscal context, in order to support a conclusion about ‘purpose’ that is essentially myopic”.

79 It is a corollary of the conclusion I have reached when looking to s 177D(2) and s 177C(1) that, with all respect to the Commissioner, I agree with this characterisation. Indeed, it is likewise applicable, in my view, to the s 177E aspect of this matter. In each, another ophthalmological analogy is also applicable, “tunnel vision”.

80 There is a considerable risk in the administration of taxation legislation of seizing upon beneficial taxation outcomes and seeing in them a dominant purpose on the part of a person to obtain the tax benefit. It is all too easy in such circumstances to leap to that conclusion and to tailor the logic to fit. Especially that is so where there is revealed in exchanges with tax advisors references to apprehended tax benefits. The Commissioner’s role in the general administration of taxation legislation and as a revenue collector makes him peculiarly prone to his decision-making being affected by this risk. Tax collection is, after all, “core business” for him. Outside the Commissioner’s office, in businesses large and small across Australia, taxation considerations, including tax benefits, are often but one of the many factors those in business routinely take into account. As Peabody illustrates, where discernible commercial purposes are present, as well as the obtaining of a tax benefit, a conclusion that the latter is the dominant purpose is fraught. On the other hand, as Spotless Services and Hart illustrate, where a scheme can, objectively, be seen to be but an artificial construct inexplicable in its occurrence other than for the purpose of obtaining a tax benefit, it is likely that purpose will be the dominant, if not sole, purpose.

I certify that the preceding eighty (80) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Logan. |

Associate:

Dated: 22 April 2025

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MCELWAINE AND HESPE JJ:

81 The primary judge heard three appeal proceedings brought by Mr Gordon Merchant and a related corporation against amended assessments issued by the Commissioner of Taxation concerning transactions entered into between September 2014 and April 2015 relating to a sale of shares in Billabong International Ltd (BBG) and in Plantic Technologies Ltd. For reasons published on 14 May 2024, his Honour dismissed each proceeding: Merchant v Commissioner of Taxation [2024] FCA 498 (PJ).

82 Broadly, on 2 September 2014, Gordon Merchant (No 2) Pty Ltd (GM2) as trustee of the Merchant Family Trust (MFT) transferred approximately 10 million BBG shares to GSM Superannuation Pty Ltd (GSMS) as trustee of the Gordon Merchant Superannuation Fund (GMSF) for a consideration of $5,844,827.82. In doing so, GM2 incurred a capital loss of $56,561,940. At the time, GM2 held all the issued shares in Plantic, which was not profitable and relied on cash injections from GM2 and loans from other Merchant Group companies.

83 In April 2015, GM2 sold all of its shareholding in Plantic to Kuraray Co Ltd, an unrelated Japanese corporation, which resulted in the MFT deriving a capital gain of approximately $85 million. A condition of the sale required that related company loans (totalling of approximately $55 million) be waived or forgiven.

84 On 20 July 2020, the Commissioner made determinations under Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (1936 Act) to cancel identified tax benefits from two schemes:

(1) the BBG Share Sale Scheme. The Commissioner made a determination under s 177F in reliance upon s 177D of the 1936 Act (s 177D Determination). The Commissioner determined that the BBG Share Sale Scheme was entered into or carried out for the dominant purpose of enabling the MFT to obtain a tax benefit, being the capital loss incurred by it on the BBG Share Sale (BBG Capital Loss), which at the time of making the determination, the Commissioner had calculated as $56.5 million. The Commissioner cancelled that benefit by determining under s 177F(1)(c) that the whole of the capital loss was not incurred by the MFT, with the effect of increasing the taxable income of the MFT. An amended assessment giving effect to the determination was issued to GSM Pty Ltd as the beneficiary presently entitled to the income of the MFT.

(2) the Debt Forgiveness Schemes. The Commissioner made determinations under s 177F in reliance upon s 177E of the 1936 Act. The Commissioner determined the debt forgiveness by each of the related company lenders, GSM and Tironui Pty Ltd, to be schemes having substantially the effect of schemes by way of or in the nature of dividend stripping under s 177E. The Commissioner determined pursuant to s 177F(1)(a) that the entirety of the forgiven amounts be included in the assessable income of Mr Merchant, the sole shareholder of each of GSM and Tironui, for the 2015 year.

85 To give effect to those determinations, on 24 and 27 July 2020, the Commissioner issued amended notices of assessment and penalties. Mr Merchant, GSM and GM2 relevantly objected. The objections were disallowed. On 3 September 2021, Mr Merchant and GSM (the appellants) commenced proceedings in this Court pursuant to s 14ZZ of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) in respect of the amended assessments for primary tax concurrently with review proceedings in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) in respect of the penalty assessments.

86 The primary judge summarised what was in issue at PJ [9]-[16] as follows:

The MFT’s capital gain on the sale of its shares in Plantic to Kuraray was around $85 million. The capital proceeds included a cash payment of about $60 million, a working capital adjustment and future payments, including what have been referred to as “Milestone Amounts” and “Earn-Out Amounts”, which were valued in the accounts at the time at around $51 million (the Future Payment Rights). The acquisition costs were around $24 million and the cost base in the Plantic shares included amounts paid to lawyers and the payout of employee options, costing a little over $2 million. The capital proceeds were calculated to be about $111 million and the cost base was about $26 million, resulting in a capital gain of about $85 million.

The preceding transactions – particularly the debt forgiveness and the crystallising of the MFT’s capital loss – piqued the interest of the Commissioner of Taxation, resulting in an audit of the affairs of Mr Merchant and the Merchant Group. After the audit, the Commissioner issued two sets of “Reasons for Decision” on 20 July 2020.

One concerned the “BBG Share Sale Scheme”. The Commissioner considered that, for the purposes of s 177D(1) in Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (ITAA 1936), it would be concluded that a person entered into or carried out a scheme, or part of it, for the dominant purpose of enabling GSM to obtain a tax benefit, GSM being the only presently entitled beneficiary of the MFT. In summary, the Commissioner took the view that the predominant reason why the GMSF acquired the BBG Shares from the MFT on 4 September 2014 was to crystallise a capital loss in the MFT which could be applied against the capital gain from the MFT’s anticipated sale of its shares in Plantic, resulting in a reduction in GSM’s assessable income. The Commissioner considered that the BBG Share Sale was analogous to a ‘wash sale’ given that the BBG Shares would remain in the Merchant Group of which Mr Merchant was the ultimate owner.

The Commissioner made a determination under s 177F(1)(c) of the ITAA 1936 that the amount of $56,561,940, referable to a capital loss incurred by the MFT in the year ended 30 June 2015, was not incurred by the MFT in relation to that financial year (the s 177D Determination). As a consequence of this:

(a) the MFT’s net income increased from $5,482,423 to $28,111,179 to reflect the net capital gain (at the 50% discount) of $22,628,756;

(b) an amended assessment dated 24 July 2020 was issued to GSM (the GSM Amended Assessment), increasing GSM’s tax payable by $12,877,000.90 (because GSM was the beneficiary with a 100% present entitlement to the income of the MFT in the 2015 year): CB695; and

(c) although no amount of the net capital gain was assessed to the [trustee of the] MFT, a penalty assessment issued to the [trustee of the] MFT on 27 July 2020, which assessed it as liable to a penalty of $6,438,500.45 being 50% of the BBG Share Sale Scheme shortfall amount, pursuant to Division 284-C of Sch 1 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (TAA 1953): CB788.

The second transaction concerned the “GSM and Tironui Debt Forgiveness Scheme”. The Commissioner considered that the forgiveness of debts by two of the three lenders – GSM and Tironui – were schemes having substantially the effect of schemes by way of or in the nature of dividend stripping within the meaning of s 177E(1)(a)(ii) in Part IVA. No consideration was provided for the forgiveness of debt such that the forgiveness had the effect of:

(a) reducing the undistributed profits of GSM and Tironui; and

(b) converting the Plantic Loans to equity, thereby increasing the value of Plantic’s shares and the consideration paid by Kuraray for those shares.

The Commissioner made a determination under s 177F(1)(a) of the ITAA 1936, that the debts forgiven by GSM and Tironui be included in Mr Merchant’s assessable income in the 2015 income year as dividends (the s 177E Determination).

To give effect to the s 177E Determination, on 27 July 2020, the Commissioner issued an amended assessment to Mr Merchant (the Merchant Amended Assessment) in relation to the 2015 year. This increased Mr Merchant’s assessable income by $54,407,000 (being the tax benefit considered by the Commissioner to have been obtained from the release and forgiveness of the Plantic Loans) with the result that Mr Merchant’s tax liability increased to $30,570,438.12, comprising an increase in tax payable and a shortfall interest charge: CB696.

Mr Merchant, the MFT and GSM lodged a joint objection on 22 September 2020 objecting to each of the assessments: CB790. The objections were disallowed on 27 July 2021: CB797; CB798; CB5. In deciding the objections, the Commissioner concluded:

(a) that the MFT had obtained a tax benefit from the BBG Share Sale Scheme, and that the MFT and the GMSF entered into the BBG Share Sale Scheme for the dominant purpose of obtaining a tax benefit such that s 177D(1) applied, with the consequence that the Commissioner was entitled to make a determination under s 177F(1)(c) cancelling the capital loss: CB798; and

(b) in respect of Mr Merchant, that the GSM and Tironui Debt Forgiveness Schemes had the substantial effect of a dividend stripping scheme, attracting the operation of s 177E of the ITAA 1936: CB797 at [59].

87 Another issue before the primary judge concerned the application of Div 230 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (1997 Act) (the TOFA Provisions) to the right of the MFT to receive the Milestone Amounts, where the right to receive components of those amounts expired in the 2017 and 2018 income years. Mr Merchant had originally claimed the expiry of the rights as capital losses in the amounts of $1,019,505 and $418,558. Mr Merchant objected to his assessments for the 2017 and 2018 income years to claim the amounts as deductions on revenue account pursuant to the TOFA Provisions. The Commissioner disallowed the objection and on 10 November 2021, Mr Merchant commenced a further appeal proceeding in this Court (the TOFA Proceeding).

88 On the matters in issue before the primary judge, his Honour:

(i) Concluded that s 177D was satisfied. It was not disputed that the MFT had obtained a tax benefit for the purposes of s 177C, being a capital loss on the sale of the BBG shares to the GMSF. The primary judge found that it was reasonable to conclude that the dominant purpose of each of Mr Merchant, the MFT and the GMSF in entering into and carrying out the BBG Share Sale Scheme was one of obtaining a tax benefit for the MFT. The appellants failed to discharge their onus to the contrary: PJ [408]. However, his Honour was satisfied that GSM had discharged its onus of establishing that the capital proceeds were incorrectly calculated and hence the amended assessment was excessive to the extent of approximately $11 million. His Honour remitted the recalculation to the Commissioner: PJ [433];

(ii) Concluded that s 177E was satisfied. The primary judge found that the Debt Forgiveness Schemes, were each schemes having substantially the effect of a scheme by way of dividend stripping for the purposes of s 177E(1)(a)(ii). Mr Merchant failed to discharge his onus to the contrary: PJ [571]-[573]; and

(iii) Concluded that the TOFA Provisions did not apply because the exception in s 230-460(13) of the 1997 Act was satisfied: PJ [627]. Although it was unnecessary to reach a conclusion about whether the Expired Future Payment Rights were each a financial arrangement, his Honour proceeded to determine that question and concluded that they each were “when assessing the matter in a commercial, practical way in light of the apparent object of the TOFA provisions”: PJ [632].

89 The AAT proceedings in relation to the penalty assessments were adjourned, pending the determination of the primary tax assessments and the making of a request for a compensatory adjustment depending on the outcome of the proceedings relating to the primary tax assessments (PJ [489]).

90 The appellants’ Notice of Appeal to this Court was filed on 11 June 2024 and comprised 18 grounds with multiple sub-grounds. The scope of the grounds reduced somewhat in the form of the Amended Notice of Appeal as attached to the appellants’ written submissions dated 8 October 2024. The Commissioner raised no objection, and we granted leave to amend in the course of the hearing. In summary, the amended grounds traverse whether the primary judge erred in finding:

(i) That the appellants had failed to discharge the onus of proving that the BBG Share Sale was not a scheme in respect of which it would be concluded that a person who entered into or carried out the scheme did so for the dominant purpose of enabling a relevant person to obtain a tax benefit in connection with the scheme: s 177D of the 1936 Act;

(ii) That Mr Merchant had not discharged the onus of establishing that the Debt Forgiveness Schemes were each schemes having substantially the effect of a scheme by way of or in the nature of dividend stripping: s 177E(1)(a)(ii) of the 1936 Act; and

(iii) That the exception at s 230-460(13) of the 1997 Act applied to the Expired Future Payment Rights.

91 The Commissioner resists the appeal and relies on a Notice of Contention (relevant to (c)) that the order made by the primary judge ought to be affirmed on the ground that his Honour should also have found that each of the Expired Future Payment Rights were not a financial arrangement within the meaning of s 230-45 of the 1997 Act because those rights, properly construed, constituted part of a single arrangement arising under the agreement for the sale of the shares in Plantic and the other rights were not insignificant in comparison with the rights to receive future payments.

THE FINDINGS OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE

92 At the outset it should be noted that the parties requested his Honour to hear the related AAT proceedings together with the three appeal proceedings, with the evidence in the Court proceedings being evidence in the AAT proceedings and vice versa. His Honour agreed in the interests of expedition and efficiency. At PJ [24], his Honour summarised the AAT proceedings:

(1) Gordon Merchant No 2 Pty Ltd as trustee for Merchant Family Trust v Commissioner of Taxation (AAT Case 2021/6296): The Commissioner issued a notice of assessment of scheme shortfall penalties to GM2 as trustee of the MFT for 50% of a scheme shortfall of $12,877,000.90, being $6,438,500.45. This proceeding is GM2’s application for “review” of the Commissioner’s disallowance of its objection.

(2) Gordon Merchant v Commissioner of Taxation (AAT Case 2021/6294): The Commissioner issued a notice of assessment of scheme shortfall penalties to Mr Merchant in connection with the s 177E assessment. Mr Merchant was assessed as having a scheme shortfall of $26,659,429.97 and was assessed to a 25% penalty, being $6,664,857.24. This proceeding is Mr Merchant’s application for “review” of the Commissioner’s disallowance of his objection.

(3) Gordon Merchant v Commissioner of Taxation (AAT Case 2020/6932): This is Mr Merchant’s application for review of the Disqualification Decision.

93 The Disqualification Decision is a reference to a decision made by the Commissioner on 21 July 2020 pursuant to the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) (SISA) to disqualify Mr Merchant from acting as a trustee or responsible officer of corporate trustees of superannuation entities. The Commissioner made that decision on the basis GSMS as trustee of the GMSF contravened respectively the operating standards under s 34 of the SISA, by failing to give effect to the investment strategy requirements, the sole purpose rule at s 62 of the SISA and the requirement at s 65 of the SISA, by using the resources of the fund to give financial assistance to a member.

94 On 16 May 2024, the primary judge, in his capacity as Deputy President of the AAT, set aside the disqualification decision: Merchant and Commissioner of Taxation [2024] AATA 1102.

BACKGROUND FINDINGS

95 The appellants do not contend that the primary judge erred in making relevant background findings of fact. His Honour set out a detailed chronology of relevant events at PJ [1]-[240]. We summarise the material findings as follows.

96 The primary judge commenced by identifying the Merchant Group of companies and the key players at PJ [1]–[4].

97 Mr Merchant co-founded the business which became Billabong Holdings Australia Ltd in 1973. Following a name change to Billabong International Ltd, it was listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) in August 2000. Mr Merchant at all times was the director and controlling mind of each company in the Merchant Group.

98 GM2 as trustee of the MFT held 100% of the issued shares in Plantic. It first acquired 14% of the Plantic shares in 2005, and then acquired the balance of the Plantic shares in November 2010 pursuant to a scheme of arrangement. The cost base of the MFT’s entire Plantic shareholding was approximately $26.9 million. Mr Merchant at all material times was one of the directors of Plantic together with Ms Colette Paull, his management assistant and Mr Luke McGrath, an investment adviser. Plantic was established as a start-up company to develop technologies in the manufacture and distribution of plant-based packaging materials as a substitute for oil based products.

99 Mr Merchant held all of the issued shares in Tironui, GSM, Kahuna Pty Ltd as trustee of the Angourie Trust and GSMS as trustee of the GMSF.

100 The primary judge set out the history of the Merchant Group shareholdings in BBG at PJ [42]–[50], [62]–[79], [86]–[90], [101]–[102], [126]–[129]. The effect of the transactions was that by March 2014, the Merchant Group held approximately 10% of the voting power in BBG and was no longer the largest shareholder: PJ [129]. On 2 September 2014, Mr Merchant transferred 10,344,828 BBG shares from the MFT to the GMSF, in consideration of $5,844,827, a price of 56.5 cents per share: PJ [185]–[186].

101 Mr Merchant’s evidence, which the primary judge accepted, was that for many years he sought to maintain a controlling shareholder interest in BBG. When BBG was listed on the ASX in August 2000, the Merchant Group owned approximately 23% of the issued capital and Mr Merchant remained on the board as a non-executive director: PJ [43]. The Global Financial Crisis in 2008 badly affected the retail operations of BBG, but Mr Merchant remained optimistic that the corporate fortunes would improve and, to that end, continued to purchase BBG shares despite his concern that the business had moved from its core area as a wholesaler: PJ [50]. In February 2012, BBG announced that it had received a proposal from TPG Capital to acquire all of its issued shares at a price of $3 per share. Mr Merchant did not agree with the offer price and responded by causing the GMSF to purchase approximately 2.5 million BBG shares at a price of $3.13 per share. He did so because of his belief that BBG would trade out of its difficulties: PJ [70]-[78]. His Honour, contrary to the evidence of Mr Merchant, found that these shares were also acquired to maintain the position of the Merchant Group as a substantial shareholder: PJ [79]. The TPG Capital proposal did not proceed.

102 In June 2012, BBG announced a non-renounceable entitlement offer. Mr Merchant caused the margin loan facility of the MFT with NAB to be increased to $25 million to acquire more shares in BBG. The loan facility was increased and on 27 June 2012, $30 million was paid out to acquire approximately 29.5 million BBG shares: PJ [86]-[90].

103 In October 2012, the MFT acquired a further 900,000 shares in BBG for a consideration of $753,895: PJ [96]-[102].

104 In September 2013, BBG announced that it had entered into a long term financing arrangement, the effect of which was that it would borrow $386 million, an equity placement of $135 million would be issued to the lender and a $50 million renounceable rights issue would be made available to BBG shareholders. The equity placement and rights issue would dilute the interests of the Merchant Group. This caused Mr Merchant to seek advice as to whether the GMSF could acquire BBG shares through the entitlements of other Merchant Group entities. He was informed that this raised taxation issues and was decided against: PJ [114]-[115], [126].

105 More BBG shares were acquired by the Merchant Group pursuant to the rights issue. On 31 March 2014, the MFT acquired 24,679,850 shares for approximately $6.9 million, GSM acquired 850,873 shares for approximately $238,000 and the GMSF acquired 946,350 shares for approximately $265,000: PJ [128]. Mr Merchant gave as one of his reasons for these acquisitions that he disagreed with the proposal of another significant shareholder to cheapen the Billabong brand by selling at discount through lower end retailers: PJ [130].

106 As at 30 June 2014, the GMSF recorded the value of its BBG shareholding at $1,734,975: PJ [140].

107 By May 2014, Mr Merchant was frustrated with the fact that Plantic continued to require funding from him. Mr Merchant had considered that Plantic should have been self-funding by that time: PJ [131]. In about May 2014, Mr McGrath approached Ernst & Young (EY) to provide taxation advice on an appropriate structure for the sale of Plantic: PJ [134].

108 Negotiations for the sale of Plantic to Sealed Air Corporation Inc commenced in June 2014. A non-binding offer was proposed by 24 July 2014 with a target closure date of 30 September 2014 and an up-front payment of between USD $55 and $70 million: PJ [141]-[147]. Mr Merchant received advice from EY that a sale of shares rather than an asset sale was preferable: PJ [149]-[152].

109 On 24 July 2014, Sealed Air provided a letter of intent to Plantic for USD $70 million: PJ [153]. The offer was conditional on completion of due diligence. A closing date of 15 September 2014 was contemplated. A draft share purchase agreement was provided by Sealed Air’s solicitor on 19 August 2014.

110 Between August and September 2014, Mr Merchant sought taxation advice about the potential sale of Plantic. Modelling was undertaken comparing the consequences of an asset sale or a share sale, including the waiver of the loans from the Merchant Group entities: PJ [157]-[164]. Draft taxation calculations were provided to the Merchant Group on 21 August 2014, which his Honour summarised at PJ [166], [168] and [169]:

The calculations in relation to a sale of Plantic’s business considered alternatives on the basis that the business would be sold at $75 million or $100 million: CB264. The analysis shows that it would not have been necessary to use capital losses from a sale of BBG shares if the Plantic business was sold for $75 million. However, if the business was sold for $100 million, the analysis was that the best tax result would be achieved if the MFT realised a capital loss of $51,426,942 from the sale by the MFT of BBG shares to the GMSF, and then applied about $30.3 million of that loss to offset the capital gain on the windup of Plantic, following the sale of its business.

The calculations show that EY had estimated that the number of BBG shares that the GMSF could acquire with available cash of $6 million, being 10.3 million shares, would give rise to a capital loss on those shares of $51,426,942 in the MFT.

It is clear from these calculations that, whether the sale of shares in Plantic occurred at $75 million or $100 million, it was desirable for the BBG Share Sale to occur. It was also desirable for the BBG Share Sale to occur if the sale was a sale of Plantic’s business, because it was only if the business was sold at the lowest end of the range that the capital loss would not be required. EY had consistently been advising that it was preferable for Mr Merchant that the transaction occur by way of share sale.

111 More taxation advice was received between 21 August 2014 and 3 September 2014: PJ [171]-[178]. This culminated in the preparation of a document provided to the Merchant Group on 3 September 2014 which the primary judge summarised at PJ [179]:

The email attached a document headed “Project Maize – Summary of Sale Options and Tax Outcomes”: CB270. The document stated that its purpose was to “illustrate the tax implications of the different alternatives for disposing of Plantic Technologies Limited” but did “not constitute advice in relation to any scenario”. It stated that its analysis was based on the following assumptions:

• Regardless of the form that the deal takes, consideration for the disposal will be an upfront payment of AU$75M, plus deferred consideration contingent on the quantum of future sales of product by Sealed Air.

• We have assumed that AU$25M will be received from the earn out right. We have also assumed that this is the market value of the rights at the date of sale. However, it may be that a much lower value of the earn out can be supported at sale date because of the contingent nature of the right. Where this would make an impact on the option under consideration we have highlighted this (in particular, the ‘Business Sale 5’ scenario).

• The value of the loans to Plantic from GSM Pty Ltd (GSM) and Tironui Pty Ltd (Tironui) at the time of the transaction is $50M.

• The Merchant Family Trust’s (MFT) cost base in Plantic is $24M.

• The issued capital in Plantic is $76M.

• As at 30 June 2014, Plantic has group losses of $20M and transferred losses of $58M with an available fraction of 0.840.

• MFT has $10M capital losses at 30 June 2013. MFT will sell Billabong International Limited (BBG) shares to the Gordon Merchant Superannuation Fund (GMSF) during the 2015 year and realise further capital losses of $60M.

112 The document also addressed the anticipated taxation outcome if the related party loans were forgiven: PJ [183]-[184]. The primary judge emphasised the summary of the analysis conclusion at PJ [184]:

The ‘Summary’ on the right hand side states:

• Debt forgiveness gives a higher capital gain (and therefore use of more capital losses) but a reduction in top-up tax payable i.e. reduce current tax but potentially increase future taxes if would otherwise be able to use capital losses.

• Risk of anti-avoidance provisions applying to this tax benefit mitigated because occurs as normal part of commercial sale process with an arm’s length party.

113 In an email sent on 3 September 2014 to BBG, Mr Merchant advised that on 2 September 2014, he had transferred 10,344,828 BBG shares from GM2 to the GMSF. He signed a standard transfer form to that effect on 4 September 2014 for a consideration of $5,844,827.82. The consideration was paid to the MFT on 5 September 2014: PJ [185]-[186].

114 The primary judge rejected Mr Merchant’s evidence that the BBG shares were sold for the purpose of funding Plantic, or the MFT more generally: PJ [187]-[194]. His Honour found that the BBG shares were sold, consistently with the taxation advice received, to “crystallise a capital loss which could be used against the capital gain which was anticipated to be higher by reason of the proposed forgiveness of the Plantic Loans”: PJ [189].

115 His Honour also found that Mr Merchant “must have known” that the BBG Share Sale would result in a large capital loss in the MFT: PJ [192].

116 Negotiations with Sealed Air continued until 26 November 2014, but did not result in a concluded contract because of the assessed taxation consequences for the purchaser of a share sale: PJ [197]-[212].

117 In the meantime, Kuraray had expressed interest in purchasing Plantic. By 26 February 2015, the board of Kuraray resolved to approve the acquisition of Plantic as a share purchase if the related party debts were forgiven: PJ [214]-[221]. A Share Sale Agreement (SSA) was executed on 31 March 2015: PJ [222]-[226]. The SSA contained clauses requiring that the GSM, Tironui and Angourie debts must be forgiven before settlement.

118 A Deed of Forgiveness of debt was executed on 2 April 2015 between GSM, Tironui, Angourie and Plantic, by which each lender “irrevocably and unconditionally forgives and releases Plantic from all liability under or in respect of the total amount owing” by Plantic: PJ [227].

119 The sale of the Plantic shares to Kuraray completed on 2 April 2015 and the MFT received USD $45,558,827.30 as the up-front payment: PJ [228]-[229].

120 Something more needs to be said about the operation of the GMSF. From 1 July 2009, an account based pension was paid to Mr Merchant, who was then aged 66 and had retired. Thereafter, various resolutions were passed to commute the income stream pension and to start a new income stream pension in the 2010, 2011 and 2012 financial years. Mr Merchant received a pension of at least $450,000 in 2010: PJ [54]-[55]. Consideration was given to Mr Merchant accessing funds from the GMSF in July 2012. Mr Merchant received advice that as he was over age 65, he was not restricted as to the amounts he could withdraw as tax free lump sum benefits: PJ [91]-[94]. As at 30 June 2009, the GMSF balance was approximately $17.8 million: PJ [51]-[53]. As at 30 June 2012, the GMSF balance was approximately $10 million: PJ [55].

121 The GMSF adopted an investment strategy on 15 March 2012, following resolutions made at a meeting on 16 February 2012: PJ [80]-[85]. That strategy determined that the primary investment objective was to achieve an after tax rate of return above the rate of inflation by, inter alia, not holding any investments in real estate and investing up to 40% of the fund assets in listed securities. That, as the primary judge noted, did not reflect the fact that at that time approximately 9% of the fund assets were invested in real estate.

122 Dividends had not been paid on BBG shares since 2012 (PJ [50]). A consequence of the BBG Share Sale was that the GMSF ceased to pay a pension to Mr Merchant from 1 July 2015 and reverted to the accumulation phase: PJ [55], [232] – [236].

123 A new investment strategy for the GMSF was formulated on 19 November 2015: PJ [238]-[240]. It targeted asset allocations of up to 80% in listed securities and up to 20% in real property, amongst other forms of investment.

124 The primary judge made multiple findings about the financial support provided by the Merchant Group to Plantic over time. It will be recalled that the MFT acquired all of the shares in Plantic in November 2010. Mr Merchant, Ms Paull and Mr McGrath were each the appointed directors of Plantic until it was sold on 2 April 2015.

125 Initially, Plantic received funding from government grants, which reduced over time. It was not profitable, and funding from external sources proved difficult to secure: PJ [58]-[59]. The MFT provided “comfort letters” to the effect that it would ensure that sufficient funds were made available to Plantic to meet its financial obligations in the ordinary course of its business. Those letters were essential to be satisfied that Plantic was solvent: PJ [60]-[61].

126 The primary judge made findings about the extent to which Plantic was reliant on continued funding from the Merchant Group before the events of September 2014: PJ [256]-[261], [293]-[309]. In oral submissions, the appellants and the Commissioner differed in their interpretation of the financial evidence. We return to this point when considering the appeal grounds. For present purposes we reproduce the ultimate finding of the primary judge at PJ [309]:

There was ample funding available as at 4 September 2014 to meet the forecast funding requirements of Plantic if the funding needed to be met. The funding would not be required if Plantic was sold, which was strongly desired on the part of Mr Merchant. The additional forecast cash requirements of Plantic up until 30 June 2015 could have been met from existing cash reserves and, to the extent these proved insufficient because of other expenditure of the MFT or for other reasons, could have been met in the same way as the MFT had funded its expenditure over the period 2012 to 2014. That is not to say that any such funding requirement had to be funded in that way; it is only to say that – objectively – Plantic’s funding did not need to be sourced from the sale of BBG shares by the MFT to the GMSF. There was no expenditure of an unusual or unforeseen nature on the part of Plantic that Mr Merchant pointed to in connection with the assertion in his affidavit at [243], that he “transferred the BBG shares to GMSF on 2 September 2014 because I needed to free up cash as soon as possible to continue funding Plantic”.

127 The appellants challenge that finding as impermissibly intruding into the subjective purpose of Mr Merchant in respect of the BBG Share Sale.

SECTION 177D FINDINGS

128 At PJ [241], the primary judge set out the Commissioner’s identification of the BBG Share Sale Scheme:

The scheme includes all of the actions and decisions that resulted in the transfer of 10,344,828 BBG shares from MFT to GMSF. This includes Mr Merchant and Ms Paull, as directors of GM2 executing a standard share transfer form to transfer the BBG shares off-market to GMSF for $5.8 million, with a recorded transfer date of 2 September 2014.

129 The parties to the BBG Share Sale Scheme include Mr Merchant, GM2 as trustee of the MFT and GSMS as trustee of the GMSF: PJ [242].

130 At [243]-[245], the primary judge recorded the narrow field of dispute:

There is no dispute that:

• the BBG Share Sale Scheme so identified is a scheme within the meaning of that term as defined in s 177A(1) of the ITAA 1936;

• the BBG Share Sale Scheme so identified resulted in a tax benefit under section 177CB(2); and

• Division 6 of the ITAA 1936 operated such that GSM was properly assessed to 100% of the net income of the MFT.