Federal Court of Australia

Charlie v State of Queensland [2025] FCAFC 55

Appeal from: | Charlie on behalf of the North Eastern Peninsula Sea Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 2) [2024] FCA 612 |

File number(s): | QUD 348 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | PERRY, BURLEY AND SARAH C DERRINGTON JJ |

Date of judgment: | 17 April 2025 |

Catchwords: | NATIVE TITLE – where primary judge on separate question upheld validity of special leases granted by the Governor in Council over land excluded from consent determination – whether special leases were validly granted and constituted previous exclusive possession acts as defined in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) which wholly extinguished native title in the land by force of s 20(2) of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld) – construction of s 203 of the Land Act 1962 (Qld) vesting power to grant special leases in the Minister – whether the Governor in Council had power to grant special leases under the general power in s 6(1) of the Land Act concurrently with the power vested in the Minister under s 203 – whether principle in Anthony Hordern & Sons Ltd v Amalgamated Clothing and Allied Trades Union of Australia (1932) 47 CLR 1 applied – appeal dismissed |

Legislation: | Migration Act 1958 (Cth), ss 200, 201 and 501 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), ss 23B(2) and 85A(1) Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), r 30.01 Crown Lands Act 1884 (Qld), s 94 Crown Lands Alienation Act 1860 (Qld), s II Forestry Act 1959 (Qld) Harbours Act 1955 (Qld) Land Act 1897 (Qld), s 188 Land Act 1910 (Qld), ss 6 and 179 Land Act 1962 (Qld), ss 6, 202, 203, 205 and 343 Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld), s 20(2) Property Law Act 1974 (Qld), s 102 Residential Tenancies Act 1975 (Qld), s 12 |

Cases cited: | Anthony Hordern & Sons Ltd v Amalgamated Clothing and Allied Trades Union of Australia (1932) 47 CLR 1 Azimitabar v Commonwealth (2004) 303 FCR 282 Boensch v Pascoe (2019) 268 CLR 593 Bone v Mothershaw [2003] 2 Qd R 600 Charlie on behalf of the North Eastern Peninsula Sea Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 2) [2024] FCA 612 David on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim v State of Queensland [2022] FCA 1430 FAI Insurances Ltd v Winneke (1982) 151 CLR 342 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Media Holdings Ltd (2012) 250 CLR 503 Kuru v New South Wales (2008) 236 CLR 1 Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs v Nystrom (2006) 228 CLR 566 Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355 SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 262 CLR 362 Theiss v Collector of Customs (2014) 250 CLR 664 Vincentia MC Pharmacy Pty Ltd v Australian Community Pharmacy Authority 280 FCR 397 Wik Peoples v Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Queensland |

National Practice Area: | Native Title |

Number of paragraphs: | 60 |

Date of hearing: | 18 November 2024 |

Counsel for the Appellants | Mr D. Yarrow SC |

Solicitor for the Appellants | Cape York Land Council Aboriginal Corporation |

Counsel for the First Respondent | Mr G. Del Villar KC with Mr M. McKechnie and Ms F. Nagorcka |

Solicitor for the First Respondent | Crown Law |

Counsel for the Second Respondent | Ms R.J. Webb KC appears with Mr M. Sherman |

Solicitor for the Second Respondent | Australian Government Solicitor |

Counsel for the Third Respondent | The Third Respondent submitted to any order, save as to costs |

Counsel for the Fourth Respondent | The Fourth Respondent submitted to any order, save as to costs |

ORDERS

QUD 348 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | BERNARD RICHARD CHARLIE First Appellant PAUL JOSEPH AH MAT Second Appellant TREVOR HENRY LIFU (and others named in the Schedule) Third Appellant | |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND First Respondent COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Second Respondent COOK SHIRE COUNCIL (and another named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | PERRY, BURLEY AND SARAH C DERRINGTON JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 17 April 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal is dismissed.

2. There be no order as to costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

[1] | |

[11] | |

[18] | |

[27] | |

[27] | |

4.2 The appellants’ submissions as to the proper construction of s 203 | [33] |

4.3 The primary judge’s construction of s 203 of the Land Act 1962 is correct | [39] |

[59] |

1 INTRODUCTION

1 On 30 November 2022, a consent determination was made in David on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim v State of Queensland [2022] FCA 1430 (the Determination), recognising native title over part of the land and waters covered by the appellants’ claim in this proceeding.

2 This is an appeal from the interlocutory judgment of a single judge of this Court (the primary judge) in Charlie on behalf of the North Eastern Peninsula Sea Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 2) [2024] FCA 612 (the primary decision) with respect to an area of land falling within the external boundaries of the appellants’ claim area. This area was excluded from the Determination by agreement between the appellants and the first respondent, the State of Queensland, because there was an unresolved dispute concerning the validity of two special leases and whether they operated to extinguish native title.

3 The dispute was encapsulated in the separate question set down for determination by the primary judge under r 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), namely:

On the basis of the agreed facts filed on 17 February 2023 as amended, and such other evidence as the parties adduce, were the special leases listed in Attachment A to these orders, or either of them, invalid by reason that the responsible Minister did not sign the relevant lease instrument?

4 The leases listed in Attachment A to the orders of the primary judge are:

(1) special lease SL28274 granted under s 203 of the Land Act 1962 (Qld) on 28 May 1964 over the parcel of land described as “Portion 18 on SO18” (the 1964 Special Lease); and

(2) special lease SL47434 granted under s 203 of the Land Act 1962 on 28 November 1985 over the same parcel of land (the 1985 Special Lease).

(Together, the Special Leases.)

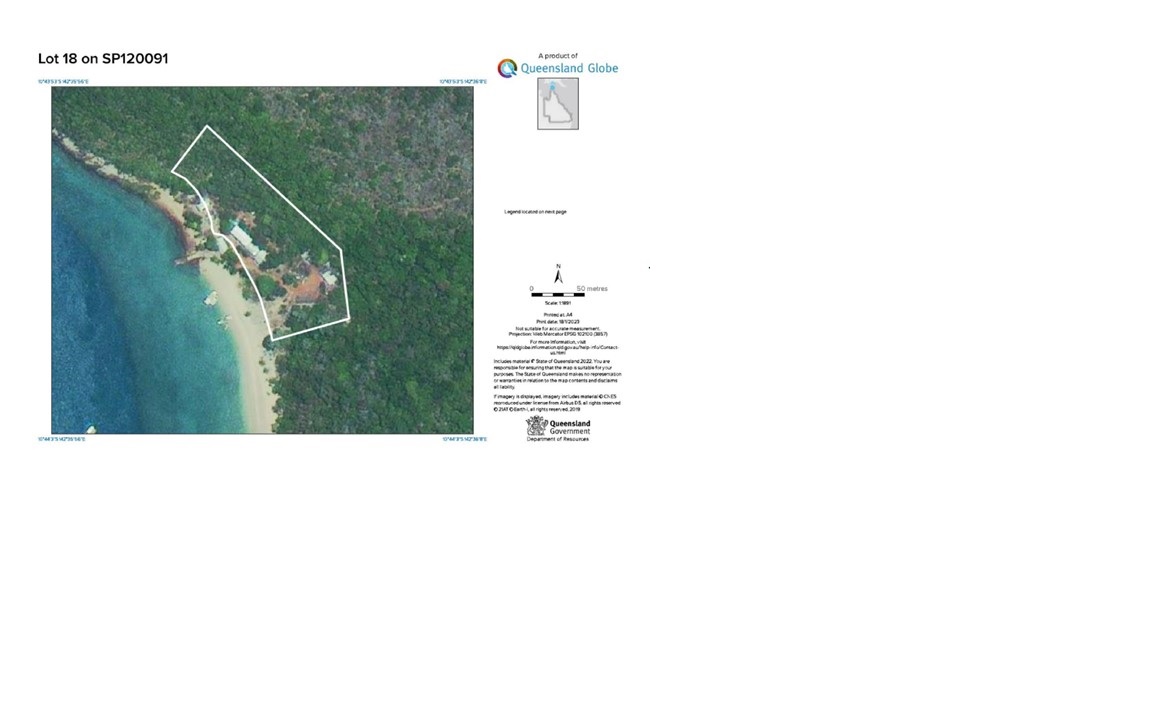

5 While the Special Leases were granted over land historically described as Portion 18 on SO18, the land is identified today as Lot 18 on SP120091 (the Land). The Land covers an area of 1.39 hectares and is located above high-water mark on Albany Island in the Adolphus Channel off the north-eastern coast of Cape York Peninsula. The Land is presently subject to a term lease TL219534 for commercial/business purposes, namely, land-based pearl culture purposes including low-key tourism. An aerial map of the Land is reproduced at Annexure A to these reasons.

6 The parties were agreed at trial and on the appeal that if either of the Special Leases was valid, it would constitute a “previous exclusive possession act” within s 23B(2)(c)(iv) and (viii) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA (Cth)) which operated to extinguish native title in the Land in whole by virtue of s 20(2) of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld) (NTA (Qld)).

7 The primary judge held that the Special Leases were validly issued, and the separate question was therefore answered, “No”. As a result, his Honour held that the Special Leases had extinguished native title in whole.

8 The application for leave to appeal from the primary decision was granted by consent on 24 July 2024.

9 At the heart of the appeal is whether, as the appellants submit, the primary judge erred in holding that, by reason of s 6(1) of the Land Act 1962, the Governor in Council had power to grant special leases of the kind described in s 203 concurrently with the power vested in the responsible Minister under s 203 of the Land Act 1962. In the appellants’ submission, the primary judge should have held that, properly construed, the power was vested exclusively in the responsible Minister under s 203 and this required the Minister to sign the instruments of lease personally. Based on this construction, the appellants submit that the Special Leases were not validly issued by the Governor in Council because he lacked the legal authority to do so and, therefore, native title in the Land was not extinguished.

10 For the reasons set out below, the appellants’ construction should be rejected and the appeal therefore dismissed. It follows that it is unnecessary to consider the State’s notice of contention which alleged that the Minister “issued” the leases for the purposes of s 203 of the Land Act 1962. Furthermore, in our view this is a case where it is appropriate for this Court, as an intermediate appellate court, to confine itself to the “decisive” ground or grounds raising “only those issues which it considers to be dispositive of the justiciable controversy raised by the appeal before it”: see Boensch v Pascoe (2019) 268 CLR 593 at [7]–[8] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ), and at [101] (Bell, Nettle, Gordon and Edelman JJ agreeing); see also Kuru v New South Wales (2008) 236 CLR 1 at [12] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ).

2 THE ISSUE OF THE SPECIAL LEASES

11 The Minute of Proceedings of the Executive Council of Queensland from 9 April 1964 contains a minute proposing the 1964 Special Lease “at the instance of the Honourable … Minister for Lands” (the 1964 Minute). The 1964 Minute was signed and approved by the Deputy Governor, acting for and on behalf of the Governor. Annexure 7 to the 1964 Minute refers to s 203(a) of the Land Act 1962 and identified the term of the lease, the purpose of the lease, and several conditions of the lease.

12 The lease instrument itself had the heading “Lease for Special Purposes, under Section 203(a) of the [Land Act 1962]”. After referring to the application under s 203(a) of the Land Act 1962 for the 1964 Special Lease by Barrier Pearls Pty Limited, the recitals to the lease instrument relevantly state:

the Governor of Our State of Queensland, with the advice of the Executive Council thereof, has granted such application, and has agreed to issue a Lease of the said Land …

13 The lease instrument was signed by the Deputy Governor, acting for and on behalf of the Governor, and sealed with the Public Seal of Queensland.

14 The Minute of Proceedings of the Executive Council of Queensland from 7 November 1985 (the 1985 Minute) was in a similar form to the 1964 Minute, as the primary judge held at paragraph [15] of the primary decision. The 1985 Minute proposed “[t]hat Deeds of Grant and Instruments of Lease be issued, in accordance with the accompanying Schedules marked “A”, “B” and “C”.” The 1985 Special Lease was noted in Schedule “C” of the 1985 Minute.

15 The lease instrument for the 1985 Special Lease, which was also issued to Barrier Pearls, was headed “Special Lease under the [Land Act 1962]”. The recitals to the lease instrument record that it was issued “with the advice of the Executive Council of Our State of Queensland, and in pursuance of the provisions of section 203(a) of the [Land Act 1962]”. The lease instrument was signed and approved by the Governor and sealed with the Public Seal of Queensland.

16 Thus, both Special Leases were issued with the approval of the Executive Council. The Executive Council Minutes in each case also reveal that:

(1) the decision to issue the leases was at the instance of the relevant Minister; and

(2) the Minister decided that the relevant leases should be granted and the conditions of each lease were suitable.

17 As earlier explained, at trial, the appellants contended that neither Special Lease was valid on the basis that the responsible Minister was the exclusive repository of the power to grant special leases under s 203 of the Land Act 1962 and the Minister was required to sign the leases personally. As the Minister did not sign either lease, the appellants therefore submitted that both leases were invalid. The primary judge rejected both contentions and concluded that s 6(1) of the Land Act 1962 authorised the Governor in Council to issue the Special Leases concurrently with the power of the responsible Minister to do so. Accordingly, the primary judge held that the Special Leases were validly issued.

3 LEGISLATIVE PROVISIONS

18 When the 1964 Special Lease was granted, s 203 of the Land Act 1962 provided that:

The Minister, with the approval of the Governor in Council, may, without notification published in the Gazette, issue to any person a special lease of-

(a) any Crown land, for any manufacturing, industrial, residential or business, or for any racecourse or recreational purposes; or

(b) any land reserved and set apart for public purposes, for any purpose not inconsistent with the reservation,

for such term not exceeding thirty years and subject to such conditions as to rent or otherwise as the Minister thinks fit.

19 At the time that the 1985 Special Lease was granted, s 203 of the Land Act 1962 had been amended to provide:

The Minister, with the approval of the Governor in Council, may, without notification published in the Gazette, issue to any person a special lease of:

(a) any Crown Land;

(b) any land reserved and set apart for public purposes, for any purpose declared by the Governor in Council to be not inconsistent with the reservation or this Act,

subject to such conditions as to rent or otherwise as the Minister thinks fit.

20 The differences between the two provisions are underlined.

21 At all relevant times, s 6(1) of the Land Act 1962 provided that:

Subject to this Act, the Governor in Council may, in the name of Her Majesty, grant in fee simple, or demise for a term of years or in perpetuity or deal otherwise with any Crown land within Queensland.

22 That power, by s 6(6), “includes power to make such a grant or demise to the Commonwealth of any Crown land in Queensland acquired by the Commonwealth by agreement between the Commonwealth and the Governor in Council (who is hereby thereunto authorised) or between the Commonwealth and any person or authority thereunto authorised by any other Act of the Parliament of this State”.

23 The effect of a grant under s 6(1) was prescribed by s 6(2), which provided:

The grant or lease shall be made subject to such reservations and conditions as are authorised or prescribed by this Act or any other Act, and shall be made in the prescribed form, and being so made shall be valid and effectual to convey to and vest in the person therein named the land therein described for the estate or interest therein stated.

24 As such, s 6(2) of the Land Act 1962 overcame the common law doctrine whereby a lease did not vest until the lessee entered into possession, prior to which a lessee had only an interest known as an interesse termini conferring a right of entry: Wik Peoples v Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1, 83 (Brennan CJ), 130 (Toohey J), 153 (Gaudron J), 198-199 (Gummow J). This common law doctrine was ultimately abolished by s 102 of the Property Law Act 1974 (Qld) and s 12 of the Residential Tenancies Act 1975 (Qld): Wik at 198-199 (Gummow J).

25 Finally, underlying s 6(1) of the Land Act 1962 is the principle of responsible government, namely that the Governor “acts on the advice of his Ministers, and it is to be expected that such advice will be based upon the recommendation of the Minister in charge of the Department concerned”: FAI Insurances Ltd v Winneke (1982) 151 CLR 342 at 349 (Gibbs CJ); see also FAI at 365 (Mason J), 382 (Aickin J), 400-401 (Wilson J), and 414-415 (Brennan J). Thus, as Brennan J explained in FAI at 415, “a decision made by a Governor … is no more than the formal legal act which gives effect to the advice tendered to the Crown by its Ministers”. Moreover, as Mason J held in FAI at 365:

When Parliament by statute confers a discretionary power on the Governor acting with the advice of the Executive Council it ordinarily assumes that the convention will apply and that the Governor will act in accordance with the advice tendered to him and not otherwise, ultimately, if not sooner.

26 This convention must equally be taken to have been assumed by the legislature in enacting s 6(1) of the Land Act 1962 and its predecessors. As the Commonwealth submitted, “the legislature can be taken to have intended that the Minister would issue the lease by taking steps to advise the Governor to effect the issuance of the lease by exercising his power to demise under s 6(1) and otherwise facilitating the execution of the lease instrument by the Governor and its transmission to the relevant lessee”.

4 CONSIDERATION

4.1 Relevant principles of statutory construction

27 Sections 6(1) and 203 of the Land Act 1962 fall to be construed according to the ordinary principles of statutory interpretation. As the primary judge held at [59] of the primary decision, “the task of statutory construction involves the attribution of meaning to statutory text”, citing Theiss v Collector of Customs (2014) 250 CLR 664 at [22].

28 The relevant principles of statutory construction are well-established.

29 In Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355 at [69]-[70], McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ explained that:

The primary object of statutory construction is to construe the relevant provision so that it is consistent with the language and purpose of all the provisions of the statute. The meaning of the provision must be determined “by reference to the language of the instrument viewed as a whole”. In Commissioner for Railways (NSW) v Agalianos [(1955) 92 CLR 390 at 397], Dixon CJ pointed out that “the context, the general purpose and policy of a provision and its consistency and fairness are surer guides to its meaning than the logic with which it is constructed”. Thus, the process of construction must always begin by examining the context of the provision that is being construed.

A legislative instrument must be construed on the prima facie basis that its provisions are intended to give effect to harmonious goals. Where conflict appears to arise from the language of particular provisions, the conflict must be alleviated, so far as possible, by adjusting the meaning of the competing provisions to achieve that result which will best give effect to the purpose and language of those provisions while maintaining the unity of all the statutory provisions.

(Emphasis added.)

30 The importance of starting with the statutory context and text was also emphasised by Kiefel CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ in SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 262 CLR 362 at [14]:

The starting point for the ascertainment of the meaning of a statutory provision is the text of the statute whilst, at the same time, regard is had to its context and purpose [citing Project Blue Sky with approval]. Context should be regarded at this first stage and not at some later stage and it should be regarded in its widest sense. This is not to deny the importance of the natural and ordinary meaning of a word, namely how it is ordinarily understood in discourse, to the process of construction. Considerations of context and purpose simply recognise that, understood in its statutory, historical or other context, some other meaning of a word may be suggested, and so too, if its ordinary meaning is not consistent with the statutory purpose, that meaning must be rejected.

31 Perry and Stewart JJ in Vincentia MC Pharmacy Pty Ltd v Australian Community Pharmacy Authority [2020] FCAFC 163; 280 FCR 397 at [48] expanded upon the meaning of context:

Context “in its widest sense”, as referred to in this passage, includes “such things as the existing state of the law and the mischief which … one may discern the statute was intended to remedy”: CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd (1997) 187 CLR 384 at 408 (Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gummow JJ) (cited with approach in SZTAL at [14]). To have regard to context in this sense, as integral to the process of statutory construction irrespective of whether ambiguity or inconsistency exists in the literal text, accords with the mandate in s 15AA of the Acts Interpretation Act that the interpretation which best gives effect to the legislative purpose must be preferred to any other interpretation: Mills v Meeking (1990) 169 CLR 214 at 235 (Dawson J). As a result, as Dawson J also explained with respect to Victoria's equivalent to s 15AA, the approach required by interpretive provisions of this kind “allows a court to consider the purposes of an Act in determining whether there is more than one possible construction” (ibid) … it must also be borne steadily in mind that, as Hayne, Heydon, Crennan and Kiefel JJ cautioned in Alcan (NT) Alumina Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Territory Revenue (NT) (2009) 239 CLR 27, “[h]istorical considerations and extrinsic materials cannot be relied on to displace the clear meaning of the text. The language which has actually been employed in the text of legislation is the surest guide to legislative intention”.

32 Thus, while “[l]egislative history and extrinsic materials cannot displace the meaning of the statutory text”, they may be of “utility if, and in so far as, it assists in fixing the meaning of the statutory text”: Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Media Holdings Ltd (2012) 250 CLR 503 at [39] (French CJ, Hayne, Crennan, Bell and Gageler JJ).

4.2 The appellants’ submissions as to the proper construction of s 203

33 First, the appellants submitted that the plain terms of s 203 of the Land Act 1962 are consistent with their construction that s 203 conferred power on the responsible Minister exclusively to grant special leases. In their submission, if s 203 were construed as authorising the Governor both to approve the Minister to issue a lease and to execute the lease, this would leave no work to be done on the part of the Minister.

34 In aid of their construction, the appellants relied upon the fact that s 203 had effected a change in the repository of the power to grant special leases, as s 179 of the Land Act 1910 (Qld) had conferred the power to issue special leases upon the Governor. That deliberate change in the repository of the power was said by the appellants to demonstrate an intention by the legislature that the function of issuing special leases formerly vested in the Governor in Council was thereafter to be performed exclusively by the Minister.

35 Secondly, and relatedly, the appellants relied upon the fact that s 6(1) of the Land Act 1962 is expressed to be “subject to this Act”. In their submission, this indicates that, in the event of a conflict between the power in s 6(1) and another provision of the Act, the latter should prevail. The appellants relied upon an alleged “collision” between ss 6(1) and 203 of the Land Act 1962, namely, that s 6(1) conferred a power to “demise” Crown land in general, whereas s 203 concerned a specific form of statutory lease, being a special lease issued without notification under Part 7 of the Land Act 1962. As such, the appellants contended that the Governor in Council’s power under s 6(1) should be construed as applying to any demise of Crown land in the form of a statutory lease, with the exception of the power to issue certain special leases under s 203 which was vested instead in the Minister.

36 Accordingly, in their submission the primary judge wrongly concluded at [103] of the primary decision that s 6(1) on its face applied to a demise of any kind, and therefore erred in finding at [110] that the powers in ss 6(1) and 203 “were consonant with each other” such that “either power should be available depending on the circumstances”. By contrast to s 203, which vests the power to grant special leases without notification expressly in the Minister, s 6(1) is relevant to (i) an auction for a special lease with notification, where the Land Act 1962 is silent as to the specific repository of the power to grant the special lease to which the successful bidder is entitled under s 202, and (ii) the express power of the Governor in Council under s 205 to grant a special lease for land that is “abnormally costly to develop”.

37 Thirdly, the appellants contend that the same constructional result is achieved by applying the principle in Anthony Hordern & Sons Ltd v Amalgamated Clothing and Allied Trades Union of Australia [1932] HCA 9; (1932) 47 CLR 1. We explain that principle in the context of considering the appellants’ submissions. In broad terms, the principle in Anthony Hordern is to the effect that an express power which prescribes conditions and restrictions governing the exercise of that power will exclude the operation of general provisions which might otherwise have been relied upon as the source of the same power.

38 Finally, the appellants correctly accepted at trial and on the appeal that, if, contrary to their submissions, the Governor in Council and the Minister had concurrent powers to grant the Special Leases under s 6(1) and s 203 of the Land Act 1962 respectively, the Special Leases were validly granted. As the primary judge explained at [124]:

While the Governor in Council proceeded upon a misunderstanding that its power to issue the Special Leases arose under s 203, that error does not affect the validity of the Special Leases. That is because a mistake as to the source of a statutory power does not render an action invalid if another power was in fact available: see Eastman v Director of Public Prosecutions (ACT) (2003) 214 CLR 318 at [124] (Heydon J); Australian Education Union v Department of Education and Children’s Services (2012) 248 CLR 1 at [34]. The applicant’s concession was properly made.

4.3 The primary judge’s construction of s 203 of the Land Act 1962 is correct

39 As the primary judge held at [69] of the primary decision, the premise underlying the appellants’ submissions is that, properly construed, s 203 was the only provision in the Land Act 1962 which authorised the grant of the Special Leases, and there was no provision in the Land Act 1962 which authorised the Governor in Council to grant the Special Leases. In our view, that premise is not made out on a proper construction of ss 6(1) and 203 of the Land Act 1962 and the primary judge correctly held that s 203 did not operate to the exclusion of the broad power under s 6(1) vested in the Governor in Council to grant a special lease with characteristics of the kind described in s 203. The following matters support that conclusion.

40 First, there is nothing in the express words of s 6 which indicate that the power conferred by s 6(1) did not extend to a power to grant a special lease for a purpose of the kind identified by s 203. As such, any such limitation must be inferred, as the primary judge held at [103].

41 Secondly, there is no “collision” or conflict between ss 6(1) and 203 which must be alleviated by a construction that s 203 confers an exclusive power on the Minister to grant leases having the same characteristics: cf Project Blue Sky at [70]. Rather, the different scope and operation of the two provisions shows that they were intended to serve different purposes and is strongly suggestive of an intention by the legislature that both powers should be available to be exercised depending on the circumstances, as the primary judge held at [110]. Thus, different legal consequences flow from a demise under s 6(1) which, by operation of s 6(2), vested upon the grant of the lease, and from the issue of a special lease under s 203 which vested only on entry. The appellants’ construction, therefore, would mean that, unlike all other leases of Crown land under the Land Act 1962, including all other kinds of special leases, special leases having the characteristics prescribed by s 203 could vest only upon entry. In addition, their construction would mean that special leases of the kind capable of being granted under s 203 could not have been demised to the Commonwealth under s 6(6). Yet the appellants were unable, with respect, to point to any reason why the legislature might have intended to create such obviously anomalous consequences.

42 Against this, the appellants submit that these contextual matters do not provide a clear legislative indication because other leasing powers under the Land Act 1962 did not attract the operation of the provisions in question. They pointed to s 343 of the Land Act 1962, which limited the power of “the trustees of a reserve that is an environmental park” to lease the reserve. However, as the State submits, s 343 was solely concerned with leases granted by the trustee of such a reserve and says nothing about the demise of Crown land by the Crown. As such, the appellants’ reliance upon s 343 in support of their construction is, with respect, misplaced.

43 The appellants also submit that cognate statutes for the leasing of government land did not apply provisions such as ss 6(2) and 6(6) of the Land Act 1962, referring to the Forestry Act 1959 (Qld) and the Harbours Act 1955 (Qld). However, these Acts operate in different contexts and do not advance the appellants’ construction of the Land Act 1962.

44 Thirdly, the historical context against which the Land Act 1962 was enacted does not suggest an intention to limit the power in s 6(1) so as to exclude special leases of the kind described by s 203 from its ambit, notwithstanding that on its enactment, s 203 vested the power to issue certain leases in the Minister for the first time.

45 As the primary judge explained at [87] of the primary decision, when Queensland was established as a colony in 1859, the Letters Patent of 6 June 1859 vested in the Governor the “full power and authority” to grant and dispose of Crown land on the advice of the Executive Council, subject to the laws of the colony. The prerogative power with respect to the disposition of Crown land was, however, swiftly abrogated by s II of the Crown Lands Alienation Act 1860 (Qld) (Crown Lands Act 1860) which provided that:

Under and subject to the provisions of this Act … the Governor with the advice of the Executive Council is hereby authorised in the name and on behalf of Her Majesty to convey and alienate in fee simple or for a less estate or interest any waste lands of the crown within the said colony which conveyances or alienations shall be made in such forms as shall from time to time be deemed expedient by the Governor with the advice aforesaid and being so made shall be valid and effectual in the law to transfer and vest in possession such lands as aforesaid for such estate or interest as shall be granted by any such conveyance as aforesaid.

46 The similarity between the terms of s II of the Crown Lands Act 1860 and ss 6(1) and 6(2) of the Land Act 1962 is readily apparent: see also s 94, Crown Lands Act 1884 (Qld) and s 6, Land Act 1910. As McPherson JA (with whose reasons Williams JA and Byrne J agreed) explained in Bone v Mothershaw [2002] QCA 120; [2003] 2 Qd R 600 at [18] with respect to s 6 of the Land Act 1962:

The section is one of several successive re-enactments of earlier statutory provisions, of which in Queensland the first was the Crown Lands Alienation Act 1860; 22 Vic. No. 1 (1 Pring’s Statutes 833). Section 2 of that Act, and comparable provisions of other statutes that applied here before Separation in 1859, represented the culmination of a political struggle with the imperial government over local control of the waste lands of the Crown and the revenue arising from their sale. As sovereign of Australia, the King exercised through the colonial governor as his local representative a prerogative power at common law of granting out parcels of the unalienated land of the Crown that in English legal theory was vested in him in that capacity. The immediate effect of the legislation in question was to supersede the Crown’s prerogative by a statutory power to make grants of land, and so to bring its alienation or disposal under the authority of the colonial legislature.

47 Accordingly, McPherson JA continued in Bone at [18] that:

The primary function of s. 6(1) and other such legislation is facultative. Its object and effect are to confer on the Crown legislative, as distinct from prerogative, authority to grant waste lands, and so to transfer the power of doing so from the uncontrolled discretion of the Crown to the Governor in Council acting under the direction of the legislature, while at the same time limiting the range of interests that can be granted in such land to those designated in the section. Crown land may be granted, demised or dealt with only “subject to this Act”.

48 Understood, therefore, in their historical context, the words “[s]ubject to this Act” in s 6(1) of the Land Act 1962 (and its predecessors) do not lend any support to the appellants’ construction. Rather, those words made clear the legislature’s intention to limit the authority of the Governor in Council to grant in fee simple or a lease to that conferred by the Act and, as such, were apt to pick up such other provisions of the Land Act 1962 as otherwise regulated the grant of an estate in fee simple or demise for a lease. These provisions included s 6(2) which provided, relevantly, that a lease granted under s 6(1) was subject to reservations or conditions authorised or prescribed by the Land Act 1962, “shall be made in the prescribed form” and, so made, “shall be valid and effectual to convey to and vest” the estate or interest in question.

49 It is in this context that s 203 of the Land Act 1962 falls to be construed. As mentioned, that section, for the first time, vested power to issue a special lease in the Minister acting with the approval of the Governor in Council. The predecessors to s 203, being s 188 of the Land Act 1897 (Qld) and s 179 of the Land Act 1910, had vested the power to grant special leases simply in the Governor in Council. However, the change effected by the enactment of s 203 of the Land Act 1962 was not accompanied by any “amendment” to s 6 so as to carve out, from the Governor in Council’s general power to deal with Crown land, the grant of special leases under s 203. Nor is that surprising given that the Governor had the power to grant every other kind of lease of Crown land under the Land Act 1962, s 203 being the only provision under that Act which conferred power on the Minister rather than the Governor in Council to grant or issue a lease (other than a “new lease”) of Crown land.

50 These considerations equally militate against any inference that the vesting of the power to issue special leases in the Minister under s 203 was intended to deprive the Governor in Council of the power under s 6(1) to issue a lease of the kind for which s 203 made provision. Rather, as the primary judge held at [115]:

In the context of the Governor in Council being conferred with power to grant every other type of lease of Crown land, a legislative intention to remove the power of the Governor in Council to grant a lease of the kind described in s 203 would seem quite anomalous. That is particularly so when there is nothing peculiar about a lease of that kind that would suggest an advantage in granting the Minister exclusive power to grant such a lease. The extrinsic material does not explain why the Minister was conferred with the power under s 203. It can be surmised that the power was devolved to the Minister because a lease of that kind was subject to greater legislative restrictions than many other types of leases were. A special lease of that kind could only be granted for specified purposes, and for not more than 30 years (subject to exceptions by the time of the 1985 Special Lease). It may have been seen as administratively convenient for the Minister to have power to grant such a lease, perhaps, as the applicant submitted, for reasons of speed (although there would not seem to be much time-saving in the Governor in Council approving the issuing of a lease compared to granting a lease). However, the conferral of that power on the Minister did not indicate that it was intended to deprive the Governor in Council of the power under s 6(1) to also grant a lease of that kind.

51 By way of illustrating the anomalies which the appellants’ construction would give rise to, on their construction the Governor in Council could, on the advice of his or her Ministers, have granted a lease for 31 years for a specified purpose of a kind identified in s 203, but could not have granted a lease in exactly the same terms for the same purpose for a term of 30 years. Given that in any event, the Governor in Council must act on the advice of his or her Ministers in accordance with constitutional convention, there is no apparent reason why one would infer that the legislature intended such a result. Nor, as the State contends, did the appellants point to any reason why the legislature in 1962 would have intended to strip the Governor in Council of the power to grant leases of the kind described in s 203 and to vest that authority exclusively in the hands of the Minister acting with the approval of the Governor in Council.

52 Finally, the appellants’ construction is not assisted by calling the principle in Anthony Hordern in aid. That principle was explained by Gavan Duffy CJ and Dixon J in Anthony Hordern (at 7) as follows:

When the Legislature explicitly gives a power by a particular provision which prescribes the mode in which it shall be exercised and the conditions and restrictions which must be observed, it excludes the operation of general expressions in the same instrument which might otherwise have been relied upon for the same power.

53 Furthermore, in Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs v Nystrom (2006) 228 CLR 566, Gummow and Hayne JJ held (at [59]) that, in order for that principle to apply:

it must be possible to say that the statute in question confers only one power to take the relevant action, necessitating the confinement of the generality of another apparently applicable power by reference to the restrictions in the former power. In all the cases considered above, the ambit of the restricted power was ostensibly wholly within the ambit of a power which itself was not expressly subject to restrictions.

(Emphasis added.)

54 In Nystrom, the High Court held that the principle in Anthony Hordern did not apply to ss 200, 201 and 501 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth). This was because the power to deport was not wholly subsumed within the power to cancel a visa by reference to the “character test” in s 501(2), even though a deportation order under ss 200 and 201 could result in the cancellation of a visa. Therefore, while one “practical consequence” of the exercise of the different powers may be the same, the two powers did not deal with the same subject matter in law: Nystrom at [61] (Gummow and Hayne JJ). Similarly, Heydon and Crennan JJ held that the principle in Anthony Hordern did not apply because there was “no repugnancy between the two powers”. Rather, they were “consonant with each other”: at [165].

55 Equally here, the principle in Anthony Hordern has no application.

56 In the first place, s 203 cannot be characterised as prescribing the mode in which the general power in s 6(1) to grant a lease is to be exercised, nor as imposing restrictions or relevant limitations on the exercise of the power, where the lease is a lease of the kind described in s 203. In particular, as the State contends, the requirement in s 203 that the lease be executed by the Minister, rather than the Governor in Council, cannot be characterised as a “restriction” or “limitation” on the general power in s 6(1) in circumstances where the Minister could only execute the lease under s 203 with the approval of the Governor in Council: see also Azimitabar v Commonwealth [2024] FCAFC 52; (2004) 303 FCR 282 at [73]-[74] (the Court).

57 Moreover, the legal consequences of an exercise of the power under s 6(1) of the Land Act 1962 were not wholly co-extensive with the legal consequences of an exercise of the power to grant a special lease under s 203. This is because, as earlier explained, leases made by the Governor in Council under s 6(2) conferred a right of exclusive possession from the time that the lease was issued, irrespective of whether the lessee had entered into possession. As such, it cannot be said that the power in s 203 of the Land Act 1962 fell “wholly within the ambit” of s 6(1). In other words, the two powers “are distinct and cumulative even if their factual operation may overlap on occasions”: Azimitabar at [75].

58 It follows that the principle in Anthony Hordern has no application to the present case.

5 DISPOSITION

59 For these reasons, the appellants’ contention that s 203 of the Land Act 1962 was the only source of the power to grant the Special Leases must be rejected. It follows, as the primary judge held, that the Special Leases were validly granted and constituted previous exclusive possession acts as defined in s 23B(2)(iv) and (viii) of the NTA (Cth). As such, they extinguished native title in the Land in whole by operation of s 20(2) of the NTA (Qld). The appeal must therefore be dismissed.

60 Finally, in line with s 85A(1) of the NTA (Cth), there should be no order as to costs.

I certify that the preceding sixty (60) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Perry, Burley and Sarah C Derrington. |

Associate:

Dated: 17 April 2025

ANNEXURE A: AERIAL MAP OF THE LAND

SCHEDULE OF PARTIES

Appellants | |

Fourth Appellant: | MICHAEL THOMAS SOLOMON |

Fifth Appellant: | JENNIFER JILL THOMPSON |

Sixth Appellant: | REGINALD WILLIAMS |

Respondents | |

Fourth Respondent: | TORRES SHIRE COUNCIL |